Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/19/04. The contractual start date was in September 2010. The draft report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Lewis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Depression in older adults

Depression accounts for the greatest burden of disease among all mental health conditions and is expected to become the second most common of all general health problems by 2020. 1 Projected demographic changes mean that population strategies to tackle depression will increasingly have to address the specific needs of older adults. 2 Depression often occurs alongside long-term physical health conditions3 and/or cognitive impairment, and it is more prevalent in people who live alone in social isolation. All these factors tend to disproportionately affect the older adult population. Among older adults, a clinical diagnosis of a major depressive disorder is the strongest predictor for impaired quality of life. 4 Indeed, beyond personal suffering and family disruption, depression worsens the outcomes of many medical disorders and promotes disability. 5 In 2009, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidelines that acknowledged the coexistence of physical health problems and depression. 6,7 Furthermore, it was recognised that the impairments in quality of life associated with depression are comparable to those associated with major physical illness. 4

In 2006, as part of the primary care framework, Quality and Outcomes Framework indicator DEP1 (Depression Indicator 1) was introduced to encourage screening for depression among individuals with a diagnosis of either coronary heart disease and/or diabetes. 8 This was achieved using two standard screening questions. 9 If depression was detected, evidence-supported guidance advocated the prescription of antidepressant drugs and appropriate provision of psychological care. 6,7,10 However, this indicator was retired in 2013 as part of the 2013/14 General Medical Services contract changes. 11 Irrespective of these recent Quality and Outcomes Framework changes, the focus to date has been on identifying and treating those with more severe depressive syndromes as set down in classificatory systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)12 (major depressive disorder) or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision13 (moderate/severe depressive disorder). 14

Subthreshold depression

Less attention has been paid to those with mild disorders/subthreshold depression or those who give positive responses to screening questions but who do not have sufficient levels of depressive symptoms to meet diagnostic criteria. 10 A large cross-sectional study conducted in 20 countries4 showed that even relatively minor levels of depression are associated with a significant decrement in all quality-of-life domains and with a pattern of negative attitudes towards ageing. Subthreshold depression is also a clear risk factor for progression and the development of more severe depressive syndromes. 15 The focus of the CollAborative care and active surveillance for Screen-Positive EldeRs with subthreshold depression (CASPER) study was on a population of screen-positive subthreshold older adults.

Rationale for the CASPER trial

Guidance issued by NICE in 20097 supported screening and case finding for depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem. The recommendation was intended to enable primary care providers to identify and treat those with severe depressive syndromes. However, the screening programme also identified those with subthreshold depression, yet there was no clear evidence-based guidance regarding treatment for this patient group. Although NICE guidelines6,7 for adults with a chronic physical health problem acknowledged that patients with subthreshold depression need to be provided for, there was no evidence of what works for this group. Yet the case for screening for depression among older adults was clear, given that a substantial proportion of that age group who have a depressive syndrome go unrecognised and untreated. 10 Indeed, the Chief Medical Officer’s 2013 annual report,16 which focused on mental health, highlighted that depression is poorly detected in primary care and that around 10–20% of people aged ≥ 65 years have depression. Given that the proportion of older people with subthreshold depression is likely to be far greater than the proportion with case-level depression, the rationale for the CASPER trial is strong.

Collaborative care: an organisational model of providing care

The vast majority of depression in older adults is managed entirely in primary care without recourse to specialist mental health services. 2,10 Although a range of individual treatments have been shown to be effective in the management of clinical depression in older adults, including antidepressants and psychosocial interventions,10 a repeated observation among those with depression has been the failure to integrate these effective elements of care into routine primary care services. 17 Additionally, the implementation of any form of care will require a strategy that both is of low intensity and can be offered within primary care. 18

In recent years an organisational model of care has been introduced called collaborative care. 19 Collaborative care borrows much from chronic disease management and ensures the delivery of effective forms of treatment (such as pharmacotherapy and/or brief psychological therapy) through augmenting the role of non-medical specialists in primary care. Collaborative care is a model whereby the non-medical specialists, or case managers in this case, form a close collaboration with the participant and others involved in his or her care. The case manager acts as a conduit for the passage of information between all individuals involved and supports the participant to enable effective discussion of important issues. Case managers provide information and help participants to access appropriate services such as social care and voluntary sector services.

The ubiquity of depression in primary care settings along with the poor integration and co-ordination of care has led to the development and increased use of this model of care. In a recent Cochrane Collaboration review20 of 79 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (24,308 participants), clear and robust evidence of the effectiveness of collaborative care was shown. It improved depression outcomes in both the short term and the medium term. Moreover, there was evidence to suggest that collaborative care can be cost-effective by reducing health-care utilisation and improving overall quality of life. 21 However, the greater proportion of studies related to working-age adults. A relative lack of any evidence for older adults was identified, which resulted in a call for further research on collaborative care among that age group. One important exception was the evidence provided by the US Improving Mood – Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment study of the effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults. 22

The IMPACT study was conducted by Unützer and colleagues22 among those aged > 60 years with case-level clinical depression. The main finding was that at 12 months almost half of the participants in the intervention group were at least 50% improved in depression severity from baseline compared with only one in five of those receiving usual care. The only UK trial of collaborative care in older adults showed some positive results but focused on more severe depression, with participants meeting a diagnostic threshold. 23 A smaller US trial has used a collaborative-care model in low-severity depression (DSM-IV minor depression and dysthymia) and has shown good clinical improvements at 12 months in the collaborative-care group compared with the usual-care group [50% reduction in depressive symptoms: odds ratio (OR) 5.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.01 to 13.49]. 24 Most recently, the CollAborative DEpression Trial (CADET) has shown that collaborative care improves depression outcomes in a UK primary care population but this is for case-level not subthreshold depression. 25

In addition to the provision of collaborative care, the studies also provide information and support to enable participants to undertake brief psychological therapies, in this case behavioural activation. Behavioural activation for this trial was adapted from the behavioural activation intervention delivered in the CADET. 25 Low-intensity psychological interventions such as behavioural activation may benefit individuals experiencing depressive symptoms. Behavioural activation focuses on addressing the behavioural deficits common among those with depression, reintroducing positive reinforcement and reducing avoidance. Such interventions aim to manipulate the behavioural consequence of a trigger (environmental or cognitive), rather than directly interpret or restructure cognitions. 26 Behavioural activation is about helping patients to ‘act their way out’ of depression rather than waiting until they are ready to ‘think their way out’. Helping people to identify and reintroduce valued activities that they have stopped doing, or ones that they would like to take up, is an important component. The effectiveness of this psychological approach is now well demonstrated. 27 Behavioural activation can be readily delivered by a trained case manager either over the telephone or face to face for those who experience difficulty using or accessing telephone-based therapy. 28

Limitations of previous trials

The major limitations of previous trials are twofold. First, preceding trials have focused on or included participants with above-threshold depression and have not looked exclusively at subthreshold depression. Second, a key component of collaborative care is ‘medication management’ – encouragement of compliance and guideline-concordant prescription of antidepressants – but antidepressants are not indicated in those with subthreshold depression. 6,7,10 It was from this context that the need to find an intervention appropriate for older adults with subthreshold depression was recognised and the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme commissioned the CASPER trial. We proposed to measure the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of using collaborative care in older adults with subthreshold depression in response to a lack of evidence on its benefit to the older population in UK primary care.

Identifying depressive symptoms and validating measures of depression

The two tools that we selected for screening and measuring depression were in regular use in primary care at the time that this study was designed. These included the Whooley questions,9 an ultra-brief two-item depression screen that asks about depressed mood and lack of interest/pleasure in activities, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9),29 used to measure depression severity once a diagnosis of depression has been made. These two tools were adopted in primary care to fulfil Quality and Outcomes Framework objectives30 in operation when the study was designed, although both have subsequently been retired (Whooley questions)/replaced (PHQ-9). 11 Before commencing the trial, we acknowledged that there was a lack of evidence for either tool in older adults or in identifying subthreshold rather than case-level depression. Indeed, the Whooley questions had been validated only against above-threshold depression in working-age adults31 and/or in non-primary care populations;9 they had not been validated in older adults in UK primary care or against subthreshold depression. Moreover, little was known about the ability of either instrument to identify and measure levels of subthreshold depression.

Further uncertainty related to what should be offered to patients who screened positive but who, following diagnostic assessment, did not meet the threshold for case-level depression. At present, no treatment is offered, yet it seems likely that individuals with subthreshold depression have substantial decrements in their quality of life4 and are at increased risk of developing more severe depressive disorders in the future. 15

In summary, it is currently estimated that in the UK around 10–20% of people aged ≥ 65 years have depression. 16 This underlines the need for the CASPER trial to provide evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of delivering collaborative care to older adults.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

Screening for depression, collaborative care and a low-intensity psychological intervention represent a complex intervention. Given that there is currently insufficient evidence and experience with regard to identifying subthreshold depression in older adults, we needed to refine the collaborative-care intervention to tailor it to this particular patient group. We chose to include only those aged ≥ 75 years for the pilot phase to ensure that the sample was representative of ‘older’ older adults. We were concerned that the relatively small pilot sample size would have been overpopulated by ‘younger’ older adults, those aged between 65 and 74 years. This group would have been less likely to inform us of the challenges associated with delivering the intervention to older people, which we sought to identify before the main trial commenced. Although there is no clear definition on the age of older adults, more developed countries use ≥ 65 years as their marker. 32 To reflect this, we changed the inclusion criterion for the main trial to include those aged ≥ 65 years (see Chapter 4), which is more in line with definitions of older adults from the developed world – an age associated with retirement and changing roles. We therefore had two sets of objectives: the first set (objectives 1–4) related to the pilot trial; the second set (objectives 5 and 6) related to the ‘definitive RCT’, which was seamlessly adopted following successful completion of the first set of objectives.

Pilot study

-

To develop a low-intensity collaborative-care intervention based on evidence-supported models of care for those aged ≥ 75 years with screen-positive subthreshold depression who represent ‘older’ older adults.

-

To establish the acceptability and uptake of this service by ‘older’ older adults with screen-positive subthreshold depression in primary care.

-

To test the feasibility of conducting a successful trial of a low-intensity intervention of collaborative care for adults aged ≥ 75 years with screen-positive subthreshold depression.

-

To validate the Whooley questions9 as a screening tool for depression in a UK ‘older’ older adult population.

Main study (the CASPER trial)

-

To establish the clinical effectiveness of a low-intensity intervention of collaborative care for older adults aged ≥ 65 years with screen-positive subthreshold depression.

-

To examine the cost-effectiveness of a low-intensity intervention of collaborative care for older adults aged ≥ 65 years with screen-positive subthreshold depression across a range of health and social care costs.

Chapter 3 Methods

Trial design

We conducted a pragmatic, multicentred, two-arm, parallel, open RCT. Participants with subthreshold depression were individually randomised (1 : 1) to receive either collaborative care or usual general practitioner (GP) care.

Approvals obtained

This study was approved by the NHS Leeds East Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 28 September 2010 (reference number 10/H1306/61). Research management and governance approval was obtained for each trial centre thereafter (see Appendix 1). This trial was assigned the number ISRCTNO2202951.

Trial centres

Four centres in the north of England were selected as trial sites: York centre (core study centre) covering the cities of York, Harrogate and Hull and the surrounding areas; Leeds centre and the surrounding area; Durham centre and the surrounding area; and Newcastle upon Tyne centre, including Northumberland and North Tyneside. Each centre was responsible for co-ordinating the recruitment of participants into the study (trial and epidemiological cohort).

Duration of follow-up

All participants were followed up at 4 and 12 months.

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

Those for whom the following criteria applied were eligible for inclusion in the trial:

-

aged ≥ 75 years during the pilot phase or ≥ 65 years during the main trial (see Chapter 4)

-

identified by a GP practice as being able to take part in collaborative care.

Exclusion criteria

Potential participants were excluded if identified by a primary care clinician as:

-

having a known alcohol dependency (as recorded on GP records)

-

experiencing psychotic symptoms (as recorded on GP records)

-

having any known comorbidity that would, in the GP’s opinion, make entry to the trial inadvisable (e.g. recent evidence of suicidal risk/self-harm, significant cognitive impairment)

-

being affected by other factors that would make an invitation to participate in the trial inappropriate (e.g. recent bereavement, terminal malignancy).

Sample size

We estimated that to detect a minimum effect size of 0.3 (with 80% power and a two-sided 5% significance level) would require 352 patients, 176 in each arm. Although this was an individually randomised trial, there may have been potential clustering at the level of each collaborative-care case manager, hence we needed to inflate the sample size to account for this. Based on an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 and a projected caseload size of 20, the design effect would be 1.38 {1 + [(20 – 1) × 0.02]}, which meant that we required 486 patients or 243 in each group. Allowing for a potential loss to follow-up of 26%, the final sample size needed to be at least 658 patients or 329 in each group.

Epidemiological cohort

The CASPER study was originally designed to assemble an epidemiological cohort of people aged ≥ 75 years; after the pilot phase the age threshold was reduced to include adults aged ≥ 65 years (see Chapter 4). Through our broad inclusion criteria we successfully recruited a total of 4668 patients aged ≥ 65 years into the CASPER cohort, from which we identified those eligible to participate in the CASPER trial, a trial of collaborative care in older adults with subthreshold depression. The reasoning behind this strategy was twofold: first, to enable us to recruit an adequate number of potential participants who would subsequently be identified as suffering from subthreshold depression, as we believed that this would not necessarily be recorded in GP records; second, to establish an epidemiological cohort of older adults who could be followed up and who would help inform the knowledge base around the health and well-being of older adults. This type of study design is termed a cohort multiple randomised controlled trial. 33

Recruitment into the trial

Recruitment of all participants into the trial took place through primary care. GP practices agreed to participate after a member of the study team had introduced the trial to them and provided the practice with written information followed by a face-to-face visit to explain the study and what participation would involve. Patients were identified by a computer search and were then invited to participate in the study by their GP practice, who posted an invitation pack to all of their eligible patients. The packs included an invitation letter (see Appendix 2.1) signed from the GP practice, a consent form (see Appendix 2.2), a decline form (see Appendix 2.3), a participant information sheet (see Appendix 2.4), a background information sheet (see Appendix 2.2) and a prepaid return envelope addressed to the core study centre. No patient-identifiable data were available to the study teams until a patient returned his or her consent form. Although it had been stated in the grant application that we would recruit participants directly from residential care as well as from primary care, this proved unnecessary; we were able to access all patients living in residential care through their GP practices. In total, 4% of the CASPER trial lived in residential care.

