Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/77/01. The contractual start date was in December 2011. The draft report began editorial review in May 2016 and was accepted for publication in October 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Catherine E Hewitt declares membership of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) commissioning board, and Sarah E Lamb declares membership of the NIHR HTA prioritisation board. Lorraine Green reports that she works as an independent private practitioner and is an associate of Mr Andrew Horwood, design consultant at Healthystep Ltd. Robin Hull reports that his employers, North Yorkshire and York Primary Care Trust (now Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust), received payment for clinical assessment of REducing Falls with ORthoses and a Multifaceted podiatry intervention (REFORM) patients from the REFORM HTA grant.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Cockayne et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Burden of falls and falling in the UK

Falls and fall-related fractures are a serious cause of morbidity and cost to individuals and society. 1 This burden is likely to increase owing to an ageing population. Falls are associated with a loss of independence and functional decline, and may result in the need for long-term care. 2 Each year, approximately 30% of people aged ≥ 65 years living in the community will have a fall, and among those aged ≥ 80 years this increases to 50%. 3,4 Older adults who fall once are two to three times more likely to fall again within 1 year. One-fifth of all falls require medical attention, with 5% of falls leading to a fracture. 5 The financial cost of injurious falls has been estimated at £2B per annum, a cost that is mainly attributed to resultant hip fractures. 6 The National Service Framework for Older People highlighted the importance of fall-related injuries and called for health improvement plans to reduce this burden. 7

Risk factors for falling

It is well recognised that falls occur for a variety of reasons. They may result from interactions between environmental hazards, medical conditions and physiological risk factors. 3 Foot problems, which affect one in three community-dwelling people aged ≥ 65 years,8 have been associated with reduced walking speed and difficulty in performing activities of daily living. Results from cohort studies have indicated that there is a relationship between foot and ankle problems and risk of falling. 9,10

In addition to causing foot problems, inappropriate footwear may contribute to poor balance and an increased risk of falling. 11 Footwear characteristics that are considered detrimental to balance include higher heels, soft soles and inadequate slip resistance. 11,12 Prospective studies have shown that walking barefoot, wearing only stockings inside the home and wearing shoes with an increased heel height and smaller contact area all increase the risk of falling. 9,13,14

Podiatry interventions to improve balance

Given the emerging evidence that foot problems and inappropriate footwear increase the risk of falling, it has been suggested that podiatry may have a role to play in falls prevention, with several guidelines recommending that older people have their feet and footwear examined by a podiatrist. 15,16 Previous studies have looked at treatments that may improve balance in older adults, such as lesion debridement,17 foot orthoses,18 foot and ankle exercises19,20 and footwear advice. Lesion debridement can improve function during gait if pain is reduced, exercise programmes focus on internal strengthening and flexibility, and appropriate footwear fitted with orthotic devices can provide external support, improved kinaesthesia and improved function. Combining these therapies could, therefore, improve function and stability.

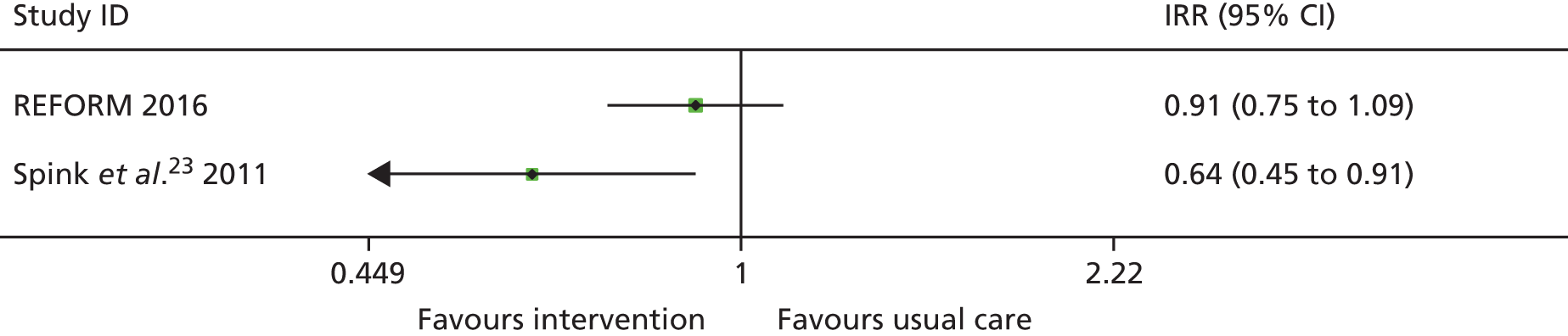

At the time of designing the current study there were two published Cochrane reviews on falls prevention. One related to falls in community-dwelling older people21 and one focused on falls in hospitals and aged care facilities. 22 Neither identified any randomised controlled trials (RCTs) focusing on podiatry-related interventions. A subsequent update identified one Australian trial of a podiatry-based intervention for the prevention of falls. 23 In this study of 305 community-dwelling older people who had foot pain, participants allocated to receive a multifaceted podiatry intervention (n = 153) experienced 36% fewer falls than participants in the control group [incidence rate ratio (IRR) 0.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.45 to 0.91; p = 0.01]. The intervention comprised foot and ankle exercises, foot orthoses, footwear advice, subsidy for new footwear and a falls prevention booklet combined with routine podiatry care and was compared with those receiving only routine podiatry. This trial did not include an economic evaluation.

Aims and objectives of the podiatry intervention for podiatry patients at increased risk of falling

The REducing Falls with ORthoses and a Multifaceted podiatry intervention (REFORM) study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme in response to a call to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of foot orthoses. Its aim was to establish the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a package of podiatric care within a UK health-care setting.

The main objectives of the REFORM study were to:

-

investigate the clinical effectiveness of a multifaceted podiatry intervention for falls prevention

-

investigate the cost-effectiveness of a multifaceted podiatry intervention for falls prevention

-

assess the participants’ and podiatrists’ views and experiences of the intervention and trial processes.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The REFORM study was a pragmatic multicentred cohort RCT. 24 We chose this approach to test whether or not the cohort RCT design could address some of the issues that other trial designs encounter with regard to recruitment, attrition and participant preference. We expected that using this design would offer the following advantages. First, trial recruitment rates would be enhanced. Some participants would be immediately eligible for the study and could be randomised straight away and others who subsequently fell over time would become eligible and could also then be randomised. If a traditional trial design had been used, then these additional participants who were not immediately eligible would have been lost. In addition, as we were undertaking an internal pilot, this could be undertaken while recruitment proceeded for the main study. Second, we expected that this design would minimise the possibility of introducing attrition and reporting bias. As participants were receiving routine podiatry care outside the study, the only incentive to take part in the study, apart from altruistic reasons, was the possibility of receiving the intervention. Under this design, all participants were informed upon enrolment into the cohort that they may at some point be offered a package of podiatry care. This was offered to participants subsequently randomised into the intervention group of the RCT; however, the usual-care group were not explicitly notified of their group allocation as they would have been in the classic randomised design. We expected that this would reduce attrition caused by ‘resentful demoralisation’ and minimise the risk of participants in the usual-care group either knowingly or unknowingly biasing the trial by reporting the number of falls they had experienced less conscientiously than those allocated to the intervention group. Third, we also expected that that the inclusion of a ‘run-in’ period of falls data collection before randomisation would reduce post-randomisation attrition rates and, therefore, the risk of selection bias. Participants had to demonstrate engagement with the study by returning at least one falls calendar before they were randomised, which enriched the sample with those participants most likely to keep responding.

The cohort RCT design allowed us to test the feasibility of this design and determine whether or not it would enhance recruitment, minimise attrition and lower participant preference effects. It also enabled us to establish a cohort of older adults who could be followed up, thereby helping to inform the knowledge base around health and well-being in older adults. This approach also allowed the possibility for us to invite participants, who had agreed to be contacted again, to take part in future studies.

Participants in the REFORM trial were randomised to receive one of either:

-

a multifaceted intervention consisting of footwear advice (and footwear provision if required), an orthotic insole or review of an existing insole prescription, a programme of foot and ankle balance exercises and a falls prevention leaflet

-

a falls prevention leaflet and usual care from their podiatrist and general practitioner (GP).

Approvals obtained

The study protocol was approved by the East of England – Cambridge East Research Ethics Committee (REC) (multicentre REC) (and substantial amendments) on 9 November 2011 (REC reference number 11/EE/0379). Galway REC approved the study (and substantial amendments) on 26 April 2013 (REC reference number C.A 886). The University of York, Department of Health Sciences Research Governance Committee approved the study (and substantial amendments) on 2 August 2011. Research management and governance approval was obtained for each trust thereafter (see Appendix 1).

The trial was registered as ISRCTN68240461 on 1 July 2011.

Study sites

Recruitment of all participants into the study took place through 37 NHS podiatry clinics based in either primary or secondary care in nine NHS trusts across the UK, and at one international site in a university school of podiatry in Ireland. Each participating podiatry clinic was associated with the trust under which it operates, and each trust acted as a trial ‘centre’, except the Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust, which cares for the population of North Yorkshire. As this is a particularly large and diverse area, the clinics in this trust were split into four groups according to their geographical location: Scarborough, York, Harrogate and Skipton. These four groups were also considered as trial ‘centres’, resulting in a total of 13. The Ireland centre was set up to aid study recruitment. This site was chosen because some of the authors had previously collaborated with this site on another NIHR HTA-funded podiatry study in which recruitment had gone well. The NIHR HTA programme gave permission to include the site.

REFORM observational cohort

The REFORM study was initially designed to include people aged ≥ 70 years; however, following the pilot phase, the age limit was reduced to include adults aged ≥ 65 years (see Chapter 3) to facilitate recruitment and reflect the age range seen within the routine podiatry clinics. Participants were first recruited to the REFORM observational cohort. While this cohort was being assembled, we invited a selection of eligible participants from the pilot sites to take part in the internal REFORM pilot trial. After completion of the pilot phase, the remaining eligible participants were invited to take part in the REFORM trial. Figure 1 reports how participants were recruited to the observational cohort and when they were randomised to the trial.

