Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/33/03. The contractual start date was in November 2012. The draft report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in August 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Joanna M Charles and Rhiannon T Edwards declare grants from Public Health Wales outside the submitted work. Clare Wilkinson is the chairperson of the Health Technology Assessment programme Commissioning Panel – Primary Care Community Preventive Interventions.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Williams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Proximal femoral fracture, more commonly referred to as hip fracture, is a common major health problem in old age. It refers to a fracture in the area between the femoral head and 5 cm distal to the lesser trochanter. These fractures are further subdivided into those proximal to the insertion of the joint capsule, termed intracapsular, subcapital or femoral neck fractures, and those distal to the joint capsule, termed extracapsular, which can be split further into trochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures. The total number of patients entered into the National Hip Fracture Database in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2012/13 was 61,5081 and, as the population ages, the number of elderly people falling and fracturing their hips is projected to increase further. Hip fracture is strongly associated with decreased bone mineral density, increased age, prior fragility fracture, cognitive impairment, other health problems, undernutrition, frailty, poor physical functioning, vision problems and weight loss. 2 Mortality is high, with 25% of patients dying within the following 12 months. A review of the long-term disability associated with proximal femoral fracture found that 29% of patients did not regain their level of functioning after 1 year in terms of restrictions in activities of daily living (ADL). 3 Many who were living independently before their fracture lose their independence afterwards and so a large cost burden on society is imposed, amounting to about £2B per year. 4 Particularly frail individuals may go on to have a further proximal femoral fracture, resulting in additional disability and death. Risk factors for subsequent fracture include older age, cognitive impairment, lower bone mass, impaired depth perception, impaired mobility, previous falls, dizziness and poor self-perceived health. 5

Three phases of recovery from proximal femoral fracture have been proposed. 6 The first phase occurs in hospital, with the patient recovering from injury and surgery and becoming safe to discharge. The second phase consists of rehabilitation, either in an institution or at home. The final phase is the enduring stage in which patients use their own previous health belief strategies to determine if and when they have recovered. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued guidelines for the management of hip fracture. 7 As well as prompt surgical treatment, the guidelines recommend that associated medical needs are assessed promptly by a physician specialised in caring for this patient group, who can also identify goals for a programme of multidisciplinary rehabilitation. Such rehabilitation starts while in hospital during post-operative recovery and continues in the community following hospital discharge. Patients should be offered physiotherapy assessment and mobilisation on the day after surgery unless medically or surgically contraindicated. They should be offered mobilisation at least once a day and receive regular physiotherapy. They should receive a formal hip fracture programme that includes all of the following: orthogeriatric assessment, rapid optimisation of fitness for surgery, early identification of individual goals for multidisciplinary rehabilitation to recover mobility and independence and, to facilitate return to pre-fracture residence and long-term well-being, continued co-ordinated orthogeriatric and multidisciplinary review, and communication with the primary care team. Patients with cognitive impairment should be actively sought and offered individualised care to minimise delirium and maximise independence.

Rehabilitation has the potential to maximise recovery, enhance quality of life and maintain independence, but what is the evidence in this patient group? There have been three relevant Cochrane systematic reviews. 8–10 A review of multidisciplinary rehabilitation for older people with hip fractures identified 13 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving 2498 older patients who received rehabilitation interventions following hip fracture surgery. 8 The majority of participants in these RCTs were women, with a mean age of 78–84 years. There was substantial clinical heterogeneity in the trial populations and the trial interventions. Inpatient rehabilitation was examined in 11 RCTs. In six of these trials patients either were transferred to a geriatric orthopaedic rehabilitation unit (intervention group) or received usual care from the orthopaedic team (control group). The main component of the intervention was close co-operation between geriatricians and orthopaedic surgeons in the medical care of patients, together with multidisciplinary teamwork from allied health professionals. Four inpatient RCTs compared a more intensive rehabilitation programme with usual rehabilitation care. The intervention consisted of early assessment by a rehabilitation physician or geriatrician, an emphasis on re-establishing physical independence and discharge planning. One RCT compared multidisciplinary rehabilitation in a geriatric ward with care in local community hospitals supervised by general practitioners (GPs). Two RCTs examined home-based rehabilitation. One RCT compared discharge home after 48 hours to home-based interdisciplinary rehabilitation with usual hospital-based interdisciplinary rehabilitation. The home-based intervention concentrated on early resumption of self-care and domestic activities. The other RCT compared intensive home-based rehabilitation (six weekly visits) with less intensive home-based rehabilitation (three or fewer weekly visits). A meta-analysis of eight RCTs examining multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation combined death and deterioration as ‘poor outcome’ and showed a non-statistically significant tendency in favour of the intervention at long-term follow-up [risk ratio 0.89, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 1.01]. All 11 RCTs of inpatient rehabilitation reported mortality and a meta-analysis found no statistically significant difference (risk ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.07) between the groups. Hospital readmissions were reported in six RCTs but did not differ significantly between the groups (risk ratio 0.99, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.19). Individual RCTs found better results in the intervention group than the control group for ADL. There was much heterogeneity in the data for length of hospital admission and costs. Carer burden was not increased by the intervention in three RCTs. The RCT comparing home-based rehabilitation with inpatient care found a marginal improvement in function for patients and a clinically significant reduction in burden for carers in the intervention group. The RCT examining different intensities of home-based rehabilitation found no difference between the groups. Overall, the review concluded that the results were inconclusive and that more RCTs examining clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness were needed.

A systematic review of mobilisation strategies9 identified 19 small RCTs and quasi-RCTs involving 1589 participants. Twelve of these examined early mobilisation strategies following surgery. Single trials found improvements in mobility from an early weight-bearing programme, quadriceps muscle strengthening and pain-relieving electrical stimulation. Single trials did not find a significant improvement in mobility following treadmill gait retraining, a 12-week resistance training programme and a 16-week programme of weight-bearing exercise. There were contradictory results from an early ambulation intervention. One trial that was 40 years old did not find any significant differences between starting weight bearing at 2 weeks or starting weight bearing at 12 weeks. Two trials evaluated more intensive physiotherapy, with one finding no differences between the intervention group and the control group and one reporting a higher dropout rate in the intervention group. Two trials tested electrical stimulation of the quadriceps. In one of the trials this was poorly tolerated and ineffective, whereas in the other it was well tolerated and improved mobility. Seven trials examined community interventions following hospital discharge. Two trials found that exercise interventions started soon after discharge were effective. One of these compared 12 weeks of intensive physical training with placebo motor activities; the other compared a home-based physical therapy programme with unsupervised home exercises. Five trials began after usual physical therapy care had been completed and compared an extra physical training intervention with no or a low-intensity intervention. The results of these trials were mixed. One trial found increased activity levels after 1 year of exercises led by a personal trainer. One trial found improved outcome after 6 months of intensive physical training, whereas another trial found no significant effects of 12 weeks of home-based resistance or aerobic training. One trial found improved outcome after practice of home-based exercises started at 22 weeks, whereas another trial found that home-based weight-bearing exercises started at 7 months were ineffective. In conclusion, it was possible to enhance mobility after hip fracture, but the best method to achieve this was unclear. There was insufficient evidence to determine the effects of any particular mobilisation strategy.

Psychological factors such as fear of falling, perceived control and coping strategies have been identified as influencing recovery following hip fracture. 11–14 Fear of falling is present in at least half of patients following hip fracture. It is associated with loss of mobility, institutionalisation and mortality and is related to less time spent on exercise and an increase in falls. 14 Psychosocial factors associated with healthy ageing are protective, such as being married, living in present accommodation for at least 5 years, having private health insurance, using proactive coping strategies, having a high level of life satisfaction and engagement in social activities. 15 A systematic review of rehabilitation for improving physical and psychosocial functioning after hip fracture identified nine small RCTs involving 1400 patients. 10 The trials were clinically heterogeneous and involved different interventions, providers, settings and outcomes. Three RCTs examined inpatient interventions: reorientation measures, intensive occupational therapy and cognitive–behavioural therapy. These trials found no significant differences in outcomes between the intervention group and the control group. Two RCTs examined nurse specialist care carried out mostly or completely after hospital discharge, with one finding a short-term reduction in ‘poor outcome’ in the intervention group and the other finding no differences between the groups. Two RCTs examined educational and motivational coaching. One trial in hospital found that educational and motivational coaching had no effect on function or mortality at 6 months; the other trial, which started at home after discharge from rehabilitation, found that coaching improved self-efficacy at 6 months, but not when combined with exercise. Two RCTs starting several weeks after hip fracture found no effect on outcomes of home rehabilitation and a group learning programme. Further research on psychosocial interventions was recommended.

Patients with cognitive impairment make up a large proportion of patients presenting with a hip fracture and several studies have shown a worse outcome for cognitively impaired patients following hip fracture. 16 Indeed, patients with cognitive impairment were either excluded from or not commented on in 60% of hip fracture studies reviewed for the NICE guidelines. 7 However, a systematic review of rehabilitation in patients with dementia following hip fracture found that those with mild to moderate dementia showed similar relative gains in function to those without dementia. 17 In addition, hip fracture patients with cognitive impairment are at increased risk of delirium, medical complications, death, prolonged stay and loss of independence. According to the NICE guidelines on delirium,18 patients with memory problems are known to benefit from comprehensive geriatric assessment and targeted intervention to reduce the risk of delirium.