Consenting participants

During the consent stage potential participants were asked to complete the Whooley questions,9 a two-item depression screening/case-finding tool. These questions were asked at two different time points – on the background information sheet at invitation and in the baseline questionnaire – both times as self-reports. At the consent stage, participants were informed about the opportunity of participating in other related studies (e.g. qualitative studies); they were asked to indicate if they agreed to be approached in the future by ticking a box on the consent form (see Chapter 4). All participants who consented to take part in the CASPER study at this stage became part of the CASPER cohort. Participants did not become part of the CASPER trial until they had been subsequently assessed for suitability by completing a standardised diagnostic interview and randomised.

Baseline assessment

On receipt of written consent from participants, baseline data were collected through a self-report questionnaire. All participants who returned a completed consent form to the core study centre were sent a baseline questionnaire (see Appendix 3). Participants were asked to respond to the Whooley questions9 for a second time and to provide self-report medication data. They were also asked to complete a range of health surveys consisting of the PHQ-9,34 a measure of depression severity using a nine-item depression scale in reference to how a respondent has been feeling over the past 2 weeks; the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12),35 a measure of health-related quality of life; the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),36 a standardised measure of health state utility, designed primarily for self-completion by respondents; the Generalised Anxiety Disorder seven-item scale (GAD-7),37 a severity measure of generalised anxiety used to gauge anxiety in the past 2 weeks; the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 items (PHQ-15),38 a measure of somatic complaints using a 15-item scale in reference to the last month; and the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale two-item version (CD-RISC 2),39 used to measure an individual’s resilience and ability to bounce back.

Randomisation

Randomisation was carried out by the York Trials Unit Randomisation Service [see www.yorkrand.com/ (accessed 16 September 2015)]. Participants were automatically randomised into the trial on a 1 : 1 basis to either the intervention group or the control group following the completion of a diagnostic interview. All diagnostic interviews were conducted by a trained researcher from the study team over the telephone. The major depressive episode module of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)14 was used to ascertain the presence or absence of core depressive symptoms. This allowed potential recruits to be identified as having major depressive disorder (five or more symptoms), subthreshold depression (two to four symptoms) or no depression (one symptom) (Box 1). 14,40,41 All participants diagnosed with subthreshold depression were randomised to either the intervention arm or the control arm.

Depressed mood.

Loss of interest.

Other symptomsSubstantial changes in weight/appetite.

Change in sleep patterns.

Change in energy levels.

Movement slowing down or speeding up.

Feeling guilty or worthless.

Unable to make decisions.

Thinking about death or suicide.

Once participants had been randomised they were sent a letter informing them of the outcome of their diagnostic interview; if identified as having subthreshold depression they were informed of their group allocation, either collaborative care or usual care. Each participant’s GP was also sent a letter informing him or her that the named patient was eligible to take part in the CASPER trial because of the outcome (subthreshold depression) of the diagnostic interview (MINI) and specifying which arm of the trial he or she had been randomised to.

Ineligible participants

For all those participants whose outcome was not subthreshold depression (either non-depressed or major depressive disorder), a letter was sent informing them that they were ineligible for the CASPER trial but that they would remain in the CASPER epidemiological cohort and continue to be followed up by questionnaire. Their GPs were also informed of this.

Whooley questions validation

One of the main aims during the pilot phase of the study was to validate the two-item screening tool known as the Whooley questions,9 as this instrument had not been validated in the UK among an older adult population. The validation, published in 2015 in the Journal of Affective Disorders,42 was carried out during the pilot phase of the study in which all participants who consented and completed a baseline questionnaire were eligible for a diagnostic interview. Eligibility was not affected by how a participant scored on the Whooley questions – even those who scored negatively at both consent and/or baseline were eligible for a diagnostic interview. The validation showed that the Whooley questions performed with high sensitivity (94.3%, 95% CI 80.8% to 99.3%) and modest specificity (62.7%, 95% CI 59.0% to 66.2%). They proved effective at ruling out depression in older adults: a negative response to both questions was 99.6% likely to be a true negative. However, they were responsible for a high rate of false positives, which creates added burden for GPs, who have to conduct further investigations on patients who screen positive, many of whom turn out not to have depression.

Amendment to those eligible for randomisation

The decision to make recruitment to the fully powered trial more targeted had been taken at the design stage of the CASPER trial [see original protocol National Institute for Health Research Evaluation, Trials and Studies (NETS) website: www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hta/081904 (accessed 24 September 2015)]. This decision was supported by the validation of the Whooley questions, which provided evidence of a negative response being effective at ruling out depression. The randomisation process changed once the pilot was completed. For the main trial, only those participants who responded positively to at least one of the two Whooley questions, at either consent or baseline, were eligible for a diagnostic interview using the MINI. This amendment was necessary to increase the capacity for recruitment of subthreshold participants into the trial. All participants who responded negatively to both the Whooley questions at both time points were informed that they were not eligible for the CASPER trial but would remain in the CASPER study (epidemiological cohort) and would be followed up at 4 and 12 months using the same questionnaires as those used for the trial participants.

Trial interventions

Control group

Participants in the control group were allocated to receive usual GP care. They received no additional care to the usual primary care management of subthreshold depression offered by their GP, in line with NICE depression guidance as implemented by their GP and local service provision. 6,7

Intervention group

Participants in the intervention group were allocated to receive a low-intensity programme of collaborative care using behavioural activation, designed specifically for those aged ≥ 65 years with subthreshold depression. Collaborative care was delivered by a case manager [a primary care mental health worker/Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) worker] for an intended 8–10 weeks. This took place alongside participants’ usual GP care. The defining feature of collaborative care is a collaboration of expertise to help support the participant: the case manager works alongside the participant, sharing any relevant information with the GP and a mental health specialist (psychiatrist or psychologist). The case manager is a cohesive link between the participant and other professionals involved in his or her care. For example, if a case manager deemed a participant’s depressive symptoms to have deteriorated (moving from subthreshold to above-threshold depression), he or she informed the GP to optimise the management of the patient’s condition.

Collaborative care in the CASPER trial included telephone support, symptom monitoring and active surveillance, facilitated by a computerised case management system [Patient Case Management Information System (PC-MIS); see www.york.ac.uk/healthsciences/pc-mis (accessed 16 September 2015)], and low-intensity psychosocial management (behavioural activation). Participants randomised to the collaborative-care intervention group were contacted by a case manager within a week of their randomisation to arrange their first session of collaborative care. This was carried out face to face, usually at their home unless they preferred an alternative venue. After this initial meeting subsequent sessions were carried out on a weekly basis by telephone unless the participant had sensory impairments or preferred to have face-to-face visits. Case managers worked collaboratively with participants, liaising with GPs and other health professionals involved in their care. They contacted them to discuss issues relating to participants’ mental and physical health, both in routine updates and when any concerns were identified. Case managers worked with participants to identify problems and agree goals for the intervention. They also worked with participants to identify and subsequently provide information about other services that may be helpful, such as voluntary and statutory sector organisations and services.

Refinement of collaborative care/behavioural activation

The delivery of collaborative care and behavioural activation had been established in working-age adults and an appropriate training package and manual already existed. 28 However, these had not been tailored for use with older adults diagnosed with subthreshold depression. Before the study began, necessary changes were made to both the training package and the manual (see following sections) to account for differences that may exist in the older adult population. Further refinement was made following the pilot phase, based on feedback from participants to case managers.

Adaptations to language and content

Adaptations were made to the information gathered at the initial assessment. Older adults are more likely to experience long-term health problems and a reduced level of functioning, with their psychological status often closely linked to their physical functioning. 43 Additional questions regarding health conditions and their impact were added to the standard assessment format. However, case managers were reminded to use a person-centred approach and not let preconceptions about the level of functioning of older adults influence their information gathering. Liaison with health professionals involved in treating participants’ long-term health conditions was encouraged to promote a depth of understanding of these issues. Depression in older adults is associated with impaired social support44 and therefore additional questions regarding social contacts and family were added. The risk assessment (see Appendix 4) was also adapted to enquire about past passive and past active suicide ideation as well as current plans and preparations, as past suicidality is a risk factor for current suicidal behaviour. 45

Information in the manual was tailored to meet the needs of older adults. Age-appropriate examples were used, such as bereavement and loss of role, to facilitate engagement and make it easier to relate to. The psychoeducation material given to participants was also modified to include information about depressive symptoms specifically in older adulthood. As depression is associated with cognitive impairment in older people,46 a larger font and increased space for writing was introduced. In addition, when individuals displayed mild cognitive impairment, simpler language was used and the steps in each session were reduced along with homework. Questions were also added to help case managers assess participants’ understanding of the treatment principles.

Functional equivalence and the Keeping Well Plan

Further adaptations were made in response to participant feedback during the pilot phase. Case managers were made aware of the importance of helping patients to identify functionally equivalent activities. Case managers then suggested that adding a section in the participant pack on functional equivalence would help them to engage participants with this subject more effectively. Consequently, a section was added to the Keeping Well Plan, prompting participants to identify functionally equivalent activities that might replace enjoyable or rewarding activities that they were no longer undertaking. It became apparent during the pilot phase that a significant number of participants with subthreshold depression were active and able to carry out the activities that they wished to undertake; they did not wish to add anything else to their usual activities. Behavioural activation is a behavioural treatment which involves the monitoring and scheduling of activities that are being avoided. Therefore, working through behavioural activation was not something that these active participants wanted to do. A step-down option was added to the case managers’ manual that bypassed activity scheduling and allowed more time to focus on the Keeping Well Plan. Further details of the adaptations made can be found in Pasterfield et al. 47

Participant follow-up

All participants in the CASPER trial were followed up with questionnaires at 4 months (see Appendix 5) and 12 months (see Appendix 6). Post-randomisation questionnaires were posted to participants from the York Trials Unit, along with a pre-addressed prepaid envelope. Participants could complete the questionnaires manually and return them by post to the York Trials Unit, or they could complete the questionnaire online; an instruction sheet explaining how to log onto the CASPER website and complete the process was included with each questionnaire. Reminder letters were sent by post to any participants who at 2 weeks had not returned their questionnaire. Telephone follow-up by one of the study team’s researchers was conducted for any participants who had not returned a questionnaire, to enable the primary outcome measure (PHQ-9) to be completed at the very least.

Trial completion and exit

Participants were deemed to have exited the trial when they:

-

withdrew consent (wished to exit the trial with no further contact for follow-up or objective data)

-

had been in the trial for 12 months post randomisation

-

had reached the end of the trial

-

died

-

moved GP practice to one not participating in the CASPER study

-

had another reason to exit according to clinical judgement from a health professional.

Withdrawals

Withdrawal could occur at any point during the study at the request of the participant. If a participant indicated that he or she wished to withdraw from the study, a researcher would speak to the participant to clarify to what extent he or she wished to withdraw (withdrawal from the intervention, from follow-up or from all aspects of the study). When withdrawal was only from the intervention, follow-up data continued to be collected. Data were retained for all participants up to the date of withdrawal, unless they specifically requested that their details be removed.

Objective data

Once all of a GP practice’s participants had completed their follow-up, objective data were collected for each trial participant. Objective data consisted of details on participants’ prescribed medication and the number of contacts that they had with their GP practice during their time in the trial. The only exception was for those participants who had withdrawn in full, thereby withdrawing consent to access their medical records. Objective data were collected from GP practices by request from the core study centre. A spreadsheet template was emailed to the key contact of each GP practice, which included each of the practice’s trial participants’ identification codes along with pre-written frozen headings; no identifiable data were included. Also listed were the search dates for each participant, from the date that they were randomised until either the date that they completed the study 12 months later or the date that they had died if that was the case. Data were still collected on participants who had withdrawn from treatment or follow-up as they had provided us with consent to access their health records for the 12 months that they would have been in the study. All objective data were collected by e-mail and this method was approved by the University of York’s data protection team on the basis that no identifiable data were transferred; patients were identified by GP practices using the administration code assigned to them at the recruitment stage.

Suicide protocol

A small but elevated risk of suicide and self-harm was inherent in the population studied, who had all been identified as having subthreshold depression. All participants (both usual care and collaborative care) were subject to usual GP care. GPs were responsible for the day-to-day management of subthreshold depression. GPs were accountable for all treatment and management decisions, including prescribing, referral and assessment of risk. This arrangement was made clear to all clinicians and GP practices who agreed to participate in the study. The pragmatic nature of the CASPER trial meant that we did not seek to influence this arrangement. However, we did follow good clinical practice by monitoring for suicide risk during all of our encounters with participants. When a patient expressed a risk through thoughts of suicide or self-harm, we followed the study-specific procedure for suicide risk (see Appendices 7.1 and 7.2).

Patient and public involvement in research

The CASPER trial was informed by the involvement of users of mental health services and carers throughout the research period. An advisory group was established at the end of the pilot phase to review the materials used in the study. This consisted of a number of older adults, some of whom had mental health conditions, along with a carer representative. This group provided valuable insights into the relevance and readability of the study documentation. In the future we plan to engage with patient and public involvement in our dissemination strategies to guide on how best to share the findings.

Further studies

Following validation of the Whooley questions during the CASPER pilot phase42 it was acknowledged that a sizeable number of participants (approximately 5%) were identified with case-level depression after completing the diagnostic interview. The CASPER Plus trial was born out of an aspiration to be able to offer collaborative care and behavioural activation to older adults with more severe depression [see www.trialsjournal.com/content/15/1/451 (accessed 16 September 2015)].

