Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/129/61. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The draft report began editorial review in January 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by McDermott et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Burden of disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for more than one-quarter of all deaths in the UK, with about 155,000 deaths per year. 1 Diabetes mellitus is increasing in frequency and now affects around 6.2% of the UK population2 and the importance of early detection and treatment of chronic kidney disease is increasingly recognised. 3,4 Dementia shares many risk factors for CVD5 and might be reduced through more effective cardiovascular prevention. The British Heart Foundation estimates that the cost to the UK of premature death, lost productivity, hospital treatment and prescriptions relating to CVD is approximately £19B each year. Health-care costs alone may account for £8B per year. 1 The cost of informal care for people with CVD in the UK was around £3.8B in 2009. 6

Inequalities and cardiovascular risk

There are substantial social inequalities in the distribution of CVD. During 2001–3, CVD mortality was 2.8 times higher for men in routine occupations than for men in higher managerial and professional occupations; for women, mortality was 3.8 times higher for routine occupations than for managerial and professional occupations. 6 Mortality from CVDs has been declining but gains in life expectancy have not been equally shared by all groups; deprived communities have generally shown smaller mortality reductions than more affluent areas. There is also ethnic patterning of risk, with diabetes mellitus being more frequent in people of African, Caribbean and South Asian origins, stroke being more frequent among those of African origin and coronary heart disease being more frequent among those of African origin.

The major risk factors for CVD are well characterised. An analysis of the burden of disease for the UK in 20107 revealed that smoking, high blood pressure, overweight and obesity, low levels of physical activity, poor diet and elevated cholesterol accounted for the highest proportion of burden of disease measured in disability-adjusted life-years.

The NHS Health Check programme

The NHS Health Check programme is a cardiovascular risk assessment programme, which was introduced by the Department of Health in 2009. 8 The programme aims to identify people who are at increased risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, with the intention of delivering individualised interventions to reduce risk, and enable treatment of people with established disease. The Department of Health estimated that the NHS Health Check programme could potentially prevent 2000 deaths and 9500 non-fatal myocardial infarctions and strokes each year. 8 Maximising the uptake of health checks across all groups is important in realising this aim and ensuring that the programme does not perpetuate existing health inequalities.

Programme implementation

The NHS Health Check programme has been rolled out across England. 9 The first full year of the programme began in April 2011, but in many areas the programme was initiated from April 2010 or before. From 2011/12, the NHS Health Check programme aimed to enrol 90% of the eligible population into a 5-yearly cycle of call–recall through the participation of all primary care organisations (PCOs). PCOs invite 18% of their eligible cohort each year, with about 1.8 million individuals receiving an invitation to a health check in 2011/12. 9 Since 2013, the NHS Health Check programme has been a responsibility of local authorities,10 supported by Public Health England (PHE), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Local Government Association. Implementation is through commissioned services from NHS clinical commissioning groups and other providers. Implementation of health checks is a key indicator in the Public Health Outcomes Framework in domain 2, health improvement. 11

Eligibility for the NHS Health Check programme

Adults aged 40–74 years are eligible to be offered health checks. People who have previously been diagnosed with clinical disease (including ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, peripheral vascular disease) are excluded, as are people being treated for increased vascular risk (including those with hypertension or hypercholesterolaemia or who are being treated with antihypertensive drugs or statins). 1,6

Health check process

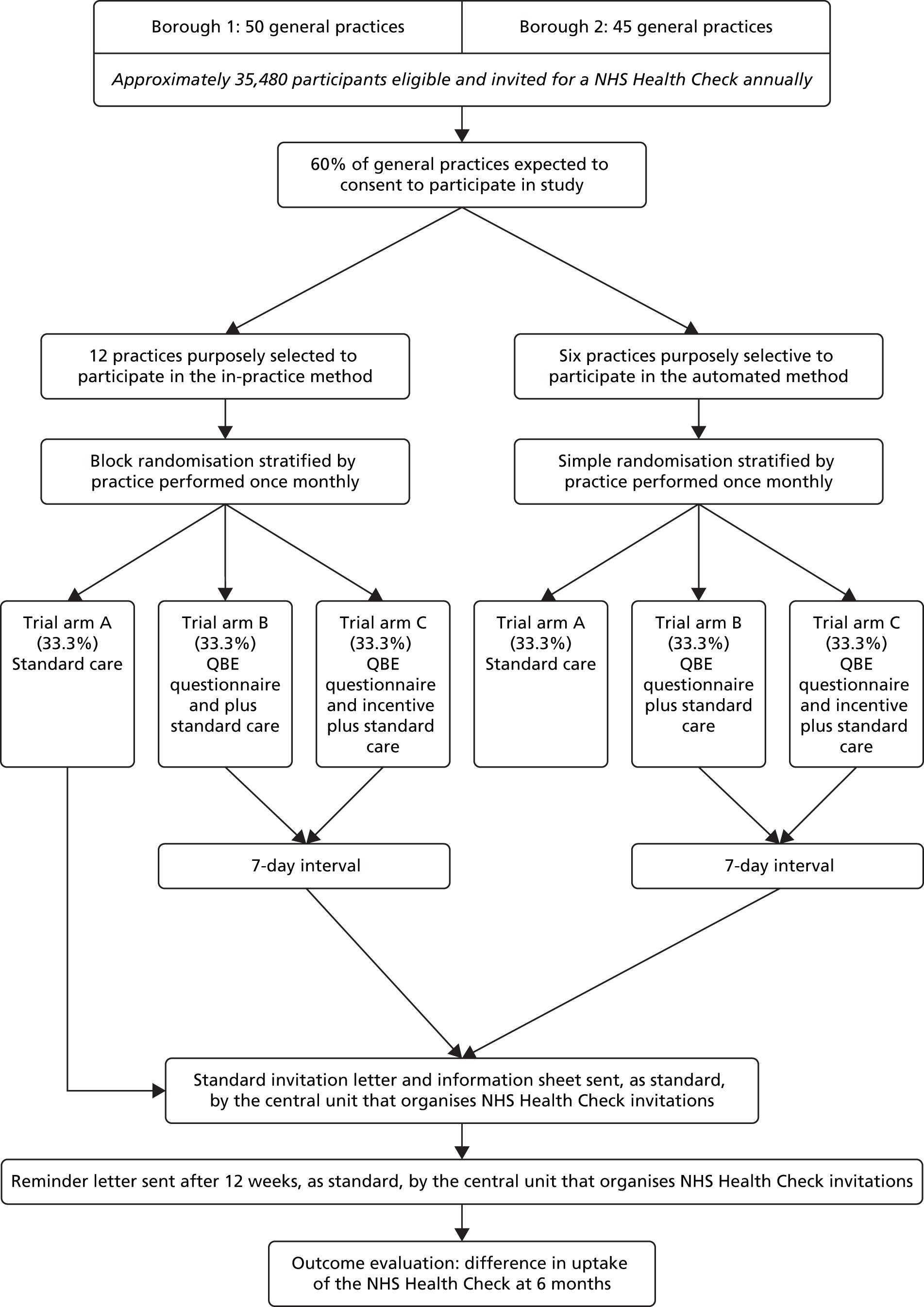

Each NHS health check consists of recording personal history, including age, ethnic group, smoking status, family history, assessment of physical activity, dietary quality including fruit and vegetable and salt intake, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, smoking status, renal function, lipid levels and blood glucose when indicated. The patient’s risk of developing CVD is then calculated using a CVD risk score calculator, which may include the Joint British Societies (JBS)12 calculator or the QRISK®2 score. 13 During the period of this trial, the JBS calculator was mandated by the Health Check programme in the study area. The cardiovascular risk assessment implemented as part of the health check is used to inform graded intervention. 14 Individuals whose risk of a cardiovascular event is > 20% over 10 years are classified as ‘high risk’ and exit the Health Check programme to enter a high-risk register with a designated care pathway. Individuals who are identified as having clinical disease, such as diabetes mellitus or atrial fibrillation, also enter appropriate care pathways based in primary care. Other individuals, especially those with a risk of a cardiovascular event of 10–20%, are offered advice on reducing risk, or maintaining low risk, primarily through lifestyle advice. The individual elements of the health check intervention follow recognised and evidenced-based clinical pathways approved by NICE to improve outcomes for individual patients15 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of the health check. Reproduced from Putting Prevention First. NHS Health Check: Vascular Risk Assessment. Best Practice Guidance. 8 Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; PCT, primary care trust. a, People recalled to separate appointments for diagnosis; b, professionals with suitable patient information and prescribing rights.

Evidence of effectiveness

It is beyond the scope of this report to review the evidence for or against a national programme of health checks, nor do we aim to review the criteria to be satisfied that a programme of health checks is effective or discuss the appropriate balance between ‘population’ and ‘high-risk’ strategies for disease prevention. The purpose of this research was to evaluate methods for improving the delivery of an established policy of health checks.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) from earlier decades, when arguably fewer effective interventions were routinely available, are not supportive of cardiovascular risk screening. 16 In a Cochrane systematic review, Krogsbøll et al. 16 identified 16 trials of health checks in unselected adults, with 155,899 participants and 11,940 deaths. Risk ratios for total and cardiovascular mortality were 0.99 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.95 to 1.03] and 1.03 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.17), respectively. The review concluded that general health checks were unlikely to be effective. Twelve of the 16 studies were from 1982 or before and this represents an important limitation because older studies were less likely to use current methods of risk assessment and risk management. However, more recent studies, including the Oxford and Collaborators Health CHECK (OXCHECK)17 and British Family Heart18 studies, suggest that health checks in primary care are unlikely to provide a cost-effective approach to cardiovascular prevention. Other arguments19 against the use of health checks in their current form include the inefficiency of using predictive risk scores to allocate treatments,20 the small effects resulting from risk factor intervention and the high costs of the programme. 19

The Health Check programme is consistent with the vision, proposed in the Wanless report,21 of a health service that ‘invest[s] in reducing demand by enhancing the promotion of good health and disease prevention’ (p. 3), with ‘health services evolving from dealing with acute problems through more effective control of chronic conditions to promoting the maintenance of good health’ (p. 10). This is even more relevant at the present time with growing problems of obesity, pre-diabetes, alcohol and physical inactivity. The Health Check programme offers opportunities to address health problems of obesity, initiate diabetes prevention interventions and identify lifestyle concerns, as well as detecting other conditions including atrial fibrillation or cognitive decline. There may be insufficient evidence to reach clear conclusions concerning the value of the Health Check programme. There is evidence for the effectiveness of the individual interventions that may be delivered through health checks, as summarised in guidance from NICE,3,15,22,23 but the question remains whether the Health Check programme can be used to improve implementation of this guidance into practice.

