Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/01/21. The contractual start date was in April 2009. The draft report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Helen Snooks is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Snooks et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Structure of this report

This study was a cluster randomised controlled trial (C-RCT) of a protocol for emergency ambulance paramedics to assess, and to refer to community-based care, older adults who had fallen and incorporated an economic evaluation and qualitative research.

The report begins with an overview of the literature and policy relating to older adults falling, avoidable conveyances to hospital, current paramedic practice, community falls services and the use of protocols for paramedics. We describe the underpinning theoretical framework for the intervention, clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness results and the qualitative findings.

We report a systematic review of the literature relating to interventions in the ambulance setting with older people who fall, and then describe the methods used to conduct the main C-RCT. We report the results of the trial, followed by results from the economic analysis and the qualitative components.

In the final chapter, we summarise and synthesise the findings from all three components of the study, the systematic review, C-RCT and qualitative study, providing interpretation in the light of other studies. We discuss the strengths and limitations of the research and generalisability to the NHS. The conclusions are followed by recommendations for future research.

Background

Falls in older people

Falls in older people are recognised as an important issue internationally,1,2 with high human costs, for the individual and their carers, and high organisational costs. It is estimated that around 30% of home-dwelling people aged ≥ 65 years fall every year,3–8 and the rate of falls is even higher among care home residents. 9 Studies suggest that falls in older people are the cause of 20–30% of mild to severe injuries and 10–15% of emergency department (ED) attendances in this group. 10,11 Falls in older people are often due to more than one underlying cause or risk factor; as the number of risk factors rises, so does the risk of falling. 12 Risk factors include muscle weakness, balance and gait, low blood pressure (or drop in blood pressure on assuming upright posture) and cognitive decline. The severity of fall-related complications increases with age. 13,14 Falls are a cause of substantial rates of mortality and morbidity, as well as considerable contributors to immobility. 8 Reduction in quality of life and physical activity leads to social isolation and functional deterioration with a high risk of resultant dependency and nursing home institutionalisation. 15–18 Recovery from fall injury is often delayed in older people, which increases the risk of subsequent falls. 8 Recurrent falls are associated with greater physician contact and functional decline. 19–21 An additional complication is post-fall anxiety, leading to a fear of falling, which in turn can further contribute to deconditioning and weakness and in the long run may actually increase risk of falls. 8

The About the National Health Interview Survey22 indicates that falls are the largest single cause of restricted activity days among older adults. Most people who fall do not seek any medical advice, and those who do are more likely to report to their general practitioner (GP). 23,24 The combination of high falls with a high susceptibility to injury makes a relatively mild fall dangerous. This is because of a high prevalence of clinical diseases such as osteoporosis and age-related changes, that is slowed protective reflexes. 8 In the UK, it has been estimated that falls account for 3% of total NHS service expenditure,10 with additional costs incurred by social care providers. 25 The prevention of falls in older people has been highlighted as a priority. 11,26

Although prevention appears effective,11 reducing falls and associated morbidity depends on early identification of people at high risk and delivery of interventions across traditional service boundaries;27 these priorities are now reflected in national and international guidelines. 28–30

Emergency department overcrowding and potentially avoidable attendances

Population growth, the increasing burden of chronic disease and population ageing, and the shortage of health-care workers are affecting health-care systems in many countries. 31 EDs are under considerable pressure and overcrowding is a significant international problem, with a negative impact on both patient care and providers. 32 Department of Health data33 show that from 2003/4 to 2012/3 the number of attendances in English NHS ED units increased by nearly 32% (from 16.5 million to 21.7 million), although the majority of the increase was in minor injuries units and walk-in centres. Many of the older people presenting to EDs have had a fall. 34 One study showed that older people presenting to EDs after a fall represented 20% of all attendances and 14% of all hospitalisations in people aged > 65 years,35 and the size of the problem is likely to be underestimated as falls are poorly defined, coded and recorded. 36

Older people can be kept for a longer time in the ED than younger adults because of difficulties in assessment and management, that is, they undergo more tests than younger adults, they are more likely to have cognitive limitations37 and potential underlying diseases or, if they have common diseases, atypical symptoms,38 and they are also more likely to be admitted than younger adults. 39 Pressures on acute services to discharge patients as soon as possible may mean that there is little focus on fall prevention interventions. 36 Older people taken to EDs following a fall are at high risk of falling again in the next year, with a 30% chance of sustaining fracture or dislocation. 35

It has been argued that many admissions of older people are avoidable, and that the demands placed on the hospital system may be relieved if alternatives can be found. 40 The 2006 White Paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say set the direction on ‘improving patient experience and significantly reducing unnecessary admissions to hospital’,41 with paramedics and enhanced/senior paramedics to play a role in providing care at the scene. The National Medical Director of NHS England recently proposed key areas of change in the 2013 Keogh report Transforming Urgent and Emergency Care Services in England 2013. 42 The reports look at developing the ambulance service into a mobile urgent treatment service capable of treating more patients at the scene so they do not need to be conveyed to hospital to initiate care. The report highlights opportunities to shift care closer to home, stating that 40% of ED patients are discharged requiring no treatment, up to 1 million emergency admissions were avoidable in 2012 and up to 50% of calls could be managed at the scene.

Conveyance rate of older adults who fall

Although demand on UK ambulance services continues to increase steadily, a recent study found that only 10% of calls are life-threatening, and an estimated half of all emergency calls relate to patients who could be treated at home. 43

People aged ≥ 65 years commonly call an emergency ambulance (through the emergency services) following a fall. In London (UK), this group accounts for about 60,000 attendances (8% of emergency ambulance attendances) each year. 44 This is very similar to the proportion reported in an urban emergency medical services (EMS) system in the USA. 43

Non-conveyance to EDs is high in this group, at close to 40% in London,44 elsewhere in the UK45,46 and the USA. 43 In most cases (90%), patients who fall and are not conveyed to an ED have fallen in the home. 46 Non-conveyance of patients is recognised internationally as a safety and litigation risk. 47 In some UK ambulance services, performance targets are set for individual enhanced paramedics and paramedics regarding the percentage of patients they should leave at home, and the enhanced paramedic or paramedic decides who can be safely left at home. In 2011/12, the Department of Health, in conjunction with the College of Emergency Medicine, introduced eight accident and emergency (A&E) clinical quality indicators as part of the NHS Outcomes Framework. These became mandatory from 1 April 2011. Indicator 1 (ambulatory care) measures the proportion of patients who are able to be treated at home by improved pathways of care for patients to avoid hospital admission. 48

Little is known about how, in the absence of specific guidelines or training to leave older people who fall at home, paramedics make these decisions. A study acknowledged the pragmatic nature of negotiation with patients whether or not to go to hospital. 49 A UK study identified that the non-clinical factors affecting these decisions include experience and confidence of ambulance staff, time into the shift, presence of carers, quality of the accommodation, waiting times at the local ED and prior knowledge of the patient. 50

Ambulance services, with key stakeholders, have been required to develop alternative care pathways, some of which involve the direct referral of older patients who have fallen to primary51 or community services. 52 This is particularly relevant at a time when pressures on EDs give rise to safety concerns and challenges to demand management;53 general practice and wider community services are being required to support the ED directly in order to avoid secondary care, in a time of major system reorganisation. 54 Alternative care pathways (avoiding use of the ED) for ambulance clinicians have been incentivised through local targets in the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation payment framework. 55 This emphasis is likely to continue given the pressure on EDs.

The National Service Framework for Older People26 advocates that ambulance staff/clinicians refer to community-based care older people who have fallen, although this reflects consensus rather than research evidence. Previous studies in this setting have found that change in practice is difficult to achieve and new pathways of care are difficult to exploit. 56

Service models: community falls services

A range of different types of trial performed in community-dwelling individuals (someone who lives among the general population and is not living in an institution),57 care home residents and hospital patients has established the evidence base for falls interventions. 11 Recent clinical guidelines from the American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons panel on falls prevention29 have strongly advocated preventative approaches based on multidimensional risk factor assessment, exercise programmes (which include balance, strength and endurance training) and environmental assessment and modification. A 2004 meta-analysis demonstrated a 37% risk reduction in the monthly rate of falling for community-dwelling individuals when multifactorial intervention was implemented. 58 Falls clinics are one approach by which falls and injuries can be managed multifactorially. 59 A falls clinic is a space where older adults prone to falling can receive holistic support and treatment from nurses, physiotherapists and other health professionals. A recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) showed that the Chaos Falls Clinic in Finland is effective in preventing falls in home-dwelling people over 70 years of age at high risk of falling. 60 Patients in this trial were guided towards the falls clinic by regional health-care professionals (physicians, nurses or GPs), but relatives of patients could also contact the clinic for an assessment for eligibility.

A recent study found that referral to a community-based falls prevention of older people who had fallen and been left at home by their attending ambulance clinicians, service reduced further falls and improved clinical outcomes,61 and achieved cost-effectiveness. 62 Recent policy changes in the UK have encouraged the development and implementation of alternative models of care for the delivery by the ambulance service. The literature points to the development of extended skills paramedics in line with government policies and supported by protocols. The use of enhanced paramedics has the potential to reduce running costs of the service considerably, while improving quality and focus, although significant ‘one-off’ costs associated with training are also necessary. However, Newman63 noted, the ‘emphasis on the national standards plus local flexibility appeared to reflect supposed shifts in the role of state’ but more particularly presented a range of models which resulted in ‘confusing messages about the relationship between government, the professionals and the public’.

