Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/01/07. The contractual start date was in January 2009. The draft report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in February 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Marion F Walker declares a consultancy with Allergan on long-term problems after stroke.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Clarke et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects over 1% of people older than 60 years and the prevalence is set to rise with the ageing population. 1 PD causes significant problems with activities of daily living (ADL) that are only partially treated by medication and occasionally surgery. Despite treatment, patients go on to develop intractable motor problems (e.g. imbalance and falls), along with mental-health problems and other non-motor symptoms.

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy

Physiotherapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) are traditionally used later in the course of PD. 2 PT aims to promote and maintain mobility and activity by treating motor impairments with task-related practice and exercise. Core work areas are motor practice and exercise prescription for gait, balance, posture and transfers. 3 A recent summary of the role of PT included the prevention of inactivity and falls. 4

Occupational therapists work in partnership with patients to address personal rehabilitation goals through activity and participation, helping them to remain as independent as possible and to reduce carer strain. When delivered in a domiciliary setting, OT includes equipment provision and environmental adaptations to facilitate independence in the home. Therapists provide task-related training and educate patients and carers. 5,6

Evidence for physiotherapy and occupational therapy in Parkinson’s disease

Cochrane reviews of PT and OT for PD found insufficient evidence of their individual effectiveness, but the trials included in the reviews were methodologically flawed with small size and short-term follow-up. 7–9 Despite this lack of evidence, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, although recognising these shortcomings and recommending further trials, stated that all patients should have access to both therapies. 2

Objective of the PD REHAB trial

The objective of this large-scale pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of individualised PT and OT in patients with PD. The current trial (PD REHAB) design was informed by our pilot study of OT in PD (PD OT). 10

Systematic reviews

Physiotherapy versus no or placebo intervention

This review was published by the trial team in The Cochrane Library8 and subsequently in the British Medical Journal9 © 2016 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. All rights reserved.

Methods

A systematic search of the literature to the end of January 2012 was undertaken using a highly sensitive search strategy as recommended by Cochrane. We combined text and, where appropriate, medical subject headings terms for PT, physical therapy, exercise or rehabilitation and for Parkinson, PD or Parkinsonism. No language restrictions were applied. Relevant trials were identified by electronic searches of general biomedical and science electronic databases, English-language databases of foreign-language research and third-world publications, conference and grey literature databases and trial registries. Hand searching of general and specific journals in the field, abstract books and conference proceedings was also undertaken, as well as examination of the reference lists of identified papers and other reviews.

Studies eligible for this review were RCTs (including the first phase of crossover trials) in PD patients comparing a PT intervention with no intervention or placebo control. PT encompasses a wide range of techniques, so we were inclusive in our definition of PT intervention, with trials of general PT, exercise, treadmill training, cueing, dance and martial arts versus no intervention being included. We excluded trials of multidisciplinary team interventions, as it was difficult to ascertain the amount of PT input.

All articles were read by two independent review authors and data extracted according to pre-defined criteria, with any discrepancies resolved by discussion. In addition, publications were assessed for methodological quality.

Results of each trial were combined using standard meta-analytic methods to estimate an overall effect for PT versus no intervention. All outcomes were continuous variables so weighted mean difference methods were used with a fixed-effects model.

The primary analysis was a comparison of PT and no intervention (control) using change from baseline to the first assessment after the treatment period (which in most cases was immediately after the intervention). This was chosen as the primary analysis, as in most trials this was the main data analysis, and few trials reported data at longer-term assessment points (i.e. after 6 months).

To assess for differences between the different interventions used, indirect comparisons using tests of heterogeneity were used to investigate whether or not the treatment effect differed across the different interventions.

Results

We identified 76 potentially relevant studies; 31 were excluded (e.g. not properly randomised, crossover trial with data not reported for first intervention period) and six were ongoing trials for which no data were available. Therefore, 39 RCTs involving 1827 patients were included in the systematic review. These 39 trials contributed data to 44 comparisons within the six different PT interventions (PT, n = 7; exercise, n = 14; treadmill training, n = 8; cueing, n = 9; dance, n = 2; and martial arts, n = 4) (Table 1).

| PT intervention | Number of trials | Total number of participants (% male) | Mean age (years) | Mean Hoehn and Yahr | Mean duration of PD (years) | Duration of treatment sessions (minutes) | Trial period | Examples of types of therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | 7 | 244 (69) | 65 | 2.4 | 4 | 30–60 | 4–12 months | Bobath training, gait and balance exercises, hands-on techniques, education and advice on transfer, posture and physical fitness |

| Exercise | 14 | 769 (61) | 69 | 2.6 | 6 | 30–120 | 3–24 weeks | Strengthening and balance training, walking, falls prevention, neuromuscular facilitation, resistance exercise, aerobic training, education and relaxing techniques |

| Treadmill | 8 | 179 (61) | 68 | 2.4 | 5 | 30–60 | 4–8 weeks | Walking on treadmill with speed or incline adjustments. Body weight-supported treadmill training, step and gait training |

| Cueing | 9 | 371 (59) | 67 | 2.6 | 7 | 4–30 | Single session–13 weeks | Three types of cueing: audio (music, spoken instructions), visual (computer images), sensory (vibration) |

| Dance | 2 | 120 (63) | 69 | 2.3 | 7 | 60 | 12–13 weeks | Tango, waltz and foxtrot |

| Martial arts | 4 | 143 (74) | 65 | 2.1 | 6 | 60 | 12–24 weeks | Tai chi and qigong |

The amount of methodological detail reported in the trials was variable, with several quality indicators not fully discussed in many publications. Only six studies (15%) reported a sample size calculation. Fewer than half of the trials described the randomisation method used, and information on concealment of treatment allocation was also poorly reported (36%). 62% of the studies used blinded assessors. Only nine trials stated intention to treat as the primary method of analysis. Three trials stated per protocol as the primary method of analysis and in the remaining trials the method of analysis was not described.

The effects of the various PT techniques are summarised in Table 2.

| Outcome | Number of trials; comparisons | PT interventions | Number of participants | Mean difference (95% CI) | Heterogeneity between trials | Indirect comparison between subgroups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait outcomes | ||||||

| Speed (m/s) | 15; 19 | General PT, exercise, treadmill, cueing, dance, martial arts | 814 | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.06), p = 0.0002 | p = 0.55 | p = 0.25 |

| 2- or 6-minute walk test (m) | 6; 7 | Exercise, treadmill, dance, martial arts | 242 | 13.37 (0.55 to 26.20), p = 0.04 | p = 0.44 | p = 0.19 |

| 10- or 20-metre walk test (s) | 4; 4 | Exercise, treadmill | 169 | 0.40 (0.00 to 0.80), p = 0.05 | p = 0.19 | p = 0.51 |

| Freezing of Gait questionnaire | 4; 4 | Exercise, cueing, dance | 298 | –1.41 (–2.63 to –0.19), p = 0.02 | p = 0.74 | p = 0.55 |

| Cadence (steps/minute) | 7; 9 | General PT, exercise, treadmill, cueing | 350 | –1.57 (–3.81 to 0.67), p = 0.17 | p = 0.73 | p = 0.97 |

| Stride length (m) | 6; 9 | General PT, exercise, treadmill, cueing, dance, martial arts | 225 | 0.03 (–0.02 to 0.08), p = 0.24 | p = 0.33 | p = 0.23 |

| Step length (m) | 5; 6 | General PT, exercise, treadmill, cueing | 383 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04), p = 0.06 | p = 0.71 | p = 0.47 |

| Functional mobility and balance outcomes | ||||||

| Timed Up and Go test (seconds) | 9; 10 | Exercise, cueing, dance, martial arts | 639 | –0.63 (–1.05 to –0.21), p = 0.003 | p = 0.12 | p = 0.33 |

| Functional reach (cm) | 4; 4 | Exercise, cueing | 393 | 2.16 (0.89 to 3.43), p = 0.0008 | p = 0.15 | p = 0.48 |

| Berg Balance Scale | 5; 6 | Exercise, treadmill, dance, martial arts | 385 | 3.71 (2.30 to 5.11), p < 0.00001 | p = 0.06 | p = 0.47 |

| Activity-specific balance confidence | 3; 3 | Exercise, cueing | 66 | 2.40 (–2.78 to 7.57), p = 0.36 | p = 0.61 | p = 0.32 |

| Falls | ||||||

| Falls Efficacy Scale | 4; 4 | Exercise, treadmill, cueing | 353 | –1.91 (–4.76 to 0.94), p = 0.19 | p = 0.44 | p = 0.28 |

| Clinician-rated disability – Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale | ||||||

| Total | 3; 4 | General PT, exercise, treadmill | 207 | –6.15 (–8.57 to –3.73), p < 0.00001 | p = 0.03 | p = 0.01 |

| Subscore – mental | 2; 3 | General PT, treadmill | 105 | –0.44 (–0.98 to 0.09), p = 0.10 | p = 0.80 | p = 0.82 |

| Subscore – ADL | 3; 4 | General PT, treadmill, dance | 157 | –1.36 (–2.41 to –0.30), p = 0.01 | p = 0.28 | p = 0.19 |

| Subscore – motor | 12; 14 | General PT, exercise, treadmill, cueing, dance, martial arts | 593 | –5.01 (–6.30 to –3.72), p < 0.00001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| Patient-rated quality of life – Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 | ||||||

| Summary index | 7; 8 | General PT, exercise, treadmill, cueing, dance, martial arts | 405 | –0.38 (–2.58 to 1.81), p = 0.73 | p = 0.89 | p = 0.87 |

| Subscore – mobility | 2; 3 | General PT, dance, martial arts | 105 | –1.43 (–8.03 to 5.18), p = 0.67 | p = 0.11 | p = 0.11 |

Only one outcome, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor subscore, showed significant heterogeneity between the treatment effects of the different classes of intervention. An outlying trial was the cause of this heterogeneity; when this trial was excluded, the result remained statistically significant [–3.77 points, confidence interval (CI) –5.15 to –2.39 points; p ≤ 0.00001], but the test for between-trial and between-subgroup heterogeneity was no longer significant (p = 0.44 and p = 0.08, respectively).

