Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/22/163. The contractual start date was in November 2011. The draft report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jon Deeks is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Thangaratinam et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Burden of pre-eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia is a multisystem disorder in pregnancy associated with hypertension and proteinuria. 1–3 Hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure (BP) of ≥ 140 mmHg and diastolic BP of ≥ 90 mmHg on two occasions between 4 and 6 hours apart. 1–3 Proteinuria is defined as ≥ 300 mg of protein in a 24-hour urine collection period or urine dipstick of 1+ or more in two samples collected 6 hours apart or a spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (PCR) of at least 30 mg/mmol. 2–4 Hypertensive diseases in pregnancy remain one of the leading causes of direct maternal deaths in the UK and account for 20% of all stillbirths. 5 In 1% of pregnant women, pre-eclampsia develops before 34 weeks’ gestation and thus is called early-onset pre-eclampsia. 6,7

Early-onset pre-eclampsia is considered to be a pathophysiologically different disease from late-onset pre-eclampsia, with considerably increased risk of maternal complications, including a 20-fold higher maternal mortality. 8–10 The only known cure for this condition is delivery of the baby and placenta. In women with early-onset pre-eclampsia, decisions on the timing of delivery can be difficult, as fetal and neonatal benefits from prolongation of pregnancy beyond preterm gestation need to be balanced against the risk of multisystem dysfunction in the mother. Preterm delivery accounts for 65% of neonatal deaths and 50% of neurological disability in childhood. 11 Many of the current practice guidelines do not consider gestational age at presentation as a criterion for diagnosis, severity or subclassification to stratify risk in women with pre-eclampsia. 2,12

The complexity of the treatment in early-onset pre-eclampsia gives rise to high health-care costs. 6,7 Women are often admitted to a tertiary care facility, and one-third experience complications, which may necessitate admission to an intensive care facility. 13 Infants usually need prolonged intensive care treatment for the management of complications, including lifelong handicaps arising as a result of prematurity. The additional cost to the NHS of caring for a preterm baby born before 33 weeks’ gestation is £61,509 and and of a baby born before 28 weeks’ gestation is £94,190. 14 Each year, the care of preterm babies costs the NHS £939M, largely accounted for by neonatal care such as incubation and hospital readmissions. 14 Delaying premature births by a week could potentially save £260M a year. 14

One of the key recommendations in the last Confidential Enquiries into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) report for policy-makers, service commissioners and providers, and health-care professionals (now known as the Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries, CMACE) is the need to adopt an early-warning system to help in the timely recognition, referral and treatment of women who have or are developing critical conditions. 5 This applies to women with early-onset pre-eclampsia, as early recognition of women at risk of adverse outcomes will allow timely transfer from a secondary to a tertiary unit to enable care in a high-dependency unit or neonatal intensive care unit if needed.

Timely prediction of complications in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia involves the use of a combination of patients’ characteristics, symptoms, physical signs and investigations;15 these ‘tests’ are performed routinely in all obstetric units, but, in the absence of a structured approach, somewhat haphazardly. Gestational age is the most important determinant of perinatal outcome with more than half the chance of intact fetal survival when the gestational age is > 27 weeks and the birthweight is > 600 g. 16 Clinicians are hesitant to advocate expectant management because of uncertainties about the scale of maternal risk. Development of a prediction model for adverse maternal and fetal outcomes will help clinicians make appropriate decisions, after discussion with the parents.

Existing evidence

Evidence on assessment of risk of complications in early-onset pre-eclampsia

At present, it is difficult to identify those mothers with early-onset pre-eclampsia at increased risk of developing complications, and individual risk estimates for complications at various time points cannot be provided. 9 Current classification systems of pre-eclampsia [Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG); Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZOG); International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP); Community Health Partnerships (CHP); and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in Canada (SOGC)] are based on the severity of the disease. 9,12,17–19 All of them include BP and proteinuria to dichotomise the severity but do not take into account gestational age to assess severity of pre-eclampsia, with the exception of the SOGC, which classifies all early-onset pre-eclampsia as severe. 19 However, in this subgroup the predictors that influence maternal and fetal outcomes are not well established.

Our systematic reviews on the accuracy of tests in predicting complications in women with pre-eclampsia were based on very few, poor-quality primary studies. 20–23 They did not take into account the predictive role of more than one test result on the outcome. Furthermore, there was no separate quantification of risks, especially in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia.

Prediction models, such as Pre-eclampsia Integrated Estimate of RiSk (PIERS), were developed in women with any onset pre-eclampsia and not particularly in those with early onset. 9 Furthermore, the PIERS model did not fully account for the treatment paradox, whereby a strong predictor of a common complication triggers an effective treatment, thereby preventing the occurrence of a certain proportion of adverse outcomes. In this situation, the predictor that triggered the treatment in the first place will look poorer in its predictive performance in a simple model. 24 Hence, tests such as BP and proteinuria were not identified to be significant in the PIERS model. This had a negative impact on the face validity of the model, as traditionally clinicians prioritise these tests and have a very low threshold for intervention when they are abnormal.

Management of early-onset pre-eclampsia

Currently, the only definitive treatment in pre-eclampsia is delivery. Antenatal corticosteroids are administered to improve fetal lung maturation whenever preterm delivery is anticipated. As steroids achieve their optimal effect after 48 hours,25,26 clinicians tend to postpone delivery until this time unless complications have occurred or are anticipated. Neonatal morbidity from early preterm delivery could be reduced by stabilising the woman’s condition and, if possible, by delaying delivery. Expectant management of early-onset pre-eclampsia has been shown to improve perinatal outcomes in randomised trials. 27,28 A Cochrane review13 that compared early intervention with expectant management in women with early-onset severe pre-eclampsia27,28 showed that babies born to mothers in the early intervention group had more hyaline membrane disease [relative risk (RR) 2.3, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.4 to 3.8] and more necrotising enterocolitis (RR 5.50, 95% CI 1.04 to 29.60) and were more likely to be admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (RR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.6) than those allocated an expectant policy. Infants in the expectant group were delivered approximately 2 weeks later and were 300 g heavier at birth than infants in the early intervention group. A recent systematic review of observational studies suggested that expectant management in carefully selected cases of pre-eclampsia before 34 weeks’ gestation was associated with few serious maternal complications (median < 5%), similar to interventionist care. 9,29 There is consensus that fetal outcome is poor before 24 weeks’ gestation in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia. 27,30,31 However, many centres do not practise expectant management because of the poorly quantified maternal risk. Our study will establish a predictive rule to allow clinicians to confidently provide expectant care when risk of complications in early-onset pre-eclampsia is low.

Objectives

-

To develop, and internally validate, a prediction model in women admitted with early-onset pre-eclampsia from 20+0 weeks to 33+6 weeks’ gestation, for assessment of the risk of adverse maternal outcome by discharge and at various time points after diagnosis.

-

To externally validate and update the model through two external data sets of patients with a diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia.

-

To assess the risk of adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes at birth and at any time until discharge, and to summarise the unadjusted and adjusted prognostic ability of a set of candidate predictor variables.

Chapter 2 Development and internal validation of the prediction model: PREP prospective observational study

Study methods

The study protocol was developed according to existing recommendations on prognostic research, model development and validation, and prediction rule development,32–34 and reported in line with the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement. 35 The study received ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee West Midlands (approval number 11/WM/0248).

Study design and conduct

We undertook a prospective, observational cohort study to develop the prediction model(s). All consecutive women with suspected or confirmed diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia were approached to take part in the study. Women were recruited from December 2011 to April 2014 based on a set of prespecified eligibility criteria and the follow-up of the last participant was completed in July 2014. Potential mothers were identified and recruited by research midwives and clinicians from the antenatal clinics, wards, day assessment units and delivery suites. We obtained information routinely collected as part of the antenatal booking process in the UK such as maternal age, ethnicity, smoking, alcohol intake and substance misuse. The ethnicity classification was applied using the NHS criteria. 36,37

Setting

The multicentre study was conducted in 53 obstetric units within secondary and tertiary care hospitals in England and Wales.

Participants

Women with suspected or confirmed diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia (before 34 weeks’ gestation) were recruited to the study. Only women with confirmed early-onset pre-eclampsia were included in the final models.

Patient and public involvement

The Action on Pre-Eclampsia Charity (APEC) was vital in providing important input. The charity was involved from the very start with the development and design of the study protocol and will help with the dissemination of findings from the study. A member of the organisation sat as an independent member of the study steering committee and contributed to the overall supervision and management of the research project. They were also involved with the development of study materials, including the informed consent forms and patient information sheets. The APEC was involved in promoting the study to midwives and clinicians, attending the study days and meetings.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were gestational age between 20+0 and 33+6 weeks; maternal age of ≥ 16 years; and a diagnosis of new-onset or superimposed pre-eclampsia. We also included women with a diagnosis of haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) syndrome with no proteinuria or hypertension and those with one episode of eclamptic seizures but no hypertension or proteinuria. 9,38 All women provided written informed consent and were capable of understanding the information provided. We used an interpreter if required.

The definitions for diagnosis of pre-eclampsia are provided in Table 1.

| Condition | Definition |

|---|---|

| New-onset pre-eclampsia | New-onset hypertension (systolic BP of ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP of ≥ 90 mmHg on two occasions between 4 and 6 hours apart in women) after 20 weeks of pregnancy and new-onset proteinuria (≥ 2+ on urine dipstick or PCR of > 30 mg/mmol or 300 mg of protein excretion in 24 hours)39 |

| Suspected pre-eclampsia | New-onset hypertension (systolic BP of ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP of ≥ 90 mmHg on two occasions between 4 and 6 hours apart in women) after 20 weeks of pregnancy, and 1+ proteinuria on urine dipstick |

| Superimposed pre-eclampsia | |

| In women with chronic hypertension and no proteinuria before 20 weeks’ gestation | New-onset proteinuria (as defined previously) |

| In women with significant proteinuria before 20 weeks’ gestation | Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase concentration (> 70 units per litre) or worsening hypertension (either two diastolic BP measurements of at least 110 mmHg 4 hours apart or one diastolic BP measurement of at least 110 mmHg if the woman had been treated with an antihypertensive drug), plus one of the following: increasing proteinuria, persistent severe headaches or epigastric pain |

| HELLP syndrome | HELLP syndrome: presence of haemolysis based on examination of the peripheral smear, elevated indirect bilirubin levels, or low serum haptoglobin levels in association with significant elevation in liver enzymes and a platelet count below 100,000/mm3 after ruling out other causes of haemolysis and thrombocytopenia |

| One episode of eclamptic seizures without hypertension or proteinuria9,38 | Other neurological conditions of seizures have been excluded |

Exclusion criteria

Women were excluded if the outcome (including recurrent eclamptic seizures) occurred prior to the tests or if there was insufficient time for gaining informed consent or if the mother did not comprehend spoken and written English adequately. A flow chart of study conduct is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the Prediction of Risks in Early-onset Pre-eclampsia (PREP) study conduct. a, Only reduced PREP logistic model validated.