The NICE clinical practice guideline for the assessment and prevention of falls in older people19 is relevant for the secondary prevention of falling in hip fracture patients. The guidelines recommend that older people with recurrent falls should be considered for an individualised multifactorial intervention programme including strength and balance training, home hazard assessment and intervention, vision assessment and referral and medication review with modification and withdrawal of psychotropic medication. Following treatment for an injurious fall, such as a hip fracture, older people should be offered a multidisciplinary assessment to identify and address future risks and individualised intervention to promote independence and improve physical and psychological function.

In conclusion, previous systematic reviews have not found sufficient evidence that multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes have demonstrated overall effectiveness or cost-effectiveness. Individual components of such packages show promise, but it needs to be determined which components work for which patient group in which circumstances. Guidelines have stated that rehabilitation programmes may be effective but that more research is needed.

Study objectives

Phase I: developing the intervention

-

To undertake a realist review to identify the important components of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme following surgical treatment for hip fracture in older people and to understand the mechanism, context and outcome of successful interventions.

-

To assess the current provision of rehabilitation programmes following hip fracture surgery in the NHS throughout the UK.

-

To assess the views of patients, their carers and health professionals in multidisciplinary rehabilitation teams on the rehabilitation that they received or provided following surgical repair of a proximal hip fracture; how programmes could be improved; and the findings from the realist review and survey.

-

To design a rehabilitation programme based on the findings from the realist review, survey and focus groups.

Phase II: feasibility study

-

To assess the feasibility of a future definitive RCT by assessing the number of eligible patients, monitoring recruitment and retention rates and exploring the willingness of patients to be randomised and the willingness of patients and carers to complete process and outcome measures.

-

To produce means and standard deviations (SDs) of the quantitative measures so that effect sizes can be calculated for planning the future RCT.

-

To assess the acceptability of, and compliance with, the rehabilitation programme among patients, carers and clinicians and the fidelity of its delivery and to identify any adverse events (AEs).

-

To explore the methodological issues associated with conducting an economic evaluation alongside a future RCT.

