Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/64/01. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The draft report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in July 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Raashid Luqmani received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Nordic and Chemocentryx for training in the use of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score and Vasculitis Damage Index, and personal fees from Roche outside the submitted work. Raashid Luqmani received grants from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Portugal), Canadian Institute of Health Research, Arthritis Research UK, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust Innovation Challenge Competition and Vasculitis UK. Raashid Luqmani has patents pending for a mechanical arm to automate acquisition of ultrasound images and analysis for reviewing ultrasound images. Bhaskar Dasgupta received personal fees from GSK, Servier, Roche, Merck, and Mundipharma and grants from Napp outside the submitted work. Andrew Hutchings was funded by a Medical Research Council special training fellowship in health services research during the development of the study. Jennifer Piper has a patent pending for an ultrasound arm.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Luqmani et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

General introduction to giant cell arteritis

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), also known as temporal arteritis, is a common form of vasculitis that affects people typically aged > 50 years. 1 GCA often progresses rapidly and, if left untreated, leads to severe pain, permanent visual loss, stroke and, in some cases, death. The incidence is approximately 220 per million per year in the UK in people aged ≥ 40 years. 2 Elsewhere, the incidence varies across the world, with published figures ranging from 150 to 250 new patients per million per year. It is more common in northern European countries, particularly in Scandinavia (313 per million per year in people aged > 70 years)3 and in Minnesota, USA, which has a large Scandinavian-origin population (198 per million per year),4 and it is much less common in other parts of the world such as Japan, China and Australia.

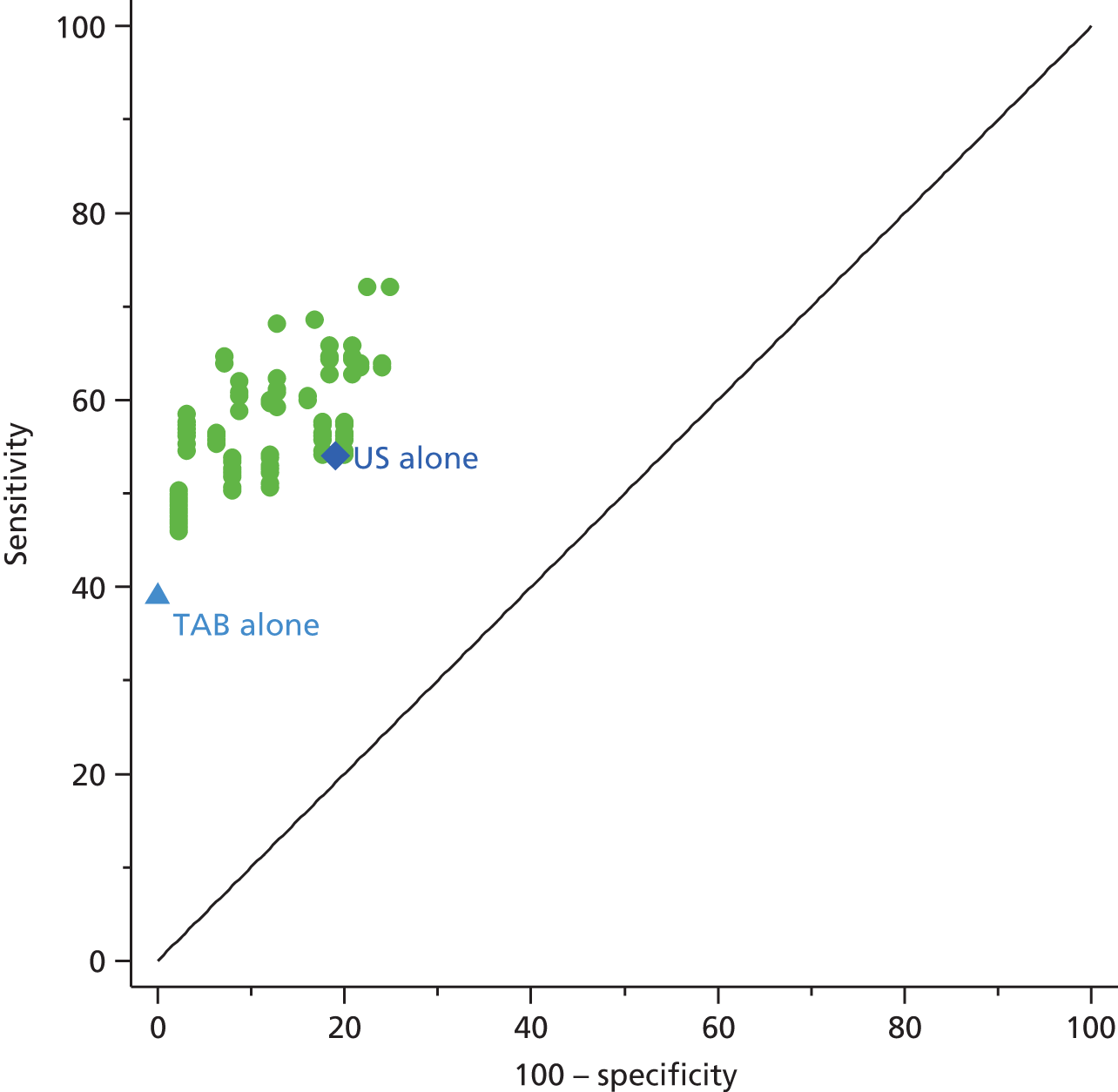

Rapid diagnosis and glucocorticoid treatment are recommended,5 but both are problematic. Glucocorticoid treatment is usually started before a formal diagnosis is made, meaning that a proportion of patients are treated unnecessarily and are thereby exposed to side effects including weight gain, altered body habitus, hypertension, infection, osteoporosis, cataract, mood swings and thin skin. Glucocorticoid treatment also affects the accuracy of the diagnosis. The heterogeneous nature of GCA means that its diagnosis is not straightforward, but is usually based primarily on temporal artery biopsy (TAB) and supported by presenting symptoms. Glucocorticoids, by their nature, impact on inflammation; if there is a large time difference between commencement of glucocorticoids and biopsy, this reduces diagnostic accuracy. Although a positive biopsy usually (although not always) confirms GCA, the sensitivity of TAB has been estimated to vary from 39% to 91%,6,7 resulting in a large number of false negatives in the screened population. This has led to high-dose glucocorticoid therapy being continued as a precaution (in case the patients actually have GCA), even in the absence of a positive biopsy.

Ultrasound and other forms of imaging compared with the traditional role of biopsy

An alternative to biopsy has been the development of ultrasound and other imaging techniques for the diagnosis of GCA. Imaging first emerged in the 1990s as a potential means by which to provide evidence to support a diagnosis of GCA. 8–15 High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of temporal arteries offers a non-invasive technique for investigating suspected GCA, but it is limited by availability and cost. Ultrasound is the most practical and widely used modality. Three meta-analyses have supported the role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of GCA. 16–18 The presence of bilateral ultrasound abnormalities (both temporal arteries involved) provides high specificity (100%) for the diagnosis of GCA, but its sensitivity was 43%. 17 Two of the meta-analyses reported concerns with the quality of the included studies16,18 and the third did not assess the methodological quality of the included studies. 17 Currently, the use of ultrasound as a diagnostic tool for GCA is relatively limited, perhaps as a result of practical reasons relating to training to use ultrasound or equipment availability to facilitate rapid access and evaluation of patients with suspected GCA.

Ultrasound examination of temporal arteries is non-invasive and there is no ionising radiation involved. Furthermore, it can provide information about the entire length of both temporal arteries. Additional examination of the axillary arteries improves the sensitivity of ultrasound19 because some individuals with GCA (especially those without headaches) will have isolated abnormalities in the axillary arteries but not in the temporal arteries. This may be because of the longer persistence of scan abnormalities in larger vessels than in temporal arteries, despite the use of steroids. The chief abnormality on ultrasound that suggests the diagnosis of GCA is a halo, which is defined as a dark hypoechoic area around the vessel lumen and is thought to represent inflammatory change and oedema present in the wall and surrounding tissues of the affected blood vessel.

The role of temporal artery biopsy in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis

A recent study of biopsy-proven GCA disease in South Australia suggested an incidence in people aged > 50 years of only 32 per million per year,20 although the relatively low incidence may be a result of the inclusion of biopsy-confirmed cases only. Biopsy for the diagnosis of GCA has a relatively low yield. 16 The difficulty in diagnosis of GCA, which forms the main underlying question of this project, is the lack of a high-quality gold standard test. Although biopsy is reported to be the current gold standard test for diagnosis, the majority of patients in whom a diagnosis of GCA is suspected do not actually have a positive result. This may reflect the fact that there is a lower index of suspicion for diagnosis, and, therefore, more people with headaches are being evaluated for GCA; equally, it may reflect the relatively poor association between the true multivessel disease of GCA and the TAB findings to support a diagnosis of GCA.

The spectrum of different forms of giant cell arteritis

In about 50% of patients with GCA, branches of the aorta, and even the aorta itself, may be involved, suggesting that there is probably much more widespread inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis) than previously considered. 21 In a study of 120 patients with large vessel vasculitis and 212 with more conventional cranial symptoms of GCA, but without the evidence of large vessel disease, patients with large vessel disease were significantly younger, by about 7 years, and had longer duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis (3.5 months compared with 2.2 months). There was a strong association with pre-existing polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) in 26% of patients, compared with 15% of patients with cranial GCA, and fewer cranial symptoms (41% of patients, compared with 83% of patients with cranial GCA). Visual loss was also much less likely in large vessel GCA (4% compared with 11%). The risk of relapse of GCA features was higher in patients with large vessel disease than in patients with cranial manifestations only (4.9/10 person-years, compared with 3/10 person-years) and these patients were likely to require higher doses of steroids for longer periods of time.

Clinical presentation of giant cell arteritis

Recognising new features of GCA can be very straightforward in a patient with no previous history of headache who suddenly develops unaccustomed discomfort on the side of the head with swelling or tenderness of the temporal arteries, general systemic onset and scalp tenderness. Although symptomatic headache is very troublesome, the most feared complication of GCA is neuroischaemic damage, which can result in inflammation and occlusion of small branches of the cranial arteries (including the posterior ciliary artery and the ophthalmic artery) and ultimately in permanent visual loss. A warning symptom of ischaemia is the presence of jaw or tongue claudication, typically reported by around 50% of patients with GCA at presentation. 22 Jaw and tongue claudication refers to discomfort in the patient’s masseter muscles or tongue which stops them from eating or talking. When they stop to rest their jaw or tongue, the pain resolves because it is a result of claudication of those muscles as a result of narrowing of the blood vessel supply (e.g. the facial artery and its branches). Patients who have tongue or jaw claudication are at risk of blindness because the disease can involve the posterior ciliary arteries, which supply the retina and cause unilateral, and occasionally bilateral, permanent sight loss. Sometimes the visual loss starts on one side and subsequently becomes bilateral. In an early series of 90 cases from neurology and ophthalmology clinics, up to 60% of patients presented with permanent loss of vision attributable to either ischaemic papillopathy or retinal artery occlusion;23 other cases presenting primarily to physicians demonstrated a much lower risk of sight loss of 7.4% to 19.1%. 24–27 The risk of sight loss associated with GCA has fallen in recent decades, from 15% of cases with ischaemic optic neuropathy between 1950 and 1979 to only 6% between 1980 and 2004. 28 There is a small but significant risk of stroke, highlighted as possibly being between 2.8% and 6% in two recent studies. 29,30 Therefore, an early diagnosis and initiation of immunosuppressive treatment with high doses of steroids is required, making the condition a medical emergency.

It is likely that the mechanisms driving the neuroischaemic complications are different from those driving the systemic inflammatory response. There is a suggestion that interleukin (IL)-12 and interferon-gamma are the main cytokines responsible for myointimal proliferation leading to vessel occlusion; by contrast, the mechanisms driving the systemic inflammatory response are likely to be IL-6 and IL-17. 31 The underlying pathological changes involve invading macrophages and lymphocytes which gain access to the blood vessels via the vasa vasorum. They generate a local inflammatory response in the blood vessel wall, starting in the adventitia, migrating through to the media and intima, with proliferation of the internal elastic lamina, intimal proliferation and swelling, and eventually resulting in vessel narrowing and complete occlusion in some cases.

Although intimal proliferation with intimal thickness and internal elastic lamina reduplication are typical features, the hallmark histological finding is the presence of multinucleated giant cells, hence the term GCA. These pathological mechanisms are the basis for the histological diagnosis of the condition, which was first recognised by Horton et al. 1 in 1932 who described two patients who were initially thought to have a fungal infection (actinomycosis) of the temporal arteries.

