Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/93/01. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The draft report began editorial review in October 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The Institute for Social Marketing is a member of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (UKCTAS; www.ukctas.ac.uk). Funding for UKCTAS from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Bauld et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and aims

This monograph reports the findings of the ‘Barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy and following childbirth’ study. The study was funded to conduct evidence syntheses and primary qualitative research to enhance understanding of how these barriers and facilitators are perceived and experienced from the perspectives of women, their partners, family and friends, and health-care professionals (HPs). Through this enhanced understanding, the study provides a platform to inform recommendations for current practice and provide pointers for the design of future interventions with promise for improving smoking cessation in pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

This chapter describes the health implications and epidemiology of smoking in pregnancy, the importance of cessation and, hence, the rationale for conducting this study. The chapter concludes with the aims of the study.

Impact of smoking in pregnancy

Maternal smoking during pregnancy can cause substantial harm. 1,2 It increases the risk of miscarriage, premature birth, stillbirth and low birthweight. 3–7 Smoking during pregnancy also increases infant mortality by 40%8 and is estimated to account for 150 UK infant deaths each year. 9–12 Furthermore, 5% of all admissions to hospital in the first 8 months of life are attributable to smoking in pregnancy. 13 Children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy have twice the risk of being diagnosed with asthma,14 and bronchiolitis and other serious respiratory illnesses such as pneumonia are 25% more common than in children whose mothers did not smoke during pregnancy. 15 Prenatal smoking is also associated with an elevated risk of hyperactivity disorders and disruptive behaviour in children,16 and as having a detrimental effect on educational performance. 17 The risk of obesity and diabetes is also increased. 18

Maternal smoking in pregnancy also has significant implications for the NHS, as it impacts on limited health-care resources through the treatment of women for smoking-related illnesses and pregnancy complications, and the treatment of their infants for a range of smoking-related health problems. A 2010 study19 estimated the total extra annual NHS cost caused by smoking during pregnancy to be £8.1–64M for treating mothers and £12–23.5M for treating infants (aged 0–12 months).

Epidemiology of smoking in pregnancy

Accurate rates of smoking in pregnancy are difficult to obtain. Current monitoring practices, and thus smoking policy, are based on self-reported smoking rates that underestimate prevalence and overestimate quit rates in pregnancy. 20–22 Nonetheless, estimates show that one in four women smokes before or during her pregnancy and one in eight continues to smoke throughout. 23

In high-income countries, smoking in pregnancy is strongly associated with social disadvantage. 24 Compared with women in advantaged circumstances, women in disadvantaged circumstances are four times more likely to smoke prior to pregnancy and half as likely to quit during pregnancy. 25 Although rates of under-reporting may be similar across socioeconomic groups,26 reliance on self-reporting can result in twice as many undetected smokers in the most deprived areas as in the least deprived areas. 22,27

Social disadvantage also increases the chances of living with a partner who smokes,27,28 and the smoking status of partners and other household members is a predictor of maternal smoking habits before and during pregnancy,29,30 and of returning to smoking after birth. 27,31,32 Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study33 indicate that 70% of partners of women who smoked in pregnancy also smoked and that > 70% of these partners neither cut down nor quit. Underscoring the role of partners, maternal smoking in pregnancy is associated with difficulties in the relationship with the partner. 34 Social disadvantage is also associated with an elevated risk of mental illness; estimates suggest that approximately 50% of pregnant smokers have depression or another common mental disorder. 35 Given that around 80% of UK women have at least one baby,36 pregnancy is an opportunity to reach women who smoke and help them quit before their own health is permanently compromised. 37 Stopping during pregnancy also reduces the likelihood of a child growing up with parents who smoke and becoming a smoker him- or herself. 38

Smoking cessation in pregnancy

Reducing the numbers of women smoking in pregnancy is a policy priority in many countries. 39 In England, for example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2010 emphasised the importance of smoking cessation in pregnancy,40 and targets to reduce smoking in pregnancy have been introduced. Over the past decade there has been significant investment in providing tailored evidence-based smoking cessation services to support pregnant women who find it difficult to stop. 41 For example, NHS Stop Smoking Services (SSSs) in the UK offer behavioural support delivered by trained advisors, in clinic settings, in the home and by telephone, along with access to smoking cessation medications and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for smokers motivated to quit. Behavioural support helps pregnant women to stop smoking at least in the short term42 but only a small minority of women take up the offer of help during pregnancy or after childbirth; the majority of those making quit attempts therefore do so without professional assistance – and most will not succeed. 28 Among those women who do quit during pregnancy, nearly all wish to remain abstinent after the birth of their baby;43 however, the vast majority relapse within 12 months of the birth. 44,45 Much less is known about effective interventions to prevent postnatal relapse;45 behavioural support has not been shown to be effective for preventing postnatal relapse and is offered by only a minority of UK SSSs. 45 Smoking in pregnancy and postnatal relapse rates therefore remain high, particularly for women living in disadvantaged circumstances,46 suggesting that this group of smokers face particular social and economic barriers that may inhibit their ability to access support and/or to stop smoking. Understanding these barriers (and facilitators) offers scope for identifying other ways of reducing smoking in pregnancy and supporting women to remain abstinent after childbirth.

Rationale for conducting this study

Identifying and overcoming barriers to service access and, equally importantly, barriers to women’s motivation to try to stop smoking is challenging. Understanding what helps and hinders pregnant smokers in quitting and remaining abstinent post partum, from a range of perspectives, is essential if effective interventions are to be accessed by more women and if more women are to be supported to stop smoking.

Pregnant and postpartum women’s perspectives

Greater insight is required into how barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy and after birth are perceived and experienced by women. To date, systematic reviews of qualitative studies involving pregnant women have had a broad focus on perceptions and experiences; barriers and facilitators may be identified but are not the primary concern. 47,48 For example, the systematic review by Flemming et al. 49 demonstrated how smoking in pregnancy was shaped by the contexts of women’s lives, including the embeddedness of smoking in their lives and the importance of it in the couple’s relationship. Although this review focused on studies of women’s experiences of smoking in pregnancy, it did not explicitly examine the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation faced by women while they are pregnant, and it also excluded papers that examined women’s experiences post partum.

Significant others’ perspectives

The smoking habits of women’s significant others (SOs) (i.e. partners, family and friends) are recognised as important barriers to sustained quitting,27,31,50 but these remain relatively under-researched in relation to smoking in pregnancy. Partners’ smoking status and attitudes to smoking cessation are identified as potentially important influences in a pregnant woman’s attempt to quit;30 for example, partners who try to quit at the same time as the pregnant woman can be seen as more supportive,51 whereas a partner’s failed quit attempt may reduce the chances of the woman succeeding. 52 Men may be less likely than their pregnant partners to receive advice to stop smoking from HPs and may be exposed to less pressure from friends and family to quit. 53 Further understanding of how SOs perceive the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy is needed, particularly from qualitative studies in which participants describe these issues in their own words.

Health-care professionals’ perspectives

The problems that women face in accessing effective support to stop smoking may involve structural, organisational and cultural barriers in the NHS or other services, rather than a reluctance or lack of knowledge among pregnant women. Recent studies in Scotland and England highlight a number of limitations to smokers being identified, referred and then supported to stop smoking. 54,55 For example, perceptions that HPs offered inconsistent advice on, and support for, quitting in pregnancy has emerged as a potential barrier. HPs themselves may fail to facilitate smoking cessation through, for example, midwives’ reluctance to ask about smoking, a lack of training in smoking cessation, organisational factors and HPs’ own smoking behaviour. 56 Fundamentally linked to the role of the HPs is the context in which services are delivered, the configuration and quality of which varies greatly throughout the country. To our knowledge, no review has been conducted of qualitative studies reporting HPs’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators when addressing smoking in pregnancy. Given the pivotal role of many HPs involved in the care of women throughout their pregnancy, a better understanding is needed of the impact of the diversity of professional roles and practice, and how different organisational practices may both facilitate and create barriers to the delivery of cessation support that meets pregnant women’s preferences and needs.