Economic modelling for cost-effectiveness estimates

The case for implementing health checks was made through health economic modelling. The Department of Health’s economic model24 provided evidence to show that the costs of the NHS Health Check programme would be between £180M and £243M per year (2008 costs). The cost of the health checks was estimated to be about £40M, with additional treatment costs accounting for the remainder. Health benefits were estimated to be substantial and the intervention was judged to be cost-effective, with a cost of < £3000 per quality-adjusted life-year. 24

The economic model incorporated a range of assumptions concerning population engagement with the programme and the likely effectiveness of interventions in the context of the present quality of care. The present research focuses on one key assumption, the uptake of health checks. The Department of Health model assumed that overall uptake of the health check would be about 75%; 70% of individuals were assumed to always attend, 15% might never attend and 15% might have a 33% probability of attending. These assumptions were informed by data on the uptake of the national breast screening programme. Women are generally more likely than men to seek help and engage with health services.

Uptake of the NHS Health Check programme

At the time that this trial was initiated in 2012, early indications were that uptake of health checks was lower than anticipated. Dalton et al. 25 reported a 45% uptake of health checks in west London. This was consistent with experience in south London, where uptake was running at < 40%. In national data for English PCOs in the third quarter of 2011/12,9 the median uptake was 52%, with values in different PCOs ranging from 0% to 100%, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 35–67%. Only 30 (20%) out of 151 PCOs had an uptake of ≥ 75%. 9 At that stage of the implementation of the NHS Health Check programme, 80% of PCOs were reporting that uptake of the checks was lower than expected based on the health economic model. In more recent cumulative data for 2013–15, it was reported that 48.4% of people offered a NHS health check received a check. Uptake ranged from 21% to 100% in different local authority areas, with 143 out of 161 (89%) local authorities failing to achieve the lowered target of 66% uptake (Figure 2).

Evaluations of the roll-out of health checks

Local evaluations have confirmed a pattern of low uptake of health checks. Dalton et al. 25 reported on the uptake of health checks in Ealing, a deprived and culturally diverse setting in London, with an estimated uptake of 44.8%. Attendance was found to be significantly lower among younger patients and smokers, consistent with the later findings of Artac et al. 27 Uptake was significantly higher for those with a South Asian background (53.0%) or a mixed ethnic background (57.8%), those with hypertension and those from smaller general practices. 28

A 3-year observational cohort study conducted by Robson et al. 29 evaluated the implementation of the NHS Health Check programme among general practices in East London serving an ethnically diverse and socially disadvantaged population. Coverage in this period ranged from 33.9% in the first year to 73.4% in year 3. Older people were more likely to attend than younger people. Attendance was similar across deprivation quintiles and was in accordance with population distributions of black African/Caribbean, South Asian and white ethnic groups. One in 10 attendees had a high CVD risk (≥ 20% 10-year risk). In the two PCOs stratifying risk, 14.3% and 9.4% of attendees had a high CVD risk compared with 8.6% in the PCO using an unselected invitation strategy. 29

In a previously reported study,30 which is discussed further in Chapter 7, we evaluated some of the influences on an individual’s decision to take up the offer of a health check. We identified several issues that contribute to the low uptake of checks. There is a lack of public awareness of the Health Check programme. This may have arisen from the decision not to mount a national communications campaign to promote the Health Check programme from the outset. Beliefs about susceptibility may influence uptake if individuals believe that they have a healthy lifestyle or are free from symptoms and do not have other chronic conditions. Practical difficulties of gaining access to appointments for a blood test or a health check may represent a significant barrier to accessing a check for patients at some practices. Finally, receiving advice to change lifestyle behaviours may be unwelcome to some patients. This is consistent with the low uptake of health checks observed among smokers. 31

Evidence regarding effective interventions to increase the uptake of health checks or screening

Health checks have similarities with other population-based screening programmes. Both invite individuals who believe themselves to be healthy to undergo a risk assessment procedure that may result in the attendee discovering that they have a serious health problem or are at high risk of a serious health problem in the future. The literature on interventions to increase screening uptake may reasonably be applied to the uptake of health checks.

Interventions to increase uptake can have a number of foci: changes to the method of delivering the programme, different patterns of invitation letters and reminders or provision of additional information at the time of invitation. Camilloni et al. 32 recently updated the landmark review by Jepson et al. ,33 focusing on methods to increase uptake of screening for breast, cervical or colorectal cancer. The review suggested that postal reminders in addition to the initial invitation could significantly increase uptake, whereas the evidence for telephone reminders was largely favourable, although some primary studies did not demonstrate significant effects. The review identified one trial which found that patients were more likely to attend if they were invited by telephone rather than by letter. In the context of health checks, an observational study found significantly higher uptake at practices using telephone or verbal health check invitations, either singly or in combination with letters. 34 Telephone or face-to-face invitations to promote health check uptake may be difficult to implement on a large scale, as would be required for the national Health Check programme.

In the cancer screening literature, providing a stated appointment time led to significantly higher uptake of screening than open appointments for cervical [relative risk (RR) 1.49, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.75] and breast (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.75) cancer screening. 32 Kumar et al. 35 compared health check uptake by patients offered only a booked appointment with uptake by patients offered a choice of a booked appointment or attending a drop-in clinic. Uptake rates for the two groups separately are not reported, but the authors suggested that use of drop-in clinics may be less costly. Norman et al. 36 found a 70% attendance rate for an invitation letter with a given appointment time compared with 37% for an open letter invite.

Evidence of factors that may be associated with improved uptake of health checks was reviewed by Cooper and Dugdill. 37 They identified from existing studies, deemed transferable to a UK context, the key factors influencing the uptake of health screening, including demographic, social, cultural and psychological influences. Demographic and cultural factors that affect uptake may not be modifiable, whereas psychological factors may be more amenable to change. In cancer screening, the impact of providing additional information, such as leaflets or pamphlets, was mixed. 32 The reviewers noted that the interventions assessed were perhaps not entirely comparable. Different health conditions, and different types of screening test [e.g. the self-completed faecal occult blood test (FOBT) for colorectal cancer vs. attending a mammography appointment at a hospital], may additionally account for variation in results. We next consider interventions targeting psychological factors to increase health check uptake.

One useful intervention may be providing invitees with planning prompts, asking them to form concrete plans about when, where or how to perform a behaviour. Such prompts can help motivated individuals be more likely to act on their intentions. Sallis et al. (cited in Perry et al. 38) found that an enhanced health check invitation letter, which included a tear-off slip for individuals to write the date and time of their health check, led to a 33% uptake of health checks in Medway, compared with 29% uptake for individuals receiving the original, control invitation letter. Although this is a small absolute increase, it was achieved using minimal extra resource. Planning prompts are not always effective. For example, they have failed to increase the uptake of colorectal cancer screening among first-time invitees39 or antenatal screening. 40 In field settings, a substantial proportion of participants asked to do so may not record a plan. 41 Moreover, plan formation has been shown to be most effective for individuals who are already motivated to perform the behaviour,42 for example those who accepted a previous round of colorectal cancer screening. 43

An alternative brief intervention that may be useful to increase uptake was demonstrated by Conner et al. ,44 who reported a study conducted in one general practice in 1991. Sending a preliminary questionnaire prior to inviting individuals for a health check enhanced uptake, with 68.3% of the intervention group having a health check compared with 53.5% of the control (no questionnaire) group. This increase in uptake was attributed to the question–behaviour effect (QBE), a phenomenon in which asking questions about people’s views on a behaviour or their current behaviour increases the likelihood that individuals will later perform that behaviour. The potential of the QBE to increase uptake was also demonstrated in a study focusing on cervical cancer screening uptake. 45 Uptake increased from 21% in the control group to 26% in the two experimental questionnaire groups, with those in one of the groups being asked to complete additional questions about whether or not they anticipated regretting not being screened. Among individuals who returned the questionnaire in these two experimental groups, those who had been asked about anticipated regret had a higher screening uptake (65%) than those in the other questionnaire group (44%). Taken together, these two studies suggest that the QBE might be a useful intervention to increase NHS health check uptake. Subsequent to the initiation of the present study, a further trial reported no significant QBE on the uptake of colorectal cancer screening via a FOBT in Scotland. 46

How does the question–behaviour effect work?

Psychologists have long been aware that asking questions about a behaviour may change the respondent’s future behaviour. 47 A number of mechanisms have been proposed for the operation of the QBE. 48 The attitude accessibility account suggests that asking people to report their attitudes or intentions for a behaviour makes the attitude about that behaviour more accessible in memory. The increased accessibility makes it more likely that a person will perform the behaviour (e.g. have a health check) when the opportunity arises.

A second explanation concerns cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance is a mental state that occurs when a person’s behaviour is not consistent with his or her beliefs about how he or she should behave. Experiencing cognitive dissonance is uncomfortable and so individuals are motivated to try to reduce it. In terms of the QBE, cognitive dissonance can arise when completing a questionnaire leads individuals to realise that their current or past actions are incompatible with their beliefs about how they should act. To reduce the cognitive dissonance aroused by completing a questionnaire, people may subsequently change their behaviour to be more in line with their beliefs.

A final explanation for the QBE concerns behavioural simulation and processing fluency. In this account, the QBE is driven by questioning, leading individuals to form behavioural scripts, that is, mental representations of how to carry out that behaviour. These scripts are stored in memory and can be reactivated when the individual encounters an opportunity to perform the relevant behaviour. This reactivation of the mental representation makes it seem easier for the person to perform that behaviour than it would otherwise, which then increases the likelihood that he or she proceeds to perform the behaviour in question.

