Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/144/04. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The draft report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in November 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Lisa Hampson reports grants from the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work. Francesco Muntoni reports grants from the European Union 7th Framework Programme, MRC, Ionis Pharmaceuticals/Biogen, Inc., PTC Therapeutics, Summit Pharmaceutical International, Roche, L’Association Française contre les Myopathies and Muscular Dystrophy UK and personal fees from Pfizer, Biogen, Inc. and Summit outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Hind et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Epidemiology

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a genetic disease mainly affecting boys. It affects between 1 in 3600 and 1 in 6000 live male births;1–3 the prevalence is 5 in 100,000. 4

Aetiology

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is caused by deletions, duplication or point mutations in a gene on the X chromosome. 5 The gene codes for a protein, dystrophin, that links the cell’s cytoskeleton to a transmembrane complex. Absence of this protein causes disease in muscle cells and brain neurons. The precise mechanism is still uncertain.

Pathology

In muscle, pathological studies show a ‘dystrophic’ picture in which there are dying muscle cells and regenerating muscle cells, together with inflammatory cells and excess amounts of fat and connective tissue. 6,7 Clinically, this manifests as weakness, first of the larger skeletal muscles around the shoulders and hips, and later of all skeletal muscles in the limbs and trunk. With increasing age, this causes a progressive loss of functional abilities that affect mobility (going up stairs, walking, standing, sitting and transferring between objects such as a chair or bed), activities of daily living (dressing, bathing and eating) and eventually breathing. As the disease progresses, muscles and tendons become shorter. These ‘contractures’ then prevent the joints they operate from moving through their full range, because the muscle can no longer stretch as completely as it should. The calf and long finger muscles are often involved by the age of 5 years, causing an inability to bend the foot fully up towards the shin (dorsiflexion) or straighten the fingers back. If untreated, contractures become more severe with time. Later, weakness of the trunk muscles causes scoliosis or curvature of the spine. The heart muscle is increasingly affected with age, eventually leading to impaired function and cardiac failure. The smooth muscle of the bowel deteriorates, affecting bowel function. The lack of dystrophin subtypes in the brain increases the risk of non-progressive cognitive dysfunction, which is associated with communication difficulties. 8

Prognosis

Untreated, half of boys will lose independent ambulation by the age of 9 years, and all will do so by the age of 12 years. Scoliosis and impaired heart function start in early adolescence, whereas breathing difficulty develops later in adolescence. In the 1960s, survival beyond mid-adolescence was unusual. With better therapies, survival increased to late adolescence in the 1970s to the 1990s. In the past two decades, the introduction of more effective respiratory support and heart treatment has increased survival into the early 30s, or longer. The more widespread use of corticosteroids from a young age has slowed disease progression; in those taking daily steroids, the average age at loss of ambulation has increased to 14 years. 9

Significance in terms of ill health

Health-related quality of life for boys with DMD and their carers is lower than for the general population. 10,11 Although physical and psychosocial domains of health-related quality of life are comparatively low in boys with DMD, psychosocial quality of life is sometimes higher in adolescents than in school-age children, indicating the development of coping strategies. 12–14 The psychosocial well-being of parents is greatly impacted, particularly around the time of a boy’s transition to wheelchair use. 15,16 Parents, especially mothers, report high levels of anxiety, depression and guilt. 17,18 Early diagnosis and the resilience of the family unit, expressed as their commitment and control, were associated with improved psychological adjustment by the parent, resilience on the part of the boy and response from siblings. 18–22 Parents, and mothers in particular, report care activities, such as including help for bathing and toileting, as time-intensive and contributing to social isolation. 23

Health-care costs are associated with access to specialist paediatricians/physicians in neurology, respiratory, cardiac and endocrine fields, orthopaedic surgeons, psychologists, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Boys will sometimes have care co-ordinators or advisors, dietitians or nutritionists, or speech/language/swallowing therapists. Young men older than most of those in our study are likely to make increased use of emergency and respite care. Outside the health services, older boys may access home help, personal assistants and transportation services. From around 8 years of age, the median age of boys entering our study, families will typically make investments in and reconstructions of the home, for instance making adaptations for wheelchair accessibility. 24 Adaptations may also be required to educational facilities. A systematic review of the cost of illness4 noted only three studies that reported cost-impact data, all of which were > 20 years old. 25–27 However, a questionnaire study24 involving people with DMD in Germany, Italy, the UK and the USA provided per-patient annual costs of DMD in 2012 in international dollars. The questionnaire elicited information about hospital admissions, visits to health-care professionals, tests, assessments, medications, non-medical community services, aids, devices, alterations to the home and informal care. Mean per-patient annual direct cost was $23,920–54,270, which is between 7 and 16 times higher than the mean per-capita health expenditure. The total societal costs were $80,120–120,910 per patient per annum, increasing sharply with disease progression. Mean household costs were estimated at $58,440–71,900. 24

Current service provision

Pharmacological management and multidisciplinary care excluding physiotherapy

At diagnosis, a boy and his family will typically be seen by a paediatrician at their local hospital, often a district general hospital. They will then be referred to a specialist muscle clinic, usually involving a paediatric neurologist, in their regional teaching hospital. 28 Regular review and ongoing medical care is provided by these services. The boy and his family will also be seen by the regional genetics service. As part of this service provision they will also be referred to the local paediatric physiotherapy team for assessment and management (see Physiotherapy). If needed, they may be referred for occupational therapy advice as well. Educational services will also be involved. Some children and their families may also benefit from psychological support.

From the age of 3–4 years, most boys will start treatment with corticosteroids, which requires 6-monthly monitoring visits. If complications develop, extra visits and referrals may be needed. One frequent early complication is excess weight gain, which would lead to referral to dietetic services. Approximately one-third of the current population of ambulant boys is eligible for trials of newer treatments designed to increase the amount of the missing dystrophin protein in muscle cells, leading to a milder disease course. If successful, these treatments are likely to become generally available, and additional products are likely to be designed to expand the number of boys who could benefit.

Physiotherapy

Although physiotherapy has been a mainstay of treatment since the 1960s, there is relatively little evidence for its efficacy. There have been no generally accepted guidelines on what type or dose of physiotherapy intervention should be provided. 29,30 Many recommendations are based on animal studies in which contraction-induced muscle injury was observed in dystrophinopathy. 31 A Muscular Dystrophy Campaign workshop29 agreed that the main aims of physiotherapy in neuromuscular disease should be to:

-

maintain or improve muscle strength by exercise

-

maximise functional ability through the use of exercise and the use of orthoses

-

minimise the development of contractures by stretching and splinting.

The prevention of joint contractures is a multidisciplinary effort, involving specialist hubs and community spokes. 32 Regional consultant neurologists and specialist neuromuscular physiotherapists review disease progress and treatment regimens at clinic visits, typically twice a year, and offer management suggestions to community physiotherapists. 28 While a boy is still able to walk, a community paediatric physiotherapist will monitor him for hip and ankle contractures until he becomes wheelchair dependent. 33 The community physiotherapist is responsible for tailoring a programme of stretches and exercises to the boy’s individual needs and tolerance levels,28 and for training parents, carers, school staff or, occasionally, other health and social care staff to deliver the stretches. 33

Management should consist of a variety of treatment options aimed at maintaining the length and extensibility of affected muscle groups. 34 Although evidence to support interventions aimed at improving the range of movement is lacking, there are generally recognised principles that should be carried out to delay or, where possible, prevent the development of contractures. 35 These include the prescription of a regular targeted stretching regime and the use of specific orthotics (e.g. resting or night splints are generally recommended). Stretches are typically prescribed to be performed at home, in school or occasionally in community clinics, on a minimum of 4–6 days per week. 28 They are intended to maintain dorsiflexion and hip flexion range, among other targets, with a view to postponing the onset of contractures and prolonging the length of time the child can walk independently. 33 There are no clear guidelines to specific exercise prescription, but regular submaximal exercise is recommended to maintain existing muscle strength and avoid secondary disuse atrophy,36,37 along with general advice on regular activity such as walking, cycling and swimming. Although there is still the need for further research, there is general agreement that exercise that contains a substantial eccentric component (such as trampolining, stair descending) should be avoided because of the risk of exacerbating muscle damage. 38

Physiotherapy plays its part in the holistic, multidisciplinary management of children with DMD, providing specialist assessment, physiotherapy prescription and ongoing monitoring and evaluation of a complex and progressive condition. 28 Liaison with other specialist services, such as orthotics, wheelchair services, social and housing services, and schools to ensure the provision of appropriate equipment and support in a timely manner to maximise function and independence wherever possible is key. Hyde et al. 39 recommend the use of night splints. Resting or night splints, generally ankle–foot orthoses, are provided for use in combination with a regular stretching regime to optimise the length of the tendo-Achilles complex and maintain ankle dorsiflexion at night. 28,33,39 Children who are losing the ability to walk may be provided with knee–ankle–foot orthoses and may have surgical intervention to release tendons with a view to maintaining joint motion and independent ambulation. 28,33 Postponing wheelchair use may also defer the more or less inevitable associated onset of spinal scoliosis. 33

Aquatic therapy

Introduction

Exercise that is safe and controlled but still sufficiently intense to maintain physical function is a challenge for children with altered muscle tone, balance or motor control problems and severe contractures. 40 Warm water allows children with DMD to perform targeted stretches, exercises and function-based and play activities that are progressively lost to them on dry land. 33 An aquatic therapy (AT) pool may be the only setting in which these children can learn new postures or skills and maintain fitness without damaging their joints.

Although definitions sometimes overlap, common usage distinguishes hydrotherapy and ‘aquatic therapy’ and, especially, ‘aquatic exercise’, from ‘balneotherapy’, which denotes seated immersion or spa therapy without exercise. 41–43 The Aquatic Therapy Association of Chartered Physiotherapists (ATACP) defined aquatic physiotherapy as:

A physiotherapy programme utilising the properties of water, designed by a suitably qualified Physiotherapist. The programme should be specific for an individual to maximise function which can be physical, physiological, or psychosocial. Treatments should be carried out by appropriately trained personnel, ideally in a purpose built, and suitably heated pool.

ATACP43

They permit the use of the term ‘aquatic therapy’ for water-based programmes, designed by a suitably qualified physiotherapist, but carried out by non-specialist physiotherapists, or by carers and teaching assistants without specialist knowledge of anatomy and physiology.

Theoretical basis

In addition to the theories underpinning land-based therapy (LBT) (see Physiotherapy), the theoretical bases for AT are our understanding of the physical properties of water and a learning theory that accounts for developmental aquatic readiness, a model of systematic desensitisation44 and the biomechanical principles of the floating human body,45 as encapsulated in the Halliwick Concept. 46

The physical properties of water that are relevant to physiotherapy are density and specific gravity, hydrostatic pressure, buoyancy, viscosity and thermodynamics. 47 For DMD, a musculoskeletal condition, immersion brings the following benefits. First, warm water may increase cardiac output away from the splanchnic beds to the skin and musculature. 48–50 Blood flow to the muscles may be enhanced at rest51 and during exercise. 52 Second, body weight is offloaded with immersion, with the desired amount of loading variable by depth. 53 In musculoskeletal conditions, then, it is hypothesised that the hydrostatic effects and the warmth of the water, compared with cooler water in community swimming pools, make muscles more supple. The buoyancy and antigravity effects relieve pressure on joints, leading to a reduction in pain and an increase in joint mobility compared with strengthening and stretching exercises performed on dry land. 47 The metacentric or rotational effects, caused by altering the amount of the body that is immersed or the shape of the body in water so that the body is displaced requiring postural adjustments, are used to develop balance, core/proximal stability (stomach, shoulder and hip muscles) and to simulate function (transitions between positions – sit to stand, rolling over, going up steps, lying to sitting).

Systems such as Halliwick, which teach people with disabilities to return to a safe breathing position in water,46 thereby producing confidence and safety, are essential for an AT/physiotherapy programme. 54 They combine two elements: first, the ‘Ten Point Program’, which covers aspects of mental adjustment (including water confidence and breath control), balance control and movement; and, second, a protocol for ‘Water Specific Therapy’, involving assessment and objective setting, based on which the therapist chooses appropriate exercise patterns and treatment techniques. 46

Intervention methods and materials

Aquatic therapy pools typically operate at temperatures of 32–36 °C, higher than the 28 °C of conventional swimming pools, with a greater level of disinfectant and more frequent microbial sampling. 55 Pool size varies, with a recommended minimum space of 2.5 m × 2.25 m per patient and a typical depth of 1–1.2 m, often on a gradient. The provision of changing rooms with adequate space and wide entrances is optimal, along with hoists, both in the changing rooms and to get in and out of the pool. An ATACP foundation programme for chartered physiotherapists is necessary for safe and effective treatment. 56 Subjective, Objective, Assessment and Plan (SOAP) record keeping is recommended. 33

Evidence for effectiveness

In an overview,42 three systematic reviews evaluating aquatic exercise against controls in adults with musculoskeletal conditions showed small post-intervention improvements in function [n = 648, standardised mean difference 0.26, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.11 to 0.42], quality of life (n = 599, standardised mean difference 0.32, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.61) and mental health (n = 642, standardised mean difference 0.16, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.32). 57–59 They also found a 3% absolute reduction and a 6.6% relative reduction in pain, measured on a visual analogue scale (n = 638, standardised mean difference 0.19, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.35). The meta-analyses identified no differences for walking ability or stiffness.

Although annotated bibliographies on the use of AT in disabled children exist,60,61 we are aware of only one relevant systematic review of aquatic interventions for children with neuromotor or neuromuscular impairments. 62 It included one randomised controlled trial (RCT) and 10 observational studies. Only three studies, all with low levels of evidence, investigated neuromuscular disorders. Seven articles indicated improvements in physical function and activity level, and two out of four articles investigated levels of participation-indicated improvements. The review concluded that there was a lack of quality evidence on the effects of AT in this population.

