Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/116/300. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The draft report began editorial review in August 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Torsten Lauritzen reports unrestricted grants from Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Servier and HemoCue during the conduct of the study. Torsten Lauritzen also owns stock/shares in Novo Nordisk. Guy EHM Ruttem reports grants from Novo Nordisk, GlaxoSmithKline and Merck during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Novo Nordisk and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. Melanie J Davies has acted as a consultant, advisory board member and speaker for Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche. Melanie J Davies has also received grants in support of investigator and investigator-initiated trials from Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, Merck Sharp & Dohme and GlaxoSmithKline. Kamlesh Khunti has acted as a consultant and speaker for Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company and Merck Sharp & Dohme and has received grants in support of investigator and investigator-initiated trials from Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Simon J Griffin reports grants from the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council, NHS Research and Development, the National Institute for Health Research and the University of Aarhus (Denmark) and non-financial support from Bio-Rad Laboratories during the conduct of the study. Simon J Griffin has also received personal fees from Eli Lilly and Company, the Royal College of General Practitioners and Astra Zeneca outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Simmons et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Burden of diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is a common chronic disease, which affected 382 million people worldwide in 2013. 1 It is estimated that there will be 592 million individuals living with diabetes by 2035. Diabetes is a major cause of premature death. Global mortality attributable to known diabetes in adults aged 20–79 years in the year 2013 is estimated at 5.1 million deaths, which is 8.4% of total world mortality. 1 Diabetes is ranked among the leading causes of blindness, renal failure and lower limb amputation in virtually every developed society. People with diabetes have an increased risk of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease (PVD) and have a reduced risk of survival after suffering from silent ischaemia and myocardial infarction (MI) (compared with those without diabetes). Around 65% of individuals with type 2 diabetes die of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Diabetes is a very expensive chronic condition. It imposes a huge burden on national economies and health-care systems, as well as costs for individuals with diabetes and their families. Expenditure related to diabetes in 2010 was estimated to be approximately 10% of total health-care budgets in the UK and is projected to rise to 17% in 2035. 2

Preventing diabetes

The high social and economic cost of diabetes makes a compelling case for prevention of the disease. But where should governments and health services focus their attention? Most research has been completed on the tertiary prevention of diabetes, that is, the treatment of people with established disease. There have been significant improvements in the treatment of individuals with diabetes3 and there is good evidence that the development of long-term complications of diabetes can be significantly decreased by intensive treatment (IT) (see Screening and early treatment for early diabetes). We also have long-term evidence that diabetes can be prevented among those at high risk of developing the disease (primary prevention). 4 Intensive lifestyle and pharmacological interventions reduce the rate of progression of type 2 diabetes among people with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). In a meta-analysis of published diabetes prevention trials, Gillies et al. 4 reported pooled hazard ratios of 0.51 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.44 to 0.60] for lifestyle interventions compared with standard advice and 0.70 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.79) for oral diabetes drugs compared with the control. Longer-term follow-up of these trials provides evidence of the sustained prevention of diabetes. 5–7 Delaying or preventing diabetes in this way also reduces the risk of microvascular complications and reduces cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. 8,9

Secondary prevention strategies (i.e. earlier detection, e.g. by screening) have received little attention in the past. The current evidence base for the recommendation of screening and early treatment for diabetes is limited.

Screening and early treatment for diabetes

Type 2 diabetes meets many of the formal criteria for a disease for which screening is justified. 10 The condition is an important health problem associated with a substantial burden of suffering and health service cost. The natural history of the disease is well characterised. 11,12 The condition is frequently asymptomatic,13 with the true onset occurring several years before diagnosis. 11,14 Although detection of the condition may be improving in some parts of the world,15 nearly half of all people with diabetes remain undiagnosed. 1 When patients are diagnosed, many already have complications, such as CVD, chronic kidney disease and heart failure, retinopathy and neuropathy. 16–18 This suggests a potential window for earlier detection and treatment. Furthermore, there are a number of screening tests that are simple, safe and validated and that perform reasonably well when evaluated against recommended diagnostic criteria. 19 Modelling studies suggest that a programme of screening for diabetes would reduce both all-cause and diabetes-related mortality. 20–22 However, these estimates depend on a number of key assumptions. The only published trial of screening to date did not show an effect of population-based screening on mortality over 10 years of follow-up. 23

The National Screening Committee states that there should be an effective treatment for individuals identified through early detection, with evidence of early treatment leading to better outcomes than late treatment. 10 A screening programme for diabetes is most likely to seek to prevent CVD, the leading cause of premature death and disability among patients with diabetes. There is good evidence that the development of long-term complications of diabetes can be significantly decreased by IT. Results from the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) and the Kumamato trials have demonstrated the benefits of tight glycaemic24,25 and blood pressure control,26 whereas several trials, including the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study27 and the Heart Protection Study (HPS),28 have confirmed the benefits of lipid-lowering drugs. The Steno study is one of the few trials to compare the benefits of targeted intensive multifactorial treatment with those of routine care (RC) for risk factors for CVD in individuals with established diabetes. 29 After 13 years of follow-up, patients receiving the IT had a 59% (95% CI 0.25% to 0.67%) lower risk of a CVD event and a 46% (95% CI 0.32% to 0.89%) lower risk of all-cause mortality than those receiving RC. When we started our research in 2010, there was no trial evidence that intensive multifactorial treatment improved CVD outcomes when commenced in the lead time between detection by screening and diagnosis in routine clinical practice.

In terms of preventing microvascular complications, treatment of individual risk factors such as blood pressure and glucose level reduces the risk of microvascular complications among clinically diagnosed patients. 24,30–32 IT of multiple risk factors in the Steno study was associated with a 61% (95% CI 13% to 83%) lower risk of nephropathy, a 58% (95% CI 14% to 79%) lower risk of retinopathy and a 63% (95% CI 21% to 82%) lower risk of autonomic neuropathy. 33 However, the effects on microvascular outcomes of starting multifactorial treatment earlier in the course of the disease are uncertain. Data from trials of IT of hyperglycaemia suggest that beneficial effects can be seen for microvascular outcomes in the short term, whereas cardiovascular benefits are evident only with longer follow-up. However, there remains some uncertainty about the merits of tight glycaemic control. 34,35

Little research has been completed on the potential effects of intensive multifactorial treatment on patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) early in the course of the disease. For largely asymptomatic patients, such a treatment regime might be burdensome. Health practitioners might be reluctant to offer IT including the prescription of several medications and recommendations to change several lifestyle behaviours; this might lead to psychosocial stress and reduced satisfaction with treatment. 36 When assessing the effectiveness of early treatment, PROMs are a valuable complement to hard outcomes such as mortality and cardiovascular events. They are also increasingly being used as key performance indicators in chronic illness. PROMs reflect a patient’s assessment of his or her own health and well-being and involve questions about physical and social functioning and mental well-being. They may include both generic and disease-specific questions. The reliability of PROMs is similar to that of clinical measures such as blood pressure or blood glucose monitoring. 37 The use of PROMs has been recommended in the evaluation of health-care services and in regulatory decision-making. 38 Their use provides an opportunity to help drive changes in how health care is organised and delivered. 37

Evidence from the UKPDS study suggests that IT of blood pressure and blood glucose among newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients is not associated with adverse effects on quality of life. 39 The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial of intensive glycaemic control in US patients with long-standing type 2 diabetes was associated with modest improvements in satisfaction with diabetes treatment and did not lead to an increase in health-related quality of life. 40 The effects of intensive multifactorial treatment on PROMs among people with type 2 diabetes detected by screening are not known.

In addition to a lack of information on the effects of intensive multifactorial intervention on macrovascular, microvascular and PROMs early in the diabetes disease trajectory, little is known about the cost-effectiveness of such treatment. It is expected that increasing numbers of new patients will be identified as governments introduce national assessment programmes, such as the NHS Health Checks programme. 41 The balance of benefits, harms and costs of IT may not be the same for screen-detected individuals as for those with clinically diagnosed and long-standing diabetes.

The ADDITION-Europe trial

In 2001 a group of colleagues from Cambridge in the UK, Utrecht in the Netherlands and Copenhagen and Aarhus in Denmark came together to answer some of the outstanding questions about screening and early treatment for diabetes. Colleagues in Leicester were later invited to join the collaboration. The main aim of the Anglo–Danish–Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People with Screen-Detected Diabetes in Primary Care (ADDITION-Europe) was to investigate whether or not intensive multifactorial treatment improves outcomes compared with RC when commenced in the lead time between detection by screening and clinical diagnosis. This was a two-phase study consisting of a screening phase and a pragmatic, cluster-randomised, parallel-group trial. Results from the screening phase of the study have previously been reported. 42–46 This report concerns the results from the 5-year follow-up of the trial, which was funded in the UK by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme.

Aims

To examine the effect of intensive multifactorial treatment compared with RC on (1) cardiovascular outcomes, (2) microvascular outcomes and (3) self-reported health status, well-being, diabetes-specific quality of life and treatment satisfaction after 5 years’ follow-up. A further aim was to assess the cost-effectiveness of intensive multifactorial treatment compared with RC in the UK setting.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Design

The ADDITION-Europe trial was set up to evaluate the effectiveness of intensive multifactorial treatment with regard to macrovascular, microvascular and PROMs among individuals with screen-detected diabetes. It consisted of two phases – a screening phase and a pragmatic cluster-randomised parallel-group trial – in four centres (Denmark, Cambridge, UK, the Netherlands and Leicester, UK). This report concerns the results of the treatment trial (see Chapter 3). The main trial was supplemented with an economic evaluation to consider the cost-effectiveness of the intervention in the UK (see Chapter 4). A description of the trial protocol has already been published. 47

Ethical approval and research governance

The study was approved by local ethics committees in each centre and participants provided informed consent.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Of 1312 general practices invited to participate, 379 (29%) agreed and 343 clusters (26%) were randomised. Practices were randomly assigned by statisticians independent of the measurement teams to screening plus routine diabetes care or screening followed by intensive multifactorial treatment in a 1 : 1 ratio. Randomisation included stratification by county and number of full-time family physicians in Denmark and by single-handed or group status in the Netherlands. In Cambridge, randomisation included minimisation for the local district hospital and the number of patients per practice with diabetes. In Leicester, randomisation included minimisation for practice demographics, deprivation status and prevalence of type 2 diabetes.

Population-based stepwise screening took place between April 2001 and December 2006 among people aged 40–69 years (50–69 years in the Netherlands) without known diabetes, as previously described. 43,48–50 Screening programmes, which varied by centre (Table 1), consisted of a risk score51 (Cambridge) or self-completion questionnaires (Denmark52 and the Netherlands54) followed by capillary glucose testing or an invitation to attend an oral glucose tolerance test without prior risk assessment (Leicester). Individuals were diagnosed with diabetes according to the World Health Organization (WHO)’s 1999 criteria,56 including the requirement for confirmatory tests on separate occasions.

| Centre | Screening programme | Intervention delivery | Outcome ascertainment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambridge, UK |

|

|

|

| Denmark |

|

|

|

| Leicester, UK |

|

|

|

| The Netherlands |

|

|

|

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes were eligible to participate in the treatment study unless their family physician indicated that they had contraindications to the proposed study medication, an illness with a life expectancy of < 12 months or psychological or psychiatric problems that were likely to invalidate informed consent. Overall, 3057 eligible participants with screen-detected diabetes agreed to take part (Denmark, n = 1533; Cambridge, n = 867; the Netherlands, n = 498; Leicester, n = 159).