Theoretical underpinning for intervention

Explicit definition of the theoretical underpinning for an intervention to be evaluated is a necessary step in the process for developing both the intervention to be tested as well as the methods for its evaluation. The theoretical basis for the Support and Assessment for Fall Emergency Referrals (SAFER) 2 study intervention – the protocol for emergency ambulance paramedics to assess older patients attended for a fall, and allowing referral for those not needing immediate care at ED to a falls service for community-based care (see Appendix 1) – was built on work carried out previously by the research team and other published research in the two areas of emergency prehospital care paramedic practice and service delivery, and care of older people who fall.

The intervention is hypothesised to work by improving the decision-making of paramedics in terms of safe non-conveyance and referral to appropriate community-based services of older people who have had a fall. Through the protocol, pathway, training, support and feedback, the intervention provided a formalised framework for decision-making and referral for this patient group. This is hypothesised to make a difference by one or more of the following four mechanisms:

-

increasing paramedics’ clinical knowledge of how to make appropriate non-conveyance decisions

-

increasing paramedics’ knowledge of falls services and pathways for referral

-

increasing paramedics’ confidence about making a non-conveyance decision and reducing anxiety about risk

-

increasing awareness and likelihood that paramedics will consider non-conveyance and referral pathways as an option in appropriate cases.

For the intervention to make a difference to practice and to patient outcomes, a number of factors needed to be in place, including:

-

effective referral pathways, and sufficient capacity in falls teams to respond to referrals

-

training and support provided to paramedics that is appropriate and effective

-

motivation on the part of paramedics to use the new protocol and referral pathway, including them not finding it too onerous or time-consuming.

If improved decision-making can be achieved, based on our best knowledge, we can expect the following beneficial effects:61,62,64–66

-

better outcomes (fewer subsequent falls and emergency episodes; higher satisfaction with care) for patients, in particular for those who would have been left at home with no further care but who are now referred to falls services, and also for those who may have been taken to the ED unnecessarily, with related risks of inpatient admission and hospital-related adverse events (AEs)

-

reduced costs to the NHS and patients because of fewer initial ED episodes, inpatient admissions and subsequent falls and related care

-

improved paramedic skill sets, level of professionalisation and practitioner morale.

Uncertainties lie at the certain points on the required causal pathway in terms of the feasibility of implementation and uptake by paramedics; acceptability to patients of non-conveyance/referral; improvements to processes of care for patients; of any wider impact on the operation of the ambulance service, such as increased job cycle times; and of patient health outcomes, including their perception of their own health.

We designed the SAFER 2 trial to gather data about each of these elements of the pathway in order to assess not only outcomes but also processes that may lead to improved outcomes. Study objectives and outcomes reflect the theoretical underpinning and hypothesised causal pathway.

Research aim and objectives

Aim

To assess the benefits and costs to patients and the NHS of a complex intervention comprising education, clinical protocols and pathways enabling paramedics to assess older people who have fallen and refer them to community-based falls services when appropriate.

Objectives

-

To compare outcomes, processes and costs of care between intervention and control groups:

-

patient outcomes: rate and pattern of subsequent emergency health-care contacts or deaths, for any reason; health-related quality of life; psychological status, especially fear of falling; and change in place of residence

-

processes of care: pathway of care at index incident; subsequent health-care contacts; ambulance service operational indicators; and protocol compliance including clinical documentation

-

costs of care: provided by NHS and personal social services (PSS); incurred by patients or carers in seeking care.

-

-

To estimate wider system effects of the introduction of the intervention on ambulance service performance and costs.

-

To understand how patients experience the new health technology.

-

To identify factors which facilitate or hinder the use of the intervention.

-

To inform the development of methods for falls research especially outcome measures recommended for trials of interventions for older people who fall. 59

-

To carry out a systematic review on the implementation and impact of interventions by emergency medical staff who care for older people who fall.

Chapter 2 Systematic review of literature on effects of interventions by emergency medical staff for older people who fall

Abstract

Background

Since the publication of the National Service Framework for Older People 2001,26 the NHS has prioritised older people who fall. As the overall use of EDs increases, policy is shifting to encourage ambulances to convey fewer patients and refer them to other services, when appropriate.

Objective

To review evidence about effects of interventions within EMSs for older people who fall, which aim to reduce demand for EDs.

Method

We undertook a systematic search of 18 electronic databases. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they included empirical data on novel interventions by EMS in the community for older people who fall. We extracted outcomes, assessed studies for methodological quality and used narrative synthesis to analyse results.

Results

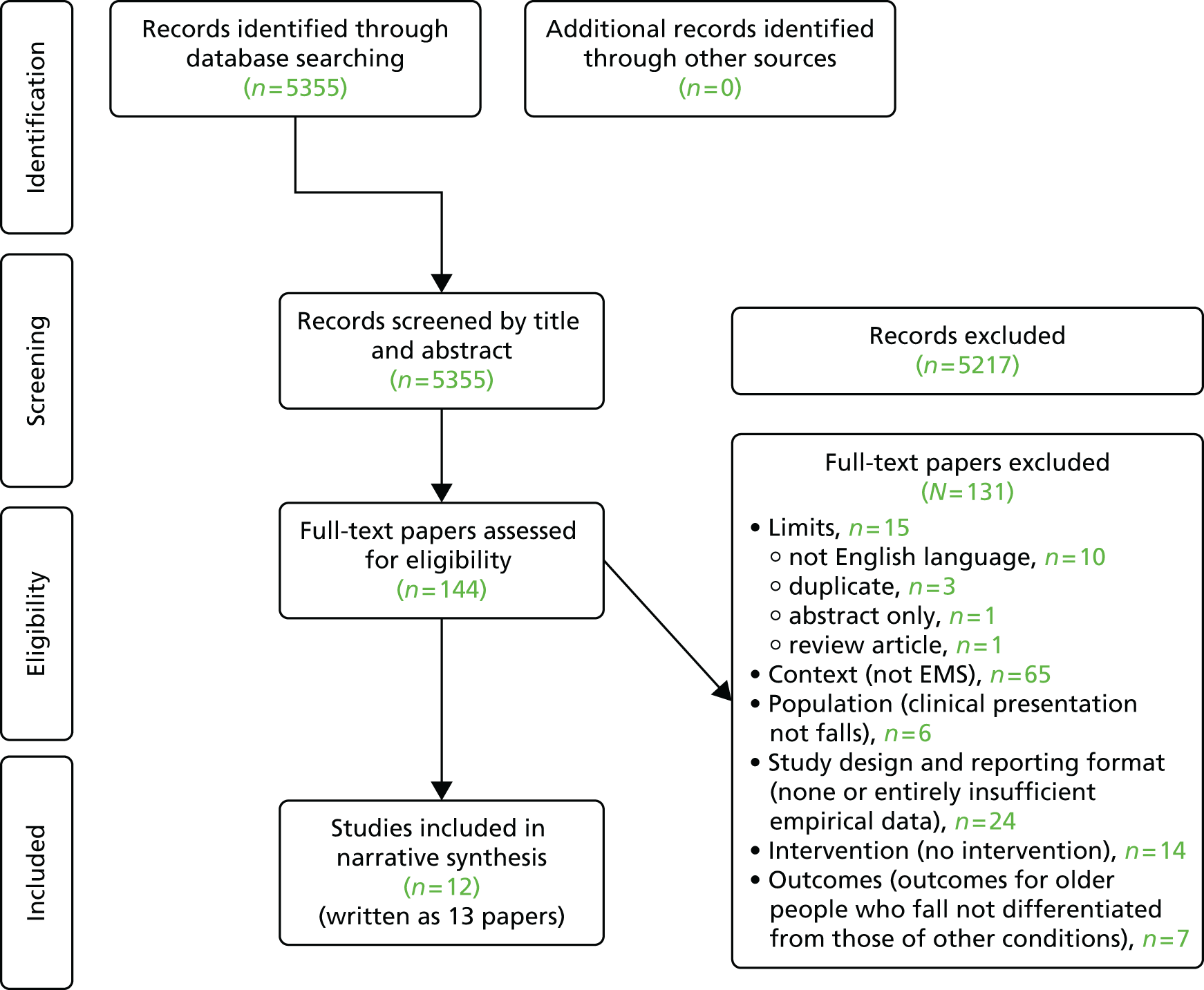

Of the 5355 articles identified, we selected 12 studies reported in 13 papers. Identified studies were excluded for the following main reasons: not English language, not EMS, not falls, no or entirely insufficient empirical data, no intervention or the outcomes of falls were not differentiated. The 13 papers reported data from 7411 participants: 7399 patients and 12 paramedics. Interventions fell into two groups: prospective screening on-scene or at the time of the emergency call and retrospective screening and referral to falls prevention.

Up to half of patients screened on-scene were conveyed to hospital, and referrals to falls services were low except when automatic (retrospectively). The majority of studies were judged to be of poor quality and data were heterogeneous, limiting opportunities for comparison and meta-analysis. Of the higher-quality studies, one trial reported a reduction in ED attendance and hospital admission and increased patient satisfaction; the other reported a reduction in ambulance calls over 12 months, with patients reporting fewer falls and increased confidence.

