Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/107/01. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The draft report began editorial review in March 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The insulin pumps were provided free of charge and unconditionally by Medtronic, which had no involvement in the design of the protocol; the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; the writing of this report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. Simon Heller is a Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board Member, who reports personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, and personal fees and other from Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work. Katharine Barnard reports personal fees from Roche Diabetes Care, outside the submitted work. Michael Campbell was a National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Board Member from 2010 to 2014. Jackie Elliott reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Merck Sharpe & Dohme and Takeda, and personal fees and non-financial support from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi-Aventis, outside the submitted work. Mark Evans reports personal fees and other from Abbott Diabetes Care, Medtronic, Roche, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Cellnovo, and grants from Senseonics and Oxford Medical Diagnostics, outside the submitted work. Peter Hammond reports personal fees from Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson, Roche, Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work. Alan Jaap reports personal fees and non-financial support from Novo Nordisk, and personal fees from Eli Lilly, Takeda, Merck Sharpe & Dohme and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Heller et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Type 1 diabetes mellitus and its treatment

People with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), around 250,000 individuals in the UK, have lost the ability to make insulin because of autoimmune destruction of the insulin-secreting β cells within the islets of the pancreas. Insulin is essential in the short term to prevent the onset of ketoacidosis, a potentially fatal condition. In the long term, the aim of insulin therapy is to keep blood glucose close to normal and so prevent the development of microvascular complications, such as retinopathy, neuropathy and diabetic kidney disease. Insulin is generally administered by intermittent subcutaneous injection, with the dose adjusted according to eating and other activities, such as exercise. Traditionally, insulin was given twice a day, often as premixed insulin, but such an approach imposes a rigid lifestyle and makes it difficult to maintain a glucose level close to normal. The need for intensification of therapy and its integration into flexible lifestyles is promoted in DAFNE (Dose Adjustment for Normal Eating) and other structured education courses. It involves giving quick-acting insulin just before eating and administering longer-acting background insulin, preferably twice daily, to maintain blood glucose levels in between meals. 1,2 This multiple daily injection (MDI) regimen involves a total of five or six injections a day. Blood glucose levels are monitored from finger-prick samples using a portable meter, and insulin dose calculations are based on self-assessed carbohydrate estimations on a meal-by-meal basis.

Insulin given subcutaneously cannot reproduce the physiological insulin profiles of non-diabetic individuals because of the limitations of insulin formulations and the site of delivery. The relatively slow rate of insulin absorption leads initially to postprandial hyperglycaemia, followed, 1 or 2 hours later, by an increased risk of postabsorptive hypoglycaemia, particularly during the night. Thus, keeping blood glucose close to normal can delay or prevent complications, but brings with it frequent periods of hypoglycaemia. These are categorised as mild, moderate or severe episodes, ranging from mild symptoms, self-managed by ingesting rapid-acting carbohydrate, through to greater disruption in daily routine due to cerebral dysfunction, through to major episodes of coma and seizure requiring third-party assistance. The inability of intermittent injection therapy to control blood glucose tightly without an attendant risk of hypoglycaemia results in many individuals keeping their blood glucose at higher than desirable levels. This leads to an increased risk of serious diabetic complications, which can affect the eyes, feet and kidneys. These complications, plus the associated high risk of cardiovascular disease, reduce both the length and quality of the individuals’ lives.

Insulin analogues

Short- and long-acting insulin analogues have slightly more physiological profiles than insulins of human or animal structure, but cannot reproduce those observed in people without diabetes. 2 Systematic reviews of clinical trials of insulin analogues involving people with T1DM have reported only minor advantages compared with human insulin, with a reduced risk of symptomatic hypoglycaemia, particularly at night. 3,4 This may be, in part, because those people who are at the greatest risk of hypoglycaemia are frequently excluded from clinical trials. Interestingly, in a recent crossover trial comparing MDI of human insulin with analogue insulin, the investigators specifically recruited individuals who had experienced problems with hypoglycaemia, and found that those using analogue insulin had significantly lower risks of severe hypoglycaemia, particularly at night. 5

Insulin pumps

There is clearly an urgent need for better methods of insulin delivery. Insulin pumps were first used clinically in the early 1980s, but randomised controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in the UK failed to show any clinical benefit. At the time, the technology was poorly developed, but has advanced considerably, particularly in the last few years. Insulin pumps are now the size of a small mobile phone and deliver insulin continuously under the skin via a small plastic tube and cannula [continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII)]. 6,7 These devices are filled with reservoirs of quick-acting insulin only (usually an insulin analogue), which provides insulin replacement by delivering both the mealtime and background insulin. When infused continuously at low rates they ‘mimic’ basal insulin secretion, and this is generally delivered more consistently and accurately than is achievable by the longer-acting insulins, particularly at night. The insulin boluses used to cover meals and correct high blood glucose levels are delivered much more rapidly. All of the insulin doses can be controlled by the patient, based on calculations similar to those required for insulin dosing with a MDI regimen.

The purchase and use of pumps is more expensive than MDI, with pumps at current prices costing around £2500 each, plus £1500 per year extra for running costs. 8 The marginal cost per annum over MDI is about £1800. 9 The potential advantages are more stable blood glucose levels, a reduced risk of hypoglycaemia and a more flexible lifestyle. Pump treatment may deliver insulin more effectively than MDI but does not provide a technological ‘cure’. The same competencies needed for successful insulin self-management, previously described for MDI, are required for pumps, but with additional skills required to operate the pump device itself. Thus, pumps are probably more useful to those individuals who are actively and effectively self-managing their diabetes rather than those who expect the pump to ‘manage’ their diabetes for them.

Pumps are currently used by around 40% of people with T1DM in the USA and > 15% in Europe. 10 In contrast, the proportion in the UK was around 6% in adults in 2012. 11,12 Proponents of pump treatment have proposed that far more patients should be offered treatment in the UK and that current policies are depriving many of the opportunity to improve glycaemic control, reduce hypoglycaemia and improve quality of life (QoL). 12 The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recently extended recommendations for the use of pumps for adults with T1DM. The guidance suggests that pump treatment be considered for individuals who are experiencing problems with hypoglycaemia, particularly when this limits the ability to improve glycaemic control. NICE has noted the paucity of evidence for efficacy from RCTs. 13

Problems with evidence in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence appraisals

There have been two appraisals9,14 of pumps by NICE, both supported by technology assessment reports undertaken by some of the present authors, which reviewed the evidence on clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. The first report14 noted that there were no trials of pumps against ‘best MDI’ with long- and short-acting analogue insulins; some trials had unequal amounts of education in the arms (with more in the pump arms); and the trials had focused on easily measurable outcomes such as glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), rather than on benefits in terms of flexibility of lifestyle and QoL. The report recommended trials of pumps against analogue-based MDI.

The second report9 found that few such trials had been done: one in children, not relevant to this work, and three in adults. Furthermore, the three adult studies15–17 presented data for a small number of participants who were followed over a short period only. The first of these studies was a 24-week pilot study15 in adults with altered hypoglycaemia awareness and debilitating hypoglycaemia. The three study arms consisted of seven patients each and compared (1) analogue MDI, (2) pump and (3) education and relaxation of glycaemic targets. All of the subjects were naive to analogue insulin use and some had never tried MDI, and so were not representative of the type of patients for whom NICE recommends pumps.

The second trial16 recruited 39 adults with T1DM, who had already been on pump therapy for at least 6 months, and who were randomised to stay on pump or switch to glargine (Lantus, Sanofi-Aventis, Guildford, UK)-based MDI for 4 months. The primary end point was glucose variability, which was 5–12% less with the pump. Despite this, there was no significant difference in the frequency of hypoglycaemic episodes or HbA1c.

The third study17 studied 50 patients with T1DM from Italy, UK (Newcastle, Bournemouth) and France, who were naive to pumps and glargine, to which they were switched for the trial, having been previously managed on neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH)-based regimens. Follow-up was for 24 weeks. Patients were randomised to pump or analogue MDI in an equivalence study. The difference in HbA1c at the study end was only 0.1% (approximately 1 mmol/mol) and the costs with the pump were three times higher.

Thus, the evidence base from trials for comparing pumps and ‘best MDI’ remains weak in terms of numbers, with a total of only 103 patients and short-term follow-up. Furthermore, the patients in the trials were dissimilar to those considered suitable for a pump by NICE, which expects patients to have tried analogue-based MDI before using the pump.

Given the paucity of RCTs, the assessment group also looked at observational studies of adults in which a pump was clinically indicated, mostly because of the limitations of intermittent injections. This comparison has the advantage of measuring change in glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia in those who have most to gain, and these studies showed improved HbA1c of the order of around 0.5% (5.5 mmol/mol). Interpretation of data from observational studies face limitations from bias, and, furthermore, of the 48 observational studies, only nine reported QoL. Study numbers were small and duration was usually short. The longest study noted that initial benefits from pumps might not be sustained.

Therefore, again, NICE was faced with an evidence base with considerable shortcomings, too few trials, durations too short, numbers too small and a need to use observational studies. A recent meta-analysis by Monami et al. 18 concluded that ‘available data justify the use of CSII for basal-bolus insulin therapy in type 1 diabetic patients unsatisfactorily controlled with MDI’. However, most of the RCTs in their analysis were NPH-based and the Bolli et al. 17 trial, with its negative result, was missed.

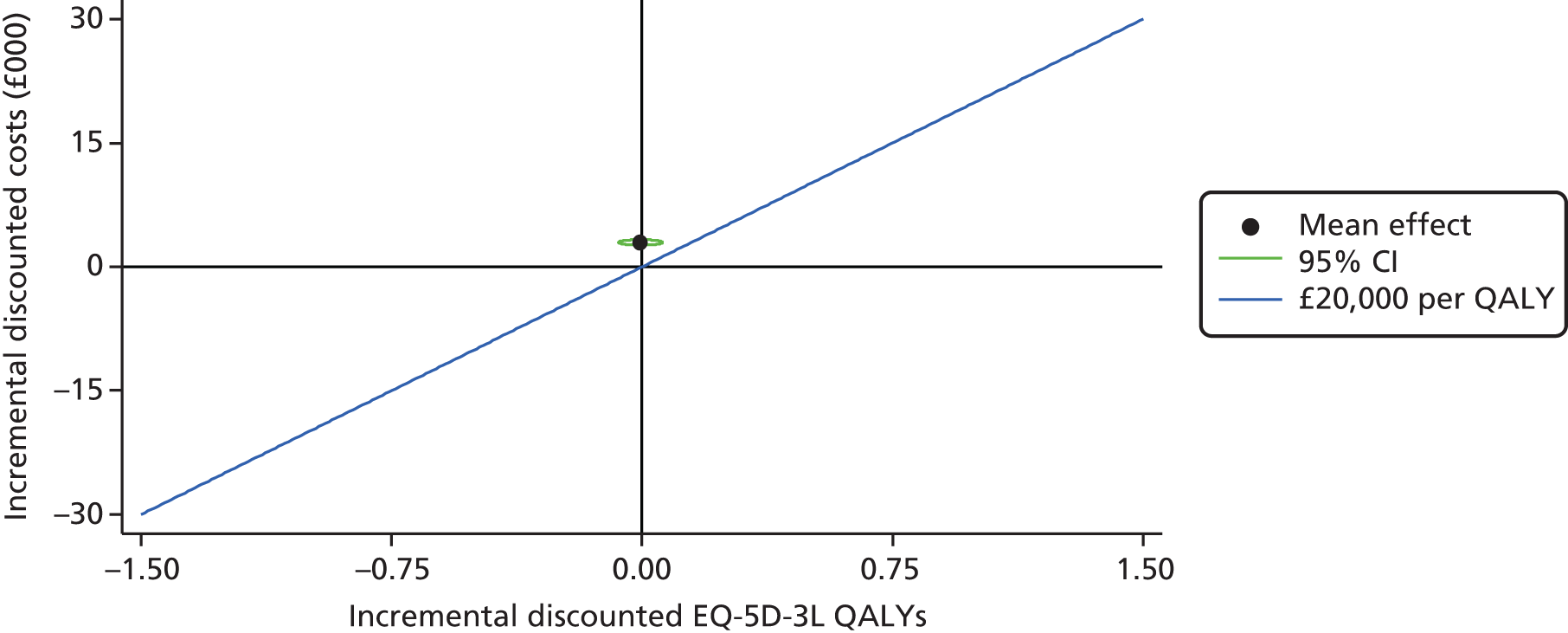

A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of insulin pump therapy in adults with T1DM was conducted by Roze et al. 19 They identified four cost-effectiveness studies in the UK setting, three of which presented an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). 9,14,20,21 The ICERs in these studies were £11,461 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, £25,648 per QALY gained and £37,712 per QALY gained. Two out of the three studies had ICERs that lie within, or below, the £20,000 to £30,000-per-QALY-gained range that NICE usually uses to determine if a health technology is cost-effective. 22 These two studies did receive commercial sponsorship, whereas the study with an ICER of £37,712 was commissioned on behalf of NICE.

