Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/75/01. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in December 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Claire Goodman is a National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator. Rowan Harwood is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Primary Care, Community and Preventive Interventions Panel. Jo Rycroft-Malone is Programme Director and Chairperson of the Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Goodman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Being incontinent of faeces is distressing for any adult to experience. Adults who are unable to care for themselves, such those with dementia, must rely on others to provide care for them. In group residential settings such as care homes, preventing and managing faecal incontinence (FI) is a significant and persistent challenge for staff and visiting clinicians.

This realist synthesis draws together evidence from different strands of research to inform interventions that address the realities of working in and across complex overlapping systems of care. For example, we sought evidence on the physiology and management of FI and urinary incontinence (UI) in ageing populations and those living with dementia in care homes, and the relative availability, acceptability and efficacy of different types of incontinence products. We also included experiential evidence on living with dementia and incontinence from the perspectives of people with dementia and their paid and unpaid carers. Realist methodology enables us to deconstruct the component theories of different FI-related interventions and to consider relevant contextual data to test the applicability of different approaches for this population and setting.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this review is to provide a theoretical explanation of how different interventions support (or do not support) the reduction and management of FI in people with advanced dementia living in care homes.

The objectives are:

-

to identify which interventions could potentially be effective, how they work, on what range of outcomes (i.e. organisational, resource use and patient’s level of care) and for whom (or why they do not work);

-

to establish what evidence there is on the relative feasibility and (when appropriate) cost of interventions to manage FI.

Background

Care homes

In England, there are approximately 17,500 care homes that are home to about 487,000 older people, the majority of whom are women aged ≥ 80 years. 1 Care homes are the main providers of long-term care for older people in the UK, and there are approximately three times as many beds in the care home sector as there are NHS hospital beds. 2 The terms ‘care home’ and ‘long-term care’ refer to residential care provided to older people who require help with personal care and cannot be supported in their own home because of frailty, lack of mental capacity and/or functional limitations. The terms include homes that have on-site nursing provision and those that do not. In this report, the phrases ‘long-term care’ and ‘care home’ are used interchangeably. In the UK, care homes are run by both for-profit and not-for-profit provider organisations. The care home sector is diverse, varying in size, ownership, funding sources, focus, education of the workforce and organisational culture. 3 This variability in provision has implications for the way in which interventions to support continence care are understood and implemented, for example the presence or absence of on-site nurses, topic expertise in the workforce, organisational structure, funding and staffing.

Care home residents rely on primary health-care professionals, and general practitioners (GPs) in particular, for access to medical care and referral to specialist services, including continence services. 4–7 Public funding for care varies by region,8 and a recent review of health service provision to care homes9 concluded that access to specialist services is unpredictable and inequitable.

Residents living with dementia

Almost all care home residents have three or more health conditions, with 80% living with dementia, one-third of whom may be at the advanced stage of the disease, although a diagnosis is not always documented. 7,10 In clinical practice, severe or advanced dementia is variably defined but usually includes almost complete loss of memory and recognition, severe dependency in everyday activities, poor or absent communication, incontinence and poor mobility, and often swallowing difficulty and weight loss. 11 Reisberg et al.,11 in their review of severe dementia and how the stages of dementia are assessed, define the phase of severe dementia as that time when:

. . . the cognitive deficits are of sufficient magnitude as to compromise an otherwise healthy person’s capacities to independently perform basic activities of daily life such as dressing, bathing and toileting.

p. 8311

Care homes have been crucial in the service response to the rapidly increasing number of people with dementia who need this kind of continuous care and support.

Faecal incontinence prevalence, evidence, guidance and impact on residents and staff

Faecal incontinence is the involuntary loss of liquid or solid stool that is a social or personal hygiene problem. 12 The prevalence of FI in people aged > 80 years is estimated to range from 12% to 22%. 13,14 Epidemiological studies have identified dementia as an independent risk factor for FI,15–17 and a study of primary care patients found FI to be four times higher in people with dementia than in a matched community-dwelling sample with FI but without a diagnosis of dementia. 18 Studies suggest that the prevalence of FI in care homes is between 30% and 50%. 15,19–23 The level of variation is believed to reflect differences in care and the way in which continence is defined (by frequency, amount and detection method) as well as the individual characteristics of older people. It is unclear how dementia has an impact on a person’s gut and anal sphincter, but there is a widely held, albeit untested, view that eventually everyone with dementia will become incontinent if they live long enough. 11

The evidence about the prevention and treatment of FI in care homes is variable. Although there is evidence about risk factors and associations, there are few intervention studies. Research on continence care in care homes tends to focus on UI. 24–27 It is also important to understand the ways in which public funding is deployed for continence care in care home settings and any consequences for FI management at the individual and organisational levels.

The most recent Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions for the prevention and treatment of FI found no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) focusing specifically on people living with dementia (PLWD) in care homes. 28–30 Care home residents can experience dermatitis, discomfort, delirium and unplanned hospital admissions secondary to FI. 31,32 FI frequency is strongly linked to negative impact on quality of life. 33–37 It affects opportunities for social interaction and stimulation and can compound the isolation created by living with dementia. 38 Dealing with FI may also affect care home staff turnover and morale in a workforce that is already low paid and receives little clinical support. 39 The effectiveness of programmes to address the known problems of FI in care homes is, therefore, contingent not only on specific bowel-focused interventions, but also on contextually situated decision-making. 40 Interventions designed to improve FI for PLWD in care homes will perforce be multicomponent, shaped by the choices and behaviours of those delivering and receiving the care, and be characterised by a context-dependent effectiveness.

National and international guidelines33,41 emphasise that all patients with FI should be assessed for treatable causes, regardless of their cognitive status. Particularly relevant to care home residents living with dementia are overflow from faecal impaction and FI from loose stools, both of which can be assessed and managed in the care home setting. Treating constipation has been found to be effective in improving overflow FI and reducing staff workload (based on soiled laundry counts) by 42% in those with effective bowel clearance. 42 Loose stool may be a result of reversible causes, such as dietary intolerances, medication side effects including laxative use,21,43 and antibiotic-related diarrhoea. 44 For patients living with dementia who lack cortical control of the defaecation process, and who void a formed stool following mass peristaltic movements, prompted or scheduled toileting (preferably after meals) can increase the number of dependently continent bowel movements. 45,46

In 2012, a specific care home continence audit, educational and care planning tool was piloted in the UK. This highlighted some of the process and organisational problems that can be barriers to implementing FI programmes. 47 Ageism, lack of training, pad restrictions due to cost control and poorly integrated services were identified as likely contributors to low standards of care for FI. A review of local continence guidelines in England48 revealed a paucity of dementia-specific information.

There is, however, an extensive, more general care home and dementia-specific research literature, including intervention research, on the impact of the leadership, culture of care and care home routines on residents’ health and well-being. 49 Care home studies that are relevant but do not focus specifically on FI include those on nutrition and hydration,50 patterns of meal times,51 medication use52,53 and activities of daily living. 54,55

Some studies based in care homes can also offer transferable learning about how interventions are developed and implemented. For example, research to support people living with depression or identify residents at risk of unplanned hospital admission has moved towards advocating interventions targeted at specific subgroups rather than care home-wide strategies. 56 Others query the sustainability of interventions that were not developed in collaboration with staff and in consultation with residents or their representatives, and how to maintain clinician involvement. 6,57,58 It is the complexity of the relationships between evidence use, care experiences, quality of life and overall standards within care homes that pose particular challenges for intervention studies. 59

We now turn to report the methods of the realist synthesis.