Considering each of these three perspectives – pregnant and postpartum women, their SOs and HPs – the evidence suggests that a deeper understanding of what helps and hinders pregnant smokers to quit and remain abstinent post partum is needed; more specifically, how these barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation are perceived and experienced by women and their families, and how they are accounted for by HPs in their approach to facilitating smoking cessation in pregnancy.

This study, therefore, takes into account the household and family context of smoking in pregnancy and compares and contrasts the views of women and their SOs with those of professionals involved in maternity and smoking cessation services. This is the first study in the UK to do this. By taking this more holistic approach, the study aims to both inform the delivery of existing interventions and serve as the foundation for the development of improved interventions to support pregnant women to quit.

Project aims

This study aims to explore and identify barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy and post partum, and to explore the feasibility and acceptability of improved interventions to reach and support pregnant women to quit and remain abstinent. It builds on what is already known and explores, in more depth than in previous studies, what prevents, as well as facilitates, women quitting and how these factors can be used to improve existing interventions. The specific objectives of the study are to:

-

Briefly describe the current configuration of services within the UK and the available interventions to support pregnant women to quit smoking, to establish study context and inform the last objective in this list.

-

Examine existing qualitative literature on the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy and post partum from three perspectives (pregnant and postpartum women, the SOs of pregnant women and HPs who support pregnant women), building on a recently completed systematic review conducted by members of the study team. 25

-

Explore the views of pregnant women and women who have recently given birth regarding smoking, smoking cessation and interventions to support cessation with a specific focus on the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy and post partum. This will include women who have accessed support to stop and those who have not accessed such support.

-

Explore the views of the SOs of pregnant women regarding smoking, smoking cessation and interventions to support cessation, with a specific focus on the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy and post partum. This will examine, when relevant, their smoking as well as that of the woman.

-

Explore the views of HPs and advisors who support women to stop smoking regarding the barriers and facilitators related to their role to support smoking cessation in pregnancy and post partum, and their views on the barriers and facilitators facing pregnant women outside the health-care context. This group includes midwives and midwifery managers, health visitors, consultant obstetricians, general practitioners (GPs), and smoking cessation managers and advisors.

-

Make recommendations to inform proposals for interventions that could be tested to improve the current provision of interventions for pregnant women to stop smoking.

The study outcomes include barriers and facilitators that can contribute to changes in smoking behaviour during and immediately following pregnancy. A description of the barriers and facilitators from each of the participant groups in the study is developed. This is compared and contrasted with the barriers and facilitators identified through the three systematic reviews57–59 in a narrative synthesis to inform recommendations for changes to practice and proposals for future interventions.

Chapter 2 Research design and theoretical framework

This chapter presents an overview of the research design together with a description of the two study sites participating in the primary qualitative element of the research. It then describes the rationale for the choice of theoretical framework to represent the evidence on barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation. The chapter concludes with an overview of the remaining chapters included in the report.

Research design

This was a mixed-methods study with three key elements:

-

element 1 – systematic reviews of qualitative studies covering three populations (pregnant and postpartum women, SOs of pregnant women and HPs)

-

element 2 – qualitative research with pregnant and postpartum women, their SOs and HPs at two study sites

-

element 3 – recommendations for new interventions for smoking cessation in pregnancy and postpartum abstinence to inform the development of proposals that can be tested in future research.

Before the main elements of the study were conducted, a brief mapping exercise was carried out to describe the available cessation interventions for pregnant women in the UK, including availability at each study site. This exercise was important to understand the framework within which interventions are delivered, and it is reported in Chapter 4. The catchment profile for each study site is outlined in Study sites.

Study sites

The qualitative interviews for element 2 took place in two NHS areas: one in Scotland (area A) and one in England (area B). Area A serves a mixed urban and rural population of around 850,000 people. It has an adult smoking rate of 20.5%, which is slightly lower than the Scottish average of 23.0%. 60 In area A, 17.3% of women smoke in pregnancy and 15.1% of women smoke post partum; both figures are a little lower than the Scottish averages of 20.0% and 16.9%, respectively, and are probably reflective of a slightly more affluent population than in Scotland as a whole. There is a very steep inequalities gradient, with approximately 6% of the most affluent quintile and 34% of the most deprived quintile of pregnant women smoking, an almost sixfold difference. SSSs are organised in area-based teams relating to the new Health and Social Care Partnership (Council) boundaries.

Area B also serves a mixed urban and rural population; it has around 796,000 people61 and is scattered over a wide geographical region, encompassing three principal urban centres as well as many small villages and market towns, where access to services, including smoking cessation services, may be an additional barrier to cessation. Levels of deprivation vary widely, with pockets of both affluence and high deprivation. In 2012, the region had an adult smoking rate of 18.9%, only slightly lower than the rate for England of 19.5%. 62 The prevalence of smoking in pregnancy (measured at time of delivery) in 2012–13 was 13.7%, ranging from 21.4% for women giving birth in areas of high deprivation to 10.8% for those in more affluent areas. 62 These figures may be compared with the national prevalence of 12.7% for smoking in pregnancy in 2012 and the national ambition of a smoking in pregnancy prevalence of ≤ 11% by the end of 2015. 63 The responsibility for commissioning SSSs recently transferred to local authorities, which have contracted a local provider to manage the service.

Theoretical framework

Our protocol64 identified the theory of planned behaviour (TPB)65 as an appropriate theoretical framework for the project. The TPB is a theoretical approach used in a number of other studies of smoking in pregnancy (e.g. Godin et al. ,66 de Vries and Backbier67 and Ben Natan et al. 68). It focuses on social–ecological framework (SEF) individual-level influences on behaviour (beliefs and intentions) alongside an appreciation of contextual factors, such as perceived social norms about smoking and the consideration that environmental and demographic influences on behaviour are mediated by individual-level influences.

However, the first stage of the project (the systematic reviews of qualitative studies57–59) made clear that environmental barriers and facilitators were key to understanding smoking cessation in pregnancy. These barriers and facilitators were embedded in the individual’s domestic, community and workplace settings and relationships.

Although individual-level factors were evident, they represented only one layer in a multitiered set of social factors that operated to promote or impede positive changes in smoking behaviour and, in the case of HPs, the provision of smoking cessation support. Both singly and together, the three systematic reviews57–59 pointed to the importance of a systems perspective that located the individual within their broader social environment (including the health-care environment). The initial stages of data analysis of the qualitative studies confirmed the importance of this wider perspective. Although the TPB incorporates context as an influence on behaviour, social psychological models are not focused on capturing the multifaceted and multilayered structure of the individual’s social environment. However, the evidence from the two major data sources for the project (the systematic reviews and primary studies) indicated that key barriers and facilitators resided in these environments. We therefore considered other frameworks that provided a more comprehensive description of the multitude of influences on behaviour than models such as the TPB. The capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM-B) model69 was one of those considered, as it parsimoniously specifies determinants of behaviour from 83 models of behaviour change70 and includes emphasis on environmental barriers to and facilitators of behaviour.

However, following an integrated review of the findings from the project’s systematic reviews and primary studies, the project team concluded that the evidence on barriers and facilitators was better represented by a framework that gave greater attention to the individual’s wider environment including its constituent domains and the interactions between them. Social–ecological perspectives (also called ecological systems perspectives) provide such a framework. With its origins in biology, the term ‘ecology’ refers to the inter-relations between organisms and their environments; social ecology focuses specifically on the social and institutional environments of which individuals are part. Similar to the TPB and COM-B models, SEFs are theory based, in this instance conceptualising behaviour as the outcome of an individual’s interactions with their environment. In consequence, SEFs typically locate the individual spatially in a set of concentric circles (or layers) ranging from micro to macro levels, with the circles/layers influencing behaviour synergistically.

