Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/104/20. The contractual start date was in October 2013. The draft report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in February 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Michael Kerr reports personal fees from Johnson & Johnson outside the submitted work. Paul Deslandes and the Cardiff and Vale University Health Board department he previously worked for received an honorarium from Janssen-Cilag Ltd for a speaking engagement in 2014 and funding for conference registration fees in 2015. Kerry Hood is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee and a member of the Health Technology Assessment General Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by McNamara et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Prevalence of learning disability and antipsychotic prescribing

The age-specific rate of registered learning disability (LD) in people aged ≥ 16 years in Wales is 0.47% (Local Government Data Unit 2011)1 and the rate of adult users of LD services in England is also estimated to be 0.47% of the adult population. 2 In the two countries combined, this results in an estimated 200,000 adults with LDs.

An audit of adults with LDs in primary care in Wales (n = 9947) found that 29% were prescribed antipsychotic medication. 3 An earlier and smaller primary care study in England4 found that 21% of 357 adults with LDs were prescribed antipsychotic medication. Applying the average of the two estimates to the number of people above suggests that there are 50,000 adults with LDs in England and Wales who are prescribed antipsychotic drugs. A comparison of the Perry et al. 3 and Molyneux et al. 4 rates of antipsychotic prescribing for adults with LDs in primary care gives no reason to think that the prescription of antipsychotics is declining. Indeed, a more recent North American survey5 found that 45% of 4069 individuals with a LD who lived in the community and received services from the New York State Office for People with Developmental Disabilities received antipsychotic medication, with 39% receiving atypical drugs and 6% being prescribed typical drugs.

The rate of prescription of antipsychotic medication in this population far exceeds the estimated prevalence of psychosis (3–4%). 6,7 The discrepancy may be accounted for by the use of antipsychotic medications for the treatment of behavioural problems, which is the most common reason that they are prescribed. 4,8–10 Rates of prescription among samples of people with LDs with challenging behaviour cluster around 50%11,12 and may be as high as 80–95% among those in specially designated services. 13,14 After taking account of prescription of antipsychotics for the treatment of psychosis, about 42,000 of the estimated 50,000 adults with LDs in England and Wales may be receiving these medications to treat or control challenging behaviour. In a recent study of primary care prescribing commissioned by Public Health England,15 it was estimated that between 30,000 and 35,000 adults with a LD were being prescribed an antipsychotic, an antidepressant or both, despite having no recorded diagnosis of psychosis or affective disorder. This estimate equates to 16.2% of adults in England registered as having a LD by their general practitioner (GP).

Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antipsychotics for challenging behaviour

The clinical effectiveness of antipsychotic medications in treating or controlling challenging behaviour has not been demonstrated. 16 Their use may, therefore, be considered mistreatment in some cases. 10 A Cochrane review failed to find evidence to support such treatment17 and a review of 56 treatment trials found that the great majority lacked scientific rigour and the remainder found conflicting results. 18 A more recent review19 found evidence to suggest that a number of atypical antipsychotics are effective in treating challenging behaviour in adults with LDs and autism, although the authors acknowledge that tolerability and the balance of benefit versus adverse effects is unclear in this population. A recent cohort study of mental illness, challenging behaviour and psychotropic drug use in LD also concluded that more evidence with regard to the safety and efficacy of these medications is needed when prescribed for challenging behaviour without a corresponding diagnosis of severe mental illness. A double-blind randomised controlled trial (RCT) exploring the impact on aggression of haloperidol (a typical antipsychotic), risperidone (an atypical antipsychotic) and a placebo found that patients who were given the placebo showed no evidence of worse response than patients assigned to either of the antipsychotic drugs at any time point. 20 An accompanying economic evaluation concluded that the treatment of challenging behaviour among people with LDs by antipsychotic medication is not a cost-effective option. 21

Perry et al. 3 reported that there were 4714 prescriptions among the 2891 people who were prescribed antipsychotic medication, of which 2008 (43%) were for atypical medications. Romeo et al. 21 reported mean half-year medication costs for groups enrolled in a trial of risperidone and haloperidol as £127 and £8, respectively. Using these as estimates for the cost of all atypical and typical medications prior to the start of this trial produced an estimate of the full-year treatment costs for the 2891 people in the Perry et al. 3 audit of £553,328. Extrapolated to the 42,000 figure estimated above gave an annual total cost of £8M for England and Wales without including GP consultation or other NHS costs. However, medication costs are subject to change over time and the cost of risperidone has decreased since these calculations were made.

Known side effects of antipsychotic medications

Apart from a lack of therapeutic and cost-effectiveness for the treatment of challenging behaviour, concern about the high use of antipsychotic medication for this purpose is related to the common occurrence of a range of possible adverse medication side effects in LD populations. 22 These include possible adverse cardiovascular side effects, including thromboembolism, and central and autonomic nervous system and endocrine function side effects, including extrapyramidal side effects, akathisia and other muscle or movement disorders, which may in the case of tardive dyskinesia or tardive akathisia become permanent. 23 Moreover, certain atypical medications are associated with an increased risk of obesity and diabetes mellitus. 24,25 Mahan et al. 26 found that individuals taking psychotropic medication had significantly higher scores on the Matson Evaluation of Drug Side-effects scale in four domains: skin/ allergies/temperature, central nervous system: general, central nervous system: Parkinsonism/dyskinesia and central nervous system: behavioural/akathisia.

These side effects are consistent with those in other populations, such as in adults with schizophrenia,27 in whom movement disorder (typical antipsychotics in particular), weight gain (atypical antipsychotics) and sedation (typical and atypical) are commonly reported, and in adults with dementia, in whom the use of antipsychotics has been associated with stroke and increased mortality. 28–30

Prescribing guidelines for the management of challenging behaviour

The recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance31 acknowledges the limited and low-quality evidence supporting the use of antipsychotics for the management of challenging behaviour in adults with a LD. The guidance also states that antipsychotics should be prescribed only if (1) psychological or other interventions have been unsuccessful in managing behaviour, (2) treatment for any comorbid conditions (physical or psychological) has not resulted in improved behaviour and (3) risk to the individual or others is significant, owing to aggression, violence or self-injury. Further recommendations include the use of medication only in conjunction with behavioural/other interventions, ensuring that appropriate strategies are in place to review prescribing and any benefits or adverse effects and ensuring that there is a plan in place to stop medication, particularly when prescribing is transferred to community or primary care.

In 2014, NHS England commissioned the Winterbourne Medicines Programme32 to review use of antipsychotic prescribing in adults with LDs. The work has identified high levels of inappropriate psychotropic drug prescribing in primary care and in adults with LDs who are detained under the Mental Health Act 2007,33 medication, in some instances, appearing to have been prescribed for challenging behaviour rather than for the underlying mental health condition. As a result of this work, a number of recommendations have been made, including greater involvement of people with LDs, their families and carers in decision-making, provision of active care pathways for challenging behaviours and instigation of a collaborative ‘call to action’34 approach, bringing together patients, families, carers, health professionals and improvement experts to agree the actions required to reduce inappropriate use of antipsychotics. This approach has been used successfully in reducing antipsychotic prescribing in dementia. 28 As a result of the work undertaken by NHS England, The Royal College of Psychiatrists35 has issued a recent report on psychotropic drug prescribing in this population, recommending regular (preferably 3-monthly) review of treatment response and side effects. The report also includes a foreword from Dr Paul Lelliott, Deputy Chief Inspector Hospitals: Mental Health, Care Quality Commission, who states:

There is compelling evidence that a significant number of people with intellectual disabilities are prescribed psychotropic medication that, at best, is not helping them. In particular, there is a risk that doctors are prescribing medication to treat behaviour that is an expression of distress or a mode of communication rather than a mental disorder.

Reproduced with permission from the Royal College of Psychiatrists35 © 2016 The Royal College of Psychiatrists

Withdrawal of antipsychotic medication

A number of drug withdrawal studies have investigated predictors of successful withdrawal from antipsychotic medication,36,37 but these are limited by being retrospective, non-randomised, uncontrolled or inadequately rigorous in measurement. A retrospective clinical audit investigating change from thioridazine for safety reasons among 119 adults with LDs reported poor clinical outcomes. Most adults with LDs were given alternative antipsychotics and a few withdrew. Significant minorities experienced onset or deterioration of adverse effects with the introduction of new drugs or of challenging behaviour or mental ill health, and costs to the specialist psychiatric service rose. 38 However, a randomised controlled withdrawal study reported more positive results. Ahmed et al. 39 conducted a trial in which 56 participants were randomised to an experimental group (n = 36) or a control group (n = 20). In the experimental group drug dose was to be reduced over a 6-month period, in four stages, approximately 1 month apart, between baseline and post-intervention evaluation. Overall, full withdrawal was achieved in 33% of the this group and a reduction of at least 50% was achieved in a further 19%; in 48%, medication was reinstated to baseline levels after partial to full withdrawal. Drug reduction was not associated with higher levels of challenging behaviour and drug reinstatement was not associated with either staff-reported or directly observed measures of challenging behaviour. A recent systematic review40 of reduction or withdrawal of antipsychotics concluded that these drugs can be reduced in adults with a LD, although the authors noted that some participants in some studies did experience adverse effects. However, the authors also note that much of the evidence to date is from relatively small and biased samples and that interventions and comparators are generally inadequately described. It is not possible from the available evidence to identify individual characteristics that could predict a poor response to withdrawal.

A large controlled and blinded randomised trial of the impact of planned withdrawal on resulting drug dosage, behaviour, psychiatric symptoms, safety and the consequent costs of treatment is therefore required.

The ANDREA-LD trial

The initial purpose of this study was to conduct a sufficiently large blinded RCT to investigate whether or not antipsychotic medication prescribed to adults with LDs for the treatment of challenging behaviour could be reduced or withdrawn entirely without adversely affecting their behaviour or mental health or causing a corresponding increase in financial costs. We proposed to limit recruitment to patients receiving risperidone or haloperidol in order to increase the feasibility of blinding while including, within the trial, both atypical and typical medications, specifically those found to be ineffective for challenging behaviour by Tyrer et al. 20 Moreover, as Ahmed et al. 39 found in their open study that reinstatement of medication occurred for almost half of the sample, despite being unrelated to reported or directly observed changes in the level of challenging behaviour, this study was designed to compare the extent of medication change between blinded and unblinded conditions and explore the perceptions of clinicians and carers about medication usage. However, as Chapter 2 describes, poor recruitment led to modified aims for the study.