Recent systematic review and other evidence regarding the question–behaviour effect

The QBE has been tested in a wide range of behaviours, including not only health-related behaviours but also consumer and prosocial behaviours. Dholakia et al. 49 provided an overview of the literature but did not subject it to meta-analysis. Subsequent to the initiation of this project, two systematic reviews of the QBE with meta-analyses have been published. 50,51 The two differ in their inclusion criteria and aims and so both are discussed here.

Wood et al. 50 reviewed literature published up to March 2013. They set out to examine the impact of asking intention or self-prediction (i.e. rating the likelihood that one will perform a behaviour) questions on subsequent behaviour. Intentions are a key component of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB),52 a psychological model which states that behaviour is determined by an individual’s behavioural intention and perceived behavioural control (PBC). Intentions reflect the individual’s motivation to engage in a particular behaviour. PBC is very similar to the concept of self-efficacy, concerning the extent to which people perceive that they have control and ability to engage in the behaviour. Intentions, in turn, are determined by an individual’s attitude towards the behaviour (whether the outcomes of performing the behaviour are considered positive or negative), subjective norms (e.g. perceptions of whether or not others think one should engage in a behaviour) and PBC. Therefore, the review by Wood et al. 50 examined whether including questionnaire items relating to other TPB variables, such as attitudes, subjective norms or PBC, or including additional questionnaire items about anticipated regret altered the effect of intention or self-prediction questions on behaviour. This review also attempted to explore the mechanisms by which the QBE might operate by examining the effect of different study characteristics on effect sizes. The measure of effect size used was the standardised mean difference, Cohen’s d.

Overall, this review included 116 tests of the QBE. It found a small, statistically significant positive effect on behaviour of asking intention or self-prediction questions (pooled effect size, d+ = 0.24, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.30). There was evidence of publication bias, with a disproportionate concentration of studies with larger effect sizes and larger standard errors. There was also evidence of significant heterogeneity in effect sizes. The effects for health (d+ = 0.29), consumer (d+ = 0.34) and prosocial (d+ = 0.19) behaviours were significantly larger than those for risky or undesirable behaviours (d+ = –0.05, 95% CI –0.23 to 0.13). Larger effect sizes were observed for behaviours that the reviewers rated as easier to perform and more socially desirable.

A number of methodological factors were also significantly related to observed effect sizes. In particular, smaller effects were observed for studies conducted in field rather than laboratory settings (d+ = 0.17 vs. d+ = 0.38). The longer the time interval between answering questions and the measurement of the behaviour, the smaller the effect size tended to be. Providing an incentive for study participation was associated with a larger effect size (d+ = 0.36) than not doing so (d+ = 0.19).

The types of question asked also influenced the observed effects on behaviour. Studies that asked only self-prediction questions (‘How likely is it that you will . . .’) reported significantly larger effects (d+ = 0.29) than studies that asked a mix of self-prediction and intention questions (d+ = 0.14). Measuring TPB constructs other than intentions did not significantly influence effect sizes. Asking anticipated regret items was associated with smaller effects on behaviour (d+ = 0.08) than not doing so (d+ = 0.26).

In contrast to Wood et al. ’s50 review, that of Rodrigues et al. 51 focused only on studies published up to December 2012 examining the QBE on health behaviours. Also, in contrast to Wood et al. ’s50 focus on intention and self-prediction questions, Rodrigues et al. 51 included studies that measured cognitions, behaviours or a mix of cognitions and behaviours, as long as the effects of the questionnaire condition(s) were contrasted with the effects of a no-measurement condition. The review also aimed to examine the impact of study methodological features on observed effects.

The results were based on 38 papers reporting 41 studies of the QBE. The overall effect size was statistically significant but small [standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.09, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.13], with moderate heterogeneity. Again, there was significant evidence of publication bias. Moreover, there was considerable risk of bias when assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. 53 There was no significant effect of risk of bias on observed effects. Effect sizes varied by behaviour type, with the largest for physical activity (SMD 0.20) and the smallest for drinking (SMD 0.04). Most relevant to health checks, the SMD for screening was 0.06 (95% CI 0.003 to 0.12). The review concluded by calling for future QBE trials to be preregistered, to focus on reducing risk of bias and to provide detailed descriptions of the procedures in each trial arm.

Financial incentives to increase questionnaire return rates

Financial incentives for questionnaire return are known to increase response rates. A systematic review including 94 trials with a pooled total of 160,004 participants found that the odds of returning a postal questionnaire were considerably increased if a financial incentive was offered [odds ratio (OR) 1.87, 95% CI 1.73 to 2.04]. 54 As the QBE is greater among individuals who return a questionnaire,44 incentivising questionnaire return may increase the size of any effect of a questionnaire on uptake of health checks. A meta-analysis of 85,671 participants in 88 randomised trials of financial incentives to increase response rates for mailed questionnaires reported that there was a significant increase in response rates for incentives up to the value of $5. 55 There is strong evidence to suggest that the offer of a financial incentive may increase the rate of return of the QBE questionnaire.

What is the potential impact of the question–behaviour effect on socioeconomic inequalities in uptake?

Death rates from coronary heart disease are highest in areas of greatest deprivation,6 so considering socioeconomic inequalities in the evaluation of any intervention to increase the uptake of NHS health checks is important. Although evidence suggests that enhanced invitation methods such as a QBE-based questionnaire increase the uptake of screening and the performance of health-related behaviours, we do not know their impact on NHS Health Check, a relatively new programme. Theoretical arguments suggest that uptake inequality might be either reduced or increased.

One argument is that it may be more difficult for those experiencing higher levels of deprivation to convert their positive attitudes and intentions with regard to health checks into action. The QBE may increase the cognitive accessibility of attitudes towards the behaviour, thereby increasing the likelihood that the behaviour is performed. This increased cognitive accessibility may make it easier for people experiencing more socioeconomic deprivation to find an opportunity to act on their intentions, thereby increasing health check uptake.

Another argument is that the strength of the QBE is affected by individuals’ beliefs about the behaviour in question, being stronger for individuals who hold positive attitudes to, and intentions for, the behaviour. 44 The extent to which any socioeconomic inequality in health check uptake may be the result of more socioeconomically deprived individuals having more negative views of health checks than less deprived individuals is unclear. If socioeconomic deprivation is associated with fewer perceived benefits of and greater perceived barriers to uptake, as it is for cancer screening, then an intervention using the QBE may increase uptake inequality. 56

How might offering an incentive for questionnaire return affect the social patterning of responses to the question–behaviour effect?

The offer of a financial incentive may increase questionnaire return rates only among those with already positive attitudes towards health checks, in which case it would result in increased uptake. If the offer of a financial incentive increases questionnaire return rates among those with less positive attitudes, the incentive is likely to have less of an impact on uptake. There is little research examining how and if incentives influence uptake of screening differentially across different levels of deprivation. 57 The offer of a financial incentive may be most attractive for individuals who are experiencing deprivation and so may increase the strength of the QBE on health check uptake particularly in individuals from deprived backgrounds.

According to a cognitive dissonance explanation of the QBE an incentive may backfire and not result in an increase in attendance. This argument suggests that having an incentive gives respondents a reason for completing questions and reduces the cognitive dissonance that might be experienced. It is the dissonance that drives the behaviour and removing it reduces the impact on behaviour. Such an effect has been suggested in studies in progress on bowel cancer screening and cervical cancer screening (Professor Mark Conner, University of Leeds, 2015, personal communication). It will be important to consider inequalities in uptake in any investigation of the impact of the QBE, with or without the provision of an incentive for questionnaire return, on the uptake of health checks.

Will informed choice be evaluated?

The concept of informed choice has received considerable attention in the context of the offer of screening tests and is relevant here even though NHS health checks are offered as a clinical service, not as a screening programme. Marteau et al. 58 defined an informed choice as an action ‘based on relevant knowledge, consistent with the decision-maker’s values’. Marteau and Kinmonth59 argued that, in the context of cardiovascular screening, participation on the basis of informed choice might encourage the participation of individuals who were more motivated to reduce their level of risk. This might have the unwanted consequence of increasing inequalities in cardiovascular risk. 59 These hypotheses were not supported by the results of a study of diabetes mellitus screening in which individuals’ knowledge, and the receipt of an invitation that promoted informed choice, were only weakly associated with screening attendance. 60 In the context of the present study, we believe that it will not be feasible to evaluate whether the uptake of NHS health checks is adequately informed. Distributing questionnaires to assess informed choice in the no-questionnaire control condition would obviously contaminate the control condition. Including the questionnaire items to measure knowledge of health checks and their potential outcomes, which would be required to assess informed choice, would increase questionnaire length and potentially dilute the QBE in those allocated to questionnaire conditions. Questions of informed choice and NHS health checks are left for a future study.

Uptake patterns

As previously explained, the NHS Health Check programme in England aims to identify people at risk of developing preventable illness, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus and kidney disease. Any individual between the ages of 40 and 74 years without an existing chronic condition should be invited for a health check once every 5 years.

Initial modelling of the cost-effectiveness of the programme was based on a 75% uptake. Since implementation, uptake of the health checks remains below the national target. Research on NHS health checks has identified some patterns in uptake that are often observed in screening programmes. These include lower uptake rates in men, people at the younger end of the target age range and people with better health profiles. 37 Associations between deprivation and uptake have been less consistent. Higher deprivation has been linked with lower uptake,61 which is consistent with evidence from other screening programmes,16 whereas some studies have reported higher uptake in more deprived areas27 or no relationship. 25 In the same trial,25 the proportion of health checks and demographic characteristics were compared between patients who received a postal invitation and those whose health checks were performed opportunistically.

Research objectives

The aim of this research was to determine whether enhanced invitation methods, using the QBE, lead to increased uptake of NHS health checks. The project aimed to rapidly implement a RCT to generate evidence in the short term to inform decision-making in the NHS.

