Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/05/01. The contractual start date was in December 2009. The draft report began editorial review in December 2015 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Bernadka Dubicka is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Mental, Psychological and Occupational Health Panel and has received personal fees as a consultant to Lundbeck. She also has a licensed patent: there is a licence to Lundbeck to use brief psychosocial intervention in their current trial (future payment anticipated). Peter Fonagy is in receipt of a National Institute for Heath Research Senior Investigator Fellowship. Paul Wilkinson has received personal fees as a consultant to Lundbeck, a consultant to Takeda and a supervisor in interpersonal psychotherapy. He has also had non-financial support from the interpersonal psychotherapy UK Training Committee. Ian M Goodyer has received personal fees as a consultant to Lundbeck, is supported by a strategic award from the Wellcome Trust, research support from the Friends of Peterhouse and is senior scientific advisor to and chairperson of the Peter Cundill centre for research into mood disorders in young people, University of Toronto, ON, Canada. Raphael Kelvin has received personal fees as a consultant to Lundbeck.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Goodyer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some of the information in this report is based on Goodyer et al. 1 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

Unipolar major depression in adolescents

Unipolar major depression is a significant mental illness affecting a substantial proportion of the adolescent population worldwide. 2 The disorder presents in episodes and the estimated 12-month period prevalence of major depression episodes in teenagers is 7.5%. Approximately twice as many girls as boys are affected and an estimated one in four cases experience a severe, impairing and clinically referable condition. 3,4 There is a growing concern based on longitudinal evidence that the consequences of some adolescent emergent major depression episodes include suicide, persistent and chronic mental health disorders, substance misuse, and failure to achieve both educationally and in the work place. 5 Furthermore, in adults there is evidence that a history of depression may interfere with treatment compliance and self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease,6 which suggests that reducing incident risk for depression early in life may have wider physical health-care benefits for later in the life course. These medium- and long-term negative outcomes also come at great economic cost to the UK and other nations, including in the developing world where depression has been noted to be at least as disabling as any other chronic illness in adult life as urbanisation increases. 7,8 Therefore, clinical methods for the treatment of depressed adolescents must go beyond short-term remission of a single episode; objectives should include reducing the risks for diagnostic relapse and recurrence risk by lowering depressive symptoms before independent adult life.

The combined effect of a high level of emerging mental illness with long-term consequences for health, together with the increasing demands for treatment from adolescents and their parents/guardians, makes it imperative to provide effective interventions that can be implemented by developing the current mental health workforce. 9,10 From this policy perspective it is also essential to consider the extent to which any effective treatment is deliverable and affordable. Currently, the cost-effectiveness of treatments aimed at reducing recurrence risk by lowering depressive symptom rate and avoiding diagnostic relapse up to 18 months after entering treatment are not known.

Are there effective treatments for depressed adolescents?

Over the past 20 years there have been a series of important randomised controlled trials (RCTs) determining both the efficacy and clinical effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for depression in adolescents that result in remission in the short term, that is by 28 weeks. 11,12 Original guidance compiled in 2005 by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the treatment of a moderate to severe depression episode, referred to and treated in NHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), advised the use of evidence-based psychological therapies, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), as the first-line treatment, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants constituting the pharmacological treatment of choice only if there was no satisfactory response. 13 The 2015 revisions now recommend that a SSRI may be used as a first-line treatment in combination with psychological therapy (individual CBT, interpersonal therapy, family therapy or psychodynamic psychotherapy) that runs for at least 3 months for a major depression episode, defined as five or more symptoms (of which one must be a depressed or irritable mood state of at least 2 weeks, most days of the week and most hours of the day) and associated with observable personal impairment. 14 However, the revised 2015 guidelines continue to warn against the use of SSRIs on their own. Furthermore, this revision applies only to patients with moderate to severe depression, defined as five or more symptoms associated with concurrent impairments in personal, social or educational life domains for longer than 2 weeks.

Research studies in adults have provided evidence for the clinical effectiveness of a number of psychological therapies for inducing clinical remission for adult patients suffering with a moderate to severe depression episode. These include CBT,15 interpersonal therapy, short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy (STPP)16 and non-directive brief psychosocial interventions (BPIs). 17 Overall, psychological therapies appear to be effective in a broadly equivalent manner, although results vary with methods and measures. 18 Current evidence indicates that findings from adult patients cannot be assumed to reflect comparable efficacy or effectiveness for depressed adolescents. 19

Evidence to date from RCTs on adolescents suggest that CBT is not rapidly therapeutic in the acute phase of treatment. 11 Furthermore, in the short term, CBT may not provide added clinical value when patients are already receiving fluoxetine plus active specialist clinical care in a UK CAMHS setting. 12 There is relatively little evidence on the use of STPP with children or adolescents, although the one clinical trial with this population had encouraging outcomes. 20

Interpersonal psychotherapy is effective for adolescents with mild to moderate depression in the short term, but there is no evidence for efficacy in patients with moderate to severe depression episodes. However, interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A) is not widely available on the NHS in the UK to treat depression in adolescents, although this problem is being addressed as part of the Improved Access to Psychological Therapies initiative of NHS England. 21 Relatively brief, problem-solving, approaches with a focus on promoting good interpersonal relationships may be of value in more severe forms of these illnesses but this remains to be fully evaluated. 22,23

Brief psychosocial intervention incorporates general principles from psychological therapies (e.g. agenda setting, problem-solving and facilitating relationships with peers, school and family). BPI has recently been formalised into a manual for systematic delivery within CAMHS clinics for the treatment of major depression aimed at inducing short-term remission. 24 A previous RCT reported that BPI combined with fluoxetine is as effective as BPI combined with fluoxetine and CBT in producing remission at 28 weeks of treatment. 12 It is not known if BPI alone is efficacious and clinically effective in the short term for patients suffering from a moderate to severe depression episode.

Only one study has tested the efficacy of psychological treatments against placebo and showed that time to remission is significantly quicker for SSRIs and SSRIs plus CBT against pill placebo. 11 All RCTs to 2016 have focused on establishing clinical effectiveness in reducing immediate symptoms and restoring personal functioning. 11,12,25 Although there is evidence for clinical effects, there is no evidence that any of the aforementioned treatments, individually or in combination, is efficacious in reducing recurrence risk by lowering depressive symptom rate or diminishing diagnostic relapse in the medium term (i.e. ≥ 1 year following intervention).

This lack of understanding about therapeutic effects on recurrence risk and clinical relapse is compounded by a remaining concern regarding the extent of the effectiveness of existing treatments and the natural history of these disorders. 4,5,26 RCT data to date have shown that, even when treatment is successfully delivered, a substantial number of depressed adolescents do not recover or they relapse following recovery. Thus, the proportion of depressed patients who meet the criteria for clinical remission did not rise above 70% by 28 weeks from the start of treatment. Indeed, in studies of moderate to severely depressed adolescents, one RCT in the UK reported that only 42% were very much or much improved by 12 weeks, rising to 53–61% by 28 weeks. 27 Of the remaining patients, a further 30% described themselves as no better or worse at 12 weeks, which fell to 18–24% by 28 weeks. 27 A recent meta-analysis noted that, compared with CBT alone, the combination of fluoxetine and CBT may produce greater improvement in psychosocial functions but no greater reduction in residual symptoms. 28 Even for successfully treated cases, there is a high relapse rate in the next 5–10 years. Overall, approximately 50–70% of patients attending a NHS CAMHS clinic may relapse in the 10 years between mid-adolescence and young adulthood, coinciding with some of the largest educational milestones and social changes they may face over their lifetime. 4,5,26

To date, there have been two naturalistic follow-up investigations of psychological treatment effects in the medium term (i.e. > 52 weeks) in depressed adolescents entered into RCTs. Both of these studies show that the likelihood of recurrence and relapse of diagnosis following successful treatment is substantial, occurring in 50–75% of treated patients, beginning within 1 year of clinical remission and being significantly higher in patients with recurrent versus single episodes. 29–31 These studies were, however, conducted with < 150 patients each and did not plan to investigate the relative effects of treatment in maintaining reduced depressive symptoms in the medium term.

There are no studies in the NHS that have investigated clinical effectiveness of specialist or general psychological treatments in reducing symptomatic recurrence risk or diminishing clinical diagnostic relapse of depression in the medium term up to 18 months following treatment. Therefore, it is unclear if there are superiority effects of one psychological treatment over another in reducing and maintaining lower depressive symptoms over time and, therefore, diminishing symptomatic recurrence risk.

Theoretically, psychodynamic practitioners suggest that potentially more enduring changes will be associated with this form of psychological treatment, as it aims to address and repair underlying mental models of interpersonal relationships that may be associated with the depressive symptoms. In a similar way, cognitive–behavioural therapists theoretically aim to teach new, more adaptive, methods of behaving and thinking, which should continue after therapy ends and, thus, reduce long-term relapse of disorder. These forms of therapy are therefore hypothesised to be more likely, if successful, to predict more enduring recovery than therapies simply addressing current symptom reduction, alleviating the impact of provoking life events and difficulties, providing psychoeducation and offering problem-solving advice.

Rationale for the current study

The current study was devised knowing that there is now a clear evidence base for implementing psychological treatments that are clinically effective for inducing short-term remission but whose efficacy for (1) reducing recurrence risk indexed by rising depressive symptoms in the medium term 18 months after treatment began or (2) preventing clinical diagnostic relapse after treatment is completed, remains unknown. The literature implicates a number of candidate specialist psychological treatments for putative effects on reducing recurrence risk and relapse rates, among which are CBT and STPP. Both treatments aim to reduce symptoms and future risk of relapse. Given clear-cut evidence that, in depressed adolescents, active psychological treatments are clinically more effective than no treatment, a pragmatic effectiveness superiority trial was conceived as the best design. The standard treatment chosen as the reference therapy was BPI, a relatively brief (i.e. maximum of 12 sessions) psychosocial approach to problem-solving, mental hygiene and well-being management with education about depressive illnesses. BPI was designed to be shorter than specialist psychological therapies and is aimed, theoretically, at gaining remission as quickly as possible from the depression episode. Therefore, the therapeutic protocol focuses on practical advice giving, psychoeducation about depression and how to manage daily life challenges.