Discussion

Despite national policy to prevent falls and reduce use of emergency services, studies were few and evidence was mainly weak on effective ways to provide emergency care to older people who fall. When high-quality trial data were available, positive impact on patient and service outcomes was reported.

Study registration

This systematic review is registered on PROSPERO number CRD42013006418.

Introduction

This chapter presents a systematic review of the literature on the effects of novel interventions by EMSs for older people who fall. It describes the background and rationale for the review in the context of the SAFER 2 study, defines the methods used and presents findings to identify existing evidence and topics for further research.

Background and rationale for the review

Since the publication of the National Service Framework for Older People 2001,26 the NHS has prioritised older people who fall. These people have reduced quality of life and levels of physical activity, leading to social isolation and functional deterioration with high risk of increased dependency and institutionalisation. 15–17 Treatment of falls is a major and rising cost for health systems internationally. In the UK, falls cost the NHS more than £2.3B per annum,67 about 3% of total expenditure. 10 In the USA, costs will increase by almost 75% between 2010 and 202068 and in Australia by more than double between 2004 and 2021. 69 Older people who fall and need emergency attention make up a substantial part of the EMS workload. In London, for example, they generate over 60,000 attendances, about 8% of the workload. 44,51 International proportions are similar. 70 Standard paramedic practice is to assess injury and immediate care needs, move patients from where they have fallen and convey them to an ED unless they refuse. 71 In the face of rising ED attendances, policy is shifting to encourage emergency ambulance services to convey fewer patients to EDs in the UK and internationally. 40,72

Research has highlighted opportunities for alternative treatment for older people who fall that reflect their health status and risk. 43,46,73,74 Some older people who fall and call the emergency services can be identified in the ambulance call centre, allowing rapid and targeted alternative responses. 75 The cost of EMS attendance to older people who fall is high. 76 Innovative approaches are necessary and feasible,77,78 but evidence about cost-effectiveness of alternative treatment is needed. 76

A Cochrane review11 of 159 randomised trials of interventions to reduce incidence of falls among older people living in the community reported that exercise interventions reduce risk and rate of falls. However, very few studies reported interventions by EMS staff. 61,62,71,79 Gates et al. 65 found limited evidence supporting fall prevention programmes in EDs, primary care or the community but did not evaluate of any initiatives delivered by EMS. More recently a systematic review by Mikolaizak et al. 74 reported that one study found that 49% of non-transported patients who had fallen had unplanned health contact within 14 days;44 another study reported that 33% of such patients were admitted to hospital within 28 days;80 and two studies that found that attendance by specially trained paramedics reduced subsequent falls, hospital attendance and other AEs. 61,66,74 However, this review did not assess the quality of included studies or observe Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines,81 thus limiting interpretation of findings. None of these reviews considered issues affecting implementation of interventions for older people who fall, notably the views of EMS staff delivering care.

Methods

Protocol and registration

We registered this review with PROSPERO and the All Wales Systematic Review Register. We adhered to the guidance for reviews of health care by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination82 and PRISMA. 81

Eligibility criteria

We defined inclusion and exclusion criteria in terms of the population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, context and study design (PICOCS) of included studies, which is an adaption of population, intervention, comparator, outcomes (PICO). The additional ‘C’ in the acronym recognises the importance of the context within which the intervention is delivered. 82,83

We included studies that evaluated interventions by EMS staff in the community to older people who had fallen and generated an emergency service call. We considered any treatment above the care routinely provided by a paramedic or other EMS staff. Table 1 shows our inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| PICOCS and limits | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Comparator | No comparator required since any study design included | |

| Outcome |

|

|

| Context |

|

|

| Study design and reporting format |

|

|

| Limits |

|

|

Sources and search strategy

We searched published and grey literature and reference lists of included studies. We searched the electronic databases listed in Table 2 during the first week of July 2013 using a search strategy focusing mainly on the target population and the setting of the intervention. We used medical subject headings (MeSHs) and keywords when available. Table 3 shows the search strategy for MEDLINE, the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Plus.

| Type of literature | Data sources |

|---|---|

| Reviews | The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Cochrane Register of Methodological Reviews) |

| Reference lists of included articles | |

| General journal articles | AMED |

| ASSIA | |

| BNI | |

| CINAHL Plus | |

| EMBASE | |

| Internurse | |

| MEDLINE | |

| PsycINFO | |

| PubMed | |

| Scopus | |

| Reference lists of included articles | |

| Grey literature | The British Library |

| UK Institutional Repository Search | |

| GreyNet | |

| Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Web of Science) | |

| OpenGrey | |

| Zetoc | |

| Reference lists of included articles | |

| Journal citation reports | Web of Science |

| Search identification | Search terms | Search options |

|---|---|---|

| Limiters – English language | ||

| S22 | S4 AND S11 AND S20 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S21 | S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S20 | (MH ‘Ambulatory Care’) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S19 | (MH ‘Ambulances’) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S18 | (MH ‘Emergency Medical Services’) OR (MH ‘Emergency Medical Technicians’) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S17 | urgent care | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S16 | emergency care | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S15 | pre hospital | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S14 | pre-hospital | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S13 | ambulance | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S12 | S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S11 | age* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S10 | (MH ‘Aged’) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S9 | (MH ‘Health Services for the Aged’) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S8 | (MH ‘Frail Elderly’) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S7 | old* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S6 | elder* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S4 | (MH ‘Accidental Falls’) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S3 | trip* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S2 | slip* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

| S1 | fall* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

Our search strategy focused on two elements of PICOCS:

-

population, using terms such as ‘aged’, ‘health services for the aged’, ‘frail elderly’, ‘age’, ‘accidental falls’, ‘trip’ and ‘slip’

-

context, using terms such as ‘emergency medical services’, ‘ambulatory care’, ‘ambulances’, ‘emergency medical technicians’, ‘urgent care’, ‘emergency care’ and ‘prehospital’.

The terms for each database varied slightly according to MeSH or other indexed terms. The key terms were included, as well as keywords in title, abstract or text.

The search strategy used in three of the databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and PubMed) can be summarised as follows:

-

population, using the MeSH terms of ‘Aged’, ‘Health Services for the Aged’, Frail Elderly’, ‘Accidental Falls’ and the keywords of ‘age*’, ‘trip’ and ‘slip’

-

context, using the MeSH terms of ‘Emergency Medical Services’, ‘Ambulatory care’, ‘Ambulances’, ‘Emergency Medical Technicians’ and the keywords of ‘urgent care’, ‘emergency care’, ‘prehospital’, ‘pre-hospital’ and ‘emergency medical service*’

-

combination of elements, combining each of the population terms and each of the context terms with ‘OR’; and combing the population and the context terms with ‘AND’.

Study selection

We downloaded electronic search results into the EndNote bibliographic software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). One researcher (RC, MH or MK) screened the title, abstract and keywords of each study using the inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 1. A second researcher, blind to the first researcher’s decision, screened 1 in 10 references, to ensure consistent decision-making. We resolved differences in discussion with the third researcher. We retrieved the full text of papers whose abstract met the inclusion criteria. We compared final recommendations and again achieved consensus on eligible studies in discussion with the third researcher.

Data extraction

We developed and piloted a data extraction framework reflecting the objectives of the review in line with guidance. 82 Two researchers independently extracted the following items:

-

year of publication, country of origin, setting, study design

-

aim or research question, outcome measure(s), method(s), study population, sample size

-

description of intervention

-

key findings.

When possible, we used the taxonomy developed by the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE),84 from the work of Hauer et al. ,85 to describe these data, thus increasing consistency of extraction across the included studies and opportunity for synthesis. The full data extraction table can be found in Appendix 2. We compared completed forms and agreed on content in discussion with the third researcher.

Assessment of the risk of bias (quality)

We assessed quality of included studies using checklists recommended by Centre for Reviews and Dissemination82 to inform comparisons and guide interpretation. 85 We identified these checklists as potentially suitable in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance. We used the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network checklist86 for all study methods except qualitative reports, for which we used the summary criteria of Walsh and Downe. 87 We assessed general methodological quality as high, acceptable or low, defined by Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network86 thus:

-

high: almost all criteria met; low risk of bias; conclusions unlikely to change after further research

-

acceptable: most criteria met; some flaws with an associated risk of bias; conclusions may change after further research

-

low: either most criteria not met or clear flaws in study design; conclusions likely to change after further research.

Data synthesis

We assessed quantitative results for their potential to contribute to a meta-analysis. We used narrative synthesis to synthesise heterogeneous data. 88 We explored relationships within and between studies, seeking to explain similarities and differences between study findings.