The specific objective of this research was to implement a RCT using individual participants who are eligible for NHS health checks as the unit of allocation. The trial compared the effects of (1) standard invitation only, (2) a QBE questionnaire followed by a standard invitation 1 week later and (3) a QBE questionnaire with an offer of a retail voucher as an incentive for questionnaire completion followed by a standard invitation 1 week later.

The intervention effect was evaluated using the primary outcome of whether or not each individual completed their NHS health check within 182 days (6 months) of the standard invitation being sent.

The research also evaluated the feasibility of a rapid trial using electronic health records, with an automated randomisation procedure embedded into the Health Check programme management information system.

We also conducted a cohort study of all health checks conducted during the study period at general practices participating in the trial with the aim of comparing the characteristics of participants receiving invited health checks with the characteristics of participants receiving ‘opportunistic’ health checks.

We also conducted a qualitative interview study with the aim of evaluating the views of health-care professionals and patients concerning the uptake of health checks to identify factors that influence uptake and response to the trial interventions.

Context

This research was conducted in the inner London boroughs of Lambeth and Lewisham. The age structure of the resident population at the 2011 census is shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that both boroughs have a strikingly young population, with a low proportion of older adults. Table 1 shows the distribution of the population in the age range 40–74 years, which is the group eligible for NHS health checks. This age range accounts for only about 30% of the total population in these boroughs, with only some 7% or 8% of the total population being in the age range 60–74 years.

| Age group (years) | Lambeth | Lewisham | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | % | Population | % | |

| ≤ 40 | 199,929 | 66.0 | 170,288 | 61.7 |

| 40–44 | 23,088 | 7.6 | 21,919 | 7.9 |

| 45–49 | 20,897 | 6.9 | 20,481 | 7.4 |

| 50–54 | 15,601 | 5.1 | 15,750 | 5.7 |

| 55–59 | 11,372 | 3.8 | 11,523 | 4.2 |

| 60–64 | 9012 | 3.0 | 9789 | 3.5 |

| 65–69 | 6623 | 2.2 | 7284 | 2.6 |

| 70–74 | 5994 | 2.0 | 6357 | 2.3 |

| ≥ 75 | 10,570 | 3.5 | 12,494 | 4.5 |

| Total | 303,086 | 275,885 | ||

At study initiation, Lambeth was the 22nd most deprived local authority in England and Lewisham was the 26th most deprived. 64 Both boroughs have large ethnic minority populations, with black African and black Caribbean groups being the largest minority groups (Table 2). The black African population generally has a higher proportion with a university education than the local white population.

| Ethnicity | Lambeth | Lewisham | London | England | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| White | 173,025 | 57 | 147,686 | 54 | 4,887,435 | 60 | 45,281,142 | 85 |

| Mixed | 23,160 | 8 | 20,472 | 7 | 405,279 | 5 | 1,192,879 | 2 |

| Asian | 20,938 | 7 | 25,534 | 9 | 1,511,546 | 18 | 4,143,403 | 8 |

| Black African | 35,187 | 12 | 32,025 | 12 | 573,931 | 7 | 977,741 | 2 |

| Black Caribbean/black other | 43,355 | 14 | 42,917 | 16 | 514,709 | 6 | 868,873 | 2 |

| Other | 7421 | 2 | 7251 | 3 | 281,041 | 3 | 548,418 | 1 |

| Total | 303,086 | 100 | 275,885 | 100 | 8,173,941 | 100 | 53,012,456 | 100 |

The Health Check programme in the two boroughs utilises a call–recall system. This is operated through the offices of the primary care shared services but is supported by a private sector company called Quality Medical Solutions (QMS) Ltd (Bournemouth, UK). QMS has developed a software system, known as Health Check Focus, that links the general practices in the boroughs to primary care shared services to enable invitations to health checks to be organised. Standard invitations are sent out using a slightly modified version of the national invitation template. The operation of this system is discussed further in Chapter 2. Patients who receive a standard invitation to a health check are offered a choice of making an appointment with their general practice or attending for a check at a local pharmacy. In general, a two-stage process is followed, with a blood test followed by a health check appointment. Most general practices offer opportunistic health checks in addition to any health checks carried out in patients who respond to a standard invitation letter. Both boroughs also commission outreach teams to conduct health checks opportunistically among high-risk groups. About 25% of health checks in Lewisham and 20% in Lambeth are conducted by third-party providers, with pharmacy-based checks accounting for the majority and outreach teams accounting for < 5% of all health checks. Results of third-party checks are communicated to general practices through the Health Check Focus software. The ratio of invited to opportunistic health checks is discussed further in Chapter 6.

Chapter 2 Methods

The protocol for the trial has been reported previously. 65 The trial was registered on 21 March 2013 (trial registration number ISRCTN42856343).

Trial design

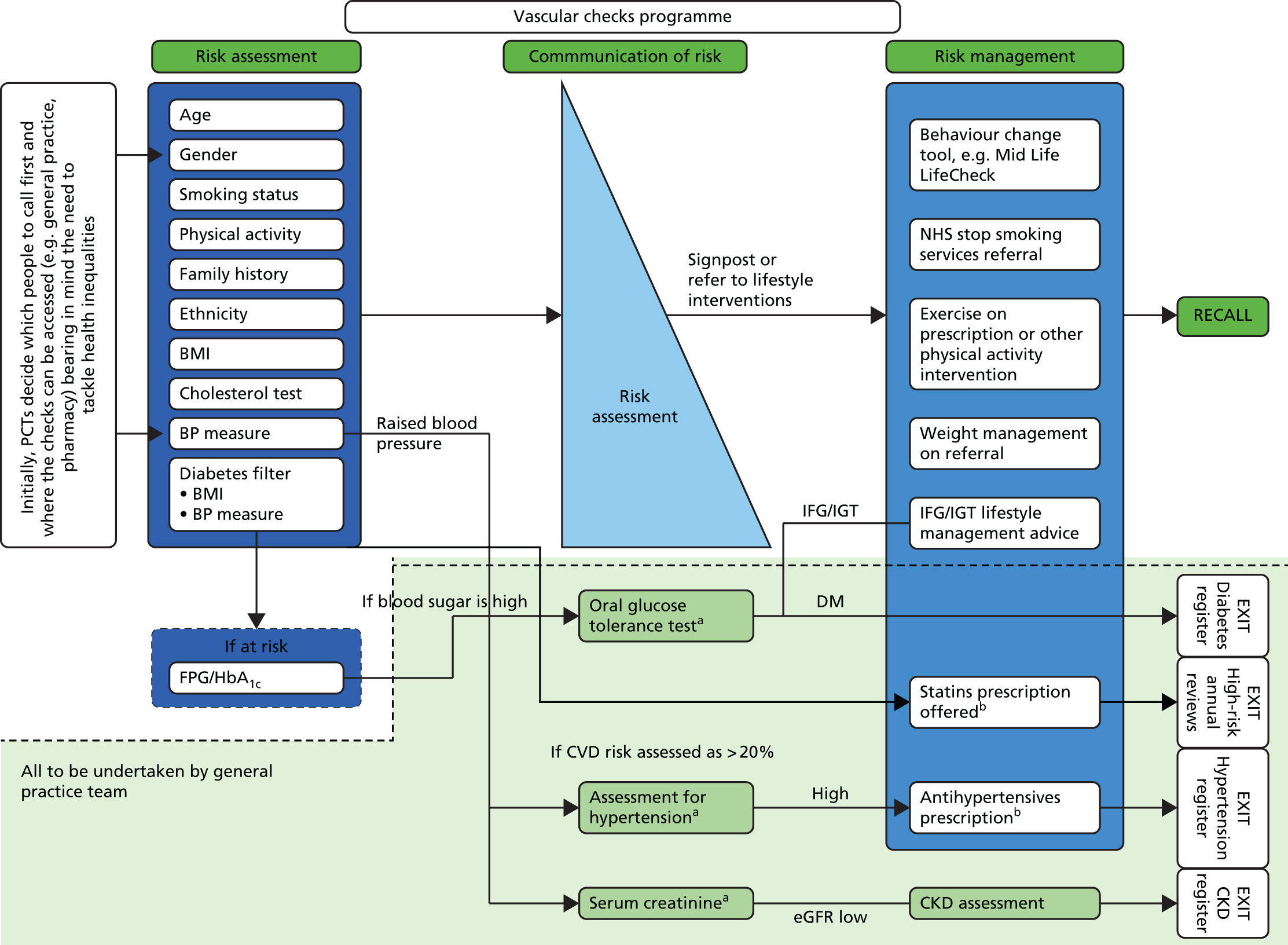

This was a three-arm superiority RCT with equal allocation to each arm (Figure 4). The trial interventions consisted of (1) standard invitation only to a NHS health check, (2) a QBE questionnaire followed by a standard invitation and (3) a QBE questionnaire and offer of a financial incentive to complete the questionnaire followed by a standard invitation. Participants in all three trial arms received a reminder letter at 3 months following the initial invitation.

Setting

The trial was conducted in two London boroughs, Lambeth and Lewisham, which are described briefly in Chapter 1. Both boroughs are typical of areas that are in need of intervention to increase the number of individuals attending for their NHS health check; uptake is below the national average (48%). In 2012/13, 31% of individuals invited for a health check in one borough attended and 45% in the other.

General practice recruitment

General practices in the two participating boroughs were eligible to participate in the trial. Each practice participated in the trial for a minimum of 12 months to allow for seasonal variation in uptake of health checks.

General practice recruitment was facilitated by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) South London Clinical Research Network, which advertised the trial to its general practices and offered reimbursement of costs for participation. In addition, practices were recruited into the trial based on existing working relationships either with members of the research team or with the borough NHS Health Check programme co-ordinators. A non-probability sampling strategy was used because conducting the trial required a significant level of access to, and co-operation from, general practices to utilise the general practice electronic health record system and participating practices were necessarily volunteers. To evaluate selection bias, general practices that participated in the trial were compared with all general practices in the two boroughs with respect to general practice list size, area deprivation [Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2010 score66], proportion of ethnic minorities and achievement of Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) targets, both overall and for public health. Although the method of general practice selection might be associated with patients’ uptake of health checks, it was not considered likely that general practice selection would be associated with patients’ propensity to respond to the study interventions.

