Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/402/94. The contractual start date was in December 2008. The draft report began editorial review in September 2014 and was accepted for publication in January 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rachel CM Brierley, Alan Cohen, Alice Miles, Andrew D Mumford, Gavin J Murphy (up to 31 August 2012), Rachel L Nash, Katie Pike, Sarah Wordsworth, Elizabeth A Stokes and Barnaby C Reeves had varying percentages of their salaries paid for by the grant awarded for the trial. Some or all of the time contributed by Gianni D Angelini, Gavin J Murphy (from 1 September 2012) and Chris A Rogers was paid for by the British Heart Foundation. Barnaby C Reeves is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board, Systematic Reviews Programme Advisory Board and the Efficient Studies Design Board.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Health Technology Assessment programme, the National Institute for Health Research, the British Heart Foundation, the UK NHS or the Department of Health.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Reeves et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Perioperative anaemia is strongly associated with adverse outcomes in cardiac surgery patients. 1–3 Transfusion of allogenic red blood cells is the preferred treatment to reverse acute anaemia and, on average, > 50% of adult cardiac surgery patients receive a perioperative transfusion. 4,5

Cardiac surgery consumes a substantial proportion of blood supplies – > 6% of all red blood cell use in the UK occurs in cardiac surgery. 6 Red blood cell transfusion is essential in some cardiac surgical patients for the management of life-threatening haemorrhage. In most cases, however, decisions to give a red blood cell transfusion are made because the haemoglobin concentration has fallen to a level or threshold at which the physician is uncomfortable. 2,7,8 The transfusion threshold varies across different cardiac surgery units and between different surgeons, which contributes to the wide variation in blood usage observed in cardiac surgical units (25% to 95%). 4,5,9 The threshold variation stems from a lack of evidence regarding what constitutes a safe level of anaemia following cardiac surgery.

Background and rationale

The clinical benefits of red blood cell transfusion beyond increasing circulating haemoglobin concentrations are unclear. Observational analyses suggest that transfusion after cardiac surgery may not, in fact, improve outcome where, in an apparent paradox, reversal of anaemia with transfusion has been shown to be consistently associated with increased infection, low cardiac output state, acute kidney injury (AKI) and death. 2,10,11 In contrast, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing a restrictive red blood cell transfusion threshold (allowing a participant’s haemoglobin level to drop to a lower level before transfusing) with a more liberal strategy (transfusing a participant at a higher haemoglobin level) have not demonstrated adverse effects directly attributable to transfusion in patients undergoing major surgery or in the critically ill. 12–14

The absence of harm from restrictive practice in RCTs combined with the evidence from observational studies has been interpreted as being supportive of restrictive transfusion practice. 15 Alongside the well-documented risks of more liberal transfusion (including haemolytic and non-haemolytic transfusion reactions and transfusion-associated lung injury,16 increasing demands on blood services17 as well as additional and important cost implications associated with the storage, handling and administration of red blood cell units18), this evidence has led to an emphasis on restrictive transfusion in contemporary blood management guidelines19–21 and increasingly in health policy. 22,23

The Transfusion Indication Threshold Reduction (TITRe2) trial was designed in 2006 and was prompted by the widely varying transfusion thresholds that were being applied at the time and by a detailed observational analysis of data from the hospital in which the triallists worked. 2 Existing RCTs at the time that had compared liberal with restrictive transfusion in cardiac surgery, including our own pilot trial, had lacked sufficient statistical power to demonstrate clinical benefits attributable to restrictive transfusion. 24–26 A contemporary systematic review of RCTs of liberal compared with restrictive transfusion, most of which were not conducted in cardiac surgery, also concluded that there is uncertainty as to the benefits of more restrictive transfusion in patients with unstable cardiac disease. 12

Aims and objectives

To address this uncertainty, we undertook the TITRe2 RCT. The trial was designed to test the hypothesis that a restrictive threshold for red blood cell transfusion (haemoglobin 7.5 g/dl and/or haematocrit 22%) would reduce post-operative morbidity and health service costs compared with a liberal threshold (haemoglobin 9 g/dl and/or haematocrit 27%).

Specific objectives of the TITRe2 trial were:

-

to estimate the difference in the risk of a post-operative infection or ischaemic event between restrictive and liberal transfusion thresholds

-

to compare the effects of restrictive and liberal transfusion thresholds with respect to a range of secondary outcomes

-

to estimate the cost-effectiveness of a restrictive compared with a liberal haemoglobin transfusion threshold.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The study was a multicentre RCT. The objectives were addressed by randomising participants to either a restrictive (transfuse if post-operative haemoglobin dropped below 7.5 g/dl, or haematocrit below 22%) or a liberal (transfuse if post-operative haemoglobin dropped below 9 g/dl, or haematocrit below 27%) strategy for red blood cell transfusion. The trial is registered, number ISRCTN70923932.

Participants provided written, informed consent pre-operatively but only became eligible for randomisation if their haemoglobin fell below 9 g/dl, or haematocrit below 27%, at some point postoperatively. Therefore, postoperatively, haemoglobin/haematocrit levels were monitored according to usual care and if the relevant threshold was breached at any time on the cardiac unit the participant was randomised as soon as possible, at the latest within 24 hours. (Note: thresholds were expressed as haemoglobin or haematocrit, and randomisation or transfusion was indicated if either value fell below the allocated threshold. Hereinafter, haemoglobin should be interpreted as haemoglobin or haematocrit.) A UK NHS Research Ethics Committee approved the study (08/H0606/125). Full details of all methods are reported elsewhere. 7

Changes to study design after commencement of the study

There were no major changes to the study design after commencement. Some changes were made to eligibility criteria and outcomes, which are discussed in Changes to study eligibility criteria after commencement of the study and Changes to study outcomes after commencement of the study, respectively.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

The study inclusion criteria were:

-

adults of either sex, aged ≥ 16 years, undergoing cardiac surgery [defined as coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), heart valve replacement or repair, aortic surgery or surgical correction of congenital cardiac disease]

-

post-operative haemoglobin level < 9 g/dl at any stage during the patient’s post-operative hospital stay [i.e. on cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) or cardiac surgical ward]

-

written informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

patients undergoing emergency cardiac surgery

-

patients prevented from having blood and blood products according to a system of beliefs (e.g. Jehovah’s Witnesses)

-

patients with congenital or acquired platelet, red blood cell or clotting disorders

-

patients with ongoing or recurrent sepsis

-

patients with critical limb ischaemia

-

patients unable to give full informed consent for the study (e.g. learning or language difficulties)

-

patients already participating in another interventional research study.

Changes to study eligibility criteria after commencement of the study

In April 2009 (before starting recruitment to the study), two exclusion criteria were removed:

-

patients with a critical carotid artery stenosis (> 75%)

-

patients with flow limiting (> 70% luminal stenosis) coronary artery disease not undergoing complete revascularisation.

These exclusion criteria were included originally on the basis of the exclusion criteria used in the pilot study for this trial. 26 The pilot study used different thresholds, notably a lower haemoglobin threshold of 7 g/dl for the restrictive group. At the time of designing the pilot study it was felt that, because patients entering the pilot study could potentially experience haemoglobin levels as low as 7 g/dl, these exclusion criteria were needed to avoid non-adherence by intensivists, who might consider such patients to be more at risk of experiencing ischaemic adverse effects. TITRe2 used the higher haemoglobin level of 7.5 g/dl for the restrictive threshold and this threshold was already used routinely at some centres for all patients. Therefore, after discussing these exclusion criteria again, the study team believed they were not necessary for TITRe2.

In August 2010, the previously stated upper age limit of 80 years for the inclusion of participants was removed. This decision was a result of feedback from sites that they did not consider older age to be a contraindication for randomisation to the study and that the exclusion would substantially limit the pool of eligible patients for the study. After removal of this criterion surgeons were still able to refuse to include patients aged > 80 years on a case-by-case basis.

Settings

Patients were recruited to the trial in 17 specialist cardiac surgery centres in UK NHS hospitals.

Interventions

The trial compared two thresholds for blood transfusion, liberal and restrictive. The thresholds were defined as follows:

-

Liberal group: participants randomised to this group were eligible for transfusion if their post-operative haemoglobin level fell < 9 g/dl at any time during their post-operative hospital stay on the CICU or cardiac surgical ward. Therefore, all participants in this group should have received one red blood cell unit soon after randomisation. The objective was to maintain the haemoglobin level at or above 9 g/dl.

-

Restrictive group: participants randomised to this group were eligible for transfusion if their post-operative haemoglobin level fell < 7.5 g/dl at any time during their post-operative hospital stay on the CICU or cardiac surgery ward. The objective was to maintain the haemoglobin level ≥ 7.5 g/dl.

The protocol specified that, in both groups, one red blood cell unit should be transfused, the haemoglobin rechecked and a second unit transfused only if the haemoglobin remained below the relevant threshold. Clinicians were allowed to transfuse, or refuse to transfuse, in contravention of the allocated threshold but were required to document their reason for doing this and the haemoglobin level at the time. Furthermore, a clinician could decide it was in the best interests of a participant to permanently discontinue treatment according to the allocated group, which did not constitute a withdrawal and the participant was followed up as normal. Other aspects of post-operative care were provided in accordance with the institution’s usual care.

The duration of intervention in the trial was the duration of the participant’s care under the consultant cardiac surgeon or a maximum of 3 months after the date of randomisation, whichever was shorter. Almost always, the duration of care under the cardiac surgeon was the period of hospitalisation after surgery. However, a few participants who developed serious complications were transferred to the care of another consultant in the same hospital, at which time the interventional period for the study ended.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was a binary composite outcome of any serious infectious (sepsis or wound infection) or ischaemic event [permanent stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), gut infarction or AKI] in the first 3 months after randomisation. The qualifying events listed in Table 1 were included; the table also describes the manner in which each qualifying event was verified.

| Infectious events | Definition/method of verification |

|---|---|

| Sepsis | During index admission: |

|

|

| In follow-up period: | |

|

|

| Wound infection | ASEPSIS score of > 20.27 Two scores were calculated and summed: |

|

|

| A follow-up score derived from the in-hospital score and a questionnaire either posted for self-completion or administered by telephone, at 3 months post randomisation28,29 | |

| Ischaemic events | Definition/method of verification |

| Permanent stroke | Clinical report of brain imaging (CT or MRI), in association with new onset focal or generalised neurological deficit (defined as a deficit in motor, sensory or co-ordination function) |

| MI | Elevated post-operative peak serum troponin I or T, verified by an adjudication committee. Further details are given in Primary outcome |

| Gut infarction | Documented reason for laparotomy or post-mortem report |

| AKI | AKI network criteria for AKI, stage one, two or three:30 |

| Stage one: | |

|

|

| Stage two: | |

|

|

| Stage three: | |

|

Events occurring after discharge only contributed to the primary outcome if the potentially qualifying event resulted in admission to hospital or death. Wound infection identified as a result of adding post-discharge information was the only exception to this rule. For example, information ascertained using the additional treatment, serous discharge, erythema, purulent exudate, separation of deep tissues, isolation of bacteria, and stay duration as inpatient (ASEPSIS) post-discharge surveillance assessment questionnaire (see Table 1), when added to the ASEPSIS score derived for the index admission, sometimes resulted in a total ASEPSIS score for the index admission that was > 20. Other suspected infectious events treated in the community that did not cause readmission to hospital were not recorded as they could not be validated and are less serious than perioperative infections.

Events suspected to qualify for the primary outcome but that were not supported by objective evidence were referred to an independent adjudication committee. In practice, the adjudication committee only considered suspected MIs because documentary objective evidence for sepsis, stroke, AKI and gut infarction was verified by research nurses at the co-ordinating centre who were blinded to the random allocation. The adjudication committee consisted of a cardiac surgeon, cardiologist and anaesthetist who were blinded to allocation and each other’s assessments. They were required to classify a suspected MI as definite or not based on participant’s medical history, echocardiograms (ECGs) (both pre-operatively and at the time of the suspected MI) and troponin levels at the time of the suspected MI. Agreement between at least two of the three specialists was required to reach a final adjudicated classification.

Death was not included as a component of the primary composite outcome because, if death occurred following a qualifying event, the event would precede death itself. Deaths that occurred for other reasons were not hypothesised to increase because of red blood cell transfusion.

Secondary outcomes

All secondary outcomes were collected in the time between randomisation and 3-month follow-up, unless otherwise stated.

