Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/17/05. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in January 2016 and was accepted for publication in April 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Julie Mytton is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health Panel.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Jackson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The focus of this study was Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities in England and Scotland. Throughout this report we use the term ‘Traveller’ to include distinct and diverse Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities, who may be settled or nomadic or live on authorised or unauthorised sites or in houses.

Traveller identity and history

Travellers in the UK are a heterogeneous group consisting of North Welsh Kale, South Welsh and English Romanichals, Irish Travellers (Pavees, or Mincéirs), Scottish Travellers and, increasingly, European Roma. 1 There is an ongoing debate in the UK concerning the definition of Travellers, whether they are defined by their ethnicity or their nomadic lifestyle. As Clark2 suggests, the continuing question of who are Travellers may, in part, be because of the lack of neutrality of the terms ‘Gypsy’ and ‘Traveller’ either within or outside the communities. In the Caravan Sites Act,3 Travellers are defined as ‘people of nomadic habit and lifestyle whatever their race or origin’. This definition, however, does not include those who live on permanent private sites or in houses. In contrast, Oakley4 suggests a definition of Travellers based on descent. She argues that a Traveller’s status is ascribed at birth and reinforced by their upbringing and commitment to Travellers’ values and lifestyle.

Gypsies have a very long history and are believed to have moved from India to Persia at the end of the ninth century, moving across the Middle East and becoming established all over Europe by the fifteenth century. 5 They are said to be one of the oldest ethnic minorities in the UK and were thought to have established themselves in Britain by the sixteenth century. The first official reference of Gypsies in the UK was in Scotland in 1505. 4,5 However, by 1554, Gypsies were considered ‘felons’ and executed. 2 Irish Travellers are thought to have originated from itinerant craftsmen and peasants who were forced on the road by war, famine and poverty. 6

In the twentieth century, Travellers again were a persecuted group. During the period between 1938 and late 1943, they were subjected to an extreme form of exclusion in Germany, which has been described as ‘The Great Devouring’ or ‘Gypsy Holocaust’,2 with an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 killed during this episode in history. 7 As recently as 2004, the forced sterilisation of Traveller women in Eastern Europe during communist rule has been reported. 8,9

Travellers hold a strong sense of their cultural identity, viewing themselves as separate from non-Traveller communities. 10 Nickson and Sudbery11 describe persecution as being at the ‘heart’ of Traveller identity, considering that the continued persecution of Travellers throughout history to the present day contributes to the maintenance of this. This identity based on persecution has implications for understanding the relationship between Travellers and the wider community, and the importance of ‘understanding the ethnic and cultural context’ in delivering services. 10

Traveller communities in England and Scotland

There are an estimated 54,895 ‘white: Gypsy or Irish Traveller’12 and 193,297 ‘migrant Roma’ living in England. 13 The Scottish Traveller population has been estimated at 421212 to 15,000. 14 The diversity of Travellers in the UK is increasing with greater ease of movement of populations within Europe. There are now an estimated 4400 Eastern European Roma across the UK. 15 All of these are likely to be underestimations because of the poor recording of Traveller ethnicity on public service systems, a reluctance to self-identify attributed to the history of persecution and rapidly changing inward migration. The figure of 360,000 Travellers in the UK is commonly cited. 16

The health of Travellers

Travellers typically experience significantly poorer health and shorter life expectancy than the general population. 17–24 For example, Parry et al. 20 reported that Travellers in England were 11% more likely than their age- and sex-matched comparators in the general population to have a self-reported long-term illness which limited daily activities. The life expectancy of Irish Travellers is 15 years shorter than the national average for men, and 12 years shorter for women. 25 Despite this greater health need, there is low uptake of health services by Travellers, including preventative health care. 17–22,24 As an example, individuals living in Roma communities in England were found to be less likely than non-Roma to visit a dentist, chiropodist or practice nurse, to contact NHS Direct or to be registered with a general practitioner (GP). 26 Barriers to uptake stem partly from a lack of consideration of Traveller culture by health providers when developing services, for example, reluctance by GP practices to register transient Travellers. 27 Further barriers include a history of discrimination leading to mistrust of people and institutions, poverty, low health literacy, language barriers, lack of knowledge of health systems in new countries to which they travel,21 and, in some communities, strong beliefs of ‘stoicism’, ‘self-reliance’ and ‘fatalism’ about health. 27

The UK immunisation programme

The public health benefits and cost-effectiveness of immunisation are well established,28 preventing globally between 2 and 3 million deaths each year in children and adults from diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, measles, mumps and rubella. 29 In the UK, effective and safe vaccines against 13 potentially damaging infections [diphtheria, tetanus, poliomyelitis, pertussis (hereafter referred to as whooping cough), Haemophilus influenzae type b, meningococcal ACWY, meningococcal B, pneumococcal, measles, mumps, rubella, influenza and rotavirus] are routinely offered to children and young people up to 18 years as part of the UK childhood immunisation programme. 30 Since 2008, girls aged 12–13 years are also offered the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to protect against infections that can lead to cervical cancer. Children in specific at-risk groups are offered additional vaccines; for example, the bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine is offered to infants in areas where the incidence of tuberculosis is above a specific rate or whose parents or grandparents were born in a country with high rates of tuberculosis. 31

The uptake of immunisations across the population needs to be sufficiently high so that the few individuals who are unable to be immunised, because of genuine contraindications, are protected from disease by living in a community in which there is very little circulating infection. This concept is known as herd immunity. The UK uptake rates for most of the routine vaccines in children up to 6 years are generally high and stable, approaching or meeting the 95% target required for herd immunity. 32,33 A notable exception is the seasonal flu vaccine for which 2014/15 uptake rates in England for children aged 2, 3 and 4 years were 38.5%, 39.5% and 32.9%, respectively. 34 Yet, even with good national coverage, social clustering of unprotected individuals (unimmunised/partially immunised) can lead to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. 35 Coverage of the routine three-dose HPV vaccination programme was consistently over 86% in England from 2012 to 201436 and over 80% in Scotland. 37

In addition to routine flu vaccination for children aged 2 to 17 years, which was introduced in 2013 and is gradually being rolled out and offered to the youngest children first,30 the flu vaccine is recommended for all adults over 65 years and for adults/children with chronic health conditions which put them at higher risk of serious complications of the illness, for example pregnant women, children/adults with underlying disease particularly chronic respiratory or cardiac conditions. 38 In the winter of 2014/15 uptake in England in those aged over 65 years was 73%34 and 76% in Scotland,39 close to the 75% target. However, among those at-risk under 65 years, uptake was just 50% and 54% in England 34 and Scotland,39 respectively, with the uptake by pregnant women even lower (44% and 47%, respectively). 34,39 Following a rise in cases of whooping cough in all ages and, in particular, among babies < 3 months old with deaths in infants too young to have been protected by their own immunisation course, it has been recommended since 2012 that pregnant women be offered the whooping cough vaccine between 28 and 38 weeks of pregnancy. Current uptake is 58% and 65% in England and Scotland, respectively. 40,41

One of the challenges for ensuring that groups at risk of poor immunisation uptake are targeted effectively is their identification. Until the 2011 census, ethnic group classifications did not provide for Travellers to ‘self-identify’. 42 Indeed, ethnic group is not routinely collected during registration with a GP and, even now, may be incomplete or poorly coded. 43 There is, therefore, a lack of accurate information about immunisation uptake in Traveller communities. A small number of local studies using parent self-report1,44–46 and NHS records1,47 suggest low or variable uptake of childhood immunisation. These patterns mirror data for other disadvantaged groups who are more likely to be unimmunised or not up to date, significantly increasing their risk (and consequent spread) of vaccine-preventable disease. 35,48,49 Indeed, there have been several, well-documented, outbreaks of measles and whooping cough in Traveller communities. 50,51 Adolescent girls from Traveller communities may no longer be attending school,52,53 reducing the likelihood of receiving sufficient doses of the HPV vaccine (which is now given in two doses). 30 Traveller girls were identified in a recent report54 as one of the target groups to ensure equitable uptake of the HPV vaccine. Unfortunately, most of the studies of vaccine uptake in Traveller communities are dated and it is unclear if these reflect current uptake rates in Traveller communities. In terms of adult vaccines, we found no adult whooping cough or flu vaccine uptake data for Travellers; however, they tend to have larger families,20,22,55 which is a risk factor for reduced vaccine uptake and higher prevalence of asthma20,22 and bronchitis20 (both indications for flu vaccine). This coupled with low uptake of health care, including maternity services,18 suggests uptake of both vaccines may be low.

