Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/127/41. The contractual start date was in December 2011. The draft report began editorial review in September 2015 and was accepted for publication in February 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Robertson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Childhood obesity, both in the UK and internationally, is known to be a major public health burden. The most recent Health Survey for England found that between 1995 and 2005 obesity in children aged 2–10 years in England rose from 10% to 17% in boys and from 11% to 17% in girls. 1 However, the trend may now be reversing, with 13% of boys and 12% of girls found to be obese in 2013. 1 Analysis of general practice data found a similar trend, with the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity stabilising from 2004 to 2013 in children aged 2–10 years. 2 This prevalence is still too high, with over one-third (33.5%) of children in year 6 (aged 10–11 years) in England classified as either overweight or obese in the 2013/14 school year. 3 This translates to over 172,000 children in year 6 alone who are overweight or obese.

Childhood overweight and obesity have been linked to a number of long-term and immediate physiological and psychological health risks,4,5 with associations between childhood body mass index (BMI) and type 2 diabetes, hypertension and coronary heart disease in adulthood. 6 This means that the prevention and management of childhood obesity is a public health priority. Effective interventions to treat children who are obese, to reduce ill health in children and to reduce the proportion of children whose obesity continues into adulthood are needed.

In 2008, there were an estimated 314–375 weight management programmes for children in operation in England at any one time. 7 These lifestyle interventions focused on diet, physical activity, behaviour change or any combination of these factors, and included programmes, courses or clubs, and online services. They could include programmes that were designed for overweight or obese children and young people, or for their parents, carers or families; designed primarily for adults but that accept, or may be used by, children and young people; or provided by the public, private or voluntary sector, in the community or in (or via) primary care organisations. Aicken et al. 7 noted that some were small local schemes, whereas others were available on a regional or national basis.

Care pathway for weight management of children and young people

Government guidelines describe a three-tier pyramid model for weight management, with three levels of service, from universal services, offered to everybody, through to specialist services, provided to those with particular needs. 8 Level 1 represents the core preventative services that all children, young people and their families should have access to, while level 2 represents targeted weight management services. The Families for Health intervention fits into level 2. This level of intervention is often aimed at children and young people with a BMI between the 91st and 98th centile, and services typically take the form of multicomponent family-based interventions, often taking place in community settings. They may also be called ‘early intervention services’. Level 3 is specialist support, offered to children with a BMI ≥ 99.6th centile, with a medical cause of obesity, significant comorbidity or complex needs. The Department of Health has recommended that overweight or obese children should be referred to appropriate weight management services. 9

Evidence for effectiveness of level 2 child obesity interventions

A Cochrane systematic review of interventions to treat obesity identified 64 randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 10 Thirty-seven studies were lifestyle interventions for children aged < 12 years (four dietary, nine physical activity and 24 behavioural). The authors concluded that it is difficult to recommend any particular intervention, but indicated that family-based lifestyle interventions combining dietary, physical activity and behavioural components can produce a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in overweight. Parental involvement was identified as useful with children aged < 12 years.

Recent UK-based trials of interventions targeting children who are obese have covered a variety of approaches. A RCT of the 9-week family-based community programme MEND (Mind, Exercise, Nutrition . . . Do it!; Mytime Active, Bromley, UK) with 116 children (aged 8–12 years) showed a between-group difference in the BMI z-score at the 6-month follow-up of –0.24 [95% confidence interval (CI) –0.34 to –0.13; p < 0.0001; n = 82] in favour of MEND over the waiting list control. 11 A further RCT compared paediatric dietitians using a one-to-one behavioural approach (5 hours) with standard dietetic care (1.5 hours) in 134 children (aged 5–11 years). 12 No significant differences in BMI z-scores were found at 6 or 12 months. A feasibility RCT that compared the community-based Watch It programme (delivered by health trainers) with a waiting list control, in 70 children and adolescents, found no significant change in BMI z-score and treatment. 13 A RCT of Epstein’s family-based behavioural treatment in a UK hospital, with 72 participants, found that there was no significant difference between the intervention and waiting list groups in BMI z-score, although both treatment and control groups showed significant reductions. 14

A National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on managing overweight and obesity among children and young people suggested that targeting both parents and children, or whole families, is effective in reducing BMI z-scores. 15 By the end of a programme, evidence on interventions involving families showed no negative effect on well-being and, in some cases, showed positive effects. Similarly, a review of the limited research on interventions focusing on parenting to treat childhood obesity shows a small positive effect on weight-related outcomes. 16

Family-based interventions rooted in behaviour theory have been shown to achieve better treatment effectiveness than those rooted in family systems theory. 17 A recent review of published studies18 investigating family-based childhood obesity interventions in the UK included 10 studies. The majority of programmes reviewed lasted 12 weeks, with only three studies providing follow-up data at 12 months or longer. Change in adiposity was a short-term benefit of participation, but there was insufficient robust evidence to suggest that this benefit was long-lasting and many studies were methodologically weak with limited internal validity. The authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence on how the inclusion of parents and the wider family may impact on the effectiveness of UK community-based weight management programmes for children and young people. 18

Evidence for cost-effectiveness of child obesity interventions

Oude Luttikhuis et al. 10 point to a paucity of cost-effectiveness studies in this area. A recent US study of families in which both children and parents were overweight or obese found that the cost per unit weight lost by parents and children was lower for family-based group treatment than for an intervention that treated the parent and child separately. 19 Evidence from seven short-term health economic analyses suggests that, in the short term, lifestyle weight management programmes will result in an increased cost to the NHS in terms of BMI z-score gains when compared with routine care. However, overall small (and in some cases non-significant) improvements in BMI z-scores can be achieved. 15 Interventions that lead to even small reductions in BMI can be cost-effective in the long term at conventional cost-effectiveness thresholds, provided that the short-term effects on BMI can be sustained into adulthood. The NICE guidance suggested that evidence from these studies is directly applicable, but there were some potentially serious limitations to the studies. 15

From randomised controlled trial to practice

Two recent studies have investigated the roll-out of an intervention tested in a RCT into the community. 20,21 Both were based on the multicomponent family-based weight management intervention, MEND, which addresses diet and physical activity through education, skills training and motivational enhancement. When delivered at scale, the rolled-out intervention resulted in the improvement of BMI and psychosocial outcomes but worked less well for some groups of children (certain ethnic groups and those from more deprived areas). This was not because of variations in uptake of the programme, which was good in deprived groups, but because of differing experiences in completing, with more disadvantaged groups being less likely to complete the programme. The intervention, therefore, had the potential to widen inequalities. The authors suggested that further research should investigate how completion rates could be improved for particular groups. 21 They felt that the intervention should be implemented in such a way as to achieve sustained impact for all groups by modifying content, training and implementation. 20

Parenting programmes

It has been argued that parenting programmes have potential to improve the mental health and well-being of children, as well as improve family relationships and benefit the community as whole. 22 A public health approach to parenting is needed to ensure that more parents benefit and that a societal-level impact is achieved. 22 The effectiveness of parenting interventions in the treatment and prevention of childhood obesity has shown a small positive effect on weight-related outcomes,16 but this approach has not been investigated in a RCT in the UK.

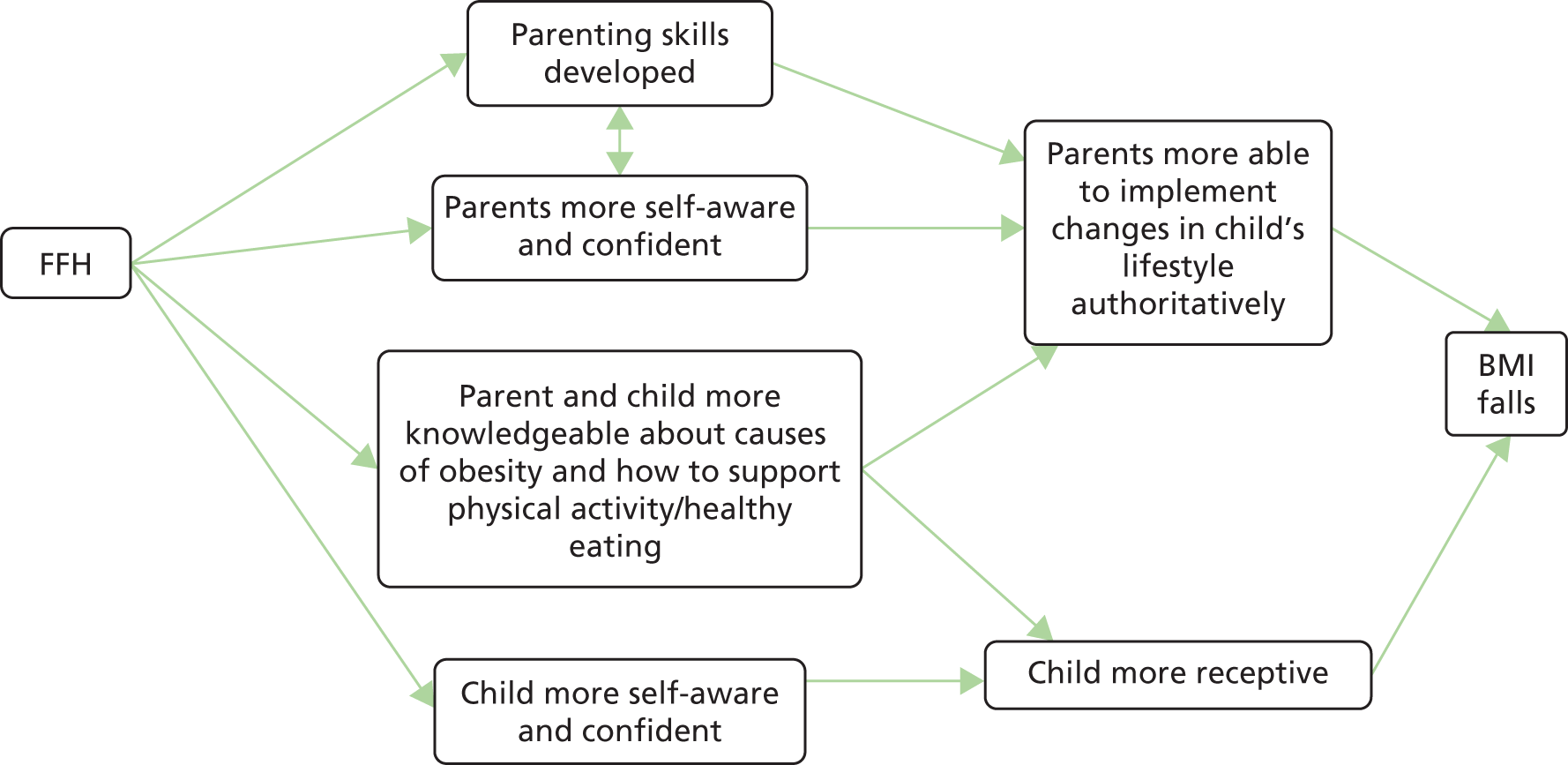

Development of the Families for Health intervention

‘Families for Health’ is a manualised group-based family intervention for the treatment of children aged 6–11 years who are overweight or obese, which could be an option in the care pathway as a targeted ‘early-intervention’ service. The programme was developed at Warwick University and supported by a Department of Health career development award to the principal investigator. The programme differs from other interventions for childhood obesity being used or tested in the UK by offering a greater emphasis on parenting skills, relationship skills and emotional and social development, combined with information about lifestyle. Parents and children attend separate groups, meeting mid-way for a healthy snack and activity. The groups are led by two trained facilitators.