For one trial, 60 patients who were split between PT and treadmill categories are not included in the table, as group split was not given. For multiple-arm trials, the control-arm patients are counted twice (n = 59).

All results (except for the 10- or 20-m walk test) favoured PT intervention.

Conclusions

This review provides evidence on the short-term (mean follow-up < 3 months) efficacy of PT in the treatment of PD. Significant benefit of PT was reported for nine outcomes: gait speed; 2- or 6-minute walk test; Freezing of Gait questionnaire; Timed Up and Go test; Functional Reach Test; Berg Balance Scale; and UPDRS total, ADL and motor subscores. The relevance of these differences to PD patients must be put into the context of what is considered a minimal clinically important change (MCIC). What few data are available on MCIC for the impairment measures suggest the differences are below those relevant for patients. The benefits in UPDRS total, ADL and motor scores approach the MCIC, suggesting that a PT intervention is beneficial in improving clinician-rated symptoms. However, the only patient-rated quality of life (QoL) outcome measure (Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39; PDQ-39) showed no statistically significant benefit from treatment with PT and was reported in only eight trials.

The review also highlights the wide range of PT techniques being used in the treatment of PD. Indirect comparisons provided no evidence that differences in the treatment effect existed between the different types of PT.

The majority of the studies in this review were small and had a short follow-up period. Larger RCTs are required, particularly focusing on improving trial methodology and reporting. Rigorous methods of randomisation should be used and allocation of treatment should be adequately concealed. Data should be analysed according to intention-to-treat principles and trials should be reported according to the guidelines set out in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. This review also illustrates the need for the universal employment of relevant, reliable and sensitive outcome measures. Further, only three trials looked at the longer-term benefit of PT intervention. In order to assess whether or not and how long any improvement due to PT intervention may last, it is important that long-term follow-up is performed without crossover from control to active intervention. Finally, the review highlights the variety of PT interventions used in the treatment of PD. There is a need for more specific trials with improved treatment strategies to underpin the most appropriate choice of PT intervention.

Considering the low methodological quality, small size and short duration of many of the included trials, this evidence supporting the use of PT for people with PD must be balanced against the lack of long-term evidence currently available.

Physiotherapy versus alternative physiotherapy intervention

This review was published by the trial team in The Cochrane Library. 11

Methods

See review in previous section: Physiotherapy versus no or placebo intervention.

Results

In total, 78 randomised trials of PT intervention in PD patients were identified. Twenty-nine studies were excluded because they were not properly randomised (n = 12), they were a crossover trial with data not adequately separated (n = 4), the treatment in the trial was not usually used by physiotherapists (such as Whole Body Vibration technique) (n = 4), they had no outcome measures relevant to our review (n = 2), they were a multidisciplinary therapy rehabilitation trial (n = 2), the trial was under 1 day (n = 1), they had insufficient information available for inclusion in review (n = 1), they had an unsuitable comparator arm (n = 1), the study was confounded (n = 1) or they were a comparison of PT delivery rather than technique (n = 1). There were also six ongoing trials for which data were not yet available. Therefore, there were 43 trials available for inclusion in the review.

The number of participants randomised in the 43 trials ranged from 8 to 210, with 1673 participants randomised in total (giving an average trial size of 39 participants). The assessment period ranged from 2 weeks to 24 months. The mean age of participants in the trials was 67 years, 62% were male, the mean Hoehn and Yahr stage was 2.4 and participants had had PD for approximately 7 years.

Physiotherapy interventions were placed into one of the six categories (general PT, exercise, treadmill training, cueing, dance and martial arts) according to the type of treatment administered. However, the content and delivery of the interventions within each category was diverse. Further, a wide variety of validated and customised outcome measures were used to assess the effectiveness of PT interventions. Consequently, it was inappropriate to combine the results of studies or perform any statistical analysis.

Conclusions

Considering the small number of participants, the methodological flaws in many of the studies, the wide variety of PT interventions and the outcome measures used, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of one approach of PT intervention over another for the treatment of PD. Larger RCTs with longer follow-up are required, particularly focusing on improving trial methodology and reporting. Rigorous methods of randomisation should be used and the allocation adequately concealed. Data should be analysed according to intention-to-treat principles and trials should be reported according to the guidelines set out in the CONSORT statement. There is a need for more specific trials with improved treatment strategies to underpin the most appropriate choice of PT intervention and the outcomes measured. This review also reinforces the need for the universal employment of clinically relevant, reliable and sensitive outcome measures with a predefined outcome in each trial. Future trials should be designed such that the interventions are transferable and cost-effective in mainstream care.

Occupational therapy versus no or placebo intervention

This Cochrane review was published by collaborators of the trial team. 7

Methods

Relevant trials were identified by electronic searches of general biomedical and science electronic databases, English-language databases of foreign-language research and third-world publications, conference and grey literature databases and trial registries.

Only RCTs were included; however, those trials that allowed quasi-random methods of allocation were allowed. Data were abstracted independently by two authors and differences were settled by discussion.

Results

Two trials were identified, with 84 patients in total. Although both trials reported a positive effect from OT, all of the improvements were small. The trials did not have adequate placebo treatments, they used small numbers of patients and, in one trial, the method of randomisation and concealment of allocation was not specified. These methodological problems could potentially lead to bias from a number of sources.

Conclusions

Considering the significant methodological flaws in the studies, the small number of patients examined and the possibility of publication bias, there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the efficacy of OT in PD. There is now a consensus as to UK current and best practice in OT when treating people with PD. Large, well-designed, placebo-controlled RCTs are required to demonstrate the effectiveness of OT in PD. Outcome measures with particular relevance to patients, carers, occupational therapists and physicians should be chosen and the patients monitored for at least 6 months to determine the duration of benefit. The trials should be reported using CONSORT guidelines.

Parkinson’s disease occupational therapy pilot trial

The PD OT pilot trial was done to inform the design of the PD REHAB trial and was published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry10 © 2016 BMJ Publishing Group. All rights reserved.

Method

This pilot study was a RCT with masked assessment of standard community-based individual OT targeting functional independence and mobility versus usual NHS care with OT deferred until the end of the trial.

We aimed to recruit 50 patients with idiopathic PD, defined by the UPDRS,12 with Hoehn and Yahr stages 3–4. We excluded patients with dementia, since they would be unable to complete trial forms, and those who had received OT in the last 2 years or PT in the last year, to avoid carry-over effects.

Patients were recruited from four neurology and elderly care PD clinics in the West Midlands. After patients were identified and informed about the study, written consent was taken and baseline information was collected. Patients were randomised by the therapist between the two trial groups (1 : 1) using a computer-generated random number list via a telephone call to the University of Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit. Patients were informed of their treatment allocation. The trial manager and chief investigator were masked to treatment allocation.

The intervention was developed by combining existing evidence from our surveys of current and best-practice OT in PD5,6 and the consensus of a group of expert occupational therapists. 13 The intervention was provided by an experienced occupational therapist and was delivered at the level of the individual. Primary interventions were targeted towards limitations in ADL (self-care and instrumental); mobility (indoor and outdoor); and home safety. Six sessions of 45 minutes each were administered over 2 months. Content was dependent on the patient’s and therapist’s agreed goals. OT followed a routine process using a ‘client-centred approach’,14 with a continuous process of assessment, treatment and re-evaluation.

The content of the OT intervention addressed specific tasks (e.g. eating, mobilising) within the participant’s home. Techniques employed by the therapist included task-specific practice (e.g. dressing, transfers, mobility training), reducing the complexity or demands of tasks and/or altering the environment through provision of aids and adaptations. The therapist also provided advice and information to patients and carers and referral to other health-care workers when appropriate. When time allowed, secondary interventions addressed fatigue management, leisure therapy, continence, speech and communication interventions, and relaxation techniques.

Since the intervention was targeted towards improving functional ability, we assessed instrumental ADL with the Nottingham Extended Activity of Daily Living Scale (NEADL). This has been validated in stroke15 and has been shown in other community OT trials to be relevant and sensitive to change. 16 We also explored the use of the Rivermead Mobility Index (RMI); the patient-completion UPDRS ADL scale; PDQ-39; European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D); and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

For economic analysis, resource-use data were collected in a patient-completed questionnaire at the end of the trial to estimate the costs associated with treatment and management over the previous 6 months.

At baseline (before randomisation), patients completed assessments by interview. At 2 and 8 months after randomisation, assessments were posted to all patients for self-completion.

As this was a pilot study, definitive answers to the randomised comparison were not expected, so formal statistical hypothesis testing was not performed. Differences between the two arms in change from baseline at 2 and 8 months were calculated with 95% CI. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to correlate outcome measures. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The PD OT trial was approved by Sandwell and West Birmingham Local Research Ethics Committee, funded by the Parkinson’s Disease Society and sponsored by the University of Birmingham. Professor Sackley was funded by a National Primary Care Career Scientist award.

Results

Over 16 months (July 2005 to October 2006), 39 patients were recruited from four centres (25 male; mean age 73 years). Patient eligibility was assessed in one centre’s movement disorders clinics (City Hospital, Birmingham) over 9 months. Only 11 patients (6%) attending 196 PD patient visits (some patients attended more than once) were eligible for the trial. The reasons for exclusion were early PD without significant difficulties with ADL (61%), recent OT or PT (21%), dementia (7%), advanced PD (1%) and other (10%).

