Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/28/02. The contractual start date was in August 2014. The draft report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Peter Tyrer and Irwin Nazareth were members of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment commissioning board that commissioned this research.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Buszewicz et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Clinical background

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is an anxiety disorder characterised by excessive, uncontrollable and often irrational worry that interferes with daily functioning and can cause physical symptoms. People with GAD often anticipate the worst and are very preoccupied with matters such as health issues, money, death, interpersonal problems or work difficulties. Typical physical symptoms include fatigue, nausea, muscle tension, palpitations or shortness of breath, difficulties concentrating and sleep difficulties, which can lead to a misdiagnosis. These symptoms must be consistent and ongoing, persisting at least 6 months, for a formal diagnosis of GAD to be made. The disorder often begins at an early age, and signs and symptoms may develop more slowly than in other anxiety disorders.

Generalised anxiety disorder is common, with a prevalence of 4.7% in the 2007 English National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey,1 but with lower rates of identification in primary care than expected. 2 As symptoms have to have been present at least 6 months before the diagnosis can be made, it is often a chronic disorder by the time it is identified. 3 It is often comorbid with depression or other anxiety or physical health disorders, worsening the prognosis. 4 In community samples, GAD is more common than depression,1 with higher associated health and societal costs,5 but it has received much less attention, so establishing the most effective treatments is crucial.

Generalised anxiety disorder is often associated with significant morbidity in terms of distressing psychological and physical symptoms, and significant functional impairment. 4 The degree of disability has been described as similar to that in major depression or chronic physical illness. 6 Rates of unemployment and social isolation are high,4 as is concomitant alcohol and substance misuse in an attempt to alleviate symptoms. 7 People with GAD have high numbers of general practitioner (GP) visits and secondary care contacts, both because of associated physical/somatic symptoms and because GAD is often comorbid with chronic physical health problems. 8

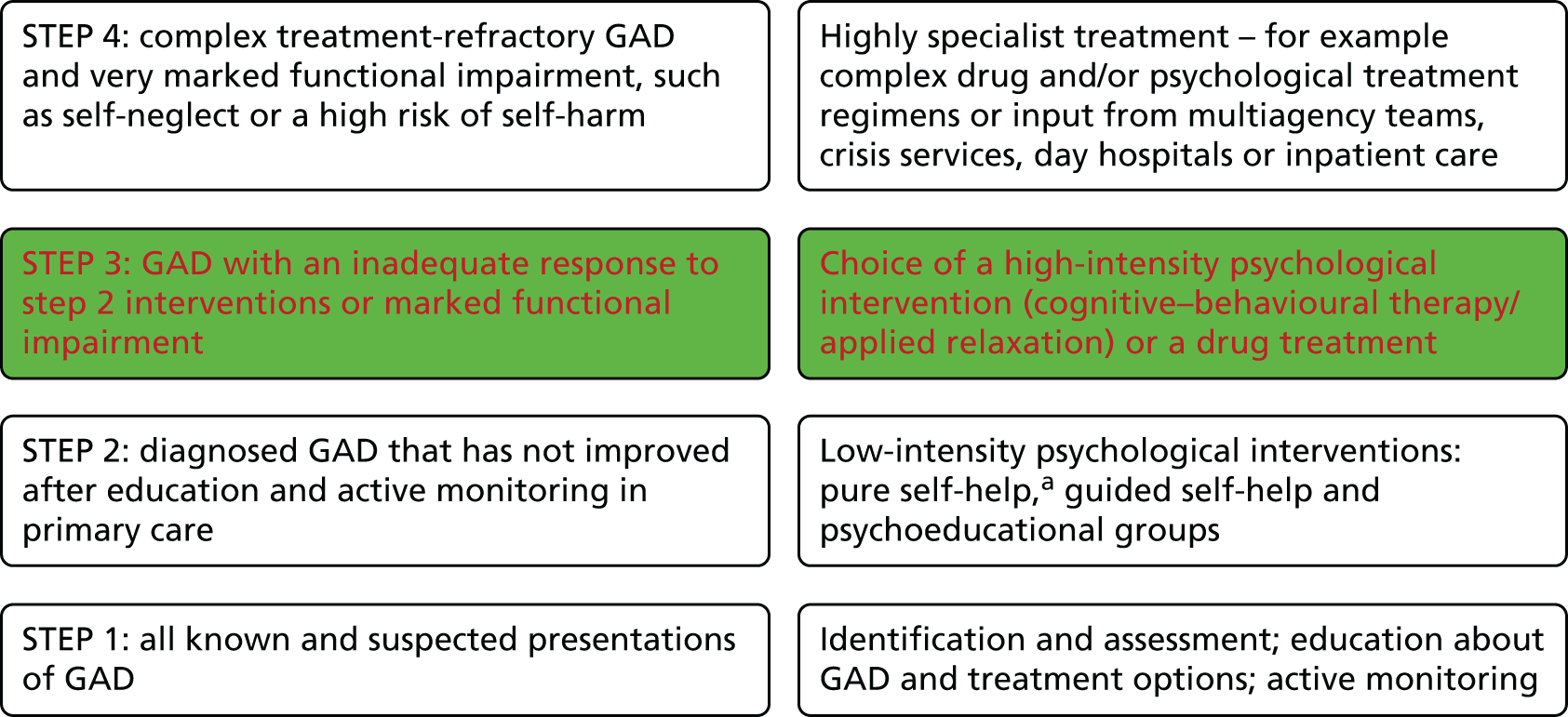

The 2011 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines entitled Generalised Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder (With or Without Agoraphobia) in Adults: Management in Primary, Secondary and Community Care9 established good evidence for the effectiveness of low-intensity psychological interventions in GAD. Step 1 interventions are usually delivered within primary care, involving identification, assessment, education and active GP monitoring. If symptoms persist, referral to a step 2 low-intensity psychological intervention is recommended [e.g. self-help interventions or psychoeducation groups, usually facilitated by a low-intensity Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) psychological worker]. 10 However, a significant number of patients will not respond to these interventions and require ‘stepping up’ to more intensive step 3 interventions (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Stepped-care model for GAD. a, Pure self-help is defined as a self-administered intervention intended to treat GAD and involves self-help materials (usually a book or workbook). It is similar to guided self-help but without any contact with a health-care professional. Red font shows the step or choice of treatments that are assessed in this trial.

A substantial percentage of people with anxiety and/or depression referred to IAPT low-intensity workers still have high Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire scores after receiving a step 2 intervention, indicating that they have not yet been effectively treated. 11 GAD is also potentially a long-term, relapsing condition. Thus, providing the most effective treatment, with a reduced likelihood of relapse, should provide significant benefits in terms of both individual morbidity and accompanying health and social costs to society, and was the focus of this study.

Existing research

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence conducted a systematic review of placebo-controlled antidepressant studies in GAD. 9 Thirty-four studies were identified that were generally rated as being of high quality, although relatively short in duration (8–12 weeks). Of these trials, 17 involved selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), whereas 16 involved the serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) venlafaxine and duloxetine. Both of the SNRIs, as well as the SSRIs paroxetine and escitalopram, have marketing authorisations for the treatment of GAD. The NICE summary concluded that, relative to placebo, SNRI and SSRI treatments were efficacious in the treatment of GAD in that they produced greater reductions in Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) scores12 and increased the probability of patients responding to treatment.

Generally, the effect sizes of antidepressants relative to placebo were in the low to moderate range and did not apparently vary between the different antidepressants to a clinically meaningful extent. 9 There was no clear evidence of a dose–response relationship for any particular antidepressant, and the most commonly experienced side effects were nausea and insomnia. These placebo-controlled studies were generally not more than 12 weeks in duration, although GAD is considered to be a chronic disorder and guidelines recommend the continuation of treatment in responders. A meta-analysis of available relapse prevention studies suggested an important effect of continuing effective pharmacological treatment for up to 1 year in patients with GAD who have responded to pharmacological therapy,13 although there is currently no evidence that sertraline is effective in preventing relapse. 14

Although there is evidence of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of sertraline for GAD compared with placebo, and also of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) compared with waiting list controls,1 there have been no head-to-head comparisons of sertraline (or any other SSRI) versus CBT to evaluate which treatment is the most clinically effective and cost-effective. Currently NICE guidelines suggest that choice of treatment between a pharmacological or psychological treatment at step 3 should be based mainly on patient preference, although availability of CBT may determine if patients have such a choice in some areas.

