Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/110/01. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The draft report began editorial review in February 2015 and was accepted for publication in July 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Macdonald et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background, aims and objectives

Child maltreatment is a serious public health issue and a major cause of health inequality. 1 Children who experience serious or persistent maltreatment are at risk of a range of social, emotional, behavioural and economic adversities, alongside the impact of maltreatment on their physical and mental health. The major focus of UK policy has been on preventing serious abuse and neglect, triggered and sustained by periodic reports of the circumstances surrounding child deaths. 2–4 Little attention has been given to how best to address the consequences of maltreatment for those who have experienced it or been adversely affected by it. While prevention is preferable to dealing with the consequences of maltreatment, the reality is that in 2014 almost 50,000 children in England were subject to a child protection plan because of maltreatment or risk of significant harm. Behind those 50,000 children are many more who also experience maltreatment, but who either do not come to the attention of social services or whose maltreatment falls below the undoubtedly high thresholds of harm currently operated by Children’s Services Departments. In 2012, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme commissioned two evidence syntheses that were relevant to the needs of maltreated children. One was a review of interventions aimed at improving outcomes for children exposed to domestic violence (PHR 11/3007/01). 5 The second was an evidence synthesis of psychosocial interventions aimed at improving outcomes for children who experienced maltreatment, and this is the focus of this report.

Categories of maltreatment

Child maltreatment has been defined as any act or series of acts of commission (physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional/psychological abuse) or omission (neglect) by a parent, caregiver or other person, which leads to harm, the potential for harm, or threat of harm to a child (someone under 18 years). Most child maltreatment takes place within the family home, but it can also occur in an institutional or a community setting. The perpetrators of maltreatment are usually known to the children concerned, but more rarely they may be strangers. Although most maltreatment is attributable to adults, child-to-child maltreatment is also a concern. Some forms of maltreatment can take place on the internet.

Detailed definitions can be found in a number of guidelines. 6–9

Briefly:

-

Physical abuse may involve hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning, suffocating or otherwise causing physical harm to a child. Physical harm may also be caused when a parent or carer fabricates the symptoms of, or deliberately induces, illness in a child.

-

Emotional/psychological abuse is the persistent emotional abuse of a child such as to cause severe and persistent adverse effects on the child’s emotional development. Emotional maltreatment may take the form of age or developmentally inappropriate expectations on children. It may involve conveying to children that they are worthless or unloved; not giving them opportunities to express their views or ‘making fun’ of what they say or how they communicate; seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another; being seriously bullied (including cyberbullying), or exploited or corrupted. Emotional abuse is involved in all types of maltreatment, although it may occur alone. Children who are the subject of fabricated illness are also subject to emotional abuse, either as a result of being brought up in a fabricated sick role, or because of an abnormal relationship with their carer, or disturbed family relationships. 10–15 More recently, domestic violence has been recognised as maltreatment, and is a common cause of emotional or psychological harm to children.

-

Sexual abuse involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. Activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration or non-penetrative acts and non-contact activities, such as involving children in watching sexual activities, encouraging them to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming them in preparation for abuse (including via the internet). Sexual abuse is perpetrated by men and women, although the majority of sexual abuse of children is by male perpetrators against female children, typically someone known to them (i.e. a family member or family friend). Abuse by a stranger is less common. Sexual abuse can occur between children.

-

Neglect is the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical and/or psychological needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of his or her health or development. Neglect may occur during pregnancy as a result of maternal substance abuse. Once a child is born, neglect may involve a parent or carer failing to provide a child with adequate food, clothing and shelter (including exclusion from home or abandonment); failing to protect him or her from physical and emotional harm or danger; or failing to ensure access to appropriate medical care or treatment. It may include neglect of, or unresponsiveness to, a child’s basic emotional needs.

Most children experience more than one form of maltreatment, and there is growing recognition of the need to better take into account children’s profiles of maltreatment in order to improve policy and practice. 16–18 Although maltreatment can result in death, serious injury or impairment (see below), it is not itself a disorder but an event or exposure; not all maltreated children experience impairment.

Prevalence, aetiology, contributory factors

Child maltreatment poses significant threats to children’s health, development and well-being. It is recognised that statistics on the number of referrals to child protection services, and the numbers of children for whom there is a child protection plan, let alone the number of criminal offences against children, are an underestimate of the scale of the problem within the UK. The term ‘registration’ is used here to describe children for whom there is a child protection plan (England) or whose names are on child protection registers (Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland). As at March 2009, registrations in the UK were England, 34,100; Wales, 2512; Northern Ireland, 2488; and Scotland, 2682. It is important to note that these data may not be measuring precisely the same thing in each jurisdiction. Data on trends in child maltreatment are difficult to interpret,19 but, overall, the numbers of children registered in each jurisdiction has increased steadily since 2002, although there is some evidence of a fall in the numbers of violent child deaths in infancy and middle childhood within the UK. 20 The 2014 figure for children subject to a child protection plan in England as at 31 March was 48,300 (excluding unborn children), an increase of 12.1% on the numbers at the same time in 2013. This represents an increase of 23.4% since 31 March 2010. In 2011 the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) published a cross-sectional, self-report survey of 2275 children aged 11–17 years and adults aged 18–24 years. Their findings indicated that 18.6% of the 11- to 17-year-olds ‘had been physically attacked by an adult, sexually abused, or severely neglected’ and 25.3% of the 18- to 24-year-olds reported severe maltreatment during childhood. 21

Consequences of maltreatment

A growing body of evidence suggests that being exposed to maltreatment may result in structural and functional changes to the developing brain,22–24 as well as long-lasting changes in the way genes are expressed in the brain. 25–27 The adverse effects of maltreatment can be found across multiple domains of functioning, including physical and mental health and well-being, security of attachment, cognitive and emotional development, aggression, violence and criminality, and socioeconomic attainment. 28–33 Maltreatment is a non-specific risk factor for a wide range of adverse long-term health and social care outcomes, and children who experience multiple forms of maltreatment are at increased risk. 34–36 There is also some evidence of maltreatment type-specific risks, although generally this is stronger for sexual abuse than other forms of child maltreatment. Widom et al. 37 found that both child physical abuse and neglect, but not sexual abuse, were associated with an increased risk for lifetime major depressive disorder in young adulthood, with children exposed both to physical abuse and neglect being most at risk. A longitudinal study by Kotch et al. 38 concluded that neglect within the first 2 years of life, in the absence of other forms of maltreatment, predicted levels of aggression at ages 4, 6 and 8 years. Preschool children exposed to severe physical neglect have been found to evidence increased rates of internalising symptomatology and withdrawn behaviour compared with other maltreated children. 39 Generally though, the fact that few children experience only one form of maltreatment makes it difficult to link particular forms of maltreatment with specific risks or adverse outcomes.

The impact of maltreatment may depend on the interaction of a number of factors, including the child’s genetic endowment, age, gender, type(s) of abuse, severity, frequency and duration of maltreatment, and the availability of protective factors that function to enhance a child’s resilience. 40–45 Children who appear to be ‘asymptomatic’ following maltreatment may, nonetheless, be at risk for the development of later psychosocial problems, triggered by subsequent stressors and the need to negotiate key developmental tasks, for example forming intimate relationships, managing interpersonal conflict, becoming a parent and so on.

For the child who is removed from their birth parents or other primary carers under relevant legislation, the adverse effects of maltreatment may be compounded by delays arising from lengthy care proceedings and instability of placements. For infants and young children, these factors may exacerbate attachment difficulties or disorders. In developing effective interventions, it is therefore important to understand how and why maltreatment impacts throughout the life course, and the variables that either mediate or moderate adverse sequelae.

Economic consequences of maltreatment

The economic costs of maltreatment, both to individuals46–50 and to society,51–55 are well documented. Costs to individuals include adverse effects on physical and mental health; social and emotional development; cognitive development and levels of educational attainment; and employment status and earnings. Societal costs include the health and social care costs of illness or injury; the intergenerational costs of teenage pregnancy and poor parenting; criminal justice system costs; and losses in productivity.

Psychosocial interventions

There is a wide range of psychosocial interventions currently available to children and young people who have experienced maltreatment, although availability varies enormously. 56–58 These are based on a variety of theoretical underpinnings and include:

-

interventions based on cognitive theories, including cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) and abuse-focused CBT

-

eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR)

-

interventions based primarily on forms of expression and communication drawn from the arts, including art therapy, drama therapy, music therapy, play therapy and narrative group therapy

-

attachment-based interventions

-

interventions based on psychoanalytic theories, offered to the child or parent–child dyad.

-

family/systemic interventions.

-

multisystemic therapy (MST)

-

peer mentoring.

-

enhanced foster care, including treatment foster care

-

residential care, including models of therapeutic residential care, such as CARE® (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA) and Sanctuary® (Sanctuary Institute, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Interventions may be delivered in one or more of a range of contexts, for example clinic, school, community. Interventions may be individual or group based, or a combination, and may involve only the child or the child and his or her primary carer(s). Some entail a change of caregiver, as in adoption, kinship care, foster care or residential care. Most are commissioned, or provided by, the UK NHS. Some are available from a range of voluntary and private sector providers, and some are primarily social care or education based.

Timing of, and pathways to, treatment

For some forms of maltreatment, treatment can be offered appropriately only after the child is protected from further abuse. This applies to sexual abuse and serious physical injury, and here protection can be ensured only when the contact between the child and the abuser is constantly supervised or halted. In the more persistent or chronic forms of maltreatment – emotional abuse and neglect – treatment may be offered to the child and caregivers simultaneously to deal both with the effects of the maltreatment and with the harmful parent–child interactions.

Maltreatment per se may be the trigger for some referrals to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). For example, a child may be referred following recognition of a specific form of maltreatment, most commonly sexual abuse. Sometimes children are referred as a result of maltreatment although the precise nature of that maltreatment may not be known. Other children may be referred because they have experienced several forms of maltreatment. Emotional maltreatment is often seen as integral to other forms of abuse or neglect.

Some children will be referred for help with specific symptoms, for example post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression or anxiety. In some cases this will be clearly identified as the results of exposure to maltreatment, such as physical or sexual abuse or intimate partner violence (IPV). Others will be referred when there is no mention or initial awareness of the existence or relevance of previous maltreatment, but where a causal link is subsequently found. This review focuses on those children whose pathways to referral are clearly linked with maltreatment.

Treatment acceptability and engagement

Children who have experienced abuse and neglect can be difficult to engage, not least because of the adverse impact of maltreatment on their ability and willingness to engage with, or trust, adults. Evidence from a NSPCC survey21 indicated that some 80% of young adult women who reported abuse by a caregiver said they had talked to a professional following the abuse taking place, compared with just 18% of boys. However, those who sought help from a professional did not always think that it had brought about a better outcome. Carers too can feel excluded from some therapeutic approaches, when their involvement may be critical.

But many children do not have the opportunity of help. Historically, child maltreatment has been seen as a problem for social care, rather than CAMHS,59 and effective interagency working between CAMHS and social services continues to be elusive. Referral pathways to CAMHS are long and complex,60,61 and, for those referred, acceptance thresholds are high and waiting lists are often extremely long. Little, if anything, is known about what maltreated children want from health-care professionals or what kinds of intervention or service arrangements they find acceptable, and possible to engage with, or unacceptable.

Importance of this evidence synthesis

Reviews in this area suffer from a number of weaknesses. 62 These include (1) searches that are out of date, have restricted search dates or language restrictions; (2) the predominance of research conducted in North America, with little or no consideration of the generalisability of evidence to other policy contexts; (3) a lack of adequate consideration of the maltreatment profiles of study participants; (4) a lack of consideration of the logic models underpinning included interventions; (5) inadequate, and sometimes no, consideration of the risk of bias of included studies; (6) heterogeneity of outcomes and measures used; and (7) a lack of consideration of issues of acceptability or accessibility of interventions for children and their families.

Most reviews, for good methodological reasons, restrict their inclusion criteria to randomised or quasi-randomised trials. Although it is arguably unethical to expose maltreated children to interventions of unknown effectiveness, the technical challenges of implementing randomised trials of maltreatment interventions are considerable, sometimes resulting in studies with high risk of bias63,64 or little useful information. Other types of study may provide valuable information about interventions not yet subjected to more rigorous evaluation, and may provide a picture of the evidence gaps when compared with the profile of available services.

As with studies and reviews of interventions, most studies of the cost-effectiveness of interventions appear to have focused on primary prevention rather than secondary and tertiary prevention, or the treatment of children who have experienced maltreatment. 65–67 A review by Goldhaber-Fiebert et al. 68 identified 19 reviews and 30 original papers reporting research on the costs and effectiveness of interventions for children at risk of (the majority), or already involved in, child welfare (protection) services. They observe that existing model-based evaluations of secondary prevention have, so far, used ‘relatively simple multiplicative decision trees’ that do not reflect the variety of pathways that children follow, how these may impact on the effectiveness of subsequent interventions or adequately address factors such as the child’s age (p. 737). They concluded that current epidemiological data, combined with evidence from well-conducted outcome studies and improved modelling techniques, make it timely to revisit the cost-effectiveness of interventions for maltreated children.