Chapter 2 Methods

Rationale for using a realist review

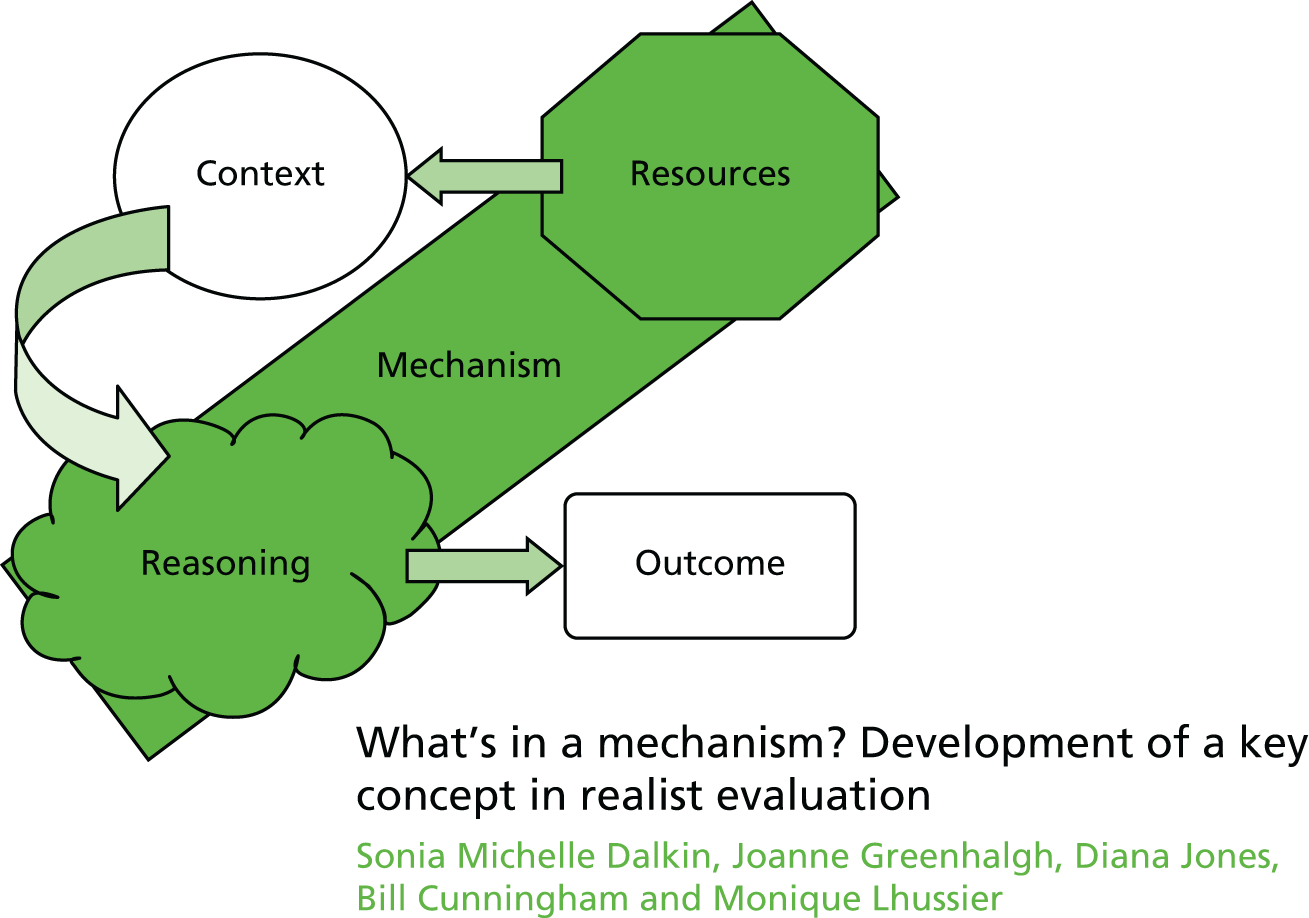

The rationale for using a realist synthesis approach is twofold: (1) the absence of evidence of what is effective in the reduction and management of FI in care homes and (2) a recognition that future interventions designed to address FI in PLWD will need to be multicomponent, depending on the behaviours and choices of those delivering and receiving the care. Realist review is a theory-driven interpretive approach to evidence synthesis. 60–62 It assumes that there is more to reality than the way in which it is socially constructed. There is an external reality or world that can be observed and measured; however, how this reality is articulated and responded to is constantly being shaped by individuals’ perceptions and reasoning and/or dominant social and cultural mores. It is this constant interaction that creates particular responses that lead to observed outcomes. 63 Realist synthesis, therefore, endeavours to go beyond lists of barriers to and enablers of care to unpack the ‘black box’ of how interventions to reduce and manage FI work. The often repeated statement used to explain the focus and purpose of realist synthesis is that it makes explicit ‘what works, for whom, in what circumstances?’. It uses a theory-driven approach to articulate how particular contexts (C) or resources, have prompted certain mechanisms (M) or responses by those providing and receiving care to lead to the observed outcomes (O). The underlying premise is that the observed ‘demi-regular patterns’ of interactions between the components that make up complex interventions in the evidence reviewed can be explained through theoretical propositions. The iterative process of the review tests those theories that are thought to work against the observations reported in the evidence included in the syntheses. 64 This enables us to take account of a broad evidence base as well as the experiential and clinical knowledge that relates to the physiology and management of FI in older people, and specifically in older people with advanced dementia living in long-term care. It will also help us to take account of the heterogeneity of care home provision in the UK (Box 1).

-

Context (C): that is, the ‘backdrop’ conditions (which may change over time), for example provision of training in FI continence care, residents’ level of nutrition and hydration and cost of continence aids. Context can be broadly understood as any condition that triggers and/or modifies the behaviour of a mechanism.

-

Mechanism (M): a mechanism is the generative force that leads to outcomes. Often denotes the reasoning (cognitive or emotional) of the various ‘actors’, that is, care home staff, residents, relatives and health-care professionals. Mechanisms are linked to, but are not the same as, the strategies of a service. Identifying the mechanisms goes beyond describing ‘what happened’ to theorising ‘why it happened, for whom and under what circumstances’.

-

Outcomes (O): intervention outcomes, for example reduction in episodes of FI, resident distress and costs and increase in staff confidence.

-

Programme theory: those ideas about what needs to be changed or improved in how FI is reduced and managed in care homes for PLWD, what needs to be in place to achieve an improvement and how this is believed to work. It specifies what is being investigated and the elements and scope of the review.

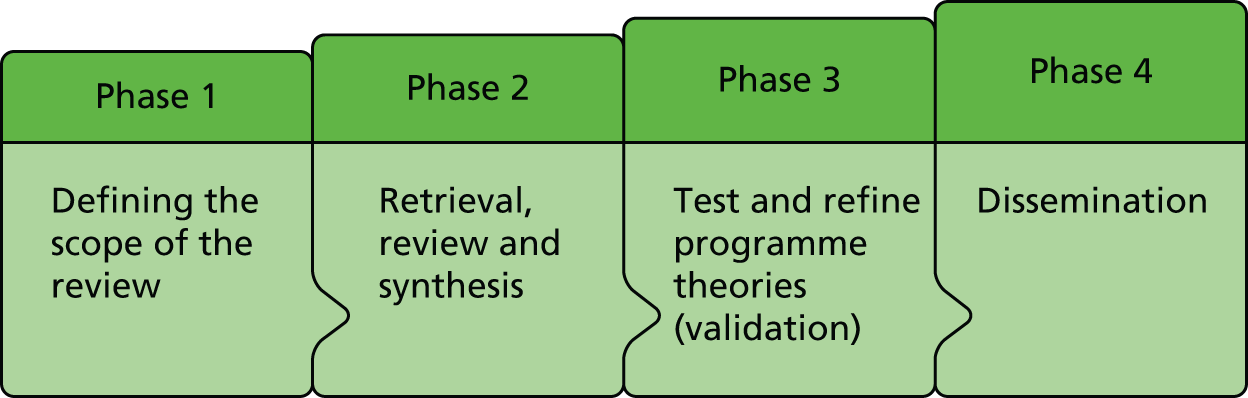

A realist review does not follow a neat linear process, although it does have distinct phases summarised in Figure 1. This process was specified in the review protocol. 65

FIGURE 1.

Four-phased approach to the synthesis.

It is an assumption that mechanisms will only activate in the right conditions, providing a context + mechanism = outcome formula. Explicit disaggregation of resources as a component of a context helps to be more explicit about the aspects of an intervention that trigger different responses. We have characterised this as context (intervention)–mechanism–outcome (C–M–O) and used this approach in our analysis of the evidence.

Changes from the submitted protocol in the review process

A realist review is an iterative process, and adjustments are made to the review protocol in the light of emerging or new lines of enquiry. Changes to the protocol submitted to the funder are outlined in Table 1.

| Protocol | Change | Agreed |

|---|---|---|

| Target population: people with advanced dementia in care homes | We dropped the term ‘advanced’ from the synthesis title. ‘Advanced’ dementia was considered too narrow and not clearly defined as a concept in the literature | Study Steering Committee December 2014 |

| Focus on FI only | Consider FI in the context of double incontinence as FI alone accounts for only a small proportion of residents living with FI | Core team |

| Timing of searches: protocol proposes a final search strategy will be developed after phases 1 and 2 | Searches carried out in phases 1, 2 and 3. Scoping searches in phase 1, main searches in phase 2 and follow-up searches in phase 3 | Core team |

| Health Technology Assessment protocol suggests we will look at research with older people with dementia living at home or in hospital | Although wider literature is not ignored we retained a focus on care home research. Context of care for people living at home or in hospital is very different in terms of resources and practitioners involved in providing care | Core team |

| Timings of stakeholder input: phase 4 – consensus meeting in London with online link | The consensus meeting was held as part of a meeting of the National Care Home Research and Development Forum. There was insufficient time to complete the synthesis and organise a standalone consensus meeting with online link | Study Steering Committee September 2015 |

Phase 1: defining the scope of the realist synthesis – concept mining and theory development

Concept and theory development by the team

A realist synthesis often uses input from content experts to help develop programme theories. In this project our Research Management Team (RMT) and Study Steering Committee (SSC) included many of the national experts in the field of continence care and care home research in the UK (see Appendix 1). The first RMT meeting in September 2014 included an open discussion by the team in which they were asked to draw on their expertise to articulate:

-

the dominant approaches and assumptions that informed current thinking about what supported (and how) the reduction and management of FI

-

important outcomes and how impact was measured.

The full notes from this meeting are included in Appendix 2. After the meeting all RMT members were asked to send relevant reviews, papers or guidelines that had been referred to at the meeting to the core team. The early progress was reported to the SSC in November 2014.