Predictors

Identification of predictors

Our previous Delphi survey of international experts on pre-eclampsia prioritised the tests that were considered to be clinically important in women with pre-eclampsia. 15,41 Additional predictors were identified from our systematic reviews on the accuracy of tests for complications in pre-eclampsia and other relevant studies. 9 This provided face validity to the choice of tests evaluated in the development of the Prediction of Risks in Early-onset Pre-eclampsia (PREP) model.

The list of preselected candidate predictor variables evaluated in the PREP study is provided in Box 1 and the list of predictor variables for fetal complications in the study is shown in Box 2. In addition, we included management strategies that had the potential to reduce risk of complications to minimise bias from treatment paradox. 24 This included administration of antihypertensive drugs (oral and/or parenteral) and/or magnesium sulphate if women were on them at the time of diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia, or if they were commenced within a day of diagnosis. We forced maternal age and gestational age at diagnosis into the model.

Maternal age at diagnosis (years).

Gestational age at diagnosis (weeks).

Number of fetuses in pregnancy at time of consent (1, 2 or 3).

HistorySummary score for medical history – 1 point for each of the following: pre-existing hypertension, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disease, previous history of pre-eclampsia (0, 1, 2 or more).

SymptomsHeadache and/or visual disturbance (yes/no).

Epigastric pain, nausea and/or vomiting (yes/no).

Chest pain and dyspnoea (yes/no).

Bedside examination and testsSystolic BP (mmHg, highest measurement over 6 hours).

Diastolic BP (mmHg, highest measurement over 6 hours).

Clonus (yes/no).

Exaggerated tendon reflexes (yes/no).

Abnormal oxygen saturation (< 95% on air) (yes/no).

Urine dipstick (0, 1+, 2+, 3+, 4+ or more).

Laboratory testsHaemoglobin (g/l).

Platelet count (× 109/l).

ALT concentration (IU/l).

Serum uric acid concentration (µmol/l).

Serum urea concentration (mmol/l).

Serum creatinine concentration (µmol/l).

Urine PCR (mg/mmol).

Management at baselineAdministration of oral and/or parenteral antihypertensives (ongoing or commenced within 1 day of diagnosis) (yes/no).

Administration of magnesium sulphate (commenced before or within 1 day of diagnosis) (yes/no).

ALT, alanine aminotransaminase; IU, international unit.

Maternal age at diagnosis (years).

Gestational age at diagnosis (weeks).

Number of fetuses in pregnancy at time of consent (1, 2 or 3).

HistorySummary score for history, for example 1 point for each of pre-existing hypertension, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disease, previous history of pre-eclampsia (0, 1, 2 or more).

SymptomsHeadache and/or visual disturbance (yes/no).

Epigastric pain, nausea and/or vomiting (yes/no).

Chest pain and dyspnoea (yes/no).

Bedside examination and testsSystolic BP (mmHg, highest measurement over 6 hours).

Diastolic BP (mmHg, highest measurement over 6 hours).

Clonus (yes/no).

Exaggerated tendon reflexes (yes/no).

Abnormal oxygen saturation (< 94% on air) (yes/no).

Urine dipstick (0, 1+, 2+, 3+, 4+ or more).

Laboratory testsHaemoglobin (g/l).

Platelet count (× 109/l).

ALT concentration (IU/l).

Serum uric acid concentration (µmol/l).

Serum urea concentration (mmol/l).

Serum creatinine concentration (µmol/l).

Urine PCR in 24 hours (mg/mmol).

Ultrasound and cardiotocographyUterine artery Doppler at 20–24 weeks’ gestation (normal/abnormal).

CTG findings (normal/abnormal).

Estimated fetal weight by ultrasound (< 10th centile).

Liquor volume (normal/abnormal).

Management at baselineAdministration of oral and/or parenteral antihypertensives (ongoing or commenced within 1 day of diagnosis) (yes/no).

Administration of magnesium sulphate (commenced within 1 day of diagnosis) (yes/no).

Administration of corticosteroids (commenced within 1 day of diagnosis) (yes/no).

ALT, alanine aminotransaminase; CTG, cardiotocography; IU, international unit.

Outcome

The primary outcome was composite adverse maternal outcome that included at least one of the components in Table 2. In addition to maternal complications, prior to the analysis, we added delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation as an additional component to the composite maternal adverse outcome to minimise bias caused by treatment paradox. The components of the composite outcome were developed through Delphic consensus and had previously undergone piloting and validation in the Canadian cohort of patients in the PIERS (Pre-eclampsia Integrated Estimate of RiSk) study. 9 A composite measure for fetal outcome was also developed by the Delphi consensus9 (Table 3).

| Outcome | Definition |

|---|---|

| Mortality | Maternal death attributable to complications of pre-eclampsia |

| Hepatic dysfunction | INR > 1.2 indicative of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in the absence of treatment with warfarin. DIC is defined as having both abnormal bleeding and consumptive coagulopathy (i.e. low platelets, abnormal peripheral blood film or one or more of the following: increased INR, increased PTT, low fibrinogen, of increased fibrin degradation products that are outside normal non-pregnancy ranges) |

| Hepatic haematoma or rupture | Blood collection under the hepatic capsule as confirmed by ultrasound or laparotomy |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score of < 13 | Based on the Glasgow Coma Scale score system42 |

| Stroke | Acute neurological event, with deficits lasting > 48 hours |

| Cortical blindness | Loss of visual acuity in the presence of intact papillary response to light |

| Reversible ischaemic neurological deficit | Cerebral ischaemia lasting > 24 hours but < 48 hours revealed through clinical examination |

| Retinal detachment | Separation of the inner layers of the retina from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (choroid) and is diagnosed by ophthalmological examination |

| Acute renal insufficiency | For women with an underlying history of renal disease defined as a creatinine concentration of > 200 µM; for patients with no underlying renal disease defined as a creatinine concentration of > 150 µM |

| Dialysis | Including haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis |

| Transfusion of blood products | Includes transfusion of any units of blood products: fresh-frozen plasma, platelets, red blood cells, cryoprecipitate or whole blood |

| Positive ionotropic support | The use of vasopressors to maintain a systolic BP of > 90 mmHg or mean arterial pressure of > 70 mmHg |

| Myocardial ischaemia/infarction | ECG changes (ST segment elevation or depression) without enzyme changes and/or any one of the following:

|

| Require > 50% oxygen for > 1 hour | Oxygen given at greater than 50% concentration based on local criteria for > 1 hour |

| Intubation other than for caesarean section | Intubation may be by ventilation, electrical impedance tomography or continuous positive airway pressure |

| Pulmonary oedema | Clinical diagnosis with radiographic confirmation or requirement of diuretic treatment and SaO2 < 94% |

| Postpartum haemorrhage | Blood loss of > 1 l after delivery |

| Early preterm delivery | Delivery at a gestational age of < 34 weeks |

| Outcome | Definition |

|---|---|

| Perinatal or infant mortality | Death of a fetus or neonate. Infant mortality is the death of a child < 1 year of age |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | Oxygen requirement at 36 weeks corrected gestational age unrelated to an acute respiratory episode |

| Necrotising enterocolitis including only Bell’s stage 2 or 3 | Evidence of pneumatosis intestinalis on an abdominal radiography and/or surgical intervention |

| Grade III/IV intraventricular haemorrhage | Bleeding into the brain’s ventricular system, where ventricles are enlarged by the accumulated blood or bleeding extends into the brain tissue around the ventricles |

| Cystic periventricular leukomalacia | Softening and necrosis in the hemispheric white matter in newborns that may result from impaired perfusion at the interface between ventriculopetal and ventriculofugal arteries |

| Stages 3–5 retinopathy of prematurity | Abnormal blood vessel development in the retina of the eye, where blood vessel growth is severely abnormal, where there is a partially or totally detached retina |

| Hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy | Apgar score of ≤ 5 at 10 minutes and/or pH 7.00 in first 60 minutes of life and/or base deficit ≥ –16 in first 60 minutes of life associated with abnormal consciousness level (lethargy, stupor or coma) and seizures and/or poor/weak suck and/or hypotonia and/or abnormal reflexes |

When more than one outcome occurred in the same woman, we chose the adverse outcome that occurred first for the purpose of the survival model. A panel of clinicians with expertise in pre-eclampsia and prognosis research ranked the maternal outcomes for their importance to clinical care (see Appendix 1).

Sample size

We aimed to examine about 10 candidate predictor variables for inclusion in the model(s). Simulation studies examining predictor variables for inclusion in logistic regression models suggest that approximately 10 events are necessary for each candidate predictor to avoid overfitting. 43–45 Therefore, to examine 10 candidate predictors, we required at least 100 women with adverse maternal outcomes in our cohort. From our systematic reviews,20–23 20% of women (100 of 500) with early-onset pre-eclampsia were expected to have adverse maternal outcomes at any time before discharge. Thus, the original target sample size was 500 women with confirmed pre-eclampsia. As the event rate was lower than predicted, we revised the sample size to continue recruitment until 100 women had experienced adverse events. Appendix 2 lists the changes compared to the original protocol submitted to the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme.

Prior to analysis, after discussion with the steering committee, the study group additionally classified delivery before 34 weeks’ gestational age as an adverse maternal outcome to avoid treatment paradox from delivery. The sample size criteria remained the same. With the increased number of outcomes, we were able to consider about 20 candidate predictors but we maintained at least 10 events per predictor in the modelling process.

