Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/303/205. The contractual start date was in April 2007. The draft report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor James reports trial support (free trial drug for the Phase II part of the trial and a grant awarded to investigation sites for recruitment of Phase III patients with trial numbers 301–700) and lecturing fees from Sanofi-aventis. He also reports free trial drug for the Phase II part of the trial followed by a trial-linked discount for sites ordering trial drug for Phase III patients and lecturing fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd. In addition, there was a trial-linked discount for sites ordering trial drug from GE Healthcare. Professor James also reports trial support, consultancy work and lecture fees from Sanofi-aventis and Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd who were directly related and consultancy work and lecture fees from Bayer HealthCare, Algeta, Amgen, Janssen, Astellas Pharma and Affinity OncoGeneX Pharmaceuticals Inc. who were related to prostate cancer but not the drugs in this study. Dr Pope reports trial support (free trial drug for the Phase II part of the trial and a grant awarded to investigation sites for recruitment of Phase III patients with trial numbers 301–700) from Sanofi-aventis; trial support (free trial drug for the Phase II part of the Phase III patients) from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd; and trial support (trial-linked discount for sites ordering trial drug) from GE Healthcare from GP Health Care, during the conduct of the study. Dr Parker reports personal fees from Bayer HealthCare, BN ImmunoTherapeutics Inc. (BNIT), Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Sanofi-aventis and Takeda UK Ltd, outside the submitted work. Dr Stanley reports that Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd supported his attendance at European Society for Medical Oncology, he received personal fees from Calgene, Inc., and Amgen, Inc. supported part of his attendance at British Oncology Pharmacy Association, outside the submitted work. Dr Brown reports personal fees and non-financial support from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd for advisory board in different cancer and writing assistance for different cancer outside the submitted work. Dr Billingham reports personal fees from Eli Lilly, and from Pfizer, both for expenses paid for contributing to educational events, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by James et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Prostate cancer

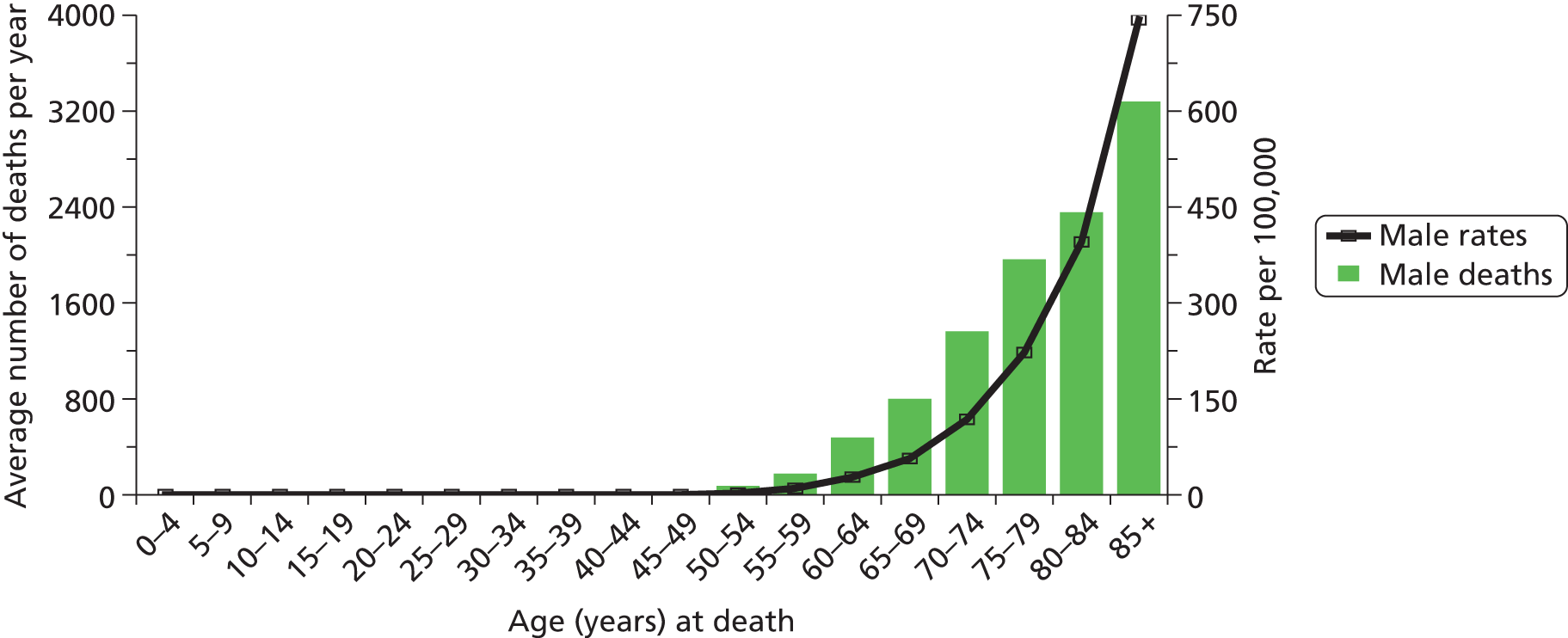

Prostate cancer is a major worldwide health problem which accounts for nearly one-fifth of all newly diagnosed male cancers. In the UK, approximately 35,000 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer each year, and in 2008 almost 10,000 men died from the disease. 1 The disease is mostly one of older age, but significant numbers of men of working age will develop the disease. Figure 1 summarises the age distribution of incident cases and deaths.

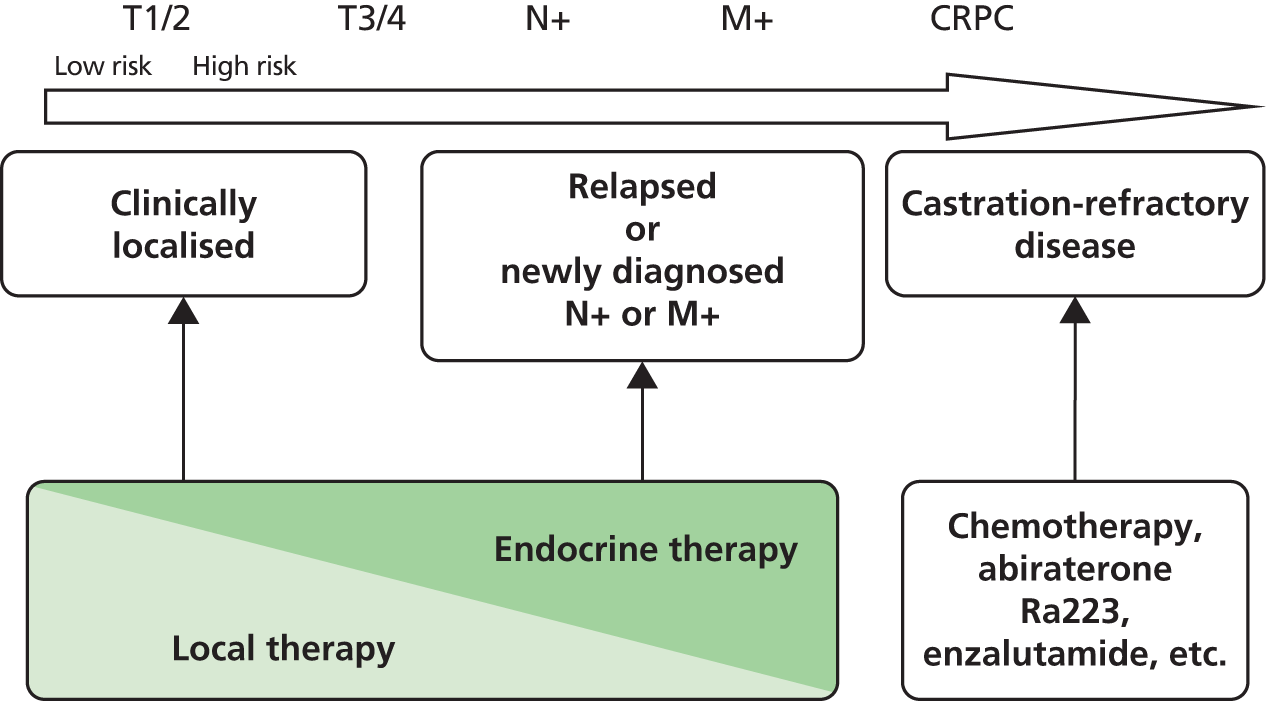

Although adenocarcinoma of the prostate most often presents as local (stage T1 or T2) disease, in which the malignancy is confined to the prostate, a significant proportion of patients progress despite initial treatment with ablative surgery or radiotherapy, often in combination with hormonal therapy. A minority of patients present with de novo metastatic disease. Figure 2 summarises the treatment options across the disease spectrum.

FIGURE 2.

Prostate cancer treatment paradigm. Cancer has spread to the pelvic lymph nodes (N+) or to lymph nodes, organs, or bones distant from the prostate (M+). CRPC, castration-refractory prostate cancer; Ra223, Radium-223.

Hormone therapy

A hormone (from the Greek ὁρμή, meaning ‘impetus’) is a chemical released by a cell in one part of the body to affect cells in other parts of the organism. Cells respond to a hormone when they express a specific receptor for that hormone. The hormone binds to the receptor protein, resulting in the activation of a signal transduction mechanism that ultimately leads to cell type-specific responses. Hormone therapies can thus work on a number of points in this pathway and there are examples of all of these in prostate cancer, which are summarised in Table 1.

| Target | Example in prostate cancer therapy |

|---|---|

| Block synthesis of regulator of hormone | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and antagonists, e.g. goserelin, leuprorelin, triptorelin |

| Block binding of secreted hormone to receptor | Bicalutamide, enzalutamide, cyproterone acetate |

| Block post-receptor effects | Enzalutamide |

| Block synthesis of hormone | Cyp17 inhibitors, e.g. abiraterone |

| Add alternative hormones to alter environment | Diethylstilboestrol, dexamethasone |

Hormone therapy has been a mainstay of prostate cancer since the seminal studies of Huggins and Hodges,5 published in 1941, demonstrating substantial and prolonged remissions from prostate cancer with the use of either surgical castration or oestrogen therapy. Diethylstilboestrol is the first example of a successful drug treatment for advanced cancer, and, while now supplanted in this role, it remains in use 70 years later. As is now well known, while responses to hormone therapy may be dramatic, with durations running into many years, they are rarely curative and typically last 18–24 months depending on disease stage. This period after failure of initial androgen deprivation therapy has been known by many terms over the years, including androgen-independent prostate cancer and castration-refractory prostate cancer (CRPC). However, with the recognition that relapsing tumours remain dependent on androgen receptor-mediated pathways and the licensing in relapsing disease of abiraterone,6–8 a steroid synthesis inhibitor, and enzalutamide,9 an androgen receptor-targeting agent, the term castration-refractory prostate cancer is increasingly used. This term is, however, unpopular with patient groups and, while accurate, may yet also be supplanted if anyone can think of a term with less pejorative overtones.

Broadly speaking, there are two routes into long-term hormone therapy: via localised disease, radical therapy and relapse, and de novo advanced disease (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Pathways to advanced disease. Natural history for metastatic patients. ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Figure 3 shows disease burden expressed via the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level on the vertical axis. For most purposes, however, PSA does equate with disease burden. In particular, in late-stage disease managed with non-hormonal therapies the relationship is not that close and PSA is not recognised as a surrogate end point for clinical trials. In early hormone-sensitive disease, the concordance between PSA changes and clinical ones is close. One consequence of the use of the PSA test is that managment tends to be PSA-driven rather than clinically-driven. In the case of patients relapsing after failed local therapy, clinicians are faced with a rising PSA but often no radiological evidence of disease for many years – termed a biochemical relapse. Patients in this situation will often be started on hormone therapy many years before any clinical consequences of relapse. Randomised trials in this setting have shown that intermittent therapy is as good as continuous therapy and probably should be regarded as the standard of care.

Management of metastatic disease

Initial management of men with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer is some form of androgen deprivation therapy. This will generally control disease for 1–3 years, following which progressive clinical failure will ensue – CRPC. In patients with metastatic CRPC (mCRPC), one of the most common sites of spread is bone. The development of bone metastasis, and the associated pain, results in a high level of mobility problems, leading to a loss of functional independence in men, and is a major cause of mortality [bone marrow failure, pathological fractures, spinal cord compression (SCC) and other bone-related complications]. Bone morbidity is often quantified in clinical trials via a composite end point termed the skeletal-related events (SREs). The elements that make up this end point are summarised as:

-

pathological fracture

-

SCC

-

radiotherapy to bone

-

hypercalcaemia

-

change in anticancer treatment to treat bone pain.

The reduction in the frequency or severity of SREs that any particular patient experiences during the individual disease pathway may provide additional health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) benefits. The true benefit in terms of HRQoL is not yet completely known, although recent data from clinical trials have begun to show the HRQoL benefits of bisphosphonates. 10,11 In addition to the potential quality-of-life (QoL) benefits, patients may also gain actual survival benefit from either mono or combination therapy. Although bisphosphonates therapy and/or chemotherapy may be considered as central to the treatment of patients with bone metastases, other therapies such as radioisotopes are available and are widely used for patients with mCRPC.

Chemotherapy

For many years chemotherapy was considered too toxic to be of value in men with advanced prostate cancer. There were a number of reasons for this, including later diagnosis in the pre-PSA era, difficulty in assessing responses and problems in managing toxicity, such as nausea and vomiting. The advent of PSA-driven diagnosis and management, while remaining controversial in terms of use as a screening test, has undoubtedly resulted in a strong trend to earlier diagnosis now dating back several decades. This in turn has meant that men are diagnosed younger with advanced disease. Secondly, the use of PSA monitoring post-primary treatment has meant that men relapsing after failed radical therapy are picked up early and so, when mCRPC does develop, treatment can be instigated when men remain fit enough to cope with it. Definitive proof of benefit from palliative chemotherapy came from a landmark National Cancer Institute of Canada trial led by Ian Tannock from Toronto. The trial compared prednisone alone with prednisolone plus mitoxantrone given 3-weekly for up to 10 cycles. This relatively small study of 161 patients published in 1996 set out to compare palliative end points rather than survival-based ones. 12

A palliative response was observed in 23 out of 80 patients who received mitoxantrone plus prednisone, compared with 10 out of 81 patients who received prednisone alone. In an additional seven patients in each group, analgesic medication was reduced without an increase in pain. The duration of palliation was longer in patients who received chemotherapy (with a median of 43 weeks to symptom worsening) than in those treated with prednisone alone (median of 18 weeks to symptom worsening). There was significant crossover from the prednisone arm to the chemotherapy arm and no difference in overall survival. Thus, this study clearly established the principle that chemotherapy could provide palliative benefit but did not show a survival benefit. Subsequent mitoxantrone trials produced similar results, although the crossover between the chemotherapy and no-chemotherapy arms means that, essentially, it is not known whether or not chemotherapy with this agent produces a survival benefit.

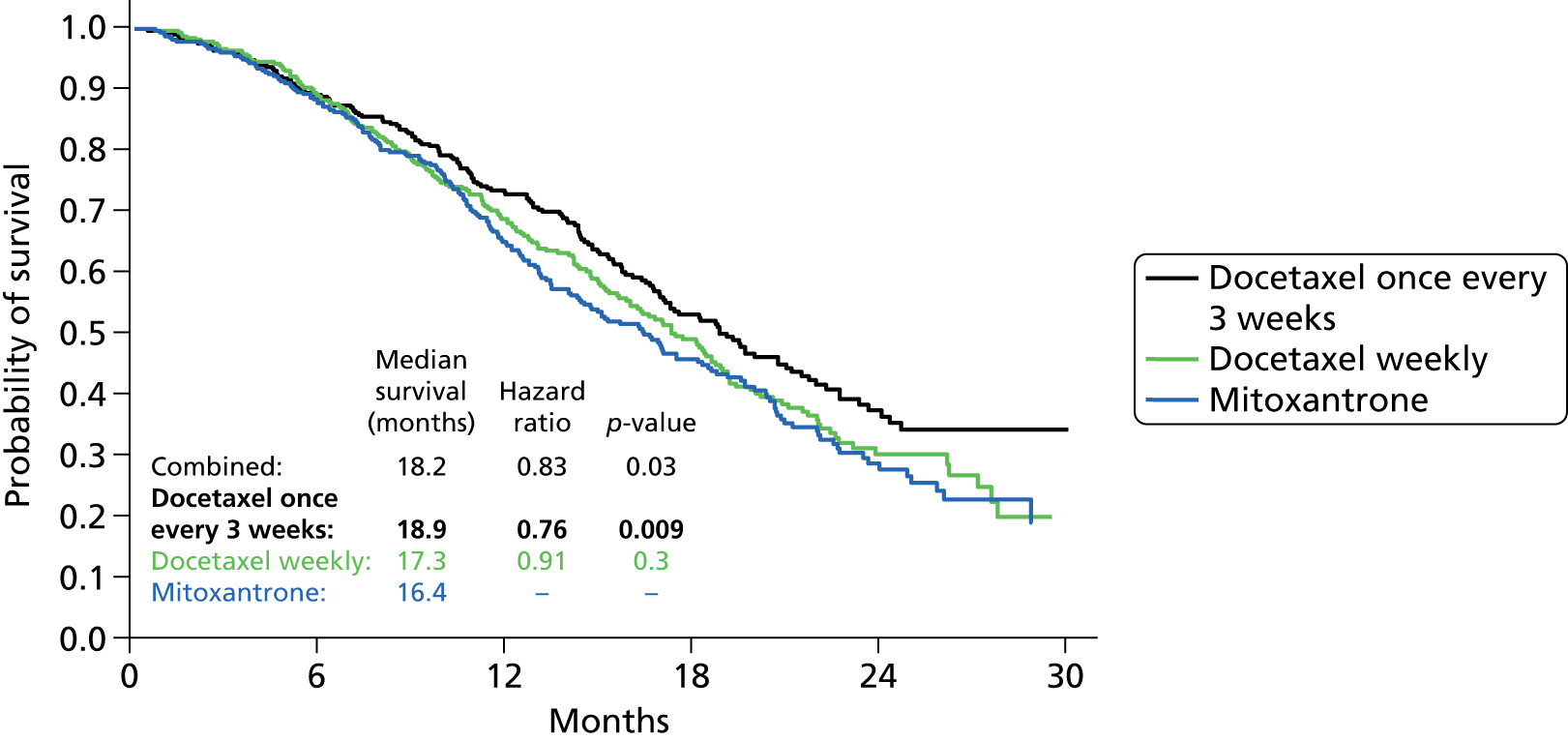

In the late 1990s, a variety of agents started to be evaluated in what was then called hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC). Docetaxel emerged as the lead candidate for evaluation in large phase trials, and two landmark studies were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2004. 13,14 One trial, the TAX327 study,13 compared weekly or 3-weekly docetaxel with the Tannock mitoxantrone regimen. The second trial (SWOG 991614) compared a combination of docetaxel and estramustine with the same control arm. Both trials showed improved palliative outcomes compared with mitoxantrone and, very importantly, an overall survival (OS) advantage for 3-weekly docetaxel and the docetaxel–estramustine combination with hazard ratios (HRs) of 0.76 and 0.8, respectively, despite significant crossover to docetaxel in the mitoxantrone arms of both studies. All patients in both trials received prednisone as per the original Tannock paper. These trials confirmed unequivocally that chemotherapy could both prolong survival and give worthwhile palliation without undue toxicity. They also established that docetaxel is a superior agent to mitoxantrone. On the basis of these trials, a 3-weekly schedule of docetaxel plus prednisolone for up to 10 cycles has emerged as the standard of care for mCRPC and was approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for this purpose in 2006 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of estimated probability of overall survival of mitoxantrone and docetaxel for CRPC. 15

A number of agents have been studied in the second-line chemotherapy setting. Of these, to date only cabazitaxel has shown a survival advantage and obtained a licence. The key trial, TROPIC, compared cabazitaxel with mitoxantrone given on the standard Tannock trial schedule and showed an improvement in median survival from 12.7 to 15.1 months. 16 Cabazitaxel was licensed in 2010 ahead of abiraterone, which obtained a licence in 2011 in the same post-docetaxel setting. As both drugs improve survival, although they have completely different modes of action, there is clearly an unresolved issue over choice and sequencing (or indeed combination) of agents. The position has now been further complicated by the licensing of enzalutamide post chemotherapy based on the AFFIRM trial,9 plus the extension of the abiraterone licence to chemo-naive patients. 6 The licence for enzalutamide was also expanded to cover pre-chemotherapy patients following the PREVAIL trial. 17

Additionally, the recent publication of the results of the ALSYMPCA trial of radium-22318 demonstrated both improved OS and reduced skeletal complications with six injections, one every 28 days, of radioisotope compared with placebo. 18 How chemotherapy should best be integrated with other therapeutic options for patients with bone metastasis is at present not defined.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates inhibit bone catabolism by reducing the numbers of functioning osteoclasts and have been used to manage bone metastases. Zoledronic acid (ZA), but not some older bisphosphonates, also arrest cell proliferation, induce apoptosis, and inhibit the growth factor stimulation of cultured prostate cancer cells. 14 In trials in relapsing mCRPC, ZA reduced the time to SRE as well as the frequency of subsequent SREs. 19,20 The ZA licensing trials19,20 have proved very controversial, as the fracture end point was assessed by regular skeletal survey with blinded radiological assessment. Hence, there is significant doubt as to whether many of the small fractures detected were precursors of a subsequent real ‘clinical’ SRE or radiological features of no significance. ZA is not currently recommended for use in the UK by NICE because of doubts as to its cost-effectiveness.

Radioisotopes have been used to palliate bone pain for over 20 years. A variety of radioisotopes are available; the most commonly used during the trial recruitment era were strontium-89 (Sr-89)21,22 and samarium-153. 23 Both accumulate selectively in bone metastases compared with non-involved bone. There is some evidence that Sr-89 may reduce overall health-care costs compared with standard methods of delivering radiotherapy. 24 There are a number of previous studies of combined use of chemotherapy with radioisotopes. Of particular note, Tu et al. 25 combined combination chemotherapy with Sr-89 in a small randomised trial with promising results suggesting a survival advantage in chemotherapy responders allocated to Sr-89.

Since the publication of the MRC PR05 study,26,27 more potent bisphosphonates have been evaluated in mCRPC. The most widely studied has been zoledronate, which has a 40- to 850-fold higher potency than clodronate in pre-clinical models of bone resorption. 28 It has also been shown to be more effective than pamidronate (90 mg) in controlling malignant hypercalcaemia29,30 In addition, zoledronate has demonstrated direct anticancer activity, including inhibition of proliferation of breast cancer and prostate cancer cells in vitro. 31,32

In prostate cancer trials in relapsing mCRPC, ZA reduced the time to SREs as well as the frequency of subsequent SREs. 19,20 However, it is clear from looking at the components that make up the SREs that these vary hugely in clinical significance and, in addition, are to a degree subjective. In particular, the ZA licensing trials19,20 have proved very controversial as the fracture end point was assessed by regular skeletal survey with blinded radiological assessment. As such there is significant doubt about whether many of the small fractures detected were precursors of a subsequent real ‘clinical’ SRE or radiological features of no significance. The subsequent trials comparing ZA with denusomab33 used the same methodology and so can be subject to the same criticism. As a result, neither agent is recommended for use in the UK by NICE. The impact of ZA on SREs is illustrated in Figure 5; the bisphosphonate showing decreases in skeletal complications in both lytic and blastic lesions in a comparison with pamidonate. 20

FIGURE 5.

Proportion of patients with SREs, demonstrating reduction with ZA.

In vitro evidence suggests synergistic killing of breast and prostate cancer cells when combined with chemotherapy. 32 Furthermore, ZA was licensed in the ‘pre-docetaxel’ era; hence, whatever the merits of SRE prevention, the role of zoledronate in the chemotherapy era was effectively undefined. It was therefore logical to evaluate docetaxel with ZA in men with mCRPC affecting bone. In view of the controversy over the SRE as an end point, we did not undertake routine skeletal evaluations as in the zoledronate and denosumab licensing trials but collected data only on ‘clinical’ SREs; that is, those reported by the patient or diagnosed on the basis of symptoms such as those from SCC. We combined this clinically orientated approach to the SRE with a health economic assessment of the impact of the various trial interventions, the intention being that, if the clinical utility of combination therapy were confirmed, we should be able to produce robust estimates of the cost-effectiveness at the same time.

