Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/116/12. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The draft report began editorial review in November 2015 and was accepted for publication in April 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Thomas RE Barnes reports personal fees from Roche, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Otsuka Pharmaceutical/Lundbeck, outside the submitted work. Carol Paton reports personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Eli Lilly and Company, outside the submitted work. Linda Davies reports a grant from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to the University of Manchester, during the conduct of the study. Patrick Keown reports personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical/Lundbeck and other from Janssen-Cilag, outside the submitted work. Hemant Bagalkote reports personal fees from Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck and Eli Lilly and Company, outside the submitted work. Peter M Haddad reports grants from the NIHR during the conduct of the study; personal fees for lecturing and/or consultancy (including attending advisory boards) from Allergan plc, Eli Lilly and Company, Galen Limited, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Quantum Pharmaceutical, Roche, Servier Laboratories, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd; and received conference support from Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Servier Laboratories and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., outside the submitted work. Mariwan Husni reports other from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Barnes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In around one-third of people with schizophrenia, the illness shows a poor response to standard treatment with antipsychotic medication. Although a relatively small proportion will fail to achieve remission even after the first exposure to antipsychotic medication, with either first- or second-generation drugs,1 more commonly the illness becomes progressively more unresponsive to medication with subsequent relapses. 2,3 This treatment-resistant subgroup of patients represents a major clinical challenge in everyday psychiatry, and consumes a disproportionate amount of NHS funding. 4–6 Mangalore and Knapp7 estimated that the total societal cost of schizophrenia in the UK in 2004/5 was £6.7B. The direct cost of treatment and care, falling on the UK public purse, was around £2B, whereas the burden of indirect costs to society was approaching £4.7B. The cost of informal care and private expenditures by families and carers was around £615M, whereas the loss of productivity as a result of unemployment, absence from work and premature mortality of people with schizophrenia was estimated to be £3.4B and the lost productivity of their carers estimated to be around £32M. Furthermore, Mangalore and Knapp7 calculated that, in addition to costs to the criminal justice system, around £570M was being paid out in benefit payments, associated with about £14M administration costs. Treatment-resistant illness is considered to be more costly, usually requiring longer-term residential and intensive community treatments. There is clinical and economic need to evaluate treatments to improve outcomes in this group of patients.

Clozapine augmentation with a second antipsychotic

For treatment-resistant schizophrenia, a common therapeutic approach is to use more than one antipsychotic, although a robust evidence base to justify this is lacking. Recent surveys of prescribing patterns in the USA suggest that about 15% of outpatients and up to 50% of inpatients with schizophrenia receive two or more antipsychotics. 8 In the UK in 2012, national clinical audit data from the Prescribing Observatory for Mental Health (POMH-UK) on over 5000 acute inpatients and over 3000 forensic patients prescribed antipsychotics revealed regularly prescribed combined antipsychotics in 14% and 17%, respectively. 9 A common reason given by clinical teams for prescribing such a combination was failure of the illness to respond to treatment with a single antipsychotic. In the POMH-UK audit, just under 5% of prescriptions for combined antipsychotics in acute adult wards represented the augmentation of clozapine with another antipsychotic, whereas in rehabilitation/complex needs services and forensic services the respective figures were in excess of 20%. These figures are in line with other reports of the prevalence of clozapine augmentation, ranging from 18% to 44% depending on the clinical setting and country. 10–12 In summary, it seems that around one-third of all clozapine-treated patients receive augmentation with another antipsychotic. 13 This is because it is one of the few therapeutic strategies available to clinicians for those people with schizophrenia that has proved to be poorly responsive to clozapine.

Clozapine is the only antipsychotic for which there is convincing evidence of efficacy in strictly defined treatment-resistant schizophrenia, but in such cases it has limited effectiveness, with 30–40% of patients showing an inadequate response to the drug. 14 In some patients, a range of potentially serious side effects such as seizures, sedation and tachycardia may prevent the optimal dose being reached. In addition, weight gain and metabolic side effects that increase the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease become apparent in many.

In an attempt to improve efficacy and limit tolerability problems, clinicians commonly augment clozapine with another antipsychotic, despite limited evidence on the potential risks and benefits of this practice. 15 In 2005, Kontaxakis et al. 16 identified 15 case studies, with a total of 33 patients, of adjunctive agents in clozapine-resistant schizophrenia, 10 of which involved a second antipsychotic (eight using risperidone, one using sulpiride and one using olanzapine). They concluded that various methodological shortcomings limited the impact of the findings. These authors came to a similar conclusion after conducting a critical review of 11 randomised controlled trials (RCTs; with a total of 270 participants) of clozapine augmentation in treatment-resistant schizophrenia,17 in only one of which was an antipsychotic (sulpiride) used as the adjunctive medication. Methodological weaknesses included the fact that only one trial adequately reported the dose and duration of the clozapine monotherapy phase. Similarly, Remington et al. 15 noted that the current body of evidence for clozapine augmentation consisted of data from a limited number of small open trials and case series reports. But they suggested that systematic research was warranted and argued for detailed cost–benefit analysis. Buckley et al. 11 agreed, stating that there was ‘a dearth of double-blind studies’, and concluded that these adjunctive therapies were worthy of further testing in carefully controlled clinical trials.