Giant cell arteritis typically affects people aged over 50 years; it is two to three times more common in women than in men. PMR is a related clinical syndrome characterised by generalised muscles aches and pains. PMR is common in patients over the age of 50 years and presents with widespread aches and pains, particularly involving proximal muscles. Criteria for classifying PMR are based on the presence of bilateral limb girdle discomfort, early-morning stiffness and an elevated inflammatory response. 32 Additional ultrasound evidence of bursitis around the hips improves the specificity of the criteria from 78% to 81% and maintains sensitivity of between 66% and 68%. PMR can be present in up to 50% of individuals with GCA and it may occur either before, during or after the manifestations of GCA appear, suggesting significant overlap between these two disease processes. 33 Therefore, our interpretation of any individual patient’s diagnosis of GCA would be influenced by either pre-existing or concomitant diagnosis of PMR or might be validated by subsequent development of PMR.

Diagnosis and classification of giant cell arteritis

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for GCA are based on the following:

-

aged at least 50 years

-

new onset of headache

-

temporal artery abnormality on physical examination

-

elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) typically ≥ 50 mm/hour

-

abnormal TAB showing features of vasculitis.

Classification of a patient as having GCA requires at least three of these criteria to be present. 34 The classification criteria are not diagnostic tests and are limited by the technology available at the time when the criteria were being developed. As technology has improved, there are more sophisticated methods available for evaluating the temporal artery with ultrasound, MRI and computerised tomography (CT). Furthermore, it is possible to image the whole arterial tree more effectively for evidence of widespread vascular abnormality using CT angiography, magnetic resonance angiography and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography CT. These techniques have revealed that some cases of GCA have much more extensive vessel involvement than previously suspected. 21 Imaging has demonstrated that GCA can present without headaches but with other features such as constitutional symptoms and polymyalgia, which is also termed polymyalgia arteritica. 35

The awareness of GCA has probably increased and it is likely that the concern regarding the threat of visual loss may affect a clinician’s decision to pre-emptively treat any patient who might have the condition as soon as possible, in order to prevent these complications from occurring. As a result, it is likely that we are starting to see a change in the level of suspicion of symptoms at which a clinician is confident in starting treatment on the basis of a presumed diagnosis of GCA. Tests used for diagnosing GCA would now be performed in different circumstances than existed previously. We may be dealing with milder cases of the disease and/or more patients with a GCA-like symptom complex who do not actually have GCA. If these patients are given steroids, the standard test result from a TAB may be significantly influenced by the fact that the biopsy was performed on mild disease that had already been partly treated and/or was performed in patients who do not actually have GCA. Kisza et al. 36 assessed over 700 cases of GCA from 1994 to 2011, with 215 biopsy-positive cases, observing a peak incidence in 1996. Machado et al. 37 observed a reduction in the frequency of patients presenting with classical features, but no change in the likelihood of a positive biopsy from 1950 to 1985. In fact, Gonzalez-Gay et al. 38 found that the incidence of biopsy-proven GCA actually increased from 1981 to 2005. A more recent study3 of 840 biopsy-positive cases of GCA in Sweden reported a reduction in incidence between 1997 and 2010, from 15.9/100,000 to 13.3/100,000, although this contrasts with an earlier Swedish study39 that reported an increased incidence from 1976 to 1995, especially in women. In the UK, there was no evidence to suggest a change in incidence between 1990 and 2001. 2 This suggests that, although there may have been some changes to the epidemiology of GCA over time, with possibly a rise in incidence in women, there has been no significant change in the overall incidence of GCA. There is evidence of a diagnostic shift in other diseases too; hypothyroidism is now recognised as significant and is associated with increased comorbidity at lower levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone than before. 40

The Diagnostic and Classification Criteria for Vasculitis Study

As a result of concerns about the classification and diagnosis of GCA and other forms of vasculitis, an international effort to improve criteria for the diagnosis of vasculitis has been under way since 2009. 41 The Diagnostic and Classification Criteria for Vasculitis Study (DCVAS) had, by 2015, recruited over 4000 patients with either a form of vasculitis or a comparator condition and included over 900 individuals with a clinical diagnosis of GCA. Patients are recruited if they have any clinical features that might be consistent with vasculitis. This includes patients who do not actually have vasculitis, because they are considered to be part of the comparator population for the study. Patients are either newly diagnosed with vasculitis or a comparator condition or have had a diagnosis made within 2 years of recruitment into the study. A detailed pro forma is used to report standardised information regarding symptoms, signs and test results (including blood tests, imaging and biopsy data) available at the time of diagnosis. A subsequent follow-up visit 6 months later is required, so that any change in the original diagnosis can be reported and used as the final submitting clinician’s diagnosis. The DCVAS study has not yet reported results, but limited access to the DCVAS data was granted for The Role of Ultrasound Compared to Biopsy of Temporal Arteries in the Diagnosis and Treatment of GCA (TABUL) study.

Difficulty with diagnosis of giant cell arteritis based on the gold standard temporal artery biopsy

For clinicians managing patients who may have GCA, untreated disease can result in permanent visual loss (as discussed in González-Gay et al. 24) and the condition is therefore considered to be a medical emergency. However, there are far more people with headache (it is an almost universal experience) than there are patients with GCA.

Toxicity of treatment versus need for urgent treatment

The other main consideration is that treatment for GCA, which involves high doses of glucocorticoids such as prednisolone over a prolonged period and which will result in rapid control of the inflammatory process and reduce the risk of ischaemic manifestations, is very toxic and results in side effects in over 80% of patients. 42 The most common side effects reported in the study by Proven et al. 42 included cataracts in 41% of patients, fractures in 38% of patients, infection in 31% of patients, hypertension in 22% of patients, diabetes mellitus in 9% of patients and gastrointestinal bleeding in 4% of patients.

With modern therapy, such as the prophylactic use of calcium, vitamin D and bisphosphonates to prevent fractures, some of these complications can be avoided. Further measures to reduce risk of treatment-related toxicity include better control of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, as well as prophylactic use of proton pump inhibitors to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding (which could relate to previous use of high doses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs combined with high doses of prednisolone). The risk of serious infections remains significant and has been estimated to be 55% higher than in age- and sex-matched controls. 43

Therefore, the balance of risk versus benefit in a patient with suspected GCA rests heavily on our ability to be confident that the diagnosis is correct. A patient who is incorrectly diagnosed with GCA will be subjected to significant risk of steroid toxicity without experiencing any advantage. However, if the patient does have GCA but the diagnosis was not made and the patient was not established on high doses of steroids, then there is a significant risk of ischaemic complications, including permanent visual loss or stroke, which are the most important complications of the disease and which makes sight loss (and other acute ischaemic complications) from GCA a preventable medical emergency.

Diagnosis of giant cell arteritis relying on a gold standard of temporal artery biopsy

Since 1932 the conventional gold standard investigation for GCA has been a TAB. 1 The characteristic finding of histiocytes, epithelioid and giant cells (large multinucleated cells present in the arterial wall) at the intimal–medial junction is useful in diagnosis,41 but not always present (e.g. giant cells were found in 75% of positive biopsies in a recent series). Other pathological features include transmural inflammation, adventitial infiltrates or localised infiltrates of inflammatory cells, especially lymphocytes in the media or intima. Reduplication of the internal elastic lamina and fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina are also described. Intimal cellularity and increased thickness can occur and, in a number of cases, the vessel lumen is narrowed to occlusion with associated thrombus formation.

Most patients have headache, which on closer questioning is localised around the temporal artery and is usually worse on one side than the other. The most symptomatic artery is usually selected for biopsy and is most likely to show evidence of pathological findings. In some centres, it has previously been a routine procedure to sample both temporal arteries in suspected cases, but the value of bilateral testing is relatively low,44 with only one of 91 bilateral biopsies showing discordance. In a recent study of 132 cases undergoing bilateral biopsies, the diagnostic yield increased by 12.7%45 as a result of the second simultaneous biopsy (38 patients had bilateral findings of GCA, compared with an additional 13 patients whose biopsies showed abnormalities confined to one side only).

The purpose of high doses of glucocorticoid therapy is to resolve inflammation. Therefore, the characteristic findings of cellular infiltration of the vessel wall with lymphocytes and giant cells may have disappeared by the time the biopsy is performed if there is a significant delay between starting treatment and obtaining the biopsy. Because of the ‘clock ticking’ as a result of glucocorticoids being administered as a precautionary measure (in case the patient really does have GCA), it is not usually helpful to perform a second biopsy of the opposite (and possibly asymptomatic) artery if the first biopsy is negative for patients in whom there is a suspicion of GCA. A biopsy from the opposite artery is feasible but is less likely to have a positive result, unless the patient has active symptoms of GCA in the artery to be biopsied. Cellular infiltration is the most important histological finding but can potentially resolve within 7–10 days of commencing high-dose glucocorticoid therapy. 46 Therefore, in some patients, biopsy evidence for GCA is inadequate. Many of the changes seen in the intima and internal elastic lamina can also be found in older people who do not have any features of GCA. 47 A recent surgical series of 237 patients undergoing TABs reported positive findings of GCA in only 36 (15.1%) cases48 and the result of the biopsy did not significantly contribute to the diagnosis. Changes suggestive of GCA are not consistently present throughout the course of the vessel.

The biopsy may not actually contain any arterial tissue. Nerves or veins were sampled in error in 14 of 567 consecutive biopsies (2.5%). 49 Biopsies of temporal arteries are typically sectioned transversely to provide an overall assessment of the artery. If the pathological abnormalities are present in the areas of artery that have not been cut, it is possible to miss the relevant findings. If the biopsy length is small, the characteristic histological features, which may occur sporadically along the length of the tissue obtained (skip lesions), may be missed. The biopsy is typically sectioned in cross-section and it is possible that, if the material obtained is quite small, only a few cross-sections will be available to view. If the abnormalities to be detected are not seen in these cross-sections, the interpretation would be that the biopsy was normal. However, it is possible that if a longer specimen had been obtained and more cross-sections had been viewed then the pathological changes might have been evident. Obtaining specimens that have been subjected to more sections increases the diagnostic yield slightly but leads to significantly more work and expense for the pathology laboratory. 50

Biopsy length (after fixation) varies in different studies. Shrinkage is well recognised, with a recent study of 62 biopsies showing an average of 4.6 mm of shrinkage from the time of surgical excision to fixation. 51 A study of 966 biopsies from six different hospitals suggested that a length of at least 0.7 cm increased the diagnostic yield from 12.9% to 24.8% positive results. 52 By contrast, another study of 151 biopsies from 149 patients yielded 20 positive biopsies (13.3%), and there was no difference in the length of positive (mean 0.7 cm) compared with negative (mean 0.65 cm) biopsies. 53 The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) guidelines recommend between a 1- and 2-cm length of artery to provide an adequate specimen, usually from only the symptomatic or most symptomatic side. 5

The presence of inflammatory infiltrates in the vasa vasorum was reported in 6.5% of 354 biopsies considered positive in one large study of patients with clinical features of GCA. 54 However, it remains controversial whether or not these findings, as well as some of the other ‘characteristic findings’ suggesting GCA, may in fact occur in patients with other forms of vasculitis such as antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis. 55–58

It has been suggested that TAB may be a useful test to diagnose other forms of vasculitis, which could mimic GCA. 59

There is an inevitable tension between obtaining enough material to make a diagnosis and initiating therapy before disease-related complications set in. In practice, it is common for patients to start on treatment as soon as a physician suspects the diagnosis, typically based on symptoms suggesting the diagnosis of GCA and possible laboratory investigations such as an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level or ESR. Treatment is commonly initiated in primary care and the primary care physician would typically contact secondary care services to request confirmation of the diagnosis with a biopsy. However, the acute phase response markers are not reliable tests to diagnose GCA, although if they are elevated, the ESR and CRP level are supportive of the diagnosis but cannot be used on their own because of their lack of specificity.

Standards for diagnosis of giant cell arteritis

The BSR guidelines on managing GCA recommend that biopsy should be considered if a diagnosis of GCA is suspected and state that an early biopsy is desirable in patients with suspected cranial GCA, preferably within 7 days of initiating high-dose steroid therapy. 5 The biopsy should be carried out by experienced surgeons to give the highest yield of positive results. Similar recommendations were made by the European League Against Rheumatism in their guidelines for the management of large vessel vasculitis. 60 Unfortunately for the NHS in England and for other health-care systems, there may be difficulty in accessing a surgical list promptly. This can result in significant delay in a biopsy being performed. Furthermore, the procedure is often performed by a relatively junior and inexperienced member of the team. The overall impact of these factors could be a reduction in the sensitivity of biopsy as a test for GCA.

Accuracy of temporal artery biopsy versus ultrasound or other imaging modalities

A meta-analysis of the use of ultrasound in GCA16 examined 23 studies and involved 2036 patients. The weighted sensitivity and specificity of the halo sign was 69% [95% confidence interval (CI) 57% to 79%] and 82% (95% CI 75% to 87%), respectively, compared with biopsy, and 55% (95% CI 36% to 73%) and 94% (95% CI 82% to 98%), respectively, compared with ACR criteria. A study of 55 patients who underwent colour Doppler ultrasound for suspected GCA61 reported a sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 91%, respectively, suggesting that an ultrasound scan could be a good alternative to biopsy in many patients.

