Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/31/01. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The draft report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in December 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

All authors report grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme during the conduct of the study. Martin Underwood also reports personal fees from the NIHR HTA programme and personal fees from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Martin Underwood was also chairperson of the NICE back pain development group that produced the 2009 guidelines and is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group. James HL Antrobus was a pain physician with a NHS practice and an independent practice. He offered a service for and performed facet joint injections in both the NHS and independent sector while this study was in progress. James HL Antrobus was a member of the British Pain Society and a member of the British Pain Society Interventional Medicine Special Interest Group. David A Walsh reports consultancy on over-the-counter analgesic preparations that is not directly relevant to the submitted work (Novartis Consumer Health S.A).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Ellard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Low back pain

A global problem

Low back pain (LBP) is ranked as highest in the Global Burden of Disease in terms of years lived with disability. 1 The most recent UK ‘cost-of-illness’ study was in 1998. 2 At that time, the direct health-care costs of LBP were £1067M for the UK NHS and £565M for private health care, resulting in a cost of £28 per head of population. A 1998 US study3 estimated direct health-care costs as US$90,601M and a cost of US$335 per person. Much has changed since then. In the USA, there has been a 2.4-fold increase in spinal fusions and a massive increase in facet joint interventions, both of which are still increasing. 4,5 In response to this problem, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) commissioned guidelines for the management of non-specific LBP lasting between 6 weeks and 1 year. 6 The excluded treatment approaches included the injection of therapeutic substances into the back. Deep divisions in the scientific and clinical communities have become clear since the publication of the 2009 NICE guidelines and the 2009 American Pain Society guidelines for LBP,7 which also indicated that there was insufficient evidence to support the injection of therapeutic substances into the back. 8 Although the methodological approach used by the American Pain Society has been challenged, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians also concluded that the evidence for therapeutic intra-articular facet joint injections (FJIs) was limited. 9,10 A new NICE guideline for LBP and sciatica,11 published in 2016, did not support the use of intra-articular FJIs (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/musculoskeletal-conditions/low-back-pain). It does, however, in contrast to the 2009 guidance, support the use of radiofrequency denervation in people who have had a positive diagnostic medial nerve branch block.

There is a variety of different interpretations of the available evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies on the effectiveness of intra-articular FJIs. 12–18 Controversy surrounding this issue remains in the USA, and in the UK there has been new research evaluating lumbar facet joint interventions. 9,19,20 However, the outcome of all this work was that, at the outset of this study, the data were not a robust evidence base on which to inform decisions about the use of therapeutic intra-articular FJIs. Notwithstanding current NICE guidance and insufficient evidence to justify the use of FJIs, Hospital Episode Statistics21 record that, in 2014/15, 81,963 FJI procedures were performed in England for the NHS, an increase from 62,671 in 2012/13. Although there may be some inaccuracies in the coding of different facet joint-related procedures, this still represents a 30% increase in activity over 2 years.

Thus, there was a clear need for a trial to test the effectiveness of adding intra-articular FJIs to usual care for the treatment of persistent LBP when usual care as recommended by NICE or the American Pain Society has been ineffective. It is important that the proposed trial provides data that all parties can agree on. If the trial has positive results, then reinvestment in this treatment will be justified. If the trial has negative results, its conclusions need to be sufficiently robust that all parties to the debate on current guidance are satisfied that the evidence does not support the use of therapeutic intra-articular FJIs.

The UK National Institute for Health Research, via a specific call, funded two feasibility studies in preparation for trials of therapeutic intra-articular FJIs. We were funded to carry out one of these studies. Our proposed main study will test the addition of a therapeutic intra-articular FJI to best usual care (BUC) [Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme reference number 11/31/01]. 22 A different team is funded to test the feasibility of a more explanatory trial comparing active intra-articular injection with a sham control in people with a positive diagnostic medial branch nerve block (HTA 11/31/02). 23 These two studies will produce complementary data that will inform decisions on the merit of offering therapeutic intra-articular FJIs to selected people with LBP.

Diagnosis of low back pain

Low back pain is pain or discomfort felt in the back between the bottom of the rib cage and the buttock creases. Once medically serious causes of LBP have been excluded (infection, fracture, malignancy, inflammatory disorders such as ankylosing spondylitis), LBP is labelled as being non-specific. None of the early treatment options recommended in the 2009 NICE guidance requires any further diagnostic work-up.

Unless there is a concern that there is a serious medical cause for the pain, imaging of the lumbar spine is not indicated. This approach recognises the difficulty of reliably identifying subgroups of people who may respond better to any particular treatment approach. 24,25 Notwithstanding this overall approach to the diagnosis of LBP, it is possible that there are subgroups of individuals who would benefit from one or more specific approaches to the treatment of their LBP. One subgroup who may benefit from a more specific back treatment is patients whose pain wholly, or partially, arises from the facet joints. This notion is supported by the 2016 NICE back pain guideline, which recommends the use of diagnostic medial branch nerve blocks before considering radiofrequency denervation in people with suspected facet joint pain. The clinical assessment of suspected facet joint pain suggested in NICE 2016 guidance is based on work described later in this report. 26

Facet joint pain

The facet joints are paired structures between the superior and inferior articular processes of adjacent vertebrae that, in the lumbar spine, allow flexion and a degree of rotation of the spine. They are synovial joints whose capsule is richly innervated. With increasing age, progressively more people develop radiological osteoarthritis of the facet joints. A systematic review estimated the prevalence of facet joint degeneration increased from 4% for those in their twenties through 32% for those in their fifties to 83% for those in their eighties. 27 There is not, however, an association observed between radiological change in facet joints and the presence of back pain. 28 If pain arising from the facet joint is suspected clinically, it may be abolished temporarily by the injection of local anaesthetic, which may be used as a diagnostic test. A depot preparation of steroid added to the injection may prolong the analgesic benefit. The relief or reduction of pain may facilitate compliance with a programme of exercise designed to improve lumbar range of movement and muscular stability.

Clinical features of facet joint pain

There are few good epidemiological data on the prevalence of facet joint pain in different populations or on how to diagnose suspected facet joint pain clinically. In some studies, 5–15% of people with chronic LBP are believed to have disease of one or more facet joints that is contributing to their pain. 29 The gold-standard test for the presence of facet joint pain is pain relief after the injection of affected joints with a local anaesthetic. There is considerable diagnostic uncertainty about how to identify people with pain of facet joint origin among the wider chronic LBP population.

Revel et al. 30 in 1998 found that people with pain of facet joint origin were characterised by:

-

being aged > 65 years

-

pain that is well relieved by recumbency

-

absence of pain exacerbation

-

by coughing

-

by forward flexion

-

when rising from flexion

-

by hyperextension

-

by extension rotation.

-

All predicted a benefit from injection of anaesthetic into facet joints. The presence of five of these characteristics, including pain on recumbency, correctly identified 92% of responders and 80% of non-responders. 30 Others, however, were unable to replicate their findings. 31 Subsequent reviews suggest that 62% of those with these clinical features of facet joint pain obtained immediate relief from FJIs; one-third of these were false positives. 32,33

Laslett et al. 34 in 2006 found that seven factors were predictive of facet joint pain:

-

age ≥ 50 years

-

pain is best when walking

-

pain is best when sitting

-

onset of pain is paraspinal

-

modified somatic perceptions questionnaire score exceeding 13 (suggesting a somatisation disorder)

-

positive extension/rotation test

-

absence of centralisation during repeated movement testing.

