Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/403/51. The contractual start date was in October 2008. The draft report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Hywel C Williams is Programmes Director for the Health Technology Assessment programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Chalmers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

What is pemphigoid?

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common form of a group of autoimmune pemphigoid diseases characterised by autoantibodies directed at skin adhesion proteins of the epidermal–dermal junction. 1 BP often starts with intense itching followed by an urticated and/or eczematous-looking rash and tense blisters on erythematous or normal-looking skin (Figure 1). The blisters may develop several months after the appearance of the initial symptoms and may be quite large and filled with blood. They often break down to form raw skin erosions, which can become infected.

FIGURE 1.

Large tense blisters and erosions in a man with BP (by kind permission of Professor Enno Schmidt with written consent from the patient).

The pain and severe itching associated with BP can greatly impair quality of life. BP typically affects people aged around 80 years and the incidence, which appears to be on the increase, is estimated to be between 6 and 43 cases per million per year. 2,3 The cause of BP is unknown but it is associated with neurological conditions such as cerebrovascular disease, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy and multiple sclerosis4,5 and the chronic use of several drugs including spironolactone (Aldactone®, Pharmacia Ltd), neuroleptics, certain diuretics and phenothiazines in some patients. 4,6–9 Neurological disease has been suggested as a predisposing and prognostic factor. 10

Increased mortality

Mortality rates are increased for people with BP. In one study the risk of death was more than six times that of the general population. 11 Mortality rates for people with BP of between 11% and 41% have been suggested to be related to advanced age and comorbid medical conditions rather than the disease itself. 12,13 It is likely that the increase in mortality rate is owing, at least in part, to side effects of oral prednisolone, which is commonly used to treat BP. 14–17

Topical treatment

Some widely reported studies have shown that superpotent topical corticosteroids applied to the whole skin surface are effective and safer than oral corticosteroids. 18,19 Practical guidance on how this can be carried out is provided elsewhere. 15 However, the application of topical steroids to the whole body for weeks or possibly months is not a practical option in many elderly outpatients with limited support. Therefore, there still remains a need for a convenient oral treatment that is both effective and safe.

Rationale for testing tetracyclines further

Treatment of BP with antibiotics possessing anti-inflammatory actions, such as those from the tetracycline group, is widely used in clinical practice. In a national survey of 326 UK dermatologists conducted in 2013, around 80% stated that they had used doxycycline (Efracea®, Galderma), minocycline (Aknemin®, Almirall Hermal GmbH) or lymecycline (Tetralysal®, Galderma). 20 However, a Cochrane systematic review21 found only one small poorly reported clinical trial22 and concluded that further evidence was needed before the effectiveness of tetracyclines could be established. No further trials of tetracyclines were identified in a subsequent systematic review23 nor in a search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials using ‘pemphigoid’ as a search term (28 May 2015). The limited data available and practical experience to date suggest that it is very unlikely that tetracyclines would be more effective than long-term use of oral corticosteroids, yet they are likely to be safer in this elderly population given the known adverse effects of oral corticosteroids, including diabetes mellitus, serious infections and osteoporosis, leading to fractures and death. Because some patients with BP might not respond to tetracyclines at all, it was clearly important to test how they might be used in clinical practice by permitting additional application of potent topical corticosteroids to affected areas or a switch to oral corticosteroids if symptoms and blister control were inadequate. Similarly, in the UK, those initiated on oral steroids are typically given topical corticosteroids for localised application to blisters to help with initial control and doses of oral corticosteroids are typically adjusted over several months, according to blister control or side effects. We therefore sought to investigate whether or not a strategy of initial treatment of BP with anti-inflammatory tetracyclines (200 mg/day of doxycycline) is effective enough to produce an acceptable degree of blister control compared with initial treatment with oral corticosteroids (0.5 mg/kg/day of prednisolone) in a non-inferiority comparison and whether or not tetracyclines confer a long-term advantage in terms of safety over oral corticosteroids in a superiority comparison.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this report are based on Williams et al. 24 This article is published open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence (CC-BY) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0).

Trial design

The Bullous Pemphigoid Steroids and Tetracyclines (BLISTER) trial was a two-arm, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational randomised controlled trial of 52 weeks’ duration. The design was towards the pragmatic end of the explanatory–pragmatic spectrum. 25 We recruited patients with BP from the UK and Germany who had not started systemic treatment. Participants were randomised to receive either doxycycline or prednisolone as initial treatment and were followed up at weeks 3, 6, 13, 26, 39 and 52, with unscheduled visits as required to reflect normal clinical care.

The two primary outcomes in this trial reflect the need for patients and clinicians to balance the likely differences in effectiveness and safety for oral prednisolone and doxycycline when making a shared decision on treatment. Although topical corticosteroids have been shown to be effective for BP, it is not always practical or cost-effective to admit elderly people into hospital for whole body application15 and therefore oral treatment alternatives are needed. Although oral prednisolone is thought to be effective at reducing the blisters in BP, it has many side effects as indicated in previous trials comparing topical corticosteroids with oral corticosteroids. 18,19,26 Doxycycline, on the other hand, is perceived to be less effective by clinicians but probably has fewer side effects. Therefore, a non-inferiority comparison was used to assess effectiveness, the results of which could be considered alongside the superiority comparison of safety in clinical decision-making.

The trial protocol was published prior to the analysis. 27

Choice of intervention

At baseline, patients were randomised to receive either 0.5 mg/kg/day of prednisolone or 200 mg/day of doxycycline, both taken as a single, daily dose (brand not specified). We chose a starting dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day for prednisolone based on safety concerns over higher doses such as 0.75–1 mg/kg/day highlighted in the Cochrane systematic review. 22 The study protocol encouraged investigators to stick to the allocated treatment and dose for the first 6 weeks unless it was medically necessary to change, but after the 6-week effectiveness assessment investigators were free to modify the dose as needed, switch to the other treatment arm or administer an alternative treatment if appropriate, to reflect normal clinical practice. Participants were followed up for the full 52 weeks when possible, regardless of any changes to treatment. Participants recorded study medication use in their diary.

Rescue medication

Up to 30 g/week of topical corticosteroids in the potent class [preferably mometasone furoate (Elocon®, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd)] was permitted throughout the study, except between weeks 3 and 6. The cessation of topical corticosteroids from week 3 to week 6 provided a washout period to minimise the potential effect of systemic absorption of topical corticosteroids on the primary effectiveness outcome at 6 weeks. To minimise potential systemic effects, topical corticosteroids were applied only to blisters and erosions. Participants were permitted to apply a moisturiser to blisters and erosions at any time.

Choice of tetracycline

Doxycycline was chosen for this trial because (1) it is associated with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects than other tetracyclines and (2) the alternative option of oxytetracycline would have required participants to swallow approximately eight large tablets a day.

Although the only published randomised controlled trial investigating tetracycline antibiotics for the treatment of BP used a combination therapy of tetracycline plus nicotinamide,21 a single therapy of doxycycline was chosen for this trial to allow the effects of the tetracycline to be clearly defined.

Trial outcomes

We did not identify any core outcome sets for BP when this study was designed, although some consensus criteria have subsequently been suggested by an international group. 28

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were the absolute difference between the two treatment arms in the:

-

Non-inferiority comparison. The proportion of participants classed as a treatment success (three or fewer significant blisters present on examination) at 6 weeks. A significant blister was defined as an intact fluid-filled blister at least 5 mm in diameter or a ruptured blister with a flexible (not dry) roof over a moist base. Mucosal blisters were excluded from the count.

-

Superiority comparison. The proportion of participants with grade 3 (severe), 4 (life-threatening) and 5 (death) adverse events that were possibly, probably or definitely related to the treatment in the 52 weeks following randomisation. A modified version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 was used [see http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf (accessed 12 November 2015)] and the relatedness of grade 5 (fatal) adverse events was judged by an independent adjudicator. Although only grade 3 and above related adverse events were captured in the primary outcome, less medically important related adverse events (such as weight gain and skin fragility) can bother patients when taking corticosteroids and so were included in a secondary outcome.

For the primary outcome, treatment success was defined as three or fewer significant blisters, regardless of whether or not treatment had been modified because of a poor response (either by changing the dose or by changing the treatment) during the first 6 weeks. However, for all secondary and tertiary end points, participants were classed as a treatment success at each visit only if (1) they had three or fewer significant blisters present on examination and (2) their treatment had not been altered because of a poor response prior to that visit.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were the absolute difference between the two treatment arms in the following:

-

non-inferiority comparisons:

-

proportion of participants classed as a treatment success (three or fewer significant blisters present on examination and no treatment modification) at 6 weeks

-

proportion of participants classed as a treatment success at 13 and 52 weeks

-

proportion of participants who had a further episode of BP during the study

-

-

superiority comparisons:

-

proportion of participants reporting adverse events of any grade that were possibly, probably or definitely related to BP medication in the 52 weeks following randomisation

-

quality of life [European Quality of Life-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaires at 6, 13, 26, 39 and 52 weeks]

-

cost-effectiveness over 12 months from a NHS perspective

-

-

combined comparison: proportion of participants classed as a treatment success at 6 weeks and who were alive at 52 weeks.

Tertiary outcomes

The tertiary outcomes were the absolute difference between the two treatment arms in the following:

-

non-inferiority comparisons:

-

proportion of participants completely blister free at 6 weeks

-

proportion of participants classed as a treatment success at 3 weeks (to compare the speed of onset of action)

-

-

superiority comparisons:

-

mortality over the 52-week follow-up period

-

amount of potent and superpotent topical corticosteroids used during the 52 weeks following randomisation.

-

Participants

Adults (aged ≥ 18 years) who were capable of giving written informed consent and who had a clinical diagnosis of BP were eligible. To ensure that active disease was present, at least three significant blisters (defined as intact, fluid-filled blisters measuring ≥ 5 mm) must have appeared within the week prior to screening and must have been present across at least two body sites. Recent erosions could be included provided that they had a flexible (not dry) roof over a moist base. Positive direct (skin biopsy) or indirect (serum) immunofluorescence [immunoglobulin G (IgG) and/or complement component 3 (C3) at the epidermal basement membrane zone) was required to confirm diagnosis. Anonymised samples were tested at the Immunofluorescence Laboratory at the Department of Dermatology, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, and the Institute of Dermatology Immunodermatology Laboratory at St John’s Institute of Dermatology, St Thomas’s Hospital, London. Samples with appropriately obtained consent were sent to the Clinical Immunological Laboratory, University of Lübeck, Germany, for additional immunology substudies, which will be published separately.