However, ultrasonography of the temporal and axillary arteries is highly operator dependent and it is important to develop and maintain expertise in the technique before it can be applied. Therefore, any ultrasound study requires quality assurance of the adequate training of sonographers prior to the evaluation of patients with suspected GCA. By contrast, MRI is much less operator dependent. In a recent multicentre study, the diagnostic accuracy of MRI was investigated in 185 patients referred for suspected GCA, of whom 53% underwent TAB. The sensitivity and specificity of MRI for diagnosing GCA was 78.4% and 90.4%, respectively, and for TAB (in those patients who had biopsy), the sensitivity and specificity were 88.7% and 75%, respectively. 13 The accuracy of the imaging was high if the patients had received either no glucocorticoids or glucocorticoids for no more than 5 days, but more than 5 days of therapy resulted in a significant fall in diagnostic accuracy. A combined approach that used ultrasound to try to identify the most appropriate site for biopsy had no effect on the sensitivity of detecting histological evidence of GCA. 62

Summary

In summary, the management of GCA requires a balance between ensuring that patients with GCA are diagnosed and treated promptly (to avoid complications such as sight loss) and avoiding the burden of unnecessary steroid treatment in people without GCA. TAB is useful in assisting with diagnosis but lacks sensitivity. Research since the 1990s on the accuracy of ultrasound suggests that ultrasound has a role as an alternative to, or in addition to, biopsy. However, within the UK, the routine use of ultrasound for GCA is restricted to only a few centres; TAB remains the standard test for the majority of patients suspected of having GCA.

Aims and objectives

The main aim of the TABUL study was to assess the relative merits of TAB and ultrasound in contributing to the diagnosis of GCA. The objectives of the TABUL study are based on two assumptions about diagnosing and treating GCA.

First, patients with suspected GCA are treated with steroids as soon as the diagnosis is suspected (in order to reduce the risk of serious vascular complications) and before any biopsy results might be available. Therefore, the potential benefit of an ultrasound examination instead of, or in addition to, biopsy is the ability to either continue or withdraw high-dose glucocorticoid treatment appropriately owing to greater certainty of diagnosis.

Second, TAB is itself very problematic as a reference standard, because up to half or more patients with true GCA may have a negative biopsy. 6,7 This may be for a number of reasons including biopsy size, delay between onset of symptoms followed by early use of high-dose glucocorticoid therapy before biopsy and obtaining the biopsy specimen within 7–10 days of therapy commencing; furthermore, the processing and interpretation of biopsy itself can influence the outcome. A positive biopsy does confirm the diagnosis in most patients suspected of having GCA, with specificity approaching 100%. There are some exceptions because other forms of vasculitis may produce exactly the same biopsy appearances as seen in GCA. The difference for other forms of vasculitis is that patients experience clinical features in other organ systems that support that diagnosis, such as the involvement of airways or kidneys in patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) or eosinophilic GPA (EGPA). Ultrasound is not going to be able to achieve greater specificity than biopsy but may achieve better sensitivity if used either instead of, or in addition to, biopsy.

The first primary objective of the study was to evaluate the diagnostic performance (sensitivity and specificity) of ultrasound as an alternative to biopsy for diagnosing GCA in patients who are referred with suspected GCA and in whom a biopsy was going to be carried out.

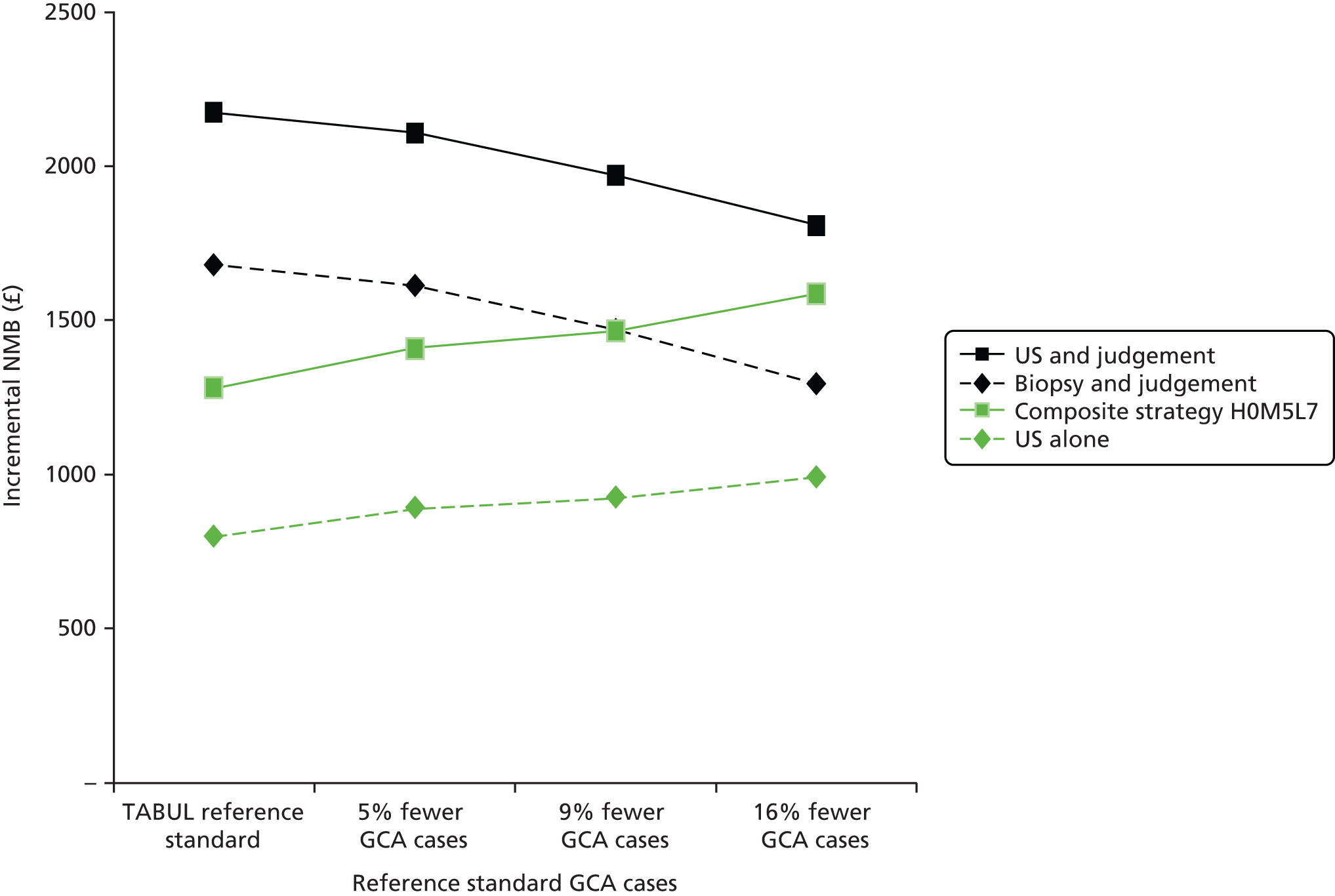

The second primary objective was to perform a cost-effectiveness analysis to compare ultrasound as an alternative to biopsy for diagnosing GCA.

The secondary objectives in the study were to evaluate:

-

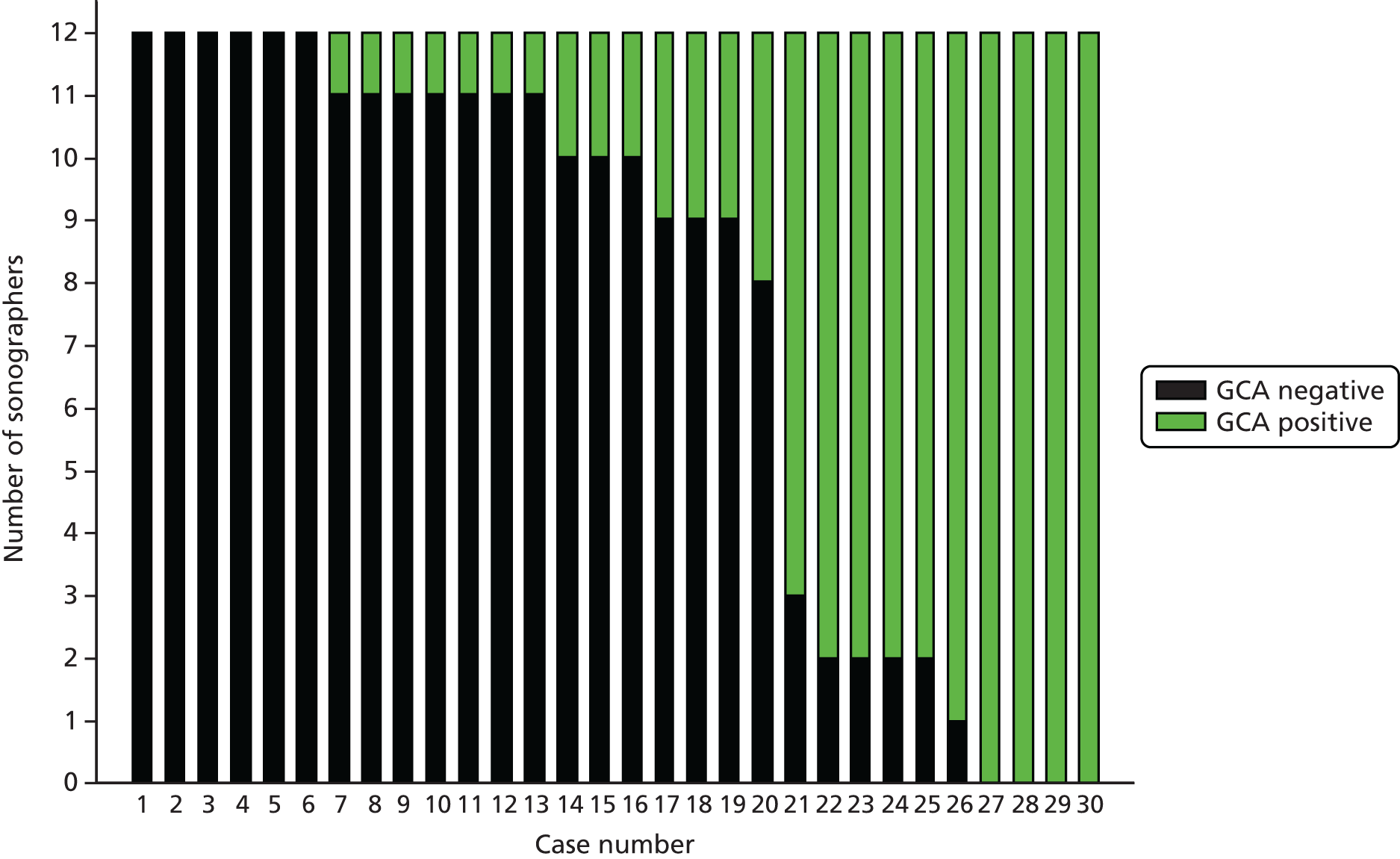

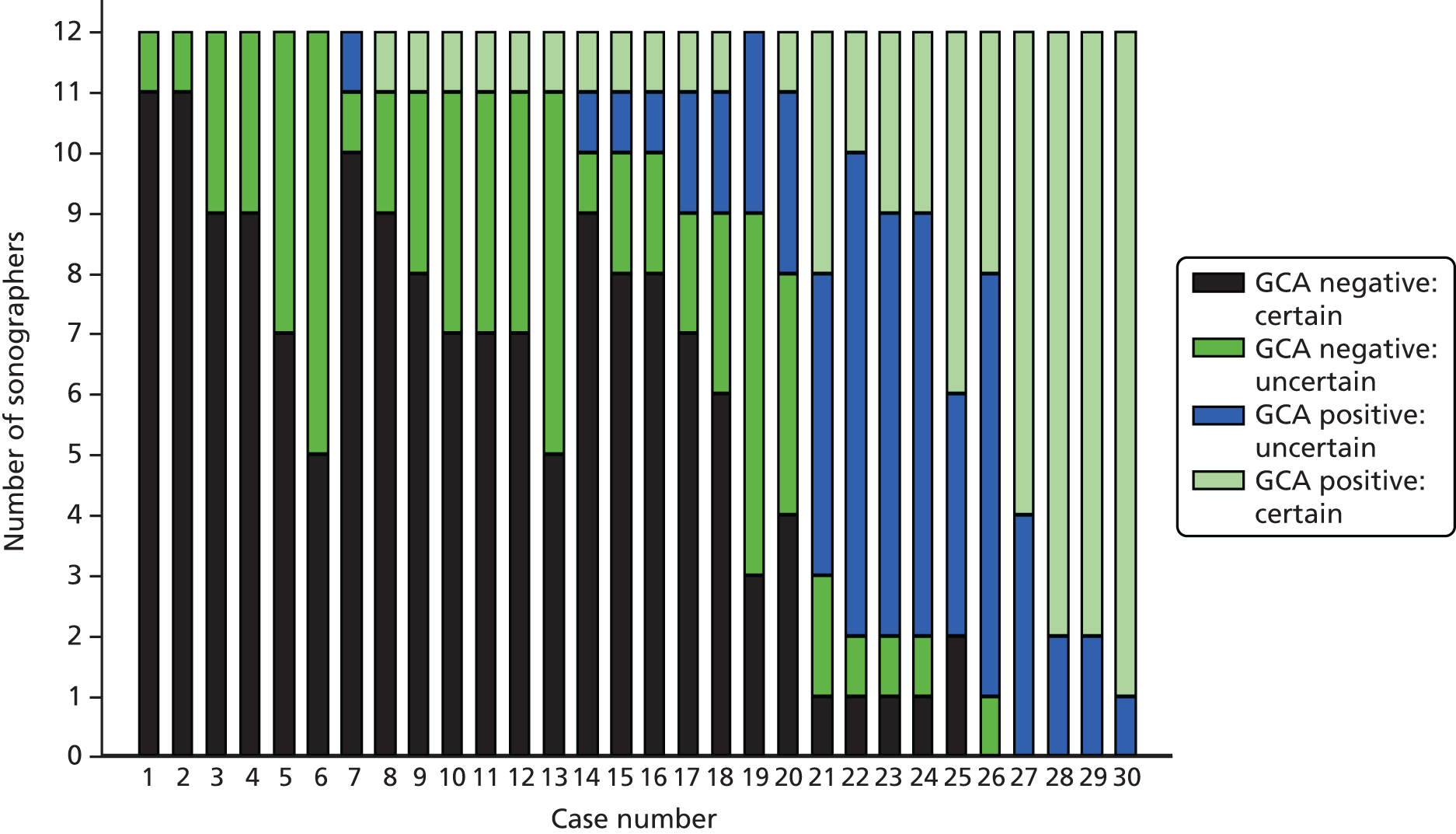

interobserver agreement in the assessment of ultrasound and biopsy

-

the performance (sensitivity and specificity) of alternative strategies involving ultrasound and biopsy for diagnosing GCA

-

the cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies involving ultrasound and biopsy for diagnosing GCA.

Chapter 2 Methods

Summary of study design

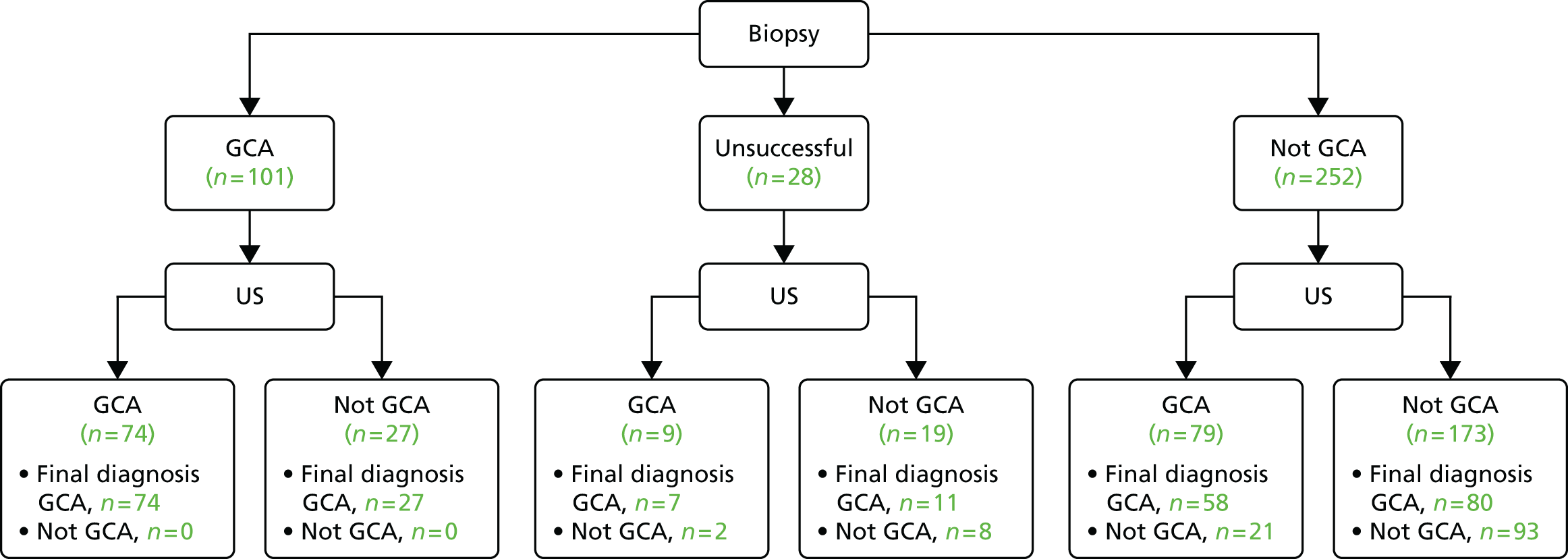

The study used a prospective cohort design and recruited patients with suspected GCA who were undergoing a TAB, the standard diagnostic test, as part of their routine care in order to assist with establishing the diagnosis. Patients were recruited following referral from their primary care physician or a secondary care physician and consented to have an additional diagnostic test, namely an ultrasound investigation of their temporal and axillary arteries, before having their biopsy. The clinician treating the patient, as well as the patient, was blinded to the results of the ultrasound. Patients were assessed at presentation, at 2 weeks and after 6 months. The performances of TAB and ultrasound were evaluated against a reference diagnosis derived from the clinician’s final diagnosis, which included any changes to the diagnosis during the follow-up period, such as the emergence of any GCA-related complications. The reference diagnosis confirmed the clinician’s final diagnosis using an algorithm based on the ACR classification criteria; any unconfirmed cases (and all cases in which the ultrasound result was unblinded and seen by the clinician) were independently reviewed by a panel of experts.

Agreement between sonographers and between pathologists in their interpretation of videos and images was assessed in an inter-rater agreement exercise for a sample of recruited patients. Clinical vignettes for these patients were constructed and assessed by clinicians to see what decisions about diagnosis and treatment might have been made if ultrasound results were provided instead of biopsy results. The cost-effectiveness of the different tests and combinations of tests was assessed in an economic evaluation.

Patient and public involvement

Advice on study design was sought and obtained from patients through the registered charity Polymyalgia Rheumatica & Giant Cell Arteritis UK. Patient representatives on the Trial Steering Committee and the Data Monitoring Committee provided valuable advice and input during the study (see Acknowledgements).

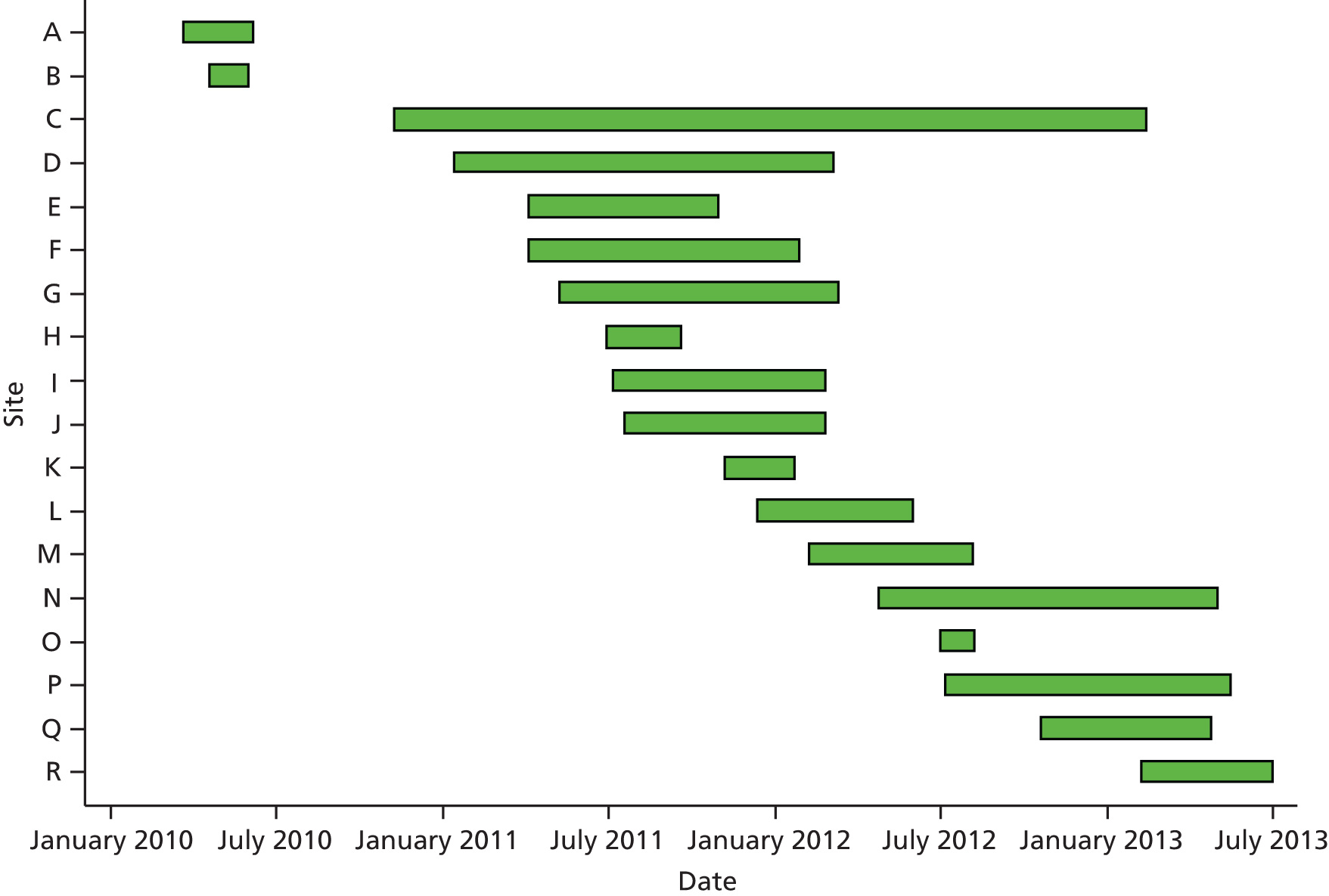

Recruitment of sites

Sites were eligible to take part in the study if they were responsible for seeing patients with suspected GCA and used TAB as a routine test for its diagnosis. Sites were not eligible if they used ultrasound for diagnosing GCA as part of their routine practice.

Prior to study commencement, 19 hospitals in England indicated their interest in becoming study sites for potential recruitment. Sites were eligible to take part if a site principal investigator, typically a clinician (e.g. a rheumatologist or ophthalmologist) involved in the management of patients with GCA, could be identified who would have overall responsibility for the site’s involvement in the study. Sites also needed to be able to identify the minimum of one pathologist who would have responsibility for assessing TABs and one sonographer with responsibility for performing and assessing ultrasound. Study sonographers needed to have some previous experience in the use of ultrasound but did not need to have specific experience in ultrasound of the temporal or axillary arteries for GCA. Sonographers could come from a variety of clinical disciplines and included rheumatologists, radiologists and radiographers. Sites also needed to provide assurance that, for any individual patient, the roles of the sonographer and the clinician managing the patient were separate. This was to prevent the managing clinician from knowing the results of the ultrasound scan, except when specifically allowed in the study protocol. It did not preclude a clinician (e.g. a rheumatologist who carries out ultrasound) from performing either role in different patients provided that the separation of responsibilities was maintained for each participant.

All sites needed to obtain the relevant local approvals before training could be commenced. Site participation required sonographers to successfully complete a training package in ultrasound for GCA. No training was provided to the site surgeons, who were asked to perform the biopsies as part of routine care, or to pathologists, given that TAB specimen assessment is part of standard care. At some sites, additional clinicians were involved in the management of study patients and this was a requirement if the site’s principal investigator was designated as the study sonographer to ensure that the ultrasound result was blinded for all patients. Research nurses at each site were responsible for co-ordinating recruitment and arranging tests to ensure that both ultrasound and biopsy procedures could be performed within 7 days of commencing high-dose glucocorticoid therapy. All these site personnel comprised the local TABUL team with responsibility for co-ordinating the study locally and completing the clinical, pathology and ultrasound data collection. The process for ultrasound training is described in the next section.

Each site was provided with study training during an initiation visit from the central TABUL study team which consisted of advice on data collection (including completion of study forms) and the process for submitting data. Specific training was provided on the completion of two measures used to assess patients: the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) and the Vasculitis Damage Index (VDI). Clinicians and research nurses were required to achieve test scores of 85% for the BVAS and 75% for the VDI (and at least 50% of all individual cases had to be correct) before they were approved for scoring the two measures. Monitoring visits were conducted as per the study standard operating procedures to ensure that the correct procedures were being followed.

