Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/99/02. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The draft report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in January 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Farrar et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Normal pregnancy is associated with insulin resistance that is similar to that found in type 2 diabetes. Physiological resistance to insulin action during pregnancy becomes apparent in the second trimester, and insulin resistance increases progressively to term. These changes facilitate transport of glucose across the placenta to ensure normal fetal growth and development. Transfer of glucose across the placenta stimulates fetal pancreatic insulin secretion, and insulin acts as an essential growth hormone. However, if resistance to maternal insulin action becomes too pronounced then maternal hyperglycaemia occurs and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) may be diagnosed.

Associated risks

Gestational diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, including large-for-gestational-age (LGA) birthweight (BW), macrosomia (defined as BW of > 4 kg) and Caesarean section (C-section). 1 There is also limited evidence that GDM is associated with increased risk of longer-term ill health outcomes in the mother (e.g. type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease)2,3 and offspring (e.g. obesity and associated cardiometabolic risk). 4,5

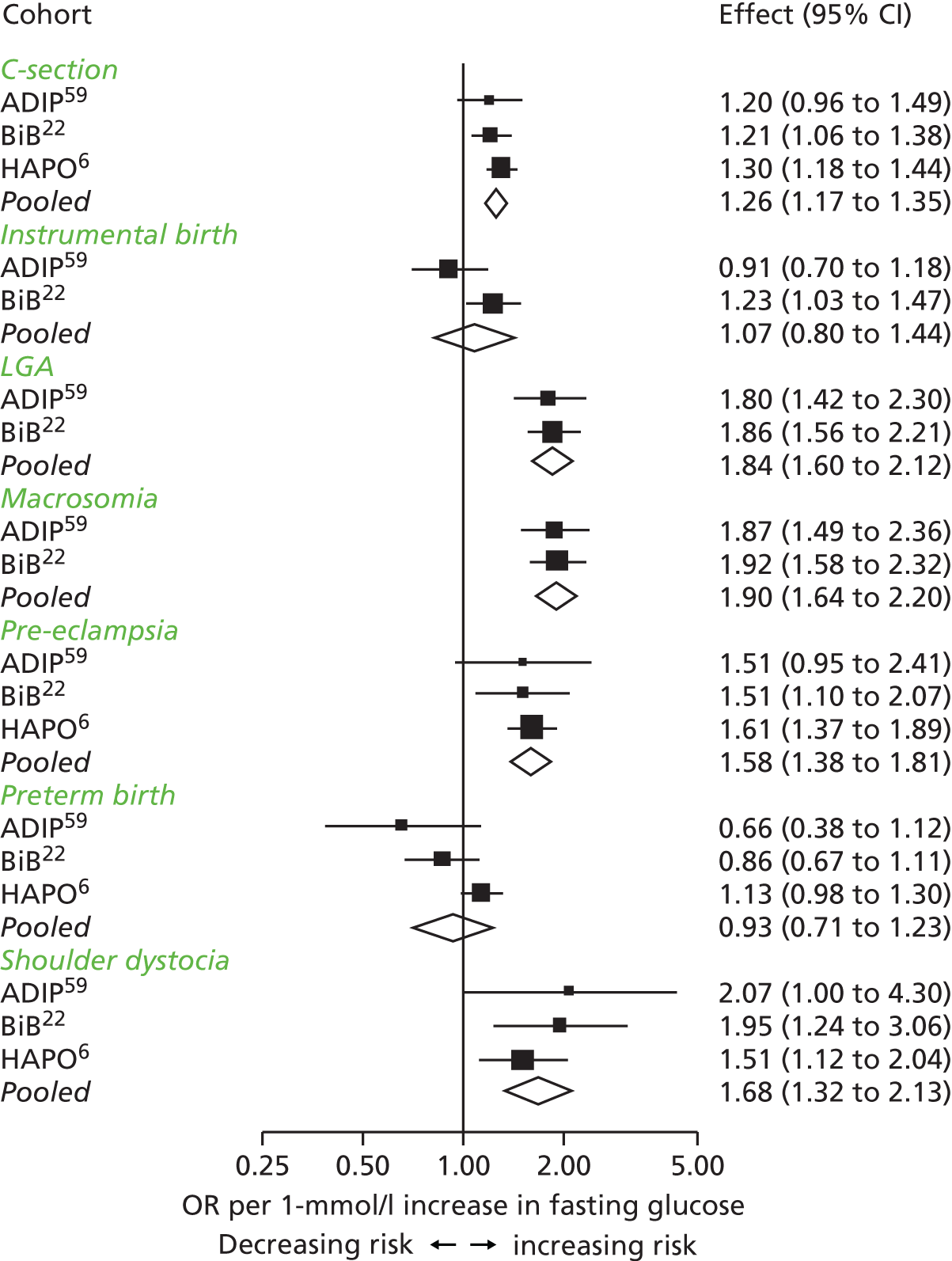

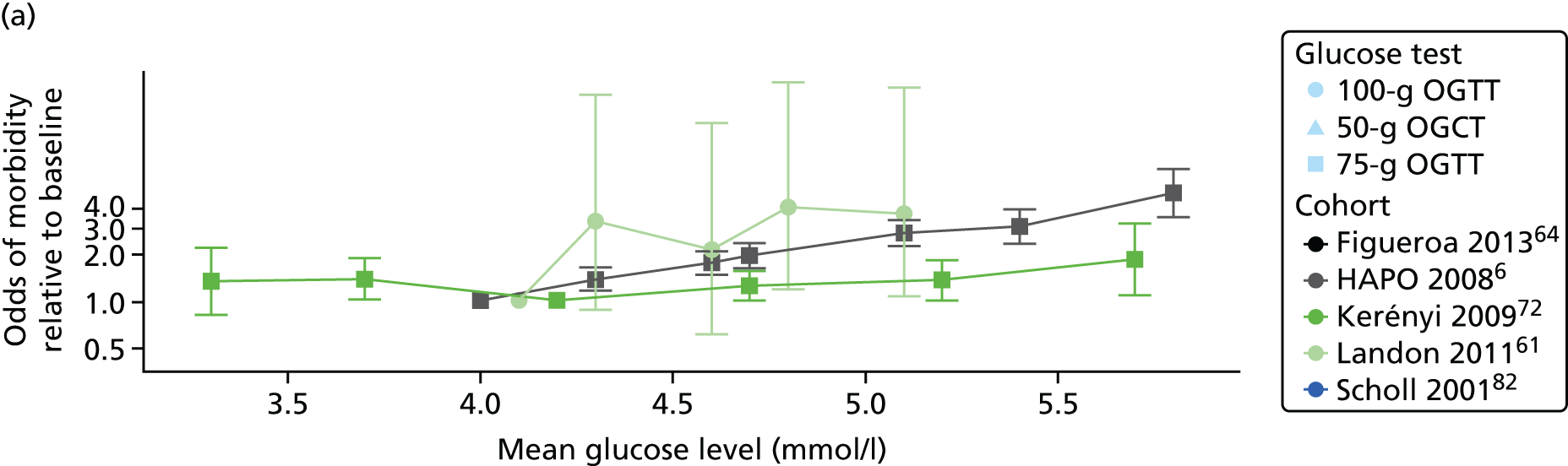

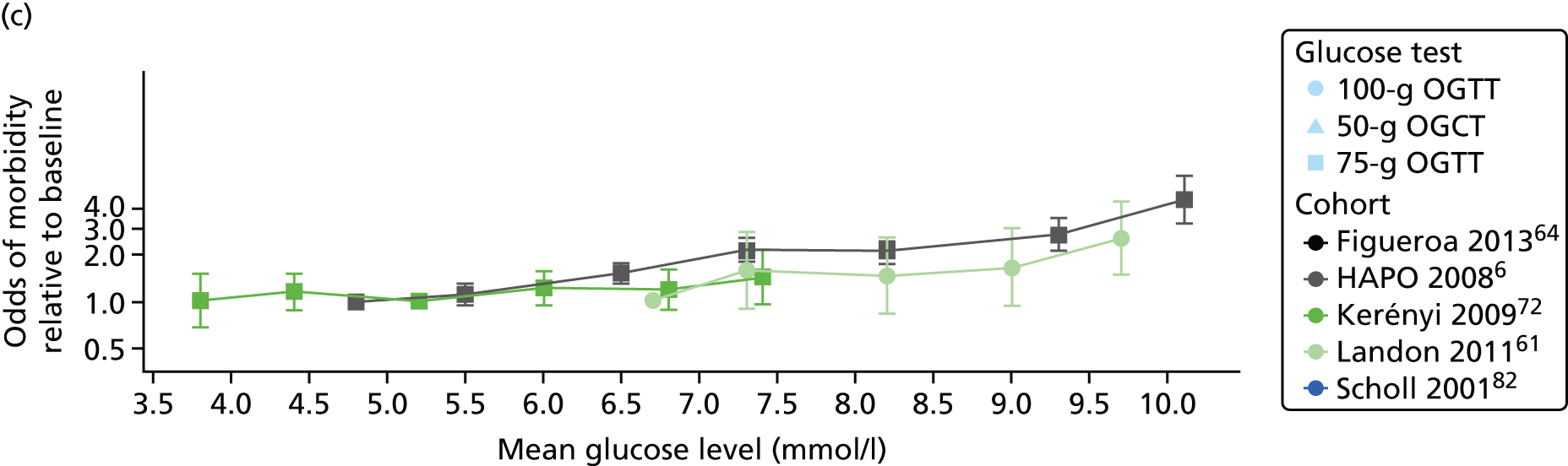

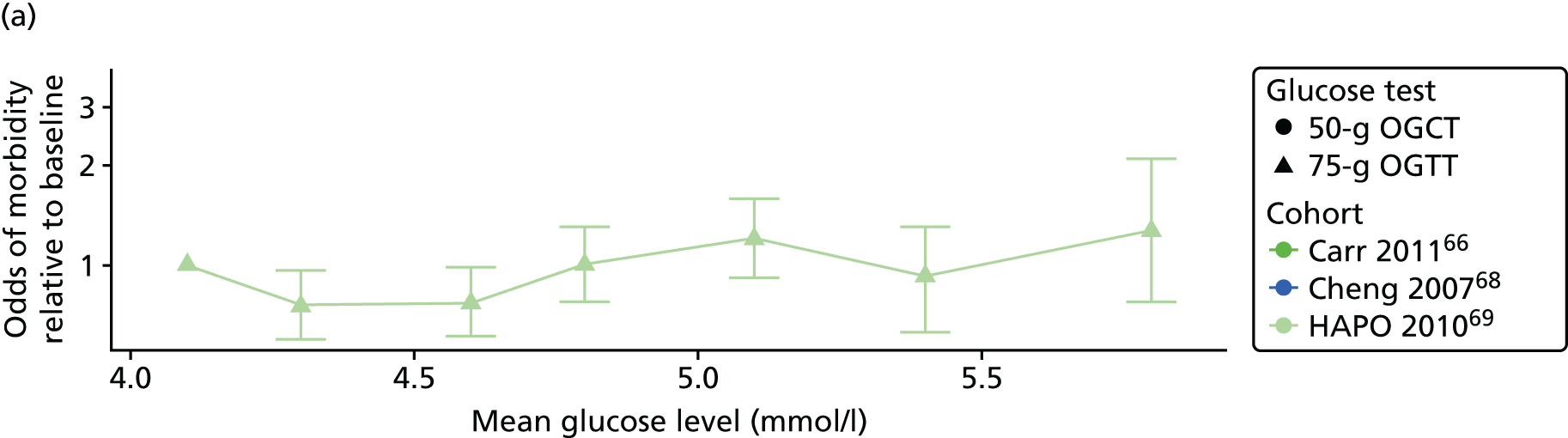

Recently, the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study6 examined the association between gestational fasting and post-load glucose levels in women without diabetes. These findings have been used by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) to inform their criteria to diagnose GDM. The HAPO study6 reported graded linear increases in the odds of four primary outcomes (BW of > 90th centile for gestational age, primary C-section, diagnosed neonatal hypoglycaemia and cord blood C-peptide of > 90th percentile) across the whole distribution of fasting and post-load glucose levels, illustrating no clear threshold below which there is no increase in risk. There were also graded monotonic associations with a majority of secondary outcomes, including preterm birth, shoulder dystocia and pre-eclampsia. However, there were limited numbers of South Asian (SA) women included and no SA centres. In Chapters 2 and 3 we report analyses (using similar methods to those used by the HAPO study6) using individual participant data (IPD) and data from published studies to determine the risk of adverse outcomes associated with graded increases in maternal glucose levels, in the BiB study,7 to determine the differences in risk between SA and white British (WB) women, and, in IPD and published studies, combined, for all women.

Screening

An important question regarding the diagnosis of GDM is what glucose thresholds (fasting or post load) are most clinically effective and cost-effective. Appropriate identification of women who develop GDM is essential so that treatment can be provided to reduce the associated risks. However, diagnosis is complex and there are a number of different criteria with different thresholds used internationally and nationally (Table 1). This lack of a clear threshold to signify increased risk means that somewhat arbitrary thresholds need to be used to define GDM, an issue that is similar to the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia [which, like GDM, are diagnoses made to indicate risk of later disease (cardiovascular disease for these exposures) that might be prevented by appropriate intervention (lifestyle change and medication)]. In Chapters 2–4 we report details of our derived thresholds using IPD and published data for diagnosing GDM and prevalences using past and current criteria.

| Criteria | Fasting | 1-hour post load | 2-hour post load | 3-hour post load |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75-g OGTT (plasma glucose) | ||||

| aIADPSG8 (2010), ADIPS9 (2013), WHO10 (2013) | ≥ 5.1 | ≥ 10.0 | ≥ 8.5 | – |

| aWHO11 (1999) | ≥ 6.1 | – | ≥ 7.8 | – |

| aADA12 (2006) | ≥ 5.3 | ≥ 10.0 | ≥ 8.6 | |

| aADIPS13 (1998) | ≥ 5.5 | – | ≥ 8.0 | – |

| 100-g OGTT (plasma or serum glucose) | ||||

| bACOG14/C&C | ≥ 5.3 | ≥ 10.0 | ≥ 8.6 | ≥ 7.8 |

| bNDDG15 | ≥ 5.8 | ≥ 10.6 | ≥ 9.2 | ≥ 8.0 |

| bO’Sullivan16 | ≥ 5.0 | ≥ 9.2 | ≥ 8.1 | ≥ 6.9 |

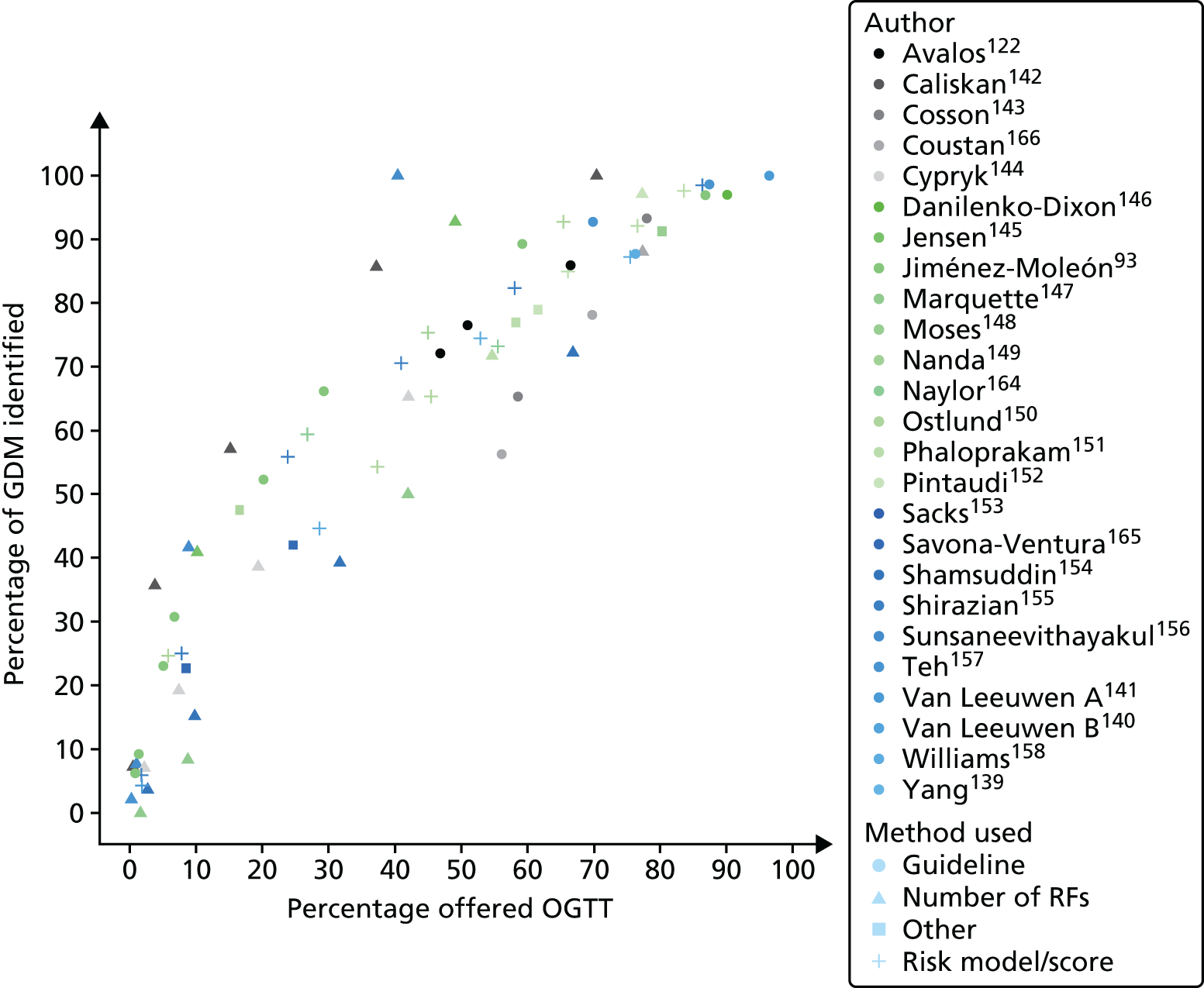

There are two main strategies to identify women with GDM: (1) universal testing, through which all women are offered a diagnostic test [usually an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)]; or (2) selective testing, through which those women identified as having an increased risk of developing GDM are offered a diagnostic test. The second strategy is closer to the more usual screening model described by the UK National Screening Committee (NSC). 17

Once risk is identified (in universal screening/selective testing), those at high risk (however defined) will be offered a diagnostic test (usually an OGTT) and, depending on those results, will be given advice and/or medical treatment or not. 17 Screening is therefore undertaken to (1) identify those women at greatest risk, to prevent unnecessary diagnostic testing of those women unlikely to develop GDM, and (2) reduce costs associated with universal diagnostic testing.

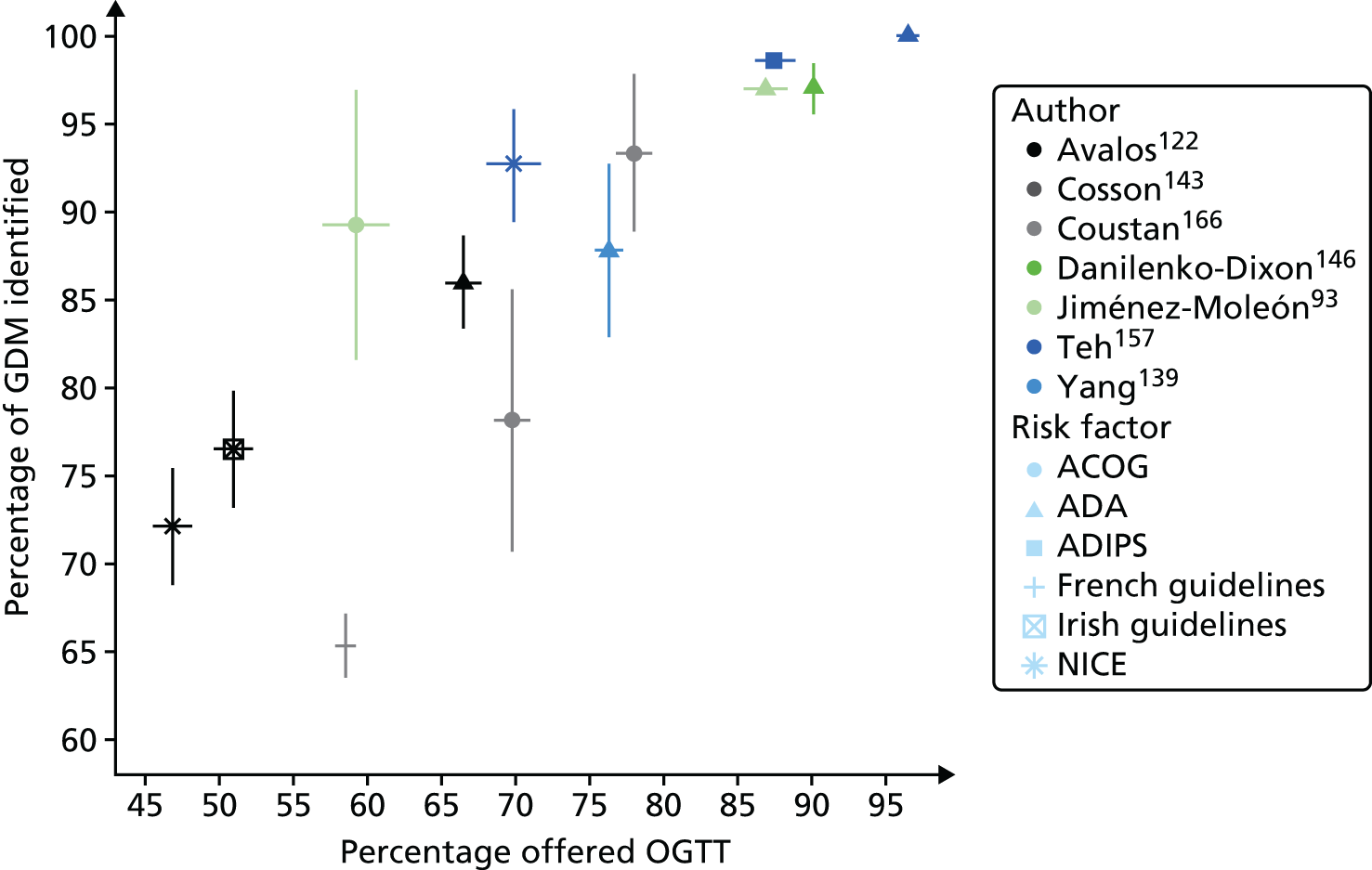

Several health-care agencies including the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)18 recommend that pregnant women should have their risk evaluated by assessment of maternal characteristics (risk factors) (see Table 14). Those with one or more risk factor should be offered a diagnostic OGTT. Chapter 5 of this report examines the accuracy of maternal characteristics as risk factors for the identification of women who are most likely to develop GDM. We have examined the performance of maternal characteristics, first using IPD, and second using published data. Maternal risk factors for GDM include advanced maternal age, high body mass index (BMI), previous GDM, previous macrosomic infant, family history of type 2 diabetes or GDM (in a previous pregnancy), and ethnicity with a high associated prevalence of diabetes. We have chosen to focus on maternal characteristics (and not to include invasive screening tests, including blood tests) because this strategy is recommended for use by several agencies including NICE. 19

Diagnostic testing

Gestational diabetes mellitus is generally diagnosed using an OGTT. The OGTT is normally conducted in the morning following an overnight fast. A baseline plasma glucose sample is obtained; the woman then consumes a drink containing typically 75 g or 100 g of glucose and then at hourly intervals plasma glucose level is measured. The frequency of measurement depends on the glucose load and local policy. Women with an ‘elevated’ glucose level at one or two or more measurements are classified as having GDM.

There are some limitations to the OGTT as a diagnostic test, however: (1) a negative OGTT does not mean a woman will not develop GDM later in pregnancy, because as gestation progresses, insulin resistance may increase, therefore repeat glucose testing may be required; (2) glucose thresholds for diagnosis are arbitrary cut-off points and vary depending on the recommending agencies (see Table 1); and (3) the reproducibility of the OGTT is only around 75%20,21 (we have not examined the performance of the OGTT within this report).

