Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/72/01. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in May 2015 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

James Raftery is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Editorial Board and the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group. He was previously Director of the Wessex Institute and Head of the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Co-ordinating Centre (NETSCC). Amanda Blatch-Jones is a senior researcher at NETSCC.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Raftery et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Assessing the impact of health research has become a major concern, not least because of claims that the bulk of research currently undertaken is wasteful. 1 As publicly funded research is often organised in ‘programmes’, assessment of impact must consider a stream of projects, sometimes interlinked. The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, as the name implies, is such a programme, funding mainly a mix of systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials (RCTs). In a previous review, Hanney et al. 2 assessed the impact of the first 10 years of the NHS HTA programme from its inception in 1993 to June 2003 and identified factors that helped make an impact, including, first, the fact that the topics tend to be relevant to the NHS and to have a policy customer and, second, the strengths of the scientific methods used coupled with strict peer review. 2,3 That assessment included a review of the literature published up to 2005 on the methods for assessing the impact from programmes of health research.

Evidence explaining why this research is needed now

Internationally, there has been a growing interest in assessing the impact of programmes of health research, and recent developments in the UK have created a new context for considering impact assessment. Besides the claim that much research is wasteful, other factors include pressure on higher education institutions to demonstrate accountability and value for money, the expansion in routine collection of research impact data and the large-scale assessment of research impact in higher education through case studies in the Research Excellence Framework (REF).

Aim

To review published research studies on tools and approaches to assessing the impact of programmes of health research and, specifically, to update the previous 2007 systematic review funded by the HTA programme. 2

Objective

Our objective was to build on the previous HTA review2 (published in 2007, covering the literature up to 2005) to:

-

identify the range of theoretical models and empirical approaches to measuring impact of health research programmes, and collate findings from studies assessing the impact of multiproject programmes

-

extend the review to examine (1) the conceptual and philosophical assumptions underpinning different models of impact and (2) emerging approaches that might be relevant to the HTA programme, such as studies focusing on monetised benefits and on the impact of new trials on systematic reviews

-

analyse different options for taking impact assessment forward in the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)/HTA programme, including options for drawing on routinely collected data.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 describes the methods used for the review, Chapter 3 reports the findings from the updated review, Chapter 4 presents a broader taxonomy of impact models, Chapter 5 provides the findings on the monetary value of the impact of health research, Chapter 6 reports on the impact of trials on systematic reviews, Chapter 7 summarises the impact of trials on discontinuing the use of technologies and Chapters 8 and 9 provide a discussion of the main findings, including options for NIHR/HTA to take research impact assessment forward and draw conclusions from the report, and discuss recommendations for future impact assessment.

Chapter 2 Methods

The work was organised into three streams: the first stream focused on updating and extending the previous 2007 review;2 the second stream involved an extension of the literature in relation to the conceptual and philosophical assumptions on different models of impact and their relevance to the HTA programme; and the third stream considered the different options for taking impact assessment forward in the NIHR/HTA programme.

This chapter provides an account of the methods common to these streams of work. Where there were differences because of the type of review conducted, further explanation is provided under the relevant work stream.

Review methods

Given the nature and scope of the reviews included, a range of methods were used to identify the relevant literature:

-

systematic searching of electronic databases

-

hand-searching of selected journals

-

citation tracking of relevant literature

-

literature known to the team (i.e. snowballing)

-

bibliographic searches of other reviews

-

bibliographic searches of references in identified relevant literature.

Search strategies

Although different search strategies were conducted for the different elements, details of the individual search strategies can be found below (see Appendix 1 for full listing of the search strategies used).

Update to the previous review methods

The previous assessment of the impact of the HTA programme2 was informed by a review of the literature on assessing the impact of health research. It found an initial list of approximately 200 papers, which was reduced to a final ‘body of evidence’ of 46 papers: five conceptual/methodology, 23 application and 18 combined conceptual and application (please refer to the original Hanney et al. 2 report for a full list of these references). (In that review, as in the current one, ‘paper’ refers generically to the full range of publications, including reports in the grey literature.) The discussion included an analysis of the strengths, and weaknesses, of the conceptual approaches. The Payback Framework, the most widely used approach, was considered the most appropriate framework to adopt when measuring the impact of the HTA programme, notwithstanding the limited progress made in various empirical studies in identifying the health and economic benefit categories from the framework.

The first question for the updated review was: ‘what conceptual or methodological approaches to assessing the impact of programmes of health research have been developed, and/or applied in empirical studies, since 2005?’. 2

The second question was: ‘what are the quantitative findings from studies (published since 2005) that assessed the impact from multiproject programmes (such as the HTA programme)?’.

Search strategy development

The information scientist (Alison Price) evaluated the search strategy run in the previous report. 2 We used the same search strategy, but checked to identify any new medical subject headings and other new indexing terms. We also reviewed Banzi’s search strategy,4 a modified version of our original strategy. The review by Banzi et al. 4 searched in only two bibliographic databases (MEDLINE and The Cochrane Library), whereas we searched a larger number (see Databases searched). By not including the EMBASE database, Banzi et al. 4 may have missed some relevant indexed journals. For example, the journal in which the Banzi review was published, Health Research Policy and Systems, was indexed in EMBASE and not in MEDLINE until later. We included EMBASE indexing terms, as applied to the Banzi et al. 4 paper, in our expanded EMBASE search strategy.

Any new and relevant indexing terms were evaluated and added to the revised search strategies. The search strategies used text words and indexing terms to capture the concept of the impact of health research programmes. The search results were filtered by study and publication types. The new terms increased the sensitivity of the search, while the filters improved the precision and study quality of the results.

Databases searched

The searches were run in August 2014 for the publication period from January 2005 to August 2014 in the following electronic databases: Ovid MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), The Cochrane Library, including the Cochrane Methodology Register, HTA Database, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), which includes grey literature such as unpublished papers and reports (see Appendix 1 for a full description of the search strategies).

Other sources to identify literature

A list of known studies, including those using a range of approaches in addition to the Payback Framework, was constructed by SH. This list was used to inform aspects of the database search and help identify which journals to hand-search. These journals were Health Research and Policy and Systems, Implementation Science, International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care and Research Evaluation.

A list of key publications was constructed and the references were searched for additional papers. The list consisted of major reviews published since 2005 (that were already known to the authors, and/or were identified in the search) and key empirical studies. 4–19

For studies reporting on the development and use of selected conceptual frameworks, we took the main publication from each as the source for citation tracking using Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The list was supplemented by citation tracking of selected key publications, although we considered only post-2005 citations of any papers that were published before that date.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included studies if they described:

-

conceptual or methodological approaches to evaluating the impact of programmes of health research

-

the empirical evaluation of the impact of a particular programme of health research.

Studies were excluded if they provided only speculation on the potential impact of proposed (future) research [including recent studies on the value of information (VOI)], discussed the impact of research solely in the context of wide and intangible benefits (such as for the good of society and for the overall benefit of the population), or only considered impact in terms of guidance implementation. These inclusion/exclusion criteria repeated those used for the original review that aimed to identify appropriate approaches for retrospective assessment of the impact from the first decade of the HTA programme. VOI studies were not seen as relevant for such a review. Similarly, our review focused on the impact of specific pieces and programmes of research; it was beyond the scope of this study to consider the impact of guidelines based on multiple studies from different programmes of research. Therefore, our focus was on the implementation of that specific research and not on the implementation of guidelines in general.

Our focus on programmes of research highlights the perspective of funders who are interested in identifying the impact of the body of work, at some level of aggregation. We also expanded the use of the term ‘programme’ to included empirical studies focusing on bodies of research conducted by research centres or groups, or a collection of studies around a common theme and conducted in a way that the researchers collectively might view as a programme.

In the 2007 report, we distinguished ‘first, studies that start with a body of research and examine its impact and, second, those that consider developments within the health sector, especially policy decisions, and analyse how far research, from whatever source, influenced those developments’. 2 The latter category of studies, which would have been large, was excluded to allow us to focus on studies that worked forwards to trace the impact from specific programmes of research. Since 2005, there have been further major reviews of studies of policy-making and how research evidence is used. 5,8,20,21 We examined these reviews to help identify studies to include. Again, we did not include studies that explored how research was utilised by policy-makers unless the focus was on the impact made by a specific body of research.