Clinical effectiveness

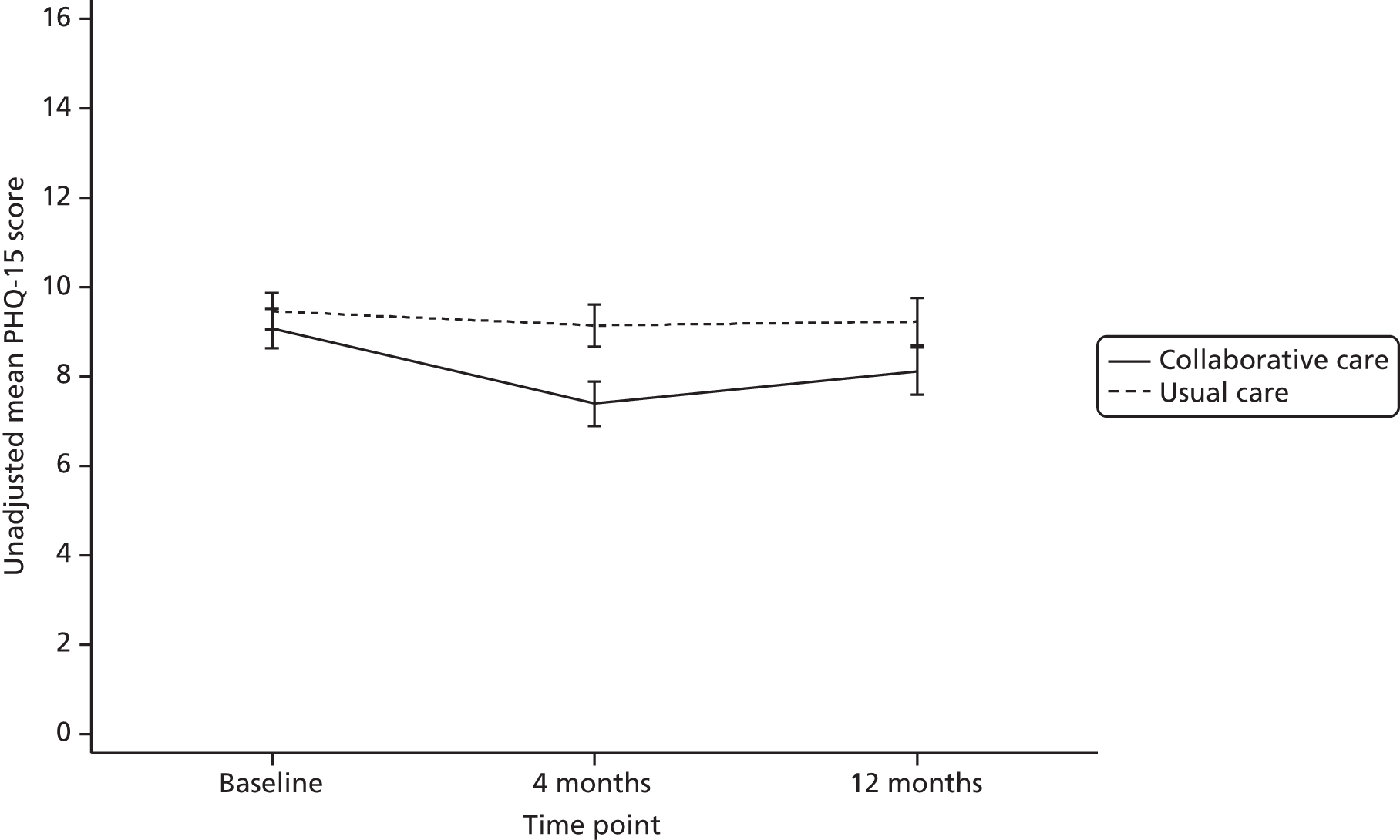

Primary outcome

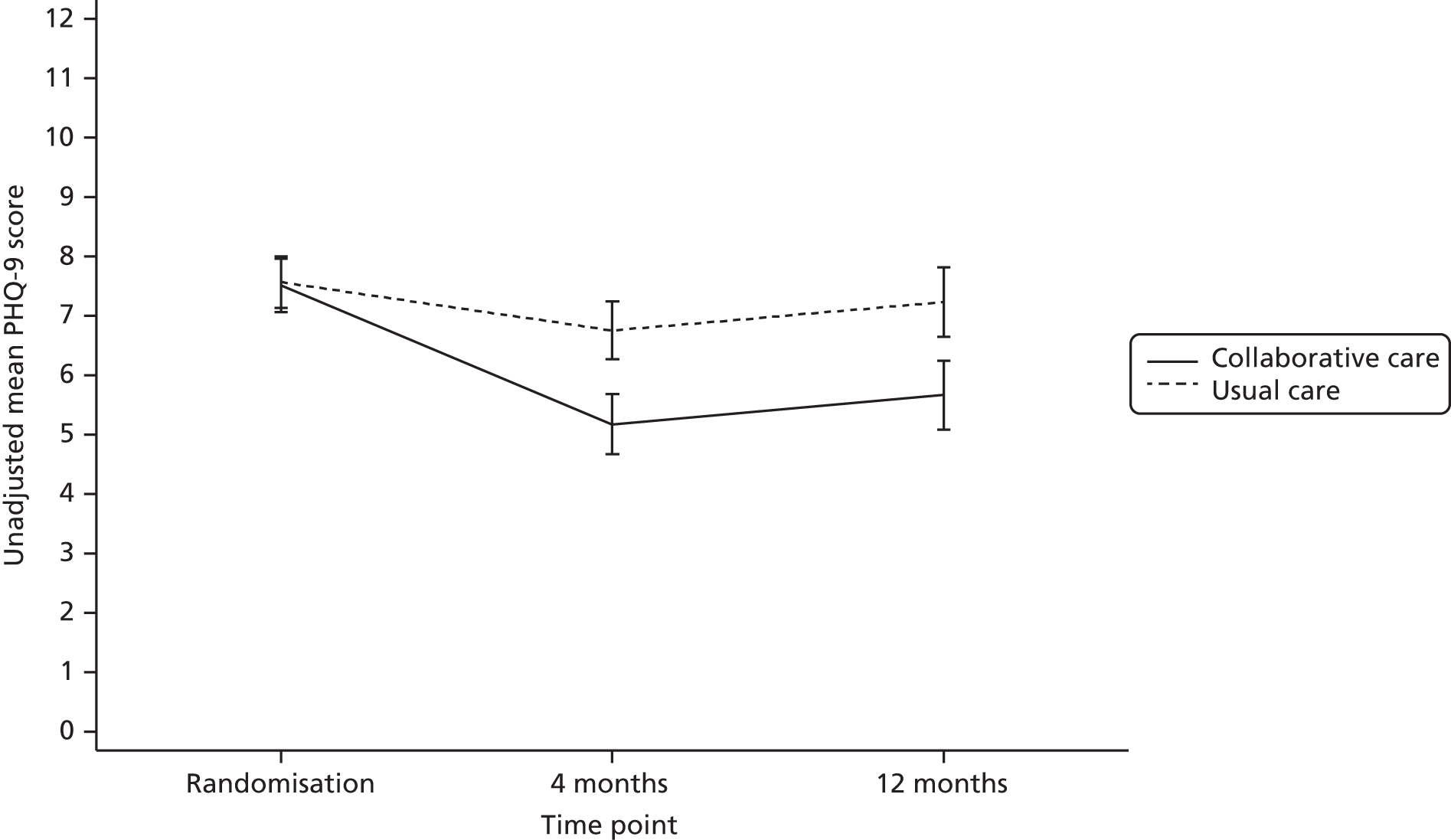

The primary end point for the trial was patient-reported depression severity as measured by the PHQ-9 at 4 months’ follow-up. Each item is scored between 0 and 3 and thus PHQ-9 scores can range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater depression. Total scores from 0 (not depressed) to 27 (severely depressed) were calculated based on the nine PHQ-9 items. These data were collected via self-report on the follow-up questionnaire. Any participants who did not return a completed questionnaire were sent a reminder; those participants who did not respond were telephoned by one of the study team’s researchers to ask them to complete the PHQ-9 over the telephone. If one or two items were missing, missing items were replaced with the mean of the remaining items.

The PHQ-9 data were collected at baseline and randomisation as well as at 4 and 12 months’ follow-up. Scores at baseline and randomisation are reported in Baseline characteristics. When analyses were adjusted for initial PHQ-9 score, the score at randomisation was used. The primary end point for the CASPER trial was at 4 months’ follow-up. A standard effect size of 0.3 for mean PHQ-9 difference was sought between treatment arms, equivalent to a PHQ-9 score difference of approximately 1.35 points, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 4.5. The standard effect size of 0.3 is of moderate size for psychological interventions and in line with collaborative care effects observed in other studies. Cohen48 classifies a standard effect size of 0.3 as a small to medium effect size and this is in line with NICE guidelines for depression,6 in which a similar grading of clinical significance is adopted.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures used were:

-

depression severity and symptomatology at 12 months (PHQ-9)

-

binary depression severity at 4 and 12 months (PHQ-9) using scores of ≥ 10 to designate moderate depression caseness

-

quality of life at 4 and 12 months (SF-12 and EQ-5D)

-

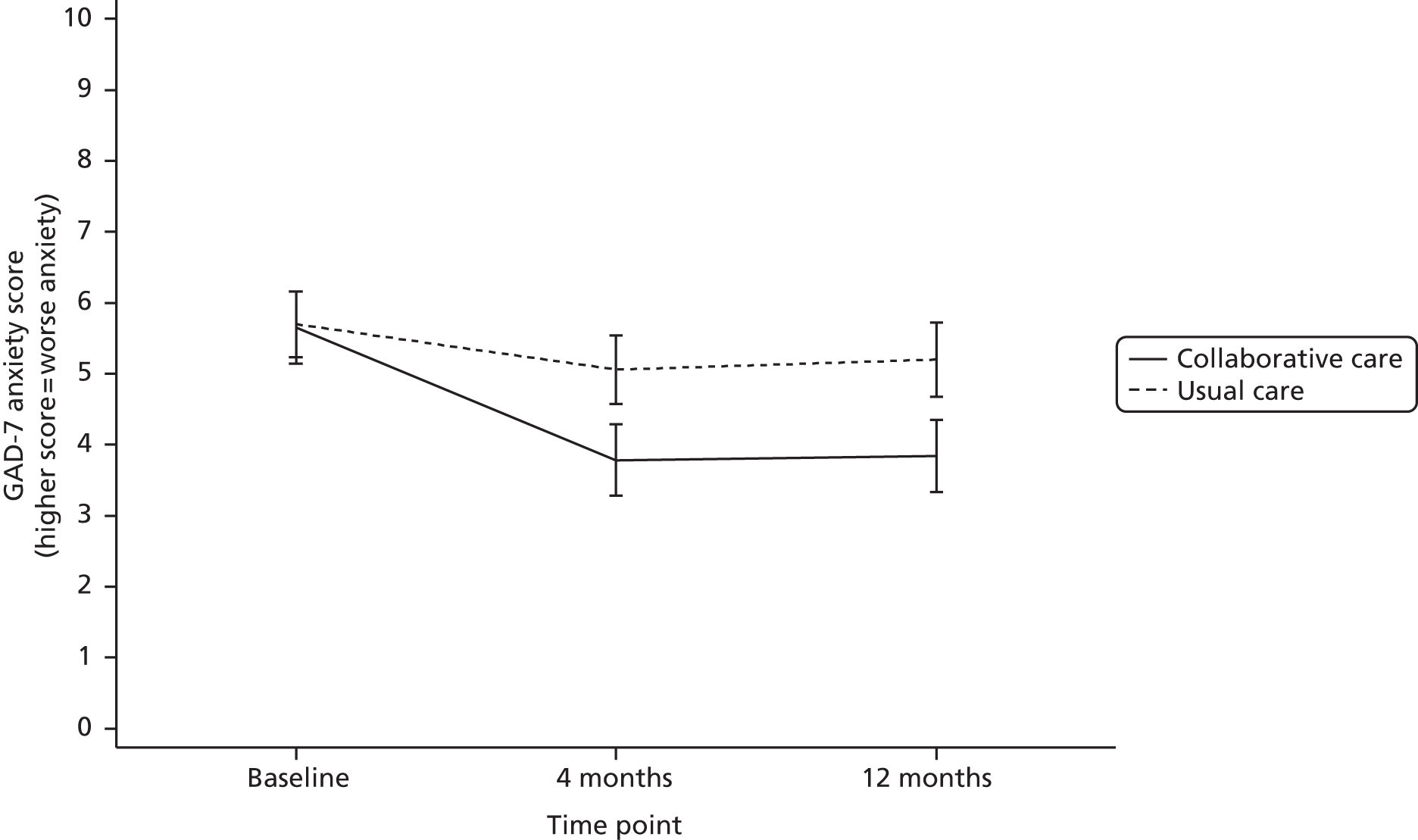

psychological anxiety at 4 and 12 months (GAD-7)

-

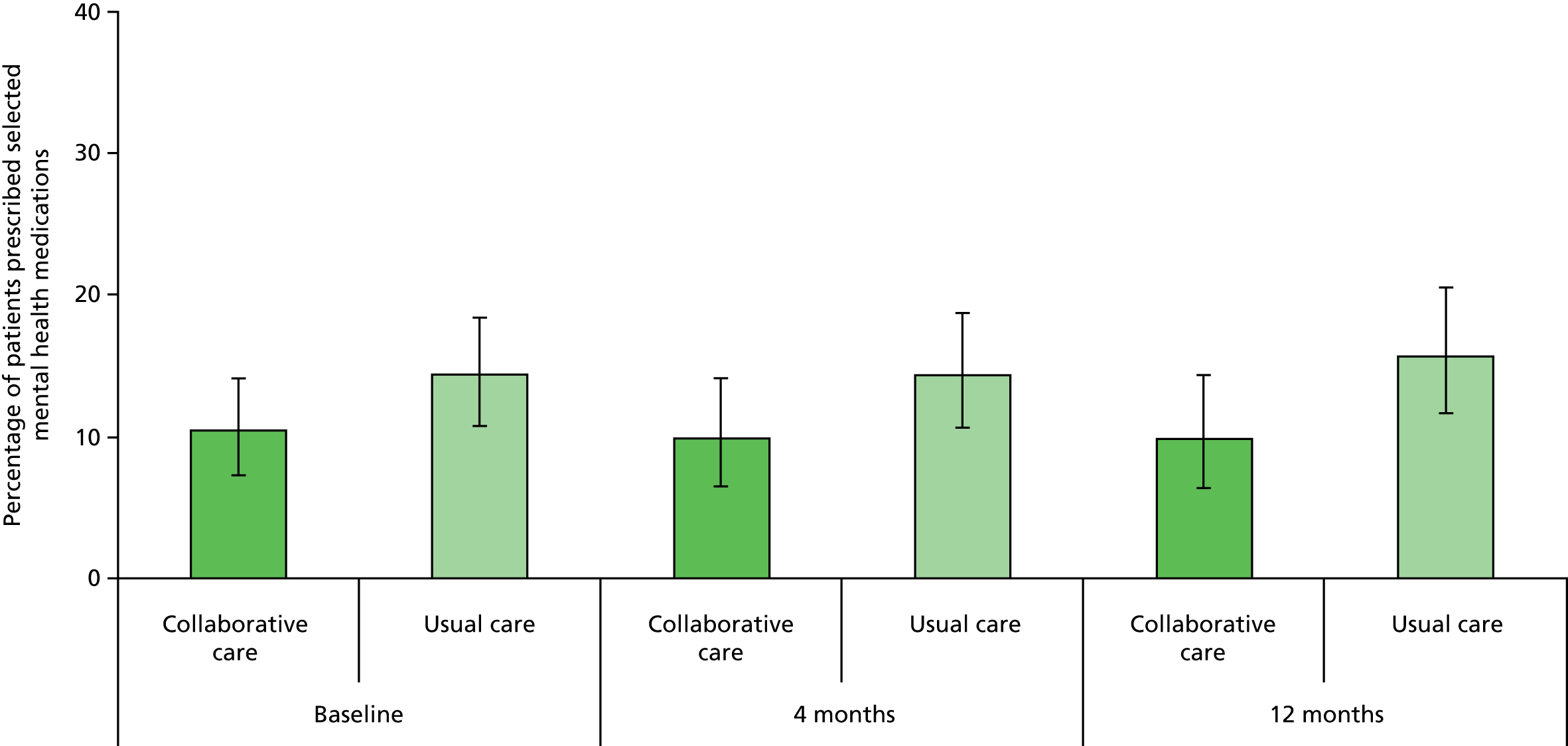

mental health medication at 4 and 12 months

-

mortality at 4 and 12 months.

