Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/65/01. The contractual start date was in February 2015. The draft report began editorial review in August 2015 and was accepted for publication in December 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Huxley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

Aetiology and pathology

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also referred to as bowel cancer, is any cancer that affects the colon (large bowel) and rectum. It usually develops slowly over a period of 10–15 years. The tumour typically begins as a non-cancerous polyp. A polyp is a growth of tissue that develops on the lining of the large intestine (colon or rectum) that can become cancerous. Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) refers to disease that has spread beyond the large intestine and nearby lymph nodes. 1 This type of cancer most often spreads first to the liver, but metastases may also occur in other parts of the body including the lungs, brain and bones. 1

The pathology of the tumour is usually determined by analysis of tissue taken from a biopsy or surgery. The extent to which the cancer has spread is described as its stage. 2 Staging is essential in determining the choice of treatment and in assessing prognosis. 2 More than one system is used for the staging of cancer. CRC stage can be described using the modified Dukes’ staging system (based on postoperative findings – a pathological staging based on resection of the tumour and measuring the depth of invasion through the mucosa and bowel wall) or the more precise tumour invasion, nodal involvement and metastatic spread (TNM) staging system, which is based on the depth of tumour invasion (T), nodal involvement (N) and metastatic spread (M) assessed preoperatively by radiological examination (Table 1). 2 Metastatic disease is classified as stage IV or modified Dukes’ stage D.

| Staging group | TNM staging and sites involved | Modified Dukes’ stage |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ (Tis, N0, M0) | |

| Stage I | No nodal involvement, no distant metastases | A |

| Tumour is confined to submucosa (T1, N0, M0) | ||

| Tumour has grown into (but not through) muscularis propria (T2, N0, M0) | ||

| Stage II | No nodal involvement, no distant metastases | B |

| Tumour has grown into (but not through) the serosa (T3, N0, M0) | ||

| Tumour penetrates through the serosa and peritoneal surface, directly extends to other organs or body structures or perforates the bowel (T4a/b, N0, M0) | ||

| Stage III | Nodal involvement, no distant metastases (any T, N1/N2, M0) | C |

| Stage IV | Distant metastases (any T, any N, M1) | D |

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

In terms of incidence, CRC is the fourth most common cancer in the UK behind breast, lung and prostate cancer, accounting for 13% of all new cancer cases. 3 It is the third most common cancer in both men (14% of the total for men) and women (11% of the total) separately. 3 Table 2 summarises the number of new cases and incidence rates in the UK.

| Variable | England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||||

| Cases, n | 18,971 | 1297 | 2239 | 664 | 23,171 |

| Crude rate | 72.6 | 86.2 | 87.9 | 74.7 | 74.6 |

| AS rate (95% CI) | 56.7 (55.9 to 57.5) | 60.2 (57.0 to 63.5) | 67.4 (64.6 to 70.2) | 66.4 (61.3 to 71.4) | 58.0 (57.3 to 58.8) |

| Female | |||||

| Cases, n | 15,073 | 1046 | 1756 | 535 | 18,410 |

| Crude rate | 55.9 | 67.1 | 64.9 | 57.8 | 57.2 |

| AS rate (95% CI) | 36.8 (36.2 to 37.4) | 40.6 (38.2 to 43.1) | 41.9 (39.9 to 43.9) | 42.9 (39.3 to 46.5) | 37.6 (37.1 to 38.2) |

| Total | |||||

| Cases, n | 34,044 | 2343 | 3995 | 1199 | 41,581 |

| Crude rate | 64.1 | 76.5 | 76.0 | 66.1 | 65.8 |

| AS rate (95% CI) | 46.0 (45.5 to 46.5) | 49.6 (47.6 to 51.6) | 53.3 (51.7 to 55.0) | 53.5 (50.5 to 56.5) | 47.0 (46.6 to 47.5) |

Approximately two-thirds (66%) of cancer cases affect the colon and one-third (34%) affect the rectum, although this distribution varies by sex. 3 The crude incidence rates show that there are 46 and 41 new colon cancer cases per year for every 100,000 men and women in the UK, respectively, and around 29 and 17 new rectal cancer cases per year for every 100,000 men and women in the UK, respectively. 3

Approximately 25% of people present with metastases at initial diagnosis and almost 50% of people with CRC will develop metastases. 4

Prevalence refers to the number of people who have previously received a diagnosis of cancer and who are still alive at a given time point. Some people will have been cured of their disease and others will not. In the UK, > 143,000 people were still alive at the end of 2006, up to 10 years after being diagnosed with CRC (Table 3). 3

| Group | Prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 5 years | 10 years | |

| Male | 14,635 | 51,183 | 78,483 |

| Female | 11,415 | 40,594 | 65,075 |

| Total | 26,050 | 91,777 | 143,558 |

Risk factors

Risk factors for CRC include age and family history. In the UK between 2009 and 2011, an average 43% of bowel cancer cases were diagnosed in people aged ≥ 75 years and 95% of cases were diagnosed in those aged ≥ 50 years. 3 The lifetime risk of developing bowel cancer in the UK is 1 in 14 for men and 1 in 19 for women. 3

Mortality

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the UK (2012 data), accounting for 10% of all deaths from cancer. 5 In 2012 there were 16,187 deaths from CRC in the UK (Table 4). The crude mortality rates show that there are 28 CRC deaths per year for every 100,000 men in the UK and 23 per year for every 100,000 women. 5

| Group | England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||||

| Cases, n | 7200 | 525 | 837 | 233 | 8795 |

| Crude rate | 27.3 | 34.8 | 32.5 | 26.0 | 28.1 |

| AS rate (95% CI) | 20.0 (19.5 to 20.4) | 23.0 (21.1 to 25.0) | 23.3 (21.7 to 24.8) | 22.2 (19.3 to 25.0) | 20.5 (20.1 to 20.9) |

| Female | |||||

| Cases, n | 6036 | 387 | 784 | 185 | 7392 |

| Crude rate | 22.2 | 24.7 | 28.7 | 19.9 | 22.8 |

| AS rate (95% CI) | 12.6 (12.3 to 12.9) | 13.1 (11.8 to 14.4) | 16.2 (15.1 to 17.4) | 12.8 (10.9 to 14.6) | 13.0 (12.7 to 13.3) |

| Total | |||||

| Cases, n | 13,236 | 912 | 1621 | 418 | 16,187 |

| Crude rate | 24.7 | 29.7 | 30.5 | 22.9 | 25.4 |

| AS rate (95% CI) | 15.9 (15.7 to 16.2) | 17.6 (16.5 to 18.7) | 19.2 (18.3 to 20.1) | 17.0 (15.3 to 18.6) | 16.3 (16.1 to 16.6) |

Around 6 in 10 (61%) CRC deaths are due to cancers of the colon and around 4 in 10 (39%) are due to cancers of the rectum. 5 Almost one-fifth (18%) of CRC deaths occur in people aged 60–69 years. 5

Survival and prognosis

Approximately 77% of men survive CRC for at least 1 year, which is predicted to fall to 59% at ≥ 5 years, as shown by age-standardised net survival for people diagnosed with CRC during 2010–11 in England and Wales. 6 Survival for women at 1 and 5 years is slightly lower, with 74% surviving for ≥ 1 year and 58% predicted to survive for at least 5 years. 6

Survival is, however, highly dependent on the stage of disease at diagnosis. Survival by stage is not yet routinely available for the UK because of inconsistencies in the collecting and recording of staging data in the past. However, published estimates suggest that approximately 90% of people diagnosed at the earliest stage will survive for > 5 years, whereas < 10% of people diagnosed with distant metastases will survive for > 5 years. 7 In general, the earlier the diagnosis the higher the chances of survival. 7

Impact of the health problem

Colorectal cancer is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. 8 When treating people with mCRC, the main aims of treatment are to relieve symptoms and to improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and survival. 1

Measurement of disease

The outcome end points of CRC can be measured in a variety of ways.

-

Overall survival (OS): defined as the time from randomisation to death from any cause. 9

-

Progression-free survival (PFS): defined as time from randomisation until disease progression or death. 9

-

Objective response rate (ORR): defined as either a partial response (PR) or a complete response (CR). The numbers of CRs and PRs are important as the benefits from CRs tend to be greater:

-

CR – all detectable tumour has disappeared

-

PR – roughly corresponds to at least a 50% decrease in the total tumour volume but with evidence of some residual disease still remaining

-

Stable disease – includes either a small amount of growth (typically < 20% or < 25%) or a small amount of shrinkage

-

Progressive disease – means that the tumour has grown significantly or that new tumours have appeared. The appearance of new tumours is always progressive disease, regardless of the response of other tumours. Progressive disease normally means that the treatment has failed.

-

-

HRQoL: how a person’s well-being is affected by treatment.

Current service provision

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance is available on the diagnosis and management of mCRC1 and first-line chemotherapeutic treatments for mCRC10–12 [see Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines: biological agents (first line)]. NICE guidance on the use of second-line or subsequent treatments is also available;13 however, it is not discussed in detail in this report as it is beyond the scope of this multiple technology appraisal (MTA). 14

Management of disease

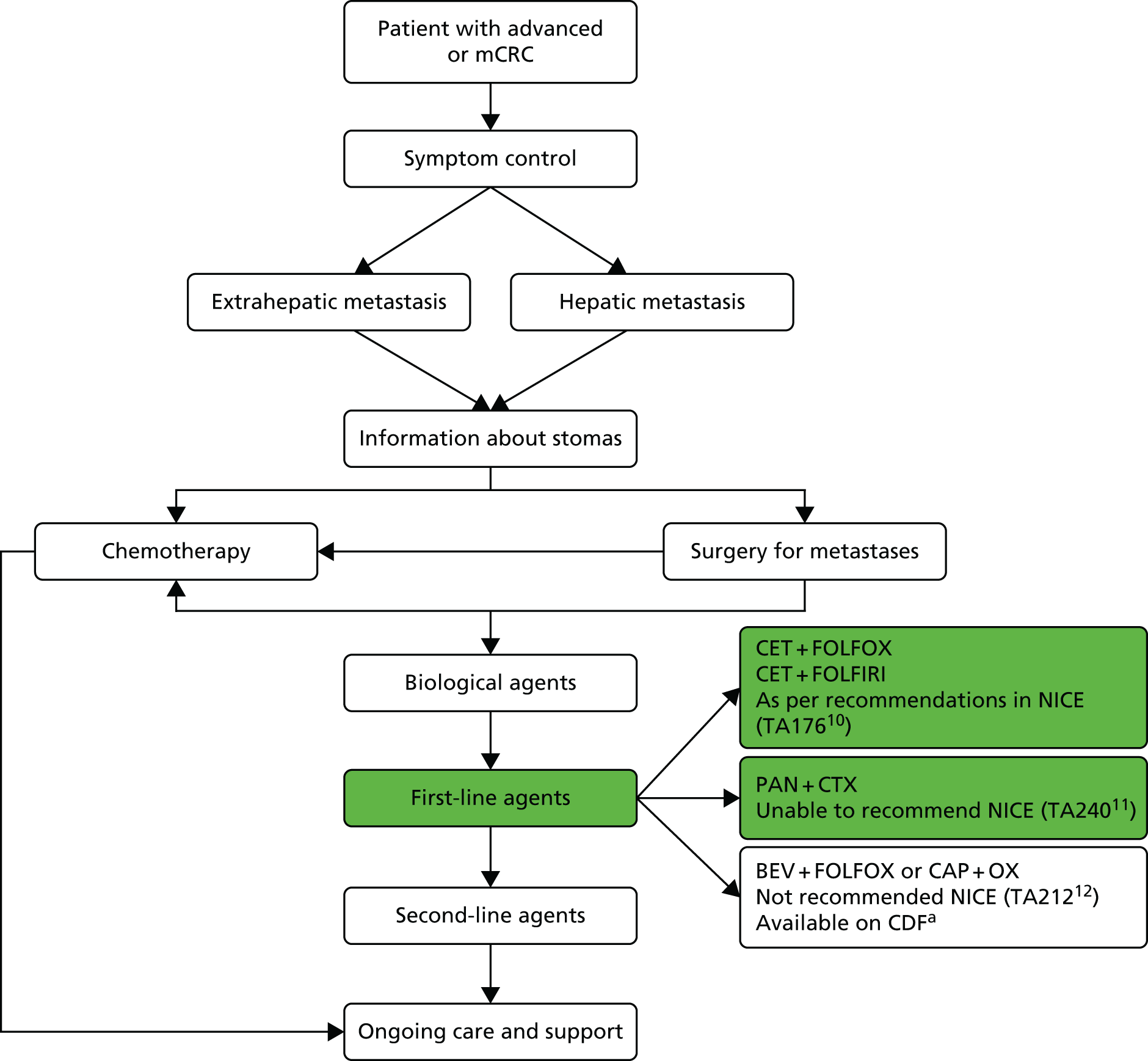

Treatment of mCRC may involve a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and supportive care (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Managing advanced and metastatic CRC (NICE pathways). BEV, bevacizumab; CAP, capecitabine; CDF, Cancer Drugs Fund; CET, cetuximab; CTX, chemotherapy; FOLFIRI, folinic acid + 5-fluorouracil + irinotecan; FOLFOX, folinic acid + 5-fluorouracil + oxaliplatin; OX, oxaliplatin; PAN, panitumumab; TA, technology appraisal. a, Bevacizumab is not recommended by NICE (TA21212). At the time of scoping bevacizumab was available (subject to satisfying criteria for access) via the CDF; however, this drug was delisted for the indication under review in this TA in March 2015. Adapted with permission from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s publication entitled NICE Pathway: Managing Advanced and Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Available from http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/colorectal-cancer13 (accessed 13 March 2017). Content accurate at time of going to press.

The majority of people with metastatic disease are not initially suitable for potentially curative resection. 1,4 Up to 30% of people may be cured if metastases in the liver can be resected. For surgery to be considered, there must be no evidence of cancer outside the liver and there must be an adequate amount of normal liver left behind after the resection to sustain life. 1 Surgical skill is crucial to outcomes and there is evidence of wide variation in survival rates depending on the individual surgeon who operates. 15 Chemotherapy may be recommended before surgery in some cases, even if the metastatic disease appears to be confined to the liver. 1,4 This approach may help a person who is a borderline candidate for surgery (because of the size or location of the tumours) to become suitable for resection, after a response has been achieved with combination chemotherapy. 1,4

For the majority of people, however, surgery with curative intent is not an option because of the widespread nature of their disease and/or their poor suitability for surgery. 1 These people are treated with palliative intent using a combination of specialist treatments – palliative surgery (e.g. in cases in which the tumour is causing an obstruction), chemotherapy or radiotherapy – to improve both the duration and the quality of their remaining life. 1 NICE recommends chemotherapy options including 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid in combination with oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), tegafur (UFToral®, Merck Serono UK Ltd, Feltham, UK; no longer produced in the UK) in combination with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid, capecitabine in combination with oxaliplatin (XELOX) and capecitabine alone. 1 In practice, 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid may also be used in combination with irinotecan (FOLFIRI) in some people for whom oxaliplatin is not suitable. 1 FOLFOX may be administered in different regimens, most commonly FOLFOX4 and FOLFOX6. The differences in drug acquisition and administration costs of all of these regimens are discussed in Chapter 6 (see Model parameters, Costs), but in effectiveness they are widely considered by the clinical community to be equal. Single-agent fluoropyrimidine regimens (tegafur, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil and capecitabine monotherapy) are generally given to patients for whom combination therapy is not suitable (Dr Mark Napier, Royal Devon & Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, 2015, personal communication; Merck Serono submission version 2, 15 June 2015, Table 4, p. 22).

Folinic acid is also known as leucovorin (Sodiofolin®; medac GmbH, Stirling, UK) and is given alongside 5-fluorouracil to improve the response rate compared with 5-fluorouracil alone. It is given as calcium folinate (also known as leucovorin calcium) or less frequently as disodium folinate. 16 Folinic acid (and calcium folinate and disodium folinate), unless otherwise stated, are racemic mixtures (with equal amounts of left- and right-handed enantiomers), in which only the levoisomer (left-handed form) is pharmacologically active. 17 The levoisomer, levoleucovorin, has marketing authorisation in the UK [as calcium levofolinate (Isovorin®; Pfizer Limited, Sandwich, UK) and disodium levofolinate (levofolinic acid; medac GmbH, Stirling, UK)] and is administered at half the dose of standard (racemic) leucovorin. There appears to be no significant difference between levoleucovorin and leucovorin in terms of efficacy or adverse events (AEs), but levoleucovorin is significantly more expensive than leucovorin at present. 17

Chemotherapy may be combined with biological agents such as cetuximab (Erbitux®, Merck Serono) (currently recommended for people satisfying criteria specified in NICE technology appraisal (TA) no. 17610), panitumumab (Vectibix®, Amgen, Cambridge, UK) and bevacizumab (Avastin®, Roche Products Ltd) [see Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines: biological agents (first line)]. Although bevacizumab is included in the final scope for this TA, it is not recommended by NICE (TA21212). It was available subject to satisfaction of criteria for access via the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF), but has recently (March 2015) been delisted for the indication under review in this TA. 18 As of 17 July 2015, bevacizumab remains delisted for this indication.

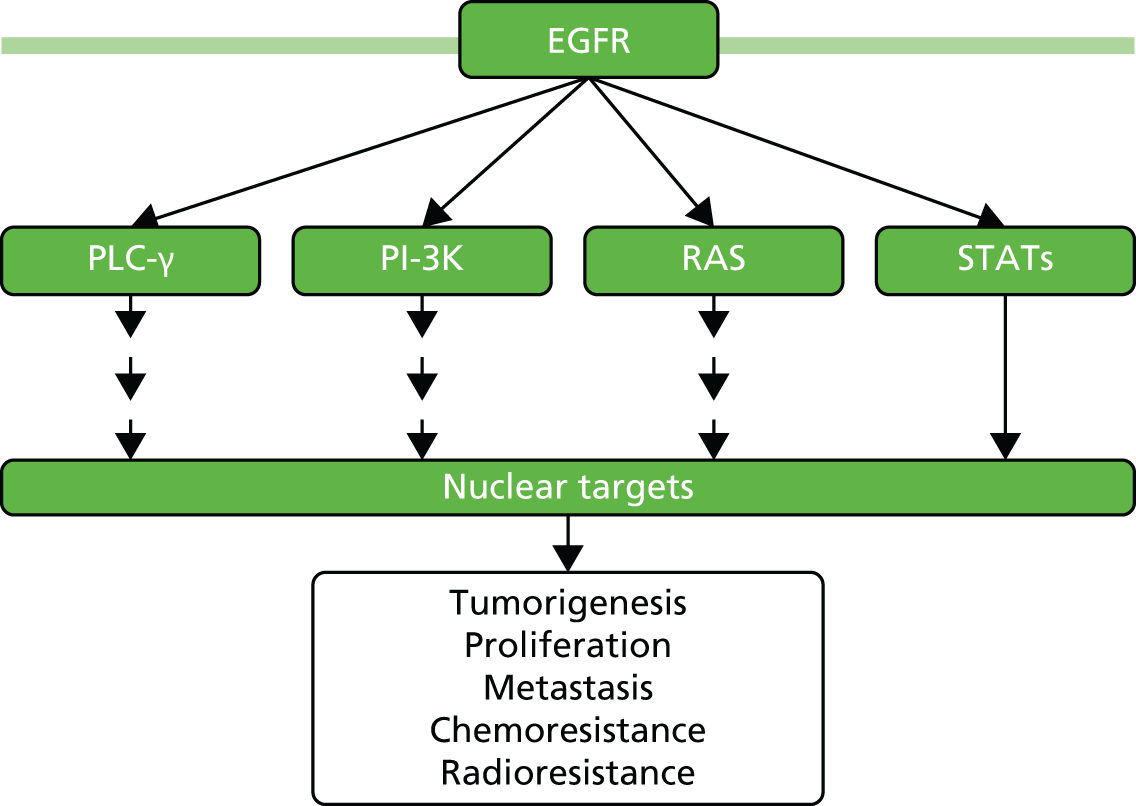

Personalised treatment

Normal cell behaviour in multicellular organisms is controlled by a complex network of signalling pathways that ensures that cells proliferate only when they are required to, for example in wound healing. 19 Cancer occurs when normal growth regulation breaks down, usually because of defects within these signalling mechanisms. 19 The rat sarcoma (RAS) genes play an important role in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway, a complex signalling cascade that is involved in the development and progression of cancer (Figure 2). 20 Signals are passed from protein to protein along several different pathways. Disruption of the signals through mutation of the RAS gene is involved in many tumour types.

FIGURE 2.