Radioisotopes

A variety of radioisotopes are available, the most commonly used during the trial recruitment era being Sr-89 and samarium-153. Both accumulate selectively in bone metastases compared with uptake rates in non-involved bone. Sr-89, a bone-seeking radionuclide, is a pure β-emitter with a half-life of 50 days, has a high uptake in osteoblastic metastases, and remains in tumour sites for up to 100 days. Sr-89 provides pain relief in up to 80% of patients, and complete freedom from pain in approximately 10%, for periods that can exceed 3 months. 21,34 In a randomised controlled Phase III trial, the combination of Sr-89 injection and external beam radiotherapy improved pain relief, delayed disease progression and enhanced some QoL measures compared with external beam radiotherapy alone. 21 However, another Phase III randomised controlled trial has suggested that, in some patients, systemic Sr-89 may be inferior to local-field radiotherapy in terms of survival (7.2 months vs. 11.0 months; p = 0.0457). 22 The selection of patients has a significant impact on outcome, response and duration of response to radionuclide therapy, as bone pain palliation is reduced in those who have widespread metastatic disease or a short life expectancy. 35–38 Consequently, the use of radionuclides appears to be optimal at an early stage in disease management. However, their efficacy is reduced or lost with repeated use, and overtreatment can also lead to irreversible pancytopenia. As noted above (see Bisphosphonates), there is some evidence that Sr-89 may reduce overall health-care costs compared with standard methods of delivering radiotherapy. 39

There are a number of previous studies of combined use of chemotherapy with radioisotopes. Tu et al. combined combination chemotherapy with Sr-89 in a small randomised trial with promising results suggesting a survival advantage in chemotherapy responders allocated to Sr-89. 25 More recently, Fizazi et al. ,40 Tu et al. 41 and Morris et al. 42 have combined docetaxel with samarium-153 in Phase I/II trials, confirming safety for the combination. No published randomised trials have addressed the safety or efficacy of docetaxel with either Sr-89 or samarium-53.

As new treatments have appeared for CRPC, these treatments have been less frequently used. However, recent data with a new radioisotope radium-223 seem set to change this picture. Like Sr-89, radium-223 is a calcium mimetic. Recently completed placebo-controlled Phase III trials in symptomatic CRPC patients showed a prolongation of survival and also a delay and reduction in symptomatic (as opposed to radiological) SREs. 18 Levels of adverse reactions reported in the trial were low. The agent was licensed in 2013 and is an important new therapeutic option for men with CRPC, especially as the trial included men both pre and post chemotherapy, as well as those deemed unfit to ever receive chemotherapy.

Osteoporosis

Patients eligible for the study are at risk of osteoporosis in view of their previous therapy (androgen deprivation, possible steroid exposure, age) as well as from some on-study therapies (steroids, docetaxel). Osteoporosis was therefore considered in the causality of any SRE. A bone density substudy formed part of this trial.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was originally a four-arm randomised controlled Phase II trial, which proceeded seamlessly to a Phase III trial. In order to increase efficiency and reduce the trial duration, the Phase III design was switched from a four-arm comparison to a two-by-two factorial design. The end points changed as the trial progressed from Phase II to Phase III, as summarised in Table 2.

| Phase | Primary | Secondary | Tertiary |

|---|---|---|---|

| II |

|

|

|

| III |

|

|

|

The Phase II objectives were to compare the four trial arms with respect to feasibility, tolerability and safety. The Phase III objectives were to assess treatments with respect to efficacy within a two-by-two factorial design framework; that is, the trial compared ZA versus no ZA (stratified for Sr-89 use) and Sr-89 versus no Sr-89 (stratified for ZA use). The Phase III trial had dual primary end points of effect of each treatment on time to bony disease progression and cost and cost-effectiveness.

During the chemotherapy treatment period, participants were assessed at 3-weekly intervals. Irrespective of treatment arm, all patients were assessed at the end of the sixth cycle of chemotherapy to ensure their fitness to receive Sr-89.

Phase II participants ceased primary trial treatment after cycle 6 of Sr-89 administration, where relevant. Clinicians were encouraged to give further docetaxel off-trial up to a total of 10 cycles in keeping with NICE guidance, where appropriate. In order to streamline data collection, cycles 7 to 10 of docetaxel were designated as trial therapy for Phase III of the study.

Participants

Male patients over the age of 18 years were recruited into the trial. The trial recruited sufficient patients to ensure that at least 618 participants reached the primary end points. The entry criteria primarily included proven mCRPC, with one or more of progressive sclerotic bone metastases, progression of measurable malignant lesions or elevated and rising PSA levels on blood analysis. Consenting participants had to have had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale score of up to 2, be fit enough to receive trial treatment and have adequate haematological, renal and hepatic function.

Exclusion criteria included prior chemotherapy or radionuclide therapy for CRPC, prior radiotherapy to more than 25% of bone marrow or whole-pelvic irradiation, prior bisphosphonate therapy within 2 months of trial entry, other malignant disease within the previous 5 years (excluding adequately treated basal cell carcinoma), known brain metastases, symptomatic peripheral neuropathy of National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology for the Criteria for Adverse Events grade 2 or more, concurrent participation in any other clinical trial involving an investigational therapeutic compound or treatment with other investigational compound within the 30 days prior to trial entry.

Owing to the nature of the treatments under investigation, this was not a blinded trial for patients or caregivers.

Interventions

Arm A: control – docetaxel plus prednisolone

Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 (up to a maximum dose of 165 mg) was administered intravenously at 3-weekly intervals (21 days). Participants also received oral prednisolone 10 mg daily throughout trial treatment or until disease progression or associated treatment toxicity.

Trial chemotherapy ceased after cycle 6 for Phase II participants but continued for up to 10 cycles for Phase III participants, ceasing for pain or tumour disease progression, or other cause decided by the treating clinician or patient choice. As noted above (see Trial design) patients could receive further chemotherapy off-trial in keeping with NICE guidance.

Arm B: docetaxel, prednisolone plus zoledronic acid

Docetaxel and prednisolone were administered as per the control arm. ZA was administered intravenously after completion of docetaxel administration at a dose of 4 mg, subject to pre-treatment creatinine clearance being greater than 60 ml/minute; creatinine clearance of < 60 ml/minute would incrementally reduce the dose given, as detailed in section 6.1.3 of the protocol (see Appendix 1). Following the completion of chemotherapy, participants received continuing ZA at 4-weekly intervals, as clinically indicated, until pain or tumour disease progression or withdrawal. It was recommended that patients treated with ZA also receive vitamin D and calcium supplements throughout treatment.

Arm C: docetaxel, prednisolone plus strontium-89

Docetaxel and prednisolone were administered as per the control arm, for six cycles. Subject to satisfactory haematological and clinical parameters on clinical assessment 21 days after the sixth docetaxel treatment, participants received a single 150-MBq dose of Sr-89 on the 28th day after the sixth cycle.

Chemotherapy ceased after cycle 6 for Phase II participants, but for Phase III participants continued for up to 10 cycles after a period of between 28 and 56 days of Sr-89 administration, allowing for bone marrow function to be adequately recovered.

Arm D: docetaxel, prednisolone, zoledronic acid plus strontium-89

Patients in this arm received docetaxel, prednisolone and ZA for six cycles, as per arm B participants, plus clinical and haematological assessment and Sr-89 administration, as per arm C participants. Following a recovery period of between 28 and 56 days, chemotherapy, prednisolone and ZA treatment resumed until disease progression, associated treatment toxicity or patient withdrawal. As per the arm B treatment regime, following the end of chemotherapy, patients received continuing ZA administrations at 4-weekly intervals, as clinically indicated, until disease progression or until other discontinuation criteria were met. It was again recommended that patients treated with ZA also receive vitamin D and calcium supplements throughout treatment.

Further off-study treatment

All further off-study treatment, for example chemotherapy, bisphosphonate and radioisotope therapy, as well as newer drugs, such as abiraterone, enzalutamide and radium-223, received after study treatment were captured on the Concomitant Medication Running Form. The choice of further treatment was at the discretion of the participant’s clinician.

Objectives

The primary objective of the Phase II component was to assess the feasibility, tolerability and safety of the four treatment arms.

Phase III assessed treatments within a two-by-two factorial design framework; that is, ZA versus no ZA (stratified for Sr-89 use) and Sr-89 versus no Sr-89 (stratified for ZA use). Each of these treatment comparisons was made in terms of clinical efficacy, with primary outcome clinical progression-free survival (CPFS) interval and health economic outcomes. In addition, the trial assessed the presence of any association between biomarkers and clinical outcomes.

Data collection

Case report forms

Data collected on each subject were recorded by the investigator or his/her designee on case report forms (CRFs). Originals of the CRF were returned to the trial management office, whereas photocopies were retained by the site.

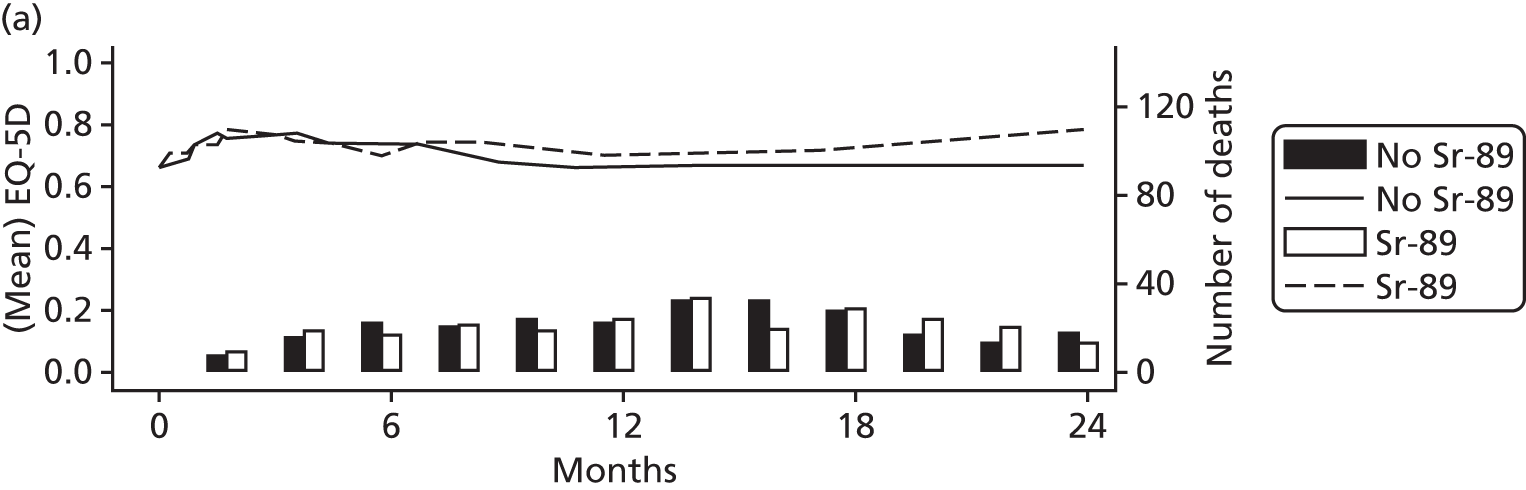

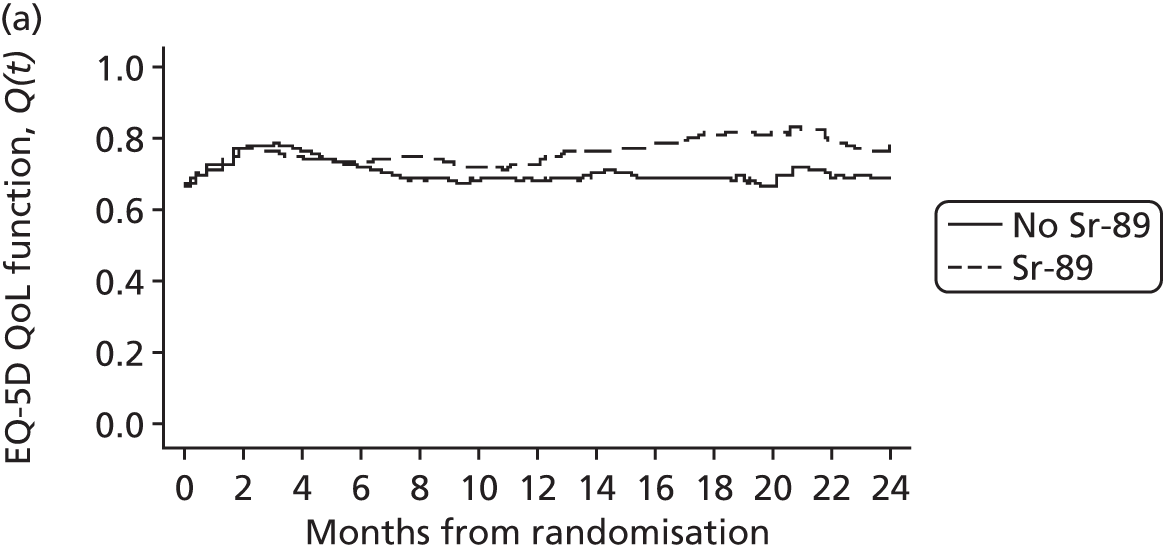

Quality-of-life data

All eligible participants were asked to consider taking part in the QoL part of the study. QoL was assessed using patient-completed questionnaires, i.e. the European Quality of Life 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Prostate (FACT-P), while pain and analgesic use diaries were used to facilitate changes in participants’ pain perception and management. An example of both the QoL booklet and pain diary are part of the protocol in Appendix 1. A QoL booklet and pain diary were completed at baseline and subsequently prior to each treatment and follow-up visit. Completion of these documents remained voluntary and continued throughout patient follow-up (pre and post clinical progression), irrespective of any further therapy a patient may have received.

Monitoring

The study was conducted under the auspices of the Cancer Research Clinical Trials Unit (CRCTU) according to current guidelines for good clinical practice. Participating centres were monitored by CRCTU staff to confirm compliance with the protocol and the protection of patients’ rights as detailed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participating centres were monitored by checking incoming forms for compliance against the protocol, consistent data, missing data and timing. CRCTU onsite monitoring was carried out as detailed by the trial’s risk assessment, primarily of all sites that had enrolled four or more patients into the trial. Patients’ records to be audited at such visits were selected randomly from the different treatment arms.

Sample size

Sample size calculations were based on the primary outcome measure of CPFS. The calculations were the same for both the comparison of ZA with no ZA and that of Sr-89 with no Sr-89. The trial aimed to detect a HR of 0.76, which would be equivalent to 1-year CPFS rates of 30% versus 40%, assuming that CPFS follows an exponential distribution. The number of events required to detect this difference in each group for either treatment comparison, using a two-sided 5% significance level and 80% power, was 206. It was estimated that approximately 294 participants would be required in each group, that is 588 patients in total, to observe this number of events at 1 year’s follow-up. We aimed to recruit a minimum of 618 evaluable patients, which allowed for 5% dropout.

The analysis of the Phase II component of the trial was entirely descriptive and did not involve any statistical hypothesis testing. The primary outcomes were feasibility, tolerability and safety, and these will be measured as proportions or means, as appropriate. Recruitment of 50 patients into each arm ensured that percentages could be estimated with a precision of at least 15% and provided sufficient data to be able to assess the arms in terms of their suitability for progression into the Phase III component of the trial.

Randomisation

Stratified randomisation

Stratification was used to ensure the balance of participant characteristics as well as numbers within each treatment group. Patients were randomised to treatment arms in a 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 allocation ratio using a computerised minimisation algorithm. If the minimisation is balanced, then allocation is random with equal chance of allocation to all arms. Randomisation was stratified by centre and ECOG performance score (0, 1 or 2) to avoid imbalance.

Implementation

Prior to randomisation, patients gave their informed consent to take part in the trial and the clinician or research nurse completed a pre-randomisation checklist to ascertain that the patient met all the entry criteria.

The process of entering a patient into the trial was conducted by telephone with the CRCTU randomisation office. Using either a computerised randomisation program or a paper equivalent should the computer system be out of commission, the CRCTU randomisation officer re-ascertained the patient’s eligibility, after which the computer program allocated the next available trial number and randomised treatment arm for the participant. When the randomisation was conducted while the computer was out of commission, systems were in place to allocate the next available trial number and random treatment.

The allocated trial number and treatment arm were communicated to the site by telephone and confirmed by fax.

Follow-up

Patients were assessed every 3 weeks during the study treatment period. After treatment completion or withdrawal for any reason except disease progression (pain or tumour growth), participants were followed up monthly for 3 months and subsequently every 3 months until either patient death or withdrawal of the patient’s consent for further follow-up.

Patients progressed to 3-monthly follow-up following clinical progression; that is, increasing pain, tumour growth or SREs.

Trial management

Trial Management Group

The Trial Management Group comprised the chief investigator, a few co-investigators and members of the CRCTU, as detailed in the front sleeve of the protocol (see Appendix 1). The Trial Management Group was responsible for the day-to-day running and management of the trial and met by teleconference or in person, as required.

Data Monitoring Committee

An independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC; see Appendix 2), comprising an independent statistician, oncologist and urologist, met approximately annually to review the accumulating confidential trial data. Their main objective was to advise the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) whether or not there was any evidence or reason to amend or terminate the trial based on the recruitment rate or safety. Reports to the DMC were produced by the CRCTU.

Trial Steering Committee

An independent TSC (see Appendix 2) provided overall supervision for the trial and advised the trial management group. Members included an independent statistician, oncologist and two urologists. The ultimate decision regarding continuation of the trial lay with the TSC, based on the advice received from the DMC. The TSC met approximately annually, shortly after the DMC met.

Outcomes

Primary end points

Phase II: feasibility, tolerability and safety

The primary end points of the Phase II study were feasibility, tolerability and the safety of each treatment arm. Analysis was purely descriptive, while the control arm data acted as a benchmark against which to assess the experimental treatment arms. Percentages and means were calculated, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) constructed as appropriate.

Phase III: clinical progression-free survival

The primary Phase III analysis compared ZA versus no ZA (stratified for Sr-89 use) and Sr-89 versus no Sr-89 (stratified for ZA use) in terms of CPFS. CPFS was defined as the number of whole days from the date of randomisation to the first occurrence of SRE, pain progression or death. Patients not experiencing clinical progression were censored at the date last known to be progression free.