Patients must have been free of blisters and have not received treatment for previous episodes of BP in the preceding year. Patients were excluded if they had predominantly mucosal pemphigoid, had received any systemic medication for the current episode of BP or had received oral prednisolone or doxycycline for any other conditions in the preceding 12 weeks. Women of childbearing potential who were not taking adequate contraception, as well as those who were pregnant or who planned to become pregnant during the study or who were currently lactating, were excluded. Additional exclusions for safety reasons were live virus vaccine administration within the previous 3 months, allergy to any member of the tetracycline family or a pre-existing condition or use of a medication that precluded the use of either study drug or that made the patient unsuitable for this trial, as assessed by the investigator.

Retention of participants

To help retain participants in the study, in addition to being able to speak to the investigator, participants were able to telephone the trial manager if they wished to discuss any aspect of the study. For medical queries, participants were directed to a medical member of staff. In addition, the trial administrator made telephone calls to participants to support them throughout the duration of the study. Participants were sent birthday and Christmas cards while they were participating in the study.

Withdrawal of participants

Patients whose immunofluorescence test results were not available until after randomisation and which were subsequently both negative, indicating that they did not have BP, were withdrawn from the trial, replaced and not included in the analysis. This approach reflects normal practice: if there is a clinical picture of BP, treatment is commenced and this is changed later if the laboratory tests are subsequently negative.

Participants who withdrew from study treatment were followed up for the remainder of the year unless they had withdrawn their consent.

Informed consent

Patients presenting with suspected BP were assessed by the recruiting investigator as per normal clinical practice. If a diagnosis of BP was suspected, the patient was given details of the study verbally. If the patient was interested in taking part he or she was given time to read the full participant information leaflet and the investigator answered any questions. A consent form was signed before any study procedures were carried out.

If the disease severity was such that immediate oral treatment was required or the patient did not wish to delay the start of treatment, he or she was able to give consent and be randomised to the study during the first visit to the dermatologist. Otherwise, the patient was given a second appointment for consent and randomisation.

Recruitment

To meet the target for this rare disease, recruitment took place at a large number of hospitals, mainly in dermatology clinics (54 in the UK and seven in Germany).

Randomisation

Randomisation was based on a computer-generated pseudorandom code using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size, created by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) in accordance with its standard operating procedure and held on a secure server. Access to the sequence during the trial was confined to the NCTU data manager.

Participants were allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio to the doxycycline and prednisolone treatment arms. Randomisation was stratified by disease severity, which was defined as the number of blisters present at baseline (mild: 1–9; moderate: 10–30; severe: > 30).

The investigator or research nurse randomised participants using the web-based NCTU randomisation system. The treatment allocation was sent directly to the pharmacist who dispensed the appropriate medication directly, which allowed the investigator to remain blinded.

Blinding

Investigators (outcome assessors) were unaware of treatment allocation and remained blinded to treatment allocation for the first 6 weeks of the trial. At the week 6 visit, the investigators carried out the blister count (primary effectiveness outcome) while blinded to treatment allocation. The investigators were unblinded for the remaining assessments: that is, for the primary safety outcome (adverse events over the full 52 weeks) and the long-term effectiveness outcomes. Unblinding before the 6-week point was permitted if required for treatment decisions that affected patient safety. Investigators were asked at week 6 if they were aware of the treatment allocation prior to carrying out the blister count for the primary effectiveness outcome to capture the rate of unblinding. A subgroup analysis to assess any potential bias of unblinding on the blister count at 6 weeks was performed. The patients and pharmacists were not blinded to treatment allocation.

Sample size

In total, 256 participants were needed to detect a clinically important absolute difference of 20% in grade 3, 4 and 5 (mortality) side effects within 1 year of randomisation (primary safety outcome). This was based on an expected 60% incidence with prednisolone compared with 40% with doxycycline29 with 80% power at the 5% significance level allowing for a 20% loss to follow-up by 1 year using a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. A survey of UK dermatologists showed that a 20% absolute reduction in side effects was considered to be an acceptable and worthwhile clinical difference. More detailed results can be found in Appendix 1.

The effectiveness outcome at 6 weeks was expressed as a two-sided 90% confidence interval (CI) for the absolute difference in success rates (based on blister count) between the prednisolone (control) arm and the doxycycline (intervention) arm. It was assumed that the point estimate for this difference would be 25%, based on an expected response rate of 95% in the control (prednisolone) arm and 70% in the intervention (doxycycline) arm. The acceptable non-inferiority margin was set at 37% based on the upper bound of the 90% CI for an expected 25% difference. Because the non-inferiority margin is inversely proportional to the sample size, the number of patients who we could realistically expect to recruit in a rare disease of the elderly was factored in when setting the non-inferiority margin. The closer to the expected difference of 25% we set the non-inferiority margin, the larger the sample size that would be required. With 80% power, a total of 111 evaluable participants per group was required. The attrition rate in the initial 6 weeks was expected to be low (5%) and so a total of 234 participants was required, that is, within the 256 required for the primary safety outcome.

Analysis

All superiority analyses were conducted on a modified intention-to-treat (mITT) basis and all non-inferiority analyses were performed on both the mITT and the per-protocol (PP) population according to recommended practice. 30

The mITT population consisted of those participants who fulfilled the eligibility criteria, who were randomised to receive either study drug and who had data on the outcome of interest.

For each non-inferiority outcome, the doxycycline arm was considered to be non-inferior to the prednisolone arm if the upper bound of the CI for the difference in proportions was less than the agreed non-inferiority margin of an absolute difference of 37% in both the mITT and the PP analyses.

All analyses were adjusted for baseline disease severity to optimise power and reduce possible imbalances in possible response predictors. Age and Karnofsky score31 were also adjusted for in analyses as continuous variables when possible using a binomial regression with identity links. Methods for dealing with missing data can be found in the statistical analysis plan [see www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/cebd/projects/5rareandother/index.aspx (accessed 19 May 2015)]. Multiple imputation was used to handle missing data because of missed visits for the primary safety analysis.

Patients were excluded from the PP analysis of the primary outcome if, before their 6-week visit, for reasons other than treatment success or failure, they had:

-

increased the dose of their allocated treatment

-

changed treatment or added a new treatment to their allocated treatment (for a reason other than for treatment failure or success)

-

used topical steroids between visit weeks 3 and 6

-

missed more than 3 consecutive days of treatment.

For non-inferiority outcomes after week 6, the PP populations consisted of those participants who were included in the PP analysis of the 6-week primary effectiveness outcome and who had:

-

not missed more than 3 consecutive weeks of allocated treatment between 6 and 52 weeks (regardless of whether the dose had been increased or decreased) unless they had stopped for good clinical response

-

used no more than 30 g of topical steroids per week after week 6

-

not added systemic steroids to doxycycline (if allocated) or doxycycline or an immunosuppressant to prednisolone (if allocated) unless for poor clinical response.

For the non-inferiority outcomes, 90% CIs are presented. For the study treatment doxycycline to be considered non-inferior to the control treatment, the upper bound of the 90% CI should fall below 37%. For the superiority outcomes, 95% CIs are presented. A difference between treatment arms was considered statistically significant at the 5% level, that is, the 95% CIs do not contain zero (no difference between arms).

The primary analysis had a dual outcome, one primary outcome for effectiveness and one for safety. For the study treatment doxycycline to be considered acceptable as an alternative to prednisolone, non-inferiority had to be demonstrated (as defined above) with regard to effectiveness, as well as the superiority of doxycycline over prednisolone for safety.

Subgroup analyses

For some patients the blister count at 6 weeks may have been performed by an investigator who knew what treatment the patient was on. To determine whether or not this introduced bias into the results of the 6-week effectiveness outcome, an interaction test was performed to compare the treatment effects in patients who were and patients who were not assessed by an investigator who knew the treatment allocation. This interaction analysis was performed on both the primary and the secondary definition of treatment success at 6 weeks.

Subgroup analyses of treatment success (using both definitions) at 6 weeks by the three categories of baseline disease severity (mild, moderate and severe) were also performed. A global test for a treatment interaction was used to determine whether or not treatment effects were different in the three categories of disease severity.

Cost-effectiveness

The EuroQoL tool

The EuroQol tool is a two-page questionnaire consisting of the EQ-5D descriptive system and the EuroQol visual analogue scale (EQ VAS). 32 The tool is a standardised measure of current health status developed by the EuroQol group for clinical and economic studies. The EQ-5D three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) was used, consisting of five questions addressing the health dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension is assessed at three levels: no problems, some problems and extreme problems. EQ-5D and EQ VAS data were collected using patient-completed questionnaires at baseline and 6, 13, 26, 39 and 52 weeks. Scores were converted to a single health-related index ranging from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health), with negative scores possible for some health states. Patients who died during the study were subsequently scored 0 at later scheduled follow-up visits.

Resource use

Resource use assessments were carried out at 3, 6, 13, 26, 39 and 52 weeks during mandatory clinical visits and were augmented by telephone calls. Recall was assisted by the use of patient diaries. Patients’ use of study and non-study drugs was recorded and costed using weighted average prices determined from Prescription Cost Analysis (PCA) data. 33 Health service contacts were recorded by asking patients to recall general practitioner (GP) clinic and home visits, practice and district nurse visits, outpatient visits and inpatient stays. Health-care resource use was costed using published national reference costs. 34–36 Patient-level resource costs were estimated as the sum of resources used weighted by their national reference costs.

Economic analysis

The economic analysis followed intention-to-treat (ITT) principles and a prospectively agreed analysis plan (see Appendix 2). No discounting was applied to economic data reflecting the follow-up period of 1 year. Costs were estimated in UK pounds sterling using patient resource use and 2013 reference costs. 35 The analysis took an English NHS perspective, reporting generic (EQ-5D, EQ VAS)32 and disease-specific (DLQI)37 health outcomes. Repeated scores over time were used to construct area under the curve (AUC) estimates for each patient, using the trapezoidal method. Missing values at individual follow-up points were managed using two scenarios: multiple imputation (the base-case analysis38) and analysis of complete cases (in which patients with any missing data were excluded).