Scoping interviews

To complement the expertise provided by the team we interviewed key stakeholders. They were identified through the clinical and research networks of the RMT, and five key groups were identified and approached to inform the scoping process (Table 2).

| Target stakeholder group | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Providers of care | |

| Care home managers from different provider organisations identified through representative organisations and charities [My Home Life, Enabling Research in Care Homes (ENRICH) and Alzheimer’s Society] | Care home managers know and understand organisational processes, protocols and ‘industry’ best practice and are aware of how well all these rules and guidelines are applied within the care homes in which they work. In addition, they will be aware of factors that inhibit or facilitate the implementation of the rules and guidelines |

| Care home staff | Distinct from managers, care home staff understand actual practice and therefore provide an invaluable insight into how continence care is managed |

| Recipients of care | |

| User representatives (identified through the resident and relatives representatives of the Bladder and Bowel Foundation and family carers with experience of caring for a relative living with FI in a care home) | Resident representatives were chosen to give the closest possible approximation of residents’ own opinions of continence care |

| Academics and practice educators with an interest in care homes | |

| A meeting of the National Care Home Research and Development Forum | To ensure we are up to date with the most relevant current research, particularly work that may not yet be published |

| Clinicians with a special interest in FI | |

| Special interest group on continence of the British Geriatrics Society | To gain the perspective of clinicians and other specialists who have an interest in continence management for older people generally |

| Continence specialists, commissioners and providers of continence services | |

| Continence specialists, commissioners and providers of continence services identified through NHS trusts, providing and professional associations and charities | To gain the perspective of continence nurses and community providers who are likely to provide advice and services into care homes |

Interviews

Interviews were conducted either one to one or in a group by Claire Goodman, Marina Buswell and Bridget Russell. All interviews were face to face. Interviews were recorded, when possible, and transcribed. A set of interview prompts was developed and tailored to reflect the focus and expertise of each group. We wanted to explore:

-

participants’ experience of working with and for people with dementia and FI in care homes

-

estimates of how severe FI is in care home residents

-

why they think FI occurs

-

what good continence care looks like and what is necessary to achieve that and why

-

who needs to be involved in providing and reviewing care

-

how having dementia specifically affects continence care, assessment and decision-making, and what needs to be in place to address the effects of dementia

-

how they would define success from the perspective of the resident, the care home staff, visiting clinicians and family carers

-

when and why the decision would be made to use pads.

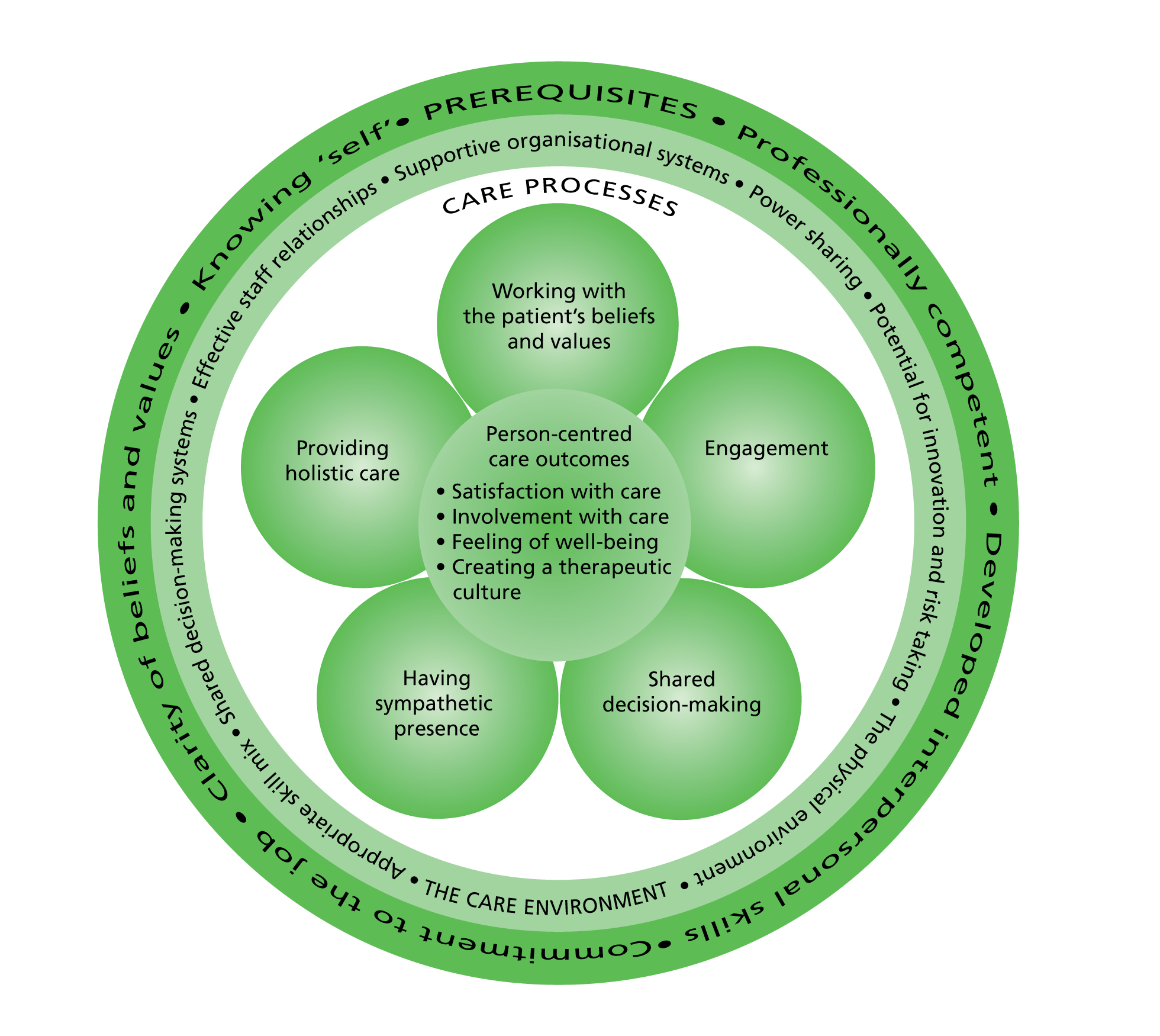

All participants highlighted the importance of person-centred care. The interviewers sought to understand how this approach to care was articulated in the assessment, care and review of continence care provided in care homes. In many of the interviews the prompts led to narratives of success and failure with particular residents; these examples demonstrated the participant’s understanding of what needed to be done and what good care looks like.

Continence specialists

Interviews were completed at the continence specialists’ place of work. We approached three continence specialist teams but were able to access only one team and interviewed three nurses who visited care homes. This was supplemented with a group discussion with members of the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) continence special interest group, which included physicians and nurses.

Interviews with care home managers and care home staff

We recruited care home managers through two care home provider organisations, one not for profit and one commercial chain. Meetings were organised by the two care home organisations on our behalf and held on their premises.

Care home staff involved in providing direct care to residents were recruited through contacts with local care homes (which were not part of the care home chain that managers were recruited from) and via the networks of the RMT. We recruited seven care home staff, one of whom was a senior care worker. Two of the participants worked nightshifts in separate care homes and were interviewed face to face. The remaining five worked in the same care home and were able to participate in a focus group discussion. Questions focused on their experiences of providing care, how they defined good care, what they thought about how a person’s dementia affected their ability to provide continence care and what was important to enable them to achieve that.

Interviews with family members of residents with dementia and experienced faecal incontinence

In phase 1, we attempted to recruit family members who had experience of supporting a relative with FI and dementia through relevant charities [a local branch of the Alzheimer’s Society and the Bladder and Bowel Foundation (BBF)]. Despite several attempts, these approaches were unsuccessful. An invitation through a local care home provider to invite participants yielded three expressions of interest; two of these people participated in a group interview. An analysis of the phase 1 interviews was undertaken thematically using the prompts as the organising framework, and the findings from this were fed into the RMT deliberations and workshop.

In phase 3, to identify people with personal experience of FI and dementia through caring, we renewed our request for help to the BBF. This time the BBF supported a mail-out to their members that elicited responses from interested relatives (see Appendix 3).

To ensure transparency of approach and an audit trail, focus group discussions and interviews were recorded and transcribed. Structured field notes were kept about which sources of evidence and experiential knowledge may be linked to which strands of theoretical development.

Literature scoping: phase 1

Search methods

We conducted four separate searches. The initial search built on literature identified as relevant at the first RMT meeting. This focused on evidence on continence-related research in care homes, dementia and continence, older people and continence, implementation research in care homes and person-centred care. A second search was then conducted that was designed to identify papers on FI and care homes and incontinence pads (see Appendix 4).

The scoping interviews with geriatricians at the BGS highlighted the link between diet and hydration and good bowel health, and a further search was conducted to capture literature on interventions to promote nutrition and hydration (eating and drinking) for PLWD in care homes. This search was conducted to test whether or not this body of work included outcomes related to continence and FI. After the second SSC meeting in November 2014, a decision was made to scope the learning disability literature for continence-related research.

