Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 05/501/04. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The draft report began editorial review in January 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The probiotic and placebo used in this trial were manufactured and transported to the UK free of charge by the Yakult Honsha Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan. The company had no involvement in the trial design or conduct or in the analysis and interpretation of the data, nor has the chief investigator had any direct contact with the company. Edmund Juszczak has been a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board since November 2013. Michael Millar was a member of the Diagnostic and Screening panel of the HTA throughout the trial. Peter Brocklehurst has been chairperson of the HTA Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health panel since December 2014. He received money from Oxford Analytica for consultancy and as chairperson of the Medical Research Council Methodology Research Programme panel; his Institution received money from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for his role as lead for maternal health review updates and for evidence updates of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance during the conduct of the trial. He also reports that his institution received money for numerous Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research and National Institute for Health Research HTA programme grants.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Costeloe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This is a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial to study possible benefits of the early administration of the probiotic Bifidobacterium breve strain BBG-001 to babies born before 31 weeks’ gestation and recruited within 48 hours of birth. The primary end points are late-onset bloodstream infection diagnosed on a sample drawn after 72 hours, necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) and death. The trial aimed to recruit 1300 babies from approximately 20 UK neonatal units.

Chapter 2 Scientific background

Acquired infection and necrotising enterocolitis in preterm babies

Hospital-acquired infection is reported in about 25% of babies with birthweight < 1500 g who survive the first 3 days,1 and it contributes to the high mortality and morbidity in this population.

Necrotising enterocolitis is the most common serious gastrointestinal complication of preterm birth and has high mortality and morbidity. 2,3 The pathogenesis of NEC is multifactorial,4 related to immaturity of the immunological and barrier functions and involving bacterial invasion of the intestinal mucosa. There is no agreed international diagnostic case definition for NEC; the system most widely used is the ‘modified’ Bell classification,5 which involves a range of clinical, haematological and radiological criteria. Bell stage 1 is very non-specific, whereas Bell stages 2 and 3 have more objective radiological features and are often considered interchangeable with the terms ‘proven, confirmed or serious’ NEC used in some publications. Estimates of the incidence of ‘confirmed’ NEC in babies with a birthweight of < 1500 g vary between about 6% and 10%.

The microbiome in the newborn baby and its relation to late-onset sepsis and necrotising enterocolitis

The microbiome is the term used to describe the population of micro-organisms with which individual humans co-exist, predominantly within the bowel. Healthy breastfed term infants become colonised early in life with a wide range of bacteria dominated by bifidobacteria and lactobacilli acquired during and after birth from close contact with the mother;6 these microbes are believed to confer a range of health benefits. By comparison, preterm infants nursed in neonatal units become colonised with a more limited range of bacteria and fungi. 7–9 The pattern of colonisation reflects the micro-organisms found in the ‘antibiotic-rich’ environment of the neonatal unit and is dominated by members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, Pseudomonas, enterococci, yeasts, staphylococci and clostridia that are potentially pathogenic and may cause infection in the colonised infant or may spread and cause disease in other infants.

The specific mechanisms by which anaerobic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria protect against infection with pathogenic organisms are believed to involve increased secretion of immunoglobulin A and upregulation of immunoglobulin A receptor sites, strengthening of epithelial tight junctions, lowering the intraluminal pH through acid fermentation and modification of intestinal inflammatory responses through preferential stimulation of T-helper cells, all resulting in reduced bacterial translocation. 10 This subject has been the focus of a number of reviews. 11–13

The extent to which abnormal patterns of early colonisation of the intestine have deleterious effects on later health is also incompletely understood. A number of recent studies have shown changes in the patterns of stool bacterial colonisation in the period preceding the clinical onset of NEC and late-onset sepsis,14–17 but whether or not these changes are causative or part of the disease process is unclear.

For the context of this trial a probiotic is defined as a live microbial supplement that colonises the gut and improves health. 18

The extent to which intestinal colonisation with probiotic bacteria can be achieved in the preterm newborn baby is unclear. However, the concept of active management of the bowel flora to prevent hospital-acquired infection and NEC is an attractive therapeutic option that seems likely to have a good safety profile.

Probiotics and the prevention of late-onset sepsis and necrotising enterocolitis

Randomised controlled trials

When the Probiotics in Preterm infantS (PiPS) trial was designed, we believed that only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) had been published that reported the effect of probiotics on late-onset sepsis and/or NEC in preterm babies. This was an Italian trial published in 2002 and involving 585 babies below 33 weeks’ gestational age19 treated with a product containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. It failed to show a significant reduction in NEC incidence or blood culture-positive episodes of late-onset sepsis (probiotic vs. placebo: NEC, 1.4% vs. 2.7%; septic episodes, 4.1% vs. 4.7%). The results are difficult to interpret, as the analysis was not by intention to treat; babies dying in the first 2 weeks were excluded and only septic episodes and episodes of NEC with onset at least 7 days after commencement of the intervention were considered in the analysis. This probably accounts for the low reported rates of adverse outcomes.

When recruitment to the PiPS trial began in 2010, four20–23 further trials with clinical primary outcomes had been published.

The first two trials were reported in 2005 and showed a reduction in the incidence of NEC in infants given probiotic mixtures; both studies recruited at a single site. The first was from a hospital in Taiwan,20 in which a mixture of L. acidophilus and B. infantis or placebo was given in breast milk twice daily until discharge from hospital to 367 babies of birthweight < 1500 g, who had survived beyond 7 days and were clinically stable with umbilical lines removed and commencing milk feeds. Reductions in incidence were seen for NEC, from 5.3% to 1.1% (p = 0.04); blood culture-positive late-onset sepsis, from 19.3% to 12.2% (p = 0.03); death, from 10.7% to 3.9% (p = 0.009); and for the combined outcome of NEC, late-onset sepsis or death from 32.1% to 17.2% (p = 0.009). The second study21 recruited 145 babies at an Israeli hospital, who were randomised to receive a product containing three probiotic strains (B. infantis, Streptococcus thermophilus and B. bifidus) or unsupplemented milk feeds given once a day. The median age at commencement of the intervention was 3 days and the intervention was continued until 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. There was no difference in episodes of blood culture-positive infection or of death, but episodes of NEC appeared to be reduced in the intervention arm (16.4% vs. 4.0%; p = 0.03) and it was reported that there was a reduction in the severity of the illness. These two studies, the first to report prevention of NEC, were subject to considerable interest and extensive review. 24–26

In 2007 a meta-analysis27 was published including these three trials19–21 together with four others designed to study different outcomes, one of which involved a fungal rather than a bacterial intervention. 28 A total of 1393 babies were involved, and the conclusion was that there was evidence that probiotic interventions might reduce the incidence of NEC and all-cause mortality, apparently without adverse effects, but that there were important outstanding questions about choice of probiotic product and dosing.

The third and fourth RCTs with clinical primary outcomes were published in 2008 and 2009, a single-site trial from a hospital in India22 and a multicentre trial from Taiwan. 23 In the trial from India, a combination of B. infantis, B. bifidum, B. longum and L. acidophilus given with breast milk twice daily to 186 babies of < 32 weeks’ gestation and birthweight < 1500 g was compared with breast milk alone. Participants were clinically stable and, as in the previous studies, receiving milk feeds. The end points included feed tolerance, length of stay and serious neonatal morbidities. Babies dying from causes other than late-onset sepsis or NEC were excluded and no power calculation was given. A significant reduction in time to achieve full feeds and length of stay was reported to be associated with probiotic use. There was an overall reduction in all stages of NEC from 15.8% in the control group to 5.5% in the probiotic group (p = 0.04), but no significant reduction in the incidence of NEC of Bell stage ≥ 2. There was a significant reduction in culture-positive late-onset sepsis, from 29.5% to 14.3% (p = 0.02), and of death, from 14.7% to 4.4% (p = 0.04).

The multicentre trial from Taiwan23 recruited a total of 434 babies of birthweight < 1500 g and gestational age < 4 weeks from seven centres. A product containing B. bifidum and L. acidophilus was added to the milk feed; babies entirely fed with formula were excluded, as were babies in whom feeds had not been started by 3 weeks of age. There was a composite primary outcome, death or NEC Bell stage ≥ 2, which was significantly lower in the intervention group (1.8% vs. 9.2%; p = 0.002). In addition, there were more babies with late-onset sepsis in the intervention group (18.4% vs. 11.1%.) A large number of infants died (98 out of a potential 580 eligible infants) without ever achieving the study entry criteria.

In the period leading up to the start of recruitment to the PiPS trial in 2010 and during recruitment there have been sharp divisions in the paediatric literature about the use of probiotics. Some authors have strongly advocated a change of practice to routine use29 because of the apparent association with a reduction in NEC and death, as suggested in a series of meta-analyses,30–32 whereas others have recommended caution because of the heterogeneity of the participants and of the interventions and the methodological failings of some trials. 33,34

At the time of writing, 11 RCTs designed to study the efficacy of a bacterial probiotic intervention, with late-onset sepsis and/or NEC and/or death as the primary outcome, have been published in English. These trials account for 4396 of the 5529 (80%) babies randomised in 20 trials included in the most recent Cochrane review of probiotics to prevent NEC in preterm babies. 35 These trials are characterised by a range of inclusion and exclusion criteria and by varying exposure to maternal breast milk. This may, in part, explain the wide reported ranges of rates of late-onset sepsis, NEC and death. Of those studies reporting such data, mortality and NEC rates among excluded infants are in some cases high (Table 1). The extent to which reviews such as this may be subject to publication bias is difficult to assess owing to the inclusion of a large number of trials. Many of which are small and not designed to study clinical outcomes.