Current aquatic therapy provision in the UK

Although many health professionals believe that AT can improve mobility, strength, flexibility and cardiopulmonary fitness,63 and although AT is a routine part of care in other countries, access is uneven and restricted in the UK. 64 At the end of 2015, the charity Muscular Dystrophy UK (MDUK) identified 179 AT pools in the UK that people with muscle-wasting conditions could potentially use, but highlight that:

many hydrotherapy pools are based in schools and are only open during school hours and terms

privately-owned hydrotherapy pools can be expensive to access – often more than £75 for a half-hour session

people have to travel long distances to get to a pool, and this is not sustainable

hydrotherapy pools do not always have hoists, or accessible changing facilities.

Reproduced with permission from MDUK, Hydrotherapy in the UK: The Urgent Need for Increased Access64

Muscular Dystrophy UK asserts that NHS-funded AT ‘is often restricted to patients whose improvements can be demonstrably measured’;64 as such, functional improvements are difficult to demonstrate in degenerative conditions and funding is often absent or limited. In MDUK’s report, a young person with DMD is quoted as saying:

We have an ongoing need for hydrotherapy, which is not fulfilled by just being given a block of sessions for six weeks. This does not allow us to continue to maintain our condition because once our block of six sessions is over we struggle to be able to access hydrotherapy treatment anywhere else.

Reproduced with permission from MDUK, Hydrotherapy in the UK: The Urgent Need for Increased Access64

The aspiration to access AT throughout the year, rather than in 4- to 6-week blocks, is confirmed by our patient and public involvement (PPI) author, James Parkin, who notes ‘If you have AT regularly, it improves self-esteem; self-esteem improves how you deal with self-management’. A long hiatus between sessions can decrease water confidence and result in a loss of skills. Our qualitative research (see Chapter 5, Environmental factors and Operational work) confirms that, where publicly funded AT is available, it often comes in blocks of 4 or 6 weeks, ≥ 6 months apart, and is not necessarily routine but may be contingent on a successful application. MDUK end their report by arguing that access to AT helps people with muscle-wasting conditions ‘to manage their condition and improve their quality of life by reducing pain and increasing mobility’. 64 They make an appeal to equity, proposing that access should not depend on where a person lives or their disposable income. 64

Rationale and objectives

Rationale

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) published a commissioning brief (commissioning brief HTA 12/144) requesting a ‘feasibility study’ to evaluate the addition of ‘manualised hydrotherapy’ to ‘optimised land-based exercise’ for children and young people with DMD who still have some mobility. There are several ways in which we might have interpreted and responded to this brief so, at this point, it is worth taking the reader through the choices we made and why we made them. First, confusion about the definition of feasibility studies, which has since been widely acknowledged,65,66 meant that a decision had to made on the primary objective of this study. The request for a control group, and the focus on the ability to recruit and randomise, led us to interpret the brief as requiring an external pilot RCT, sometimes defined as ‘a version of the main study run in miniature to determine whether the components of the main study can all work together’. 66 In other words, we interpreted the brief primarily as a study to understand the feasibility of a research protocol for a full-scale RCT, rather than of the feasibility of delivering manualised AT per se. As the reader will see, an understanding of both issues is likely to be important for future clinical decision-making and the commissioning of further research.

Primary objective

A future full-scale trial would test the hypothesis that AT in addition to LBT is more effective than LBT alone for the maintenance of functional, participation or quality-of-life outcomes. The primary objective of this external pilot RCT was to determine the feasibility of a full-scale trial, defined in terms of participant recruitment.

Secondary objectives

Secondary objectives were the identification of:

-

the best primary outcome for a full-scale trial

-

the consent rate among eligible boys with DMD who were approached about the study

-

why boys with DMD refuse consent

-

the proportion of boys who provide valid outcome data 6 months after entering the trial

-

reasons for attrition from the trial

-

the views of participants and their families on the acceptability of the research procedures and the AT intervention

-

the robustness of the intended data collection tools

-

the willingness of participating centres to provide an AT service and to recruit participants

-

the ability of participating physiotherapists to deliver the AT intervention faithfully in accordance with a manualised protocol

-

therapist views on the feasibility of the AT intervention and the acceptability of the research protocol.

Chapter 2 Methods

The final protocol for this study can be found on the NIHR website. 67

Developing the intervention and associated theory

Overview

None of the team’s specialist physiotherapists knew of intervention manuals tailored to the needs of boys with DMD, as per the NIHR brief. As they would be interventions ‘with several interacting components’, we followed the steps recommended by the Medical Research Council Framework in developing them in parallel with the grant application process. 68 The first step, identification of the evidence base, has been discussed: there is no standard approach to LBT or AT for boys with DMD based on evidence for improvement in function, participation and emotional well-being. Either may help children with DMD maintain physical function but certain types of exercise are thought to be dangerous (see Chapter 1, Physiotherapy and Evidence for effectiveness). The second step, identifying/developing intervention theory, is addressed in The development of treatment manuals and theory. The third and final step is modelling the process and outcomes of implementation, culminating in the development of a programme theory (see Modelling process: developing programme theory). As researchers do not always have the same vision of what theory is supposed to be or do,69 to clarify, then:

-

The function of a pilot RCT is not to test physiological treatment theory, but to determine whether a future full-scale RCT would be capable of doing so. 70,71

-

Initial testing of the programme theory, using linear logic modelling, is one subject of this report.

-

We also access theory to consider why patterns of observations may have occurred. We use general theories and conceptual frameworks, concerning disability and participation, the burden and implementation of services and the character of AT service delivery traditions, to better understand how the social context mediates programme delivery.

The development of treatment manuals and theory

Key stakeholders attended an all-day meeting on 27 March 2013, 4 hours of which were set aside to inform the design of the study intervention (Table 1).

| Name by category of expertise | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| DMD family | |

| Victoria Whitworth | Parent of service user |

| AT | |

| Heather Epps | Epps Consultancy, Dorking |

| Physiotherapists specialising in DMD | |

| Michelle Eagle | Newcastle University |

| Marion Main | Great Ormond Street Hospital, London |

| Lindsey Pallant | Leeds Teaching Hospitals |

| Elaine Scott | University of Sheffield |

| Allison Shillington | Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, Liverpool |

| Neurology | |

| Peter Baxter | Sheffield Children’s Hospital |

| Valeria Ricotta | University College London (also the North Star Project)a |

| Trials Unit | |

| Daniel Hind | University of Sheffield |

Specialist physiotherapists proposed a set of exercises appropriate to manage the development of DMD in the target population group (see Figure 1 and Interventions). They also agreed that there should be free play at the end of the session, that disease progression should be monitored throughout the study with exercise prescription adapted accordingly and that, in the context of this study, it was worth experimenting with a twice-weekly programme that continued for as long as possible. Members of the team felt that, with no reliable ‘dose–response’ data available for the use of AT in people with DMD, maximising the dose would improve the chances of detecting a treatment effect, if one existed, in any future, full-scale trial. After the meeting, Heather Epps modified an AT manual created for the management of junior idiopathic arthritis,73 Marion Main adapted an existing LBT manual for the management of DMD,34 and the physiotherapists agreed that the manual was suitable for testing. The intervention protocols are described in Interventions.

At successive meetings we developed a treatment theory that hypothesises links between ingredients (observable measurable actions, chemicals, devices or forms of energy), mechanisms of action (processes through which the ingredients bring about change) and targets (measurable aspects of the individual’s functioning that is predicted to be directly changed). 74,75 Figure 1 shows the treatment theory, with ingredients 1 and 2 applying to LBT and all three ingredients applying to the AT intervention. Stretches (ingredient) provide mechanical traction for,76 and relax,37 muscles (mechanisms), which tend to tighten with the progression of DMD, thereby maintaining muscle length and soft tissue structure, while deferring the development of contractures (target). 37 Muscle training and general aerobic, submaximal exercises (ingredients) create biochemical adaptations that increase muscle mass by means of muscle fibre hypertrophy37 and maintained stroke volume77 (mechanisms) to prevent disuse atrophy and maintain or improve skills such as sit to stand, getting up from the floor and stair climbing (targets). Warm water (ingredient) creates haemodynamic changes78 and offers properties such as buoyancy and turbulence (mechanisms)47 that are not available in land-based physiotherapy, thereby reducing mechanical stress during muscle strengthening and allowing activation of muscles in ways not possible on land (target). The mental adjustment and disengagement stages of the Halliwick Concept46 (ingredients) may use mechanisms (e.g. reciprocal inhibition,79 systematic desensitisation80 and extinction81) that psychologists associate with exposure with graded support to achieve water confidence and participation (targets).

FIGURE 1.

Treatment theory for AT programme. VO2, oxygen consumption.

Modelling process: developing programme theory

A treatment theory is essentially physiological and, in this project, limited in scope to the prescribed exercises performed in the pool. Around these exercises is a ‘programme’, that is, a ‘set of planned activities directed toward bringing about specified change(s)’82 in boys with DMD through prescribed exercises. A programme theory recognises that, around the AT exercises, there is a complex series of contracts, actions, interactions and emergent relationships between people and organisational units. For many researchers, the purpose of evaluating a programme is to develop or test a theory about how it works, rather than merely evaluating whether it works. 83 If the programme is successful, then the evaluation can identify essential elements for replication; if the programme is unsuccessful, then it can identify whether or not this was through failures of implementation, translation to unsuitable contexts or treatment theory. 84 A programme theory, then, is broader than a treatment theory; it focuses on assumptions about background behavioural, social and economic mechanisms that operate if the treatment is to be delivered as scheduled. 85 Programme theory was developed iteratively: (1) deductively, through a review of the literature, (2) by articulating mental models, through discussions at stakeholder meetings, and (3) inductively through interviews with participants and professionals. 86

We searched the literature to inform an initial thematic framework about how children with neurological or musculoskeletal problems, their parents and physiotherapists respond to physical therapy programmes. We used Medical Subject Headings, such as ‘musculoskeletal diseases’, ‘nervous system diseases’, ‘children’, ‘adolescents’ and ‘physical therapy modalities’, as well as free-text terms such as ‘qualitative’ and ‘themes’ in a MEDLINE search to find papers. We found four relevant qualitative research studies on the acceptability of physiotherapy in children with neuromuscular conditions, consisting mainly of inductive thematic analyses. 87–89 One study90 drew on two social science theories. The themes of social model theory, distinguishing impairment from disability and eliminating discrimination and removing barriers to access91,92 have been incorporated into the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health – Children and Youth version (ICF-CY)93 (see Modelling process: developing programme theory), which is recommended for understanding context in evaluative studies. 94 The theory of psychosocial development95 was used to understand how changes brought on by adolescence affect adherence to therapy and adaptation to illness. Our population was younger and more compliant than that in that study. As neither theory seemed suited to this population, we constructed an initial framework by which to understand responses to the interventions from themes observed in the four studies. Table 2 shows the key themes of the a priori framework.

| Theme | Christy et al., 201089 | Capjon and Bjørk, 201087 | Wiart et al., 201088 | Redmond and Parrish, 200890 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Improvement in physical function | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| (b) Improvement in confidence and independence | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| (c) Increased participation | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| (d) Achievement of goals | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| (e) Fatigue during the programme | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| (f) Pain during the programme | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| (g) The duration and spacing of therapy sessions | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| (h) The quality of the relationship with the therapist and communication between therapist and families | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| (i) Stress associated with the programme and balancing therapy with the demands of everyday life | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| (j) Responsiveness of schools to children’s therapy schedule | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

We later employed a number of conceptual frameworks and models to ‘make sense of or shed light on’69 the empirical data we gathered, to better understand the implementation and acceptability of the AT programme and to consider how processes could be improved.

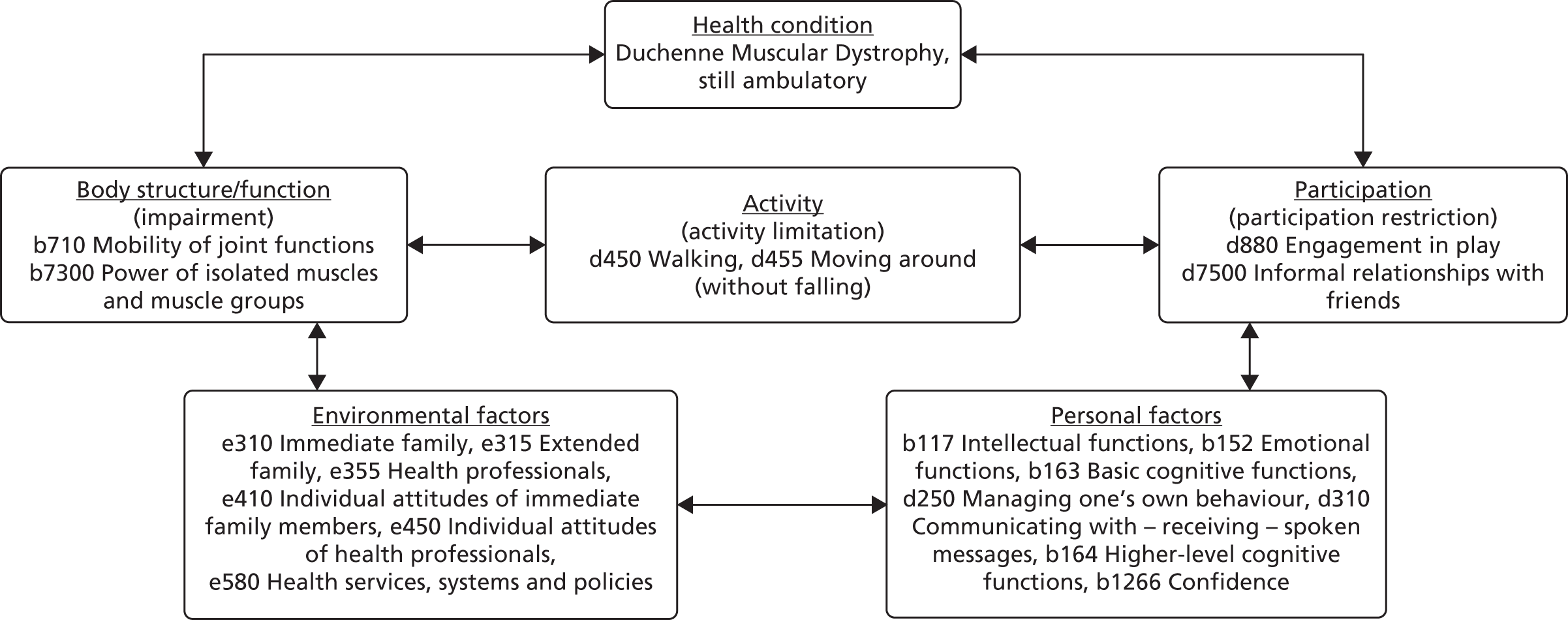

The ICF-CY is a conceptual framework used to define disability, which has widespread appeal and acceptance among physiotherapists, one target audience of this work. 93 It describes functioning in terms of body structures and function, desired activity or activity limitations, and participation restrictions (the inclusion of the young person in social situations). The ICF-CY Environmental factors component views disability as the outcome of interactions of these factors with other contextual factors, both environmental and personal.

