Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/81/01. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The draft report began editorial review in October 2015 and was accepted for publication in April 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Karina Lovell, Sarah Byford and Shirley Reynolds report grants from the National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study. Michael Barkham reports that he was the lead investigator in the development of the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure, which is used in the trial. Simon Gilbody reports previous membership of the Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials Board.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Lovell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterised by:

-

intrusive, unwanted, recurrent and distressing thoughts, images or impulses (i.e. obsessions)

-

repetitive actions/rituals (i.e. compulsions), which serve to reduce the distress and anxiety evoked by the obsessions.

Typical examples of obsessions include excessive doubts regarding the maintenance of safety and security (e.g. fears of failing to lock doors, or turning off electrical or gas appliances), intrusive thoughts, images or impulses of contaminating or harming others, or repugnant, sexual thoughts of abusing others.

Typical compulsions include repetitive washing or cleaning, and checking or repeating numbers, words or phrases. The majority of people with OCD understand that their thoughts and rituals are senseless.

Prior to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition,1 OCD was grouped as an anxiety disorder, but it is now incorporated into a separate chapter on OCD and related disorders. For a definitive diagnosis, obsessions and compulsions (or both) must:

-

be distressing

-

impair functioning

-

be time-consuming (> 1 hour per day).

There are only a few minor differences in the criteria for OCD between the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Editions III, III Revised and IV (DSM-IV),2 and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition. 3

Obsessive–compulsive disorder has an estimated lifetime prevalence of 2–3%4 and, in the absence of adequate treatment, will usually follow a chronic course. OCD is associated with reduced quality of life and substantial impairment of role, specifically work, social, home and family/relationship functioning. 5 In addition to the individual costs, the economic burden of OCD is high, with an estimated US$8.4M being attributed to the direct and indirect costs of the illness in the USA. 6 The World Health Organization rates OCD as one of the top 10 leading causes of disability worldwide. 7 High levels of comorbidity are associated with OCD, most notably other anxiety disorders, depression, impulse control disorders and substance misuse. 8 There is significant evidence to suggest that people with OCD are often left untreated or are inappropriately or inadequately treated, with consistent reports of a marked time delay between OCD onset and diagnosis. One study found a 10-year gap between onset and seeking professional help, and 17 years between onset and receipt of an effective intervention. 9

Context of the Obsessive–Compulsive Treatment Efficacy randomised controlled Trial

To understand the rationale for the Obsessive–Compulsive Treatment Efficacy randomised controlled Trial (OCTET), we first describe the following contextual issues:

-

cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and low-intensity psychological interventions

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for OCD

-

service delivery models for psychological therapies in the UK

-

summary of the evidence for low-intensity interventions for OCD.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy and low-intensity interventions

Therapist-delivered CBT, including exposure and response prevention (ERP), is a mainstay of psychological treatment for OCD. 10 CBT is a ‘talking therapy’ that aims to change unhelpful thoughts and behaviour. ERP are specific CBT techniques used in the treatment of OCD. Exposure therapy involves confronting the feared stimuli until fear subsides, through a process known as extinction. Response prevention means resisting the need to ritualise (i.e. perform a compulsive reaction).

One of the major problems related to the management of OCD is access to CBT, with many patients traditionally facing significant delays and spending large amounts of time on waiting lists for this treatment. This reflects a lack of trained therapists and the significant amount of therapist time traditionally seen as necessary for each individual treatment.

There has been significant interest in ways of overcoming this issue that are sustainable for health-care systems. A key development has involved ‘low-intensity’ interventions. Although there is a lack of consensus over precise definitions, common features of low-intensity interventions include:11

-

typically CBT based

-

communicate CBT principles in accessible ways and delivered in flexible forms (e.g. telephone, e-mail)

-

involve a health technology (e.g. a computer package or book) to deliver key ‘active ingredients’ of therapy

-

usually delivered by a low-intensity worker [psychological wellbeing practitioner (PWP)]

-

use fewer resources (in terms of therapist time) than conventional CBT.

Low-intensity interventions can be used by patients unsupported (reducing therapist time to zero). However, they are often used in a ‘guided’ or ‘supported’ form, with some therapist time, often with a therapist who is fully trained but has less experience than a conventional CBT therapist. Two key forms of low-intensity interventions are ‘guided self-help’ (use of a book providing instruction in CBT principles), often supported via telephone by a professional; and computerised CBT (cCBT), using computer- or web-based systems to provide instruction in CBT principles, again supported by a professional.

An advantage of low-intensity interventions that use health technologies (cCBT) or are delivered by technology (telephone) is that they are more readily accessed by those who are unable to attend scheduled clinic appointments because of geographical, social, physical or psychological difficulties.

Low-intensity interventions complement, rather than replace, existing CBT provision. The way in which conventional therapist-delivered CBT and low-intensity treatments are delivered as part of a system of care is the subject of the next section.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines

The NICE guidelines for OCD12 recommend management using a ‘stepped-care’ approach. 13 Stepped care is viewed as a potential solution to poor access to traditional treatments by increasing the efficiency of service provision and better-matching treatment to patient need.

In stepped-care models, different ‘steps’ or levels of treatment intensity exist. However, there are two ways in which patients are assigned to different steps.

-

Stepped care: a sequential approach in which all patients move through steps in a systematic way irrespective of illness severity, patient need or choice. Under this model all patients will initially receive low-intensity treatments and only ‘step up’ if and when these first-line interventions fail.

-

Stratified care: a targeted approach in which patients are assessed and referred to an appropriate step of treatment based on severity, complexity or other agreed criteria. Patients can thus access an appropriate level of treatment and, if needed, access a more intensive intervention without first having had to receive a lower-intensity treatment. 14

Although these can be considered as alternatives, models of care can include aspects of both models (i.e. the majority of patients use the stepped model, but patients with certain characteristics are stratified).

The NICE model uses stratification based on (1) severity of OCD symptoms and (2) functional impairment. The model consists of six steps divided into three stages: awareness (step 1), recognition and assessment (step 2) and treatment (steps 3–6). Our focus is on steps 3–6.

-

At step 3, adults with OCD with mild functional impairment, low-intensity psychological (CBT) treatments are recommended. Low-intensity treatments are delivered by a PWP and defined as < 10 hours of therapist time per patient. Treatments include (1) brief individual CBT using structured self-help materials, (2) individual CBT delivered by telephone or (3) group CBT.

-

At step 4, adults with OCD who have moderate functional impairment (or who have mild functional impairment, but have failed to engage or improve with lower-intensity treatments) will usually be offered a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and/or higher-intensity CBT delivered by a high-intensity therapist (HIT).

-

Step 5 is recommended for those with severe functional impairment and delivered within secondary care by mental health professionals with expertise in OCD. Treatment recommendations include a combination of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and CBT.

-

Step 6 is reserved for people presenting with severe and chronic functional impairment, treatment refractory, and/or a risk to self or others. Specialist inpatient treatment and care may be offered at this step.

The NICE guidelines for OCD have been in existence since 2005. 12 An evidence update was set for February 2014, but no significant evidence was identified to change the recommendations. During the completion of the evidence update, the effectiveness of technology-enhanced treatment for OCD was identified as an evidence gap and, as a result, was registered on the UK Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments. 15

Service delivery models for psychological therapies in the UK

Psychological interventions for OCD are usually delivered in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services. 16 IAPT commenced in 2007 with the aim of achieving a better balance between supply of psychological therapies and demand.

Since its inception, > 5000 new psychological therapists have been trained. IAPT training, which follows a national curriculum, produces two types of therapists:

-

low-intensity therapists, also known as PWPs

-

HITs.

Psychological wellbeing practitioners are tasked with facilitating a range of low-intensity interventions including guided self-help, cCBT and psychoeducational groups for mild to moderate depression and anxiety disorders. HITs provide predominantly CBT interventions for moderate to severe cases. The amount of time allocated to individuals varies but, on average, PWPs provide 3–4 hours of therapeutic support per person over 6–8 weeks, whereas HITs provide weekly 60-minute sessions over 8–16 weeks.

Given the NICE guidelines, it would be sensible to assume that low-intensity interventions for OCD (guided self-help or cCBT) would be supported by a PWP and provided in IAPT services for people with mild functional impairment.

However, the NICE model is not being implemented precisely, as designed in practice,17 for a number of reasons:

-

In most IAPT services, people with OCD are referred directly to, and treated by, HITs regardless of their illness severity. OCD is perceived as a complex mental health disorder and hence the PWP IAPT National Curriculum18 does not address OCD knowledge or treatment.

-

Although the NICE guidelines recommend low-intensity interventions for mild OCD, there is evidence that people with OCD with mild functional impairment do not present to services. Consequently, a substantial proportion of patients seen by IAPT practitioners will be experiencing OCD with at least a moderate level of functional impairment.

-

Discrepancies exist between the definitions of low-intensity treatments adopted by IAPT services and NICE. Although there is no formal consensus regarding the precise number of therapist hours required by low-intensity interventions, NHS and IAPT services typically presume no more than 3–6 hours of input. The NICE guidelines advocate up to 10 hours of support for low-intensity interventions for OCD, thereby positioning at least some of these treatments within the remit of higher-intensity services.

Summary of the evidence for low-intensity interventions for obsessive–compulsive disorder

Despite NICE’s recommendations for low-intensity interventions for OCD, evidence of the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of these interventions is limited. Effective synthesis is hampered by confusion over the scope of low-intensity interventions.

Lovell and Bee19 completed a systematic review of 13 studies (n = 492 participants) of CBT-based treatments that used health or communication technology in adults with OCD, including self-help manuals and cCBT alongside telephone and videoconferencing. Heterogeneity of populations, interventions and outcomes across the studies prevented meta-analysis. Self-help manuals were assessed in five small, uncontrolled, quasi-experimental studies and found moderate to large improvements in OCD symptoms; however, the absence of controlled trials means that the generalisability of the findings is unclear. cCBT was assessed in five studies, four of which were of BT Steps [now called OCFighter version 1.0 (CCBT Ltd, Birmingham, UK)]. The results revealed significant moderate to large effects on OCD symptoms score in favour of BT Steps. However, all studies were undertaken by the developers of the software and no independent analysis was available. The authors concluded that preliminary data support the idea that technology holds promise in treatment for OCD. Nevertheless, definitive conclusions about the relative efficacy of using health technologies as a replacement for therapist contact needed stronger evidence from rigorous randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Herbst et al. 20 similarly examined telemental health applications for adults and children with OCD and included studies delivered by computer, the internet, telephone or self-help literature either delivered alone or supported by a health professional. No meta-analysis was completed and individual effect sizes ranged from 0.46 to 2.5. Of the 24 studies (n = 839 participants) included in this review, seven used written self-help materials (guided self-help), 11 were delivered by telephone, three were computer assisted, one comprised an online self-help group and two used videoconferencing. The review suggested that telemental applications may have promise but, once again, clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and small sample sizes precluded definite conclusion.

A more recent review21 looked at the efficacy of all types of technology-delivered CBT for OCD versus control conditions and in comparison with high-intensity CBT. Eight RCTs (n = 420 participants) were included and results found that CBT delivered by technology was superior to the control intervention in reducing OCD symptoms but not on comorbid depression. There were no differences in reductions in OCD symptoms between CBT delivered by technology and therapist-delivered CBT. Similar to previous reviews, this review concluded that further RCTs are warranted to examine the efficacy of technology-delivered CBT.

Guided self-help

Although NICE recommended the use of brief CBT (guided self-help) supported by a therapist, there is only a very limited evidence base to support this. A limited number of small open/uncontrolled trials22–26 of self-help materials, with guidance from a therapist have demonstrated promising results. One RCT25 randomised 41 patients with OCD to a self-help book with two contacts with a therapist or to 15 sessions of face-to-face therapist-delivered CBT including self-administered or therapist-administered ERP. Patients in both treatment conditions showed statistically and clinically significant symptom reduction, but therapist-delivered CBT was superior in OCD symptom and functional impairment reduction.

Since commencing OCTET, two RCTs have been published,27,28 neither of which used ERP (both RCTs used different unsupported self-help interventions). The first27 focused on a self-help book based on metacognitive training for OCD. Patients with OCD (n = 87) were randomised to either metacognitive training for OCD or a waiting list control and results showed significant changes in OCD symptoms in the intervention group post treatment.

The second RCT28 randomised 70 patients with OCD to either an unsupported self-help manual focusing on meridian tapping (a body-oriented technique from the field of alternative medicine) or progressive relaxation. The study did not lead to improvement in OCD symptoms.

Computerised cognitive–behavioural therapy

As a treatment option, cCBT is not recommended by NICE. A systematic review29 of cCBT for OCD found only four studies, all using the software program OCFighter (previously known as BT Steps). The results showed significantly better outcomes and less attrition for scheduled than for unscheduled telephone support. The conclusion of the review found OCFighter to be as good as standard high-intensity CBT in reducing time spent in rituals and obsessions, and in improving work and social functioning. Overall, standard high-intensity CBT was more effective than OCFighter, but not for those who actually started the intervention as opposed to those who failed to begin self-exposure therapy.

A key limitation of this work is that all OCFighter evaluations have been conducted by the commercial company who developed the program. Furthermore, this program was originally delivered with an interactive voice response and workbook. A more recent version, which has not yet been evaluated in a RCT, comprises a web-based platform in conjunction with brief support via telephone, face-to-face or e-mail contact with a mental health worker. A cost-effectiveness analysis has been completed30 with the original BT Steps program, but this was not independent from the developers of the commercially produced package.

Since the beginning of our study a further RCT has been published with BT Steps. 31 Eighty-seven participants with OCD were randomised to cCBT with (1) no therapist support, (2) lay (non-therapist) support or (3) support from an experienced CBT therapist. The results showed a positive change post treatment compared with pretreatment, with no significant difference between the three treatment arms in OCD symptoms or sessions completed. A number of internet-delivered CBT studies have been published including open studies. 32,33 Andersson et al. 33 randomised 101 adults with OCD to either 10 weeks of internet CBT or to an attention control condition, with online supportive therapy. Results found that both interventions led to significant improvements in OCD symptoms, but internet CBT resulted in greater improvements in OCD symptoms.

Summary

The provision of high-intensity CBT is ‘current best practice’ according to NICE OCD clinical guidelines. Despite the introduction of IAPT, access to high-intensity CBT can still involve significant delay, and the requirement to visit a therapist for treatments is poorly suited to the needs of some patients (e.g. the housebound, those with caring responsibilities, those whose OCD makes it difficult to be with people or to attend NHS settings, or those who live in rural locations).

There is clearly a potential role for low-intensity interventions as part of a stepped-care model. However, current evidence concerning low-intensity interventions (such as cCBT or guided self-help) is insufficient to provide accurate estimates of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. No studies have compared different low-intensity interventions (such as cCBT vs. guided self-help), nor do we know the numbers of people who will not improve with low-intensity interventions and who will require more intensive CBT in the stepped-care model.

The core question for patients, clinicians and policy-makers is ‘what is the role of low-intensity interventions in relation to “usual care” (i.e. referral to a waiting list for high-intensity CBT)?’. Implicit in the stepped-care model is the idea that giving patients on a waiting list for high-intensity CBT access to low-intensity interventions, prior to high-intensity CBT, could potentially augment care by:

-

improving patient outcomes either through more rapid improvement in clinical outcomes prior to high-intensity CBT or by augmenting the effect of high-intensity CBT in the longer term

-

reducing costs either by reducing the numbers of patients who need to access high-intensity CBT or by reducing general health-care utilisation in the short and longer term.

The aims of the Obsessive–Compulsive Treatment Efficacy randomised controlled Trial

The Obsessive–Compulsive Treatment Efficacy randomised controlled Trial emerged from a research recommendation in the NICE OCD guidelines that specified the need to evaluate CBT treatment intensity formats among adults with OCD.

In response to this recommendation, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Health Technology Assessment programme commissioned research on ‘self-managed therapy packages’ for OCD, with specific reference to cCBT and guided self-help compared with treatment as usual. In this case, treatment as usual was defined as being placed on a waiting list for high-intensity CBT.

The Obsessive–Compulsive Treatment Efficacy randomised controlled Trial was designed to address this commissioned call. Our aims were to determine:

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of low-intensity interventions (guided self-help and supported cCBT) versus a waiting list for high-intensity CBT in the management of OCD at 3 months

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of low-intensity interventions (guided self-help and supported cCBT) plus high-intensity CBT versus a waiting list for high-intensity CBT plus high-intensity CBT in the management of OCD at 12 months

-

the acceptability of low-intensity interventions (guided self-help and supported cCBT) among patients and professionals.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

The Obsessive–Compulsive Treatment Efficacy randomised controlled Trial was a pragmatic, three-arm, multicentre RCT and the primary outcome was OCD symptoms using the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale – Observer Rated (Y-BOCS-OR) that aimed to determine:

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of low-intensity interventions (guided self-help and supported cCBT) versus a waiting list for high-intensity CBT in the management of OCD at 3 months

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of low-intensity interventions (guided self-help and supported cCBT) plus high-intensity CBT versus a waiting list plus high-intensity CBT in the management of OCD at 12 months

-

the acceptability of low-intensity interventions (guided self-help and supported cCBT) among patients and professionals.