| Reference | Eligibility criteria | Exclusions (other than congenital malformations and lack of consent) and their outcomes if available | Intervention including whether or not in milk | Placebo | Blind | Age at starting intervention | Rates of late-onset sepsis, NEC and death in non-intervention group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dani et al. 200219 | < 33 weeks old and < 1500 g in weight; randomised, n = 585 | Death within 2 weeks of birth, n = 29 | Lactobacillus GG with milk | Yes | Yes | Mean 3.4 days (SD 3.7 days) | After 7 days of intervention: late-onset sepsis, 12 of 290; NEC, 8 of 290; death, N/A |

| Bin-Nun et al. 200521 | < 1500 g in weight; randomised, n = 148 | N/A | B. bifidus, B. infantis and S. thermophilus with milk | No | Yes | Mean 2.7 daysa (SD 2.3 days) | Late-onset sepsis, 24 of 73; NEC, 12 of 73; death, 8 of 73 |

| bLin et al. 200520 | > 7 days old, < 1500 g in weight, central lines removed > 24 hours; randomised, n = 367 | 50 of 417 potential recruits died or had NEC < 7 days | L. acidophilus and B. infantis with breast milk | No | Unclear | N/A, but after 7 days | Late-onset sepsis, 36 of 187; NEC, 10 of 187; death, 20 of 187 |

| Lin et al. 200823 | < 34 weeks old, < 1500 g in weight ‘who survived to feed enterally’; randomised, n = 443 | Exclusive formula feeds, nil by mouth > 3 weeks, 98 of 580 assessed for eligibility died before milk started | L. acidophilus and B. bifidum with breast milk | No | Unclear | Mean 4.5 daysa (SD 3.0 days) | Late-onset sepsis, 24 of 217; NEC, 14 of 217; death, 9 of 217 |

| cSamanta et al. 200922 | < 32 weeks old, < 1500 g in weight, survived 48 hours; randomised, n = 186 | Died from ‘other’ illnesses | B. infantis, B. bifidum, B. longum and L. acidophilus with breast milk | No | Not known | Mean 6.0 daysd (SD 1.4 days) | Late-onset sepsis, 28 of 95; NEC, 15 of 95; death, 14 of 95 |

| Mihatsch et al. 201036 | < 30 weeks old; randomised, n = 183 | None | B. lactis BB12 with milk | Yes | Yes | Mean 5 days (SD 2.7 days) | Late-onset sepsis, 40 of 89; NEC, 4 of 89; death, 1 of 89 |

| Sari et al. 201137 | < 33 weeks old; < 1500 g in weight;e randomised, n = 242 | None | L. sporogenes with milk | No | Unclear | Mean 2 daysd | Late-onset sepsis, 26 of 111; NEC, 10 of 111; death, 4 of 111 |

| fBraga et al. 201138 | 750–1499 g in weight;g randomised, n = 243 | Congenital infection | B. breve and L. casei with donor breast milk | No | Yes | Day 2 | Late-onset sepsis, 42 of 112; NEC, 4 of 112; death, 27 of 112 |

| Rojas et al. 201239 | ≤ 48 hours old, < 2000 g in weight, haemodynamically stable;h randomised, n = 750 | None | L. reuteri DSM 17938i | Yes | Yes | Day 2 | Late-onset sepsis, 40 of 378; NEC, 15 of 378; death, 28 of 378 |

| Fernández-Carrocera et al. 201340 | < 1500 g in weight, randomised, n = 150 | Apgar score of < 6 at 5 minutes, NEC Bell stage 1 | L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, L. casei, L. plantarum, B. infantis and S. thermophilus with milk | No | Unclear | Median 5 days (range 1–23 days) | Late-onset sepsis, 44 of 75; NEC, 12 of 75; death, 7 of 75 |

| jJacobs et al. 201341 | < 32 weeks old, < 1500 g in weight, randomised < 72 hours;k randomised, n = 1099 | Likely to die within 72 hours, mother taking non-dietary probiotics | B. infantis, B. lactis and S. thermophilus with milk | Yes | Yes | Median 5 days (IQR 4–7 days) | Late-onset sepsis, 89 of 551; NEC, 24 of 551; death, 28 of 551 |

| jOncel et al. 201442 | < 33 weeks old, ≤ 1500 g in weight; randomised, n = 424l | L. reuteri DSM 17938i | Yes | Yes | Median 1 day (range 1–5 days) | Late-onset sepsis, 25 of 200; NEC, 10 of 200; death, 20 of 200 |

With the exception of a multicentre trial published in 2012 and recruiting babies of birthweight up to 2000 g,39 the probiotic intervention was given either in milk or, in one study,42 separately but coincident with the start of feeding. This suggests that babies with perceived contraindications to starting feeds, who are likely to be those babies at highest risk of NEC, might be excluded or have deferred entry to the trials. The majority of the trials were not placebo controlled and relied on the responsible clinical staff being blind to the allocation through the use of unsupplemented milk as the comparator (see Table 1).

None of the trials was designed with statistical power to study NEC or death rates as separate outcomes.

In contrast to NEC and death, the various meta-analyses do not suggest a protective effect of probiotics for late-onset sepsis. The assessment of efficacy to reduce late-onset sepsis is complicated by the lack of a standardised definition of the outcome.

This problem was addressed by the multicentre Australasian ProPrems trial,41 which is the largest of the previously published trials. The results were presented in 2012 but were not published until after the completion of PiPS trial recruitment. A rigorous definition of late-onset sepsis was used and the trial was statistically powered to show a reduction from 23% to 16%. The event rates of both late-onset sepsis and NEC in this trial were lower than predicted and a non-statistically significant reduction in late-onset sepsis, from 16.2% to 13.1%, was observed.

It is generally held that, in order for a probiotic intervention to be effective, it should ‘colonise’ the intestine and the administered bacteria should multiply within it. Successful colonisation is likely to be influenced by local factors such as feeding and antimicrobial use. Human breast milk contains oligosaccharides known to promote colonisation by bifidobacteria while many probiotic strains are sensitive to commonly administered antimicrobials, for example bifidobacteria are sensitive to penicillins. Manufacturers of probiotics inevitably select strains that readily colonise the intestine and, theoretically, these strains might be particularly likely to spread between babies, especially in hospitals where cots are close together or the nurse-to-baby ratio is low. In this respect, the efficacy of a probiotic intervention might be expected to vary more between different institutions than a standard chemical drug intervention. Of the 20 RCTs included in the most recent Cochrane review,35 the only trial to report colonisation by allocated group in detail is the single-site study reported by Kitajima et al. ,43 which involved the administration of a single-strain probiotic product containing B. breve YIT4010 (BBG-001). Of 45 babies in the probiotic group, 73% were colonised at 2 weeks and 91% at 6 weeks, whereas, of the 46 babies given placebo, 12% were colonised at 2 weeks and 44% at 6 weeks. This adds a level of complexity to the interpretation of all data from trials of probiotics, particularly for those using polymicrobial products, as it is likely that different components will colonise babies in both groups so that at different time points in their clinical course babies might be colonised with anywhere between none or all of the administered strains.

Observational studies/historic comparisons

Despite the frequent calls for probiotics to be used routinely for preterm babies, there are few published accounts of their impact in routine use.

An early report44 of a trial in a tertiary hospital in Colombia, in which a product containing L. acidophilus and B. infantis was given for 1 year to all admitted newborn infants, reported a decrease in all stages of NEC compared with the previous year, from 6.6% (n = 1237) to 3.0% (n = 1282); all other aspects of care were unchanged.

There have been more recent reports of use targeted towards preterm babies.

In 2010 Luoto et al. ,45 reported on 12 years’ experience in five tertiary neonatal units in Finland. In one neonatal unit, following an outbreak of NEC, administration of Lactobacillus GG was introduced for all babies of birthweight < 1500 g. In three other neonatal units, the same product was administered to babies with gastrointestinal problems and the final neonatal unit used no probiotic. The standard of care in all hospitals was to use donor breast milk in the absence of maternal milk. The authors did not find a protective effect in the hospital using ‘prophylactic’ probiotics when the incidence remained higher than in the other hospitals or any effect on the clinical course of NEC in those hospitals in which probiotics were given to symptomatic babies.

A further three retrospective cohort studies have been published. 46–48

A report from a single site in the USA46 compared the incidence of NEC in 79 babies (of birthweight ≤ 1000 g) born between 2009 and 2011 in whom L. reuteri was routinely administered and babies born in the previous 5 years; detailed feeding data were not reported and infants who died in the first week were excluded. A reduction in NEC Bell stage ≥ 2 from 15.1% to 2.5% was reported (p = 0.0475); there were baseline differences in the characteristics of the babies and between-year variation in NEC incidence.

In a study in France,47 during a 3-year period from 2008, babies born between 24 and 31 weeks’ gestation (n = 347) and starting feeds within 48 hours of birth on a tertiary neonatal unit were administered L. casei rhamnosus, Lcr35 strain from the beginning of feeding, their outcomes were compared with those of unsupplemented babies born in the previous 5 years (n = 783). Babies dying in the first week were excluded from the analysis. 47 In the second period, the incidence of late-onset sepsis was reduced from 16.6% to 10.7% [odds ratio (OR) 0.60, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40 to 0.89], the incidence of NEC Bell stage ≥ 2 was reduced from 5.3% to 1.2% (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.69) and the mortality rate fell from 4.8% to 2.3% (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.00).

A Canadian study48 published in 2014 reported NEC Bell stage ≥ 2 and the composite outcome NEC or death of babies born before 32 weeks’ gestation for 17-month periods before (n = 317) and after (n = 294) the introduction of a product containing B. breve, B. longum, B. bifidum, B. infantis and Lactobacillus GG was given with the first feed at a single site. The incidence of NEC decreased from 9.8% to 5.5% (p < 0.02) and the incidence of death or NEC fell from 17.0% to 10.5% (p < 0.05). There was a non-significant reduction in death as a separate outcome. After adjustment for gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction and sex, the OR for NEC in the second period was 0.51 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.98) and for death or NEC was 0.56 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.93).

Safety

None of the published RCTs or non-randomised studies, including a summary of 6 years’ use of Lactobacillus GG across two neonatal units in northern Italy49 that contains no efficacy data, reports any complications of probiotic administration; most importantly, no instances were recorded of late-onset sepsis with the administered probiotic strains.

Before the beginning of recruitment to this trial there had been occasional reports, including in the paediatric literature,50,51 of disseminated infection following enteral supplementation with Lactobacillus species, but no reports of late-onset sepsis with Bifidobacterium. In 2010, what we believe to be the first case of a Bifidobacterium septicaemia was reported. 52 This involved a positive blood culture for B. breve strain BBG-001 (the strain used for the PiPS trial) in a full-term baby recovering after surgery for exomphalos. The baby is described as having a mild illness that was treated with standard empirical antibiotic treatment involving ampicillin/sulbactam and amikacin; the child made an uneventful recovery.