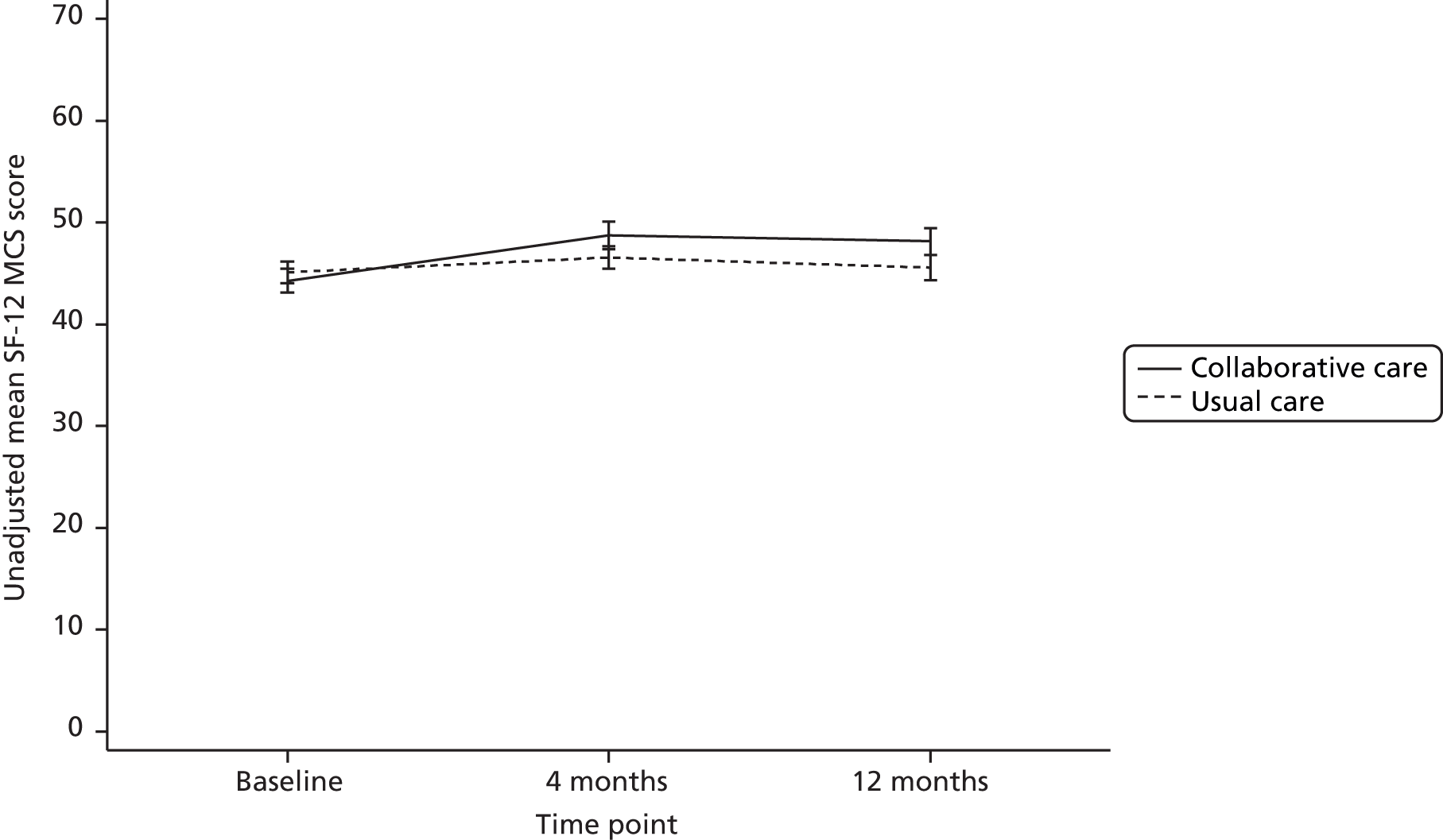

Short Form questionnaire-12 items

The SF-12 is a generic health status measure and a short form of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items health survey. It consists of 12 questions measuring eight domains (physical, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health) rated over the past month. Questions have three or five response categories and responses are summarised into physical and mental component summary (PCS and MCS) scores. The PCS and MCS scores range from 0 (lowest level of health) to 100 (highest level of health) and were designed to have a mean score of 50 in a representative sample of the US population. Thus, scores > 50 represent above average health status and vice versa.

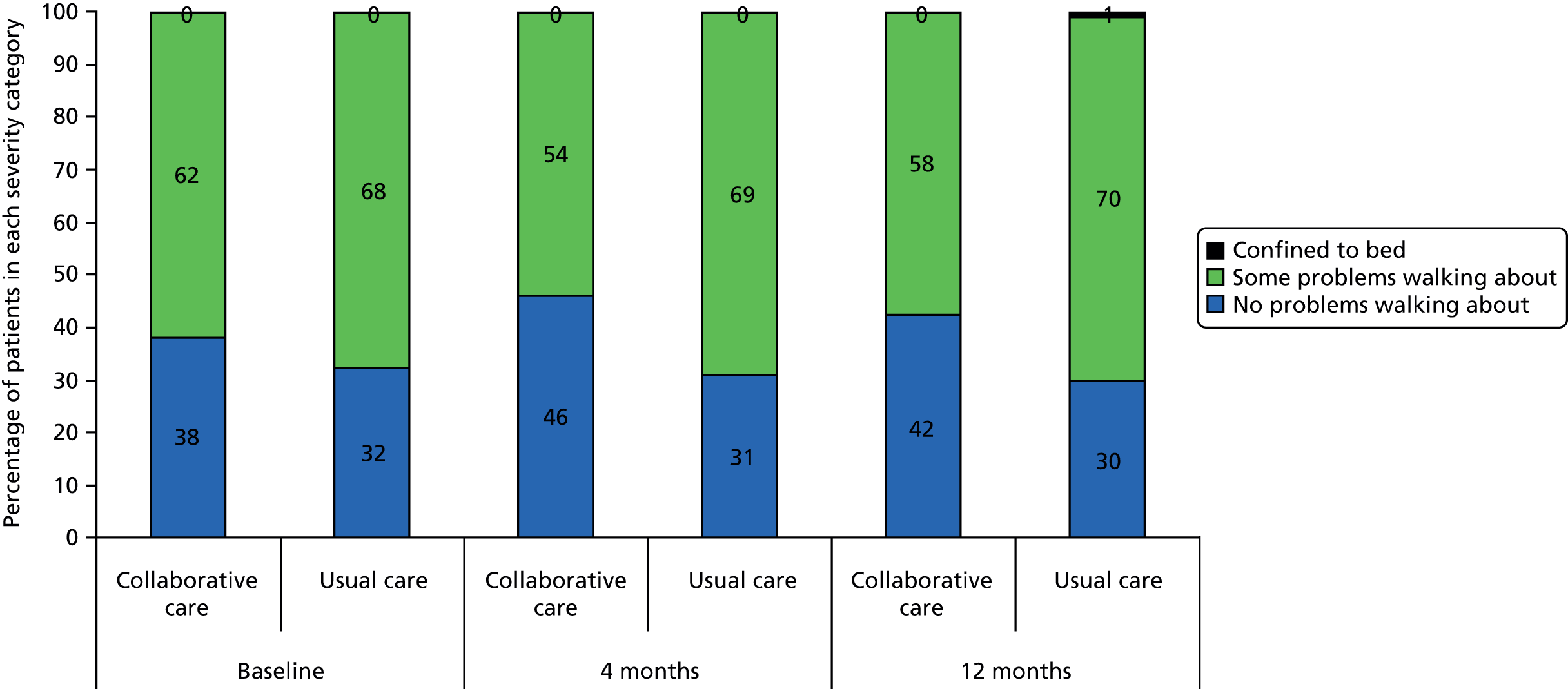

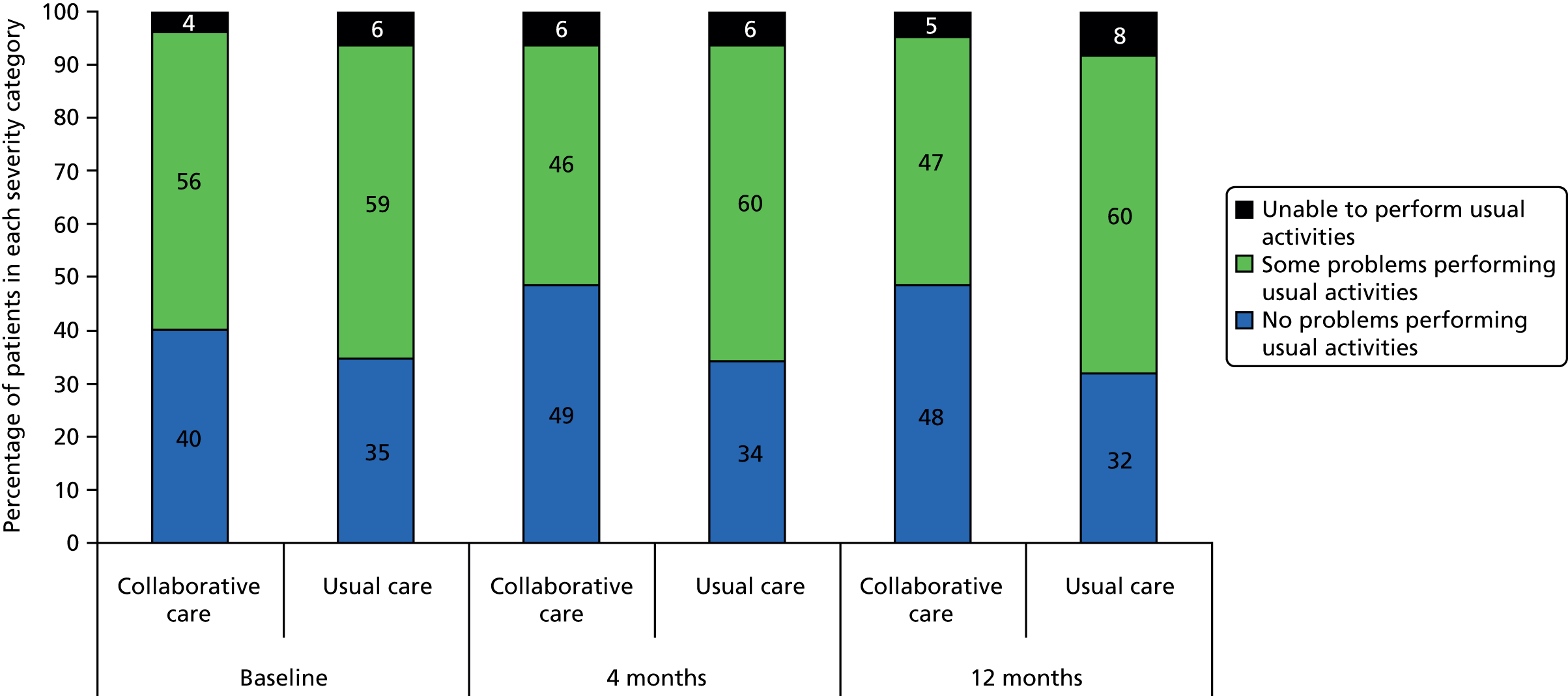

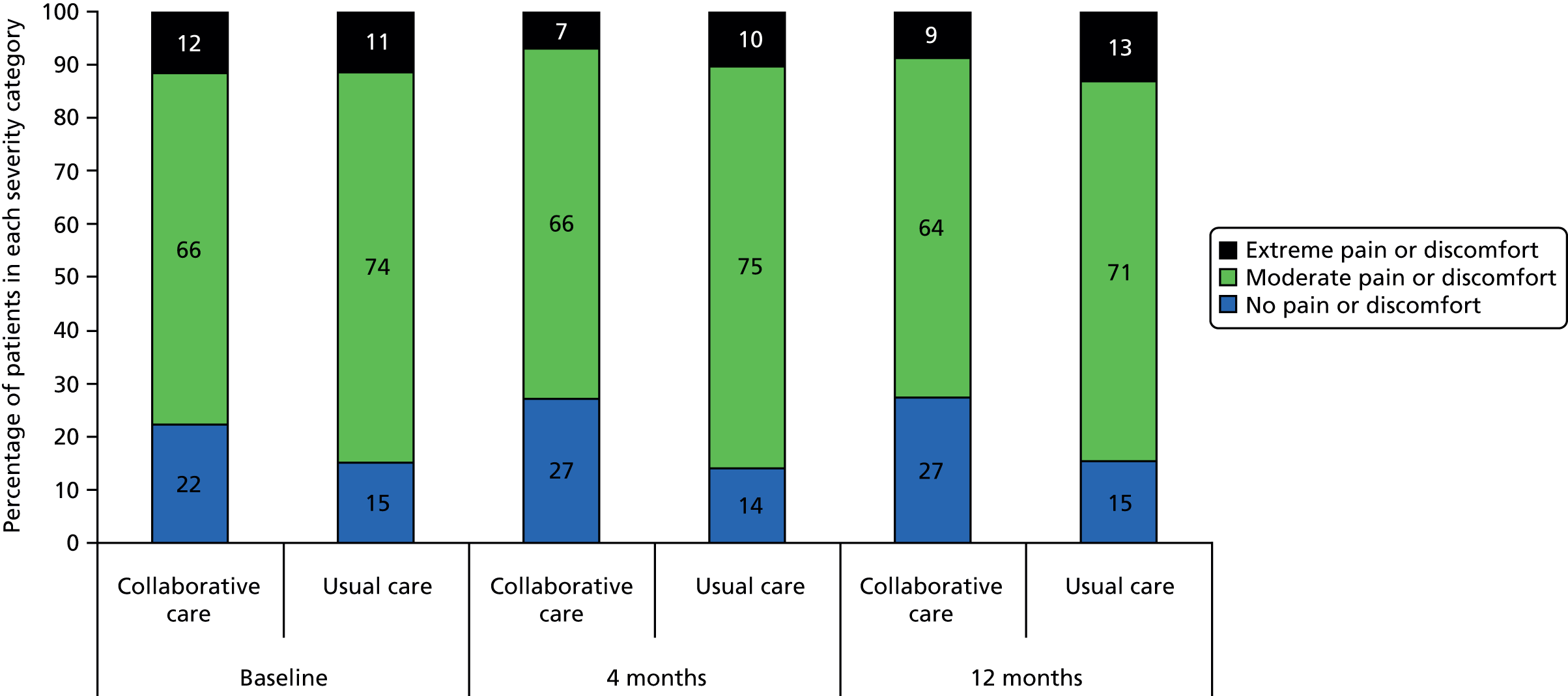

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions

The EQ-5D is a standardised measure of current health status developed by the EuroQol Group for clinical and economic appraisal. The EQ-5D consists of five questions, each assessing a different quality-of-life dimension (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each dimension is rated on three levels: ‘no problems’ (score = 1), ‘some problems’ (score = 2) and ‘extreme problems’ (score = 3). A weighted summary index can be derived to give a score between 1 (perfect health) and 0 (death). For the purpose of the clinical effectiveness analysis, only scores for the individual dimensions were utilised. The summary index was analysed as part of the cost–utility analysis.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder seven-item scale

