Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/139/12. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The draft report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in November 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Norrie is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board and the NIHR HTA and the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board. Linda Irvine was the Trial Manager on the NIHR Public Health Research funded study 11/3050/30 [Texting to Reduce Alcohol Misuse (TRAM): a multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a text message intervention to reduce binge drinking among disadvantaged men] while the current study was being conducted.

Disclaimers

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Crombie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This feasibility study was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. The remit was to develop an intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in obese men and to assess the feasibility of a trial investigating the effectiveness of an intervention. The intervention used the motivation of weight loss to promote moderated drinking. The commissioning brief is included at the end of the report (see Appendix 1). This chapter provides the scientific background and the aims and objectives of the study, and gives an overview of the study methods. It also outlines the structure of the report, as well as detailing ethics approval and modifications to the protocol.

Background

Heavy alcohol consumption by men who are obese increases their risk of death from liver disease 19-fold. 1 Having a raised body mass index (BMI) and consuming > 14 units of alcohol per week are both factors that independently increase the risk of liver disease. However, the combination of the two leads to a substantially greater risk. 1 The commissioning brief described this as the supra-additive effect of obesity and alcohol. The problem is compounded by the high prevalence of heavy drinking and of obesity. The English Health Survey 20122 found that 24% of men aged ≥16 years drank more than the then government-recommended 21 units per week. Data from 2011 revealed that 24% of men in England3 and 28% of men in Scotland4 were obese. Based on current trends, the UK government’s Foresight programme predicted an increase in the prevalence of obesity among men. 5 Furthermore, heavy alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of obesity. 6–8 Abdominal obesity is more common among men who drink beer. 9 Heavy drinking leads to overeating,10 thus increasing the potential for weight gain.

An intervention that could reduce both alcohol consumption and weight in obese men could make a significant contribution to improving public health. However, it is far from certain that obese men who drink heavily would engage in such an intervention. They may not regard their drinking as problematic and may not think it could contribute to weight gain. Many obese men want to lose weight, but are reluctant to try conventional weight loss approaches, because these are generally targeted at women. 11 Men are under-represented in weight loss interventions12 and attrition is high in weight loss studies. 13,14

Previous research has identified many features of an intervention that could make it attractive to potential male participants. Convenience and compatibility with a busy life are important,15–17 as is the use of community settings for intervention delivery. 18 The style and tone should be relaxed and friendly as opposed to strict and regimented. 16,17 The content should be personalised and accessible,15,18 but should be delivered in a matter-of-fact way. 18,19 The aim of the intervention should also be realistic and achievable. 17 The recently completed Football Fans in Training study20,21 provides an excellent example of an engaging community-based intervention that effectively changed behaviour. This previous research clarifies many of the requirements of an intervention for obese men. The present study aims to identify the specific content that would be required to change their drinking behaviour and to assess the feasibility of a trial to test the effectiveness of the intervention.

The feasibility study

This study aimed to develop a gender-specific extended alcohol intervention that could reduce alcohol consumption among obese men. The remit stated that it should use the motivation of weight loss to achieve this. The study also aimed to develop and test all the methods for a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of this intervention. Feasibility/pilot studies provide the opportunity to test and improve all study procedures. 22,23 Guidance from national funding bodies in the UK24 and Canada25 stress the need for these preliminary studies. The intention is to ensure that design weaknesses, technical problems and methodological flaws do not compromise the full RCT. 26

The challenges for this feasibility study arise from the nature of the study group and the design and delivery of the intervention. Identifying obese men who drink heavily could be difficult. Recruiting and retaining these men in the study would require a study design that elicits and sustains engagement. Part of the intervention was to be delivered by laypeople (study co-ordinators) whose training and support are crucial to the effective delivery of the intervention. Finally, sensitive process measures would be required to determine the fidelity of delivery and the extent to which there is engagement with the intervention.

The objectives for the feasibility study were:

-

to determine the best ways to recruit and retain obese men in a study aimed at reducing heavy drinking

-

to design an intervention that is an acceptable way to achieve a sustained reduction in alcohol consumption

-

to identify the content and timing of the delivery that is most likely to engage obese men in an intervention to reduce alcohol consumption

-

to develop high-quality training to enable the trained laypeople (study co-ordinators) to deliver their component of the intervention

-

to devise process measures to detect engagement with the steps on the causal model for behaviour change

-

to compile a manual of methods for participant recruitment, the training of lay staff and the design and delivery of the intervention.

The use of language

This study dealt with the issue of obesity but avoided the use of this term except in a few places. There were several reasons for avoiding the term obesity. People can be sensitive to terminology and do not like to be classified as ‘obese’. 16,27–29 Possibly the term is associated with pictures of extreme overweight seen in media images27 and would therefore appear inappropriate. This is supported by the finding that most men who are obese consider themselves to be overweight rather than obese, and some consider themselves to be of normal weight. 30 Obesity is considered a medical term that conveys society’s disapproval of overweight people. 28 Thus, the term very overweight was preferred to obese.

Study overview

This 21-month study was conducted in two phases. Phase 1 was to develop the recruitment strategy and the novel alcohol intervention. It was to comprise six focus groups with obese men aged 35–64 years, who would be recruited from a variety of community locations. In-depth interviews with six key stakeholders would also be conducted to help develop the strategy for the recruitment of participants.

Phase 2 was intended to recruit 60 men aged 35–64 years. Two complementary recruitment strategies were to be used. One would identify obese men from primary care records. The other would adopt a community outreach approach, time–space sampling (TSS), which was designed to identify hard-to-reach groups. 31 A key feature of the study is that trained laypeople would be involved in intervention delivery. The training programme used would be developed from the Department of Health manual,32 taking into account recent recommendations for training laypeople. 33 Each study co-ordinator would only deliver one type of intervention (either novel intervention or comparator) to prevent contamination across treatment arms.

The men in phase 2 would be randomised to a novel extended intervention group or a comparator group (a conventional alcohol brief intervention). The novel extended intervention would be informed by literature on changing health behaviours including recent systematic reviews34,35 and taxonomies of behaviour change techniques,36,37 including one specific to alcohol brief interventions. 38 The intervention would also draw on techniques developed for our successful NIHR feasibility study of a text message delivered intervention to reduce alcohol-related harm in disadvantaged men (project number 09/3001/09). 39 The comparator group was to receive a conventional brief alcohol intervention,40 which would be delivered in a face-to-face session by a trained layperson.

Ethics approval

The study received ethics approval from the East of Scotland Research Ethics Service REC2 on 28 May 2014 (reference 14/ES/0050).

Modifications to the initial protocol

Three changes were made to the intervention. One part of the intervention was to be a series of text messages encouraging behaviour change. A small number of text messages were to include images, which would extend the ideas conveyed in words. This approach was used successfully in a NIHR Public Health Research (PHR)-funded feasibility study (project number 09/3001/09). 39 However, unanticipated technical difficulties were recently encountered in the NIHR PHR-funded RCT (project number 11/3050/30). 41 Exploration of the problem suggests that changes in the commercial technology used to transmit images (Multimedia Messaging Service images), and variations in the systems used were the cause of the difficulties. Text messages that do not contain images are sent without problems. The proposal to use Short Message Service (SMS)-only messages was approved as a contract variation by NIHR HTA before the intervention was developed.

The second change to the intervention was the omission of a volitional help sheet which participants were to have been given at the end of their face-to-face session. This help sheet would have identified ways in which participants could cope with situations that might weaken their resolve to reduce their alcohol consumption. 42 However, a preliminary assessment of the face-to-face session showed that it would be best used to focus on increasing motivation to drink less. The next phase of the intervention, the text messages, would cover the specific techniques of goal-setting, action planning and relapse recovery. As the volitional help sheet is intended to assist in these steps, similar approaches were incorporated into the text messages.