Intervention

The characteristics of the interventions to promote IT in each centre have been described previously47–49,57 and are summarised in Table 1. We aimed to educate and support general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses in target-driven management (using medication and promotion of a healthy lifestyle) of hyperglycaemia, blood pressure and cholesterol, based on the stepwise regimen used in the Steno-2 study. 29 Treatment targets and algorithms (Table 2) based on trial data in people with type 2 diabetes24,26,29,58,59 were the same for the IT groups in all centres. GPs were advised to consider prescribing an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor for patients with blood pressure ≥ 120/80 mmHg or a previous cardiovascular event58 and 75 mg of aspirin daily to patients without specific contraindications. Although treatment targets were specified and classes of medication recommended, prescribing decisions, including choice of individual drugs, were made by practitioners and patients. Following publication of the results of the HPS,28 the treatment algorithm included a recommendation to prescribe a statin to all patients with a cholesterol level of ≥ 3.5 mmol/l.

| Treatment target | Treatment threshold | Baseline | Review 1 | Review 2 | Review 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | < 7.0% | > 6.5% | Diet | If HbA1c > 6.5%, prescribe metformin | If HbA1c > 6.5%, increase metformin dose/add a second medication (PGR or SU or TZD) | If HbA1c > 6.5%, add a third medication (PGR or SU or TZD) and consider adding insulin |

| BP | ≤ 135/85 mmHga | ≥ 120/80 mmHg | If BP > 120/80 mmHg or CVD+, prescribe an ACE inhibitor titrated to the maximum dose | If BP > 135/85 mmHg, add a thiazide diuretic or calcium antagonist | If BP > 135/85 mmHg, add a thiazide diuretic or calcium antagonist | If BP > 135/85 mmHg, add a beta-blocker or alpha-blocker |

| Cholesterol IHD– | < 5.0 mmol/l | ≥ 3.5 mmol/l | If TC ≥ 3.5 mmol/l, prescribe a statin | If TC > 5.0 mmol/l, increase statin dose up to the maximum | If TC > 5.0 mmol/l, increase statin dose up to the maximum | Consider adding a fibrate if TC > 5.0 mmol/l |

| Cholesterol IHD+ | < 4.5 mmol/l | ≥ 3.5 mmol/l | If TC ≥ 3.5 mmol/, prescribe a statin | If TC > 4.5 mmol/l, increase statin dose up to the maximum | If TC > 4.5 mmol/l, increase statin dose up to the maximum | Consider adding a fibrate if TC > 4.5 mmol/l |

| Aspirin | 75/80 mg of aspirin daily to all patients treated with antihypertensive medication and without specific contraindications | |||||

Intensive treatment was promoted through the addition of several features to existing diabetes care. Small group or practice-based educational meetings were arranged with GPs and nurses to discuss the treatment targets and algorithms and lifestyle advice, including supporting evidence. Audit and feedback were included in follow-up meetings up to twice per year (the total number of practice meetings ranged from 2 to 10) or co-ordinated by post. In the Netherlands patients were seen in general practice by diabetes nurses who were authorised to prescribe medication and adjust doses under GP supervision. In Denmark and Cambridge practice staff were provided with educational materials for patients. In Denmark and the Netherlands patients were sent reminders if annual measures were overdue. In all centres practices received additional funding to support the delivery of care (up to the equivalent of three 10-minute consultations with a GP and three 15-minute consultations with a nurse per patient per year for 3 years). Leicester patients were referred to the Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND) structured education programme53 and were offered 2-monthly appointments with a diabetes nurse or physician in a community peripatetic clinic for 1 year and 4-monthly appointments thereafter. Clinic staff were prompted to contact patients defaulting from appointments.

In the RC group, GPs were provided only with the diagnostic test results. Patients with screen-detected diabetes received the standard pattern of diabetes care according to the recommendations applicable in each centre. 60–63

Data collection

Centrally trained staff undertook health assessments at baseline and after 5 years, including biochemical and anthropometric measures, and administered questionnaires, following standard operating procedures. Staff were unaware of study group allocation. Follow-up examinations took place from September 2008 until the end of December 2009. The mean [standard deviation (SD)] follow-up period was 5.3 (1.6) years. All biochemical measures were analysed in five regional laboratories at baseline and follow-up. Standardised self-report questionnaires were used to collect information on education, employment, ethnicity, lifestyle habits (smoking status, alcohol consumption), prescribed medication and health status. Questionnaires were completed at the same health assessment visit as the anthropometric and biochemical measurements. If participants did not complete follow-up questionnaires or measurements then the most recent values were obtained from general practice records along with information on prescribed medication.

Primary end point

The primary end point was a composite of first cardiovascular event, including cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular morbidity (non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke), revascularisation and non-traumatic amputation. All-cause mortality and each of the individual components of the primary end point were secondary outcomes. In each centre participants’ medical records or national registers were searched for potential end points by staff unaware of group allocation. For each possible end point, packs containing relevant clinical information (such as a death certificate, post-mortem report, medical records, hospital discharge summary, electrocardiographs and laboratory results) were prepared and sent to two members of the expert committees, who were unaware of group allocation, for independent adjudication according to an agreed protocol using standardised case report forms. Committee members met to reach consensus over discrepancies. The date of completion of follow-up for the primary end point was deemed to be the date of the first primary end point, the date of remeasurement at 5 years if no end point occurred or the date that the end-point search was undertaken if the participant did not experience an event or attend follow-up.

Secondary end points

Microvascular outcomes

Prespecified secondary outcomes included measures of kidney function, retinopathy and peripheral neuropathy.

Nephropathy was assessed by the urinary albumin–creatinine ratio (ACR) and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). The urinary ACR was measured on spot urine and analysed at Aarhus Hospital (Aarhus, Denmark) and Steno Diabetes Centre (Gentofte, Denmark) using a Hitachi 912 Chemistry Analyzer (Tokyo, Japan); at Addenbrooke’s Hospital (Cambridge, UK) and Leicester Royal Infirmary (Leicester, UK) using an Olympus AU400 Chemistry Analyzer (Tokyo, Japan); and at the SHL Centre for Diagnostic Support in Primary Care (Etten-Leur, the Netherlands) using a Roche Hitachi Modular P Chemistry Analyzer (Basel, Switzerland). Repeated analyses of standardised trial control samples for urine creatinine during follow-up confirmed the reliability and precision of the laboratory methods with coefficients of variation (CVs) < 3.4% in all laboratories. Analyses of trial and external quality control samples of urine albumin revealed CVs between 2.0% and 9.8% in the Etten-Leur, Leicester and Gentofte laboratories and CVs of 4.9% for low concentrations and 3.4% for high concentrations in the Addenbrooke’s laboratory in Cambridge during the period of trial testing. Microalbuminuria was defined as an ACR of ≥ 2.5 mg/mmol for men and ≥ 3.5 mg/mmol for women and macroalbuminuria was defined as an ACR of ≥ 25 mg/mmol. Nephropathy was defined as the presence of either microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria. The eGFR was calculated using data on serum creatinine, age, sex and ethnicity for each individual using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula64 at baseline and follow-up. Change between the two time points was analysed as a continuous variable. Plasma creatinine was analysed with kinetic colourimetric methods at all laboratories at baseline and follow-up except in the Netherlands where an enzymatic method was used at follow-up. Repeated analyses of standardised control samples for creatinine during follow-up the confirmed reliability and precision of the laboratory methods, with CVs between 1.3% and 6.4%.

Retinopathy was assessed using gradable digital images taken using a retinal camera (two from each eye, one with the fovea in the centre and one with the macula in the centre). In the Netherlands and Leicester all retinal images were taken as part of the follow-up examination. In Denmark 81% of the images were taken as part of the study follow-up, with the remainder being obtained from routine health service records. All retinal images in Cambridge were retrieved from routine medical records. Only images taken in the 2 years preceding the follow-up visit were included in this analysis. Information on retinal photography devices used at the four centres is available on the study website [see www.addition.au.dk/ (accessed 30 June 2014)]. Retinal images were graded by three certified graders, who were unaware of the participants’ study group allocation, using a quantitative grading system and subsequently categorised according to the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) semiquantitative scale. 65 Two binary end points were then defined: (1) any retinopathy compared with no retinopathy and (2) severe or proliferative retinopathy compared with no, mild or moderate retinopathy.

Peripheral neuropathy was assessed using the self-administered Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument,66 which includes 13 questions about neuropathic symptoms. Responses to the questions are summed to calculate the total score. Responses of ‘yes’ to items 1–3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14 and 15 each score 1 point and ‘no’ responses on items 7 and 13 each score 1 point. Item 10 is not included in the calculation of a score for neuropathy. Participants were defined as having peripheral neuropathy if they had a score of ≥ 7. The peripheral neuropathy scores were considered missing if categorisation was not possible because of unanswered items. 67

Patient-reported outcomes

As the participants were screen detected, no diabetes-specific measures were obtained at baseline. At follow-up, questionnaires were used to cover both generic and diabetes-specific measures.

Health status was assessed using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), a generic health-related quality of life questionnaire consisting of a classification system (EQ-5D profile) and a visual analogue scale [European Quality of Life visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS)]. The EQ-5D profile was completed by participants at baseline and follow-up; the EQ-VAS was completed at follow-up only. The EQ-5D profile covers five domains of health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), each with three levels of functioning: level 1, no problems; level 2, some problems; level 3, severe problems. This results in 243 health states, which are converted to a single index (‘utility’) using a population-specific algorithm. The standard UK value set gives utilities ranging from –0.594 to +1.00 (full health). 68 A value of 0 represents death; negative values imply a health state worse than death. The EQ-VAS is a graded, vertical line, anchored at 0 (worst imaginable health state) and 100 (best imaginable health state). Patients were asked to mark a point on the EQ-VAS that best reflected their actual health state. 69

The Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)70 generates a profile of scores on eight dimensions of health: (1) physical functioning; (2) role limitations because of physical problems; (3) social functioning; (4) bodily pain; (5) general mental health; (6) role limitations because of emotional problems; (7) vitality; and (8) general health perceptions. Two summary scales can be calculated: the physical component summary score and the mental component summary score. For all dimensions an average score can be calculated, with a range from 0 (least favourable health state) to 100 (most favourable health state). The SF-36 was completed at follow-up.

General well-being was assessed using the previously validated 12-item short form of the Well-Being Questionnaire (W-BQ12),71 which measures different aspects of the well-being of individuals, including diabetes patients. It can be scored as three subscales: negative well-being (a higher score means more negative well-being), energy (a higher score means more energy) and positive well-being (a higher score means more positive well-being). Each subscale consists of four items with a score range of 0–12. Furthermore, a score for general well-being can be calculated;72 this has a score range of 0–36 and a higher score indicates better well-being. The W-BQ12 was completed at follow-up.

Diabetes-specific quality of life was assessed using the previously validated Audit of Diabetes-Dependent Quality of Life (ADDQoL),73 a measure of patients’ perceived importance of diabetes and its treatment and its impact on quality of life. We used the ADDQoL 19, which includes 19 diabetes-specific items. For each item patients are asked how things would be without diabetes, with scores ranging from –3 (a great deal better) to 1 (worse), and to rate each item, with scores ranging from 3 (very important) to 0 (not at all important). A weighted rating per item can be calculated by multiplying the unweighted rating by the importance rating. The total ADDQoL score is the mean of all weighted ratings of applicable domains and ranges from –9 (maximum negative impact of diabetes) to 3 (maximum positive impact of diabetes). The ADDQoL was completed at follow-up.

Satisfaction with diabetes treatment was assessed using the previously validated Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ). 74 It consists of a six-item scale assessing treatment satisfaction and two items assessing the perceived frequency of hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia. The treatment satisfaction score ranges from 0 (very dissatisfied) to 36 (very satisfied). The DTSQ was completed at follow-up.

Sample size

An individually randomised trial would have required a total of 2700 individuals (1350 per group) to detect a 30% reduction in the cumulative risk of the primary end point at a 5% significance level and with 90% power, allowing for 10% loss to follow-up and assuming an event rate in the RC group of 3% per year (based on results from the UKPDS24). We expected a minimal effect of clustering within general practices, with an estimated intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.01; assuming an average of 10 participants per general practice, the design effect was 1.09 and so we inflated the estimated sample size for this cluster trial to 3000.

Statistical analysis

The analysis and reporting of this trial were undertaken in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines [see www.consort-statement.org/ (accessed 27 January 2016)]. Statistical analysis was undertaken in Stata 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Review Manager v5.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark), following a predefined analysis plan, which was finalised before preparation of the end-point data set, agreed with the Trial Steering Committee and deposited on the study website (see www.addition.au.dk/). The primary comparative analyses between the randomised groups were conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis without imputation of missing data.

Preliminary analyses

We summarised the baseline characteristics of individuals and general practices within each randomised group, by centre and overall.

Changes in mean values or percentages of other clinical and medication variables from baseline to follow-up were summarised in each randomised group and intervention effects and 95% CIs for these changes were estimated using the methods described in the primary and secondary analysis sections. We also calculated 10-year modelled CVD risk using the UKPDS model (version 3)75 at 5 years post diagnosis. This is a diabetes-specific risk assessment tool that estimates the absolute risk of fatal or non-fatal CVD within a defined time frame. The variables include age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level, systolic blood pressure, total to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio, atrial fibrillation (AF), previous MI or stroke, macroalbuminuria (ACR ≥ 30 mg/mmol), microalbuminuria (ACR ≥ 2.5 mg/mmol in men or ≥ 3.5 mg/mmol in women), duration of diagnosed diabetes and body mass index. We did not have data on AF in ADDITION-Europe participants and so all individuals were coded as zero (no AF). Centre-specific estimates of the difference in modelled CVD risk between treatment groups were combined using fixed-effects meta-analysis. Odds ratios (ORs) of meeting each of three treatment targets [HbA1c < 53 mmol/l (7.0%) if HbA1c > 6.5%; blood pressure ≤ 135/85 mmHg if ≥ 120/80 mm Hg; cholesterol < 5 mmol/l without ischaemic heart disease or < 4.5 mmol/l with ischaemic heart disease) comparing IT with RC were also estimated.