Training in ultrasound for giant cell arteritis

Ultrasound assessment of temporal arteries is an established technique for the diagnosis of GCA but there is no standardised protocol in widespread use. We therefore developed a training package for performing and analysing ultrasound scans for the TABUL study. The purpose of the training package was to provide assurance that the sonographers in the study had achieved competence in scanning the temporal and axillary arteries and interpreting the results before recruiting patients to the study.

The training package included a standardised protocol for performing ultrasound in the TABUL study and an accompanying presentation. Sonographers’ competence in ultrasound for GCA was assessed in three ways: (1) undertaking ultrasound assessment of 10 patients or volunteers without GCA; (2) passing an examination that tested each sonographer’s competence in interpreting ultrasound videos; and (3) successfully completing a ‘hot case’ ultrasound assessment of a patient with active GCA. Sonographers were encouraged to attend the TABUL training day for sonographers in Oxford and/or participate in site visits from the TABUL study team. After successful completion of training, sonographers were required to submit recorded scans of recruited patients for ongoing assessment of competency in scanning and interpretation.

Sonographers were required to complete all components of the training before they were deemed eligible to assess patients recruited to the main study. An exception was made for sonographers who were already performing routine assessment for GCA; these sonographers were required to undergo part of the training protocol by scanning 10 control cases and completing their online assessment. These sonographers were exempt from completing the ‘hot case’ assessment on the merit of their curriculum vitae, which was assessed by the ultrasound experts for the study.

Ultrasound protocol and training requirements

The standard protocol for ultrasound and training was set out in the standard operating procedure for ultrasound and is available via the NIHR Journals Library website (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk).

The study required the use of a linear probe with a grey-scale frequency of 10 MHz or greater and a colour Doppler frequency of at least 6 MHz, using a vascular pre-set and applying colour Doppler mode as opposed to power Doppler mode. It was important to ensure that the focus was positioned around 5 mm below the skin surface for temporal artery ultrasound, in order to detect the artery. Grey-scale frequency was required to be > 10 MHz and the pulse repetition frequency was set at approximately 2–3 kHz. This was dependent on machine and vessel and would need to be altered according to the velocity of flow because this differs from artery to artery. The colour box required angle correction of at least 60º to avoid poor colour Doppler signals and inaccurate readings. The gain setting had to be adjusted to be able to just fill the lumen with colour to avoid over- or under-filling, therefore creating a potential halo or ‘bleeding’ over the vessel wall, which might give a false reading. We did not routinely employ a compression test to occlude the artery completely to eliminate flow; however, this is a useful test and was described to all sonographers to facilitate distinction between a true halo sign and a false one. 63

Each site sonographer was required to register the model number and manufacturer of his or her ultrasound machine with the TABUL office to ensure that it was of sufficiently high resolution for the purposes of the study; this was also reported for the subsequent economic analysis. If the sonographer changed the machine, he or she was required to inform the central TABUL office of the change, and the TABUL office had to confirm that the machine that had been substituted was of sufficiently high quality for the study.

The protocol required each patient to lie in a recumbent or semirecumbent position on their side and pull back their hair behind their ears. Gel was applied to the area of the temporal artery and the probe was placed over the middle of the common superficial temporal artery at the level of the tragus, and the position of the probe was adjusted if necessary to locate the artery. The probe was applied in the transverse and subsequently the longitudinal plane or vice versa. After completing a sweep of the artery in one plane, the probe was rotated by 90° and a further sweep was performed in the opposite plane. The level of the bifurcation between frontal and parietal branches of temporal arteries serves as the marker point to define the start of the frontal and parietal branches, respectively. The patient was then asked to turn over to the other side so that the opposite temporal artery could be scanned. The axillary artery was examined by asking patient to remove outer clothing to expose the axilla. Gel was applied to the inner aspect of the upper arm and the ultrasound probe was placed over the midaxillary line, and swept along the expected course of the artery. The probe was applied in either the longitudinal or the transverse plane and swept along until the brachial artery branch was identified. The sweep was then repeated with the probe rotated at 90º, so that both longitudinal and transverse scans were performed. A longitudinal static image was obtained for normal cases and a transverse and longitudinal static image was obtained for abnormal cases.

The sonographers were required to sequentially scan the complete length of common superficial temporal arteries with their frontal and parietal branches in transverse and longitudinal views. The axillary arteries were also assessed in transverse and longitudinal views. The assessors were required to provide video and static images in both transverse and longitudinal planes as evidence that they had adequately scanned arteries. Each video or still image had to be labelled with the patient’s study identification number, and the location of the image was defined using the standard formatting abbreviation listed in Table 1; for example, a video sweep image of the transverse view of the left temporal artery was labelled LTSN.

| Site | Image | Abnormality | Left | Right |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal artery | Initial sweep with transverse video (for normal scans) | None | LTSN | RTSN |

| Axillary artery | Initial sweep with longitudinal video (for normal scans) | None | LALN | RALN |

| Common superficial temporal artery | Transverse video | Halo | LCTH | RCTH |

| Longitudinal video | Halo | LCLH | RCLH | |

| Transverse video | Occlusion | LCTO | RCTO | |

| Longitudinal video | Occlusion | LCLO | RCLO | |

| Doppler pulse wave | Stenosis | LCDS | RCDS | |

| Longitudinal still image | Stenosis | LCLS | RCLS | |

| Parietal ramus of superficial temporal artery | Transverse video | Halo | LPTH | RPTH |

| Longitudinal video | Halo | LPLH | RPLH | |

| Transverse video | Occlusion | LPTO | RPTO | |

| Longitudinal video | Occlusion | LPLO | RPLO | |

| Doppler pulse wave | Stenosis | LPDS | RPDS | |

| Longitudinal still image | Stenosis | LPLS | RPLS | |

| Proximal frontal ramus of superficial temporal artery | Transverse video | Halo | LPFTH | RPFTH |

| Longitudinal video | Halo | LPFLH | RPFLH | |

| Transverse video | Occlusion | LPFTO | RPFTO | |

| Longitudinal video | Occlusion | LPFLO | RPFLO | |

| Doppler pulse wave | Stenosis | LPFDS | RPFDS | |

| Longitudinal still image | Stenosis | LPFLS | RPFLS | |

| Distal frontal ramus of superficial temporal artery | Transverse video | Halo | LDFTH | RDFTH |

| Longitudinal video | Halo | LDFLH | RDFLH | |

| Transverse video | Occlusion | LDFTO | RDFTO | |

| Longitudinal video | Occlusion | LDFLO | RDFLO | |

| Doppler pulse wave | Stenosis | LDFDS | RDFDS | |

| Longitudinal still image | Stenosis | LDFLS | RDFLS | |

| Axillary artery | Transverse still image | Halo | LAFTH | RAFTH |

| Longitudinal still image | Halo | LAFLH | RAFLH | |

| Transverse still image | Occlusion | LAFTO | RAFTO | |

| Longitudinal still image | Occlusion | LAFLO | RAFLO | |

| Doppler pulse wave | Stenosis | LAFDS | RAFDS | |

| Longitudinal still image | Stenosis | LAFLS | RAFLS |

The minimum recordings consisted of a 10-second transverse sweep along the length of each of the temporal arteries up to and beyond the bifurcation of the frontal and parietal branches and a still image of each axillary artery. All images had to be scanned using colour Doppler to assess for complete filling of the vessel and accurate assessment of stenosis, and aliasing of colour within the vessel. Doppler pulse wave was used to further characterise any areas of stenosis. The sonographers were asked to report the presence or absence of any abnormalities for each of the temporal and axillary arteries on the ultrasound case report form (see Appendix 1) while they were scanning and to indicate the relevant section(s) for abnormalities in the temporal arteries.

If any abnormality was detected, then additional information by artery and section was collected in the case report form and recordings of the abnormalities were required. For a halo, the sonographer reported the maximum thickness and length and whether or not it ran along the entire length of the section. A 3-second transverse and longitudinal video was recorded to support evidence of any reported halo, stenosis or occlusion in sections of the temporal artery. A transverse and longitudinal still image was recorded to demonstrate halo or occlusion in either axillary artery. If stenosis was reported then the velocity in and out of the stenosis (and the minimum and maximum luminal diameter for axillary arteries) was reported and a longitudinal still image and Doppler pulse wave were recorded. The presence of arteriosclerosis was reported separately as an abnormality but no images of this were required. On completion of the scanning, the sonographer was required to document whether or not the ultrasound results were consistent with a diagnosis of GCA. The completed case report forms and recordings (on compact disc) were submitted to the TABUL office.

We expected the scanning protocol to take between 20 and 45 minutes for each patient. The start time, end time and total scanning time were collected for each training case or patient. The protocol also required the sonographer to ensure that the results of the ultrasound, the case report form and the recordings were not given to, or discussed with, the clinical staff involved in treating the patient. Each site was supplied with guidance on how to perform the scans (see Appendix 2).

Ultrasound training programme

Although the biopsy of temporal arteries has been an established test in widespread use all over the world for decades, the use of ultrasound as a diagnostic test is much more limited. Very few of the sites involved in the study had sufficient expertise to undertake proficient vascular ultrasound scanning for GCA. We therefore developed a pragmatic training programme consisting of attendance at a training day or a site visit with hands-on training. Competence in ultrasound was assessed using a video examination to correctly identify normal or abnormal scan appearances, evidence of successfully performed scans of 10 healthy control subjects, and evidence of a successfully performed scan of at least one patient with scan findings of active GCA. Sonographers were allowed to take part in the study only once all elements had been successfully completed. In addition, we required sonographers to submit recordings of scans from all patients recruited into the study for ongoing quality control.

Ultrasound protocol training was provided during a training day in Oxford at the start of the study or at site visits by the TABUL study team. The protocol and training emphasised the importance of keeping the ultrasound result blinded from the clinician treating the patient. Sonographers were also provided with a presentation on how to scan temporal and axillary arteries to look for evidence of GCA and how to document the site and nature of the findings using standardised abbreviations (see Table 1). The presentation was developed with the supervision of one of the authors (WAS) who had extensive expertise in GCA ultrasound. The presentation provided information on recommended techniques and described the minimum equipment required to perform optimal scanning.

Video examination

An online assessment was developed specifically for the study and consisted of groups of ultrasound images of 20 cases representing patients with or without active GCA. The cases comprised still images and videos of approximately 10 seconds’ duration from consenting patients (not part of the TABUL study), supplied by two of the authors (WAS and BD). Sonographers could view the images by accessing a secure password-protected online site designed for the study. For each case, the sonographer was required to indicate the presence or absence of hypoechoic vessel wall oedema (the ‘halo’). Sonographers submitted their responses to the online system for marking; they had to achieve a minimum of 75% correct answers to pass the evaluation. Sonographers who failed to pass the test at their first attempt were required to repeat the entire test or specific questions, depending on how many errors they had made.

Scanning training cases

Sonographers’ competence in performing ultrasound was assessed by their provision of satisfactory scans from 10 healthy or non-GCA training cases. All training case participants were screened and consented prior to the ultrasound scan. Training cases had to be at least 50 years old and willing to attend for an ultrasound scan of their temporal and axillary arteries. Anyone with suspected GCA or a history of diagnosed or suspected GCA was ineligible, as were patients with any inflammatory condition or anyone who had taken systemic steroids or immunosuppressants in the previous 3 months.

Scanning followed the process described in the protocol. Briefly, the sonographer was required to provide correctly labelled (and anonymised) video images of both temporal and axillary arteries from 10 individual training cases, with documentation of the findings in the case report form. The case report forms and recordings were reviewed by four expert sonographers (WAS, BD, EM, APD), who assessed the sonographers’ competence and provided feedback. Sonographers were required to assess additional cases as specified by the reviewer if there were concerns over their scanning. If any of the control patients showed any evidence of an abnormality consistent with GCA then the general practitioner (GP) of the individual would be informed of the result.

Assessment of a patient with active giant cell arteritis (‘hot case’)

All sonographers were required to scan at least one patient who had active GCA as part of their training assessment in order to demonstrate competence in detecting and reporting the abnormal findings. The ‘hot case’ patient was consented to the study using NHS or local hospital consent but could not be a patient recruited to the main TABUL study. The sonographer scanned the patient, completed the case report form and submitted recordings following the ultrasound protocol. The expert reviewers assessed the submitted recordings and case report form to ensure that (1) the ultrasound features were consistent with GCA and (2) that the appropriate images had been recorded, were of suitable quality and were consistent with the case report form. If the reviewers were not satisfied then the sonographer was required to complete another ‘hot case’ and resubmit.

Monitoring ultrasound during the study: quality control by expert review

Once a sonographer had successfully completed and passed all three components of the training assessment, they were approved to scan patients with suspected GCA who were recruited to the study. In order to ensure that the quality of scanning was maintained, a process of ongoing quality control was developed and implemented. The ultrasound case report forms and recordings for each patient were submitted and reviewed by at least one of the four expert reviewers. Recordings were uploaded to a central ultrasound database which allowed remote access for reviewers. Reviewers assessed the quality of images collected and their agreement or otherwise with the sonographer’s interpretation of the recordings. If the expert reviewers had concerns about the performance of a sonographer, then the sonographer was required to undergo additional training before being approved for scanning patients in the study.