Study design

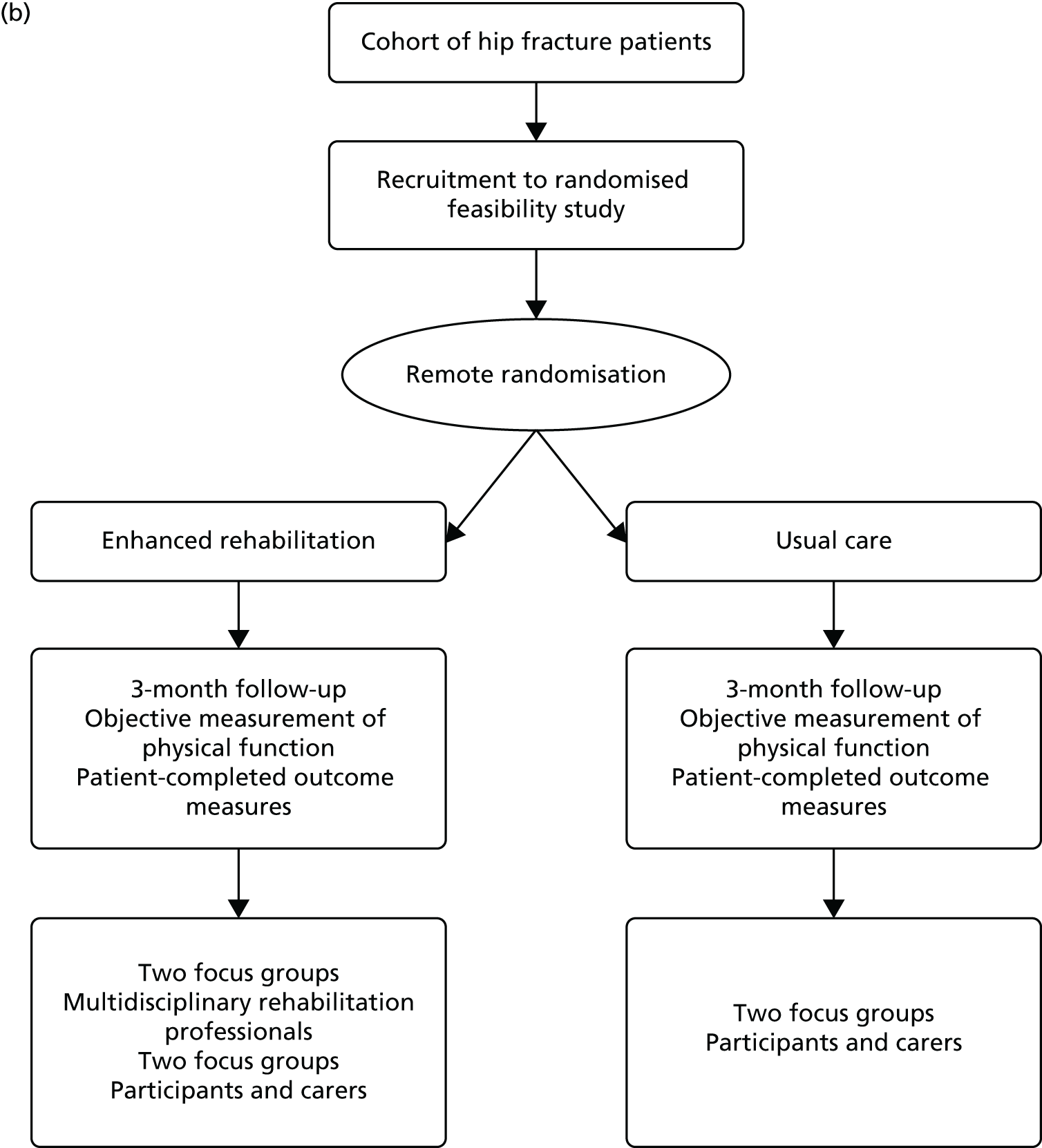

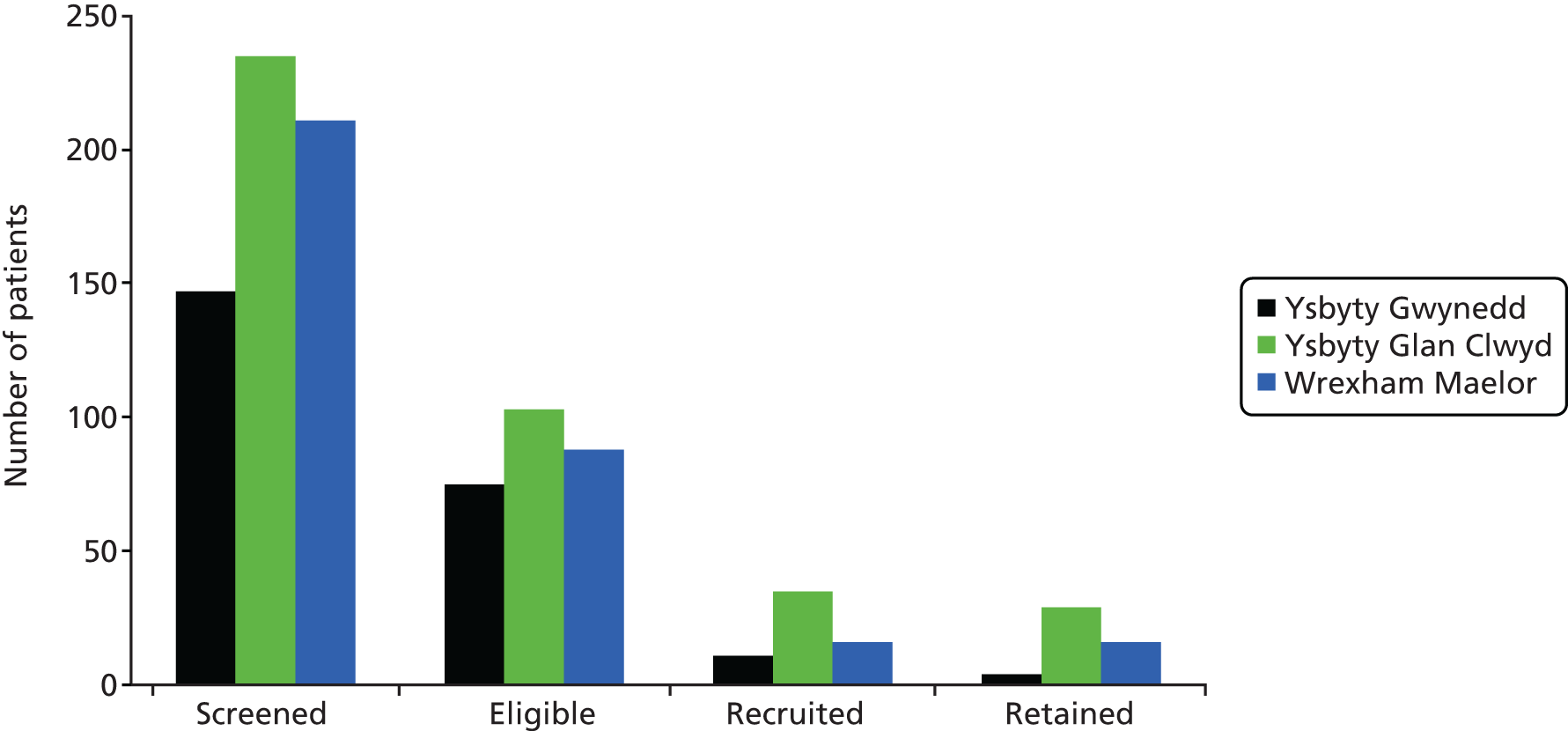

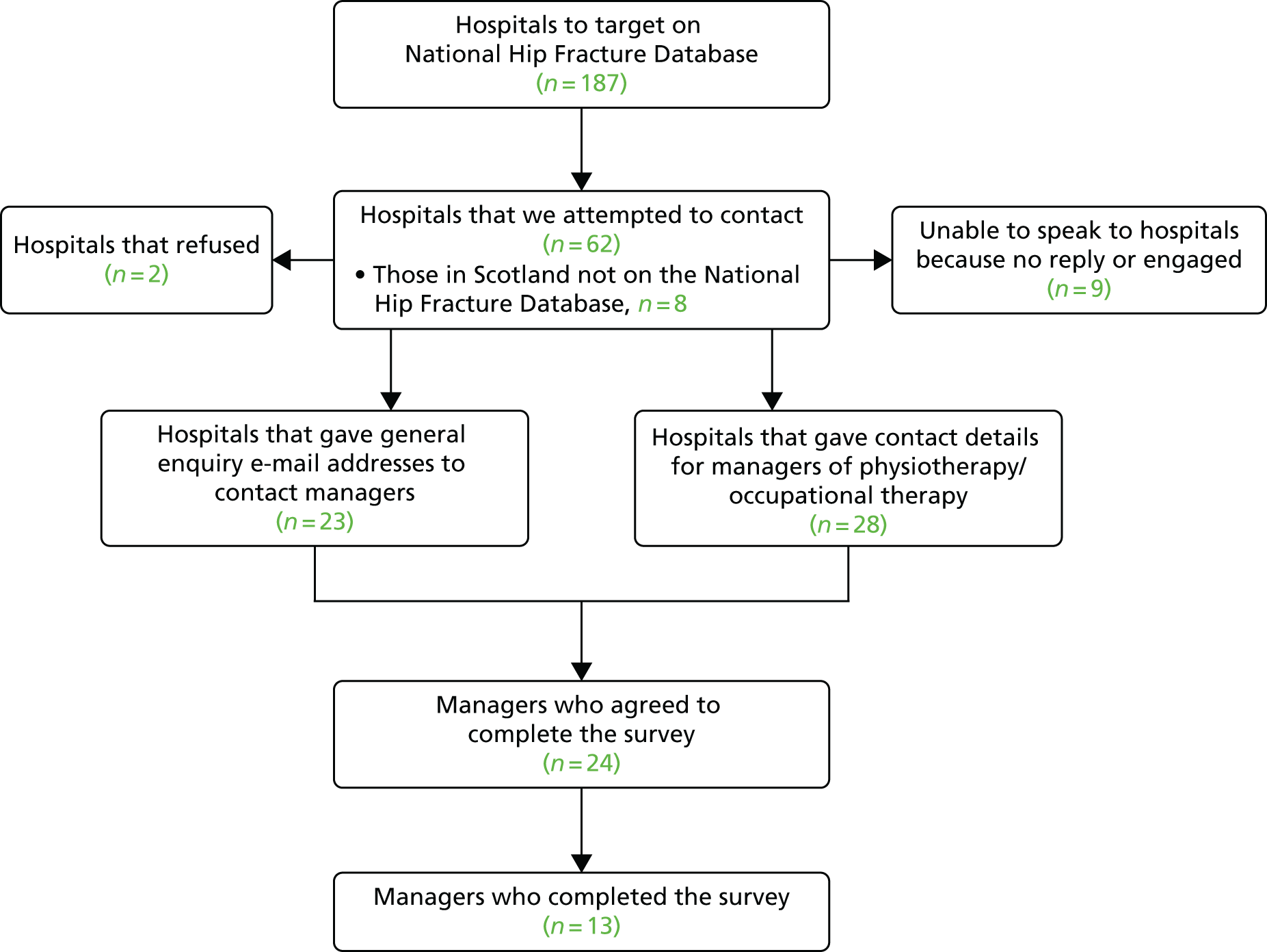

This was a preliminary study to complete the first two stages of the Medical Research Council’s framework for the development of complex interventions. 20 In the first stage a realist literature review was used to identify the relevant existing evidence base and a coherent theoretical basis for the rehabilitation intervention was developed. The literature review incorporated the principles of realist synthesis to identify the implicit or explicit theories that explain the mechanisms of interventions (how they are expected to work and why they work or did not work). 12–15 A survey of current services determined usual practice and was an additional source of relevant theories that contributed to the realist synthesis review. Focus groups with multidisciplinary rehabilitation teams, as well as hip fracture patients and their carers, informed the design of a complex multicomponent community-based rehabilitation programme (Figure 1a). The second stage assessed the feasibility of the new rehabilitation programme and consisted of a randomised feasibility study to assess recruitment and retention rates, the acceptability of randomisation and the change in outcome measure scores for a sample size calculation for a future definitive trial. A cohort study of all hip fracture patients admitted to the three acute hospitals in the Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board (BCUHB), North Wales, over a 6-month period allowed us to assess the representativeness of our recruited population. The acceptability and feasibility of the new rehabilitation programme was assessed further using focus groups with multidisciplinary rehabilitation team members and hip fracture patients and their carers (see Figure 1b).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart: (a) Phase I – developing the new rehabilitation intervention; and (b) Phase II – cohort and feasibility study.

Chapter 2 Developing a community-based multidisciplinary rehabilitation package for hip fracture patients using realist review methods: Fracture in the Elderly Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation (FEMuR)

Background

Previous systematic reviews3,9,10,21–38 have found insufficient evidence for the overall effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes following proximal femoral fracture. However, the recommendations made by such reviews, as well as existing guidelines, suggest that individual components show promise but it needs to be determined which components work for which patient groups in which circumstances. The hip fracture population is heterogeneous and the important contextual factors need to be determined. NICE guidelines7 for the management of hip fracture relevant to rehabilitation interventions recommend the following research:

What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of additional intensive physiotherapy or occupational therapy (for example, resistance training) after hip fracture? The rapid restoration of physical and self-care functions and the maintenance of independent living are important goals. Approaches worthy of future development and investigation include progressive resistance training, progressive balance and gait training, supported treadmill gait re-training, dual task training and Activities of Daily Living training.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s publication entitled Hip Fracture: Management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg124. 7 NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England, and is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE has not checked the use of its content in this publication to confirm that it accurately reflects the NICE publication from which it is taken. The information provided by NICE was accurate at the time this publication was issued

Rationale for the review

This realist review, along with a national UK survey of current rehabilitation practice and focus groups with patients, carers and multidisciplinary rehabilitation teams, was performed to inform the development of an enhanced rehabilitation programme following proximal femoral fracture.

Objectives and focus of the review

The main objective of this review was to identify the important components of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme following surgical treatment for hip fracture in older people, in particular to distil and understand the evidence relating to how successful interventions work, in which setting and context, for which outcome and in which group of patients.

Research questions

-

What community-based multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes have been developed and what were their main aims (intended outcomes)?

-

What were the mechanisms by which community-based rehabilitation of hip fracture patients is believed to result in its intended outcomes?

-

What are the identified contexts that determine whether different mechanisms yield intended outcomes?

Given the evidence in response to questions 1–3 we also drew conclusions regarding the following questions.

-

In what circumstances are the rehabilitation programmes likely to be clinically effective and cost-effective if implemented in the NHS?

-

In what circumstances and with which combination of mechanisms and contexts are the rehabilitation programmes likely to generate unintended effects or costs?

Methods

Rationale for using realist synthesis

A realist review was undertaken to identify suitable components for an enhanced multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme following proximal femoral fracture. Such rehabilitation programmes are complex interventions because they are multifaceted and interact in complex ways with many contextual factors39 (see Appendix 1). Compared with systematic reviews, realist reviews aim to build a deeper understanding of the mechanisms behind an intervention and to identify ‘what works, for whom, in what circumstances and why’. 39,40 Whereas conventional systematic reviews judge the overall effectiveness of an intervention and pay less attention to context, realist reviews attempt to explain mechanisms by which interventions produce different patterns of outcomes according to different contextual factors (see Appendix 2). The realist review was conducted by a researcher experienced in large-scale systematic reviews, traditional and network meta-analyses, large-scale database analyses and mixed-method process evaluations of policy or intervention trials, supported by team members with expertise in realist review and realist evaluation methodology.