Treatments for gestational diabetes

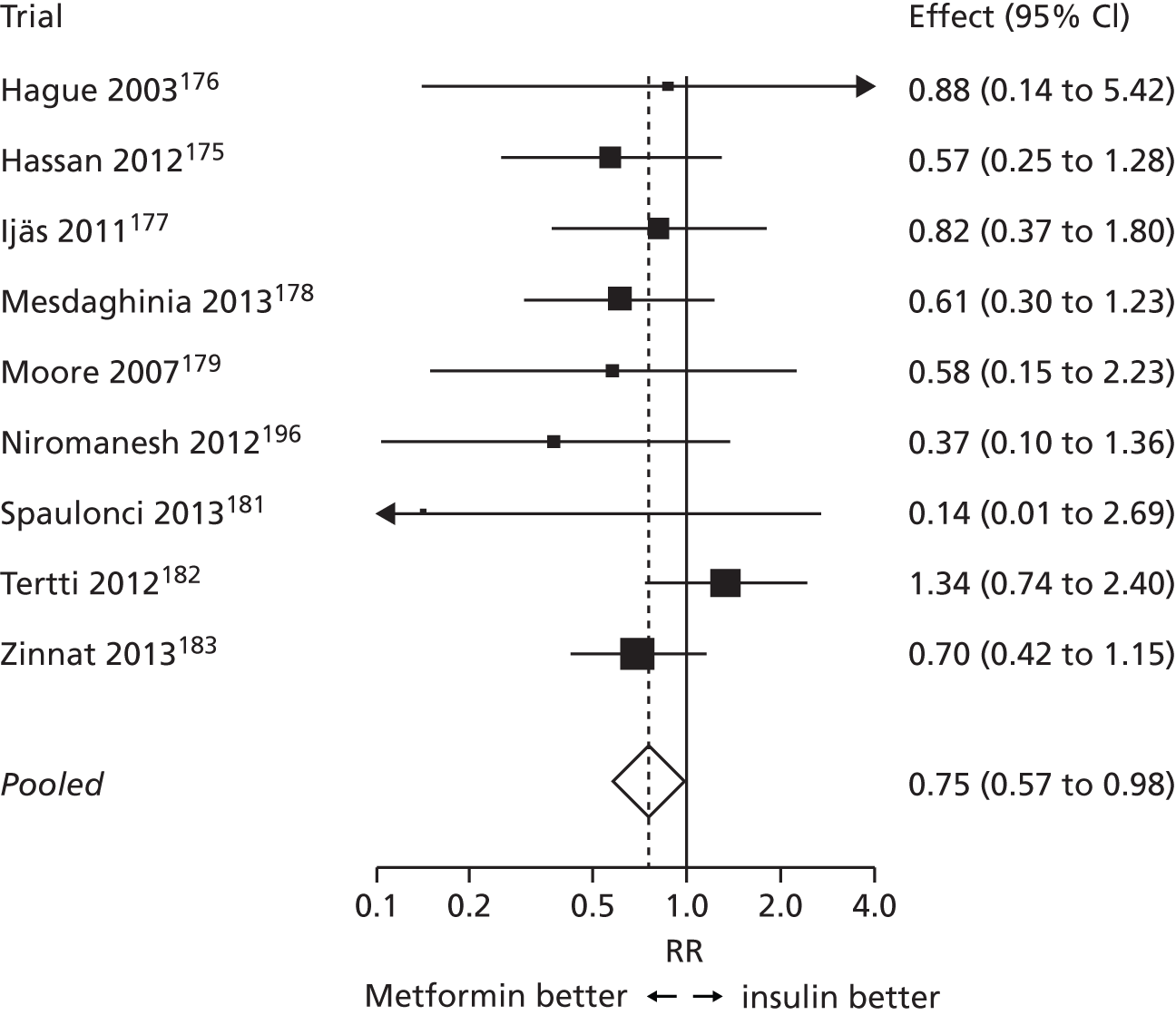

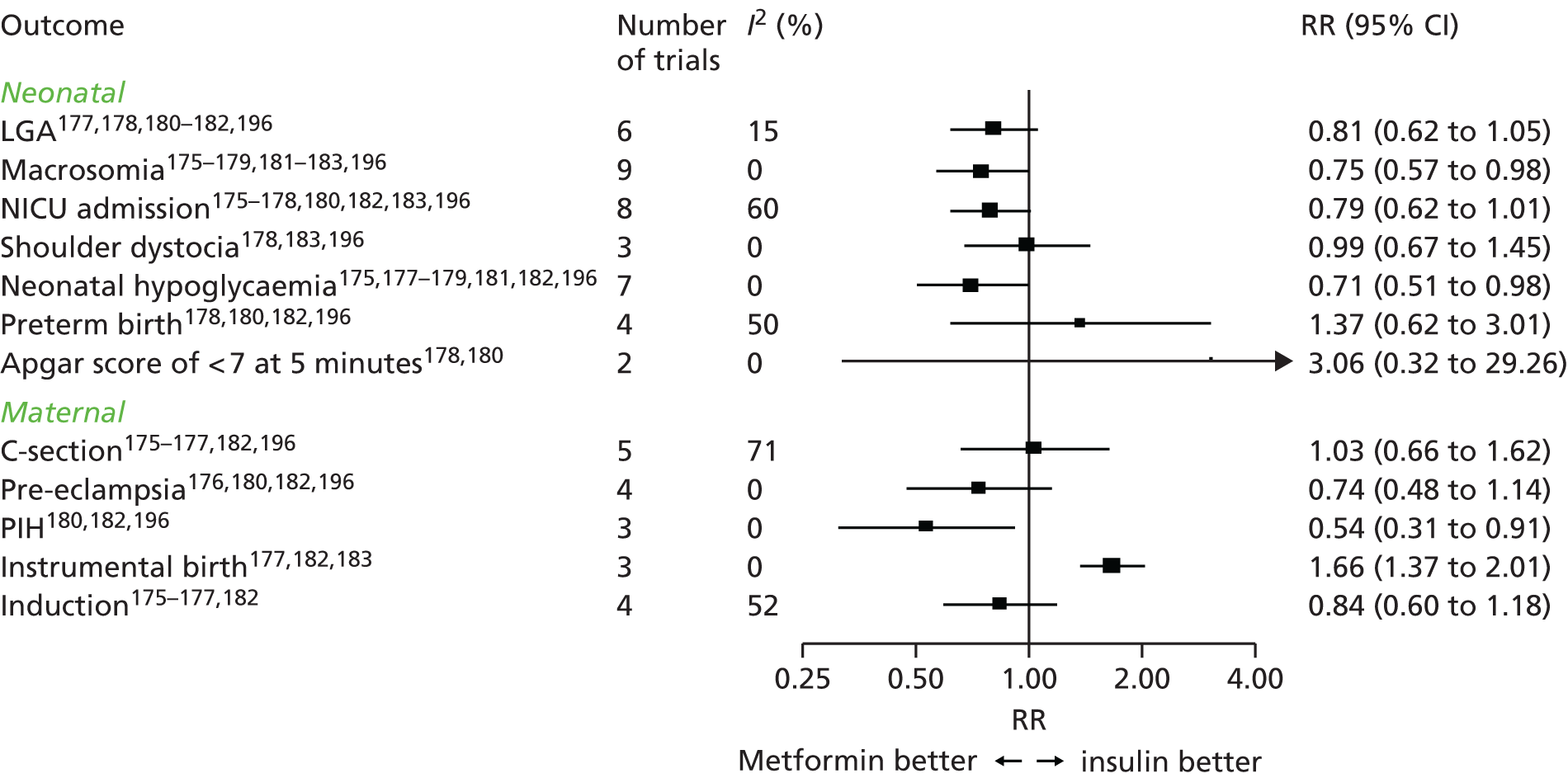

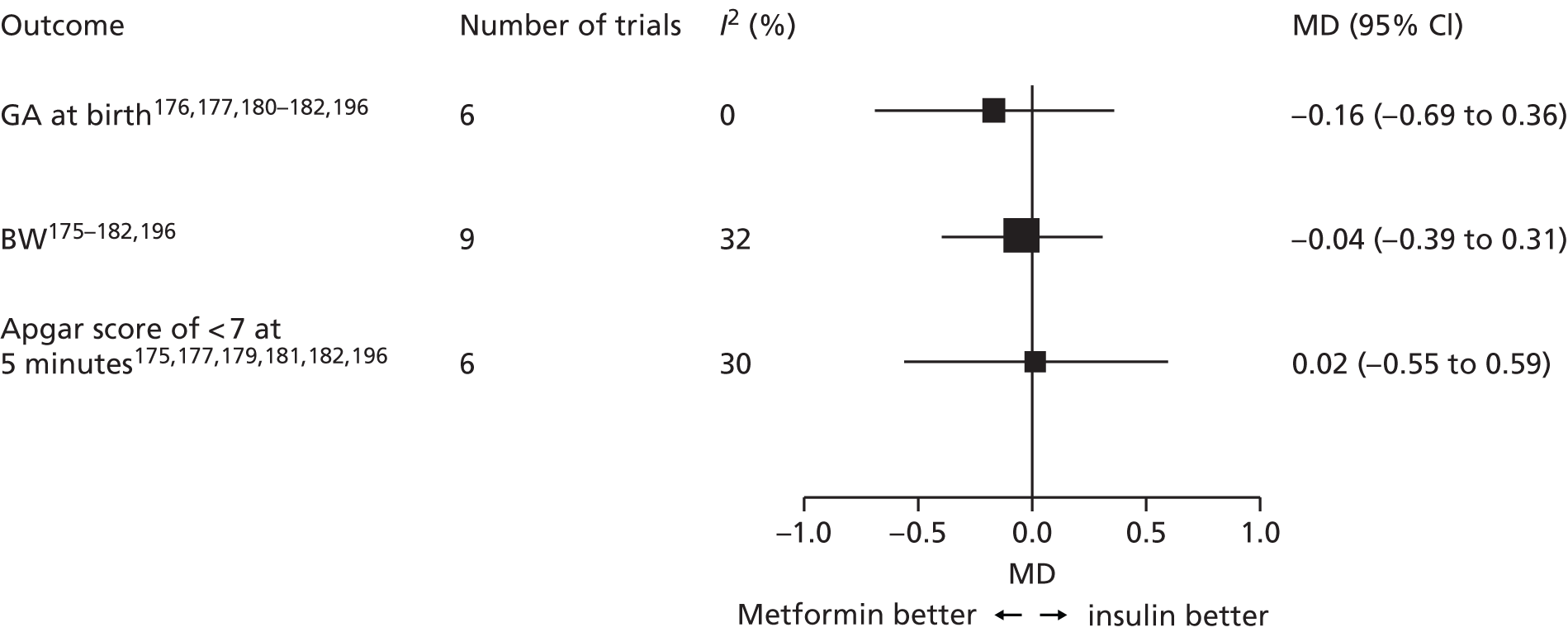

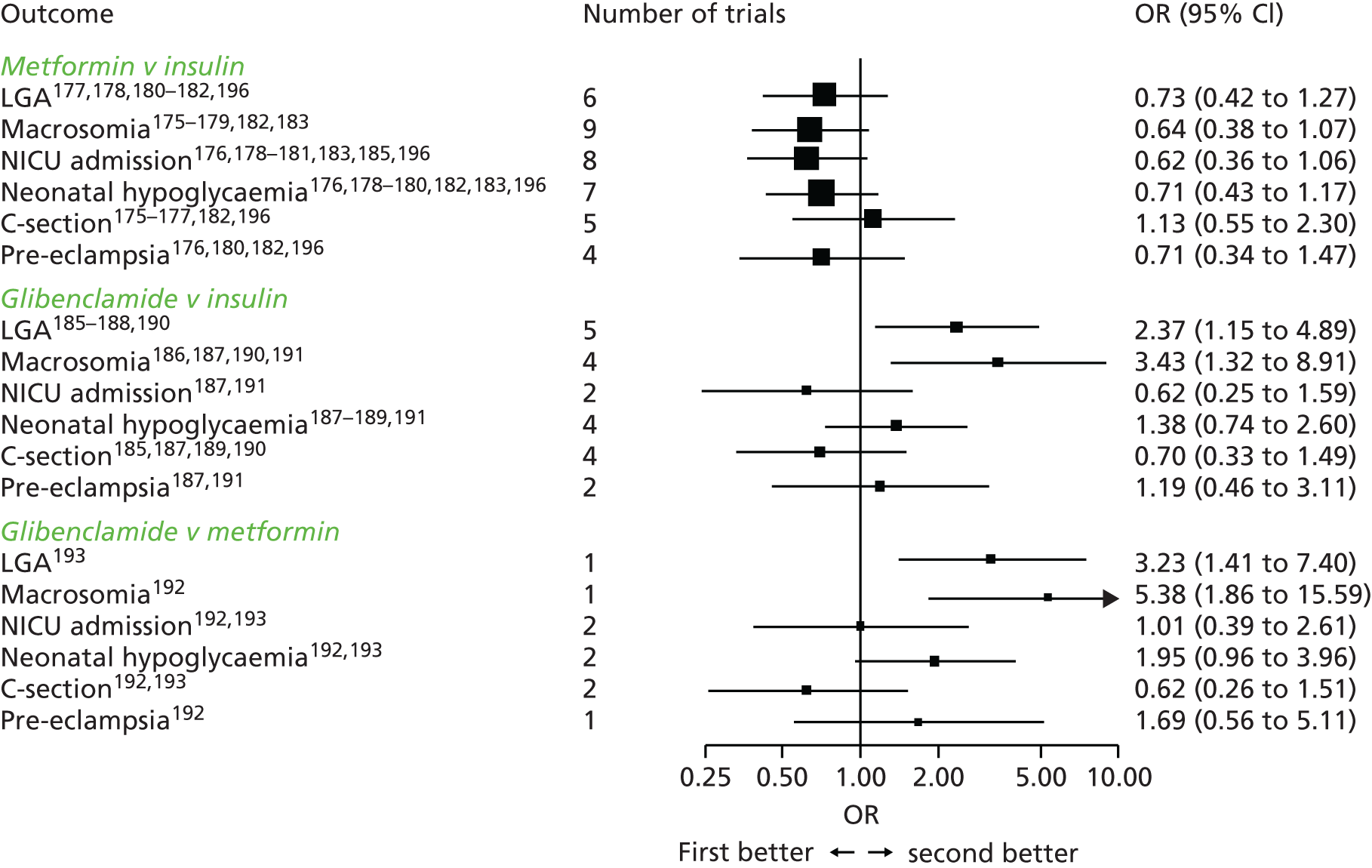

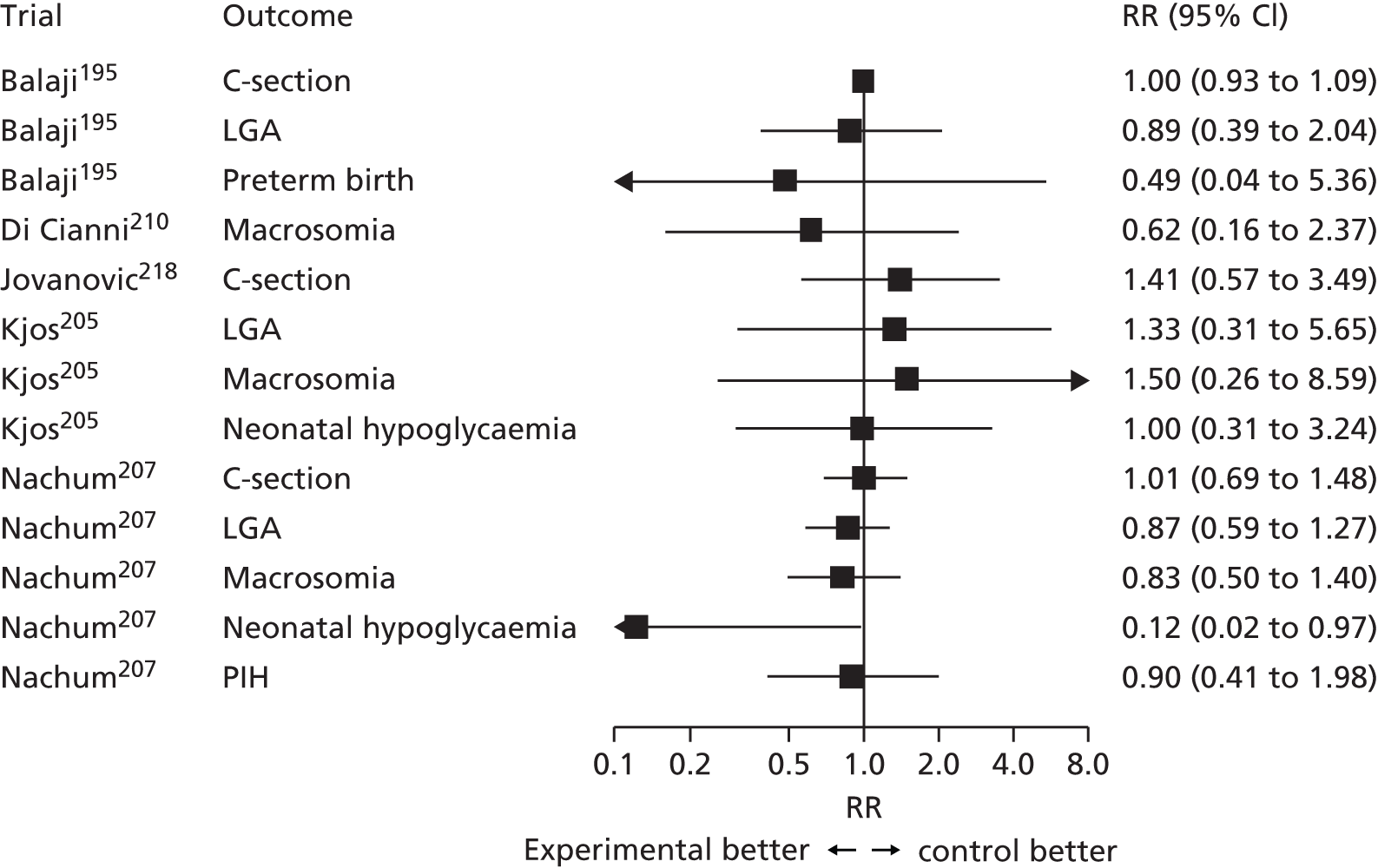

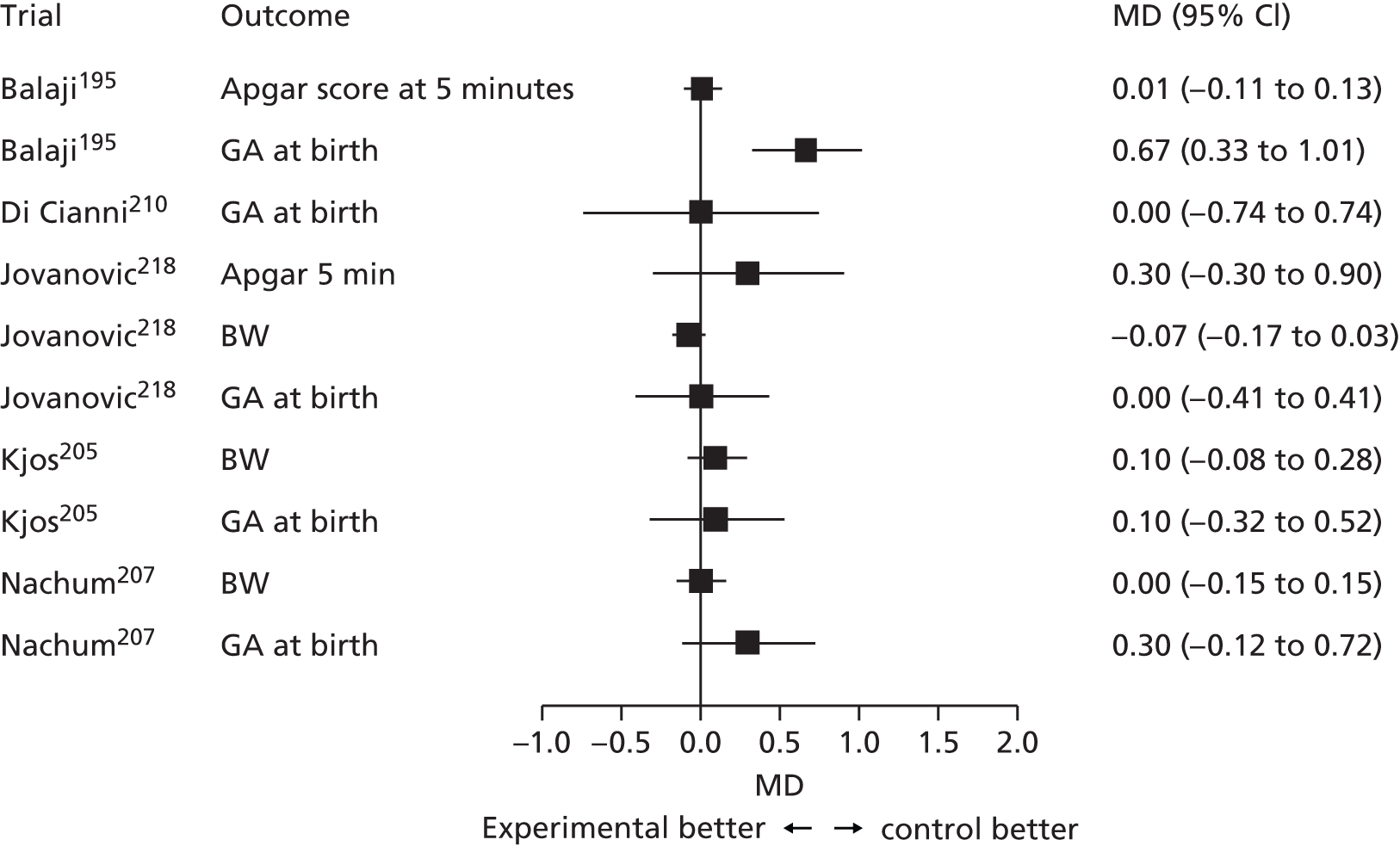

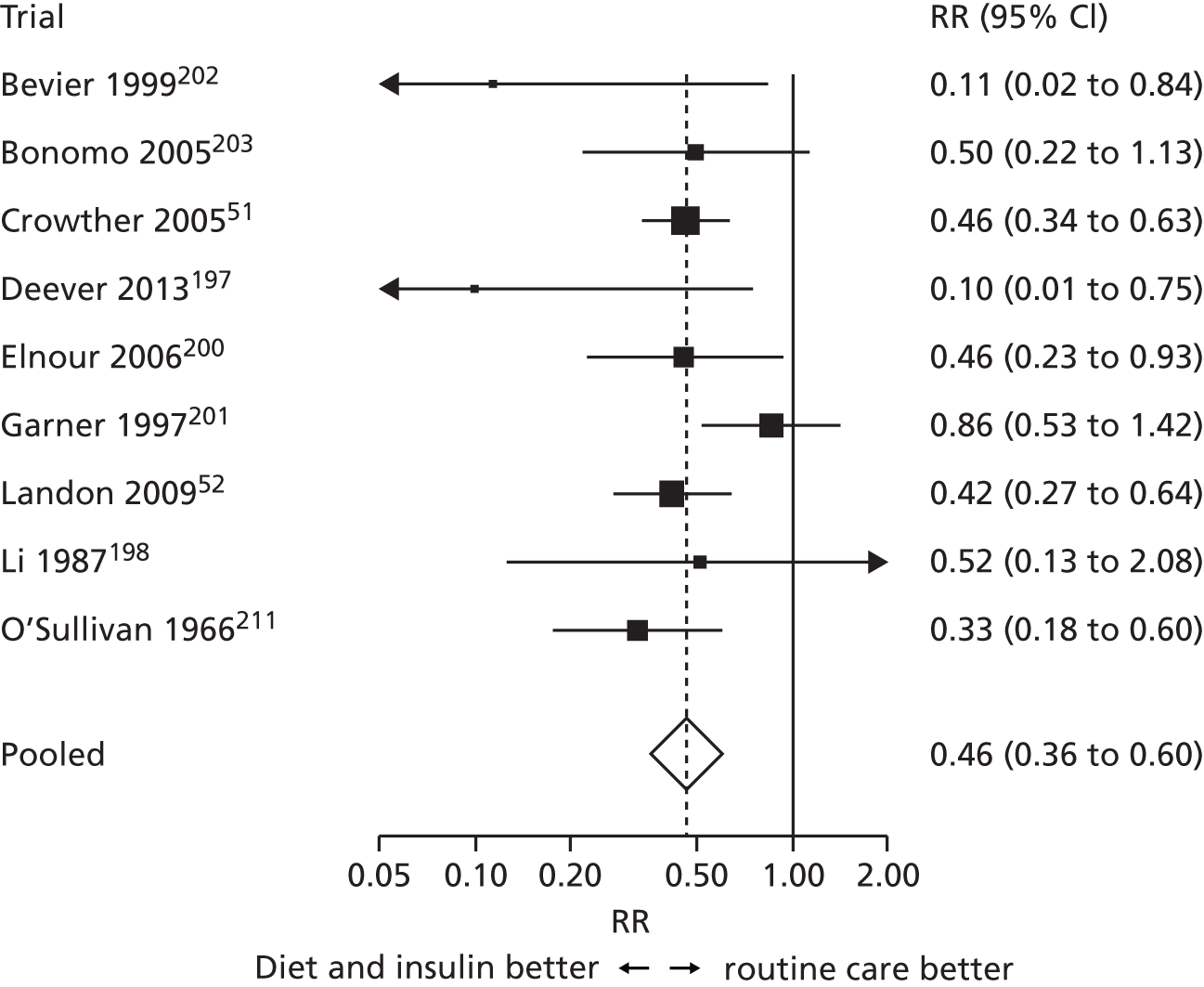

Treatment of GDM aims to reduce hyperglycaemia and, in doing so, reduce the risk of adverse outcomes. Diet/lifestyle modification is often used as first-line treatment; if this does not adequately reduce and control glucose levels or if glucose level is substantially elevated then pharmacological interventions [e.g. metformin (hydrochloride) (Glucophage,® Teva UK Ltd, Eastbourne, UK) and/or insulin] may also be given. Oral agents, including metformin and glibenclamide (Aurobindo Pharma – Milpharm Ltd, South Ruislip, Middlesex, UK), present a possible alternative to injected insulin and may be as effective, with the added benefit of being more acceptable to women.

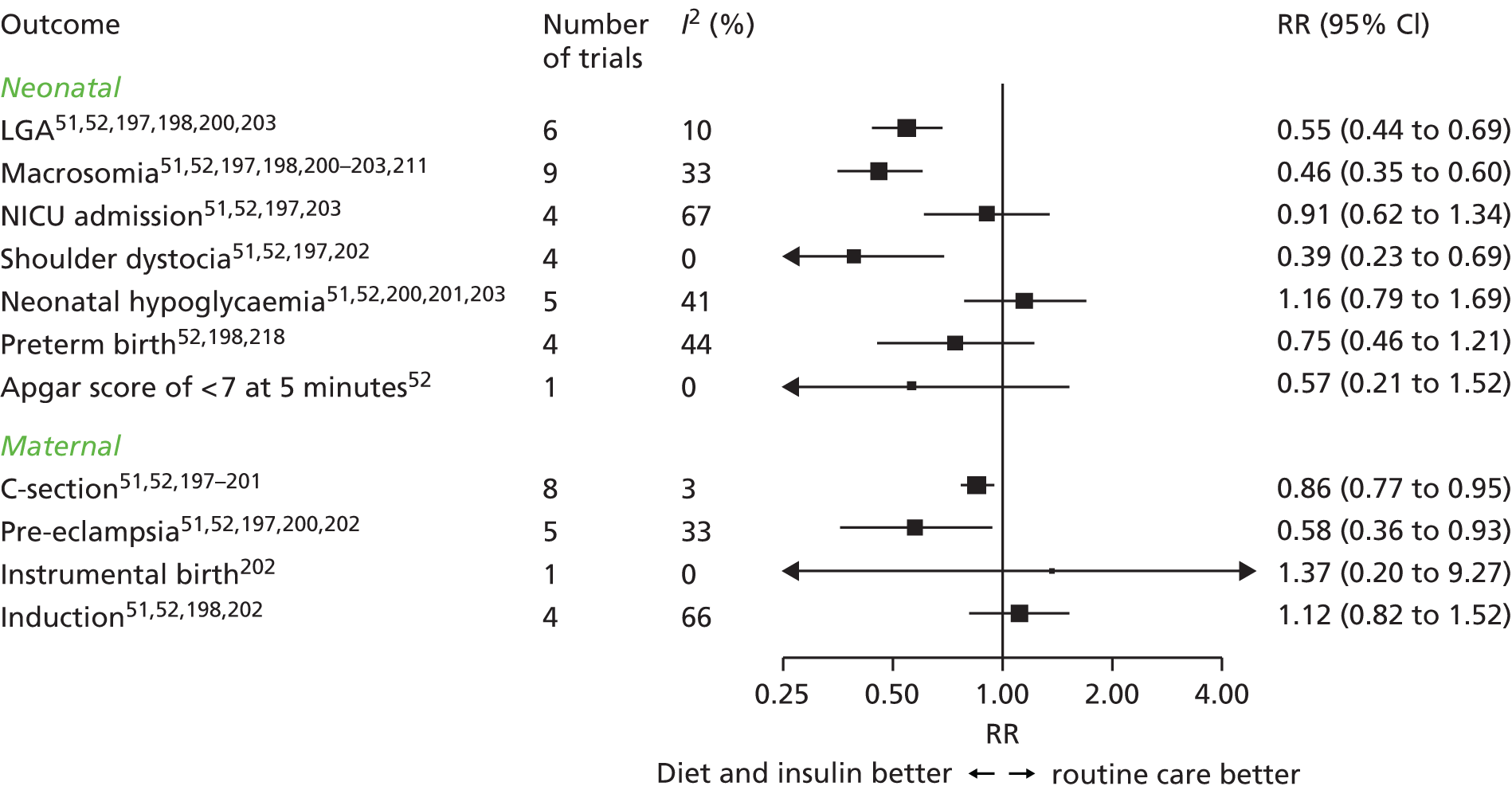

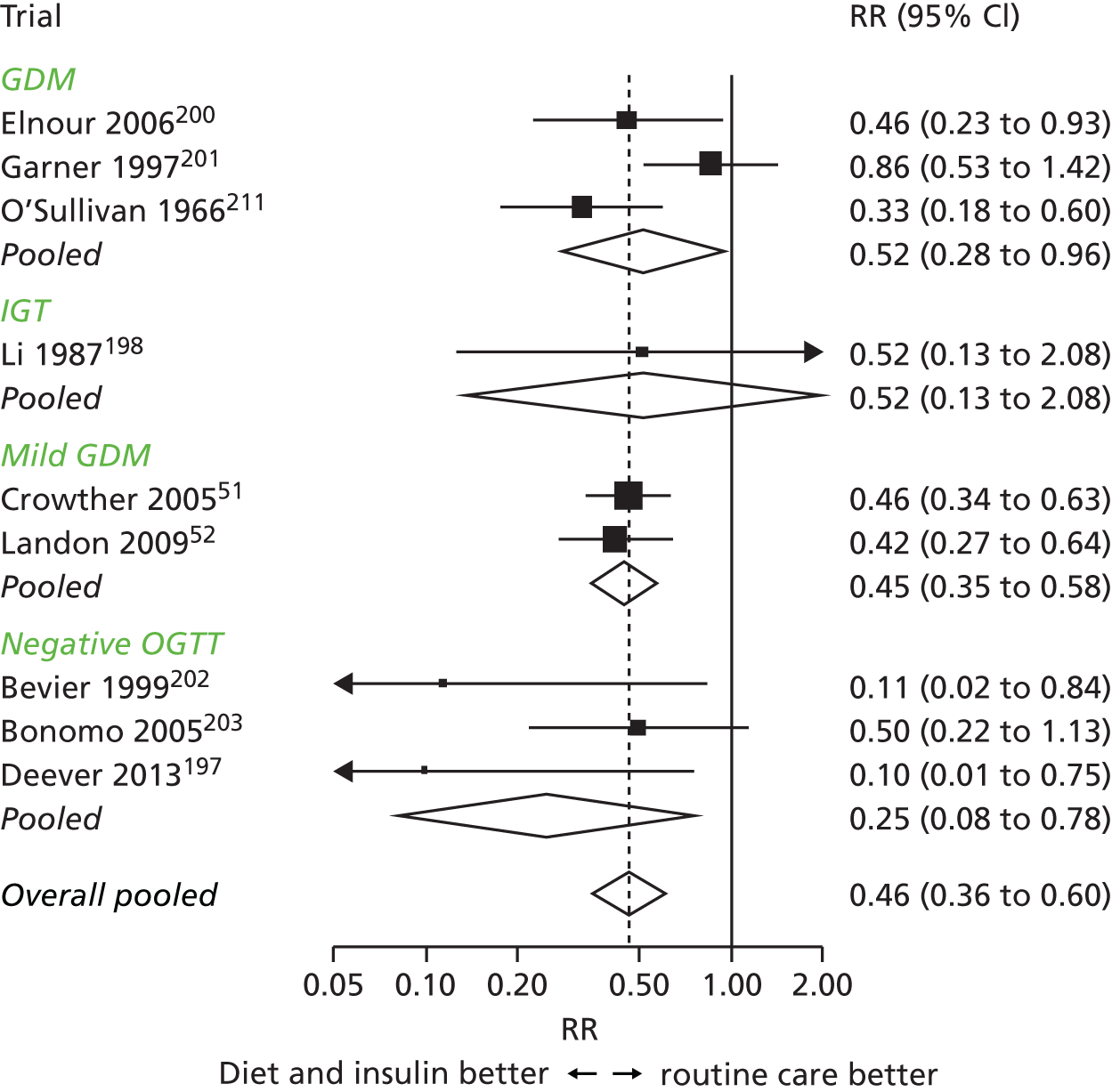

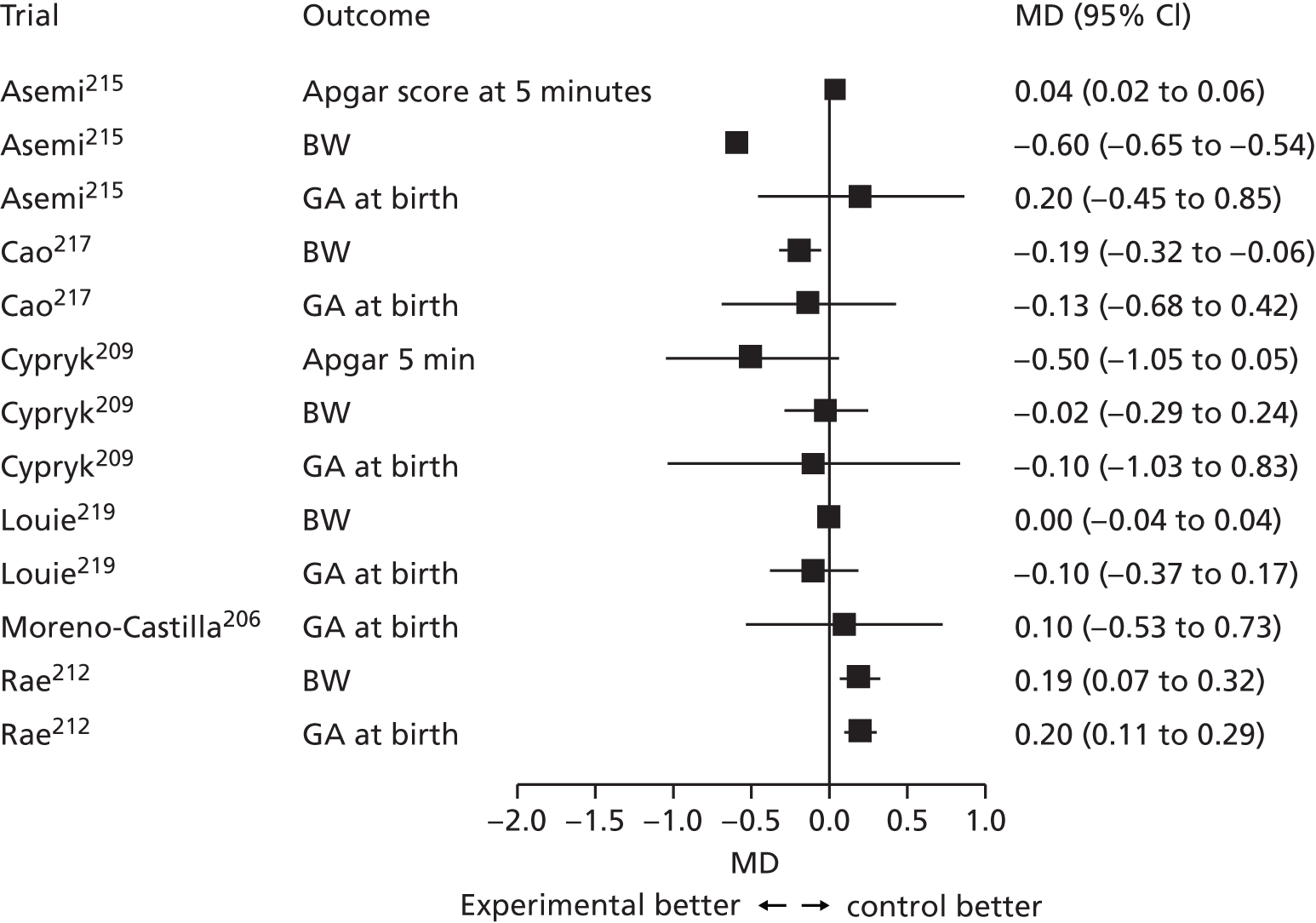

Chapter 6 reports a systematic review investigating the effectiveness of different treatments for GDM to improve maternal and infant health outcomes. Meta- and network-analyses have been carried out where appropriate.

Economic evaluation

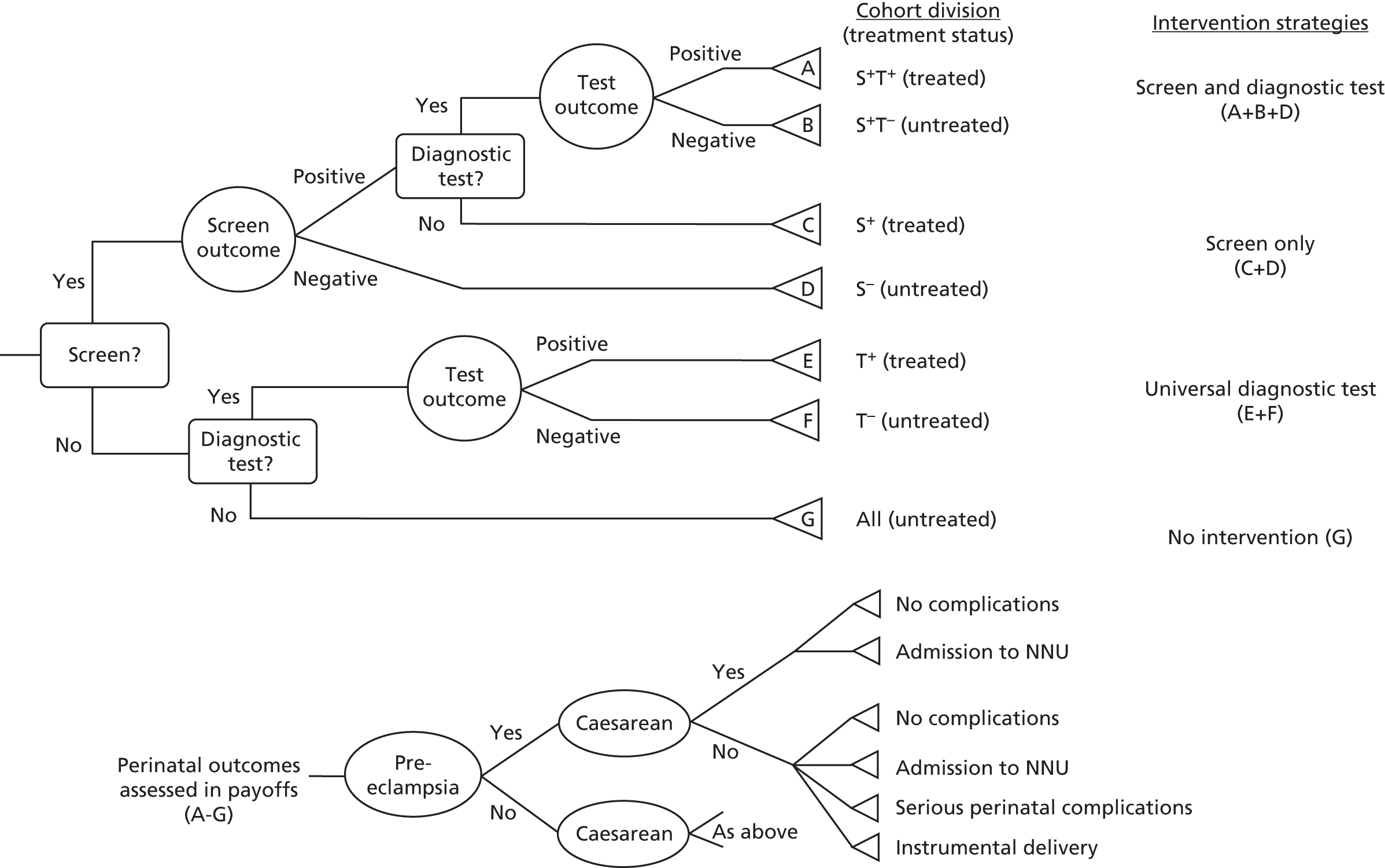

Chapter 7 details an economic evaluation of screening and diagnostic tests to identify and treat women with GDM. Current evidence on the cost-effectiveness of identifying and treating women with GDM is limited; the increasing prevalence of GDM, however, along with increasing demands on health service budgets, makes this evaluation central to the future planning of care pathways and resource allocation. We also report analyses in this chapter that examine the value of undertaking further research to understand the effects of treatments of GDM.