Rationale for the trial

We hypothesised that much of the benefit of pumps may come from the retraining and education in intensive insulin management, which allows patients to use pumps safely. 23 In many DAFNE centres, reimbursement for pump use is conditional on patients having attended a DAFNE education course and so some patients undertake DAFNE training with the intention of moving to pump treatment thereafter. It has been our clinical experience that many individuals decide not to switch to the pump after attending a DAFNE course, as they then realise that what they required was training in insulin self-adjustment rather than a different technical way of delivering insulin. Ray et al. 24 found that 69% of those being considered for insulin pump therapy stay on MDI after completing DAFNE. Importantly, trials and observational studies of high-quality training alone (with standard insulin injections) show benefits in blood glucose control, hypoglycaemia and QoL, which are as good, if not better, than those reported after pump therapy. 2,25,26

To our knowledge, no trials in adults, comparing pump treatment with modern MDI, used the same structured training in insulin adjustment, resulting in the added benefit of the pump technology remaining unclear. 23 There was an urgent need to establish this, and identify patients who benefit the most. A RCT was needed to establish these outcomes without bias.

The DAFNE course is a 1-week structured education course, teaching adults with T1DM the skills in insulin self-adjustment and carbohydrate counting. 2 DAFNE courses are currently delivered in more than 70 centres across the UK, with over 37,000 individuals (DAFNE graduates) now trained. We therefore set out to conduct a novel study in which adults waiting for a DAFNE course were randomly allocated to undertake either the standard MDI course or DAFNE incorporating use of pump therapy.

The investigators involved in this work have been undertaking research into other aspects of DAFNE for many years. During recent work funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme grant [Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR)] we measured cost-effectiveness and identified which components of the course are crucial, as well as identifying the factors determining which DAFNE patients managed their diabetes more effectively. 27 This work included funding to pilot a combined DAFNE and pump course, which enabled us to develop a pump curriculum and associated pump-specific resources, ensure that the outcome measures that we wanted to use were feasible and estimate the likely recruitment and retention rates.

We then assembled a study group with expertise in structured T1DM education, pump therapy (having trained in total over 700 pump patients) and health economic assessment of diabetes interventions.

Decision problem: aim of the REPOSE Trial

The aim of our trial was to establish for patients, professionals and those funding the service, the added benefit of using a pump during intensive insulin therapy. We conducted a RCT comparing optimised MDI therapy (using rapid and twice-daily, long-acting insulin analogues) with pump therapy in adults with T1DM, for which both were provided with high-quality structured education (DAFNE).

Research objectives

The project had the following specific objectives:

-

To measure, over 2 years, (1) biomedical, (2) psychosocial (quantitative and qualitative) and (3) adverse event (AE) outcomes. The primary outcome was HbA1c at 2 years, with a minimum clinically significant difference defined as 0.5% (5.5 mmol/mol).

-

To undertake a cost-effectiveness analysis to determine whether or not the marginal benefits of pump therapy over optimised MDI (if demonstrated) are commensurate with the marginal costs, as reflected in an ICER, expressed in terms of a cost per QALY gained that is acceptable to NICE.

-

To conduct a mixed-methods psychosocial evaluation of pump therapy in order to identify factors that predict and/or help explain outcomes on the pump.

Members of the research team have been involved in the NICE appraisal of insulin pumps, have been members of NICE appraisal committees and have a good understanding of what evidence NICE needs. Thus, a further objective was to inform the next NICE reviews of insulin pumps and structured education.

Chapter 2 Overview of evidence base for pump therapy

As noted in Chapter 1, the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness up to June 2007 was reviewed in the two assessment reports for NICE,9,14 both published in this monograph series. This chapter is concerned mainly with studies that have emerged since 2007, but we also provide a complete overview of all of the trials.

Methods

Searches were performed for RCTs that compared the clinical effectiveness of pump and MDI in adults, from June 2007 to the present in MEDLINE and EMBASE (see Appendix 1 for search methods). We checked inclusion lists of seven past systematic reviews. 9,14,18,28–31

Reasons for exclusion included:

-

control group not on MDI

-

pump therapy from diagnosis of diabetes

-

studies in pregnancy

-

paediatric age group

-

studies in type 2 diabetes mellitus

-

pump plus continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) versus MDI plus self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) levels

-

closed-loop trials

-

low-glucose suspend (LGS) pumps

-

all on pump therapy, with different pumps

-

trials of catheter duration in pump therapy

-

not a trial

-

peritoneal infusion

-

protocols

-

pumps infusing substances other than insulin

-

reviews

-

trials of exercise on pump therapy.

During the course of the REPOSE Trial, weekly auto-alerts were run in MEDLINE and EMBASE to identify any emerging research that might affect the trial. The search strategy used was:

-

(insulin and pump*).tw.

-

(CSII or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion).tw.

-

(continuous adj3 insulin adj3 infusion).tw.

-

(subcutaneous adj3 insulin adj3 infusion).tw.

-

1 or 2 or 3 or 4.

-

DAFNE.tw.

-

(dose adjust* adj2 normal eating).tw.

-

6 or 7.

-

5 or 8.

In addition, final searches were performed for RCTs that compared the clinical effectiveness of pump and MDI in adults, from 2007 to 7 January 2016 in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

Trials may be done in selected groups of patients and, as noted in Chapter 1, they are often of short duration. We therefore carried out a search for longer-term observational studies in large groups of patients as a guide to the results of pump therapy in routine care. We selected studies with at least 3 years of follow-up, and ≥ 100 patients, published since January 2008. Older observational studies were reviewed in a previous monograph,9 and the findings summarised as follows:

-

There were much greater improvements in HbA1c in observational studies than reported in the RCTs.

-

There were considerable reductions in severe hypoglycaemia. This may reflect selection for pump therapy of people having particular problems with hypoglycaemia, but that would make the results more applicable to the patients who would get a pump in routine care.

-

The majority of studies showed no increase in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

-

Weight gain was reported but usually minor.

-

There was a reduction in daily insulin dose, which will provide some savings to offset the cost of pump therapy.

-

There were gains in QoL, with comments on items such as flexibility of meal choices and timings and other aspects of lifestyle, and diabetes being easier to manage.

During the course of the REPOSE Trial, we looked for any important developments in:

-

pump therapy

-

structured education

-

new insulins used in MDI or pump

-

the evidence base on QoL on pump and MDI.

Findings

Pump therapy

Table 1 shows the trials of pump therapy against MDI in adults with T1DM, excluding those in pregnancy. There have been only four trials of pump versus MDI with analogue insulin use in both arms, and the longest follow-up period was 24 weeks, which, as we will show in Chapter 3, is insufficient to achieve the full potential of pump therapy.

| Trial | Year of publication | n of participants | Design | Pump | MDI | Duration on pump |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bak et al., 198732 | 1987 | 20 | Crossover | Actrapida | Actrapid and NPH | 6 months |

| Bode et al., 199633 | 1996 | 55 | Crossover | Soluble | 12 months | |

| Bolli et al., 200917 | 2009 | 43 | Parallel | Lisprob | Lispro t.i.d., glargine once | 24 weeks |

| Bruttomesso et al., 200816 – incorporates Maran et al., 200534 | 2008, 2005 | 42 | Crossover | Lispro | Lispro, glargine | 4 months on each |

| Chiasson et al., 198435 | 1984, 1985 | 12 | Crossover | Regular | Regular and Ultralente | 3 months on each |

| DeVries et al., 200236 | 2002 | 55 completed of 79 starters | Started as crossover but reduced to parallel | Aspart | Aspart and NPH | 16 weeks |

| Düsseldorf Study group (Ziegler et al., 199037) | 1990 | 96 | Parallel | Not specified | Mixture of b.i.d. and MDI with regular and NPH | 2 years |

| Haakens et al., 199038 | 1990 | 52 started, 35 completed | Crossover | Soluble | Soluble, Ultralente, isophane | 6 months |

| Hanaire-Broutin et al., 200039 | 2000 | 40 | Crossover | Lispro | Lispro and NPH | 4 months on each |

| Hirsch et al., 200540 | 2005 | 100 | Crossover | Aspart | Aspart and glargine | 4 weeks |

| Home et al., 198241 | 1982 | 10 | Crossover | Actrapid | Actrapid, Ultralente | 10 weeks |

| Hoogma et al., 200642,43 | 2006 | 256 | Crossover | Lispro | Lispro and NPH | 6 months on each |

| Lepore et al., 200344 | 2003 | 32 | Parallel | Lispro | Lispro and NPH | 12 months |

| Nathan et al., 198245 | 1982 | 5 | Crossover | Soluble | NPH and regular | 8–12 weeks |

| Nosadini et al., 198846 | 1988 | 44 | Parallel | Soluble | Soluble t.i.d. and NPH | 1 year |

| Oslo, 1988,47 198648 | 1985–92 | 30 | Parallel | Velosulina | Regular porcine and NPH | 4 years |

| Saurbrey et al., 198849 | 1988 | 21 | Crossover | Actrapid | Actrapid (NovoPena) and NPH | 10 weeks |

| Schiffrin and Belmonte, 198250 | 1982 | 16 | Crossover | Soluble | Three soluble, one NPH | 6 months |

| Schmitz et al., 198951 | 1989 | 10 | Crossover | Velosulin, porcine regular | Velosulin and Insulatarda NPH | 6 months on each |

| Schottenfeld-Naor et al., 198552 | 1985 | 9 | Crossover | Velosulin | Velosulin and Insulatard | 4 months on each |

| Thomas et al., 200715 | 2007 | 14 | Parallel | Lispro | Lispro and glargine | 24 weeks |

| Tsui et al., 200153 | 2001 | 27 | Parallel | Lispro | Lispro and NPH | 9 months |

Table 1 shows that only five trials (assuming that Lepore et al. 44 is a trial – the paper does not mention randomisation but Misso et al. 31 in the Cochrane review say it was a RCT and that it had access to unpublished data) had a duration of ≥ 12 months, and none used analogue MDI. Lepore et al. 44 report HbA1c only at baseline and 12 months. 44 Dahl-Jørgensen et al. 54 reported a steep drop in HbA1c with a plateau after 3 months, but this reduction started in the 2-month run-in period before pump therapy was started.

Four trials15–17,40 used analogue insulin in both arms. The Hirsch et al. 40 trial had patients on pump and MDI for only 4 weeks. The Thomas et al. 15 trial was a pilot, with only seven patients per arm.