Findings

Inclusion

We identified a total of 5355 references. Our review of titles and abstracts suggested that 138 articles might be eligible. After studying full texts, we confirmed that 13 papers61,62,66,80,89–97 reporting 12 studies met our inclusion criteria, as detailed in Figure 1. Table 4 summarises the 12 included studies; Tables 5 and 6 describe them in more detail and Table 7 assesses their quality. Appendix 3 lists excluded studies (at full-text screening stage) with reasons for exclusion.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow chart.

| First author | Year of publication | Country | Study design | Study population | Sample size | Description of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metcalfe89 | 2006 | UK | Cohort | Patients aged ≥ 65 years, but not transported | 49 | Provision of clinical assessment tool to paramedics with follow-up referral to rapid response team |

| Shah et al.90 | 2006 | USA | Cohort (with control group) | Patients aged ≥ 65 years | 258 | Screening tool used by paramedics |

| Mason et al.66 | 2007 | UK | C-RCT | Individuals aged > 60 years calling the emergency services and presenting with minor acute conditions in the scope of practice of the paramedic practitioner | 3018 | Assessment by a paramedic with an enhanced scope of practice in on-scene assessment, treatment and referral (paramedic practitioner) |

| Shandro et al.91 | 2007 | USA | Cohort | Patients aged ≥ 65 years, but not transported | Not reported | Paramedic referral to falls prevention |

| Gray and Walker80 | 2008 | UK | Cohort (with control group) | Patients aged ≥ 65 years | 233 attended by ECPs; 772 attended by ED | Provision of care by ECP (paramedic with further training) |

| Kue et al.92 | 2009 | USA | Retrospective cohort | Patients aged ≥ 60 years, but not transported | 721 | Paramedic referral to social services |

| aLogan et al.61 | 2010 | UK | RCT | Patients aged ≥ 60 years living in defined area, but not transported | 204 | Retrospective referral to falls prevention team following attendance by paramedic |

| aSach et al.62 | 2012 | UK | Cost-effectiveness | Patients aged ≥ 60 years and not transported | 157 | Retrospective referral to falls prevention service following attendance by paramedic |

| Shah et al.93 | 2010 | USA | Cohort | Patients aged ≥ 60 years | 814 | Provision of screening question to paramedics; follow-up referrals |

| Halter et al.94 | 2011 | UK | Qualitative | 12 ambulance staff who were trained in, and used the, clinical assessment tool | 12 paramedics | Provision of clinical assessment tool to paramedics |

| Hoyle et al.95 | 2012 | New Zealand | Retrospective cohort | Average age 62 years, but not all had suffered from falls | 131 | Provision of treatment protocols to ECPs |

| Studnek et al.96 | 2012 | USA | Retrospective cohort (with control group) | 911 callers to whom medical priority dispatch system sent ambulance | Phase 1, n = 160; phase 2, n = 101 | Triage led by despatch nurse |

| Comans et al.97 | 2013 | Australia | Cohort | Patients aged ≥ 65 years | 21 | Paramedic referral to falls prevention |

| Study | Number of patients screened using tool/total number of patients | Number of referrals/number of patients screened for referral (%) | Number of referrals accepted/number of patients referred (%) | Number conveyed to ED/number screened (% conveyed to ED) | Percentage admitted to hospital | Paramedics views of the intervention | Other outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metcalfe, 200689 | – | 53/89 (60%) | 51/53 (96.2%) | – | – | – | – |

| Shah et al., 200690 | 210/258 (79%, 95% CI 74% to 84%) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mason et al., 200766 | – | – | – | ED attendance 0 to 28 days: intervention group, 62.6%; control group, 87.5% (p < 0.001) | Admittance to hospital 0 to 28 days: intervention group, 40.4%; control group, 46.4% (p < 0.001) | n/a | Total episode time: intervention group, 235 minutes; control group, 278 minutes (p < 0.001). Investigations received: intervention group, 49.7%; control group, 67.9% (p < 0.001). Treatment received: intervention group, 81.3%; control, group 72.8% (p < 0.001) |

| Shandro et al., 200791 | – | 17 (number screened not reported) | 11/17 (64.7%) | – | – | – | – |

| Gray and Walker, 200880 | – | – | – | 62/233 (27%) | 25% reduction in intervention group | – | – |

| Kue et al., 200992 | – | 7/721 (1%) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Shah et al., 201093 | 814 (total number not reported) | 124/814 (15%) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Halter et al., 201194 | – | – | – | – | – | Paramedics: reluctant to use novel intervention | – |

| Hoyle et al., 201295 | – | – | – | 44/131 (34%) | – | – | – |

| Studnek et al., 201296 | – | – | – | – | 9.3% reduction in intervention group | – | – |

| Comans et al., 201397 | – | 21/638 (3%) | 13/17 (76.5%) | – | – | – | – |

| Study | Further falls | EMS calls | Fear of falling | Costs and QALYs | Admission to hospital (outcome measure), (p-value) | Other outcomes (outcome measure: results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah et al., 200690 | – | – | – | – | – | Discussion with physician to discuss risk of falls:a intervention, n = 8/82 (9.8%); control, n = 1/37 (2.7%); p = 0.30 Receipt of changes to home environment:a intervention, n = 12/82 (15%); control, n = 4/37 (11%); p = 0.91 Recollection of educational materials: n = 17/82 (21%); control not applicable |

| Mason et al., 200766 | – | – | – | – | See Table 5 | Subsequent unplanned contact with secondary care services (up to 28 days): intervention, 21.3%; control, 17.6% (p < 0.001) Worsening of physical health: intervention, 21.7%; control, 25.6%; p = 0.13 EQ-5D: no significant difference (p-value, NR) Mortality: no significant difference (p-value, NR) Patient satisfaction: very satisfied 85.5% intervention group vs. 73.8% control group; p < 0.001 |

| Gray and Walker, 200880 | – | – | – | – | Avoided admission rate: intervention group, 44%; control group, 52%; n = 1005; p = 0.05. 17% reduction at 28 days | – |

| Logan et al., 2010;61 Sach et al., 201262 | 55% reduction in intervention group (95% CI 42% to 65%; p < 0.001) | 40% reduction in intervention group, 95% CI 8% to 60%; p = 0.018) | 22% reduction in intervention group (95% CI 13% to 31%; p < 0.001) | Mean NHS and PSS costs: –£1551.00 less in intervention group (95% CI –£5932.00 less to £2829.00 more) Mean QALYs: 0.070 more in the intervention group (95% CI −0.010 to 0.150; p = 0.086) |

Number of hospital days: intervention group, 1257; control group, 1141; p = 0.70 | Nottingham extended activities of daily living scale medians: intervention group, n = 8; control group, n = 6; p < 0.001 |

| Comans et al., 201397 | – | – | – | – | – | Patients completing referral programme: 5/8 (62.5%) |

| Study | Internal validity score/total possible score (n n/a) | How well was the study done to minimise bias? | Particular limitations noted during quality appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled trials | |||

| Shah et al., 200690 | 4/5 (5 n/a) | Moderate quality | Potential bias from choosing intervention cluster from two without randomisation; cofounding not controlled for |

| Mason et al., 200766 | 8/9 (1 n/a) | High quality | Participants could not be blinded; as some outcomes were self-reported, there was potential for reporting bias; high level of attrition (50%) |

| aLogan et al., 201061 | 7/9 (1 n/a) | High quality | Participants could not be blinded |

| aSach et al., 201262 | 7/8 (1 n/a) | High quality | As outcomes were self-reported, there was potential for reporting bias |

| Qualitative study | |||

| Halter et al., 201194 | 10/12 (0 n/a) | High quality | Lacks detail about ethics, researchers and analysis |

| Cohort studies | |||

| Kue et al., 200992 | 3/7 (7 n/a) | Low quality | Data not presented clearly; limited by small study numbers and being in one site |

| Comans et al., 201397 | 5/11 (3 n/a) | Low quality | Very high attrition (75%); limited data used as the basis for evaluation |

| Hoyle et al., 201295 | 3/6 (8 n/a) | Low quality | Subjective assessment and possibly bias in dispatch, disparity in transportation rates; uncontrolled evaluation with limited follow-up data |

| Gray and Walker, 200880 | 3/10 (4 n/a) | Low quality | Nominally controlled but collected different data from intervention and control groups, limiting comparison |

| Studnek et al., 201296 | 4/8 (6 n/a) | Low quality | Nominally controlled but study sites changed between phases without relevant comparator/baseline data; very limited in terms of outcomes measured |

| Shandro et al., 200791 | 4/8 (6 n/a) | Low quality | Uncontrolled evaluation; very limited presentation of EMS-specific data and outcomes of care; number of exposed patients not stated |

| Shah et al., 201093 | 2/9 (5 n/a) | Low quality | Feasibility study without controls or patient outcome measures |

| Metcalfe, 200689 | 2/9 (5 n/a) | Low quality | Uncontrolled evaluation with poorly reported methods; authors’ conclusions do not match results |

Study characteristics

Of the 12 studies, six61,62,66,80,89,94 came from the UK, four90–93 came from the USA, one97 came from Australia and one95 came from New Zealand. Study designs comprised two RCTs61,66 (one of which61 published a separate paper evaluating cost-effectiveness element of the study),62 nine cohort studies (of which six did not include a comparator arm89,91–93,95,97 and three included intervention and control arms80,90,96) and one qualitative study. 94 Of the nine cohort studies, three were retrospective,92,95,96 five were prospective80,89–91,97 and one had both prospective (screening) and retrospective (referral) elements. 93 These study characteristics are summarised in Table 4.

