Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 09/119/01. The protocol was agreed in July 2014. The assessment report began editorial review in May 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

We would like to acknowledge that Stephen Marks received grants from Astellas and Novartis for immunosuppressive randomised controlled studies in paediatric renal transplant recipients during the conduct of the study. In addition, Jan Dudley was a member of an expert review panel in January 2008 and developed consensus recommendation on the optimal use of CellCept® (Roche Products) in paediatric renal transplantation and received an honorarium for Roche for this work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Haasova et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

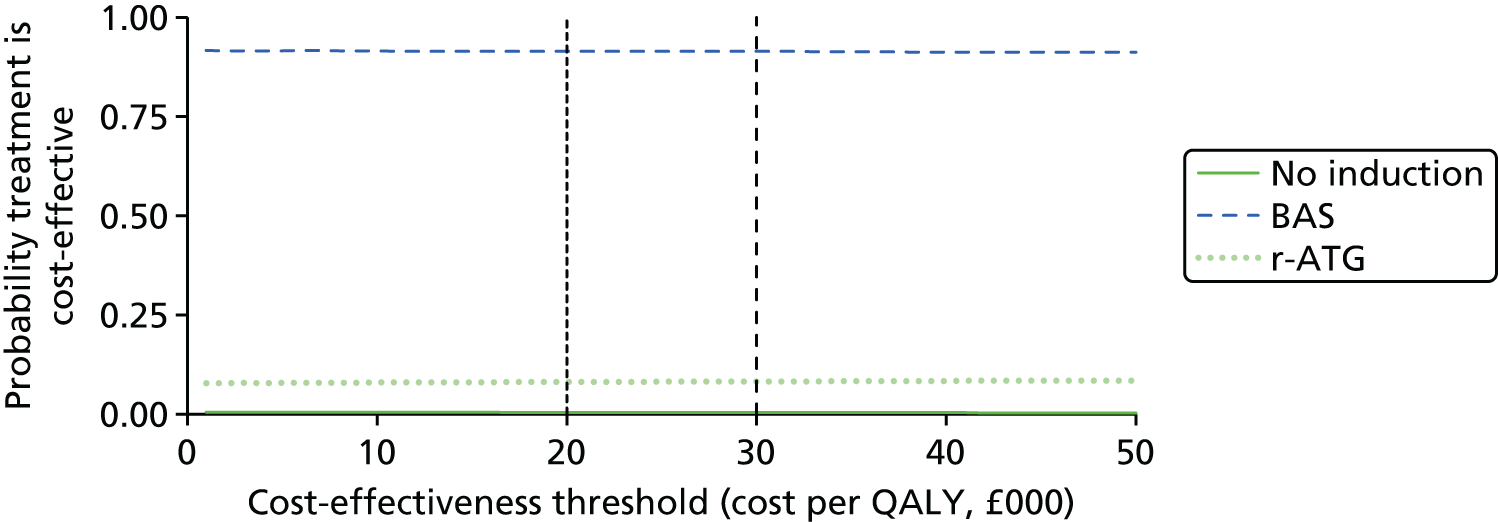

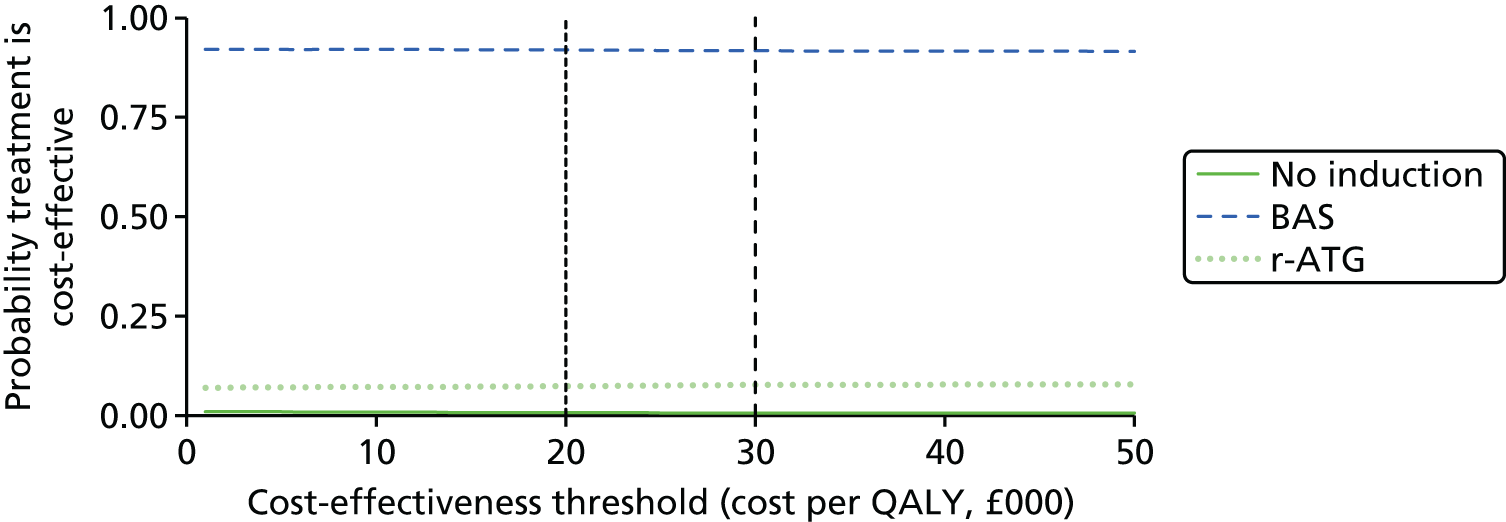

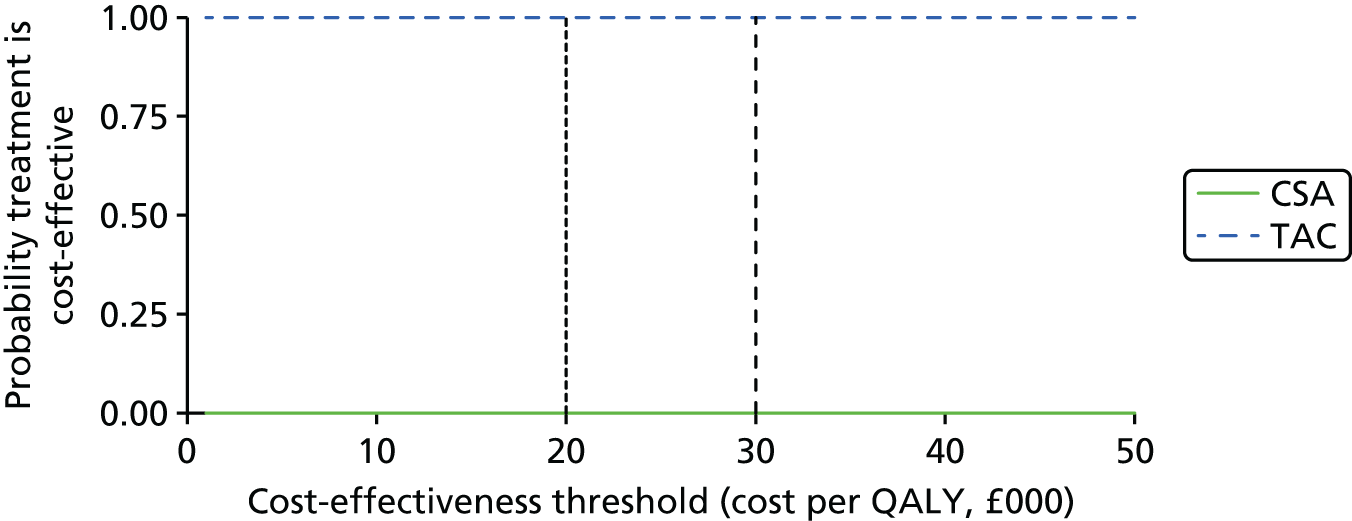

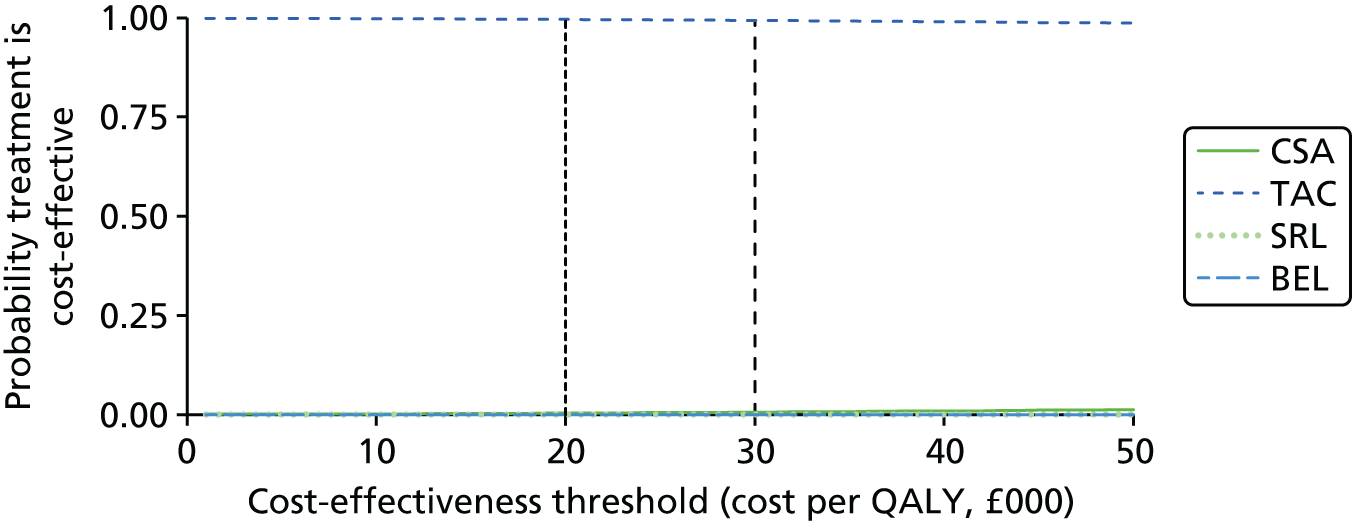

Chapter 1 Background

The aim of this assessment is to review and update the evidence of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of immunosuppressive regimens for renal transplantation in children and adolescents [a review of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance TA99]. 1 Two therapy stages are assessed: induction therapy [regimens including basiliximab (BAS) (Simulect,® Novartis Pharmaceuticals) or rabbit antihuman thymocyte immunoglobulin (r-ATG) (Thymoglobuline,® Sanofi)] and maintenance therapy [regimens including immediate-release tacrolimus (TAC-IR) [Adoport® (Sandoz); Capexion® (Mylan), Modigraf® (Astellas Pharma); Perixis® (Accord Healthcare); Prograf® (Astellas Pharma); Tacni® (Teva); Vivadex® (Dexcel Pharma)], prolonged-released tacrolimus (TAC-PR) (Advagraf,® Astellas Pharma), belatacept (BEL) (Nulojix,® Bristol-Myers Squibb), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) [Arzip® (Zentiva), CellCept® (Roche Products), Myfenax® (Teva), generic MMF is manufactured by Accord Healthcare, Actavis, Arrow Pharmaceuticals, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, Mylan, Sandoz and Wockhardt], mycophenolate sodium (MPS) (Myfortic,® Novartis Pharmaceuticals), sirolimus (SRL) (Rapamune,® Pfizer) and everolimus (EVL) (Certican,® Novartis Pharmaceuticals), alone or in combination].

The systematic review and economic evaluation developed to support the current NICE guidance TA99 was published by Yao et al. in 2006. 2 This assessment incorporated relevant evidence presented in the previous report and report new evidence.

Description of health problem

End-stage renal disease

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) in childhood leads to lifelong health complications, often resulting in the need of a kidney transplant. 3 In 2013, 891 children and adolescents < 18 years of age were receiving treatment at paediatric nephrology centres for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). 4 ESRD is a long-term irreversible decline in kidney function, for which renal replacement therapy (RRT) is required if the individual is to survive. ESRD is often the result of an acute kidney injury or primarily a progression from CKD, which describes abnormal kidney function and/or structure. Although RRT can take a number of forms (kidney transplantation, haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis), the preferred option for people with ESRD is kidney transplantation, rather than dialysis, owing to improved duration and quality of life with transplantation compared with dialysis. 5

Transplantation

Kidney transplantation is the transfer of a healthy kidney from a donor to a recipient. Kidneys for transplantation may be obtained via living donation (related or unrelated), donation after brain death (DBD; those with deceased heart-beating who are maintained on a ventilator in an intensive care unit, with death diagnosed using brain stem tests) or donation after circulatory death [DCD; non-heart-beating donors who cannot be diagnosed as brainstem dead but whose death is verified by the absence of a heart beat (cardiac arrest)].

Children and adolescents represent a distinct group of transplant recipients and can differ from adults in several important aspects, including the cause of established renal failure, the complexity of the surgical procedure, the metabolism and pharmacokinetic properties of immunosuppressants, the developing immune system and immune response following organ transplantation, the measures of success of the transplant procedure, the number and the degree of comorbid conditions, the susceptibility to post-transplant complications, and the degree of adherence to treatment. 6,7 The metabolism of many immunosuppressive medications substantially differs in young children compared with adults and drug metabolism changes as children grow and develop.

Following kidney transplantation, major clinical concerns for children and adolescents are acute kidney rejection, graft loss and diminished growth. Acute kidney rejection occurs when the immune response of the graft recipient attempts to destroy the graft as the graft is deemed foreign tissue. 5 Therefore, immunosuppressive therapy is implemented to reduce the risk of kidney rejection and prolong survival of the graft. Prior to renal transplantation, growth retardation in children and adolescents with CKD may already be an issue owing to a combination of inadequate nutritional intake, acidosis, renal osteodystrophy and alterations to the growth hormone insulin-like growth factor. 8 However, post transplant, the steroidal therapy often included in immunosuppression regimens can affect longitudinal growth and calcium/phosphorous metabolism. 9,10

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

Aetiology

In children, ESRD is usually due to innate structural abnormalities or genetic causes or is acquired in childhood through glomerulonephritis. 11 Figure 1 displays the causative diagnoses for children and adolescents (< 16 years old) with primary renal disease in 2013.

FIGURE 1.

Causative diagnoses for children and adolescents; primary renal disease percentage in incident and prevalent children and adolescents with established renal failure patients < 16 years old in 2013. Reproduced with permission from UK Renal Registry 17th Annual Report (figure 4.3, p. 99). 4 The data reported here have been supplied by the UK Renal Registry of the Renal Association. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the UK Renal Registry or the Renal Association.

Pathology

Table 1 displays the distribution of the UK primary renal diagnosis for end-stage renal failure over time, reported from 1999 to 2003, 2004 to 2008 and 2008 to 2013 in children and adolescents aged < 16 years. Renal dysplasia, which is abnormal tissue development in the kidney, is the primary renal disease diagnosis in approximately one-third of all children and adolescents with ESRD.

| Primary renal diagnosis | 1999–2003 | 2004–8 | 2009–13 | 1999–2013 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | % change | |

| Renal dysplasia + reflux | 157 | 29.1 | 191 | 33.7 | 182 | 33.7 | 4.6 |

| Obstructive uropathy | 80 | 14.8 | 75 | 13.3 | 97 | 18 | 3.1 |

| Glomerular disease | 130 | 24.1 | 112 | 19.8 | 83 | 15.4 | –8.7 |

| Tubulointerstitial diseases | 42 | 7.8 | 46 | 8.1 | 41 | 7.6 | –0.2 |

| Congenital nephrotic syndrome | 27 | 5 | 33 | 5.8 | 35 | 6.5 | 1.5 |

| Metabolic | 29 | 5.4 | 25 | 4.4 | 31 | 5.7 | 0.4 |

| Uncertain aetiology | 12 | 2.2 | 32 | 5.7 | 29 | 5.4 | 3.1 |

| Renovascular disease | 23 | 4.3 | 19 | 3.4 | 19 | 3.5 | –0.7 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 16 | 3 | 19 | 3.4 | 19 | 3.5 | 0.6 |

| Malignancy and associated disease | 10 | 1.9 | 9 | 1.6 | 4 | 0.7 | –1.1 |

| Drug nephrotoxicity | 14 | 2.6 | 5 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | –2.6 |

When chronic renal failure occurs, children and adolescents may experience malaise, nausea, loss of appetite, change in mental alertness, bone pain, headaches, stunted growth, change in urine outputs, urinary incontinence, pale skin, bad breath, poor muscle tone, tissue swelling and hearing deficit. Treatment of chronic renal failure depends on the degree of kidney function that remains and the age of the child/adolescent. Treatment may include dialysis, kidney transplantation, diet restrictions, diuretic therapy and medications (to help with growth and prevent bone density losses). 12

Acute rejection

In patients who survive transplantation, acute rejection (AR) may occur when the immune response of the host attempts to destroy the graft as the graft is identified as foreign tissue. 5 AR is treated by modifying the immunosuppressive regimen (increasing doses or switching treatments). Untreated AR will ultimately result in destruction of the graft; however, high levels of immunosuppression may also increase the risk of other infections and malignancy. 5 AR is primarily measured following a biopsy and graded according to Banff criteria (grades I–III, for which grade III indicates the most severe). The Banff classification13 is:

-

Banff grade I: tubulointerstitial inflammation only.

-

Banff grade IA: interstitial inflammation moderate–severe and/or tubulitis moderate.

-

Banff grade IB: tubulitis severe.

-

Banff grade II: intimal arteritis.