Chapter 2 Hyperglycaemia and the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes in South Asian and white British women: the Born in Bradford cohort

This chapter presents the methods and results of a study to determine the nature of the association between maternal pregnancy glucose levels and risk of perinatal outcomes using IPD from the Born in Bradford (BiB) study. 22 This study7 compares the associations of gestational glucose level with risk of adverse perinatal outcomes between SA and WB women (unless shown within the text sections, figures and tables are shown in the appendices and referred to within the text). A version of this chapter has been published in Farrar et al. 7 This is an Open Access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits use, distribution and reproduction, provided the original work is properly cited (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

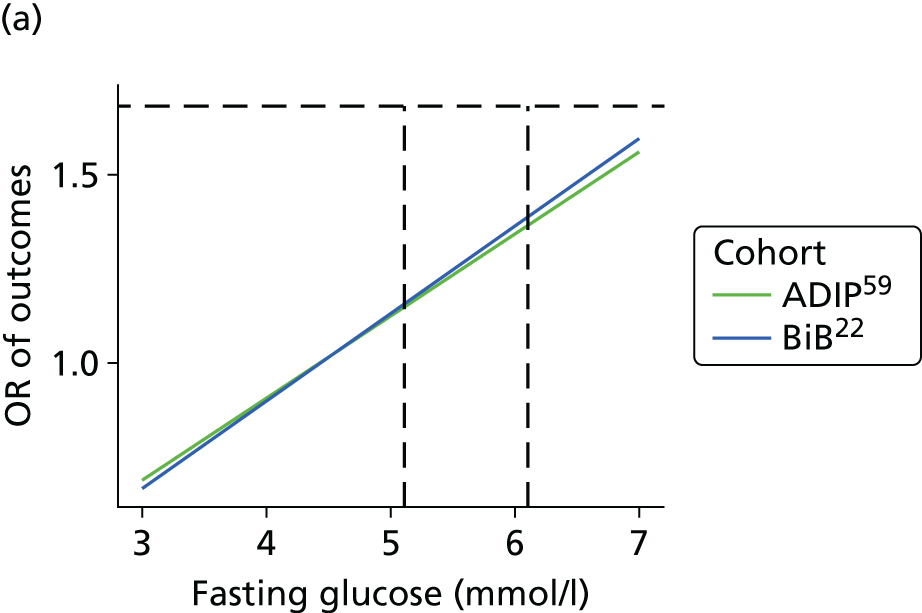

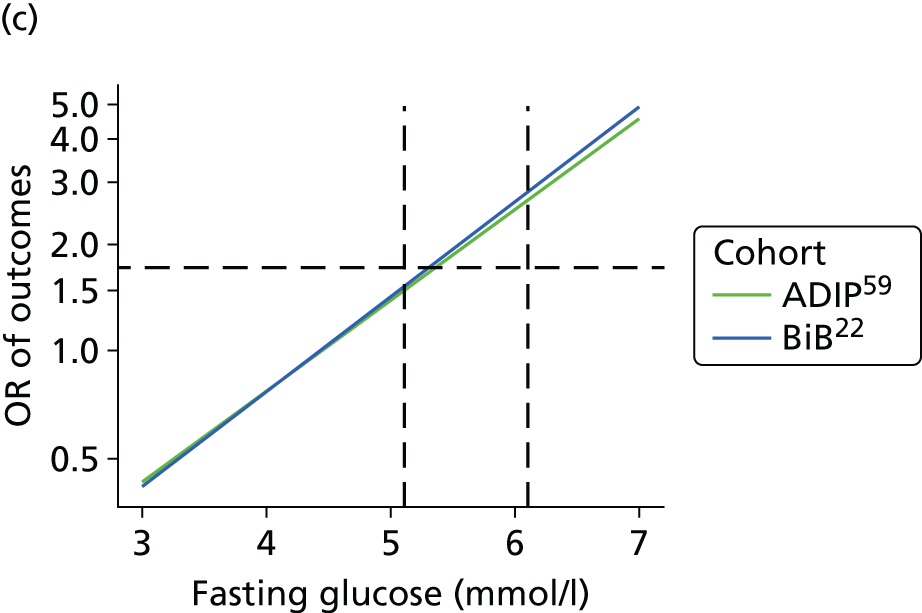

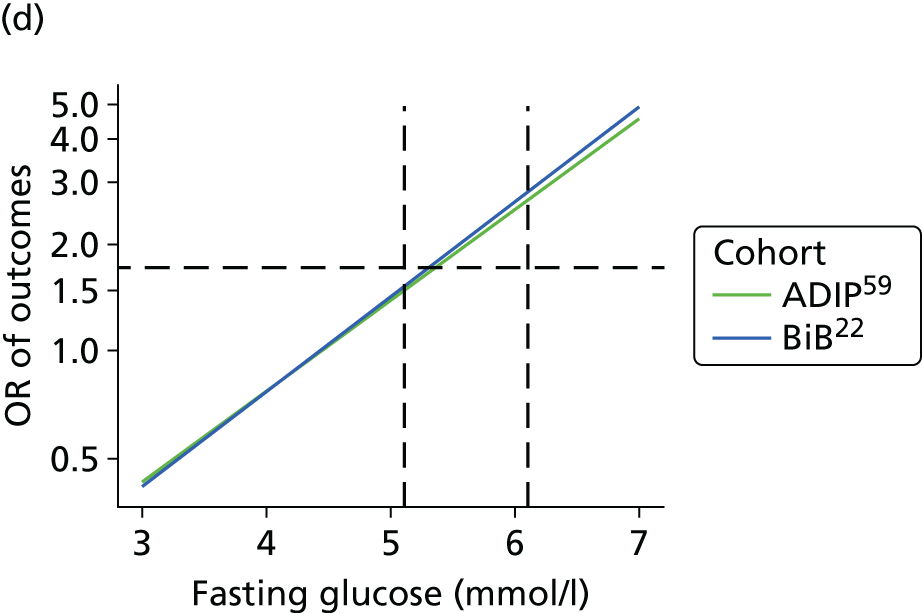

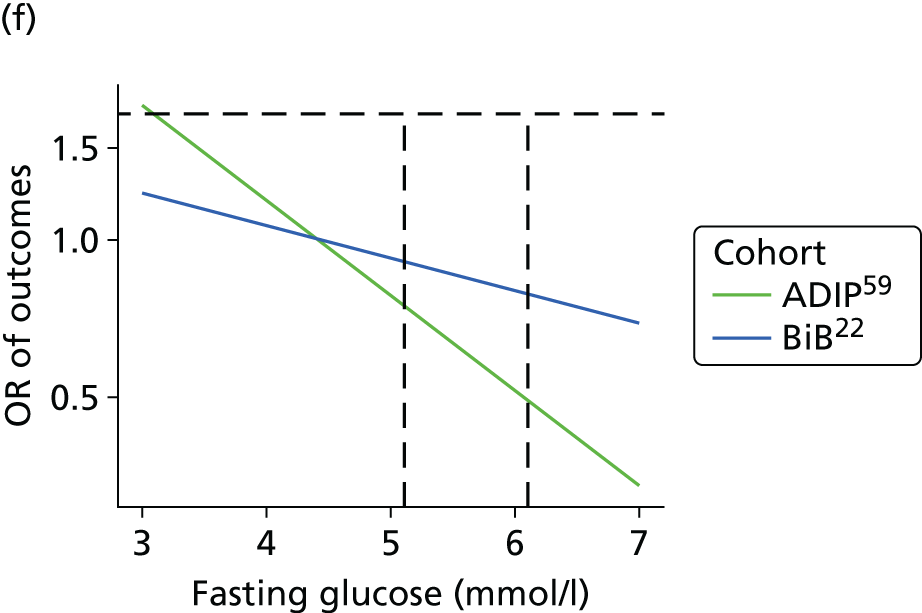

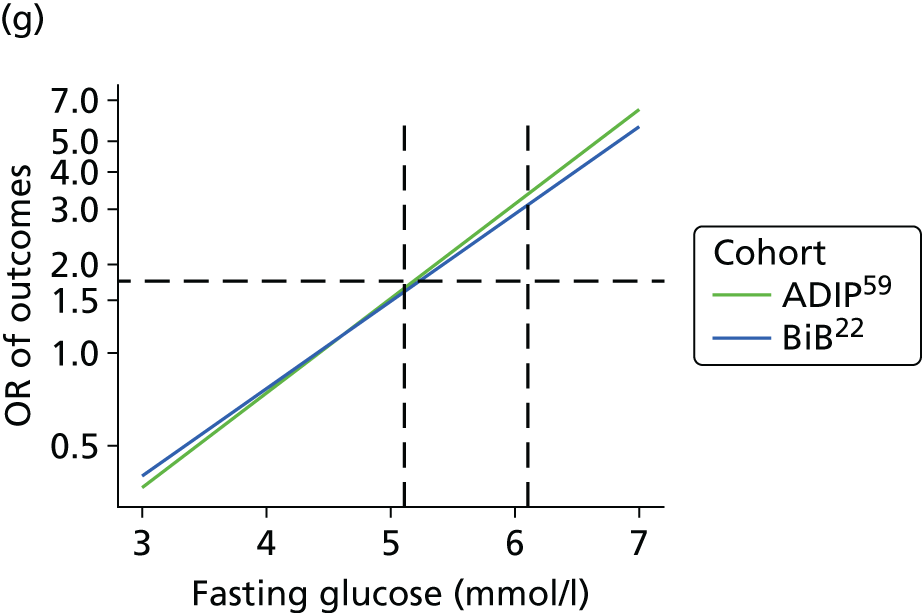

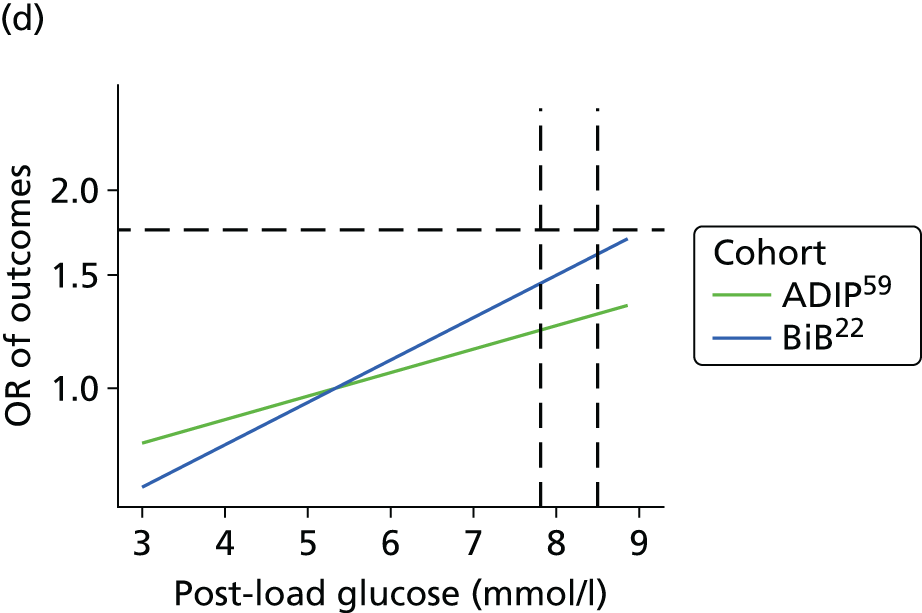

Gestational diabetes increases the risk of several adverse perinatal outcomes. 1 In recent years, there has been much debate about how GDM should be diagnosed. In 2010, IADPSG recommended new thresholds for the diagnosis of the disease, which aimed to reduce obesity risk by identifying infants who were LGA, with high adiposity at birth, and who had high concentrations of cord blood C-peptide. 8 In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO),10 whose previous criteria for diagnosing GDM have been widely used, endorsed the IADPSG criteria. The IADPSG criteria were produced with results from the HAPO study,6 which aimed to establish the association between maternal glucose concentrations that did not meet criteria for overt diabetes (pre-existing diabetes or GDM) and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes. The HAPO study6 found graded linear associations of fasting and post-load maternal glucose level with LGA, high adiposity and high concentrations of cord blood C-peptide, and similar linear associations with several other perinatal outcomes. In view of the absence of any clear threshold of glucose concentration at which risk of adverse outcomes increased, the IADPSG reached a consensus on how to calculate the new criteria. They decided that the thresholds for diagnosing GDM would be the glucose values at which the odds ratios (ORs) reached 1.75 for BW of > 90th percentile, per cent infant body fat (based on skinfolds) > 90th percentile,8 and concentration of cord C-peptide > 90th percentile. Although in most populations the application of the IADPSG criteria increases the number of women diagnosed with GDM compared with most previously used criteria (Table 2),24 they might not identify women at risk who have a high 2-hour post-load glucose result but which is still below that specified by the IADPSG criteria. 6

| Criteria | Glucose thresholds (mmol/l)a | Criteria | Coverage of use | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting | 1-hour post load | 2-hour post load | |||

| HAPO exclusion11 | 5.8 | 11.1 | 2002 | Some US cities | |

| WHO (previous)11 | 7.0 | 7.8 | 1999–2013 | Widespread globally | |

| WHO (previous, modified)23 | 6.1 | 7.8 | 1999 to current | UK | |

| NICE18 | 5.6 | 7.8 | 2015 | UK | |

| IADPSG and WHO (current)8,10 | 5.1 | 10.8 | 8.5 | 2010/2013 to present | Widespread globally |

It is unclear whether or not the association between maternal glucose level and perinatal outcomes and the IADPSG criteria for diagnosing GDM should be the same in SA women, who are at higher risk of GDM than white European women. 25 The shift in the aim of diagnosing GDM from one of identifying women at risk of type 2 diabetes to one of identifying risk of future offspring obesity is especially important for SAs, because SA women, on average, have infants of markedly lower BW and a reduced risk of LGA than white European women. 18,24 However, lower BW of SA infants masks a propensity to greater adiposity and associated cardiometabolic risk in later life. 26–32 High maternal pregnancy glucose level is an important mediator of greater birth adiposity in SA compared with white European infants. 23 Although findings of the HAPO study6 showed similar associations across different geographical centres, there were no SA centres, and too few SA participants to assess the association between maternal glycaemia and perinatal outcomes.

We aimed to establish whether or not the IADPSG criteria for diagnosis of GDM are appropriate for SA women and to assess how the prevalence of GDM varies when different criteria for its diagnosis are used in SA and WB women. Our specific objectives were to establish the nature of the association of fasting and post-load glucose levels with adverse perinatal outcomes in a large cohort of SA women and compare those findings with a similarly sized cohort of WB women; to use our results to identify appropriate thresholds for diagnosing GDM in SA and WB women; and to compare the prevalence of GDM in these two groups with different criteria. We hypothesised that the association between fasting and post-load glucose levels, and BW and infant adiposity, and the thresholds used to diagnose GDM, would differ between SA and WB women. Furthermore, we predicted that prevalence of GDM would be greater in SA women than WB women irrespective of criteria used. Our findings should inform clinical practice for diagnosing GDM.

Methods

Study design and participants

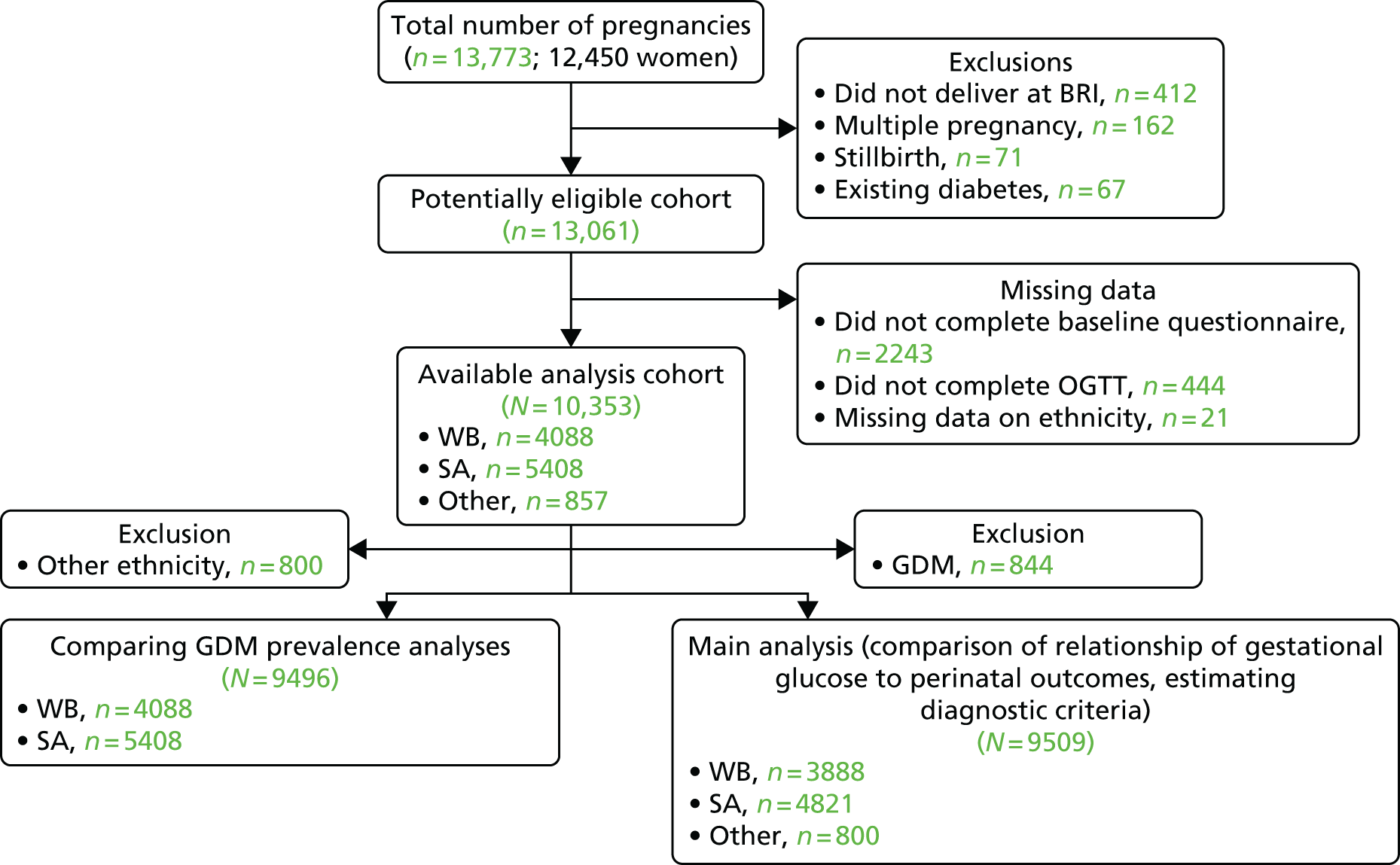

‘Born in Bradford’ is a prospective birth cohort study22 of women who delivered a live singleton baby at the Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford, UK. Figure 1 shows full inclusion and exclusion of women from the BiB study22 in this study. Women were excluded from all analyses if they did not complete a baseline questionnaire or the OGTT or had missing data for ethnic origin. For the main analyses of the association of gestational glucose level with perinatal outcomes and development of GDM diagnostic criteria, we excluded women who were diagnosed with GDM. GDM was defined according to modified WHO criteria operating at the time (either fasting glucose level of ≥ 6.1 mmol/l or 2-hour post-load glucose level of ≥ 7.8 mmol/l). 11,23 The cohort is broadly representative of the obstetric population in Bradford. 22 All women booked for delivery in Bradford are offered a 75-g OGTT (comprising fasting and 2-hour post-load samples) at around 26–28 weeks’ gestation, and women were recruited mainly at their OGTT appointment. At recruitment, women had their height and weight measured, completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire, and provided written consent for information to be abstracted from their medical records. Interviews were undertaken in English or in SA languages (including Urdu and Mirpuri). The analysis of glucose samples was carried out using a Siemens Advia 2400 analyser from the ADVIA® 2400 Clinical Chemistry System (Siemens Healthcare Ltd, Camberley, UK). The coefficients of variation range between 1.73% at 3.2 mmol/l and 0.64% at 19.1 mmol/l. Ethics approval was obtained from the Bradford Research Ethics Committee (07/H1302/112). All participants provided informed written consent.

FIGURE 1.

Study sample flow chart. The criteria used in the hospital in which study participants were recruited to diagnose GDM (and hence exclude them from the analyses presented here) was either fasting glucose level of ≥ 6.1 mmol/l or 2-hour post-load glucose level of ≥ 7.8 mmol/l. BRI, Bradford Royal Infirmary.

Participants completed a morning OGTT after fasting overnight. A baseline venous blood sample was taken. Participants then consumed a standard solution containing the equivalent of 75 g of anhydrous glucose over 5 minutes. After 2 hours a second sample was taken. Fasting and post-load plasma glucose assays were undertaken immediately using a glucose oxidase method. The analyses were undertaken using the Siemens Advia 2400 analyser following a standard protocol. The coefficients of variation range between 1.73% at 3.2 mmol/l and 0.64% at 19.1 mmol/l.

We assessed associations of maternal glucose concentrations with:

-

three primary outcomes – LGA (defined as BW of > 90th percentile for gestational age), infant adiposity (defined as sum of skinfolds > 90th percentile for gestational age) and C-section

-

five secondary outcomes – pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, shoulder dystocia, instrumental vaginal delivery and admission to the neonatal unit.

These outcomes are established clinical complications of GDM, and similar to the primary and secondary outcomes in the HAPO study. 6 We did not have information about cord blood C-peptide or neonatal hypoglycaemia in our cohort. We were unable to calculate percentage body fat from skinfolds as done in the HAPO study6 because no equivalent formulae exist for SA infants; thus, we used a cut-off of > 90th percentile for the sum of skinfolds. We included C-section in our analyses as, although it is not used to predict future risk of adiposity and ill health, it is an important perinatal outcome and is associated with LGA, greater infant adiposity and increased health service costs. 33

Birthweight, mode of delivery (normal vaginal, instrumented vaginal or C-section), gestational age, pre-eclampsia, shoulder dystocia and admission to the neonatal unit were obtained from hospital records. C-section was compared with all vaginal deliveries. Pre-eclampsia was defined as new-onset proteinuria (> 300 g in 24 hours) together with blood pressure (BP) of ≥ 140/90 mmHg after 20 weeks’ gestation on more than one occasion. BWs were converted into standard deviation (SD) scores standardised for gestational age and gender relative to the UK-WHO growth standard. 34,35 Infants were then categorised as either being > 90th percentile or not. 27 The UK-WHO growth standards are based on data from six counties (USA, Norway, Oman, Brazil, India and Ghana) and describe the optimum pattern of growth for all children, rather than the prevailing pattern in the UK. 35 Skinfold thickness (triceps and subscapular) were summed and the 90th percentile was established from quantile regression using six gender–ethnic groups [combining gender and ethnic origin (WB, SA, and other)] and adjusted for parity (0, 1, 2, 3+). 36 The intra-rate and inter-rate technical error of measurements for the skinfold thicknesses were, respectively, 0.22–0.35 mm and 0.15–0.54 mm for triceps, and 0.14–0.25 mm and 0.17–0.63 mm for subscapular skinfolds. 37

Statistical analyses

Associations of fasting and post-load glucose levels with outcomes were assessed by categories, and with glucose as a continuous variable (per SD). We used multivariable logistic regression with clustered sandwich estimators38 (to account for some women in the cohort having more than one pregnancy) to assess associations of fasting and post-load glucose levels with each outcome. We followed the analytical protocol used in the HAPO study6 as closely as possible, with fasting and post-load glucose concentrations divided into seven categories (see the Table 3 footnotes for definition of categories). In order to explore any extreme threshold effects, the top two categories for fasting and post-load glucose levels included about 1% and 3% of women, respectively. Models were adjusted for gestational age at OGTT, presence or absence of family history of diabetes, family history of hypertension, previous GDM, previous macrosomia, smoking status, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, maternal age and BMI, maternal education, baby gender and parity. Models for all women were additionally adjusted for ethnic origin. Models for SA women were not adjusted for alcohol consumption during pregnancy because most reported never drinking alcohol. Additionally, preterm delivery was adjusted for squared maternal BMI because of evidence of a quadratic relationship of BMI with preterm delivery. Shoulder dystocia models were not adjusted for previous GDM because of small numbers. Ethnicity was categorised as WB, SA and other ethnicity according to UK Office for National Statistics criteria. 39 Education was equivalised to UK standard attainments, and participants were included in one of five mutually exclusive categories (< 5 GCSE equivalent, 5+ GCSE equivalent, A level equivalent, higher than A level, other). 23 Parity was categorised as 0 or ≥ 1 previous pregnancies. Smoking was categorised as never, past (not during this index pregnancy), current (during this pregnancy) and alcohol as consumed during this pregnancy or not.

Maternal BMI was calculated from height measured at the time of recruitment and from weight measured at booking antenatal clinic, which was obtained from electronic hospital records. Expected date of birth (40 weeks) was estimated from a gestation ultrasound scan at ≈ 10 weeks then, using the date of OGTT and date of birth, gestational age at OGTT and birth were calculated. Infant gender was obtained from electronic hospital records, and family history of diabetes and hypertension were abstracted from paper hospital records.

We established fasting and post-load glucose thresholds for BW of > 90th percentile and standardised sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile that equated to an OR of 1.75, using the methods of IADPSG. 8 We estimated the ORs of these outcomes at mean glucose levels and the ORs at 0.1-mmol/l intervals across the full range of fasting and 2-hour post-load glucose levels. We then plotted this range of ORs and used the plots to estimate the thresholds of fasting, and 2-hour post-load glucose that were closest to ORs for each outcome of 1.75 in both ethnic groups. These analyses were carried out with adjustment for the same potential confounders as in all multivariable regression analyses. All analyses were undertaken separately in WB and SA women, and we tested for differences in associations by including an interaction term between glucose and ethnic origin. Because women of SA origin were mainly Pakistani, we undertook a sensitivity analysis in which we repeated analyses including only Pakistani women. To maximise statistical power and minimise bias that might occur if women with missing data were excluded from analyses, we used multivariate multiple imputation with chained equations to impute missing values40 (see Appendix 1, Table 50). We repeated all analyses with the complete data cohort for comparison.

Levels of missing data range from 0% to 32% for the different variables (see Appendix 1, Table 50), and 5056 (53%) had complete data on all variables included in any analyses. To maximise statistical power and minimise bias due to excluding those with any missing data, we used multivariate multiple imputation, with chained equations to impute missing values for covariables and outcomes for the main analyses. 40 We generated 50 imputed data sets and combined these using Rubin’s rules, using the ‘mi’ commands in Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Distributions of variables from pooling of the data sets with imputed variables were similar to those for observed variables (see Appendix 1, Table 50). We repeated all analyses with the complete data cohort for comparison.

Results

Women were recruited to the BiB study22 between March 2007 and November 2010; investigators collected detailed information from 12,450 women (13,773 pregnancies resulting in 13,818 births). After exclusions, 9509 women (4821 SA and 3888 WB) were included in the main analyses looking at associations of fasting and post-load glucose levels with adverse perinatal outcomes. A total of 844 women with GDM who were excluded from main analyses were included in the analyses that compared the prevalence of GDM with different criteria. Table 3 shows characteristics of the women and infants in the eligible cohort: 51% were SA, 41% were WB and 8% were of other ethnic origin. Median fasting and post-load glucose concentrations were slightly higher in SA than WB women. WB infants were almost three times more likely than SA infants to have a BW of > 90th percentile, but the frequency of sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile was similar in WB and SA infants. Characteristics were similar in the larger cohort of eligible women to those that were included in the main analysis cohort (see Appendix 1, Table 51).

| Outcome | N | All women: mean (SD), median (IQR) or n (%) | N | WB: mean (SD), median (IQR) or n (%) | N | SA: mean (SD), median (IQR) or n (%) | N | Other: mean (SD), median (IQR) or n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||

| BW of > 90th percentilea | 9508 | 592 (6.2) | 3887 | 361 (9.3) | 4821 | 164 (3.4) | 800 | 67 (8.4) |

| Sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentileb | 6458 | 687 (10.6) | 2510 | 270 (10.8) | 3409 | 365 (10.7) | 539 | 52 (9.7) |

| Caesarean delivery | 9509 | 1983 (20.9) | 3888 | 870 (22.4) | 4821 | 907 (18.8) | 800 | 206 (25.8) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| Pre-eclampsia | 9120 | 229 (2.5) | 3724 | 97 (2.6) | 4629 | 115 (2.5) | 767 | 17 (2.2) |

| Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks) | 9509 | 471 (5.0) | 3888 | 204 (5.3) | 4821 | 227 (4.7) | 8000 | 40 (5.0) |

| Shoulder dystociac | 7526 | 105 (1.4) | 3018 | 42 (1.4) | 3914 | 50 (1.3) | 594 | 13 (2.2) |

| Instrumental vaginal deliveryc | 7519 | 930 (12.4) | 3015 | 417 (13.8) | 3913 | 417 (10.7) | 591 | 96 (16.2) |

| Intensive neonatal care | 9509 | 412 (4.3) | 3888 | 166 (4.3) | 4821 | 213 (4.4) | 800 | 33 (4.1) |

| Glucose levels | ||||||||

| Fasting | 9509 | 4.4 (4.2–4.7) | 3888 | 4.3 (4.1–4.6) | 4821 | 4.5 (4.2–4.8) | 800 | 4.4 (4.1–4.6) |

| Two-hour post load | 9509 | 5.4 (4.7–6.1) | 3888 | 5.3 (4.5–6.0) | 4821 | 5.4 (4.8–6.2) | 800 | 5.3 (4.6–6.0) |

| Maternal and infant characteristics | ||||||||

| Maternal age at delivery (years) | 9509 | 27.3 (5.5) | 3888 | 26.8 (6.1) | 4821 | 27.7 (5.0) | 800 | 27.4 (5.7) |

| Aged ≥ 35 years | 1092 (11.5) | 487 (12.5) | 503 (10.4) | 102 (12.8) | ||||

| BMI (at booking) | 9073 | 25.8 (5.6) | 3708 | 26.7 (5.9) | 4596 | 25.2 (5.3) | 769 | 25.7 (5.5) |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 1808 (19.9) | 899 (24.2) | 768 (16.7) | 141 (18.3) | ||||

| Maternal education | 9383 | 3847 | 4755 | 781 | ||||

| < 5 GCSEs | 2024 (21.6) | 788 (20.5) | 1140 (24.0) | 96 (12.3) | ||||

| ≥ 5 GCSEs | 2954 (31.5) | 1336 (34.7) | 1453 (30.6) | 165 (21.1) | ||||

| A level | 1389 (14.8) | 652 (17.0) | 639 (13.4) | 98 (12.6) | ||||

| Higher than A level | 2402 (25.6) | 739 (19.2) | 1352 (28.4) | 311 (39.8) | ||||

| Other | 614 (6.5) | 332 (8.6) | 171 (3.6) | 111 (14.2) | ||||

| Smoking status | 9494 | 3886 | 4809 | 799 | ||||

| Never | 6518 (68.7) | 1589 (40.9) | 4428 (92.1) | 501 (62.7) | ||||

| Before pregnancy | 1359 (14.3) | 973 (25.0) | 227 (4.7) | 159 (19.9) | ||||

| In pregnancy | 1617 (17.0) | 1324 (34.1) | 154 (3.2) | 139 (17.4) | ||||

| Any alcohol during pregnancy | 9477 | 1950 (20.6) | 3875 | 1715 (44.3) | 4805 | 40 (0.8) | 797 | 195 (24.5) |

| Primiparity | 9151 | 3813 (41.7) | 3762 | 1821 (48.4) | 4623 | 1566 (33.9) | 766 | 426 (55.6) |

| Family history of diabetes | 9212 | 2313 (25.1) | 3782 | 508 (13.4) | 4660 | 1657 (35.6) | 770 | 148 (19.2) |

| Family history of hypertension | 9203 | 2519 (27.4) | 3774 | 909 (24.1) | 4654 | 1412 (30.3) | 775 | 198 (25.6) |

| Previous GDMd | 5338 | 56 (1.1) | 1941 | 19 (1.0) | 3057 | 35 (1.1) | 340 | 2 (0.6) |

| Previous macrosomia (≥ 4 kg)d | 4464 | 359 (8.0) | 1662 | 212 (12.8) | 2523 | 124 (4.9) | 279 | 23 (8.2) |

| Gestational age at OGTT (weeks) | 9509 | 26.3 (1.9) | 3888 | 26.2 (1.9) | 4821 | 26.3 (1.9) | 800 | 26.4 (1.7) |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 9509 | 39.7 (1.7) | 3888 | 39.8 (1.8) | 4821 | 39.6 (1.7) | 800 | 39.7 (1.7) |

| Male gender | 9509 | 4884 (51.4) | 3888 | 2006 (51.6) | 4821 | 2464 (51.1) | 800 | 414 (51.8) |