Although the term may not be widely used within the health community, social–ecological approaches have long informed research and policy. 71–74 One influential example is Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework. 75,76 Developed to highlight the influence on child development of environments external to the family, this model comprises a series of concentric layers, running from the ‘microsystem’ (the family), through the ‘mesosystem’ and ‘exosystem’ (e.g. the economy and welfare services) to the ‘macrosystem’ (e.g. the wider culture). Dahlgren and Whitehead’s ‘rainbow’ model of the social determinants of health77 provides a further example. In this widely used model,78–80 health is represented as the outcome of a set of interlocking factors, running from broad societal-level factors (described as ‘general socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions’) through both distal (‘living and working conditions’) and proximal (‘individual lifestyle factors’) determinants. 81

Social–ecological frameworks tend to be specific to the population and outcome of concern; those relating to child development75 are, therefore, likely to be different from those relating to adolescent smoking. 82 However, the frameworks conform to a common structure, with hierarchically ordered domains representing the interlocking influences on the outcome. The project’s overarching SEF is represented in Figure 1 and consists of the following factors:

-

individual characteristics, including knowledge and beliefs, mental health and well-being, and material circumstances

-

interpersonal factors, including relationships with SOs and health-care providers

-

community factors, including neighbourhood quality and local resources, cultural norms and social networks

-

organisational factors, including service provision, workplace resources, practices and regulations

-

societal factors, including the structure of the labour market, welfare systems and family policies.

FIGURE 1.

A SEF for smoking cessation in pregnancy: spheres of influence on barriers and facilitators.

A social–ecological perspective can be particularly helpful in the development of interventions. For example, it can inform approaches to improving health care by highlighting the importance of changes at multiple levels: individual, group, organisational and ‘larger system/environment’. 83 The perspective also provides a resource for health behaviour change interventions. As an example, the behaviour change wheel of Michie et al. 69 is structured around an understanding of behaviour as shaped by the interplay of individual-level and environmental factors. In particular, a SEF can help inform understandings of behaviour change through its recognition that:

-

multiple factors act as barriers to and facilitators of behaviour change; the approach therefore points to the importance of interventions (or packages of interventions) that address multiple levels simultaneously by, for example, integrating patient-focused interventions with ones that address barriers at the interpersonal, community and organisational levels82

-

the inter-relationships between an individual and their environment are dynamic and reciprocal, as individuals and environments change and influence each other73

-

positive changes in health behaviour are likely to require positive and sustained changes in the individual’s environment.

As detailed in Chapters 5–10, the significance and content of these domains varied among the three study populations of pregnant and postpartum women, their SOs and HPs. Thus, the organisational domain was a more important consideration for barriers and facilitators for service providers than for pregnant smokers and SOs, and, within this domain, workplace cultures and practices were more prominent as a barrier to quitting among SOs who smoke than among pregnant smokers.

The SEF, therefore, informed the analysis of primary data from this study and the synthesis of findings between the systematic reviews and interviews. In the concluding chapters of this report, we refer back to this framework and use it as a ‘lens’ through which to examine and explore our findings.

Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows.

-

Chapter 3 details the methods used in the study.

-

Chapter 4 describes the available cessation interventions for pregnant women in the UK, including those available at each study site.

-

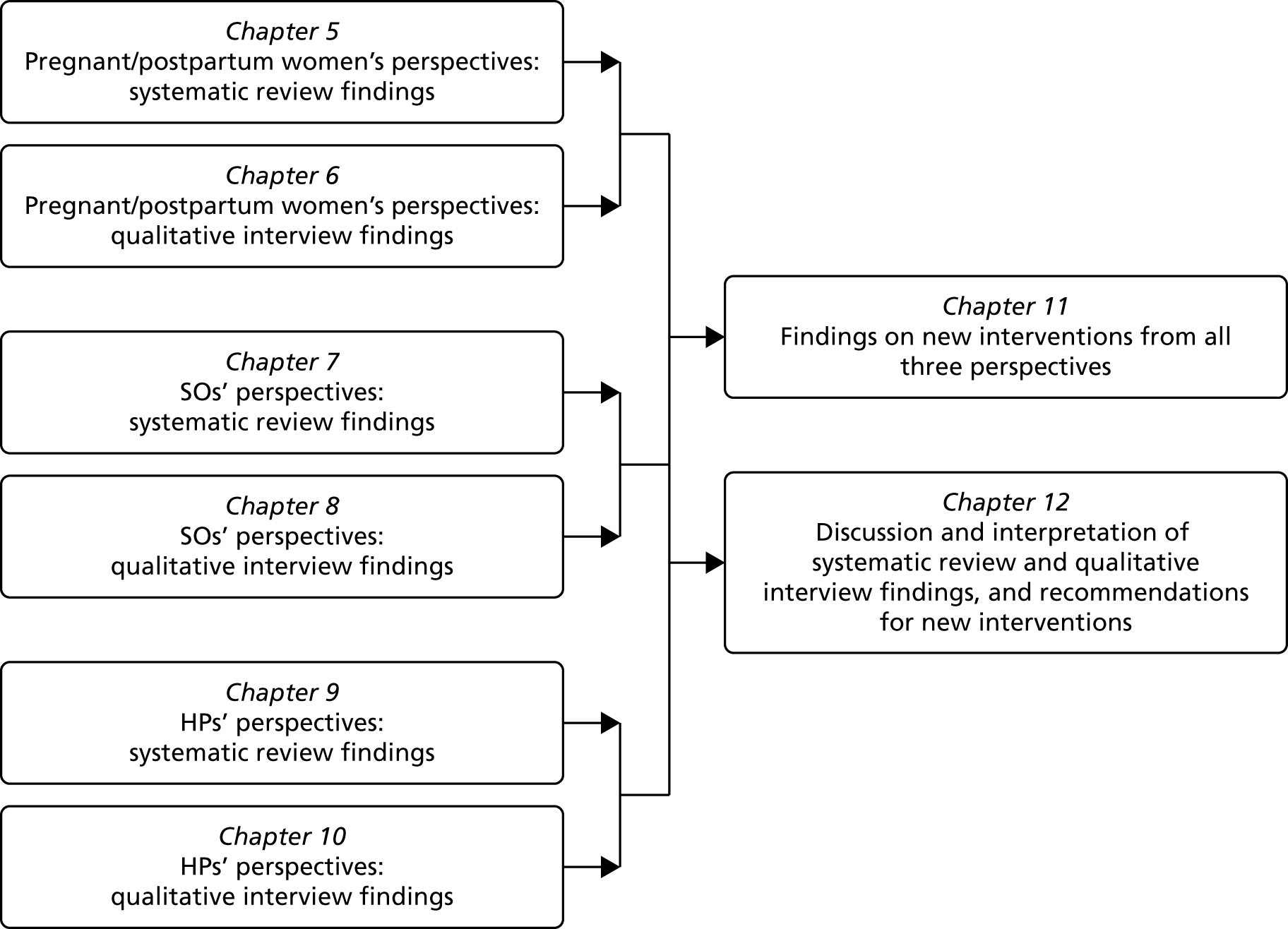

Chapters 5–10 present the findings of each of the systematic review and qualitative interview components of the study for each of the three populations of interest: pregnant and postpartum women, SOs and HPs (Figure 2). Each chapter concludes with a brief summary and discussion of the common themes emerging around smoking and smoking cessation, with concluding remarks in each of the qualitative chapters also taking into account the systematic review findings in the preceding chapter.

-

Chapter 11 presents findings for new interventions for smoking cessation in pregnancy and post partum as suggested by all three participant groups.

-

Chapter 12 presents an overall discussion of the findings from the systematic reviews and qualitative interviews, reflects on the differences between current and suggested interventions, draws out the implications for health care and makes recommendations for new interventions for smoking cessation in pregnancy and post partum that can be tested in future research.

FIGURE 2.

Chapter structure for findings and discussion of mixed-methods design components.