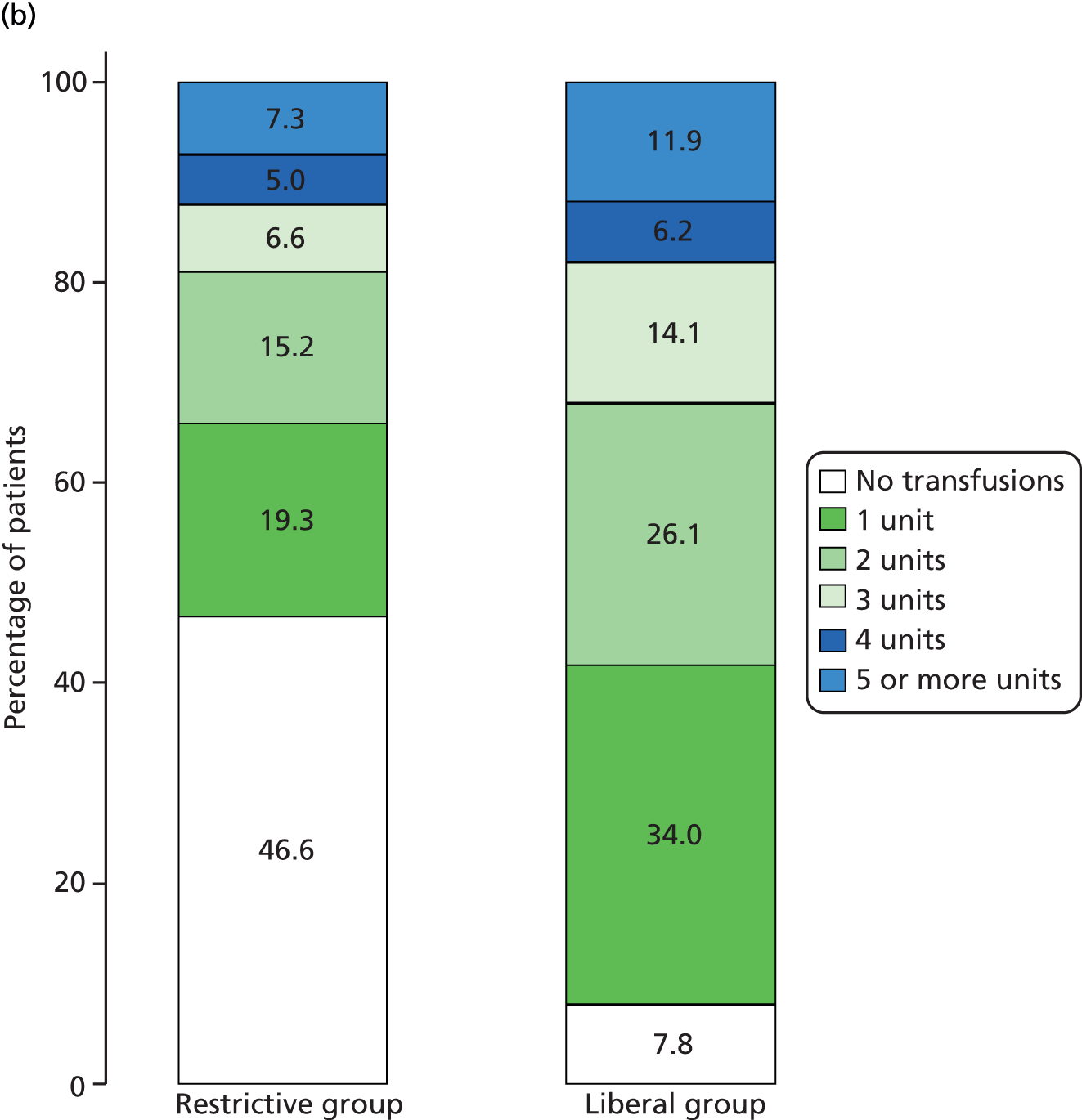

-

Units of red blood cells and other blood components [fresh frozen plasma (FFP), platelets, cryoprecipitate, activated factor VI (NovoSeven, Novo Nordisk) and Beriplex® (CSL Behring UK Ltd)] transfused during a participant’s hospital stay. Red blood cells transfused pre-randomisation (either intraoperatively or postoperatively but prior to randomisation) were collected and described separately. However, it was only possible to collect information about other blood components transfused over the pre-randomisation and post-randomisation periods combined.

-

Occurrence of an infectious qualifying event, defined as sepsis or wound infection.

-

Occurrence of an ischaemic qualifying event, defined as permanent stroke, MI, AKI or gut infarction.

-

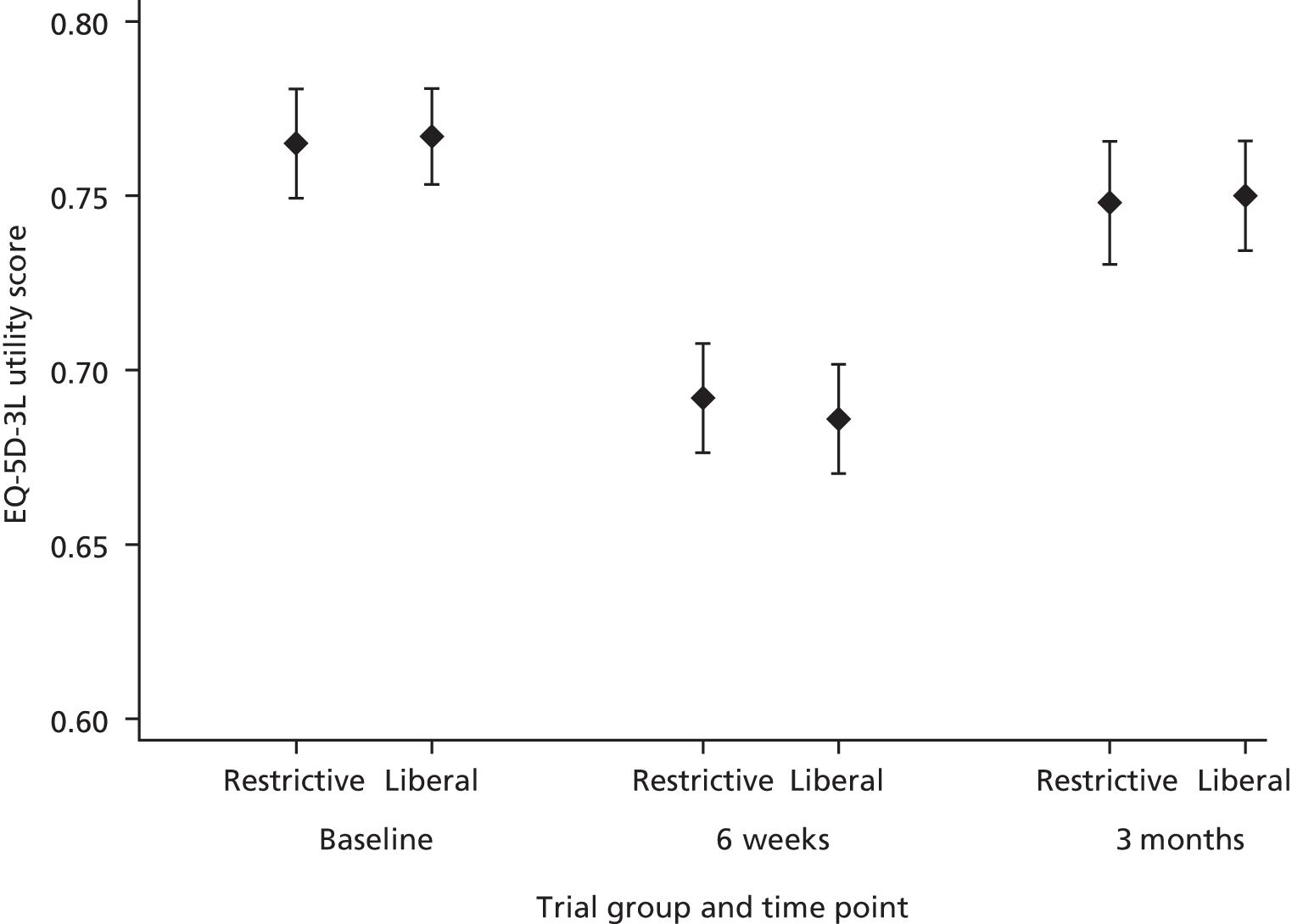

Quality of life measured using European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions-3 Level (EQ-5D-3L),31 assessed pre-operatively and at 6 weeks and 3 months post randomisation.

-

Duration of intensive care unit (ICU) or high-dependency unit (HDU) stay; calculated as the total time between randomisation and discharge from the cardiac unit that the participant was in either the CICU, HDU or general ICU wards, including any periods of readmission to that area.

-

Duration of hospital stay, calculated as the time between randomisation and discharge from the cardiac unit.

-

Significant pulmonary morbidity, comprising initiation of non-invasive ventilation [e.g. continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ventilation], reintubation/ventilation or tracheostomy.

-

All-cause mortality.

-

Health and Personal Social Services resource use and their costs.

(Durations of ICU, HDU and hospital stay were originally specified as ‘postoperative’. We specified randomisation as the time origin for these durations in the analysis plan, for consistency with the primary and other secondary outcomes.)

Changes to study outcomes after commencement of the study

The following changes were made to study outcomes after the trial had commenced.

-

In April 2009, before starting recruitment, there were some amendments made to the definitions of infectious and ischaemic events that qualified for the primary outcome.

-

In March 2010, an amendment was made to include troponin T in addition to troponin I in defining MI. This amendment was required after discovering that some participating centres habitually used troponin T rather than I. In addition, as part of this change, the troponin threshold for MI that was previously stated was removed; the decision was made, instead, to collect the highest troponin reading for all participants with suspected MI and to adjudicate suspected MIs (see Primary outcome).

-

In March 2011, the secondary outcome ‘significant pulmonary morbidity’ was added. This was initially named transfusion-associated circulatory overload and then subsequently renamed. The outcome was added because information from the haematology community had highlighted pulmonary morbidity as a potentially important outcome for patients receiving blood transfusions. The outcome was defined with respect to data already being collected on the study case report forms (CRFs) before the amendment so that the outcome could be identified consistently across the entire duration of the trial.

-

Furthermore, in March 2011, ‘A&E [accident and emergency] admission’ was removed from the primary outcome as qualifying event. This change arose from discussion with clinicians on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) who agreed that a participant experiencing any element of the primary outcome would be admitted to hospital if they attended the emergency department (ED) within the follow-up period.

Adverse events

Expected adverse events (AEs) were specified in the study protocol and captured via the study CRFs, both for the post-operative in-hospital period (serious and non-serious), and at the 3-month follow-up (serious only).

A serious adverse events (SAE) is any untoward medical occurrence that either results in death, is life-threatening, requires in-patient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or results in a congenital anomaly/birth defect.

All other AEs were considered unexpected, any such events satisfying one or more criteria for classification as serious were recorded in detail on purpose-designed SAE forms. Unexpected SAEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 14.1 (MedDRA; McLean, VA, USA) independently by two research nurses blinded to randomised allocation. Any discrepancies were resolved by a consultant cardiac surgeon also blinded to allocation.

Sample size

The trial was designed to answer superiority questions. The following steps were taken to calculate the sample size.

-

From observational data, we assumed that approximately 65% of patients would breach the threshold of 9 g/dl and 20% would breach the 7.5 g/dl threshold. 2 Therefore, with complete adherence to the transfusion protocol, we assumed that transfusion rates should be 100% in the liberal group and ≈30% (0.20/0.65) in the restrictive group.

-

In the observational analysis,2 63% of patients with a nadir haematocrit between 22.5% and 27%, and 93% of patients with a nadir haematocrit below 22.5%, were transfused. Therefore, in combination with the proportions of patients expected to breach the liberal and restrictive thresholds, these figures were used to estimate conservative transfusion rates of 74% for the liberal group and ≤ 35% for the restrictive group. These percentages reflected the rates of transfusion documented in the observational study (Figure 1) and assumed non-adherence with the transfusion protocol of approximately 26% in the liberal group and 5% in the restrictive group.

