Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/37/69. The contractual start date was in June 2009. The draft report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in May 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Simon Gates was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Board until February 2015 and the NIHR Standing Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials Units until December 2014 and is a member of the Medical Research Council Methodology Research Programme Panel. Sarah E Lamb is chairperson of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board and member and chairperson of the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee. Gavin D Perkins is a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Researcher-led Panel and is a NIHR Senior Investigator. Claire Hulme is a member of the HTA Commissioning Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Gates et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Description of condition

Definition

Cardiac arrest is defined as the cessation of cardiac mechanical activity, as confirmed by the absence of signs of circulation. 1 The majority of cardiac arrests outside a hospital occur as a result of cardiac causes (e.g. ischaemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia). Other causes of cardiac arrest include trauma, submersion, drug overdose, asphyxia, exsanguination or other medical causes (e.g. stroke, pulmonary embolus). 1,2

There are three different mechanisms through which cardiac arrest occurs – the development of an arrhythmia that leads to loss of cardiac output [ventricular fibrillation (VF) or ventricular tachycardia (VT)], insufficient cardiac contraction to generate a cardiac output, pulseless electrical activity (PEA) and a failure of the electrical conduction system of the heart (asystole). 3

The manifestations of cardiac arrest are dramatic: within seconds of it occurring the blood supply to the brain and vital organs ceases. The victim loses consciousness and the process of cell death commences. There is a narrow window of opportunity (minutes) during which, if the heart can be restarted, the victim may be successfully resuscitated. The longer the victim remains in cardiac arrest, the worse the outcome and if attempts at restarting the heart are either delayed or unsuccessful then death will occur.

Chain of Survival

The Chain of Survival (Figure 1) describes a series of steps that need to be in place to optimise the chances of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). 4

FIGURE 1.

The Chain of Survival. Reprinted from Jerry Nolan, Jasmeet Soar, Harald Eikeland. The Chain of Survival. Resuscitation (2006), 71;270–1 with permission from the Resuscitation Council (UK) and Laerdal Medical.

Early access

The first link in the chain is early access, which highlights the importance of identifying a patient at risk of cardiac arrest (e.g. someone suffering from an acute myocardial infarction) or someone who has sustained a cardiac arrest (identified by the loss of consciousness and absence of normal breathing) and getting a trained advanced life support (ALS) team to them as rapidly as possible.

High-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation

The second link in the Chain of Survival is early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). CPR is the combination of chest compressions and ventilations and is optimally started by those who are initially at the scene of the collapse. This is known as bystander CPR. Bystander CPR increases the odds of survival by 1.23 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71 to 2.11] in the studies with the highest baseline survival rates and by 5.01 (95% CI 2.57 to 9.78) in the studies with the lowest baseline rates. 5 When the emergency services arrive on scene they will take over CPR. Current resuscitation guidelines highlight the importance of high-quality CPR for ensuring optimal outcomes from cardiac arrest. 6 High-quality CPR is defined as CPR that ensures that an adequate chest compression depth is achieved (5–6 cm), the compression rate is 100–120 per minute, interruptions are minimised and the chest is allowed to recoil between chest compressions.

Evidence supporting the importance of high-quality CPR is observational: there are no randomised trials evaluating different compression parameters. Nevertheless, high-quality CPR appears to be important to outcomes. 7 Experimental studies show a linear increase in cardiac output and coronary perfusion pressure with increasing compression depths. 8,9 Observational studies in humans found improved shock success10 and better return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) rates and long-term survival with deeper chest compressions. 11,12 Faster chest compression rates (> 100 minutes) are associated with improved survival13–15 and ensuring that the chest is allowed to recoil between sequential chest compressions also appears to be important. 16

Interruptions in CPR are harmful. 17 A particularly critical time to minimise interruptions to CPR is around the time of attempted defibrillation. Prolonged pre-shock and peri-shock interruptions in CPR reduce the chances of shock success10 and survival. 18

Early defibrillation

Approximately one-quarter of OHCA in the UK occurs as a result of an arrhythmia: either VF or VT. These rhythms are referred to as shockable rhythms, as the arrhythmias may be terminated and cardiac function restored by the successful delivery of defibrillator shocks. The time from the onset of VF/VT to the delivery of a shock is critical to shock success and chances of survival. For every 60–90 seconds that a shock is delayed, the chance of survival falls by approximately 10%. 19

If a defibrillator is immediately available at the scene of a cardiac arrest, defibrillation should be attempted without delay. Where there is a delay in initiating CPR, there is a theoretical rationale that providing CPR before a shock improves coronary perfusion and thereby the chances of achieving sustained ROSC. 20 This concept was evaluated by the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium in a cluster randomised trial that compared early analysis [30–60 seconds of emergency medical services (EMS)-administered CPR before initial rhythm analysis] with later analysis (180 seconds of CPR, before the initial electrocardiographic analysis). 21 The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge with satisfactory functional status [a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of ≤ 3, on a scale of 0–6, with higher scores indicating greater disability]. The study21 enrolled 9933 patients (5290 to early analysis and 4643 to late analysis), but found no difference in outcomes (cluster-adjusted difference of –0.2%, 95% CI –1.1% to 0.7%).

Post hoc analyses found that for ambulance services with baseline VF survival of < 20%, ‘analyse late’ compared with ‘analyse early’ was associated with a lower chance of favourable functional survival (3.8% vs. 5.5%; OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.90). Conversely, in ambulance services with VF survival of > 20%, ‘analyse late’ was associated with a higher likelihood of favourable functional survival than ‘analyse early’ (7.5% vs. 6.1%; OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.52). 22

In the UK, the Joint Royal College Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) recommended that defibrillation should not be delayed to allow for a set period of predefibrillation CPR. In practical terms, this means that when an ambulance crew arrive at the scene of a cardiac arrest they will start CPR while the defibrillator/monitor is attached. Once attached, rhythm analysis and, if indicated, defibrillation should take place without further delay.

Post-resuscitation care

The return of a spontaneous circulation marks the start of the post-resuscitation care phase of treatment. 23 Unless the arrest has been relatively brief, most patients who achieve a ROSC will have an obtunded consciousness level, necessitating admission to intensive care. The focus of the post-resuscitation care phase of treatment is upon stabilising cardiac function to prevent a further arrest and minimising the consequences of the cardiac arrest on neurological outcome. This involves the use of targeted temperature management, avoidance of hyperglycaemia and cardiac reperfusion treatments. Most post-resuscitation care treatments are initiated following arrival in the emergency department and in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Incidence and burden of disease

Data from NHS England indicate that UK NHS ambulance services attend approximately 60,000 cardiac arrests each year; of those arrests attended, resuscitation is attempted in just less than half (28,000 cases). 24 Approximately 25% achieve an initial ROSC. However, only approximately one-third of those who achieve a ROSC survive to go home from hospital; thus, the overall survival to discharge rate is approximately 8%. The burden of disease is high, with an estimated 460,000 potential years of life lost, 270,000 of which are working years of life lost.

Functional survival after cardiac arrest is generally good, with the majority of those surviving doing so with a favourable neurological outcome. 25 Survivors may experience post-arrest problems, including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress and difficulties with cognitive function. 26

Despite the annual death toll exceeding that of dementia, stroke or lung cancer, there has been relatively little investment in research into this lethal condition. This has created a relatively weak evidence base compared with other diseases (e.g. there are 50-fold more trials per 10,000 deaths from myocardial infarction than deaths from cardiac arrest). A review of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) cardiovascular portfolio identified only 4 of 624 studies related to cardiac arrest. Until recently, the pattern was similar in the USA. 27

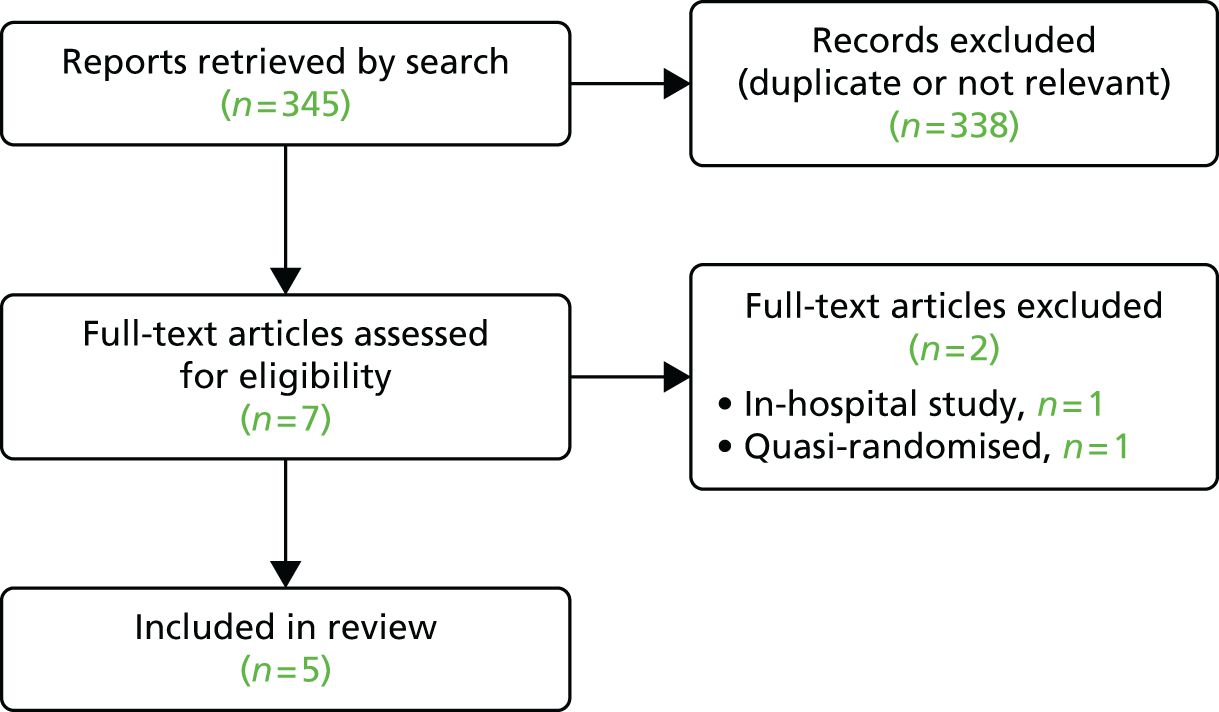

Existing evidence

At the time of initiating the PARAMEDIC (prehospital randomised assessment of a mechanical compression device in OHCA) trial, there were no large published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the LUCAS-2 (Lund University Cardiopulmonary Assistance System-2; Jolife AB, Lund, Sweden) device. A systematic review of the literature in 201228 identified 16 studies investigating the LUCAS-2 device. Four of the studies were animal studies and 12 were human studies. Of the 12 human studies, one was a RCT and 11 were observational studies using either a cohort or before-or-after design (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot from Gates et al. ’s28 systematic review of studies examining the LUCAS-2 device. M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; RR, risk ratio. Reproduced from Heart, Gates S, Smith JL, Ong GJ, Brace SJ, Perkins GD, 98, 908–13, 2012 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

The main finding of this review was that the existing evidence about the use of the LUCAS device is inconclusive. The animal studies tended to provide evidence that the LUCAS-2 device improved physiological end points, although the results were not consistent across studies.