Individual participant recruitment

Patients were included in the trial only if the senior partner at the practice provided written informed consent. All participants in the consented practices who were eligible to be invited for an NHS health check were included in the trial. There were no exclusion criteria for trial recruitment.

A cross-borough call–recall system is used to recruit patients into the NHS Health Check programme. The call–recall system is commissioned by the boroughs and is implemented by the primary care shared services team, working in association with the commercial information technology company, QMS. QMS has developed bespoke software (Health Check Focus) that is used in the management of the Health Check programme. All general practices in the two boroughs utilise Health Check Focus software.

Invitations to the programme are issued through a monthly cycle. This begins with the ‘harvesting’ of eligible patients from general practice information systems. All general practices in the two boroughs use EMIS (EMIS Health, Cambridge, UK) electronic health records software. Eligibility for the NHS Health Check programme is initially defined on the basis of age and comorbidity. Individuals who are registered with general practices in Lambeth and Lewisham form the initial population. Participants are eligible for invitation for a NHS health check if they are aged from 40 to 74 years. Participants are ineligible if they already have a defined comorbidity, including CVD, or treated risk states. Participants are excluded if they have diagnosed ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease or peripheral vascular disease. Participants are also excluded if they have diagnosed hypertension or hypercholesterolaemia or are being treated with antihypertensive drugs or statins.

General practice data are uploaded into Health Check Focus on a monthly basis and bespoke software is used to remove ineligible participants on the basis of Read codes that identify patients already included on CVD registers. An initial pre-notification list (PNL) is prepared by QMS and sent to general practices for review. Any participants whom the general practice considers should not be invited (e.g. they have died, are terminally ill or have left the practice) are excluded. The exclusions are confirmed by practice staff prior to patient invitations being sent each month by checking the records of patients included in the PNL. Only a very small number of patients are removed at the PNL stage. The final list of participants eligible for invitation is then forwarded to primary care shared services by the 21st of each month and standard NHS Health Check programme invitation letters are then sent out on the 28th of each month. A commercial mailing house is used to send the invitation letters.

Recruitment and randomisation

To conduct the trial, we negotiated with the borough teams, QMS, the primary care shared services team and general practices to introduce modifications into the standard NHS Health Check programme invitation process. Our aim was to introduce an automated recruitment and randomisation procedure into the standard invitation process, through modifications to QMS Health Check Focus software. At the start of the trial the feasibility, reliability and likely time scale for such a modification were unknown. We considered that reliance on an unproven recruitment and randomisation procedure might carry a significant risk to the successful conduct of the trial. We therefore developed an alternative method of recruitment and randomisation that could be implemented through visits to general practices. The trial was delivered through the use of these two different recruitment and randomisation procedures, which will be referred to as the ‘automated’ and ‘in-practice’ recruitment methods, respectively.

In-practice method for recruitment and randomisation

For the in-practice method of allocation, members of the research team visited each practice monthly to access the practice-approved PNL. Participants included in the approved PNL were allocated to the three trial arms using previously prepared randomisation lists. Each month, the trial statistician drew up randomisation lists, stratified by general practice. As all patients within a practice were assigned simultaneously, participants were allocated to intervention arms in a ratio of 1 : 1 : 1 by means of a computer-generated randomisation list stratified by general practice and month using permuted blocks of three. Randomisation lists were generated using the Stata command ‘ralloc’ in Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The randomisation list was applied to the approved PNL by the trial researcher, who assigned the trial arm in the existing order of the approved PNL. Practice staff responsible for preparing the approved PNL never had access to the randomisation list for the practice. This process was considered to provide adequate concealment of the allocation procedure.

Automated method for recruitment and randomisation

For general practices assigned to the automated method for recruitment and allocation, randomisation was performed automatically using a randomisation procedure programmed into QMS Health Check Focus software, used to manage the Health Check programme. Randomisation lists were generated using a bespoke algorithm embedded within the QMS software. Simple randomisation, stratified by practice and month, was employed. Participants were automatically assigned a study identification number and group allocation when the PNL was electronically approved by the general practice.

Pilot study

During the first 2 months of use of the automated recruitment method, a review of the trial data showed that the correct allocation ratio was not being achieved. Further adjustment to the software was therefore made. The first 2 months were therefore considered to act as a pilot study and data from these months were excluded from the main trial analysis.

Once randomisation was completed, the PNL list, with trial arm allocations included, was forwarded to the offices of the primary care shared services team. Here, trial research staff arranged for intervention materials to be sent to participants, as outlined in the following section. Initially, an in-house mailing procedure was used; later, we used the services of the commercial mailing house, Docmail (Radstock, UK). Table 3 displays the procedure for mailing invitations during the trial.

| Procedure | Standard practice | Standard invitation | QBE questionnaire | QBE questionnaire and incentive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNL list sent to practice | 21st day of month | 21st day of month | 21st day of month | 21st day of month |

| Randomisation completed by 28th day of month | Randomisation completed by 28th day of month | Randomisation completed by 28th day of month | ||

| QBE questionnaire and covering letter sent on 28th day of month | QBE questionnaire and covering letter offering incentive sent on 28th day of month | |||

| Standard invitation letter sent to participants | 28th day of month | Standard invitation letter delayed by 7 days | Standard invitation letter delayed by 7 days | Standard invitation letter delayed by 7 days |

Intervention rationale and development

The original study by Conner et al. ,44 which suggested that the QBE may promote health check uptake, employed a questionnaire that assessed constructs from the TPB in relation to health check attendance. The questionnaire employed as the intervention in the present study was based on the same theory. It was also decided to add items assessing anticipated regret because a previous QBE study45 found that, among participants who returned completed questionnaires, those who completed a TPB with anticipated regret questionnaire had a significantly higher cervical cancer screening attendance rate (65.1%) than those who received a TPB-only questionnaire (44%).

The questionnaire employed in the previous study using the QBE to promote health check uptake44 included 23 items, each in relation to health check attendance: eight measuring attitudes, nine measuring subjective norms, three measuring PBC and three assessing intentions. The study by Conner et al. 44 was conducted in a single general practice in rural England. In contrast, the present trial was implemented in two London boroughs ranked among the most deprived local authorities in England. 62 Given the known relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and low levels of literacy,67 there were concerns that employing a questionnaire of similar length in these boroughs would deter questionnaire completion, inhibiting the operation of the QBE. A decision was made to reduce the questionnaire length for use in the present study so that it contained two items for each psychological concept specified by the TPB and for anticipated regret, giving a total of 10 items.

For all questionnaire items, wording was based as much as possible on items that had been employed in previously successful QBE studies. When a number of possible items were available for assessing a construct, the choice was guided by considering which options had the best readability. One of the intentions items was asked in the interrogative form, that is, as a self-posed question (‘Will I . . .?), because a previous study found that the QBE was stronger when intentions items were asked in the interrogative. 68 All items were rated on a 7-point scale with labelled end points. The questionnaire items were printed in 16pt font in an effort to maximise legibility in line with ‘clear print’ standards. 67

The questionnaire was tested with six individuals attending for a NHS health check at a local community event. Most completed it within 5 minutes and made favourable comments on the layout and font size. However, respondents did not use the full range of response options, with responses instead clustered around the labelled end points. Another version of the questionnaire was developed that had all response options labelled. Further pilot testing with five people in the target age range for a health check found that this format was associated with respondents using a wider range of the response options. Comments were made on the repetitiveness of some items and a suggestion was made to reduce the number of questions. At this stage the questionnaire was circulated for feedback to members of the project management team, including local general practitioners (GPs) and NHS Health Check programme leaders. It was agreed that the questionnaire was too long as the items covered three A5 sides in a booklet. The study team decided to have only one item for each of the two concepts that were thought to be less central to the operation of the QBE, namely subjective norms and PBC. The PBC item retained reflected perceived confidence and so might also be referred to as self-efficacy.

Table 4 presents the intervention questionnaire items in order. The full version of the questionnaire began with an example of how to record one’s response to a question, about a different topic (television viewing). Appendix 1 provides a fully formatted version of the questionnaire, as received by participants, including this example item. The leaflet had a Flesch reading ease score of 80.1 and a Flesch–Kincaid grade level of 5.9, suggesting that it was accessible to people with the reading ability of an 11-year-old.

| Construct | Item stem | Response options | Previously used to promote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intentions | I intend to go for a health check in the next few weeks | Strongly disagree to strongly agree | Health check uptake44 |

| Attitudes | For me, going for a health check in the next few weeks would be . . . | Very bad to very good | Health check uptake44 |

| Anticipated regret | If I did not go for a health check in the next few weeks, I would feel regret | Strongly disagree to strongly agree | Cervical cancer screening uptake45 |

| Intentions | Will I go for a health check in the next few weeks? | Definitely no to definitely yes | Physical activity68 |

| Anticipated regret | If I did not go for a health check in the next few weeks, I would later wish I had | Strongly disagree to strongly agree | Cervical cancer screening uptake45 |

| Attitudes | For me, going for a health check in the next few weeks would be . . . | Very worrying to very reassuring | Health check uptake44 |

| PBC (self-efficacy) | I’m confident I can go for a health check in the next few weeks | Strongly disagree to strongly agree | Health check uptake44 |

| Subjective norms | People who are important to me would . . . . . . of me going for a health check in the next few weeks | Completely disapprove to completely approve | Flu vaccination uptake44 |

Patient and public involvement

In addition to patient involvement in questionnaire development, as outlined in the previous section, patient feedback was also obtained on the use of an incentive, the study invitation letter and the protocol. The six patients interviewed during questionnaire development in addition to three members of the public who met the target age range for a health check were questioned regarding the acceptability of the incentive for questionnaire completion and the trial invitation letter (both of which were considered acceptable). In addition, members of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), which included stakeholders (NHS Lambeth and Lewisham Health Check programme and CVD managers) and patient representatives, discussed and provided feedback on the study documents and the protocol, which led to general acceptability and some minor amendments being made before documents were sent out.

