Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/302/129. The contractual start date was in April 2007. The draft report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Hisham Mehanna reports that he is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials Board and Claire Hulme reports that she is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board. Andrew GJ Hartley and Max Robinson report grants during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Mehanna et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide, with approximately 500,000 new cases per year. 1 It poses a significant therapeutic problem and has a high mortality and morbidity. Survival rates [apart from those for oropharyngeal cancer (OPC)] have not considerably improved over the past three decades despite newer aggressive surgical and chemoradiotherapy (CRT) regimens. Furthermore, both the disease and its treatments have considerable effects on vital functions (such as speech, eating, swallowing and appearance) and can result in significant functional deficits and quality-of-life effects.

Organ preservation treatment protocols, using radical concomitant CRT, have evolved in the past three decades, resulting in improved control rates (6.5% absolute improvement) at the primary site compared with radiotherapy alone. 2–4 Therefore, in many centres, CRT has become the preferred first line of treatment for several types of HNSCC, especially of the base of the tongue, tonsil, larynx and hypopharynx.

For patients who have advanced nodal metastasis in the neck [tumour, node, metastases (TNM) stages N2 or N3 nodes > 3 cm in size], the evidence for management is controversial. 1 Previously, the standard care in these patients was to perform a neck dissection (ND) (an operation to remove all lymph glands in the neck), either before or after CRT. A ND can result in morbidity, which can be lifelong, and (even a small risk of) mortality. 4 Since 2000, it appears that there has been a shift towards active surveillance guided by imaging, but there remains a significant proportion of patients being treated by planned routine ND. 5 Therefore, there continues to be lack of consensus regarding the best management for advanced nodal disease in patients receiving CRT.

This controversy continues mainly because of the poor quality and contradictory evidence (level 3/4) from prospective and retrospective case series for both management strategies. Furthermore, the advent of newer and more accurate functional modalities for the detection of persistent disease [such as positron emission tomography (PET)–computerised tomography (CT) scanning6,7] has further strengthened this debate. Several studies and systematic reviews have reported a high negative predictive value for PET scanning for the detection of persistent nodal disease. However, studies are small, mainly retrospective, single-centre studies. Many authorities on head and neck (H&N) cancer and literature reviews7,8 have stressed the need for a multicentre randomised trial to obtain an answer to this important question.

Existing research

Evidence in support of planned (routine) neck dissection

Until recently the standard care in the UK was to perform a ND with CRT. In other countries, a significant proportion of patients are still treated with planned ND. 5 Proponents of this management policy maintain that CRT does not eradicate large-volume nodal disease in a large proportion of patients (up to 50%), putting them at risk of recurrence. Some believe that for most of these patients, salvage by surgery will not be possible,9 resulting in devastating consequences.

The only randomised controlled trial available in the literature on the subject compared conservative follow-up with planned ND before radical CRT. 10 It found that there was significantly improved disease-specific survival following ND. However, it was small (50 patients) and had several major limitations, casting strong doubts on the validity of its results and findings. Other single-arm and retrospective studies have reported that planned ND demonstrated excellent locoregional control, although some did not detect improvement in overall or disease-specific survival in their series. 11–14

In addition, it has been found that in up to 40% of patients who show a complete clinical response to CRT but who undergo ND 8–10 weeks later tumour deposits can still be detected histologically in the ND specimen. 11,14,15 It has therefore been suggested that CRT does not completely eradicate the tumour in up to 40% of patients. Furthermore, proponents of ND maintain that selecting patients at a high risk of persistent disease is not possible using CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as studies have found that clinical and imaging evidence of complete response (CR) of nodal disease to CRT does not predict a complete pathological response (i.e. it does not correlate with an absence of pathological evidence of the disease in the ND specimen). 12,14

Evidence supporting a watch-and-wait policy in patients with complete response to chemoradiotherapy

Many clinicians now advocate a conservative surveillance policy, performing ND only if there is clinical evidence of persistent nodal disease after CRT. The rationale is that, among patients who exhibit a clinical CR in the neck following CRT, the recurrence rate in the neck is low (< 10%), and similar to that (8%) in patients with pathologically negative neck following ND. 8,16 Other level 2/3 studies9,17,18 have also found that ND in patients who show a CR to CRT does not confer any benefit in terms of improved survival or reduction in nodal recurrence compared with a watch-and-wait policy. Importantly, a large retrospective cohort study found that 43% of patients showed CR on CT, with a control rate of 92% at 5 years. Among those who experienced less than a CR, the 5-year control rate among those who underwent ND was similar, at 90%, but among those who did not undergo ND it was significantly lower (76%). 19

There is also evidence to suggest that, in many cases, the cells in the residual nodal deposits found on histology in ND specimens following CRT are not viable. 7,18 An experimental study, examining a proliferation marker, Ki-67, appears to confirm this hypothesis. 20

Accuracy of PET–CT scanning in the assessment of response to chemoradiotherapy and detection of residual nodal disease

Crucial to a watch-and-wait policy is the ability to detect residual disease in the neck post CRT, so that these patients can be targeted to have a ND. Detection of residual disease in the neck is not accurately assessed by examination in the clinic or by CT and/or MRI. Evidence suggests that PET is able to accurately identify those patients who do not have residual tumour in their neck following CRT (i.e. PET has a high negative predictive value).

Positron emission tomography has been reported in several small single-institution prospective and retrospective series and two meta-analyses21,22 to have a negative predictive value of 90–100% for the detection of persistent nodal metastasis following radiotherapy or CRT, with a variable positive predictive value of approximately 30–60%. 23–31 It has also been shown in several studies to have higher predictive values than CT and/or MRI,21,27,32,33 and better than combined clinical examination and ultrasound. 31 Finally, studies have found that co-registering PET and CT (PET–CT) is even more accurate than PET alone33,34 (Table 1).

| Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET–CT | 98 | 92 | 94 | 88 | 99 |

| PET | 87 | 91 | 90 | 85 | 92 |

| CT | 74 | 75 | 74 | 63 | 83 |

There is also evidence from same studies that PET–CT is highly sensitive to the detection of residual tumour at the primary site following CRT and radiotherapy, with a high negative predictive value of 90–100%. 35–37 Indeed, it has been suggested that PET–CT may have similar a predictive value in the exclusion of residual disease at the primary site to examination under anaesthesia (EUA), the current gold standard, and may be capable of replacing it as a result of it being less invasive. 38,39 However, there is no existing level 1 evidence to corroborate this theory.

The study had not intended to measure human papillomavirus (HPV) status at the time of inception. However, over the past 5 years, there have been reports on the significant increasing incidence of HPV-associated OPC, with the proportion of OPCs that are HPV associated increasing from 40.5% to 72% over a period of 20 years. 40 HPV association appears to have a remarkable effect on the prognosis and outcomes of treatment, with a 58% reduction in the risk of death [hazard ratio (HR) 0.42, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.27 to 0.66]. 41 This has necessitated examining outcomes by HPV status. 42

Research objectives

-

To test the hypotheses that a PET–CT-guided watch-and-wait policy (experimental arm) is non-inferior to the current practice of planned ND (control arm) when comparing overall survival (OS) in the management of advanced (N2 or N3) nodal metastasis in patients treated with CRT for primary HNSCC.

-

To assess the cost-effectiveness of the PET–CT-guided watch-and-wait policy.

-

To compare, as secondary outcomes, the efficacy of the PET–CT-guided watch-and-wait policy in terms of disease-specific survival, recurrence and quality of life.

-

To describe the accuracy of PET–CT in the detection of persistent disease at the primary site and the neck following CRT.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

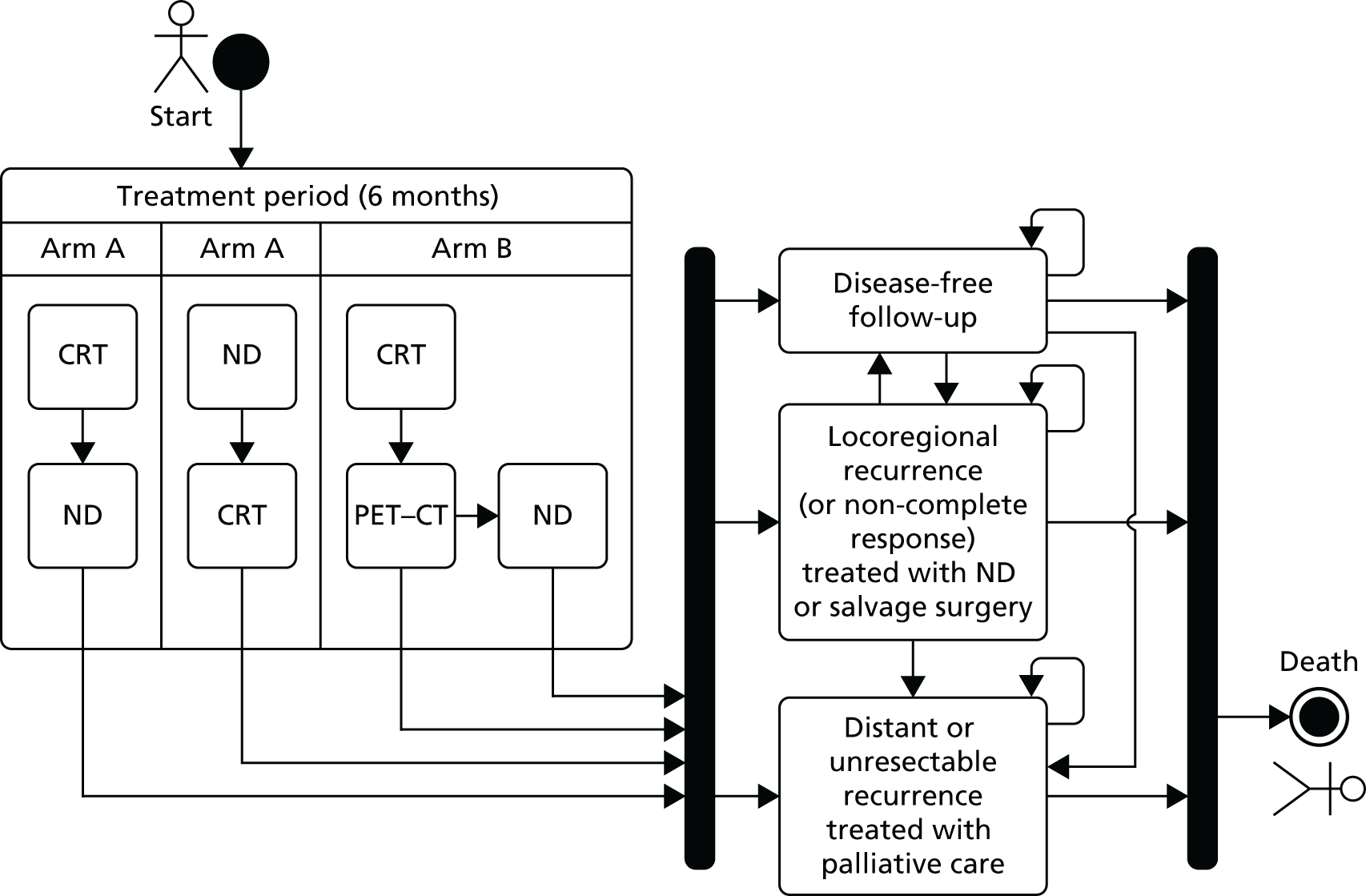

The trial was a two-arm, pragmatic, multicentre, randomised, non-inferiority trial comparing a PET–CT-guided watch-and-wait policy (experimental arm) with the current planned ND policy (control arm) in HNSCC patients with advanced neck metastases and treated with radical CRT.

Target recruitment was 560 patients. Patients were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio. Primary outcomes were OS and health economics. Secondary outcomes were recurrence in the neck, complication rates and quality of life.

Amendments to the protocol

Substantial amendments to the trial protocol were approved since conception, which were significant to evaluate the economic costs, to help increase recruitment and to clarify eligibility and which included the following:

-

The introduction of health economics evaluation at local sites. A health economic cost analysis was required because the avoidance of a ND with its costs and possible complications and morbidity is expected to be one of the most significant benefits of the watch-and-wait policy. Furthermore, the economic effect of replacing EUA and CT with a PET–CT scan would need to be evaluated to assess its potential for the future. The aim of the economic evaluation was to identify the within-trial (WT) and long-term incremental cost-effectiveness of PET–CT-guided watch-and-wait compared with planned ND in HNSCC patients.

-

To extend the inclusion criteria to allow patients with occult primary tumours to enter the PET-NECK trial. Patients occasionally have pathologically occult tumours but, if all other diagnostic procedures point towards a H&N primary, and all other primary sites are excluded, they are routinely diagnosed and treated as having H&N cancer. There was no reason why these patients should not also have been given the opportunity to enter the PET-NECK trial if they wished and if they met all other criteria.

-

To allow ND to be performed before or after CRT in patients randomised to receive standard ND (control arm). There had been a change in practice in the previous 2–3 years regarding the timing of planned ND. In the USA and Europe, planned ND is usually carried out after CRT, rather than before, and there has been a gradual shift towards this practice in the UK over the previous 2–3 years. Therefore, amending the control arm to allow this was intended to increase recruitment and ‘future-proof’ the study if this trend continues in the UK.

-

To exclude patients with tumours that were not histologically squamous cell carcinoma and patients with primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Both non-squamous cell carcinomas and nasopharyngeal carcinomas have different biological behaviours and natural histories from squamous cell carcinoma of the H&N, and they should not be treated in a similar manner. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is highly sensitive to radiotherapy and should not be treated by a ND. Non-squamous cell carcinoma is much less radiosensitive and, therefore, a ND is indicated in these cases. The literature available pertains to only squamous cell carcinoma in sites of the H&N other than nasopharyngeal.

-

To clarify that patients with equivocal PET–CT scans should receive a ND. The management policy in the UK for patients with equivocal PET–CT scans at the time of conducting the study was that they should receive a ND.

Ethics and research and development approvals

A favourable opinion was given by the Oxfordshire Multi-Research Ethics Committee in May 2007 (reference number 07/Q1604/35). Research and development approval was obtained from University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) in June 2007, and permissions to conduct the study at each site were obtained from the NHS trusts covering the Heart of England, Coventry and Warwickshire, Bath, Velindre, London North West, London Central, London South East, Marsden, Poole, Barnet and Chase Farm, Blackpool, Lancashire, Beatson West of Scotland, Abertawe Bro Morgannwg, Sunderland, Luton and Dunstable, Hull and East Yorkshire, Basildon and Thurrock, Southend, Sheffield and Chesterfield, Bradford, Nottingham, East Lancashire, Mid Essex, Aintree, Derby, Royal Devon, Bristol North, Bristol South, East Kent, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Manchester Central, Christie, Pennine, Hertfordshire, Dumfries and Galloway, Lothian, Royal Surrey, Newcastle Upon Tyne, Dudley, Grampian, Wolverhampton, Belfast, South Devon, Gloucestershire, Walsall, Birmingham West Midlands and South Tees. Participating hospitals are listed in the Acknowledgements of this report. All sites were activated between September 2007 and May 2012.

Sponsorship

The PET-NECK trial was co-ordinated by the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit and it has a co-sponsorship agreement with UHCW. The Warwick Clinical Trials Unit stores the data within the University of Warwick central information technology service host computers. All data are securely stored under the Data Protection Act 200443 and adhere to the University of Warwick Clinical Trials Unit data sharing standard operating procedure in which data sharing agreements have to be approved by both the Trial Management Group and the sponsor.

Participants

The study sought to recruit patients diagnosed with HNSCC with advanced nodal metastases who had not received previous treatment for their HNSCC and who had had no other cancer diagnoses within the past 5 years (exceptions given in Exclusion criteria), from H&N cancer-treating centres throughout UK NHS hospital trusts.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who met all of the criteria listed below were eligible to participate in the study:

-

had a histological diagnosis of oropharyngeal, laryngeal, oral, hypopharyngeal or occult HNSCC

-

had a clinical and CT/MRI imaging evidence of nodal metastases, stage N2 (a, b or c) or N3

-

had a multidisciplinary team (MDT) decision to receive curative radical concurrent CRT for primary

-

had an indication to receive one of the CRT regimens approved by the study

-

were fit for ND surgery

-

ND was technically feasible to perform to remove nodal disease (e.g. no carotid encasement, no direct extension between tumour and nodal disease)

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

were able to provide written informed consent.