Studies involving humans similarly lack consistency in the direction of benefit compared with harm. We chose not to perform any meta-analyses because of observed heterogeneity, varying study design and the high risk of bias in most of the included studies.

We concluded that the evidence base is insufficient for making any recommendations about the routine use of the LUCAS-2 device in clinical practice.

This conclusion is similar to the International Liaison Committee for Resuscitation Consensus on Science and Treatment’s recommendation,20 which advised that:

. . . there are insufficient data to support or refute the use of LUCAS-2 CPR instead of manual CPR. It may be reasonable to consider LUCAS-2 CPR to maintain continuous chest compression while undergoing computed tomography (CT) scan or similar diagnostic studies, when provision of manual CPR would be difficult.

Deakin et al. 20

Rationale for intervention

Because of the problems with manual chest compression, several mechanical devices have been proposed. These have potential advantages: they are able to provide compressions of a standard depth and frequency for long periods without interruption or fatigue and they free emergency medical personnel to attend to other tasks.

The LUCAS-2 is a mechanical device that provides automatic chest compressions. It delivers sternal compression at a constant rate, to a fixed depth, by a piston with the added feature of a suction cup that helps the chest return back to the normal position. It compresses 100 times per minute to a depth of 4–5 cm. It is easy to apply, stable in use, relatively light in weight (7.8 kg) and well adapted to use during patient movement on a stretcher and during ambulance transportation. The device is Conformité Européenne (CE) marked and has been on the market in Europe since 2002.

Detailed descriptions of the device and experimental data from animal studies showing increased cardiac output and cortical cerebral flow compared with manual standardised CPR have been published. 35,38

The LUCAS-2 device was introduced into a small number of ambulance services in the UK several years ago, despite the absence of evidence of its effectiveness from randomised trials. 39 It was subsequently withdrawn from routine use by several of the services because of lack of evidence about safety and efficacy and is now used only under restricted conditions. In the absence of evidence of clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness and the presence of some concerns regarding safety, the JRCALC, in discussion with the Department of Health, identified the need for large-scale clinical trials to evaluate the device. 40 Until such studies are completed, no further new purchases of the device are recommended by the JRCALC. A briefing note commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded that ‘there is therefore an urgent need to evaluate this technology to discover whether it is effective and cost-effective in improving survival after cardiac arrest’. The need for a definitive trial is reinforced in the International Liaison Committee for Resuscitation’s analysis of knowledge gaps in resuscitation. 41

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial design

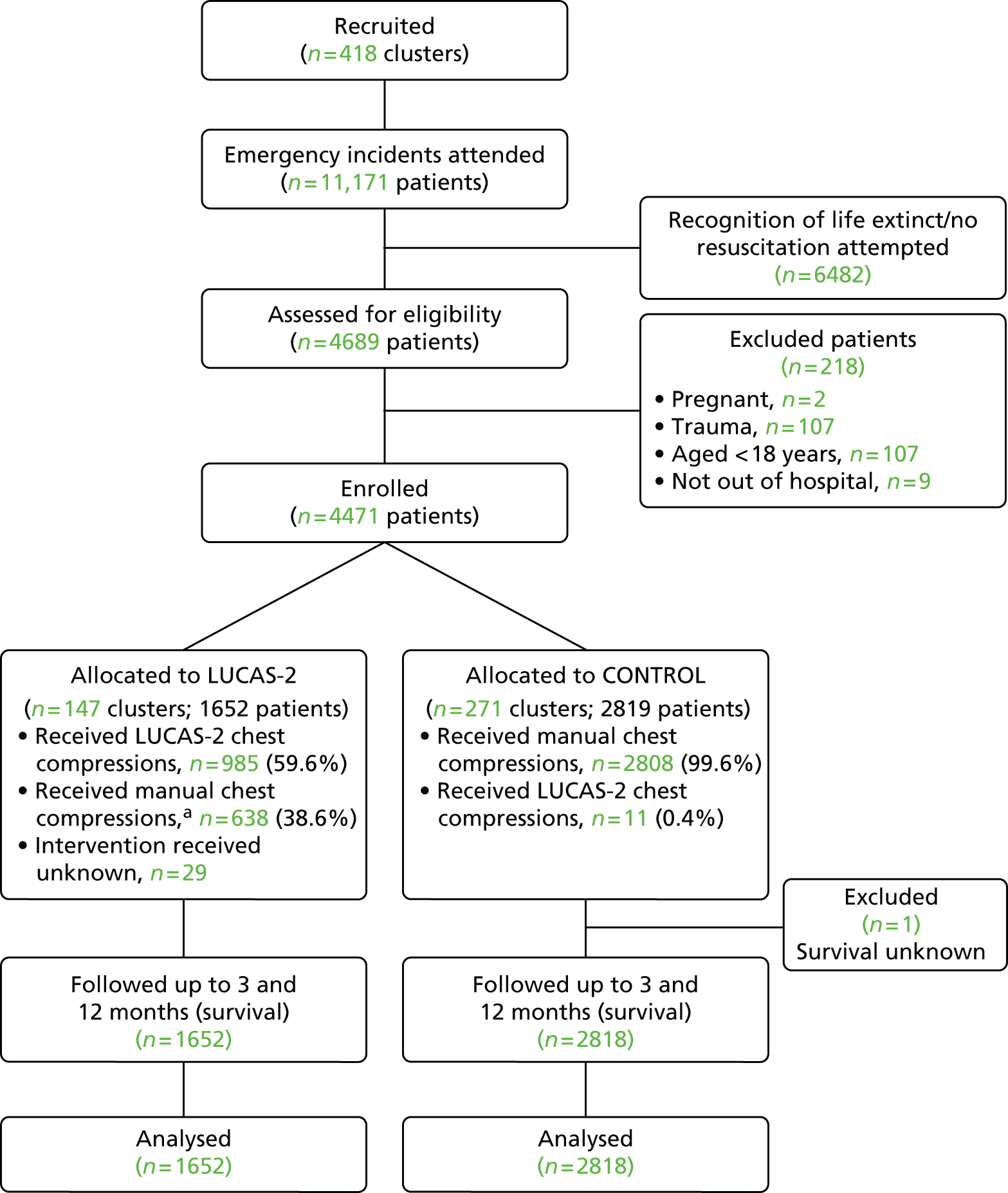

The PARAMEDIC trial was a pragmatic, cluster randomised trial, with ambulance service vehicles as the unit of randomisation, comparing mechanical chest compression using the LUCAS-2 device with standard manual chest compression, for patients in OHCA. The trial protocol has been published elsewhere. 42

The trial was undertaken in partnership with four NHS ambulance services (West Midlands, North East England, Welsh Ambulance Service and South Central). These organisations serve a total population of 13 million, spread over 62,160 km2. Vehicles were randomly allocated before the start of recruitment to carry the LUCAS-2 device (LUCAS-2 arm) or not (manual compression arm).

We chose to use a cluster randomised design because of costs and concerns that an individually randomised design would have a substantial risk of contamination among the manual compression arm. With individual randomisation, all vehicles taking part in the trial would have to carry a LUCAS-2 device and there would be a strong possibility that it would be used for patients who were allocated to manual compression, especially if the perception of paramedics was that the LUCAS-2 device made chest compression easier and allowed them to carry out other tasks more effectively.

Objectives

Primary objective

To evaluate the effect on mortality of using the LUCAS-2 device rather than manual chest compression during resuscitation by ambulance clinicians (paramedics, technicians, emergency care assistants, etc.) after OHCA at 30 days after the event.

Secondary objectives

To evaluate the effects of LUCAS-2 treatment on survival to 12 months, the cognitive and neurological outcomes of survivors and the cost-effectiveness of the LUCAS-2 device.

Selection of trial sites

The NHS organisations that delivered the trial were ambulance trusts. Initially (at the time of the funding application), we anticipated that three trusts would participate covering the West Midlands, Wales and Scotland. However, the Scottish Ambulance Service withdrew from the trial before the start of recruitment because its legal team was not happy with the research contract. The North East Ambulance Service and South Central Ambulance Service subsequently joined the trial.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Survival to 30 days post cardiac arrest.

Secondary outcomes

-

Survived event (sustained ROSC, with spontaneous circulation until admission and transfer of care to medical staff at the receiving hospital).

-

Survival to hospital discharge (the point at which the patient is discharged from the hospital acute care unit regardless of neurological status, outcome or destination).

-

Survival to 3 and 12 months.

-

Health-related quality of life (HRQL) at 3 and 12 months [Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12)43 and EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)]. 44

-

Neurologically intact survival to 3 months [survival with a Cerebral Performance Category (CPC)45 score of 1 or 2].

-

Cognitive outcome at 12 months [as measured via the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)]. 46

-

Anxiety and depression at 12 months [as measured via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)]. 47

-

Post-traumatic stress at 12 months [as measured via the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Civilian Checklist (PCL-C)]. 48

-

Hospital length of stay.

-

Intensive care length of stay (see Appendix 1).

The outcomes defined by the Utstein convention1 for reporting outcomes from cardiac arrest are reported, as well as long-term follow-up at 12 months. We did not measure the incidence of injuries resulting from CPR, for three reasons: first, they are of little importance unless they result in differences in more substantive outcomes such as survival or duration of hospitalisation; second, they are difficult to measure and classify and may not be detected reliably; and, third, organising injury data collection from a large number of hospitals was felt to add significant organisational complexity to the trial, for little benefit.

The CPC score is a 5-point scale for describing the neurological outcome after cardiac arrest and is recommended by the Utstein guidelines. 1 There is a generally accepted split into good neurological outcome (CPC score of 1 or 2) and poor outcome (CPC score of 3–5). The definitions of the categories are:

-

CPC 1 Good cerebral performance: conscious, alert, able to work.

-

CPC 2 Moderate cerebral disability: conscious, sufficient cerebral function for independent activities of daily life. Able to work in sheltered environment.

-

CPC 3 Severe cerebral disability: conscious, dependent on others for daily support because of impaired brain function. Ranges from ambulatory state to severe dementia or paralysis.

-

CPC 4 Coma or vegetative state: any degree of coma without the presence of all of the brain death criteria.

-

CPC 5 Brain death.

However, recent studies have demonstrated that this score may be insensitive to some of the more subtle, but nevertheless important, longer-term neurocognitive and functional impairments that are experienced by survivors of cardiac arrest. 49,50 The spectrum of impairment of HRQL following cardiac arrest includes memory and cognitive dysfunction, affective disorders and PTSD. 48 The number of patients who are expected to survive to hospital discharge was anticipated to be in the region of 200–300, which allowed more intensive follow-up. We used four clinical outcome measures: the SF-12 is a standard quality-of-life measure that is short and easy to complete. The PTSD PCL-C48 is a 17-item questionnaire measuring the risk of developing PTSD and has been used in previous studies as a good surrogate for the clinical diagnosis of PTSD, which would require a face-to-face interview by a suitably trained professional. The HADS47 is a 14-item self-administered questionnaire, which has been previously used successfully to measure affective disorders in those surviving cardiac arrest. 51 The MMSE measures cognitive impairment. 52 In addition, the EQ-5D44 was used as a health utility measure for the health economic analysis.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Eligibility for clusters

All vehicles that were in service at each participating ambulance station, eligible to attend patients and could carry the device were included in the trial and randomised to one of the trial arms before the start of recruitment.