In relation to studies setting out options for research impact assessment, we generally included the study if it made some proposal based on the review or analysis, and if the proposed approach could, at least in theory, have a reasonable chance of being used to assess impact of health research programmes. 8 We also included reviews that usefully collated data on issues such as the methods and conceptual frameworks used in studies. 5

Steve Hanney and AY independently went through the papers and applied the criteria (set out above) to at least the abstract of each paper identified. The studies were classified using the same criteria as previously applied; ‘includes’, ‘possible includes’ and ‘interest papers’, with scope for iteration. Agreement on inclusion was resolved by discussion by SH and AY. Where agreement could not be made, the final decision was made through further discussion with JR and/or TG.

Data extraction

We constructed a data extraction sheet based on a simplified version of the one previously used. 2 It covered basic details such as author, title and date; type of study; conceptual framework and methods used in impact assessment; categories of impacts assessed and found; identification of whether or not the study attempted to assess the impact from each project in a multiproject programme; conflicts of interest declared; strengths and weaknesses; factors associated with impact; and other reviewer comments and quotes (see Appendix 2 for full details).

The data extraction sheet was applied to the papers by SH, TG, MG, JR and AY. Each member of the team considered the list of ‘includes’, avoiding papers on which he/she had been an author. As anticipated, some papers were removed following more detailed examination at the data extraction stage.

Extension of the literature methods

The second stream formed four parts:

-

exploring the conceptual and philosophical assumptions of models of impact

-

monetary value on the impact of health research

-

the impact of randomised trials on systematic reviews

-

the impact of randomised trials on stopping the use of particular technologies.

The methods for each part are discussed below.

Conceptual and philosophical assumptions of models of impact

This stream aimed not merely to update the previous review but to extend its scope. Although much has been published in the past 10 years on different models of impact, less attention has been paid to theorising these models and critically exploring their conceptual and philosophical assumptions. We sought to identify, and engage theoretically with, work from the social sciences that questioned the feasibility and value of measuring research impact at all.

For this extension, we captured key papers from the main search described above and added selected studies published before 2005 if they provided important relevant insights. A modified data extraction sheet was developed (see Appendix 2).

For the theoretical component, we grouped approaches primarily according to their underlying philosophical assumptions (distinguishing, for example, between ‘positivist’, ‘constructivist’, ‘realist’, and so on) and, within those headings, by their theoretical perspective. We compared the strengths and limitations of different philosophical and theoretical approaches using narrative synthesis.

This stream also sought to tease out any approaches from the sample of papers identified in the updated review that might be especially relevant to the HTA programme. We were already aware of some papers on monetisation of research impacts, quantifying the contribution of RCTs to secondary research and to discontinuation of ineffective technologies. These three topics were themes in our searches and analysis.

Monetary value on the impact of health research

We considered approaches to monetising the value of the health gain arising from medical research. We reviewed key recent developments in this field, in the context of prior knowledge of several recently published studies, including the Medical Research: What’s it Worth report,22 which was widely cited to support medical research funding in the Government’s 2010 Spending Review. 23 We also included work by members of the review team (SH and MG), and others, on the monetised benefits from cancer research, and studies from Australia. 24–26 These studies also provided the context for an analysis to examine a subset of research supported by HTA. 27 An additional, complementary, thorough search of the literature was performed using Buxton et al. 28 as a starting point.

The purpose of this additional search was to identify studies since 2004 that have used any methods to attempt to value (in monetary terms) the benefits (health and cost savings) of a body of health research (e.g. disease-specific level, programme level, country level) and link that with an investment in the body of research.

Economic returns from health research can be considered in two categories: (1) the population health gains from improvements in mortality and morbidity, which can be monetised using various approaches (cost savings or increases in cost of delivery of new technologies can be incorporated into this monetisation); and (2) the wider economic benefits that contribute to gross domestic product (GDP) growth through mechanisms such as innovation, new technologies and patents – ‘spill-over’ effects.

The focus was on identifying studies that have at least included a component concerned with the first category of returns. Although the main literature review was limited to programmes of health research, this extension included studies that considered other units of analysis, such as by disease.

Search strategy

A supplementary search to the main review was run in October 2014 to ensure that no relevant papers were omitted. Searches of the following databases were performed: Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, NHS EED and the HMIC from January 2003 to October 2014 (see Appendix 1 for full details of the database searches).

Studies were included if they contained a component that quantified the returns from investment in medical research, by attaching a monetary value to hypothetical or realised health gains of conducted research. Studies that discussed or estimated the value of conducting future research to eliminate decision uncertainty (expected VOI) were excluded.

Impact of randomised trials on systematic reviews

The importance of summarising available evidence before conducting new trials and using new trials to update and correct systematic reviews has long been argued29 and was embraced by the HTA programme from its start. 30 Impact on policy, such as guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), relies, where possible, on systematic reviews rather than on individual trials. Although some 70% of HTA-funded trials cite a preceding systematic review, little work has been done on the impact such trials have on updating and correcting systematic reviews. 31 This element of the review tried to identify examples of attempts to do this, and explore literature relating to how the contribution of a randomised trial to a subsequent systematic reviews might be established.

Search strategy

Alison Price conducted a supplementary search to the main review in October 2014. The search identified 54 articles (see Appendix 1 for search terms). Two were added based on the review of citations. In addition, the literature on VOI was reviewed, as variants of this rely heavily on systematic reviews.

The identified articles comprised those that were descriptive, those relating to the use of systematic reviews in designing future trials and relating to VOI (and its variants).

Impact of randomised trials on stopping the use of particular technologies

This considered the impact that single randomised trials might have in stopping the use of particular technologies. Examples of such trials funded by the HTA programme include trials of water softening for eczema,31 and larvae for wound healing. 32 Their negative findings were probably definitive, but conventional methods might not capture their full impact. We explored the relevant literature with a focus on trials that were ‘first in class’ or ‘biggest in class’.

Search strategy

Alison Price conducted two supplementary searches to the main literature review in March 2015 on the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE without Revisions from 1996 to March 2015, week 2; EMBASE from 1996 to 2015, week 10; and Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations.

The first search (using Ovid MEDLINE) identified 52 articles (see Appendix 1 for full details of the database searches) and the second search (again using Ovid MEDLINE) identified 55 articles.

Data extraction

If there was more than one version of a report, only one version was included. For example, we included only one 2012 report from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) outlining plans for the assessment of the impact of research conducted in UK higher education through means of the REF. 33 Similarly, the same criteria applied to annual sets of publications of research impact from funders such as the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Wellcome Trust.

Rather than having two lists of partially overlapping papers relating to Chapters 3 and 4, we merged the two emerging lists into one list of papers. Thus, the numbers in Chapter 3 represent the numbers for both the updated review plus key papers from those described in Chapter 4.

EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) reference management database was used to store the relevant papers obtained from the different sources used.

Chapter 3 Updated systematic review

The purpose of the current review was to update the previous review,2 including a summary of the range of approaches used in health research impact assessment, and to collate the quantitative findings from studies assessing the impact of multiproject programmes. First, we present a summary of the literature that is reported in the large number of studies. Second, we describe 20 conceptual frameworks, or approaches that are the most commonly used and/or have the most relevance for assessing the impact of programmes such as the HTA programme. Third, we briefly compare the 20 frameworks. Fourth, we discuss the methods used in the various studies, and describe a range of techniques that are evolving. Fifth, we collate the quantitative findings from studies assessing the impact of multiproject programmes, such as the HTA programme, and analyse the findings in light of the full body of evolving literature.

Review findings

The number of papers identified though each source is set in Table 1. A total of 513 records were identified, of which 161 were eligible; databases directly identified only 40 of these 161 (see Appendix 3, Table 14, for a brief summary of each of the 161 references) (Figure 1).

| Source used to identify the literature | Number of records identified |

|---|---|

| Database | 40 |

| Hand-search | 14 |

| Reference list | 41 |

| Citation track | 23 |

| Known to the team/snowballing | 43 |

| Total | 161 |

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of identified studies.

Summary of the literature identified

From the initial searching and application of the inclusion criteria, the number of publications identified this time was approximately three times the 46 included in the ‘body of evidence’ for the 2007 review. 2 Using wider criteria, we ended up with a list of 161.