In assessing the effectiveness of CBT or SSRIs for GAD, it is necessary to consider both clinical symptoms and functional impairment. It is also important to assess outcomes of more than a few months, given that most pharmacological studies do not have follow-ups of > 12 weeks9 and there is some limited evidence that CBT may have a protective effect against future episodes. 15 Longer follow-up is also crucial in making future recommendations, as the longer-term costs of prescriptions and use of health-care resources associated with each type of treatment are required to evaluate their relative cost-effectiveness.

Following the updated NICE guidelines, there has been increased interest in GAD in the primary care community, but uncertainty remains regarding whether pharmacological or psychological treatment is indicated in more persistent cases. 16 Clinicians can be reluctant to prescribe the SSRI sertraline, which, although found by NICE to be the most cost-effective acute drug therapy for GAD, does not currently have marketing authorisation for this use. Clear data regarding whether the SSRI sertraline or CBT is most effective longer term in treatment of GAD, as well as further information about the safety and efficacy of sertraline in this patient group, is of direct relevance to the NHS.

The NICE committee conducted a search for relevant updates to the 2010 guideline in 2012, but no relevant trials adding to the literature were identified. 17 The authors of this report have also conducted a further rapid search of the literature to see if they could identify any relevant trials published between 2013 and early 2016, but none was found. Most of the studies continue to evaluate the effect of either CBT or medication for patients with GAD with no head-to-head comparison of a recommended psychological treatment versus pharmacotherapy. One study by Crits-Christoph et al. 18 combined treatment with venlafaxine with 12 sessions of CBT for patients who wished to have this and found no added benefit from the CBT at the 24-week follow-up, although the numbers in both groups were relatively small and those in the venlafaxine-only group showed quite a marked benefit from this treatment.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines research recommendation

The research recommendation from the NICE GAD Guidelines Group9 suggested the following: ‘A comparison of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of sertraline and CBT in people with GAD that have not responded to guided self-help and psycho-education’.

This recommendation suggested using a randomised controlled design in which people who had not responded to low-intensity step 2 interventions for GAD would be allocated openly to one of three groups: sertraline, CBT or waiting-list control for 12–16 weeks, with the control group being important to assess whether or not the two active treatments would produce effects greater than that of natural remission. It was suggested that follow-up assessments should be continued over the next 2 years to establish whether or not any short-term benefits were maintained and whether or not either active treatment produces a better long-term outcome.

Health Technology Assessment-commissioned research proposal

The research proposal commissioning brief published subsequently by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme panel in 2013 was a little different, in that it gave the following brief for the research question, omitting the third control arm to the trial and not stipulating assessment after 12–16 weeks:

Is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) more clinically and cost-effective for patients with generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) who have not responded to low intensity psychological interventions recommended in a stepped-care model?

Following from this, our final approved proposal was for a ‘Randomised controlled trial of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline versus cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for anxiety symptoms in people with Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) who have failed to respond to low intensity psychological interventions as defined by the NICE GAD guidelines’, with the primary outcome being assessed at 12 months (see Chapter 2, Methods, for further details).

Background to the choice of interventions to be assessed

Sertraline

The NICE Guidelines Advisory Group proposed sertraline as a first-choice pharmacological treatment, although this agent does not have a marketing authorisation for GAD and there are relatively few randomised trials (only two trials with 706 patients in total19,20). 9 Nevertheless, in terms of risk of discontinuation because of adverse effects, sertraline was the best tolerated antidepressant and was available as a generic brand, making it the most cost-effective choice. Duloxetine (a SNRI) had a greater probability of producing clinical response in a network meta-analysis, but this is not commonly prescribed in UK primary care. The SSRIs paroxetine and escitalopram both have marketing authorisation for GAD, and there is little pharmacological difference between them and the SSRI sertraline. However, paroxetine has a more marked withdrawal syndrome than sertraline21 and escitalopram was still on patent and significantly more expensive at the time of submitting the proposal. There are also more concerns about it extending the QT interval, although it is recognised that sertraline can do this in vulnerable cases. 22 In the two sertraline studies in GAD, sertraline was dosed flexibly between 50 and 150 mg daily (mean dose at the end of treatment about 90 mg). In one study sertraline was started at 25 mg daily for 1 week to improve tolerance early in therapy,23 and this acclimatisation period is also recommended by the manufacturer in the licensed use of sertraline in post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder and panic disorder. 24

Cognitive behavioural therapy

There are a number of cognitive behavioural models of GAD. Examples include the cognitive avoidance model,25 the metacognitive model26 and the emotion dysregulation model. 27 Dugas and Koerner28 have also developed a model of GAD known as the intolerance of uncertainty model. Stated simply, the model proposes that negative beliefs about uncertainty (or intolerance of uncertainty) lead to difficulty dealing with real or imagined uncertainty-inducing situations, which can then lead to excessive worry and GAD. Research has shown a consistent and robust relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and GAD; for example, their relationship is not accounted for by shared variance with other anxiety disorders, mood disorders or negative affect. 29,30 Data also suggest that intolerance of uncertainty is a causal risk factor for high levels of worry and GAD; for example, changes in intolerance of uncertainty precede changes in worry over the course of treatment,31 and the experimental manipulation of intolerance of uncertainty leads to corresponding changes in worry and monitoring behaviour. 32,33 Thus, data from correlational, longitudinal and experimental studies suggest that intolerance of uncertainty plays a key role in GAD. The Dugas and Koerner model28 is one of three CBT protocols for GAD, which guides IAPT services in how to carry out CBT effectively and in line with best practice. The treatment aims to help affected individuals develop beliefs about uncertainty that are less negative, rigid and pervasive. This is accomplished with the use of treatment strategies (such as behavioural exposure to uncertainty, problem-solving training and imaginal exposure) that aim to help patients confront uncertainty-inducing thoughts and situations. The treatment has been tested in four published randomised clinical trials, with results showing that it is more efficacious than a waiting list control,34,35 supportive therapy36 and applied relaxation. 37 The findings also show that 60–77% of patients attain GAD remission and that 50–55% achieve high-end state functioning following the treatment. The CBT protocol developed by Dugas and Robichaud (i.e. based on the intolerance of uncertainty model of GAD) was therefore used in this trial. 38

Time course of therapeutic effect and longer-term benefits

The planned comparison was between SSRI medication and CBT, which are both active treatments. However, we considered that in a pragmatic trial the time course of benefit is likely to differ. The SSRI medication might have a benefit earlier on, but it is likely that this effect could reduce over time, largely because many of the participants may stop taking their medication. In contrast, CBT is an educational approach that should be providing the participants with skills that they may use in the future. We would therefore expect that CBT would continue to have benefit for the 12-month duration of the trial. As a result, our hypothesis was that CBT would lead to a better outcome than SSRIs at the 12-month follow-up point.

Chapter 2 Trial design: aims, objectives and methods

This chapter details the aims, objectives and methods of the trial as originally planned and approved by the funder, and subsequent modifications made as a result of discussions among the Trial Management Group (TMG) and with the sponsor.

Summary of proposed research

The trial was entitled the ‘Randomised controlled trial of the SSRI sertraline versus CBT for anxiety symptoms in people with GAD who have failed to respond to low-intensity psychological treatments as defined by the NICE guidelines’. The trial acronym decided was ToSCA (Trial of Sertraline versus Cognitive behaviour therapy for generalised Anxiety).

Overall aim

To conduct a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in terms of symptoms and function of a pharmacological treatment (the SSRI sertraline) prescribed at therapeutic doses, with a manualised psychological intervention (CBT) delivered by trained psychological therapists, to patients with persistent GAD that has not improved with low-intensity psychological interventions as defined by NICE.

Hypothesis

Our hypothesis was that in people with GAD who had not responded to low-intensity psychological interventions, as recommended by NICE, CBT would lead to a greater improvement in their GAD symptoms as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety component (HADS-A)39 at the 12-month follow-up than prescription of the SSRI sertraline by their GP in accordance with recommended clinical guidelines.

Primary aim

To assess the clinical effectiveness at 12 months of treatment with the SSRI sertraline compared with CBT for patients with persistent GAD that has not improved with low-intensity psychological interventions.

Secondary aim

To calculate the cost-effectiveness at 12 months with the SSRI sertraline compared with CBT for patients with persistent GAD that has not improved with low-intensity psychological interventions.

Detailed objectives

Internal pilot (first 12 months of the recruitment period)

-

To test and refine the recruitment methods for the main trial.