Factors influencing the uptake of immunisation

A large body of literature56–63 identifies two broad categories of parental factors influencing uptake of childhood immunisation in the general population and high-risk groups. The first relates to socioeconomic disadvantage for which, despite not objecting to vaccines, parents lack access to resources and support to overcome logistical barriers such as having no private transport. The second relates to parents’ concerns about the safety or beliefs about the necessity of vaccines. There are differences in parents who accept immunisation but do not complete the course (partial immunisers), those who have concerns about the safety of some vaccines but not others (selective immunisers) and those who reject immunisation altogether (non-immunisers). 64 These different groups are likely to require different support and information to enable them to take up immunisation opportunities. Regardless of parental position on immunisation, trust in health professionals and services is paramount. 63,65 Studies have also explored factors influencing uptake of immunisation in adults 66,67 including those with high-risk conditions,68 pregnant women69,70 and minority ethnic groups. 71 The barriers appear to broadly fall into the same two categories, access and beliefs, including the perception that healthy people do not need immunisations. 72

Although many of the issues influencing vaccine uptake described in the literature are likely to be similar for Travellers, further research is needed to understand the specific issues affecting diverse Traveller communities to inform the development of interventions tailored to their needs and cultural context. To date, only a few studies1,44–47 have explored the barriers specific to immunisation uptake in Traveller communities. These identify multiple issues reflecting the difficulties in accessing wider health services experienced by marginalised, socially excluded communities. 17–21,24,73–75 Issues particular to immunisation include barriers to accessing primary care services (e.g. the absence of a permanent postal address for recall letters),45 parental concerns about the safety of vaccines46,76 and objection to immunisation arising from strongly held cultural beliefs and traditions. 18 A reluctance to ‘self-identify’ as Travellers for fear of discrimination77 and the challenge of maintaining reliable health records for transient communities19 hinder record keeping of immunisation uptake in Traveller communities.

These studies are typically small, dated or focused on one Traveller community. Although Traveller communities may share similar features of lifestyle that distinguish them from the general population, beliefs and cultural traditions can vary. 77 It is, therefore important to understand whether or not, and how, factors that promote or inhibit immunisation differ between specific communities. Moreover, immunisation has often been only one small part of studies exploring several health issues with Travellers. This limits the extent to which the complex nature of barriers to and facilitators of immunisation is explored. For example, barriers may be specific to particular vaccines [e.g. measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine], differ for adult and childhood vaccines or be specific for different Traveller communities. Many vaccines have been introduced in the last three decades (MMR in 1988; Haemophilus influenzae type b in 1992; meningococcal C in 1999; pneumococcal conjugate in 2006; HPV in 2008; rotavirus in 2013; and childhood flu in 2013) or indications for established vaccines have expanded (e.g. pregnancy flu and whooping cough vaccines in 2010 and 2012, respectively). Since several studies among Travellers were conducted in 1980/90s, issues associated with these newer vaccines have not always been considered, neither have evolving views about previously controversial vaccines (e.g. whooping cough, MMR) or the views of more recent migrant communities in the UK (e.g. Romanian and Slovakian Roma). Finally, we were unable to locate any studies on immunisation uptake in adults living in Traveller communities.

Interventions to increase the uptake of immunisation

The effectiveness of interventions to increase immunisation uptake among children48,78–82 and adults68,78,83,84 have also been reviewed and there are many examples of innovative health- and social-care provisions aimed at improving the health of Travellers. 17,18,85,86 Some target immunisation specifically (e.g. outreach immunisation programmes, tailored health promotion resources), whereas others are generic yet relevant to immunisation (hand-held patient records, specialist health visitors17 and cultural competence training of health professionals). 87 These interventions are rarely rigorously evaluated so it is unclear which are feasible, acceptable and (cost-)effective, in which communities they work and how they may or may not work. Finally, existing interventions are rarely informed by theoretical frameworks which can increase effectiveness by aiding understanding of the likely mechanisms of change. 88 This study set out to advance the understanding by addressing these limitations of previous research.

Research aims and objectives

Aims

-

To investigate the barriers to and facilitators of acceptability and uptake of immunisations among six Traveller communities across four UK cities.

-

To identify possible interventions to increase uptake of immunisations in these Traveller communities that could be tested in a subsequent feasibility study.

Objectives

-

To investigate the views of Travellers on the barriers to and facilitators of acceptability and uptake of immunisations and explore their ideas for improving immunisation uptake.

-

To investigate the views of service providers on the barriers to and facilitators of uptake of immunisations within the Traveller communities with whom they work, and explore their ideas for improving immunisation uptake.

-

To examine whether or not and how these responses by Travellers and service providers vary within and across communities and for different vaccines (childhood and adult).

-

To use the data collected from (1–3) to identify possible interventions to increase uptake of immunisations in the six Traveller communities.

-

To conduct workshops in each community to discuss findings and to produce a prioritised list of potentially feasible and acceptable interventions to be considered for testing in a subsequent feasibility study.

Chapter 2 Methods

Approvals and registration

The National Research Ethics Service Committee Yorkshire and The Humber – Leeds East approved the study on 23 August 2013. Research and development approval was secured from the relevant NHS organisations: Bristol Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Vale of York CCG, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust, Homerton University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust and Guys’ and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. The study was assigned the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number of ISRCTN20019630 and UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio number 15182.

Study design

This was a three-phase qualitative study. The three phases and the aims they each address are presented in Figure 1. The study design comprised the first stage of the Medical Research Council’s framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions. 88 The aim of this stage is to ensure that a complex intervention ‘can reasonably be expected to have a worthwhile effect’. To this end, this stage is used to identify the components of the intervention and the mode of delivery. Questions of whether or not and how the content and delivery of the intervention might need to differ within and across populations and settings, and what are the potential barriers to and facilitators of implementation are also addressed. This stage of the framework also includes identification of an appropriate theoretical framework to inform the intervention and to aid understanding of the likely mechanisms of change. This increases the likelihood of an intervention being effective. 88

FIGURE 1.

Mapping of study aims against the phases of the UNderstanding uptake of Immunisations in TravellIng aNd Gypsy communities (UNITING) study.