The one-armed nature of six89,91–93,95,97 of the studies restricted them to reporting descriptive outcomes. All but Logan et al. 61 reported outcomes at the time of the intervention or soon after. The most common outcome measures were referrals made to a receiving unit or service,66,89,91–93,97 acceptance of referral by the patient66,89,91,92,97 and patient conveyance following attendance by EMSs. 66,80,95 Five studies reported follow-up outcomes for patients receiving a novel intervention (see Table 6). 61,66,80,90,97 Three66,80,90 used short follow-up periods (14 and 28 days) with limited inclusion of outcome measures in two,80,90 whereas another collected physical health, quality-of-life and mortality outcomes. 66 One written as two research papers reported outcomes over 12 months;61,62 but one did not report the period of follow-up. 97

Ten61,66,80,89,90,92,93,95–97 of these studies included a total of 7399 patients and the qualitative study interviewed 12 paramedics. 94 However, one study did not specify its sample size. 91

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the studies was variable, but was generally weak (see Table 7). The controlled trials,61,66,90 economic evaluation62 and qualitative study94 were considered acceptable or high quality and scored highly for internal validity. The cohort studies were mostly of weak quality and did not report sufficient information to determine if their methods minimised risk of bias or confounding. Seven out of eight of the cohort studies80,89,90,92,93,96,97 failed to identify potential confounders in study design and analysis. Shah et al. 93 and Metcalfe89 did not provide a focused research question. Gray and Walker80 scored fairly low using the quality assessment tool, but reviewers defined this study as of acceptable quality as, compared with the other studies included in this review, it included a control arm, a clearly focused aim and clearly written methods and results sections. Kue et al. 92 did not define outcomes or reliably assess exposure. However, reviewers considered all studies that reported data that were directly relevant to this review, and all were included. 98 The full quality assessment for each included study is presented in Appendix 2, with a brief summary of the internal validity score, risk of bias and noted limitations given in Table 7.

Study findings

Interventions within ambulance services to treat older people who fall

The 12 evaluated interventions fell broadly into two main types; 10 encouraged EMS staff on-scene to adopt a new approach when making their initial assessment of the older person who had fallen;66,80,89–92,94,95,97 two did so retrospectively61,96 and one study93 did both through intervention on-scene by EMS staff and retrospective action by other staff. Of the others in the first group, eight used paramedics/paramedic practitioners to intervene at the time of attendance66,80,90–92,94,95,97 whereas the other did so within the despatch centre, also known as ambulance control. 96 The two other studies used individuals not participating in the initial EMS care retrospectively to screen patients for referral. 61,89

Seven interventions screened patients on-scene with a predefined tool to decide whether or not to make a referral with the option of referring to a community-based service,89–94,97 one used the expertise of health professionals other than paramedics to decide upon conveyance,96 three used paramedic practitioners trained to provide community-based clinical assessment for patients aged > 60 years,66,80,95 and one referred all eligible patients who were not conveyed following attendance by EMSs. 61 Screening tools ranged from a single question about the patient’s risk of falling,90 through several questions about eligibility for referral90–93,97 to a flow chart to guide the EMS staff through decision-making. 94 One study screened the patients off-scene, with a nurse who retrospectively screened ambulance service records to decide whether or not to refer patients to a community service. 89 Once the patient was successfully screened and a decision was made to refer the patient, the studies referred them to a falls prevention service,61,91,97 social services,66,92 the patient’s GP,66,90,94 district nurse,66 a rapid response service89 or a case management service. 93

Of the four66,80,95,96 studies not using predefined screening tools, but using the expertise of paramedic practitioners or health professionals other than paramedics, three assessed patients to decide whether to convey patients to hospital or to leave them at home;66,80,95 Mason et al. 66 used paramedic practitioners, and Gray and Walker80 and Hoyle et al. 95 both used emergency care practitioners (ECPs) on-scene, paramedics with extended skills but without specific screening questions or falls service referral routes. Studnek et al. 96 transferred patients with medical problems deemed of ‘low acuity’ to a nurse-led advice line while an ambulance was travelling to their location. The nurse provided advice on alternative modes of care or transportation. The ambulance response was stopped only if the patient requested it.

Effect of interventions by emergency medical services for older people who fall

The outcomes measures assessed by the included studies were heterogeneous. Only a minority of the studies followed up patient outcomes: five89,91–93,95 collected outcomes only from the initial contact with the patient, relating to the emergency service call itself or the ambulance service’s care of the patient on-scene; the remaining five reported outcomes after initial contact with the patient; and four66,80,90,97 studies reported both initial and subsequent outcomes. Among those reporting later outcomes, follow-up intervals were varied. Comans et al. 97 did not report this interval; two studies used periods of ≤ 1 month80,90 and the randomised trial assessed effectiveness and cost-effectiveness over 1 year. 61,62 To try to synthesise the effect of the novel interventions on patients, we stratify the findings of the included studies by the time point at which the outcome was collected.

Outcomes pertaining to initial patient contact

Referrals

The most widely reported outcome measure was numbers of patient referrals to a community service following screening prompted by a fall, as reported by five studies89,91–93,97 (Table 8). Referral rates were generally low (between 1% and 15% of screened patients). However, Metcalfe89 reported that 53 (60%) out of 89 patients screened by an experienced nurse within 24 hours of their fall were referred to a rapid response team or another appropriate service.

| Referral component | Study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kue et al., 200992 | Comans et al., 201397 | Shandro et al., 200791 | Shah et al., 201093 | Metcalfe, 200689 | |

| Intervention | Referral pathway from EMS to community service | ||||

| Outcome | Number of referrals | Number attempted to refer | Number of referrals | Number of patients referred because of falls | Number of referrals made for patients experiencing a fall |

| Number of referrals | 7 | 21 | 17 | 124 | 53 |

| Sample size (patients screened for referral) | 721 | 638 | Unknown | 814 | 89 |

| Percentage referred | 1 | 3 | Unknown | 15 | 60 |

Three studies89,91,97 reported numbers of patients accepting referrals (Table 9). The acceptance rate was high, reported by Comans et al. 97 and Shandro et al. 91 to be 76% and 65%, respectively. Metcalfe89 reported that just two patients (3.8%) refused the referral generated by the rapid response team, giving a 96% acceptance rate. Although we have presented these data together, it should be noted that these studies measured referral acceptance at different time points in the referral process, with Comans et al. 97 reporting patients who consented to the study and underwent initial assessments, Shandro et al. 91 assessing the number of patients enrolling on the programme, and Metcalfe89 assessing the number of patients who accepted referrals.

| Referral component | Study | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comans et al., 201397 | Shandro et al., 200791 | Metcalfe, 200689 | |

| Intervention | Referral pathway from EMS to community service | Provision of screening tool with referral to community service | |

| Outcome | Consented to study and underwent initial assessment | Number of enrolments on falls prevention programme from EMS referrals | Number patients accepting referrals |

| Data | 13 | 11 | 51 |

| Sample size (number of patients referred) | 17 | 17 | 53 |

| Percentage consented/accepted | 76.5 | 64.7 | 96.2 |

Referral mechanisms that required on-scene referrals by EMS staff91,92,97 were undertaken less frequently and had lower patient acceptance rate than retrospective referrals, which had high patient acceptance. 89 As all these studies were of low quality, however, findings are not robust.

Conveyance to emergency department

In three studies,66,80,95 ECPs or PPs (paramedics with enhanced training) took the decision to convey a patient to ED. ECPs or PPs did not use any additional decision-making tool above clinical judgement. Conveyance to the ED can only be reported here for two of the studies80,95 as the third study combined reporting of conveyance at the time (0 days) with conveyance at 28 days66 and was varied (Table 10).

| Referral component | Study | |

|---|---|---|

| Hoyle et al., 201295 | Gray and Walker, 200880 | |

| Intervention | Paramedics with extended training (with no referral pathway) | |

| Outcome | Percentage of patients transported to ED | Patients attending ED |

| Data | 44 | 62 |

| Sample size (number of patients screened/attended) | 131 | 233 |

| Percentage of patients transported to ED | 34 | 27 |

Admission to hospital

Two studies80,96 assessed whether or not patients who received a novel EMS intervention after making the emergency service call experienced reduced hospital admissions. Studnek et al. 96 found that hospital admissions fell from 35% (n = 56) to 25.7% (n = 26) when emergency service callers who had sustained a fall were screened to receive nurse-led telephone advice, in addition to a standard EMS attendance. Studnek et al. 96 did not calculate individual significant values for patients who had fallen, but found that, for all patients (with all possible medical complaints), there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients discharged home following attendance at the ED (i.e. not admitted to hospital) compared with the control period (p = 0.03; CIs not reported). Gray and Walker80 assessed hospital admittance at 72 hours post EMS attendance. Admission rates decreased from 51% (n = 396) during the control period to 26% (n = 62) during the intervention period (significance levels not reported).

Outcomes collected following initial contact with patients

Five studies, written as six research papers,61,62,66,80,90,97 reported follow-up outcomes. Five reported the impact on subsequent falls and health service utilisation61,66,80,90,97 and one reported the impact on costs to the NHS. 62

Subsequent falls and use of health care

Logan et al. 61 reported that patients referred to a falls prevention team experienced 55% fewer falls over 12 months than the control group [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.35 to 0.58; p < 0.001]. Patients also had reduced fear of falling (assessed by the falls efficacy scale, mean difference –16.5, 95% CI –23.2 to –9.8; p < 0.001), were more active [assessed by the Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index, odds ratio (OR) 2.91, 95% CI 1.18 to 7.20]. There was also a significant reduction in emergency ambulance calls for falls over 12 months (effect size 0.60, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.92; p = 0.018).