The trial protocol has been published. 34 No major changes to the protocol were made after its publication.

The Obsessive–Compulsive Treatment Efficacy randomised controlled Trial involved two phases: an internal pilot, moving seamlessly into the substantive trial. We describe the methods and outcomes of the internal pilot, with a focus on the impact on the recruitment strategies used for the substantive trial. We then describe the methods used for the substantive trial.

Internal pilot

An internal pilot study is defined by NIHR as:35

. . . a version of the main study that is run in miniature to test whether the components of the main study can all work together. It is focused on the processes of the main study, for example to ensure recruitment, retention, randomisation, treatment, and follow-up assessments all run smoothly.

The OCTET pilot study therefore resembled the substantive study in all respects, including an assessment of the feasibility of the proposed primary outcome time point.

The internal pilot was conducted over 9 months and was designed to assess three questions:

-

Is it feasible to recruit the number of participants required to meet the planned sample size?

-

Do participants remain on a high-intensity CBT waiting list for a sufficient length of time (i.e. at least 3 months) to conduct an evaluation of the short-term clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-managed therapies, prior to access to high-intensity CBT?

-

Should the primary outcome point be 3 or 6 months? The commissioning call specified 6 months as the primary assessment point but given the pressure of IAPT sites to minimise waiting lists we were unsure if 6 months would be achievable.

Results of the internal pilot

In terms of question 1, the internal pilot proved that recruitment was feasible (with the addition of more sites) and that the planned sample size could be achieved in principle. The pilot recruitment graph is presented in Appendix 1.

However, evaluation of questions 2 (time patients spent on the high-intensity CBT waiting list) and 3 (timing of a 3- or 6-month outcome for the primary assessment point) demonstrated significant challenges. As highlighted in the introduction, one of the key reasons for conducting OCTET was that the need for psychological therapy services for OCD exceeds demand, meaning that patients often face long waiting lists for high-intensity CBT treatment. Low-intensity interventions are designed to allow more rapid access and better management of demand.

The OCTET recruitment method was to screen existing high-intensity CBT IAPT waiting lists for potentially eligible patients where OCD was known or noted in the referral letter. Similar methods (large-scale screening of existing lists of potentially eligible patients) have underpinned a number of our successful large multicentre mental health trials [e.g. the Randomised Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Acceptability of Computerised Therapy (REEACT trial),36 cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care trial (CADET)37].

Extensive mapping of IAPT high-intensity CBT waiting lists at recruitment sites was conducted prior to the trial commencing, which identified waiting lists of between 60 and 800 patients and between 40 and 100 OCD referrals per year. Therefore, it was predicted that we would be able to achieve and maintain the required recruitment rate.

During the internal pilot, the Department of Health informed all IAPT sites in England that patients should be offered more rapid access to treatment as part of the IAPT initiative. This had two major effects:

-

A proportion of participants randomised to a low-intensity intervention were offered their high-intensity CBT appointment prior to commencing the intervention or before completing the low-intensity intervention. One waiting list reduced from in excess of 700 patients to < 50 patients in 4 weeks.

-

A proportion of participants were ‘removed’ from the high-intensity CBT waiting list and offered access to a form of low-intensity intervention. In many cases, these interventions were in line with current good practice (including written material focusing on understanding and managing anxiety, supported by a PWP), but were not OCD specific or recommended by the NICE OCD guidelines. However, having been removed from the waiting list, such patients were lost to the OCTET recruitment procedure, significantly reducing the numbers of potentially eligible patients who could be contacted.

These changes to the high-intensity CBT waiting list procedure had significant implications for OCTET. In response, we made the following changes:

-

As a proportion of participants were reaching the top of the CBT waiting list prior to 12 weeks, we proposed to services that regardless of the length of waiting list, patients would be asked to wait at least 12 weeks before high-intensity CBT was offered. This proposal was supported by the Health Technology Assessment programme, the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC), and was approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee North West Lancaster. Despite this, only one site agreed to implement this change because of concerns that such a strategy contradicted the requirements of the Department of Health.

-

We initiated a new strategy in some sites, whereby all patients on waiting lists for high-intensity CBT were mailed with an invite to OCTET rather than the original strategy that restricted mailing to patients with an indication of OCD on NHS records. The rationale was that OCD is often underdiagnosed and in consultation with clinical colleagues it transpired that many referrals from general practitioners (GPs) did not indicate OCD on the referral letter. The trial consent procedures and inclusion criteria remained the same. This strategy proved successful in increasing numbers, but was more time-consuming as a number of people who self-reported OCD did not meet our trial inclusion criteria.

-

We extended self-referral opportunities in two sites (as recruitment was low at these particular sites) by placing adverts in local newspapers, on social media [e.g. local OCD group Facebook page (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA)], in GP surgeries, community centres, trust magazines and in other local publications in one site. The trial consent procedures and inclusion criteria remained the same.

-

We engaged additional IAPT services within 10 NHS trusts in addition to our existing sites. Despite increasing the number of potential participants, this raised logistical and resource challenges, as additional recruitment and training of researchers and PWPs was required.

-

Given the directive from the Department of Health regarding high-intensity CBT waiting lists, it was not feasible to use the proposed 6-month follow-up as the primary outcome assessment point, and hence it was agreed to retain the 3-month assessment as the primary outcome assessment point. Given that removing the 6-month assessment would result in a variety of ethical issues and could potentially reduce participant engagement at 12 months, it was decided that the 6-month assessment should be retained.

Main trial methods

Ethics and governance

Ethics approval for the study was granted by National Research Ethics Service Committee North West – Lancaster (reference number 11/NW/0276). Site-specific approvals were obtained from the relevant local research governance offices covering the trusts involved in the trial. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN73535163).

Low-intensity interventions

Experimental group: supported computerised cognitive–behavioural therapy

Supported cCBT was delivered using OCFighter, a commercially produced cCBT program for people with OCD. OCFighter consists of a nine-step CBT approach (focused on ERP) to help people with OCD to design, carry out and monitor their treatment and progress.

Participants randomised to OCFighter were given an access ID and password to log in to the system and advised to use the program at least six times over a 12-week period. OCFighter was available to patients for 12 months following activation.

Participants received six brief (10-minute) scheduled telephone calls from a PWP (total direct clinical input 60 minutes). The support offered consisted of a brief risk assessment, ensuring patients had been able to access OCFighter, reviewing progress and solving any difficulties that were impeding progress.

Experimental group: guided self-help

The guided self-help consisted of a self-help book, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: a Self-Help Book, written by the chief investigator. 38 The self-help book focused on information about OCD, maintenance and provided guidance on how to implement the NICE-recommended treatment for OCD (i.e. CBT using ERP). The self-help book was a refined and expanded version of a previous free-to-use self-help manual by the trial team and a user and carer from an OCD self-help group. 39 The self-help book was sent to the participant immediately following randomisation.

Participants received weekly guidance from a PWP, with one initial session of up to 60 minutes (either face to face or by telephone, dependent on patient preference) followed by up to 10 30-minute sessions over a 12-week period (total direct clinical input 6 hours).

The role of the PWP was to conduct a semistructured interview, to explain the structure and content of the book and devise patient-centred goals. PWPs supported patients to use CBT (ERP) as described in the self-help book, reviewed progress, pre-empted difficulties as they arose and engaged the participants in collaborative problem-solving as required.

Comparator group: waiting list for high-intensity cognitive–behavioural therapy

The comparator group for the short-term outcomes (3-month follow-up) was a waiting list for high-intensity CBT. In the longer term (12-month follow-up), the comparator was a waiting list for high-intensity CBT plus high-intensity CBT. High-intensity CBT is typically 8–20 face-to-face, 45- to 60-minute weekly sessions and uses a combination of ERP and cognitive therapy.

Psychological wellbeing practitioner training and supervision

Psychological wellbeing practitioners were trained in both the guided self-help and supported cCBT interventions. Training was delivered in all IAPT services in the 15 NHS sites. Top-up training was provided to PWPs at sites where a large delay between training and participant recruitment occurred, and because of the high turnover of PWPs the training was repeated at a number of sites.

The standardised training consisted of 3 days, and included 1 day explaining the nature, features, treatment and NICE recommendations for the management of OCD. In addition, day 1 also explained OCTET in terms of study design, rationale and trial procedures.

Day 2 focused on guided self-help and involved small- and large-group work and skills practice of ERP with specific feedback using exemplar cases. Training was delivered by the chief investigator and two coapplicants. cCBT training for OCFighter was delivered at the participating sites for 1 day by CCBT Ltd (the commercial producers of OCFighter). The training was standardised, using the same trainers (OCTET chief investigator, coapplicants and CCBT Ltd), materials and intervention manuals.

Training manuals for PWPs were developed by the trial team for guided self-help and by CCBT Ltd for the supported cCBT arm. A reference manual for PWPs was also generated that included general information about OCTET, recruitment, randomisation and allocation procedures, recording and storage of session recordings and monitoring of allocated participants.

Psychological wellbeing practitioners delivering the interventions were provided with telephone supervision on a 2-weekly basis for between 10 and 30 minutes (dependent on the number of patients to be discussed). Supervision was delivered by OCTET applicants or CBT therapists within IAPT services. All supervisors (two senior clinicians within a service and coapplicants) were required to attend the 3-day training).

Adherence and fidelity

To ensure the adherence to the guided self-help and supported cCBT interventions, and potentially enhance the reliability and internal validity of the trial, a number of strategies were implemented during trial development and completion.

Treatment adherence was examined by requesting PWPs complete contact sheets detailing dates of all sessions attended, length of sessions and mode of contact (face to face, telephone or e-mail). CCBT Ltd provided automated recordings of frequency and duration of supported cCBT use.

Fidelity was examined by asking PWPs to record all face-to-face and telephone sessions (with participant consent), using a digital recorder and (when required) a telephone-recording device.

These recordings were used to examine fidelity to the low-intensity interventions. A rating scale was developed based on the low-intensity intervention PWP manuals, which defined specific tasks to be carried out in session 1 and in subsequent sessions for both supported cCBT and guided self-help. Criteria for the fidelity scale were established via discussions within the OCTET team. The components extracted for fidelity were rated as ‘implicit’, ‘explicit’ or ‘absent’, and an overall rating generated using a 5-point Likert scale from ‘unacceptable’ to ‘excellent’. Fidelity was evaluated by a rater (a PWP independent of OCTET), who was blind to the treatment outcome.

Site recruitment

Mental health trusts across four UK centres in England (Manchester, York, East Anglia and Sheffield) were involved in the trial. A dedicated site lead was allocated at each centre. Trusts were recruited throughout the trial and further support was sought from the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) to engage with additional trusts.

Patient recruitment

Inclusion criteria

-

Adults aged ≥ 18 years.

-

On a waiting list for high-intensity CBT in either primary or secondary mental health-care settings.

-

Met DSM-IV criteria for OCD, assessed using six OCD questions from the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview,40 module G.

-

Scored ≥ 16 on the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale – Self-Report (Y-BOCS-SR), indicating a moderate level of OCD. This is the cut-off score used in most trials. Previous studies suggest that only a minority of people are referred for treatment or excluded from trials with a Y-BOCS score of < 16 (e.g. 2.3%,41 0%,42 14%25).

-

Reported an ability to read English at a level of age ≥ 11 years.

Exclusion criteria

-

Actively suicidal.

-

Had organic brain disease.

-

Currently experiencing psychosis.

-

Had a diagnosis of alcohol or substance dependence using DSM-IV criteria (assessed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview,40 modules I and J).

-

Currently receiving psychological treatment for OCD.

-

Had literacy or language difficulties to an extent that would preclude them from reading written or web-based materials.

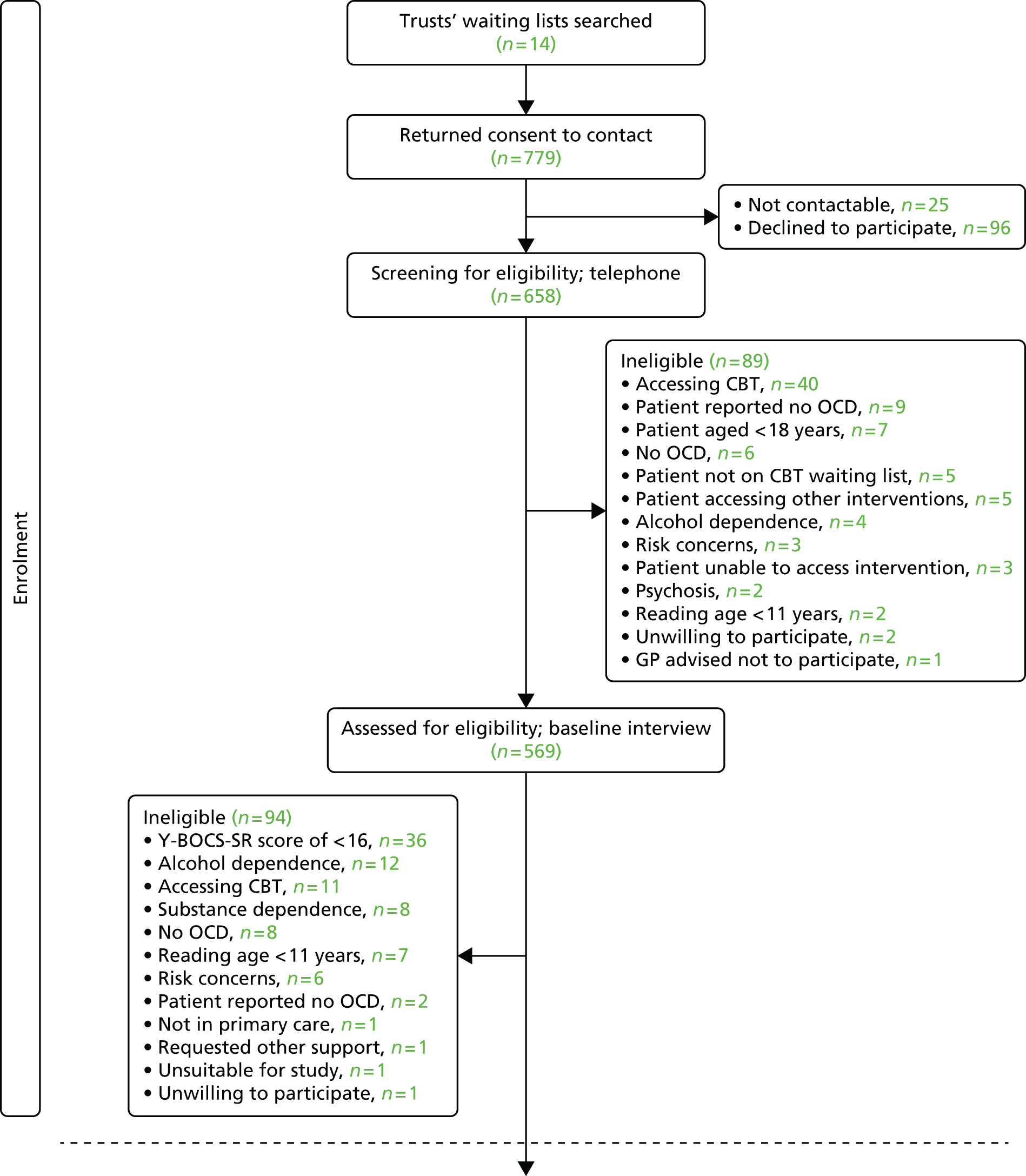

Potential participants were identified using a variety of recruitment methods: waiting lists in primary and secondary care in our clinical sites were screened by administrative and clinical staff; PWPs screening patients entering services identified those who may be eligible; and self-referral options were used at one site (i.e. via adverts in local newspapers, GP surgeries, on social media sites and community centres).

Individuals who were waiting for high-intensity CBT or responded to an advert were provided with a participant information pack (including an invitation letter, patient information sheet and consent-to-contact form) in the post or in person. Those who returned a completed consent-to-contact form initially took part in a brief telephone eligibility screen to determine that they were aged > 18 years, not currently receiving a psychological therapy for their OCD symptoms or experiencing severe and distressing psychotic symptoms. Where participants met the initial eligibility screen they were offered a face-to-face eligibility appointment (either at the clinical site or in their own home). During the interview, individuals had the opportunity to ask any further questions prior to providing consent and completing the eligibility assessment.