Primary analyses: cardiovascular outcomes

We plotted the cumulative probability of the primary end point. To assess intervention effects we used Cox regression to estimate a hazard ratio and 95% CI within each centre. As there were few participants and hence events in the Leicester centre, data for the primary end point and its components were grouped with data from Cambridge, the other UK centre. Because randomisation was at the practice level, robust standard errors (SEs) were calculated that take into account the two-level structure of the data (individuals clustered within practices) and any potential correlation between individuals within practices. We calculated the intracluster correlation coefficient for the primary end point. We combined centre-specific log-hazard ratios and SEs using fixed-effects meta-analysis and calculated the I2-statistic, which represents the proportion of variability (in log-hazard ratios) between centres that is due to heterogeneity. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by including a parameter for treatment × time interaction in each centre-specific Cox regression model. We analysed continuous intermediate end points within each centre using normal errors regression, with adjustment for the baseline value of the end point, excluding individuals who died or who were lost to follow-up. We combined the estimated differences in mean change from baseline across centres using fixed-effects meta-analysis. In the regression models we included individuals with a missing value of the outcome at baseline using the missing indicator method;76 variables with a skewed distribution were log-transformed. We estimated the effect of the intervention on prescribing end points using logistic regression within each centre and combined the estimated ORs across centres using fixed-effects meta-analysis. We undertook sensitivity analyses by excluding follow-up clinical data obtained from general practice records and prespecified subgroup analyses for the primary end point by including interaction terms between the intervention group and patient age and self-reported history of CVD, which were then pooled across centres. The cumulative incidence of the composite cardiovascular end point was calculated using the method for competing risks described by Gooley et al. ,77 with the competing events here being the primary end point and death from non-cardiovascular causes.

Secondary analyses: all-cause mortality

All-cause mortality data were analysed using the method described in the previous section for the composite CVD end point. Kaplan–Meier estimates of cumulative incidence were calculated.

Secondary analyses: microvascular outcomes

Binary end points (any albuminuria and any retinopathy) were analysed using a logistic regression model estimating the OR and 95% CI for the comparison between IT and RC separately within each centre. The continuous end points (ACR, eGFR) were analysed using a normal errors regression model with adjustment for baseline.

In both logistic and normal errors regression models, given the cluster-randomised design, SEs were adjusted using the cluster option in Stata to allow for correlation between patients within practices. The estimated ORs and differences in means from the four centres were pooled using fixed-effects meta-analysis and a forest plot was used to display the results. The I2-statistic, representing the proportion of variability between centres that is due to heterogeneity, was calculated. Intracluster correlation coefficient values were estimated for all of the microvascular outcomes.

Prespecified analyses of potential interactions between randomised groups and subgroups defined by the following baseline variables were undertaken: age (< 60 and ≥ 60 years), sex, HbA1c [< 6.6% (< 49 mmol/mol) and ≥ 6.6% (≥ 49 mmol/mol), which was the median value] and the presence of albuminuria. For ACR and eGFR, those participants with a missing baseline value of the variable were included in the analysis using the missing indicator method. 76 A sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation was used to investigate the impact of missing data on the retinopathy and peripheral neuropathy end points.

Secondary analyses: patient-reported outcomes

We presented mean scores and SDs for all PROMs at follow-up by centre and by randomised group. We used linear mixed-effects regression models to estimate the difference in each PROM at follow-up and 95% CI, comparing the IT group with the RC group. A random effect per general practice was included to account for intracluster correlation. All PROMs were left skewed. As an alternative to transformation, we wished to control for baseline levels of PROMs. These were not available for all measures so we included baseline EQ-5D score as a proxy for baseline quality of life; correction for baseline EQ-5D score greatly improved the normality of the residuals. The estimated differences in means from the four centres were then pooled using random-effects meta-analysis and a forest plot was used to display the estimated mean differences and 95% CIs for each centre and overall. We calculated the I2-statistic to represent the proportion of variability between centres attributable to heterogeneity.

Individuals who were lost to follow-up or who did not complete both the baseline and the follow-up questionnaires were excluded. Patients with missing data may be those who experienced more serious illness and greater disability and therefore these missing data are unlikely to be ‘missing completely at random’ but will rather be ‘missing at random’. Simply excluding these patients may lead to selection bias and therefore we used multiple imputation78 to perform a sensitivity analysis, imputing five data sets using patient characteristics at baseline and at 5 years’ follow-up and including all patients who were alive at follow-up.

Patient and public involvement

In the development of the ADDITION-Cambridge study, patients were involved in two pilot studies. The first was to assess the feasibility and uptake of the diabetes screening programme and to examine the effects of invitation to diabetes screening on anxiety, self-rated health and illness perceptions. 79 The second was a qualitative study of patients’ experiences of being screened for diabetes. 80 Further qualitative work was undertaken exploring practitioners’ experiences of taking part in the main ADDITION-Cambridge study. 81 In terms of patient involvement during the 5-year follow-up phase of the trial, we sent a newsletter to all ADDITION-Cambridge participants in 2008 outlining the results to date and informing them of our intention to invite them back for the 5-year follow-up assessment. We said to participants: ‘[a]ny ideas that you may have on the conduct and planning of the 5-year follow-up health check would be welcomed – please get in touch if you have any comments’. Responses fed into our 5-year planning. We also sent participants a newsletter in May 2012 with the 5-year study results and invited them and a guest to attend a local meeting during June/July 2012 where they had the chance to meet with ADDITION staff and hear about the results of the study. The five meetings were very well received and gave this special group of patients a chance to ask questions about the study and their diabetes treatment. Comments ranged from ‘very informative’ and ‘the content was useful and excellent’ to ‘the results of the study will motivate me to work harder at controlling my diabetes’. There was very strong support for being involved with a 10-year follow-up study. Similar feedback to study participants took place in the Netherlands and Denmark.

In ADDITION-Leicester, the intervention model was particularly suited to patient and public involvement, with ongoing contact with the clinical care team facilitating continuity and dialogue. IT participants were consulted and offered continued post-trial care delivered in a setting of their choice (primary or secondary care). A number of participants have become members of the local patient and public involvement group and are actively involved in steering local research. A newsletter describing the final results and thanking participants for their involvement was sent following completion of the 5-year outcome ascertainment for the entire cohort (July 2014). A significant number of participants were identified as being at high risk of diabetes during the ADDITION-Leicester study and have subsequently been involved with other studies aimed at the prevention of diabetes. We have also developed a black and minority ethnic panel that has contributed more widely to diabetes research in hard-to-reach groups.

Chapter 3 Trial results

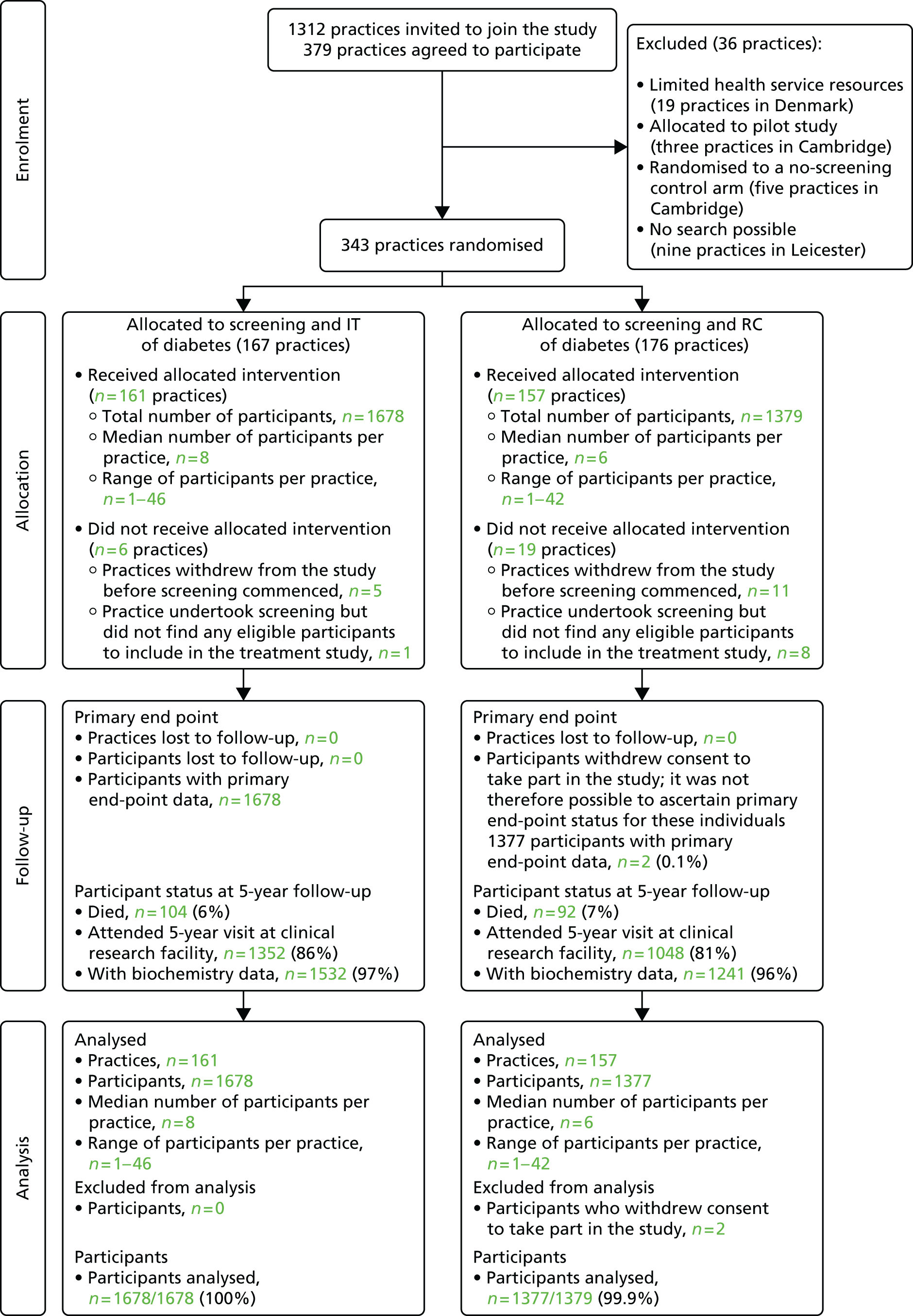

Of the 343 general practices that were randomised, 318 (RC, n = 157; IT, n = 161) completed screening and included eligible participants. Participating practices in the Netherlands and the UK have been described previously. 43,48,49 All four centres had a diabetes prevalence of 3.5% and a nationally representative mean patient list of ≈7000 individuals (n = 7378 RC group, n = 7160 IT group). Baseline sociodemographic, biochemical, clinical and treatment characteristics of individuals in the two randomised groups were well matched overall (see Table 3). However, more patients were identified in IT than in RC practices in Denmark (n = 910 and 623, respectively) and more IT than RC participants had a previous history of ischaemic heart disease [International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) codes I20–25: 11.2% vs. 8.5%, respectively] or other cardiac diagnoses (ICD-10 codes I30–I52: 8.4% vs. 4.5%, respectively). The mean age of ADDITION-Europe participants was 60 years and 58% were male, 94% were Caucasian and 41% were employed. Levels of CVD risk factors among participants at diagnosis were high and many participants were not receiving treatment for these risk factors. 50 Participant and practice flows are shown in Figure 1 (CONSORT diagram).