Therefore, we designed a RCT to test the risk reduction effect of two specialist psychological treatments against a BPI primarily focused on short-term clinical remission. In each of the three arms of the RCT, SSRIs were available as a combination treatment option following the 2005 NICE guidelines. 13

The study must allow for the prescribing of SSRIs because short-term clinical effectiveness is also achievable with fluoxetine without the addition of a protocol driven psychological therapy. 11 However, as with psychological treatments, the contribution of SSRIs to reduce recurrence risk and relapse rate remains unknown. There is also evidence that cases which have been resistant to other antidepressant medication may show significant clinical improvement with a change to a different SSRI, if prescribed in conjunction with CBT. 25 This is the only published study25 of treatment resistance in depressed adolescents and suggests that medium-term treatment goals may be best achieved by combination therapies. This remains to be evaluated in a systematic RCT in which reduction in recurrence risk and relapse rates is the clinical outcome objective. Nevertheless, in the current study we judged it essential to abide by current NICE guidelines14 for the NHS and allow SSRI prescribing within each arm based on clinical judgement of psychological treatment progress.

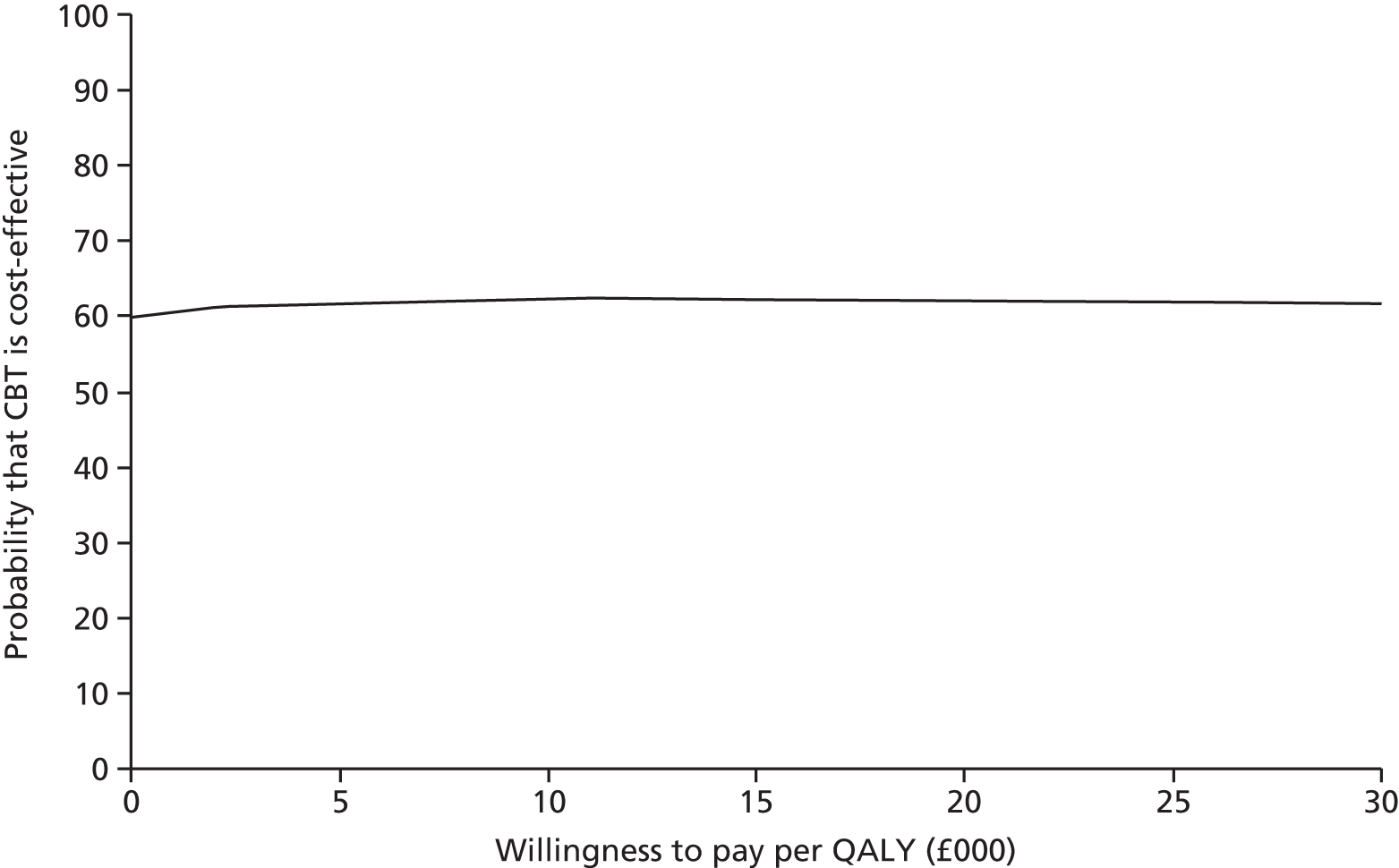

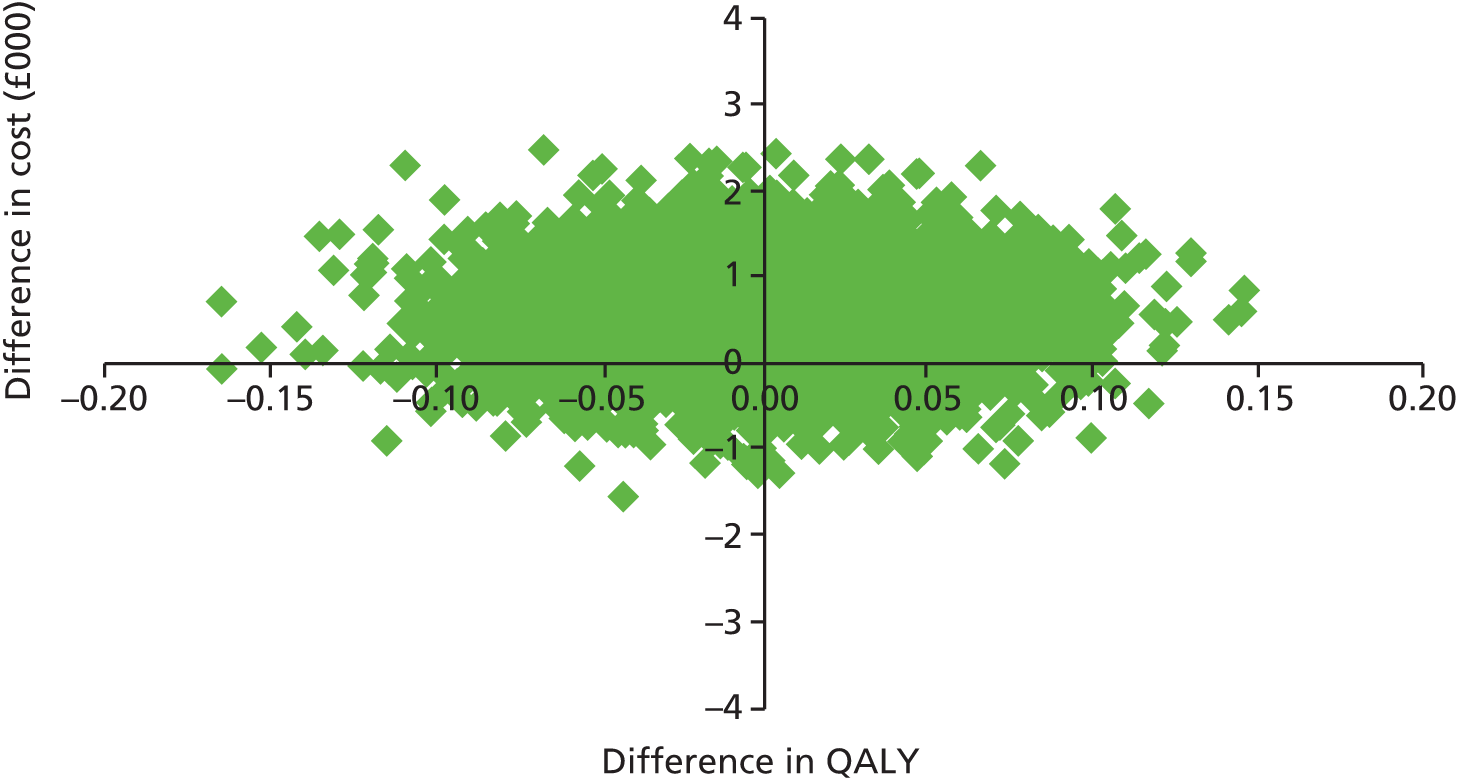

Given the importance of cost-effectiveness and deliverability within the NHS, we also included an economic evaluation component to the trial. Results from a previous RCT conducted in the USA suggest that CBT alone is relatively expensive and cost-ineffective compared with a SSRI alone. 32 The same RCT demonstrated that fluoxetine alone was much more cost-effective than combined fluoxetine and CBT over 12 weeks. 32 In the UK, a RCT reported that adding CBT to an existing combination treatment of fluoxetine plus active specialist clinical care (the non-manualised forerunner of BPI) in a CAMHS setting was not cost-effective over 28 weeks. 33 Whether or not more expensive psychological treatments may become cost-effective in the medium term by diminishing the subsequent use of health, education and social services more than the use of a ‘treatment as usual’ or BPI protocol is not yet known.

For this study, clinic-referred depressed adolescents only were considered for recruitment. To make the results applicable to NHS CAMHS services, we included those with suicidal thoughts, psychotic behaviours and non-depression comorbid disorders. This is comparable to the Adolescent Depression Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT)12 but distinguishes both of these UK studies from the major study of adolescent depression [Treatment of Adolescent Study (TADS)11] in the USA, as suicidal and psychotic cases were excluded from TADS and participants were recruited by advertisement. 11,27,34

Participants were recruited from patients referred to routine NHS clinics. All trial participants were treated in standard clinical settings using NHS staff to deliver treatments under supervision. This maximised ecological validity and generalisability to NHS settings and was intended to assure commissioners and providers that the study results could inform routine NHS service design, delivery and implementation.