Randomisation, concealment of allocation and blinding

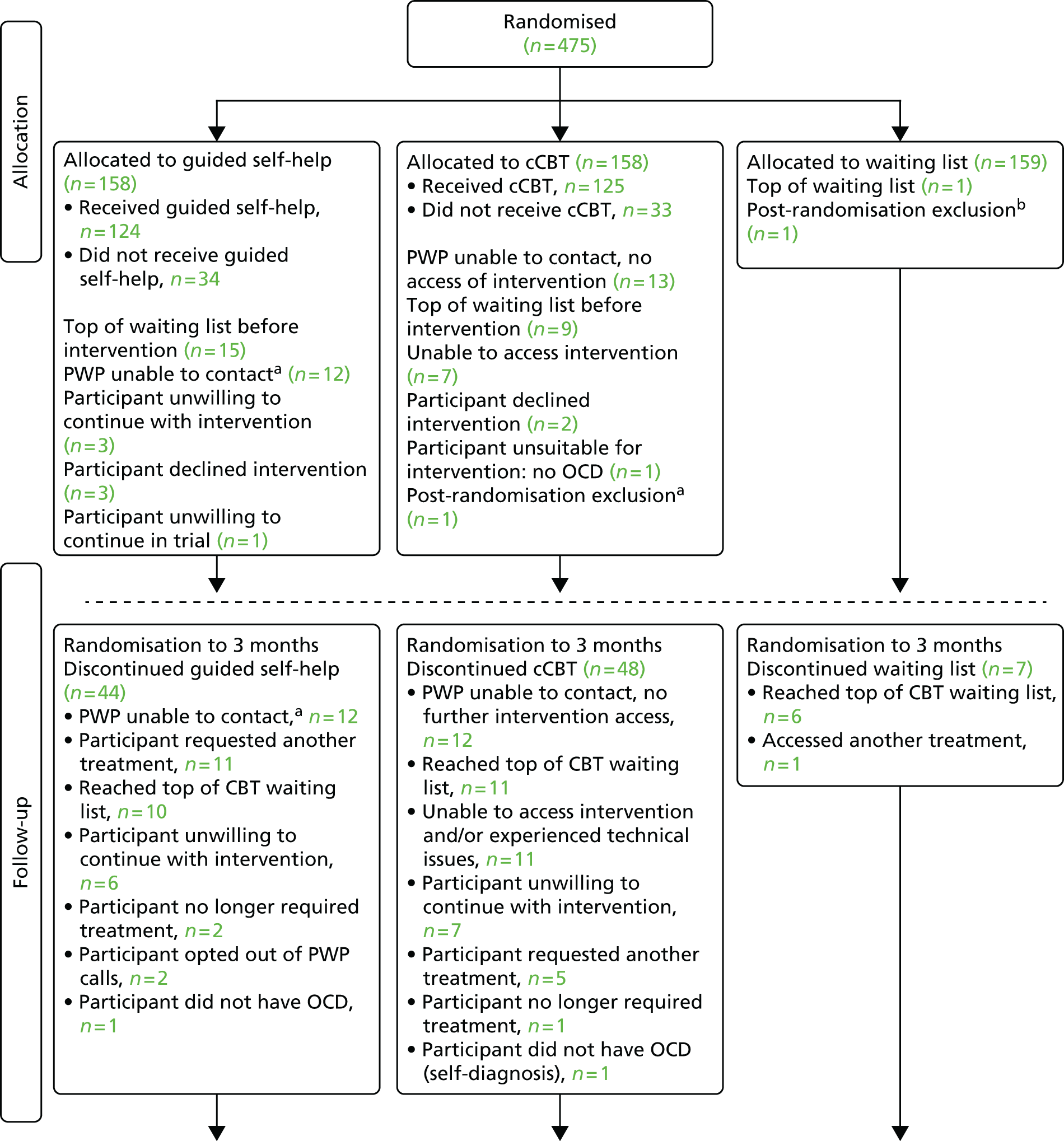

Patients were randomised (in a ratio 1 : 1 : 1) into one of the three arms using a central randomisation service, via a secure web-based system administered by the York Trials Unit (YTU).

Allocation involved minimisation on the following factors:

-

OCD severity on the Y-BOCS-SR (16–23, moderate; 24+, severe/very severe)

-

current antidepressant medication use (yes/no)

-

depression on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (< 10, mild depression; 10–14, moderate depression; 15–19, moderate to severe depression; > 20, severe depression)

-

duration of OCD (0–5 years; 6–10 years; > 10 years).

Researcher blinding

We attempted to blind outcome assessors to allocation; by ensuring that outcome assessments by researchers were separate from days and locations in which treatment was delivered, asking OCTET participants to refrain from revealing allocations during assessments and restricting researcher access to the group allocation section of the trial database.

Blinding was monitored throughout the trial. Researchers were asked to complete an unblinding report form at all follow-up time points, indicating if they had been unblinded and, if so, at what point during the interview this occurred. Partial (treatment/no treatment) or full unblinding (trial arm) was recorded. Researchers were also asked to complete an unblinding form if they became unblinded at any other point during the trial (e.g. when arranging a follow-up interview with the participant).

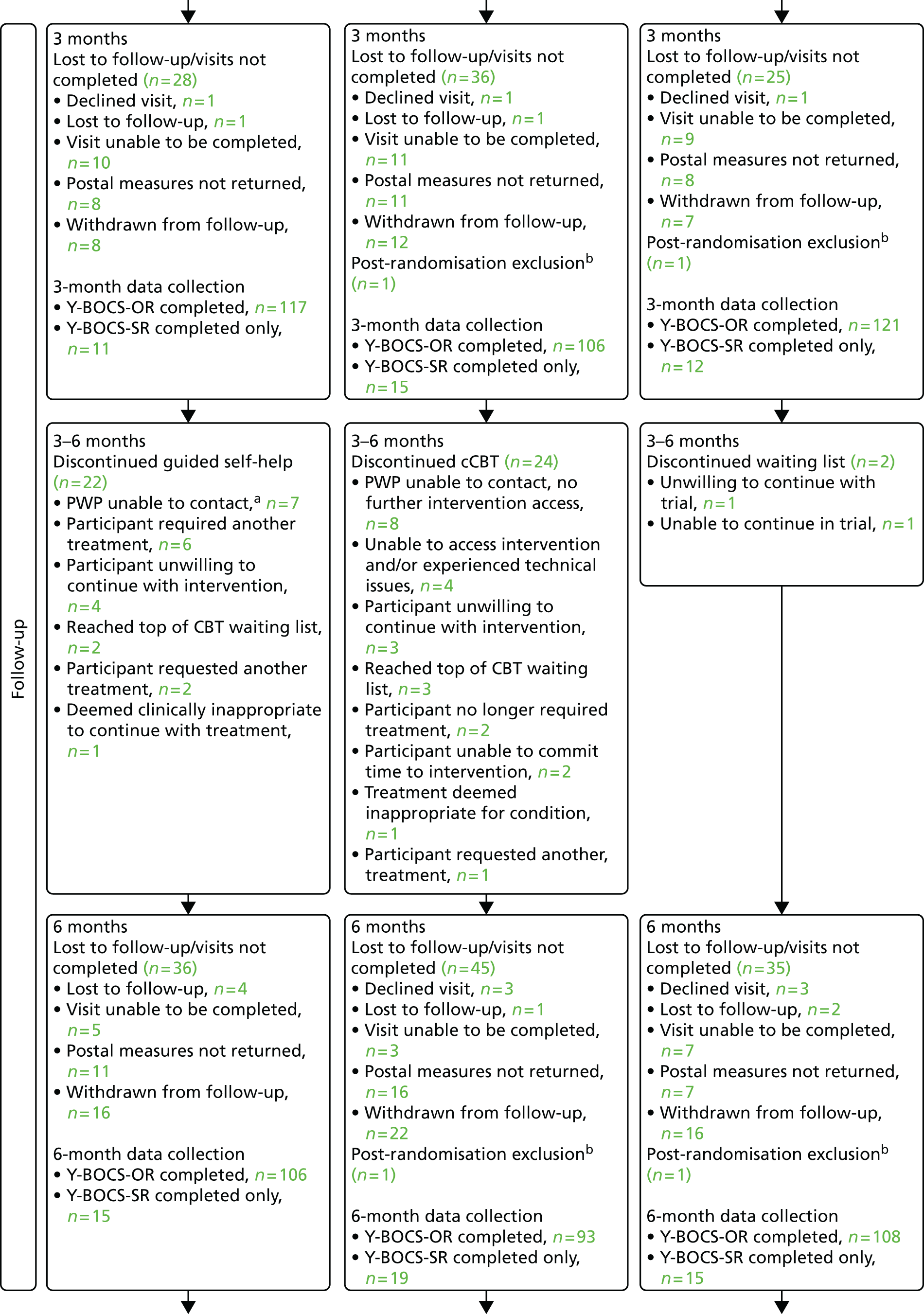

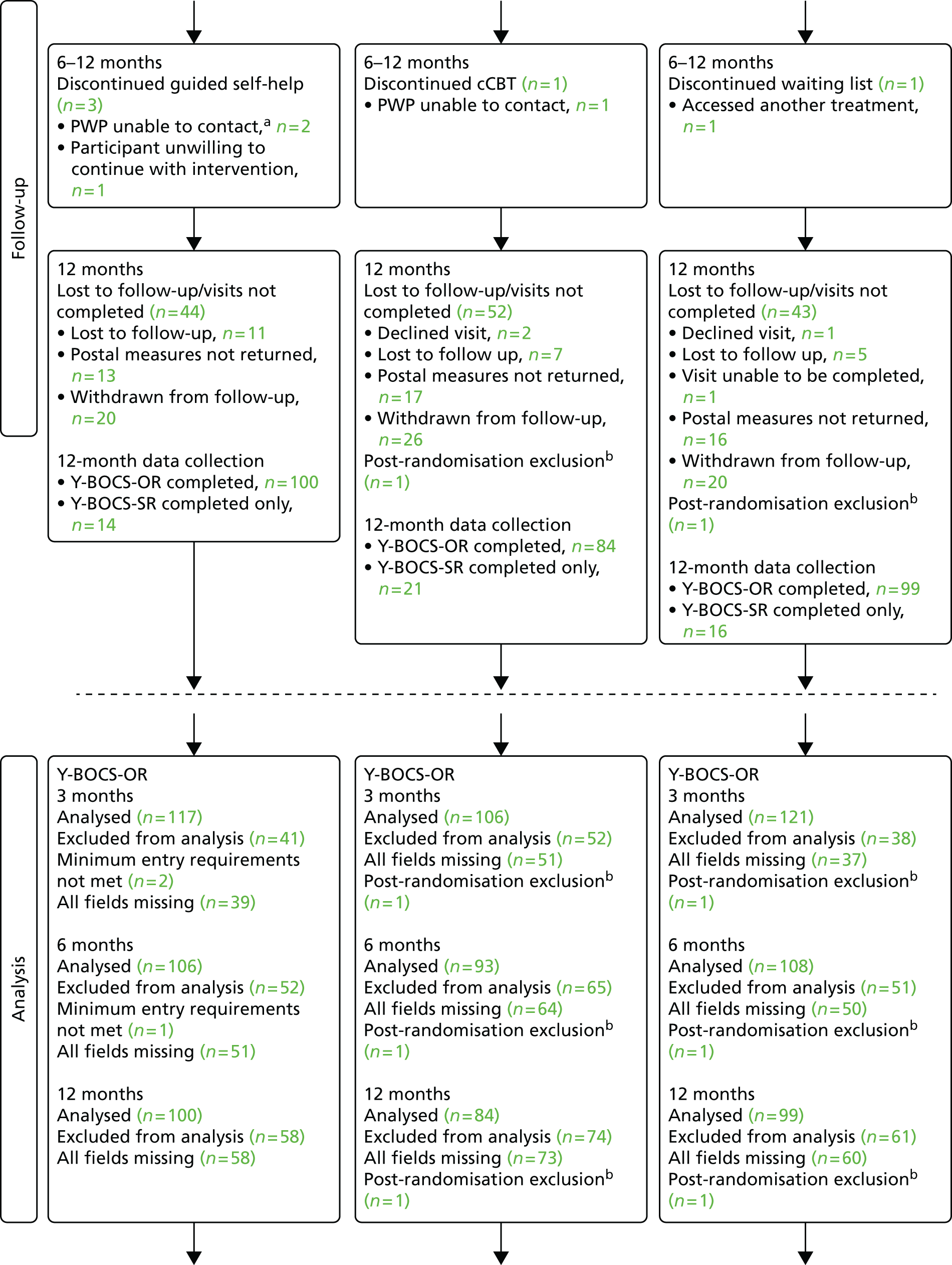

Follow-up assessments

Follow-up assessments were conducted 3, 6 and 12 months following randomisation. Participants were contacted approximately 1 month to 1 fortnight prior to the follow-up time point to arrange a suitable time and location to meet (either at the clinical site or in their own home). To reduce the chance of the researcher becoming unblinded, the Adult Service Use Schedule (AD-SUS) self-complete, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (CSQ-8) and Pathway questionnaire were posted prior to the visit for return in a Freepost envelope to the YTU. Participants were given a £5 shopping voucher to thank them for their time for each follow-up they completed or partially completed.

Outcome assessments

As the primary outcome was the Y-BOCS-OR, the collection of data was face to face. However, we acknowledged that achieving this with all follow-ups could prove difficult. Therefore, we developed a highly structured standardised operating procedure (SOP) to assist researchers with participants who were difficult to contact, to ensure retention rates were maximised. These procedures included contacting participants using a scaling-down approach (i.e. if not willing/unable to attend face to face we offered telephone assessment using Y-BOCS-SR and if this failed, to post the primary outcome with a Freepost envelope for return to the YTU).

Measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was OCD symptoms as measured by the Y-BOCS-OR. 43 The Y-BOCS-OR is an interview-administered structured assessment that measures symptom severity in individuals with obsessive and compulsive symptoms. It consists of two comprehensive symptom checklists, exploring current (over the past week) and past symptoms, and a 10-item severity scale with obsession and compulsion subscales exploring current symptoms. The severity scale is designed to identify the impairment experienced by individuals over five clinical domains: time consumed, functional impairment, psychological distress, efforts to resist and perceived sense of control. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (none) to 4 (extreme). Responses to all items are added to generate subscale scores and a total Y-BOCS-OR score. Scores are indicative of OCD severity over five severity categories: 0–7 (subclinical), 8–15 (mild), 16–23 (moderate), 24–31 (severe) and 32–40 (extreme).

The interview took, on average, 30–40 minutes to complete. Individuals conducting the interview required prior training on OCD symptomatology and in how to rate respondents’ responses. The Y-BOCS-OR has good psychometric properties. 43,44

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes are listed in Table 1, adapted with permission from Gellatly et al. 34

| Secondary outcome | Measured using/by |

|---|---|

| Self-reported OCD symptoms | Y-BOCS-SR |

| Self-reported health-related quality of life | SF-36 |

| Health-related quality of life | EQ-5D-3L |

| Resource use | AD-SUS |

| Generic mental health | CORE-OM |

| Depression | PHQ-9 |

| Anxiety | GAD-7 |

| Functioning | WSAS |

| Employment status | IAPT employment status questions A13–14 |

| Patient satisfaction | CSQ-8 |

| Patient progress through mental health services/proportion of patients not improved or partially improved and requiring more intensive CBT | Pathway questionnaire |

| Comorbiditiesa | CIS-R |

| Attachmenta,b | Relationship Styles Questionnaire |

| Perceived criticisma,b | Perceived Criticism Scale |

| Expressed emotiona,b | Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale |

Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale – Self-Report

The Y-BOCS-SR43 is a modified version of the Y-BOCS-OR scale for completion by individuals in the absence of an interviewer. Identical questions from the Y-BOCS-OR 10-item severity scale are presented along with responses for each for the individual to select.

As research has demonstrated a moderate relationship between the Y-BOCS-OR and Y-BOCS-SR in a clinical sample of OCD patients,45 it was agreed at the inception of the trial that, where it was not possible to complete the Y-BOCS-OR (primary outcome measure), the Y-BOCS-SR would be used as a proxy for the primary outcome.

Short Form questionnaire-36 items

The Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)46 is a widely used generic measure of health-related quality of life. It has eight dimensions of health: physical functioning; social functioning; physical role limitations; emotional role limitations; energy; pain; mental health; and general health perceptions. Individuals provide responses based on how they have felt over the previous week on Likert-type scales. Each question carries equal weight, and is transformed into a 0–100 scale. Lower scores denote more disability. Two summary scores are produced: the mental health component score and the physical health component score. The scale has good psychometric properties. 47

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions-3 levels

The European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions-3 levels (EQ-5D-3L)48 is a self-complete instrument used to measure health-related quality of life, providing health utility scores capable of generating quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). It consists of five questions addressing five dimensions of health: mobility; self-care; ability to undertake usual activities; pain and discomfort; and anxiety and depression. Respondents report difficulties in each area on three levels (none, some/moderate, extreme), generating individual health states that can be converted into a weighted health index score, based on values derived from general population samples. 49 The measure has been extensively used and its psychometric properties are adequate. 50

Adult Service Use Schedule

The AD-SUS was used to measure individual-level resource use over the period of the trial. The AD-SUS is used to collect service use and related data, and has been successfully applied in a range of adult mental health populations, including common mental disorders. 51–53

The AD-SUS was adapted for OCD on the basis of clinical expertise and refined using feedback from a stakeholder group of service users and carers to assess coverage, acceptability, ‘user friendliness’ and ease of completion. The AD-SUS was completed in an interview with participants and recorded all-cause hospital- and community-based health- and social-care services, use of psychotropic medication and out-of-pocket expenses and savings. Use of psychological therapies (‘talking therapies’) was recorded using a separate self-complete version of the AD-SUS to ensure that interviewers remained blinded to randomisation allocation status.