-

Banff grade IIA: intimal arteritis mild–moderate.

-

Banff grade IIB: intimal arteritis severe.

-

Banff grade III: transmural arteritis and/or fibrinoid necrosis.

Although the incidence of AR following a transplant is included in this appraisal, its treatment is outside the scope. In addition to AR affecting the survival of the graft, other reasons which may instigate graft loss include blood clots, narrowing of an artery, fluid retention around the kidney, side effects of other medications and recurrent kidney disease. 14

It is important to note that failing to stay on the immunosuppression regime prescribed following a kidney transplant will also significantly increase the risk of AR and/or graft loss. 15 If the kidney is lost, ultimately the patient will need to return/start on dialysis, for which the quality of life is reduced and overall costs are higher. 5

Graft function

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) describes the flow rate of filtered fluid through the kidney. GFR is expressed in terms of volume filtered per unit time [sometimes this is also expressed per average surface area (1.73 m2)]. There are various methods used to calculate GFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)] from serum creatinine levels, age, sex and ethnic group (e.g. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease, Cockcroft–Gault, and Nankivell). Different methods are used for children and adolescents (e.g. Schwartz and Counahan–Barratt equations). Levels of eGFR represent the level of kidney function and Table 2 presents the NICE cut-off values for classification of CKD (NICE guidelines CG182). 16 These values apply to children aged > 2 years and up to (and including) adulthood. 17

| GFR category | GFR (ml/minute/1.73 m2) | Terms |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | > 90 | Normal or high |

| 2 | 60–89 | Mildly decreased |

| 3a | 45–59 | Mildly to moderately decreased |

| 3b | 30–44 | Moderately to severely decreased |

| 4 | 15–29 | Severely decreased |

| 5 | < 15 | Kidney failure |

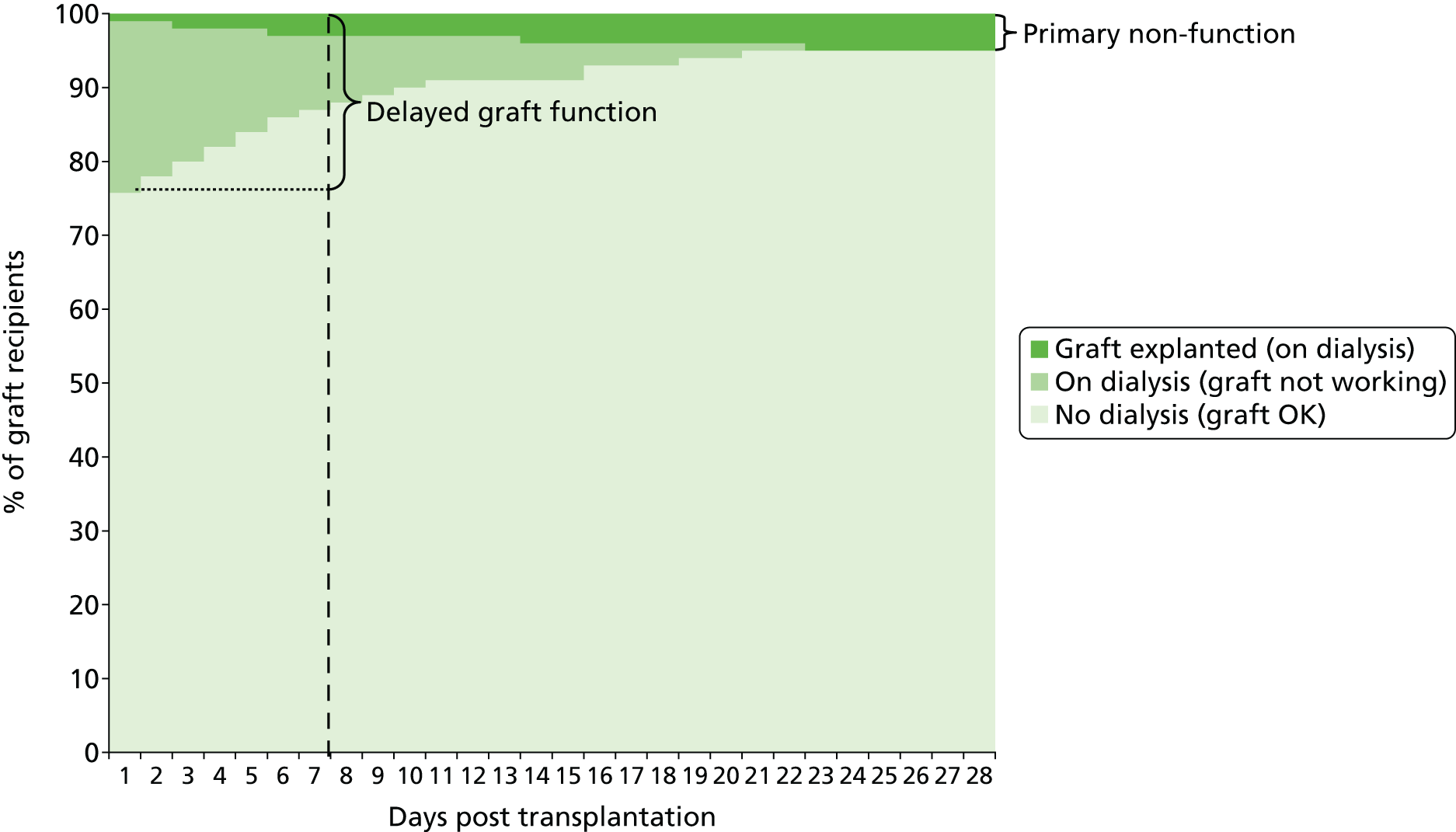

Some children and adolescents may experience delayed graft function (DGF) after transplantation and Figure 2 shows a hypothetical graph to explain the relationship between normally functioning grafts, DGF and primary non-functioning (PNF) grafts. At 7 days post transplant, some of the children and adolescents who need dialysis and whose grafts are therefore classified as DGF will have grafts that never function. When this has been established, these grafts are classified as PNF.

FIGURE 2.

Hypothetical graph to explain graft function, DGF and primary non-functioning graft. Reproduced with permission from Bond et al. 18 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v1.0.

Growth

Normal growth is often affected in children and adolescents with ESRD; short stature is diagnosed if the height standard deviation score (SDS) is < 2.5 of the target height. 19 There are three main factors that may impact post-transplant growth:

-

Age at transplantation. Following a transplant, post-transplantation catch-up growth is not uncommon; however, it is unlikely to be sufficient to compensate for the pre-transplant accrued deficit. 20 Data from the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) indicated that children < 6 years of age exhibit catch-up growth whereas children > 6 years at the time of transplantation exhibit limited to no catch-up growth.

-

Allograft function. An increase of 1.0 mg/dl in serum creatinine level (indicating a decrease in kidney function) has been associated with a decrease of 0.17 in SDS. 21

-

Corticosteroid (CCS) dose. For example, reducing steroids to every other day22 and withdrawing or avoiding steroids23 have been associated with improved growth. Similarly, Grenda et al. 24 reported an increase of 0.13 in SDS in a group of primarily pre-pubertal children who withdrew from steroids on day 5 compared with those in whom the dose was tapered to 10 mg/m2.

UK data are not available on growth changes following kidney transplant in children and adolescents; however, data from the NAPRTCS are available. The NAPRTCS 2010 annual report indicates that at transplantation, the mean height deficits for all children and adolescents is –1.75 SDS (–1.78 for boys and –1.70 for girls). 25 For children and adolescents who have reached their adult height following kidney transplant (n = 2867), the average SDS is –1.40, with 25% having a SDS of –2.2 or worse and 10% are > 3.24 SDS below the population average. 25 In addition, German data reported by Nissel et al. ,26 who followed 37 children for a mean duration of 8.5 years to monitor their growth, showed that those children who received their transplant before the start of puberty attained an adult height that was on average 5.2 cm (boys) and 13.0 cm (girls) lower than predicted while those who received their transplant after the onset of puberty had a final adult height that was on average 12.6 cm (both boys and girls) lower than the target.

Prognosis

Data collected for survival rates of children and adolescents < 16 years of age starting RRT between 1999 and 2012 were collected from UK paediatric centres. 4 The median follow-up time was 3.5 years (ranging from 1 day to 15 years). There were a total of 99 deaths reported. Table 3 shows the survival hazard ratios (HRs) (following adjustment for age at start of RRT, sex and RRT modality) and highlights that children starting RRT at < 2 years of age, compared with 12- to 16-year-olds starting RRT, had a worse survival outcome with a HR of 5.0.

| Hazard ratio | Confidence interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 0–< 2 years | 5.0 | 2.8–8.8 | < 0.0001 |

| 2–< 4 years | 2.9 | 1.4–5.7 | 0.003 |

| 4–< 8 years | 2.2 | 1.3–4 | 0.006 |

| 8–< 12 years | 1.4 | 0.7–2.9 | 0.400 |

| 12–< 16 years | 1.0 | – | – |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.2 | 0.7–1.9 | 0.5 |

| Male | 1.0 | – | – |

| Modality | |||

| Dialysis | 7.1 | 4.7–10.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Transplant | 1.0 | – | – |

Various factors may influence survival following a kidney transplant. A study of 1189 child/adolescent kidney transplants in England between April 2001 and March 2012 found that 33 children and adolescents did not survive. 27 The most common causes of these 33 deaths were renal (n = 8; classified as ESRD, renal dysplasia and disorder of kidney/ureter), infections (n = 6) and malignancy (n = 5). 27 The age of the recipient was not found to significantly impact patient survival: age 0–1 years (100% survival), age 2–5 years (96% survival), age 6–12 years (97.5% survival) and age 13–18 years (97.4% survival). 27

Important prognostic factors

A number of important factors have been identified within the research literature that may influence overall survival and graft survival. These factors are summarised below:

-

Age: both the age of the recipient and the age of the donor will influence the survival of the transplant. The number of kidney transplants performed is much lower in infants and small children than in older children. This has been attributed to some centres keeping a child on dialysis until they reach an arbitrary age when they are deemed suitable for a transplant. 28

-

Recipient ethnicity: black patients tend to have worse graft function, shorter graft survival and higher rates of chronic allograft nephropathy than white patients. 29 Racial differences have also been indicated in American children, with poorer outcomes in black children following a kidney transplant than in white or Hispanic children. 30

-

Waiting time to transplant: the longer a person is on dialysis waiting for a kidney transplant, the poorer their outcomes post transplantation. 31

-

Cold ischaemia time: the shorter this time (≤ 20 hours), the better the immediate and long-term outcomes. 32

-

Donor type: receiving a donated kidney from a live donor will probably result in better outcomes than receiving a kidney from a deceased donor. 29 Similarly, receiving a kidney from extended criteria donors (donors who may for example be older, have a history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension or have an increased risk of passing on an infection or malignancy) will have inferior graft survival rates and increased incidences of AR when compared with receiving a standard donated kidney. 33

-

Immunological risk, to include human leucocyte antigen (HLA) and blood group incompatibility: if the number of mismatches from the donor to the recipient are higher, there is an increased likelihood of AR and graft loss. 29

-

Comorbidities, for example diabetes mellitus, cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD): the higher a patient score on the Charlson Comorbidity Index, the lower the patient and graft survival is likely to be. AR is not significantly correlated to the Charlson Comorbidity Index. 34

Incidence and/or prevalence

In 2013, 891 children and young people < 18 years of age were receiving treatment for ESRD at UK paediatric nephrology centres, of whom 80.2% had a functioning kidney transplant, 11.7% were receiving haemodialysis and 8.1% were receiving peritoneal dialysis. 4 When comparing RRT data from the most recent 5-year period (2009–13) with the two previous periods (1999–2003 and 2004–8), a sustained increase in the number of younger children (aged 0 to < 8 years when starting RRT) can be seen, while the number of older children (8 to < 16 years when starting RRT) has decreased. Consequently, the total number of children starting RRT has remained relatively constant; 546 children between 1999 and 2003, 575 children between 2004 and 2008, and 560 children between 2008 and 2013. 4

Table 4 presents the number of children and adolescents commencing RRT in 2013 with data presented by age and by sex.

| Age group | All patients n (pmarp) | Male n (pmarp) | Female n (pmarp) | M : F ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–< 2 years | 19 (11.8) | 13 (15.7) | 6 (7.6) | 2.1 |

| 2–< 4 years | 17 (10.6) | 11 (13.4) | 6 (7.6) | 1.7 |

| 4–< 8 years | 14 (4.5) | 4 (2.5) | 10 (6.6) | 0.4 |

| 8–< 12 years | 31 (11.0) | 20 (13.9) | 11 (8.0) | 1.7 |

| 12–< 16 years | 31 (10.7) | 12 (8.1) | 19 (13.4) | 0.6 |

| Under 16 years | 112 (9.3) | 60 (9.7) | 52 (8.8) | 1.1 |

Although the number of children and adolescents starting RRT has not changed significantly, the number of children and adolescents actively waiting for a kidney transplant fell from 112 in 2005 to 70 in 2014. Figure 3 displays the number of children and adolescents on the transplant list both active and suspended over time from 2005 to March 2014 (when suspension from the list may occur if the transplant cannot go ahead, e.g. further medical problems making the operation unsafe).

FIGURE 3.

Children and adolescents on the kidney-only transplant waiting list at March 2013. Reproduced with permission from NHS Blood and Transplant. 32

One hundred and twenty five kidney transplant operations were performed on children and adolescents in the UK between April 2013 and March 2014. 32 The total number of transplants in children and adolescents and the graft type (living, DBD and DCD) performed each year from 2004 to 2014 are displayed in Figure 4. In children and adolescents, most donated kidneys are from living and DBD donors, with very few kidneys being form DCD donors.

FIGURE 4.

Kidney-only transplants in children and adolescents 2004–2014. Reproduced with permission from NHS Blood and Transplant. 32

Overall survival reported in children and adolescents following kidney transplants from deceased and living donors is similar at both 1- and 5-year follow-up; however, graft survival at 5 years is improved if the donors are living (Table 5). 32

| Kidney graft survival | Patient survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year,a % (95% CI) | 5 years,b % (95% CI) | 1 year,a % (95% CI) | 5 years,b % (95% CI) | |

| Deceased donors | 96 (93 to 98) | 84 (79 to 88) | 99 (97 to 100) | 99 (96 to 100) |

| Living donors | 95 (92 to 97) | 94 (89 to 96) | 99 (97 to 100) | 99 (96 to 100) |

Data on incidence and prevalence of AR in children and adolescents are not available for the UK. However, they are likely to be similar to those reported in the NAPRTCS, which indicates that for transplants occurring between 1987 and 2010, the prevalence in children and adolescents of at least one episode of AR following a kidney transplant is 46% (41% in live donors and 51% in deceased donors). 25

Impact of kidney transplantation

Significance for patients

Living with ESRD may substantially challenge the well-being of children and adolescents. Not only will the disease impact physical health, but mental and social health may also be affected owing to increased hospital visits and the child or adolescent’s inability to take part in the same activities as their peers. 35 However, having a kidney transplant will improve the symptoms associated with ESRD and dialysis and reduce the time spent in hospital. 36 The median wait time for a child/adolescent requiring a kidney transplant in the UK is 342 days. 32

Kidney transplantation requires a lifelong regimen of immunosuppressive medication. Immunosuppressants may produce unpleasant side effects (including possible skin cancer, crumbling bones, fatigue, body hair growth, swollen gums and weight gain). 37 Nevertheless, favourable social and professional outcomes have been observed from a long-term follow-up (15.6 years ± 3 years) of people who had a kidney transplant as a child (aged 10 years ± 5 years). 38 Adherence to post-transplant immunosuppressive regimens is important for favourable clinical outcomes in children and adolescents39 and has been suggested as a core strategy to improve clinical outcomes. 40 In addition, failing to follow treatment may result in an increase in medical costs. 41

Acute rejection is common in the first year after kidney transplantation and treatment of AR involves a more intensive drug treatment than standard maintenance regimens, which in turn increases the possibility of adverse events (AEs). Should a graft be lost, the child/adolescent will face another wait for transplantation (if appropriate) and will need to undergo dialysis while waiting for transplantation (although a pre-emptive transplantation may be available), or need to undergo dialysis for life where transplantation is not possible.

The impact on a child/adolescent returning to or starting dialysis (of the psychological burden of graft failure and going back to a previous treatment) is little researched, but necessarily includes the impact of being on dialysis per se: dialysis is time-consuming and may affect education and normal family life and require changes in diet and fluid intake. Common side effects of dialysis (either haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) include fatigue, low blood pressure, invasive staphylococcal infections, muscle cramps, itchy skin, peritonitis, hernia and weight gain. 42

Finally, growth retardation in children and adolescents with ESRD is thought to be a combination of inadequate nutritional intake, acidosis, renal osteodystrophy and alterations to the growth hormone insulin-like growth factor. 8 Ensuring optimal growth or optimisation of final height is a major concern for children and adolescents with ESRD, as short stature may have an impact on social development, self-esteem and quality of life and is associated with an increase in the number of hospitalisations and behavioural and cognitive disorders, and a decrease in the level of education and employment in adulthood. 20,43–45

Unfortunately, data relating specifically to quality of life are currently available only in the adult population, among whom there are clear quality-of-life improvements from having a functioning kidney transplant compared with being on dialysis. 46–52

Significance for the NHS

Treatment for ESRD is considered resource-intensive for the NHS because current costs have been estimated to use 1–2% of the total NHS budget to treat 0.05% of the population (both adult and child/adolescent). 53 Based on data from the Department of Health, it is estimated that in 2008/9, the total expenditure on ‘renal problems’ in England was £1.3B, representing 1.4% of the NHS expenditure. 53 An economic evaluation of treatments for ESRD by de Wit et al. 54 showed that transplantation is the most cost-effective form of RRT with increased quality of life and independence for an individual.