Chapter 2 Methods

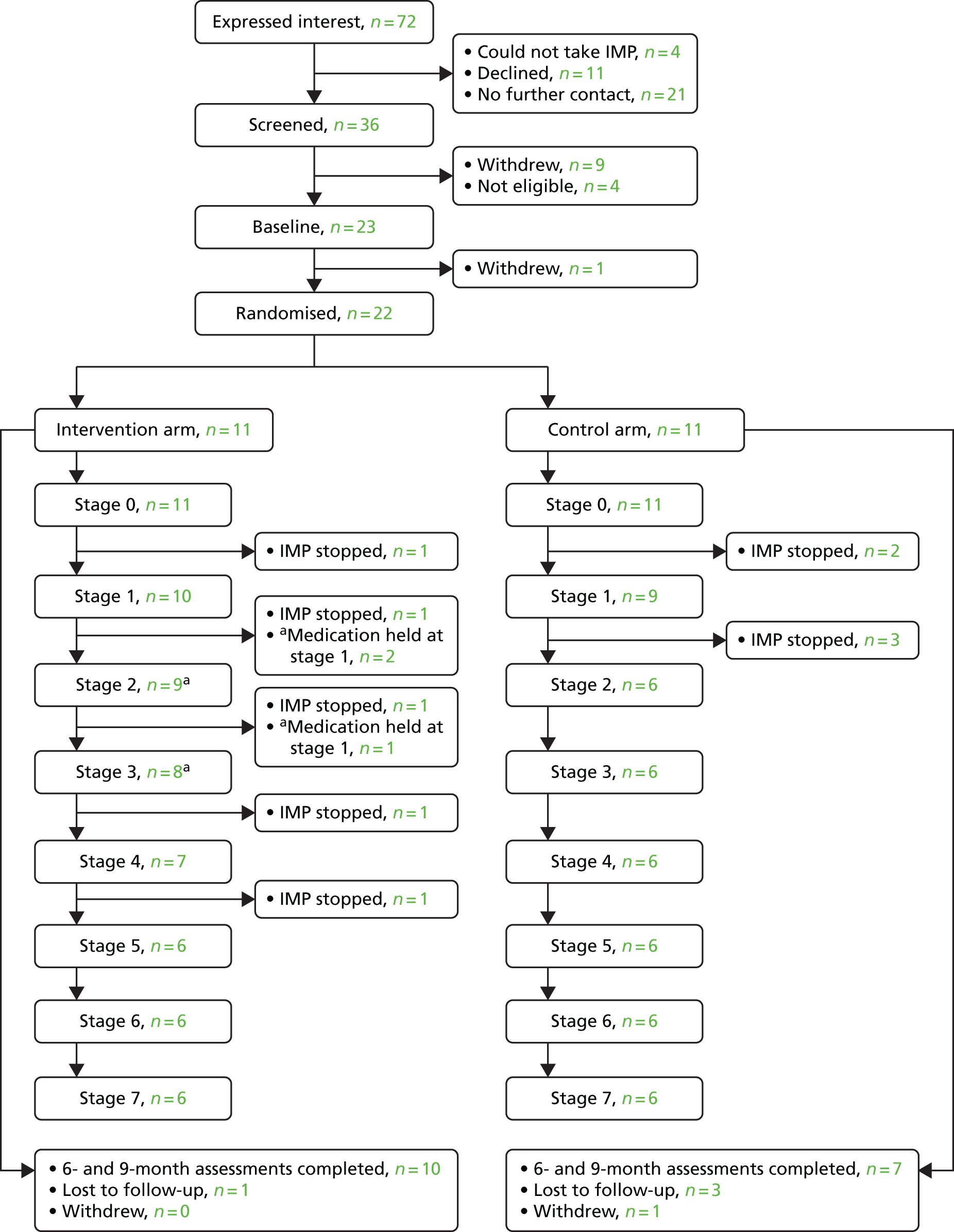

The community-led ANtipsychotic Drug REduction for Adults with Learning Disabilities (ANDREA-LD) trial was originally designed as a large-scale non-inferiority trial of an antipsychotic withdrawal programme in primary care. The main outcome was the level of reported aggression at 9 months post randomisation. With slower than expected recruitment in primary care, the study was expanded to recruit via community learning disability teams (CLDTs). However, because of significant challenges to various elements of set-up and recruitment, the trial closed early and is therefore reported as an exploratory pilot study (as defined by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme). Sections Design, Objectives, Site selection, Participants, Recruitment process, Interventions, Procedures, Outcomes and Statistical methods detail the trial as it was originally designed, and Alterations to study design describes the changes made in response to lower than expected recruitment rates. Exploratory pilot study design details the final presentation of the trial following the decision to close early.

Design

The ANDREA-LD trial was a two-arm randomised (1 : 1) double-blind placebo-controlled non-inferiority withdrawal trial. Those randomised to the intervention arm progressed through a dose reduction regime, while those in the control arm received their treatment as usual. After the baseline assessment, follow-up assessments were planned for 6, 9 and 12 months. The aim was to recruit 310 adults with LDs without psychosis and who were currently receiving one of two antipsychotics (risperidone or haloperidol) for the treatment of challenging behaviour. Ethics approval was given by Wales Research Ethics Committee 3.

Objectives

Primary objectives

The primary objective was to evaluate the impact of a blinded antipsychotic medication withdrawal programme for adults with LDs without psychosis compared with treatment as usual. More specifically, we wanted to determine whether or not reduction or withdrawal of antipsychotic medication prescribed for challenging behaviour without psychosis could be safely achieved without a corresponding increase in aggression, as indicated in previous non-blinded studies. The primary outcome (aggression) was to be assessed at baseline and 9 months (blinded) with levels of aggression compared between the intervention (reduced medication) and control (standard treatment) arms.

Secondary objectives

A secondary objective was to explore the potential non-efficacy-based barriers to drug reduction in clinical practice. We aimed to complete qualitative telephone interviews with principal investigators (PIs), carers and participants to explore their perceptions of involvement in the trial and medication usage, in addition to a final assessment of medication dosage at 12 months.

Site selection

Sites were originally intended to be general practices. Research-active general practices across four health boards in south Wales (Cardiff and Vale University, Cwm Taf, Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University and Aneurin Bevan health boards) were approached to participate in the trial. One GP at each site would be recruited to act as PI and at least one practice nurse was recruited to the task of taking delivery of and handing out study medication to participants.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults with a LD were eligible for the trial if they met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were that the patient:

-

was aged ≥ 18 years

-

had a recognised LD as judged by administrative classification (e.g. on LD register, in receipt of an annual LD health check or in receipt of LD services)

-

was currently prescribed risperidone or haloperidol for the treatment of challenging behaviour.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if:

-

they had a current diagnosis of psychosis

-

they had had a known recurrence of psychosis following previous drug reduction in the past 3 years

-

the clinician primarily responsible for their care judged for any other reason that participation in a drug reduction programme may be contraindicated

-

the research team were unable to identify an appropriate individual to complete outcome assessments.

Recruitment process

Participating sites were asked to identify all patients in their records who had a LD and were receiving either risperidone or haloperidol. PIs then examined the list and excluded any patient who they felt met the exclusion criteria. It was then up to the PI to approach the remaining individuals (or their carers if appropriate) with information about the trial and details of how to indicate a willingness to be approached to participate. This could have been either via completion of an expression of interest form returned in a pre-paid envelope to the study team or by the PI handing contact details directly to the study team, with the individual’s permission.

Once an expression of interest was received, the study team made contact with the patient (or their carer) to discuss the study in more detail, identify key personnel (to provide consent if necessary and complete outcome assessments) and arrange a screening assessment. The screening assessment would be carried out in order to assess the potential participant’s capacity, to gain informed consent and to ensure that inclusion criteria were fully met. Approximately 2 weeks after the screening assessment had taken place, a baseline assessment was carried out. The participant was then randomised by a member of the study team to either experimental reduction or to control treatment as usual (i.e. maintenance of current medication level).

Informed consent

It was expected that although some participants would have the capacity to give informed consent, there would also be a proportion judged by researchers to lack capacity. In such cases, consent from a personal legal representative was sought instead (failing that, from a professional legal representative). Assessment of capacity was made by members of the trial team or the research network, who were professionals with considerable experience in assessing capacity in this population. It was permitted for assessments of capacity and consent to be undertaken by the PI at site if necessary. Criteria for consent included presumption of capacity, an assessment of the individual’s understanding of the risks or benefits of taking part in the trial, their ability to retain this information and their ability to communicate their decision-making. Potential participants were given a plain language and pictorial participant information sheet at least 24 hours in advance of their meeting with the trial team that they could go through with a carer or legal representative (as appropriate) in their own time and at their own speed.

Potential participants with capacity

Upon meeting with the researcher, the trial and potential risks and benefits were explained verbally in simple terms. The researcher checked frequently that the potential participant understood the explanation. Once all questions had been answered individuals who indicated that they were happy to take part in the trial were asked to tick or initial each statement on the consent form as a means of indicating their consent and to sign the form. This process was witnessed and signed off by a carer who was independent of the research team. Participants could decide to withdraw their consent at any stage. A small sample of participants with capacity were also invited to take part in a qualitative interview at the end of the study. Capacity was assessed again at this time.

Potential participants who lacked capacity

When capacity was judged by an experienced researcher to be lacking, a similarly straightforward explanation of the trial and its potential risks and benefits was given verbally to a personal legal representative or, failing that, to a professional legal representative. Neither the personal nor the professional legal representative was connected with the conduct of the trial (e.g. the PI). That individual was asked to give consent on the participant’s behalf. Again, consent could be withdrawn at any stage. Legal representatives were kept informed of all material changes to the trial or participant’s condition to enable them to exercise their right of reviewing the person’s participation in the trial.