-

The observational frequencies of infectious and ischaemic events for transfused and non-transfused patients were adjusted to reflect the estimated transfusion rates in the two groups (i.e. 74% and ≤ 35%), giving event rates for the proposed composite outcome of 17% in the liberal threshold group and 11% in the restrictive threshold group. A sample size of 1468 was required to detect this risk difference of 6% with 90% power and 5% significance (two-sided test), using a sample size estimate for a chi-squared test comparing two independent proportions (applying a normal approximation correction for continuity) in Stata version 9 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

-

The target sample size was inflated to 2000 participants (i.e. 1000 in each group) to allow for uncertainty about non-adherence and the estimated proportions of participants experiencing the primary outcome. We regarded these parameter estimates as uncertain because (1) they were estimated from observational data, (2) they were based on the red blood cell transfusion rate only in Bristol, (3) they were based on routinely collected data, using definitions for elements of the composite primary outcome which are not identical to those proposed for the trial, and (4) they were based on any compared with no red blood cell transfusion, rather than on the number of units of red blood cells likely to be transfused in participants who breach the liberal threshold. No adjustment was made for withdrawals or loss to follow-up, as both rates were expected to be very low.

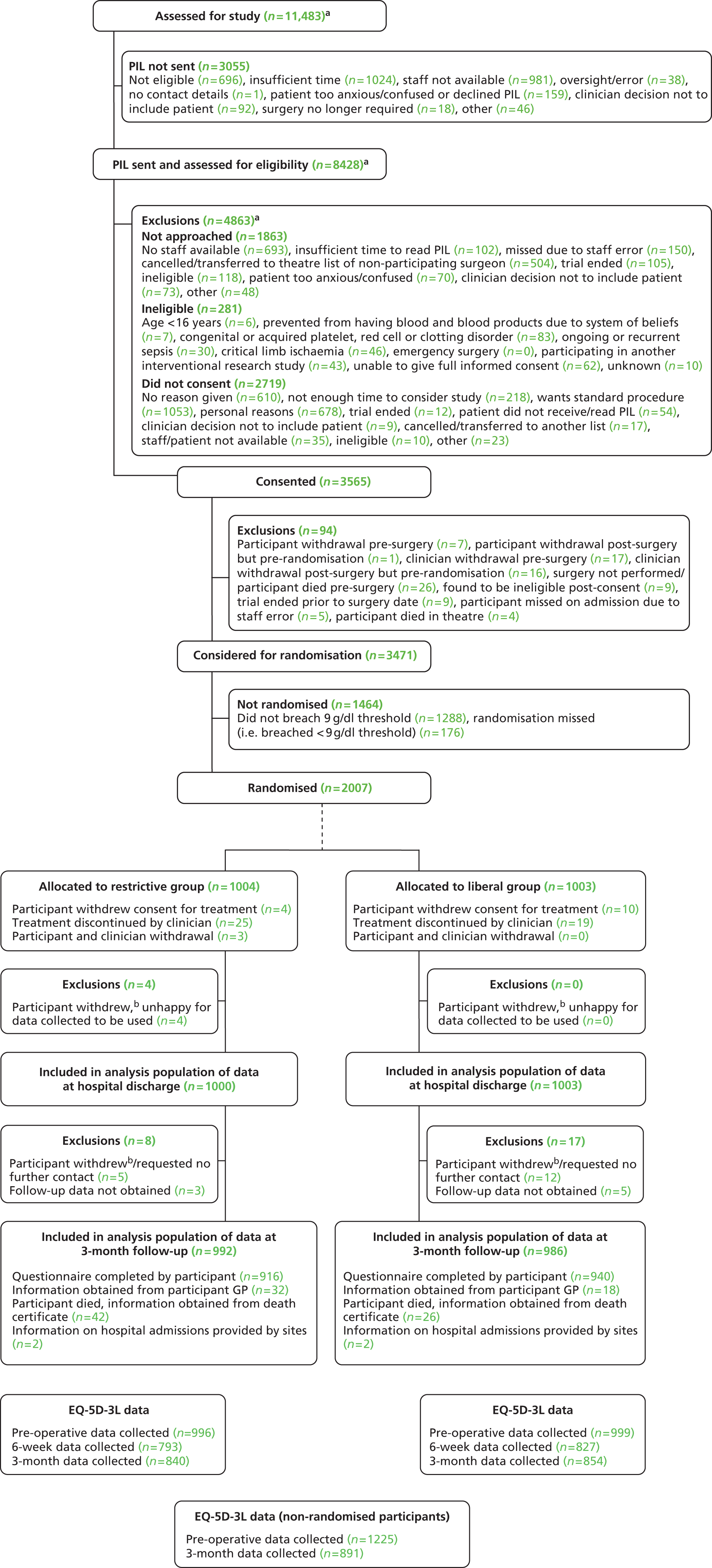

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram summarising TITRe2 trial design. Percentages are based on data from the cardiac surgery registry in Bristol for the period January to September 2007. An unknown percentage of patients are excluded by the exclusion criteria because the registry does not contain sufficient detail to apply the definitions proposed for the trial. However, patients meeting one or more of these criteria are extremely rare and we expected all of the exclusion criteria to account for a maximum of 5% of cardiac surgery patients. Hb, haemoglobin.

We expected approximately two-thirds of participants to breach the haemoglobin threshold for eligibility. 2 Therefore, we predicted that we needed to register approximately 3000 participants into the study as a whole to allow 2000 participants to be randomised into the main study.

The main outcome measure for the economic evaluation was quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which are derived from EQ-5D-3L utilities measured on a continuous scale and time under observation. The analysis of QALYs requires baseline utility to be modelled as a covariate; the correlation between baseline and 3-month EQ-5D-3L utilities was assumed to be ≥ 0.3. With a total sample size of 2000, the trial had more than 95% power to detect a standardised difference in continuous outcomes between groups of 0.2 with 1% significance (two-sided test). This magnitude of difference is conventionally considered to be ‘small’. 32

Interim analyses

One formal, pre-specified interim analysis was carried out in June 2012 after 50% of the participants had been recruited and followed up for 3 months. Extreme criteria for stopping the trial (p ≤ 0.001) were set and, therefore, no adjustment was made to the sample size and statistical significance levels for this interim analysis.

Randomisation

Participants were randomly allocated to either the liberal or restrictive transfusion strategies using cohort minimisation to achieve balance across the two arms of the trial; minimisation factors were centre and operation type (CABG, valve, CABG and valve combined, or other cardiac surgery). Participants were randomly assigned in a 1 : 1 ratio. Allocations were generated by computer and concealed using an internet-based system provided by Sealed Envelope Ltd (London, UK). Staff in participating centres were able to gain secure limited access to the system using a password and PIN (personal identification number). Information to identify a participant uniquely and to confirm eligibility had to be entered before the system assigned the randomised treatment allocation, ensuring concealment of allocations. Randomisation occurred postoperatively and as soon as possible after the participant’s haemoglobin level fell below 9 g/dl (at the latest within 24 hours). If randomisation did not occur within 24 hours, the patient was considered to have become ineligible and should not have been randomised unless the haemoglobin fell below 9 g/dl again (when the clock for the ‘24 hour rule’ was restarted; see Non-adherence with randomisation protocol).

Blinding

It was not possible to blind clinicians, research staff and other NHS staff caring for participants to the randomised allocation. However, outcomes were defined on the basis of objective criteria as far as possible, in order to minimise susceptibility to bias. Furthermore, both the research nurses reviewing the documentary evidence relating to primary outcome events and the adjudication committee assessing MIs were blinded to treatment allocation.

Every effort was made to blind participants to their allocation. The success of blinding was checked by asking participants if they knew what their allocation was at the time of discharge from hospital and their 3-month post-randomisation follow-up.

Data collection

In-hospital data collection (see Appendix 4 for the CRFs) included the following elements.

-

Screening log of all non-emergency patients having cardiac surgery

-

distinguishing patients but without recording identifiable data electronically

-

whether or not a patient information leaflet (PIL) was sent

-

whether or not a patient was approached for the trial

-

assessment of eligibility; if ineligible, reasons for ineligibility

-

whether or not a patient was asked to give written informed consent for the trial.

-

-

For all registered participants (randomised and non-randomised)

-

pre-operative characteristics, including operation category

-

a summary of blood products received

-

daily haemoglobin levels to check compliance with protocol.

-

-

For all randomised participants

-

date and time when the haemoglobin fell below 9 g/dl

-

operative details, including duration of surgery and use of any blood products

-

observations required for the primary and secondary outcomes, including dates and times of relevant events

-

other key resource use

-

any AEs

-

information about whether or not a participant was blinded to allocation at discharge.

-

Research staff in participating centres collected data on the trial screening log and pre-printed CRFs. These data were transferred promptly to a secure computerised database maintained on a NHS computer, allowing data to be checked centrally. Queries about specific data items were listed on the database and were immediately apparent to centre staff when they logged on.

Post-operative haemoglobin levels in consented participants were measured at regular intervals and the lowest level observed on each post-operative day was recorded on the CRF. After randomisation, the threshold to which a participant had been randomised was communicated to attending medical and nursing staff and recorded on the CRF. Centres used varying methods to highlight to staff that a participant had been randomised. Details of red blood cell transfusions were recorded and haemoglobin levels continued to be monitored. If a non-adherent transfusion decision was made for a randomised participant (i.e. a decision which did not adhere to the allocated protocol, see Non-adherence with transfusion protocol), the attending doctor was required to give a reason for the decision. This reason was documented on the CRF.

Data collection after hospital discharge consisted of the following elements.

-

The EQ-5D-3L was posted to randomised participants at 6 weeks and 3 months after randomisation. Participants who consented to the study but were not randomised also received a postal EQ-5D-3L 3 months after their operation.

-

Three months after the operation, a questionnaire was posted for self-completion, or administered by telephone (if a participant elected to be telephoned or failed to return the postal questionnaire), by staff at the co-ordinating centre. The questionnaire was composed of items eliciting information about:

-

AEs occurring after discharge, with further details of any event suspected to contribute to the primary outcome or meet the definition of a SAE sought from either the admitting hospital or the participant’s general practitioner (GP).

-

surgical wound infections occurring after discharge (ASEPSIS post-discharge surveillance questionnaire). 28,29

-

resource use after discharge from hospital.

-

a participant’s awareness of his/her random allocation.

-

-

Occasionally data collection was delayed beyond the planned follow-up times; when this occurred the following rules were used to determine whether or not data should be included in analyses:

-

EQ-5D-3L – the time between questionnaire completion and operation date was examined by group, blinded to allocation, separately for each time point. The distributions did not differ; therefore, data corresponding to times that were extreme outliers (identified by eye) were excluded but all other data included.

-

Three-month telephone/postal questionnaire – questionnaire items were phrased specifically in relation to the 3-month post-operative period and staff completing the telephone questionnaires were trained only to record information regarding this period. Therefore, data from all questionnaires were used.

-

Data collection is summarised in Table 2.

| Data collected | Pre-surgery | Day of surgery | At randomisation | In CICU/ward | At discharge | 6 weeks after randomisation | 3 months after randomisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | ✓a | ||||||

| Written consent | ✓a | ||||||

| Demographics and medical history | ✓a | ||||||

| EQ-5D-3L questionnaire | ✓a | ✓b | ✓a,b | ||||

| Operative details | ✓ | ||||||

| Haemoglobin/haematocrit level | ✓a | ✓a | ✓ | ✓a | |||

| Summary of blood components transfused | ✓a | ||||||

| Details of red blood cell transfusion | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Randomised allocation | ✓ | ||||||

| Surgical complications and AEs | ✓ | ✓c | |||||

| ASEPSIS assessment of wound infection | ✓ | ||||||

| Resource use data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓c | ||||

| ASEPSIS post-discharge surveillance | ✓c | ||||||

| Check participant blinded to allocation | ✓ | ✓c |

Adherence

Non-adherence with randomisation protocol

Non-adherence with the randomisation protocol was defined as any of the following:

-

Participant did not meet one or more of the pre-consent study eligibility criteria but was consented into the study. Any randomised participant to whom this applies was classified as ‘randomised in error’ and excluded from the analysis population.

-

Participant consented and met the post-consent inclusion criteria (i.e. haemoglobin dropped below 9 g/dl) but was not randomised. Any randomised participant to whom this applies was not randomised and, therefore, was excluded from the analysis population.

-

Participant did not meet the post-consent eligibility criteria (i.e. haemoglobin did not drop below 9 g/dl) but was randomised. Any randomised participant to whom this applies was classified as ‘randomised in error’ and excluded from the analysis population.

-

Participant was randomised more than 24 hours after meeting the post-consent inclusion criteria (i.e. randomised more than 24 hours after haemoglobin dropping below 9 g/dl). Any participant to whom this applies was classified as non-adherent with the randomisation protocol, but was included in the analysis population.