We classified 51 as conceptual/methodological papers (including reviews), 54 as application papers and 56 as both conceptual and application papers (these are classified and reported in Appendix 3, Table 14, under column ‘Type’). The 51 conceptual and methodological papers not only reflect an increase in the discussion about appropriate frameworks to use but also reflect the wider criteria used in the extension to the update, including some pre-2005 publications. Thus, a simple comparison between the 51 conceptual papers in the update and the five in the previous review would not be appropriate.

The papers come predominantly from four English-speaking nations (Australia, Canada, the UK and the USA), with clusters from the Netherlands and Catalonia/Spain. We also identified an increasing number of health research impact assessment studies from individual low- and middle-income countries, as well as many covering more than one country, including European Union (EU) programmes and international development initiatives.

Some of the studies on this topic are published in the ‘grey literature’, which probably means they are even more likely to be published in local languages than they would be if they were in the peer-reviewed literature. This exacerbates the bias towards a selection of publications from English-speaking nations that arises from the inclusion of publications if they are available only in English.

Appendix 3 (see Table 14) lists the 161 included studies with a brief summary of each. We note basic data such as lead author, year, type of study (method, application, or both) and country. The last item has become more complicated with the increase in the range of studies conducted. We prioritised the location of the research in which impact was assessed rather than the location of the team conducting the impact assessment. Similarly, for reviews or other studies intended to inform the approach taken in a particular country, it is important to identify the location of the commissioner of the review, if different from the team conducting the study. We also recorded the programme/specialism of the research in which impact was assessed, and the conceptual frameworks and methods used to conduct the assessment. A further column covers the impacts examined and a brief account of the findings. The final column offers comments, and quotes, where appropriate, on the strengths and weaknesses of the impact assessment and factors associated with achieving impact.

We also identified a range of papers that were of some interest for the review, but the papers did not sufficiently meet the inclusion criteria (see Appendix 4 for further details of these papers).

The included studies demonstrate that the diversity and complexity of the field has intensified. It has long been recognised that research might be used in many ways, even in relation to just one impact category, such as informing policy-making. 34,35 Within any one impact assessment, there can be many different ways and circumstances in which research from a single programme might be used. Furthermore, as a detailed analysis of one of the case studies described in Wooding et al. 36 illustrated, even a single project or stream of research might make an impact in various different ways, some relying on interaction between the research team and potential users and some through other routes.

The diversity in the approaches is also linked to the different types of research (basic, clinical, health services research, etc.) and fields, the various modes of research funding (responsive, commissioned, core funding, research training), and the diverse purposes and audiences for impact assessments. These are considered at various points in this review.

The 51 conceptual/methodological papers in Table 14 (see Appendix 3) illustrate the diversity. Some of these 51 papers developed new conceptual frameworks and some reviewed empirical studies and used the review to propose new approaches. Others analysed existing frameworks trying to identify the most appropriate frameworks for particular purposes. RAND Europe conducted one of the major streams of such review work. These reviews include background material informing the framework for the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS),37 an analysis commissioned by the HEFCE to inform the REF,38 and a review commissioned by the Association of American Medical Colleges. 9

Such reviews represent major advances in the analysis of methods and conceptual frameworks, and each compares a range of approaches. They often focus on a relatively small number of major approaches. Although Guthrie et al. 9 identified 21 frameworks, many are not health specific and they vary in how far the assessment of impact features in the broader research evaluation frameworks.

Our starting position was different, and aimed to complement this stream of review work. We collated and reviewed a much wider range of empirical studies, in addition to the methodological papers. We not only identified the impacts assessed, but also considered the findings from empirical studies, both to learn what they might tell us about approaches to assessing research impact in practice and also to provide a context for the assessment of the second decade of the HTA programme.

In selecting the conceptual frameworks and methods on which to focus, we thought it was important to reflect the diversity in the field as far as possible, but at the same time focus on analysis of approaches likely to be of greatest relevance for assessing the impact of programmes such as the HTA programme.

Conceptual frameworks developed and/or used

We identified a wider range of conceptual frameworks than in the previous review. How the 20 frameworks were used can be seen later (see Table 2). We have grouped the discussion of conceptual frameworks into three main sections. The data are presented in ways that allow analysis from several perspectives. First, we present a historical analysis that helps to identify which frameworks have developed from those included in the 2007 review. Second, we order the frameworks by the level of aggregation at which they can be applied. Having briefly introduced each of the frameworks we then present them in tabular form under headings, such as the methods used, impacts assessed, strengths and weaknesses. Finally, in our analysis comparing the frameworks we locate each one on a figure with two dimensions: categories of impacts assessed and focus/level of aggregation at which the framework has primarily been applied.

The three main groups of frameworks are:

-

Post-2005 application, and further development, of frameworks described in the 2007 review, and reported in the order first reported in 2007 (five frameworks).

-

Additional frameworks or approaches applied to assess the impact of programmes of health research, and mostly developed since 2005 (13 frameworks). (These are broadly ordered according to the focus of the assessment, starting with frameworks that are primarily used to assess the impact from the programmes of research of specific funders, then frameworks that are more relevant for the work of individual researchers and, finally, approaches for the work of centres or research groups.)

-

Recent generic approaches to research impact developed and applied in the UK at a high level of aggregation, namely regular monitoring of impacts [e.g. via researchfish® (researchfish Ltd, Cambridge, UK)] and the REF (two frameworks or approaches).

Post-2005 applications of frameworks described in the 2007 review

Five are listed as follows:

-

the Payback Framework39

-

monetary value approaches to estimating returns from research (i.e. return on investment, cost–benefit analysis, or estimated cost savings)

-

the approach of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (2002)40

-

a combination of the frameworks originally developed in the project funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) on the non-academic impact of socioeconomic research41 and in the Netherlands in 199442 [this became the Social Impact Assessment Methods through the study of Productive Interactions (SIAMPI)]

-

detailed case studies and follow-up analysis, on HTA policy impacts and cost savings: Quebec Council of Health Care Technology assessments (CETS). 43,44

The Payback Framework

The Payback Framework consists of two main elements: a multidimensional categorisation of benefits and a model to organise the assessment of impacts. The five main payback categories reflect the range of benefits from health research, from knowledge production through to the wider social benefits of informing policy development, and improved health and economy. This categorisation, which has evolved, is shown in Box 1.

-

Journal articles, conference presentations, books, book chapters and research reports.

-

Better targeting of future research.

-

Development of research skills, personnel and overall research capacity.

-

A critical capacity to absorb and appropriately utilise existing research, including that from overseas.

-

Staff development and educational benefits.

-

Improved information bases for political and executive decisions.

-

Other political benefits from undertaking research.

-

Development of pharmaceutical products and therapeutic techniques.

-

Improved health.

-

Cost reduction in delivery of existing services.

-

Qualitative improvements in the process of delivery.

-

Improved equity in service delivery.

-

Wider economic benefits from commercial exploitation of innovations arising from R&D.

-

Economic benefits from a healthy workforce and reduction in working days lost.

Although a detailed account of the various impact categories is available elsewhere,2 key recent aspects of the framework’s evolution relate to headings number 2 and 5 in Box 1.

In the ‘Benefits to future research and research use’ category, the subcategory termed ‘A critical capacity to absorb and appropriately utilise existing research, including that from overseas’ had proven difficult to operationalise in applications of the Payback Framework. However, a more recent evidence synthesis46 incorporated this concept into a wider analysis of the benefits to the health-care performance that might arise when clinicians and organisations engage in research. Although the evidence base is disparate, a range of studies was identified that suggested when clinicians and health-care organisations engaged in research there was a likelihood of improved health-care performance. Identification of the mechanisms through which this occurs contributes to the understanding of how impacts might arise, and increases the validity of some of the findings from payback studies in which researchers claim that research is making an impact on clinical behaviour in their local health-care systems.

In the ‘Broader economic benefits’ category, recent developments emphasise approaches that monetise the health gains per se from research, rather than assessing the economic benefits from research in terms of valuing the gains from a healthy workforce. 26 Nason et al. 47 applied the Payback Framework in a way that highlighted the economic benefits category and identified various subcategories.