Data sets for external validation: PIERS and PETRA studies

The PREP model was externally validated in two external independent data sets from the PIERS9 and the Pre-Eclampsia TRial Amsterdam (PETRA)46 studies.

PIERS study

The aim of this prospective observational study was to develop a prediction model for adverse maternal outcomes in women with pre-eclampsia of any onset (both early and late). 9 Two thousand and twenty-three women were recruited from tertiary perinatal units in Canada, New Zealand, the UK and Australia between 1 September 2003 and 31 January 2010. Women were included if they were admitted with pre-eclampsia or had developed pre-eclampsia after admission. Women were excluded if they were admitted in spontaneous labour or had achieved any component of the maternal outcome before either fulfilling eligibility criteria or collection of predictor data. The primary outcome was a composite maternal outcome. The combined adverse maternal outcome included one or more of the following: maternal mortality or a serious central nervous system, cardiorespiratory, hepatic, renal, or haematological morbidity. We used the anonymised data set of women with early-onset pre-eclampsia in the PIERS study to validate the PREP model.

PETRA study

The PETRA study was a randomised controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of plasma expansion in expectant management of early-onset hypertensive disease in pregnancy, including pre-eclampsia. 46 Women were recruited from two university hospitals, the Department of Obstetrics at the Academic Medical Centre and the Vrije University Medical Centre Amsterdam, between April 2000 and May 2003. Patients across the spectrum of severe hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were included in the trial. Patients were excluded if severe fetal distress or lethal fetal congenital abnormalities were diagnosed, if language difficulties prevented informed consent-taking, or if plasma volume expansion had already been given. A total of 216 women were randomised, 111 to plasma volume expansion and 105 to no plasma volume expansion (the control group). The primary outcomes were neonatal neurological development at term age (Prechtl score),47 perinatal death, neonatal morbidity and maternal morbidity. The intervention showed no significant difference in outcomes between the two groups. Data from the entire study cohort were used in the external validation of the PREP model.

Analysis plan development

We convened a panel of 24 experts in the field of pre-eclampsia and prognostic research, to explore the challenges and potential solutions in the development of a prediction model. The panel focused its discussion on methods to reduce the risk of bias in the PREP models as a result of treatment paradox. 24 After consideration of various methods, it was decided to include effective treatments such as antihypertensive drugs and magnesium sulphate as predictors to avoid bias. The appropriateness of the population, predictors and outcomes was discussed. The methodological issues pertinent to the analysis, such as the choice of model (logistic or survival), were considered and the panel suggested the development of both models.

Statistical analysis

We used a transparent process with appropriate prognostic research methodology for our analysis, and reported using TRIPOD recommendations. 35 We developed and externally validated two models: a logistic model (PREP-L) for overall risk of any adverse outcome by discharge, and a survival model (PREP-S) to assess the risk of adverse outcomes at various time points from diagnosis of pre-eclampsia until 34 weeks’ gestation.

Data preparation

We produced descriptive tables of baseline characteristics, candidate predictors and outcomes. Candidate predictors were checked for normality and log-transformed if applicable. We avoided dichotomisation of continuous variables to avoid loss of information. Only pulse oximetry findings were dichotomised because of the very small variations in values.

Methods for handling missing values

During model development, to deal with missing predictor values in some patients, multiple imputation was performed (under a missing at random assumption) using the user-written ICE package in Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) with five imputations. We combined the estimates across imputed data sets using Rubin’s rules to produce final parameter estimates for the model. 48 All missing values of candidate predictor variables were multiply imputed except for pulse oximetry and previous occurrence of pre-eclampsia. Previous occurrence of pre-eclampsia was always classed as a ‘no’ in nulliparous women. Pulse oximetry was assumed normal if missing. The imputation of missing data was performed on the complete data set of all participants with suspected or confirmed pre-eclampsia. This was to allow as much information as possible into the imputation procedure. Apart from the eight women lost to follow-up after baseline, no outcome data were missing; therefore, no outcomes were imputed.

Selection of predictor variables

For both primary models, all 22 variables listed in Box 1 were considered to be candidate predictor variables for inclusion in our maternal model. A backwards selection procedure was used to decide which of the candidate predictor variables should be included in the final prediction model (with a p-value of < 0.15 conservatively taken to warrant inclusion and prevent omission of important predictors). Gestational age and maternal age at diagnosis were forced into the model, to ensure clinical acceptability of the final model. For categorical variables, such as medical history and urine dipstick, we used the lowest p-value of any category (relative to the reference category) to indicate inclusion or exclusion.

Continuous variables were initially selected based on an assumed linear trend. After inclusion, non-linear trends were also evaluated using fractional polynomials (FPs), with a p-value of < 0.01 (for the change in model fit) used to justify the inclusion of non-linear trends. Any continuous variables that were originally dropped were double-checked for whether or not non-linear trends would alternatively suggest their inclusion.

Model development for adverse maternal outcomes

We applied the modelling process to women with confirmed diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia and had complete outcome data (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Flow of women recruited in the PREP study for development of the prediction model(s) for adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

Definition of survival time

For survival analysis, the end of follow-up was defined as the time of occurrence of the first adverse outcome or end of 34 weeks’ gestation, whichever occurred first. A woman was considered to be at risk from the time of diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia and the failure event was defined as maternal adverse outcome occurring before 34 weeks’ gestation. The survival data information was described in the original data set and copied into all five imputed data sets. The survival information was independent of the multiple imputation, as no outcome was imputed and the time of diagnosis data were available for all women.

Survival model: flexible parametric model

A flexible parametric survival model was used via the Royston–Parmar approach,49–51 with the cumulative baseline hazard scale modelled using restricted cubic splines (implemented as the stpm2 package in Stata12). We chose this approach over a Cox regression as it allowed us to explicitly model the baseline hazard rate allowing non-linear functions via cubic splines, which are very flexible and relatively simple to work with. Simpler parametric models may not be flexible enough to adequately represent the hazard function.

Splines are flexible mathematical functions defined by piecewise polynomials, with some constraints to ensure that the overall curve is smooth. The points at which the polynomials join are called knots. Royston and Lambert50 explain that the stpm2 uses restricted cubic splines which force the function to be linear before the first knot and after the final knot. Let s(x) be the restricted cubic spline function. Defining m interior knots, k1, . . ., km, and also two boundary knots, kmin and kmaxs(x), can be written as a function of parameters γ and some newly created variables z1, . . ., zm + 1 giving:

The derived variables zj (also known as the basis functions) can be calculated as follows:

where j = 2, . . ., m + 1,

When choosing the location of the knots for the restricted cubic splines, it is useful to have some sensible default locations. In stpm2, the default knot locations are at the centiles of the distribution of uncensored log-event times.

Survival null model

We identified the number of knots to go into the model by fitting the null model with an increasing number of knots. The number of knots was chosen based on the lowest Akaike information criterion/Bayesian information criterion (AIC/BIC) and visual inspection of the change in fitted shape, with preference for simplicity (i.e. fewer knots) to avoid overfitting. AIC and BIC are measurements of model fit.

Univariable model, full model and variable selection process

Univariable analyses were performed for both models on all 22 candidate predictors in their linear (log-transformed, if applicable) form. These were fitted in each imputed data set and combined using Rubin’s rules. 48 Univariable analyses were performed only to summarise the unadjusted associations in the data, and were not used to inform the selection of predictors in the final multivariable models. Where applicable and computationally possible, all analyses were performed with the imputed data sets and the results were combined appropriately. A backwards selection procedure was applied to both full models as previously described. Maternal age and gestational age at diagnosis were forced into the model. The model was refitted after dropping each individual predictor.

Non-linear terms

We identified the non-linear terms using the multivariable FP (MFP) procedure in Stata, which selects the MFP model that best predicts the outcome variable. The MFP procedure allows the selection of non-linear terms for continuous variables and the procedure was applied to each of the five multiply imputed data sets separately, and the pattern that was identified by the majority of multiply imputed data sets was used (on consensus between the lead statisticians). In order to avoid overfitting, only non-linear terms that improved the model fit at a minimum significance level of 1% (test of deviance) were considered. The final models were refitted by including the FP terms and checked for dropping further predictors at a p-value of < 0.150. Such variables were dropped only if their exclusion did not change the FP terms already identified in the previous step. This step was performed only once and was not repeated if additional predictors had p-values of ≥ 0.150.

Sensitivity analyses

Logistic and survival model

We included treatment with any antihypertensive drug (oral and/or parenteral) within 1 day of diagnosis in the final models. As parenteral antihypertensive drugs are usually commenced in severe pre-eclampsia to prevent complications, the predictive values could be different for oral and parenteral antihypertensive drugs. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by including oral and parenteral antihypertensive drugs separately in the final models to check if model fitting is improved.

Survival model only

The full survival model needed to be fitted in each of the imputed data sets and the results combined using Rubin’s rules. This procedure is not officially supported for use with the stpm2 command in Stata, although it does perform the estimation if forced. In order to confirm accuracy of the results, we fitted a Cox regression for the same model. The stcox command is supported for the combination of estimations using Rubin’s rules. We also checked the final survival model for time-dependent effects.

Apparent performance

The apparent performance of the fitted models was examined by calculating discrimination performance using the c-statistic for the logistic model and Harrell’s c-statistic for the survival model,52 with a 95% confidence interval (CI), in the same data used to generate the model. A c-statistic close to 1 indicates excellent discrimination and 0.5 indicates no discrimination beyond chance. The calibration performance (fit of observed to expected risk across all individuals) was examined by checking that the calibration slope was 1. As the model was developed using the same data, we expected the calibration to show perfect agreement on average across the individuals.

Internal validation

To evaluate the potential for overfitting of our developed models, we used non-parametric bootstrapping. The variable selection procedure was repeated in 100 bootstrap data sets from each of the five multiple imputation data sets (thereby giving a total of 500 data sets). This led to a new final model being produced in each of the bootstrap samples. The performance of the models (in terms of c-statistic and calibration slope) in the bootstrap sample itself represents an estimation of the apparent performance, and their performance in the original sample represents test performance. The difference between these performances is an estimate of the optimism in the apparent performance. This difference was averaged to obtain a single estimate of optimism for the c-statistic and the calibration slope. This optimism was then subtracted from the original apparent performance statistics to produce optimism-adjusted performance statistics.