To maximise the efficiency of the trial, recruitment was concentrated predominantly in urban areas, where each vehicle would attend a higher number of cardiac arrests per year. This avoided the costs of supporting clusters in rural areas that were able to recruit very few patients, increased the size of clusters and increased the survival rate for the trial population by omitting patients who could not be reached quickly and had a very low chance of survival. These considerations should all have helped to improve power to detect a difference between the LUCAS-2 device and manual compression arms in the trial.

Eligibility for individual patients

Patients were eligible if they met all four of the criteria below:

-

Cardiac arrest in the out-of-hospital environment.

-

First ambulance resource was a trial vehicle.

-

Resuscitation attempt was initiated by the attending ambulance clinicians, in accordance with JRCALC guidelines. 53

-

The patient was known, or believed to be, aged ≥ 18 years.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

cardiac arrest caused by trauma

-

known or clinically apparent pregnancy.

All patients who fulfilled the eligibility criteria were included in the trial. The JRCALC Recognition of Life Extinction (ROLE) guidelines53 were applied to determine patients for whom a resuscitation attempt was inappropriate. This is the case when there is no chance of survival; when the resuscitation attempt would be futile and distressing for relatives, friends and health-care personnel; and when time and resources would be wasted undertaking such measures. If there was clear evidence that life was extinct (Box 1) or if the patient had a ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ order, ambulance staff were authorised to recognise death and withhold CPR.

Massive cranial and cerebral destruction.

Hemicorporectomy.

Massive truncal injury incompatible with life (including decapitation).

Decomposition/putrefaction.

Incineration.

Hypostasis.

Rigor mortis.

A valid ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ order or an advanced directive (living will) that states the wish of the patient not to undergo attempted resuscitation.

When the patient’s death is expected as a result of terminal illness.

Efforts would be futile, as defined by the combination of all three of the following being present:

-

more than 15 minutes since the onset of collapse.

-

no bystander CPR prior to arrival of the ambulance.

-

asystole (flat line) for > 30 seconds on the ECG monitor screen.

Exceptions are:

-

drowning

-

drug overdose/poisoning

-

trauma

-

submersion of adults for longer than 1 hour.

ECG, electrocardiography.

The LUCAS-2 device cannot be used if patients are too large or too small: the device fits patients with a sternum height of 17.0–30.3 cm and a chest width of < 45 cm. However, patient size was not an exclusion criterion because it would be impossible to apply correctly to the manual compression group, hence potentially introducing bias. Moreover, it was appropriate to include the small proportion of patients who were too large or too small for the LUCAS-2 device in the trial, in accordance with intention-to-treat (ITT) principles. The trial estimated the impact of the LUCAS-2 device on the survival rate among the whole cardiac arrest population. In one Swedish study,29 only 3 out of 159 patients (1.9%) were found to be too small or too large for the LUCAS device. We therefore anticipated that there would be only a small number of patients for whom the LUCAS-2 device could not be used, especially as the LUCAS-2 device accommodates larger patients than the LUCAS version 1 device that was used in the Swedish study.

Randomisation

Randomisation of trial vehicles to the LUCAS-2 and control arms was performed by the study statisticians before the devices were supplied to participating stations. As the number of LUCAS-2 devices was limited, it was inefficient to randomise vehicles in a 1 : 1 ratio. This would have entailed some vehicles at each station not contributing to the trial and, hence, non-inclusion of potentially eligible cardiac arrest patients. It would also be operationally more difficult for ambulance service staff, as procedures would be different between trial and non-trial vehicles. Because there was little cost associated with including additional standard care clusters, we included all eligible vehicles at each station in the trial, with the majority allocated to the control arm and a random selection (stratified by type of vehicle) allocated to the LUCAS-2 arm. This ensured that all eligible cardiac arrests were included in the trial. The number of LUCAS-2 devices allocated to each station was determined by the number of vehicles. In all of the stations, at least one device was allocated to a rapid response vehicle (RRV) and one to an ambulance (unless there were no vehicles of a type at a station). The number of vehicles available varied and it was not possible to ensure that allocation was in any precise ratio, but we aimed for the ratio of LUCAS-2 to standard care vehicles to be approximately 1 : 2. If new vehicles were brought into service at participating stations during the recruitment period, these were also randomised.

The randomisation sequence was computer generated, with stratification by station and type of vehicle. Once randomised, a vehicle’s allocation could not be changed and it remained in that group throughout the trial. Clusters were terminated if a vehicle left the trial permanently (e.g. was scrapped or withdrawn from front-line service).

Early in the trial it became apparent that ambulances and RRVs frequently moved between stations, and it was not possible to identify a set of vehicles that would be consistently present at a participating station. Hence, many of the vehicles initially randomised at a station moved elsewhere and were replaced by vehicles that had not been randomised. This resulted in a low proportion of potentially eligible cardiac arrests being attended by trial vehicles. We therefore tried as far as possible to randomise stations that were geographically close, so that most transfers of vehicles between stations would be to another station that was participating in the trial. This reduced the proportion of cardiac arrests that were attended by non-trial vehicles.

A slightly different method of randomisation was used by the North East Ambulance Service. This region used a different system of allocation of vehicles, in which vehicles did not have a base station, but were based at two main depots. From here, vehicles were allocated to stations as needed. This meant that there was a major problem with vehicle rotations; vehicles rarely stayed at the same station for a prolonged period, and there were no geographically close sets of stations around which vehicles tended to rotate. Because it was possible (for logistical reasons) to include only a limited number of stations in this region in the trial, the investigators and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) felt that it was appropriate to use a different system of randomisation for this region. This was intended to be equivalent to the usual system of randomisation by vehicle. The North East Ambulance Service randomisation system used ‘virtual vehicles’; at each station, each vehicle place was randomised to the LUCAS-2 or control arm, with stratification by type of vehicle. So, for example, if there were three ambulances at a station, number two might be randomised to the LUCAS-2 arm, so whichever ambulance filled that position on a particular day would carry the LUCAS-2 device and recruit patients to the LUCAS-2 arm. The disadvantage of this system was that the LUCAS-2 devices did not stay with the same vehicle, but had to be loaded on to the correct vehicle at the beginning of each shift and removed afterwards. However, the crews had done this for a previous trial, so were used to the process, and no problems of missing LUCAS-2 devices were encountered. This system ensured that cardiac arrests attended by ambulances from participating stations would be recruited to the trial. If we had used the same system in the North East Ambulance Service as elsewhere, then the recruitment rate would have been much lower.

Treatment allocation

A dispatch centre in each region co-ordinated the emergency response. The nearest available RRV or ambulance was dispatched to cases of suspected cardiac arrest. Back-up was provided by a second vehicle as soon as possible.

Treatment allocation of each individual participant was determined by the first trial vehicle to arrive on scene. If this was a LUCAS-2 device-containing vehicle, the patient was assigned to the LUCAS-2 arm, and if it was a non-LUCAS-2 device-containing vehicle (control), the patient was allocated to the manual compression arm. If the trial vehicle was not the first ambulance service vehicle to arrive on scene – that is, a double-manned ambulance or a single-manned RRV that was not part of the trial had already arrived and commenced resuscitation – the patient was not included in the trial. If the first response on scene was a community responder (volunteer members of the public trained in basic life support and defibrillation, despatched by ambulance control) or other responses (such as motorbike, helicopter or unmarked car) then the patient was included and their allocation was determined by the first trial vehicle to arrive, providing that continued resuscitation was indicated.

We aimed to include all eligible patients who were attended by a participating vehicle during the trial recruitment period. The attending ambulance clinicians determined whether or not a resuscitation attempt was appropriate, according to the JRCALC guidelines. 53 Patients were regarded as participating in the trial when a resuscitation attempt was initiated by the attending ambulance service personnel.

Consent

Ethical considerations

The occurrence of a cardiac arrest out of hospital is unpredictable. Within seconds of cardiac arrest, a person becomes unconscious and thus incapacitated. It was not therefore possible to obtain prospective consent directly from the research participant.

Treatment (in the form of CPR) must be started immediately in an attempt to save the person’s life. In this setting it was not practical to consult a carer or independent registered medical practitioner without placing the potential participant at risk of harm from delaying treatment.

Conducting research in emergency situations in which a patient lacks capacity is regulated by the Mental Capacity Act (2005)54 for England and Wales. The PARAMEDIC trial was approved in accordance with these requirements by the Coventry Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number 09/H1210/69). Ethics approval was also gained from the Scotland A REC, but the Scottish Ambulance Service subsequently withdrew from the study.

Approaching survivors

The nature of the condition meant that the majority (85–90%) of people in the study would not survive. Of those patients admitted to hospital alive, the majority (approximately 80%) would be comatose and admitted to an ICU (and thus remain incapacitated). Following admission to intensive care, approximately half of the people who initially survive die without regaining capacity (on average within 48 hours). The average duration of hospital stay for survivors is 18 days. 55

To avoid unnecessary distress to the relatives of the deceased, the timing of the approach was important and had to balance the need to inform at an early opportunity while determining – as accurately as possible – which patients had died. Pilot work for this trial established that it is not possible for ambulance services to determine with sufficient accuracy which patients have died, so the procedure was revised, based on the procedures of the ICON (Intensive Care Outcome Network) study. 56

The participating ambulance services conducted their own checks on patients’ survival using existing data systems, which differed between services. Where possible, ambulance services consulted the NHS Patient Demographics Service. Other checks carried out by either the ambulance service and/or the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (WCTU), included contacts with hospitals, general practitioners (GPs), the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) and local registrars of births and deaths (see Identification of cardiac arrests).

If a patient was transported to hospital, his/her clinical and contact details were sent to the study co-ordinating centre at the WCTU. Staff at the co-ordinating centre checked the status of each potential survivor with the Medical Research Information Service (MRIS) approximately 6 weeks after the patient’s cardiac arrest. This timing of the approach was selected to ensure that the majority of deaths had been included in the MRIS database. All of the survivors were flagged on the MRIS database and the trial co-ordinating centre was informed of any subsequent deaths.

After these checks, if someone was still believed to be alive then the co-ordinating centre contacted the person at his/her home address by letter to provide information about the study and the follow-up. If there was no response after 2 weeks, then the co-ordinating centre tried to contact the patient by telephone (if the telephone number was known) or by letter. If the patient wished to take part in the follow-up, then they could contact the WCTU by using the reply slip, telephone or e-mail. This gave the participants an opportunity to discuss the study and, if they were happy to proceed, a 3-month follow-up appointment was made. The consent form was either returned by post or signed at the 3-month follow-up visit. Patients who did not respond were approached again at 10 months post cardiac arrest in an attempt to invite them to participate in a 12-month visit.

In the event that the co-ordinating centre was notified (or had reason to believe) that a patient lacked capacity, an approach was made to his/her GP in order to establish if the patient had capacity to consent. In the event that a patient lacked capacity to consent, we sought the views of a personal consultee in order to establish the patient’s wishes. If a personal consultee could not be identified, a carer (unconnected with the study) determined if the patient would be likely to consent to follow-up.