The final change concerned measuring weight. The protocol stated that men would be asked to monitor and report their weight during the intervention phase. On reflection, the intervention period of 2 months was thought insufficient to achieve substantial change in weight. Worthwhile, but modest, reductions in alcohol consumption would yield small reductions in weight over such a short period. Thus, measuring weight loss might reduce rather that increase motivation to maintain reduced consumption. Consequently, the men were not asked to monitor their weight.

Conclusion

This study seeks to address an important public health problem. The approach that was taken was to develop each component of the feasibility study and then test its suitability. The intention was to create an initial robust design, then identify opportunities to improve it during the conduct of the feasibility study. Based on an evaluation of the success of the study, this report will make a recommendation on whether or not a full RCT is warranted. This will be based on technical feasibility and the likelihood of whether or not a meaningful answer will be supplied.

Structure of the report

Feasibility studies involve the development of study methods accompanied by a careful evaluation of whether or not each method achieves its objectives. This study comprises a series of substudies. For clarity, this report presents each substudy as a separate chapter, together with its methods and findings and a discussion of the implications. Thus, Chapters 2–11 describe these substudies. The final summary and conclusions chapter (see Chapter 12) summarises the findings from the separate chapters and highlights issues that involve a comparison of the findings from the separate chapters. It assesses whether or not the study objectives were met and makes recommendations for improvements to the design of the full RCT.

Chapter 2 Focus groups to explore drinking and losing weight

Introduction

The remit of this study stipulated that weight loss was to be used as a motivator to drink less among men who are obese and who drink heavily. The rationale for this is clear: alcohol is high in calories and drinking increases snacking and the consumption of high-calorie food. 43 However, the use of one behavioural outcome, weight loss, as the motivation to change a separate behaviour, alcohol consumption, is unusual. This approach is not one that has been well covered in the literature, so focus groups were conducted to explore it. Because the logic of the intervention, although compelling, is far from straightforward, the issue was approached indirectly. Initially, participants’ attitudes and motivation to drink less and to lose weight were explored separately. Once ideas on each topic had been reviewed, issues around using reduced alcohol consumption as a means of weight loss were discussed. The aim was to clarify opportunities and strategies for an intervention to promote reduced drinking and to identify potential barriers to engagement with the intervention.

Methods

Six focus groups were conducted with middle-aged men who drank regularly and were overweight. Socioeconomic status was measured using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD),44 which is similar to the English Index of Multiple Deprivation. 45 Systematic reviews have shown that the provision of monetary incentives can significantly increase recruitment to research studies. 46,47 Consequently, men who agreed to take part were given a £10 gift voucher and were reimbursed for their travel expenses.

Sampling and recruitment

Focus group participants (Table 1) were purposively sampled from a variety of venues likely to represent the diversity of the target population, ensuring variation in age and level of deprivation. 48

| Focus group | Recruited from | Venue for focus group | Number of participants | Age range of participants (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Community centre (job shop attendees) | Community centre | 6 | 51–62 |

| 2 | University (estates staff) | University staffroom | 4 | 48–67 |

| 3 | University (nursing students) | University meeting room | 3 | 33–57 |

| 4 | Golf club (club members) | Golf club | 3 | 39–64 |

| 5 | Sports centre (sport and leisure staff) | Sports centre | 4 | 42–62 |

| 6 | Amateur radio society and Rotary club (mixed group) | Hotel | 3 | 38–67 |

The venues comprised a community centre, two workplaces [a university (staff and students) and a sports centre], a golf club, an amateur radio society and a Rotary club. Twenty-three men who drank alcohol regularly and were overweight were recruited to the focus groups. The summary characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2. The men spanned the age range 33–67 years, although most groups were within the narrower range of 39–62 years. Most of the men were married or lived with a partner and were in employment. The participants covered a wide range of socioeconomic statuses, measured by the SIMD44 and educational attainment.

| Factor | Number of participants (n = 23) |

|---|---|

| Participants’ age (years) | |

| 30–39 | 4 |

| 40–49 | 4 |

| 50–59 | 8 |

| 60–69 | 7 |

| Marital status | |

| Married/lives with a partner | 14 |

| Single | 7 |

| Separated/divorced | 1 |

| In a relationship | 1 |

| SIMD quintilea | |

| 1 (most disadvantaged) | 8 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 5 |

| 5 (least disadvantaged) | 5 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 16 |

| Unemployed | 6 |

| Other | 1 |

| Highest educational attainment | |

| University degree | 6 |

| Vocational qualification/further training | 8 |

| High school | 9 |

Data collection and analysis

Focus groups encourage interaction between participants49 and can result in increased disclosure,50 particularly when the participants are peers. 51 This is especially useful for exploring topics influenced in part by group norms and social expectations. 52 Alcohol intake in middle-aged men was expected to be one such topic. The topic guide explored three main topics: (1) reducing alcohol consumption, (2) losing weight and (3) potential intervention components. The first three focus groups explored benefits and barriers to drinking less and losing weight. To facilitate these discussions, participants were given cards and asked to write down their individual views on the benefits of drinking less, and then, on separate cards, to give their views on losing weight. There was no involvement of the researchers in these tasks. The cards were collected and used as a basis for discussion of the issues around drinking less and, after that, of losing weight. The comments on the cards were subsequently coded by two researchers (LI and IKC). The topic guide was revised following the first two focus groups to facilitate the further exploration of emerging issues. It was revised again following the third focus group as saturation had been reached in discussions of the benefits of reducing alcohol intake and weight. These were replaced with evaluations of activities that could be included in the intervention. The aim was to assess the ways in which participants responded to tasks such as calculating the units of alcohol they consumed in a week.

All participants were informed of the confidential nature of the research. All group sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed. An analysis of the transcripts was conducted by two members of the research team (KBC and AM) using a thematic approach. All data were coded by both analysts. Emerging findings were discussed with other members of the research team (IKC and LI). This encouraged the consideration of additional perspectives and interpretations. 53 Direct quotations are provided to illustrate the findings. 54

Results

The findings are organised by the three main sections of the topic guide: (1) reducing alcohol consumption, (2) being overweight and losing weight and (3) assessing intervention components.

Reducing alcohol consumption

The men in the focus groups were willing to discuss their alcohol intake. They talked openly and honestly about the amount of alcohol they consumed. Their drinks of choice varied and included different types of beer, cider, spirits, wine and cocktails. The environments in which they consumed alcohol were also diverse. Some men reported drinking mainly in their homes, others reported drinking mainly in public houses or clubs, and still others mentioned friends’ homes, golf clubs and social events.

Benefits of reducing alcohol consumption

The self-completed cards identified a wide range of potential benefits of reduced drinking (Table 3). Most frequent was the avoidance of the morning-after effects of drinking too much. However, long-term health, saving money and better relationships with family and friends were also common. Weight loss was seldom mentioned.

| Benefit | Frequency of reporting |

|---|---|

| Freedom from acute debilitating effects of alcohol | 29 |

| Mental well-being | 7 |

| Avoidance of hangover | 9 |

| More alert | 5 |

| Other (e.g. improved sleep, motivation, more energy) | 8 |

| Improved health | 15 |

| Financial | 11 |

| Improved relationships | 11 |

| Weight loss | 3 |

| Other (e.g. improved fitness, work opportunities) | 7 |

On completion of the task, the men were prompted to expand on the benefits they had identified from reducing their drinking. They often gave quite detailed personal benefits.

Hangover free

. . . enjoy your weekends more instead of having a hangover on the Saturday and the Sunday. Yes, just . . . more energy, and you’d get up and go and do stuff rather than just get up and feel bad for a few hours, and then maybe go out for a few hours and then come back.