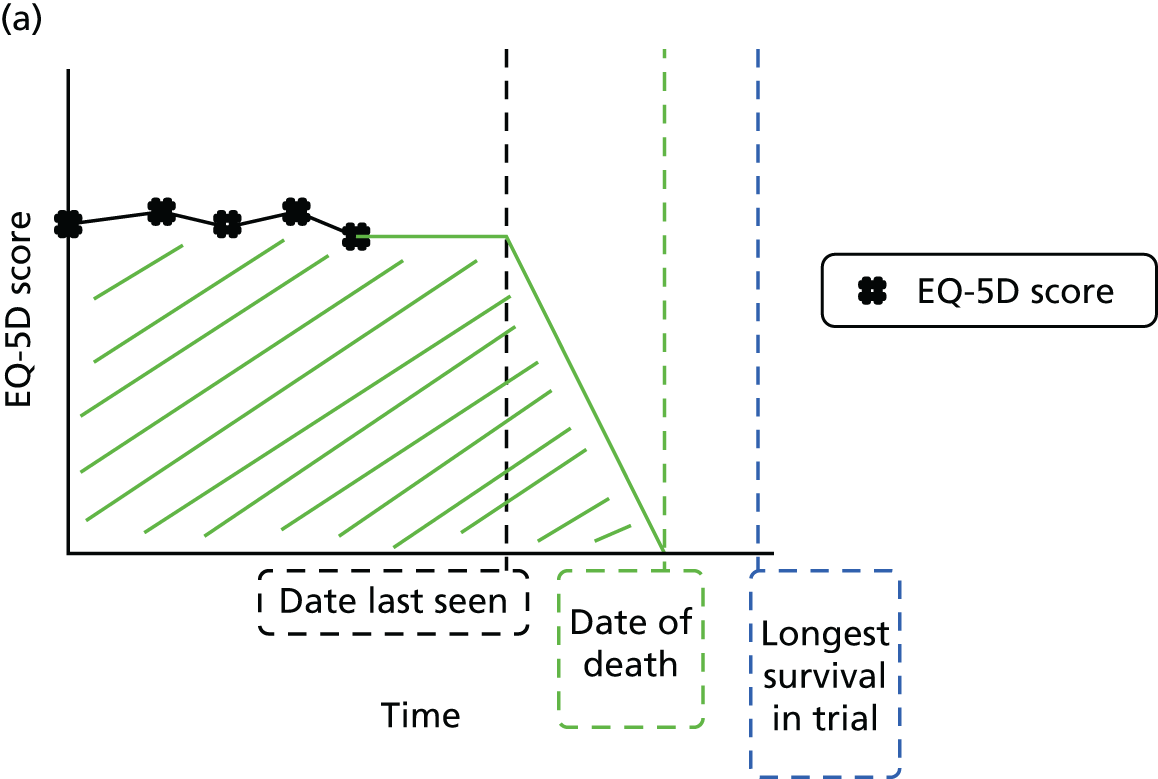

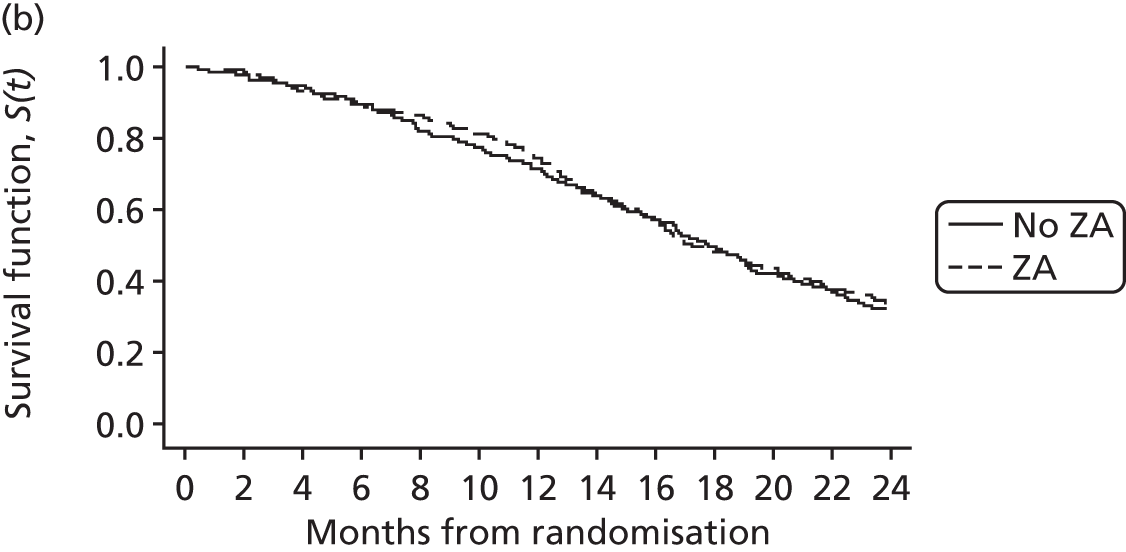

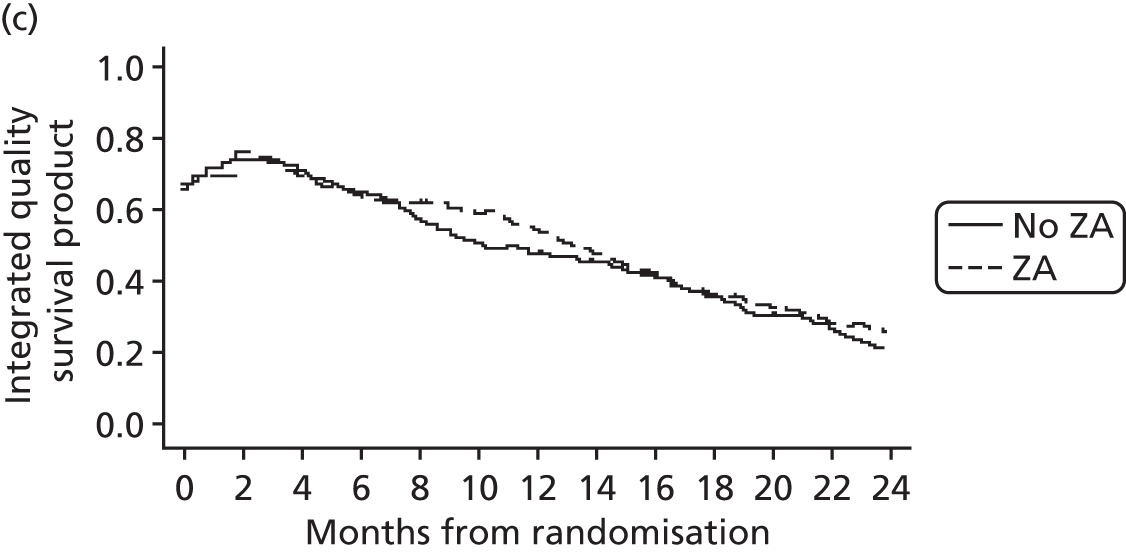

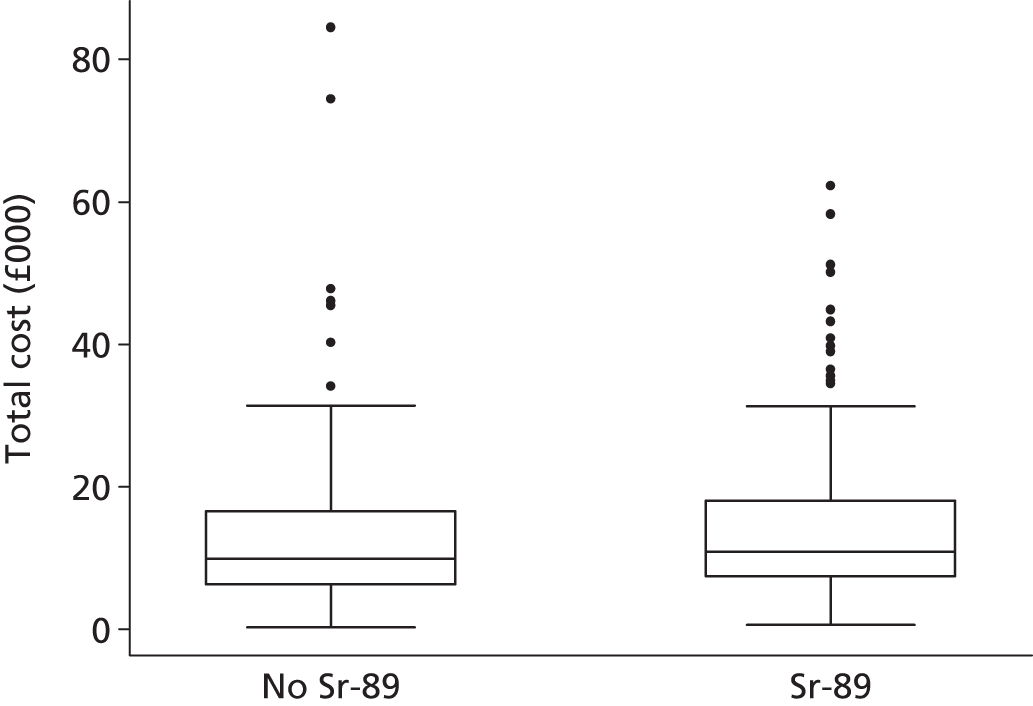

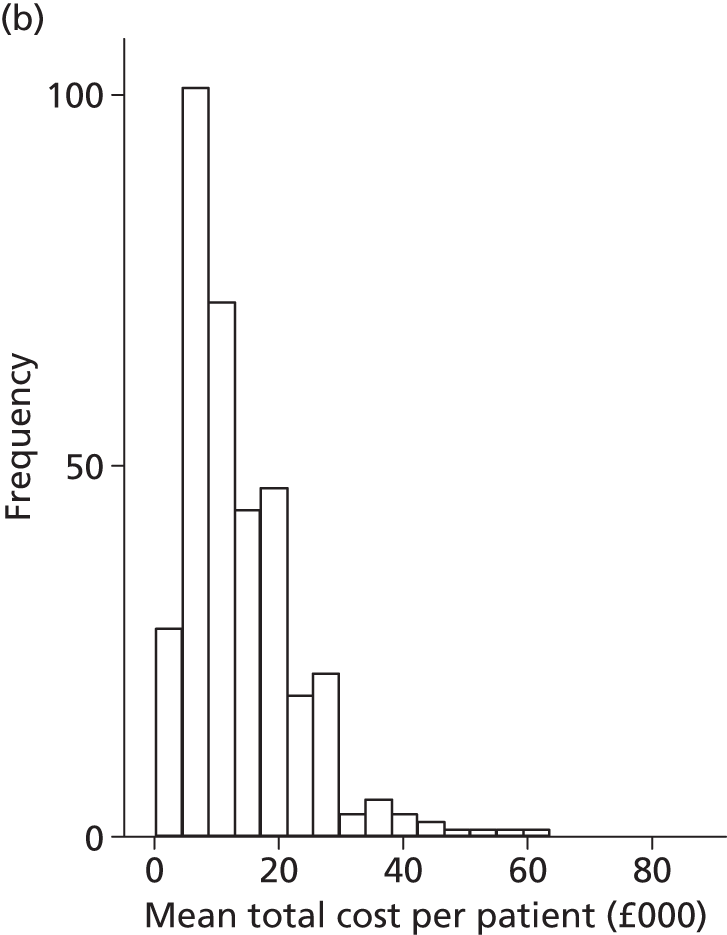

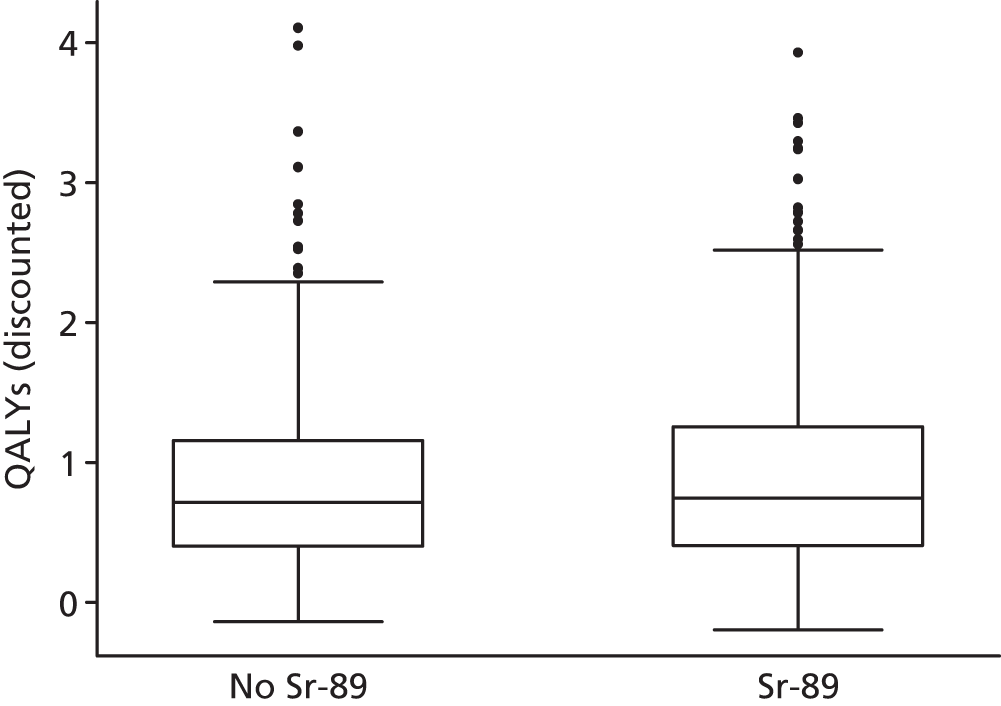

Economic analyses

Economic evaluations were carried out to assess the cost-effectiveness of the relevant comparisons – ZA versus no ZA and Sr-89 versus no Sr-89 – for patients with mCRPC. The analyses were carried out from the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services and involved calculating estimates of mean per-patient costs and health outcomes for each of the compared treatment options. Costs were calculated on the basis of treatment acquisition and administration costs, cost of concomitant medications and use of NHS primary and secondary care resources. Outcomes were expressed as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), calculated on the basis of patients’ responses to the EQ-5D (three-level) instrument. Mean values were reported together with their 95% CIs. To account for the skewed distributions of costs and QALYs, CIs were obtained through bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap methods. In line with current recommendations, costs and QALYs accruing in the future were discounted at an annual rate of 3.5%.

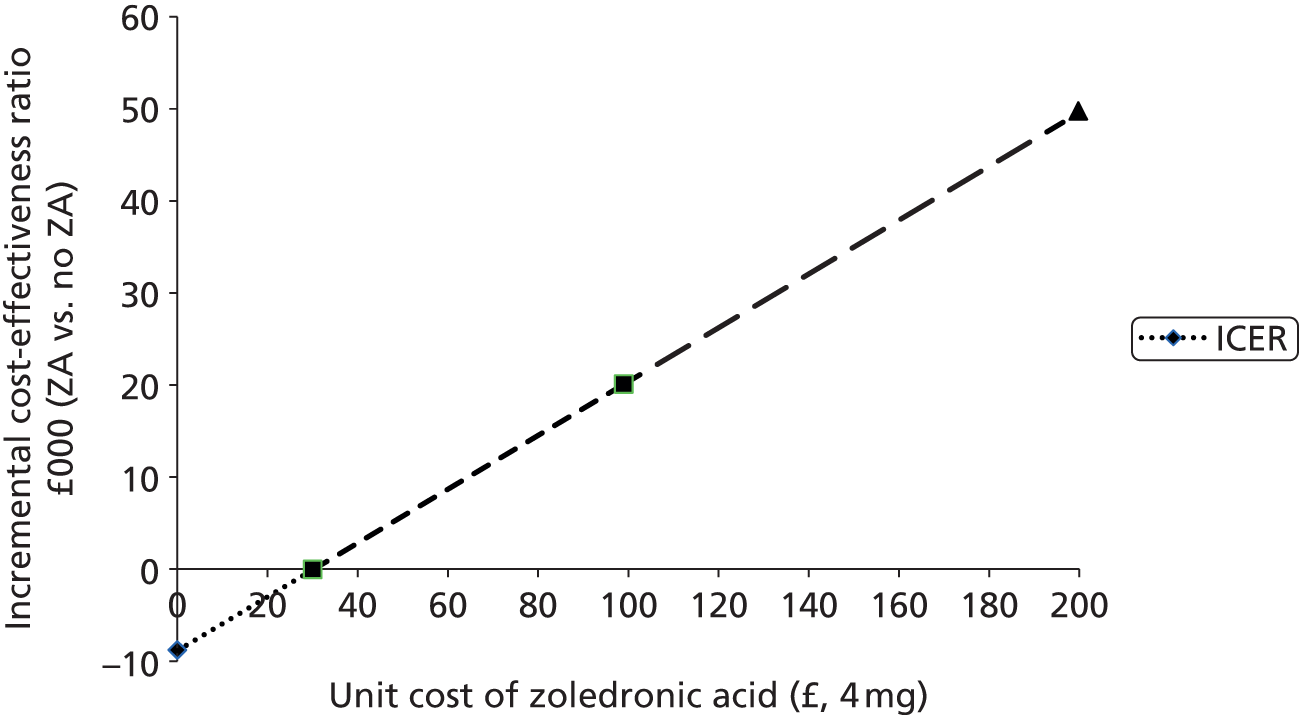

Incremental analysis was undertaken to obtain a ratio of the difference in costs over the difference in QALYs for each comparison. Results were presented in the form of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), reflecting the extra cost for an additional QALY. 43 To account for the inherent uncertainty as a result of sampling variation, the joint distribution of differences in cost and QALYs was derived by carrying out a large number of non-parametric bootstrap simulations. 44,45 The simulated cost and effect pairs were depicted on a cost-effectiveness plane46 and were plotted as cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs). 47,48 A series of sensitivity analyses was carried out to assess the impact of key assumptions on the obtained results. Given the short expected survival time of mCRPC patients and the long-term follow-up of patients in the trial, lifetime costs and effects were largely observed and so extrapolation beyond the trial was not necessary.

Secondary end points

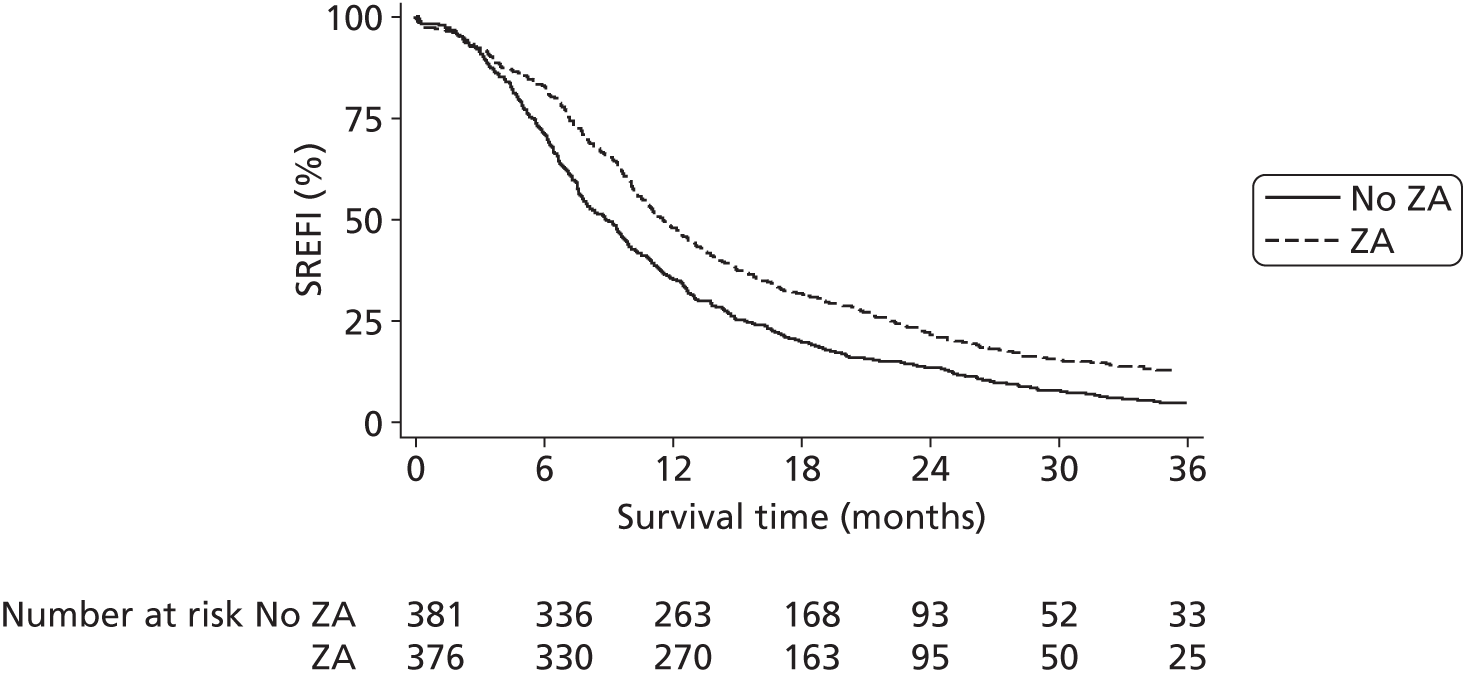

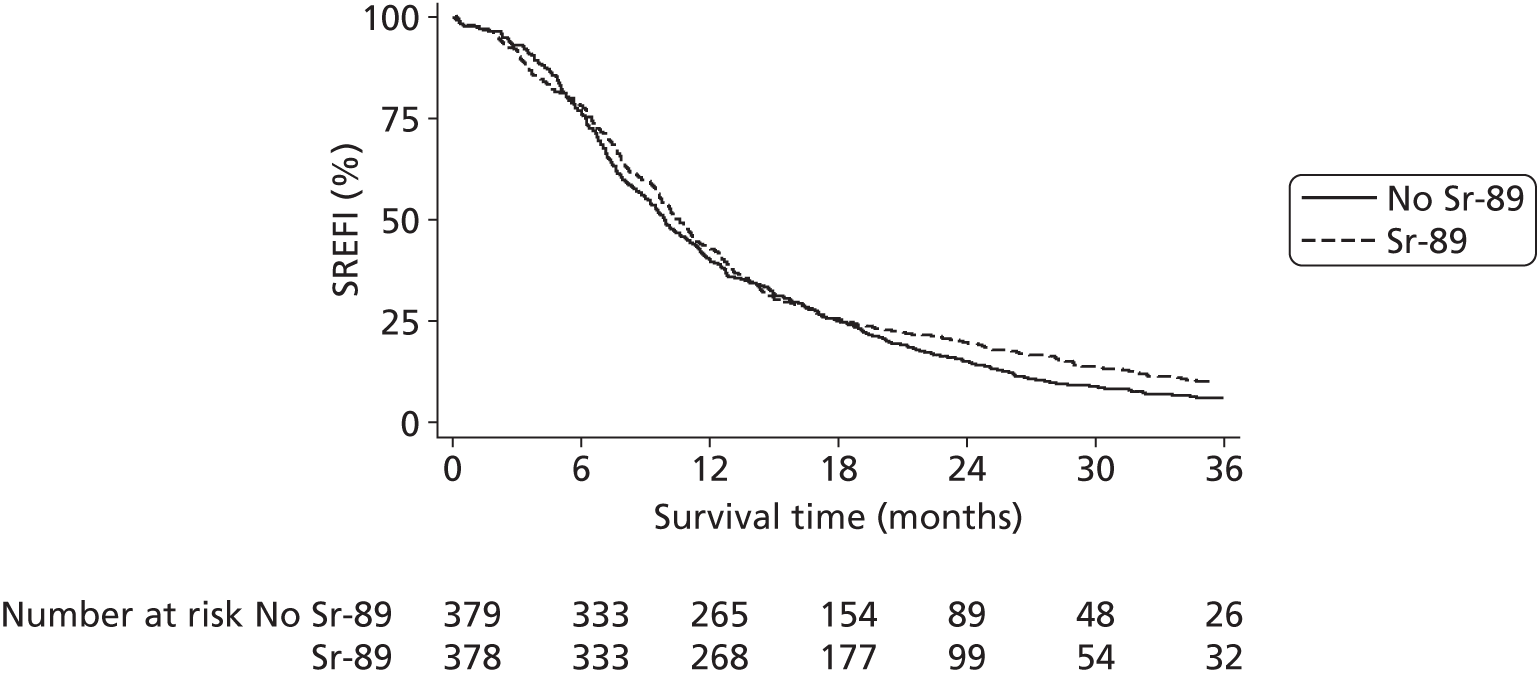

Skeletal-related event-free interval

A skeletal-related event-free interval (SREFI) was defined as the time in whole days from the date of randomisation to the date of the first occurrence of a SRE. A SRE was defined as any one of the following:

-

symptomatic pathological bone fracture

-

spinal cord or nerve root compression likely to be related to cancer or treatment

-

cancer related surgery to bone

-

radiation therapy to bone (including use of radioisotopes)

-

change of antineoplastic therapy to treat bone pain due to prostate cancer

-

hypercalcaemia.

Patients who did not experience a SRE were censored at death or the date last known to be alive.

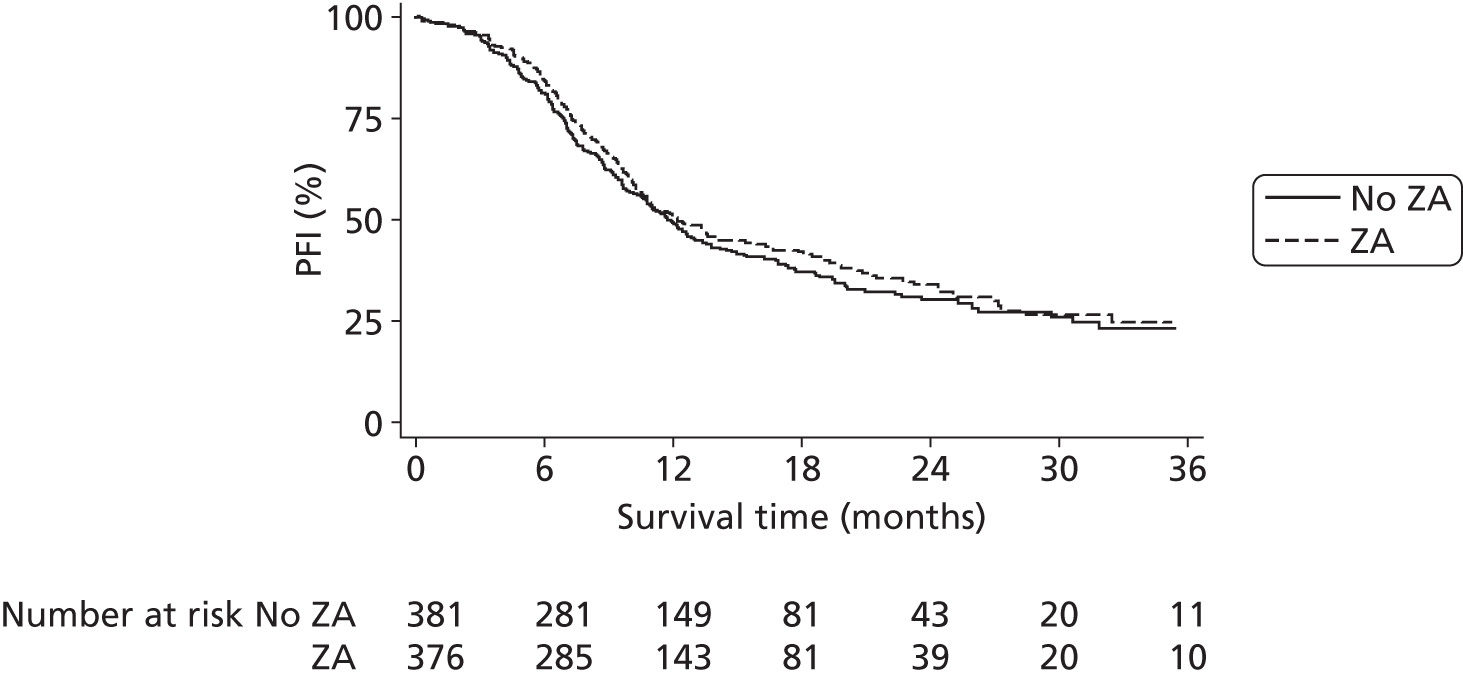

Pain progression-free interval

Pain progression-free interval (PPFI) was defined as the time in whole days from the date of randomisation to the date of clinician-determined pain progression. Patients not experiencing pain progression were censored at the date of death or the date last known to be alive.