Selection and appraisal of documents: phase 1

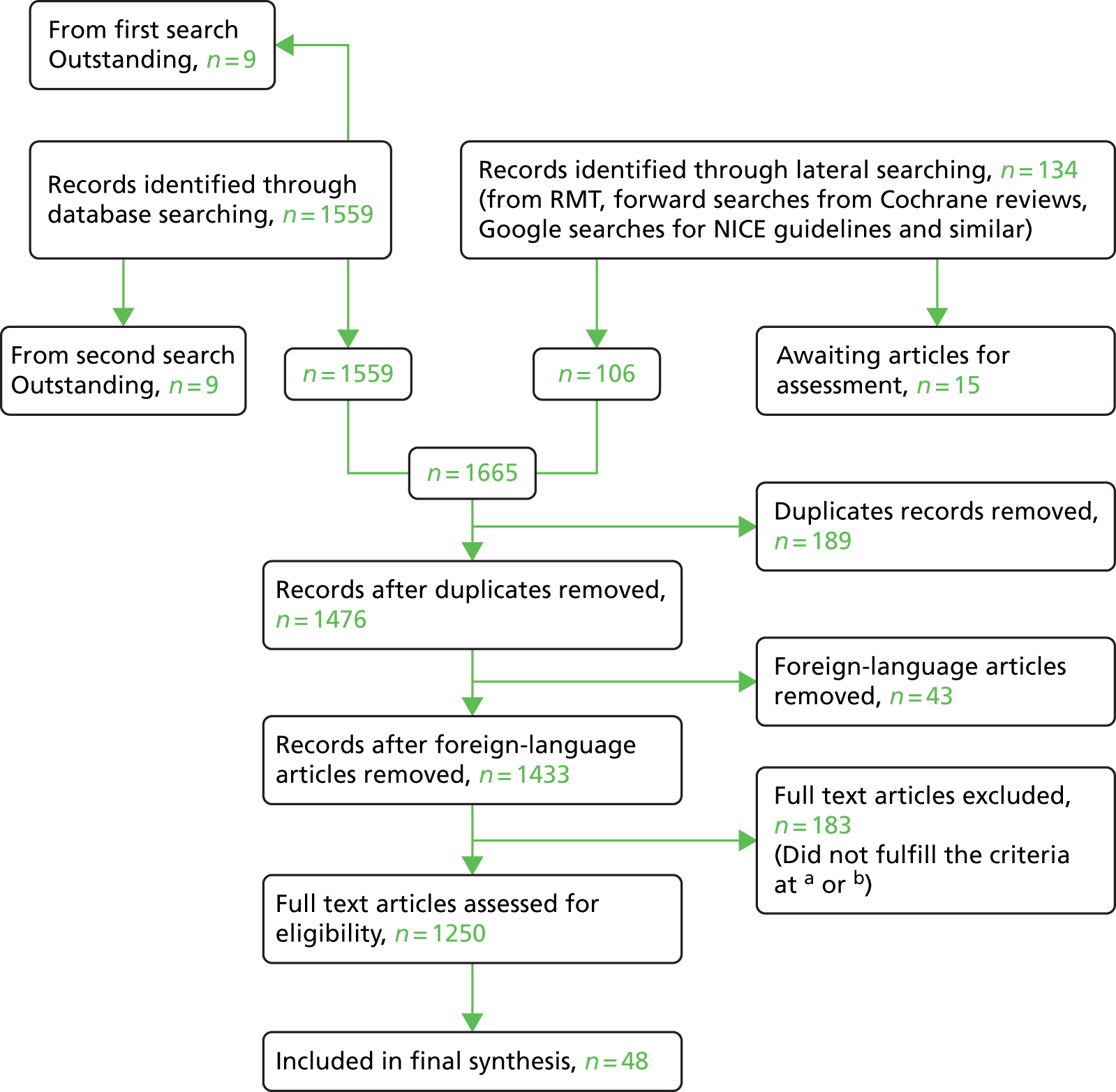

Frances Bunn, Claire Goodman and Bridget Russell carried out the first searches and selected studies for initial inclusion based on the broad themes outlined by the RMT. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram was produced, although as the review progressed it did not capture the iterative process of searching, selecting and appraisal of documents for this process (ultimately replaced by a flow diagram; Figure 2). A summary of this scoping search was presented to the RMT in January 2015.

FIGURE 2.

Document flow and review of progress: conceptual diagram. CH, care home; PCC, patient-centred care.

Data extraction: phase 1

A narrative process rather than a formal data extraction was used to produce the first scoping summary (see Appendix 2). In phase 1, however, we began to develop a data extraction process that captured our thinking about the putative theories and context–mechanism–outcomes (C–M–Os) of interest (see Phase 1: defining the scope of the realist synthesis – concept mining and theory development, and Prototype data extraction form).

Analysis and synthesis processes: phase 1 (concept mining and theory development)

Meetings

Team meetings formed an essential and productive part of the analysis and synthesis process. Formal meetings of the SSC and RMT were recorded and detailed meeting notes were made. Informal team meetings of the smaller core team (FB, MB, CG and BRu) were not recorded but notes and actions of these meetings were kept in log books (see Log books).

Log books

Log books were used as project notebooks to record when and how important decisions, thinking, sourcing of papers or documents and actions occurred. They provided a useful source of ‘raw’ data and reference points for analysis, and included notes about key papers that informed a shift in thinking and synthesis. These became the structured field notes on suggestions and decision-making processes about which sources of evidence were linked to which strands of theoretical development.

‘If . . . then’ statements

At the end of the RMT meeting in January 2015, a series of ‘if . . . then’ statements were tabled that drew on the interview and scoping data. ‘If . . . then’ statements are the identification of an intervention/activity linked to outcome(s) and contain reference to contexts and mechanisms (although these may not be very explicit at this stage) and/or barriers and enablers (which can be both mechanism and context). 66 Although we did not use logic models, the ‘if . . . then’ statement route of thinking logically and working back from outcomes provided a helpful way of structuring our thinking. It also helped to focus the process of taking ideas and assumptions about how interventions work and testing them against the evidence we found (see Appendix 5).

Prototype data extraction form

Early data extraction was carried out in parallel with development of ‘if . . . then’ statements and developing a framework using diagrams and mind mapping. At this point, the data extraction process was more a matter of concept mining. We developed a table in Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and used headings that drew on findings from the early scoping and discussions within the team. This form was piloted on five initial papers recognised as important in FI and care home research and then refined further.

Diagrams and concept mapping

The diagrams and concept mapping captured a summary of evidence and thinking, overarching themes, likely barriers, enablers, contexts and outcomes. This was the basis for conversations about possible interactions and the identification of areas for which there was consensus about what ‘good FI care’ may look like for PLWD in care homes. We also used flip charts to map possible C–M–O configurations and these helped in the development of the data extraction form.

Narratives

Narratives were an important tool for making thought processes explicit and facilitating theory development. We used two main formats for narratives.

In the first, we created detailed narratives around specific research areas, for example a historical narrative of prompted voiding (PV) studies and care home research, or a summary of guidelines and reviews relevant to continence care in older people. While we were ‘data extracting’ individual sources, our core team discussions started to cluster around themes and particular areas and programmes of research.

The second format was ‘working paper’ narratives, which were presented to the wider team to ensure that everyone could keep up to date with methods, results, idea flows and theory development between meetings. In a realist review it is not possible for the process to be completely transparent. However, capturing our narrative thinking in this way should help others to understand and critically evaluate how we have come to our conclusions. It also meant that the process for developing theory could be understood, and challenged, by the research team, the SSC and our stakeholders. Pearson et al. 66,67 have commented on how little information is available about how the realist review process is enacted; these working papers helped to make explicit our thinking and decision-making.

Phase 2: retrieval, review and synthesis

Searching processes: phase 2

In March 2015 the scoping searches conducted in phase 1 were refined and expanded to include additional evidence sources (see Appendix 4). The RMT agreed that literature regarding facilities other than care homes was unlikely to add to what had already been obtained; however, relevant UI literature and care home studies with transferable methods and similar aims were to be included.

We included studies of any design including RCTs, controlled studies, effectiveness studies, uncontrolled studies, interrupted time-series studies, cost-effectiveness studies, process evaluations, surveys and qualitative studies of participants’ views and experiences of interventions. We also included unpublished and grey literature, such as policy documents and information about locally implemented continence programmes or proceedings, which could provide a model for future practice or merit future evaluation.

The search was limited to papers published between 1990 and 2014, although we did include seminal papers from earlier, such as the work of Tobin and Brocklehurst,68 and those identified from lateral searches. There were several reasons for this time limit. Health-care research in care homes is a relatively recent phenomenon. Gordon et al. 69 identified that of 292 RCTs conducted in care homes between 1974 and 2009, half had been published after 2003. Dementia research has been significantly influenced by the work of Kitwood,70 whose seminal work was first published in 1990. Furthermore, the organisation and funding of care homes was radically altered in 1993 by the implementation of the 1990 National Health Service and Community Care Act. 71 This led to progressive changes in the overall size, ownership and structure of the sector. The increased emphasis on domiciliary care has also meant that the level of dependency and frailty of older people now admitted to long-term care has increased. 72

Previous dementia reviews undertaken by members of the project team73,74 have highlighted the importance of lateral searching for identifying studies for dementia-related reviews. Therefore, in addition to the above electronic database searches, we undertook the following lateral searches:

-

checking of reference lists from primary studies and relevant systematic reviews (snowballing)75

-

citation searches using the ‘cited by’ option on Web of Science, Google Scholar and Scopus and the ‘related articles’ option on PubMed and Web of Science (‘lateral searching’)

-

contact with experts and those with an interest in dementia, care homes and FI to uncover grey literature (e.g. National Library for Health Later Life Specialist Library, Alzheimer’s Society, Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Nursing and The Queen’s Nursing Institute)

-

contact with disease-specific charities and user groups, residents and relatives associations

-

internet searches for grey literature and searches for continence-related evaluations or intervention research that makes specific reference to FI and/or people with a dementia diagnosis, national inspection and regulation quality reports by the UK regulator (Care Quality Commission and predecessors).

Four overlapping searches were completed that built on and expanded the search completed in phase 1 (see Appendix 4).

-

Searches 1a and 1b searched for evidence on care home research, either continence or FI related, that included PLWD, and care home research covering implementation or patient-centred care (PCC) that included people with dementia.

-

Search 2 focused on continence literature in care homes that may be about factors associated with FI, such as the use of incontinence pads or constipation.

-

Search 3 focused on research in care homes for people with dementia that concerned nutrition and/or hydration in the care home population. We were interested both in whether or not this research mentioned outcomes relevant to FI or continence generally and in discussion about how eating and drinking interventions may be implemented.

-

Search 4 focused on literature on continence care for people with learning disabilities living in residential care.

As the review progressed, and particularly the idea of needing to fit into care home routines, wider literature that discussed the impact of care home routines and working practices was consulted by team members (see note on bias in Strengths and limitations of the review). Further papers, professional journals and books were identified through lateral searches, alerts from professional networks, recommendations from the SSC and conference abstracts.