Research aims and objectives

This review aimed to bring high standards of evidence synthesis to bear in this important but challenging area of public health. It provides an up-to-date overview of research on interventions aimed at addressing the adverse consequences of child maltreatment, and a synthesis of what we know about their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. The objectives of the research were to answer the following questions:

-

Which interventions are effective, for which children, with what maltreatment profiles, in what circumstances?

-

When two or more interventions might be appropriate, which is most likely to be effective?

-

Which interventions are of no benefit or may result in harm?

-

Which interventions are most accessible and acceptable to carers, children and young people?

-

What do we know about the economic benefits of interventions, and the potential value of undertaking future research?

Chapter 2 Review methods

Focus of the review

In line with the HTA brief, this review sought to include effectiveness studies of any psychosocial intervention provided to maltreated infants, children or adolescents in any setting (e.g. family, community, residential) specifically to address the consequences of maltreatment. We included studies of any intervention aimed at addressing the consequences of any type of maltreatment, irrespective of service provider or setting (e.g. family, institution, school), whether or not provided to children individually or in a group format, and whether or not the treatment involved parents or other carers. We included studies in which the intervention was delivered to a child by, or through, a parent or other carer, as long as this was concerned with addressing the consequences for the child of his or her experiences of maltreatment.

This meant excluding two groups of studies that are also relevant to improving outcomes for children experiencing maltreatment or who are at risk of maltreatment, namely:

-

Studies aimed at the secondary prevention of maltreatment. These are studies of interventions aimed primarily at improving quality of parenting in families in which there are concerns about maltreatment. Arguably, by improving parenting in ways that prevent future maltreatment and enhance the quality of parenting and family relationships, such interventions make an important contribution towards addressing the adverse consequences caused by maltreatment to children within these families. There are a number of parenting programmes that specifically target these vulnerable families, but their focus is primarily the parents and their parenting, rather than the children. Only if the programme combined an intervention aimed specifically at the child, as well as the parents, were such studies included in this review.

-

Studies concerned with evaluating interventions that addressed problems known to be associated with maltreatment (such as depression or PTSD) but for which the target population was any child experiencing the health problem. In other words, these studies did not set out to recruit children who, because of maltreatment, were experiencing depression, anxiety, behaviour problems and so on. Our searches identified many studies of this kind, in which the study sample included participants (typically adolescents or young adults) who might have experienced maltreatment, but whose maltreatment was not the reason for their recruitment.

Project oversight

The research team were experienced in systematic review methodology and provided topic expertise in this field. Alongside the research team, a Steering Group was established to guide the overall direction of the project, and to ensure that a range of expertise and perspectives, particularly those of guideline developers, were properly considered in decisions taken during the course of the review. The research team and Steering Group members are listed in Appendix 1.

Professional Advisory Group

To enhance the clinical and professional representation in the project, a Professional Advisory Group (PAG) was established to help shape the work, interpret the evidence and draw conclusions from the data. Approximately 50 professionals were invited to participate. They represented a range of disciplines (including mental health nursing, general practice, psychology, psychiatry, social work, teaching and foster care) from different settings (tertiary care, CAMHS, residential care, community, etc.) and different providers (NHS, private and voluntary sectors). The objective of the PAG consultations was to help ensure relevance to health and social care provision in the UK. In particular, these consultations helped with the identification of potential barriers and facilitators to implementation from the perspective of those (1) involved in identifying children who need psychosocial interventions as a result of maltreatment; (2) responsible for referring them to appropriate services; and (3) delivering services. Information was shared with the PAG throughout the project and two face-to-face meetings were convened in London. The first meeting, involving around 40 participants, took place near the start of the project on 1 May 2013, and was designed to help identify and prioritise key issues. The second meeting, involving around 20 participants, took place on 27 November 2014 once the initial findings were available, and was intended to take the form of a consensus meeting. The names of PAG participants are provided in Appendix 2.

Young Persons’ Advisory Groups

Several Young Persons’ Advisory Groups were convened to provide advice on general issues relevant to the project. In particular, the groups were established to help us understand the experience of receiving treatment from professionals concerned with maltreated children, the factors that enhance acceptability of treatment, and what outcomes matter most to children and adolescents. One group in Belfast, Voice of Young People in Care (VOYPIC) and one Cardiff-based group, Voices from Care, were approached and invited to participate in the project. At the beginning of the project, an initial meeting of seven young people aged between 16 and 24 years from the VOYPIC group was convened in Belfast on 27 March 2013. A subsequent meeting of seven young people aged ≥ 18 years from the Voices from Care group was convened in Cardiff on 9 April 2013. Both meetings were coconvened by dedicated facilitators from their respective organisations, who were experienced in consulting with young people in care or previously in care, as well as one member of the research team (either NL or JH). Towards the end of the project, a group of six young people aged between 15 and 19 years contributed to the interpretation of the project’s findings during a NSPCC participation event held on 27 October 2014.

Early planning with advisory groups

A plan for undertaking consultations was agreed with the project Steering Group. The early advisory groups were intended to help shape the plan of the review. The key questions and methods used for these initial advisory group meetings were broadly similar. Both professionals and Young Persons’ Advisory Groups were consulted on relevant outcomes following psychosocial interventions for maltreated young people, factors that would facilitate their getting the help they needed, and factors that would act as barriers to their getting that help. The Young Persons’ Advisory Groups were asked to consider three additional questions:

-

What difference would ‘helpful help’ make for a child or young person who had been treated badly?

-

What would make it easier to ask for help or get help?

-

What would make it harder to ask for help or get help?

In both the PAG and the Young Persons’ Advisory Groups, a sorting and ranking exercise called the Q-sort was used to elicit individual views and help develop some consensus views. On the basis of their knowledge of the field, the research team and the Steering Group agreed an initial set of potential outcomes, facilitators for getting help, and barriers to getting the help they needed. Group members were presented with a group of cards, each of which had a different possible outcome, facilitator or barrier. Group members were first asked to review the cards individually and consider their own opinions on where each card should be placed on the large Q-sort pyramidal grid. They were then asked to discuss their opinions in the group, and to work together to create one single agreed Q-sort pyramid. Cards placed to the right of the grid would be those that were the most important outcomes/facilitators/barriers and the least important to the left. Group members were informed that they could amend the cards if necessary. They were also welcome to add new cards if they felt that any potential factors were missing and to remove any cards that they felt were irrelevant.

The Q-sort process proved to be quite effective at engaging the young people and serving as a basis for discussion. Based on the experience of the first group, the process was slightly modified for the following sessions, so that the sequence of issues was revised and part of the session was spent in smaller subgroup discussions.

In view of the large size of the PAG, to enable meaningful discussion the Steering Group decided to establish smaller groups based on professional discipline for the Q-sort task. This allowed all groups to contribute, but also highlighted areas of agreement and differences between the groups, so that potential reasons could be discussed. Each small group was facilitated by a member of the research team/Steering Group.

Final Professional Advisory Group meeting

A detailed and technical presentation of the review findings was provided for this PAG. The smaller number of participants at this meeting enabled whole-group discussion.

Participants were first asked to consider a series of questions about the findings of the review, including whether or not there were any important studies missing, any surprises about the coverage of maltreatment types or the profile of evidence across different types of intervention, and whether or not any of the findings were puzzling/unexpected. Participants were also asked the extent to which the review findings matched their experience of what is offered through health and social care services and, if different, what might account for this (e.g. training, therapeutic context, therapeutic preferences, resource constraints or other explanations).

They were then asked to consider how clinicians were likely to react to the messages about the weight of evidence in favour of CBT interventions, whether or not there were likely to be any barriers to implementing the findings and how these issues might be considered in the final report.

Finally, in light of existing evidence, participants were asked to identify any priorities for future research.

Final Young Persons’ Advisory Group meeting

The young persons’ group was cofacilitated by members of the research team and Steering Group, without an adult present whom the young people knew well. This session was part of a broader participation event, for which known and trusted adults were available to support the young people should they become distressed. We explained to them that during the session they would hear quite powerful quotations from young people, which they might find unsettling. In such an event we told them that they could let us know if they wanted a break or simply take themselves off to the agreed point to find their identified adult supporter.

In the first part of the session, members of the research team provided an overview of the key intervention types that were identified through the review: CBT; counselling or psychotherapy; family intervention; attachment therapy; activity-based interventions; and therapeutic residential care. In addition to talking about these, pictures were provided on large laminated sheets to help illustrate key features of these approaches. The main part of the session was focused around three sets of questions/statements:

-

Prioritising between interventions:

-

Which of these intervention types would young people want more?

-

Some therapies have a lot of evidence showing that they work, but others do not. If you were the government, to which ones would you give the money?

-

-

Responses to ‘acceptability’ statements:

-

‘Therapy doesn’t help people to forget about abuse, they just make them talk about it over and over again.’

-

‘In some situations where the child starts therapy, they can get upset, and the parent then doesn’t want them to go. What advice would you give a parent if their child was upset for the first time?’

-

‘It’s not just the child that needs help, parents do too.’

-

‘Do other people need to know what the therapist and child talk about?’

-

‘Does a young person have to like their therapist for treatment to help?’

-

-

Disseminating research evidence and findings to young people: suggestions for how to do this most effectively.

The group was given a range of tools to help the discussion. For example, they were given a pile of fake bank notes to help them allocate the funds to different intervention types. The visual component to this was important and the young people ensured that they distributed the money carefully, to reflect their priorities. They were also given voting cards with which to respond to the acceptability statements, with different colours representing different options.

Protocol

The evidence synthesis work was planned in accordance with guidance provided by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination69 and the Cochrane Collaboration. 70 The nature of the research objectives required evidence syntheses of (1) studies of the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions provided for children and adolescents who have suffered maltreatment; (2) studies of their acceptability to children, adolescents and their carers; and (3) the cost-effectiveness of these interventions.

A protocol for the review based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria71 was developed and agreed with the Steering Group. The review protocol, which details the objectives, types of study design, participants, interventions and outcomes considered, is registered with PROSPERO (PROSPERO 2013: CRD42013003889). A copy of the review protocol is available at www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42013003889.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As this review was designed to address questions of effectiveness, acceptability and economic benefits, it was necessary to consider different study types. The inclusion criteria were tailored accordingly and our inclusion criteria and associated searches were kept deliberately broad to identify studies relevant to the aims set out in Chapter 1. The review considered both published and unpublished literature.

Types of study

Synthesis of evidence of effectiveness

Any controlled study (CS) in which psychosocial interventions were evaluated for this population was considered, including randomised and quasi-randomised trials, quasi-experimental (QEx) controlled studies and controlled observational studies (COSs). We used the following definitions.

Randomised controlled trial (RCT) Individuals followed in the trial are actively assigned to one of two (or more) alternative forms of intervention or health care, using an entirely random method of allocation (such as computer random number generation).

Quasi-randomised trial Individuals followed in the trial are actively assigned to one of two (or more) alternative forms of intervention or health care, using a quasi-random method of allocation (such as alternation, date of birth or case record number).

Quasi-experimental study Individuals followed in the study are actively assigned to one of two (or more) alternative forms of intervention or health care, using a non-random method of allocation (such as assignment based on experimenter’s choice).

Controlled observational study Individuals followed in the study are receiving one of two (or more) alternative forms of intervention or health care. However, they are not actively assigned to the alternative forms of intervention or health care. The control group is likely to comprise those who were not offered the intervention or who refused to participate in the intervention.

Uncontrolled study All individuals followed in the study are given the same treatment or health care, and simply followed for a period of time to see if they improve, with no comparison against another group (control group) that is either taking another treatment or no treatment at all.

Where no controlled effectiveness studies were identified, other study designs were considered, but purely for the purposes of informing the development of future research.

Case studies, descriptive studies, editorials, opinion papers and evaluations of pharmacological or physical interventions without an adjunctive psychosocial component were excluded from the synthesis of effectiveness studies.

Synthesis of acceptability studies

For this part of the review, studies that asked participants for their views were included, irrespective of study design or data type.

Any studies that provided quantitative data on non-participation, withdrawal and adherence rates were included as part of the effectiveness synthesis. We imposed no restrictions on design for this synthesis, as long as the study was about psychosocial interventions for treating the consequences of child maltreatment.

Economic evaluation

For this part of the review, we included economic evaluations that were carried out alongside trials and decision-analytic models, and uncontrolled study designs – such as uncontrolled costing studies – were considered, in addition to the study designs included in the synthesis of evidence of effectiveness. For the purposes of the synthesis of economic studies, whether trial based or decision model, economic evaluations based on data from RCTs were prioritised, although QEx controlled studies and COSs (cohort studies and case–control studies) were also considered. Uncontrolled study designs and descriptive costing studies were also considered, in addition to the study designs included in the synthesis of evidence of effectiveness, for the purposes of populating a decision model.