Patients with N2 or N3 histologically and/or cytologically proven squamous cell carcinoma and an occult primary (after EUA and PET–CT scan) were eligible for the trial if they were going to be treated with CRT.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who met any of the criteria listed below were ineligible:

-

had tumours that were not squamous cell carcinomas histologically

-

were undergoing resection for their primary tumour, for example resection of the tonsil or base of tongue with flap reconstruction (diagnostic tonsillectomy was not considered an exclusion criteria)

-

had N1 stage nodal metastasis

-

were receiving neoadjuvant CRT with no concomitant chemotherapy

-

were receiving adjuvant chemotherapy

-

were undergoing chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy for palliative purposes

-

were undergoing radiotherapy alone (this is not an optimal treatment for neck node disease)

-

had distant metastases to the chest, liver, bones or other sites

-

were unfit for surgery or CRT

-

had received previous treatment for HNSCC

-

had primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma

-

were pregnant

-

had had another cancer diagnosis in the past 5 years (with the exception of basal cell carcinoma or carcinoma of the cervix in situ).

Patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by concomitant CRT were eligible to enter the trial.

The patients in the study were similar to those in the studies that established the efficacy of CRT of the larynx42 and oropharynx,44 and were similar to the patients included in a wide range of studies examining PET–CT in the assessment of persistent nodal disease. 21,22

Settings and locations

In total, 38 centres (57 NHS hospitals) throughout the UK took part in the study. Participating centres were Department of Health-approved MDTs working in NHS clinics and undertaking the management of H&N cancer. MDTs are assessed according to defined criteria set by the Department of Health, including national standards for diagnosis, staging, therapy, radiology, pathology and patient support. 45 All clinicians have to be core members of the approved MDTs meeting minimum qualifications and throughput criteria. All trusts undertaking the management of H&N cancer undergo regular peer review and quality assurance (QA). 46 To participate, centres had to have centrally satisfactorily conducted a peer review report in the last 2 years. A list of participating hospitals is given in the Acknowledgements of this report.

All centres were required to provide confirmation of trust research and development and Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee (ARSAC) approval to conduct the study at each site. Centres also needed access to a PET–CT scanner either locally or at a distant site.

Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee approval

Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee licences were study specific and related only to the PET–CT centre, which was stated on the application.

Therefore, when a licence was held for the PET-NECK trial at a particular PET–CT centre, the site could send their patients to be scanned there as long as the ARSAC licence holder agreed to oversee the safety of the patients. The trials office had a list of ARSAC licence holders and arranged this for the centre. However, when PET–CT centres were not close by or when the site had its own PET–CT centre but did not hold a licence, its radiologist had to make an application under the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) 2000 Regulations47 to the appropriate ARSAC. Approval of applications took around 1 month and patients could not be scanned without the licence being in place. ARSAC licences were issued for 2 years and had to be renewed after that time. The trials office kept a log of all expiry dates for ARSAC certificates and reminded the radiologist to renew them and send a copy of the renewal. A list of ARSAC licence holders is given in the Acknowledgements section of this report.

Quality assurance testing for PET–CT scanners

Before sites could scan patients in the surveillance arm of the trial, the PET–CT scanner to be used had to receive a successful QA review by the study’s central physicist.

All scanners had to be quality assured by the physicist. Each site had to arrange with the PET–CT centre to send a test case to the PET-NECK trial core laboratory for standardisation and quality control for each scanner that would be used in the trial.

The test case had to be an 18F or 68Ge Dicom phantom scan. All Dicom images had to be anonymised with patient trial number and initials and the compact disc or digital versatile disc had to be correctly labelled with ‘PET-NECK Trial’, scan date, site name and coded identifier and be sent along with an anonymised copy of the local report and a completed study Dicom patient scan transfer form.

Providers of PET–CT scanning units used in the study were InHealth (InHealth Group, High Wycombe, UK), Alliance (Alliance Healthcare, Hinckley, UK) and Cobalt Healthcare (Cobalt Healthcare, Cheltenham, UK). Scanners used for the study were either ‘static’, that is, fixed at a specific hospital site, or ‘mobile’, that is, able to travel various hospitals around the country.

Static scanners had to be quality assured every 2 years; however, mobile scanning units had to be tested by the core laboratory half yearly. The trial team kept a log of the pass dates for scanning units and organised with the PET–CT providers to renew the QA review.

A set-up visit to each centre by the trial co-ordinator also took place, during which information about the trial protocol was presented and site staff were given the opportunity to clarify information. Each site was provided with the TNM staging manual and written procedural requirements for PET–CT scanning and reporting. Once all approvals were in place, an activation letter was sent to the principal investigator and trust research and development department for each site to activate the start of recruitment.

Recruitment procedure

Participants were identified following pre-study assessments for diagnosis and tumour staging. Clinical, radiological and pathological staging was performed in accordance with the Union for International Cancer Control’s TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours staging manual. 48

Assessments for diagnosis and tumour staging

Each of the following assessments had to be done within the 4 weeks prior to randomisation, or at least CT/MRI or EUA had to have been carried out within the 4 weeks before randomisation:

-

CT/MRI of the primary site and neck (which had to be carried out before biopsy or not less than 2 weeks after biopsy).

-

Examination of the primary site with biopsy. In most cases, this necessitated examination under general anaesthesia. However, it was not mandatory if adequate clinical examination and biopsy could be performed without general anaesthetic.

-

CT of the chest.

-

Assessment for fitness for anaesthetic by treating clinician or anaesthetist.

Patient treatment was discussed by the MDT and each patient was considered for the PET-NECK trial. Eligible patients were invited to the clinic to discuss treatment and were told about the PET-NECK study. The study was discussed in detail with the patient and carer and all questions were answered. Once a patient decided to enter the study, informed consent was taken.

Informed consent

Adequate time was allowed for patients to consider their participation in the trial. There was no pre-agreed specified time by which to consent. Consent was required to be informed and voluntary, with time for questions and reflection. However, the patient also had the right to make an immediate decision to consent.

Consent to participate in the PET-NECK study was sought by the clinician involved in the patient’s care, with the involvement of the research nurse in the consent discussion. Patients were asked to confirm their consent to participate in the PET-NECK trial by initialling the appropriate boxes on the consent form and signing the form in the presence of the person taking consent. A copy was given to the patient, another copy was kept in the patient notes and the original was kept in the local site file.

The PET-NECK trial intervention

Patient randomisation

In total, 564 patients were recruited from 37 centres (43 NHS hospitals). For all patients recruited to the study, written informed consent was obtained.

Randomisation occurred centrally through the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit, where the study was being managed. Treatment allocation was performed using a minimisation algorithm and was stratified by the following: centre, timing of planned ND (before or after CRT), chemotherapy schedule {concomitant platinum, concomitant cetuximab [Erbitux® (Merck Biopharma, Darmstadt, Germany)], neoadjuvant and concomitant platinum, neoadjuvant docetaxel [Taxotere® (Sanofi-Aventis, Gentilly, France)] and platinum and 5-fluorouracil (TPF) with concomitant platinum} disease site (oropharyngeal, laryngeal, oral, hypopharyngeal or occult), tumour (T) stage (T1–T2 vs. T3–T4) and nodal (N) stage (N2a–N2b vs. N2c–N3) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Trial schema. a, EUA; b, if the patient’s primary tumour showed no response or an incomplete response to CRT or the patient developed a recurrence in primary site or neck, the patient was immediately referred back to the MDT for consideration for salvage surgery.

At randomisation, the eligibility of the patient was checked and the trial number and treatment arm allocated. Before being informed of the random allocation, each patient was asked to complete a quality-of-life questionnaire. Following randomisation, the patient’s general practitioner (GP) was notified of study participation by letter.

Treatment

Chemoradiotherapy regimens

To be enrolled in the study, patients had to have been recommended for concomitant CRT by the MDT. Patients randomised to the ND arm underwent ND either within 4 weeks before or within 4–8 weeks after CRT. For each patient, the participating centre had to specify at randomisation the schedule to be used. The CRT schedule was required to be one that the centre uses in its normal peer-reviewed practice and on the list of approved trial schedules in Box 1.

The recommended standard schedule for the trial was:

-

radiotherapy doses of 65–70 Gy in 30–35 daily fractions of 2 Gy or more with at least two doses of concomitant 3-weekly i.v. cisplatin (100 mg/m2) or carboplatin (4.5–5 AUC). 2,3

The following radiotherapy schedules are examples of approved schedules and are considered equivalent: 70 Gy in 35 fractions and 65 Gy in 30 fractions.

Approved variations to the recommended trial chemoradiotherapy scheduleThe following variations to the recommended trial standard regimen were also permitted:

-

Radiotherapy schedule variations: doses of 55 Gy in 20 daily fractions or equivalent.

-

Concomitant chemotherapy schedule variations:

-

Weekly cisplatin doses (30–40 mg/m2) to a minimum cumulative cisplatin dose of 200 mg/m2 or more or weekly carboplatin (1.5 AUC). 49,50

-

The use of epidermal growth factor receptor modulation with cetuximab instead of cisplatin-based chemotherapy was permitted: loading dose of 400 mg/m2 body surface area followed by weekly i.v. infusions of 250 mg/m2. 51,52

-

Variations from the approved trial schedules above as a result of emerging evidence or changes in the practice of a centre were at times permitted, after consultation with the PET-NECK trial management team.

-

-

Patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by concomitant CRT were eligible for the trial. If these patients were randomised to the ND (control) arm, it was recommended that patients have their ND within 2 weeks of randomisation if possible, followed by the neoadjuvant schedule.

-

Neoadjuvant with concomitant chemotherapy schedules could be used at the centre’s discretion, provided that the following schedules were used:

-

Up to three cycles of neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy were permissible, for example cisplatin 75–100 mg/m2 or carboplatin AUC 5–6 and 5-fluorouracil 1000 mg/m2 a day for 4–5 days or equivalent.

-

Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 with platinum (75–100 mg/m2) and 5-fluorouracil (1000 mg/m2) schedules were also permitted. 53

-

-

Variations from the approved trial schedules above, as a result of emerging evidence or changes in the practice of a centre may have been permitted, after consultation with the PET-NECK trial management team.

-

Adjuvant CRT and neoadjuvant-only chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy schedules were not permissible.

AUC, area under the curve; i.v., intravenous.

The recommended CRT schedule and the approved variations to the schedule were selected after consultation with several oncologists nationwide. The approved schedules were selected because they each fulfilled the following criteria: the schedule was supported by a strong evidence base and the schedule was well established and a standard schedule in UK centres. Variations from the approved trial schedules as a result of emerging evidence or changes in the practice of a centre were individually appraised and approved when appropriate by the PET-NECK trial management team. Patients receiving radiotherapy only (even if receiving accelerated radiotherapy schedules) were not eligible to enter the trial.

Planned neck dissections

The randomising centre was required to decide before randomisation whether, in the case of a patient being randomised to the ND (control) arm, the planned ND would be performed before or after CRT.

Timing of neck dissection

If the ND was to be performed before CRT, it had to be performed within 4 weeks of randomisation.

If the ND was to be performed after CRT, it had to be performed 4–8 weeks after completion of CRT. It was recommended that patients undergo assessment by CT when possible to assess the primary site (but this was not mandatory) and clinical examination with or without EUA before ND.

Type of neck dissection

The recommended surgical procedure was a modified radical ND. This involves the removal of lymphatic structures in levels I–V, with preservation of one or more of the following: spinal accessory nerve, internal jugular vein and sternocleidomastoid muscle. 54

Selective NDs (including lymphatic tissues in fewer than the five levels I–V) were also acceptable provided the following conditions were met:

-

All clinically evident involved nodal groups were included in the ND.

-

The lymphatic tissues of levels I–V that had not been removed in the ND were included in the radiotherapy fields to a minimum of 50 Gy.

The type of access incision was left to the surgeon to decide.

Quality assurance of histological assessment of neck dissection specimens

Histological assessment of ND specimens was performed in accordance with the requirements and standards of the minimum pathology data set published by the Royal College of Pathologists. 46

A central pathology review of 10% of pathology specimens was performed for the purposes of ensuring quality control. The cases were selected at random by the PET-NECK trial office and requested from the participating centres. There were no differences in the results of the local centre pathologist and the central pathology reviewer.

Three-month post-chemoradiotherapy assessment

All patients were assessed for response after CRT. In the case of patients randomised to the PET–CT (surveillance) arm, this assessment took place 9–13 weeks after completion of CRT. In patients who were randomised to ND (control) arm and who received ND before CRT, assessment was performed 9–13 weeks after CRT. In patients in the control arm who received ND after CRT, assessment for response to CRT was done 4 weeks prior to the ND.

The timing of the assessment was chosen to reflect literature findings that PET–CT is most accurate when done at least 8 weeks post CRT, and preferably > 12 weeks after CRT. However, this was balanced by the need to perform the ND as soon as possible to avoid regrowth of the residual tumour post CRT, and the increased technical difficulty in performing ND later than 12 weeks post CRT because of ensuing fibrosis and scarring. As this was a pragmatic trial, some flexibility was afforded.

At any time, if a patient was found to have residual primary disease, he or she was immediately referred back to the treating clinician and MDT for consideration for salvage treatment.

Neck dissections for persistent disease identified on PET–CT post chemoradiotherapy

Persistent disease on PET–CT was defined as metastatic nodal disease in the neck identified by PET–CT at the 3-month post-CRT assessment. Patients in whom PET–CT findings 3 months post CRT were equivocal had to be treated as if they had persistent disease and had to undergo ND. The ND had to be performed within 4 weeks of a decision at the multidisciplinary meeting (MDM) to perform surgery following identification of residual disease on PET–CT. As for planned NDs, both modified radical ND and selective NDs were acceptable, provided that the conditions were met. The type of access incision was left to the surgeon to decide.

Recommended clinical guidelines for PET–CT scanning

-

Patient scheduling:

-

PET–CT should have ideally been performed between 10 and 12 weeks after completion of the last dose of CRT. However, it could be performed between 9 and 13 weeks after completion of CRT and before any biopsies.

-

-

Preparation:

-

Patients had to fast for 6 hours prior to the scan.

-

Patients had to be weighed without shoes and coats (ensuring that the weighing device was calibrated).

-

Blood glucose had to be recorded using Boehringer Mannheim’s Glucometer (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) (ensuring that the device was calibrated).

-

Patients had to drink 2–3 glasses of water prior to the test to ensure hydration.

-

Metal denture fixtures had to be removed whenever possible (to reduce CT artefacts and improve semiquantitative accuracy).

-

-

Injection:

-

Fludeoxyglucose had to be injected via a butterfly cannula under quiet conditions.

-

The patient had to be asked to remain silent.

-

The injected dose had to be 4.5 MBq of fludeoxyglucose per kilogram of body weight up to a maximum of 400 MBq.

-

-

Fludeoxyglucose uptake:

-

The patient had to remain inactive in a comfortable and quiet environment during the uptake.

-

The patient had to empty their bladder just prior to positioning on scanner bed.

-

The emission scan had to start at 90 minutes post injection.

-

-

Positioning:

-

The patient had to be scanned on a regular couch top.

-

Scanning had to begin at the skull vertex and end at the groin.

-

The scan had to be done with arms down if a single whole-body scan was performed. If the body was scanned separately from the H&N, then the body had to be scanned with the arms up.

-

-

Acquisition parameters:

-

Each PET–CT centre was advised to use routine local protocols.

-

-

Reconstruction parameters:

-

The PET–CT centre was advised to use ordered subset expectation maximisation, with CT for attenuation correction using local routine parameters.

-

-

Archive:

-

The reconstructed CT, PET attenuation-corrected and non-attenuation-corrected data had to be archived locally.

-

-

QA and quality control:

-

This was done under an agreed QA and quality control protocol.

-

-

Reporting PET–CT findings:

-

A standardised criterion was used for reporting PET–CT findings.

-

The PET–CT findings had to be reported by the local hospital imaging team.

-

The PET–CT findings had to be reviewed at the central laboratory by an expert in the PET core laboratory, who was independent of the local report.

-

Differences in reporting between the local hospital and the central laboratory were resolved by consensus, otherwise a third expert at the core laboratory reported on the scan and the majority view was taken.

-

-

PET–CT data transfer to the central laboratory:

This was under an agreed protocol transfer following reconstructed and anonymised files:

-

CT

-

PET attenuation corrected

-

PET non-attenuation corrected

-

PET–CT report from local imaging team.

-

-

Adverse events and serious adverse events (SAEs) during PET CT:

-

Adverse events and SAEs were required to be recorded and documented by the local investigational team in accordance with agreed protocols. However, none of these was reported.

-

Quality assurance review of PET–CT scans

For patients in the PET–CT arm of the trial, the PET–CT scan was reviewed by both the local reporter and the trial core laboratory radiologist. When there were significant differences between the reports of the local PET–CT clinician and the central PET–CT reviewer that might have affected patient management, the central PET–CT reviewer (from the core laboratory) and the participating centre radiologist conferred and a final report was agreed. If agreement could not be reached, a second independent reviewer from the core laboratory was asked to review the scans and issue a second opinion report. If there was still a significant difference between the local PET–CT report and the core laboratory reports, the final decision on which report to use rested with the local PET–CT clinician, local treating clinicians and MDT.