In 2012, a second report53 described a twin born at 27 weeks’ gestation, birthweight 600 g, who was fed with maternal breast and in whom a probiotic preparation containing B. infantis and L. acidophilus was instituted on day 8. On day 18 the infant became unwell with abdominal symptoms. A blood culture grew two species, B. infantis and B. longum. She was treated with vancomycin, cefotaxime and metronidazole, and recovered.

There is an anxiety that, theoretically, manipulating the developing microbiome by administering probiotics might modify the immunological function of the intestine or that antibiotic resistance genes might be transferred from the probiotic to pathogenic bacteria, thereby putting the individual at increased short-term risk of infection or possibly of unpredictable long-term health change. 54

Studies on the effect of probiotics on intestinal colonisation with potential pathogens are few, and the results inconsistent. A small study involving 30 babies, with a mean gestational age of 33 weeks and a mean birthweight of 1486 g, was suggestive that B. breve administration might be associated with reduced colonisation with Enterobacteriaceae. 55 However, a more recent placebo-controlled randomised trial56 of formula-fed babies, born before 32 weeks’ gestation, found increased colonisation with Enterobacteriaceae, enterococci and staphylococci in 21 of 47 babies whose feed was supplemented with Lactobacillus GG. This was not associated with increased late-onset sepsis in these babies. Of the 12 clinical trials listed in Table 1, all of which were designed to study clinical outcomes, five reported higher rates of sepsis in the active arm than in the placebo arm,19,21,23,37,39 although only one was statistically significant. 23 These trials use various definitions of late-onset sepsis.

A RCT studying a product with six bacterial strains, four species of Lactobacillus and two of Bifidobacterium, in 296 adult patients with acute pancreatitis reported increased mortality in the active arm, [24/152 (16%) vs. 9/144 (6%) in the placebo arm (p = 0.01)]. 57 The most frequent cause of death was multiorgan failure and there were no reports of probiotic bacteraemias. In 9 of the 24 patients in the active group who died, ischaemic bowel was found at either laparotomy or autopsy; ischaemic bowel was not found in those patients in the placebo group who died. The intervention in this trial was given twice daily directly into the jejunum and represents a huge bacterial load, estimated at 1010 bacteria. The reasons for the increased mortality are unclear. This trial might be interpreted as a reminder that, despite worldwide extensive consumption of probiotics, it should not be assumed that they are safe in extremely ill patients with compromised intestinal function; this would include preterm babies, particularly those with problems establishing enteral nutrition.

The justification for continued recruitment to the PiPS trial was kept under review throughout its progress as reports of more trials of routine use and of probiotic septicaemias became available; at no time was it considered that the accumulating evidence either of efficacy or safety was such that a recommendation to stop the trial early should be made. The overarching consideration was whether or not the findings of the various trials were applicable to the population of preterm babies at risk of late-onset sepsis and NEC in UK neonatal units. Rates of late-onset sepsis and NEC are inversely related to gestational age at birth2,58–60 and become relatively low from around 32 weeks’ gestation; the requirement of clinicians is for a preventative intervention that can safely be given to all babies at risk of late-onset sepsis and NEC.

The choice of probiotic

The ideal probiotic for a clinical trial would have extensive preclinical data, including experience in the preterm newborn infant and information about dosage, supporting its probable efficacy and safety. In addition, it would be available in a stable pure form known to be free of contaminants; a suitable and indistinguishable placebo would be available; and it would be easy to grow and identify the bacterium in the laboratory so that colonisation of participants could be monitored and probiotic infection easily detected. None of the interventions used in the published studies in the newborn infant fulfils these criteria.

There are also choices to be made regarding whether or not a single or multistrain product is used.

There are very few studies comparing different probiotic interventions in the preterm baby. One recent Phase 1 study61 suggested different effects of a B. infantis species compared with B. longum in respect of bacterial diversity and total counts of bifidobacteria, particularly when augmented by administration of maternal milk. A second study62 comparing a product containing a single strain of B. breve with a product providing the same quantity of B. breve together with two species of B. longum suggested that the three-strain product was associated with increased colonisation with B. breve and fewer Enterobacteriaceae species; whether or not these effects are attributable to the diversity or to the greater bacterial load of the three-strain product is unclear.

Of the 12 trials included in Table 1, four used products containing a single strain, three contained different strains of Lactobacillus, one contained B. lactis BB12 and the remaining four studies used combinations of up to six different bacterial strains. In large part, the choice of product appears to have been governed by availability and the ability to mix it with milk.

Although not explicitly stated in the text, in one trial conducted in Israel by Bin-Nun et al. ,21 and reported at a scientific meeting (Dr C Hammerman, Zedek Medical Center, Jerusalem, personal communication), the intervention [ABC Dophilus® (Solgar®), which contained B. infantis, S. thermophilus and B. bifidus], was selected because of anxiety about possible infection with Lactobacillus-containing products. The same product was used in the recent and heretofore the largest published trial, ProPrems, carried out in Australia. 41 When asked about the choice, the author explained that it was not because of the bacterial content but simply that it had been previously evaluated and shown to have efficacy against NEC incidence, was available and could be imported under licence into Australia (Dr SE Jacobs, Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, VIC, personal communication). The formulation of that product has now changed so that it contains Lactobacillus.

Two published meta-analyses34,63 attempt to group trials to study the effects of different organisms and combinations, but they fail to reach clear conclusions and highlight the need for further study.

Quality

Of the 12 trials detailed in Table 1, nine quote the manufacturer’s data describing the content of the product but do not describe the storage conditions or any further testing to confirm the contents, their purity or their stability through the course of trial recruitment. The B. lactis used by Mihatsch et al. 36 was checked monthly to ensure the viability and purity of the product together with the 24-hour stability of the prepared suspension. The six-strain product used by Fernández-Carrocera et al. 40 (four strains of Lactobacillus, one of B. infantis and one of S. thermophilus) was checked twice against the manufacturer’s quality control register and the ABC Dophilus used for the ProPrems trial41 was imported under licence into Australia. Each batch was then subjected to independent confirmation of taxonomy and quality by checking the probiotic content using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the purity by culture.

Experience with Bifidobacterium breve BBG-001

Use of B. breve BBG-001, the probiotic strain used for the PiPS trial, was first reported by a Japanese group. 43 Ninety-one infants of birthweight < 1500 g were randomised to receive active product or placebo. The trial commenced with milk feeds, administered twice daily and continued for 28 days, by which time 82% of the active intervention group and 28% of the placebo group were colonised with B. breve BBG-001. Clinical outcomes analysed whether or not the baby was successfully colonised with the probiotic organism. Improved food tolerance, accelerated time to establish full feeds and increased weight gain that was sustained after discontinuation of administration of probiotic were reported. No other clinical outcome was published and none is available; probiotic use with this product became and remains routine in that investigator’s department (Dr Kitajima, Osaka Medical Center and Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health, Osaka, Japan, 2013, personal communication).

A single-site pilot study using the same product, B. breve BBG-001, was undertaken by the current investigators. 64 B. breve BBG-001 was used because at the time the study was designed it was the only probiotic strain reported to confer any clinical benefit in the preterm baby. 43 The primary objectives of the pilot were to study whether or not the intervention was tolerated this early in development and to confirm that colonisation was achieved with a once-daily dosage regimen. The design differed from previous studies in that the study product was commenced within 48 hours of birth, whether or not milk feeds had been started. This was to avoid excluding those babies at greatest risk of adverse outcomes and to maximise the possibility of early colonisation with the probiotic organism, even in babies from whom the responsible clinician might choose to withhold milk feeds because of a perceived high risk of NEC. The products were prepared as described in the report by Kitajima et al. ,43 but only a single 1-ml dose was given, as opposed to the whole content of the sachet given in two or three 1-ml doses. We estimated the dose given to be around 5 × 108 colony-forming units (CFUs) of B. breve BBG-001. The colonisation rates we achieved were similar to those quoted by Kitajima et al. 43 and the numbers of bifidobacteria in the stools of those babies who were colonised were the same whether they were in the active intervention or placebo groups: at 14 days, 12 out of 19 (63%) infants in the active intervention group were colonised with a mean 7.3 [standard deviation (SD) 1.7] log10 CFUs per gram wet weight of stool and 4 out of 17 (24%) infants in the placebo group were colonised with a mean with 7.4 (SD 3.0) CFUs per gram wet weight of stool. These data support the conclusion that B. breve had actively colonised the babies and the same dose was therefore used in the main trial.

Forty infants of birthweight < 1500 g were randomised at a single site (Homerton University Hospital Foundation Trust, London, UK) over a 6-month period in 2004 to receive B. breve BBG-001 or placebo; both products were well tolerated by all babies. Quantitative microbiology was undertaken on stools. Analysis of the stool passed closest to 28 days showed that 79% of the group receiving probiotic and 35% receiving placebo were colonised with B. breve BBG-001; this high cross-contamination rate is comparable with published experience43 and was considered likely to have occurred both in the milk kitchen and between babies in the ward. All babies who commenced enteral feeding did so with maternal breast milk.

Analysed by intention to treat, probiotic supplementation was associated with improved feed tolerance and weight gain, and there were fewer babies with episodes of infection at 28 days (23% vs. 44%). The study was too small to allow any estimate of an impact on the incidence of NEC (nine suspected or proven cases, of whom five were randomised to receive probiotic and four placebo). When outcomes were analysed by whether or not the infant was colonised with the administered probiotic, it was found that colonisation was associated with a reduction in the number of babies with any episode of infection over the entire hospital stay (from 66% to 24%; p = 0.017) and also that fewer colonised babies remained oxygen dependent at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age (40% vs. 79%; p = 0.038). In addition, there was some evidence of increased microbial diversity in the stools of colonised babies, although the numbers are small. In particular, at 28 days, no stool of non-colonised babies was also colonised with anaerobic bacterial species; in contrast, 66% of those colonised with B. breve BBG-001 were also colonised with anaerobic bacterial species. Colonisation with Gram-negative organisms was high in both groups. When analysed by intention to treat, there was no difference in the duration of antibiotic use in the two groups, but, when analysed by whether or not there was successful colonisation, there was a significant reduction in the number of days on antibiotics over the whole hospital stay in those colonised, from a mean of 39 days to 19 days (p = 0.04).