One new trial has been published since the last appraisal by NICE: Bruttomesso et al. 16 This trial recruited 42 patients already well controlled on the pump (mean HbA1c 7.4% at randomisation) and randomised them to continuing pump therapy, or to MDI with lispro and glargine. The aim was to see if the need for pump therapy was reduced by the arrival of the analogue insulins. Patients had only 4 months on MDI. Three patients withdrew shortly after starting MDI because of poorer glycaemic control. After 4 months the patients switched to the other treatment arm. The primary outcome was glucose variability, as assessed by SMBG. HbA1c during the study was 7.3% in both arms. There was no difference in the frequency of severe hypoglycaemia, but moderate hypoglycaemia was about 23% less frequent on pump therapy, although the definition of this is not stated in the published study. Glucose variability was 5–12% less on pump therapy, depending on time of day and method used. At the study end, patients could choose between pump therapy and glargine-based MDI. Thirty patients chose pump, five chose MDI and four opted for summer MDI and winter pump. The study was supported by Disetronic and one author worked for the company. 16

The Bolli et al. 17 trial (see Table 1) was published in 2009 but had been available in abstract form for the last assessment report.

Overall, therefore, there was still a poor evidence base with only one new trial, and that being of short duration (4 months on each arm) and limited sample size (only 39 patients).

Observational studies

Bacon et al. 55 reported 10-year follow-up data on 197 patients on pump therapy. The main indications for the pump were recurrent hypoglycaemia and poor control. HbA1c improved by about 0.7% and the number of severe hypoglycaemic episodes by about 80%. Only about 5% discontinued pump therapy.

Beato-Vibora et al. ,56 from King’s College Hospital, looked back over 12 years of pump therapy in 327 patients, with a mean duration of 4.3 years on the pump. An initial reduction in HbA1c of 8 mmol/mol or 0.7% was partially maintained with reduction at year 5 of 0.4%. The proportion of people having frequent mild-to-moderate hypoglycaemia fell from 29% to 12% and the frequency of severe hypoglycaemia was halved.

Bruttomesso et al. ,57 from the Veneto region of Italy, provide a retrospective study of all patients in their region who started pump therapy. Of 138 patients, 20 stopped pump therapy, although mostly in the earlier years. Strict eligibility criteria had to be met, including ‘the technical, physical and intellectual abilities’, plus motivation, stable personality and realistic expectations of pump therapy. All were familiar with MDI and received extra education. HbA1c was 9.3% when starting pump therapy, fell to 7.9 by end of year 1 and was largely sustained there for 7 years.

Carlsson et al.,58 from Sweden, reported results of 272 patients with at least 5.5 years of follow-up. They compared their results with a much larger group on MDI. HbA1c was reduced by 0.42% at 1 year and 0.43% at 2 years, but some of the effect was lost by 5 years when the reduction compared with the MDI group was only 0.2%. 58 A later paper59 reported that the reduction in HbA1c varied by baseline levels, with a small reduction of 0.29% (85% CI 0.11% to 0.47%) in those with baseline HbA1c of 7%, a reduction of 0.39% (85% CI 0.27% to 0.52%) in those with baseline HbA1c of 8% and a larger reduction of 0.50% (85% CI 0.36% to 0.67%) in those with baseline HbA1c of 9%, which would take them nowhere near target.

Cohen et al. 60 compared two cohorts from Melbourne in a non-randomised comparison. One group received pump therapy and the other received intensified MDI. Both were previously on analogue MDI. Among 126 patients on the pump, HbA1c fell by 0.64% at 6 months, but then rose again, with a reduction of about 0.4% at 2 years and about 0.2% at 5 years. The reduction in HbA1c on intensified MDI was smaller: 0.15% at 6 months. This was despite a similar programme of education, based on DAFNE but shorter, in both pump and MDI groups.

Lepore et al.,61 from three Italian centres, compared results in two matched groups of 110 patients on pump therapy and 110 on MDI, followed for 3 years. HbA1c fell by 0.7% in the pump group and this reduction persisted for the 3 years. HbA1c fell by 0.3% in the MDI group at 3 years.

Nixon et al. 62 reported a study of 35 patients on pump therapy. There was an initial fall of 1.7% in HbA1c but by 5 years the reduction was only 0.9%. However, this reflected a mix of results, with one-third of patients reducing HbA1c by 2.2% and maintaining it there, whereas others had no change on the pump or had an initial reduction not sustained.

Orr et al. ,63 from Ontario, report results among 235 patients on pump therapy. The overall baseline HbA1c was 8.7%, which was reduced to 7.5% after 6 months on the pump, after which it drifted up again to 8.2% in years 3–10. In 39 patients who were followed for 10–15 years, the mean HbA1c was 8.03%. However, two groups of patients who started with high baselines (8.5–10% and > 10%) reduced their HbA1c to about 8% by 8–10 years.

Quiros et al. ,64 from Barcelona, followed 151 patients on pump therapy for 5 years. Overall, HbA1c was reduced from a mean of 8.0% at baseline to 7.8% at 5 years. However, in the 61% of patients who started pump therapy because of poor glycaemic control, HbA1c fell from 8.4% at baseline to 8.0% at 5 years. There was a marked reduction in severe hypoglycaemia. 64

Rosenlund et al. 65 from Denmark looked at the effects of 4 years of pump therapy on albuminuria compared with an unmatched group on MDI. On pump therapy, HbA1c fell from 8.4% to 7.8%, maintained to 4 years. 65

Steineck et al. 66 from Sweden reported mortality data from a cohort of 18,168 people with T1DM in Sweden, of whom 13% were on pump therapy. Total mortality at 7 years was 6% in the pump group and 8% in the MDI group. There were many small differences that would increase the risk in the MDI group – more hypertension, more on lipid-lowering drugs, more with low physical activity, more smokers and more with low education levels. Steineck et al. 66 used propensity matching to adjust for the differences, and concluded that those on pump therapy had a 0.73 hazard ratio for total mortality. However, there could have been confounding factors for which they could not allow.

Most long-term studies show a disappointing waning of the initial HbA1c improvement. Perhaps there is a case for educational updates. In a small trial with only 23 patients, Carlone et al. 67 randomised patients on long-standing pump therapy to standard care or to six educational weekly group meetings on advanced features of the pump, carbohydrate counting and other aspects of diet. After 6 months, the intervention group had reduced their HbA1c by 1%. The control group did not change.

New developments

The main developments in pump therapy have been the use in combination with CGM systems, of which there are two forms that are now relevant to the pump. The first is when the CGM device is integrated with the pump, which means that it sends glucose results to the pump every 5 minutes or so, from a sensor just under the skin. Strictly speaking this means that the glucose result is for the level in interstitial tissue, not in the bloodstream, but the two are closely related. With the integrated CGM system, the pump can send alarms to the user, following which they can take action. This helps users to avoid hypoglycaemic episodes, but some find the alarms to be a nuisance and may disable the alarms. False alarms are not uncommon.

Four trials of CGM compared the pump with CGM against MDI with SMBG, which confounds things [Hermanides et al. (Eurythmic trial),68 Lee et al. ,69 Peyrot and Rubin,70 Bergenstal et al. (STAR-3)71]. The durations of these trials were only 6, 3.5, 3.7 and 12 months, respectively.

Continuous glucose monitoring would have implications for the use of pump therapy rather than MDI if the effectiveness of CGM differed between the two forms of treatment. Garg et al. 72 found that the effects of real-time CGM in reducing HbA1c and hypoglycaemia were similar in two matched groups on MDI and pump.

More recently, the Medtronic Veo (Medtronic, Watford, UK) has been introduced, which has a facility to link with a CGM system and suspend insulin infusion (the LGS facility) if the glucose level goes too low, for up to 2 hours. This means that the pump can take action. In practice, most suspensions are for much less than 2 hours because the wearer takes action. However, at night when the wearer is asleep, this may not happen. 73

There have been two trials of the Veo suspend pump. In the ASPIRE (Automation to Simulate Pancreatic Insulin Response) trial74 in the USA and Canada, the recruits were familiar with pump therapy. They had a 2-week run-in period and were selected for the trial if they had nocturnal hypoglycaemia (defined as plasma glucose < 3.7 mmol/l) at least twice in that period. They also had to be prepared to wear the sensors at least 80% of the time. They were randomised to the Veo with its LGS facility, or to the Medtronic Paradigm Revel, which has integrated CGM but no LGS action. The trial was sponsored by Medtronic, and Medtronic staff were involved in data analysis and editorial assistance. 74 The trial showed no difference in HbA1c after 3 months, perhaps not surprisingly because the baseline HbA1c was very good at 7.2% or 55 mmol/mol. There was reduced hypoglycaemia, especially nocturnal. In the Veo group, 111 of 121 patients had at least one nocturnal suspension on the pump that lasted 2 hours. A 2-hour suspension does not lead to significant ketosis. QoL measures, EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and the Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey (HFS) score, showed no difference between the arms of the trial. There were only four severe hypoglycaemic episodes, none in the Veo arm.

So the main benefit of the Veo LGS over the integrated CGM pump system is reduction of nocturnal hypoglycaemia. There is quite a large extra capital cost for the device (£2692) with an annual cost, including consumables, of £4862. This will make it difficult to prove cost-effectiveness. The group in which the Veo is most likely to be cost-effective will be patients with recurrent severe hypoglycaemia, but that group is covered by existing NICE guidance on the pump and is not recruited to the REPOSE Trial.

The other trial of the Veo was by Ly et al. 75 in Australia. This trial recruited mainly children and adolescents, with only 31% aged > 18 years. Patients were selected on the basis of impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia. They had been on pump therapy for an average of 4 years. They were randomised to the Veo suspend pump or to stay on their previous pump and use SMBG – not CGM. This immediately raises a problem because the Veo arm has both the LGS facility and CGM. It would have been better to have CGM in both arms. A more serious problem with the study is that, despite reasonable numbers (49 to pump plus SMBG, 45 to the Veo) and randomisation, there was a very marked baseline mismatch in previous severe (defined as seizure or coma) and moderate (defined as requiring assistance) hypoglycaemia, with a rate of 130 per 100 patient-months [95% confidence interval (CI) 111 to 150 patient-months] in the Veo group, but only 21 per 100 patient-months in the control arm (95% CI 14 to 30 patient-months). At study end after 6 months, the rate of moderate and severe hypoglycaemic episodes was 28.4 in the Veo group and 11.9 in the control arm. However, these figures were reversed when the authors adjusted for baseline rates, from 28.4 to 9.5, and from 11.9 to 34.2, all per 100 patient-months. There were no significant changes in HbA1c, but both groups started with quite reasonable levels of 7.6% and 7.4%.

The analysis by Ly et al. 75 has been strongly criticised by the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare [Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG)], as reported by Heinemann and Hermanns. 76

The Veo has been appraised by the NICE Diagnostics Assessment Programme. Their guidance is shown in Box 1.

1.1 The MiniMed Paradigm Veo system is recommended as an option for managing blood glucose levels in people with type 1 diabetes only if:

-

they have episodes of disabling hypoglycaemia despite optimal management with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and

-

the company arranges to collect, analyse and publish data on the use of the MiniMed Paradigm Veo system (see section 7.1).

1.2 The MiniMed Paradigm Veo system should be used under the supervision of a trained multidisciplinary team who are experienced in continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and continuous glucose monitoring for managing type 1 diabetes only if the person or their carer:

-

agrees to use the sensors for at least 70% of the time

-

understands how to use it and is physically able to use the system and

-

agrees to use the system while having a structured education programme on diet and lifestyle, and counselling.

1.3 People who start to use the MiniMed Paradigm Veo system should only continue to use it if they have a decrease in the number of hypoglycaemic episodes that is sustained. Appropriate targets for such improvements should be set.

1.4 The Vibe and G4 PLATINUM CGM system shows promise but there is currently insufficient evidence to support its routine adoption in the NHS for managing blood glucose levels in people with type 1 diabetes. Robust evidence is needed to show the clinical effectiveness of using the technology in practice.