Carers of potential participants/principal investigators

The participant’s main carer was also asked to give separate consent to complete assessments designed to be completed by a third party and to consent to taking part in the qualitative interviews at the end of the trial if selected. PIs were also asked to consent to participate in the qualitative interviews.

Risks and expected benefits

Risk was considered against the recognised risks of long-term antipsychotic medication and, therefore, the potential benefits of withdrawal. Benefits would include reduction of cardiovascular risk, in particular stroke, reduction of musculoskeletal risk from tardive dyskinesia and other extrapyramidal side effects, reduction in acute life-threatening risk of malignant neuroleptic syndrome and a broad spectrum of psychosocial benefits from reduction of sedation, associated alertness and concentration and learning. Societal benefits would include increased contribution from adults with LDs who are not constrained by unnecessary medication and reduced expenditure/resource use on unnecessary treatment and medical complications of long-term antipsychotic medication use. However, withdrawal may be associated with the following risks.

-

The emergence of tardive dyskinesia. Advice for PIs on the recognition, assessment and management approaches was included in the detailed treatment and safety package prepared by the trial team.

-

Emergence of unrecognised psychiatric illness. There remained a slight possibility that, especially in the case of those on very long-term antipsychotics, the drugs masked an underlying mental illness. This, if present, was most likely to be an anxiety disorder. Advice for PIs on the recognition and assessment of psychiatric symptoms was included in the detailed treatment and safety package prepared by the trial team. A clinical algorithm (described in Interventions) was developed to support the primary care team to follow the appropriate treatment and care pathways. Clear guidance was available for predicted scenarios in which unblinding may be necessary, such as the emergence of psychotic symptoms.

-

Deterioration in behaviour. A previous study39 showed that measurable behavioural deterioration was uncommon following drug reduction, but other studies have shown greater deterioration and that carer concern can be high. Advice on assessing a meaningful behaviour change was provided in the PI support package. As behavioural signs and psychiatric symptoms for this population are intertwined, the clinical algorithm referred to above also dealt with behaviour change.

Supporting secondary care services

In the case of individuals recruited through general practice and who had involvement with LD services, contact was made with these teams regarding confirmation of eligibility. At this time, a description was given of the study protocol, the PI support package (see Interventions) and the procedure for accessing the code break.

It was not expected that the study would have a considerable impact on the current well-developed specialist LD services. These services would most probably already be aware of many of the individuals involved in the study, and we estimated that the chance of severe deterioration would be small and would be distributed across at least six health boards. It was possible that the study might have increased the referrals to LD services because of a greater awareness of the issue of antipsychotic drug prescribing across primary care. Such referrals would be a positive outcome; LD teams are skilled in drug assessment, and regular review is a key component of good clinical care.

Interventions

The intervention group progressed through up to four approximately equal reduction stages to full withdrawal over a 6-month period while the control group maintained baseline treatment. The following rules were used to decide each participant’s Investigational Medicinal Product (IMP) regime:

-

Participants in both arms stayed on the same number of tablets throughout the study when feasible.

-

For those in the intervention arm:

-

Reductions from stage to stage were as equal as possible, but when this was not possible larger reductions were made first.

-

Reductions were made in such a way that there was only one tablet in each encapsulation.

-

If a participant was on multiple doses per day, preference was given to reducing the middle of the day doses, later doses and then earlier doses.

-

Schedules were reviewed by clinicians and could be changed if there was a valid clinical reason.

-

Drugs were supplied to ensure blinding, but treatment was led by PIs, and, although blinded to whether or not medication was being reduced, the PI retained discretion to delay progression to the next step (i.e. to maintain current medication level).

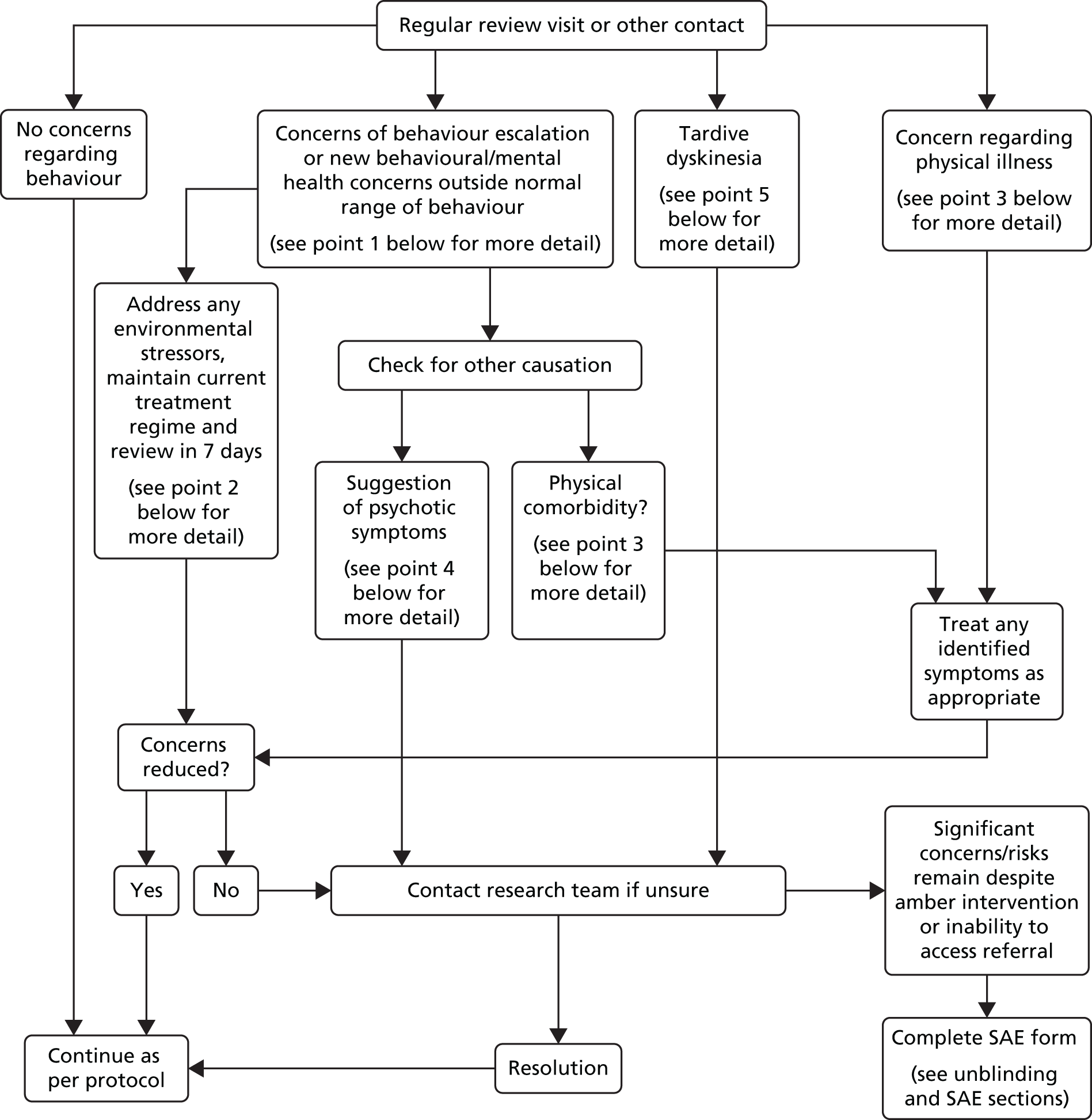

Sites were supported by a detailed treatment and safety package showing clear clinical contact and decision-making to support drug reduction. The chief investigator and co-applicants produced this guidance, focusing on how to respond to participant and carer queries, including those concerned with behavioural deterioration, emergent features of tardive dyskinesia or psychiatric symptomatology. The guidance started with a ‘management flow chart’ and this was followed by more detail on elements such as history taking, examination, consultation with the research team, making appropriate referrals and information on the code-breaking practice. The flow chart (Figure 1) was designed as an easy-access decision-making tool. Each box in the flow diagram pertains to specific issues that were addressed in more detail over the following pages of the support package. PIs were given training in how to use the manual and its content at the point of site initiation and were provided with contact details of the study’s chief investigator and clinical reviewer. As part of their training, PIs were also requested to add labels to participants’ medical notes in order to flag their participation in the trial.

FIGURE 1.

ANDREA-LD clinicians ‘management flow diagram’. Note that the cross-references within the figure refer to those within the support package.

Treatment achieved at 6 months was maintained for a further 3 months under blind conditions. At 9 months following collection of follow-up data, the blinding was broken. PIs were informed of the participant’s treatment allocation and current medication dosage. It was the responsibility of the PIs to then reveal the allocation to the participant and their carer, to handle any further prescribing and to communicate with the participant’s wider care team.

Supply of blinded medication

In order to achieve effective blinding, medication was encapsulated. Risperidone and haloperidol tablets of varying doses were encapsulated based on estimates of the likely numbers of participants recruited on each medication at the common doses. Encapsulated placebo medication that was identical in appearance to active medications was also produced. All participants experienced a change in the supply of their antipsychotic medication at the outset of the study. Although individuals started the trial on their usual dose of medication, it was important to ensure that the number of tablets that they took daily remained constant over the blinded period and that the effective dose could be reduced across dose reduction steps. In order to allow participants to familiarise themselves with their new medication, a run-in period was built into the programme for all participants, regardless of allocation and prior to any reduction.

Manufacturing estimates assumed that all participants would achieve at least a 50% reduction. In reality, the number of reduction steps achieved was likely to be much more variable, although this assumption allowed for a reasonable degree of flexibility. Manufacturing estimates included provision of medications to all participants up to 9 months, when the blind was lifted.

Investigational Medicinal Products were manufactured by St Mary’s Pharmaceutical Unit (SMPU) under its Manufacturer’s Authorisations for IMPs licence and dispensed using Nomad® Clear 2 trays (Omnicell Ltd, Manchester, UK) in accordance with participant-specific prescriptions. SMPU was to do this under section 37 of the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations (2004)41 as ‘post (Qualified Person) certification labelling for safety purposes’. Nomad Clear 2 trays are disposable trays with separate compartments for days of the week as well as times of day – morning, midday, evening and bedtime. IMP was dispensed monthly for 9 months. Although participants were to take 28 days of medication at each stage, enough IMP was provided for 33 days (to allow for a +5-day window around the planned 28-day time frame between medication review visits) in case of any delays or issues in getting the prescription.