The intervention was continued for a shorter time period (28 days) in this pilot study than in the subsequently published studies that found a reduction in NEC incidence with probiotic use, all of which continued the intervention to either 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age or discharge from hospital. Two babies randomised to receive probiotic in the pilot study developed proven NEC that was fatal: one at 29 days and one at 30 days (one of these infants was not successfully colonised). When the PiPS trial was designed it was recognised that babies at high risk of developing NEC may do so later than 4 weeks’ postnatal age, it is now known from observational studies that more immature babies develop the disease at an older postnatal age with the peak age at onset around 31–34 weeks’ postmenstrual age. 65,66

Subsequent to the design of the PiPS trial, we are not aware of any published reports of the use of B. breve BBG-001 in the newborn baby.

Regulatory status of probiotics

At the time of the pilot study using B. breve BBG-001 that we conducted in 2004,64 probiotics were considered as food supplements and the trial was not conducted to International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use – Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) standard. A product given to prevent such serious complications of prematurity as NEC, late-onset sepsis and death clearly fulfils the definition of a medicinal product used within the European Community: ‘Any substance or combination of substances presented as having properties for treating or preventing disease in human beings’ (Article 1, Directive 2001/83/EC). 67 The regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), required that for this trial the probiotic intervention should be considered as a medicine and the PiPS trial, unlike all other published trials investigating the use of probiotics in newborn babies, was conducted to ICH-GCP standard.

Rationale for the design of the Probiotics in Preterm infantS trial

When the PiPS trial was designed, there had been no published trials, apart from the study of Dani et al. ,19 that reported effects of probiotics on NEC, late-onset sepsis and death, and no trials reporting benefits of probiotic use. Despite this, in the context of the current understanding of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of NEC and late-onset sepsis and the importance of identifying preventative strategies, the probability that a probiotic intervention might be both efficacious and safe seemed high.

Choice of product

When our trial was designed, as far as we were aware the only study to report any benefit associated with probiotic use in the newborn infant was the trial by Kitajima et al. 43 published in 1997, studying nutritional outcome, although the analysis was based on whether or not the baby had been successfully colonised rather than by intention to treat. We were also aware that the product used in that trial, B. breve BBG-001, had been in routine use in Japan for a number of years, seemingly without problems. These observations underpinned our decision to use this product for our pilot study, in which we found it to be well tolerated and confirmed that we could achieve good colonisation rates with a single daily dose.

We were keen to monitor colonisation of all participants, and B. breve BBG-001 had the further advantage that the manufacturer was able to provide a selective strain-specific medium so that it could reliably be cultured and identified.

Population

The study population was selected as being that at greatest risk of NEC. In particular, we were keen to start the intervention as soon as practicable, not only because babies begin to acquire intestinal flora from birth, whether or not fed, but also because as the clinical course progresses and complications arise we believe that it is easier to find reasons not to recruit babies into trials and we thought it essential that we recruit a trial population that was as representative as possible of all preterm admissions so that at trial conclusion we could address the question of whether or not probiotics should be given routinely to this population.

Chapter 3 Methods

This was a multicentre, double-blind RCT.

Objective

The objective of the trial was to determine whether or not early administration of the probiotic B. breve strain BBG-001 to preterm infants reduced the incidence of episodes of infection, NEC and death.

The trial protocol is available on the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) website at www.nets.nihr.ac.uk.

Participants

Participants were preterm babies born between 23+0 and 30+6 weeks’ gestation and recruited with informed signed parental consent within 48 hours of birth. Babies were eligible for recruitment whether or not they had been born in the recruiting centre. Those with a lethal congenital malformation or any malformation of the gastrointestinal tract detected before 48 hours or who were considered to have no realistic chance of survival were excluded. Receiving antibiotics for proven or suspected infection was not an exclusion criterion.

Trial sites

The trial was conducted at 57 sites. Of these, 24 were recruitment sites and 33 were sites to which participants were transferred for continuing care. A complete list of the recruitment sites is available in Appendix 1.

Interventions

The active intervention was B. breve BBG-001, suspended in one-eighth strength of the infant formula Neocate® (Nutricia Ltd, Trowbridge, UK). The placebo was one-eighth-strength Neocate. A description of Neocate is available at www.neocate.co.uk/uploadedFiles/Neocate/Resources_Library/Documents/Neocate_LCP_data_card.pdf (accessed 26 August 2016).

The probiotic and placebo powders were manufactured and supplied by the Yakult Honsha Co. Ltd (Tokyo, Japan) in identical square foil sachets each containing 1 g of product. The sachets of active product contained B. breve BBG-001 freeze-dried with maize starch and those of placebo contained freeze-dried maize starch alone; the appearance of the powders was identical. The trial was conducted using a single batch of products manufactured specifically for this study, the release criteria for this batch stated that each sachet of the active product contained between 2 × 108 and 2 × 1010 CFUs. After importation to the UK, the sachets were packed at Bilcare Global Clinical Supplies (Europe) Ltd into packages each containing 91 sachets (the maximum number of sachets a baby might require) of either active product or placebo. Each of the 91 sachets and the package was labelled with a unique five-digit alphanumeric identifier.

Product preparation, administration and blinding

The manufacturer’s instructions involved suspending the powders in water, allowing the maize starch to settle for 30 minutes and administering the supernatant within the next 2.5 hours. Prepared in this way, the supernatant of the active product was cloudy and that of the placebo clear. This was overcome by substituting one-eighth-strength Neocate for the water. Occasionally the turbidity of the supernatant still varied slightly and, therefore, to be completely confident that the active intervention and placebo were indistinguishable, they were prepared in specially manufactured amber-coloured bijou bottles (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Prepared product in amber-coloured bijou bottle.

Kitajima et al. ,43 using the same product, prepared it using 2 ml of water. During our preliminary work we found that when using 2 ml that it was sometimes difficult, using a syringe, to withdraw 1 ml without disturbing the maize starch residue. We were keen not to increase the volume that we were administering to the babies but equally keen to ensure, with minimal evidence to guide us, that we gave adequate numbers of bacteria. By a process of trial and error we found that, if we increased the volume used to suspend the powder to 3 ml, then only rarely were we unable easily to withdraw 1 ml. We emphasised to investigators the importance of not disturbing the maize starch and suggested that, if they had any difficulty withdrawing 1 ml, they could simply give less on that day.

The products were prepared in the milk kitchens on the neonatal units of the participating hospitals, usually by one of the nurses engaged in clinical care. In order to minimise the possibility of cross-contamination of the placebo by B. breve BBG-001, members of the trial team provided on-site training with an emphasis on handwashing and decontamination of working surfaces in between preparing each baby’s intervention. This teaching was repeated, on request, for new staff and was supported with detailed guidance on laminated sheets for display in milk kitchens. The guidance sheet for product preparation is available in Appendix 2.

Dosage

The range of values quoted by the manufacturers of products used in published trials is from 106 to 109 CFUs per dose. The dose used in the study of Kitajima et al. 43 is the most relevant for this trial because the same product was used. The babies in the study of Kitajima et al. 43 were given the contents of a whole sachet (estimated in the publication to contain 1 × 109 CFUs) in two or three divided doses (i.e. 3.3 × 108 to 5.0 × 108 CFUs per dose) each 1 ml in volume. In our pilot study we achieved colonisation rates similar to Kitajima et al. 43 with a single dose. The manufacturer stated that each sachet of the batch used for the PiPS trial contained between 2 × 108 and 2 × 1010 CFUs. Preparing the product as we did, using 3 ml of Neocate, suggests that the range of bacterial counts in a 1-ml dose would be between 6.7 × 107 and 6.7 × 109 CFUs of B. breve BBG-001.

A record was kept of doses omitted and of sachets wasted, and was reconciled centrally against the number of unused sachets in the package after it was collected by the trial research nurses when the baby had completed the intervention.

Administration

The intervention was prescribed using the five-digit alphanumeric identifier for the pack allocated for that baby. This was written on the side of the bijou bottle during preparation and checked by the nurses before administration. A feeding syringe was used to withdraw 1 ml of supernatant, which was given to the baby.

Extension of the shelf-life of the interventions: viability counts for B. breve BBG-001 in the active intervention

The manufacturer supplied data documenting the decline of viability and lack of contamination of previous batches of the product extending for 42 months from manufacture. As there was a lack of evidence beyond that time, the stated shelf life for the batches provided for the PiPS trial extended to the end of August 2012 for the active product and September 2012 for the placebo. During 2011 and 2012 it became clear that recruitment would need to continue until mid-2013 and that a second batch of interventions would be needed. It emerged that circumstances had changed and that new batches of intervention, particularly of placebo, could not easily be provided. We knew from work with the previous batch of the active product used for the pilot study and from monitoring undertaken in the early stages of this trial that the counts of viable B. breve BBG-001 were declining only slowly.

In the absence of any other guidance we accepted 2 × 108 (8.3 log10) CFUs of B. breve BBG-001 per sachet (6.7 × 107 or 7.8 log10-CFUs per dose) as the minimum figure that we should accept for this trial.

Analysis of unused sachets returned from centres during the early stages of the PiPS trial had been carried out and corrected to give the viable count per 1-ml dose. A plot of these data (Figure 2) showed a gradual decline in viable counts (solid blue line). The manufacturer provided stability data from two different batches of material for 42 months from manufacture, shown as CFUs per sachet for comparison (see Figure 2, solid black and green lines). All three lines are roughly parallel and extrapolation from the data obtained from the batch being used for the PiPS trial indicated that the number of viable organisms per dose would remain well above 6.7 × 107 or 7.8 log10-CFUs for at least 48 months (i.e. until October 2013) and probably beyond.

FIGURE 2.