Mason et al. 66 reported several patient outcomes with a significant difference for the intervention group (those attended by a paramedic practitioner): a 25% decrease in attendance at an emergency department at 0 and 28 days following the incident (relative risk 0.72, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.75; p < 0.001), a 6.1% decrease in hospital admission during the same period (relative risk 0.87, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.94; p < 0.001), an increase in subsequent unplanned contact with secondary care services (relative risk 0.1.21, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.38; p < 0.001), and an 11.7% increase in those reporting being ‘very satisfied with their care’ (relative risk 1.16, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.23; p < 0.001).

The other three studies80,90,97 reporting follow-up outcomes were cohort studies collecting outcome measures associated with specific aspects of the novel intervention. Shah et al. 90 assessed whether or not patients had discussed their risk of falls with their doctor and if they had received changes to their home environment. Although increased numbers of patients had these attributes in the intervention arm, the difference was not significant.

Gray and Walker80 reported a 17% reduction in admissions at 28 days following EMS attendance during the intervention period than in the control period when patients were attended by paramedics with usual training (reduction from 52% to 44%, n = 1005, df = 1; p = 0.05).

Comans et al. 97 reported the number of patients who completed the referral programme, with five patients who were referred to a falls prevention service completing the programme, out of the eight patients who initially enrolled on the programme.

Effect on cost

One paper62 found that the referral of patients who had been attended and left at home by EMS to a falls prevention service, carried out within a randomised trial,60 was cost-effective. The mean difference in NHS and PSS costs between the intervention and control groups was –£1551.00 per patient over 1 year (95% CI –£5932.00 to £2829.00). The mean difference in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) was 0.070 (95% CI −0.010 to 0.150) in favour of the intervention group.

What is the impact on and views of emergency medical services staff of interventions designed to improve the care of and outcomes for older people who fall?

Staff appeared reluctant to use new interventions to treat older people who fall, according to two studies. 94,97 Halter et al. 94 reported variable use of a clinical assessment tool to review whether to safely leave a patient at home or convey him or her to the ED. This qualitative study reported that paramedics were reluctant to use a systematic decision-making tool but instead relied on informal processes, showing the need for a consistent message and support for ambulance staff. Comans et al. 97 identified that repeated education sessions, good relations and regular contact between falls services and paramedics raised referral rates, but these were not sustained when awareness-raising ended.

Discussion

This systematic review identified limited and mainly weak evidence regarding the most effective ways to deliver alternative treatments to older people who fall. The 12 studies that were included in this review implemented variable novel interventions, limiting comparisons that can be made between studies. We classified the interventions within two groups: (1) on-scene screening during patient assessment or triage during the emergency service call to refer them to a community health service or hospital conveyance; or (2) retrospective screening and referral to a community health service.

The studies included in this review are heterogeneous in terms of interventions and outcomes, and, while this is a finding in itself, we have considered the studies to be similar enough, in a small research field, to analyse as a group because of the similarity of the context and patient group included in all the studies. We have not attempted meta-analysis for this reason, and it is the heterogeneity of outcome measures, and a lack of follow-up outcomes to assess the long-term effect of the novel interventions on patients, that means it is difficult to assess the impact of these interventions. The majority of outcome measures were descriptive, detailing the number of referrals that were made and the acceptance of these referrals to patients. Studies utilising these descriptive outcome measures identified that a low percentage of the overall number of screened patients were referred, except where the referral was made retrospectively externally to the ambulance service. Similarly, acceptance of the referral by patients increased when the referral was undertaken externally to the ambulance service. Although these outcome measures are useful for understanding the paramedics’ and patients’ adoption of the intervention, they do not allow understanding of the effect of the novel intervention on the patient.

Five studies, written as six research papers, undertook follow-up of patients beyond the initial contact with EMS,61,66,80,90,96 five of which undertook between-group analyses. They identified that, compared with the control groups, patients who were treated for a fall by EMS had fewer future falls, called the EMS less often and received cost-effective care when referred to a fall prevention service;61 were less likely to be admitted to hospital when being treated by a paramedic practitioner66 or ECP;80 and were more likely to discuss fall risk with their doctor when a referral was made. 90 The study not undertaking between-group analyses found that five out of eight patients who enrolled in a fall prevention programme completed it. 97

Emergency medical services staff’s views of the novel interventions were seldom reported; the one qualitative study included in this review concluded that EMS staff were reluctant to use formalised assessment techniques, instead relying on their usual decision-making process. 94 One study did not directly report paramedics’ views, but did suggest that use of the intervention increased with regular contact and good relations. 97 Although other included studies did not directly assess EMS staffs views of the novel interventions, the studies that reported referral rates reported a low percentage of referrals taking place. These findings highlight the difficultly of changing practice with EMS.

Assessment of study quality, using recommended tools, identified that the included papers were mostly poorly reported and overall quality of the evidence was not high. Most of the studies were single-arm cohort studies and many had methodological drawbacks leaving them open to bias. The majority of the included studies were single-group cohorts and only one RCT was identified. Seven of the included papers were deemed to be of low quality, two of acceptable quality and three of high quality.

Previous systematic reviews undertaken to assess the effect of referral mechanisms on patients who fall have found varying level of benefits for patients. A review looking to assess the effect of multidisciplinary falls prevention service treatment on patients referred from community settings found limited evidence to support a reduction in falls or fall- related injuries for referred patients. 65 Another review, undertaken to identify evidence regarding patients who are not conveyed following a fall, found that appropriate interventions can benefit patients who have fallen, including reducing AE and EMS calls. 74

The current review identified benefits within a minority of the included studies – one study reported significant decreases to future EMS attendances and hospital admissions when patients are referred retrospectively to a falls prevention service, while two studies described a reduction in admission to hospitals when patients are attended by an ECP. These positive findings on patient and service outcomes are, however, set in the context of the number of studies for which such outcomes are not explored and the low quality of the majority of the included studies.

High-quality evidence from well-designed and rigorously conducted research is needed to understand how effective services can be adopted and delivered which will provide appropriate and safe care for patients. Future research should focus on the ability of paramedics to make decisions regarding a patients’ conveyance, paramedics’ views of the intervention and the long-term health consequences for patients of such interventions.

Strengths and limitations of this review

We used a systematic process in line with good practice82,99 to identify international research and review reported data. In undertaking this review, we were unable either to consider papers in languages other than English or to request original data from study authors because of time constraints.

Heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes and low study quality mean data should be interpreted with caution. It also limits ability to generalise findings.

The quality assessment tools that were utilised were not tailored to single-group cohort studies. Therefore, many of the questions were not relevant to the majority of studies that were included in this review. Nevertheless, the inability to answer a question was regarded as a sign of low quality.

Review findings as context for Support and Assessment for Fall Emergency Referrals 2

The SAFER 2 trial selected the age of 65 years and older as its cut-off point for inclusion, as both the National Service Framework for Older People 200126 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for falls67 use this cut-off point, although they recognise this as an arbitrary point that varies in relevance to individual health and disability.

In the systematic review, however, we chose to also include studies that stated their lower age for inclusion to be 60 years, as we were aware from our reading on the topic that two61,66 UK trials had used this slightly lower age breakpoint.

Although we recognise that this might suggest that the cut-off point of ≥ 60 years of age could or should have been used for the SAFER 2 trial, we are reassured that our results are comparable when we look at the mean age of participants in the 10 of the 12 studies that provide us with this demographic information about participants:61,66,89–93,95–97 7 of these 10 studies report mean ages of participants in the ‘frail older people’ group, ranging from 77 to 83 years61,66,90–93,97 and one of the most common age group of participants as 80–89 years. 89 The two studies of exception were those where fall was one condition only amongst a range studied, and these reported average ages of 4796 and 62 years. 95 We therefore feel confident that the different lower age parameter for the systematic review and the trial did not impact on relevance of one to the other.

We suggest that the fact that this review found limited evidence on the topic of support and assessment for older people who fall and are attended by the emergency ambulance service, and even more limited evidence of high quality, is the context and justification for the SAFER 2 trial, the findings of which are now reported.

Chapter 3 Methods

Overview

The SAFER 2 study design comprised a C-RCT, with economic evaluation and qualitative component.

Aim

To assess the benefits and costs to patients and the NHS of a complex intervention comprising education, clinical protocols and pathways enabling paramedics to assess older people who have fallen and refer them to community-based falls services when appropriate.

Objectives

-

To compare outcomes, processes and costs of care between intervention and control groups:

-

patient outcomes: rate and pattern of subsequent emergency health-care contacts or deaths; health-related quality of life; falls efficacy (fear of falling); and change in place of residence

-

processes of care: pathway of care at index incident; subsequent health-care contacts; ambulance service operational indicators and protocol compliance including clinical documentation

-

costs of care.

-

-

To understand how patients experience the new health technology.

-

To identify factors which facilitate or hinder the use of the intervention.

-

To inform the development of methods for falls research.

Cluster randomised controlled trial

Trial design

The trial was conducted in geographically defined sites within three UK ambulance services. The unit of clustering at each site was an ambulance station. The clusters comprised the paramedics based at eligible stations who volunteered to participate in the trial. Once stations had been randomly allocated to intervention or control groups, participating paramedics based at those stations were asked to deliver care according to their group allocation, irrespective of their location on any particular shift.