Associations of fasting and post-load glucose levels with primary outcomes

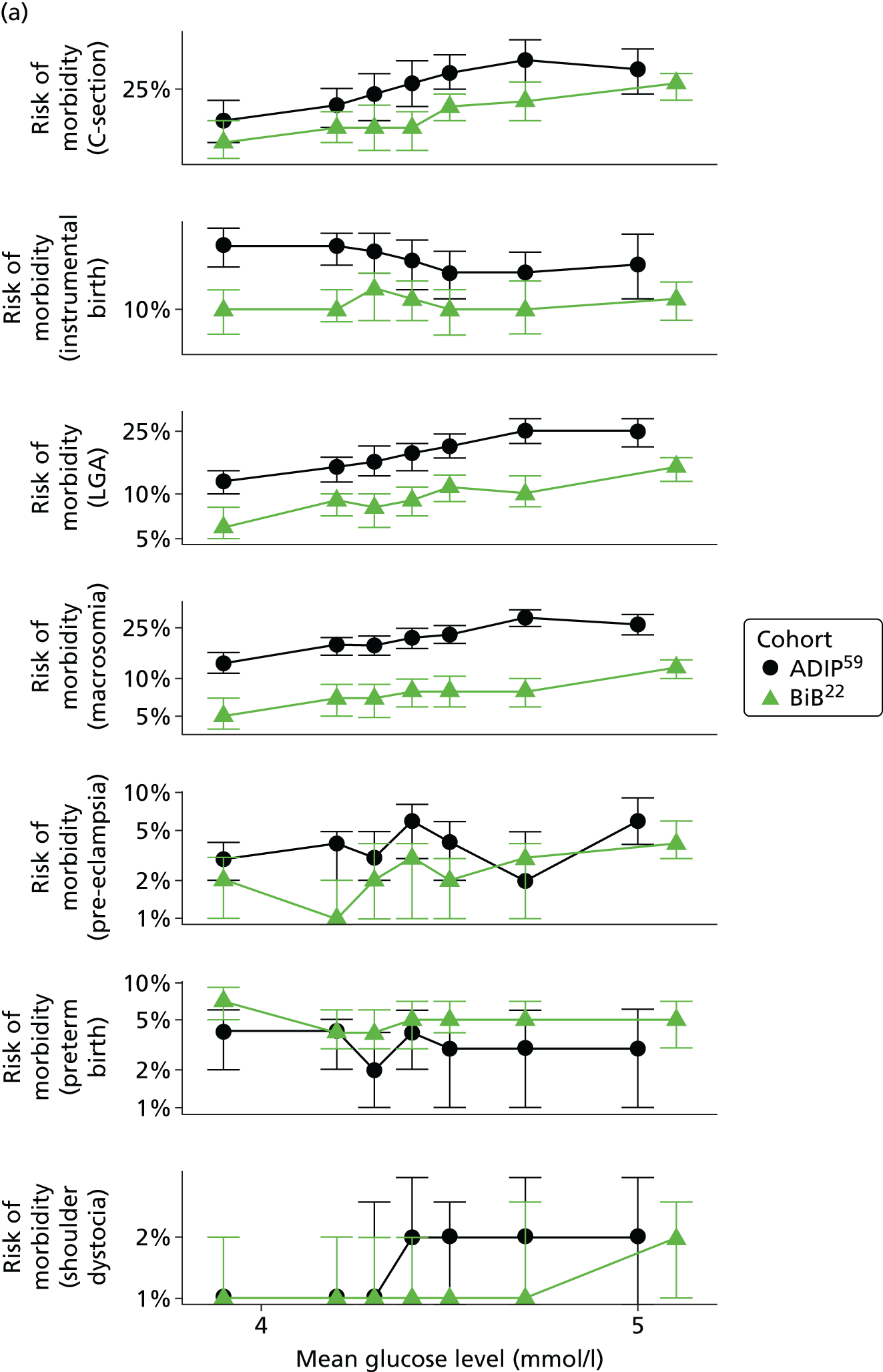

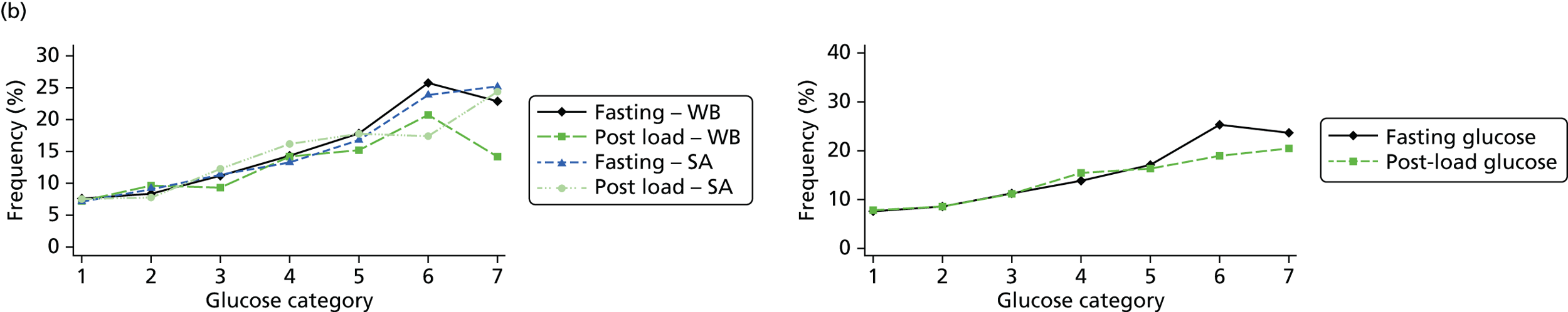

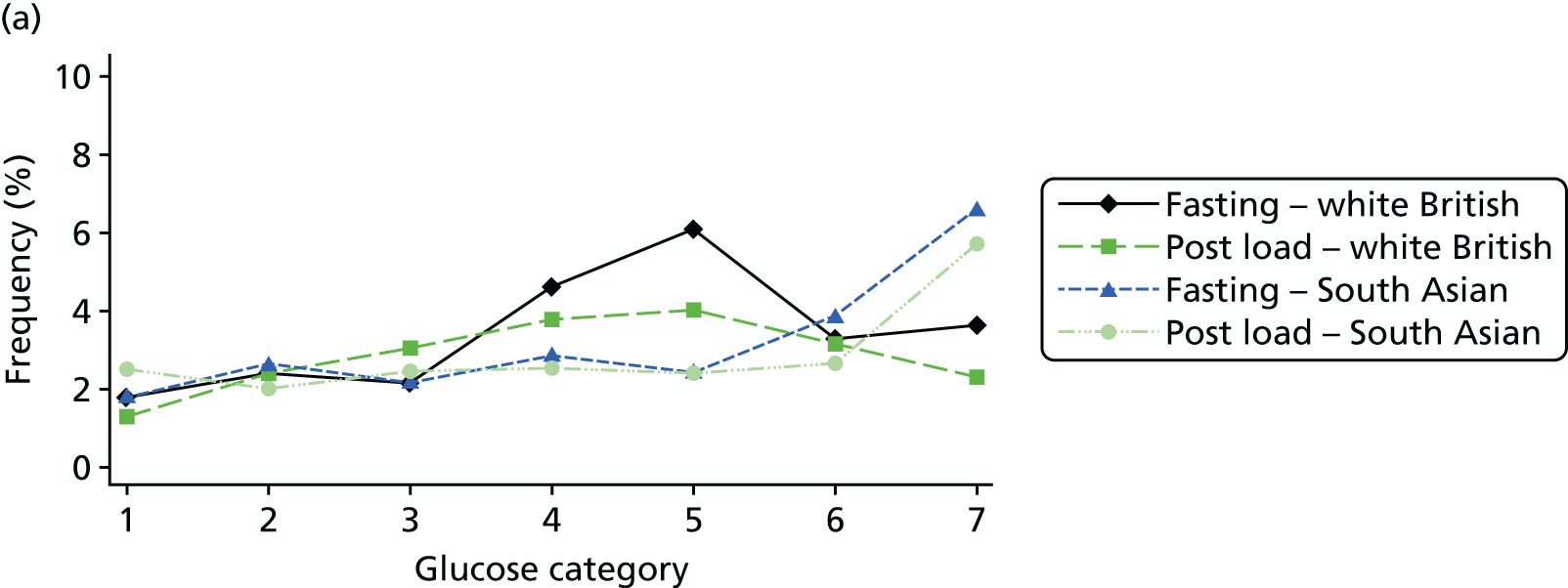

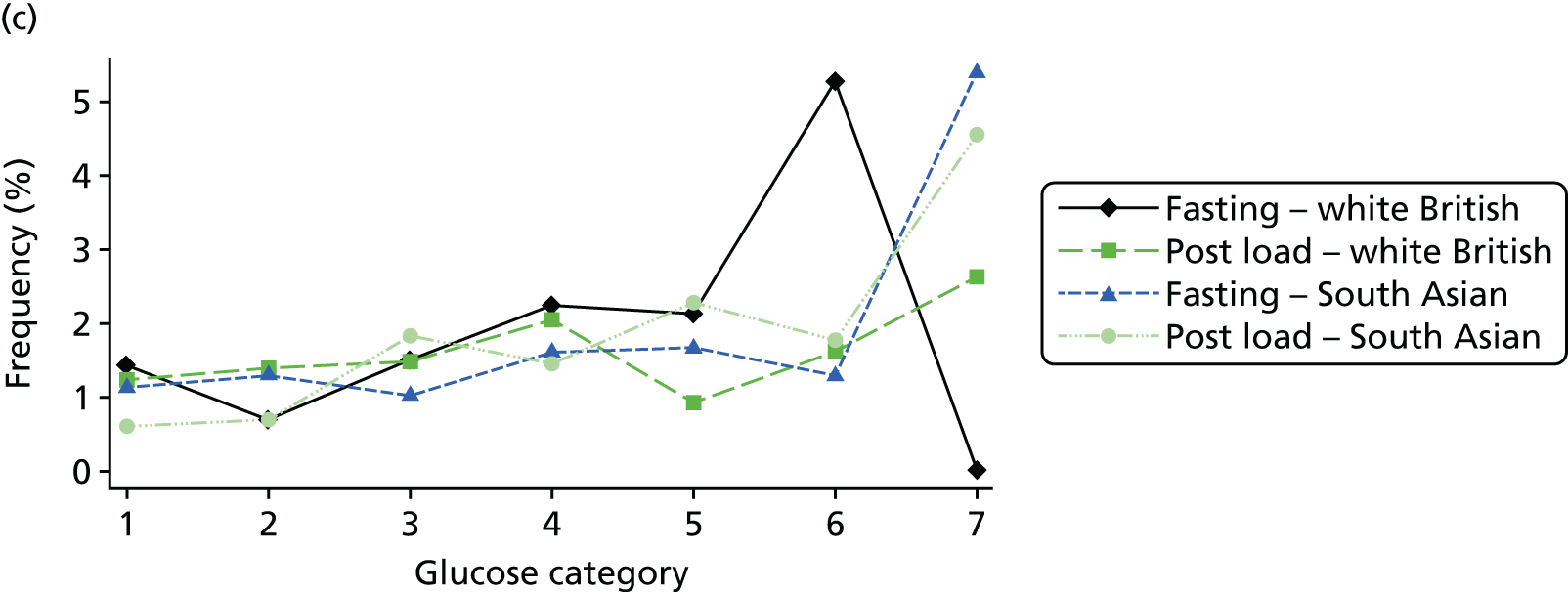

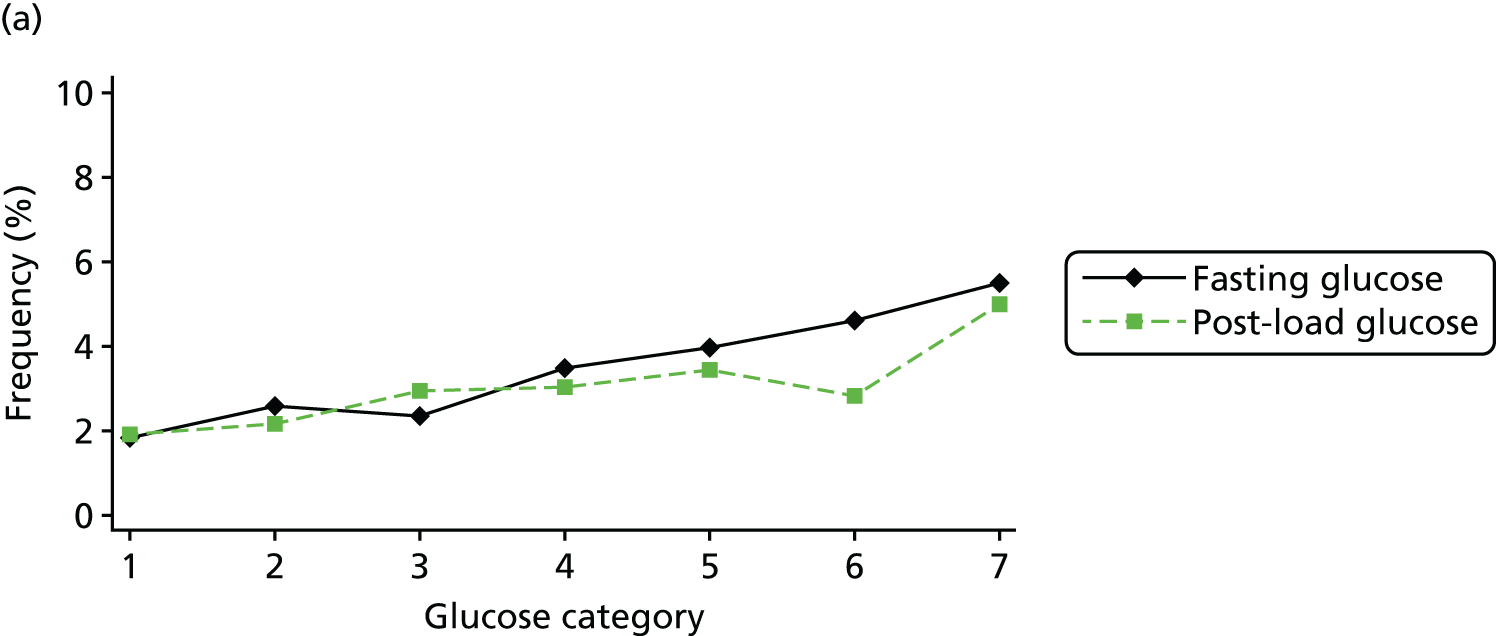

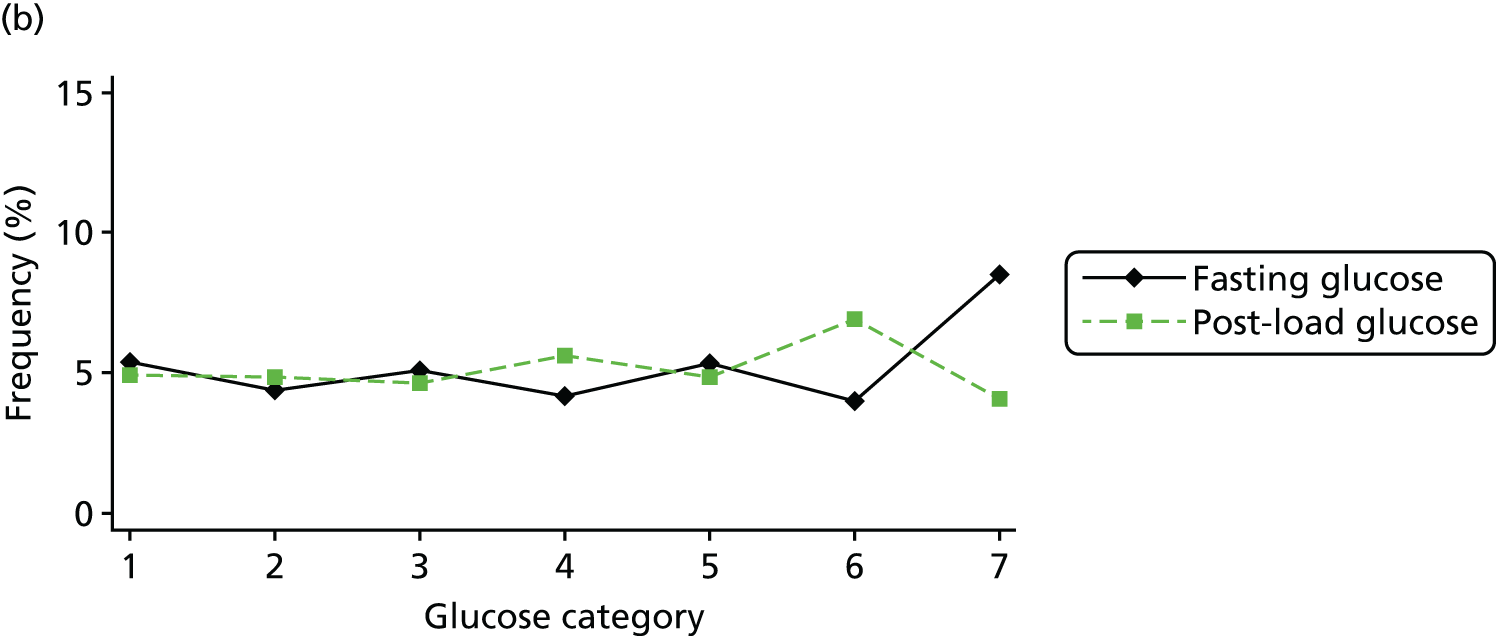

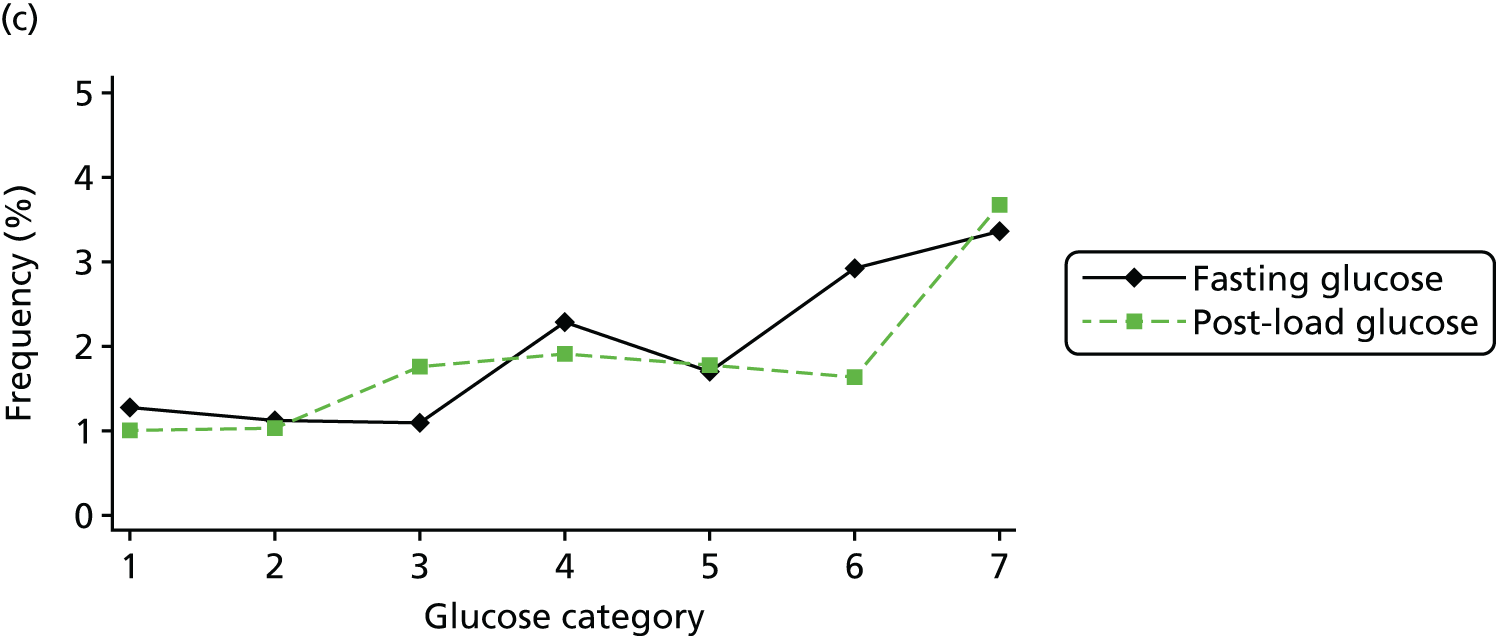

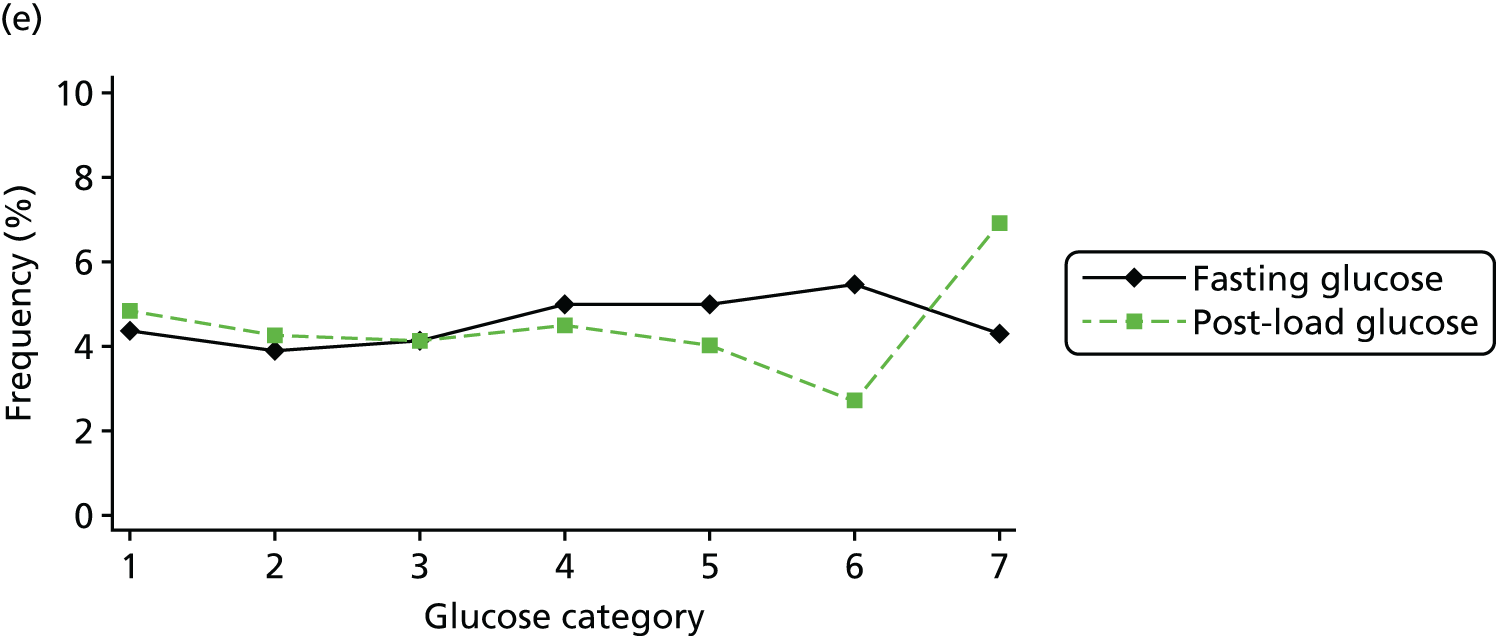

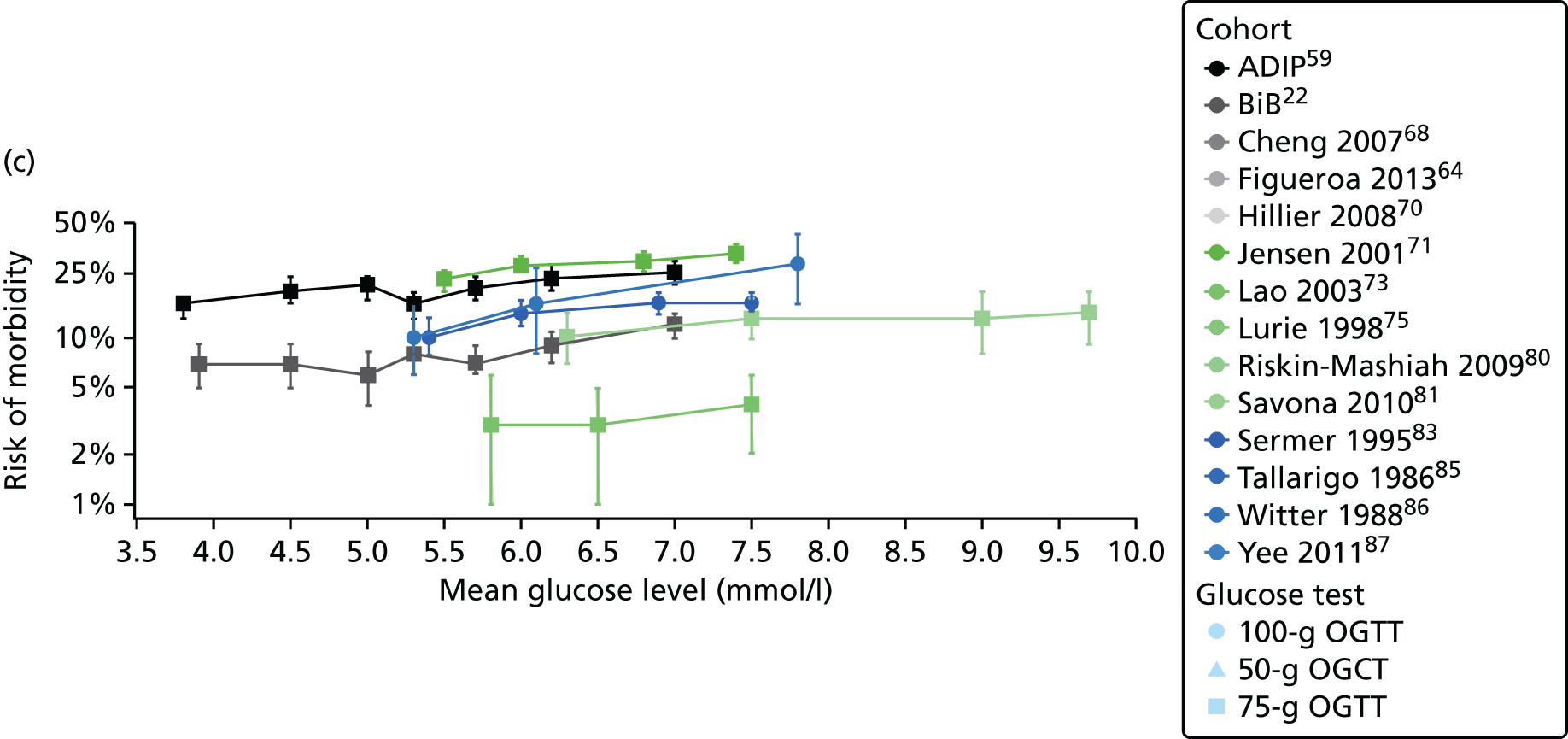

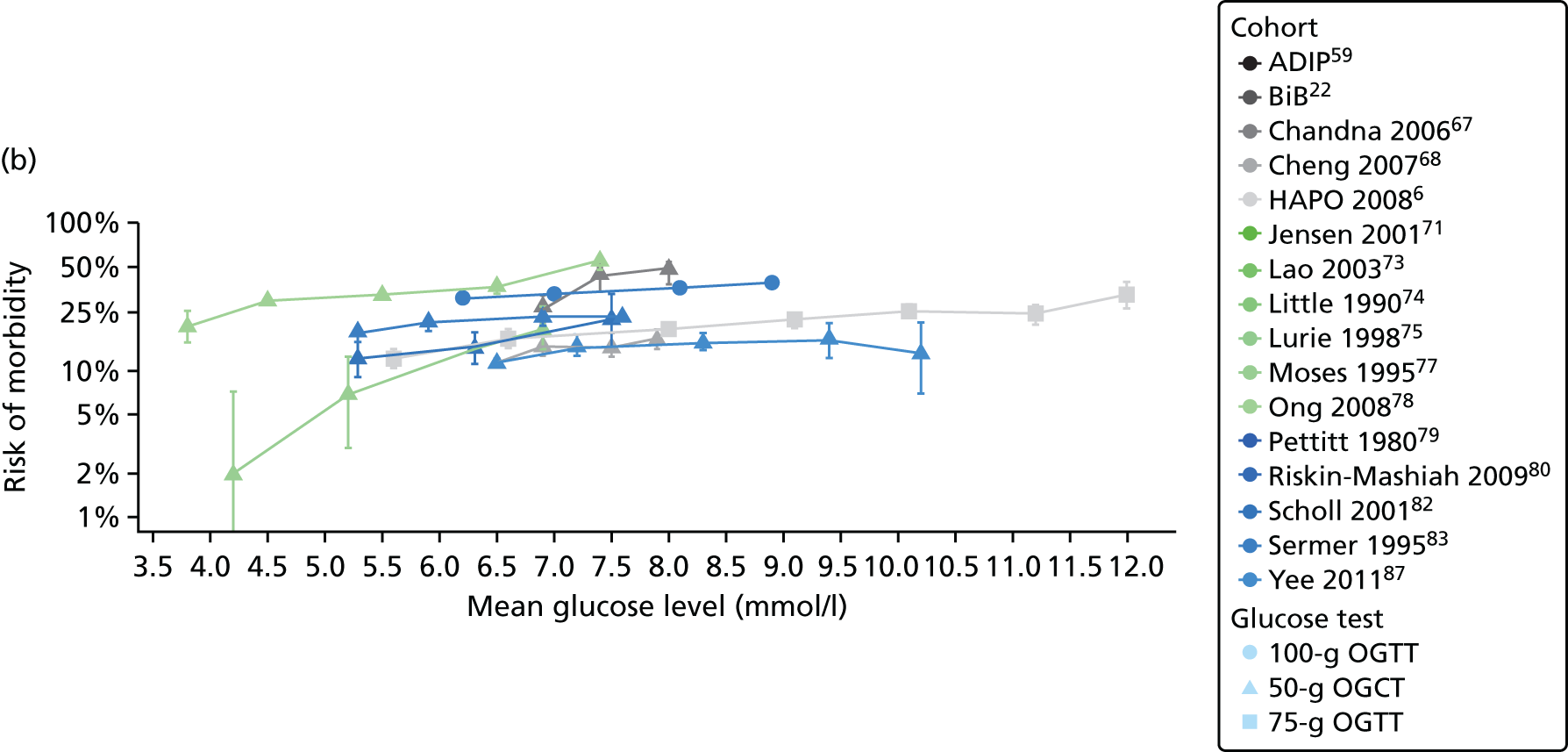

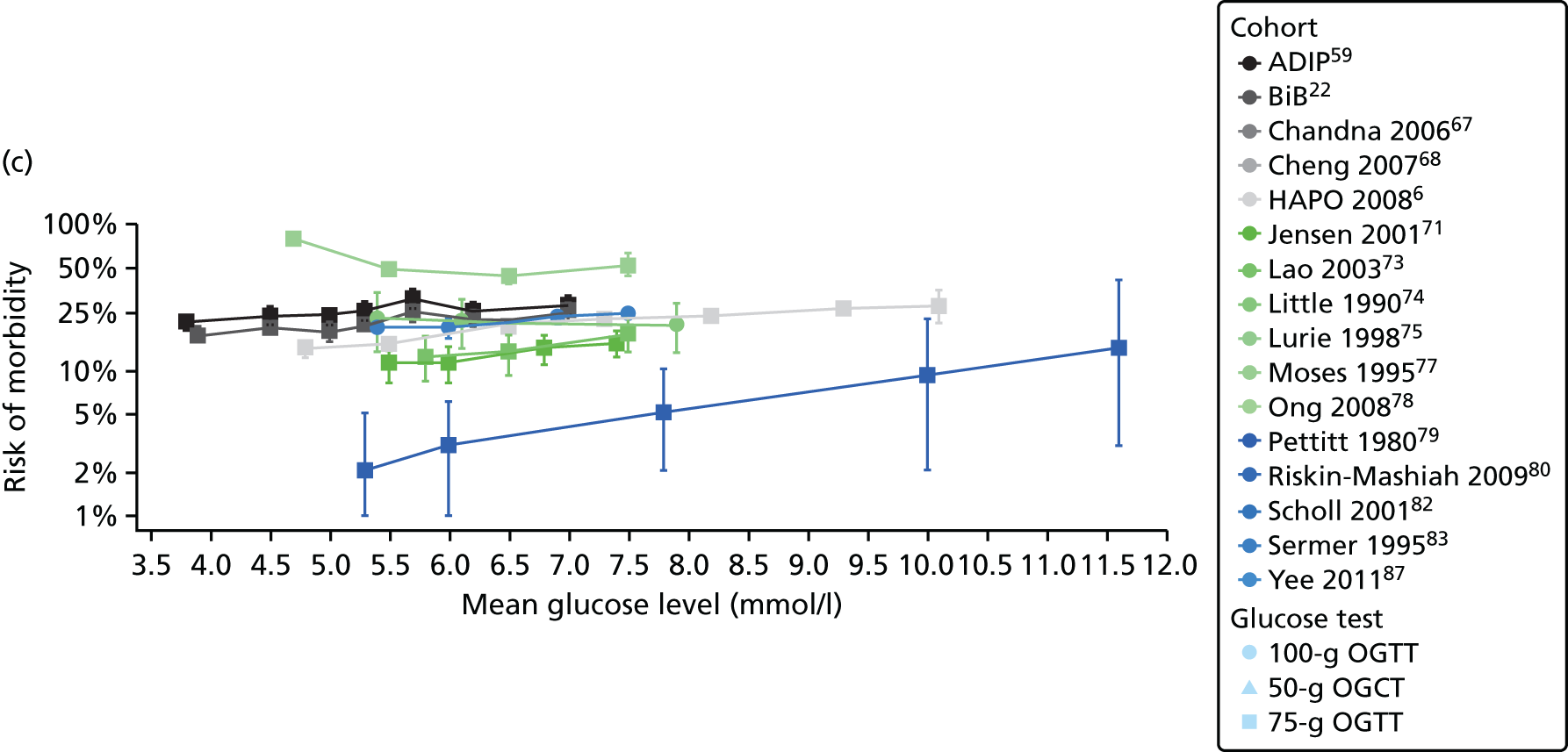

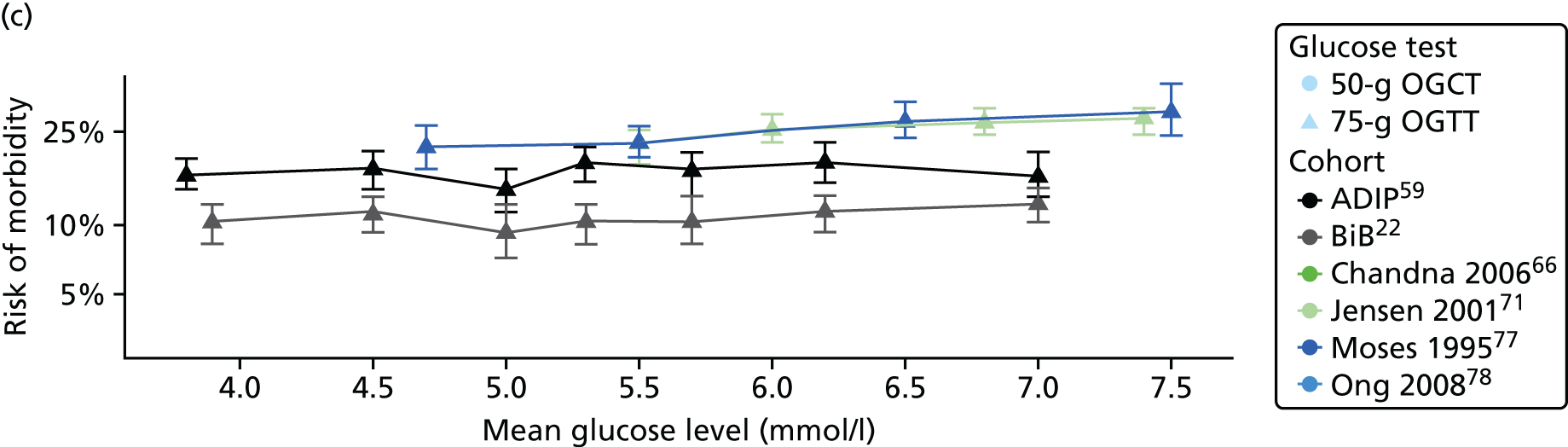

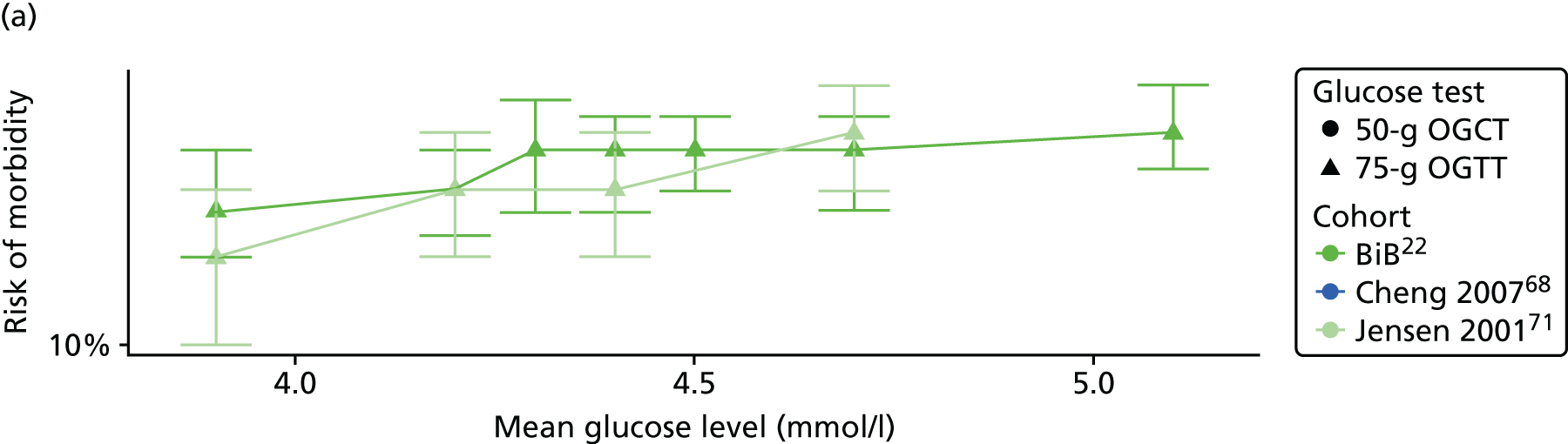

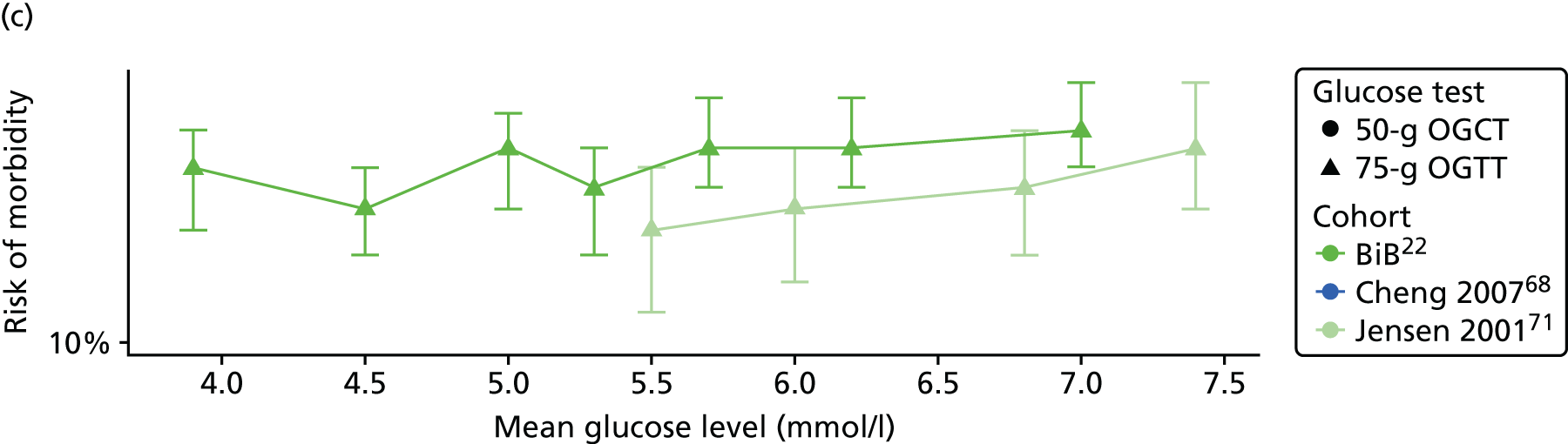

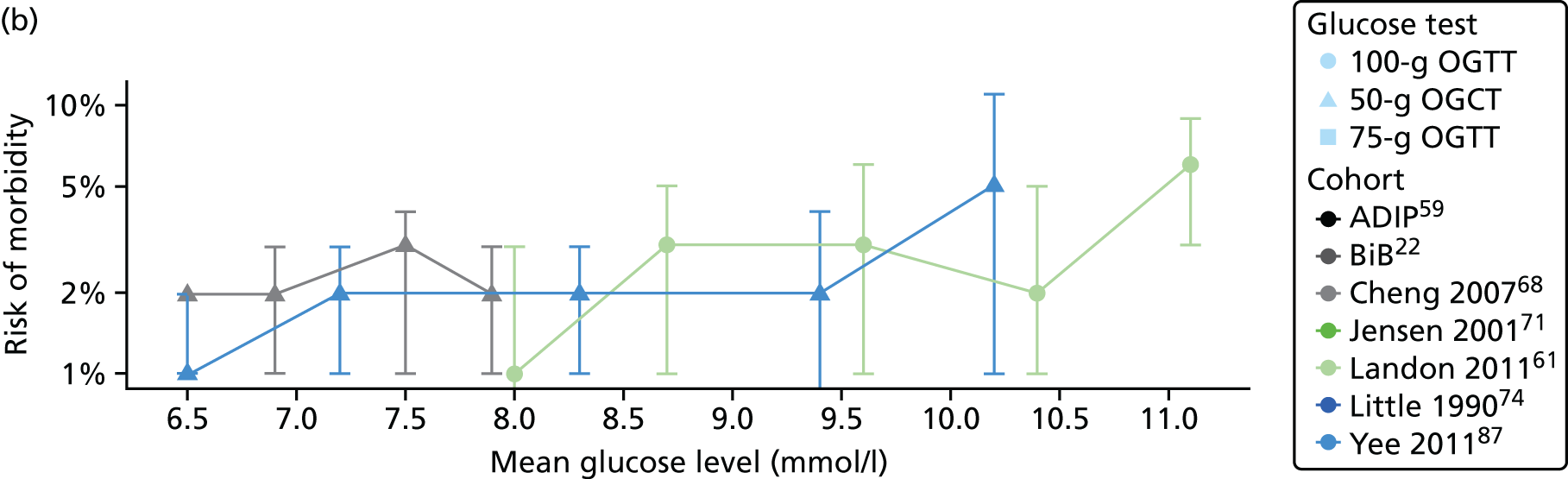

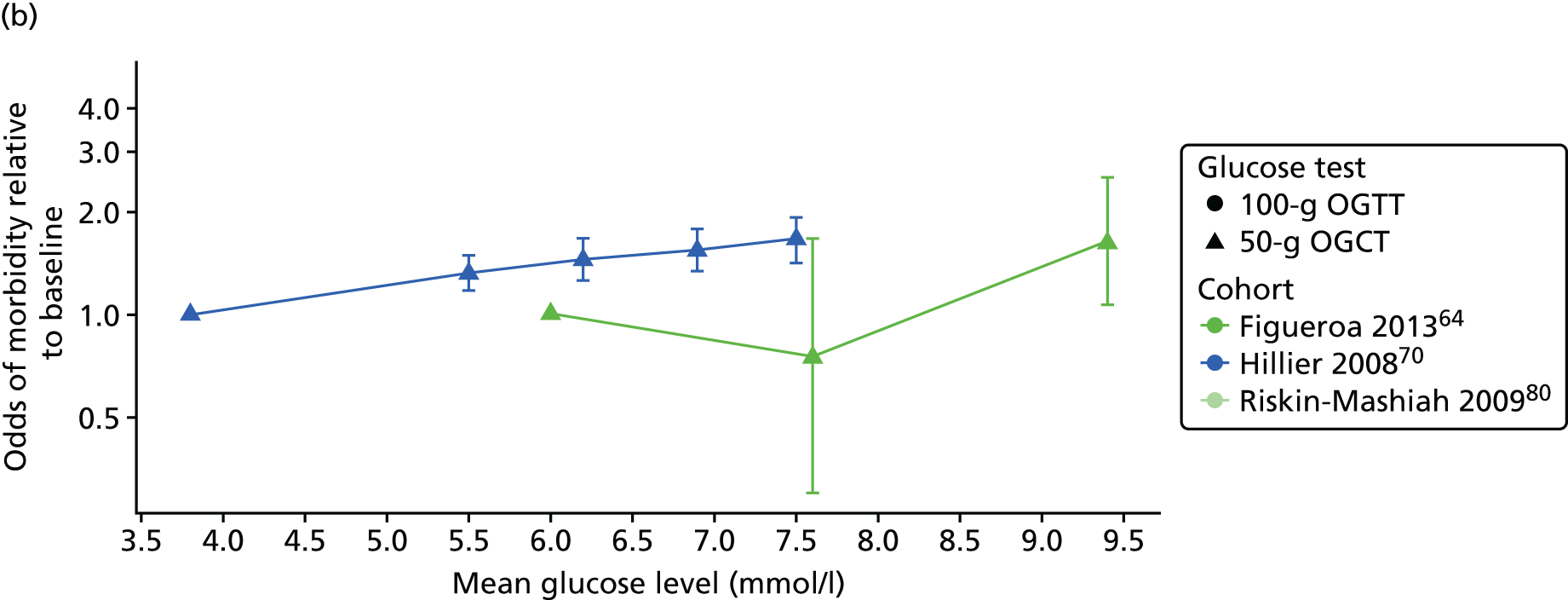

Figure 2 shows the unadjusted percentage of women in each group who had each of the three primary outcomes by categories of fasting and 2-hour post-load glucose level by ethnicity and for all women. Generally, the frequency of each of the three primary outcomes increased across the seven categories of fasting and post-load glucose levels, with no evidence of a threshold at which risk markedly increases, except for the association of fasting glucose level with C-section in SA women. The higher prevalence of BW of > 90th percentile in WB infants than in SA infants is consistent across all glucose categories. Combining data for all women (i.e. including 99% of the cohort) showed monotonic relationships of fasting and post-load glucose levels up to the sixth category (see Appendix 1, Figures 45 and 46).

FIGURE 2.

Frequency of primary outcomes across glucose categories by ethnicity: WB (n = 3888) and SA (n = 4821), and for all pregnancies (N = 9509). (a) BW of > 90th percentile; (b) sum of skinfolds > 90th percentile; (c) C-section. Glucose categories are defined as follows: FPG level: category 1, < 4.3 mmol/l; category 2, 4.3–4.4 mmol/l; category 3, 4.5–4.7 mmol/l; category 4, 4.8–4.9 mmol/l; category 5, 5.0–5.2 mmol/l; category 6, 5.3–5.6 mmol/l; category 7, 5.7–6.0 mmol/l. Post-load plasma glucose level: category 1, < 4.7 mmol/l; category 2, 4.7–5.4 mmol/l; category 3, 5.5–6.2 mmol/l; category 4, 6.3–6.6 mmol/l; category 5, 6.7–7.2 mmol/l; category 6, 7.3–7.5 mmol/l; category 7, 7.6–7.7 mmol/l. FPG, fasting plasma glucose.

Regression analyses confirmed monotonic associations of glucose level with each of the primary outcomes, in each group, without (see Appendix 1, Table 52) and with adjustment for confounders (Table 4). In view of the monotonic nature of the associations, we focused our comparisons on results with fasting or post-load glucose level as a continuous variable (per 1 SD). Although there was not strong statistical evidence of differences, the point estimates suggested stronger associations of fasting and post-load glucose levels with all three outcomes, except for those of fasting glucose level with LGA and post-load glucose level with C-section. However, there was no strong statistical evidence that the associations differed between the two groups for any primary outcome (p interaction of ≥ 0.2 for all associations).

| Outcome | All women (N = 9509) | WB (n = 3888) | SA (n = 4821) | p-interactiona | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| By fasting glucose categoryb and per 1 SD | |||||||

| BW of > 90th percentile | |||||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 0.39 |

| 2 | 1.18 | 0.90 to 1.54 | 1.15 | 0.83 to 1.59 | 1.07 | 0.59 to 1.94 | |

| 3 | 1.35 | 1.04 to 1.74 | 1.38 | 1.01 to 1.90 | 1.10 | 0.65 to 1.88 | |

| 4 | 1.42 | 1.02 to 1.97 | 1.57 | 1.04 to 2.37 | 1.05 | 0.56 to 1.98 | |

| 5 | 1.90 | 1.35 to 2.67 | 1.59 | 0.97 to 2.62 | 2.12 | 1.20 to 3.76 | |

| 6 | 3.10 | 2.00 to 4.79 | 2.21 | 1.07 to 4.54 | 3.35 | 1.72 to 6.51 | |

| 7 | 2.60 | 1.35 to 5.04 | 2.09 | 0.80 to 5.48 | 3.25 | 1.29 to 8.21 | |

| Per 1 SD | 1.31 | 1.20 to 1.43 | 1.22 | 1.08 to 1.38 | 1.43 | 1.23 to 1.67 | |

| Sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile | |||||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 0.98 |

| 2 | 1.11 | 0.88 to 1.40 | 1.04 | 0.74 to 1.46 | 1.29 | 0.92 to 1.82 | |

| 3 | 1.40 | 1.14 to 1.72 | 1.35 | 0.96 to 1.88 | 1.56 | 1.15 to 2.13 | |

| 4 | 1.61 | 1.24 to 2.09 | 1.69 | 1.09 to 2.62 | 1.70 | 1.18 to 2.45 | |

| 5 | 2.02 | 1.54 to 2.64 | 2.05 | 1.26 to 3.36 | 2.15 | 1.49 to 3.10 | |

| 6 | 3.23 | 2.29 to 4.56 | 3.20 | 1.52 to 6.74 | 3.18 | 2.01 to 5.02 | |

| 7 | 2.73 | 1.53 to 4.87 | 2.71 | 0.97 to 7.58 | 3.06 | 1.44 to 6.51 | |

| Per 1 SD | 1.35 | 1.25 to 1.45 | 1.35 | 1.18 to 1.54 | 1.35 | 1.23 to 1.49 | |

| Caesarean delivery | |||||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 0.47 |

| 2 | 0.98 | 0.84 to 1.13 | 1.03 | 0.83 to 1.27 | 0.99 | 0.79 to 1.24 | |

| 3 | 1.11 | 0.96 to 1.28 | 1.06 | 0.86 to 1.32 | 1.20 | 0.97 to 1.49 | |

| 4 | 1.17 | 0.97 to 1.41 | 1.11 | 0.81 to 1.51 | 1.33 | 1.03 to 1.73 | |

| 5 | 1.20 | 0.98 to 1.48 | 1.18 | 0.83 to 1.69 | 1.18 | 0.88 to 1.56 | |

| 6 | 1.14 | 0.84 to 1.55 | 1.42 | 0.83 to 2.45 | 1.02 | 0.67 to 1.56 | |

| 7 | 2.14 | 1.34 to 3.41 | 1.25 | 0.57 to 2.77 | 2.88 | 1.58 to 5.25 | |

| Per 1 SD | 1.09 | 1.03 to 1.15 | 1.06 | 0.97 to 1.16 | 1.11 | 1.02 to 1.20 | |

| By 2-hour post-load glucose categoryb and per 1 SD | |||||||

| BW of > 90th percentile | |||||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 0.60 |

| 2 | 0.95 | 0.74 to 1.23 | 1.00 | 0.73 to 1.37 | 0.96 | 0.56 to 1.66 | |

| 3 | 1.08 | 0.83 to 1.39 | 0.98 | 0.71 to 1.36 | 1.04 | 0.61 to 1.76 | |

| 4 | 1.29 | 0.92 to 1.80 | 1.20 | 0.78 to 1.84 | 1.39 | 0.72 to 2.66 | |

| 5 | 1.58 | 1.14 to 2.19 | 1.18 | 0.76 to 1.82 | 2.12 | 1.15 to 3.93 | |

| 6 | 1.71 | 1.04 to 2.81 | 1.74 | 0.90 to 3.36 | 1.66 | 0.69 to 3.98 | |

| 7 | 1.29 | 0.65 to 2.60 | 1.27 | 0.50 to 3.26 | 1.64 | 0.54 to 5.05 | |

| Per 1 SD | 1.17 | 1.07 to 1.29 | 1.10 | 0.98 to 1.24 | 1.28 | 1.06 to 1.55 | |

| Sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile | |||||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 0.23 |

| 2 | 1.02 | 0.81 to 1.29 | 1.24 | 0.88 to 1.73 | 0.96 | 0.68 to 1.35 | |

| 3 | 1.32 | 1.05 to 1.65 | 1.13 | 0.78 to 1.63 | 1.51 | 1.10 to 2.07 | |

| 4 | 1.84 | 1.40 to 2.41 | 1.76 | 1.12 to 2.76 | 1.94 | 1.33 to 2.83 | |

| 5 | 1.94 | 1.47 to 2.55 | 1.79 | 1.13 to 2.82 | 2.22 | 1.52 to 3.25 | |

| 6 | 2.29 | 1.54 to 3.39 | 2.63 | 1.35 to 5.14 | 2.13 | 1.25 to 3.64 | |

| 7 | 2.53 | 1.53 to 4.17 | 1.80 | 0.68 to 4.77 | 3.13 | 1.71 to 5.74 | |

| Per 1 SD | 1.31 | 1.21 to 1.42 | 1.26 | 1.11 to 1.42 | 1.38 | 1.23 to 1.54 | |

| Caesarean delivery | |||||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 0.54 |

| 2 | 0.95 | 0.82 to 1.10 | 0.89 | 0.72 to 1.11 | 1.06 | 0.84 to 1.32 | |

| 3 | 1.07 | 0.92 to 1.24 | 1.09 | 0.87 to 1.37 | 1.01 | 0.80 to 1.27 | |

| 4 | 1.11 | 0.91 to 1.36 | 0.96 | 0.70 to 1.32 | 1.19 | 0.89 to 1.60 | |

| 5 | 1.00 | 0.81 to 1.23 | 1.03 | 0.76 to 1.42 | 0.97 | 0.71 to 1.33 | |

| 6 | 1.31 | 0.96 to 1.79 | 1.12 | 0.68 to 1.85 | 1.35 | 0.88 to 2.07 | |

| 7 | 1.15 | 0.76 to 1.74 | 0.86 | 0.43 to 1.72 | 1.29 | 0.72 to 2.29 | |

| Per 1 SD | 1.05 | 0.99 to 1.11 | 1.02 | 0.94 to 1.10 | 1.05 | 0.96 to 1.14 | |

Associations of fasting and post-load glucose levels with secondary outcomes

Associations with secondary outcomes were similar in the two ethnic groups [see Appendix 1, Table 53 (unadjusted) and Table 54 (confounder adjusted)]. The frequency of pre-eclampsia, shoulder dystocia and, with a weaker magnitude, instrumental delivery, also increased across each glucose category, especially with fasting glucose level (see Appendix 1, Figures 45 and 46). Neither fasting nor post-load glucose concentrations were clearly associated with preterm delivery or admission to the neonatal unit.

Criteria for diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus

Table 5 shows the thresholds of fasting and glucose that would result in an OR of 1.75 for BW of > 90th percentile, and sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile in each group. Fasting and post-load glucose thresholds based on the average of BW and skinfolds of > 90th percentile for all women irrespective of ethnic origin were 5.3 mmol/l and 7.5 mmol/l, respectively. Fasting glucose thresholds based on BW or the average of BW and skinfolds of > 90th percentile were higher for WB women than for SA women (see Table 5); with skinfolds of > 90th percentile alone as the outcome, the fasting glucose threshold was the same in both ethnic groups. There was no 2-hour post-load threshold that reached an OR of 1.75 for BW of > 90th percentile in either ethnic group. A threshold for sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile was found only in SA women (see Table 5).

| Outcomes | All women (N = 10,356) | WB women (n = 4105) | SA women (n = 5445) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting | 2-hour post load | Fasting | 2-hour post load | Fasting | 2-hour post load | |

| BW of > 90th percentile | 5.3 | NP | 5.6 | NP | 5.1 | NP |

| Sum skinfolds of > 90th percentile | 5.2 | 7.5 | 5.2 | NP | 5.2 | 7.2 |

| Average glucose level for both BW and sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile | 5.3 | 7.5 | 5.4 | NP | 5.2 | 7.2 |

Table 6 shows GDM prevalence by past and present diagnostic criteria, and the criteria derived from our data. For our study criteria, we show prevalences with the same thresholds in both ethnic groups (the thresholds derived for all women) and also ethnic-specific thresholds. Prevalence of GDM was about twice as high in SA women using any criteria range (4.1–17.4%) than in WB women (1.2–8.7%) for all non-ethnic specific criteria. Prevalence was greater in both ethnic groups with the recently derived IADPSG, NICE and our criteria than the 1999 WHO criteria. Of the three recent criteria, the NICE criteria resulted in the lowest prevalences in WB women and our criteria the highest. In SA women, the NICE criteria resulted in the lowest prevalence. If we applied criteria derived in our study for all women (i.e. not taking account of ethnic origin) to the SA women, the prevalence of GDM was the same using either IADPSG/WHO or our criteria. However, when we applied our ethnic-specific criteria, prevalence in SA women was nearly three times that in WB women (see Table 6).