Production of the final models

The coefficients in the final models were adjusted for optimism. The optimism-adjusted calibration slope was taken as the uniform shrinkage factor, and the original predictor effects (beta coefficients) were multiplied by this value. Following this, the intercept (for the logistic model) or baseline hazard (for the survival model) were re-estimated to ensure that the overall calibration of the final model predictions to the observed data were maintained, that is, to ensure that calibration-in-the-large was zero. For the survival model, only the intercept term was modified in the baseline hazard function (i.e. the shape of the original baseline hazard was maintained). For sensitivity analysis, we applied these optimism-adjusted models to women with an unconfirmed diagnosis of pre-eclampsia.

After developing and validating the prediction model based on the final set of (close to) 20 predictors, we additionally investigated whether or not any of the candidate predictors we excluded would actually significantly improve the accuracy of the model; however, this was clearly noted as secondary analyses.

The models were available as Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) files (see Appendices 3 and 4) to allow clinicians to input the findings of their patients, and obtain estimates of overall risk of adverse outcomes (PREP-L) and risks at daily intervals after diagnosis (PREP-S).

External validation

The final models were externally validated using the PIERS and PETRA data. We compared the availability of predictors, missing values and the outcome components in the external data sets with the PREP data. If there were any missing predictors in the external cohorts, we planned to re-estimate a reduced version form of our model (using exactly the same process as above) using only those predictors that were available in the external data sets.

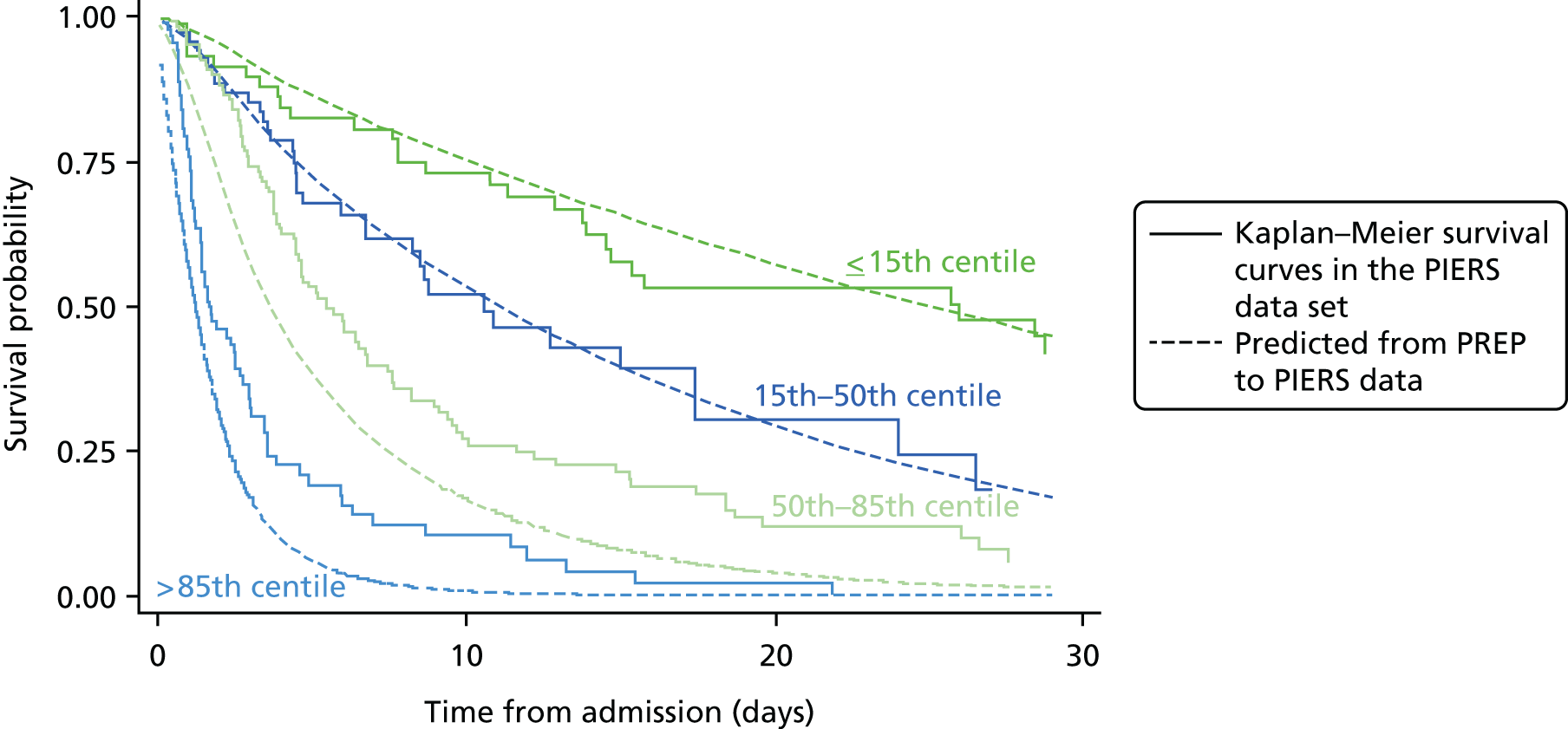

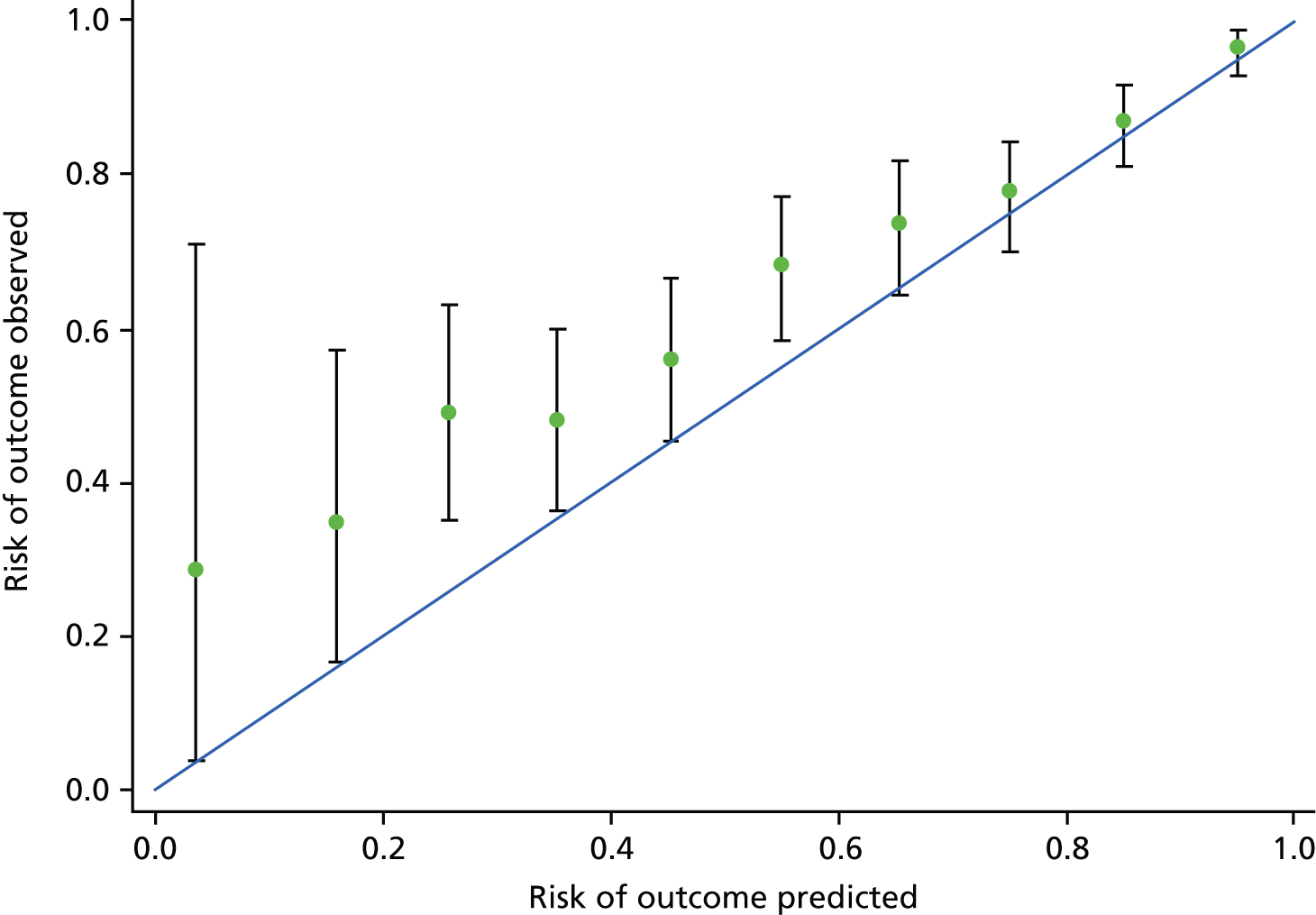

If predictors were centred in the PREP model, then predictors in the external data were centred by the same value. The reduced PREP models were used to estimate predicted risks (or risk scores) for women in the PIERS or PETRA population. To produce calibration plots, the risks were grouped into tenths (defined by centiles) of predicted risk in the PREP-L model and into four risk groups for the PREP-S model. As the predictions were not compatible with the Stata 12.1 facilities for combining results using Rubin’s rules, we calculated the fitted values or predictions of risk within each imputed data set and then averaged them.

Secondary analysis of fetal outcomes

The analysis of fetal outcomes by discharge was done in the same way as for the logistic model described above, although non-linear terms were not considered. Analysis was performed on the level of the mother/pregnancy rather than on the fetal level. In multiple pregnancies with multiple sets of predictors and outcomes, we used the worst predictor and considered any outcome regardless of whether an outcome occurred in one of the babies or in both. A variable selection process on the full list of maternal and fetal candidate predictors provided the final fetal model. No adjustment for optimism, external validation or sensitivity analyses was performed for the fetal model.