In the treatment group (11 male; mean age 73 years), 15 were living with someone, three were living alone and one was living in a care home. The mean number of treatment visits was 5.7 (range 3–9). The interval between visits varied from 3 to 63 days. The total time spent by the therapist with patients was 103.1 hours (mean 5.4 hours per patient).

The differences between the OT and no OT arms at 2 and 8 months for the main outcome measures are shown in Table 3. There were strong correlations between the mobility, ADL and emotional well-being domains of PDQ-39 and RMI, UPDRS ADL subscale and anxiety and depression subscores of the HADS.

| Outcome measure | Baseline to 2 months, mean difference in outcome measures (95% CI) | Baseline to 8 months, mean difference in outcome measures (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Nottingham Extended ADL | 0.04 (–4.74 to 4.82) | 3.50 (–3.24 to 10.24) |

| RMI | –0.46 (–1.89 to 0.97) | –0.70 (–2.87 to –1.47) |

| UPDRS ADL Score | –1.46 (–5.36 to 2.44) | 0.39 (–3.32 to 4.10) |

| PDQ-39 Summary Index | 1.69 (–5.17 to 8.55) | 3.82 (–4.94 to 12.57) |

| EQ-5D score | –0.01 (–0.17 to 0.16) | 0.08 (–0.04 to 0.21) |

| HADS Anxiety Score | 1.53 (–0.72 to 3.78) | 1.44 (–1.20 to 4.09) |

| HADS Depression Score | –0.50 (–2.31 to 1.30) | –1.42 (–3.66 to 0.82) |

The health economics questionnaire piloted in the trial adequately captured data on health service utilisation.

Conclusions

Recruitment

We aimed to recruit 50 PD patients over 12 months, but succeeded in recruiting only 39 patients over 16 months. This stemmed from patients with early disease not having significant problems with ADL, patients recently undergoing OT or PT and, rarely, dementia.

Future trials of OT and PT in PD may require better co-ordination with service user groups, longer recruitment periods of incident cases and a large number of centres. Consideration should be given to combining PT and OT in a future trial to better reflect standard NHS practice and to allow inclusion of PD patients with a wider spectrum of disease, particularly earlier-stage patients who may not currently be automatically referred.

Intervention

The intervention was successfully delivered to all 19 patients randomised to OT. The 5 hours’ dose of therapy was similar to that described in other trials. 17–20 Loss to follow-up was small, with data missing for one patient at 2 months and for two patients at 8 months. This is similar to another community study of PT (8% loss at 6 months),21 but higher retention than an outpatient rehabilitation study (30% loss at 6 months). 22 Delivery of OT to the control arm after the trial may have helped with retention.

Outcome measures

The NEADL and PDQ-39 measures were well completed by patients. The NEADL score showed strong correlation with the UPDRS ADL subscale and has the benefit of being used in a variety of conditions including stroke and ageing. There were strong correlations between the mobility, ADL and emotional well-being domains of PDQ-39 and RMI, UPDRS ADL subscale and HADS anxiety and depression subscale scores. Therefore, PDQ-39 could be used as a single scale replacing a collection of scales that are often used in PD trials.

Sample size calculation

Minimally clinically relevant changes in NEADL and PDQ-39 are probably 1–2 points19 and 1.6 points,23 respectively. Such minimal changes may be of only small benefit to patients, so we view a clinically meaningful change as around double this, that is 2.5 points for NEADL and 3.5 points for PDQ-39. To detect such differences, at two-tailed p = 0.05 with 90% power, at the end of treatment will require 340 patients in each arm for NEADL [standard deviation (SD) from PD OT 10.1] and 310 patients in each arm for PDQ-39 Summary Index (SD from PD OT 13.5). To allow for around 10% dropout rate, we suggest randomising 750 patients.

Parkinson’s disease occupational therapy trial intervention

We described the intervention delivered in the PD OT pilot trial in a paper published in the British Journal of Occupational Therapy24 © Sage Publishing. All rights reserved.

Method

The development of the PD OT intervention followed a three-step approach:

-

Published trial evidence was gathered (until recruitment commenced in July 2005) to ensure that the PD OT intervention was evidence-based where possible; the evidence considered included OT-specific PD studies, multidisciplinary PD interventions which incorporated OT, studies from the wider PD rehabilitation literature and clinical guidelines.

-

Current UK practice was examined through two published surveys. 25,26

-

The expert steering group met to evaluate and synthesise the findings of the first two steps with expert opinion consensus, formalising the PD OT intervention.

The aim was to provide treatment that was informed by best practice but could be delivered within the structure and format of the NHS: an enhanced current practice intervention.

Results

All 19 participants completed both their initial assessments and the treatment sessions required to address the goals identified. Treatment was delivered by one occupational therapist. The mean number of visits was 5.7 (range 3–9). A total of 108 therapist visits were carried out. The interval between visits varied from 3 days to 63 days. The initial assessment took a median of 60 minutes (range 45–90 minutes). Subsequent visits lasted a median of 50 minutes (range 5–180 minutes). On average, the occupational therapist spent a mean of 5.4 hours in total with each patient. The mean duration of the complete intervention (from first to last visit inclusive) was 60.3 days.

The content of the intervention for each patient was categorised and recorded as time (minutes) spent under the appropriate headings by the treating therapist. Two hundred and seventy-four interventions were delivered in total. The most common types of intervention were adaptive equipment (n = 56), transfers/mobility training (n = 46), environmental adaptations (n = 38), daily living activities training (n = 35), techniques/education (n = 25) and goal setting (n = 15).

Following completion of the trial, the treating therapist provided feedback on the intervention log. The log was reported as easy to use and was seen to contain categories that were relevant to the treatment being delivered. Difficulties in using the tool were also noted; overlap between categories and issues in identifying the primary aim of an intervention both led to problems with accurate categorisation.

Health economics literature review

We reviewed the literature for economic evaluations involving PT and PD to identify the existing economic evidence. Three studies were identified through the search. 27–29 Previous economic evaluations involving PT or exercise-based interventions in PD have typically focused on multicomponent interventions. Of the included studies, only one provided information in terms of cost-effectiveness on an exercise intervention versus a do-nothing comparator. 27 The results of this study were promising in terms of cost-effective acceptability, but the primary outcome showed no statistically significant improvement and the economic study was uncertain. As with the other two studies,28,29 the time horizons of the evaluations were short, such that it is unclear whether or not any improvement in patient physical functioning was sustained over the long term (i.e. beyond 6 months).

Chapter 2 Methods

The PD REHAB trial protocol is available at www.birmingham.ac.uk/pdrehab-docs (accessed 28 July 2016). Reproduced with permission from JAMA Neurology 2016; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4452. Copyright © American Medical Association. All rights reserved. 30

Patients

Patients with idiopathic PD as defined by the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Criteria12 were eligible for PD REHAB if they reported limitations in ADL and the investigator was uncertain that they would require PT and/or OT during the 15 months of the trial, that is if equipoise about the need for therapy existed. Exclusion criteria included dementia, as locally defined, and receipt of PT or OT for PD in the past 12 months. All patients gave written informed consent before randomisation. Ethics approval was granted by the West Midlands Research Ethics Committee (08/H1211/168) and local research and development approval was obtained at each participating centre.

Randomisation and therapy allocation

Patients were randomised (1 : 1) to combined PT and OT (therapy group) or no therapy (control group) using an online randomisation service at the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU), University of Birmingham, Randomisation used a computer-based algorithm with minimisation by baseline NEADL total score (severe 0–21; moderate 22–43; and mild 44–66), Hoehn and Yahr stage (≤ 2; 2.5; 3; and ≥ 4) and age (< 60 years; 60–69 years; 70–79 years; and ≥ 80 years) to ensure balance of patients with differing disability levels between the two groups.

Procedures

Inclusion criteria were broad to allow inclusion of a wide spectrum of PD patients to provide a generalisable result. PT and OT were delivered in the community and/or outpatients by qualified therapists. A framework for therapy content was developed and agreed by expert therapist groups based on previous work on standards of UK NHS PT and OT and European guidelines. 3–6 A standard rehabilitation approach was used. Following initial assessments by both a physiotherapist and an occupational therapist, therapy was tailored to the individual patient’s requirements using a joint goal-setting approach. Interactions between therapists and patients were described and quantified using pre-defined recording forms, and included non-contact time. Control patients consented to have therapies deferred until the end of their 15 months’ trial participation, unless pressing reasons for therapy developed. As therapies may have been arranged outside the trial, control patients were asked whether or not they had received any therapy at the 15-month assessment.

The primary outcome measure was the total score on the NEADL scale at 3 months after randomisation. 15 The NEADL measures instrumental ADL which is specifically addressed by PT and OT, and addresses more complex ADL issues such as making a meal, cleaning and travelling on public transport. The NEADL scale was developed for stroke trials but is now used widely as a generic outcome measure for rehabilitation trials of older people and has been used in PD trials before. It has been shown to be sensitive to change in trials of OT16 and was successfully used in our pilot study of OT for PD. 10 Secondary outcome measures included patient-rated QoL using the PDQ-39,31 which is the most widely used disease-specific QoL rating scale for PD; the EQ-5D (3-level version), a generic QoL scale; adverse events; and carer well-being using Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12; version 2). Following a risk assessment, targeted adverse event reporting was deemed to be appropriate, so only therapy-related adverse events and serious adverse events were recorded, such as falls or equipment failure leading to injury requiring a hospital, general practitioner (GP) or ambulance visit. Outcomes were collected in person at baseline before randomisation, and then by post at 3, 9 and 15 months after randomisation. Antiparkinsonian medication dosage was converted into levodopa dose equivalents using a standard formula. 32

Statistical analysis

In stroke patients, the MCIC in NEADL is 1–2 points. 19 However, such a small change may be of only little benefit to PD patients; a clinically meaningful change in NEADL for PD patients is likely to be around double this, at 2.5 points. A 2-point change on the NEADL represents becoming independent in one item (e.g. stair climbing, crossing roads or feeding oneself) or improvement in two items (e.g. from being dependent on another person with help to being fully independent). To detect a 2.5-point difference in NEADL at 3 months (using the observed SD from the PD OT pilot trial10 of 10.1 points; p < 0.05 two-tailed; 90% power) required 340 patients in each group, increased to 750 participants (375 per group) to allow for around 10% non-compliance and dropout.