The subsequent publication of several new open studies and small RCTs testing the therapeutic value of augmenting clozapine with another antipsychotic prompted us to conduct a meta-analysis of eligible RCTs. 18 A systematic literature search identified eight open studies and four eligible RCTs in which clozapine was augmented with a second antipsychotic, with a total of 166 participants. The two RCTs that had lasted 10 weeks or more gave an odds ratio (OR) of response to treatment of 4.41 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.38 to 14.07]. We concluded that for clozapine-refractory schizophrenia, augmentation of clozapine with another antipsychotic drug is worthy of an individual clinical trial, but this may need to be longer than the 4–6 weeks usually recommended for acute antipsychotic monotherapy, a view supported by Correll et al. 19 Mouaffak et al. 13 noted that the discrepant results of the published studies of clozapine augmentation with another antipsychotic; they identified methodological shortcomings that related to the heterogeneity of definitions of resistance to clozapine, choice of outcome measures, and the dose and duration of the adjunctive drugs, which they considered ‘a major limitation for drawing conclusions’. Clinical response in such studies has generally been defined as a 20% reduction in total score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Both the BPRS and the PANSS assess a broad range of symptoms, including both positive symptoms (e.g. delusions, hallucinations and thought disorder) and negative symptoms (e.g. blunted affect and emotion, poverty of speech, lack of motivation, and social and emotional withdrawal).

The updated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2009 guideline for the treatment of schizophrenia20 supported the augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic in patients with an inadequate response to clozapine alone; advice that was in accord with our own meta-analysis. 18 After the publication of our meta-analysis, data became available for four further, short-term, clozapine augmentation RCTs, one each for risperidone21 and haloperidol,22 and two using aripiprazole,23,24 a medicine that has a different pharmacology to other antipsychotic drugs in that it is a D2 partial agonist. All four studies were reported as negative, although the trial by Chang et al. 23 showed a statistically significant advantage for augmentation with aripiprazole in regard to a reduction in negative symptom score.

By 2012, Sommer et al. 25 were able to identify 10 RCTs of augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic and found only modest or absent efficacy. Also in 2012, Taylor et al. 26 conducted a meta-analysis of 14 such studies. These investigators were more positive about this strategy for clozapine-refractory illness, concluding from their findings that augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic was modestly superior to placebo and equally well tolerated. Looking at effect size by treatment duration, they found no significant relationship between duration of treatment and reduction in symptoms. In other words, there was no confirmation of the earlier suggestion that longer trials might produce relatively more robust outcomes for adding a second antipsychotic.

Risks of clozapine augmentation

When adding one drug to another it is important to consider any potential interactions that could lead to adverse consequences for the patient. Drug interactions can be either pharmacokinetic, where one drug interferes with the way the body handles the other, usually by increasing or decreasing metabolism or pharmacodynamic, where one drug enhances or opposes the pharmacological action of the other. Case reports have described clinically significant elevations in serum clozapine levels after augmentation with the second-generation antipsychotic, risperidone. 27 The potential clinical relevance of such a pharmacokinetic effect is, first, that it could cause clozapine plasma levels to reach an individual patient’s threshold level for response, a benefit that might be erroneously attributed to a pharmacodynamic synergy between clozapine and the augmenting drug. Second, the increased clozapine plasma levels could be associated with the development of serious dose-related side effects. However, clozapine levels had been systematically measured before and after antipsychotic augmentation in four23,28–30 of the clozapine-augmentation RCTs included in our meta-analysis,8 and in one of these RCTs30 the clozapine metabolite norclozapine was also measured and no significant changes in mean plasma clozapine levels were reported.

In terms of side effects, RCTs and open studies have found clozapine augmentation with a second antipsychotic to be relatively well tolerated. The main treatment-emergent side effects have been predictable from pharmacology of the augmenting drug, with extrapyramidal side effects (EPSs) and prolactin elevation being the most common problems. However, there are isolated case reports of more serious side effects. Published case reports of clozapine augmentation with risperidone have noted agranulocytosis, atrial ectopic beats and possible neuroleptic malignant syndrome,31–33 whereas case reports of clozapine augmentation with aripiprazole have mentioned nausea, vomiting, insomnia, headache and agitation in the first 2 weeks,34 tachycardia23 and also modest weight loss. 34,35 Clozapine itself is commonly associated with sedation, weight gain and postural hypotension. Any augmenting antipsychotic should ideally have a low propensity to compound these side effects.

In summary, the studies of augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic for schizophrenic illness that has shown an insufficient response to clozapine have shown only modest improvements in overall symptom severity that may take 10 weeks to be evident. No particular augmenting antipsychotic has been shown to be consistently superior to any other. Any benefit seen is not obviously attributable to pharmacokinetic interaction: clozapine and norclozapine levels have not been found to be significantly raised in studies when measured. The augmenting antipsychotic drugs tested have generally not been systematically assessed for compounding clozapine side effects (e.g. sedation, weight gain, metabolic side effects) or problems such as akathisia or significant elevations in serum prolactin. Furthermore, any uncommon but severe side effects with this strategy are unlikely to have been detected in the relatively small studies conducted thus far.

Amisulpride augmentation of clozapine

Despite the lack of robust clinical evidence on the potential risks and benefits of clozapine augmentation with amisulpride, this is a strategy commonly used by clinicians in the NHS. The POMH-UK clinical data from 20129 revealed that amisulpride was the antipsychotic most commonly prescribed in association with clozapine.