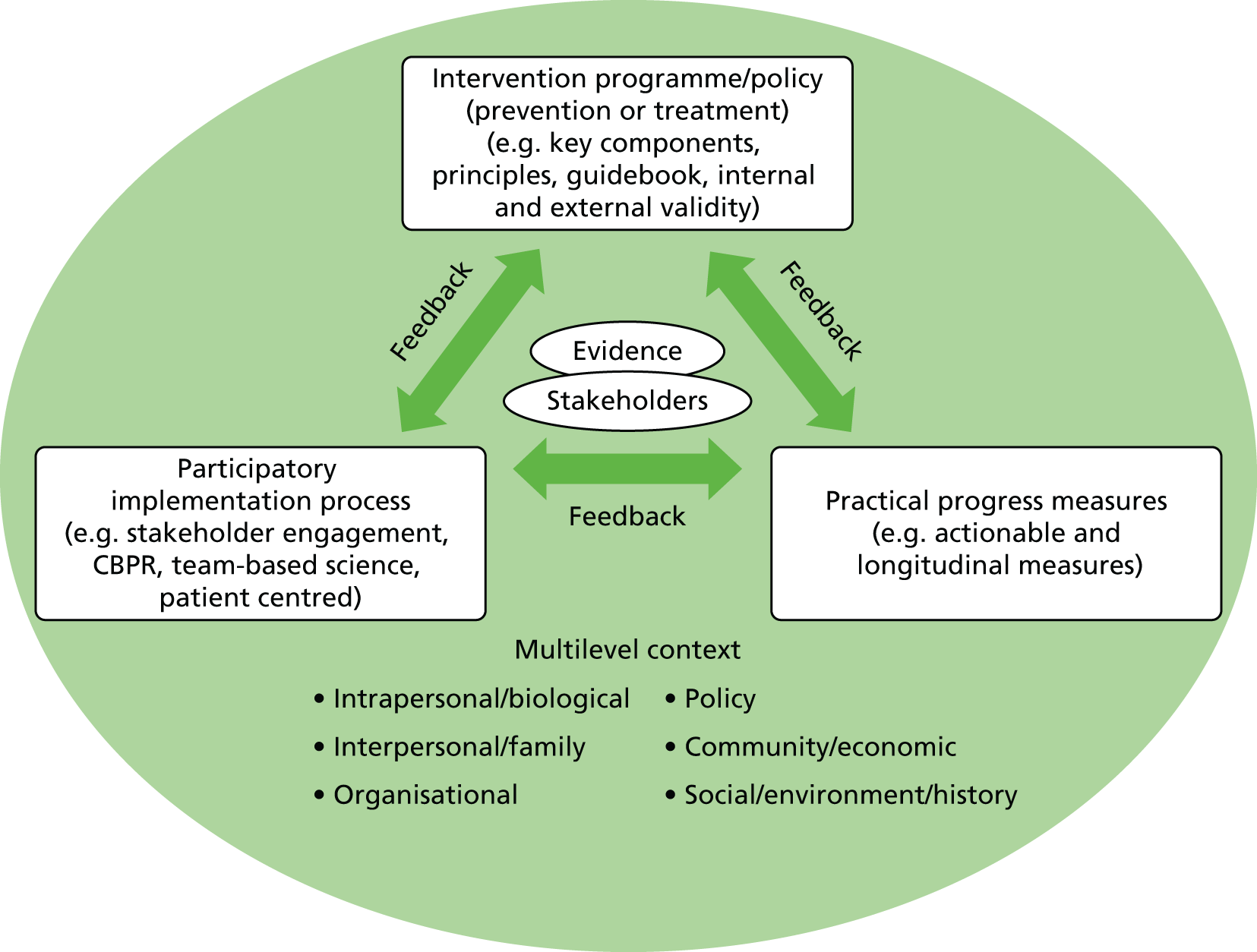

The payback model is intended to assist the assessment of impact and is not intended necessarily to be a model of how impact arises. It consists of seven stages and two interfaces between the research system and the wider environment, with feedback and also the level of permeability at the interfaces being key issues: developments do not necessarily flow smoothly, or even at all, from one stage to the next (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The Payback Framework: model for organising the assessment of the outcomes of health research. Reproduced with permission. 48

As noted in the 2007 review,2 although the framework is presented as an ‘input–output model’, it ‘also captures many of the characteristics of earlier models of research utilisation’ such as those of Weiss34 and Kogan and Henkel. 49 The framework recognises that research might be utilised in various ways. It was devised to assess the impact of the Department of Health/NHS programme of research, a programme in which development was informed by Kogan and Henkel’s earlier analysis of the department’s research and development. 49 That analysis had promoted the idea that collaboration between potential users and researchers was important in encouraging the commissioning of research that was more likely to make an impact. Partly, the development of the Payback Framework was a joint enterprise between the Department of Health and the Health Economics Research Group. 50 The inclusion in the updated review of the findings from the application of the framework to the assessment of the first decade of the HTA programme illustrates the context within which the framework seems best suited.

The conceptual framework informs the methods used in an application; hence, documentary analysis, surveys and case study interview schedules are all structured according the framework, which is also used to organise the data analysis and present case studies in a consistent format. The various elements were devised both to reflect and capture the realities of the diverse ways in which impact arises, including as a product of interaction between researchers and potential users at agenda-setting and other stages. The emphasis on examining the state of the knowledge reservoir at the time of research commissioning enables some evidence to be gathered that might help explore issues of attribution, and possibly the counterfactual, because it forces consideration of whatever other work might have been going on in the relevant field.

One of the limitations of the Payback Framework, and various other frameworks, arises because of the focus on single projects as the unit of analysis, when it is often argued that many advances in health care should be attributed to a body of work. This ‘project fallacy’ is widely noted, including by many who apply the framework. In some studies applying the framework, for example to the research funded by Asthma UK,51 the problem was acknowledged in the way in which case studies that started with a focus on a single project were expanded to cover streams of work. Although some studies have been able to apply a version of the framework to demonstrate considerable impact from single studies,52 this has tended to be in particular types of research – in this case, intervention studies.

Some studies applied the framework in new ways, as noted in Table 14 (see Appendix 3). This might lead to welcome innovation, but also to applications that do not recognise the importance of features such as the interfaces between the research system and the wider environment and the desirability of capturing aspects such as the level of interaction prior to research commissioning.

Despite the challenges in application, 27 of our 110 empirical studies published since 20052,36,47,51–74 claim their framework is based either substantially or partly on the Payback Framework (Table 2).

| Framework/approach (in order presented in text of Chapter 3) | Empirical studies applying the framework or drawing on aspects of it |

|---|---|

| Payback Framework | Action Medical Research, 2009;54 Anderson, 2006;55 Aymerich et al., 2012;56 Bennett et al., 2013;57 Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research, 2006;58 Bunn, 2010;59 Bunn and Kendall, 2011;60 Bunn et al., 2014;61 Cohen et al., 2015;52 Donovan et al., 2014;62 Engel-Cox et al., 2008;63 Expert Panel for Health Directorate of the European Commission’s Research Innovation Directorate General, 2013;53 Guinea et al., 2015;64 Hanney et al., 2007;2 Hanney et al., 2013;51 Kalucy et al., 2009;65 Kwan et al., 2007;66 Longmore, 2014;67 Nason et al., 2011;47 NHS SDO, 2006;68 Oortwijn, 2008;69 Reed et al., 2011;70 RSM McClure Watters et al., 2012;71 Schapper et al., 2012;72 Scott et al., 2011;73 The Madrillon Group, 2011;74 and Wooding et al., 201436 |

| Monetary value | Deloitte Access Economics, 2011;25 Guthrie et al., 2015;27 Johnston et al., 2006;75 MRC, 2013;76 Murphy, 2012;77 and Williams et al., 200878 |

| Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences and others | Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences 201079 |

| Social impact assessment model through the study of productive interactions | Meijer, 2012;80 and Spaapen et al., 201181 |

| Quebec Council of Health Care Technology’s assessments | Bodeau-Livinec et al., 2006;82 and Zechmeister and Schumacher, 201283 |

| CAHS | Adam et al., 2012;84 Aymerich et al., 2012;56 Cohen et al., 2015;52 Graham et al., 2012;85 Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, 2013;86 and Solans-Domenèch et al., 201387 |

| Banzi’s research impact model | Laws et al., 2013;88 and Milat et al., 201389 |