The primary analysis was change in NEADL total score in the therapy group at the 3-month assessment (immediately after the therapy period) compared with that in the no therapy group. An independent two-sample t-test compared changes between baseline and 3 months in the NEADL score between the two groups. Results are presented as mean difference between groups with 95% CI. This analysis was repeated for individual NEADL domains and for the QoL secondary outcome measures using the PDQ-39, EQ-5D and carer-completed SF-12.

The different questionnaires included in PD REHAB are interpreted differently. For example, for the NEADL scale higher scores are better, so a positive change over time is an improvement in score. However, for the PDQ-39 lower scores are better, so a negative change over time is an improvement in score. To aid interpretation of the mean differences and CI, regardless of scale, a positive mean difference favours the no therapy group and a negative mean difference favours the therapy group.

The long-term effect or whether or not any benefit of treatment persisted beyond the initial intervention period was compared at 9 and 15 months after randomisation, using both t-tests at each time point and a mixed-model repeated-measures analysis across all time points for all outcomes.

Analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis, whereby patients were analysed according to the group to which they were randomised, regardless of whether or not they complied with their allocation. Missing data in PDQ-39 domain scores were imputed using an expectation maximisation algorithm. 33,34 There is no established imputation method for the NEADL scale; therefore, the primary analyses used available data only, with no imputation for missing values. However, sensitivity analyses using a best (score 3), worst (score 0), middle (score 1.5) and average (at participant level) case score for missing items on the NEADL were explored.

Three a priori subgroup analyses were planned to compare the effect of combined PT and OT at different levels of ADL disability (analysis stratified by the patient’s baseline NEADL total score: severe, 0–21; moderate, 22–43; and mild, 44–66), disease stage (Hoehn and Yahr stage ≤ 2, 2.5, 3 and ≥ 4) and age (< 60 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years and ≥ 80 years). Subgroup analyses employed a test of interaction to explore whether or not there was evidence that any effect of therapy differed across these subgroups at 3-month follow-up. However, as with all subgroup analyses, these results were interpreted cautiously.

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2. Interim analyses of unblinded efficacy and safety data were reviewed annually by an independent data monitoring committee.

Economic evaluation

The study compared the costs and cost-effectiveness of combined PT and OT with no therapy in the treatment of patients with PD from the NHS and Personal Social Services perspective over 15 months.

Data collection

The PD REHAB trial prospectively collected resource-use data as an integral part of the clinical trial using a collection instrument adapted from the PD MED35 and PD SURG trials. 36 The resources monitored include use of therapy services, primary care consultations including GP and practice nurse appointments, hospital inpatient stays, outpatient visits and accident and emergency attendances. For patients admitted to hospital, the length of stay and reason for admission were noted. All resource use relevant to PD was collected. The use of OT and PT services were recorded in detail by the therapists using the data acquisition forms; use of other primary and secondary care services was collected after randomisation using a postal resource-utilisation questionnaire for patient completion. All resource-use data were collected at 3, 9 and 15 months. PD-related medication was recorded by the clinician at baseline and at 15 months. Health-related QoL was measured by the EQ-5D at baseline and at 3, 9 and 15 months.

Estimating the costs

Primary care visits

Primary care costs including GP and nurse visits were obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit 2012 (PSSRU; Table 4). 37

| Resource item | Unit cost (£) | Basis of estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Therapy services | ||

| Physiotherapist/occupational therapist/speech and language therapist time (minutes) | 0.55 | Derived from the cost per hour of face-to-face contact time from PSSRU (2012)37 including qualifications |

| Primary care | ||

| GP clinic appointment | 43.00 | Per patient contact lasting 11.7 minutes from PSSRU (2012)37 including qualifications and direct care staff costs |

| GP home visits | 110.00 | Per out of surgery visit lasting 23.4 minutes from PSSRU (2012)37 (including travel time/cost) |

| Practice nurse clinic appointmenta | 13.69 | Per face-to-face patient contact lasting 15.5 minutes, at £53 per hour from PSSRU (2012)37 including qualifications |

| Practice nurse home visits | 20.67 | Per home visit lasting 27 minutes (duration based on most recently available estimate of a nurse home visit duration, i.e. PSSRU 2010), unit cost derived using cost per minute of £0.88 from PSSRU (2012)37 including qualifications |

| Social care | ||

| Health visitor | 21.00 | Per visit lasting 20 minutes (PSSRU 2012) |

| Social worker | 214.00 | Per hour face-to-face consultation, including qualifications (PSSRU 2012) |

Therapy services

Staff time for PT and OT involved in the delivery of the intervention was recorded via treatment record forms completed by the therapist after each treatment session. Although the control patients consented to have the therapies deferred until the end of their 15 months’ participation in the trial, some control patients still did receive therapy during the trial. The number of appointments with therapists for the control patients was reported by patient-completed questionnaire. For control patients whose contact time with therapists was not available, the average contact time was used. Costs per minute of both PT and OT were derived from PSSRU (see Table 4). We multiplied the therapist time by unit cost per minute to estimate cost per consultation.

Aids and adaptations

Aids and adaptations acquired during the trial were recorded through treatment logs or patient-completed questionnaires. The unit costs of these were extracted from the PSSRU (2012). 37 The value of the aid or adaptation was annuitised over a period of 10 years (reflecting an assumed typical lifetime of that aid or adaptation) and discounted at the recommended rate of 3.5%. 37 When such information was not available in PSSRU, we looked for an equivalent or similar cost item in the PSSRU to impute an appropriate median annuitised cost (Table 5).

| Aid or adaptation | Median annual equipment cost (£) |

|---|---|

| Wheelchair (self- or attendant-propelled) | 86.00 |

| Wheelchair (active user) | 172.00 |

| Wheelchair (powered) | 400.00 |

| Grab rail | 6.00 |

| Hoist | 319.00 |

| Walking stick | 4.44 |

| Low-level bath | 81.00 |

| New bath/shower room | 1820.00 |

| Relocation of bath/shower room | 247.00 |

| Relocation of toilet | 211.00 |

| Shower over bath | 107.00 |

| Shower replacing bath | 107.00 |

| Stair lift | 402.00 |

| Single concrete ramp | 47.00 |

Hospital costs

For costs relating to secondary (i.e. inpatient) care, a health-care resource group (HRG) applicable to patients with PD, HRG code AA25Z, descriptor ‘Cerebral degenerations of the nervous system or miscellaneous’, was identified from discussion with the trial investigators as relevant (Table 6). As the National Reference Costs (2011/12) did not record activity data under this HRG,38 the cost of an inpatient hospital spell was extracted from the National Tariff. 39

| Resource item | Unit cost (£) | Basis of estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital inpatient stay, HRG code AA25Z | 3159.00 | 2011–2012 NHS National Tariff39 non-elective spell tariff ‘Cerebral degenerations of the nervous system or miscellaneous’, HRG code AA25Z (for stays up to the trim point of 31 days, long stay per day payment of £209 applied) |

| Outpatient attendance | 106.00 | 2011–2012 NHS National Reference Costs publication38 (average unit cost, all outpatient attendances) |

| Accident and emergency attendance | 143.00 | 2011–2012 NHS National Reference Costs publication,38 Category 2 Investigation with Category 2 Treatment |

| Day care admission (per day) | 641.00 | Based on National Tariff 2011–2012,39 ‘Cerebral degenerations of the nervous system or miscellaneous’, HRG code AA25Z |

| Parkinson’s disease nurse (in clinic) | 23.67 | Based on an advanced nurse specialist and a 20-minute consultation37 |

Medication

Use of medication was recorded by clinicians via entry forms when patients were recruited into the trial and at the time of trial exit. The main medications included levodopa, dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors, catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors, amantadine, apomorphine and intrajejunal levodopa–carbidopa gel infusion. However, we did not include medication costs in our cost analysis for several reasons: PD is a long-term condition and there is a low likelihood that patients with early disease would change their medication in the 15 months of the trial. Although drug use data were collected at baseline and at 15 months, no interim data on medication were collected at other assessment points.

Analysis

The analysis followed that specified in the health-economic analysis plan in the protocol. The economic analysis was based on patient-specific resource use and costs, and patient-specific outcome and QoL data. The base-case analysis was framed in terms of costs and consequences, reporting the incremental costs and consequences in a disaggregated manner. As stated in the protocol, if this convincingly identified a situation of dominance (i.e. one arm is associated with both better outcomes and a lower cost), then further analysis would not be required. If no dominance was found, then cost–utility analysis [i.e. cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)] would be employed.

Accumulated total costs per patient were calculated by the sum of the products of resources used and the associated unit costs, aggregated over the study period. The mean costs associated with the therapy and control group were evaluated and the differences in costs were compared according to the intention-to-treat allocation. No discounting rate was applied, as the follow-up period was 15 months.