Amisulpride has been tested in case reports and case series36–38 and open studies of clozapine augmentation. 39–41 Augmentation with amisulpride was found to be well tolerated, and clinical responses (again defined as a ≥ 20% reduction on PANSS total score) in the open studies by Munro et al. 40 and Ziegenbein et al. 39 occurred in around 70% of patients. Hotham et al. 42 augmented clozapine with amisulpride in six forensic (high-secure) patients and reported a reduction in aggression and violence. There has been one previous pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT of clozapine augmentation with amisulpride43 for 6 weeks in 16 patients, with established schizophrenia, who were partially responsive to clozapine. The primary outcome measures, such as reduction in BPRS total score, failed to show a significant improvement, which the investigators attributed to the study’s lack of power.

Study aims

The main aims of the study were:

-

to test the benefits, costs and risks of augmenting clozapine with amisulpride compared with placebo

-

to add to the clinical and economic evidence base for clozapine augmentation with a second-generation antipsychotic

-

to examine the potential benefits, costs and risks of clozapine augmentation in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

The key aim of the economic analysis was to assess whether or not augmenting clozapine with amisulpride was likely to be cost-effective. To address this aim, two sets of analyses were conducted. The first set used the trial data set (within-trial analyses) and the 3-month, scheduled, follow-up period to:

-

estimate the use of health- and social-care services to manage participants who were treated with clozapine and placebo and those who had clozapine plus amisulpride

-

estimate the direct costs of health- and social-care services to manage participants who were treated with clozapine and placebo and those who had clozapine plus amisulpride

-

estimate the overall health status of participants who had clozapine and placebo and those who were treated with clozapine plus amisulpride

-

estimate the utility and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) of participants who were treated with clozapine and placebo and those who had clozapine plus amisulpride

-

estimate the net costs, QALYs and incremental cost per QALY gained associated with augmenting clozapine with amisulpride.

The second set of analyses used an economic model to explore the following questions over the longer term:

-

What are the likely net costs, QALYs and incremental cost per QALY gained, if symptom response of augmenting clozapine with amisulpride increases/decreases in the long term?

-

What are the likely net costs, QALYs and incremental cost per QALY gained, if augmenting clozapine with amisulpride is associated with increased/decreased side effects in the long term?

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The study was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial lasting 12 weeks. Eligible patients, all receiving continuing clozapine treatment, were randomised 1 : 1 to receive augmentation with either amisulpride or placebo. Researchers, participants and care providers were blinded to patients’ treatment randomisation until the end of their participation by the use of identically matched placebo medicine. The trial recruited from November 2011 to December 2014.

Sample size

In previous augmentation studies of clozapine with a second antipsychotic lasting ≥ 10 weeks, 35%28 and 50%44 of the actively augmented arm responded compared with 10% in those augmented with placebo. Response was defined as a > 20% improvement on the BPRS or PANSS. To detect a more conservative response of 30% in our amisulpride arm and 10% in the placebo arm, with 90% power and an alpha of 0.05, we required 92 participants per group (two-sided). Using existing continuous data, detecting an effect size of 0.5 BPRS score standard deviations (SDs; compared with the final placebo group mean BPRS score) would require 85 participants per arm. This held whether we used the results from Josiassen et al. 28 [mean BPRS: 44.7 (placebo) vs. 40.1 (active arm), SD 9.2] or Shiloh et al. 44 [mean BPRS: 41.2 (placebo) vs. 35.1 (active), SD 12.2], both using 90% power and a two-sided alpha of 0.05.

The plan was to randomise 230 patients (including 20% inflation for drop-outs) on clozapine 1 : 1 to receive augmentation with placebo or amisulpride. Clinical protocols for the use of clozapine involve regular attendance for haematological testing and most patients either are inpatients or attend clozapine clinics. Once stabilised on treatment, the attrition rate is low. Small studies of clozapine augmentation report completion rates of > 80%, so we estimated there would be 184 study completers (i.e. 92 completers in each treatment group).

Our sample size calculation was based on results from previous studies. 28,44 These studies were comparable with the proposed study in terms of length of follow-up, intervention used and proposed primary outcome. From these we based our sample size on 30% of participants in the amisulpride arm of the trial achieving a > 20% improvement on the BPRS or on the PANSS, which is slightly lower than those shown in the literature. 28,44 Therefore, it was expected that there would be a large difference in the percentage achieving such a threshold level of improvement on the BPRS or on the PANSS between the amisulpride and placebo groups at the end of follow-up, and so there was no statistical justification for increasing the sample size.

As part of the amisulpride augmentation in clozapine-unresponsive schizophrenia (AMICUS) study rescue plan submitted to the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme in March 2013, the sample size was recalculated with the same assumptions but with 80% power. This gave 72 participants in each arm (144 in total); accounting for 20% drop-out, the revised target was 90 participants in each group (180 participants in total). This was a pragmatic decision to determine the sample size needed while maintaining power at an acceptably high level.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients with a criterion response threshold of a 20% reduction in total PANSS score. This is a commonly used criterion for therapeutic response in schizophrenia trials, which allows for comparison with other published trials18 and inclusion of the study results in any appropriate systematic review or meta-analysis. The PANSS45,46 is a 30-item rating scale designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in adult patients with schizophrenia.