They found that presence of three or more factors of age ≥ 50 years, pain is best when walking, pain is best when sitting, onset of pain is paraspinal and positive extension/rotation test was 85% sensitive and 91% specific for facet joint pain. 34 In a 2007 systematic review, Hancock et al. 35 did not find evidence for a robust diagnostic test for facet joint pain. In an initial scoping review in preparation for this work, we found one additional relevant article. In a retrospective chart review (n = 170), DePalma et al. 36 found that the presence of isolated paramidline LBP increased the probability of facet or sacroiliac joint dysfunction and slightly reduced the likelihood of lumbar disc degeneration. The sensitivity of reporting paramidline pain if the patient has facet joint pain was 96% [95% confidence interval (CI) 83% to 99.4%] for sacroiliac pain and 67% for internal disc disruption. This supports other work indicating that paraspinal or paramidline pain is a clinical indicator of possible facet joint involvement. Similarly, although not empirically proven, lumbar segmental motion may also be useful in identifying the level of facet joint involvement. 37 A 2007 consensus study38 identified clinical features thought to be associated with facet joint pain, such as:

-

localised unilateral LBP

-

lack of radicular features

-

pain eased in flexion

-

pain, if referred, is above the knee

-

palpation: local unilateral passive movement shows reduced range of motion or increased stiffness on the side of pain

-

unilateral muscle spasm over the affected facet joint

-

pain in extension

-

pain in extension, lateral flexion or rotation to the ipsilateral side.

In a prospective cohort study of medial branch blocks for suspected lumbar or cervical facet pain, Wasan et al. 39 used selection criteria including a history of axial pain with radiation in an established facet joint referral pattern and tests for facet joint loading signs (extension, side bending and rotation). Although they acknowledged that their study was not designed to confirm diagnosis, Wasan et al. 39 concluded that the selection criteria reduced the likelihood of radicular pain due to nerve root involvement or non-specific LBP.

In the 2011 protocol for a trial of specific physiotherapy compared with advice, Hahne et al. 40 argued that if three or more of the following factors are present then there is facet joint dysfunction:

-

unilateral LBP

-

pain reproduced with lumbar extension and ipsilateral lateral-flexion movements

-

pain on ipsilateral passive postero-anterior accessory movement applied through the transverse process or zygapophyseal joint at one or two segments

-

improvement in pain or range of movement following a ‘mini-treatment’ of manual therapy directed at the zygapophyseal joint.

The choices of Hahne et al. are grounded in the Maitland’s clinical reasoning approach to identifying a group who would respond to manual therapy. 41 The use of such phenotypically defined subgroups, grounded on clinical reasoning, may be the most appropriate approach to subgroup identification in LBP. 42 This approach has not been tested empirically and may not be directly relevant to identifying people likely to respond to FJIs. It does, however, represent current best practice to identify people likely to respond to the physical component of our proposed control intervention. Interestingly, this trial is restricted to people aged < 65 years, even though others have found increasing age to be a feature predicting the presence of facet joint pain. Nevertheless, 20% of recruits were identified clinically as having facet joint dysfunction. Diagnoses were not confirmed using diagnostic injections.

During the early stage of this study we identified a further study, published as a conference abstract,43 that identified combined movements as a predictor of pain relief from a diagnostic lumbar medial branch block.

Why might injecting facet joints be helpful?

The use of corticosteroid injection has been shown to be effective in producing, at least in the short term (1–4 weeks), benefits for a range of musculoskeletal disorders including frozen shoulder and osteoarthritis of the knee and hip. 44–46 Analgesic benefits of intra-articular injection of corticosteroids in rheumatoid arthritis may be more sustained (up to 3 months). 47 Drawing on these data from other parts of the musculoskeletal system, it is a reasonable hypothesis that intra-articular injection of corticosteroids could produce at least short-term pain relief in a different synovial joint that is causing pain. The focus of this study is on intra-articular FJIs.

Evidence on the safety of facet joint injections

Robust evidence on the complications from FJIs is very sparse. Manchikanti et al. ,15 however, in an observational study of facet joint nerve blocks (3162 LBP episodes with 15,654 lumbar nerve blocks) found no major complications. However, 73% of encounters had local bleeding, 10% had oozing, 4% had intravascular injection and 0.4% had profuse bleeding. These figures may be indicative of minor adverse event rates from FJIs. The number of people with a short-term increase in pain was not reported.

Evidence for treatment of facet joints

That pain can arise from facet joints has been proven. There are several good double-blind studies that show, in selected patients, that immediate pain relief can be obtained from injecting local anaesthetic into facet joints that is not obtained from injecting saline. 48 Indeed, demonstrating such pain relief is the gold-standard test for diagnosing facet joint pain.

Observational studies

There is a body of observational data suggesting that FJIs are an effective treatment for lumbar facet joint pain. Boswell et al. 49 identified six prospective studies (n = 253) of FJIs. All but one of these studies found positive short- and long-term effects. There are, of course, substantial limitations to using such uncontrolled observational data to inform practice because of the natural history of LBP. There is substantial improvement even in the usual-care arms in nearly all trials of chronic LBP. 50

Placebo-controlled trials

At the time this research started, there were five recent reviews of the RCT evidence for FJIs compared with a placebo or sham procedure. NICE7 and Boswell et al. 51 each identified one trial (Carette et al. 52); Chou et al. 53 and Henschke et al. 54 each identified two trials (Carette et al. ,52 n = 97; Lilius et al. ,55 n = 86). 54 Datta et al. 56 identified both of these studies but excluded them: Carette et al. ,52 unusually, because they had not excluded placebo responders, and Lilius et al. 55 because theirs was considered to be an observational study. Neither of these trials was reported by the original authors as showing a positive result.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, in both 20096 and 2016,11 and Chou et al. 7 concluded that the evidence did not support the use of FJIs. Henschke et al. 54 concluded, based on very low-quality evidence, that there was no difference between FJIs with placebo and corticosteroids. Datta et al. 56 concluded that, because of the lack of evidence, there could be only a very weak positive recommendation or a recommendation not to provide FJIs. Boswell et al. ,49 on the other hand, felt that there was evidence for a positive effect from FJIs. This was based on categorising one study (Carette et al. 52) as a positive trial. This was because, although there was not a positive effect at 3 months, there was a strong positive effect in the 6-month analysis. Both Carette et al. 52 and Chou et al. 53 discounted this observation because the patients who gained a benefit at 6 months were not the same as those who had gained a benefit at 1 month and because of the large number of cointerventions in the steroid arm of the trial. Neither group felt it to be biologically plausible that a steroid injection would be effective at 6 months if it had not been effective at 1 month. Notwithstanding differences in interpretation, and the absence of statistical significance at 3 months, the point estimates for benefit from FJIs in the Carette et al. 52 study are competitive with currently recommended treatments. 57 The proportion of patients who reported substantial improvement was 42% versus 33% (95% CI –11% to 28%) and 46% versus 15% (95% CI 14% to 48%) at 3 and 6 months, respectively. These equate to numbers needed to treat (NNTs) of 11 and 5, respectively. If such NNTs were reproduced in a definitive trial, then FJIs could be an attractive addition to recommended treatments for selected people with LBP. These results, however, were obtained in participants who had already had a diagnostic FJI, suggesting that this study was carried out in patients who were most likely to benefit. Not excluding those with a placebo response to the diagnostic injections might also have reduced the apparent effect size. Carette et al. 52 also did not include those who found the diagnostic injections too painful; 7 out of 110 participants (6%) with a positive result from diagnostic injections did not want therapeutic injections because they found the process too painful.

Facet joint injections compared with other treatments

At the start of this study there were two reviews of FJIs compared with other treatments. Henschke identified five studies (n = 420) of FJIs with corticosteroids compared with other interventions. 13,16–18,58 Marks et al. 18 found that FJIs gave superior pain relief to facet nerve blocks (both used corticosteroid and lignocaine) at 1 month but not at immediate follow-up or at 3 months (n = 86). Mayer et al. 58 found no benefit from adding a FJI with local anaesthetic and corticosteroid to a home stretching exercise programme (n = 70). Fuchs et al. 13 found no significant differences between FJIs with steroid and sodium hyaluronate (n = 60). Manchikanti et al. 16 found no difference when comparing multiple medial facet nerve blocks with local anaesthetic with or without steroids (n = 84). Manchikanti et al. 17 found no differences between medial branch blocks with and without corticosteroid (n = 120). Datta et al. 56 identified two of the same trials of facet joint blocks. 16,17 and concluded that there was strong evidence for facet joint nerve blocks because of the good outcome in both groups. Celik et al. 12 reported a positive effect from FJIs in a subsequent trial (n = 80) comparing FJIs with a combination of bed rest, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and a muscle relaxant. In a subsequent trial (n = 100) comparing FJIs with facet joint radiofrequency denervation, Civelek et al. 59 found better immediate results from injection and better long-term results from denervation.