Any discordance between the reports of the local PET–CT clinician and central PET–CT reviewer was documented in the patient’s assessment form including which report was used to make the final clinical decision.

Quality assurance review of staging and response scans

Central QA review was performed on 10% of staging scans (and response scans for patients in the ND arm) to check for concordance. The results of the review are not yet finalised and this will be reported in a later paper.

Patient assessments

The schedule of assessments is shown in Table 2. All biobank samples collected at baseline and follow-up will be retained for future work.

| Assessments | Time point | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-study entry | 2 weeks post NDa | Last CRT dose | Monthly follow-up visits during year 1 | Post-CRT assessmentb | 6-month follow-upb | 12-month follow-upb | 2-monthly follow-up visits during year 2 | 24-month follow-upb | |

| MDM discussion | ✗ | ||||||||

| Informed consent for trial | ✗ | ||||||||

| Evaluations | |||||||||

| Complete history/physical | ✗ | ✗c | ✗ | ✗c | ✗c | ✗c | ✗c | ||

| Complications reporting | ✗d | ✗e | |||||||

| Examination with or without biopsyf | ✗g | ✗h | ✗ | ||||||

| Imaging | |||||||||

| H&N CT/MRI | ✗i | ✗i | |||||||

| Thoracic CT | ✗g | ||||||||

| PET–CT | (✗j) | ✗k,l | |||||||

| CXR | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Quality-of-life assessments | |||||||||

| EORTC QLQ-C30 and H&N35 | ✗ | ✗m | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| MDADI | ✗ | ✗m | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| EQ-5D | ✗ | ✗m | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Health economic questionnairesn | ✗ | ✗m | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Blood sample collectiono | ✗ | ✗o | ✗o | ||||||

Patient follow-up

Patient follow-up was monthly for the first year up to the 12th month after randomisation, and 2-monthly for the second year up to the 24th month after randomisation. It was recommended, but not mandatory, that patients should have chest radiography annually.

At each follow-up visit, the patient received a full clinical examination with palpation of the neck and visualisation of primary site when possible, with appropriate trial forms and questionnaires completed at the completion of CRT, and at 6, 12 and 24 months after randomisation.

Patients with confirmed recurrence

Recurrent disease was defined as a confirmed tumour in the primary site after a clear 3-month post-CRT assessment or metastatic nodal disease identified in the neck after negative PET–CT post CRT or after a ND, during the follow-up period. A tumour was confirmed as recurrent if disease was confirmed by biopsy or radiological cross-sectional imaging.

Patients with recurrence, confirmed by biopsy or needle aspiration and CT/MRI or by their PET–CT scan were referred back to the treating clinician and MDM urgently for consideration for salvage treatment, including ND for patients with isolated nodal recurrence.

Serious adverse events

Investigators were required to inform the trials unit immediately of any SAEs following CRT, PET–CT or ND.

Each time the patient was seen in clinic he or she was asked if any SAEs had occurred. The occurrence of SAEs was based on information provided by either patients or their carers. The following adverse events were considered serious:

-

death

-

life-threatening disease

-

hospitalisation or prolongation of hospitalisation

-

congenital abnormality

-

persistent disability

-

other medically significant event.

Trial-specific exclusions from reporting SAEs included any of the following:

-

elective hospitalisations for the treatment of the primary cancer and its effects

-

elective hospitalisation for social reasons

-

elective hospitalisation for pre-existing conditions that were not exacerbated by the treatment.

Adverse effects of PET–CT scanning

If, after administration of the radiopharmaceutical required for PET–CT, the biodistribution within the patient was not as would be expected, the ARSAC certificate holder had to be informed and a check made to determine that the correct radiopharmaceutical was administered. If the correct radiopharmaceutical was administered, the supplier of the radiopharmaceutical had to be informed.

In the case of an incorrect radiopharmaceutical being administered to a patient, the ARSAC licence certificate holder and a senior member of staff had to be informed immediately who was then required to follow the guidance in Health and Safety Guidance Number 95. 55

-

The ARSAC certificate holder was required to inform the patient of the error.

-

The referring clinician had to be informed.

-

The GP of the patient had to be informed.

-

A risk assessment was required to be requested from the radiation protection advisor.

-

The staff member was required to inform the chief investigator and the sponsor.

A report of any incident, including action taken in order to prevent a recurrence, was required to be compiled by the radiation protection supervisor and forwarded to the radiation protection advisor. Any such incident was required to be recorded as an unexpected SAE and also reported through the individual trust critical incident policies.

Patient withdrawal

Patients were informed about the right to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. However, site staff were asked to make every effort to identify the reason for withdrawal. Withdrawn patients were asked if any data collected prior to their withdrawal could be used in the analyses.

The reason for withdrawal (when known) was recorded on the patient notes and the trial office was informed of the withdrawal.

Patients who elected to withdraw from the trial interventions remained in the trial for follow-up per protocol unless they withdrew their consent.

Patients who changed their mind about withdrawal and wished to rejoin the study could chose to do so at any time, but they needed to be reconsented and follow-up data were to be collected only from that point onwards.

Patients moving out of the area

When patients moved away from the area to another participating centre, every effort had to be made, with the patients’ consent, to transfer the follow-up of patients so that the new centre could take over the responsibility for follow-up. Close co-ordination with the PET-NECK trial office was essential for this.

Outcomes

Overall survival (primary outcome)

Information on death and survival was obtained from centres via death and follow-up forms.

Cost-effectiveness (primary outcome)

Data for the health economic analysis were collected from the trial EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and resource use questionnaires, as well as the case report forms. Full details of the health economic analysis are given in Chapter 4.

Complication rates

Complications following ND surgery were reported.

Disease-specific survival

Causes of death were reported on the death form. Deaths were regarded as caused by H&N cancer if they were reported as such, if there was persistent, recurrent or metastatic disease present at death or if the patient died as a result of complications of treatment for H&N cancer.

Recurrence in neck nodes

Details of recurrences were reported at follow-up visits. Any notification of recurrence within 3 months of radiotherapy was regarded as persistent disease and notifications after that date were regarded as recurrences. Recurrences in the neck nodes were reported as ipsilateral or contralateral in the notification of recurrence.

Quality of life

The questionnaires included the following instruments:

-

EQ-5D: five 3-point scales and one summary 100-point scale. This was used for the health economics evaluation

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire for Cancer (with 30 questions) (QLQ-C30): five functional, three symptom and a global scale and six single items for assessment of general quality of life

-

EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire for Cancer head and neck module with 35 questions (QLQ-H&N35): seven scales and 11 single items for H&N cancer-related quality of life

-

MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI): an overall function scale and four subscales.

Patients were requested to complete these questionnaires at five time points. The first was completed in clinic prior to randomisation. Later questionnaires were received either in clinic or through the post before the assessment dates were due at these time points: within 2 weeks of CRT completion, 6 months after randomisation, and 12 and 24 months after randomisation.

Accuracy of PET–CT scanning

Positron emission tomography–computerised tomography scans were assessed both by the local radiologist and by the trial core radiologist.

Sample size

The trial was designed to allow demonstration of non-inferiority of the PET–CT surveillance arm compared with the control arm (planned ND), which was assumed to have a 2-year OS of 75%. The margin for non-inferiority was set at 10%, implying that the 2-year OS of the experimental arm should not be below 65%, a difference equivalent to a HR of 1.50.

The trial was expected to recruit for 3 years, with an additional follow-up period of 2 years. The sample size was set at 560 patients in total (280 in each treatment arm), giving a 90% power with a type I error of 5%, allowing for a 3% loss to follow-up. The sample size was calculated by simulation assuming unadjusted analysis by a Cox’s proportional hazards model and assuming follow-up to the end of the trial 5-year period (using data from the Office for National Statistics). If no follow-up existed beyond the 2-year requested data, then the power would be 76%. It was expected that the true power would lie between these figures (i.e. 76% and 90%). The assumptions underlying the sample size calculation were monitored by the Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (IDSMC) throughout the study.

Randomisation

Treatments were centrally allocated through the PET-NECK trial office at the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit. Allocation was performed using a minimisation algorithm balancing by the following: centre, timing of planned ND (before or after CRT), chemotherapy schedule (concomitant platinum, concomitant cetuximab, neoadjuvant and concomitant platinum, neoadjuvant TPF with concomitant platinum, other approved), disease site (oropharyngeal, laryngeal, oral, hypopharyngeal or occult), T stage (T1–T2 vs. T3–T4) and N stage (N2a–N2b vs. N2c–N3). At randomisation, the eligibility of the patient was checked and the trial number and treatment arm were allocated. Each patient was asked to complete a quality-of-life questionnaire (before being informed of the randomisation allocation).

Allocation concealment

When the randomisation service was telephoned, participant details were taken and registration into the trial followed. The allocation was then generated, ensuring concealment.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind either the doctor or the patient to the allocated treatment.

Statistical methods

Participants were analysed according to the treatment group to which they were randomised. Analyses were guided by an analysis plan prepared before data were available.

A preplanned early stopping guideline was applied, assuming that at least 2 years’ follow-up would be available for each patient, and that 140 deaths (25%) would be expected. Three analyses of the primary outcome were prespecified, equally spaced at 47, 94 and 140 deaths, to be viewed only by the IDSMC and trial statistician. At each of these points, it could be concluded that the experimental treatment is equivalent (non-inferior). The 5% one-sided type I error rate for testing non-inferiority was controlled by an O’Brien–Fleming-like alpha spending rule set at p-values of 0.004, 0.007 and 0.047. It could alternatively be concluded that the experimental arm is inferior. A similar 10% type I rate for testing non-equivalence was used, with p-values set at 0.02, 0.032 and 0.084. At the first interim analysis (48 deaths), when 84% of patients had been randomised, the p-value for non-inferiority was 0.0025, which was below the (0.004) threshold for consideration of stopping. The IDSMC considered that data were immature and that the trial should continue. At the second interim analysis (102 deaths) the p-value for non-inferiority was 0.008, that is, above the threshold for the second analysis, and the trial continued to the final analysis.

Demographic and clinical characteristics and baseline measurements are presented to evaluate the comparability of intervention groups and generalisability to clinical settings. A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram was produced. 56