Types of populations/patients

Studies were eligible if recruitment was targeted at maltreated. Because young people in care remain entitled to support up until the age of 25 years, and because the effects of maltreatment are not always immediate, we included studies in which maltreatment took place before 17 years 11 months, but where the participants were aged up to 24 years 11 months. This also enabled us to minimize the loss of potentially relevant data. If the age range of participants was broader (e.g. 10–30 years) but the study met all other criteria, authors were contacted for further information, as appropriate.

Studies of interventions for a wide range of maltreatment types, including physical abuse, emotional and psychological abuse (including those witnessing domestic violence), sexual abuse and neglect were included. Studies were included if they involved maltreated participants as well as children and young people who had suffered other kinds of trauma (e.g. violent assault by a stranger) only if the participants were randomised and data for analyses were presented separately (or were obtainable). Studies that described children as ‘at risk’ because they had already experienced maltreatment were included. Studies involving children in care were included only if there was evidence that the participants were maltreated and the focus of the intervention was designed to address the sequelae of maltreatment. Studies were included whether or not the children involved were displaying any symptoms.

We excluded studies that were designed to evaluate interventions for other kinds of trauma, including teenage dating violence, those with children who had experienced violent physical assault by a stranger, and those where maltreatment had occurred during a conflict/war situation. We excluded studies that may have involved, but did not specifically target, maltreated children (e.g. studies of psychosocial interventions for depression in children and adolescents) and studies in which children were described as ‘at risk’ of maltreatment but which provided no evidence that they had already experienced maltreatment.

Types of interventions

Any psychosocial intervention provided to maltreated infants, children or adolescents in any setting (e.g. family, community, residential, school), and by any provider, aiming specifically to address the consequences of any form of maltreatment, with or without the involvement of a carer or carers.

Examples of eligible psychosocial interventions are listed in Chapter 1. We included any intervention based on cognitive theories (e.g. CBT, TF-CBT and abuse-focused CBT); EMDR; interventions based primarily on forms of expression and communication drawn from the arts (e.g. art therapy, drama therapy, music therapy, play therapy and narrative group therapy); attachment-based interventions; interventions based on psychoanalytic theories, offered to the child or parent–child dyads; family/systemic interventions; MST; peer mentoring; enhanced foster care, including treatment foster care; and residential care, including models of therapeutic residential care, such as CARE® and Sanctuary®. Further details about included interventions are provided in Appendix 5.

We included studies in which interventions were targeted at those responsible for the child (e.g. parents or services) and included outcomes for the children studied. Studies in which psychotropic medication was provided alongside psychosocial interventions were included.

As the review was focused on interventions addressing the consequences of maltreatment, we excluded studies that were aimed at the prevention, identification and cessation of maltreatment. We also excluded any study that assessed outcomes of those in standard foster care or standard residential care, for which no specific therapeutic aspect was being evaluated.

Types of comparisons

Studies comparing psychosocial interventions with no-treatment arms, wait-list control groups, ‘treatment as usual’ (TAU) and ‘other active treatment controls’ were included.

Types of outcomes

As described above, consultations were undertaken with key stakeholders in order to ensure appropriate primary and secondary outcomes were considered and at meaningful time points. We were interested in the following broad core outcome domains.

Primary outcomes of interest for children included the following domains: (1) psychological distress/mental health (particularly PTSD, depression and anxiety and self-harm); (2) behaviour (particularly internalising and externalising behaviours); (3) social functioning, including attachment and relationships with family and others; (4) cognitive/academic attainment; and (5) quality of life.

Secondary outcomes included (1) substance misuse; (2) delinquency; (3) resilience; and (4) acceptability.

We were also interested in recording any outcome related to carer distress, carer efficacy (the degree to which they feel empowered to care for the child appropriately and safely) and, where appropriate, placement stability. Outcomes themselves were not used as inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Search methods

One overarching search strategy was developed to ensure coverage across all elements of the review. Research, professional, policy and grey literature was searched using systematic and comprehensive search strategies of appropriate bibliographic databases and relevant websites.

Search term generation

Search terms relating to the key concepts of the review were initially identified through discussion between the research team and information scientists working for the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Review Group and the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group. Background literature and controlled vocabulary lists of relevant databases (e.g. medical subject heading terms in MEDLINE) were also scanned. Initial pilot search strategies were developed and discussed by the research team and Steering Group, and the electronic search strategy was modified and refined several times before implementation. No language limits or study design filters were applied. Examples of final electronic search strategies for several different databases [via MEDLINE Ovid; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (via The Cochrane Library); ProQuest; EBSCOhost; eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases] are provided in Appendix 3.

Electronic searches

The following databases were first searched from the date of their inception between 28 February and 5 March 2013. Updating searches of the main databases were undertaken between 29 May 2014 and 2 June 2014. A full list of databases searched, with exact dates, is provided in Appendix 6.

-

Health and allied health literature [Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL PsycINFO, EMBASE, CENTRAL, CDSR, DARE, Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC)].

-

Social sciences and social welfare literature [Social Services Abstracts, Social Care Online, Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), Campbell Library of Systematic Reviews].

-

Education literature [Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Australian Education Index, British Education Index].

-

Other evidence-based research repositories [Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER), Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions (TRoPHI).

-

Economic databases [NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Paediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE), Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED), EconLit and the IDEAS economics database.

Updating searches planned prior to publication included trials registers [International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov; UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) Study Portfolio].

Grey literature and other resource searches

Material generated by user-led or voluntary sector enquiry was identified via OpenGrey, searching the internet (using Google and Google Scholar) and browsing the websites of relevant UK government departments and charities (Mental Health Foundation, Barnardo’s, Carers UK, ChildLine, Children’s Society, Depression Alliance, MIND, Anxiety UK, NSPCC, Princess Royal Trust for Carers, SANE, The Site, Turning Point, Young Minds and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network). These sites were systematically searched by members of the research team or members of the wider Steering Group using a selection and combination of search terms as appropriate. The process is described in detail in Appendix 7. Grey literature searches were up to date as of 25 June 2014. Requests were also sent to members of the Steering Group for additional studies.

Reference lists

We checked references in studies that met the inclusion criteria, in previous reviews and other studies.

Targeted author searches

We conducted targeted author searchers following the identification of key researchers in the field and looked for follow-up studies using Google Scholar. Authors of ongoing and recently completed research projects were also contacted directly as required to establish whether or not any results were available.

Data collection and analysis

Screening of citations and study selection

The original search was completed on 26 June 2013 and an updated search was undertaken on 4 June 2014. Search results were either imported into EndNote version 4 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) or saved as text files. After removing obvious duplicates and irrelevant records, remaining records were imported into EPPI-Reviewer 4.7172 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK), through which further duplicates were removed. Duplicates were removed by two reviewers (NL and JH). Citations were then stored for sifting and management using EPPI-Reviewer.

Owing to the volume of citations identified, it was not possible to double-code the screening of all citations. To ensure that reviewers were consistent in their decisions, five reviewers (JH, NL, CMcC, MC, GM) initially coded the same 300 citations. Decisions were discussed, and selection criteria refined and clarified. Once this process was complete and reviewers were satisfied that selection criteria were being understood and applied consistently, each reviewer was assigned citations in batches of 1000 citations at a time. To ensure that reviewers decisions remained consistent, 10% of citations were double-coded and disagreements were resolved by discussion before moving on to the next batch of citations. Wherever a reviewer was uncertain about which code should be applied a second opinion was sought from another member of the research team.

When both reviewers agreed on inclusion, or whenever there was disagreement or uncertainty about inclusion, the full-text article was obtained. When potentially relevant studies were published as abstracts, or when there was insufficient information to assess eligibility or extract the relevant data, authors were contacted directly. To ensure consistency in the application of inclusion criteria for full-text articles, the same checking procedures were used. Each reviewer was assigned full-text articles in batches of 500 articles. Although 10% of full-text articles were initially cross-checked, second opinions were required on almost every article. Therefore, two reviewers read full reports and determined eligibility for all studies.

Any unresolved disagreements were discussed with the research team and, where necessary, eligibility criteria were further operationalised through discussion with input from the Steering Group. When maltreatment was not confirmed in the population but was considered likely to have occurred (e.g. concern from referring person that neglect was occurring), authors were contacted for further information. Principal reasons for the exclusion of studies were recorded.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction forms tailored to review objectives were developed for both the effectiveness and acceptability studies. These were piloted and refined using the first 10 papers marked for inclusion. For each included study, two review authors independently extracted and recorded the following data using a data collection form: study design and methods, sample characteristics, intervention characteristics (including theoretical underpinning of services, delivery, duration, outcomes and within-intervention variability), outcome measures and assessment time points. Where necessary, study investigators were contacted for clarification about study characteristics and data. Any differences that could not be resolved were noted.

As expected, the studies that met our inclusion criteria covered a heterogeneous group of psychosocial interventions designed to address the adverse consequences of child maltreatment. For the purposes of this review, we sought to group these according to common factors in their underlying theories of change. We recognise that there is much debate about the theoretical underpinnings and classification of different types of therapy, and that some may disagree about the decisions we have made.

We summarised therapies according to the groupings below. Further details and descriptions of the therapeutic approaches can be found in Appendix 5.

-

Cognitive–behavioural therapies:

-

CBT

-

behavioural therapies

-

modelling and skills training

-

TF-CBT

-

EMDR.

-

-

Relationship-based interventions (RBIs):

-

attachment-orientated interventions

-

Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC)

-

parent–child interaction therapy (PCIT)

-

parenting interventions

-

dyadic developmental psychotherapy (DDP).

-

-

Systemic interventions:

-

systemic family therapy (FT)

-

transtheoretical intervention

-

MST

-

multigroup FT

-

family-based programme.

-

-

Psychoeducation

-

Group work with children

-

Psychotherapy (unspecified)

-

Counselling

-

Peer mentoring

-

Intensive service models:

-

treatment foster care

-

therapeutic residential/day care

-

co-ordinated care.

-

-

Activity-based therapies:

-

arts therapy

-

play/activity interventions

-

animal therapy.