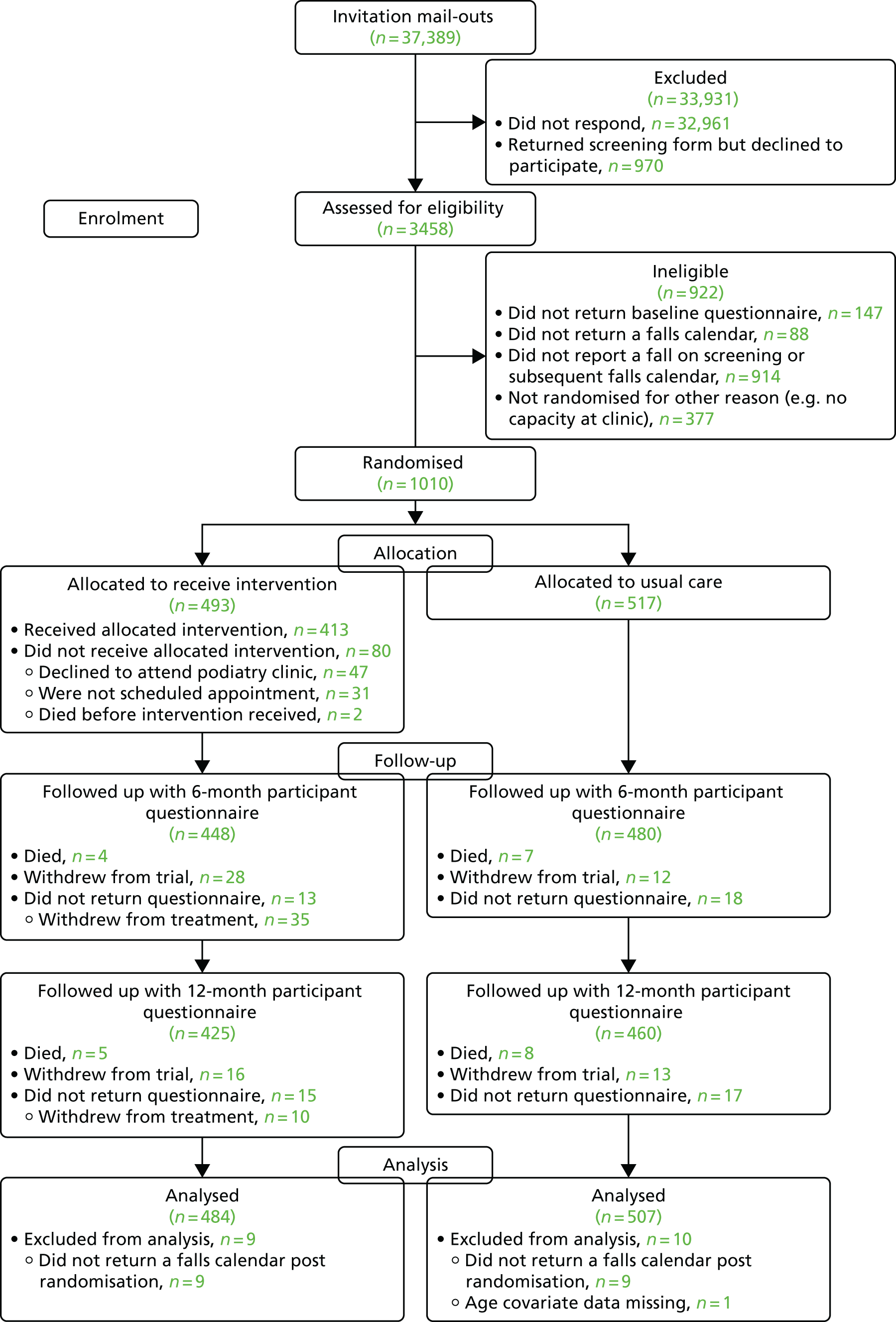

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment of participants to the REFORM study.

Participant recruitment

Recruitment of all participants into the study took place through NHS podiatry clinics based in either primary or secondary care in the UK and at one international site in a university school of podiatry in Ireland. The reasoning for recruiting only from podiatry clinics and not from general practices was because of the requirement for all participants to be receiving routine podiatry care so that we could disentangle the effects of the novel intervention from those of routine podiatry care. Recruitment directly from general practices would most probably have identified many patients who were not receiving routine podiatry care. For these patients to have been entered into the REFORM study, they would have to have been receiving routine podiatry care. NHS podiatry service managers informed us that the burden of providing routine podiatry care for all trial participants as well as delivering the intervention would have made the study unfeasible.

Potential participants were identified by either the REFORM research podiatrist or a podiatrist within the clinic undertaking a search of either electronic or paper medical records of patients registered with the service. Two search criteria were used: (1) age ≥ 65 years and (2) having attended routine podiatry services within the past 6 months from the date of the search. People living in nursing homes were excluded, as participants had to be community dwelling to be eligible for the study. At the time of undertaking the search, it was not possible to easily identify those patients with neuropathy who would be ineligible for the study. Therefore, to minimise the risk of approaching these patients, those who had attended high-risk clinics, for example diabetes mellitus clinics, were excluded from the search. Potential participants were invited to participate in the REFORM study by their podiatry clinic via a postal recruitment pack. This pack comprised an invitation letter (see Appendix 2) electronically signed by the principal investigator (PI) at the site, a consent form (see Appendix 3), a participant information sheet (see Appendix 4), a background information form (see Appendix 5) and a prepaid return envelope addressed to the York Trials Unit (YTU). During the pilot phase of the study, a decline form (see Appendix 6) was also included so that data could be collected on people’s reasons for declining to participate. No identifiable data were available to the study teams until a participant had returned their consent and background information forms.

To aid recruitment, the opportunistic screening of patients attending routine podiatry clinics was undertaken when clinics had capacity to do so. Potential participants were given the recruitment pack and verbal information about the study.

Potential participants who wished to take part in the REFORM study returned their completed consent and background information forms by post to the YTU. The research team assessed the forms for eligibility.

Consenting participants

Participation in the REFORM study was voluntary. Participants who wished to take part were given written information about the study and contact details for the research team should they have had any queries about the study. The participants were asked to complete a consent form to indicate that they wished to take part in the study. The qualitative researcher obtained consent for the qualitative study either face to face or, for interviews conducted over the telephone, by post.

At the consent stage, participants were informed about the opportunity to participate in other related studies. Participants were informed about the ‘possibility’ of being offered an additional podiatric intervention for the prevention of falls and were asked to tick a box if they were interested in taking part in such an intervention. If participants did not wish to be contacted about these studies, they were asked to indicate this by ticking a box on the consent form.

Baseline assessment

On receipt of written consent, researchers at the YTU assessed the participants’ responses on the background information forms for eligibility. Participants assessed as being ineligible for the study were notified in writing and no further correspondence was sent. Participants who were deemed eligible were then sent a baseline questionnaire (see Appendix 7) and a pack of falls calendars (see Appendix 8).

Participant eligibility

Exclusion criteria for the REFORM cohort

Participants were ineligible for the REFORM cohort if they:

-

were > 65 years of age

-

reported having neuropathy, dementia or another neurological condition such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Lou Gehrig’s disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Huntington’s disease

-

were unable to walk household distances (10 metres) without the help of a walking aid, such as a walking frame, a walker or a person to assist

-

had had a lower limb amputation

-

were unwilling to attend their podiatry clinic for a REFORM appointment.

Inclusion criteria for the REFORM cohort

All eligible consenting participants who completed a baseline questionnaire and at least one monthly falls calendar were eligible for inclusion in the REFORM cohort.

Inclusion criteria for the REFORM trial

Participants in the cohort were eligible for inclusion in the REFORM trial if they:

-

had had a fall in the past 12 months, or a fall in the past 24 months requiring hospital attention, or reported worrying about falling at least some of the time in the 4 weeks prior to completing their baseline questionnaire

-

were community dwelling

-

were able to read and speak English.

If participants did not report a recent fall on their screening form but later reported a fall on the baseline questionnaire or monthly falls calendar, they became eligible to be randomised.

REFORM internal pilot

An internal pilot was conducted at the start of the study. The objectives of the pilot trial were to:

-

develop and pilot the multifaceted podiatry intervention

-

develop the podiatry training package

-

pilot the falls calendar and other participant data collection questionnaires

-

pilot, review and refine if necessary the recruitment methodology for the main trial.

In order to progress to the main REFORM trial, the study team were asked by the NIHR HTA monitoring team to fulfil the following progression criteria by the end of November 2013:

-

Recruit 580 participants to the REFORM cohort study.

-

Randomise 70 participants to the REFORM pilot trial.

-

Decide which orthotic insole would be used in the main trial.

Sample size

Pilot sample size

The pilot phase of the study ran from October 2012 until November 2013. No formal sample size calculation was conducted but we aimed to randomise at least 70 participants into the pilot trial (35 in each group), which we believed to be sufficient to test the objectives.

REFORM trial sample size

The primary outcome measure for the trial was the incidence rate of falls reported by the participants over the 12 months post randomisation. This was analysed using a mixed-effects negative binomial regression model. However, because of the inherent difficulties of estimating the parameters required to power a trial for a count outcome, such as the IRR to detect and the measure of overdispersion, the trial was instead powered for the binary outcome of whether or not the participants experienced at least one fall, which was one of our key secondary outcomes. We retained incidence rate of falls as the primary outcome as we believed the extra information contained in this outcome would result in the sample size being conservative for this outcome.

A previous falls prevention trial conducted by some of the authors in community-dwelling older adults with a history of recent falls found a 12% absolute reduction in the proportion of participants who fell among those allocated to receive an environmental falls prevention intervention delivered by qualified occupational therapists, relative to the control group. 25 The REFORM trial was powered at 80% using a two-sided 5% significance level to detect a more conservative absolute difference of 10 percentage points from 50% to 40% in the number of people experiencing at least one fall over the 12 months following randomisation. The total sample size required, allowing for a 10% loss to follow-up, was 890 participants (445 in each group).

Randomisation

Participants who fulfilled the eligibility criteria for the REFORM trial and who had provided written informed consent and indicated that they were interested in receiving the intervention were eligible for randomisation. Randomisation was carried out by the YTU secure remote computer randomisation service. Trial clinics informed the YTU when they had capacity to schedule baseline appointments for participants and how many participants they felt that they could manage to schedule appointments for at that time. A group of participants waiting to be randomised from the centre associated with that clinic were selected and randomised in a single block (mainly) 1 : 1 to either the intervention or usual-care groups; however, when clinics had the capacity to see more or less than half the group size, an appropriate alternative allocation ratio was used. Prediction of allocated group by clinician was not possible because of the dynamic nature of the randomisation and the use of a remote service; thus, allocation concealment was maintained. Once intervention participants had been randomised, they were sent a letter informing them of their group allocation and that the podiatry clinic would be in contact to arrange a trial appointment. Participants who were allocated to the usual-care group were not informed of their group allocation in order to minimise potential attrition and the possibility of resentful demoralisation.

Trial interventions

Intervention group

Participants in the intervention group were allocated to receive a multifaceted intervention comprising footwear advice (and footwear provision if required), an orthotic insole or review of an existing prescription, a programme of foot and ankle balance exercises and a falls prevention leaflet. The trial protocol recommended that participants be invited to attend two appointments: the first as soon as possible after randomisation and the second 2–4 weeks later. Further trial visits could be offered if required, in addition to routine podiatry care appointments in accordance with usual practice.

Footwear advice and provision

Participants were asked to bring their indoor and outdoor footwear to their REFORM appointment. The podiatrist assessed the following characteristics of the participant’s footwear that have been identified in the literature as risk factors for falls in older people:12 correct size, method of fastening, height and width of the heel, thickness of outsole, heel counter stiffness, longitudinal sole rigidity, sole flexion point and tread pattern. Footwear was assessed as inappropriate if it had any of the following characteristics: (1) heel height > 4.5 cm, (2) no adjustable fixation of the upper, (3) no heel counter or a heel counter that could be depressed to > 45°, (4) a fully worn/smooth/thin sole, (5) heel width narrower than the participant’s heel width by ≥ 20% or (6) incorrect shoe size. Participants were counselled about any hazardous footwear features identified during the assessment and advised on safer footwear characteristics to select when purchasing footwear in the future.

If a participant’s footwear was deemed inappropriate, and they did not own a suitable pair of shoes that they could be advised to wear instead, new footwear was provided where possible. The podiatrists ordered footwear directly from one of two companies participating in the Healthy Footwear Guide scheme:26 DB shoes (DB Shoes Ltd, Rushden, UK) or Hotter company (Beaconsfield Footwear Limited, Skelmersdale, UK). Not all of the footwear manufactured by these companies fulfil the characteristics of a ‘safe’ shoe; therefore, participants chose footwear from a catalogue of preselected makes and models that the trial team had previously assessed as being suitable. In order to avoid incentivising participants to take part in the study, participants were told about footwear provision only if they were assessed as requiring new footwear.