Protection against bias

Cluster design

One of the major potential sources of bias in cluster randomised trials is selection bias, which can arise if different patients are selected for inclusion in the two trial arms. This can arise when clinicians or people selecting patients are aware of the allocation of the cluster and they may consciously or unconsciously apply inclusion criteria differently depending on the randomised intervention. There is greater scope for selection bias if a large proportion of potentially eligible patients are not included in the trial. In this trial, paramedics assessing patients for inclusion were aware of the allocations; however, we aimed to identify and include close to 100% of the eligible patients, using a combination of methods for identifying eligible patients (see Eligibility for individual patients). This should avoid most selection bias.

Threshold for resuscitation

As the ambulance clinicians who were delivering the interventions were not blinded, there was a possibility that bias could be introduced by different thresholds for resuscitation between the LUCAS-2 and standard care arms: if they believed strongly that the LUCAS-2 device was effective, some of them might have attempted resuscitation in the LUCAS-2 arm on patients who had no chance of survival, and for whom a resuscitation attempt was therefore inappropriate. This would have resulted in a group of patients with a very low probability of survival being recruited to the LUCAS-2 arm but not to the standard care arm, potentially masking any beneficial effect of the LUCAS-2 device. We used several strategies to prevent this bias from occurring, to detect if it was to happen and to correct it if necessary.

First, the criteria that were used to determine whether or not a resuscitation attempt was appropriate, and hence whether or not the patient was eligible, were as objective as possible. The JRCALC ROLE criteria53 were used by all of the participating ambulance services to determine when a resuscitation attempt is inappropriate, and this continued in the trial (see Eligibility for individual patients). Ambulance clinicians were therefore familiar with the application of these criteria and no change of practice was needed during the trial. However, there remained scope for differential application of the criteria to the two trial arms, so further strategies were devised.

Second, all ambulance clinicians in the trial were trained in the trial procedures57 to ensure that they understood the rationale for the trial and the importance of following the trial procedures. The training included a review of existing evidence so that participating ambulance clinicians understood the current position of equipoise regarding the effectiveness of the LUCAS-2 device and discussion of potential sources of bias in the trial and the importance of applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria rigorously to both arms. Training continued throughout the recruitment period to ensure that any new staff were trained before recruiting and that important messages were continually and correctly reinforced (see Appendix 2).

Third, we instituted a programme of regular monitoring of the characteristics of patients who were recruited to the two trial arms, the number of cardiac arrests in each arm when no resuscitation attempt was made and the proportion of cardiac arrests included in the trial in order to detect any imbalances that may be caused by different thresholds for resuscitation. We also monitored the presenting rhythm, proportion of witnessed and unwitnessed arrests, presence of bystander CPR and time from ‘999’ call to crew arrival (using ambulance computer log data). If a lower threshold for attempting resuscitation in the LUCAS-2 arm existed, then we would find a greater number of recruits and a greater proportion of cardiac arrests with resuscitation attempts, a greater proportion with unfavourable presenting rhythms, a lower proportion of witnessed arrests and with bystander CPR and longer times from ‘999’ call to start of resuscitation in the LUCAS-2 group.

Finally, if necessary, we corrected for any inclusion bias in the statistical analysis of the trial, by adjustment of the analysis to take account of imbalance in factors such as presenting rhythm, time since ‘999’ call and presence of bystander CPR. We expected any potential inclusion bias to affect only the group of patients who were least likely to survive and that it would not affect patients in whom a resuscitation attempt would always be made (e.g. those with presenting rhythms with the highest probability of survival) and therefore a comparison between the LUCAS-2 device and manual compression in the subgroups of patients in whom resuscitation was known to be appropriate would be unaffected.

Monitoring device usage

The LUCAS-2 devices continuously record data when switched on. Data on the date, time and duration of use are stored in the device’s internal memory and can be downloaded when the device is serviced. We intended to use these data to verify whether or not the LUCAS-2 device was used for all cardiac arrests in the LUCAS-2 group or any in the control group. However, in practice, obtaining access to the data was difficult, as they can be accessed only by the manufacturers at the time of device servicing and special software is required to interpret the data. Data were extracted from the devices during recruitment, and supplied to the trial team, but, through efforts to match up LUCAS-2 device usage with dates and times of resuscitations of recruited patients, it became apparent that it was possible to verify LUCAS-2 device use during resuscitation for only a small number of patients. The main reasons for this were, first, the lack of LUCAS-2 device clock synchronisation with the Universal Time clock; second, the difficulty of identifying the dates and times of LUCAS-2 device use for a resuscitation attempt, as opposed to device testing, demonstration or training; and, third, the lack of correspondence between the times of use recorded by the devices and those of recruitments recorded by ambulance services. Efforts to verify LUCAS-2 device use for resuscitation attempts based on the data recorded by the devices were discontinued.

Compliance was monitored by the direct report of ambulance service personnel on the patient report form (PRF). For each cardiac arrest, ambulance clinicians were asked to report whether or not the LUCAS-2 device had been used, and instances of non-compliance were followed up with the crews involved by the paramedic research fellows.

Monitoring quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation

For interpretation of the trial’s results, it is helpful to understand the quality of CPR provided as standard care during the trial, as this may help to explain the observed differences. For example, if the CPR quality in the control group was extremely high, it would make it less likely that a treatment benefit would be seen in the LUCAS-2 group.

We originally planned to monitor CPR quality using data recorded by defibrillators during resuscitation attempts, from which we would calculate the compression fraction, that is, the percentage of time in which chest compressions are carried out (to ascertain pauses in the chest compressions). This would provide a measure of CPR quality in the control group and would allow verification of LUCAS-2 device use in the LUCAS-2 group. However, direct measurement of the quality of CPR in trial patients proved unachievable, for several reasons. First, different defibrillators were in use in the four ambulance services, which required different approaches to extract data. In two services, memory cards were required. These needed to be inserted before use, then removed and data extracted before the next use. This was operationally impractical. In the remaining two ambulance services, data were stored in the defibrillators, but extraction and analysis of them were challenging, and it proved to be extremely difficult to download the data reliably after resuscitation attempts. We were therefore forced to abandon attempts to collect data on CPR quality from trial patients.

Instead, we performed a study to estimate the ‘background’ CPR quality in each ambulance service. Approximately 20% of staff working in the trial areas were invited to take part in an evaluation of the quality of simulated CPR (using a manikin). Between February 2013 and June 2013 each staff member was asked to demonstrate ALS of an adult patient in VF, as they would do normally in the field. Data were recorded for around 5 minutes. The staff were able to work solo or as a double-person crew, whichever was their usual practice. We recorded compression depth, compression rate and compression fraction. Data were recorded anonymously and were not related back to staff performance.

Blinding

Because of the nature of the interventions, ambulance clinicians could not be blinded and were aware of treatment allocations. Control room personnel were blinded to the allocation of the ambulance service vehicles, to ensure that there was no bias in whether a LUCAS-2 device-containing or control vehicle was sent to an incident that was likely to be a cardiac arrest. Normally, the closest vehicle would be sent, which would not favour either LUCAS-2 or control arms of the trial. Ambulance service clinical staff were not blinded; vehicles randomly assigned to the LUCAS-2 arm were identified to them at the start of the shift during vehicle checks and through stickers in the cab and outside the vehicle.

Patients themselves were unconscious and therefore unaware of their treatment allocation at the time of the intervention, although 19 patients may have been subsequently unblinded by relatives or friends who were aware that the LUCAS-2 device was used. We sought to ensure blinding of outcome assessment as far as possible. Research nurses/paramedics assessing outcomes at 3 and 12 months’ follow-up were blinded to treatment group and endeavoured to maintain their blinding during the follow-up assessments. Mortality is an objective outcome, and its assessment was very unlikely to be influenced by knowledge of the treatment allocation.

Training

Paramedics seconded to work on the trial, along with clinical educator staff, trained all of the operational ambulance staff to use the LUCAS-2 device. Because of vehicle movements and staff rotations, staff-serviced vehicles were randomly assigned to both LUCAS-2 and manual groups; hence, all staff would potentially treat patients in the intervention arm. Training was carefully designed by the ambulance services on the basis of the manufacturer’s guidance. Because of the pragmatic design of this trial, training was developed in accordance with the process by which new technology would be introduced in routine practice into NHS ambulance services. This preparation included access to online training resources56 and included 1–2 hours of face-to-face training, updated annually. Training covered the study protocol and procedures, how to operate the LUCAS-2 device and the importance of high-quality CPR. Training included hands-on device deployment practice with a resuscitation manikin and emphasised the importance of rapid deployment with minimum interruptions in CPR. A competency checklist was completed before authorising staff to deploy the LUCAS-2 device correctly (see Appendix 2). Research paramedics reviewed all cases and provided feedback to individual staff as required. The rate of device use and reasons for non-use were fed back to participating services on a quarterly basis.

Clinical management of patients in the trial

The clinical management of patients in the trial was undertaken in accordance with the details given in the trial protocol.

The CPR that was delivered to all of the patients followed the International Liaison Committee for Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council and Resuscitation Council (UK) guidelines that were in force during the study period. These guidelines are adopted for ambulance use by the JRCALC and the JRCALC’s guidelines for clinical practice form the basis for all of the resuscitation attempts that are delivered by ambulance crews. 53 At the commencement of the trial, the 2005 resuscitation guidelines were in place, but new resuscitation guidelines were published on 18 October 201058 and incorporated by all ambulance trusts that were involved in the trial during the following 12 months. All standard ALS interventions were provided, including drug administration, defibrillation and advanced airway management as required.

In both arms, if the patient did not respond despite full ALS intervention and remained asystolic for > 20 minutes, the resuscitation attempt could be discontinued. Unless these criteria were met, resuscitation was continued and the patient was transported to the nearest emergency department with ongoing CPR.

Intervention arm

The LUCAS-2 device used in the trial was the latest version of the LUCAS-2 device, manufactured by Jolife AB and distributed by Physio-Control UK, Watford, UK.

Patients who were allocated to the intervention arm (LUCAS-2 device) received mechanical chest compressions in place of standard manual chest compressions.

On arrival, after confirming cardiac arrest, manual CPR was commenced while the LUCAS-2 device was prepared and applied. Following this, the initial cardiac rhythm was assessed. If the patient was in VF or VT then a countershock was administered in accordance with JRCALC/ALS guidelines. Operational experience showed that the LUCAS-2 device could be deployed within 20–30 seconds of arrival at the patient’s location. Prior to intubation, compressions were provided using the 30 compressions/two ventilations mode. If the patient was intubated, asynchronous compressions and ventilations were provided, with a ventilation rate of 10 per minute.

Defibrillation was performed using the following sequence: pause LUCAS-2 device, analyse heart rhythm; if shock indicated, restart LUCAS-2 device, charge, deliver shock and continue CPR for 2 minutes. This minimised deleterious pre- and post-shock pauses in compressions. The LUCAS-2 device was used in place of standard chest compressions as long as continued resuscitation was indicated, including resuscitation in the field and during transport to hospital.