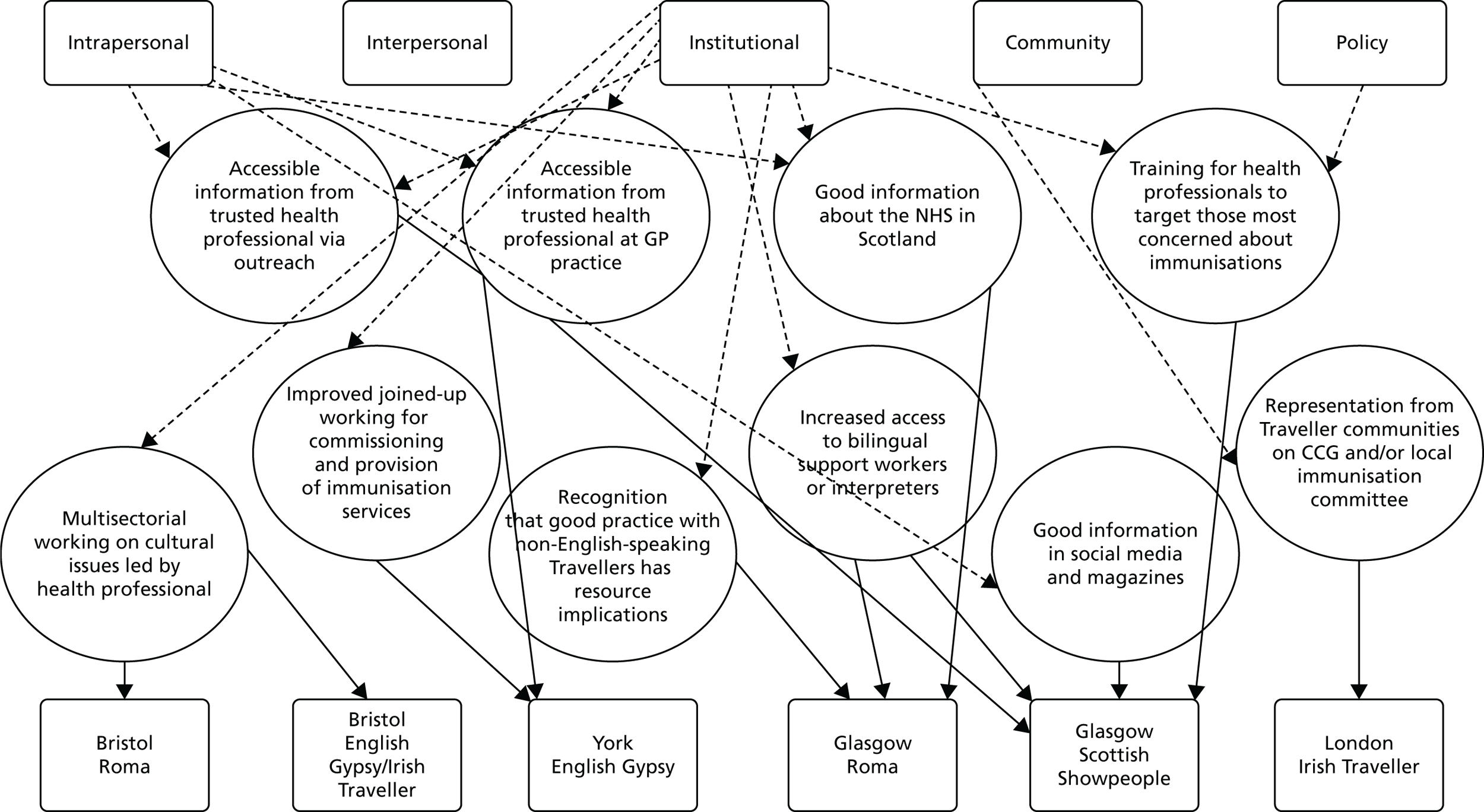

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework underpinning the research was the social ecological model (SEM),89 which recognises that individuals’ behaviour is affected by, and affects, multiple levels of influence (intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, policy; Table 1). Levels are interactive and reinforcing. 90 This multilevel focus is consistent with the World Health Organization (WHO)’s conceptualisation of health. 90 The model also identifies intervention strategies for each level of influence and it is proposed that, to achieve long-term health improvements, all five levels should be targeted simultaneously. If this is not possible, then at least two levels should be targeted. 90 We used the SEM to ensure that all levels of potential influence on immunisation behaviours were considered and we proposed to identify interventions at all five levels. Although we did not anticipate designing interventions to change national immunisation policy in a subsequent feasibility study, we considered it possible that there may be local policies and/or approaches to communicating national initiatives that fail to meet the needs of these communities and we would identify strategies to tackle this. Acknowledging these complex multifaceted determinants on behaviour is considered to be of particular relevance to understanding health behaviours (to inform future interventions) in socially excluded communities with specific health needs such as Travellers. The SEM has previously been used in the context of flu immunisation,91 child health92 and with culturally diverse93 and disadvantaged populations. 94

| Level | Level-specific influences on health behaviour | Examples of level-specific influences on immunisation behaviour | Level-specific intervention strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Characteristics of the individual, for example knowledge, attitudes, behaviour, self-concept and skills | Perceptions of risk from disease and effectiveness of vaccine, attitudes towards immunisation, past immunisation behaviour, perceived membership of a vaccine priority group and trust in ‘experts’ | Education, training and skill enhancement of target population |

| Interpersonal | Formal and informal social networks and social support systems, for example family and friendship groups | Beliefs that friends and families (do not) want them to vaccinate, number of people vaccinating in the social network (social norm) and social capital | Education, training and skill enhancement of people who interact with target population (e.g. family members, friends, teachers) |

| Institutional | Social institutions with organisational characteristics and (in)formal rules and regulations for operation | Access to a health-care provider, reminders and amount of information from health-care provider, and recommendation to vaccinate by health-care provider | Education, training and skill enhancement of general community beyond target population and immediate contacts including institutional leaders |

| Modifications to institutional environments, policies or services | |||

| Community | Relationships among organisations, institutions and informal networks within defined boundaries | Presence of disease in community, perceived risk for self and of infecting others | Education, training and skill enhancement of general community beyond target population and immediate contacts including community leaders |

| Modifications to institutional environments or services | |||

| Policy | Local, state and national polices | Presence in vaccine priority group and access to immunisation (free of charge, location of services) | Education, training and skill enhancement of general community beyond target population and immediate contacts specific to policy change |

| Creation or modification of public policies |

Setting

The research was undertaken in four UK cities and focused on six Traveller communities (see Table 2), who predominantly, but not exclusively, lived in houses or on authorised sites (privately owned, council managed). This was a complex, multisite study working with socially excluded, marginalised communities who are traditionally considered to be hard to engage in research. 95 For reasons of practicality, and to enable our approach to be refined in the light of experience, we conducted the study in two waves (wave 1, York and Bristol; and wave 2, Glasgow and London). This enabled us to learn important lessons in wave 1 to inform wave 2, for example about gaining the trust of communities to facilitate recruitment and about the organisation of the phase 3 workshops.

A description of the six Traveller communities is presented in Table 2. The English Gypsy, European Roma and Irish Traveller communities are recognised in the Race Relations Act 197696 as ethnic minorities, replaced now by the Equality Act 2010. 97 Although they have different beliefs, customs and languages, they share common features of lifestyle and culture,27 and are genealogically and linguistically related. 98 In contrast, the Scottish Showpeople are not recognised in the Race Relations Act 197696 or by the aforementioned communities to be part of the ‘traditional Travellers’ ethnic group. Indeed, it is reported that they do not want to have recognised ethnic minority status, self-defining as business/cultural communities. It is only their traditionally nomadic lifestyle that means that, legally, they are labelled as Travellers. 99

| City | Community | Overview |

|---|---|---|

| Bristol | Romanian Roma | Descended from the same people as British Romany Gypsies and have recently moved to the UK from Central and Eastern Europe. Recognised as the same ethnic category as British Gypsies, yet distinct from the UK community. A total of 40 families in shared rented accommodation in relative proximity to each other. Families are mainly Romanian |

| English Gypsy | Recognised in British law as an ethnic group. More than 100 families living on two council-managed sites (one a transit site) in Bristol. Families live on a privately owned site in North Somerset (117 caravans) and a council run site (250 caravans) in South Gloucestershire. These are all mixed sites, home to both English Gypsies and Irish Travellers | |

| Irish Traveller | ||

| York | English Gypsy | Recognised in British Law as an ethnic group. More than 350 families living across three official sites and some in housing |

| Glasgow | Romanian and Slovakian Roma | Descended from the same people at British Romany Gypsies and have recently moved to the UK from Central and Eastern Europe. Recognised as the same ethnic category as British Gypsies, yet distinct from the UK community. An estimated 3500 Roma live in Glasgow,15 mainly in a small geographical area (6–8 streets) in the Govanhill area of the city. The settled population in Govanhill are mainly Slovakian. However, there has been an increase in the Romanian population since migration restrictions were lifted in January 2014 |

| Scottish Showpeople | Scottish Showmen/Showpeople or travelling show, circus and fairground families. Not recognised in British law as an ethnic group. Approximately 300 live in fixed sites in the north-east of Glasgow (these numbers are likely to be an underestimate; accurate numbers are not available). Some sites are council owned, others privately owned. Travelling with shows is becoming less common, and many families own and run snack vans and children’s fun rides in shopping malls, etc. | |

| London | Irish Traveller | Traditionally nomadic people of Celtic descent arriving in Britain in 1850s. Recognised in British law as an ethnic group. A total of 17,000 live in London. Most are in rented accommodation and on local authority sites. Three areas were included: Hackney, Lewisham and Southwark. In Hackney, 17 families live across five official sites and 54 families live in houses (temporary/emergency, private and social housing). Lewisham currently has no official Traveller sites and the population live in either social or private housing. Researchers were advised that the vast majority live in privately rented accommodation and are now being significantly impacted on by the introduction of the ‘benefit cap’ with rental costs being high. In Southwark, there are four official Traveller sites, but many more families live in social and private housing |

We included two English Gypsy (Bristol and York) and two Eastern European Roma communities (Bristol and Glasgow). This enabled us to consider whether or not Travellers’ views and experiences of immunisation were specific to those particular communities (e.g. English Gypsy people living in York) or reflected more widely the experiences of communities of the same descent (e.g. English Gypsy communities across the UK). Romanian Roma participated in Bristol, whereas both Romanian and Slovakian families were included in Glasgow. The intention at the outset was to work with the English Gypsy community in the Bristol area and sites were selected for recruitment where predominantly English Gypsy populations reside. However, as members of the Irish Traveller community also live on the same sites, it was not considered equitable by the gatekeeper to recruit solely English Gypsies which meant we included Irish Travellers in Bristol in the study. Therefore, we also included two Irish Traveller communities (Bristol and London), which facilitated further cross-community comparison.