Participant-specific prescriptions were issued to SMPU by the research team following consent and randomisation. SMPU then dispensed and dispatched these directly to site, where they were formally received and kept secure by a practice nurse (or designated individual). Accountability documentation was completed on receipt of the IMP and returned to the study team, thus evidencing the ownership of the IMP. Prescriptions were handed out only to the patient or their carer, legal representative or researcher by authorised site staff. Again, accountability documentation was completed and returned to the study team at this time. This process was repeated for the IMP of each new month following the PI’s decision to allow the participant to progress through the trial.

When any new prescriptions of study drug were collected from site, unused IMP from previous stages had to be returned by the participant or their carer. Sites were then responsible for the destruction of any unused study medication in accordance with local procedure and following authorisation from the trial manager. Completion of accountability documentation at various time points allowed the study team to evidence the location of IMP throughout the trial.

Toxicity was not expected and use of all pro re nata (PRN) medication was permitted and recorded in study diaries during the trial. Drug reduction was unlikely to cause interaction with other drugs; however, it was recommended that participants taking warfarin underwent more frequent international normalised ratio tests. All concomitant medication was permitted and details of any medications that had been taken were collected by the research team. IMP was stored at ambient temperatures at site; therefore, no temperature monitoring was undertaken.

Procedures

Piloting

Once the trial was open for recruitment, arrangements were piloted in primary care for 6 months in order to test the assumptions and practicalities of trial processes and recruitment. At the end of this period, any adjustments would be made as necessary and the study was to then continue until full recruitment.

Principal investigator visits/contact

Participants in both trial arms (intervention and control) had five appointments with the PI in total. The first four took place in the 2 weeks preceding the release of each new batch of blinded medication and were approximately 28 calendar days apart. The purpose of the appointments was for the PI to make an assessment of whether or not there were any concerns about the participant’s progression to the next stage of the trial. When face-to-face appointments could not be held, the PI could consult over the telephone. It was the responsibility of participating PIs to provide participants and the study team with details of each of these appointments. The PI provided appointment cards to the participant or their carer and were responsible for reminding participants of the appointment nearer the time of the visit to ensure attendance. The site was also responsible for rearranging any appointments as necessary. The appointment card contained the contact details of the PI, an emergency number for participants or carers to use should they need to and a reminder of the amount of medication the participant had been taking when they started the study. It was important that the PI was the first point of contact for participants or carers if they had any concerns. The fifth PI visit took place after the 9-month assessment and was for the PI to unblind the participant and their carer and reveal the treatment allocation. It was also the point at which a discussion would take place regarding the participant’s care from there on.

Practice nurse visits

Participants (or their carer/representative) in both trial arms (intervention and control) collected their prescribed study medication from the practice nurse monthly until the blind was broken at 9 months. At each of these visits, the practice nurse took receipt of any unused medication from the previous prescription before distributing any new medication. The practice nurse would then complete accountability paperwork before destroying any unused medication on confirmation from the trial manager.

Assessments and follow-up

Eligibility data were collected at screening. Full data were to be collected at baseline and post intervention, approximately 9 months from randomisation (Table 1). Data on medication and psychopathology [Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), Aberrant Behaviour Checklist (ABC), Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disability (PAS-ADD) checklist] and costs [Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)] were to be obtained at 6 months and 12 months. All data collection was face-to-face, either at site or during home visits.

| Assessment time points | Measures and data collection | Participant involved | Estimated time to complete appointment (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Age, gender, current medication, ABS, Mini PAS-ADD checklist | Carer | 1.5 |

| Baseline | Medication, MOAS, ABC, PAS-ADD checklist, CSRI | Carer | 1.5 |

| ASC, DISCUS | Participant/carer | ||

| 6 months | MOAS, ABC, PAS-ADD checklist, CSRI | Carer | 1.5 |

| 9 months | MOAS, ABC, PAS-ADD checklist, DISCUS, ASC, CSRI | Carer | 1.5 |

| 12 months | Medication, MOAS, ABC, PAS-ADD checklist, CSRI | Carer | 1.5 |

Details of outcomes and follow-up time points can be seen in Table 2 and were the same for both experimental and control groups.

| Outcomes | Measure | Time point | Estimated time to complete assessment (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive behaviour | ABS | Screening | 40 |

| Mental health | PAS-ADD checklist | Screening,a baseline, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months | 30 |

| Adverse effects of psychotropic medication | ASC | Baseline, 9 months | 15 |

| Movement disorders | DISCUS | Baseline, 9 months | 7 |

| Aggression | MOAS | Baseline, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months | 5 |

| Other challenging behaviour | ABC | Baseline, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months | 10 |

| Costs | CSRI (modified) | Baseline, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months | 10 |

Outcomes

Screening measure

Information collected included age, gender, current medication and psychiatric history. In addition, adaptive behaviour was assessed using the Adaptive Behaviour Scale (ABS)42 as a means also to estimate intelligence quotient (IQ). 43 Current mental health status was assessed using the PAS-ADD interviews. 44 The data gathered were used to confirm inclusion and exclusion criteria. If required, clinical review was undertaken for those exceeding thresholds for the ABS (a score that converts to an estimated IQ of > 70 using the method described by Moss and Hogg43) and/or the Mini PAS-ADD checklist (a score for section M, potentially indicative of psychotic disorder, of > 2).