Justification of the incentive

Strong evidence suggests that financial incentives for questionnaire return increase response rates. A systematic review including 94 trials with a pooled total of 160,004 participants found that the odds of returning a postal questionnaire were almost doubled if a financial incentive was offered. 54 As the QBE is greater among individuals who return a questionnaire,44 incentivising questionnaire return may increase the size of any effect of distributing a questionnaire on uptake of the NHS health check. A meta-analysis of 85,671 participants in 88 randomised trials of financial incentives to increase response rates for mailed questionnaires reported a significant increase in response rates for incentives up to the value of $5. 55 It was decided to offer participants in one arm of the trial the incentive of a £5 gift voucher to complete and return the questionnaire. The gift voucher scheme employed (Love2shop) provided vouchers that could be exchanged at a wide variety of shops and so was intended to appeal to as many participants as possible.

Details of the interventions received in each trial arm

Participants in the standard invitation trial arm received the standard invitation letter for a NHS health check, sent from the primary care shared services team that organises health check invitations. This consisted of a single-page letter from the participants’ GP inviting them to make an appointment at their general practice to receive a health check or to visit a local participating pharmacy. Participants also received an information sheet. Individuals were sent a reminder letter if they did not attend for a health check within 12 weeks of their first invitation.

Participants in the QBE questionnaire trial arm were sent the QBE questionnaire with a prepaid return envelope and covering letter (see Appendix 2) 7 days before they were sent the standard NHS health check invitation letter and information sheet. They were also sent a reminder letter at 12 weeks if appropriate.

Participants in the QBE questionnaire and incentive trial arm were sent the QBE questionnaire with a prepaid return envelope and covering letter (see Appendix 3) 7 days before they were sent the standard NHS health check invitation letter and information sheet (plus a reminder letter at 12 weeks if appropriate). The covering letter in this trial arm offered the £5 retail voucher as an incentive to return the questionnaire.

Languages other than English

In the study areas, the London boroughs of Lambeth and Lewisham, ethnic minority groups account for a high proportion of the population. The major ethnic groups are of black African and African Caribbean origins and are English speaking. There are significant groups of European origin who speak languages other than English, but these groups are generally literate in English.

Standard invitation letters were sent in English. A single sentence was included on the reverse side of the letter, translated into 11 different languages, offering translated versions of the invitation letter and leaflet if required. Up to the study start date, no translations had been requested (primary care shared services, 10 September 2012, personal communication). In view of this, we sent the QBE questionnaire and covering letter in English only and included a telephone number to call on the final page of the questionnaire if a translation was required. In a randomised study any differences in literacy between the two arms will occur at random.

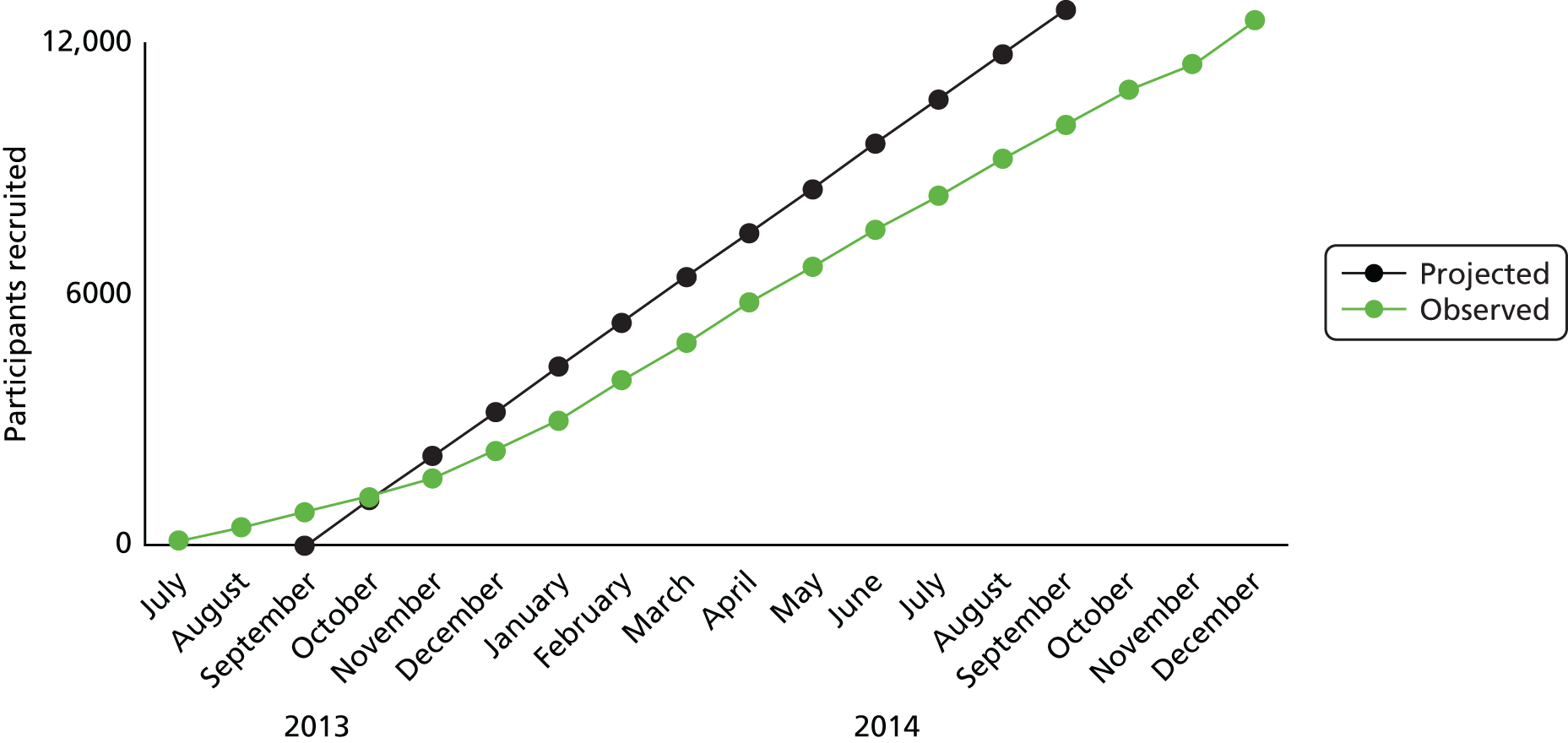

Sample size

It was important to detect even modest increments in screening uptake between trial arms because in a public health programme small effects may yield substantial benefits across the population at risk. We made the statistically conservative assumption that the underlying proportion of people invited who actually receive a health check is about 50%. If there are 4263 participants in each trial arm, with 12,789 in total, this will provide > 90% power to detect a difference in uptake of health checks between each active treatment arm and the standard intervention arm of at least 4%. These calculations are based on a 5% significance level using a Bonferroni correction for three comparisons (i.e. 0.0167). Calculations were performed in Stata 12. As present rates of health check uptake are < 50% in the study area, slightly greater power may be realised in the study. There were no planned interim analyses and no stopping guidelines as this trial had a low risk of adverse events.

In the study by Conner et al. 44 47% of intervention group participants returned the QBE questionnaire and health check uptake was 78% among participants who completed the questionnaire, compared with 60% among non-completers and 54% in control participants. Based on experience in the study area in London, we expected that the response rate to the QBE questionnaire would be about 40%. 69

The anticipated flow of patients through the intervention trial arms is shown in Table 5. If the QBE effect was restricted to questionnaire returners, then to achieve an overall increment in health check uptake of 4% we expected that uptake would have to be 10% higher in questionnaire returners than non-returners. Conner et al. 44 found that health check uptake was 24% higher in questionnaire returners than in control participants. In this study there was also a modest increment in uptake in questionnaire non-returners.

| Invited participants | QBE questionnaire | Health check uptake by QBE return | Overall health check uptake |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 400 return questionnaire | 240 receive health check | 540 receive health check in total |

| 600 do not return questionnaire | 300 receive health check |

Blinding

Participants’ GPs provided consent to their participation in the trial and so participants were not overtly aware that there were other trial arms. However, participants in the QBE questionnaire and QBE questionnaire and incentive groups received a postal intervention and thus could not be blinded to their trial arm allocation. Members of the study team were blind to participants’ details during trial arm allocation and were blind to group allocation during extraction of participant data and outcomes from general practice records.

Duration of the treatment period

Participants were followed up for a minimum of 6 months after the first NHS health check invitation was sent.

Outcome data collection

No data were collected directly from patients. Data were extracted from electronic health records into a spreadsheet and were then transferred to a database for statistical analysis.

The primary outcome was uptake of a NHS health check within 182 days (6 months) of receiving the standard invitation letter. Secondary outcomes included uptake of a NHS health check 91 days (3 months) post standard invitation and time elapsed between participants receiving the standard invitation and uptake of a health check.

Outcome data were extracted from participant electronic health records by members of the research team using nationally specified Read codes to record completion of NHS health checks (Table 6). Participants frequently had more than one code recorded to identify the completion of a health check. The codes 8BAg (NHS health check completed) and 38B1 (vascular disease risk assessment) were often co-recorded. At the time of data extraction, participants’ postcodes were linked to the IMD 2010 score66 as a marker of deprivation. Data for gender, year of birth and practice-recorded ethnicity were also extracted. Data were extracted in a single batch for each practice between 1 June 2015 and 2 July 2015.

| Read code | Read term |

|---|---|

| Codes for completion of the NHS health check | |

| 8BAg | NHS health check completed |

| 8BAg0 | NHS health check completed by third party |

| 38B1 | Vascular disease risk assessment |

| 38B10 | CVD risk assessment by a third party |

| 9OhA | CVD risk assessment carried out |

| Codes for CVD risk score recording | |

| 38DF | QRISK CVD 10-year risk score |

| 38DP | QRISK2 CVD 10-year risk score |

| 662k | JBS CVD risk < 10% over next 10 years |

| 662l | JBS CVD risk 10–20% over next 10 years |

| 662m | JBS CVD risk > 20% up to 30% over next 10 years |

| 662n | JBS CVD risk > 30% over next 10 years |

| 38DR | Framingham 1991 CVD 10-year risk score |

Analysis of the data extracted on health check completion revealed a high proportion of health checks completed in non-trial participants. To investigate this observation further, we subsequently collected data for CVD risk scores (see Table 6) and BMI for registered patients either who had a health check recorded during the study period or who were trial participants. Data were extracted from general practice systems between 17 August 2015 and 2 September 2015. Because there may have been changes to practice populations and health check recording between the first and second data extraction, the evaluation of case mix for invited compared with opportunistic checks was treated as a separate analysis from the trial analysis. At the time of the study, the JBS risk score calculator12 was mandated by the NHS Health Check programme locally. Values for the QRisk2 score13 were utilised if the JBS score was not recorded.