The development and evaluation of the Families for Health programme has followed the Medical Research Council (MRC)’s framework for complex interventions. 23 A pre–post pilot study in Coventry of 27 children showed that a mean reduction in children’s BMI z-scores from baseline was sustained at 9 months (–0.21, 95% CI –0.35 to –0.07; p = 0.007) and 2 years (–0.23, 95% CI –0.42 to 0.03; p = 0.027). 24,25 There were also other health-related improvements. Interview data showed that parents found the parenting approach helpful, providing the tools for them to become ‘agents of change’ in the family. The NHS costs to deliver the programme were £517 per family or £402 per child. 25 The process evaluation of the pilot study showed the need for minor modifications to the programme including more physical activity, removal of some unnecessary material, a reduction in the number of sessions and addition of follow-up sessions. These changes to the intervention might increase effectiveness.

The materials for version 1 of this programme were developed by Candida Hunt and the University of Warwick team, including investigators in this trial (WR and SS-B). 26 Following development and evaluation of the original programme Families for Health version 1,24,25 changes were made including shortening the delivery from 12 to 10 sessions, adding two follow-up sessions and enhancing the information given to families on healthy eating and pedometers. The programme combines information on parenting skills, social and emotional development, as well as lifestyle change. The parenting aspects are based on the Nurturing Programme from Family Links (Family Links, Oxford, UK),27 and the circle time elements in the children’s programme have parallels with the Family Links Nurturing Programme for schools. 28

Delivery is group based involving 8–12 families, with children and parents attending parallel groups. The intervention is delivered in a community setting (e.g. a leisure centre or school), to enhance access and ensure adequate space and facilities for physical activity. The parents’ group covers both support with parenting skills and family lifestyle, which are integrated in the weekly sessions. The approaches include facilitated discussion, role-play, goal-setting, skill practice, a solution-focused approach and homework. The children’s programme includes a focus on healthy eating using the ‘Eatwell plate’ (Food Standards Agency, London, UK) as the basis; circle time to discuss emotional aspects of their lives and enhancing self-esteem; and physical activity aimed at increasing activity levels by participation in games, the use of pedometers and introduction to new physical activities. The parents and children meet mid-way in each session for a healthy snack and an active game. This gives facilitators an opportunity to act as role models, for example showing parents how they might reward or praise their children, and to introduce ways in which children and parents can interact at home. It also provides an opportunity for children to prepare healthy snacks and to try new foods.

The main principles underpinning the Families for Health intervention are that the parents are identified as the agents of change responsible for implementing lifestyle change in the family. 29 The parenting aspects aim to support and increase parental capacity to implement and maintain the lifestyle changes that they would like to try each week. The focus is on healthy eating (not dieting) and activity for the whole family (that is, not just for the child who is overweight), with an emphasis on children growing into their weight rather than weight loss. The programme aims to promote a sustainable, healthy approach to family-wide lifestyle change. The programme puts greater emphasis on parenting skills, relationship skills, and emotional and social development than other similar interventions, and combines this with information about lifestyle. These form a core theme throughout and are integrated alongside topics in each weekly session.

Rationale for research

Although family-based interventions for the treatment of childhood obesity have become more common, the inclusion of parenting skills within a programme is less so. Such a programme may be effective in the treatment and prevention of childhood obesity,16,24,25 and so it is important to investigate the impact on families with overweight and obese children.

This RCT provides evidence of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Families for Health programme, which emphasises parenting alongside a healthy lifestyle as an alternative approach for the treatment of obesity in 6- to 11-year-olds.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the trial was to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Families for Health programme delivered within the NHS.

The objectives were to:

-

assess the effectiveness of the Families for Health programme in reducing the BMI z-score in children aged 6–11 years who are overweight or obese

-

evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the Families for Health programme [expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained]

-

investigate parents’ and children’s views of the programme and their observations on approaches to maximising impact

-

investigate facilitators’ views of the programme and their observations on approaches to maximising impact.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

The ‘Families for Health’ trial evaluated the effectiveness of the Families for Health programme in comparison with usual care in children aged 6–11 years who were overweight or obese. The trial was a multicentre RCT with parallel economic and process evaluations. Families were randomised (1 : 1) to one of two arms: Families for Health (target 60 families) or usual care (target 60 families). Further details of the interventions are described in Treatment groups.

The primary outcome measure was the change in children’s BMI z-score at 12 months. All primary and secondary outcomes were assessed at baseline, the end of the programme (3 months) and 12 months post randomisation, to evaluate both the short- and long-term effects.

Study settings

The Families for Health study agreed collaborations with three West Midlands primary care trusts. These primary care trusts offered Families for Health as part of their care pathway for the treatment of childhood obesity, alongside their usual care. The three sites are referred to as site A, site B and site C in this report.

In sites A and C, the Families for Health intervention was run in a leisure centre (local authority) and in site B it was run in a community centre with a sports hall.

Ethical approval and research governance

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) West Midlands – Coventry and Warwickshire (reference number 11/WM/0290) on 3 October 2011.

The trial was sponsored by the University of Warwick. NHS Research and Development approvals were obtained with the participating NHS trusts. The trial was conducted in accordance with the standard operating procedures of the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit. 30

A Trial Steering Committee (TSC) was convened every 6 months, comprising four independent members [chairperson, topic expert, statistician and parent (service user)] who advised on changes to the protocol, the analyses plans and oversaw the management of the trial. A Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) was convened annually, comprising three independent members (chairperson/topic expert, statistician and health economist). The DMEC considered any ethical issues and adverse events, and reviewed the interim analyses including BMI z-score, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions Youth version (EQ-5D-Y) and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) (presented blind) data.

All data were stored securely and anonymised in accordance with the Data Protection Act,31 and the trial was conducted in compliance with the principles of MRC’s Good Clinical Practice guidelines,32 the Declaration of Helsinki33 and other requirements as appropriate. All research staff were trained in good clinical practice in a paediatric setting and child protection awareness training.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained in three steps, giving parents and children time to consider whether or not they wished to participate. Each potential participant was given, or sent by post, information sheets about the trial (child and parent versions). After a minimum of 3 days, parents were contacted by telephone to ask whether or not they were interested in taking part in the trial and to answer any questions. A researcher then visited the parent(s) and child(ren) at their home, and obtained the parent’s written consent and the child’s written assent. All research staff were trained in informed consent, including methods for assessing competence for consent, agreement to participate and obtaining assent from children.

User involvement

Parents

A parent who had been a participant in the pilot of the Families for Health intervention was a member of the TSC. She attended seven of the eight TSC meetings and contributed to discussions on the intervention and study design.

Children

The aim for user involvement, as stated in the protocol, was met using the following approach. Claire Callens and Carly Tibbins, from the user involvement team of the West Midlands Medicines for Children’s Research Network carried out patient and public involvement consultation exercises with children from the West Midlands prior to recruitment from January to February 2012, comprising two stages: stage 1, two focus groups with hospital-based young person’s advisory groups (aged 8–18 years), which aimed to develop and pilot questions for the second stage, and also included obtaining views on the acceptability of wearing accelerometers to measure physical activity; and stage 2, consultation on the proposed intervention and the research measurements (including accelerometers) with children in the target age range for the trial (key stage 2, aged 7–11 years) from two primary schools from the areas in which the trial was to be delivered.

A specific area of inquiry in the second stage of consultation was about the types of activities children most enjoyed, which was used to inform the ‘activity tasters’ within the Families for Health intervention. Older children (years 5 and 6) completed a questionnaire and younger children (years 3 and 4) voted, by show of hands, on the options given for physical activity. Once they understood the concept of a children’s gym, all children felt that they would like to attend one to see what it was like.

Across the two stages of consultation, 35 young people aged 7–18 years were consulted on accelerometers in five focus groups. Prior to participation in the focus group discussion, 18 children were given the opportunity to wear an accelerometer (GT1M ActiGraph; ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA). First impressions of the acceptability of the accelerometer were often negative relating to comfort and unwanted attention from friends, indicating that this may be a difficult tool to use. Others felt that an increased attention from others would be positive. Ways to increase use by participants were suggested as presenting the accelerometer in a very positive way, include a trial wearing period and providing incentives. 34 A full report of the user involvement consultation with children is available. 35

Changes to project protocol

Some parts of the original protocol were changed, as can be seen in Table 1, which also shows where appropriate approval was obtained.

| Change to protocol | Approval | Type and date approved |

|---|---|---|

| The CSRI was developed and given ethical approval prior to piloting | NRES | Substantial amendment 1, 17 January 2012 |

| The inclusion criterion was changed from children aged 7–11 years to 6–11 years (parents of 6-year-old children were coming forward requesting to participate) | NRES/HTA programme | Amendment 2, 27 April 2012 |

| The formatting of CSRI was changed after piloting, the poster for recruitment was revised and the letter used for recruitment via the NCMP was changed | NRES | Amendment 3, 21 May 2012 |

| Interviews were originally just going to be with families in the FFH arm, but the protocol was changed to include interviews with UC families as well in order to improve comparison with UC | NRES | Substantial amendment 4, 6 August 2012 |

| HTA programme | 11 July 2012 | |

| Recruitment rates were slower than initially anticipated. The emphasis on the type of recruitment method used changed along with the study timelines as the study progressed. Approval was given for GP databases to be searched for potential overweight/obese children, who, once identified, were contacted via letter | NRES | Substantial amendment 5, 8 May 2013 |

| Addition of a seventh FFH programme in order to reach sufficient study participant numbers. This required a 9-month no-cost extension (to 31 August 2015) to the study to enable the 12-month follow-up of participants | HTA programme | Approved by HTA on 19 June 2014 |

Treatment groups

The intervention: Families for Health

Families for Health version 2 is a family-based programme aimed at the treatment of children (aged 6–11 years) who are overweight or obese. Delivery is group based, and the aim was to recruit groups of 8–12 families, with children and parents attending parallel groups. In families randomised to this arm, both parents were invited, together with all overweight and non-overweight siblings in the target age range. Where necessary, the start of a programme was delayed so that viable attendance numbers could be obtained. The programme was manualised, with detailed handbooks available to facilitators, parents and children. Groups were run on a Saturday morning or afternoon for 2.5 hours each week for 10 weeks. Follow-up sessions were planned for 1 and 3 months post intervention.

The main principles underpinning the Families for Health intervention were that the parents were identified as the agents of change responsible for implementing lifestyle change in the family. 29 A solution-focused approach was employed, focusing on solutions rather than the problem. The programme emphasises parenting skills, relationship skills, and emotional and social development, and combines this with information about lifestyle, all of which are key to implementing and maintaining behaviour change. Table 2 shows an outline of the main content of the parallel parents’ and children’s groups for the 10 weeks. The weekly topics in the Families for Health programme were broadly the same for both parents’ and children’s groups, in order to promote greater understanding and discussion at home. The parents and children met mid-way each week for a healthy snack and an active game, with an aim of introducing ways in which children and parents could interact at home.

| Week | Parents’ programme | Children’s programme |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Let’s get started

|

Let’s get started

|

| 2 | Balancing acts

|

Balancing acts

|

| 3 | Inner power – our ally for health

|

Inner power – our health helper

|

| 4 | The question of choice

|

Our choices

|

| 5 | Health is a family affair

|

Liking ourselves

|

| 6 | Feelings – a guide to our emotional health

|

Getting to know our feelings

|

| 7 | Solutions to stress

|

Time to chill out

|

| 8 | A world of labels

|

Food detectives

|

| 9 | Taking charge

|

Living healthily

|

| 10 | A healthy family future

|

(Combined session with parents) |

The parents programme of the Families for Health programme shared some of parenting skills topics from the Nurturing Programme from Family Links,27 and included both behavioural (e.g. positive discipline, family rules) and relationship (e.g. giving praise, raising self-esteem, emotional health) approaches to parent training. The support with parenting skills were integrated with family lifestyle topics around healthy eating and physical activity in the weekly sessions. The approaches include facilitated discussion, role-play, goal-setting, skill practice, a solution-focused approach and homework.

The children’s programme included a focus on healthy eating using the Eatwell plate as the basis; circle time to discuss emotional aspects of their lives and enhancing self-esteem; and physical activity aimed to increase activity levels by participation in games, the use of pedometers and introduction to new physical activities.