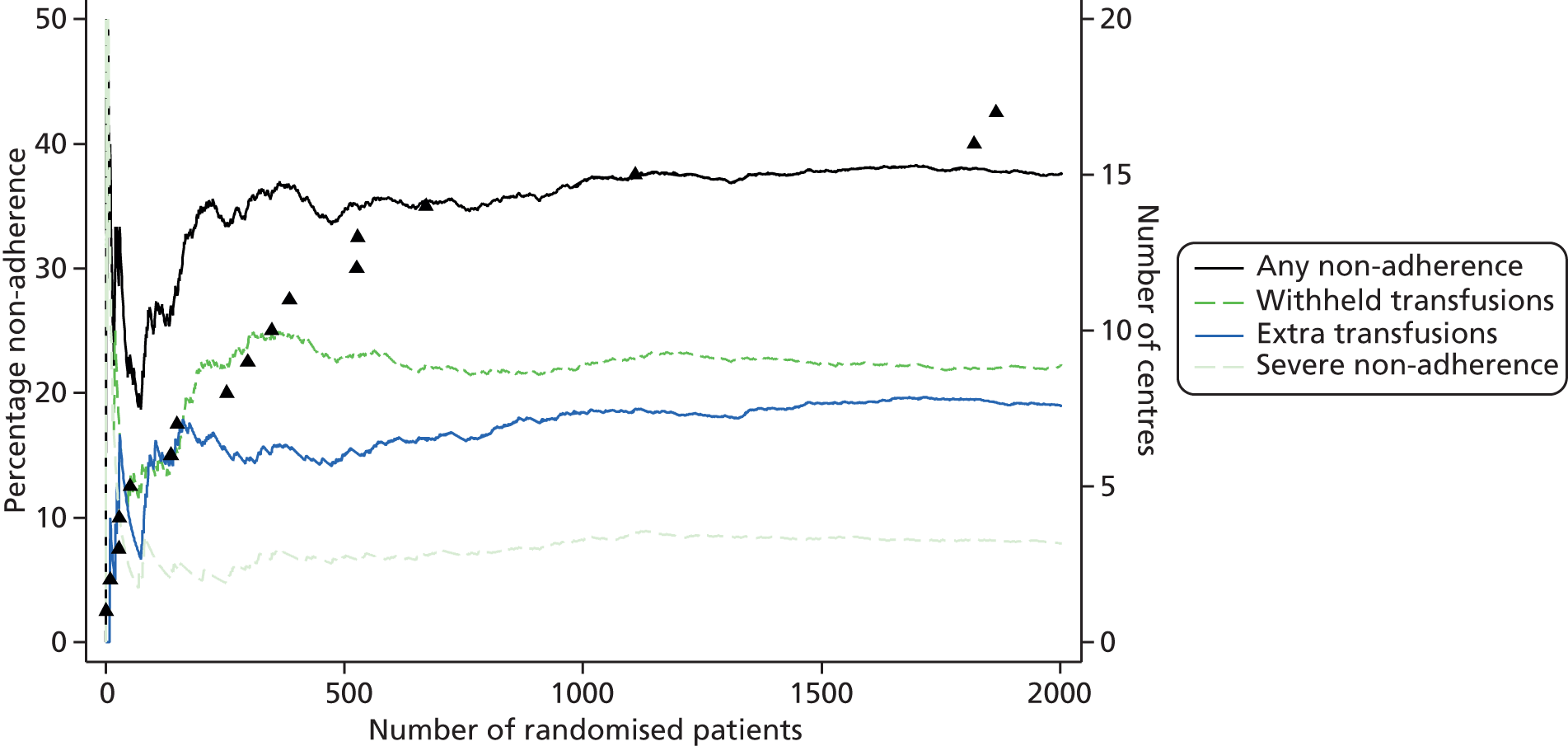

Non-adherence with transfusion protocol

Measuring and assessing adherence with the transfusion protocol was identified as a critical element of the study owing to the assumptions about adherence made in the sample size calculation. 33 The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) also highlighted the importance of non-adherence, as they had concern that doctors might otherwise make transfusion decisions in different ways in the two groups. For example, a decision to transfuse in the liberal group could be delayed up to 24 hours without contravening the protocol and such behaviour would have been missed if data about haemoglobin levels measured during this period, their times and consequent actions had not been recorded.

Two types of non-adherence were defined: (1) a participant received a red blood cell transfusion outside of protocol (‘extra’ transfusion) and (2) a participant was not given a red blood cell transfusion that, according to the protocol, should have been given (‘withheld’ transfusion). Adherence was assessed for the period from randomisation to hospital discharge so multiple instances of non-adherence could be documented for a participant. If a participant withdrew or had their treatment according to their allocation discontinued, adherence after the time of withdrawal/discontinuation was not assessed. For both of the above types of non-adherence, instances were classified into mild, moderate or severe (Table 3). Non-adherence was classified as severe only if the non-adherent instant changed the participant’s overall classification as transfused or not.

| Non-adherence type | ‘Extra’ transfusion outside of protocol | ‘Withheld’ transfusion according to protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | N/A | A transfusion took place, but more than 24 hours after the relevant breach of the transfusion threshold |

| Moderate | Participant transfused outside of protocol, but participant breached the threshold for transfusion at least once postoperatively | Participant was not transfused following a breach, but the participant had previously had at least one post-randomisation transfusion |

| Severe | Participant transfused outside of protocol and participant did not breach the threshold for transfusion at any point postoperatively | Participant was not transfused following a breach and participant had no post-randomisation transfusions |

In addition to describing the amount of non-adherence, work has been done to further describe and characterise non-adherence, including:

-

characteristics of each instance of non-adherence (including reasons, haemoglobin levels and timing) have been described

-

logistic regression models were fitted to identify predictors of non-adherence

-

non-adherence trends both by centre and over the course of the trial have been described.

Statistical methods

The analysis and safety populations consisted of all participants randomised into the study, excluding participants who withdrew and who were unwilling for the data already collected to be used. All analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis and were directed by a pre-specified analysis plan. 34 Continuous variables were summarised via the mean and standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range (IQR) if distributions were skewed. Categorical data were summarised as a number and percentage. Pre-randomisation characteristics were described by allocated treatment. Similarly, pre-operative and intraoperative characteristics, transfusions, EQ-5D-3L scores and mortality of randomised and non-randomised (but consented) participants were described but no formal comparisons made.

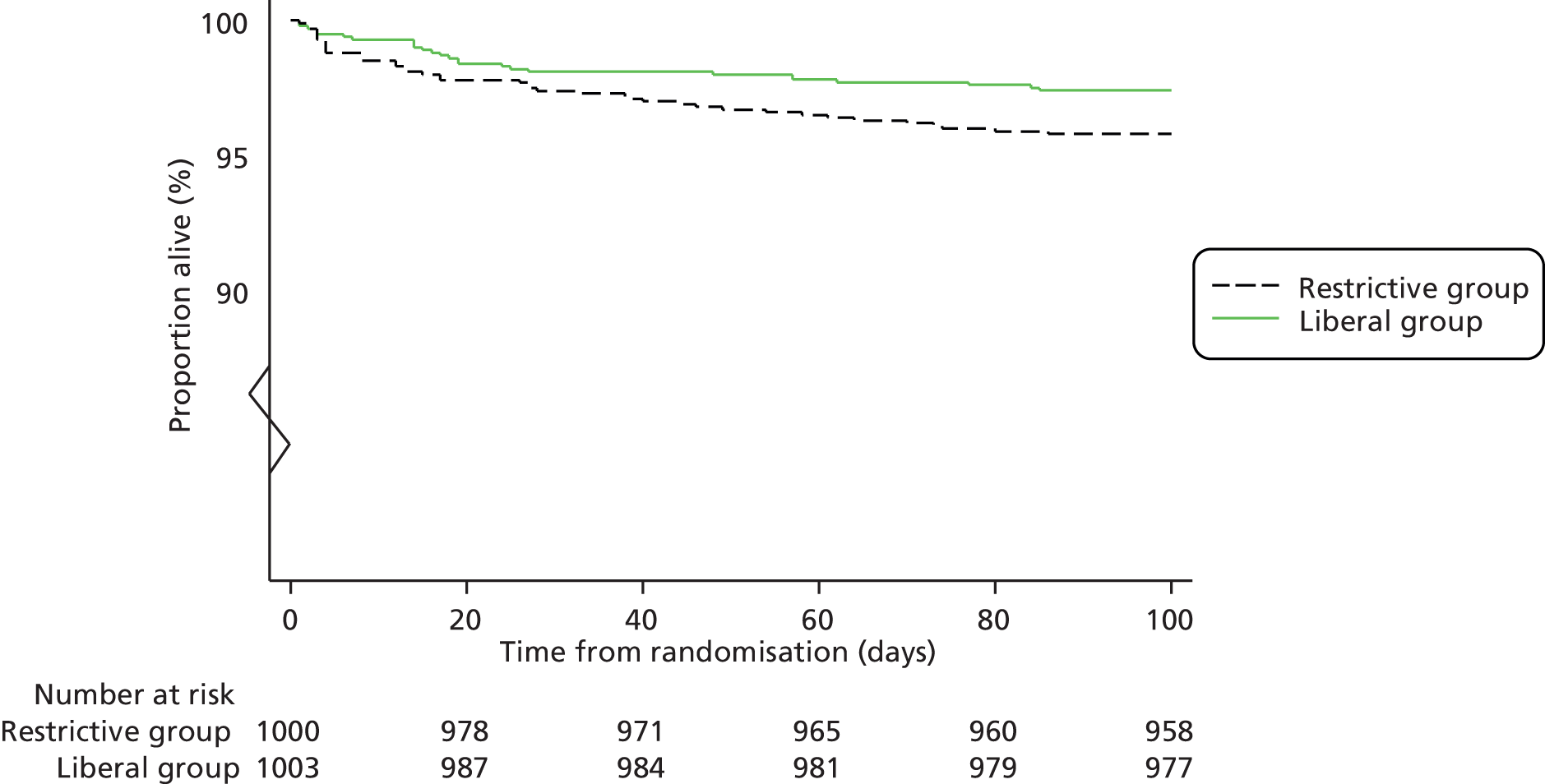

Comparisons of outcomes

All outcomes were analysed using mixed-effects regression models, adjusting for all factors included in the cohort minimisation: operation type as a fixed effect and centre as a random effect (or a shared frailty term in time-to-event models). The primary outcome and other binary outcomes (numbers of participants experiencing infectious or ischaemic events, any transfusions of red blood cells and non-red blood cell products and significant pulmonary morbidity) were analysed using logistic regression, with treatment estimates presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For the analysis of the transfusion of any red blood cells, treatment estimates were analysed using unadjusted logistic regression, with results presented as a risk ratio (RR) and 95% CI, as the OR proved difficult to interpret and an adjusted model did not converge. Time-to-event outcomes were analysed using Cox proportional hazards models and treatment estimates presented as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CI. Durations of ICU/HDU stay and hospital stay were censored at the time of death if the participant died before discharge from hospital. All-cause mortality was censored at the time of last follow-up for survivors. A secondary analysis of the primary outcome, analysing the time to first occurrence of the primary outcome, was also undertaken using a Cox proportional hazards model, censoring at the time of last follow-up or death.

Longitudinal data (EQ-5D-3L scores) were analysed using mixed-effects mixed-distribution models;35 this method was used because the distribution of the data was non-monotonic, with many participants scoring perfect health. Both types of score (utility and visual analogue scores) were dichotomised into less than perfect health compared with perfect health. There were two-parts to each fitted model: (1) an occurrence model, a logistic regression model for the occurrence of less than perfect health compared with perfect health, and (2) an intensity model, a log-linear model for the score, conditional on a non-perfect health score. Correlated participant-term random effects (for occurrence and intensity) were included in each model to allow for the repeated measures. Separate parameter estimates were incorporated into models for the mean baseline response across both treatment groups and for each treatment post intervention, avoiding the necessity to either exclude cases with missing baseline measures or to impute missing baseline values. A time by allocation interaction (post intervention) was added to each of the models; an overall treatment effect is reported unless the interaction was statistically significant at the 10% level, in which case separate treatment effects at each post-intervention time are given.

Safety data

The AEs and SAEs were described by allocated treatment but no formal comparisons made.