There are no apparent reasons why RRT demand may dramatically increase in children and adolescents. However, it is projected that an increasingly overweight population will increase the demand for RRT, with a consequent increase in pressure on services from renal units and other health-care providers dealing with comorbidities. Increased resources may be needed for dialysis, surgery, pathology, immunology, tissue typing, histopathology, radiology, pharmacy and hospital beds. Demand is likely to be particularly significant in areas where there are large South Asian, African and African Caribbean communities and in areas of social deprivation, where people are more susceptible to kidney disease. 4

Measurement of disease

The outcome of kidney transplants (and of the success of immunosuppressive regimens) can be measured in a variety of ways. These include:

Short term

-

Immediate graft function: the graft works immediately following transplantation, removing the need for further dialysis.

-

Delayed graft function: the graft does not work immediately and dialysis is required during the first week post transplant. Dialysis has to continue until graft function recovers sufficiently to make it unnecessary. This period may last up to 12 weeks in some cases.

-

Primary non-function: the graft never works after transplantation.

Long term

-

Rejection rates: the percentage of grafts that are rejected by the recipients’ bodies; rejection can be acute or chronic.

-

Graft survival: the length of time that a graft functions in the recipient.

-

Graft function: a measure of the efficiency of the graft by various markers, for example GFR and serum creatinine levels.

-

Patient survival: how long the recipient survives.

-

Quality of life: how a person’s well-being is affected by the transplant.

Current service provision

Management of end-stage kidney disease

End-stage renal disease is primarily managed by RRT. The patient pathway leading to RRT for those with ESRD can be seen in Figure 5. Once a child/adolescent has been diagnosed with ESRD, the RRT options are a transplant (from a living or deceased donor) or dialysis (haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis). If suitable, the option of a pre-emptive kidney transplant (when transplantation is performed without the child/adolescent spending any time on dialysis) is also available.

FIGURE 5.

The care pathway for RRT. Reproduced with permission from The National Service Framework for Renal Services. Part One: Dialysis and Transplantation. 11 © Crown Copyright 2004. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

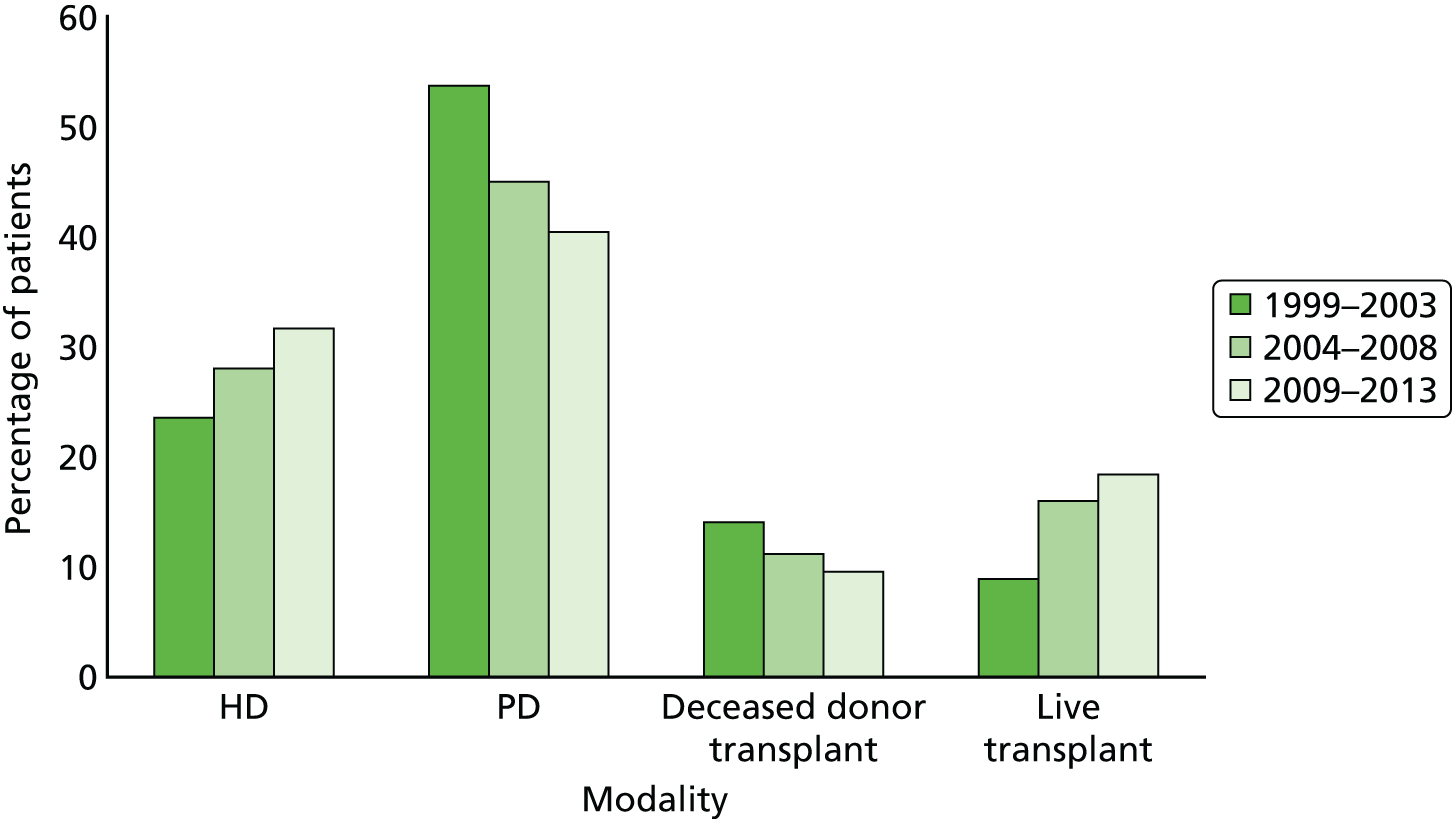

The form of treatment modality at the start of RRT changed from 1999 to 2013 (Figure 6). The primary changes are an increase in the number of kidney transplants from living donors and a simultaneous decrease in donations from deceased donors. In addition, an increase in haemodialysis and a concurrent decrease in peritoneal dialysis are seen (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Type of treatment at start of RRT for incident children and adolescents < 16 years old by 5-year time period. HD, haemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis. Reproduced with permission from UK Renal Registry 17th Annual Report (figure 4.4. p. 102). 4 The data reported here have been supplied by the UK Renal Registry of the Renal Association. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the UK Renal Registry or the Renal Association.

The 2013 data suggest that most children and adolescents receive a kidney transplant (78%) and that the proportion of living and deceased kidney donations is equal: 50% and 50%, respectively (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Renal replacement therapy treatment used by prevalent children and adolescents < 16 years old in 2013. HD, haemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis. Reproduced with permission from UK Renal Registry 17th Annual Report (figure 4.1. p. 98). 4 The data reported here have been supplied by the UK Renal Registry of the Renal Association. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the UK Renal Registry or the Renal Association.

Management of kidney transplants

If transplantation is the chosen method for RRT for a child/adolescent with ESRD then there are three main service provision steps required for the management of the transplant.

The first of these is organ procurement, which includes the identification and management of potential donors and assessment of donor suitability. HLAs are carried on cells within the body, enabling the body to distinguish between its ‘self’ or to recognise ‘non-self’ that should be attacked. The closer the HLA matching, the less vigorously the body will attack the foreign transplant and, consequently, the chances of graft survival are improved. HLA mismatch refers to the number of mismatches between the donor and the recipient at the A, B and DR loci, with a maximum of two mismatches at each locus. 32 Therefore, a match would have a score of zero and a complete mismatch would have a score of six. However, it should be noted that with the improvements in immunosuppressants, the significance of HLA matching has diminished. 55

The second step is the provision of immunosuppressive therapy. Immunosuppressants are the drugs taken around the time of, and following, an organ transplant. They are aimed at reducing the body’s ability to reject the transplant and thus at increasing patient and graft survival and preventing acute and/or chronic rejection (while minimising associated toxicity, infection and malignancy). Immunosuppressants are required in some form for all kidney transplant recipients (KTRs), except potentially when the donor is an identical twin.

The final service provision step is short- and long-term follow-up following transplantation. This step involves looking for indications of any kidney graft dysfunction and other complications. Complications fall into four categories.

-

Medical follow-ups to include rejections, nephrotoxicity of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) and recurrence of the native kidney diseases.

-

Anatomic complications of surgery to include renal artery thrombosis, renal artery stenosis, urine leaks from disruption of the anastomosis, ureteral stenosis and obstruction and lymphocele.

-

Other complications include infection, malignancy, new-onset of diabetes mellitus, liver disease, hypertension, CVD.

-

Ensuring growth is not impeded and maximal ‘catch-up’ growth is achieved. The 2010 NAPRTCS report suggests that the average final adult height of a renal transplant recipient has increased significantly from –1.93 SDS between 1987 and 1991 to –0.94 SDS between 2002 and 2010. 25

If the kidney loses its function, many of the physiological changes that occur mimic those seen with progressive renal diseases from other causes. Therefore, these symptoms should be managed in a similar way to the non-transplant population. However, it should be noted that the loss of a kidney transplant carries increased susceptibility to bruising and infection compared with pre-transplant kidney failure. 56

Once the kidney is confirmed to have been lost, the graft may or may not need to be surgically removed. The decision of whether or not the graft is removed is often made on a case-by-case basis taking into consideration all perceived benefits and risks. The immunosuppression regimen can then be tapered and withdrawn while the patient returns to dialysis and waits for a new kidney to become available.

Current service cost

The overall cost of CKD to the NHS in England was estimated as £1.45B in 2009–10, with more than half of total estimated expenditure for RRT. 57 The costs of RRT can be divided into costs associated with the transplantation and costs associated with dialysis. Transplantation costs can include the cost of workup for transplantation (assessing recipient suitability), maintaining and co-ordinating the waiting list, obtaining donor kidneys (harvesting, storage and transport for deceased donors; nephrectomy procedure for living donors), cross-matching for donor–recipient compatibility, the transplantation procedure, induction immunosuppression, hospital inpatient stay following procedure, initial and long-term maintenance immunosuppression, prophylaxis and monitoring for infections, monitoring of graft function and general health, adjustment of immunosuppressant dosages, treatment of AR, and treatment of associated AEs. Should the kidney be lost, the costs of restarting dialysis (dialysis costs, the cost of treatment for AEs attributable to dialysis and the cost of dialysis access surgery) would be incurred.

Data from the NHS Reference Costs 2013 to 2014 indicated that the cost of kidney transplantation in those < 19 years of age is, on average, £20,576. 58 Paediatric nephrology outpatient clinics are, on average, £249 and the cost of haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis is, on average, £79,807 and £41,382, respectively. 58

Variation in services

There are currently 13 paediatric renal centres in the UK, nine that offer dialysis and perform transplantations [Birmingham, Bristol, Glasgow, Leeds, London (Guys and Great Ormond Street), Nottingham, Belfast and Manchester] and four that offer renal care but not transplantations (Cardiff, Liverpool, Newcastle and Southampton).

After kidney transplantation, recipients are prescribed an immunosuppression regimen consisting of both induction and maintenance therapy. Following this, they are offered check-up appointments with their clinic (consultant nephrologist) to monitor general health, kidney function, immunosuppressive drugs, infections (prophylaxis and treatment) and to address any social or psychological concerns. The Renal Association Guidelines59 suggest the following frequency of clinic appointments:59

-

two to three times weekly for the first month after transplantation

-

one to two times weekly for months 2 to 3 after transplantation

-

every 1 to 2 weeks for months 4 to 6 after transplantation

-

every 4 to 6 weeks for months 6 to 12 after transplantation

-

once every 3–6 months thereafter

-

detailed annual post-operative reviews.

Clinician estimations of average frequency of outpatient visits have been reported as 34.3, 6.3 and 4.7 visits for the first, second and third years post transplant, respectively, with UK database figures suggesting 39.7, 11.0 and 9.2 visits for the first, second and third years post transplant, respectively. 60

Service provision (clinic appointments or other services) is likely to increase if AR occurs (possibly requiring hospital admission and escalating treatment) and when there is declining graft function (which might necessitate more regular clinic visits, blood tests and other investigations and changes to treatment regimens). Patients may also present to their general practitioner (GP) or accident and emergency department with AEs related to kidney transplantation or immunosuppressive regimen and this may be followed by an additional referral to the consultant nephrologist or other appropriate specialist (e.g. renal dietitian), followed by management as required (e.g. additional prescribing and monitoring).

In addition to these services, The Renal Association Guidelines59 also recommend that recipients of a transplant should have the following:59

-

online access to their results via the ‘Renal Patient View’ service

-

open access to the renal transplant outpatient service

-

an established point of contact for enquiries

-

access to patient information (which should be available in both written and electronic formats).

Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance

Current NICE guidance on immunosuppressive therapy for renal transplantation in children and adolescents (NICE technology appraisal guidance, TA99) has the following recommendations for induction and maintenance therapy. 1

Induction therapy

Basiliximab or daclizumab (DAC), used as part of a ciclosporin (CSA)-based immunosuppressive regimen, is recommended as an option for induction therapy in the prophylaxis of acute organ rejection in children and adolescents undergoing renal transplantation, irrespective of immunological risk. The induction therapy (BAS or DAC) with the lowest acquisition cost should be used, unless it is contraindicated. 1 The marketing authorisation for DAC has been withdrawn at the request of the manufacturer.

Maintenance therapy

Tacrolimus (TAC) is recommended as an alternative option to CSA when a CNI is indicated as part of an initial or a maintenance immunosuppressive regimen for renal transplantation in children and adolescents. The initial choice of TAC or CSA should be based on the relative importance of their side effect profiles for the individual patient. 1

Mycophenolate mofetil is recommended as an option as part of an immunosuppressive regimen for child and adolescent renal transplant recipients only when:

-

there is proven intolerance to CNIs, particularly nephrotoxicity which could lead to risk of chronic allograft dysfunction or

-

there is a very high risk of nephrotoxicity necessitating the minimisation or avoidance of a CNI until the period of high risk has passed. 1

The use of MMF in CCS reduction or withdrawal strategies for child and adolescent renal transplant recipients is recommended only within the context of randomised clinical trials. 1

Mycophenolate sodium is currently not recommended for use as part of an immunosuppressive regimen in child or adolescent renal transplant recipients. 1

Sirolimus is not recommended for children or adolescents undergoing renal transplantation except when proven intolerance to CNIs (including nephrotoxicity) necessitates the complete withdrawal of these treatments. 1

As a consequence of following this guidance, some medicines may be prescribed outside the terms of their UK marketing authorisation. Health-care professionals prescribing these medicines should ensure that children and adolescents receiving renal transplants and/or their legal guardians are aware of this and that they consent to the use of these medicines in these circumstances. 1

Description of technology under assessment

Summary of intervention

This technology assessment report considers nine pharmaceutical interventions. Two are used as induction therapy and seven are used as a part of maintenance therapy in renal transplantation. The two interventions considered for induction therapy are BAS and r-ATG. The seven interventions considered for maintenance therapy are TAC-IR and TAC-PR, MMF, MPS, BEL, SRL and EVL.

Induction therapy

Basiliximab (Simulect,® Novartis Pharmaceuticals) is a monoclonal antibody which acts as an interleukin 2 receptor antagonist. It has a UK marketing authorisation for prophylaxis of AR in allogeneic renal transplantation in children (aged 1–17 years). The summary of product characteristics (SPC) states it is to be used concomitantly with CSA for microemulsion- and CCS-based immunosuppression, in patients with panel reactive antibodies < 80%, or in a triple maintenance immunosuppressive regimen containing CSA for microemulsion, CCSs and either azathioprine (AZA) or MMF. 7

Rabbit antihuman thymocyte immunoglobulin is a gamma immunoglobulin. It has a UK marketing authorisation for the prevention of graft rejection in renal transplantation. The SPC states it is usually used in combination with other immunosuppressive drugs. It is administered intravenously. The UK marketing authorisation is not restricted to adults only. 7

Maintenance therapy

Tacrolimus is a CNI that is available in an immediate-release formulation (Adoport,® Sandoz; Capexion,® Mylan; Modigraf,® Astellas Pharma; Perixis,® Accord Healthcare; Prograf,® Astellas Pharma; Tacni,® Teva; Vivadex,® Dexcel Pharma). All of these formulations of TAC have UK marketing authorisations for prophylaxis of transplant rejection in kidney allograft recipients. The marketing authorisations include adults and children. 7 TAC (Modigraf®, Astellas Pharma) is available in a granule form which can be suspended in liquid and may be more suitable for those who struggle swallowing pills.