We chose a cluster design, as opposed to a patient-level RCT, as the intervention included training and new assessment skills, and it would be impossible to switch on and off as would be required in a patient-level RCT. Other units of randomisation have been used in trials based in prehospital emergency care, with limited success. 100 We chose to randomly allocate stations in order to allow the hosting ambulance services to support change in practice for paramedics based at intervention stations while minimising contamination to practice by paramedics based at control stations.

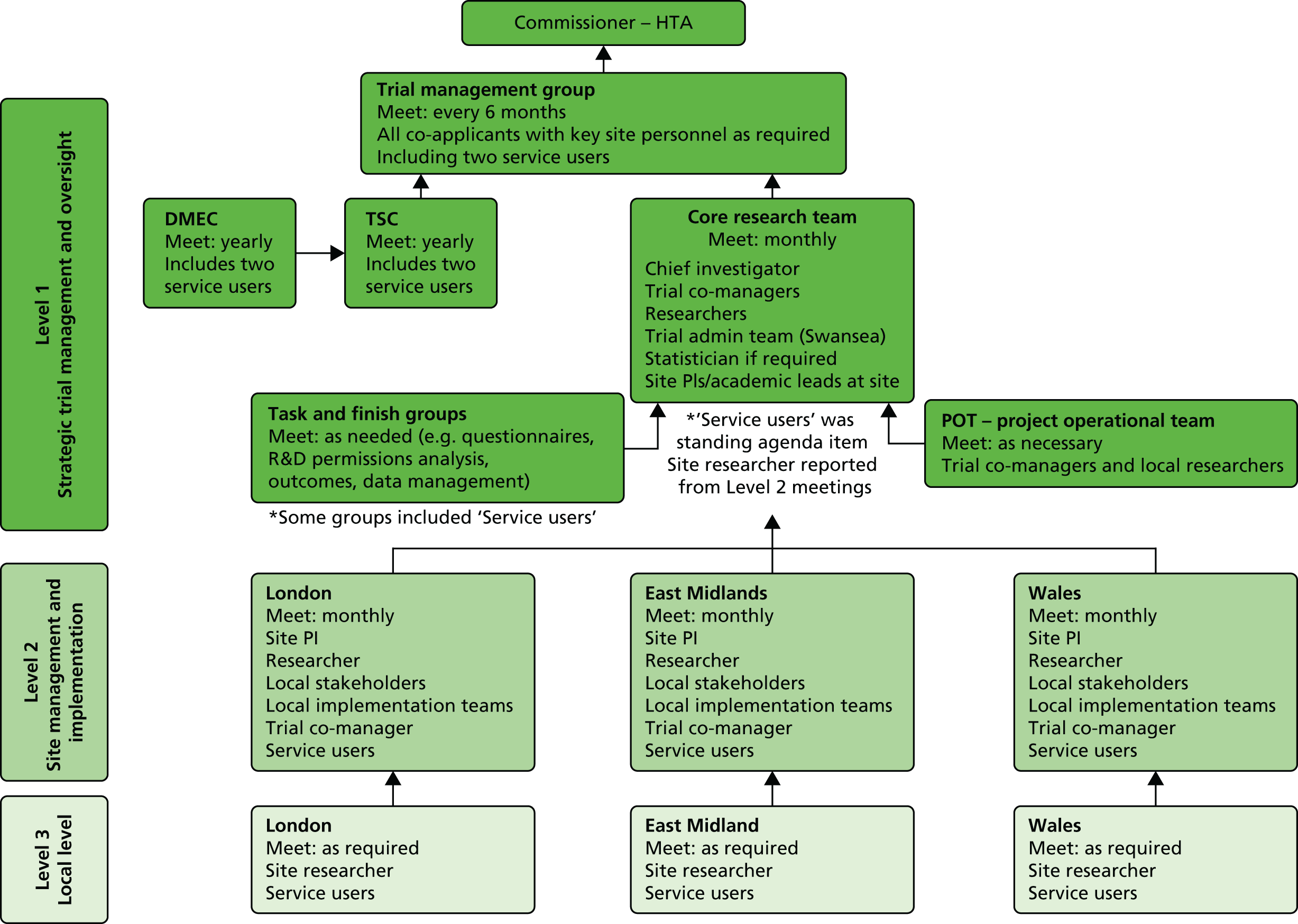

Trial management

Following the Medical Research Council guidelines for good practice in clinical trials,101 the management structure for the trial (see Appendix 4) included an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), with an internal Trial Management Group (TMG), local implementation team (LIT) in each area, core research team, and task and finish groups for specific aspects of the trial such as data management. The TSC provided external oversight and advice to the chief investigator, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme and the sponsor on all aspects. The DMEC had access to unblinded comparative data to monitor the data and make recommendations to the TSC if there were ethical or safety reasons why the trial should not continue. The TMG managed the trial at an overarching level. The LITs dealt with operational issues at each site and provided liaison opportunities between participating services. The core team that managed the trial at a day-to-day operational level was smaller and included the chief investigator, site principal investigators and researchers.

Setting

We undertook the trial in prehospital emergency care, with paramedics delivering the intervention in partnership with community-based falls services (known as falls prevention services). We selected sites within three ambulance services in England and Wales in which a falls service was available, but no process was in place for paramedics to make direct referrals from the scene of emergency service call attendances. Appendix 5 maps stations and hospitals with ED departments at each site.

Participants

Ambulance stations were eligible for inclusion in the study as a cluster if they were situated within a participating ambulance service and were a base for paramedics who regularly attended patients within a participating falls prevention service’s catchment area.

We invited paramedics based at selected ambulance stations to participate in the trial before allocating those stations randomly between intervention and control groups. Paramedics were approached via e-mail, letter and station posters and were asked to return a reply slip if they were interested in participating. Paramedics who volunteered to participate were given a £50.00 voucher.

Patients received either intervention or control group care, depending on the group allocation of the attending paramedic. During training, intervention paramedics were instructed to lead on care if there was also a control group paramedic on-scene, and these patients were included in the intervention group for analysis.

Inclusion criteria:

-

aged ≥ 65 years

-

resident in the catchment area of participating falls services

-

attended by a study paramedic following an emergency call to the ambulance service which was coded by a dispatcher as a fall without priority symptoms (Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System Code 17)

-

first eligible call during the trial period.

Randomisation

Randomisation of stations to groups was carried out in accordance with principles related to cluster randomisation and blinding of analysis team, as outlined in the West Wales Organisation for Rigorous Trials in Health and social care (WWORTH) standard operating procedure (SOP) on randomisation. 102 The trial statistician (WYC) and manager (JP) undertook randomisation after recruitment of paramedics had closed, to avoid selection bias, using trial site, volume of calls, falls service and the number of participating paramedics as stratification variables.