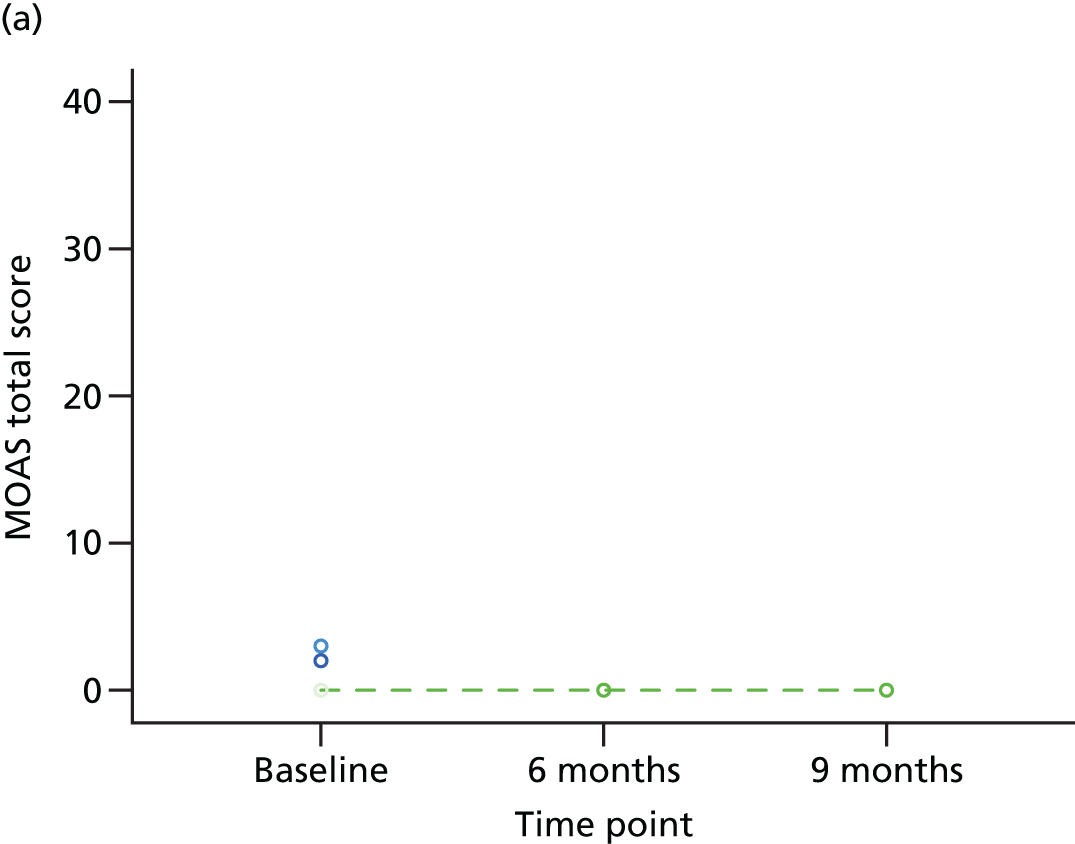

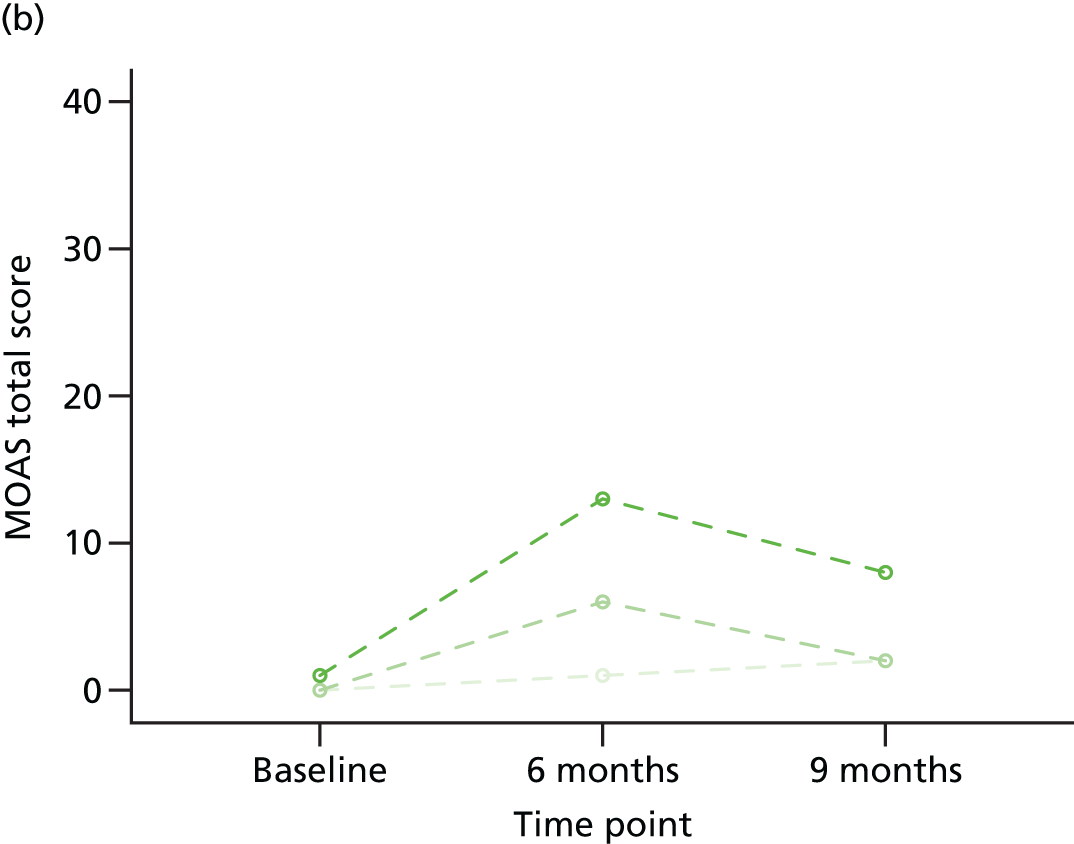

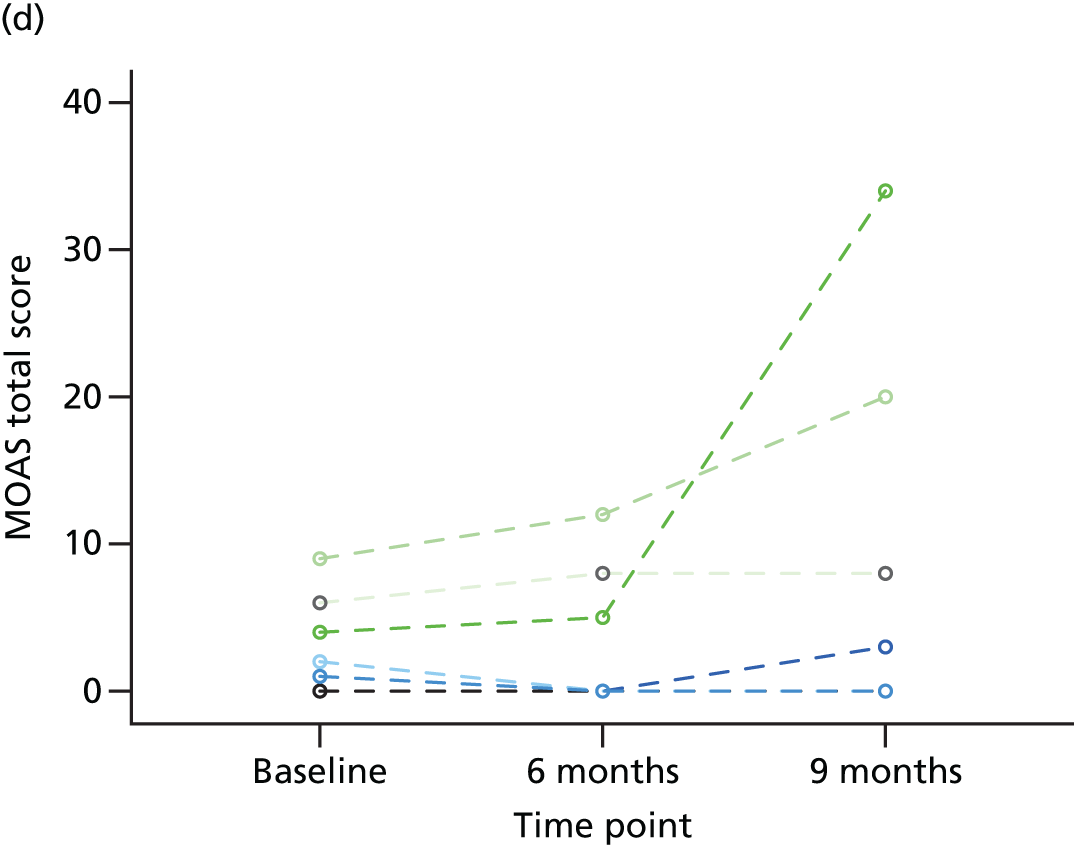

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was aggression and was evaluated using the MOAS. 45 The MOAS rates four categories of aggression (verbal aggression, destruction of property, self-mutilation and physical aggression to others) each on a scale of 0–4 but then weighted by an ascending index of seriousness. The measurement to be used here was a non-inferiority comparison; therefore, a score difference of ≤ 3 was to be taken as clinically non-significant.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures at baseline, 6-month, 9-month and 12-month assessments were as follows.

-

The ABC46 comprising 58 behaviours, each relating to one of five subscales, to assess other challenging behaviour.

-

The PAS-ADD checklist47 to monitor mental health. The PAS-ADD checklist is a 25-item questionnaire designed for use primarily with care staff and families. The scoring system includes threshold scores, which, if exceeded, indicate the presence of a potential psychiatric problem in the scale’s three diagnostic domains (affective or neurotic disorder, possible organic condition and psychotic disorder). The proportions of people reaching threshold scores for possible mental ill health were to be compared.

-

The Antipsychotic Side-effect Checklist (ASC)48 was used to measure adverse effects of psychotropic medication. The ASC comprises a list of the more common or clinically important side effects of antipsychotic treatment.

-

The Dyskinesia Identification System Condensed User Scale (DISCUS)49 was used to assess movement disorders. A psychometrically derived DISCUS threshold of 5 was to be used.

-

The CSRI was modified for use in those with LDs and has been used previously in LD research. 21,50 The CSRI was used to collect data on a comprehensive range of services used and support received by each individual in the study. The collection of these data facilitated the calculation of the cost of medication, health, social care and unpaid carer inputs incurred by trial participants because of challenging behaviour or mental ill health.

The primary and secondary outcomes relating to challenging behaviour and mental health were to be analysed for non-inferiority with other secondary outcomes, such as medication usage and adverse effects, to be analysed for difference. A description of all scales, the range of their possible values and their interpretation is given in Appendix 4.

Statistical methods

Randomisation and unblinding

The offline password-protected randomisation programme was designed by the trial statistician and based on the method of minimisation. Allocations were balanced with respect to medication type (risperidone/haloperidol) and dose: low (< 4 mg for risperidone and < 5 mg for haloperidol) and high (at least 4 mg for risperidone and at least 5 mg for haloperidol). A random component, set at 80%, was used alongside the minimisation procedure to increase the integrity of the minimisation process (i.e. there was an 80% chance that the allocation would minimise the imbalance with respect to the aforementioned balancing variables).

Following consent and baseline assessments, participants were randomised to either the intervention arm (gradual reduction) or the control arm (treatment as usual) in a 1 : 1 ratio by a member of the study team. Any unblinding was performed only after authorisation from the chief investigator or (if not available) an authorised clinical reviewer who was an appropriately qualified clinician and member of the trial management team. In the event of an emergency, the treating clinician would have access to details of the participant’s baseline dose (i.e. the dose at which they entered the study) and so could treat accordingly.

Sample size

We originally aimed to randomise 310 participants (155 per group) in total, which would have provided 90% power to fit a one-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) around the between-group difference in mean MOAS scores at 9 months post randomisation. A sample size of 310 assumed a non-inferiority margin of 3 and a standard deviation (SD) of 8 (i.e. an effect size of 0.375) and had been adjusted to allow for 20% attrition.

Main analysis

The original proposed primary analysis focused on a comparison of MOAS scores at 9-month follow-up between the two trial arms. An analysis of covariance model, with baseline MOAS score and variables balanced on/stratified by at randomisation (medication type, dosage and recruitment source) controlled for as covariates, would have been fitted. Using the estimates from this model, a one-sided 95% CI of the adjusted mean difference in MOAS scores at 9-month follow-up (intervention – control) would be calculated. Non-inferiority would have been concluded if the limit of the CI was < 3 in all study populations [complete case (CC); full intention to treat (ITT), with multiple imputation used to impute missing outcome data; and a per protocol (PP), which would include participants who had outcome data available, had not withdrawn from trial treatment and, if they were allocated to the intervention group, had experienced at least one reduction].

A complier average causal effect analysis would have been performed as a secondary analysis of the primary outcome, to obtain an ITT estimate in the treatment adherent. If non-inferiority was concluded, a superiority analysis of the difference in MOAS scores between trial arms was planned in the CC and ITT populations, using a two-sided 90% CI.

All secondary analyses (antipsychotic medication use, other challenging behaviour, mental health, adverse effects, movement disorders) would have been conducted using the CC population, with those secondary outcomes assessed for non-inferiority (challenging behaviour and mental health) and adverse effects also being analysed using the PP population.

Potential moderators of the effect of the intervention on MOAS score (e.g. age, gender, medication type or adherence to intervention) would have been explored in multivariable analyses using interaction terms. It was also originally proposed to model aggression levels using mixed models to explore changes over time.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The original proposed main cost-effectiveness analysis focused on the comparison of the two trial arms through the calculation of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, defined as the difference between trial arms in mean costs divided by the difference in mean outcome (MOAS score) over 9 months.

It was proposed to conduct the main cost-effectiveness analyses from health and social care agencies and a wider societal perspective to include health and social care agencies and unpaid carers. To inform the cost-effectiveness analyses from these two perspectives, it was proposed that comprehensive data on health, social care and other services used by individuals were included in the study, using a tailored version of the CSRI. To estimate component costs, service use data were due to be combined with the unit costs for each service using long-run marginal opportunity cost principles. For services in which national figures were not available or not suitable, we proposed to calculate best estimates of long-run marginal cost; values and time spent by friends or relatives providing support were due to be estimated using the unit costs of a local authority care worker. Three main categories of costs due to be analysed were (1) medication costs; (2) medication costs, aggregated health and social care costs, consisting of inpatient admissions, outpatient appointments, accident and emergency department contacts and community-based health and social care contacts; and (3) medication costs, aggregated health and social care costs and cost of time spent caregiving by relatives and friends.