Patient estimates of costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) at 1 year were used to derive an estimate of the cost-effectiveness of doxycycline-initiated therapy compared with prednisolone-initiated therapy for patients with BP. Estimates using imputed missing data provided the base-case analysis and estimates using complete data provided supportive sensitivity analysis. Analysis and modelling were undertaken in Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The base-case analysis included the imputed within-trial incremental cost/QALYs gained, adjusted for trial covariates (age, sex, baseline blister severity and baseline Karnofsky score). QALY estimates were also adjusted for baseline EQ-5D score.

Chapter 3 Results

Study population

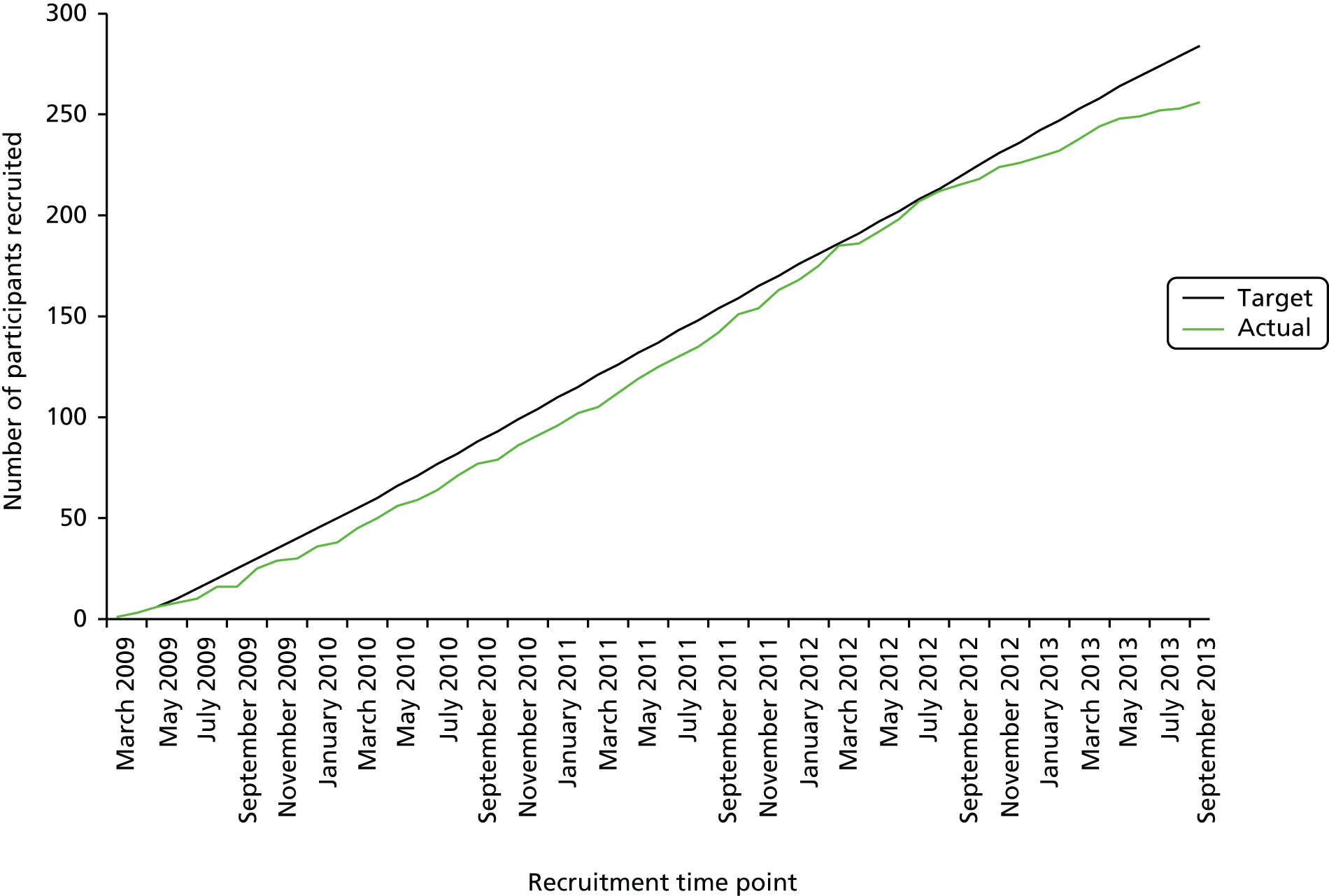

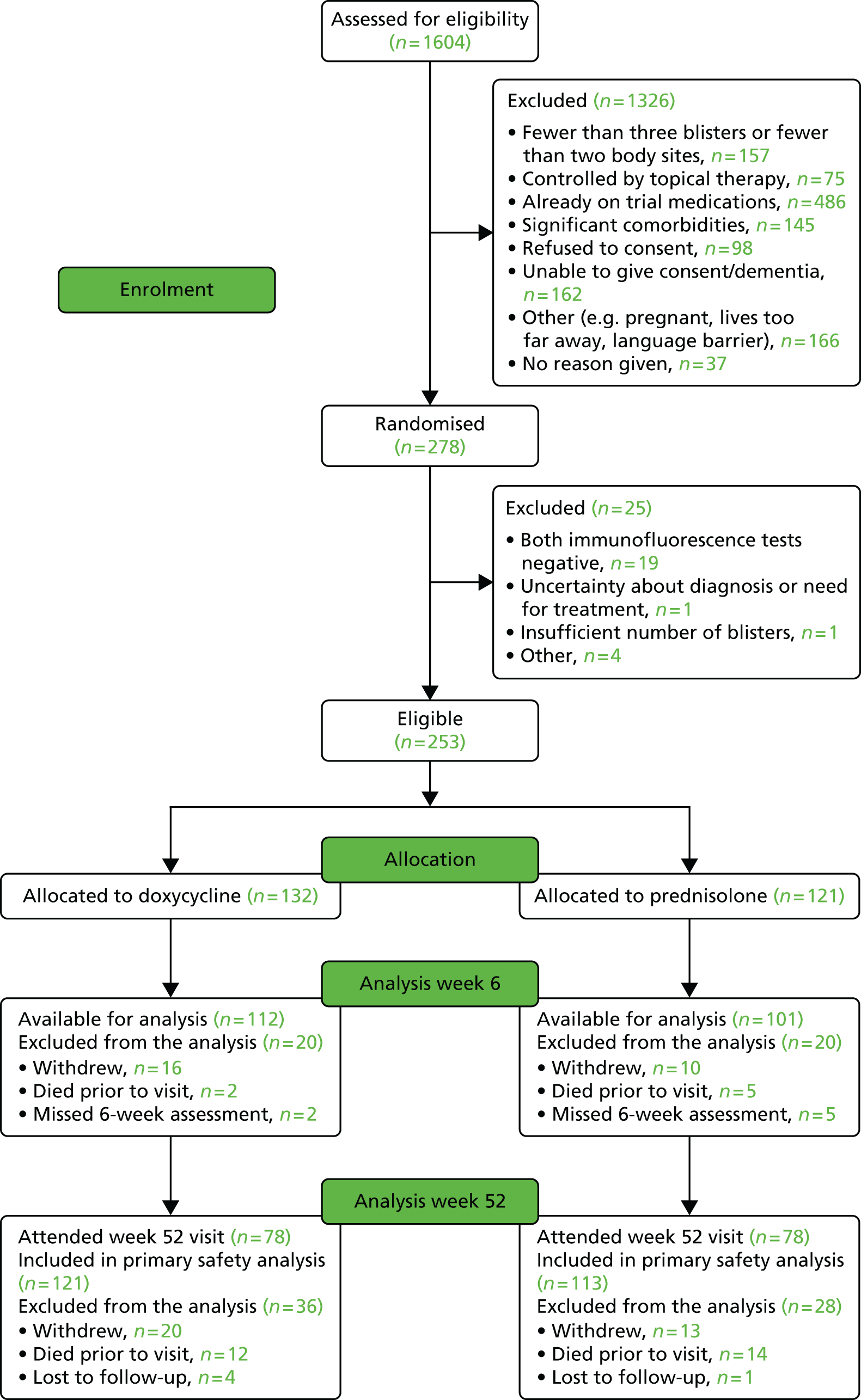

Recruitment commenced in March 2009 in the UK and in February 2010 in Germany and was completed in October 2013. In total, 278 patients were randomised from 54 centres in the UK and seven centres in Germany (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment graph.

Of the 1604 patients screened for eligibility, 1326 were excluded, mainly because of an inability to provide informed consent, frailty or their disease being too mild or because they had already been started on prednisolone by their GP (Figure 3). Of the 278 patients randomised, 140 were allocated to the doxycycline arm and 138 to the prednisolone arm (Table 1). However, 19 patients were excluded because both the direct and the indirect immunofluorescence tests were negative and a further six were excluded for other eligibility reasons. Therefore, 253 patients were included in the analyses, 132 in the doxycycline arm and 121 in the prednisolone arm (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow chart. Those patients excluded from analysis at week 6 because they missed the week 6 assessment are included in the denominator at week 52 as they have the possibility of attending a visit after week 6 and therefore are not considered lost to follow-up at week 6. Patients who did not attend their week 52 visit are designated as lost to follow-up at week 52. Reproduced from Williams et al. 24 under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence (CC-BY) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0).

| Patient status | Doxycycline | Prednisolone | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 140 | 138 | 278 |

| Number withdrawn because of ineligibility | 8 | 17 | 25 |

| Reasons for ineligibility | |||

| Both direct and indirect immunofluorescence tests were negative | 4 | 15 | 19 |

| Investigator felt on reflection that patient did not have sufficient blisters to meet the inclusion criteria and therefore should be withdrawn from the trial | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Uncertainty initially about diagnosis, negative indirect immunofluorescence, need for treatment | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Patient ineligible for other reasons | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Number to be analysed | 132 | 121 | 253 |