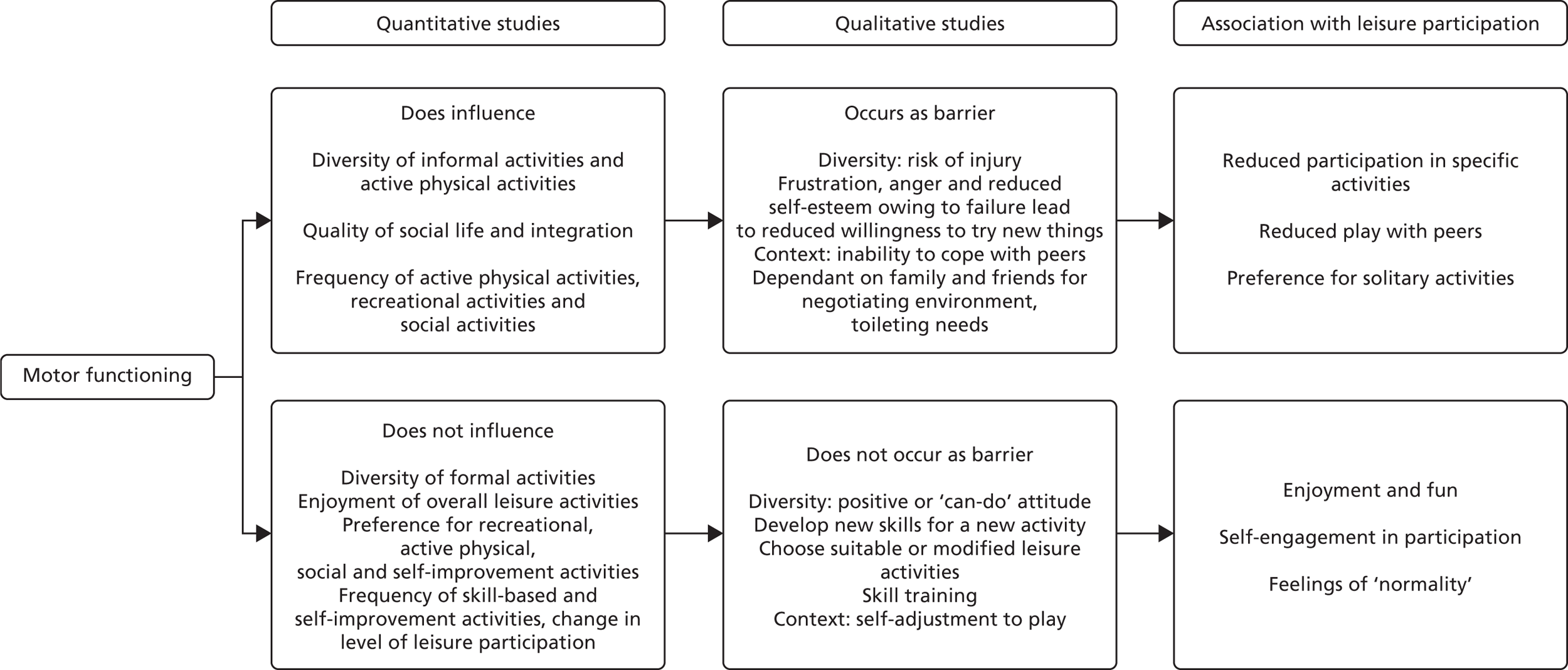

The way in which participation is understood has developed rapidly since this work was commissioned. 96–99 The conceptual framework developed through an integrative review by Kanagasabai et al. 100 suggests contextual conditions under which participation is reduced or maintained (Figure 2). Another review, by Kang et al. ,101 proposes that participation is optimised with physical, social and self-engagement. Social engagement refers to interpersonal interactions during activities, feelings of being included or belonging. Self-engagement refers to feelings of enjoyment, self-determination and how a person thinks about themselves, especially in the setting and achievement of goals.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual framework of association between motor functioning and leisure participation. Reproduced with permission from Kanagasabai et al. , Association between motor functioning and leisure participation of children with physical disability: an integrative review, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology,100 John Wiley and Sons © 2014 Mac Keith Press.

A range of child-, family- and environment-related attributes affect participation. Personal factors covered later in Figure 23 relate to how children adapt to keep engaging with peers or to cope with rejection. 102,103 Age, gender and preferences for particular activities or experiences also play a part in the extent of participation. 104–106 Family socioeconomic status,104 functioning,105 mental well-being,107 orientation towards physical activity105,106 and other factors108 also contribute. A physical environment, societal attitudes and supportive services can provide physical assistance, guidance and broader opportunities for activity. 109–112

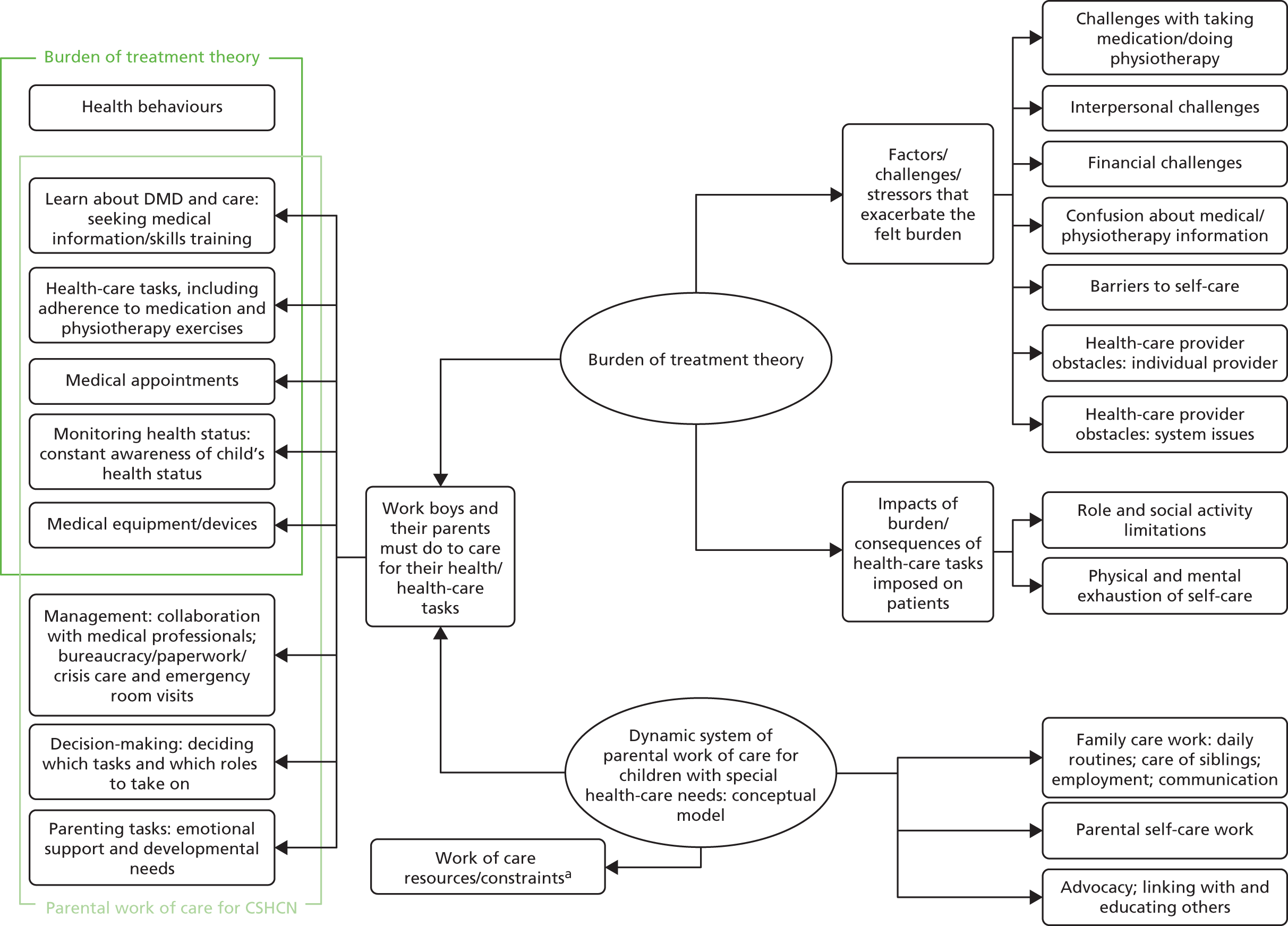

Often, the strategies that we develop to manage chronic disease created additional burdens of work for patients, leading to poor adherence and clinical outcomes, as well as wasted resources. 113,114 Minimally disruptive medicine should identify this burden, encourage improved co-ordination of care and design, or prioritise care from the patient perspective. 115 Burden of treatment theory provides a way of understanding the relationship between health-care users, their social networks and the health services they use, with a view to redesigning those services to make them minimally disruptive. 113,116 As burden of treatment theory has been developed around the adult service user, it is useful to consider it in tandem with a conceptual model of parental work of care for children with special health-care needs (Figure 3 and Table 3). 117

FIGURE 3.

The burden of health care in chronic conditions: two conceptual models. a, See Table 3. Adapted from Tran et al. ,114 Hexem et al. 117 and Eton et al. 118 All articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. CSHCN, children with special health-care needs.

| Category | Selected codes relevant to study population |

|---|---|

| Child | |

| Disease | Severity, symptoms and child’s quality of life |

| Episodic quality of illness and uncertainty | |

| Medical care | Type of technology or equipment |

| Frequency of treatments | |

| Behaviour | Cognitive and emotional function/expression |

| Functional ability/activity limitations | |

| Location | Home, hospital or elsewhere |

| Parent | |

| Gender roles | How the roles of mothers and fathers differ |

| Mental health | Emotions, quality of life and stress |

| Personality | Hardiness, self-esteem and coping style |

| Knowledge | Medical and parenting skills and experience |

| Education level | |

| Social support | Availability of friends and family |

| Family | |

| Family structure | Family cohesion, including marital dynamics |

| Single parents | |

| Siblings | |

| Finances | Employment, income and expenses |

| Society | |

| Geographic locale | Different regions, countries. Immobility |

| Attitudes and norms | Disability and disease in childhood |

| Parental responsibility and gender norms | |

| Health services | Availability of care facilities and providers |

| Awareness of available services | |

| Political system | Government policies and funding |

Burden of treatment theory helps us to understand the response of patients and carers to complex interventions. To understand the perspectives of physiotherapists delivering AT, we draw on normalisation process theory (NPT), a general theory of how complex interventions become routinely embedded in health services. 119,120 NPT categorises the different kinds of work that people do when they implement a new practice as sense-making, relational, operational and appraisal. Problems in any of the categories can result in implementation failure.