Quality-of-life data were measured using EQ-5D questionnaires, which were collected at baseline and at 3, 9 and 15 months. The UK Tariff was used to produce utility scores. QALYs for each patient were calculated based on the utility scores at different points using area-under-the-curve. We assumed linear interpolation between two points of measurements.

Missing data because of non-completion in the resource use and EQ-5D questionnaires were imputed by substituting the mean adjusted by treatment groups. We did not employ multiple imputation, as there were few missing values. The costs and QALYs for the cases of death and withdrawals were assumed to cease at the time points when such event occurs.

The bias-corrected bootstrap method was used to estimate mean costs, QALYs and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) with the associated 95% CI. Uncertainty around the costs and effectiveness estimates was illustrated using scatterplots with confidence ellipses and addressed by plotting cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

All analyses were based on the principle of intention to treat. The analyses were conducted in SAS 9.2.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and carer involvement was incorporated at all levels of the PD REHAB trial. A representative from the charity Parkinson’s UK (Miss Ramilla Patel, Regional Manager, Parkinson’s UK) was a co-applicant on the grant, being involved in the design of the study and a member of the Trial Management Group. With the initial leadership of Dr Sandy Herron-Marx and then Ms Sunil Shah and Dr Caroline Rick, we and Parkinson’s UK developed a Patient Advisory Group of PD patients and carers. This was a virtual e-network following an initial face-to-face meeting. Members were supported by Mrs Ramilla Patel and the person leading the group at the time.

The Patient Advisory Group contributed to the development of the participant information sheets, consent forms and resource use questionnaire. It was planned for the group to be involved with the interpretation of the findings through the development of recommendations for practice and patient information leaflets (top-tip leaflet) about therapy choices, although the results have not required such input. The group will also be involved with the dissemination of the findings through existing patient networks, mainly through the auspices of Parkinson’s UK and its newsletter service.

Chapter 3 Results

Reproduced with permission from JAMA Neurology 2016; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4452. Copyright © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. 30

Patients

Between October 2009 and June 2012, 762 people with PD from 38 neurological or geriatric medicine outpatients centres across the UK were randomised to either combined PT and OT or no therapy (381 per group; Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups (Table 7). The mean age was 70 years, 65% were male and the median duration of disease was 3.1 years (mean 4.6 years). The majority of patients had mild to moderate disease, with 67% in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2 or less, and the median NEADL total score was 54 (mean 51).

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram for PD REHAB: patient recruitment and follow-up. a, Eight patients randomised to the PT and OT group were later found to be ineligible, as they had received PT and/or OT for PD in the 12 months prior to randomisation (exclusion criteria). One patient did not receive any PT or OT post randomisation (crossover: only baseline data available – diagnosed with cancer and died at 5 months post randomisation). One patient did not receive PT or OT within 3 months, but was referred for PT outside the trial at 6 months (3-, 9- and 15-month data available). The other six patients all received PT and/or OT post randomisation (baseline and 3-month data available, except for one patient for whom only baseline data are available). b, Three patients randomised to the no therapy group were subsequently found to be ineligible as they had received PT and/or OT for PD in the 12 months prior to randomisation (exclusion criteria). One patient received PT and/or OT within 3 months of randomisation (crossover). For all three patients, baseline and 3-month data were available. c, Thirteen patients randomised to the PT and OT group are known to have not received any PT or OT. Baseline and 3-month data are available for two of these patients (for the other 11 patients, only baseline data are available). Twelve patients did not receive PT or OT by 3 months post randomisation, but did start therapy after 3 months; baseline and 3-month data are available for all patients (except two: one has baseline data only and one has 3-month data only). d, Nine patients randomised to no therapy had some PT and/or OT before their 3-month NEADL form was completed; all patients had baseline and 3-month data available. e, Partially withdrawn patients did not wish to complete patient forms but agreed to clinical follow-up.

| Characteristic/demographic | PT/OT | No therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients randomised | 381 | 381 |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 70 (9.1) | 70 (9.3) |

| Range | 35–90 | 35–91 |

| Age category (years) | ||

| < 60 | 47 (12%) | 46 (12%) |

| 60–69 | 129 (34%) | 129 (34%) |

| 70–79 | 148 (39%) | 151 (40%) |

| ≥ 80 | 57 (15%) | 55 (14%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male, n (%) | 240 (63%) | 258 (68%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| n | 327 | 333 |

| Mean (SD) | 27.2 (5.4) | 26.9 (4.4) |

| Range | 16.5–54.9 | 16.8–44.0 |

| Stage of Parkinson’s disease | ||

| Duration of PD (years) | ||

| n | 381 | 379 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.5 (4.9) | 4.6 (4.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–6.1) | 3.3 (1.3–6.4) |

| Range | 0.01–29.9 | 0–25.6 |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | ||

| ≤ 2.0 | 254 (67%) | 254 (67%) |

| 2.5 | 46 (12%) | 46 (12%) |

| 3.0 | 61 (16%) | 61 (16%) |

| ≥ 4.0 | 20 (5%) | 20 (5%) |

| Levodopa equivalent dose (mg/day) | ||

| n | 381 | 381 |

| Mean (SD) | 453 (357.9) | 498 (372.8) |

| Range | 0–1877 | 0–2181 |

| NEADL scale total score | ||

| n | 381 | 381 |

| Mean (SD) | 51 (12.9) | 51 (13.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 53 (43–61) | 54 (42–62) |

| Range | 6–66 | 8–66 |

| NEADL total score category | ||

| 0–21 (severe) | 14 (4%) | 14 (4%) |

| 22–43 (moderate) | 88 (23%) | 88 (23%) |

| 44–66 (mild) | 279 (73%) | 279 (73%) |

| PDQ-39 summary index | ||

| n | 380 | 377 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.8 (14.5) | 23.7 (14.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 22.4 (12.6–32.3) | 21.1 (12.2–33.0) |

| Range | 2.4–78.4 | 1.9–67.4 |

Loss to follow-up

In total, 350 (92%) of 381 patients randomised to the therapy arm completed the NEADL at 3 months, compared with 349 (92%) of 381 patients randomised to the no therapy arm (see Figure 1). Of 381 patients randomised in the therapy arm, 311 (82%) completed the NEADL at 15 months, compared with 322 of 381 patients randomised in the control arm (85%). Overall, by 15 months, 48 (6%) patients had exited the trial (eight patients had withdrawn, 17 had partially withdrawn and 23 had died).

Compliance

In total, 25 patients (6%) allocated to PT and OT did not receive therapy by 3 months after randomisation (12 started PT and/or OT after 3 months and 13 never received any therapy; Figure 1). Nine patients (2%) allocated to no therapy received therapy for PD-related problems within 3 months, mainly because of worsening PD symptoms including falls and imbalance.

Therapy content

In those who received therapy in the PT and OT group, the median total number of therapy sessions was four (range 1–21) (Table 8), with a mean time per session of 58 minutes. The mean duration of therapy was 8 weeks. The mean total dose of both therapies was 263 minutes (range 38–1198 minutes; Table 8). Most PT was performed in an outpatient setting (53%) rather than in the community (39%) or other setting (8%), whereas OT was more commonly performed in the community (69%) than outpatients (29%) or other (2%).

| Item | PT/OT (n = 381) | Control (n = 381) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients who received PT and/or OT during 15-month trial | ||

| n (%) | 365 (96%) | 53 (14%) |

| Patients with treatment logs available | ||

| n | 355a | 12b |

| Sessions | ||

| n | 355 | 12 |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 2 (1–6) |

| Range | 1–21 | 1–11 |

| Total time (minutes) | ||

| n | 355 | 12 |

| Mean (SD) | 263 (178.6) | 246 (332.6) |

| Range | 38–1198 | 60–1070 |

| Time per session (minutes) | ||

| n | 355 | 12 |

| Mean (SD) | 58 (27.2) | 58 (19.2) |

| Range | 19–399 | 30–97 |

| Treatment duration (weeks) | ||

| n | 355 | 10 |

| Mean (SD) | 8 (9.0) | 7 (11.1) |

| Range | 0.1–62 | 0.1–35 |

| Intervention location (OT) | ||

| n | 274 | 4 |

| Community | 188 (69%) | 3 (75%) |

| Outpatient | 80 (29%) | 1 (25%) |

| Other | 6 (2%) | 0 (–) |

| Intervention location (PT) | ||

| n | 318 | 9 |

| Community | 124 (39%) | 3 (33%) |

| Outpatient | 170 (53%) | 4 (44%) |

| Othera | 24 (8%) | 2 (23%) |

The PT logs (Table 9) showed that the most frequent interventions were for gait (96% of patients), posture (93%), balance (90%), physical conditioning (81%) and transfers (78%). The OT logs (Table 10) showed that the most frequent interventions were for transfers (45%), dressing and grooming (36%), sleep and fatigue (31%), indoor mobility (28%), household tasks (28%) and other environmental issues (27%).