Theory development: phase 2

In parallel with the second phase of literature searching just described, mid-range theories were developed. This process is represented in Figure 2 and the results of theory development are described in the results. Six mid-range theories or ‘theory areas’ were developed and assessed against the selected literature using the data extraction process described in Data extraction: phase 2.

Selection and appraisal of documents: phase 2

Management of references

Search results from electronic databases were imported into EndNote bibliographic reference management software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and, when possible, duplicates were deleted. Documents from other sources were manually recorded in the same EndNote library. At least two reviewers (BRu, MB, CG and FB) independently screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant documents to be retrieved and assessed. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. To enable us to keep track of the large body of literature and the changing ‘inclusion’ criteria as the mid-range theories emerged, decisions made at different points in time were recorded in the EndNote record for each paper.

Although literature was considered for inclusion in terms of its relevance to the UK care home sector, the nature of a realist review meant a linear included/excluded paradigm was not wholly appropriate. Instead the team regularly revisited the literature to assess whether or not, in the light of evolving theory development, previously ‘excluded’ sources may in fact be relevant.

Data extraction: phase 2

The second phase of data extraction took place from July 2015 to October 2015.

Development of data analysis and synthesis form

We developed a prototype data analysis and synthesis form (DASF) tailored to reflect the phase 1 findings; this reflected the six mid-range theories which were to be tested. All RMT members completed data extraction on at least two of three papers, with all papers and other sources of evidence (e.g. books and professional papers) being reviewed by at least two members of the team. Most of the reviewing was completed by the core team (MB, BRu, CG and FB).

It should be noted that ‘data’ in a realist sense are not just restricted to the study results or outcomes measured. Author explanations and discussions can provide a rich source of ‘data’, and so these were included in the DASF. Box 2 summarises the six sections of the DASF.

Section 1: relevance is when the source is assessed against the theories being tested, which were restated briefly (theories 1–6) within the form to keep focus.

Section 2: interpretation of meaning. Here, an attempt is made to explicitly identify C–M–Os in the relevant text.

Section 3: judgements about C–M–O configurations. Once C–M–Os are identified, they need to be ‘configured.’ This is what takes us from a simplistic understanding of ‘barriers and enablers’ to a richer description in which we try and understand which context–resource combinations trigger which mechanisms, resulting in different outcomes (intended or unintended).

Section 4: judgements about mid-range theory. Here we attempt to complete the analysis circle. Taking sections of the text and assessing them as relevant, unpicking with respect to C–M–O configurations then referring those C–M–O configurations back to the proposed mid-range theories.

Section 5: rigour. This is the realist ‘quality assessment’ and is not conceptualised in the same way as in a systematic review. It is an assessment based on the weight that should be given to the C–M–O configurations found within the source, dependent on the quality of the study and also the richness of the explanations.

Section 6: population. This section keeps a focus on which groups the source is addressing so that an assessment can be made of how transferable the C–M–O configurations would be to our population of older people with dementia living in care homes.

The ‘questions raised not captured elsewhere’ and ‘notes’ sections are included to try to keep a track of all thinking and for future reference in combined synthesis meetings.

Three exemplar DASFs are given in Appendix 6.

Synthesis

The process of synthesising the data from the individual DASFs included:

-

the organisation of extracted information into evidence tables representing the different groups of literature (i.e. care home interventions, FI and UI and person-centred care)

-

theming across the evidence tables in relation to the C–M–Os and emerging patterns of association seeking confirming and disconfirming evidence

-

linking these observed demi-regularities (patterns) to develop hypotheses.

Integral to this process were cross-team discussions about the integrity of each theory and the competing accounts of why interventions did or did not work. This included a consideration of the unintended consequences of some approaches to continence care: what appeared to be true regardless of setting (e.g. by national care system or presence or absence of clinical staff), what was a setting-specific outcome, what were intermediate outcomes (e.g. changes in staff behaviour and knowledge) and what was a FI-specific outcome (e.g. reduced episodes of FI).

The findings were discussed by the core team and with some members of the wider team. In addition, a full draft was circulated to the team for detailed comment. Time constraints meant that it was not possible to hold a second workshop with the RMT as originally planned. Moreover, the team considered that at this stage it was more important to focus on presenting and discussing the findings and resultant hypotheses with the stakeholder groups. Initially, we had proposed that these would be presented to the stakeholders as a series of C–M–O links and the characteristics of the evidence underpinning them. The nature of the evidence (and lack thereof) ultimately led the team to focus on the development of programme theory that posited the likely C–M–O configurations that would lead to improved continence care.

Phases 3 and 4: test and refine programme theories (validation) and develop actionable recommendations and evidence-informed framework

To enhance the trustworthiness of the resultant hypotheses and to develop a final review narrative to address what is necessary for the effective implementation of programmes to manage FI in care homes, we reviewed the hypotheses and supporting evidence through consultation with the SSC and interviews with stakeholder groups, some of whom had participated in the scoping. Findings were presented to:

-

the continence specialist interest group at the BGS who had participated in the phase 1 interviews; approximately 60 delegates attended the conference on 6 November 2015 – 11 provided active feedback and comment during the discussion and six did so during the lunch break, and comments from four other speakers provided support for aspects of the emergent findings;

-

members of the BBF who had personal experience through their caring roles of living with FI and dementia;

-

a meeting of the National Care home Research and Development Forum (1 January 2015);

-

organised meetings in two separate care homes with staff involved in providing direct care from one of the care home organisations that had participated in phase 1 (9 December 2015).

Discussion focused on stakeholders’ views on the resonance and significance of the programme theory and the suggested C–M–O threads from both a practice and a service user perspective. In addition, there was an invited presentation at an Evidence Synthesis Network [hosted by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the University of Manchester] workshop on realist methodology held on 17 November 2015. The presentation using the Faecal INcontinence in people with advanced dementia resident in Care Homes (FINCH) study and its findings was an exemplar of how the programme theory was developed and tested, focusing on how we differentiated between contexts and outcomes in the evidence reviewed.

Ongoing dissemination work on the FINCH study was planned through seminars and a plan for publications and briefings in association with the care home manager member of the RMT and the SSC.

Public and patient involvement

The proposal was circulated and discussed with members of the public and patient involvement group at the University of Hertfordshire and amended accordingly. In addition to public and patient involvement representation on the SSC (Paul Millac), engagement with user and patient representative groups was key to stages 1 and 3 of the synthesis. There was public and patient involvement in the National Care Home Research and Development Forum meeting, during which emergent findings were discussed.

It was not possible to involve residents with dementia and experience of FI in the study. Karen Cummings and Victoria Elliot of the Orders of St John Care Trust care home group provided input to the RMT and SSC as individuals with direct experience of providing and managing continence care in care homes.

Chapter 3 Results

Document flow diagram

The document flow and review progress conceptual diagram (see Figure 2) shows the iterative nature of realist searching and concurrent theory development and synthesis over phases 1 and 2.

Phase 1: concept mining and theory development

Scoping: phase 1

Scoping meetings

After the first RMT meeting, the wide-ranging discussions were organised and structured under three main headings that reflected the idea that FI is affected by biomedical, psychosocial and wider organisational factors: (1) bowel-related causes of FI, (2) the physical, social and cultural environmental impact on FI and (3) how FI is defined, recognised and managed in a care home setting for PLWD.

Three clear themes emerged from the discussions as key to understanding what supported or inhibited practices that in turn supported or inhibited the reduction and management of FI:

-

the ‘normalisation’ of incontinence and pad use in long-term care settings

-

theories of learning and groups in long-term care settings

-

interprofessional working, staff turnover and workforce capacity, and the role of the regulator.

The commissioning brief had specified that people with advanced dementia in care homes should be the focus of the review. Based on the first cut of the literature, and on previous experience of working and completing research in care homes, the RMT argued that this was an unhelpful distinction. Changes in functional performance and activities of daily living skills characterise the dementia trajectory. There are tools that measure these changes. 11 Many care home residents, however, do not have a formal dementia diagnosis, and living with mild to moderate dementia can still have a major impact on an individual’s ability to recognise the need to eliminate, recognise the toilet, undress or respond to prompts to use the toilet. The SSC agreed that dementia should replace ‘advanced dementia’ as the search term for the reviews.

Scoping interviews

Details of the participants of the scoping interviews are given in Table 3.

| Stakeholder group | Details |

|---|---|

| Carers of people with dementia resident in care homes who have FI (n = 2) | Interview in one of the participants’ homes with the spouses of two residents living in a local care home. Both residents had dementia and one resident had almost constant UI; neither was represented by their carer as having FI, apart from what were described as accidents from difficulties getting undressed, finding the toilet or staff not being present to help their relative |

| Geriatricians with interest in incontinence and continence specialists (n = 15) | A focus group was held at the 2014 BGS Bladder and Bowel Conference. Fifteen delegates participated. They were geriatricians at registrar and consultant grade and continence nurse specialists |

| Interview with three continence specialist nurses who provided support to their local care homes in the west of England (n = 3) | Part of their service provided continence assessment and support to the local care homes |

| Care home managers (n = 17) | Two focus groups were held with care home managers from two care home provider organisations that included care homes with and without on-site nursing (n = 5 and n = 12, respectively) |

| Direct care staff (n = 7) | Two care workers known to a member of the RMT were interviewed separately. Both worked night shifts in two different care homes. Both had > 6 years’ experience of working in care homes Focus group with four care staff and one senior care worker of a local care home without on-site nursing |

All participants in the scoping interviews highlighted the importance of knowing the resident and how distressing FI could be for both residents and staff. There were differences in emphasis between the stakeholder groups; for example, person-centred care was central to one group but secondary to a knowledge of the causes of FI or being able to provide care using the resources of the care home. Unsurprisingly, participants’ views reflected their training, background and personal experiences of care.