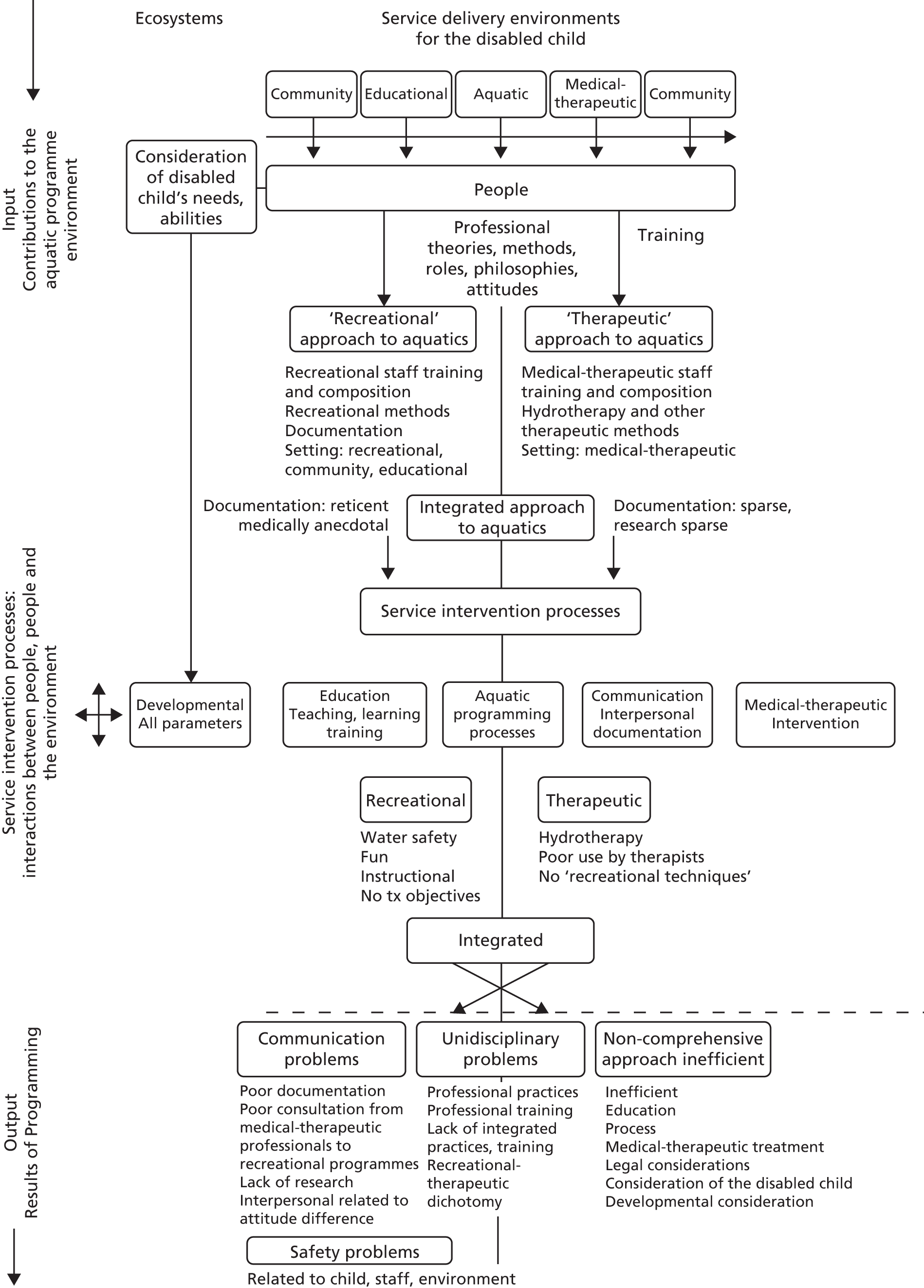

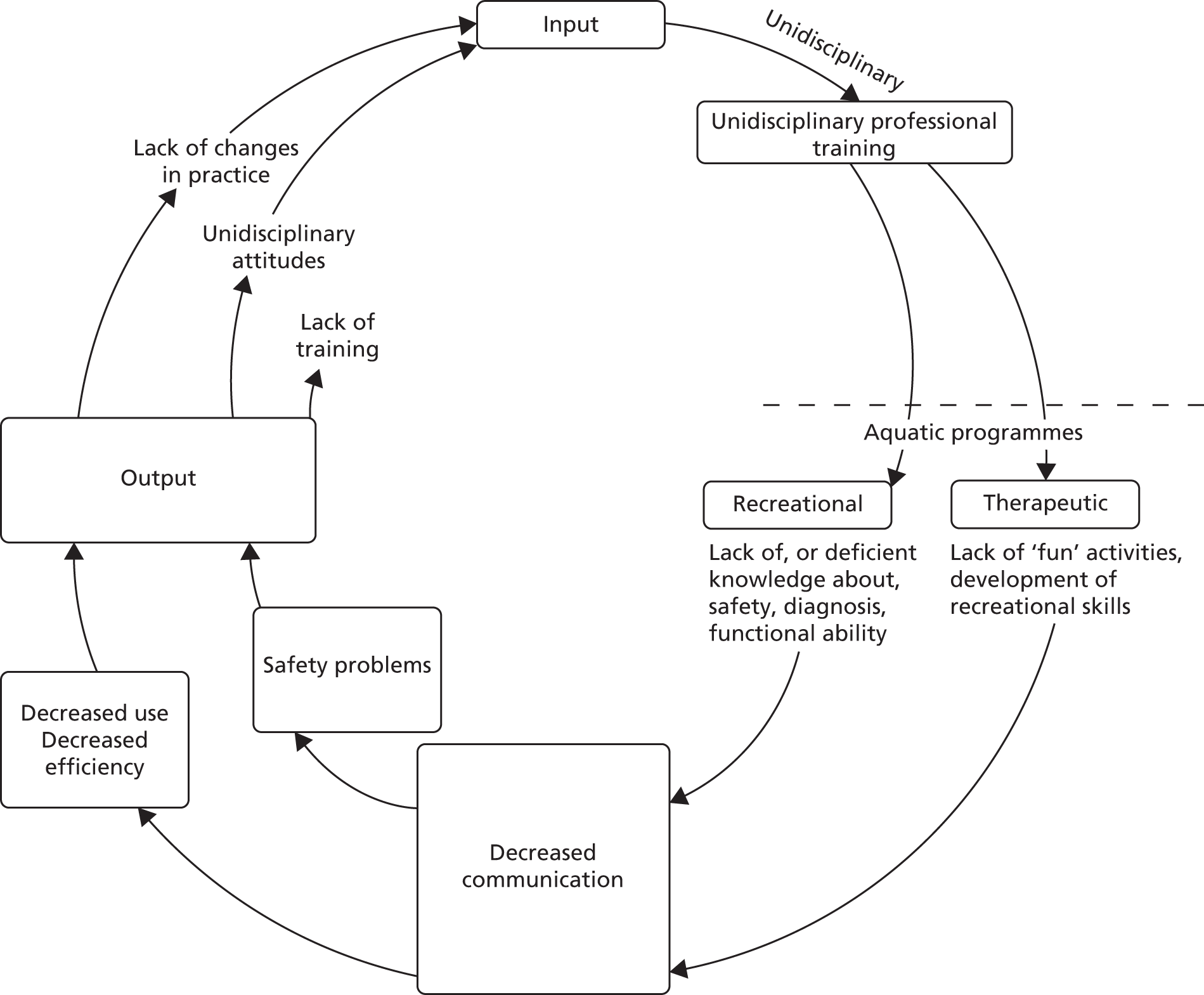

Finally, we draw on themes identified by a systems analysis of problems encountered in aquatic programmes for disabled children (Figure 4). 121 The author describes a split between recreational and therapeutic approaches that existed in both practice and the literature of the early 1980s. 121,122 She identified problems in this division of philosophy, principles, staff composition, roles and training (Figure 5), and described an integrated approach to aquatic intervention for disabled children. Retrospectively, we find this theory useful to interpret the responses of some participating physiotherapists to manualised AT.

FIGURE 4.

Dulcy’s systems analysis of problems in aquatic programmes for disabled children. Copyright 1983 from Aquatic programs for disabled children by Faye H. Dulcy. 121 Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis, LLC (www.tandfonline.com). Tx, treatment.

FIGURE 5.

Dulcy’s vicious cycle of problems in aquatic programmes. Copyright 1983 from Aquatic programs for disabled children by Faye H. Dulcy. 121 Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis, LLC (www.tandfonline.com).

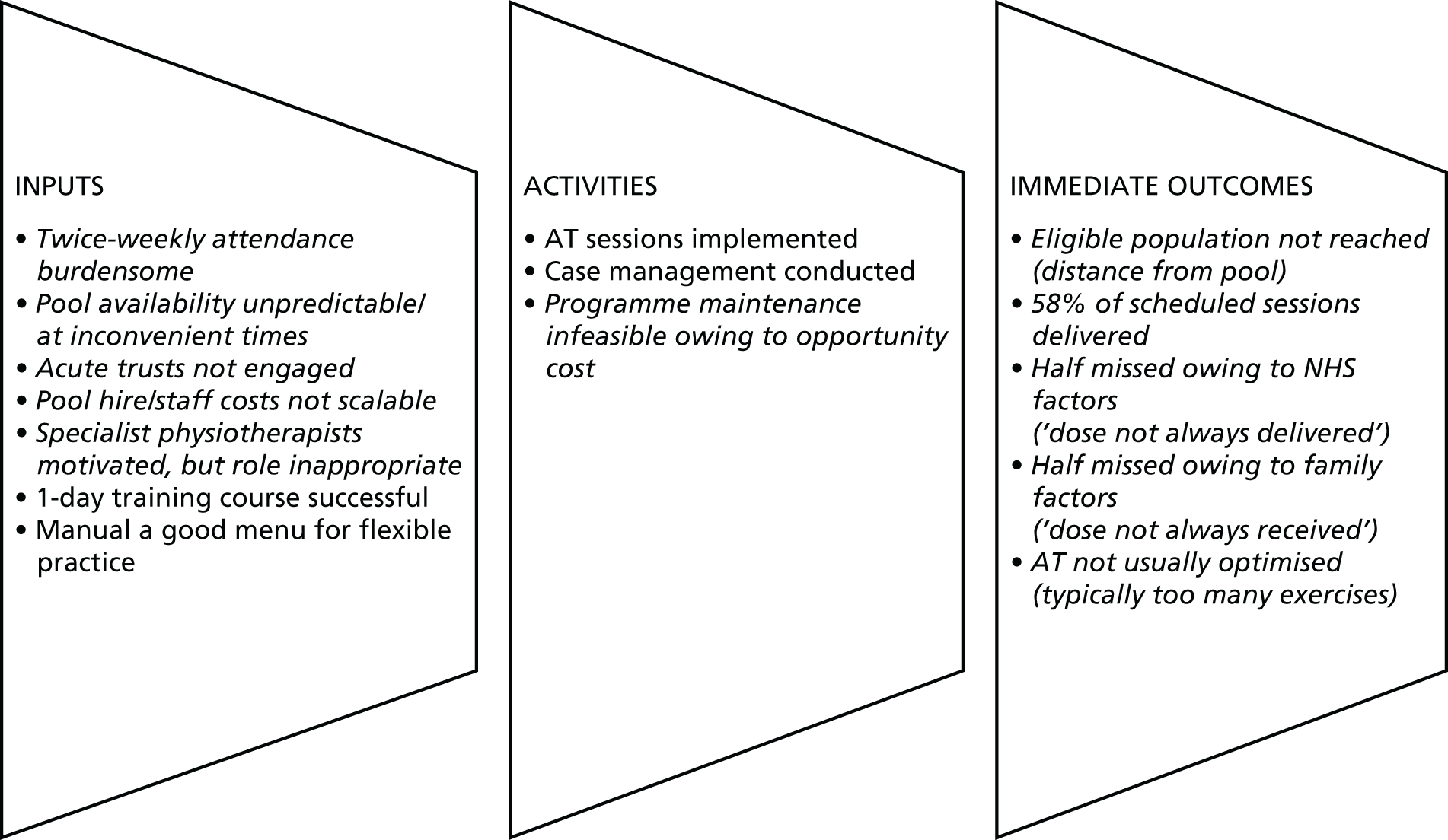

Based on the above literature and through team discussions, we developed the programme theory, which could be briefly described as follows:

Boys, parents, specialist physiotherapists will be willing and able to conduct twice-weekly AT and tertiary centres will allocate resources for this (inputs and activities). This will be manageable within the existing roles, interactions and relationships that characterise the management of DMD (context). Delivery of the programme per protocol (immediate outcomes) will bring about physiological benefits described in the treatment theory (intermediate outcomes).

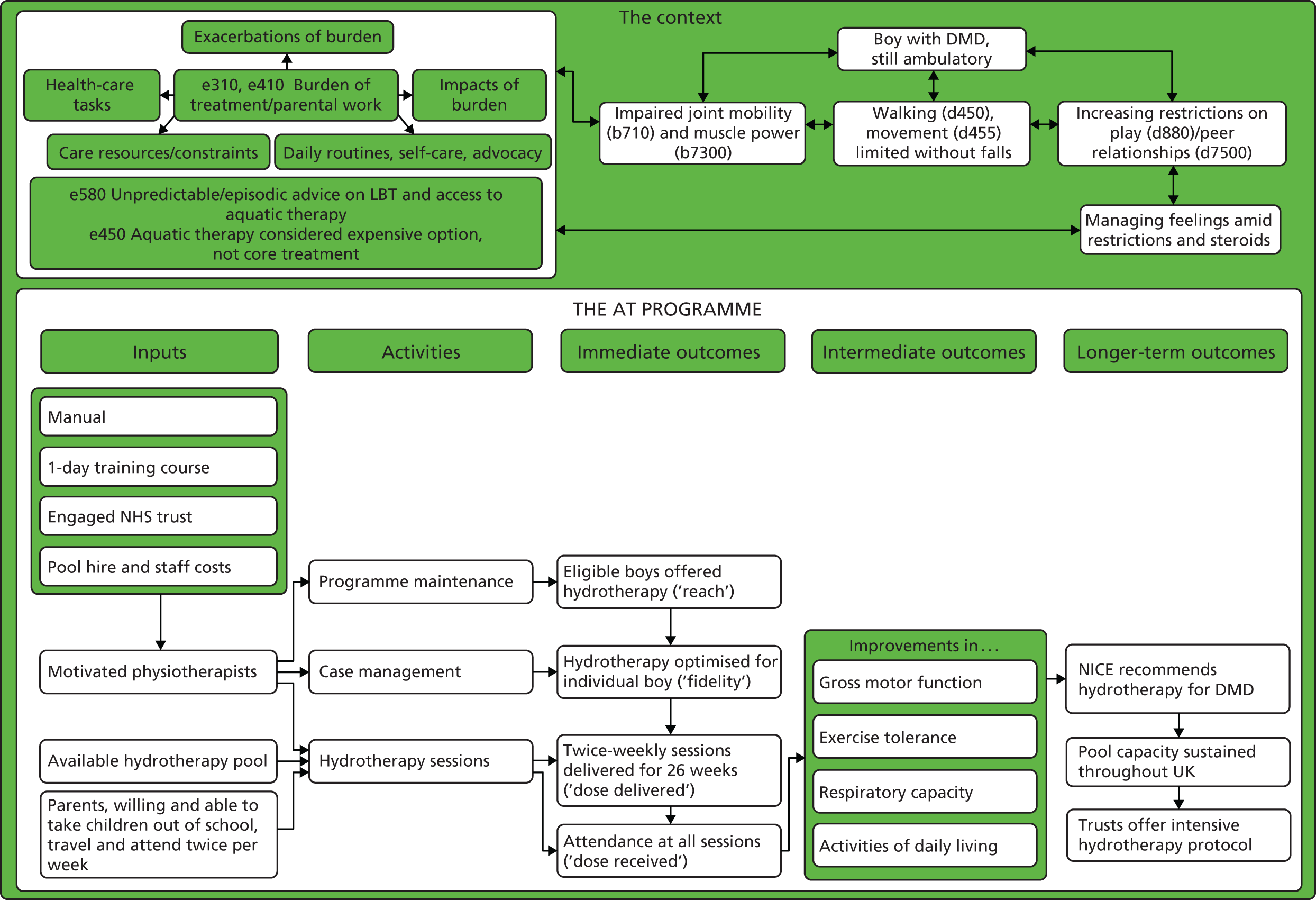

We developed a logic model to illustrate how chains of events over time were to bring about the desired outcomes, in accordance with the programme theory (Figure 6). 123,124 Contextual factors that can influence and be influenced by implementation are included.

FIGURE 6.

Logic model (initial).