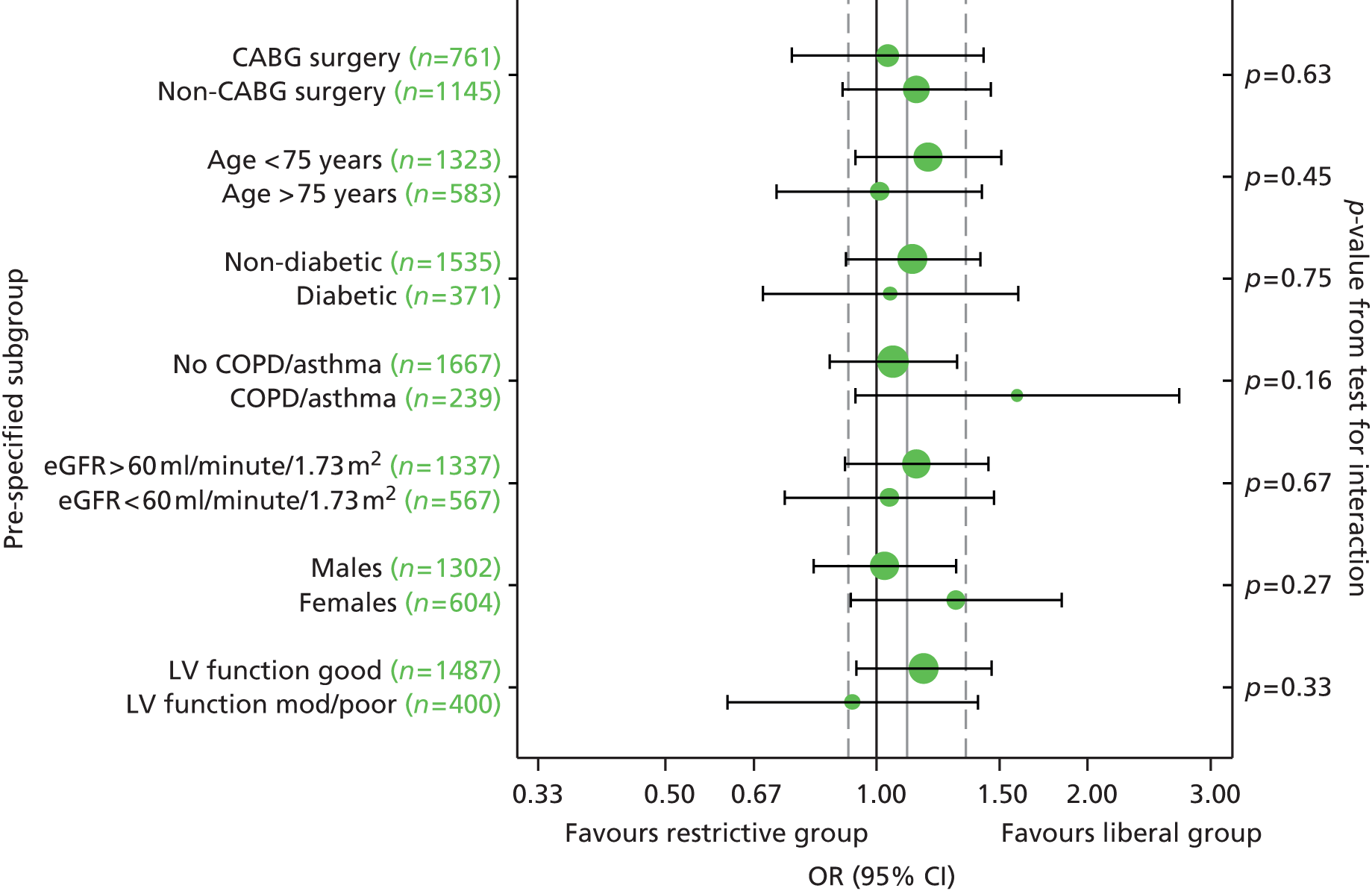

Subgroup analyses

Pre-planned subgroup analyses were specified because of clinical opinion that transfusion decisions should be influenced by patients’ characteristics, notably that ‘at-risk’ patients should be transfused at a different threshold. The subgroups defined in the protocol were: operation type (isolated CABG vs. other operation types), age (< 75 years vs. ≥ 75 years), pre-operative diagnosis of diabetes (none vs. diet, oral medication or insulin controlled), pre-operative diagnosis of lung disease (none vs. chronic pulmonary disease or asthma), pre-operative renal impairment [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) > 60 ml/minute vs. eGFR ≤ 60 ml/minute], sex (males vs. females) and ventricular function (good vs. moderate or poor). Such analyses were implemented by adding a relevant treatment allocation by subgroup interaction term into the primary outcome model; the hypothesis for all subgroup analyses was that there would be no interaction. The pre-operative renal impairment subgroup analysis was defined in the study protocol as pre-operative creatinine ≤ 177 µmol/l versus creatinine > 177 µmol/l. However, during the course of the trial, use of pre-operative creatinine for risk stratification was superseded by estimated eGFR and, therefore, the subgroup analysis for renal impairment was based on eGFR as described above (this change was not covered by a protocol amendment).

Sensitivity analyses

A number of sensitivity analyses were pre-specified for the primary outcome in the analysis plan, although such analyses were not specified in the study protocol.

-

Examining treatment effect estimates for the primary outcome by site, ordering sites by rates of severe non-adherence with the transfusion protocol. This was implemented by a forest plot displaying site-specific treatment estimates. It provided a way of assessing the effect of non-adherence on the overall treatment estimate for the primary outcome, without excluding non-adherent participants. (We considered that an analysis excluding non-adherent participants would be inappropriate because it would be very likely to be biased as non-adherent participants were hypothesised to be the sicker participants in the restrictive group and the healthier participants in the liberal group.) As non-adherence represents a dilution of the allocated intervention, we hypothesised that the treatment effect would tend towards the null with increasing non-adherence.

-

Excluding all events that occurred in the first 24 hours after randomisation. The rationale was that such events could have an onset that actually preceded randomisation and, hence, be unrelated to the intervention. Therefore, we hypothesised that the treatment effect would tend away from the null with exclusion of these events.

-

Excluding participants who were transfused before randomisation. The rationale was that transfusions before randomisation, expected to occur with similar frequency in both groups, would dilute any effect of a difference between groups in the number of transfusions after randomisation. Therefore, we hypothesised that the treatment effect would tend away from the null with exclusion of pre-randomisation transfusions.

-

In collecting AKI data it became apparent that prospective data collection by research nurses in centres failed to identify AKI events that were apparent from routinely collected serial creatinine data. We attribute this discrepancy to differences between centres in the ‘baseline’ creatinine value used to define AKI, which can be confusing to implement as the specified creatinine rise should occur in a 48-hour period. 30,36 However, highest daily creatinine levels were recorded separately, so the following sensitivity analyses were planned:

-

excluding AKI events when the clinical diagnosis was not verified by routinely recorded creatinine levels. This analysis would exclude potentially ‘false’ AKI events, although AKI events in these participants may have been ‘true’ events classified on the basis of urine output (which was not documented routinely).

-

including additional AKI events when the participant was reported not to have had AKI according to clinical judgement but when highest daily creatinine levels supported a diagnosis of AKI. This analysis would include AKI events that were missed, assuming that the creatinine levels recorded for usual hospital care were accurately transcribed on to the CRF.

Assuming that false AKI events would arise in proportion to the incidence of true AKI events, they would not bias the treatment effect. Therefore, we hypothesised that the effect in the first analysis would reduce precision but not shift the estimate predictably either towards or away from the null. Similarly, assuming that missed AKI events would arise in proportion to the incidence of true AKI events, they would also not bias the treatment effect. Therefore, we hypothesised that the effect in the second analysis would increase precision but not shift the estimate predictably.

-

-

Including only ‘serious’ primary outcome events, defined as either stroke, MI, gut infarction, AKI stage three events, pre-discharge sepsis plus organ failure [MI, stroke, laparotomy for gut infarction and one or more of reintubation, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), low cardiac output and/or tracheostomy] and/or post-discharge sepsis that required hospital readmission. This analysis arose from the pre-planned interim analysis that showed a higher primary outcome event frequency than was anticipated when the study was designed, with a large majority of qualifying events arising from sepsis and AKI, which were considered to be clinically less serious. We considered that this sensitivity analysis would better reflect our original intention in formulating the composite outcome and the outcome events that were included in the observational analysis, which led to the superiority hypothesis for the trial. This analysis would necessarily have less precision but we did not have a strong hypothesis about the way in which the treatment effect might be affected. If transfusion were to have the same effect on more and less serious events, the treatment effect should be unaltered; if transfusion were to have a differential effect on more and less serious events, the treatment effect should be moved towards or away from the null in a manner consistent with the differential effect.

Post-hoc analyses

In addition, a secondary post-hoc analysis of severe in hospital events was performed, which involved refitting the primary outcome model with an outcome of death, severe sepsis [as defined in sensitivity analysis (e) above], ARDS, tracheostomy, low cardiac output, MI, AKI stage three, gut infarction and/or stroke. This analysis was performed because it was judged to be of key interest to hospital-based clinicians caring for patients. As for analysis (e) above, it would necessarily have less precision but we did not hypothesise that the treatment effect would be moved towards or away from the null.

Two further post-hoc sensitivity analyses were carried out for the secondary outcome of mortality; these comprised analyses (b) and (c) above (i.e. excluding deaths within 24 hours of randomisation and participants transfused before randomisation). These were suggested during the peer review process, on account of the seriousness of the outcome, and we agreed that they were worthwhile. Our (post hoc) hypotheses were the same as that for the corresponding sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome. These were the only additional analyses requested in this way, the decision to perform them was made without knowing the results and the results are fully reported.

Observational analyses

Three observational analyses were pre-specified in the study protocol.

-

Estimating the relationship between the number of red blood cell units transfused and the risk of mortality and morbidity, stratified by trial arm.

-

Investigating the relationship between percentage decline in haemoglobin from the pre-operative level and the risk of primary and secondary outcomes, taking into account the number of red blood cell units transfused.

-

Investigating whether or not red blood cell age (i.e. time since donation and processing) is associated with the risk of primary and secondary outcomes, achieved by linking batch numbers of all red blood cells transfused to a blood bank database and determining the age of each unit donation and transfusion dates.

For the purposes of these observational analyses, a composite outcome of the trial primary outcome or death was defined in the statistical analysis plan (SAP). In addition, all red blood cell units transfused or haemoglobin levels recorded after the time of the first occurrence of the primary outcome (or censoring) were excluded to ensure the relevant exposure occurred before the outcome. (More complex methods to deal with this issue were outlined in the SAP but these have not been attempted owing to the complexity of the analyses.) For all three analyses, pre-operative and intraoperative characteristics and trial outcomes were described by exposure [i.e. any red blood cells vs. no red blood cells, minimum haemoglobin < 7.5 g/dl vs. ≥ 7.5 g/dl, and transfusion of any red blood cells aged over 21 days old (median age) vs. only younger blood (< 21 days) vs. no red blood cell transfusions].

For analyses (b) and (c), the exposure definitions differ slightly from those used in the protocol/SAP. With respect to analysis (b), the protocol stated that haemoglobin would be defined in terms of percentage decline; however, exploratory analyses suggested this was not sensible (e.g. a participant with pre-operative haemoglobin 12 g/dl and post-randomisation haemoglobin 6 g/dl would be treated in the same way as a participant with pre-operative haemoglobin 18 g/dl and post-randomisation haemoglobin 9 g/dl, as the percentage decline is 50% in both cases) and that it would be more informative to include both pre-operative and post-randomisation haemoglobin levels in any analysis model. For analysis (c), various methods of defining age of blood were described in the SAP (using the age of the ‘oldest’ red blood cell unit given, the mean age of all red blood cells, the use of any red blood cells more than 14 days old, the number or percentage of red blood cells given over 14 days old, the use of red blood cells older than the median age of all red blood cells transfused) and it was stated that the age of the oldest unit would be used as the primary analysis. Owing to the large volume of missing data for age of blood, it was decided instead only to provide descriptive analyses by the receipt of any red blood cells older than the median age.