Tacrolimus is also available in a prolonged-release formulation (Advagraf,® Astellas Pharma). It has a UK marketing authorisation for prophylaxis of transplant rejection in kidney allograft recipients. The marketing authorisation is restricted to adults. The Commission on Human Medicines advises that all oral TAC (including both TAC-IR and TAC-PR) medicines in the UK should be prescribed and dispensed by brand name only. 7

Belatacept is designed to selectively inhibit CD28-mediated co-stimulation of T-cells. BEL has a UK marketing authorisation for prophylaxis of graft rejection in adults receiving a renal transplant, in combination with CCSs and a mycophenolic acid (MPA; Myfortic,® Novartis Pharmaceuticals). The SPC recommends that an interleukin 2 receptor antagonist for induction therapy is added to this BEL-based regimen. The SPC states that the safety and efficacy of BEL in children and adolescents aged 0–18 years have not yet been established. This formulation does not have a UK marketing authorisation for the prophylaxis of transplant rejection in renal transplantation in children and adolescents. 7

Mycophenolate mofetil is a prodrug of MPA which acts as an antiproliferative agent (Arzip,® Zentiva; CellCept,® Roche Products; Myfenax,® Teva); generic MMF is manufactured by Accord Healthcare, Actavis, Arrow Pharmaceuticals, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, Mylan, Sandoz and Wockhardt). It has a UK marketing authorisation for use in combination with CSA and CCSs for the prophylaxis of acute transplant rejection in people undergoing kidney transplantation. The UK marketing authorisation is not restricted to adults (dosage recommendations for children aged 2–18 years are included in the SPC). 7

Mycophenolate sodium is an enteric-coated formulation of MPA. This formulation has the same UK marketing authorisation as MMF; however, this is restricted to adults. This formulation does not have a UK marketing authorisation for the prophylaxis of transplant rejection in renal transplantation in children and adolescents. 7

Sirolimus (Rapamune,® Pfizer) is an antiproliferative with a non-calcineurin-inhibiting action. It has a UK marketing authorisation for the prophylaxis of organ rejection in adult patients at low to moderate immunological risk receiving a renal transplant. It is recommended to be used initially in combination with CSA and CCSs for 2–3 months. It may be continued as maintenance therapy with CCSs only if CSA can be progressively discontinued. This formulation does not have a UK marketing authorisation for the prophylaxis of transplant rejection in renal transplantation in children and adolescents. 7

Everolimus (Certican,® Novartis Pharmaceuticals) is a proliferation signal inhibitor and is an analogue of SRL. EVL does not currently have a UK marketing authorisation for immunosuppressive treatment in kidney transplantation in children and adolescents. 7

Current usage in the NHS

There is a variation in the use of induction and maintenance therapy in the UK. Table 6 provides an overview of immunosuppression regimens for low-risk first renal transplants (e.g. blood group and HLA compatible) in the 10 paediatric transplant centres in the UK. Four out of the 10 centres use BAS as a part of induction therapy. Apart from the use of antibody induction, all centres use a single dose of methylprednisolone at the time of transplantation. The table also illustrates the difference in the use of the two proliferative agents (MMF and AZA), the agreement in the use of CNI across all centres (TAC; usually Adoport), and the use of steroids as a part of maintenance therapy. The current NICE guidelines are followed by using TAC + AZA + CCS ± BAS regimens. 1 However, the use of MMF is not limited to proven intolerance to CNIs, or to a very high risk of nephrotoxicity necessitating a temporary minimisation or avoidance of CNI (see Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance for more details).

| Hospital | Antibody used for induction therapy | Maintenance therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Birmingham Children’s Hospital | BAS | TWIST protocol: TAC + MMF + CCS |

| Bristol Children’s Hospital | Nonea | Triple therapy: TAC + AZA + CCS |

| Glasgow, Yorkhill | BAS | TWIST protocol: TAC + MMF + CCS |

| Leeds, Paediatric Unitb | Nonec | Triple therapy: TAC + AZA + CCSd |

| London, Evelina Children’s Hospital | BAS | Triple therapy: TAC + AZA + CCSe |

| London, Great Ormond Street | None | Triple therapy: TAC + AZA + CCS |

| Newcastle Great North Children’s Hospital | None | Triple therapy: TAC + AZA + CCS |

| Nottingham Children’s Unit | Nonef | Triple therapy: TAC + AZA + CCSg |

| Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children | Nonec | Triple therapy: TAC + MMF + CCSh |

| Royal Manchester’s Children’s Hospital | BAS | TWIST protocol: TAC + MMF + CCS |

Anticipated costs associated with intervention

The cost of the intervention (immunosuppressive regimen) is determined primarily by the choice and combination of the drugs and their dosages. Indicative costs for different immunosuppressive agents are given in Table 7. Caution should be exercised in interpreting these as dosages are commonly titrated and may differ from those indicated.

| Compound | Unit cost | Recommended dose | Estimated weekly cost for 31.5 kg body weight, surface area 1.1 m2 (10-year-old male)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| AZA | Hospital pharmacy: 0.1 p per mgb | 1–3 mg/kg per day, adjusted according to responsec | Hospital pharmacy: 22.05 p to 66.15 p |

| Community pharmacy: 0.1 p per mgd | Community pharmacy: 22.05 p to 66.15 p | ||

| BAS | £75.87 per mg (10-mg vial) and £42.12 per mg (20-mg vial)c | Child > 1 year, body weight < 35 kg, 10 mg within 2 hours before transplant surgery and 10 mg 4 days after surgery | Cost calculated based on recommended dose: |

| Child body weight ≥ 35 kg, 20 mg within 2 hours before transplant surgery and 20 mg 4 days after surgeryc | Child < 35 kg: £1517.38 (induction period only) | ||

| Child ≥ 35 kg: £842.38 (induction period) | |||

| BEL | £1.42 per mgc | Not licensed for use in childrenc | £55.83 (adult, weight-based dose) |

| Adult dose 5 mg/kg per 4 weeks | |||

| CSA | Hospital pharmacy: 1.65 p per mgb | 8–12 mg/kg/daye | Hospital pharmacy: £29.10–43.66 |

| Community pharmacy: 2.55 p per mgc | Community pharmacy: £44.98–67.47 | ||

| CCSs | Hospital pharmacy: 0.3 p per mgb | Methylprednisolone: 10–20 mg/kg or 400–600 mg/m2 (maximum 1 g) once daily for 3 daysc | Hospital pharmacy: £2.83–5.67 |

| Community pharmacy: 0.9 p per mgd | Prednisolone: consult local treatment protocols for details.c An example: 60 mg/m2/day during first week, eventually weaned down to < 10 mg/m2 on alternate days | Community pharmacy: £8.49–17.01 | |

| EVL | £9.90 per mgf | Not licensed for use in childrenc | £103.95 (adult non-weight-based dose) |

| Adult dose of 1.5 mg per dayg | |||

| TAC-IR | Hospital pharmacy: 52.0 p per mgb | 150 µg/kg twice daily, adjusted according to whole blood concentration | Hospital pharmacy: £34.40 |

| Community pharmacy: 118.6 p per mgc,d | Community pharmacy: £78.45 | ||

| MMF | Hospital pharmacy: 37.74 p per gb | 300 mg/m2 twice daily (maximum 2 g) if in addition with TAC and CCSsc | Hospital pharmacy: £1.74 |

| Community pharmacy: 40.44 p per gd | 600 mg/m2 twice daily (maximum 2 g) if in addition with CSA and CCSsc | Community pharmacy: £1.86 | |

| Hospital pharmacy: £3.48 | |||

| Community pharmacy: £3.73 | |||

| MPS | 0.5 p per mgc | Not licensed for use in childrenc | £50.4 (adult non-weight-based dose) |

| Adult dose 1440 mg per dayc | |||

| TAC-PR | 106.8 p per mgc | Not licensed for use in childrenc | £47.10 (adult weight-based dose) |

| Adult dose 0.2 mg/kg per day | |||

| r-ATG | £6.35 per mgc | Not licensed for use in childrenc | £2100.52 (induction period only) |

| 1.5 mg/kg/day administered by intravenous infusion for 7–14 daysh | |||

| SRL | £2.88 per mgc,d | Not licensed for use in childrenc Adult dose 2 mg per dayc |

£40.36 (adult non-weight-based dose) |

In addition, drug administration costs are also incurred for some maintenance agents. CSA, TAC, SRL and EVL are routinely titrated using therapeutic drug monitoring, which is estimated to cost approximately £26 per test (testing frequency is reduced as patients become stabilised in dosage), and BEL requires intravenous (i.v.) infusion, entailing catheterisation and nursing time. The cost of this is difficult to estimate but estimates range from £15466 to £320. 11

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The purpose of this assessment is to answer the following question:

What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the following immunosuppressive therapies in renal transplantation in children and adolescents:

-

Basiliximab and r-ATG as an induction therapy, and

-

TAC-IR, TAC-PR, MMF, MPS, BEL, SRL, and EVL as a maintenance therapy

-

including a review of TA99.

The project was undertaken based on a published scope7 and in accordance with a protocol. 67

Interventions

A total of nine interventions are considered, two for induction therapy and seven for initial and long-term maintenance therapy.

The two induction treatments are:

-

BAS

-

r-ATG.

The seven maintenance treatments are:

-

TAC-PR formulation (Advagraf,® Astellas Pharma)

-

TAC-IR formulations [Adoport® (Sandoz); Capexion® (Mylan); Modigraf® (Astellas Pharma); Perixis® (Accord Healthcare); Prograf® (Astellas Pharma); Tacni® (Teva); Vivadex® (Dexcel Pharma)]

-

BEL MMF

-

MPS SRL

-

EVL.

These treatments are described in Chapter 1, Summary of Intervention. Several of the drugs being assessed are used in the NHS outside the terms of their UK marketing authorisation, for example in children and adolescents, or in high-risk people, or in unlicensed drug combinations. Specifically EVL, TAC-PR, BEL, MPS and SRL are not currently licensed for the prophylaxis of transplant rejection in renal transplantation in children and adolescents.

Under an exceptional directive from the Department of Health, the Appraisal Committee may consider making recommendations about the use of drugs outside the terms of their existing marketing authorisation when there is compelling evidence of their safety and effectiveness. Accordingly, the review included controlled studies that used drugs outside the terms of their marketing authorisations.

Populations including subgroups

The population being assessed are children and adolescents aged 0–18 years (inclusive) undergoing kidney transplantation. Patients receiving multiorgan transplants and those who have received transplants and immunosuppression previously were excluded.

If data allow, the following subgroups were considered:

-

different age groups

-

level of immunological risk (including HLA compatibility and blood group compatibility)

-

people at high risk of rejection within the first 6 months

-

people who have had a retransplant within 2 years

-

previous AR

-

people at high risk of complications from immunosuppression (including new-onset diabetes mellitus).

Relevant comparators

For induction therapy, the treatments are to be compared with each other, as data permit, or with other regimens that do not include monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies. For maintenance therapy, each treatment or regimen (combination of treatments) is to be compared with the other treatments or regimens as data permit, or with a CNI with or without an antiproliferative agent and/or CCSs.

Outcomes

The health-related outcomes to be included in this technology assessment are:

-

patient survival

-

graft survival

-

graft function

-

time to and incidence of AR

-

severity of AR

-

growth

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Key issues

A number of factors may influence the survival and function of transplanted kidney and the survival of the recipient.

The viability of the kidney may depend on the type of donor (living related, living unrelated, DBD, DCD or expanded criteria donor), the age of the donor, whether or not they had comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, and the length of cold ischaemia. Furthermore, the age, sex, ethnicity and health of the recipient, and the length of time the recipient is on dialysis prior to transplantation may affect the outcome of transplantation. These issues have been discussed in more detail in Chapter 1, Important prognostic factors.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

This assessment reviewed and updated the evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapies in children and adolescents renal transplantation. This was to be done by conducting a systematic review of clinical effectiveness studies and a model-based economic evaluation of induction and maintenance immunosuppressive regimens to update the current guidance (TA99). We have incorporated relevant evidence presented in this previous report and report new evidence. This included a new decision-analytic model of kidney transplantation outcomes to investigate which regimen is the most cost-effective option.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

This systematic review was commissioned by NICE to update the previous guidance (TA99). 1 The systematic review and economic evaluation developed to support current NICE guidance TA99, was published by Yao et al. in 2006. 2 The differences between the remit of the previous review and the protocol of the current one are discussed in The previous assessment report.

There was one departure from the protocol:67 the age of population eligibility criterion was changed from < 18 years (a common definition of children and adolescents) to ≤ 18 years [the age inclusion criterion applied by the three eligible randomised controlled trial (RCTs)].

The aim was to systematically review the clinical effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapies in child and adolescent (≤ 18 years) renal transplantation; that is to determine their effect on patient survival, graft survival, graft function, time to and incidence of AR, severity of AR and quality of life, growth, and their impact on AEs.

Identification of studies

Bibliographic literature database searching was conducted on 14 April 2014 and updated on 7 January 2015. The searches for individual effectiveness studies (RCTs and controlled clinical trials) took the following form: (terms for kidney or renal transplant or kidney or renal graft) AND (terms for the interventions under review) AND [a study design limit to randomised control trials (RCT) or controlled trials]. In order to update the previous assessment,2 the searches were date limited (2002–current). These searches were not limited by language or to human-only studies because such a limit may have blocked retrieval of includable studies for R-ATG (line 8 of the MEDLINE search). The following databases were searched: MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via Wiley Online Library) and Web of Science [via Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) – including conference proceedings]. In addition, the following trials registries were hand-searched in January 2015: Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, FDA website, EMA website (European Public Assessment Reports).

Separate searches were undertaken to identify systematic reviews of RCTs and non-randomised studies. These searches took the following form: (terms for kidney or renal transplant or kidney or renal graft) AND (terms for the interventions under review) AND (a pragmatic limit to systematic reviews). The same population and intervention search terms were used as in the individual studies search. A pragmatic, methodological search filter was used to limit by study design. No other limits (e.g. language) were applied to this search. The search was run from database inception in the following databases: MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) (The Cochrane Library via Wiley Online Library) and Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (via Ovid).

The search strategies are recorded in Appendix 1.

The database search results were exported to, and deduplicated using, EndNote (X5) (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). Deduplication was also performed manually.

Furthermore, the following websites were searched for background information.

Renal societies (UK)

-

British Renal Society (www.britishrenal.org/).

-

Renal Association (www.renal.org/).

-

UK Renal Registry (www.renalreg.com/).

-

Kidney Research UK (www.kidneyresearchuk.org/).

-

British Kidney Patient Association (www.britishkidney-pa.co.uk/).

-

National Kidney Federation (www.kidney.org.uk/).

Renal societies (international)

-

American Society of Nephrology (www.asn-online.org/).

-

American Association of Kidney Patients (www.aakp.org/).

-

National Kidney Foundation (US; www.kidney.org/).

-

Canadian Society of Nephrology (www.csnscn.ca/).

-

Kidney Foundation of Canada (www.kidney.ca/).

-

Australian and New Zealand Society of Nephrology (www.nephrology.edu.au/).

-

Kidney Health Australia (www.kidney.org.au/).

-

Kidney Society Auckland (www.kidneysociety.co.nz/).

Previous Health Technology Assessment review

Studies included in the previous HTA review (Yao et al. 2) were screened using the inclusion criteria for the Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG) review (Inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Reference lists

Reference lists of included guidelines, systematic reviews, company submissions and clinical trials were scrutinised in order to identify additional studies.

Ongoing trials

Searches for ongoing trials were also undertaken. Terms for the intervention and condition of interest were used to search the following trial registers for ongoing trials: ClinicalTrials.gov and Controlled Trials (ISRCTN). Trials that did not relate to immunosuppressive therapies for kidney transplantation in children and adolescents were removed by hand-sorting. All searches for ongoing trials were carried out in January 2015. The search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Adult randomised controlled trial evidence

In addition, as specified in the review protocol, all child/adolescents RCT and non-RCT evidence included in this review was compared with adult evidence identified from parallel HTA 09/46/01 appraisal. 68 This parallel HTA was conducted by PenTAG to inform the ongoing technology appraisal of immunosuppressive therapy for kidney transplantation in adults (review of technology appraisal guidance 85; NICE appraisal ID 456). The NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre reference for the adult report is 09/46/01 (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-tag348/documents).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies retrieved from the literature searches were selected for inclusion according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria specified below. Studies available only as abstracts were included provided sufficient methodological details were reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality. We also contacted authors for additional data.

Study design

The clinical effectiveness review included:

-

eligible studies – RCTs in children and adolescents (≤ 18 years), RCTs of adults and children/adolescents in which a subgroup analysis of children and adolescents is reported, and non-randomised controlled studies (comparative quasi-experimental and observational studies were considered)

-

search strategy – databases were searched to identify RCTs, systematic reviews of RCTs and systematic reviews of non-randomised controlled studies. Individual non-randomised controlled studies were identified via the bibliographies of systematic reviews (i.e. individual non-randomised controlled studies were not searched for directly).

For the purpose of this review, a systematic review was defined as one that has:

-

a focused research question

-

explicit search criteria that are available to review, either in the document or on application

-

explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria, defining the population(s), intervention(s), comparator(s), and outcome(s) of interest

-

a critical appraisal of included studies, including consideration of internal and external validity of the research

-

a synthesis of the included evidence, whether narrative or quantitative.

Interventions

Studies evaluating the use of the following immunosuppressive therapies for renal transplantation were included.

Induction therapy

-

Basiliximab.

-

Rabbit antihuman thymocyte immunoglobulin.

Maintenance therapy

-

TAC-PR formulation.

-

TAC-IR formulations.

-

Belatacept.

-

MMF (generic MMF manufactured by Accord Healthcare, Actavis, Arrow Pharmaceuticals, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, Mylan, Sandoz and Wockhardt).

-

Mycophenolate sodium.

-

Sirolimus.

-

Everolimus.

All treatments are described in detail in Chapter 1, Summary of intervention.