Realist reviews use a theory-driven approach with a philosophy of realism and adopt an explanatory rather than a judgemental approach to evidence synthesis. 40 They seek to produce more transferable findings by taking into account, for example, the heterogeneous nature of rehabilitation programmes and the heterogeneous hip fracture population. The findings are then formulated into statements, the ‘programme theories’, which are propositions for how a programme is considered to produce intended outcomes. They can be generated from various sources of evidence such as the literature, discussions with experts and, as in our study, a survey of current practice (see Chapter 4) and focus groups with patients, carers and rehabilitation professionals (see Chapter 5). During the review process, these intermediate theories are tested, rejected or developed into the final programme theories to make recommendations for future practice, policy and research. We used the guidelines developed by the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards) collaboration41,42 (see Appendix 3) to report our methods and findings.

Extending the realist review to include any economic evidence allows the consideration of behavioural economic theories relating to factors such as welfare judgements,43 expected utility gains44 and choice architecture. 45 Additional costs may be accrued when modifying the setting in which the rehabilitation takes place (e.g. home based vs. hospital based) or the delivery team responsible for the rehabilitation programme (e.g. multidisciplinary vs. a single practitioner). The intervention itself could accrue additional costs, for example through additional training required by practitioners, additional time required by practitioners to deliver the rehabilitation programme and additional technology or equipment required for the rehabilitation programme (e.g. instruction packs for exercises). However, we recognised that the literature may not be rich enough to provide understanding of all behavioural economic factors in this field.

Scoping the literature

A scoping search of the literature was carried out in MEDLINE, EMBASE and PubMed for relevant systematic reviews concerning multidisciplinary rehabilitation following hip fracture and stroke and in the frail elderly using the broad search terms ‘rehabilitation’, ‘frail’, ‘elderly’, ‘stroke’, ‘hip/femur fracture’. The reviews identified3,5,9,10,14,17,21–38,46–60 and their reference lists were the starting point for identifying both the implicit and the explicit theories behind the success or failure of rehabilitation programmes or their components. Existing UK and international guidelines were also searched for additional contributions to theory development.

Immersion in the literature to develop initial theory areas

Initial immersion in the rehabilitation literature sought to identify an initial list of relevant intermediate programme theories. We scanned relevant primary studies and other linked papers with a strong theoretical content identified from the reference lists of the included reviews. This process helped to map out important areas and research gaps in the literature, resulting in a list of unanswered questions under different domains related to receivers (patients), deliverers (health-care and rehabilitation teams), programmes (rehabilitation) and settings or systems (hospital, community, etc.) used to deliver such rehabilitation programmes (see Appendix 4).

Developing and refining the intermediate programme theories in interactive workshops

These lists of questions were formulated into statements (see Appendix 5) to signify how the different domains of a programme interact and might affect all of the agencies (stakeholders) involved. These intermediate programme theories were refined during discussions between members of the evaluation team and with other researchers engaged in similar realist evaluations (at two realist evaluation workshops in the School of Healthcare Sciences, Bangor University, convened by one of the senior researchers, JR-M). To keep track of these emerging programme theories a table was constructed in which the theories could be recorded, cross-referenced and commented on. Feedback from the workshops was integrated into this table.

The list of questions enabled the building of context, mechanism and outcome (CMO) configurations that formed the basis of the development of the final programme theories of how complex programmes (systems) work in certain contexts to produce intended (or unintended) outcomes. The initial list of these CMO configurations is presented in Appendix 6; again, this was refined iteratively in team meetings.

Feedback from patient/carer interviews and the health professional survey

Results from the survey of health professionals (see Chapter 4) and focus groups with patients, carers and rehabilitation professionals (see Chapter 5) were also used to refine these programme theories. These refined theories were incorporated into the review as it progressed. Findings from the health professional survey that contributed to theory development included the importance of tailoring, the importance of feedback mechanisms and variation in the delivery of rehabilitation in different areas based on the availability of staff and facilities (see Chapter 4). The focus groups with patients and their carers highlighted unmet information needs with regard to the process of recovery, the availability of services that patients are entitled to access but which they are not necessarily aware of and geographical variation in the provision of services (see Chapter 5).

Developing programme theories

As already described, the summary of findings from our initial immersion in the literature, feedback from meetings and workshops (from experts in health psychology, rehabilitation and implementation research) and the findings from the patient/carer focus groups and health professional survey were integrated into our candidate programme theories. The emergent list of intermediate working theories was used as the basis for the development of bespoke data extraction forms.

Developing bespoke data extraction forms

Two sets of bespoke data extraction forms were developed using a Microsoft Access® database (2013; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to extract data from both comparative studies (RCTs/quasi-RCTs/non-RCTs, comparative cohort and case–control studies) and non-comparative studies (qualitative studies involving patients or health professionals, service evaluations, routinely collected database studies). The data extraction form for comparative studies (see Tables 37 and 38) was designed to collect data from each study on study characteristics (design, sample type, sample size), the intervention/programme and the control, process details (fidelity of the intervention, dosage), contextual factors in the study setting, outcomes collected and theories or mechanisms postulated by the authors to explain the results. The data extraction form for non-comparative studies (see Table 39) was designed to collect data on study characteristics, research methods, the theoretical approach, the sample type, the intervention/programme and the method of analysis as well as evidence to test the programme theories.

The forms were used in two stages to extract data from included studies and test the intermediate and final programme theories. The first set of forms was used to populate the initial themes with evidence from effective (or ineffective) components of rehabilitation programmes and how these interacted with outcomes in given contexts. These themes were then refined into statements, which led to the development of intermediate programme theories. The second set of forms was used to test these theories and adjudicate between competing theories (see Table 40).

Literature search

The literature search strategy used in the NICE guideline review of multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes for hip fracture7 was adapted to encompass all of the theory areas of the first phase of the review process. No filters for study design were applied so that all study designs such as RCTs and non-RCTs and observational, economic and qualitative studies could be included. Full details of the search strategies for the major electronic databases are reported in Appendix 8.

The following databases were searched from inception to February 2013 for published, semi published and grey literature:

-

MEDLINE

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

-

OLDMEDLINE

-

EMBASE

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

-

Allied and Complementary Medicine Database

-

British Nursing Index

-

Health Management Information Consortium

-

PsycINFO

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

-

Health Technology Assessment database

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database

-

Science Citation Index

-

Social Science Citation Index

-

Index to Scientific & Technical Proceedings

-

Physiotherapy Evidence Database

-

Biosciences Information Service

-

System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe

-

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database.

Identified references were deduplicated and transferred to bibliographic software (EndNote X5; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) to facilitate assessment for inclusion and the categorisation of relevant studies. Multiple publications arising from the same study were identified, grouped together and represented by a single reference.

Realist review involves iterative and purposive literature searching39,41 and so citations were tracked (forwards and backwards) and internet search engines, such as Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), and individual publisher websites were used to identify additional evidence as the review progressed and new ideas emerged. The reference lists of previous systematic reviews and included studies were also screened to identify relevant studies. Using this method, no attempt was made to include every relevant study but materials were retrieved purposively to answer specific questions or test-specific theories. The process stopped when sufficient evidence had been collected to answer these questions or test the theories. Conversely, if a new question arose, it triggered further literature searching to answer the question posed and to determine its fit within existing theory or whether or not a new theory needed to be formulated.

Screening of references for relevance

A working definition of multidisciplinary rehabilitation to be used for screening sources of evidence (Table 1) was adapted from a review of intermediate care services;61,62 the working definition in this review had been adapted, in turn, from Godfrey et al. 63

| Component | Definition |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Supports re-enablement of the frail elderly following proximal hip fracture to achieve their functional potential and maintain independent living when possible |

| Functions | A bridge between (a) the hospital and the community and between (b) different health-care sectors and personal social care |

| Views people holistically | |

| Time limited | |

| Structure | Teams based in hospitals or the community or across both sectors |

| Content | Treatment and therapy (to increase strength, confidence, ADL and functional abilities) |

| Psychological, practical and social support | |

| Support/training to develop skills and strategies | |

| Delivery | Care delivered by a multidisciplinary team or teams |

This definition was used when screening the titles and abstracts of identified studies in the EndNote library for relevance. Screening was carried out independently by separate reviewers and discrepancies were resolved after discussion. In addition, potentially relevant studies were categorised according to study type: systematic review, RCT or non-RCT, observational study, economic evaluation or qualitative study. There were no language restrictions and non-English publications were translated whenever possible using Google Translate (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) or by other research colleagues who could speak the relevant language.

Participants of interest were elderly adults with proximal hip fracture. The intervention of interest was multidisciplinary rehabilitation following proximal hip fracture. The outcomes of interest were mortality, pain, functional status, quality of life, health utility, health service use, costs and patients’ experiences.

Literature identified in the initial search was screened in two stages for both behavioural economic evidence and evidence of economic evaluation (e.g. cost analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost–benefit analysis, cost–utility analysis). Screening for economic studies at the title and abstract stage was conducted by the four main reviewers. Potential economic studies identified in the initial search were then screened by two experienced health economists, who excluded studies based on the following criteria:

-

clearly falls outside the definition of multidisciplinary rehabilitation for hip fracture (see Table 1)

-

clearly is not an economic evaluation or comparative cost study or does not include behavioural economic theory

-

does not involve services users who belong to our service user group of interest.