Chapter 3 Research methods

This chapter describes the methods used for the rapid mapping exercise of existing services for smoking cessation in pregnancy and each of the three key study components: systematic reviews, qualitative research and development of recommendations for new interventions. Any deviations from the original protocol study design are described throughout. The chapter concludes with details of the patient and public involvement in the study.

Rapid mapping exercise of existing services

The study team already had much of the information to feed into this exercise through their involvement in a range of ongoing research projects on smoking cessation in pregnancy, membership of key committees and networks, and extensive knowledge of the field. This information was supplemented with local details of services obtained from NHS colleagues who were coapplicants on the study, discussion with key management and commissioning staff at each study site, updates from relevant organisations such as Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), ASH Scotland, the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training, the Department of Health (DH) and the Scottish Government, and brief appraisal of studies under way testing new interventions for smoking cessation in pregnancy in the UK. A description of the available interventions and services was produced to inform the development of proposals for interventions that could be tested in future research.

Element 1: systematic reviews of qualitative research evidence

Three systematic reviews57–59 of the evidence relating to barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy were conducted, building on the 2011 review for the DH on using qualitative research to inform interventions to reduce smoking in pregnancy in England. 25 The reviews covered three populations: (1) pregnant and postpartum women, (2) their SOs and (3) HPs with a role in supporting pregnant women to stop smoking.

Aims of the three reviews

-

To explore the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation experienced by women during pregnancy and post partum.

-

To explore the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation experienced by women’s SOs during pregnancy and post partum.

-

To explore HPs’ perceptions and experiences of the barriers to and facilitators of providing support for smoking cessation during pregnancy and post partum.

Approach to searching and data sources

For each review, we undertook comprehensive pre-planned searches that aimed to find all available studies. Search terms were developed in conjunction with an information specialist. A draft search strategy was developed for each review in the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and these were then adapted to run in MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Social Sciences Citation Index, the Economic and Social Research Council database and Google Scholar Advanced (GoogleTM, Mountain View, CA, USA), for both published and unpublished studies. In addition, a PubMed ‘ahead of print’ citation search identified papers yet to be indexed. We also used publication alerts to inform us of any papers published during the process of the review after the formal searches had been completed to ensure that the most up-to-date studies were included in the review. The reference lists of full-text papers were checked and consultation was undertaken with experts known to the project team, to identify papers not found through electronic searching. Details of the search strategies for each review are available in Appendix 1. Databases were searched from 1990 onwards for each review. As the reviews were undertaken sequentially, the end dates of searching varied as follows.

-

Review 1: May 2013 (from January 2012). For the period to December 2011, searches for studies relating to smoking during pregnancy and post partum had been undertaken for an earlier review. 49 The recently published (September 2015) thematic synthesis of qualitative data on postpartum smoking relapse is therefore not included in this review. 84

-

Review 2: January 2014.

-

Review 3: January 2015.

Inclusion criteria

Published and unpublished studies were eligible for inclusion if they:

-

were reported in English

-

used qualitative research methods

-

were conducted in a high-income country in which the stage of the cigarette smoking epidemic matched that reached in the UK (i.e. a strong association between social disadvantage and cigarette smoking).

Additional inclusion criteria relevant for each review were:

-

review 1 – studies investigating the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation that women experience during pregnancy and post partum

-

review 2 – studies investigating the views of women’s SOs of the barriers to and facilitators of smoking and smoking cessation in pregnancy and after childbirth

-

review 3 – studies investigating HPs’ experiences of the barriers to and facilitators of supporting smoking cessation during pregnancy and post partum.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Relevant data were extracted from papers in each review (aim, type and number of participants, methodology used, methods of data collection, analysis and results). The data were extracted and checked by two reviewers. The papers were appraised for quality by two reviewers using an established checklist,85 with disagreements in scoring resolved by consensus. There was no a priori quality threshold for excluding papers; assessment was undertaken to ensure transparency in the process.

Synthesis methodology

All three reviews were undertaken using meta-ethnography. 86 Meta-ethnography is an interpretative approach to research synthesis that enables conceptual translation between different types of qualitative research. This approach consists of four iterative stages (Table 1). In each review, the following processes occurred: in phase 1, two reviewers read all papers in depth. Phase 2 involved the line-by-line coding of data (participant accounts and authors’ interpretations) in each paper relating to the focus of the review using ATLAS.ti 2010 software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

| Phase of meta-ethnography | Processes involved |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: reading the studies | Studies read to develop an understanding of their position and context before being compared with others. Repeated rereading of studies to identify key findings |

| Phase 2: determining how the studies are related | Determining the relationships between individual studies by compiling a list of the key findings in each study and comparing them with those from other studies |

| Phase 3: translating the studies into one another | Determining the similarities and differences of key findings in one study with those in other studies and translating them into one another. The translations represent a reduced account of all studies (first level of synthesis) |

| Phase 4: synthesising translations | Identification of translations developed in phase 3 which encompass each other and can be further synthesised. Expressed as a ‘line of argument’ (second level of synthesis) |

The codes were then compared and grouped by the reviewers into broad areas of similarity through reciprocal translation analysis (phase 3) to generate a reduced set of codes (translations) about barriers and facilitators relevant to each review. Phase 4 focused on these translations; the reviewers examined and compared them to identify the ‘lines of argument’ emerging from the review.

Reporting

Reviews were reported in accordance with the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement,87 as recommended by the Equator Network for reporting syntheses of qualitative research (www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/entreq/).

Element 2: qualitative research interviews and focus groups

This element of the research involved interviews with (1) pregnant women and women who had recently given birth, (2) their SOs and (3) HPs (e.g. midwives, health visitors, obstetricians, GPs) and SSS advisors with a role in caring for pregnant women. For the purposes of this report, further reference to HPs also includes SSS advisors. NHS ethics approval to conduct the research was received from South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference 13/SS/0077).

Aims of the three qualitative studies

-

To explore the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation experienced by women during pregnancy and post partum, and elicit views on interventions to support cessation.

-

To explore the barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation experienced by women’s SOs during pregnancy and post partum, and elicit views on interventions to support cessation.

-

To explore the perceptions and experiences of HPs with a role in supporting women to stop smoking regarding the barriers to and facilitators of providing support during pregnancy and post partum, elicit HPs’ views on the barriers to and facilitators of cessation experienced by women during pregnancy and post partum, and views on interventions to support cessation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria for participants in each group are listed in Table 2.

| Pregnant women | Pregnant women’s SOs | HPs |

|---|---|---|

| Aged ≥ 16 years | Aged ≥ 16 years | Aged ≥ 16 years |

| English speakinga | English speakinga | English speaking |

| Referred to NHS obstetrics services at study area A or B | Lives in same household as pregnant women or close friend/relative who spends at least 1 hour per week with pregnant woman | Significant role in the provision of care or smoking cessation support to pregnant women referred to NHS obstetric services at study area A or B |

| 6–15 weeks’ gestation at maternity booking | ||

| Self-reported smoker at maternity booking | Smoker or non-smoker | Smoker or non-smoker |

Sampling strategy

Purposive sampling was used to achieve maximum diversity within the recruited sample of pregnant women, their SOs and HPs. A sampling frame was used to obtain, as far as possible, a sample of pregnant women recruited for interview that took into account maternal age, that is 25% of the sample were to be aged < 25 years including two pregnant smokers aged < 20 years, and deprivation (i.e. 75% of sample from postcodes with the lowest Indices of Multiple Deprivation), and included both continuing smokers and quitters at around 20 weeks’ gestation. The professional sample was selected to reflect the perspectives of a range of professional groups on smoking cessation in pregnancy, and the various intervention options and opportunities available.