Inter-rater reliability

Following initial training sessions on the PANSS for the study researchers, the reliability of PANSS ratings by researchers across the various research sites was formally tested. Sixteen researchers were asked to independently rate the same PANSS interview (video of an actor). The intraclass correlation for individual items was 0.63 (moderate agreement) and subscales at 0.86 (substantial agreement). Discrepancies on the ratings of scale items between the researchers who had taken part were then reviewed and discussed with them, in order to further improve the reliability of the ratings.

Secondary outcomes

Negative symptoms

The PANSS negative symptom subscale score was used to assess negative symptoms. The validity and reliability of this negative subscale have been established. 47,48

Social and occupational function

Impact on social and occupational function was measured using the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS),49 which was derived from the Global Assessment Scale but more focused on a patient’s social and occupational functioning; for an impairment to be rated, it must relate to psychological problems not lack of opportunity. Note that higher scores on the SOFAS indicate a better level of functioning.

Treatment-refractory, target symptoms or behaviours

As part of the final assessment of eligibility for each participant, the PANSS and SOFAS assessments were reviewed with members of the participant’s clinical team. The team was asked to identify up to three critical, target symptoms and/or behaviours that were refractory to treatment; these were phenomena that had proved to be persistent and were judged clinically to have made a major adverse impact on the participant’s social function and community reintegration, been a major cause of psychological distress and/or precluded discharge from hospital.

Service engagement

The level of engagement with clinical services was assessed using the Service Engagement Scale (SES),50 a 14-item measure consisting of statements that assess client engagement with services, rated on a 4-point Likert scale from ‘not at all or rarely’ to ‘most of the time’. Four subscales assess availability, collaboration, help-seeking and treatment adherence. High internal consistency and retest reliability, including discrimination between criterion groups, have been demonstrated for the SES in a community setting. 50

Depression

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Calgary Depression Rating Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS),51 a scale designed to minimise the potentially confounding symptom overlap between depressive features and both negative symptoms and EPSs.

Insight

Insight was assessed using the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight (SAI). 52 This scale comprises a semistructured interview that obtains measures of three dimensions of insight: (1) awareness of mental illness, scored 0–6; (2) the ability to correctly attribute psychotic experiences, scored 0–4; and (3) acceptance of the need for treatment, scored 0–4. The maximum total score on the three dimensions is 14, but the scale also includes a supplementary question on hypothetical contradiction, scored 0–4. Thus, the maximum total score for the scale is 18, which indicates full insight.

Side effects

The Antipsychotic Non-Neurological Side Effects Scale (ANNSERS)53 has 44 clinician-judged items with good inter-rater reliability. It was designed to systematically and comprehensively assess the full range of side effects (weight gain, sexual dysfunction, aversive subjective experiences, etc.), other than movement disorders, that are recognised as occurring with first- and/or second-generation antipsychotics. For this study, an enhanced version of the ANNSERS was generated (ANNSERS-E) by adding potential cardiac symptoms such as palpitations, dizziness and syncope.

Metabolic side effects were assessed at baseline, and at the 12-week follow-up only, using an obesity measure [body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference] and assessment of blood pressure, serum prolactin concentration, plasma glucose concentration (non-fasting sample) and lipid profile. In line with best practice safety monitoring,54 an electrocardiogram (ECG) was done and reported on at baseline, before the study medication was initiated, to establish a baseline for any subsequent cardiac monitoring and exclude cardiac contraindications to potentially high-dose antipsychotic medication, including long QT syndromes.

With regard to EPSs, drug-induced parkinsonism was assessed using the Simpson and Angus55 Extrapyramidal Side Effects Scale (EPSE). 56 The Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS)57 was used to assess akathisia, and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS)58,59 for rating tardive dyskinesia. Researchers received thorough training on the use of these scales.

Health economics measures

The costs and health benefits for a cost-effectiveness acceptability and net benefit analysis were also measured. The primary economic measure was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of clozapine augmentation with amisulpride, estimated as net cost of such clozapine augmentation divided by net QALY of clozapine augmentation.

Protocol changes

In addition to wording changes to clarify procedures, a number of amendments were made to the protocol during the trial, as described in sections The addition of study sites to Changes to study medication procedures.

The addition of study sites

Additional sites were added as the trial progressed and, in total, took the number of study sites from 4 to 23.

The addition of screening electrocardiography

Electrocardiography to exclude cardiac contraindications and establish a baseline for any subsequent cardiac monitoring was added to the protocol prior to randomisation of the first participant.

Payment of participants for study assessments

In line with a number of contemporaneous studies that were remunerating participants for their time, a payment to participants of £20 for each assessment was introduced, in recognition of any expenses incurred (e.g. travel) and inconvenience. This was backdated for any participants who were already randomised.

Changes to study medication procedures

Several changes were made to allow clinicians and site pharmacies more flexibility to manage the study medication. The option of repackaging trial medication into dose administration boxes (1 week at a time) was introduced, and a standardised approach to the management of temperature excursions in pharmacies was added for recorded temperatures between 25 °C and 30 °C. Moreover, the addition of an option for the prescriber to provide a further 28-day supply of study medication after the final 12-week follow-up assessment was added. In combination with the direct unblinding of the referring psychiatrist, this allowed time for participants allocated to the amisulpride arm of the trial to be provided with a standard prescription of amisulpride and, therefore, allowed an uninterrupted supply of medication when the participant and prescribing clinician agreed that this was desirable.