Cost-effectiveness

Our scoping reviews did not identify any studies of the cost-effectiveness of FJIs. FJIs require specialist facilities and experienced operators but the potential benefit observed in observational studies may well outweigh these costs.

Conclusion of initial scoping literature review

In our own 2016 review,60 we identified six relevant randomised placebo/sham-controlled trials of intra-articular FJIs. 12,52,55,58,61,62 Two studies (Lilius et al. ,55 n = 109; Carette et al. ,52 n = 97) used placebo injections into the facet joints as the control treatment, one study (Ribeiro et al. ,62 n = 60) used intramuscular corticosteroid as the control treatment, two studies (Mayer et al. ,58 n = 70; Kawu et al. ,61 n = 18) used exercise as the control treatment and one (Celik et al. ,12 n = 80) used bed rest plus analgesia and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as the control treatment. Four studies made a clinical diagnosis of facet joint pain,12,55,61 one study62 used clinical and radiographic features to make the diagnosis and two studies52,58 used diagnostic blocks. We considered the study populations, and the comparisons made, to be too heterogeneous for any robust conclusions to be drawn. 60

The quality of reporting of these trials of FJIs is generally poor and it is not a robust evidence base to inform decisions about the use of FJIs.

Measurement of outcome

The measurement of outcome in LBP trials is problematic. 63–65 Although there are well-established standard packages of outcome measures, endorsed by expert groups, the theoretical underpinning of these is poor and they may not capture those outcomes that are important to individuals. 63,66 It is of note that neither of these consensus exercises included input from patients and the decision about which outcomes should be measured in LBP trials was from a consensus of clinicians and researchers. 67 More recent recommendations from the expert advisory group, the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT), do include patient group consultations to explore the relevance and acceptability of outcomes used to determine recovery. 68

Studies of patients suggest that other domains, not included in current recommendations, may be of similar or even greater importance. For example, domains such as enjoyment of life and fatigue were rated most highly in a patient survey. 69 A review of outcomes measured in RCTs of LBP found that 5 out of 19 outcomes rated as important by respondents to the patient survey were never reported and a further eight measured only rarely. 70 There is a need to broaden the pool of outcome measures used beyond the established package to include measures that more effectively capture the patient perspective.

Where might facet joint injections fit in the care pathway?

For people with acute or subacute LBP or early persistent LBP, the prognosis is generally very good and there is little need for invasive treatments. Low-intensity, low-risk and therapist-delivered interventions, as recommended by NICE, are sufficient. Although there are some differences between the 2009 NICE guidance6 and the 2016 guidance,11 both support the use of therapist-delivered interventions as the first treatment approach after advice and analgesics. Those with substantial problems persisting after such interventions (typically ≥ 6 months from onset) require more intensive treatment. Persistent LBP is a complex biopsychosocial phenomenon. In those people with pain persisting beyond 6 months, in spite of good conservative care, a syndrome of chronic pain and disability will already be present. For this reason, one would not expect FJIs, on their own, to resolve the problem. Rather, pain relief obtained from a FJI may give the person with back pain the confidence and a window of opportunity to engage more fully with a rehabilitation programme.

There is a clear need for a trial to test the effectiveness of adding FJIs to usual care as recommended by NICE for the treatment of persistent LBP. It is important for this trial that it provides conclusive results. If the trial has positive results then this will be a justification for investment in this area. On the other hand, if the trial is negative then its conclusions need to be sufficiently robust that all parties to the debate on the role of therapeutic intra-articular FJIs are satisfied that the evidence does not support their use. There are methodological challenges to setting up and running such a trial; principally, these centre on the identification of people with LBP that is, at least in part, from facet joints. Our feasibility study addressed these methodological issues, tested trial processes and recruitment in an external pilot, conducted an interim analysis and identified sites to conduct the main study.

For the NHS to consider reinstating FJIs for people with otherwise non-specific LBP, a package of care including FJIs, for selected patients, needs to be an effective and cost-effective addition to BUC. This is true regardless of the result of any placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy of FJIs. The components of any overall effect (positive or negative) of FJIs will be the non-specific effects of attending for the injection (including any advice from the treating clinician), any local effects from injecting fluid into the facet joint and the specific effects of the drug/s injected. A positive efficacy study in a tightly controlled population will not necessarily transfer to a treatment that is effective in real life. Conversely, failure to show a positive effect in an efficacy study using a placebo or sham injection would not necessarily exclude the possibility that the overall package of care is effective. Furthermore, such an efficacy study will not be able to answer a question on the cost-effectiveness of adding the intervention to usual care.

The situation here is perhaps analogous to interpreting the evidence on the use of acupuncture, a treatment with a much weaker theoretical base than FJIs. There is a substantial body of evidence that acupuncture is superior to usual care for a range of common disorders, with meaningful effect sizes. The evidence that verum acupuncture is superior to a sham control is, however, much weaker, with very small apparent effect sizes. Nevertheless, acupuncture was recommended by NICE for LBP in 2009,6 although not in 2016 guidance,11 and for headaches in 2012. 71 For these reasons we propose a two-arm study testing the effect of adding FJIs to a BUC package.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the study was to carry out a feasibility study for a trial to assess the clinical effective and cost-effectiveness of intra-articular FJIs for selected patients with chronic LBP.

In this feasibility study we explored the feasibility of running a RCT to test the hypothesis that, for people with suspected facet joint pain contributing to persistent LBP, the addition of the option of FJIs, with local anaesthetic and corticosteroids, to best usual non-invasive care available from the NHS is clinically effective and cost-effective.

The specific objectives for this feasibility study were to:

-

develop, and evaluate, agreed criteria for identifying people with suspected facet joint pain

-

develop an agreed protocol for the injection of facet joints in a consistent manner

-

develop, and evaluate, a standardised control treatment deliverable in the NHS and congruent with NICE guidance (BUC)

-

develop and test systems for collecting short-term and long-term pain outcomes, including measures required for economic evaluation

-

demonstrate that recruitment to the main trial is feasible

-

collect the recruitment and outcome data required to inform sample size and number of sites needed for the main study

-

conduct a between-group trial to inform the decision on the need for a full trial

-

do a process evaluation of patient experience within the trial.

Overview of the Facet Injection Study

This report is split into a number of key sections. The Facet Injection Study (FIS) includes a considerable body of development work to inform the study processes, the diagnoses and the feasibility study’s control, intervention and injection technique as well as the pilot trial. The feasibility trial was terminated by the funder because of poor recruitment.

First, we present this development work, which was mostly informed by a consensus conference. We summarise the methodologies used and the outcomes that informed the development of the trial protocol, a diagnostic manual, a ‘BUC manual’ and an injection manual. Reports of the full consensus methods, results and conclusions are available elsewhere as online resources. 72–76 Second, we report the experience of running the feasibility RCT research methods, including the process evaluation, and the outcome/results of the study. The final section, the discussion and conclusion, is a synthesis of all of the results and outcomes.

Patient and public involvement

We are not able to report on patient and public involvement (PPI) in the framing of the original commissioning brief from the HTA programme. Throughout the development of this proposal, in response to the HTA brief, and subsequent conduct of the study there has been input from PPI representatives and groups. All of the project’s development work and interpretation of the results have had input from PPI representatives.

-

Two very active co-applicant PPI representatives on the studies trial management group played an important part in the development of study material and intervention development at the consensus conference, and one provided a reflection of their experience working on the trial (see Appendix 1).

-

One PPI representative on the trial steering committee who gave clear guidance throughout.

-

Six lay representatives participated in our consensus meeting. 74,76

We also acknowledge the help and support provided by University/User Teaching and Research Action Partnership (UNTRAP) at the University of Warwick, which provides training and support to ensure effective PPI.