Productivity losses were also recorded, using the absenteeism questions from the World Health Organization’s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). 54,55

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM)56 is a self-complete measure designed to measure global distress. Thirty-four questions explore how individuals have been feeling over the last week, using a 5-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘most or all of the time’. Four dimensions of global distress are addressed: subjective well-being; problems/symptoms; life functioning; and risk/harm. Eight items are positively framed and scoring for these is reversed. Higher scores indicate higher levels of distress. The CORE-OM has high internal and test–retest reliability, and demonstrates convergent validity with other measures. 57

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

The PHQ-958 is a 9-item self-report scale that facilitates the recognition and diagnosis of depression. Scores range from 0 to 27, with a score of ≥ 10 considered to be a clinically significant level of depression. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated good reliability and validity. 59

Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale-7

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7)60 is a 7-item self-report scale used to identify and measure the severity of generalised anxiety disorder. Scores range from 0 to 21, with a cut-off score of ≥ 8 distinguishing between clinical and non-clinical populations. Good psychometric properties have been reported. 60

Work and Social Adjustment Scale

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)61 is a 5-item self-report measure that assesses functional impairment. Scores range from 0 to 40. The scale assesses the impact on work, home, social and private activities, and personal or family relationships. A score of > 20 provides indication of severe functional impairment, whereas scores between 10 and 20 suggest less severe but significant functional impairment. Scores of < 10 are considered subclinical. The scale is reported to display good reliability and validity. 61

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies employment status questions A13–14

This consists of two questions addressing the employment status of individuals and if statutory sick pay is being received. This measure is used as part of the IAPT minimum data set. 62

Pathway questionnaire

This is a self-complete measure developed specifically for use within OCTET to identify whether patients had or had not stayed on the waiting list for high-intensity CBT.

Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised

The Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised (CIS-R)63 is a self-administered computerised assessment of psychiatric disorder. The interview begins with general questions to establish an overall picture of health, appetite and physical activity. The main body of the CIS-R contains 14 sections labelled A–N. Each section scores a symptom, which may range in severity between 0 and 4. These symptoms are somatic symptoms, fatigue, concentration and forgetfulness, sleep problems, irritability, worry about physical health, depression, depressive ideas, worry, anxiety, phobias, panic, compulsions and obsessions.

The diagnostic output corresponds to the ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders64 diagnostic criteria for mild, moderate and severe depressive episodes. CIS-R has established reliability and validity in primary care, occupational and community studies. 63

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8

The CSQ-865 is a self-report scale that asks patients to assess their satisfaction with a service on a 4-point Likert scale. Scores range from 8 to 32, with higher values indicative of higher satisfaction. The measure has been tested with diverse client samples and demonstrates good retest reliability, internal consistency and sensitivity to treatment. 66

Table 2 provides detail about the time points at which each measure was completed.

| Outcome measures | Time point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Y-BOCS-OR | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Y-BOCS-SR | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| SF-36 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| CORE-OM | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| PHQ-9 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| GAD-7 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| WSAS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| EQ-5D-3L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| IAPT employment status questions A13–14 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| CSQ-8 | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| CBT uptake (Pathway questionnaire) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| AD-SUS – interview | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| AD-SUS – self-complete | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| CIS-R | ✗ | ||||

Researcher training

Researchers and clinical study officers (CSOs) from the MHRN involved in the recruitment of participants were provided with a 1-day training session covering trial procedures and completion of eligibility, baseline and follow-up interviews. The trial manager provided training. A proportion of the day was spent equipping individuals with the necessary skills to complete the Y-BOCS-OR. Inter-rater reliability among the researchers/CSOs was employed to measure agreement between ratings for the Y-BOCS-OR. Top-up training was provided throughout the trial.

Inter-rater reliability: Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale – Observer Rated

All researchers and CSOs who undertook the 1-day training were trained on the purpose, content and conduct of the Y-BOCS-OR. During the training, a practice recording of a Y-BOCS-OR interview (conducted by an expert clinician) was played and ratings were collected and discussed in a group format. Researchers were informed that if they were experiencing difficulties making a decision about the score to any of the questions, they should allocate the higher of the two scores. All researchers had the opportunity to ask questions and any queries were addressed. The aim was to investigate the inter-rater reliability between researchers/CSOs and the expert rating of the practice sessions. Total scores for the measure were compared; a difference of 4 points between researcher/CSO ratings and expert ratings was tolerated. In addition, if differences in ratings crossed diagnostic boundaries a reassessment may be required. Where the tolerance criterion was not met, a discussion was held with the researcher/CSO and additional training and advice provided.

Following the training day an additional practice recording was provided and researchers/CSOs were asked to return their rating to the trial manager within 2 weeks. Ratings were again compared with the expert score. During the trial (6 months following commencement) researchers were asked to rate a third practice tape. A ‘cues and prompts’ sheet was prepared to assist with the conduct of the Y-BOCS-OR.

Sample size calculation

At each time point three pairwise comparisons were carried out between the three intervention options: supported cCBT, guided self-help and a waiting list for high-intensity CBT. The study was therefore powered using a 1.67% significance level.

The comparison of either supported cCBT or guided self-help is a partially nested design for which the sample size calculation needs to consider the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for therapist. The comparison of supported cCBT with guided self-help is a crossed therapist design, as support for both treatments was delivered by the same therapists. Sample size for crossed therapist design depends on the ICC for therapist for treatment within therapist, which is smaller than the ICC for therapists. Formulae for this calculation are given in Walwyn and Roberts. 67 In the absence of estimates of the two ICCs required for the two calculations, sensitivity of study power to larger values was considered in the calculation below.

Assuming a standard deviation (SD) for the primary outcome (Y-BOCS-OR) at 6 months of 7.3 units, a correlation between baseline Y-BOCS-OR and 6-month Y-BOCS-OR of 0.43,41 a study with 366 service users followed up to the primary end point has a power > 80% to detect a difference of 3 Y-BOCS points for each comparison. We were unable to find evidence for a ‘clinically important difference’. A reduction of 3 points was agreed based on clinical consensus with the study team. This calculation assumed that supported cCBT and guided self-help were delivered by 24 therapists. It also assumes that the ICC for therapists was 0.06 and an ICC for treatment within therapist was 0.015, which implies that the correlation between the random effect for supported cCBT and guided self-help is 0.75. The design effects, sometimes called the sample size inflation factor, were 1.1225 and 1.06125 for the partially nested and crossed designs, respectively. We considered these values of the ICC to be plausible, but in the event that the ICC for therapist was as large as 0.1 and the ICC for treatment within therapist was 0.05, the power of the trial is still > 75% for all three comparisons.

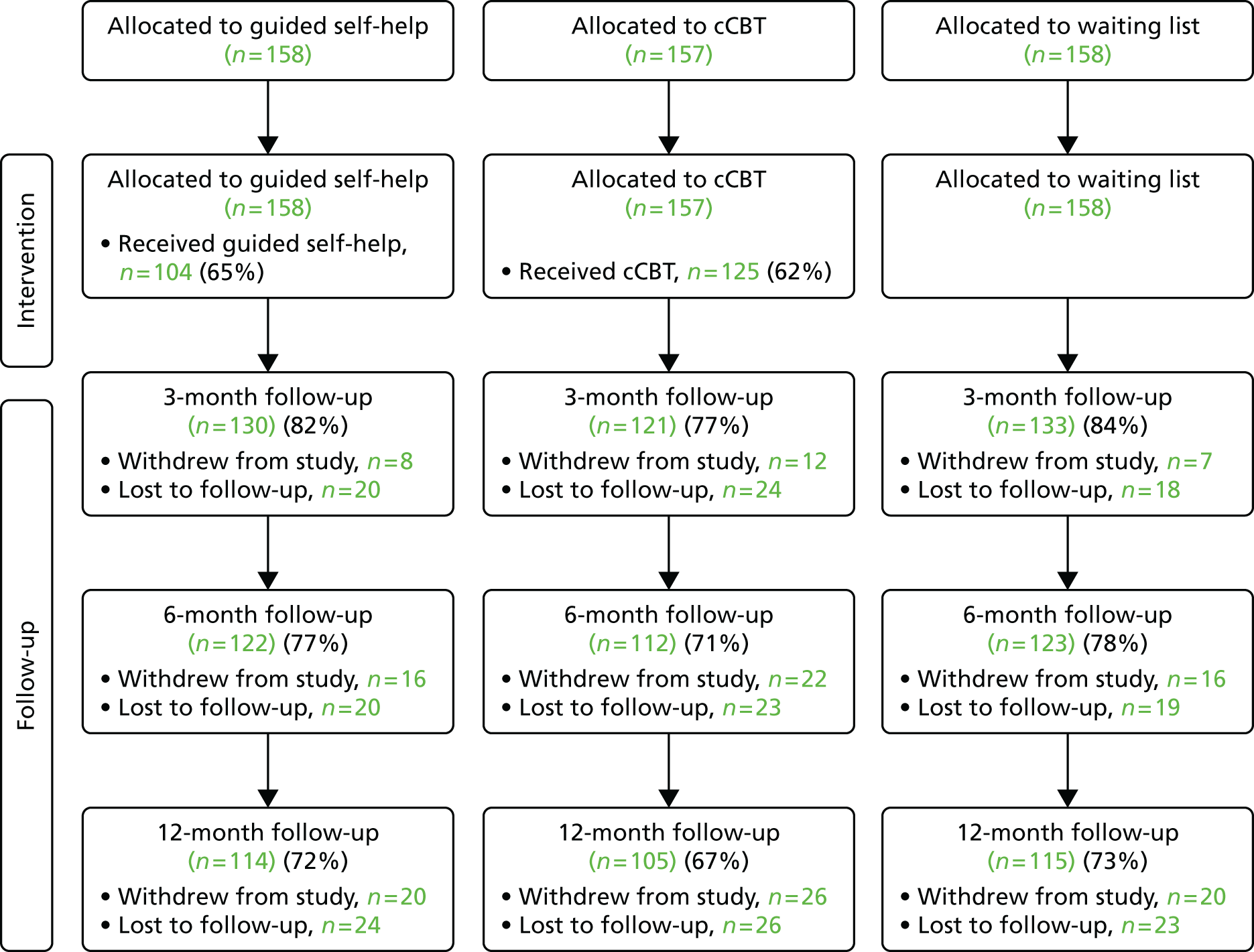

Based on an 85% follow-up rate, the target sample size for the trial was set at 432 in the initial application. Monitoring during the trial suggested that the follow-up rate to the primary end point (3 months) was likely to be lower rather than the assumed 85%. Assuming a follow-up rate of 78%, total sample size was increased to 472.

Analysis

Low-intensity intervention uptake

Patient engagement with the treatment process was summarised and reported descriptively. There is no consensus for the level of uptake of low-intensity treatments that might define an appropriate ‘dose’.

Analysis of the primary outcome measure and secondary quantitative outcome measures

Cleaning of outcome and baseline data was conducted without the treatment group allocations in view. Summary statistics from these preliminary analyses were reviewed by the trial research team to identify data errors.

Preliminary analyses compared the characteristics of subjects with and without complete data at follow-up time points, by treatment group, using a logistic regression model. This was carried out for the primary outcome at the three follow-up assessment points. This analysis was used to develop an understanding of the missing data mechanism and to determine the appropriate methods for dealing with missing outcome data.

Statistical analyses of the primary outcome measure, Y-BOCS-OR, are based on a linear mixed model with random effects for supported cCBT and guided self-help therapist using restricted maximum likelihood. As therapist is crossed with treatment, separate random effects were included for each treatment enabling the estimation of the intracluster correlation for supported cCBT and guided self-help. In addition to treatment, the following fixed baseline or demographic covariates were included to improve statistical efficiency:

-

OCD duration (by categories 0–5, 5–10, > 10 years)

-

OCD severity (as measured by Y-BOCS-OR at baseline)

-

anxiety (as measured by GAD-7)

-

depression score (as measured by PHQ-9)

-

antidepressant drug use (yes/no)

-

sex.

A small number of baseline covariates were missing for those covariates not used in the minimisation. To maximise the number of subjects included in the model, these values were imputed by single imputation using other covariates in keeping with the method suggested by White and Thompson. 68 Using this procedure, statistical modelling can be carried out on all participants with outcome data. A logistic regression model was used, fitted to CBT uptake, with treatment allocation, sex, duration of OCD, baseline Y-BOCS-OR, GAD-7, PHQ-9 and antidepressant medication on entry into the trial as covariates.

The same analyses were carried out for quantitative secondary outcomes. These analyses assume that subjects are missing at random.

Uptake of high-intensity cognitive–behavioural therapy

Uptake of high-intensity CBT was recorded at the 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. A logistic regression model was used to estimate the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for uptake (as a binary outcome of a patient attending at least one CBT appointment), comparing the two low-intensity interventions separately with a waiting list for high-intensity CBT. The models included treatment allocation, sex, duration of OCD, baseline Y-BOCS-OR, GAD-7, PHQ-9 and antidepressant medication on entry into the trial as covariates. Where presented, tables give the adjusted ORs with confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values and the exponent of the model constant.

Recovery and remission

Recently, expert consensus guidelines for defining treatment response and remission in OCD have been published based on YBOC-OR. 69 These are defined as ≥ 35% reduction on the Y-BOCS-OR for response and Y-BOCS-OR score of ≤ 12 for remission. A logistic model was fitted to responses at 12 months adjusting for sex, baseline GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores, antidepressant medication use at randomisation and duration of OCD. The analysis is additional to the statistical analysis plan as this was signed-off prior to publication of the guidelines.

Moderator analyses

A subgroup analysis by severity specified in the trial protocol was conducted by adding a treatment severity interaction term to the analysis of the primary outcome at the primary end point (3 months). In addition, analysis of treatment effect moderation by both age and chronicity of OCD was carried out.

Two types of interactions between moderators and treatment can occur. If the moderator is just affecting the magnitude of the treatment effect it is called a quantitative interaction. If the moderation causes a reversal of the treatment effect it is called a qualitative interaction. Interactions of treatment with both chronicity and severity were hypothesised to be quantitative, whereas interactions of treatment with age were hypothesised to be qualitative (representing potential difficulties of older patients in engaging with supported cCBT relative to guided self-help). Thus, a significant treatment effect would be required before assessing treatment moderation via severity and chronicity of OCD.

The analyses were carried out by adding a treatment with moderator interaction terms to the primary analysis model. For severity and chronicity, an overall test of the interaction was carried out. The hypothesis related to age concerned only the low-intensity interventions, so the contrast between guided self-help and supported cCBT was estimated.

Data were analysed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Economic evaluation

Perspective

The primary perspective of the economic evaluation was the NHS/Personal Social Services perspective preferred by NICE. Secondary analyses included all additional resources likely to be relevant to a societal perspective in this population: productivity losses (as a result of time off work resulting from illness), and out-of-pocket expenses and savings.

Data collection

An adapted version of the AD-SUS was used to measure individual-level resource use. The AD-SUS is used to collect service use and related data, and has been successfully used in a range of adult mental health populations. 51–53 The AD-SUS was adapted for OCD, as described above (see Secondary outcomes), and used to record all-cause hospital and community-based health- and social-care services, medication and out-of-pocket expenses and savings. Information on medications used including drug, dose and duration were collected for economic purposes only. Productivity losses were recorded using the World Health Organization’s HPQ. 54,55 The AD-SUS and HPQ were administered by interview at baseline, and the 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups, and covered the previous 6-month period at baseline interview and the time since last interview at each follow-up point. Data on the number and duration of supported cCBT and guided self-help contacts were recorded on a session-by-session basis by PWPs using an intervention proforma. Use of all other psychological therapies, including high-intensity CBT, was collected and self-reported by participants in a separate self-complete proforma kept separate from the AD-SUS in order to ensure that interviewers remained blinded to randomisation allocation status. Participants completed the form alone and placed it in a sealed envelope before handing it to the interviewers. Data on the number and duration of intervention contacts were recorded on a session-by-session basis by PWPs using an intervention proforma.