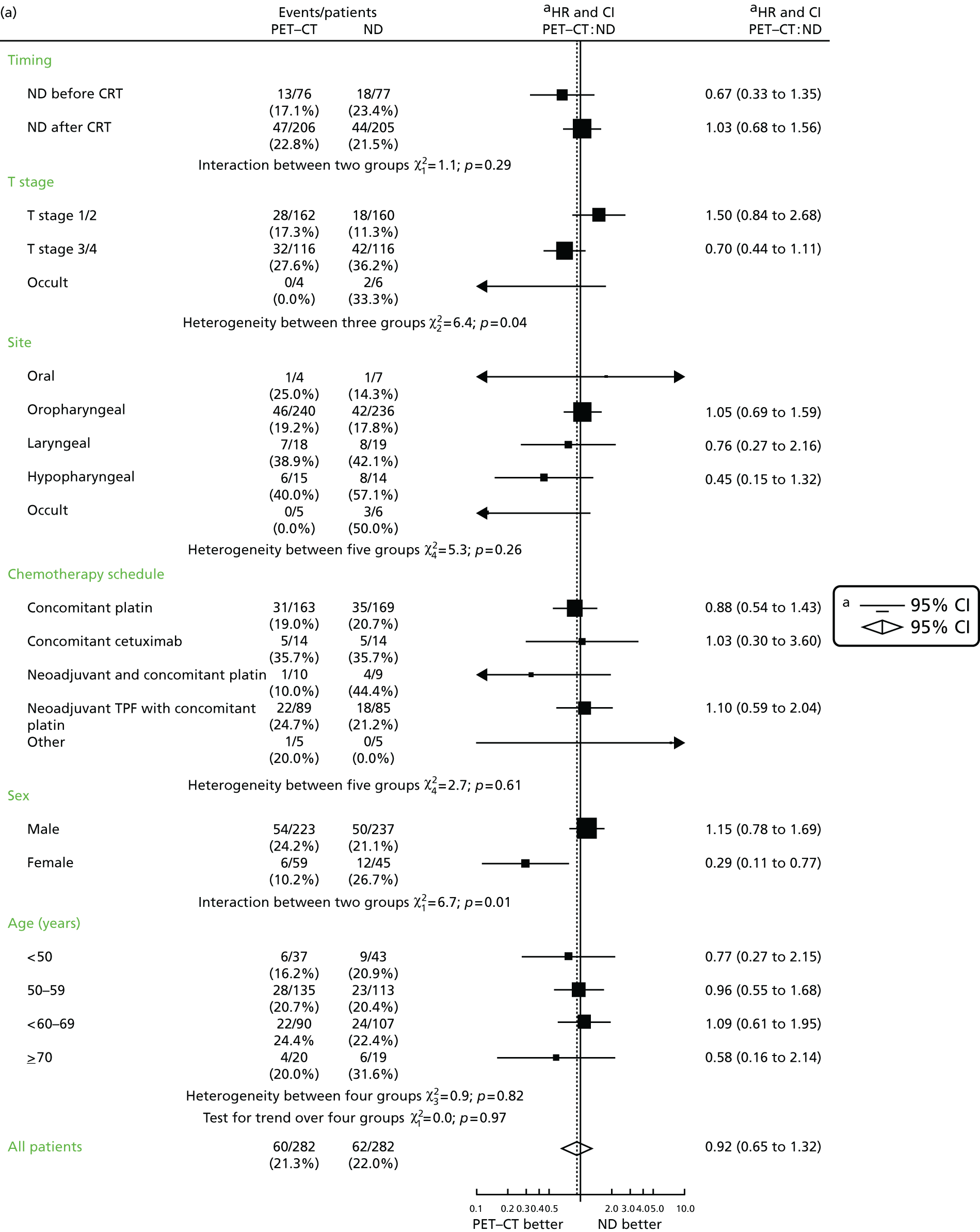

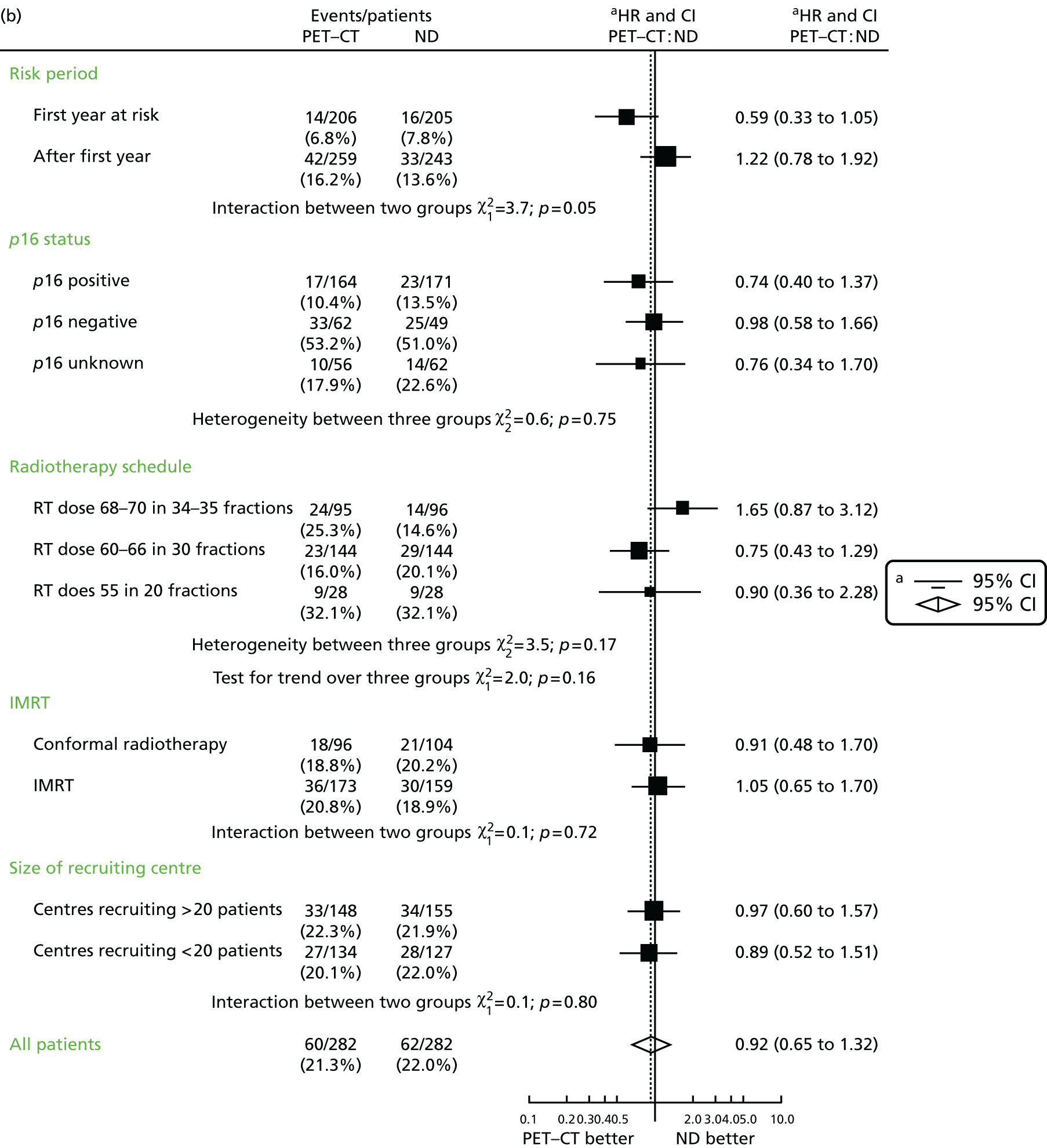

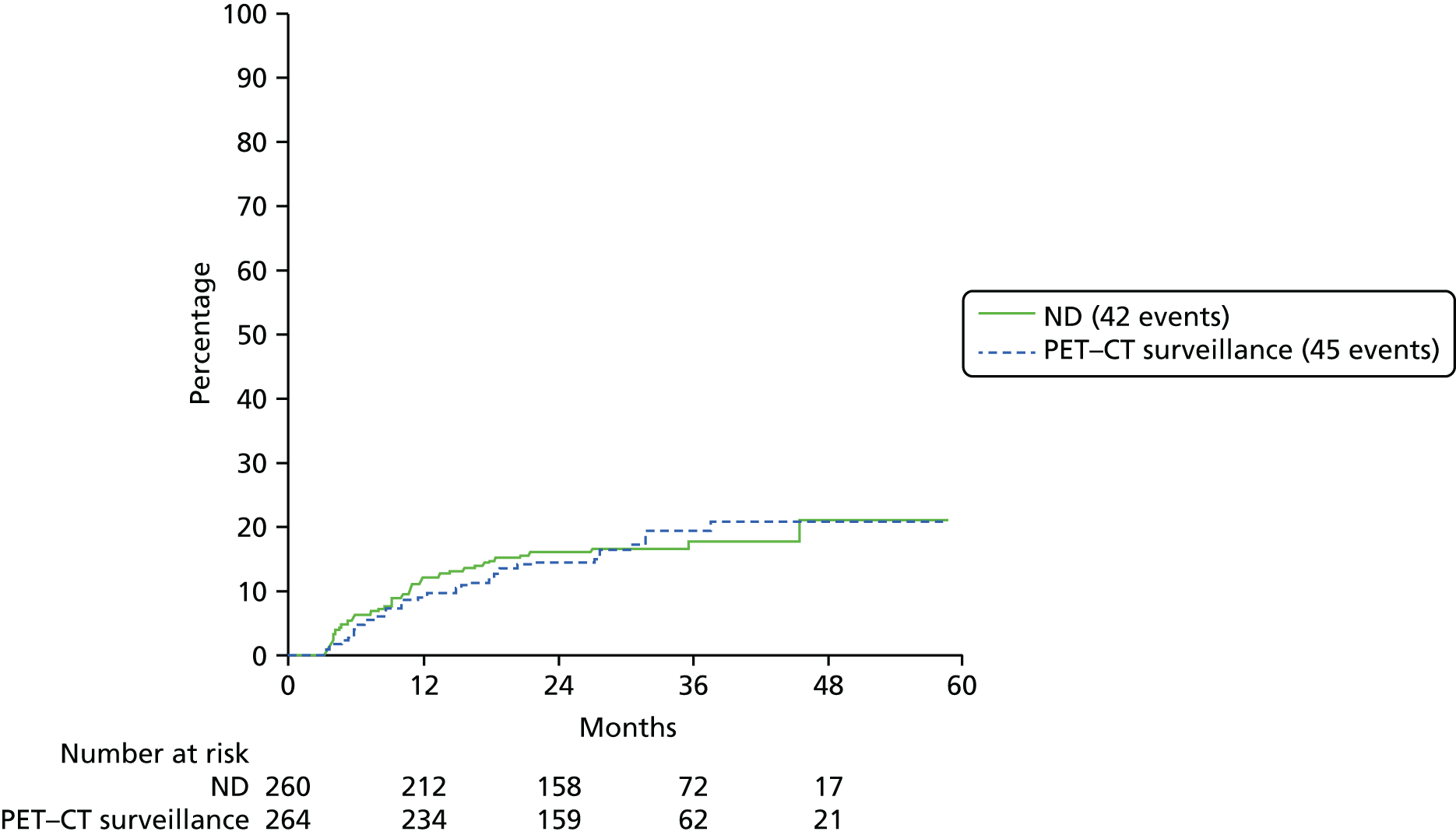

The primary end point, OS, was measured for every patient from the date of randomisation to the date of death. Survival times for patients on follow-up and patients lost to follow-up were censored at the latest date at which they were known to be alive. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted. To test non-inferiority of the surveillance arm the HR was estimated using a Cox’s proportional hazards model stratified by intended timing of planned ND (before or after CRT), with the trial treatment arm as the only covariate. Non-inferiority is demonstrated by the 95% quantile of the estimated HR of the surveillance arm being less than the inferiority limit (HR 1.50). Proportionality of hazards was checked using a time-dependent treatment effect. A secondary analysis adjusting for N stage, T stage, tumour site, chemotherapy schedule and timing, sex and centre was performed. Kaplan–Meier OS was also calculated for the planned timing of ND (before or after CRT) subgroups and also for p16-positive and -negative tumours. The treatment effect on OS was also presented for subgroups of site of tumour, T stage, planned chemotherapy schedule and p16 status, using HR plots with interaction statistics using methods described by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. 57

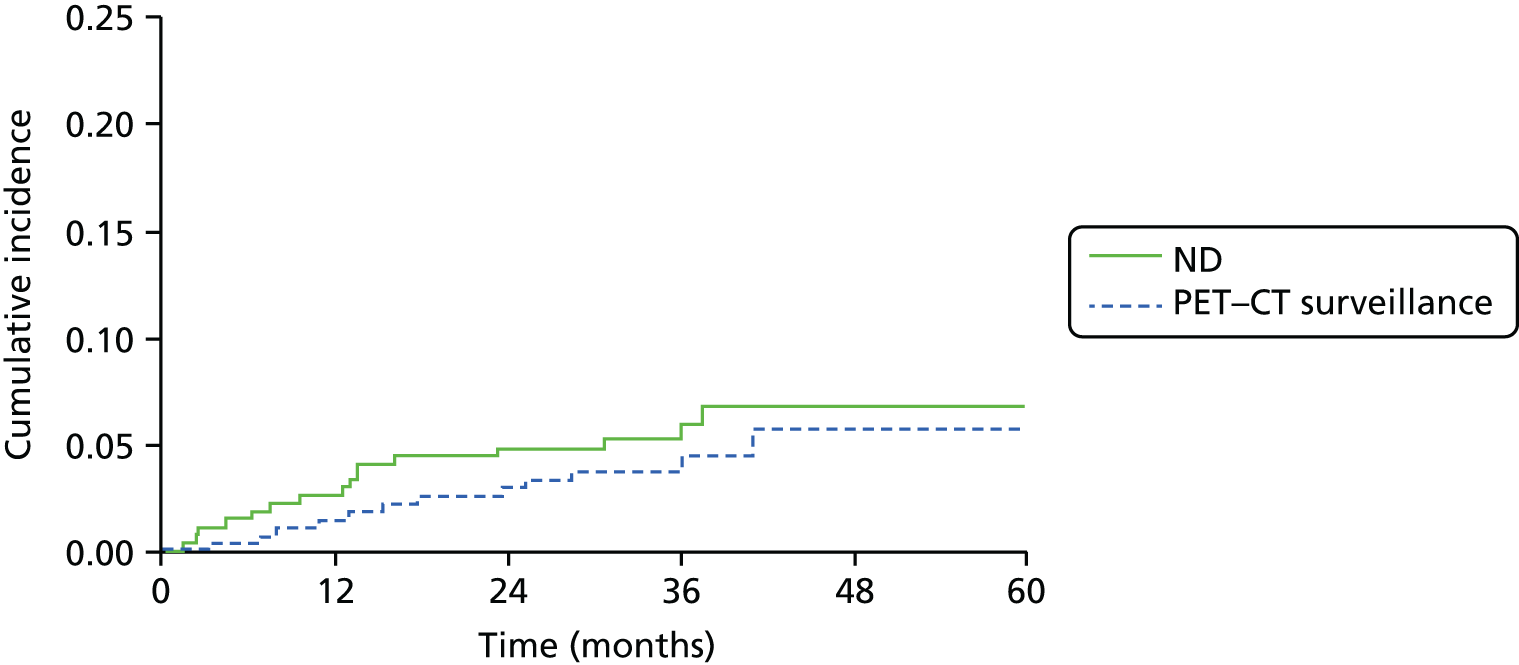

Causes of death were classified as H&N cancer or other causes. Cumulative incidence rates by treatment arm were plotted for these competing risk groups and the difference between treatments was tested using Gray’s test. 58

Patients were deemed at risk of recurrence when they completed their CRT and time to recurrence was measured from that date. This meant that patients in the planned ND group who underwent surgery before CRT were not at risk until they had finished all their treatment. Counts of neck node recurrences by treatment were reported.