Costs were proposed to cover the period from baseline to 6 months (the end of the full treatment withdrawal period) and 6–9 months (3 months following the full treatment withdrawal period). The MOAS score was to be used as the primary measures of effectiveness in a series of cost-effectiveness analyses. As cost data are likely to be skewed, and to explore if unobserved difference in service use at baseline between the allocation groups may result in differences in cost between treatment groups, regression analysis using bootstrapping was proposed, adjusting for baseline covariates (MOAS score, baseline costs and variables balanced on/stratified by at randomisation: medication type, dosage and recruitment source).

A series of cost-effectiveness analyses was to be conducted by combining outcomes with costs from health and social care agencies and unpaid carers in turn. In the event that the experimental reduction group had lower costs and better outcomes than its comparator, it would have been interpreted as the dominant treatment, and if the experimental reduction group had higher costs and worse outcomes than the comparator treatment, the experimental reduction group would have been dominated by the comparator. If the experimental reduction group was both more effective and more costly than its comparator, the nature of the trade-offs to be made would have been made using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs). To generate the CEAC and non-parametric bootstrapping of the costs and effectiveness, data would have been used to generate the joint distribution of incremental mean costs and incremental effects. The CEAC shows the likelihood of one treatment arm being seen as cost-effective relative to another treatment arm given different (implicit monetary) values placed on incremental outcome improvements.

We originally planned to use one-way sensitivity analyses to examine robustness of the findings to (1) changes in the unit costs of informal support, (2) analyses based on all randomised participants whose 9-month follow-up MOAS score is known (CC population) and (3) analyses based on all randomised participants (ITT population).

Qualitative study

We undertook qualitative telephone interviews with a proportion of carers, PIs and participants who took part in the trial. One of the main purposes of these interviews was to gain insight into the non-efficacy-based barriers to drug reduction in clinical practice, as well as attributions of behavioural changes in relation to potential reduction of medication. The interviews were scheduled to take place during the unblinded phase of the trial between the 9- and 12-month time points and were to ascertain (1) views about participating in the study, (2) reasons for any partial or full reinstatement of medication after unblinding and (3) views about antipsychotic medication use to treat or control challenging behaviour for the participant, in particular, and the patient group in general. PI interviews also focused on PI views of the support package and views about how the patient and carer(s) managed during the trial period. Interviews were expected to take up to 30 minutes.

We aimed to interview up to 60 carers and the corresponding PI. It was hoped that both parties would agree to take part in these paired interviews, but we accepted that this was not guaranteed. The sample was to be selected, purposefully incorporating participants from both trial arms and from across the geographical recruitment areas.

We also hoped to interview a proportion of participants of the ANDREA-LD trial. Those taking part would be required to have the capacity to provide consent for a face-to-face interview. Interview topics for participants focused on (1) the reasons of participants for participating in the trial, (2) how they felt they managed during the trial period and (3) their views about taking medicines to help with their behaviour.

Carers and participants who agreed to take part in an interview were offered a £10 high street shopping voucher to thank them for their time and considered views. PIs who participated in interviews were offered £50. With the participants’ consent, all interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and anonymised.

Qualitative analysis

It was proposed that data from the transcribed anonymised telephone interviews would be subject to thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke. 51 Thematic analysis allows researchers to take an initial inductive approach towards the data set. Following familiarisation with the data, researchers index data according to a priori and emerging themes. A priori themes are informed by the research literature on the topic of antipsychotic medication for people with LDs. Analysis is facilitated by use of the computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software package NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Data from each data set (participants, carers and PIs) would be analysed separately and then comparisons made across data sets.

Alterations to study design

Recruitment via community learning disability teams

Despite expansion of recruitment in primary care to areas in England, it was apparent that targets would not be achieved in the predicted time frames by relying on this route. We gained approval from the funders to expand recruitment to CLDTs, with LD psychiatrists acting as PIs and hospital-based pharmacies taking on the role of the practice nurses and dispensing trial medication.

Twenty LD psychiatrists from six trusts in Wales and England were then recruited to act as sites in the trial. An additional 13 hospital pharmacies were recruited in order to dispense trial medication.

Other alterations

Evidence from screening logs showed that the number of potential participants receiving haloperidol was much lower than expected. For this reason, the decision was taken not to manufacture blinded haloperidol medication but to continue to recruit only those taking risperidone. With these changes in place, the randomisation programme was also altered so that allocations were stratified by recruitment source (general practice/CLDT) and balanced with respect to medication dose only: low (< 4 mg for risperidone) and high (at least 4 mg for risperidone).

Exploratory pilot study design

Exploratory pilot study methods

In November 2015, the decision was taken to close the trial to recruitment because of the difficulties described. At this point, 22 participants had been recruited into the trial. The study team submitted a close-down plan to the funders and it was agreed that all randomised participants would continue to receive the intervention and follow-up to 9 months. This meant that the trial would be complete by the end of June 2016 and would be reported as an exploratory pilot study (as defined by the Health Technology Assessment programme). As such, there were a few key alterations to the methods previously described, which are detailed in Table 3.

| Change | Study component | Changes to design |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sample size, recruitment and retention | No specified sample size; 22 recruited |

| 2 | Length of follow-up | Reduced from 12 months to 9 months post randomisation |

| 3 | Intervention | No change |

| 4 | Analysis of primary and secondary outcomes | Still pre-planned, but primarily focusing on outcomes related to conducting antipsychotic drug withdrawal trials in a LD population (see Exploratory study analysis for more details) |

| 5 | Qualitative analysis | Interviews brought forward to 4- to 6-month time point. Focus shifted to feedback on involvement in the trial and sample reduced |

| 6 | Economic evaluation | Not reported |

Exploratory study analysis

As the required sample size would not be achieved, we planned to focus on estimating feasibility outcomes. With a particular interest in recruitment and retention, we planned to estimate the following:

-

the number and proportion of primary care practices/CLDTs that progressed through the various stages from initial approach to recruitment of participants

-

the number and proportion of recruited participants who progressed through the various stages of the study.

We also compared trial arms regarding the following clinical outcomes:

-

MOAS at 6 and 9 months post randomisation

-

level of psychotropic medication use, assessed at the 6-month and 9-month post-randomisation assessments

-

ABC at 6 and 9 months post randomisation

-

PAS-ADD checklist at 6 and 9 months post randomisation

-

ASC at 9 months post randomisation

-

DISCUS at 9 months post randomisation

-

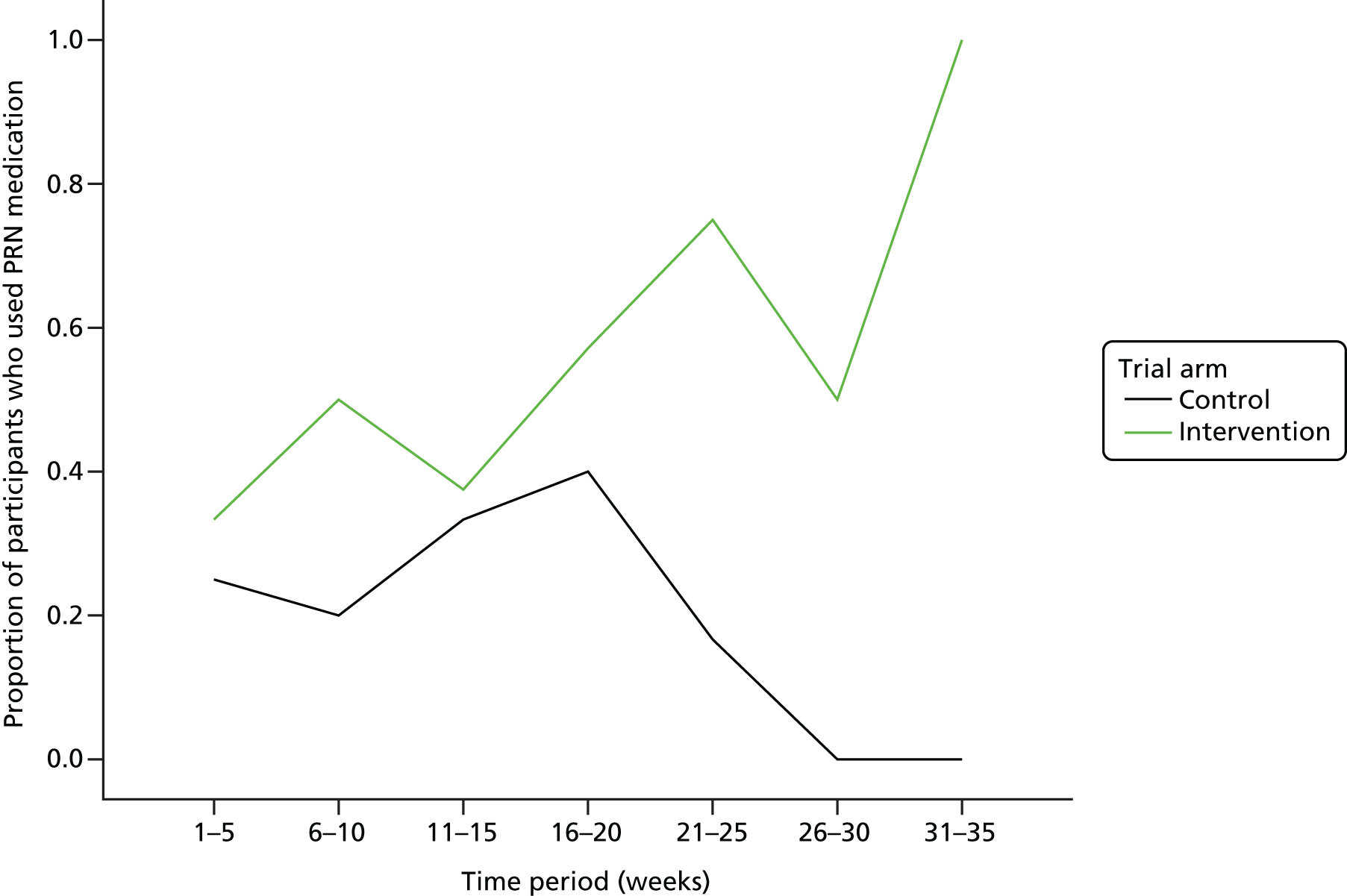

use of PRN medication over the study period

-

use of other interventions to manage challenging behaviour at 9 months post randomisation, including:

-

physical intervention/restraint

-

seclusion

-

PRN medication

-

-

costs and service utilisation at 6 and 9 months post randomisation.