All recruited patients had their scans reviewed unless no uploaded images were submitted. At least one expert sonographer reported their agreement, disagreement or uncertainty with the assessment made by the sonographer and, if uncertain, an indication of whether or not this was attributable to concerns over the quality of the scanned images that were submitted.

Study population, recruitment and sampling

The study aimed to recruit all eligible patients who were undergoing a TAB for suspected GCA. Patients were eligible if there was a clinical suspicion of a new diagnosis of GCA and the treating clinician had decided that the patient required an urgent TAB to help determine whether or not the diagnosis was GCA. No particular symptoms were specified, although it was expected that patients would have typical symptoms of GCA such as a new onset of headache, scalp tenderness, elevated CRP level or ESR, jaw or tongue claudication or visual loss. Patients had to be at least 18 years of age and be willing to attend for an ultrasound scan of their temporal and axillary arteries.

Patients were not eligible for the study if they had had a previous diagnosis of GCA or if it was not possible to arrange for their ultrasound and biopsy to be performed within 7 days of starting higher doses of glucocorticoids (defined as > 20 mg of oral prednisolone or equivalent daily). Patients were also ineligible if they had prolonged use (> 1 month) of higher dose glucocorticoids (> 20 mg of prednisolone or equivalent per day at any time) within the previous 3 months for any condition other than PMR. A current or previous diagnosis of PMR or presenting symptoms of PMR were not exclusion criteria, because this group of patients would be likely to require investigations for possible associated GCA, if they presented with new features suggesting the diagnosis. No other selection criteria were used for the recruitment of patients.

All patients were required to give written informed consent. Additional consent was required to allow serum, plasma and deoxyribonucleic acid samples to be taken at the first assessment and serum and plasma to be taken at the second and third assessments for future, currently undefined studies. Patients were also invited to consent to allow their remaining tissue biopsy samples (not required for diagnosis) to be stored centrally in the Oxford Musculoskeletal Biobank for further, future currently undefined studies. All slides that were originally required for diagnostic purposes were stored in the Oxford Musculoskeletal Biobank or returned to the site pathologists, after they had been photographed. All screened patients were allocated a unique screening number and a screening case record form (CRF) was completed for each case (see Appendix 3). All eligible patients who consented were allocated a unique study identification number.

It was expected that the majority of patients would be recruited from referrals from general practice to secondary care (either to rheumatology and/or ophthalmology on-call teams). The clinician responsible for the patient’s care obtained verbal consent from the potential patient and passed on their contact details to the local TABUL team. Following an initial telephone call the TABUL team provided the potential patients with the study invitation letter and participant/patient information sheet (see Appendix 4) and discussed the study with them. Alternatively, if a patient was attending the hospital, the study documents were given directly to them by the clinician or study team. The potential patient would then have sufficient time to read and understand the information and to ask any questions before providing written informed consent (see Appendix 5).

Study recruitment at sites was encouraged by providing study information flyers in non-patients areas of sites as an aide-memoire for research teams and clinicians. Awareness of the study was raised with rheumatologists at local, regional, national and international meetings such as the BSR, local meetings with GPs, ophthalmologists, vascular surgeons, rheumatologists and clinicians treating other forms of vasculitis. Guidance on recruitment was provided to all sites (see Appendix 6).

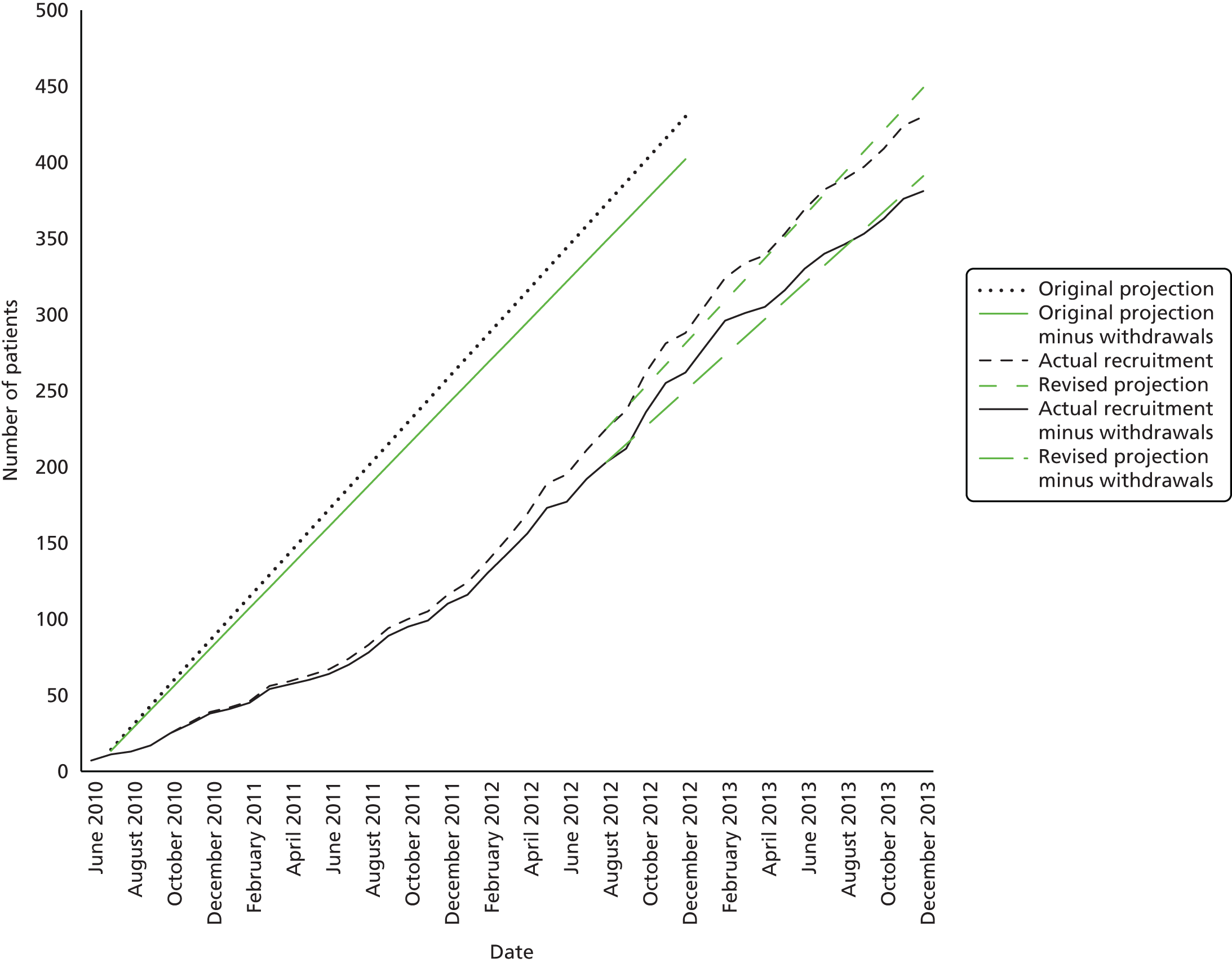

Sample size calculation

The sample size of 402 patients was calculated to provide 90% power at a 5% type I error rate to test the joint hypotheses that:

-

ultrasound has greater sensitivity than TAB (based on an assumed sensitivity of 76% for TAB and 87% for ultrasound)

-

the specificity of ultrasound is no less than 83% using the reference diagnosis.

The postulated sensitivity and specificity figures were based on a previous meta-analysis. 16 The sample size would allow estimation of a one-sided rectangular confidence region for ultrasound false- and true-positive fractions, assuming 80% prevalence of GCA in patients having a biopsy for suspected GCA, with the sample size inflated (gamma 0.1) because of uncertainty in the ratio of cases to controls in a cohort design. 64

In order to allow for losses to follow-up (failure to have either test done, lack of a follow-up assessment or patient withdrawal) the plan was to recruit 430 participants to the study. After monitoring actual recruitment and withdrawals during the course of the study, the target recruitment was increased to the range 435–445.

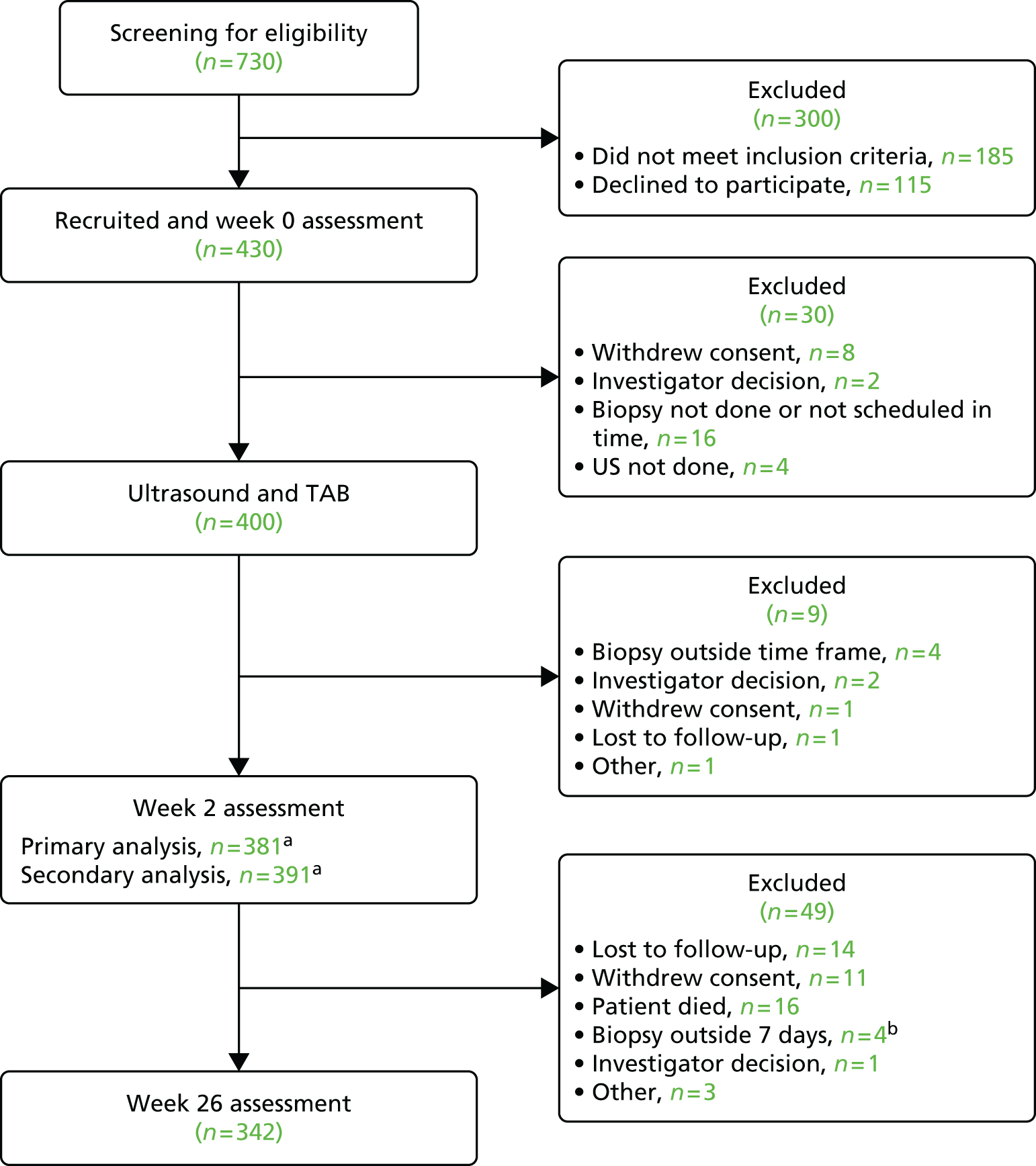

Clinical data collection

Patients who were referred with suspected GCA were screened to check their eligibility for recruitment into the study. Patients who were eligible and gave informed consent had a full clinical assessment at presentation. Appointments for ultrasound scans and then biopsy were arranged and patients returned for a follow-up clinical assessment after 2 weeks (Figure 1). After the 2-week assessment and after seeing the biopsy report, the clinician (who remained blinded to the ultrasound results) decided whether or not the patient had features consistent with a diagnosis of GCA.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of patients in the study. US, ultrasound; V, visit.

The result of the ultrasound was unblinded only if the clinician concluded that the patient did not have features consistent with GCA and was therefore planning to withdraw steroid therapy rapidly. The procedure for doing so is described below (see Ultrasound test results: procedure for revealing test results). Clinicians were allowed to alter their decision to withdraw steroids rapidly following unblinding of the ultrasound result. Patients attended a final clinical assessment after 6 months.