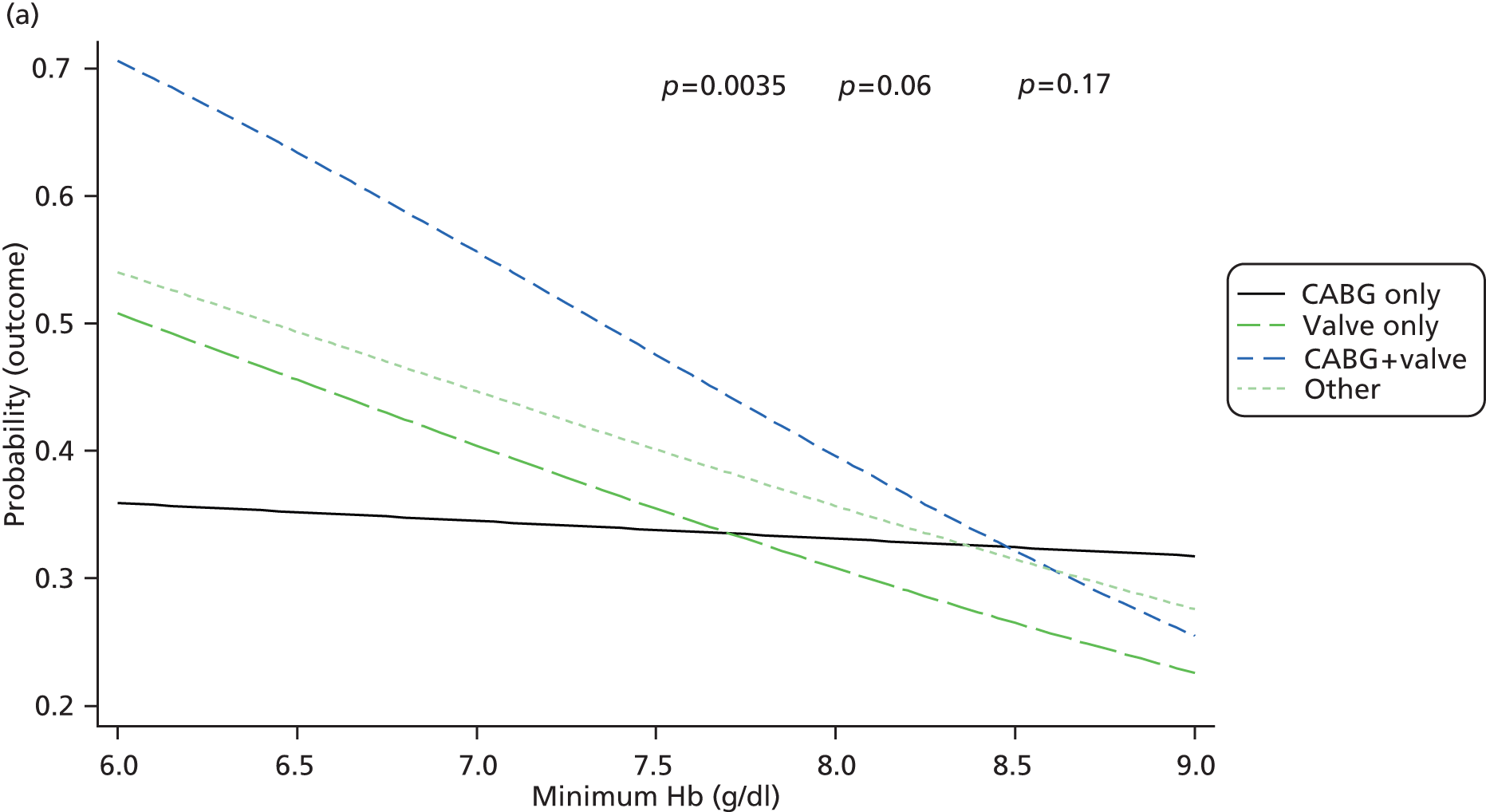

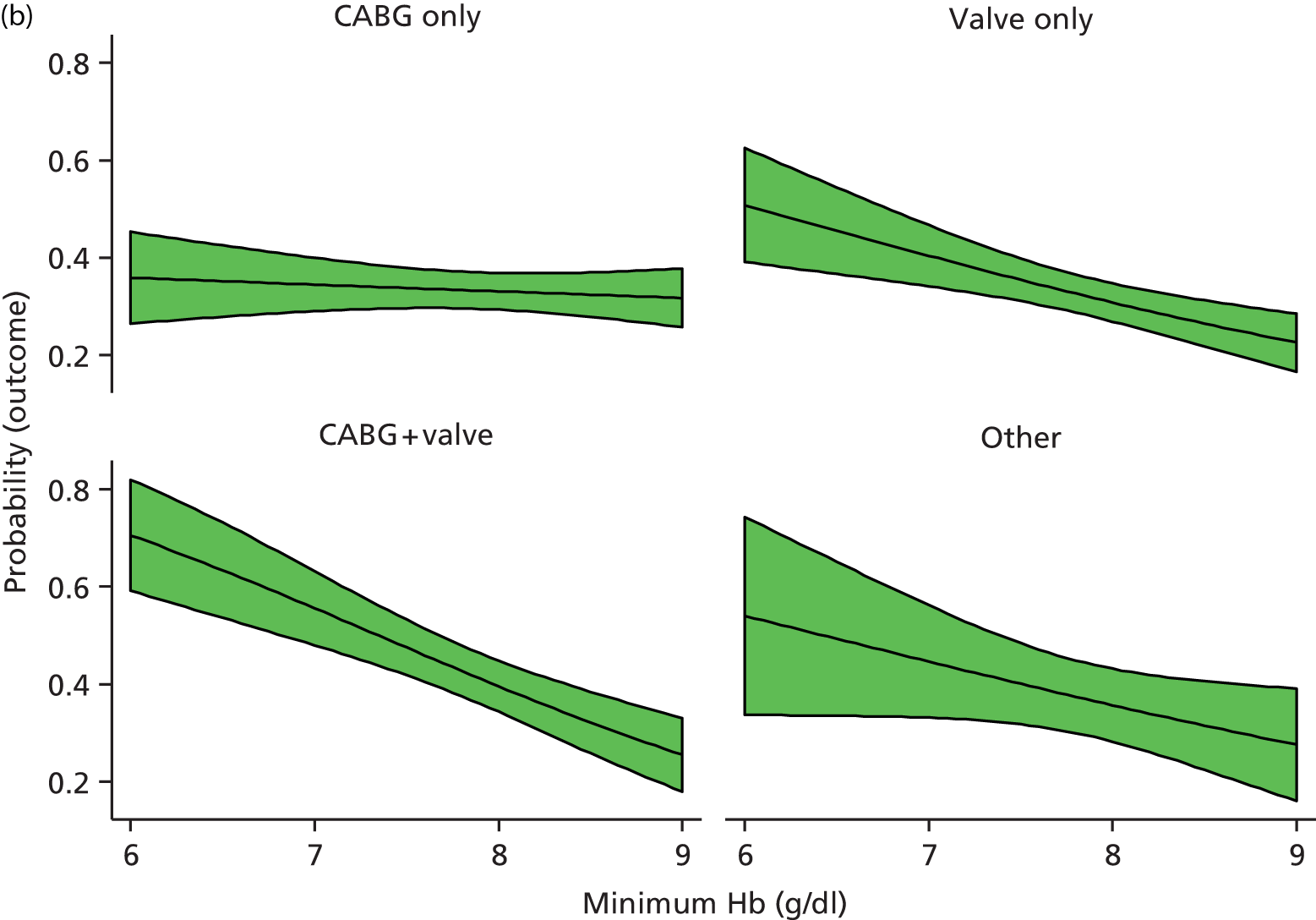

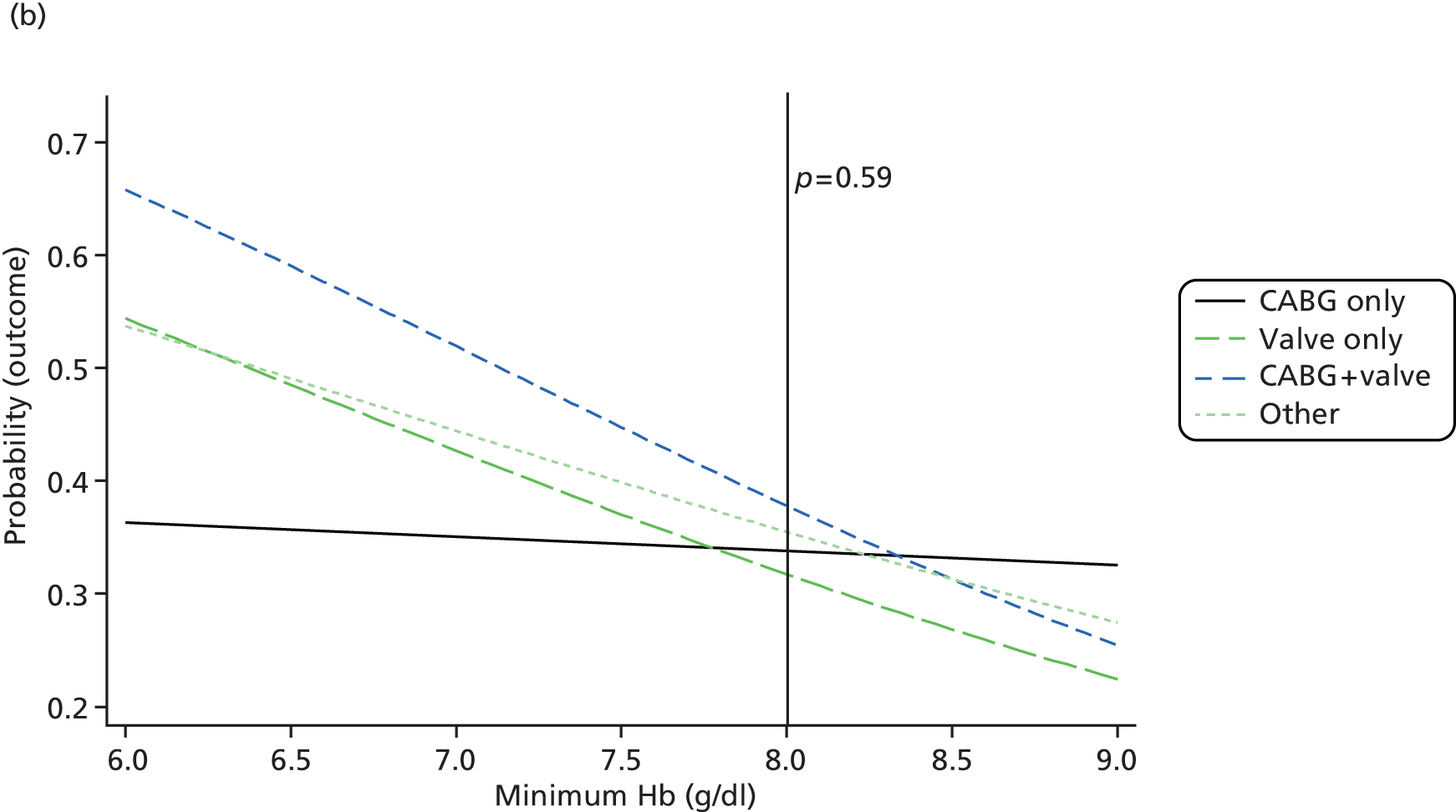

For parts (a) and (b), further analyses have been undertaken. Univariate analyses exploring the relationship between exposures and the outcome were performed. Two separate adjusted models [one for analysis (a) and one for analysis (b)] were then fitted adjusting for the following, if found to be potential confounders: operation type, centre (as a random effect), European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE), age, sex and pre-randomisation red blood cell transfusions [for analysis (a) only]. A model building strategy was used whereby variables were sequentially added to the model, at each step including the variable that improved the model fit the most (as determined by a likelihood ratio test). Variables were included in the model if they were (1) associated with both the exposure and the outcome but did not lie on the causal pathway between the exposure and outcome, and (2) significantly contributed to the relevant multivariate model (defined by a likelihood ratio p < 0.05 or modifying the effect estimate by greater than 10%). If pairs of variables were considered to be collinear or strongly related (e.g. EuroSCORE and age), only one of the pair was included. In addition, interaction terms were included in models if significant at the 5% level. The parameterisation of the exposure variable (e.g. continuous linear, continuous including additional power terms, ordinal categorical or binary) was explored using fractional polynomial models and likelihood ratio tests to compare nested models. Marginal plots were used to describe interactions between continuous and categorical covariates graphically. Models were refitted separately within each randomised group. Finally, instrumental variable (IV) methods were used to estimate the associations of interest free from confounding, separately for analyses (a) and (b); models used the multiplicative generalised method of moments estimation (the ivpoisson command in Stata).