Families in the intervention arm were also eligible for usual-care interventions and any usual care they received was documented.

Training and selection of facilitators: Families for Health

Four facilitators, two for the children’s group and two for the parents’ group, were required to run each Families for Health programme. Facilitators were identified from the local NHS or other services, and selected on the basis of personal attributes including empathy for families with overweight children and previous relevant experience, for example with running groups with parents and children. In site A, a formal application process was set up, whereas for sites B and C nominations were received through the leads for obesity. Professional backgrounds of facilitators included community nursing, teaching, youth work, leisure services and nutritionists.

Nineteen facilitators attended a 4-day training course in February 2012 provided by two trainers from Family Links. Trainers from Family Links were used to deliver the training because of the close association of the Families for Health programme with the Nurturing Programme from Family Links. 27,28 The training covered the content, philosophy and logistics of running the programme. For some sessions facilitators were divided up into subgroups of whether they were facilitating the children’s or parents’ group, and practised facilitating parts of the programme. Participants completed an evaluation form for each day of the training, including the level of confidence in delivering the Families for Health programme and rating the usefulness of the topics covered. Training increased facilitators’ confidence in delivering the programme and most found the training a positive and useful experience. Further details of the evaluation of the training of the facilitators are in Appendix 1.

Usual-care control group

Families assigned to the control arm were offered any usual care that was available in their area. During the duration of the study, usual care for each locality varied.

Site A had the One Body One Life (Coventry City Council, Coventry, UK) 10-week programme, which is a group-based family intervention that has been subject to published evaluation. 36 This was available throughout the study. The eligibility criteria for the One Body One Life programme was children aged 7–16 years, but was offered to the whole family if one or more member of the family was an ‘unhealthy weight’. The programme took a solution-focused approach, with the 1.5-hour sessions comprising a 45-minute physical activity workshop and a 45-minute healthy eating workshop.

Site B had Change4Life (Department of Health, London, UK) advisors who offered one-to-one support for weight management for children aged 4–13 years who were overweight or obese. Recruitment to their service was via self-referral, referral from school health or other health professionals, and via the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP). Visits were mainly undertaken at the child’s home. This service was available for the majority of the study, though in the final few months of recruitment funding for Change4Life advisors was withdrawn and a single telephone call was instead being offered.

In site C, usual care was one of the following: (1) a weight management programme for children and young people aged 7–15 years, comprising a two-step programme, MEND and Choose It (Wolverhampton City Council, Wolverhampton, UK), focusing on taster sessions for physical activity and healthy eating. Funding for this programme was withdrawn halfway through the study and so two alternatives were offered as ‘usual care’ in site C, depending on the age of the child; (2) Weight Watchers® (Weight Watchers UK Ltd, Maidenhead, UK) for young people aged ≥ 10 years, who had to be accompanied by a parent; and (3) a referral to the school nurse for children aged 6–9 years, where children would be weighed and measured and offered advice. This type of usual care was not standard at the start of the study and, therefore, did not always occur as hoped. Table 3 gives further details of the usual-care programmes.

| Usual-care programme | Delivery | Core themes |

|---|---|---|

| One Body One Life (site A) | Parent and child group based 1.5 hours weekly for 10 weeks Delivery at school or community venue |

Healthy eating Physical activity Health checks |

| Change4Life advisor (site B) | Parent and child one to one with Change4Life advisor First session ≈ 1.5 hours, subsequent visits ≈ 45 minutes Number of visits varies according to family needs (average 5 visits) Majority of visits at home, occasionally at school or clinic |

Healthy eating (Eatwell plate; portion sizes, food labelling) Increasing physical activity Self-esteem |

| Weight management programme for parents and children (site C) | Parent and child group based 2 hours weekly for 10 weeks Delivery at community venue |

MEND programme and Choose It (focusing on taster sessions for physical activity and healthy eating) |

| Weight Watchers for children aged ≥ 10 years (site C) | Parent and child group based 1 hour weekly for 12 weeks Delivery at community venue |

Healthy eating (portion sizes) Encourage increased physical activity (pedometers for sale) |

| School nurse referral for children aged 6–9 years (site C) | One to one | Weighed and measured Offered advice |

Participants

The study recruited children aged 6–11 years who were overweight or obese and their parent(s) from the three primary care trusts.

Inclusion criteria

Families were considered for inclusion if:

-

they had at least one overweight (≥ 91st centile for BMI) or obese (≥ 98th centile for BMI) child aged 6–11 years, based on the UK 1990 BMI37

-

at least one parent or guardian and the overweight child was willing to take part.

Exclusion criteria

Families were excluded if:

-

the parent or child had an insufficient command of English and would find it difficult to participate in the group

-

the child had a metabolic or other recognised medical cause of obesity

-

the child had severe learning difficulties and/or severe behavioural problems, and would find it difficult to participate in a group-based programme.

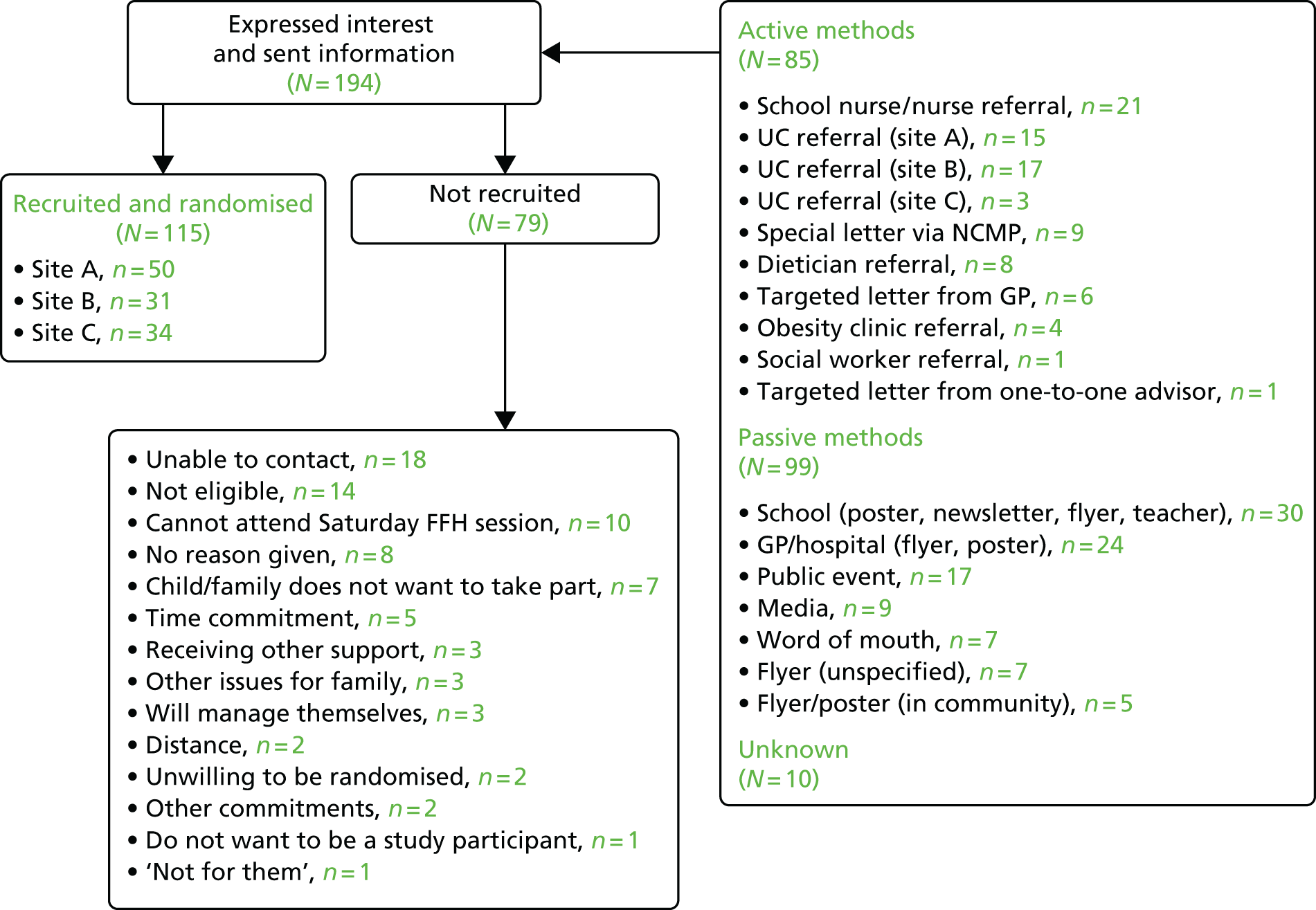

Recruitment

The aim was to recruit 40 families from each of the three primary care trusts. At the time of recruitment, data from the NCMP 2008/938 showed an abundant pool of potential participants in just one school year (year 6) (Table 4).

| Location | Number eligible | Number measured | Participation rate (%) | Prevalence of obesity, % (95% CI) | Number of obese Year 6 children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site A | 3477 | 3152 | 90.7 | 19.4 (18.0 to 21.3) | 611 |

| Site B | 5548 | 4584 | 82.6 | 15.1 (14.1 to 17.2) | 692 |

| Site C | 2827 | 2649 | 93.7 | 23.5 (21.9 to 25.5) | 623 |

| West Midlands SHA | 62,526 | 55,993 | 89.6 | 19.8 (19.5 to 20.8) | – |

| England | 558,633 | 497,680 | 89.1 | 18.3 (18.2 to 19.1) | – |

Both active and passive recruitment methods were used. Initially, passive recruitment included advertisements in newspapers and local radio interviews, whereas active recruitment involved letters to families with an overweight or very overweight child, who had recently been measured in the NCMP, and referrals from health-care professionals. However, recruitment was slower than planned so further recruitment strategies were employed including letters to families from the family’s general practitioner (GP) and approaches from Change4Life advisors. Flyers and posters were also sent to be displayed in schools, the community, primary care surgeries and the local hospital, and there were recruitment stands at local public events. As recruitment continued, word of mouth from families enrolled in the trial became a successful recruitment method.

Randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding

The unit of randomisation was the family. Researchers registered families after confirming eligibility and obtaining consent, and after completing the baseline data collection in order to ensure allocation concealment. The term ‘control’ was not used at any time with the families and they were told that they would be receiving one of two possible programmes, either Families for Health or usual care. After consent, the family was allocated to intervention or control by the central telephone registration and randomisation service at the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit. Randomisation was stratified by locality (site A, B or C) using a biased-coin (p = 2/3) minimisation method within each locality to ensure that approximately equal numbers of families were randomised to the Families for Health programme and control. The trial administrator (EH) assigned the participants to the interventions that they were allocated to.

The families could not be blinded to treatment allocation, but every effort was made to ensure that the research personnel involved with data collection remained blind to treatment allocation until the initial data collection was complete. Blinding was not an issue at baseline because all data collection was done before randomisation. A ‘blinding protocol’ recorded the systems in place to keep the researchers blind to treatment allocation at the 3- and 12-month follow-up visits, which included the following.

-

The family was reminded via letter and telephone call by the trial administrator that they were not to discuss their allocation with the researcher at the visit until requested.

-

The researcher took all anthropometric measurements first and then the parent(s) and child(ren) completed their self-administered questionnaires. The Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI) questionnaire and the interview (if being carried out) both unblinded the researcher and so these were administered last.

-

The researcher that conducted the 3-month follow-up visit (who was now unblinded) did not conduct the 12-month follow-up visit for the same family. A different researcher who was blind to treatment allocation conducted the 12-month follow-up visit.

In order to ascertain whether or not the assessors were blind to the allocated arm, an ‘unblinding log’ was kept by the trial administrator to record if a researcher was inadvertently unblinded to allocation. On 21 occasions the follow-up visits were completed by an unblinded researcher who knew the treatment allocation at the start of the research visit (e.g. because a family mentioned the name of the programme that they had been on at the start of the home visit).