| Characteristic | RC | IT | Between-group difference in change from baseline to follow-up | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | |||||||||||

| % missing | n | % | % missing | n | % | % missing | n | % | % missing | n | % | Beta/OR | 95% CI | |

| Demographic variables | ||||||||||||||

| Male sex | 0 | 790 | 57.3 | – | – | – | 0 | 981 | 58.5 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Age at diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 0 | 60.2 | 6.8 | – | – | – | 0 | 60.3 | 6.9 | – | – | – | – | – |

| White ethnicity | 3 | 1246 | 93.4 | – | – | – | 4 | 1539 | 95.8 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Employed | 27 | 425 | 42.0 | – | – | – | 29 | 482 | 40.3 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Clinical variables | ||||||||||||||

| History of MI | 7 | 79 | 6.1 | – | – | – | 5 | 109 | 6.8 | – | – | – | – | – |

| History of stroke | 8 | 24 | 1.9 | – | – | – | 7 | 45 | 2.9 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Current smokers | 2 | 375 | 27.8 | 21 | 187 | 18.4 | 2 | 444 | 26.9 | 18 | 261 | 20.2 | 1.06 | 0.77 to 1.45 |

| Units of alcohol per week, median (IQR) | 14 | 4.0 | 1 to 13 | 22 | 3.0 | 0 to 10 | 11 | 4.0 | 1 to 13 | 19 | 3.0 | 0 to 10 | –0.24 | –0.77 to 0.29 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 3 | 31.6 | 5.6 | 14 | 31.0 | 5.6 | 4 | 31.6 | 5.6 | 11 | 31.1 | 5.7 | 0.03 | –0.17 to 0.22 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 3 | 90.3 | 17.6 | 7 | 88.4 | 17.8 | 4 | 90.9 | 17.5 | 5 | 89.1 | 18.2 | –0.02 | –0.58 to 0.55 |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 2 | 106.8 | 13.5 | 17 | 105.3 | 13.6 | 4 | 107.1 | 13.5 | 13 | 105.4 | 13.6 | –0.30 | –1.01 to 0.42 |

| HbA1c (%), median (IQR) | 6 | 6.6 | 6.1 to 7.3 | 5 | 6.5 | 6.1 to 7.1 | 5 | 6.5 | 6.1 to 7.3 | 4 | 6.4 | 6.0 to 6.9 | –0.08 | –0.14 to –0.02 |

| HbA1c (%), mean (SD) | 6 | 7.0 | 1.5 | 5 | 6.7 | 0.95 | 5 | 7.0 | 1.6 | 4 | 6.6 | 0.95 | –0.08 | –0.14 to –0.02 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 2 | 149.8 | 21.3 | 6 | 138.1 | 17.6 | 4 | 148.5 | 22.1 | 4 | 134.8 | 16.8 | –2.86 | –4.51 to –1.20 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 2 | 86.5 | 11.3 | 7 | 80.7 | 10.8 | 4 | 86.1 | 11.1 | 4 | 79.5 | 10.7 | –1.44 | –2.30 to –0.58 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 6 | 5.6 | 1.2 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 5 | 5.5 | 1.1 | 3 | 4.2 | 0.9 | –0.27 | –0.34 to –0.19 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l), median (IQR) | 7 | 1.2 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 7 | 1.3 | 1.1 to 1.6 | 7 | 1.2 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 4 | 1.2 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 0.00 | –0.03 to 0.02 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 10 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 9 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 10 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 6 | 2.1 | 0.8 | –0.20 | –0.26 to –0.13 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l), median (IQR) | 6 | 1.7 | 1.2 to 2.4 | 6 | 1.6 | 1.1 to 2.3 | 6 | 1.6 | 1.2 to 2.3 | 4 | 1.5 | 1.0 to 2.1 | –0.05 | –0.12 to 0.01 |

| Creatinine (µmol/l), mean (SD) | 8 | 84.9 | 18.6 | 6 | 79.8 | 29.9 | 7 | 83.4 | 17.1 | 5 | 81.0 | 30.5 | 1.81 | 0.10 to 3.53 |

| Self-reported medication | ||||||||||||||

| Any glucose-lowering drug | 3 | 7 | 0.5 | 6 | 681 | 56.4 | 4 | 8 | 0.5 | 3 | 990 | 65.0 | 1.53 | 1.25 to 1.89 |

| Number of glucose-lowering drugs, median (IQR) | 3 | 0 | 0 to 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 to 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 to 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 to 1 | – | – |

| Metformin | 3 | 5 | 0.4 | 6 | 583 | 48.3 | 4 | 6 | 0.4 | 3 | 835 | 54.8 | – | – |

| Sulphonylurea | 3 | 2 | 0.1 | 6 | 215 | 17.8 | 4 | 2 | 0.1 | 3 | 291 | 19.1 | – | – |

| Thiazolidinedione | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 50 | 4.1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 69 | 4.5 | – | – |

| Insulin | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 43 | 3.6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 96 | 6.3 | – | – |

| Other glucose-lowering drugs | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 31 | 2.6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 81 | 5.3 | – | – |

| Any antihypertensive drugs | 3 | 585 | 43.7 | 6 | 911 | 75.4 | 4 | 752 | 46.7 | 3 | 1274 | 83.6 | 1.61 | 1.27 to 2.04 |

| Number of antihypertensive drugs, median (IQR) | 3 | 0 | 0 to 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 to 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 to 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 to 3 | ||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 3 | 248 | 18.5 | 6 | 721 | 59.7 | 4 | 345 | 21.4 | 3 | 1126 | 73.9 | 1.84 | 1.52 to 2.22 |

| Beta-blocker | 3 | 252 | 18.8 | 6 | 285 | 23.6 | 4 | 366 | 22.7 | 3 | 462 | 30.3 | – | – |

| Calcium antagonist | 3 | 166 | 12.4 | 6 | 326 | 27.0 | 4 | 202 | 12.6 | 3 | 446 | 29.3 | – | – |

| Diuretic | 3 | 330 | 24.6 | 6 | 529 | 43.8 | 4 | 415 | 25.8 | 3 | 767 | 50.3 | – | – |

| Other antihypertensive drugs | 3 | 23 | 1.7 | 6 | 49 | 4.1 | 4 | 32 | 2.0 | 3 | 70 | 4.6 | – | – |

| Any cholesterol-lowering drugs | 3 | 206 | 15.4 | 6 | 889 | 73.6 | 4 | 274 | 17.0 | 3 | 1241 | 81.4 | – | – |

| Statins | 3 | 200 | 14.9 | 6 | 864 | 71.5 | 4 | 271 | 16.8 | 3 | 1217 | 79.9 | 1.46 | 1.20 to 1.78 |

| Aspirin | 3 | 169 | 12.6 | 6 | 504 | 41.7 | 4 | 249 | 15.5 | 3 | 1078 | 70.7 | – | – |

FIGURE 1.

Practice and participant flows in the ADDITION-Europe trial. Source: reproduced open access from Griffin et al. 55

Of those who were still alive in 2009, 2400 (84%) individuals returned to a clinical research facility for a 5-year follow-up health assessment. We obtained biochemical and clinical data from GP records for a further 328 (11.5%) participants. Compared with those with follow-up data, participants with missing data were more likely to be from an ethnic minority group (10.2% vs. 5.7%; p = 0.04) and to have higher cholesterol (5.9 mmol/l vs. 5.6 mmol/l; p = 0.004) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol values (3.7 mmol/l vs. 3.4 mmol/l; p = 0.009) at baseline.

Changes in biochemical, clinical and treatment variables in the two trial groups are shown in Table 3. Prescription of antihypertensive, glucose-lowering and lipid-lowering medication increased in both groups. At follow-up, compared with the RC group, approximately 10% more participants were prescribed glucose-lowering, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medication in the IT group. In addition, 15% more IT patients were prescribed ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and 30% more IT patients were prescribed aspirin at follow-up. Cardiovascular risk factors in both groups improved over 5 years of follow-up. The modest but statistically significant between-group differences in change from baseline for total and LDL cholesterol, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and HbA1c favoured the IT group.

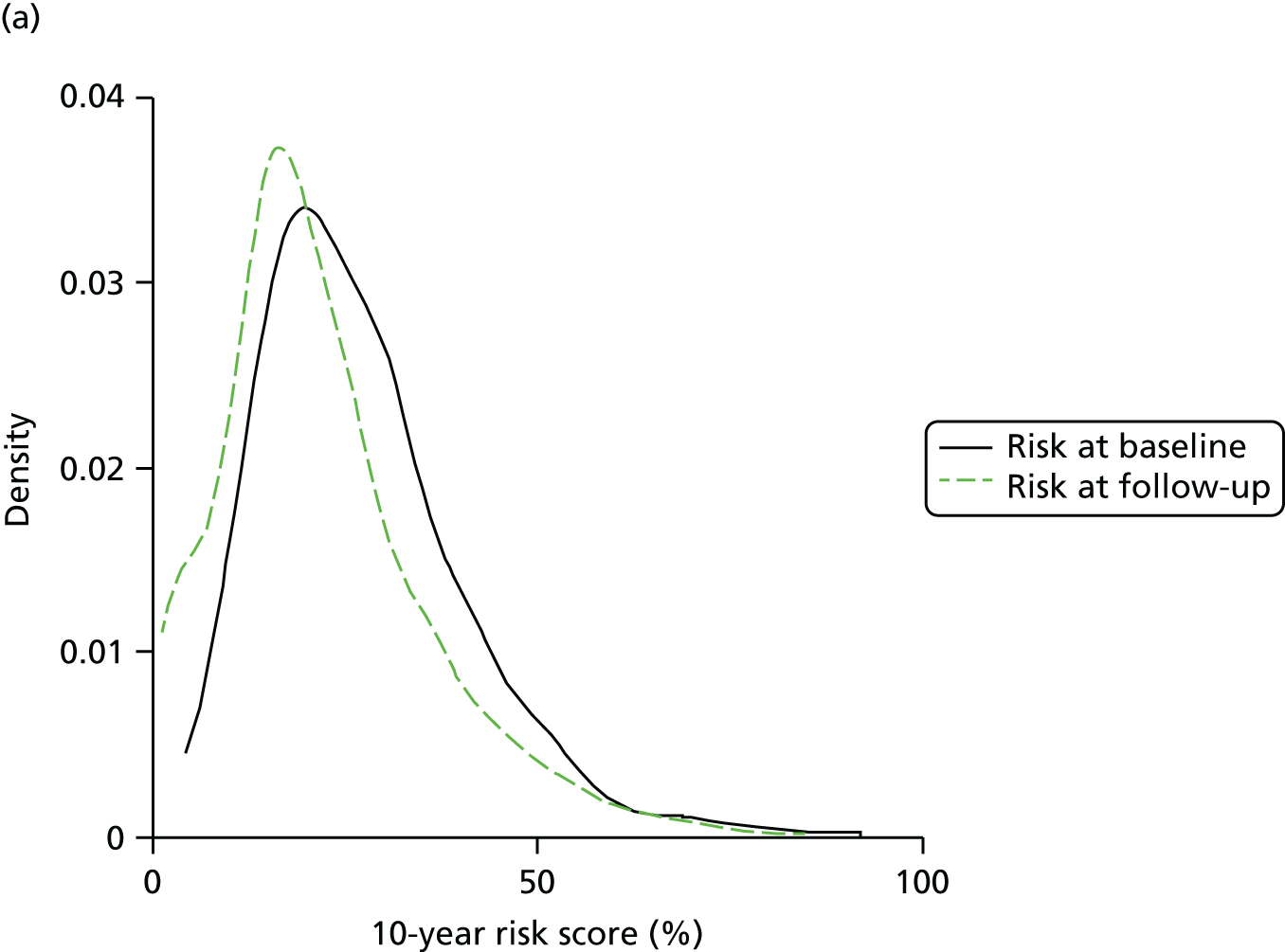

The 10-year modelled CVD risk was 27.3% (SD 13.9%) at baseline in the whole trial cohort and 21.3% (SD 13.8%) at 5 years. Across all four centres there was a reduction in modelled CVD risk from baseline to 5 years in both the RC group (–5.0%, SD 12.2%) and the IT group (–6.9%, SD 9.0%). Figure 2 shows the distribution of CVD risk at baseline and follow-up by treatment group; the distribution of modelled CVD risk shifted to the left for both groups.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of the UKPDS (version 3) modelled CVD risk score at baseline and 5 years’ follow-up in the ADDITION-Europe trial cohort by treatment group. (a) RC; and (b) IT. Source: reproduced open access from Black et al. 82

Within all four centres the modelled CVD risk was lower in the IT group than in the RC group at 5 years (Figure 3). The difference between the groups varied from –0.9% (95% CI –3.6% to 1.7%) in Cambridge to –4.8% (95% CI –8.4% to –1.3%) in the Netherlands. There was moderate variation between centres (I2 = 53.6%). For all centres combined, the 10-year modelled CVD risk was significantly lower (–2.0%, 95% CI –3.1% to –0.9%) in the IT group after adjustment for baseline cardiovascular risk and clustering by general practice.

FIGURE 3.