1.5 People with type 1 diabetes who are currently provided with the MiniMed Paradigm Veo system or the Vibe and G4 PLATINUM CGM system by the NHS for clinical indications that are not recommended in this NICE guidance should be able to continue using them until they and their NHS clinician consider it appropriate to stop.

Reproduced with permission from NICE. © National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2016. Integrated sensor-augmented pump therapy systems for managing blood glucose levels in type 1 diabetes (the MiniMed Paradigm Veo system and the Vibe and G4 PLATINUM CGM system). Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg21. NICE guidance is prepared for the NHS in England, and is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE has not checked the use of its content in this article to confirm that it accurately reflects the NICE publication from which it is taken.

The patient group in which it has been recommended is different from that in the REPOSE Trial, and so the arrival of the Veo and its LGS facility has no implications for the implementations of the results of the REPOSE Trial.

Findings: structured education

The DAFNE course has changed little since the original trial published in 2002. 2 A programme of work has included a trial comparing the 5-day course in 1 week with 1 day a week for 5 weeks, which found little difference in outcomes. 78

One finding from the DAFNE research programme has been that many patients doing the DAFNE course, in preparation for going on to pump therapy, no longer need to progress to a pump after completing the course. Ray et al. 24 reported that after DAFNE education, 69% of patients previously being considered for pump therapy could remain on MDI.

However, another study from the programme (Mansell et al. 79) found that some patients who had been through DAFNE education still benefited from pump therapy in terms of a reduction in stress [measured by the PAID (Problem Areas in Diabetes Questionnaire) score] and improved glycaemic control at 12 months of follow-up. This may have been because individuals who progress to the pump after doing a DAFNE course have higher pre-course stress levels. 80

Conversely, attendance at DAFNE courses sometimes identifies individuals for whom pump therapy is indicated because of a troublesome dawn phenomenon.

Research into DAFNE education has also been undertaken by the Irish DAFNE group. 81 They carried out a large randomised trial of group follow-up compared with individual clinic visits for patients who had completed the DAFNE course. The intervention group received group education at 6 and 12 months after DAFNE, following a semistructured curriculum, whereas the control group had individual clinic appointments with doctor, nurse or dietitian. The additional education conferred no benefit over individual clinic visits.

The Irish DAFNE group also carried out a qualitative study to identify factors that influenced how well DAFNE graduates incorporated what they had learned into long-term daily living. 82 They identified four themes:

-

Being empowered, and feeling able to manage their diabetes, which some people did not manage to do.

-

Embedded knowledge, which increased over time, for example as patients got better at carbohydrate counting.

-

Maintaining motivation, including coping with uncertainty. The researchers commented that this was most marked at 6 months but improved later. Reducing the risk of complications was a strong motivation factor.

-

Continued support from health-care professionals.

The Australian OzDAFNE group83 also looked at psychological changes after the DAFNE course, and found increases in what they called ‘mastery/control’ and a reduction in diabetes-related distress. One of their key points was that the mean duration of diabetes in their participants was 18 years, but they had low self-assessment of their ability to manage their diabetes, so they recommended that referral to DAFNE courses should not be restricted to recently diagnosed patients.

Findings: new insulins

Some new basal insulins have been introduced, including degludec (Tresiba, Novo Nordisk, Gatwick, UK) and glargine 300 (Toujeo, Sanofi-Aventis, Guildford, UK). However, these are very long-acting basal insulins, and may not have the flexibility in dosing that is needed in MDI for T1DM, and with no data to date about how these might be used effectively in patients with T1DM who are undergoing structured education.

Newer short-acting insulins include ‘fast aspart’, which, in pump therapy, is reported to have a faster glucose-lowering effect but with the same effect overall. The implications for glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia were not reported by Zijlstra et al. 84

Findings: quality of life

Past reviews found a disappointingly low amount of evidence on QoL. This has implications for cost-effectiveness analysis. The Thomas et al. 15 pilot trial of pump therapy versus analogue MDI reported QoL as measured by the Diabetes Quality of Life questionnaire (DQOL) but found no difference. With only seven patients in each arm this may not be surprising. The 2008 health technology assessment (HTA)9 for NICE identified 48 observational studies of pump therapy, but only one reported QoL in adults, and it was a before-and-after study in which patients switched to the pump from conventional insulin therapy, not analogue MDI.

One observational study85 published since then has compared QoL. This study85 by the EQuality1 Study Group from Italy, has both strengths and weaknesses. It was a very large case–control study, with 1341 people with T1DM from 62 clinics, with 481 on the pump and 860 on MDI. The MDI patients came from centres both with and without pump services. Reliable instruments were used: the diabetes-specific quality of life scale (DSQOL) for QoL, Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) for treatment satisfaction and Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) for health status. Eighty-four per cent of patients on the pump had been on it for > 1 year; 90% of the MDI group were on glargine-based MDI with the rest using NPH. All of the MDI patients had been on at least four insulin injections a day for > 6 months. The pump and MDI groups were well matched on some variables, but there were striking differences in carbohydrate counting (56% of pump group vs. 40% on MDI) and self-adjustment of insulin doses (80.5% vs. 66.5%), suggesting a marked educational imbalance.

Some DSQOL results were slightly better among the pump group, but this was statistically significant only for diet restrictions (65.5 vs. 60.8; p = 0.0003). DTSQ scores were better on pump (30.2 vs. 26.2; p < 0.0001). SF-36 scores were better on MDI, but in most domains, not statistically significantly so. However, the authors report that multiple regression analysis (details not provided, but adjusted for clinical factors including complications, which were more common in the pump group) showed that the pump group had significantly better scores in DSQOL diet, daily hassles and fear of hypoglycaemia. No differences were found between NPH and glargine-based MDI. The study was supported by Medtronic.

The lack of difference between the QoL effects of NPH and glargine-based MDI may not apply to detemir (Levemir, Novo Nordisk, Gatwick, UK)-based MDI, because detemir given twice daily may provide a more flexible lifestyle than once-daily glargine.

The Five Nations Study43 was a good-quality trial completed before long-acting analogues became available. It compared pump therapy with lispro and NPH-based MDI, but, unusually, the NPH insulin could be given up to four times a day and only 41% of patients had it once daily, with 32% getting it twice a day and 23% thrice daily. The study reported QoL using DQOL and Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12). With SF-12 there was no difference in physical state but the pump group did better on mental health. The end of trial DQOL was 75 on pump and 71 on MDI, a small but statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). The difference reflected gains in treatment satisfaction, flexibility of eating and lifestyle, and reduced worry.

Conclusions

The evidence base for pump therapy compared with modern MDI is still quite sparse, and REPOSE has more participants than in all of the previous trials put together, even if we include the Hirsch et al. trial40 with its 100 patients on very short duration of 4 weeks on each therapy. If we exclude the Hirsch et al. trial,40 REPOSE has more than double the number in the other three trials, which had a total of 99 patients. 15–17 It also recruited a different group of patients from most previous trials, as it excluded those who met the NICE criteria for pump therapy. So it recruited patients in a band of need below those for whom the pump has been approved by NICE.

Chapter 3 Methods

Methods for the randomised controlled trial

The trial protocol was published in a separate paper. 86

Study design

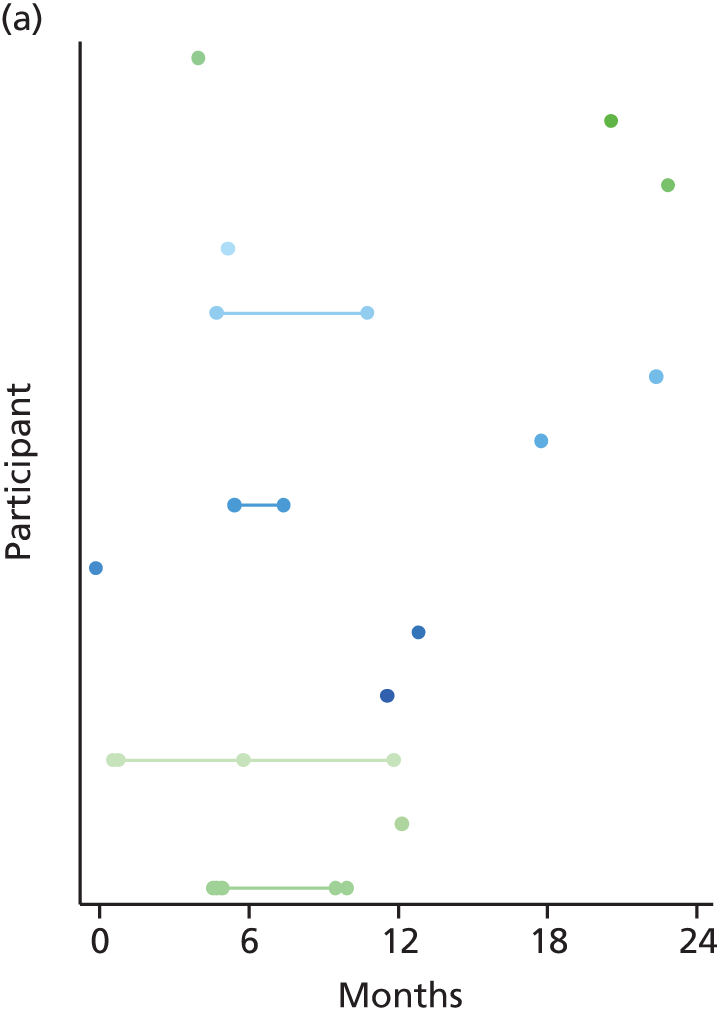

The REPOSE Trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, parallel-group, open-label, confirmatory cluster RCT. Participants were allocated a place on a week-long DAFNE course, depending on their availability to attend the course. The course (cluster element) groups were then randomly allocated in pairs to either pump or MDI treatment, with allocation concealed. A cluster design was chosen because of the impracticality of randomising individuals and then finding suitable times for that participant to attend a course of the correct allocation. 23 Such an approach was more likely to have resulted in significantly higher attrition rates pre course. Following the course, participants received the trial treatment for 2 years and outcome measures were collected at 6, 12 and 24 months post course. Outcome measurement was not blinded (see Data collection).

Approvals obtained

The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) North West, Liverpool East, on 26 April 2011 (REC reference number 11/H1002/10). Each participating centre gave UK NHS Research and Development (R&D) approval (see Appendix 2). The protocol received Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) clinical trials authorisation on 26 May 2011 [European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) reference no: 2010-023198-21].

Setting

The trial was conducted in eight secondary care diabetes centres in Sheffield, Cambridge, Dumfries and Galloway, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Harrogate, London and Nottingham (see Table 11). Participating centres all had experience in delivering high-quality structured education using DAFNE and had variable levels of experience delivering pump therapy; most were established pump centres but some were relatively new to pump therapy. Nottingham was a reserve centre, activated midway through the trial. The seven centres involved from the outset were asked to recruit 40 participants to three pump and three MDI courses (5–8 patients on each course) over 11 months. Owing to a higher than anticipated dropout rate prior to the DAFNE courses we then recruited to an additional pair of courses at Harrogate, and a pair of courses at the reserve centre, Nottingham.

Participants

Participants were eligible for the trial if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

had T1DM for at least 12 months at the time of the DAFNE course

-

were fluent in speaking, reading and understanding English

-

were willing to undertake intensive insulin therapy with SMBG, carbohydrate counting and insulin self-adjustment

-

had no preference for either pump or MDI, and were happy to be randomised

-

were currently using, or willing to switch to, insulin detemir

-

had a need for structured education to optimise diabetes control.

Furthermore, participants were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

-

had already completed a diabetes education course

-

used a pump in the previous 3 years (defined as > 2 weeks’ use in the last 3 years) or had strong clinical indications for pump therapy in the view of the investigator

-

had renal impairment with a chance of needing renal replacement therapy within the next 2 years (enrolment staff to check that creatinine levels not > 200 µmol/l).