| Activity | Numbera | %b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Assessment | Treatment | Assessment | |

| Gait and indoor mobility | 330 | 122 | 96 | 36 |

| Posture | 318 | 100 | 93 | 29 |

| Balance and falls | 309 | 99 | 90 | 29 |

| Physical conditioning | 277 | 61 | 81 | 18 |

| Transfers | 268 | 41 | 78 | 12 |

| Upper limb function | 259 | 54 | 76 | 16 |

| Outdoor mobility | 183 | 35 | 54 | 10 |

| Leisure-related activities | 184 | 21 | 54 | 6 |

| Domestic ADL | 135 | 13 | 39 | 4 |

| Self-care | 131 | 5 | 38 | 1 |

| Other (e.g. handwriting practice) | 123 | 20 | 36 | 6 |

| Work-related activities | 60 | 3 | 18 | 1 |

| Activity | Numbera | %b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Assessment | Treatment | Assessment | |

| Transfers | 145 | 294 | 45 | 91 |

| Dressing and grooming | 118 | 274 | 36 | 85 |

| Sleeping and fatigue | 101 | 245 | 31 | 76 |

| Indoor mobility | 91 | 290 | 28 | 90 |

| Household tasks | 90 | 258 | 28 | 80 |

| Environmental issues | 88 | 262 | 27 | 81 |

| Eating and drinking | 86 | 251 | 27 | 77 |

| Communication | 82 | 227 | 25 | 70 |

| Emotional support | 77 | 212 | 24 | 65 |

| Cognition | 73 | 246 | 23 | 76 |

| Social activities | 65 | 248 | 20 | 77 |

| Falls | 57 | 224 | 18 | 69 |

| Employment | 15 | 144 | 5 | 44 |

A further validation of PT and OT treatment logs was done by comparing them with the full-text patient notes for 38 patients chosen at random from 10 geographically diverse centres. Therapist interventions were listed and thematically grouped into five categories: assessment, equipment and adaptation prescription, exercise recommendations, referral to other specialists and ‘other advice’. Physiotherapists prescribed a range of exercise programmes tailored to their assessment of the patient’s physical strength and range of movement. Only three physiotherapists provided a specific PD exercise programme accompanied by a booklet, and there was no evidence of a formal progression protocol. PT included the prescription of walking aids. OT assessed the full range of ADL activities including socialising and work. However, the predominant interventions were equipment provision (such as bed levers or adaptive cutlery), onward referral (such as speech and language therapy and cognitive assessment), with ‘other advice’ including recommendations on how to manage sleep problems and how to apply for state benefits. There was little task-related practice.

Primary outcome

The mean NEADL total score deteriorated from baseline to 3 months by 1.5 points in the therapy group compared with 1.0 point in the no therapy group (difference 0.5 points, 95% CI –0.7 to 1.7 points; p = 0.4) (Table 11). No difference was seen in any of the individual categories of the NEADL scale (see Table 11). Repeated measures analysis of the NEADL across all time points showed no difference between the treatment arms (Table 12 and Figure 2a).

| Subscale | Baseline | 3 months | Mean change from baseline | Mean difference (95% CI)a | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT/OT | No therapy | PT/OT | No therapy | PT/OT | No therapy | |||

| NEADL | ||||||||

| Total score | 381 | 381 | 294 | 304 | 294 | 304 | – | – |

| 50.5 (12.9) | 50.9 (13.3) | 49.6 (14.0) | 50.3 (14.5) | –1.5 (7.8) | –1.0 (7.4) | 0.5 (–0.7 to 1.7) | 0.4 | |

| Mobility | 376 | 372 | 338 | 338 | 334 | 330 | 0.1 (–0.3 to 0.5) | 0.6 |

| 13.9 (4.0) | 13.8 (4.2) | 13.6 (4.2) | 13.6 (4.4) | –0.4 (2.6) | –0.2 (2.4) | |||

| Kitchen activities | 379 | 373 | 337 | 337 | 335 | 329 | 0.005 (–0.3 to 0.3) | 1.0 |

| 13.0 (2.7) | 13.0 (2.9) | 13.0 (3.0) | 12.9 (3.2) | –0.2 (2.2) | –0.2 (1.9) | |||

| Domestic tasks | 374 | 370 | 330 | 332 | 325 | 323 | 0.5 (–0.06 to 1.0) | 0.08 |

| 10.9 (4.2) | 11.1 (4.3) | 10.4 (4.5) | 10.8 (4.4) | –0.8 (3.4) | –0.3 (3.2) | |||

| Leisure activities | 376 | 365 | 318 | 329 | 316 | 318 | 0.01 (–0.4 to 0.4) | 0.9 |

| 12.9 (4.1) | 13.0 (4.0) | 13.0 (4.1) | 13.1 (4.0) | –0.2 (2.4) | –0.1 (2.4) | |||

| PDQ-39 | ||||||||

| n | 380 | 377 | 349 | 351 | 348 | 347 | – | – |

| Mobility | 32.7 (26.1) | 31.3 (25.8) | 33.2 (27.3) | 33.3 (28.0) | 1.1 (17.1) | 2.6 (15.8) | –1.5 (–3.9 to 1.0) | 0.2 |

| ADL | 31.3 (23.1) | 30.6 (21.8) | 32.1 (23.8) | 31.5 (23.8) | 1.6 (14.3) | 1.0 (16.7) | 0.7 (–1.7 to 3.0) | 0.6 |

| Emotional well-being | 23.9 (18.5) | 23.0 (18.1) | 25.9 (19.8) | 25.5 (20.3) | 2.6 (13.1) | 3.0 (16.8) | –0.5 (–2.7 to 1.8) | 0.7 |

| Stigma | 18.3 (22.9) | 17.1 (21.0) | 19.8 (23.1) | 17.6 (21.3) | 1.6 (17.7) | 0.9 (17.5) | 0.7 (–2.0 to 3.3) | 0.6 |

| Social support | 6.6 (14.0) | 5.7 (11.0) | 10.3 (17.4) | 9.3 (15.1) | 3.6 (15.6) | 3.8 (14.9) | –0.2 (–2.5 to 2.0) | 0.8 |

| Cognition | 26.6 (20.1) | 27.3 (21.1) | 28.8 (20.6) | 29.6 (21.6) | 2.2 (16.5) | 2.2 (17.0) | –0.05 (–2.6 to 2.4) | 1.0 |

| Communication | 16.5 (18.2) | 18.5 (19.8) | 20.8 (20.1) | 21.8 (21.1) | 4.8 (15.7) | 3.0 (17.4) | 1.8 (–0.7 to 4.2) | 0.2 |

| Bodily discomfort | 34.8 (23.4) | 35.9 (24.0) | 36.5 (24.4) | 38.6 (24.1) | 2.0 (20.7) | 2.8 (21.1) | –0.8 (–3.9 to 2.3) | 0.6 |

| Summary index | 23.8 (14.5) | 23.7 (14.4) | 25.9 (16.5) | 25.9 (16.5) | 2.4 (9.5) | 2.4 (10.8) | 0.007 (–1.5 to 1.5) | 1.0 |

| EQ-5D quotient | ||||||||

| n | 378 | 374 | 345 | 345 | 342 | 338 | – | – |

| Score | 0.64 (0.27) | 0.66 (0.25) | 0.65 (0.25) | 0.63 (0.26) | 0.002 (0.23) | –0.03 (0.21) | –0.03 (–0.07 to –0.002) | 0.04 |

| EQ-5D visual analogue scale | ||||||||

| n | 376 | 376 | 346 | 347 | 341 | 342 | – | – |

| Score | 68.5 (17.5) | 68.6 (17.0) | 67.4 (18.2) | 66.8 (17.8) | –1.8 (17.1) | –1.9 (14.3) | –0.2 (–2.6 to 2.2) | 0.9 |

| Subscale | Baseline vs. 3 months | Mean difference (95% CI)a | Baseline vs. 9 months | Mean difference (95% CI)a | Baseline vs. 15 months | Mean difference (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT/OT | No therapy | PT/OT | No therapy | PT/OT | No therapy | ||||

| NEADL | |||||||||

| Total score | 294 | 304 | – | 289 | 303 | – | 268 | 283 | – |

| –1.5 (7.8) | –1.0 (7.4) | 0.5 (–0.7 to 1.7), p = 0.4 | –3.6 (8.1) | –3.0 (8.4) | 0.6 (–0.7 to 1.9), p = 0.4 | –3.8 (8.6) | –5.0 (9.8) | –1.2 (–2.8 to 0.3), p = 0.1 | |

| Mobility | 334 | 330 | – | 314 | 315 | – | 294 | 301 | – |

| –0.4 (2.6) | –0.2 (2.4) | 0.1 (–0.3 to 0.5), p = 0.6 | –1.0 (2.6) | –0.7 (2.7) | 0.3 (–0.1 to 0.7), p = 0.1 | –1.1 (2.7) | –1.3 (3.1) | –0.2 (–0.6 to 0.3), p = 0.4 | |

| Kitchen activities | 335 | 329 | – | 321 | 319 | – | 306 | 312 | – |

| –0.2 (2.2) | –0.2 (1.9) | 0.005 (–0.3 to 0.3), p = 1.0 | –0.5 (2.5) | –0.6 (2.2) | –0.04 (–0.4 to 0.3), p = 0.8 | –0.6 (2.5) | –0.9 (2.5) | –0.3 (–0.7 to 0.05), p = 0.4 | |

| Domestic tasks | 325 | 323 | – | 307 | 314 | – | 292 | 302 | – |

| –0.8 (3.4) | –0.3 (3.2) | 0.5 (–0.06 to 1.0), p = 0.08 | –1.0 (3.3) | –0.8 (3.5) | 0.1 (–0.4 to 0.6), p = 0.7 | –1.1 (3.6) | –1.4 (3.7) | –0.3 (–0.9 to 0.2), p = 0.2 | |

| Leisure activities | 316 | 318 | – | 302 | 307 | – | 292 | 291 | – |

| –0.2 (2.4) | –0.1 (2.4) | 0.01 (–0.4 to 0.4), p = 0.9 | –0.9 (2.4) | –0.8 (2.5) | 0.04 (–0.3 to 0.4), p = 0.8 | –1.1 (2.7) | –1.3 (2.9) | –0.3 (–0.7 to 0.2), p = 0.2 | |