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis was performed analysing mortality from TITRe2 and all other RCTs that have compared liberal and restrictive red blood cell transfusion strategies in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. This analysis was undertaken to place the findings of TITRe2 in the context of the evidence base. Eligible RCTs24–26,37,38 were identified from a previous review of RCTs comparing restrictive versus liberal transfusion thresholds12 and an on-going review comparing RCT and observational evidence about the effects of red blood cell transfusion in cardiac surgery patients. 39 The previous Cochrane review searched multiple databases including the Cochrane Injuries Group’s Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE and ISI Web of Science (both the Science and Conference Proceedings Citation Indices). The review included RCTs with a concurrent control group in which participants were assigned to groups with different transfusion triggers or thresholds, for which the thresholds were defined by a haemoglobin or haematocrit level that a participant had to reach before a red blood cell transfusion could be administered. For the purposes of the current meta-analysis, we included RCTs identified from either review that were deemed to have taken place in the context of cardiac surgery. Therefore, we included RCTs with different group-specific transfusion thresholds to those used in TITRe2 and which included all participants, irrespective of whether or not the liberal threshold was breached (i.e. without the post-operative eligibility criterion adopted in the TITRe2 trial). When writing the SAP, we also intended to perform a meta-analysis for the primary outcome; however, outcomes were too dissimilar between included RCTs. The meta-analysis was performed using standard meta-analysis methods for binary outcomes with a random effects model.

Missing data

Missing data are indicated in all of the tables. Rules for imputing missing data were outlined in the analysis plan, dependent on the level of missing data. However, the majority of outcomes had levels of missing data below the defined thresholds in the plan (5% for outcomes measured at one time point and 20% for longitudinal data) and imputation methods were not generally used. The first exception was for the infectious events secondary outcome (5.6% missing), whereby separate estimates were made prior to hospital discharge and overall. A second exception was the in-hospital component of the ASEPSIS score from which wound infection events were identified; this was one of the rarer components of the primary outcome but the in-hospital component of the score was the outcome data item that was most likely to be missing. If the in-hospital ASEPSIS score was missing, the participant was assumed not to have had a serious wound infection if the following criteria were met: participant did not have antibiotics for suspected wound infection prescribed in hospital and follow-up was completed, and the participant reported no problems with the healing of chest, leg and/or arm wound up to 3 months after the operation.

Significance levels

For hypothesis tests, two-tailed p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, with the exception of tests for interactions between group and time in longitudinal models when a 10% significance level was used. Likelihood ratio tests were used in preference to Wald tests. No formal adjustment was made for multiple testing. When interpreting the results, consideration has been given to the number of tests performed and the consistency, magnitude and direction of estimates for different outcomes. 40 All data management and analyses were performed in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) or Stata version 12.1 or 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

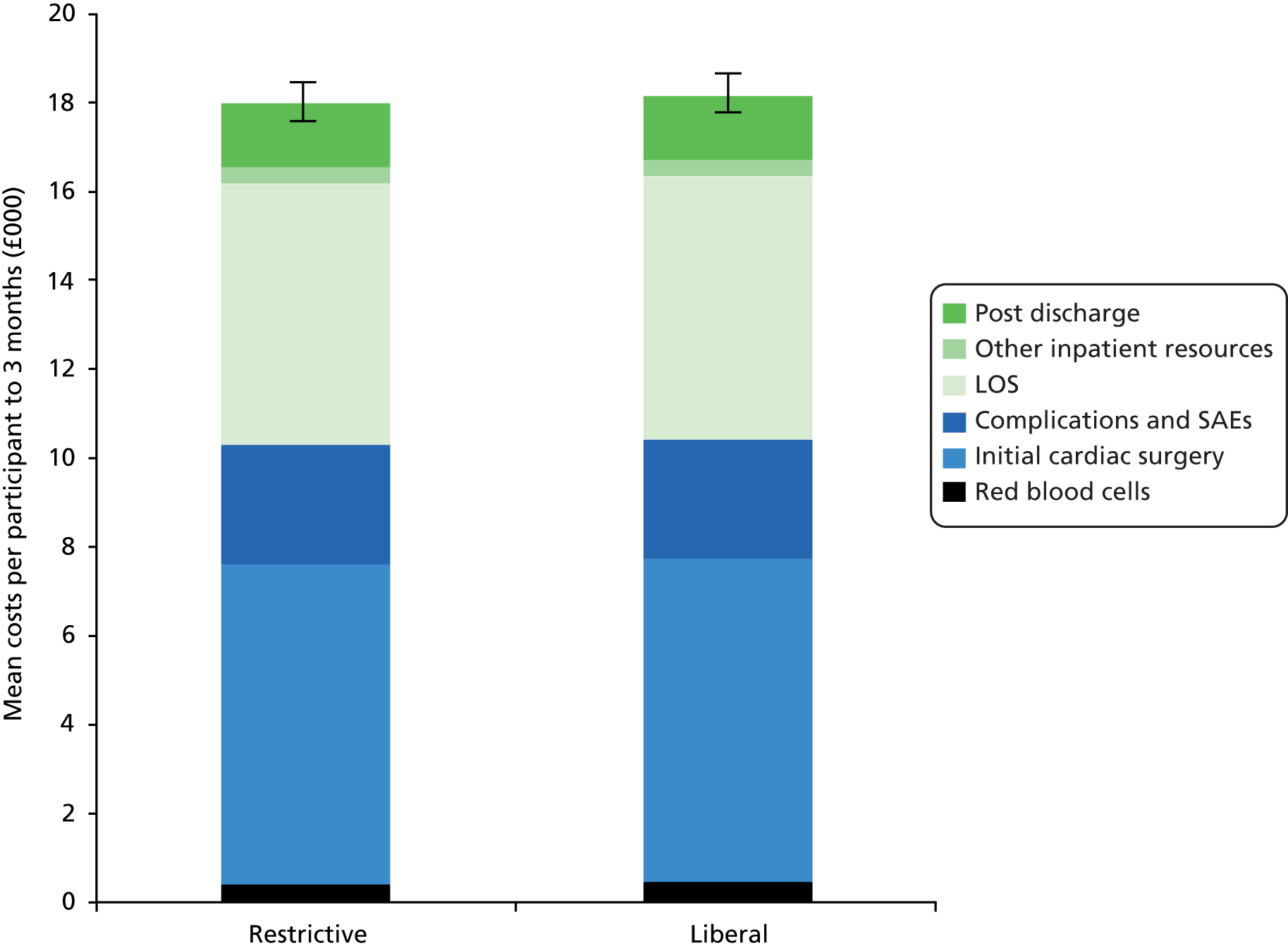

Health economics

Aims and objectives

The economic evaluation aimed to estimate the cost-effectiveness of the restrictive compared with the liberal haemoglobin transfusion threshold as compared in TITRe2. Our main objective was to estimate the incremental cost and the incremental cost-effectiveness of the restrictive compared with the liberal haemoglobin transfusion threshold after cardiac surgery.

Economic evaluation methods overview

A cost–utility analysis was conducted, with outcomes measured using the EQ-5D-3L. The restrictive haemoglobin threshold was considered as cost-effective if the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) fell below £20,000, which is generally considered as the threshold at which the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) considers an intervention to be cost-effective. 41 Good practice guidelines on the conduct of economic evaluations were followed for the economic evaluation. 42–44 Table 4 summarises the methods for the economic evaluation, with further details provided in the text following the table.

| Aspect of methodology | Strategy used in base-case analysis |

|---|---|

| Form of economic evaluation | Cost–utility analysis for comparison between restrictive and liberal transfusion thresholds |

| Perspective | NHS and Personal Social Services |

| Time horizon | A within-trial analysis, taking a 3-month time horizon (up to the primary clinical time point) |

| Population | All randomised participants were included, except those randomised in error |

| Costs included in analysis | Index admission |

|

|

| Post discharge | |

|

|

| Utility measurement (primary economic outcome) | EQ-5D-3L (administered pre-operatively and at 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively) |

| QALY calculations | Assume that participants’ utility changes linearly between utility measurements |

| Adjustment for baseline utility | Regression used to adjust QALY calculations for differences in baseline utility |

| Missing data | Mean imputation and multiple imputation |

Form of analysis and primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure for the economic evaluation was QALYs, as advocated by NICE. 44 This outcome combines quantity and quality of life into a single measure. Our evaluation took the form of a cost–utility analysis in which the difference in mean costs between the two transfusion threshold groups is divided by the difference in mean QALYs between the two groups to calculate an ICER and, specifically, the incremental cost per QALY gained by switching from using a liberal threshold to using a restrictive threshold.

Perspective

The primary perspective of the evaluation was that of the UK NHS and Personal Social Services, as recommended by NICE. 44 However, data were collected on some types of non-NHS costs including expenditure incurred by a participant when travelling to hospital. We planned to include these costs in a wider perspective in a sensitivity analysis, if resource use for these non-NHS costs differed between the trial groups. The perspective for outcomes was that of the participants undergoing treatment.

Time horizon

A within-trial analysis, taking a 3-month time horizon, was conducted. It was anticipated that all major resource use would occur within this timeframe and, therefore, be captured. The start of our analysis was from the point of surgery. Surgery was chosen as the time origin, rather than the point of randomisation as was the case with the analysis of effectiveness, in order to capture the resources that would be required for the intervention from a decision-maker’s perspective, that is, to include all relevant costs (and effects) involved in delivering an intervention. Our time horizon continued until 3 months postoperatively. Ideally, the time point for baseline costs and outcomes should be the same; however, the EQ-5D-3L was collected pre-operatively whereas detailed resource use collection began on the day of surgery.

Population

Our base-case analysis included all participants randomised into the trial except those randomised in error, which is consistent with the main effectiveness analyses. Analyses were performed on an ITT basis.

Collection of resource use and cost data

Resource use data were collected on all significant health service resource inputs for the trial participants up to the point of the 3-month follow-up. The main resource use categories that were costed are listed in the first column of Table 5, along with the sources of information for both the resource use and unit costs. Costing decisions (such as resource use assumed for complications) were made without knowledge of the allocation of participants to trial groups.

| Resource category | Sources for resource use informationa | Sources for unit cost information |

|---|---|---|

| Initial cardiac surgery | CRF C1 | National Schedule of Reference Costs (2012–13);45 NHSBT National Comparative Audit of Blood Transfusion;5 NHSBT price list46 |

| Blood products | CRFs B1, B2 | NHSBT price list;46 primary data collection for the costs of administering blood products (further details in Appendix 3, Table 60) |

| Initial stay in hospital post surgery | CRFs D1, H5 | National Schedule of Reference Costs (2012–13)45 |

| Medications | CRF D2 | eMIT;47 BNF48 |

| Complications, including re-operations; SAEs | CRFs C1, C2–C4, C5, C6, C7, F1–F3, H5, X1 | National Schedule of Reference Costs (2012–13);45 eMIT;47 BNF48 |

| Hospital readmissions | CRF X1, 3-month follow-up questionnaire – section 2a | National Schedule of Reference Costs (2012–13)45 |

| Outpatient attendances and visits to ED | 3-month follow-up questionnaire – sections 2b, 2c | National Schedule of Reference Costs (2012–13)45 |

| Community health and social care contacts | 3-month follow-up questionnaire – section 3 | National Schedule of Reference Costs (2012–13);45 Unit Costs of Health and Social Care49 |

Initial cardiac surgery and blood products

As the type of surgery itself was not the main factor being assessed within the trial, we used published cardiac surgery costs rather than performing a detailed microcosting. We used cost figures from the cardiac surgery Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) codes from the elective inpatient spreadsheet in the National Reference Costs database45 and subtracted costs relating to length of stay (LOS) and blood products to calculate the cost of the surgery itself.

The LOS in hospital was removed by using the average LOS associated with each HRG and each specialty (cardiac surgery or cardiothoracic surgery) at a cost of £392 per day; this cost is a weighted average of elective inpatient excess bed-days for relevant cardiac procedures (see Appendix 3, Table 60 for further details). For valve surgery, there were HRG codes for single-valve procedures and for procedures on more than one valve. The costs are higher for procedures involving more than one valve; 25% of the activity reported in Reference Costs was for procedures involving multiple valves45 but in TITRe2 this proportion is only 10%. To reflect this fact, we created a weighted average of the costs of single- and multiple-valve procedures, with the weighting being according to the proportion of these types of participants recruited to TITRe2.

The costs of blood products (red blood cells, FFP and platelets) were removed from HRG costs by using the average numbers of products reported to be used by CABG, valve, and CABG and valve patients in the NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) national audit in 2011,5 and valued using published NHSBT prices. For our surgery category of ‘other’, the costs of average blood products were removed by applying the information used for CABG and valve participants because the average operation time for ‘other’ was lengthy and most similar to the CABG and valve group.

The total number of red blood cells transfused each day was recorded on the trial CRFs. The costs of administering red blood cell transfusions were added to the costs of the units of red blood cells. The costs of administering transfusions were based on primary data collection of the nursing time and consumables associated with administering transfusions collected by the authors as part of another study (see Appendix 3, Table 60 for more information).