Unlike the UK ADAPT RCT,12 those who responded to an initial phase of BPI (2–3 weeks) and who therefore may have been close to remission or were especially responsive, were not excluded. This is because all participants were prescribed fluoxetine in ADAPT and it was in keeping with the clinical practice at the time of offering a BPI before patients were committed to a 6-month course of fluoxetine. At the time of starting Improving Mood with Psychoanalytic and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (IMPACT), it was standard practice (in keeping with NICE guidelines) to start treatment with specific psychological therapy. In addition, unlike prior UK RCT studies,12,35 we added potential moderators of recurrence risk and relapse rates. These were individual differences in (1) self-reported rumination (persistently brooding or dwelling, often to the exclusion of other themes in the patient’s life)36,37 and (2) depressive thinking style (the extent to which patients with clinical depression may be characterised in terms of immaturity of the cognitive styles of self-criticism and perfectionism). 38–40

Aims and objectives

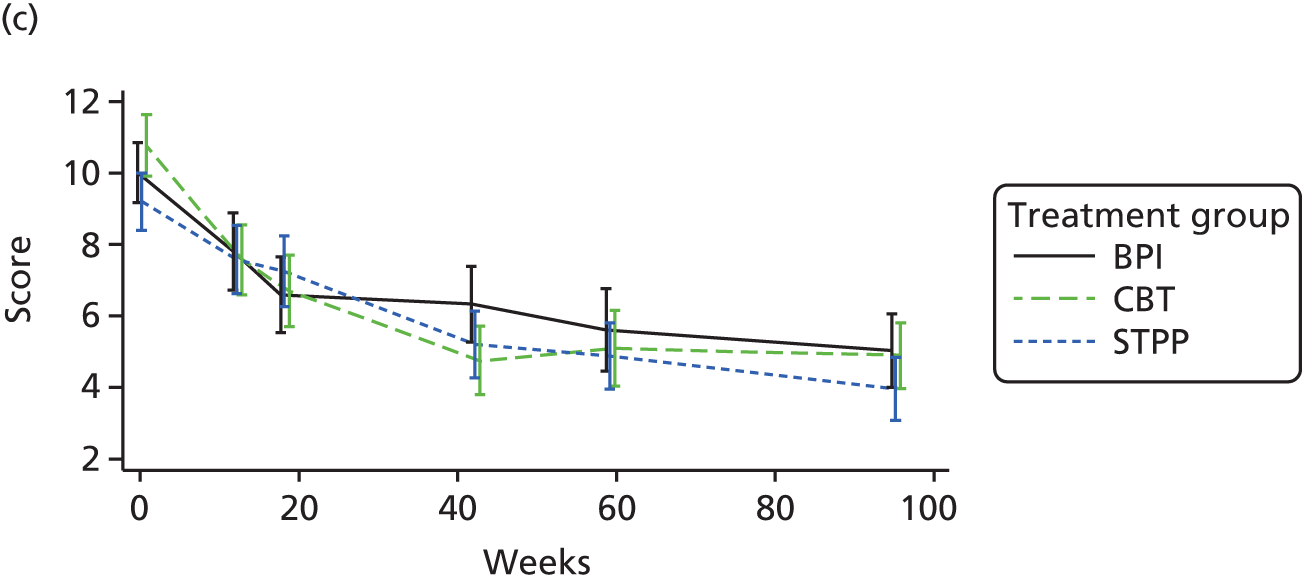

This superiority powered pragmatic effectiveness RCT was designed to determine whether or not psychological treatment delivered to adolescents with unipolar major depression would reduce the risk of recurrence through lowering depressive symptoms by 86 weeks post randomisation. As this was designed as a superiority effects trial, we tested whether or not, compared with a standard BPI, two specialist psychological treatments were more likely to result in lowering the rate of depressive symptoms from randomisation to 86 weeks after beginning treatment.

The primary objective contained two related questions. The first was to determine whether or not, in a specialist CAMHS setting, CBT and STPP were superior to a standardised BPI in reducing self-reported depressive symptoms over time. The second was to test if there were non-inferiority effects of CBT compared with STPP for lowering depressive symptoms by 86 weeks. The secondary hypothesis tested whether or not self-reported anxiety symptoms and research interviewer-evaluated psychosocial function were also significantly more likely to remain improved in those receiving STPP or CBT as opposed to BPI. An additional objective was to evaluate whether or not these specialist individual psychological treatments were more effective than standard BPI at reducing the clinical diagnostic rate for a major depression episode by 18 months after randomisation. However, the study was not powered to consider this outcome as a formal hypothesis.

Specific hypotheses

The hypotheses of the trial relate to the treatment effect in the post-treatment period (≥ 36 weeks).

The study had four primary hypotheses.

When comparing CBT with STPP:

-

CBT will show non-inferiority effects compared with STPP at 52 weeks

-

STPP will show superiority effects compared with CBT at 86 weeks

and when comparing CBT and STPP with BPI:

-

the specialist intensive interventions (CBT/STPP) will show superiority effects compared with BPI at 52 weeks

-

the specialist intensive interventions (CBT/STPP) will show superiority effects compared with BPI at 86 weeks.

This RCT tested a primary superiority clinical effectiveness hypothesis that, when compared with the reference BPI treatment:

-

STPP and CBT are both more clinically effective at maintaining a reduction in depressive symptoms at 52 and 86 weeks reassessment after randomisation.

The secondary hypothesis tested was:

-

STPP is superior in maintaining a reduction in depressive symptoms over the follow-up assessments (52 and 86 weeks) compared with CBT.

The RCT also tested an economic hypothesis to determine:

-

whether or not any additional costs of specialised treatments accrued by the end of treatment are justified by decreased use of resources (health, education and social care services, voluntary agencies) by 86 weeks of follow-up.

Chapter 2 Methods

The procedure for the study was to ascertain and recruit patients with an episode of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) major depression from routine NHS specialist CAMHS in three parts of the UK: East Anglia, North London and the north-west of England (Manchester and the Wirral).

East Anglia is a largely rural area of 3 million people, with four cities each containing approximately 100,000 people; North London is a densely populated urban sector of the metropolitan London region with around 4 million people; and north-west England is a region covering approximately 4 million people, of whom about 1 million are living in rural surroundings, with a further 3 million residing in the northern and central sectors of the large metropolitan area of the city of Manchester. Participants were recruited from 16 routine CAMHS clinics that agreed to participate from within these three regions.

The RCT was approved and monitored by the Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee in Cambridgeshire. The sponsors were Cambridge and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridgeshire; Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust, North London; Cheshire and Wirral Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, Chester; and the Central Manchester University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester. A scientific steering committee met every 6 months over the course of the RCT (chairperson: Professor Philip Cowen, University of Oxford; Professor Paul Stallard, University of Bath; Professor David Brent, University of Pittsburgh; and Professor Sabine Landau, King’s College London) and a Data Management Committee which also met every 6 months (chairperson: Professor Rona Campbell, University of Bristol; members: Dr Nicola Wiles, University of Bristol; and Professor Anna Marie Albano, Columbia University). The NHS Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment audited accrual, progress and quality of the study throughout.

Participants and patient involvement

Patients from a prior treatment study provided advice on formulating the research question and evolving the BPI manual described in Chapter 3. Patients did not contribute to the recruitment procedure but those recruited provided ongoing feedback on the burden of assessment over the course of the study. This resulted in a 30–50% time reduction in the length of reassessment in the post-treatment follow-up phase. All participants and their families will receive a summary document of the main findings. Families will be informed that the full details of the study will also be posted on a weblink41 and be available through mandatory open access arrangements for published work under the auspices of the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

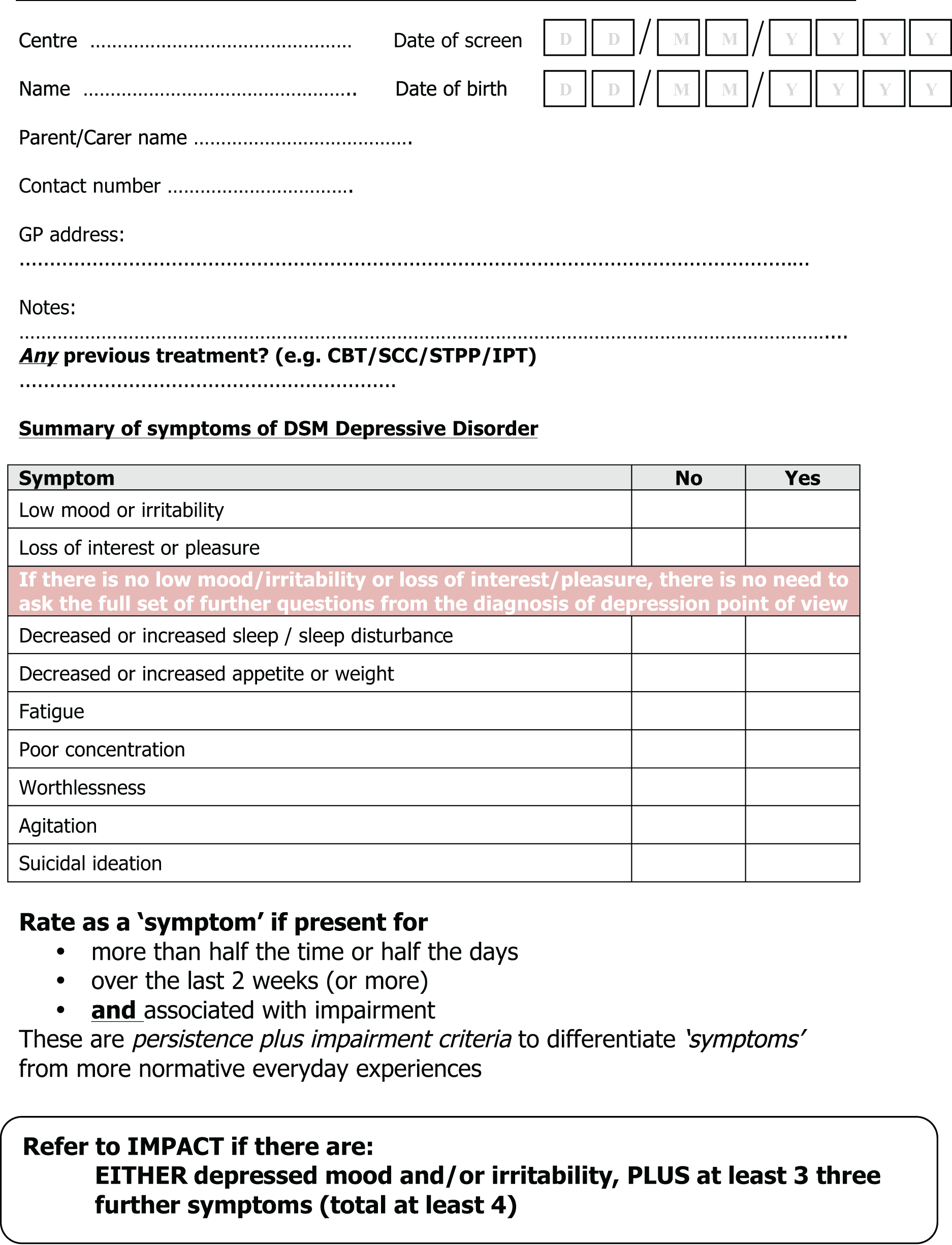

The research teams in each of the three regions contacted their regional clinics on a weekly basis to ascertain if there were any patients referred. The first point of contact was with clinical NHS staff who determined if their patient was in scope for the RCT. An initial screening checklist for major depression episode provided to the clinics by the research team and used to inform the research assessors of potential cases aided this clinical task (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Screening to assess suitability for full assessment and recruitment.