Participants

Phase 1

Within each Traveller community we recruited both men and women living in extended families across generations. We included young women planning families, parents and grandparents to capture a lifespan/cross-generational perspective, as well as adolescents eligible for their three-in-one booster (diphtheria, tetanus, poliomyelitis, given at age 13–18 years), girls eligible for HPV vaccine (given at age 12 or 13 years in school); and adults eligible for the flu vaccine (pregnant women, over 65 years and with specified long-term conditions) and whooping cough vaccine (pregnant women). Childhood immunisation decisions are typically made by mothers;56,57 however, we were keen to recruit both men and women to explore any potential gender differences in views. We aimed for one-quarter of participants to be male. We also purposively sought to recruit a mix of full immunisers/partial immuniser and non-immunisers (based on self-report). We planned to interview approximately 22–32 participants in each of the six Traveller communities (total 132–192 participants). The upper limit was subsequently increased to 45 (see Chapter 3, Participants). An overview of the target sample for each Traveller community is presented in Table 3. We were confident that this sample size would enable us to look for potential differences and similarities in views within a community as well as draw out meaningful comparisons across Traveller communities, both across gender and for different vaccines (childhood and adult) to allow robust conclusions to be made.

| Gender | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||

| Fathers | Grandfathers | Adolescents/young women | Mothers | Grandmothers | |

| 2–4 | 2–4 | 6–8 | 6–8 | 6–8 | 22–32 |

Phase 2

Service providers able to influence local policy making, drive health improvement, and/or providing or commissioning services for Traveller communities in the four cities were recruited to the study. We purposively sampled service providers in each of the four cities to ensure we interviewed a mix of ‘frontline workers’ (e.g. health visitors, practice nurses, community midwives, school nurses, GPs, range of community workers including third sector) and those working in more strategic/commissioning roles (e.g. local decision-makers in health protection/public health/health and wellbeing boards/CCGs). We set out to interview 6–8 service providers in each city (total 24–32 participants). In Bristol and Glasgow, where we were working with two Traveller communities, some of the service provider participants worked specifically with one Traveller community, whereas others had a more city-wide role.

Phase 3

A subsample of participants from phases 1 and 2 who had agreed to be reapproached were recruited to take part in the workshops. We aimed to include 10–12 Traveller participants per community, comprising a mix of Traveller men and women, across generations. We set out to recruit three or four service providers to each workshop, both frontline workers and those with a more strategic role. When we were unable to recruit sufficient numbers of phase 1 and phase 2 participants, other Travellers and service providers who had not been interviewed were invited to attend. The target participant numbers for the workshops were 13–16 per workshop, with a total of 78–96 participants.

Access and recruitment

Phase 1

We were aware that the ‘outsider’ position of researchers, with few similarities of experience and no ‘network connections’ with Traveller communities, might lead to mistrust meaning that gaining access could be difficult and time-consuming. 95 Therefore, our research team included gatekeepers in all four cities who had long-standing trustful relationships with the communities and who could ‘vouch’ for our trustworthiness, enable access and help recruit participants to the study. Our proposed approach in each Traveller community was based on the experience of these gatekeepers, as well as drawing on established good practice. 100

Recruitment and data collection in wave 1 (Bristol and York) occurred from December 2013 to March 2014. In wave 2, recruitment was March to April 2014 (Glasgow Roma), July 2014 to April 2015 (Glasgow Scottish Showpeople) and June to November 2014 (London Irish Travellers). A description of the approach to access and recruitment for each Traveller community is presented in Table 4. In all communities the gatekeepers (e.g. a member of the Bristol City Council Gypsy and Traveller Team who is an English Gypsy, a health visitor who works with Roma families in Glasgow) first spoke with community members about the study, and handed out the participant information sheet (PIS) for people to take away with them and discuss with others. These documents had been developed with the community partners (see Community partners) and used simple language and pictures (see Appendix 1). Documents were translated for the Roma communities in Bristol and Glasgow. Roma language, Romani, is predominantly oral with a wide number of dialects. Roma people from one area may not speak or understand a dialect spoken in another area; however, they often understand languages such as those spoken in the country from which they migrated. For this reason study documents were translated into Romanian and Slovakian for the Roma communities to improve accessibility to the study, although it was recognised that the primary route to engagement for these communities was oral. The gatekeepers then identified potential participants for the study and either booked interviews on behalf of the local researcher or passed on the contact details of participants for the researcher to book the interviews. Throughout the recruitment phase these gatekeepers continued to promote the study with community members, discussing it with them and reminding them to attend interviews they had booked. Snowballing95 occurred in the Bristol English Gypsy/Irish Traveller, York English Gypsy, Glasgow Roma, Glasgow Scottish Showpeople and London Irish Travellers communities, with community members telling others about the study. We constantly reviewed our sampling to ensure that we met our target for different family roles (see Table 3). Participants were given a £15 gift voucher to thank them for their time. The shop for which the voucher could be redeemed was recommended by the community partners (see Community partners), so as to be the most useful for the community.

| City | Community | Overview |

|---|---|---|

| Bristol | Romanian Roma | Phase 1: a member of Bristol City Council Gypsy and Traveller Team who is an English Gypsy and part of the research team attended the existing Roma drop-in centre, handed out the PISs and explained the project. She returned a week later to compile a list of people willing to be interviewed. The drop-in centre manager and interpreter/advisor also told people about the project using the PISs. The interpreter/advisor further discussed the study with Roma families who she met as a bilingual family mentor. The drop-in centre manager and interpreter/advisor booked appointments for the next few weeks on behalf of the local researchers and the advisor/interpreter reminded participants to attend on the morning prior to the interview (by telephone or text) |

| Phase 3: the interpreter from the Roma drop-in centre telephoned phase 1 participants and then visited them at home to deliver the PISs about the workshop. She then reminded participants to attend on the morning prior to the workshop (by telephone or text) | ||

| English Gypsy and Irish Traveller | Phase 1: a member of Bristol City Council Gypsy and Traveller Team who is an English Gypsy and part of the research team spoke to Travellers on two sites, both close to the Bristol local authority boundary, but located in neighbouring authorities. On the north Somerset site, she handed out the PISs and explained the project. She then visited the site with the local researcher, introduced her to some participants who then suggested others to be interviewed | |

| In South Gloucestershire the health visitor for Travellers used the same approach on the local sites and passed on the details of potential participants to the local researcher. The researcher then visited the site, initially with the health visitor. The researcher was known to the community as she had previously worked on this site as a health professional and knew key members of the community. Snowball sampling was again used as some participants suggested others to be interviewed. In this way some housed Travellers were accessed | ||

| Phase 3: the same gatekeeper from phase 1 (who no longer worked for Bristol City Council by this stage of the study) spoke to phase 1 participants and handed out the PISs about the workshop. She then brought the participants to the event on the day | ||

| York | English Gypsy | Phase 1: the chief officer of YTT and a member of the community (both part of the research team) spoke to people attending YTT about the project and handed out the PIS. The community member passed on the study information to others who did not attend YTT. Interview sessions were organised on ‘busy’ days when lots of people attended for literacy and other classes. The local researchers attended YTT on those mornings to interview participants who turned up. Snowballing also occurred at this time with families telling other families to attend the interview sessions. Later in the study when we were interviewing the final few people (to meet our sampling criteria) interviews were booked with specific participants. Throughout recruitment YTT staff encouraged participants to attend for interviews when they saw them |

| Phase 3: the chief officer of YTT spoke to phase 1 participants and handed out the PISs about the workshop, compiled a list of participants and reminded people to attend | ||

| Glasgow | Romanian and Slovakian Roma | Phase 1: members of the local EU Team (i.e. a health visitor with a specialist role and a bilingual support worker) spoke to people about the project and handed out the PISs. The local researcher then attended a ‘drop-in’ clinic run by the EU team to answer questions. Interview slots were booked at particular dates/times. Those wishing to participate/hear more about the study were asked to attend at these dates/times. Adolescent girls were recruited with the assistance of the Deputy Head and bilingual support workers in the local secondary school. Those who wished to participate attended an interview on an agreed date. Snowballing occurred within the Roma community |

| Phase 3: the EU team discussed the workshop with families and handed out the PISs. They then invited the families to attend on an agreed date/time | ||

| Scottish Showpeople | Phase 1: two community partners shared the PISs with potential participants and asked for permission to pass on contact details to the local researcher of those who may be interested in taking part in the study. The researcher then contacted these potential participants (by text, telephone call, e-mail) discussed the study, answered any questions and booked an interview. The researcher also asked participants if they had contacts who might be interested in taking part | |

| Phase 3: the researcher recontacted phase 1 participants who had agreed to be recontacted. The PISs were provided and participants were invited to attend on an agreed date/time | ||

| London | Irish Traveller | Phase 1: in Lewisham, the gatekeeper and/or a local researcher who was known to the community approached individuals about the study, gave them copies of the PIS and booked interviews. In Southwark, a member of the Irish Traveller community who worked as a volunteer with Southwark Travellers’ Action Group was particularly influential in promoting the study and organising and encouraging participation. The Southwark Travellers’ Action Group Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) page was also used. In Hackney and Southwark, the local researchers were invited to attend established groups for Traveller women and girls to promote the study |

| Phase 3: the researchers and gatekeepers recontacted participants. The PIS was provided and participants were invited to attend on an agreed date/time. As it was decided that the workshop would be held in Hackney, transport was provided for the Travellers who were coming from the other side of the city |

We did not formally record how many Travellers were approached and then agreed/declined to be interviewed in each city. The gatekeepers in Bristol reported that one adolescent Roma girl refused to take part having asked for permission from her mother-in law, and one man (who turned up in place of the two women booked for interviews) refused to be interviewed as he did not wish to sign a consent form or be audio-recorded. No English Gypsy or Irish Travellers in Bristol, York or London were reported to have declined to participate. In Glasgow, gatekeepers observed that the majority of the Roma people approached agreed to take part. Approximately 25 Scottish Showpeople were approached and 14 were recruited.