Baseline characteristics

Of the 253 eligible patients randomised, 52.6% were men and 47.4% were women. The average age was 77.7 years, with 25.3% aged > 85 years, 37.9% aged from 75 to < 85 years, 28.1% aged from 65 to < 75 years and 8.7% aged < 65 years. There was a good distribution of baseline severity of disease: 29.3% of patients had severe BP (> 30 blisters), 39.1% had moderate disease (10–30 blisters) and 31.6% had mild disease (three to nine blisters). The two groups were also balanced for Karnofsky score of functional impairment and ethnicity (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Doxycycline, n (%) | Prednisolone, n (%) | Total, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 63 (47.7) | 57 (47.1) | 120 (47.4) |

| Male | 69 (52.3) | 64 (52.9) | 133 (52.6) |

| Age (years)a | 78.1 (9.5) | 77.2 (10.0) | 77.7 (9.7) |

| < 65 | 8 (6.1) | 14 (11.6) | 22 (8.7) |

| 65 to < 75 | 38 (28.8) | 33 (27.3) | 71 (28.1) |

| 75 to < 85 | 51 (38.6) | 45 (37.2) | 96 (37.9) |

| ≥ 85 | 35 (26.5) | 29 (24.0) | 64 (25.3) |

| Karnofsky scorea | 69.0 (18.3) | 70.5 (17.6) | 69.7 (18.0) |

| < 40 | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (1.6) |

| 40 to < 55 | 32 (24.2) | 26 (21.5) | 58 (22.9) |

| 55 to < 70 | 21 (15.9) | 24 (19.8) | 45 (17.8) |

| 70 to < 85 | 45 (34.1) | 38 (31.4) | 83 (32.8) |

| ≥ 85 | 31 (23.5) | 32 (26.4) | 63 (24.9) |

| Unable to care for self | 16 (12.1) | 11 (9.1) | 27 (10.7) |

| Unable to work | 55 (41.7) | 51 (42.1) | 106 (41.9) |

| Ableb | 61 (46.2) | 59 (48.8) | 120 (47.4) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 112 (84.8) | 100 (82.6) | 212 (83.8) |

| Black – African | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| Black – other | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Asian – Indian | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.2) |

| Asian – Chinese | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Asian – other | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.2) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Not known/given | 14 (10.6) | 16 (13.2) | 30 (11.9) |

| Severity of BP | |||

| Mild (3–9 blisters) | 42 (31.8) | 38 (31.4) | 80 (31.6) |

| Moderate (10–30 blisters) | 53 (40.2) | 46 (38.0) | 99 (39.1) |

| Severe (> 30 blisters) | 37 (28.0) | 37 (30.6) | 74 (29.2) |

| Total n | 132 | 121 | 253 |

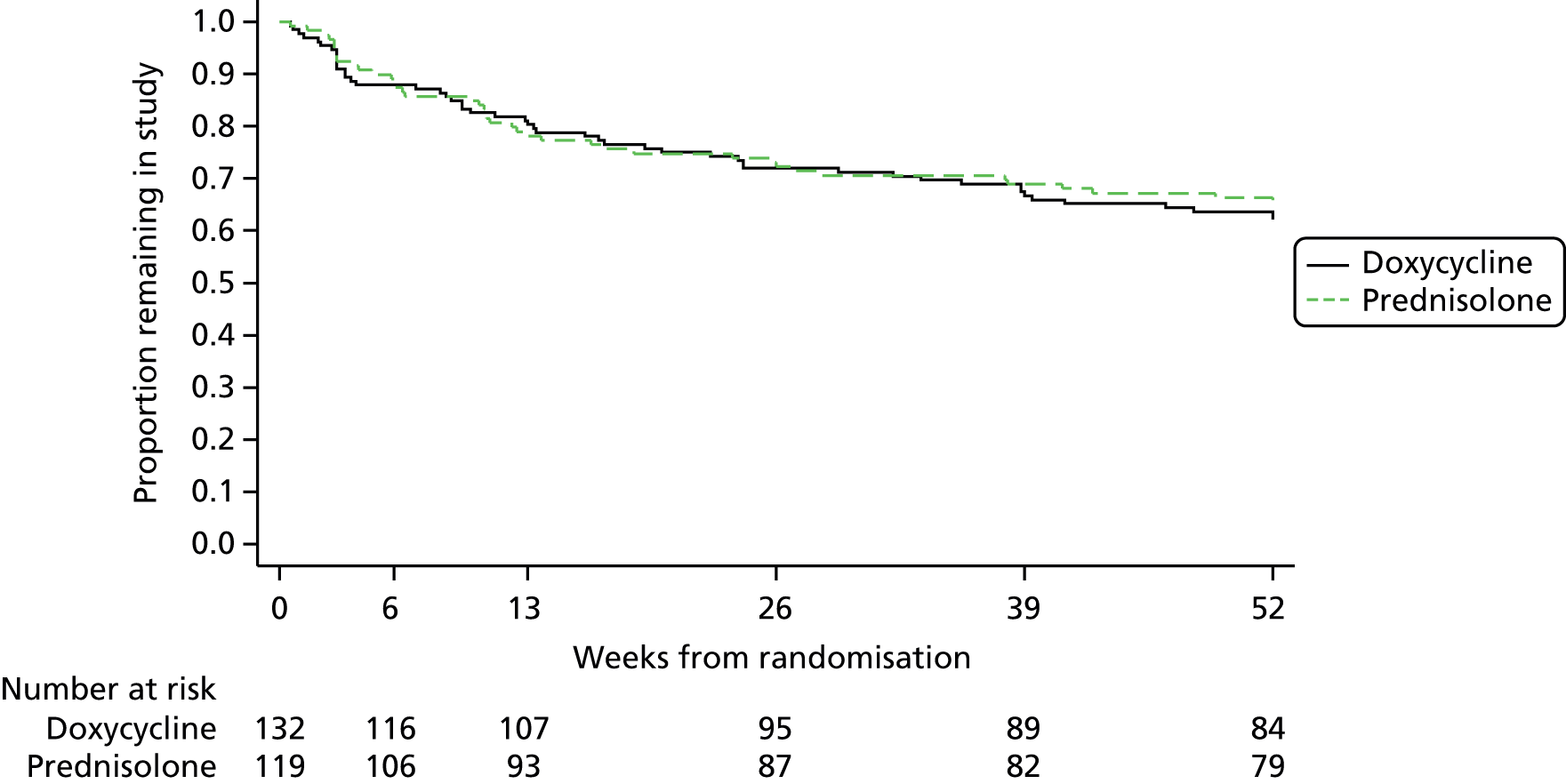

Withdrawals

A total of 92 patients (36.8%) withdrew from the trial with a similar rate between the two arms (Tables 3 and 4). The most common reasons were withdrawal of consent and patient died. The withdrawal rate remained similar throughout the 52-week follow-up period (Table 5 and Figure 4).

| Primary reason for withdrawal | Doxycycline (n = 132), n | Prednisolone (n = 121), n | Total, N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 14 | 19 | 33a |

| Adverse event | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Lost to follow-up | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Treatment failure | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Withdrew consent | 23 | 16 | 39 |

| Unable to tolerate trial medications | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 50 | 42 | 92 |

| Week | Patient status | Doxycycline (n = 132), n (%) | Prednisolone (n = 121), n (%) | Total (N = 253), N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Seen | 120 (90.9) | 110 (90.9) | 230 (90.9) |

| Died before visit | 1 (0.8) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (2.0) | |

| Withdrew before visit | 9 (6.8) | 5 (4.1) | 14 (5.5) | |

| Visit not conducted/status not known | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (1.6) | |

| Total expected | 132 | 121 | 253 | |

| 6 | Seen | 112 (91.8) | 101 (90.2) | 213 (91.0) |

| Died before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Withdrew before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 7 (5.7) | 5 (4.5) | 12 (5.1) | |

| Visit not conducted/status not known | 2 (1.6) | 5 (4.5) | 7 (3.0) | |

| Total expected | 122 | 112 | 234 | |

| 13 | Seen | 99 (86.8) | 94 (88.7) | 193 (87.7) |

| Died before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 5 (4.4) | 5 (4.7) | 10 (4.5) | |

| Withdrew before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 3 (2.6) | 6 (5.7) | 9 (4.1) | |

| Visit not conducted/status not known | 7 (6.1) | 1 (0.9) | 8 (3.6) | |

| Total expected | 114 | 106 | 220 | |

| 26 | Seen | 88 (83.0) | 81 (85.3) | 169 (84.1) |

| Died before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 2 (1.9) | 6 (6.3) | 8 (4.0) | |

| Withdrew before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 9 (8.5) | 4 (4.2) | 13 (6.5) | |

| Visit not conducted/status not known | 7 (6.6) | 4 (4.2) | 11 (5.5) | |

| Total expected | 106 | 95 | 201 | |

| 39 | Seen | 81 (85.3) | 79 (92.9) | 160 (88.9) |

| Died before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 3 (3.2) | 2 (2.4) | 5 (2.8) | |

| Withdrew before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 5 (5.3) | 3 (3.5) | 8 (4.4) | |

| Visit not conducted/status not known | 6 (6.3) | 1 (1.2) | 7 (4.4) | |

| Total expected | 95 | 85 | 180 | |

| 52 | Seen | 78 (89.7) | 78 (97.5) | 156 (93.4) |

| Died before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (1.8) | |

| Withdrew before visit, but after last scheduled visit | 3 (3.4) | 0 | 3 (1.8) | |

| Visit not conducted/status not known | 4 (4.6) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (3.0) | |

| Total expected | 87 | 80 | 167 |

| Week | Patient status | Doxycycline (n = 132), n (%) | Prednisolone (n = 121), n (%) | Total (N = 253), N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Died before visit | 1 (0.8) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (2.0) |

| Withdrew before visit | 9 (6.8) | 5 (4.1) | 14 (5.5) | |

| 6 | Died before visit | 2 (1.5) | 5 (4.1) | 7 (2.8) |

| Withdrew before visit | 16 (12.1) | 10 (8.3) | 26 (10.3) | |

| 13 | Died before visit | 7 (5.3) | 10 (8.3) | 17 (6.7) |

| Withdrew before visit | 19 (14.4) | 16 (13.2) | 35 (13.8) | |

| 26 | Died before visit | 9 (6.8) | 16 (13.2) | 25 (9.9) |

| Withdrew before visit | 28 (21.2) | 20 (16.5) | 48 (19.0) | |

| 39 | Died before visit | 12 (9.1) | 18 (14.9) | 30 (11.9) |

| Withdrew before visit | 33 (25.0) | 23 (19.0) | 56 (22.1) | |

| 52 | Died before visit | 14 (10.6) | 19 (15.7) | 33 (13.0) |

| Withdrew before visit | 36 (27.3) | 23 (19.0) | 59 (23.3) |

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival plot showing time to withdrawal (including death).