Epidermal growth factor receptor signalling pathway. PI-3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PLC-γ, phospholipase C gamma; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription. Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd on behalf of Cancer Research UK: British Journal of Cancer. Lo HW, Hung MC. Nuclear EGFR signalling network in cancers: linking EGFR pathway to cell cycle progression, nitric oxide pathway and patient survival. British Journal of Cancer 2006;94(2):184–8. Copyright 2006. 21

The three RAS genes – Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS), Harvey rat sarcoma (HRAS) and neuroblastoma rat sarcoma (NRAS) – are the most common oncogenes in human cancer. 19,20 All three are widely expressed, with KRAS expressed in almost all cell types. 19 Published research has demonstrated that mutations in codons 12 and 13 of exon 2 of the KRAS gene are predictive of a reduced response to anti-EGFR therapies in mCRC. 22–29 For this reason, only people with KRAS exon 2 wild-type (WT) tumours were initially approved for treatment with this class of agents. 30–32

More recently, it has been shown that other mutations in genes of the RAS family (mutations in codon 61 of exon 3 and codons 117 and 146 of exon 4 of KRAS, and mutations in exons 2, 3 and 4 of NRAS) are also associated with a reduced response to anti-EGFR therapy. 4,26,28,29,33,34 These developments led the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to update the marketing authorisations for cetuximab and panitumumab in 2013 by restricting the indication in mCRC to the treatment of people with RAS WT tumours (see Interventions considered in the scope of this assessment). 35–40

Exon 2 mutations in the KRAS gene occur in approximately 40% of mCRC cases and other KRAS and NRAS mutations occur in approximately 10% of mCRC cases (Figure 3). 22,26,33,41–44 Approximately 50% of people do not have RAS mutations and are classified as RAS WT.

FIGURE 3.

Grouping of molecular characteristics of tumours: research progress. ID, identification; MT, mutant.

RAS mutation testing

A biomarker test is a simple way of looking at the type and status of particular genes of interest in a cancer. Biomarkers have been found for many different types of cancer, such as colorectal, breast and lung cancer, and have an increasingly important role in helping physicians to tailor care and treatment on an individual basis, known as ‘personalised medicine’. RAS − a predictive biomarker − is a group of genes that includes KRAS and NRAS and can be used to help select the most appropriate therapy for each individual mCRC.

Methods for RAS mutation testing, whose use in the UK has been identified in a previous Health Technology Assessment report45 and by the Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG), are summarised in Table 5. Additional techniques have also been developed and are in use internationally, including the Randox KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA* Array (Randox Laboratories Ltd, Crumlin, UK) and the SNaPshot® Multiplex kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

| Test | Limit of detection (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| KRAS and NRAS | ||

| Sanger sequencing | 10–20 | Wong et al.46 |

| Pyrosequencing | 5 | Wong et al.46 |

| High-resolution melt | 1–5 | Wong et al.46 |

| StripAssay® (ViennaLab Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria) | 1 | ViennaLab Diagnostics47 |

| Next-generation sequencing | ≈5 | Westwood et al.45 |

| KRAS | ||

| Cobas® (Roche Diagnostics Limited, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) | 5 | Wong et al.46 |

| Therascreen® (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands) | 1–5 | Wong et al.46 |

| Peptide Nucleic Acid Clamp® (Panagene, Daejeon, Republic of Korea) | 1 | Panagene48 |

Many techniques and products reported are assays associated with the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or that require use of PCR techniques prior to their implementation. Additionally, some laboratories offer their own in-house variant of real-time PCR. 45

Currently, there are no NICE recommendations for which mutation test should be used in the NHS. A NICE diagnostics review of KRAS mutation testing for identifying adults with mCRC was suspended in 2013, following notification of potential changes to clinical practice over who may benefit from first-line treatment with cetuximab or panitumumab. 49 A review by Westwood et al. 45 did demonstrate that evidence linking test accuracy with treatment effects is unavailable for most techniques currently in use. It concluded that there were ‘no clear differences in the treatment effects . . . regardless of which KRAS mutation test was used to select patients’. 45 Further discussion of the tests available and their impact on this review is reported in Appendix 1.

Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines: biological agents (first line)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence TA176: cetuximab for the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence TA176 states that:

Cetuximab in combination with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), folinic acid and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), within its licensed indication, is recommended for the first-line treatment of mCRC only when all of the following criteria are met:

the primary colorectal tumour has been resected or is potentially operable

the metastatic disease is confined to the liver and is unresectable

the person is fit enough to undergo surgery to resect the primary colorectal tumour and to undergo liver surgery if the metastases become resectable after treatment with cetuximab

the manufacturer rebates 16% of the amount of cetuximab used on a per patient basis.

Reproduced with permission from National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) TA176 Cetuximab for the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA176. 10 Content accurate at time of going to press

Cetuximab in combination with 5-FU, folinic acid and irinotecan (FOLFIRI), within its licensed indication, is recommended for the first-line treatment of mCRC only when all of the following criteria are met:

the primary colorectal tumour has been resected or is potentially operable

the metastatic disease is confined to the liver and is unresectable

the patient is fit enough to undergo surgery to resect the primary colorectal tumour and to undergo liver surgery if the metastases become resectable after treatment with cetuximab

the patient is unable to tolerate or has contraindications to oxaliplatin.

Reproduced with permission from National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) TA176 Cetuximab for the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA176. 10 Content accurate at time of going to press

Patients who meet these criteria should receive treatment with cetuximab for no more than 16 weeks. 10 At 16 weeks, treatment with cetuximab should stop and patients should be assessed for resection of liver metastases. 10

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence TA240: panitumumab for the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer

The appraisal of panitumumab in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of mCRC (TA240) was ended because no evidence submission was received from the manufacturer or sponsor of the technology. 11 Therefore, NICE was unable to make a recommendation about the use in the NHS of panitumumab in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of mCRC. 11

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence TA212: bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin and either 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid or capecitabine for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer

Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin and either 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid or capecitabine is not recommended by NICE for the treatment of mCRC. 12

Current usage in the NHS

Currently, only cetuximab is recommended by NICE and is available for use on the NHS in England subject to satisfaction of criteria set out in TA17610 [see Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines: biological agents (first line)]. For people with mCRC not meeting the criteria set out in TA176, cetuximab is available through the CDF. 50

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence was unable to make a recommendation about the use in the NHS of panitumumab in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of mCRC [TA240;11 see Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines: biological agents (first line)]. Panitumumab is currently available for the first-line treatment of mCRC through the CDF. 51

Bevacizumab was not recommended by NICE for the treatment of mCRC [TA212;12 see Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines: biological agents (first line)]. At the time of scoping, bevacizumab was available (subject to satisfaction of eligibility criteria) through the CDF; however, it was delisted in March 2015. 18

Almost one-third of patients in the UK receive cetuximab or panitumumab in combination with oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based chemotherapy (Table 6).

| Regimen | Estimated current proportion of first-line mCRC patients in UK (%) | Estimated proportion of first-line mCRC patients in UK if CET/PAN/BEV no longer available through CDF and not recommended by NICE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| FOLFOXa | 30 | 60 |

| FOLFIRIb | 10 | 20 |

| Tegafur, FA + 5-FU, capecitabinec | 20 | 20 |

| BEV + OX- or IRIN-based CTX | 10 | NA |

| CET/PAN + OX- or IRIN-based CTX | 30 | NA |

Current service cost

Treatment costs can include the following: cost of first-line chemotherapy drugs (cetuximab, panitumumab, irinotecan or oxaliplatin, folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil), cost of administration in the first line, cost of curative intent liver surgery, cost of post-resection therapy in those who underwent curative resection of liver metastases, cost of management of AEs in the first line, cost of treatments in the second line, cost of treatment in the third line and cost of RAS screening.

Description of technology under assessment

Interventions considered in the scope of this assessment

The scope of this review was to ascertain the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of two interventions for previously untreated mCRC. These interventions were cetuximab and panitumumab.

Cetuximab

Cetuximab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody that blocks the human EGFR and therefore inhibits the proliferation of cells that depend on EGFR activation for growth. 35

Previously, cetuximab was indicated for use in people with EGFR-expressing KRAS WT mCRC. 30,31,52,53 In November 2013, in response to new biomarker data, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) changed the indication to clarify the particular genetic make-up of the cancer that must be present before treatment with cetuximab is initiated. 37,39 Based on this recommendation, cetuximab is now indicated for the treatment of people with EGFR-expressing RAS WT mCRC:

-

in combination with irinotecan-based chemotherapy

-

in first line in combination with FOLFOX

-

as a single agent in people who have failed oxaliplatin- and irinotecan-based therapy and who are intolerant to irinotecan. 35

In this label change, the combination of cetuximab with oxaliplatin-containing chemotherapy is now contraindicated for people with RAS mutant mCRC or for whom the RAS status is unknown. 35

Premedication with an antihistamine and a corticosteroid at least 1 hour prior to the administration of cetuximab should be given. This premedication is recommended before the initial and subsequent infusions. Cetuximab is administered once a week; the initial dose is 400 mg/m2 of body surface area, with subsequent weekly doses of 250 mg/m2 of body surface area. 35

One common AE related to cetuximab treatment is the development of skin reactions, which occurs in > 80% of people and mainly presents as an acne-like rash or, less frequently, as pruritus, dry skin, desquamation, hypertrichosis or nail disorders (e.g. paronychia). 35 The majority of skin reactions develop within the first 3 weeks of treatment. 35 The Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) notes that, if a person experiences a grade 3 or 4 skin reaction, cetuximab treatment must be stopped, with treatment being resumed only if the reaction resolves to grade 2. 35 Other common AEs of cetuximab include mild or moderate infusion-related reactions such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness or dyspnoea that occur soon after the first cetuximab infusion. 35

Panitumumab

Panitumumab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody that targets the EGFR, thereby inhibiting the growth of EGFR-expressing tumours. 36

In June 2013, the CHMP changed the indication for the use of panitumumab for the treatment of mCRC,38,40 restricting use to the treatment of adults with RAS WT mCRC:

-

in first line in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI

-

in second line in combination with FOLFIRI for people who have received first-line fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy (excluding irinotecan)

-

as monotherapy after failure of fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin- and irinotecan-containing chemotherapy regimens. 36

In this label change, the combination of panitumumab with oxaliplatin-containing chemotherapy is now contraindicated for people with RAS mutant mCRC or for whom the RAS mCRC status is unknown. 36

The recommended dose of panitumumab is 6 mg/kg of bodyweight given once every 2 weeks. 36 Before infusion, panitumumab should be diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride to a final concentration not exceeding 10 mg/ml. 36

Panitumumab is contraindicated in people with a history of severe or life-threatening hypersensitivity reactions to the active substance or to any of the excipients. 36 The most common AEs observed (incidence ≥ 20%) are skin toxicities (i.e. erythema, dermatitis acneiform, pruritus, exfoliation, rash and fissures), paronychia, hypomagnesaemia, fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea and constipation. 36

As noted, recent research (see Personalised treatment) has resulted in the CHMP adopting a change to the licensed indication for both cetuximab and panitumumab, restricting use to people with RAS WT mCRC. These developments and changes to the licensed indications provide the rationale for this MTA.

Cetuximab and panitumumab for previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (review of TA176 and partial review of TA240) (ID794)

Although this MTA seeks to update previous guidance (TA17610 and TA24011), it is important to note the differences between the scope for the previous single technology appraisals (STAs) and the scope for this current MTA review (ID794). 14 The main difference is in the population criterion. The current scope specifies people with RAS WT mCRC, whereas previous STA reviews specified EGFR-expressing mCRC (TA176)54 and KRAS WT mCRC (TA240). 11 A summary of the differences between the scopes for the reviews and how the product licences have changed is provided in Table 7.

| Variable | CET | PAN | CET | PAN | CET + PAN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHMP30,31,52,53 | TA17654 | CHMP32,55 | TA24011 | CHMP37,39 | CHMP38,40 | Current MTA (ID794)14 | |

| Year | 2008, 2011 | 2009 | 2011 | 2011 | 2013 | 2013 | 2014–16 |

| NICE appraisal method | NA | STA | NA | STA | NA | NA | MTA |

| NICE guidance | NA | TA176 | NA | TA240 (suspendeda) | NA | NA | Due 2017 |

| Population | KRAS WT mCRC | Untreated mCRC, first-line palliative | KRAS WT mCRC | NA | RAS WT-expressing mCRC | RAS WT-expressing mCRC | RAS WT-expressing mCRC |

| Metastases | Any location | Untreated, any location | Any location | NA | Any location | Any location | Untreated, any location (subgroup of interest liver metastases)14 |

| Intervention (first line) | CET + FOLFOX4 or IRIN-based CTX | CET + CTX54 | PAN + FOLFOX | NA | CET + FOLFOX or CET + FOLFIRI | PAN + FOLFOX | CET + FOLFOX or IRIN-based regimens; PAN + FOLFOX regimens |

| Comparators | NA | OX-based CTX; IRIN-based CTX54 | NA | NA | NA | NA | FOLFOX; XELOX; FOLFIRI; CAP; TEG + FA + 5-FU; BEV + OX- or IRIN-based CTXb |

| Supporting trials | CRYSTAL, OPUS, COIN, NORDIC VII | CRYSTAL, OPUS | KRAS WT subgroup from PRIME | NA | RAS WT subgroup from OPUS, CRYSTAL, FIRE-3 | RAS WT subgroup from PEAK, PRIME | RAS WT subgroup from CRYSTAL, OPUS, PRIME, PEAK, FIRE-3 |

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Cetuximab and panitumumab (interventions of interest to this appraisal) were evaluated separately in 2009 (TA17610) and 2011 (TA24011) [see Chapter 1, Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines: biological agents (first line)].

At the time of TA176 (2009), RAS WT status was defined based on a single part (‘exon’) of the KRAS gene and testing typically focused on KRAS codons 12 and 13. 56 However, subsequent research has suggested that mutations in other KRAS codons and other genes downstream of the EGFR may also confer drug resistance, explaining why some individuals with KRAS codon 12 and 13 WT tumours did not respond to therapy. 56 The absence of mutations in the NRAS gene and in two further exons (3 and 4) of KRAS was found to improve the effectiveness of cetuximab and panitumumab. 56 These developments led the EMA to update the marketing authorisations for cetuximab39 and panitumumab40 in 2013 by restricting the indication in CRC to the treatment of people with RAS WT tumours. It is this change to the licensed indications for these products that provides the rationale for this appraisal. 14

Population, including subgroups

The population specified in the final scope issued by NICE was people with previously untreated RAS WT mCRC. 14

The subgroup of interest was based on the location of metastases, specifically liver- and non-liver-limited disease. 14

Interventions

This MTA considered two interventions.

-

Cetuximab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody that blocks the human EGFR, inhibiting the growth of tumours expressing EGFR. 35 Cetuximab has a UK marketing authorisation for the treatment of people with EGFR-expressing RAS WT mCRC, in combination with either FOLFOX or irinotecan-based chemotherapy. 10

-

Panitumumab is a recombinant, fully human immunoglobulin G2 monoclonal antibody that binds to the EGFR, blocking its signalling pathway and inhibiting the growth of tumours. 36 It has a UK marketing authorisation for use in combination with FOLFOX for treating previously untreated RAS WT mCRC. 36 Panitumumab is also licensed for use second line in combination with FOLFIRI for people who have received first-line fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy (excluding irinotecan), although clinical trials have also measured the effectiveness of panitumumab in combination with FOLFIRI for previously untreated mCRC. 36

Comparators

The scope issued by NICE14 specified that the interventions should be compared with each other and with:

-

FOLFOX

-

XELOX

-

FOLFIRI

-

capecitabine

-

tegafur, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil

-

bevacizumab, in combination with oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based chemotherapy.

The Assessment Group noted that tegafur/uracil was discontinued in 2013 (Merck Serono submission version 2, 15 June 2015, section 1.2, p. 19). Capecitabine and folinic acid plus 5-fluorouracil are typically preferred for patients with poor performance status (Dr Mark Napier, 2015, personal communication, and Merck Serono submission version 2, 15 June 2015).

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest considered in this review included:

-

OS

-

PFS

-

response rate (including ORR, CR, PR, progressive disease, stable disease)

-

rate of resection of metastases

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

HRQoL. 14

Overall aims and objectives of the assessment

The aim of this project was to review the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cetuximab and panitumumab in a MTA. This included a review of TA17610 (cetuximab) and a partial review of TA24011 (panitumumab) for adults with previously untreated mCRC with RAS WT status. The medical benefits and risks associated with these treatments were assessed and compared across the treatments and against available standard drug treatments. The review also assessed whether or not these drugs are likely to be considered good value for money for the NHS.

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Evidence for the clinical effectiveness of cetuximab and panitumumab for people with previously untreated RAS WT mCRC was assessed by conducting a systematic review of published research evidence. The review was undertaken following the general principles published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). 57 The project was undertaken in accordance with a protocol (PROSPERO number CRD42015016111). There were no major departures from this protocol.

Individuals respond differently to some drugs. 58,59 Genotype is an important determinant of both the response to treatment and the susceptibility to adverse reactions for a wide range of drugs,60,61 for example response to EGFR inhibitors has been shown to be dependent on gene expression in colon cancer, with studies demonstrating a treatment interaction between RAS status and the effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors. 62–64 In line with research evaluating the negative impact of RAS mutations on the effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors, approval for the use of anti-EGFR antibodies has now been limited to people with mCRC with RAS WT tumours. 44,65 Tumour samples from trial populations supporting the original licensed indications were evaluated retrospectively for RAS status. Importantly, therefore, data supporting this recent licence change and this NICE assessment are not from the intention-to-treat (ITT) population for any of the included studies but from a subgroup of people contained within the original randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and the results are therefore subject to uncertainty. However, no RCTs with an ITT population by RAS WT status were identified.

Previously, NICE has appraised cetuximab (TA17610) for the treatment of people with EGFR-expressing mCRC, in line with the licensed indication at the time. Two of the identified cetuximab trials were included in the last appraisal; however, only data from the subgroup of people evaluated as RAS WT from those trials are relevant to the scope of this review, as set out in the final scope from NICE (see Chapter 2, Population, including subgroups). The appraisal of panitumumab in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of mCRC (NICE TA24011) ended because no evidence submission was received from the manufacturer or sponsor of the technology. As such, NICE was unable to make recommendations relating to the use of panitumumab in the NHS. All data included in this update review for both cetuximab and panitumumab have been identified by the Assessment Group’s searches.

Identification of studies

The search strategy for clinical effectiveness studies included the following search methods:

-

searching of bibliographic and ongoing trials databases

-

searching of conference proceedings

-

contact with experts in the field

-

scrutiny of bibliographies of retrieved papers and company submissions.

The following bibliographic and ongoing trials databases were searched for clinical effectiveness studies: MEDLINE (Ovid), MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), The Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and Health Technology Assessment database, Web of Science (Thomson Reuters), ClinicalTrials.gov, the UK Clinical Research Network’s (UKCRN) portfolio, the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) registry and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

The bibliographic database searches were developed and run by an information specialist (SB) in January 2015. Search filters were used to limit the searches to RCTs, when appropriate, and all searches were limited to English-language studies when possible. No date limits were used. An update search was carried out on 27 April 2015. No papers or abstracts published after this date were included in the review. The ongoing trials databases were searched by a reviewer in March 2015. The search strategies for each database are detailed in Appendix 1.

In addition to the clinical effectiveness searches, the Health Management Information Consortium Ovid) database was searched for grey literature; this produced no new studies.

The following websites were searched for conference proceedings:

-

National Cancer Research Institute [http://conference.ncri.org.uk/ (accessed 7 March 2017)]

-

American Association for Cancer Research [http://aacrmeetingabstracts.org/ (accessed 7 March 2017)]

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/abstracts (accessed 7 March 2017)].

The bibliographic search results were exported to, and deduplicated using, EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). Deduplication was also performed using manual checking. Titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were examined independently by two researchers (LC and MB) and screened for possible inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Full texts of potentially relevant studies were ordered. Full publications were assessed independently by two reviewers (LC and MB) for inclusion or exclusion against prespecified criteria, with disagreements resolved by discussion.

After the reviewers had completed the screening process, the bibliographies of included papers were scrutinised for further potentially relevant studies. The manufacturers’ submissions were assessed for unpublished data.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of clinical effectiveness and safety evidence were defined according to the decision problem outlined in the NICE scope;14 inclusion criteria are summarised in Table 8.

| Study characteristic | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Adults with previously untreated, RAS WTa mCRC |

| Intervention | Cetuximab, in combination with FOLFOX or irinotecan-based chemotherapy |

| Panitumumab, in combination with 5-fluorouracil-containing regimens | |

| Comparator | FOLFOX |

| XELOX | |

| FOLFIRI | |

| Capecitabine | |

| Tegafur, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil | |

| Bevacizumab, in combination with oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based chemotherapy | |

| Outcomes | OS |

| PFS | |

| Response rate | |

| Rate of resection of metastases | |

| AEs | |

| HRQoL | |

| Study design | RCTs |

| Systematic reviews of RCTsb |

The systematic review of clinical effectiveness was based on RCT evidence. Studies published as abstracts or conference presentations were included only if sufficient details were presented to allow both an appraisal of the methodology and an assessment of the results to be undertaken. Systematic reviews of RCTs (although not formally included in the systematic review) were used as potential sources of additional efficacy evidence. A systematic review was defined as including:

-

a focused research question

-

explicit search criteria that were available to review, either in the document or on application, and explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria defining the population(s), intervention(s), comparator(s) and outcome(s) of interest

-

a critical appraisal of included studies, including consideration of internal and external validity of the research

-

a synthesis of the included evidence, whether narrative or quantitative.