Phase 2

Recruitment and data collection in wave 1 occurred from April to June 2014 (Bristol) and from June 2014 to February 2015 (York). In wave 2, recruitment was from October 2014 to April 2015 (Glasgow) and from February to August 2015 (London). In each of the four cities we drew up a list of relevant service providers (their organisations and roles). These lists were derived from conversations with gatekeepers and local service providers (e.g. lead for children and families in north-east Glasgow, health improvement practitioner specialist at York City Council), interviews with Travellers and service providers as well as our own knowledge and professional practice. Potential participants were approached by telephone, e-mail or face to face, and given the PIS (see Appendix 2) to review before an interview was booked. In Bristol, York and London service providers were not offered financial reimbursement for their time. In Glasgow, financial reimbursement was offered, in order to facilitate recruitment of GPs and practice nurses.

As in phase 1, we did not formally record how many service providers were approached and subsequently agreed/declined to be interviewed. In Bristol and London everyone who was approached agreed to participate. In York, with the exception of health professionals at two GP practices, everyone approached agreed to be interviewed or suggested a colleague to participate in their place. In Glasgow, 20 were approached and 14 were recruited.

Phase 3

Recruitment and the workshops in wave 1 took place in November 2014 (combined workshop for Roma and English Gypsy/Irish Traveller communities in Bristol) and March 2015 (York English Gypsy). The wave 2 workshops took place in June 2015 (Glasgow Roma), August 2015 (Glasgow Scottish Showpeople) and September 2015 (London Irish Travellers). Traveller participants from phase 1 who had agreed to be recontacted about phase 3 were approached by the gatekeepers to take part in the workshop and given a PIS about the workshop (see Table 4). As in phase 1, these documents had been developed with the community partners (see Community partners) and used simple language and pictures (see Appendix 3). They were translated into Romanian and Slovakian for the Roma communities. The gatekeepers then confirmed the participants for the workshop and reminded them to attend. Service providers from phase 2 were recontacted by telephone or e-mail and invited to attend the workshop (see Appendix 3 for PIS). Traveller participants were given a certificate of attendance and a £25 gift voucher (the shop was decided by the community partners; see Community partners) to thank them for their time. Service providers also received a certificate of attendance. They did not receive financial reimbursement for their time.

We did not formally record how many Travellers were reapproached and subsequently attended the workshop. Two service providers in Bristol declined to attend the workshop, as they were too busy or their work no longer focused on the Traveller communities. They were replaced by people in similar roles. In York, all of the participants in phase 2 attended or sent a colleague in their place. In Glasgow, three service providers working with the Roma community who were interviewed attended or sent a colleague in their place. One service provider working with the Scottish Showpeople attended a workshop. In London, one participant identified a replacement. One of the three London localities was not represented by any service providers.

Data collection

A data collection protocol was developed to ensure that a consistent approach was employed across the research team.

Phase 1

A mix of one-to-one and small-group interviews with members of the same family/peer groups were conducted. The number of people in the interview depended on participant preference and who attended for the interview. As recommended in the literature95,100 and by the local gatekeepers, the interviews were held in locations known to participants: at the Roma drop-in (Bristol Roma), at home (Bristol English Gypsy and Irish Travellers), at the York Travellers Trust (YTT) premises and at home (York English Gypsy), in a building adjacent to the local health centre or in the local secondary school (Glasgow Roma) and at home or a local café (Glasgow Scottish Showpeople). In London, interviews were carried out in people’s homes, the café of a local library, a community organisation office and a community centre. Interviews with the Roma participants were conducted with the assistance of an interpreter. In York, two Travellers (one of whom is a member of the research team) were trained by a researcher to conduct the interviews on one of the Traveller sites considered by the gatekeeper to be inaccessible to the researchers.

With the consent of participants, interviews were recorded digitally. For the group interviews the researcher took brief notes to identify who was speaking to facilitate accurate transcription. Prior to commencing the interview written consent was collected from participants. If Traveller participants reported that they struggled with reading, the researcher read out the PIS and each item on the consent form (see Appendix 4) and asked participants to mark or initial the item if they consented.

Phase 2

Interviews with service providers were predominantly one to one, with the exception of a small number of small-group interviews. They were conducted in the participants’ workplace or at the university leading the study in that city. With consent, interviews were recorded digitally. Prior to commencing the interview written consent was obtained from participants (see Appendix 5).

Focus of the interviews

In this study we focused primarily on issues arising from the UK childhood immunisation schedule30 and also, to better understand issues relating to adult immunisation, we explored views on flu and whooping cough vaccinations in adults either identified at risk of developing serious complications of flu themselves, or, in the case of whooping cough vaccine, to prevent potentially life-threatening infection in their newborn infants.

Topic guides for the interviews (individual and small group) were developed to ensure consistency both within and across the six communities (see Appendices 6 and 7), although the format was flexible to allow participants to generate naturalistic data on what they viewed as important. An overview of the interview topics is presented in Table 5. Throughout, the SEM89 informed the questions that we asked, ensuring that we explored all five levels of influence on immunisation behaviour. Researchers’ local knowledge of immunisation and of the Traveller community also fed into the development of the topic guides to prompt dialogue of particular local issues (e.g. outbreaks of measles and whooping cough in the community, introduction/removal of specialist services). The topic guides for phase 1 were reviewed and piloted with the community partners in York (see Community partners) and questions were reworded to improve comprehension.

| Phase of study | Interview topics |

|---|---|

| Phase 1 interviews with Travellers |

|

| Phase 2 interviews with service providers |

|

The original intention was to integrate paper-based vignettes into the phase 2 interviews with service providers and to present verbatim quotations87 from the Traveller interviews on key issues that emerged in each of the five levels of the SEM, in terms of both the influences (barriers and facilitators) on immunisation behaviour and ideas for interventions to increase uptake. This was to stimulate discussion of local issues identified as important by the Traveller communities, as well as the service providers who have responsibility for designing and delivering immunisation programmes locally. Following discussion at a research team meeting, a decision was taken not to do this as it might influence the expressed views of the service providers. Instead, key emerging issues from phase 1 were integrated into the topic guide for phase 2 (see Table 5).

Phase 3

The workshops were held in local venues known and accessible to the Travellers: a church hall in Bristol, YTT premises, a local neighbourhood centre in Govanhill, Glasgow, a function suite in a local Glasgow hotel and a children’s centre in London. The workshops with the Roma participants were conducted with the assistance of interpreters (Romanian and Slovak). To capture the discussions at the workshops, local researchers (who were not facilitating the sessions) took detailed notes. Prior to commencing each workshop, written consent was collected from participants (see Appendix 8). As before, with those Traveller participants who offered that they struggle with reading, the researcher read out the PIS and each item on the consent form and asked participants to mark or initial the item if they consented.

The aim of the workshops was to disseminate the findings of phases 1 and 2 and to discuss and ‘co-produce’95 ideas for the content and delivery of potentially feasible and acceptable interventions at all five levels of the SEM, with a view to then identifying one priority intervention at each level (intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community and policy). The duration of the five workshops varied slightly depending on the availability of participants, ranging from 2 hours (Glasgow) to 3 hours (York and London).

Following the spoken presentation of the key findings of the phase 1 and phase 2 interviews, a structured two-step process101 was used to prioritise the interventions. On the advice of our independent project advisory group (IPAG; see Independent project advisory group), this approach replaced the nominal group technique102 that we had originally planned to use. It was considered that the revised method involved more detailed discussion of the importance and feasibility of potential interventions to increase uptake of immunisation.

First, the Travellers and service providers worked in two separate groups. The researcher presented the ideas for interventions to improve uptake of immunisations that had emerged from the interviews. To do this, each idea for an intervention to improve uptake of immunisations was written on an A4 sheet of coloured paper and read out to the group. The idea was then discussed and scored in terms of potential impact (If this idea happened how much of a difference would it make to your/the local Traveller community in having injections? 1 = no difference to 5 = a lot of difference). At the end of this session, each group had a ranked list of interventions based on their impact scores. The Travellers and service providers then came together and presented their ranked list of interventions to each other. The final workshop session was a facilitated discussion to jointly agree a prioritised list of potentially feasible and acceptable interventions which could positively impact on immunisation uptake in their community.