Adherence to interventions for primary effectiveness at 6 weeks

Of the participants who had data available for the week 6 primary effectiveness analysis (mITT population), 18.8% in the doxycycline group missed > 3 days of treatment during the first 6 weeks, compared with 5.0% in the prednisolone group (Table 6). Nausea was cited as the most frequent reason for reduced adherence to doxycycline in the first 6 weeks (mentioned in 10/21 cases).

| Missed > 3 consecutive days of treatment before week 6 | Doxycycline, n (%) | Prednisolone, n (%) | Total, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 21 (18.8) | 5 (5.0) | 26 (12.2) |

| No | 91 (81.3) | 96 (95.0) | 187 (87.8) |

| Total | 112 | 101 | 213 |

Primary outcomes

Primary effectiveness outcome

The primary effectiveness outcome was a non-inferiority comparison of the proportions of patients achieving treatment success at 6 weeks, defined as three or fewer significant blisters. It was anticipated that doxycycline would be less effective than prednisolone but that this would be accompanied by an improvement in the safety profile. As is best practice for non-inferiority comparisons, both mITT and PP analyses were performed.

Modified intention-to-treat analysis

The mITT population included all participants regardless of any changes to treatment, provided that they had survived to week 6 and had received a blister count. This analysis reflects the comparison of the two strategies of starting on doxycycline or starting on prednisolone. In total, 91.1% of patients who were randomised to the prednisolone group were considered to be a treatment success at 6 weeks compared with 74.1% of patients who were randomised to the doxycycline group (Table 7). Although this is an 18.6% adjusted difference in effectiveness in favour of prednisolone (90% CI 11.1% to 26.1%), the upper CI falls well within the prespecified bounds of non-inferiority (37%) and doxycycline can therefore be considered non-inferior.

| Outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 83 (74.1) | 92 (91.1) |

| Failure | 29 (25.9) | 9 (8.9) |

| Total | 112 | 101 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) | Adjusted:a 18.6% (90% CI 11.1% to 26.1%) | |

| Unadjusted: 17.0% (90% CI 8.7% to 25.2%) | ||

There was no evidence of an interaction between disease severity and treatment effect in either the mITT or the PP population.

Per-protocol analysis

Patients were excluded from the PP analysis for deviations from the protocol that could significantly affect the outcome. Patients may appear more than once under the various reasons for exclusion if they met more than one of the criteria. The results of the PP analysis were very similar to the results of the ITT analysis, with 92.3% of patients in the prednisolone group achieving success compared with 74.4% in the doxycycline group, an adjusted difference of 18.7% (90% CI 9.8% to 27.6%) (Table 8), which falls well within the 37% upper bound for the 90% CI.

| Outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone, n (%) | |

| Success | 58 (74.4) | 84 (92.3) |

| Failure | 20 (25.6) | 7 (7.7) |

| Total | 78 | 91 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 18.7 (9.8 to 27.6) | |

| Unadjusted: 17.9 (8.6 to 27.3) | ||

Both the mITT and PP analyses are represented graphically in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Proportions of participants who achieved treatment success at 6 weeks: mITT and PP analyses.

Subgroup analyses

Two subgroup analyses were performed to test for treatment interactions. There were no significant interactions in either the mITT or the PP populations between effectiveness at 6 weeks and baseline disease severity (mild, moderate and severe) (Tables 9 and 10 respectively) or between effectiveness at 6 weeks and the blinding status of the investigator who carried out the week 6 blister count (Tables 11 and 12, respectively).

| Outcome | Subgroupa | Number (%) of patients | Proportion a treatment success (90% CI) (%)b | Difference in proportionsb (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Interaction test p-valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 112) | Prednisolone (N = 101) | Doxycycline | Prednisolone | ||||

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline)b | Mild baseline severity | 37 (33.0) | 31 (30.7) | 75.7 (64.1 to 87.3) | 96.8 (91.6 to 102.0) | 21.1 (8.4 to 33.8) | – |

| Moderate baseline severity | 46 (41.1) | 42 (42.6) | 78.3 (68.3 to 88.3) | 97.6 (93.7 to 101.5) | 19.4 (8.6 to 30.1) | 0.863 | |

| Severe baseline severity | 29 (25.9) | 28 (27.7) | 65.5 (51.0 to 80.0) | 75.0 (61.5 to 88.5) | 9.5 (–10.3 to 29.3) | 0.417 | |

| Outcome | Subgroupa | Number (%) of patients | Difference in proportions achieving treatment success (prednisolone – doxycycline)b (90% CI) (%) | Interaction test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 78) | Prednisolone (N = 91) | ||||

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline)b | Mild baseline severity | 22 (28.2) | 26 (28.6) | 23.4 (6.6 to 40.2) | – |

| Moderate baseline severity | 34 (43.6) | 40 (44.0) | 24.8 (9.8 to 43.0) | 0.672 | |

| Severe baseline severity | 22 (28.2) | 25 (27.5) | 7.3 (–13.1 to 27.7) | 0.477 | |

| Outcome | Subgroup | Number (%) of patients | Difference in proportions achieving treatment success (prednisolone – doxycycline)a (90% CI) (%) | Interaction test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 112) | Prednisolone (N = 101) | ||||

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline)a | Medication was not known | 70 (62.5) | 64 (63.4) | 20.6 (9.8 to 31.4) | 0.333 |

| Medication was known | 42 (37.5) | 37 (36.6) | 21.9 (10.2 to 33.5) | – | |

| Outcome | Subgroup | Number (%) of patients | Difference in proportions achieving treatment success (prednisolone – doxycycline)a (90% CI) (%) | Interaction test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 78) | Prednisolone (N = 91) | ||||

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline)a | Medication was not known | 53 (68.0) | 59 (64.8) | 21.5 (10.0 to 33.0) | 0.356 |

| Medication was known | 25 (32.1) | 32 (35.2) | 10.6 (5.0 to 26.3) | – | |

Primary safety outcome

The primary safety outcome was the proportion of patients who, during the 52 weeks following randomisation, experienced at least one adverse event that was judged to be either grade 3 (severe), grade 4 (life-threatening) or grade 5 (death) and possibly, probably or definitely related to study treatment. The mITT population for this primary safety outcome included all those with data from at least one scheduled visit, regardless of any changes to treatment. An adjusted regression model in which preceding visits were set to zero was used to impute missing data to determine the sensitivity of the observed results to the missing data.

The risk of experiencing a treatment-related severe, life-threatening or fatal adverse event for patients started on doxycycline was 18.2%; this compared with 36.3% for those starting on prednisolone (Table 13). This represents a difference of 19.0% (95% CI 7.9% to 30.1%) after adjusting for baseline severity of BP. Similar results were obtained from a regression model in which missing data had been imputed: 22.5% of patients in the doxycycline group experienced a treatment-related severe, life-threatening or fatal adverse event compared with 40.0% in the prednisolone group, a difference of 18.4% (95% CI 6.0% to 30.8%) after adjusting for baseline severity of BP (Table 14).

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients with an adverse event of grade 3 or above (%)a | 18.2 | 36.3 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (95% CI) (%) | Adjusted:b 19.0 (7.9 to 30.1); p = 0.001 | |

| Unadjusted: 18.1 (6.9 to 29.3); p = 0.002 | ||

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients with an adverse event of grade 3 or above (%)a | 22.5 | 40.0 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (95% CI) (%) | Adjusted:b 18.4 (6.0 to 30.8); p = 0.004 | |

| Unadjusted: 17.5 (4.8 to 30.1); p = 0.007 | ||

A higher number of participants in the prednisolone group than in the doxycycline group had a maximum grade of adverse event of grade 3 (severe) and grade 5 (death) (Table 15). The pattern was the same for the total number of adverse events of each grade (Table 16).

| Adverse event | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 121) | Prednisolone (N = 113) | |

| No adverse events or maximum grade of 1 (mild) or 2 (moderate) | 99 (81.8) | 72 (63.7) |

| Maximum grade of 3 (severe) | 14 (11.6) | 25 (22.1) |

| Maximum grade of 4 (life-threatening) | 5 (4.1) | 5 (4.4) |

| Maximum grade of 5 (death) | 3 (2.5) | 11 (9.7) |

| Maximum grade of 3, 4 or 5 | 22 (18.2) | 41 (36.3) |

| Adverse event | Number (%) of adverse events (mean per participant) | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 121) | Prednisolone (N = 113) | |

| Grade 3 (severe) | 33 (0.3)a | 59 (0.5) |

| Grade 4 (life-threatening) | 9 (0.1) | 9 (0.1) |

| Grade 5 (death) | 3 (< 0.1) | 11 (0.1) |

| Grades 3–5 | 45 (0.4) | 79 (0.7) |

Secondary outcomes

Secondary effectiveness outcome: weeks 6, 13 and 52

For secondary effectiveness outcomes, the definition of treatment success was different from that used for the primary effectiveness outcome. A participant was required to have three or fewer significant blisters present on examination to be considered a treatment success but, unlike the primary effectiveness analysis, patients who had had their treatment modified because of a poor response (change of medication or dose of randomised medication increased) prior to the visit did not qualify as a success in the secondary analyses. This difference is because the primary effectiveness outcome assessed the strategy of starting on doxycycline or starting on prednisolone, whereas the secondary outcomes assessed the effectiveness of the treatments used as longer-term monotherapy. All secondary effectiveness outcomes are non-inferiority analyses.