Foot orthoses

Participants were considered for fitting with an X-Line standard orthotic insole (Healthystep, Mossley, UK). If required, the insole was modified with prefabricated self-adhesive additions to improve the participant’s foot posture. For those participants already wearing an orthotic insole, the treating podiatrist made a clinical judgement on the suitability of replacing the insole with one used in the trial. If the participant’s current insole was replaced, then any current prescription or modifications were repeated. If, however, the podiatrist deemed it to be detrimental to replace their current insole with that of the trial insole, then the participant continued to wear their own insole and this component of the intervention was considered to be addressed. In cases in which the treating podiatrist felt that the participant required more or a prescription that the trial insole could not provide, then a referral was made in line with routine practice.

Participants were advised to ‘wear-in’ the orthotic insole slowly. It was suggested that it should be worn for 1 hour on the first day and wear time increased by a few hours each day, and that the insole could be transferred from one pair of shoes to another.

Home-based foot and ankle exercise programme

When safe and appropriate, participants were prescribed a 30-minute home-based foot and ankle exercise programme to be undertaken three times a week, indefinitely. The aim of the exercises was to stretch and strengthen the muscles of the foot and ankle and improve balance. The exercises were based on the programme developed by Spink et al.,23 which had been adapted for a UK and Irish setting during the pilot phase of the study. A summary of the individual exercises is listed in Table 1. The podiatrist assessed competence and safety at the baseline appointment through demonstration and participant repetition of the exercises. These were supplemented by an explanatory illustrated booklet and a digital versatile disc (DVD), which the participant took home along with the resistive bands and therapy ball that were required to undertake the exercises. At subsequent appointments the podiatrists reviewed the participant’s exercise techniques and, when required, advised the participant to ensure that the exercises were being conducted safely and as intended.

| Activity | Description | Dosage | Increments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ankle range of motion/warm-up | Sitting, with the knee at 90°. Lift the foot to clear the ground and then rotate the foot slowly in a clockwise direction and then an anticlockwise direction | 1 × 10 repetitions for each foot in each direction | None |

| Ankle inversion strength | Sitting upright, with the hip, knee and ankle at 90°. Invert foot against resistive exercise band. The band should be fixed at 90° to the foot from an additional chair/table leg | 3 × 10 repetitions for each foot | Increase resistance strength of resistive exercise band |

| Ankle eversion strength | Sitting upright, with hip, knee and ankle at 90°. Evert foot against resistive exercise band. The band should be fixed at 90° to the foot from an additional chair/table leg | 3 × 10 repetitions for each foot | Increase resistance strength of resistive exercise band |

| Ankle dorsiflexion strength | Sitting, with hip, knee and ankle at 90°. Dorsiflex both feet to end range of motion and hold. Keep pulling feet up towards the body during the hold | Hold feet in dorsiflexion for 3 × 10 seconds | Increase repetitions up to a maximum of 10 |

| Intrinsic strengthening, toe plantarflexion strength and toe stretch | Sitting, with hip, knee and ankle at 90°. (1) Use the therapy ball under the toes to stretch the toes. The rest of the foot should be plantigrade. Then curl and point the toes up and over the ball. (2) Use the therapy ball under the toes to stretch the toes. The rest of the foot should be plantigrade. With the heel on/close to the floor, curl the toes over the ball and attempt to pick up the ball with the toes | 3 × 10 repetitions for each exercise for both feet. Have a 30-second break between each repetition | Increase up to a maximum of 50 repetitions |

| Ankle plantarflexion strength | From standing position, rise up onto toes of both feet and then slowly lower back down. Just before the heels contact the floor, rise back up onto the toes | 3 × 10 repetitions | Increase repetitions up to a maximum of 50 |

| Calf stretch | Facing a wall and using hands on the wall for balance, step one foot in front of the other keeping feet hip width apart and hips, knees and feet facing the wall. Bend the knee closest to the wall and keep the back leg straight. Keep both heels in contact with the floor | Hold stretch for 3 × 20 seconds on each leg | Increase the stride length and forward lean to increase the stretch |

| Proprioception/balance training | From a standing position and holding on to a work surface/chair/wall for support, stand on one leg. Repeat on the other side | Hold for 30 seconds, repeat for three repetitions | Increase slowly to hold for 1 minute per repetition. If competent, rise up on to toes on the one supporting leg: 3 × 10 repetitions |

Routine podiatry care

Participants continued to receive routine podiatry care as separate podiatry appointments in accordance with usual practice. The aim of these appointments was to reduce painful conditions such as corns and calluses that have been found to be associated with an increased risk of falls.

Podiatrist training to deliver the intervention

The podiatrists delivering the trial intervention attended a half-day face-to-face training session facilitated by the research podiatrist (author LG). The training included instructions on the delivery of the individual components of the intervention including footwear assessment and provision, prescribing and fitting trial insoles and prescribing foot and ankle exercises. Podiatrists were given the opportunity to practice delivering the intervention during role-play sessions. In addition, information about the day-to-day management of podiatry tasks, for example booking appointments or ordering footwear, adverse event reporting and completion of trial paperwork, was provided. When possible, the research podiatrist attended the first participant appointment delivered by each podiatrist to give advice on the delivery of the intervention when requested.

Falls prevention leaflet and trial newsletter

Participants were sent a falls prevention leaflet in the post along with their baseline questionnaire. Participants living in the UK received the Age UK Staying Steady leaflet27 and those in Ireland received the Irish Osteoporosis Society Fall Prevention leaflet. 28

A postal group-specific trial newsletter was sent to participants at 3 months post randomisation, as well as a generic trial newsletter at 12 months. The aim of the newsletters was to keep participants updated with the progress of the trial in an attempt to minimise attrition and improve response rates to postal questionnaires. 29 The 3-month newsletter to the intervention group also included information about how to undertake the foot and ankle exercises and wear the insoles and it aimed to aid compliance. It included anonymised quotations reporting the benefit some participants had experienced after following the package of care. The content of the newsletter was informed by issues raised by participants with the research team during the course of the trial.

Usual-care group

Participants in the control group continued to receive usual care from their podiatrist and GP, which may have included prescription of an orthosis and footwear advice. They also received the same falls prevention advice leaflet sent to the intervention participants and a group-specific trial newsletter at the same time points.

Participant follow-up

All participants in the REFORM trial were followed up with monthly falls calendars for 12 months post randomisation. If a participant did not return their falls calendar after 10 days, a member of the study team telephoned or wrote to them to collect the primary outcome data. The study team contacted participants who had reported a fall to collect further information relating to the nature, cause and location of the fall (see Appendix 9). Participants were also sent follow-up questionnaires at 6 (see Appendix 10) and 12 months (see Appendix 11) post randomisation. Follow-up questionnaires were posted to participants, along with a pre-addressed envelope, and reminder letters were sent after 2 and 4 weeks if unreturned. Participants also received an unconditional £5 in cash with their 12-month postal questionnaire in recognition of their participation in the study and to offset any incidental expenses that they may have incurred when completing postal questionnaires. Telephone follow-up by one of the study team’s researchers was conducted 2 weeks after the second postal reminder for any participant who had not returned a questionnaire to complete the primary outcome data as a minimum. In addition, intervention participants were sent an exercise and orthosis compliance questionnaire at 3, 6 and 12 months (see Appendix 12). Any change in the participant’s trial status during the course of the study was recorded by the study team (see Appendix 13). Data collection ceased in December 2015.

Trial completion and exit

Participants were deemed to have exited the trial when they:

-

had been in the trial for 12 months post randomisation

-

withdrew from the trial, that is, they wished to exit the trial with no further contact for follow-up or treatment

-

were lost to follow-up

-

died.

Withdrawals

Withdrawals could occur at any point during the study at the request of the participant. The reason for their withdrawal did not have to be declared; however, if a reason was provided, then it was recorded. Participants could inform the trial team of their decision to withdraw from the study by contacting them either by telephone or in writing. When possible, a researcher would clarify to what extent they wished to withdraw: from the intervention only or from all aspects of the study. Treating podiatrists could also withdraw participants from the intervention or from all aspects of the trial when they felt that this was appropriate. When withdrawal was from the intervention only, follow-up data continued to be collected. Data were retained for all participants, unless a participant specifically requested that their details be removed.

Patient and public involvement in research

The REFORM trial was informed by the involvement of older people with a history of falls throughout the research period. A patient reference group was established at the start of the study. The group comprised four older people who provided valuable insights into the relevance and readability of the study documentation and advice regarding recruitment methods. They provided input into the content and layout of the patient information sheet, the exercise booklet, newsletters and recruitment posters. They reviewed the exercise DVD and the package of care, and provided feedback on the selection of footwear offered to participants. The patient reference group contributed to this HTA report by reviewing the plain English summary and they will provide guidance about our dissemination strategies on how best to share the study findings with trial participants.

Clinical effectiveness

Primary outcome

The primary end point for the trial was the incidence rate of falls per participant in the 12 months following randomisation. A fall was defined as ‘an unexpected event in which the participant comes to rest on the ground, floor, or lower level’. 30 Data were collected via participant self-reported monthly falls calendars. These took the form of A5 pieces of card with a calendar grid of individual months printed on one side along with a definition of a fall and a freepost address to the YTU on the other. Participants were asked to record the day of the month on which they fell or to record that they did not fall that month and return the calendar to the YTU. Participants who did not return their monthly falls calendar were either telephoned or written to by the YTU to obtain the missing data. Participants were also given a freephone number to report any falls as soon as possible after they occurred, and these were recorded by research staff on a falls telephone data collection sheet (see Appendix 9). The information collected included the date and location of fall, the reason for the fall, any injuries sustained (e.g. a superficial wound or a broken bone), hospital admissions, the footwear worn at the time of the fall and if the participant was wearing an insole or using a walking aid.

Secondary outcomes

All secondary outcomes were self-reported by the participant and collected by questionnaires at 6 and 12 months post randomisation or by monthly falls calendars. Secondary outcomes include:

-

proportion of fallers (at least one fall and multiple falls)

-

time to first fall from date of randomisation

-

incidence rate of falls in 12 months post randomisation as recorded on the 6- and 12-month participant questionnaires

-

fear of falling as measured by the question ‘During the past 4 weeks have you worried about having a fall?’ at 6 and 12 months

-

fear of falling as measured by the Short Falls Efficacy Scale – International (FES-I) at 6 and 12 months31

-

activities of daily living as measured by the Frenchay Activities Index (FAI) at 6 and 12 months32

-

depression as measured by the short form Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) at 6 and 12 months33

-

proportion of participants with depression (score of ≥ 6 on GDS) at 12 months

-

adaptability and resilience as measured by the 2-item abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC2) at 6 months34

-

level of pain in the feet as measured on a visual analogue scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) at 12 months

-

fracture rate (single and multiple)

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as measured by the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions-3 Levels (EQ-5D-3L)35

-

health service utilisation.

Scoring of instruments

Fear of falling

Fear of falling was measured by the question ‘During the past 4 weeks have you worried about having a fall?’ at screening and baseline and at 6 and 12 months. Response categories were all of the time, most of the time, a good bit of the time, some of the time, a little of the time and none of the time. These were scored from 1 to 6 and were treated as continuous data for analysis.

Short Falls Efficacy Scale – International

The Short FES-I asked participants at baseline and at 6 and 12 months to indicate how concerned they were about falling when performing seven different activities: not at all concerned, somewhat concerned, fairly concerned or very concerned. These were scored from 1 to 4, and a total score for the Short FES-I was obtained by summing the seven item scores. When a participant selected two or more responses to an item, this was treated as missing data. If data were missing on two or more items then the questionnaire was considered invalid. If data were missing on no more than one of the seven items then the total score was calculated for the six completed items, divided by six and multiplied by seven. The new total score was then rounded up to the nearest whole number. 31 A final total score of 7 or 8 indicates no/low concern, 9–13 indicates moderate concern and 14–28 indicates a high degree of concern about falling.