The trial intervention ceased after care was handed over to the medical team in the hospital or the patient was declared deceased according to the ROLE criteria. 53

Manual chest compression arm

On arrival, after confirming cardiac arrest, manual CPR was commenced and the initial cardiac rhythm was assessed. If the patient was in VF or pulseless VT, then a countershock was applied. Prior to intubation, compressions were provided using the 30 compressions/two ventilations mode. If the patient was intubated, asynchronous compressions and ventilations were provided, with a ventilation rate of 10 per minute.

Minimising interruptions in chest compressions is critical for optimising the chances that a shock is successful. However, it is currently considered unsafe to perform defibrillation during manual chest compression. Defibrillation was therefore performed using current UK recommendations, which are as follows: stop CPR; analyse heart rhythm, charge defibrillator, deliver shock, restart chest compressions and continue CPR for 2 minutes.

Serious adverse event reporting

Definitions

Adverse events

An adverse event (AE) is ‘Any untoward medical occurrence in a patient or clinical investigation participant taking part in health-care research, which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the research’. 59

Serious adverse events

The definition of a serious adverse event (SAE) is an untoward and unexpected occurrence that:

-

results in death

-

is immediately life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability, or incapacity

-

consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect (not relevant to this trial population). 59

Additional terms for device trials

For trials of devices, additional terms are used and are defined as follows.

Adverse device effect/event

Any unfavourable or unintended response to a medical device.

Serious adverse device effect/event

A serious adverse device effect/event (SADE) is an adverse device effect/event (ADE) that has resulted in any of the consequences of a SAE or might have led to those consequences if suitable action/intervention had not been taken.

Incident

Any malfunction or deterioration in the characteristics and/or performance of a device, as well as any inadequacy in the labelling or instructions for use, which, directly or indirectly, might lead or might have led, to the death of a patient or user, or other persons or to the serious deterioration in their state of health. 59

Events that should be reported

All AEs and SADEs and incidents were reported to the trial co-ordinating centre on the appropriate forms (see Appendix 3).

All of the patients in this trial were in an immediately life-threatening situation; many would not survive and all of those who did were hospitalised. These situations were, therefore, expected, and events leading to any of them were reported as SAE/SADEs only if their cause was clearly separate from the cardiac arrest. Events that were related to cardiac arrest and would be expected in patients undergoing attempted resuscitation (including death and hospitalisation) were not reported.

Therefore, events were reported as SAE/SADEs if they were:

-

serious

-

and were potentially related to trial participation (i.e. they may have resulted from study treatment such as use of the LUCAS-2 device)

-

and were unexpected (i.e. that the event was not an expected occurrence for patients who have had a cardiac arrest).

Examples of events that may be SAE/SADEs were the use of the LUCAS-2 device causing a new injury that endangered the patient, malfunction of the device causing injury to ambulance clinicians and malfunction of the device leading to inadequate chest compression.

Reporting serious adverse events

Events satisfying the criteria given above were reported to the study co-ordinating centre, using the event report form, as soon as they became apparent (see Appendix 3).

The SAE/SADE reports that were received by the co-ordinating centre were reviewed on receipt by the chief investigators, and those that were considered to satisfy the criteria for being related to the device and unexpected were notified to the main REC, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulation Agency (MHRA) and manufacturer within 15 days of receipt.

The SAE reports were also reviewed by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) at its regular meetings. AEs that were not considered to be serious were logged and included in annual progress reports.

Data collection

Identification of cardiac arrests

Data were recorded on all of the cardiac arrests within the trial areas. This allowed assessment of the proportion of cardiac arrests that were enrolled into the trial and helped to ensure that no eligible cardiac arrests were missed. Data were collected by the attending ambulance clinicians, using the routinely completed PRF. Data from the PRFs were then transcribed on to the trial case report forms (CRFs) by the trial research fellows (see Appendix 4). The data collection was retrospective and each ambulance service had its own system, which meant that identifying cardiac arrest cases was challenging. The ambulance services, generally, had more than one system for identifying cardiac arrest cases to ensure that none was missed. One ambulance service had to go through all daily paper PRFs on station; others had electronic PRFs and were able to perform searches through a database. Other methods included linking in with national reporting of cardiac arrests to the Department of Health.

Data forms were collected in a central place at participating ambulance stations and collected by research paramedics on a weekly basis. For ineligible cardiac arrests (no resuscitation attempt, aged < 18 years, pregnant, traumatic aetiology, non-trial vehicle was first on scene), the ambulance service also sent the trial co-ordinating centre details of the arrests for monitoring purposes.

Hospitals did not undertake prospective data collection for trial participants because of the logistical difficulties that this would present. Hospitals were contacted, as necessary, to seek information about whether patients had been discharged or had died in hospital before contacting them for follow-up. Further details about length of stay in the ICU and hospital were also sought from hospitals, ICNARC and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES). Authority was granted by the Confidentiality Advisory Group to collect these data without seeking consent from the next of kin.

Deaths

Before admission

Deaths before admission to hospital were recorded by ambulance services and data for these patients were supplied to the trial database in anonymised form, as no personal identifiers were needed for follow-up. If a patient was transported to hospital, before transfer of identifiable data to the study co-ordinating centre, ambulance services conducted their own checks for survival. When access was granted locally, research fellows were able to search NHS Summary Care Records. They would also check with hospitals, where relevant.

To identify later deaths, all of the potential survivors had their status checked with MRIS approximately 6 weeks after their cardiac arrest. Therefore, the majority of deaths should have been included in the MRIS database. Deaths are normally included within 4 weeks of issue of a death certificate and we anticipated that the majority of certificates would be issued within a few days. All survivors were flagged on the MRIS database to ensure that the study was notified immediately if their death was registered. Issue of a death certificate may be delayed in some cases by referral to a coroner, but, in most cases, the coroner’s investigation will be concluded quickly and the delay to inclusion of the death on the MRIS database will be small. In addition, before writing to patients we also contacted their GP (if known) to check on survival.

At follow-up

Survivors were followed up approximately 90 days after their cardiac arrest, by a home visit or telephone contact from a study research nurse/paramedic. At this visit quality-of-life tools (SF-1243 and EQ-5D44) and an assessment of CPC score were completed.

If a patient was believed to be alive but had not responded to the invitation to take part in the follow-up or did not want to take part, we approached his/her GP, hospital or ambulance service for any repeat visits for information on the patient’s CPC score.

The second follow-up visit at 12 months included measurement of quality of life (SF-1241 and EQ-5D42), anxiety and depression (HADS47), post-traumatic stress (PCL-C48) and cognitive outcome (MMSE46). The NHS Demographics Batch Service was used to identify participants who had changed address since the last contact. Health service and social care resource use was reported in a patient self-completed questionnaire that was provided to participants at the 3- and 12-month follow-up visits (see Appendix 5).

Data management

All of the data collected during the trial were handled and stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 60 Data were, as far as possible, anonymised, but this trial involved the use of identifiable personal data for follow-up. All transfer of data between ambulance services and the study co-ordinating centre used secure methods, such as encrypted e-mail. All of the study data were entered into a study-specific database, which was set up by the programming team at the WCTU at the start of the study. All specifications (i.e. database variables, validation checks, screens) were agreed between the programmer, statistician, chief investigators and trial co-ordinator. All trial documentation and data were archived after completion of the trial and are stored in accordance with the WCTU standard operating procedures61 (see Appendix 7).

Statistical methods

Power and sample size

Incidence of primary outcome

At the time of initiation of this trial, there were few data on the incidence of survival after cardiac arrest, and most of these referred to survival to hospital discharge rather than survival to 30 days. However, as most mortality will occur in the first days after cardiac arrest, we expected survival to hospital discharge and to 30 days to be similar. A systematic review, published in 2005,62 has summarised all European data. The overall incidence of survival to hospital discharge was 10.7%, with 21.2% survival to discharge for patients with an initial rhythm of VF. This review62 included eight studies from the UK, in which the mean survival to hospital discharge was 8.1% overall and 17.7% for patients with initial VF rhythm. Data on survival to discharge from audits of UK ambulance services were limited, because at the time of the study few ambulance services collected outcome data for patients beyond admission to hospital. Figures from the London Ambulance Service (2006–7) indicated a survival rate to discharge of 5.2% (95% CI 4.4% to 6.0%). 63 National audit data for England (2006) indicate that the proportion of patients for whom resuscitation is attempted (and who have ROSC at admission to hospital) varied between 10% and 26% for different ambulance services. 64 The overall national figure (2004–6) was 14–16%. Estimates of mortality in hospital vary from 50% to 70%; hence, the incidence of survival to discharge is expected to be between 4.5% and 8%. 65 A reasonable conservative estimate of survival to 30 days is 5% and we have used this value in the sample size calculations.

Intracluster correlation coefficient

No data currently exist from which a relevant intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for this trial can be calculated. We have therefore assumed a conservative value of 0.01 for the sample size calculation. We expected that, because the LUCAS-2 device and manual compression clusters recruited from the same geographical areas and hence the same populations, the ICC would be low. The value of the ICC was monitored at the interim analyses by the DMC.