In addition (as evidence allows), adherence to treatment and the use of treatments in conjunction with either CCS or CNI reduction or withdrawal strategies is considered. To achieve this, only studies that meet the inclusion criteria are examined. As such, studies in which the intervention is identical in both study arms, but dose reduction or withdrawal of CCSs or CNIs occurs in one arm, were excluded.

Comparator

Studies using the following comparators were included.

Induction therapy

-

Regimens without monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies, for example regimens that include methylprednisolone or placebo (PBO).

-

Interventions should also be compared with each other.

Maintenance therapy

-

A CNI with or without an antiproliferative agent and/or CCSs.

-

Interventions should also be compared with each other.

In addition, when appropriate, the interventions were appraised as part of combination regimens.

Population

The population is children and adolescents aged ≤ 18 years undergoing kidney transplantation. The kidney donor may be living related, living unrelated or deceased. Patients receiving multiorgan transplants and those who have received transplants and immunosuppression previously were excluded.

Outcomes

The outcome measures to be considered are:

-

patient survival

-

graft survival

-

graft function

-

time to and incidence of AR

-

severity of AR

-

growth

-

adverse effects (AE) of treatment

-

HRQoL.

Screening

All records were dual screened. First, titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were screened for inclusion. The screening was distributed across a team of five researchers (TJ-H, LC, MHa, MB and HC). Update searches were screened by two reviewers (MHa and JV-C) and disagreements were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer (TJ-H or MHa) if necessary. Full texts of identified studies were obtained and screened in the same way. Studies reported only as abstracts were included provided sufficient methodological details were reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality. In addition, studies included in the review conducted by Yao et al. 2 were screened for inclusion.

As specified in the review protocol, the searches for systematic reviews were separately screened to identify systematic reviews of non-randomised studies and these in turn were screened to identify non-randomised studies for inclusion in the review.

Data extraction

Information from new studies (not included in TA99) was extracted and tabulated; information included details of the study design and methodology, baseline characteristics of participants and results including HRQoL and any AEs if reported (see Appendix 1). All included studies (including those in TA99) were quality appraised.

If we identified several publications for one study, we evaluated the effectiveness data from the most recent publication and amended this with information from other publications. For quality appraisal purposes, all publications relating to a study were assessed together.

Critical appraisal strategy

Randomised control trials

Four reviewers (LC, MHa, HC and TJ-H) independently assessed the quality of all studies included in the clinical effectiveness review. The internal and external validity of RCTs was assessed according to criteria based on Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance69 (Table 8).

| Bias | Criteria for assessment of risk of bias |

|---|---|

| Treatment allocation | 1. Was the assignment to the treatment groups really random? 2. Was treatment allocation concealed? |

| Similarity of groups | 3. Were the groups similar at baseline in terms of prognostic factors? |

| Implementation of masking | 4. Were the care providers blinded to the treatment allocation? 5. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the treatment allocation? 6. Were the participants blinded to the treatment allocation? |

| Outcomes | 7. Were all a priori outcomes reported? 8. Were complete data reported, e.g. was attrition and exclusion (including reasons) reported for all outcomes? 9. Did the analyses include an ITT analysis? |

| Generalisability | 10. Are there any specific limitations which might limit the applicability of this study’s findings to the current NHS in England? |

Non-randomised control trials

There is no agreed recommended appraisal tool for the assessment of non-randomised studies. 70 The CRD handbook suggests considering the study design, risk of bias, other issues related to study quality, choice of outcome measure, statistical issues, quality of reporting, quality of the intervention and generalisability. 69 Therefore, the internal and external validity of non-RCTs was assessed according to criteria based on CRD guidance69 (Table 9).

| Bias | Criteria for assessment of risk of bias |

|---|---|

| Treatment allocation | 1. Was the method of allocation reported? 2. Is the allocation to groups or to the study a source of selection bias? |

| Similarity of groups | 3. Were the groups similar at baseline in terms of prognostic factors? |

| Implementation of masking | 4. Were the care providers blinded to the treatment allocation? 5. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the treatment allocation? 6. Were the participants blinded to the treatment allocation? |

| Outcomes | 7. Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur? 8. Were complete data reported, e.g. was attrition and exclusion (including reasons) reported for all outcomes? 9. Were statistical analyses adjusted to account for any between-group differences? |

| Generalisability | 10. Was the group(s) representative of NHS renal transplant patients? |

Methods of data synthesis

Data were tabulated and discussed in a narrative review. The subgroups defined in Chapter 2, Populations including subgroups, were considered in the analyses.

Meta-analyses

When data permitted, the results of individual studies comparing the same regimens were pooled using the methods described below.

A random-effects model was assumed for all meta-analyses. For binary data, an odds ratio (OR) was used as a measure of treatment effect and the DerSimonian–Laird method was used for pooling. 71 For continuous data (e.g. graft function), mean differences were calculated if the outcome was measured on the same scale in all trials. If applicable, publication bias was assessed using funnel plots, the Harbord test was used for binary outcomes [OR, log-standard error (SE)] and the Egger test for continuous data. All analyses were performed in Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

For studies with more than one intervention arm (that were separately compared with the same control arm), the number of events and the total sample size in the control arm were divided equally across the comparisons, and when pooling mean differences the total sample size in the control arm was adjusted and divided equally across the comparisons. However, if only one experimental arm was eligible for the analysis, all participants and events assigned to the control arm were included. If the number of events was zero in one of the studies arms, a value of 0.5 was added to all study arms to allow for statistical analyses.

Results of the systematic review

Quantity and quality of research available

The current review summarises both randomised and non-randomised controlled evidence. The assessment of clinical effectiveness is reported separately for induction and maintenance regimens.

Randomised control trials

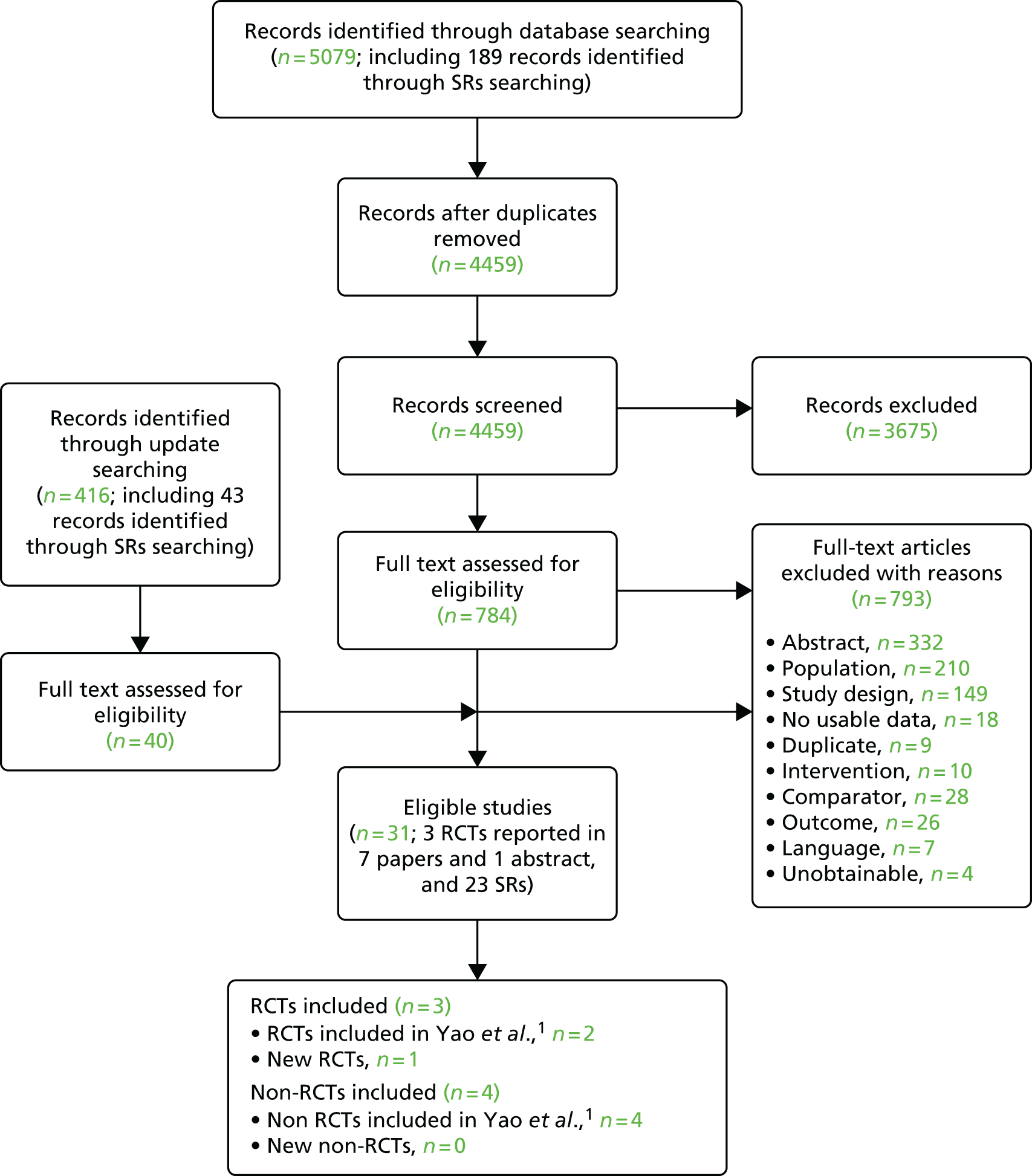

Our searches returned 5079 unique titles and abstracts, with 784 papers retrieved for detailed consideration. To ensure the inclusion of trials with mixed child/adolescent and adult populations that reported separate results for children and adolescents, the searches and title and abstract screening were not limited to children and adolescents. Update searches conducted on 7 January 2015 returned 416 unique titles and abstracts. Forty papers were retrieved for detailed consideration.

Of the 824 full-text papers retrieved, 793 were excluded (a list of these records with reasons for their exclusion can be found in Appendix 2, Table 135). Although RCTs in mixed populations were identified, none included subgroup analysis by age – providing separate results for children/adolescents and adults – and were therefore excluded from the review (a list of these records can be found in Appendix 2, Table 136). Three RCTs (published in one abstract72 and seven papers73–79) met the inclusion criteria.

Only one abstract72 was included in the review. This abstract included new data related to Offner et al. 73 and sufficient methodological information to inform the quality appraisal. In addition, there were 23 articles that were systematic reviews and all eligible systematic reviews were tabulated (see Appendix 3, Table 137).

The process is illustrated in detail in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8.

Clinical effectiveness review: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. SR, systematic review.

In summary, three RCTs (published in seven papers73–79 and one abstract72) were found eligible and are included in this review (Table 10).

| Study | n a | Agent (n) | Control (n) | Outcomes | Multiple publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction therapy | |||||

| Offner et al.73 | 192 | BAS + CSA + MMF + CCS (100) | PBO + CSA + MMF + CCS (92) | Mortality, graft loss, graft function, BPAR, AE | Höcker et al.,74 Jungraithmayr et al.72 |

| Grenda et al.75 | 192 | BAS + TAC + AZA + CCS (99) | NI + TAC + AZA + CCS (93) | Mortality, graft loss, graft function, BPAR, AE | Webb et al.76 |

| Maintenance therapy | |||||

| Trompeter et al.77 | 196 | TAC + AZA + CCS (103) | CSA + AZA + CCS (93) | Mortality, graft loss, graft function, BPAR, AE | Filler et al.,78 Filler et al.79 |

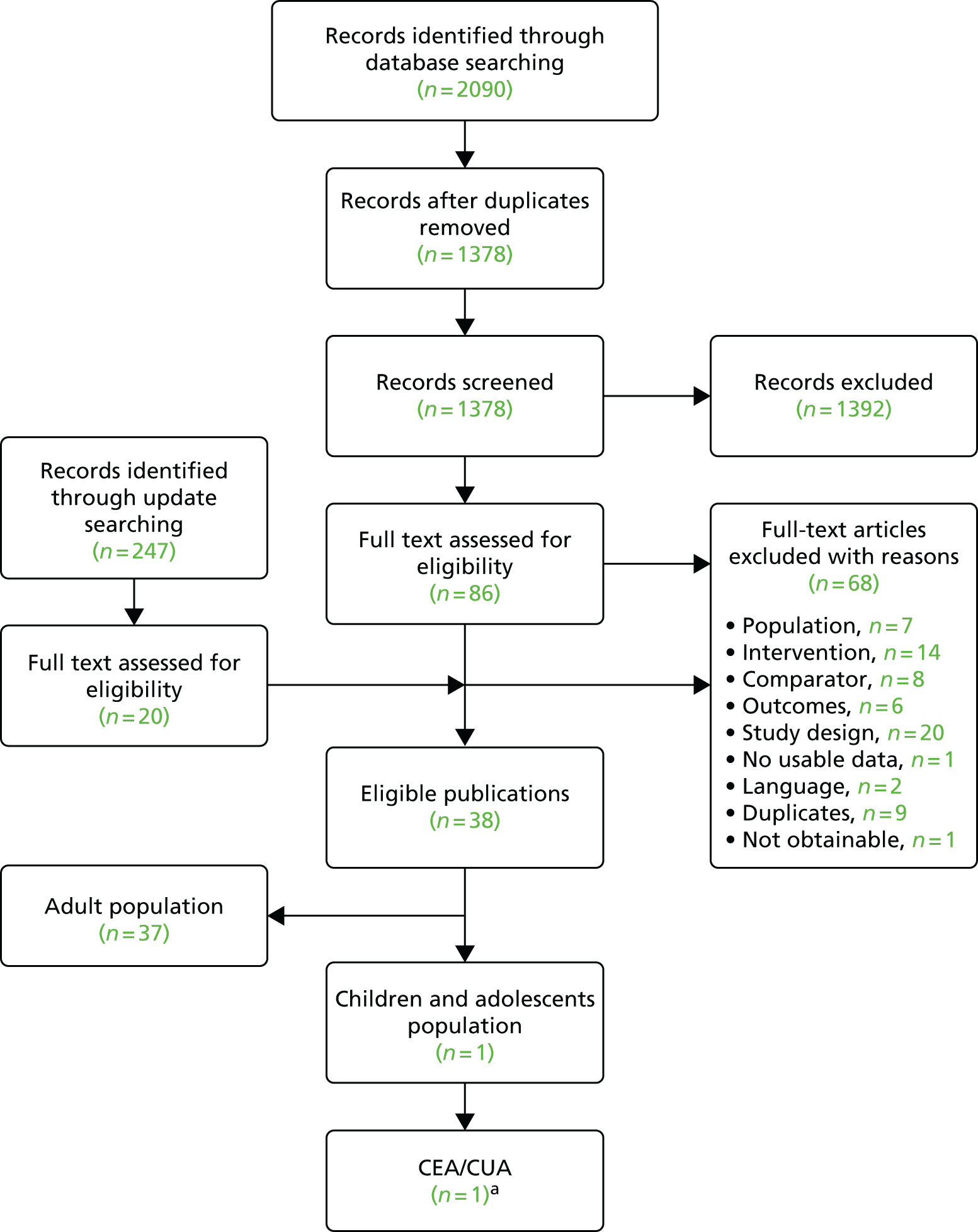

Non-randomised trials

The systematic reviews were used to identify non-RCTs. We screened the titles and abstracts of 226 unique references identified by the PenTAG systematic review searches (including 43 records from update searches) and retrieved 38 papers for detailed consideration. All eligible systematic reviews were tabulated (see Appendix 3, Table 137).

In total, four non-RCTs met the inclusion criteria and were considered eligible for inclusion (Table 11). All of these were included in the previous HTA by Yao et al. 2 so no new non-RCTs were identified. However, in 2007 one of the four non-RCT studies83 published 5-year follow-up data85 that were not included in the previous HTA.

| Study | n a | Treatment | Outcomes | Multiple publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction and maintenance therapy | ||||

| Garcia et al80 | 24 | BAS + TAC + AZA + CCS vs. BAS + CSA + MMF + CCS | Mortality, graft loss, graft function, BPAR, AE | N/A |

| Maintenance therapy | ||||

| Antoniadis et al.81 | 14 | CSA + MMF + CCS vs. CSA + AZA + CCSb | Graft function, BPAR, AE | N/A |

| cBenfield et al.82 | 67 | (OKT3 or CSA) + MMF + CCS vs. (OKT3 or CSA) + AZA + CCS | Mortality, graft loss, graft function, BPAR | N/A |

| Staskewitz et al.83 | 139d | CSA + MMF + CCSe vs. CSA + AZA + CCS | Mortality, graft loss, graft function, BPAR, AE | Jungraithmayr et al.,84 Jungraithmayr et al.85 |

Ongoing studies

Eleven ongoing trials were considered relevant to this review and were investigated further. An overview of the 11 trials with reasons for inclusion/exclusion in PenTAG review is provided in Appendix 4, Table 138. Only one of these ongoing trials was identified as potentially eligible for inclusion. The methods and design of this trial (A2314) were reported as conference abstracts. 86–89 This international trial investigates the efficacy, tolerability and safety of early introduction of EVL, reduced CNIs and early steroid elimination compared with standard CNI, MMF and steroid regimen in paediatric renal transplant recipients and is sponsored by Novartis. The estimated date of completion is December 2016, so it was not included in this review. The search of ongoing studies in trial registries did not identify any additional RCTs for inclusion in the PenTAG systematic review.