Focus group 4, golf club members

. . . might be dinnertime before you come through the tunnel and be able to do anything, so that would give you . . . that’s time lost isn’t it, if you’re walking about in some sort of daze, with this hangover.

Focus group 2, estates staff

Health and weight

If I stop drink, better for my stomach, liver, everything.

Focus group 2, estates staff

Like I say, I think you get a lot of guys that have got big beer bellies, so that’s obviously not good for them, so the less you drink, especially if you’re drinking beer I would have thought, obviously you’re going to put on the weight if you’re standing propping up the bar every night.

Focus group 3, undergraduate nursing students

Financial

If you go to the pub you’re looking at two and a half, maybe three pound a pint, depends on where, so I would drink maybe five or six pints a night, so that’s . . . that’s 18 quid. That £18 can go towards maybe a pair of trainers, if you’ve got a family . . . you know what I mean?

Focus group 1, job shop attendees

If you want to buy yourself some clothes, or new trainers or shoes, whatever, yeah. That’s got to be better than just drinking it away.

Focus group 2, estates staff

Family

I suppose if you spend less time in the pub, you’re going to have more time for other things obviously. Spend time with your kids, spend time with your wife, spend time with the rest of your family, spend time doing things you like doing outside of alcohol I suppose, less in the pubs.

Focus group 2, estates staff

Career prospects

If you’re sober you’ve got a better chance of career prospects as well. They’ll say, ‘Well he seems alright, he does his work, and there’s them vacancies coming up, we’ll put him in for it’.

Focus group 1, job shop attendees

Barriers to reducing alcohol consumption

Some men thought that it would be difficult to reduce their alcohol consumption. Drinking was thought to form the basis of their social lives so that changes to customary drinking patterns would seriously affect friendships:

I think it’s hard to stop drinking because social life in this country is based around alcohol. I mean, you can’t go any place now, you can’t go to a disco, any place like that, without drink. Everybody drinks.

Focus group 2, estates staff

I couldn’t come down here with the guys, I couldn’t go to a Wednesday [usual drinking session] and sit down with orange juice.

Focus group 4, golf club members

It’s the only time I see my mates and that, they’ve got their own kids and families, and that, and the only time I really see them is in the pub. We don’t work together or anything like that, so if I didn’t meet them in the pub I would never see them.

Focus group 4, golf club members

The men also thought that peer pressure would make it difficult to reduce alcohol consumption. The importance of socialising when drinking may also lead to an expectation that everyone will drink and that not drinking or reducing drinking is abnormal:

Peer pressure . . . you might find yourself, you’re an oddball if you don’t drink. Social, mostly the pressure is social.

Focus group 2, estates staff

I think the biggest one, myself, would probably be socialising. Going out, you’ve got peer pressure to keep on drinking, this, that . . . your friends . . .

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

Drinking as part of a celebration or through having nothing else to do were offered as reasons for continuing current drinking practices. These had less force than social factors but still contributed to the perceived difficulty of reducing alcohol consumption:

Even if there’s a thing going on, like a celebration or something, there’s always something going on isn’t there? You’ve got the Commonwealth Games haven’t you?

Focus group 1, job shop attendees

One of my mates will tell you, we would be in the local five nights a week . . . both single guys, just nothing else to do, ‘We’ll go for a pint, we’ll go for a pint’.

Focus group 3, undergraduate nursing students

Being overweight and losing weight

The men were also willing to discuss their weight and to classify themselves as overweight. (For the focus groups the term obesity was not used as men can find it stigmatising.) The self-completed cards identified several potential benefits of losing weight. These can be conveniently grouped into four categories covering health, physical functioning, mental and social well-being and body image (Table 4).

| Benefit | Frequency of reporting |

|---|---|

| Increased fitness/physical ability | 19 |

| Improved health | 18 |

| Mental/social well-being | 16 |

| Improved body image/appearance | 10 |

The subsequent discussion on weight centred around two inter-related subthemes: the limitations of being overweight and the benefits of losing weight. Being overweight is more than a measurement; its importance lies in its immediate impact on physical and emotional well-being. The men were remarkably frank in their assessment of excess weight on both their appearance and their capacity for physical activity. It is clear that their concerns were deeply felt because of the extent to which they adversely impacted on their lives:

Well you just get about . . . obviously if you’re overweight, not so much necessarily big, fat, but like you say you can’t get about so much, you’re out of breath or energy, doing whatever. Obviously . . . well that’s what I feel . . . I’ve got a bit of a fat stomach right, that’s obvious, but I feel it when I’m walking up big steep braes . . . my heart’s pounding, so obviously it’s affecting my health.

Focus group 2, estates staff

This might sound daft, but when the lifts are off at work, if we have to run up all those stairs, personally, I’m out of breath. And it’s got to be weight connected.

Focus group 2, estates staff

Self-image is strongly affected by being overweight, with most attention to stomach size:

I’d like to not have that . . . paunch . . . [his stomach] because I realise it’s bad for me, and especially at my age. And when I see it I’d rather not have it.

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

I would like not to have that [his stomach], because like I said, it’s only there that it seems to manifest. Say, if you’re swimming . . . I’m like, ‘My arms are fine!’ And you’ve just got this thing there, and you’ve got your moobs and it’s . . . I’ve never had any problem putting fat on anywhere apart from a little bit in the moobs, but mainly in the gut. So I’ve never really care about how much I am on the scales, for me it’s a bit more aesthetic . . .

Focus group 3, undergraduate nursing students

And you don’t feel dressed, it doesn’t matter what you wear you look terrible in it, if you’ve overweight.

Focus group 2, estates staff

Yes, well obviously it’s not ideal wandering about with your stomach hanging out, it’s embarrassing . . . overhanging your jeans.

Focus group 2, estates staff

The men also identified the impact of losing weight on physical activity:

Yes, I would say if you’re more healthier and less overweight, you’re going to want to go out more aren’t you? More outgoing, definitely, but a walk through the park, go for walks in the countryside with the kids.

Focus group 1, job shop attendees

. . . just being able to do things without worrying about it, like . . . going hill climbing with your mates or whatever, and you just think, ‘Christ, that’s a bit of a bugger’, but you know you’re going to be able to do it if you’re fitter.

Focus group 3, undergraduate nursing students

Aye, it’s all walking . . . nearly every place. It’s a lot easier to walk [if you lose some weight].

Focus group 1, job shop attendees

Alcohol consumption and weight

When the link between alcohol consumption and weight was raised, the participants acknowledged that this existed, although they thought that many people would be unaware of it:

I think it’s getting people to recognise that the amount they’re drinking, contributes to, not only the risk of this, but also their weight as well. And I don’t think, necessarily, folk think that.

Focus group 5, sport and leisure staff

. . . but I don’t think a lot of folk . . . just talking . . . would associate that alcohol can also contribute to that [weight].

Focus group 5, sport and leisure staff

Many men believed that reducing alcohol intake would help with losing weight. Some of the men had experienced this for themselves, or had noticed an increase in their weight following an increase in their alcohol intake:

From my personal experience, I know it works. I lost a tremendous amount of weight, I lost 6 kilos . . . and largely because I’d stopped drinking . . . So, yeah, there’s no question, cutting out the alcohol makes a big difference.

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

on times when I have stopped for a while, I have lost weight . . . So it definitely has an effect.

Focus group 1, job shop attendees

I’ve been putting on weight because of the fact I’m not working, you’re drinking more.

Focus group 1, job shop attendees

However, other men had experienced the opposite: an increase in their weight following a reduction in their alcohol consumption. They attributed this to eating as a replacement for drinking:

But I don’t think, now, stopping, made any difference to me. I didn’t lose any weight. I probably put on weight because I was just eating more.