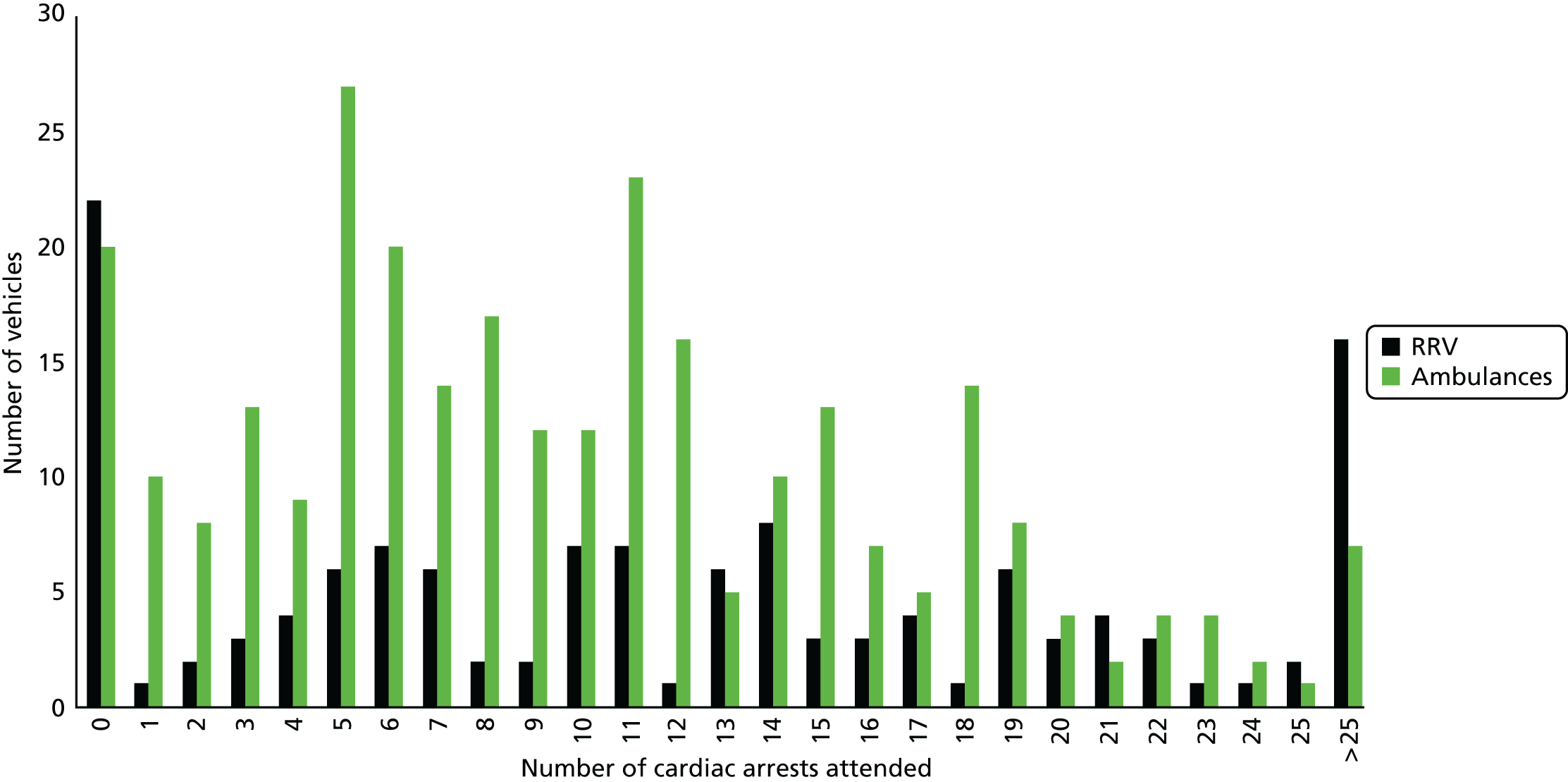

Cluster size

Predicting the expected cluster size during the trial was difficult because of expected changes in the vehicles in service and the proportion of eligible cardiac arrests that they were likely to attend. Moreover, there was likely to be considerable variation in the number of cardiac arrests attended by each vehicle (i.e. variation in cluster size). Data from the West Midlands Ambulance Service suggested that each vehicle would attend around 10–20 cardiac arrests per year; allowing for non-resuscitations and periods off the road, a reasonable estimate of the cluster size over a 2-year recruitment period was 15.

The sample size was revised during recruitment in response to information that some of the parameters differed from the assumptions that were made at the start of the trial. The original sample size calculation is given, followed by the revised version.

Original sample size

The required sample size is sensitive to variation in several parameters that were not precisely known at the start of the trial, including the incidence of the primary outcome in the manual compression group and the ICC. We aimed to be able to detect, with 80% power, an increase in the incidence of survival to 30 days from 5% in the manual compression group to 7.5% in the LUCAS-2 group [a risk ratio (RR) of 1.5]. An increase in survival from 5% to 7.5% corresponds with a number needed to treat of 40 – or one extra life saved per 40 resuscitation attempts. This would translate into around 625 lives saved per year in the UK. In an individually randomised trial this would require 2942 participants. Allowing for clustering, assuming an ICC of 0.01 and a cluster size of 15, this would require 224 clusters if using a 1 : 1 randomisation ratio (112 LUCAS-2 group, 112 manual group; 3360 participants in total).

Because the number of LUCAS-2 devices that were available to the trial was limited, it was more efficient not to use a fixed 1 : 1 randomisation ratio (see Randomisations), but to randomise a number of LUCAS-2 devices among all of the vehicles at each ambulance station. This allowed inclusion in the trial of all cardiac arrests attended by vehicles from that station. The numbers of clusters required for 80% power to detect the difference specified above, with different randomisation ratios and cluster sizes, is shown in Table 1.

| Cluster size | Control | Clusters required | Total number of participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | LUCAS-2 | Control | |||

| 14 | 1 : 1 | 238 | 119 | 119 | 3332 |

| 1 : 2 | 260 | 87 | 173 | 3640 | |

| 15 | 1 : 1 | 224 | 112 | 112 | 3360 |

| 1 : 2 | 245 | 82 | 163 | 3675 | |

| 16 | 1 : 1 | 212 | 106 | 106 | 3392 |

| 1 : 2 | 231 | 77 | 154 | 3696 | |

| 18 | 1 : 1 | 192 | 96 | 96 | 3456 |

| 1 : 2 | 210 | 70 | 140 | 3780 | |

| 20 | 1 : 1 | 176 | 88 | 88 | 3520 |

| 1 : 2 | 192 | 64 | 128 | 3840 | |

Our target was to randomise 82 LUCAS-2 clusters and 163 standard care clusters and a total sample size of 3675 participants. We expected to determine the primary outcome for close to 100% of trial participants, so no inflation of the sample size to allow for losses to follow-up of individual participants was proposed. With this sample size, the 95% CI around an estimated treatment effect of a RR of 1.50 would be 1.14 to 1.94, including adjustment for clustering.

Within this sample size we expected around 25% of patients to have an initial rhythm of VF (approximately 920 patients). This subgroup was expected to have significantly higher survival than the rest of the population, of around 15%. The number in this subgroup was sufficient to show an increase from 15% to 22.8% (RR 1.52) with 80% power, allowing for clustering.

The DMC monitored the values of all of the parameters of the sample size calculation at interim analyses and advised on any necessary modifications to the sample size.

Revision to sample size

The target sample size was reviewed in September 2012, after recruitment of 2469 patients, in response to an observed high level of non-compliance in the LUCAS-2 arm and to incorporate updated figures for the expected cluster size, ICC and ratio of control to LUCAS-2 clusters. The sample size re-estimation did not use any information from comparisons between the trial groups.

Because non-compliance would reduce the difference between the groups and potentially obscure a treatment effect due to the LUCAS-2 device, we used complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis66,67 as well as ITT analysis. This approach estimates the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for the treatment effect among compliers, without introducing bias by ignoring the random assignment to groups. For re-estimating the sample size, we defined compliance in the LUCAS-2 group as use of the device, or non-use for legitimate reasons that would preclude its use in normal clinical practice (such as patients in whom the LUCAS-2 device was contraindicated or if space restriction meant that the LUCAS-2 device could not be deployed). Using this definition, we estimated that compliance would be around 70% at the end of the trial.

The expected average cluster size was calculated to be approximately nine and the control-to-LUCAS-2 ratio was 1.5 : 1. It was not possible to calculate an ICC from the interim trial data, but it was expected to be low and a lower value than was assumed in the original calculation (0.001 rather than 0.01) was used.

Using these figures, a sample size of 4344 would maintain the original power of the trial to detect an increase in survival from 5% to 7.5%, using CACE analysis rather than ITT analysis. The change to the sample size was approved by the DMC and TSC and the revised target of 4344 was adopted in December 2012.

Statistical analysis

We performed ITT analyses to estimate the treatment effect of the LUCAS-2 device and presented results as a point estimate (RR or mean difference), with uncertainty estimated by the 95% CI.

We also used CACE analyses to estimate the effect in cardiac arrests when the protocol was followed. 66 CACE estimates the treatment effect in people who were randomly assigned to the intervention and who actually received it, by comparing compliers in the intervention group with those participants in the control group who would have been compliers if they had been allocated to the intervention group. This analysis retains the advantages of randomisation and avoids introducing bias, hence CACE is preferred to per-protocol analysis. 67 CACE assumes that the probability of non-compliance with the LUCAS-2 device would be the same for people who were actually randomised to the control as for those who were randomised to the LUCAS-2 arm. If allocation is random, this assumption will hold. A second assumption is that outcomes are not affected just by being randomised to the LUCAS-2 or control groups; in other words, there is no systematic difference in outcomes between patients attended by LUCAS-2 device-containing vehicles and those attended by control vehicles, except that caused by the different treatments provided. CACE analysis enables us to estimate the unobserved proportion of the control group who would have been non-compliers if randomised to the LUCAS-2 group. We did two CACE analyses, defining compliers in different ways. In CACE 1, we treated as non-compliant those cases in which the LUCAS-2 device was not used for unknown or trial-related reasons that would not occur in real-life clinical practice (e.g. crew was not trained in trial procedures, crew misunderstood the trial protocol, the device was missing from the vehicle). This analysis omits trial-related non-use and should be a better estimate of the treatment effect in real-world clinical practice than an ITT analysis. In the CACE 2 analysis, we treated as compliant only those cases in which the LUCAS-2 device was actually used and this analysis therefore estimates efficacy, that is, the treatment effect in patients who received LUCAS-2 device treatment.

For ITT analyses, we used logistic regression models to obtain unadjusted and adjusted ORs and 95% CIs. The prespecified covariates used in the adjusted models were age, sex, response time, bystander CPR and initial rhythm. We attempted adjusting for the clustering design using multilevel logistic models using the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) GLIMMIX procedure with logit link function based on the binomial distribution. Because of the extremely low survival rates in each cluster (vehicle), the multilevel models could not be fitted with the vehicle random effect, as this effect was not estimable. As a result, ordinary logistic regressions were fitted. We also undertook prespecified subgroup analyses by (1) initial rhythm (shockable vs. non-shockable); (2) cardiac arrest witnessed versus not witnessed; (3) type of vehicle (RRV vs. ambulance); (4) bystander CPR versus no bystander CPR; (5) region; (6) aetiology (presumed cardiac or non-cardiac); (7) age; and (8) response time. The analyses by region and type of vehicle were added during recruitment on the recommendation of the TSC. We fitted logistic regression models for the primary outcome measure with the inclusion of an interaction term to examine whether or not the treatment effect differed between the subgroups. Age and response times are continuous variables and we assessed these using multivariate fractional polynomials68 (see Appendix 8).

We did all analyses using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Marlow, UK). Interim analyses were conducted at least once per year during recruitment and supplied confidentially to the DMC. The DMC considered the results of the interim analysis and made recommendations to the TSC about continuation of recruitment or any modification to the trial that may have been necessary.

Approvals, registration and governance

The study was approved by the Coventry REC (reference number 09/H1210/69) and sponsored by the University of Warwick. It was conducted in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice and the Mental Capacity Act (2005). 54,69 The trial was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN08233942). Approval was given by the National Information Governance Board for Health and Social Care Ethics and Confidentiality Committee for access to personal data without consent (reference number ECC 2–02 (c)/2011). The manufacturers (Jolife AB) and distributors (Physio-Control UK) of the LUCAS-2 device had no role in the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of the trial. Their role was limited to supply and servicing of the LUCAS-2 devices and training of study co-ordinating centre personnel.

Several changes to the protocol and procedures were made during the trial (see Table 2). When these fulfilled the definition of ‘substantial amendments’ according to the UK Clinical Trials regulations, they were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee.