The following study types were excluded: animal models, preclinical and biological studies, narrative reviews, editorials, opinions and non-English-language papers.

Data extraction and management

Included papers were split between two reviewers for the purposes of data extraction, which was carried out using a standardised data specification form. Data extraction was checked independently by another reviewer. Information extracted and tabulated included details of the study design and methodology, baseline characteristics of participants and results, including any AEs if reported. When information on key data was incomplete, we attempted to contact the study’s authors to gain further details. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. When multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were extracted and reported as a single study. In addition, the companies (Merck Serono and Amgen) were approached through NICE to provide missing data for the RAS WT population; this information was provided as commercial-in-confidence (CiC).

Assessment of risk of bias

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, using criteria based on those proposed by the NHS CRD for RCTs (Table 9). 57 The potential generalisability of the studies was also assessed, as well as the judged applicability to the current organisation, clinical pathways and practices of the NHS in England.

| Study characteristic | Assessment criteria |

|---|---|

| Treatment allocation | 1. Was the assignment to the treatment groups really random? |

| 2. Was treatment allocation concealed? | |

| Similarity of groups | 3. Were the groups similar at baseline in terms of prognostic factors? |

| Implementation of masking | 4. Were the care providers blinded to the treatment allocation? |

| 5. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the treatment allocation? | |

| 6. Were the participants blinded to the treatment allocation? | |

| Completeness of trial | 7. Were all a priori outcomes reported? |

| 8. Were complete data reported [e.g. was attrition and exclusion (including reasons) reported for all outcomes]? | |

| 9. Did the analyses include an ITT analysis? | |

| Generalisability | 10. Are there any specific limitations that might limit the applicability of this study’s findings to the current NHS in England? |

Methods of data analysis/synthesis

The results of the clinical effectiveness and quality assessment for each included study are presented in structured tables and as a narrative summary. The possible effects of study quality on the clinical effectiveness data and review findings are discussed.

Network meta-analysis

Network meta-analyses (NMAs) were undertaken within a Bayesian framework in WinBUGS (version 1.4.3; MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). When prior distributions were used these were defined to be as vague as possible. The NMAs could have been conducted outside of WinBUGS (especially because of the low number of RCTs); however, the approach taken here allowed calculation of the probability that each treatment was the most effective compared with all others within the network.

Two networks were analysed: those using FOLFOX regimens and those using FOLFIRI regimens. The treatment FOLFOX was the baseline treatment in the FOLFOX regimens network, whereas FOLFIRI was the baseline treatment in the FOLFIRI regimens network.

For the analysis of PFS, OS and ORR, models with a normal likelihood and identify link were used. 66 Analysis of AEs used a model with a binomial likelihood and logit link. 66 For the analysis of AEs, when no events were reported in a study arm, a continuity correction of 0.5 was added to every cell for that particular study to allow analysis to be conducted. 66

Analyses were run with three chains and an initial burn-in of 50,000 iterations, followed by an additional 100,000 iterations, on which the results were based. Because of the small number of RCTs contributing to each network, only fixed-effects models were used. Convergence of the models was assessed visually using the autocorrelation, density and trace plots for all monitored variables, and checking that each chain was sampling from the same posterior distribution. The posterior means and 95% credible intervals (CrIs) from these analyses are reported. The probability that each treatment in the network was ranked as the most effective (rank 1) down to the least effective (rank 4) was also calculated.

Results

The results of the included studies are discussed in the following sections. Results relating to the patient population of interest (RAS WT) are subgroup analyses of the original studies. Initially, a summary of the quantity and quality of the evidence is provided, together with a table presenting an overview of the included trials. This is followed by a more detailed narrative description, together with an overview of trial quality, for each included trial. A narrative description of population baseline characteristics and potential imbalances is provided for each trial. The clinical effectiveness results are reported by outcome (OS, PFS, ORR, resection rate, HRQoL and AEs). For the efficacy outcomes of OS, PFS and ORR, the results are presented separately for cetuximab and panitumumab.

Studies identified

We screened the titles and abstracts of 2636 unique references identified by the PenTAG searches and additional sources and retrieved 52 papers for detailed consideration. Of these, 45 were excluded (a list of these items with reasons for their exclusion can be found in Appendix 2). Of the excluded items, four abstracts were identified as relevant to the review33,34,67,68 (see Appendix 3) but were excluded as not enough information was available to adequately appraise their quality. The authors of the abstracts were contacted, which led to the identification of an additional two full papers. 43,65 In total, post hoc analyses from five RCTs28,29,43,44,65 met the inclusion criteria. In assessing titles and abstracts, agreement between the two reviewers was substantial (κ = 0.801). At the full-text stage, agreement was good (κ = 0.636). At both stages, initial disagreements were easily resolved by consensus.

Update searches were conducted on 27 April 2015 using the same methodology as described earlier. A total of 175 records were screened by two reviewers (LC and JVC) and four records were selected for full-text retrieval. Of these, none was formally included in the review; although three were considered to meet the eligibility criteria for the review,69–71 they were available only in abstract form and, as such, could not be quality appraised (see Appendix 3).

No studies comparing either cetuximab or panitumumab with the following comparators met the eligibility criteria for the review: XELOX, capecitabine monotherapy and tegafur plus folinic acid + 5-fluorouracil (specified in the NICE scope14). In addition, no studies evaluating panitumumab plus FOLFIRI met the eligibility criteria for the review.

The study selection process is outlined in Figure 4.

Cetuximab

Study characteristics

The 2009 STA (TA17610) identified two RCTs investigating the effectiveness of the addition of cetuximab to either oxaliplatin- (FOLFOX) or irinotecan-based (FOLFIRI) chemotherapy [CRYSTAL (Cetuximab Combined with Irinotecan in First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer)24 and OPUS (Oxaliplatin and Cetuximab in First-line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer)23]. As research into the impact of KRAS and NRAS tumour mutations on the effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors developed, the ITT populations from the pivotal trials were re-evaluated, forming the basis for the revision of the licensed population.

In total, three subgroup analyses from three randomised, open-label trials {OPUS,65 CRYSTAL43 and FIRE-3 [5-FU, Folinic Acid and Irinotecan (FOLFIRI) Plus Cetuximab versus FOLFIRI Plus Bevacizumab in First Line Treatment of Colorectal Cancer]28} were included in the update review. Of note, in the FIRE-328 trial a protocol amendment was made, restricting eligibility for the ITT population to those with KRAS WT exon 2 tumours, because of the emerging evidence on the negative predictive value of KRAS exon 2 mutations and the subsequent changes to the licence for cetuximab. However, in all of the included trials the extended RAS subgroup analysis of interest to this review was conducted retrospectively.

Of the included trials, two evaluated the addition of cetuximab to background chemotherapy (FOLFOX65 or FOLFIRI43) and one evaluated the addition of cetuximab or bevacizumab to background chemotherapy (FOLFIRI)28 (Table 10). All of the trials evaluated the same dose of cetuximab and administration method.

| First author (trial); study design | Included in TA176a | Included in update review | Inclusion criteria | ITT (n)b | RAS WT (n)/analysed (N)c | Randomisation stratification factors | Interventions evaluated and dose | Primary end point | Treatment duration (months), median (IQR) | Follow-up (months), median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokemeyer 201523,33,65 and data on file [Merck Serono, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)] (OPUS; NCT00125034); retrospective subgroup analysis | No | Yes | Aged ≥ 18 years; ECOG PS ≤ 2; first occurrence of metastatic disease | 337 | 87/118 | ECOG PS 0–1 or 2 | CET + FOLFOX4 vs. FOLFOX4 | ORR | CET + FOLFOX4 5.7 (NR) vs. FOLFOX4 4.7 (NR) | NR |

| CET: 400 mg/m2 on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 per week | ||||||||||

| FOLFOX: Q2W as 85 mg/m2 of IV OX on day 1 + 200 mg/m2 i.v. infusion of folinic acid (over 2 hours) on days 1 and 2 + 400 mg/m2 bolus i.v. infusion of 5-FU (2–4 minutes) then 600 mg/m2 infusion (during 22 hours) on days 1 and 2 | ||||||||||

| Van Cutsem 201543 and data on file [Merck Serono, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)] (CRYSTAL; NCT00154102); retrospective subgroup analysis | No | Yes | Aged ≥ 18 years; ECOG PS ≤ 2; first occurrence of metastatic disease | 1198 | 367/430 | ECOG PS 0–1 or 2; region (Western Europe vs. Eastern Europe vs. outside Europe) | CET + FOLFIRI vs. FOLFIRI | PFS | CET + FOLFIRI 7.41 (NR) vs. FOLFIRI 5.77 (NR) | NR |

| CET: 400 mg/m2 on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 per week | ||||||||||

| FOLFIRI: 30- to 90-minute infusion of 180 mg/m2 of IRIN + 120-minute infusion of 400 mg/m2 of racemic leucovorin or 200 mg/m2 of L-leucovorin + 5-FU bolus of 400 mg/m2 then continuous infusion for 46 hours at 2400 mg/m2 | ||||||||||

| Heinemann 201428 and data on file [Merck Serono, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)] (FIRE-3; NCT00433927); retrospective subgroup analysis | No | Yes | Aged ≥ 18 years; ECOG PS ≤ 2; first occurrence of metastatic disease | 592 | 342/542 | ECOG PS 0–1 or 2; number of metastatic sites (one or more than one); white blood cell count | CET + FOLFIRI vs. BEV + FOLFIRI | ORR | NR | CET + FOLFIRI 33.0 (19.0–55.4) vs. BEV + FOLFIRI 39.0 (22.5–56.9) |

| CET: 400 mg/m2 on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 per week | ||||||||||

| BEV: 90-minute infusion of 5 mg/kg on day 1, 60-minute infusion of 5 mg/kg 2 weeks later; 30-minute infusion of 5 mg/kg every 2 weeks thereafter | ||||||||||

| FOLFIRI: 60- to 90-minute infusion of 180 mg/m2 of IRIN + 120-minute infusion of 400 mg/m2 of racemic leucovorin + 5-FU bolus of 400 mg/m2 then continuous infusion for 46 hours at 2400 mg/m2 |

All of the included trials measured the following outcomes: ORR, PFS, OS, secondary resection of liver metastases with curative intent and safety and tolerability (including the incidence and type of AEs). 28,43,65

In two of the included trials the primary end point was the proportion of participants who had an ORR. 28,65 In the OPUS trial65 tumour response was assessed by an independent review committee according to modified WHO criteria, whereas in the FIRE-3 trial28 tumour response was measured according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.0, as assessed by the study investigators. The independent review committee conducted a blinded review of images and clinical data. In the CRYSTAL trial,43 the primary end point, PFS time, was defined as the time from randomisation to disease progression or death from any cause (within 60 days following randomisation or the last tumour assessment). No data were identified for HRQoL for the RAS WT population from any of the included trials.

Median follow-up was not reported in the OPUS trial65 or the CRYSTAL trial. 43 In the FIRE-3 trial28 the median follow-up was 33.0 months [interquartile range (IQR) 19.0–55.4 months] in the cetuximab plus FOLFIRI arm and 39.0 months (IQR 22.5–56.9 months) in the bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI arm.

Population characteristics

The baseline demographic and disease characteristics for the RAS WT subgroup are reported in Table 11.

| First author (trial) | Intervention | n | Age (years), median (range) | Male, n/N (%) | ECOG PS, n/N (%) | Number of metastatic sites, n/N (%) | Primary tumour diagnosis, n/N (%) | LLD, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokemeyer 201533,65 and data on file [Merck Serono, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)] (OPUS) | CET + FOLFOX4 | 38 | 60.5 (24–75) | 19/38 (50.0) | 0: 18/38 (47.4); 1: 19/38 (50.0); 2: 1/38 (2.6) | 1: 22/38 (57.9); 2: 12/38 (31.6); ≥ 3: 4/38 (10.5) | NR | 15/38 (39.5) |

| FOLFOX4 | 49 | 59.0 (36–79) | 29/49 (59.2) | 0: 16/49 (32.7); 1: 29/49 (59.2); 2: 4/49 (8.2) | 1: 18/49 (36.7); 2: 21/49 (42.9); ≥ 3: 10/38 (26.3) | NR | 12/49 (24.5) | |

| Van Cutsem 201543 (CRYSTAL) | CET + FOLFIRI | 178 | 60.0 (24.0–79.0) | 109/178 (61.2) | 0: 97/178 (54.5); 1: 76/178 (42.7); 2: 5/178 (2.8) | ≤ 2: 157/178 (88.2); ≥ 2: 17/178 (9.6); othera: 4/178 (2.2) | Colon: 106/178 (59.6); rectum: 68/178 (38.2); colon and rectum: 4/178 (2.2); missing: 0/178 (0) | 43/178 (24.2) |

| FOLFIRI | 189 | 59.0 (19.0–82.0) | 120/189 (63.5) | 0: 114/189 (60.3); 1: 68/189 (36.0); 2: 7/189 (3.7) | ≤ 2: 161/189 (85.2); ≥ 2: 25/189 (13.2); othera: 3/189 (1.6) | Colon: 117/189 (61.9); rectum: 70/189 (37.0); colon and rectum: 2/189 (1.1); missing: 0/189 (0) | 46/189 (24.3) | |

| Heinemann 201428 and data on file [Merck Serono, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)] (FIRE-3) | CET + FOLFIRI | 171 | 64.0 (41.0–76.0) | 125/171 (73.1) | 0: 87/171 (50.9); 1: 82/171 (48.0); 2: 2/171 (1.2) | 1: 75/171 (43.9); 2: 56/171 (32.7); ≥ 3: 38/171 (22.2) | Colon: 106/171 (62.0); rectum: 55/171 (32.2); colon and rectum: 7/171 (4.1); missing: 3/171 (1.8) | 62/171 (36.3) |

| BEV + FOLFIRI | 171 | 65.0 (33.0–76.0) | 114/171 (66.7) | 0: 87/171 (50.9); 1: 81/171 (47.4); 2: 3/171 (1.8) | 1: 76/171 (44.4); 2: 54/171 (31.6); ≥ 3: 41/171 (24.0) | Colon: 105/171 (61.4); rectum: 59/171 (34.5); colon and rectum: 7/171 (4.1); missing: 0/171 (0) | 58/171 (33.9) |

For the ITT population, for each of the included trials the baseline demographic and disease characteristics were well matched between the groups. In all studies, existing deoxyribonucleic acid samples from KRAS exon 2 WT tumours were reanalysed for other RAS mutations in four additional KRAS codons (exons 3 and 4) and six NRAS codons (exons 2, 3 and 4). Mutation status was evaluable in 796 (73.0%) of 1090 trial participants with KRAS exon 2 WT tumours (see Table 10). The proportions of study participants evaluated to be RAS WT in the different trials are summarised in Table 10. In all trials, the baseline and disease characteristics were comparable with those seen for the KRAS WT population (see Appendix 4 for baseline and disease characteristics for the KRASWT population).

Participants were similar in terms of age, sex distribution and site of primary cancer (see Table 11). However, as is usually the case with cancer trials, the study populations were significantly younger than the general population presenting with mCRC, with a median age of 59–65 years for the study populations (see Table 11) compared with a peak in number of cases in the UK at between 70 and 79 years of age for men and 75 and 85 years for women.

Panitumumab

Study characteristics

The appraisal of panitumumab in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of mCRC (TA24011) was suspended as no evidence submission was received from the manufacturer or sponsor of the technology. As such, all data included in this update review for panitumumab were identified by the Assessment Group’s searches. It is also important to consider that, as for cetuximab, the ITT population from the pivotal trials for panitumumab were re-evaluated in line with research developments on the impact of RAS mutations on the effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors.

For this MTA review, a total of two subgroup analyses of the RAS WT population from two RCTs29,44 evaluating panitumumab were eligible for inclusion. In the PEAK [Panitumumab Plus mFOLFOX6 vs. Bevacizumab Plus mFOLFOX6 for First Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC) Patients With Wild-Type Kirsten Rat Sarcoma-2 Virus (KRAS) Tumors] study29 the extended RAS subgroup analysis was prespecified. In the PRIME (Panitumumab Randomized trial In combination with chemotherapy for Metastatic colorectal cancer to determine Efficacy) study44 the extended RAS subgroup analysis was noted alongside a protocol amendment restricting the analysis of the ITT population to compare PFS and OS according to KRAS status.

Of the two included trials, one evaluated the addition of panitumumab to background chemotherapy (FOLFOX4)44 and one evaluated the addition of panitumumab or bevacizumab to background chemotherapy [modified FOLFOX6 (mFOLFOX6)]. 29 All trials evaluated the same dose of panitumumab and administration method (Table 12). No clinical evidence assessing the effectiveness of panitumumab in conjunction with FOLFIRI was identified.

| First author (trial); study design | Included in TA176a | Included in update review | Inclusion criteria | ITT (n)b | RAS WT (n)/analysed (n)c | Randomisation stratification factors | Interventions evaluated and dose | Primary end point | Treatment duration (months), median (IQR) | Follow-up (months), median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douillard 201344 and data on file [Amgen, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)] (PRIME; NCT00364013); retrospective subgroup analysis | No | Yes | Aged ≥ 18 years; ECOG PS ≤ 2; first occurrence of metastatic disease | 1183 | 512/1060 | ECOG PS (0–1 vs. 2); region (Western Europe, Canada, and Australia vs. rest of the world) | PAN + FOLFOX4 vs. FOLFOX4 | PFS | PAN + FOLFOX 46.47 (3.68– 11.40) vs. FOLFOX4 (NR) | PAN + FOLFOX 22.31 (10.12–35.65) vs. FOLFOX4 17.71 (8.74–32.20) |

| PAN: 60-minute i.v. infusion of 6 mg/kg Q2W on day 1 | ||||||||||

| FOLFOX4: Q2W as 85 mg/m2 of i.v. OX on day 1 + 200 mg/m2 i.v. infusion of racemic leucovorin on days 1 and 2 + 400 mg/m2 i.v. bolus of 5-FU followed by a 600 mg/m2 infusion over 22 hours on days 1 and 2 | ||||||||||

| Schwartzberg 201429 and data on file [Amgen, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)] (PEAK; NCT00819780); prospective subgroup analysis | No | Yes | Aged ≥ 18 years; ECOG PS ≤ 2; first occurrence of metastatic disease | 285 | 170/250 | Prior adjuvant OX therapy | PAN + mFOLFOX6 vs. BEV + mFOLFOX6 | PFS | PAN + mFOLFOX 67.45 (3.91–11.66) vs. BEV + mFOLFOX 65.86 (3.13–9.57) | PAN + mFOLFOX 14.97 (8.83–22.81) vs. BEV + mFOLFOX 14.93 (8.76–21.39) |

| PAN: 60-minute i.v. infusion of 6 mg/kg Q2W on day 1 | ||||||||||

| BEV: 90-minute infusion of 5 mg/kg on day 1, 60-minute infusion of 5 mg/kg 2 weeks later; 30-minute infusion of 5 mg/kg every 2 weeks thereafter | ||||||||||

| mFOLFOX6: Q2W as 85 mg/m2 i.v. infusion of OX (over 2 hours) on day 1 + 400 mg/m2 i.v. infusion of leucovorin (over 2 hours) on day 1 + 400 mg/m2 i.v. bolus of 5-FU (over 2–4 minutes) on day 1 followed by a 2400 mg/m2 ambulatory pump (46–48 hours) |

Both of the included trials measured the following outcomes: ORR, PFS, OS, secondary resection of liver metastases with curative intent, and safety and tolerability (including the incidence and type of AEs). 29,44 The primary end point in both trials was PFS, defined as the time from randomisation to disease progression or death from any cause within 60 days after the last tumour assessment or after randomisation. No data were identified for HRQoL for the RAS WT population from the included trials.