Chapter 2 Consensus: developing the study protocols

A four-stage process was adopted to ensure that the FIS protocol was robust and informed by current evidence and expert opinion, was acceptable to the academic community and practising clinicians and reflected NHS practice. First, the FIS team identified key design considerations that are of vital importance for the production of robust and acceptable evidence on an implementable FJI programme. Second, an evidence review of each design consideration was conducted using systematic methodology. Third, an evidence document was prepared that contextualised the pragmatic FIS, outlined the methodological challenges of designing a credible pragmatic trial and presented the outputs from the evidence reviews. Fourth, using the evidence document as a delegate pack, the FIS design considerations were considered by a consensus conference of clinicians, experts, academics and lay representatives.

Methods

Before the conference

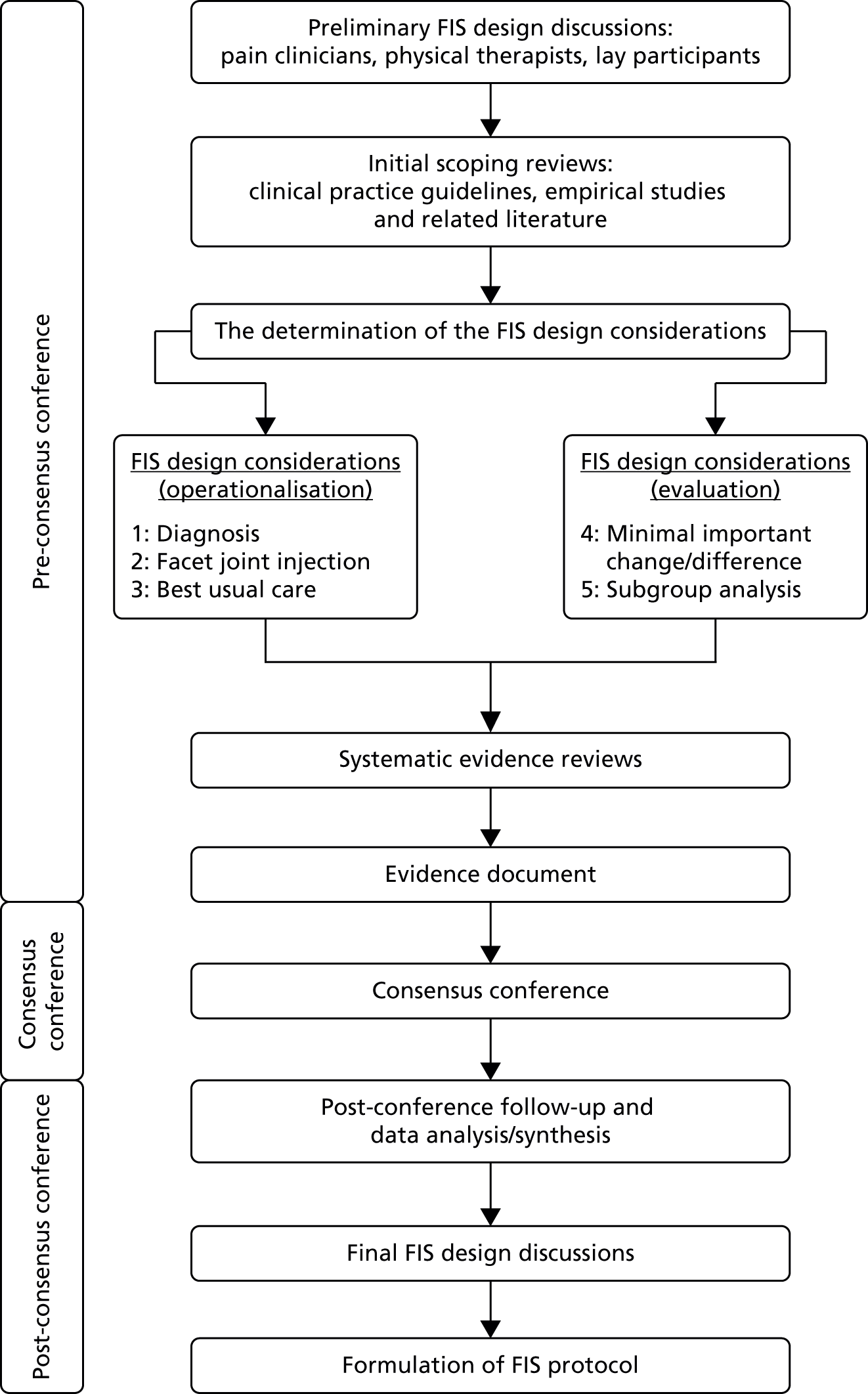

The three stages of the study are presented in Figure 1: (1) scoping review and identification of key design considerations, (2) evidence reviews and (3) consensus conference.

FIGURE 1.

Facet Injection Study protocol development process. Adapted with permission from Mars et al. 26

Scoping reviews and formulation of key design considerations

Our study team includes pain clinicians, physical therapists, radiologist and lay representatives, as well as research methodologists. Based on scoping reviews of clinical practice guidelines, empirical studies and related literature and team discussion, five design considerations for the proposed trial were identified and questions posed, as follows.

-

Diagnosis: what is the best choice of clinical assessment to identify patients with facet joint pain?

-

Injection technique: what is the agreed technique for the therapeutic intra-articular injection of facet joints?

-

BUC: what is the optimal conservative management/rehabilitation for patients with LBP for whom facet joints have been identified as a contributing source of symptoms?

-

Between-group differences: what is the difference in magnitude of response between treatment and control groups that should be considered large enough to establish the scientific or therapeutic importance of the results?

-

A priori subgroup analyses: which variable(s) should be used for a priori subgroup analyses in the main trial?

The consensus conference

Potential conference participants were invited through relevant professional and lay organisations (Box 1). We sought participation from experts from across the UK. By expert, we mean that participants were professionals or lay people with an interest in, or experience of, back pain, its treatment and, in particular, its treatment with therapeutic intra-articular FJIs. The invitation was to a 1-day conference with no attendance charge and travel expenses were reimbursed. This was held at the University of Warwick on 27 June 2014.

-

Professors/consultants in pain management via Binley mailing services (www.binleys.com) (accessed 22 February 2014).

-

British Association of Spinal Surgeons (www.spinesurgeons.ac.uk) (accessed 3 March 2014).

-

Association of British Neurologists (www.theabn.org) (accessed 3 March 2014).

-

British Society of Skeletal Radiologists (www.bssr.org.uk) (accessed 3 March 2014).

-

British Society of Interventional Radiologists (www.bsir.org) (accessed 5 March 2014).

-

Primary Care Rheumatology Society (www.pcrsociety.org) (accessed 19 March 2014).

-

Council for Allied Health Professions Research (www.csp.org.uk/professional-union/research/networking-support/council-allied-health-professions-research) (accessed 28 March 2014).

-

Midlands Health Psychology Network (www.mhpn.co.uk) (accessed 19 March 2014).

-

Back Care – a lay advocacy and support organisation (www.backcare.org.uk) (accessed 14 March 2014).

-

UNTRAP is a partnership between users of health and social care services and carers, the University of Warwick and the NHS (www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/healthatwarwick/untrap) (accessed 10 March 2014).

Adapted with permission from Mars et al. 26

Approximately 1 week before the consensus conference, a document consisting of the design considerations and related evidence was sent to all those registered to attend.

We used nominal group technique to gain consensus. This allows for discussion, while avoiding individuals or groups dominating the consensus process, and allows participants to draw on available evidence and expertise. 79 We started the conference with a brief reminder of the key design considerations and evidence. We then held 15 small group consensus sessions, each lasting 1 hour, with five groups meeting in parallel at any one time (Figure 2). Small group results were fed back to a plenary session, in which final consensus was reached. With participant consent, all sessions were audio-recorded for reference during analysis. Participants were randomly assigned to small group sessions stratified by profession (approximately 10–12 per group) with each participant discussing three different design considerations. Each small group had a trained facilitator, a scribe and a subject expert from our team. The subject expert did not participate in the discussions but answered questions about technical issues when invited to by the facilitator. Discussions centred on the particular design consideration, with the suggested ‘protocol’ as a starting point when appropriate. Nominal group technique was adapted to the design consideration under discussion as described in Figure 2. Each participant confidentially ranked the acceptable approaches identified by the group. Results were collated by the scribes.