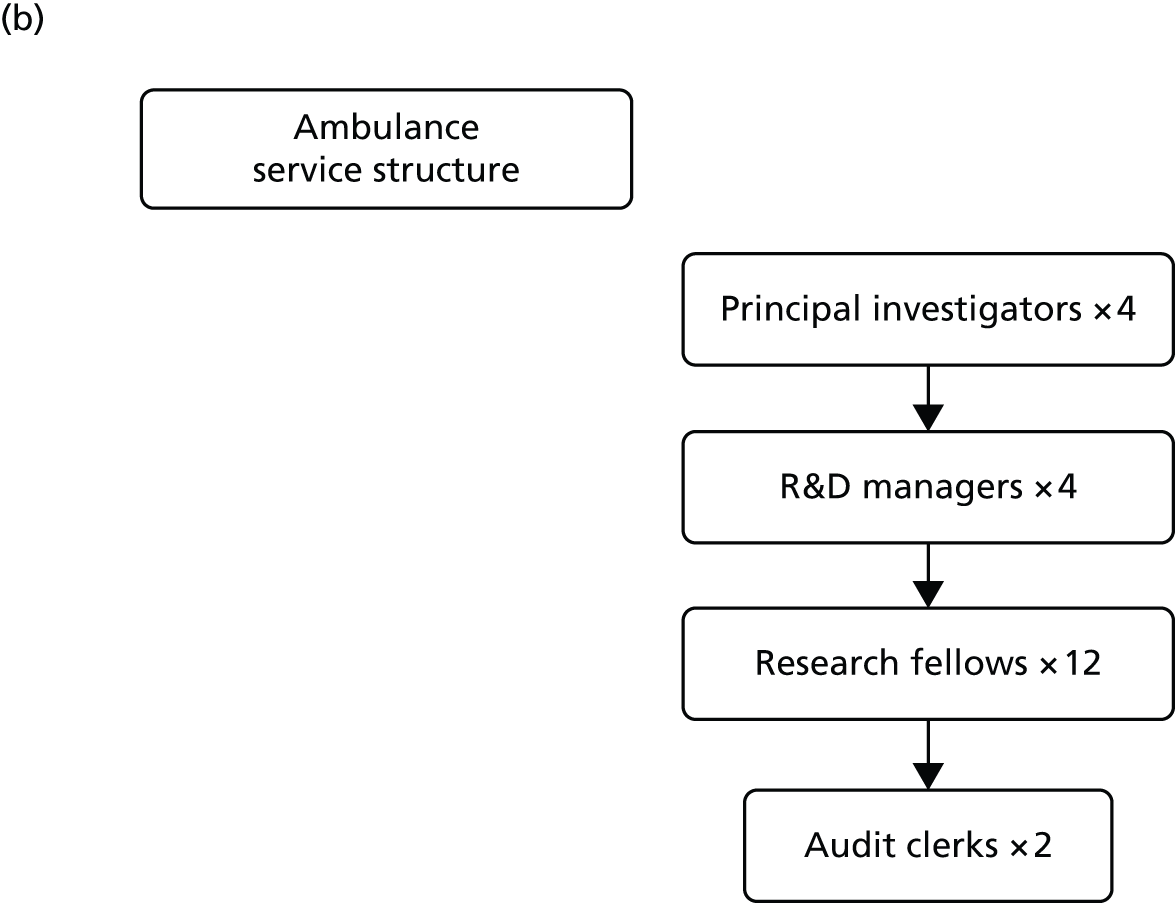

Staffing

The trial was co-ordinated by a team based at the WCTU. The exact personnel varied during the course of the trial but included a trial co-ordinator (who had overall management responsibility for the team), trial administrator, data manager and research nurse (who was responsible for co-ordinating follow-up) (Figure 3). The statistician, senior project manager and programmer were also based at the WCTU. Each ambulance service employed a number of research paramedics, who were seconded to the trial for its duration and had primary responsibility for delivering the trial in their area. They were based with the ambulance services, but worked closely with the central co-ordinating team. Their role was to deliver training, manage the devices and organise data collection. Some of the research paramedics additionally performed follow-up visits. These personnel were key to the successful delivery of the trial. As active paramedics, they had detailed knowledge of the procedures and challenges of their own ambulance service, and were able to design systems and procedures that would be successful in their area.

FIGURE 3.

Staff organogram. R&D, research and development.

Protocol amendments

There have been 11 substantial and non-substantial amendments to the trial documentation (Table 2).

| Date of amendment | Amendment no. | Document(s) affected | Changes | New version number, date | Date approved by REC – Coventry | Date approved by lead R&D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 April 2015 | 11 | N/A | MSc project: contact survivors enrolled in the PARAMEDIC trial to explore patient views and experiences of being Enrolled in an emergency care trial with a waiver of consent |

N/A | 5 May 2015 | |

| 17 February 2015 | 10 | N/A | Extension to end date of trial to end of June 2015 | N/A | 5 March 2015 | N/A |

| 1 May 2013 | 9 | Protocol, PIS | Clarifications to protocol, revised patient letters | Version 4.3, 1 April 2013 | 6 June 2013 | 8 July 2013 |

| Version 5.1, 1 April 2013 | ||||||

| 4 March 2013 | 8 | Protocol | Revised sample size of 4344 | Version 4.2, 4 March 2013 | 25 March 2013 | 3 April 2013 |

| 8 November 2012 | 7 | N/A | MSc dissertation to go a full amendment | N/A | 21 November 2012 | 24 June 2013 |

| 12 June 2012 | 6 | PIS, ICF | Revise patient letter and add in another contact at 12 months | Version 5.0, 12 June 2012 | 3 July 2012 | 9 July 2012 |

| 5 April 2012 | 5 | N/A | Letter to inform REC of reward scheme (pilot) in Coventry area | N/A | 11 May 2012 | 9 July 2012 |

| 29 March 2012 | N/A | N/A | Letter to inform REC of Ian Jones’ dissertation | N/A | 13 July 2012 | |

| 22 December 2011 | 4 (minor amendment 2) | Information sheets | Minor changes to the invite letter and information sheets so that if we are doing only a 12-month visit the documents make more sense | Version 4.1, 15 December 2011 | 22 December 2011 | 6 January 2012 |

| 14 June 2011 | 3 (minor amendment 1) | N/A | Clarification that we will seek information from hospitals with regard to secondary outcomes | N/A | 20 June 2011 | 13 July 2011 |

| 21 March 2011 | 2 | Protocol | Sample size change Approaching survivors now we have NIGB approval Change from ‘paramedics’ to ‘ambulance clinicians’ throughout |

Version 4.1, 21 March 2011 | 4 May 2011 | 5 May 2011 |

| 21 March 2011 | 2 | Information sheets | Changes now we have NIGB approval Reply slip for patient representative to reply on behalf of patient |

Version 4.0, 16 December 2010 | 4 May 2011 | 5 May 2011 |

| 21 March 2011 | 2 | Consent form | Changes to consultee form – title changed from ‘Consent’ to ‘Agreement’. [Patient name] added instead of friend/relative, etc. | Version 4.0, 16 December 2010 | 4 May 2011 | 5 May 2011 |

| 12 August 2010 | 1 | Protocol | Several minor changes to text throughout, highlighted in yellow Change to primary outcome sections 2.2.1 and 2.3 Changes to sample size in section 2.4.4 Clarification of process if the first resource on scene is not a trial vehicle (section 2.5.2) Changes to section 2.10: Protection against bias: addition of subheadings Sections ‘7.3 Relationship with manufacturer’ and ‘8.4 Training’ added in Clarification that data will be collected for all of the cardiac arrest patients attended by trial vehicles, non-trial vehicles and those for which resuscitation attempts were not made for monitoring purposes. Only eligible cardiac arrests will be followed up and included in the analysis Addition of device related event capture to section 4 |