-

To ascertain recruitment rates across sites and the acceptability of the overall recruitment process.

-

To examine the extent of comorbidity between GAD, depression and other anxiety disorders in the population referred into the study.

-

To ensure that the intervention can be delivered in accordance with the protocol in both arms, with satisfactory delivery of training and monitoring procedures.

-

To monitor and assess follow-up rates of the completed primary outcome measure (HADS-A) at 3 and 6 months within the pilot trial.

Overall trial (whole 24 months of the recruitment period including the internal pilot)

-

To recruit sufficient eligible patients with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)40 diagnosis of GAD willing to participate.

-

To compare the effect of high-quality, reproducible pharmacological and psychological interventions delivered in accordance with clear criteria and evidence-based guidelines. We asked participating GPs to follow established clinical guidelines for delivery of the pharmacological intervention, and the psychological intervention was manualised and quality controlled.

-

To obtain high rates of follow-up data on a minimum of 80% of those recruited into this trial at 12 months in order to provide a definitive answer to the research question and assess the longer-term outcomes of both interventions.

-

To analyse the results in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) guidelines.

-

To disseminate the outcomes to the NHS, academic colleagues, relevant service user groups and the wider community.

Methods

Setting

The study was community based and linked with local IAPT services. 10 We aimed to work with five recruitment sites in southern England during the pilot phase and up to 15 sites across the whole of England in the full trial.

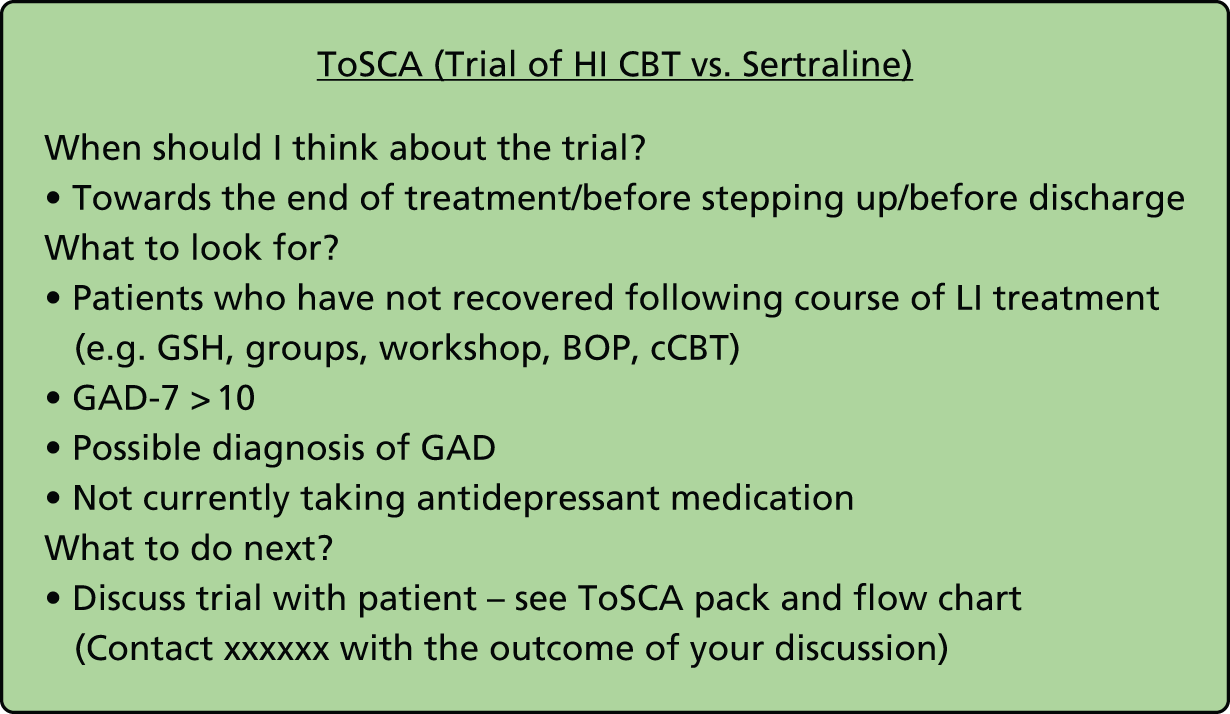

Recruitment of participants

People who had not responded to step 2 low-intensity psychological interventions for anxiety or depression who were being considered for step 3 interventions within their local IAPT services were considered eligible (Box 1 contains a list of step 2 low-intensity interventions meeting the inclusion criteria). Identification was by low-intensity IAPT workers, who routinely administer the GAD-7 anxiety measure41 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression measure,42 reviewing patients. Those patients scoring ≥ 10 on the GAD-7 were given brief details about the trial and if they were interested in finding out more, and possibly taking part, their permission was sought for contact by the research team. If they were unsure about their interest at this stage they were given a brief flyer about the aims of the trial and invited to contact the research team for more information or to discuss things further.

A key inclusion criterion for the study is that patients should have received an initial low-intensity intervention but still have above-threshold symptoms (GAD-7 score of ≥ 10). Set out below are the types of low-intensity intervention (and the minimum number of sessions for each) that meet this inclusion criterion and also some excluded interventions.

Included interventions-

Guided self-help carried out by a PWP or equivalent low-intensity worker: patient needs to have had at least two treatment sessions after initial assessment session.

-

Pure self-help (non-facilitated self-help): patient needs to have had at least one follow-up session after the self-help resource was recommended.

-

cCBT: patient needs to have logged on and completed at least two cCBT sessions.

-

Psychoeducational or similar group facilitated by a PWP or equivalent low-intensity worker: patient needs to have attended at least two sessions of the group.

-

Exercise intervention if the exercise is for mood/anxiety: patient needs to have tried the recommended exercise intervention at least twice.

-

One-off workshop lasting at least half a day, facilitated by a PWP or equivalent low-intensity worker.

-

Signposting interventions (signposting to other services).

-

Guided self-help carried out by a qualified (or trainee) CBT therapist or other high-intensity therapist.

-

Psychoeducational or similar group, or one-off workshop facilitated by a qualified (or trainee) CBT therapist or other high-intensity therapist.

cCBT, computerised cognitive behavioural therapy; PWP, psychological well-being practitioner.

The central research team (trial manager/research assistant) were faxed the details of those who had agreed to be contacted by the research team and aimed to respond within 1 week (preferably by telephone or e-mail or, if not, by letter) offering them an appointment at the IAPT premises or their own home, whichever was preferred. A full study information sheet was sent to potential participants at this stage (see Appendix 1) and the patient’s GP was contacted, with their permission, and asked to complete a Medical Suitability Review form to check that there were no known medical contraindications to them being prescribed sertraline if they were randomised to that intervention arm in the trial (see Appendix 2).

Recruitment appointment/baseline assessment

The baseline interviews and assessments were conducted by a member of the central or local research team (research assistant or clinical studies officer). They checked, at the outset, that potential participants had read and understood the study information leaflet, and answered any queries. They also checked that the patient understood the reasons for the study and confirmed at that point that they were interested in taking part on the understanding that, if randomised to the drug arm, they would receive the SSRI sertraline that, although proposed for use outwith a marketing authorisation for GAD, was recommended by NICE on the basis of its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in randomised trials. They also ensured prior to the appointment that there were no medical contraindications to receiving the medication sertraline recorded on the Medical Suitability Review form as returned by the GP (see Recruitment of participants, above).

Those agreeing to take part were asked to give fully informed consent before undergoing the eligibility check and baseline assessment. It was expected that most patients would be willing to consent to the study at the baseline visit, but if they were unsure they could be rescheduled for consent and baseline assessment at a later date. The assessment was conducted at the IAPT site or GP surgery in accordance with patient preference. Written consent was obtained by a delegated and appropriately trained member of staff. No clinical trial procedures, including confirmation of eligibility, were conducted prior to taking consent. A copy of the consent form was given to the patient, the original retained in the investigator site file and a further copy sent to the patient’s GP for their medical notes (see Appendix 3).

If potential participants were happy to proceed, then the inclusion and exclusion criteria were checked (see Inclusion criteria and Exclusion criteria), which included administering a pregnancy test to females of child-bearing potential. In assessing whether or not the potential participant fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for GAD, the relevant sections of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) questionnaire43 were administered by the research team member (depression, panic, social anxiety, alcohol and substance misuse, and GAD). If the DSM-IV criteria for GAD were fulfilled, potential participants were asked to confirm whether their GAD or worry symptoms were more severe and of more concern to them than any symptoms that they might have associated with psychological comorbidities, such as depression and other anxiety disorders, and that this was an important problem for them that they wanted to address.