| PDQ-39 | |||||||||

| n | 348 | 347 | – | 325 | 327 | – | 310 | 319 | – |

| Mobility | 1.1 (17.1) | 2.6 (15.8) | –1.5 (–3.9 to 1.0), p = 0.2 | 4.5 (17.5) | 5.9 (16.7) | –1.3 (–4.0 to 1.3), p = 0.3 | 6.4 (19.4) | 9.3 (20.5) | –2.9 (–6.0 to 0.2), p = 0.07 |

| ADL | 1.6 (14.3) | 1.0 (16.7) | 0.7 (–1.7 to 3.0), p = 0.6 | 3.1 (15.5) | 4.1 (16.7) | –1.0 (–3.5 to 1.5), p = 0.4 | 4.1 (17.1) | 7.0 (18.9) | –2.8 (–5.7 to –0.02), p = 0.05 |

| Emotional well-being | 2.6 (13.1) | 3.0 (16.8) | –0.5 (–2.7 to 1.8), p = 0.7 | 3.5 (15.0) | 6.0 (15.3) | –2.5 (–4.9 to –0.2), p = 0.03 | 4.6 (16.1) | 7.7 (17.5) | –3.1 (–5.7 to –0.5), p = 0.02 |

| Stigma | 1.6 (17.7) | 0.9 (17.5) | 0.7 (–2.0 to 3.3), p = 0.6 | 2.5 (16.1) | 3.3 (17.8) | –0.8 (–3.4 to 1.8), p = 0.5 | 2.8 (18.0) | 4.5 (18.0) | –1.6 (–4.5 to 1.2), p = 0.3 |

| Social support | 3.6 (15.6) | 3.8 (14.9) | –0.2 (–2.5 to 2.0), p = 0.8 | 3.9 (14.7) | 5.6 (15.3) | –1.8 (–4.1 to 0.5), p = 0.1 | 4.3 (14.7) | 6.3 (15.8) | –2.0 (–4.4 to 0.4), p = 0.09 |

| Cognition | 2.2 (16.5) | 2.2 (17.0) | –0.05 (–2.6 to 2.4), p = 1.0 | 3.0 (16.7) | 4.4 (17.7) | –1.4 (–4.1 to 1.2), p = 0.3 | 4.2 (17.7) | 6.0 (18.5) | –1.8 (–4.7 to 1.0), p = 0.2 |

| Communication | 4.8 (15.7) | 3.0 (17.4) | 1.8 (–0.7 to 4.2), p = 0.2 | 5.1 (15.9) | 5.0 (17.2) | 0.1 (–2.4 to 2.7), p = 0.9 | 6.0 (16.2) | 5.9 (17.1) | 0.1 (–2.5 to 2.7), p = 0.9 |

| Bodily discomfort | 2.0 (20.7) | 2.8 (21.1) | –0.8 (–3.9 to 2.3), p = 0.6 | 2.2 (20.6) | 2.3 (22.1) | –0.07 (–3.3 to 3.2), p = 1.0 | 2.3 (20.9) | 5.6 (22.9) | –3.3 (–6.7 to 0.2), p = 0.06 |

| Summary index | 2.4 (9.5) | 2.4 (10.8) | 0.007 (–1.5 to 1.5), p = 1.0 | 3.5 (9.7) | 4.6 (10.7) | –1.1 (–2.7 to 0.5), p = 0.2 | 4.3 (10.6) | 6.5 (11.4) | –2.2 (–3.9 to –0.5), p = 0.01 |

| EQ-5D quotient | |||||||||

| n | 342 | 338 | – | 321 | 322 | – | 304 | 313 | – |

| Score | 0.002 (0.23) | –0.03 (0.21) | –0.03 (–0.07 to –0.002), p = 0.04 | –0.02 (0.26) | –0.05 (0.22) | –0.03 (–0.07 to 0.008), p = 0.1 | –0.05 (0.27) | –0.09 (0.23) | –0.04 (–0.08 to 0.004), p = 0.08 |

| EQ-5D visual analogue scale | |||||||||

| n | 341 | 342 | – | 319 | 323 | – | 305 | 309 | – |

| Score | –1.8 (17.1) | –1.9 (14.3) | –0.2 (–2.6 to 2.2), p = 0.9 | –3.5 (16.6) | –4.5 (16.1) | –1.0 (–3.5 to 1.6), p = 0.4 | –4.7 (7.3) | –5.8 (16.3) | –1.1 (–3.7 to 1.6), p = 0.4 |

FIGURE 2.

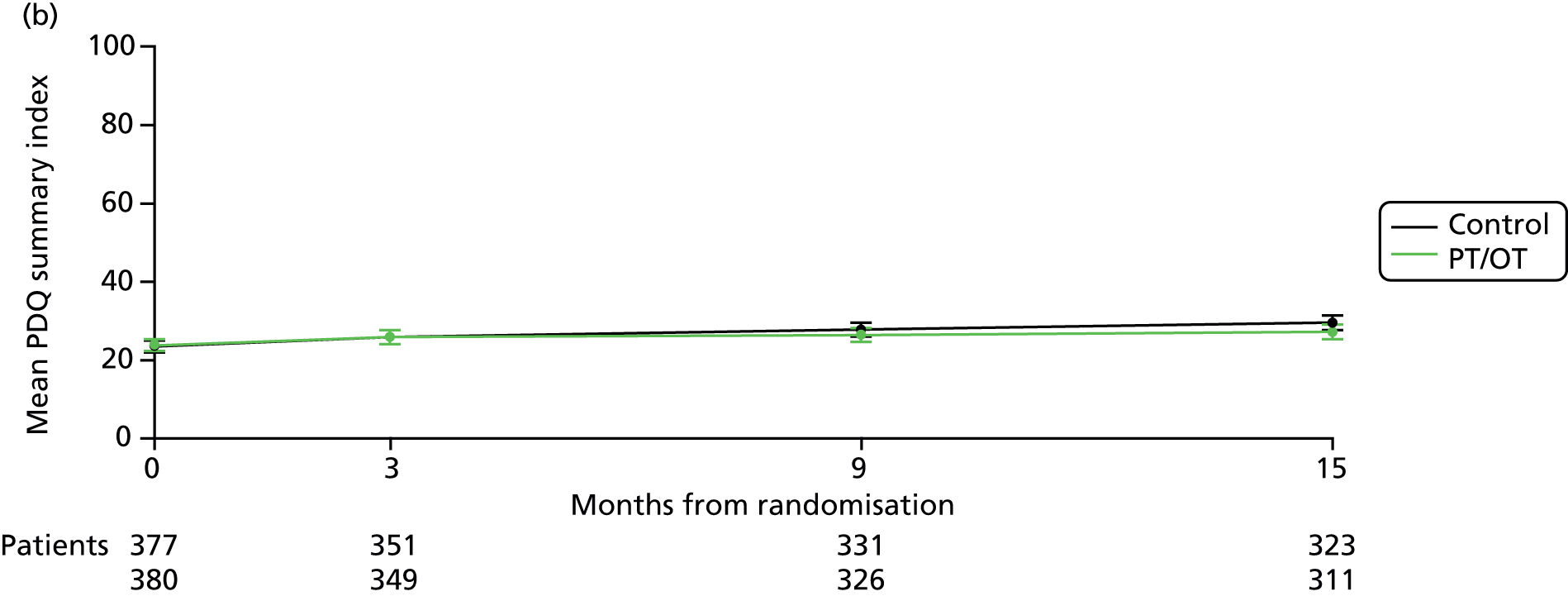

Long-term changes in ADL and QoL scores. (a) Mean NEADL summary index over time by treatment. Test for increasing difference over time: p = 0.3. Average difference (favours PT/OT): 0.07 points (–0.64 to 0.77 points); p = 0.9; (b) mean PDQ-39 summary index over time by treatment. Test for increasing difference over time: p = 0.005. Slopes diverge in favour of PT/OT: –1.55 (–2.62 to –0.47); p = 0.005; and (c) mean EQ-5D QoL score over time by treatment. Test for increasing difference over time: p = 0.2. Average difference (favours PT/OT): 0.02 points (0.00007 to 0.03 points), p = 0.04.

Secondary outcomes

The mean PDQ-39 summary index deteriorated by 2.4 points in both groups from baseline to 3 months (difference 0.007 points, 95% CI –1.5 to 1.5 points, p = 1.0; Table 11). No difference was seen in any of the eight domains of the PDQ-39 (Table 11). The slight improvement of 0.002 points in the EQ-5D quotient in the therapy group between baseline and 3 months compared with a 0.03-point deterioration in the no therapy group was of borderline significance (difference –0.03, 95% CI –0.07 to –0.002; p = 0.04; see Table 11). There was no difference in the EQ-5D visual analogue score (difference –0.2, 95% CI –2.6 to 2.2; p = 0.9; see Table 11).

Repeated measures analysis over the whole 15 months found significant divergence in PDQ-39 summary index (curves diverging at 1.55 points per annum, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.62 points; p = 0.005; see Figure 2b) and the ADL, emotional well-being and social support domains in favour of therapy but no difference in the mobility domain. There was also a borderline significant difference in the EQ-5D quotient in favour of the therapy arm over time (0.02 points, 95% CI 0.00007 to 0.03; p = 0.04; see Figure 2c).

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis with imputation of missing values on the NEADL scale [assuming a best (score 3), worst (score 0), middle (score 1.5) and average (at participant level) case score for missing items] did not change the results. Therefore, we can be reasonably confident that the results are robust and that missing data do not influence the results at any time point. Similarly, repeating the PDQ-39 analysis without imputation of missing values using the expectation maximisation algorithm also did not affect the results at any time point.

We also analysed the primary outcome of mean change between baseline and 3 months for the NEADL total score data using analysis of covariance adjusting for baseline NEADL score and the minimisation variables used in the randomisation algorithm, and for both analyses this made no difference to the results (difference 0.5; 95% CI –0.7 to 1.7; p = 0.4).