All the above analyses were carried out using Stata version 12.0. Definitions of key terms are provided in Table 4.

| Terms | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Calibration | Calibration indicates the ability of the model to correctly estimate the absolute risks and was examined using calibration plots |

| Reproducibility (internal validation) | The process of determining internal validity. Internal validation assesses validity for the setting from which the development data originated |

| Generalisability/transportability (external validation) | The process of determining external validity of the prediction model to populations that are plausibly related |

| Discrimination | Discrimination describes the ability of the model to correctly distinguish those who will have an adverse outcome from those who will not |

| Calibration plot | In a calibration plot the predictive risk plotted against the observed incidence of the outcome. Ideally the predicted risk equals the observed incidence throughout the entire risk spectrum and the calibration plot follows the 45° line |

Chapter 3 Maternal characteristics, predictors and outcomes in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia

Flow of participants in the study

Between December 2011 and April 2014, we screened 3302 pregnant women from 53 maternity units for inclusion in the PREP study. Of these, 2099 did not meet the inclusion criteria: 882 did not have raised proteinuria, 650 did not have raised BP readings, 457 were classed as other, 53 had underlying comorbidities, 36 were participating in a clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product and 21 did not understand English and an interpreter could not be used at the time of recruitment. Of the 1203 eligible women, 1101 were recruited to the study with a suspected or confirmed diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia. Of those recruited, 954 women had confirmed pre-eclampsia, 142 women had a suspected diagnosis of pre-eclampsia that was not subsequently confirmed, baseline information data were not available in five participants and nine were lost to follow-up. The final maternal prediction models included data from 946 women and the fetal prediction model included data from 945 pregnancies (see Figure 2).

Baseline characteristics of women included in the PREP study

Table 5 shows the women recruited into the study according to the various inclusion criteria. Over 90% (866/954) of all participants had a diagnosis of new-onset pre-eclampsia, 75 women (75/954, 7.9%) had superimposed pre-eclampsia, 10 (10/954, 1.0%) had HELLP syndrome and three women (3/954, 0.3%) had a single episode of eclamptic seizure in the absence of raised BP or proteinuria.

| Inclusion criteria | Women, n (%) |

|---|---|

| New-onset pre-eclampsia | 866 (91.0) |

| Superimposed pre-eclampsia | 75 (7.9) |

| HELLP syndrome | 10 (1.0) |

| Eclamptic seizures | 3 (0.3) |

| Total | 954 |

The mean age of participants was 30.2 years [standard deviation (SD) 6.1 years] (Table 6). Two-thirds of women identified themselves as European (631/950, 66%), one-fifth as South or South-East Asian (18%, 172/950) and about one-tenth (81/950, 9%) as African. Around 3% of all women were from the Caribbean (31/950), 1% from the Far East (8/950) and 1% from the Middle East (6/950). Ninety-one per cent (866/954) of all pregnancies were singletons, while twins and triplets accounted for 9% (83/954) and 1% (5/954) of pregnancies, respectively. More than half of all women were nulliparous (551/954, 58%). Recurrent miscarriage (three or more) had occurred in 42 women (4.4%). About one-tenth (87/943, 9%) of women reported smoking in pregnancy at booking appointment and alcohol intake in pregnancy was reported by 5% (47/937) of all participants.

| Maternal characteristics | Women with early-onset pre-eclampsia (n = 954) |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Maternal age (years), mean (SD) | 30.2 (6.1) |

| Alcohol intake | 47 (5%) |

| Currently smoking | 87 (9%) |

| Drug use | 4 (0.4%) |

| Mother’s ethnic group | |

| Europe | 631 (66%) |

| Africa | 81 (9%) |

| South and South East Asia | 172 (18%) |

| Far East | 8 (1%) |

| Middle East | 6 (1%) |

| Caribbean | 31 (3%) |

| Other | 21 (2%) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 551 (58%) |

| 1 | 207 (22%) |

| 2 | 109 (11%) |

| 3 | 55 (6%) |

| 4 | 20 (2%) |

| 5–9 | 12 (1%) |

| Total number of miscarriages | |

| 0 | 607 (64%) |

| 1 | 225 (24%) |

| 2 | 72 (8%) |

| > 3 | 42 (4%) |

Predictor characteristics in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia

The values of the various candidate predictors of women in the PREP study are shown in Table 7. The mean gestational age at which the diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia was made was 30.5 weeks (SD 2.9 weeks) and there were no missing values for gestational age at diagnosis.

| Candidate predictor | Women with early-onset pre-eclampsia (N = 954) | Women with missing data, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | ||

| Maternal characteristics | ||

| Maternal age (years), mean (SD) | 30.2 (6.1) | 2 (0.2) |

| Gestational age at diagnosis (weeks), mean (SD) | 30.5 (2.9) | – |

| Number of fetuses in pregnancya | ||

| Singleton | 866 (91%) | – |

| Twins | 83 (9%) | – |

| Triplets | 5 (1%) | – |

| History | ||

| Summary score for medical historyb | 1 (0.1) | |

| 0 | 601 (63%) | – |

| 1 | 251 (26%) | – |

| ≥ 2 | 101 (11%) | – |

| Chronic hypertension | 139 (15%) | 10 (1.0) |

| Renal disease | 30 (3%) | 10 (1.0) |

| Previous history of pre-eclampsia | 169 (43%) | 558c |

| Autoimmune disease | 18 (2%) | 32 (3.4) |

| Pre-existing DM | 109 (11%) | 6 (0.6) |

| Type I DM | 56 (51%) | – |

| Type II DM | 16 (15%) | – |

| Gestational DM | 37 (34%) | – |

| Symptoms | ||

| Headache and/or visual disturbance | 382 (40%) | 28 (2.9) |

| Headache generalised | 293 (31%) | 36 (3.8) |

| Headache localised | 121 (13%) | 92 (9.6) |

| Visual disturbance | 139 (15%) | 56 (5.9) |

| Epigastric pain, nausea and/or vomiting | 202 (22%) | 47 (4.9) |

| Epigastric pain | 131 (14%) | 68 (7.1) |

| Nausea | 111 (12%) | 130 (13.6) |

| Vomiting | 54 (6%) | 120 (12.6) |

| Chest pain and/or breathlessness | 60 (6%) | 126 (13.2) |

| Chest pain | 30 (3%) | 164 (17.2) |

| Breathlessness | 38 (4%) | 162 (17.0) |

| Bedside examination and tests | ||

| Systolic BP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 159 (19) | 5 (0.5) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 99 (12) | 5 (0.5) |

| Clonus | 95 (10%) | 403 (42.2) |

| Exaggerated tendon reflexes | 147 (15%) | 353 (37.0) |

| Oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (%), mean (SD) | 98 (2) | 521 (54.6) |

| Oxygen saturation abnormal (< 94%) | 4 (≥ 1%) | 521 (54.6) |

| Urine dipstick | ||

| None/trace | 39 (4%) | – |

| 1+ | 170 (18%) | – |

| 2+ | 314 (33%) | 19 (2.0) |

| 3+ | 306 (32%) | – |

| ≥ 4 | 106 (11%) | – |

| Laboratory tests | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/l), mean (SD) | 11.9 (1.3) | 37 (3.9) |

| Platelet count (× 109/l), mean (SD) | 226 (78) | 41 (4.3) |

| ALT concentration (U/l), mean (SD) | 31.0 (71.0) | 75 (7.9) |

| Serum uric acid concentration (µmol/l), mean (SD) | 0.6 (2.7) | 165 (17.3) |

| Serum urea concentration (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 4.6 (4.4) | 70 (7.3) |

| Serum creatinine concentration (µmol/l), mean (SD) | 61.0 (17.8) | 38 (4.0) |

| Urine PCR 24 hour (mg/mmol), mean (SD) | 273 (492) | 109 (11.4) |

| Treatment provided | ||

| Any antihypertensive therapyd | 753 (79%) | 6 (0.6) |

| Oral antihypertensive therapy | 734 (77%) | 6 (0.6) |

| Parenteral antihypertensive therapy | 111 (12%) | 6 (0.6) |

| Intravenous magnesium sulphatee | 144 (15%) | 6 (0.6) |

Clinical history

One-quarter (251/953, 26%) of all women for whom data were available had at least one of the following risk factors: previous history of pre-eclampsia (169/396, 43%), chronic hypertension (139/944, 15%), diabetes mellitus (109/948, 11%), renal disease (30/944, 3%) and autoimmune disease (18/922, 2%). One-tenth (101/953, 11%) had two or more risk factors.

Symptoms

Symptoms such as headache and/or visual disturbances were experienced by 41% (382/926) of women, epigastric pain and/or vomiting by 22% (202/907) and chest pain and/or dyspnoea by 7% (60/828).

Bedside examination and tests

The mean systolic and diastolic BP at the time of diagnosis of early-onset pre-eclampsia was 159 mmHg (SD 19 mmHg) and 99 mmHg (SD 12 mmHg), respectively. Around two-thirds of women had demonstrable clonus (551/954, 58%) and exaggerated tendon reflexes (601/954, 63%). The oxygen saturation levels were ≤ 94% in only 1% (4/433) of women, and more than half of the women did not have documented results (521/954, 55%). There were no missing values for BP or proteinuria.

Laboratory tests

Serum alanine aminotransaminase (ALT) was measured more often than aspartate transaminase (AST) (in 93% of women vs. 30%); consequently, ALT was used in the analysis. Less than one-tenth of values were missing for haemoglobin level, platelet count and concentrations of serum urea and serum creatinine concentration. Furthermore, < 20% of values were missing for serum uric acid concentration.

Treatment provided

More than three-quarters (753/948, 79%) of women were previously on antihypertensive drugs or were started on them within the first 24 hours of diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. Three-quarters of women (734/948, 77%) were on oral antihypertensive therapy and 12% (111/948) were receiving parenteral antihypertensive therapy. Fifteen per cent (144/948) of women started magnesium sulphate treatment to prevent or treat eclamptic seizures in the first 24 hours after diagnosis.