Frenchay Activities Index

This 15-item instrument was administered at baseline and at 6 and 12 months and assessed a broad range of activities of daily living. The frequency with which each item or activity was undertaken over the previous 3 or 6 months (depending on the nature of the activity) was assigned a score of 1–4, where a score of 1 is indicative of the lowest level of activity (e.g. never performed). The scale provides a summed total score from 15 to 60. When a participant selected two or more responses to an item, this was treated as missing data. Only when there were no missing item responses was a total score computed for an individual for this instrument.

Geriatric Depression Scale

The GDS is a 15-item scale used as a screening tool for geriatric depression and was administered at baseline and at 6 and 12 months. Each item requires a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response. A score of 1 is assigned when the item response indicates a negative state of mind, for example responding ‘no’ to ‘Are you basically satisfied with your life?’. A total score out of 15 can be calculated. When a participant selected both ‘yes’ and ‘no’, the worst-case scenario was assumed and a score of 1 was assigned to the item. More than five missing item responses invalidated the scale; otherwise, a total score when there were missing data was calculated by summing the item scores, dividing by the total number of completed items and multiplying by 15. The new total score was then rounded up to the nearest whole number to give the score for an individual (https://web.stanford.edu/∼yesavage/GDS.html). A score of 0–5 is considered normal, whereas a score of > 5 suggests depression. Any participant reporting a score of ≥ 10 on the GDS,33,36 that is, more severe depression, was referred to their GP.

The two-item abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

The CD-RISC2 is a two-item abbreviated version of the full 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale. It is based on items 1 (‘I am able to adapt to change’) and 8 (‘I tend to bounce back after illness or hardship’) of the original instrument. Each item is scored from 0 (‘not true at all’) to 4 (‘true nearly all the time’), so the CD-RISC2 can be scored from 0 to 8. Higher scores reflect greater ‘bounce-back’ and adaptability. This instrument was administered at baseline and at 6 months.

Other data collected

Non-consenting participants

Participants who did not wish to take part in the study were not required to return any forms to the YTU; however, some chose to complete the screening form, thus providing us with some demographic information. In addition, all participants in the pilot phase of the study were sent an invitation pack that included a decline form, so that if they were willing they could provide a reason for declining. This provided us with sufficient information to document the reasons why participants did not wish to take part in the study, and allowed us to compare participants who declined with those who participated. The recruitment pack in the main study did not contain a decline form.

Intervention: details and adherence

Treatment details were recorded by the podiatrist, including the number of podiatry visits, an eligibility checklist with details on relevant health conditions and test results, characteristics of current indoor and outdoor shoes, details relating to shoes ordered, details on the type and prescription of any current insole use, the type of insole issued/retained with any modifications made, details of the size of any therapy ball and the strength of any resistive band prescribed and any amendments or advice given on the intervention owing to safety reasons.

Information on adherence to the exercise, footwear advice and orthotic insole components of the intervention was collected from participant self-reported questionnaires at 3, 6 and 12 months from participants in the intervention group only. Participants were asked if, during the past month, they had worn their insole all of the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time or none of the time. Participants were also asked, for the past month, typically how many times a week they had done the exercises: not at all, once, twice, three times or more than three times. In addition, all participants were asked on the 12-month follow-up questionnaire if they had been given footwear advice by the trial podiatrist and whether or not they had followed the advice given.

Adverse events

Details of any adverse events reported to the YTU directly by the participant, a member of their family or by a member of the research team at the recruiting site were recorded. Details of the event were recorded on a REFORM Adverse Event Form (see Appendix 14). Any serious adverse events (SAEs) judged to have been related and unexpected were required to be reported to the REC under the current terms of the standard operating procedures for RECs.

In this study, a SAE was defined as any untoward occurrence that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Expected events included aches and pains in the lower limb, new callus/corn formation, blisters or ulcers and skin irritation/injury including pressure sores and soft tissue injury.

The occurrence of adverse events during the trial was monitored by an independent Data Monitoring Ethics Committee and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee/TSC would have immediately seen all SAEs that were thought to be related to treatment.

Clinical effectiveness analysis

All analyses were conducted on a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) basis using available cases, using a two-sided statistical significance level of 0.05 unless otherwise stated. The analyses were conducted using Stata® version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Data collected at screening and on the baseline questionnaire are summarised for (1) consenting individuals and those who assented to provide screening data but not to enter the trial, (2) the cohort and (3) trial participants as randomised and as analysed in the primary outcome model by treatment group. Comparisons between groups were made using chi-squared tests for categorical data, independent t-tests for continuous variables and negative binomial regression for count data.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis model controlled, as fixed effects, for sex (coded 0 = female, 1 = male), age at randomisation in years (integer) and history of falling. All participants had to have fallen at least once in the previous 12 months, have had a fall in the last 24 months requiring hospitalisation or have a fear of falling in order to be eligible for randomisation. Participants were classified into two groups for the history of falling covariate: (1) one or no falls in the 12 months prior to completion of the background information sheet; or (2) two or more falls reported in the 12 months prior to completion of the background information sheet. These were coded as 0 and 1, respectively.

As there was evidence of overdispersion in the data, Poisson regression was not considered to be appropriate, and so the incidence rate of falls was analysed using a mixed-effects negative binomial regression model. Participants recruited from the same centre, and therefore residing in a particular geographical area, are more likely to be similar to one another than to participants from other centres. This can result in a correlation between participant outcomes within centres. Failure to account for this clustering of outcomes in the analysis can lead to an increase in the type 1 error rate. Therefore, to account for the potential correlation of participant outcomes from participants in the same centre, we included trial centre (n = 13) as a random effect in the model. The model also took account of the different observation periods for each individual by including a variable for the number of months for which the participant returned a monthly falls calendar (using the exposure option within the Stata command).

The model equation is:

where

-

E(yij) is the expected number of falls for participant i in centre j in time tij

-

tij is the length of exposure (follow-up) for participant i in centre j

-

β is a vector of fixed-effect regression coefficients and

-

exp(β) is a vector of the IRRs.

Coefficients are presented as IRRs with 95% CIs and p-values.

Sensitivity analyses

A sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome was conducted, adjusting for any pre-randomisation variables found to be imbalanced by chance between the randomised groups.

Non-compliance

A complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis to assess the impact of compliance on the treatment estimate was undertaken for the primary analysis. CACE analysis allows an unbiased treatment estimate of, in this case, the podiatry intervention in the presence of non-compliance. It is less prone to biased estimates than the more commonly used approaches of per protocol or ‘on treatment’ analysis, as it preserves the original randomisation and uses the randomisation status as an instrumental variable to account for the non-compliance. The CACE analysis employed a two-stage regression process: first, compliance with the intervention was predicted using a linear mixed model adjusted for randomised group, sex, age and history of falling, with centre as a random effect; and, second, the primary analysis model was repeated but the variable for group allocation was replaced with the variable for compliance and the predicted residuals from the first regression was added as a covariate.

Compliance was based on whether or not the participant was seen in clinic for a trial appointment; therefore, all participants in the usual-care group and those in the intervention group who did not attend an appointment were assigned a compliance value of 0 and those in the intervention group who attended an appointment were assigned a value of 1. As this was a multifaceted intervention, it did not make sense to try and measure the extent to which participants used the orthotic insole, performed their prescribed exercises or wore their provided footwear. This would have been measured with too much error.

Excluding fear of falling participants

Over the course of the trial, it was observed that having a fear of falling was a strong predictor of having a fall in the near future. A protocol amendment was submitted to, and approved by, the REC to include ‘fear of falling’ as an inclusion criterion. Therefore, a small number of participants in the cohort were randomised into the trial who reported a fear of falling on their baseline form but who had not reported a previous fall. On advice from the TSC and the HTA programme, the trial over-recruited to make up for the number of participants recruited using the fear of falling criterion. A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding these ‘fear of falling’ participants from the primary analysis to determine their effect on the estimates.

Missing data

We compared data collected prior to randomisation for participants who are included in the primary analysis to ensure that any attrition had not produced imbalance in the groups in important covariates. To account for any possible selection bias, univariate logistic regressions were run to predict missing outcome data. As the number of participants who did not return any falls calendars after randomisation was low, missing outcome data were based on returning fewer than 6 months’ worth of data post randomisation. All variables found to be predictive of missingness were then included in a single stepwise logistic regression model, which used a p-value of 0.1 to refine the covariates. The primary analysis was then repeated including as covariates the variables found to be significantly predictive of non-response to determine if this affected the parameter estimates.

Podiatrist effects

In 6 of the 13 sites, only one podiatrist delivered the intervention; therefore, podiatrist effects are to some extent captured by centre effects that are being accounted for in the primary analysis. However, in other sites, more than one podiatrist delivered the intervention to the participants. We therefore have potential clustering by podiatrist in the intervention group that is not completely captured by centre. The success of the intervention may depend on the skill/experience of the podiatrist and their relationship with the participant. To account for this variation between podiatrists, a sensitivity analysis was conducted in which every participant, whether allocated to the intervention or usual-care group, was associated with a podiatrist. For intervention participants, this podiatrist was the podiatrist who delivered their intervention appointments. For usual care participants or intervention participants who did not attend an appointment, we assigned them a counterfactual podiatrist, that is, one that they could have seen had they received the intervention. All participants at sites with only one trial podiatrist were assigned this podiatrist. In sites with more than one trial podiatrist, the participants were randomly assigned one of the podiatrists who saw participants who were randomised in the same month as them, in the proportion that they saw intervention participants. Each podiatrist then had their own cluster of usual care and intervention participants. The primary analysis was then repeated with podiatrist, rather than centre, as a random effect.

Secondary analyses

The incidence rate of falls over the 12 months following randomisation (as reported for the previous 6 months on the 6- and 12-month participant questionnaires) was analysed in the same way as the primary outcome.