Clinicians from the BGS group and the continence services believed that care home managers and senior care staff did not know what causes FI in older people. They highlighted limited knowledge about the impact of polypharmacy, misuse of laxatives, failures to address resident dehydration and diet that lacked fibre, and about how to assess whether or not someone was constipated. This lack of knowledge was seen as being compounded by the inappropriate use of pads.

Staff can’t do the right thing if they lack the information, knowledge, skills. From understanding the causes of FI and how to address them to knowing which size of pad to use for which person [when pads have to be used]. If pads must be used getting the right size and design make all the difference in terms of comfort and confidence for the wearer.

Continence nurse specialist

In contrast, group discussions with the two groups of care home managers and, to a lesser extent, those involved in providing direct care to residents provided a counter narrative. The care home managers were able to discuss the multiple causes of FI, the role of constipation in FI and the importance of hydration, nutrition, physical activity and person-centred care. Managers emphasised the value of reinforcing with staff the need for empathy and reflection in how they approached the care of the resident. In one example, a manager overheard a carer telling a resident who had asked to be taken to the toilet to relieve themselves in their pad instead. In another example, when a resident asked if she could be taken to the toilet, the carer asked if she could wait until after breakfast. These examples of bad practice were used to illustrate the importance of learning ‘on the job’ and of the managers’ role in reinforcing what good, and bad, care looks like.

Care home managers viewed person-centred care in a communal environment as important but difficult to implement or apply to the specific continence needs of residents. They recognised, from a person-centred care perspective, that certain behaviours such as repetitive vocalisation (e.g. calling for the toilet), constantly visiting the toilet or refusing to go to the toilet may arise because a person is communicating an unmet need. This was often difficult for care home staff to interpret. The care home managers suggested that their staff would all err on the side of caution and always respond on request, but that this was not always possible when the care home was short of staff or reliant on agency staff. Similarly, when residents resisted being taken to the toilet by staff and became distressed, staff members did not want to be seen to be forcing someone to do something or to go against their wishes. Staff involved in direct care emphasised the importance of residents’ cleanliness and comfort; their job was to change pads and to make sure that people who could go to the toilet were helped to do so and had enough time when there. This work was described as ‘common sense’.

There was no consensus when those in the groups were asked how long they might persevere with trying to help someone to become continent. There was little evidence from the within-group conversations to suggest that participants would persevere with a toileting regime for longer than 4 weeks. Direct care staff saw the value of regular toileting but described their work more in terms of ensuring dignity and comfort. A continence assessment when someone entered a care home was more about ensuring that the care home could access pads than informing decisions about how to support continence.

The interpretation of resident choice around toileting, and whether or not to persevere, was an issue raised by the two relatives who were interviewed. One woman saw this as evidence of lack of training in how to respond to PLWD. She thought that those staff members who were less qualified or less experienced in working with PLWD were more likely to accept a resident’s refusal to go to the toilet. More skilled staff were more likely to try other strategies to encourage residents to walk and use the toilet. She could differentiate between staff who were thoughtful and understood her husband and his needs and those who were less able to find alternative ways of engaging with her husband when his dementia affected his ability to respond. In the following quotations, text marked in bold highlights what the research team identified as being significant for understanding the processes of care.

There is a difference in knowledge [about dementia] needed for people at the different stages of the disease, there was one carer [name] who was very good at caring for my husband when he was able to have a conversation but who then did not have the skills to engage with him now that there is very little response. In contrast [name] does have these skills, I can trust him to be caring to be able to get my husband up and about.

Wife of resident in care home

Both relatives highlighted practical issues of location of toilets and difficulties that their relatives had with clothing and recognising when they needed to eliminate:

I don’t know if he is incontinent or if it is just about getting to the toilet. They have put a picture on his toilet. I bought him pull-up trousers but they have disappeared. I don’t know how severe his incontinence is, though he is weeing everywhere and that is partly the dementia and partly not thinking far enough ahead and being able to manage the trousers.

Wife [2] of resident in care home

The erratic level of clinical support that the care home received was also seen as contributing to problems of assessment and management, and this was not specific to their relatives’ incontinence but was seen as an important contextual factor. One relative referred to 14 GPs from one practice who visited the care home as ‘a fleet of GPs’ who did not know much about frailty or dementia.

We found it useful to summarise these discussions with stakeholders by interventions thought likely to be helpful, elements of intervention, outcome, enablers and inhibitors (Table 4). The data from the interviews ensured that we had considered the different perspectives of how good continence care is achieved. They also informed, along with the scoping of the literature, the development of the programme theories.

| Resource/context | Response/mechanism | Reported outcomes | Enablers | Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family carers of people with dementia resident in care homes that have FI | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| Geriatricians with specialist interest in continence | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| Continence specialists | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| Care home managers | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| Direct care staff (including night shifts) (n = 6) | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

Literature scoping: phase 1

Search results

The first electronic search focused on incontinence and care homes, person-centred care and implementation in care homes. This resulted in > 1000 hits, of which 75 were deemed potentially relevant. These were then reduced to 31 priority records for in-depth review. Additional searches around FI and the use of pads, nutrition and hydration (systematic reviews only) and learning disability resulted in 193, 10 and 20 records, respectively (see Figure 2 and Appendix 4). These, along with some papers from lateral searches, informed the first overview presented for discussion to the SSC and the RMT.

Scoping summary

The literature was summarised for the RMT into four broad topic areas:

-

biomedical approaches to the assessment and management of FI

-

person-centred care

-

care home implementation

-

nutrition and dementia in care homes (reviews only).

For each area, a summary was provided of the interventions, the outcomes measured and the reported barriers and enablers (see Appendix 2).

Analysis and synthesis processes: phase 1 (concept mining and theory development)

The RMT meeting in January 2015 mapped the findings (literature scoping and stakeholder scoping) to a framework that considered the different types of FI, as defined by the work of Saga,76 that reflected a trajectory from continence to incontinence. Initially, it helped to conceptualise whether or not a particular type of FI intervention/approach would be more amenable to management (i.e. it may be time limited or could be treated and reduced) or to containment (treatment not possible).

‘If . . . then’ statements

A set of ‘if . . . then’ statements were produced ahead of the May RMT meeting based on earlier discussions and iterations. They were divided into:

-

‘What to do?’ – intervention/management to address review objective 1.

-

‘How to do it?’ – implementation, sustainability and feasibility to address review objectives 2 and 3.

‘How to do it?’ was further split into the ‘level’ of the intervention, staff, care home and wider organisational/policy, to ensure that the different audiences for the review findings were kept in mind. Table 5 gives some examples of these statements and a fuller version with more statements and cross-referencing to the literature is included in Appendices 2 and 3.

| If | Then |

|---|---|

| What to do | |

| If FI is not ‘curable’ (neurogenic disinhibition/dementia-caused/anorectal dysfunction/dyssynergia) | Then appropriate containment is required, which may be timed toileting/PV, bowel regime or use of most appropriate pads |

| If a person has regular bowel movements and responds well to being taken to the toilet | Then PV will reduce FI episodes |

| If FI is a result of functional reasons (access and ability to get to the toilet) | Then a suitably adapted environment and staff on hand to assist as needed will reduce FI episodes |

| How to do it | |

| Staff level | |

| If staff have more time with residents and opportunity to know and document what is normal for them | Then they will deliver better continence care and FI will reduce |

| If staff have specialist dementia and FI training/knowledge | Then they will deliver better continence care and FI will reduce |

| Care home level | |

| If staff experience a supportive working environment | Then residents will experience less FI and be more content |

| If it is considered normal that all residents are in pads | Then FI will not improve |

| Wider organisational/policy level | |

| If provision of pads is dependent on assessment protocols | Then FI will be overdiagnosed and managed with pads |

| If care homes were performance managed on FI | Then practitioners would be more aware and there would be less FI (or FI would be recorded more accurately) |

The statements aimed to capture the range of possible theories/contexts/mechanisms suggested by all of our stakeholders and the literature viewed to date. We included a section for enablers and barriers if we felt that they were cross-cutting or not fully captured in the statements.

The RMT were asked if these ‘if . . . then’ statements:

-

covered outcomes sufficiently, for example comfort, minimisation of distress, reduction of FI episodes, reduction of FI (incidence vs. prevalence) resource use, restoring normal bowel function and staff outcomes

-

fitted with professional understanding of how continence is defined and understood, for example the International Continence Society paradigm, independent continence, dependent continence and containment

-

addressed dementia factors well enough

-

could be collapsed further.

Prototype data extraction form

We piloted the phase 1 data extraction form with five papers. This resulted in the addition of 10 new fields, most of which annotated additional possible outcomes from FI-related interventions. The different literature sources consulted in the scoping included research on continence care in care homes, person-centred care and psychosocial interventions in care homes and related FI- or dementia-specific studies. The data extraction form fields of particular interest at this point in the study were the implicit or explicit study hypotheses about what was likely to support good (continence) care for care home residents.