Patient and public involvement

A service user group contributed to the design of the study at the proposal stage. In particular, feedback from qualitative interviews with service users highlighted the relevance of a systematic assessment of side effects, including subjective experience. Once funded, two experts by experience, were involved in the trial throughout: one a service user and the other a parent and carer of a service user. These individuals sat on the Trial Steering Committee and the Trial Management Group, respectively, and, as a result, contributed to both trial oversight and the strategic direction of the trial, including ways to improve the recruitment rate.

Both of the experts by experience who were members of the trial’s oversight committees made additional contributions. These included shaping the content of the website and newsletters, and communicating the importance of the study to health-care professionals through the Clinical Research Network. The last, in particular, was well received and influenced clinician engagement in the trial.

One further issue that was felt to particularly necessitate the perspective of service users was whether or not to introduce remuneration for completing assessments, and we sought the opinion of a wider network of service users through support from the Clinical Research Network on this issue before making a decision.

Participants

People aged 18–65 years with schizophrenia that had proved to be unresponsive, at a criterion level of persistent symptom severity (as used by Honer et al. 30) and impaired social function, to an adequate trial of clozapine monotherapy in terms of dosage, duration and adherence, and who were competent and willing to provide written, informed consent.

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for enrolment, a patient’s illness had to meet a criterion level of persistent symptom severity (as used by Honer et al. 30) and the patient had to exhibit impaired social function, despite an adequate trial of clozapine monotherapy in terms of dosage, duration and adherence:

-

treatment for at least 12 weeks at a stable dose of 400 mg or more per day of clozapine, unless the size of the dose was limited by side effects

-

a total score of ≥ 80 at baseline on the PANSS;45,46 the range of possible scores is 30–210, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms

-

a clinical global impression (CGI)58 score of ≥ 4 (range of possible scores 1 = not mentally ill to 7 = extremely ill)

-

a SOFAS49 score of ≤ 40; range of possible scores 1–100, with lower scores indicating impaired functioning

-

clinically stable for the last 3 months, with a consistent clozapine regimen.

Exclusion criteria

-

Clinically significant alcohol/substance use in the previous 3 months.

-

The presence of a developmental disability.

-

Indication for current treatment with clozapine was intolerance or movement disorder rather than a treatment-refractory schizophrenic illness.

-

A previous trial of clozapine augmentation with amisulpride.

-

Existing relevant physical health problems such as cardiovascular disease, previous problems with prolactin levels or impaired liver/renal function.

-

Any woman who was pregnant or planning a pregnancy, and any woman of child-bearing potential unless using adequate contraception.

Pharmacological intervention

The pharmacological intervention was the augmentation of clozapine treatment with another second-generation antipsychotic, amisulpride, or placebo: 400 mg of amisulpride or two placebo capsules for the first 4 weeks, with the option of titrating up to 800 mg of amisulpride or four placebo capsules for the remaining 8 weeks. The amisulpride and placebo tablets were encapsulated to look identical. A fully automated online (and telephone) randomisation service was provided by the Clinical Trials Research Unit, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK. In addition, a 24-hour unblinding service was provided by Emergency Scientific and Medical Services (ESMS Global; Medical Toxicology Information Service Ltd, London, UK).

Data analysis

Clinical data analysis

All the main analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Baseline summary statistics by randomised group were calculated. Group differences in the primary outcome (criterion response threshold of > 20% reduction in total PANSS score) and other binary outcome measures were evaluated through the use of logistic regression after allowing for stratification by baseline symptom severity. Differences in quantitative outcome measures were evaluated through corresponding analysis of covariance model, controlling for baseline symptom severity (the stratification variable) and baseline values of the outcome in question. The results of the trial are presented following the standard Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) recommendations.

There were three interim analyses carried out by the trial statistician for the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) for the first three meetings. Baseline sex, age and PANSS score, by randomised group, were shown to check for imbalances between randomised groups. Analyses were limited to the primary outcome and adverse events. However, as fewer participants than projected had been recruited and completed the 12-week follow-up at these time points, it was not possible to analyse data in a similar way to the final analysis. For the second and third meetings, Fisher’s exact tests and chi-squared tests were carried out to assess randomised group comparisons. There were alpha spending plans in place for efficacy (> 20% reduction in PANSS score) and safety (adverse events). However, all interim analyses showed p-values greater than those set in the alpha spending plan. At subsequent meetings, overall statistics were presented (i.e. without disclosure of treatment allocation). Additionally, as the final study population was much smaller than the sample size calculation (approximately one-third recruited), it was decided to revert to the conventional threshold of p < 0.05 to signify statistical significance. With the data available, to show a significant difference between randomised groups would have required a very large difference in outcome, so it would have been futile setting the p-value lower than the conventional p-value (as would have been the case if we had used the final p-value from the alpha spending plan).

Given the tentative evidence in the published literature, suggesting that a significant clinical response to the amisulpride intervention being assessed may not be evident before 10 weeks of treatment, the 6-week data were used to determine whether or not there was earlier benefit from the intervention. The 6-week outcome data were also examined as a (tertiary) outcome, looking at the data longitudinally using mixed-effects modelling using both 6-and 12-week outcomes and controlling for baseline values of the given measure. Mixed-effects modelling does not assume that outcome data are independent of one another (in this case, outcome values at 6 weeks are related to outcome values at 12 weeks), as standard methods such as multiple linear regression do. If methods that assume independence were used with longitudinal data, then it is likely the standard errors would be too small, giving 95% CIs that were too narrow. This mixed-effects modelling included a dichotomous time variable indicating the time point (6 or 12 weeks) and a variable indicating randomised group. It was possible to undertake this analysis only on outcomes that were measured at all three time points (baseline, 6 weeks and 12 weeks); however, it is possible to include those participants in whom data from only one of the two follow-up time points were available. There was a random intercept for each participant.