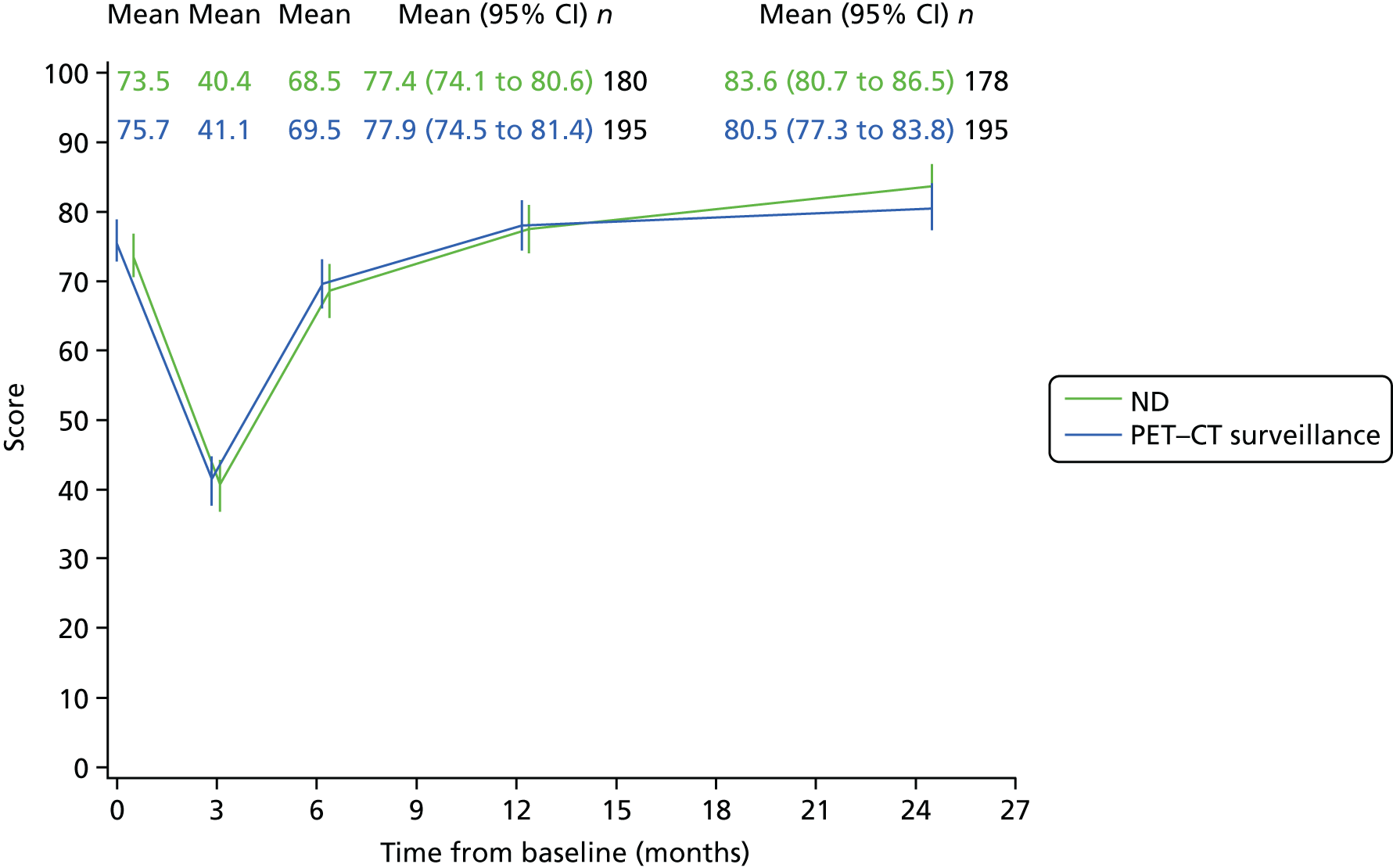

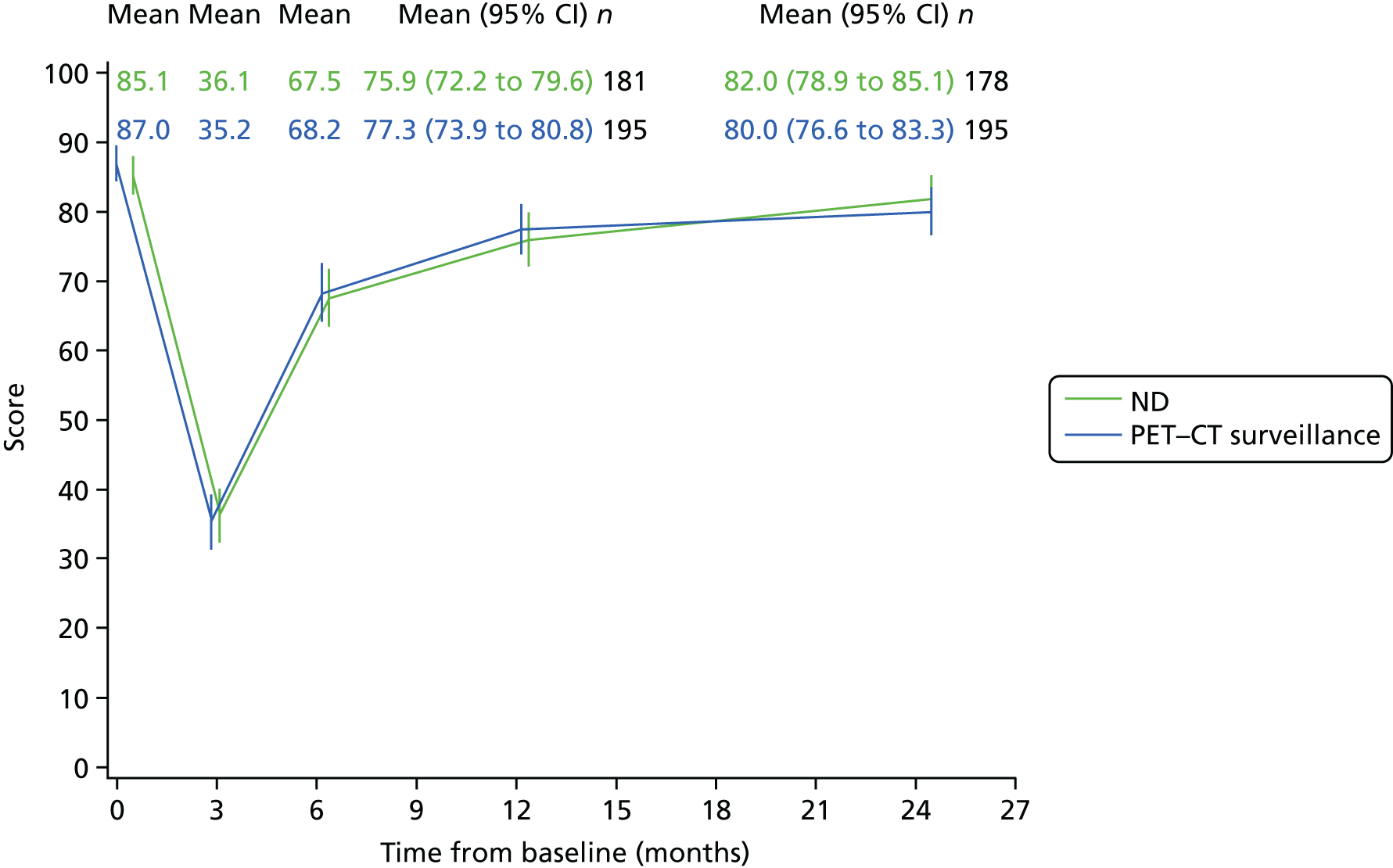

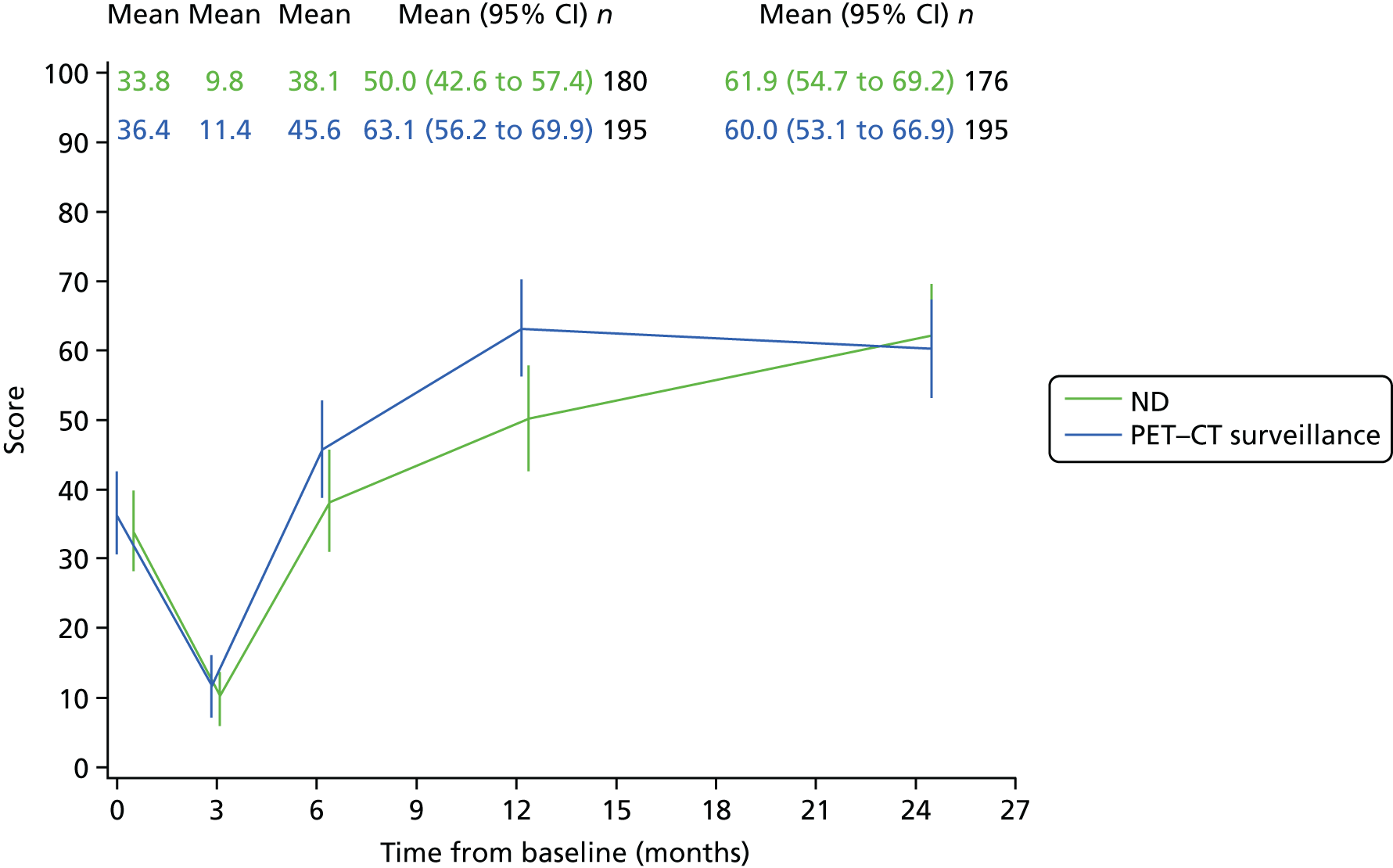

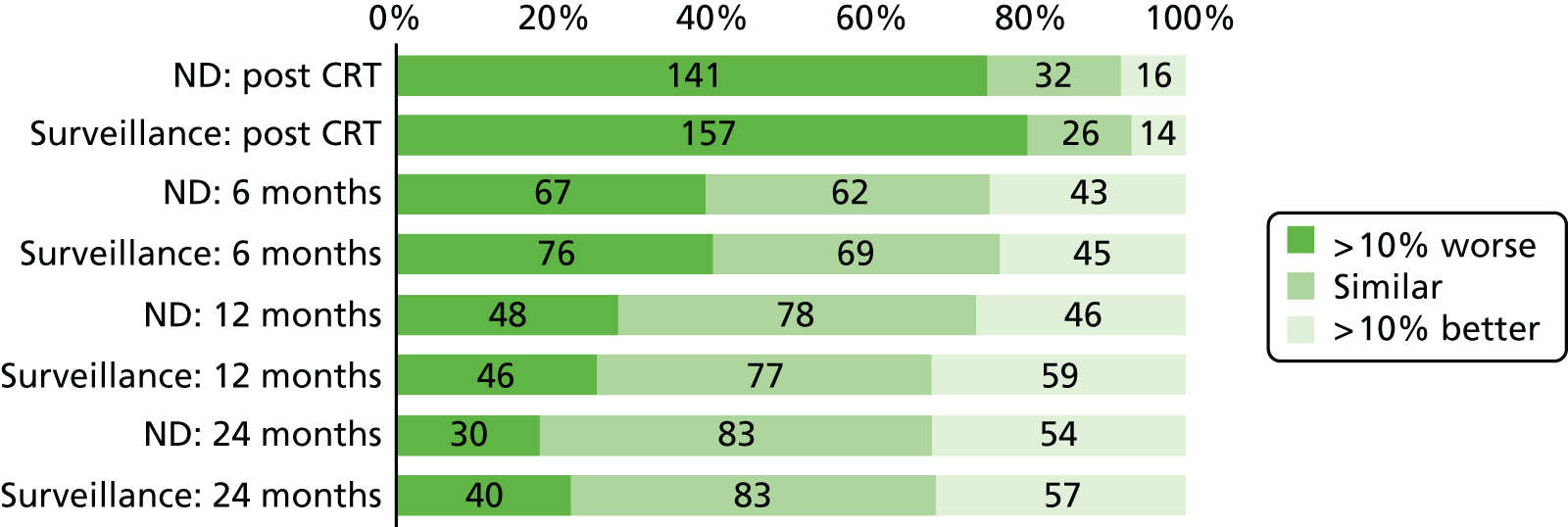

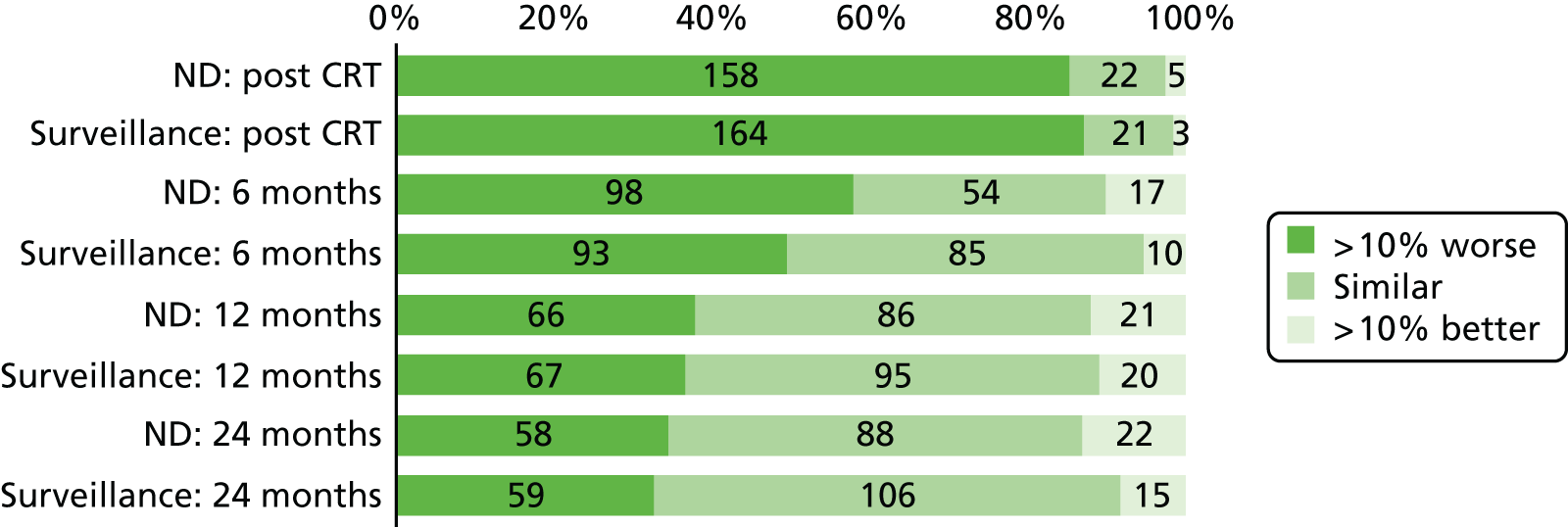

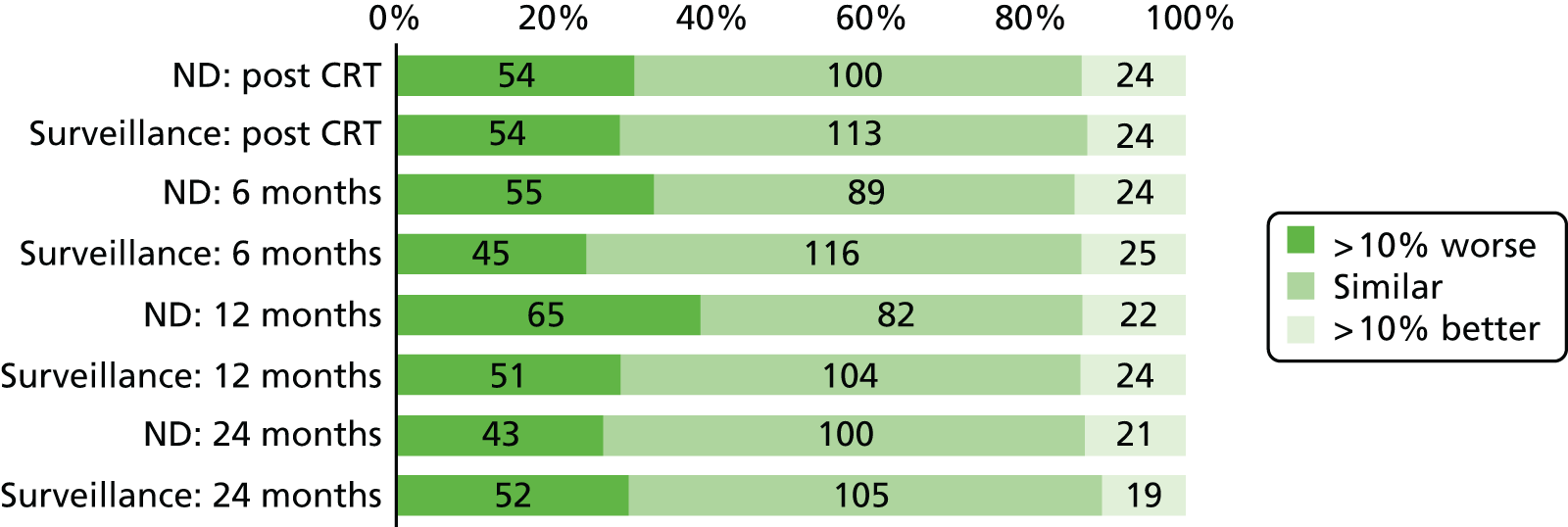

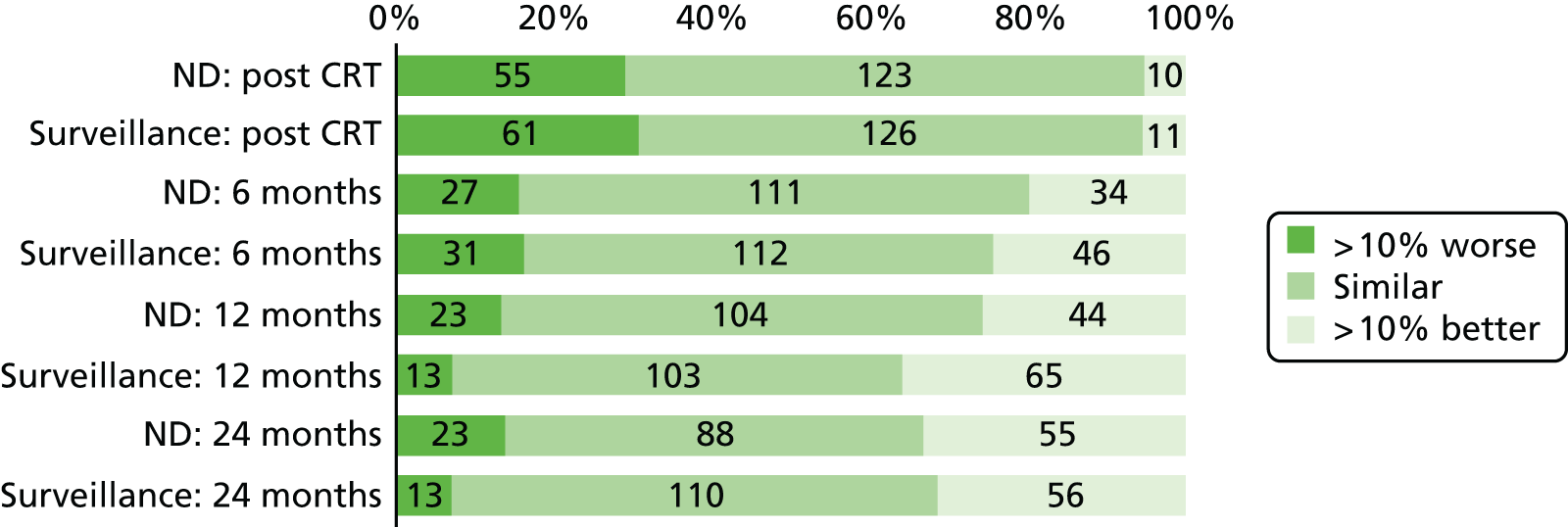

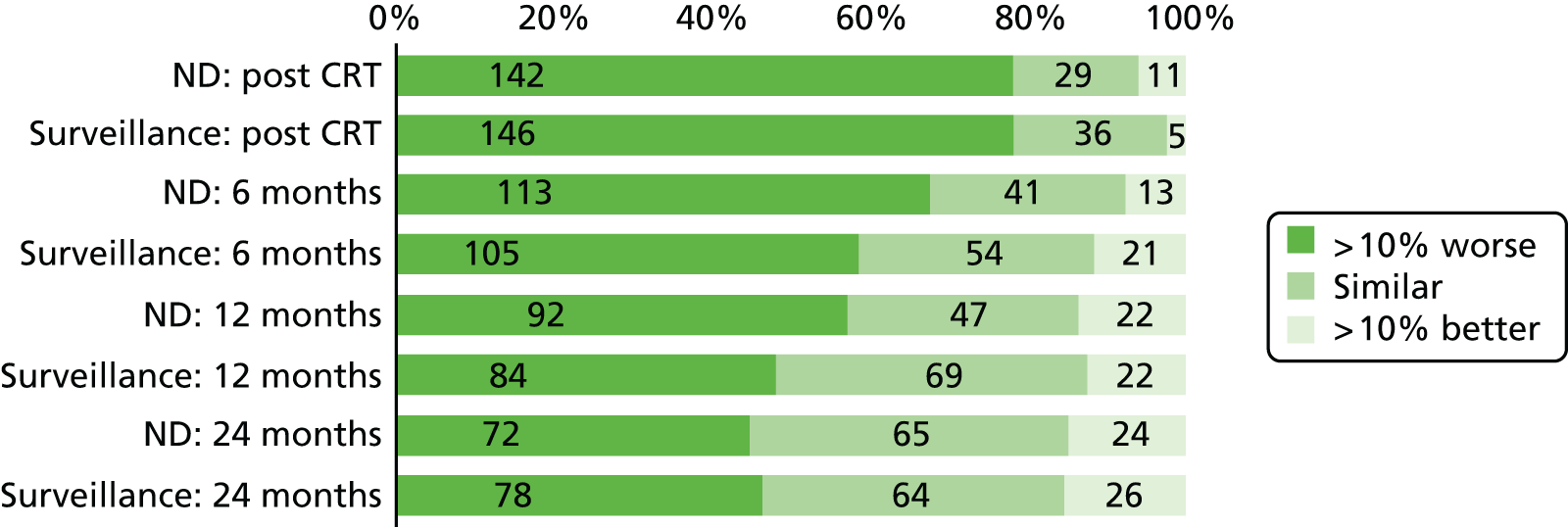

Quality-of-life scales at five time points were available for the EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3, EORTC QLQ-H&N35 H&N-specific quality-of-life questionnaire and the MDADI. The recommended scoring methods were applied59 (see also Fayers60 and Chen et al. 61). The differences between treatments in mean changes from baseline scores were calculated and compared for each of the assessment points separately using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The proportion of patients whose scores changed by at least 10% was also reported.