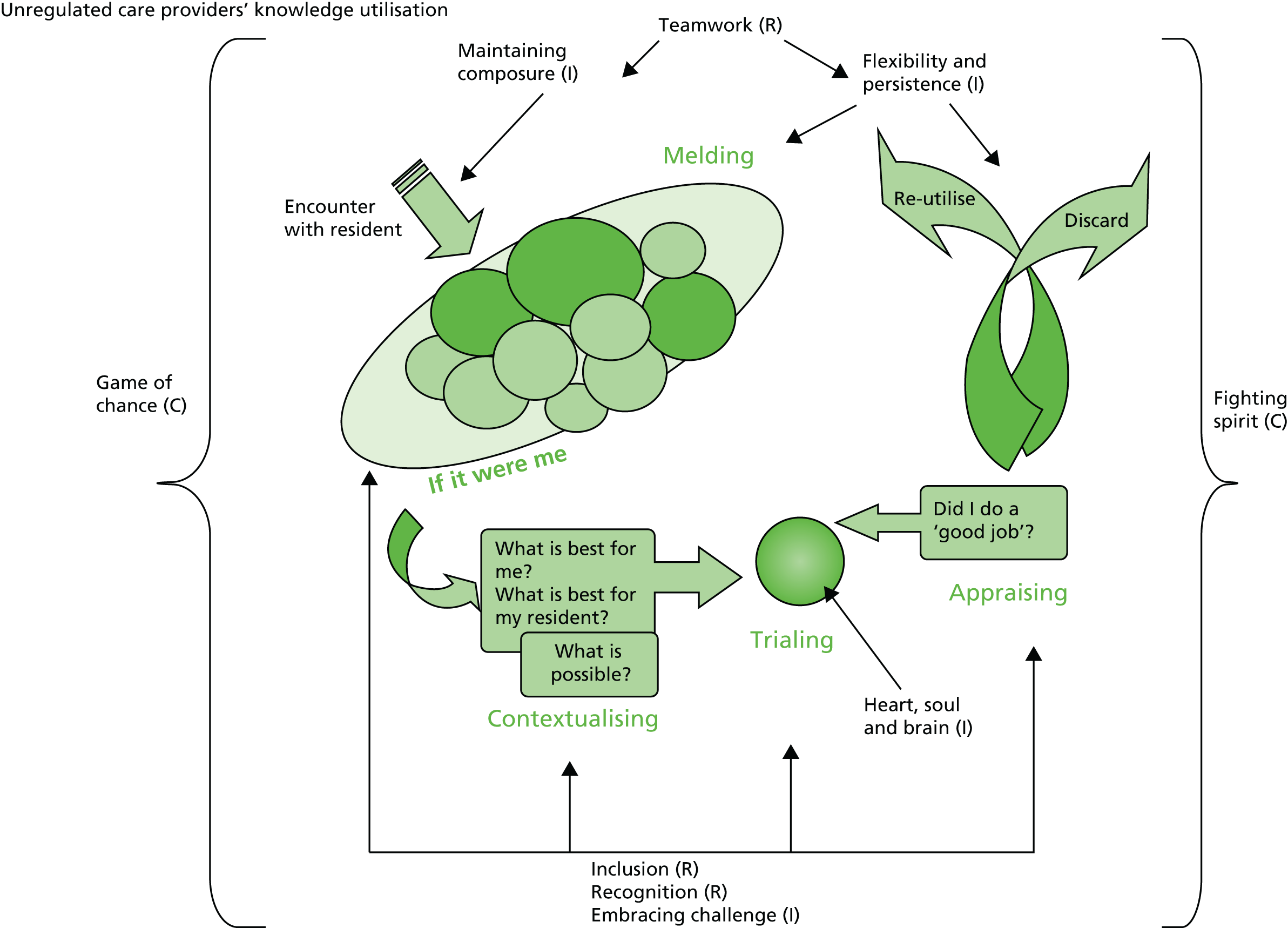

Discussions among the core team about the original data extraction form, the ‘if . . . then’ statements and the flip chart diagrams and mapping we had produced were pulled together in a conceptual diagram77 that mapped outcomes, contexts, barriers and enablers (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Conceptual diagram mapping outcomes, contexts, barriers and enablers.

Narratives

General narratives were written that kept the team up to date on the flow of ideas. As working papers for the team, they did not have a clear distinction between methods, results and discussion. These are all held together in a narrative format (see Appendix 2).

-

FINCH working paper: presented to the RMT in May 2015.

-

Flow of ideas from the six theory areas emerging from the RMT in May 2015: sent to RMT members in August 2015 to help with data extraction.

-

FINCH ideas flow paper; presented to the SSC in September 2015.

These narratives suggested that we return to thinking about dementia. The following excerpt summarises our thinking:

We are concerned that we lose the focus on (advanced) dementia as in so much of the evidence this is not described in particular detail and because it is care homes there is an implicit (correct) assumption that most residents have a degree of cognitive impairment. We suggest that we need to always keep dementia as a context with the other contexts and so always think, ‘with these contexts, this mechanism triggers such and such; how does dementia affect that?’ (However, going back to Kitwood dementia in itself isn’t the context, because when you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia . . .) Should we be listing some of the behaviours and morbidities and psychological symptoms of dementias as contexts?

Log book notes RMT meeting May 2015

The narratives took a historical view of the literature in the sense of understanding how research in continence, particularly FI, has developed over time and, similarly, how research in care homes has developed.

There were two main strands to these narratives. The first was to understand how best practice in the treatment and management of FI, when relevant to older PLWD, is articulated in professional guidance and reviews. The second was to identify the potential for transferable learning from research with older PLWD in care homes, but that was not continence specific.

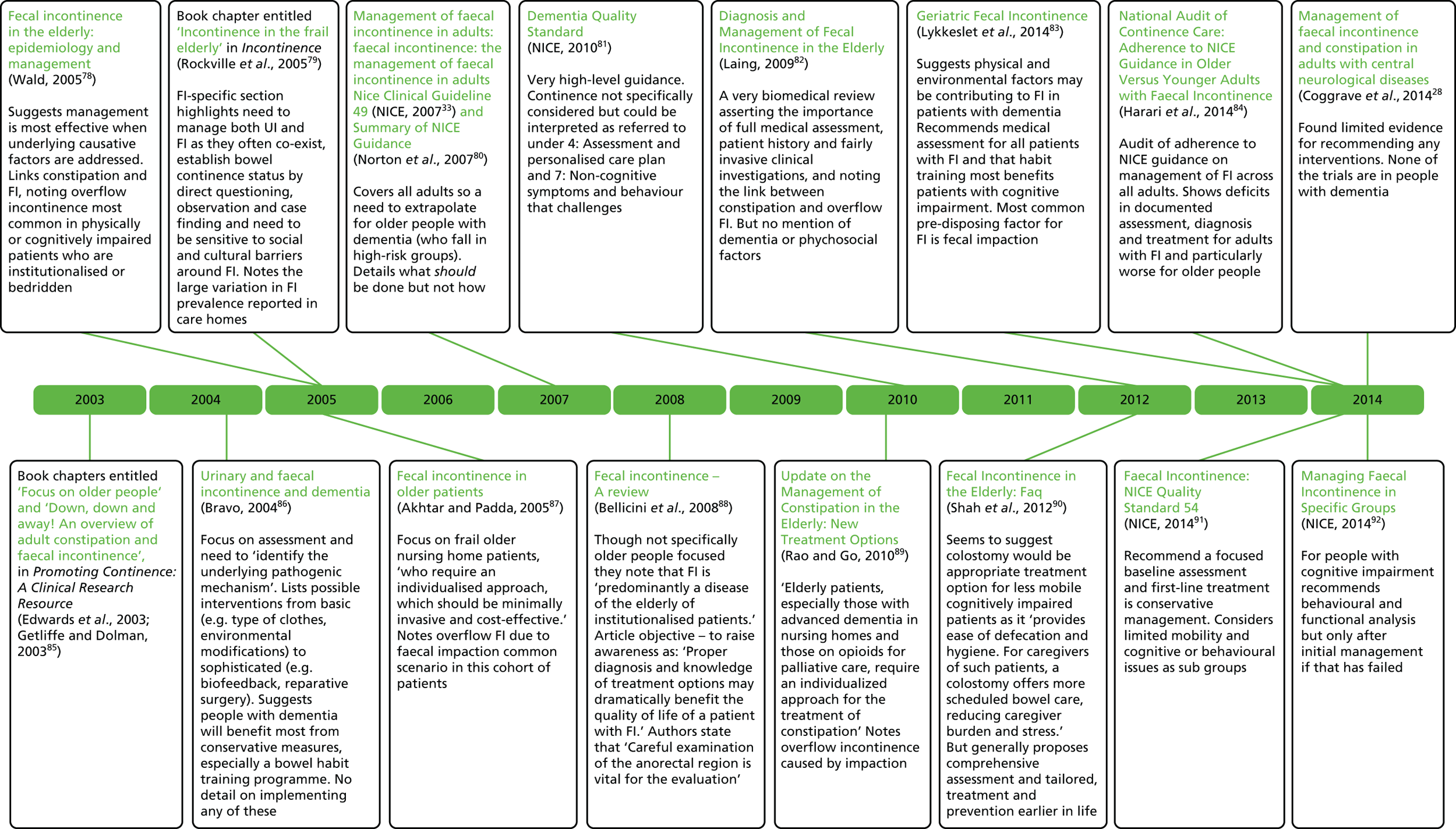

The first strand summarises the guidance and review articles relevant to the management of FI in older people living in care homes/long-term care. This is presented in a timeline format (Figure 4) and demonstrates how thinking about FI is discussed for health-care professionals and where the sources of evidence and guidance are located. The importance attributed to assessment and the diagnosis of faecal impaction is emphasised. There is limited acknowledgement or guidance about how to implement this essentially biomedical guidance (e.g. careful examination of the anorectal region is recommended) in settings with limited access to clinicians and lack of discussion about how to implement assessment or treatment options for PLWD. A strong theme that emerges is the belief that direct clinical assessment is essential but that there is little direction on how this could be achieved, particularly in care home settings for PLWD.

FIGURE 4.

Timeline of guidance and review articles relevant to the management of FI in older people in care homes/long-term care.