The analysis of recruitment and retention outcomes was descriptive, with frequencies and percentages reported both overall and split by recruitment route (primary care or CLDTs). Pre-randomisation variables, including those related to the participant, their recruitment route and their starting medication, were used to explore the association between participant characteristics and their progression through the study post randomisation (to stage 4 of the intervention).

Clinical outcomes were compared between arms using appropriate regression models (linear or logistic, depending on type of variable). Data transformations were made, when required, to fulfil regression assumptions. The analyses were also adjusted for the corresponding clinical score at baseline (if measured), as well as variables that were balanced on at randomisation [dose of antipsychotic medication (< 4 mg or ≥ 4 mg) and recruitment route (primary care or secondary care)].

Three analysis sets were considered:

-

The ITT population, which comprised all randomised participants. When participants had either withdrawn from the study intervention (but remained in the trial for follow-up assessments) or not provided follow-up assessments at 6 or 9 months post randomisation, it was assumed that they returned to their original starting dose.

-

The modified intention-to-treat population (MITT), which comprised all randomised participants whose follow-up data were known.

-

The PP population, which comprised all randomised participants who had progressed to stage 4 of the intervention (regardless of the trial arm to which the participant was randomised).

The analysis of the level of psychotropic medication at 6 and 9 months was conducted in the ITT, MITT and PP populations. The remaining clinical outcomes analyses were conducted in the MITT and PP populations only.

As it was the original primary outcome, further exploratory analyses were performed with the MOAS score:

-

The MOAS score at 9 months post randomisation was fitted with a two-sided 90% CI in order to reflect the original primary analysis intended for this study.

-

Individual trajectories for the MOAS scores at baseline, 6 months and 9 months post randomisation were plotted and described, with particular attention paid to individuals whose MOAS scores changed by at least 4 points (a change considered to be clinically meaningful).

Economic analysis

Owing to the small sample size of the exploratory pilot, economic analysis was not reported as planned.

Chapter 3 Setting up and delivering a drug reduction trial for adults with learning disabilities: challenges and lessons learned

The unique nature of this trial meant that there were particular challenges faced that had not been experienced by other research in this area. These have been summarised under the following headings.

Recruitment

Recruitment of sites

Research-active general practices in south Wales and south-west England were recruited into the study in the first instance. Initially, the number of practices interested was quite low; therefore, we expanded our approach to include practices that were not known to be research active. In total, approaches were made to 351 practices in four health boards in south Wales and 127 in eight Clinical Commissioning Groups in south-west England using a variety of methods, including e-mails, mailshots, articles in GP magazines/circulars and follow-up phone calls. The result was an active decline response from 204 practices across Wales and 17 practices in England and no response from the rest.

When recruitment later moved to CLDTs, we approached 30 LD psychiatrists also in south Wales and south-west England. While the decision to participate in the research could be made at a practice level by GPs, this decision required buy-in not only from the whole health board or trust at secondary care level but also from the LD services and teams. In one area, meetings were held with a member of the trial team and representatives from the whole LD directorate before a decision was made to participate. Concerns centred mainly around the buy-in from wider care teams and how any escalations in behaviour would be handled and communicated between relevant parties. Of the 30 LD psychiatrists approached, 20 across six health boards/trusts agreed to take part in the trial.

In primary care, a site was considered to be the general practice, and in secondary care a site referred to the LD directorate of each health board or trust. Owing to the changing nature of the NHS, establishing which was the appropriate body to obtain approval from was more complex than expected. In one area of England, provision of LD services was provided on behalf of the NHS by a community interest company. Research was not something commonly dealt with by the company; therefore, the permissions process was unclear and took time to establish. This had the knock-on effect of delaying the recruitment of investigators and, thus, of participants.

Gaining permissions to use community LD services in south Wales was also challenging. The Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board LD directorate acts as the provider of LD services across Bridgend, Cardiff, Merthyr, Neath Port Talbot, Rhondda Cynon Taf and Swansea. This meant that permission to recruit participants through the LD clinics in these areas was gained through the Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board but the permission to use hospital pharmacies that were local to those clinics was gained through each individual health board.

Recruitment of participants depended on ensuring that approvals were in place for an investigator and a local hospital pharmacy at the same time. This had an impact on recruitment in one health board, as approval had been granted to recruit through a LD clinic by one health board but the health board in charge of the local hospital pharmacy delayed granting permission for some months while the board reviewed the request. Securing NHS costs added to the delay in gaining permission to recruit in certain areas, as the allocation process had become more complex with this change in study recruitment.

Recruitment of investigators

Along with permission from research and development boards, it was necessary for investigators to have undertaken Good Clinical Practice (GCP) training before undertaking research activities. This proved to be an obstacle for many, particularly in secondary care settings in which clinician involvement in research was less common. GCP training is specific to clinical trials and typically takes up to 3 hours to complete – a time commitment that was not always easy for clinicians to accommodate. Despite having 16 investigators based in primary care sites and 20 in CLDTs, only 14 of these recruited any participants into the trial: three GPs and 11 community LD psychiatrists. Low recruitment rates on the part of PIs are explored in more detail through interviews that are reported in Chapter 6.

Of the 11 psychiatrists who recruited participants, three were specialist registrars in LDs. The specialist registrars were able to provide invaluable support for the trial in that they took on the role of investigator, obtained GCP training and were able to see a number of participants on behalf of other clinicians who might not have had the time to get involved in research. Specialist registrars worked on rotation, however, and if they moved to different health boards or trusts there were difficulties in maintaining care of participants as part of the trial. Fortunately, we were able to overcome this in the current trial and arrange for other clinicians to take on the role of investigator.

Recruitment of participants

Details of the eligibility criteria were clearly laid out in the trial protocol, and practices and LD teams were able to identify sufficient numbers of potentially eligible patients. However, the number of potentially eligible patients who were actually approached with details about the trial was fairly low, particularly among primary care clinicians.

The study team drafted an audit tool that provided search terms and Read codes for general practices to help them identify those who might be eligible to take part. Once patients had been identified, GPs appeared reluctant to directly approach these patients or their carers about the study and to invite them to take part. It is not clear what the reasons for this were, as we did not gain any feedback through interviews with primary care clinicians (this is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6). Anecdotal feedback suggests that it may have been in part because of the nature of the consent procedure as well as concern about taking on decisions for care that are normally the domain of secondary care LD clinicians. However, following the change in recruitment from primary care to CLDTs, primary care practices became participant ID (identification) centres, rather than full sites, in an attempt to mitigate this issue. When clinicians had identified patients who might potentially be eligible, it was then possible to refer them to the CLDT clinicians who would be able to discuss the study in more detail. This potential was not subsequently utilised by GPs and did not result in participants coming from leads in primary care.

Consent procedure

There is understandable anxiety over the capacity of individuals with intellectual impairment to participate in clinical trials. Within the drafting of the Mental Capacity Act 200552 specific provision was made relating to the care, treatment and decisions on behalf of people who lack capacity, including participation in clinical trials. Further, important information is contained in the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations (2004). 41 As a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP), the ANDREA-LD trial was required to adhere to the latter regulations (which supersede the Mental Capacity Act 2005), meaning that, in the case of those who lacked capacity, consent would need to be given by a personal or professional legal representative of the participant. Although clinicians (particularly CLDT psychiatrists) are well versed in the Mental Capacity Act 2005,52 a lack of experience in research means that many are not familiar with differences in the consent procedure as specified under the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations (2004). 41

It was expected that many potential participants in the ANDREA-LD trial would probably lack capacity to give informed consent, and so clear study-specific guidance explaining the Regulations was drafted. The guidance specified that the following factors needed to be taken into consideration.

-

First, no patient would be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practical steps to help them to do so had been taken without success.

-

Second, even if an individual lacked capacity, their opinion would still be taken into consideration.

-

Third, should they lack capacity, the research team would, in accordance with due legal process, consult with relevant parties to clarify whether or not their participation was in the patient’s best interest.

Even with this guidance and reassurance, it became apparent that the consent process for the trial would be more challenging than expected.

Not only were clinicians apprehensive regarding the consent regulations, but wider care teams, carers and support staff were as well. The impact of this meant that it took much longer than hoped to explain the consent procedure to individuals and also to identify someone willing to act as a legal representative when the participant lacked capacity. On average, anecdotal evidence suggests it was taking between 2 and 3 weeks just to complete phone calls and arrange a meeting in order to complete the consent procedure. This was especially the case in residential settings, where carers, who would be well placed to provide consent, were required to refer this decision to managers and seniors, whose involvement often meant that a best interests meeting was called with wider care teams. With added layers of referral, it was often difficult to identify an individual who would be willing to provide any necessary consent.

Intervention delivery

Dosing

After extensive discussions, the decision was made by the trial team to include patients on any dose of risperidone, provided it was not being prescribed for psychosis and that the participant showed no evidence of psychosis. The rationale for this was that, if the withdrawal programme was to be shown to be effective and safe, it needed to work for individuals who would be on varying doses of medication. If the patient was deemed clinically eligible to enter the trial on all other criteria, their dose of risperidone should not be a restricting factor. By not limiting the entry criteria in this way, the pool of potentially eligible participants was also increased. We hypothesised, based on clinical experience, that doses of risperidone would be relatively low in the target population given that it was being prescribed for challenging behaviour as opposed to psychosis, for which larger doses are clinically indicated. The trial team, therefore, felt that there would probably be a limited number of dose combinations to cover as part of the trial. Careful consideration was given to the practicalities of how participants would receive their individually tailored medication regime.