FIGURE 2.

A diagrammatic representation of the consensus process. Adapted with permission from Mars et al. 26 NGT, nominal group technique.

In the sections following, we outline the five design considerations and how the discussions on these were conducted during the consensus conference day. More detailed information is provided in three documents:

Diagnosis: assessment for facet joint pain

Participants were presented with summaries of the information about diagnosis from the evidence reviews and asked to suggest components of clinical assessment (Box 2). These were then discussed to identify any that were similar and then grouped as sets forming complete clinical assessments. Participants then ranked the clinical assessments.

-

Current empirical evidence on the clinical diagnosis of facet joint pain is limited.

-

Some signs/symptoms or aggravating factors have been suggested to be indicative of facet joint pain but their use is not supported by the research evidence.

-

Small-scale and provisional research suggests that a regular compression pattern when testing combined movements may have some validity for identifying facet joint pain.

-

The ability to identify patients where the facet joints are a suspected source of pain is important as it is one of the entry criteria for enrolment in the study.

-

Being able to accurately identify a relatively homogenous group of back pain patients with facet joint pain will allow a true evaluation of the potential benefits of FJIs.

Injection technique

Participants were presented with summaries of the information about injection technique from the evidence reviews (Box 3).

-

Key educational/instructional texts for FJI describe details of each author’s technique. A broad methodology emerges that varies in detail within a narrow range of options.

-

For this study we need to achieve a single detailed process for therapeutic injection of lumbar facet joints that is acceptable to the professional community and can be applied consistently across all participating study centres.

A potential protocol was presented to them to aid with discussions (Box 4). This included 14 different aspects of the process of injection. For each aspect a proposal was made for the technique to be used. Group members first identified which of these they considered acceptable. After collation of these results, the facilitator invited discussion in turn on each of the aspects for which there was not agreement on acceptability. For each of these, alternative processes were identified and then ranked.

When they attend for injection the operator will make a brief clinical assessment to satisfy themselves that FJIs are appropriate. Consent for the procedure will be obtained and the current pre-injection risk management procedures of the participating study centres will be adhered to. The operator will then inject the facet joint(s). We expect to inject up to six facet joints in each individual (L3/L4, L4/L5 and L5/S1) bilaterally. However, when, on clinical assessment, there is unilateral pain or involvement of only some levels the operator may choose to do unilateral injection or be selective on levels injected. We expect that everyone should receive at least two injections. This pragmatic approach reflects what actually happens in NHS practice. This approach is consistent with that used in trials of other complex interventions for LBP, for example manual therapy or a cognitive–behavioural approach, where practitioners choose from a limited range of options based on their clinical assessment of the patient.

Procedure to position the needle-

We do not expect to use intravenous sedation.

-

Prone position with pillow under abdomen to flatten lumbar lordosis.

-

Intravenous access, resuscitation equipment available.

-

Skin cleansing with 0.5% or 2% chlorhexidine in alcohol, sterile drapes. (Some clinicians think that 2% chlorhexidine is neurotoxic and like to use 0.5% as skin cleansing before nerve blocks. On the other hand, 2% chlorhexidine is recommended by the control of infection experts as optimum skin cleansing before intravenous cannulation and may be preferred in some trusts.)

-

Radiography (C-arm fluoroscopy) oblique view to visualise joint.

-

The dose of radiation used will be adequate to visualise the joint while minimising X-ray exposure.

-

Skin weal at needle entry point: 1% lidocaine via a 25-gauge hypodermic needle.

-

22-gauge × 3.5-in (0.7 × 90 mm) needle with Quincke type point: guide needle to joint cleft.

-

Entry to the joint cleft may be indicated by radiograph appearance: observation of the needle tip on the joint line with medial/lateral movement of the X-ray beam to cause parallax shift.

-

If entry to the joint has not been achieved after repositioning the needle twice, the needle will be positioned on the joint line without further attempts at capsular puncture.

-

Aspiration should be negative for blood or cerebrospinal fluid.

-

We do not expect to use contrast medium because of the restriction of available joint volume and the risk of serious allergic reactions.

-

The immediate post-injection advice will be in accordance with the current procedures of the participating study centre.

-

Pre-filled syringes containing 7.5 mg of bupivacaine and 20 mg of methyl prednisolone in total volume; 2 ml will be used for each joint.

-

The full volume, 2 ml, will be injected through the spinal needle placed into each joint. Some facet joints may not be sufficiently large to take this volume of injectate meaning in practice that the injections will be intra- and periarticular. This reflects what we believe to be current practice in the UK.

-

Resistance to injection may occur because of abutment of the needle bevel to a surface or because of filling of the intra-articular space:

-

Force should not be used.

-

The needle should first be rotated 90° and a further attempt at injection made.

-

If, after two further 90° rotations resistance to injection persists or if, after successful injection of a part-volume resistance develops, gentle pressure should be maintained on the plunger and the needle withdrawn gradually until resistance to injection falls.

-

-

After completion of the injection, the needle is removed and a sterile dressing applied.

Adapted with permission from Mars et al. 26

Best usual care

Group participants were asked to suggest what treatment approaches should be included in the package from which a therapist could pick and tailor treatment for each patient. This could include manual therapy, home exercises and cognitive approaches. The content of the initial assessment and the number and duration of individual treatment sessions was also discussed. A basic outline and protocol was presented to the groups to aid in the discussions (Box 5). Group participants identified which aspects of the proposed BUC they considered acceptable. After collation of these results, the facilitator invited discussion in turn on each of the treatment approaches for which there was no agreement on acceptability. The group voted on inclusion/exclusion of treatment approaches from the ‘toolbox’ and assessment session content. They ranked alternatives for the number/duration of individual treatment sessions.

Initial assessment of 60 minutes. Assessment includes discussion of expectations, fear avoidance and self-efficacy to assess any perceived challenges and barriers that patients feel may be preventing them from engaging in self-management of chronic pain and to allow subsequent treatment sessions to be tailored to individual need. For the intervention group, the FJIs are given in the period between this first assessment and the first follow-up appointment.

Individual sessionsFive further sessions each of 30 minutes incorporating elements of manual therapy, pacing, motor control retraining, therapeutic exercise, soft tissue stretches/release, postural and general advice, goal-setting and challenging negative thoughts associated with physical activity and chronic LBP, as appropriate.

Manual therapy intervention may include-

Passive accessory intervertebral movements: either central or unilateral applied to either the symptomatic level or the level adjacent depending on the severity and irritability.

-

Soft tissue release/trigger point release/muscle energy techniques: as indicated in order to facilitate motor control retraining and effectiveness of manual therapy.

-

Manipulation treatment: as indicated.

-

Active exercise: to increase mobility, improved motor control and core stability, improve overall strength and stretch any tight muscle groups.

-

Mobility techniques: such as flexion in lying, pelvic tilt, side glides in standing and gym ball exercises.

-

Motor control retraining exercises (depending on individual assessments): this may include all muscles involved in core stabilising of the spine and also reducing activity in more superficial muscles that have been shown to become overactive in the presence of LBP. Treatment focuses on retraining the ‘coactivation’ pattern of stabilising muscles such as transversus abdominus and lumbar multifidus. This includes retraining of lumbar multifidus, as it is innervated by the medial branch and becomes inhibited ipsilateral to the pain in chronic back pain conditions. There is also evidence that specific retraining of ‘core muscles’ can improve pain and disability in some back pain patients.

-

Passive stretches: muscle groups identified during assessment as tight or overactive may be stretched within the therapy sessions in order to allow for improved spinal mobility and facilitate motor control retraining. Stretches are taught as part of the home exercise regime.

-

Bespoke exercise programme to complement face-to-face sessions: prescription to include frequency, dose, repetitions and progressions.

-

Advice on positions of ease, strategies to use in event of a ‘flare-up’ and strategies to reduce increasing pain: for example use of pelvic tilt prior to standing after prolonged sitting.

-

Pacing: including discussion of what is meant by pacing, relevance of pacing and methods to incorporate pacing into daily activities such as pacing by time, pacing by numbers or pacing by grading activities.