Recruitment

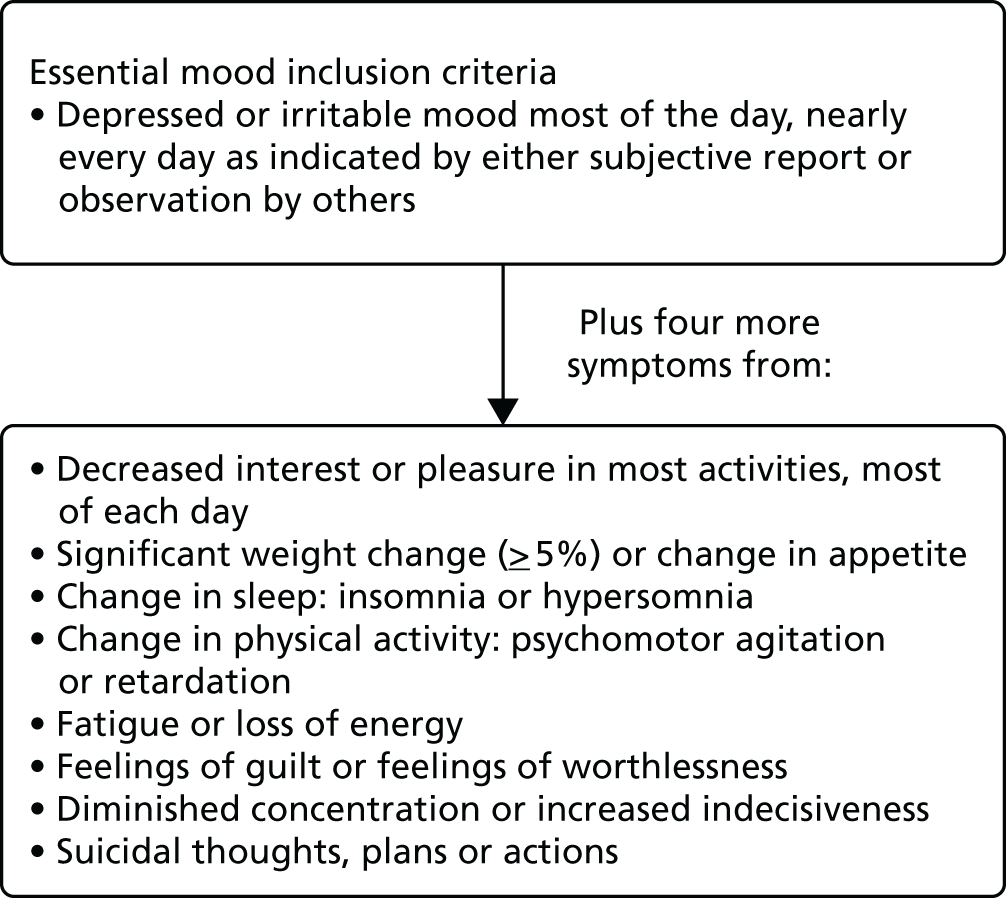

Participants were recruited if they met criteria for an episode of DSM-IV major depression and were aged between 11 and 17 years. This diagnosis is achieved by the presence of at least five symptoms, one of which must be a mood symptom present nearly every day and most of the day for at least 2 weeks, together with four others and accompanied by observable personal and/or social impairment. The criteria are shown in Figure 2. Mood change plus four other symptoms are required for the diagnosis.

FIGURE 2.

The DSM-IV criteria for major depression disorder.

Participants were recruited when clinical staff considered a patient to be depressed and requested that they completed the research checklist and asked them and their parents/guardians if they would consider taking part in a RCT investigating the extent to which treatment was able to lower recurrence risk and relapse rate. They were informed that the trial only included and compared treatments already known to contribute to producing clinical remission. If they expressed interest in the study, their contact details were passed to the research group and research staff contacted the patient with an expression of interest letter and a reply-paid envelope.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged 11–17 years.

-

Current diagnostic episode of DSM-IV unipolar major depressive disorder (MDD).

Patients with suicidal intent, past or recent suicidal behaviour, psychotic symptoms or any comorbidity, other than those specifically defined in the exclusion criteria below, were included.

Patients who met the inclusion criteria but had started a SSRI within 1 month were included.

As part of the screening process prior to enrolment, individuals were asked if their current depressive illness was a first episode or a relapse.

Exclusion criteria

-

Generalised learning difficulties.

-

Pervasive developmental disorder.

-

Pregnancy.

-

Currently taking another medication that may interact with a SSRI and unable to stop this medication.

-

Substance abuse.

-

A primary diagnosis of bipolar type I, schizophrenia or eating disorders.

Individuals who had received a psychological therapy consistent with the trial protocol for CBT, STPP or BPI were excluded.

Overall, 470 individuals were recruited and provided written informed consent, as did their parents/guardians. Ethics approval was by the Cambridgeshire 2 Research Ethics Committee, Addenbrooke’s Hospital Cambridge, UK. Follow-up was undertaken with repeated reassessments at nominal points time periods set at 12, 36, 52 and 86 weeks after randomisation to evaluate recurrence of self-reported depressive symptoms and enable re-evaluation of clinical diagnosis of an episode of major depression.

Chapter 3 Measures

A multimethod measurement approach of current mental state and psychosocial impairment was used. Measures for the adolescent patients included a selected set of self-report measures on current moods, feelings and behaviours, an interviewer-based assessment of current and previous psychiatric disorder completed by patients and a parent/guardian, an assessment of suicidal behaviour and non-suicidal self-harm behaviours and, finally, self-reported assessment of current cognitive ruminations and depressive cognitive style. The purpose of these measures was to test the primary and secondary hypotheses and to examine whether or not there were any moderating cognitive processes influencing treatment response or outcome.

Psychopathology

Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime

The Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime (K-SADS-PL) version is a semistructured interview measure which was used to establish the presence of DSM-IV diagnoses at all research assessments (baseline, 6, 12, 36, 52 and 86 weeks). 42 Each symptom is rated on a 3-point scale: 1 = non-clinical, 2 = being subthreshold and 3 = being a clinically relevant symptom, with the additional option of rating 0 = no information given to make a rating. Only symptoms rated as 3 were taken as clinically significant and DSM-IV criteria were used to ascertain the presence of current and past major and subthreshold depression episodes. Patients and parents/guardians completed the measure and both interviews were used to construct a diagnosis based on positive symptom reporting from either respondent. Interinterviewer agreement on the presence or absence of diagnoses has previously been assessed as satisfactory in adolescents with current mental illness (kappa, range for all diagnoses 0.70–0.85). 43 The K-SADS-PL was also used to generate DSM-IV current comorbid diagnoses.

Reliability was assessed for Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) depression diagnosis on 30 randomly selected cases. There was 100% agreement between two research assistants. For individual variables within K-SADS (660 items in total for 30 cases), there was agreement on 628 items and disagreement on the remaining 32 (5%).

Mood and Feelings Questionnaire

The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) is a 33-item self-report measure completed by the adolescent with current depressive symptoms present over the past 2 weeks and was administered at all research assessments. The instrument is designed to cover symptom areas specified in DSM-IV for an episode of MDD. 44,45 It has good test–retest reliability (Pearson’s r = 0.78)46 an α coefficient of 0.82 and discriminant validity for detecting an episode of major depression in clinical adolescent samples. 47 The MFQ is sensitive to change and can predict depression over time (weeks and months) in healthy adolescents with higher scores. 48,49 It is scored on a 3-point Likert scale of 0–2, giving a range of 0–66 and the higher the score, the greater the likelihood of increased number and severity of depressive symptoms.

Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale

This self-report questionnaire contains 28 items that measures current general anxiety, including physiological anxiety, worry/oversensitivity and social concerns. 50,51 Scoring is on a 4-point Likert scale and higher scores indicate greater levels of anxiety. 50,51 The internal reliability is good (Cronbach’s alpha < 0.80).

Short Leyton Obsessional Inventory

The short Leyton Obsessional Inventory (LOI) (child version) is an 11-item, self-report questionnaire for current symptoms of obsessive–compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. 52 Internal reliability of the scale is high for the short scale total (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86). It is scored on a 4-point Likert scale and higher total sum scores indicate greater obsessional thinking and compulsive behaviour.

Behaviours checklist

The behaviours checklist is an 11-item self-reported checklist for symptoms of antisocial behaviour based on DSM-IV criteria for conduct and oppositional disorders. It is a self-report measure, scored on a 4-point Likert scale. 13

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale

This instrument is designed to track suicidal adverse events across a treatment trial. 53 It is a prospective version of the system developed for the Food and Drug Administration of the USA54 as a way to get better safety monitoring and avoid inconclusive reporting of these events. Being feasible and of low burden (typical administration time 5 minutes), it assesses both behaviour and ideation and appropriately assesses and tracks all suicidal events. It uniquely addresses the need for a summary measure of suicidality. The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale was administered in the form of an interviewer-led respondent-based semistructured interview, at all time points, alongside the K-SADS-PL.

The Risk-Taking and Self-Harming Inventory for Adolescents

This is based on existing instruments for assessing self-harm and risk-taking behaviour, and on clinical descriptions of these behaviours, using items that tap into these in both direct and indirect ways. 55 The 20 items range from milder behaviours, such as picking at wounds and pulling one’s hair out, to more serious self-harm, such as taking an overdose and attempting to commit suicide. Most items contain the word ‘intentionally’ or end with the phrase ‘to hurt or punish yourself’. The items are on a 4-point Likert scale, referring to lifelong history. The higher the score, the greater the general risk-taking and self-harm, and the two subscales (risk-taking and self-harm) can be scored separately. The instrument was administered at all time points.