| Criteria | Criteria (all define GDM as the presence of having glucose levels at or above one or more of the following) | Prevalence in our study population: % (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting glucose | 1-hour post-load glucose | 2-hour post-load glucose | WB | SA | |

| Older, used in recent past | |||||

| Exclusion in HAPO exclusiona | 5.8 | – | 11.1 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 4.1 (3.6 to 4.7) |

| WHO (previous)b | 7.0 | – | 7.8 | 4.7 (4.1 to 5.4) | 10.4 (9.6 to 11.2) |

| WHO (previous, modifiedc | 6.1 | – | 7.8 | 4.9 (4.3 to 5.6) | 10.8 (10.0 to 11.7) |

| Recently proposed | |||||

| NICEd | 5.6 | – | 7.8 | 5.9 (5.2 to 6.6) | 12.5 (11.7 to 13.4) |

| IADPSG/WHO (current)e | 5.1 | 10.8 | 8.5 | 7.6 (6.8 to 8.5) | 17.3 (16.3 to 18.3) |

| Our study | |||||

| Same criteria for all womenf | 5.3 | – | 7.5 | 8.7 (7.9 to 9.6) | 17.4 (16.4 to 18.4) |

| For WB | 5.4 | – | 7.5 | 8.3 (7.5 to 9.2) | – |

| For SA | 5.2 | – | 7.2 | – | 24.2 (23.1 to 25.3) |

Additional sensitivity analyses

The number of missing data ranged from 0% to 32% for the different variables (see Appendix 1, Table 50) and 5056 of the 9509 (53%) had complete data on all variables for the main analyses. Distributions of any variable with missing data were the same in the imputation data sets (see Table 4 and Appendix 1, Table 54) and for observed complete case data (see Appendix 1, Tables 56 and 57). There was no strong evidence for a quadratic curvilinear association between fasting or post-load glucose level and any of the primary or secondary outcomes (see Appendix 1, Table 55). The results of analyses restricted to Pakistani women did not differ from those presented for all SA women (see Appendix 1, Tables 58 and 59).

Discussion

We recorded graded monotonic associations of fasting and 2-hour post-load glucose level with LGA and high adiposity (as assessed by skinfold thickness) across most of the glucose distribution in both SA and WB women. The associations of glucose level with LGA appeared stronger in SA than WB women, but there was no statistical evidence of an interaction with ethnic origin. Applying the same method as the IADPSG to our data, we estimated fasting and post-load glucose thresholds for diagnosing GDM that are lower in SA women than in WB women. For WB women, our criteria included a fasting glucose threshold that was slightly higher, and a 2-hour glucose threshold that was markedly lower, than those recommended by IADPSG and WHO. Our results support a lower threshold for both fasting and 2-hour post-load glucose level for diagnosing GDM than is currently recommended by NICE in both WB and SA women. NICE supports higher fasting glucose thresholds to those proposed by the IADPSG and WHO in WB and SA women, but lower 2-hour post-load glucose thresholds. Using existing criteria, the prevalence of GDM in our cohort was about twice as high in SA than in WB women; when we applied the ethnic-specific criteria derived from our data, the prevalence was three times higher in SA women, and identified about 25% of SA women as having GDM.

Overall patterns of associations in our study, for both primary and secondary outcomes, were similar to those seen in the HAPO study,6 especially for fasting glucose levels. 6 Because of differences between ours and the HAPO study6 in the post-load glucose threshold used to exclude women from the study cohort, our highest 2-hour post-load category (category 7) was similar to category 4 in the HAPO study. 6 As a result, for some outcomes, the linear relationship seems to flatten at the upper end of the 2-hour post-load glucose categories.

Compared with the IADPSG, who used data from the HAPO study,6 we could not identify a 2-hour post-load threshold: there was no threshold that reached an OR of 1.75 for BW of > 90th percentile, and only SA women reached a threshold for this OR for sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile. The IADPSG consensus panel chose 1.75 to represent the lowest level of clinically important risk; a lower OR was not considered clinically important. GDM was diagnosed in our study using a lower 2-hour post-load glucose threshold than in the HAPO study;6 both studies excluded women with GDM as it would be unethical not to treat them. If we had applied the same high 2-hour post-load glucose threshold as in the HAPO study6 to diagnose GDM and to exclude women from the main analysis, we would have been more likely to identify an OR of 1.75, because women with higher glucose concentrations and greater associated risk of the primary outcomes would have been included in our analyses. The 2-hour post-load glucose level used to exclude women with GDM in the HAPO study6 was much higher than that recommended by WHO, and also by other criteria recommended at the time that the HAPO study6 began, including the Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society criteria. Thus, the 2-hour post-load glucose threshold used to define GDM in the IADPSG and WHO criteria is higher than that suggested by our study (see Table 1). Because the diagnostic criteria for GDM in our study meant that we excluded women from the main analyses with a much lower post-load glucose threshold than was the case in the HAPO study,6 we had difficulty identifying a glucose threshold that reached an OR of 1.75 for sum of skinfolds of > 90th percentile in WB women. Therefore, our GDM diagnostic criteria for this group are mainly driven by results of the associations with LGA.

Consistent with other studies,42–45 we have shown that using any criteria the prevalence of GDM is greater in SA women than in WB women. When we used the same criteria for both ethnic groups, the criteria derived from our study resulted in a higher prevalence of GDM than the NICE criteria for both WB women and SA women, but broadly similar prevalences for both groups to those found with the IADPSG/WHO criteria. When we used ethnic group-specific criteria, the prevalences for WB women remained higher than the NICE criteria, but were similar to IADPSG/WHO criteria, whereas those for SA women became higher for both of these other two criteria. Our study cohort is large and well characterised. The broad consistency of our findings with the results of the HAPO study,6 and the fact that our results were unchanged when we limited the analyses in SAs to those of Pakistani origin, suggests that the results might be generalisable to all white Europeans and SAs. Some participants had missing data for some variables, but the distribution of recorded variables and those from the pooled multiple imputed data sets were similar, as were the association results. We did not collect data for 1-hour post-load glucose concentrations, which were measured in the HAPO study,6 and a 1-hour post-load glucose threshold is included in IADPSG/WHO criteria for GDM. Although the HAPO study6 found linear associations of 1-hour post-load glucose levels with adverse perinatal outcomes, none of the randomised trials that have shown the effect of treatments on adverse perinatal outcomes had used this to define GDM. Furthermore, it is unclear how many additional women in different populations are identified by this additional glucose measurement. Thus, the benefit of this additional measurement remains somewhat unclear. We do not have data for cord blood C-peptide concentrations or neonatal hypoglycaemia. High cord blood C-peptide concentrations were one of the criteria used by the IADPSG in the development of their diagnostic criteria; this additional information might have affected our results. However, the similar prevalences of GDM in WB women using the IADPSG/WHO criteria or our study criteria suggest that including these data would not have markedly changed our results.

Concerns have been raised about the increased prevalence of GDM and hence the cost to health services if the IADPSG criteria are used worldwide in place of the previously widely used 1999 WHO criteria. 25,46,47 Until the late 1990s, the main aim of diagnosing GDM was to identify women at risk of subsequent type 2 diabetes. 48 By contrast, the outcomes used to develop the IADPSG criteria, which we also used, were chosen to identify offspring at risk of future high adiposity and cardiometabolic risk. 48 Although there is evidence that GDM causes greater adiposity in offspring in later life,48,49 there is still debate about the validity of that evidence. 50 Thus, the extent to which the IADPSG or our criteria will accurately predict future adverse offspring health remains to be established. Conversely, in view of the graded association of maternal glucose concentrations with adverse perinatal outcomes, lowering the thresholds used to diagnose GDM would identify more pregnancies at risk of these outcomes. Because effective, safe, and cheap treatments are available for GDM (e.g. lifestyle advice, metformin and insulin) that reduce glucose level across its distribution and help prevent adverse perinatal outcomes,51,52 applying the IADPSG/WHO 2013 or our criteria in place of the WHO 1999 criteria, and also in place of the recently suggested NICE criteria, might improve perinatal outcomes. Because the NICE 2015 criteria recommend higher thresholds of fasting and post-load glucose levels than the IADPSG/WHO or our newly defined criteria, their use will identify fewer women who are at increased risk of adverse outcomes. 53

To conclude, our data support the use of lower fasting and post-load glucose thresholds in SA women than in WB women. They also suggest that compared with our criteria or those of the IADPSG/WHO, the criteria recommended by NICE might underestimate the prevalence of GDM, especially in SA women. The use of our ethnic-specific thresholds for diagnosing GDM in SA women, and of either our – or the IASPSG/WHO – criteria for white European women might reduce the occurrence of adverse perinatal outcomes, in particular LGA, as more at-risk women would be treated. However, the effect of applying any of the recently proposed criteria on later life adiposity and associated cardiometabolic health in offspring are unknown and require further investigation. Furthermore the effectiveness of identifying and treating women with GDM at different cost-effectiveness thresholds, together with the use of varying glucose level thresholds, is also unclear. Our comprehensive analysis detailed in Chapter 7 of this report examines this area and provides information about uncertainties and the value of further research evidence.