Difference in the UKPDS (version 3) modelled CVD risk score between treatment groups at 5 years’ follow-up in the ADDITION-Europe trial cohort, adjusted for baseline risk and accounting for clustering by general practice. Source: reproduced open access from Black et al. 82

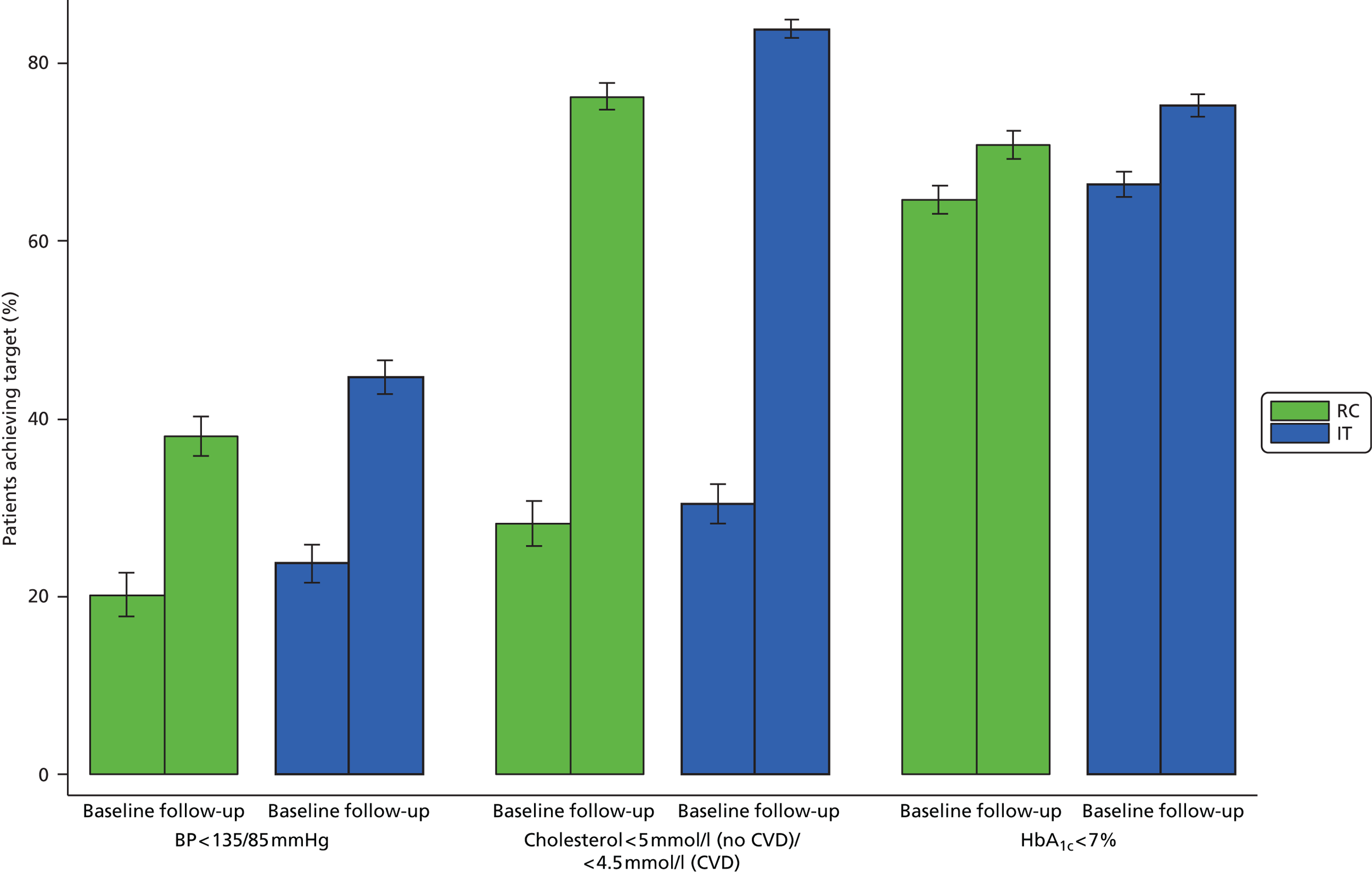

Figure 4 shows the percentage of participants meeting treatment targets for cholesterol, HbA1c and blood pressure in each group at baseline and follow-up. More patients met treatment targets at follow-up than at baseline in both groups. The proportion meeting the targets was higher in the IT group than in the RC group. There was no difference between groups in the percentage of those reporting hypoglycaemia (χ2 = 4.44; p = 0.62). 74 The results were the same when excluding participants with follow-up clinical data obtained from GP records.

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of participants in each group of the ADDITION-Europe trial (±1 SE) for whom the treatment targets were met at baseline and follow-up at a mean of 5.3 years. BP, blood pressure. Source: reproduced open access from Griffin et al. 55

Primary analyses: cardiovascular outcomes

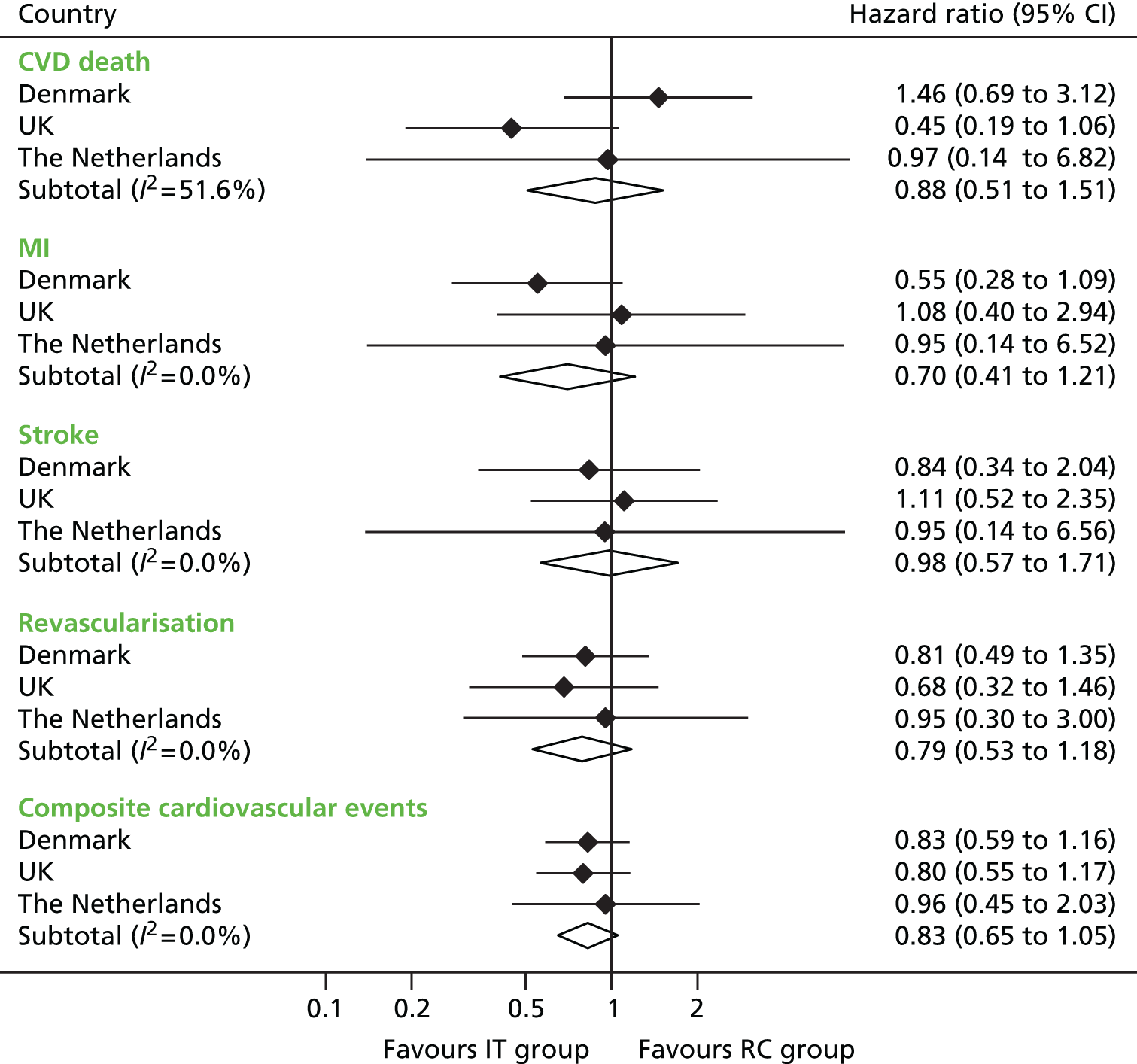

Primary end-point data were available for 99.9% (3055/3057) of participants. In total, 238 first cardiovascular events occurred during a mean (SD) follow-up period of 5.3 (1.6) years (Table 4). There were 121 events among 1678 participants (7.2%) in the IT group (incidence 13.5, 95% CI 11.3 to 16.1 per 1000 person-years) and 117 events among 1377 participants (8.5%) in the RC group (incidence 15.9, 95% CI 13.3 to 19.1 per 1000 person-years). The hazard ratio for the IT group compared with the RC group was 0.83 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.05; p = 0.12). The cumulative probability for the primary CVD end point appeared to diverge after 4 years of follow-up (Figure 5). In predefined subgroup analyses there were no interactions between the intervention and age or previous cardiovascular event (p > 0.1). The p-value was calculated using Cox regression and fixed-effects meta-analysis.

| End point | RC (n = 1377), n (%) | IT (n = 1678), n (%) | IT vs. RC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratioa | 95% CI | I2 (%)b | p-valuec | |||

| Primary end point: composite cardiovascular eventsd | 117 (8.5) | 121 (7.2) | 0.83 | 0.65 to 1.05 | 0 | 0.12 |

| Components of primary end point | ||||||

| CVD death | 22 (1.6) | 26 (1.5) | 0.88 | 0.51 to 1.51 | 52 | |

| MI | 32 (2.3) | 29 (1.7) | 0.70 | 0.41 to 1.21 | 0 | |

| Stroke | 19 (1.4) | 22 (1.3) | 0.98 | 0.57 to 1.71 | 0 | |

| Revascularisation | 44 (3.2) | 44 (2.6) | 0.79 | 0.53 to 1.18 | 0 | |

| Amputation | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| Total mortality | 92 (6.7) | 104 (6.2) | 0.91 | 0.69 to 1.21 | 55 | |

FIGURE 5.

Cumulative incidence of the composite cardiovascular end point in the RC and IT groups of the ADDITION-Europe trial (p = 0.12). Source: reproduced open access from Griffin et al. 55

However, estimated hazard ratios were 0.70 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.95) in those aged ≥ 60 years and 1.12 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.79) in those aged < 60 years. Hazard ratios for individual components of the composite end point all favoured the IT group (see Table 4), although none achieved statistical significance (Figure 6). There were no amputations as first events. The intracluster correlation coefficient for the primary end point was 0.002 (Denmark 0.014, UK 0.0000016, the Netherlands 0.025). This suggests that the cluster design had little effect on study power.

FIGURE 6.

The relative risk of the development of cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke and revascularisation as a first event and the composite cardiovascular end point by country and overall in the IT group compared with the RC group. Source: reproduced open access from Griffin et al. 55

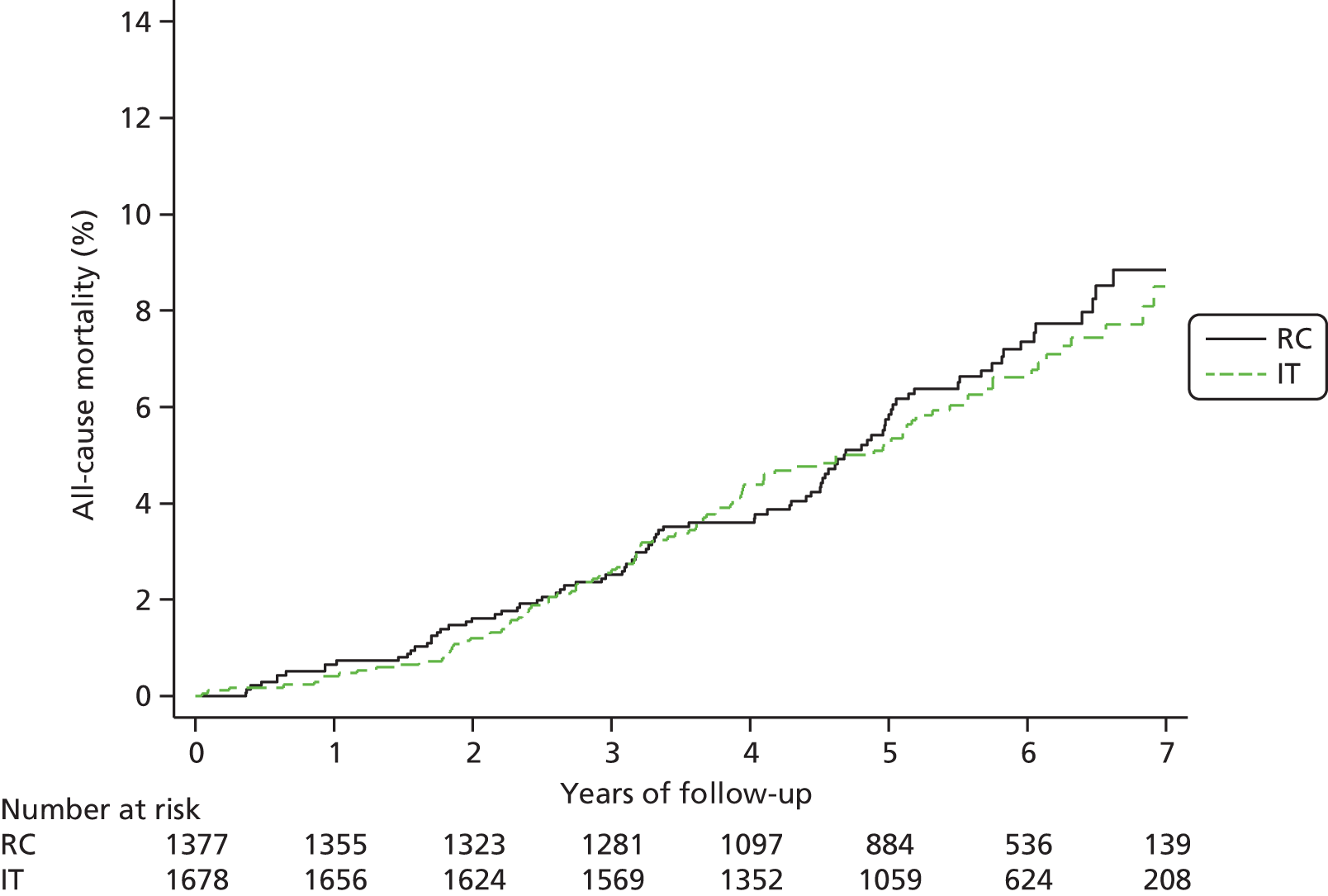

In total, there were 196 deaths (n = 60 cardiovascular, n = 97 cancer and n = 39 other), 104 (6.2%) in the IT group (mortality rate 11.6, 95% CI 9.6 to 14.0 per 1000 person-years) and 92 (6.7%) in the RC group (mortality rate 12.5, 95% CI 10.2 to 15.3 per 1000 person-years) (see Table 4). The combined mortality hazard ratio for the IT group compared with the RC group was 0.91 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.21). A Kaplan–Meier plot is shown in Figure 7 and country-specific hazard ratios in Figure 8. The heterogeneity of results between countries was not statistically significant. In the UK there were significantly fewer deaths in the IT group, whereas in Denmark there was a non-significant reduction in cumulative risk in the RC group.