Subgroup analyses

Planned subgroup analyses for the NEADL total score found no evidence of a difference in treatment effect at 3 months according to baseline NEADL total score, disease severity or age (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Subgroup analyses for NEADL total score at 3 months. NEADL total score: ranges from 0 to 66 where higher scores are better and a positive change is an improvement in score. Diff., difference; var., variance.

Carer data

In total, 473 (62%) patients stated that they had a carer and 406 (86%) carers agreed to take part in the trial. Carer mean age was 67 years and 76% were female. The relationship between patient and carer was partner or spouse in the majority (72%). Although there was no difference in the carer SF-12 physical component summary score at 3 months, there was less decline in the carer SF-12 mental component summary score (difference –2.1, 95% CI –3.9 to –0.3; p = 0.02) (Table 13), although this was not maintained with longer follow-up.

| Subscale | Baseline | 3 months | Mean change from baseline | Mean difference (95% CI)a | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT/OT | No therapy | PT/OT | No therapy | PT/OT | No therapy | |||

| Physical functioning | ||||||||

| n | 171 | 181 | 169 | 181 | 151 | 156 | –5.6 (–11.0 to –0.2) | 0.04 |

| Score | 70.3 (35.4) | 76.0 (30.5) | 68.6 (35.8) | 70.3 (30.0) | –0.7 (24.8) | –6.3 (23.0) | ||

| Role physical | ||||||||

| n | 173 | 183 | 169 | 185 | 155 | 163 | –0.5 (–5.3 to 4.3) | 0.8 |

| Score | 75.4 (28.5) | 76.7 (26.8) | 69.8 (28.8) | 71.0 (27.1) | –5.4 (19.6) | –5.9 (23.8) | ||

| Role emotional | ||||||||

| n | 172 | 182 | 170 | 183 | 155 | 162 | –4.4 (–9.0 to 0.2) | 0.06 |

| Score | 83.6 (23.1) | 81.9 (22.9) | 80.4 (24.2) | 76.4 (24.9) | –1.7 (20.0) | –6.1 (21.5) | ||

| Social functioning | ||||||||

| n | 175 | 186 | 171 | 189 | 157 | 169 | –3.8 (–8.9 to 1.3) | 0.1 |

| Score | 84.9 (22.9) | 83.3 (23.6) | 81.0 (24.5) | 78.3 (26.9) | –2.9 (21.9) | –6.7 (24.5) | ||

| Mental health | ||||||||

| n | 174 | 183 | 170 | 188 | 156 | 167 | –4.3 (–8.2 to –0.4) | 0.03 |

| Score | 68.8 (21.1) | 68.6 (18.5) | 67.6 (20.2) | 64.6 (21.9) | –0.2 (16.7) | –4.5 (18.9) | ||

| Vitality | ||||||||

| n | 175 | 184 | 170 | 188 | 156 | 167 | –4.6 (–9.2 to 0.05) | 0.05 |

| Score | 57.4 (25.6) | 61.8 (22.6) | 53.8 (25.9) | 53.2 (24.5) | –3.5 (21.0) | –8.1 (21.1) | ||

| Bodily pain | ||||||||

| n | 173 | 184 | 170 | 189 | 156 | 168 | 2.9 (–2.2 to 7.9) | 0.3 |

| Score | 77.7 (29.3) | 76.4 (28.7) | 74.1 (28.8) | 74.2 (28.5) | –4.6 (25.0) | –1.8 (21.1) | ||

| General health | ||||||||

| n | 174 | 186 | 170 | 190 | 155 | 170 | –0.9 (–5.0 to 3.3) | 0.7 |

| Score | 64.2 (25.3) | 65.6 (26.1) | 58.9 (26.0) | 61.0 (25.3) | –4.4 (18.6) | –5.3 (19.5) | ||

| Physical component summary | ||||||||

| n | 166 | 171 | 165 | 174 | 146 | 144 | –0.6 (–2.3 to 1.2) | 0.5 |

| Score | 47.1 (12.5) | 48.2 (11.4) | 45.1 (13.3) | 46.4 (11.6) | –1.6 (7.5) | –2.1 (7.5) | ||

| Mental component summary | ||||||||

| n | 166 | 171 | 165 | 174 | 146 | 144 | –2.1 (–3.9 to –0.3) | 0.02 |

| Score | 51.1 (10.2) | 50.1 (8.9) | 49.7 (10.2) | 48.0 (10.5) | –0.5 (7.6) | –2.6 (7.9) | ||

Safety

By 3 months in the therapy group, falls had occurred in 10 patients (some patients reported multiple fall episodes), resulting in 17 GP, one ambulance and three hospital visits (accident and emergency, outpatient). In the no therapy group, falls were reported in nine patients, resulting in 11 GP, two ambulance and eight hospital visits. There were also six falls in another six patients that resulted in an overnight stay in hospital or prolongation of hospitalisation (four patients in the therapy group and two in the no therapy group). Duration of hospital stay ranged from 1 to 31 days. Injuries using equipment were reported by two patients (one in each group), both when the patient was using a rollator or frame.

Over the 15-month duration of the trial, 43 patients in the therapy group reported having had a fall (some patients reported multiple fall episodes), resulting in 68 GP, 17 ambulance and 34 hospital visits (accident and emergency, outpatient). In the no therapy group, 49 patients reported falls, resulting in 69 GP, 21 ambulance and 37 hospital visits. There were also in total 27 falls that resulted in an overnight stay in hospital or prolongation of hospitalisation (13 falls in 10 patients in the therapy group and 14 falls in 12 patients in the no therapy group). Duration of hospital stay ranged from 1 to 72 days.

Economic evaluation

Table 14 presents data on resource use by type of contact for each arm of the trial. Data are presented for all participants after randomisation using intention-to-treat analysis. Table 15 presents data on the associated costs by category of resource use for each arm of the trial. Aggregation of the categories of all costs identified in Table 15 result in mean costs per patient of £1708 (95% CI £1379 to £2072) and £1541 (95% CI £1329 to £1752; Table 14) for the PT/OT and control arms, respectively.

| Contact type | PT/OT (n = 381) | Control (n = 381) |

|---|---|---|

| PT/OT service | ||

| PT appointment number, mean (SD) | 3.52 (4.02) | 1.31 (2.79) |

| OT appointment number, mean (SD) | 1.73 (2.23) | 0.43 (1.13) |

| Primary care | ||

| GP appointment number, mean (SD) | 4.49 (4.53) | 4.76 (4.42) |

| GP home visit number, mean (SD) | 0.47 (1.61) | 0.38 (1.24) |

| Practice nurse appointment number, mean (SD) | 2.19 (3.86) | 2.05 (4.08) |

| Nurse home visit number, mean (SD) | 0.50 (2.28) | 0.56 (2.37) |

| Private GP appointment number, mean (SD) | 0.38 (1.79) | 0.52 (2.70) |

| Speech/language appointment number, mean (SD) | 0.60 (2.04) | 0.85 (3.30) |

| Secondary care | ||

| Outpatient bed-days, mean (SD) | 0.14 (0.67) | 0.08 (0.47) |

| Inpatient bed-days, mean (SD) | 0.19 (0.58) | 0.20 (0.58) |

| Outpatient appointment numbers, mean (SD) | 3.71 (3.95) | 3.29 (4.26) |

| Accident and emergency attendance, mean (SD) | 0.06 (0.34) | 0.07 (0.48) |

| PD nurse appointment number, mean (SD) | 1.88 (2.09) | 1.69 (1.78) |

| Social care | ||

| Health visitor contact number, mean (SD) | 0.26 (1.00) | 0.12 (0.55) |

| Social worker contact number, mean (SD) | 0.36 (2.15) | 0.16 (0.75) |

| Cost category | Mean cost (£) per patient | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT/OT, n = 381 | Control, n = 381 | ||

| PT/OT | 136 | 62 | 74 (61 to 88) |

| Primary care | 322 | 336 | –15 (–54 to 25) |

| Secondary care | 1150 | 1084 | 65 (–163 to 308) |

| Aid or adaptation | 18 | 22 | –5 (–15 to 7) |

| Social care | 82 | 36 | 44 (9 to 92) |

| Total NHS and Personal Social Services | 1708 (1379 to 2072) | 1541 (1329 to 1752) | 164 (–141 to 468) |

The mean number of QALYs gained per patient was 0.791 (95% CI 0.765 to 0.818) in the therapy arm and 0.764 (95% CI 0.737 to 0.791) in the control arm (Table 16). Compared with the control group, therapy resulted in an incremental cost per patient of £164 (95% CI –£141 to £468) and an incremental QALY gain of 0.027 (95% CI –0.010 to 0.065). Combining incremental costs and consequences into a single summary score resulted in an incremental cost per QALY gained (ICER) of £3493 (95% CI –£169,371 to £176,358).

| Allocation | Total cost (£) | Incremental cost (£) | QALYs | Incremental QALYs | ICER (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1541 (1329 to 1752) | – | 0.764 (0.737 to 0.791) | – | – |

| PT/OT | 1708 (1379 to 2072) | 164 (–141 to 468) | 0.791 (0.765 to 0.818) | 0.027 (–0.010 to 0.065) | 3493 (–169,371 to 176,358) |

Figure 4 presents the scatterplot of incremental costs and incremental QALYs with 95% confidence ellipse on the cost-effectiveness plane. Figure 5 presents the CEAC at different values as the threshold value of the ICER is raised. At a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 per QALY, the probability of PT/OT being more cost-effective at £20,000 was 50.5%.

FIGURE 4.

Incremental costs and QALYs for therapy compared with control: cost-effectiveness plane.

FIGURE 5.