-

Goal-setting: including discussion of setting mutually agreed goals related to functional activities as well as general daily goals and long-term goals. Goals agreed between the physiotherapist and patient participant. In line with a cognitive–behavioural approach, goals may be based on Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and have a Time frame (a date for competition) (SMART) principles.

-

Challenging negative automatic thoughts (cognitive restructuring): including working with patients to identify particular negative thoughts they may have in relation to physical activity, fear avoidance and helping patients challenge their thoughts and adapt positive coping strategies.

Homework tasks between each session tailored to each individual and what is discussed during the session. For example, using pacing on a particular activity identified by the patient, keeping a diary of negative automatic thoughts that may trigger anxieties about movement or exercise and pain.

Adapted with permission from Mars et al. 26

Between-group difference

Participants were asked to consider each of the questions based on the evidence with which they were provided. These were quite technical questions, and the ‘expert’ in the room provided much needed support and clarification. Participants provided suggestions that were then voted on and/or rank-ordered. This particular topic is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

Subgroups for analysis

Participants were presented with a list of potential moderators from the evidence reviews. These were discussed and edited by either the addition of new items or the removal of an item (through agreement within the group). Items were ranked in order of preference/importance.

The results from all the small group sessions were collated and presented to the plenary session. When small group results were consistent, no further discussion took place. When there were inconsistencies between small group results, these were discussed and further ranking undertaken, collated and reported to the plenary session. We discussed and reranked issues until one option was clearly the preferred option and there was no objection to its adoption from conference delegates. We considered consensus to have been reached when there was 75% agreement.

Post conference

All results were checked and verified from all small group sessions and the plenary session. A small number of errors were found in the collation of rankings. The team therefore contacted participants with relevant expertise via e-mail to clarify and reach a consensus on these items.

Results

Fifty-seven people confirmed their attendance, of whom 52 attended on the day. Table 1 summarises their professional or lay roles. Of the 52 attendees, three asked not to be associated with the final consensus document: one was not happy with the way the day was organised and with the involvement of laypersons, one did not agree with having a physiotherapist-led BUC package and one noted no conflict but stated that they felt unable to contribute as they were not statistically minded. All other attendees agreed to being identified as part of the consensus group.

| Specialty/role | Number of attendees |

|---|---|

| Pain consultants and physicians | 19 |

| Anaesthetists | 6 |

| Physiotherapist or physical specialists | 12 |

| Academics | 4 |

| Psychologists | 3 |

| Radiographers | 2 |

| Lay representatives | 6 |

Evidence reviews

A full evidence document was produced for each delegate, which was distributed electronically before the day and provided in hard copy on the day. 76 This included tabulated results of the searches, brief summaries and, in several cases, suggested ‘protocols’.

Consensus conference

We present a brief summary of the results from the consensus conference for each of the five design considerations. Full data are available. 74 Results related to the first three of these design considerations (diagnosis, injection technique and BUC) have been published elsewhere and data and a number of tables have been reproduced here with the full permission of the editors.

Diagnosis

The four ‘diagnosis’ group sessions all approached the problem in different ways. In three of the groups lists were generated and items were then ranked, with the top-ranked items going forward to the plenary discussions. However, in one group there was considerable discussion and the group agreed/proposed a diagnostic pathway. This was taken forward to the plenary session. Key components of diagnostic assessment that were discussed in all groups included increased pain on extension/rotation and extension/lateral flexion and no pain on rising from flexion. In addition, the following were considered: no radicular symptoms, no sacroiliac joint pain on pain provocation testing and flexion less painful than extension. Consensus was not reached on the day.

Injection technique: the process of therapeutic intra-articular facet joint injection

There were 14 aspects of the injection process for the groups to consider. In each group a number of these were considered acceptable without discussion, although these varied between the groups. All 14 aspects were brought to the plenary session, but 10 were discussed very briefly before consensus was reached. The following items prompted considerable discussion and were ranked: administration of local anaesthetic and its composition, confirmation of needle position, injectate volume and injectate composition. Owing to errors in ranking identified, we undertook post-conference ranking of injectate volume and composition among participants with experience of injecting.

Best usual care

All four of the BUC group discussions followed a similar format. First, the group discussed and voted on agreement/disagreement with the suggested protocol items. The groups then proposed and voted on new items for inclusion. Comprehensive packages were proposed in all groups and these were taken forward to the afternoon plenary session. Although a consensus was reached regarding the key components to be included, some clarification was sought after the conference with participants who had experience of treatment delivery.

Size of signal

Table 2 summarises the results of the consensus meeting discussions on the size of the signal. There was considerable discussion in these groups and some questions were not covered because of time constraints.

| Question | Group 1 (total votes) | Group 2 (total votes) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1: at 3 months, should we be seeking a mean between-group difference in change scores that is smaller/the same/or larger than that observed for the trials of manual therapy? | |||

| A | Smaller | 1 | 0 |

| B | Larger | 6 | 9 |

| C | Same | 2 | 2 |

| 1.1a: additional question asked in group 1 – should we be asking for the number who got better/the difference in benefit? | |||

| A | Smaller | 2 | N/A |

| B | Larger | 4 | N/A |

| C | Same | 3 | N/A |

| 1.2: informed by the MID units calculated for the trials of manual therapy (supporting evidence), at 3 months should we be seeking a small (< 0.5), medium (0.5–1.0) or large (> 1.0) MID unit as proof of important difference? | |||

| A | Small (< 0.5) | 8 | 2 |

| B | Medium (0.5–1.0) | 1 | 5 |

| C | Larger (> 1.0) | 0 | 1 |

| 1.3: what magnitude of reduction in pain after the injection constitutes immediate pain relief? | Group 1 (ranking)a | ||

| A | 80% | 2 | N/A |

| B | > 50% | 4 | N/A |

| C | 0% | 3 | N/A |

| D | 60% | 1 | N/A |

The results from the morning sessions were taken forward to the afternoon plenary session, in which there was a considerable amount of discussion about this topic. As there was a difference of opinion from the morning session for question 1.2, the whole group were asked to vote on the two items, (A) small (< 0.5) and (B) medium (0.5–1.0). There were 48 out of 49 valid votes, with the outcome of eight votes for small (< 0.5) and 40 votes for medium.

An additional question was posed: ‘What difference in those who achieve minimally important change (MIC) is good?’. The group was asked to vote on three options: larger, the same and smaller. In total, 44 out of 49 ballots were valid, with the result of 22 votes for larger, nine votes for the same and 13 votes for smaller.

During discussion, the question of measuring pain relief at 1 hour in the study was raised. A vote was therefore held that asked participants ‘should we assess pain at 1 hour?’. The result was inconclusive, with a total of 46 out of 49 valid votes: 22 said yes and 24 said no.

Finally, the group revisited question 1.3: ‘What magnitude of reduction in pain after the injection constitutes immediate pain relief?’. Four options were suggested (some extracted from the morning session) and 46 out of 48 valid votes were included. There were four votes for 30%, 22 votes for 50%, 12 votes for 60% and eight votes for 80%.

Subgroup analysis

There was only one group discussion on this topic. The participants were presented with current evidence and asked to consider the variables that they felt were important. Lists were generated and items collapsed into categories. This resulted in a list of 10 variables, which were then ranked in order of importance.

Table 3 summarises the result from this group (concerning subgroup analysis).

| Final rank | Identifier | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | Severity |

| 2 | D | Anxiety/depression |

| 3 | M | Do you think you need an injection to get better |

| 4 | E | Treatment expectations |

| 5 | H | Back beliefs |

| 6 | G | Quality of life |

| 7 | B | Age |

| 8 | F | Self-efficacy |

| = 9 | L | Forward flexion pain (yes/no) |

| = 9 | N | Does the therapist think the treatment is effective |

The top five ranked items were presented to the plenary session as the adopted items (see Table 3).

Post conference

Clarifications were needed for three of the design considerations (diagnosis, the process of FJI and the BUC package).