Costs

All costs are reported in pounds sterling at 2013/14 prices. Discounting was not relevant, as the follow-up did not exceed 12 months. Unit costs were applied to individual-level resource use data to calculate total costs per participant and are detailed in Appendix 2. In summary, unit costs for most hospital and primary care services were obtained from NHS Reference Costs,70 Unit Costs of Health and Social Care71 and the British National Formulary for medications. 72

Productivity losses because of OCD were calculated using the human capital approach by multiplying days off work attributable to illness by the individual’s salary and not accounting for early retirement resulting from illness. 73 Lost productivity costs were capped at 5 days per week (maximum of 130 days for the 6-month period and 65 days for the 3-month period).

Intervention costs

Psychological wellbeing practitioner sessions were costed using published data on the cost of low-intensity IAPT interventions,74 inflated to 2013/14 prices using the Hospital and Community Health Services Pay and Prices Index. 71 The approach is outlined in Appendix 3.

Training for PWPs to provide supported cCBT and guided self-help support was provided to all PWPs, and associated costs were calculated as outlined in Appendix 4.

For the supported cCBT arm, the cost to the trial of the OCFighter program was £10,000. This was divided by the 157 participants who were randomised to supported cCBT to give a cost per participant in this group of £63.69. In the guided self-help arm, participants were provided with a self-help manual (£1.87 per manual for printing costs only, excluding development and design costs as these are sunk costs), photocopied worksheets (£0.81 per set of photocopied sheets per participant) and a CD (£1.18 per CD, one per participant), plus £1.68 postage charge. Thus, the total cost of guided self-help materials per participant was £5.54.

Access to high-intensity CBT, for all groups, was recorded using the intervention proforma. Unit costs for CBT are reported in Appendix 2.

Analysis

Data were analysed using Stata. Participants were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis (i.e. according to the group to which they were randomised regardless of intervention compliance).

Costs and outcomes were compared at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months and are presented as mean values by arm with SDs. Mean differences and 95% CIs were obtained by non-parametric bootstrap regressions (1000 repetitions) to account for the non-normal distribution commonly found in economic data, with adjustment for clustering at the therapist level, using the ‘cluster’ option in Stata. To provide more relevant treatment-effect estimates75 regressions to calculate mean differences in costs were repeated with the further inclusion of covariates for the baseline value of the relevant variable (costs or EQ-5D-3L utility) plus variables thought to influence costs and outcomes: antidepressant drug use; anxiety (GAD-7); depression score (PHQ-9); sex; OCD duration (0–5, 5–10 and > 10 years); and Y-BOCS-OR score.

The primary analysis was a complete-case analysis (i.e. excluding those lost to follow-up or with missing ADSUS and/or EQ-5D-3L data at a particular time point). To explore the potential impact of excluding non-responders, we examined the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of those included in the analyses and those in the full sample. A secondary analysis was carried out with missing baseline, 3-month and 12-month total costs and outcomes imputed using the input imputation command in Stata (version 11) and including the baseline variables described above.

Cost-effectiveness was explored in terms of QALYs calculated using the EQ-5D-3L measure of health-related quality of life, assessed at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months. Appropriate utility weights were attached to health states76 and QALYs were calculated using the total area-under-the-curve approach with linear interpolation between assessments. 77