Ruminative Responses Scale

The Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS) is a 39-item measure taken from the Nolen-Hoeksema’s Ruminative Depression Questionnaire. 36 It describes responses to low mood that are self-focused, symptom-focused and focused on the possible consequences and causes of the mood using a 4-point Likert scale. Rumination is a potential cognitive vulnerability factor for depressive symptoms among adolescents. 56 High rumination predicts onset of depressive disorder in healthy adolescents. 27,57 Preliminary data from the previous ADAPT RCT suggested that CBT may reduce rumination. Although this had no effect on depressive symptoms over 28 weeks, it may reduce relapse risk. 37

The Depressive Experience Questionnaire for Adolescents – Short Version

Adult patients with clinical depression may be characterised by putative cognitive style. 38–40 This cognitive style has been described generically as one of immaturity which is characterised by an excessive preoccupation with relatedness with others (principally focused on disappointment with relationships) and self-definition or identity (principally focused on self-criticism). In this study, relatedness and identity were measured by the short version of the Depressive Experiences Scale for Adolescents (DES-A). 58

The RRS and DES-A scales were completed prior to randomisation. The planned use was to determine individual differences in the baseline total score of the RRS and the subscale scores for relatedness and self-definition/criticism of the DES-A, and to test if they acted as potential moderators of treatment effects.

Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Children and Adolescents

The Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA) is a routine outcome measurement tool that assesses the behaviours, impairments, symptoms and social functioning of children and adolescents with mental health problems. 12,59,60 It provides a global quantitative measure of an individual’s current mental health status. The instrument consists of 13 scales and each scale is interviewer-rated on a score between 0 and 4 (total range 0–52). The higher the sum and subscale scores, the greater the level of overall mental health problems within the adolescent. The measure is sensitive to change in mental state and psychosocial functioning over a brief (weeks and a few months) period. The measure was used at all time points as a semistructured interview with both subjects and parents/guardians. The planned use of the measures was as a correlate and adjunct to self-reported depression scores revealing the level of personal impairment for each patient over time.

Health economic measures

Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule

Data on the use of all services included in the study were collected using the Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS), as previously used in the ADAPT. 33 Information about the study participants’ use of services was collected by an interviewer at baseline and at 6-, 12-, 36-, 52- and 86-week follow-up assessments with the adolescent and parents/guardians. At baseline, information covered the previous 3 months. At each of the follow-up interviews, service use since the previous interview was recorded; in this way, the entire period from baseline to final follow-up was covered. The CA-SUS asks participants for the number and duration of contacts with various services and professionals. At each treatment contact, BPI, STPP and CBT therapists recorded information on the details of the treatment session including the start and end time as well as attendance.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) is a standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome. 61 Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were calculated from EQ-5D scores taken at baseline, 6-, 12-, 36-, 52- and 86-week follow-up interviews. The EQ-5D is a non-disease-specific measure for describing and valuing health-related quality of life and it includes a rating of own health in five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) plus a rating of own health by means of a visual analogue scale (a ‘thermometer’) (on a scale of 0–100). 62 A recent study provided initial evidence to support the relevance of the EQ-5D in adolescents with major depression63 and it was used successfully in a previous study of treatment for adolescent depression in the UK. 33 QALYs were calculated using the area under the curve approach after the health states from the EQ-5D were given a utility score using responses from a representative sample of adults in the UK. 64 It is assumed that changes in utility score over time followed a linear path. 65 QALYs in the second year were discounted at a rate of 3.5%, as recommended by NICE. 66

Chapter 4 Ascertainment

The trial recruited patients from three regional centres and utilised local CAMHS teams within those sites for trial recruitment. The local CAMHS teams (n = 15, five in each regional centre) were visited by principal investigators (PIs) based within their regional academic centre and had the study plan introduced to them. Three seminar days, one in each regional academic centre, were run to introduce the study design and planned recruitment procedures to clinical staff and service managers. NHS staff had the opportunity to inform the recruitment process by asking questions and seeking further information and clarification from the PIs about the science, the design and the objectives of the trial. Each clinic that was involved designated a clinical staff member to champion the study to other staff on a weekly basis to encourage recruitment invitations to patients. Clinical staff working within CAMHS conducted identification and initial screening of potential participants.

All study participants were identified from routine NHS (tier 3) referrals to the participating specialised (tier 3) CAMHS clinics. There were no recruitment strategies unique to the study and no use of advertisement. At the first assessment to CAMHS, the assessing clinicians were invited to complete a depression symptom screen designed to assist referral to IMPACT. Using a combination of routine clinical methods at first assessment, aided by a depression screen based on DSM-IV criteria, potential cases were identified as being within the scope of the study. The assessing clinicians informed the young person and their parents/guardians/carers about the trial and invited them to consider taking part. If an expression of interest to take part was obtained, then their details were passed to the research group. They were informed at this point that the study team would be in touch if they expressed an interest to participate. The potential participants were informed that recruitment was dependent on the research team assessments and whether or not the patient met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The participants and their parents/guardians were sent information sheets about the trial and a reply envelope indicating they had read the information and were willing to be contacted by a researcher who then scheduled an initial meeting during which the participants were invited to sign a consent form. In line with good clinical practice, young people under 16 years of age provided consent along with their parents/guardians, and those who did not wish to involve their parents/guardians or carers were encouraged to do so. Participants who were 16 or 17 years old, who met the criteria and had mental health capacity but did not want their parents/guardians or carers involved were included.

Two researchers working on parallel sessions administered all research baseline assessments to the young person and their parents/guardians/carers. After this, researchers confirmed whether or not the participants met the diagnostic and other entry criteria. When there was uncertainty, the parent/guardian/carer report, if available, was combined with the young person’s responses and, if still not clear, a consensus discussion was held with the local PI to establish eligibility. If they met criteria and gave consent, participants were randomised remotely into one of the treatment arms. The trial co-ordinator in each regional site then informed the young person and the referring clinic about the treatment allocation. Other researchers, some of whom conducted follow-up assessments, remained blind to treatment allocation. Following randomisation, trained and supervised CAMHS staff working in the participating clinics treated all patients in the trial.

The trial co-ordinator carried out treatment allocation using stochastic minimisation controlling for age, sex and self-reported depression sum score. The patients were followed up and reassessed at five planned time points from randomisation. The primary outcome was self-reported depression symptoms at the planned end point 86 weeks post randomisation (mean duration of last assessment for each arm = 95 weeks), which was at least 52 weeks after the end of treatment. The primary analysis was based on intention to treat.

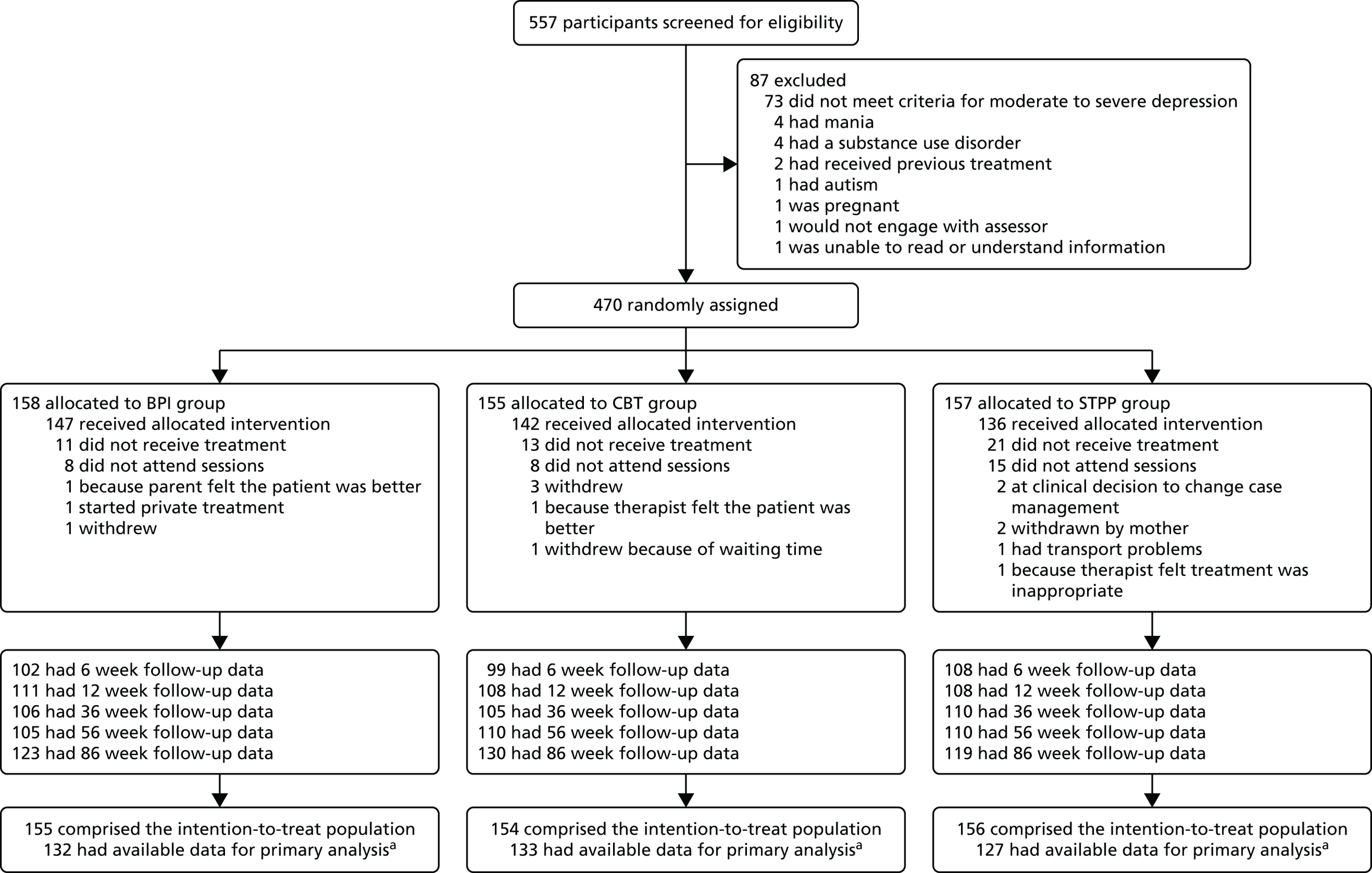

The study sample recruitment procedure is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT diagram of patient ascertainment for IMPACT. a, The primary hypothesis was analysed in 392 (84%) of 465 who were randomised, accepted treatment, and provided one or more self-reported depression symptom score over the 36-, 52- or 86-week assessment points. Five patients withdrew consent before starting treatment (n = 3 in the BPI group, n = 1 each in the CBT and STPP groups) and requested their data be deleted. Reproduced with permission from Goodyer et al. 1 © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

The patients approached were those considered by the CAMHS staff through routine clinical assessments to be clinically depressed. Therefore, those randomised are representative of the clinical populations at moderate to severe levels of severity attending these clinics.