The second strand considers the potential for transferable learning. Essentially, there is a body of continence research in US nursing homes (some of which is focused on FI) by Ouslander et al. ,45,93,94 Leung et al. ,95,96 Levy-Storms et al. ,97 Rahman et al. 98,99 and Schnelle et al.,100–106 but there is little consideration of the impact of dementia on continence or implementing the interventions (based around PV). There is also a body of literature on the non-pharmacological approaches to the reduction and management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in UK care homes by Ballard et al. ,107 Fossey et al. ,108,109 Lawrence et al. 110,111 and Whitaker et al. 112,113 We theorised parallels between the experience of FI and BPSD and the use of ‘containment’ as the predominant but not ideal approach to management:

-

There is stigma and revulsion at FI and BPSD.

-

Containment is the ‘easier’ option (either pads or antipsychotics).

-

Alternatives to this option (PV for FI and psychosocial interventions for BPSD) are difficult to implement and need to draw on the assumptions of individualised care and person-centred approaches.

Figure 5 demonstrates how both these programmes of work have developed over time from a specific intervention through multicomponent intervention trials to more detailed work around implementation in the care home/nursing home setting. The continence studies give specific results around FI and the BPSD studies on working with PLWD. The learning from these programmes of work suggests that training, learning, mentoring and post-training support are important contexts but do not, of themselves, lead to staff engagement and motivation to change practice or care routines.

FIGURE 5.

Schematic showing of the development over time in two research groups of a common understanding of the need for multicomponent interventions and the complexity of implementing new practices in care homes. QoL, quality of life.

In addition, the recent work on the prevalence and management of FI in Norwegian nursing homes76 confirmed earlier discussions by the RMT that double incontinence is more prevalent than FI alone and that double incontinence is associated with more cognitive impairment.

Outcomes

We categorised outcomes identified in the phase 1 scoping work as resident, staff or organisational outcomes. These outcomes were identified from the phase 1 stakeholder input (interviews, focus groups and RMT and SSC discussions) and from the continence, PCC and care home implementation literature reviewed in phase 1. This is summarised in Table 6, which clearly shows the different outcomes prioritised between the different research perspectives. Particularly notable are the gaps between the resident outcomes in the continence literature (which has more of a biomedical focus) and the PCC and care home intervention literature (which has more of a quality-of-life focus). Distress and improvement in symptoms are noted in both.

| Resident outcomes | Staff outcomes | Organisation outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Outcomes proposed by stakeholders | ||

|

|

|

| Outcomes from the continence literature | ||

|

|

|

| Outcomes from the PCC literature | ||

|

|

|

| Outcomes from the care home implementation literature | ||

|

|

|

Outcomes identified by stakeholders and not explicit in the research literature include resident outcomes of comfort and dignity, staff outcomes of change in attitude and work satisfaction, organisational outcomes of workforce turnover and organisational reputation. These staff and resident outcomes identified by stakeholders as important for PLWD in care homes who experience FI are more aligned to the outcomes measured in dementia care and care home implementation studies.

Cost outcomes are not well defined by studies or stakeholders. Resource use is broad and not care home specific (staff, buildings, laundry, continence aids and prescribing).

The use of pads to manage FI is the most common continence aid used in care homes. The following provides an account of the literature on this topic and related outcomes; however, we did not extract data from the majority of the literature. There was insufficient detail to test our programme theories in the evidence reviewed. The impact of a person’s dementia, the level of staff preparedness and how use was linked to clinical assessment were not discussed.

Literature on use of continence aids for care home residents

The initial searches identified only one study on the use of pads. This study114 focused on the incorporation of a pocket with wipes in the design of the pads. It tested how this design change affected pad changes, and how staff used the equipment/resources available.

A further scoping by Mandy Fader considered a wider literature on absorbent pads and products (colloquially known as ‘pads’) that was not necessarily dementia or care home specific. This literature on the management of FI with products can be broadly divided into three areas:

-

management of FI with absorbent products

-

incontinence-associated dermatitis and development of pressure ulcers

-

management of FI with mechanical devices.

Management of faecal incontinence with absorbent products

Very few studies have compared the different designs of absorbent products for FI, and the emphasis has been mainly on testing pads with patients with UI. It is recognised that different absorbent designs are more or less likely to be effective and acceptable, depending on patient attributes (e.g. ability to stand, ability to toilet independently and sex) and preferences. 115–120 However, these attributes and preferences do not consider issues directly related to how dementia affects the person’s continence. These designs may also be cost-effective in different settings [e.g. day vs. night and easier to use or change than others (by carers and residents)]. A putative C–M–O configuration from this would, therefore, suggest that a patient decision-making tool (resource) may be valuable in determining which products to use for a particular patient, taking into account when it is to be used (C) and how easy users (carers or residents) find it to use (C) because it could trigger regular toileting ‘being less of a practical difficulty’ (M) and thus FI may be reduced – even if pads are being worn (O).

Incontinence-associated dermatitis

There is a considerable body of literature from baby and adult nappy studies that shows the effect of urine and/or faeces on skin health and describes the processes that lead to dermatitis and to pressure ulcers. 121–124 There is some evidence that liquid stool or a combination of urine and faeces provide the most damaging skin environment. A further body of literature focuses on skin protection and skin cleansing as methods of avoiding skin damage. Hypothetically, the management of UI (e.g. the use of a catheter or penile sheath) separately from FI (mechanical device or absorbent pad) may reduce incontinence-associated dermatitis. However, this is an option for women only if a urinary catheter is used, and this is not recommended for long-term use. Neither does this management option really take any account of the acceptability of these sorts of options for people with dementia. 114

Management of faecal incontinence with mechanical devices

A Cochrane review on anal plugs and a literature on the use of catheter/tube devices to drain liquid stool. 125–131 The studies included mainly reported on dependent bed-bound patients in intensive care units who had a urinary catheter, and are, therefore, not relevant to care home settings. Studies reported risks and some major adverse events (e.g. haemorrhage132,133) related to the use of some mechanical devices. Moreover, there are consent and ethical issues related to the use of these devices. It is, therefore, unlikely that mechanical devices would play a major role in the management of FI in care homes.

Tables 7–9 summarise the evidence on absorbent designs that is relevant to the review and the limited sources of evidence that address the needs of PLWD and FI resident in care homes.

| Reference | Main subject areas |

|---|---|

| Fader et al., 2008115 | Research evidence of absorbents’ design features and their suitability/popularity among different types of incontinence and users |

| Fader et al., 2010116 | Literature review of current product design for FI/UI. Need for different designs to accommodate variety of needs |

| Bliss and Savik, 2008119 | Use of a small absorbent dressing to contain FI |

| Bliss et al., 2011118 | Survey of the use of absorbents by community-living elderly. Preferences for design of products for FI |

| Beguin et al., 2010120 | Described and tested pads that create an acidic surface and breathable side panels to reduce skin moisture and damage |

| Reference | Main subject areas |

|---|---|

| Shigeta et al., 2009122 | Research study showed association between diarrhoea and contact dermatitis |

| Shigeta et al., 2010121 | Research study in nursing homes found skin hydration and pH higher in residents with faecal and double incontinence |

| Rohwer et al., 2013123 | Found an association between dermatitis and FI. Community-based study |

| Beeckman et al., 2014124 | Found double incontinence to be a significant predictor of pressure ulcers |

| Reference | Main subject areas |

|---|---|

| Denat and Khorshid, 2011125 | Use of perianal pouch for bed-ridden patients |

| Jones et al., 2011126 | Description of rectal catheter for the containment of faeces and Clostridium difficile |

| Allymamod and Chamanga, 2014131 | Used faecal collecting device for bed-bound community patients. Used fewer sacral wound dressing changes, increased comfort and fewer nurse visits |

| Mulhall and Jindal, 2013132 | Case study of gastrointestinal haemorrhage as a result of using a faecal management system |

| Shaker et al., 2014133 | Case study of rectal ulceration as a result of using a faecal management system |

At the end of phase 1 (see Figure 2), we had established how effective reduction and management of FI for PLWD is represented in the literature and the range of outcomes that are used to measure this. Practitioner accounts, professional literature and discussions with stakeholders raised issues around the specific problems of PLWD and what supports or inhibits implementation of best practice in care home settings.

The scoping work led us to clarify and expand our definitions of dementia and continence for PLWD in care homes.

Definitions

Dementia

The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10),134 defines dementia as a disorder with deterioration in both memory and thinking that is sufficient to impair personal activities of daily living. The definition requires that the patient have deficits in thinking and reasoning in addition to memory disturbance. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition135 (DSM-IV) defines dementia as a syndrome characterised by the development of multiple cognitive deficits including memory impairment and at least one of the following cognitive disturbances: aphasia, apraxia, agnosia and a disturbance in executive functioning. The deficits must be sufficiently severe to cause impairment in occupational or social functioning and must represent a decline from a previously higher level of functioning. The lack of continence studies addressing dementia and an inconsistency in how dementia is assessed and recorded for care home residents, coupled with the lack of consensus on how to define advanced dementia in relation to continence care, meant that the working definition of advanced dementia was loosely defined and sometimes had to be inferred when undertaking the review.

Continence

The protocol definition and starting point of the review was ‘leakage of solid or liquid stool that is a social or hygienic problem’;41 the sense that it can be a ‘social or hygienic’ problem did not capture the behavioural aspects of FI that had been raised in scoping.

The scoping of the literature identified two ways of defining and categorising different types of continence for older people with dementia and, specifically, FI. Saga76 provides a list of clinical or physiological causes that identifies dementia-related incontinence as a particular cause of FI. Stokes,136 in contrast, sees incontinence and specifically FI as a single factor (of nine causes or contexts) for ‘toileting difficulties’ (Table 10).