Most elements of the logic model are self-explanatory, but some are worth unpacking. First, there are a number of definitions of ‘case management’ containing functions that also appear in definitions of ‘programme management’. 125,126 Although we acknowledge this overlap, we use the term to mean a micro-level episode of health-care management in a health-care setting in which one is accountable for service user outcomes. To simplify, by ‘case management’, we mean everything that a physiotherapist does with a boy with DMD and their notes, from identifying a boy as suitable for AT to discharging them from the service. By ‘programme maintenance’, we mean everything that the physiotherapist, his or her colleagues and organisation do to sustain (continue and institutionalise) an AT service beyond case management. 127–130

The programme theory and the logic model form the starting point for a process evaluation, which investigates what is delivered and how, mechanisms of impact (broadly defined) and how context affects implementation and outcomes. 131 In the standard format of a process evaluation, there is an imperative to evaluate implementation fidelity,131–134 which is typically interpreted as the consistency with which intervention components are delivered. 135 However, insofar as front-line physiotherapy often involves making sense of rapidly changing and ambiguous phenomena to revise treatment plans, it is not the kind of work that benefits from standardisation. 136 A body of theoretical literature suggests that the standardisation of function, that is, being faithful to the intervention theory, is more important than standardising the form of an intervention. 137–139 In this study, standardisation would not meet the physical and psychological needs or capabilities of individual children. For these reasons, we evaluate treatment optimisation to the child’s needs and capabilities, adjudicated by an independent physiotherapist, rather than fidelity to intervention components. We define optimisation as good adherence to a good-quality prescription (see Optimisation of prescription).

The pilot trial

Trial design

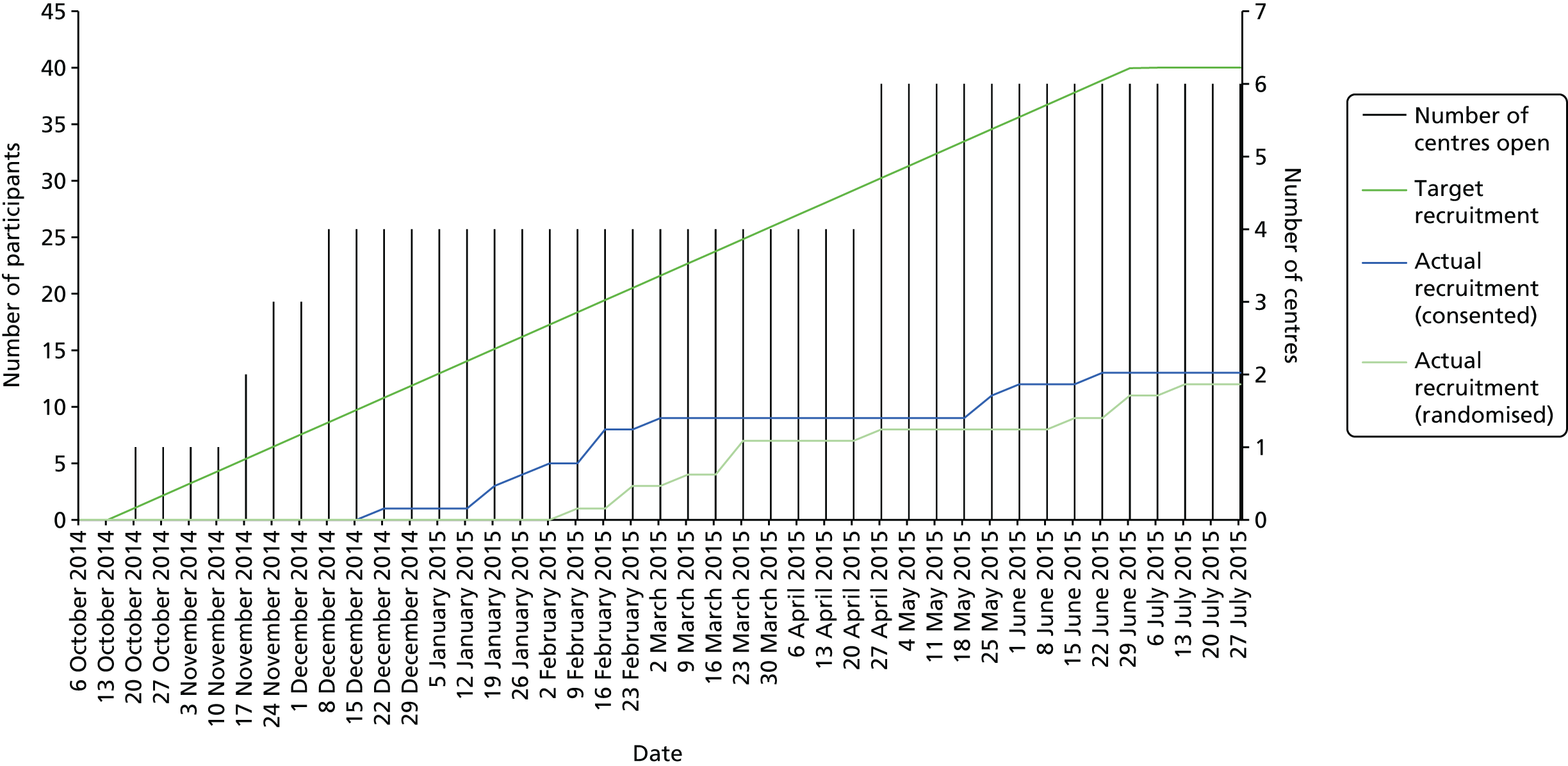

This was a parallel-group, open-label, randomised external pilot trial with a 1 : 1 allocation ratio (Figure 7). Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines are observed. 140 Important changes to the methods after trial commencement are reported in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 7.

Pilot RCT summary. 6MWD, Six-Minute Walk Distance; ACTIVLIM, Activity Limitations Measure; CarerQol, Care-related Quality of Life; CHU-9D, Child Health Utility 9D Index; FVC, forced vital capacity; NSAA, North Star Ambulance Assessment.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

-

Genetically confirmed DMD: a muscle biopsy report from a registered NHS pathology laboratory showing dystrophin deficiency compatible with DMD and/or a report from a registered NHS molecular genetics laboratory showing the DMD gene to have a pathogenic deletion, duplication or point mutation.

-

Aged 7–16 years: children aged < 7 years were excluded because natural history studies have shown that there is a continuing improvement in the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) up until that age and, therefore, any improvement might be spontaneous rather than a result of the intervention. 141

-

Established on glucocorticoid corticosteroids [patient has been treated with prednisolone or deflazacort (Calcort®, Sanofi-Aventis) for at least 6 months with no major change in drug, dosage or frequency for at least 3 months before the initial assessment]. Such changes were defined as follows:

-

Frequency covered a change from daily dose to alternate day or another non-daily regimen (or vice versa).

-

A dose increase in line with weight was acceptable. Any other change was an exclusion criterion.

-

A change in prescription from prednisolone to deflazacort (or vice versa) was an exclusion criterion.

-

-

A North Star Ambulatory Assessment (NSAA) score of ≥ 8 to 34. Those with more than a 20% variation between baseline screens 4 weeks apart (at pre-screen and initial assessment) were excluded.

-

Able to complete a 10-m walk test with no walking aids or assistance.

Exclusion criteria

-

Involvement in another RCT.

-

More than a 20% variation between screening and baseline NSAA scores.

-

Unable to commit to the programme of twice-weekly AT for 6 months.

-

Any absolute contraindications or precautions to AT43 listed in Table 4 at the point of determining eligibility.

| Absolute contraindications | Precautions |

|---|---|

| Severe cardiac failure | Fear of water |

| Resting angina | Behaviour problems that prevent participation in physiotherapy or AT |

| Shortness of breath at rest | Arterial hypotension/hypertension |

| Renal failure | Chemical sensitivity |

| Proven allergy to chlorine or bromine | Indwelling catheter/PEG tube |

| Uncontrolled epilepsy | Tracheostomy |

| Uncontrolled faecal incontinence | Poor skin integrity/open wounds |

| Febrile conditions: acute systemic illness or pyrexia (until resolved) | Unstable angina, cardiac arrhythmias or additional cardiac considerations |

| Acute vomiting/diarrhoea (until resolved) | Dizziness/vertigo |

| Wound infection (until resolved) | Diabetes mellitus |

| Weight in excess of available pool evacuation equipment | Thyroid problems |

| Widespread MRSA (until resolved) | |

| HIV/AIDS | |

| Haemophilia |

Settings and locations where the data were collected

Staff at six specialist neuromuscular clinics identified a sufficient pool of eligible patients. Each expected to be able to recruit 10 patients in the 6-month accrual window, during which all patients would have one routine clinic visit. Site staff received training in protocol procedures by the trials unit; many of the research procedures, especially matters of documentation, were already routine in clinical practice.

Screening and consent

Recruitment was undertaken by good clinical practice-trained site staff who screened health records to identify study candidates. Candidates with absolute contraindications were excluded at this stage. A cover letter and information sheet were sent to the carers of study candidates. Carers were invited to discuss the trial by telephone. For those interested, an appointment was booked at the site at which candidates and carers were invited to ask further questions. We acquired full written consent and assent from carers and participants, respectively.

Assessment of eligibility

Confirmation of eligibility (including repeat NSAA) took place 4 weeks later.

Interventions

Research arm: aquatic therapy programme

Materials

A manual providing a ‘menu’ of aquatic exercises is available as a web-only appendix. 142

Procedures

Exercises, using the properties of water (buoyancy, turbulence, etc.), included:

-

Stretches – active assisted and/or passive regime that targets key muscle groups in ambulatory boys (e.g. hip flexors, hip abductors; iliotibial band; hamstrings; knee extensors, ankle plantar flexors; supination, pronation; wrist and finger flexors; neck flexors). Some movements used the properties of ‘drag’, for example for a passive trunk side flexion stretch.

-

Muscle training/strengthening – hip extension, abduction; knee extension; ankle dorsiflexion; shoulder abduction, horizontal extension, flexion; elbow extension; wrist extension.

-

General aerobic – walking backwards and sideways, bobbing, swimming, punching, ball activities. Submaximal exercise in the water.

-

Simulated or real functional activities (e.g. sit to standing, running, jumping, hopping, using the unencumbered, three-dimensional properties of water). For example, going from a seated to a standing position in water, when there is no actual seat, uses the metacentric effect and the properties of water to develop core strength and balance, and to learn or maintain the task, which is becoming more difficult out of water. A previous protocol was adapted for this aspect, with the exception that children would not be asked to lie fully prone, but only three-quarters prone (face not quite submerged). 34

-

Breath control exercises and games.

-

Swimming and other ‘fun’ activities.

Provider

The intervention was delivered by suitably qualified physiotherapists who worked in tertiary paediatric neuromuscular centres and had experience in the management of DMD. Most, but not all, physiotherapists had previously attended foundation training courses and had experience of delivering aquatic exercise, but not necessarily using the properties of water. Those delivering the intervention from four trusts attended a specialist day course, delivered by Heather Epps, an accredited trainer, in which they were trained in the principles and practice of AT; a training video was also provided. Physiotherapists at a further trust did not attend face-to-face training but did receive the video.

Location and mode of delivery

Aquatic therapy was delivered face to face in a NHS AT pool, heated to a temperature of 34–36 °C. Although group sessions were anticipated, participating trusts could schedule only individual sessions with one exception, in which brothers were randomised to AT.

Schedule

Aquatic therapy was to be delivered twice a week for a maximum of 30 minutes per session in the water (to avoid fatigue) for a period of 6 months. The research physiotherapists at the site were responsible for booking participants into sessions for those randomised to the AT arm and for supervising their treatment regime throughout the study. The research protocol specified that study interventions should commence within 4 weeks of randomisation.

Tailoring

It was intended that the treating physiotherapist should choose options appropriate to each child’s level of ability and particular presenting clinical problems. The prescription should be focused and achievable; it was not expected that most/all exercise categories in the manual would be represented in a prescription or that prescribed LBT exercises would be replicated in the water (training session minutes, Birmingham, 19 November 2014). To avoid excessive fatigue, participants were asked not to undertake their LBT on days that they received AT.

Modifications

No modifications were made to the manual during the project.

Optimisation

We define optimisation as good adherence to a good-quality prescription (see Optimisation of prescription). Details of the AT prescribed for and delivered to the participant were entered on to the patient’s care plan/AT log. An independent physiotherapist who was not a co-applicant was commissioned to assess if AT and LBT had been optimised to the need and capacity of the participant (see Optimisation of prescription). We asked physiotherapists to complete a form detailing why sessions did not take place, with the following options: did not attend, unable to attend (cancelled), pool closed, no pool time available, staff unavailable or other.

Control arm: land-based therapy

Materials

A manual was developed, based on best existing practice, again providing a ‘menu’ of exercises from which the treating physiotherapist could choose options appropriate to the child’s level of ability and particular presenting clinical problems. Physiotherapy intervention/prescription depended on the clinical need and capability of the individual patient (see Chapter 1, Physiotherapy).

Procedures

Depending on the needs and capability of the individual participant, a regular stretching regime (4–6 days/week) would target key muscle groups in ambulatory boys (triceps surae complex, hamstrings, hip flexors, iliotibial tract, long finger flexors). To avoid disuse atrophy, while being aware of the potentially detrimental effects of overexercising, particularly with regard to activities that promote eccentric activity, a directed programme of exercises dependent on the individual’s need was prescribed. General advice on regular activity was also recommended (e.g. walking, cycling and swimming).

Provider and locations

Although it is normal for community physiotherapists to prescribe therapy for children with DMD,28,33 for the purposes of this trial (see Chapter 3, Problems with the delivery of land-based therapy), LBT exercises were prescribed by the research physiotherapist at participating tertiary centres. They informed the community physiotherapist of the exercises prescribed, and asked them to feed back if the prescription changed. Exercises were delivered, in varying proportions, by parents at home, by support workers in school and, less commonly, by local community physiotherapists. Parents and support workers were trained in the delivery of exercises by the prescribing physiotherapist, as is routine practice.

Schedule

Typically 4–6 days per week.

Tailoring

The number of sessions, schedule, duration and intensity were based on the child’s level of ability and particular presenting clinical problems.

Modifications

As in usual practice, community therapists could modify prescriptions depending on the rate of functional change. They were asked to notify the study team when they did so.