The GAD-7 is a brief measure of symptoms of anxiety based on diagnostic criteria described in the DSM-IV. It consists of seven questions and is calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2 and 3 to the response categories of ‘not at all’, ‘several days’, ‘more than half the days’ and ‘nearly every day’ respectively. The GAD-7 total score for the seven items ranges from 0 to 21. Scores of 5, 10 and 15 represent cut-off points for mild, moderate and severe anxiety respectively.

Mental health medication

Medication data were captured by self-report on the follow-up questionnaires. Participants indicated prescribed medication by selecting from a list of 10 antidepressants as well as listing any other medications that they had been prescribed. Independent objectively collected medication data from GP records were incorporated in the economic analysis.

Mortality data

A data linkage service was established with the Health and Social Care Information Centre to provide regular updates from the Office for National Statistics mortality data on any trial participants who had died while in the study.

Members of the research team recorded any identified deaths on the study management database.

Other patient questionnaire data collected

Patient Health Questionnaire-15 items

The PHQ-15 is a 15-item physical health problems questionnaire. Each health issue is rated as 0 (‘not bothered’), 1 (‘bothered a little’) or 2 (‘bothered a lot’). The total score ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating worse symptom severity. Scores of 5, 10 and 15 have been used as cut-offs for low, medium and high symptom severity. Item 4 of the PHQ-15 (menstrual problems) was not deemed relevant for the elderly patient population in the CASPER trial and was omitted from all questionnaires. Therefore, the total possible PHQ-15 score was 28.

Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale two-item version

The CD-RISC 2 is a two-item short form of the full Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 25). It is a psychological resilience measure with specific items for bounce back from adversity and adaptability to change. The two items are scored from 0–4, resulting in a total score of 0–8, with a higher score indicating greater resilience.

Adverse events

The CASPER study was a non-clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product and was therefore not subject to any additional restrictions. Decisions regarding prescription of medications were made by the participants in conjunction with their GP; participation in the study had no bearing on this process. If participants asked a member of the CASPER study team for an opinion on medication issues, they were strongly encouraged to seek advice from their GP.

The study recorded details of all serious adverse events (SAEs); any judged to have been related to the study were required to be reported to the main REC under the terms of the Standard Operating Procedures for RECs. 49 In the context of the CASPER study’s older adult population the occurrence of many of the SAEs was expected; unscheduled hospitalisations, life-threatening conditions, incapacitating illnesses and deaths were not perceived as unexpected events and therefore they would be reported as SAEs only if they appeared to be related to an aspect of taking part in the study (e.g. participation in treatment, completion of follow-up questionnaires, participation in qualitative substudies or participation in telephone contact).

When a SAE was identified, the Trial Manager was informed by e-mail using a participant’s trial identification number, not any identifiable data. The Trial Manager then informed the Chief Investigator and two members of the Trial Management Group (TMG), who jointly decided if the event should be reported to the REC as a SAE. A SAE form was completed and a copy filed securely at the core study centre. Any unexpected SAEs that were also judged to have been related were to be reported to the REC within 15 days of the Chief Investigator becoming aware of them. In the CASPER study none of the SAEs appeared to have been related to the trial.

The occurrence of adverse events during the trial was monitored by an independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The DMEC/TSC would have seen immediately all SAEs thought to be treatment related.

Data collection schedule

An overview of the time points at which trial data were collected is presented in Table 1.

| Data collection | Invitation | Baseline | Diagnostic interview/randomisation | 4-month follow-up | 12-month follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent/decline | • | ||||

| Demographic questionnaire | • | ||||

| Whooley questionnaire | • | • | |||

| Physical health problems | • | ||||

| Falls questions | • | ||||

| PHQ-9 | •a | •b | • | • | |

| SF-12 | • | • | • | ||

| EQ-5D | • | • | • | ||

| GAD-7 | • | • | • | ||

| PHQ-15 | • | • | • | ||

| CD-RISC 2 | • | • | • | ||

| Medication questionnaire | • | • | • | ||

| MINI | • | ||||

| Economic evaluation | • | • | • | ||

| Objective medication data | • | • | • |

Statistical assumptions

The CASPER trial was powered to detect a standard effect size of 0.3 for PHQ-9 depression severity between treatment arms, assuming 80% power, 5% two-sided significance, an ICC of 0.02 (based on a caseload of 20 patients) and 26% loss to follow-up (a revised figure following interim data review). The total sample size required based on these criteria was 658 patients (329 in each arm). Participants were randomised 1 : 1 using simple randomisation to either collaborative care or usual care.

Participants, care deliverers and the study team were not blinded to treatment allocation. However, allocations were concealed (group A and group B) for interim study reports, for example for the purpose of independent data monitoring reporting. The trial statistician responsible for the final statistical analysis was kept blind to group allocation until the primary analysis had been completed.

All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, using a two-sided statistical significance level of 0.05 unless otherwise stated. All statistical analyses followed a prespecified statistical analysis plan.

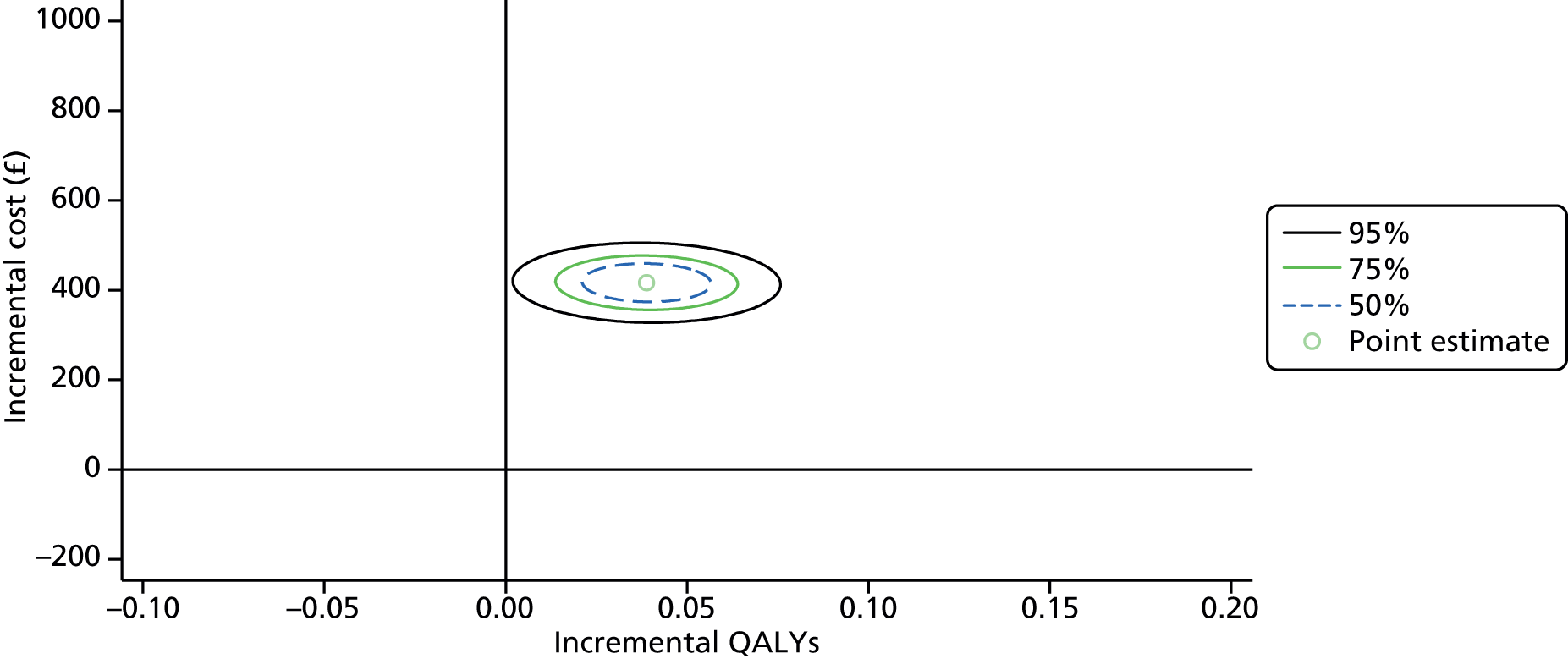

Economic analysis

Economic analysis took the form of a cost-effectiveness analysis and, in line with NICE guidance,50,51 adopted the perspective of the health and personal social services. The aim of the analysis was to estimate the value for money of providing collaborative care compared with usual care. The time horizon for the analysis was 12 months from the date of randomisation; therefore, costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were not discounted. The analysis was conducted in Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Quality-adjusted life-years were estimated using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions three-level version questionnaire to enable comparisons to be made across different health interventions and provide extra information for decision-makers. QALYs were estimated by measuring the area under the curve,52 which joins baseline and follow-up EQ-5D utility scores derived from population-based values.

A base-case cost of collaborative care was estimated based on the case managers’ training manual, which describes the treatment protocol (manual available on request). Participants’ health-care resource use during the study was assessed to indicate the total cost of health care during the treatment and follow-up periods. Various methods of collecting resource use data were initially considered (e.g. self-report questionnaires and medical records checks). Objective data were obtained from GP practices giving information on (1) participants’ contacts with GPs (appointments, home visits or telephone consultations), (2) participants’ contacts with practice nurses (appointments or telephone consultations) and (3) prescriptions. Given the sample age (≥ 75 years for the pilot phase and ≥ 65 years for the main trial), additional ‘self-report questions’ were not added to limit the overall questionnaire burden. National unit costs were applied to the quantities of resources utilised. 53

For decision analysis, the costs of the intervention, health-care use and changes in QALYs in the RCT were combined to calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) using the following formula:

where C is the costs and E is the effects (as QALYs) in the intervention (I) or control (C) group.

To estimate the joint distributions of costs and QALYs, non-parametric bootstrapping was conducted on the observed data. 54 This non-parametric bootstrap resampling technique allows us to assess uncertainty in the ICER. 55 First, the results of the bootstrapped costs and QALYs were presented on the cost-effectiveness plane. Confidence ellipses illustrate the uncertainty in the joint distribution of costs and QALYs on the cost-effectiveness plane; this shows the probability space (50%, 75% and 95% respectively) within which we are confident the true ICER is found.