Patient assessment at presentation

The first clinical assessment at presentation collected data on demographic information, relevant conditions and past medical history, symptoms, physical examination findings, laboratory test results and medication. Clinicians were also asked how certain they were of the diagnosis of GCA (definite, probable or possible). Patient data included the patient’s age, sex, ethnicity, weight, blood pressure and smoking history. Comorbidity was assessed by reporting relevant current and previous medical history, and the assessment included specific questions on diabetes mellitus, hypertension, angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, low trauma fractures and neoplasia.

Information on symptoms was collected separately for symptoms that the patient had experienced prior to commencing higher-dose glucocorticoid therapy, as well as symptoms present at the first assessment (if the patient had already started on glucocorticoid treatment). This allowed us to separately report whether or not the presenting symptoms had changed as a result of glucocorticoid therapy. The presence of the following symptoms (typically seen in GCA) was reported: anorexia, fatigue, fever/night sweats, localised pain in the head, scalp tenderness, swelling over the temporal artery, pain over the temporal artery, jaw claudication, tongue claudication, reduced or lost vision, double vision and amaurosis fugax. Symptoms of PMR (early-morning stiffness lasting longer than 1 hour, bilateral shoulder pain and bilateral hip pain) were also collected. In addition, any other symptoms that the clinicians thought were relevant could be reported manually.

Physical examination of the patient required an assessment of both temporal arteries for evidence of thickening, tenderness and reduced or absent pulsation, and of both axillary arteries for tenderness. Examination also included, if assessed, evidence of anterior or posterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, relative afferent pupillary defect, III/IV/V nerve palsy or bruits on either side and evidence of stroke, aneurysm or other features such as scalp or tongue necrosis.

The results of laboratory tests that were required for the study protocol before starting steroids and at presentation comprised ESR, CRP level and/or plasma viscosity. Additional tests included measurement of full blood count, haemoglobin, biochemistry, ANCA and urine dipstick testing if there was a clinical indication. Data were also collected on whether or not, and when, treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids for suspected GCA had been started, the route and dose and any treatment with an immunosuppressant agent. The patient was asked to complete a EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) 3-levels questionnaire at the assessment. 65 EQ-5D is a generic measure of health-related quality of life, necessary for the calculation of the cost-effectiveness of the two main diagnostic tests.

Patient assessment at 2 weeks and 6 months

The biopsy and ultrasound tests were completed prior to the patient assessment at 2 weeks. The results of the biopsy were provided to the clinician before the 2-week assessment but the ultrasound results were not shown. The 2-week assessment included the clinician’s assessment of the biopsy report and whether or not the biopsy was consistent with GCA. It was therefore possible for the pathologist and clinician to have different opinions on whether or not the biopsy result was consistent with GCA. The patient assessments at 2 weeks and 6 months comprised changes in current conditions and symptoms, a repeat of the physical examination performed at presentation and the results of laboratory tests.

Data for two measures of disease activity and damage were also collected at 2 weeks and 6 months. The BVAS is a validated assessment questionnaire reported by the clinician in the evaluation of disease activity in systemic vasculitis. 66,67 It consists of a list of clinical features that commonly occur in patients with vasculitis together with a weighted score to provide a measure of severity of disease activity; it is widely used for clinical studies and is increasingly used in the clinical management of patients with small vessel vasculitis. It can be used to define how active disease is, to measure response to therapy or to define relapsing disease66,68 for the purpose of clinical trials. The most current validated version of the BVAS was used. 67 The VDI is a structured assessment to evaluate damage occurring in patients diagnosed with systemic vasculitis. 69 It is a record of irreversible consequences of having a diagnosis of vasculitis. Items are reported in the VDI if they have been present for at least 3 months and have occurred since the onset of vasculitis. There is no attribution to cause and it has been used in large cohorts of patients with primary systemic small vessel vasculitis. 70 Data from the BVAS and the VDI can also be used to examine the possible presence of an alternative form of vasculitis. Data were also collected on weight, blood pressure, treatment with steroids and immunosuppressive drugs, and quality of life using the EQ-5D.

At the 2-week assessment, the clinician was required to state whether or not the patient had features consistent with GCA and, if responding yes, to indicate which of the following influenced the response: symptoms, signs, blood abnormalities, biopsy or other (to be specified). If the patient’s features were not consistent with GCA then the clinician was required to give at least one alternative diagnosis. After providing the clinical diagnosis at 2 weeks, in the event that the clinician did not plan to continue high-dose glucocorticoid therapy because they did not think that the patient had GCA, they were required to contact the TABUL office for the ultrasound result. At the 6-month assessment the clinician was required to indicate if the diagnosis had changed and to indicate the influences for any patients in whom the decision was made to alter the diagnosis to GCA. At least one alternative diagnosis was required for any decision to alter the diagnosis away from GCA. The clinical CRF is shown in Appendix 7 and guidance on completion of the CRF is shown in Appendix 8.

Adverse events (AEs) and any attribution to either of the diagnostic test procedures were reported on AE CRFs (see Appendix 9). Guidance on completion of the AE CRFs is shown in Appendix 10.

The standard test: temporal artery biopsy

The standard test for GCA is TAB. This normally involves a minor surgical procedure to remove a small sample of temporal artery (the BSR recommends a minimum length of 1 cm5) which is examined for abnormalities by a pathologist. Guidance on the collection, processing and storage of biopsy samples is shown in Appendix 11. Sites followed their usual practice for obtaining and processing TABs. The only changes to routine practice required by TABUL were that sites were instructed to send the actual pathological slides used to make their diagnosis to the TABUL office and that, in addition to their standard reporting of biopsy results, pathologists were required to complete a study-specific CRF (see Appendices 12 and 13) to report their pathological findings. We did not require any specific information from any of the surgeons undertaking the biopsy but they were all informed that the patient had been recruited to the TABUL study.

The pathologist was required to report which side or sides the biopsy had been taken from as well as the length of the biopsy (after freezing or fixation), and a note was made of whether or not it was bifurcated. They were able to add other comments on the macroscopic appearance of the sample. For each biopsy, the staining protocol was reported. The macroscopic appearance was described and a note was made of whether or not the biopsy was from the temporal artery and which sections were cut. The presence of abnormalities in the intima (arteriosclerosis or intimal hyperplasia) and the internal elastic lamina (fragmentation or reduplication) were reported. Pathologists were required to indicate if there was an inflammatory infiltrate in the sample (and the predominant site of any inflammation) and indicate if any of the following features were present: normal areas, giant cells, calcification or any other unusual features. Data were also captured on presence and causes of complete occlusion of the vessel or presence of thrombus or evidence of recanalisation in at least one section of the vessel.

The pathological diagnosis was reported as either normal or any the following: compatible with a diagnosis of GCA, compatible with another vasculitis, compatible with arteriosclerosis and compatible with any other diagnosis as specified by the pathologist. The actual pathological slides were sent to the TABUL office for image acquisition. Digital image acquisition was achieved using an Aperio Scanscope Turbo AT (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Slides were loaded onto the machine’s autoloader and pre-snapped to obtain a macroscopic image before proceeding with digital scanning. The macroscopic image was used to set the tissue area, focal plane, focus points, white balance, scan/slide settings and labelling description. Once the settings had been optimised the slides were scanned in fragments and digitally stitched together to form one high-resolution virtual representation of the pathology slide. These virtual slides were stored on an external physical server and a web-based database (Aperio eSlideManager V1.0, Leica Biosystems) was used to archive and store the eSlides. Slides could be viewed remotely using Aperio’s web-based viewing systems (Leica Biosystems).

The biopsy result, which was the primary standard test, was defined as positive by the pathologist if the pathological diagnosis was compatible with a diagnosis of GCA. This included patients whose biopsy samples did not contain temporal artery (e.g. vein, fat, muscle or other tissue) or for whom no sample was obtained from surgery. An alternative standard test result was defined as the clinician’s interpretation of the biopsy result as reported on the clinical CRF at the 2-week assessment. This was reported because we expected that the clinician might reach a different conclusion from the pathologist, based on the biopsy report.

The main analyses included patients who had no sample from surgery or a biopsy sample that did not include temporal artery; these were categorised as not compatible with a diagnosis of GCA. Additional analyses excluded the indeterminate biopsy results.

The index test: ultrasound of the temporal and axillary arteries

The index test, an ultrasound of both temporal and both axillary arteries, was performed following the protocol described earlier and is available on the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre website (www.nets.nihr.ac.uk) and was subject to ongoing monitoring for quality assurance. The presence of ultrasound abnormalities (halo, occlusion, stenosis and arteriosclerosis) in different segments of the temporal arteries and in the axillary arteries (as defined in Table 1) was captured in the ultrasound case report form (see Appendix 1). The primary test result for ultrasound was defined as positive and was used for the main analyses if the sonographer responded ‘yes’ to the question ‘In your opinion are the results consistent with a diagnosis of GCA?’. Additional analyses used alternative definitions of a positive result based on the presence or absence of a bilateral halo and on the interpretation of the ultrasound images from the expert review.

Ultrasound test results: procedure for revealing test results

The clinician treating the patient was provided with the biopsy result but did not have access to the results of ultrasound at the 2-week assessment. Study sonographers were required to keep the results of each patient’s scans blinded from the managing clinician for the duration of the study. The only exception was if the managing clinician had completed the 2-week assessment and was planning to withdraw steroid treatment rapidly. In these circumstances the clinician was required to contact the TABUL office and was provided with the scan results as reported by the sonographer. The clinician then had an opportunity to reconsider their decision to withdraw steroids and alter their diagnosis. Thus, the 2-week assessment included a report of the clinician’s original assessment of the diagnosis and any revision following the revealing of the ultrasound result.

The reference diagnosis

The ideal reference diagnosis for evaluating diagnostic tests is one that is independent of the tests being evaluated. No such reference diagnosis exists for GCA for evaluating the performance of biopsy and ultrasound. Criteria for classifying GCA and usual clinical practice for reaching a GCA diagnosis incorporate the results of the biopsy; therefore, they cannot be truly independent methods for defining a reference diagnosis. Furthermore, the ACR classification criteria were not intended to be used as diagnostic criteria. 34 For the purposes of the study, a partially independent approach was used, which combined elements of a clinician’s final diagnosis, the ACR classification criteria (incorporating the biopsy result), the emergence of complications consistent with GCA during follow-up, the emergence of alternative vasculitis diagnoses during follow-up and expert review to determine the reference diagnosis. The process started with the clinician’s final diagnosis for the patient as reported on the 6-month (or in its absence, 2-week) assessment. An algorithm was devised to determine if evidence from the biopsy and the presence or absence of symptoms and emerging complications and diagnoses on follow-up supported the clinician’s diagnosis or if expert review was required to determine the reference diagnosis.

If the clinician’s final diagnosis was GCA, then a reference diagnosis of GCA was given if any of the following criteria were met:

-

a stricter version of the ACR classification criteria using either the standard or tree method was met based on the patient’s symptoms and physical examination from their baseline assessment (Table 2)

-

the emergence of PMR during follow-up in patients with no previous history of PMR and no symptoms of PMR at presentation

-

the emergence of new or worsening jaw claudication, tongue claudication, abnormal anterior optic neuropathy, abnormal posterior optic neuropathy, or relative afferent pupillary defect during follow-up.

| Criterion | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Age at disease onset of at least 50 years | Development of symptoms or findings beginning at ≥ 50 years of age | Baseline patient assessment: symptoms started at ≥ 50 years of age pre-steroids or at presentation |

| (2) New headache | New onset of or new type of localised pain in the head | Baseline patient assessment: symptoms of new onset or type of localised pain in head pre-steroids or at presentation |

| (3) Temporal artery abnormality | Temporal artery tenderness to palpation or decreased pulsation unrelated to arteriosclerosis of carotid arteries | Baseline patient assessment: abnormal tender temporal artery on physical examination |

| (4) Elevated ESR (at least 50 mm/hour) | ESR at least 50 mm/hour as assessed by the Westergren method | Baseline patient assessment: laboratory test results ESR at least 50 mm/hour pre-steroids or at presentation |