Optimisation

Parents were asked to complete the LBT log every week, indicating the number of days on which they had completed each exercise; they were provided with self-addressed envelopes and asked to return completed forms. Research physiotherapists sent out a maximum of three letters reminding participants to return overdue LBT logs over the course of the period of trial involvement. An external assessor evaluated if therapy had been optimised for each participant.

Outcomes

Outcomes are summarised in Table 5.

| Assessment | Where | Completed by | Paper | Electronic | Consent and screen (visit 1) | Eligibility and baseline (visit 2) | Intervention | 26 weeks (visit 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility criteria form including | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| NSAA | Clinic | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 6MWD | Clinic | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| FVC | Clinic | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Patient-reported outcomes | ||||||||

| CHU-9D | Clinic | Participant | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| ACTIVLIM | Clinic | Participant | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| CarerQoL | Clinic | Carer | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Health and social care resource use | Clinic | Participant/carer | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Pain (VAS) | Participant/carer | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| OMNI scale of perceived exertion | Clinic | Participant/carer | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Concomitant medications | Clinic | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Adverse and serious adverse events | Clinic, home, other | Participant/carer/ physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Process evaluation | ||||||||

| AT log | Pool, clinic | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| LBT log | Clinic, home | Participant/carer/ physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Participants’ views on intervention and research procedures | Home, CTRU | Participant/researcher | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Therapists’ views on intervention/research protocol | Clinic, CTRU | Physiotherapist/researcher | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Care plan prescribed for intervention and control | Clinic, pool | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Feasibility outcomes | ||||||||

| Number and characteristics of eligible patients approached: screening form | Clinic | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Reasons for refused consent: screening form | Clinic | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Reasons for attrition: withdrawal form | Clinic, home | Physiotherapist | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Participant attrition rate | CTRU | Researcher | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Number of missing values/incomplete cases | CTRU | Researcher | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Participants’ and therapists’ views on acceptability | Research site, home | Participant/researcher | ✗ |

Primary outcome

Recruitment rate.

Other feasibility outcomes

-

Decision on the primary end point for the main trial.

-

Number and characteristics of patients who were identified as potentially eligible, approached for the study, at each study visit, randomised, withdrawn and lost to follow-up, discontinued from the AT intervention (with reasons), and included and excluded from analysis (with reasons). We also report the recruitment rate (defined as the proportion of patients approached that consent into the study).

-

Reasons for refused consent.

-

Participant attrition rate (the proportion of the consented and randomised participants who withdrew or were lost to follow up).

-

Reasons for attrition.

-

Number of missing values/incomplete cases. For questionnaires we report the item response rate at each time point.

-

Feasibility of recruiting participating centres and estimation of costs, given as a narrative assessment.

-

Therapist views on intervention/research protocol acceptability/perceived contamination of control arm.

Clinical outcomes

The following outcomes, assumed to be those of any future full-scale trial, were assessed during routine clinical visits at baseline and 6 months (* indicates routine assessment):

-

6MWD disease-related limitations on ambulation143

-

forced vital capacity (FVC)146*

-

Child Health Utility 9D Index (CHU-9D) health-state utility147

-

Activity Limitations Measure (ACTIVLIM) measure of independence and activity148

-

Care-related Quality of Life (CarerQoL) measure of carer burden149

-

health and social care resource use questionnaire for economic evaluation.

The following safety outcomes were assessed at the AT session for those in the intervention arm only after each AT session:

-

pain (visual analogue scale)

-

Children’s OMNI Scale of Perceived Exertion. 150

Changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced

Changes to outcome assessments, made during the study, are detailed in Appendix 1.

Sample size

The sample size was based on a recommended minimum of 30 participants (15 per group) for feasibility objectives involving parameter estimation. 151 Assuming a dropout rate at 6 months of 20%, we set a target of randomising at least 40 participants (20 per group).

Feasibility criterion

This pilot aimed to recruit 40 children in 6 months and to deliver AT to 20 of them. If this objective success criterion was met, then a full-scale study would be deemed feasible.

Generation of the random allocation sequence

The randomisation schedule was computer generated prior to the study by the clinical trials research unit (CTRU) in accordance with standard operating procedures. It was stratified by centre with randomly permuted blinded block sizes to ensure that enough patients were allocated evenly.

Allocation concealment

The allocation schedule was concealed through the use of the centralised web-based randomisation service.

Implementation

After eligibility and written consent were confirmed, patient details were entered into the randomisation system by good clinical practice- and protocol-trained site staff (physiotherapists), and the treatment allocation was returned.

Blinding

Although the physiotherapists, physicians and participants were not blinded, the data analysts remained blind to treatment allocation until after the statistical analysis plan was finalised, the database was locked and the data review was completed. Initially, blinded data were delivered to the statistician by the data manager to define analysis sets and to test statistical programs. Any queries were communicated to the study and data manager prior to database lock. The database was locked after agreement between the statistician, data manager and study manager. No changes were made once the data had been locked. Database freeze and lock were conducted in accordance with CTRU standard operating procedures.

Statistical methods

Analysis population

The intention-to-treat population included all patients for whom consent was obtained and who were randomised to treatment. This was the primary analysis set, and end points are summarised for the intention-to-treat population unless stated otherwise.

Baseline characteristics

For continuous variables (e.g. age), either mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) have been presented, along with minimum and maximum variables. The number of observations used has been presented alongside the summaries. For categorical variables (e.g. ethnicity), the number and percentage of participants in each of the categories and the total number of observations are presented.

Feasibility outcomes

Subject-specific AT adherence is reported as the number of AT sessions attended within 6 months and the per cent compliance (out of the 52 anticipated sessions) with mean (SD), median (IQR) and minimum–maximum values for the number of sessions attended. We also report the number and percentage of participants who attended all AT sessions and tabulate reasons for missed sessions. LBT adherence is reported as the number of days for which a participant was prescribed exercise and compliance is reported as the percentage performance (over the total number of days for which exercise adherence was recoded).