| National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’s logic model | Drew et al., 2013;90 Engel-Cox et al., 2008;63 Liebow et al. 2009;91 Orians et al. 200917 |

| Medical research logic model (Weiss) | Informed various approaches rather than being directly applied |

| National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety’s logic model | Williams et al., 200992 |

| The Wellcome Trust’s assessment framework | Wellcome Trust, 201493 |

| VINNOVA | Eriksen and Hervik, 200594 |

| Flows of knowledge, expertise and influence | Meagher et al., 200895 |

| Research impact framework | Bunn, 2010;59 Bunn and Kendall, 2011;60 Bunn et al., 2014;61 Caddell et al., 2010;96 Kuruvilla et al., 2007;97 Schapper et al., 2012;72 and Wilson et al., 201098 |

| Becker Medical Library model | Drew et al., 2013;90 and Sainty, 201399 |

| Societal quality score (Leiden University Medical Centre) | Meijer, 2012;80 and Mostert et al., 2010100 |

| Research performance evaluation framework | Schapper et al., 201272 |

| Realist evaluation | Evans et al., 2014;101 and Rycroft-Malone et al., 2013102 |

| Regular monitoring | Drew et al., 2013;90 MRC, 2013;103 MRC, 2013;76 and Wooding et al., 2009104 |

| REF (informed by Research Quality Framework) | Cohen et al., 2015;52 Group of Eight and Australian Technology Network of Universities, 2012;105 and the HEFCE, REF Main Panel A, 2015106 |

In addition, the Payback Framework also informed the development of several other frameworks, especially the framework from the CAHS. 7 Furthermore, the framework based on the review by Banzi et al. 4 built on both the Payback Framework and the CAHS’s Payback Framework. The Payback Framework also contributed to the development, by Engel-Cox et al. ,63 of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) framework.

Monetary value approaches to estimating returns from research (i.e. return on investment, cost–benefit analysis or estimated cost savings)

These approaches differ in the scope of the impacts that are valued and the valuation method adopted. In particular, since 2007 further methods have been developed that apply a value to, or monetise, the health gain resulting from research. Much of this work assesses the impacts of national portfolios of research, and is thus at a higher level of aggregation than that of a programme of research. Most of the studies of this are, therefore, not included here in Chapter 3, but are described in Chapter 5, which looks specifically at such developments. Nevertheless, three studies25,27,75 from this stream do assess the value of a programme of work and so are included in the update. Of the three, Guthrie et al. 27 and Johnston et al. 75 are the clearest applications of this approach to specific research programmes.

Furthermore, many econometric approaches to assessing research impact do not relate to the impact of specific programmes of research. However, an increasing number of frameworks have been developed that propose ways of collecting data from specific projects or programmes that can be built up to provide a broader picture of economic impacts. For example, Muir et al. 107 developed an approach for measuring the economic benefits from programmes of public research in Australia. Other work includes the development of frameworks by the UK department responsible for science; the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) and, earlier, the Department for Innovation, Universities and Science108 developed frameworks under which the department collects data on economic benefits from each research council’s programmes of research, including the MRC. 76 The impacts include patents, spin-offs, intellectual property income; and data collection overlaps with the approach of regular collection of data from the MRC described below (see Regular monitoring or data collection). 76

A further category in the BIS framework is data on the employment of research staff. The classification of such data as a category of impact is part of a wider trend, but is controversial. However, in political jurisdictions, such as Ireland47 or Northern Ireland,6 it might be appropriate to consider the increased employment that comes as a result of local expenditure of public funds leveraging additional research funds from other sources.

To varying degrees the assessment of economic impacts can form part of wider frameworks, including the Payback Framework, as in the two Irish examples above, and the VINNOVA approach described by Eriksen and Hervik94 (see VINNOVA).

The approach of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The report from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences79 updated the evaluation framework previously used by the academy to assess research, not just impact, at the level of research organisations and groups or programmes. The approach combines self-evaluation and external peer review, including a site visit every 6 years. The report listed a range of specific measures, indicators or more qualitative approaches that might be used in self-evaluation. They included the long-term focus on the societal relevance of research, defined as ‘how research affects specific stakeholders or specific procedures in society (for example, protocols, laws and regulations)’. 79 The report proceeds to give the website for the Evaluating Research in Context (ERiC) project, which is described in Spaapen et al. 109 as being driven partly by the need, and/or opportunity, to develop methods to assist faculty in conducting the self-evaluation required under the assessment system for academic research in the Netherlands.

A combination of the frameworks originally developed in 2000 in the project funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council on the non-academic impact of socioeconomic research and in the Netherlands in 1994 (this became the Social Impact Assessment Methods through the study of Productive Interactions)

In 2000, a team led by Molas-Gallart,41 working on the project funded by the UK’s ESRC on the non-academic impact of socioeconomic research, developed an approach based on the interconnections of three major elements: the types of output expected from research; the channels through which their diffusion to non-academic actors occurs; and the forms of impact. Later the team combined forces with Spaapen, whose early work with Sylvain42 on the societal quality of research had long been influential in the Netherlands, and, collectively, they led the SIAMPI approach. 110 This overlaps also with the development of the SciQuest method by Spaapen et al. 109 that came from the ERiC project described in The approach of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Its authors described SciQuest as a ‘fourth-generation’ approach to impact assessment. The previous three generations were characterised, they suggested, by measurement (e.g. an unenhanced logic model), description (e.g. the narrative accompanying a logic model) and judgement (e.g. an assessment of whether the impact was socially useful or not). The authors suggested that fourth-generation impact assessment is fundamentally a social, political and value-oriented activity and involves reflexivity on the part of researchers to identify and evaluate their own research goals and key relationships.

SciQuest methodology requires a detailed assessment of the research programme in context and the development of bespoke metrics (both qualitative and quantitative) to assess its interactions, outputs and outcomes. These are then presented in a unique research embedment and performance profile, visualised in a radar chart.

In addition to these two papers,109,110 the study by Meijer80 was partly informed by SIAMPI (see Appendix 3).

Detailed case studies and follow-up analysis on Health Technology Assessment policy impacts and cost savings: Quebec Council of Health Care Technology assessments

In the 2007 review,2 we described a series of studies of the benefits from HTAs conducted by the CETS. 43,44 They conducted case studies based on documentary analysis and interviews, and developed a scoring system for an overall assessment of the impact on policy that went from 0 (no impact) to +++ (major impact). They also assessed the impact on costs. Bodeau-Livinec et al. 82 assessed the impact on policy of 13 HTAs conducted by the French Committee for the Assessment and Dissemination of Technological Innovations. Although they did not explicitly state that they were using a particular conceptual framework, their approach to scoring impact appears to follow the earlier studies of CETS in Quebec.

Zechmeister and Schumacher83 assessed the impact of all HTA reports produced in Austria at the Institute for Technology Assessment and Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for HTA aimed at use before reimbursement decisions were made or decisions for disinvestment. Again, they developed their own methods, but the impact of these HTA reports was analysed partly by descriptive quantitative analysis of administrative data informed by the Quebec studies. 43,44

Additional frameworks or approaches applied to assess the impact of programmes of health research and mostly developed since 2005

Many other conceptual frameworks have been developed to assess the impacts from programmes of health research, mostly since 2005. Some studies have combined several approaches. Below we list 13 frameworks that have also been applied at least once. Some frameworks combine elements of existing frameworks, an approach recommended by Hansen et al. 111 This means that in the list of studies that have applied different conceptual frameworks (see Table 2), there are some inevitable overlaps. Scope exists for different interpretations of exactly how far a specific study does draw on a certain framework. An important consideration in deciding how much detail to give on each framework has been its perceived relevance for a programme such as the HTA programme.

The 13 conceptual frameworks are presented as follows: first, frameworks applicable to programmes that have funded multiple projects; second, frameworks devised for application by individual researchers; third frameworks devised for application to groups of researchers or departments within an institution; and, finally, a generic evaluation approach that has been applied to assess the impact of a new type of funded programmes. Inevitably, it is not this clear-cut and there are some hybrids.