Statisticians (TH and NS) were blinded for the interim analysis for the DMEC, but neither the statisticians nor health economists were blinded for the final analysis presented to the combined meeting of the TSC and DMEC. This policy was agreed by the TSC.

Data collection and management

All members of the research team were trained to use standard operating procedures for each stage of data collection. Data entry was carried out by the trial administrator and members of the research team and then checked by a different team member to minimise data entry errors. The software for data entry was bespoke, in that it was custom made and managed by the University of Warwick Clinical Trials Unit programming team.

A number of different measures were used to collect information on the impact of the intervention (see Table 5). All of these were measured in the family home at baseline, at the end of the 10-week Families for Health programme (or approximately 3 months in the usual-care arm) and at 12 months from baseline. In families with more than one eligible child who met the inclusion criteria, data were collected on all participating overweight or obese children. Research visits in the family home took, on average, between 1 and 3 hours, depending on whether they were baseline or follow-up and whether or not interviews were carried out.

Baseline assessment

All baseline visits took place between 16 March 2012 and 11 February 2014. A researcher assessed the family’s eligibility for the trial and obtained the parents’ consent and children’s assent. Parents were asked to complete a brief baseline questionnaire that included the parent’s date of birth (needed for randomisation), the child(ren)’s date of birth (age), sex and ethnic group, and primary care contact details. At the same time, parents were asked whether or not they were consulting anyone else about their child’s weight, whether the child suffered from any medical conditions or allergies, whether or not either of them was taking part in any other research project and what the main reasons were for wanting to address their child’s weight or lifestyle. Family structure was categorised into five groups: (1) two-parent family, (2) single mother, (3) single father, (4) stepfamily or (5) other. The researcher also asked how the family heard about the Families for Health programme. Subsequently, the researcher took the parent and child through all of the questionnaires described in detail below.

For families allocated to the Families for Health programme, the period between the baseline visit and the start of the intervention was, on average, 94 days, with a minimum waiting time of 1 day and a maximum waiting time of 346 days. In site A the mean waiting time was 93 days, in site B it was 73 days and in site C it was 114 days. No equivalent information was available for families allocated to usual care.

Follow-up

All 3- and 12-month follow-up visits took place between 27 July 2012 and 9 May 2014 and between 12 March 2013 and 11 March 2015, respectively. Follow-up data collection was scheduled at 3 and 12 months post randomisation. The 3-month visit had been planned to coincide with the completion of the Families for Health intervention. However, some families had to wait until there was a viable number of families to form a group (a minimum eight families) before starting the intervention. Therefore, some post-intervention follow-ups were more than 3 months after randomisation. For families receiving usual care, 3-month follow-up visits were always scheduled for 3 months post randomisation regardless of whether or not they had accessed a usual-care intervention at that point. All 12-month follow-up visits were carried out at 12 months from baseline, by a different researcher from the one who carried out the 3-month follow-up, in order the maintain blinding. Where the 3- and 12-month follow-up were too close, that is, when a family had waited so long for the intervention group to start that there would be less than 1 month between 3 and 12 months, then a combined 3- and 12-month visit was carried out. Separate one-to-one in-depth interviews with the parent and child were carried out at the 3- and 12-month follow-up, respectively, with an original plan of carrying out interviews with 24 families from each trial arm. The following table (Table 5) demonstrates the different measures used in the study, who (child or parent) this was collected from and at what time point.

| Measure | Reference | Validated | Children | Parents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 12 months | Baseline | 3 months | 12 months | |||

| Anthropometric | ||||||||

| Weight and height (BMI) | LMSgrowtha | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Waist circumference | McCarthy et al.39 | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | – | – | – |

| Percentage body fat | Wells and Fewtrell40 | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Physical activity and diet | ||||||||

| Accelerometry (ActiGraph GT3X) | Evenson et al.41 | Evenson et al.;41 Trost et al.42 | ✗ | – | ✗ | – | – | – |

| Fruit and vegetable consumption – Day in the Life Questionnaire | Edmunds and Ziebland43 | Edmunds and Ziebland43 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | – | – | – |

| Family Eating and Activity Habits Questionnaire | Golan44 | Golan44 | – | – | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Physical and mental health | ||||||||

| Child’s quality of life – PedsQL (both child’s own and parent-proxy recording for the child) | Varni45 | Varni et al.46 (US); Upton et al.47 (UK) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | – | – | – |

| Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale | Tennant et al.48 | Tennant et al.48 | – | – | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Family relationships | ||||||||

| Child–Parent Relationship Scale | Pianta49 | Pianta49 | – | – | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Parenting | ||||||||

| PSDQ | Robinson et al.50 | Robinson et al.50 | – | – | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Economic outcomes | ||||||||

| EQ-5D-Y (both child’s own and parent-proxy recordings for the child) EQ-5D health state valuation (parent’s own) |

Wille and Ravens-Sieberer51 (children); Dolan52 (parents) | Eidt-Koch et al.53 (children) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| CSRI | Beecham and Knapp54 | – | – | – | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Family characteristics | ||||||||

| Socioeconomic status | ONS55 | – | – | – | – | ✗ | – | – |

| Qualitative | ||||||||

| One-to-one interviews (selected) | – | – | – | ✗ | ✗ | – | ✗ | ✗ |

Outcomes

Anthropometric

Child weight and height (body mass index)

The primary outcome measure was the change in children’s BMI z-score at 12 months compared with the change in the control arm. Weight was measured using the Tanita body composition analyser (model BC-420S MA; Tanita Europe B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands) to the nearest 0.1 kg, taken without shoes and in light, indoor clothing. Children were asked to stand still on the scales with arms by their side. Height was measured by a Leicester stadiometer (Harlow Healthcare, South Shields, UK) to the nearest 0.1 cm, without shoes, with feet together and flat on the floor with heels touching the base of the stadiometer. Children were asked to put their arms by their side and look straight ahead, and then their head was adjusted if required so that their ear hole was aligned with the bottom of the eye socket (the Frankfurt plane). The measuring arm of the stadiometer was lowered onto the top of the head to measure height. BMI was calculated using the following equation:(1)BMI=weight (kg)height2 (m), and then was converted into standard deviation (SD) scores (z) from 1990 UK growth reference curves, giving a BMI z-score. 37 The BMI z-score is used because it takes into account children’s age and sex, and indicates how many SDs a child’s BMI is above or below the average BMI for their age and sex. This was carried out using LMSgrowth (version 2.77; Harlow Healthcare, South Shields, UK; www.healthforallchildren.com/shop-base/shop/software/lmsgrowth), which is a Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) add-in, designed to manipulate growth data using growth references based on the LMS method.

Child waist circumference

Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a Seca 200 tape (Seca, Birmingham, UK) taken at the level of the umbilicus, consistent with the method of Daniel et al. 56 Measurements were made without compressing the skin, taken while standing with feet together, arms hanging by side and looking straight ahead. Measurements were taken under clothes, unless a child was uncomfortable with this and then the measurement was taken over a thin layer of clothing. Where this was the case, a note was made at the time of data collection. Waist circumference was translated into z-scores for age and sex using 2001 reference data for British children aged 5–16 years. 39

Percentage body fat

An indirect measure of percentage body fat was made using the Tanita scales using bioelectrical impedance analysis. 40 An electrical signal (50 kHz, 800 µA) is sent through the body via the pressure-contact electrodes on which the participant stands, to get a measure of impedance (Ohms). The percentage of body fat is calculated using an in-built equation based on impedance, height, age, sex and body type.

Parent weight and height (BMI)

Height was recorded using a Leicester stadiometer and weight with Tanita scales, as with children. No waist circumference measurements were taken for parents. BMI and percentage body fat were calculated.

Physical activity and diet

Accelerometry: time spent in physical activity and intensity

All children on the trial were asked to wear an accelerometer for 7 days following the baseline and 12-month follow-up assessments in order to provide an objective measure of the amount of physical activity undertaken over a period of 7 days. Accelerometers are able to record the participant’s movement such that their physical activity level can be translated into a number of different outcomes, including total step count, bouts of physical activity at specified intensities or energy expenditure. Accelerometry data were collected using the ActiGraph GT3X, programmed to record using 15-second epochs. Data were analysed using the Actilife 6 Data Analysis Software (ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA).

Children, with help from parents, were asked to complete an activity diary alongside the accelerometer for 7 days. This was a pictorial ‘tick-box’ diary recording activities each hour, with a column for free-text additional comments. There was also a place to record the time the accelerometer was put on and taken off. The purpose of the diary was to aid interpretation of the accelerometer output. 57 Children and parents were provided with instructions on receiving the accelerometer about how to wear it. Children were fitted with accelerometers located at the waist at the left-hand side of the body on an elastic belt, with the open/close button (to connect accelerometer to computer) facing upwards. They were asked to wear the device under or on their clothes during all waking hours, except when undertaking water-based activities.

Data were collected for 7 consecutive days and thus included both weekdays and weekends. Owing to previous evidence suggesting that differences in activity levels exist during school time and out of school time,58 where possible accelerometers were worn during the school term, in order to keep measurements consistent across participants. If this was not possible (e.g. a child did not feel comfortable in wearing it during term time) it was worn during holiday time in order that some (rather than no) activity data were collected. In all circumstances, the 12-month follow-up data collection took place at the same time of year and consistently in either term time or holiday time. The outcome was measured at baseline and 12 months in order to minimise seasonal effects. 59 The date of wearing the accelerometer was recorded in the project management file. At the end of the 7-day period, the researcher collected the accelerometer and accompanying activity diary from the participant’s home.

Children’s fruit and vegetable consumption

Children completed a 24-hour recall using the ‘Day in the Life Questionnaire’. 43 This also asked about transport to and from school and daily activity, but the primary aim was to assess the number of portions of fruit and vegetables consumed the previous day. The questionnaire was checked and clarification sought, if necessary, with parents (e.g. orange juice: was this ‘squash’ or ‘fruit juice’?). In line with national recommendations (NHS Choices60), fruit juice could account for only one portion of fruit and vegetables per day, regardless of how much was consumed, and how often. Similarly, baked beans were counted as one portion regardless of how many times they were consumed in a single day. Composite foods (e.g. curry, pizza) that contained a unknown number portions of fruit and vegetables were excluded.

The questionnaire has been validated for measuring fruit and vegetable consumption with 7- to 9-year-olds. 43 The validation was done with four schools, comparing the questionnaire with observation by a researcher for fruit and vegetables eaten at lunchtime, achieving a modest kappa of 0.54–0.58. The reliability was assessed both by a test–retest, which was acceptable, and by inter-rater reliability of two coders assessing the portions of fruit and vegetables, with a high kappa of 0.85–0.92, indicating high agreement between coders. The questionnaire was also shown to be sensitive to change following the distribution of free fruit, confirming it as a good questionnaire to use in the current study, in order to measure any change in fruit and vegetable intake.

Family eating and activity

Eating and activity behaviour in the family was assessed using a modified version of the Family Eating and Activity Habits Questionnaire (FEAHQ) from Israel. 44 Slight modifications were made to make it suitable for use in the UK. This was principally in the list of snacks in question 5, excluding those not heard of in the UK (e.g. Chitos, Ruffles) and adding in those that were common in the UK (e.g. crisps). The questionnaire includes the following four subscales: (1) activity level (four items), to record the balance between physical activity and sedentary pastimes (e.g. television); (2) stimulus exposure (eight items), for example presence and visibility of unhealthy snacks kept at home, allowed to eat snacks/sweets without parental permission, allowed to buy own sweets; (3) eating related to hunger (four items), for example who initiates the eating in the family or behaviour if the child is not hungry; and (4) eating style/rites (13 items), for example where and with whom does eating take place and second helpings. Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of internal consistency reliability was calculated at α = 0.83 for the questionnaire overall and α = 0.82, 0.78, 0.86 and 0.88 for the subscales 1–4, respectively. 44 Parents completed the questionnaire and then summary scores were calculated for the children’s score for the four sections in accordance with the scoring instructions. Lower scores are classed as ‘better’ on each section.