Additional fetal predictors

For the analysis of fetal outcomes, five additional predictors were included, as shown in Table 8. Around one-quarter (91/342, 27%) of women had an abnormal uterine artery Doppler at 20–24 weeks’ gestation. Only 6% of women had abnormal liquor volume (57/898) and 5% had abnormal cardiotocography (CTG) findings (46/713). Over 40% (291/717) of pregnancies had an estimated fetal weight < 10th centile. More than half (430/783, 55%) of the women received treatment with corticosteroids at baseline.

| Additional fetal predictors | Women with early-onset pre-eclampsia (n = 954), mean (SD) or n (%) | Women with missing data, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Abnormal uterine artery Doppler | 91 (10%) | 612 (64) |

| Abnormal liquor volume | 57 (6%) | 56 (6) |

| Abnormal CTG findings | 46 (5%) | 241 (25) |

| Estimated fetal weight < 10th centile | 291 (31%) | 237 (25) |

| Baseline treatment: steroids | 430 (45%) | 171 (18) |

Maternal and fetal adverse outcomes in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia

Outcome data were available for 99% (946/954) of all participants in the PREP study. The rates of individual components of the composite adverse maternal and fetal outcomes are provided in Tables 9 and 10, respectively.

| Adverse maternal outcome | Women with complications (N = 946), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal death | – |

| Neurological | |

| Eclamptic seizures | 12 (1.3) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score of < 13 | 3 (0.3) |

| Stroke or RIND | – |

| Cortical blindness | – |

| Retinal detachment | – |

| Posterior reversible encephalopathy | 2 (0.2) |

| Bell’s palsy | – |

| Hepatic | |

| Hepatic dysfunction | 12 (1.3) |

| Subcapsular haematoma | – |

| Hepatic capsule rupture | – |

| Cardiorespiratory | |

| Need for positive inotrope support | 1 (0.1) |

| Myocardial ischaemia or infarction | – |

| At least 50% FiO2 for > 1 hour | 7 (0.7) |

| Intubation | 9 (1.0) |

| Pulmonary oedema | 6 (0.6) |

| Renal | |

| Acute renal insufficiency | 5 (0.5) |

| Dialysis | 5 (0.5) |

| Haematological | |

| Transfusion | 51 (5.4) |

| Abruptions | 25 (2.6) |

| Postpartum haemorrhage | 74 (7.8) |

| Preterm delivery | |

| Delivery at < 34 weeks’ gestational age | 580 (61.3) |

| At least one of the above occurred by discharge | 633 (66.9) |

| At least one occurred before 34 weeks’ gestational age | 584 (61.7) |

| Adverse fetal outcome | Pregnancies with complications (N = 945a), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Neonatal death | 23 (2.4) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 41 (4.3) |

| Necrotising enterocolitis | 34 (3.6) |

| Grade III/IV intraventricular haemorrhage | 11 (1.2) |

| Cystic periventricular leukomalacia | 5 (0.5) |

| Stage 3–5 retinopathy | 7 (0.7) |

| Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy | 2 (0.2) |

| Stillbirth | 16 (1.7) |

| Admission to NICU at any time | 681 (72.1) |

| At least one of the above occurred by discharge | 702 (74.3) |

Overall, 66.9% (633/946) of all women with early-onset pre-eclampsia experienced at least one adverse maternal outcome and 74.3% (702/945) had at least one adverse fetal outcome. The most frequently reported outcome was preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, occurring in 61.3% (580/946) of women. The second most common outcome was postpartum haemorrhage (7.8%, 74/946), followed by transfusion of any blood products (5.4%, 51/946) and abruptio placentae (2.6%, 25/946). The least reported maternal complications were need for positive inotrope support (0.1%, 1/946), posterior reversible encephalopathy (0.2%, 2/946) and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of < 13 (0.3%, 3/946). When preterm delivery was excluded as a component of the composite outcome, 15.5% of all women (147/946) had at least one adverse maternal outcome.

Chapter 4 Prediction of overall risk of adverse maternal outcome by discharge in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia: PREP-L model

Of the 946 women for whom outcome data were available, 633 (67%) experienced at least one adverse maternal outcome at any time from diagnosis to discharge. The number of women who had experienced an adverse outcome was 228 (24%) at 48 hours, 410 (43%) at 1 week and 624 (66%) at 30 days after diagnosis.

Modelling continuous predictors

Maternal age, systolic and diastolic BPs, haemoglobin level and platelet count were normally distributed, and hence we did not apply any transformation. Concentrations of ALT, AST, serum uric acid, serum urea and serum creatinine and the PCR were strongly right skewed, and we log-transformed these values. As gestational age at diagnosis was an inclusion criterion and limited to 34 weeks, a log transformation was applied to decrease the range. We were not able to fully evaluate serum uric acid concentration as a predictor because of data coding issues in this variable at the time of model development. Subsequent to model development being completed, and after the data coding issues were resolved for this variable, we calculated how the c-statistic changed after adding log-transformed serum uric acid concentration to the final models to assess whether or not this variable improved model performance (see Apparent performance and internal validation of the PREP-L model).

Development of PREP-L model: predictor selection

Table 11 shows the univariable and multivariable analysis for association of predictors and adverse maternal outcomes. The models were fitted in each of the imputed data sets and the results combined using Rubin’s rules. In the univariable analysis, lower gestational age at diagnosis, symptoms of epigastric pain and/or nausea and vomiting, clonus, exaggerated tendon reflexes, raised systolic and diastolic BPs, urine dipstick-detectable proteinuria, high levels of haemoglobin, low platelet counts, raised concentrations of ALT, serum urea, serum uric acid and creatinine, increased urine PCR, management with antihypertensives and use of magnesium sulphate were significantly associated with adverse maternal outcomes (p < 0.05). Relevant medical history of one or more conditions such as chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, autoimmune disease and a history of pre-eclampsia in previous pregnancy were associated with a reduced risk of complications.

| Candidate predictors | Women,a n | No adverse maternal outcome (n = 313), mean (SD) or n (%) | Adverse maternal outcome (n = 633), mean (SD) or n (%) | Univariable models after multiple imputation (n = 946) | Multivariable full model after multiple imputation (n = 946) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| Maternal age (years) | 944 | 30.7 (6.3) | 30.0 (6.0) | 0.981 (0.959 to 1.003) | 0.088 | 0.978 (0.951 to 1.006) | 0.123 |

| Log-transformed gestational age at diagnosis | 946 | 3.4 (0.1) | 3.4 (0.1) | 0.005 (0.001 to 0.028) | < 0.001 | 0.001 (0.000 to 0.009) | < 0.001 |

| Multiple pregnancy | |||||||

| Singleton (reference) | 946 | 284 (91%) | 579 (91%) | ||||

| Twins | 28 (9%) | 51 (8%) | 0.893 (0.552 to 1.447) | 0.647 | 1.381 (0.790 to 2.416) | 0.257 | |

| Triplets | 1 (< 1%) | 3 (< 1%) | 1.472 (0.152 to 14.209) | 0.738 | 2.826 (0.257 to 31.104) | 0.396 | |

| Global test | 0.849 | 0.556 | |||||

| Medical history score | |||||||

| 0 (reference) | 945 | 170 (54%) | 425 (67%) | ||||

| 1 | 98 (31%) | 152 (24%) | 0.622 (0.456 to 0.848) | 0.003 | 0.708 (0.487 to 1.030) | 0.071 | |

| ≥ 2 | 45 (14%) | 55 (9%) | 0.488 (0.317 to 0.753) | 0.001 | 0.515 (0.296 to 0.897) | 0.019 | |

| Global test | < 0.001 | 0.032 | |||||

| Symptoms | |||||||

| Headache and/or visual disturbance | 920 | 128 (42%) | 252 (41%) | 0.967 (0.734 to 1.275) | 0.813 | 0.839 (0.582 to 1.210) | 0.349 |

| Epigastric pain, nausea and/or vomiting | 901 | 52 (18%) | 148 (25%) | 1.491 (1.035 to 2.147) | 0.033 | 1.001 (0.610 to 1.643) | 0.997 |

| Chest pain and/or dyspnoea | 822 | 17 (6%) | 43 (8%) | 1.254 (0.644 to 2.441) | 0.510 | 1.074 (0.441 to 2.618) | 0.876 |

| Bedside examination and tests | |||||||

| Clonus | 545 | 19 (12%) | 75 (19%) | 1.976 (1.127 to 3.464) | 0.029 | 1.157 (0.537 to 2.492) | 0.716 |

| Exaggerated tendon reflexes | 594 | 25 (15%) | 121 (29%) | 2.244 (1.534 to 3.284) | < 0.001 | 1.037 (0.643 to 1.673) | 0.881 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 942 | 151 (15) | 162 (20) | 1.038 (1.029 to 1.047) | < 0.001 | 1.025 (1.013 to 1.038) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 942 | 96 (10) | 101 (12) | 1.047 (1.032 to 1.061) | < 0.001 | 1.009 (0.989 to 1.029) | 0.384 |

| Oxygen saturation: abnormal (< 94%) | 429 | 0 (0%) | 4 (< 1%) | No abnormal values in women without outcome | No abnormal values in women without outcome | ||

| Urine dipstick: none/trace (reference) | 928 | 16 (5%) | 23 (4%) | ||||

| 1+ | 80 (26%) | 89 (14%) | 0.780 (0.384 to 1.584) | 0.491 | 0.884 (0.404 to 1.933) | 0.757 | |

| 2+ | 120 (39%) | 193 (31%) | 1.133 (0.575 to 2.233) | 0.719 | 0.894 (0.420 to 1.905) | 0.772 | |

| 3+ | 71 (23%) | 232 (37%) | 2.243 (1.117 to 4.501) | 0.023 | 1.171 (0.520 to 2.637) | 0.703 | |

| ≥ 4 | 19 (6%) | 85 (14%) | 3.035 (1.355 to 6.794) | 0.007 | 1.233 (0.484 to 3.145) | 0.661 | |