FIGURE 7.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of all-cause mortality in the RC and IT groups in the ADDITION-Europe trial. Source: reproduced open access from Griffin et al. 55

FIGURE 8.

The relative risk of all-cause mortality by country and overall in the IT group compared with the RC group in the ADDITION-Europe trial. Source: reproduced open access from Griffin et al. 55

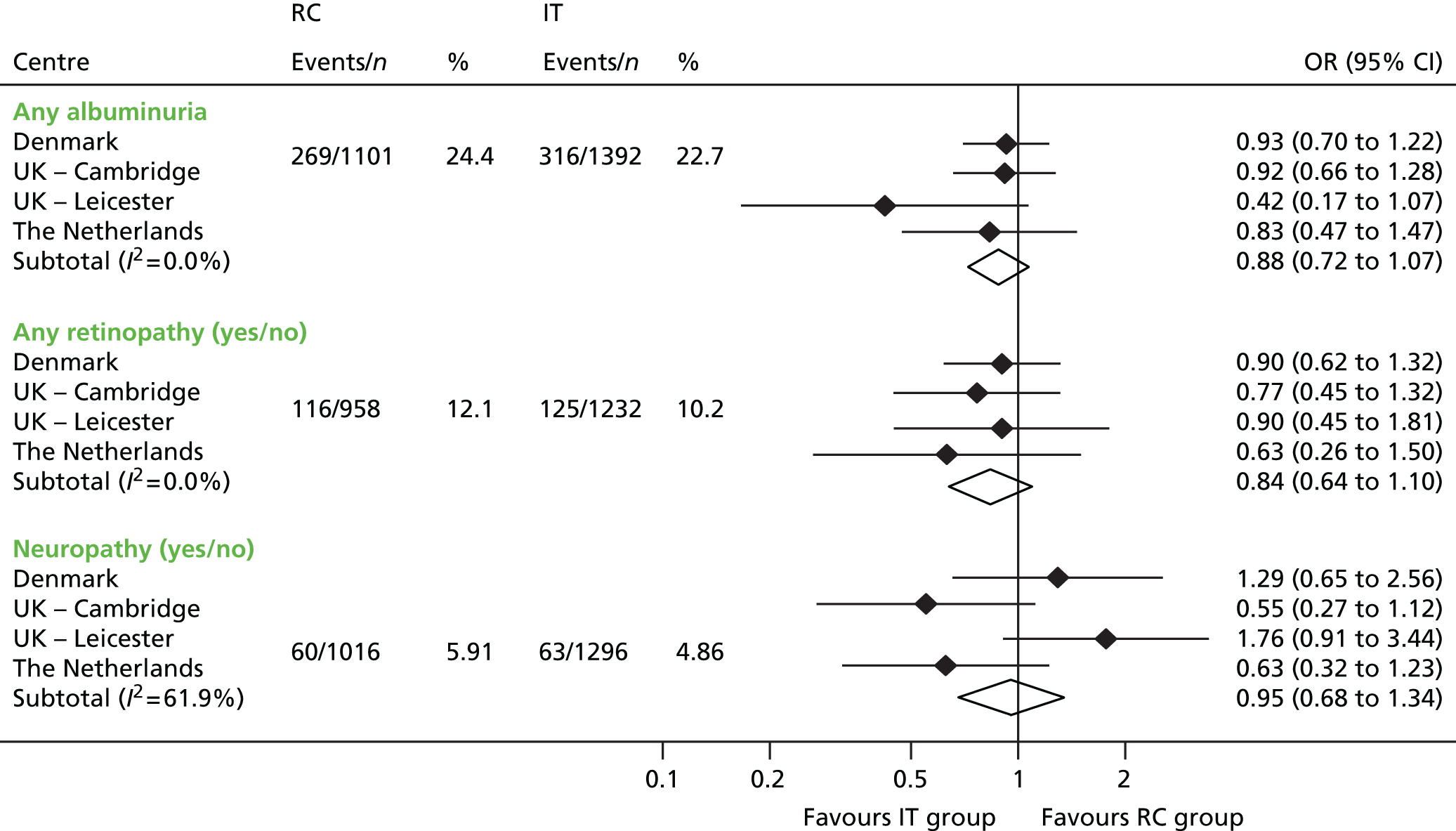

Secondary analyses: microvascular outcomes

Of the 2861 patients still alive at 5 years, 2493 (87.1%), 2710 (94.7%) and 2312 (80.8%) had data for urinary ACR, eGFR and peripheral neuropathy, respectively. Retinal photographs were retrieved for 2190 (76.5%) participants.

At 5 years’ follow-up any albuminuria was present in 316 (22.7%) participants in the IT group and 269 (24.4%) participants in the RC group. Macroalbuminuria was present in 56 (4.0%) and 37 (3.4%) participants in the IT and RC groups, respectively. Centre-specific ORs for any albuminuria favoured the IT group, but the pooled OR was not statistically significant (0.88, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.07; Figure 9). The pooled OR for macroalbuminuria was 1.15 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.74). In both groups the urinary ACR increased between baseline and follow-up. In the IT group the mean (SD) increase was 1.45 (SD 0.60) mg/mmol and in the RC group the mean (SD) increase was 1.30 (0.66) mg/mmol. The overall difference in means was –0.02 (95% CI –0.96 to 0.91) mg/mmol. There were no significant interactions between study group and any of the subgroups.

FIGURE 9.

Odds ratios and frequencies of any retinopathy, any peripheral neuropathy and any albuminuria at follow-up by study group in the ADDITION-Europe trial. Source: reproduced from Sandbæk et al. ,83 under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 licence (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

The mean (SD) eGFR increased between baseline and follow-up in both the IT group and the RC group [IT 4.31 (0.49) ml/minute, RC 6.44 (0.90) ml/minute; difference in means –1.39 (95% CI –2.97 to 0.19) ml/minute]. There were no significant interactions between treatment group and any of the subgroups concerning eGFR. The number of missing data was equally distributed between the two groups.

Retinopathy was present in 125 (10.1%) participants in the IT group and 116 (12.1%) patients in the RC group. Centre-specific ORs favoured the IT group but the pooled OR was not statistically significant (0.84, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.10) (see Figure 9). Imputation of missing values did not affect the estimates.

Individuals without retinal images at follow-up had significantly higher baseline mean HbA1c levels than individuals with retinal data [7.18% (55 mmol/mol) vs. 6.99% (53 mmol/mol), respectively; p = 0.044]. However, there was no difference between randomised groups (interaction p-value = 0.78). There was a significant interaction between retinopathy, randomised group and baseline HbA1c level (p = 0.007). IT appeared to be more effective among individuals with HbA1c ≥ 6.6% (≥ 49 mmol/mol) at baseline (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.93) than among individuals with HbA1c < 6.6% (< 49 mmol/mol) at baseline (OR 1.17, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.82). There was no evidence of an interaction with either age or sex. Severe retinopathy was present in one participant in the IT group and in seven participants in the RC group.

Peripheral neuropathy was present in 63 (4.9%) participants in the IT group and 60 (5.9%) participants in the RC group (pooled OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.34) (see Figure 9). Non-responders to the neuropathy questionnaire had a higher body mass index (p = 0.055) and were more likely to be from a ethnic minority group (p = 0.004) than responders. Imputation of missing values did not affect the estimates.

The overall intracluster correlation coefficient values were as follows: retinopathy 0.014 (95% CI 0.00017 to 0.55), albuminuria 0.025 (95% CI 0.0066 to 0.091) and neuropathy 0.011 (95% CI 4.6 × 10–7 to 1). These results indicate that the impact of clustering on study power was small.

Secondary analyses: patient-reported outcomes

Data from 2861 participants were included in the multiple imputation analyses. Patients who completed questionnaires at baseline and follow-up (n = 2217) were more likely than those who did not complete questionnaires (n = 644) to be male (59.5% vs. 50.8%), of white ethnicity (95.2% vs. 89.9%) and employed (44.8% vs. 32.7%). Questionnaire completers were also less likely to smoke (24.3% vs. 34.0%), had higher levels of alcohol consumption (median 5 units per week vs. 3 units per week) and had higher EQ-5D scores (median 0.85 vs. 0.81) at baseline. They also had lower systolic blood pressure levels (148.5 mmHg vs. 151.4 mmHg). Other characteristics were comparable between treatment groups (data not shown).

Table 5 shows the PROM scores at follow-up, separately for each centre and by randomised group. EQ-5D values did not change between diagnosis and follow-up: the median (interquartile range) score was 0.85 (0.73 to 1.00) at baseline and 0.85 (0.73 to 1.00) at 5 years’ follow-up.

| Measure | Centre | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | Cambridge | Leicester | The Netherlands | |||||||||||||

| IT | RC | IT | RC | IT | RC | IT | RC | |||||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| SF-36 | ||||||||||||||||

| PCS score | 665 | 46.7 (10.0) | 428 | 46.7 (9.6) | 350 | 43.9 (11.6) | 310 | 44.6 (11.3) | 59 | 44.3 (11.4) | 84 | 43.4 (10.5) | 177 | 46.8 (10.4) | 144 | 47.0 (10.5) |

| MCS score | 665 | 55.3 (9,1) | 428 | 54.9 (8.5) | 350 | 53.4 (9.0) | 310 | 54.6 (8.4) | 59 | 50.9 (10.1) | 84 | 52.2 (9.8) | 177 | 54.3 (8.2) | 144 | 53.7 (7.4) |

| EQ-5D score | 695 | 0.85 (0.21) | 463 | 0.84 (0.22) | 351 | 0.81 (0.23) | 312 | 0.83 (0.22) | 60 | 0.75 (0.31) | 85 | 0.79 (0.23) | 176 | 0.86 (0.18) | 144 | 0.82 (0.26) |

| EQ-VAS | 691 | 76.9 (16.9) | 462 | 76.4 (18.5) | 355 | 76.1 (18.0) | 316 | 78.4 (16.4) | 60 | 78.3 (16.3) | 88 | 74.8 (18.4) | 175 | 76.5 (13.7) | 144 | 75.3 (15.6) |

| W-BQ12 score | ||||||||||||||||

| General | 680 | 28.5 (5.9) | 447 | 28.1 (6.3) | 346 | 25.5 (6.5) | 310 | 26.4 (5.9) | 58 | 25.3 (6.7) | 78 | 25.0 (6.3) | 171 | 27.6 (6.3) | 141 | 27.4 (5.7) |

| Negative | 689 | 1.1 (2.0) | 458 | 1.1 (1.8) | 351 | 1.7 (2.4) | 314 | 1.4 (2.1) | 59 | 1.9 (2.5) | 86 | 2.1 (2.5) | 175 | 1.1 (1.9) | 143 | 1.1 (1.8) |

| Energy | 691 | 8.1 (2.7) | 453 | 8.0 (2.8) | 352 | 7.0 (2.7) | 315 | 7.3 (2.6) | 58 | 7.1 (2.7) | 82 | 7.1 (2.3) | 174 | 8.5 (2.6) | 142 | 8.5 (2.3) |

| Positive | 692 | 9.4 (2.5) | 456 | 9.2 (2.8) | 352 | 8.2 (2.8) | 315 | 8.4 (2.7) | 59 | 8.2 (2.6) | 85 | 8.0 (2.9) | 177 | 8.0 (3.1) | 144 | 8.1 (2.6) |

| ADDQoL score | 552 | –0.73 (1.15) | 348 | –0.69 (1.07) | 315 | –0.84 (1.29) | 271 | –0.87 (1.30) | 50 | –1.20 (1.78) | 76 | –2.39 (2.52) | 169 | –0.55 (0.86) | 135 | –0.55 (0.92) |

| DTSQ score | 648 | 30.9 (6.2) | 405 | 30.1 (6.7) | 344 | 31.5 (4.9) | 305 | 31.2 (5.4) | 60 | 33.0 (3.8) | 85 | 29.1 (7.3) | 174 | 31.2 (5.6) | 140 | 31.0 (5.6) |