Physical and mental health

Children’s quality of life

Children’s quality of life was measured using the Pediatric Quality of Life InventoryTM (PedsQL) version 4.0 (UK) for ages 8–12 years. 45 Children completed the 23-item self-report version and the parents completed the almost identical parent-proxy version about their child’s quality of life. This measures four domains of health-related quality of life: (1) physical health (eight questions), (2) emotional health (five questions), (3) social functioning (five questions) and (4) school functioning (five questions). All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never a problem) to 4 (almost always a problem), which are then rescored: 0 = 100, 1 = 75, 2 = 50, 3 = 25, 4 = 0. Summary scores are then derived for the physical domain (eight questions), the psychosocial health domain (emotional/social/school) (15 questions) and for a total scale score (all 23 questions), with the best possible score being 100 (range 0–100).

Varni et al. 46 measured the internal consistency reliability of PedsQL using Cronbach’s alpha, with 963 children and 1629 parents in a US sample. The Cronbach’s alpha scores showed that the questionnaire had internal reliability for the total score (all 23 questions, α = 0.88 for child report, α = 0.90 for parent report), the physical health score (eight questions, α = 0.80 for child-report, α = 0.88 for parent report) and the psychosocial summary score (15 questions, α = 0.83 for child report, α = 0.86 for parent report). This study demonstrated the reliability and validity of the PedsQL version 4.0. The reliability of the UK version of the PedsQL was also assessed in a sample of 1399 children and 970 parents from south Wales, and was shown to have similar internal reliability with all subscales on both the child and parent reports, reaching α = 0.70 (minimum standard) and exceeded α = 0.90 for the total score. 47 They recommend the UK version of the PedsQL for assessment of quality of life in UK children.

Parents’ mental health

Parental mental health was measured using the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS). 48 WEMWBS is a measure of mental well-being focusing entirely on positive aspects of mental health. The scale consists of 14 items, covering aspects of mental health including positive affect (feelings of optimism, cheerfulness, relaxation), satisfying interpersonal relationships and positive functioning (energy, clear thinking, self-acceptance, personal development, competence and autonomy). Individuals completing the scale are required to tick the box that best describes their experience of each statement over the past 2 weeks using a 5-point Likert scale (none of the time, rarely, some of the time, often, or all of the time). The Likert scale represents a score for each item from 1 to 5, respectively, giving a minimum score of 14 and a maximum score of 70. All items are scored positively. The overall score for the WEMWBS is calculated by totalling the scores for each item, with equal weights. Therefore, a higher WEMWBS score indicates a higher level of mental well-being. WEMWBS has shown good content validity. In addition, WEMWBS has shown high correlations with other mental health and well-being scales, and partial correlations with scales measuring overall health. 48

Family relationships

Relationship between parents and children

Assessment of the quality of the parent–child relationship was made using the Child–Parent Relationship Scale (CPRS),49 which was self-completed by parents. The CPRS assesses parents’ perceptions of their relationships with their sons and daughters. The short-form version was used, which has 15 items assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, with eight of the questions reverse scored. A mean score is derived with the best possible score being 5 (range 1–5).

The eight-item conflict subscale measures the degree to which a parent feels that his or her relationship with a particular child is characterised by negativity. In order to test the validity of the CPRS, structured interactions between parents and study children were videotaped at 54 months and 6–7 years old. The Cronbach’s alpha for maternal conflict was 0.84 at 54 months and 0.84 at 6–7 years old, whereas the Cronbach’s alpha for paternal conflict was 0.80 at 54 months and 0.78 at first grade. The seven-item closeness scale assesses the extent to which a parent feels that the relationship is characterised by warmth, affection and open communication. The Cronbach’s alpha for maternal closeness was 0.69 at 54 months and 0.64 at first grade, whereas the Cronbach’s alpha for paternal closeness was 0.72 at 54 months and 0.74 at first grade. The conflict and closeness scales of the CPRS represent two distinct domains of parent–child relationships, as evidenced by a relatively low correlation between the scales (r = 0.16).

Parenting style

Parenting style was measured using the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ). 50 The PSDQ assesses how often a parent exhibits certain behaviours towards his or her child. It has 32 items contributing to three factors: (1) authoritative parenting style (measuring parent–child warmth and connection, parental use of reasoning, and inductive parenting and autonomy granting, e.g. ‘I help my child to understand the impact of behaviour by encouraging my child to talk about the consequences of his/her own actions’); (2) authoritarian parenting style (measuring physical coercion, verbal hostility and non-reasoning/punitive disciplinary practices, e.g. ‘When my child asks why he/she has to conform, I state: because I said so, or I am your parent and I want you to’); and (3) permissive parenting style (measuring parental indulgence and inconsistency, e.g. ‘I give into my child when the child causes a commotion about something’). Parents were asked to respond by indicating on a scale of 1–5 (never to always) how frequently they performed the behaviour in question. The PSDQ has been shown to demonstrate adequate reliability and validity. 50

Economic outcomes

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions Youth version health-state valuation of the child

Children completed the descriptive system and the visual analogue scale from the EQ-5D-Y questionnaire at each visit, with the view to describing their health-related quality of life. 51,53 The descriptive system comprises the following five dimensions: (1) mobility; (2) self-care; (3) usual activities; (4) pain/discomfort; and (5) anxiety/depression. Each dimension has three levels: no problems, some problems and extreme problems. The respondent is asked to indicate their health state by ticking (or placing a cross) in the box against the most appropriate statement in each of the five dimensions. The 20-cm visual analogue scale is anchored by the descriptors ‘best possible health’ (100%) and ‘worst possible health’ (0%), with children placing a mark on how they valued their health on the day of the visit.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions Youth version health-state valuation of the child by parent

Parents also completed the EQ-5D-Y questionnaire describing their child’s health-related quality of life on the day of each visit. This included the same descriptive questions as those asked of the child (as detailed in European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions Youth version health-state valuation of the child). On the visual analogue scale, parents were asked how they thought their child would value their own health.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions health-state valuation: parent’s own

Parents completed the EQ-5D questionnaire describing their own health-related quality of life on the day of each visit. 52

Services received by child

A modified version of the CSRI was used to record hospital and community health and social services received by each child, as well as broader service utilisation (adaptation of CSRI from Beecham and Knapp54), at baseline, 3 and 12 months. The unit costs of each resource item were valued using both primary research, based on established accounting methods, and data collated from secondary national tariff sets. 61–64 Further details of the methods used are provided in Chapter 5.

Socioeconomic classification

Families’ socioeconomic classification was measured using details of parental employment. Employment status and type of employment of the mother and/or father was recorded, including their actual occupation and whether they were self-employed or an employee. This information was used to code families into eight socioeconomic classes using the The National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification. 55 As the number of families was small, this was subsequently collapsed into three classes, plus a fourth category of ‘never worked and long-term unemployment’ (Table 6).

| Eight classes | Three classes |

|---|---|

| 1. Higher managerial and professional occupations | 1. Managerial and professional occupations |

| 1.1 Large employers and higher managerial occupations | |

| 1.2 Higher professional occupations | |

| 2. Lower managerial and professional occupations | |

| 3. Intermediate occupations | 2. Intermediate occupations |

| 4. Small employees and own-account workers | |

| 5. Lower supervisory and technical occupations | 3. Routine and manual occupations |

| 6. Semiroutine occupations | |

| 7. Routine occupations | |

| 8. Never worked and long-term unemployed | Never worked and long-term unemployed |

Sample size

Original sample size justification

Power calculations assumed a residual SD in the BMI z-score of 0.22, a SD of the random family effects of 0.14, an intracluster correlation of 0.1 in the intervention groups, a two-sided significance of 5% and that 60% of participating families have one overweight or obese child and 40% have two with a within-family intracluster correlation of 0.27. Allowing for clustering effects by family and for group effects in the intervention arm, a sample size of six groups of 10 families (60 families) in the intervention arm and 60 families in the control arm gives a power of 94% to detect an intervention effect of 0.2 in BMI z-scores based on pilot study data and relevant literature. 24,65 If 30% of families were to drop out, the study retains a power of 88%. As a check, the power was calculated when no families have more than one overweight or obese child. In this case, the power is 92% or 83% if 30% of families drop out. Power values were estimated using a simulation study including 10,000 simulated trials.

Updated sample size calculation

Recruitment to the trial was slower than expected, leading to smaller groups for the Families for Health programme than planned; therefore, the addition of a seventh Families for Health programme was proposed. On 19 June 2014 this amendment to the Families for Health protocol was approved by Health Technology Assessment. The sample size calculation was updated to incorporate the additional programme and recruitment thus far (all other assumptions of the sample size calculation remained the same). A sample size of seven groups of eight families (56 families) in the intervention arm and 56 families in the control arm yields a power of 91% to detect an intervention effect of 0.2 in BMI z-scores if seven families (one with two children) were providing 12-month follow-up data (12.5% dropout) and 88% power if six families (one with two children) were providing 12-month follow-up data (25.0% dropout). If no families had more than one child, then the power would be 89% and 85% for the 12-month follow-up of seven and six families per programme, respectively.

Chapter 3 Statistical analysis methods

Analysis of accelerometer data

Accelerometer data were reduced and analysed as follows. Evenson et al. ’s41 activity count cut points for the ActiGraph for physical activity intensities (sedentary, light, moderate or vigorous) were used for the analysis, as recommended by Trost et al. 42 (Table 7). The Evenson cut point associated with moderate to vigorous physical activity in children is 2296 counts per minute.

| Time period | Cut points | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary | Light | Moderate | Vigorous | |

| Per 15 seconds | 0–25 | 26–573 | 574–1002 | ≥ 1003 |

| CPM | ≤ 100 | 101–2295 | ≤ 2296 (moderate to vigorous) | |

Not all the accelerometer records were complete. A child’s record was included in the analysis if there were at least 3 complete days of data, taken as the minimum needed to obtain a reliable measurement of habitual physical activity in children, at both baseline and 12-month follow-up. A complete day was defined as one where there was ≥ 8 hours of data, after excluding periods in the day when the accelerometer appeared not to have been worn. Although 10 hours of worn time is often used, the reliability between 7 and 10 hours is not substantially different. 66 Non-wear time was identified from the data by periods of ≥ 60 minutes of consecutive zero counts, making it unlikely that the monitor was being worn.

At each time point for each child with complete records, the mean daily time spent in moderate and vigorous physical activity, sedentary time, accelerometer counts per minute and daily step count were calculated using the Actilife 6 Data Analysis Software.

Statistical methods

A comprehensive statistical analysis for the Families for Health trial was conducted with the aim of assessing the effectiveness of the Families for Health programme, in comparison with usual care, in the treatment of overweight and obesity among children aged 6–11 years. The prespecified primary outcome measure in the statistical analysis was the change in children’s BMI z-score from baseline to 12 months’ follow-up so that clinical effectiveness would be declared based on a reduction in BMI z-score relative to the comparator. Secondary outcomes in the statistical analysis fell into four categories: (1) anthropometric measures in children; (2) anthropometric measures in parents; (3) (validated) questionnaires completed by children; or (4) (validated) questionnaires completed by parents. Table 5 provides an overview of all outcomes analysed and the time points at which they were measured.

General statistical considerations

The primary outcome analysis as well as all secondary outcome analyses were conducted at the conventional (two-sided) 5% level and, corresponding to this, all presented CIs are 95% CIs. As specified in the statistical analysis plan, no formal adjustment for multiple testing among the secondary end points was used as outcomes are likely to be highly correlated so that standard adjustment techniques, such as the Bonferroni method, would be conservative. All outcome measures and child/parent characteristics were summarised by the trial allocation group and for outcome measures by follow-up period. The distribution of outcome data was investigated and transformations applied, if necessary, before performing statistical tests and modelling. The main analysis of clinical outcome data was the comparison of change from baseline between treatment groups. Using the change from baseline has a ‘normalising’ effect so that standard techniques could generally be used.