The proportion of patients classed as a treatment success at 6 weeks in the mITT analysis, according to the definition of success described above, was 85.4% in the prednisolone group and 53.6% in the doxycycline group (Table 17). This represents a difference of 31.8% (90% CI 22.5% to 41.2%) in favour of prednisolone after adjusting for baseline severity of BP and age. The PP analysis showed similar results, with a difference of 34.4% (90% CI 23.7% to 45.1%) in favour of prednisolone after adjusting for baseline severity of BP and age (Table 18). The upper CIs for both analyses fall just outside the prespecified upper bound of 37%. Subgroup analyses of the effectiveness outcome data at week 6 using the secondary outcome definition failed to show any evidence of interaction between disease severity and treatment effect (Tables 19 and 20) in either the mITT or the PP population. There was no interaction between blinding status and treatment effect at 6 weeks using the secondary outcome definition in the mITT analysis (Table 21) but there was some evidence of an interaction effect when a PP analysis was done (Table 22).

| Treatment outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Successa | 60 (53.6) | 88 (85.4) |

| Failure | ||

| High blister countb | 29 (25.9) | 9 (8.7) |

| Changed treatment | 23 (20.5) | 4 (3.9) |

| Died before week 6 | 0 | 2 (1.9) |

| Total | 112 | 103 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:c 31.8 (22.5 to 41.2) | |

| Unadjusted: 31.9 (22.2 to 41.5) | ||

| Treatment outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 41 (52.6) | 81 (87.1) |

| Failure | ||

| High blister count | 20 (25.6) | 7 (7.5) |

| Changed treatment | 17 (21.8) | 3 (3.2) |

| Died before week 6 | 0 | 2 (2.2) |

| Total | 78 | 93 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 34.4 (23.7 to 45.1) | |

| Unadjusted: 34.5 (23.6 to 45.4) | ||

| Outcome | Subgroup | Number (%) of patients | Difference in proportions achieving treatment success (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Interaction test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 112) | Prednisolone (N = 103) | ||||

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline)a | Mild baseline blister severity (< 10) | 37 (33.0) | 32 (31.1) | 28.5 (12.9 to 44.2) | – |

| Moderate baseline blister severity (10–30) | 46 (41.1) | 42 (40.8) | 31.7 (17.5 to 45.8) | 0.806 | |

| Severe baseline blister severity (> 30) | 29 (25.9) | 29 (28.2) | 37.9 (18.0 to 58.8) | 0.543 | |

| Outcome | Subgroup | Number (%) of patients | Difference in proportions achieving treatment success (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Interaction test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 78) | Prednisolone (N = 93) | ||||

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline)a | Mild baseline blister severity (< 10) | 22 (28.2) | 27 (29.0) | 33.4 (14.3 to 52.5) | – |

| Moderate baseline blister severity (10–30) | 34 (43.6) | 40 (43.0) | 34.2 (18.2 to 50.2) | 0.956 | |

| Severe baseline blister severity (> 30) | 22 (28.2) | 26 (28.0) | 36.1 (14.1 to 58.1) | 0.878 | |

| Outcome | Subgroup | Number (%) of patients | Difference in proportions achieving treatment success (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Interaction test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 112) | Prednisolone (N = 101) | ||||

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline)a | Medication was not known | 70 (62.5) | 64 (63.4) | 25.1 (13.7 to 36.5) | – |

| Medication was known | 42 (37.5) | 37 (36.6) | 46.2 (31.6 to 60.9) | 0.059 | |

| Outcome | Subgroup | Number (%) of patients | Difference in proportions achieving treatment success (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Interaction test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 78) | Prednisolone (N = 91) | ||||

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline)a | Medication was not known | 53 (67.9) | 59 (64.8) | 25.0 (12.2 to 37.8) | – |

| Medication was known | 25 (32.1) | 32 (35.2) | 57.7 (40.3 to 75.1) | 0.013 | |

At 13 weeks, in the mITT analysis, 75.3% of patients in the prednisolone group were considered a treatment success compared with 58.6% in the doxycycline group, a difference of 17.5% (90% CI 6.8% to 28.2%) in favour of prednisolone after adjusting for baseline severity of BP and age (Table 23). Again, similar results were noted for the PP analysis (a difference of 17.3% in favour of prednisolone, 90% CI 4.9% to 29.7%) (Table 24).

| Treatment outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 58 (58.6) | 76 (75.2) |

| Failure | ||

| High blister count | 12 (12.1) | 6 (5.9) |

| Changed treatment | 29 (29.3) | 12 (11.9) |

| Died before week 13 | 0 | 7 (6.9) |

| Total | 99 | 101 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 17.5 (6.8 to 28.2) | |

| Unadjusted: 16.7 (5.9 to 27.4) | ||

| Treatment outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 38 (60.3) | 71 (78.0) |

| Failure | ||

| High blister count | 5 (7.9) | 5 (5.5) |

| Changed treatment | 20 (31.8) | 9 (9.9) |

| Died before week 13 | 0 | 6 (6.6) |

| Total | 63 | 91 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 17.3 (4.9 to 29.7) | |

| Unadjusted: 17.7 (5.3 to 30.1) | ||

The longer-term assessment of effectiveness (the proportion classed as a success at 52 weeks) shows that, in the adjusted mITT analysis, 41.0% of patients started on doxycycline compared with 51.1% of those started on prednisolone achieved treatment success, a difference of 10.0% (90% CI –2.3% to 22.2%) in favour of prednisolone (Table 25). Similar results were seen for the PP analysis, with a difference of 7.1% (90% CI –7.1% to 21.3%) in favour of prednisolone (Table 26).

| Treatment outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 34 (41.0) | 45 (51.1) |

| Failure | ||

| High blister count | 3 (3.6) | 3 (3.4) |

| Changed treatment | 43 (51.8) | 29 (33.0) |

| Died before week 52 | 3 (3.6) | 11 (12.5) |

| Total | 83 | 88 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 10.0 (–2.3 to 22.2) | |

| Unadjusted: 10.2 (–2.3 to 22.6) | ||

| Treatment outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 24 (45.3) | 41 (53.3) |

| Failure | ||

| High blister count | 2 (3.8) | 3 (3.9) |

| Changed treatment | 25 (47.2) | 23 (29.9) |

| Died before week 52 | 2 (3.8) | 10 (13.0) |

| Total | 53 | 77 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 7.1 (–7.1 to 21.3) | |

| Unadjusted: 8.0 (–6.7 to 22.6) | ||

Secondary outcome: relapse rates

Another measure of the long-term effectiveness of the two treatments was the proportion of participants who had a further episode of BP during their participation in the study after previously being classed as a treatment success. A participant was classed as having a relapse if he or she had a further episode of BP, defined as more than three significant blisters, or a change or escalation of treatment because of worsening of disease during participation in the study after previously being classed as a treatment success (either three or fewer significant blisters present on prior examination or previously classed as a treatment success on the treatment log). After adjusting for baseline severity, age and Karnofsky score, a similar number of relapses occurred in the doxycycline group and the prednisolone group in the mITT population (2.1% more in the prednisolone group, 90% CI –8.3% to 12.5%) (Table 27). A larger difference was noted in the PP analysis (11.0% more relapses in the prednisolone group, 90% CI –1.2% to 23.2%) (Table 28).

| Outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Relapse | 37 (32.5) | 39 (35.8) |

| No relapse | 77 (67.5) | 70 (64.2) |

| Total | 114 | 109 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 2.1 (–8.3 to 12.5) | |

| Unadjusted: 3.3 (–7.1 to 13.8) | ||

| Outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Relapse | 20 (27.0) | 34 (38.6) |

| No relapse | 54 (73.0) | 54 (61.4) |

| Total | 74 | 88 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 11.0 (–1.2 to 23.2) | |

| Unadjusted: 11.6 (–0.4 to 23.7) | ||

Secondary outcome: combined outcome of effectiveness at 6 weeks and safety over 52 weeks

To provide an overall measure of success, a combined analysis of effectiveness and safety is presented in a superiority analysis. In the prednisolone group, 74.8% of patients were classed as a treatment success at 6 weeks and were alive at 52 weeks whereas in the doxycycline group 50.0% of patients were classed as a treatment success at 6 weeks and were alive at 52 weeks (Table 29). This represents a difference of 25.0% (95% CI 13.1% to 37.0%) in favour of prednisolone after adjusting for baseline severity and age.

| Treatment success | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 56 (50.0) | 77 (74.8) |

| Failure | ||

| Success at week 6 but not alive at week 52 | 4 (3.6) | 11 (10.7) |

| Not successful at week 6 because of high blister count | 29 (25.9) | 9 (8.7) |

| Not successful at week 6 because of treatment change before week 6 | 23 (20.5) | 4 (3.9) |

| Not successful at week 6 because of death before week 6 | 0 | 2 (1.9) |

| Total | 112 | 103 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (95% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 25.0 (13.1 to 37.0); p < 0.001 | |

| Unadjusted: 24.8 (14.3 to 35.2); p < 0.001 | ||

Secondary safety outcome: all adverse events

This secondary outcome includes all adverse events that are possibly, probably or definitely related to the trial medication, regardless of severity. All analyses were carried out on a superiority basis. The maximum grade of related adverse events experienced by participants during the trial is shown in Table 30. Patients in the prednisolone group were significantly more likely to experience an adverse event that was related to the study medication than those in the doxycycline group (95.7% vs. 86.2%, 95% CI 1.8% to 17.2%; p = 0.016, unadjusted because of non-convergence in the model) (Table 31). The total numbers of related adverse events by grade (raw data) are shown in Table 32.

| Adverse event | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 121) | Prednisolone (N = 113) | |

| No adverse events | 23 (19.0) | 13 (11.5) |

| Maximum grade of adverse event grade 1 (mild) | 20 (16.5) | 16 (14.2) |

| Maximum grade of adverse event grade 2 (moderate) | 56 (46.3) | 43 (38.1) |

| Maximum grade of adverse event grade 3 (severe) | 14 (11.6) | 25 (22.1) |

| Maximum grade of adverse event grade 4 (life-threatening) | 5 (4.1) | 5 (4.4) |

| Maximum grade of adverse event grade 5 (death) | 3 (2.5) | 11 (9.7) |

| Adverse event of any grade | 98 (81.0) | 100 (88.5) |

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of patients with an adverse event (%)a | 86.2 | 95.7 |

| Difference in proportion of patients with an adverse event (prednisolone – doxycycline) (95% CI) (%) | Unadjusted:b 9.5 (1.8 to 17.2); p = 0.016 | |

| Adverse event | Number of adverse events (mean per participant) | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (n = 121) | Prednisolone (n = 113) | |

| Grade 1 (mild) | 210 (1.7) | 234 (2.1) |

| Grade 2 (moderate) | 158 (1.3) | 129 (1.1) |

| Grade 3 (severe) | 33 (0.3) | 59 (0.5) |

| Grade 4 (life-threatening) | 9 (0.1) | 9 (0.1) |

| Grade 5 (death) | 3 (< 0.1) | 11 (0.1) |

| Grades 1–5 | 413 (3.4) | 442 (3.9) |

Secondary outcome: quality of life

Quality of life was assessed using the generic EQ-5D and the skin-specific DLQI. For a specific visit, the EQ-5D tabulations and analyses were conducted on all patients in the ITT population who had all five scores for the five questions for that visit (mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Only patients who had at least one visit (not including baseline) for which data were available were included in the analysis. The EQ-5D score (social preference score) was obtained, with a value assigned to each combination of scores from the individual five questions (see Chapter 4, Data sources). For the DLQI, the tabulations and analyses were conducted for a specific visit on all patients in the ITT population who had all 10 scores for the 10 questions for that visit. Only patients who had at least one visit (not including baseline) for which data were available were included in the analysis. The DLQI score was calculated as the sum of each of the scores for the 10 questions asked at each visit.