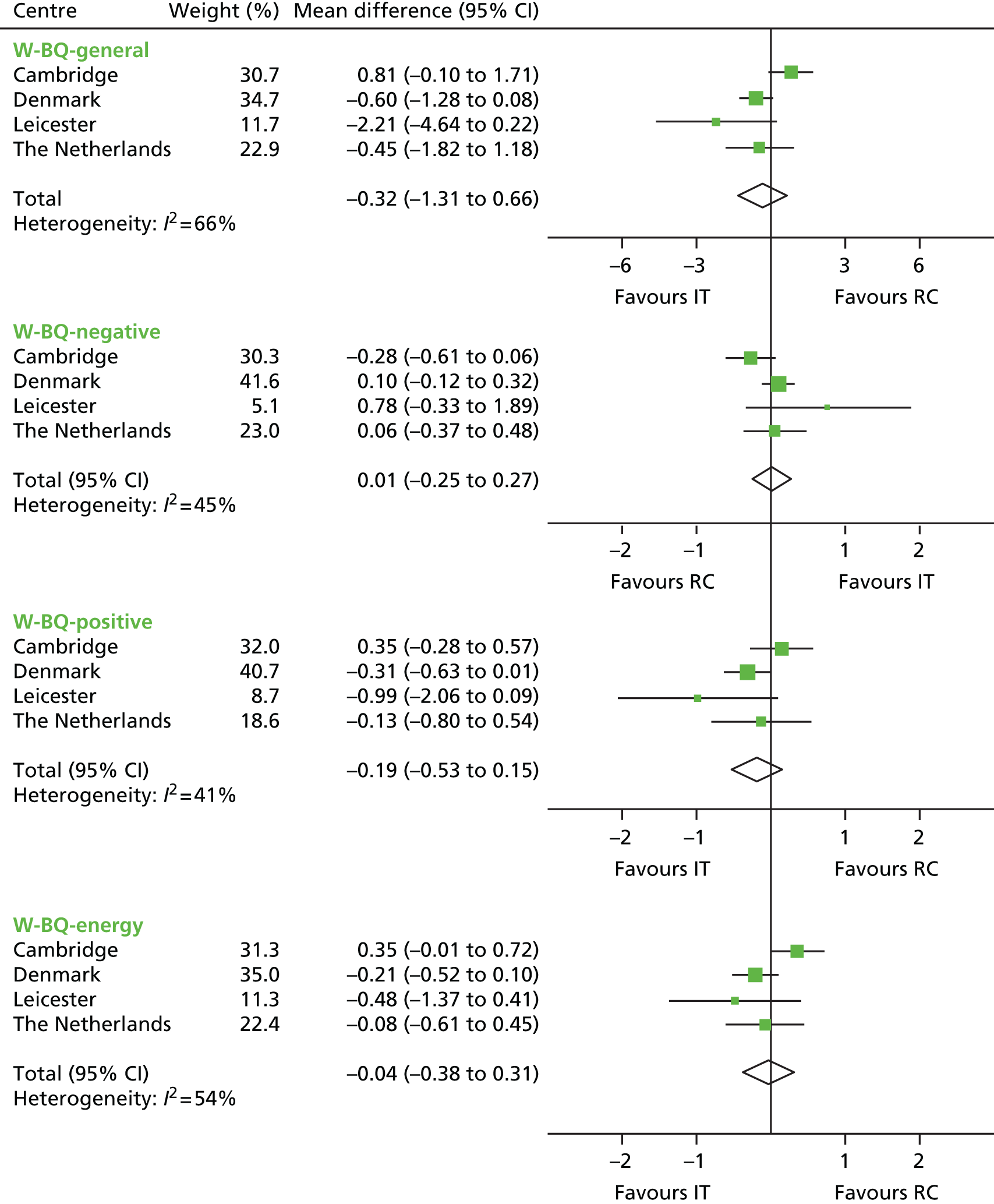

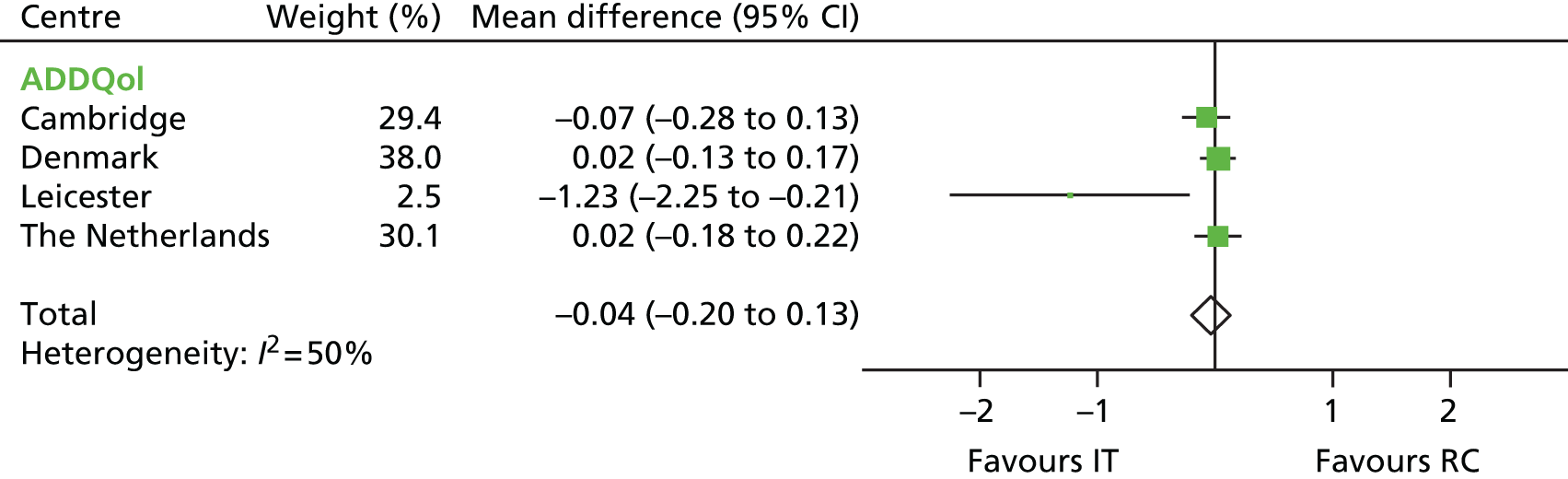

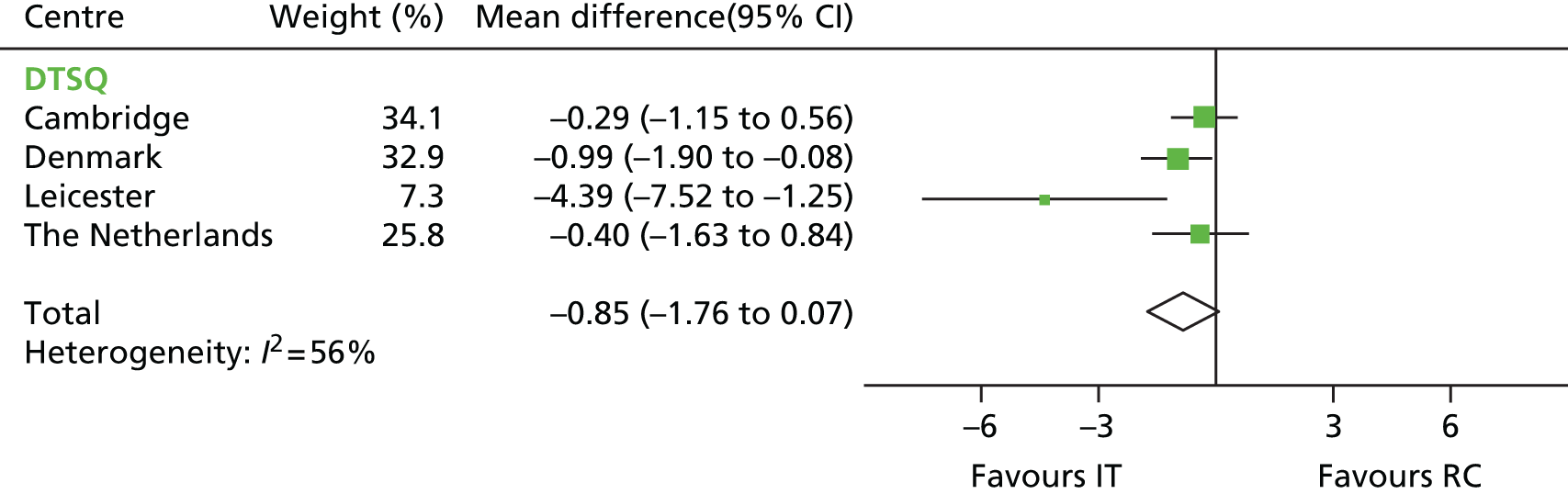

The mean differences in PROMs comparing the IT group with the RC group are shown in Figures 10–13. There were no statistically significant differences in health status (see Figure 10), well-being (see Figure 11), diabetes-specific quality of life (see Figure 12) and satisfaction with diabetes treatment (see Figure 13) between the two groups. There was some heterogeneity between centres. The I2-statistic varied between 41% (W-BQ-positive) and 73% (EQ-VAS).

FIGURE 10.

Mean difference in health status between the IT group and the RC group by centre (boxes) after 5 years’ follow-up in the ADDITION-Europe trial and pooled estimates (diamonds) calculated by random-effects meta-analysis. Horizontal bars and diamond widths denote 95% CIs and box sizes indicate relative weight in the analysis. MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary. Source: reproduced from van den Donk et al. ,84 under the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial licence.

FIGURE 11.

Mean difference in W-BQ12 scores between the IT group and the RC group by centre (boxes) after 5 years’ follow-up in the ADDITION-Europe trial and pooled estimates (diamonds) calculated by random-effects meta-analysis. Horizontal bars and diamond widths denote 95% CIs and box sizes indicate relative weight in the analysis. Source: reproduced from van den Donk et al. ,84 under the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial licence.

FIGURE 12.

Mean difference in ADDQoL scores between the IT group and the RC group by centre (boxes) after 5 years’ follow-up in the ADDITION-Europe trial and pooled estimates (diamonds) calculated by random-effects meta-analysis. Horizontal bars and diamond widths denote 95% CIs and box sizes indicate relative weight in the analysis. Source: reproduced from van den Donk et al. ,84 under the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial licence.

FIGURE 13.

Mean difference in DTSQ scores between the IT group and the RC group by centre (boxes) after 5 years’ follow-up in the ADDITION-Europe trial and pooled estimates (diamonds) calculated by random-effects meta-analysis. Horizontal bars and diamond widths denote 95% CIs and box sizes indicate relative weight in the analysis. Source: reproduced from van den Donk et al. ,84 under the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial licence.

Multiple imputation analyses resulted in slightly different point estimates. However, the overall patterns remained the same and there were no statistically significant differences in any of the PROMs (results not shown).