Data analysis

Within-community analysis

Phase 1 and 2 interviews were transcribed verbatim and data subjected to thematic analysis using the framework approach103 which is designed to address applied policy-related questions. All of the transcripts were checked for accuracy against the audio-recording by the researcher who conducted the interview. The certainty that the data represent the views of participants is very important, particularly so in cross-cultural research in which interpreters are required. 104 A randomly selected sample of audio-recordings (four Bristol Romanian Roma, two Glasgow Romanian Roma and one Glasgow Slovakian Roma) were checked against the transcripts by an independent interpreter, and the level of accuracy deemed satisfactory overall. A small number of errors revealed by this process were corrected in the transcript or the data were removed from the analysis; for example, in one of the Glasgow interviews, the HPV vaccine was incorrectly translated in the interview as flu and so could not be included.

The stages of framework analysis, detailed below, were undertaken independently for each of the six Traveller communities and for both phase 1 and phase 2 data. Participant-based group analysis105 was used to analyse the group interviews, with the contribution of each individual within the interview being analysed separately. The analysis was undertaken by seven researchers. Other members of the research team were involved at different stages to enhance rigour and to ensure that the local context in which the data were collected was retained. A data analysis protocol was developed to ensure consistency across the research team. NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) software packages facilitated data management.

Familiarisation

Two researchers read the interview transcripts to record emerging ideas and recurrent themes that were relevant to the aims of the study.

Constructing a thematic framework

A thematic framework for the Traveller data was developed using 16 phase 1 interview transcripts (four from Bristol, 12 from York). The framework was applied to a further four transcripts (from Bristol) by a second researcher and refined as necessary (see Appendix 9). A second framework was developed in the same way for the phase 2 service provider interviews using all eight interview transcripts from Bristol and then applied to three transcripts from York (see Appendix 10). At this point, the SEM89 was put to one side so that the data were organised by the views expressed by participants rather than forced into a prespecified framework.

Indexing and charting

The thematic frameworks (one for Travellers, one for service providers) were systematically applied to the interview data by a team of seven researchers. On the rare occasion when the data did not easily fit into the framework, the ‘other’ category within each theme was used to ensure that these data were captured. Charts were produced in NVivo for each theme and summaries of responses from participants and verbatim quotations were entered. A subsample of the completed charts for each Traveller community and group of service providers (by city) was reviewed by a second researcher to check the detail and sufficiency of the summaries and quotations.

Mapping and interpretation

The completed charts were exported from NVivo into Microsoft Excel. These were then reviewed and interrogated to compare and contrast views and to seek patterns, connections and explanations within the data (by a team of four researchers). Descriptive findings documents were written up for each Traveller community and the service providers in each city focusing on the barriers to and facilitators of uptake of immunisation and ideas for interventions for improving uptake. The local research teams then reviewed their documents (1) to check that the interpretation of the local data by the analysis team reflected the intended meaning spoken during the interviews and (2) when necessary to provide local context; for example, the Glasgow team provided information on the role of the European Union (EU) team in working with the Roma community.

Cross-community synthesis

The next step of the analysis of the phase 1 and 2 data was a thematic cross-community synthesis that took account of the inferences derived from all the interview data for the sample as a whole. 106 Using the descriptive findings documents and the charts created in the charting stage of analysis for each Traveller community (both Traveller participants and service providers), the data across all six communities were synthesised to explore similarities and difference in views on barriers to and facilitators of immunisation. We particularly looked for similarities and difference by gender and vaccine (within the UK childhood immunisation schedule, adult flu/whooping cough). The SEM89 was reintroduced into the process at this stage in that the themes and subthemes were mapped to the five levels of influence.

Identifying the interventions to take to the workshops

A modified intervention mapping approach107 was used to identify the interventions to take to the phase 3 workshops. This method ‘maps the path from recognition of a need or problem to the identification of a solution’. First, a matrix was developed using the descriptive findings documents for the Bristol Roma and English Gypsy/Irish Traveller communities. This matrix combined the barriers to and facilitators of immunisation uptake that had emerged from the phase 1 and phase 2 interviews with ideas for interventions to increase uptake of immunisation. In order to generate as many ideas as possible for interventions, these were drawn from interviews with Travellers and service providers for that particular community, knowledge and experience of the research team and the IPAG, as well as existing literature. Two researchers then independently matched interventions to potentially relevant barriers and facilitators and then met to agree a final list of interventions to take to the first workshop (see Chapter 4, Identifying the interventions to take to the workshops) which was held in Bristol. At this point, detail from the phase 1 and phase 2 interviews pertinent to each intervention were included; for example, for the intervention ‘Identify Travellers in health records’ specific suggestions about how to do this in GP practices and across immunisation databases were added. This process enabled us to produce a detailed list of interventions to take to the workshop that we were confident addressed the identified issues for both the Bristol Romanian Roma and English Gypsy/Irish Traveller communities.

To identify the interventions to take to the workshops for the other Traveller communities, the descriptive findings documents were discussed by the local research teams with the lead researcher to agree the barriers to and facilitators of immunisation uptake. When these were the same as for Bristol, the interventions identified for the Bristol workshop were chosen. When additional issues emerged for a community, additional interventions were taken to the workshop. This meant that many of the interventions were considered at several workshops, whereas others were only discussed at one workshop (see Chapter 4, Table 34).

Community partners

In each Traveller community we worked in partnership with ‘community partners’ for the duration of the study in that city. Our approach in each community (Table 6) was based on the experience of the local gatekeepers. Community partners were offered a £40 gift voucher of their choice per meeting that they attended. The number of meetings held ranged from two (Glasgow Roma, London Irish Travellers) to four (Bristol – across both communities). Over the duration of the study the community partners changed in Bristol and London, and were the same people in York and Glasgow.

| City | Community | Overview |

|---|---|---|

| Bristol | Romanian Roma, English Gypsy and Irish Traveller | Meeting 1 (October 2013, Bristol City Council premises): local researchers and an interpreter met with three English Gypsies/Irish Travellers, one Roma person and one Showperson. Discussed how best to work with the local Traveller communities in terms of recruitment and conduct of interviews. Commented on the phase 1 PIS. Decided on gift voucher |

| Meeting 2 (March 2014, local health centre): a researcher and interpreter met with four Roma people. Plan was to discuss themes emerging from the phase 1 interviews and to identify key issues to be taken forward into the phase 2 interviews with service providers. In reality, it became more a focus group about immunisation as the purpose of the meeting was difficult for attendees to grasp | ||

| Meeting 3 (October 2014, local secondary school): local researchers and an interpreter met with seven community partners, a mix of English Gypsies/Irish Travellers (including the member of the research team) and Roma. Discussed location and organisation of the phase 3 workshop | ||

| Meeting 4 (May 2015, local Traveller site – local church for Roma): a researcher and specialist health visitor met with five English Gypsies. A researcher and an interpreter met with five Roma mothers. Discussed how to disseminate study findings to community | ||

| York | English Gypsy | Meeting 1 (October 2013, YTT premises): a researcher met with the YTT Advisory Steering Group (nine Travellers, including the research team member) who were willing to act as community partners. Discussed how best to work with the local community in terms of recruitment and conduct of interviews. Commented on the phase 1 PIS and study flyer. Decided on gift voucher |

| Meeting 2 (January 2015, YTT premises): a researcher met with the YTT Trust Advisory Steering Group (eight Travellers including the research team member) to feedback a summary of the phase 1 and 2 interview findings and discuss how best to run the phase 3 workshop | ||

| Meeting 3 (June 2015, YTT premises): a researcher met with one community partner to discuss how to disseminate the findings of the study across the community | ||

| Glasgow | Romanian and Slovakian Roma | Meeting 1 (September 2013, South Sector Health Board premises): two researchers met with a group of service providers including two members of the community who worked as bilingual support workers. Discussed how best to work with the Roma community in terms of recruitment, conducting interviews and collaborating with community partners |

| Meeting 2 (November 2013, South Sector Health Board premises): two researchers met with the same group (only one member of the community attended) to further discuss the logistics of recruitment and to comment on the phase 1 PIS | ||

| Scottish Showpeople | Meeting 1 (October 2013, Glasgow Caledonian University): a researcher met with one member of the community to discuss how the community partner group would work, discussed approach to recruitment and commented on the phase 1 PIS. Decided on gift voucher | |

| Meeting 2 (November 2013, Glasgow Caledonian University): two researchers met with two community partners to finalise approach to recruitment to phase 1 interviews | ||

| Meeting 3 (May 2015, Glasgow Caledonian University): two researchers met with one community partner to feedback a summary of the phase 1 and 2 interview findings and discuss location and organisation of the phase 3 workshop | ||

| London | Irish Traveller | Meeting 1 (May 2014, London Gypsy and Traveller Forum, City Hall): a researcher attended and identified/met with potential gatekeepers for the study |

| Meeting 2 (September 2015, London Gypsy and Traveller Forum, Kings Place): a researcher discussed the plans for the phase 3 workshop with some Travellers at the meeting |