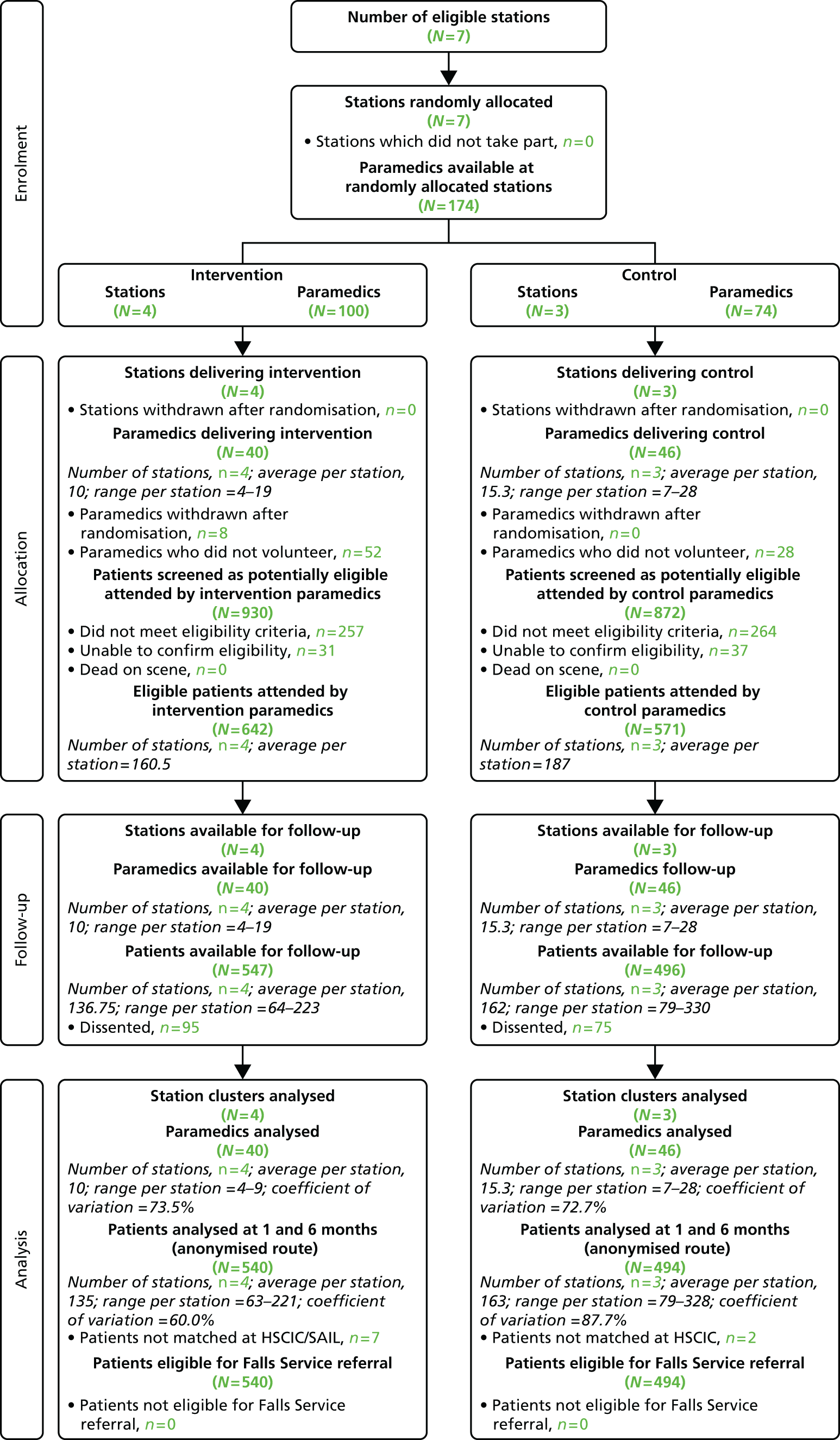

Recruitment

Patients were identified as being potentially eligible for study inclusion from routine emergency service dispatch records through standardised queries written for each site. Site researchers confirmed eligibility of individual patients by retrieving corresponding patient report forms (PRFs), which are routinely completed by paramedics when they attend a patient. PRFs include patient identifiers and demographics; and operational, clinical assessment and treatment information.

In this cluster trial we did not ask paramedics to approach patients for consent to participate in the trial during the emergency episode. Instead, following identification of eligible patients as detailed in Participants, we sought consent from patients for follow-up through routine medical records and by postal questionnaire. Following considerable discussion with the Research Ethics Committee, our consent process included contacting patients by post and then, if necessary, by telephone or a home visit. Patients then had the opportunity to actively ‘consent’ or ‘decline consent’ (dissent). However, we were unable to contact some patients at all (no response by post or telephone). We had Health Research Authority Confidentiality Advisory Group (HRA CAG) permission to follow up this group anonymously (but they neither ‘consented’ nor ‘declined consent’). The group we analysed consisted of those who had consented and those who we could not contact (follow-up was through an anonymised route). Only those who had actively declined consent (dissented) were excluded from this group. The postal consent pack (see Appendix 6) included:

-

covering letter

-

consent form

-

patient information sheet

-

1-month questionnaire (see Appendix 7)

-

Freepost return envelope

-

£5.00 voucher, to thank participants for their time.

Interventions

Experimental: intervention group care

The core of the health technology we evaluated was a clinical protocol for the care of older people who have fallen, enabling emergency ambulance paramedics to assess and refer them to community-based falls services (see Appendix 1). During a workshop held to define the intervention, participants from across specialties and sites agreed common minimum standards for each component of the intervention, with flexibility allowed for local differences in processes such as referral and documentation. The complex intervention comprised the assessment protocol (the health technology being trialled) and six other components, as shown in Table 11. Local variations are shown in detail in Appendix 8.

| Component | Core minimum standard | Local variation permitted |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment protocol | Clinical protocol to guide paramedic through the decision-making process and assess the patient’s risk of further falls and safety for non-conveyance | Consent process for patient agreement to be referred to falls service |

| Protocol may be used as aide memoire or as a specific additional form to the PRF | ||

| Training | One full day, with training package including programme, written materials and DVD (see Appendix 9) | Background and role of trainers, including members of falls teams when possible |

| Referral pathway | A pathway to allow intervention paramedics to refer patients to a falls prevention service, including a system to allow auditing of receipt of referral forms | Method and process of referral, to minimise any delays on-scene |

| Participation of GP practices across falls servicea catchment area | ||

| Referral tool | A form recording information to be passed to the falls prevention service, including basic demographic, clinical and contact details | Other information included in referral form |

| Falls service response to referral | Telephone contact with patient, by professional with ability to recognise cases where urgent input is needed | Time frame for initial patient contact and assessment |

| Initial face-to-face multifactorial assessment; multidisciplinary assessment if appropriate | ||

| Falls service provision | NICE guidance-adherent service: multidisciplinary treatment delivered by team of appropriately qualified professionals (may include, e.g. equipment, balance training, medical review) | Details of service and patient intervention |

| Clinical and operational support | Clinical support debrief with ED every 2–4 weeks plus feedback on outcomes for individual patients referred to falls service | Exact method and means of clinical support and feedback |

Control group care

Control group paramedics did not receive training in the intervention. We asked paramedics based at control stations to continue their usual practice. Although we know that conveyance rates vary considerably among services, stations and paramedics, we did not seek to standardise practice, as we were unable to identify best practice. Current practice in the control group was therefore care as usual comprising assessment of injury or other condition requiring immediate care, assistance in moving and conveyance to ED unless the patient refused.

Outcomes

Outcome measures at 1 month and 6 months after the patient’s index incident were consistent with recommendations of ProFaNE. 103

Primary outcome

A composite outcome of subsequent emergency health-care contacts (in order of severity, i.e. death, emergency admissions, ED attendances or emergency service calls), summarised by:

-

proportion of patients who suffer these events

-

interval to first event

-

event rate.

Secondary outcomes

At index incident:

-

onward pathway of care (conveyed to the ED; referred to falls service; referred to other provider)

-

compliance with guidelines for ambulance service clinical documentation

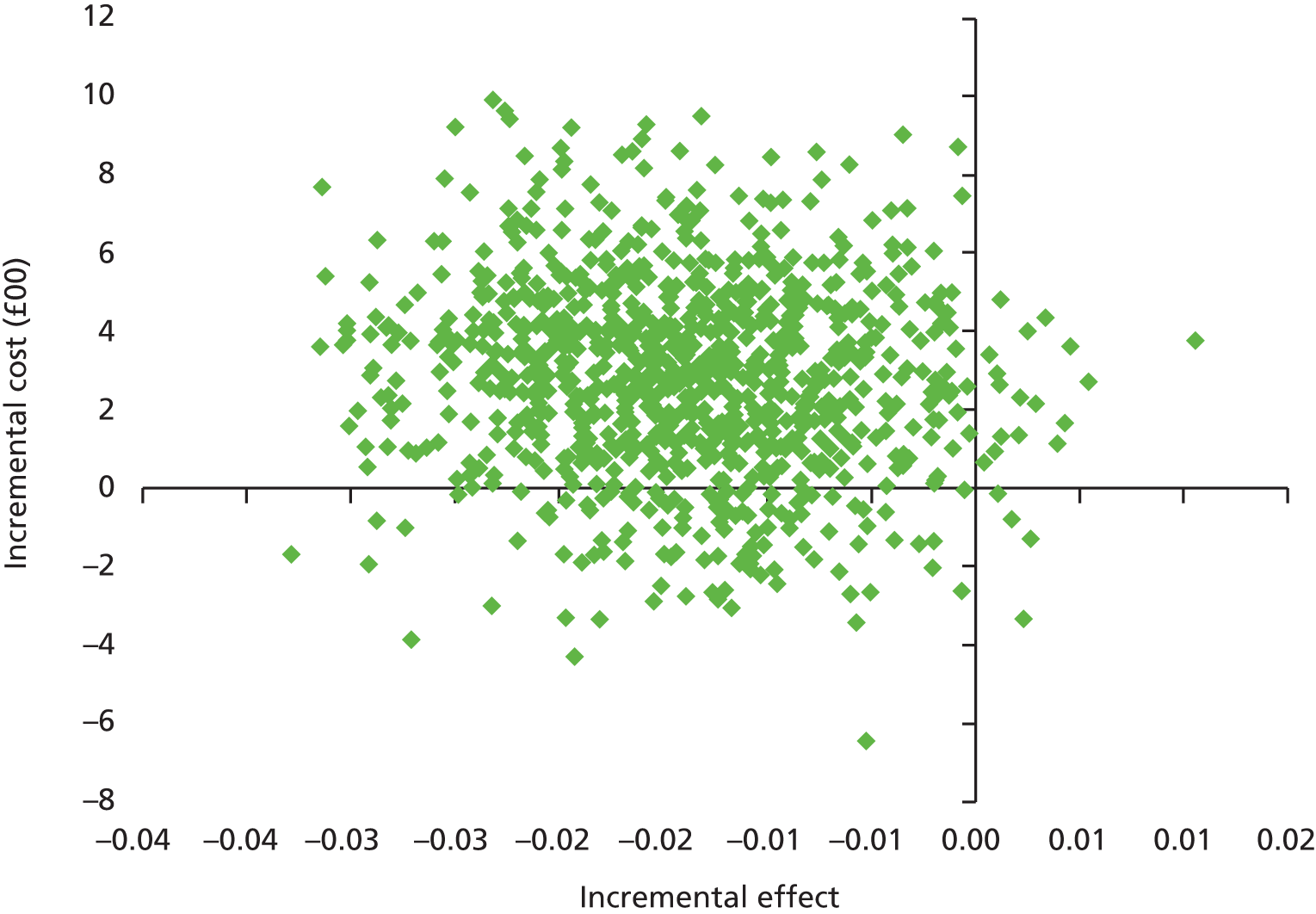

-