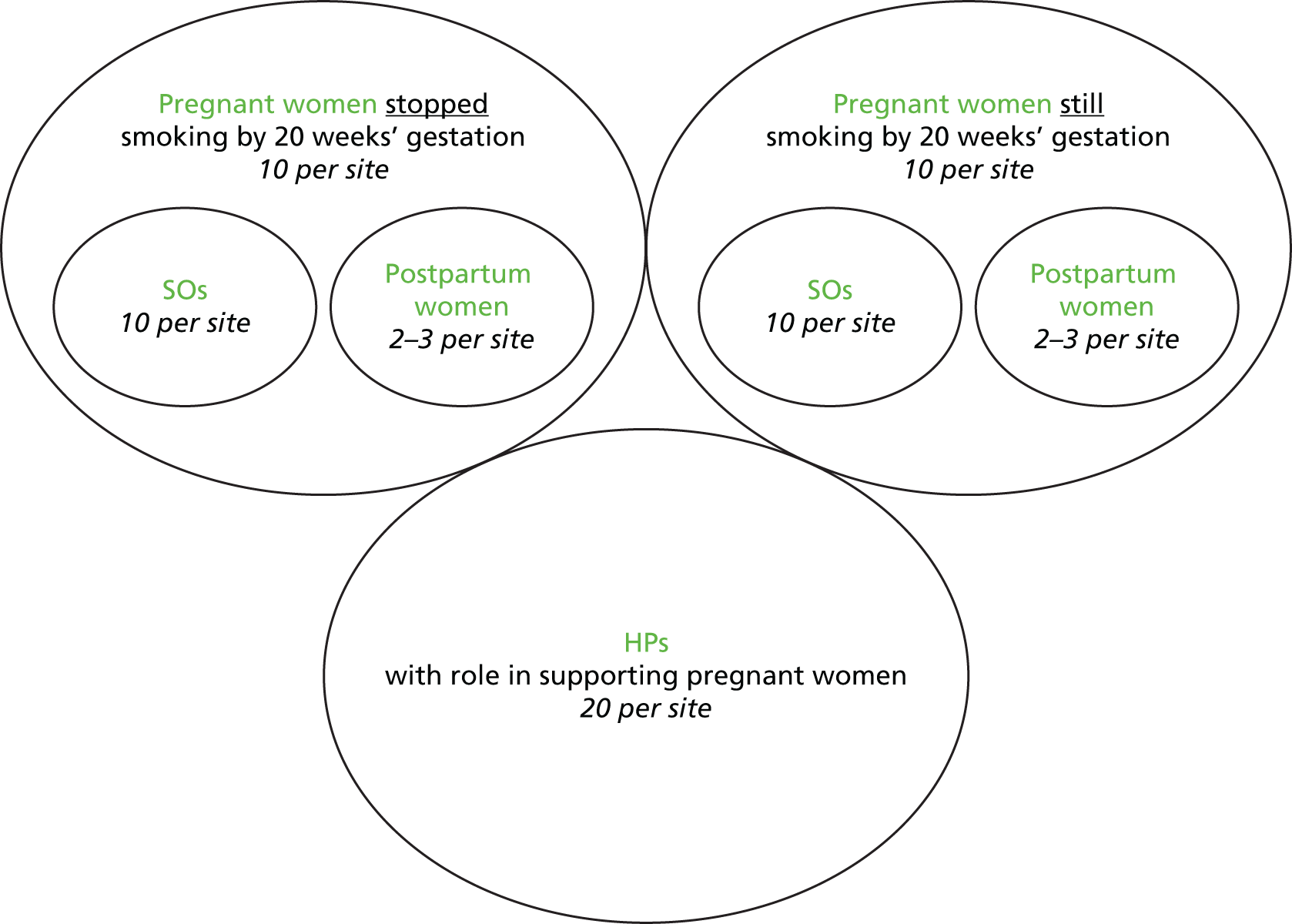

At the outset, the intention was to interview the following number of participants over the two study sites, as indicated in Figure 3: up to 40 pregnant women who were self-reported smokers at maternity booking, 20 of whom had stopped smoking by 20 weeks’ gestation and 20 of whom had not; 10 of these women a second time at up to 6 weeks after the birth of their babies; around 40–50 of these women’s SOs; and 40 HPs with a role in supporting pregnant women.

FIGURE 3.

Proposed participants for qualitative study at two study sites.

These targets were achieved, albeit by recruiting over a longer time period than planned, for pregnant women (9 months vs. the planned 5 months), postpartum women (7 months vs. the planned 4 months) and HPs (10 months vs. the planned 4 months). Interviews with HPs commenced earlier than planned (October 2013 rather than June 2014) because of delays in obtaining research and development (R&D) approvals to recruit pregnant women. In addition, for pragmatic reasons (i.e. when there was a significant number of relevant staff in similar roles, e.g. smoking cessation advisors and midwives) HPs (n = 26) participated in a focus group or a paired interview rather than an individual interview. Difficulties in recruiting women’s SOs, however, meant that the original target for this group of participants was unable to be reached despite an extended recruitment period (10 months vs. the planned 4 months). Further details of the changes made to recruitment approaches are described in Recruitment of participants.

A total of 121 individuals recruited from NHS study areas A and B participated (Table 3). A description of the characteristics of each group of participants is presented at the beginning of each of the qualitative findings chapters for pregnant and postpartum women (see Chapter 6), SOs (see Chapter 8) and HPs (see Chapter 10).

| Sample | Recruitment period | Area A | Area B | Total | Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | November 2013–September 2014 | 21 | 20 | 41 | 40 |

| Number of whom were also interviewed post partum | June 2014–December 2014 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 |

| SOs | November 2013–September 2014 | 20 | 12 | 32 | 40–50 |

| HPs | October 2013–July 2014 | 26 | 22 | 48 | 40 |

Recruitment of participants

To encourage participation in the study, pregnant and postpartum women and SOs were offered a £15 Love2shop voucher as an incentive and as a way of thanking them for taking part in the study. No incentives were offered to HPs to participate in the study. SOs were also interviewed around the same time as the pregnant women rather than a few months later, as originally planned, following feedback from potential participants at the start of the study. Some interviews, however, still took place after the findings from the systematic review element of the study became available, thus allowing discussion of any new data emerging from the review to be incorporated into the interviews.

Pregnant and postpartum women

Pregnant women were recruited with the support of maternity services and/or SSS colleagues in each study site. Recruitment and consent processes differed between sites to fit around the structure of existing services.

In study area A, where pregnant smokers are routinely identified at maternity booking and referred (through an opt-out system) to the NHS SSS, recruitment was initiated by smoking cessation advisors. Women attending a face-to-face appointment with a smoking cessation advisor were informed about the study during this appointment. Those interested were given a study information sheet and permission was obtained for their contact details to be passed to the study team. Women who did not attend a face-to-face appointment were told about the study during routine telephone contact by the smoking cessation advisor. Those interested were sent a study information sheet by post. All women whose contact details were passed to the study team were called by a member of the local research team within an average of 14 days (range 2–43 days) of receiving the information sheet. At this call, the researcher explained the study, answered any questions that the woman had and obtained her verbal consent for participation. The research team remained in contact with those who consented through mobile phone text messaging until they were around 20 weeks pregnant, at which point they were contacted by the researcher to arrange an interview. A consent form was signed by the women prior to the interview commencing.

At study area B, self-reported smokers at the maternity booking appointment (at around 6–10 weeks’ gestation) were given a copy of the information sheet and asked to consider taking part in the study. At the dating or nuchal translucency scan that takes place at around 12 weeks’ gestation, they were invited to meet with the research midwife, who explained the study and discussed the information sheet. Women were invited to participate by the research midwife who also obtained written consent at that time from those who wished to be involved. Details of those consenting were entered into the participant database by the research midwife. At around 20 weeks’ gestation, the women were contacted by a member of the local research team to arrange a suitable interview date.