If they fulfilled this criterion and all the other eligibility criteria, the researcher then administered the HAM-A questionnaire12 and asked the participant to complete the primary and secondary outcome measures at baseline, aiming for 100% completion of measures at baseline (see Outcome measures).

Inclusion criteria

-

Age ≥ 18 years.

-

Positive score of ≥ 10 on the GAD-7.

-

Primary diagnosis of GAD as diagnosed on the MINI.

-

Failure to respond to NICE-defined low-intensity interventions.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were expanded from those in the initial approved protocol after discussion with the sponsor [University College London (UCL) Joint Research Office (JRO)].

-

Inability to complete questionnaires because of insufficient English or cognitive impairment.

-

Current major depression.

-

Other comorbid anxiety disorder(s) of more severity or distress to the participant than their GAD.

-

Significant dependence on alcohol or illicit drugs.

-

Comorbid psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder.

-

Treatment with antidepressants in past 8 weeks or any high-intensity psychological therapy within past 6 months.

-

Currently on contraindicated medication: monoamine oxidase inhibitors within the past 14 days or pimozide.

-

Patients with poorly controlled epilepsy.

-

Known allergies to the investigational medicinal product or excipients.

-

Concurrent enrolment in another investigational medicinal product trial.

-

Severe hepatic impairment.

-

Women who are currently pregnant or planning pregnancy, or lactating.

-

Patients on anticoagulants.

-

History of bleeding disorders.

Randomisation and notification of general practitioner and cognitive behavioural therapists

A copy of the completed baseline assessment form was forwarded by the researcher to the chief investigator (CI) or delegated clinician in order to confirm participant eligibility. After confirming eligibility, the CI or delegated clinician accessed a web-based interface using a unique username and password, and entered the unique study identification number for the participant in order to randomise them to one of the two intervention arms via an independent computerised service (Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK) provided by the PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). There were no stratification variables. The randomisation outcome was transmitted electronically to the trial manager who then contacted the individual participants within 2 working days of their baseline assessment to inform them of which treatment group they were in.

The research team (trial manager or research assistant) ensured that the patient’s GP was notified about their patient being enrolled in the trial and which treatment arm they were in. They were also notified if the patient was not eligible for inclusion in the trial (see Appendix 4).

If they had been randomised to the medication/sertraline arm, the patient was asked to make an appointment within the next 2 weeks to see their GP to discuss starting the treatment, and the research team let their GP know that they would be doing this (see Appendix 5).

The research team also gave the relevant local IAPT services the details of participants randomised to the CBT arm – the IAPT team then contacted the patient to arrange a course of treatment.

Interventions

Pharmacological intervention: sertraline

The medication sertraline was prescribed by the patient’s GP in accordance with recognised clinical guidelines. The GPs were asked to review these patients regularly (at least six times in 12 months) and patients were to take the medication for 1 year unless they had significant adverse effects. The GPs were given details of the suggested timing and content of each of these appointments with the trial participants (see Appendix 6).

The GP was to act in the best interests of the participant at all times, so was free to refer them to secondary care services or psychological treatments if indicated. We explained that we would prefer patients in the SSRI arm not to be referred to or receive CBT while in the trial, but appreciated this might occasionally happen and should be documented in their GP notes.

If the patient made any interim visits to the surgery to discuss their treatment for GAD or issues to do with the medication being received, we asked for these to be clearly documented in their notes (we costed for up to four additional visits per GP to cover this possibility).

The GP was asked to record any adverse events and both the participants and their GPs were asked to report any serious adverse events (SAEs) or suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) to the trial team (see Appendix 7).

Psychological intervention: cognitive behavioural therapy

This was delivered by high-intensity therapists from local IAPT services who were trained to deliver 14 (± 2) 50-minute sessions of a manualised treatment developed for use in GAD.

This covered six treatment modules:

-

Psychoeducation and worry awareness training – the first few sessions of treatment are devoted to psychoeducation in which patients begin to monitor their worrying on a day-to-day basis, and learn to distinguish between worries about current problems and worries about hypothetical situations.

-

Re-evaluation of the usefulness of worry – patients identify and re-evaluate their positive beliefs about worry using strategies such as role-play and hypothesis testing. Patients are helped recognise that their beliefs about the usefulness of worry are interpretations and not facts, and begin the process of ‘imagining a life without worry’.

-

Uncertainty recognition and behavioural exposure – participants learn that intolerance of uncertainty contributes to worry and anxiety, and that uncertainty-inducing situations are largely unavoidable. They then learn to seek out and experience uncertainty-inducing situations.

-

Problem-solving training – for worries about current problems, participants learn to use a problem-solving procedure targeting problem orientation, problem definition and goal formulation, generation of alternative solutions, decision-making, and solution implementation and verification. 44

-

Written exposure – in the field of health psychology, a method known as written emotional disclosure has been shown to lead to positive health outcomes. 45 Written exposure sessions are continued until writing about the feared outcome no longer provokes anxiety (typically 8–10 exposure sessions).

-

Relapse prevention – the final component is relapse prevention, the aim of which is to consolidate the attitudes, beliefs and skills acquired during therapy. Patients are encouraged to continue practising their new skills and prepare for stressors that may arise.

Sessions were to be digitally recorded and a random 10% to be assessed for quality (fidelity to the manual and therapist competence) by an independent external assessor according to prespecified criteria (see Chapter 6 for further details).

Usual care by general practitioner

Randomisation was between sertraline prescribed by the participant’s GP and CBT provided within an IAPT service, and both interventions were to be in addition to any other usual care provided by the GP. As always, the patients could be offered other medication or psychotherapy as part of their usual care, although we encouraged the GPs not to change the patient’s medication unless clinically indicated or requested by the patient, and not to refer them for CBT while in the sertraline arm if possible. Usual practice would be to allow the patient with GAD to choose, with the help of their GP, between a SSRI and CBT if they met the criteria for a step 3 intervention and if neither was contraindicated.

Patients in the CBT arm were likely to receive their CBT treatment more quickly than is usual in most NHS settings, and it was a psychological intervention specifically developed for people with GAD that is not current UK practice. NHS waiting lists mean that patients in the SSRI arm who then asked to be referred for CBT were likely to experience significant delays in receiving this. We proposed to record and measure all use of antidepressants and other forms of counselling or psychotherapy, whether NHS or private, and to take account of these in the analysis.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures to be collected during the trial are summarised in Table 1, according to the time at which each would be collected.

| Assessment/measure | Time point (months) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | |

| Informed consent | ✓ | ||||

| Establishing eligibility | ✓ | ||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | ||||

| Urine pregnancy test | ✓ | ||||

| MINI (relevant sections) | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| HADS-A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| GAD-7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| HAM-A | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WSAS | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| EuroQol-5 Dimensions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Health economics questionnaire: ESC questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Patient preference rating scale | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Treatment acceptability scale: Client Satisfaction Questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Health service outcomes | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the HADS-A measured at 12 months. This is the 7-item anxiety component of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, a very widely used 14-item scale that can be self-administered. It has high validity and reliability, and the anxiety and depression components have been assessed separately as primary outcomes. 39

The primary outcome measure was initially the GAD-7,41 but this was changed to the HADS-A about 6 months after the study had started and before the recruitment of any trial participants had begun. This was done because we had originally understood, when selecting the GAD-7 as our primary outcome measure for both intervention arms, that it would be possible to ask participants seeing IAPT high-intensity therapists for treatment in the CBT intervention arm not to complete the GAD-7 questionnaire at every CBT session, which is IAPT’s current usual practice. Unfortunately, it was not possible to negotiate this in all the pilot study areas. As a result of this we were concerned that using the GAD-7 in the trial as the primary variable when this is associated with treatment in one of the groups (i.e. the CBT group) was a source of potential bias, and we therefore decided to change the primary outcome measure to the HADS-A.

Secondary outcomes

These were all self-completed measures to be collected by postal questionnaire, apart from the researcher-administered MINI and health service outcomes collected from patient notes.

-

HADS-A: the HADS-A was collected at baseline and then as a secondary outcome measure at 3, 6 and 9 months. 39

-

HAM-A: this is a 14-item observer-rated anxiety scale, which has been widely used, particularly in pharmacological studies. 12 It was to be administered by a member of the research team at baseline and at the 12-month follow-up.