The general levels of comorbidity, impairments and self-harm found in this study indicate comparability with previous studies12 for which depressed patients were recruited from general routine NHS CAMHS.

A total of 470 patients from 557 baseline assessments aged between 11 and 17 years were recruited and randomised. Of these, five subjects withdrew consent after baseline assessment and randomisation and have had their study records destroyed (two from North London and three from north-west England). There was no indication that this was related to treatment allocation. Out of the remaining 465 randomised patients, 185 (40%) were from East Anglia, 127 (27%) were from North London and 153 (33%) were from north-west England. Furthermore, a total of 348 patients (75%) were girls.

Chapter 5 Trial procedures

IMPACT compares three psychological interventions (STPP, CBT and BPI), which are delivered to treat an episode of DSM-IV major unipolar depression and to reduce the risks of recurrence of depression through reducing symptom levels over the follow-up period of 36–86 weeks.

After patient consent had been obtained and the baseline assessment had been carried out, a trial identifier was assigned. Treatment allocation was carried out by the trial co-ordinator using stochastic minimisation controlling for age (11–13 years, 14–15 years and 16–17 years), sex, self-reported depression sum score (≤ 29, 30–39, 40–49 and ≥ 50) and region (East Anglia, North London and north-west England). In view of the nature of the interventions, patients and clinicians were aware of treatment allocations. This was conducted by the trial co-ordinator using an online randomisation service (www.sealedenvelope.com). 67 Information about treatment allocation was forwarded to a clinic champion who ensured allocation of a therapist to the participants. To minimise bias, the outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation and did not communicate with each other or with therapists about case assessments. All interviews were audiotaped and a random sample was rerated by independent raters. If blindness was broken, an alternative assessor carried out all subsequent assessments.

Planned interventions

IMPACT was a pragmatic superiority trial comparing the relative clinical effectiveness of three psychological treatments each with evidence of clinical efficacy being associated with clinical remission in the short term (i.e. 3–6 months). These treatments are available in CAMHS NHS practice, although distribution around the UK is not standardised. The three treatment approaches tested in this study were all manualised.

A duty of care by clinical staff to patients was observed in all clinical arms. This included parent/guardian support and engagement, explanation of treatment principles, maintenance and support of family during individual treatment, individual risk management strategies and contact with other agencies, if appropriate.

Comprehensive treatment protocols were developed for the trial and designed for delivery by practitioners working in routine NHS CAMHS settings. The rationale for using treatment manuals as guides to therapy is that manuals:

-

aid dissemination of treatment methods into clinical practice

-

help to standardise the intervention between therapists and across sites

-

form the basis for audio tape ratings of treatment adherence and differentiation; thus, ensuring that the interventions have been given properly in keeping with the trial protocol.

The three treatments differed in the total number of sessions they offered over the study period. The number of sessions offered for each treatment were as follows.

-

BPI: up to 12 sessions, consisting of up to eight individual and four family/parent/guardian sessions, to be delivered over 20 weeks.

-

STPP: up to 28 individual sessions plus up to seven parent/guardian sessions to be delivered over 30 weeks.

-

CBT: up to 20 individual sessions plus up to four family/parent/guardian sessions to be delivered over 30 weeks.

The treatments are described below.

Brief psychosocial intervention

Brief psychosocial intervention is a brief structured intervention for the treatment of moderate to severe unipolar major depression in adolescents. 68 The clinical care approach originally used in ADAPT was the basis for BPI used in this trial. 12,24,27 In ADAPT, the forerunner of BPI (described as non-manualised treatment as usual in CAMHS), together with 20–60 mg of fluoxetine daily, was as effective as treatment as usual + fluoxetine + CBT for moderate to severely depressed adolescents in routine NHS practice. 12,27 This clinical care was reformulated for the current study and formalised into a treatment manual. 24 Prescribing a SSRI is not a part of BPI per se but can be added and fully integrated if improvement is not judged to be occurring after 2–4 weeks, as per the NICE guidelines of 2005. 13

Meta-analytic studies of adolescent psychotherapies highlight the central therapeutic importance of care that is structured, evidence driven and founded on interpersonal effectiveness, warmth and trust. 69,70 The incorporation of collaborative care for depression in adults has been shown to provide added value for the treatment of depression in adults over and above psychological and/or medication treatments. 71,72

The BPI treatment manualised for this study emerged from the treatment as usual in ADAPT. The intervention is a treatment based on restructuring and codification of the principles and practices found in the domains of skilled assessment, listening, information-giving, advising, problem-solving, safety, caring and explaining about adolescent depression. The duration and number of treatment sessions in the BPI manual is based on clinical experience gained through ADAPT.

The BPI was delivered in this study as the standard control psychosocial intervention. Emphasis was placed on the importance of psychoeducation about depression and action-oriented, goal-focused, interpersonal activities as therapeutic strategies. Specific advice was given on improving and maintaining mental and physical hygiene, engaging in pleasurable activities, engaging with and maintaining school work and peer relations, and diminishing solitariness. BPI did not use cognitive or reflective analytic techniques. Therefore, there was no discussion of unconscious conflict and no deliberate effort to modify maladaptive models of attachment relationships. Neither was there any focus on changing cognitions and negative cognition-driven behaviours were not deconstructed. BPI consisted of up to 12 sessions, made up of up to eight individual and four family/parent/guardian sessions, delivered over 20 weeks. Liaison with external agencies and personnel (e.g. teachers, social care workers and peer groups) were commonly undertaken.

Case management in brief psychosocial intervention

As BPI case management has a rationale and relational framework, case management is founded on the three principles of:

-

interpersonal effectiveness

-

understanding of mental states

-

activation and problem-solving.

The case management process is integrated through the development of a formulation which is a general construct summarising the probable relationship between the three constructs above. The formulation is developed as a series of prospective working hypotheses that can be tested and evaluated against subsequent progress within the therapy. BPI is delivered within this framework in up to 12 sessions, consisting of up to eight individual and four family/parent/guardian sessions, over 20 weeks.

Therapy was delivered with the following strategies and principles being utilised throughout:

-

effective engagement, activation and problem-solving

-

diagnostic accuracy and mental state evaluation

-

sharing understanding and knowledge of the impairments and consequences of symptoms; the ‘lived experience’ including effects in other settings, such as school or peer relationships

-

attention to accuracy in conducting a risk assessment and its management

-

sharing aetiological description: defining risk and protective factors

-

a psychoeducative approach that at all points aims to help ‘activate’ and empower, including parents/guardians and family as necessary

-

an approach that includes understanding of the role of medication, its appropriate use and how it sits within the care package

-

a jointly agreed, collaboratively developed, and shared, management plan.

All of the above are delivered in a fashion that can help the child, young person and parents/guardians to manage and cope with their emotional expression.

Therapists, training and supervision

The BPI therapists in this study were drawn from a range of professional backgrounds, including mental health nursing, clinical psychology, psychiatry and mental health social work. However, the majority (> 80%) of therapists were psychiatrists in specialist CAMHS training as well as consultants. In IMPACT, clinicians had to have the following in order to be eligible for training as a BPI therapist:

-

a minimum of 6 months’ supervised or independent work in a multidisciplinary child and adolescent mental health setting

-

already established sufficient competence and skills to be allowed to undertake independent mental health assessment and treatment of adolescents with moderate to severe depression.

The BPI practitioners had basic training in BPI: reading of the manual, confirmation by the supervising clinician that they met the criteria to become a BPI therapist, attendance at a BPI training day, continued access to the BPI manual and ongoing supervision fitting in with usual local CAMHS NHS supervisory structures. The regional leads for BPI met and problem-solved supervisory issues in relation to BPI on a regular basis across the IMPACT period.

Short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy

Psychoanalytic psychotherapy with children and young people is a well-established specialist treatment for emotional and developmental difficulties in childhood and adolescence, with an emerging evidence base. 73,74 It is one of several psychological therapies recommended by NICE as equally effective in the acute treatment of child and adolescent depression. 75 Its intellectual roots are drawn from psychoanalysis, child development, attachment theory and developmental psychopathology.

In this trial, all therapists were approved as psychoanalytically trained by the Association of Child Psychotherapists, UK. The STPP used shared therapeutic principles with time-limited psychodynamic work for adults with depression for which there is now a substantial evidence base. 73 It is a 28-session model, with parents/guardians or carers being offered up to seven additional sessions by a separate parent/guardian worker. STPP aims to elaborate and increase the coherence of the young person’s mental models of attachment relationships and thereby improve their capacity for affect regulation as well as the capacity for making and maintaining positive relationships with others. 76

The STPP method73,77 draws on a long history in the UK of psychoanalytic work with depressed children and young people,77,78 including an earlier clinical trial, in which STPP for children with depression demonstrated good outcomes. 35 As with the other manuals used in IMPACT, the STPP manual74 provided a guide to practice but not a recipe or a step-by-step guide, and drew on the existing skills and training of child and adolescent psychotherapists already working in the NHS.

The STPP method aims to elaborate and increase the coherence of the young person’s mental models of attachment relationships and thereby improve their capacity for affect regulation as well as the capacity for making and maintaining positive relationships with others. When treatment is successful, it should free the young person to engage in normal adolescent development including educational attainment and independent peer group development involving a degree of separation from their primary carers. 79

The techniques of child and adolescent psychotherapy are primarily based on close and detailed observation of the relationship the child or young person makes with their therapist. The therapist introduces the therapeutic task to the young person as one of understanding feelings and difficulties in their life. The therapist’s stance is non-judgemental and enquiring, and conveys the value of understanding; the aim is to put into words conscious and unconscious thoughts and feelings. Through actions and words, the therapist attempts to convey an openness to all forms of psychic experience – current preoccupations, memories, day dreams, nocturnal dreams and phantasies – but will be attuned specifically to evidence of unconscious phantasies which underlie the young person’s relationship to themself and others. This attentiveness to unconscious phenomena is specific to psychoanalytic psychotherapy and is related to the theoretical importance attributed to these deeper, less accessible, layers of the mind.