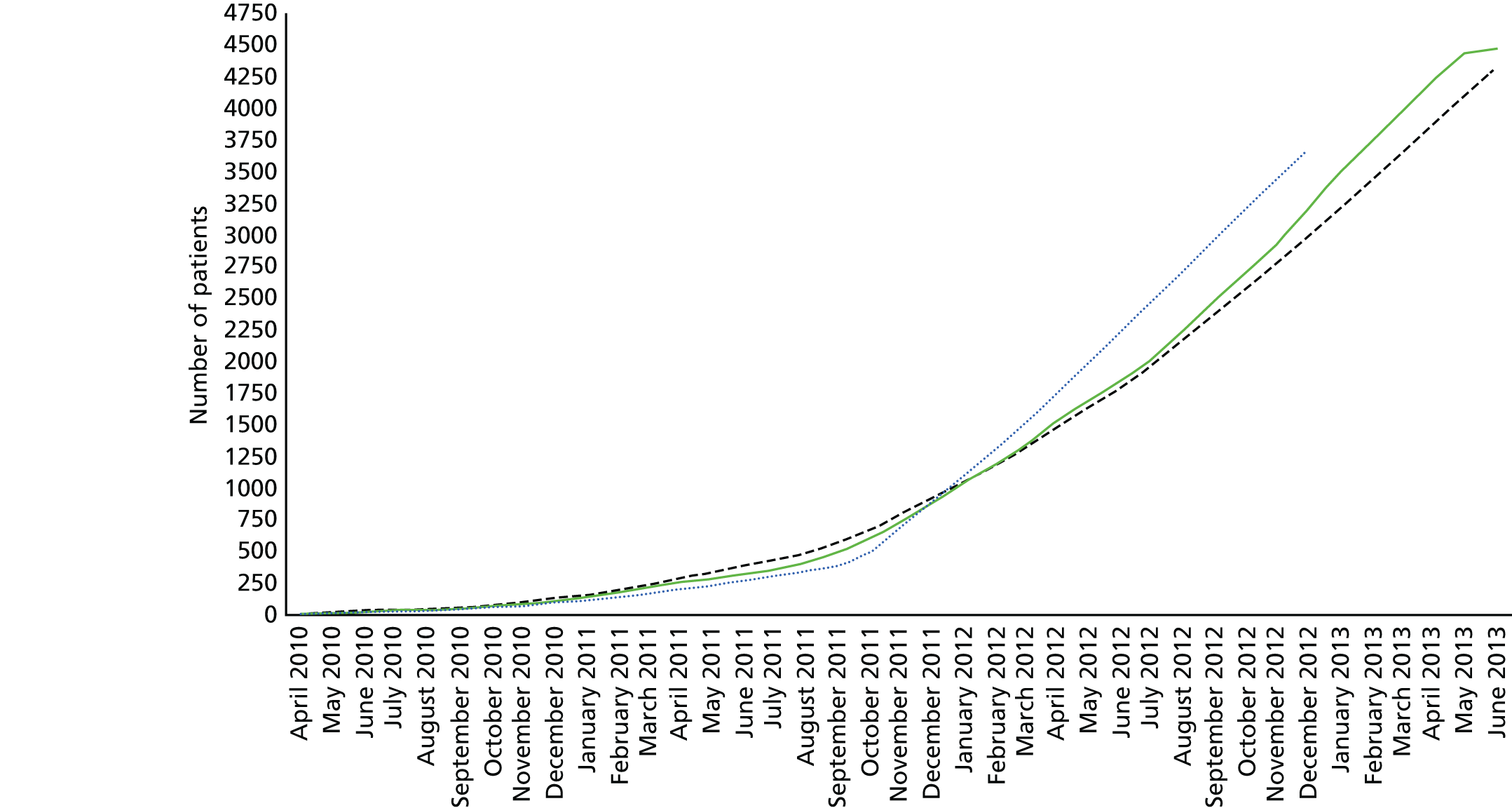

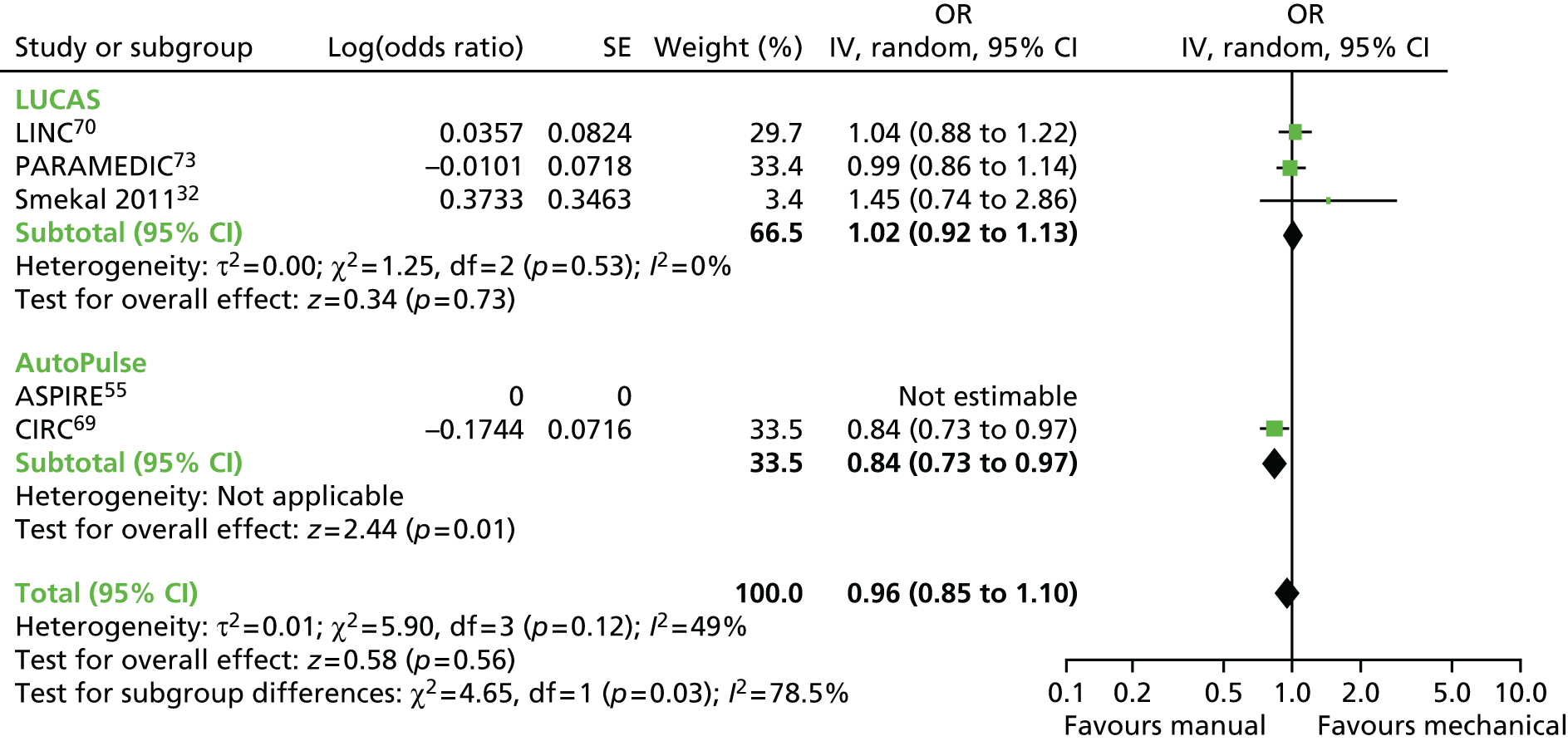

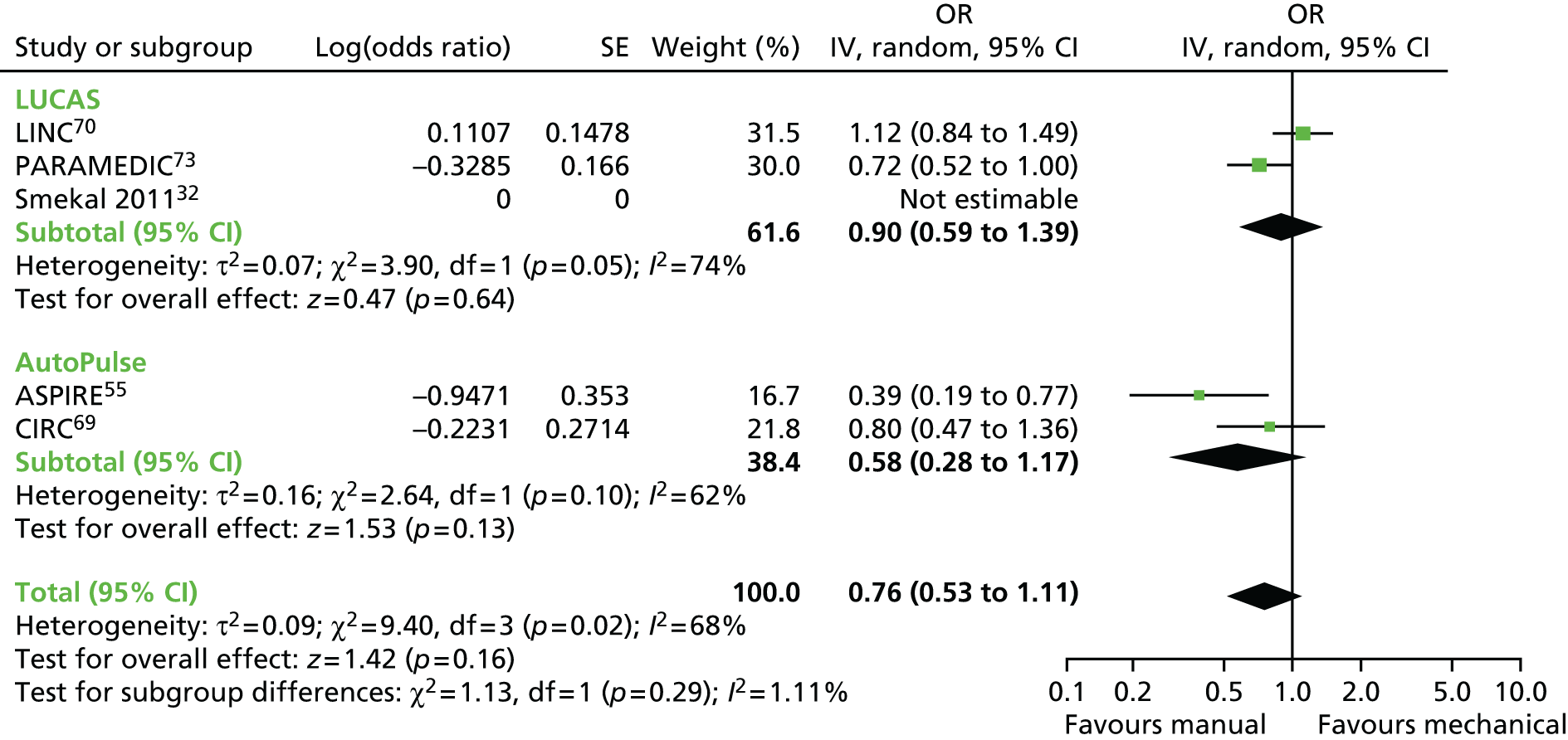

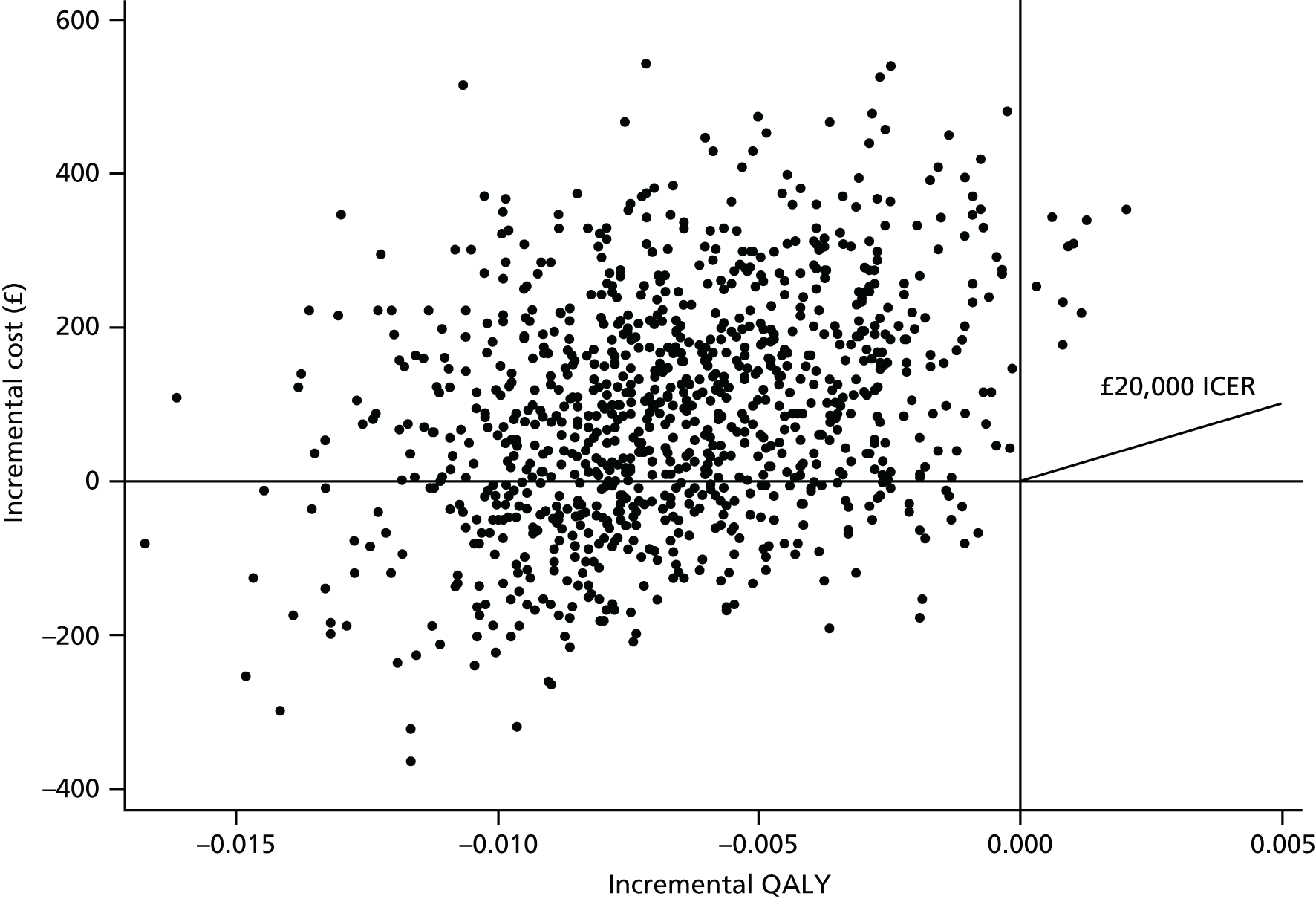

Version 3.0, 12 August 2010 | 16 September 2010 | 11 October 2010 (WMAS only) |