Canadian Academy of Health Sciences

The CAHS established an international panel of experts, chaired by Cyril Frank, to make recommendations on the best way to assess the impact of health research. Its report, Making an Impact: A Preferred Framework and Indicators to Measure Returns on Investment in Research,7 contained a main analysis, supported by a series of appendices by independent experts. The appendices discuss the most appropriate framework for different types of research and are analysed in Table 14 (see Appendix 3). 37,112–114

The CAHS framework was designed to track impacts from research through translation to end use. It also demonstrates how research influences feedback upstream and the potential effect on future research. It aims to capture specific impacts in multiple domains, at multiple levels and for a wide range of audiences. As noted in several of the appendices, it is based on the Buxton and Hanney Payback Framework (see Figure 2). 39 The framework tracks impacts under the following categories, which draw extensively on the Payback Framework: advancing knowledge; capacity building; informing decision-making; health impacts; broader economic; and social impacts. 7,115 The categories from the Payback Framework had already been adopted in Canada by the country’s main public funder of health research, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, for use in assessing the payback from its research.

The main difference in the categorisation from that in the original Payback Framework is the substitution of ‘informing decision-making’ for ‘informing policy and product development’. The CAHS return on investment version,7 allows the categorisation to include decisions by both policy-makers and individual clinicians in the same category, whereas the Payback Framework distinguishes between policy changes and behavioural changes, and does not specifically include decisions by individual clinicians in the policy category. Therefore, the CAHS framework explicitly includes the collection of data about changes in clinical behaviour as a key impact category, but in studies applying the Payback Framework any assessments that can be made of behavioural changes by clinicians and/or the public in the adoption stage of the model help form the basis for an attempt to assess any health gain.

The CAHS’s logic model framework also builds on a Payback logic model, and combines the five impact categories into the model showing specific areas and target audiences where health research impacts can be found, including the health industry, other industries, government and public information groups. It also recognises that the impacts, such as improvements in health and well-being, can arise in many ways, including through health-care access, prevention, treatment and the determinants of health.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research divided its research portfolio into four pillars. Pillars I–IV cover the following areas: biomedical; clinical; health services; and social, cultural, environmental and population health. The CAHS team conducted detailed work to identify the impact from the different outputs arising in each of these areas.

The team also developed a menu of 66 indicators that could be collected. It was intended for use across Canada, and has been adopted by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and in some of the provinces, for example by Alberta Innovates: Health Solutions (AIHS), the main Albertan public funder of health research. AIHS also further developed the framework into a specific version for their organisation and explored how it would be implemented and developed. Implementation had to do with standardising indicators across programmes to track progress to impact. It was developed to improve the organisation’s ability to assess its contributions to health systems impacts, in addition to the contributions of its grantees. 85 The CAHS framework has also been applied in Catalonia by the Catalan Agency for Health Information and Quality. 84

Banzi’s research impact model

Banzi et al. ,4 in a review of the literature on research impact assessment, identified the Payback Framework as the most frequently used approach. They presented the CAHS’s payback approach in detail, including the five payback categories as listed above. Building on the CAHS report, Banzi et al. 4 set out a list of indicators for each domain of impact and a range of methods that could be used in impact assessment. The Banzi research impact model has been used as the organising framework for several detailed studies of programmes of research in Australia.

A number of the applications have suggested ways of trying to address some of the limitations noted in the earlier account of the Payback Framework. For example, the study by Laws et al. 88 applied the Banzi framework to assess the impact of a schools physical activity and nutrition survey in Australia. They found it difficult to attribute impacts to a single piece of research, particularly the longer-term impacts, and wondered whether or not the use of contribution mapping, as proposed by Kok and Schuit may provide an alternative way forward (see Chapter 4 for a description of Kok and Schuit116).

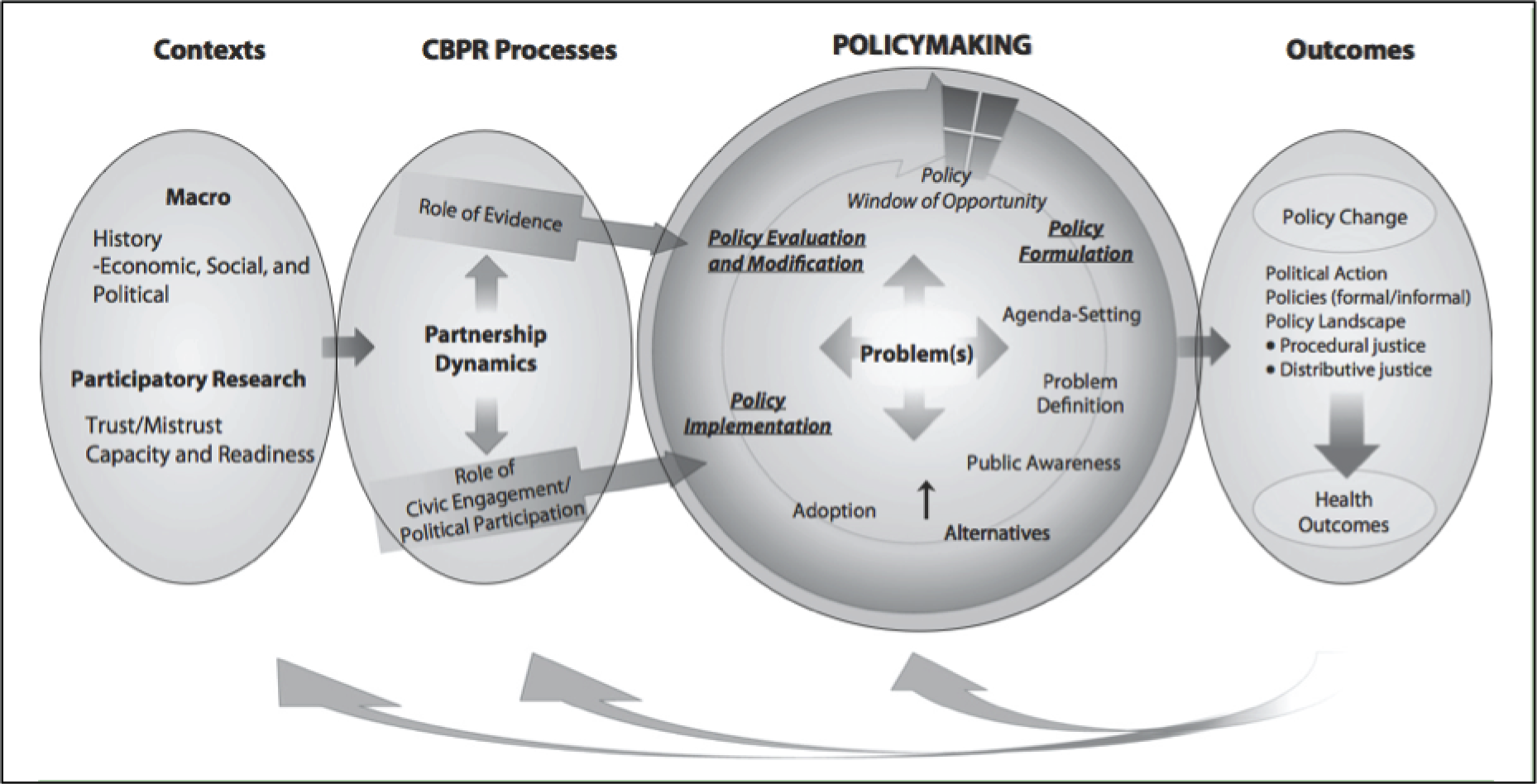

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’s logic model

The US NIEHS developed and applied a framework to assess the impact from the research and the researchers it funded. Engel-Cox et al. 63 developed the NIEHS logic framework and identified a range of outcomes by drawing on the Payback Framework and Bozeman’s public value mapping. 117 These outcomes included translation into policy, guidelines, improved allocation of resources, commercial development; new and improved products and processes; the incidence, magnitude and duration of social change; health and social welfare gain and national economic benefit from commercial exploration and a healthy workforce; and environmental quality and sustainability. They added metrics for logic model components. The logic model is complex; in addition to the standard logic model components of inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes (short term, intermediate, long term), there are also four pathways: NIEHS and other government pathways, grantee institutions, business and industry, and community. The model also included the knowledge reservoir and contextual factors (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The NIEHS’s logic model. Reproduced with permission from Environmental Health Perspective. 63

The various pathways allow a broader perspective to be developed than that of individual projects, for example by the grantee institution pathway, and by focusing on streams of research from multiple funders. Challenges identified in the initial case studies included ‘the lack of direct attribution of NIEHS-supported work to many of the outcome measures’. 63 The NIEHS put considerable effort into developing, testing and using the framework. Orians et al. 17 used it as an organising framework for a web-based survey of 1151 asthma researchers who received funding from NIEHS or comparison federal agencies from 1975 to 2005. Although considerable data were gathered, the authors noted that ‘this method does not support attribution of these outcomes to specific research activities nor to specific funding sources’. 17

Furthermore, Liebow et al. 91 were funded to tailor the logic model of the NIEHS’s framework to inputs, outputs and outcomes of the NIEHS asthma portfolio. Data from existing National Institutes of Health databases were used and, in some cases, data matched with that from public data on, for example the US Food and Drug Administration website for the references in new drug applications, plus available bibliometric data and structured review of expert opinion stated in legislative hearings. Considerable progress was made that did not require any direct input form researchers. However, not all the pathways could be used and they found their aim to obtain readily accessible, consistently organised indicator data could not in general be realised.