Reliability and data checking

Extensive checks were performed to ensure that the recruitment and randomisation procedures were working as intended:

-

We evaluated the recording of completed health checks during the course of the trial and found that health checks in non-trial patients outnumbered health checks in trial patients by a ratio of about 2 : 1.

-

We checked the details, including name and NHS number, of participants included in the approved PNL against general practice records. These checks identified a small number of discrepancies in NHS numbers on the PNL list prepared through QMS Health Check Focus. This was drawn to the attention of QMS who corrected the problem and there was no further recurrence.

-

We conducted checks that confirmed that standard invitation letters were sent to the correct patients identified on the approved PNL list for practices using both the in-practice and the automated recruitment methods.

-

During the trial, we checked the recording of completed health checks for a 10% sample of patients in 1 month using general practice records. This check revealed 100% accuracy of recording of the completion or non-completion of health checks.

At the protocol stage we envisaged using outcome data extracted centrally for the NHS Health Check programme through the health check management information system, QMS Health Check Focus. During the conduct of the trial, we decided that higher-quality data could be obtained by using data extracted by trial staff from general practice systems. Following the completion of the trial, we evaluated the reliability of the trial data against data extracted from the health check management information system. We evaluated the number of patients invited for health checks during the trial period at each practice. We also evaluated the number of completed health checks in invited and non-invited patients at each practice. Completed health checks were divided into those delivered by the general practice and those delivered by third-party providers, including pharmacies and outreach services.

Before analysis, basic checks to view incomplete or inconsistent data were performed. These included assessment of missing data, data outside the expected range and other inconsistencies between variables. When any inconsistencies were found, data were double-checked and corrected if necessary or set to missing otherwise. All changes were documented.

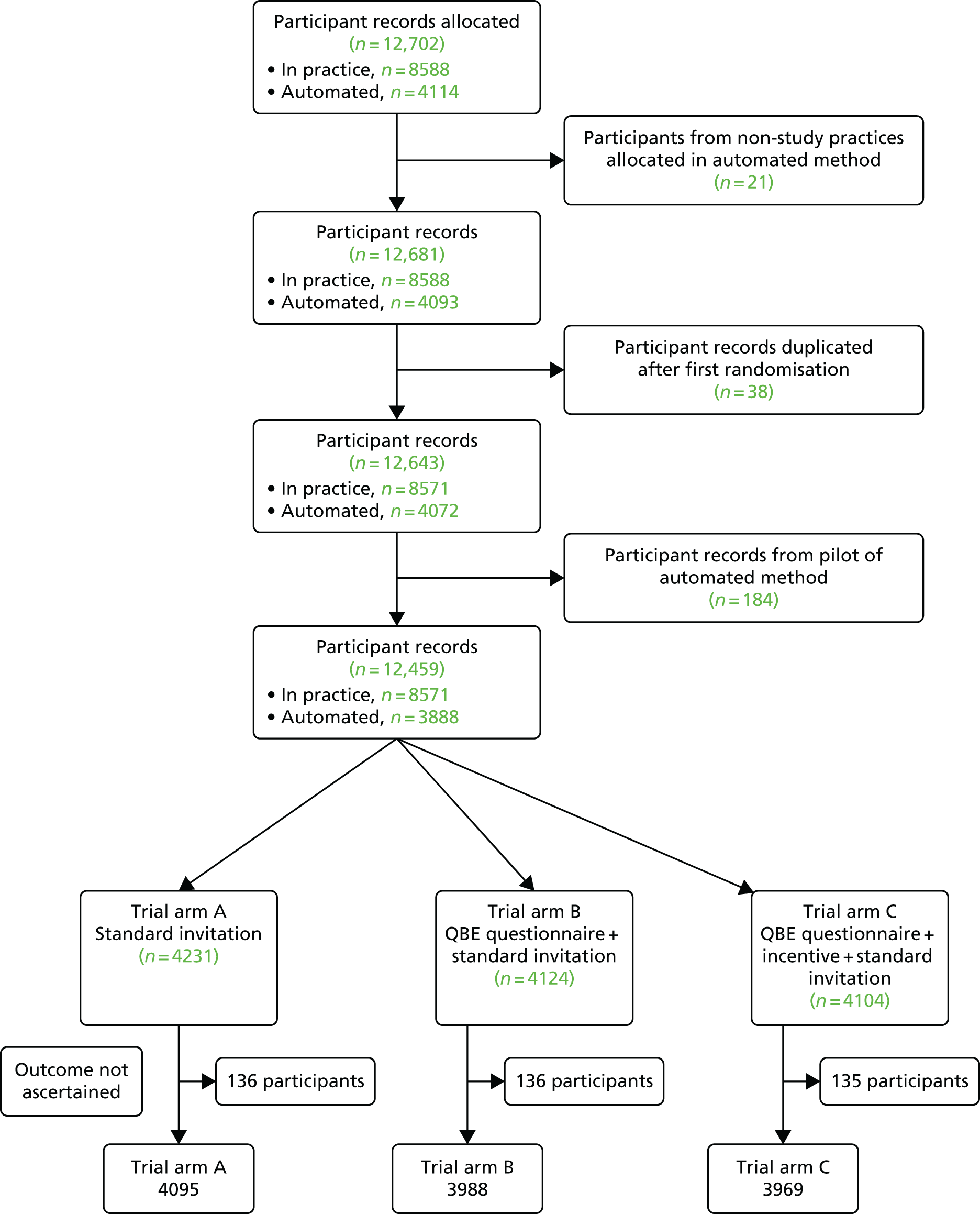

Data analysis plan: data description

A detailed statistical analysis plan was drawn up by the study statistician, principal investigator and study psychologist prior to completion of participant follow-up and compilation of the study data set. Recruitment and flow of participants through the study was depicted using a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart.

Baseline comparability of randomised groups

Baseline descriptive variables of participants were summarised by treatment arm. Mean and standard deviation (SD) or median (range, IQR) were reported for continuous outcomes, whereas frequencies and proportions were reported for categorical outcomes. Data available for analysis included participant age, gender and ethnicity and deprivation quintile. Participants were divided into the age groups 40–59 years and ≥ 60 years for analysis. Practice-recorded data for ethnicity were recoded to six categories based on the 2011 census question as shown in Table 7. It should be noted that general practice ethnicity recording often includes non-standard terminology, including details of nationality or religion. IMD 2010 scores66 at the lower super output area level were mapped to quintiles of score for England. No significance testing of differences in baseline values was undertaken.

| Ethnicity | Included categories |

|---|---|

| ‘White’ | White; English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British |

| White; Irish | |

| White; gypsy or Irish traveller | |

| White; other white | |

| ‘Black’ | Black/African/Caribbean/black British; African |

| Black/African/Caribbean/black British; Caribbean | |

| Black/African/Caribbean/black British; other black | |

| ‘Asian’ | Asian/Asian British; Indian |

| Asian/Asian British; Pakistani | |

| Asian/Asian British; Bangladeshi | |

| Asian/Asian British; Chinese | |

| Asian/Asian British; other Asian | |

| ‘Mixed’ | Mixed/multiple ethnic groups; white and black Caribbean |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups; white and black African | |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups; white and Asian | |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups; other mixed | |

| ‘Other’ | Other ethnic group; Arab |

| Other ethnic group; any other ethnic group | |

| ‘Missing’ | Not recorded |

Data analysis plan: inferential analysis

Analysis of the primary outcome

Uptake of a NHS health check was defined as having taken place if any of the codes shown in Table 6 were recorded within 6 months of the randomisation date.

The primary analysis was an intention-to-treat analysis including all participants who were randomised regardless of whether the intervention was subsequently received. Patients who died or left the practice prior to the 6-month follow-up period were included in the analysis using the status at their last recorded follow-up.

The distribution in time of health checks following randomisation was evaluated in a time-to-event framework. This allowed us to evaluate the impact of interventions on the primary outcome over time up to 6 months’ follow-up. To visualise the cumulative proportion of participants having a health check by trial arm, a Kaplan–Meier curve was plotted for each trial arm.

The number and proportion of health checks were tabulated by practice and between-practice variation was quantified by estimating the intraclass correlation coefficient using analysis of variance separately for each trial arm.