-

GAD-7: a 7-item self-completion questionnaire with very good sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%) for GAD. 41 It is one of the core measures regularly administered by the IAPT services. 10 It was to be collected at baseline, and at 6 and 12 months.

-

PHQ-9: this is a 9-item self-rate scale widely used to monitor the severity of depression. 41 It was to be collected every 3 months for the 12-month duration of the study, along with the HADS-A and EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L).

-

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS): this is a 5-item self-completion questionnaire that we planned to use to assess participants’ difficulties with physical and social functioning. 46 It was to be collected at baseline and at the 12-month follow-up.

-

EQ-5D-3L: a 5-item self-completion measure used to assess quality of life and calculate utility scores for quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). 47 It was to be collected every 3 months for the 12-month duration of the study, along with the HADS-A and PHQ-9.

-

Employment and Social Care questionnaire (ESC): relevant data on services used and productivity losses were to be collected using this modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory48 at baseline, and at the 6- and 12-month follow-up.

-

Patient acceptability measure: we planned to use the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ), a brief 8-item self-completion questionnaire administered at 3 and 12 months. 49

-

Patient preference rating scale: we planned to use a Likert scale used by our team in other studies, also administered at baseline and at the 12-month follow-up.

-

MINI:43 it was an addition to the original protocol to also administer the MINI questionnaire at the 12-month follow-up to assess the depression, panic, social anxiety and GAD components, with the intention of establishing whether or not the participant met the criteria at follow-up for DSM-IV caseness for GAD or any of the common psychological comorbidities.

-

Health service outcomes: we planned to collect health service use data from both intervention arms at baseline, capturing health service use for the preceding 6 months, and again at 12-month follow-up for the following items of health service use during the preceding 12 months: total GP consultations as well as those coded for GAD, psychotropic drug prescriptions from the GP surgeries, and secondary care attendances including mental health and psychological services. The IAPT sites agreed to inform the research team of the attendance rates for CBT sessions attended by trial participants in the CBT intervention arm.

-

Serious Adverse Events Monitoring Form: we planned to use the standard SAE template provided by the PRIMENT CTU, modified for use in this study.

Final assessment at 12 months

A member of the research team would have administered the HAM-A face to face to all participants at 12 months and encouraged them to complete the 12-month outcome measures at this point to ensure optimum data collection. This would have involved a different member of the research team from the original assessor, who would have been blind to the participant’s trial allocation. As a check on this, they would have been asked to say which trial arm each participant they assessed had been randomised into.

Procedures for reporting and recording serious adverse events

Patients were asked at each GP visit about side effects or health issues occurring while on medication, as is normal clinical practice, and both the patients and GPs were asked to let the study team know about any serious medical problems that may have occurred between consultations or be reported at the time of the medication review. All patients recruited to the study were given a card with details of how to contact the central research team about any serious medical problems occurring while they were in the trial at the time that they were informed about the outcome of the randomisation procedure. The same applied to both the GPs and IAPT CBT intervention therapists, who were given a brief explanatory sheet indicating when they should be informing the research team about any serious medical problem affecting a participant in the trial (see Appendix 7).

Both the GPs and the IAPT therapists were asked to notify the CI about any serious medical problems (to cover SAEs, SUSARs or important medical events) that might affect any participant in the trial as soon as they were aware of this. The CI or an appropriate delegated member of staff would then be asked to complete the sponsor’s SAE form and to e-mail this to the PRIMENT CTU on behalf of the sponsor within 24 hours of his/her becoming aware of the event. The CI was expected to respond to any SAE queries raised by PRIMENT CTU as soon as possible. All SAEs were to be recorded in the relevant case report form and the sponsor’s adverse event log, which was to be reportable to the sponsor once per year.

The CI or delegate might also contact the patient’s GP, depending on the nature of the SAE, to obtain more information regarding the adverse event. All SUSARs were to be notified to the sponsor within 24 hours according to the sponsor’s written standard operating procedure.

Sample size calculation

The principal outcome variable is the change from baseline to 12 months in the HADS-A score which we planned to compare between treatment groups in a regression model that accounted for baseline scores. Tests and confidence intervals for treatment effects would be based on the normal distribution – an assumption justified by the central limit theorem. Estimates for the standard deviation (SD) of HADS-A scores are available from Tyrer et al. 50 In this study, SDs between 4 and 5 were found for the change of score between baseline and 12 months for both randomised conditions. Therefore, we used an estimate of 5 for the SD of our outcome measure, overlaid with an additional component of variance (essentially attributable to the therapist) sufficient to give an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.02. Then, making the conservative assumption of a cluster size of 7 and an allowance of 20% for dropout and other challenges, this meant we would require a total sample size of 360 patients to detect a (‘true’) average difference of 2 between treatments with 90% power at p < 0.05 (two-sided). Furthermore, the expected half-width of the 95% confidence interval for the treatment difference is then 1.2.

With this sample size, we would have retained ≥ 80% power should the intraclass correlation coefficient turn out to be 0.05 rather than 0.02. Alternatively, we would retain 80% power should the SD of our outcome measure turn out to be 5.8 rather than 5. This design had the advantage of providing robust interpretation in a number of circumstances as a result of the planned precision. Thus, with no impact on alpha spending, it would be possible to interpret a significant difference between the groups of > 2 points as also being clinically relevant and, additionally, a non-significant result that excludes a difference of 2 points (i.e. the upper confidence interval range < 2 points) as demonstrating non-inferiority. Furthermore, a non-significant difference in which the outer bands of the confidence interval are < 2 points on the HADS-A would indicate equivalence. The planned precision of the trial is such that it should have provided a firm basis for decision-making even if opinions as to the correct size of the minimally important difference were to have altered somewhat before the results became available.

Statistical analysis plan

Summary of baseline data and flow of patients

We planned to follow the CONSORT guidelines in reporting and analysing our data. This included presenting a table of summary statistics for those secondary outcome variables collected at baseline showing clinical characteristics for each group along with (baseline) demographic characteristics. We also planned to create a flow chart that would provide the number of potential participants who were screened, eligible, randomised and followed up at each time point.

Primary outcome analysis

The principal outcome variable was the change from baseline to 12 months in the HADS-A score, which we aimed to compare between treatment groups in a regression model that accounted for baseline scores. Tests and confidence intervals for treatment effects would be based on the normal distribution – an assumption justified by the central limit theorem. Given that there is a single primary outcome, no corrections for multiple comparisons would be required for the statistical inference. The principal analyses would have been conducted according to a prespecified statistical analysis plan to be finalised before database lock. The principal analyses would have been conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle using generalised mixed models. The primary analysis would have used a generalised mixed model accounting for clustering of therapist effects, investigational sites (both as random effects) and a limited number of prespecified patient-level factors, including baseline HADS-A score. The principal analyses would have been based on available data, and supportive analyses would examine the extent to which the principal analyses are robust to the challenge presented by the observed loss to follow-up. Exploratory analyses would have been carried out to describe how patient preferences along with a limited number of other prespecified characteristics of participants may modify treatment effects. 50 Any subgroup analyses conducted would also have been regarded as exploratory.

Secondary outcome analysis

The secondary outcome variables would have been analysed using the same (generalised mixed model) framework as for the primary outcome variable. However, the presentation of the results would have been restricted to the confidence intervals that come out of the analysis, rather than the p-values.

Economic evaluation

We planned to calculate the net monetary benefit (NMB) of CBT compared with sertraline for patients with persistent GAD who had not improved with step 2 low-intensity psychological interventions. A higher NMB indicates greater relative cost-effectiveness. Health- and social-care resource use would have been collected for both interventions over the 12-month duration of the trial using patient GP records, and patients asked to complete a significantly reduced version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (the Employment and Social Care questionnaire) at baseline and 12 months. The health service resource use data collected would have focused mostly on primary care and psychological therapies. Details of secondary care and mental health resource use would also have been collected. Health-care resource use for the preceding 6 months would have been collected at baseline for adjustment purposes only. Resource use would be multiplied by costs from nationally published sources and summed to calculate the total cost per patient. The health-care resource use associated with the interventions would have been captured in each arm as follows: the cost of sertraline and any follow-up, training or monitoring costs; the cost of CBT based on the number of sessions attended per patient, session duration, the staff type and grade delivering the CBT; and training and any overhead costs.