Projected decline in dosage of B. breve BBG-001 beyond November 2011 compared with decline in sachet content of two earlier batches supplied by the manufacturer. The y-axis shows the count of B. breve BBG-001 expressed in log10-CFUs. The x-axis shows the actual date for the trial batch of B. breve BBG-001 and time in months since manufacture for all batches. The solid green and black lines were provided by the manufacturer and relate to two earlier batches of the product. The counts are per sachet and extend for 42 months after manufacture. The solid blue line is the count per dose of B. breve BBG-001, as made up for the PiPS trial. The blue triangles represent the mean of all measurements made since the previous triangle. The regression line is extended beyond the final measurement in November 2011 to estimate the likely viability at the projected end of use of intervention in the trial in October 2013. The dashed green line at around 8.7 log10-CFUs represents the estimated single dose used in the trial of Kitajima et al. 43 The dashed blue line at 8.3 log10-CFUs represents the lower cut-off point per sachet of the batch of B. breve BBG-001 provided by the manufacturer for the PiPS trial, when prepared as for the trial this equates to 1 ml providing a dose of 6.7 × 107 or 7.8 log10-CFUs.

On the basis of these data, a successful application was made to the MHRA to extend the shelf life of both probiotic and placebo to the end of October 2013 and all sachets and boxes were relabelled accordingly. It was agreed that we should continue to monitor the counts of viable bacteria in a randomly selected unused sachet from each pack after the baby had completed its course of treatment to confirm both that the rate of decline was not accelerating and that the products remained free of contamination. It was agreed that if the viable counts fell below 2 × 108 CFUs (8.3 log10-CFUs) per sachet, or if any contamination was identified, recruitment would stop.

Outcomes

The rationale and definitions of outcomes are detailed in appendices 1–4 of the trial protocol, which is available on the NETSCC website. 68

Primary outcomes

-

Any baby experiencing an episode of bloodstream infection, with any organism other than a skin commensal, diagnosed on a sample of blood drawn more than 72 hours after birth and before 46 weeks’ postmenstrual age, death or discharge from hospital, whichever is soonest. Skin commensals include coagulase-negative staphylococci and Corynebacterium.

-

NEC, Bell stage 2 or 3.

-

Death before discharge from hospital.

Secondary outcomes

-

Number of babies with the composite outcome of any or a combination of the three primary outcomes.

Secondary microbiological outcomes

Outcomes 2–7 are for samples taken > 72 hours after birth and before 46 weeks’ postmenstrual age, death or discharge home:

-

Number of babies with any positive blood culture with an organism recognised as a skin commensal (e.g. coagulase-negative staphylococci or Corynebacterium).

-

Number of babies with blood cultures taken.

-

Number of blood cultures taken per baby.

-

Number of babies with episodes of bloodstream infection with organisms other than skin commensals by organism, for example Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., fungi, and by antibiotic resistance types, specifically meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Gram-negative bacteria.

-

Number of babies with isolates of organisms other than skin commensals from a normally sterile site other than blood, for example cerebrospinal fluid, suprapubic aspiration of urine, pleural cavity, etc.

-

Number of babies with a positive culture of B. breve BBG-001 from any normally sterile site.

In addition:

-

Total duration of days of antibiotics and/or antifungals administered per baby after 72 hours and until 46 weeks’ postmenstrual age, death or discharge from hospital, whichever is soonest, for treatment of suspected or proven late-onset sepsis, that is, excluding prophylactic use.

-

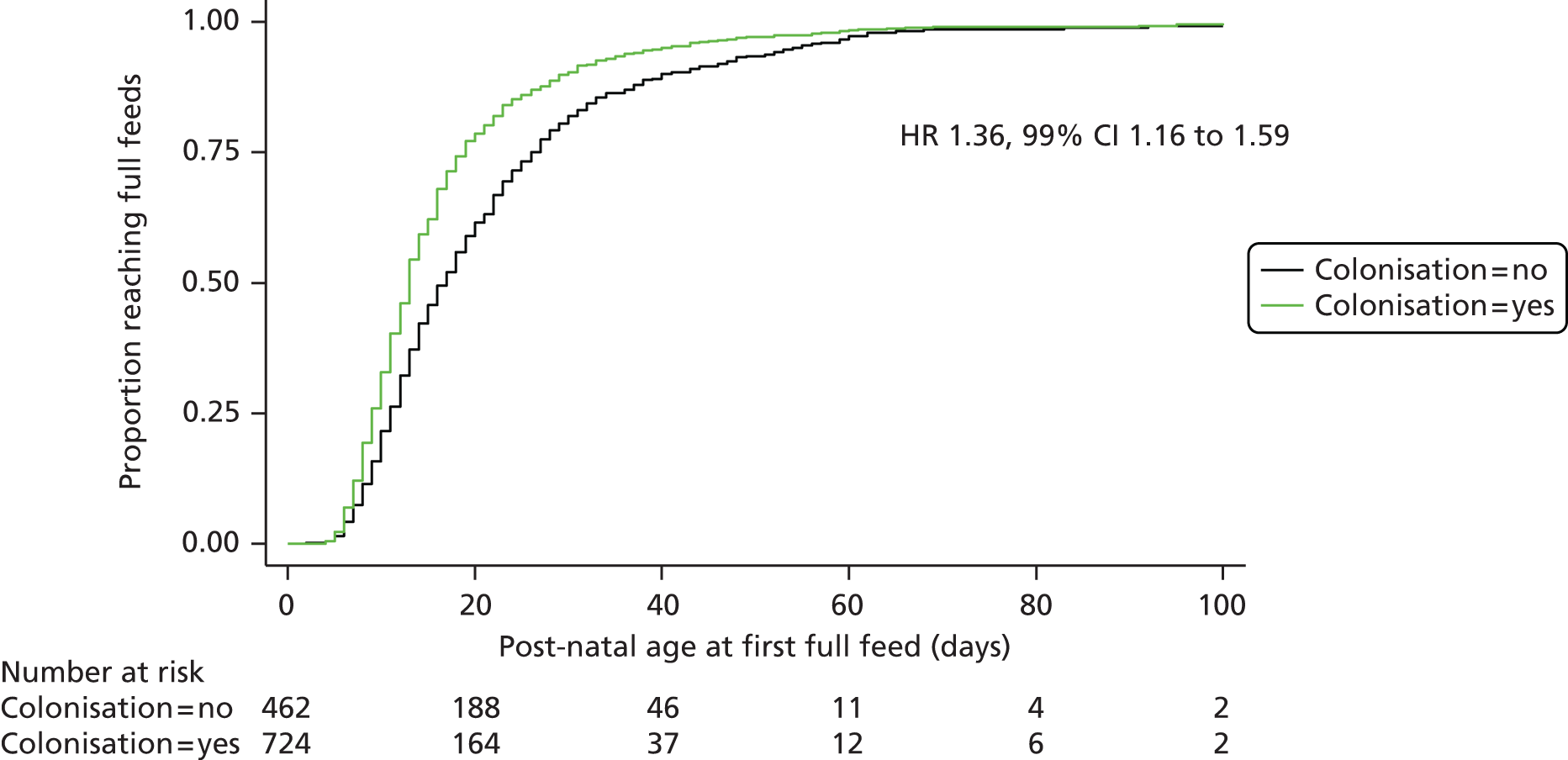

The number of babies colonised with the administered probiotic strain defined by the isolation of B. breve BBG-001 from stool samples at 2 weeks’ postnatal age and at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

-

Stool flora: the number of babies colonised with MRSA, VRE or ESBL at 2 weeks’ postnatal and at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

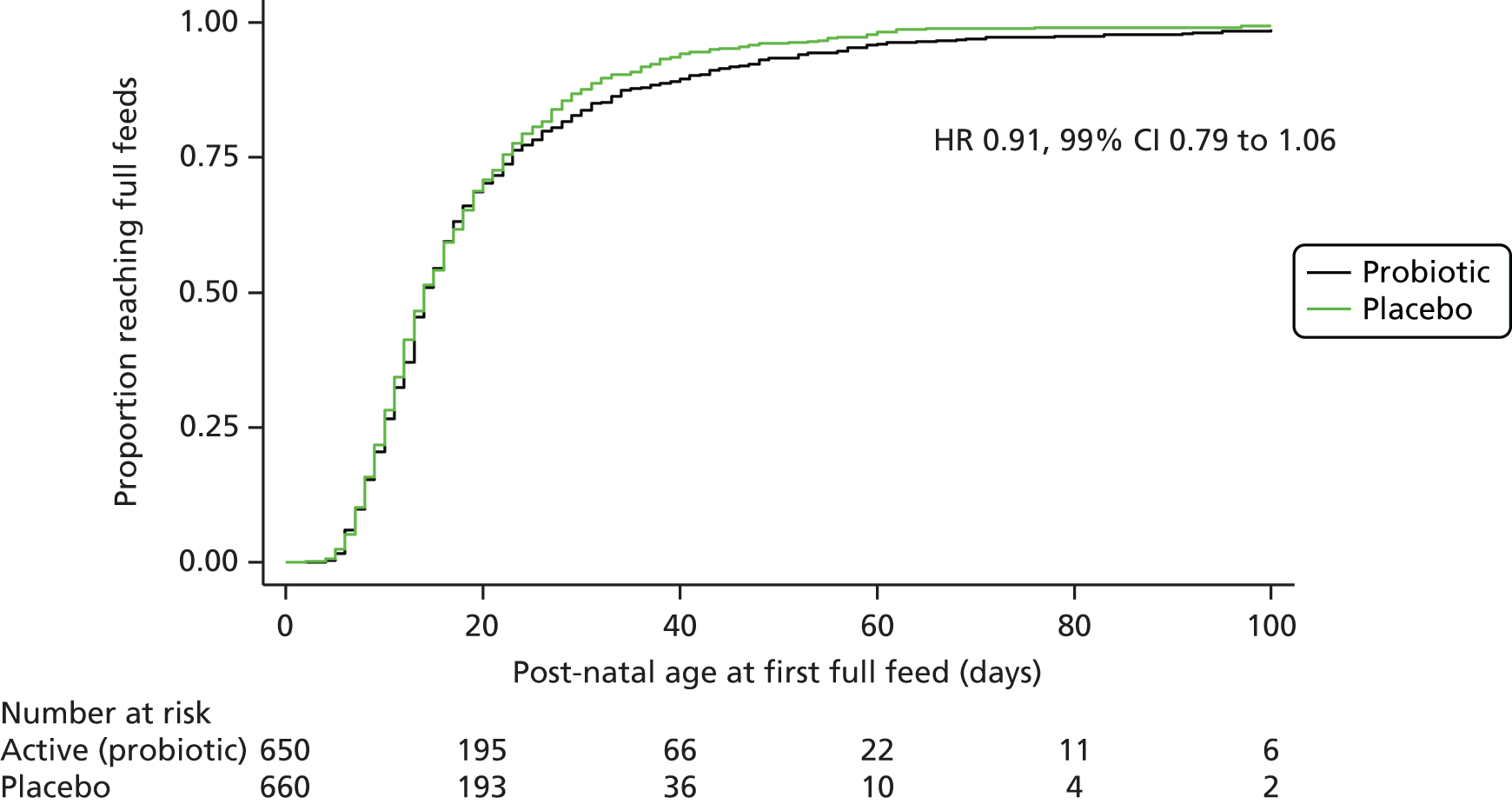

Nutritional and gastroenterological outcomes

-

Age at achieving full enteral nutrition (defined as 150 ml/kg/day for 1 day).