At the end of the interview in both study sites, women were asked if they would be willing for the researcher to contact them again around 4–6 weeks after having their baby to find out if they were smoking or not and, when appropriate, ask them to participate in a second interview. Of the 41 women interviewed while pregnant, all but one indicated that they would be willing to participate in a second interview. At the outset of the project, the intention was to purposively select women for a second interview depending on their smoking status when contacted in the postpartum period in order to gain a range of views based on diverse experiences. However, unexpected difficulties in contacting women again in the postpartum period, particularly in area A, meant that these criteria had to be modified. In area A, only half of the participants were able to be successfully contacted post partum, with only half of those contacted agreeing to participate; in total, therefore, five women were interviewed. In area B, the first five women we contacted postnatally agreed to participate. A further consent form was signed prior to the interview commencing.

Significant others

The recruitment of SOs to the study involved a number of different processes; most of these were influenced by recommendations from the REC that we not recruit SOs by the method of pregnant women asking their SOs to participate. Although this would have been the most straightforward recruitment approach, the REC felt that it might have caused tension or confrontation between women and their SOs if women had to ask these individuals to take part. Thus, we modified our approach in line with this.

At both sites, pregnant women were asked to simply pass on a brief information sheet to any of their SOs that they believed might be interested in taking part in an interview. This request was made either prior to the woman’s first interview [i.e. when arranging and confirming the first interview with the women (area A) or at the time of consent by the research midwife (area B)] or at the end of the woman’s first interview (both sites). The brief information sheet included a tear-off slip for SOs to complete and send to a member of the research team to indicate interest in the study. On receipt of this slip, a longer information sheet was sent to the individual, followed by a telephone call from a researcher to confirm participation and arrange an interview appointment. All SOs at both sites were asked to complete a consent form at the beginning of the interview.

It became clear during the course of fieldwork that the process recommended by the REC to recruit SOs was failing to produce the required number of participants, which prompted the research team to alter their approach. Attempts continued to attract participants using the brief information sheet/tear-off slip approach. At the same time, however, the study was also promoted to all SOs attending antenatal appointments with pregnant smokers rather than only the SOs of women who had agreed to take part in the study. This change was approved by the REC. This amendment to the recruitment process enabled the project team to attract further SOs to participate, although the original target set out in the protocol was still unable to be reached (32 of the target 40–48 SOs recruited). Nonetheless, the systematic review of qualitative studies of SOs (see Chapter 7) indicates that this qualitative study involving the 32 pregnant women’s SOs represents the largest UK study to date.

Health-care professionals

All professionals recruited to participate in the study had a role in supporting women during pregnancy. This included midwives and midwifery managers, health visitors, GPs, pharmacists, obstetricians, smoking cessation service managers and advisors. The recruitment of professionals was facilitated by study coapplicants and took place through the respective organisational structures. A multichannel approach to recruitment of HPs was applied, for example through team leaders, attendance at team meetings and use of e-mail invitations. Recruitment was further guided by the introduction of a target quota of HP ‘groups’ to be achieved over the two study sites, as detailed in Table 4. Nine more SSS advisors than planned were recruited to participate in the research primarily to accommodate as many individuals as possible from this key group.

| Professional group | Target | Actual |

|---|---|---|

| Midwives/midwifery managers | 18 | 17 |

| Health visitors | 4 | 4 |

| SSS advisors/managers | 10 | 19 |

| Obstetricians | 2 | 2 |

| GPs | 2 | 2 |

| Service commissioners | 2 | 2 |

| Community pharmacists | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 40 | 48 |

Information sheets regarding the study and taking part in an interview were provided to potential HPs before they agreed to participate, with written consent obtained prior to interviews commencing. The participants were given the opportunity to ask any questions about the study before the interviews commenced and were given assurances about confidentiality and anonymity of responses.

Interviews and focus groups

All interviews and focus groups were conducted by female researchers from the University of Stirling and University of York. At area A, two researchers (AF and JM) conducted the interviews with women and SOs. Nine of these interviews had two researchers present for the purposes of shadowing prior to maternity leave for one researcher (n = 4), observation of qualitative fieldwork by a visiting researcher from the University of Ireland, Galway (n = 3), and safety concerns about visiting some participants’ homes (n = 2). In all cases the second researcher did not participate in the interview process. JM completed approximately 10 interviews with women and partners and one focus group with HPs (smoking cessation advisors) before going on maternity leave in December 2013. Three project team members (LB, LS and JM) conducted the interviews and focus groups with HPs. At area B, one researcher (DM) conducted all of the individual and group interviews.

Interviewer descriptions

Allison Ford is a qualitative researcher specialising in sensitive topics. She has worked on numerous smoking-related studies conducting and analysing interviews and focus groups with young people, adults and professionals. She is in her mid-thirties with two young children and has never smoked.

Jennifer McKell is a researcher with several years’ experience in conducting qualitative research on topics relating to health and substance use. This has included interviewing pregnant smokers. She is in her early thirties and has never smoked. She was pregnant with her first child during the fieldwork stage of the study.

Dorothy McCaughan is a qualified registered nurse who has worked in a range of health-care contexts, both in the UK and overseas. She has extensive experience of conducting qualitative interviews, with both clinicians and recipients of health care, over a period of 20 years as an applied health services researcher. She is in her early sixties, has one son and has never smoked.

Lesley Sinclair is a researcher with > 15 years’ practical experience of co-ordinating health services research involving complex interventions for a variety of patient groups. She has worked in both NHS and university settings. In recent years her research has focused on smoking in pregnancy. She is in her late forties and has never smoked.

Linda Bauld is Professor of Health Policy at the University of Stirling and holds the Cancer Research UK(CRUK)/Bupa Chairperson in Behavioural Research for Cancer Prevention at CRUK. She chairs the multiagency Challenge Group on smoking in pregnancy in England and has 20 years’ experience in conducting applied public health research, including leading a number of studies on smoking in pregnancy. She is in her mid-forties, has two children and has never regularly smoked.

The interviews with pregnant and postpartum women and SOs mostly took place in the women’s or SOs’ homes or, less frequently, in a public place, such as a coffee shop, workplace or health centre. Women and their SOs were interviewed separately (the pregnant woman first), reflecting the intention to encourage greater openness, particularly regarding family and community norms and support viewed as probable barriers and facilitators. In the majority of cases, only the interviewee was present at interview; however, there were some instances in which other individuals, including children, were present, which could create a chaotic and noisy backdrop to the interview. In several instances there were also interruptions during the course of the interview, for example a telephone call or individuals turning up at the house. On occasion, interviews with participating women and their SOs were conducted in each other’s presence (n = 6), even when separate interviews had been explicitly requested beforehand. In a very few cases, SOs seemed unreceptive or were overtly disapproving of the pregnant woman being involved in a research interview.

Forty-four of the 48 HPs participated in a face-to-face interview/focus group in their workplace and four in area A participated in a telephone interview. Twenty-two professionals were interviewed individually and 26 took part in a focus group or paired interview (n = 22 in four groups and n = 4 in two paired interviews). Focus groups were conducted when there was a significant number of relevant staff in similar roles, for example smoking cessation advisors and midwives. At area A, three focus groups were conducted: one involving midwives (n = 4), another involving team leaders from the local SSS (n = 4) and a third involving facilitators from the local SSS (n = 10). One focus group was conducted in area B involving midwives (n = 4). In addition, two paired interviews were carried out across the two study sites: two midwives in area A and a SSS manager and an administrator in area B.

Interview format and duration

The format of all interviews and focus groups conducted was intentionally relaxed and informal, with the interviewer following a semistructured topic guide (see Appendix 2) to promote a conversational style. All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded using a digital recorder.

The interviews with pregnant women ranged in duration from 25 minutes to 1 hour and 20 minutes, although most lasted between 40 and 50 minutes. Postpartum interviews tended to be shorter in duration, ranging from 17 minutes to just over 1 hour, with most lasting between 30 and 40 minutes. The shortest SO interview was 13 minutes and the longest was just under 1 hour; most interviews with this group were approximately 30 minutes long. The shorter duration of partner interviews was partially explained by fewer questions being involved, but also because most of these interviews were with men, who were briefer in their answers and/or who may have felt that some questions were not relevant to them (e.g. they were non-smokers), so questions relating to smoking were not relevant. The interviews with HPs (including smoking cessation advisors) ranged in duration from 17 minutes to 1 hour and 15 minutes. This large variation was a result of busy work schedules and limited time (i.e. interviews with GPs or obstetricians), or the extent to which smoking cessation was part of a professional’s role. The focus groups and paired interviews carried out lasted approximately 1 hour.