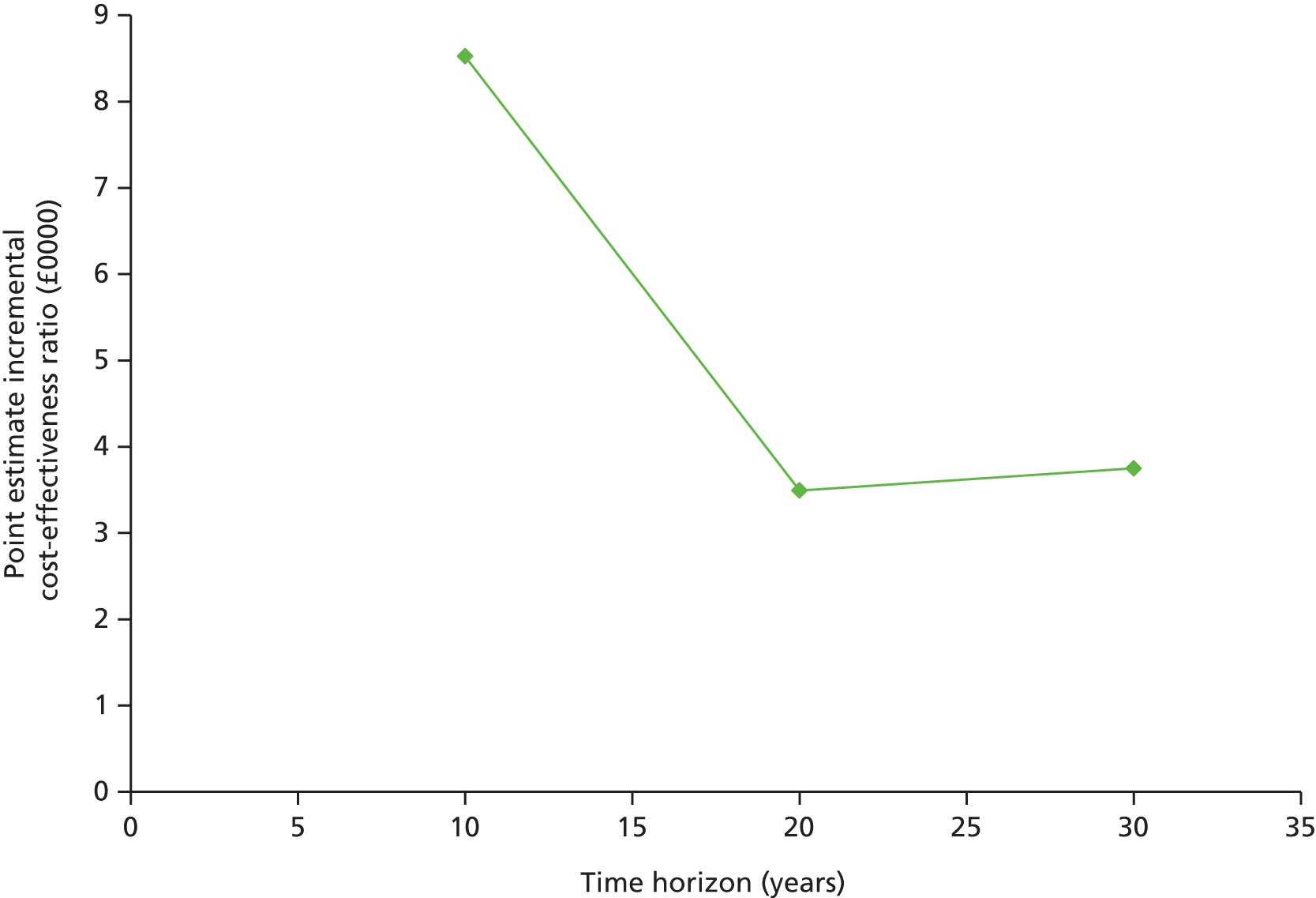

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

This chapter reports two analyses related to the cost-effectiveness of early IT of type 2 diabetes. First, we assessed the performance of the UKPDS outcomes model [UKPDS-OM, version 1.3; © Isis Innovation Ltd 2010; see www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/outcomesmodel (accessed 27 January 2016)]85 in predicting CVD risk in the ADDITION-Europe population; we wanted to investigate its suitability for modelling longer-term outcomes and costs for the ADDITION-Europe cohort. The second analysis concerns the short-term (1–6 years within-trial analysis) and long-term (10–30 years based on decision modelling) cost-effectiveness of the ADDITION intervention in the UK from a UK payer (NHS) perspective.

Validating the UK Prospective Diabetes Study outcomes model

Accurate prediction of cardiovascular risk among individuals with diabetes is important for providing prognostic information and targeting treatment to those at highest risk. It is also a key component of economic evaluations of interventions aimed at reducing the disease burden of diabetes and improving the quality and length of life for those with this chronic condition.

The UKPDS-OM is a cost-effectiveness analysis tool. It was derived from the UKPDS, a multicentre randomised controlled trial among 5102 individuals with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. 85 Participants were recruited from 23 UK centres. 86 The UKPDS-OM has been validated for the prediction of CVD and other complications in internal and external cohorts of people with clinically diagnosed diabetes. The observed and predicted cumulative incidence of CVD complications from diagnosis to 12 years’ follow-up were very similar when using an internal cohort. 85 Results varied from poor to moderate in terms of discrimination, calibration and absolute risk for external cohorts,87,88 with the UKPDS-OM tending to overestimate CVD risk. 89

The UKPDS-OM was developed using data from individuals recruited between 1977 and 1997. The treatment and costs of diabetes and related complications have changed since this time. The variables assessed by the model are also likely to vary over time and between countries. As such, we aimed to evaluate the performance of the UKPDS-OM in the ADDITION-Europe study, which included a multinational contemporary cohort of individuals with screen-detected diabetes.

Methods

The 5-year accumulated absolute risks of MI and stroke were estimated for each participant in the ADDITION-Europe study using the UKPDS-OM. 85 The model includes information on age at diagnosis, sex, ethnicity, duration of diabetes, weight, height, smoking status, presence or absence of AF, PVD, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and years since pre-existing CVD events. Values for smoking status, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol were included at both baseline and 5 years’ follow-up.

As information on AF and PVD were not collected at baseline in the ADDITION-Europe study, and given that all patients had newly diagnosed diabetes, these variables were set to 0. The number of years since pre-existing ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, amputation, blindness and renal failure were also set to 0 as this information was also not collected at baseline. Data on the number of years since any previous MI or stroke were collected in the ADDITION-Europe study and entered as appropriate into the model. As revascularisation is not a component of the UKPDS-OM and only a single case of amputation was reported during follow-up in the ADDITION-Europe study, only MI and stroke events were examined in this analysis.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the observed and predicted risk of non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke by country and trial group using the UKPDS-OM. We employed multiple imputation to deal with missing data90 using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method and assuming an arbitrary missing pattern. A multivariate normal distribution was used to impute missing values for age, sex, weight, height, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure and HbA1c. It has been previously demonstrated that multivariate normal imputation is less biased than complete-case analysis91 and produces similar results to other approaches despite the presence of binary and ordinal variables that do not follow a normal distribution. If the imputed HDL cholesterol value was greater than the total cholesterol value (five cases at baseline; one case at final follow-up), we assumed that HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) = total cholesterol – 0.1. For each patient with missing data we undertook five imputations and computed the average of the five risk estimates. 92

In the UKPDS-OM the categories of the variable ethnicity were white-Caucasian, Afro-Caribbean, and Asian-Indian. In the ADDITION-Europe cohort there were some unknown or unclassifiable values, for example mixed white + African, mixed white + Asian or others. These cases were unavoidably excluded from the analysis as ethnicity is improper for multiple imputation (156 cases).

We examined the discrimination of the UKPDS-OM by computing the area under the receiver operating characteristic (aROC) curve and assessed goodness of fit using the Hosmer–Lemeshow chi-square test. The same methods have been employed in previous studies for the validation of the UKPDS and Framingham risk engines. 87,88,93

In the UKPDS-OM, both MI and stroke are assigned a particular Weibull regression equation with age, sex, HbA1c and other variables as covariates. 85 To examine which distribution was the best fit for baseline risk of MI and stroke, we performed a number of survival regression analyses including exponential, log-normal, log-logistic, Weibull and generalised gamma. We computed minimal Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) values to assess global model fit. 94 We then analysed the covariates with the best fit distribution to determine if they were significantly associated with MI and stroke. A p-value of < 0.10 was defined as statistically significant. 95 As risk factor values were not available for every year of follow-up in the ADDITION-Europe trial cohort, the average of the baseline and final follow-up values was used.

We also conducted a complete-case sensitivity analysis to examine whether or not the results were replicated after excluding patients for whom there were missing data (n = 781/2899; 26.9%). Statistical analyses were performed with SAS v9.3.

Results

Of the 3055 ADDITION-Europe participants, 156 were excluded as a result of unclassifiable or unknown ethnicity. Baseline values for age, sex, treatment group and HbA1c did not differ significantly between the included and excluded patients.

Observed and predicted risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction and stroke

The non-fatal MI and stroke rates for the ADDITION-Europe participants were 0.0228 and 0.0152, respectively. The observed risks of MI and stroke were lower than the predicted risks using the UKPDS-OM. When the data were broken down by country, overestimation was greater in the Dutch population than in the Danish and UK populations for both non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke (Table 6).

| Event | Centre | Intervention | Total n | Number of events | Observed risk (95% CI) (%) | Average predicted risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-fatal MI | All | RC | 1314 | 39 | 2.97 (2.12 to 4.04) | 6.86 |

| IT | 1585 | 27 | 1.70 (1.13 to 2.47) | 6.77 | ||

| Denmark | RC | 601 | 25 | 4.16 (2.71 to 6.08) | 6.46 | |

| IT | 851 | 14 | 1.65 (0.90 to 2.74) | 6.16 | ||

| The Netherlands | RC | 212 | 2 | 0.94 (0.11 to 3.37) | 8.45 | |

| IT | 236 | 2 | 0.85 (0.10 to 3.03) | 8.74 | ||

| UK | RC | 501 | 12 | 2.40 (1.24 to 4.15) | 6.67 | |

| IT | 498 | 11 | 2.21 (1.12 to 3.92) | 6.87 | ||

| Non-fatal stroke | All | RC | 1314 | 19 | 1.45 (0.87 to 2.25) | 2.30 |

| IT | 1585 | 25 | 1.58 (1.02 to 2.32) | 2.34 | ||

| Denmark | RC | 601 | 8 | 1.33 (0.58 to 2.61) | 2.24 | |

| IT | 851 | 12 | 1.41 (0.73 to 2.45) | 2.05 | ||

| The Netherlands | RC | 212 | 2 | 0.94 (0.11 to 3.37) | 3.00 | |

| IT | 236 | 2 | 0.85 (0.10 to 3.03) | 3.63 | ||

| UK | RC | 501 | 9 | 1.80 (0.82 to 3.38) | 3.08 | |

| IT | 498 | 11 | 2.21 (1.11 to 3.92) | 2.21 |

Examination of the absolute event rates between intervention groups represents the impact of IT compared with RC. For non-fatal MI, the difference between intervention groups was higher than that predicted by the UKPDS-OM, suggesting that the UKPDS-OM underestimated the effect of IT. For non-fatal stroke, the difference was much smaller between the observed and predicted data, indicating only a slight overestimation (see Table 6).

Discrimination analysis

The aROC curve was 0.72 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.79) for non-fatal MI and 0.70 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.77) for non-fatal stroke, suggesting that the UKPDS-OM had moderate discriminatory ability. The Netherlands had the lowest aROC curve for MI (0.69) and the highest for stroke (0.79). Results from the Hosmer–Lemeshow test were non-significant in the overall trial cohort and in each country, suggesting that the goodness of fit was acceptable (Table 7).

| Event | Centre | aROC curve (95% CI) | Chi-square value from the Hosmer–Lemeshow test | p-value from the Hosmer–Lemeshow test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI | All centres | 0.72 (0.66 to 0.79) | 9.79 | 0.28 |

| Denmark | 0.76 (0.66 to 0.85) | 7.61 | 0.47 | |

| The Netherlands | 0.69 (0.45 to 0.94) | 7.11 | 0.53 | |

| UK | 0.70 (0.59 to 0.81) | 8.01 | 0.43 | |

| Stroke | All centres | 0.70 (0.64 to 0.77) | 9.10 | 0.33 |

| Denmark | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.84) | 7.59 | 0.47 | |

| The Netherlands | 0.79 (0.55 to 1.00) | 7.17 | 0.52 | |

| UK | 0.65 (0.54 to 0.76) | 6.07 | 0.64 |

Survival regression analysis

Following survival analysis, an exponential distribution was the best for baseline risk for both MI and stroke based on BIC values. For AIC values, log-normal and exponential distributions provided the best fit for MI and stroke, respectively. As such, we used the exponential distribution in survival regression analysis with a selection of different covariates: age, sex, treatment group, smoking status, body mass index, HbA1c level, systolic blood pressure and ln(total cholesterol/HDL) for MI or total cholesterol/HDL for stroke. Age, sex and HbA1c level were significantly associated with non-fatal MI; age and sex were significantly associated with non-fatal stroke (Table 8).

| Event | Distribution | BIC | AIC | Covariates significant (p > 0.10) from the exponential distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI | Gamma | 656.12 | 585.50 | Age, sex, HbA1c |

| Exponential | 641.45 | 583.43 | ||

| Log-logistic | 648.95 | 585.13 | ||

| Log-normal | 646.98 | 583.16 | ||

| Weibull | 649.24 | 585.43 | ||

| Stroke | Gamma | 434.02 | 364.41 | Age, sex |

| Exponential | 418.54 | 360.50 | ||

| Log-logistic | 426.21 | 362.39 | ||

| Log-normal | 426.27 | 362.45 | ||

| Weibull | 426.21 | 362.40 |

Complete-case analysis

In total, 2118 (out of 2899) participants were included in the complete-case analysis. Compared with participants excluded because of missing data, the included participants had a slightly lower mean age (60.09 vs. 60.84 years) and a higher mean HbA1c value (7.06% vs. 6.96%); there was also a higher proportion of men (59.0% vs. 55.3%) among the included participants. The results were generally similar to the results of the main imputed analysis in terms of observed and predicted risk and best fit distribution. The one exception was for the survival analysis, for which sex no longer remained significantly associated with stroke and HbA1c became significant.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

In our second analysis we aimed to examine the short- and long-term cost-effectiveness of IT compared with RC among people with screen-detected type 2 diabetes.

Methods

This analysis used data from the two UK centres (Cambridge and Leicester) in the ADDITION-Europe trial.

Costs