Per-protocol sensitivity analyses were also conducted. Those participants taking mood stabilisers, antidepressants or antipsychotic medication (other than the randomised medication and clozapine) at either 6 or 12 weeks were excluded. Analyses were then carried out using the same methods as the primary analyses, although unadjusted (that is not adjusting for baseline symptom severity or baseline values of the outcome in question) because of the large decrease in power as a result of the large numbers of participants taking one of these classes of medication (small numbers who were only taking the study medications) as a result of the stricter inclusion criteria. Predictors of missingness of the primary outcome were assessed using means (SDs), medians [interquartile ranges (IQRs)] or frequencies (%) depending on the distribution of the data. However, statistical tests were not carried out as only a small absolute number of participants had missing values for the primary outcome. It was decided, a priori, that imputation methods would not be used (i.e. complete-case analysis was used).

Data were analysed using Stata version 13.0 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Health economic analysis

Approach

The framework for the within-trial and economic model analyses was cost-effectiveness analysis, to estimate the net cost per unit of health benefit gained by amisulpride augmentation. A cost-effectiveness acceptability approach was used to estimate the likelihood that amisulpride augmentation is cost-effective.

The population for the economic evaluation (within trial and economic model) consists of people who are unresponsive to clozapine, require additional treatment and have no contraindications for amisulpride augmentation. The intervention is clozapine augmented by amisulpride compared with clozapine not augmented by amisulpride.

The measure of health benefit for the analyses is the QALY. The primary outcome measure for all the economic analyses is the ICER (e.g. cost per QALY gained). The time horizon for the within-trial analyses is the 12 weeks from entry into the trial (baseline) to the final scheduled follow-up assessment. The time horizon for the economic model is 1–10 years from initiating clozapine augmented by amisulpride. The perspective for all the economic analyses is the health- and social-care sector (that incur the costs of providing care) and the patient (for health benefits). Previous evaluations of clozapine related treatment suggest that this approximates a broadly societal perspective. 60,61

The within-trial analysis used an intent-to-treat approach and included all eligible participants randomised to start treatment in both trial groups.

Within-trial analyses

Direct costs

The range of costs included the costs of the following formal health and social care services:

-

inpatient psychiatric and non-psychiatric care (including intensive care, emergency and crisis admissions)

-

hospital outpatient and day hospital attendances

-

primary care contacts with the general practitioner (GP) and GP practice staff (including office and home visits)

-

medicines taken on a daily basis

-

community mental health-care contacts

-

social care contacts.

Most of the resource-use data were collected using an economic patient questionnaire (EPQ) for each patient to identify the services used. Participants who reported using hospital inpatient and outpatient services were asked for details of the hospitals they attended. Data on the number of admissions, length of stay, number of outpatient visits were collected from case records at each of the hospitals reported by the participants. The frequency of other service use was collected from each patient using the EPQ. The data on service use were collected at the baseline and 12-week assessments. Data on medicines (dose, frequency, duration) were collected at baseline and at 6 weeks and 12 weeks.

The direct costs were estimated from resource-use data combined with the most recent published national unit costs available at the time of data analysis. These were the Department of Health’s National Schedules of Reference Costs 2013–2014,62 the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2014 produced by the Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent63 and the British National Formulary64 for the price year 2013–14. Each item of service use was costed by multiplying the quantity of service used with the average unit cost for that item.

The cost of amisulpride augmentation was estimated from the drug accountability records collected as part of the trial. This recorded the number of 400-mg capsules per day that were prescribed at baseline, at week 4 and at week 8 and whether or not the medication was received by the participant.

Quality-adjusted life-years

Quality-adjusted life-years gained from baseline to end of the scheduled 12-week follow-up were estimated as the number of weeks multiplied by the utility of observed survival. The utility values were estimated from the EuroQol EQ-5D health status questionnaire and the associated published societal utility tariffs. The EQ-5D three levels (EQ-5D-3L) version was used in the trial (no problems, some problems, severe problems/unable to do activity) and was included in the baseline and 12-week follow-up assessment interviews conducted with all the trial participants.

The EQ-5D is a generic and validated health status questionnaire shown to have acceptable validity in people with schizophrenia in European countries. 59,65,66 The EQ-5D has been used successfully in two recent UK trials of antipsychotics in schizophrenia. 60,67 Data from these trials demonstrated that the EQ-5D correlates with clinical quality of life and effectiveness measures, and is sensitive to change.

The EQ-5D-3L gives a profile of the individual’s health state at the time of assessment. Each possible health state has a published utility weight. Using the published tariff for the UK,68 the health profile for each individual over the duration of follow-up was converted to a single utility value. QALYs were then estimated as:

where Ui = utility value and ti = number of days between assessments for participant i.

Missing data

The primary outcome for the economic analysis combines a measure of cost and a measure of health benefit. This is in contrast to the analyses of the clinical outcomes, which is conducted for a single measure. One implication is that the impact of missing observations can be higher for the economic analyses than for the clinical analyses. From experience in previous clinical and economic trials, it was anticipated that there would be missing observations about use of services, for those people who completed the 12-week assessment. 60,67 This can then lead to a low proportion of participants with complete cost and QALY data, which can increase bias and reduce the robustness of the economic analysis. Accordingly, we specified the use of multiple imputation for the economic data in the protocol and analysis plan.