Complications of ND surgery were reported as counts and as proportion of NDs with Agresti–Coull binomial CIs.

Positron emission tomography–computerised tomography accuracy was difficult to assess, as it is difficult to define a false positive. Therefore, it was not possible to measure PET–CT accuracy in a meaningful way.

Concordance of local PET–CT scan assessments with that of the trial review radiologist were reported.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Database and data processing

The database was held on the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit’s Microsoft Structured Query Language server system (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and imposed rules for data entry that included valid range for responses, linked dates and patient identification numbers.

Data were single entered into the database by study personnel. The trial statistician carried out checks of plausibility of values, missing data and form return rates to enable further queries to be resolved prior to freezing data for scheduled IDSMC reports and analysis. A 100% check on the details in death reports was applied.

Chapter 3 Results

Screening and recruitment

Recruitment

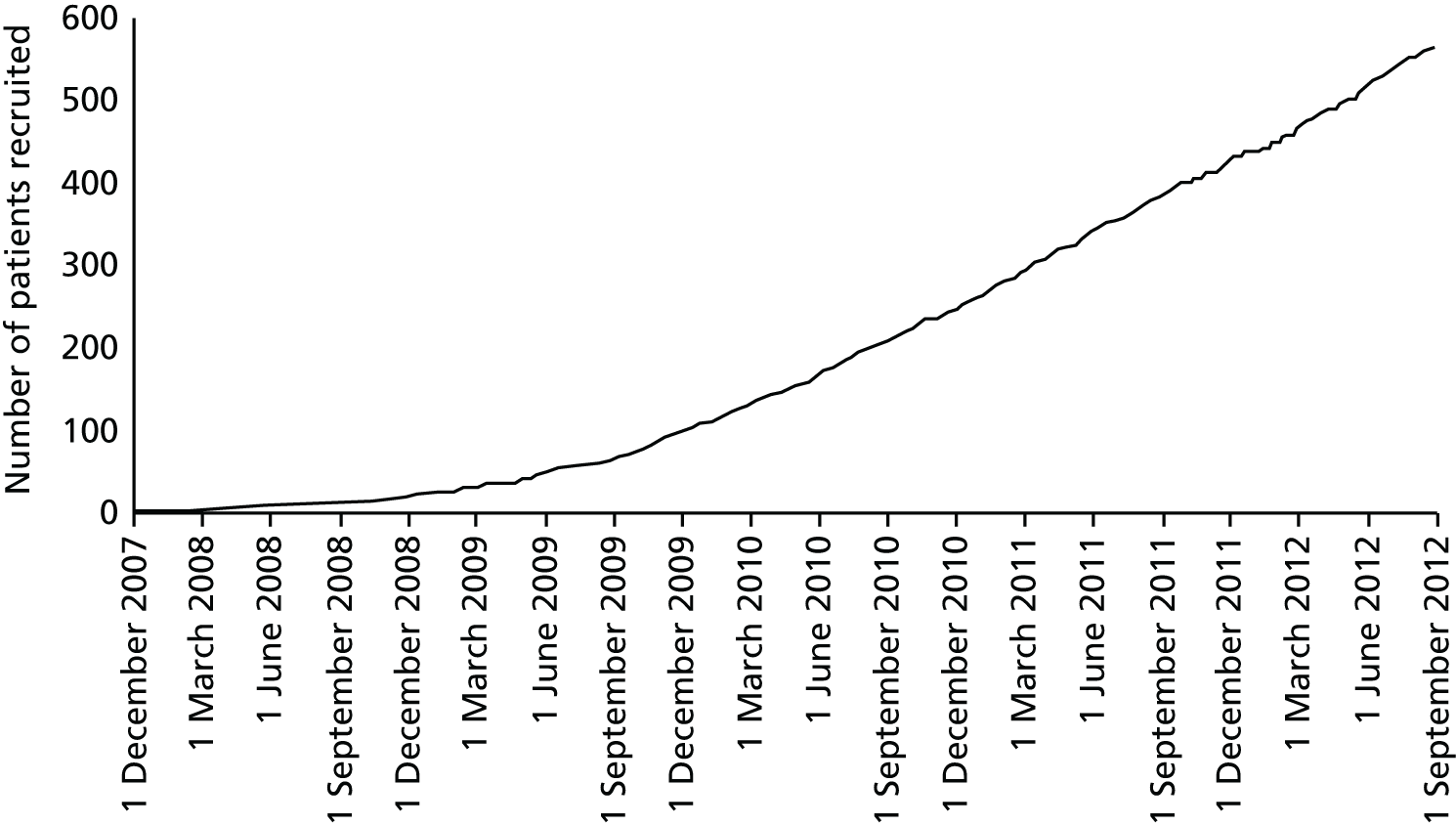

A total of 564 patients were recruited between 2 October 2007 and 23 August 2012: 282 to each trial arm (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment.

Two patients in the surveillance arm were subsequently found to be ineligible: one patient’s disease was found to be T1N1 and another patient had metastatic disease at the time of randomisation. Follow-up data were collected and the patients are included in analyses.

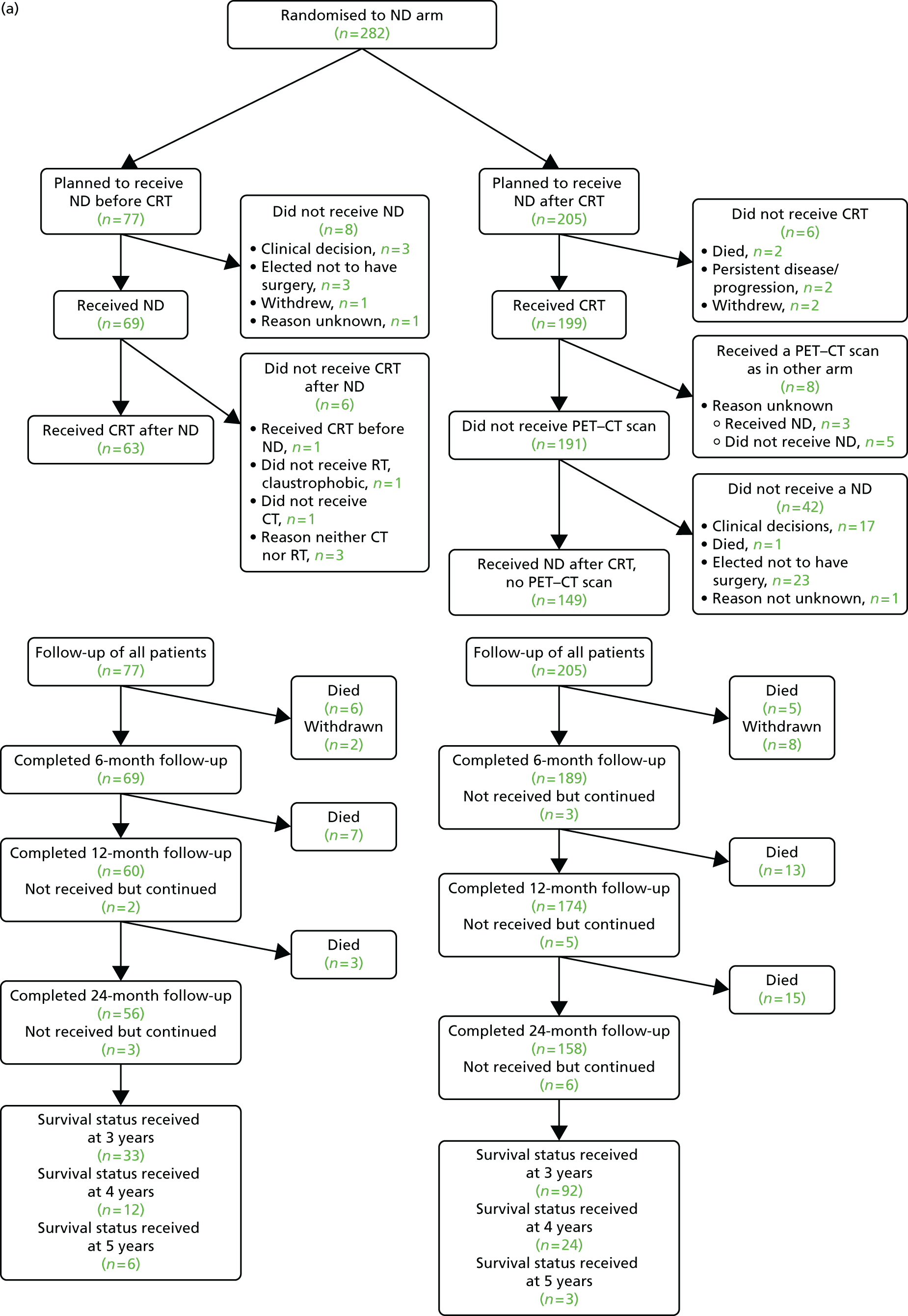

The participant flow diagram outlines the passage of patients through the study; more detail is given in later sections (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Participant flow diagram. (a) ND arm; and (b) surveillance arm. Adapted from the New England Journal of Medicine, Mehanna H, Wong W-L, McConkey CC, Rahman JK, Robinson M, Hartley AGJ, PET-CT Surveillance versus Neck Dissection in Advanced Head and Neck Cancer, 374, 1444–54. Copyright © (2016) Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission. 62

Screening

All patients newly diagnosed with HNSCC were considered potentially eligible and had to be screened by the MDT prior to their clinic appointment.

Both screened patients and those approached for study participation had to be recorded anonymously on the screening log. The log was updated monthly and passed to the co-ordinating centre.

If a screened patient was not eligible for the trial, an anonymous record of the case was recorded on the screening log. Recorded details included the name of the centre, the patient’s initials and the reason for non-randomisation, if not randomised. Patients randomised to the trial were also recorded.

In total, 1792 patients were screened. The number of patients screened by centre is given in Table 3.

| Site | Number of patients screened |

|---|---|

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 7 |

| Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals | 2 |

| Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre | 31 |

| Belfast City Hospital | 33 |

| Blackpool Victoria Hospital | 29 |

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital | 70 |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary | 23 |

| Bristol Haematology and Oncology Centre | 40 |

| Castle Hill Hospital | 22 |

| Cheltenham General Hospital | 5 |

| Christie Hospital | 25 |

| Derriford Hospital | 12 |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals | 41 |

| James Cook University Hospital | 10 |

| Kent and Canterbury Hospital | 77 |

| Mount Vernon Hospital | 17 |

| New Cross Hospital | 11 |

| North Manchester General Hospital | 12 |

| Nottingham University Hospital | 17 |

| Poole Hospital | 10 |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital | 5 |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham | 77 |

| Royal Blackburn Hospital | 126 |

| Royal Derby Hospital | 59 |

| Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital | 35 |

| Royal Marsden Hospital | 5 |

| Royal Preston Hospital | 21 |

| Royal Surrey County Hospital | 42 |

| Royal United Hospital | 44 |

| Russells Hall Hospital | 11 |

| Singleton Hospital | 101 |

| Sir Bobby Robson Cancer Trials Research Centre (Freeman Hospital) | 32 |

| Southend University Hospital | 4 |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital | 153 |

| Torbay Hospital | 11 |

| UHCW | 143 |

| University College London Hospital | 32 |

| University Hospital Aintree | 131 |

| Velindre Cancer Centre | 26 |

| Walsall Manor Hospital | 12 |

| Western General Hospital | 39 |

| Weston Park Hospital | 188 |

| William Harvey Hospital | 1 |

Of the 1792 patients screened, 564 were randomised, 1032 did not fulfil the eligibility criteria, and 196 patients refused consent. Table 4 shows reasons for patients not meeting the standard eligibility criteria and Table 5 shows reasons for unwillingness of eligible patients to enter the study.

| Ineligibility criteria | Number of patients in category |

|---|---|

| Patient did not have the required histological diagnosis | 187 |

| Patient did not have N2 or N3 disease | 223 |

| Patient had distant metastases | 57 |

| Patient had previous treatment for HNSCC | 59 |

| Previous cancer in past 5 years | 4 |

| Patient would not receive protocol-driven CRT regimen | 26 |

| Patient was unfit for surgery and/or CRT | 115 |

| Patient required resection of tumour | 151 |

| Inoperable nodes | 5 |

| Patient required palliative treatment | 69 |

| For radiotherapy only | 3 |

| Clinical decision not to enter patient in the trial | 15 |

| Other treatment planned | 41 |

| Other reasons not specified above | 47 |

| Reason for ineligibility not specified | 30 |

| Total | 1032 |

| Reason | Number of patients in category |

|---|---|

| Patient wanted ND or standard treatment | 47 |

| Patient did not want surgery | 36 |

| Patient wanted more control over the type or place of treatment | 16 |

| Patient had anxieties about the large amount of information and making decisions on randomisation and treatment | 12 |

| Patient did not want to take part in clinical study | 11 |

| Total | 122 |

The majority of patients who were ineligible either had the wrong type or severity of disease or a different type of treatment was indicated. There were 47 patients who were not approached about the study for reasons such as cognitive impairment, psychiatric issues or short-term memory problems that were likely to affect compliance. Other examples include language barriers, too much information to give to a patient as a result of having to tell them about their disease at the same time as giving study information, lack of clinicians available to discuss trial/consent patients, patient travelling elsewhere for treatment, a patient refusing to be treated or a patient being entered into another incompatible study. For 30 patients, the reason for ineligibility was not known.

Of the 196 patients who refused to participate, 74 did not give a reason for non-participation. The reasons for non-participation of the other 122 patients are given below.