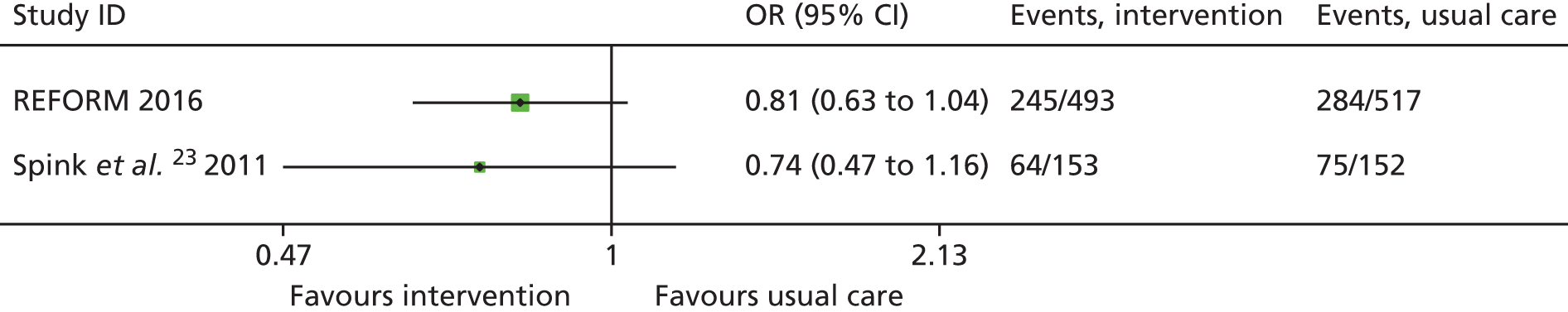

The proportion of fallers versus non-fallers, and of multiple fallers versus single or non-fallers, in each group was compared using a mixed logistic regression model adjusting for sex, age and history of falling, with centre included as a random effect. 37

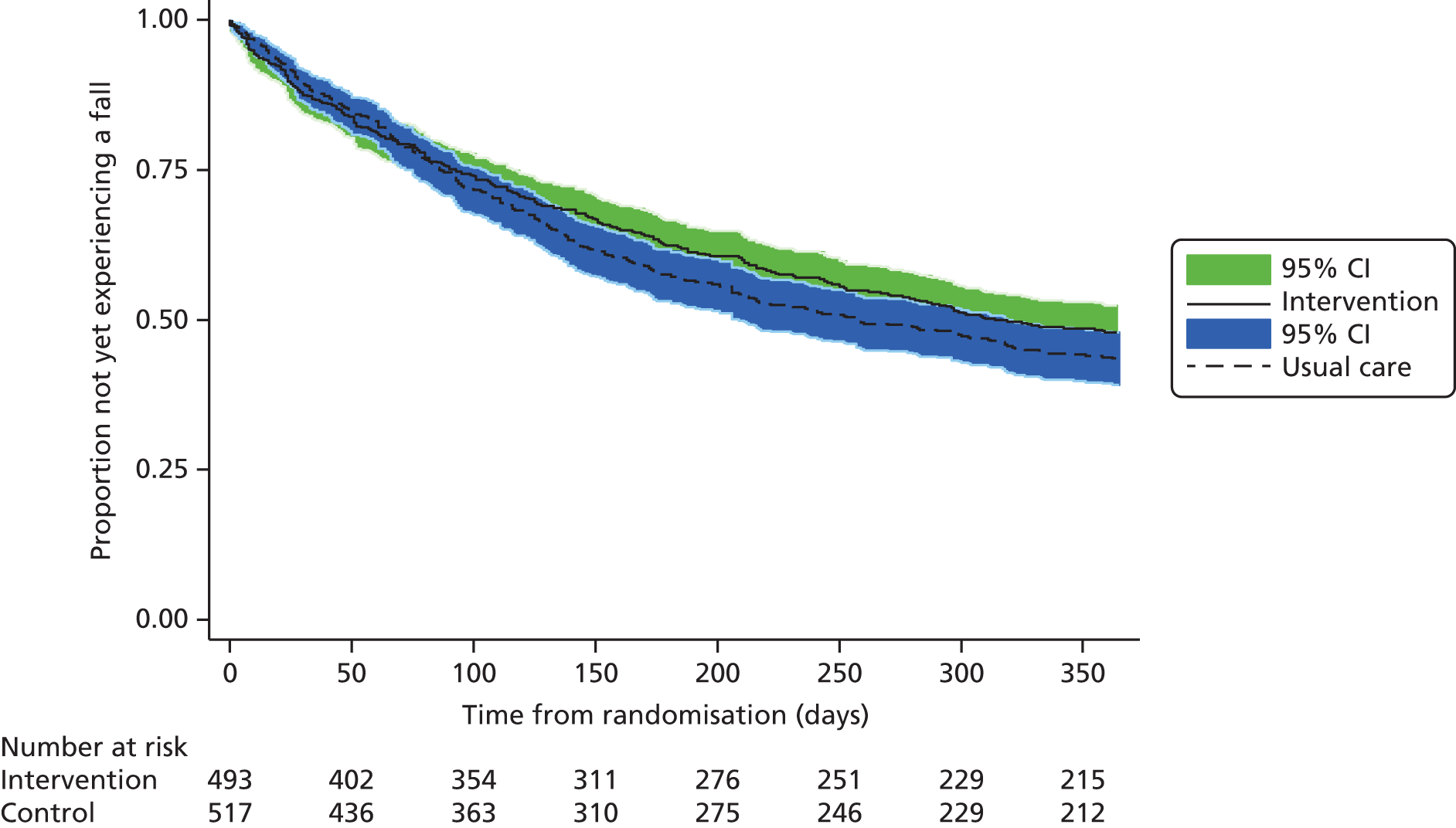

The time from randomisation to first fall in days was derived. Participants who did not have a fall were censored at their date of death or, if alive, their withdrawal from the trial, the date of the last available assessment or 365 days after randomisation, whichever was latest. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were produced for each group. The time to first fall was analysed by a Cox proportional hazard regression with shared centre frailty effects adjusting for sex, age and history of falling. 38

Fear of falling in the past 4 weeks, and the total scores for the Short Falls Efficacy Scale – International, GDS and FAI were compared between the two groups using a covariance pattern mixed model incorporating all post-randomisation time points (6 and 12 months) adjusting for baseline score, sex, age, history of falling, treatment group, time and a treatment group-by-time interaction term, with centre as a random effect. Such an approach models the correlation of observations within participants over time. Different covariance structures for the repeated measurements, which are available as part of Stata version 13 (unstructured, exchangeable, independent and banded), were explored and the most appropriate pattern used for the final model based on the Akaike’s information criterion (smaller values are preferred). 39 Participants were included in the model if they had full data for the baseline covariates and outcome data for at least one post-randomisation time point (6 or 12 months). An estimate of the difference between treatment groups in the outcome was extracted for each time point with a 95% CI and p-value.

The assumptions of the covariance pattern mixed model were checked visually. The normality of the standardised residuals was assessed via a histogram and Q–Q plot, and the homoscedasticity of the errors was checked by plotting the residuals against the fitted values.

The CD-RISC2 score at 6 months was compared between the two groups using a linear mixed model adjusting for baseline CD-RISC2 score, sex, age and history of falling, with centre as a random effect.

Participants with a score of ≥ 6 on the GDS were categorised as having depression; the proportion of people with depression in each group was compared at 12 months using a mixed logistic regression model adjusting for sex, age and history of falling, with centre as a random effect.

The proportion of participants obtaining at least one fracture over the 12-month follow-up period was compared using a mixed logistic regression adjusting for sex, age and history of falling, with centre as a random effect.

At 12 months, participants were asked to indicate their level of pain or discomfort in their feet on a visual analogue scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain). This was analysed using a linear mixed model adjusting for sex, age and history of falling, with centre as a random effect in an ITT analysis, and also in a CACE analysis. We based compliance on whether or not the participant was seen in clinic for a trial appointment. The CACE analysis employed a two-stage regression process: first, compliance with the intervention was predicted using a linear mixed model adjusting for randomised group allocation, sex, age and history of falling, with centre as a random effect; and second, foot pain score was predicted using a linear mixed model adjusting for compliance, sex, age, history of falling and the predicted residuals from the first regression, with centre as a random effect.