The mean cost per patient for patients in the sertraline and CBT groups would have been calculated and confidence intervals reported, calculated using non-parametric bootstrapping with replacement and adjusting for baseline service use. The mean QALYs per patient would have been calculated from the EQ-5D-3L51 and the UK algorithm for calculating utility scores. 52 The EQ-5D-3L would have been collected at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months to allow calculation of the area under the curve over the 12-month trial duration for the SSRI and CBT groups, adjusting for baseline differences. The NMB of both interventions would have been calculated for a range of values of willingness to pay for a QALY. Confidence intervals would have been constructed using non-parametric bootstrapping. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve would have been used to report the probability that each intervention has the higher NMB for a range of values of willingness to pay for a QALY. One-, two- and multiway sensitivity analyses would have been conducted for any assumptions made. Missing data and clustering would have been handled as specified in the statistical analysis plan.

Sensitivity and other planned analyses

The principal analyses would have been conducted according to a prespecified statistical analysis plan, to be finalised before database lock. The principal analyses would have been based on available data and supportive analyses would have examined the extent to which the principal analyses were robust to the challenge presented by the observed loss to follow-up. Exploratory analyses would have been carried out to describe how patient preferences, along with a limited number of other prespecified characteristics of participants, might modify treatment effects.

Chapter 3 Obtaining ethics and research governance approvals

Timetable: sponsor and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency approvals

The official start date of the trial as agreed with the NIHR’s HTA programme was 1 August 2014.

This was a clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product, and we started working with the sponsor (the UCL JRO) before the official start date on the sponsorship procedures required. After several iterations the JRO approved the first version of the trial protocol on 5 November 2014 (protocol number 14/0249).

Application for clinical trials authorisation was made to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) on 7 November 2014 and their approval was received on 13 November 2014.

Ethics approval and major amendments

Our local Research Ethics Committee (REC) was Brent National Research Ethics Service Committee London, and the relevant Integrated Research Application System application was submitted to them on 7 November 2014 and presented at a meeting of the REC on 24 November 2014.

We received a favourable ethics opinion, with conditions, on 3 December 2014 and gained full approval on 9 December (REC reference number 14/LO/2105).

-

Major amendment 1: at the TMG on 21 January 2015 a major protocol amendment altering the primary outcome measure from the GAD-7 to the HADS-A was suggested (see Chapter 2, Methods). This was developed and agreed with the NIHR’s HTA programme and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) before being submitted to the REC and MHRA on 9 March 2015. There were also some minor study document changes submitted with this major amendment request. Approvals were obtained from the REC on 17 March 2015 and from the MHRA on 10 April 2015.

-

Major amendment 2: a further major amendment was submitted on 13 April 2015 listing the four pilot sites for the trial and giving details of their principal investigators (PIs). This was approved by the REC on 23 April 2015.

-

Major amendment 3: a third major amendment was submitted on 23 July 2015 applying to change the named PI at the Bristol site and was approved on 30 July 2015.

-

Major amendment 4: the final major amendment was for approval for a 6-month replacement of the CI Dr Marta Buszewicz by Professor Irwin Nazareth, this amendment was submitted on 16 September 2015 and approved on 1 October 2015.

Research governance

Obtaining research governance permission proved more complicated and led to a significant delay in being able to start the trial. It was confirmed that we had submitted a full set of documents for study-wide approval on 27 January 2015, but significant delays followed while our lead Clinical Research Network (CRN) queried the governance arrangements for participating GP practices and whether or not they should be registered as individual research sites, which would have been very administratively burdensome, given that most of the planned 360 trial participants were likely to be registered at different practices. We worked with the CRN and the Health Research Authority to develop the documents required for a generic site-specific information form, which allowed us to obtain NHS approval for the collection of health service usage data for trial participants from their GP notes without registering each general practice as a research site. This was approved by the national NIHR Coordinated System for gaining NHS Permissions (NIHR CSP) co-ordinating centre on 14 April 2015 and we finally received study-wide research and development (R&D) approval on 27 April 2015 – 3 months after initial submission of the full set of documents (see Appendix 8).

Having received national approval on 14 April 2015, it then took several further months to receive local assurances for all the pilot sites – the last of these was the South London assurance for Kingston and Greenwich received on 3 July 2015.

Sponsor documentation prior to site set-up visits

From February to May 2015 the trial team worked with the PRIMENT CTU on the final documentation required for the trial management file and site files prior to the site initiation visits. This included the trial monitoring plan, trial pharmacovigilance documents and training procedures, and a formal agreement between the PRIMENT CTU and the CI because a large number of sponsor responsibilities were being delegated to the CTU.

Trial database and electronic case report form development

The trial team worked over the same period with the CTU data manager and database developer to finalise the data management plan, trial database and electronic case report forms for the study. Rigorous database testing was carried out and sign-off achieved on 25 June 2015.

Monitoring processes

The PRIMENT CTU led on developing the monitoring plan. The trial monitor was John Codington of Cod Clinical Ltd, an external monitor with whom the CTU had previously worked.

The plan was for the central research site at UCL to receive a monitoring visit 3 months after being opened and for the first monitoring visit following initiation for the IAPT pilot sites to take place after five patients had been randomised at each site. Further on-site monitoring visits were to take place annually at each site.

In the event, because of very poor recruitment no monitoring visits took place.

University College London data safe haven

We worked with the UCL Information and Services Division to set up a secure storage system for any confidential data on the UCL Data Safe Haven system, although in the event we did not need to store any data there given the lack of participant recruitment and early termination of the trial.

This service provides a technical solution for storing, handling and analysing identifiable data. It has been certified to the ISO27001 information security standard53 and conforms to the NHS Information Governance Toolkit. 54 Built using a walled garden approach, in which the data are stored, processed and managed within the security of the system, it avoids the complexity of assured end-point encryption. A file transfer mechanism enables information to be transferred into the walled garden simply and securely.

Chapter 4 Conduct of the trial: anticipated recruitment rate, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies and research staff training, and pilot site openings

Anticipated recruitment rate

To date, there have been few large-scale trials recruiting from IAPT services, and none to our knowledge that have recruited from the caseloads of low-intensity IAPT staff or that have compared psychological interventions with medication. Three of the co-applicants (JC, MS and RS) have experience of working with IAPT services as researchers, trainers and service leads. They arranged contacts between the research team and IAPT study sites to ensure local understanding of recruitment procedures and assist in troubleshooting problems, as well as arranging training and supervision of the high-intensity CBT therapists involved in delivering the intervention (see Chapter 6 for details of the training and supervision of the high-intensity CBT therapists).

Prior to writing the proposal we examined the IAPT data for the year 2011–12 for two local London boroughs with a combined population of 426,000 during the year (Camden and Islington), among which 6569 people had an initial appointment within their IAPT services. Of these, 694 people (11%) were initially seen by an IAPT low-intensity therapist and were stepped up from a low- to high-intensity intervention with a GAD-7 score of ≥ 10. Eighty-nine (13%) of these 694 people were given a provisional primary diagnosis of GAD by the low-intensity worker and would have been potential candidates for our trial. Sixty-nine per cent were given other provisional primary diagnoses, and for 18% no diagnostic coding was made. We assumed that 67% of those with a GAD-7 score of ≥ 10 and suitable to be stepped up would be on antidepressants already or decline to be randomised. Extrapolating from the 89 people with a provisional primary diagnosis of GAD, this would have excluded 60, leaving 29 suitable and potentially willing to be randomised for the study.

As low-intensity IAPT staff have minimal training in making psychiatric diagnoses, we were conscious that a recruitment strategy that relied on them identifying people with GAD would be likely to miss many suitable people with GAD. This would include people with GAD comorbid with other anxiety disorders and with depression, pure GAD being rare compared with comorbid GAD. Accordingly, our recruitment strategy would need to encourage low-intensity IAPT staff to identify people as suitable for the study if there was a possibility they might have GAD, including comorbid with depression and other types of anxiety. So, in terms of the numbers identified in our two local London boroughs above, we wanted not just the 89 people with a GAD-7 score of ≥ 10 for whom they gave a provisional diagnosis of GAD, but all 694 people with a GAD-7 score of ≥ 10 to be considered if there was a possibility they might have GAD. We assumed that if this broader identification approach was adopted, a much larger pool of potential participants would be identified and referred for baseline assessment by the low-intensity workers, although up to half of the patients assessed for the study might then be ineligible because of a comorbid major depressive disorder or because the patient identified another anxiety disorder as being more significant than their GAD.