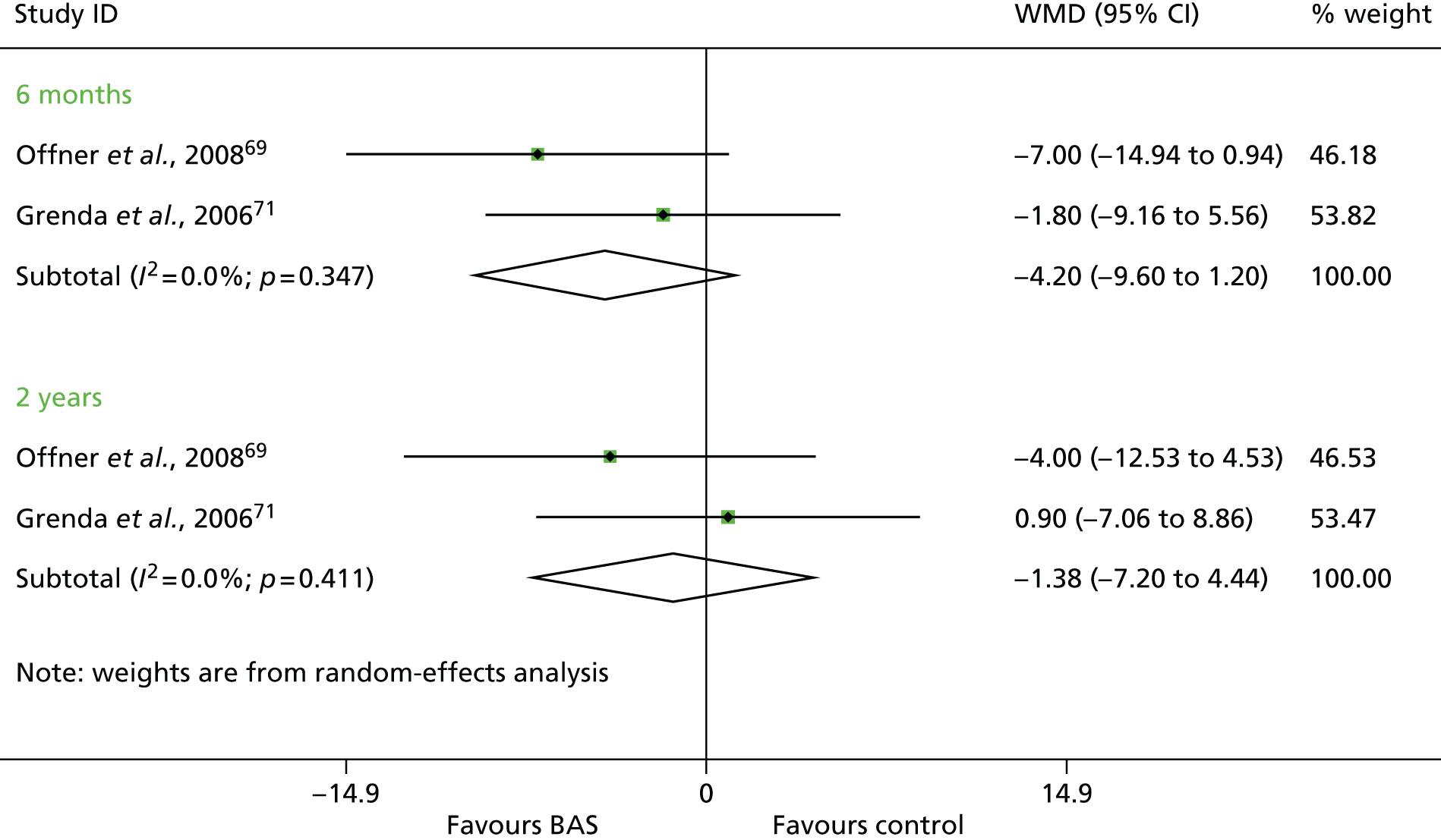

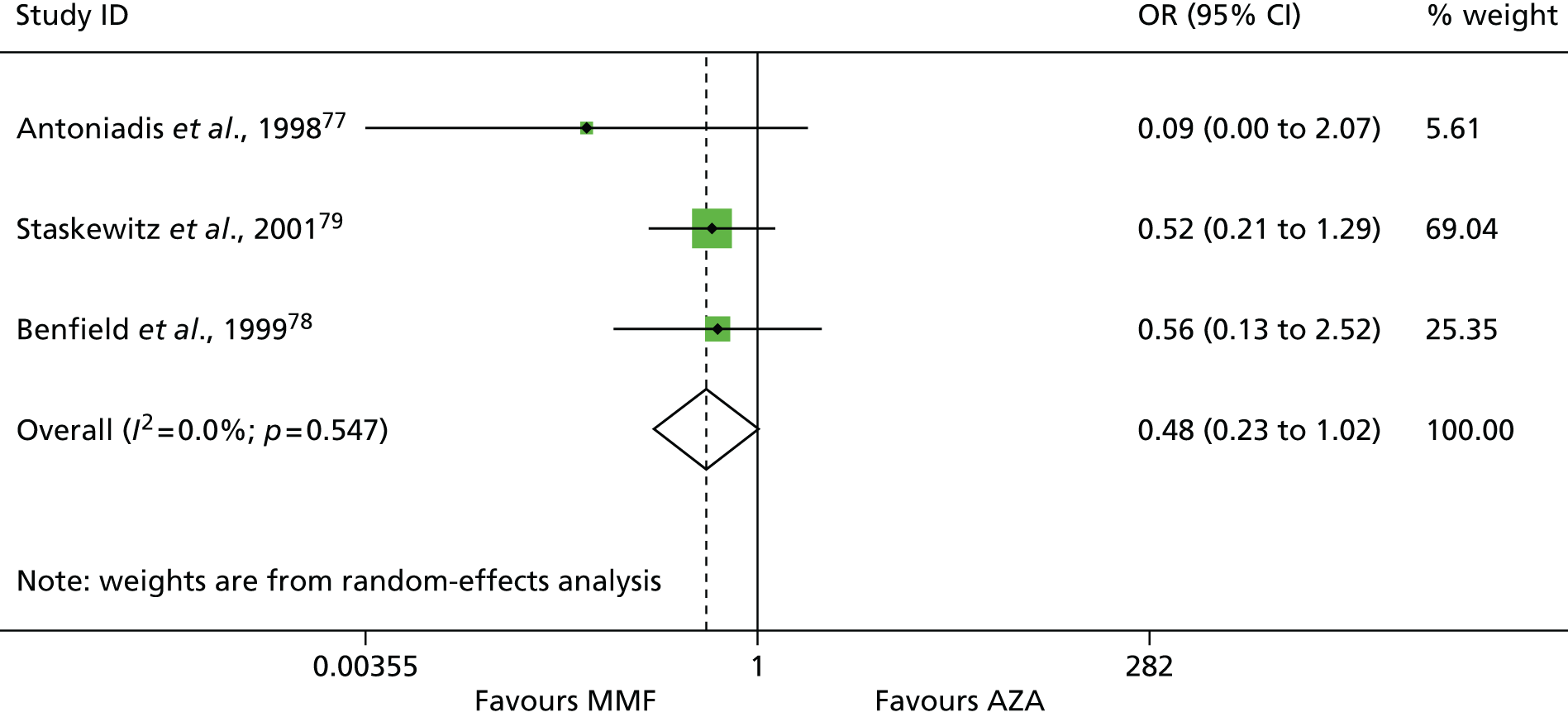

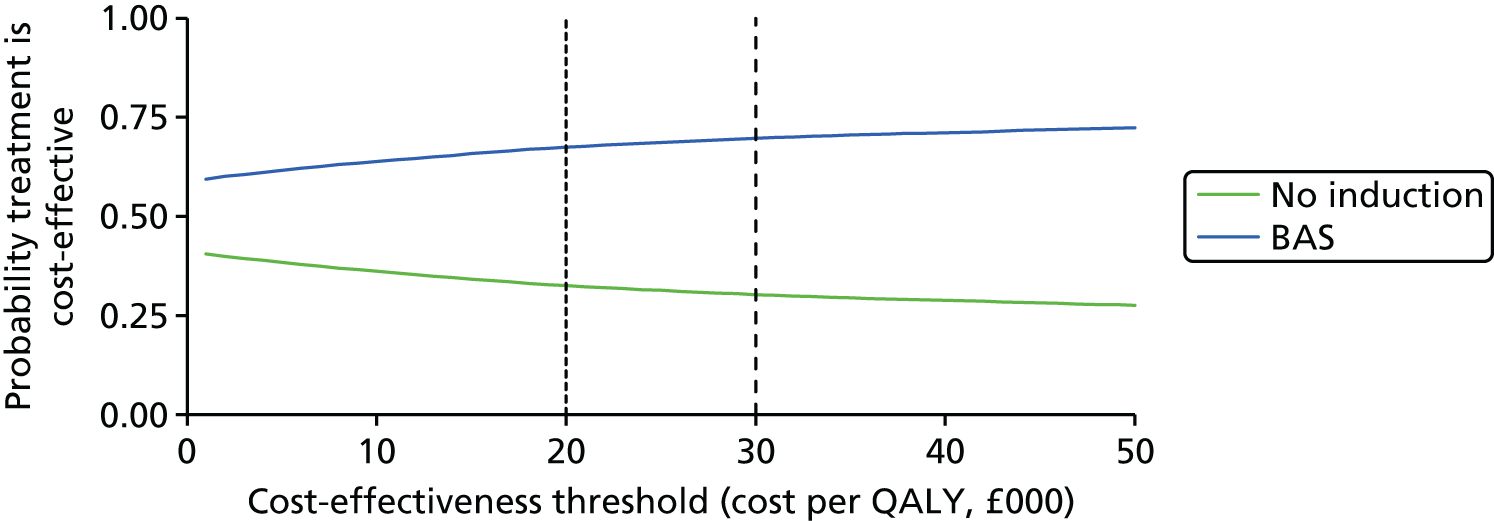

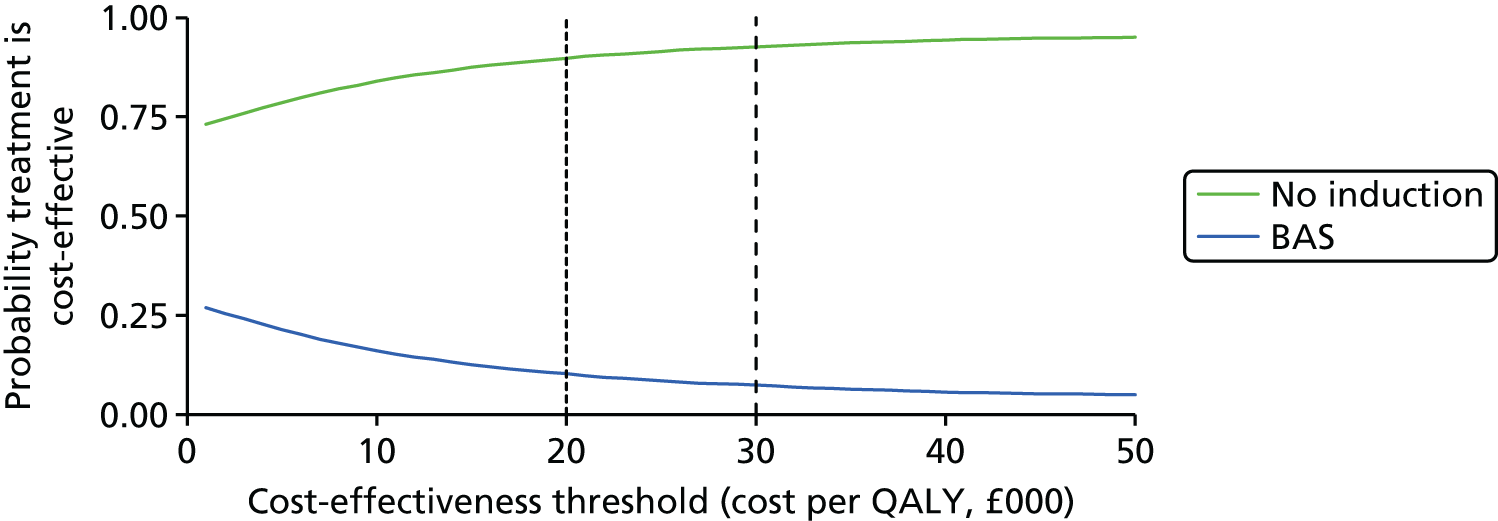

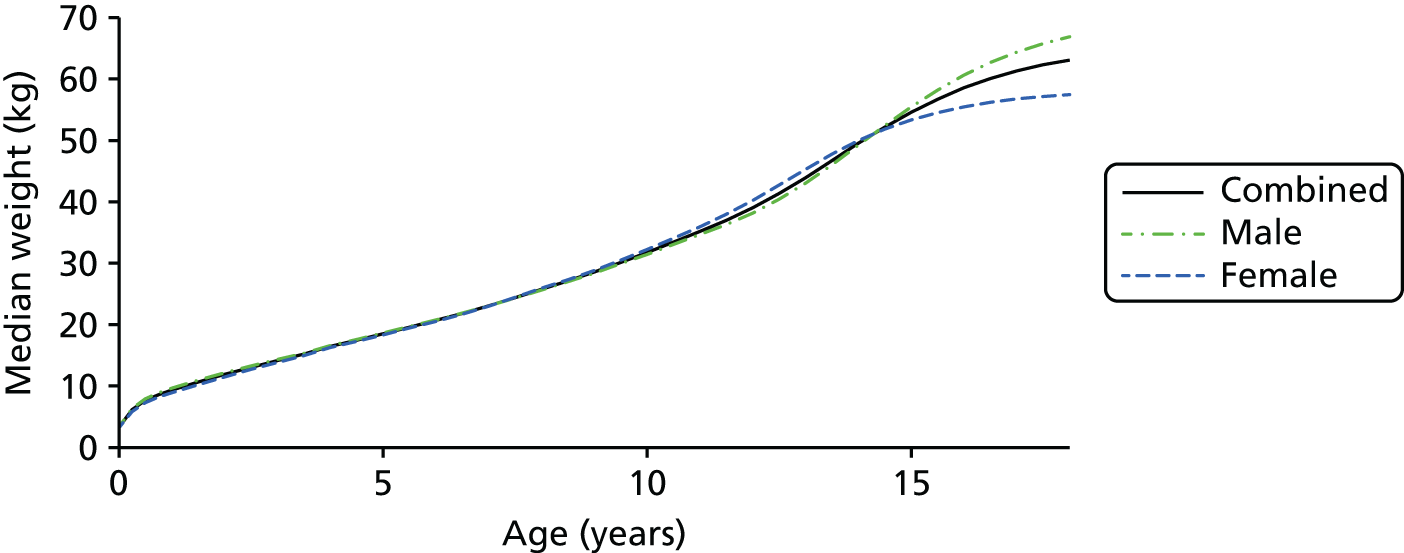

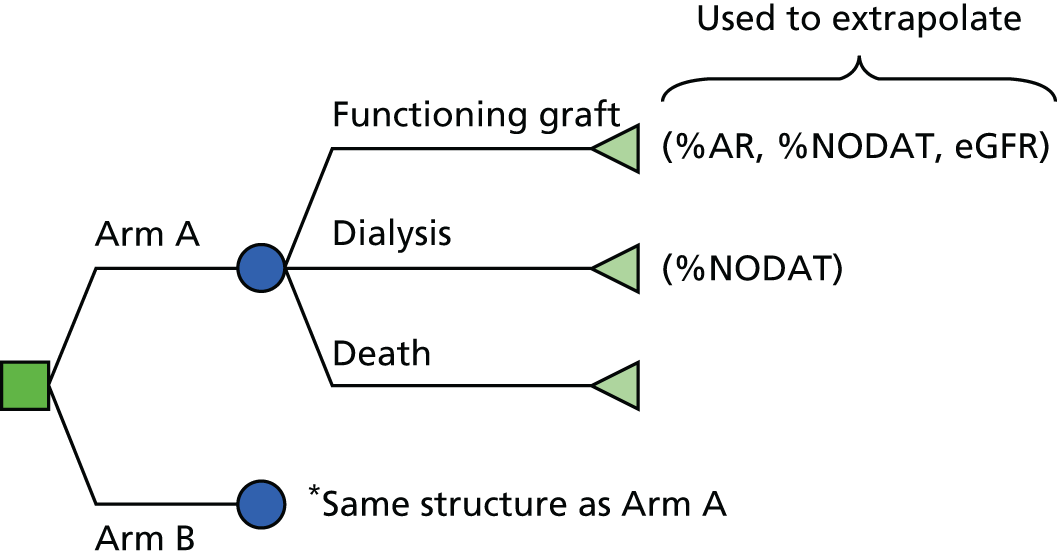

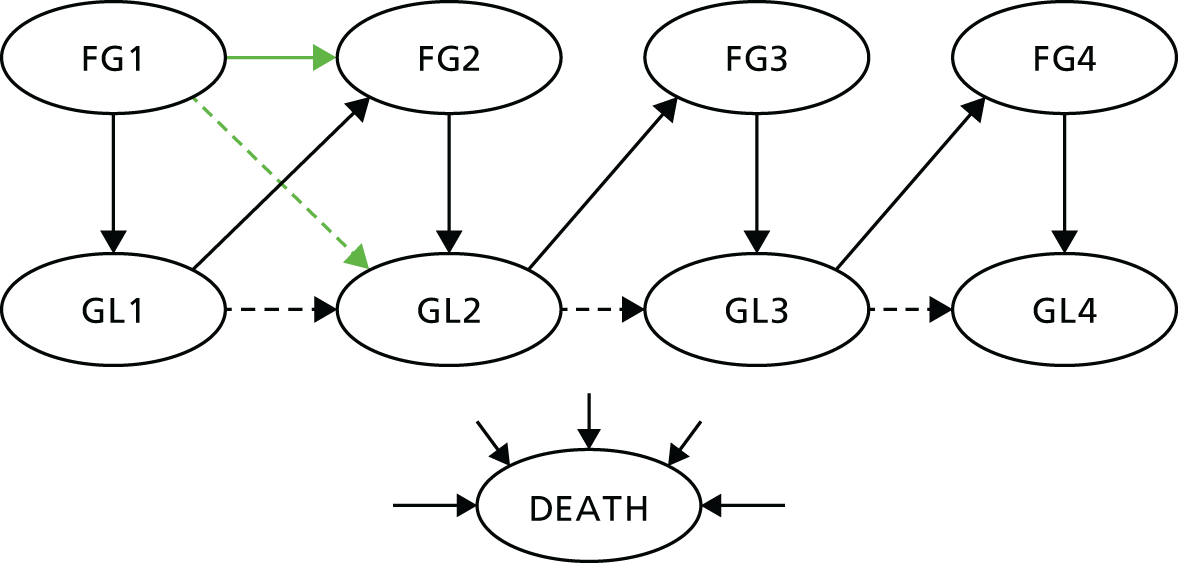