With all adolescents, most particularly those with difficult early years experiences, there is a need for the therapist to be in a state of mind characterised by availability to the reception of projected contents (anxieties, affects, uncertainties) of the adolescent’s mind. The patient’s experience of the therapist receiving, holding in mind and thinking about this projected material is a central feature of the therapy. The adolescents are helped to gain ownership of a previously disowned part of themselves and are strengthened by identification with another person (i.e. the therapist) who is experienced and capable of making meaning in this way and, thus, enabling more mature thinking to take place.

The STPP therapist and/or parent/guardian worker requires an alertness to the need, at times, for active communication and liaison with other significant individuals and agencies in the adolescent’s life. This may include external agencies such as school/college, youth and social services, and also mental health colleagues, including Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists, where there are issues about risk and a possible need for medication or hospitalisation. Prescribing a SSRI is not a part of STPP per se, but can be added and fully integrated if improvement is not seen after 2–4 weeks, as per the 2005 NICE guidelines. 13

Support for parents/guardians or carers, offered concurrently and in parallel with individual therapy for children and adolescents, is a well-established practice in the UK. There is some evidence that psychoanalytic therapy is more effective when undertaken with concurrent parent/guardian support work. 74 Parent/guardian support aims to help with parental anxieties and develop greater understanding about their relationship to their son or daughter. The duration of treatment and number of sessions prescribed is based on prior studies and clinical experience with adolescent patients.

Therapists, training and supervision

To be eligible to practise as a STPP therapist in IMPACT, the clinician had to have undertaken a 4-year postgraduate professional training, leading to membership of the Association of Child Psychotherapists or be a fourth year trainee member of the Association of Child Psychotherapists. In addition, those doing parent/guardian work had at least 6 months CAMHS experience following professional training in child psychotherapy, clinical or counselling psychology, child mental health nursing, family therapy or psychiatry.

The STPP training was designed and delivered on the basis that prospective STPP practitioners already have all the fundamental competencies and skills required to deliver all the components of STPP. Building on these existing skills, STPP training for IMPACT comprised reading of the STPP manual, confirmation by the clinician that they met the criteria to become a STPP therapist, and attendance at a STPP training day.

The STPP supervision by a consultant child and adolescent psychotherapist was provided as part of routine practice within the CAMHS team.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

Cognitive–behavioural therapy in this trial is based on the classical form originally developed for adults with depression. This posits that emotional disorders are characterised by pervasive information processing biases which increase vulnerability to depression in the context of environmental stress, and which maintain and amplify core symptoms of depression including hopelessness, low mood and irritability. The focus of CBT is to identify the information processing biases that maintain depression and low mood and to amend these through a process of collaborative empiricism between the therapist and client.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy was adapted for this study to include parental involvement, a large focus on engagement and an emphasis on the use of behavioural techniques. 80,81 CBT included up to 20 sessions plus up to four parent sessions over 30 weeks. CBT therapists were routine CAMHS clinicians and were either clinical psychologists or other clinicians who had received post-qualification training in CBT. CBT emphasises ‘collaborative empiricism’, that is explicit, tangible and shared goals between the therapist and young person, and clear structured sessions. CBT links thoughts, feelings and behaviours, and the techniques include behavioural activation, identifying and challenging negative automatic thoughts, developing adaptive thoughts, and relapse prevention. Topics introduced within a therapy session are extended and supported outside the session by tasks completed by the client between sessions and reviewed at each subsequent session. CBT was delivered to the adolescent alone or to the young person and parents/guardians flexibly. A formulation was developed at the start of therapy, which included consideration of parental and family factors in the development and maintenance of depression. If it was considered relevant, the parents/guardians were involved in therapy sessions, by negotiation, to support the young person in treatment.

In this study, CBT was manualised and it incorporated adaptations for working with adolescents (as opposed to adults), including inclusion of simplified and age-appropriate cognitive techniques, as well as the flexibility to take a behavioural focus if cognitive work was considered too demanding for a young person. A number of additional amendments were made, including a greater focus on engagement in therapy, building the therapeutic alliance and working collaboratively with parents/guardians and schools. Parents/guardians were involved in treatment sessions as indicated by the formulation and the preferences of the family. There were no separate sessions for parents/guardians.

Treatment length for CBT was a maximum of 20 sessions, delivered weekly, tapering to every 2 weeks as needed for relapse prevention, plus up to four family/parent/guardian sessions. Sessions were structured with an agenda set by the therapist and young person at the start of every session and out-of-session assignments were agreed between the therapist and young person. Typically, early sessions (the first to fourth) focused on relationship building, understanding the young person’s current presentation and experience, and psychoeducation, including the CBT model. A provisional formulation of the young person’s difficulties, incorporating family history, key life events and transitions, recent stressors and coping strategies was developed with the young person (and parent/guardian when relevant). Subsequently the formulation guided treatment. This included using CBT techniques to treat non-depressive comorbid symptoms of anxiety, obsessions and compulsions and oppositional behaviours.

The mid-treatment phase focused on identifying and modifying the behavioural and cognitive processes that maintained depression and low mood for that young person. Behavioural work included activity scheduling, ratings of mastery and pleasure and reinforcement of engagement in activities. Cognitive work included identifying dysfunctional and unhelpful automatic thoughts and thought challenging using a range of techniques, including behavioural experiments. Modifications to the core CBT model, such as the use of mindfulness, were permitted depending on the individual formulation. The end of treatment was marked by a focus on relapse prevention. Typically this included a revisit to the formulation, identifying potential risk and vulnerability factors, problem-solving and building resilience. Prescribing a SSRI is not a part of CBT per se but can be added and fully integrated if improvement has not occurred after 2–4 weeks, as per the 2005 NICE guidelines. 13

Therapists, training and supervision

The CBT therapists were NHS staff from a range of professional backgrounds, including clinical and counselling psychology, nursing and occupational therapy. They delivered CBT for depression as part of their routine clinical practice in multidisciplinary CAMHS.

The CBT therapists had to have received specialist training in CBT, either as part of their core professional training (i.e. as a clinical psychologist) or as post-qualification training (i.e. as a nurse or occupational therapist). They were eligible to be IMPACT CBT therapists if they routinely used CBT in their NHS clinical work and if they could demonstrate some pre- or post-qualification training in CBT.

The CBT training was delivered as a 1-day workshop within services. It was designed as a top-up training for individuals who already had core CBT skills. The core features of the treatment manual were described and the practicalities and constraints of delivering CBT within the context of a research trial were discussed. All clinicians had copies of the CBT manual and familiarised themselves with it. Furthermore, CBT supervision was provided as part of routine practice within the CAMHS team.

Prescribing of fluoxetine during the trial

For all three arms, fluoxetine or another SSRI could be added if clinicians judged that combination therapy may accelerate the time to remission, following NICE guidelines for a major depression episode in adolescents. 13 A test dose of 10 mg was given for 48 hours, followed by 20 mg as a single dose. If there was no improvement within 2–4 weeks then the dose could be adjusted upwards to a maximum of 60 mg.

Chapter 6 Treatment fidelity and differentiation for each therapy modality

Establishing treatment differentiation between the three interventions, and treatment fidelity to each manualised intervention, are essential validity steps towards interpreting the effectiveness of different treatment approaches. This chapter provides results of the assessment of treatment fidelity based on measures of adherence to each protocol for each therapy and also to differentiation of therapies from each other.

Treatment fidelity refers to ‘the extent to which a therapist used interventions and approaches prescribed by the treatment manual, and avoided the use of intervention procedures proscribed by the manual’. 2 Therefore, fidelity in this study is not measuring the overall clinical competence of each therapist. The key task addressed is to answer the question ‘Did the therapy occur as intended by the manual?’ (treatment fidelity) and, in addition, ‘were each of the treatment arms sufficiently distinct from the others in regards to the techniques used?’ (treatment differentiation). Establishing fidelity to the manualised therapy, and differentiation between the treatment arms, are essential validity step towards interpreting the relative effectiveness of different treatment approaches, which is key to the primary and secondary objectives of this study.

The aim of the fidelity and differentiation study was therefore to assess:

-

the degree to which the therapists utilise prescribed or proscribed procedures, based on the treatment manual used in each arm of the study (‘treatment fidelity’)

-

whether or not treatments differed from each other along critical dimensions (‘treatment differentiation’).