The detailed screening process for economic evidence and the study flow chart are presented in Chapter 3.

Conceptual categorisation of screened relevant references

Potentially relevant references were conceptually categorised as ‘rich’, ‘thick’ or ‘thin’ based on the criteria described by Ritzer64 and Roen et al. 65 and as used in a recent review of intermediate care. 61 This process made the database manageable and enabled information to be gleaned from the most appropriate studies for theory building and testing. A detailed description of the criteria used for this purpose is provided in Appendix 9.

Inclusion and exclusion of studies

Study design

All types of studies that presented explicit theories about the success or failure of an intervention in certain contexts or which had implicit information that could be used to confirm or refute a theory were included. Study designs included RCTs, quasi-RCTs, non-RCTs, cohort studies (with concurrent or historical control subjects), case–control studies, before-and-after studies, qualitative studies and full economic evaluations, as defined by Drummond et al. 66 The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions67 provided context related to the strength of evidence.

Patient population

Studies were included involving older adults who had fractured their hip, undergone surgery and received rehabilitation afterwards.

Interventions

Studies were included looking at any intervention or initiative (policy, process, etc.) used as part of a rehabilitation package following hip fracture surgery and delivered in any setting.

Outcomes

All relevant patient-based outcomes, such as pain, disability, functional status, adverse effects, health status, quality of life, health service use and costs, were considered.

Selection and appraisal of documents

After the initial screening and conceptual categorisation of the references in the EndNote library, potentially relevant studies were exported into a separate library for full document retrieval. Study inclusion criteria were applied to these retrieved documents by two reviewers independently and conflicts were resolved by discussion or after consulting a third reviewer. A list of all studies to be included was prepared for data extraction.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked for accuracy by a second. Inconsistencies or disagreements were resolved by mutual discussion and checking against the source study.

Comparative effectiveness studies

Data were extracted in the following domains.

-

Study characteristics. Author, year, location and country, setting, design, sample type, sample size, study population, conceptual categorisation.

-

Intervention characteristics. Description of the intervention and control, process details (fidelity of the intervention, dosage), duration of follow-up, any variations in intervention delivery other than those originally planned.

-

Theoretical underpinning. Explicit theories or mechanisms postulated by the authors to explain the results and/or implicit theories derived from the introduction or discussion of the study; contextual factors in the study setting.

-

Outcome measures. We did not extract final mean scores or mean change scores or their distributions because the purpose of the review was not to quantify the strength of effects but to develop an explanation for these effects. The direction of effect was described using the following symbols: ++, intervention effect statistically significant; ==, no statistically significant difference between the intervention and the control; –, control better than the intervention.

Qualitative studies

Data were extracted in the following domains.

-

Study characteristics. Author, year, location and country, setting, design, sample type, sample size, study population, conceptual categorisation, related effectiveness studies.

-

Qualitative methods. Sampling technique, theoretical approach, method of data analysis.

-

Theoretical underpinning. Explicit theories or mechanisms postulated by the authors to explain the results or implicit theories derived from the introduction or discussion of the study; contextual factors in the study setting.

-

Evidence for theory testing or explanation building. Explanations gleaned from qualitative accounts as evidence to test the programme theories.

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for mixed studies reviews,68 which can be used across different study designs (qualitative studies, trials, observational studies). The purpose of appraising the ‘quality’ of studies was to assist in the judgement of the relevance and rigour of different evidence from a ‘fitness for purpose’ perspective as opposed to scoring the studies for acceptance or rejection.

Data synthesis

The data from the quantitative, comparative effectiveness and qualitative studies were synthesised separately.

The data from the effectiveness studies were exported into structured tables to show the strength and direction of the treatment effects. Outcomes reported in the included studies were broadly categorised into four domains: physical/physiological, psychological, health service utilisation and AEs. These were subcategorised further under the following headings (the outcome measure instruments used are listed in Appendices 10 and 11):

-

physical/physiological

-

ADL

-

composite scores

-

favourable clinical outcome

-

functional recovery

-

-

exercise behaviour

-

quality of life

-

function

-

physical function

-

mobility

-

functional recovery

-

balance

-

-

physiological measurements/muscle strength

-

-

psychosocial

-

patient satisfaction

-

carer satisfaction

-

cognitive function/dementia

-

depression

-

fear of falling

-

psychological morbidity

-

self-efficacy/falls efficacy

-

socialisation

-

social support

-

-

health service use

-

physical/occupational therapy sessions

-

discharge destination/new nursing home admissions

-

falls and hospital readmissions

-

health-care utilisation

-

length of hospital stay

-

severity of illness/disease burden

-

-

AEs

-

malnourishment

-

morbidity rate

-

mortality rate

-

pain

-

rate of (repeat) falls.

-

The rehabilitation settings where the programmes were delivered varied from the acute hospital setting to the community setting and were categorised as below:

-

acute hospital

-

inpatient

-

specialised orthopaedic ward

-

specialised orthogeriatric ward

-

-

outpatient

-

general outpatient rehabilitation unit

-

specialised orthogeriatric outpatient rehabilitation unit

-

-

rehabilitation unit

-

general elderly rehabilitation unit

-

specialised orthogeriatric rehabilitation unit

-

-

-

community

-

place of residence

-

nursing, care or residential home

-

specialised nursing home rehabilitation unit

-

community hospital

-

community rehabilitation centre.

-

Testing the theories with quantitative and qualitative evidence

Data from each individual study were examined in terms of the identified programme theories and the interaction between mechanisms, context and outcomes. Next, the data across the different studies were examined to detect patterns and themes for each theory in turn. Separate fields were created in the Microsoft Access database to capture these interactions as well as raw statement data from the included studies to support reviewers’ reflections. Data synthesis involved individual reflection and team discussions to question the integrity of each theory, adjudicate between competing theories, consider the same theory in comparative settings and compare the theory with actual practice. When candidate theories failed to explain the data, new theories were sought from included studies or from the wider rehabilitation literature, such as studies of rehabilitation following stroke or following inpatient admission after being unable to stand. The narrative of the review was guided by the final theories that emerged from this process. The literature analysis relating to each identified theory is presented in detail, followed by a data summary to show the relationships between data themes and the theories in the final synthesis. Extracts were taken from participant quotations (patient, carer or health professional) reported in the included qualitative studies and used as evidence to support subthemes of the main theories. This is an established method used in a recently reported review of intermediate services61 to incorporate and integrate the theoretical perspectives from qualitative evidence into quantitative evidence.

Results

Results of the initial scoping review

The scoping search for systematic reviews and other reviews as well as guidelines relating to the rehabilitation of older frail populations identified 39 reviews, both Cochrane reviews9,10,27,33,37,49 and other traditional systematic reviews. 3,5,14,17,21–26,28–32,34–36,38,46–48,50–60 The majority of the reviews were related to hip fracture rehabilitation,3,5,9,10,14,17,21–24,26,27,29,30,32–36,49,51–57,59,60 but a few also included rehabilitation for stroke as well as for other conditions in older frail populations needing continuous care. 24,25,28,31,37,46–48,50,58 A few conceptually rich and theoretically sound primary studies from the reference lists of these reviews were also obtained. 69–73 The search also identified five sets of guidelines, from the UK [NICE,7 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)74], USA,75 Canada76 and Australia and New Zealand. 77