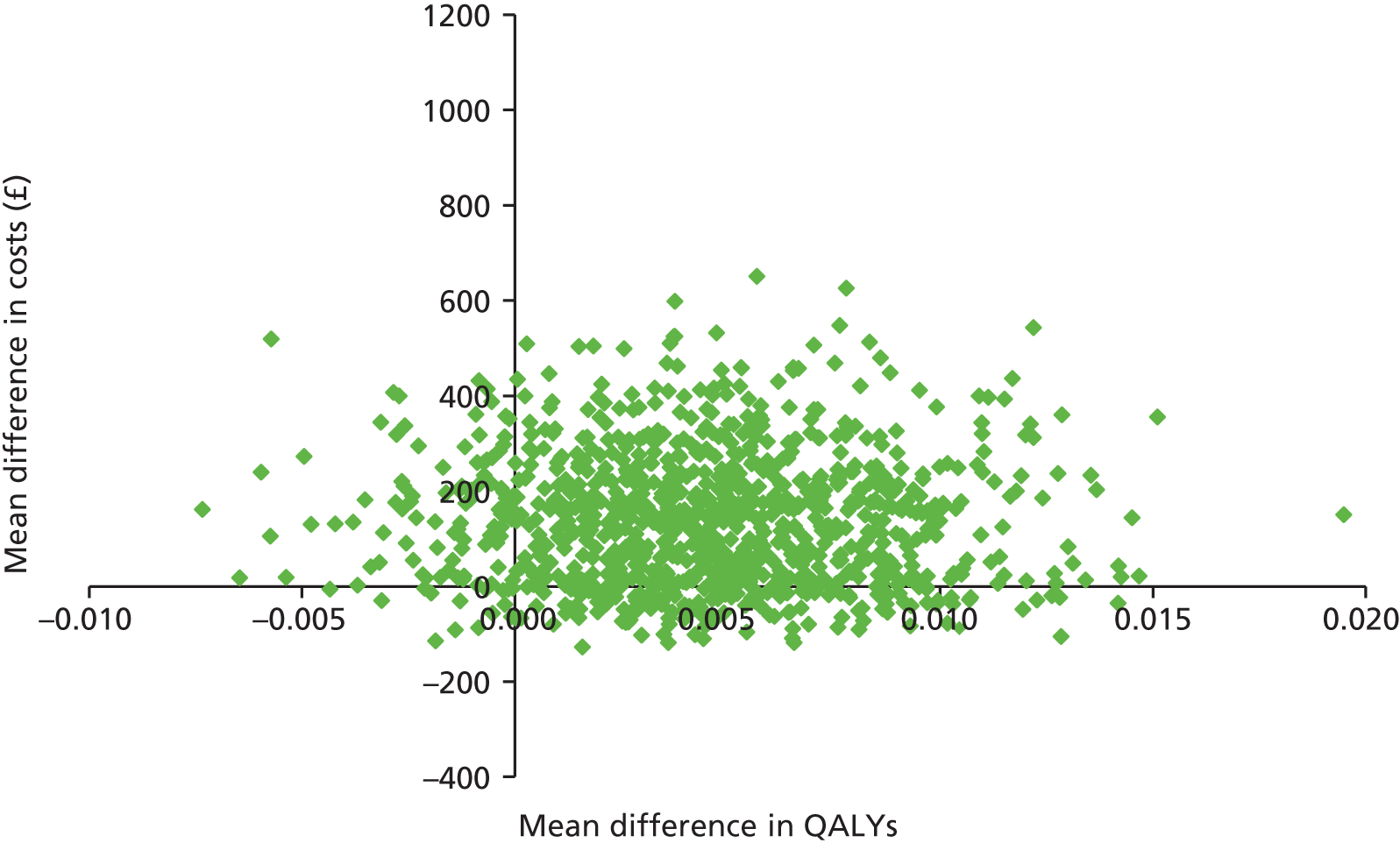

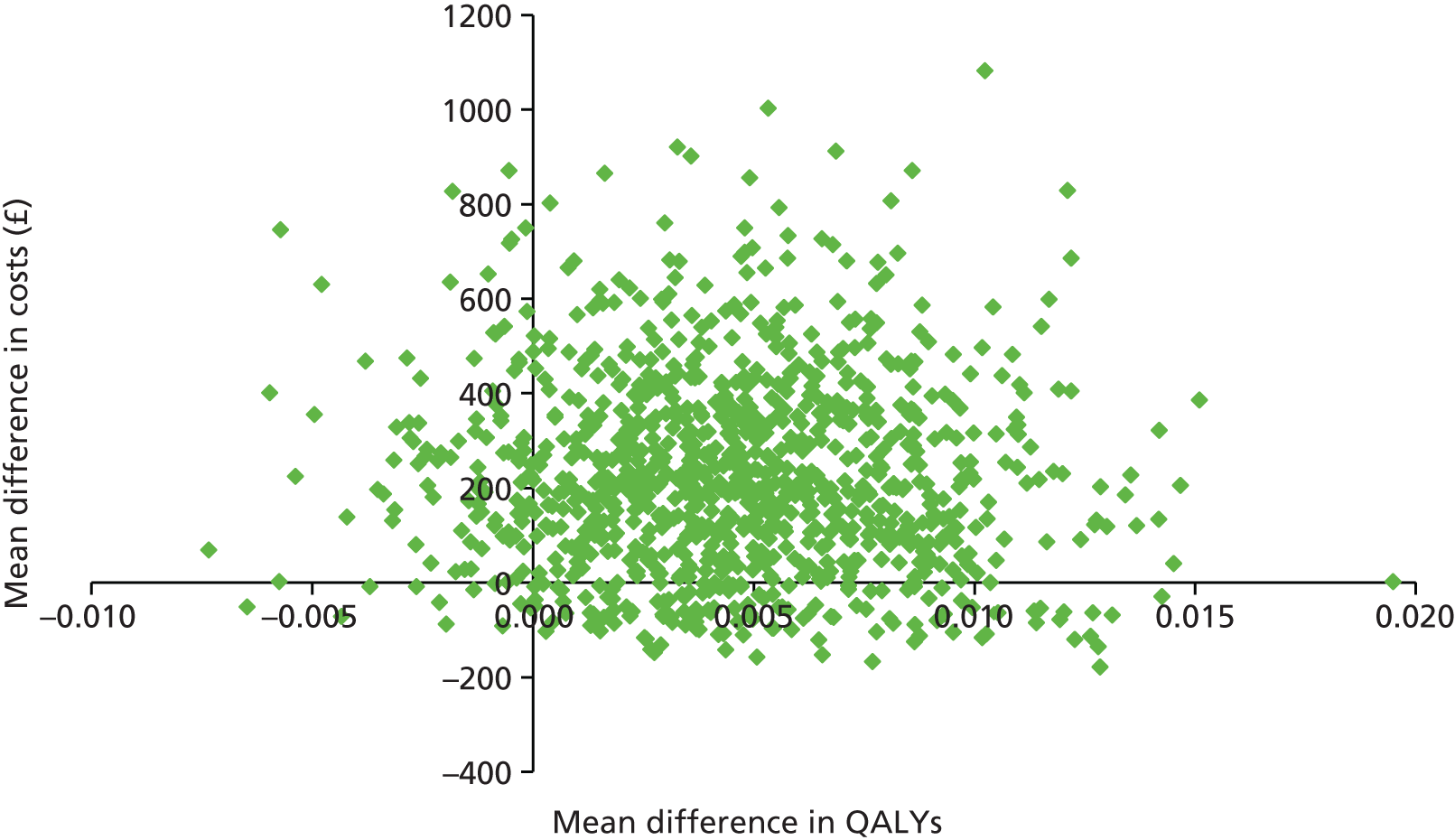

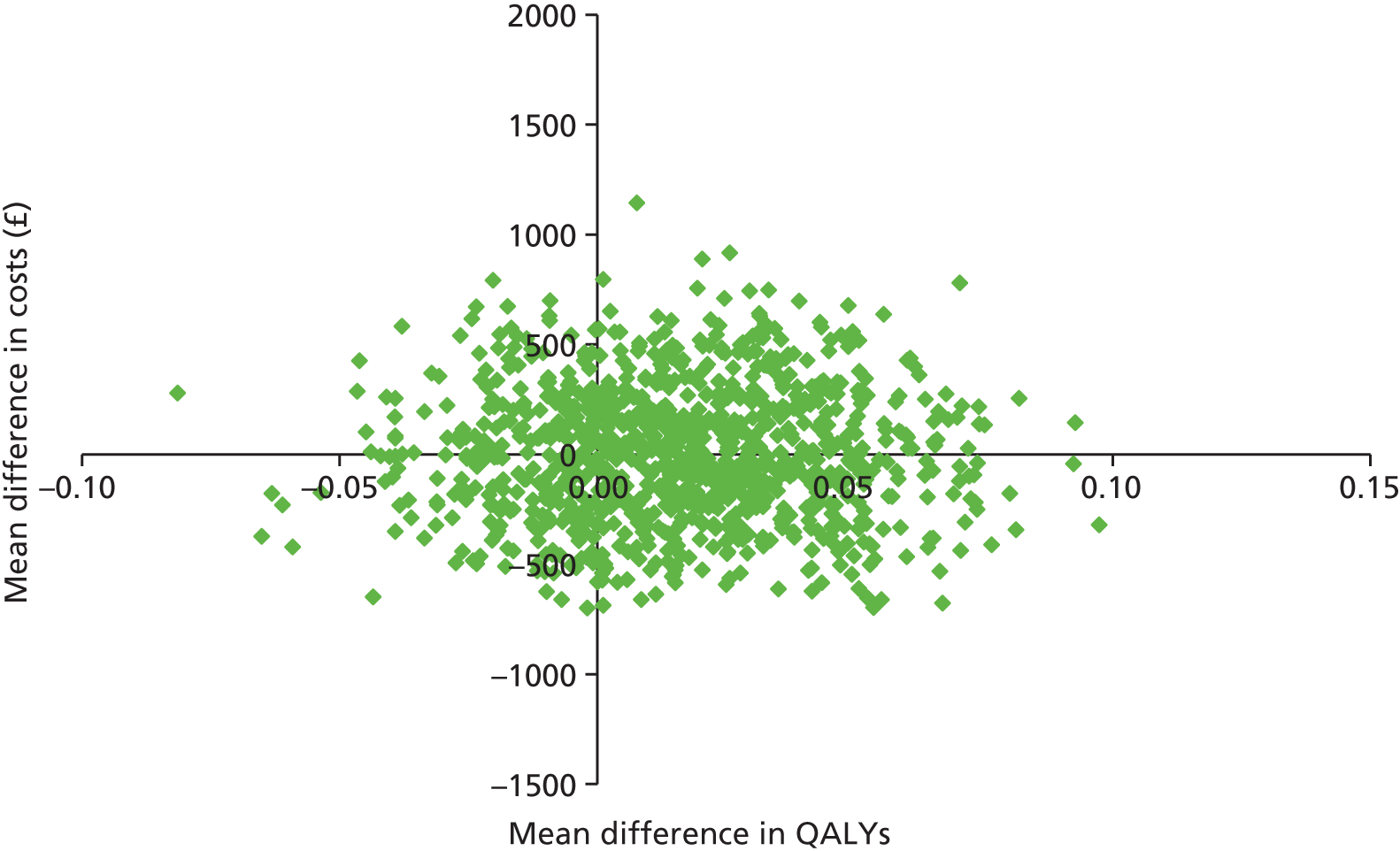

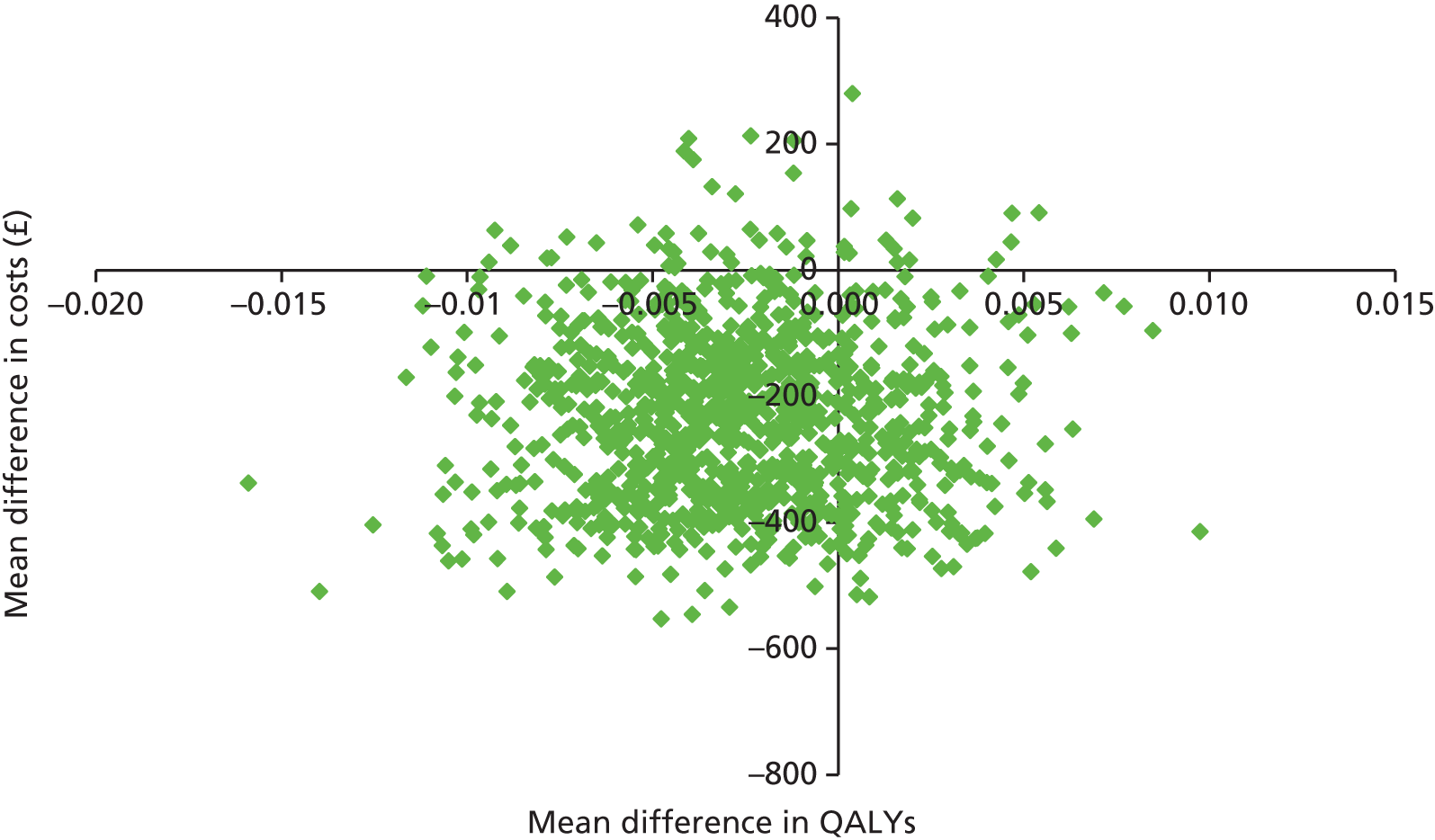

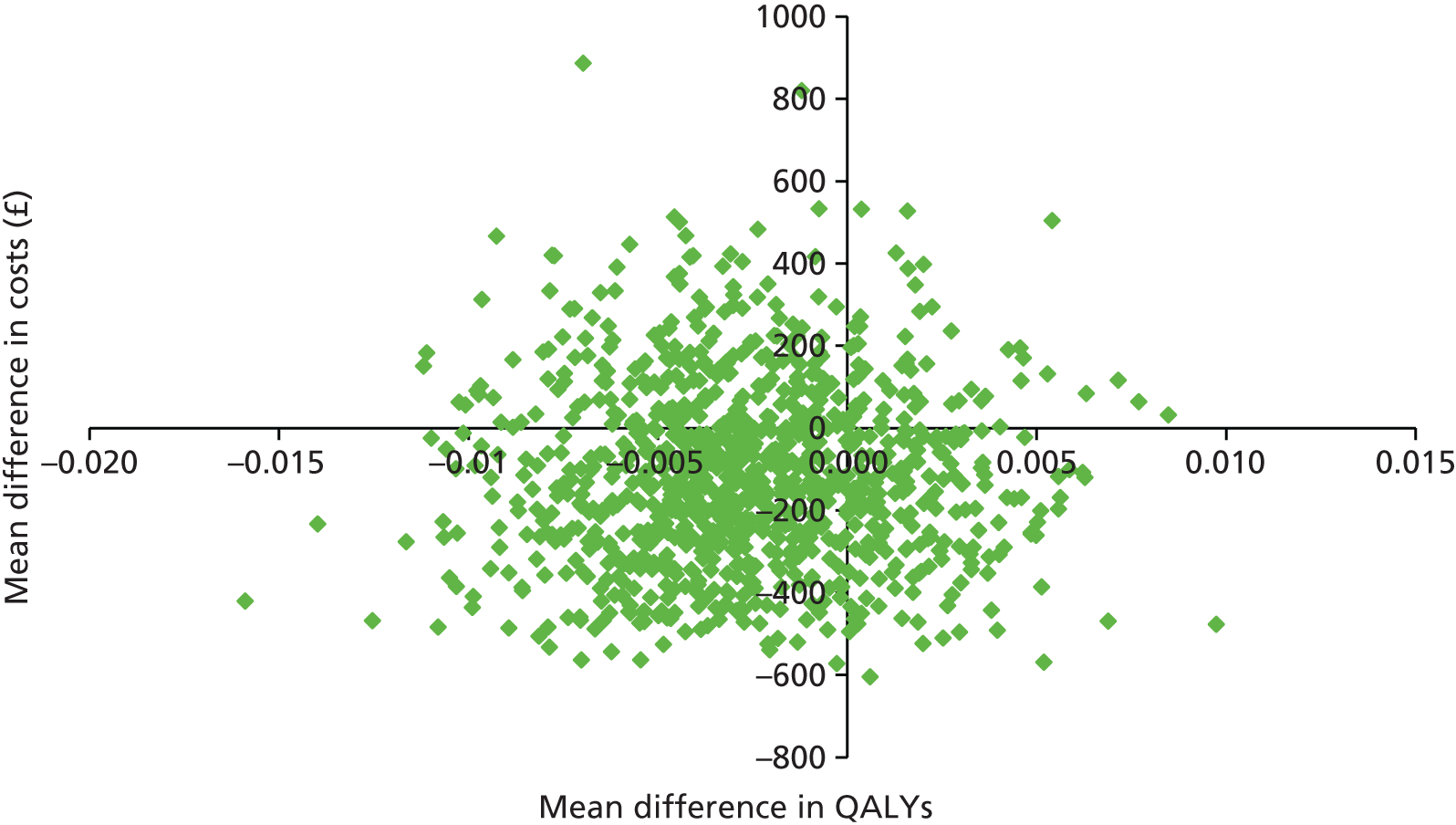

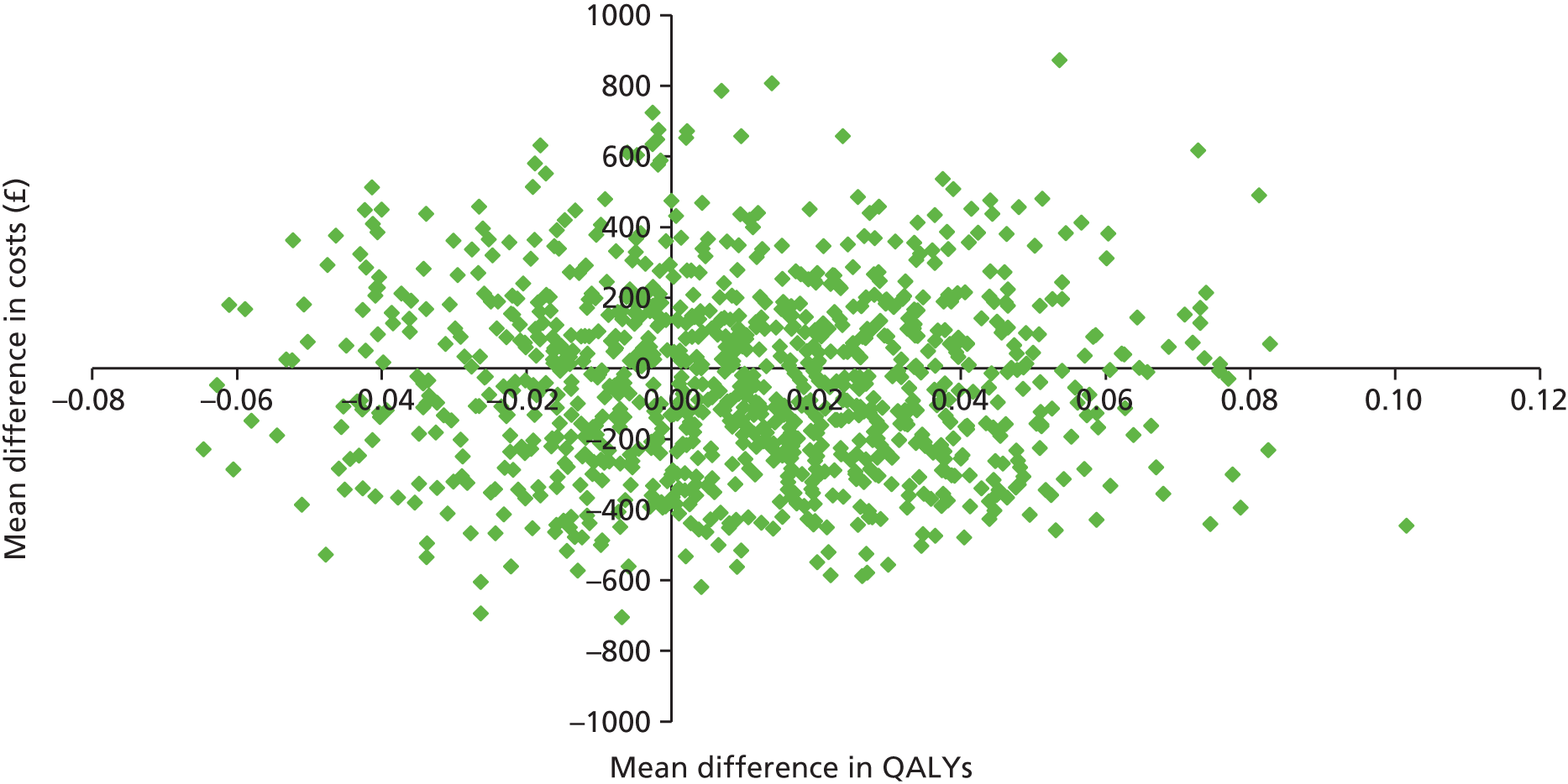

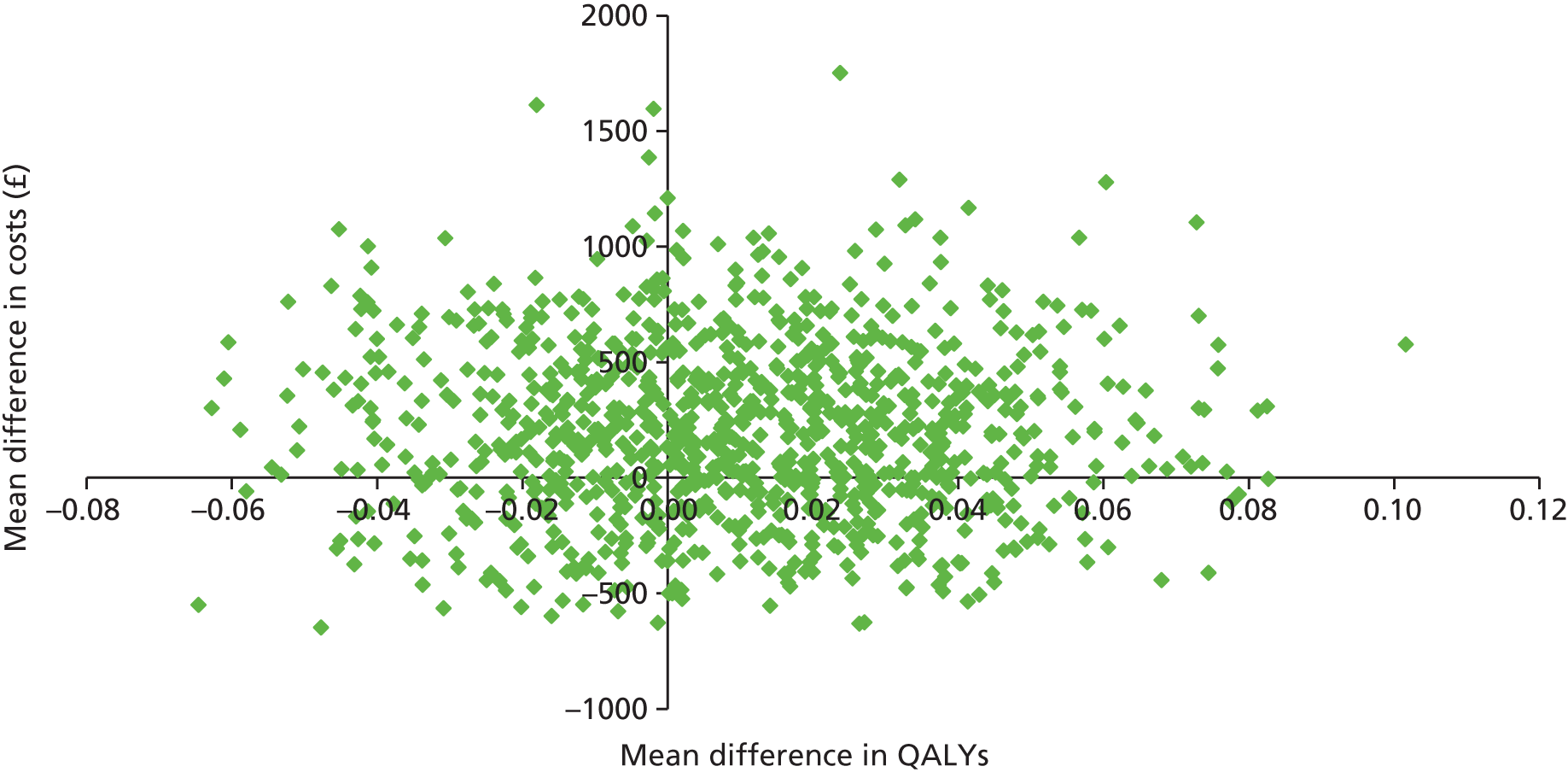

Two sets of cost–utility analyses were conducted: one compared groups at 3 months and one compared groups at 12 months (primary end point). Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated, defined as the mean difference in cost between two groups divided by the mean difference in effect.