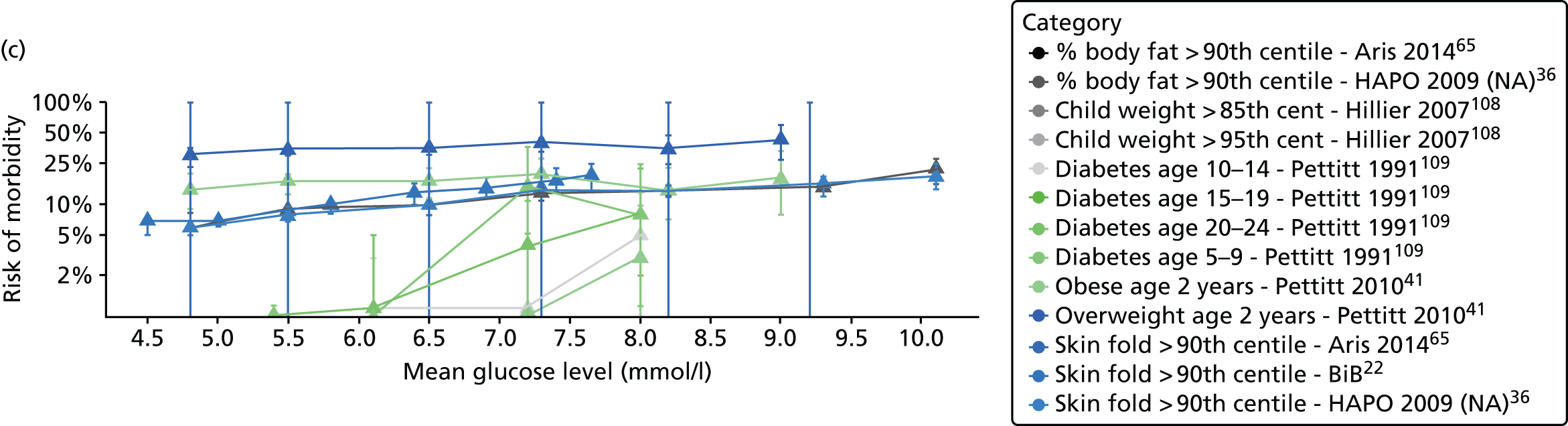

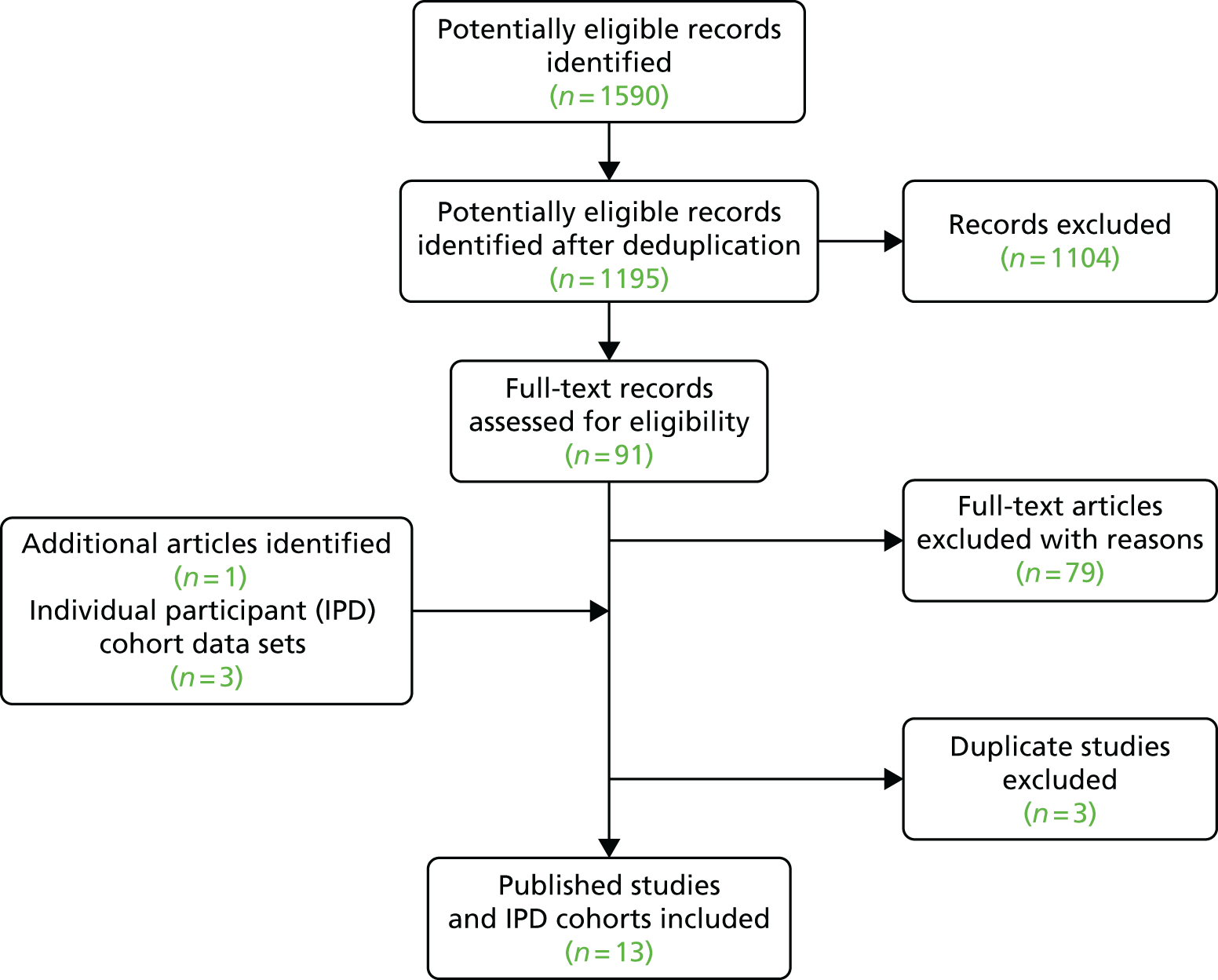

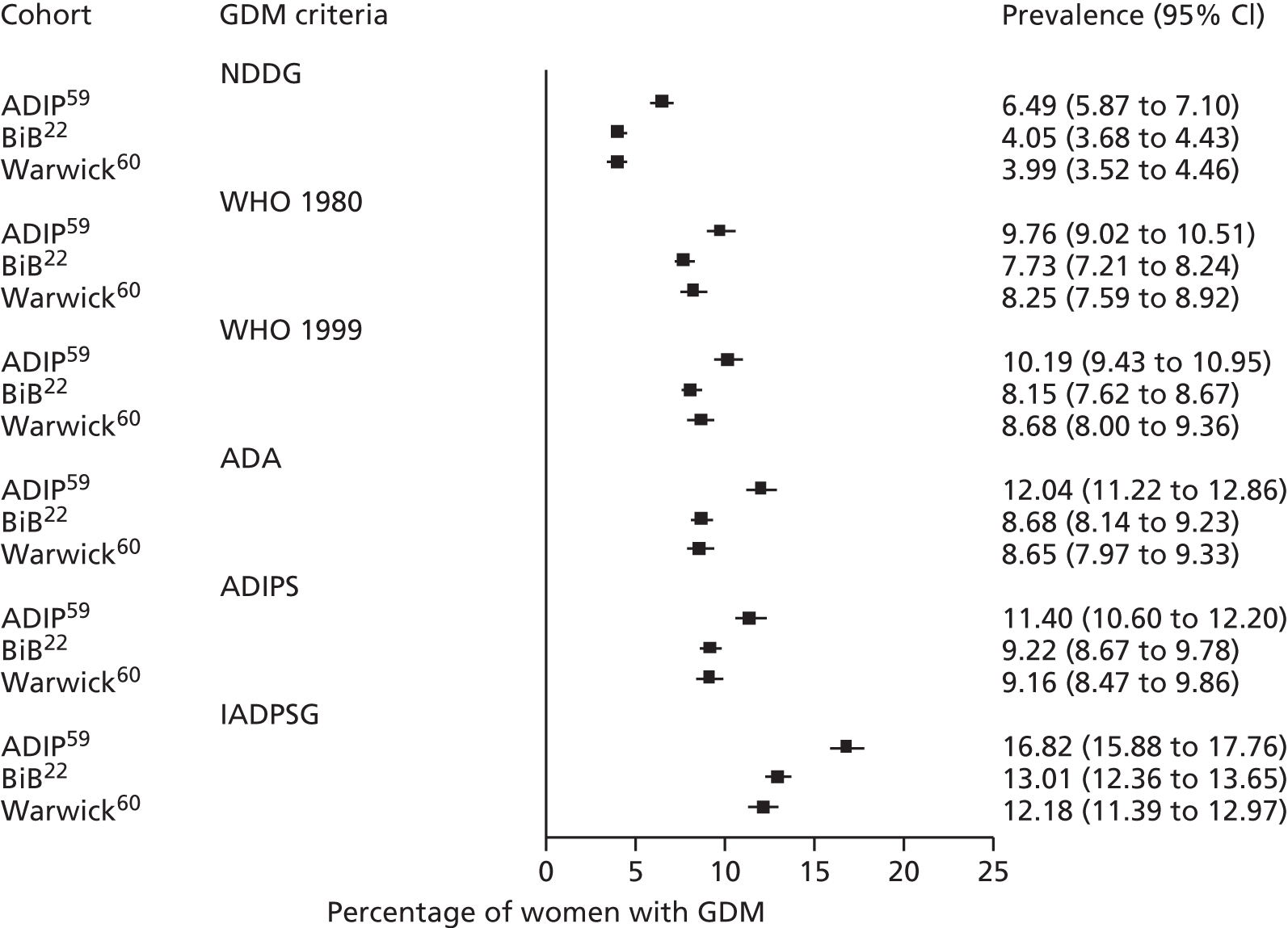

Chapter 3 Associations of gestational fasting and post-load glucose levels in women without existing or gestational diabetes with perinatal and longer-term outcomes: a systematic review

Introduction

This chapter presents a systematic review and meta-analyses to determine the association between graded increases in glucose level and risk of perinatal and longer-term outcomes. A version of this chapter has been published in Farrar et al. 54 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/.

Previous systematic reviews

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analyses examining the association of gestational glucose level with risk of perinatal and longer-term outcomes. We have previously undertaken a review as part of a master’s degree dissertation. 55 In that dissertation, a systematic search was undertaken to identify studies that investigated the association between gestational glucose levels [measured using the OGTT or oral glucose challenge test (OGCT)] and adverse outcomes. The findings of that review suggested strong associations between fasting glucose categories and both LGA and macrosomia and these associations were weaker for 2-hour post-load glucose categories. However, that review included only studies that had been published up to March 2013, and we are aware of additional studies since then. Furthermore, there was no attempt to explore sources of heterogeneity between studies.

The aim in this study was to expand and update the previous search and analyses in order to determine associations between fasting and post-load glucose levels, and both perinatal and longer-term maternal and offspring outcomes. This section is reported in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. 56

Methods

Search

The original (master’s dissertation) searches were undertaken in March 2013. 55 The search strategies including interfaces and search terms used, and how they were combined, are shown in Appendix 7 (see Tables 83 and 84). Although no date or language restrictions were placed on the searches, only studies with an English language title and/or an abstract were screened for inclusion. The same search strategy (as in March 2013) was used for updating this review, with repeat searches undertaken in September 2013 and October 2014. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE® and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations,® EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and the Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR).

The search results were downloaded into an EndNote (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) library and duplicates were removed. All records (title, publication details and abstracts if available) were screened for eligibility, independently, by two reviewers. We had previously screened the records identified by the March 2013 search; however, we rescreened these again to ensure that the screening standard was high and consistent across all searches. All studies identified as potential ‘includes’ were checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer. The reference lists of all of the included studies and any related systematic reviews identified were checked for further possible inclusions.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All studies reporting the association of fasting or post-load glucose level (obtained from an OGTT or OGCT) with perinatal and longer-term health outcomes in mother or offspring were potentially eligible. Associations in women diagnosed with GDM, however defined, were excluded. The included studies had to have the following characteristics.

Types of studies

All published and ongoing cohort studies and control (placebo or no active treatment) arms of randomised trials were considered for inclusion.

Types of participants

Pregnant women who had undergone assessment of glucose tolerance using an OGTT or OGCT were included. Women with pre-existing diabetes and those diagnosed with GDM and treated (to reduce glycaemic levels) were excluded, by excluding either whole studies (when it was impossible to exclude those with pre-existing diabetes or treated GDM from the study results) or subgroups of studies in which those with pre-existing diabetes or treated GDM had been included, if results were presented in such a way that we were able to exclude those with pre-existing diabetes or treated GDM. For the latter, we used the within-study definition of GDM and recorded that definition. Although, a priori, we assumed that GDM would have been diagnosed differently in different studies, and our preliminary review confirmed this, it is appropriate to use the within-study definition. Excluding women with treated GDM is appropriate because the reason for excluding these women is that treatment would affect the natural association of glucose levels with adverse outcomes.

Types of tests

The OGTT, including the 75-g and 100-g tests, and the 50-g OGCT. Studies of intravenous glucose testing were excluded. Each included study had to report at least two glucose categories for comparison, following exclusion of any treated group. Diagnostic criteria and threshold for treatment differed between studies.

Types of outcomes

Outcome data had to be reported as numbers of events in each of two or more defined glucose categories, as ORs or risk ratios in each category relative to a specified baseline category, or as ORs or risk ratios per SD or per 1 mmol/l of glucose. Studies reporting only correlations were excluded. Studies had to report at least one of the following outcomes.

Perinatal maternal outcomes

C-section (elective or emergency).

Induction of labour.

Instrumental (assisted delivery) (ventouse or forceps).

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) (however defined).

Pre-eclampsia (however defined).

Perinatal infant outcomes

Macrosomia (BW of ≥ 4.0 kg).

LGA (BW of ≥ 90th percentile, or however defined).

Preterm birth (< 37 weeks’ gestation).

-

Birth injury/trauma:

-

shoulder dystocia

-

Erb’s palsy

-

fractured clavicle.

-

Admission to special care or higher-care facility.

Neonatal hypoglycaemia.

Longer-term maternal or offspring outcomes

Type 2 diabetes (offspring or mother).

Cardiovascular disease (offspring or mother).

Obesity (offspring or mother) (however defined).

Quality assessment

The risk of bias in the included published studies was assessed using a modified version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme57 (CASP) and Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) quality assessment tool. 58 These tools are designed to aid the assessment of observational studies of association and prediction. The following quality criteria were considered:

-

representative nature of included population

-

loss to follow-up

-

consistency of glucose measurement and outcome assessment

-

blinding of participants and medical practitioners to glucose level

-

blinding of outcome assessors to glucose level

-

selective reporting of outcomes

-

adjustment of results for key confounding variables.

Each criterion was classified as being at low, high or unclear risk of bias. One reviewer performed the quality assessment; all assessments were then checked by a second reviewer.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from each publication on the following:

-

glucose test used:

-

OGCT or OGTT

-

glucose load (50 g, 75 g or 100 g)

-

timing (fasting, 1-, 2- or 3-hour post load)

-

-

glucose levels in each defined glucose category (when reported)

-

in millimoles per litre; levels presented as milligrammes per decilitre were converted to millimoles per litre

-

-

numbers of women in each glucose category

-

for each outcome reported:

-

definition of outcome

-

number of outcome events in each glucose category

-

relative risk (RR) or OR of outcomes in each glucose category relative to baseline category (if reported)

-

RR or OR per millimole per litre of glucose or per SD of glucose (if reported)

-

-

whether women with pre-existing diabetes and GDM were excluded

-

study location

-

how GDM was defined

-

which potential confounding factors were adjusted for

-

each quality criterion.

When presented, RR or ORs adjusted for key confounding factors (such as age, BMI, parity) were extracted for each glucose category or type of glucose measure.

One reviewer performed the data extraction. A second reviewer checked the accuracy of the data extraction for all included studies, but did not independently extract data.

Contact with authors and individual participant data

Having identified all relevant published studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, and, given that a goal of this project was to understand GDM within a contemporary UK population, we searched for recently recruited cohorts in the UK. We identified four eligible cohorts with IPD: two had sufficiently complete case data: the BiB study22 (data provided by John Wright, Bradford Institute for Health Research, September 2013) and the Atlantic Diabetes in Pregnancy cohort (Atlantic DIP59) (data provided by Fidelma Dunne, Department of Medicine, National University of Ireland, September 2013), one cohort had insufficient complete case data and was not included (Warwick/Coventry: P Saravanan, Warwick Medical School, 2013, personal communication60) and we were unable to secure data from one other (UK HAPO cohort6); however, we have included the published estimates from the whole HAPO cohort6 wherever possible.

Both the BiB and Atlantic DIP cohorts22,59 include fasting and 2-hour post-load glucose levels, obtained as part of a 75-g OGTT. When outcomes were not reported explicitly in the data set they were derived from available data if possible. For example, macrosomia, LGA and preterm birth were calculated from BW and gestational age data.

Statistical analyses

General approach

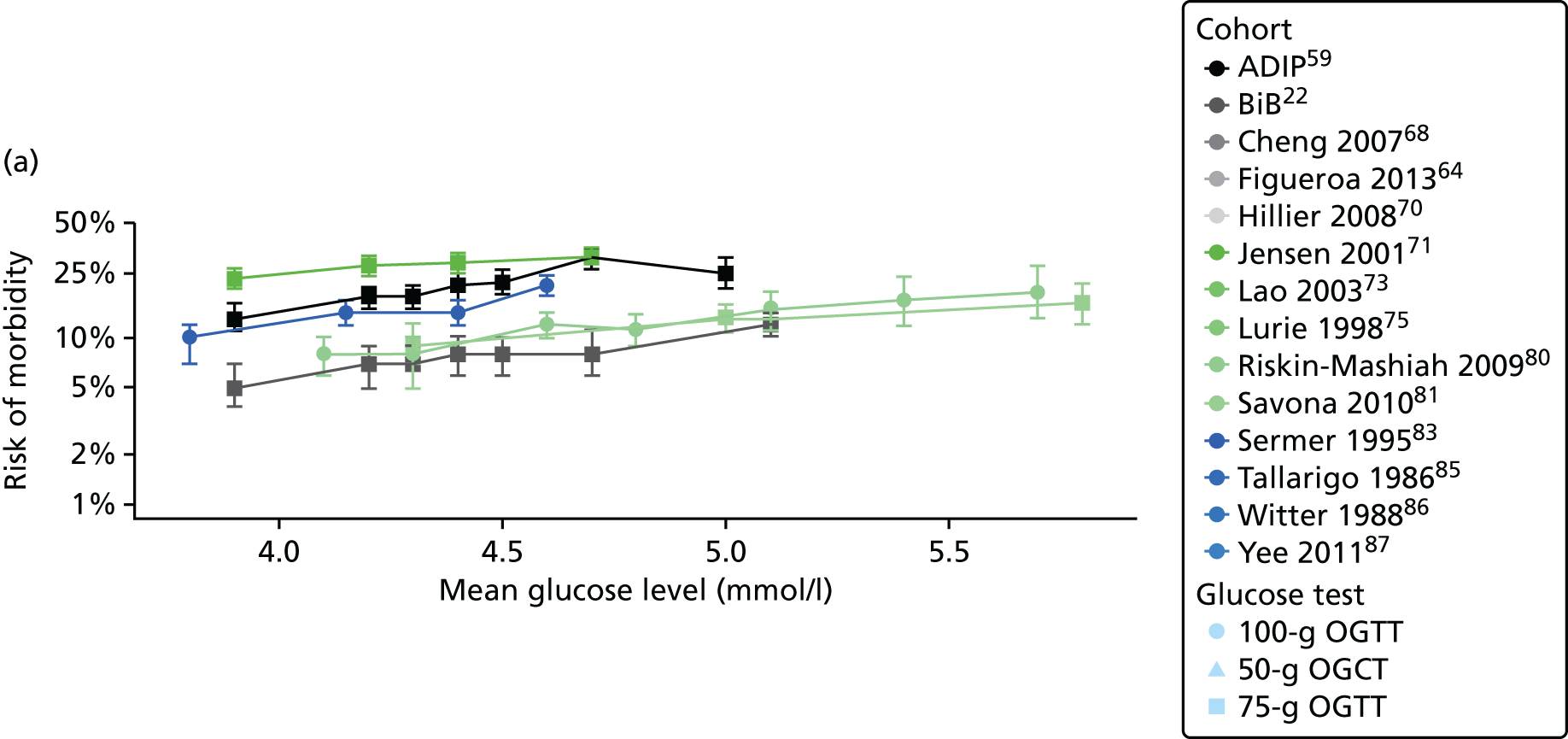

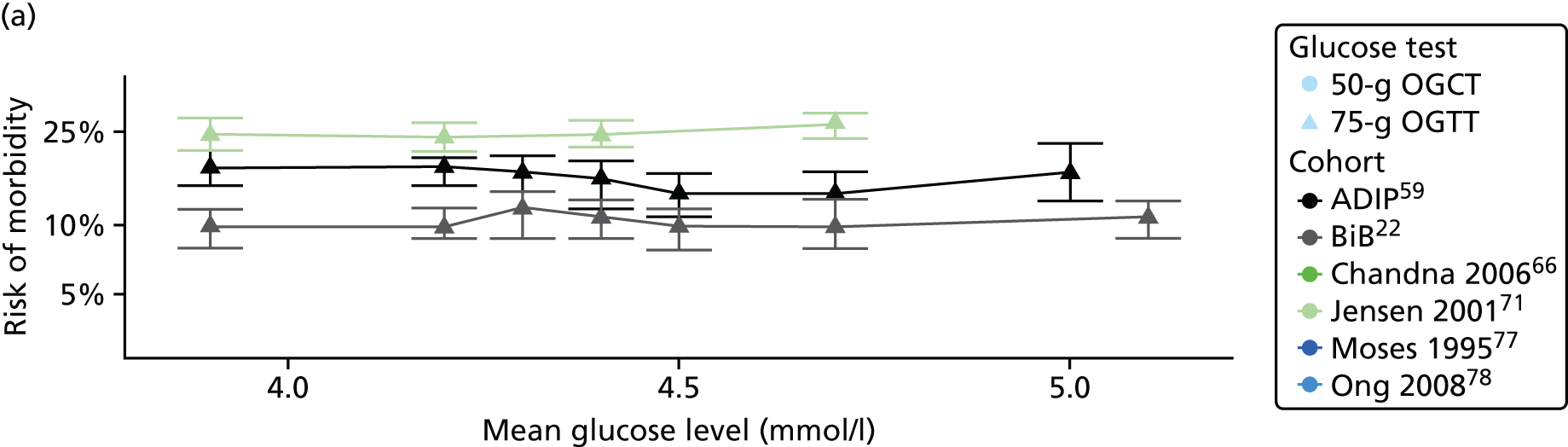

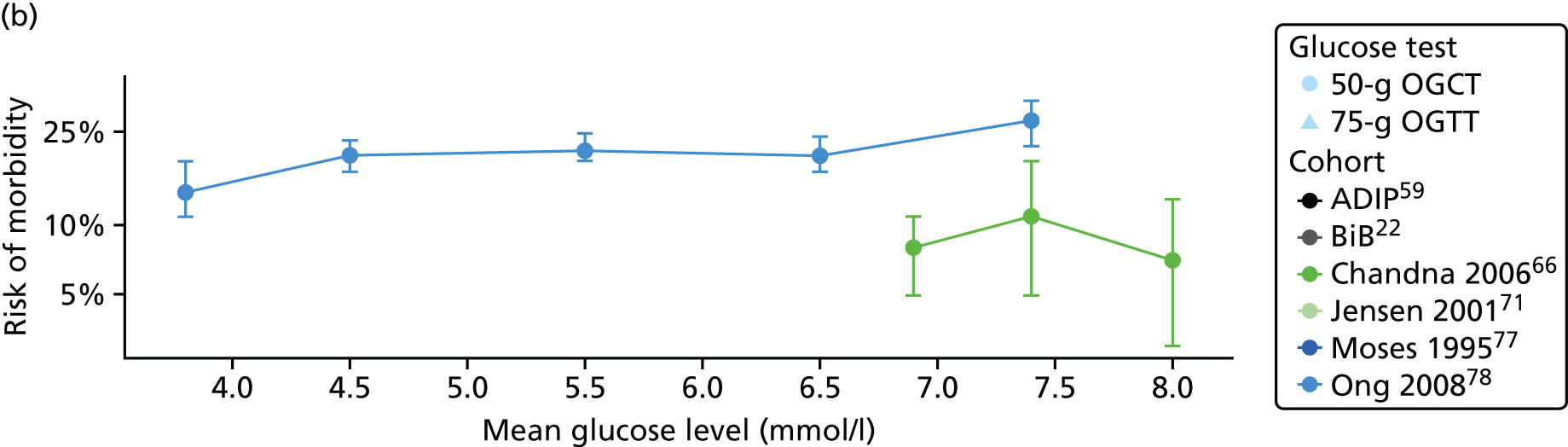

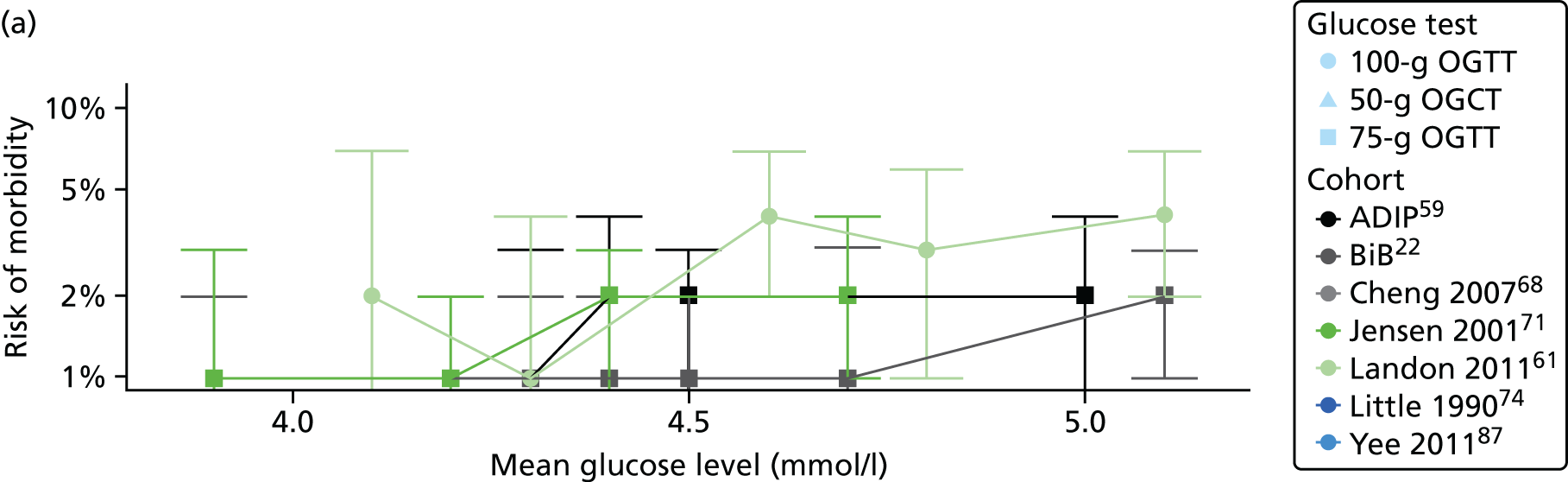

Statistical analyses were based on the number of women, and number of outcome events in each glucose category in each study. It should be noted that using these raw numbers means that these analyses are not adjusted for potential confounding factors. For the BiB and Atlantic DIP cohorts,22,59 glucose levels were divided into seven categories, with equal numbers of women in each category; for other published eligible studies we used whatever categories were used in the study. Studies that did not report outcomes by glucose categories were not included in these unadjusted analyses of outcome risk by glucose category. Within each glucose category we calculated the risk by dividing the number of outcome events by the total number of women in that category. With one exception,61 it was possible to do this for all of the published studies. In this one exception,61 only adjusted ORs were presented in each category (not numbers of events). For that study,61 numbers of each outcome were estimated, given the number of women in each glucose category (which was provided) and the ORs, using an exhaustive search approach to find numbers of outcomes that reproduced the reported ORs and their standard errors (SEs) as closely as possible. For each study that we were able to calculate risk per glucose category, we graphed these risks against the categories to assess the shape of the association and see if results looked generally linear (as in Chapter 2 for the BiB cohort), before modelling the identified associations and pooling results from studies. In studies that reported adjusted ORs or risk ratios for each glucose category, these results were similarly plotted to check the shape of the association and identify any divergence from results using unadjusted data.

Studies reporting odds ratios or risk ratios per standard deviation or 1 mmol/l of glucose

The aim of this analysis was to identify trends in outcomes with changes in glucose levels, so results reporting the trend as ORs per 1 mmol/l of glucose per SD in glucose level would be the preferred data. However, only the HAPO study6 reported such results, so no meta-analyses could be performed. The reported ORs per SD of glucose were converted into ORs per 1 mmol/l using the reported SDs. These were then compared with ORs obtained from the IPD cohorts.