Focus group 4, golf club members

It’s very strange because if I stop drink, I not lose the weight, I put on the weight. If I drink, I drink beer, beer has a lot of calories, one bottle about 300 calories.

Focus group 2, estates staff

Alcohol and eating

In laboratory studies, alcohol consumption has been shown to stimulate appetite. 55–57 The focus groups identified the ways in which this occurred: through increased consumption during and shortly after drinking sessions, by eating more the following day and in an apparent preference for less healthy foodstuffs:

Yes, because usually you’re really hungry after, it is . . . even if you’re sitting in the house . . . even like a packet of crisps, if you’re sitting and watching a film or something like that, a few beers, and a packet of crisps. It’s all tied in.

Focus group 2, estates staff

We used to call it the ‘whisky hunger’. You get the ‘whisky hunger’. And that’s been before time began! You’d get too drunk and then you’d want to eat something.

Focus group 2, estates staff

You leave the pub after four or five pints you go to the kebab shop . . .

Focus group 1, job shop attendees

But it’s true, like next Saturday we’ll be out on that night out, it’ll be a pretty heavy night, there’s a big crowd going, so we’ll all get up on Sunday, and I’ll eat junk all day. Crisps and stuff like that.

Focus group 4, golf club members

If you are drinking, you are going to eat the wrong stuff.

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

. . . you’re not going to say, ‘I’m having a glass of wine, I’ll have a carrot!’

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

And definitely, the next day, if you’ve over indulged, with the grease, just something to wrap it up and get yourself right. Like tomorrow I know I will be having a full breakfast, a full English, easily.

Focus group 3, undergraduate nursing students

Assessing intervention components

The focus groups also explored four potential activities to be undertaken as part of the intervention. These were measurement of alcohol consumption, the calculation of units of alcohol consumed, the calculation of calorie consumption from alcohol and a comparison of the calories in foodstuffs and in alcohol. These activities follow a logical sequence, as each builds on the previous one. The main reason for exploring these activities in the focus groups was to identify ways in which these activities could be used to help increase motivation to lose weight. They also provided estimates of the time taken for each task.

Measuring alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was to be measured using the Timeline Followback (TLFB) method,58 to obtain an accurate estimate of consumption. The men were provided with a calendar of the previous 28 days and were asked to write down how much alcohol they had consumed over that period. They were advised to start with regular drinking days (e.g. weekends), and then to add details of any special occasions or less usual drinking sessions. The time taken to perform this task ranged from 4 to 13 minutes. The completion of the drinking calendar highlighted how much alcohol was being consumed:

When you see it wrote down it actually makes you think, wait a minute, I’ve actually drunk that much.

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

It’s certainly made me aware. I would say . . . I stopped drinking for a year actually, a couple of years ago, and I would say, now, and often do say, well I don’t drink anymore, but these figures would belie that. I don’t feel . . . I certainly don’t drink as much as I used to, but . . . it’s kind of shocking to me, to see how much I actually do drink. Just a large brandy, every couple of nights, maybe three nights in a row, it adds up, and it’s interesting to have to confront that.

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

The calculation of unit consumption

From the 28-day calendar the men were asked to select a typical week. With the assistance of the researchers, a simple look-up table of units in common drinks and a calculator, the men calculated the number of units of alcohol consumed in their typical week. The calculation took between 2 and 5 minutes to perform. The men mentioned that totalling up the units they consumed was not something that they had done before:

I’ve never tallied it up before.

Focus group 4, golf club members

If you’re asked to do this, actually, it’s real though.

Focus group 4, golf club members

I’ve never actually dealt with them [units].

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

The calculation of calorie consumption

Using a simple look-up table, the men were asked to calculate how many calories were in the drinks they had consumed in their typical drinking week. This process also took between 2 and 5 minutes. The men were surprised at the large number of calories from the alcohol that they had consumed:

You see I’d never given that a consideration, how much calories were in alcohol, I’d never even given that a thought.

Focus group 2, estates staff

I mean, as I say, I would never have guessed that a pint of beer had 180 calories, full stop!

Focus group 2, estates staff

It’s quite surprising, I’m surprised at this . . . the amount of calories in, especially, cider, which I drink, I’m quite amazed that that’s the highest of the lot to be quite honest.

Focus group 5, sport and leisure staff

Calorie equivalence of food and alcohol

The men were provided with information about the calorie equivalence of alcoholic drinks and certain foods. The hope was that the use of familiar foodstuffs would emphasise just how many calories alcohol contained. However, the key message they took from the information was that if they did not eat the foodstuff, they could drink more:

Six chicken nuggets, I’d rather have the five whiskies.

Focus group 4, golf club members

Instead of two packets of crisps, I could have two pints!

Focus group 4, golf club members

First reaction, is, ‘I don’t need the fish and chips, but five pints of lager sounds nice’.

Focus group 6, amateur radio society and Rotary club members

Discussion

These findings have important implications for the design of the intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in obese men aged 35–64 years. They identify potential levers for behaviour change that could support the study aim of using the benefits of weight loss to promote reduced drinking (Box 1). In addition, barriers to reduced drinking were identified and an approach that was thought to have promise had the potential to be counterproductive.

-

The men were surprised by how much they drank.

-

Few men monitored their alcohol consumption.

-

Many benefits of drinking less were identified.

-

Some disadvantages of drinking less were identified, particularly effects on social life.

-

The men were aware that drinking leads to:

-

increased snacking

-

additional meals

-

eating energy-dense foods.

-

-

The men were surprised by the calorie content of alcohol.

-

Being overweight, particularly having a protruding stomach, limits ability to be active and causes considerable embarrassment.

-

Many benefits of losing weight were identified. These could feature in the intervention, increasing the salience of these outcomes without risk of antagonising the men.

-

There were no disadvantages to losing weight.

-

Comparing the calorie content of alcohol and popular foodstuffs could lead to increased alcohol consumption.

The men identified many benefits of reducing drinking. Most prominent among these were the short-term consequences of heavy drinking, such as hangovers and loss of mental clarity. Although some longer-term health concerns were identified, they were much less commonly noted by the men. This finding not only identifies an important target for increasing motivation to drink less, but also provides one for maintenance of reduced drinking. Satisfaction with outcome is crucial for the maintenance of a new behaviour. 59,60 Benefits such as improved mental clarity are immediately appreciated, whereas many health benefits, such as avoiding diabetes or heart attack, will not be reaped for many years. Thus, the intervention could use the short-term benefits of reduced drinking to increase motivation, and then use the benefits obtained to promote maintenance.

The principal barrier to reduced drinking was the impact it would have on friends and social life. However, balanced against this was the finding that one benefit of reducing alcohol intake was a positive effect on relationships with family and friends. Thus, in the intervention, increasing the salience of the benefit could reduce or negate the impact of the barrier.

The calorie content of alcohol came as a surprise to many of the men. This makes it a high priority for inclusion in the intervention. The finding that drinking makes you eat more, and more unhealthily, is another important candidate for inclusion. The literature shows that moderate alcohol intake stimulates food consumption in the short term (within 1 hour). 55–57 Men also make unhealthier food choices when drinking. 43 Although this point did not feature on the self-completed cards, it emerged frequently in discussions and attracted no dissenting voices. Given the double benefit of less alcohol and fewer calories, the links between drinking alcohol and increased consumption of food should be emphasised in the intervention.

The way in which alcohol increases food consumption, particularly by snacking, was familiar to many men, although there was a perception that this effect was not widely known. This suggests that, although known, the effect has a low salience. This makes it an attractive target for intervention, as information about it may be readily accepted. One approach could be to ask men about their own experience, and then encourage them to reflect on what effect this has on their weight.