Across the six communities, community partners advised on participant information about the study, recruitment, choice of gift voucher, the location/organisation of the workshops and dissemination of study findings across the community. Feedback on the PIS (see Appendix 1) was to use pictures that illustrate the type of people who need immunisations; and in York we learnt that while the photo of a man wearing glasses was acceptable, Travellers would know he was not a Traveller as they do not have their photo taken wearing glasses. In terms of recruitment, the community partners in York suggested conducting the phase 1 interviews on a day when lots of Travellers attend YTT for literacy classes and in Glasgow the community partners offered to publicise the study with others in the community and distribute the PIS. The community partners in all four cities informed our choice of venue for the phase 3 workshops by suggesting venues that were well known, and accessible, to their community. The community partners in Glasgow attended the workshops. Finally, for dissemination of the study findings to the community (see Appendix 11) in York a poster was developed by the community partners and displayed at YTT. Further dissemination ideas were to use gatekeeper organisation websites and Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) pages. In Bristol ideas about dissemination included a leaflet, a YouTube (YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA; www.youtube.com) video that included members of the community so that the link could be shared via Facebook, and via link workers.

Independent project advisory group

The IPAG was set up at the start of the study to provide independent advice on all stages of the study. The group comprised:

-

Dr Martin Schweiger (chairperson), Public Health Consultant, Public Health England

-

Dr Jill Edwards, research fellow, University of Leeds, experienced in research with ‘marginalised’ communities

-

Dr Patrice Van Cleemput, freelance research consultant, previously a health visitor with experience of conducting research with Travellers.

A fourth member of the group did not attend any meetings, so is not named here.

The group met four times over the duration of the study (July 2014, October 2014, June 2015 and October 2015). The group’s input focused on signposting the research team to up-to-date literature, relevant Traveller or immunisation projects/policy documents and key individuals with useful expertise; offering views on the emerging interview findings; suggesting ideas for interventions to be taken to the phase 3 workshops; and inputting on the discussion chapter of this final report.

Chapter 3 Barriers to and facilitators of uptake of immunisation: interviews with Travellers and service providers

Participants

Travellers

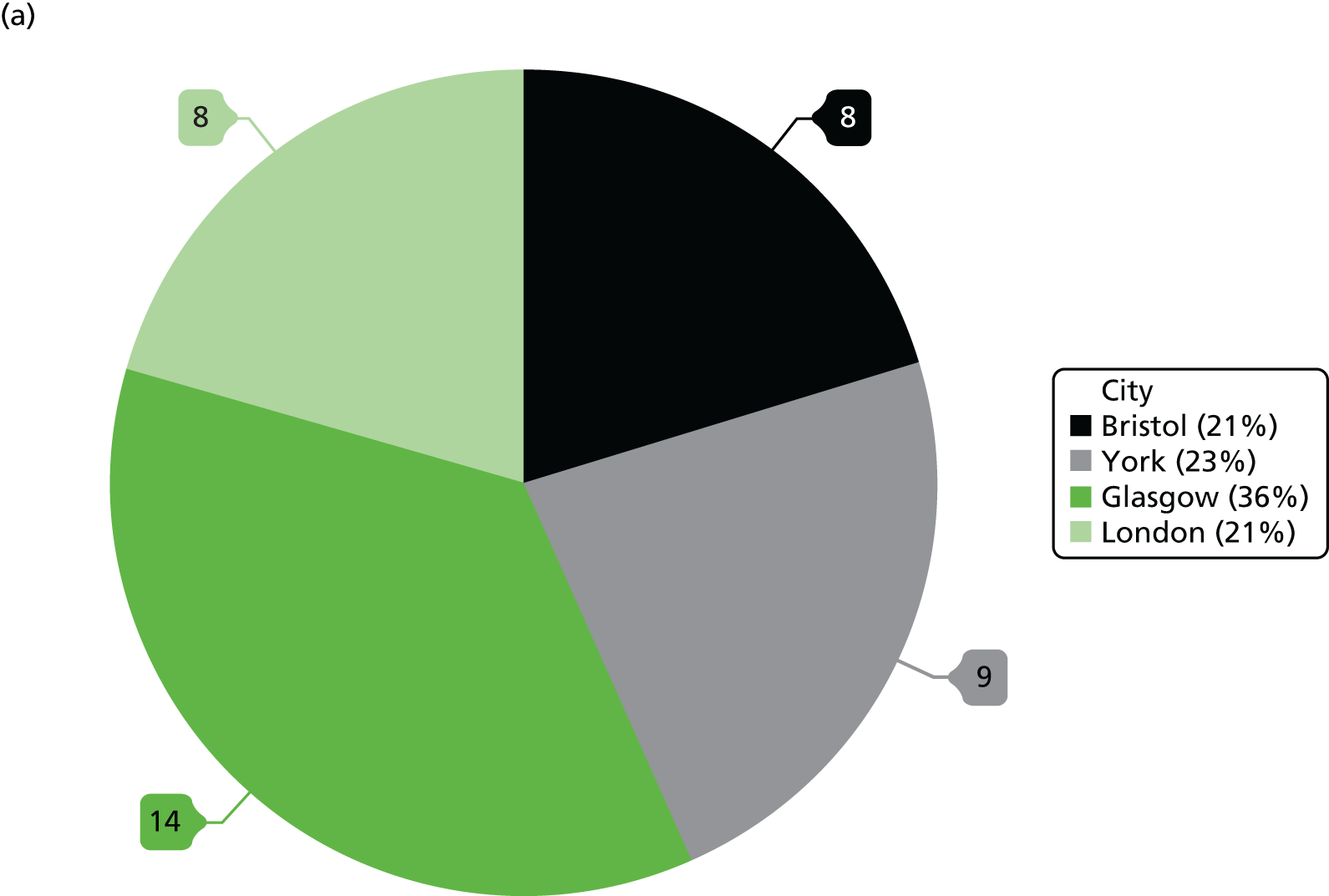

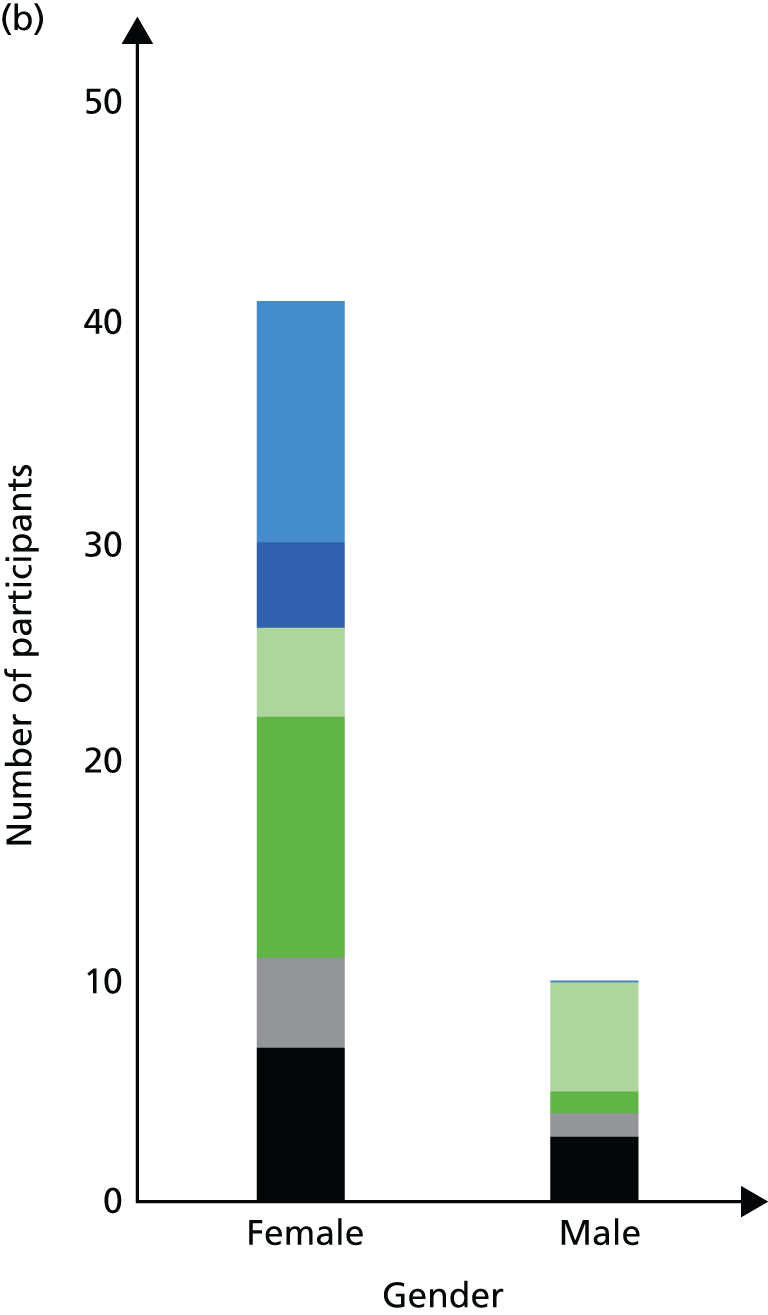

We interviewed 174 Traveller participants from six Traveller communities in four UK cities. These communities were identified as Romanian Roma and English Gypsy/Irish Traveller in Bristol; English Gypsy in York; Romanian Roma/Slovakian Roma and Scottish Showpeople in Glasgow; and Irish Travellers in London. Thirty-eight participants participated in individual interviews, while the remainder took part in group interviews. Three-quarters (n = 47) of the interviews with the Roma participants were conducted using an interpreter. A summary of the demographic characteristics of Traveller participants is presented in Figure 2 and Table 7.