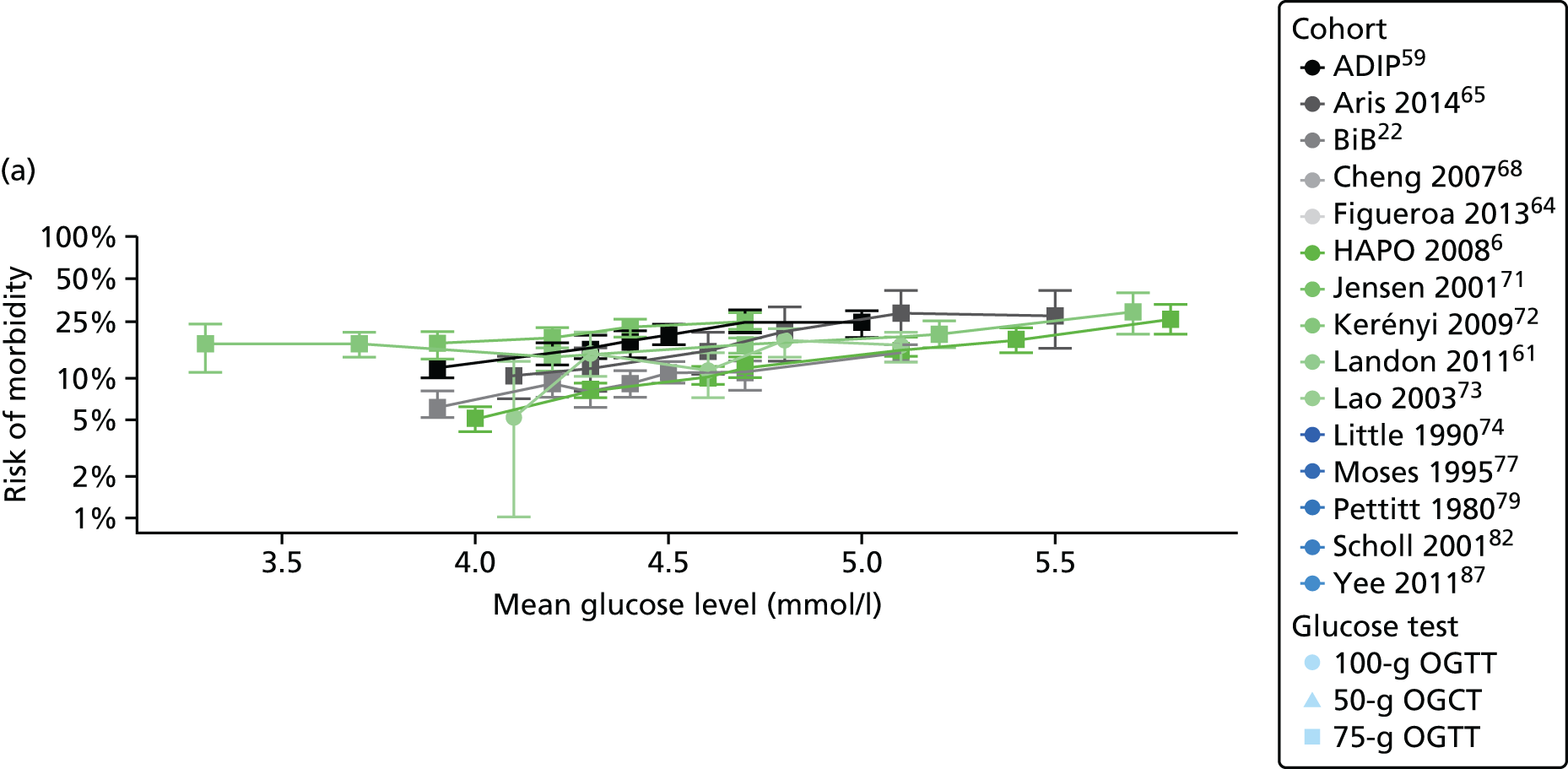

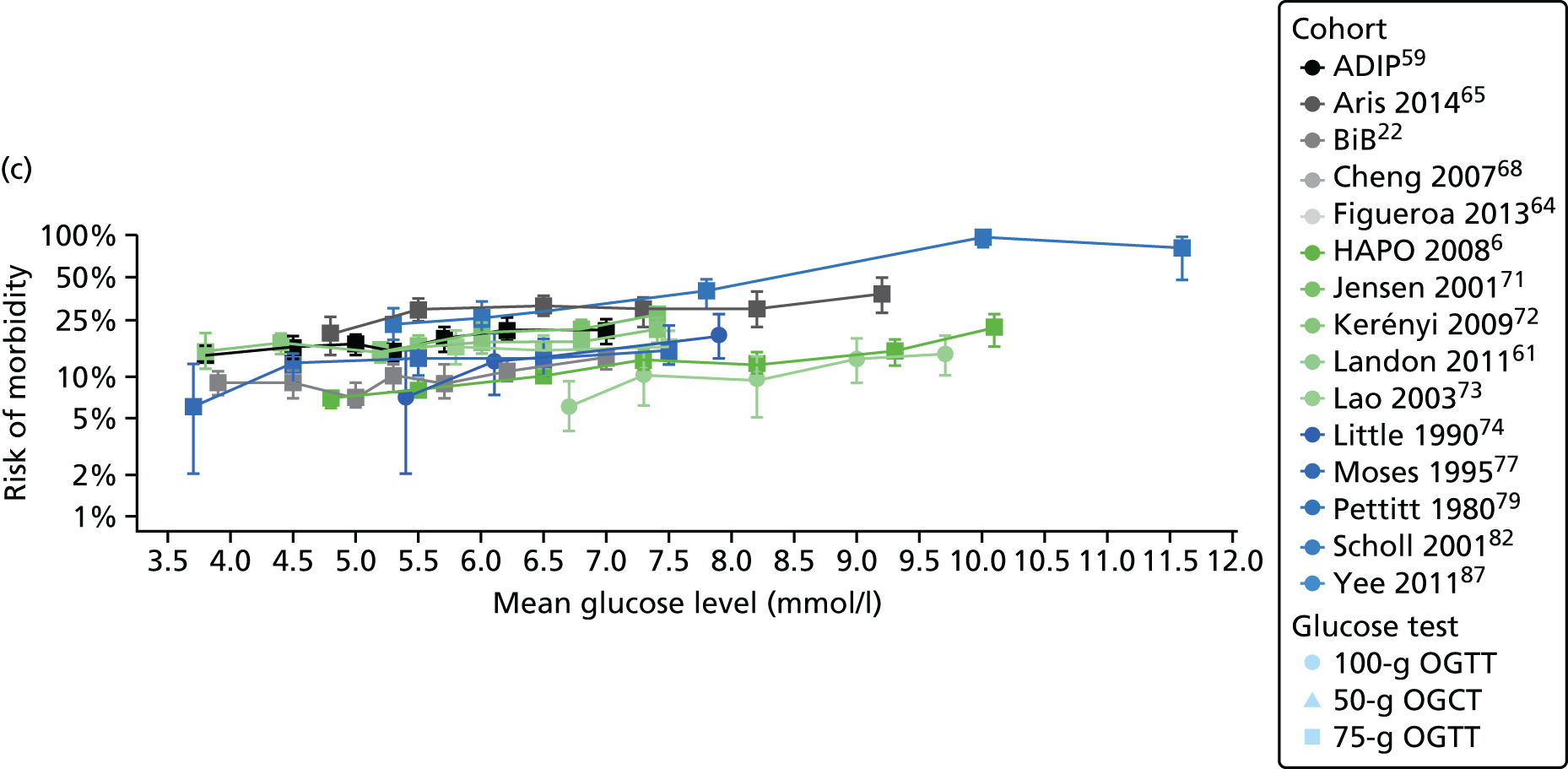

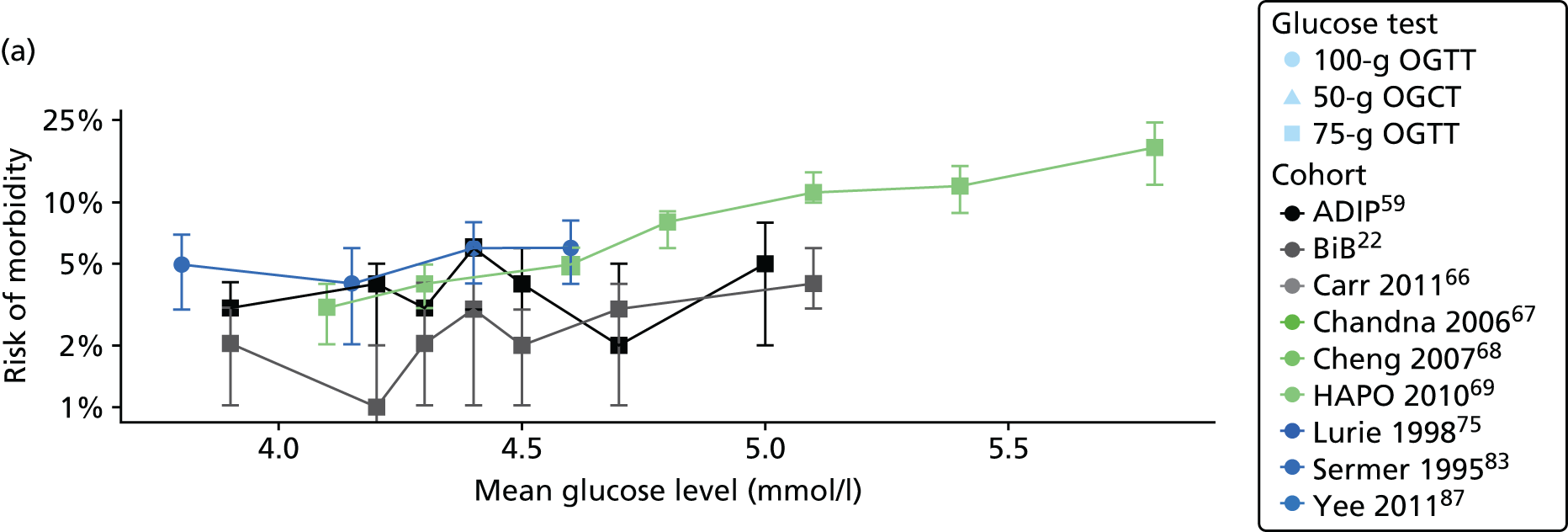

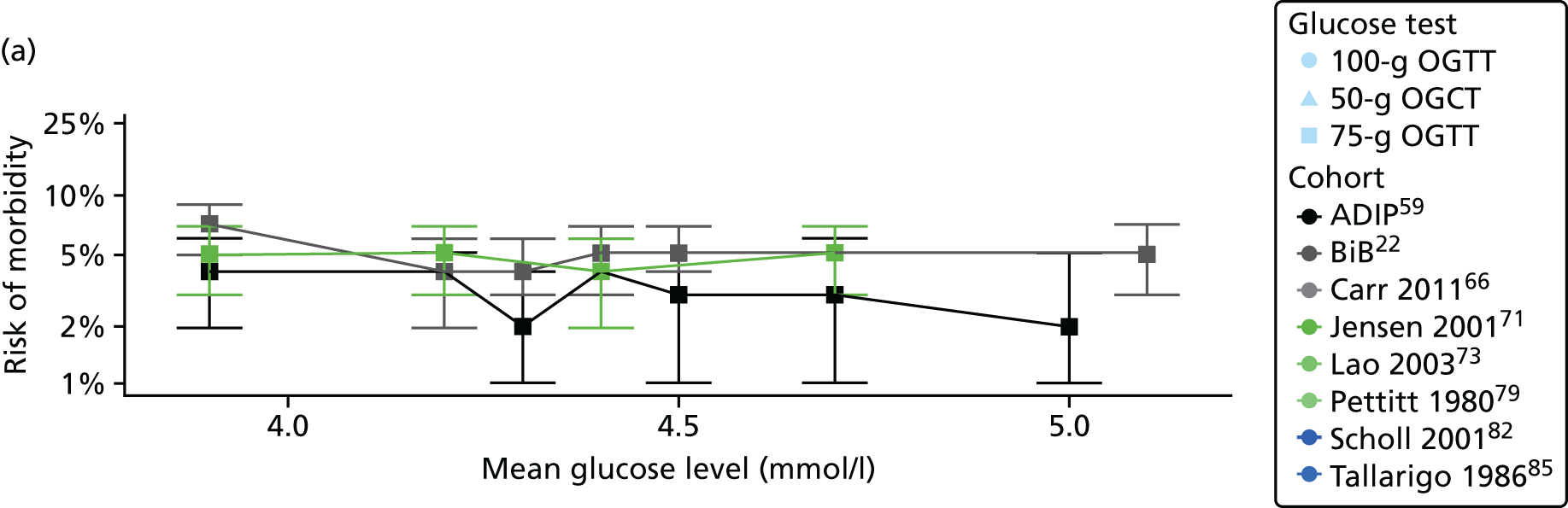

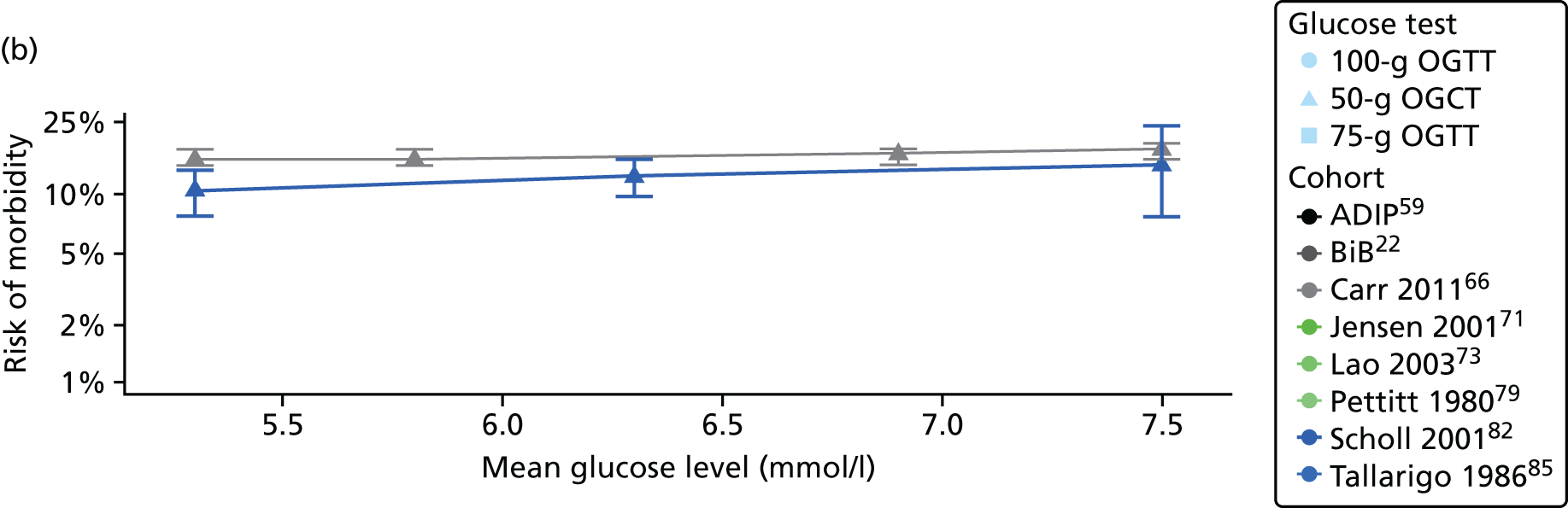

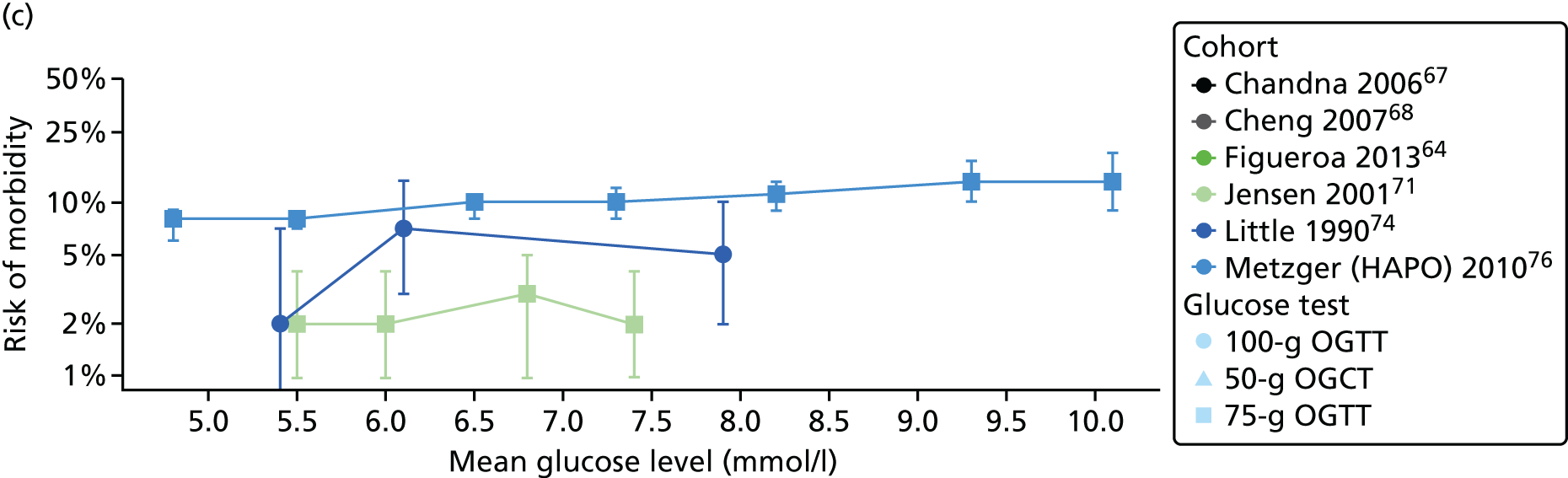

Studies reporting three or more glucose categories

For each study the risk of each GDM-related outcome along with its 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for each glucose category. For each outcome, and for each study, this risk was plotted against the level of glucose in each category, to visually inspect the trends in risk with glucose level.

Studies reporting results from only two glucose groups were excluded from these analyses because they did not report sufficient data to reliably estimate median glucose levels in each glucose category.

After inspecting risk of outcome across glucose categories for as many outcomes as possible, and in as many studies as possible, we felt that it was reasonable to assume a log–linear relationship between fasting or post-load glucose levels and all outcomes. Associations of fasting or post-load glucose levels (per 1 mmol/l) were therefore modelled separately for each study, outcome and glucose test (based on timing and load), using the following logistic regression model:

where i indicates study, j glucose test (e.g. 100-g OGTT fasting level), k the outcome of interest (e.g. macrosomia) and l the glucose category. Then pijkl is the probability of having the outcome in the relevant glucose category, Gijkl is the estimated median glucose level in that category, so ɸijkl is the baseline log odds of the outcome and θijkl is the association between glucose level and outcome, in terms of the log odds of outcome per 1-mmol/l increase in glucose level.

Estimates of association between outcome and glucose level, with their 95% CI, were pooled across studies using DerSimonian and Laird random-effects meta-analysis to account for any potential heterogeneity in the trends across studies. 62 Studies were combined in meta-analyses if there were two or more studies for the specified outcome and glucose test. Heterogeneity was examined using the I2-statistic and its 95% CI. 63

To increase the number of studies and participants in each comparison, studies were pooled if they included relevant glucose levels (fasting and/or post load) from either the 75-g or 100-g OGTT. This assumes that the trends in outcome incidence with glucose level were the same for the two OGTTs. We used a ‘one-stage’ version of model 1, above, with all studies combined in a single regression model. This model includes random intercept (ɸ) and slope (θ) terms to account for heterogeneity in the baseline odds of the outcome (i.e. the odds of each outcome in the lowest glucose category) and association between glucose levels and outcome between studies.

This analysis differs slightly from that in Chapter 2, for which results were summarised as the odds per SD. In this chapter, odds per 1 mmol/l glucose are used. This is because the SD in glucose levels varies across studies and was not generally reported; using odds per 1 mmol/l glucose permits a consistent approach to analysis across studies.

For studies that reported an adjusted OR for each outcome relative to a baseline glucose category, including the two studies for which we had IPD,22,59 we examined adjusted results. The adjusted ORs with their 95% CIs were plotted against the level of glucose in each category, so that a visual inspection of trends in risk across glucose levels could be undertaken. However, we were unable to perform meta-analyses of these results because of the limited number of studies presenting adjusted ORs.

Linearity

Following a visual inspection of figures of associations and to test the validity of our assumption of a log–linear association between outcome and glucose level (based on evidence from the HAPO6 and BiB22 studies), model 1 – presented above – was fitted again with an additional glucose-squared term (i.e. a term γijklGijkl2). A statistically significant association with glucose squared would suggest a quadratic–curvilinear relationship. Therefore, a lack of evidence suggests the relationship is not likely to be quadratic and suggests, along with the visual evidence, that there is a possibility that the relationship may be linear.

Studies reporting only two glucose categories

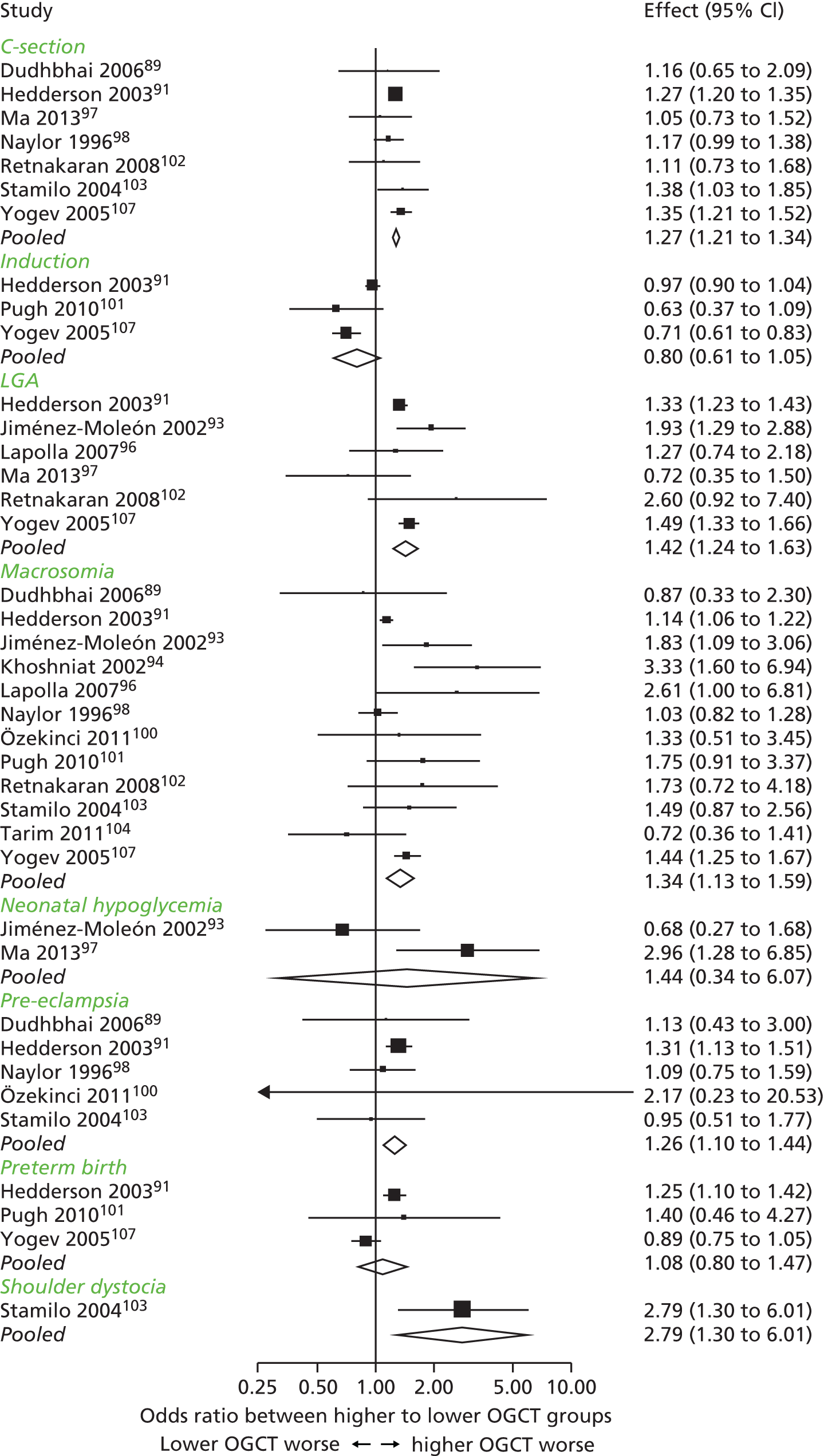

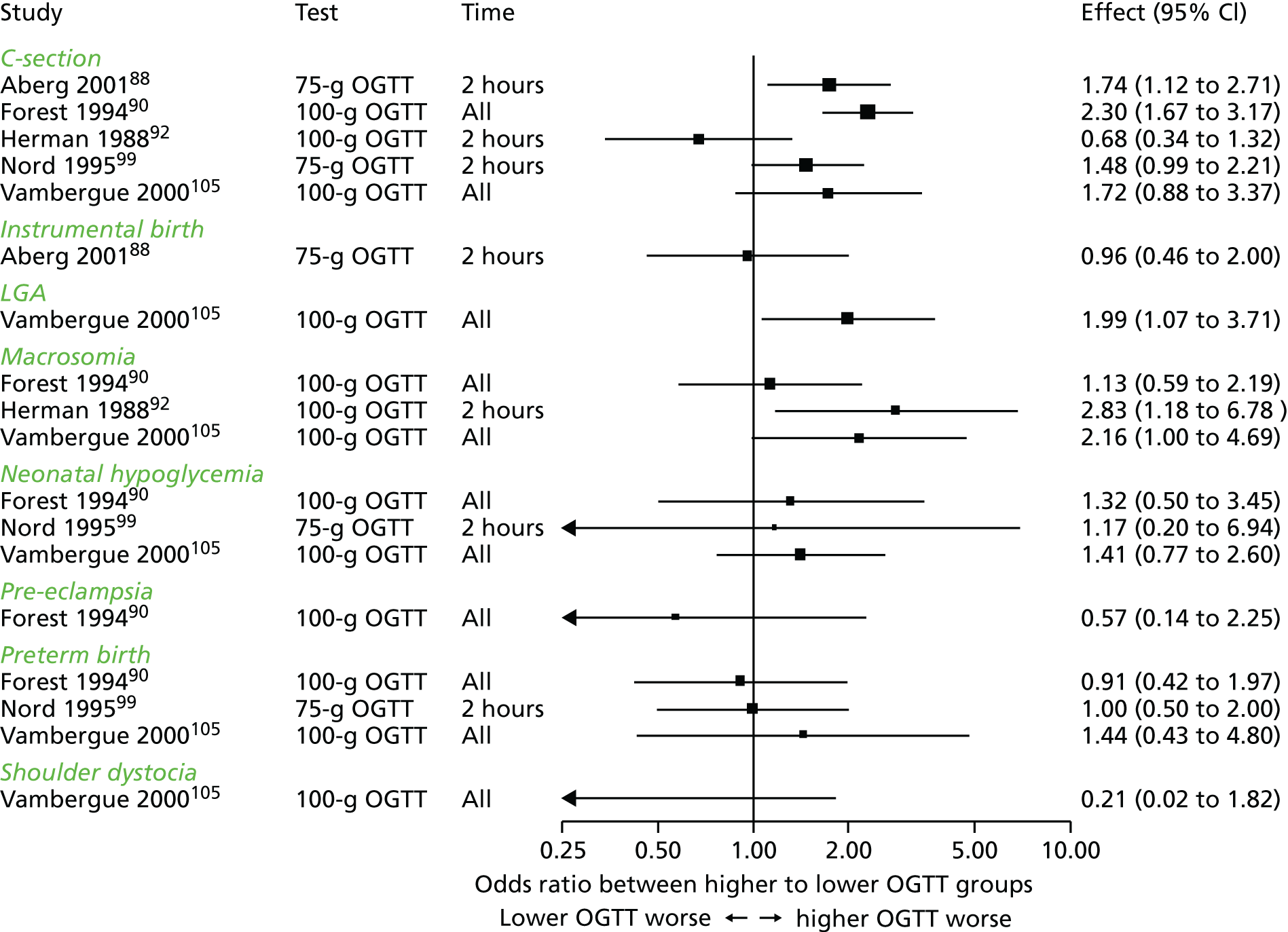

Several studies examined associations between perinatal outcomes and glucose levels following a 50-g OGCT. The OGCT was undertaken to determine whether women should (or should not) go on to have a diagnostic OGTT. Outcomes were then compared between those who did not meet the criteria for having an OGTT with those who did meet those criteria but who were not diagnosed with GDM [i.e. two groups were compared: < 130 mg/dl vs. ≥ 130 mg/dl post-challenge glucose or (for some studies) < 140 mg/dl vs. ≥ 140 mg/dl post-challenge glucose]. 14 The glucose categories in millimoles per litre (values expressed as milligrammes per decilitre were converted to millimoles per litre) in each of these two comparisons were abstracted, as were the numbers of women in each category and the number of these with outcomes in each category.

Some studies compared outcomes in women whose glucose levels were all ‘normal’ at any OGTT time point (i.e. fasting and 1, 2 or 3 hours post load, depending on which tests was undertaken) to women who had one elevated glucose level; these comparisons were undertaken in populations using criteria that required at least two elevated levels for a diagnosis of GDM to be made.

For both of these types of study, the numbers of outcomes in each group was used to calculate ORs for outcomes. The ORs for each group (lower risk vs. higher risk) were pooled across studies for each outcome using DerSimonian and Laird random-effects meta-analysis. 62

Analyses of the individual participant data cohorts

In order to perform analyses that were not possible with published data, in particular to perform adjusted analyses, further analyses of the two IPD cohorts were performed. To maintain consistency, the statistical modelling approach used was broadly similar to that used in the analyses of published studies. To maintain a consistent approach to analyses of the two cohorts the data sets were cleaned using the same rules and analyses undertaken as described below.

The shape of the association between outcomes and glucose levels were viewed. Following this assessment and to model these associations a log–linear relationship between risk and outcome was assumed; the model was adjusted for age, BMI and ethnicity (these were the potential confounders reported across both cohorts). Women with GDM according to the WHO criteria11 were excluded from analysis, as they were offered treatment (fasting ≥ 6.1 mmol/l and/or 2-hour post-load ≥ 7.8 mmol/l). This association was modelled separately for each cohort, outcome and time of glucose measurement. Formally, the models had the form:

with parameters as in model 1, above, except that Xij is a matrix of the adjusting factors (age, BMI, ethnicity). The model was fitted using logistic regression. For each cohort outcome, for both fasting and post-load glucose model results were used to calculate the estimated odds of outcome at increasing glucose levels, and the absolute risk of an outcome at increasing glucose levels, to examine the trend in risk with glucose.

The results from model 2, above, for each cohort were used to predict the OR of having an outcome relative to the mean glucose level across the full range of fasting and post-load glucose levels. This makes the assumption that the log OR increases linearly with glucose levels.

A further ‘one-stage’ model was considered, pooling the two cohorts together in a single model. The same model structure as in model 1, above, was used, but assuming that the association between glucose level and outcome was subject to a random effect across the two cohorts, that is:

where θ is the summary association between glucose level and outcome across both cohorts and τ2 is the heterogeneity in effect. To test the validity of the assumption of a log–linear association between outcome and glucose level the model presented above was fitted again with an additional glucose-squared term.

Results

Included studies

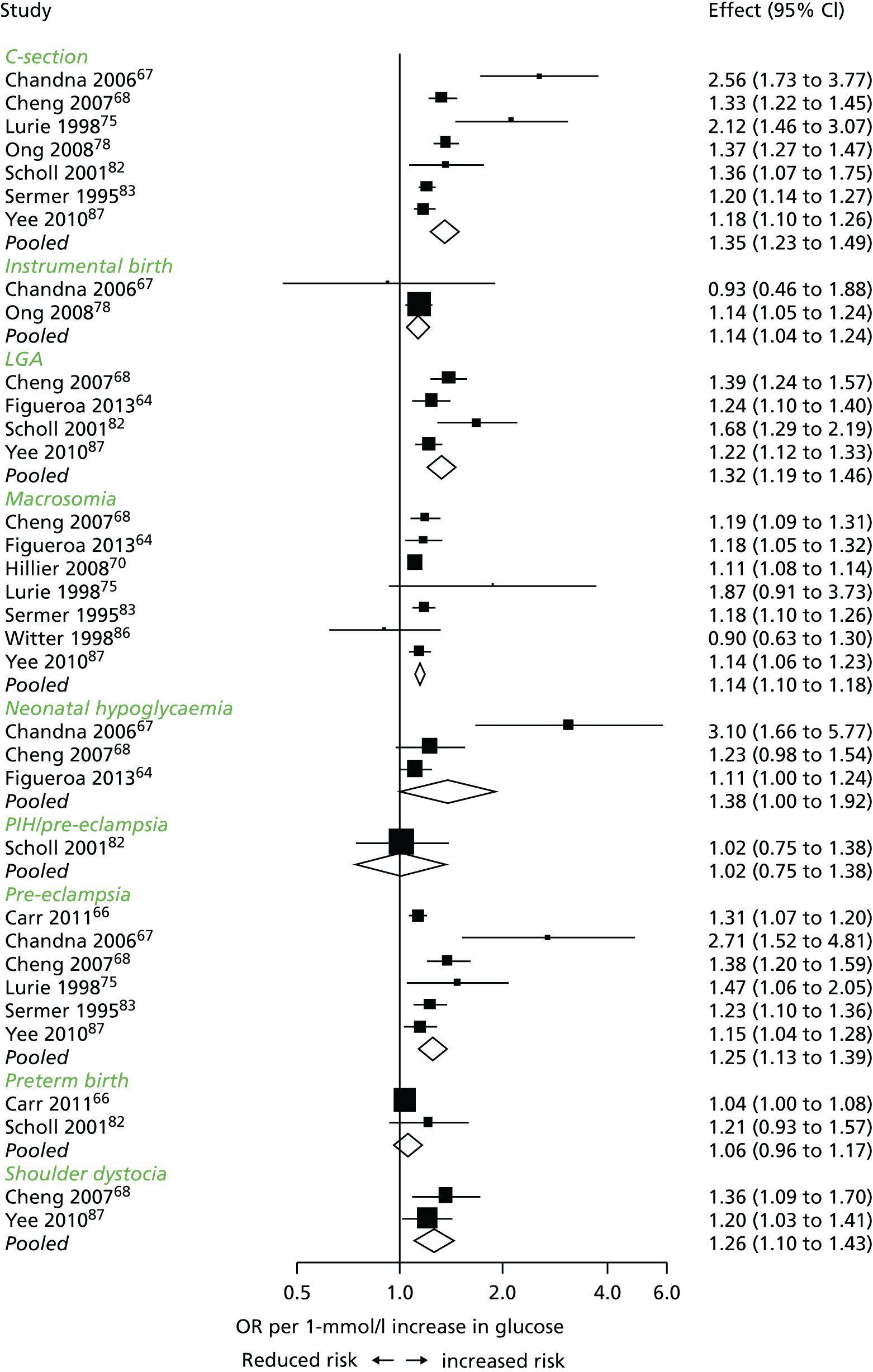

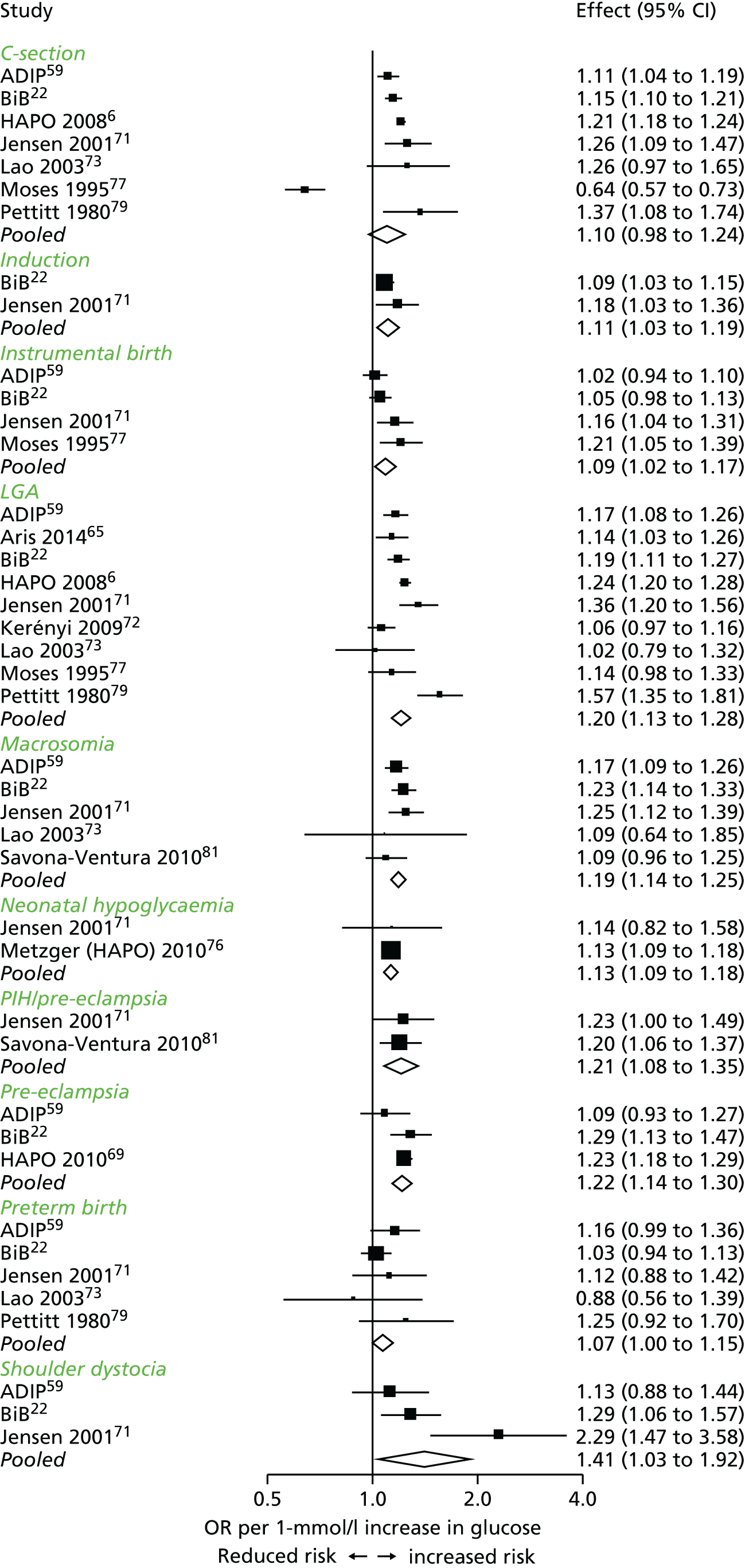

The search from the unpublished review55 and the updated searches together identified 11,219 potentially relevant studies following removal of duplicates. After title and abstract screening 125 publications were obtained for full-text review. After full-text screening, 57 studies (see Tables 7–9) were included in the review and 37 in the meta-analysis (including the two studies22,59 for which we had IPD) (see Appendix 2, Table 62 for excluded studies with reasons). Figure 3 shows the identification of these studies.

FIGURE 3.

The search process. a, Includes 7947 from the March 2013 search, 808 from the September 2013 search, and 2464 from the October 2014 search.

Several publications reported data from the same cohort. Four of the included publications used data from the HAPO cohort,6 but reported different outcomes. One of these publications (Pettitt et al. 41) was not included in the analyses because it reported associations with outcomes in a subset of participants that had been previously reported in the whole cohort. For the remaining publications, data from the most recent and comprehensive publication for each outcome were used. Two publications61,64 used data from the same cohort: Figueroa et al. 64 examined glucose levels at OGCT and risk of adverse outcomes, whereas Landon et al. 61 examined glucose levels at OGTT and risk of adverse outcomes. Data from both publications are therefore included in analyses.