Blinding medication

Blinding clinicians, carers and participants to treatment allocation presented a practical challenge. How could varying medication strengths be potentially tapered off without revealing which arm the participant had been randomised to? The decision was made to overencapsulate all trial medication using size 0 Swedish orange hypromellose capsules so that all of the strengths of risperidone and the placebo looked the same. The number of pills taken each day would also need to remain the same throughout the trial. To achieve this, the trial statistician created an algorithm that was used at baseline to create a unique dosing schedule for each participant (Table 4). Based on the participants’ prescription upon entering the trial, the algorithm calculated how many capsules each individual would need to take on a daily basis to ensure that the blind would remain intact. As a result of manufacturing constraints, only specific tablet strengths of risperidone were used in the trial (0.5 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg). The algorithm aimed to make the reductions as equal as possible using the minimum number of capsules as possible, based on up to four possible drug reduction stages within a 6-month period. (Note: it was not possible to reduce medication in four stages for participants on very low doses of risperidone, e.g. 0.5 mg daily.) If the participant had been allocated to the reduction arm, as the dose of active medication was reduced, a placebo capsule was introduced into the treatment regime. This allowed a constant number of capsules to be taken throughout the trial but with a variation in dose as necessary to accommodate the reducing regime.

| Time slot | Dose (mg) | Number of tablets |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline IMP regime: total daily dose 1.5 mg of risperidone for 33 days. To be taken as follows: | ||

| Morning | 1.0 | 1 |

| Midday | ||

| Bedtime | 0.5 | 1 |

| Stage 1 IMP regime: total daily dose 1.0 mg of risperidone for 33 days. To be taken as follows: | ||

| Morning | 1.0 | 1 |

| Midday | ||

| Bedtime | 0.0 | 1 |

| Stage 2 IMP regime: total daily dose 0.5 mg of risperidone for 33 days. To be taken as follows: | ||

| Morning | 0.5 | 1 |

| Midday | ||

| Bedtime | 0.0 | 1 |

| Stage 3 IMP regime: total daily dose 0.0 mg of risperidone for 33 days. To be taken as follows: | ||

| Morning | 0.0 | 1 |

| Midday | ||

| Bedtime | 0.0 | 1 |

| Stage 4 IMP regime: total daily dose 0.0 mg of risperidone for 33 days. To be taken as follows: | ||

| Morning | 0.0 | 1 |

| Midday | ||

| Bedtime | 0.0 | 1 |

Using the Nomad trays with separate compartments for days of the week as well as times of day meant that participant-specific doses of IMP could be safely dispensed and delivered. The trial team was able to specify which tablets (and thus which strength) should be taken at which time while maintaining the blind.

Because of the change in appearance of participants’ normal medication, a run-in period was implemented, which allowed individuals to get accustomed to using the Nomad trays and taking the slightly larger than normal capsules. For the vast majority, the change in the appearance of the medication was not a problem. Only one participant had difficulty taking the trial medication and had to be excluded. It was also important for carers to become accustomed to the new medication during this period, as they would be responsible for ensuring that participants took their medication as prescribed. Written and verbal information was provided to carers on how to handle study medication and the importance of using the Nomad trays correctly. It was important to ensure that carers fully understood how we were using the capsules and trays to blind the medication and for them to be clear on how to raise any concerns they had. In the case of participants residing in a staffed house, it was particularly important that everyone involved in providing that person with their medication knew about the trial.

A number of individuals required more tailored IMP deliveries, which included aligning IMP dispensing with that of other prescriptions the participant may be taking in order that medication administration record sheets could be completed more easily. These are sheets that serve as a record of the drugs administered to a patient at a residential setting. Although Nomad trays were used along with European Union Good Manufacturing Practice annex 13-compliant labelling, two residential settings delayed the progression of participants onto study medication by insisting that an extra label, signed off by the clinician, was included. Individual requests such as these became extremely time-consuming and difficult for the study team to manage.

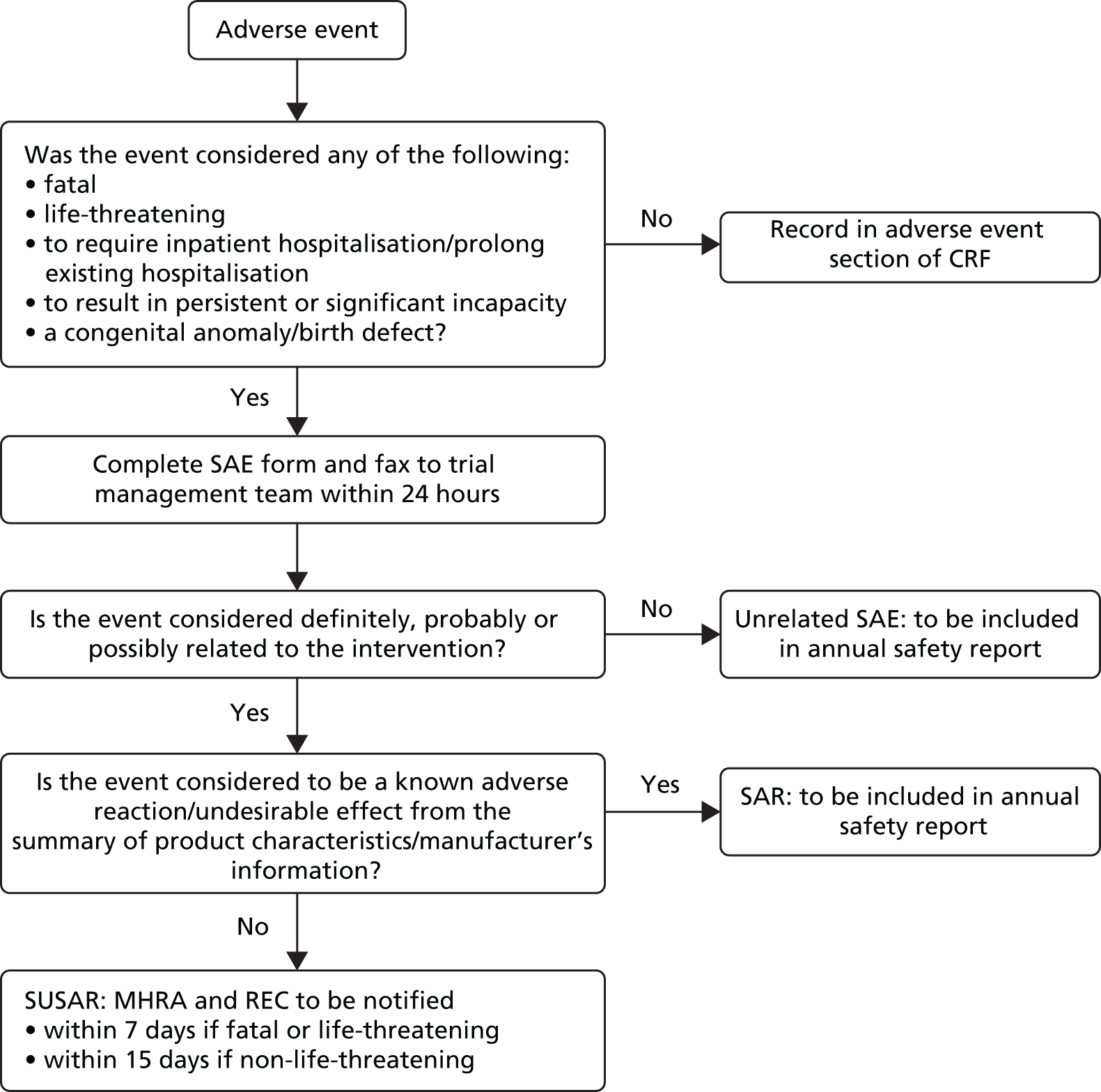

Progression through the trial

Participant safety and careful monitoring of behaviour was of utmost importance in the trial design. The programme of reducing medication was devised to allow PIs to have regular contact with participants and to provide the opportunity to delay any potential reductions at any point if there was concern about the individual. This meant that trial medication could only be given out on a monthly basis once the PI had confirmed how the participant was to progress (Figure 2). To accommodate this, monthly prescriptions were dispensed and delivered to site within a 10 working day time frame. PIs therefore made their monthly contact with participants 2 weeks from the start of a new medication stage to allow adequate time for a new batch of trial medication to be dispensed and delivered. The PI’s decision regarding progression to the next study stage was translated into an IMP order by the study team and sent through to the pharmaceutical unit for dispensing. This pattern of working required investigators to be prompt in their communication with the trial team and to see participants within the specified time frame. When this was done, the system worked well; however, it also meant that the trial team needed to provide constant oversight to investigators on a real-time basis, which increased the burden on the study team’s workload and monitoring.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram for PI visits and IMP collection.

Dispensing medication

Another challenge was to ensure that instructions for taking medication while maintaining the blind were clear. To do this, the study team chose to deliver medication using the Nomad dosing system. Some participants and carers would have been used to receiving medication in this type of dosing tray, which is designed to make it more straightforward for individuals to know how much medication to take and when.

Once IMP had been manufactured at SMPU in Cardiff, it then had to be dispensed into the Nomad trays in accordance with the participant-specific prescriptions. The trial team made extensive investigations into who would be able to carry out the dispensing and then how to get the IMP to participants in different geographical areas throughout south Wales and south-west England. After discussions with various parties, the option chosen was to use SMPU not only to manufacture the IMP but to also supply to the patient-specific orders in a Nomad system under section 37 of the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations (2004)41 as the process of ‘post (Qualified Person) certification labelling for safety purposes’. SMPU was then able to dispatch IMP orders as necessary directly to specified sites or pharmacies via courier to be received by a designated member of staff.

When recruiting in primary care settings, each practice nurse’s role was to take receipt of participants’ medication and ensure that it was handed out according to the protocol. They also completed accountability records to evidence the whereabouts of the IMP. Enough IMP for 33 days was delivered at each stage, which meant that there was usually unused IMP that needed to be returned and destroyed. Any unused IMP from a previous stage could have been at a higher dose for participants in the reduction arm. It was important that the correct blinded medication was used each time.