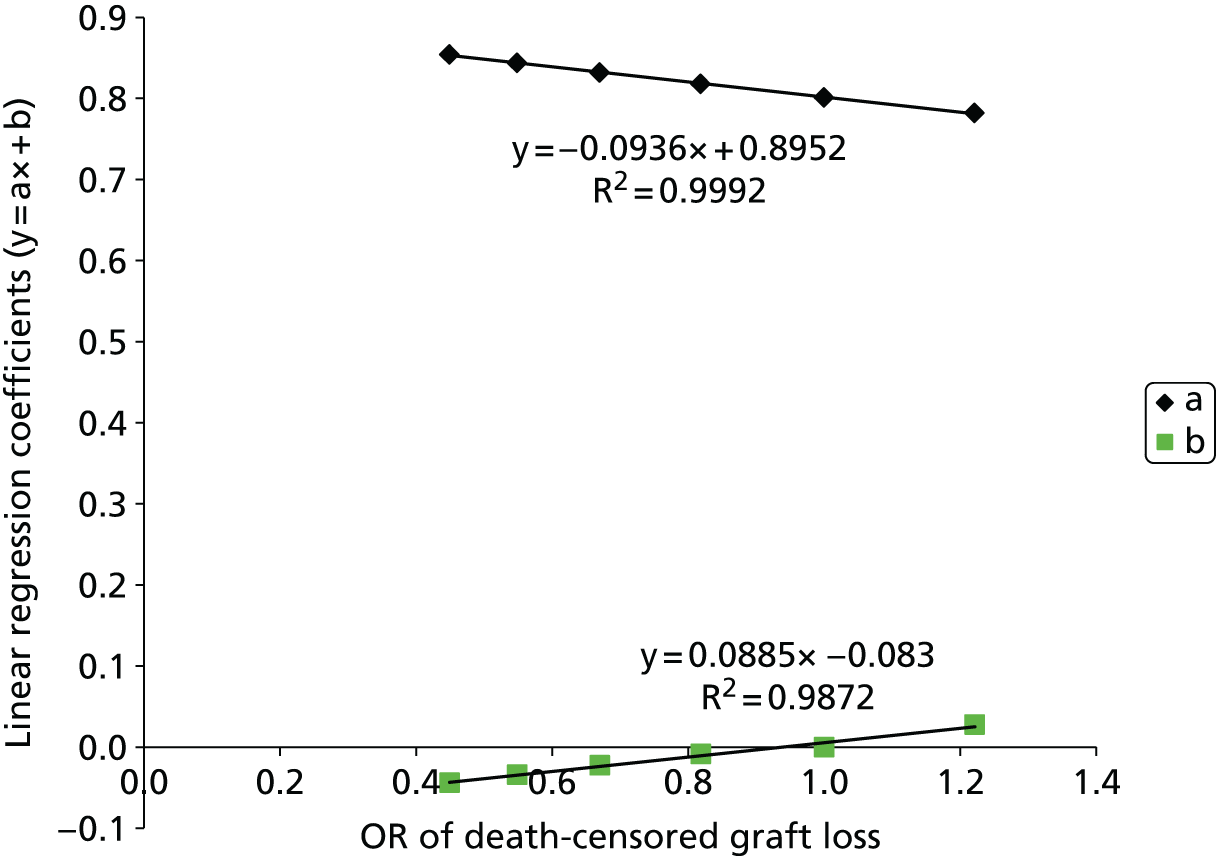

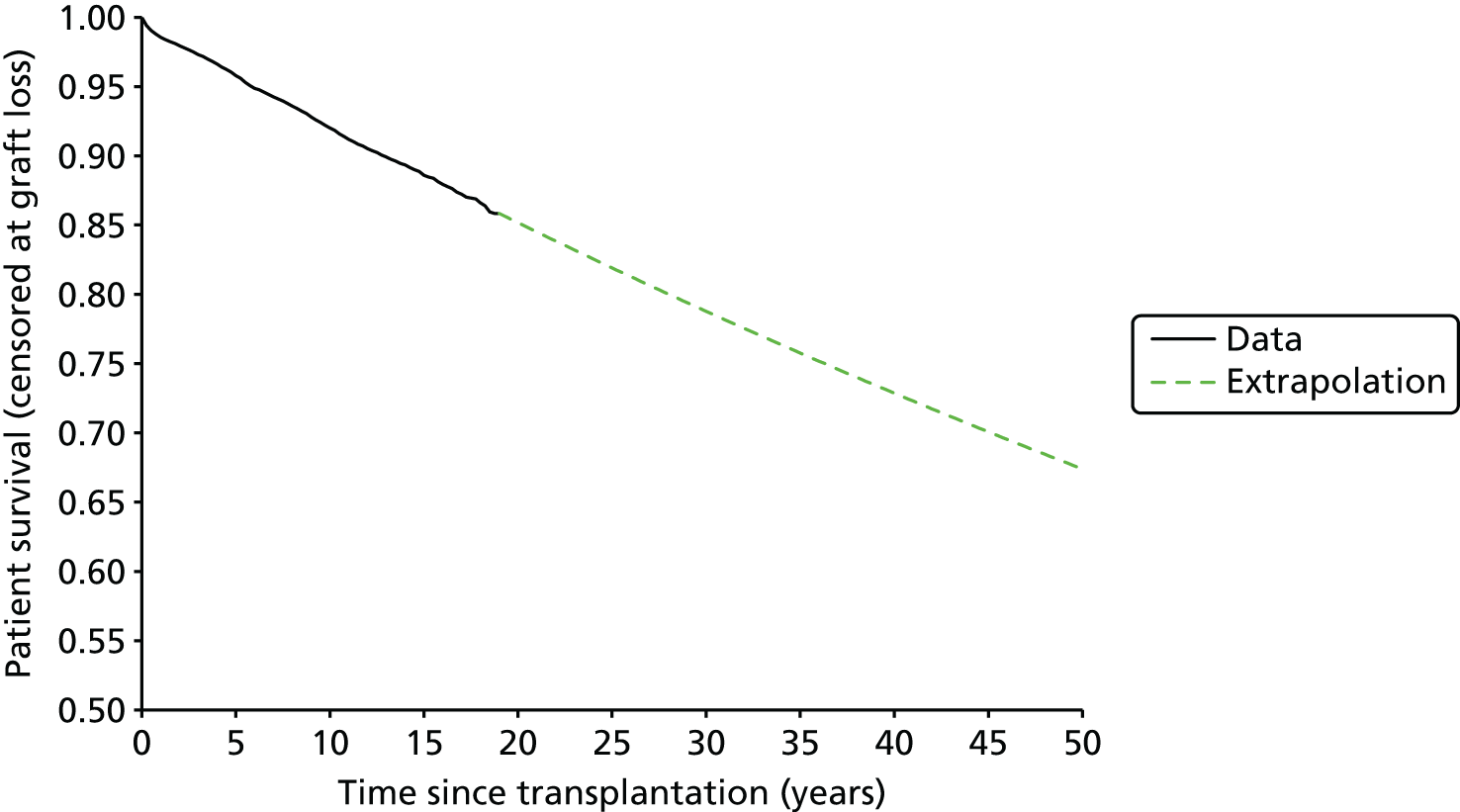

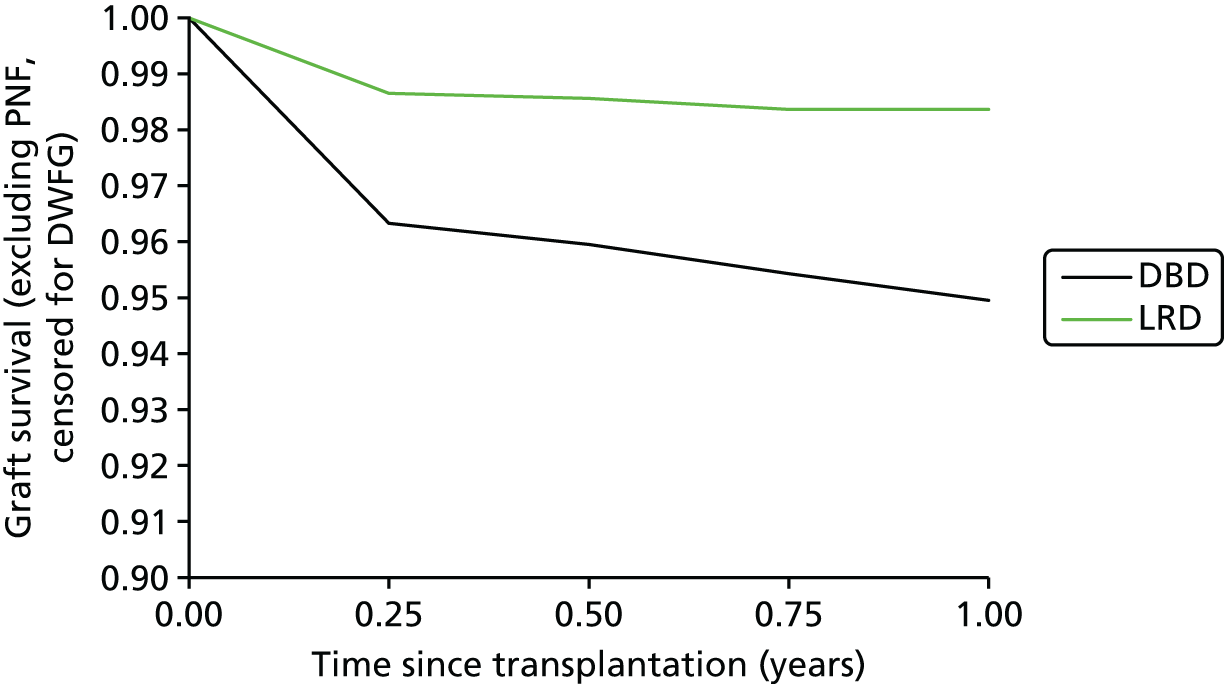

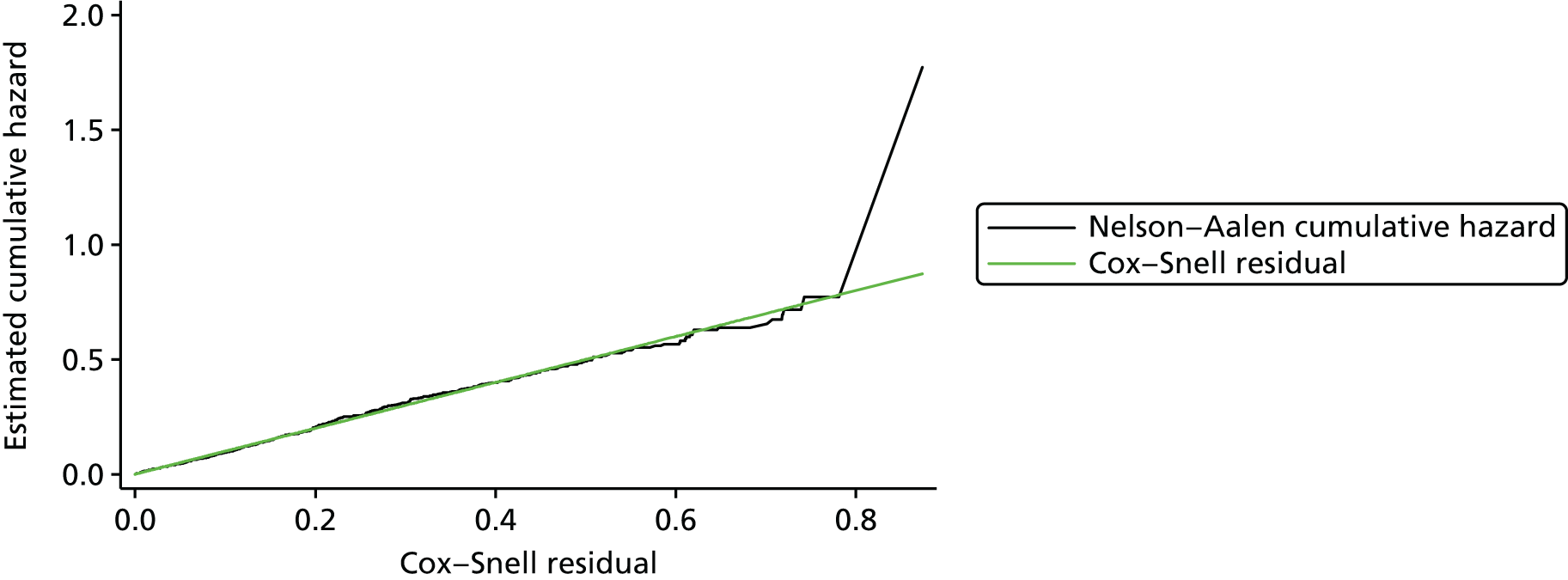

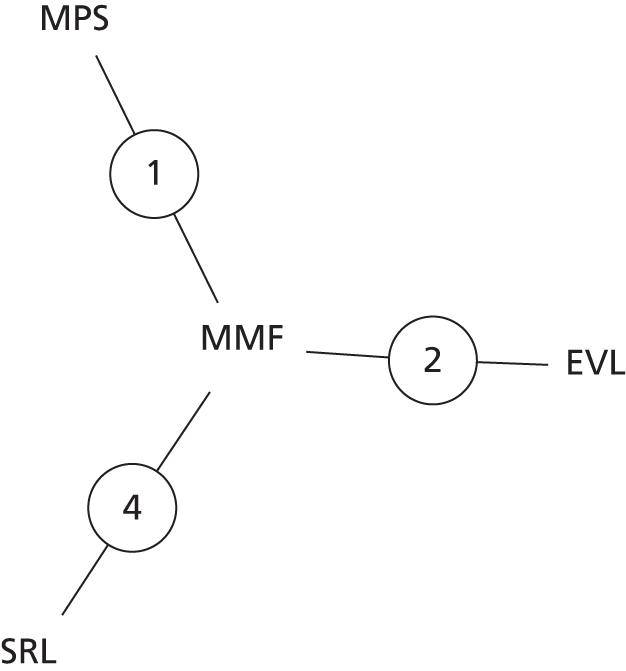

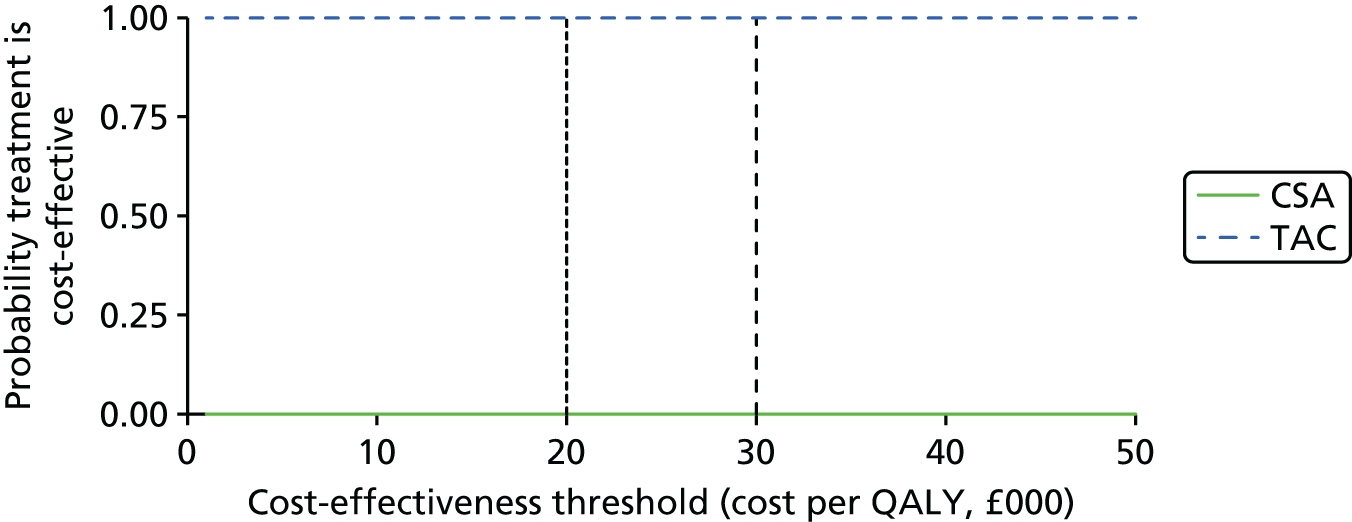

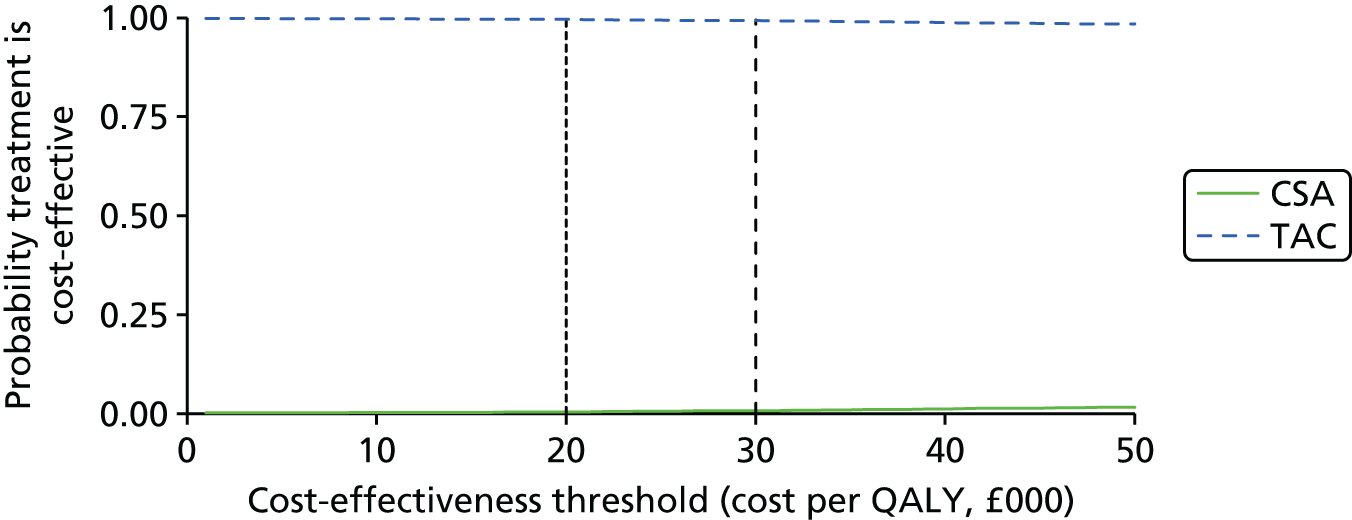