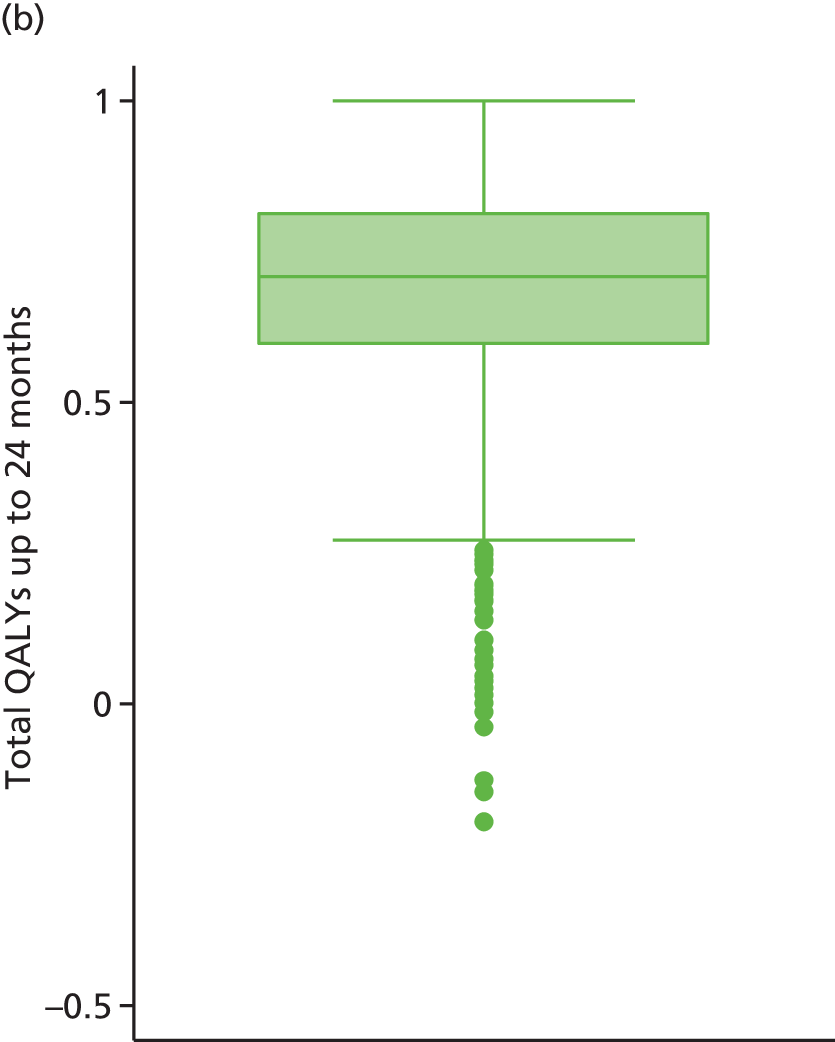

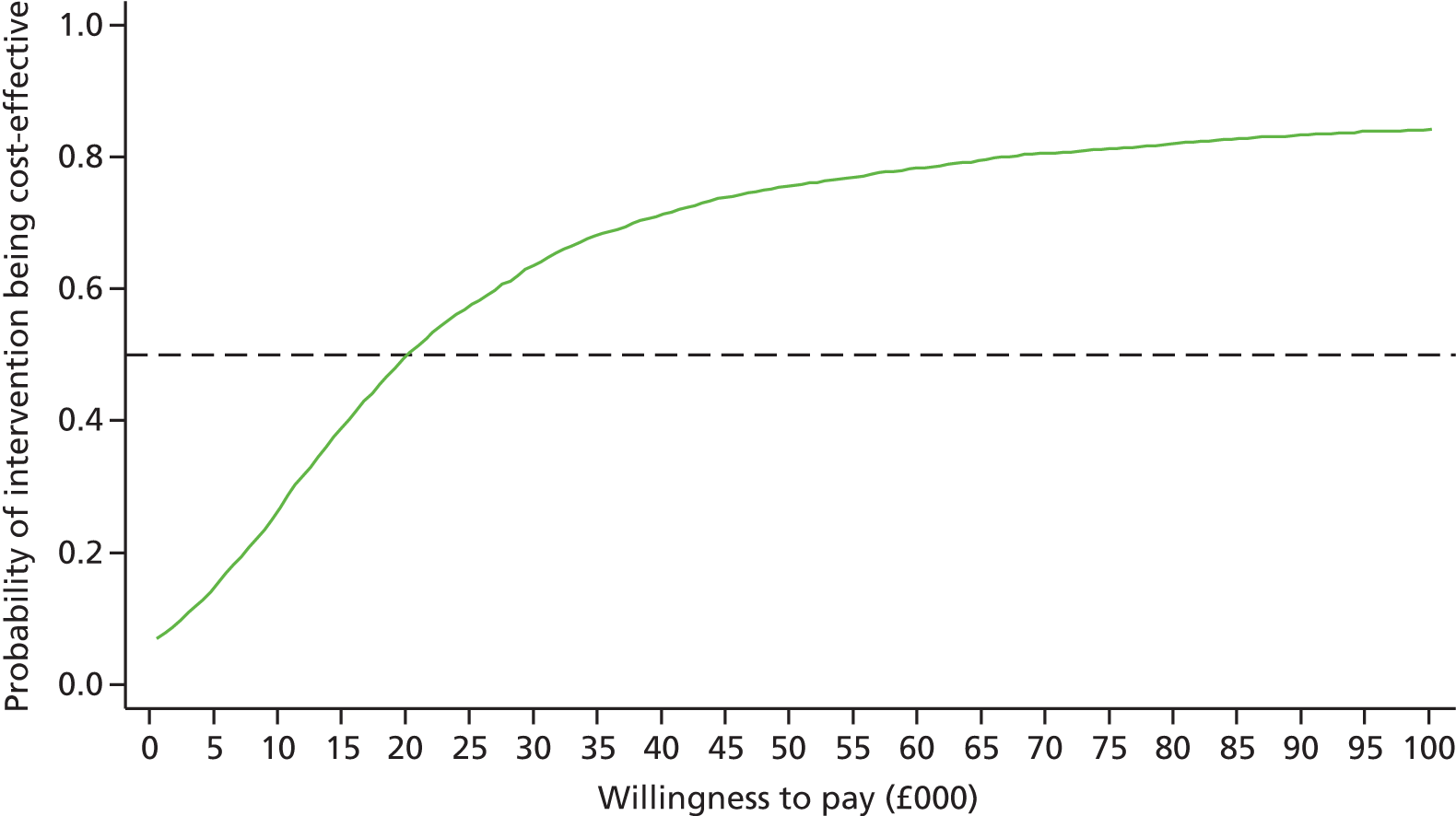

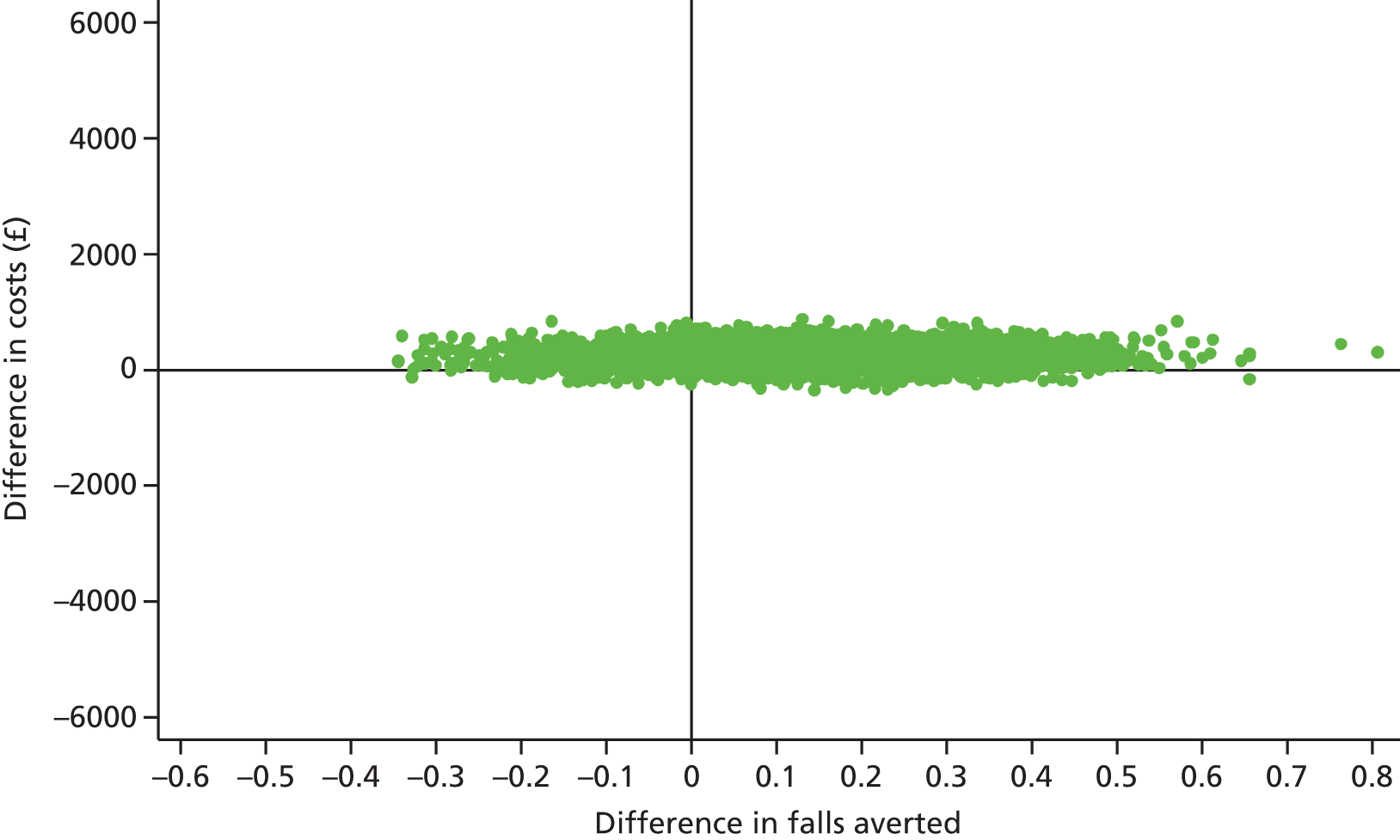

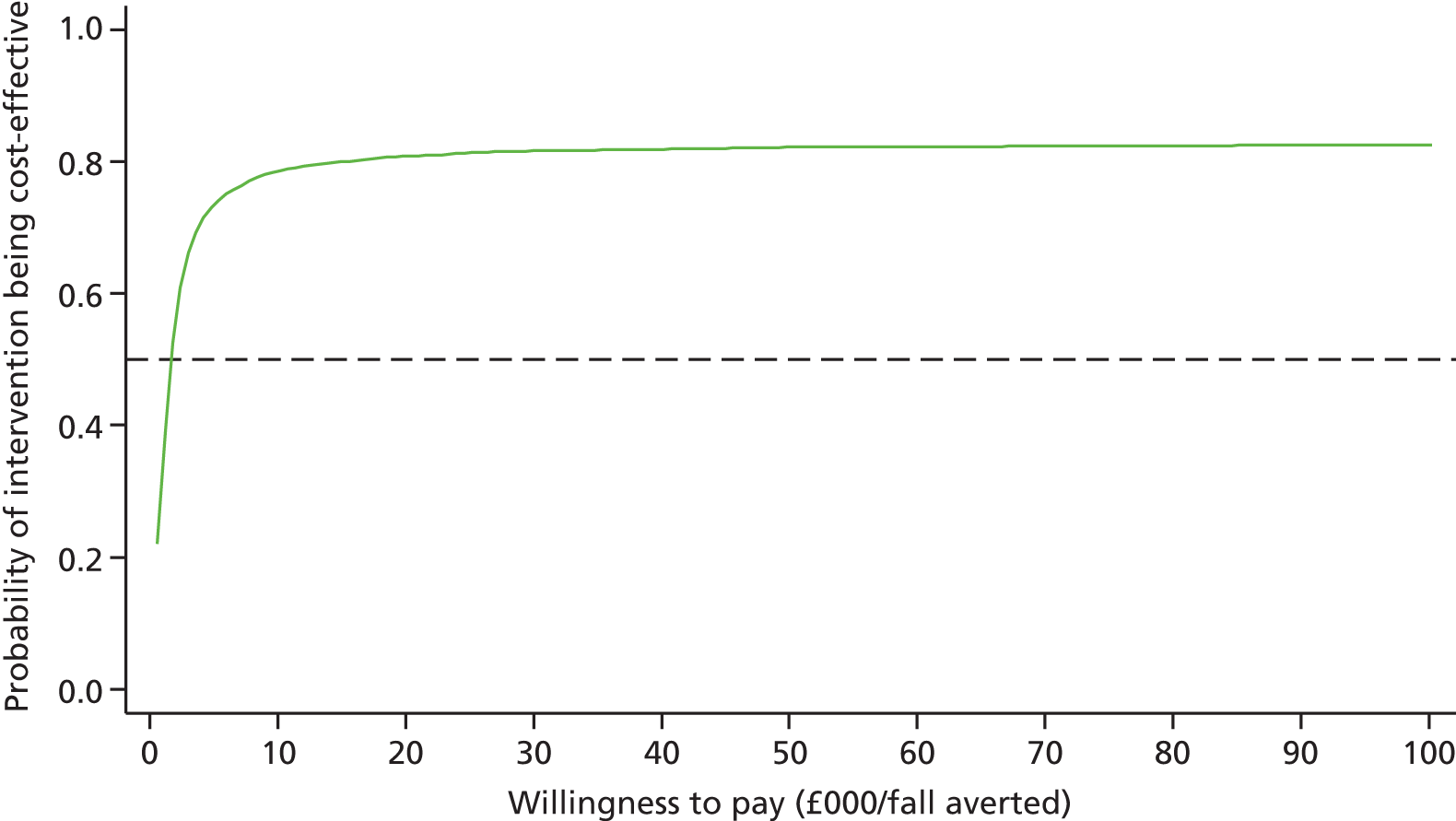

Economic analysis

The economic analysis was conducted on an ITT basis from the NHS and Personal Social Services perspective. Data on HRQoL, obtained from the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) instrument collected from self-reported questionnaires, were converted into quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for each participant using the area under the curve method. Costs were expressed in UK pounds sterling (£) at 2015 prices.