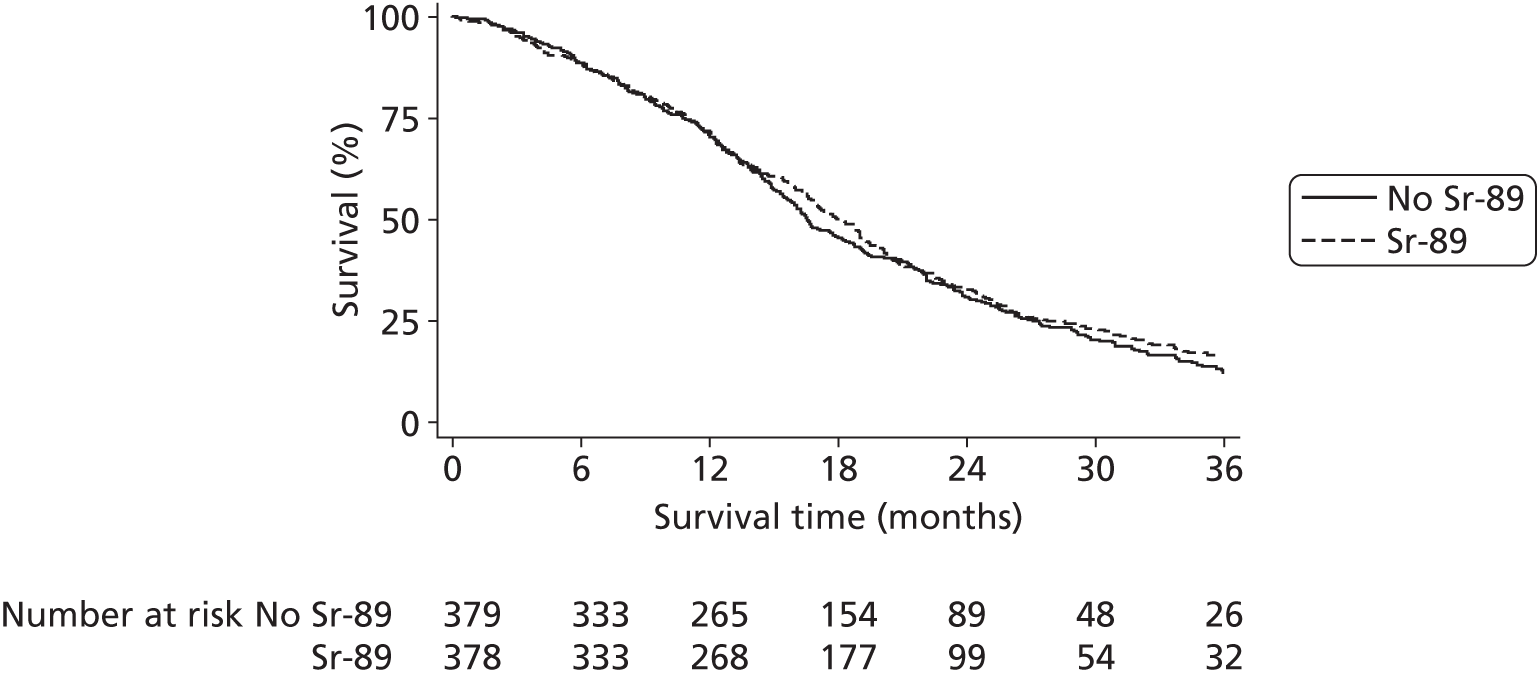

Overall survival

Overall survival was defined as the number of whole days from the date of randomisation to the date of death from any cause. Patients alive at the date of analysis were censored at the date last known to be alive.

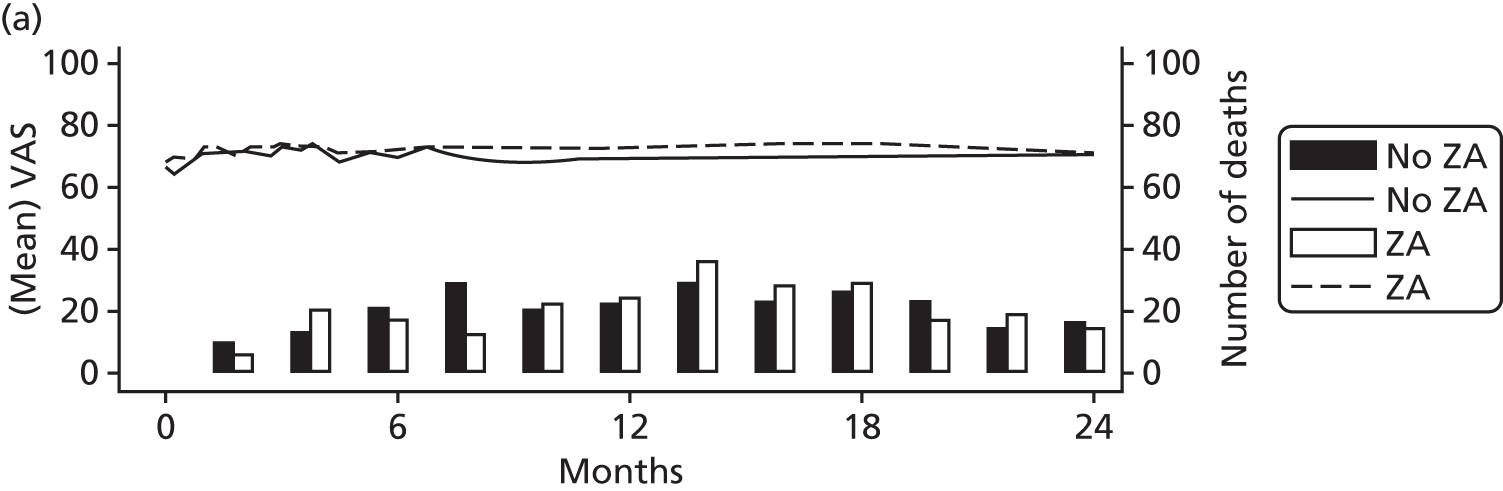

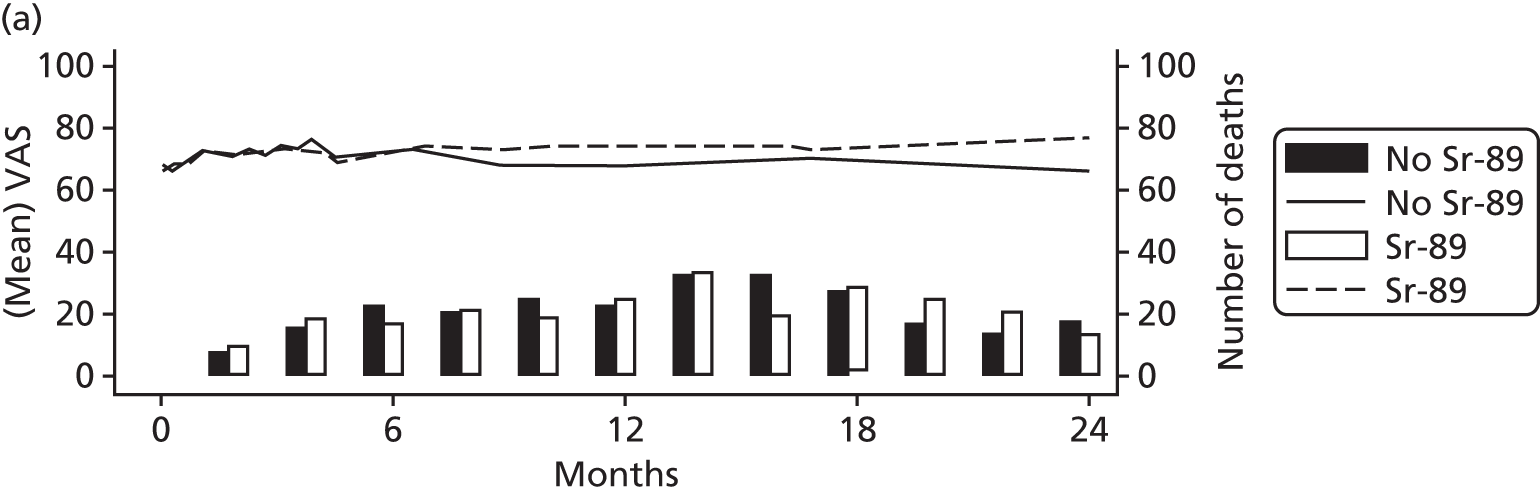

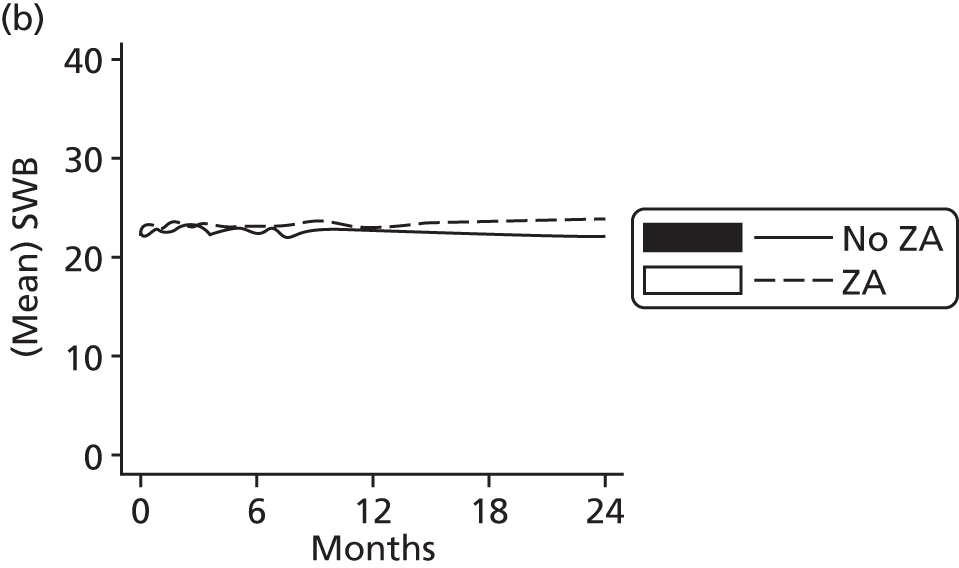

Quality of life

Quality-of-life questionnaires included the EQ-5D, which consisted of the health-state scale, the descriptive three-level system and the visual analogue scale (VAS); the FACT-P version 4; and a health-problems questionnaire focusing predominantly on resource use. The QoL form was collected 3-weekly during treatment and then monthly for 3 months and, finally, 3-monthly until death.

The EQ-5D is a generic preference-based measure of HRQoL. The instrument was designed to be self-completed and so, where possible, data were provided by the patient. Responses to the descriptive system of the EQ-5D were translated into a single summary utility index ranging from –0.59 to 1 by using a UK-relevant value set. Patients’ rating of their QoL was also collected through a vertical 20-cm VAS with the bottom end point representing the worst imaginable health state and the top end point showing the best imaginable health state. The VAS resembles a thermometer and takes values between 0 (worst imaginable state) and 100 (best imaginable state).

The FACT-P is a 40-item self-reported cancer therapy questionnaire with an additional 12-item prostate cancer subscale. Six measures were generated by this questionnaire: social well-being, personal well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, prostate cancer-specific score and an overall FACT-P score ranging from zero to 156.

Toxicity

The analysis of toxicity was purely descriptive. Proportions and means were calculated and 95% CIs constructed as appropriate.

Ancillary end points

Bone mineral density changes and biomarker substudies are detailed in the protocol (see Appendix 1); tertiary end points will not be presented at this time in this report.

Statistical methods

The definitive study analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. All tests of statistical significance were conducted at the 5% two-sided significance level. All analysis was carried out using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Descriptive comparisons not involving hypothesis testing will be presented as medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs) and ranges for numerical variables, and percentages will be given for categorical variables. Percentages will not always total exactly 100% due to rounding errors associated with reporting results to one decimal place. Percentage totals have been rounded to the nearest integer. Time-to-event analysis, multiple event analysis and QoL analysis are detailed at the start of the appropriate section. No direct statistical analysis of between randomisation arms has been conducted. The factorial design of the study assumes there is no interaction between the two agents and any treatment effects are assumed to be additive; therefore, the trial was not powered for this analysis.

Summary of changes to the trial protocol

Phase II treatment consisted of six cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy plus an additional four cycles off-study at the discretion of the treating physician. NICE, however, recommended that up to 10 cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy should be administered in one treatment block. This was not stated clearly in the Phase II protocol and the previous trial design had the inadvertent effect of preventing some patients from receiving cycles 7 to 10 at a later stage because of local policy. Adopting the NICE recommendation formally into the clinical trial design ensured that all patients had access to the NICE-recommended schedule of chemotherapy and that the control treatment arm was considered the true ‘standard of care’ (Tables 3 and 4).

| Protocol version no./date | Brief description of previous amendments |

|---|---|

| Versions 1–3 (12 July 2004, 2 August 2004, 16 August 2004) |

|

| TRAPEZE, Phase II: version 4 (1 September 2004) |

|

| Version 5 (23 March 2005) |

|

| Version 6 (7 June 2005) |

|

| Version 7 (4 May 2007) |

|

| TRAPEZE, Phase III: version 8 (24 September 2008) |

|

| Version 9 (12 April 2011) |

|

| Version 10 (25 May 2011) |

|

| Version 11 (17 February 2012) | Substantial amendments:

|

Non-substantial amendments:

|

Chapter 3 Results

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram summarising trial participation figures and analysis is included as Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. ITT, intention to treat.

Recruitment

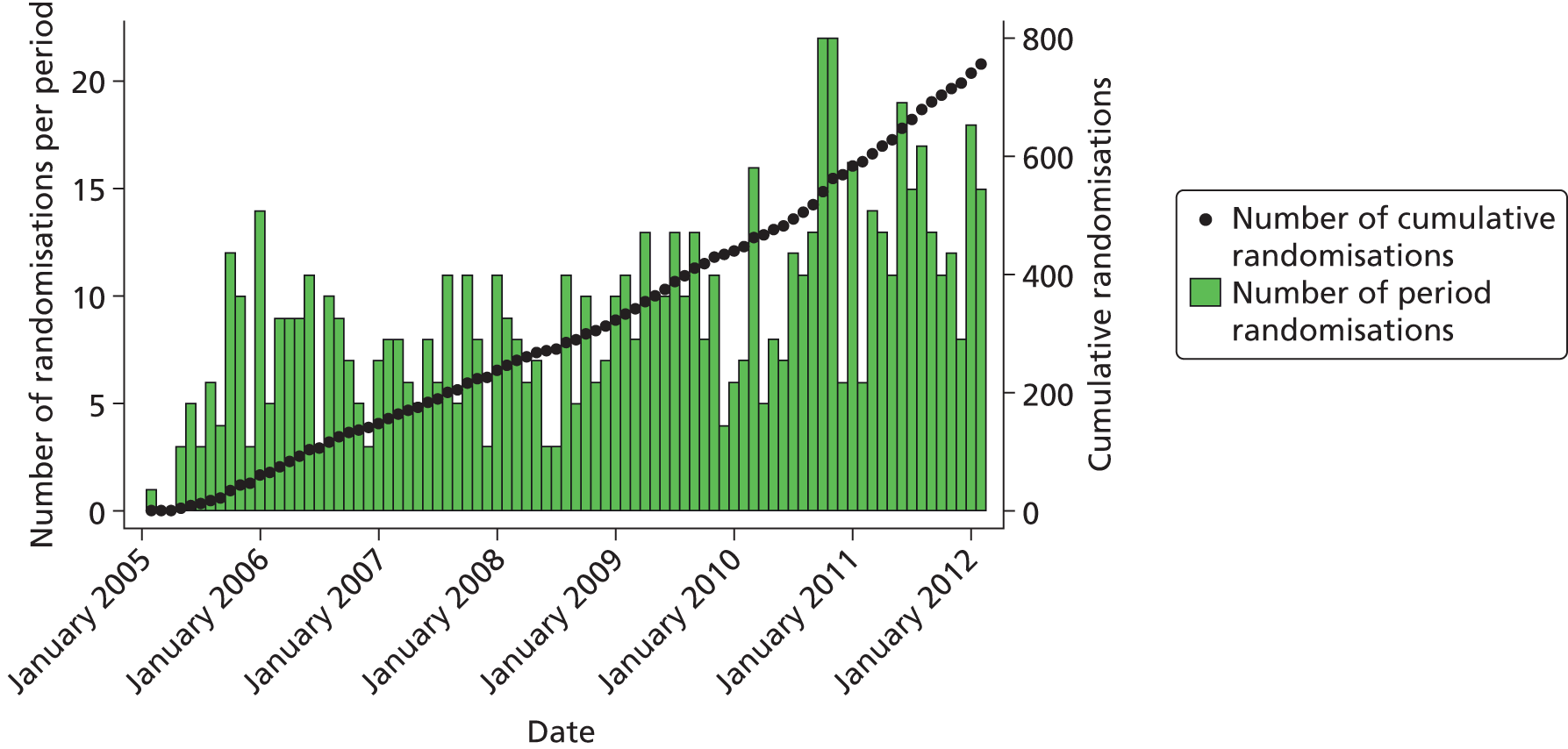

Figure 7 shows trial recruitment both by monthly randomisation periods and cumulatively over the course of the trial. Table 78 (see Appendix 5) shows recruitment by centre.

FIGURE 7.

Recruitment from January 2005 to February 2012.

Losses and exclusions

Ineligible

In total, 27 patients were found to be ineligible following randomisation. Five were randomised to docetaxel alone, 10 to docetaxel + ZA, seven to docetaxel + Sr-89 and five to docetaxel, ZA and Sr-89. All ineligible patients are included in intention-to-treat analysis.

There were three main categories of ineligibilities. These were (1) pre-randomisation blood pressure and blood tests were missed or performed outside of the allowed time frame, (2) progression on trial entry was not appropriately documented and (3) hormone therapies were not stopped at the appropriate time point, for example if bicalutamide had been stopped within 4 weeks of starting trial treatment rather than within 4 weeks of randomisation as stipulated in the eligibility criteria.

Protocol deviations

In total, 71 protocol deviations were reported: 15 in the docetaxel arm, 17 in the docetaxel and ZA arm, 18 in the docetaxel and Sr-89 arm and 21in the docetaxel, ZA and Sr-89 arm.

Table 5 provides a complete summary of all protocol deviations reported during the course of the trial.

| Deviation reason | n (N = 71) |

|---|---|

| Administrative error | 2 |

| Blood pressure consistently not done | 2 |

| Blood pressure not done at baseline | 10 |

| Bloods not done before chemotherapy | 1 |

| Calcium supplements not given with ZA | 1 |

| Calcium supplements stopped at incorrect time for Sr-89 | 1 |

| Chemotherapy capped at wrong BSA | 9 |

| Clinician chose to give lower dose of docetaxel because of patient’s age and comorbidities | 1 |

| Cycle delayed over 14 days | 6 |

| Docetaxel dose capped at BSA of 2 m2 by medical decision to prevent possible excess toxicity | 1 |

| Docetaxel dose escalated | 1 |

| Docetaxel dose reduction not per protocol | 7 |

| Dose not recalculated to BSA at cycle 5: 160 mg given instead of 150 mg | 1 |

| Incorrect dose of strontium | 1 |

| Patient did not receive scheduled ZA | 1 |

| Patient received intended dose of 67.2 mg/m2 because of diarrhoea | 1 |

| Patient received different trial arm | 5 |

| Patient recommenced bicalutamide while on study | 1 |

| Patient sensitive to prednisolone, therefore commenced on 1.5 mg of dexamethasone | 1 |

| Patient stopped taking LHRH agonist | 1 |

| Post-docetaxel assessment not done prior to Sr-89 | 6 |

| Post-docetaxel assessment performed late | 1 |

| Pre-ZA creatinine not done | 2 |

| Premature discontinuation | 2 |

| Sr-89 given at wrong time point | 5 |

| Sr-89 given prior to post-docetaxel assessment | 1 |

| Total | 71 |

Patient withdrawal of consent

Full consent for any further participation in the trial, including follow-up, has been withdrawn by 21 patients. In addition, 28 patients have withdrawn from one or more of the trial substudies. Table 6 contains a breakdown of all non-treatment withdrawals by randomisation arm and Table 7 by comparison group; a complete list of all patients who have withdrawn full consent can be found in Appendix 5.

| Withdrawal | Docetaxel (N = 191) | Docetaxel + ZA (N = 188) | Docetaxel + Sr-89 (N = 190) | Docetaxel + ZA + Sr-89 (N = 188) | Overall (N = 757) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Full withdrawal of consent | 6 | 3.1 | 13 | 6.9 | 6 | 3.2 | 3 | 1.6 | 28 | 3.7 |

| No withdrawal | 178 | 93.2 | 168 | 89.4 | 177 | 93.2 | 174 | 92.6 | 697 | 92.1 |

| Partial withdrawal: blocks | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Partial withdrawal: proteomics | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.3 |

| Partial withdrawal: Qol | 7 | 3.7 | 5 | 2.7 | 7 | 3.7 | 5 | 2.7 | 24 | 3.2 |

| Partial withdrawal: Qol + blocks | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Partial withdrawal: Qol + proteomics | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Total | 191 | 100 | 188 | 100 | 190 | 100 | 188 | 100 | 757 | 100 |

| Withdrawal | No ZA (N = 381) | ZA (N = 376) | No Sr-89 (N = 379) | Sr-89 (N = 378) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Full withdrawal of consent | 12 | 3.1 | 16 | 4.3 | 19 | 5 | 9 | 2.4 |

| No withdrawal | 355 | 93.2 | 342 | 91 | 346 | 91.3 | 351 | 92.9 |

| Partial withdrawal: blocks | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Partial withdrawal: proteomics | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Partial withdrawal: Qol | 14 | 3.7 | 10 | 2.7 | 12 | 3.2 | 12 | 3.2 |

| Partial withdrawal: Qol + blocks | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Partial withdrawal: Qol + proteomics | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Total | 381 | 100 | 376 | 100 | 379 | 100 | 378 | 100 |

Withdrawal of trial treatment

Docetaxel

In total, 408 (54%) patients received fewer than the protocol-defined number of treatment cycles, which was originally six and then increased to 10. In total, 220 (29%) patients received only six cycles because of the original protocol limitation. Table 8 shows the reasons for withdrawal from docetaxel by randomisation arm and Table 9 shows the reasons by comparison group.

| Withdrawal reason | Docetaxel (N = 107) | Docetaxel + ZA (N = 100) | Docetaxel + Sr-89 (N = 106) | Docetaxel + ZA + Sr-89 (N = 95) | Overall (N = 408) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Administration error | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Change in treatment | 4 | 3.7 | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 2.8 | 4 | 4.2 | 12 | 2.9 |

| Clinician decision | 2 | 1.9 | 3 | 3.0 | 5 | 4.7 | 8 | 8.4 | 18 | 4.4 |

| Death | 5 | 4.7 | 3 | 3.0 | 9 | 8.5 | 7 | 7.4 | 24 | 5.9 |

| Disease progression | 35 | 32.7 | 27 | 27.0 | 33 | 31.1 | 23 | 24.2 | 118 | 28.9 |

| Other condition | 36 | 33.6 | 30 | 30.0 | 31 | 29.2 | 24 | 25.3 | 121 | 29.7 |

| Patient choice | 7 | 6.5 | 7 | 7.0 | 8 | 7.5 | 6 | 6.3 | 28 | 6.9 |

| Toxicity | 11 | 10.3 | 18 | 18.0 | 9 | 8.5 | 12 | 12.6 | 50 | 12.3 |

| Unknown | 7 | 6.5 | 10 | 10.0 | 8 | 7.5 | 10 | 10.5 | 35 | 8.6 |

| Total | 107 | 100.0 | 100 | 100.0 | 106 | 100.0 | 95 | 100.0 | 408 | 100.0 |

| Withdrawal reason | No ZA | ZA | No Sr-89 | Sr-89 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Administration error | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Change in treatment | 7 | 3.3 | 5 | 2.6 | 5 | 2.4 | 7 | 3.5 |

| Clinician decision | 7 | 3.3 | 11 | 5.6 | 5 | 2.4 | 13 | 6.5 |

| Death | 14 | 6.6 | 10 | 5.1 | 8 | 3.9 | 16 | 8.0 |

| Disease progression | 68 | 32.0 | 50 | 25.6 | 62 | 29.9 | 56 | 27.9 |

| Other condition | 67 | 31.4 | 54 | 27.7 | 66 | 31.9 | 55 | 27.4 |

| Patient choice | 15 | 7.0 | 13 | 6.7 | 14 | 6.8 | 14 | 6.9 |

| Toxicity | 20 | 9.4 | 30 | 15.4 | 29 | 14.0 | 21 | 10.4 |

| Unknown | 15 | 7.0 | 20 | 10.3 | 17 | 8.2 | 18 | 8.9 |

| Total | 213 | 100.0 | 195 | 100.0 | 207 | 100.0 | 201 | 100.0 |

Strontium-89

Of the 378 patients randomised to receive Sr-89, 253 (67%) did so. The reasons for not receiving Sr-89 are reported in Table 10.

| Withdrawal reason | Docetaxel + Sr-89 (N = 67) | Docetaxel + ZA + Sr-89 (N = 58) | Overall (N = 125) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Administration error | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Change in treatment | 2 | 3.0 | 3 | 5.2 | 5 | 4.0 |

| Clinician decision | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.4 | 2 | 1.6 |

| Death | 6 | 9.0 | 7 | 12.1 | 13 | 10.4 |

| Disease progression | 22 | 32.8 | 12 | 20.7 | 34 | 27.2 |

| Other condition | 19 | 28.4 | 14 | 24.1 | 33 | 26.4 |

| Patient choice | 3 | 4.5 | 2 | 3.4 | 5 | 4.0 |

| Toxicity | 5 | 7.5 | 6 | 10.3 | 11 | 8.8 |

| Unknown | 10 | 14.9 | 11 | 19.0 | 21 | 16.8 |

| Total | 67 | 100.0 | 58 | 100.0 | 125 | 100.0 |

Lost to follow-up

Six patients in total have been reported as being lost to follow-up by site: three randomised to docetaxel alone, one randomised to docetaxel and Sr-89 and two randomised to docetaxel, ZA and Sr-89. Two of these reached the primary end point prior to being lost, one subsequently died and, although some follow-up information remains missing, the death information was obtained.