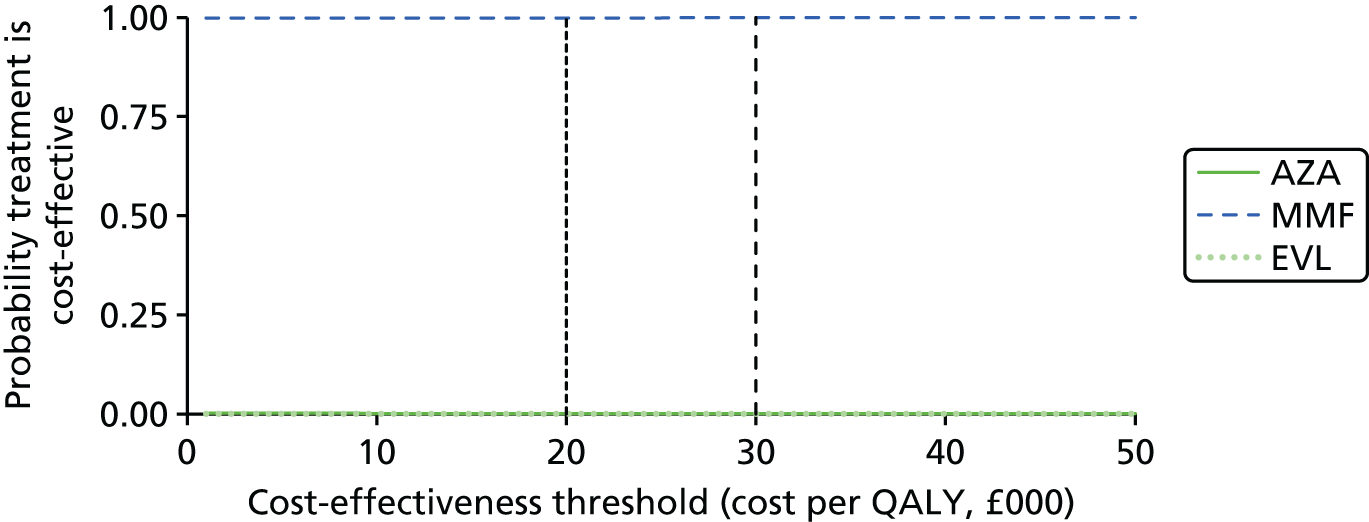

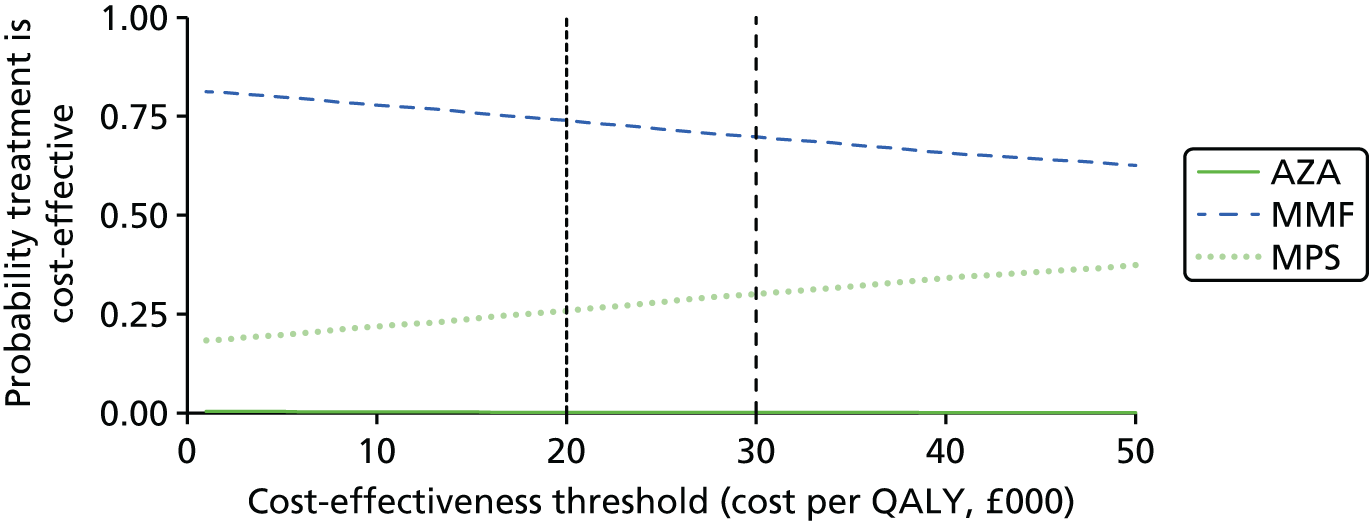

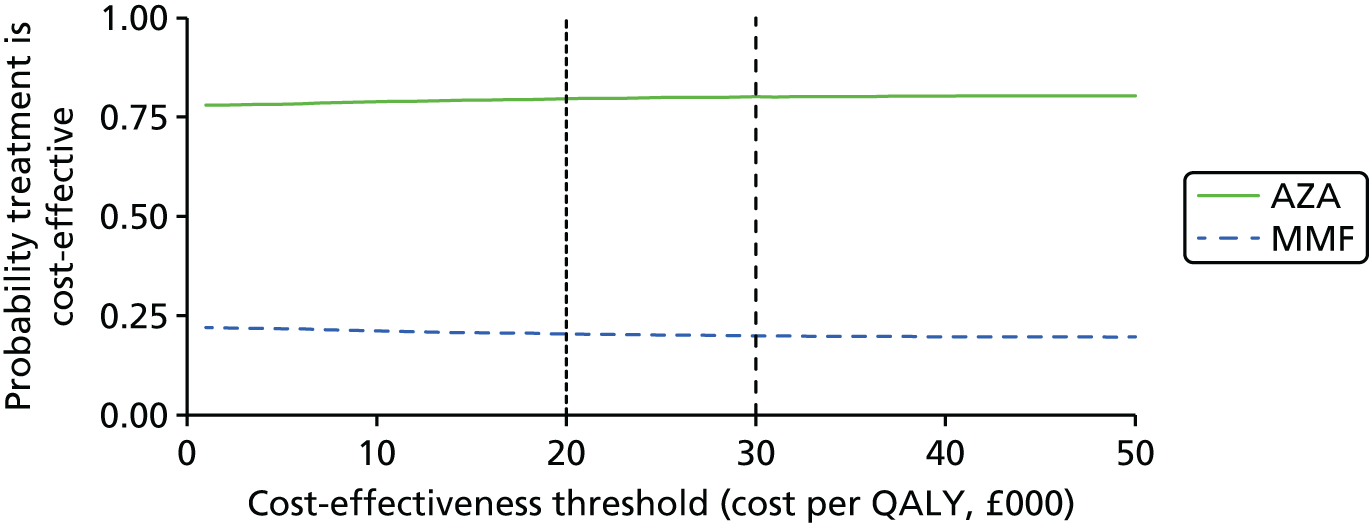

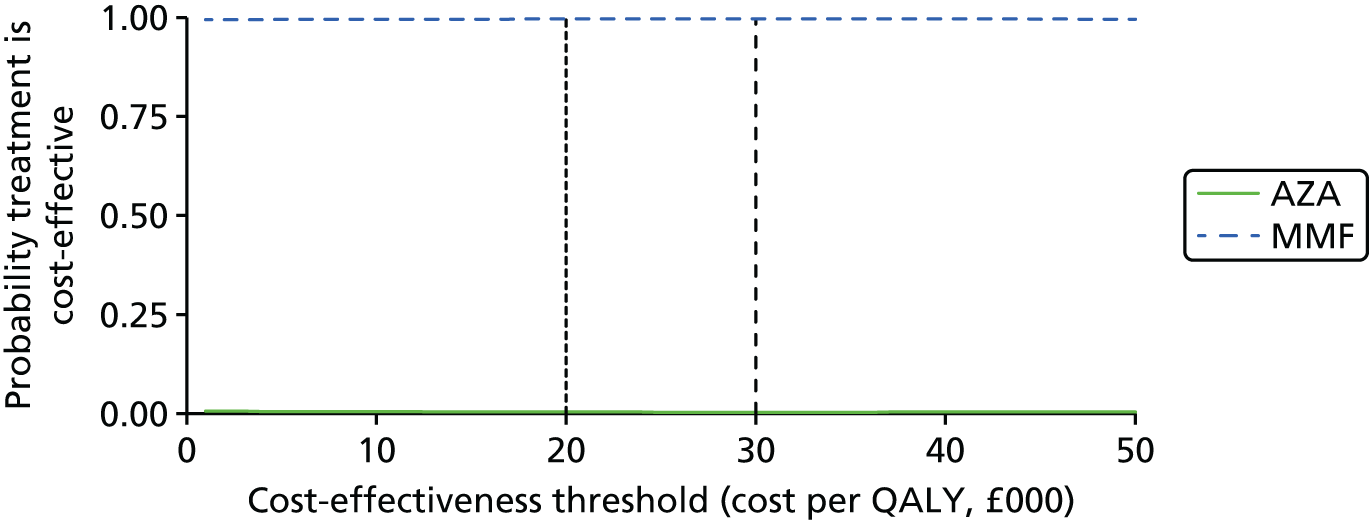

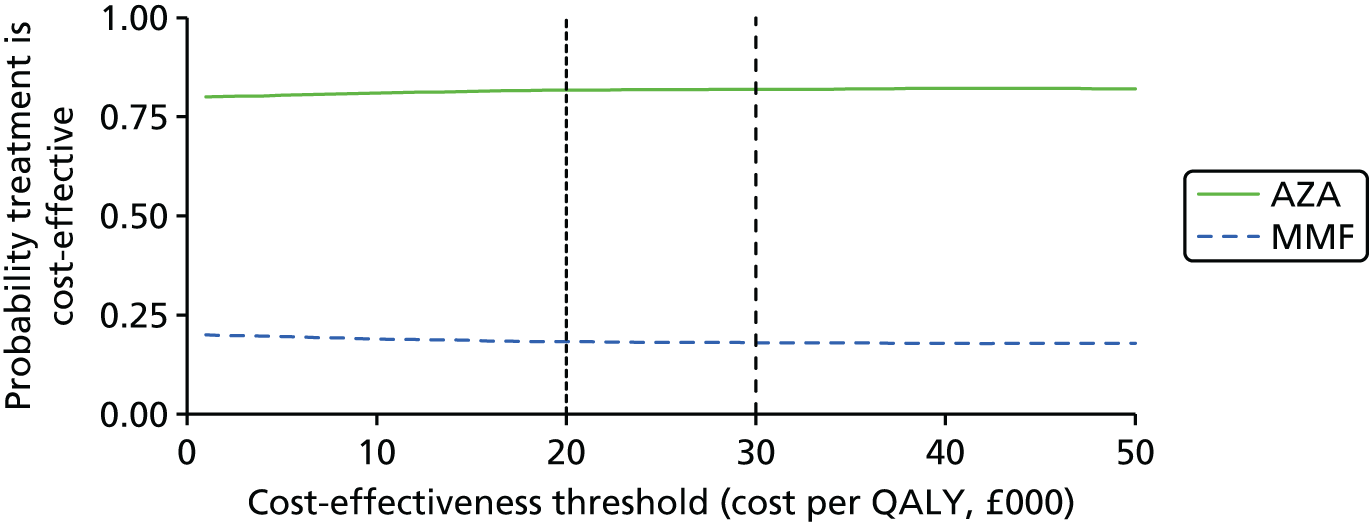

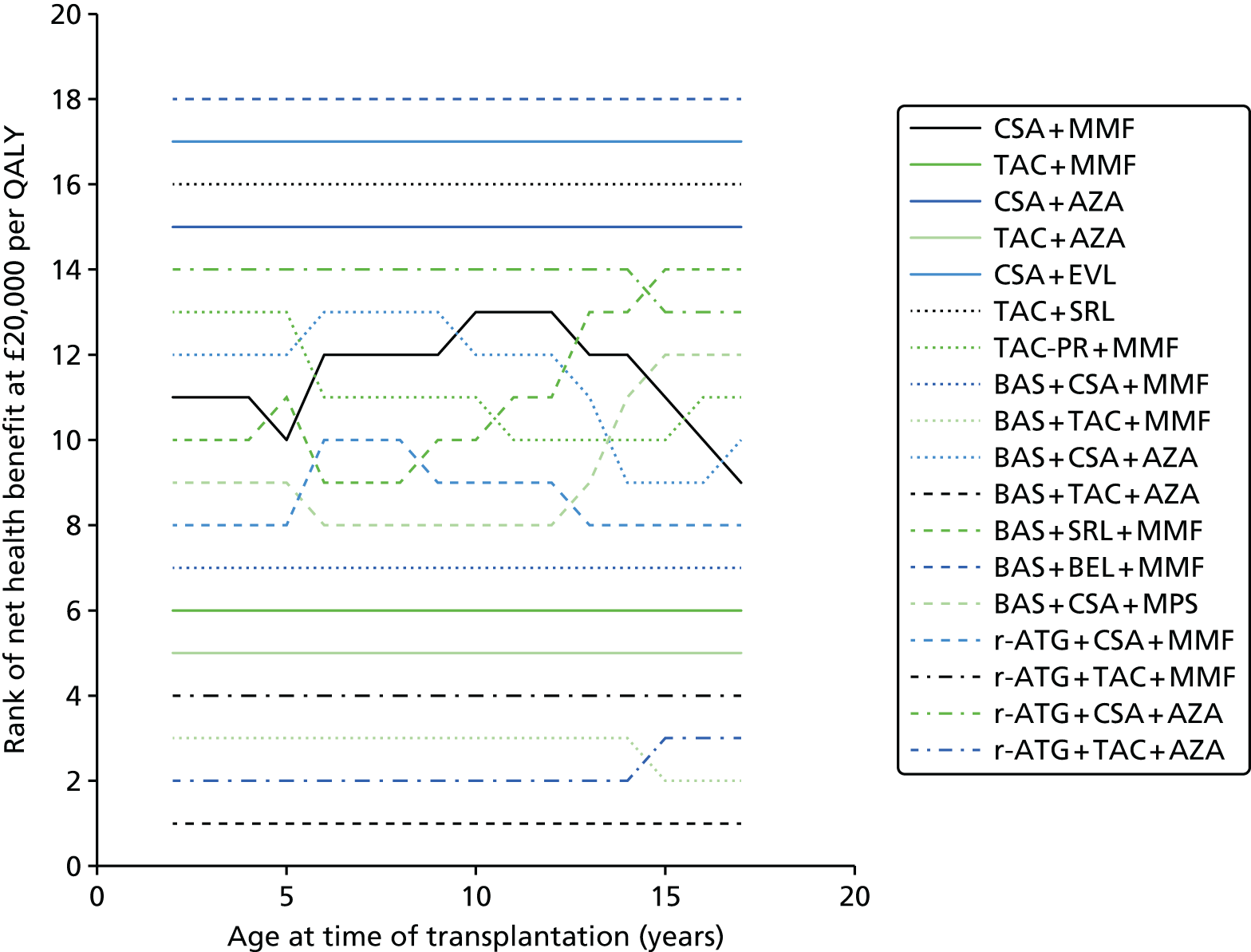

The previous assessment report