-

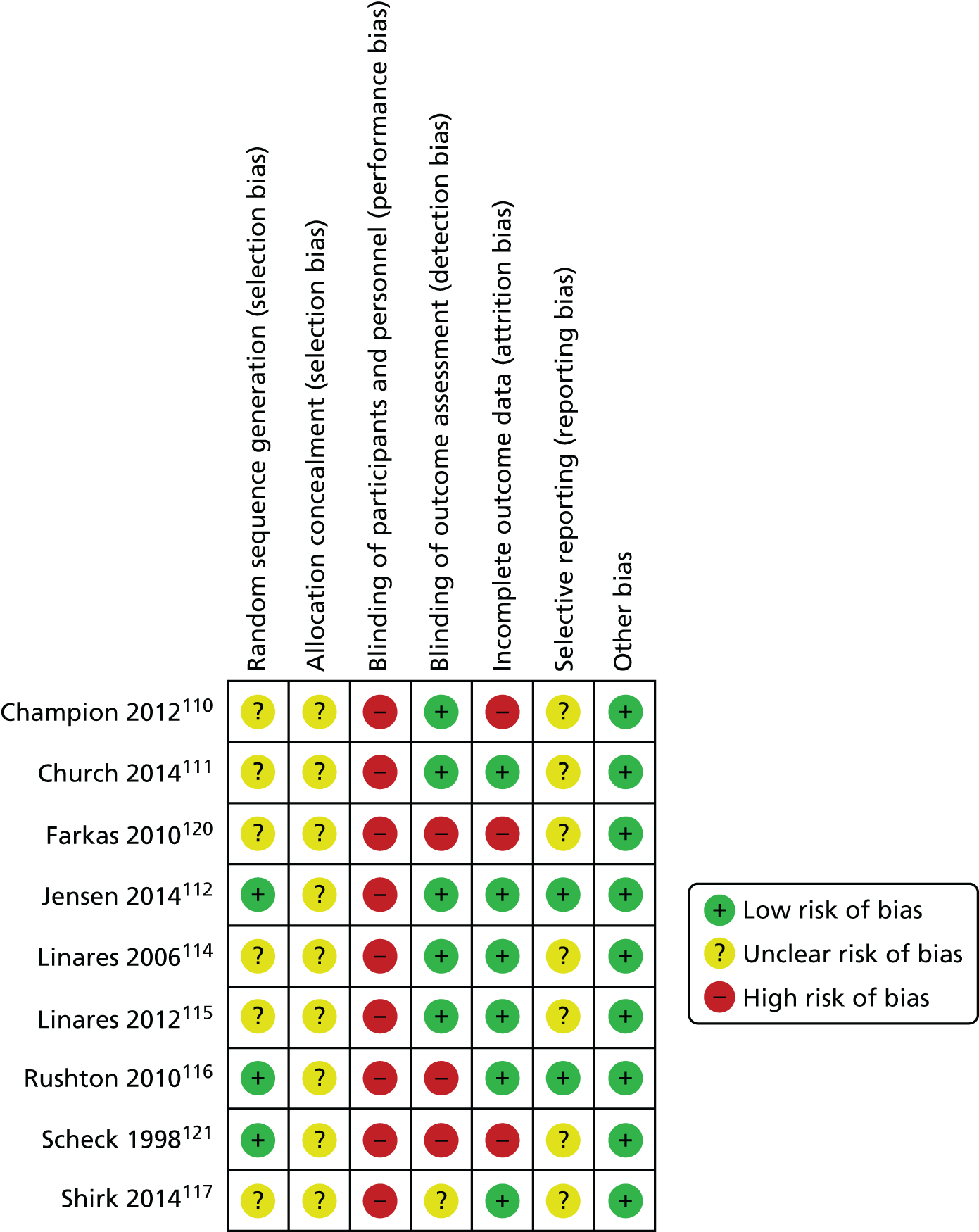

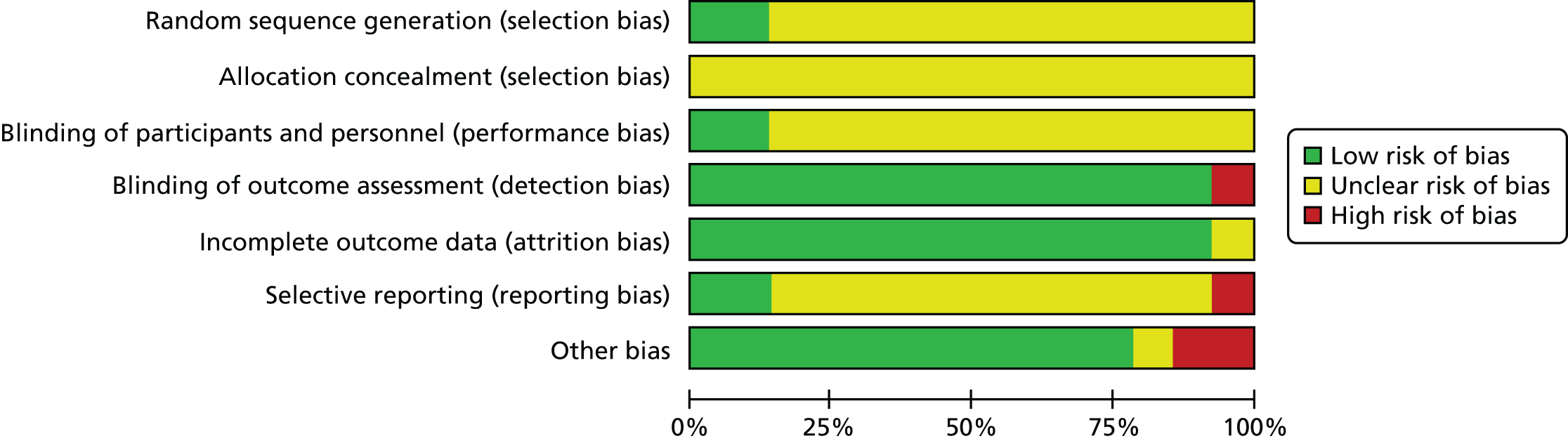

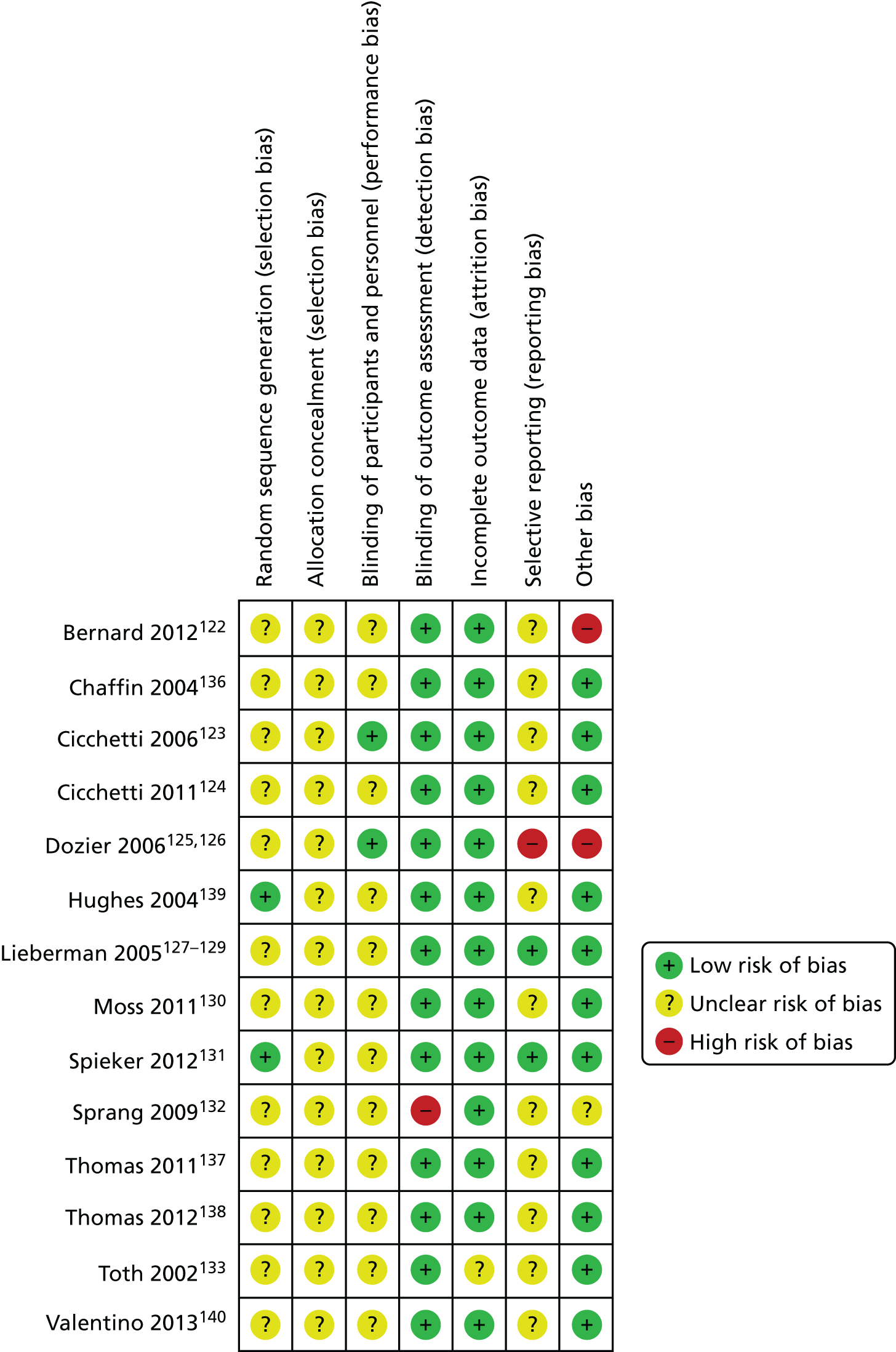

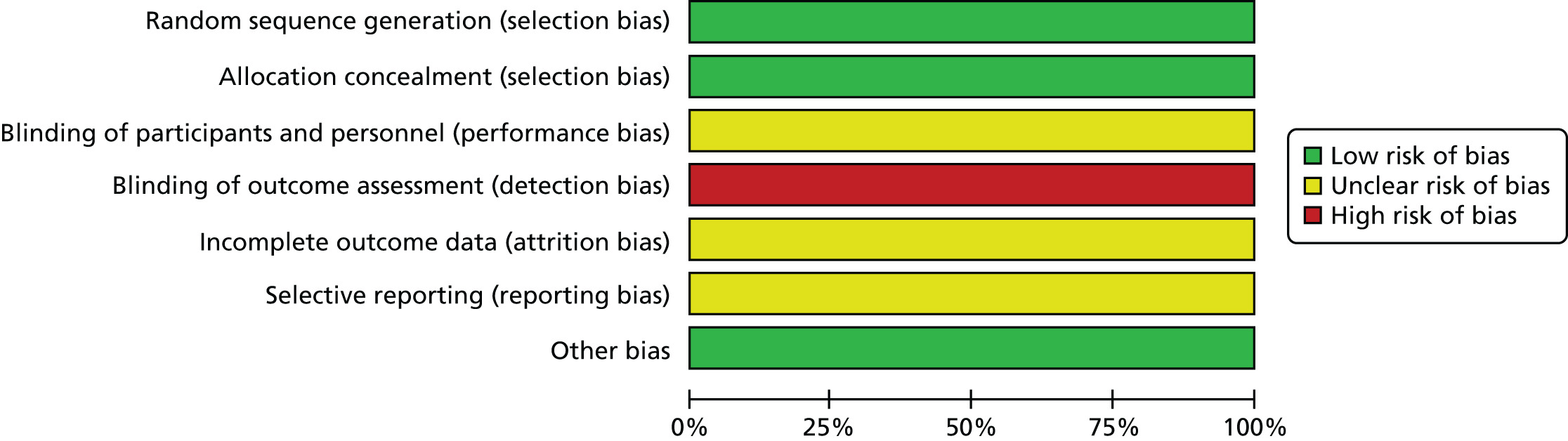

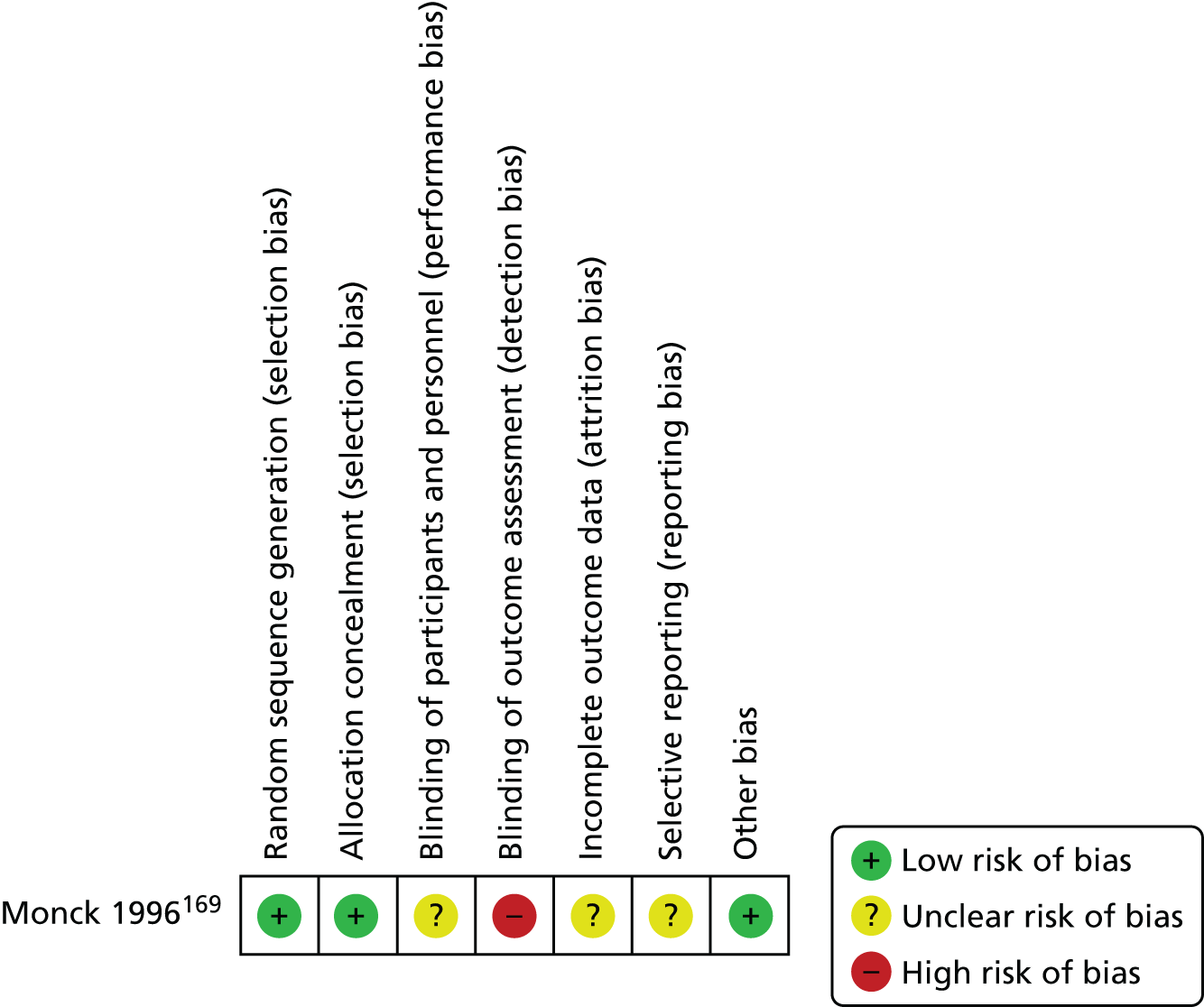

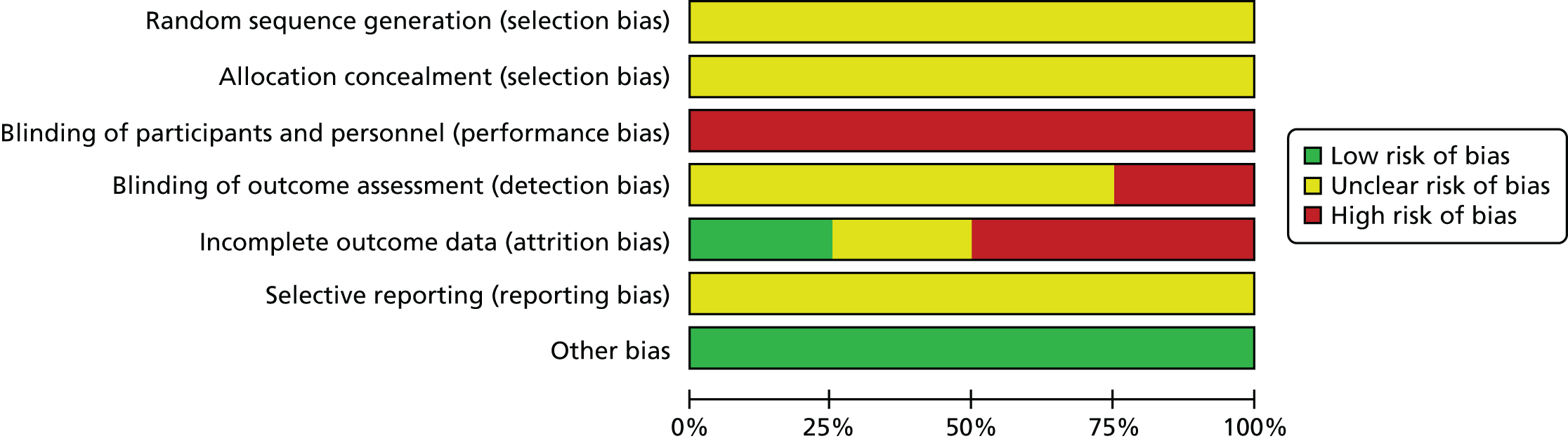

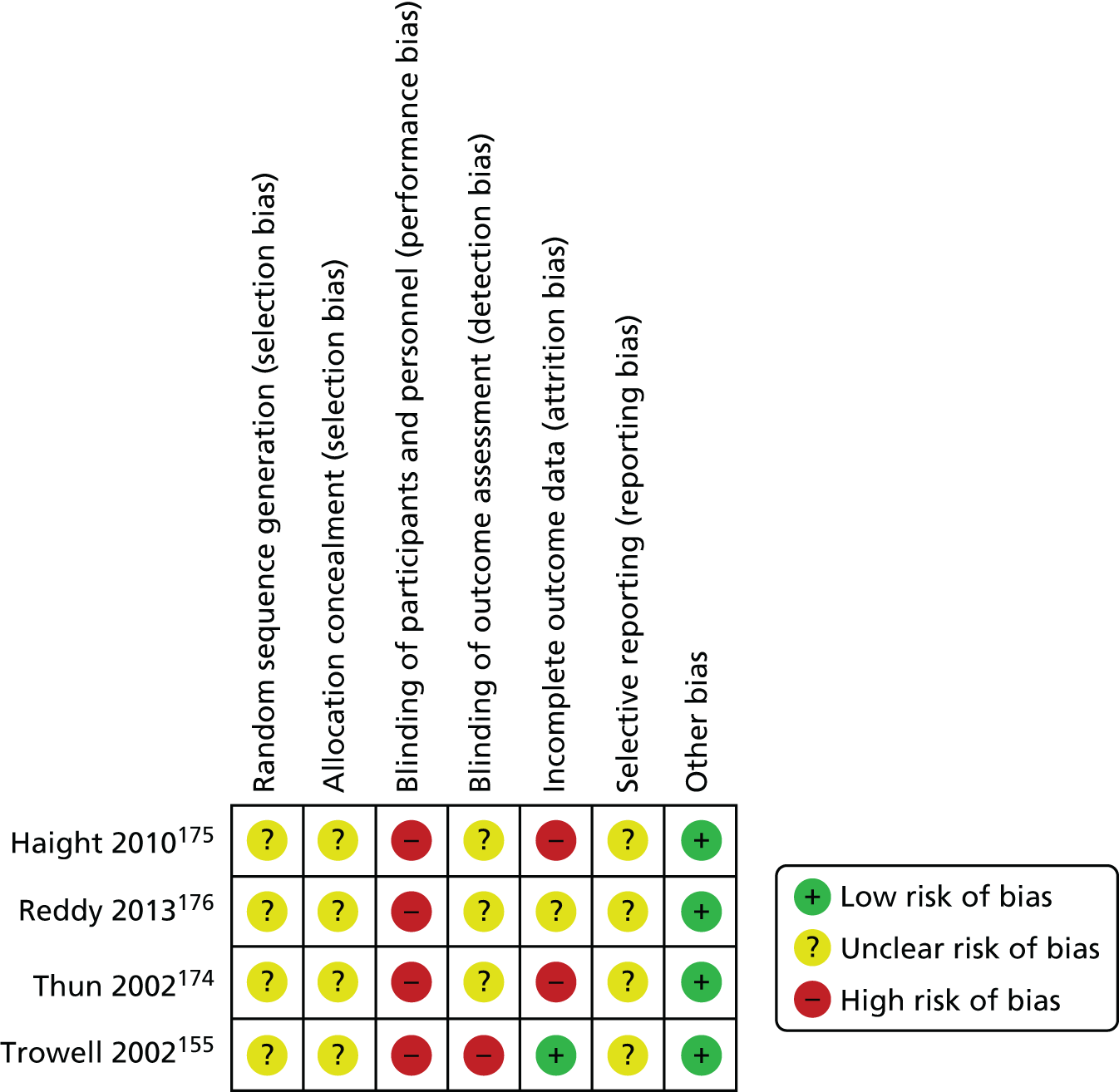

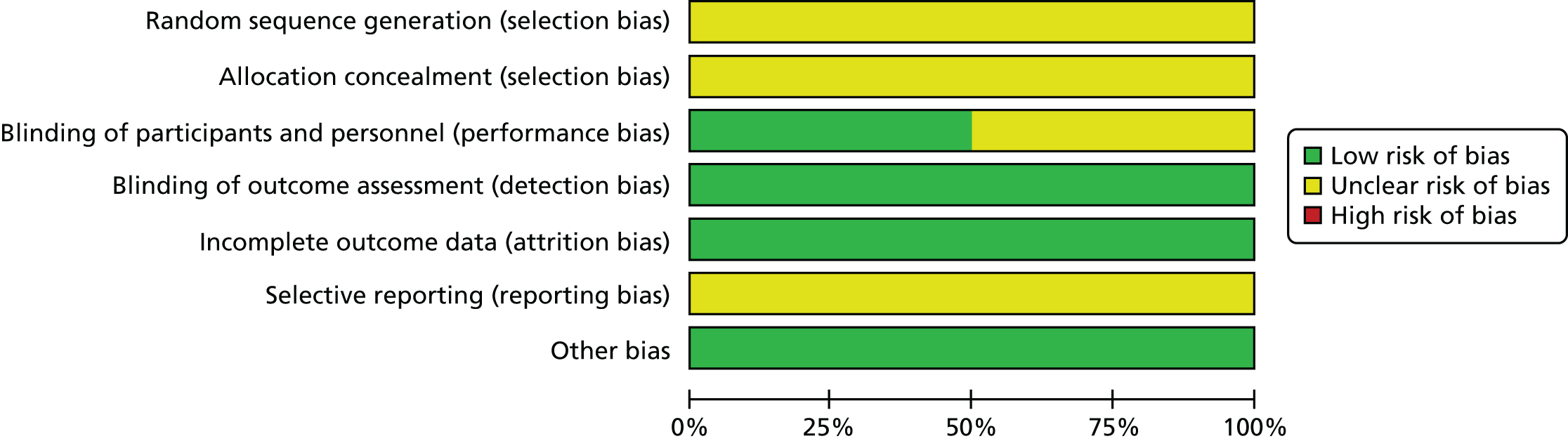

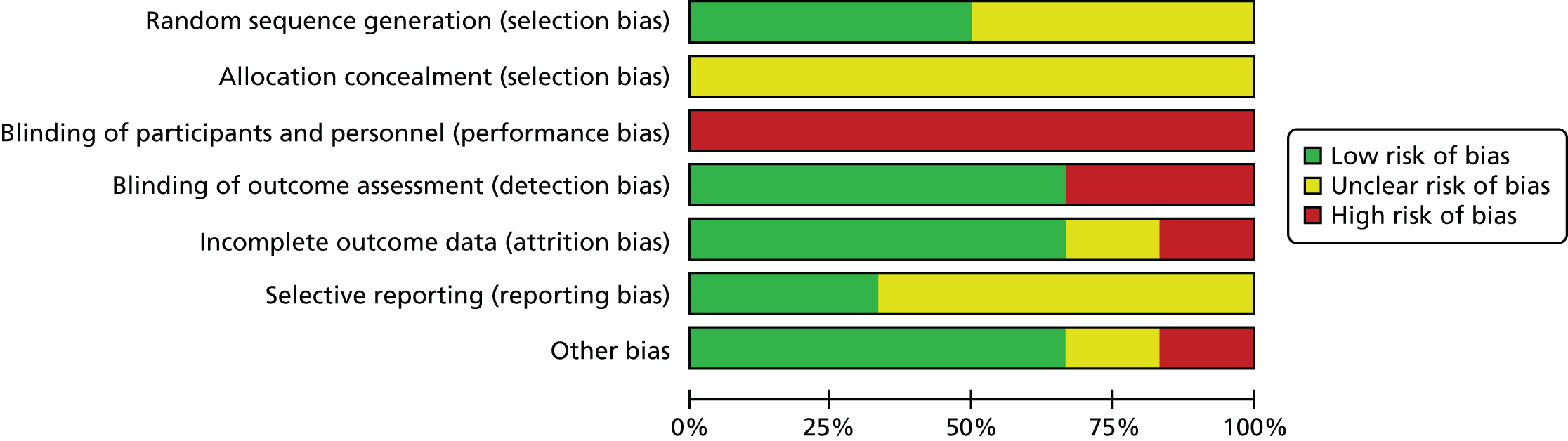

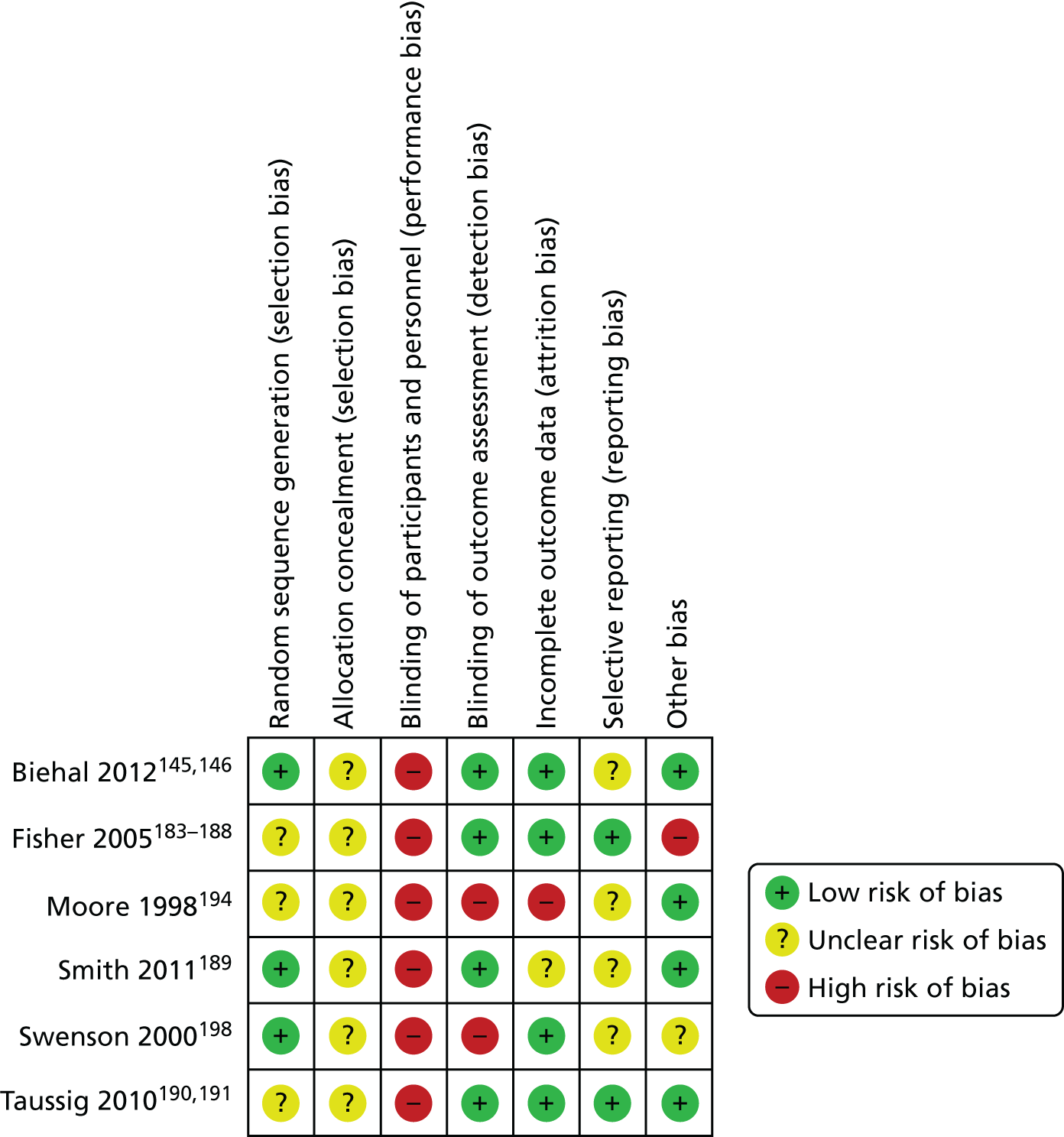

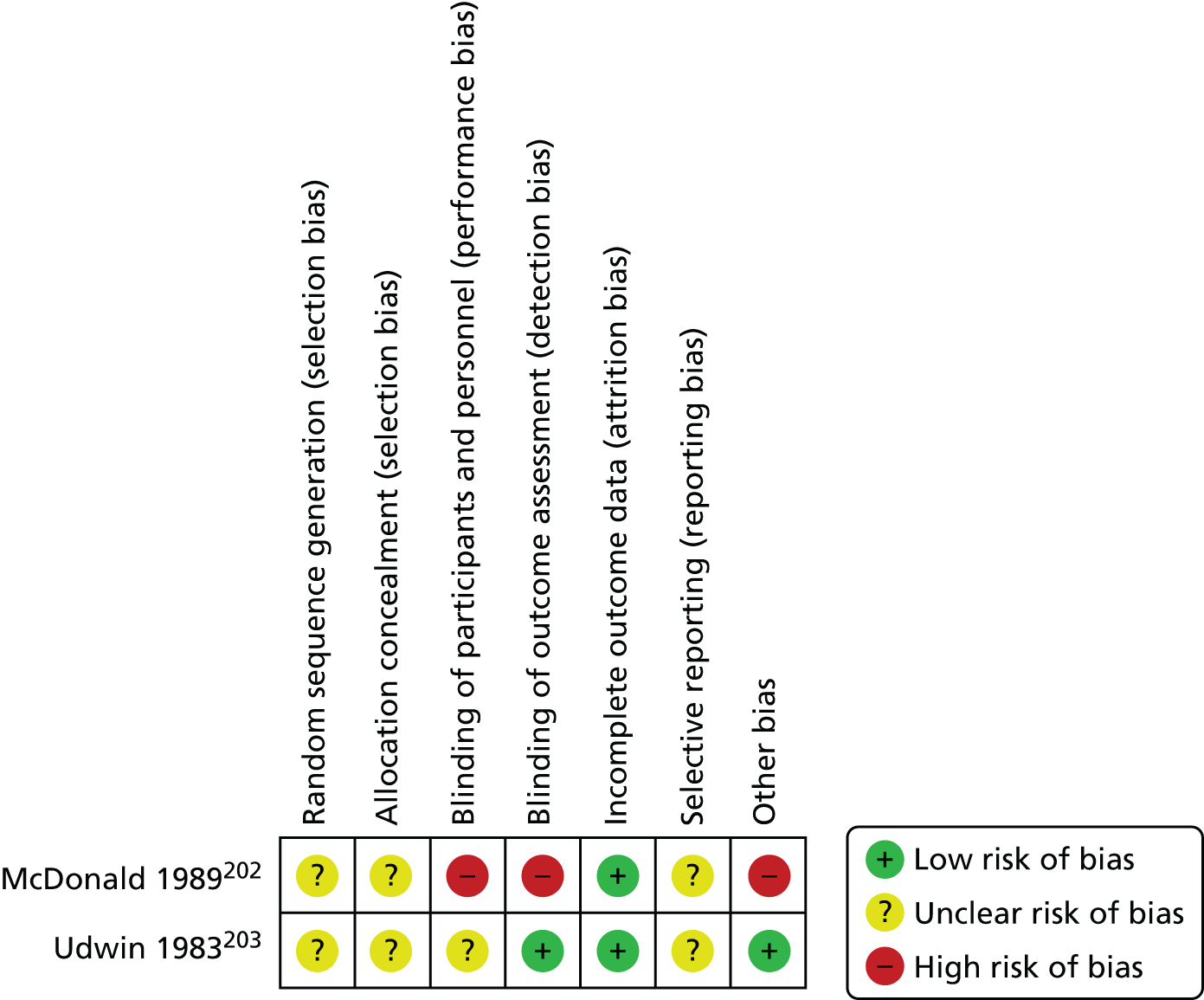

Assessment of risk of bias/study quality

Risk of bias in RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. 73 We searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform to identify prospectively registered trial.

For non-randomised studies, the Downs and Black Checklist74 for non-randomised studies was used. The quality of acceptability studies was assessed against the