Data maturity

In total, 618 patients have been followed up until death. Of the remaining 139 patients, 78 have reached the primary CPFS end point, leaving 61 patients alive without having reached the primary end point.

The average follow-up of alive patients was 1.84 years (IQR 1.4–2.4 years), and the average follow-up of the 61 patients who have not reached the primary end point was 1.7 years (IQR 1.4–2.1 years). Table 11 shows the average follow-up of the surviving patients split by randomisation arm.

| Duration of follow-up (years) | Docetaxel (N = 37) | Docetaxel + ZA (N = 32) | Docetaxel + Sr-89 (N = 35) | Docetaxel + ZA + Sr-89 (N = 35) | Overall (N = 139) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 37 | 32 | 35 | 35 | 139 |

| Median | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| IQR | 1.4–2.3 | 1.4–2.3 | 1.6–2.6 | 1.5–2.4 | 1.4–2.4 |

Figure 8 shows the time between the date of randomisation and the date when the patient was last seen and the time from that date to the date of the analysis. Each point represents a patient, and the solid black dots are patients who have not reached the primary end point of the trial. The solid black line indicates where the patients would appear on the graph if they were seen on the date of the analysis. The dashed line represents 6 months before the analysis and the dotted line represents 12 months prior to the analysis.

FIGURE 8.

Duration of follow-up. Pain, pain progression.

Stratification variables

Two stratification factors were used during the randomisation process: centre and ECOG performance status. These can be seen in Tables 12 and 13.

| Stratification variable | Docetaxel (N = 191) | Docetaxel + ZA (N = 188) | Docetaxel + Sr-89 (N = 190) | Docetaxel + ZA + Sr-89 (N = 188) | Overall (N = 757) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| ECOG performance status score | ||||||||||

| 0 | 77 | 40.3 | 76 | 40.4 | 76 | 40.0 | 76 | 40.4 | 305 | 40.3 |

| 1 | 98 | 51.3 | 97 | 51.6 | 97 | 51.1 | 97 | 51.6 | 389 | 51.4 |

| 2 | 16 | 8.4 | 15 | 8.0 | 17 | 8.9 | 15 | 8.0 | 63 | 8.3 |

| Randomisation centre | ||||||||||

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 5 | 2.6 | 5 | 2.7 | 5 | 2.6 | 6 | 3.2 | 21 | 2.8 |

| Ayr Hospital | 5 | 2.6 | 6 | 3.2 | 5 | 2.6 | 5 | 2.7 | 21 | 2.8 |

| Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre | 15 | 7.9 | 15 | 8.0 | 15 | 7.9 | 16 | 8.5 | 61 | 8.1 |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary | 3 | 1.6 | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.1 | 2 | 1.1 | 13 | 1.7 |

| Cheltenham General Hospital | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.1 | 16 | 2.1 |

| Christie Hospital | 30 | 15.7 | 31 | 16.5 | 30 | 15.8 | 31 | 16.5 | 122 | 16.1 |

| Dorset County Hospital | 2 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Forth Valley Royal Hospital | 2 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6 | 0.8 |

| Gloucester Royal Hospital | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Huddersfield Royal Infirmary | 2 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.1 | 3 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.1 | 9 | 1.2 |

| Ipswich Hospital | 5 | 2.6 | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.1 | 17 | 2.2 |

| Maidstone Hospital | 7 | 3.7 | 7 | 3.7 | 7 | 3.7 | 8 | 4.3 | 29 | 3.8 |

| Poole Hospital | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital | 4 | 2.1 | 6 | 2.7 | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.1 | 17 | 2.2 |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital | 32 | 16.8 | 15 | 16.5 | 32 | 16.8 | 31 | 16.5 | 126 | 16.6 |

| Royal Albert Edward Infirmary | 2 | 1.0 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.1 | 7 | 0.9 |

| Royal Bournemouth Hospital | 2 | 1.0 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Royal Derby Hospital | 6 | 3.1 | 31 | 3.2 | 7 | 3.7 | 7 | 3.7 | 26 | 3.4 |

| Royal Free Hospital | 3 | 1.6 | 1 | 2.1 | 2 | 1.1 | 3 | 1.6 | 12 | 1.6 |

| Royal Marsden Hospital London | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Royal Marsden Hospital Sutton | 7 | 3.7 | 0 | 4.3 | 7 | 3.7 | 8 | 4.3 | 30 | 4.0 |

| Royal Preston Hospital | 9 | 4.7 | 2 | 4.8 | 8 | 4.2 | 8 | 4.3 | 34 | 4.5 |

| Southampton General Hospital | 4 | 2.1 | 4 | 1.6 | 4 | 2.1 | 3 | 1.6 | 14 | 1.8 |

| St James’s University Hospital | 7 | 3.7 | 7 | 3.7 | 7 | 3.7 | 6 | 3.2 | 27 | 3.6 |

| Velindre Hospital | 1 | 0.5 | 5 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.1 | 7 | 0.9 |

| Western General Hospital | 28 | 14.7 | 6 | 14.4 | 28 | 14.7 | 28 | 14.9 | 111 | 14.7 |

| Weston General Hospital | 3 | 1.6 | 15 | 1.6 | 4 | 2.1 | 3 | 1.6 | 13 | 1.7 |

| Wishaw General Hospital | 2 | 1.0 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Stratification variable | No ZA (N = 381) | ZA (N = 376) | No Sr-89 (N = 379) | Sr-89 (N = 378) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| ECOG performance status score | ||||||||

| 0 | 153 | 40.2 | 152 | 40.4 | 153 | 40.4 | 152 | 40.2 |

| 1 | 195 | 51.2 | 194 | 51.6 | 195 | 51.5 | 194 | 51.3 |

| 2 | 33 | 8.7 | 30 | 8.0 | 31 | 8.2 | 32 | 8.5 |

| Randomisation centre | ||||||||

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 10 | 2.6 | 11 | 2.9 | 10 | 2.6 | 11 | 2.9 |

| Ayr Hospital | 10 | 2.6 | 11 | 2.9 | 11 | 2.9 | 10 | 2.6 |

| Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre | 30 | 7.9 | 31 | 8.2 | 30 | 7.9 | 31 | 8.2 |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary | 7 | 1.8 | 6 | 1.6 | 7 | 1.8 | 6 | 1.6 |

| Cheltenham General Hospital | 8 | 2.1 | 8 | 2.1 | 8 | 2.1 | 8 | 2.1 |

| Christie Hospital | 60 | 15.7 | 62 | 16.5 | 61 | 16.1 | 61 | 16.1 |

| Dorset County Hospital | 3 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Forth Valley Royal Hospital | 4 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Gloucester Royal Hospital | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Huddersfield Royal Infirmary | 5 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.1 | 4 | 1.1 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Ipswich Hospital | 9 | 2.4 | 8 | 2.1 | 9 | 2.4 | 8 | 2.1 |

| Maidstone Hospital | 14 | 3.7 | 15 | 4.0 | 14 | 3.7 | 15 | 4.0 |

| Poole Hospital | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital | 8 | 2.1 | 9 | 2.4 | 9 | 2.4 | 8 | 2.1 |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital | 64 | 16.8 | 62 | 16.5 | 63 | 16.6 | 63 | 16.7 |

| Royal Albert Edward Infirmary | 4 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.8 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Royal Bournemouth Hospital | 3 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Royal Derby Hospital | 13 | 3.4 | 13 | 3.5 | 12 | 3.2 | 14 | 3.7 |

| Royal Free Hospital | 5 | 1.3 | 7 | 1.9 | 7 | 1.8 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Royal Marsden Hospital London | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Royal Marsden Hospital Sutton | 14 | 3.7 | 16 | 4.3 | 15 | 4.0 | 15 | 4.0 |

| Royal Preston Hospital | 17 | 4.5 | 17 | 4.5 | 18 | 4.7 | 16 | 4.2 |

| Southampton General Hospital | 8 | 2.1 | 6 | 1.6 | 7 | 1.8 | 7 | 1.9 |

| St James’s University Hospital | 14 | 3.7 | 13 | 3.5 | 14 | 3.7 | 13 | 3.4 |

| Velindre Hospital | 3 | 0.8 | 4 | 1.1 | 3 | 0.8 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Western General Hospital | 56 | 14.7 | 55 | 14.6 | 55 | 14.5 | 56 | 14.8 |

| Weston General Hospital | 7 | 1.8 | 6 | 1.6 | 6 | 1.6 | 7 | 1.9 |

| Wishaw General Hospital | 3 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.5 |

Baseline data

In total, 752 (99%) baseline forms were returned. Table 14 shows the baseline information recorded on the on-study form by randomisation arm.

| Patient characteristic | Randomisation arm | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docetaxel (N = 191) | Docetaxel + ZA (N = 187) | Docetaxel + Sr-89 (N = 188) | Docetaxel + ZA + Sr-89 (N = 186) | Overall (N = 752) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| ECOG performance status score | ||||||||||

| 0 | 76 | 43.4 | 71 | 40.8 | 70 | 39.3 | 64 | 37.0 | 281 | 40.1 |

| 1 | 83 | 47.4 | 88 | 50.6 | 90 | 50.6 | 95 | 54.9 | 356 | 50.9 |

| 2 | 15 | 8.6 | 15 | 8.6 | 18 | 10.1 | 14 | 8.1 | 62 | 8.9 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Missing | 16 | – | 13 | – | 10 | – | 13 | – | 52 | – |

| Diagnostic indicator | ||||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 156 | 81.7 | 146 | 78.9 | 150 | 80.2 | 149 | 81.0 | 601 | 80.5 |

| PSA only | 35 | 18.3 | 39 | 21.1 | 37 | 19.8 | 35 | 19.0 | 146 | 19.5 |

| Missing | 0 | – | 2 | – | 1 | – | 2 | – | 5 | – |

| Staging: T | ||||||||||

| T1 | 2 | 1.4 | 5 | 3.8 | 2 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.7 | 10 | 1.9 |

| T1b | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.4 |

| T1c | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.7 |

| T2 | 19 | 13.3 | 16 | 12.2 | 11 | 9.1 | 17 | 12.1 | 63 | 11.8 |

| T2a | 2 | 1.4 | 2 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.7 |

| T2b | 4 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.4 | 8 | 1.5 |

| T3 | 54 | 37.8 | 53 | 40.5 | 49 | 40.5 | 63 | 44.7 | 219 | 40.9 |

| T3a | 4 | 2.8 | 3 | 2.3 | 5 | 4.1 | 4 | 2.8 | 16 | 3.0 |

| T3b | 12 | 8.4 | 10 | 7.6 | 10 | 8.3 | 9 | 6.4 | 41 | 7.6 |

| T4 | 28 | 19.6 | 22 | 16.8 | 20 | 16.5 | 25 | 17.7 | 95 | 17.7 |

| TX | 16 | 11.2 | 18 | 13.7 | 20 | 16.5 | 18 | 12.8 | 72 | 13.4 |

| T2c | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Missing | 48 | – | 56 | – | 67 | – | 45 | – | 216 | – |

| Staging: M | ||||||||||

| M0 | 44 | 30.8 | 41 | 31.3 | 33 | 27.3 | 40 | 28.4 | 158 | 29.5 |

| M1a | 20 | 14.0 | 20 | 15.3 | 22 | 18.2 | 21 | 14.9 | 83 | 15.5 |

| M1b | 8 | 5.6 | 7 | 5.3 | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 1.4 | 20 | 3.7 |

| M1c | 4 | 2.8 | 10 | 7.6 | 6 | 5.0 | 5 | 3.5 | 25 | 4.7 |

| MX | 26 | 18.2 | 14 | 10.7 | 17 | 14.0 | 26 | 18.4 | 83 | 15.5 |

| M1 | 41 | 28.7 | 39 | 29.8 | 40 | 33.1 | 47 | 33.3 | 167 | 31.2 |

| Missing | 48 | – | 56 | – | 67 | – | 45 | – | 216 | – |

| Staging: N | ||||||||||

| N0 | 59 | 41.3 | 57 | 43.5 | 46 | 38.0 | 58 | 41.1 | 220 | 41.0 |

| N1 | 42 | 29.4 | 28 | 21.4 | 32 | 26.4 | 39 | 27.7 | 141 | 26.3 |

| NX | 42 | 29.4 | 46 | 35.1 | 43 | 35.5 | 44 | 31.2 | 175 | 32.6 |

| Missing | 48 | – | 56 | – | 67 | – | 45 | – | 216 | – |

| Gleason score | ||||||||||

| 3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 4 | 2 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 2 | 1.4 | 3 | 2.1 | 2 | 1.4 | 3 | 2.2 | 10 | 1.8 |

| 6 | 9 | 6.3 | 12 | 8.4 | 12 | 8.7 | 6 | 4.5 | 39 | 7.0 |

| 7 | 43 | 29.9 | 48 | 33.6 | 39 | 28.3 | 41 | 30.6 | 171 | 30.6 |

| 8 | 30 | 20.8 | 24 | 16.8 | 35 | 25.4 | 25 | 18.7 | 114 | 20.4 |

| 9 | 57 | 39.6 | 55 | 38.5 | 41 | 29.7 | 54 | 40.3 | 207 | 37.0 |

| 10 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.7 | 8 | 5.8 | 4 | 3.0 | 14 | 2.5 |

| Missing | 47 | – | 44 | – | 50 | – | 52 | – | 193 | – |

| Prior radiotherapy received? | ||||||||||

| No | 114 | 59.7 | 107 | 57.2 | 95 | 50.8 | 98 | 52.7 | 414 | 55.1 |

| Yes | 77 | 40.3 | 80 | 42.8 | 92 | 49.2 | 88 | 47.3 | 337 | 44.9 |

| Missing | 0 | – | 0 | – | 1 | – | 0 | – | 1 | – |

| Method of castration | ||||||||||

| Surgery | 5 | 2.6 | 4 | 2.1 | 3 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.1 | 14 | 1.9 |

| Ongoing LHRH agonists | 186 | 97.4 | 183 | 97.9 | 185 | 98.4 | 184 | 98.9 | 738 | 98.1 |

| Anti-androgen received? | ||||||||||

| No | 10 | 5.2 | 19 | 10.2 | 17 | 9.1 | 14 | 7.6 | 60 | 8.0 |

| Yes | 181 | 94.8 | 168 | 89.8 | 170 | 90.9 | 171 | 92.4 | 690 | 92.0 |

| Missing | 0 | – | 0 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 2 | – |

| Flutamide, nilutamide or cyproterone acetate received? | ||||||||||

| No | 151 | 83.9 | 141 | 83.9 | 142 | 84.0 | 133 | 77.8 | 567 | 82.4 |

| Yes | 29 | 16.1 | 27 | 16.1 | 27 | 16.0 | 38 | 22.2 | 121 | 17.6 |

| Missing | 11 | – | 19 | – | 19 | – | 15 | – | 64 | – |

| Bicalutamide received? | ||||||||||

| No | 11 | 6.1 | 14 | 8.3 | 8 | 4.7 | 15 | 8.8 | 48 | 7.0 |

| Yes | 170 | 93.9 | 154 | 91.7 | 162 | 95.3 | 156 | 91.2 | 642 | 93.0 |

| Missing | 10 | – | 19 | – | 18 | – | 15 | – | 62 | – |

| Method of progression at study entry | ||||||||||

| All | 26 | 13.7 | 27 | 14.6 | 27 | 14.4 | 27 | 14.5 | 107 | 14.3 |

| Elevated PSA | 42 | 22.1 | 48 | 25.9 | 42 | 22.3 | 44 | 23.7 | 176 | 23.5 |

| New lesion | 15 | 7.9 | 16 | 8.6 | 21 | 11.2 | 19 | 10.2 | 71 | 9.5 |

| Objective | 5 | 2.6 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 8 | 1.1 |

| Objective + new lesion | 3 | 1.6 | 4 | 2.2 | 7 | 3.7 | 5 | 2.7 | 19 | 2.5 |

| PSA + new lesion | 94 | 49.5 | 85 | 45.9 | 82 | 43.6 | 88 | 47.3 | 349 | 46.6 |

| PSA + objective | 5 | 2.6 | 4 | 2.2 | 8 | 4.3 | 2 | 1.1 | 19 | 2.5 |

| Missing | 1 | – | 2 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 3 | – |

| Baseline pain diary completed? | ||||||||||

| No | 30 | 15.7 | 37 | 19.8 | 42 | 22.3 | 34 | 18.3 | 143 | 19.0 |

| Yes | 161 | 84.3 | 150 | 80.2 | 146 | 77.7 | 152 | 81.7 | 609 | 81.0 |

| Baseline QoL booklet completed? | ||||||||||

| No | 22 | 11.6 | 19 | 10.3 | 28 | 14.9 | 25 | 13.7 | 94 | 12.6 |

| Yes | 168 | 88.4 | 165 | 89.7 | 160 | 85.1 | 158 | 86.3 | 651 | 87.4 |

| Missing | 1 | – | 3 | – | 0 | – | 3 | – | 7 | – |

Table 15 repeats the baseline characteristics reported above but split by comparison groups.

| Patient characteristic | Comparison group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No ZA (N = 379) | ZA (N = 373) | No Sr-89 (N = 378) | Sr-89 (N = 374) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| ECOG performance status score | ||||||||

| 0 | 146 | 41.4 | 135 | 38.9 | 147 | 42.1 | 134 | 38.2 |

| 1 | 173 | 49.0 | 183 | 52.7 | 171 | 49.0 | 185 | 52.7 |

| 2 | 33 | 9.3 | 29 | 8.4 | 30 | 8.6 | 32 | 9.1 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 26 | – | 26 | – | 29 | – | 23 | – |

| Diagnostic indicator | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 306 | 81.0 | 295 | 79.9 | 302 | 80.3 | 299 | 80.6 |

| PSA only | 72 | 19.0 | 74 | 20.1 | 74 | 19.7 | 72 | 19.4 |

| Missing | 1 | – | 4 | – | 2 | – | 3 | – |

| Staging: T | ||||||||

| T1 | 4 | 1.5 | 6 | 2.2 | 7 | 2.6 | 3 | 1.1 |

| T1b | 2 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 |

| T1c | 2 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.4 | 3 | 1.1 |

| T2 | 30 | 11.4 | 33 | 12.1 | 35 | 12.8 | 28 | 10.7 |

| T2a | 2 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.7 | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| T2b | 5 | 1.9 | 3 | 1.1 | 5 | 1.8 | 3 | 1.1 |

| T3 | 103 | 39.0 | 116 | 42.6 | 107 | 39.1 | 112 | 42.7 |

| T3a | 9 | 3.4 | 7 | 2.6 | 7 | 2.6 | 9 | 3.4 |

| T3b | 22 | 8.3 | 19 | 7 | 22 | 8.0 | 19 | 7.3 |

| T4 | 48 | 18.2 | 47 | 17.3 | 50 | 18.2 | 45 | 17.2 |

| TX | 36 | 13.6 | 36 | 13.2 | 34 | 12.4 | 38 | 14.5 |

| T2c | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Missing | 115 | – | 101 | – | 104 | – | 112 | – |

| Staging: M | ||||||||

| M0 | 77 | 29.2 | 81 | 29.8 | 85 | 31.0 | 73 | 27.9 |

| M1a | 42 | 15.9 | 41 | 15.1 | 40 | 14.6 | 43 | 16.4 |

| M1b | 11 | 4.2 | 9 | 3.3 | 15 | 5.5 | 5 | 1.9 |

| M1c | 10 | 3.8 | 15 | 5.5 | 14 | 5.1 | 11 | 4.2 |

| MX | 43 | 16.3 | 40 | 14.7 | 40 | 14.6 | 43 | 16.4 |

| M1 | 81 | 30.7 | 86 | 31.6 | 80 | 29.2 | 87 | 33.2 |

| Missing | 115 | – | 101 | – | 104 | – | 112 | – |

| Staging: N | ||||||||

| N0 | 105 | 39.8 | 115 | 42.3 | 116 | 42.3 | 104 | 39.7 |

| N1 | 74 | 28.0 | 67 | 24.6 | 70 | 25.5 | 71 | 27.1 |

| NX | 85 | 32.2 | 90 | 33.1 | 88 | 32.1 | 87 | 33.2 |

| Missing | 115 | – | 101 | – | 104 | – | 112 | – |

| Gleason score | ||||||||

| 3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 |

| 4 | 3 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.4 |

| 5 | 4 | 1.4 | 6 | 2.2 | 5 | 1.7 | 5 | 1.8 |

| 6 | 21 | 7.4 | 18 | 6.5 | 21 | 7.3 | 18 | 6.6 |

| 7 | 82 | 29.1 | 89 | 32.1 | 91 | 31.7 | 80 | 29.4 |

| 8 | 65 | 23.0 | 49 | 17.7 | 54 | 18.8 | 60 | 22.1 |

| 9 | 98 | 34.8 | 109 | 39.4 | 112 | 39.0 | 95 | 34.9 |

| 10 | 9 | 3.2 | 5 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.7 | 12 | 4.4 |

| Missing | 97 | – | 96 | – | 91 | – | 102 | – |

| Prior radiotherapy received? | ||||||||

| No | 209 | 55.3 | 205 | 55.0 | 221 | 58.5 | 193 | 51.7 |

| Yes | 169 | 44.7 | 168 | 45.0 | 157 | 41.5 | 180 | 48.3 |

| Missing | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| Method of castration | ||||||||

| Surgery | 8 | 2.1 | 6 | 1.6 | 9 | 2.4 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Ongoing LHRH agonists | 371 | 97.9 | 367 | 98.4 | 369 | 97.6 | 369 | 98.7 |

| Anti-androgen received? | ||||||||

| No | 27 | 7.1 | 33 | 8.9 | 29 | 7.7 | 31 | 8.3 |

| Yes | 351 | 92.9 | 339 | 91.1 | 349 | 92.3 | 341 | 91.7 |

| Flutamide, nilutamide or cyproterone acetate received? | ||||||||

| No | 293 | 84.0 | 274 | 80.8 | 292 | 83.9 | 275 | 80.9 |

| Yes | 56 | 16.0 | 65 | 19.2 | 56 | 16.1 | 65 | 19.1 |

| Missing | 30 | – | 34 | – | 30 | – | 34 | – |

| Bicalutamide received? | ||||||||

| No | 19 | 5.4 | 29 | 8.6 | 25 | 7.2 | 23 | 6.7 |

| Yes | 332 | 94.6 | 310 | 91.4 | 324 | 92.8 | 318 | 93.3 |

| Missing | 28 | – | 34 | – | 29 | – | 33 | – |

| Method of progression at study entry | ||||||||

| All | 53 | 14.0 | 54 | 14.6 | 53 | 14.1 | 54 | 14.4 |

| Elevated PSA | 84 | 22.2 | 92 | 24.8 | 90 | 24.0 | 86 | 23.0 |

| New lesion | 36 | 9.5 | 35 | 9.4 | 31 | 8.3 | 40 | 10.7 |

| Objective | 6 | 1.6 | 2 | 0.5 | 6 | 1.6 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Objective + new lesion | 10 | 2.6 | 9 | 2.4 | 7 | 1.9 | 12 | 3.2 |