There was a median change in EQ-5D score from baseline to week 52 of +0.090 in the doxycycline group and +0.071 in the prednisolone group (Table 33). When this was adjusted for baseline EQ-5D score, baseline severity, age and Karnofsky score, the difference was not significant (0.045, 95% CI –0.015 to 0.106; p = 0.143) (Table 34). Patients in the two groups had a similar improvement in DLQI score, with a median improvement from baseline to week 52 of 9 points in the doxycycline group and 10 points in the prednisolone group (Table 35). When adjusted for baseline DLQI score, baseline severity, age and Karnofsky score, there was a significant difference of –1.8 (95% CI –2.58 to –1.01) in favour of doxycycline (Table 36).

| Time point | Doxycycline (n = 110) | Prednisolone (n = 101) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median change from baseline | Total patients with data | Median (IQR) | Median change from baseline | Total patients with data | |

| Baseline | 0.656 (0.273–0.796) | 0 | 110 | 0.656 (0.273–0.760) | 0 | 101 |

| Week 6 | 0.620 (0.353–0.805) | –0.036 | 108 | 0.746 (0.587–1.000) | +0.090 | 96 |

| Week 13 | 0.710 (0.450–1.000) | +0.054 | 96 | 0.779 (0.639–0.925) | +0.123 | 92 |

| Week 26 | 0.746 (0.587–1.000) | +0.090 | 85 | 0.796 (0.638–0.850) | +0.140 | 80 |

| Week 39 | 0.727 (0.587–1.000) | +0.071 | 79 | 0.710 (0.587–1.000) | +0.054 | 77 |

| Week 52 | 0.746 (0.587–1.000) | +0.090 | 78 | 0.727 (0.587–1.000) | +0.071 | 74 |

| Difference in EQ-5D scores (prednisolone – doxycycline) (95% CI) | Adjusted:a 0.045 (–0.015 to 0.106); p = 0.143 |

| Unadjusted:b 0.062 (–0.006 to 0.130); p = 0.076 |

| Time point | Doxycycline (n = 108) | Prednisolone (n = 101) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median change from baseline | Total patients with data | Median (IQR) | Median change from baseline | Total patients with data | |

| Baseline | 10 (6–15) | 0 | 108 | 11 (6–14) | 0 | 101 |

| Week 6 | 5 (2–9) | –5 | 106 | 1 (0–3) | –10 | 96 |

| Week 13 | 2 (1–6) | –8 | 98 | 1 (0–4) | –10 | 90 |

| Week 26 | 2 (0–4) | –8 | 86 | 1 (0–3) | –10 | 80 |

| Week 39 | 1 (0–4) | –9 | 80 | 1 (1–3) | –10 | 77 |

| Week 52 | 1 (0–3) | –9 | 79 | 1 (0–3) | –10 | 75 |

| Difference in DLQI scores (prednisolone – doxycycline) (95% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a,b –1.80 (–2.58 to –1.01); p < 0.001 |

Tertiary outcomes

The mITT analysis showed that there was a higher proportion of participants who were completely blister free at 6 weeks (rather than three or fewer significant blisters) in the prednisolone group (73.3% vs. 45.9%) (Table 37). This is a difference of 28.6% in favour of prednisolone after adjusting for baseline severity, age and Karnofsky score (90% CI 18.1 to 39.1%). Table 38 lists the number of patients in the mITT population excluded from the PP analysis. The PP analysis showed very similar results (Table 39).

| Outcome | Number (%) of patients) | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Blister free | 51 (45.9) | 74 (73.3) |

| Not blister free | 60 (54.1) | 27 (26.7) |

| Total | 111 | 101 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 28.6 (18.1 to 39.1) | |

| Unadjusted: 27.3 (16.7 to 38.0) | ||

| Reason for exclusion | Doxycycline, n | Prednisolone, n |

|---|---|---|

| Increased the dose of the allocated treatment before week 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Changed treatment or added a new treatment to the allocated treatment before week 6 | 17 | 3 |

| Used topical steroids between weeks 3 and 6 | 7 | 3 |

| Missed more than 3 consecutive days of treatment before week 6 | 21 | 5 |

| Total number of non-PP patients | 34 | 10 |

| Outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Blister free | 35 (45.5) | 68 (74.7) |

| Not blister free | 42 (54.5) | 23 (25.3) |

| Total | 77 | 91 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 30.2 (18.4 to 42.0) | |

| Unadjusted: 29.3 (17.3 to 41.2) | ||

Tertiary effectiveness outcome: proportion of participants who achieved treatment success at 3 weeks (non-inferiority)

As a measure of the speed of onset of action, the proportions of participants classed as a treatment success (three or fewer significant blisters) were assessed after only 3 weeks of treatment. In the mITT population, a higher proportion of those started on prednisolone were classed as a treatment success at 3 weeks than those started on doxycycline, with a difference of 23.4% (90% CI 14.4% to 32.5%) after adjusting for baseline severity, age and Karnofsky score (Table 40), although this remains within the prespecified bounds of non-inferiority. A similar difference was seen in the PP analysis (Table 41).

| Treatment outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 67 (56.3) | 90 (81.1) |

| Failure | ||

| High blister count | 42 (35.3) | 17 (15.3) |

| Changed treatment | 10 (8.4) | 3 (2.7) |

| Died before week 3 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Total | 119 | 111 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 23.4 (14.4 to 32.5) | |

| Unadjusted: 24.8 (15.1 to 34.4) | ||

| Treatment outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 56 (57.1) | 85 (81.7) |

| Failure | ||

| Severe baseline disease | 33 (33.7) | 16 (15.4) |

| Changed treatment | 9 (9.2) | 3 (2.9) |

| Died before week 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 98 | 104 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 23.7 (13.3 to 34.0) | |

| Unadjusted: 24.6 (14.3 to 34.9) | ||

Tertiary safety outcome: mortality over the 52-week follow-up period (superiority)

An assessment of all deaths, regardless of any relatedness to the study medication, was performed. Those who started on prednisolone were more likely to die during the year of follow-up than those started on doxycycline (83.5% alive at 1 year compared with 89.4%, respectively) (Table 42). The hazard ratio for reduction in death in favour of doxycycline, adjusted for baseline severity, age and Karnofsky score, was 0.61 (95% CI 0.30 to 1.24; p = 0.173) (Table 43). Time to death is shown in the Kaplan–Meier plot in Figure 6.

| Mortality outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (N = 132) | Prednisolone (N = 121) | |

| Died during trial follow-up | 14 (10.6) | 20a (16.5) |

| Relateda | 3 (2.3) | 11 (9.1) |

| Unrelatedb | 11 (8.3) | 9 (7.4) |

| Alive at the end of follow-up (1 year) | 118 (89.4) | 101 (83.5) |

FIGURE 6.

Kaplan–Meier survival plot showing time to death.

| All-cause mortality (hazard ratio) (95% CI) | Adjusted:a 0.61 (0.30 to 1.24); p = 0.173 |

| Unadjusted: 0.59 (0.29 to 1.19); p = 0.139 |

Tertiary effectiveness outcome: use of potent and superpotent topical corticosteroids during the 52-week follow-up period (superiority)

Use of topical steroids (potent or superpotent) was permitted during the first 3 weeks of treatment for symptomatic relief (no more than 30 g per week to localised lesions only) and also after 6 weeks, as might occur in normal practice in the UK. Although use of topical steroids was discouraged from the end of week 3 to the week 6 effectiveness assessment, some participants did use topical corticosteroids for local relief of the affected area. Data on quantities of topical corticosteroids used were not collected accurately over the 1-year study period and so Table 44 presents topical corticosteroid use during different study periods. As anticipated, topical corticosteroid use for symptomatic relief was greater at all time points for those initiated on doxycycline treatment.

| Time period | Doxycycline (N = 112), n (%) | Prednisolone (N = 101), n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potent | Superpotent | Patients using topical corticosteroids | Potent | Superpotent | Patients using topical corticosteroids | |

| After randomisation up to 3 weeks | 6 (5.4) | 1 (0.9) | 7 (6.3) | 3 (3.0) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (4.0) |

| After 3 weeks up to 6 weeks | 12 (10.7) | 11 (9.8) | 23 (20.5) | 6 (5.9) | 0 | 6 (5.9) |

| After 6 weeks | 5 (4.5) | 7 (6.3) | 12 (10.7) | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 2 (2.0) |

| At any time during the trial | 13 (11.6) | 11 (9.8) | 24 (21.4) | 6 (5.9) | 1 (1.0) | 7 (6.9) |

Additional post-hoc analysis

Post-hoc analysis: primary effectiveness outcome repeated at week 52

The primary effectiveness outcome at 6 weeks assessed the strategy of starting on doxycycline or prednisolone by including all participants regardless of any treatment modification. It was decided at the Trial Steering Committee meeting to conduct an additional post-hoc effectiveness analysis using the same definition of the population included to assess the strategy of starting on doxycycline or prednisolone over the whole 52-week period. There was no significant difference between the two groups when assessed over the full 52 weeks in either the mITT analysis (Table 45) or the PP analysis (Table 46).