An unexpected finding was the hazard of describing calories in alcohol in terms of common food items. This was intended to be a simple method of conveying how many calories were in alcohol and it succeeded in that aim. However, the unintended consequence was that men could use the avoidance of high-calorie foodstuffs as an excuse to consume more alcohol; therefore, this topic should be avoided in the intervention.

Previous studies have shown that men care about body image61 and engage in negative body talk (making disparaging comments about their bodies). 62 Self-image and physical functioning are important motivators for weight loss. 18 These include the desire to improve appearance and physical attractiveness,63–65 but also to increase self-esteem and a sense of self-control. 63 A key finding from this study is that the men’s body image concerns were focused on the size and unsightliness of the stomach and the embarrassment that this causes. This presents an ideal lever to increase motivation to change, but it is one that needs to be handled sensitively. The implication that a participant is unattractive because of his shape could induce annoyance and rejection of the intervention. One way to overcome this would be to suggest that the men might recapture some of the vigour of their youth if they lost some weight.

The study also found that men were concerned about function, their ability to do everyday tasks, their engagement with their families and their ability to carry out work responsibilities. 66,67 Thus, another motivator for weight loss and/or reduced alcohol consumption found in this study is increasing effectiveness at work to become a greater asset to one’s workplace. 15 The men’s concerns about being able to function competently in society provide an opportunity to increase motivation to change, and have the benefit that, because they are conventional social obligations, they are likely to be readily accepted. Indeed, men may be more likely to welcome suggestions on how to increase their ability to meet these expectations.

In summary, the focus groups have identified opportunities for the development of an intervention to reduce drinking in a social group who have not been well studied: obese men who drink > 21 units of alcohol per week. These centre on improving physical, social and mental well-being by reducing alcohol consumption and losing weight. The proposed approach to weight loss, namely drinking less alcohol, offers benefits that are important to overweight men. The aim is to increase the salience of the benefits to increase motivation for change.

Chapter 3 The stakeholder interviews

Introduction

One element of the recruitment strategy proposed to use community outreach to identify eligible men. It would focus on venues that obese men were likely to frequent. To identify potential venues and the best ways to gain access to them, interviews were conducted with key stakeholders. These were individuals in managerial positions who frequently encounter men in the target group, and who could thus act as gatekeepers for recruitment of participants. Such individuals were also likely to have insight into the willingness of potential participants to discuss taking part in the study. The stakeholder interviews investigated opportunities for meeting with potential participants and possible venues for delivering the intervention.

Methods

Sampling and recruitment

Stakeholders were purposively sampled from a variety of venues that members of the target population were likely to attend either for work or for pleasure. Six interviews were conducted with stakeholders who were managers of venues in the local community, specifically a golf club, a community centre, a sports centre, an employment support service, a concert auditorium and a theatre.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected from brief semistructured interviews. The stakeholders were told that the aim of the research was to encourage men to drink less and to lose weight. They were also told about the method of recruitment and that the intervention would be delivered by a face-to-face session followed by text messages. The interview schedule was structured around the issues of recruiting men for the study and delivering the face-to-face component of the intervention. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis was conducted by two members of the research team (KBC and AM).

Results

The interviews explored three main themes: (1) views on the research topic, (2) recruitment of participants and (3) venues for intervention delivery. The results are presented in these themes. No details of the stakeholders’ job titles or organisations are included, in order to protect their anonymity.

Views on the research topic

All of the stakeholders considered alcohol consumption and weight to be major public health issues. They believed that research exploring ways to reduce alcohol consumption in obese men aged 35–64 years would be challenging yet very worthwhile:

I think the aim is very worthy . . . if you’ve got some techniques that can pull out a bit more information around both alcohol consumption, levels of activity, that would be great, and certainly tying it into weight, that would be fantastic.

Stakeholder 6

It will be very challenging I should imagine! Because men don’t like to think they’re getting older either, so they don’t like to appreciate they need to drink less, so I think it will be very, very challenging . . . I think it’s hugely important . . .

Stakeholder 1

. . . you’ve got the social aspect, I think, of it, as well, and most of them will say to you that going for a drink is a social kind of thing to do. But then when it does start to over indulge . . . that’s where the weight comes in.

Stakeholder 3

Benefits to stakeholders

The stakeholders were willing to help to facilitate the research by assisting with the recruitment of participants and by providing venues for the delivery of the intervention sessions. The main reason for this positive response was that the aim dovetailed with their organisation’s philosophy and aims. Some commented that they saw it as part of their role and responsibility to their organisation’s staff and/or customers to provide access to health promotion initiatives:

It would be a positive for the workplace, so the aims of the study are brilliant, even as a standalone . . . in relation to work environment and management it would be useful, because obviously healthier members of staff are going to be more productive.

Stakeholder 2

Partly what we’re in the business of, is helping to improve people’s quality of life around physical activity and health . . . And the study seems to fit into that . . . So we were quite happy to support . . .

Stakeholder 6

I think it’s from the area that we work in, and what we see while we’re doing the work and the effects that alcohol and everything else has on the local community.

Stakeholder 3

I suppose because we’re interested in improving . . . anything that can improve people’s health and employment, and understanding, that’s why we’re interested in anything like that. Because it’s a whole . . . employment is a whole culmination of a lot of different things and employment and health is part of that . . . So yeah, if we can make people more aware of what’s going on, what’s surrounding them, what’s out there to help them, then that’s got to be better for us.

Stakeholder 5

Recruitment

All of the stakeholders indicated that men meeting the eligibility criteria of age 35–64 years and BMI of > 30 kg/m2 frequented their organisation either as members of staff or as customers. Some of the stakeholders were able to provide estimates of the numbers of such men. These numbers ranged from roughly 50 per week (community centre) to 200 members (golf club). No stakeholders were aware of the amount of alcohol consumed by the men meeting the eligibility criteria of age and BMI. The stakeholders were willing to identify opportunities for members of the research team to meet with potential participants and were happy to facilitate such meetings. In general they did not believe that men would be embarrassed about being approached to take part in a study on the topics of alcohol consumption and weight and they did not anticipate any adverse reactions from men approached:

We see a lot of people through the doors here, who need to take action. It’s in the press all the time isn’t it, how obesity is causing the NHS no end of grief, so from what’s coming in here, it’s not going to get any better.

Stakeholder 1

I know we have lots of candidates here!

Stakeholder 4

I would think if you send someone here on a Saturday afternoon, that’s a Saturday or a Sunday, or both preferably. If you want people who don’t know each other, come both days . . . I don’t think . . . you won’t get any abuse or adverse reactions, they’ll either say, no, or they’ll make a joke about it.

Stakeholder 4

I think once you can get them engaged, I think they’ll be OK. I think they’ll be . . . certainly on a one to one basis, we’re interviewing people pretty much all the time on a one to one, even quite disengaged people quite like speaking about themselves!

Stakeholder 5

. . . they wouldn’t think they were particularly overweight you know? But the bigger guys that we see in the main, I suppose, are usually quite jovial people, so I don’t think they would be too negative. But if they just went, ‘No’, that would be it, that’s it.

Stakeholder 1

Anticipated barriers to recruitment

The main barriers to recruitment were thought to be gaining access to individuals and reluctance because of the time it might take. The view was that people visit a location for a purpose and once that purpose is served they want to move on:

I know the initial barrier is actually accessing them, but it’s just . . . yes . . . I mean, we also have the Box Office, now whether it would be worth, sometimes, you being in there, for a couple of hours a day, you can’t guarantee who’s going to come in, but there are a certain level of people who come in who do need to look at their weight, men, you know?

Stakeholder 1

I suppose it’s just that thing of, ‘Do I want to actually participate in that?’ so it’s just time more than anything else. It depends on what they’re being required to do . . .