| Global test | < 0.001 | 0.712 | |||||

| Laboratory tests | |||||||

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 910 | 11.8 (1.2) | 12.0 (1.4) | 1.114 (1.004 to 1.237) | 0.042 | 1.054 (0.917 to 1.212) | 0.461 |

| Platelet count (× 109/l) | 906 | 245 (77) | 217 (77) | 0.995 (0.993 to 0.997) | < 0.001 | 0.996 (0.994 to 0.999) | 0.001 |

| Log-transformed ALT concentration | 871 | 2.8 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.8) | 1.561 (1.257 to 1.937) | < 0.001 | 1.189 (0.914 to 1.548) | 0.197 |

| Log-transformed serum uric acid concentration | 782 | –1.3 (1.0) | –1.0 (0.7) | 1.566 (1.210 to 2.028) | 0.001 | ||

| Log-transformed serum urea concentration | 877 | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.5) | 3.812 (2.598 to 5.594) | < 0.001 | 2.634 (1.588 to 4.369) | < 0.001 |

| Log-transformed serum creatinine concentration | 909 | 4.0 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.3) | 3.120 (1.863 to 5.226) | < 0.001 | 1.157 (0.598 to 2.240) | 0.665 |

| Log-transformed PCR | 838 | 4.2 (1.4) | 4.9 (1.5) | 1.369 (1.230 to 1.524) | < 0.001 | 1.111 (0.955 to 1.293) | 0.173 |

| Treatment provided | |||||||

| Antihypertensive therapy | 945 | 225 (72%) | 526 (83%) | 1.931 (1.398 to 2.667) | < 0.001 | 1.555 (1.055 to 2.292) | 0.026 |

| Administration of magnesium sulphate | 945 | 8 (3%) | 136 (22%) | 10.433 (5.042 to 21.587) | < 0.001 | 3.886 (1.746 to 8.653) | 0.001 |

Predictor variables were dropped stepwise based on the largest p-value. The final list of predictors for the logistic model were maternal age, log-transformed gestational age at diagnosis, summary score for medical history, systolic BP, platelet count, log-transformed serum urea concentration, log-transformed PCR, baseline treatment with any antihypertensive and baseline treatment with magnesium sulphate.

Transformation of predictors for the final PREP-L model

We considered the following continuous variables for non-linear terms: maternal age, log-transformed gestational age at diagnosis, systolic BP, platelet count, log-transformed serum urea concentration and log-transformed PCR.

Appendix 5 shows the FP terms identified within each multiply imputed data set and the p-value for the test of deviance comparing the FP model with the model including linear terms only. Non-linear terms were identified as significant at the 1% level for log-transformed gestational age at diagnosis and serum urea concentration.

Final PREP-L model before adjusting for optimism

Table 12 shows the final logistic model after multiple imputation, including FP terms, and prior to adjustment for optimism.

| Candidate predictors | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 0.977 (0.950 to 1.004) | 0.099 |

| FP (log-gestational age at diagnosis)3 | 1,188,051.840 (29,739.511 to 47,461,008.565) | < 0.001 |

| FP (log-gestational age at diagnosis)3 × ln(log-gestational age at diagnosis) | 0.000 (0.000 to 0.001) | < 0.001 |

| Effect of one pre-existing condition | 0.681 (0.467 to 0.994) | 0.046 |

| Effect of more than two pre-existing conditions | 0.510 (0.295 to 0.884) | 0.016 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 1.028 (1.017 to 1.039) | < 0.001 |

| Platelet count (× 109/l) | 0.995 (0.993 to 0.997) | < 0.001 |

| FP (log-serum urea concentration)–1 | 0.332 (0.191 to 0.575) | < 0.001 |

| Log-transformed PCR | 1.185 (1.030 to 1.362) | 0.019 |

| Baseline treatment: any antihypertensive drug | 1.607 (1.085 to 2.380) | 0.018 |

| Baseline treatment: magnesium sulphate | 4.279 (1.963 to 9.325) | < 0.001 |

| Constant | 0.000 (0.000 to 0.000) | < 0.001 |

The final PREP-L model identified that maternal age, early gestational age at diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, raised systolic BP, high urine PCR, high serum urea concentration, low platelet counts, need for treatment with antihypertensive drugs and administration of magnesium sulphate were associated with increased risk of adverse maternal outcomes. A positive medical history for pre-existing medical conditions or a previous history of pre-eclampsia was associated with a reduced risk of complications.

Apparent performance and internal validation of the PREP-L model

The apparent c-statistic for the PREP-L model (averaged across all multiply imputed data sets) was 0.84 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.87) and after adjustment for optimism it was 0.82 (95% CI 0.80 to 0.84). A sensitivity analysis showed that when all predictors were added to the final model, the c-statistic increased by < 0.01. Another sensitivity analysis of the model using oral and parenteral antihypertensive drugs separately showed no change in the c-statistic; therefore, the combined antihypertensive variable was retained. The addition of log-transformed serum uric acid concentration increased the c-statistic by < 0.004.

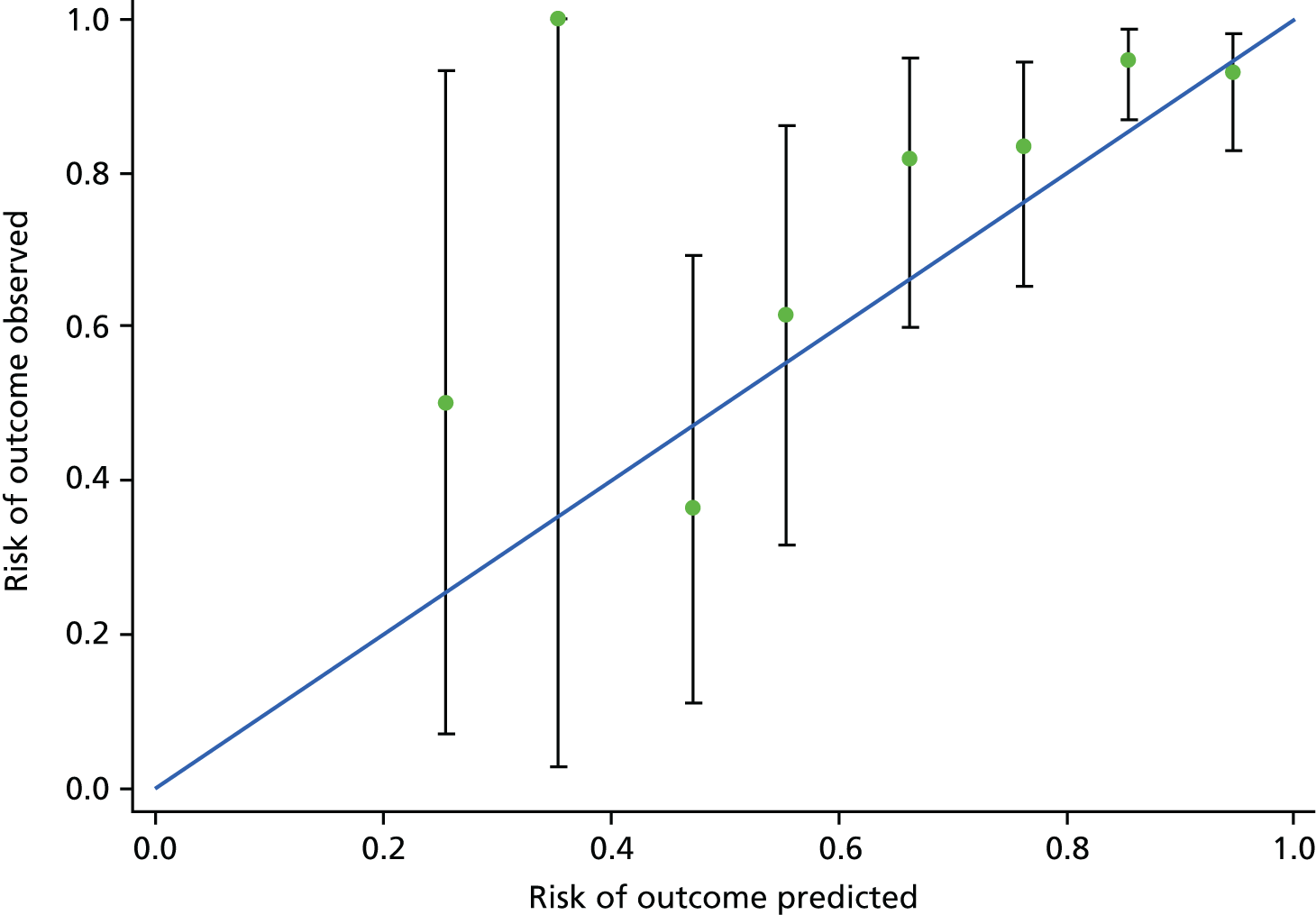

The predicted risk was grouped into tenths defined by centiles of predicted risk. Table 13 shows the proportions of outcomes observed within each centile of risk. Figure 3 shows predicted versus observed risk in the model development data set PREP.

| Centile of risk | Women, n | Outcomes observed, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| < 10th centile | 11 | 3 (27) |

| 10–20th centile | 35 | 11 (31) |

| 20–30th centile | 58 | 15 (26) |

| 30–40th centile | 78 | 20 (26) |

| 40–50th centile | 80 | 34 (43) |

| 50–60th centile | 92 | 47 (51) |

| 60–70th centile | 87 | 54 (62) |

| 70–80th centile | 122 | 86 (70) |

| 80–90th centile | 159 | 144 (91) |

| > 90th centile | 224 | 219 (98) |

FIGURE 3.

Predicted versus observed risk for maternal complications in the PREP-L model. Reproduced from Thangaratinam S, Allotey J, Marlin N, Dodds J, Cheong-See F, von Dadelszen P, et al. Prediction of complications in early-onset pre-eclampsia (PREP): development and external multinational validation of prognostic models. BMC Med 2017;15:68. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that appropriate credit to the original authors and the source is given. 40

Final adjusted PREP-L model for adverse maternal outcomes in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia

Based on the optimism in calibration, the predictor effect estimates of the developed model coefficient were reduced by the uniform shrinkage factor of 0.862. Appendix 6 shows the coefficient for the final logistic model adjusted for optimism.