In order to recruit sufficient people for this trial, we needed to recruit a total of 360 people (see Chapter 2, Sample size calculation), which equated to 24 participants per study site if there were 15 sites. This would have meant recruiting one participant per site per month over the full 24 months of the trial period, or two participants per month over a 12-month period.

During our internal pilot phase we worked on forming relationships with the local low-intensity IAPT workers during the initial 3 months and ensuring that they were committed and clear as to what was required. We then aimed to recruit two participants per month from each of the five pilot sites for the succeeding 9 months, resulting in a total planned recruitment of 90 participants during this pilot phase (i.e. 25% of our planned total recruitment of 360 participants). We also planned to consolidate our relationships with a further 10–15 sites throughout England during this time, so that we were in a good position to recruit the remaining 170 participants over the following 12 months of the main trial recruitment period.

Our assumptions regarding the number of patients to be screened and recruited across the 24 months of the whole trial are outlined in Figure 2 and the number of patients we planned to recruit at each of the pilot sites during the 12 months of the internal pilot is given in Table 2. The pilot sites would continue recruiting and treating patients until the end of the full-trial recruitment period (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Planned screening and recruitment across the 2 years of ToSCA. GAD trial recruitment includes pilot phase.

| ToSCA IAPT pilot sites | Pilot recruitment target, n |

|---|---|

| Camden and Islington with Kingston | 24–36 |

| Coventry and Warwickshire | 24–36 |

| Bristol | 12–18 |

| Greenwich | 12–18 |

| Total | 72–108 |

FIGURE 3.

Proposed timelines for ToSCA, with a start date of 1 August 2014. a, We will offer treatment to completion to all participants recruited to the internal pilot even if not proceeding to the full trial; b, Start training therapist at the other sites in preparation for the full trial. D, Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee meeting; DMEC, Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee; IMP, investigational medicinal product; SOP, standard operating procedure; TSC, Trial Steering Committee.

In the event, we had four pilot IAPT sites in London, Central and South West England that agreed to take part at this stage and would have provided a range of populations; the London boroughs of Camden and Islington together with Kingston (all managed by the same IAPT service), Greenwich, Bristol, and Coventry and Warwickshire. Because of their relatively larger populations and IAPT service throughput, Camden and Islington with Kingston and Coventry and Warwickshire had target recruitment rates during the period of the internal pilot that were double those of Greenwich and Bristol.

The IAPT sites agreed to provide high-intensity CBT for 50% of the participants recruited. The number of therapists and supervisors trained was proportional to their target.

Because of the delays described in the previous chapter with obtaining research governance approvals as well as the sponsorship and site initiation processes (see Chapter 3), the first pilot site to open to recruitment was Camden and Islington with Kingston on 1 July 2015 (see Site initiation visits, opening to recruitment and standard operating procedures below), which was 5 months later than originally planned and meant that our 12-month internal pilot phase would have been due to end on 30 June 2016.

Trial preparation: staff training

Training of high-intensity cognitive behavioural therapists

A 2-day training session in London on 22 and 23 January 2015 was arranged for the IAPT high-intensity CBT therapists and their supervisors from each of the pilot sites, and was delivered by Professor Michel Dugas who came over from Canada to deliver the training (see Appendix 9 and Chapter 6).

Liaison with and training of low-intensity psychological well-being practitioners

In preparation for each pilot site opening for recruitment, training sessions were held with the IAPT psychological well-being practitioners (PWPs) at each site. Their purpose was to prepare the PWPs for their part in identifying suitable participants for the study (see Appendix 10).

Training of research staff to conduct informed consent, eligibility assessment and baseline measures

Two half-day training sessions were conducted for any member of the research staff who might be involved in the baseline recruitment process – this included a combination of the research staff based at the UCL central trial office and lead PWPs or clinical studies officers involved in these procedures at the pilot sites. The first session was held on 5 May 2015 in London and included the trial co-ordinator, Dr Anastasia Kalpakidou, the Bristol Clinical Studies Officer, Joy Farrimond, and lead PWPs from Camden, Islington and Kingston (Tarun Limbachaya, Annie Ormond, Elliott Rose, Rachel Lawrence and Natalie Gunn).

The second training session was held on 16 July 2015 in Nuneaton near Coventry and included the trial co-ordinator, Dr Anastasia Kalpakidou, research assistant Sally Gascoine, ToSCA intern Alessandro Bosco and the Coventry and Warwickshire lead PWP and clinical studies officers (Helen Fletcher, James Tucker, Abayomi Shomoyei and Emily Benson).

Current good clinical practice accreditation was a condition of having a research staff role on the trial (see Appendix 11).

The central research team produced a full training/recruitment manual for participating sites with all the relevant questionnaires and outcome measures as appendices for reference. This was distributed in draft version to participants at the training sessions and the full electronic version sent to the pilot sites when they were open to recruitment (manual available on request).

General practitioner recruitment processes

As recruitment of patients to the trial was via the IAPT PWPs, the GPs who would potentially be taking part in the study were identified only once their patient(s) had expressed an interest in being assessed for the trial. At this point they were contacted with their patient’s consent and asked to complete a Medical Suitability Review form to check that there were no known medical contraindications to them being prescribed sertraline, should they be randomised to that intervention arm in the trial (see Appendix 2).

In order to forewarn the local GPs and hopefully gain their co-operation with the study and a speedy response to any request for completion of the Medical Suitability Review form once requested, all the GPs in the areas where the pilot IAPT sites were situated were informed about the study in advance via their local primary care leads within their CRN structure. The procedures for this varied slightly between areas according to the procedures that they normally followed, but consisted, in essence, of an e-mail notifying the practices about ToSCA with an attached flyer (see Appendix 12) that informed them about the three potential procedures that they might be asked to assist with if one of their patients was recruited to the study, and the relevant rates of reimbursement per patient:

-

completion of the GP Medication Suitability Review – reimbursed at £35

-

prescribing sertraline for a period of 12 months or as appropriate – reimbursed at £140 in accordance with clinical guidelines (only applied to patients in the sertraline arm of the trial)

-

facilitating collection of health services data at the end of the trial – reimbursed at £20.

The primary care leads of the two London CRNs involved (North Thames and South London) asked their local GPs to respond to this initial notification by sending an expression of interest in taking part in the trial, which would be the normal process for recruiting interested general practices. Very few practices responded in this way in either area, but this was not a major issue as the chances of patients being recruited to the trial from any individual practice were small.

ToSCA video

The North Central London Research Consortium, which supports primary care and mental health research in north central London where the central research site at UCL is located, also funded the production of a promotional video about ToSCA for GPs to watch. This included some educational material about GAD as well as a brief description of the background to the trial and details of the reimbursement rates for GP practices with patients involved in the trial. It was the first time this methodology had been tried.

General practices in the local area (i.e. Camden and Islington with Kingston) were reimbursed £70 if they arranged to view this video within a practice clinical meeting and could give evidence of the GPs in the practice having watched it. Ten practices were reimbursed for watching the video: seven in Camden (out of a total of 40 practices) and three in Islington (out of a total of 38 practices). Of these, all but one practice in Islington expressed an interest in taking part in the study if any of their patients were potentially eligible.

Interest was also expressed in the video by the other pilot sites where the North Central London Research Consortium was not in a position to reimburse the practices, and they were given the link to the video to watch if they wished. This has now entered the public arena via YouTube (YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA). 55

Site initiation visits, opening to recruitment and standard operating procedures

As described in Chapter 3, significant delays in obtaining research governance approval for the study as well as delays in some of the sponsorship processes meant that we were able only to start recruiting participants to the trial 5 months later than anticipated (i.e. at the beginning of July 2015 rather than 1 February 2015 as initially planned).

The central co-ordinating site based at the UCL Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health had its site initiation visit conducted by the UCL JRO on 29 May 2015 and the trial was declared open to recruitment from 1 July 2015.

The first pilot site initiation visit was at Camden and Islington with Kingston on 5 June 2015, and the site was also declared open to recruitment from 1 July 2015.

The Greenwich site initiation visit took place on 28 July 2015 and the site was declared open to recruitment on 17 August 2015.

The Coventry and Warwickshire site initiation visit took place on 29 June 2015 and the site was declared open to recruitment on 3 September 2015 (the delay between site initiation and opening to recruitment was because of discussions regarding whether or not the PI at this site might change; this was then decided against and an updating teleconference to ensure that the site was up to date with all the required procedures was held on 3 September 2015).