relevant Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool75 and the principles of good practice for conducting social research with children. The quality/risk of bias of all eligible studies was assessed, but no study was excluded from the acceptability phase of the review on the basis of its strength of evidence. The quality of data included within the economic evaluation was assessed using the critical appraisal criteria proposed by Drummond et al. 76 (see Appendix 8). The aim of the checklist is to assist users of economic evaluations to assess the validity of the results by attempting to determine if the methodology used in the study is appropriate. The checklist asks 10 questions, as reproduced in Appendix 7.

Data synthesis: effectiveness studies

We first mapped all of the studies of interventions against type of maltreatment (specific or multiple) and goals of treatment (outcome domains and measures). Interventions were grouped according to a simple classification system (e.g. whether or not the intervention had a given component, i.e. psychodynamic, cognitive). Priority was given to randomised and quasi-randomised trials, followed by non-randomised studies with comparison groups, although only data from RCTs were included in any meta-analyses, largely due to concerns about the quality of the data.

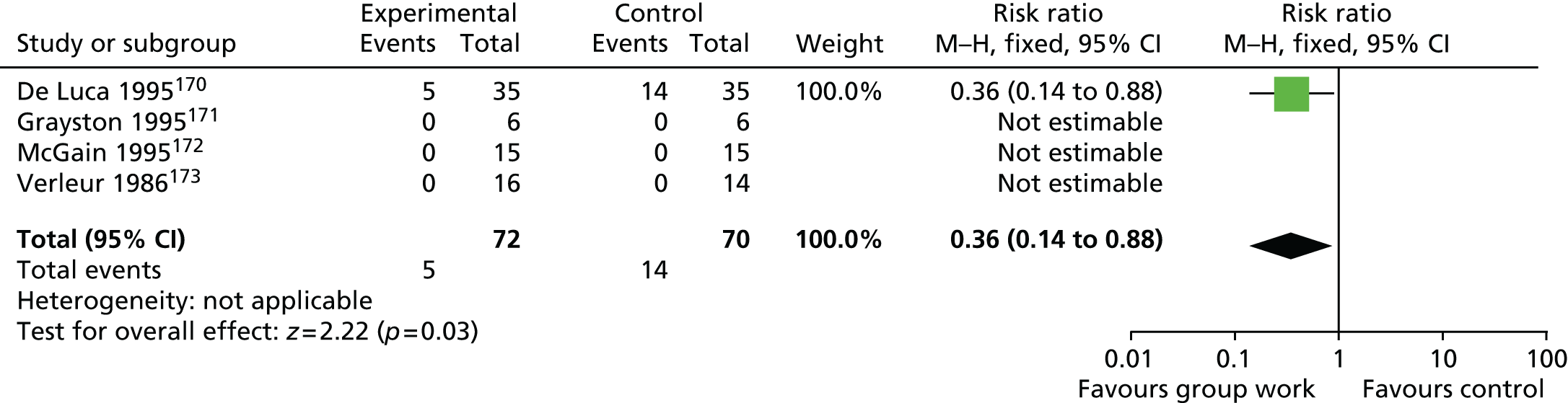

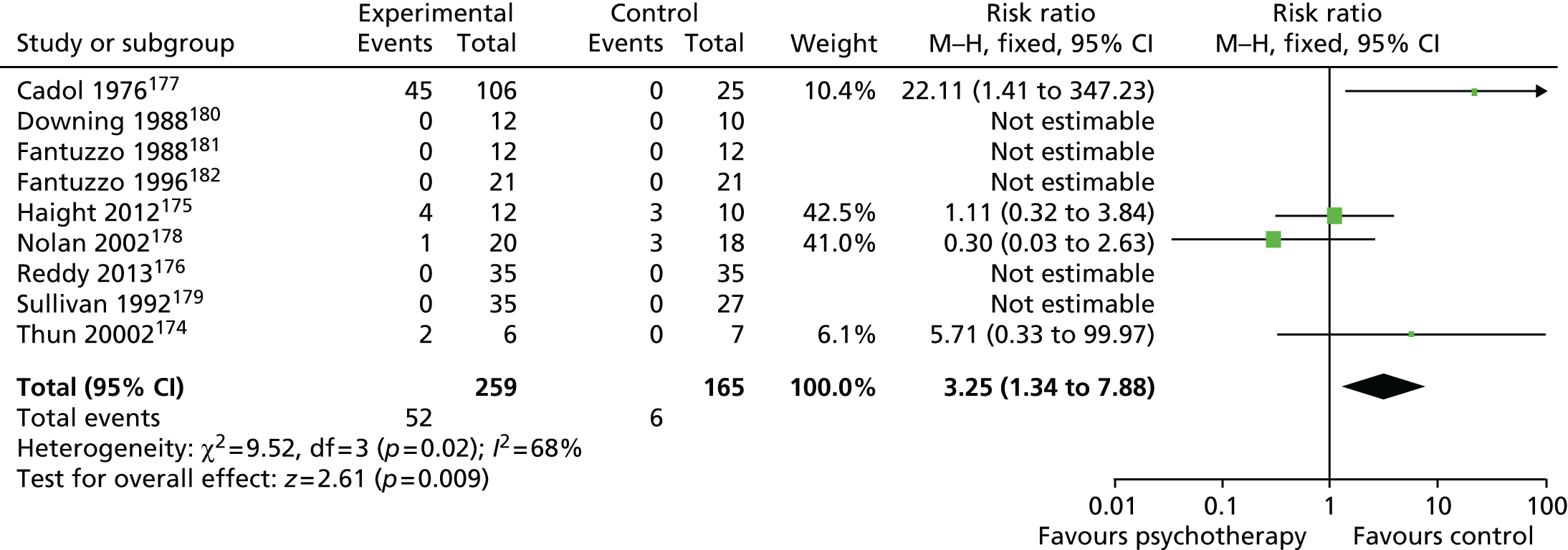

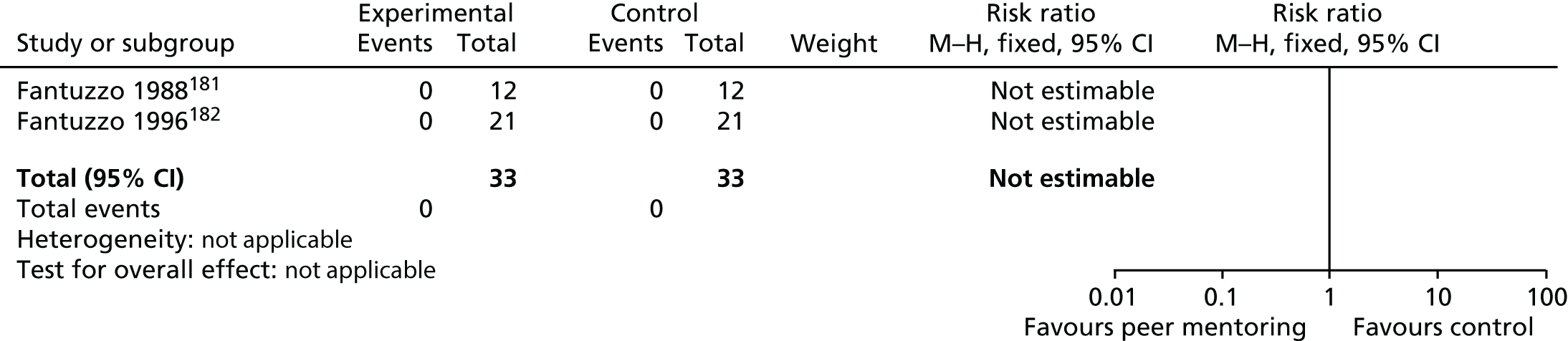

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. attachment behaviours), we calculated effect sizes as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We converted continuous outcome data (e.g. post-intervention depression) into standardised mean differences (SMDs) and presented data with 95% CIs.