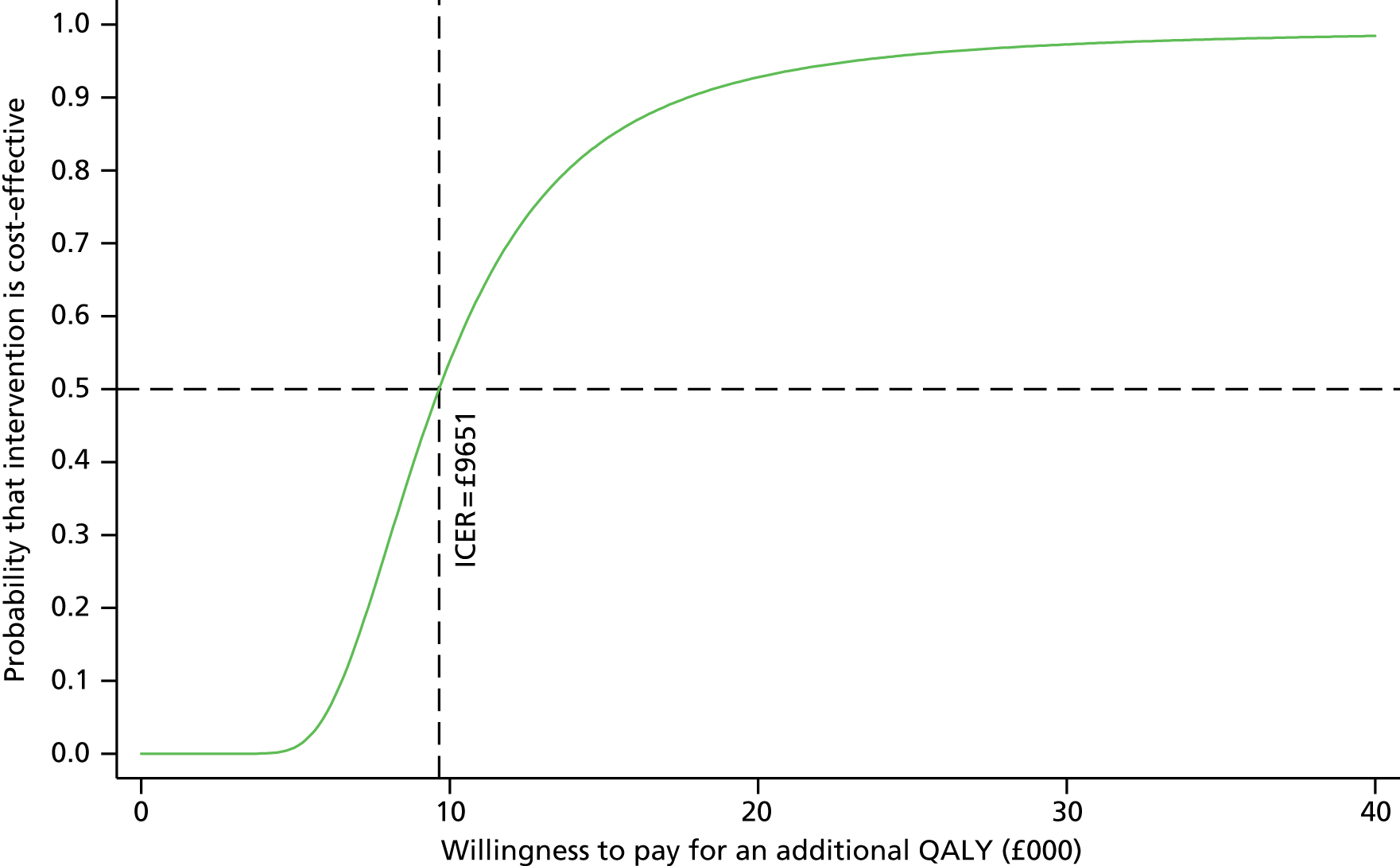

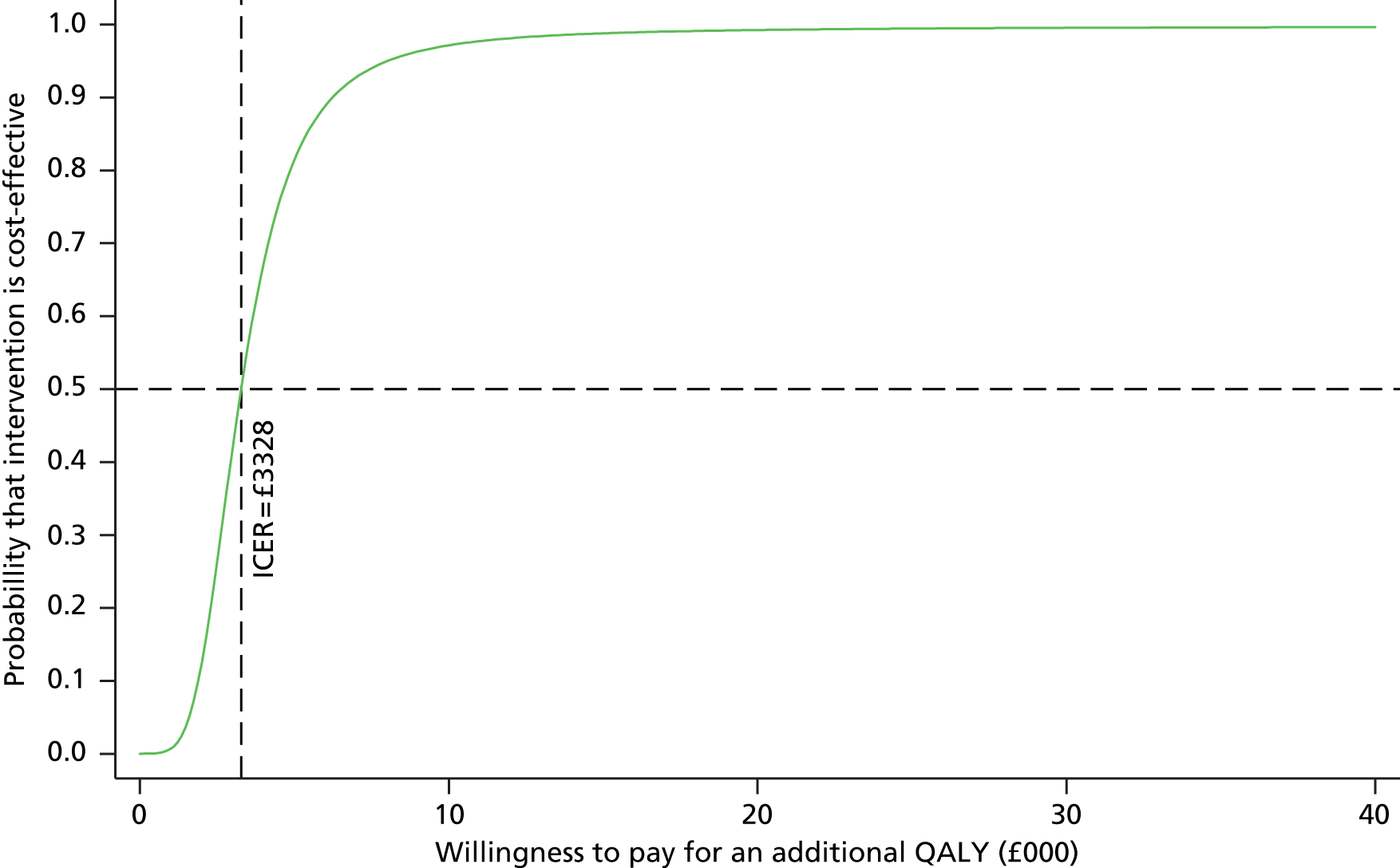

To further evaluate the joint distributions of costs and benefits, a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) was generated. 56 The CEAC illustrates how the probability that collaborative care will be cost-effective changes as decision-makers’ willingness to pay increases. According to NICE, the willingness to pay for an additional QALY ranges between £20,000 and £30,000; the CEAC indicates the probability that collaborative care is within this range.

Participants’ take-up of collaborative care was recorded during sessions by case managers. This allowed deterministic sensitivity analysis of the potential variation in direct costs of the intervention to be carried out. Over the course of treatment, for each contact with participants, the case managers recorded information on the duration of the contact and how this took place. This information was used to adjust the expected cost of collaborative care when patient, case manager and supervisors agreed to deviate from the manualised intervention. The results were expressed on a CEAC and the adjusted probabilities of falling within the NICE range of willingness to pay were presented.

Chapter 4 Protocol changes

The following changes were made to the original protocol after it was initially approved by the REC on 28 September 2010 [see NETS website: www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hta/081904 (accessed 24 September 2015)].

Consent process

In the original protocol the consent form contained a section titled Other research studies; participants were asked to tick the opt-out box if they did not wish to receive information about other studies. In response to comments from the REC, the opt-out box was removed and replaced with a ‘yes/no’ box format before permissions were granted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In the original protocol the inclusion criteria specified that participants must be aged ≥ 75 years. This was to ensure that we recruited enough ‘older’ older adults into our pilot phase to inform us of the challenges associated with delivering the intervention to older people. However, once we had completed the pilot phase and further tailored the intervention to meet the needs of older adults, we changed the inclusion criterion for age from ≥ 75 years to ≥ 65 years. This was to bring recruitment into line with the typical age used to define older adults in more developed countries and to increase the rate of recruitment into the main trial.

Participant documentation

In the original protocol it was stated that a MIND leaflet on depression would be sent to participants with their allocation letter post randomisation. However, following some negative comments from participants, who described the MIND leaflet as inappropriate for this age group, alternative leaflets were reviewed by the CASPER trial’s TMG. The MIND leaflet How to improve your mental wellbeing was replaced with a more age-appropriate leaflet produced jointly by Age Concern and Help the Aged, entitled Down, but not out factsheet: What is depression?. We also stopped sending leaflets on depression to non-depressed cohort participants as it was deemed superfluous.

New site recruitment

As outlined in the original CASPER protocol our intention was to increase the number of recruiting sites for Phase III of the study to ensure that the trial met its recruitment target. We therefore introduced Newcastle upon Tyne as a fourth site to ensure that we met our recruitment target. The trusts involved were the NHS North Tyne, Newcastle and North Tyneside Primary Care Trusts, the Northumberland Care Trust and the Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust.

Extension of recruitment

Our original sample size calculations for the CASPER trial were based on an attrition rate of 10%. In reality we experienced a higher than anticipated dropout rate, particularly among participants in the ‘collaborative care’ arm of the trial. In response, we extended our recruitment target from 540 to 658 to maintain 80% power. We actually went on to recruit a total of 705 participants, which would result in 83% estimated power.

Chapter 5 Clinical results

Recruitment and follow-up

Recruitment and flow of participants through the trial

Participants were recruited into the CASPER trial between June 2011 and July 2013 from four UK sites and their surrounding areas in the north of England: York, Leeds, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne. A total of 32 GP practices consented to screen their practice lists and identify patients who met the initial inclusion criterion: aged ≥ 75 years during the pilot phase and ≥ 65 years during the main trial (see Chapter 4). The exclusion criteria consisted of any known alcohol dependency and/or psychotic symptoms as recorded on GP records, any known adverse comorbidities or any other factors that resulted in GPs deeming it inadvisable to invite patients, such as a recent bereavement.

We were obliged to follow a broad recruitment strategy because we would not have been able to accurately identify patients with subthreshold depression using Read codes from GP records. Therefore, GP practices conducted searches with broad inclusion criteria, which meant that we invited nearly all patients aged ≥ 65 years, except for the few who met the exclusion criteria. This explains why we recruited such a large number of participants into the CASPER cohort and why the number who made it into the CASPER trial with subthreshold depression was far smaller.

A total of 37,134 patients were identified by GP practices between June 2011 and July 2013 and invited by letter to take part in the CASPER study. Of 6693 patients who consented, 4259 were excluded and 2434 patients were assessed for eligibility by diagnostic interview. Based on the diagnostic interview, 705 (29%) patients were identified to have subthreshold depression and were randomised into the CASPER trial. Of those 705 participants randomised, 344 were allocated to collaborative care and 361 to usual care. The remaining patients were classified either as being below the threshold for depression (n = 1558, 64%) or as suffering from a major depressive disorder (n = 171, 7%); they became part of the epidemiological cohort. The randomised number of 705 participants exceeded the planned sample size of 658 participants. The flow of participants is illustrated in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. IQR, interquartile range; max., maximum; min., minimum.

Trial completion and trial exit

Participants were able to withdraw from the study at any point. They were offered the options of withdrawing from the intervention only, from questionnaire follow-up or from all aspects of the study. Data were retained for all participants up to the date of withdrawal, unless they specifically requested that their details be removed. The total number of withdrawals by trial arm is given in Table 2.

| Time | Type of withdrawal | Collaborative care (n = 344) | Usual care (n = 361) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| By 4 months’ follow-up | Withdrawal from treatment | 82 | 23.8 | – | – |

| Withdrawal from follow-up | 16 | 4.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Full withdrawal | 27 | 7.8 | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Died | 1 | 0.3 | 4 | 1.1 | |

| By 12 months’ follow-up | Withdrawal from treatment | 95 | 27.6 | – | – |

| Withdrawal from follow-up | 25 | 7.3 | 4 | 1.1 | |

| Full withdrawal | 37 | 10.8 | 5 | 1.4 | |

| Died | 5 | 1.5 | 18 | 5.0 | |

A total of 28% of participants in the collaborative-care arm withdrew from treatment and the number of full and partial withdrawals was seven times greater in this group (n = 62) than in the usual-care group (n = 9). A larger number of patients in the usual-care arm died during the course of the trial (18 vs. 5).

When reasons for withdrawal were provided by the participants, these were documented in the study management database. Following completion of the trial, reasons were grouped into common categories and these are listed in Tables 3–5 for the different types of follow-up.

| Reason for withdrawal | Collaborative care (n = 95 withdrawn) | Usual care (n = 0 withdrawn) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Too busy | 14 | 14.7 | – | – |

| Carer – no time | 6 | 6.3 | – | – |

| Does not wish to engage | 21 | 22.1 | – | – |

| Not low in mood | 9 | 9.5 | – | – |

| Invasive | 6 | 6.3 | – | – |

| Ill health | 11 | 11.6 | – | – |

| Cognitive impairment | 4 | 4.2 | – | – |

| Physical disabilities | 1 | 1.1 | – | – |

| Recent bereavement | 2 | 2.1 | – | – |

| Receiving support from others | 3 | 3.2 | – | – |

| Literacy problems | 1 | 1.1 | – | – |

| Unable to contact | 2 | 2.1 | – | – |

| Unknown | 15 | 15.8 | – | – |

| Total | 95 | 100.0 | – | – |

| Reason for withdrawal | Collaborative care (n = 25 withdrawn) | Usual care (n = 4 withdrawn) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Too busy | 4 | 16.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Does not wish to engage | 4 | 16.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Not low in mood | 3 | 12.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Invasive | 2 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Ill health | 3 | 12.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Receiving support from others | 1 | 4.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Causing marital disharmony | 1 | 4.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unknown | 7 | 28.0 | 4 | 100.0 |

| Total | 25 | 100.0 | 4 | 100.0 |

| Reason for withdrawal | Collaborative care (n = 37 withdrawn) | Usual care (n = 5 withdrawn) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Too busy | 2 | 5.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Carer – no time | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Does not wish to engage | 8 | 21.6 | 1 | 20.0 |

| Not low in mood | 5 | 13.5 | 1 | 20.0 |

| Invasive | 6 | 16.2 | 1 | 20.0 |

| Ill health | 4 | 10.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Physical disabilities | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Recent bereavement | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 20.0 |

| Receiving support from others | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Literacy problems | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unable to contact | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unknown | 8 | 21.6 | 1 | 20.0 |

| Total | 37 | 100.0 | 5 | 100.0 |

The final trial sample size calculation allowed for losses to follow-up of 26% at the primary end point at 4 months. The primary outcome (PHQ-9 depression severity) was available for 586 patients at that point, equating to an actual loss to follow-up of 16.9% (23.8% in the collaborative-care arm and 10.2% in the usual-care arm).

Timing of follow-up

Different patients in the CASPER trial were followed up according to two different time schedules. Follow-up times (4 and 12 months) were initially calculated from baseline (n = 165 randomised participants, 23%), with randomisation expected shortly after. As the volume of participant throughput increased, diagnostic interview and randomisation occurred only sometime after baseline data collection; therefore, follow-up times for participants later on in the trial were calculated from the time of randomisation as the more appropriate reference point (n = 540 randomised participants, 77%). A sensitivity analysis was carried out to assess the impact of having adopted two different reference points (see Table 22).