| PSA + new lesion | 176 | 46.6 | 173 | 46.6 | 179 | 47.7 | 170 | 45.5 |

| PSA + objective | 13 | 3.4 | 6 | 1.6 | 9 | 2.4 | 10 | 2.7 |

| Missing | 1 | – | 2 | – | 3 | – | 0 | – |

| Baseline pain diary completed? | ||||||||

| No | 72 | 19.0 | 71 | 19.0 | 67 | 17.7 | 76 | 20.3 |

| Yes | 307 | 81.0 | 302 | 81.0 | 311 | 82.3 | 298 | 79.7 |

| Baseline QoL booklet completed? | ||||||||

| No | 50 | 13.2 | 44 | 12.0 | 41 | 11.0 | 53 | 14.3 |

| Yes | 328 | 86.8 | 323 | 88.0 | 333 | 89.0 | 318 | 85.7 |

| Missing | 1 | – | 6 | – | 4 | – | 3 | – |

| n | n | n | n | |||||

| Age at randomisation (years) | ||||||||

| N | 379 | 373 | 378 | 374 | ||||

| Median | 68.4 | 69.0 | 68.9 | 68.6 | ||||

| IQR | 63.6–73.6 | 64.1–73.4 | 64.3–73.8 | 63.2–73.1 | ||||

| Range | 45.9–83.8 | 45.0–83.7 | 45.0–83.8 | 49.4–82.0 | ||||

| Days from baseline ECOG to randomisation | ||||||||

| N | 349 | 339 | 341 | 347 | ||||

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | ||||

| IQR | 0.0–8.0 | 0.0–8.0 | 0.0–8.0 | 0.0–7.0 | ||||

| Range | 0.0–367.0 | 0.0–73.0 | 0.0–51.0 | 0.0–367.0 | ||||

| Months from diagnosis to randomisation | ||||||||

| N | 379 | 373 | 378 | 374 | ||||

| Median | 30.1 | 37.8 | 34.0 | 33.3 | ||||

| IQR | 18.7–61.6 | 20.2–62.1 | 19.2–57.0 | 19.0–70.1 | ||||

| Range | 1.3–246.2 | 0.3–190.3 | 0.3–246.2 | 0.4–187.2 | ||||

Treatment

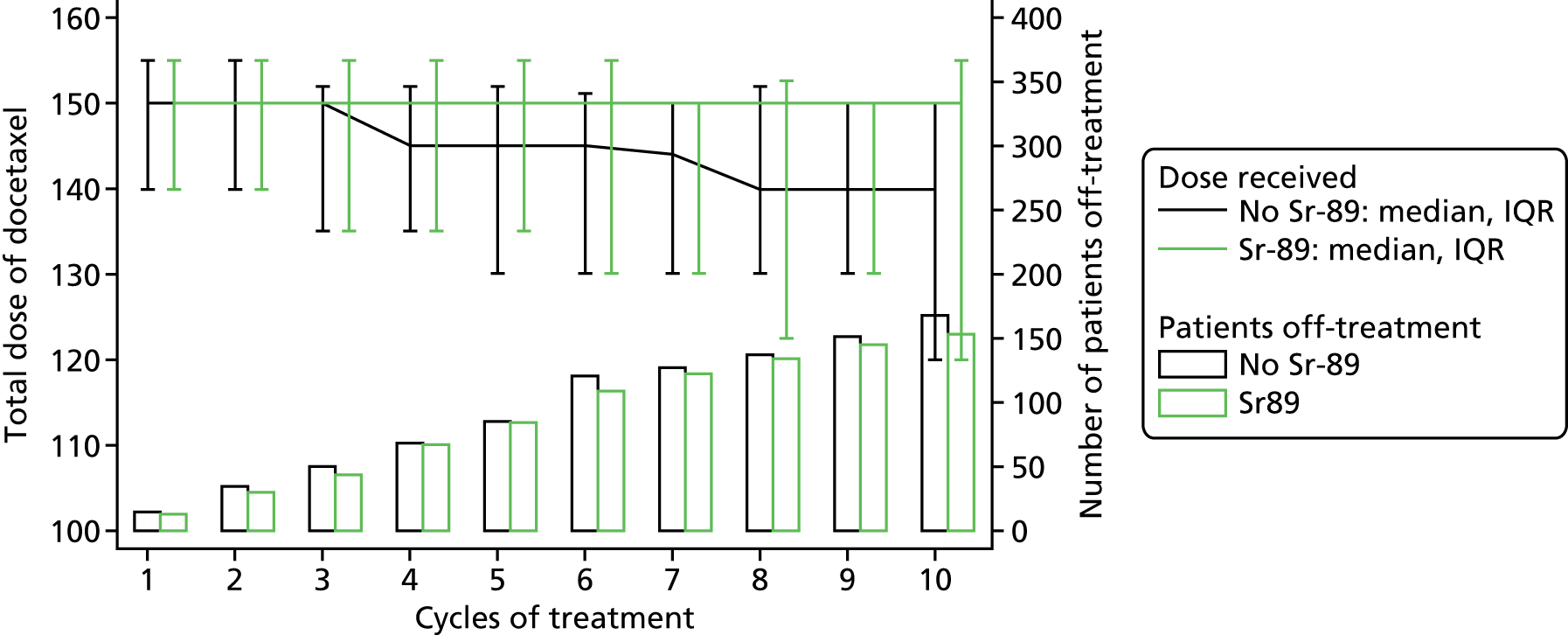

In total, 4488 treatment forms were returned. Table 16 shows the treatment information split by cycle for each of the randomisation arms and Table 17 shows the same details split by comparison groups. The data show that only 17% of patients received 10 cycles of docetaxel, with 45% stopping at cycle 6. It is important to take into account that 29% of patients were only ever intended to receive six cycles of treatment, as previously detailed in Withdrawal of trial treatment, docetaxel.

| Treatment details | Cycle | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 (N = 729) | C2 (N = 692) | C3 (N = 665) | C4 (N = 623) | C5 (N = 588) | C6 (N = 527) | C7 (N = 202) | C8 (N = 179) | C9 (N = 154) | C10 (N = 129) | |||||||||||

| Docetaxel: days since randomisation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n | 186 | 179 | 170 | 158 | 148 | 128 | 45 | 38 | 34 | 26 | ||||||||||

| Median | 6.0 | 28.0 | 49.0 | 70.0 | 91.0 | 112.0 | 133.0 | 154.0 | 175.5 | 196.0 | ||||||||||

| IQR | 2.0–8.0 | 24.0–31.0 | 45.0–54.0 | 67.0–76.0 | 88.0–98.0 | 110.0–119.0 | 130.0–140.0 | 151.0–162.0 | 173.0–183.0 | 194.0–204.0 | ||||||||||

| Docetaxel + ZA: days since randomisation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n | 180 | 167 | 163 | 156 | 148 | 132 | 57 | 53 | 43 | 34 | ||||||||||

| Median | 6.0 | 27.0 | 49.0 | 70.0 | 91.0 | 113.0 | 135.0 | 156.0 | 178.0 | 199.0 | ||||||||||

| IQR | 3.0–9.0 | 24.0–32.0 | 45.0–53.0 | 67.5–75.0 | 88.0–97.0 | 110.0–119.0 | 131.0–139.0 | 152.0–161.0 | 173.0–183.0 | 194.0–203.0 | ||||||||||

| Docetaxel + Sr-89: days since randomisation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n | 181 | 175 | 166 | 152 | 144 | 130 | 49 | 44 | 40 | 35 | ||||||||||

| Median | 7.0 | 28.0 | 49.0 | 70.0 | 92.0 | 113.0 | 174.0 | 195.5 | 218.0 | 241.0 | ||||||||||

| IQR | 3.0–9.0 | 25.0–31.0 | 46.0–53.0 | 68.0–74.0 | 89.0–97.0 | 110.0–118.0 | 170.0–183.0 | 190.5–205.0 | 212.5–228.0 | 233.0–254.0 | ||||||||||

| Docetaxel + ZA + Sr-89: days since randomisation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n | 182 | 171 | 166 | 157 | 148 | 137 | 51 | 44 | 37 | 34 | ||||||||||

| Median | 6.0 | 27.0 | 49.0 | 70.0 | 91.0 | 112.0 | 175.0 | 197.0 | 217.0 | 239.5 | ||||||||||

| IQR | 2.0–8.0 | 24.0–30.0 | 46.0–53.0 | 67.0–75.0 | 88.5–96.0 | 110.0–118.0 | 169.0–185.0 | 189.5–207.0 | 211.0–229.0 | 232.0–250.0 | ||||||||||

| Docetaxel: total dose (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n | 186 | 179 | 169 | 158 | 148 | 128 | 44 | 38 | 34 | 26 | ||||||||||

| Median | 150.0 | 147.0 | 145.0 | 145.0 | 145.0 | 145.0 | 146.5 | 140.0 | 142.0 | 139.5 | ||||||||||

| IQR | 140.0–155.0 | 140.0–152.0 | 135.0–150.0 | 130.0–150.0 | 130.0–150.0 | 130.0–150.0 | 130.0–150.0 | 120.0–150.0 | 120.0–150.0 | 120.0–150.0 | ||||||||||

| Docetaxel + ZA: total dose (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n | 180 | 167 | 162 | 155 | 148 | 132 | 57 | 53 | 43 | 34 | ||||||||||

| Median | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 148.0 | 148.0 | 143.0 | 142.0 | 140.0 | 140.0 | ||||||||||

| IQR | 140.0–156.0 | 140.0–155.0 | 140.0–155.0 | 135.0–152.0 | 130.0–155.0 | 130.0–155.0 | 130.0–152.0 | 130.0–152.0 | 130.0–150.0 | 130.0–150.0 | ||||||||||

| Docetaxel + Sr-89: total dose (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n | 181 | 175 | 166 | 152 | 144 | 130 | 49 | 44 | 40 | 35 | ||||||||||

| Median | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 148.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 149.0 | 150.0 | ||||||||||

| IQR | 140.0–158.0 | 138.0–156.0 | 135.0–156.0 | 135.0–156.0 | 130.0–156.0 | 130.0–156.0 | 130.0–156.0 | 122.5–156.0 | 124.5–155.5 | 120.0–158.0 | ||||||||||

| Docetaxel + ZA + Sr-89: total dose (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| n | 182 | 171 | 166 | 157 | 148 | 137 | 51 | 44 | 37 | 34 | ||||||||||

| Median | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 | ||||||||||

| IQR | 140.0–155.0 | 140.0–155.0 | 135.0–155.0 | 135.0–155.0 | 135.0–155.0 | 135.0–155.0 | 130.0–150.0 | 125.0–150.0 | 135.0–150.0 | 120.0–150.0 | ||||||||||

| Treatment details | C1 (N = 729) | C2 (N = 692) | C3 (N = 665) | C4 (N = 623) | C5 (N = 588) | C6 (N = 527) | C7 (N = 202) | C8 (N = 179) | C9 (N = 154) | C10 (N = 129) | ||||||||||

| Score | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Docetaxel: ECOG performance status score | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 70 | 46.4 | 65 | 42.2 | 51 | 36.2 | 53 | 40.2 | 52 | 44.1 | 40 | 37.7 | 14 | 37.8 | 12 | 34.3 | 10 | 32.3 | 8 | 34.8 |

| 1 | 70 | 46.4 | 75 | 48.7 | 80 | 56.7 | 68 | 51.5 | 62 | 52.5 | 63 | 59.4 | 20 | 54.1 | 20 | 57.1 | 19 | 61.3 | 14 | 60.9 |

| 2 | 9 | 6.0 | 14 | 9.1 | 10 | 7.1 | 10 | 7.6 | 3 | 2.5 | 3 | 2.8 | 3 | 8.1 | 3 | 8.6 | 2 | 6.5 | 1 | 4.3 |

| 3 | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 578 | – | 538 | – | 524 | – | 491 | – | 470 | – | 421 | – | 165 | – | 144 | – | 123 | – | 106 | – |

| Docetaxel + ZA: ECOG performance status score | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 67 | 43.8 | 59 | 43.1 | 53 | 39.8 | 49 | 38.0 | 47 | 39.5 | 40 | 37.4 | 23 | 45.1 | 24 | 48.0 | 24 | 64.9 | 14 | 45.2 |

| 1 | 77 | 50.3 | 70 | 51.1 | 71 | 53.4 | 71 | 55.0 | 65 | 54.6 | 65 | 60.7 | 27 | 52.9 | 22 | 44.0 | 11 | 29.7 | 17 | 54.8 |

| 2 | 9 | 5.9 | 8 | 5.8 | 8 | 6.0 | 8 | 6.2 | 7 | 5.9 | 2 | 1.9 | 1 | 2.0 | 4 | 8.0 | 2 | 5.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 576 | – | 555 | – | 532 | – | 494 | – | 469 | – | 420 | – | 151 | – | 129 | – | 117 | – | 98 | – |

| Docetaxel + Sr-89: ECOG performance status score | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 66 | 44.3 | 59 | 40.4 | 59 | 44.4 | 58 | 44.3 | 42 | 33.6 | 37 | 35.2 | 19 | 41.3 | 19 | 50.0 | 17 | 47.2 | 9 | 30 |