Continuous data Unadjusted data were extracted where possible, both for consistency of interpretation across studies and because we anticipated that this data source would be less susceptible to selective reporting bias (in particular, the strategy prevents the possibility of biased selection of covariates for inclusion in the model). Ideally we would use ‘change from baseline’ measures in the meta-analyses because these reflect the correlations between measures at baseline and follow-up within individuals, and also avoids biases that can be introduced if there is an imbalance in baseline measures across arms (The Cochrane Handbook). However, ‘change from baseline’ measures were only rarely reported. We instead use follow-up measures in the meta-analyses; however note that these measures can be biased, especially if there is an imbalance in baseline measures between arms (which may occur because of flaws in randomisation process or simply due to small numbers). We compared baseline characteristics between arms and across studies, and for outcomes where there was an indication of intervention efficacy, we checked the robustness of these results by performing a sensitivity analysis to using ‘change from baseline measures’ with assumed values for correlation (see Sensitivity analyses).

Data synthesis

Where appropriate data were available, data synthesis was performed to pool the results. As clinical and trial heterogeneity were expected (even similar interventions are provided under different circumstances, by different providers, to different groups), we used a random-effects model. 77

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored the extent to which age (< 10 years old vs. > 10 years old), gender, ethnicity, type of maltreatment (sexual vs. physical), intervention type and parent involvement (child-only intervention vs. parent-and-child intervention) might moderate the effects of psychosocial interventions.

Sensitivity analyses

Publication bias and small study effects were investigated using standards methods (e.g. funnel plots) and also within the synthesis models. 78 When the data did not support such methods, the likelihood of publication bias was summarised narratively.

We examined the impact of trial/study factors, including risks of bias domains and cointerventions.

For outcomes where there was an indication of intervention efficacy, we checked the robustness of results to using a ‘change from baseline’ measure, rather than ‘follow-up’ measure. In the sensitivity analysis, we derived ‘change from baseline’ measures by assuming values for the correlation between baseline and follow-up measures: p = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1. The standard deviation (SD) of the mean change from baseline, sdchange, can then be estimated from the SD at baseline, sd0, and the SD at follow-up, sd1, using the formula:

Data synthesis: acceptability studies

A synthesis of acceptability data was undertaken, using a narrative approach to synthesis. 79 Studies were grouped into theoretically distinct subgroups. Using these intervention subgroupings, each study was described, and data synthesis was conducted and reported using the following categories: children’s views of the intervention, caregiver views, clinician views and attrition/engagement metrics. The structure of this narrative was informed and framed by the content and methodological expertise available within the research team and consultation with Young Persons’ Advisory Groups. Thematic analysis was also carried out to identify common issues and barriers relating to acceptability.

Data synthesis: economic evidence

The economic component of the project aimed to (1) systematically review all full economic evaluations of interventions that were designed to improve outcomes for maltreated children, using a narrative approach, where full economic evaluation is defined as the analysis of both the costs and effects of one intervention compared with another (including cost-effectiveness, cost–utility, cost–benefit or cost–consequences analysis); (2) produce a decision-analytic model to quantitatively explore the relative cost-effectiveness of interventions found to show promising levels of effectiveness in the effectiveness review and meta-analyses; and (3) perform a value of information analysis to quantify the extent to which further primary research to reduce uncertainty is warranted and where additional research may be most valuable. However, lack of relevant economic evidence precluded both decision-analytic modelling and value-of-information analyses.

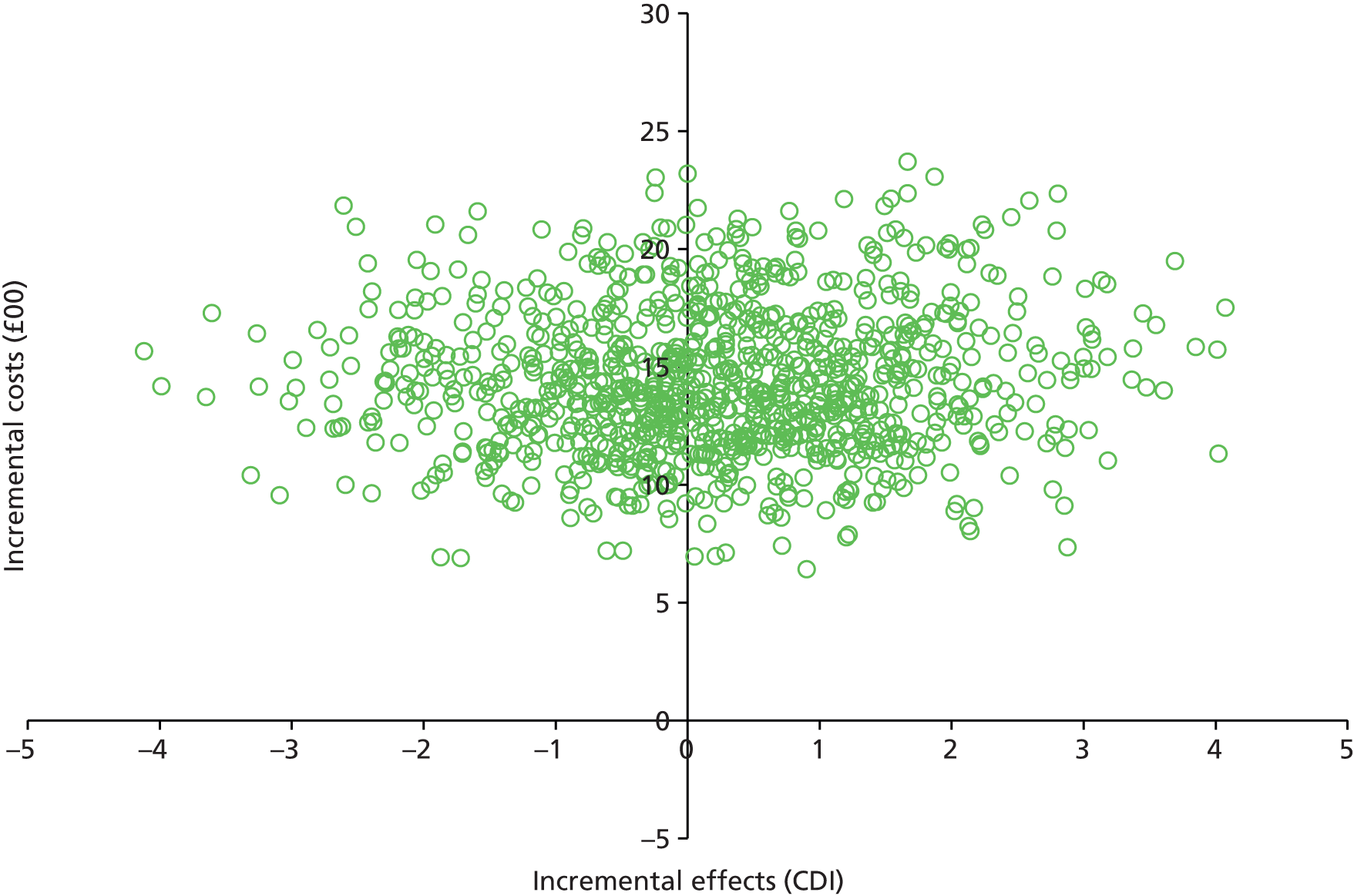

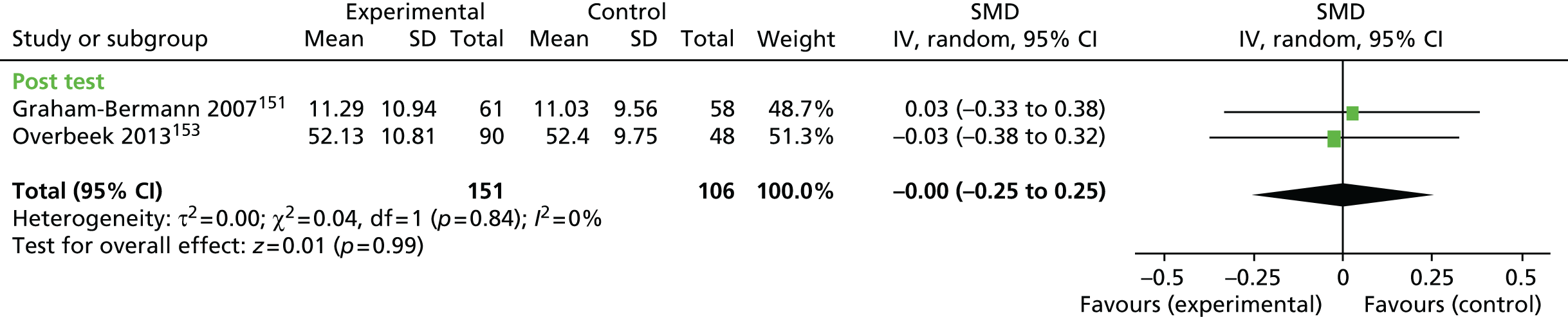

Instead, we conducted cost-effectiveness analyses for the most promising intervention using SMDs from meta-analyses as the measure of outcome, and, additionally, using the results of a meta-analysis of a subgroup of studies that reported outcomes in terms of a single clinical measure – the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). 80 Although the first analysis allowed us to utilise all the available evidence, the second analysis provides evidence that is easier to interpret, focusing on the additional cost per unit improvement in CDI score, rather than per unit improvement in SMD.

Intervention costs were calculated from data included in each paper on the nature of the intervention under evaluation, including the number and duration of sessions and the format of delivery (group or individual). Unit costs were estimated using nationally applicable UK unit costs per hour of face-to-face contact for relevant professionals81 (www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/2014/). It was not always clear from the papers which professionals had delivered the interventions and thus we estimated costs for three categories of professional: clinical psychologist, psychologist and counsellor. We applied an average cost of the three categories of professionals, weighted to take into consideration the number of group-based interventions compared with individual interventions. Data on the use of broader health and social care services were not available from the literature, so these costs were excluded.

Cost-effectiveness was explored initially through the calculation of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), defined as the difference in mean costs divided by the difference in mean effects between the two groups. 82 We report the ICERs for SMD and CDI80 post treatment (for which the greatest number of studies were available) and 12-month follow-up (to capture the longer-term implications).

Uncertainty was explored using probabilistic sensitivity analysis, a form of analysis that involves assigning probability distributions to parameters (costs and effects) and sampling at random from the distributions to generate an empirical distribution for each parameter. 83 To represent uncertainty in costs, we fitted a gamma distribution constrained between 0 and positive infinity, to reflect the fact that cost data are commonly skewed in nature. For SMD and CDI,80 we assigned a normal distribution. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) are presented, which are derived from the joint density of incremental costs and incremental effects and represent the probability of one intervention being more cost-effective than the comparison as a function of the willingness to pay for a unit improvement in outcome. 84 As willingness to pay for an improvement in SMD and CDI80 are not known, a range of possible values of willingness to pay are plotted.

Changes from the original protocol

During the course of the review, we had cause to agree several minor departures from the original published protocol, as described below.

Inclusion of unpublished dissertations We had originally intended to include unpublished dissertations. The search strategy identified a much larger than anticipated number of citations, including 290 unpublished dissertations, many of which proved very difficult to access (most were from American universities). Owing to resources constraints, we took a pragmatic decision to exclude these from the review. To minimise the loss of relevant studies, two reviewers (JH, NL) independently reviewed the title and abstract of all 290 dissertations a second time, to identify any that were clearly evaluations of relevant interventions. We then searched for published papers associated with the 36 dissertations so identified, all of which had already been found in the original search.

Population A clarification is necessary regarding eligible study participants. As per protocol, we included only papers that aimed to address the sequelae of maltreatment. We had also originally aimed to include studies in which recruitment was ‘biased towards’ maltreated children. During the course of the review, we identified studies in which recruitment may have favoured maltreated children (e.g. foster children) but which did not actually address a sequelae of maltreatment. These studies were therefore excluded.

Outcomes We originally intended to map treatment goals and measures used as part of an examination of the underpinning ‘logic model’ of interventions and to inform future research priorities. The studies identified rarely provided sufficient information to be of any value in making such an assessment. Instead, for descriptive purposes, where available, we recorded the aim of the intervention and the outcome measures reported for all included papers. This information is presented in Chapter 3 (see Tables 3 and 4).

Searches We had planned to hand-search relevant journals. In view of the considerable number of potentially relevant studies that were identified through other search strategies, the research group agreed that additional hand searches were no longer necessary. We had also planned to search Health Searches Research Projects in Progress, but this database retrieves many hundreds of records of funded projects without publication details or links to reports. It was decided that the resources required to properly search this resource could not be justified.