A further attempt was made to gather data from databases. Drew et al. 90 developed a high-impacts tracking system: ‘an innovative, Web-based application intended to capture and track short-and long-term research outputs and impacts’. It was informed by the stream of work from NIEHS,17,63 but also by the Becker Library approach118 and by the development in the UK of researchfish. The high-impacts tracking system imports much data from existing National Institutes of Health databases of grant information, in addition to text of progress reports and notes of programme officers/managers.

This series of studies demonstrates both a substantial effort to develop an approach to assessing research impacts, and the difficulties encountered. The various attempts at application clearly suggest that the full logic model is difficult and too complex to apply as a whole. Although the stream of work has, nevertheless, had some influence on thinking beyond the NIEHS, apart from the in-house stream of work no further empirical studies were identified as claiming that their framework was based on the NIEHS’s logic model approach.

Medical research logic model (Weiss)

Anthony Weiss analysed ways of assessing health research impact, but, unlike many of the other approaches identified, his analysis was not undertaken in the context of aiming to develop an approach for any specific funding or any research-conducting organisation. He drew on the United Way model119 for measuring programme outcomes to develop a medical research logic model. As with standard logic models it moves from inputs, to activities, outputs, and outcomes: initial, intermediate, long term. He also discussed various approaches that could be used, for example surveys of practitioners to track awareness of research findings; changes in guidelines, and education and training; use of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) or quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) to assess patient benefit. He also analysed a range of dimensions from the outputs, such as publications through to clinician awareness, guidelines, implementation and overall patient well-being. 120

Although this model was not developed for a specific organisation, it does overlap with the emphasis given to logic models in various frameworks and studies, including the W.K. Kellogg logic model. 121 Weiss’s account is included here because it has become quite high profile and is widely cited. It has informed a range of studies rather than being directly applied in empirical studies.

National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety’s logic model

Williams et al. ,92 from the RAND Corporation in the USA, with advice from colleagues in RAND Europe, developed a logic model to assess the impact from the research funded by the National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH). At one level the basic structure of the logic model was a standard approach, as described by Weiss120 and as in the logic model from W.K. Kellogg. 121 Its stages include inputs, activities, outputs, transfer, intermediate customs, intermediate outcomes, final customers, intermediate outcomes and end outcomes.

A novel feature of the NIOSH model was outcome worksheets based on the historical tracing approach,122 which reversed the order ‘articulated in the logic model and essentially places the burden on research programs to trace backward how specific outcomes were generated from research activities’. 92

Research programmes could apply these tools to develop an outcome narrative to demonstrate and communicate impact to the National Academies’ external expert review panels established to meet the requirements of the US Government’s Performance Assessment Rating Tool. Williams et al. 92The report stated that intermediate outcomes include adoption of new technologies; changes in workplace policies, practices, and procedures; changes in the physical environment and organisation of work; and changes in knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of the final customers (i.e. employees, employers). End outcomes include various items related specifically to occupational health, including reduced work-related hazardous exposures, and, in relation to morbidity and mortality, reductions in occupational injuries and in fatalities within a particular disease- or injury-specific area.

The outcome worksheet was primarily designed as a practical tool to help NIOSH researchers think through the causal linkages between specific outcomes and research activities, determine the data needed to provide evidence of impact, and provide an organisational structure for the evidence.

The combination of historical tracing with a logic model is interesting because previously historical tracing has been more associated with identifying the impact made by different types of research (i.e. basic vs. clinical), irrespective of how they were funded, rather than contributing to the analysis of the impact from specific programmes of research.

The Wellcome Trust’s assessment framework

The Wellcome Trust’s assessment framework has six outcome measures and 12 indicators of success. 93 A range of qualitative and quantitative measures are linked to the indicators and are collected annually. A wide range of internal and external sources is drawn on, including end-of-grant forms. The evaluation team leads the information gathering and production of the report with contributions from many staff from across the trust.

‘The Assessment Framework Report predominantly describes outputs and achievements associated with trust activities though, where appropriate, inputs are also included where considered a major Indicator of Progress.’93 To complement the more quantitative and metric-based information contained in volume 1 of the Assessment Framework Report, volume 2 contains a series of research profiles that describe the story of a particular outcome or impact associated with Wellcome Trust funding. The Wellcome Trust research profiles are agreed with the researchers involved and validated by senior trust staff.

Although there is no specific overall framework, it is a comprehensive approach. This is another example of a major funder including impact in the annual collection of data about the work funded. On the one hand, the importance of case studies is highlighted: ‘Case studies and stories have gained increasing currency as tools to support impact evaluation’,93 but, on the other hand, the report described an interest in also moving towards more regular data collection during the life of a project: ‘In future years, as the Trust further integrates its online grant progress reporting system throughout its funding activities . . . it will be easier to provide access to, and updates on grant-associated outputs throughout their lifecycle’. 93

VINNOVA

VINNOVA, the Swedish innovation agency, has been assessing the impact of its research funding for some time. The VINNOVA framework consists of two parts, an ongoing evaluation process and an impact analysis, as described in the review for CAHS by Brutscher et al. 37 The former defines the results and impact of a programme against which it can be evaluated. It allows the collection of data on various indicators. The impact analyses, the main element in the framework, are conducted to study the long-term impact of programmes or portfolios of research. There are various channels through which impacts arise, but each specific impact analysis can take a particular form.

In Table 14 (see Appendix 3) we describe one example: the analysis of the impacts of a long-standing programme of neck injuries research conducted at Chalmers University of Technology. 94 This considered the benefits to society through a cost–benefit analysis, the benefits to companies involved through an assessment of the profits expected in the future as a result of the research and the benefits to the research field through traditional academic approaches of considering the number and quality of articles and doctorates, and peer review of the quality of the institute. Eriksen and Hervik94

The aim has been, as far as possible to quantify the effects in financial terms, or in terms of other physically measurable effects, and to highlight the contribution made by the research from the point of view of the innovation system.

This approach is a hybrid in that it does relate to a stream of research funded by a specific funder, but it is at a single unit.

Flows of knowledge, expertise and influence

Meagher et al. 95 developed the ‘flows of knowledge, expertise and influence’ approach to assess the impact of ESRC-funded projects in the field of psychology research. As part of a major analysis of the ways in which research might make an impact, the authors pointed out that one limitation was that their study was on a collection of responsive-mode projects and while they did have a common funder (i.e. the ESRC), they had not been commissioned to be a ‘programme’. This again makes the example more of a hybrid, and the study is described in more detail in Chapter 4, but this is the only application of the approach that we identified in our search.

Research impact framework

The research impact framework (RIF) was developed at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine by Kuruvilla et al. ,123 who noted that researchers were increasingly required to describe the impact of their work, for example in grant proposals, project reports, press releases and research assessment exercises for which the researchers would be grouped into a department or unit within an organisation. They also thought that specialised impact assessment studies could be difficult to replicate and may require resources and skills not available to individual researchers. Researchers, they felt, were often hard-pressed to identify and describe research impacts, but ad hoc accounts do not facilitate comparison across time or projects.

A prototype of the framework was used to guide an analysis of the impact of selected research projects at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Additional areas of impact were identified in the process and researchers also provided feedback on which descriptive categories they thought were useful and valid vis-à-vis the nature and impact of their work.