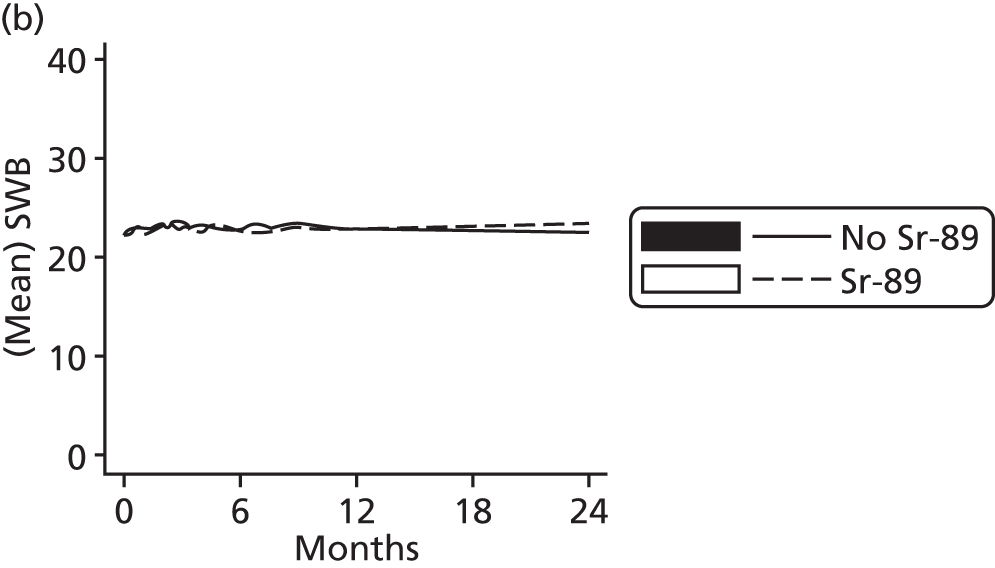

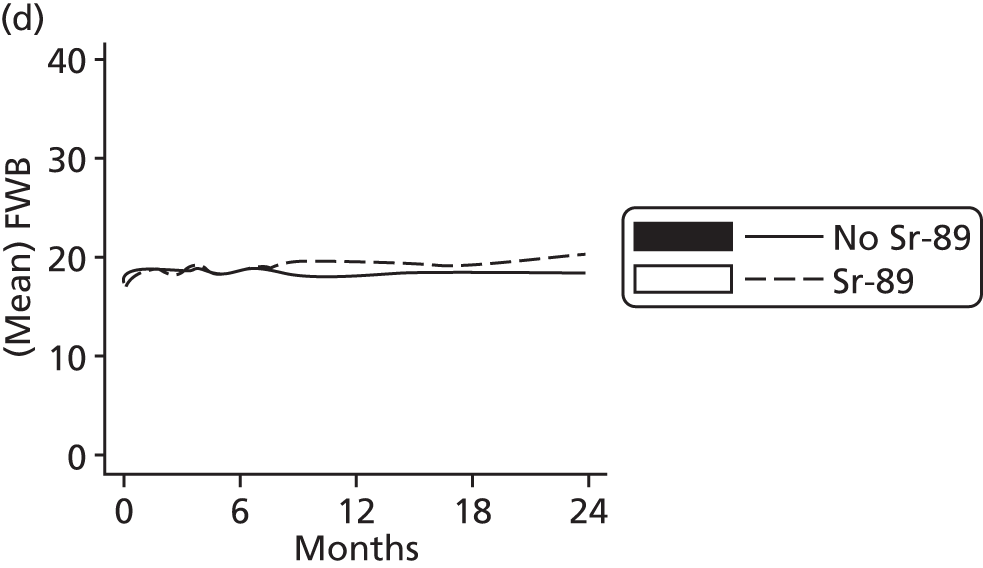

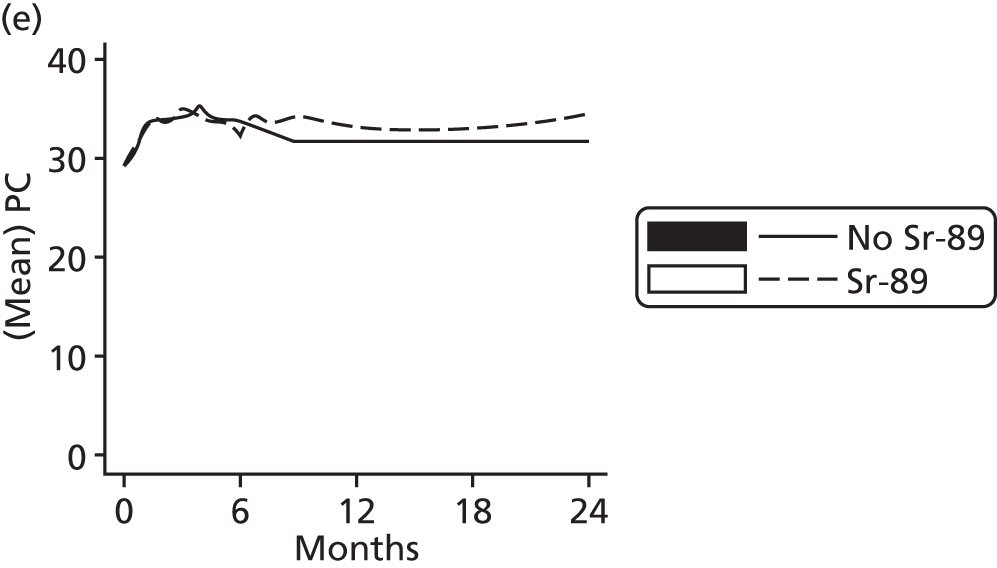

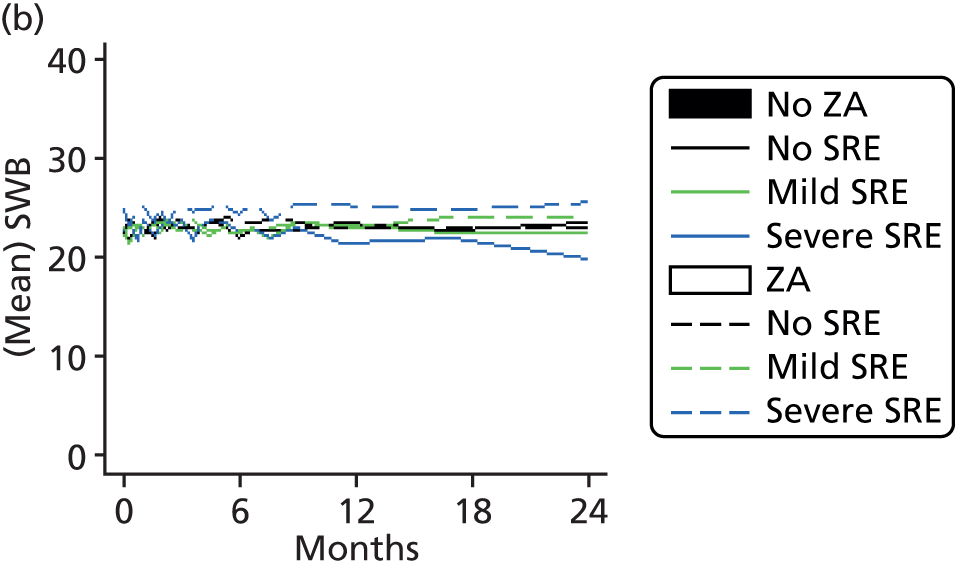

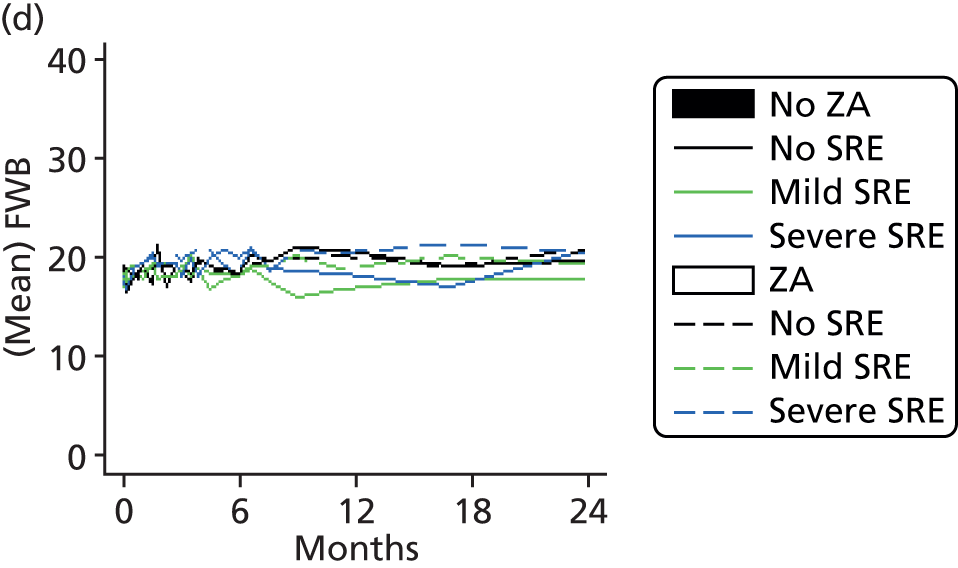

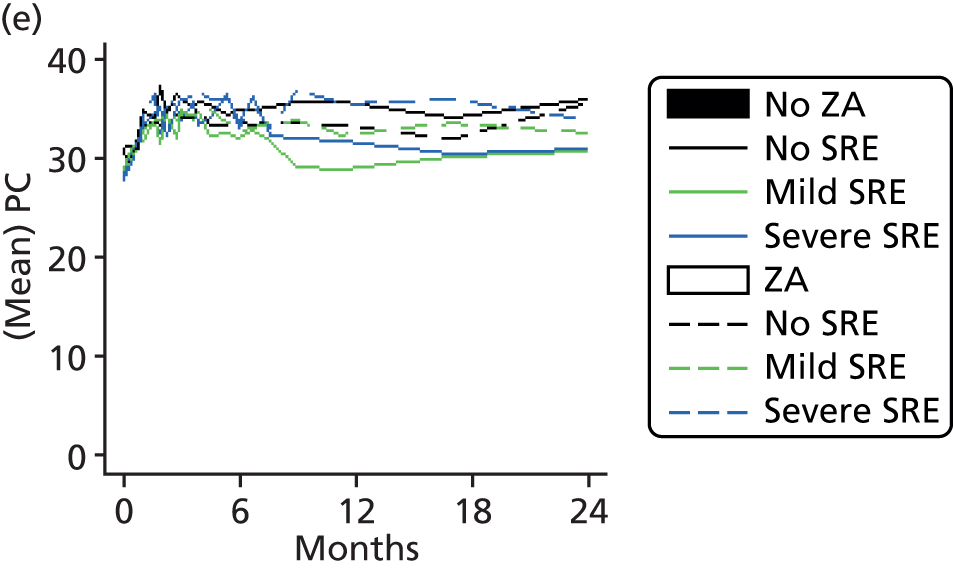

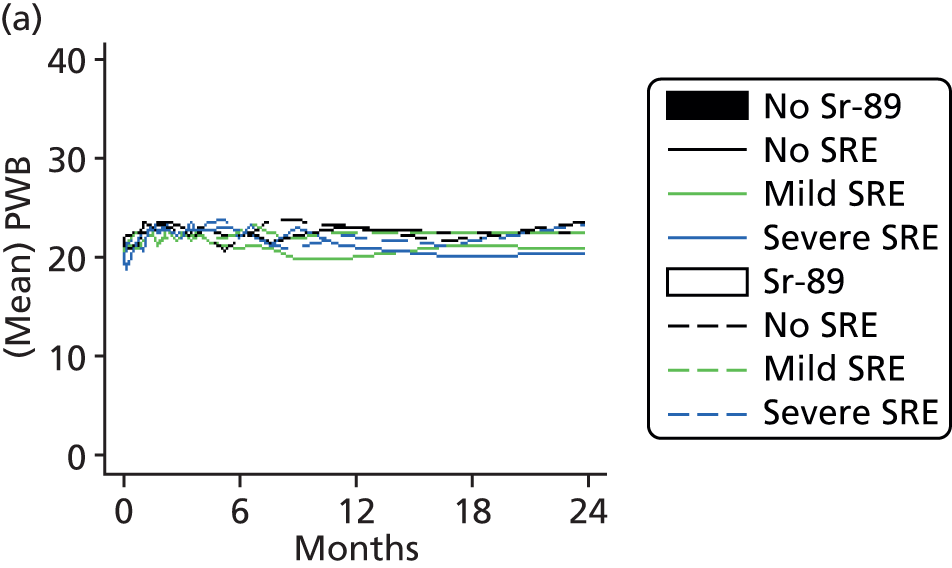

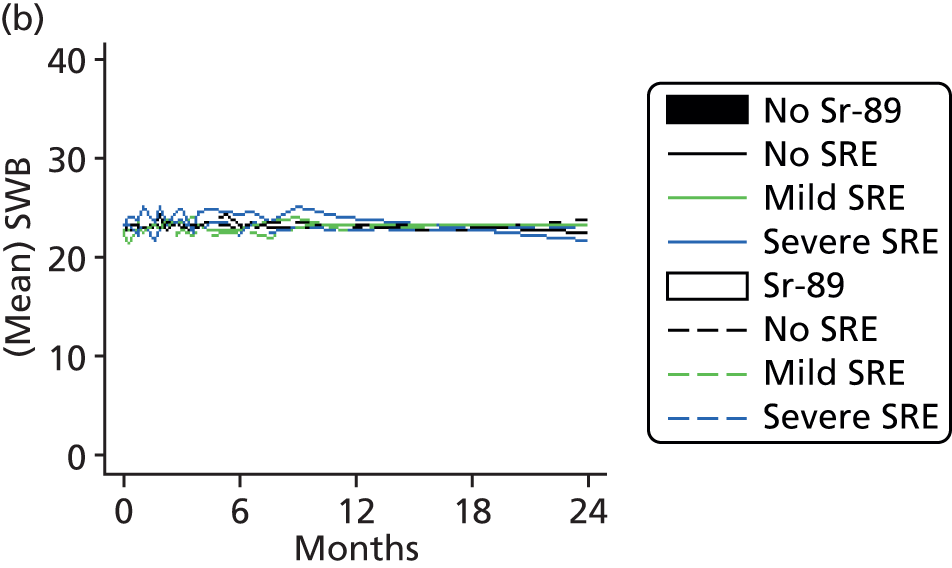

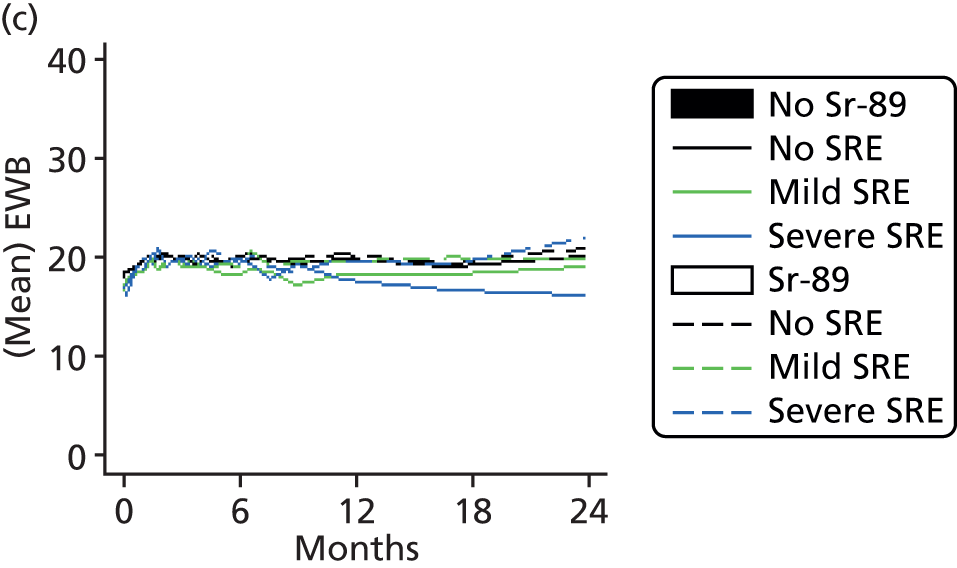

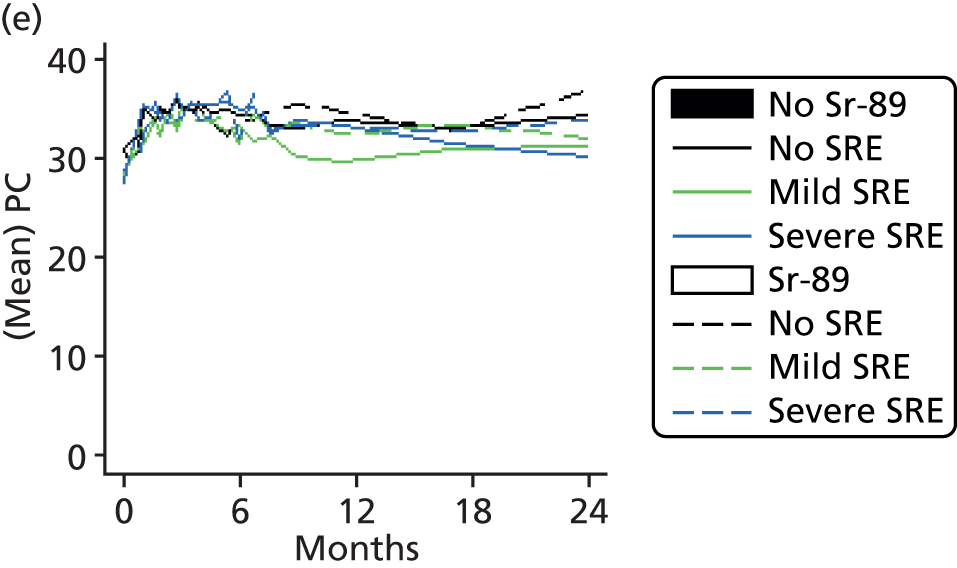

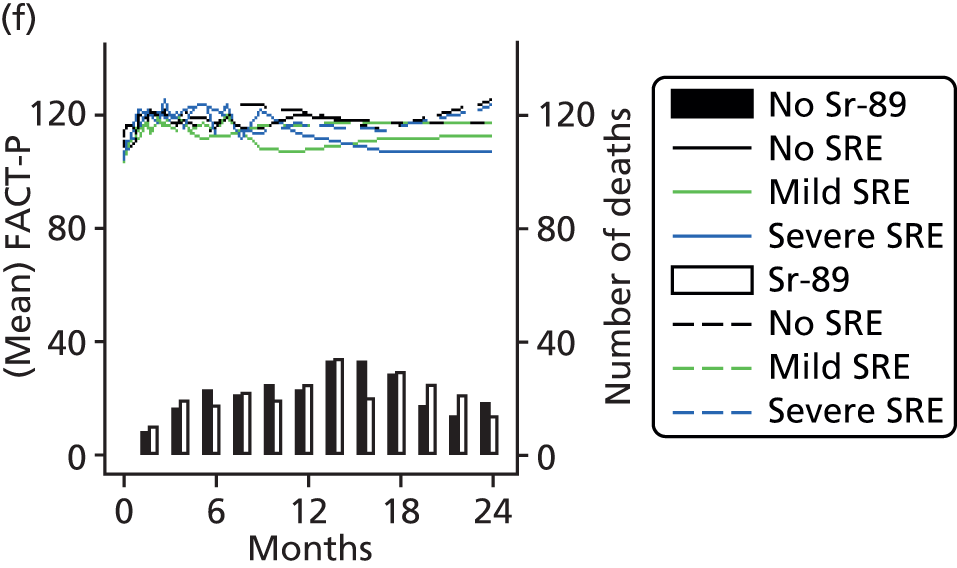

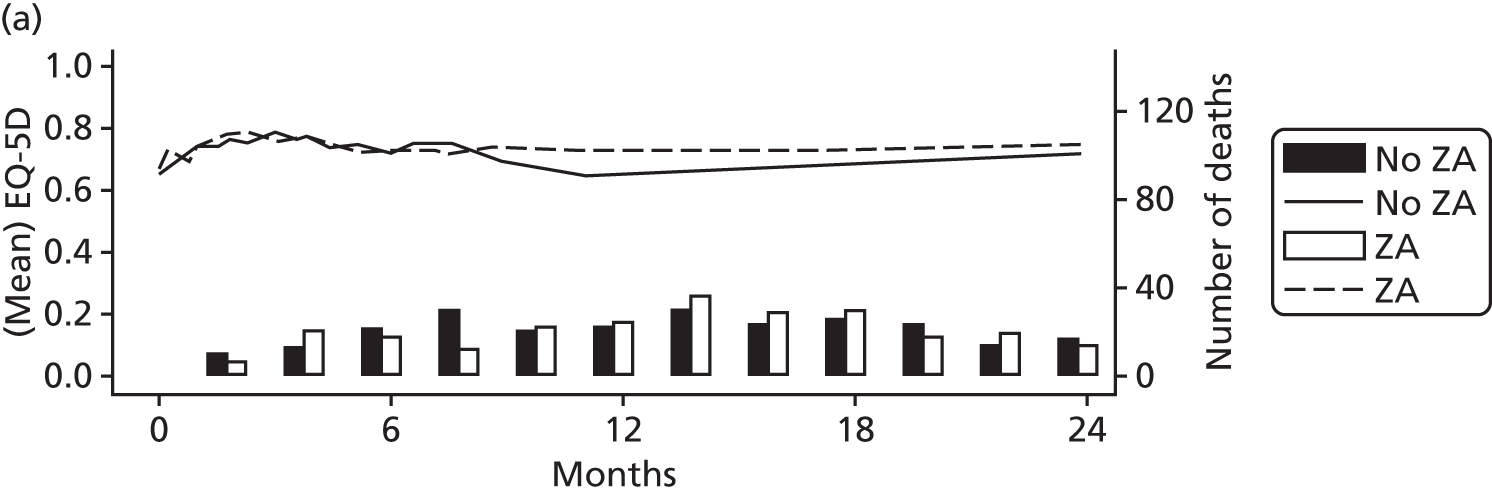

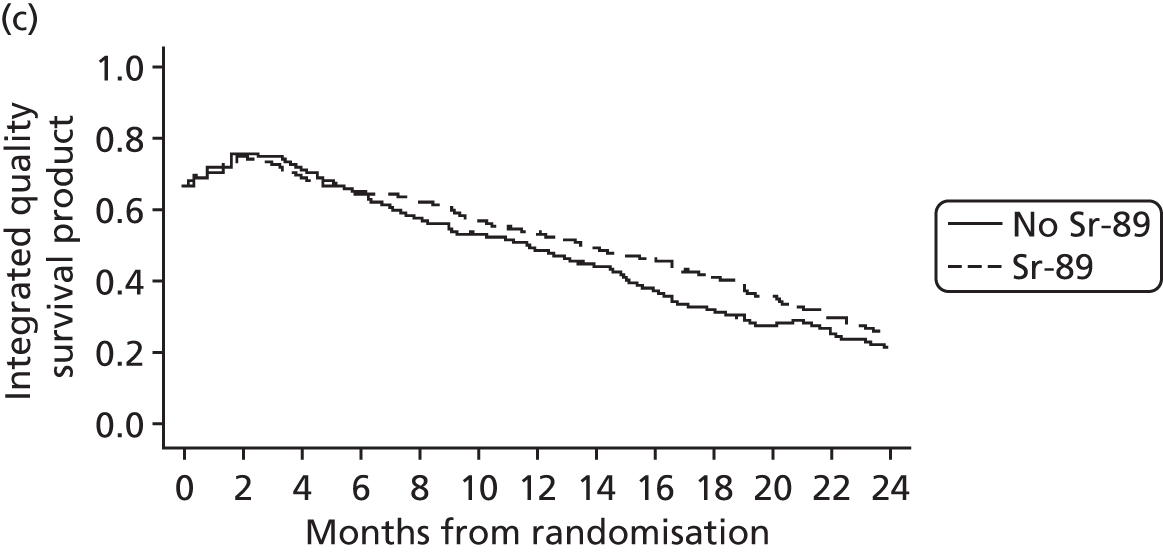