-

Change of weight z-score from birth to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age or discharge from hospital if sooner.

Other clinical outcomes

-

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

-

Hydrocephalus and/or intraparenchymal cysts confirmed by cerebral ultrasound scan performed during the baby’s inpatient stay.

-

Worst stage of retinopathy of prematurity in either eye at discharge or death.

-

Length of stay in intensive, high-dependency and special care unit.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed by health-care staff trained in trial procedures and named on the trial delegation log.

Randomisation to receive either probiotic or placebo used a central web-based service, with telephone back-up, based at the National Perinatal Epidemiological Unit (NPEU), University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. The randomisation program used a minimisation algorithm to ensure balance across site, sex, gestational age at birth (23, 24, 25, 26/27 and 28–30 weeks’ gestation) and whether or not randomisation occurred sooner than 24 hours after birth.

At randomisation the investigator was given a unique five-digit study number for the baby, which was the principal identifier throughout the trial, and a five-digit alphanumeric number for the intervention pack to be used.

Parents, clinicians and outcome assessors were blind to the allocation.

Trial procedures

Consent

Whenever possible, preliminary discussions supported by written information about the trial would be offered to parents before the birth if the baby was likely to be eligible. This happened both at recruiting centres and at local hospitals that routinely referred babies into the recruiting centres. Informed written consent was sought from a parent after the birth only when they had been given a full oral and written explanation of the study. Copies of the parent information leaflet, the consent form and the leaflet provided to investigators summarising the material that should be covered in discussions about the trial are available in Appendices 3–5.

Investigators were encouraged to discuss the trial with parents periodically during the hospitalisation to confirm their continued understanding and willingness to participate.

At all stages it was made clear to the parents that they remained free to withdraw their baby from the study at any time with no need to provide an explanation. When babies were transferred between hospitals, the parents were given written information including the name of the consultant acting as principal investigator (PI) at the receiving hospital.

Parents who did not speak English were approached only if an appropriate adult interpreter was available.

Withdrawal from the trial

When parents requested that their baby be withdrawn from the trial, we completed an additional data form (see form 6, Appendix 6) that clarified whether or not it was only administration of the intervention that was to be discontinued and whether or not the parents were willing for data already collected, for outstanding data and/or stool collection to continue and for those data to be used.

Clinical care of participants

The day-to-day clinical care of participants was entirely at the discretion of the responsible clinical team. Investigators were encouraged to use maternal breast milk, but feeding regimes were not standardised.

Discontinuation of the trial intervention

Whether or not the intervention was discontinued temporarily when babies were unwell was at the discretion of the parents and attending clinical staff. The only circumstance in which clear advice was given to withhold a dose was when intestinal perforation was suspected.

Stool sample collection

Stool samples were collected as close as possible to 14 days’ postnatal and 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. These times were chosen for practical reasons, the main objective being to gain a snapshot of stool colonisation by B. breve BBG-001 as a marker of intestinal colonisation. It was considered that, at 2 weeks of age, enteral feeds would be established in the majority of babies, who would have received the intervention for over a week, while still being before the time, for this population, of the peak incidence of NEC. Thirty-six weeks was selected, as this is the time at which outcome data describing bronchopulmonary dysplasia and growth were reported. Investigators were asked, if possible, to send three full scoops of stool. Samples were posted for processing to the Microbiology Laboratory at the Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, UK, using the Thermacor transportation system for diagnostic samples (Dyecor Ltd, Hereford, UK) and the Royal Mail.

No other biological samples were collected.

Data collection

With the exception of detailed results of routine microbiological investigations, all trial data were collected onto paper forms, which were posted to the NPEU Clinical Trials Unit for checking and double-entered onto a web-based clinical database, OpenClinica (OpenClinica, LLC, Waltham, MA, USA). Data were entered in accordance with NPEU Clinical Trials Unit OpenClinica data entry conventions. All personal details were entered into a Microsoft Access® 2013 database (version 15, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Form 1: trial entry (see Appendix 7)

Part A of this form had to be completed and the answers available to facilitate randomisation and parts B–F of the form comprised baseline maternal and neonatal information. It was requested that it was posted to the trial office within 1 week of birth.

Form 2: daily data collection (see Appendix 8)

The aim of this form was to collect details of enteral feeds and antimicrobial interventions for the first 14 days of life until the collection of the first stool sample so as to enable later detailed analysis of determinants of colonisation at 14 days with B. breve BBG-001. If the baby was transferred between hospitals during this time, then a copy was retained at the referring hospital and the original form accompanied the baby.

Form 3: clinical details of baby at transfer, discharge or death (see Appendix 9)

This form provided clinical details and was due for completion at discharge from hospital, at death or if the baby was transferred to a different hospital, that is one form was completed for each admission and a baby could accrue multiple forms. If the baby reached 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age during the admission, the details of growth and respiratory support to determine whether or not the baby had bronchopulmonary dysplasia were provided. The form included a question about whether or not the baby had experienced any episode of NEC or other abdominal pathology which, if affirmative, led to completion of form 4.

Form 4: abdominal pathology (see Appendix 10)

This form was completed for any episode of suspected abdominal pathology. Multiple forms, each for a different episode, might be completed during a single admission covered by a single form 3 and if a baby was transferred between hospitals for specialist management of NEC multiple forms might be received from different hospitals for the same episode. The staging of an episode of NEC was primarily based on that provided by the clinician on the form but the form included questions about the clinical characteristics of the episode with the intention that these would later be checked to confirm consistency with the stated NEC staging.

Form 4 review

All cases in which any form 4 had been received were reviewed by Professor Kate Costeloe (chief investigator), Dr Kenny McCormick (consultant neonatologist, PI for the PiPS trial at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK) and Mrs Michele Upton (PiPS research nurse), to determine the number of discrete episodes of NEC, the highest Bell staging of any NEC episode, the age at onset of the first episode of any NEC and of stage 2 or 3 NEC and the agreed diagnosis of episodes of other abdominal pathologies. The review involved scrutiny of all forms 4 together with the associated forms 3 and, when relevant, with postmortem reports and operation notes. Outstanding inconsistencies and queries were resolved together with the PIs with reference to the contemporaneous medical records.

Routine microbiological data

The results of routine microbiological investigations together with the antibiotic sensitivities of cultured bacteria were obtained directly from the staff in the laboratories of participating hospitals on an Microsoft Excel® 2010 spreadsheet (Version 14, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). They were scrutinised individually by Dr Michael R Millar to ensure that all positive cultures from normally sterile sites were identified. All positive cultures were entered onto the trial database together with the sampling site, species of bacteria and patterns of antibiotic resistance. The accuracy of the trial microbiological data was checked by comparing 20% of trial data entries against the Microsoft Excel-recorded laboratory returns.

Safety and adverse event reporting

Unexpected serious adverse events (SAEs) and suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) were reported using form 5 (see Appendix 11). Two SUSARs were noted prospectively:

-

intestinal obstruction associated with maize starch

-

bacteraemia with B. breve BBG-001.

Stool samples: microbiology methods

All samples were processed in the microbiology laboratory at Barts Health NHS Trust. When multiple samples were received from the same infant, then the sample collected closest to the appropriate date (14 days postnatal age or 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age) was selected for storage and analysis.

The microbiology laboratory at Barts Health NHS Trust is accredited through Clinical Pathology Accreditation (UK) Ltd (a wholly owned subsidiary of the United Kingdom Accreditation Service). The procedures used in this study, such as those used for culture, identification, antibiotic sensitivity testing of organisms and disposal of waste, were performed in accordance with laboratory standard operating procedures.

On receipt into the laboratory, specimens were weighed and divided in to two equal parts. The study number and date of receipt of each specimen were recorded. Half was frozen and stored at –80 °C; this sample was collected to allow additional chemical, immunological and molecular analyses including the molecular detection of the trial strain (B. breve BBG-001). The other half was diluted 1 : 10 in a cryopreservative broth [brain–heart infusion broth (Oxoid Microbiological Products Ltd, Basingstoke, UK) containing 10% glycerol (weight/volume)], mixed by vortexing for 10 seconds, and then placed in 1-ml aliquots into sterile 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) before freezing at –80 °C.

Detection of Bifidobacterium breve BBG-001, meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant enterococci and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Gram-negative bacteria in stool samples by culture

Samples were batch processed. Vials of frozen sample in cryopreservative were allowed to thaw at room temperature, and 100 µl of the faecal broth was serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline. Aliquots of 100 µl of the neat, 10−1, 10−3 and 10−5 dilutions were inoculated onto the agar medium plates.

Selective media were used for the detection of the trial strain (B. breve BBG-001), MRSA, VRE and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. The selective medium used for detection of the B. breve BBG-001 was Trypticase® peptone oligosaccharide (TOS) agar (Yakult Honsha Ltd, Japan) containing carbenicillin (10 µg/ml) and streptomycin (50 µg/ml). TOS agar was incubated for 48–72 hours anaerobically. ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae were cultured using MacConkey agar (Oxoid Microbiological Products Ltd, Basingstoke, UK) and Brilliance™ ESBL agar (Oxoid Microbiological Products Ltd), MRSA using mannitol salt agar with oxacillin (Oxoid Microbiological Products Ltd) and VRE using Slanetz and Bartley agar with vancomycin (Oxoid Microbiological Products Ltd). Inoculated selective media for MRSA, VRE and ESBL were incubated at 37 °C for 24–36 hours in air.