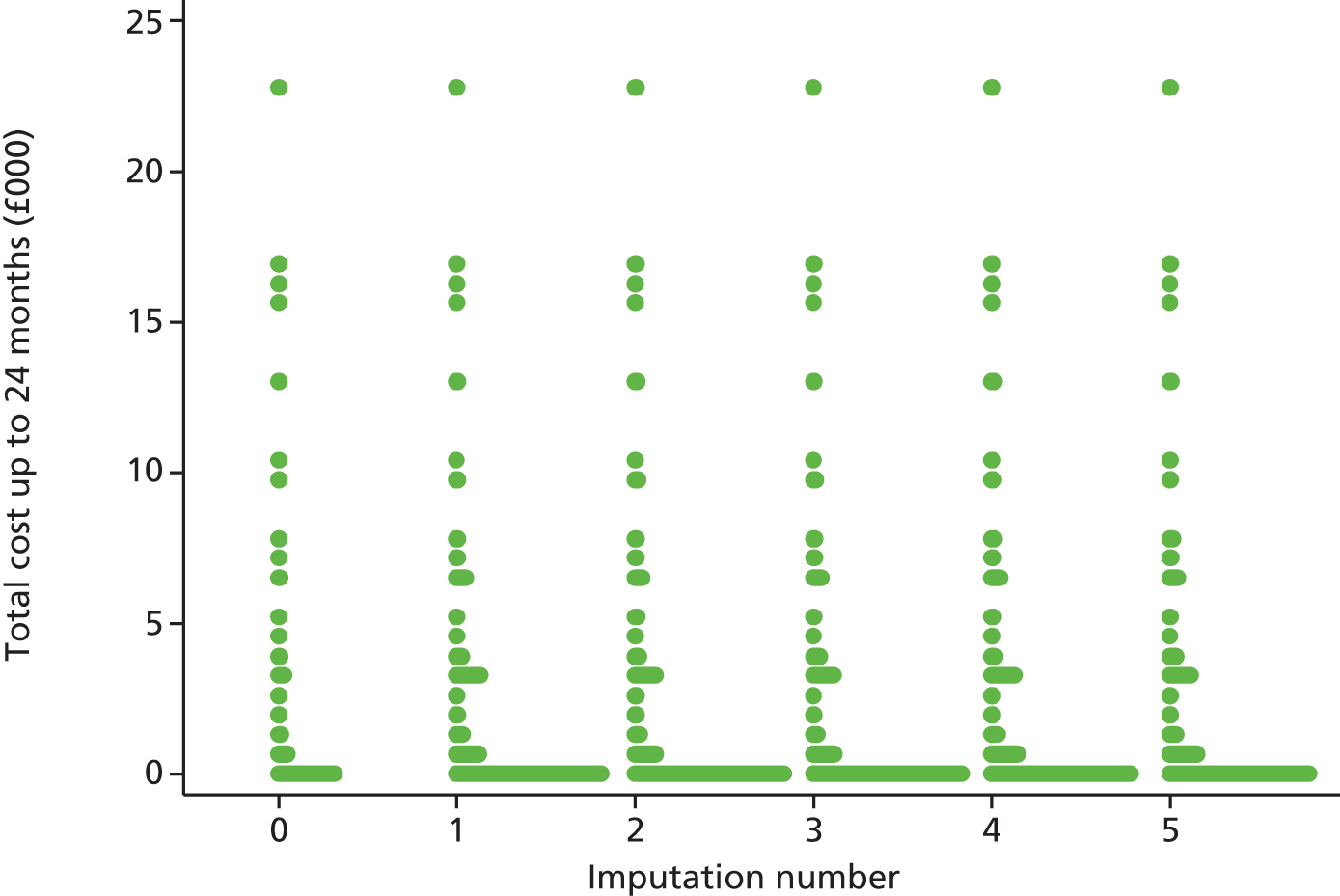

Differences in mean costs and QALYs at 12 months post randomisation, estimated by means of regression methods, were used to assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared with usual care. Multiple imputation (MI) was used to impute missing cost and QALY data, and the base-case analysis was conducted on this imputed data set. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test assumptions regarding the missing data mechanism, level of imputation on HRQoL, resource use and perspective of analysis. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were used to express the probability of whether or not the intervention is cost-effective at the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold used by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

In addition, HRQoL was extrapolated to 5 years in order to explore how the differences in HRQoL evolve beyond the study follow-up. For this exploratory projection, we used a decision-modelling approach and assumed that the difference in HRQoL and costs observed at 1 year would remain unchanged.

Qualitative study

A qualitative study was undertaken to explore the views, experiences and acceptability of the REFORM package of care from the perspective of both service users and service providers. In particular, this qualitative study considered the barriers to and facilitators of delivering and receiving the intervention, in the context of podiatry care. An in-depth appreciation of these issues is useful for the future successful implementation of complex podiatry interventions in this population group.

Design

A semistructured interview study was used to gather in-depth information on the trial participants’ experiences of receiving the podiatry intervention, alongside the podiatrists’ experiences of delivering the intervention. The interviews were conducted either face to face or over the telephone with participants and podiatrists in the trial (at the end of the intervention period).

Sampling

A purposive sampling strategy was used to achieve a hetergeneous sample of trial participants from the intervention group to ensure maximum variation40 according to age, sex and history of falls. Previous studies have indicated that a sample of approximately 20–30 trial participants is sufficient to address the aforementioned aims from the point of view of the service users.

As podiatrists delivering the intervention were based in a wide variety of clinics, it was expected that their views and experiences may differ. For example, some podiatrists worked in biomechanics and others worked in routine podiatry clinics. All 28 podiatrists who delivered the REFORM intervention were invited for interviews through the PI at each site.

Recruitment and consent

All REFORM trial participants living in the Yorkshire or Lincolnshire areas who expressed an interest in undertaking other associated REFORM research studies on the consent form and who had received the intervention were eligible for participation in the qualitative study. Following sampling, study participants were approached by letter, which contained an information sheet (see Appendix 15) and two consent forms (see Appendix 16). The letter also informed trial participants that a qualitative researcher (authors AC and SC) would contact them via telephone to find out if they would be willing to take part and, if so, to arrange a time for the interview to take place. In accordance with ethics guidelines, informed consent was gained by the researcher before the commencement of the interview. The aim of the interview was explained to the participant, and this was followed by an opportunity for them to ask questions about the study. The anonymity and confidentiality of participants’ personal information were assured by the researcher.

Podiatrists were also invited to take part in the qualitative interviews. The PI at each site was sent an e-mail asking if he or she and the podiatrists who delivered the intervention would like to be interviewed. The PI was asked to forward the e-mail on to podiatrists at their site who delivered the intervention. Podiatrists were asked to contact the research team directly if they wished to take part. The recruitment e-mail included an invitation, information sheet (see Appendix 17) and consent form (see Appendix 18). This was followed up by a telephone call or an e-mail. Prior to the interviews, podiatrists were assured anonymity and confidentiality and were given the opportunity to ask questions. For podiatrists interviewed face to face, a similar process to that used to obtain consent for trial participants was used. For interviews conducted over the telephone, verbal consent was obtained prior to the start of the interview and a copy of the consent form was sent to the qualitative researcher either in the post or via e-mail.

Data collection

The semistructured interviews with trial participants were carried out in participants’ homes or at the University of York between November 2013 and March 2016 and on average lasted 40 minutes using a topic guide (see Appendix 19). All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and anonymised before data analysis.

The semistructured interviews with podiatrists were carried out between July 2015 and January 2016 in a private room on premises where the podiatrist was based or over the telephone. The interviews lasted between 30 and 70 minutes and were conducted using a topic guide (see Appendix 20).

The topic guides provided a framework for the semistructured interviews and ensured that all podiatrists and trial participants were asked the same questions, allowing comparisons to be made during the analysis. However, the wording of questions was not fixed to allow interviews to flow and to allow for probing when more detail was required.

Data analysis

An initial thematic analysis was carried out using the stages as outlined by Braun and Clarke:41 (1) familiarisation, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes and (6) data reporting. An initial coding framework was developed based on a priori themes relating to issues included in the topic guide while allowing for emergent themes. Descriptive coding was conducted, following familiarisation with the data, by the main qualitative researcher on the project (author SC), informed by regular discussion with the qualitative team (authors JA and AC). Subsequently, initial codes were refined in order to address the aims of the qualitative study outlined above, following the analysis of the main trial. A constant comparison method42 was used to check and compare across the data set and to establish appropriate analytical categories. This also ensured that any additional codes were added to reflect as many of the nuances or outlier views in the data as possible, taking into consideration the participants’ wider contexts. Anonymised participant identifiers are used for the reporting of results.

To promote quality, the following strategies were used: description of the participants to provide context (credibility and transferability), transparency of the research process (transferability), evidence of consistency using multiple examples from data (dependability) and engagement of the wider research team with interim findings (confirmability). In addition, a reflexive approach was taken to data analysis. The main interviewers (authors SC and AC) were academic research fellows with no podiatry training. SC was the main REFORM trial co-ordinator and AC had no prior knowledge or experience of podiatry interventions, orthotic insoles or RCTs. The other member of the qualitative team (author JA) had an academic research background and also did not have previous knowledge or experience of podiatry care. This placed the qualitative research team in a very neutral position relating to any prior expectations relating to the study intervention.

Chapter 3 Protocol changes

Clarification to trial documentation and collection of data

Following review of the trial documentation in March 2012, we decided to simplify the participant self-report question regarding neuropathy status. Participants were asked to report if they had any numbness or tingling in their feet or lower limbs as opposed to being asked if they had neuropathy. This was because it was felt that participants may not have known that they had neuropathy but would be able to report if they had numbness or tingling in their lower limbs. Baseline data regarding referrals to a falls service were also collected.

Following completion of the pilot study, it was felt that sufficient data had been collected about the reasons why potential participants did not wish to take part in the study. To reduce the postage costs for the study and on advice of the patient representative, who expressed concerns about this additional data collection, it was agreed that data on reasons for declining participation in the study would not be collected in the main study.

To minimise participant burden and to improve data collection, it was agreed that qualitative data from participants could be collected over the telephone and that information regarding exercise and orthosis compliance would be collected via postal questionnaire at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation rather than by the completion of an exercise diary.

Amendments were made to the participant information sheet and consent form in August 2012 to clarify that not all participants would be offered an additional podiatry visit.

Recruitment

The original protocol stated that we planned to recruit 1700 participants to the REFORM cohort, of whom we would randomise 890 to the REFORM trial over a 24-month period from three NHS trusts (Harrogate, Sheffield and Leeds). However, the study commencement was delayed by approximately 5 months because of contractual issues and delays in obtaining service support costs for the study and research and development approval. As the trial progressed, recruitment fell below the expected level because, in the main, a lower than expected uptake rate to the study by participants and a lower than expected number of eligible participants expressing an interest in taking part. Approval was obtained from the funder to extend the study by 10 months to a total of 52 months (December 2011 to March 2016). This permitted the recruitment of seven additional sites. The details of the recruiting sites and date on which research governance approval was received can be found in Appendix 1.

With the number of eligible participants lower than expected, the number of participants in the REFORM cohort had to be increased from 1700. It was decided to aim to recruit 2600 participants into the cohort. To assist with recruitment, approval was obtained to implement the opportunistic screening of participants by podiatrists in clinics, falls practitioners, physiotherapists and the research podiatrist.

Inclusion criteria

The following changes were made to the eligibility criteria during the study.

-

Responses on the ‘decline forms’ received from participants who did not wish to take part in the study during the pilot phase indicated that participants declined because they assumed that they would not be eligible as they considered themselves either too old or too ill. The participant information sheet was modified to try and address this concern stating that, in effect, no one was ‘too old’ to take part and having a chronic illness did not necessarily exclude people from participation. In addition, the TSC reviewed the age limit and agreed to a change from ≥ 70 years to ≥ 65 years, as it was felt that younger participants may also potentially benefit from the intervention. It was hoped that this change would increase the size of the eligible population and improve recruitment. An amendment to reduce the age limit of participants in the study was approved by the multicentre REC in February 2013.

-

Responses from the screening forms sent out during the pilot phase indicated that participants were being excluded as they were already wearing an insole. In order to aid recruitment the TSC agreed that as the trial was evaluating a multifaceted intervention and not insoles on their own, from February 2013 patients could be included if they were currently wearing a full or three-quarter length insole for the purpose of altering or modifying foot function. For participants allocated to the intervention group who were already wearing an orthotic insole, the treating podiatrist made a clinical judgement on the suitability of replacing the insole with one used in the trial. Usual care participants continued to wear their insole but may have had a new insole prescribed by their podiatrist as part of their routine care.

-

To minimise post-randomisation attrition rates, participants had to demonstrate their commitment to the study by returning three falls calendars before they could be randomised. This was thought to cause considerable delay in participants being randomised at new sites. Therefore, to aid recruitment, in April 2013 the need to return a minimum of three falls calendars was reduced to a minimum of one.

-

We undertook an analysis of the predictors of falling in those participants who had been recruited to the study but were in the 3-month ‘run-in’ phase, so were yet to be randomised. As expected, those who reported having had a previous fall were at a higher risk of falling during the run-in period than those who had not [odds ratio (OR) 2.4]. We also observed that those who reported having a fear of falling on their baseline questionnaire were at an elevated risk (OR 2.1). In a previous trial of fracture prevention, a similar relationship was found: fear of falling is a risk factor nearly as strong as a history of falls. 43 Following advice from our TSC and the funders, it was agreed that from June 2014 an additional inclusion criterion (i.e. fear of falling) could be used at clinics that had the capacity to see participants but did not currently have any participants eligible under the current criteria. We felt that this would improve the generalisability of the study and aid recruitment.