One patient was anxious about being randomised in the trial, 11 patients were not interested in participating in a clinical trial, two patients did not want to travel for PET–CT if randomised to the surveillance arm of the trial, one patient felt that more imaging would be too much, four patients were overwhelmed with the amount of information given (trial information as well as diagnosis and treatment information), seven patients were too distressed after receiving diagnosis information to make a decision about the trial, one patient requested treatment at another clinic, one patient wanted to remain private, one patient wanted to retain control over his/her treatment and 93 patients had specific treatment preferences. Of these, 42 patients preferred ND and 36 patients did not want ND. There were two patients whose treatment preference was not specified. One patient wanted radiotherapy only, one wanted photodynamic therapy, four wanted CRT only, one wanted CRT followed by PET and one patient wanted to proceed immediately to adjuvant chemotherapy. Finally, five patients wanted standard CRT with ND, before or after CRT.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of participants by trial arm

Treatment allocation by minimisation was balanced by the six characteristics in Table 6. A total of 38 centres took part, randomising mainly oropharyngeal patients (84.4%). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was intended in 35.8% of patients.

| Baseline characteristic | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Surveillance | ND | |

| Centre | ||

| Arden | 30 (10.6) | 30 (10.6) |

| Sheffield and Chesterfield | 25 (8.9) | 25 (8.9) |

| Birmingham | 23 (8.2) | 24 (8.5) |

| Bristol | 19 (6.7) | 19 (6.7) |

| Edinburgh | 17 (6.0) | 19 (6.7) |

| Lancashire | 14 (5.0) | 14 (5.0) |

| Glasgow | 13 (4.6) | 12 (4.3) |

| Royal Surrey | 12 (4.3) | 13 (4.6) |

| East Peninsula | 11 (3.9) | 11 (3.9) |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ | 11 (3.9) | 11 (3.9) |

| Newcastle | 11 (3.9) | 11 (3.9) |

| Black Country | 10 (3.5) | 9 (3.2) |

| Manchester | 11 (3.9) | 8 (2.8) |

| Cardiff | 9 (3.2) | 9 (3.2) |

| Swansea | 8 (2.8) | 9 (3.2) |

| East and North Herts | 6 (2.1) | 7 (2.5) |

| Bath | 5 (1.8) | 7 (2.5) |

| West Peninsula | 6 (2.1) | 5 (1.8) |

| Nottingham | 5 (1.8) | 5 (1.8) |

| Sunderland | 4 (1.4) | 6 (2.1) |

| Derby | 5 (1.8) | 3 (1.1) |

| East Kent | 5 (1.8) | 3 (1.1) |

| Liverpool | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.4) |

| East Lancashire | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) |

| Gloucestershire | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) |

| South Tees | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) |

| Hull & East Yorkshire | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Portsmouth | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Dorset | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) |

| Essex | 3 (1.1) | – |

| Barnet | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Aberdeen | 2 (0.7) | – |

| Bradford | – | 1 (0.4) |

| Belfast | – | 1 (0.4) |

| Royal Marsden | – | 1 (0.4) |

| University College London Hospital | – | 1 (0.4) |

| ND policy before or after CRT | ||

| ND before CRT | 76 (27.0) | 77 (27.3) |

| ND after CRT | 206 (73.1) | 205 (72.7) |

| Approved chemotherapy schedules | ||

| Concomitant platinum | 163 (57.8) | 169 (59.9) |

| Concomitant cetuximab | 14 (5.0) | 14 (5.0) |

| Neoadjuvant and concomitant platinum | 10 (3.6) | 9 (3.2) |

| Neoadjuvant TPF with concomitant platinum | 89 (31.6) | 85 (30.1) |

| Other agreed schedules | 6 (2.1) | 5 (1.8) |

| Tumour site | ||

| Oral | 4 (1.4) | 7 (2.5) |

| Oropharyngeal | 240 (85.1) | 236 (83.7) |

| Laryngeal | 18 (6.4) | 19 (6.7) |

| Hypopharyngeal | 15 (5.3) | 14 (5.0) |

| Occult H&N | 5 (1.8) | 6 (2.1) |

| T stage | ||

| T1/T2 | 162 (57.4) | 160 (56.7) |

| T3/T4 | 116 (41.1) | 116 (41.1) |

| Occult H&N | 4 (1.4) | 6 (2.1) |

| N stage | ||

| N2a/N2b | 221 (78.4) | 222 (78.7) |

| N2c/N3 | 61 (21.6) | 60 (21.3) |

Other baseline characteristics of participants by trial arm

The patient characteristics in Table 7 were collected either at randomisation or via baseline information forms. The mean age was 57.9 years and 83.3% were male. Three-quarters of participants were either current or past smokers and, of those tested for p16 status, 335 out of 446 (75%) were positive.

| Baseline characteristic | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Surveillance | ND | |

| Age (years) | ||

| n | 282 | 282 |

| Mean (SD) | 57.6 (7.5) | 58.2 (8.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 57 (53–63) | 58 (53–63) |

| Minimum, maximum | 37, 79 | 38, 83 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| n | 282 | 282 |

| Male | 223 (79.1) | 237 (84.0) |

| Female | 59 (20.9) | 45 (16.0) |

| Primary site, n (%) | ||

| n | 277 | 277 |

| Tonsil | 138 (49.1) | 134 (48.4) |

| Base of tongue | 82 (29.6) | 83 (30.0) |

| Floor of mouth | 1 (0.4) | – |

| Palate | 4 (1.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Tongue | 1 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) |

| Supraglottis | 15 (5.4) | 17 (6.1) |

| Glottis/subglottis/transglottis | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Pyriform fossa | 14 (5.1) | 12 (4.3) |

| Posterior pharyngeal wall | 3 (1.1) | 6 (2.2) |

| More than one site | 17 (6.1) | 19 (6.9) |

| Tonsil, base of tongue | 9 | 9 |

| Tonsil, base of tongue, pyriform fossa | 1 | – |

| Tonsil, base of tongue, palate | 1 | – |

| Tonsil, base of tongue, post-pharyngeal wall | – | 1 |

| Tonsil, palate, tongue | – | 1 |

| Tonsil, palate | 1 | 2 |

| Tonsil, tongue | – | 1 |

| Tonsil, pyriform fossa | – | 1 |

| Tonsil, supraglottis, pyriform fossa | – | 1 |

| Tonsil, posterior pharyngeal wall | 1 | – |

| Tonsil, supraglottis | 1 | – |

| Base of tongue, supraglottis | – | 2 |

| Base of tongue, floor of mouth | 1 | 1 |

| Base of tongue, posterior pharyngeal wall | 1 | – |

| Supraglottis, posterior pharyngeal wall | 1 | – |

| T stage, n (%) | ||

| n | 282 | 282 |

| T1 | 48 (17.0) | 52 (18.4) |

| T2 | 114 (40.4) | 108 (38.3) |

| T3 | 61 (21.6) | 52 (18.4) |

| T4 | 55 (19.5) | 64 (22.7) |

| Occult | 4 (1.4) | 6 (2.1) |

| N stage, n (%) | ||

| n | 282 | 282 |

| N2a | 54 (19.1) | 44 (15.6) |

| N2b | 167 (59.2) | 178 (63.1) |

| N2c | 52 (18.4) | 52 (18.4) |

| N3 | 9 (3.2) | 8 (2.8) |

| Side of primary, n (%) | ||

| n | 280 | 278 |

| Left | 120 (42.9) | 102 (36.7) |

| Right | 129 (46.1) | 142 (51.1) |

| Midline and/or left and right | 31 (11.1) | 34 (12.2) |

| Differentiation, n (%) | ||

| n | 237 | 235 |

| Well differentiated | 15 (6.3) | 10 (4.3) |

| Moderately differentiated | 101 (42.6) | 90 (38.3) |

| Poorly differentiated | 119 (50.2) | 134 (57.0) |

| Undifferentiated | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Type of staging scan, n (%) | ||

| n | 282 | 281 |

| PET–CT | 27 (9.6) | 27 (9.6) |

| CT | 169 (59.9) | 173 (61.6) |

| MRI | 86 (30.5) | 81 (28.8) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| n | 281 | 281 |

| 0 | 220 (78.3) | 218 (77.6) |

| 1 | 60 (21.4) | 60 (21.4) |

| 2 | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||

| n | 281 | 281 |

| Current | 88 (31.3) | 76 (27.0) |

| Past | 119 (42.3) | 134 (47.7) |

| Never | 74 (26.3) | 71 (25.3) |

| Alcohol, n (%) | ||

| n | 280 | 279 |

| Current | 222 (79.3) | 234 (83.9) |

| Past | 34 (12.1) | 18 (6.5) |

| Never | 24 (8.6) | 27 (9.7) |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | ||

| n | 281 | 280 |

| White | 280 (99.6) | 278 (99.3) |

| Black or black British | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) |

| p16 status, n (%) | ||

| n | 226 | 220 |

| p16 positive | 164 (72.6) | 171 (77.7) |

| p16 negative | 62 (27.4) | 49 (22.3) |

| p16 test not done or result not available | 56 | 62 |

Further details of the tumour and nodal stages of randomised patients are given in Tables 8 and 9.

| Stage | ND intended (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before CRT | After CRT | |||

| Surveillance | ND | Surveillance | ND | |

| T1N2a | 3 | 4 | 12 | 11 |

| T1N2b | 5 | 12 | 24 | 21 |

| T1N2c | 1 | 2 | 3 | – |

| T1N3 | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| T2N2a | 14 | 4 | 12 | 11 |

| T2N2b | 21 | 24 | 48 | 50 |

| T2N2c | 2 | 4 | 12 | 12 |

| T2N3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| T3N2a | 2 | 1 | 7 | 5 |

| T3N2b | 11 | 5 | 24 | 25 |

| T3N2c | 3 | 5 | 11 | 9 |

| T3N3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| T4N2a | – | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| T4N2b | 8 | 4 | 25 | 32 |

| T4N2c | 3 | 2 | 17 | 17 |

| T4N3 | – | – | – | 1 |

| Occult N2a | – | – | 2 | – |

| Occult N2b | 1 | 3 | – | 2 |

| Occult N2c | – | – | – | 1 |

| Occult N3 | – | – | 1 | – |

| Stage | ND intended, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before CRT | After CRT | |||

| Surveillance | ND | Surveillance | ND | |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | 9 (11.8) | 19 (24.7) | 39 (18.9) | 33 (16.1) |

| T2 | 38 (50.0) | 33 (42.9) | 76 (36.9) | 75 (36.6) |

| T3 | 17 (22.4) | 12 (15.6) | 44 (21.4) | 40 (19.5) |

| T4 | 11 (14.5) | 10 (13.0) | 44 (21.4) | 54 (26.3) |

| Occult | 1 (1.3) | 3 (3.9) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| N stage | ||||

| N2a | 19 (25.0) | 13 (16.9) | 35 (17.0) | 31 (15.1) |

| N2b | 46 (60.5) | 48 (62.3) | 121 (58.7) | 130 (63.4) |

| N2c | 9 (11.8) | 13 (16.9) | 43 (20.9) | 39 (19.0) |

| N3 | 2 (2.6) | 3 (3.9) | 7 (3.4) | 5 (2.4) |

Withdrawals

There were 13 withdrawals in the ND group and three in the surveillance group (Table 10).

| Reason | Trial arm (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Surveillance | ND | |

| Ineligible | – | 1 |

| Patient did not want ND/wanted surveillance arm | – | 4 |

| Wished to consent to another clinical trial | – | 1 |

| Migrated to the USA for IMRT | – | 1 |

| Patient decision | 1 | 2 |

| Patient and clinician decision | 1 | – |

| Clinician decision | 1 | – |

| No reason given | – | 4 |

Protocol deviations

Categories and frequencies of protocol deviations are given in Table 11. A number of patients were found to have been randomised on the basis of incorrect information. The tumour site category (oral, oropharyngeal, laryngeal, hypopharyngeal or occult) was inconsistent with the more detailed subsites. These errors were later corrected. Chemotherapy schedules were incorrectly recorded because of confusion over the three schedules containing cisplatin. Correction of these errors did not adversely affect the balance of the treatment allocation (see Baseline characteristics). The reasons why some patients in the ND arm did not undergo a ND are better described in Neck dissections. Twenty patients were randomised after they had already started CRT because the centre misunderstood the correct trial procedure.

| Description | Trial arm (n) | Total number | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surveillance | ND | ||

| Related to randomisation | |||

| Randomised on the basis of incorrect ND timing | – | 4 | 4 |

| Randomised on the basis of incorrect T stage | 1 | – | 1 |

| Randomised on the basis of incorrect chemotherapy schedule | 27 | 30 | 57 |

| Randomised on the basis of incorrect tumour site | 39 | 33 | 72 |

| Subtotal | 67 | 67 | 134 |

| Others related to either trial arm | |||

| Started CRT prior to randomisation (mostly one centre) | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| Timeline of response | – | 1 | 1 |

| Chest radiography not CT of chest | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| MRI standardised uptake value details | – | 1 | 1 |

| Different chemotherapy schedule to planned | 2 | – | 2 |

| Ineligible | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Subtotal | 16 | 14 | 30 |

| Others related to surveillance arm only | |||

| No PET–CT scan done | 1 | – | 1 |

| Watch and wait on partial response | 1 | – | 1 |

| Timeline of PET–CT | 2 | – | 2 |

| Partial response in nodes led to biopsy taken after PET–CT | 2 | – | 2 |

| Subtotal | 6 | – | 6 |

| Others related to ND arm only | |||

| Randomised to ND arm but patient elected not to undergo ND | – | 25 | 25 |

| No surgery, clinician decision | – | 9 | 9 |

| ND surgery later than protocol timeline | – | 2 | 2 |

| Timing of surgery changed (before/after CRT) | – | 1 | 1 |

| Underwent PET–CT | – | 1 | 1 |

| Subtotal | – | 38 | 38 |

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy schedules planned at randomisation

Planned chemotherapy schedules are counted separately for patients in whom ND was planned to take place before CRT (Table 12) and for those in whom ND was planned to take place after CRT (Tables 13 and 14). Neoadjuvant schedules were more frequent when the planned timing was ND after CRT. A slightly higher proportion of patients in the ND arm whose ND was planned to be before CRT had a planned concomitant platin schedule.

| Schedule | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Surveillance | ND | |

| Concomitant cisplatin or carboplatin | 55 (72.4) | 63 (81.8) |

| Concomitant cetuximab | 5 (6.6) | 5 (6.5) |

| Neoadjuvant and concomitant platinum | 3 (3.9) | – |

| Neoadjuvant docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil and concomitant cisplatin | 12 (15.8) | 9 (11.7) |

| Other agreed (neoadjuvant carboplatin) | 1 (1.3) | – |

| Total | 76 | 77 |

| Schedule | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Surveillance | ND | |

| Concomitant cisplatin or carboplatin | 108 (52.4) | 106 (51.7) |

| Concomitant cetuximab | 9 (4.4) | 9 (4.4) |

| Neoadjuvant and concomitant platinum | 7 (3.4) | 9 (4.4) |

| Neoadjuvant docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil and concomitant cisplatin | 77 (37.4) | 76 (37.1) |

| Other agreed (see Table 14) | 5 (2.4) | 5 (2.4) |

| Total | 206 | 205 |

| Chemotherapy received | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Surveillance arm | |

| Neoadjuvant cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, concomitant cisplatin | 2 |

| Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil | 1 |

| TPF | 2 |

| ND arm | |

| Neoadjuvant docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, concomitant cetuximab | 1 |

| Neoadjuvant cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, concomitant cisplatin (2) | 2 |

| Induction cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil followed by concomitant cisplatin neoadjuvant and concomitant platinum | 1 |

| Neoadjuvant docetaxel and cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, concomitant carboplatin | 1 |

Type of chemotherapy delivered

Chemotherapy details were received for 272 patients in the ND arm and 277 patients in the surveillance arm. Overall, 10 ND patients and five surveillance patients did not have chemotherapy for the reasons given in Table 15.

| Reason for no chemotherapy | Trial arm (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Surveillance | ND | |

| Refused | 1 | – |

| Patient unwell | – | 2 |

| Death | 1 | 3 |

| Did not want ND | – | 2 |

| Wanted surgery | 1 | – |

| Progression/metastases | 1 | 1 |

| Went to the USA for treatment | – | 1 |

| Withdrew | 1 | – |

| Not known | – | 1 |

One patient in the ND arm, who was planned (at randomisation) to receive neoadjuvant and concomitant chemotherapy, received only concomitant chemotherapy. At the same time, two patients randomised to concomitant platinum received only neoadjuvant and concomitant therapy.