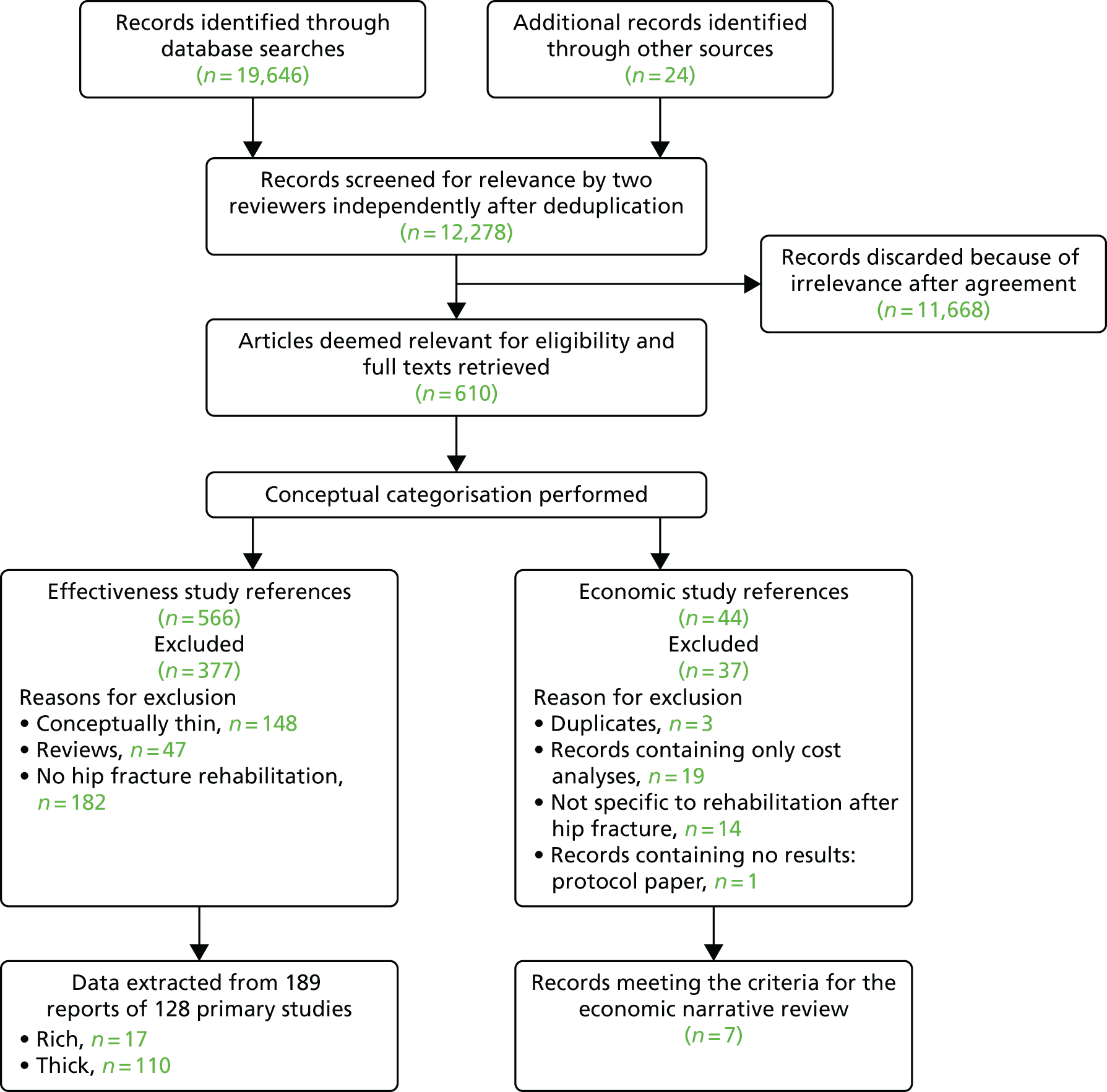

Study flow diagram for the realist review

The electronic searches identified 19,646 references, with a further 24 references identified by hand searching. Deduplication resulted in 12,278 unique references that were screened for relevance by two independent reviewers. The full texts of 610 references were obtained and, after collating multiple publications, 128 studies were included in the review12,13,69,72,78–201 (Figure 2; see Appendix 12 for the total number of references retrieved from each electronic database).

FIGURE 2.

Realist and economic review flow chart.

Study characteristics

Of the 128 primary studies included in the review, 17 were conceptually rich13,69,72,78–80,83,86,89,106,107,124,131,165,176,193,197 and 111 were conceptually thick12,81,82,84,85,87,88,90–105,108–123,125–130,132–164,166–175,177–192,194–196,198–201 (see Appendix 13). Thin sources were screened but were not included in the review for data extraction (see Appendix 14). A list of studies excluded from the review with reasons can be found in Appendix 15. Appendices 16–18 present the raw data tables describing the general characteristics of the included studies, the populations of interest, the treatment categories with characteristics of the interventions and the strengths, limitations and conclusions as presented by authors, respectively. These data are described briefly in the following sections according to the types of research methods used.

Summary of participant characteristics

The number of patients/participants included in the studies ranged from 1 to 2762. The review included a total of 22,443 patients and 97 health professionals. In total, 6282 (range 90–401) patients participated in RCTs,12,69,78,80,87,90–126,128–130,197,199 276 (range 24–95) patients participated in quasi-RCTs,83,131–133 116 (range 20–30) patients participated in non-RCTs,79,134–137 3044 (range 1–919) patients participated in historical cohort studies,13,157–165,170,173,178 7136 (range 18–946) patients participated in concurrent cohort studies,81,138–152,169,177,179,181,182,184,187,188,190–193,196,200,201 1697 (range 3–764) patients participated in controlled before-and-after studies,85,153–156,180,186,195 45 patients participated in mixed-method studies,84,89 3243 (range 130–2762) patients participated in database analyses166–168 and 521 (range 12–222) patients/health professionals participated in qualitative studies,72,82,86,88,127,174–176,183,185,189,198 with two studies involving health professionals (n = 97) rather than patients. 176,198 Two studies used administrative/work process data and did not include any patient data. 171,172

The majority of the studies included patients aged ≥ 65 years. 79,80,82–86,88,90–93,95,97,99–102,105,107,109,111,113,115,116,120,121,124–127,131,135,138–148,151,153,155–157,160,162,163,165,166,175,178–180,182–184,189–191,199,201 Six studies included adults of any age with a hip fracture and undergoing rehabilitation;78,112,167,174,185,186 two of these included carers174 or health professionals. 185 Eight studies included patients aged ≥ 50 years;87,98,103,118,173,187,188,192 18 studies included patients aged ≥ 60 years;12,89,96,104,114,117,119,122,132,133,149,154,164,193–197 19 studies included patients aged ≥ 70 years;69,72,79,88,106,108,110,111,116,120,131,136,143,148,150,161,180,183,184 and seven studies included patients aged ≥ 80 years. 13,81,123,134,137,152,178 The age of the included participants could not be determined from the study reports for four studies. 171,172,181,200 Sixteen studies included only female participants69,79,80,102,104,123,126,147,156,158,165,174,180,183,185,191 and one included only male participants. 159 The rest included participants of both genders but the majority of studies included a greater proportion of women.

The majority of studies excluded patients who had a cognitive impairment or dementia or who lacked mental capacity to give informed consent;12,13,69,72,78–100,102–109,111–118,120–122,124–138,140,142–151,153–156,158–169,171–181,183,185–201 11 studies included such patients,101,110,119,123,139,141,152,157,170,182,184 with one study stating that such patients would be included only if suitable carers ready to participate in the study were identified. 119 The majority of the studies included participants who were mobile and living independently in their own home or in a care home before their hip fracture. 12,69,72,79–86,88–90,92–114,116–119,121,123,124,126–130,132–136,138,139,143,145–149,153,156–158,161,165,166,168,169,171,175–177,179,180,183–186,191,193,194,196,197,199,201 Only seven studies included patients with a medical or psychological comorbidity;123,139,145,157,158,184,193 the majority of studies excluded such patients, especially when exercise would have been contraindicated. Only two studies included patients who had a history of a previous fracture. 175,184

The majority of the studies were carried out in English-speaking countries and involved mainly white Caucasian populations. Three Swedish studies,90,99,127 two Taiwanese studies,119,196 one German study93 and one Danish study84 included only patients who could speak, read and write in these languages, with other patients excluded.

Summary of interventional studies

Forty-eight of the studies were RCTs,12,69,78,80,87,90–126,128–130,191,197,199 with 10 from Australia,87,94,95,110,112,117,118,123,125,129 nine from the USA,69,80,91,92,107,113,121,126,191 six from the UK,12,102,109,115,128,197 four each from Sweden90,98,99,120 and Taiwan,95,105,119,122 two each from Canada,108,111 Norway,116,199 Finland,101,114 Hong Kong103,106 and Switzerland,93,96 and one each from Denmark,104 Belgium,97 Italy,78 Spain124 and Germany. 130 Only seven studies69,78,80,106,107,124,197 were categorised as being conceptually rich.

Four of the studies were quasi-RCTs83,131–133 and five were non-RCTs,79,134–137 with two each from Canada134,135 and the USA,79,83 and one each from Israel,131 Japan,137 Italy,133 South Africa136 and Taiwan. 132 Three of these studies were categorised as being conceptually rich. 79,83,131

Thirty-two of the studies were concurrent cohort studies,81,138–152,169,177,179,181,182,184,187,188,190,192–194,196,200,201 with nine from the USA,81,142,146,147,149,181,191,192,194 four each from Italy,141,143,177,182 Israel138,148,179,201 and Sweden,139,187,188,193 two each from the UK,150,200 the Netherlands,140,144 Taiwan190,196 and Germany,151,152 and one each from Norway,145 France184 and Canada. 169 None of these studies was categorised as being conceptually rich.

Eight of the studies were controlled before-and-after studies,85,153–156,180,186,195 with two each from the USA153,156 and the UK,85,155 and one each from Canada,195 Denmark,154 Sweden180 and the Netherlands. 186 None of these studies was categorised as being conceptually rich.

Thirteen of the studies were historical cohort studies,13,157–165,170,173,178 with three from the USA,159,165,173 two from the UK,13,158 and one each from Australia,161 Austria,178 Canada,157 Germany,163 Israel,162 Italy,170 Japan164 and Sweden. 160 None of these studies was categorised as being conceptually rich.

Among the non-comparative interventional studies there were two mixed-method studies,84,89 one each from the USA89 and Denmark. 84 One study from Finland166 reported a cross-sectional analysis of pre-trial data, two studies from the USA167,168 reported a hospital database analysis and another study from the USA reported longitudinal data from a survey. One study from Australia169 reported before-and-after outcome data for a cohort who underwent an intensive rehabilitation programme in the acute hospital. There were also two case report studies:13,170 one from Italy170 and one from the UK. 13 Two mixed-method studies84,89 and a case series81 were categorised as being conceptually rich.