Table 6 illustrates the average delay between baseline and randomisation, with a median delay of 2 weeks and considerable variability. Table 6 also shows that, for those patients whose follow-up reference time was at baseline, their 4-month follow-up could occur much sooner after (and for four cases before) randomisation.

| Time interval | Statistics | Follow-up reference at baseline (n = 165) | Follow-up reference at randomisation (n = 540) | Total (n = 705) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days from return of baseline questionnaire to randomisation | n | 165 | 540 | 705 |

| Mean (SD) | 23 (28.9) | 28 (34.1) | 27 (33.0) | |

| Median | 12 | 14 | 14 | |

| Min., max. | 0, 180 | 0, 214 | 0, 214 | |

| Days from randomisation to 4-month questionnaire being sent | n | 131 | 448 | 579 |

| Mean (SD) | 87 (34.4) | 134 (21.7) | 124 (32.0) | |

| Median | 96 | 125 | 124 | |

| Min., max. | –74, 162 | 120, 231 | –74, 231 |

Response types and response times

Participants had the option to complete questionnaires at baseline and follow-up on paper or online. Only a small proportion of questionnaires were completed online, which reduced over time [2.7% at baseline (3.8% collaborative-care group, 1.7% usual-care group), 1.9% at 4 months’ follow-up (2.6% collaborative-care group, 1.2% usual-care group) and 1.0% at 12 months’ follow-up (1.7% collaborative-care group, 0.4% usual-care group). Patients in the collaborative-care arm were slightly more likely to use the online option.

The average response times to questionnaires are detailed in Table 7 by trial arm for data for which completion dates were provided by participants or dates of return were logged on the trial database. Participants generally completed questionnaires within a week and returned them within 2 weeks. There were no differences in response time between treatment arms.

| Time interval (months) | Interval from date questionnaire sent | Statistics | Collaborative care (n = 344) | Usual care (n = 361) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Days to complete questionnaire | n | 242 | 298 |

| Mean (SD) | 8.7 (12.41) | 8.5 (13.47) | ||

| Median | 4 | 5 | ||

| Min., max. | 0, 93 | 0, 93 | ||

| Days to return questionnaire | n | 256 | 319 | |

| Mean (SD) | 15.8 (13.70) | 15.2 (13.65) | ||

| Median | 11.5 | 11 | ||

| Min., max. | 0, 93 | 0, 101 | ||

| 12 | Days to complete questionnaire | n | 221 | 262 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (9.73) | 6.5 (7.61) | ||

| Median | 4 | 4 | ||

| Min., max. | 0, 81 | 0, 70 | ||

| Days to return questionnaire | n | 232 | 279 | |

| Mean (SD) | 13.8 (12.27) | 13.1 (9.86) | ||

| Median | 11 | 10 | ||

| Min., max. | 0, 103 | 0, 88 |

The intervention: collaborative care

Collaborative care was offered to all patients in the intervention arm. The intervention was delivered by 18 case mangers (case load of 19.1 randomised patients and 16.2 patients who received any treatment per case manager). Further details on the case load of each individual case manager are given as part of the practitioner analysis in Adjusting for clustering by case manager.

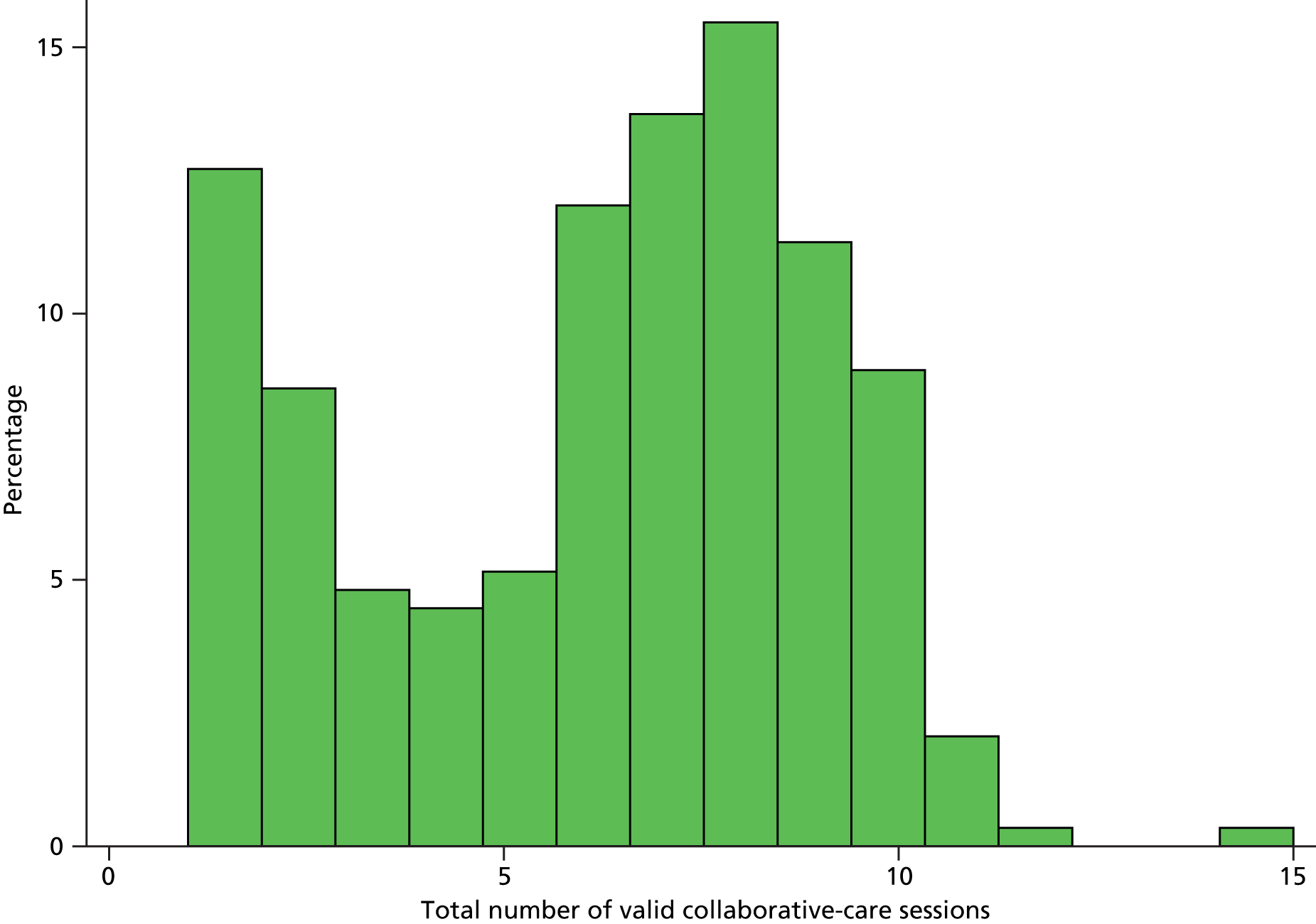

An overview of received treatments is provided in the CONSORT diagram in Figure 1 and further details are presented in Tables 8 and 9. Of 344 randomised patients, 85% had at least one collaborative-care session and 46% completed the treatment. Participants received on average six sessions over 7–8 weeks, of which two were delivered face to face and four were delivered by telephone. The average session duration was around half an hour. When reasons for not wanting to receive any collaborative care were recorded by case managers in the notes, being too busy and not being low in mood were the most frequent responses (Table 10).

| Collaborative care received | Patients randomised to collaborative care (n = 344) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Did not start treatment | 53 | 15.4 |

| Started treatment | 291 | 84.6 |

| Started but did not complete treatment | 134 | 39.0 |

| Completed treatment | 157 | 45.6 |

| Characteristic | Patients who received some collaborative care (n = 291) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | Median | Min. | Max. | |

| Days from randomisation to first session | 291 | 23.8 | 13.73 | 21 | 0 | 96 |

| Number of sessions received | 291 | 6.0 | 3.06 | 7 | 1 | 15 |

| Face to face | 291 | 1.7 | 1.65 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| By telephone | 291 | 4.3 | 3.10 | 5 | 0 | 14 |

| Average length of session (minutes) | 291 | 34.5 | 14.12 | 30 | 10 | 95 |

| Days from first to last session | 291 | 52.9 | 37.7 | 55 | 0 | 200 |

| Reason | Patients who received no collaborative care (n = 53) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Too busy | 8 | 15.1 |

| Carer – no time | 4 | 7.5 |

| Does not wish to engage | 5 | 9.4 |

| Not low in mood | 8 | 15.1 |

| Invasive | 5 | 9.4 |

| Ill health | 4 | 7.5 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 | 1.9 |

| Physical disabilities | 1 | 1.9 |

| Receiving support from others | 2 | 3.8 |

| Causing marital disharmony | 1 | 1.9 |

| Unable to contact | 4 | 7.5 |

| Unknown | 10 | 18.9 |

Baseline characteristics

Characteristics at consent, baseline and diagnostic interview (point of randomisation) for randomised participants and participants included in the primary analysis [‘as analysed’ population: patients with a valid PHQ-9 score at 4 or 12 months’ follow-up and valid covariate data (PHQ-9 score at randomisation and baseline SF-12 PCS score)] are presented in Tables 11–13 respectively.

| Characteristic | As randomised, n (%) | As analysed, n (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (n = 344) | Usual care (n = 361) | Collaborative care (n = 274) | Usual care (n = 327) | |

| Age at consent (years) | ||||

| n (%) | 344 (100.0) | 361 (100.0) | 274 (100.0) | 327 (100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 77.1 (7.08) | 77.5 (7.18) | 76.6 (7.21) | 77.4 (7.13) |

| Median (min., max.) | 77 (65, 96) | 78 (64, 93) | 77 (65, 93) | 78 (64, 93) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 159 (46.2) | 139 (38.5) | 122 (44.5) | 123 (37.6) |

| Female | 185 (53.8) | 222 (61.5) | 152 (55.5) | 204 (62.4) |

| Educated beyond 16 years | 180 (52.3) | 186 (51.5) | 146 (53.3) | 168 (51.4) |

| Degree or equivalent professional qualification | 115 (33.4) | 106 (29.4) | 95 (34.7) | 96 (29.4) |

| Smoker | 16 (4.7) | 29 (8.0) | 12 (4.4) | 25 (7.6) |

| Three or more alcohol units per day | 32 (9.3) | 21 (5.8) | 26 (9.5) | 16 (4.9) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 340 (98.8) | 358 (99.2) | 271 (98.9) | 324 (99.1) |

| Asian or Asian British | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Black or black British | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fallen in the last 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 110 (32.0) | 142 (39.3) | 89 (32.5) | 131 (40.1) |

| No | 224 (65.1) | 212 (58.7) | 176 (64.2) | 190 (58.1) |

| Cannot recall | 8 (2.3) | 5 (1.4) | 8 (2.9) | 4 (1.2) |

| If fallen, how many times | ||||

| n (%) | 105 (30.5) | 139 (38.5) | 85 (31.0) | 128 (39.1) |

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (4.91) | 2.2 (1.71) | 3.1 (5.40) | 2.2 (1.76) |

| Median (min., max.) | 2 (1, 40) | 2 (1, 14) | 2 (1, 40) | 2 (1, 14) |

| Health problems | ||||

| Diabetes | 55 (16.0) | 66 (18.3) | 43 (15.7) | 64 (19.6) |

| Osteoporosis | 33 (9.6) | 42 (11.6) | 27 (9.9) | 40 (12.2) |

| High blood pressure | 157 (45.6) | 174 (48.2) | 131 (47.8) | 160 (48.9) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 38 (11.0) | 57 (15.8) | 31 (11.3) | 53 (16.2) |

| Osteoarthritis | 98 (28.5) | 114 (31.6) | 81 (29.6) | 106 (32.4) |

| Stroke | 28 (8.1) | 31 (8.6) | 22 (8.0) | 27 (8.3) |

| Cancer | 49 (14.2) | 37 (10.2) | 38 (13.9) | 34 (10.4) |

| Respiratory conditions | 65 (18.9) | 81 (22.4) | 51 (18.6) | 73 (22.3) |

| Eye condition | 130 (37.8) | 136 (37.7) | 98 (35.8) | 117 (35.8) |

| Heart disease | 88 (25.6) | 86 (23.8) | 66 (24.1) | 75 (22.9) |

| Other | 74 (21.5) | 74 (20.5) | 64 (23.4) | 65 (19.9) |

| Whooley question: Over the past month have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless? | ||||

| Yes | 233 (67.7) | 238 (65.9) | 192 (70.1) | 218 (66.7) |

| No | 111 (32.3) | 123 (34.1) | 82 (29.9) | 109 (33.3) |

| Whooley question: Over the past month have you been bothered by having little or no interest or pleasure in doing things? | ||||

| Yes | 198 (57.6) | 199 (55.1) | 161 (58.8) | 176 (53.8) |

| No | 146 (42.4) | 162 (44.9) | 113 (41.2) | 151 (46.2) |

| Characteristic | As randomised, n (%) | As analysed, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (n = 344) | Usual care (n = 361) | Collaborative care (n = 274) | Usual care (n = 327) | |