FIGURE 2.

Travellers by community. (a) Traveller community by city; (b) gender by community; (c) housing by community; and (d) family role by community. EG, English Gypsy; IT, Irish Traveller.

| Characteristic | All (N) | Traveller community by city (n) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol | York | Glasgow | London | ||||||

| Romanian Roma | English Gypsya | Irish Travellerb | English Gypsy | Romanian Roma | Slovakian Romac | Scottish Showpeopled | Irish Traveller | ||

| Total | 174 | 24 | 15 | 9 | 48 | 17 | 20 | 14 | 27 |

| Used interpreter | 47 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 139 | 14 | 10 | 7 | 37 | 17 | 17 | 10 | 27 |

| Male | 35 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Family role | |||||||||

| Mother | 64 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 19 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 7 |

| Grandmother | 33 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Pregnant woman | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Woman, no children | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Adolescent girl with children | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Adolescent girl, no children | 24 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 7 |

| Father | 19 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Grandfather | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Male, no children | 11 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | 62 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 22 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 13 |

| Married | 74 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 17 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Common law partner | 19 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 0 |

| Engaged | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Widowed | 9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Separated | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Divorced | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Housing | |||||||||

| House/flat | 112 | 23 | 0 | 6 | 24 | 17 | 20 | 3 | 19 |

| Authorised site – caravan/trailer | 45 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Authorised site – chalet | 15 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Bed and breakfast | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-reported immunisation status of participants | |||||||||

| Full | 59 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 24 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 2 |

| Partial | 40 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| None | 11 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Missing | 64 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 7 | 12 | 0 | 15 |

| Self-reported immunisation status of participants’ children | |||||||||

| Full | 69 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 20 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 8 |

| Partial | 17 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| None | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N/A | 44 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| Missing | 42 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 13 | 2 |

| Employment | |||||||||

| Employed | 19 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Self-employed | 9 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Unemployed | 43 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 16 |

| Stay at home parent | 43 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 5 |

| Student | 24 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Disabled | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Retired | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Missing | 29 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Age (years), mean (SD); range | 32.34 (4.93); 13–82 | 33.42 (12.56); 16–65 | 33.80 (18.90); 18–82 | 28.34 (12.25); 17–50 | 34.62 (15.08); 14–65 | 25.35 (10.89); 13–44 | 25.90 (12.56); 14–60 | 42.64 (17.73); 18–72 | 32.33 (14.47); 14–63 |

| Number of children,e mean (SD); range | 3.18 (2.14); 1–12 | 3.14 (2.11); 1–8 | 2.38 (1.60); 1–6 | 3.00 (1.79); 1–6 | 3.56 (1.97); 1–10 | 4.08 (2.94); 0–12 | 1.80 (1.21); 1–5 | 1.85 (0.90); 1–4 | 4.34 (2.35); 1–9 |

| Number of grandchildren,e mean (SD); range | 7.26 (8.29); 1–41 | 7.67 (5.77); 1–11 | 7.33 (2.31); 1–10 | 5.00 (N/A); N/Af | 5.50 (4.31); 1–16 | 7.33 (3.21); 1–11 | 8.00 (10.30); 1–26 | 2.80 (2.68); 1–7 | 12.00 (15.08); 1–41 |

| Years of residency, mean (SD); range | 10.67 (9.70); 0.17–41.00 | 3.97 (1.94); 0.25–7.00 | 20.00 (1.48); 18.00–24.00 | 16.56 (9.74); 2.00–30.00 | 17.48 (9.76); 1.00–41.00 | 1.97 (1.74); 0.17–5.00 | 1.71 (1.71); 0.40–8.00 | 13.32 (12.16); 2.00–31.00 | 11.15 (7.23); 2.00–28.00 |

Our original recruitment target was 22–32 Traveller participants from each of the six communities. The upper limit was later increased to 45 to ensure that the sampling criteria were met following the large number of York English Gypsy Travellers attending for an interview on 1 day. The target sample was achieved for all of the communities, except for the Glasgow Scottish Showpeople. The Bristol English Gypsy and Irish Traveller community were viewed as one community, as were the Glasgow Romanian and Slovakian Roma (see Chapter 2, Setting).

A total of 139 Traveller participants were female and 35 were male. This ratio of female to male participants (3 : 1) achieved our proposed sampling aim for one-quarter of all participants to be male. We did not manage to recruit any men from the Irish Traveller community in London. As intended, we spoke to women across generations, including grandmothers (n = 33), mothers (n = 64), pregnant women (n = 5), women without children (n = 8), adolescent girls with children (n = 5) and adolescent girls with no children (n = 24). We achieved our target of 6–8 mothers in all but the Glasgow Scottish Showpeople community (n = 5). We achieved the targets of 6–8 grandmothers and 6–8 adolescent/young women in three communities (York English Gypsy, Glasgow Roma and London Irish Traveller). The men were a mix of grandfathers (n = 5), fathers (n = 19) and young men with no children (n = 11). We achieved our target of 2–4 grandfathers in two communities (York English Gypsy and Glasgow Scottish Showpeople). We did not set out to recruit young men without children; however, 11 took part across four communities (not Glasgow Scottish Showpeople or London Irish Travellers). Interviewing grandparents, parents and young people enabled us to explore intergenerational differences in attitudes and beliefs; speaking to pregnant women and older adults helped us to gain awareness of views relating to the adult whooping cough and flu vaccines. Adolescents gave us an insight into attitudes towards the HPV vaccine (girls only) and three-in-one booster.

We met our aim to interview a mix of full, partial and non-immunisers. Approximately one-third of participants (n = 59) self-reported that they were fully immunised, 40 were partially immunised and 11 had had no vaccinations. There were missing data from over one-third of participants (n = 64). We did not recruit any Glasgow Roma participants who reported having had no immunisations themselves. Parents (n = 130) self-reported the immunisation status of their children as follows: half (n = 69) said that their children were fully immunised, 17 reported partial immunisation and two said that their children had had no vaccinations. Once again there were missing data for one-third of participants (n = 42). We spoke with participants with non-immunised children only in the Bristol English Gypsy community (none self-identified as this in the other five communities). These immunisation status data should be viewed with caution. They were based on self-report, may be subject to recall and response bias and for some participants did not tie in with their accounts in the interviews. Validation of self-reported immunisation status against external sources was beyond the scope of this study.

Of the 145 adult participants, 74 were married, 62 were single and 19 had a common law partner. There were nine widowed participants, five were separated and one was divorced. Traveller participants predominantly described themselves as unemployed (n = 43), a stay-at-home parent (n = 43), student (n = 24) or employed (n = 19). Employment data were missing for half of the York participants (n = 23). Finally, the vast majority of those interviewed lived in either a house or flat (n = 112) or on an authorised caravan, trailer or chalet site (n = 60). One participant was in bed and breakfast accommodation. The Roma (Bristol and Glasgow) and Irish Travellers (Bristol and London) interviewed in this study tended to live in houses and flats, whereas the Bristol English Gypsy and York English Gypsy participants were more often living on official Traveller sites. We did not recruit any Travellers living on the roadside or on unauthorised encampments. Traveller participants’ ages ranged from 13 to 82 years (mean 32 years), and those with children had on average three children (range 1–12 children); those with grandchildren had on average seven grandchildren (range 1–41 grandchildren). The average number of years of residency was 11 years (range 2 months–41 years), noticeably shorter for the Roma participants. These characteristics (marital status, employment, housing, age, number of children/grandchildren and residency) were not part of the sampling strategy.

Service providers