-

had uncontrolled hypertension (diastolic blood pressure of > 100 mmHg and/or sustained systolic level of > 160 mmHg)

-

had a history of heart disease within the past 3 months

-

had severe needle phobia (severity of phobia assessed, considering if the phobia might preclude full participation in either treatment arm or influence the participant’s preference for pump therapy)

-

had a current history of alcohol or drug abuse

-

had serious or unstable medical or psychological conditions that are active enough to preclude the participant safely taking part in the trial (based on investigatory judgement)

-

had recurrent episodes of skin infections

-

were pregnant or planning to become pregnant within the next 2 years

-

had taken part in any other investigational clinical trial during the 4 months prior to screening

-

had any other issue that might have precluded them from satisfactory participation in the study based on investigatory judgement

-

were unable to give informed consent.

Interventions

Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating with multiple daily injection

Participants on the MDI arm attended a standard DAFNE structured education course, described in detail elsewhere. 2 Courses are conducted over 5 consecutive days, providing an average of 38 hours of structured education, delivered to groups of 5–8 adults, aged ≥ 18 years, in an outpatient setting. Courses are delivered by diabetes specialist nurses and dietitians who attend an educator training course, the DAFNE education programme, a seven-part programme consisting of 105 hours of structured training.

The DAFNE curriculum uses a progressive modular-based structure to improve self-management in a variety of medical and social situations. Content is designed to deliver key learning topics at the appropriate time during the week. In this way, knowledge and skills are built up throughout the course with active participant involvement and problem-solving as key methods of learning. The key modules are: ‘What is diabetes?’, ‘Food and diabetes’, ‘Insulin management’, ‘Management of hypoglycaemia’ and ‘Sick day rules’. Lesson plans give guidance on timing and a student activity section serves to give an idea of expected responses. Each meal and snack during the course is used as an opportunity to practise carbohydrate estimation and insulin dose adjustment.

Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating with pump

Participants on the pump arm attended a modified DAFNE course, which had been tested in a pilot study, previously published. 27 The 5-day structure of the standard adult DAFNE course was maintained while incorporating the additional skills and learning outcomes that were considered necessary to use pumps successfully. The principles of insulin dose adjustment taught on the standard adult course were maintained. 23 The need to introduce ‘pump skills’ required the addition of a pre-course group session, delivered 1–3 weeks before the DAFNE course. This session gave participants the opportunity to learn about the basics of insulin pump therapy, including how to set up the pump, so that they could practise using it with saline before starting on insulin at the beginning of the course. The session included the theory of pump therapy, understanding cannulas and infusion sets, skin care, pump maintenance and the advantages and disadvantages of the insulin pump. Participants switched to insulin on the evening before the DAFNE course or on the first day of the course.

Ongoing treatment

After attending the DAFNE course, participants received the trial treatment for 2 years from the secondary care service. All of the participants in both groups were invited to an additional DAFNE follow-up group session at 6 weeks post course, which is standard for DAFNE course attendees.

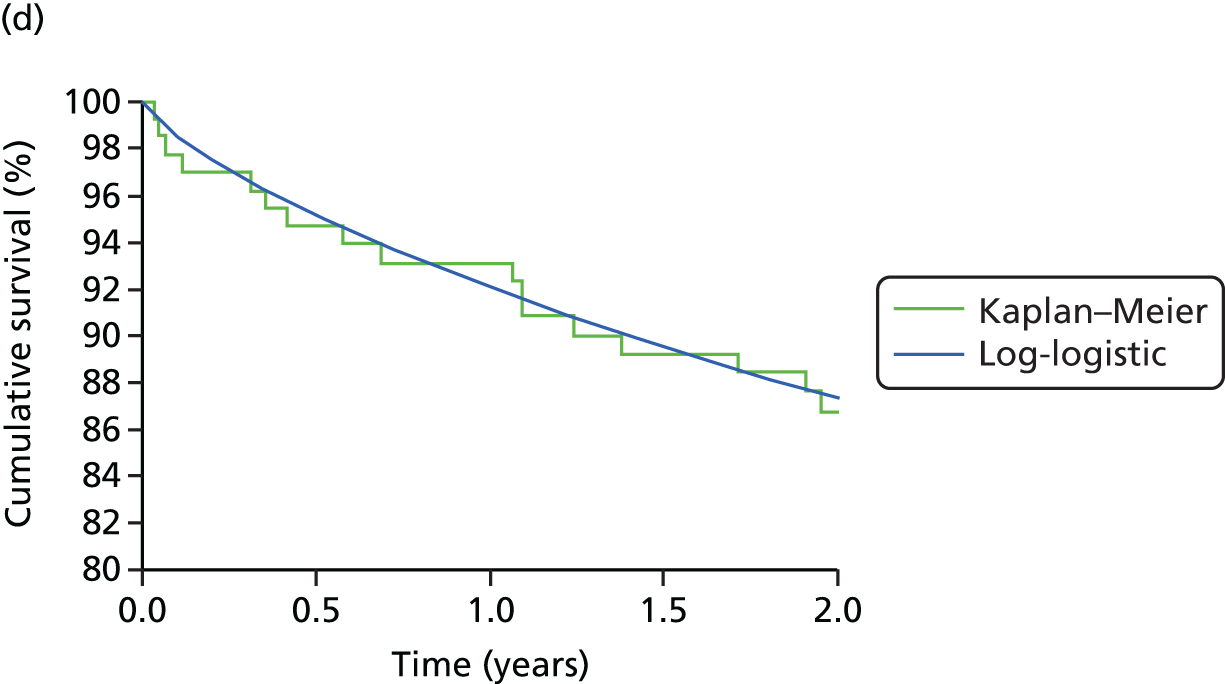

Multiple daily injection participants used a combination of quick-acting insulin analogues and twice-daily injections of insulin detemir. Pump participants used a Medtronic Paradigm® VeoTM insulin pump (Model X54) with short-acting analogue insulin, as in a meta-analysis87 this was shown to lower HbA1c to a greater extent than traditional soluble insulin. As insulin is already marketed and licensed for use, and as the participants were already accessing insulin through prescription on a regular basis, there was no need to change how the insulin was accessed for the trial – participants collected insulin from their pharmacist as normal.

The insulin pumps include, as standard, a Medtronic Bolus Wizard (Medtronic, Watford UK) to aid calculation of insulin doses. In order to reduce any potential bias, MDI participants were also given access to a bolus calculator (Accu-Chek Aviva Expert Bolus Advisor System, Roche Diagnostics Ltd, Burgess Hill, UK).

Fidelity testing (FT) of pump courses was undertaken in order to assess whether or not courses were delivered in accordance with DAFNE philosophy and principles, and that the educators had the necessary skills to deliver these principles. The results of the FT are reported in Chapter 5. Standard DAFNE courses were not tested, as there is a rigorous quality assurance programme of MDI courses in standard care.

Treatment was changed (pump to MDI or MDI to pump) at the discretion of the local principal investigator (PI) if self-management of diabetes had become ineffective and was considered a risk to the individual. If the participant failed to attend the pump course then they were withdrawn from pump treatment.