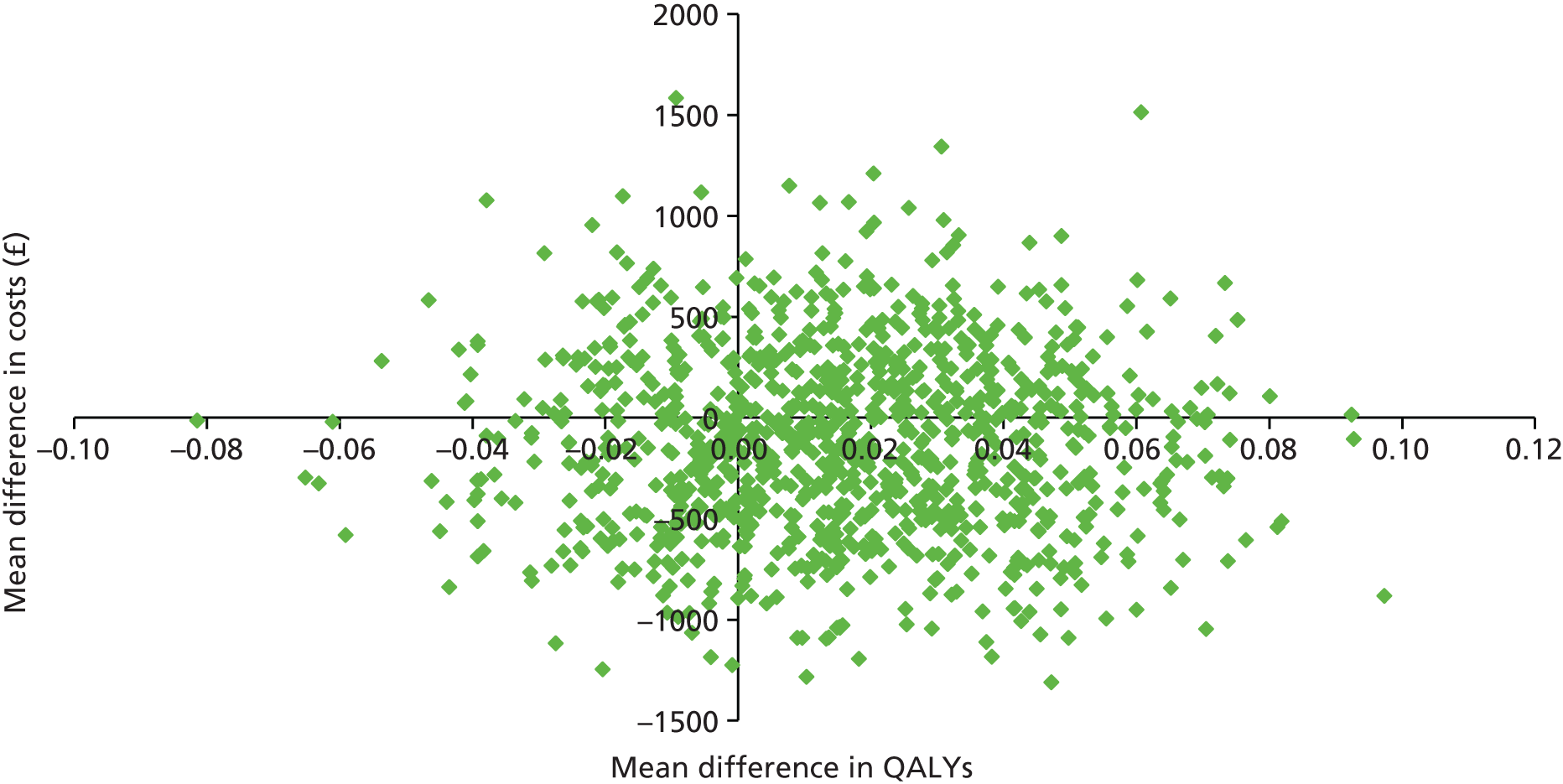

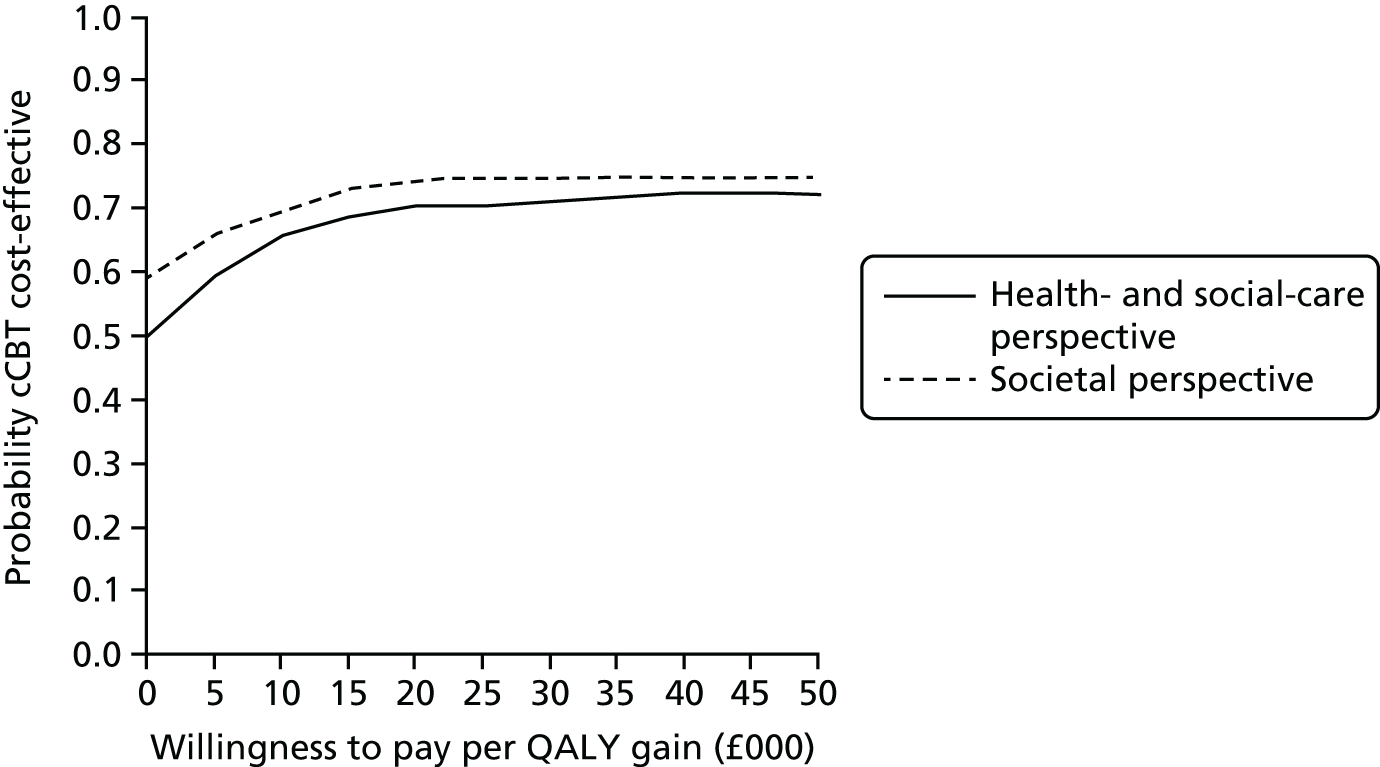

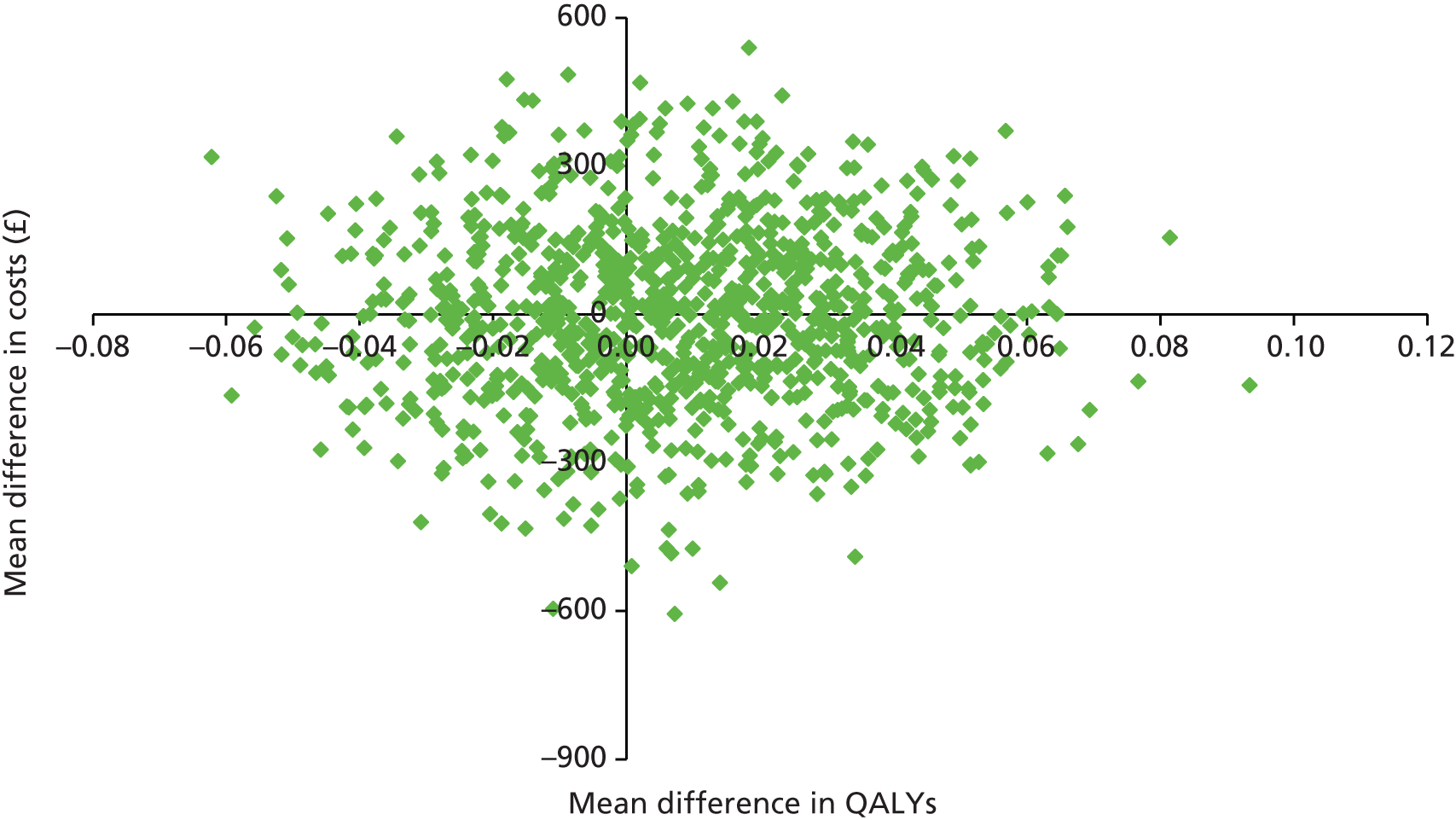

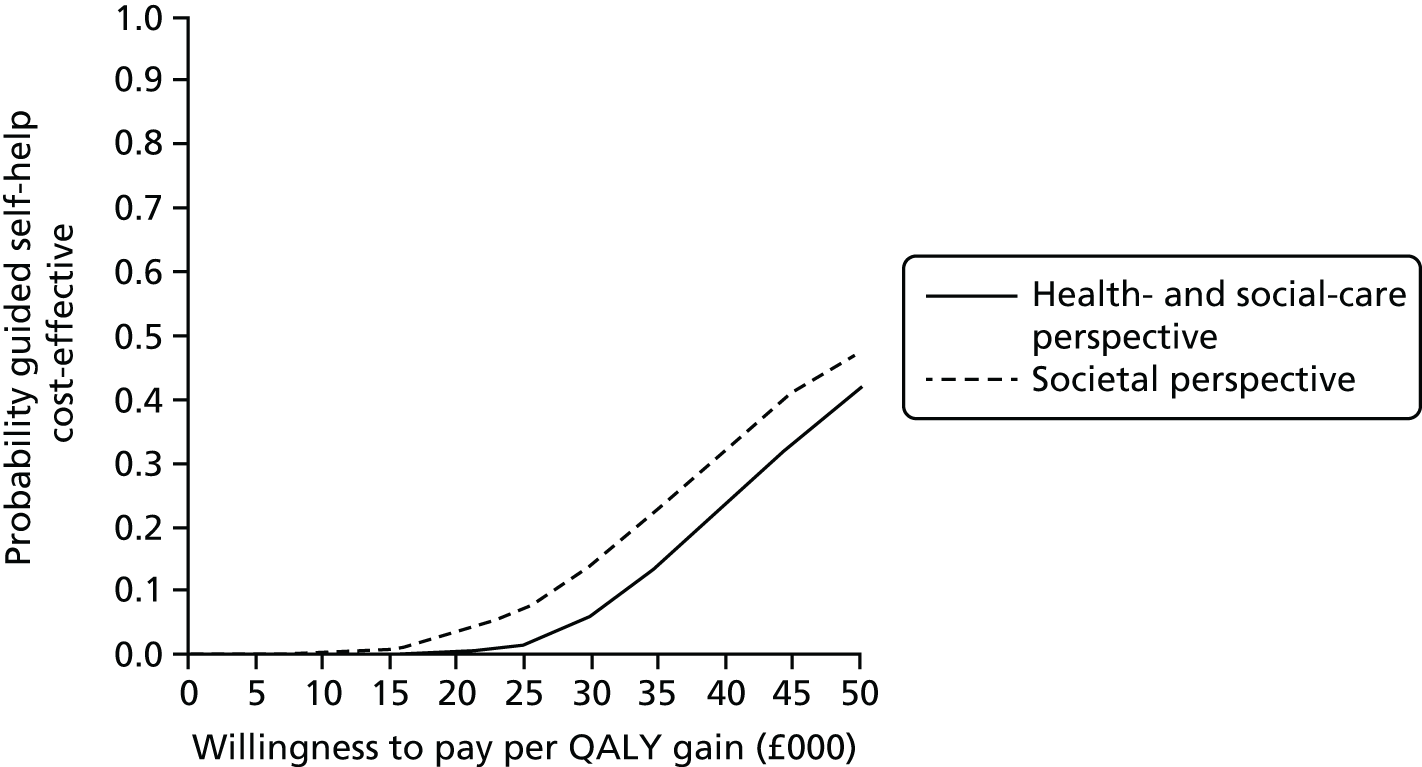

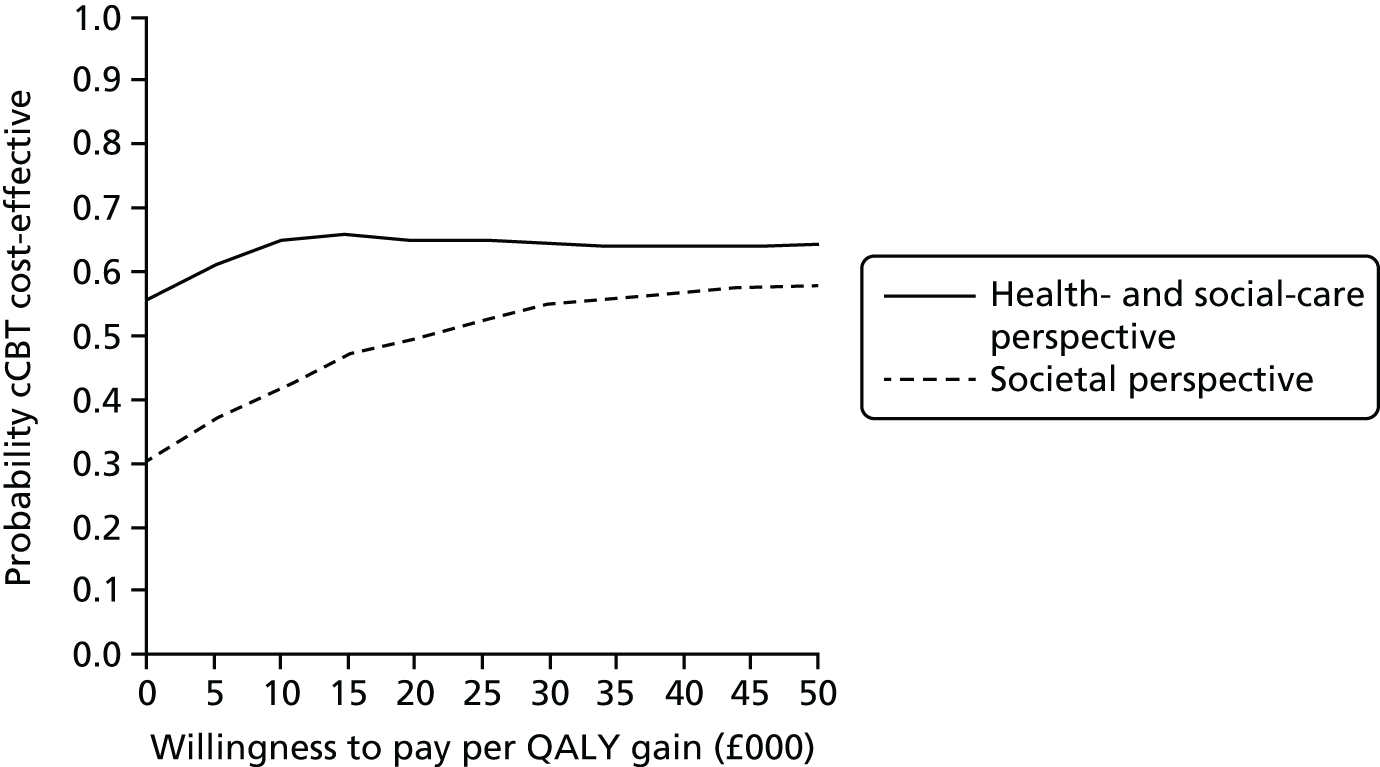

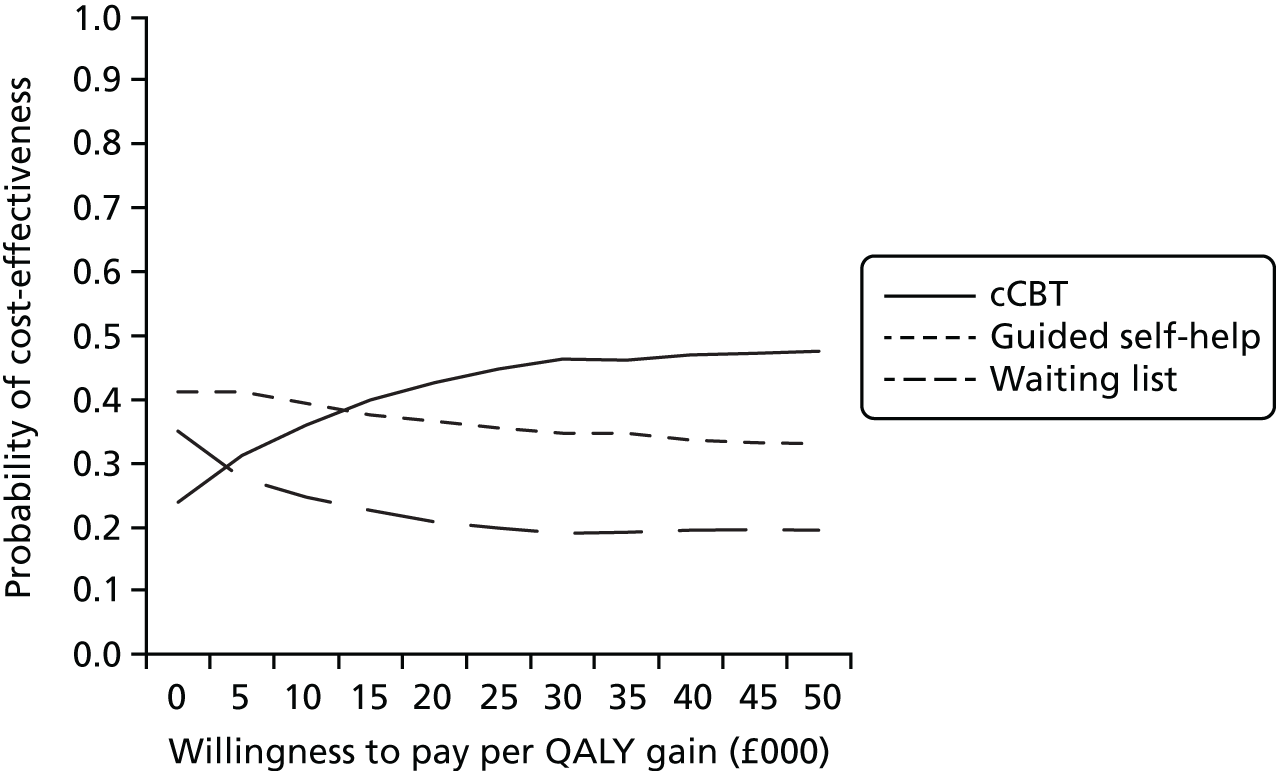

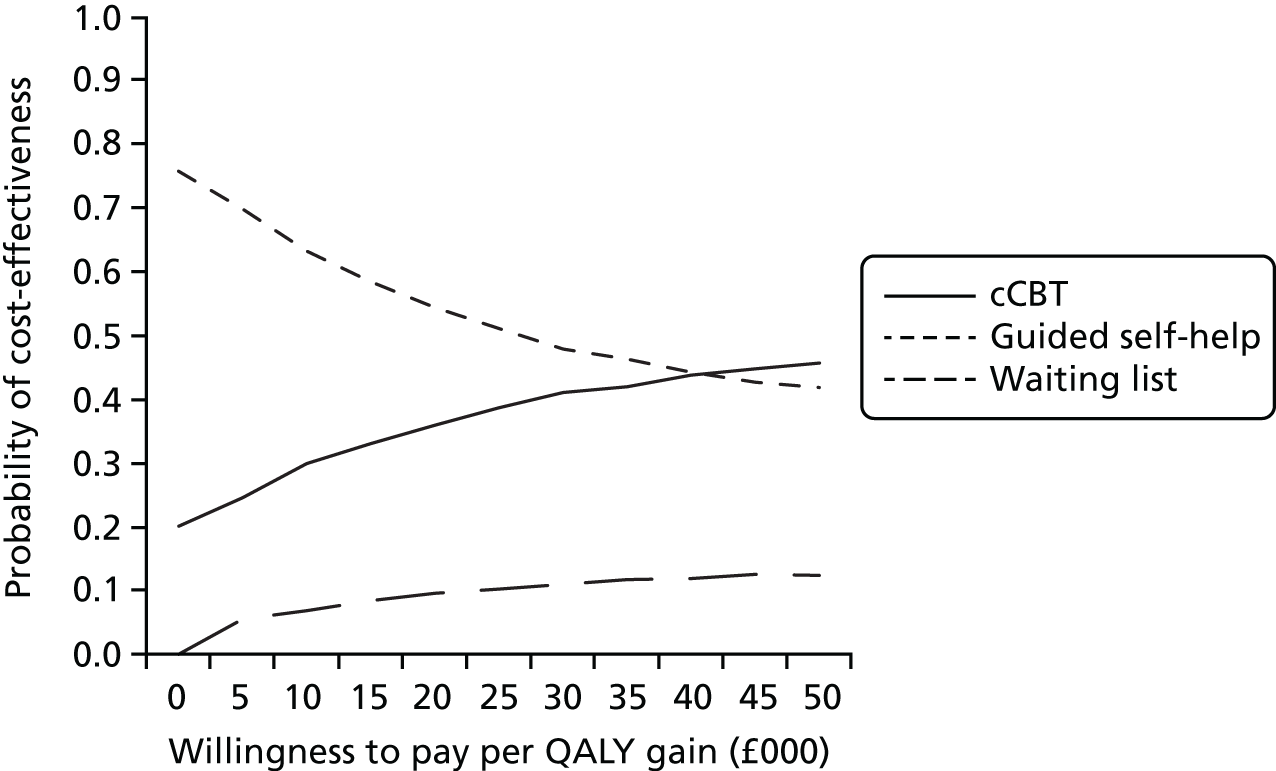

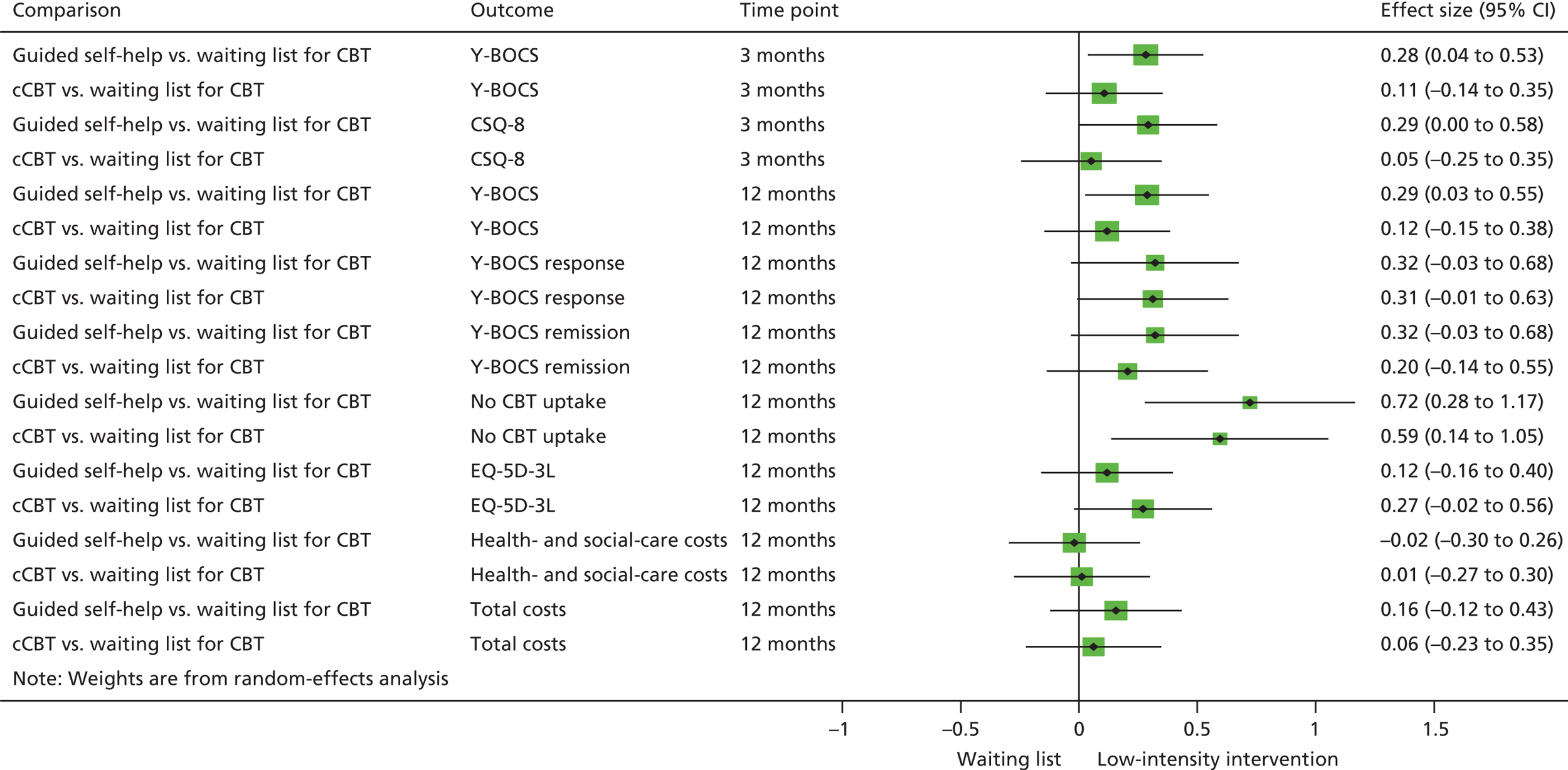

Uncertainty was explored using cost-effectiveness planes and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) based on the net-benefit approach. 78 Cost-effectiveness planes illustrate the uncertainty around the estimates of costs and effects by plotting the bootstrapped cost and effects, with points in each quadrant indicating a different implication for economic evaluation. CEACs are an alternative to CIs around ICERs and show the probability that one intervention is cost-effective compared with the other, for a range of values that a decision-maker would be willing to pay for an additional unit of an outcome. A series of net benefits were calculated for each individual for a range of values for willingness to pay for a QALY. After calculating net benefits for each participant for each value of willingness to pay, coefficients of differences in net benefits between the trial arms were obtained through a series of bootstrapped linear regressions (1000 repetitions) of group upon net benefit, which included the same covariates used for comparisons of outcomes in the primary economic analyses. The resulting coefficients were then examined to calculate the proportion of times that the intervention group had a greater net benefit than the control group for each value of willingness to pay. These proportions were then plotted to generate CEACs for all cost–outcome combinations.

This analysis takes a decision-making approach, ignoring statistical significance and focusing instead on the probability of one intervention being cost-effective compared with another intervention, given the data available. This is the recommended approach to economic evaluation, preferred over traditional reliance on arbitrary decision rules regarding statistical significance, which are being increasingly criticised as irrelevant in a decision-making context. 79,80 Instead, it is argued that the decision to adopt one intervention over another should be based on the expected cost-effectiveness of the intervention, or the probability of making the correct decision.

Patient and professional acceptability: qualitative methods

Successful implementation of research into NHS practice requires that new interventions are accepted by both patients and mental health professionals. Two qualitative acceptability studies were conducted. We conducted post-intervention interviews with a subgroup of patients in both low-intensity arms of the trial and with PWPs delivering the low-intensity interventions across clinical sites.

The methods and associated findings from these studies are presented in Chapter 5.

Trial administration

Trial monitoring

Independent committees

The TSC met twice per year, chaired by an academic GP. The TSC included an experienced PWP, a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist with a special interest in OCD, a service user with lived experience of OCD, the chief investigator and the trial managers.

The DMEC was chaired by an academic GP, and included a mental health nurse with significant experience of working with OCD and an independent statistician, with the trial statistician also in attendance. The DMEC met once per year. Terms of reference for the TSC and DMEC committees were agreed at the commencement of the study. Members of these committees are named in the Acknowledgements.

Clinical trials unit

The YTU (UKCRC registration: 40) was responsible for facilitating the randomisation of participants, establishing a study database, handling of safety reporting and the management of data for OCTET. Data management included oversight of trial retention rates and monitoring of data entry and completeness. Where required, additional procedures were generated to ensure that follow-up was completed with all consenting participants and data entry was completed promptly.