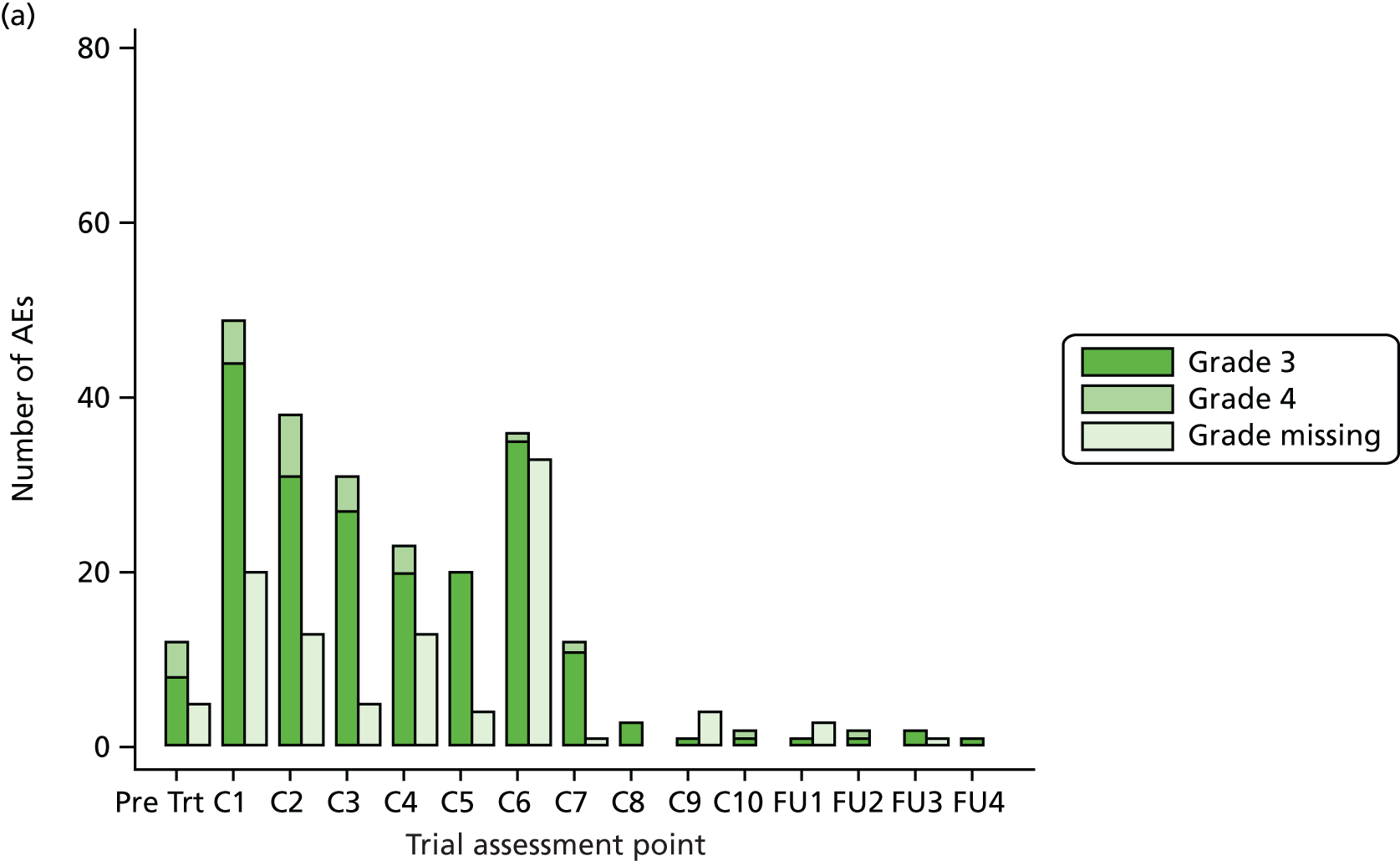

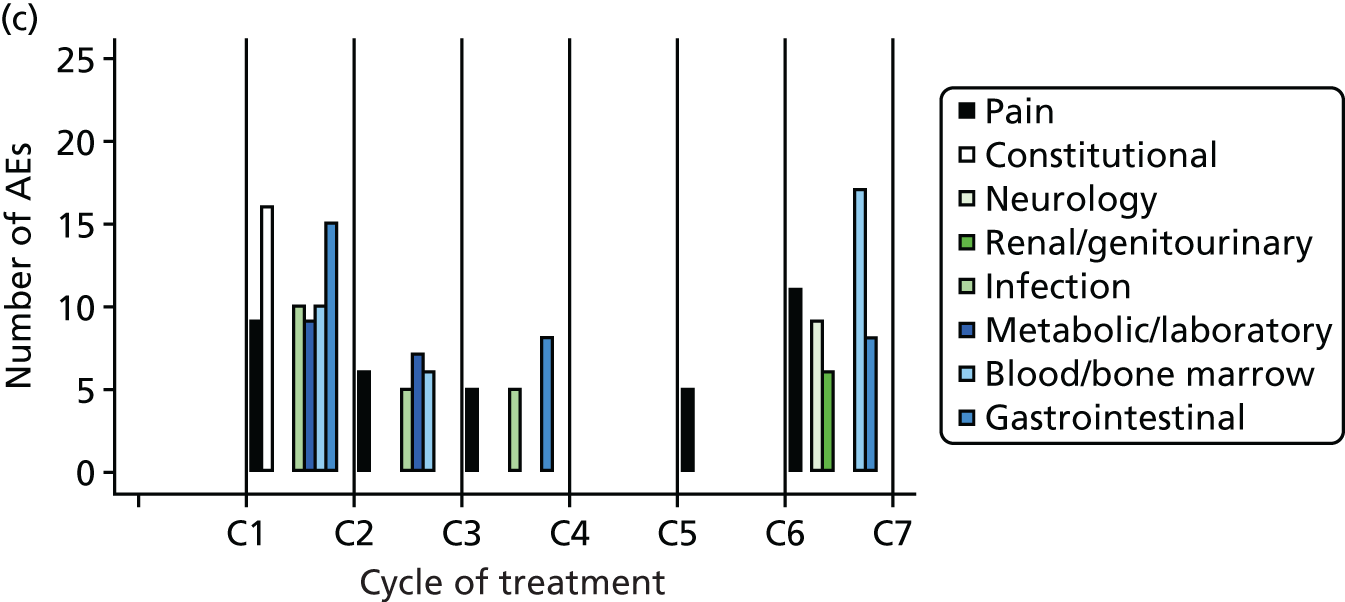

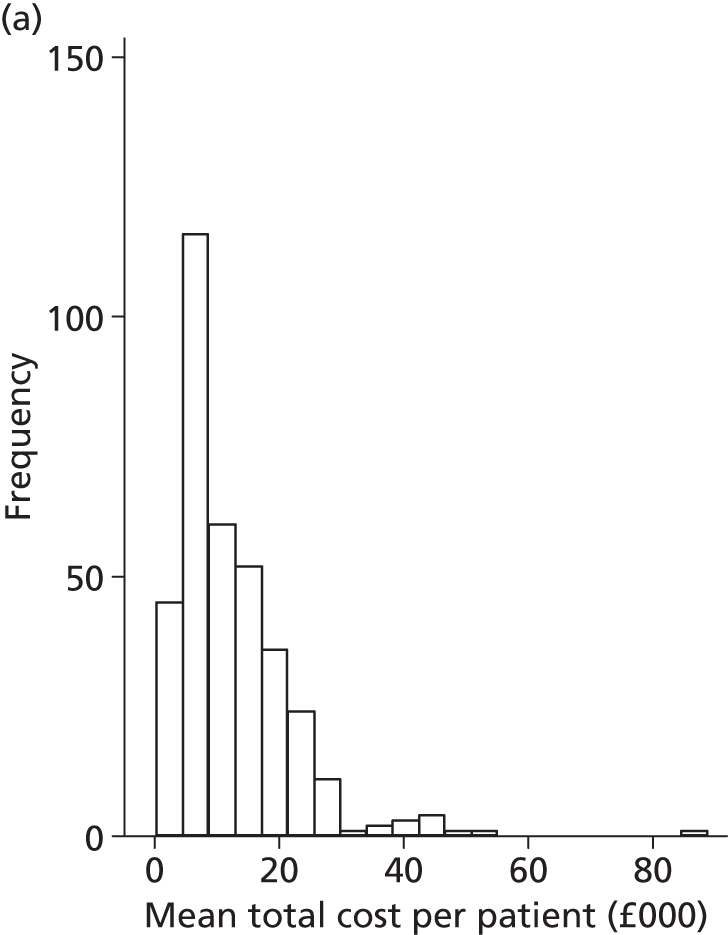

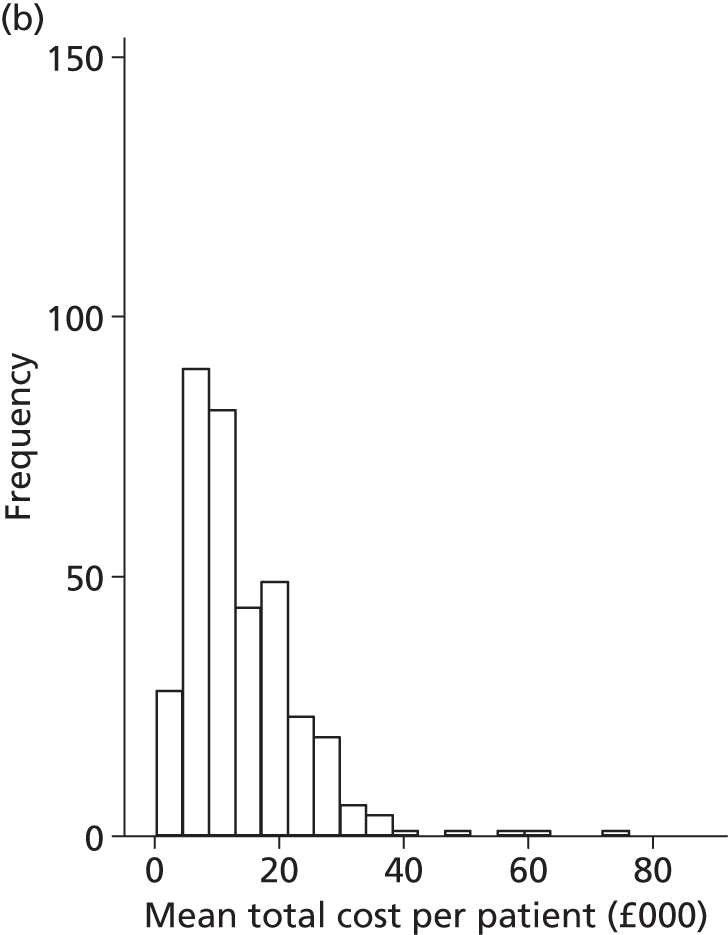

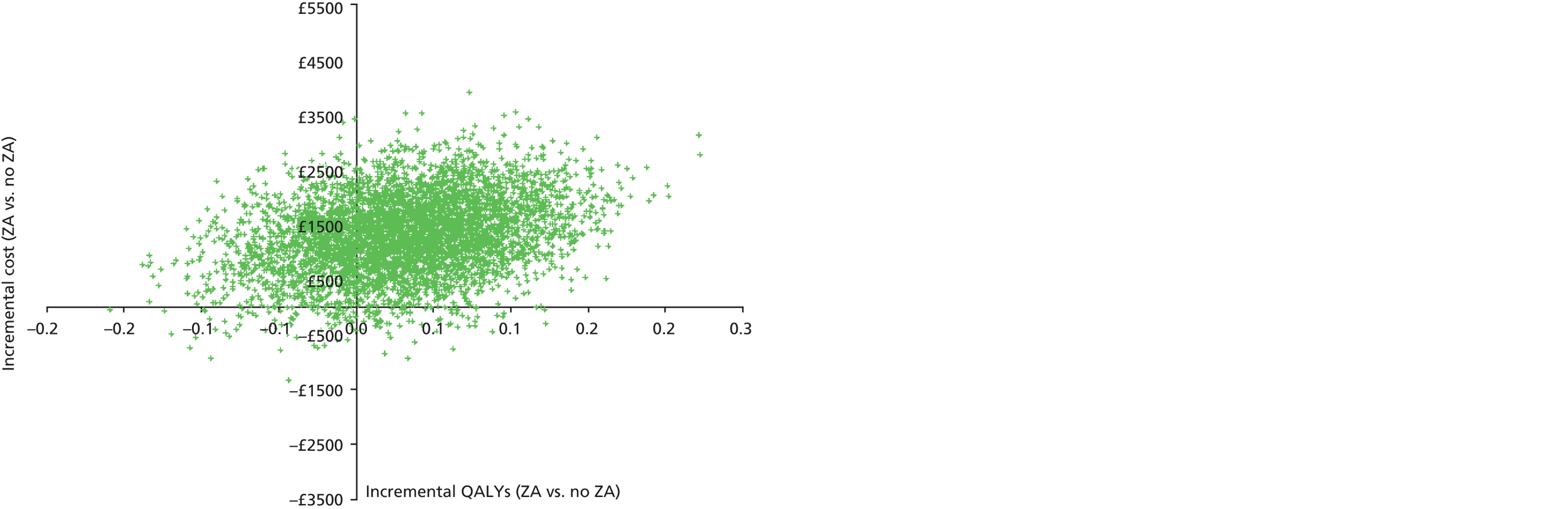

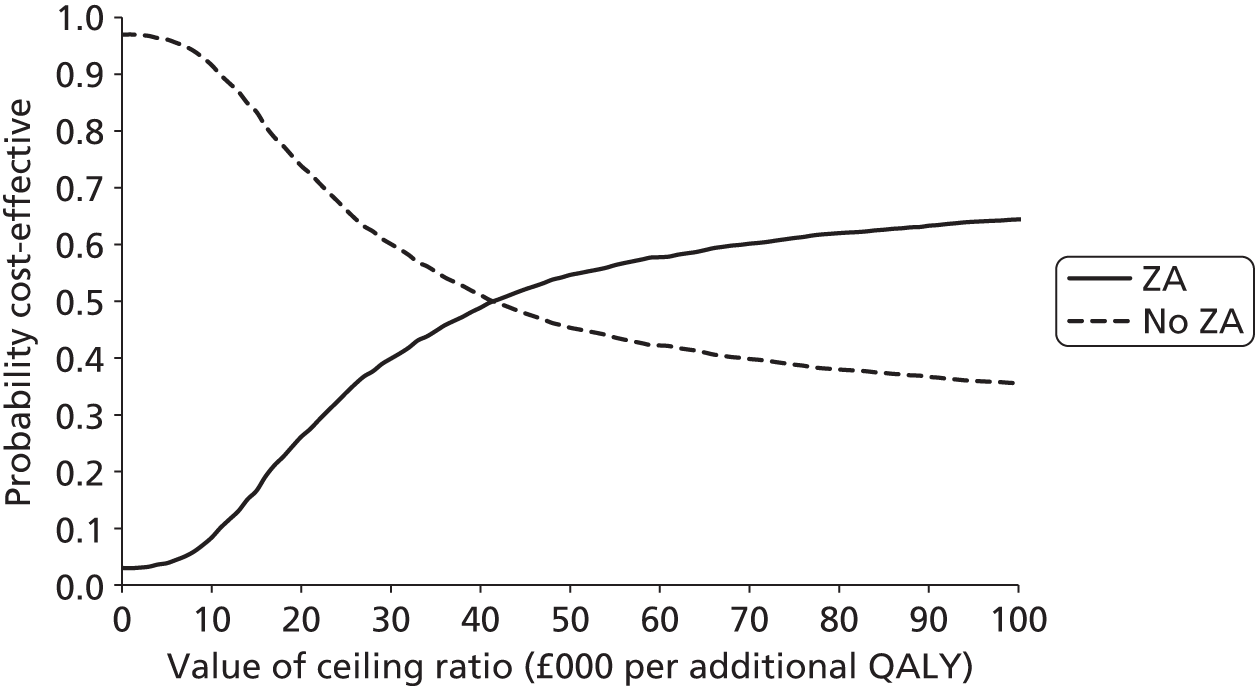

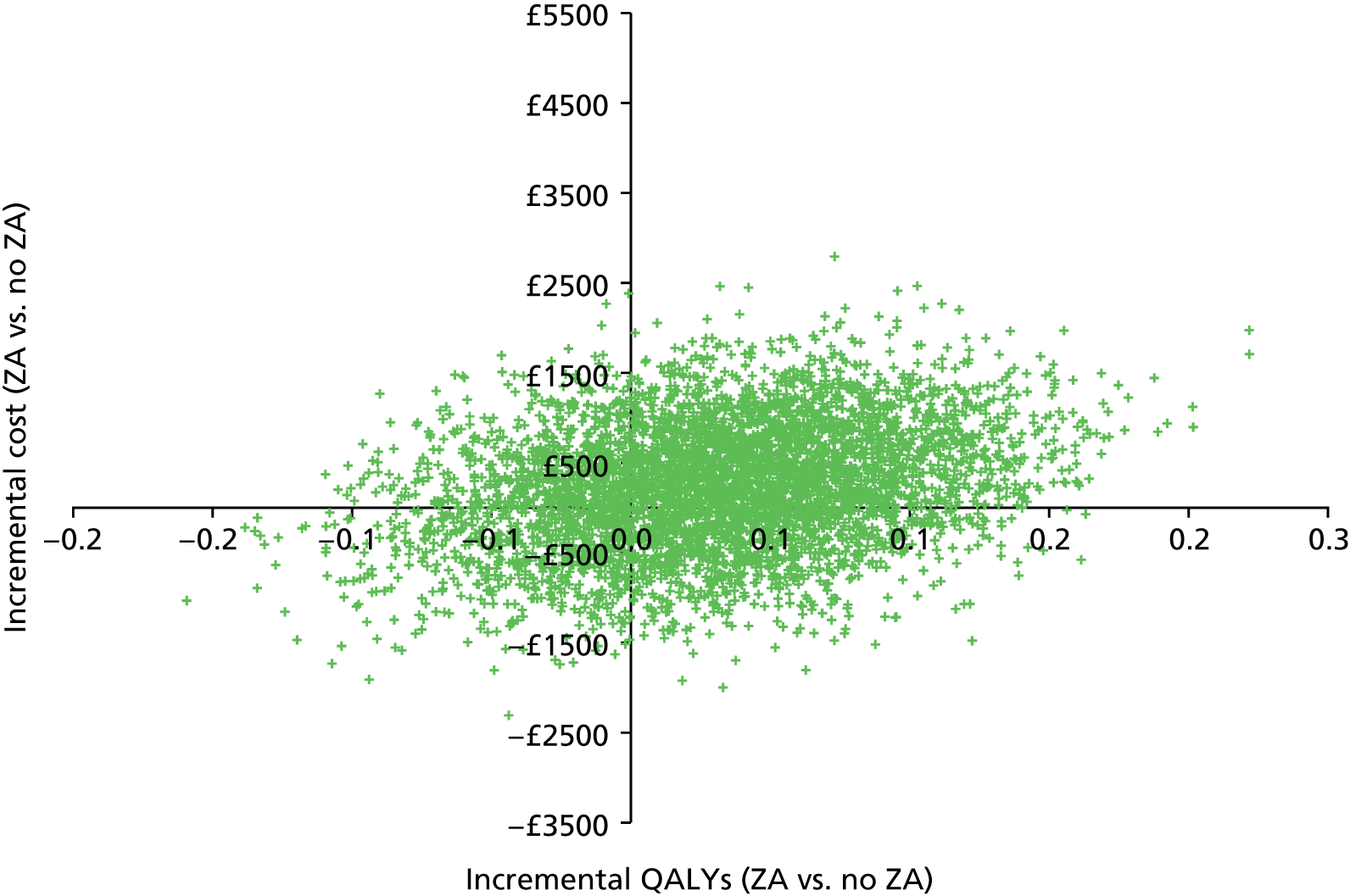

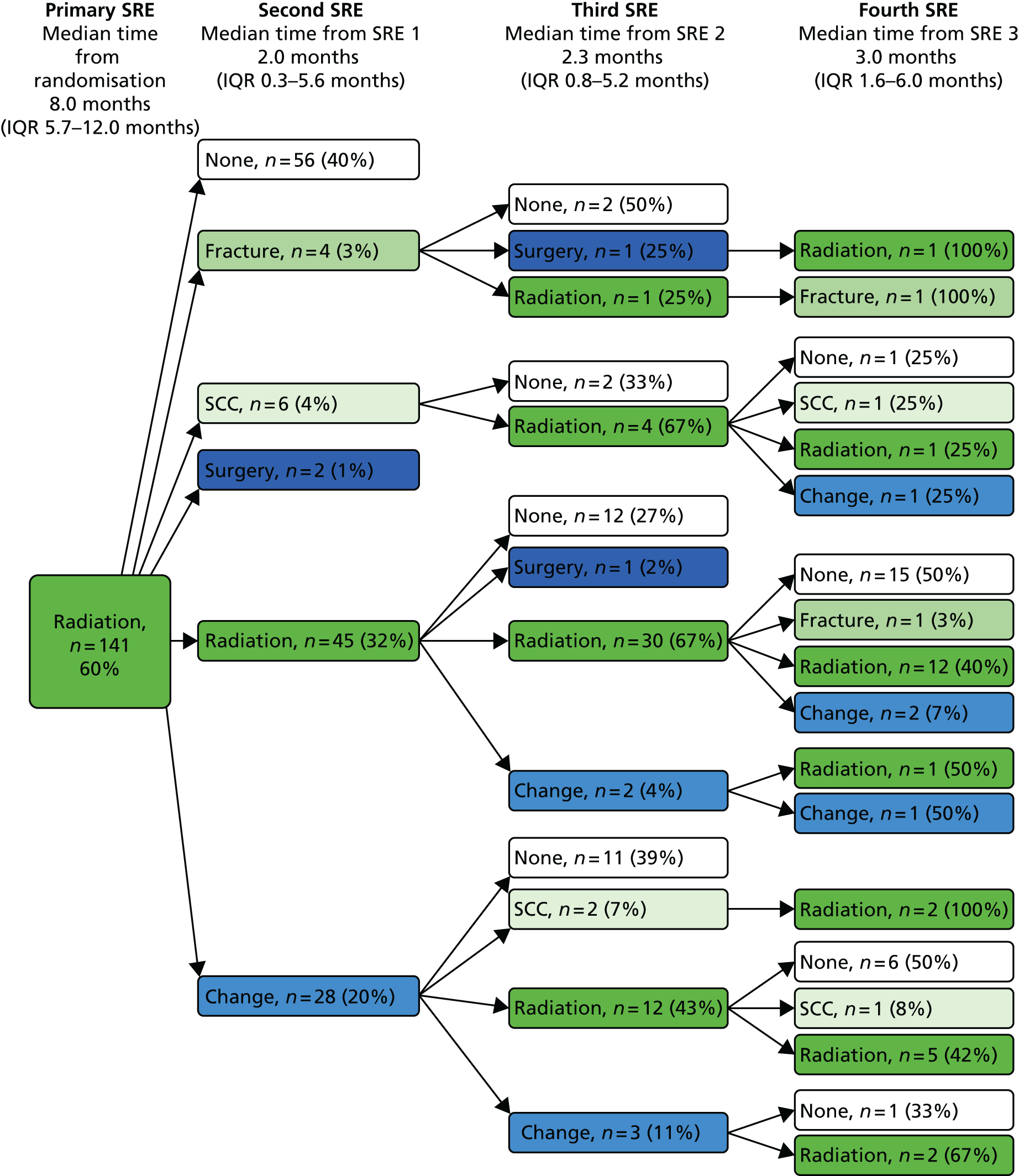

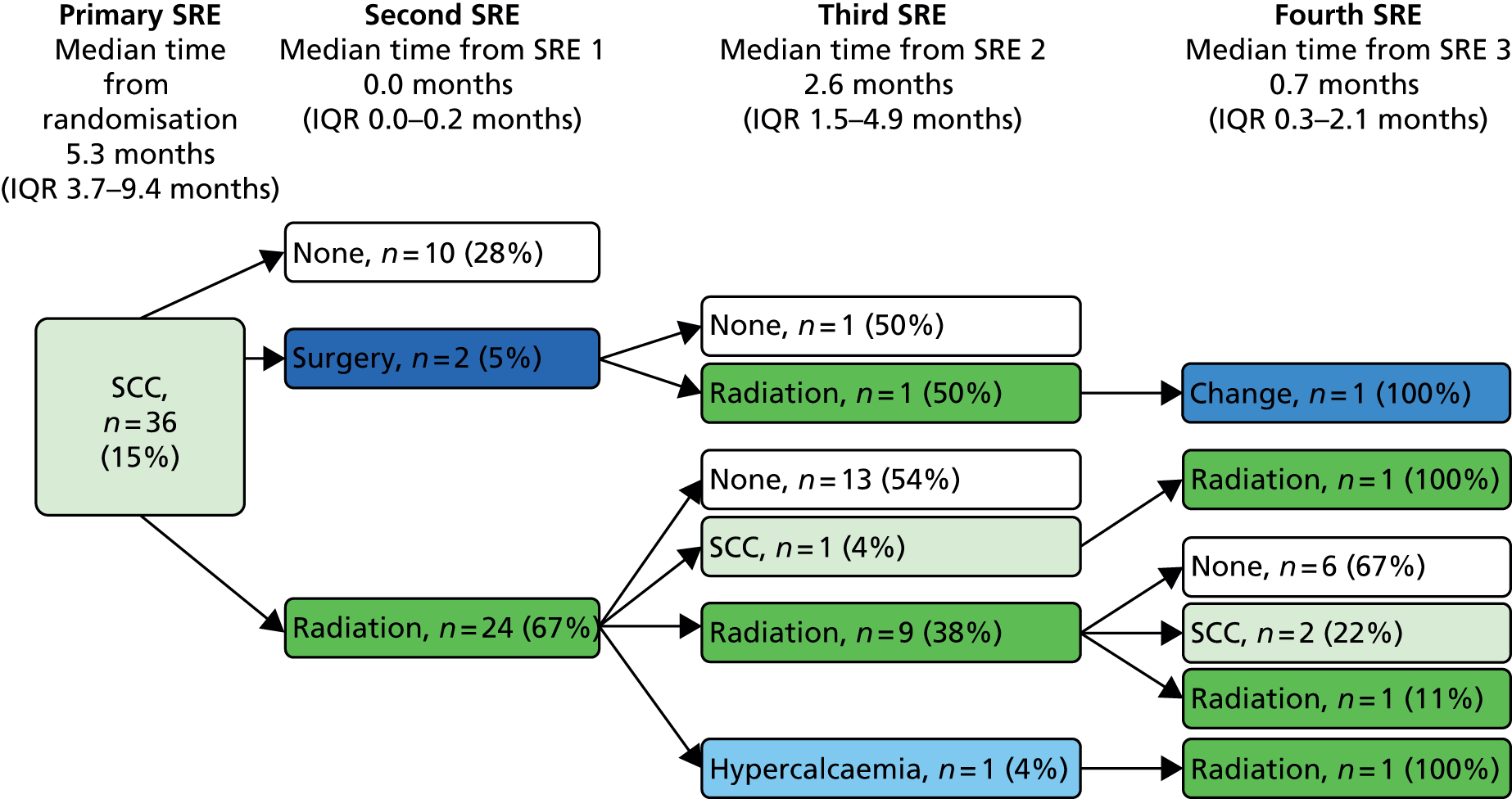

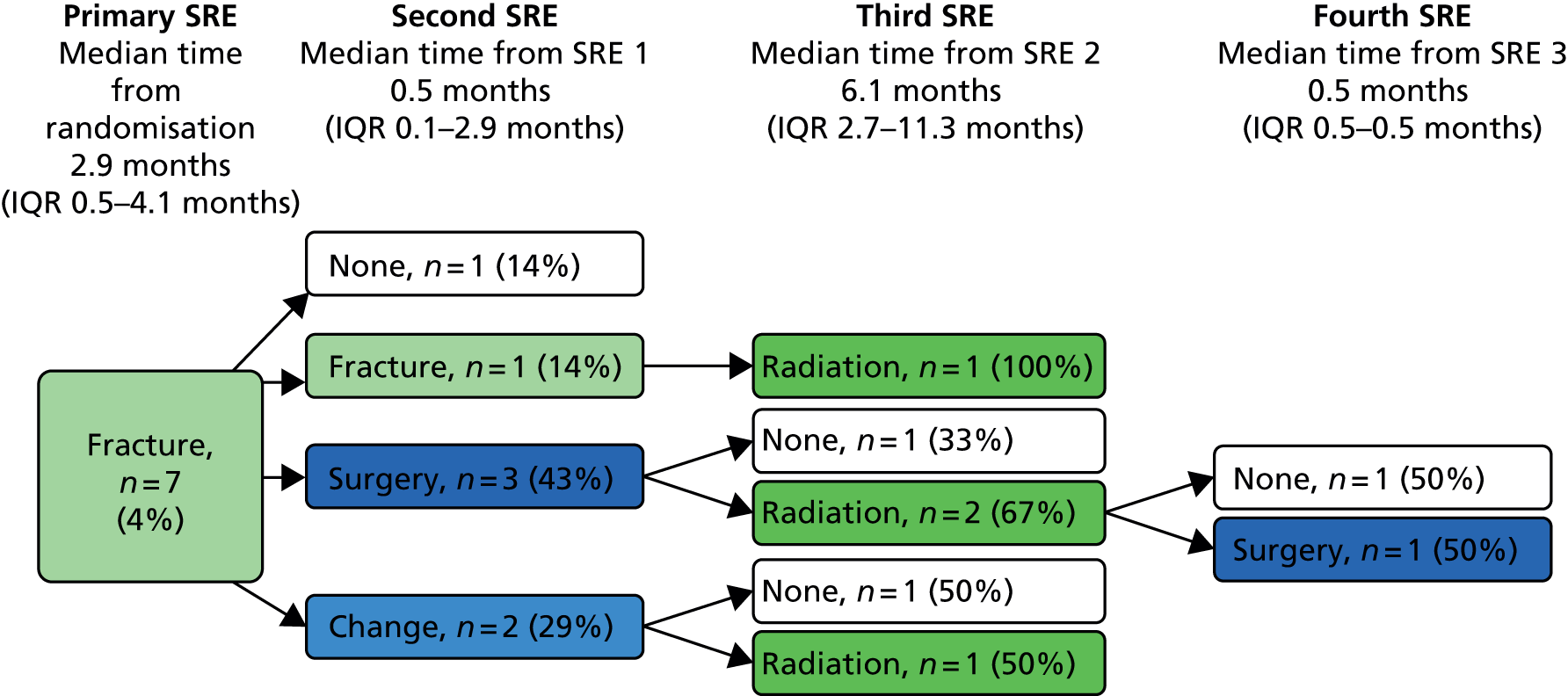

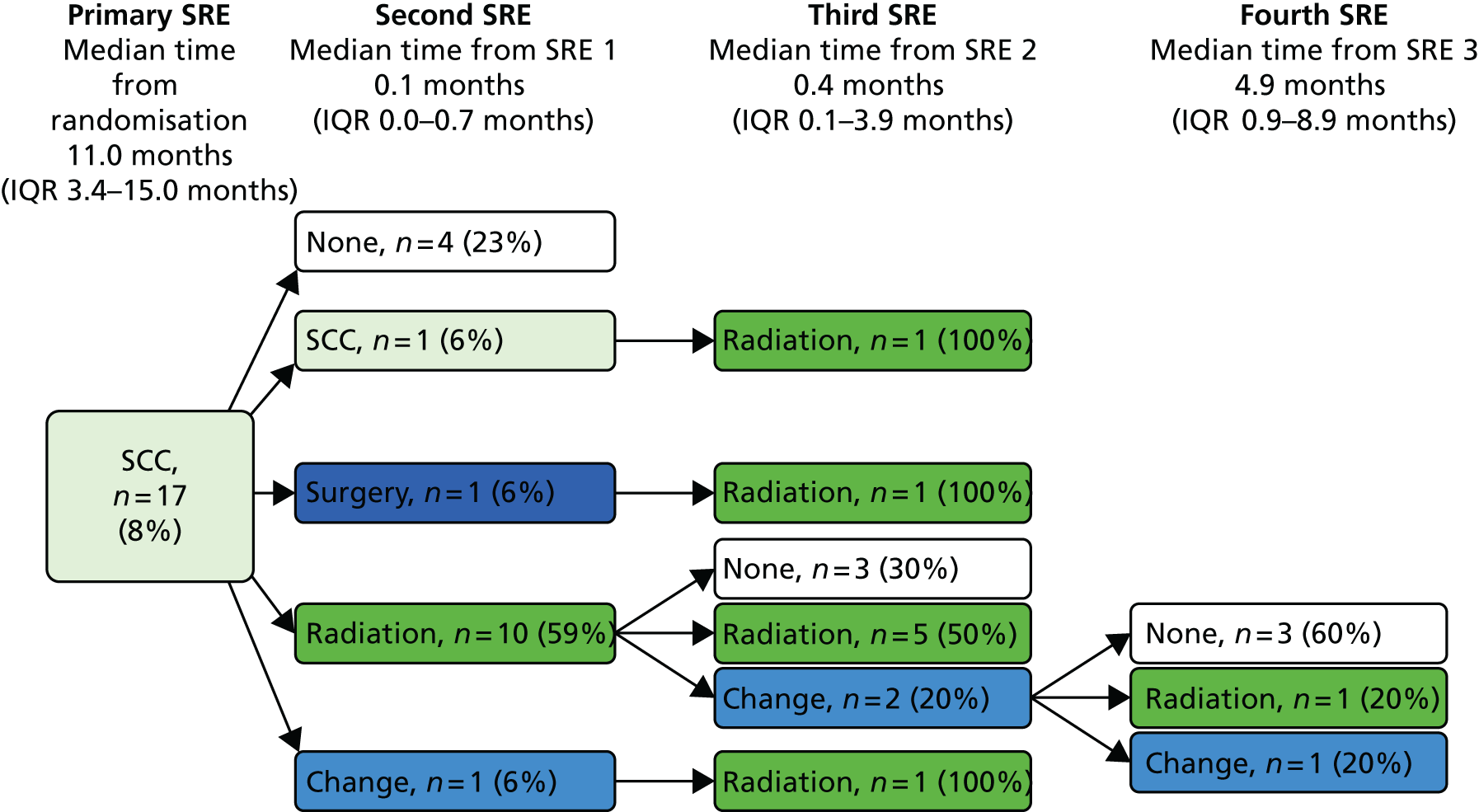

| 1 | 68 | 45.6 | 75 | 51.4 | 64 | 48.1 | 65 | 49.6 | 77 | 61.6 | 62 | 59.0 | 26 | 56.5 | 19 | 50.0 | 18 | 50.0 | 20 | 66.7 |