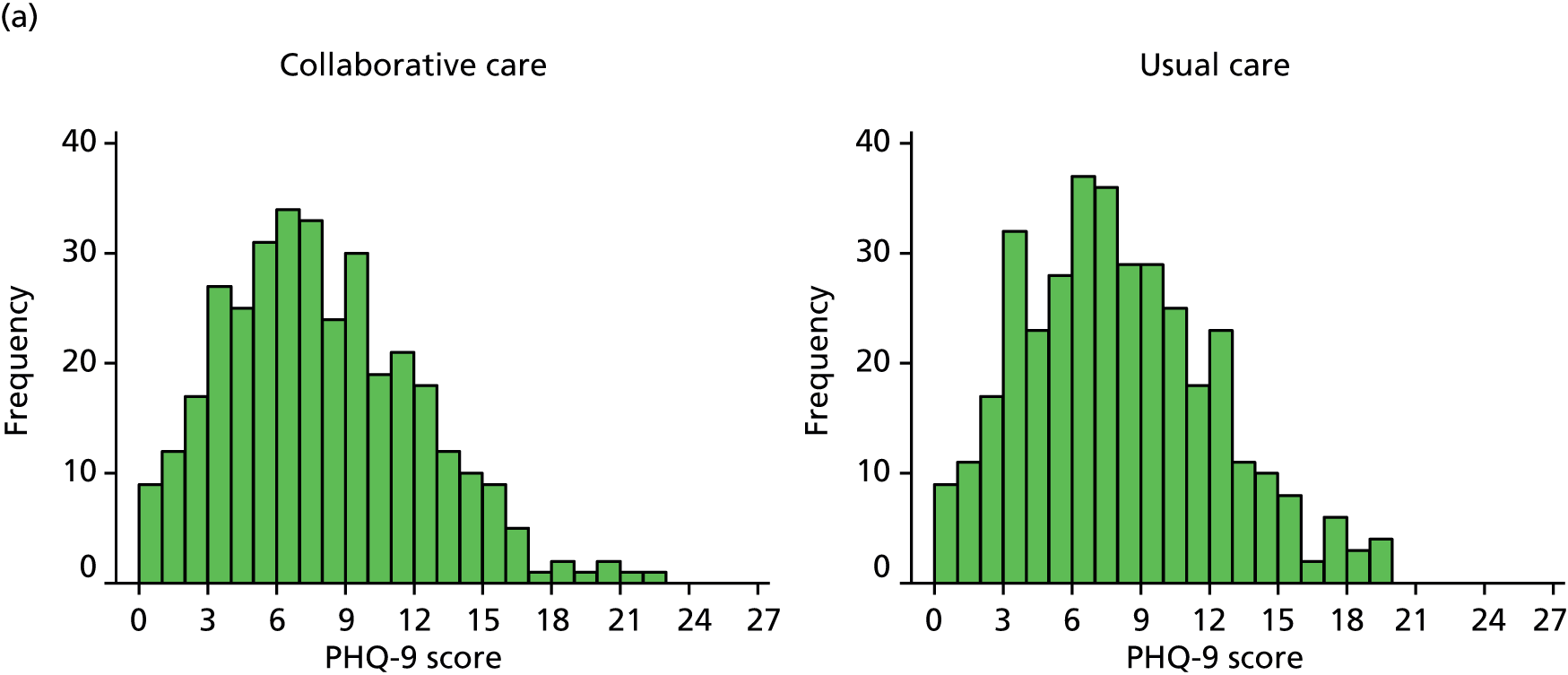

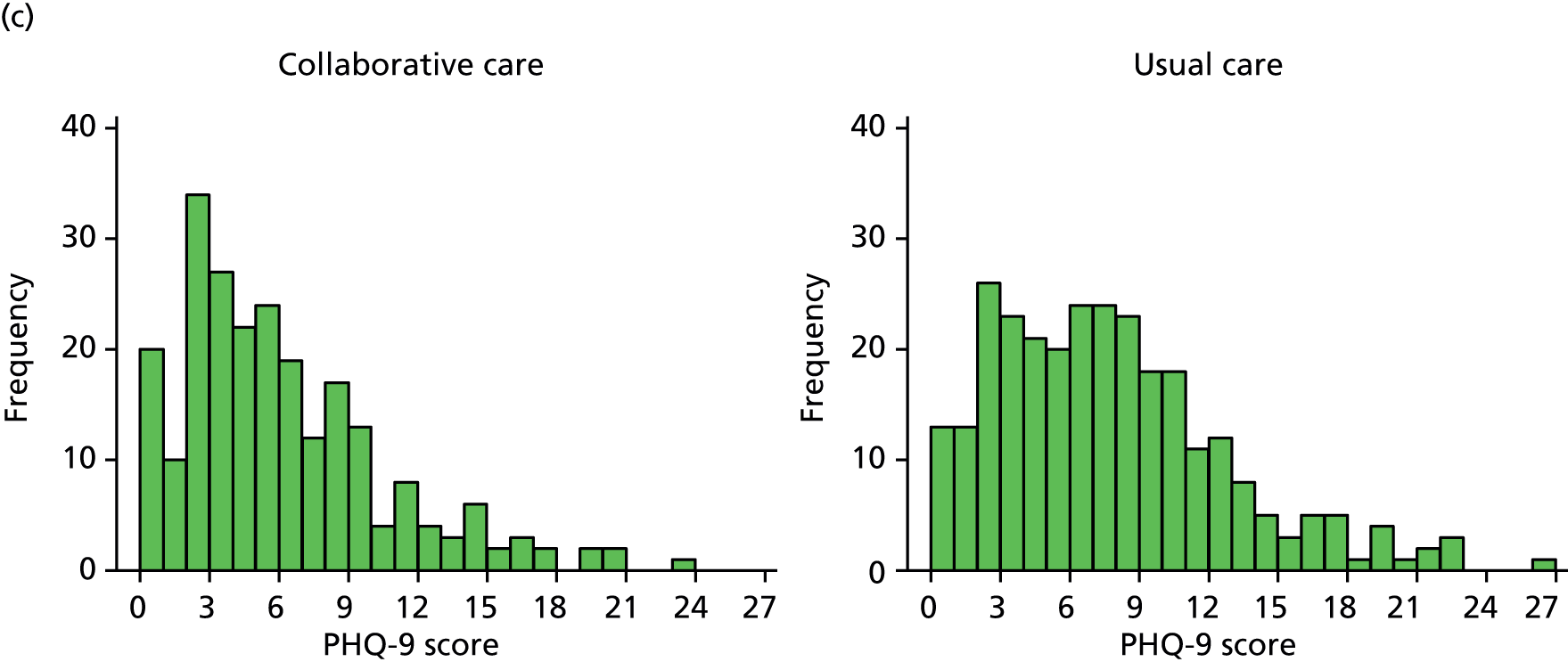

| PHQ-9 score | ||||

| n (%) | 340 (98.8) | 358 (99.2) | 274 (100.0) | 327 (100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 7.8 (4.71) | 7.8 (4.64) | 7.6 (4.32) | 7.6 (4.55) |

| Median (min., max.) | 7 (0, 27) | 7 (0, 25) | 7 (0, 27) | 7 (0, 25) |

| PHQ-9 grouping | ||||

| No depression | 96 (27.9) | 90 (24.9) | 74 (27.0) | 89 (27.2) |

| Mild depression | 137 (39.8) | 155 (42.9) | 118 (43.1) | 138 (42.2) |

| Moderate depression | 76 (22.1) | 85 (23.5) | 61 (22.3) | 77 (23.5) |

| Moderately severe depression | 23 (6.7) | 21 (5.8) | 18 (6.6) | 18 (5.5) |

| Severe depression | 8 (2.3) | 7 (1.9) | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.5) |

| PHQ-15 score | ||||

| n (%) | 339 (98.5) | 356 (98.6) | 274 (100.0) | 326 (99.7) |

| Mean (SD) | 9.1 (4.12) | 9.5 (3.94) | 9.1 (4.17) | 9.4 (3.93) |

| Median (min., max.) | 9 (0, 25) | 9 (0, 20) | 9 (0, 25) | 9 (0, 20) |

| SF-12 PCS score | ||||

| n (%) | 337 (98.0) | 356 (98.6) | 274 (100.0) | 327 (100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 38.0 (13.37) | 36.5 (13.02) | 38.5 (13.15) | 36.6 (13.11) |

| Median (min., max.) | 37.5 (4.6, 69.9) | 35.1 (5.7, 66.6) | 38.1 (4.6, 69.9) | 35.0 (5.7, 66.6) |

| SF-12 MCS score | ||||

| n (%) | 337 (98.0) | 356 (98.6) | 274 (100.0) | 327 (100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 44.3 (10.96) | 45.1 (10.02) | 44.5 (10.97) | 45.2 (10.04) |

| Median (min., max.) | 44.9 (12.5, 66.0) | 46.3 (9.6, 67.0) | 45.1 (12.5, 66.0) | 46.5 (9.6, 67.0) |

| GAD-7 score | ||||

| n (%) | 340 (98.8) | 358 (99.2) | 274 (100.0) | 327 (100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.7 (4.82) | 5.7 (4.45) | 5.5 (4.58) | 5.6 (4.38) |

| Median (min., max.) | 5 (0, 21) | 5 (0, 21) | 4.5 (0, 21) | 5 (0, 21) |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| Mobility | ||||

| No problems | 129 (37.5) | 115 (31.9) | 110 (40.1) | 106 (32.4) |

| Some problems | 210 (61.0) | 241 (66.8) | 164 (59.9) | 220 (67.3) |

| Confined to bed | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Self-care | ||||

| No problems | 287 (83.4) | 292 (80.9) | 234 (85.4) | 270 (82.6) |

| Some problems | 48 (14.0) | 62 (17.2) | 38 (13.9) | 54 (16.5) |

| Unable to wash/dress | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) |

| Usual activities | ||||

| No problems | 136 (39.5) | 124 (34.3) | 115 (42.0) | 115 (35.2) |

| Some problems | 189 (54.9) | 209 (57.9) | 148 (54.0) | 192 (58.7) |

| Unable to perform | 13 (3.8) | 23 (6.4) | 11 (4.0) | 20 (6.1) |

| Pain/discomfort | ||||

| No pain | 76 (22.1) | 54 (15.0) | 64 (23.4) | 45 (13.8) |

| Moderate pain | 224 (65.1) | 262 (72.6) | 185 (67.5) | 245 (74.9) |

| Extreme pain | 39 (11.3) | 40 (11.1) | 25 (9.1) | 37 (11.3) |

| Anxiety/depression | ||||

| Not anxious/depressed | 132 (38.4) | 133 (36.8) | 103 (37.6) | 121 (37.0) |

| Moderately anxious/depressed | 193 (56.1) | 211 (58.4) | 161 (58.8) | 196 (59.9) |

| Extremely anxious/depressed | 12 (3.5) | 11 (3.0) | 9 (3.3) | 9 (2.8) |

| Prescribed antidepressants | 35 (10.2) | 51 (14.1) | 29 (10.6) | 46 (14.1) |

| Whooley question: Over the past month have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless? | ||||

| Yes | 254 (73.8) | 258 (71.5) | 210 (76.6) | 235 (71.9) |

| No | 88 (25.6) | 103 (28.5) | 64 (23.4) | 92 (28.1) |

| Whooley question: Over the past month have you been bothered by having little or no interest or pleasure in doing things? | ||||

| Yes | 192 (55.8) | 209 (57.9) | 160 (58.4) | 188 (57.5) |

| No | 150 (43.6) | 152 (42.1) | 114 (41.6) | 139 (42.5) |

| Characteristic | As randomised, n (%) | As analysed, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (n = 344) | Usual care (n = 361) | Collaborative care (n = 274) | Usual care (n = 327) | |

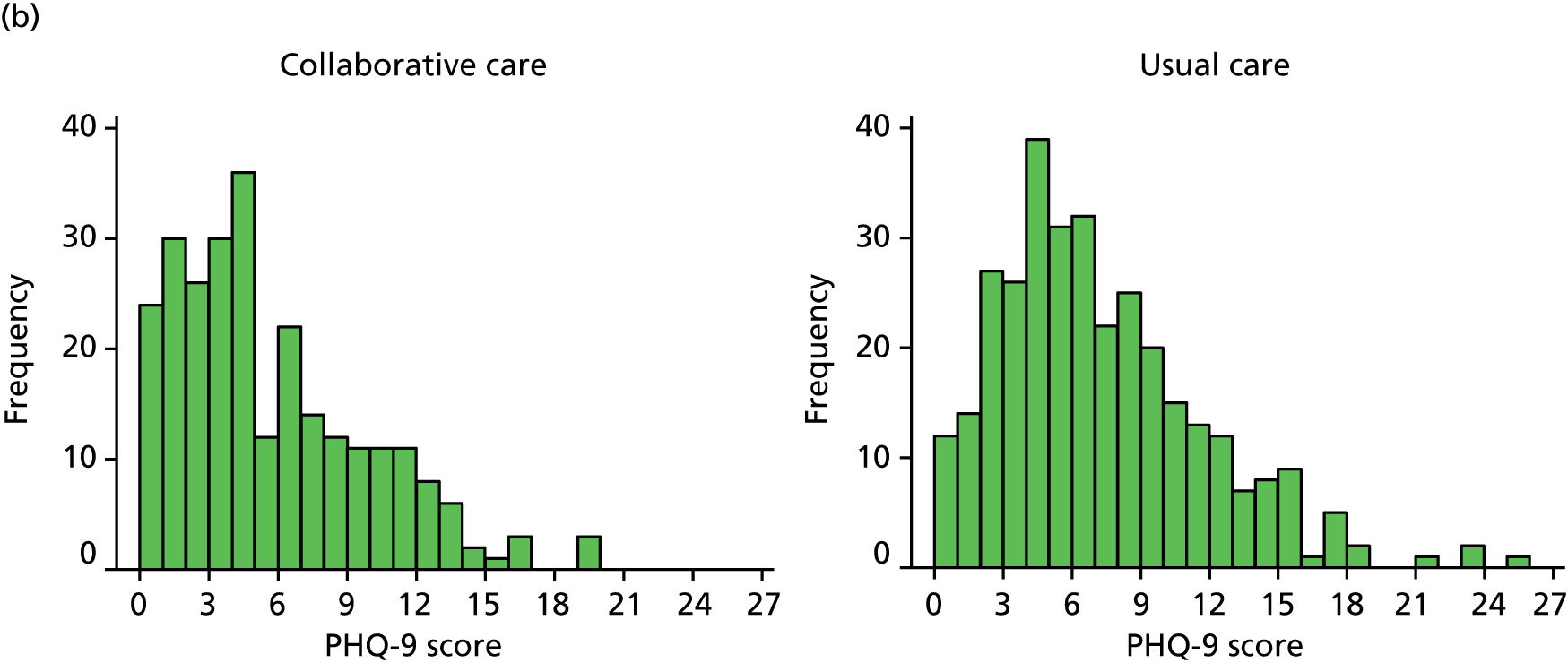

| PHQ-9 score | ||||

| n (%) | 344 (100.0) | 361 (100.0) | 274 (100.0) | 327 (100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 7.5 (4.29) | 7.6 (4.21) | 7.6 (4.24) | 7.6 (4.23) |

| Median (min., max.) | 7 (0, 23) | 7 (0, 20) | 7 (0, 23) | 7 (0, 20) |

| PHQ-9 grouping | ||||

| No depression | 90 (26.2) | 92 (25.5) | 69 (25.2) | 84 (25.7) |

| Mild depression | 152 (44.2) | 159 (44.0) | 124 (45.3) | 143 (43.7) |

| Moderate depression | 80 (23.3) | 87 (24.1) | 64 (23.4) | 79 (24.2) |

| Moderately severe depression | 18 (5.2) | 22 (6.1) | 14 (5.1) | 20 (6.1) |

| Severe depression | 4 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) |

| From MINI: Were you ever depressed or down, most of the day, nearly every day for 2 weeks? | ||||

| Yes | 148 (43.0) | 159 (44.0) | 115 (42.0) | 146 (44.6) |