There were complete EQ-5D data for all the people who completed a 12-week assessment. However, there were missing observations for the cost data. These were treated as missing at random. Multiple imputation was used to impute values for the different cost categories. Data were imputed for missing observations at both baseline and at the 12-week assessment. Total costs were generated from these imputed data (using the Stata passive estimate command).

The imputations were conducted in Stata version 13.1, using predictive mean matching and sequential chained equations. The predictive mean-matching models included demographic and clinical variables. These were initially selected from measures previously reported to be statistically and conceptually associated with costs and or QALYs. The selection of variables was further informed by correlation analyses of the pooled baseline data. 69

Economic analyses

Descriptive analysis was used to summarise the EQ-5D data, QALYs, service use and cost. Regression analysis was used to estimate incremental (net) costs and QALYs accounting for the impact of key covariates. The key covariates were identified from the literature and analyses used to identify variables for the multiple imputation models (described in Missing data).

The primary measure for the economic analysis was the ICER. Accordingly, no statistical tests of differences in mean costs or outcomes were conducted. The ICER was estimated as the net cost divided by the net QALY estimates from the regression analyses.

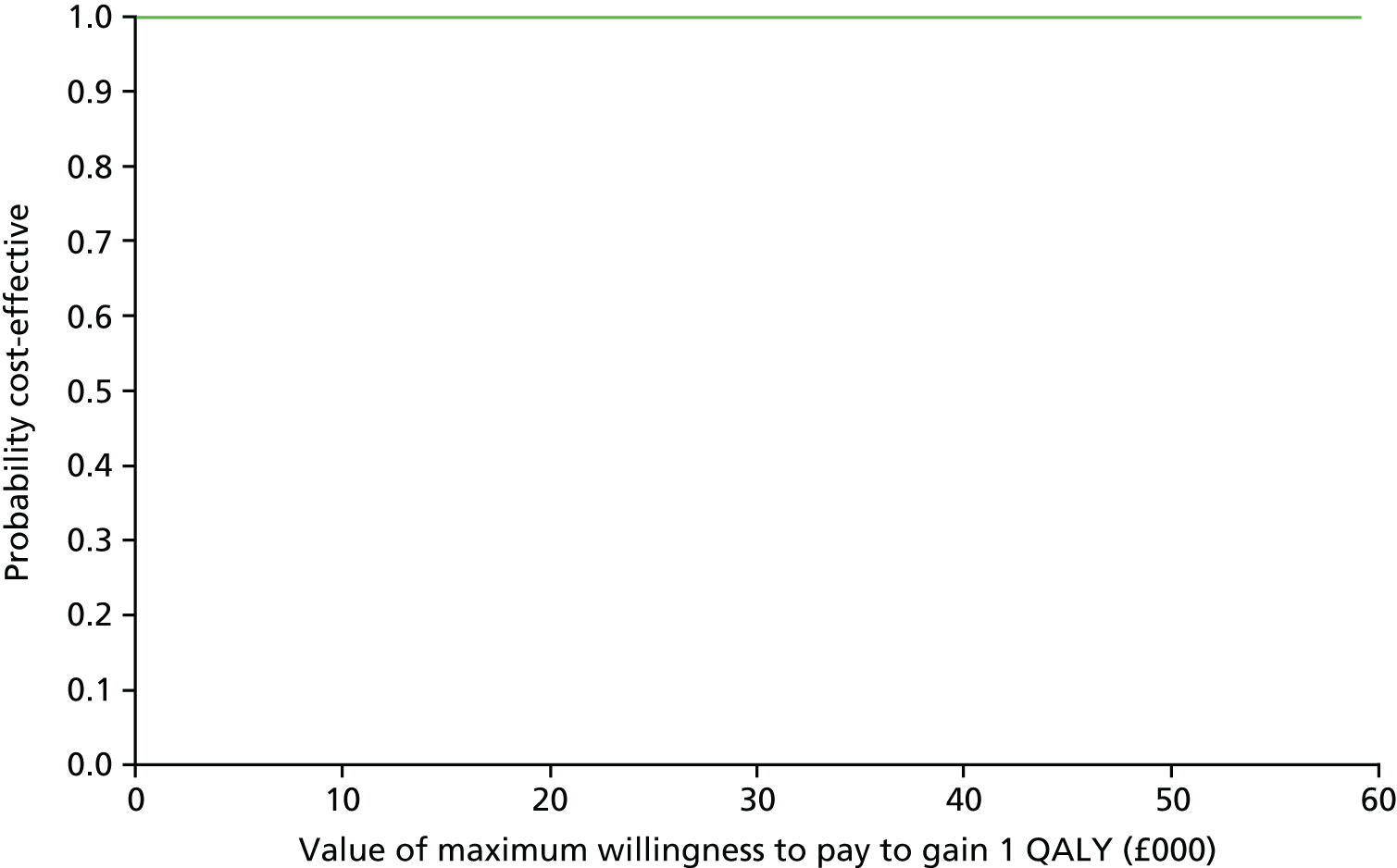

The estimates of net costs and outcomes from the regression were bootstrapped to simulate 10,000 pairs of net cost and net outcomes for the amisulpride-augmentation group. These simulated pairs of net cost and net outcomes were used to generate cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs), as recommended by NICE for health technology appraisals. 70

The simulated data were also used to estimate the probability that clozapine plus amisulpride augmentation is cost-effective compared with clozapine alone. This takes a Bayesian approach to estimating the likelihood that the intervention is cost-effective and avoids hypothesis testing and risk of a type 1 error.