Design

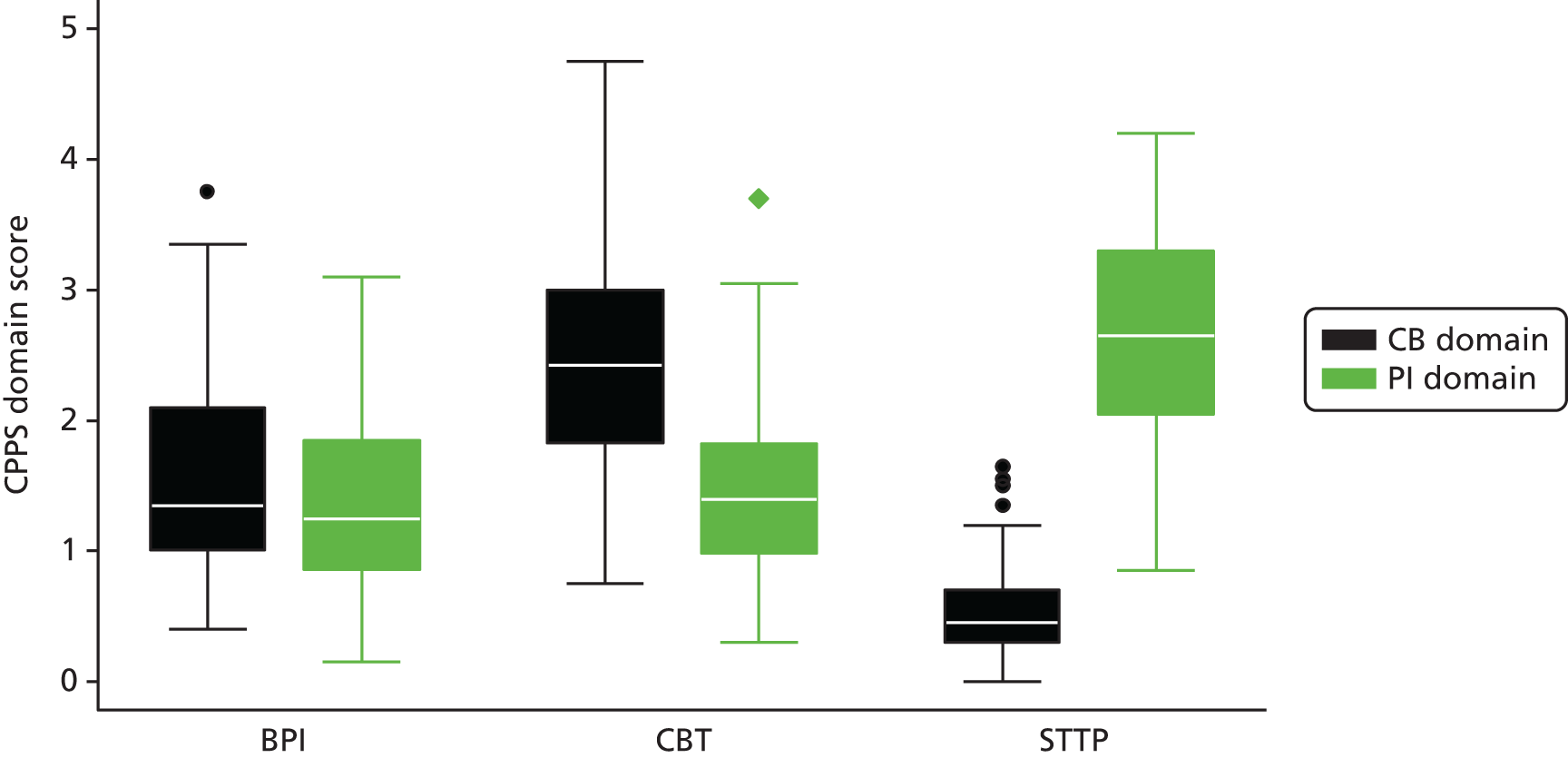

Two independent raters, blind to treatment allocation, rated each treatment session from the three treatment modalities using the Comparative Psychotherapy Process Scale (CPPS), which is a widely used measure of therapeutic techniques in psychodynamic therapies and CBTs. 82 These ratings were used to assess treatment fidelity for the CBT and STPP arms of the study and treatment differentiation between all three arms of the study. In addition, sessions from the BPI arm of the study were each rated by two raters, using a newly devised BPI fidelity measure in order to assess treatment fidelity to the BPI manual. Double ratings were used to check the reliability of each measure and improve the precision of the estimate for each tape.

Sample size

All therapists and young people in IMPACT agreed to their sessions being tape recorded for the purposes of the fidelity and differentiation analysis. Recorded sessions were categorised as either ‘early’ or ‘medium/late’ in therapy. A random sample of 232 tapes (76 CBT tapes, 81 STPP tapes and 75 BPI tapes) were selected and stratified by modality and timing (‘early’, i.e. the first third of therapy, or ‘medium/late’, i.e. the middle or last third of therapy), and were then rated on the measure of comparative (psychodynamic and cognitive–behavioural) techniques. The slight difference in the number of sessions rated by arms arose owing to the number of tapes available by treatment arm and site. As the comparative measure did not include the active features of BPI, the 75 BPI tapes were additionally rated on a treatment-specific measure.

Instruments

Comparative Psychotherapy Process Scale – External Rater form

The CPPS is a measure that assesses the degree to which a therapist uses techniques of psychodynamic interpersonal and/or cognitive–behavioural psychotherapy in an entire psychotherapy session. 82 Developed from an extensive empirical review of the comparative psychotherapy process literature,82 all items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘not at all characteristic’), 2 (‘somewhat characteristic’), 4 (‘characteristic’) to 6 (‘extremely characteristic’). The 20-item measure includes 10 psychodynamic interpersonal items and 10 cognitive–behavioural items, forming two distinct subscales. The psychometric properties of the CPPS have been well established in psychotherapy with adults. 82 Internal consistency of both scales has been good to excellent: Cronbach’s α of 0.82 to 0.92 for the psychodynamic interpersonal scale and 0.75 to 0.94 for the cognitive–behavioural scale. 82,83 Inter-rater reliability is reported as rating from good to excellent [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) 0.60–0.75]. 83,84

In the current study, the CPPS was used to assess treatment fidelity for the CBT and STPP arms of the study and to assess treatment differentiation between all three treatment modalities used in IMPACT. Overall, a CBT session was judged to be ‘adherent’ if the total mean score for items on the cognitive–behavioural subscale of the CPPS was ≥ 2, for which a mean score of 2 indicates that the use of cognitive–behavioural techniques was ‘somewhat characteristic’ of a session. A STPP therapy session was judged to be ‘adherent’ if the total mean score for items on the psychodynamic interpersonal subscale of the CPPS was ≥ 2, and a mean score of 2 indicates that the use of psychodynamic interpersonal techniques was ‘somewhat characteristic’ of a session.

The CPPS could not be used to rate treatment fidelity for BPI as it does not have a BPI subscale; however, it could be used to rate treatment differentiation between BPI and the other two therapies, as ratings of BPI sessions using the CPPS could be used to determine whether or not BPI clinicians were making use of techniques that were not part of the BPI manual but were associated with the specialist psychotherapies, whether psychodynamic (the psychodynamic interpersonal subscale) or cognitive–behavioural (the cognitive–behavioural subscale).

Raters were all postgraduate psychologists who were blind to treatment allocation. A total of seven raters went through approximately 30 hours of training on the measure until they were able to demonstrate a high level (> 80% for each pair of raters) of inter-rater reliability. Each session was listened to in its entirety, with the rater blind to treatment arm and then rated by the two judges independently.

Brief psychological intervention scale

The brief psychosocial intervention scale (BPI-S) is a new scale, developed specifically for use in this study to assess treatment fidelity to BPI. The 18 key components of the BPI manualised treatment were identified using expert consensus in the IMPACT team. A pilot investigation conducted by the BPI experts used a sample of five tapes to develop the fidelity scale. Following this phase, the measure was operationalised as an 8-item measure with three ‘core’ and five ‘general’ items, rated as a Likert scale (0 – no evidence, 1 – passing evidence, 2 – some evidence, 3 –clear evidence).

The three core items are (1) activation and problem-solving, (2) interpersonal effectiveness and (3) attention to mental state/current presentation or diagnosis. The five general items are (1) attention to vulnerability and protective factors, (2) psychoeducation, (3) setting case management within a BPI framework, (4) attending to the social context of the patient and (5) making an effort to help the patient manage their emotional expression. These eight items were chosen to (1) capture important treatment principles (relevance) based on the BPI manual and (2) cover all relevant treatment principles (comprehensiveness) as outlined in the BPI manual.

For each item, a score of ≥ 2 was considered an adequate level of fidelity. Overall, a BPI therapy session was judged to be ‘adherent’ if:

-

at least two out of three ‘core’ items were rated as ≥ 2 and

-

a total of at least four out of the eight items were rated as ≥ 2.

When this revised standard was applied to the five taped sessions previously rated, 100% agreement was obtained between the experts who rated four sessions as adherent and one session as not adherent.

Training for five independent raters was completed over 2 days. The raters were all trained in BPI and experienced senior clinicians with medical and psychiatric qualifications, and achieved high levels of inter-rater reliability (> 80%) by the end of the training. Feedback from the raters during the training process indicated high levels of face validity indicated by good comprehension of the BPI fidelity scale and an understanding of the rating measure and procedure. Each session was listened to in its entirety and then rated by the two judges independently, but raters were not blind to the treatment arm because BPI sessions only were rated using the BPI scale. The results of the reliability and validity analyses are given in Chapter 9.

Chapter 7 Moderation of treatment response

Little is understood regarding the factors that may influence treatment response in depressed adolescents. This study included two putative cognitive processes that the literature suggests may moderate therapeutic response to psychological treatments. These are as follows.

-

Individual differences in self-reported ruminative thinking while depressed. A ruminative response style is defined as persistently brooding or dwelling on current depressive thoughts and feelings, often to the exclusion of other themes in the patient’s life. 36,37

-

The quality of predominant depressive experiences which is defined as possessing a thinking style (dependent or self-critical) likely to predispose or be associated with depressive illness but not synonymous with a pattern of symptoms. 38

Ruminative response style

Rumination is the compulsively focused attention on the symptoms of one’s distress and on its possible causes and consequences as opposed to its solutions. 85 Rumination is similar to worry with the exception that rumination focuses on bad feelings and experiences from the past, whereas worry is concerned with potential bad events in the future. 86 Both rumination and worry are associated with clinical anxiety and depression. 86

Rumination has been widely studied as a cognitive vulnerability factor for depression but its measures have not been unified. 86 In the Response Styles Theory proposed by Nolen-Hoeksema,87 rumination is defined as ‘compulsively focused attention on the symptoms of one’s distress, and on its possible causes and consequences, as opposed to its solutions’. Because the Response Styles Theory has been empirically supported, this conceptual model of rumination is the most widely used.

Extensive research on the effects of rumination, or the tendency to self-reflect, shows that the negative form of rumination interferes with people’s ability to focus on problem-solving and results in dwelling on negative thoughts about past failures. 88 Evidence further suggests that the negative implications of rumination are due to cognitive biases, such as memory and attentional biases, which predispose ruminators to selectively devote attention to negative stimuli. 89 Such negative biases results in critical self-devaluing thinking and can be found in dysphoric adolescents with no history of depression but with a childhood temperamental style characterised by being easily distressed and fearful but likely to return to calm mood relatively rapidly. 90 Depressed adolescents who have high rumination scores are more likely to show persistent depression and demonstrate impairments in autobiographical memory retrieval. 91–93 Inducing ruminations in adolescents also results in increased depressive symptoms as there is a bias to ruminate on prior negative life events. 43,91,92

In this trial, self-reported rumination scores were measured by the ruminative responses styles questionnaire developed by Susan Nolen-Hoeksema and colleagues and validated independently. 94 The scale was completed prior to randomisation and the baseline raw sum score was planned (prior to analysis) to be tested as a potential moderator of treatment effects.

Hypothesis

Elevated RRS scores at baseline will be associated with the following:

-