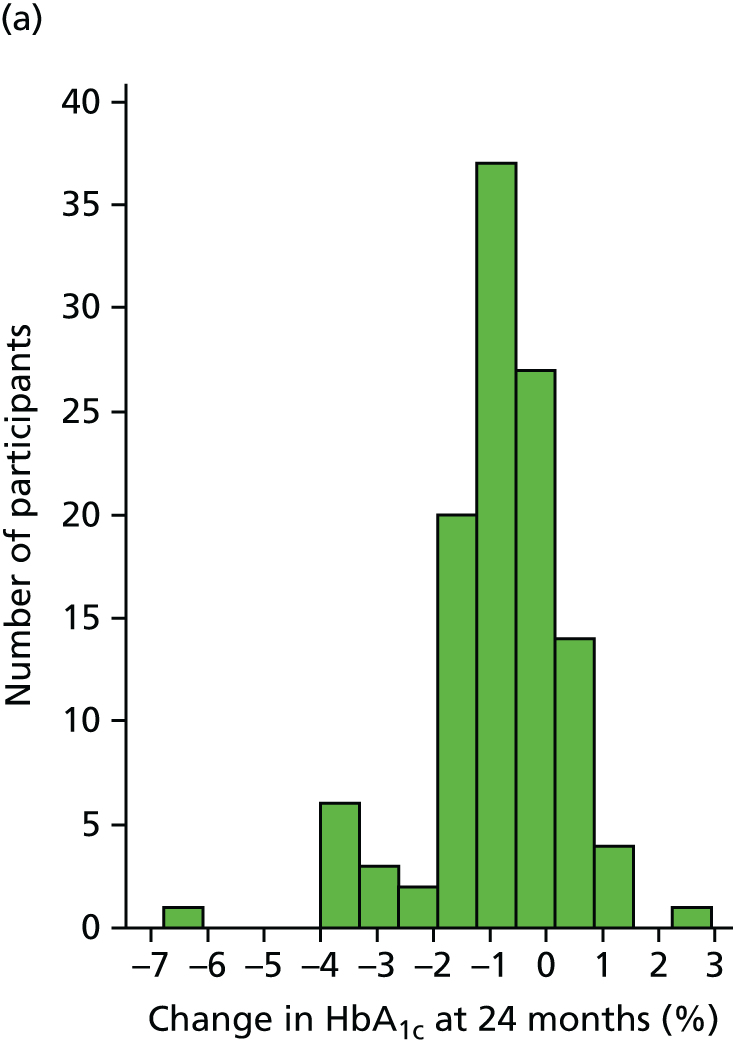

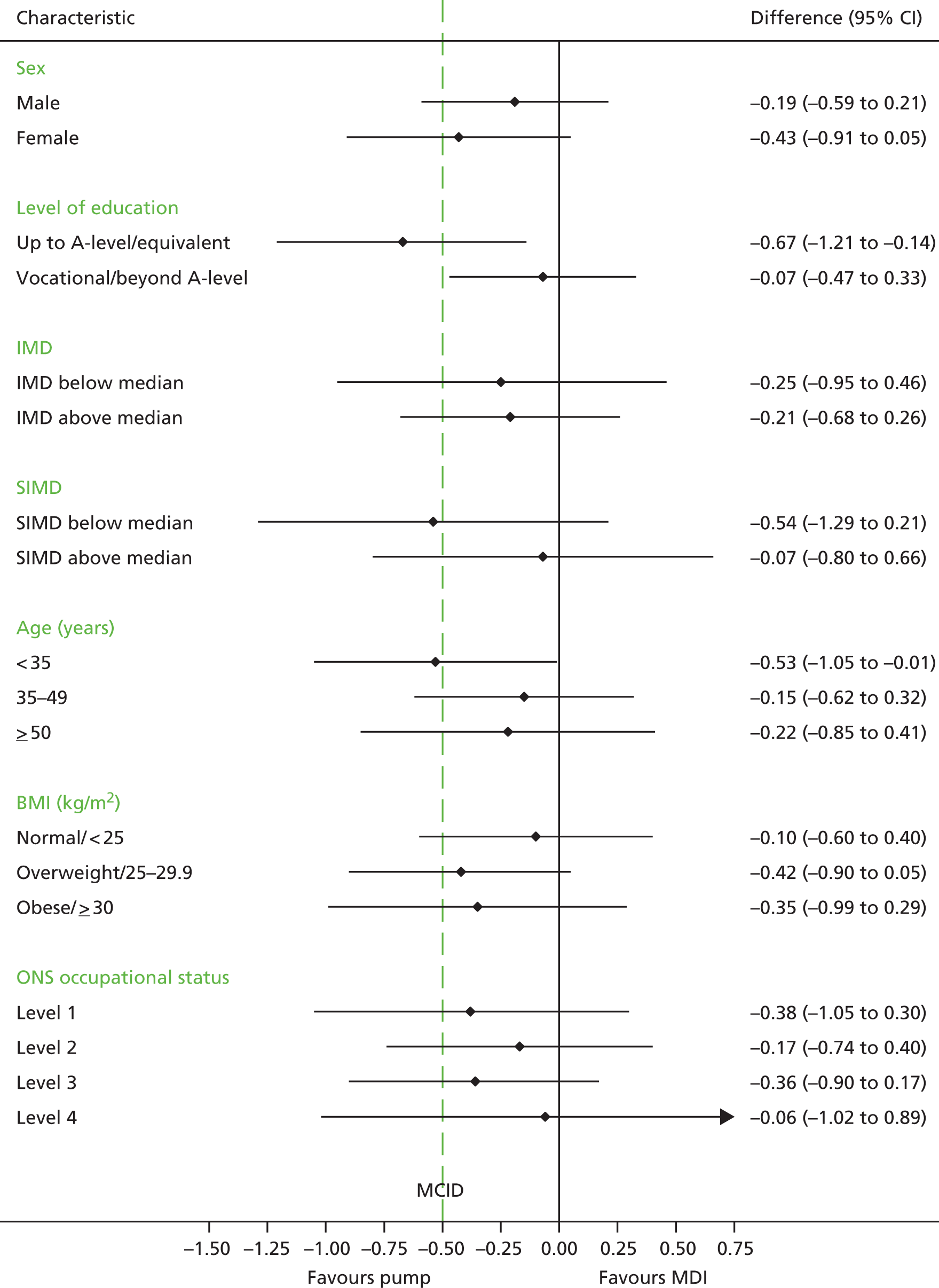

Primary outcomes

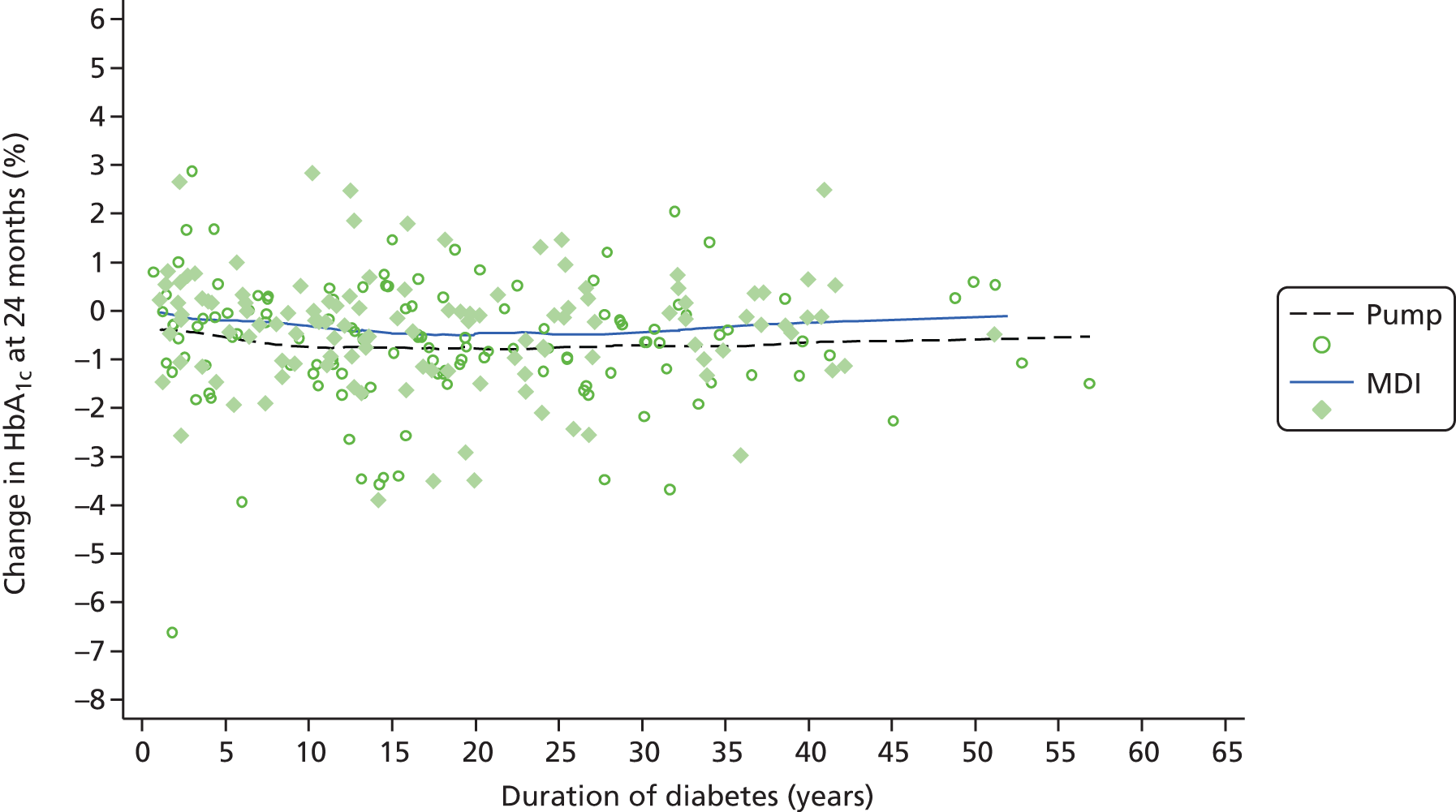

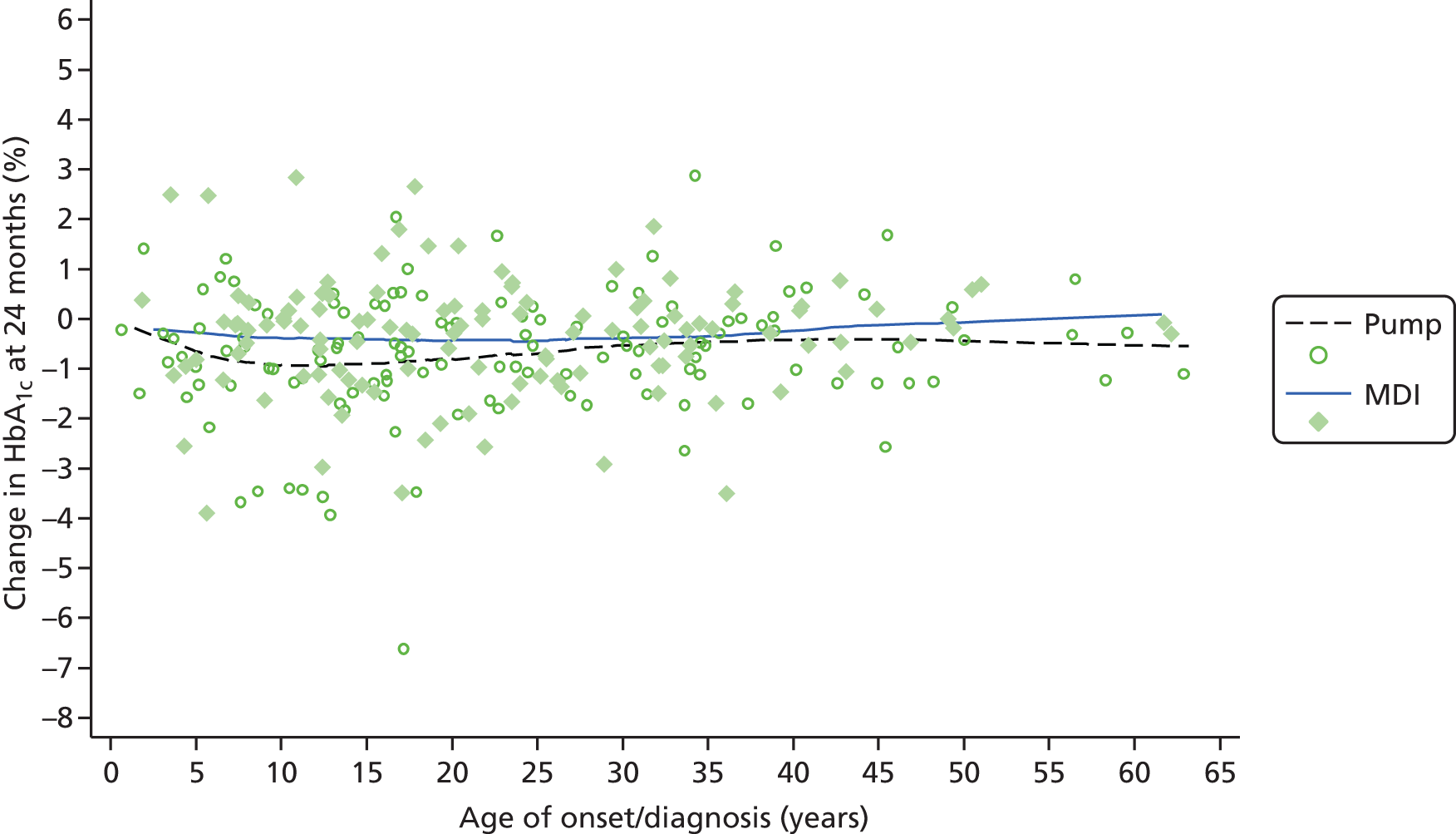

The main primary end point was the change in HbA1c at 24 months, in those participants whose baseline HbA1c was ≥ 7.5% (58 mmol/mol). The key secondary end point was the proportion of participants reaching the NICE target of a HbA1c level of ≤ 7.5% (58 mmol/mol) at 24 months (of all participants).

Glycated haemoglobin is the accepted gold standard measure of glycaemic control and provides a measure of efficacy. Most health economic models of T1DM estimate the cost-effectiveness by primarily modifying HbA1c levels, which subsequently affect the risk of diabetic complications. 88 However, it is important to note that HbA1c may not have fallen in patients who entered the trial with low baseline levels of HbA1c, but who might have been experiencing frequent hypoglycaemia or wished to increase dietary freedom. Success for such individuals would be a HbA1c level that is maintained, or even rises slightly, with a reduction in the frequency of hypoglycaemia. 23 We included such patients as they could provide important information about QoL and the potential of pump therapy to reduce rates of hypoglycaemia. However, as their glycaemic control may not alter, including their HbA1c data would have reduced our statistical power to establish improvement in our primary end point. We therefore powered the trial on the number of participants with a baseline HbA1c of ≥ 7.5% (58 mmol/mol) and in whom a fall would reflect a worthwhile improvement in glycaemic control. We ensured standardisation by testing HbA1c in a central laboratory.

Exploratory outcomes on the primary end points

The primary outcome and key secondary outcome were also evaluated at 6 and 12 months in order to explore the short- and medium-term effects of the intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were evaluated in all participants and were measured at 6, 12 and 24 months. Blood and urine samples for secondary outcomes were tested in local laboratories.