Summary of non-interventional studies

Non-interventional studies did not use any intervention or treatment to affect the outcomes but were useful for their conceptual input to the theoretical framework and provided explanations for elements of the proposed theories. Two studies, one from the USA171 and one from Canada,172 reported service and work process restructuring. One study from Australia161 utilised hospital data on hip fracture patients 4 months post surgery who had been successfully rehabilitated into the community. These patients were divided into fallers or non-fallers after their rehabilitation. None of these studies was categorised as being conceptually rich.

Twelve of the studies were qualitative studies,72,82,86,88,127,174–176,183,185,189,198 with three each from the UK86,176,198 and USA,72,174,183 two from Sweden88,127 and one each from Australia,185 Canada,175 China189 and Taiwan. 82 Six of these studies72,86,127,175,183,189 interviewed hip fracture patients after discharge about their experiences of the whole process and the rehabilitation that they went through. Two of the studies176,198 interviewed health professionals providing rehabilitation services regarding their experiences about such provision as well as any issues encountered that might be amenable to service improvement. Three of these studies were categorised as being conceptually rich. 72,86,176

Summary of the study settings

Twenty-two of the included studies69,72,82,92,107,114,115,117,118,121,122,125–127,135,142,156,161,163,165,174,201 were conducted in the community after the patients had been discharged from the acute or community hospital to either their pre-fracture place of residence or a care home. Sixty-seven studies12,13,78–80,83,87–89,93,96–98,100–102,104,106,108,111,112,116,119,124,129,132,134,137–141,146,148,152,157–160,162,164,166–173,175–187,194,195,197,198,200 were conducted while patients were still in the acute hospital following surgery. In 39 studies the intervention started in the acute hospital but continued in the community following discharge. 81,84–86,90,91,94,95,99,103,105,109,110,113,120,123,128,130,131,133,136,143–145,147,149–151,153–155,188–193,196,199

Overview of the rehabilitation programmes

Appendix 17 summarises the interventions and comparators as described in the included studies.

Physical activity components of the rehabilitation programmes

Fifty-two of the included studies reported some form of physical intervention69,78–81,83,87,91–93,96,98,99,103,104,107–110,112–115,117,118,121,122,126,130,131,134,136,148,151,153,154,156,158,162,164,169,170,177,180–182,186,187,191,192,194,199 and seven also included a psychological component. 78–80,91,148,180,191 Twenty studies compared intensive physical exercise with less intensive physical activity or an inactive control. 69,78,80,83,91–93,104,107–110,113,114,117,118,122,126,130,169 Twenty-four studies compared supervised programmes with conventional programmes that either did not include supervision as part of the programme or included only minimal supervision to ensure patient safety. 69,80,83,87,91–93,104,107–110,112–114,126,131,136,151,153,180,186,191,199 Nine studies compared specifically tailored programmes with generic rehabilitation programmes. 69,79,80,83,99,109,113–115

Psychological components of the rehabilitation programmes

Fourteen studies reported using a psychological intervention in isolation12,106,137,141,171,197,201 or as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation programme along with physical components. 78–80,91,148,180,191 Three of these studies141,171,191 did not report any outcome data but were utilised mainly for theory explanation.

Place of rehabilitation

Twenty-six studies compared different rehabilitation settings. 81,97,101,103,112,120,125,128,131,133,135,143,145–147,149,151,152,154,160,161,179,188,195,200,201 Ten of these studies compared some form of community (own home or care home) rehabilitation with hospital-based rehabilitation,101,103,125,128,131,133,135,143,145,160 with one comparing hospital plus home rehabilitation with hospital rehabilitation only. 133 Eight studies97,112,120,146,149,151,152,200 compared hospital-based rehabilitation with usual care, no post-discharge care or rehabilitation in nursing facilities. Other studies did not compare rehabilitation settings per se but included comparisons based on patients’ characteristics, such as fallers compared with non-fallers,161 very old patients compared with younger patients201 and treated in a cognitive specialised rehabilitation unit compared with treated in a non-cognitive specialised rehabilitation unit. 152 One study compared the discharge practices of four hospitals after inpatient rehabilitation. 147

Process or system improvement

Twenty-nine studies investigated the effects of improvement or change in existing health-care rehabilitation structures. 69,83,94,95,98,100,102,105,111,116,117,119,120,123,124,127,128,132,138–140,144,150,155,157,159,163,167,184 Seventeen studies compared the development of multidisciplinary co-ordination programmes with usual care or another existing programme. 69,83,98,102,111,117,119,120,123,124,127,132,144,155,157,159,184 There was large variation in these programmes from different health-care systems, but common features included comprehensive geriatric assessment both pre and post surgery, assessment of patient needs and assignment of appropriate health-care staff to address those needs, regular multidisciplinary meetings to discuss progress and care pathways that continue into the community after discharge. Usual or conventional care varied greatly among the studies, ranging from simple control of post-operative symptoms117 to comprehensive assessment. 69,83,120

Eight studies reported on structured discharge planning from hospital to the community based on patients’ abilities, the extent of support needed and the availability of support from family or friends during the recovery period. 94,95,100,105,128,139,140,150 Six studies compared the early discharge of patients to their own home with usual discharge,94,95,100,128,140,150 one study compared early discharge to a rehabilitation unit of a community hospital with early discharge home139 and one study compared early discharge to the rehabilitation ward of a nursing home with conventional (delayed) discharge to the same ward. 105

Four studies reported the implementation of new ward protocols. 116,138,163,167 One study compared a newly commissioned orthogeriatric ward with a traditional orthopaedic ward116 and another study compared comprehensive geriatric assessment with usual care. 138 The other two studies were non-interventional improvement reports that utilised routinely collected hospital data in their analyses. 163,167 One did not report any patient-related outcomes but was useful for theory development. 163

Summary of outcomes

Outcomes data were extracted from 70 of the included studies. 12,69,78,80,81,83,87,90–93,95–97,100–103,105–111,114,115,117–124,130–133,135–140,143,144,146–149,151–158,160–162,167,169,184,192,195,199–201 Sixty-five of these studies reported physical or physiological outcomes,12,69,78,80,81,83,87,90–93,95,97,100,102,103,105–111,114,115,117–124,130–133,135–140,143,144,146–149,151–157,161,162,167,169,184,192,195,199,201 22 reported psychological or social outcomes,69,80,81,83,90,95,105,106,110,115,117–119,121,130,136–138,143,151,161,169 26 reported health service utilisation83,87,90,93,97,100–102,105,111,119,120,124,138,140,143,147,148,152,154,155,157,158,160,200,201 and 16 reported AEs93,96,97,100,101,110,111,119,124,133,137,144,148,154,155,162 as their main outcomes.

The rest of the included studies13,72,79,82,84–86,88,89,94,98,99,104,112,113,116,125–129,134,141,142,145,150,159,163–166,168,170–183,185–191,193,194,196–198 mainly contributed to theory building and explanation.

The directions of effect at various follow-up points are presented in structured tables in Appendix 19. The outcomes reported are discussed further when appropriate in the following discussion of the evidence for the final programme theories.

Study quality assessment

The results of the quality assessment are presented in Appendix 20.

Final working theory

Based on the characteristics of the individual components of rehabilitation programmes, and after discussions in the interactive workshops, an overarching working theory was developed as follows: successful rehabilitation after fractured neck of femur will be dependent on the characteristics and delivery of the intervention, the co-ordination and approach of the multidisciplinary team, the fit of the multidisciplinary team with the characteristics of the patient and the types of setting in which rehabilitation will be delivered.

This was then described in its CMO configuration in terms of the realist review approach as follows: in the context of patients with a great range and variety of pre-fracture physical and mental health comorbidities affecting their ability to meet rehabilitation goals (C), a tailored (M) intervention incorporating increased quality and amount of practice of exercise and ADL (M) in addition to usual rehabilitation leads to better confidence, mood, self-efficacy, function and mobility and a reduced fear of falling (O).

This overarching theory was then broken down into three component programme theories, which are described in the following sections.

Programme theory 1: improve patient engagement by tailoring the intervention according to individual needs and preferences

Proximal hip fracture patients presenting with a range of pre-fracture physical and mental functioning and a variety of comorbidities (C) need a rehabilitation programme that is tailored to individual needs (M) to achieve appropriate outcomes such as improved physical functioning, greater mobility, reduced disability and independent living (O).

Tailoring of rehabilitation activities involved the interplay of many factors encompassing the patient, the health-care professional and the environment in which the rehabilitation took place. The main theme revolved around making rehabilitation planning patient centred and contextualising what is important for patients so that this can be incorporated into their care plan, allowing a better chance of engaging patients in their recovery.