Median follow-up in the PRIME trial was 22.31 months (IQR 10.12–35.65 months) for the panitumumab plus FOLFOX4 treatment group and 17.71 months (IQR 8.74–32.20 months) for the FOLFOX4 alone treatment group. 44 In the PEAK trial, median follow-up was 14.97 months (IQR 8.83–22.81 months) in the cetuximab plus mFOLFOX6 treatment group and 14.93 months (IQR 8.76–21.39 months) in the bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 treatment group. 29

Population characteristics

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics for the RAS WT subgroup are reported in Table 13.

| First author (trial) | Intervention | n | Age (years), median (range) | Male, n/N (%) | ECOG PS, n/N (%) | Number of metastatic sites, n/N (%) | Primary tumour diagnosis, n/N (%) | LLD, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douillard 201344 and data on file [Amgen, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)] (PRIME) | PAN + FOLFOX4 | 253a | 61 (27–81) | 170/253 (67) | 0: 150/253 (59); 1: 88/253 (35); 2: 15/253 (6) | 1: 56/253 (22); 2: 92/253 (36); ≥ 3: 104/253 (41) | Colon: 165/253 (65); rectum: 88/253 (35) | 48/253 (19.0) |

| FOLFOX4 | 252b | 61 (24–82) | 158/252 (63) | 0: 137/252 (54); 1: 98/252 (39); 2: 16/252 (6) | 1: 50/252 (20); 2: 93/252 (37); ≥ 3: 109/252 (43) | Colon: 164/252 (65); rectum: 88/252 (35) | 41/252 (16.3) | |

| Schwartzberg 201429 (PEAK) | PAN + mFOLFOX6 | 88 | 62 (23–82) | 58/88 (66) | 0: 53/88 (60); 1: 35/88 (40); other:b NA | 1: 32/88 (36); 2: 28/88 (32); ≥ 3: 28/88 (32); other:a 0/88 (0) | Colon: 64/88 (73); rectum: 24/88 (27) | 23/88 (26.1) |

| BEV + mFOLFOX6 | 82 | 60 (39–82) | 56/82 (68) | 0: 52/82 (63); 1: 29/82 (35); other:a 1/82 (1) | 1: 33/82 (40); 2: 29/82 (35); ≥ 3: 19/82 (23); other:a 1/82 (1) | Colon: 57/82 (70); rectum: 25/82 (30) | 22/82 (26.8) |

In all studies, existing deoxyribonucleic acid samples from KRAS exon 2 WT tumours were reanalysed for other RAS mutations in four additional KRAS codons (exons 3 and 4) and six NRAS codons (exons 2, 3 and 4). Mutation status was evaluable in 682 (65.6%) out of 1345 trial participants with KRAS exon 2 WT tumours (see Table 12). The proportions of study participants evaluated to be RAS WT for the different studies are summarised in Table 12. In all trials, the baseline demographic and disease characteristics were comparable to those seen for the KRAS WT population (see Appendix 4 for baseline and disease characteristics for the KRAS WT population).

Participants were similar between the arms in terms of age, sex distribution and site of primary cancer (see Table 13). However, as is usually the case with cancer trials, the study populations were significantly younger than the general population presenting with mCRC, with a median age of 60–62 years for the study populations (see Table 13) compared with a peak in the number of cases in the UK at between 70 and 79 years of age for men and 75 and 85 years for women.

Quality appraisal

We appraised the five identified subgroup analyses. On occasion, however, we referred to the original trials to clarify issues relating to study design or methods. The reason for this was to put identified limitations associated with subgroup analyses into context for this appraisal. Quality assessments of the included trials are presented in Table 14.

| First author (trial) | Random allocation | Allocation concealment | Baseline similarity | Care providers blinded | Outcome assessors blinded | Patients blinded | All a priori outcomes reported | Complete data reported | ITT analysis | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Cutsem 201543 (CRYSTAL) | Inadequatea | Unclearb | Adequate | Inadequatec | Inadequatec,d | Inadequatec | Uncleare | Inadequatef | Inadequateg | Inadequateh |

| Bokemeyer, 201523,65 (OPUS) | Inadequatea | Unclearb | Adequate | Inadequatec | Inadequatec,d | Inadequatec | Uncleare | Inadequatef | Inadequateg | Inadequateh |

| Heinemann 201428 (FIRE-3) | Inadequatea,i | Unclearb | Adequate | Inadequatec | Inadequatec | Inadequatec | Uncleare | Inadequatef | Inadequateg | Inadequateh |

| Douillard 201327,44 (PRIME) | Inadequatea,j | Unclearb | Adequate | Inadequatec | Inadequatec,d | Inadequatec | Uncleare | Inadequatef | Inadequateg | Inadequateh |

| Schwartzberg 201429 (PEAK) | Inadequatea,k | Unclearb | Adequate | Inadequatec | Inadequatec,d | Inadequatec | Uncleare | Inadequatef | Inadequateg | Inadequateh |

Overall, the risk of bias was similar between studies with regard to treatment allocation, allocation concealment, blinding, outcome reporting and loss to follow-up.

Treatment allocation

The method of random allocation, including the method of sequence generation, was clearly stated and adequate for all of the included trials. All trials used a stratified permuted block procedure. Stratification factors varied between the studies but were predominantly based on Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (0 or 1 vs. 2) and region (Eastern or Western Europe vs. outside of Europe and Western Europe, Canada and Australia vs. rest of the world).

However, data for those with RAS WT mCRC were available only from subgroup analyses and not from the ITT trial population for any of the included trials. In response to research developments demonstrating a treatment interaction of RAS and EGFR inhibitors (specifically the negative impact of RAS mutations on the effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors), tumour samples from participants of the original RCTs were re-evaluated for RAS status. None of the included studies stratified randomisation by RAS status; this was because the impact of RAS mutations on the effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors was not known at the protocol development phase. For four of the trials (OPUS,65 CRYSTAL,43 FIRE-328 and PRIME44) the subgroup analyses were retrospective. However, for two of these trials (PRIME and FIRE-3) protocol amendments were made in line with research developments. The only trial in which the extended RAS WT subgroup analysis was prespecified was the PEAK trial. 29

Tumour samples from participants in the ITT population identified as KRAS exon 2 WT were re-evaluated for RAS mutations and allocated to either the RAS WT subgroup or the RAS mutant subgroup. The methods used to detect RAS mutations varied between studies, minimising the potential for ascertainment bias. The ascertainment rate for RAS testing of participants with KRAS WT status was 78% [excluding the PRIME trial in which all participants were tested (n = 512/1060)] and the missing data largely resulted from unavailable tumour samples or inconclusive RAS test results. Of note, none of the included subgroup analyses reported the results of a test for treatment interaction.

Similarity of the groups

Three of the included trials fully reported baseline characteristics for the RAS WT population (OPUS,65 CRYSTAL43 and PEAK29). Although the other two trials (PRIME44 and FIRE-328) did not report baseline characteristics for the subgroup of interest in the trial publication, we were able to confirm these through Merck Serono and Amgen [19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)]. Of note, however, baseline characteristics provided by the manufacturer for the PRIME study were for a total of 505 participants, whereas the study publication44 reports a total of 512 participants in the RAS WT subgroup.

Given the use of subgroup data, all comparisons were made without protection by stratification/randomisation, increasing the risk of selection bias. However, from the evidence provided (published and unpublished) we were able to confirm that the treatment groups were similar at baseline on a range of prognostic factors for the RAS WT population. Moreover, the characteristics were similar to those for both the ITT population and the KRAS WT population, suggesting a low risk of selection bias in the RAS-tested trial population.

Implementation of masking

The trials had an open-label design and, as such, participants and outcomes assessors were not blinded. However, a blinded retrospective review of radiological assessment and clinical data was carried out for progression and best ORR in two of the studies43,65 and for ORR in one study. 44 In addition, in one study44 an Independent Data Monitoring Committee reviewed interim analyses of safety and one descriptive interim analysis of PFS. No independent assessment was performed in either the PEAK trial29 or the FIRE-3 trial. 28

Completeness of trial data

With regard to the reporting of a priori outcomes, all included trials were rated as unclear. This was because the original trial reports for the ITT population failed to explicitly state if all outcomes defined in the study protocol were reported. Therefore, we were by default unable to assess if all a priori outcomes had been reported for the RAS WT population. Summary data, including event numbers and denominators, were reported for the majority of expected outcomes for the RAS WT population and, when not reported, we were able to confirm data (predominantly ORRs and resection rates) using secondary sources, for example EMA documents30–32,38–40,52,53 or through the manufacturers [Merck Serono and Amgen, 19 March 2015, personal communication (via NICE)].

Withdrawals and dropouts were adequately reported in all of the original trial publications (by providing numbers and reasons by treatment group in the form of a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram) for the ITT population. Loss to follow-up was, however, unclear. With respect to the RAS WT population, missing data largely resulted from unavailable tumour samples or inconclusive RAS test results.

Currently, available data on the effectiveness of both cetuximab and panitumumab in the RAS WT population are from subgroup analyses and not from the ITT trial population and, as such, ITT analysis was not conducted. Because of the retrospective nature of the RAS analysis, a low number of samples was available for analysis, reducing the power of the studies to show statistical significance.

Applicability to the NHS in England

The population evaluated is in line with that specified in the licensed indication and the NICE final scope. 14 The study arm populations had median/mean ages of between 59 and 65 years and the majority of participants had an ECOG performance status of < 2, meaning that participants were younger and fitter than the UK population of people with mCRC. This is a recurrent problem, however, in the findings of trials of therapies for mCRC in the UK population. All of the included studies were multicentre studies (including European centres) and evaluated the study drugs in line with their licensed indications. Importantly, however, data for the RAS WT population were available only from subgroup analyses rather than ITT analyses and, as such, sample sizes were often small and the results are subject to a high degree of uncertainty.