Based on the women’s characteristics the probability of adverse outcome by discharge is:

where:

β1–βn are the coefficients for predictors in Appendix 6. Written formally, the equation used to derive individual risk predictions by discharge is as shown in Box 3.

GA, gestational age; MgSO4, magnesium sulphate; SBP systolic BP.

The predicted probability of an outcome is exp(X)/(1 + exp(X)), where X is the predicted logit-p.

Application of the PREP-L model

We have shown examples of application of the PREP-L model below for two women recruited in the PREP study.

Scenario 1

BVH007, a 24-year-old woman with no relevant medical history, was admitted with a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia at 33 + 6 weeks’ gestation. Her highest systolic BP was 200 mmHg and her urine PCR was 4907.6 mg/mmol. Her blood profile showed a platelet count of 75 × 109/l and a serum urea concentration of 9.5 mmol/l. She required parenteral antihypertensive therapy to manage her BP and was started on magnesium sulphate by her clinicians.

Applying the equation exp(3.649)/[1 + exp(3.649)], her predicted risk of adverse maternal outcome by discharge was 97%. The mother was observed to need a blood transfusion following an emergency caesarean section as a result of worsening pre-eclampsia at 9 hours after diagnosis (Table 14).

| Predictor variables | Example 1: BVH007 | Example 2: BWH012 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor values | Calculation | Predictor values | Calculation | |||

| Maternal age (years) | 24 | –0.020 × 24 | –0.480 | 28 | –0.020 × 28 | –0.560 |

| Summary score of medical history | 0 | +0 | +0 | 1 | +1 | +1 |

| Gestational age (weeks) at diagnosis | 33.857 | +12.052 × {[log(33.857)]3 – 39.90241} – 7.930 × [log(33.857)]3 × log{[log(33.857)] – 49.08188} | –1.344 | 32.857 | + 12.052 × {[log(32.857)]3 – 39.90241} – 7.930 × [log(32.857)]3 × log{[log(32.857)] – 49.08188} | –0.744 |

| PCR (mg/mmol) | 4907.6 | +0.146 × log(4907.6) | +1.241 | 0.32 | +0.146 × log(0.32) | –0.166 |

| Serum urea concentration (mmol/l) | 9.5 | –0.951 × [log(9.5) – 1] | –0.422 | 3.5 | –0.951 × [log(3.5) – 1] | –0.759 |

| Platelet count (× 109/l) | 75 | –0.004 × 75 | –0.300 | 283 | –0.004 × 283 | –1.132 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 200 | +0.024 × 200 | +4.800 | 136 | +0.024 × 136 | +3.264 |

| Baseline treatment | ||||||

| Any antihypertensive drug | 1 (‘yes’) | +0.409 | +0.409 | 1 (‘yes’) | +0.409 | +0.409 |

| Magnesium sulphate | 1 (‘yes’) | +1.252 | +1.252 | 0 (‘no’) | +0 | +0 |

| – 1.507 | –1.507 | |||||

| = 3.649 | = –1.525 | |||||

| Predicted risk by discharge | 0.976 | 0.179 | ||||

| Adverse maternal outcomes | Blood transfusion within 9 hours of diagnosis | None | ||||

Scenario 2

BWH012, a 28-year-old woman, was admitted with a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia at 32 + 6 weeks’ gestation. She had a summary score of 1 for relevant medical history and her highest systolic BP was 136 mmHg. Her PCR was 0.32 mg/mmol and her blood profile showed a platelet count of 283 × 109/l and a serum urea concentration of 3.5 mmol/l. She was started on parenteral antihypertensives by her clinician to manage her BP.

Applying the equation, exp (–1.525)/[1 + exp(–1.525)], her predicted risk of adverse maternal outcome by discharge was 18%. The mother was discharged without having any adverse maternal outcome (see Table 14).

Sensitivity analysis of the PREP-L model in participants with unconfirmed diagnosis of pre-eclampsia

Of the 142 participants recruited with a suspected diagnosis of pre-eclampsia, 138 had a 1+ urine dipstick. There were two perfect predictions by baseline treatment with magnesium sulphate and these two observations were dropped. The optimism-adjusted logistic model, as described in Appendix 6, was applied to 136 women with an unconfirmed diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. The apparent c-statistic was 0.68 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.79) and the calibration slope was 0.64 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.04).

Chapter 5 Prediction of adverse maternal outcome in women with early-onset pre-eclampsia: PREP-S model

Overall, 946 women contributed towards 584 failures. Five of these failures occurred on the same day as diagnosis and were forced into the survival model by adding 10 minutes to the time of their occurrence. The total analysis time at risk was 10,923 days, the median analysis time per participant was 6 days (interquartile range 2–14 days) and the longest follow-up period is 98 days. The mean gestational age at delivery was 33.0 weeks (SD 3.2 weeks). For the survival model, the first adverse events are defined as the failure event and are shown in Table 15. Delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation contributed the most (85%, 497/584) to failures.

| Failure defining adverse event | Number of women (N = 584), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Eclamptic seizures after diagnosis | 11 (1.9) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score of < 13 | 1 (0.2) |

| Hepatic dysfunction | 4 (0.7) |

| At least 50% FiO2 for > 1 hour | 1 (0.2) |

| Intubation | 1 (0.2) |

| Pulmonary oedema | 4 (0.7) |

| Transfusion of any blood product | 12 (2.1) |

| Abruption | 16 (2.7) |

| PPH | 31 (5.3) |

| Delivery at < 34 weeks’ gestational age | 497 (85.1) |

| Combined events | |

| Acute renal insufficiency and preterm delivery (< 34 weeks’ gestation) | 1 (0.2) |

| Abruption and preterm delivery (34 weeks’ gestation) | 3 (0.5) |

| Intubation, PPH and transfusion of any blood product | 1 (0.2) |

| Abruption and PPH | 1 (0.2) |

Modelling continuous predictors

We modelled the continuous predictors as shown in Chapter 4, Modelling continuous predictors.

Development of the PREP-S model: predictor selection

Table 16 shows the hazard ratios for adverse pregnancy outcomes for various candidate predictors by univariable and by multivariable analysis summarised across using the multiply imputed data sets. After dropping the candidate predictor variables stepwise based on the largest p-value, the following were included as the final list of predictors in the survival model: maternal age, log-transformed gestational age at diagnosis, summary score for medical history, systolic BP, clonus, exaggerated tendon reflexes, oxygen saturation, platelet count, log-transformed ALT concentration, log-transformed serum urea concentration, log-transformed serum creatinine concentration, log-transformed PCR, baseline treatment with any antihypertensive drug and baseline treatment with magnesium sulphate.

| Candidate predictors | Women,a n | No adverse maternal outcome (n = 374), mean (SD) or n (%) | Adverse maternal outcome (n = 572), mean (SD) or n (%) | Univariable analysis (N = 946) | Multivariable analysis (N = 946) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| Maternal age (years) | 944 | 30.9 (6.4) | 29.8 (6.0) | 0.972 (0.959 to 0.984) | < 0.001 | 0.968 (0.954 to 0.982) | < 0.001 |

| Log-transformed gestational age (weeks) at diagnosis | 946 | 3.45 (0.1) | 3.40 (0.1) | 10.198 (4.162 to 24.987) | < 0.001 | 22.425 (8.528 to 58.970) | < 0.001 |

| Multiple pregnancy | |||||||

| Singleton (reference) | 946 | 319 (88%) | 544 (93%) | ||||

| Twins | 41 (11%) | 38 (7%) | 0.790 (0.568 to 1.098) | 0.160 | 0.895 (0.631 to 1.270) | 0.535 | |

| Triplets | 2 (1%) | 2 (< 1%) | 0.816 (0.203 to 3.273) | 0.774 | 1.194 (0.291 to 4.904) | 0.806 | |

| Global test | 0.360 | 0.794 | |||||

| Medical history score | |||||||

| 0 (reference) | 945 | 195 (54%) | 400 (69%) | ||||

| 1 | 116 (32%) | 134 (23%) | 0.604 (0.496 to 0.736) | < 0.001 | 0.828 (0.671 to 1.022) | 0.078 | |

| ≥ 2 | 51 (14%) | 49 (8%) | 0.468 (0.347 to 0.631) | < 0.001 | 0.658 (0.479 to 0.905) | 0.010 | |

| Global test | < 0.001 | 0.017 | |||||

| Symptoms | |||||||

| Headache and/or visual disturbance | 920 | 142 (40%) | 238 (42%) | 1.136 (0.962 to 1.341) | 0.133 | 1.007 (0.835 to 1.215) | 0.940 |

| Epigastric pain, nausea and/or vomiting | 901 | 61 (18%) | 139 (25%) | 1.495 (1.223 to 1.828) | < 0.001 | 0.943 (0.745 to 1.194) | 0.627 |

| Chest pain and/or dyspnoea | 822 | 19 (6%) | 41 (8%) | 1.227 (0.844 to 1.785) | 0.293 | 1.172 (0.766 to 1.793) | 0.472 |

| Bedside examination and tests | |||||||

| Clonus | 545 | 24 (13%) | 70 (19%) | 1.622 (1.303 to 2.020) | < 0.001 | 0.763 (0.547 to 1.064) | 0.129 |

| Exaggerated tendon reflexes | 594 | 28 (14%) | 118 (30%) | 1.966 (1.602 to 2.413) | < 0.001 | 1.249 (0.996 to 1.566) | 0.055 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 942 | 151 (14) | 163 (20) | 1.028 (1.023 to 1.032) | < 0.001 | 1.018 (1.012 to 1.024) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 942 | 96 (10) | 102 (12) | 1.033 (1.026 to 1.040) | < 0.001 | 1.002 (0.993 to 1.011) | 0.695 |

| Oxygen saturation: abnormal (< 94%) | 429 | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 5.769 (2.154 to 15.449) | < 0.001 | 4.342 (1.496 to 12.607 | 0.007 |

| Urine dipstick: none/trace (reference) | 928 | 18 (5%) | 21 (4%) | ||||

| 1+ | 95 (27%) | 74 (13%) | 0.731 (0.449 to 1.190) | 0.208 | 0.864 (0.522 to 1.433) | 0.572 | |