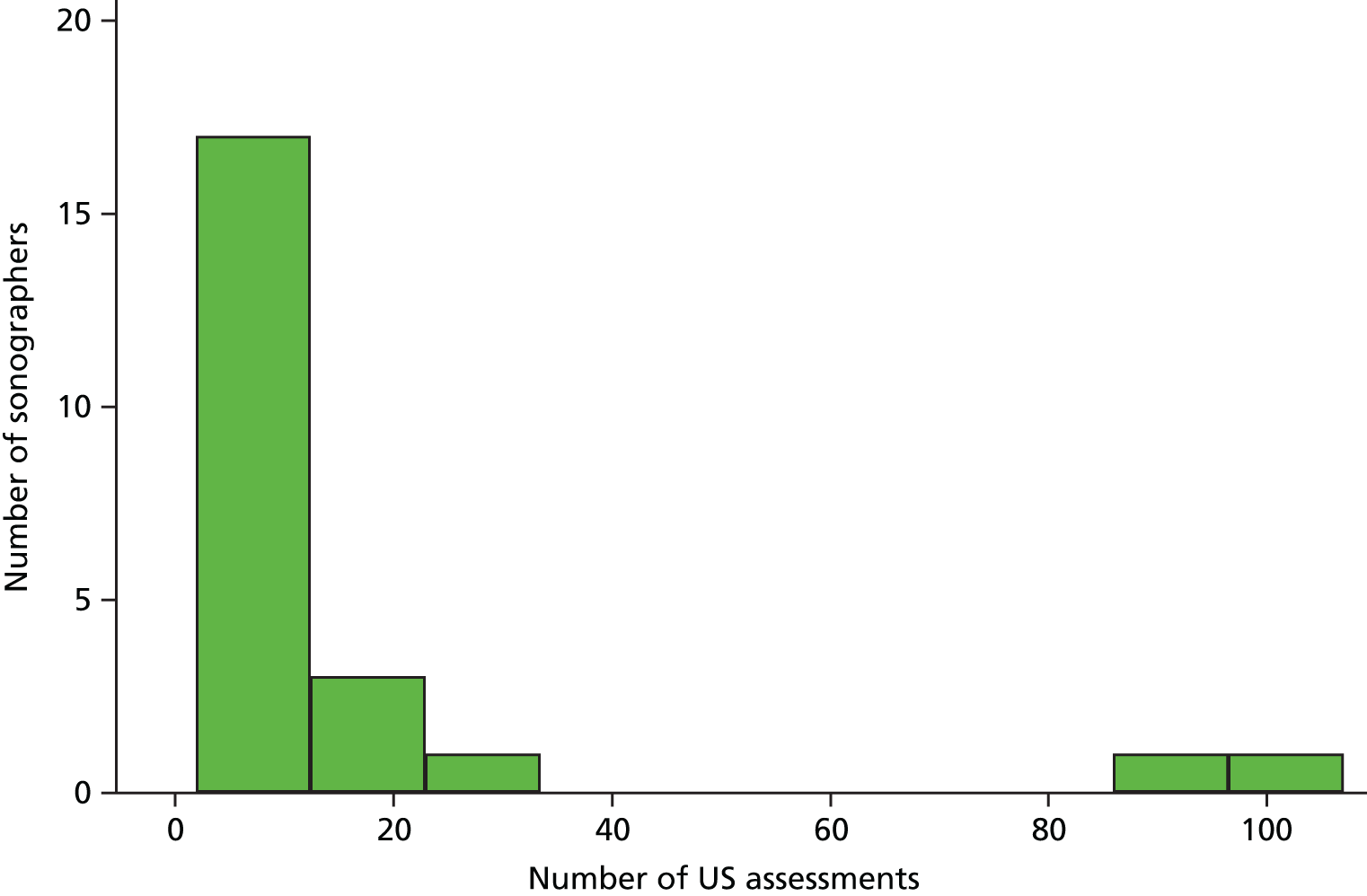

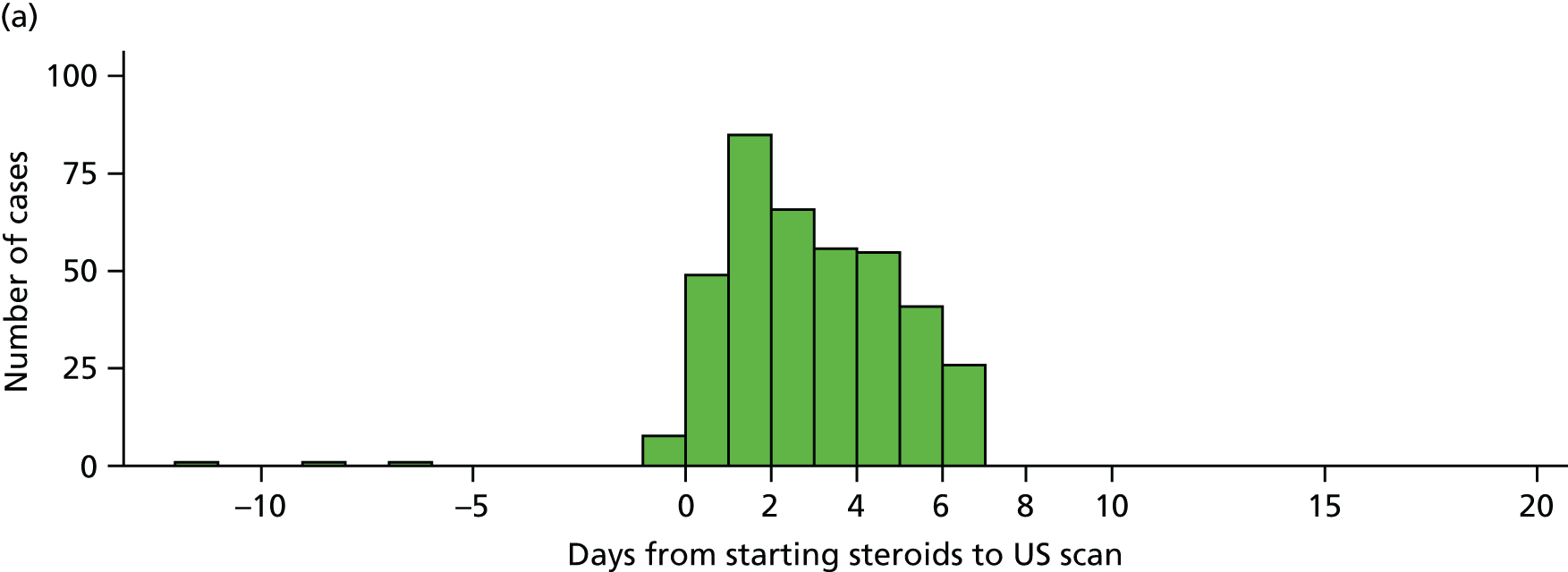

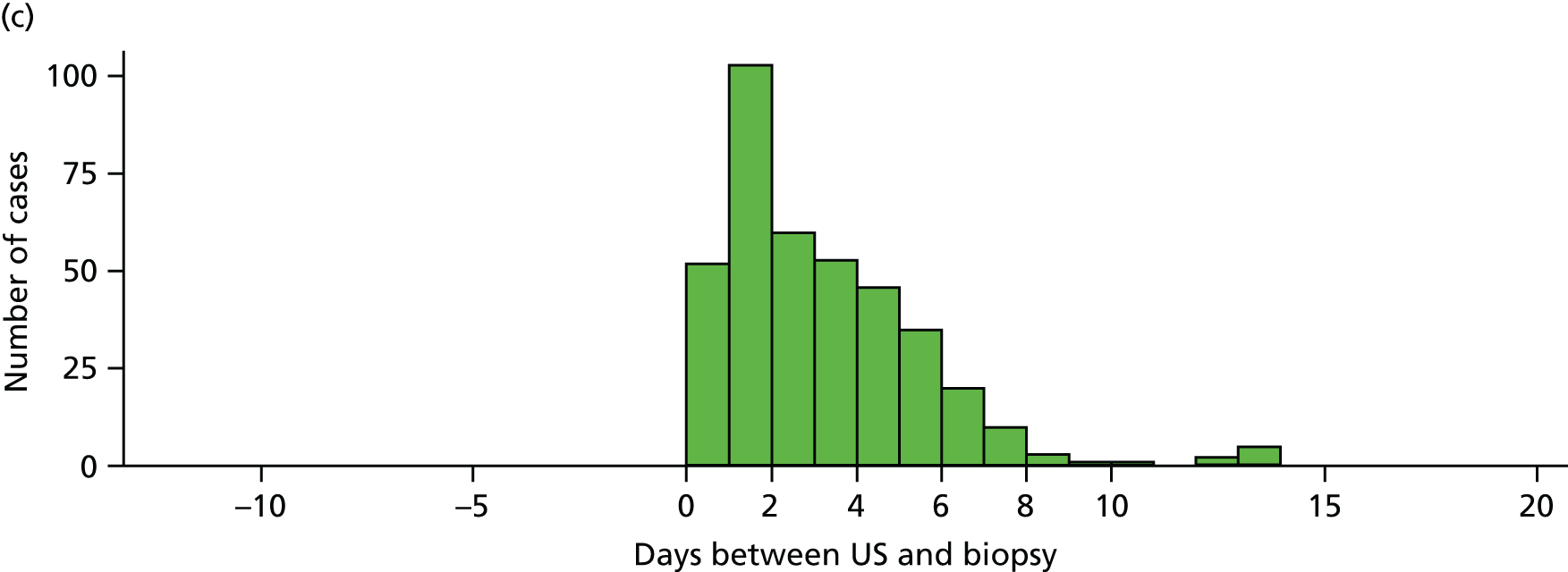

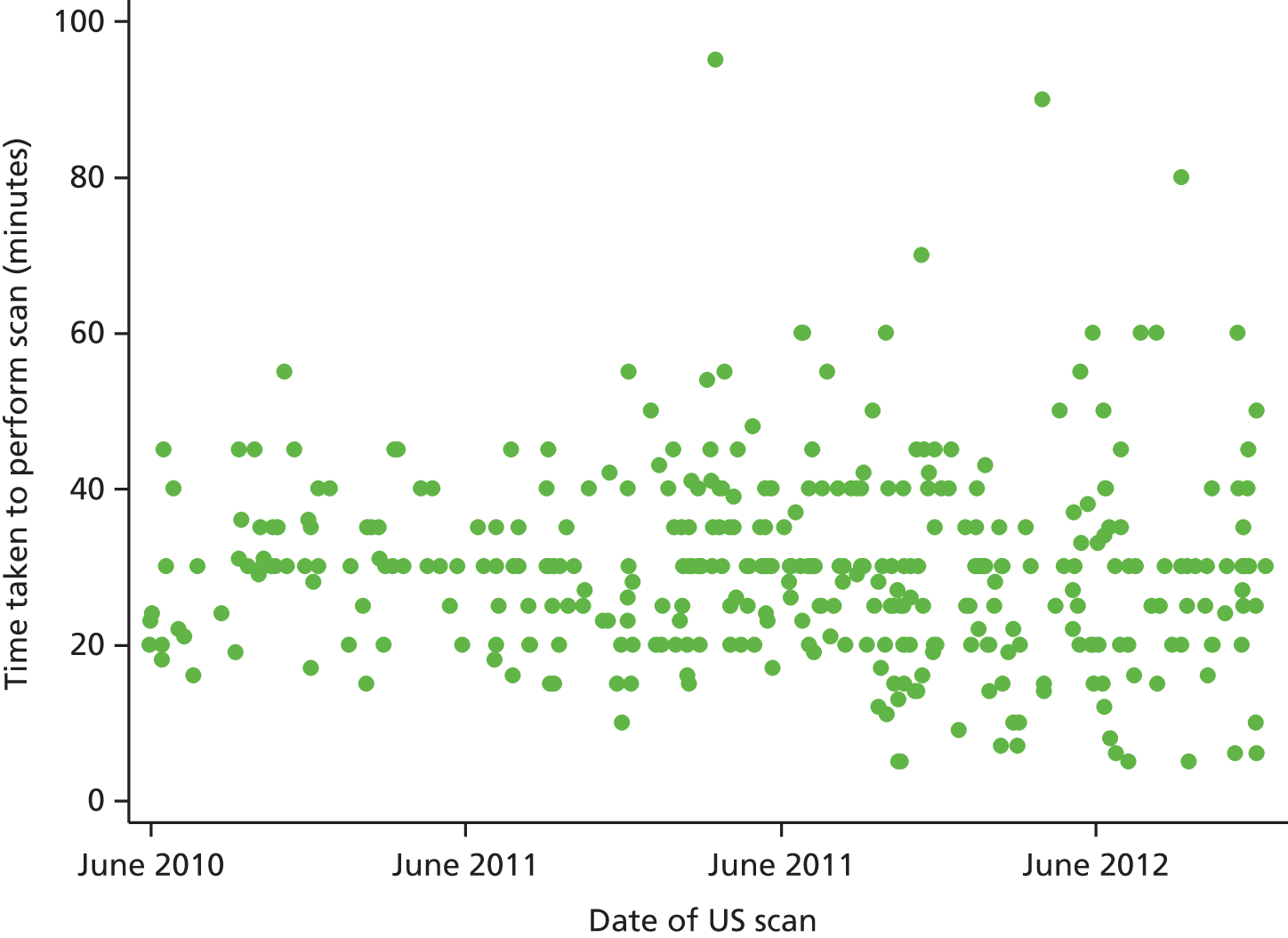

| (5) Abnormal artery biopsy | Biopsy specimen with artery showing vasculitis characterised by a predominance of mononuclear cell infiltration of granulomatous inflammation, usually with multinucleated giant cells | Pathology CRF: pathologist reports biopsy result as consistent with a diagnosis of GCA |