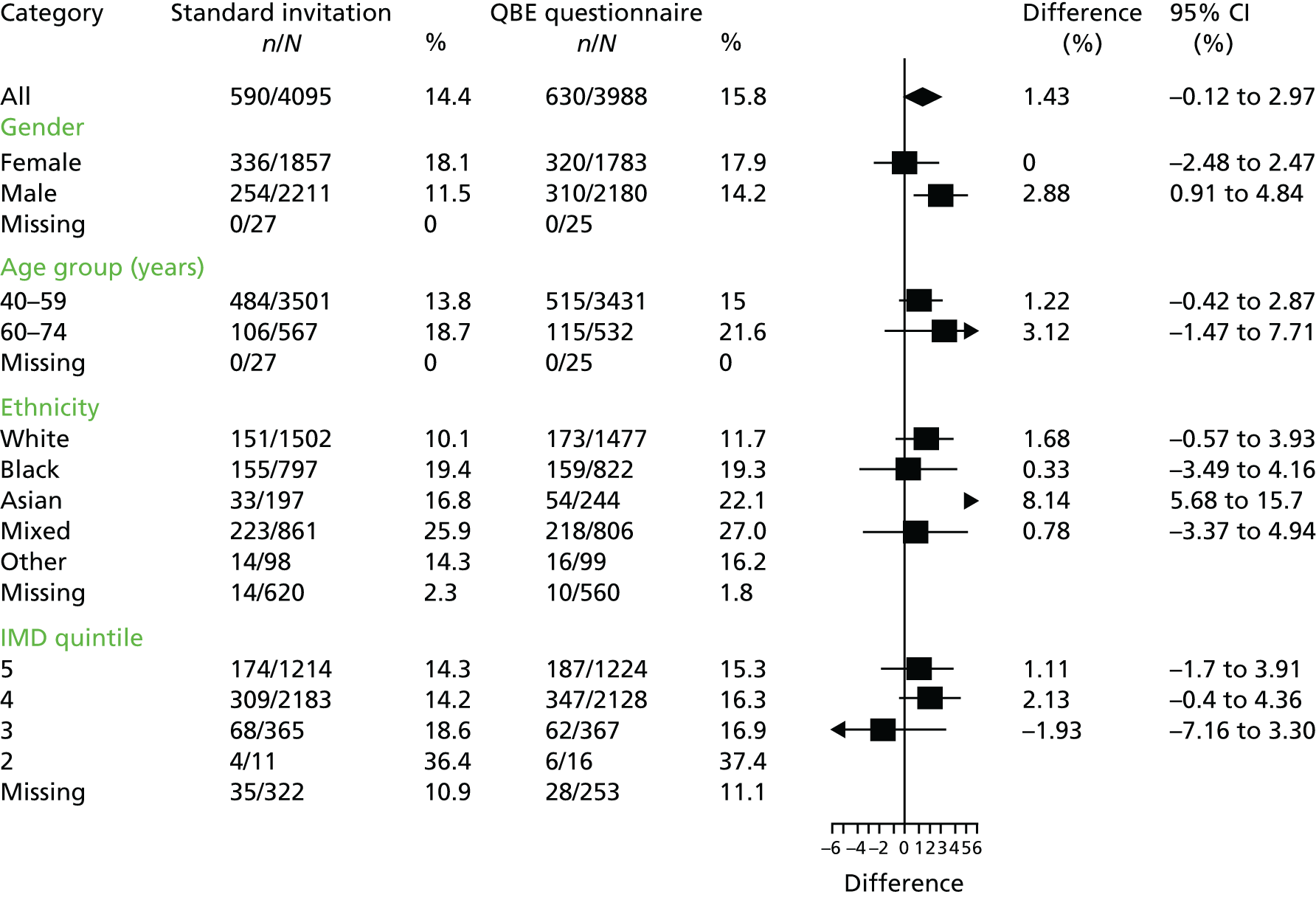

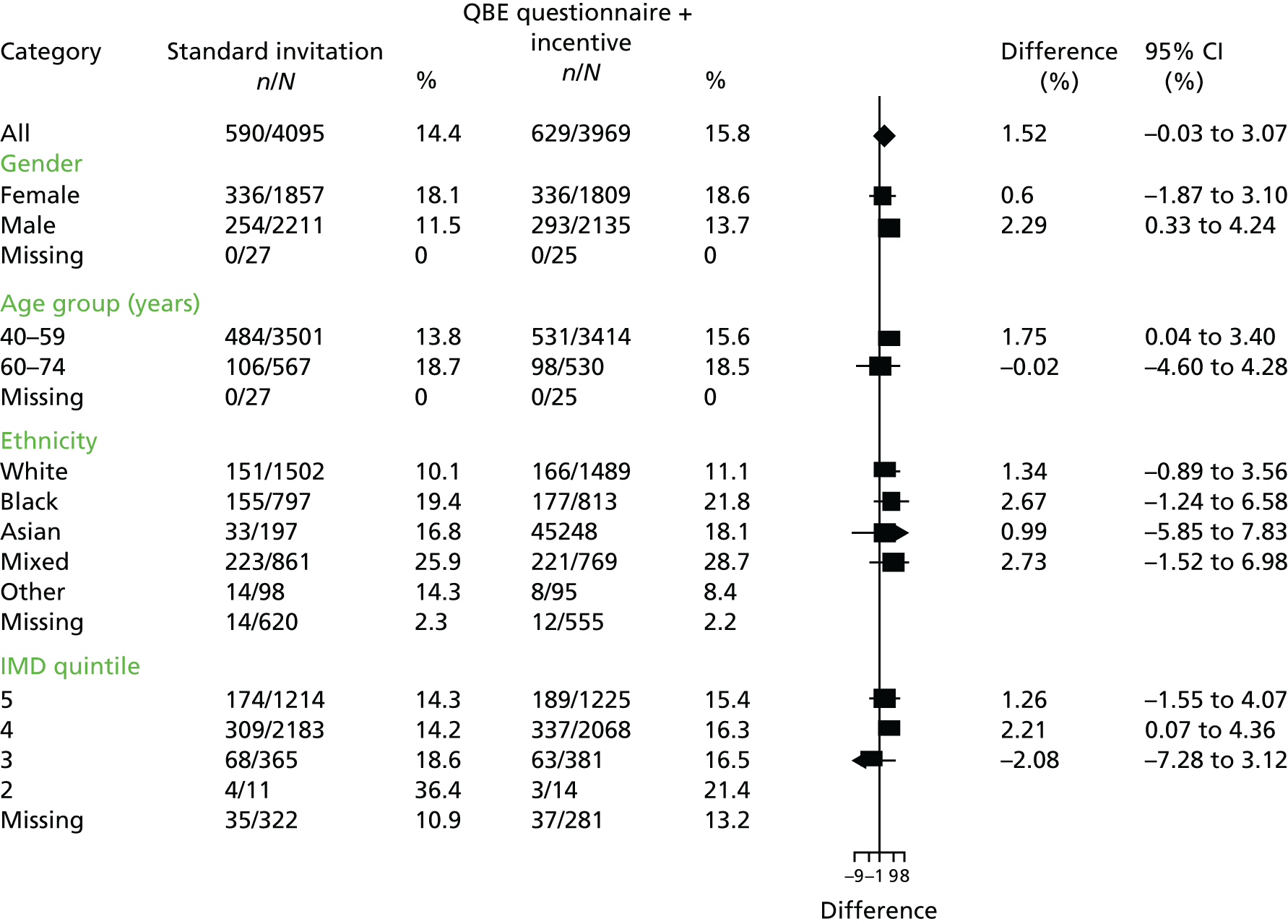

To adjust for practice effect, a marginal model using the method of generalised estimating equations (GEEs) was implemented. As the number of practices was relatively small, we used an exchangeable correlation structure with model-based variance estimates. 70 As the primary interest was to estimate absolute differences in NHS health check uptake, rather than in relative measures such as ORs, the GEE model was implemented using the binomial family and an identity link. In addition to treatment arm the model included the stratification variables month of invitation and year. The associated p-values for treatment arm were assessed at the 1.67% significance level to allow for three comparisons: standard invitation with QBE, standard invitation with QBE and incentive and QBE with QBE and incentive. Estimates were also obtained using the same methods for subgroups of gender, age group, ethnic group and deprivation quintile. Forest plots were constructed using the ‘forestplot’ package in the R program (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome

The model estimates from the primary analysis were compared using different estimation methods. The GEE model was compared with a general linear model (GLM) with and without the use of robust standard errors and the results tabulated.

A meta-analysis was used to examine the impact of recruitment and randomisation procedures by comparing automated and in-practice methods for each of the three trial arm comparisons in turn. A forest plot was used to visualise the intervention estimates for the difference in uptake between arms at practice level. Heterogeneity in estimates was assessed using the I2 statistic. 71 In the absence of heterogeneity, estimates were combined by use of a fixed-effects model.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Time to health check uptake

Time to health check uptake was calculated as the time between the invitation date and the date of the recorded health check or 6-month follow-up, whichever came first. Patients who died or who left the practice were treated as a censored observation at the last date registered. A time to health check curve was plotted by treatment arm using the method of Kaplan–Meier. 72

Inequalities

The distribution of the primary outcome was evaluated by subgroups of gender, age (5- and 10-year age groups), ethnicity (white, mixed, black Caribbean, black African, black other, other and not known) and deprivation (using deciles of the distribution of IMD 2010 scores for England66). The intervention effect was estimated for each subgroup and displayed by means of a forest plot. The impact of participant characteristics on uptake was further examined by undertaking adjusted analyses using the primary analysis model including treatment arm, month of invitation, year, age, gender and deprivation quintile. Fully adjusted analyses were conducted using a logit link, to estimate adjusted ORs.

Analysis of questionnaire responses

To explore whether or not individuals who completed the questionnaire were more likely to subsequently attend a health check and to assess whether or not offering an incentive for return differed across deprivation quintile, we fitted a marginal model with a binomial family and identity link using the method of GEEs. Covariates in the model included the stratification variable month of invitation, year, questionnaire return (yes/no), treatment arm, deprivation quintile and trial arm by deprivation quintile interaction. A complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis was performed to estimate the effect of the intervention on health check uptake in ‘compliers’. Compliers were defined as participants who returned a QBE questionnaire in either of the intervention arms, or who ‘would have’ returned a questionnaire if they were in the standard invitation arm. This analysis followed the approach laid out in Dunn et al. 73 As no participants were lost to follow-up we were able to estimate the intervention effect without taking into account the missing data mechanism. An estimate of the standard error for the statistic was obtained through bootstrapping.

Responses to questionnaire items were tabulated using means (SDs) of the seven-category scale. Pairwise correlations of relevant questionnaire items were evaluated prior to constructing scale scores for further use in the analyses. The correlations of these constructs with each other were evaluated. Analysis of variance was employed to evaluate differences in responses between the two questionnaire trial arms. The association of each construct with health check uptake was evaluated in a logistic model, with the construct fitted as a linear predictor. Robust standard errors were estimated. Finally, each construct was dichotomised at the median and the association of highly positive responses, compared with less positive responses, with health check uptake was evaluated in a logistic model.

Evaluation of the study as a rapid trial and analysis of the randomisation methods