To enhance participant safety, it was agreed that, from February 2015, participants should be excluded from the study if they:

-

Had a lower limb amputation.

-

Were unable to walk household distances without the help of a walking aid such as a walking frame, a walker or a person to assist. Participants who used one walking stick, however, were still eligible for the study.

Orthoses

In the original protocol, we intended to use the same orthotic insole (Formthotics™, Foot Science International, Sockburn, New Zealand) used by one of the authors (HBM) in an Australian study,23 as it was found to be acceptable to participants and had been associated with a reduction in falls. However, during the setup of the pilot phase of the study, podiatrists at the recruiting sites reported difficulties using Formthotics, particularly in relation to fitting and modifying. Feedback from a group of podiatrists at recruiting sites indicated that they frequently used an alternative range of orthotic insoles called the ‘X-Line range’, as they were reportedly easier to fit in participant’s current shoes and easily modifiable. In addition to basic functional foot support and control, cushioning properties were also identified as desirable. Therefore, during the pilot phase of the study, 31 participants were given both a Formthotics and an X-Line insole to take home and wear; they were then questioned about their insole preference. As the majority of participants (84%, 26/31) preferred the X-Line range, it was decided to use it in the main trial instead of the Formthotics insole.

Exercises

The exercises developed by one of the authors (HBM) for his Australian trial were reviewed and adapted to take on board lessons learned from the study and to make them more suitable for a UK population. Owing to cost and safety reasons the use of the Archxerciser™ device (Elgin Archxerciser Foot Exercisers, Elgin Division, IL, USA) and marbles were replaced with a therapy ball, which simplified the toe exercises using one device, reflecting current UK practice. Standing calf stretch exercises were adapted for an older UK population by providing an option to use a firm belt/band to stretch while in a sitting position. A further proprioception/balance training exercise was also added.

Additional criteria to expected adverse events

Following discussion with the Trial Management Group it was decided to include some additional expected adverse events relating to wearing an orthotic insole or undertaking foot- and ankle-strengthening exercises to the protocol. These included aches and pains in the lower limb for longer than 48 hours, new callus/corn formation, blisters or ulcers, skin irritation/injury including pressure sores and soft tissue injury.

Provision of footwear

In the original protocol participants were to be provided with a voucher allowing them to purchase their new footwear from participating designated shoe shops. However, this system became unworkable as the number of sites increased and sites became more geographically dispersed. Participants therefore chose their footwear from a catalogue of footwear reviewed and compiled by the research team for suitability. These were then ordered directly from the company by the podiatrist. Footwear that did not fit the participant could be returned to the supplier and exchanged for a different size.

Chapter 4 Clinical effectiveness results

Participant flow

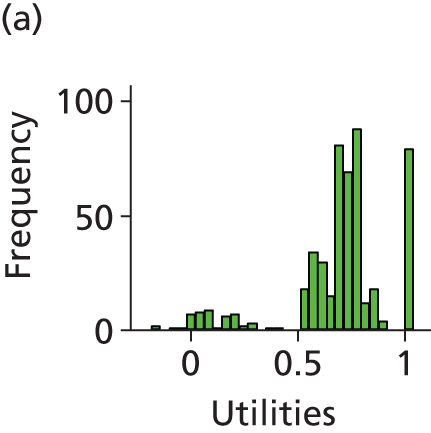

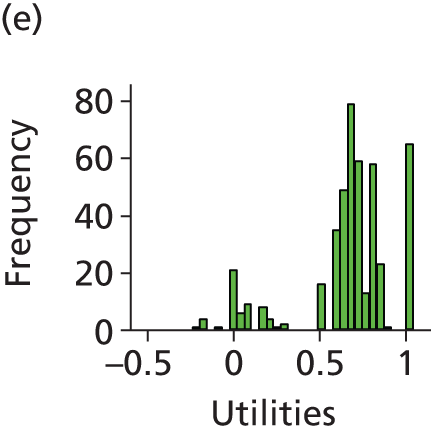

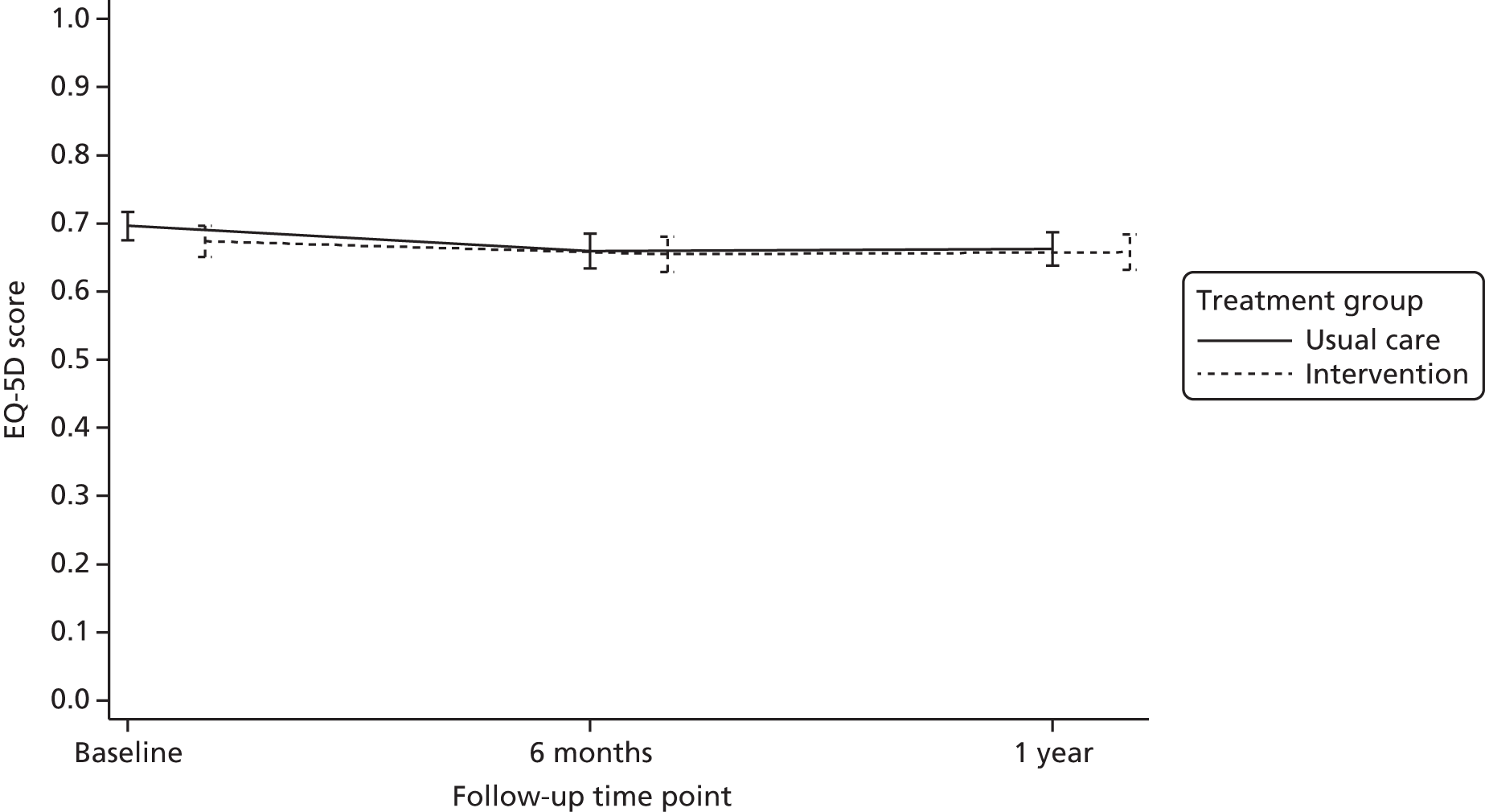

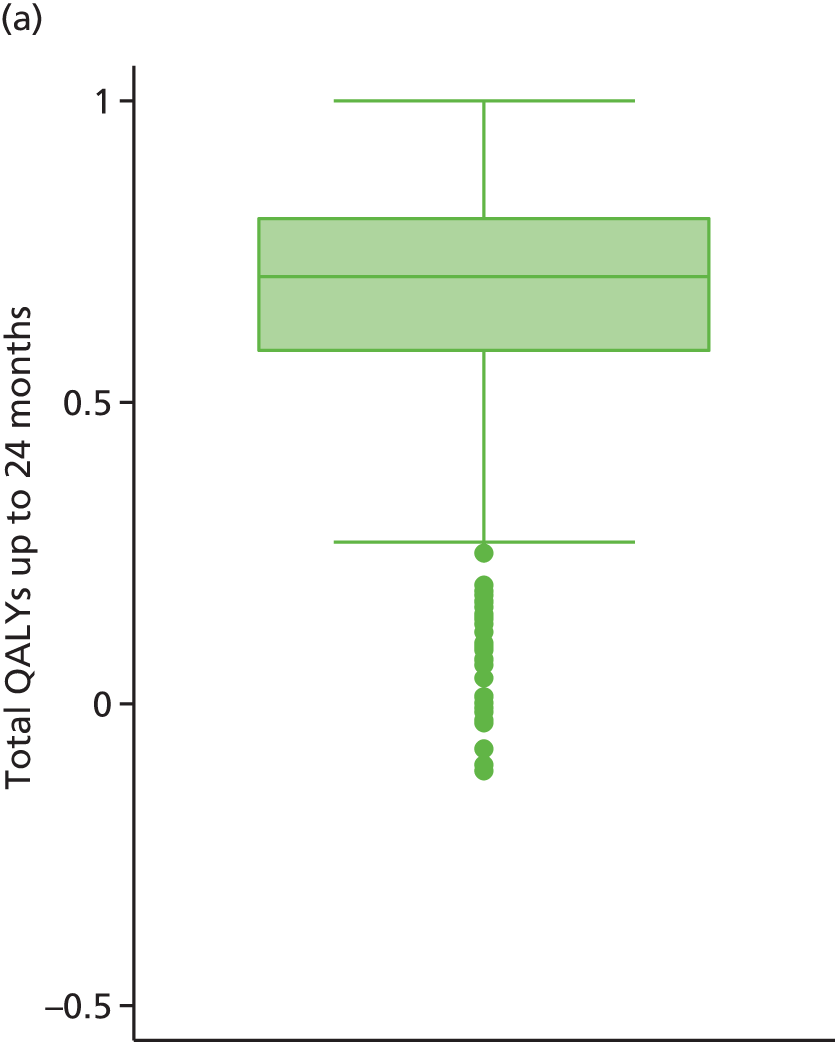

Participants were enrolled into the REFORM study from nine NHS trusts based in either primary or secondary care in the UK (Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust; Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust; Solent NHS Trust; Kent Community Health NHS Foundation Trust; Humber NHS Foundation Trust; Northern Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust; South Tyneside NHS Foundation Trust; and North Tees and Hartlepool Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) and one international site in a university school of podiatry in Galway, Ireland. Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust was split into four geographical locations, which were considered to serve distinct populations (Scarborough, York, Harrogate and Skipton), thus forming 13 trial centres. A total of 42 podiatry clinics consented to screen their practice lists and identify participants who met the initial inclusion criteria: those aged ≥ 65 years who were registered with the service and had attended routine podiatry services within the past 6 months. Patients who had attended high-risk clinics (e.g. a diabetes clinic) or who lived in a nursing home were excluded from the invitation mail-out. In addition, sites were requested to screen out, when possible, patients in the following groups: patients with a life expectancy of < 6 months, patients known to have dementia, a neurodegenerative disorder, neuropathy or a lower limb amputation, and patients who were chair or bed bound.