Stakeholder 2

I think there’s a general reluctance, and part of that is about . . . I think people who are coming into a sports centre, particularly . . . if it’s a winter sports centre or swimming pool, a lot of time they’re going there to do their activity and go away again. Particularly at lunch times or . . . they’re doing their five-a-side football, or their badminton, and they’re coming in, they’re doing their activity, getting changed and going away.

Stakeholder 3

Again, getting them at a time where it’s going to be suitable for them, and they’re going to feel like, ‘Yes, I want to’, that might be another barrier. But, I cannot think of anything else, any other barriers.

Stakeholder 6

Being aware of the potential barriers to recruitment led some stakeholders to try to identify potential solutions. It appeared that their enthusiasm for the research encouraged them to volunteer to assist in the process, often to make the first approach to potential participants:

I would say the easiest thing to do would be to use either myself or one of the administration assistants as a medium, just if you send . . . a similar e-mail to what you had sent to me, but maybe a bit more relevant to specifically what you need from them, we could pass it on, as basically an all-staff e-mail.

Stakeholder 2

If you e-mail me one [information sheet] for him, then I could just pass the e-mail on to him, and he can have a look at it, and then he can decide and get back in touch. But I’ll tell him to get back in touch and say, yes or no, just so that you know.

Stakeholder 1

I think it would be easier for us to facilitate that, but . . . , so giving us some information and we could go and set something up, to start off . . . try and get some staff’s interest.

Stakeholder 3

Venues for intervention delivery

Stakeholders were often positive about providing rooms within their organisations for the delivery of the face-to-face component of the intervention. Some were apologetic that a lack of space meant that they were unable to provide a room:

Yes, absolutely, you could do that in a number of ways. You could either do it on a general . . . setting up some sort of stall I suppose, in a reception area, whether it be here or elsewhere, or where we’ve got particular sessions that we know are attended by a number of people within that target group, you could come along and directly speak to them there.

Stakeholder 3

Yes, you could do it in here if you want. . . . This room’s only used once a month for a meeting, so . . . As long as you tell me, just give me a phone . . . As long as they know you’re coming, that’s fine, it’s not a problem.

Stakeholder 4

[Do you have a room that we could use?] Oh, there’s no problem with that, yes.

Stakeholder 1

Availability of rooms

The willingness to provide rooms was tempered in some cases by an awareness of the practical difficulty of accessing rooms. This was not meant as a barrier, but as advice on how best to ensure that rooms would be available:

Yes, we’ve got rooms and stuff that you can book, as long as it’s booked in advance, then normally we can.

Stakeholder 6

Yes, I think in principle, yes, it’s not a problem doing that. So if you’ve got a group of people who are using the [buildings mentioned], the principle is yes it’s not a problem, I think in practice it’s about finding the space at any particular time.

Stakeholder 3

And if you’re linking in with the time they’re in, then that’s fine. If you were coming into the factory and doing it there, then I imagine you’re more likely to get the factory willing to let you come in and spend whatever amount of time with each individual, rather than them having to go some place, because you’re not taking them away for any other time.

Stakeholder 5

Discussion and implications

These interviews have identified considerable enthusiasm among stakeholders for the study. Some of the stakeholders saw it as their role to provide access to health promotion for their members/customers/employees. Others did not see it as their role but still thought that weight and alcohol consumption were problems that needed to be addressed. Not only were they willing to provide access to potential participants, many could provide rooms for delivery of the face-to-face component of the intervention. This augurs well for recruitment.

The enthusiasm for the research is more than just altruism and a general willingness to help. It derives from a shared assessment of the scale of the public health problems posed by alcohol and by obesity. Furthermore, many of the organisations that were approached identified improving the health and well-being of their staff or their client group as a core value of their institution. This raises the possibility that, if the intervention proved effective, there could be opportunities for national roll-out through organisations that have similar core values. Naturally, there may be organisational obstacles that impede the progress of roll-out; however, the findings suggest that a possible approach could begin with discussions with senior staff in order to review shared values and the potential benefits arising from the intervention. This could lead to an evaluation of how the intervention could be implemented and an assessment of obstacles that would need to be overcome. A possible attraction for senior staff could be the low cost and time commitment of the intervention.

For the present study, the interviews have identified that although there may be many potential participants at some venues, accessing them may be difficult. Perceived lack of time may be the main issue. The stakeholders thought that the men would not be annoyed by being approached, although this falls some way short of being receptive to the invitation to participate in a research study. Another potential impediment is the preference of stakeholders to act as intermediaries in recruiting their staff. This could cause reluctance among staff to volunteer, as it could imply that they are overweight and drink too much.

In summary, these interviews have identified an unexpected enthusiasm for the research. This may extend to the provision of support for recruitment and of rooms for conducting face-to-face sessions. In addition, if managed sensitively, there may be opportunities for national roll-out of an effective intervention.

Chapter 4 Designing the intervention

Background

The remit for this study included the design of an intervention that used the motivation of weight loss to promote reduced drinking. The study focused on men who were obese (BMI of > 30 kg/m2) and who drank > 21 units of alcohol per week. These men are at a 19-fold increased risk of mortality from liver disease because alcohol and obesity have a supra-additive effect on risk. 1 The rationale for the intervention is that alcohol is high in calories, and therefore reducing alcohol consumption could have a similar effect to eating less, thus reducing both risk factors at once. However, the logic of the health promotion message is complex. It takes the form of: if you take this action (drink less) then, because of this fact (alcohol is high in calories), you will get this benefit (consume fewer calories) and achieve that outcome (lose weight). The challenge is to deliver this logic in a form that is understood and that engages middle-aged men. This may be difficult, as the target group comprises men who are not seeking help, who do not think they have a drinking problem and who may well believe that they drink moderately.

The intervention was planned to involve a face-to-face session at which BMI (height and weight) would be measured and alcohol consumption would be assessed. This session would be delivered by trained laypeople (study co-ordinators). It was to be followed by a series of text messages developed using the techniques established in our previous NIHR funded studies (NIHR PHR 09/3001/09,39 NIHR PHR 11/3050/3041). Together, these components would deliver a complete strategy for behaviour change. Both components of the intervention drew heavily on the elements of effective brief alcohol interventions described in systematic reviews34,68 and a review of reviews. 35

The intervention was to be based on the causal model for behaviour change specified in the protocol, with modifications made in light of the findings from the focus groups. The initial causal model for behaviour change was (1) generate interest in the study, (2) increase awareness of consumption levels that are defined as harmful, (3) identify motivational beliefs, (4) increase awareness of susceptibility to alcohol-related harm for men who are already obese, (5) increase motivation to lose weight by reducing alcohol consumption, (6) alter alcohol expectancies, (7) gain commitment to change, (8) develop goals, action plans and coping plans, (9) increase refusal skills, (10) implement strategies to prevent relapse and (11) reduce total alcohol consumption, which would in turn lead to weight loss.

This chapter describes the rationale for the activities, discussions and behaviour change techniques that were incorporated into the face-to-face session and the subsequent series of text messages. Initially, several questions were identified:

-

How should the causal model be modified by the focus group findings?

-

How should the intervention be divided between the face-to-face session and the text messages?

-

To what extent should the content of the text messages reinforce the face-to-face session?

Separate issues for the face-to-face session were how best to use the measurements of BMI and alcohol consumption in the intervention and what constraints would be imposed by the use of laypeople (study co-ordinators) to deliver the intervention. A further concern was how to design the intervention to overcome potential barriers to engagement and behaviour change.