Transcription of interviews

All interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim. Some recordings were transcribed by a member of the research team but the majority were transcribed by professional transcribers regularly employed by the University of Stirling.

Development of topic guides

Prior to commencing interviews and focus groups with the three groups of participants, topic guides were prepared to support semistructured discussions. The guides (see Appendix 2) were informed by project team members’ previous and ongoing work relating to smoking in pregnancy, the theoretical framework used in the study and a mapping of current and new interventions in this area.

In the early stages of the study, project team members identified key themes (informed by the TPB) for inclusion in topic guides for each of the participant groups: smoking behaviour and quit attempts, beliefs and feelings about smoking in pregnancy, perceived barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy, perceptions concerning the SSS, and views on available and in-development interventions for smoking cessation in pregnancy. These key themes were used as a basis for developing interview questions. The HPs’ topic guide was the first to be developed. This was initially produced by one member of the project team (FN) and reviewed by other members. Draft topic guides for interviews with pregnant women and SOs were then produced by another member of the project team (JM), taking account of relevant themes but also the style of the HPs topic guide. The draft topic guides were then reviewed by the wider project team for content, comprehensibility and ‘flow’ of questioning. A fourth topic guide was produced for interviews with postpartum women using a similar process of identifying relevant themes prior to refinement and modification.

Coding and analysis

Three separate groups within the project team analysed the data from the three different participant groups: pregnant and postpartum women (AF, JM and KA), SOs (JM, DE and KA) and HPs (FN, SH and LS). The analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke’s phases of thematic analysis88 and set within the interpretivist paradigm. This paradigm considers participant accounts elicited during research interactions as representing one of many possible ‘truths’ and recognises that interpretations of these interactions are influenced by the researchers’ knowledge, beliefs and values. For the analysis of the HPs focus group data, we did not analyse interactions or dynamics between participants (e.g. participants looking at each other, laughing at another participant’s comments, nodding), as these data were combined with individual interview data in which there were no interparticipant interactions. NVivo (version 10, QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to facilitate the coding and analysis.

Coding frameworks were developed for each qualitative study separately using mind-mapping techniques. These frameworks were informed by the SEF. 74 The following process was repeated for each of the three qualitative studies: after familiarisation with the transcripts (i.e. reading and rereading), researchers independently microcoded several transcripts and all identified codes were categorised and inserted into one of the three SEF levels being examined, individual, interpersonal or organisational; after this researchers agreed on which codes to include in the draft framework, several further transcripts were coded and any new concepts (codes) that emerged were added.

The adequacy of the coding frameworks and consistency of coding between researchers was assessed using several methods. When dual coding was employed (i.e. 10 instances of dual coding for pregnant women’s transcripts and five for HPs transcripts), NVivo’s ‘coding stripes’ and/or coding consistency assessment query function was used to identify coding with potentially poor overlap (e.g. kappa coefficient < 0.7) that should be investigated. Although the coding consistency was acceptable for most codes, some codes had poor reliability having been applied inconsistently by the different researchers. These codes were discussed and resolved by making a number of minor changes to the coding framework, including the merging of some codes and changing of code labels and descriptions to maximise coherence and validity. For the SO transcripts, two researchers coded separate transcripts and then discussed the adequacy of the coding framework, including the addition or removal of certain codes.

Owing to similarities in the topics discussed and shared environments, the coding frameworks for interviews with postpartum women and SOs drew on the coding framework developed for pregnant women. A read-through of a sample of interviews from each of the study sites allowed further development in relation to key additions and omissions. The postpartum coding framework was particularly focused on any changes in perceptions, behaviour and support as the pregnancy progressed and once the baby was born. The SOs framework focused on participant’s relationships with the pregnant woman with reference to smoking and smoking cessation and perceptions of available support for cessation.

After all transcripts had been coded, the researchers read and reread the coded content, and summarised the key findings emerging from each code into higher-level categories. In line with ‘axial coding’,89 the researchers explored how the categories related to each other, leading to the emergence of preliminary themes. These themes were then refined through exploration and discussion of how well the preliminary themes mapped back onto the coded and raw data. Throughout this process, categories and themes were integrated into one of the three levels of the SEF being used to structure the codes, although interactions between categories and themes across these SEF levels were also examined. For all groups of participants, particular attention was paid throughout to similarities and differences in findings between research sites. In addition, similarities and differences in findings were examined between (1) women who had quit smoking and those who had continued to smoke through pregnancy, (2) partners and others with relationships with the pregnant women, and also SOs’ smoking status, and (3) the different groups of HPs, for example midwives, SSS advisors, etc. Once clear themes had been identified, these were named and described, accompanied by supporting quotations, as part of the process of writing up the findings. Supporting quotations were selected that generally expressed dominant views and demonstrated significant issues but also that reflected ‘deviant’ or ‘negative’ views. 90 As recommended when undertaking qualitative analysis,88 the process of analysis was recursive and often involved multiple iterations, particularly when identifying and refining themes from codes and categories.

Element 3: informing the development of proposals for future research

The final element of the study involved reviewing findings in order to identify (1) how existing services or interventions could be improved and (2) what new or modified interventions might be tested in the future. This was a relatively modest element of the study but drew on the two main data sources. The first was findings from the interviews in which participants were specifically asked for their views on whether or not particular new interventions already mentioned in the literature (e.g. financial incentives, social network interventions) might be of interest, or if there was anything else which might help women to stop smoking. These findings are outlined in each of the chapters that report the findings from the three groups of participants (pregnant and postpartum women, SOs and HPs) in the study. The second source of data for this final element of the research was team members’ related work. This had three main forms. First, the principal investigator (PI) served, during the lifetime of this study, as a member of the World Health Organization’s Guideline Development Group on smoking cessation during pregnancy. 39 This membership involved reviewing the wider international literature on cessation in pregnancy as part of the committee and from this promising future interventions were noted. Second, several members of the research team were involved in the Smoking in Pregnancy Challenge Group91 established in 2012 following a request from the DH to develop a smoking in pregnancy action plan for England. This plan was published in June 2013 with a commitment to meet annually to review progress. The 2015 review92 involved mapping existing gaps in the evidence base that were specifically relevant to services and interventions in England, and the findings from this have informed this report. Finally, the study team were involved in a number of other separately funded projects during the study period testing new interventions for smoking cessation in pregnancy that were either not available when the project began or not reported in the literature summarised in the three systematic reviews. 57–59 These projects are on the following topics: financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy,93 self-help interventions using digital media94,95 (building on a previous systematic review by the authors96) and a scoping study on social network approaches to smoking cessation in pregnancy. Together, these data sources inform the concluding chapters of this report and have been synthesised with findings from interviews to highlight opportunities for future interventions and new research on this important topic.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement took place at all stages of the study via several mechanisms. At the research design stage, the proposal was discussed with the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (UKCTAS) smokers’ panel, an established panel of 30 active smokers and individuals trying to quit, that meet regularly in the city of Bath, UK, to discuss smoking cessation research and policy initiatives. A member of the panel (Susanna Mountcastle), a smoker with two young children, also joined the study advisory group. During the set-up phase of the study, SM reviewed interview topic guides and patient information sheets. A participant representative from study area A also helped to pilot the interview topic guide for pregnant women.

Once the study was up and running, SM attended the advisory group meetings and, thus, contributed to the discussions and decisions made in relation to managing the study. SM also assisted in developing an alternative recruitment strategy for SOs when it became clear that the recruitment method specified in the protocol for this group of participants was not achieving the desired outcome. In addition, SM commented on interim and final results.