Study screening and selection We used EPPI-Reviewer version 4 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK) rather than a project website for the submission and addition of new references so that the team could screen and discuss them. Owing to the complexity of the topic, we chose not to check inter-rater reliability for judgements on study screening and selection, instead favouring detailed discussion and consensus about studies of uncertain eligibility.

Data synthesis – effectiveness studies We originally planned to contact study authors about any missing information so that we could consider the extent to which this might alter the conclusions of the syntheses. The considerable volume of eligible studies and the poor quality of the available data meant this was not an appropriate use of resources. If the data had allowed, we had planned to extend our meta-analysis by fitting network meta-analysis models to explore in more detail the effectiveness of different types and different components of interventions. 85,86 The quantity and quality of the data did not allow for this technique to be used.

Subgroup analyses If the available data had allowed, we had planned to explore the extent to which a variety of study characteristics moderated the effects of treatment. We did not have sufficient data to support these analyses and therefore present data descriptively where available, including: impact of current symptoms; ethnicity; maltreatment history (including whether intra- or extra-familial); time since maltreatment; care setting (family/out-of-home care including foster care/residential); care history; characteristics of intervention (setting, provider, duration); and the adjunctive treatments.

We had planned to perform sensitivity analyses based on the inclusion of the QEx-randomised and non-randomised studies but, owing to concerns about the quality of the data, we pooled data only from RCTs in any of the meta-analyses.

Economic synthesis We had planned to undertake decision-analytic modelling of the relative cost-effectiveness of interventions found to show promising levels of effectiveness in the effectiveness review and meta-analyses, and to use the decision model developed to perform a value-of-information analysis to quantify the extent to which further primary research to reduce uncertainty is warranted. However, lack of relevant economic evidence precluded decision modelling and thus the value-of-information analyses, as described above.

Overview of the evidence base

The search and sifting process is summarised in the PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1. A total of 39,541 citations were identified in the search, which were either imported into EndNote or saved as text files. After removing obvious duplicates and irrelevant records, a total of 39,303 records were imported into EPPI-Reviewer, and a further 12,799 duplicates were removed, leaving 26,504 citations to be sifted by title and abstract. Reviewers excluded 21,953 citations based on title and abstract. Reasons for exclusion included:

FIGURE 1.

Maltreatment review: flow chart. Original search date 26 June 2013, search update 4 June 2014. Numbers reflect the number of records, not the included studies for which there may be multiple citations. Sifting decisions are up to date as of 30 January 2014. Green numbers refer to records and black numbers refer to studies.

-

duplicate citation (819)

-

clearly irrelevant (4634)

-

adult participants (661)

-

not a maltreated sample (1515)

-

form of maltreatment not included in the review, for example peer bullying, trauma due to war (445)

-

participants were maltreated children but study not an evaluation study (7083)

-

a relevant intervention was described but not evaluated (2348)

-

evaluation of an intervention that was not relevant, for example abuse prevention programmes or drug interventions (999)

-

evaluation used a study design excluded from the review, for example case study (2093)

-

paper contained relevant background information but not an evaluation of a relevant intervention (299)

-

paper was a review paper not primary research (1057).

The remaining 4551 were initially brought forward to be sifted by full text. However, two published papers87,88 could not be accessed despite searches via a number of university libraries, interlibrary loans and attempts to contact the authors and 36 dissertations were not accessed. An additional seven papers were identified through searches of the reference list of included studies. Of those articles reviewed at the full-text stage, 4196 were excluded (of which 81 were duplicates), leaving 324 citations brought forward for data extraction. Of these citations, 230 were potentially relevant for effectiveness, 17 cost-effectiveness, 54 acceptability, four relevant to both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, 18 relevant to both effectiveness and acceptability, and one relevant to all three.

A number of these citations were subsequently excluded after discussions within the review team (34 effectiveness, 16 cost-effectiveness – see Chapter 3, Table 7). This left 219 effectiveness citations, six economic citations and 73 acceptability papers.

Chapter 3 Description of studies

Effectiveness studies

Included studies

In total, we identified 198 studies (217 citations) assessing the effectiveness of relevant psychosocial interventions for maltreated children. Of these, 62 studies followed a randomised (n = 61) or quasi-randomised (n = 1) design. QEx designs were identified in eight studies, with a further 26 COSs and 101 uncontrolled studies. Table 1 provides an overview of evaluations of interventions by study design. Table 2 provides an overview of the distribution of evaluations across intervention category and maltreatment types, by study design (controlled, uncontrolled).

| Intervention category | Study design | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | Q-RCT | QEx | COS | UCS | |||

| CBT | CBT for sexual abuse | 11 | 1 | 30 | 56 | ||

| CBT for physical abuse | 3 | ||||||

| CBT for multiple abuse | 7 | ||||||

| EMDR | 2 | ||||||

| RBIs | Attachment-oriented interventions | 9 | 1 | 10 | 24 | ||

| PCIT | 3 | ||||||

| Parenting interventions | 2 | ||||||

| Systemic interventions | Systemic FT | 1 | 14 | 22 | |||

| Trans-theoretical intervention | 1 | ||||||

| Multisystemic FT | 3 | 1 | |||||

| Multigroup FT | 1 | ||||||

| Family-based programme | 1 | ||||||

| Psychoeducation | Psychoeducation | 7 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 28 | |

| Group work with children | Group work with children | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | ||

| Psychotherapy/counselling | Psychotherapy/counselling | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 11 | |

| Peer mentoring | Peer mentoring | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Intensive service models | Treatment foster care | 4a | 2 | 15 | 24 | ||

| Therapeutic residential/day care | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Co-ordinated care | 1 | ||||||

| Activity-based therapies | Arts therapy | 2 | 14 | 21 | |||

| Play/activity interventions | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Animal therapy | 2 | ||||||

| Totalsb | 61 | 1 | 8 | 26 | 101 | 198 | |

| Intervention category | Types of abuse (controlled, uncontrolled) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Emotional | Sexual | Neglect | Multiple | Other | |

| CBT | 21 (11, 10) | 8 (4, 4) | 45 (20, 25) | 6 (3, 3) | 11 (3, 8) | 10 (6, 4) |

| Relationship-based interventions | 13 (7, 6) | 6 (5, 1) | 7 (3, 4) | 14 (7, 6) | 7 (5, 2) | 14 (9, 5) |

| Systemic interventions | 11 (6, 5) | 5 (2, 3) | 12 (4, 8) | 5 (3, 2) | 3 (1, 2) | 4 (0, 4) |

| Psychoeducation | 9 (7, 2) | 5 (7, 1) | 21 (12, 9) | 5 (3, 2) | 4 (2, 2) | 8 (6, 2) |

| Group work with children | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 8 (5, 3) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) |

| Psychotherapy (unspecified) | 4 (3, 1) | 1 (1, 0) | 10 (6, 4) | 3 (3, 0) | 2 (2, 0) | 0 (0, 0) |

| Peer mentoring | 2 (2, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 2 (2, 0) | 1 (1, 0) | 0 (0, 0) |

| Intensive service models | 16 (7, 9) | 5 (4, 1) | 14 (5, 9) | 11 (6, 5) | 8 (6, 2) | 7 (1, 6) |

| Activity-based therapies | 8 (3, 6) | 1 (0, 1) | 16 (5, 11) | 4 (1, 3) | 2 (0, 2) | 6 (2, 4) |

| Totals | 84 (45, 39) | 30 (19, 11) | 134 (60, 72) | 49 (28, 21) | 38 (20, 18) | 49 (24, 25) |

The interventions and comparisons evaluated are summarised below and described in detail in Chapter 4. All controlled studies are summarised in Table 3 (participant characteristics), Table 4 (intervention characteristics and comparators) and Table 5 (outcomes domains and outcome measures used). The uncontrolled studies identified are summarised in Table 6. In the protocol, we specified that these studies would be included only if no other controlled studies were identified for the intervention evaluated. This was the case only for ‘systemic interventions’ for ‘other’ types of abuse (e.g. witnessing domestic violence, Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy) and ‘activity-based interventions’ for ‘emotional’ forms of abuse. We therefore consider these only in Chapter 6, in the context of highlighting important gaps in the evidence base.

| Intervention category | Design | Study/record | Country | n | Mean age (SD), range | % Female | P | E | S | N | M | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT for sexual abuse | RCT | Berliner 199689 | USA | 154 | 8 years | 89 | ✗ | |||||

| RCT | Celano 199690 | USA | 47 | 10.5, 8–13 years | 100 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Cohen 199691,92 | USA | 86 | 4.68, 2.11–7.1 years | 58 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Cohen 199893,94 | USA | 82 | 11, 7.2–15.3 years | 68 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Cohen 200495,96 | USA | 229 | 10.76, 8–14.9 years | 79 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Deblinger 199697,98 | USA | 100 | 9.89 (2) 7–13 years | 83 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Deblinger 200199 | USA | 63 | 5.45 (1.47), 2–8 years | 61 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Deblinger 2011100 | USA | 210 | 7.6 (2.07), 4–11 years | 62 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Foa 2013101 | USA | 61 | Intervention: 15.4, 14.9–15.8 years Control: 15.3, 14.7–15.9 years |

100 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Jaberghaderi 2004102 | Iran | 14 | 12–13 years | 100 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | King 2000103 | Australia | 36 | 11.4, 5.2–17.4 years | 69 | ✗ | ||||||

| COS | Paquette 2011104,105 | Canada | 35 | 14.3 (1.5) years | 100 | ✗ | ||||||

| CBT for physical abuse | RCT | LeSure-Lester 2002106 | USA | 12 | 13.16, 12–16 years | 0 | ✗ | |||||

| RCT | aKolko 1996107,108 | USA | 55 | 8.6 (2.2) years (no information on control group) | 28 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Runyon 2010109 | USA | 75 | 9.88 (2.02), 7–13 years | 47 | ✗ | ||||||

| CBT for multiple abuse | RCT | Champion 2012110 | USA | 559 | 16.46 (1.34) 14–18 years | 100 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| RCT | Church 2012111 | Peru | 16 | 13.9, 12–17 years | 0 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Jensen 2014112,113 | Norway | 156 | 15.1 (2.2), 10–18 years | 80 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| RCT | Linares 2006114 | USA | 128 | 6.2 (2.3), 3–10 years | No info | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| RCT | Linares 2012115 | USA | 94 | 6.7 (1.1) 5–8 years | 51 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| RCT | Rushton 2010116 | UK | 38 | 67 (18), 36–102 months | 55 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| RCT | Shirk 2014117 | USA | 43 | Intervention: 15.25 (1.52) years Control: 15.69 (1.55), 13–17 years |

84 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| COS | Kolko 2011118 | USA | 52 | 9.1 (3.7), 3–17 years | 48 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| COS | Rondeau 1983119 | USA | 17 | 7.6 years (median) | 24 | ✗ | ||||||

| EMDR | RCT | Farkas 2008120 | Canada | 65 | Intervention: 14.3 (1.4) years Control: 14.9 (1.3) years |

63 | ✗ | |||||

| RCT | Scheck 1998121 | USA | 85 | 20.93, 16–25 years | 100 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Attachment-orientated interventions | RCT | Bernard 2012122 | USA | 120 | Intervention: 19.2 (5.2), 1.7–21.4 months Control: 19.2 (5.8), 1.7–21.4 months |

43 | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| RCT | Cicchetti 2006123 | USA | 189 | 13.31 (0.81) months | 53 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| RCT | Cicchetti 2011124 | USA | 137 | Intervention 1: 13.36 (0.87) months Control 1: 13.32 (0.87) months Intervention 2: 13.36 (0.82) months Control 2: 13.32 (0.71) months |

51 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| RCT | Dozier 2006125,126 | USA | 60 | Intervention: 19.01 (9.64) 3.9–39.4 months Control: 16.3 (7.42) 3.6–33.6 months |

50 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Lieberman 2005127–129 | USA | 75 | 4.06 (0.82) 3–5 years | 52 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Moss 2011130 | Canada | 79 | Intervention: 3.29 (1.44) years Control: 3.42 (1.34) years |

39 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| RCT | Spieker 2012131 | USA | 210 | Intervention: 18.29 (5.32) months Control: 18.15 (4.79) months |

44 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Sprang 2009132 | USA | 58 | 42.5 (18.6) months | 49 | ✗ | ||||||

| RCT | Toth 2002133 | USA | 155 | Intervention 1: 48 (7.71) months Control 1: 49.16 (7.54) months Intervention 2: 47.86 (6.07) months Control 2: 47.77 (6.66) months |

45 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| COS | Becker-Weidman 2006134,135 | USA | 69 | Intervention: 9.4 (2.6) 6.0–15.2 years Control: 11.7 (4.0) 5.3–16.2 years |

41 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| PCIT | RCT | Chaffin 2004136 | USA | 110 | 4–12 years | No info | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| RCT | Thomas 2011137 | Australia | 150 | 5 (1.6) years | 30 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| RCT | Thomas 2012138 | Australia | 151 | 4.75 (1.3) years | 29 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||