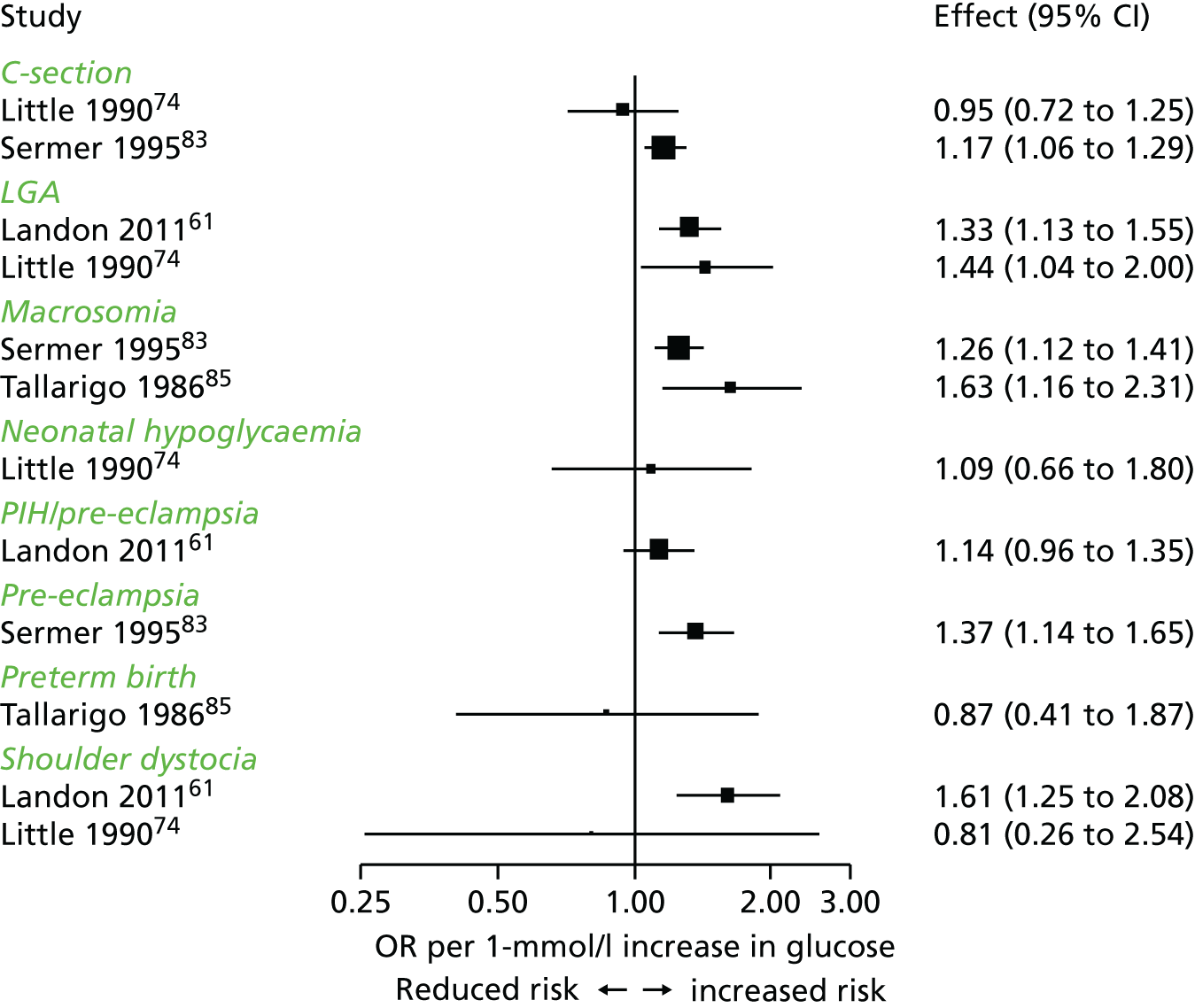

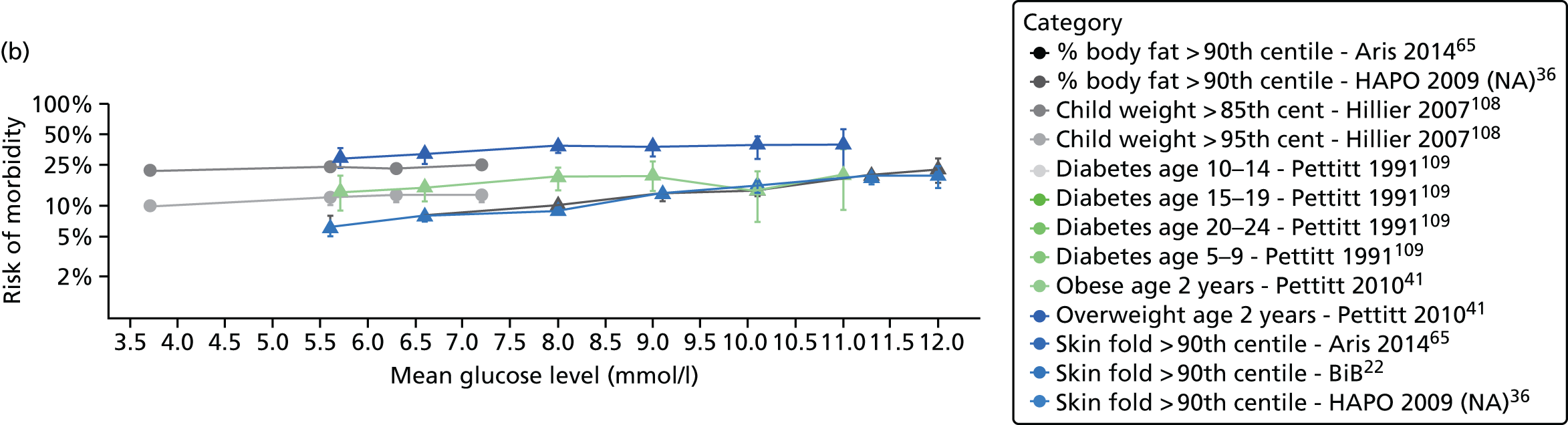

Characteristics of eligible studies are described in Tables 7–9. The studies fall into four categories: (1) 28 studies (including BiB and Atlantic DIP)6,61,64–87 reported associations between glucose levels (from OGTT or OGCT) split into three or more categories and adverse perinatal outcomes (see Table 7); (2) 20 studies88–107 reported associations between glucose levels (from OGTT or OGCT) split into two categories with adverse perinatal outcomes (see Table 8) – these studies were mostly comparisons of women with lower glucose levels at OGCT [typically < 140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/l)] compared with women with higher glucose levels at OGCT; (3) five studies36,41,65,108,109 reported longer-term outcomes in either mother or offspring (see Table 9) (it was not possible to pool studies reporting longer-term outcomes because they were too diverse); and (4) the remaining five studies110–113 did not present numerical data that were suitable for analysis and therefore could not be included in any of the meta-analyses (see Appendix 2, Table 63). One study114 used a 75-g OGTT in a non-fasted population. As there were no other studies that had used this test in this way, and post-load glucose levels from a non-fasted group are likely to differ to those from a fasted group, we did not include results from this study in any meta-analyses.

| Study | Year | Location | Women (n) | Glucose test | Timing of test | GDM diagnosis criteria | Outcomes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting | 1 hour | 2 hour | LGA | Macrosomia | Shoulder dystocia | Neonatal hypoglycaemia | Pre-eclampsia/PIH | Preterm | C-section | Induced labour | Assisted delivery | ||||||

| Aris65 | 2014 | Singapore | 1081 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | WHO | ✗ | |||||||||

| Atlantic DIP59 | 2015 | Ireland | 4869 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | WHO | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| BiB22 | 2015 | UK | 9645 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | WHO | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Carr66 | 2011 | USA | 25,969 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | C&C | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| Chandna67 | 2006 | Pakistan | 633 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | Not reported | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Cheng68 | 2007 | USA | 13,901 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | Not reported | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Figueroa64 | 2013 | USA | 1839 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | C&C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| HAPO group6 | 2008 | International | 23,316 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Defined in paper | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| HAPO group69 | 2010 | International | 21,364 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Defined in paper | ✗ | ||||||||

| Hillier70 | 2008 | USA | 41,450 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | NDDG and C&C | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Jensen71 | 2001 | Denmark | 2904 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | Defined in paper | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Kerényi72 | 2009 | Hungary | 3787 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | WHO | ✗ | |||||||||

| Landon61 | 2011 | USA | 1368 | 100-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | C&C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Lao73 | 2003 | China | 2168 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | WHO | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Little74 | 1990 | USA | 287 | 100-g OGTT | ✗ | O’Sullivan | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Lurie75 | 1998 | Israel | 353 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | NDDG | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Metzger76 [HAPO] | 2010 | International | 17,094 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Defined in paper | ✗ | ||||||||

| Moses77 | 1995 | Australia | 1441 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ADIPS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Ong78 | 2008 | UK | 3826 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | Defined in paper | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| Pettitt79 | 1980 | USA-Pima Indians | 811 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | Defined in paper | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Riskin-Mashiah80 | 2009 | Israel | 6129 | 100-g OGTT | ✗ | C&C | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| Savona-Ventura81 | 2010 | Malta | 1289 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | Not reported | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Scholl82 | 2001 | USA | 1157 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | Not reported | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Sermer83 | 1995 | Canada | 3637 | 50-g OGCT/100-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | NDDG | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Subramaniam84 | 2014 | USA | 56,786 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | Not reported | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Tallarigo85 | 1986 | Italy | 249 | 100-g OGTT | ✗ | O’Sullivan | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Witter86 | 1988 | USA | 3897 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | Defined in paper | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Yee87 | 2010 | USA | 13,789 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | C&C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Study | Year | Location | Women (n) | Glucose test used | Timing of test | Cut-off level | GDM diagnosis criteria | Outcomes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting | 1 hour | 2 hour | 3 hour | LGA | Macrosomia | Shoulder dystocia | Neonatal hypoglycaemia | Pre-eclampsia | Prematurity | C-section | Induced labour | Assisted delivery | |||||||

| Aberg88 | 2001 | Sweden | 4657 | 75-g OGTT | ✗ | 7.8 mmol/l | WHO | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Dudhbhai89 | 2006 | USA | 201 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | 140 mg/dl | Defined in paper | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Forest90 | 1994 | Canada | 4314 | 100-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | One abnormal value | Defined in paper | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Hedderson91 | 2003 | USA | 1956 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | 140 mg/dl | C&C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Herman92 | 1988 | USA | 126 | 100-g OGTT | ✗ | 140 mg/dl | Defined in paper | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| Jiménez-Moleón93 | 2002 | Spain | 1962 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | 140 mg/dl | ADA | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| Khoshniat94 | 2002 | Iran | 1801 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | 130 mg/dl | C&C | ✗ | |||||||||||

| Langer95 | 2005 | 50-g OGCT and 100-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Diagnosed GDM | C&C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Lapolla96 | 2007 | Italy | 758 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | 140 mg/dl | Defined in paper | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| aMa97 | 2013 | USA | 436 | 50-g OGCT and 75-g OGTT | ✗ | ✗ | 120 mg/dl | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

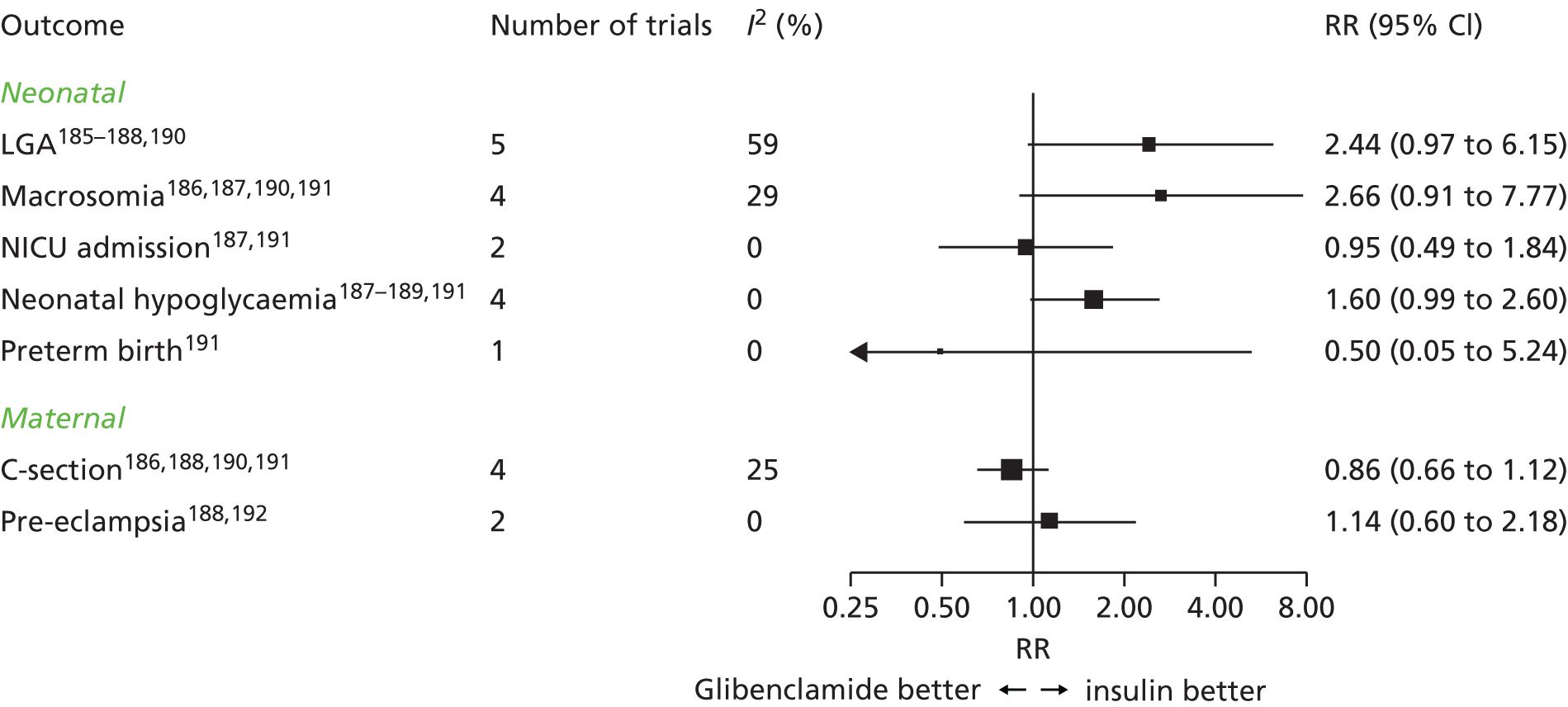

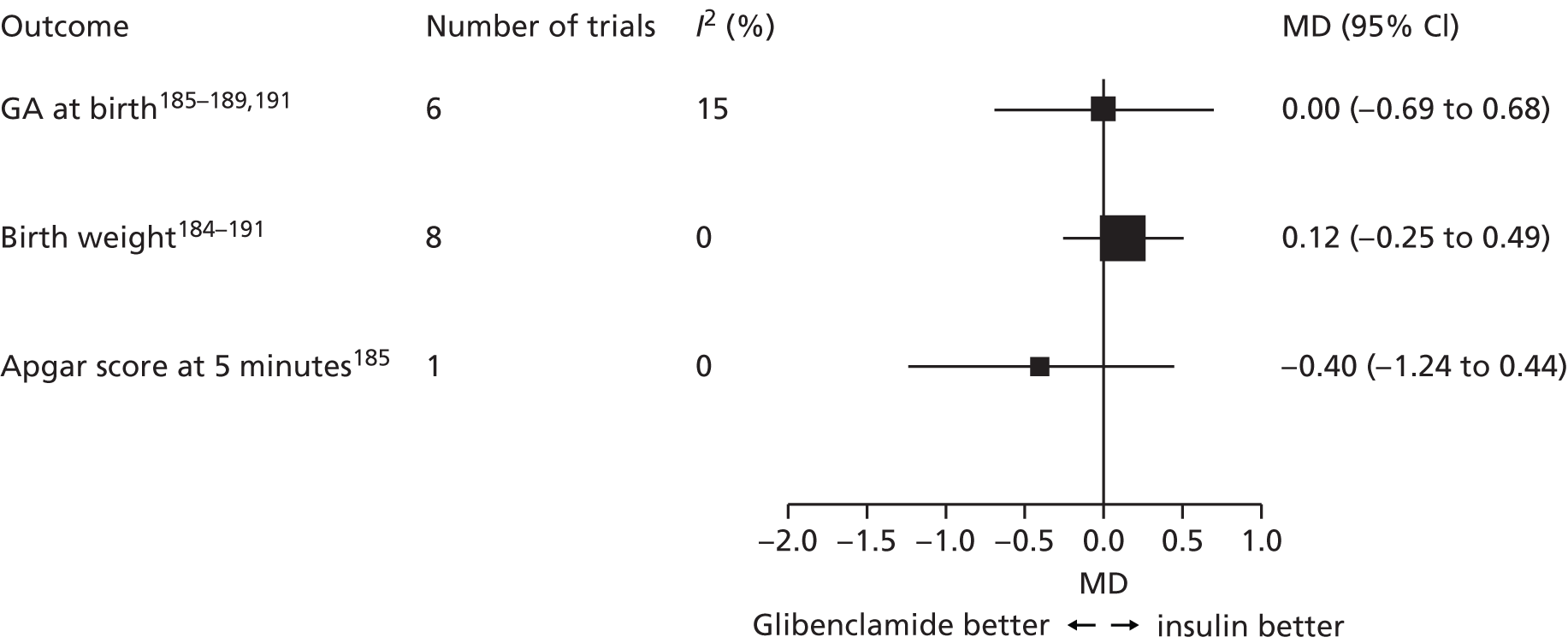

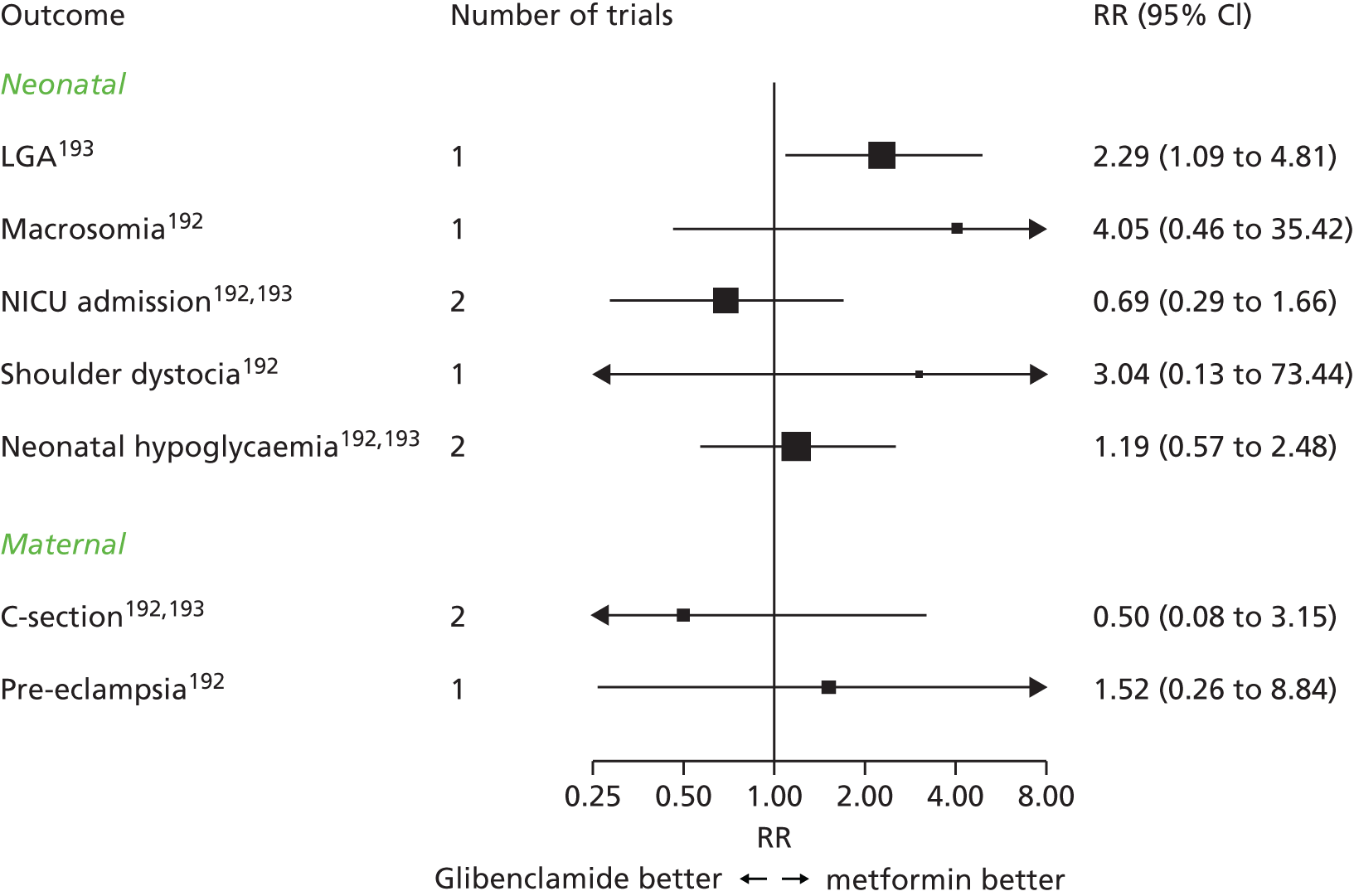

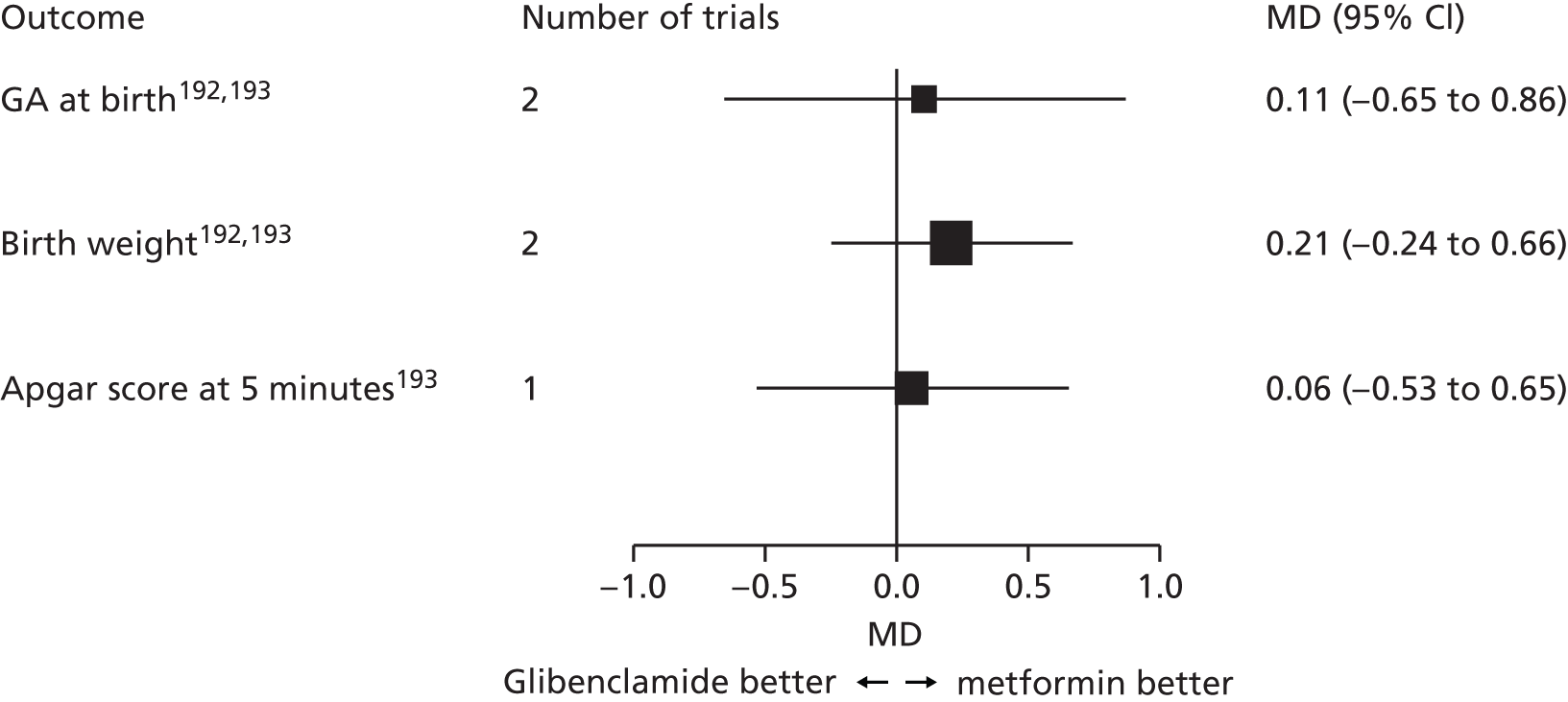

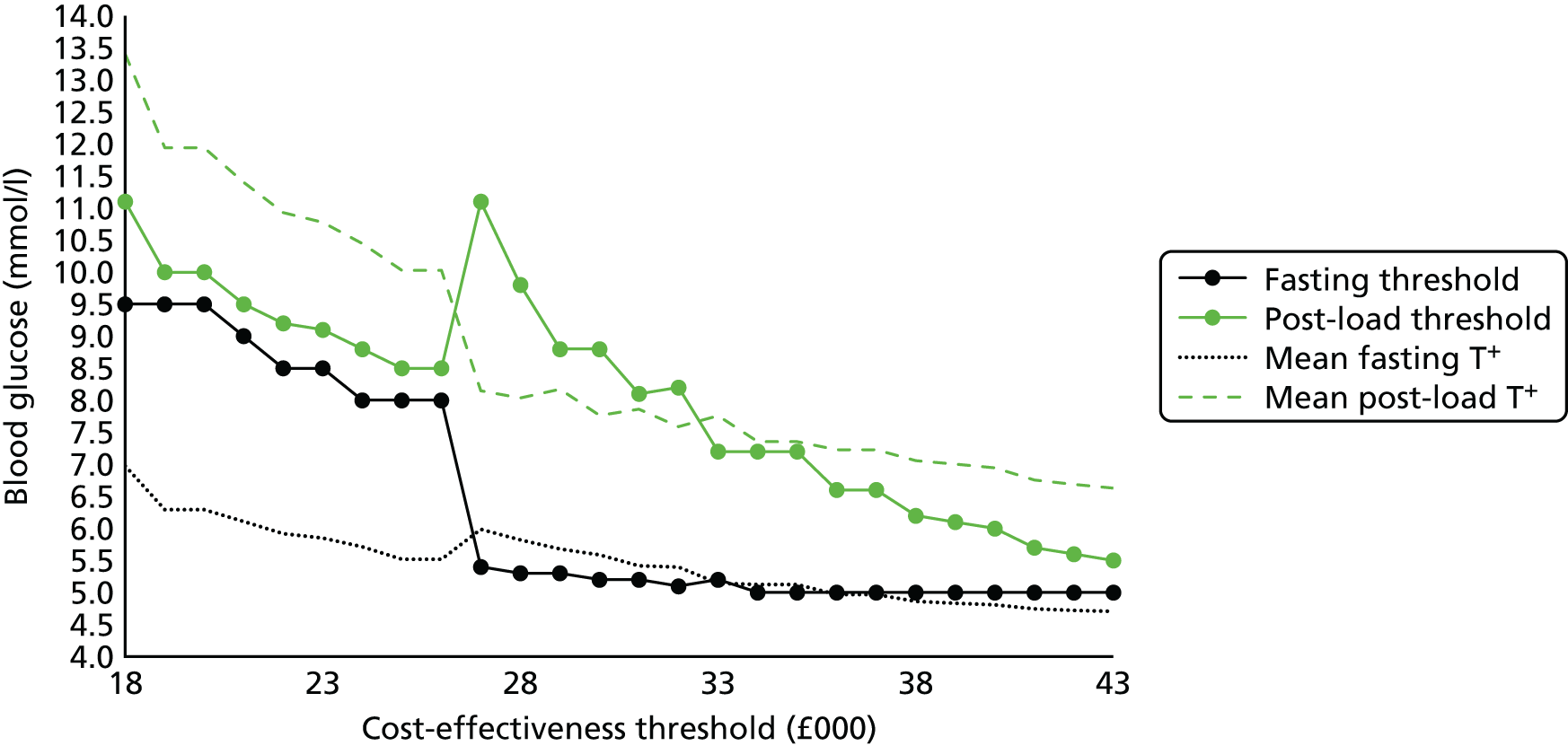

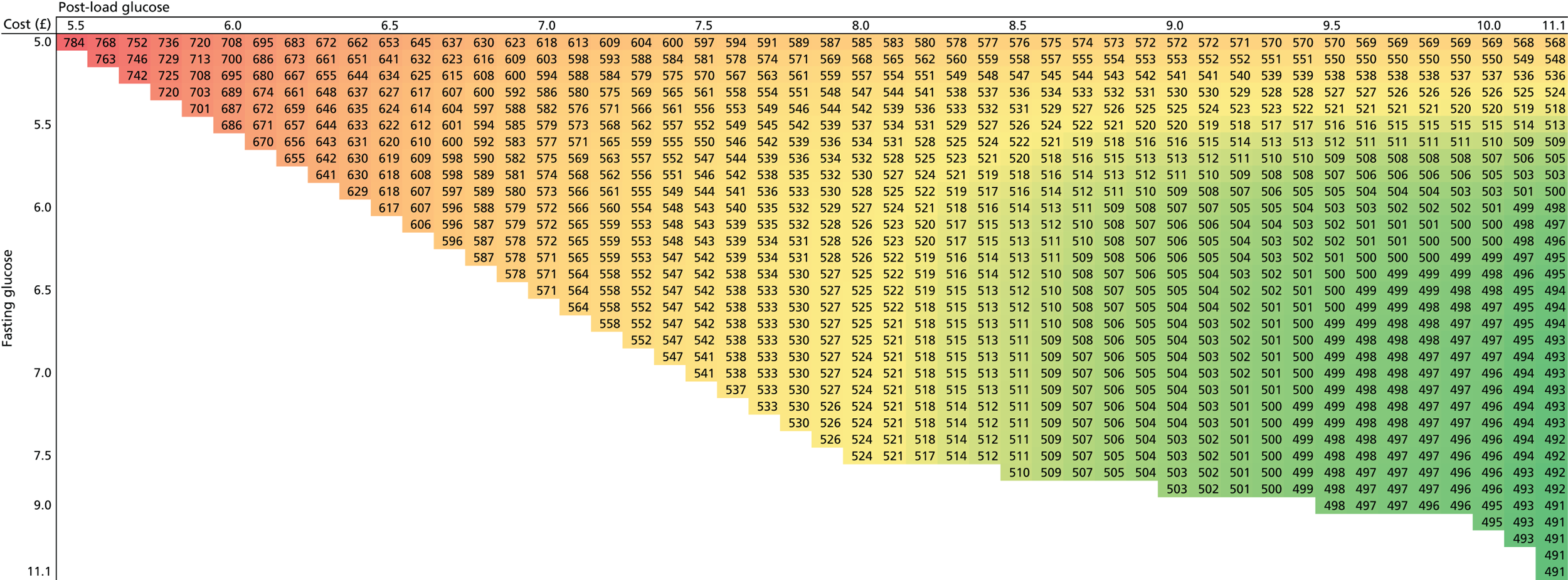

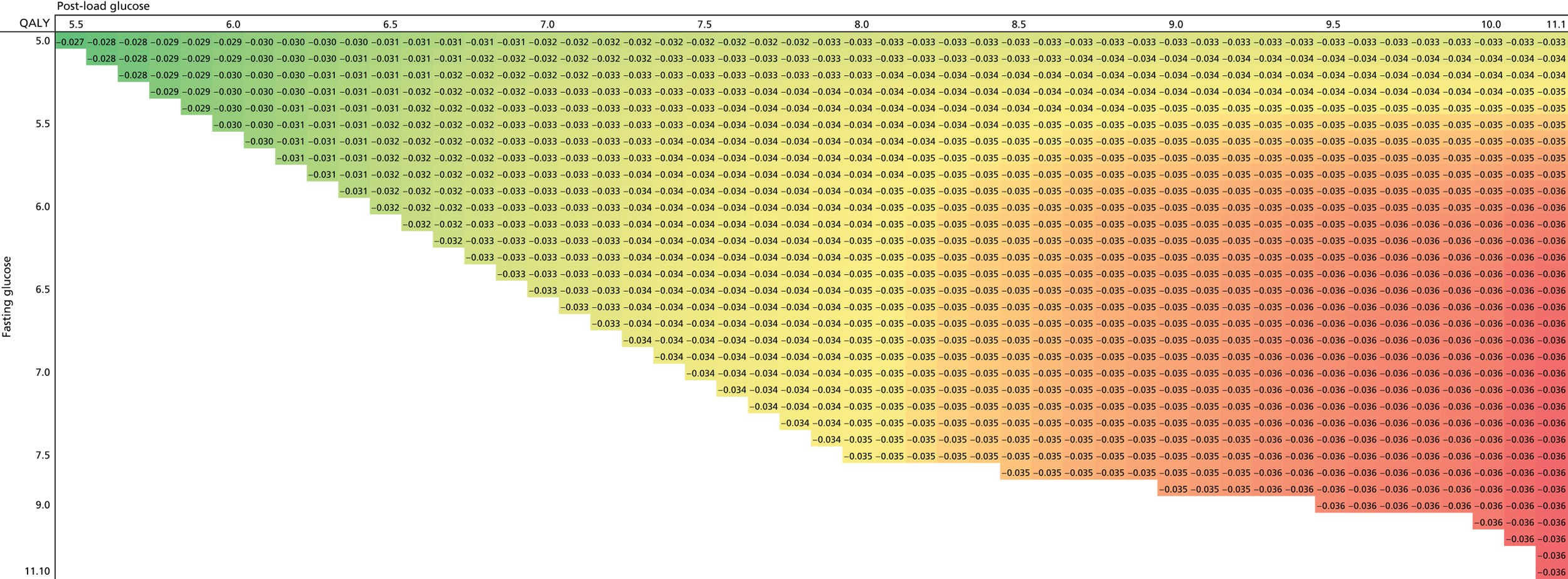

| Naylor98 | 1996 | Canada | 3778 | 50-g OGCT | ✗ | 7.8 mmol/l | C&C | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||