The Bristol site initiation visit took place on 27 August 2015 and the site was declared open to recruitment on 8 September 2015.

The research team worked with the PRIMENT CTU and the UCL JRO to identify the relevant standard operating procedures for the trial, and ensured that all relevant staff, centrally and at the pilot sites, were trained in their use and had signed the relevant registers confirming this.

Chapter 5 Participant recruitment: actual recruitment rates versus planned recruitment rate and strategies used to try and improve this

Participant recruitment to the trial

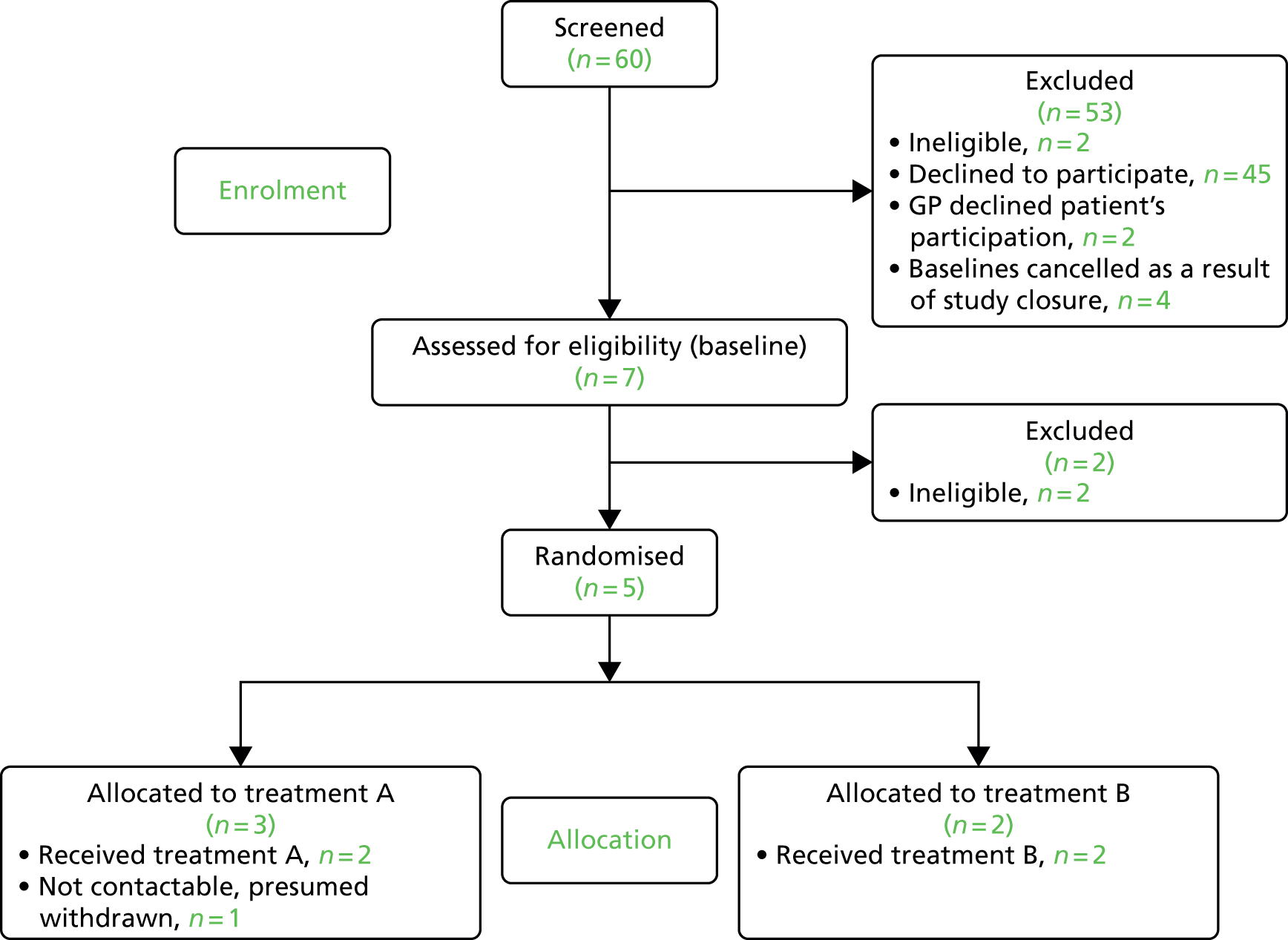

Once the sites were open to recruitment, both the screening and recruitment of trial participants was very slow. The results of screening and recruitment are summarised in Figure 4, the CONSORT diagram covering the time period from 1 July 2015 until 18 February 2016 following a monitoring meeting with the NIHR HTA programme, which took place on 14 January 2016 (see Table 3 for further details).

FIGURE 4.

The CONSORT diagram showing participant recruitment and allocation.

Details of recruitment are described in Table 3. The first participant recruited to the trial was from Camden and Islington with Kingston, and was assessed on 29 September 2015 and randomised on 1 October 2015.

| ToSCA pilot site | Open to recruitment date | Number of identified patients | Number of dropouts | Reasons for dropouts/uncertainty | Number of expressions of interest | Number of further dropouts/withdrawn patients | Number of completed baseline assessments | Number of scheduled baseline assessments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camden and Islington (with Kingston) | 1 July 2015 | 32 | 25 | 7 | 4/1 | 2 eligible | 0 | |

| Camden | 11 | 9 |

|

2 | 2/0

|

0 | 0 | |

| Islington | 16 | 12 |

|

4 | 2/1a

|

1 eligible | 0 | |

| Kingston | 5 | 4 |

|

1 | 0 | 1 eligible | 0 | |

| Greenwich | 17 August 2015 | 4 | 3 |

|

1 | 0/0 | 1 eligible | 0 |

| Coventry and Warwickshire | 3 September 2015 | 12 | 6 |

|

6 | 0/1b | 3 (2 eligible and 1 ineligible) | Two pending baselines cancelled because of study closure |

| Bristol | 8 September 2015 | 12 | 6 |

|

6 | 3/0

|

1 ineligible | Two pending baselines cancelled because of study closure |

| Total | n/a | 60 | 40 | n/a | 20 | 7/2 | 7 | Four pending baselines cancelled because of study closure |

The second participant was from Greenwich, assessed on 18 November 2015 and randomised on 20 November 2015. The next three participants recruited came from Camden and Islington with Kingston (one participant), and Coventry and Warwickshire (two participants), and were randomised on 19 November 2015 and 4 and 6 January 2016. All were assessed no more than 2 working days previously – the participant randomised on 4 January 2016 had been assessed on 30 December 2015 just prior to the New Year holiday.

In addition, two potential participants were found ineligible for the trial at the baseline assessment – one from Coventry and Warwickshire assessed on 29 October 2015, who was uncertain whether or not GAD was the most important issue affecting their mental health, and one from Bristol assessed on 7 January 2016, who was excluded because they had current major depression as assessed on the MINI questionnaire. 43

In a further two cases (both in Camden and Islington with Kingston), their GPs were not prepared to agree to have their patients in the trial or to prescribe sertraline for their GAD should they be randomised to the medication arm, so it was not possible to proceed with the baseline assessment despite the patients expressing an interest in taking part in the trial.

A little ironically, a further four potential participants identified in January 2016 (two from Coventry and Warwickshire and two from Bristol) had to have their baseline assessments cancelled following the NIHR HTA programme decision to withdraw funding from the trial (see Chapter 8).

Actual recruitment rates versus planned recruitment rate

We had anticipated that recruitment would be slow in the first 3 months of the internal pilot while we were testing our recruitment methods, but had expected it to improve after this as the pilot sites became familiar with participant identification and recruitment processes. In our submitted key progress figures we indicated that we expected to recruit two participants in the first month, three in the second, four in the third, five in the fourth and then 10 participants in each of the following 8 months – resulting in an anticipated total recruitment of 90 participants over the 12-month period of the internal pilot. We had an internal pilot target to achieve at least 70% of this (i.e. 63 participants recruited at 1 year).

The very slow rate of recruitment to the trial unfortunately meant that at the end of January 2016, 7 months into the internal pilot, we had recruited only seven participants, as opposed to the projected 40 anticipated (Figure 5). This was despite trying a variety of strategies to improve the recruitment rates, as described in following sections.

FIGURE 5.

Graph showing ToSCA actual recruitment against anticipated recruitment.

Reasons for difficulties with recruitment