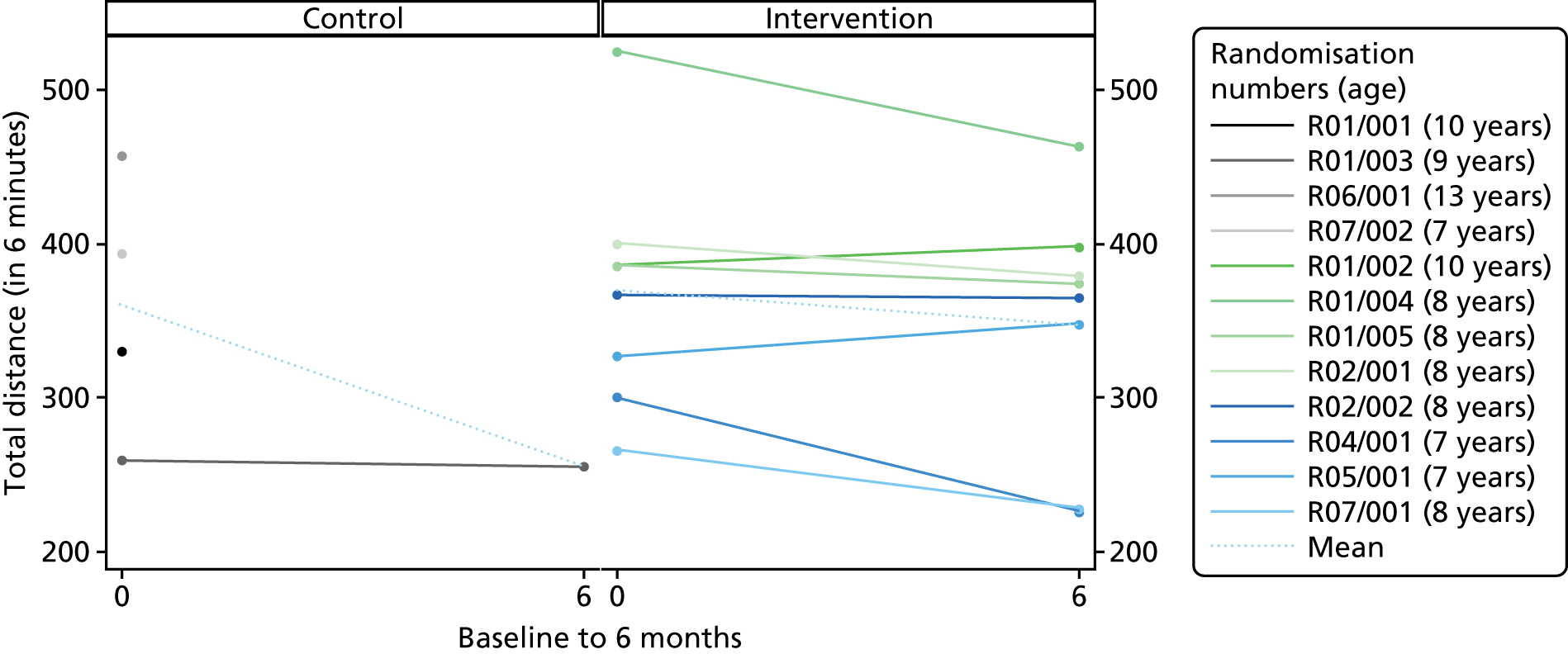

Clinical outcomes

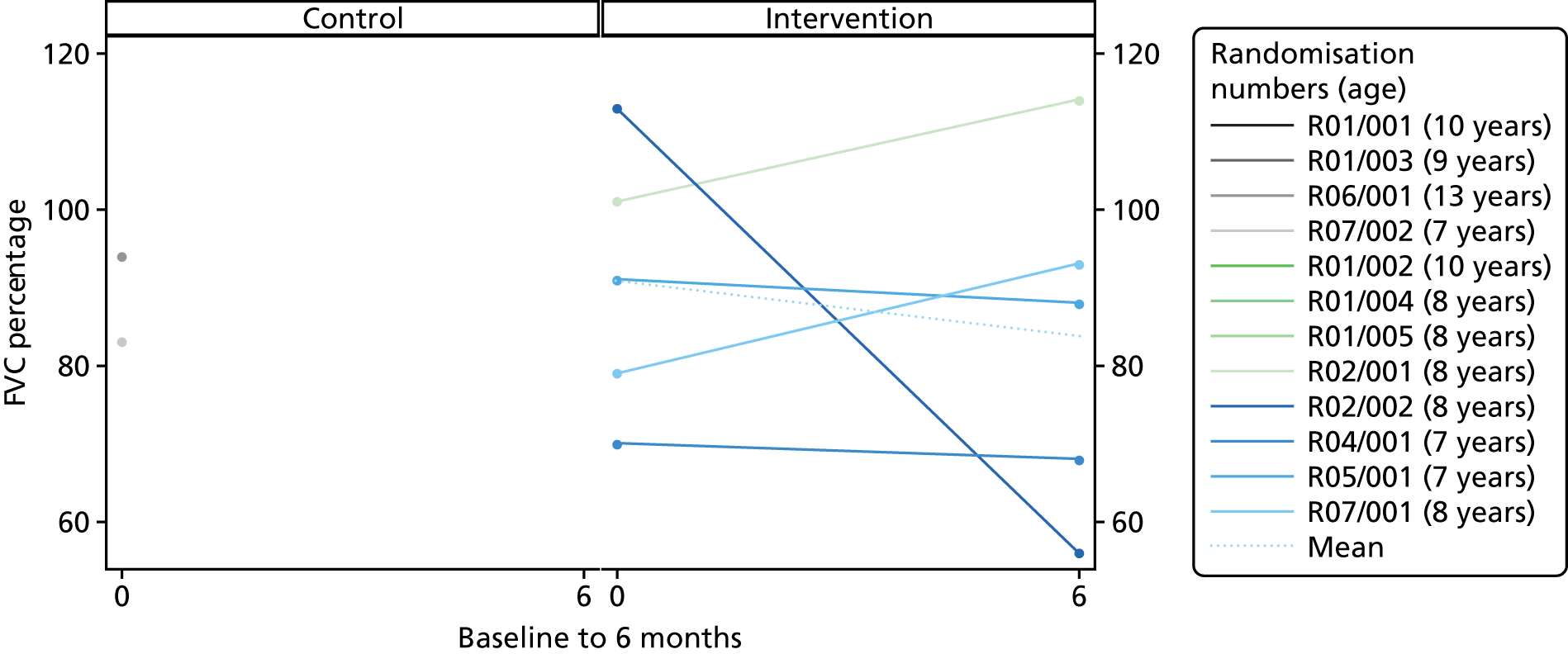

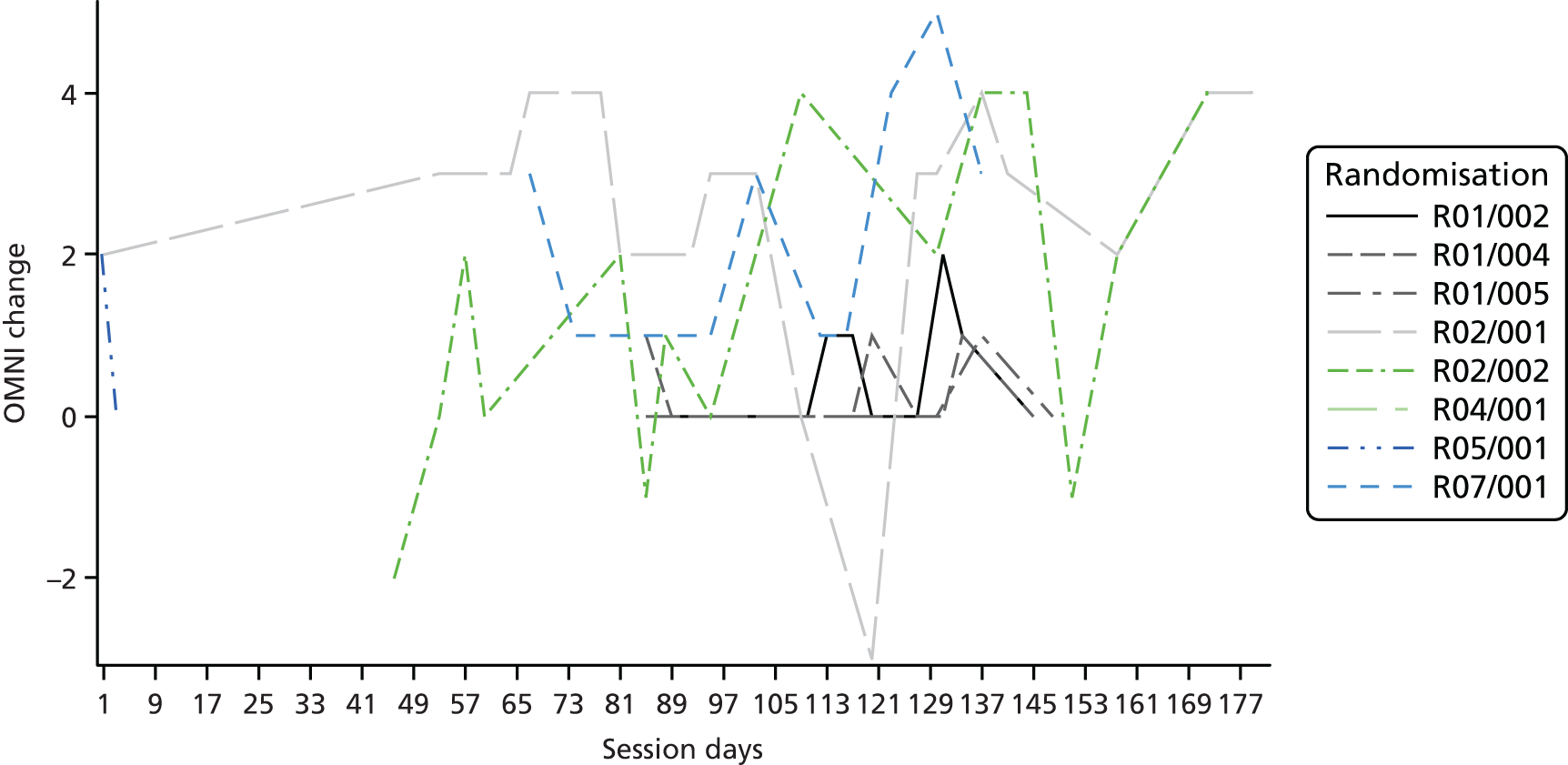

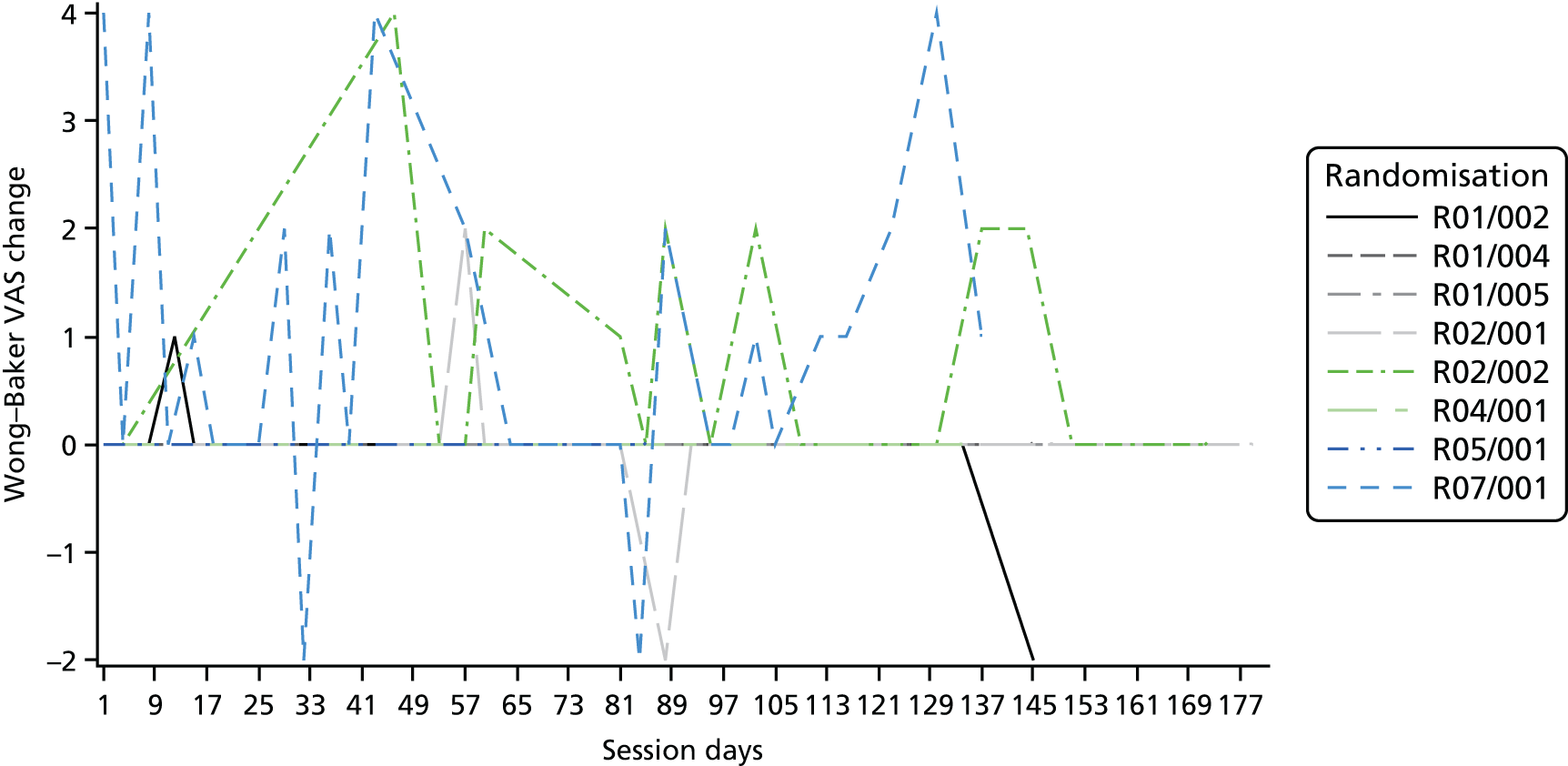

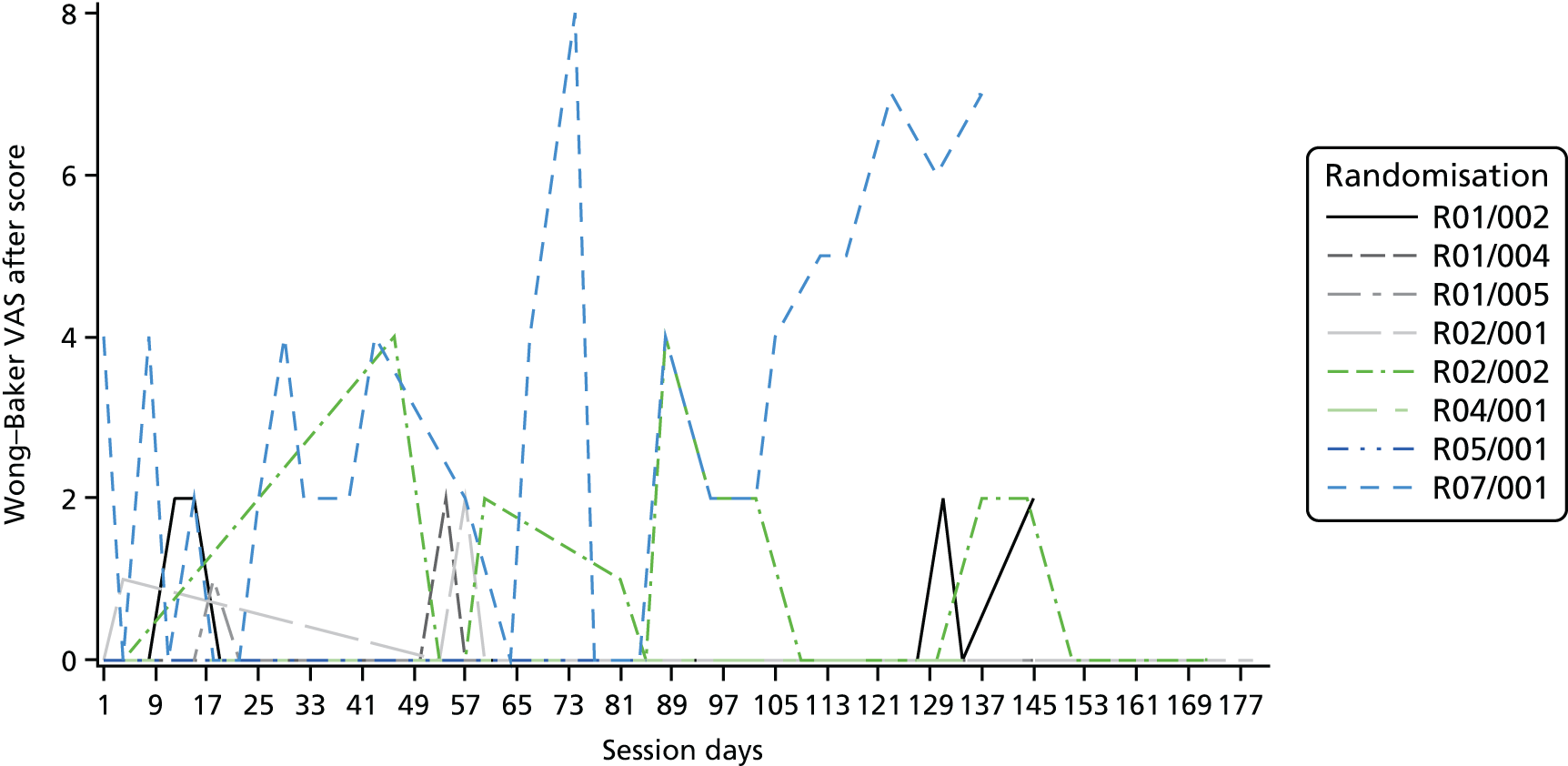

Descriptive statistics are presented for the clinical outcomes; significance testing has not been undertaken. NSAA measures (final measure and change from baseline) are presented as mean differences between groups and their associated 95% CIs. Clinical outcomes have been presented for the intention-to-treat set with available 6-month outcome data, by group and overall. Spaghetti plots of participant trajectories have been provided for various outcomes, stratified by treatment group, to provide a visual display of the change over time.

Missing spurious and unused data

The extent of missing data has been reported as it was one of the fidelity outcomes of the study. No sensitivity analyses involving imputation for missing data was performed. Any spurious data were queried and checked for consistency with data management before data lock. Patient and carer questionnaires were scored only if all relevant items that make up a domain were complete.

Ethical aspects

The study received a favourable opinion from the National Research Ethics Committee, East of England – Cambridge South, on 4 July 2014 (reference 14/EE/0204).

Patient and public involvement

James Parkin, a young man with DMD, and Victoria Whitworth, his mother and former carer, were involved in the design of the intervention, the study, the qualitative research analysis and the drafting of the report. They reviewed, made changes to and approved the final lay summary.

The intervention optimisation substudy

Introduction

Physiotherapists are legally obliged to record treatments given in a patient’s record at each intervention session. Participating physiotherapists collected standardised information on the type of exercises, number of repetitions and the time spent on each exercise, in a log based on the AT manual. Parents did the same for LBT. These data were entered onto a web-based data capture system and validated through on-site source data verification. An independent physiotherapist (JS), who was not a co-applicant, acted as an independent reviewer. She assessed whether or not prescribed treatment was ‘optimal’ given the treatment need and capacity of the boy concerned. We tabulated and charted summary data completeness. Missed/cancelled sessions were attributed to provider, patient or unknown factors. In attendance calculations we assumed that when the reasons for a missed session were unknown, then they were due to provider factors; the sum of sessions attended and sessions missed for family reasons were used as the denominator for attendance statistics.

Optimisation of prescription

The assessor made an assessment of whether AT or LBT prescriptions were optimised based on treatment logs and baseline data (NSAA, ACTIVLIM, medical/social history and schooling). The NSAA score was assessed as above or below average depending on the participant’s age and steroid regime. 9 The AT attendance was assessed as good if > 70% of available sessions were attended. The quality of the AT/LBT prescription was classified as ‘good’ if it was individualised to patient’s needs and focused on priorities, as ‘varied’ if the prescription was inconsistent, less focused or too extensive, or as ‘poor’ if it was unfocused and had too much content. In addition, prescriptions were classified as achievable if the exercises were appropriate and could be completed in a half-hour session. The LBT was also classified as realistic if it was clinically appropriate and achievable for the child’s level of ability, contractures and functional score (NSAA). This accepts that prescriptions may need to change with time, loss of function and loss of range of movement.

Adherence to the prescription

As a result of the shortfall in recruitment, sampling was unnecessary and all completed records were evaluated. Full LBT adherence would be demonstrated by completed logs, demonstrating that all prescribed exercises were performed, for each of the seven 4-week periods throughout the 26-week study. Full AT adherence would also be demonstrated by completed logs.

The number of exercises prescribed for AT and LBT is sometimes provided as a range when prescriptions changed during the trial period. Weekly (LBT) or by session (AT) percentage compliance with the prescription was described using mean, median and range values. Prescription compliance of > 50% was assessed as good for both AT and LBT. For both the AT and LBT data, Jennie Sheehan assessed whether or not priority stretches were prescribed according to baseline joint range, NSAA score and knowledge of natural history of DMD. In addition, Jennie Sheehan assessed if any changes in the LBT prescription appeared to affect compliance.

Assessment of overall treatment optimisation

To summarise, the independent reviewer was asked to assess the following:

-

Was the quality of the prescription ‘good’, ‘varied’ or ‘poor’?

-

Was adherence with the prescription ‘good’ or ‘poor’?

If the answer to both (a) and (b) was good, then we considered treatment to be optimised. We considered attendance as a separate variable, but note that it is possible for treatment to be optimised but for there still to be poor receipt of the treatment (see Figure 6). Physiotherapists were given the chance to respond to detailed feedback from the independent rater. Only two took up the opportunity.

The qualitative research

The Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative studies are observed. The topic guides used in the qualitative research are available in Appendices 2 and 3.