Initial post-surgery hospital stay

In terms of hospital stay following the actual surgery, LOS was collected for CICU/HDU, general ICU and ward during the trial. As time spent on CICU was not reported separately from time spent on HDU, and recognising that these activities probably require a different level of resources, the time of extubation was used to distinguish between time on CICU and time on HDU. Participants had an initial extubation date and time recorded in the trial, along with the dates and times of any further intubations and extubations. If data were missing on extubation date/time, we assumed that for those who died before discharge, that they were intubated until death. For participants without a tracheostomy, and no indication that they were not extubated, we assumed an average intubation duration, based on information from participants with available data. For participants who went on to have a tracheostomy, we calculated their time to tracheostomy and time to discharge and assumed the average intubation time for participants with intubation durations between these two times. Similar assumptions were made for any reintubations. CICU and HDU costs were taken from NHS Reference Costs. 45 To cost time on a cardiac ward, an average bed-day cost was created by weighting the cost of relevant cardiac procedures excess bed-day costs according to activity from the elective inpatient spreadsheet in Reference Costs45 (see Appendix 3, Table 60 for further details).

Medications and fluids

Medications and fluids given during surgery or intensive care, such as inotropes, were costed for each participant. Information on whether or not participants received these medications were collected on pre-specified yes/no tick boxes on the trial CRFs (Form D2). In order to cost these interventions, a member of the trial research team provided an estimate of the likely quantity of fluids a participant would receive. The costs of antibiotics administered after surgery for an infection were summed during the period of initial hospital stay post surgery and during any hospital stay after discharge if participants were readmitted (up to 3 months). The names of specific antibiotics were reported on the trial CRF (Form C5) as free text with the route and duration of the course. We established the most likely dose with the TITRe2 research team. If information was missing on the route of administration (oral or intravenous) or frequency of drugs, we clarified this information with the trial research team and conducted sensitivity analyses around alternative scenarios and drug costs for antibiotic treatment. The costs of antibiotics were included in the costs of complications.

In addition, the regular medications that participants were taking, such as beta-blockers, statins and warfarin, were recorded as on the medication or not by pre-specified tick boxes (yes/no) on CRF Form D2. This was recorded for two time points: at baseline – on admission to the cardiac surgery unit – and at discharge from the cardiac surgery unit. A member of the trial research team estimated the name, dose and mode of delivery (oral or intravenous) for the regular medications that participants were taking at baseline and discharge. We assumed that participants took any medications recorded at discharge for the 3-month follow-up and costed these medications for 3 months. In a separate analysis, we also costed the regular medications participants were taking at baseline and at discharge for a period of one week. Comparisons were then made between the costs of these medications taken at baseline and at discharge from hospital, to determine whether or not there were significant changes in this resource before and after surgery.

Treatment complications and serious adverse events

Primary outcome complications that were costed included serious infection, permanent stroke, MI, gut infarction and AKI. Details of these complications were recorded on CRF Forms C5 and C6. We also included the costs of any procedures or tests required to verify the complications, such as computerised tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans for permanent stroke, laparotomy for gut infarction and ECG for suspected MIs. For all participants suspected to have had a MI, the costs of diagnostic investigations were included. The costs of all other post-operative complications recorded on CRF C7 were calculated; examples include pacing (both temporary and permanent pacing), CPAP ventilation, tracheostomy and transient ischaemic attack. Cardiac surgery reoperations were also included in complication costs. Care was taken to avoid double counting of complication costs. For example, resource use associated with both ARDS and reintubation was assumed to be a transoesophageal echo and three chest X-rays. If a participant had both complications on the same day, only one echo and three chest X-rays were costed to avoid probable double counting. The trial CRFs were used to gather the types and amounts of complications the participants had experienced and also to capture resource use around SAEs. SAEs were individually reviewed and additional resources were costed if not already captured in complication costs, again to avoid double counting. Tables 64, 65, 67 and 68 in Appendix 3 show all the complications, the corresponding diagnostic tests and treatments assumed, and their unit costs.

Hospital readmissions

The costs of hospital readmissions include all expected and unexpected cardiac surgery and transfusion complications, in terms of AEs and SAEs, but excluded all unexpected unrelated complications. For example, our analysis included the cost of readmissions for hypertension and angina, but excluded the cost of readmissions for cancer treatment. Clinical opinion was sought to clarify whether unexpected complications were possibly related or were unrelated to the index surgery. A bed-day cost for readmissions was created by weighting the non-elective inpatient excess bed-days across all specialties according to activity. The cost of an ED attendance was included if a participant was admitted via ED or referred by their GP (and assumed to be admitted via ED). If participants travelled to hospital via ambulance, this was also costed.

Outpatient attendances, emergency department visits and community health and social care contacts

The type of outpatient appointment was recorded by pre-specified tick boxes on the trial follow-up questionnaire [section 2(c)] which include cardiac surgery, cardiology (non-surgical), renal/dialysis unit, stroke clinic or ‘other’. If participants specified ‘other’, we discussed with the trial research team whether or not these were likely to be linked to the surgery, in order to avoid costing any outpatient visits that were totally unlinked to the trial. Information on the number of ED visits related to the surgery and the reasons for the visits was captured on the trial CRF [section 2(b) of the follow-up questionnaire]. The reasons for visits recorded by participants were reviewed and any unrelated activity excluded. Information was also collected on how the participant travelled to ED to ensure any ambulance costs were captured. Primary care contacts with GPs and practice nurses, whether at the GP surgery or participant’s home, were costed. Other NHS or social services visits at home or elsewhere, including any visits to cardiac rehabilitation clinics or warfarin clinics, were also costed using information collected on the trial follow-up questionnaires (see section 3 of the questionnaire).

Attaching unit costs to resource use

Unit costs for hospital and community health-care resource use were largely obtained from national sources, for example, NHSBT price lists for blood products, the National Schedule of Reference Costs for ICU, HDU and cardiac ward costs, MRI and CT scans and many complications, and Unit Costs of Health and Social Care for community costs. 45,46,49 Resources were valued in 2012/13 pounds sterling (£); if any unit costs were in pre-2012/13 prices, they have been inflated to 2012/13 using the Hospital and Community Health Services (HCHS) inflation index. 49 Costs of drugs given in hospital were taken from the electronic marketing information tool (eMIT)47 when possible, which provides the reduced prices paid for generic drugs in hospital; other drug costs were taken from the British National Formulary (BNF). 48 Tables 63 and 64 in Appendix 3 lists all the medications and their costs used for the trial; further details on all unit costs and their source can be found in Appendix 3, Unit costs and resource use assumed for complications.

Measurement of health-related quality of life and quality-adjusted life-years

Measurement of health-related quality of life

The EQ-5D-3L questionnaire, advocated for use in economic evaluations by NICE,44 was used to measure health-related quality of life. 31 The EQ-5D-3L is a generic measure of health outcome covering five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Responses recorded on the instrument are converted into a single-index value using the UK valuation set, valuations from approximately 3000 members of the UK general population elicited using the time trade-off method;50 scores are then used to facilitate the calculation of QALYs in health economic evaluations. The EQ-5D-3L was used for TITRe2 as the 5-level version was not available at the start of the trial. Our trial participants completed the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire at three time points: in hospital pre-operatively and by post/telephone at 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively.

Calculation of quality-adjusted life-years

The QALY profile for each participant up to 3 months postoperatively was estimated and the area under the curve of utility measurements used to calculate the number of QALYs accrued by each participant. QALYs were calculated assuming that each participant’s utility changed linearly between each of the time points (pre-operatively, 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively). For participants who died during the trial, their utility was assumed to change linearly between the preceding time point and the time of death, and a value of zero was given to participants from death onwards.

Total QALYs gained were calculated for each participant by adding together QALYs gained from baseline to 6 weeks and from 6 weeks to 3 months. QALYs gained from baseline to 6 weeks were calculated by averaging a participant’s EQ-5D-3L scores at baseline and 6 weeks and multiplying by 42 days (or number of days until death if this was within 42 days). QALYs gained from 6 weeks to 3 months were calculated in a similar way. Once total QALYs gained were calculated for all participants, the average QALY gain for participants in each group was calculated. Alternative assumptions regarding the analysis of QALYs were investigated in sensitivity analyses, such as using the date of completion of the 6-week EQ-5D-3L rather than assuming this was at 42 days.

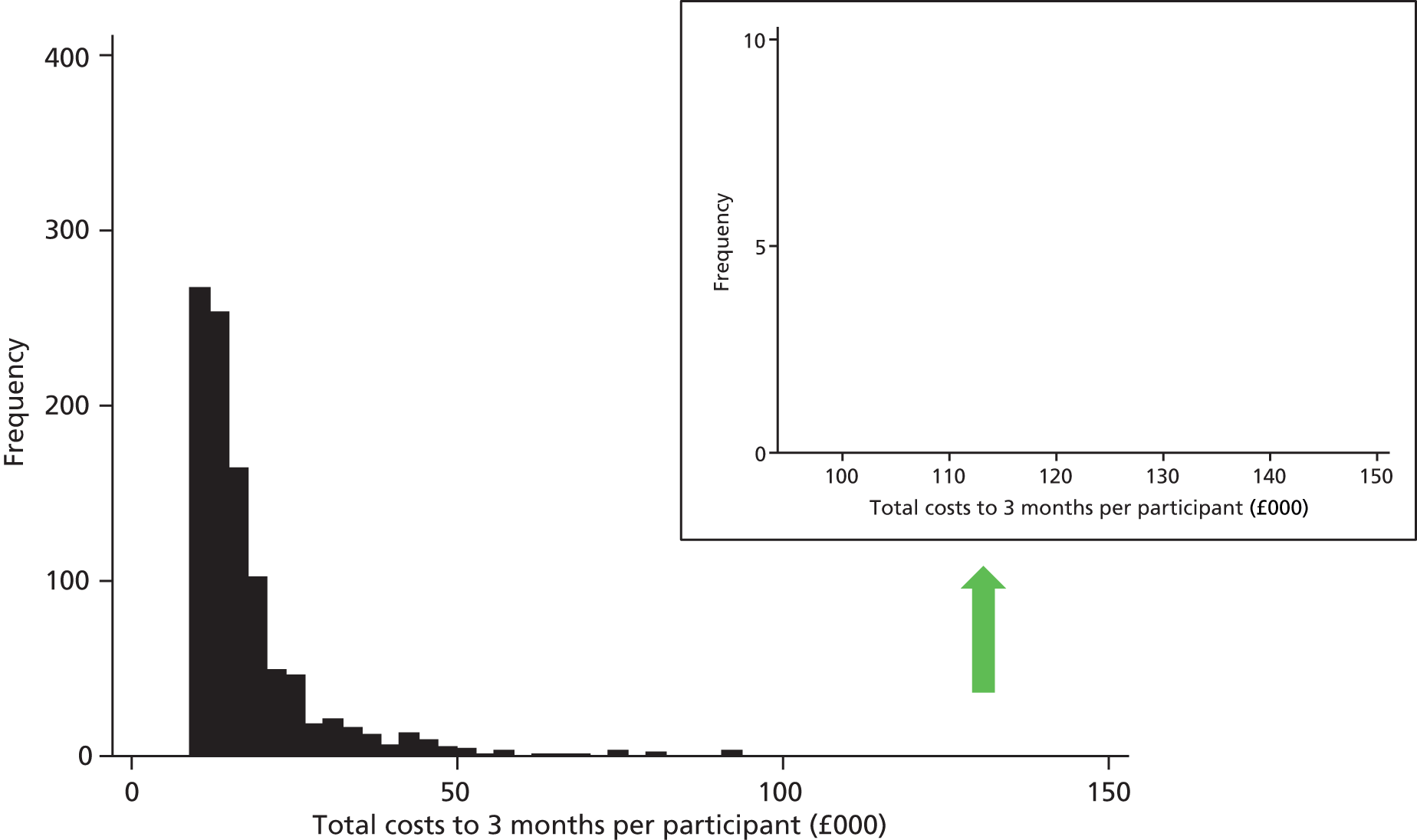

Missing data

We first summarised descriptively the volume of missing data for both resource use and EQ-5D-3L scores, which showed that 2.5% of resource use data were completely missing: 2.4% in the restrictive group and 2.5% in the liberal group. Overall, 10.7% of EQ-5D-3L scores were missing across the three time points (pre-surgery, 6 weeks and 3 months); 10.9% in the restrictive group and 10.5% in the liberal group. Although the level of missing data on resource use sounds small, because there are a large number of resource use variables for the trial, any simple methods to deal with the missing data would work poorly. For instance, using complete case analysis would leave only 61% of participants remaining for analysis. Multiple imputation was used to handle this missing data.