Diagnosis

In order to confirm the diagnostic criteria for the study, 45 of the professional delegates were e-mailed to ask the following question:

We would like you to review the following text and confirm if the suggested clinical diagnostic criteria proposed for the study is ‘acceptable’? Stating ‘YES’ or ’NO’.

Increased pain unilaterally or bilaterally, on lumbar paraspinal palpation. AND. Increased LBP on one or more of the following; Extension (more than flexion), Rotation, extension/side flexion, extension/rotation. AND. No radicular symptoms (defined as pain radiating below the knee). AND No sacroiliac joint pain elicited using a pain provocation tests.

Responses received: acceptable, n = 23; yes, n = 22, no, n = 1.

Box 6 outlines the diagnostic criteria that emerged from the consensus and which went on to be used in the study.

There is considerable diagnostic uncertainty about how to identify people with pain of facet joint origin among the wider chronic LBP population. Therefore, the diagnostic criteria used in this trial have been drawn from the available evidence base and following consensus gained from a range of experts and clinicians.

Diagnostic criteria for trialA summary of the diagnostic criteria is shown below. Criteria 1 and 2 cover the issue of presence of pain on palpation or symptom reproduction on movement testing. The second two criteria relate to the absence of symptoms, namely radicular symptoms and sacroiliac pain.

-

Increased pain unilaterally or bilaterally, on lumbar paraspinal palpation.

AND

-

Increased LBP on one or more of the following;

AND

-

No radicular symptoms (defined as pain radiating below the knee or objective neurological signs above the kneeb).

AND

-

No sacroiliac joint pain elicited using a pain provocation test.

The process of facet joint injection

Following the consensus conference there was uncertainty about the injectate to be used in the study. Six options were sent, via e-mail, to 27 pain consultants, anaesthetists or professionals (delegates) who indicated that they were responsible for injection. We received 11 responses; the results can be seen in Table 4. Box 7 provides a summary of the final agreed injection protocol.

| Injectate options | Preferred option | Acceptable | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Triamcinolone (10 mg/ml)/Levobupivacaine (2.5 mg/ml) | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Triamcinolone (10 mg/ml)/levobupivacaine (5.0 mg/ml) | 4 | 5 | 0 |

| Triamcinolone (10 mg/ml)/levobupivacaine (7.5 mg/ml) | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| Triamcinolone (20 mg/ml)/levobupivacaine (3.75 mg/ml) | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Triamcinolone (20 mg/ml)/levobupivacaine (7.5 mg/ml) | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Triamcinolone (20-mg/ml)/levobupivacaine (11.25-mg/ml) | 0 | 2 | 6 |

Prior to the study injection procedure, following normal local trust clinical practice, the investigator will obtain informed consent for the injection from the participant prior to injecting the facet joints . . .

Skin cleansing with chlorhexidine 0.5% or 2% in alcohol sterile drapes are recommended to be used.

No intravenous sedation is required.

Prone position with measures to reduce the lumbar lordosis, for example a pillow under the abdomen.

Intravenous accessRadiography (C-arm fluoroscopy or other suitable equipment) for visualisation of the joint.

The dose of radiation will be adequate to visualise the joint while minimising X-ray exposure.

Entry to the joint cleft may be indicated by radiograph appearance. Medial/lateral movement of the X-ray beam with intermittent screening to cause parallax shift may be used . . .

For the FIS, contrast will not be administered.

InjectionLocal anaesthesia at needle entry point: 1% lidocaine via 25-gauge hypodermic needle . . .

. . . The investigator responsible for the injection will prepare the injection syringe to contain 1 ml of Levobupivacaine (5 mg/ml) and 1 ml of Triamcinolone (10 mg/ml) in total volume; 2 ml will be used for each joint . . .

. . . Up to six facet joints (L3/L4, L4/L5 and L5/S1) bilaterally in each participant will be injected. However, when on clinical assessment there is unilateral pain or involvement of only some levels, the investigator may choose to do unilateral injection or be selective on levels injected.

The full volume, 2 ml, will be injected through the spinal needle placed into each joint. Some facet joints may not be sufficiently large to take this volume of injectate, meaning, in practice, that the injections will be intra- and periarticular. This reflects what we believe to be current practice in the UK.

If there is resistance to injection may occur because of abutment of the needle bevel to a surface or because of filling of the intra-articular space. Force should not be used.

The needle should first be rotated 90° and a further attempt at injection made.

If, after two further 90° rotations, resistance to injection persists or if, after successful injection of a part-volume resistance develops, gentle pressure should be maintained on the plunger and the needle withdrawn gradually until resistance to injection falls.

After completion of the injection the needle is removed and a sterile dressing applied.

Best usual-care package

Confirmation of the number and duration of sessions was sought post conference. We e-mailed 15 delegates who were physiotherapists, extended scope practitioners or clinical/health psychologists. Two alternatives, (1) and (2), were sent and delegates were asked to state a preferred option and to also say if they felt that it was acceptable or not.

There were 12 responses:

-

one session of 60 minutes plus five sessions of 30 minutes (nine preferred, seven yes, zero no)

-

up to six sessions of 45 minutes each (three preferred, six yes, one no).

Among the 12 responses reported, two responders answered that both options were acceptable, one responder provided only a preference and did not state whether the options were acceptable and two responders preferred option (1) and thought that this was the acceptable option. Box 8 summarises the agreed BUC package agreed.

Patients initially undergo a thorough physical assessment based on the principles of Maitland manual therapy assessment and clinical reasoning.

Sessions 2–6 (30 minutes each)The aim of BUC for this trial is to provide a fully integrated psychological and physical rehabilitation. It is important therefore to integrate the two elements of care as far as possible so that participants do not see them as ‘stand alone’.

Treatment should be directed at pain arising from the facet joint. Physiotherapists should use their full range of skills and knowledge in constructing a personalised rehabilitation programme using the comprehensive ‘tool kit’ provided.

The section below outlines component parts of the ‘tool kit’. The BUC manual provides full instructions and examples for the physiotherapists to use.

Acceptance (session 1), goal-setting (session 1 or 2), pacing (session 1 or 2) and challenging negative thoughts and mindfulness Manual therapy| Kaltenborn. |

| McKenzie. |

| Maitland. |

| Cyriax. |

| Osteopathic techniques. |

| Mulligans. |

| (Natural apophyseal glides/ sustained natural apophyseal glides/movement valued manual therapies.) |

| Other. |

| Myofascial. |

| Trigger point. |

| Soft tissue massage. |

| Manipulation. |

| Soft tissue release. |

| Other. |

| Specific. |

| Motor control retraining/core stability. |

| Cardiovascular. |

| Strength. |

| Stretches. |

| Other. |

| Pain terminology, mechanisms and pathways. |

| Activities of daily living. |

| Work and ergonomics. |

| Lifestyle changes. |

| Management of flare ups and changing. |

| Symptoms. |

| Paced home exercises. |

| Other. |

Summary/conclusions

We have established consensus from health professionals concerned with the treatment of facet joint pain in the UK on the assessment of facet joint pain, injection of facet joints, BUC, minimal important difference and subgroup analysis for use in a feasibility study for a proposed clinical trial of FJIs. The process was evidence based and open to all those with a professional interest in this topic. It included lay participants and was undertaken in a transparent way. The use or not of FJI is controversial internationally and, therefore, consensus and transparency is essential for the design of the proposed trial of FJIs to ensure that the results are acceptable to the whole pain treatment community. The results of the consensus process have provided much-needed clarity into key components of the study and have shaped the protocol for the subsequent feasibility RCT.

Chapter 3 Interpreting treatment effects: ‘What is the minimal between-group difference in change scores necessary for facet joint injection to be considered worthwhile?’