Interviewer characteristics

All interviews were conducted by Daniel Hind, a male graduate anthropologist, with 10 years’ experience of qualitative research, employed as a senior research fellow at the University of Sheffield.

Relationship with participants

No relationship was established with interviewees prior to commencement of the qualitative substudy. Participants were informed of the purpose of the research and the professional identity of the interviewer via the information sheet, and reminded, immediately before the interview, that he was an employee of the university, not of their care provider.The interviewer is a health services researcher with no motivational interest in either the population or the success of either intervention.

Theoretical and thematic framework

Rationale

Our rationale for using qualitative research alongside the pilot RCT is that it can tell stakeholders how to optimise interventions and research protocols, or why trials are likely to be infeasible. 152–154 Qualitative methods also enable research teams to capture how an intervention is implemented and experienced, thereby enabling better understanding of causal pathways. 131

Worldview155/epistemology156

Our rationale is pragmatic;157 it is concerned less with building, testing or advancing social science theory131,158 than with the ‘conceivable practical consequences’159 of different lines of action and with establishing a basis for ‘organising future observations and experiences’. 160 In other words, we hope to guide those who might want to develop, evaluate, commission or use AT services in the future by describing the experiences of those involved in our study. To do so, we do not rely on a single ‘favourite theory’,161 but aim to be ‘informed theoretical agnostics’,162 exploring how different theories of change might work at different levels and in different contexts.

Research design155/methodology156/approach163

Holistic single-case design with the unit of analysis at the intervention programme and research protocol level. 164

Theory

We used the four papers to inform our participant interview schedule. 87–90 To understand the conditions necessary to support the introduction and embedding of protocolised AT as a routine element of care, and to support a future evaluation, the health professional interview schedule was based around NPT. 120,165–167 Prompts related to the Theoretical Domains Framework168 were later added, but insufficient time was available for this additional coding work.

Participant selection

Convenience samples of children/parents and interventionists were taken. The consent of children and their parents was sought by the site principal investigators at the same time as RCT consent, but was not a precondition of the trial entry. Interventionists were informed at site initiation and approached for consent by a member of the research team directly. We interviewed all of the seven families whose boys (n = 8) received AT. In one case, the child was unavailable on the day and only the parent was interviewed. We interviewed seven physiotherapists who had delivered the intervention at five NHS trusts and a consultant paediatric neurologist at a sixth trust where the only participant had been randomised to the control arm (total health professional interviews, n = 8). None of the families approached declined an interview; one physiotherapist declined an interview, without giving a reason. Once recruited, no-one dropped out. All interviewed physiotherapists (n = 7) had experience of delivering AT prior to this project. Using the NHS Agenda for Change paygrade system,169 two physiotherapists we interviewed were band 6 (the most junior), three were band 7 and two were band 8. To put this in context, all those interviewed would have specialised in a particular condition (whereas it is typical that grade 5 physiotherapists rotate around specialties). Band 8 is usually an indicator that the individual is a physiotherapy service manager.

Setting

Semistructured interviews took place between 22 September 2015 and 14 January 2016 for participants and between 17 September 2015 and 29 January 2016 for physiotherapists. Parents chose the setting for data collection: most parent and child dyads were interviewed in their own home, in person; one dyad was interviewed by SkypeTM (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA); and one parent was interviewed by telephone after the failure of a Skype call. In general, interviews were conducted in quiet and private settings to reduce distractions; one interview was somewhat disrupted by the unavoidable presence of a younger child, otherwise, parents aside, no non-participants were present at interviews. All health professionals were interviewed by telephone around the time of site closure.

Data collection

In addition to the a priori themes identified in Table 2, semistructured interview guides for participants contained questions about the acceptability of intervention and research protocols. Interview guides were piloted with interventionist and patient/carer members of the study management group. The interview guide for health professionals adapted questions suggested by the NPT developers166 and was not piloted. No repeat interviews were undertaken. All interviews were recorded on an encrypted digital recorder and fully transcribed, with transcriptions anonymised. Field notes were taken after interviews as required. Participant/parent interviews lasted a median of 32 minutes (range 20–42 minutes), with durations typically related to the responsiveness of the child; the researcher’s sensitivity and judgement were used to determine the length of the interview. 170 Physiotherapist interviews took a median of 52 minutes (range 44–81 minutes). Formal assessment of whether or not saturation has occurred or of stopping criteria for qualitative data collection was not employed. 171 Although fewer than planned (because of the trial’s recruitment shortfall), some researchers would consider 16 interviews with families and professionals adequate for thematic172 (if not other sorts173,174 of) saturation. There was, for the most part, great consistency in messages from both groups. Transcripts were not returned to participants for correction.

Data analysis

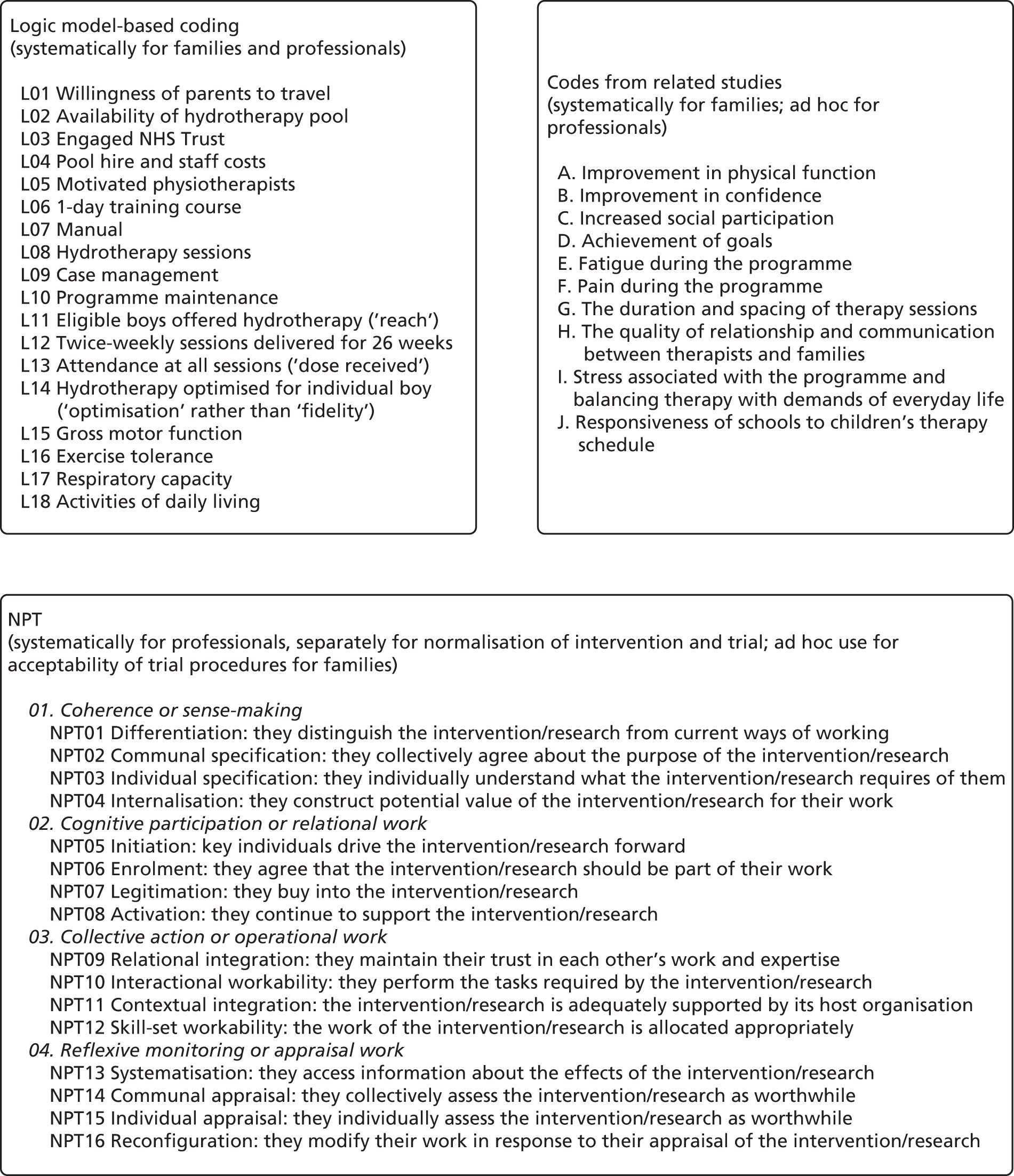

We used the National Centre for Social Research ‘Framework’ approach to analysis, with its five ‘key stages’: (1) familiarisation, (2) identifying a thematic framework, (3) indexing, (4) charting and (5) mapping/interpretation. 175 ‘Framework’ analysis allows sufficient flexibility for analysts to pre-specify themes of anticipated importance as coding categories and to combine them with others that are identified during inductive analysis, allowing the reformulation of ideas during the progress of the analytical process. 176 Transcripts were imported into NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Daniel Hind, James Parkin and Victoria Whitworth read and re-read transcripts (familiarisation), considering them in light of the initial thematic framework (see Table 2), NPT and the logic model (Figure 8; see also Figure 6), with notes being taken on new categories inductively derived from the data. We did not develop subthemes because of the number of different theoretical approaches that we were interested in accommodating. Daniel Hind, James Parkin and Victoria Whitworth independently coded a sample of the transcripts (indexing), before conferring with each other with regard to the coded transcripts for items relating to the thematic framework (see Table 2). Daniel Hind also coded within the NPT166 and against items in the logic model. Further literature reviews were conducted to understand emergent themes (see Modelling process: developing programme theory). New frameworks were added to NVivo, where necessary transcripts were recoded and categories refined or merged. We summarised coded data using NVivo matrices, linked to the relevant quotations (charting). Completed charts (available on request) were compared within and between participants.

FIGURE 8.

Coding framework.

We noted if a participant held strong views on a subject and if there was considerable agreement or disagreement between participants. Emerging ideas were mapped out on paper to aid interpretation (mapping). In addition to the involvement of patient representatives, protection against the researcher’s own views and prejudices were minimised by involving a specialist physiotherapist (ES) in three discursive debriefing sessions in which we reviewed coding and discussed interpretations. We actively sought discrepant and divergent views to combat confirmatory bias and to avoid overly simplistic interpretations of phenomena. 177 Participants were not asked to provide feedback on the findings.

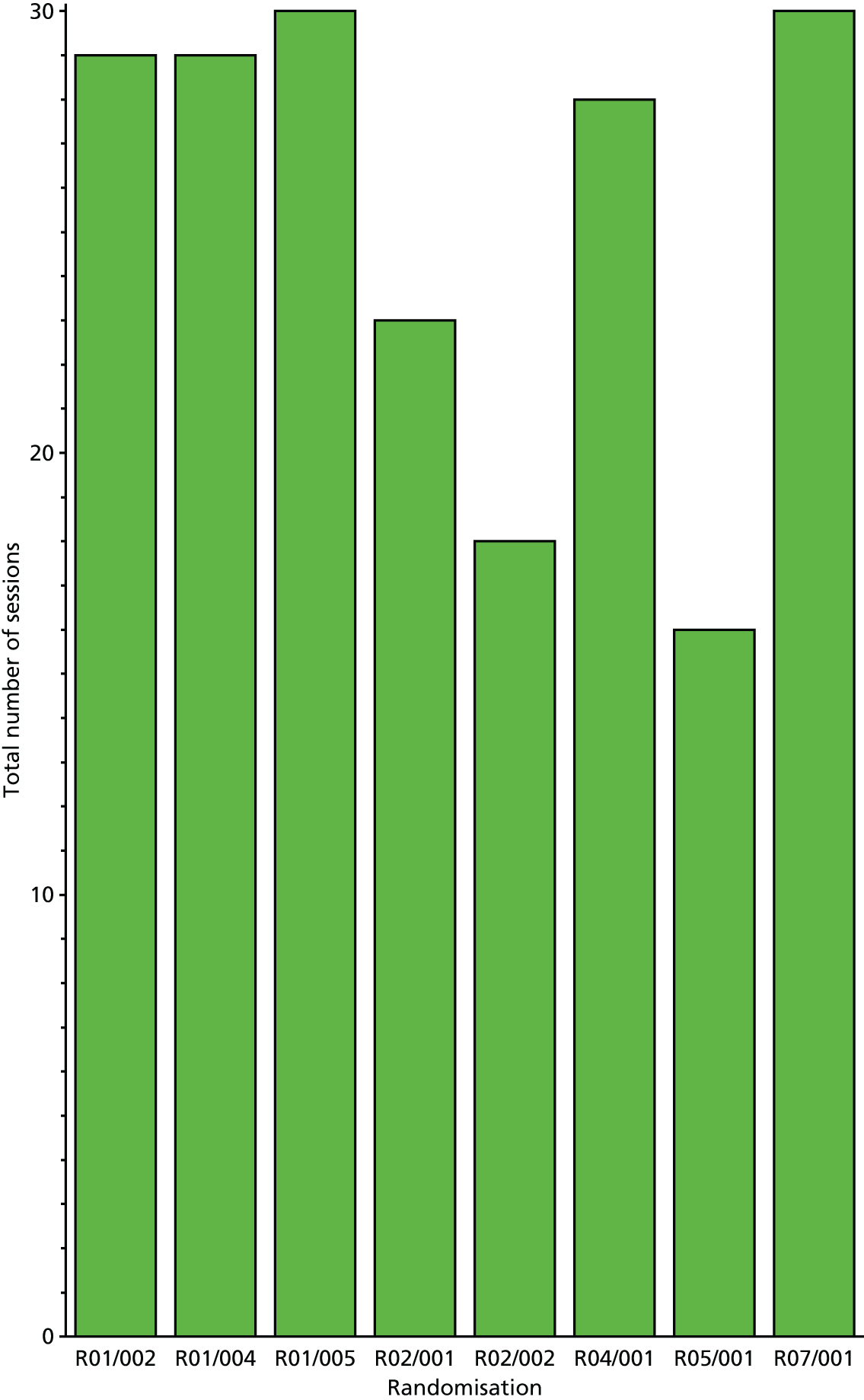

Reporting