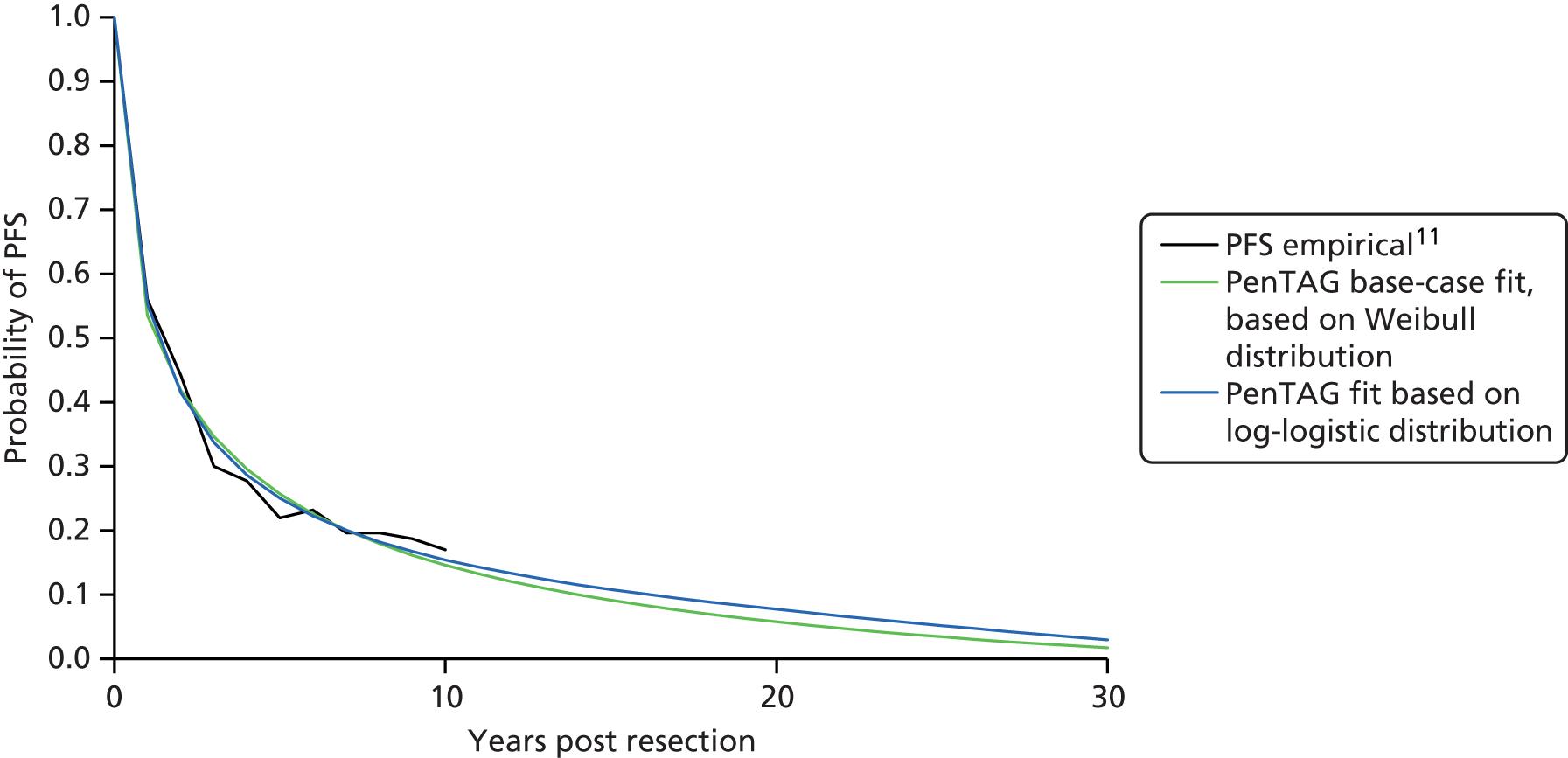

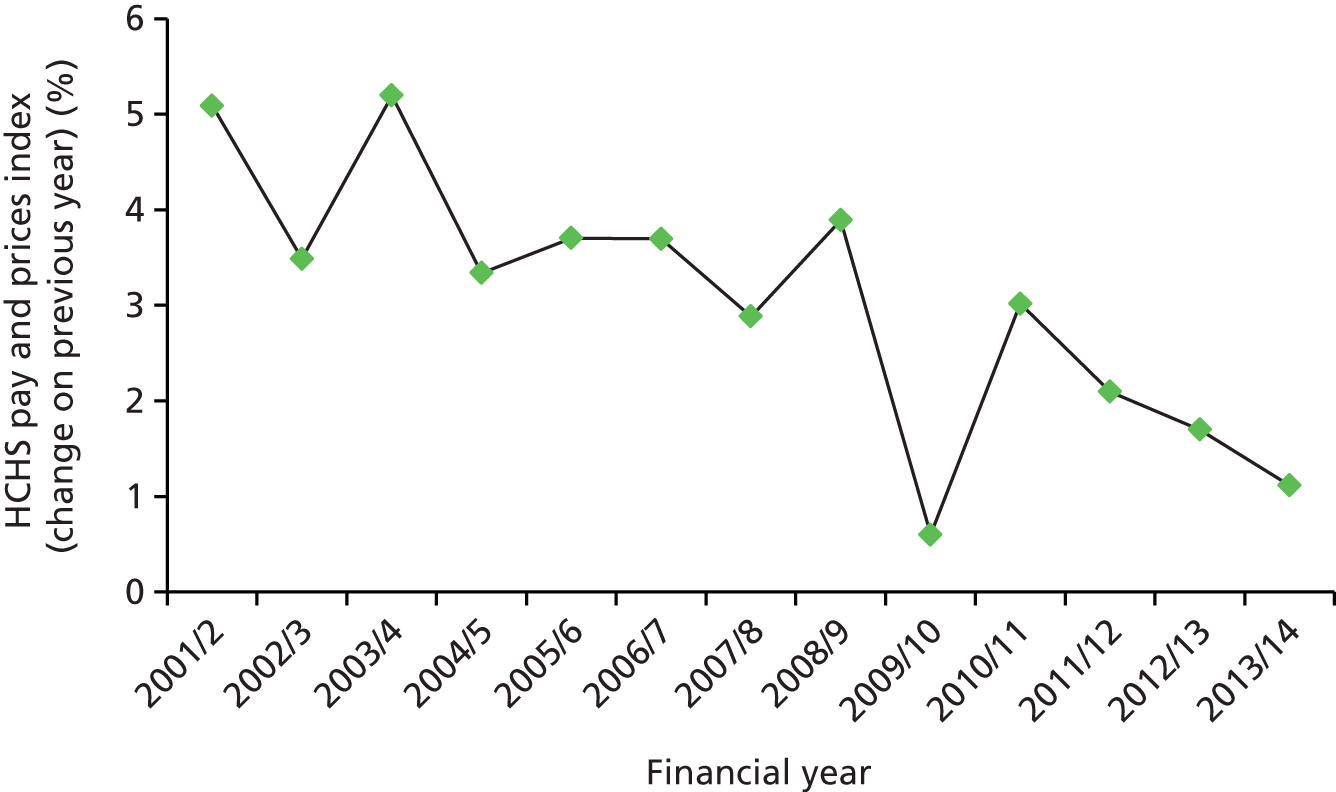

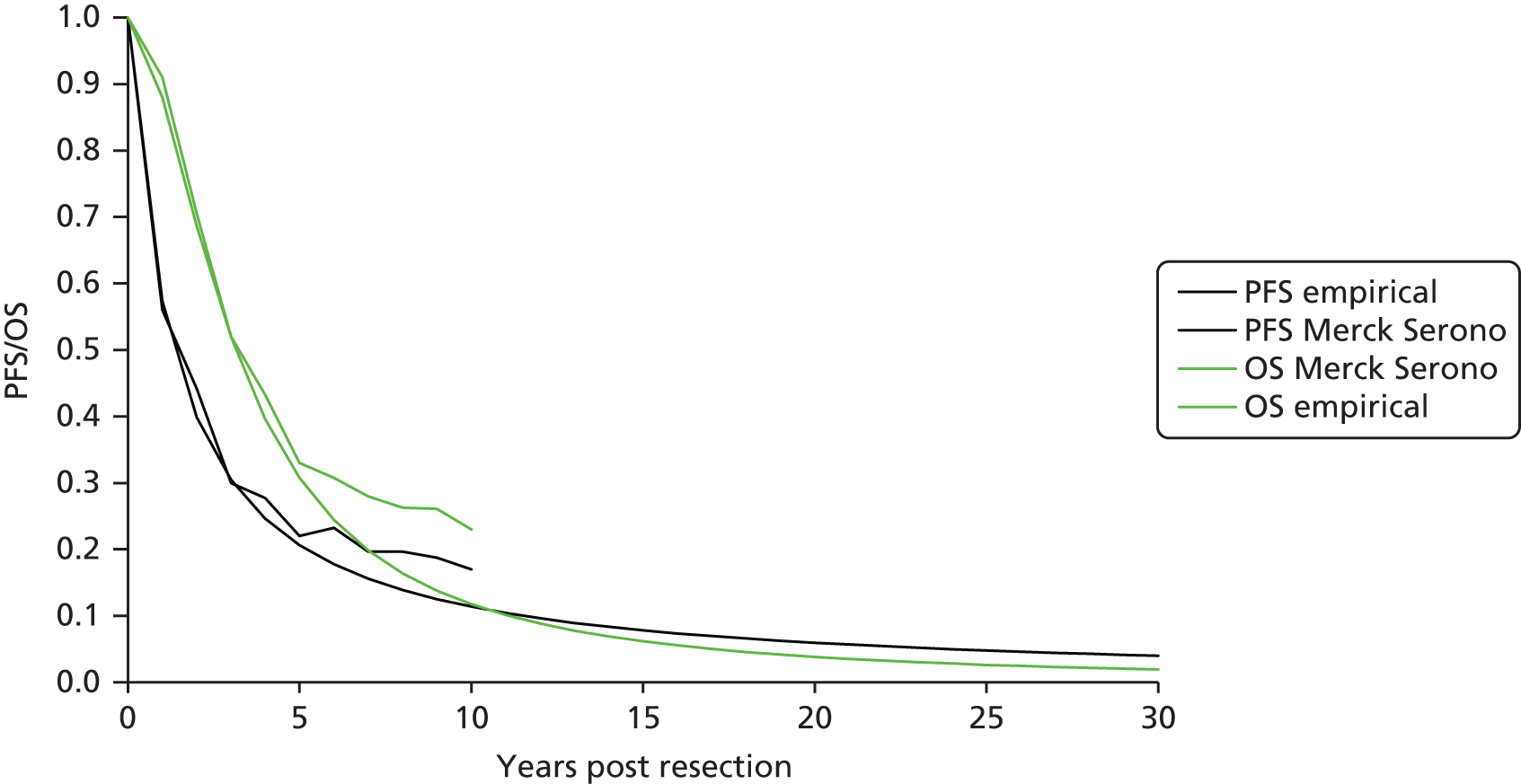

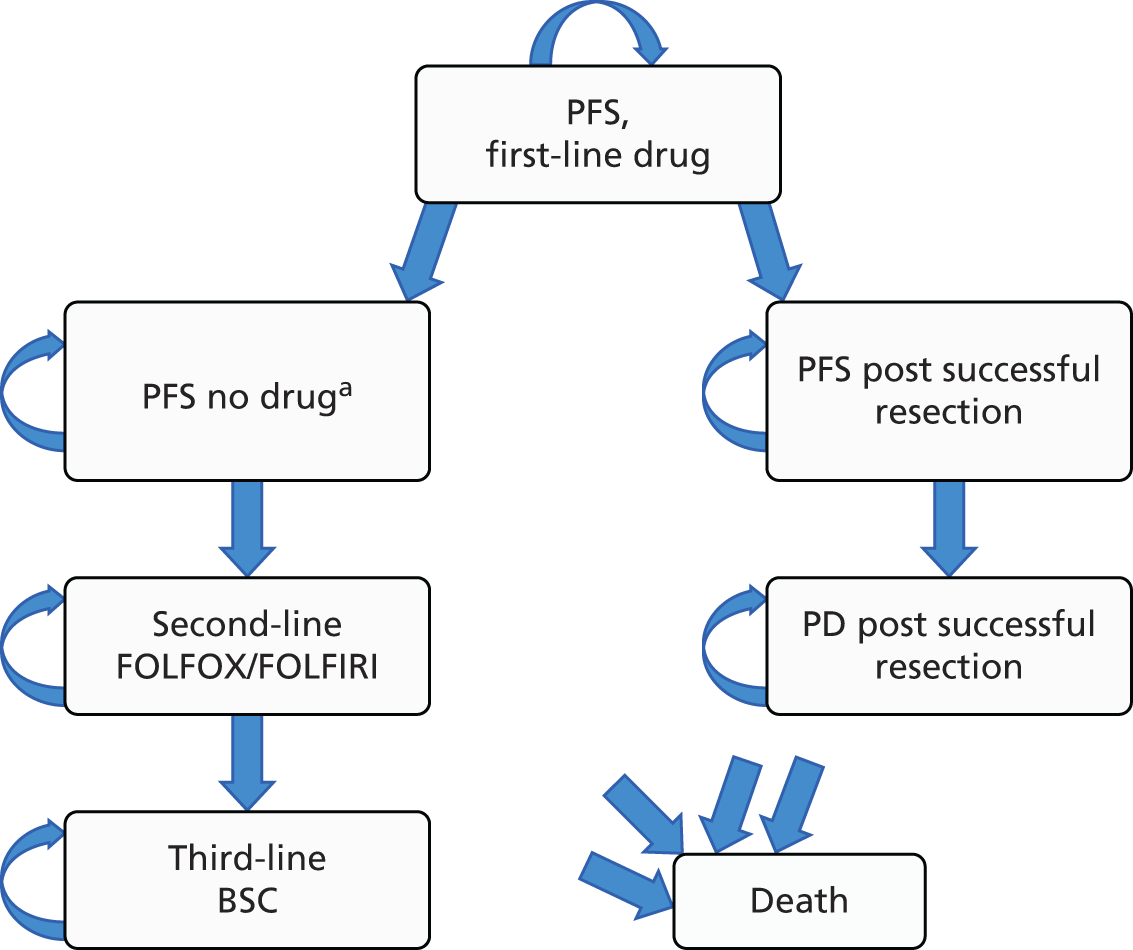

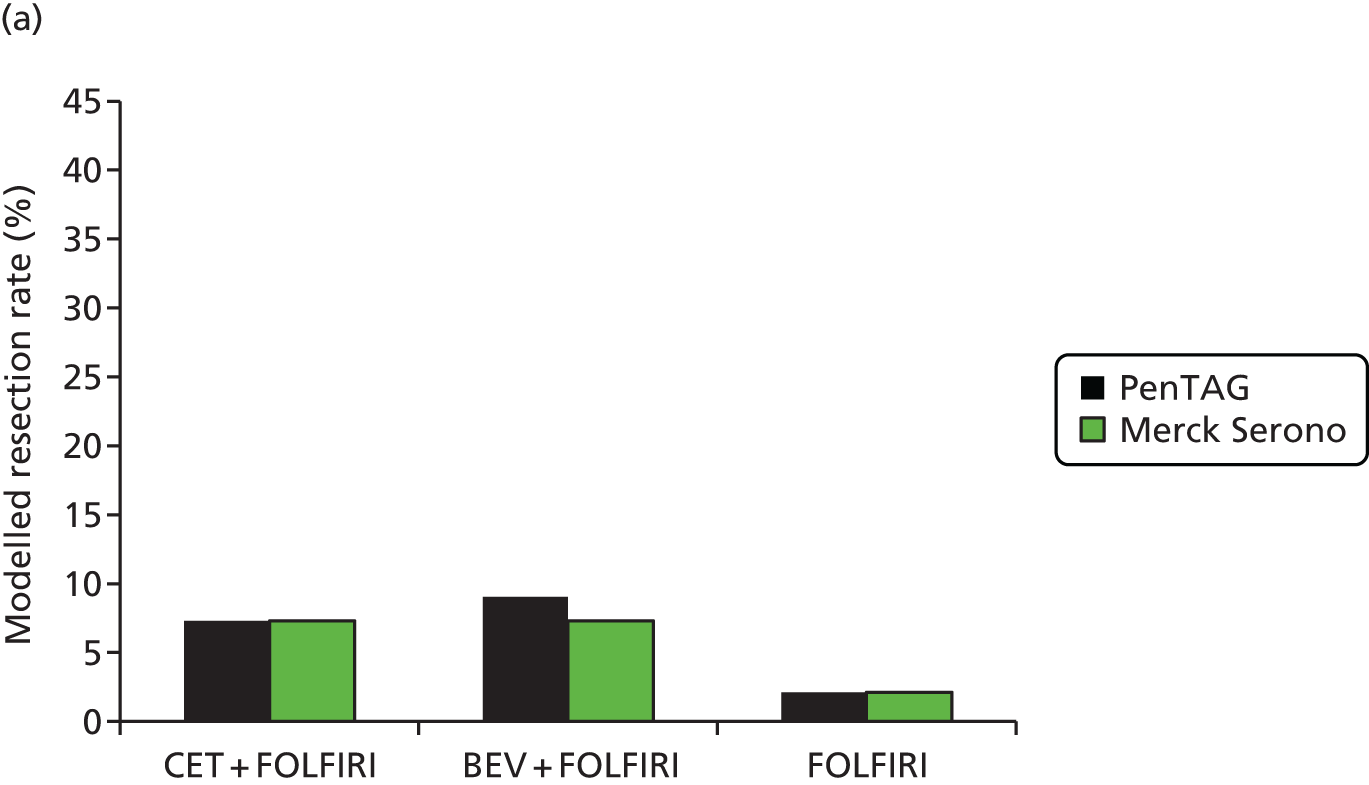

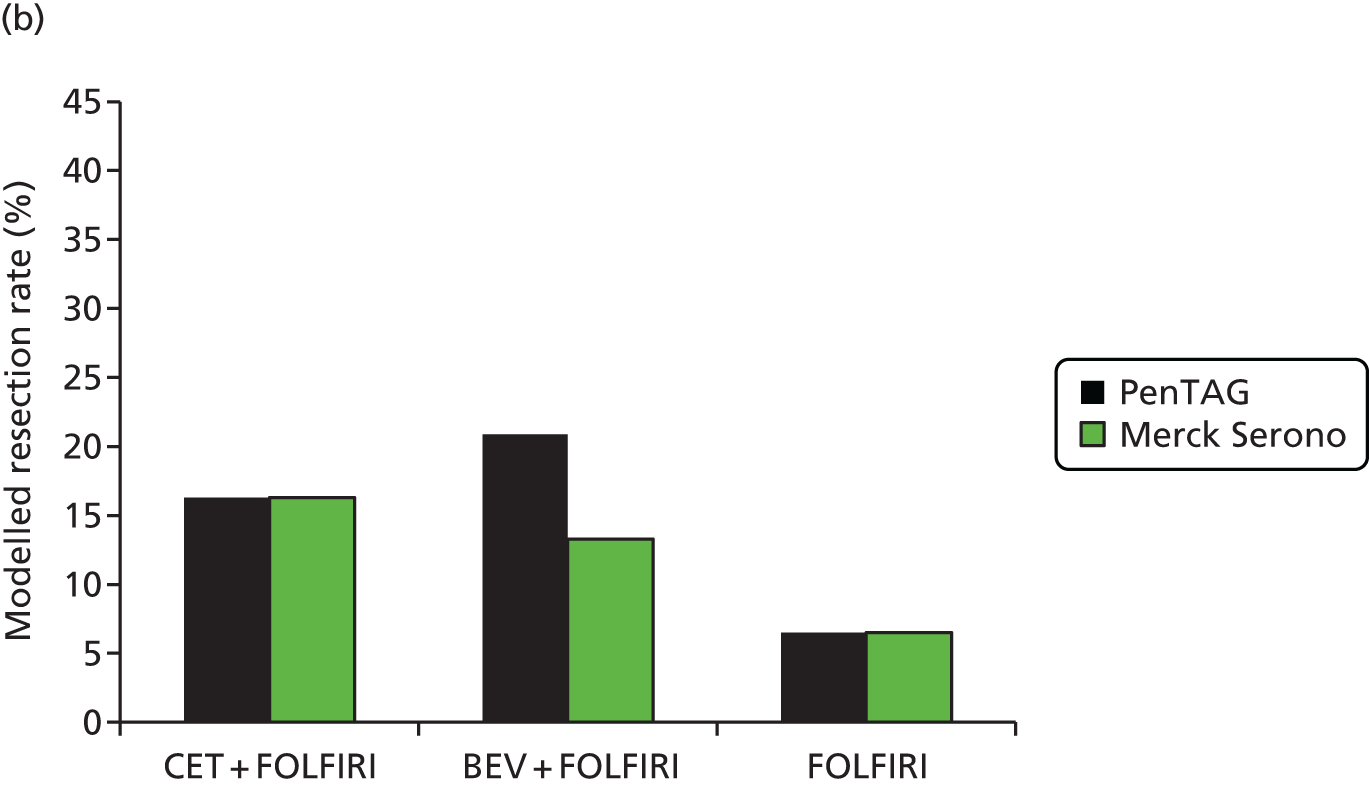

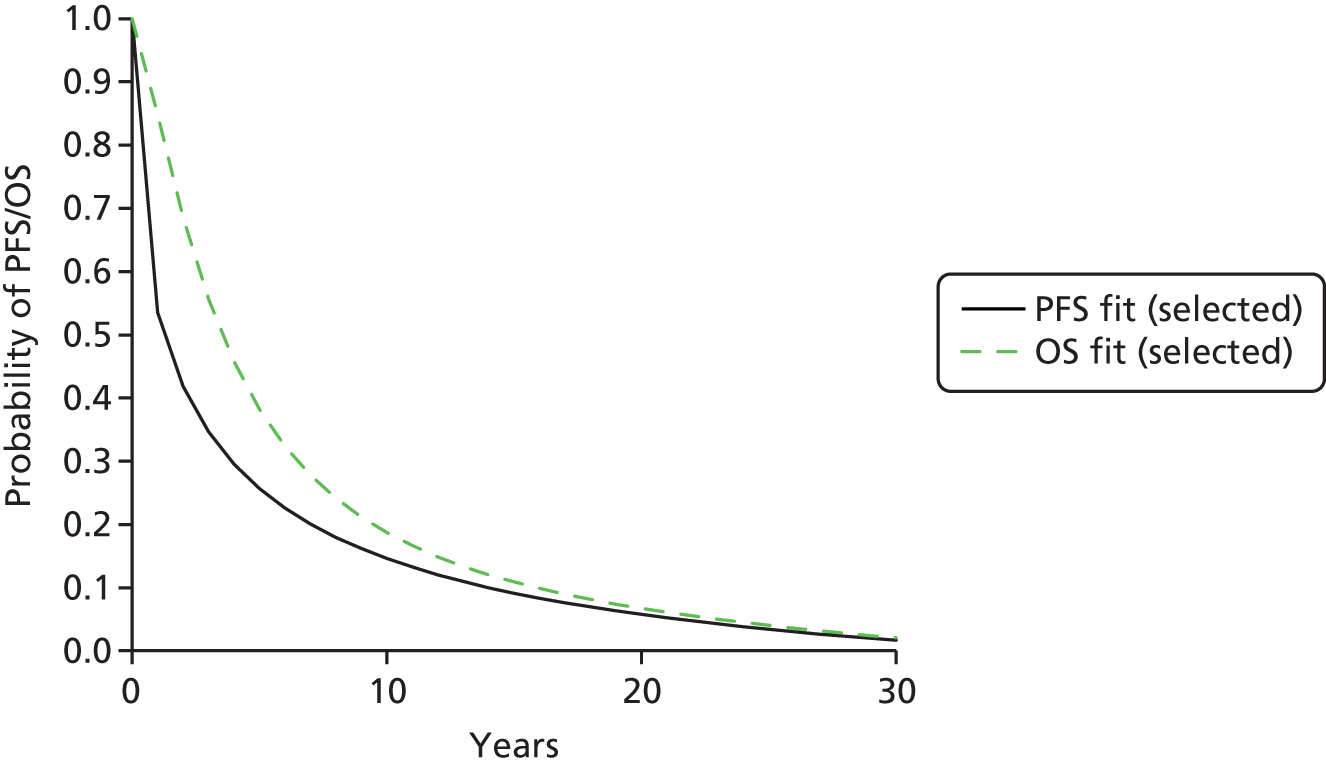

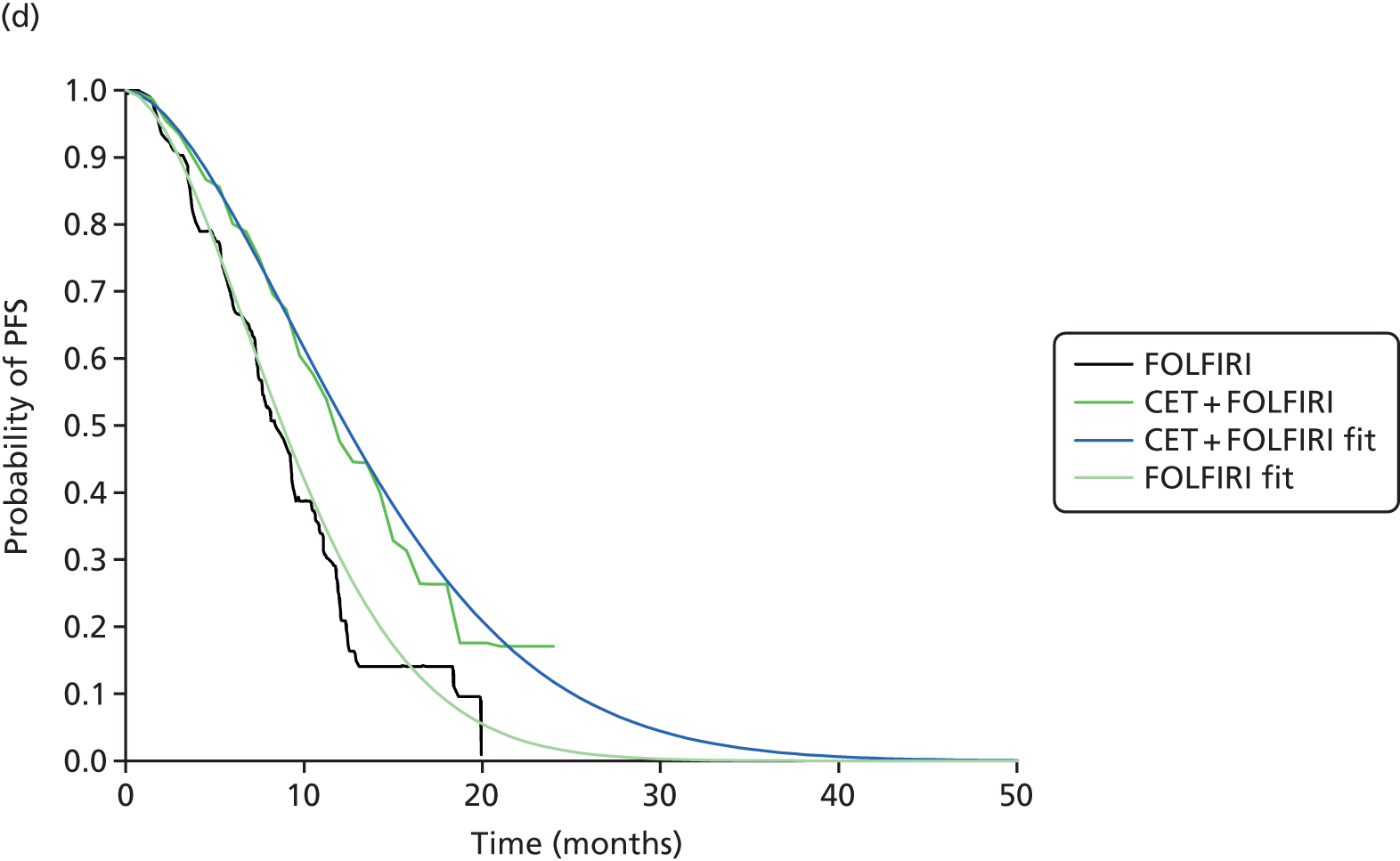

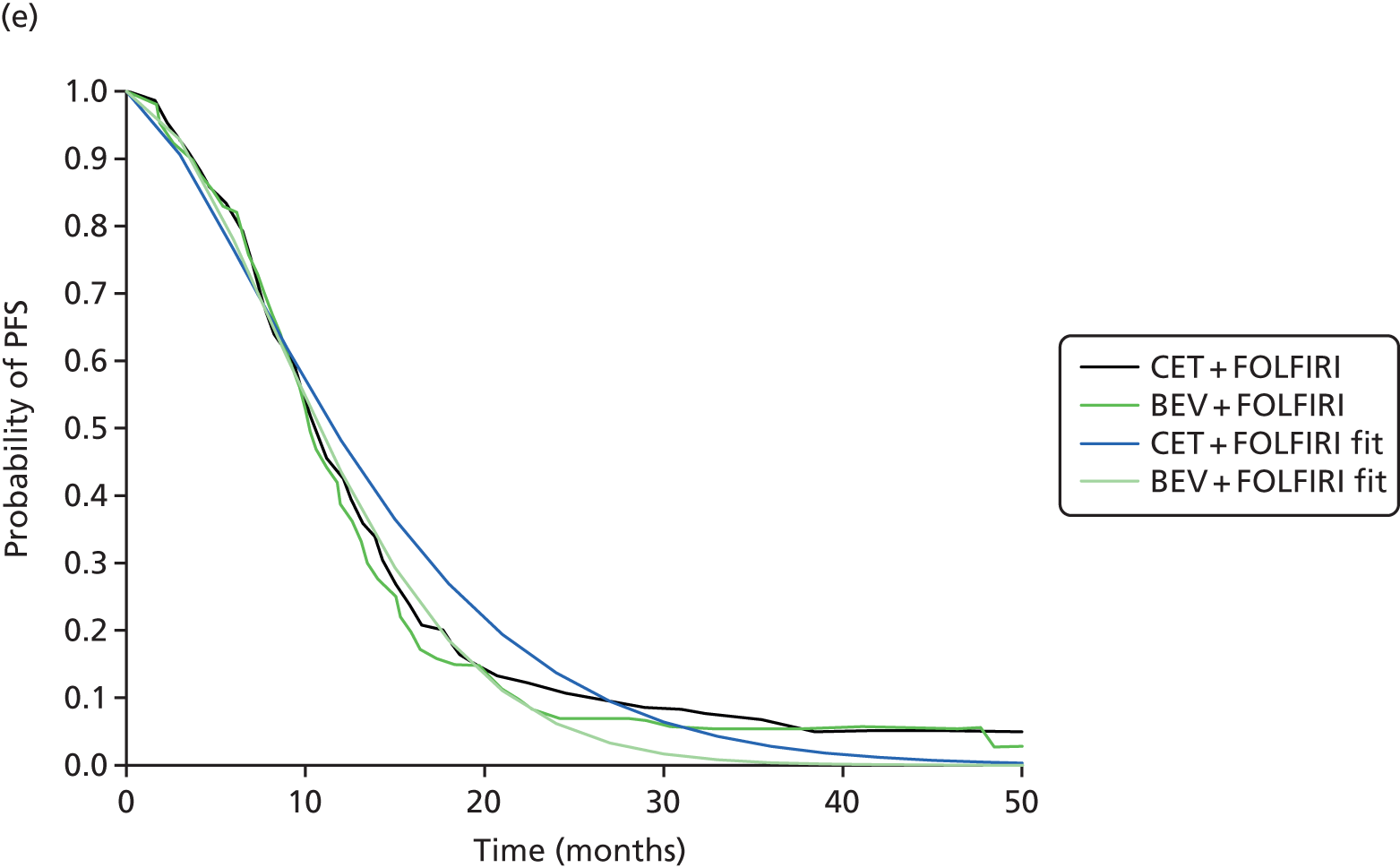

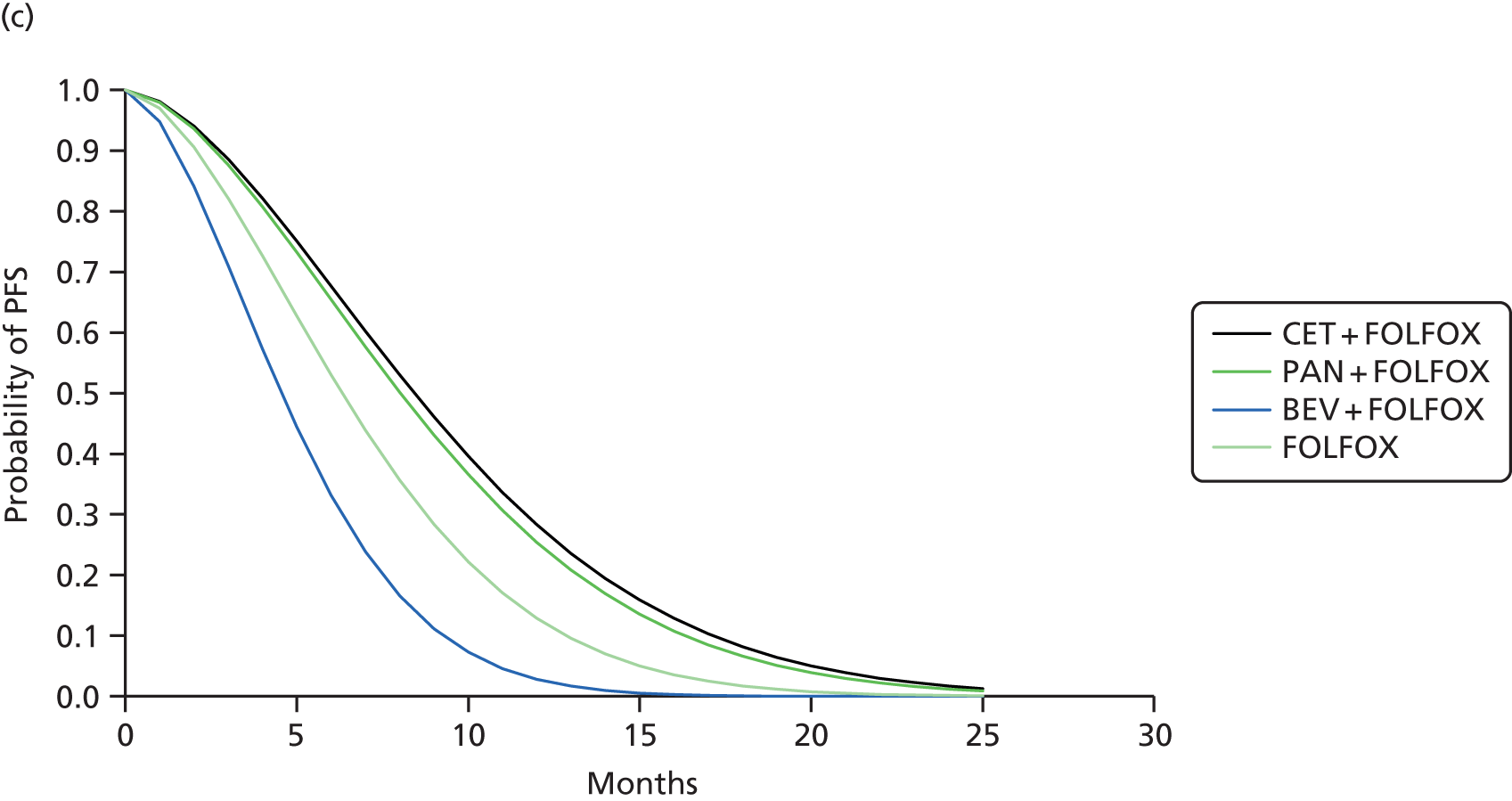

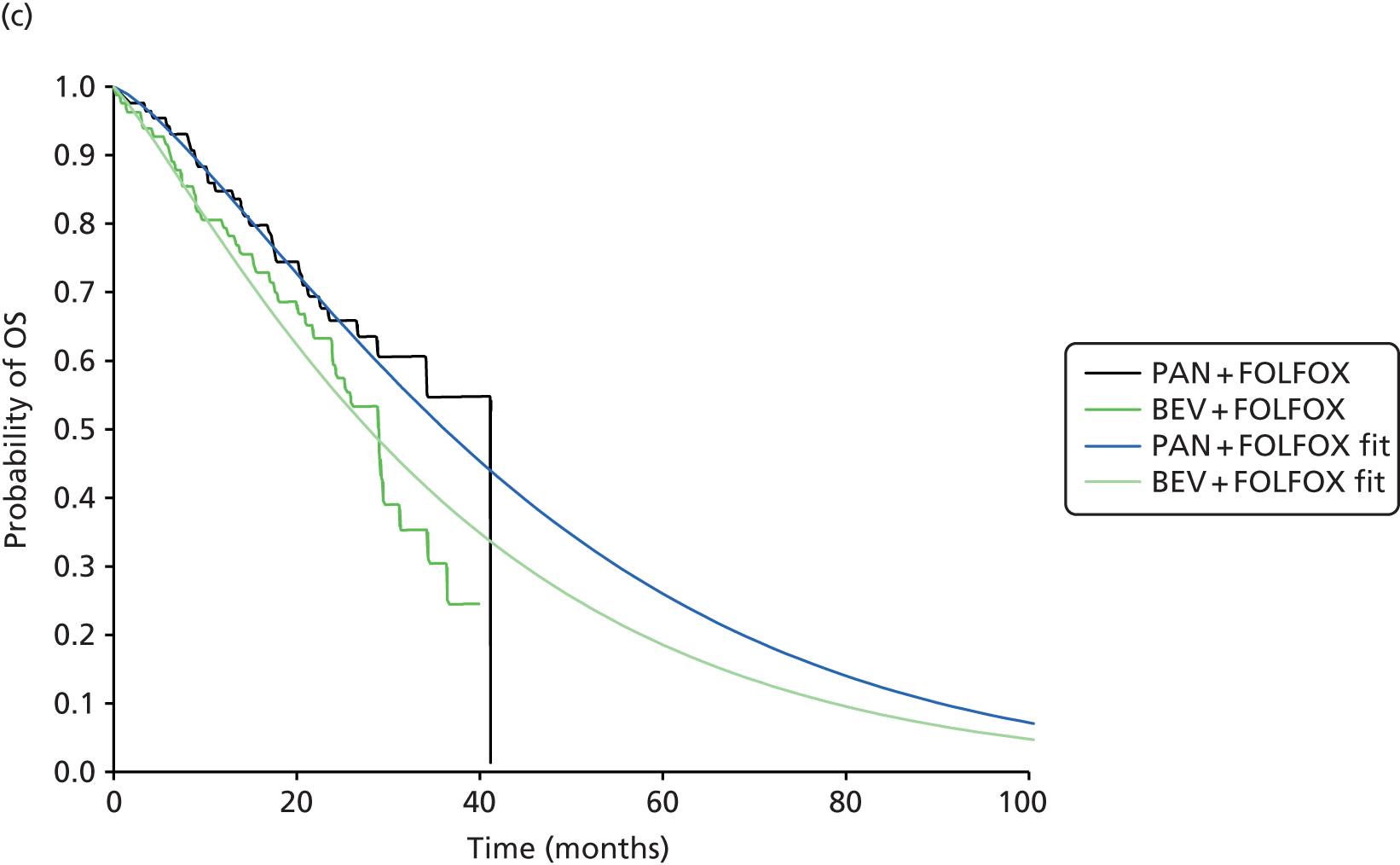

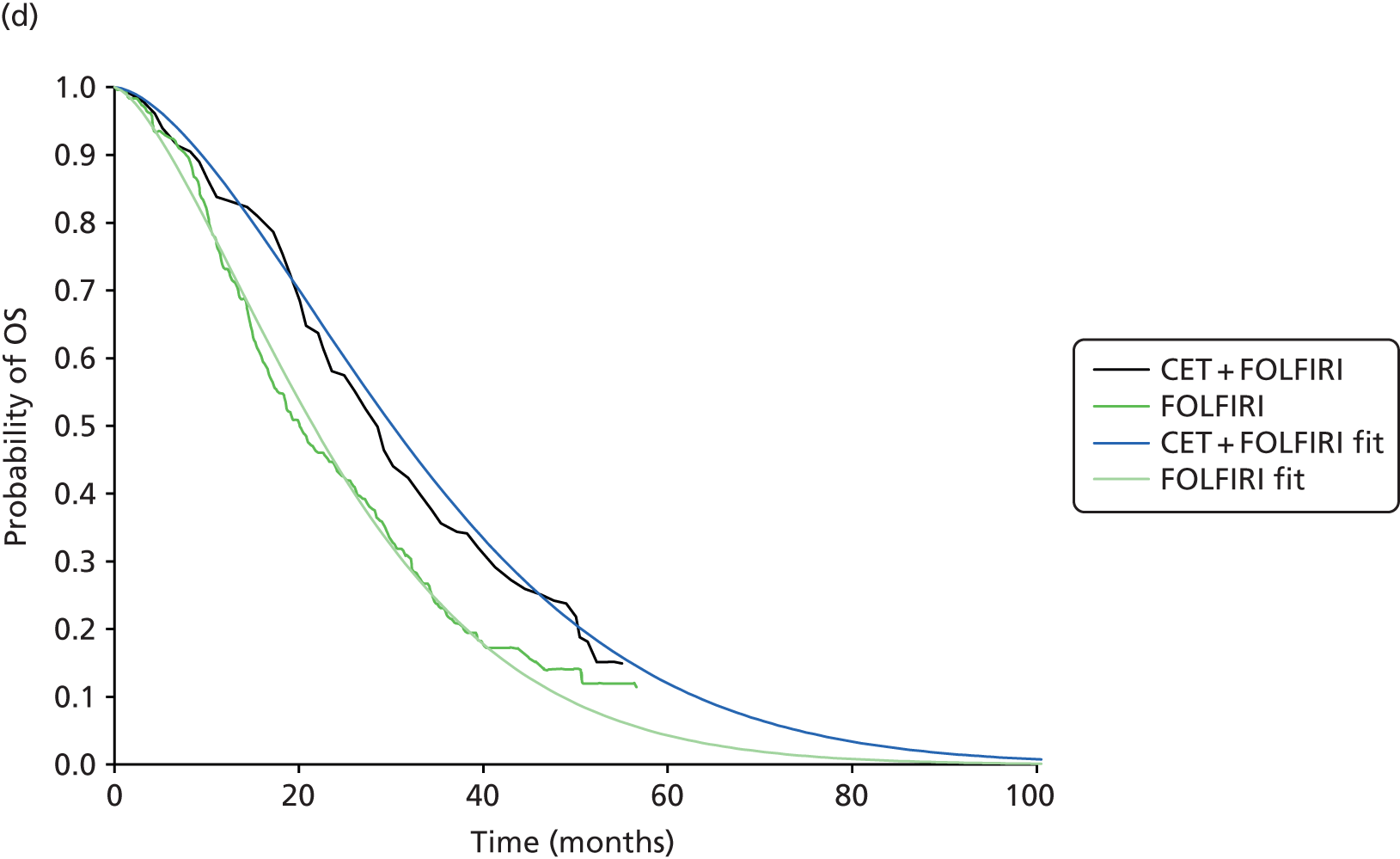