Implications of the focus group analyses

The focus group analyses identified several opportunities to increase motivation to drink less. These included feedback of data on alcohol consumption, increasing the perceived relevance and importance of the benefits of reducing alcohol consumption, highlighting the benefits of weight loss, and feedback of data on calories consumed through alcohol. Feedback of data on alcohol consumption is a common component of alcohol brief interventions. 34,68 The focus groups confirmed that men in the target group (i.e. men who are overweight and regularly consume alcohol) are often surprised by how much alcohol they drink. As few men monitored their alcohol consumption, there could be value in encouraging this to provide motivation to drink less and to sustain reduced consumption. However, men also felt that the potentially detrimental effect on their social life would make them reluctant to drink less. This issue will need to be handled sensitively in the intervention. One approach would be to draw attention to the many social benefits of drinking less that the focus groups identified, such as improved relationships with family and friends.

The focus groups also confirmed that being overweight is recognised as a major problem, because of its adverse impact on self-image and on ability to carry out everyday activities. This is consistent with the findings of a recent NIHR HTA systematic review. 18 However, the focus groups also showed that the key issue was the so-called ‘beer belly’, as this caused embarrassment and made physical activities difficult. Engaging men with the benefits of losing this unsightly protuberance is a specific target for the intervention that could increase motivation to lose weight. Given that men volunteered no disadvantages of losing weight, suggestions of easily implemented techniques to lose this ‘beer belly’ should be well received.

A key finding from the focus groups was that men were aware that alcohol was associated with increased snacking. This effect of alcohol is well established in the literature,55–57 but it was unclear whether or not the men in this study would know about it. The finding that, when prompted, men agreed that they do eat more snacks when drinking could be used to increase motivation for reducing alcohol consumption. Thus, men would experience the dual benefits of reduced calorie consumption from both alcohol and food.

The focus groups confirmed that measuring alcohol consumption could provide useful data for behaviour change. The surprise expressed by men at their consumption could lead to a discussion of the benefits of changing behaviour. The measurements could easily be arranged in a sequence following the logic of the intervention. Initially, feedback on alcohol consumption could be used to develop a discussion of the benefits of drinking less, increasing motivation to reduce consumption. BMI could then be measured, leading to a discussion of the disadvantages of being overweight thereby increasing motivation to lose weight. Finally, the calories contained in alcohol could be calculated, personalising this by using the participant’s alcohol consumption. This could be supported by reviewing the ways in which alcohol stimulates appetite and leads to increased consumption of energy dense foods. Overall, the approach dissects the logic of the behaviour change strategy, illustrating each component with personal data and building simple steps into the complex argument. Crucially, motivation for action on each component should be gained before the next component is addressed.

The focus groups also provided approximate timings for making and discussing the measurements of alcohol consumption (10 minutes), calculating units in alcohol (5 minutes) and calories in alcohol (5 minutes).

The face-to-face session

The literature and the focus group findings identified ways in which measurements of alcohol consumption and BMI could be used to increase motivation to lose weight. As these measurements would be made in the face-to-face session, the most advantage would be gained by exploiting them as the data were obtained. Whether or not this session could also cover volitional components such as goal-setting and action planning would depend on the time available. The session was designed in a pragmatic way by exploring what could consistently be achieved for all participants.

The session had to be brief to be acceptable to participants who perceive that they have limited free time. 17 In the absence of direct information on what constituted brief, the arbitrary decision was taken to work initially with a 30-minute duration, although the exact length could subsequently be modified. Within this time, height and weight had to be measured, and the TLFB58 and baseline questionnaire had to be completed.

The other components of acceptability are the style and content of the session. Previous intervention studies have found that men appreciate a friendly, relaxed and non-directive approach20 and being given easily understood information. 18 The use of laypeople, who are likely to have an informal rather than professional style, could help achieve this.

A starting assumption was that participants will vary in their readiness to reduce their alcohol consumption. Thus, the intervention has to be appropriate for men who initially have no intention to change as well as those who are currently thinking about drinking less. The alternative would be to design a series of interventions tailored to individual motivation to change. This would create considerable logistical difficulties, as participants would have to be screened and stratified prior to intervention delivery and laypeople would have to be trained to deliver different versions of the intervention. The principle of having an intervention that could easily be rolled out nationally also militates against this approach.

Another constraint was that the face-to-face session component has to be delivered by laypeople. Although training would be given, there is a limit to the demands that can be placed on laypeople. The intention was to use some techniques from motivational interviewing (MI), but full training in MI would not be possible. The question then became how much training would they need to be able to deliver what could be covered in a reasonable time in the session. This was answered by reviewing how the alcohol and BMI measurements would be made and how they would be exploited.

Using participant data on alcohol consumption

The proposed method of measuring alcohol consumption was the TLFB. 58 Men could enter their alcohol consumption over the previous 28 days on a prepared calendar. They could then select a typical drinking week and, with help from the study co-ordinator, count the units consumed. This was intended to increase ownership of the result and preclude rejection on the grounds that the week was unusual. To do the calculation, a simple look-up table of units in common drinks could be provided. Any response to the total units consumed could be used to discuss feelings about current consumption and good and bad aspects of alcohol consumption, helping build motivation to change.

Using body mass index and weight loss

The decision to avoid the term obesity was taken at an early stage because the literature clearly shows that people do not like to be classified as ‘obese’. 16,27–29 Instead the term ‘very overweight’ was used. It was important to convey that the men had a BMI that placed them at the extreme end of the overweight spectrum. If the men could gain ownership of their high BMI by being involved in its calculation, this could form a useful part of the behaviour change strategy. To simplify the process, and to provide a visual representation of each man’s BMI, a graded height and weight chart from NHS Choices was used (with permission) (www.nhs.uk/livewell/loseweight/pages/height-weight-chart.aspx). 69 This plotted height against weight using brightly shaded bands to represent normal weight (yellow), overweight (orange), obese (dark orange) and very obese (red). The terms obese and very obese were replaced on the chart with a single label very overweight. Asking participants to plot their own height and weight on the chart allowed a discussion of reactions to being in the very overweight category and of the disadvantages of being so overweight.

Extending the use of the alcohol data

Alcohol is second only to fat in the calories it contains (7 calories per gram). As the units of alcohol consumed in a typical week would have already been obtained, there would be opportunity to calculate the calories in those units. Again, a simple look-up table of calories in common drinks could be provided. The focus groups showed that men were surprised by the calories they were consuming through alcohol. As well as highlighting the contribution of alcohol to weight gain, the calculation could provide the opportunity to explore other ways in which drinking leads to increased calorie consumption (e.g. through snacking and the use of drink mixers containing sugar).

Using interviewing skills from motivational interviewing

The tasks in the face-to-face session follow a common pattern: encouraging men to engage in an activity, developing a discussion around what men felt about the measurements and guiding them to reflect on the benefits of drinking less and/or losing weight. Performing these tasks would require the core interviewing skills from MI. They are identified by the acronym OARS: open questions, affirmation, reflective listening and summarising. 70 Open questions help to reassure participants and build their trust in the relationship. They also encourage participants to talk about themselves and to begin thinking about their behaviour. Affirmations are statements that recognise the participant’s achievements, increasing their confidence in their ability to change their lives. Reflective listening involves paraphrasing what the participant has said, to demonstrate that their views are being listened to. Reflections on the benefits of behaviour change can increase motivation to change. Summarising is a form of reflective listening that is particularly useful at transition points. In this study, it would be useful when moving from one activity to the next, for example when moving from discussing alcohol to measuring height and weight. It could also be used when closing the session.