The RIF has four main areas of impact: research-related, policy, service and societal. Within each of these areas, further descriptive categories were identified, as set out in Table 3. According to Kuruvilla et al. ,123 ‘Researchers, while initially sceptical, found that the RIF provided prompts and descriptive categories that helped them systematically identify a range of specific and verifiable impacts related to their work (compared to ad hoc approaches they had previously used).’123

| Research-related impacts | Policy impacts | Service impacts | Societal impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of problem/knowledge | Level of policy-making | Type of services: health/intersectoral | Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour |

| Research methods | Type of policy | Evidence-based practice | Health literacy |

| Publications and papers | Nature of policy impact | Quality of care | Health status |

| Products, patents and translatability potential | Policy networks | Information systems | Equity and human rights |

| Research networks | Political capital | Services management | Macroeconomic/related to the economy |

| Leadership and awards | Cost-containment and cost-effectiveness | Social capital and empowerment | |

| Research management | Culture and art | ||

| Communication | Sustainable development outcomes |

Although it is multidimensional in similar ways to the Payback Framework, the categories were broadened to cover health literacy, social capital and empowerment, and sustainable development.

Another major feature of the RIF is the intention that it could become a tool that researchers themselves could use to assess the impact of their research. This addresses one of the major concerns about other research impact assessment approaches. However, while the broader categorisation has been used, on its own or in combination, in an increasing number of studies124, we are not aware of any studies that have used it by adopting the self-assessment approach envisaged. Nevertheless, it could be useful to researchers having to prepare for exercises such as the REF in the UK.

The Becker Medical Library’s model/the translational research impact scale

Sarli et al. 118 developed a new approach called the Becker Medical Library model for assessment of research. Its starting point is the logic model of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation,121 ‘which emphasises inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impact measures as a means of evaluating a programme’. 118

For each of a series of main headings, it lists the range of indicators and the evidence for each indicator. The main headings are research outputs knowledge transfer; clinical implementation; and community benefit. The main emphasis is on the indicators for which the data are to be collected, and referring to the website on which the indicators are made available the authors state: ‘Specific databases and resources for each indicator are identified and search tips are provided’. 118 The authors found during the pilot case study that some supporting documentation was not available. In such instances, the authors contacted the policy-makers or relevant others to retrieve the required information.

The Sarli et al. 118 article includes the case study in which the Becker team applied the model, but the Becker model is mainly seen as a tool for self-evaluation, with the suggestion that it ‘may provide a tool for research investigators not only for documenting and quantifying research impact, but also . . . noting potential areas of anticipated impact for funding agencies’. 118 It is generating some interest in the USA, including partially informing the Drew et al. 90 implementation of the NIEHS framework described above, and a UK application from Sainty. 99

More recently, Dembe et al. 124 proposed the translational research impact scale, which is informed not only by a logic model from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and by the RIF,123 but also by the Becker Medical Library model. 118

The authors identified 79 possible indicators, used in 25 previous articles, and reduced them to 72 through consulting a panel of experts, but further work was being undertaken to develop the requisite measurement processes: ‘Our eventual goal is to develop an aggregate composite score for measuring impact attainment across sites’. 124 However, there is no indication provided about how a valid composite score could ever be devised. Although as far as we are aware an application of it has yet to be reported, from the perspective of our review it usefully illustrates how new models are being built on a combination of existing ones.

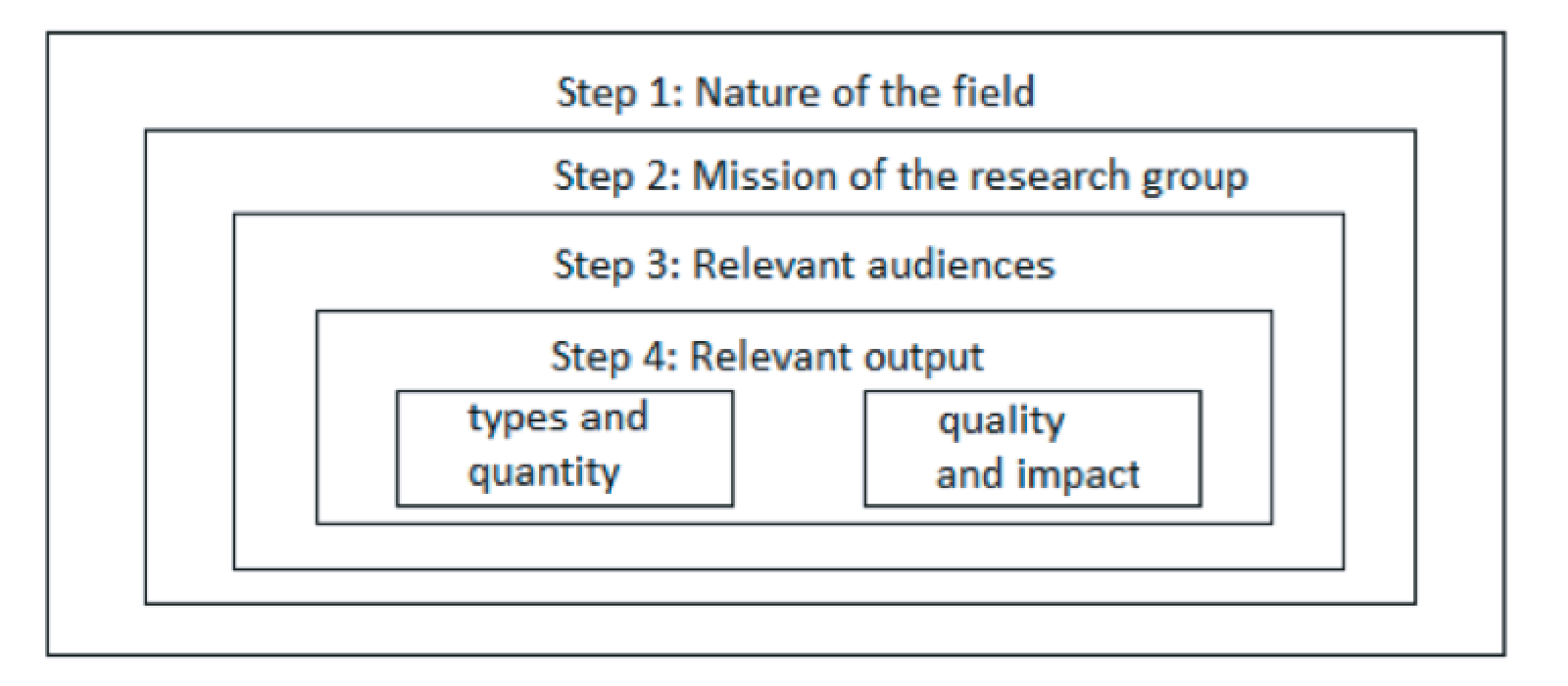

Societal quality score

Mostert et al. 100 developed the societal quality score using the theory of communication from Van Ark and Klasen. 125 Audiences are segmented into different target groups that need different approaches. Scientific quality depends on communication with the academic sector and societal quality depends on communication with groups in society; specifically, three groups: lay public, health-care professionals and private sector.

Three types of communication are identified: knowledge production, for example papers, briefings, radio/television services, products; knowledge exchange, for example running courses, giving lectures, participating in guideline development, responding to invitations to advise or give invited lectures (these can be divided into ‘sender to receiver’, ‘mutual exchange’ and ‘receiver to sender’); and knowledge use, for example citation of papers, purchase of products, and earning capacity (i.e. the ability of the research group to attract external funding). Four steps are then listed:

-

Step 1: count the relative occurrences of each indicator for each department.

-

Step 2: allocate weightings to each indicator (e.g. a television appearance is worth x, a paper is worth y).

-

Step 3: multiply 1 by 2 = ‘societal quality’ for each indicator.

-

Step 4: the average societal quality for each group is used to get the total societal quality score for each department.

It is a heavily quantitative approach and looks only at process, as the authors say that ultimate societal quality takes a long time to happen and is hard to attribute to a single research group. The approach does not appear to control for the size of the group but seems to be more applicable to research at an institution rather than project level.

Research performance evaluation framework

Schapper et al. 72 describe the research performance evaluation framework used at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia. It is ‘based on eight key research payback categories’ from the Payback Framework and also draws on the approach described in the RIF. 123