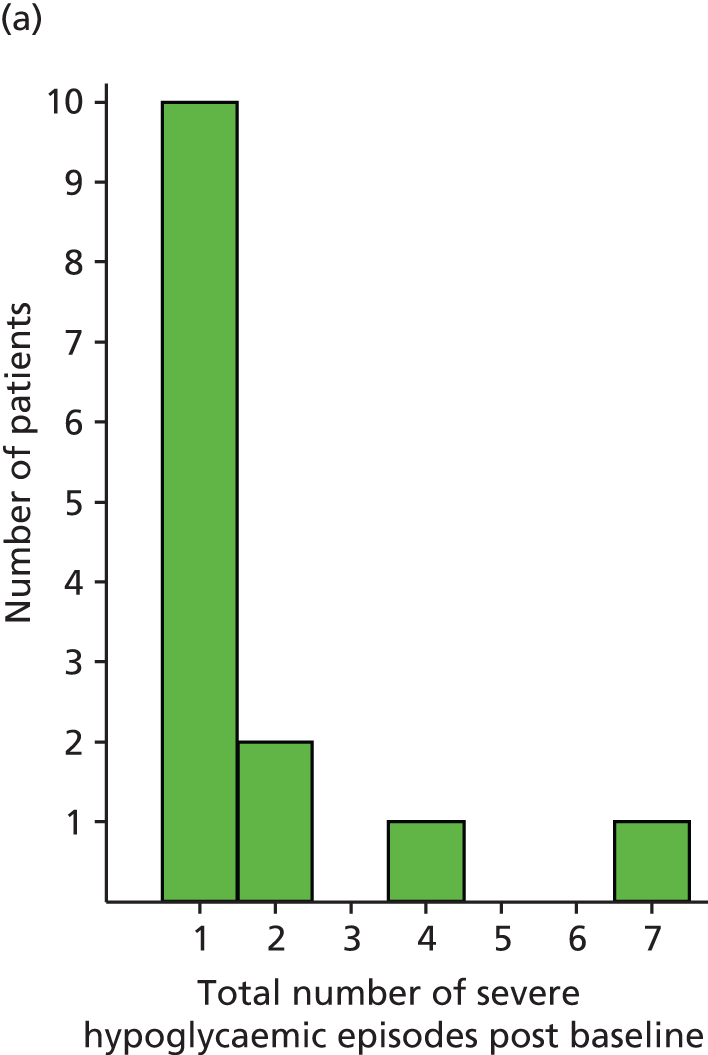

Hypoglycaemia

We recorded episodes of both moderate and severe hypoglycaemia and specifically recorded episodes at night (those occurring between 23.00 and 07.00). We used a standard definition of severe hypoglycaemia,89,90 being ‘an episode leading to cognitive impairment sufficient to cause either coma or requiring the assistance of another person to recover’. The number of severe episodes are reliably recorded by patients for up to 1 year. 91

During the last NICE appraisal of pump therapy, the question of the impact of moderate hypoglycaemia was raised. 13 The modelling had included only severe hypoglycaemia, and the point was made that moderate hypoglycaemia, sufficient to interrupt activities of daily living, might, because of greater frequency, have a more cumulative effect on QoL than severe hypoglycaemia. We therefore also recorded rates of moderate hypoglycaemia in an attempt to increase power and identify the ability of pumps to reduce rates of hypoglycaemia. With no standard definition of moderate hypoglycaemia, the Trial Management Group (TMG) agreed to define these as ‘any episodes which could be treated by that individual, but where hypoglycaemia caused significant interruption of current activity, such as having caused impaired performance or embarrassment or having been woken during nocturnal sleep’. As these episodes are more frequent, reliable recall of such events is unlikely to be sustained for more than a few weeks. We therefore asked participants to record the number and timing of moderate episodes over the 4 weeks prior to each follow-up visit. We used this approach successfully to record the frequency of mild episodes in a recent epidemiological study of hypoglycaemic burden in diabetes. 89

Insulin dose and body weight

Pump treatment may result in the use of less insulin, leading to a favourable effect on body weight. We recorded total insulin dose at each time point and calculated units per kilogram of body weight.

Lipids and proteinuria

A recent study61 reported little difference in HbA1c on pump therapy compared with MDI but found less progression to microalbuminuria in the pump group, and also lower cholesterol levels. We measured high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and total cholesterol (TC). Proteinuria was measured using the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR).

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis was measured throughout the trial through the assessment of serious adverse events (SAEs). 23 As all significant episodes of ketosis require hospital admission, we were confident in capturing all of the relevant episodes.

Quantitative psychosocial outcomes

The quantitative psychosocial outcomes are described later (see Outcomes).

Sample size

It is generally accepted that a difference of 0.5% (5.5 mmol/mol) in HbA1c is clinically worthwhile. To detect this difference with a standard deviation (SD) of 1% at 80% power and 5% two-sided significance using a t-test requires 64 patients per group, for subjects > 7.5% HbA1c. To allow for a clustering effect of the educators, with an average of seven patients per DAFNE group and a within-course intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05, common in diabetes care, the sample size increases to 84. Allowing for a 10% dropout over 24 months, the sample size per group becomes 93. Audit of the DAFNE database showed us that 75% of subjects had a HbA1c of ≥ 7.5%, therefore requiring 124 subjects per group and 248 in total. We planned to recruit 280 subjects, which increased the power to 85% but allowed for some variation in dropout rates and the proportion of patients with HbA1c ≥ 7.5%. However, monitoring of baseline data showed that the actual proportion of participants with HbA1c ≥ 7.5% was around 90% rather than 75%. A modelling exercise undertaken during recruitment, with conservative estimates of 85% (HbA1c ≥ 7.5%) and dropout rate of 15%, suggested that the trial would require at least 240 participants with primary outcome data at 2 years in order to preserve power of at least 85%. 23

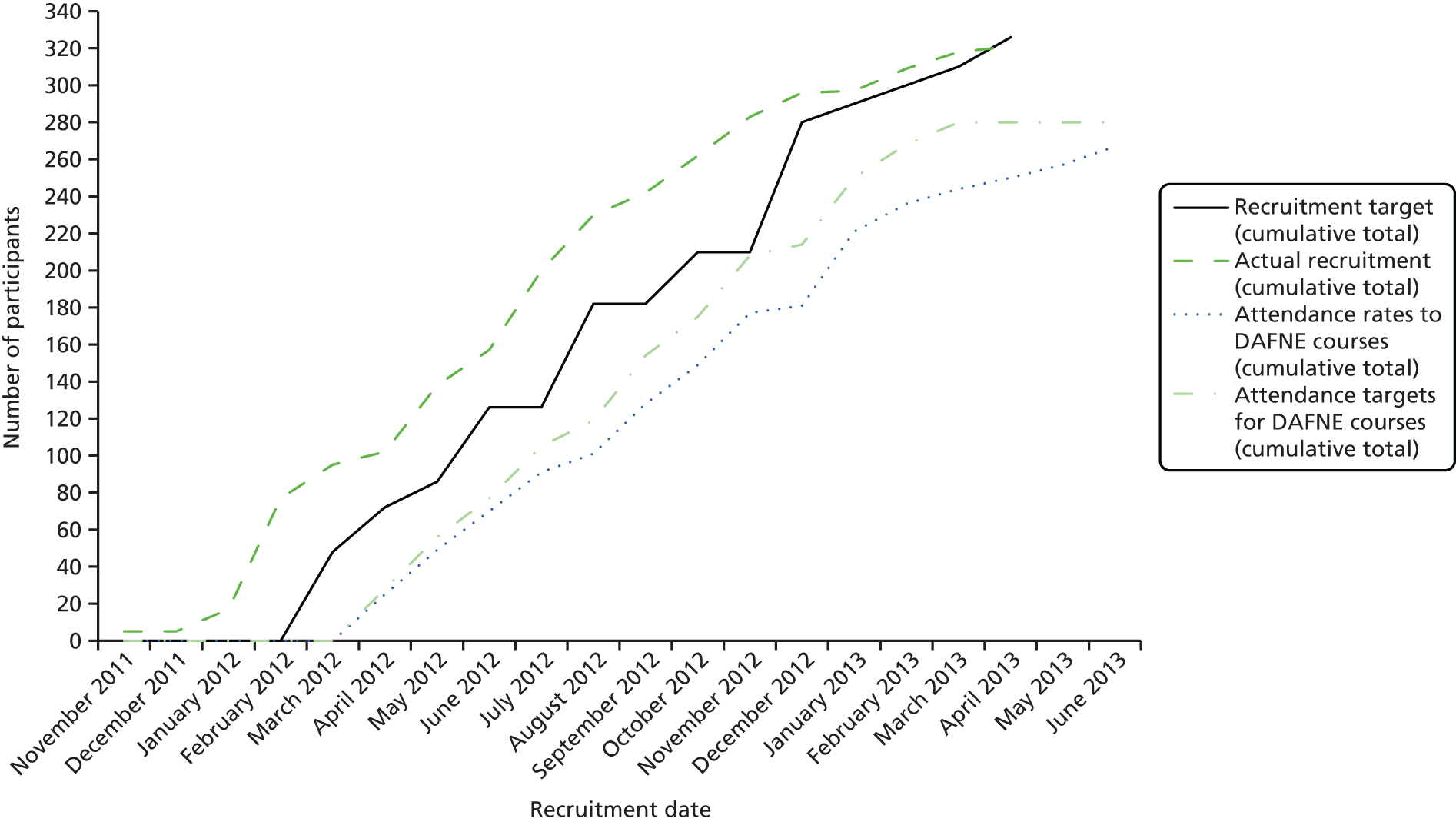

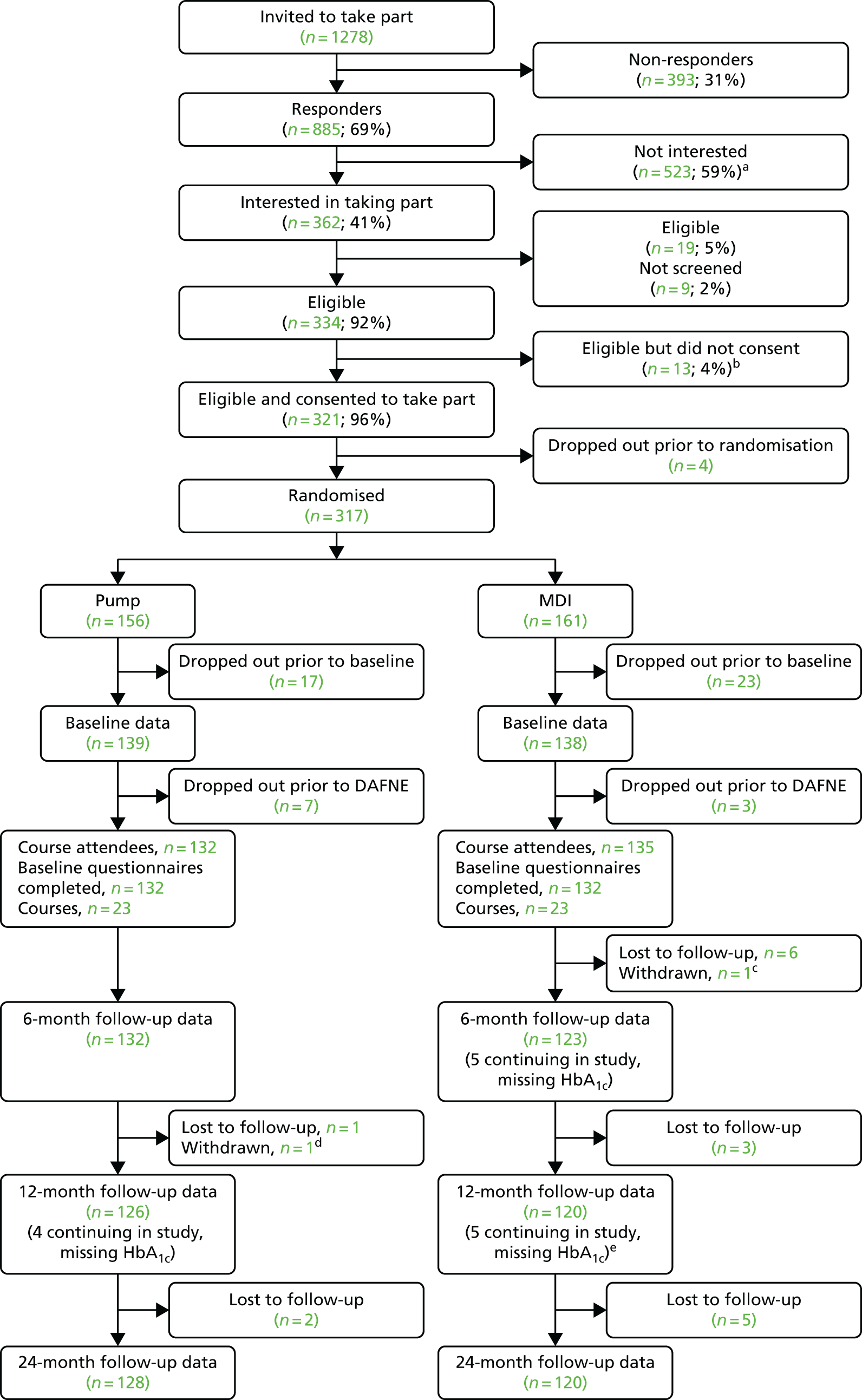

Recruitment

A number of methods were used to approach potential participants:

-

PIs or educators identified people from DAFNE waiting lists. They then telephoned or wrote to potentially eligible individuals.