Identification and enumeration of cultured Bifidobacterium breve

Bifidobacterium breve produces a characteristic white convex colony on TOS agar. The faecal concentration of B. breve was determined by counting the number of colonies of faecal dilutions on TOS agar, allowing estimation of the numbers in the undiluted samples. Cultured colonies were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Bruker UK Ltd, Coventry, UK). In the early phase of the study the identification of a proportion of representative colonies was confirmed by 16S ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequencing.

Identification and enumeration of antibiotic-resistant bacteria

Bacterial colonies growing on selective agars were enumerated. Isolates were identified using standard laboratory methods including MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Bruker UK Ltd, Coventry, UK). MRSA and VRE isolates were identified as MRSA or VRE using British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy methods and interpretive criteria. 69 Gram-negative bacilli which grew on MacConkey or Brilliance ESBL agar were tested for susceptibility to a range of antibiotics using British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy methods. 69 Antibiotics tested included cefuroxime, ceftazidime, cefpodoxime, ampicillin, gentamicin, piperacillin/tazobactam, amoxicillin with clavulanate, tetracycline, trimethoprim, amikacin, tobramycin, imipenem, ertapenem, tigecycline, colistin, ciprofloxacin, aztreonam and chloramphenicol. Antibiotic-resistant isolates were stored by emulsification of colonies into microbank storage vials (Pro-lab Diagnostics, Wirral, UK) and stored at –80 °C.

Molecular detection of Bifidobacterium breve strain BBG-001 in stool samples

Deoxyribonucleic acid was extracted from faecal matter using the QIAamp DNA stool minikit (Qiagen Ltd, Manchester, UK) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions with an added bead-beating step. A strain-specific quantitative real-time PCR method previously reported by Fujimoto et al. in 201170 was used to detect B. breve BBG-001. The forward PCR primer sequence was 5′-ATGGCAAAACCGGGCTGAA-3′ and the reverse 5′-CCCACCTCTCATCCGC-3′ to give a 313-bp PCR product. Amplification and detection was carried out in 96-well optical low-profile plates (Anachem Ltd, Luton, UK) on a Bio-Rad CFX 96 real-time PCR machine-C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The PCR assay was re-optimised for use on the Bio-Rad machine with a fast PCR mix. Several PCR mixes were tested (Bio-Rad, Molzym and Agilent). The annealing temperature was optimised using the temperature gradient function of the Bio-Rad PCR machine. A primer titration was also performed.

Each PCR reaction (final/total volume of 10 µl) contained 1 µl of DNA template, 400 nM of each PCR primer, and 2 × Brilliant III Ultra-Fast QPCR Master Mix (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The 313-bp target sequence was amplified with an initial hold of 3 minutes at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 5 seconds at 95 °C and 10 seconds at the optimised annealing temperature of 62 °C. The melt cycle involved a temperature ramp from 65 °C to 95 °C, with a 5-second hold at each 0.5 °C step of the ramp.

Each sample was analysed in triplicate at neat and 1 : 10 concentration to check for PCR inhibition. A no-template control, a faecal extraction-negative control and a faecal extraction-positive control were also included on each PCR run. A sample was scored as positive if there is amplification for two or three out of three replicates with a melt curve at 87 °C, 82 °C or 85 °C, because we found that the strain-specific sequence derived from stool samples did sometimes give an 82 °C or 85 °C melt curve. Purified B. breve BBG-001 DNA produced a melt curve of 87 °C. Serial 10-fold dilution standards were run on each plate using the trial strain DNA at concentrations from 30 ng/µl to 30 fg/µl to allow estimation of the quantity of B. breve BBG-001 in each sample.

Data validation

Validation programs performed a series of range, logic and missing data checks to identify any inconsistencies within and across forms on an ongoing basis. Some queries were resolved at the NPEU according to predefined protocols; those that could not be resolved were reconciled between the staff in the trial office, the PiPS trial research nurses, chief investigator and PI with reference to the clinical record, and documented accordingly.

Sample size

Estimating sample size was difficult because of the paucity of reliable contemporary outcome data by gestational age. Based on data collected for local service appraisals around the year 2000, it was thought that the event rate of each of the primary outcomes might be as high as 15%. At a two-sided significance level of 5%, a trial of 1300 infants would have 90% power to detect a 40% relative risk (RR) reduction from 15% to 9.1%, or a 44% RR reduction from 12% to 6.7% or from 10% to 5.6% for each of the primary outcomes. These reductions were deemed to be of clinical importance by the investigators.

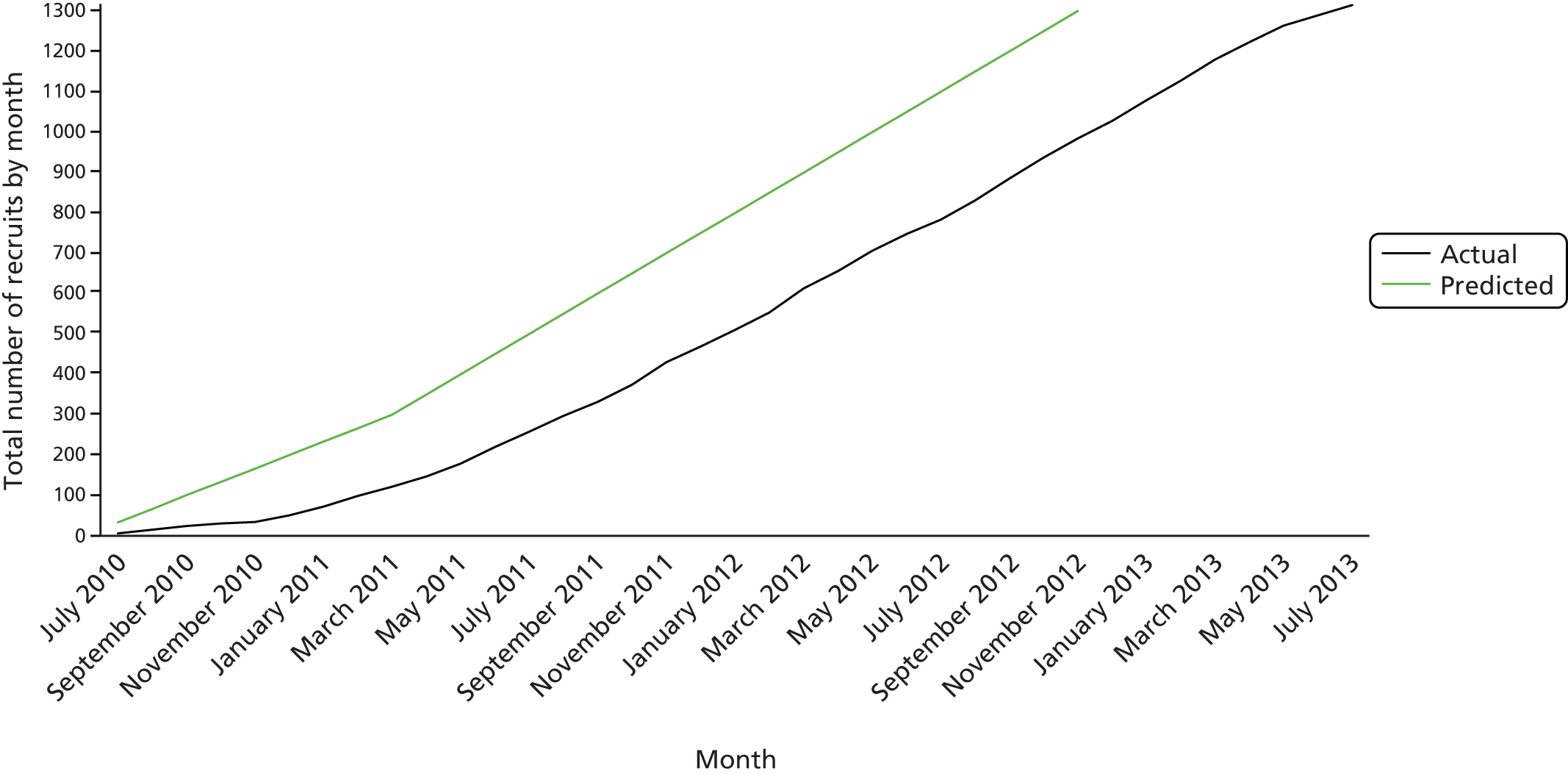

Recruitment targets

The aim was to begin recruitment within 6 months of trial commencement in September 2009, to recruit 300 babies in the first 3 months and accelerating gradually so that thereafter an average of 50 babies were recruited each month, with a total recruitment time of 2 years and 6 months.

Statistical methods

The full statistical analysis plan is available in Appendix 12.

The comparison of primary interest was whether or not there was a difference between the groups of the trial in any of the three primary outcomes. The primary analysis of primary and secondary outcomes was by intention to treat, that is the outcomes were compared across randomised groups for all infants recruited regardless of whether or not, or for how long, they received the allocated PiPS trial interventions.

Adjusted analyses were performed on all comparative analyses adjusting for the variables used in the minimisation algorithm, hospital, sex, gestational age at birth (23, 24, 25, 26/27 and 28–30 weeks’ gestation), and whether or not randomisation occured sooner than 24 hours after birth. The adjusted analyses also took into account correlation of outcomes between participating babies from multiple births.

For binary outcomes, for example whether or not a baby ever had an episode of infection, adjusted RRs and CIs were calculated. For continuous outcomes, for example the number of episodes of infection, adjusted differences in means or unadjusted differences in medians (depending on the distribution of the data) were calculated with CIs. Analysis of time-to-event outcomes, such as reaching full enteral feeding, used survival analysis techniques.