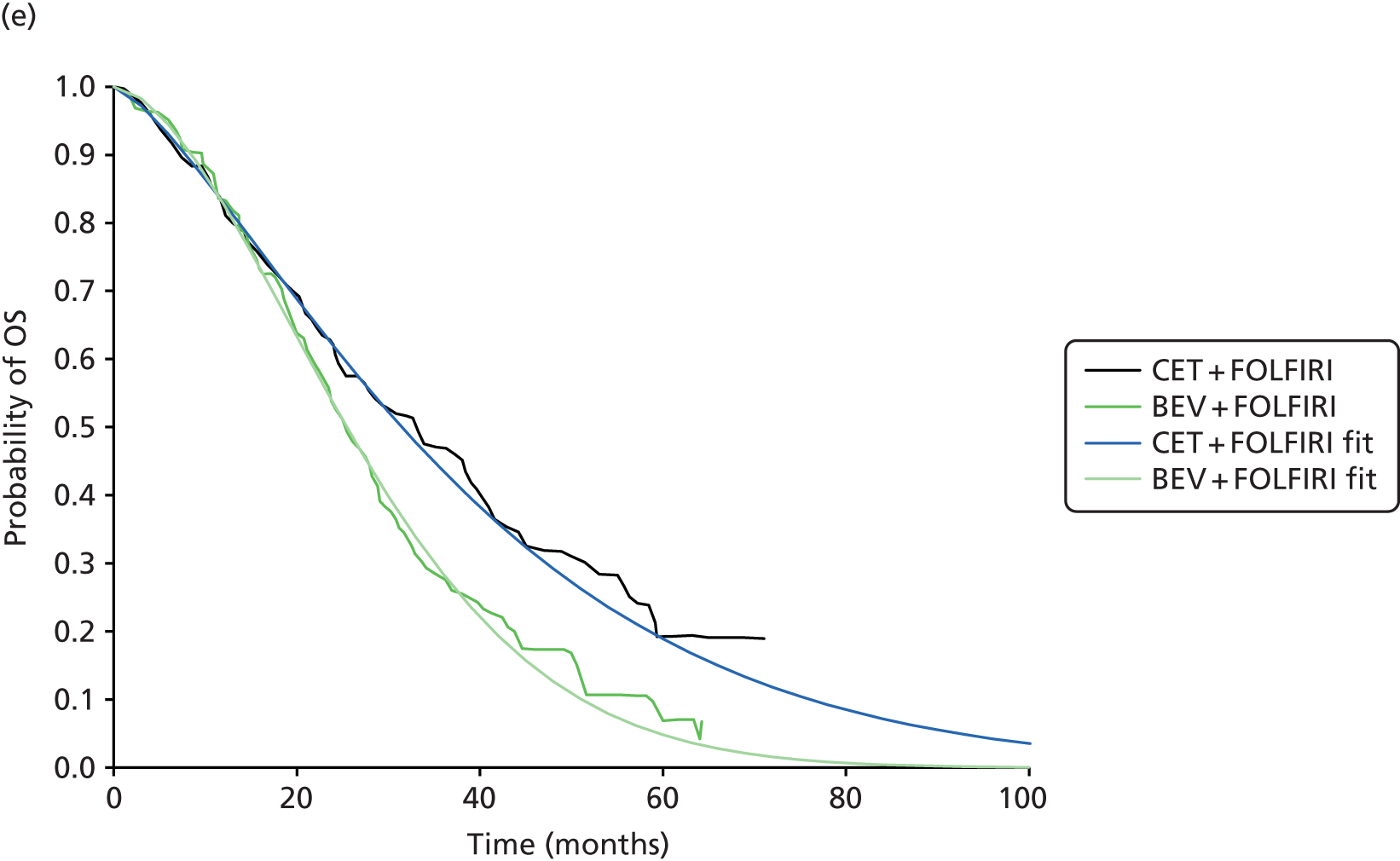

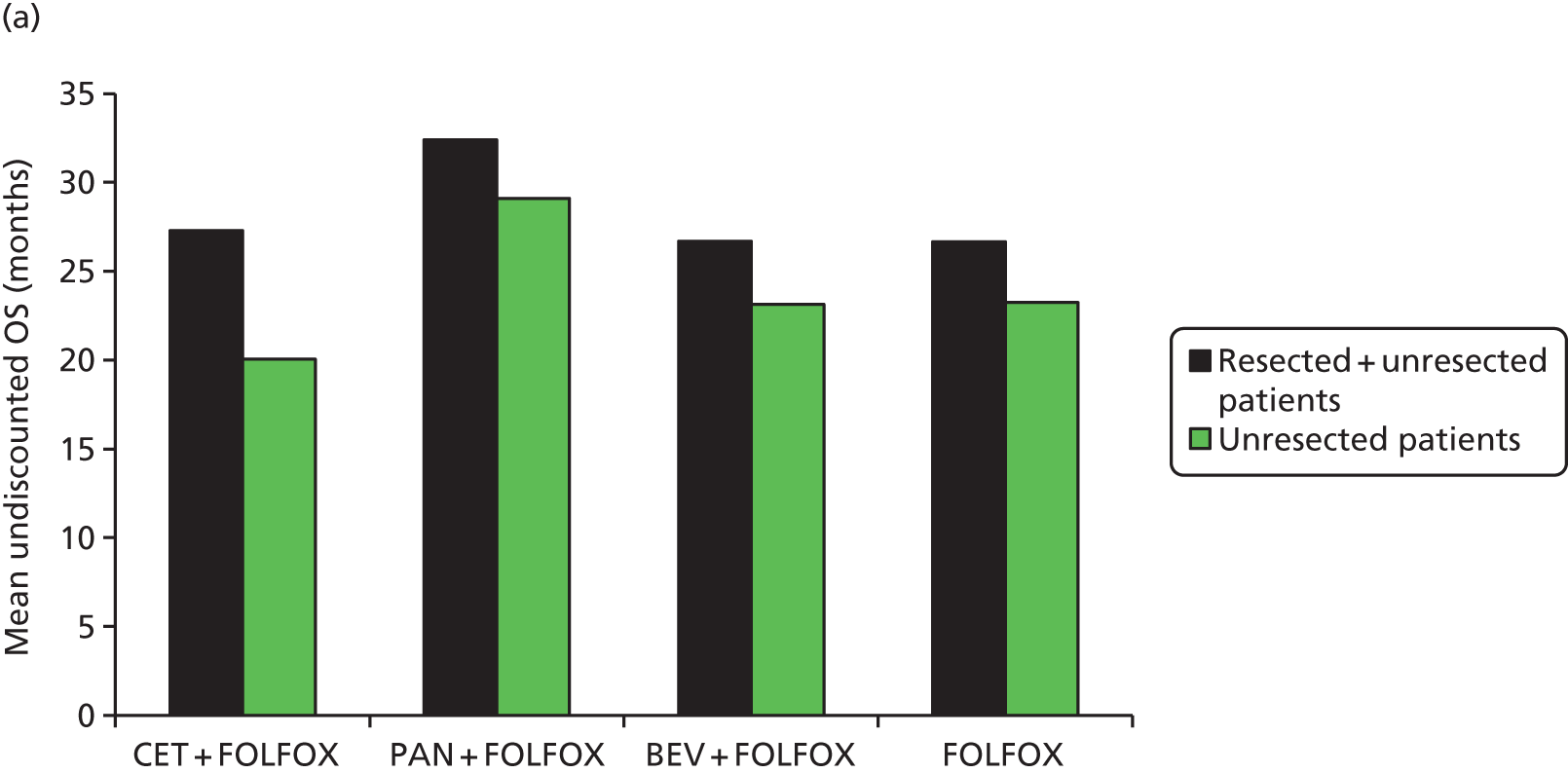

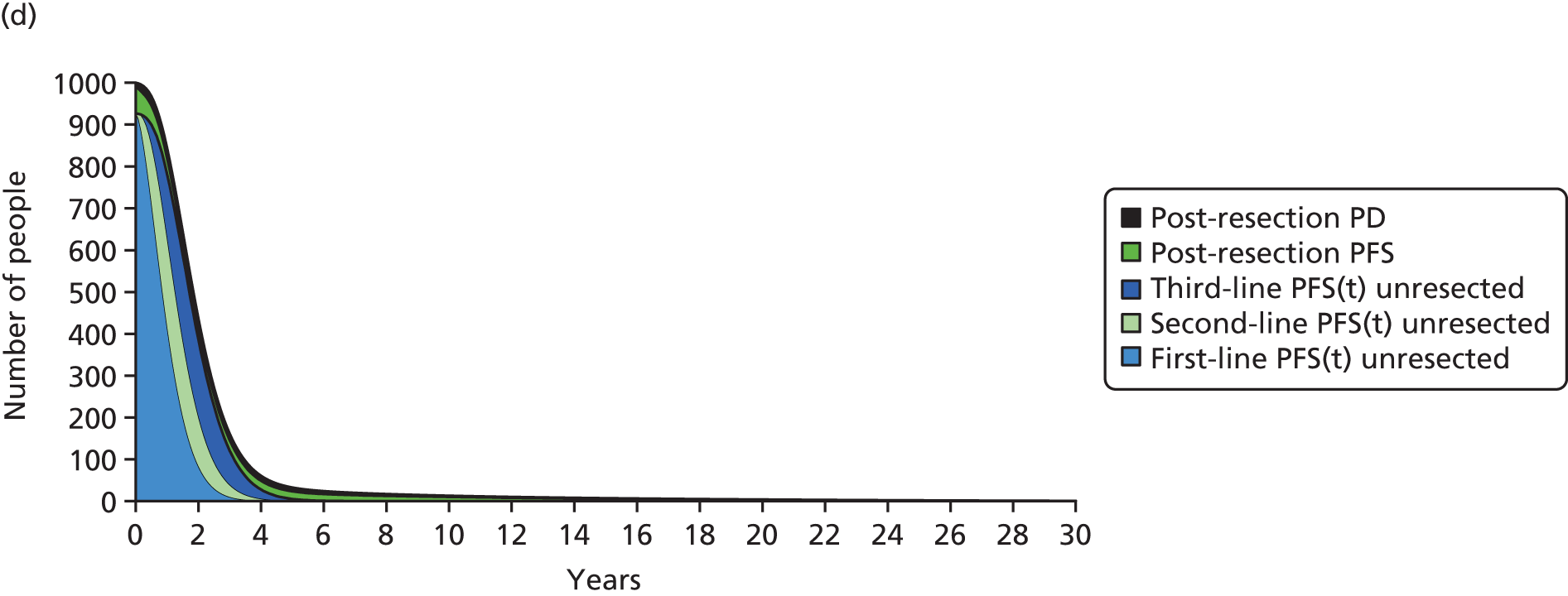

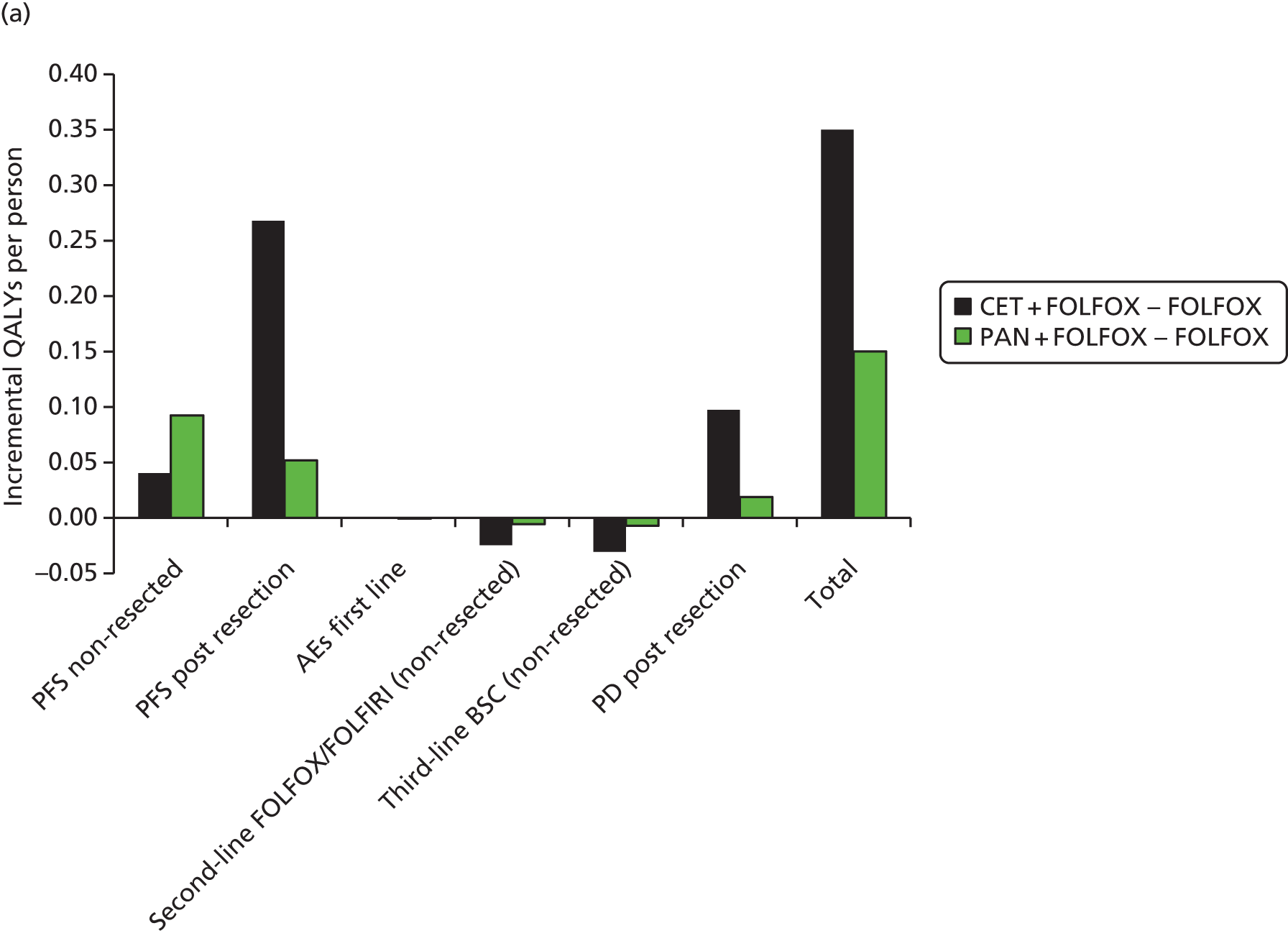

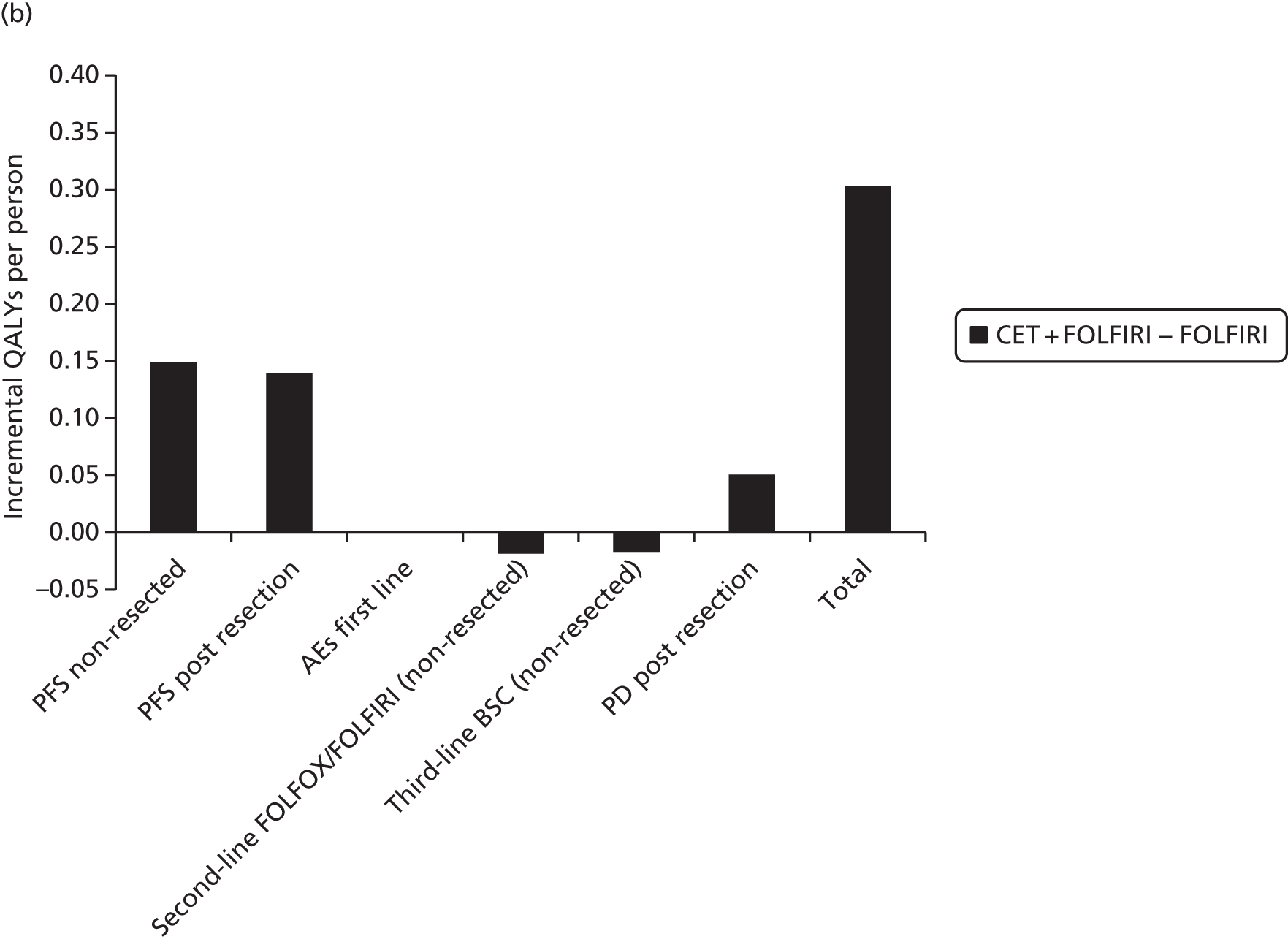

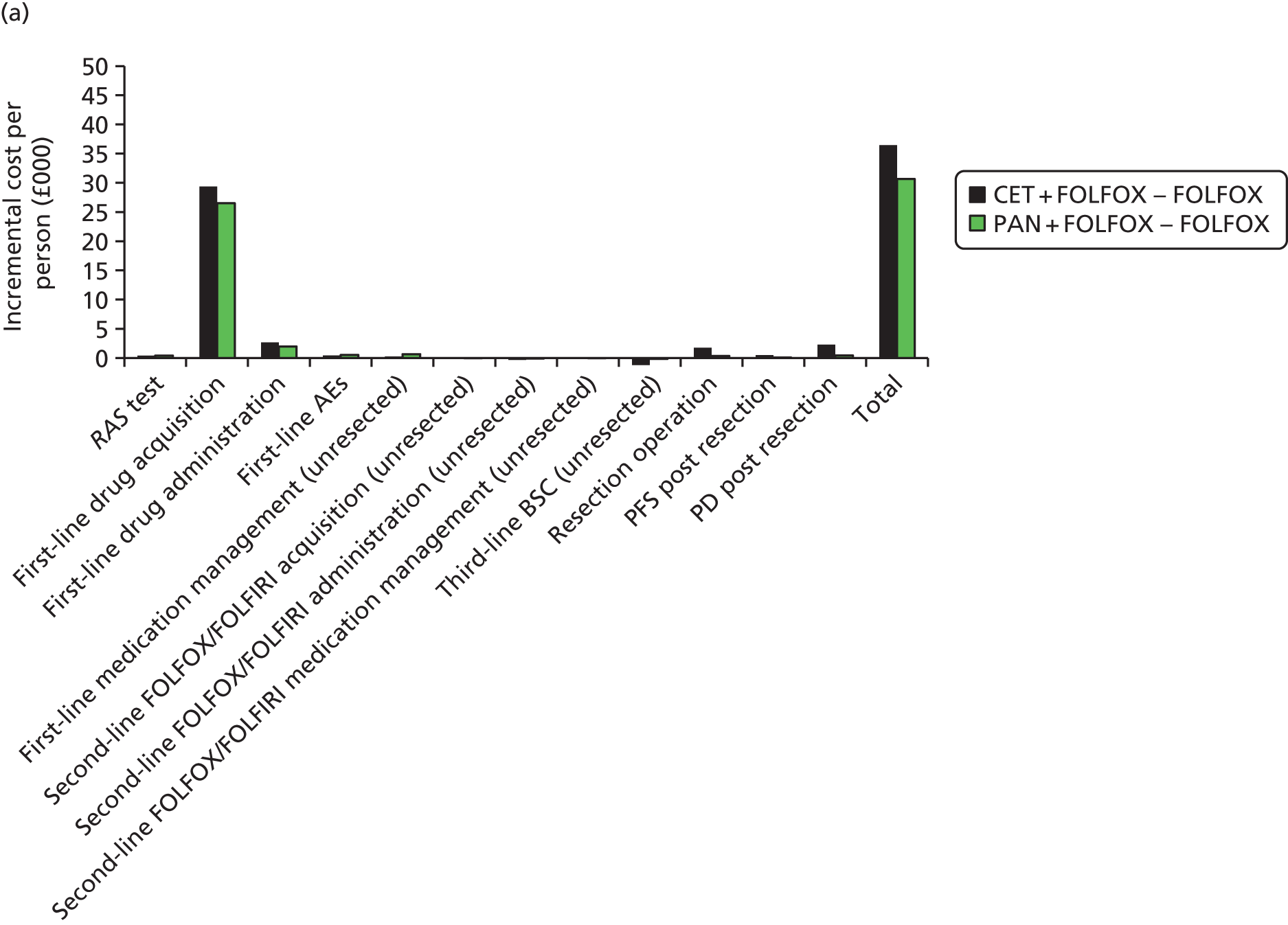

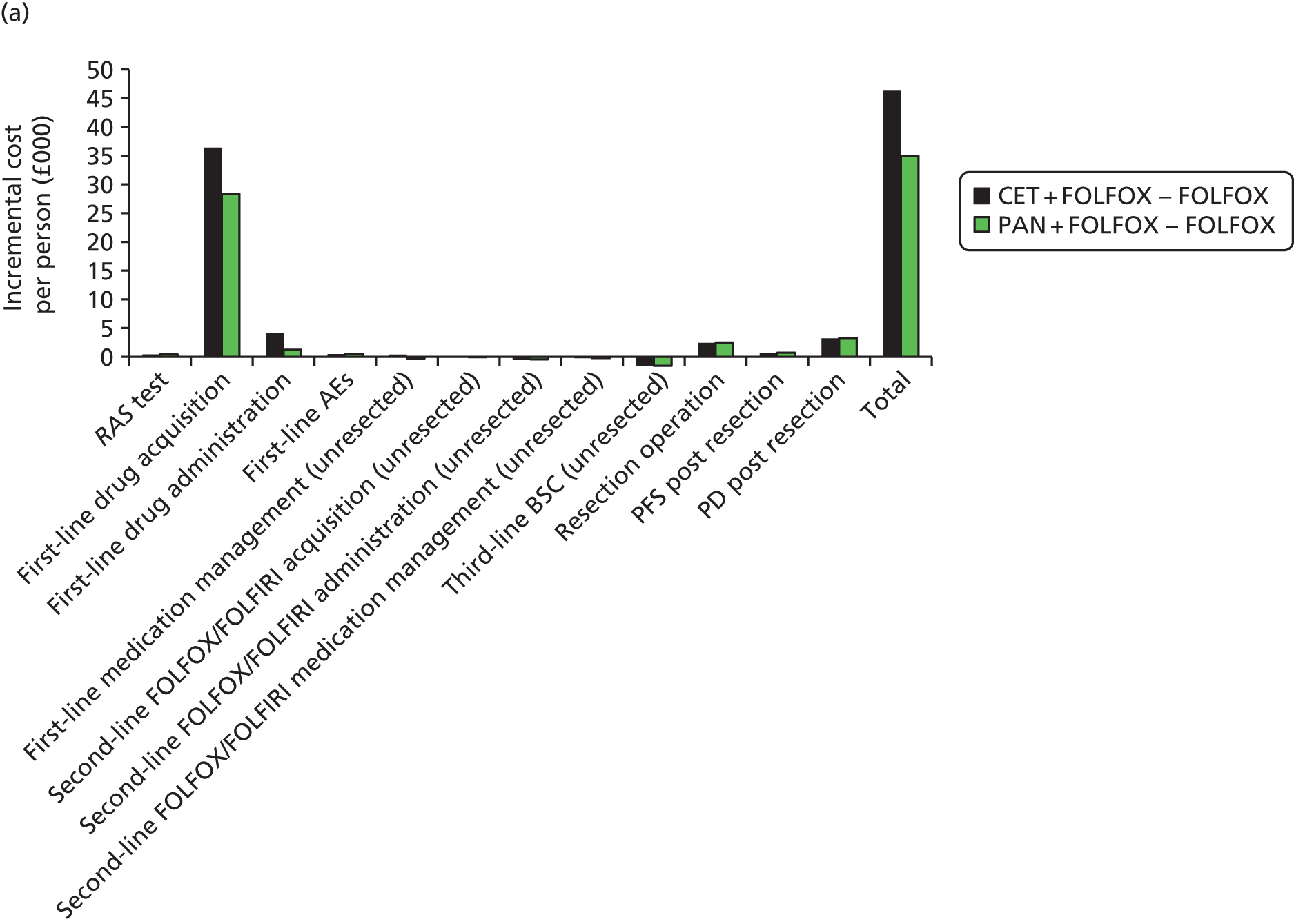

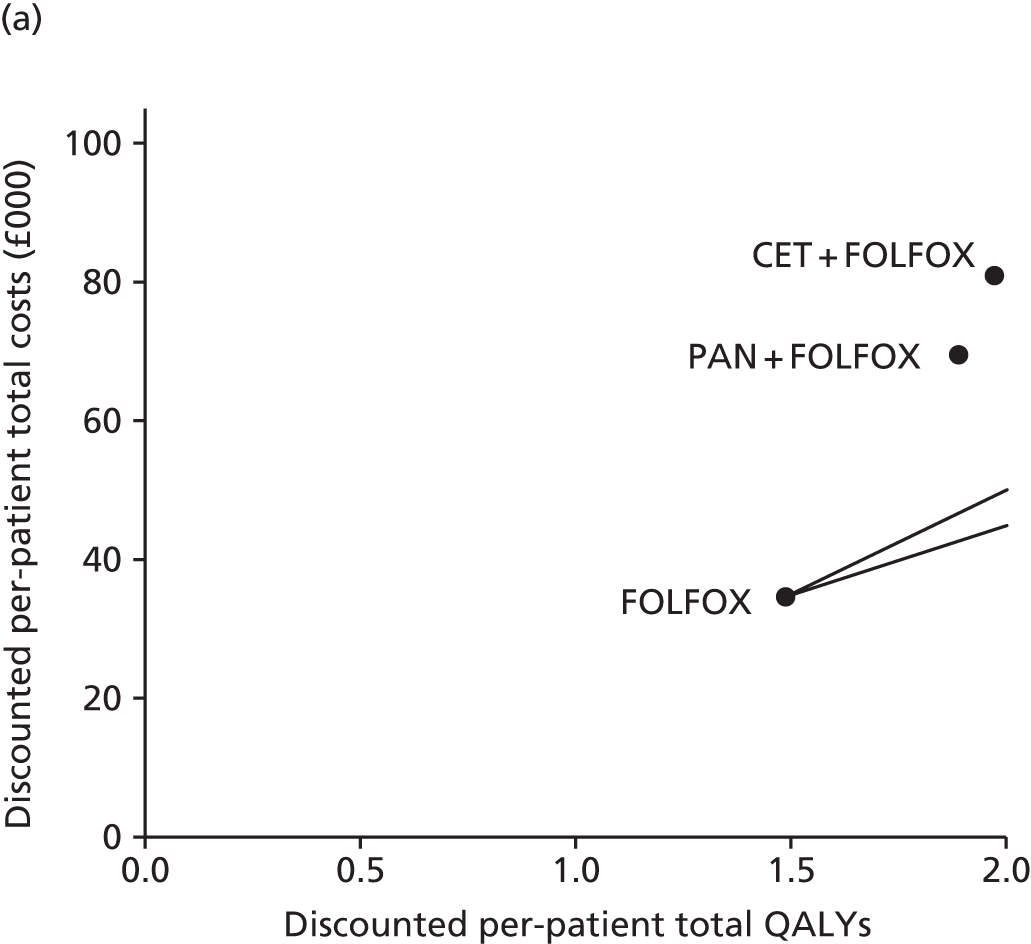

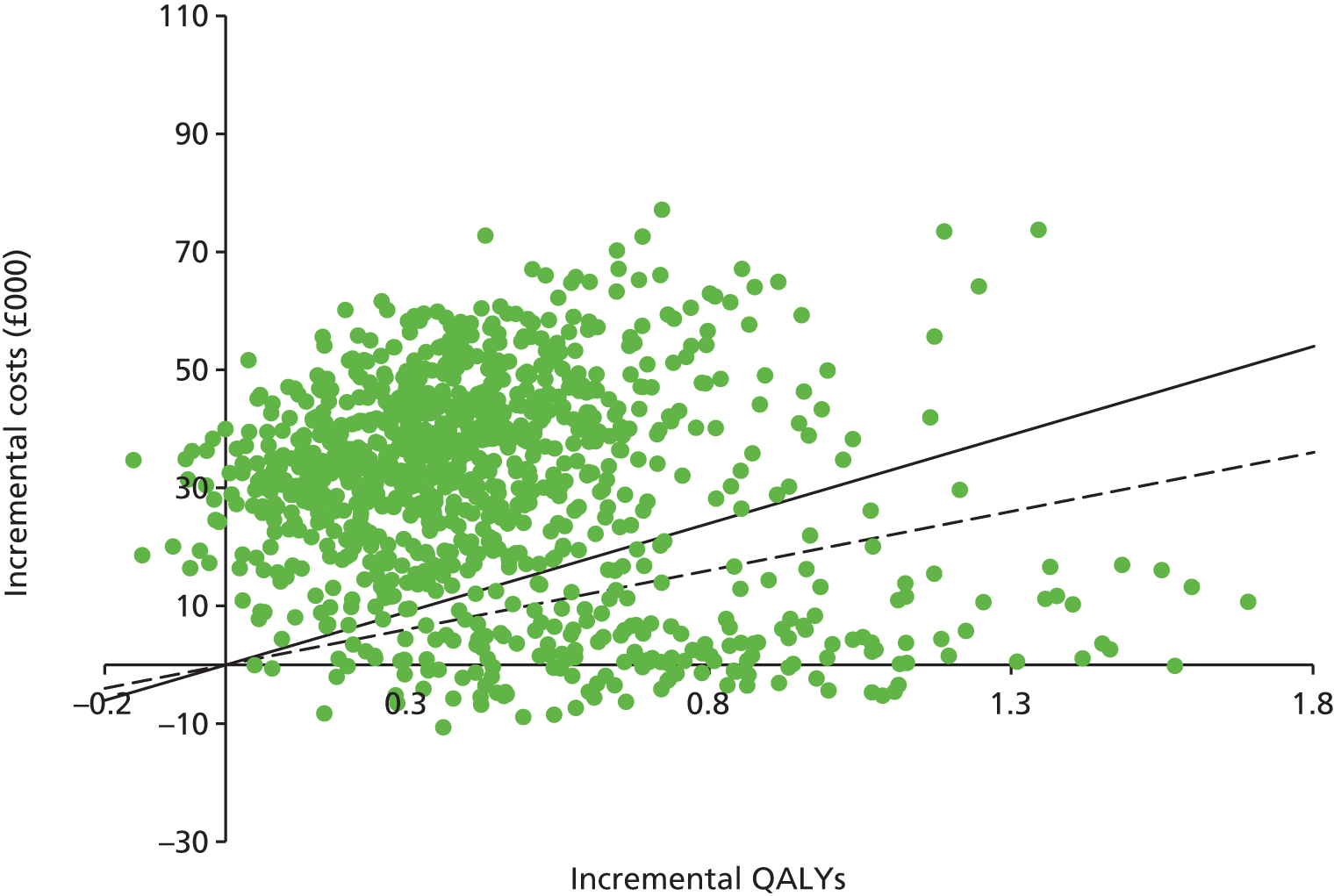

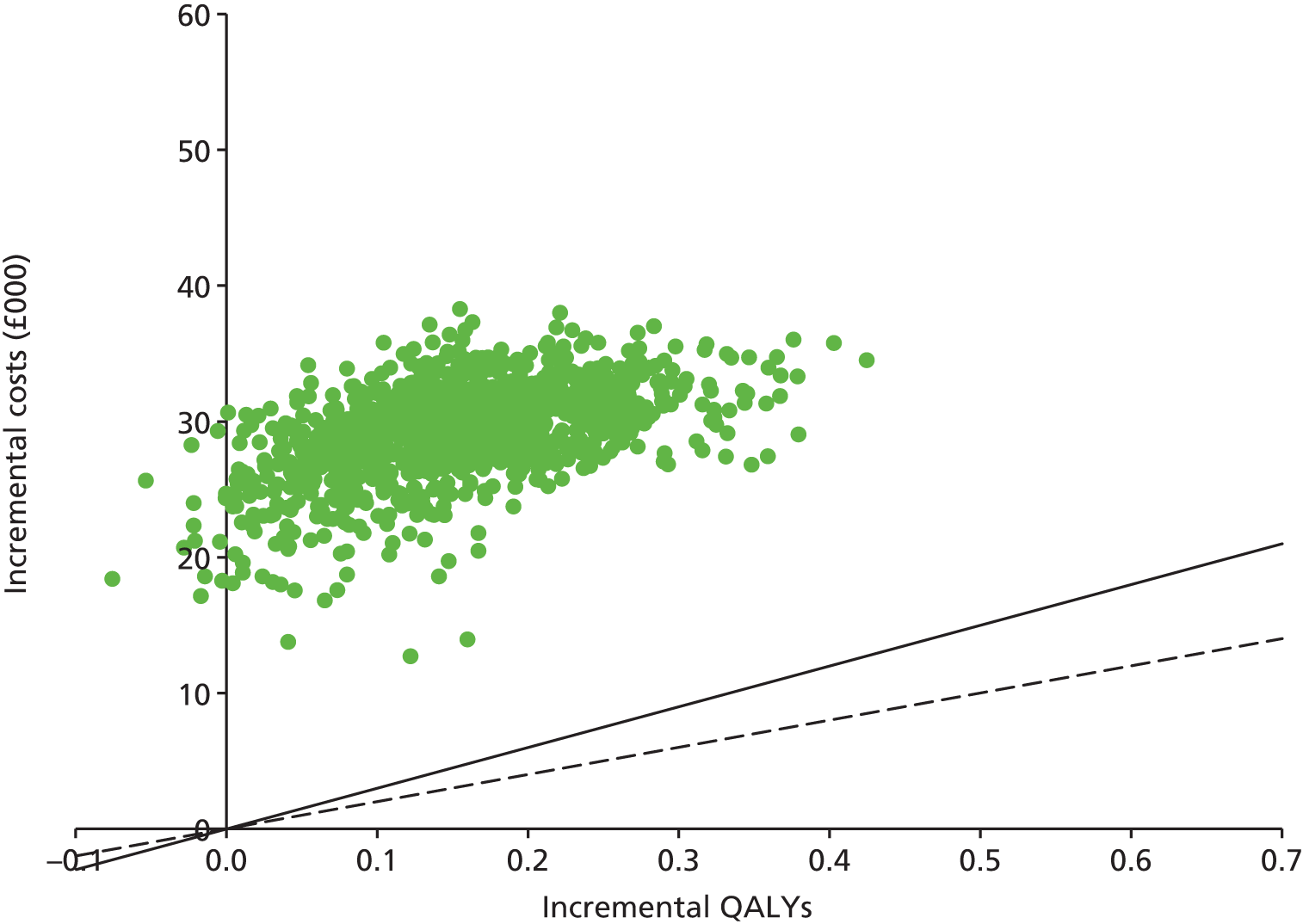

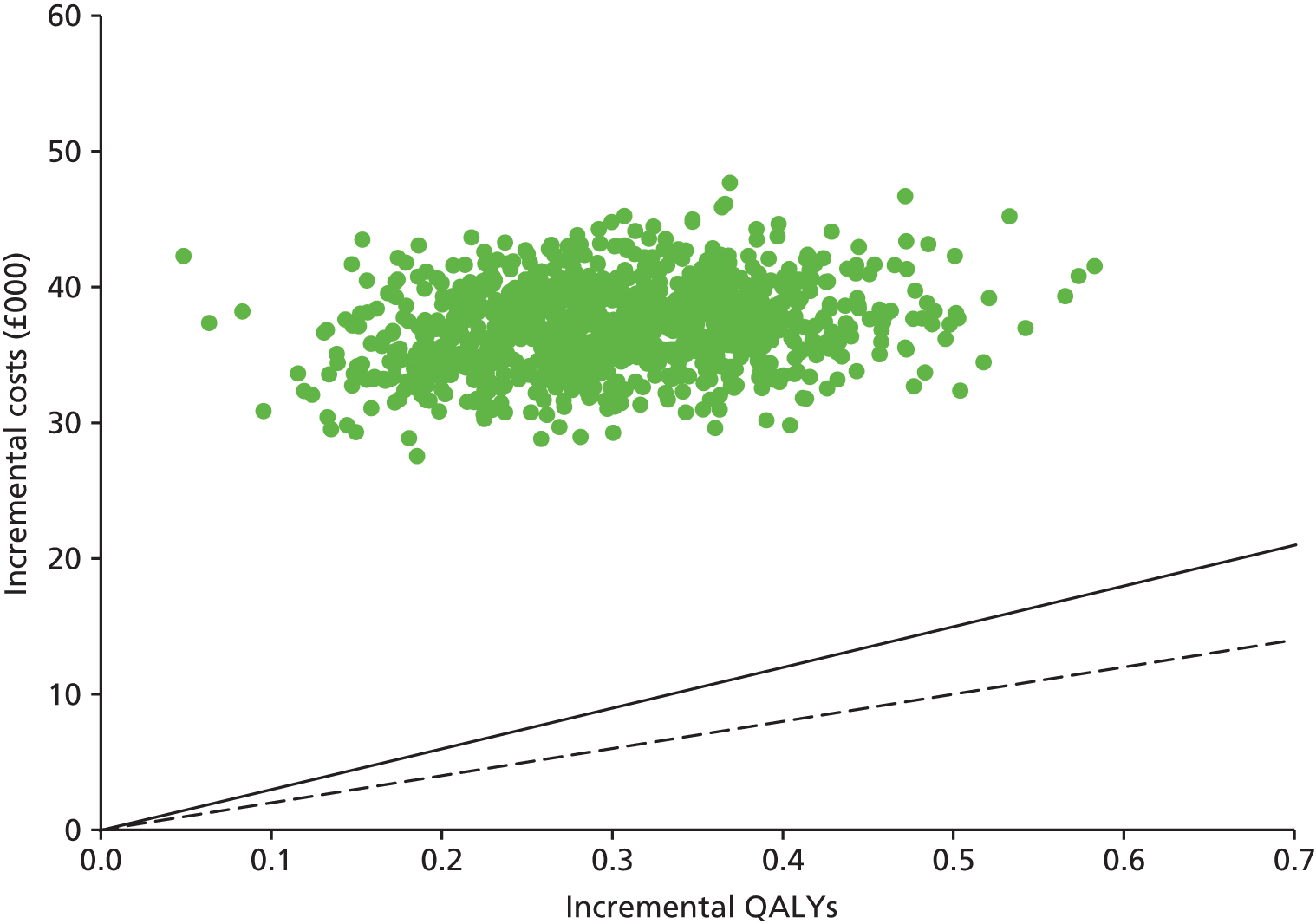

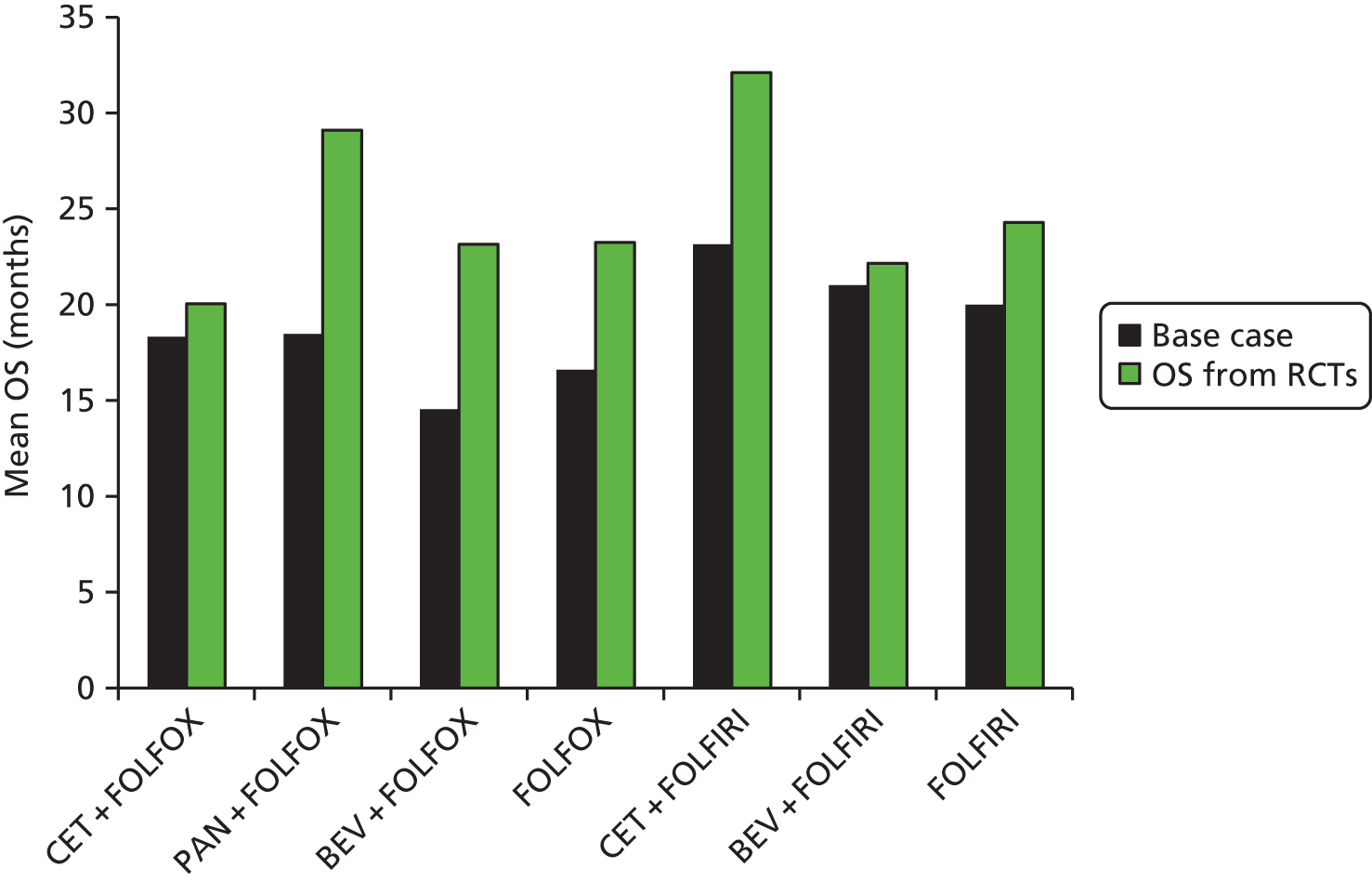