-

Individuals attending a clinic appointment with a trial PI or educator were offered the option of a future or immediate consultation regarding the trial.

-

Clinicians [general practitioner (GP), dietitian, nurse] provided information to patients and referred them to PIs to be screened and enrolled.

-

Details of the trial were advertised through the use of posters and leaflets in clinics (diabetes outpatient, dietetic, GP surgery).

-

Reception staff in diabetes clinics were informed about the trial and provided with leaflets to give to patients who expressed an interest.

-

Participant identification centres were used at some research centres to assist in the identification of suitable participants.

Interested individuals were given the opportunity to discuss the trial with the PI or educator. Those who were still interested in taking part were screened for eligibility. Those who were eligible were either invited to attend a local information meeting, at which the trial was discussed in detail and questions answered, or were provided with a patient information sheet and consent form and given the opportunity to ask further questions. Individuals who were still wanting to take part consented to the trial by one of three methods: (1) by returning a completed consent form (see Appendix 3) in the post, (2) by completing the form with the PI or educator or (3) by completing the form at a local information meeting. The participants’ contact details, GP details and ethnicity were also collected.

Allocation to Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating courses and randomisation

Following consent, participants were allocated to a REPOSE DAFNE course, depending on the participants’ availability. 23 Up to eight participants were allocated to each course, with a minimum of five preferable. Courses were randomised, in pairs, to either DAFNE with pump or DAFNE with MDI. 23 Participant allocation to courses was finalised for each course pair before randomisation took place, no less than 6 weeks prior to the date of the first DAFNE course in that pair. For the first seven centres, a simple randomisation procedure in block size of ‘2’, stratified by centre, was used for courses 1–4. Courses 5 onwards were allocated in pairs using minimisation of the overall and number of participants, with most recent baseline HbA1c value of ≥ 7.5% or < 7.5% between the treatment groups. Any additional courses were allocated using minimisation. Known dropouts prior to the DAFNE course were excluded from the minimisation algorithm for future course allocation. A validated user-written Stata® 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) code was produced to generate the allocation by a statistician within Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU), who implemented the randomisation. The trial co-ordinator revealed the allocation to study centres. 23

Blinding of the course allocation was not possible because of the nature of the treatment. Course allocations were revealed to centres 4–6 weeks prior to the date of the first course to allow sufficient preparation time. Participants were informed of the allocation of their DAFNE course no earlier than 4 weeks prior to that course. At this point they were asked to keep a record of any new episodes of moderate hypoglycaemia, which would be collected at the baseline assessment. If the course was a pump course, the participant was booked into a pre-course pump session, up to 3 weeks prior to the course date, in addition to the baseline assessment, which had to take place before the pump session.

If, for any reason, participants were unable to take part in the course at short notice, they could be allocated to a later course date, but only in the same trial arm as in the course to which they were originally allocated. Centres could also keep a list of reserve participants for courses, agreed prior to the time when the course allocation had been revealed to the educators. In the case of participants dropping out, the next person on the reserve list would be invited to participate in that course.

Data collection

Study visits took place at the participants’ diabetes centre. A data collection form (DCF) (see Appendix 4) was completed by the educator with the participant. Blood and urine samples were taken and analysed at local laboratories. Two blood samples were taken for measurement of the primary outcome (HbA1c). One of these was analysed at a central laboratory as the primary measure and the second was tested at the local laboratory as a back-up. DCF data were entered at local centres on to the in-house Prospect web-based electronic data capture system, managed by the CTRU.

Baseline assessments took place up to 3 weeks prior to the DAFNE course. The educator completed the DCF with the participant and handed him/her the self-complete psychosocial questionnaire, asking for return of the completed questionnaire at the forthcoming DAFNE course. Additional demographic data collected at baseline were date of birth, sex, qualifications (highest qualification obtained) and current occupation. Participants were also handed a SAE contact card to aid in contacting their diabetes centre in the event of an AE.

At the DAFNE course, an attendance form was completed, detailing any missed sessions. The completed baseline psychosocial questionnaire was collected and the baseline DCF moderate hypoglycaemic episodes section was updated so that a full 4 weeks of hypoglycaemic episodes were recorded. At all time points, psychosocial questionnaires were posted from centres to Sheffield CTRU and entered on to Prospect by Sheffield CTRU clerical staff.

Participants were followed up at 6, 12 and 24 months after the DAFNE course. Participants were sent the blood glucose diary (see Appendix 5) and instructions for recording moderate hypoglycaemic episodes 4 weeks prior to each visit. Additionally, participants were posted the self-complete psychosocial questionnaire pack prior to the visit and asked to bring their completed questionnaire to the appointment, along with the blood glucose diary and record of moderate hypoglycaemic episodes.

Severe hypoglycaemic episodes or SAEs were collected from participants if reported over the telephone or in clinic. Any additional diabetes-related contacts (DRCs) were also recorded (see Appendix 6 for ongoing data collection booklet).

Blinding of outcome measures was considered impractical because of the intervention-specific nature of outcome measures and the necessity of a local diabetes nurse to collect the data. However, use of an objective outcome (HbA1c) measured in a central laboratory will have minimised bias on the primary end point.

Trial completion

Participants were deemed to have completed the study if they had trial data recorded at baseline and 24 months. Participants were withdrawn from the study if:

-

The participant asked to fully withdraw from the trial. On requesting withdrawal from the trial, participants were able to consent to continue to have their routine HbA1c results recorded.

-

The participant died.

Participants who were changing treatment continued in the trial unless formally withdrawn. Participants were deemed lost to follow-up if they failed to attend the baseline visit, DAFNE course or 24-month follow-up.

Research governance

The trial sponsor was Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The trial was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. 92 All staff recruiting participants to the trial had undertaken GCP training. In line with the three-level categorisation of clinical trial risk in the Medical Research Council/Department of Health (DH)/MHRA report on risk-adapted approaches to the management of clinical trials of investigational medicinal products93 (based on the classification by Brosteanu et al. 94), the REPOSE Trial was classified as a Type A study: no higher than the risk of standard medical care. The trial treatment in REPOSE was licensed and administered according to its market authorisation. Trial-specific labelling was not used. Given the lack of criticality of the investigational medicinal product (IMP) with the data analysis and trial results, and the design of the trial being equivalent to standard care, there was no IMP tracking and accountability undertaken.

Three committees were established to govern the conduct of the study: an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC), an independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and a TMG. Full membership of the TSC and DMEC are listed at the end of this report. The committees functioned in accordance with Sheffield CTRU standard operating procedures (SOPs). The TSC was responsible for overall supervision and monitoring of the trial; it considered any recommendations from the DMEC and provided advice on any actions to be taken. The DMEC operated within a charter agreed by all members and was responsible for monitoring efficacy and safety data. Any concerns were reported to the TSC with recommendations. The TMG was responsible for supporting the implementation of the trial.

Reporting of adverse events

Adverse events were defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant to whom a medicinal product has been administered, including occurrences that are not necessarily caused by or related to that product. SAEs were defined as any AE that results in death; is life-threatening (subject at immediate risk of death); requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolonging existing hospitalisation; results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or consists of congenital anomaly or birth defect; or is another important medical event that may jeopardise the participant. Pregnancy was also recorded as a SAE, so that any AEs could be identified if and when the child was born.

Included as AEs were an increase in frequency of hypoglycaemia, a blood glucose reading > 30 mmol/l, unexplained constantly raised blood glucose readings, suspicion of pump malfunction and pump site infection. Excluded as AEs were non-serious episodes of hypoglycaemia and ketonuria.

Details of AEs were collected during follow-up appointments. Participants were also provided with a contact card and encouraged to get in touch with their diabetes team if they had experienced any adverse health events. SAEs were reported in accordance with the Sheffield CTRU and REPOSE SAE SOPs. SAEs were assessed by the local PI and reported to Sheffield CTRU within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event, with the exception of events that had been stated as exempt from immediate reporting, for which 28 days was allowed. These exemptions were episodes of severe hypoglycaemia requiring hospitalisation, episodes of DKA and pregnancy. SAEs were assessed for seriousness, frequency, intensity, relationship to study product and, when applicable, relationship to pump. The Summary of Product Characteristics for NovoRapid and Levemir (Novo Nordisk, Gatwick, UK) were kept on file as the reference safety information for the assessment of events. AEs were reviewed at regular intervals by the three study oversight committees. The chief investigator and DMEC chairperson were notified of all SAEs on the event being reported.

Reporting of protocol non-compliances

Protocol non-compliances were reported and assessed in accordance with the Sheffield CTRU and REPOSE non-compliances SOPs. A non-compliance was defined as ‘a departure from the protocol or GCP that has been identified retrospectively’. Non-compliances were addressed with staff training or, when appropriate, an amendment to the protocol. In line with MHRA guidance, deliberate prospective protocol non-compliances or ‘waivers’ were deemed to be unacceptable. A prospective list of exemptions from reporting and of pre-specified major and minor non-compliances was drawn up by the CTRU, the chief investigator and the sponsor.

Trial monitoring

Responsibility for monitoring was delegated to the CTRU and conducted in accordance with CTRU SOPs. Both on-site and central monitoring methods were adopted. Onsite monitoring visits took place at all centres at study set-up, prior to delivery of the first DAFNE course, post delivery of DAFNE course 2 and at study closeout. A further monitoring visit took place during follow-up at seven centres. At each visit, the study site file and key essential logs were reviewed for completeness. Source data verification was conducted for 100% of consent and SAE forms. Patient hospital records were reviewed to substantiate participant existence and eligibility (for which criteria were verifiable from hospital records). Monitoring reports were issued after each visit detailing any remedial actions required. Central monitoring tasks included point of entry validation, verification of data and post-entry validation checks. One participant per DAFNE course per centre was randomly selected for verification. Case report forms at all data collection time points were reviewed for completeness and quality, and verified to monitor data entry. Source data verification also took place for 100% of central laboratory HbA1c results. Feedback on verification was provided and additional verification was undertaken when concerns were identified.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed in Stata 13 onwards. The MDI is the reference group for all treatment comparisons.

Analysis populations

The intention-to-treat (ITT) data set includes all participants who were randomised according to randomised treatment assignments (ignoring any occurrences post randomisation, such as protocol or treatment non-compliance and withdrawals) with at least one HbA1c assessment measure after baseline. Sensitivity analysis of the ITT primary outcome set was performed using six additional analysis sets, as described later in this section.

The per-protocol group is a subset of the ITT group who complied with the protocol. Protocol compliance was defined as adhering to both the DAFNE course and to pump/MDI. Compliance was reviewed and assessed on a case-by-case basis with the following general considerations applied:

-

adherence to DAFNE course – in general, a participant was adherent to the course if they attended at least 4 of the 5 days, including the first 2 days (as adjudicated by the course leader)

-

adherence to the pump or MDI – a participant was classed as adherent to treatment if he/she adhered to the pump/MDI for the full 2 years (excluding any reasonable temporary interruptions of around 2 weeks).