Background

The important aspects of LBP and how it impacts individuals’ ability to live their life can be assessed using well-developed patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). 63,82 Increasingly, such measures, for example the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)83 and the Pain Numerical Rating Scale (Pain-NRS),84 are used as primary or secondary outcomes in clinical trials of LBP management. 57,85,86 However, the effect size even in positive effectiveness trials comparing physiotherapist-delivered interventions with ‘usual care’ are typically modest. These may be expressed either as natural units of measures such as the RMDQ (typically 1–2 points on a 24-point scale) or as a standardised mean difference [between-groups difference/baseline standard deviation (SD), typically 0.2–0.4 points in trials with positive results]. By way of benchmarking, there is consensus that a 5-point change, or a 30% improvement from baseline, in the RMDQ represents a worthwhile benefit to an individual patient. 87 Although determination of the clinical relevance or meaningfulness of these scores is crucial to determining if treatment is worthwhile,88 interpretation guidance is largely unavailable. 89 Moreover, the lack of interpretation guidance is often a barrier to appropriate utilisation of trial data. 90

There are two aspects of score interpretation relevant to clinical trials: (1) between-groups difference or the ‘minimally important difference’ (MID) and (2) the within-individual change (‘MIC’) or ‘responder definition’. 91,92 International consensus for the reporting of continuous patient-reported outcomes in LBP trials supports the reporting of:

-

between-group differences, with guidance for MID when available

-

a responder analysis that adopts an empirically derived MIC within patients, reporting both proportion improved and deteriorated according to a predefined responder definition

-

a calculation of the NNTs. 89 However, the authors acknowledge that guidance for MID is often lacking and is difficult to estimate empirically.

The MID compares the average change from baseline across all patients in treatment and control groups92,93 and has been defined as the difference in magnitude of response between treatment and control groups that should be considered large enough to establish scientific or therapeutic importance of the results. It is usually reported through the comparison of summary measures (e.g. mean between-group differences for continuous measures). 91 Although it is common to declare that there is a single MID for an outcome measure, in reality one might expect that the MID for an invasive procedure would be larger than that for a low-risk educational intervention. Analytical approaches that report statistical significance of score change fail to convey the clinical value or the patient perspective on the value of the difference. 88,94,95 An alternative approach that takes into consideration meaningful individual-level change is afforded by the calculation of the MID unit. 96,97 The MID unit divides the between-group difference found in a trial by the established MIC for the outcome of interest: estimates of < 0.5 MID units suggest that it is increasingly less likely that an appreciable number of patients will achieve important benefits from treatment, whereas values between 0.5 and 1.0 suggest that treatment may benefit an appreciable number of patients. This approach, increasingly used within meta-analyses of trial evidence,96,97 grounds the calculation in clinical reality (a within-person individual change) while tailoring the MID to the nature of the intervention. Interpretation provides an evaluation of whether or not an appreciable number of patients achieve clinically important benefits, with MID units of < 1 reflecting increasingly lower likelihood of benefit.

Minimally important difference units have been applied in meta-analyses supporting new treatment guidelines for knee osteoarthritis. 98 The authors concluded that for MID units < 0.5 there was a low likelihood that an appreciable number of patients achieved clinically important benefits. Although MIC guidance for several legacy measures in LBP exists,87 the application of MID units that incorporate individual MIC values has not been described. Informed by calculation of the MID unit, we sought to provide guidance for the minimal between-group difference in change scores (MID) for the RMDQ and/or the Pain-NRS necessary for FJI to be considered worthwhile.

Methods

There were three stages of this work package:

-

meta-analysis of published data from large trials of physiotherapist-delivered interventions for chronic LBP

-

calculation of the between-group differences of change scores and the MID unit from a large UK trial [the UK Back pain Exercise And Manipulation (BEAM) trial]86

-

consensus meeting – score interpretation.

Meta-analysis of data from large trials of physiotherapist-delivered interventions for chronic low back pain

To gain an indication of the likely magnitude of MID unit differences that may be expected in a positive study of an intervention to treat LBP, we conducted a meta-analysis using published data from large trials with which we were already familiar. We selected studies that we had previously included in a database of individual patient data from RCTs of physiotherapist-delivered interventions for back pain. 25 Studies were included if they included data on ≥ 300 participants and had used the RMDQ. 25 Our original intention was to also include a meta-analysis of Pain-NRSs; however, none of the studies in our sampling frame included both a RMDQ and useable Pain-NRS data. The purpose of this analysis was to obtain illustrative data for the consensus meeting rather than to systematically report all studies meeting these criteria. For this reason, we made the pragmatic decision to include only those studies that we had assessed as part of this previous project.

Full-text versions of the included studies were retrieved. Two reviewers extracted study-level information from the included articles: a standardised data extraction list included study-specific information (authors and trial population) and outcome-specific information [primary and secondary outcomes, mean (SD) between-group differences in scores at baseline and follow-up and MIC if calculated].

The mean between-group differences in change scores for the RMDQ and across treatment groups and at different time points were reported for each trial. Each value was compared with the known MIC for the RMDQ. 87

For all included studies, MID units were calculated using published MIC guidance. MID units were calculated per trial and as an overall value (all trials combined) at 3 and 12 months. As two MIC values are recommended for the RMDQ, two forms of MID unit were calculated, reflecting the MIC score change and MIC 30% improvement from baseline. 87

Calculation of the between-group differences of change scores and the minimally important difference unit from a large UK trial (UK Back pain Exercise And Manipulation trial)

We carried out a further analysis of data from a large UK trial of therapist-delivered interventions (n = 1169) (the UK BEAM trial86). Using individual patient data, we were able to obtain Pain-NRS data for pain today as a single item extracted from the Modified Von Korff pain grade scale. 86,99 For this analysis, all three active treatments in UK BEAM trial were pooled for comparison with the control intervention. Scores for the RMDQ and Pain-NRS were adjusted for sex, age and scores at baseline. Mean between-group differences of change in RMDQ and Pain-NRS scores and MID units (30% and score change) at 4 weeks, 3 months and 12 months were calculated.

Consensus meeting: score interpretation

Finally, a consensus meeting was held. 76 The results from the two previous stages were used to inform a 1-day consensus meeting of clinical and academic experts and lay representatives who sought to determine and make recommendations for between-group score interpretation. All participants received an evidence synthesis in advance of the meeting. A nominal group technique was adopted to gain consensus. Following a brief reminder of key evaluation considerations and evidence, delegates were randomly assigned to small group sessions that were stratified by profession (approximately 10–12 per group). Discussions lasted up to 1 hour. Each group had a trained facilitator, a scribe and a subject expert. Participants were invited to consider the following overall question: what is the difference in magnitude of response between treatment and control groups that should be considered large enough to establish the scientific or therapeutic importance of the results?

Specific subquestions, pertaining to the RMDQ and/or Pain-NRS, included:

-

At 3 months should we be seeking a mean between-group difference in change scores that is smaller than/the same/or larger than that observed for the trials of physiotherapy?

-

Informed by the MID units calculated for the trials of physiotherapy, at 3 months should we be seeking a small (< 0.5), medium (0.5–1.0) or large (> 1.0) MID unit as proof of important difference?

The results from all small group sessions were collated and presented during the final plenary session, in which there was considerable discussion on this topic. When there were inconsistencies between small groups, these were discussed and further ranking undertaken. Final consensus was sought for all questions.

Results

Meta-analysis of data from large trials of physiotherapist-delivered interventions for chronic low back pain

Following application of our inclusion criteria, three out of five shortlisted large trials were included in the analysis (Table 5).

| Author (year) | Treatment | Number at randomisation | Age (years), mean (SD) | Female, n (%) | RMDQ | Pain (Pain-NRS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamb et al. (2010)100 | Control | 233 | 54 (14.9) | 142 (61) | Yes | No (Von Korff)99 |

| Advice plus cognitive–behavioural therapy | 468 | 53 (14.6) | 278 (59) | |||

| UK BEAM trial (2004)86 | Control | 338 | 43 (10.6) | 178 (53) | Yes | No (Von Korff)99 |

| BUC and exercise | 310 | 44 (11.0) | 170 (55) | |||

| BUC and manipulation | 353 | 43 (11.4) | 212 (60) | |||

| BUC, manipulation and exercise | 333 | 43 (11.9) | 189 (57) | |||

| Hay et al. (2005)101 | Manual physiotherapy | 201 | 41 (11.6) | 110 (55) | Yes | No (VAS) |

| Brief pain management programme | 201 | 40 (12.0) | 100 (50) |