Individual drug details were available for 269 patients in the ND arm and 274 patients in the surveillance arm (Table 16). The type of chemotherapy delivered was very similar in the trial arms.

| Chemotherapy received | Trial arm (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Surveillance | ND | |

| Concomitant cisplatin or carboplatin schedule planned | ||

| Concomitant (cisplatin or carboplatin) | 154 | 153 |

| Concomitant (cisplatin or carboplatin) and 5-fluorouracil | – | 1 |

| Concomitant (cisplatin or carboplatin) then changed to cetuximab | – | 3 |

| Concomitant cetuximab | 1 | 2 |

| TPF | 2 | – |

| Concomitant cetuximab schedule planned | ||

| Concomitant cetuximab | 12 | 13 |

| Neoadjuvant and concomitant platin schedule planned | ||

| Neoadjuvant (cisplatin or carboplatin) and 5-fluorouracil, concomitant (cisplatin or carboplatin) | 8 | 7 |

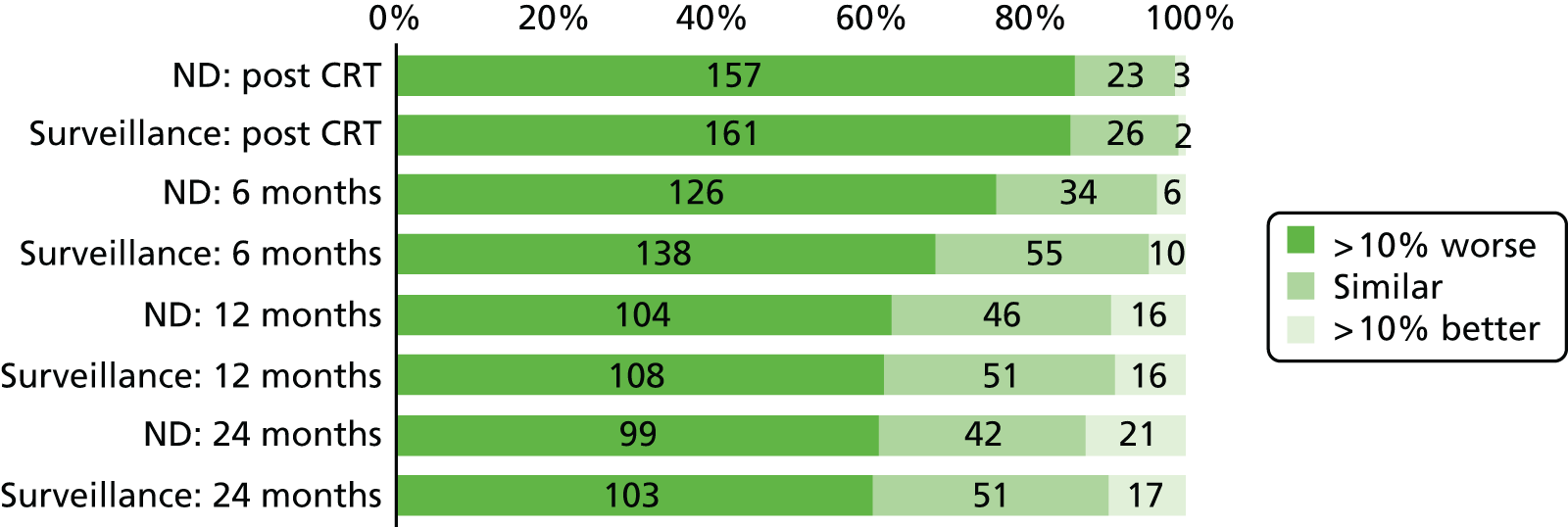

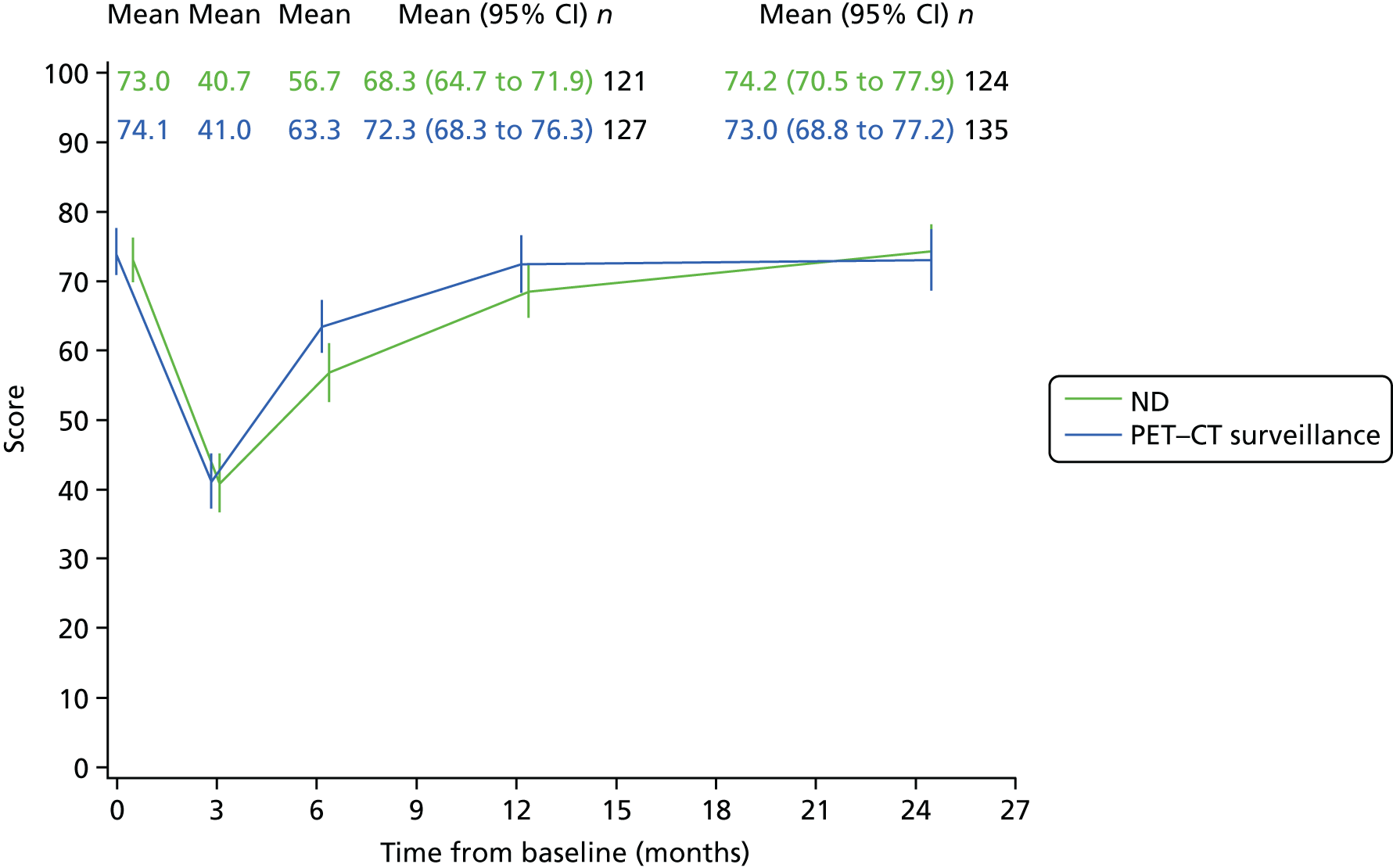

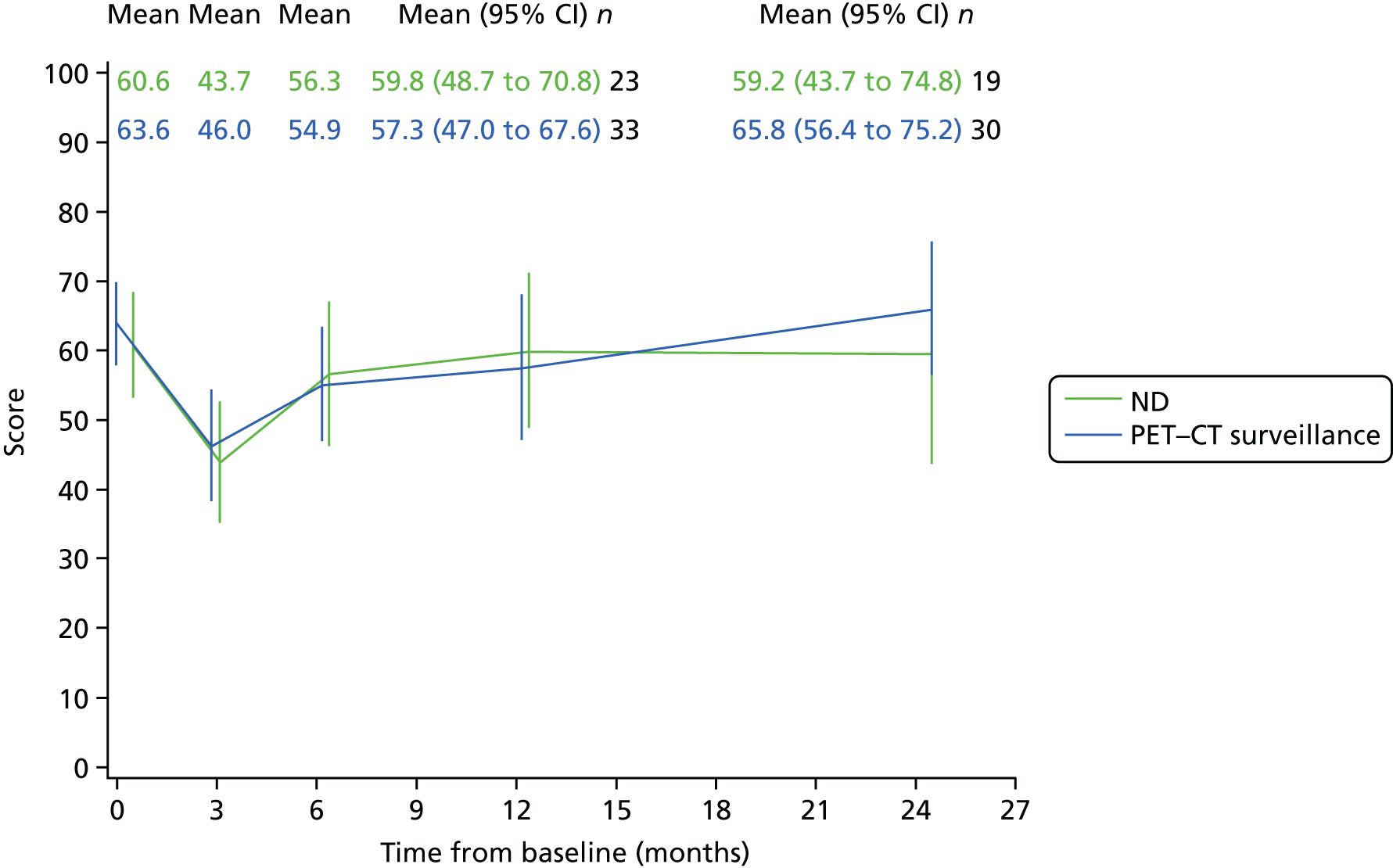

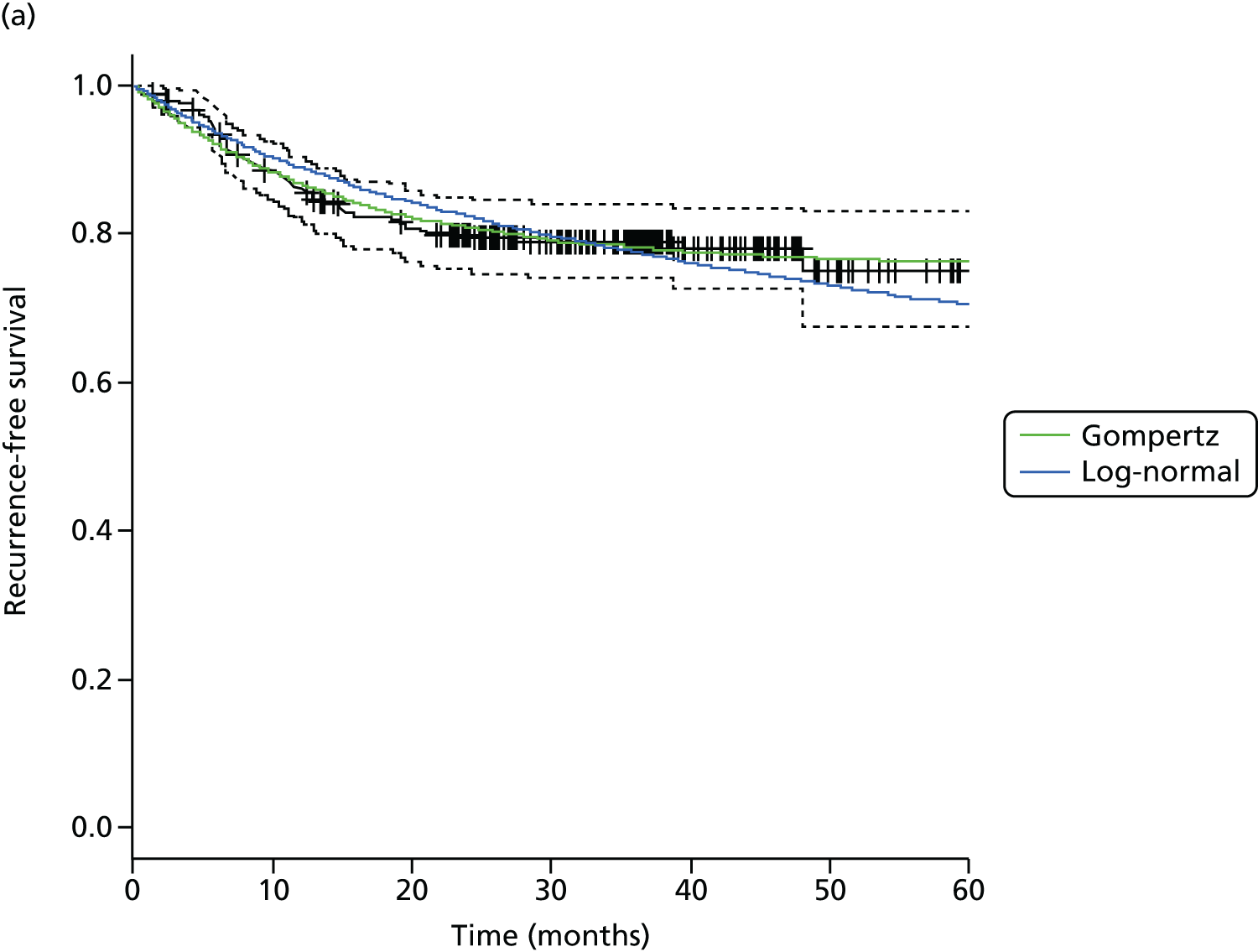

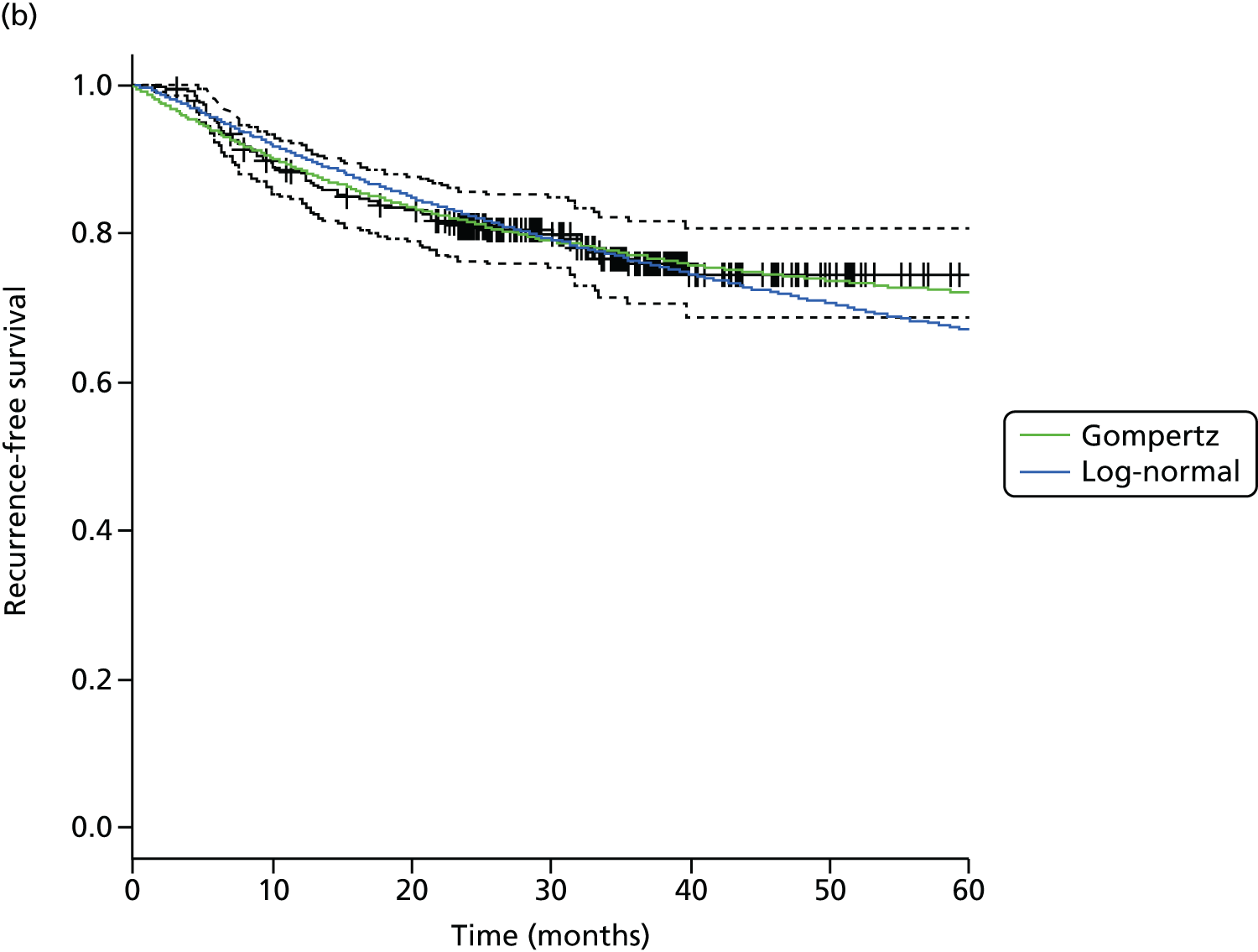

| Neoadjuvant (cisplatin or carboplatin) and 5-fluorouracil | 1 | 2 |