| Outcomea | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 77 (96.3) | 74 (96.1) |

| Failure | 3 (3.8) | 3 (3.9) |

| Total | 80 | 77 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%)b | –0.1 (–5.2 to 4.9) | |

| Outcomea | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 49 (96.1) | 64 (95.5) |

| Failure | 2 (3.9) | 3 (4.5) |

| Total | 51 | 67 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%)b | –0.6 (–6.7 to 5.5) | |

Post-hoc analysis: action (treatment changes) taken in response to relapse

In total, 76 patients were identified as having relapsed after previously being classified as a treatment success, either because they had three or fewer significant blisters present or because they had ceased trial medication because of treatment success (Table 47). For those started on prednisolone, if they experienced a relapse, patients usually either received an increased dose of prednisolone (30/39, 76.9%) or recommenced prednisolone if treatment had ceased completely (8/39, 20.5%). For those who started on doxycycline, the most common course of action on relapse after having previously achieved disease control was to change to prednisolone (13/37, 35.1%) or increase the dose of prednisolone (16/37, 43.2%).

| Action taken in response to disease relapse | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (n = 37) | Prednisolone (n = 39) | |

| Treatment changed to prednisolone | 13 (35.1) | 0 |

| Treatment changed to doxycycline | 0 | 0 |

| Dose of prednisolone increased | 16 (43.2) | 30 (76.9) |

| Dose of doxycycline increased | 3 (8.1) | 0 |

| Prednisolone restarted | 3 (8.1) | 8 (20.5) |

| Doxycycline restarted | 2 (5.4) | 0 |

| Other treatment change | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

Post-hoc analysis: time to switching treatment

For those patients who switched treatments, the time between starting the study and switching treatment was assessed in a post-hoc analysis. This included all of the patients in the mITT population who contributed to the secondary efficacy analysis at week 6. The rate of switching from doxycycline was greatest during the first 6 weeks; after 13 weeks there was very little switching (Figure 7). There was a lower rate of switching for those starting on prednisolone and the rate was more constant over the whole 52 weeks.

FIGURE 7.

Kaplan–Meier survival plot showing time to change of treatment. Note: A change in treatment refers to a change from the allocated treatment (either doxycycline or prednisolone) to the other treatment. This graph includes the 213 patients who formed the mITT population for the primary efficacy outcome.

Post-hoc analysis: sensitivity of the primary effectiveness outcome at 6 weeks to topical corticosteroid use

A slightly different definition of a PP violator was used from that defined in the statistical analysis plan so that any use of a prohibited potent or superpotent topical corticosteroid between weeks 3 and 6 resulted in exclusion from the PP analysis of blister control at 6 weeks. The results of this post-hoc analysis are shown in Table 48. This shows that the non-inferiority status of doxycycline was robust to excluding those who used additional topical corticosteroids in the 3 weeks prior to the 6-week blister count assessment, at which the presence of three or fewer significant blisters was considered a treatment success.

| Outcome | Number (%) of patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | |

| Success | 49 (74.2) | 82 (93.2) |

| Failure | 17 (25.8) | 6 (6.8) |

| Total | 66 | 88 |

| Difference in proportions (prednisolone – doxycycline) (90% CI) (%) | Adjusted:a 19.3 (9.6 to 29.0) | |

| Unadjusted: 18.9 (9.0 to 28.8) | ||

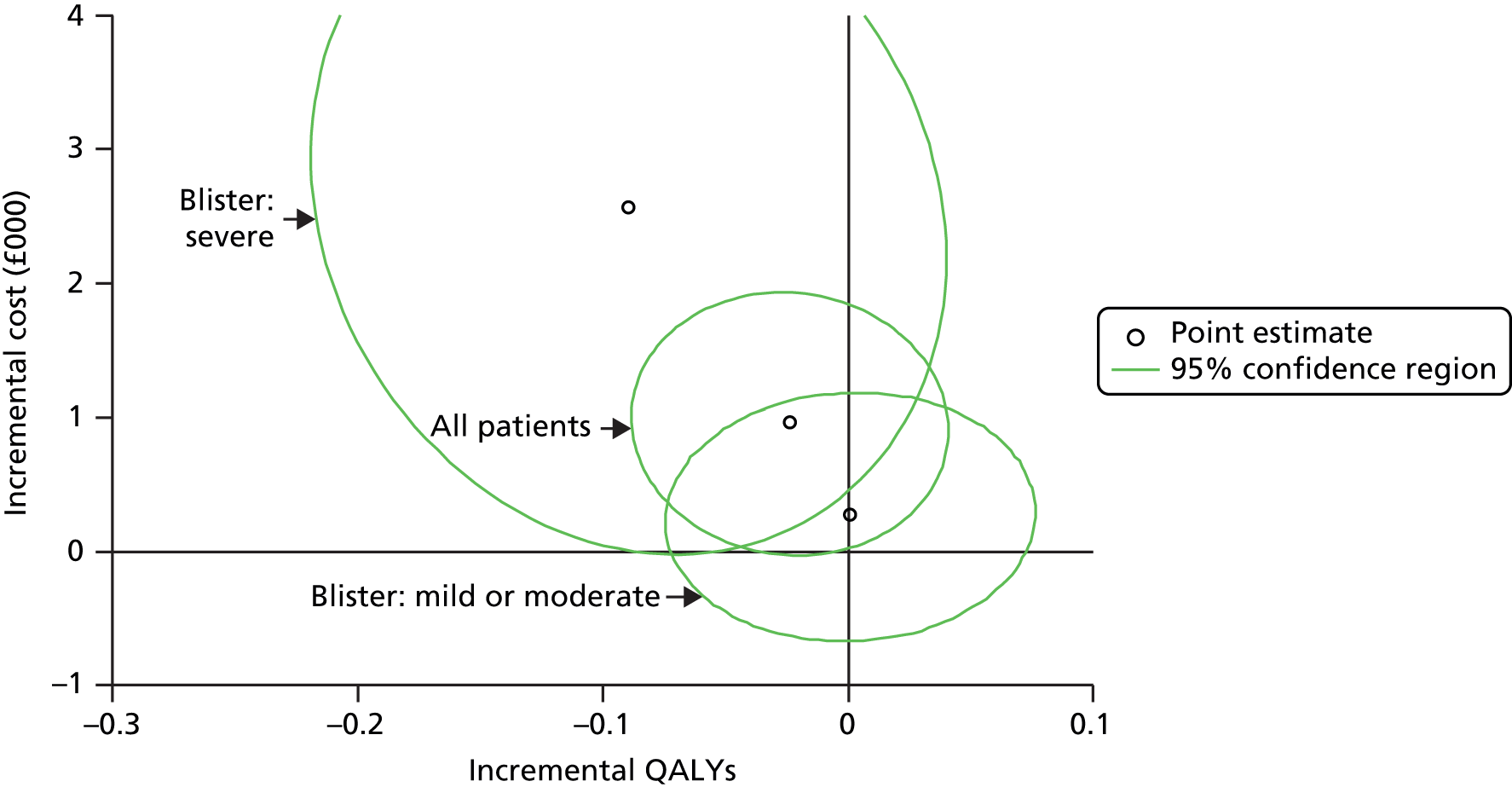

Post-hoc analysis: safety data at 52 weeks according to baseline disease severity

To assist with interpreting the health economic analysis, an additional post-hoc analysis was performed for the primary safety data according to baseline disease severity (Table 49).

| Subgroupa | Number (%) of patients | Number (%) experiencing a related adverse event (from raw data) | Difference in percentage (prednisolone – doxycycline) (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | Prednisolone | Doxycycline | Prednisolone | ||

| Mild baseline severity | 40 (33.1) | 35 (31.0) | 6 (15.0) | 14 (40.0) | 25.0 (5.4 to 44.6) |

| Moderate baseline severity | 47 (38.8) | 43 (38.1) | 5 (10.6) | 17 (39.5) | 28.9 (11.8 to 46.0) |

| Severe baseline severity | 34 (28.1) | 35 (31.0) | 11 (32.4) | 10 (28.6) | –3.8 (–25.5% to 17.9) |

| Total | 121 | 113 | 22 (18.2) | 41 (36.3) | 18.1% |

Similar post-hoc subgroup analyses for imputed data showed similar results: the differences in the percentages experiencing a related adverse event (prednisolone – doxycycline) were 25.2% (95% CI 4.0% to 46.3%) for mild baseline severity, 28.6% (95% CI 9.9% to 47.3%) for moderate baseline severity and –6.1% (95% CI –32.0% to 19.7%) for severe baseline severity.

Chapter 4 Cost-effectiveness

Objective

The objective of the economic analysis was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of doxycycline-initiated therapy compared with that of prednisolone-initiated therapy for patients with BP from the perspective of the English NHS.

Overview

Economic analysis is intended to inform decision-makers about the value for money of treatment alternatives, in a context in which health-care resources are limited and prioritisation is informed, at least in part, by the efficient use of resources. 39 The economic analysis within the BLISTER trial followed a prospectively agreed analysis plan and provides robust and unbiased evidence of cost-effectiveness, augmenting the trial estimates of clinical effectiveness. The BLISTER trial featured a pragmatic multicentre design reflecting real-world clinical practice and thus cost and outcome profiles are likely to reflect routine care in NHS settings. Individual patient data collected within the BLISTER trial included NHS treatment costs and health status, estimated as QALYs. Cost-effectiveness analysis captures the effect of treatment as changes in costs and QALYs. Given that follow-up was limited to 1 year, no discounting of future costs and benefits was applied.

The analysis followed ITT principles, with patients included in the analysis according to the treatment allocated by randomisation, irrespective of subsequent care.

Because of some missing data during trial follow-up, a base-case analysis was constructed in which missing data were imputed using multiple imputation. Supportive sensitivity analyses included only patients with complete data, thus exploring the impact of imputation.

Methods

Data sources

Resource use and quality-of-life measurements were collected from patients by health-care professionals at mandatory clinics at baseline and 6, 13, 26, 39 and 52 weeks. Generic health-related quality of life was assessed using the EuroQol questionnaire (containing the EQ-5D-3L and EQ VAS). The DLQI was included as a disease-specific quality-of-life measure.