At the end of the study, findings were discussed with the UKCTAS smokers’ panel and their help was requested on approaches for disseminating findings and integration with policy. Four study participants (two from each study site) also provided feedback on a six-page summary of the findings (see Appendix 3) from the qualitative elements of the study.

Chapter 4 Current service provision to support pregnant women to quit smoking

This chapter describes the evolution of SSSs in the UK and more specifically the development of tailored provision for pregnant women. Support for pregnant women to stop smoking outside specialist SSSs is also described. The chapter concludes with a description of the structure and nature of support and services in the two study sites.

Development of Stop Smoking Services

A national network of SSSs was established in the UK following the publication of the 1998 White Paper Smoking Kills: A White Paper on Tobacco. 97 Initially piloted in deprived areas of England in 1999, SSSs were rolled out across the UK from 2000. The services were developed on the basis of national guidance issued by the DH that built on a review of the evidence of the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions published in the journal Thorax. 98 This evidence emphasised the efficacy of intensive behavioural support (in groups or one to one) plus pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Services were established by primary care trusts and operated primarily in primary care settings delivering behavioural support and providing access to NRT and bupropion. From 2000 to 2004, a national evaluation of the services in England was conducted by members of our team. This reported in 2005 in a special issue of the journal Addiction. 99–101 The evaluation found that the services were effective in supporting smokers to quit in the short term (at 4 weeks)99 and the longer term (at 1 year),100 and were reaching smokers from more deprived groups. 101 A subsequent analysis by our team also found that they were making a contribution to reducing inequalities in health caused by smoking. 102

Since these studies were conducted, SSSs have continued to evolve, including offering more tailored support to priority groups including pregnant women, which we describe in Stop Smoking Services for pregnant women. The services overall have been affected by various financial and structural challenges. National developments including NICE guidance on services (published in 2008)103 have influenced what is available, and smoking cessation medications have also diversified, with new NRT products and the medication varenicline (not licensed for use in pregnancy but effective with the general adult population) providing additional options for smokers trying to stop.

One element that has changed in the past decade is the type and variety of behavioural support options available to smokers using the services; in particular, a heavier reliance on one-to-one support options in a far wider range of settings. Findings from our earlier research with the NHS SSS suggest that group interventions may be more effective in practice104 but that smokers, given a choice, will choose one-to-one support. Issues of perceived preference may have led to the dominance of one-to-one support in current services, although new forms of group counselling (such as ‘rolling groups’ that clients can join without having to wait for a new group to start) have emerged.

Another element that has evolved is who provides support to stop smoking. Before the services existed, this was primarily provided by doctors and nurses in primary care or hospitals with a few examples of specialist clinics. Currently, a wider variety of professionals are involved in delivering support; for example, community pharmacists can provide SSSs.

Following these changes, a second national study of effectiveness of the services in England was recently conducted and reported in 2015. 105,106 This study employed a similar research design to the 2005 research99–101 but involved more areas of the country and a larger sample of service clients. It found that overall abstinence rates from smoking had dropped from 15% to 8% at 52 weeks but that smokers who received the best combination of stop smoking medication and behavioural support delivered by trained specialists were two to three times more likely to quit than other clients. 105,106

Stop Smoking Services for pregnant women

The UK’s SSSs began to develop tailored provision for pregnant women from 2000. This involved the same combination of support developed for the general adult population (a combination of behavioural support and medication, in this case NRT, which is the only product licensed for use in pregnancy). In 2008, an observational audit of Scottish outcomes conducted by members of our research team suggested that delivering support through services developed solely for pregnant women may be more effective than supporting pregnant women through generic services, which support all smokers. 107 This involved smoking cessation advisors who had been specially trained to support pregnant women on a one-to-one basis, and to accurately convey the risks of smoking and help women to maintain their quit attempt through pregnancy and beyond. The Scottish audit found that there were five pregnancy specialist services across 10 hospitals/units (across five health boards) in which there are staff employed specifically to provide cessation support. These services, however, were often understaffed and overstretched. The remaining hospitals/units provide either ‘intermediate’ support services, that is, staff with a limited designated period for the provision of cessation support, or ‘generic’ support services in which any cessation support is not specific to pregnancy and is provided as part of community-based services. At the time of the audit’s publication, a number of services were in development.

In 2010, the first UK guidelines were released by NICE on how to stop smoking in pregnancy and following childbirth. 40 These guidelines made recommendations not only about which cessation interventions are effective for pregnant smokers, but also about ways in which health providers should try to identify and engage with pregnant women to offer them these interventions. One recommendation, for example, was that services should systematically introduce screening of exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) into routine care in order to identify pregnant smokers; the guidance also suggests that when a woman’s CO levels indicate that she is a smoker, she should be automatically offered NHS stop smoking support through an ‘opt-out’ referral pathway.

Following the release of this guidance, a national survey was conducted in England to determine how SSSs were delivering support to pregnant women. 41 It found that, in 2010–11, 55% of SSSs provided some support to pregnant women through specialist services (18% supported pregnant women only through specialist services and 37% supported them through a combination of generic and specialist services). A total of 76% of services in England had a specialist pregnancy advisor in post. Pregnant women were most commonly offered support in their home (72%), children’s centres (72%) and family doctor practices (71%). Most services offered behavioural support and either single (77%) or dual (86%) NRT. A number of services also offered relapse prevention support (65%), behavioural support only (62%) and financial incentives (35%). As an adjunct to routine support, 64% of services offered some form of self-help support (primarily a booklet/leaflet).

Other support for pregnant women to stop smoking

Support for pregnant women to stop smoking also exists outside specialist SSSs. A number of settings and HPs are involved, including the following.

-

General practitioner surgeries: GPs and other HPs sometimes offer brief advice and a prescription for NRT, although the provision of this is variable. For example, based on GP practice records between 2000 and 2009, it was estimated that 9% of pregnant smokers had been prescribed NRT. 108

-

Antenatal care: midwives are recommended to briefly discuss smoking at a woman’s booking visit and to follow this up at subsequent visits. International studies have found that midwives are more likely than GPs to advise women to cut down on smoking rather than abstain completely. For example, in one survey, only 11% of midwives said that they advised smoking clients to abstain completely, compared with 71% of GPs. In the UK, one survey found that only 31% of pregnant smokers reported being told by a midwife that they should stop smoking. Obstetricians and other antenatal HPs may also discuss smoking with clients and provide advice about cessation.

-

Telephone ‘quitlines’: pregnant women may choose to access support to stop smoking without seeing a HP, and telephone quitlines have been in place for a number of years in the UK to provide this kind of help. Examples include the NHS Smokefree helpline and telephone services offered by the baby charity Tommy’s and the National Childbirth Trust. These quitlines also make women aware that they can be prescribed NRT to help with their quit attempt and that in order to obtain this they need to see their GP or a NHS SSS, where more intensive behavioural support can also be provided.

-

Online resources: a variety of online resources also offer self-help options to women trying to stop smoking in pregnancy. For example, information is available through the ‘NHS Choices’ website and, for younger mothers, through Tommy’s ‘Baby be smokefree’ website. A number of other tailored websites exist in the UK and overseas, and increasingly research is being conducted on digital interventions for smoking cessation in pregnancy, including smoking cessation applications, text messaging and other new media forms of support. 91

Support to stop smoking in the two study sites

For women living in the two areas where this study was conducted, the structure and nature of support and services differed.

Area A had established smoking cessation support for pregnant women before the national SSS was established. From 1993, trained smoking cessation advisors, employed by a drug and alcohol service and linked to one maternity hospital in the centre of the area, were in post. These services were expanded to cover the whole area on a gradual basis when national funding for SSSs became available in Scotland from 2000. At the time of the study, a fairly comprehensive network of services was in place, involving a pathway from the identification of women who are smoking in pregnancy through to providing support to stop throughout the antenatal and into the postnatal period.