Unless otherwise stated, all analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis, that is all participants were analysed in the arm they were allocated to and included regardless of whether or not the treatment and follow-up schedule was complied with. This reflects the pragmatic nature of the trial and ensures that conclusions drawn from the analysis will reflect the impact of the Families for Health programme in a real-world setting.

The statistician conducting the statistical analysis was unblinded for the final statistical analysis and the analysis presented at the final DMEC/TSC meeting. The multilevel models originally proposed to be adopted in the analyses (see Primary outcome analysis) consist of two hierarchical levels in the usual-care arm and three levels in the intervention arm. For these models to be fitted, the participants’ group affiliation needed to be revealed. Unblinding was agreed to by the TSC.

The entire statistical analysis was conducted using SAS v9.4 TSL1M2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) with the exception of the sample size calculation, which was conducted using R versions 2.10 and 3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Primary outcome analysis

As indicated above, the primary outcome for the statistical analysis was the mean change in child BMI z-score after 12 months of follow-up compared between treatment arms. It was anticipated that these data would be correlated within families (if more than one child of a family participates in the trial) and within delivery groups in the Families for Health intervention arm. The analysis allowed for this clustering in order to obtain unbiased estimation of the treatment effect and its standard error (SE). 67

A three-level hierarchical mixed-effects model was proposed to be fitted in the statistical analysis plan. At the highest level of the model a random effect for delivery group was intended. Delivery group-level clustering would have been allowed for in the Families for Health arm only, as usual-care interventions varied by site, were not necessarily group based and precise details on usual-care treatment received were generally not available. As the statistical analysis showed, there was no evidence of delivery-group clustering and models comprising this random effect failed to converge (see Chapter 4, Main primary outcome analysis). The decision has therefore been made (and been approved by the TSC) to remove this effect from all hierarchical modelling and to use a two-level hierarchical mixed-effects model instead.

Correlation between measurements of children within family was allowed for in both arms.

The multilevel model was adjusted for the child-level characteristics, baseline BMI z-score and sex, and family-level variable ‘locality’ as fixed effects. Additionally, adjustment for the family-level characteristic socioeconomic status (SES) and child-level characteristic ethnicity was explored. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation was employed for estimating covariance parameters in the multilevel modelling. The Satterthwaite approximation68 was used for computing the denominator degrees of freedom for the test of a treatment effect difference between the allocation groups (and for tests of other fixed effects).

The primary analysis is a complete case analysis in the sense that if either the baseline or 12-month follow-up z-score was missing the subject had to be omitted from the analysis.

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome

Several sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess the impact of areas of uncertainty surrounding the primary outcome analysis and its robustness. These involved re-estimating the treatment effect under the following scenarios: (1) conducting a per-protocol analysis in which families having participated in five or more sessions of the Families for Health programme are regarded as ‘programme completers’ (i.e. as having complied with the protocol sufficiently); and (2) (multiple) imputation of missing primary outcome data.

Three standard imputation techniques were employed to assess the sensitivity of the analysis to the missing data: first, simple regression imputation, in which missing values are imputed by predicted values from a linear regression model using the same predictors as the primary outcome analysis; second, multiple imputation methods Markov chain Monte Carlo;69 and, third, fully conditional specification regression. 70 For the two multiple imputation analyses, 200 burn-in iterations were used and estimates averaged over 100 imputed data sets. Baseline BMI z-score, age, sex and site were included as explanatory variables in the imputation models. Imputations were generated separately for each treatment group.

Subgroup analyses

To explore heterogeneity in the trial population, the following prespecified exploratory subgroup analyses were conducted with respect to the primary outcome:

-

child’s sex (male or female)

-

locality (site)

-

SES (according to The National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification’s55 four-class standard classifications)

-

parent’s BMI at baseline (normal, overweight or obese)

-

age of child at baseline (6–8 years or 9–11 years).

The difference in treatment effects by subgroups was initially assessed by interaction tests. These were performed via significance tests of interaction terms in the hierarchical model utilised for the primary outcome analysis. Variables that have been categories for subgroup analyses (e.g. age, parent BMI) were also investigated as covariates on their original scale. Separate models were then fitted for each subgroup to obtain estimates of the treatment effects within subpopulations.

Repeated measures modelling

An exploratory analysis was performed for the investigation of the difference between arms in terms of change over time in the primary outcome measure rather than a comparison between arms at either 3- or 12-month follow-up. In this analysis, the time at which follow-up data were provided was fitted as a continuous variable, accounting for the fact that the actual times varied widely (especially for the 3-month follow-up). For this purpose a repeated measures mixed model was fitted. This model was based on the aforementioned hierarchical model for the primary outcome analysis comprising the same effect (plus time). Model complexity was increased as time became the new first-level (random) factor. The same model specification, as in the primary outcome multilevel model (restricted maximum likelihood estimation), was used where possible. An unstructured covariance matrix was assumed for the correlation between measuring time points.

Analysis of baseline demographic data

Baseline demographic outcomes were obtained on a family level or on a child/parent level. Summary statistics (mean and SD for continuous variables and absolute number and percentage for categorical variables) were calculated for all participants recruited to the trial and for the two treatment groups separately. The characteristics within the two treatment groups were compared using t-tests and chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The statistical comparison of baseline characteristics was considered exploratory rather than confirmatory and ignored clustering by delivery group or family. The main intention was to identify baseline variable differences that might be deemed relevant by the main investigators and would consequently require adjustment in the multilevel models fitted in the primary and secondary outcome analyses.

Secondary outcome analyses

All secondary outcomes, including subscales of questionnaires, were summarised by trial allocation group and follow-up period using mean, SDs and 95% CIs for continuous variables and absolute number, percentages and 95% CIs for categorical variables. Statistical tests of differences for child secondary outcomes were performed using the same hierarchical mixed-effects model as the primary outcome analysis. In addition, child BMI z-score was also compared as change from baseline to 3-month follow-up and change from baseline to 12-month follow-up using independent group t-tests. Parent outcomes were compared using t-tests and chi-squared tests, as appropriate, as generally only one parent provided data and within-family correlation could not be modelled. In case parents and children provided data for the same outcome, the simpler test was used to ensure comparability. Where the analysis of parent outcomes was adjusted, hypothesis testing was done within a linear regression model and the adjustment variables provided in the respective results section.