Review of the session

The foregoing review clarified the ways in which the measurements of alcohol consumption and BMI could be used to increase motivation to lose weight and drink less. The outstanding issue was whether or not the session should be extended to cover volitional processes. This was decided by the available time. The session was intended to be brief, and so around 30 minutes was decided upon as an appropriate session length. Taking the measurements, doing the calculations and developing motivation to drink less and lose weight could take most if not all of this time. The focus groups showed that the measurements alone were likely to take about 15 minutes. The initial greeting and the closing of the session, together with the other discussions, would most likely occupy the remaining time. Thus, the decision was taken to restrict the session to increasing motivation to reduce drinking, allowing the subsequent text messages to complete the behaviour change process. Although it might have been possible to incorporate other components, such as goal-setting and action planning, this would not have been without risk. Covering a larger number of topics would mean that the time spent on each would be reduced. This could lead to a session that was hurried rather than relaxed, with limited time to explore motivational factors. Without sufficient motivation, the value of the extra topics might not be realised. Furthermore, if participants felt overwhelmed or rushed into decision-making, their motivation to change could be reduced. 71 Finally, the demands placed on the laypeople would be increased, possibly reducing both job satisfaction and the fidelity of delivery of the intervention.

Two potential levers for behaviour change were not included in the face-to-face session. First, information on the harms of drinking too much or of being very overweight was not mentioned unless asked for by the participant. This is consistent with our MI-based approach, and presenting information on risk could be counterproductive if unaccompanied by guidance on how to reduce that risk. Second, a comparison of the calorie content of specific foods (e.g. a hamburger) with that of alcoholic drinks was not presented. The focus groups found that men view such information as an invitation to substitute rather than reduce calories, for example ‘I won’t have the crisps so I can have another pint’, or taking it even further: ‘I don’t eat crisps so I can have a pint’.

Aims of the face-to-face session

The assessment of the opportunities and constraints of the face-to-face session has indicated that it should focus on increasing motivation (to reduce alcohol consumption and to lose weight). Furthermore, at the end of the session men should feel well disposed to the study so that they will be receptive to the text messages following the face-to-face session.

The specific objectives were to assist the participant in realising that:

-

he drinks more than he realises

-

he is very overweight

-

his drinking contributes to his being overweight

-

being overweight could affect his health

-

losing weight could bring him personal and social benefits.

The text messages

Background

A series of text messages was to be delivered by mobile phone over a 2-month period. Text message interventions are commonly used to modify other adverse health behaviours72,73 and to increase health-care uptake. 74,75 Recent systematic reviews have shown that text messages can successfully change behaviour. 76–78 This type of intervention is particularly well suited to middle-aged men because their ownership of mobile phones is high. 79

The behaviour change strategy was based on the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA). 80 The HAPA was chosen because it is supported by evidence and provides a useful framework to integrate effective behaviour change techniques and guide decisions on the sequences in which these techniques are delivered. The strategy also used techniques shown to be effective with obese adults. 81

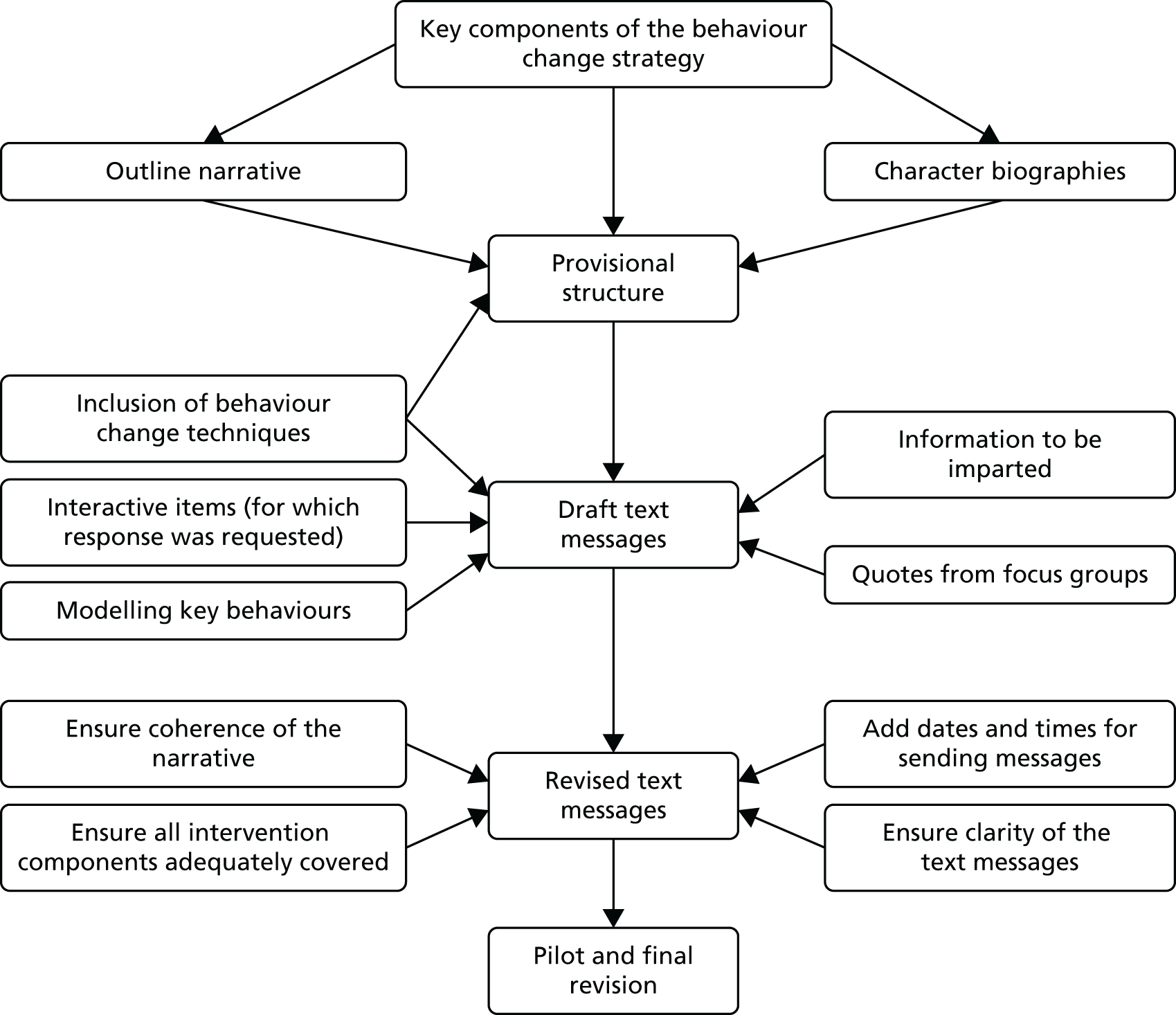

A series of interactive text messages were designed using the successful approach developed for our NIHR PHR funded feasibility study (NIHR PHR 09/3001/09)39 and its subsequent RCT (NIHR PHR 11/3050/30). 41 In particular, the texts employed many of the devices used successfully to promote engagement with the intervention such as tailoring messages to the target group, use of humour, informal text style, questions to promote interactivity and sensitive timing of messages. Findings from the focus group analyses, particularly the dislike of protruding stomachs and the perceived benefits of drinking less and of losing weight, were incorporated into the texts.

The text messages were designed to reinforce the content of the face-to-face intervention and to extend the behaviour change strategy. The logical sequence of the text messages to encourage men to drink less is shown in Box 2. The early texts sought to establish rapport with the participants and increase motivation to drink less. Subsequent texts encouraged participants to set realistic goals to reduce consumption, implement a plan of action, monitor drinking behaviour, identify barriers and construct strategies to deal with these barriers. Texts would increase self-efficacy for maintenance of reduced drinking and participants would be encouraged to develop strategies for relapse prevention. 80 This interactive intervention delivered over an extended period is designed to encourage sustained behaviour change.

-

Friendly welcome and introduction.

-

Plant idea of drinking too much.

-