The database established for use in OCTET was devised to facilitate study contacts, trial oversight and data management. This included facilities to:

-

record participant contact details

-

record contact attempts and completed visits

-

generate randomised allocation letters (for the participant and their GP)

-

facilitate the allocation of PWPs to participants

-

record documentation received at the YTU

-

enable entry of collected data for compilation for the end analysis.

The database also provided an opportunity to run routine reports on recruitment and retention rates, which facilitated the smooth administration of OCTET.

In addition, the YTU completed an independent quality control and verification process for the collected data, by checking that a random 10% sample of data (across each time point, stratified by centre) did not exceed a predefined error rate of 5%. This proportionate approach to data verification was deemed appropriate because of the nature of this trial. 81

The YTU was also available to provide trial management during periods of absence, thus ensuring continued support throughout the trial for OCTET researchers and PWPs.

Audits

To ensure that all data collected during OCTET were complete and stored correctly, internal audits of all data and documents collected at each research site were conducted. This included monitoring of the following:

-

consent-to-contact forms

-

consent forms

-

baseline/follow-up booklets

-

adverse event (AE) forms

-

risk forms

-

voucher receipts for follow-up interviews

-

sending of booklets to the YTU.

An audit procedure guidance document was prepared by the trial managers that included a data checklist for completion by each research team.

Trial-specific procedures

To standardise processes across all sites and to maximise data quality, trial-specific SOPs were generated for all individuals involved in the trial covering all procedures and frequently asked questions.

Researcher trial-specific SOPs covered booking eligibility; baseline and follow-up interviews; recruitment procedures; dealing with difficult to contact participants; retention procedures; conducting and reporting risk assessments; AEs recording and reporting; managing participants; and own distress and blinding.

Checklists and letter templates were included to assist with all aspects of the trial and the trial procedure document was updated and disseminated to all researchers as and when necessary throughout the trial.

Risk assessment

A trial-specific SOP was implemented for reporting and managing suicidal risk. Question 9 on the PHQ-9 (Have you had thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way?) was used to identify potential suicide risk. If the patient indicated risk then a series of questions were asked to determine level of risk including ‘thoughts only but no intent’, ‘thoughts with some intent but not immediate’ and ‘thoughts with immediate intent’. Where risk was identified it was referred to a trial coapplicant with clinical experience. Appropriate action was then taken usually involving informing both the clinical site and the GP. All reported risk was documented on risk forms that were signed by the research site lead.

Safety reporting and disclosure

To fulfil requirements for safety reporting and disclosure, a trial-specific procedure for detecting and reporting AEs was implemented.

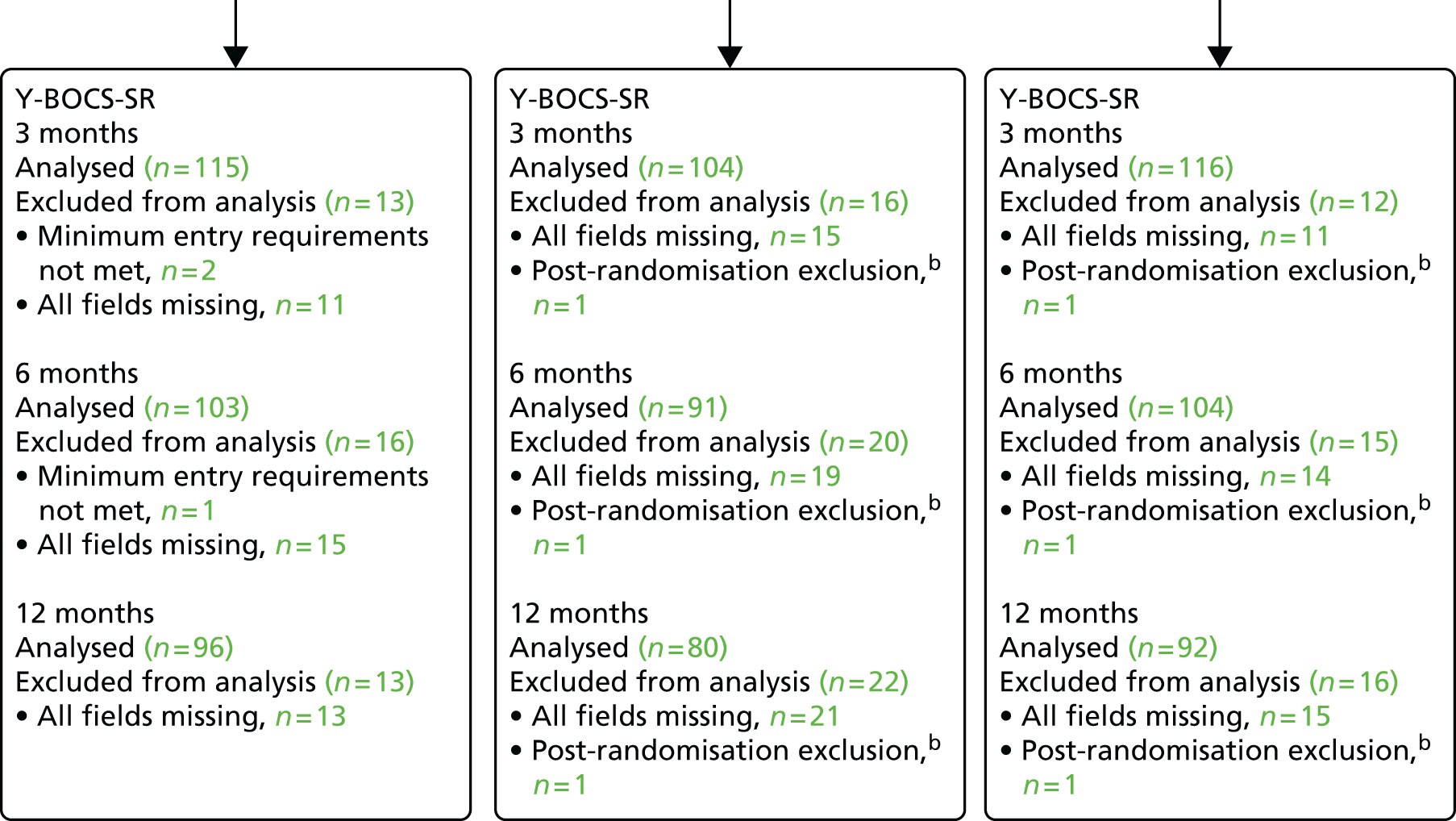

Initially in OCTET an AE was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant that may or may not have a causal relationship with the treatment. Events could then be classified as ‘serious’ or ‘non-serious’ as per The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use good clinical practice guidance. 82