Chapter 4 Trial results

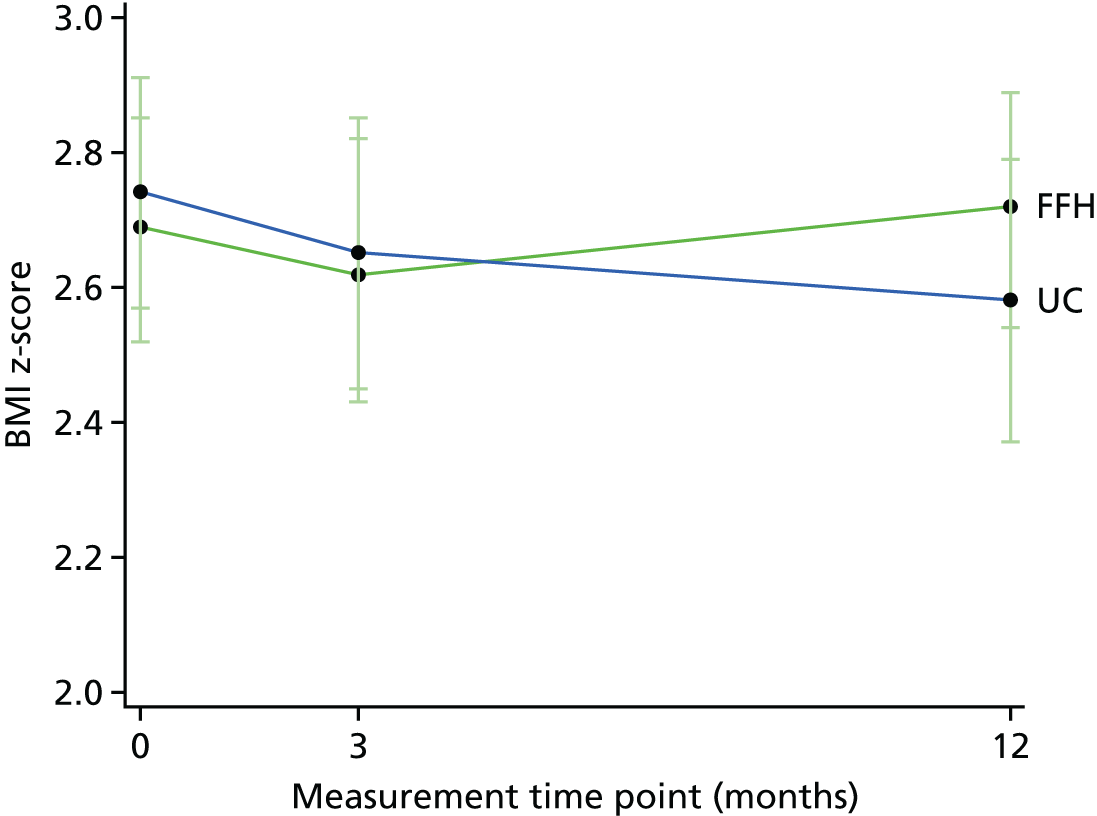

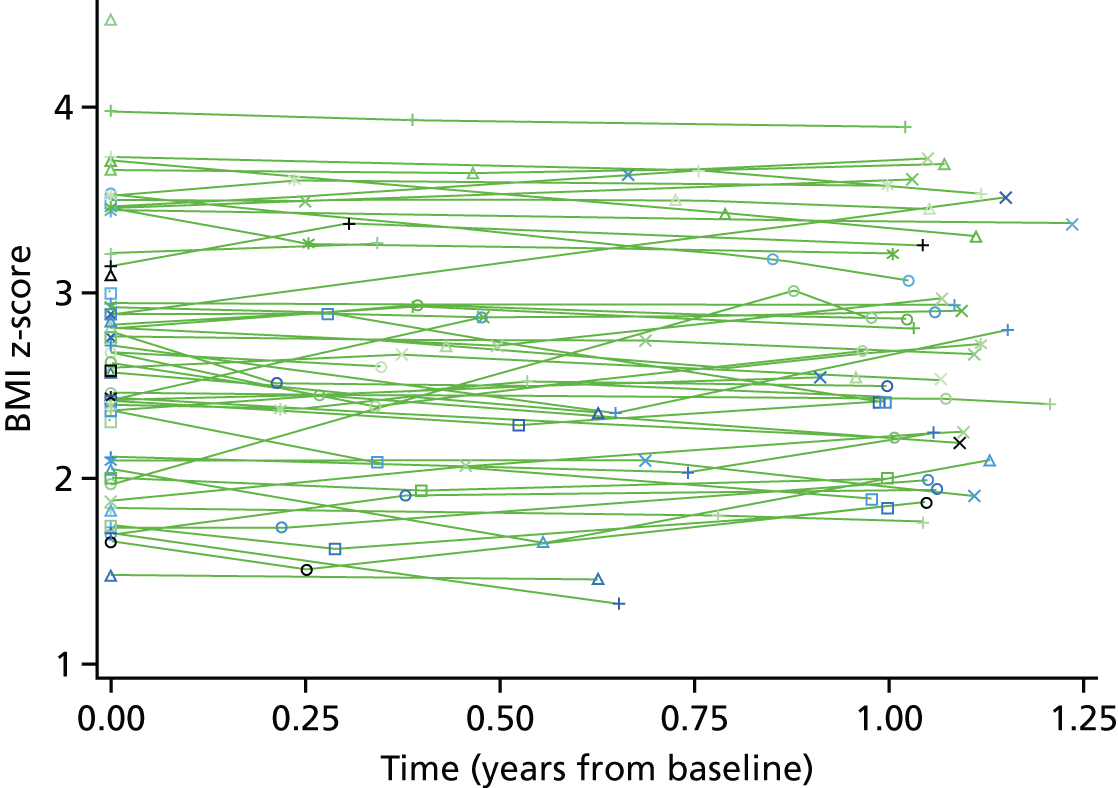

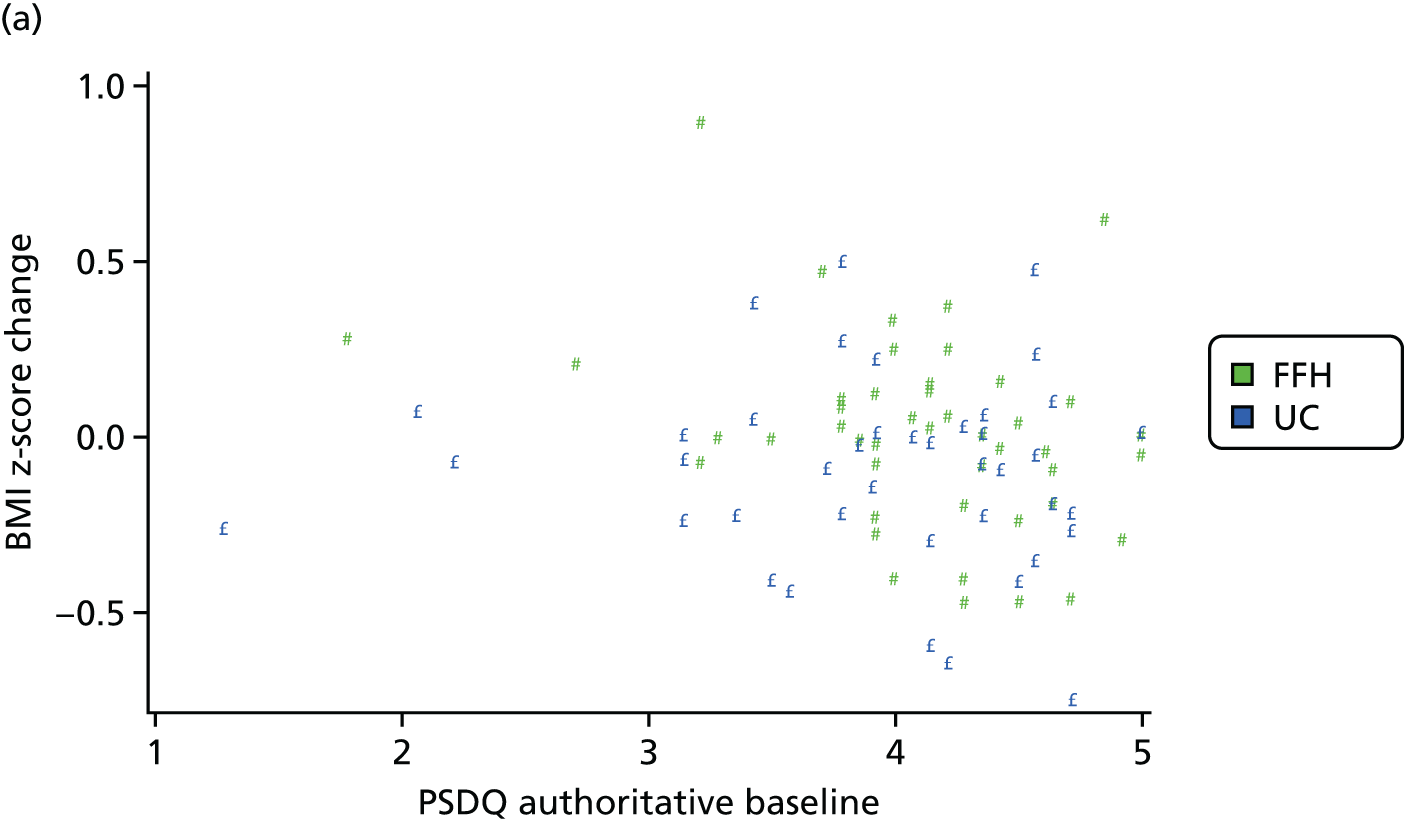

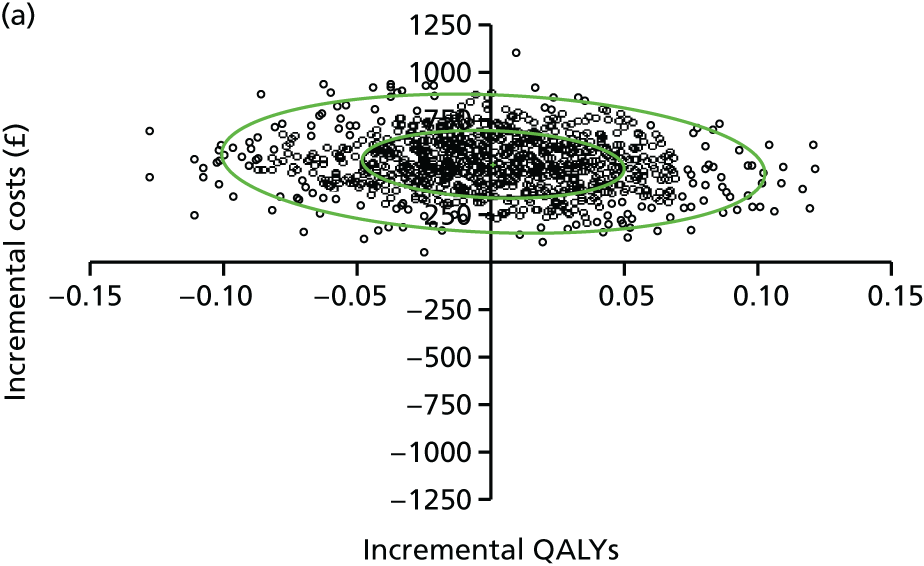

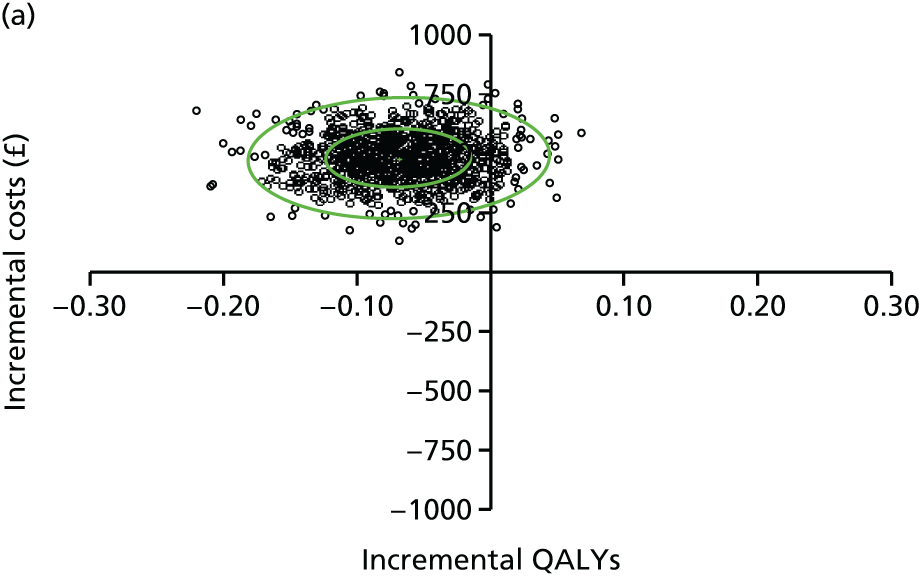

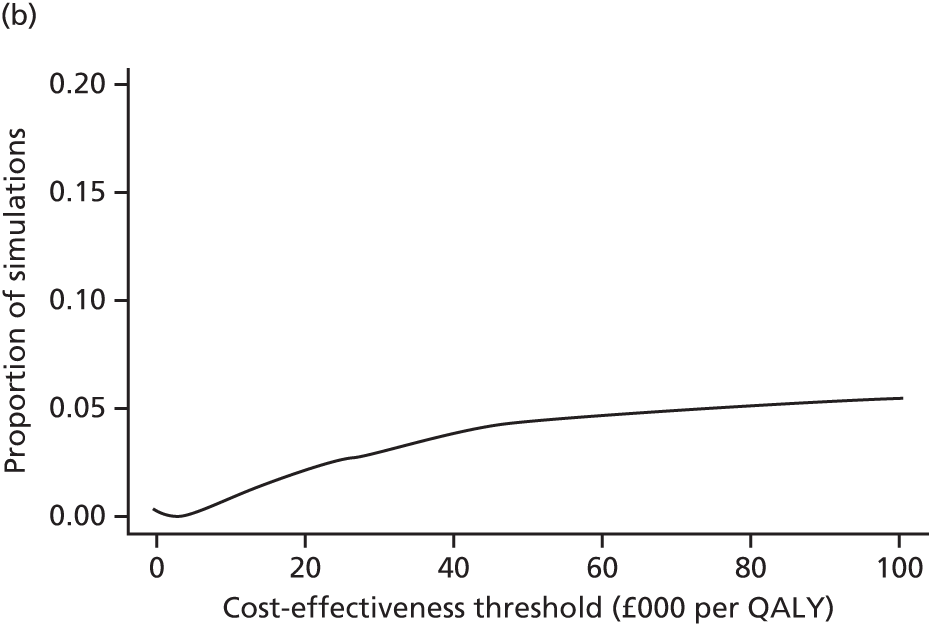

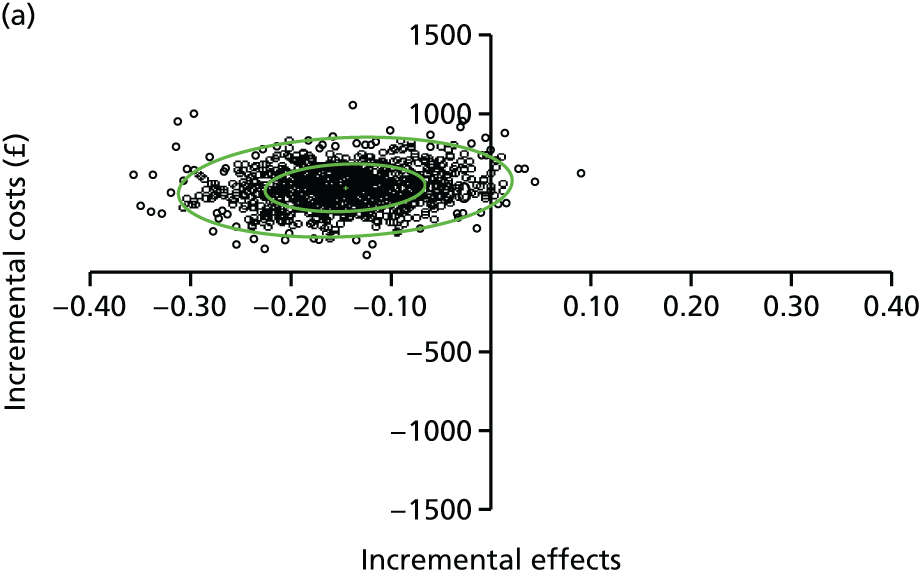