Assessment of patients’ pre-fracture function, cognitive status and comorbidities

Common sequelae of hip fracture included physical limitations,202,203 dependency in daily activities,151 social restrictions,11 malnutrition144 and depression. 196,204,205 Assessing patients’ pre-fracture level of functioning, their cognitive status and any existing comorbid conditions allowed health professionals to formulate a plan including short- and long-term goals of rehabilitation. This was important for planning the mix of skills needed to address patients’ rehabilitation needs90 and for deciding the most appropriate setting for programme delivery. It was also important for addressing other social needs,193 especially in the presence of cognitive impairment,184 with appropriate adjustment of programme delivery. These programmes needed to take into account the constraints of existing resources, which may result in the setting of revised goals. Orthogeriatric models of patient care provided good examples of comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment delivered while patients were still in hospital. 138 Addressing comorbid conditions by early geriatric intervention so that patients could participate in the subsequent rehabilitation programme led to improved function,120,138 discharge to the place of pre-fracture residence120 and a shorter length of hospital stay. 120,138

Several studies stressed that health professionals needed to know about patients’ situation, their personality and any physical or mental conditions78 to enable rehabilitation interventions to be adapted to enhance recovery. 90,163,187 Rehabilitation programmes often involved the execution and performance of new tasks after learning new skills and this could be accomplished only if patients had the capability to go through such steps. Assessment of patients’ capabilities enabled health-care professionals to design rehabilitation activities that best suited individual need, rather than using an untailored generic programme. 116 Self-efficacy, which is an important tenet of social cognitive theory, is the belief in one’s ability to successfully complete tasks, reach goals and face challenges. 69,71,73 This influences the activities that a person engages in and his or her perseverance in the face of difficulties:206

I was just determined to do them [exercises], and I was determined to walk. I was determined to do everything for myself that I could. I just knew that it was the best way to get well.

Female patient72

Fracture or surgery-related complications such as pain, or comorbid conditions, can be perceived by patients as barriers to recovery, but it was not clear whether medical contraindications arising from these complications or patients’ own self-imposed restrictions led to an inability to actively engage in rehabilitation. 207 The factors that are amenable to correction144,208,209 and those that are not should be recognised at the start of any rehabilitation programme so that proper resources can be identified and expectations adjusted when chances of improvement are minimal. 179 Health professionals could then implement interventions to effectively motivate individuals who may not have been self-directed or determined to exercise,72 especially when patients develop a sense of losing control86 and become passive receivers of a service rather than actively seeking help. Cultural factors needed to be taken into account as well, so that clinicians could determine how they could best foster social support to help older patients maintain a positive sense of self. This was achieved through engaging them in conversations to promote independence82 and by involving family members, locating needed resources and providing tailored information and education about the injury and the recovery process. 86

Patients’ experience gained through the hospital stay could be incorporated into their rehabilitation plan. For example, seeing people who were more poorly and who had more disabilities than they did allowed patients to reflect that their own situation could be worse. 90,210

I feel, now that I’ve come home [from hospital], that I have a lot to be thankful for. I’m not in a wheelchair or anything like that. I’ve been much, much more humble!

Female patient90

Positive experiences of help during their illness, as well as kind and competent treatment, helped develop such perspectives. 90,210 Such patients would then become advocates of health professionals, recommending and encouraging rehabilitation in other patients:

Listen to the advice from medical staff such as doctors, therapists, and nurses . . . Do a lot of physical and occupational therapy even if it’s painful!

Young and Resnick207

Collaborative decision-making

Collaborative decision-making between patients, their carers and health-care providers was important for deciding on an optimum plan for recovery and rehabilitation. This included the consideration of patients’ psychological make-up and their built environment, the configuration of local health services in the context of programme delivery, system constraints and the tension between health professionals’ and patients’ preferences and perceptions about the appropriate short-term and long-term goals of rehabilitation. 211,212 Inadequate involvement of patients and their carers in the decision-making process could potentially lead to barriers with regard to patients’ ability to cope with multiple issues surrounding their ill health212 and an inability of the rehabilitation programme to realise its full potential in their recovery. Collaborative decision-making involved multiple facets, which are discussed in the following sections.

Setting and agreeing goals of rehabilitation

Setting rehabilitation goals early on, such as returning home, regaining or maintaining pre-fracture function and independence or ambulation without assistance, facilitated the recovery process, as did intermediate goals such as the number of minutes exercised per day:207

The trainer told me that if I stop exercising I would be back to where I started in two weeks. I thought, I have gotten to this point I can’t quit. They said no, no you can’t! You tell yourself you have to keep it up.

Female patient72

Agreeing the goals of rehabilitation was not always straightforward, as goals that were considered appropriate by the health professional sometimes did not align with goals of the patient, resulting in a mismatch between their conceptions of short- and long-term rehabilitation goals. 211,213 Health professionals usually suggested the suitability of a setting based on a set of physical function goals to be achieved within a specific time period, whereas patients viewed the suitability of the setting in the context of their overall well-being, of which long-term physical functional improvement was only a part. 211,213,214 If such objectives were prescribed authoritatively at this time of vulnerability,211,212 patients felt forced to accept something that they did not understand, leading to them disengaging and becoming passive recipients of a service, rather than having ownership of their recovery. 214–216

Similarly, setting goals was sometimes felt by health professionals to be a constraint on their time,176 leading to low levels of communication and negotiation and resulting in a failure to engage patients and achieve desirable outcomes. Interprofessional disagreements concerning what goals were appropriate also resulted in patients’ issues not being addressed appropriately,176 for example when hospital staff did not understand how community services worked and discharged patients quickly without adequate assessment. 217 When a programme incorporated detailed discussion of and agreement on the intended goals with patients and their family or carers and then tailored programmes towards these goals in the context of locally existing health and social care systems, there was more chance of engaging patients and achieving the desired functional outcomes. 83

Agreeing the place of rehabilitation

The most appropriate setting for rehabilitation needed to be agreed between patients and their family and carers, according to patients’ needs and abilities. 95,139,218 Often patients and health professionals held differing views about the most suitable location, especially when patients had other comorbid conditions and felt vulnerable. 214 Health professionals sometimes had to make decisions based on available resources and established systems. 217 Patients’ sense of vulnerability as well as their inability to comprehend the complexities and demands posed by home-based care,216 especially when support from friends and family was limited or not available, led to them preferring a hospital setting where they felt safer. 214,217 In addition, patients feared being a burden on family and carers219 and were anxious about their ability to manage at home. 95 Given the choice, patients and their carers preferred a longer hospital stay to home rehabilitation, particularly those living alone, as they feared that they would be left on their own and would be socially isolated. 193,214 When patients were discharged home, tailored support for them and their family could help them retain control. 86,216

Home rehabilitation also had the disadvantage that equipment and facilities were limited. In addition, in rural areas, health professionals felt that their time was not being utilised efficiently because a lot of time was spent travelling. In such situations, co-ordination between social care staff and rehabilitation professionals was very important. Home rehabilitation was not necessarily cheaper. A Dutch study found that, although moving rehabilitation from the acute hospital to the community freed up much-needed hospital beds, it did not result in reduced overall costs as costs were simply transferred from the hospital to the community. 140

In the presence of minimal support patients felt abandoned, unsure of what to do and unable to achieve the full potential of a rehabilitation programme, leading to further restrictions in functioning and deterioration in quality of life:

It’s a problem when you can’t manage on your own . . . I think about my finances and about how many payment reminders are going to come . . . they have to be paid . . . I have to pay the rent. Of course you think about whether there’s anybody that can help with that!

Female patient90

In contrast, because of the drive to discharge patients more quickly, together with some evidence that home rehabilitation with appropriate support can have positive outcomes,86,95 health professionals preferred home rehabilitation. Educating providers, patients and carers about accelerated discharge and home-based rehabilitation for those with the fewest disabilities could result in improvements in independence and confidence to perform day-to-day activities. 86,220 Apart from providing cost savings, home rehabilitation was viewed as providing a familiar place to patients where they could feel comfortable carrying out the agreed activities at their own pace and in their own time. Although some studies found that patients could feel comfortable with home rehabilitation, as long as they received continuous support to see them through this transitional period of functional recovery, other studies identified feelings of worry and fear about how to deal with the aftermath of injury and the recovery process, especially if services stopped abruptly rather than there being a managed and tapered withdrawal. 217 Some patients found the hospital environment intimidating and depressing and wanted to be discharged early with the understanding that they would be better cared for at home. Such people tended to be otherwise medically fit or to have a good level of support from family and friends.

Provision of enhanced formal (professional/social services) and informal (family/friends/carers) social support

Most patients regarded support and encouragement from family, friends and carers165 as being essential to recovery, allowing them to maintain an optimistic attitude during rehabilitation:

The help, encouragement, and support that I got from my family and friends are essential . . . People around me lifted up my spirit.

Female patient207

Some patients had difficulty engaging with complex collaborative decision-making because of unfavourable professional customs and configurations of local services; increased vulnerability arising from distress, anxiety and fear; existing or future comorbid medical conditions; a rapid decline in physical ability or mental capacity; or the loss or unavailability of close family or friends. These issues could coexist with poor coping strategies, such as distancing and avoiding seeking help from support networks. 165 In such cases patients would need extra support and help. 72,165

Motivating and facilitating practice and adherence to exercise and activities of daily living