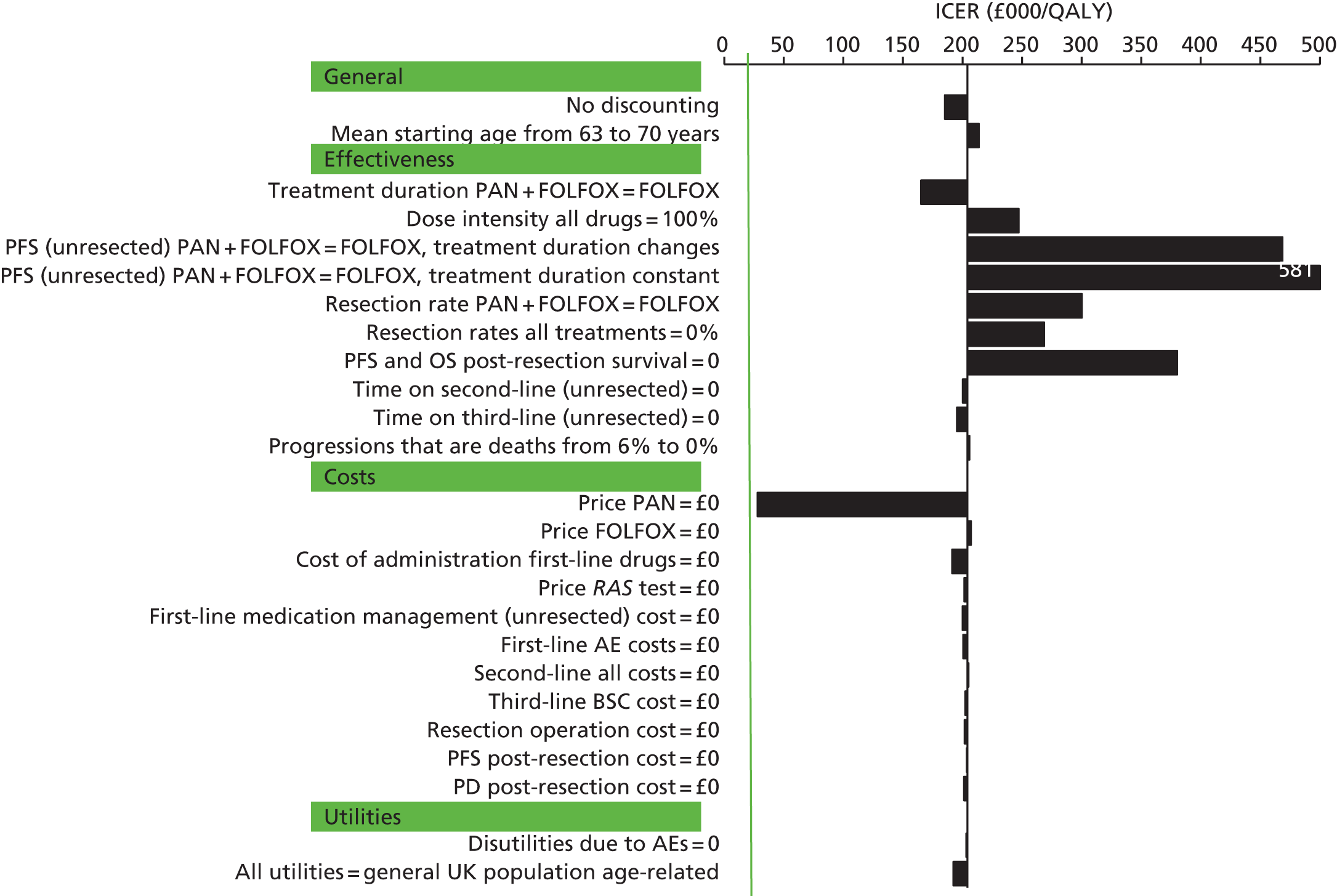

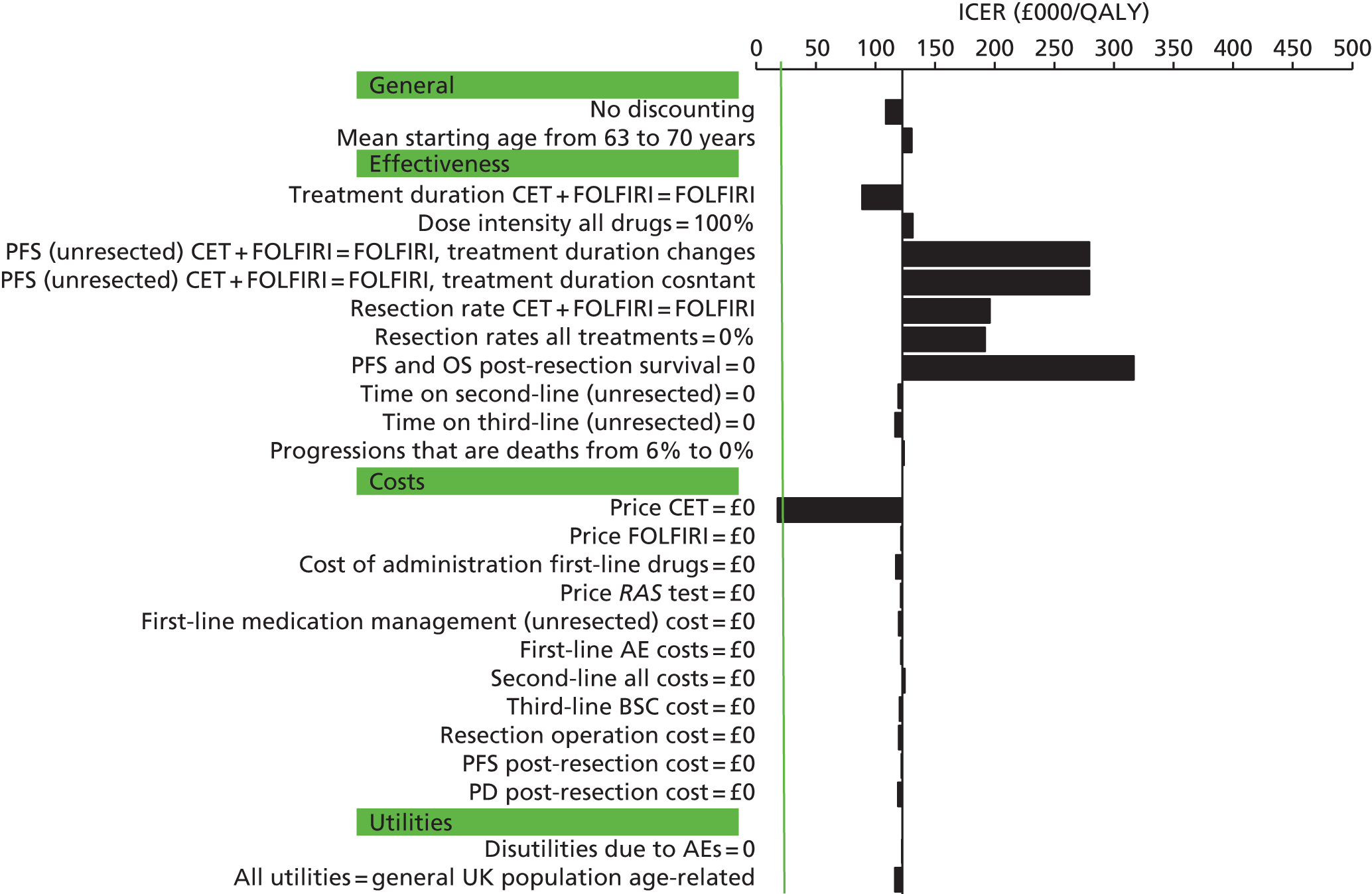

The rationale for the use of subgroup data is based on research developments that demonstrated that genotype is an important determinant of both the response to treatment and the susceptibility to adverse reactions for a wide range of drugs. 60,61 In CRC response to EGFR inhibitors has been shown to be dependent on gene expression; studies have demonstrated a treatment interaction between RAS status and the effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors. 62–64 It was in line with these research developments evaluating the negative impact of RAS mutations on the effectiveness of EGFR inhibitors that tumour samples from trial populations supporting the original licensed indications were evaluated retrospectively for RAS status. Therefore, data are not from the ITT population for any of the included studies, but are from a subgroup of people contained within the original RCTs.