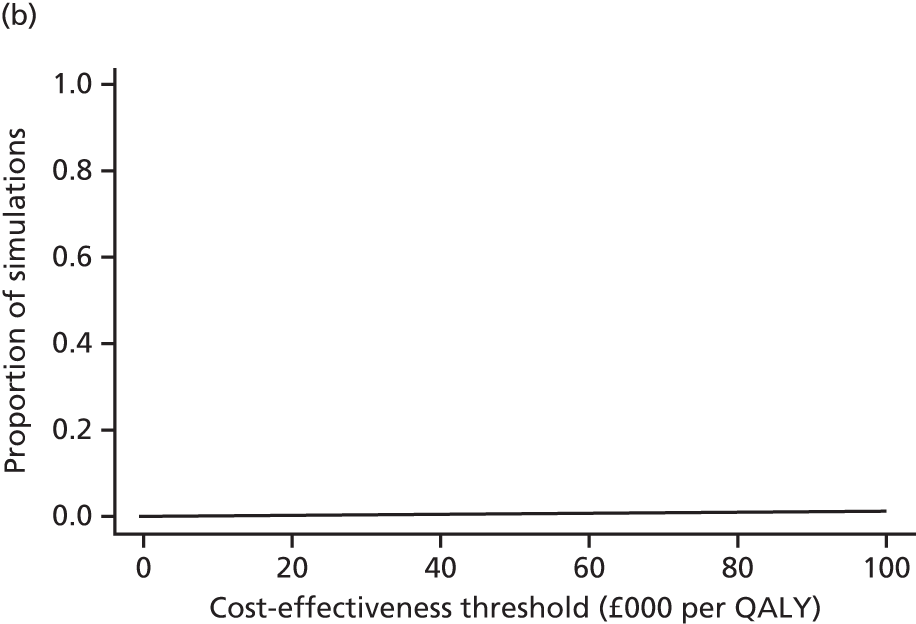

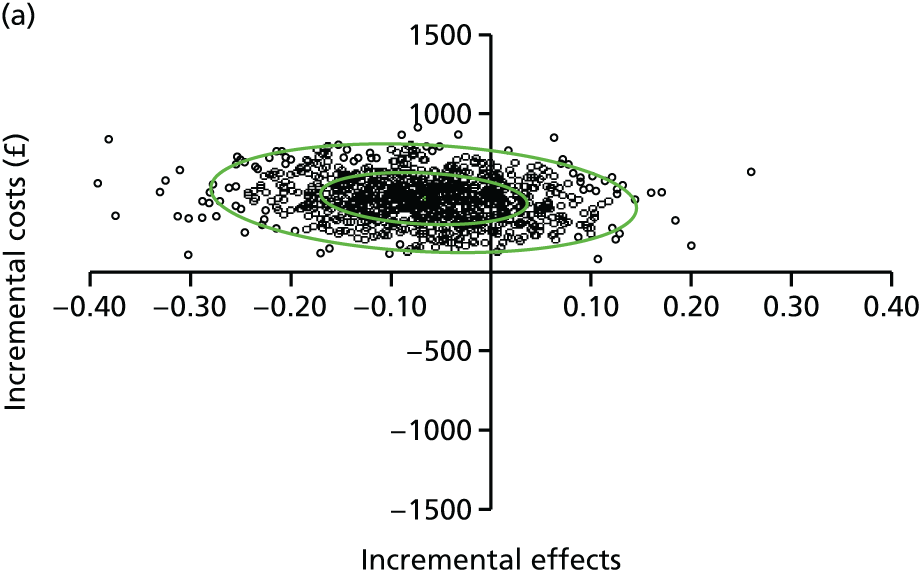

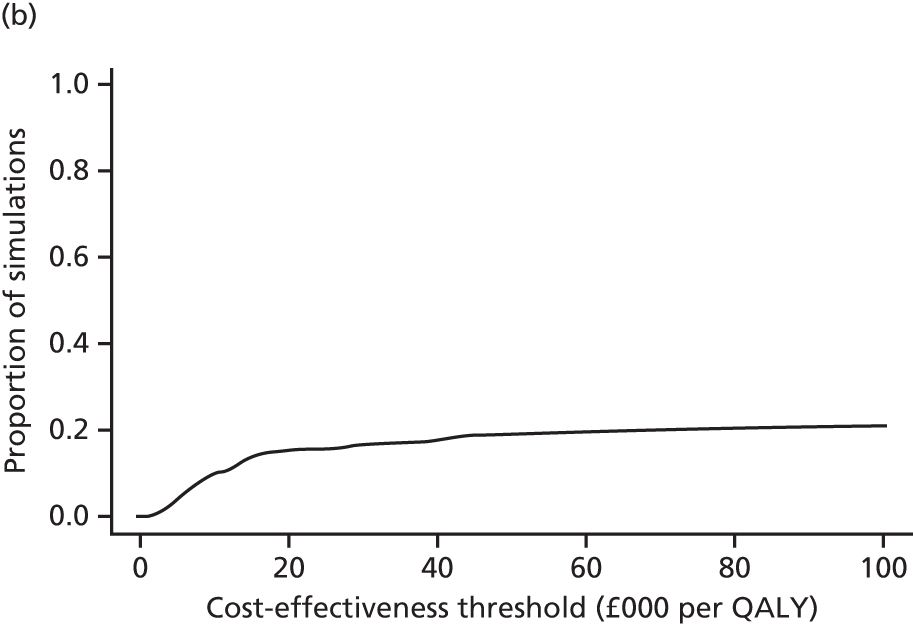

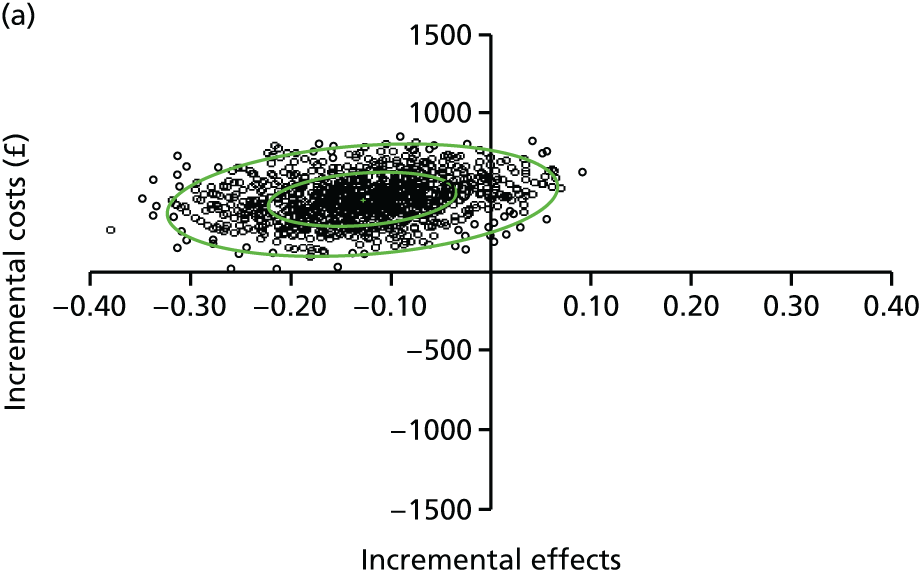

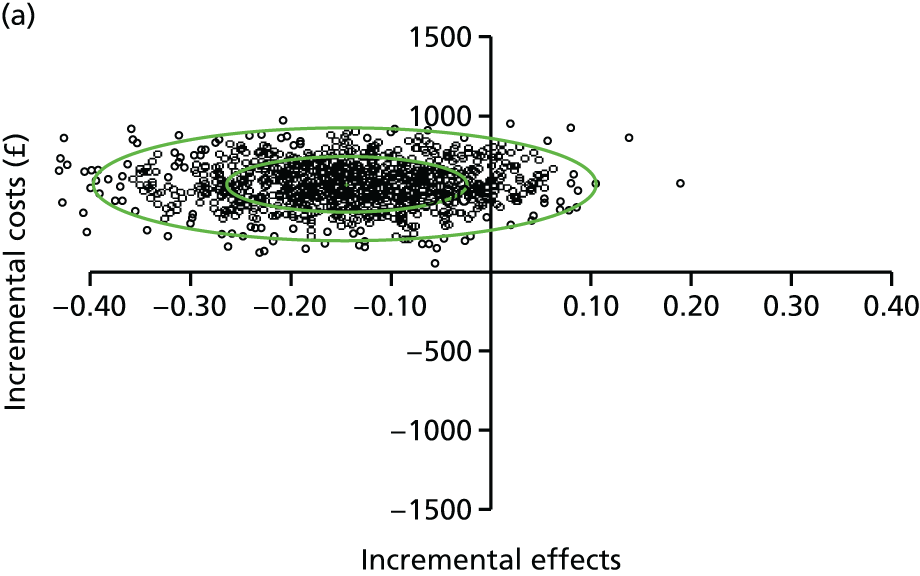

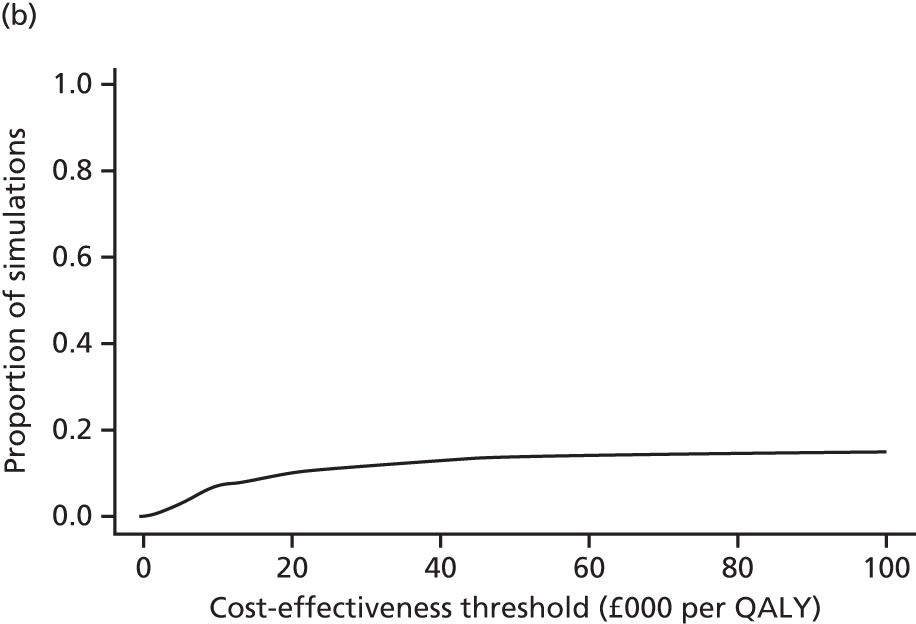

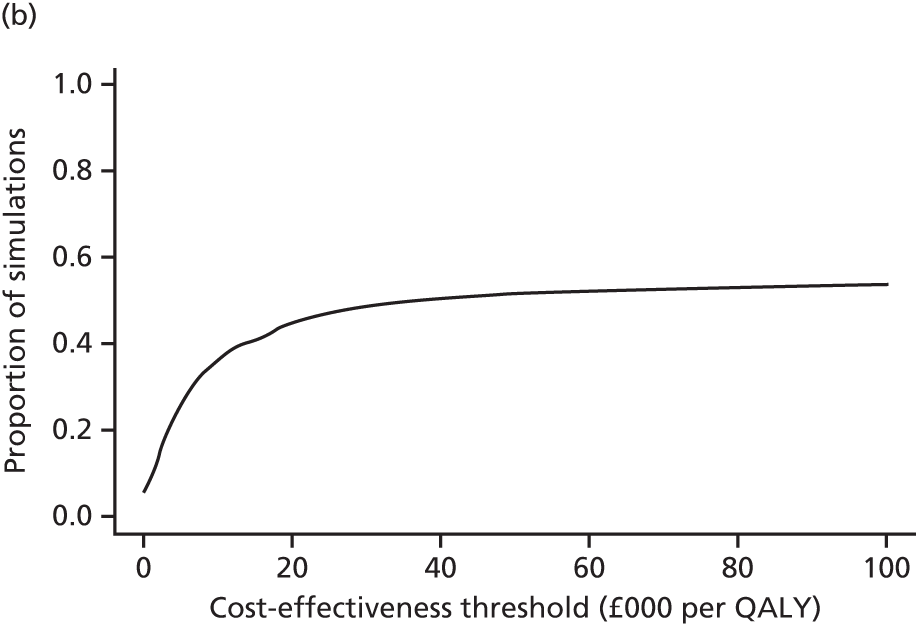

Participant flow