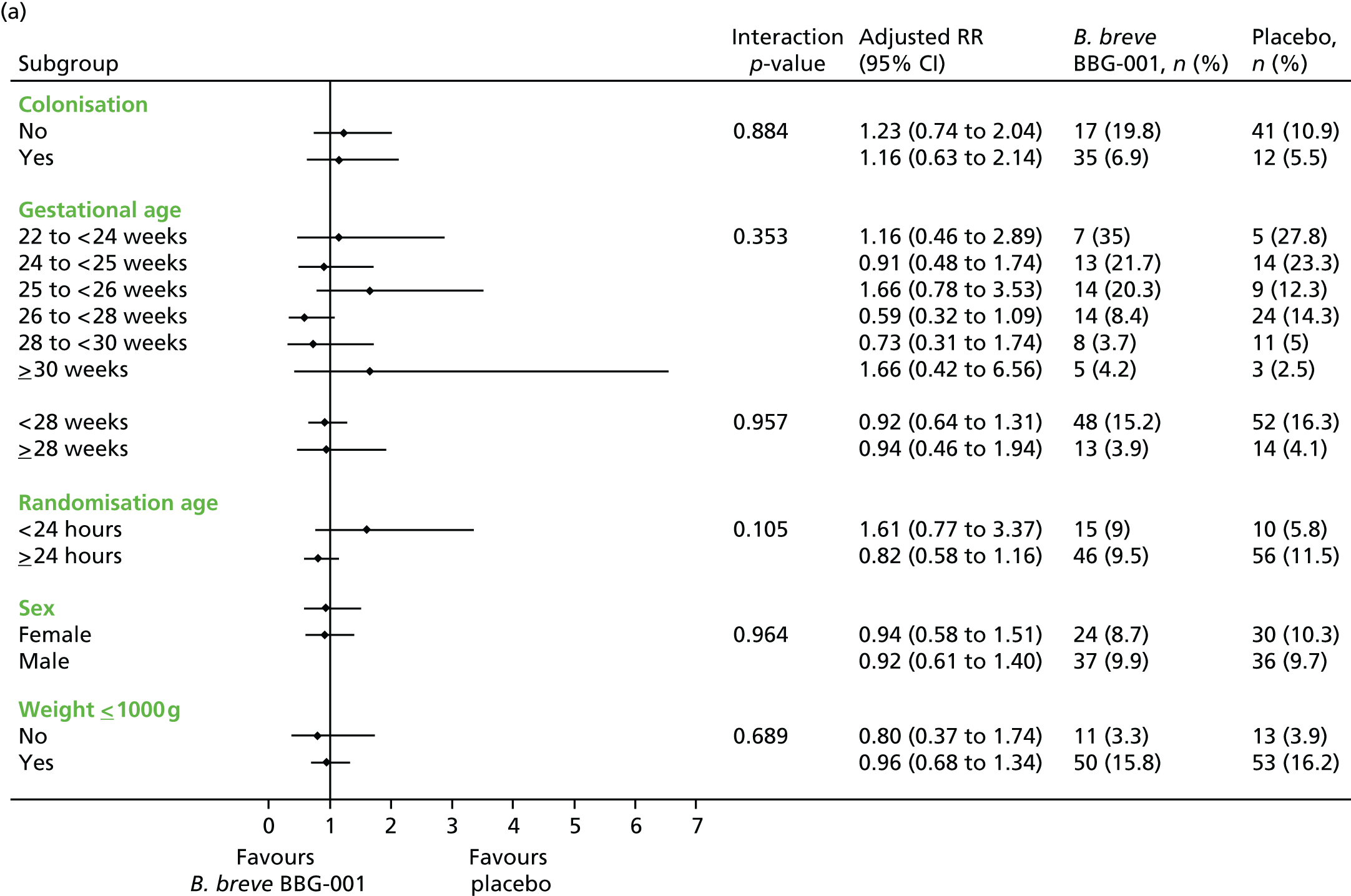

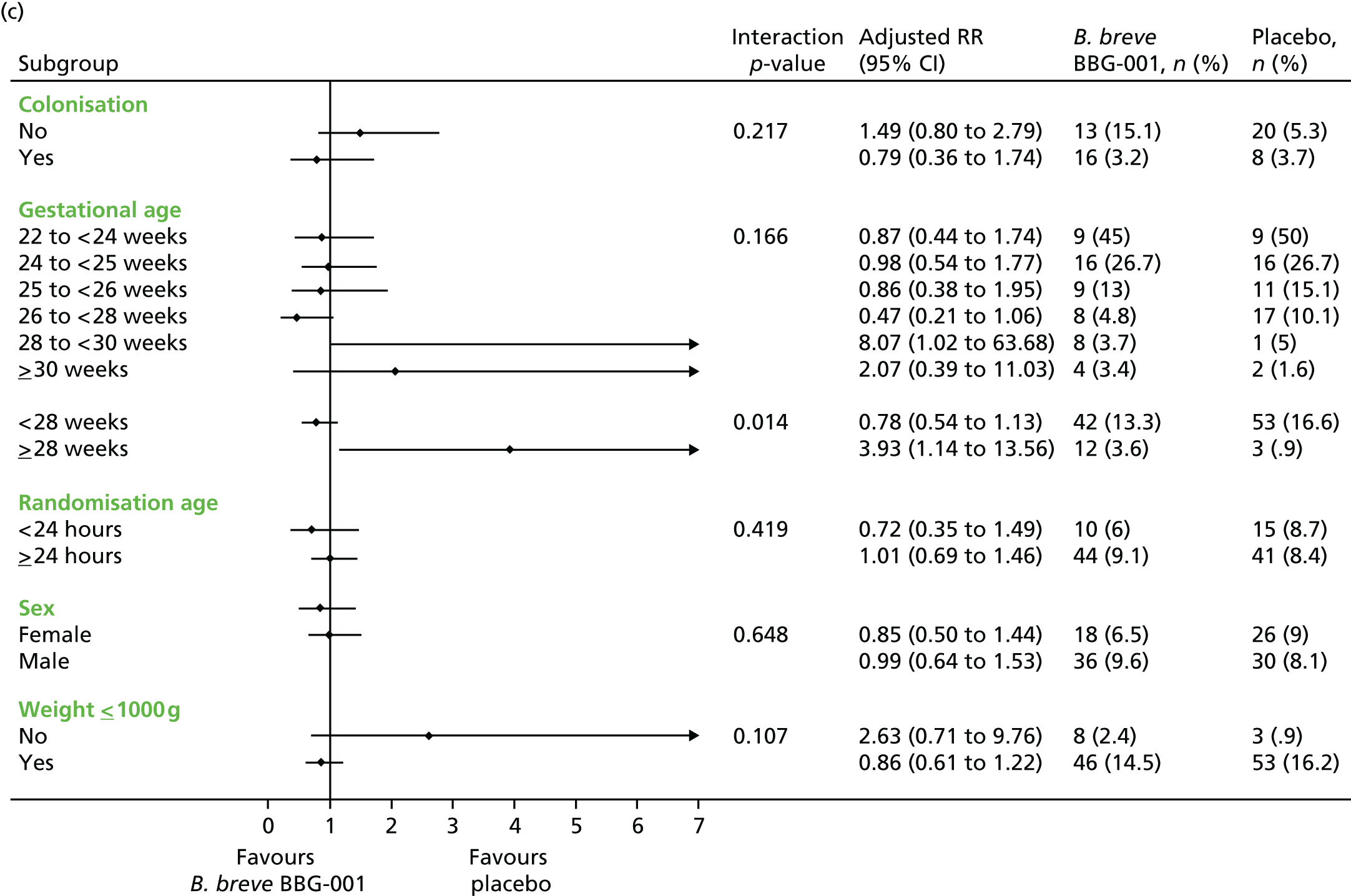

Subgroup analyses included an interaction test and, when appropriate, results are presented as adjusted RRs with 95% CIs.

Prespecified subgroup analyses were performed on the primary outcomes by intention to treat, stratified by:

-

whether or not randomised in the first or second 24 hours after birth

-

gestational age at birth as per minimisation: 23, 24, 25, 26/27 and 28–30 weeks’ gestation

-

male versus female

-

colonised versus not colonised at 2 weeks’ postnatal age

-

gestational age < 28+0 or ≥ 28+0 weeks’ gestation.

An additional subgroup analysis was performed post hoc by birthweight above or below 1 kg to facilitate comparison with data from the published ProPrems trial41 and to address recommendations made in successive systematic reviews30,32,35 concerning routine administration of probiotics in these birthweight categories.

A secondary analysis of all clinical and microbiological outcomes was conducted in those babies for whom stool colonisation data were available at 2 weeks’ postnatal age by whether or not the baby was colonised with B. breve BBG-001 identified by either culture or PCR.

Determinants of successful colonisation at 2 weeks’ postnatal age in those babies analysed to receive probiotics were investigated using forward stepwise regression. The factors assessed were baseline characteristics together with day of first feed, type of milk, use of antacid and administration of antibiotics beyond the fifth day after birth.

Significance levels and multiplicity

The 95% CIs are presented for all analyses on the primary outcomes, and a significance level of 5% (consistent with a 95% CI) used to indicate statistical significance.

Owing to the large number of secondary outcomes, all analyses are presented with 99% CIs and a significance level of 1% (consistent with a 99% CI) is used to indicate statistical significance.

The p-values are not presented for comparative analyses, but are for tests of interaction.

Regulatory approvals and protocol changes

Version 1.0 of the protocol, dated 29 January 2009, was approved by the South Central Oxford A Ethics Committee on 12 May 2009. The name of the trial was changed from PREFER to PiPS (as a condition of approval from the ethics committee) and this resulted in the protocol being amended to version 2.0, dated 18 May 2009.

Two changes to the conduct of the trial resulted in protocol version 3.0 (dated 6 October 2009): the way the investigational medicinal product (IMP) was allocated (from study number to pack number) and the duration of daily data collection of milk feeds and antibiotic/antifungal usage (from ‘until full feeds reached’ to ‘until 2 weeks’ postnatal age’). Minor typographical changes resulted in version 3.1 (dated 3 February 2010), and an update to include a more recent appraisal of the literature on Bifidobacterium use in infants led to version 4.0 (dated 13 April 2010).

Two sections relating to safety reporting and the addition of continuing care sites were updated in March 2010 (version 5.0, dated 17 March 2011). Clarification was made to safety reporting at different ‘levels’ of sites to state that safety will be assessed continuously and reported irrespective of site status. The description of how the addition and set-up of continuing care sites was achieved in practice was updated, and the implementation of the generic site-specific application system and ‘statement of responsibilities’ for gaining approvals of continuing care sites that fell outside recognised clinical pathways for transfers was added. All of these amendments received Research Ethics Committee approval.