The approach described above to estimate CEACs and probability that amisulpride augmentation is cost-effective revalues the health benefits gained by the intervention in monetary terms. However, in the UK there is no universally agreed monetary value for the types of health benefit measures (such as QALYs or criterion response) typically used in cost-effectiveness analyses. An approach used in health care is to ask the question: what is the maximum amount decision-makers are willing to pay to gain one unit of health benefit? Accordingly, the simulated net QALY values from the bootstrap simulation were revalued using a range of maximum willingness-to-pay values from £1 to £30,000 to gain one QALY. This was based on the range of willingness-to-pay value thresholds (WTPTs) historically implied by NICE decisions. 71

The data for the CEAC were derived by first revaluing each of the 10,000 net health benefit estimates from the bootstrap simulation by a single WTPT. This was repeated for each WTPT within the range used. A net benefit (NB) statistic for each pair of simulated net costs and net outcomes for each WTPT can then be calculated. For example, if the measure of health benefit is the QALY, the NB of amisulpride augmentation is estimated as:

This calculation was repeated for each WTPT. The CEACs plotted the proportion of bootstrapped simulations where the net benefit of amisulpride augmentation is > 0 for each WTPT. 72–75

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were used to explore the impact of changing the methods used on the estimates of whether or not amisulpride augmentation was cost-effective. This included rerunning the analyses:

-

for complete-case analysis rather than multiple imputation of missing observations

-

using key measures of outcome for the clinical effectiveness analysis as the measure of health benefit to estimate the cost per person with a 20% criterion response gained and cost per person with no recorded adverse event gained

-

excluding inpatient costs from the total cost (there was an imbalance in inpatient admissions at baseline and participants with inpatient admissions in the follow-up period were also inpatients at the baseline assessment)

-

excluding medication costs from the total cost (there was a higher number of missing data for medication costs, which was also dominated by the cost of clozapine)

-

for participants who did and did not have a 20% criterion response and for participants who did and did not have an adverse event recorded.

Economic model

The economic within-trial sensitivity analyses explored aspects of the trial design and participants that could affect generalisability. A key issue for the within-trial economic evaluation is the short length of follow-up and whether or not any savings in health-care costs or gains in QALYs may be sustained over a longer 12-month period.

An economic model was constructed using the same target population, perspective, health benefit measure and costs as the within-trial analyses. The intervention arm of the model was defined as clozapine with amisulpride augmentation. The control arm of the model was defined as clozapine with placebo augmentation.

A focused literature search identified no full economic evaluations of amisulpride-augmentation treatment or any clozapine-augmentation treatment that could be used to inform the economic model design or provide data to estimate model parameters. The searches were conducted in September 2015 and were restricted to the previous 10 years (restricted because of relevance in terms of resource-use and health-care service changes, as well as modelling techniques). The databases searched were: NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), the HTA database, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and EconLit. The search strategy included treatment terms, for example, ‘clozapine unresponsive’ and ‘clozapine augmentation’ and economic evaluation terms derived from the NHS EED search strategy. Two clinical effectiveness reviews were found in a search of The Cochrane Library for clozapine-augmented therapy. 76,77 These reviews revealed that there were insufficient data about the long-term effects of any augmentation on clinical outcomes or side effects. The reviews included a few studies with a follow-up of up to 1 year, which showed that some patients take longer to respond (responding between 6 months and 1 year into treatment).

Given the paucity of evidence for long-term use of clozapine augmentation, as well as the complexities of the disease area, it was concluded that there is little to gain from building a full economic model. The evidence collected in this clinical and economic trial is the most robust evidence available to inform the model structure and economic parameter estimates. Accordingly, to explore what happens after the 12-week trial period, a partial model was constructed. The model explored the impact of varying the probabilities that participants would experience improvement in symptoms (as measured by the PANSS) and that participants would experience side effects. The analyses were based on the assumption that these probabilities are key drivers of costs and QALYs.

The economic model used a simple Markov structure to model the impact of symptom inprovement and side effects over 12 months, split into four 3-month cycles (Figure 1). The initial cycle was assigned the probabilities, costs and QALYs for amisuplride and clozapine, to mirror the outcome of the trial. The subsequent cycles used pooled trial data to estimate the baseline values. For the initial cycle the mean costs/QALYs for clozapine were used. The net saving/QALYs gain from the primary analysis were applied to the clozapine values to estimate the mean costs and QALYs for the initial cycle of the amisulpride choice.

FIGURE 1.

The Markov model.

All data were entered into the model as distributions. Beta distributions were used for the probability data. Gamma distributions were used for the cost and QALY data. Monte Carlo simulation in TreeAge software (TreeAge Pro Health Care Module 2015, TreeAge Software Inc., Williamstown, MA, USA) (10,000 iterations) was used to estimate the net costs, QALYs and ICER of amisulpride augmentation. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis was used to estimate the likelihood that amisulpride augmentation was cost-effective compared with clozapine and placebo.

Chapter 3 Results

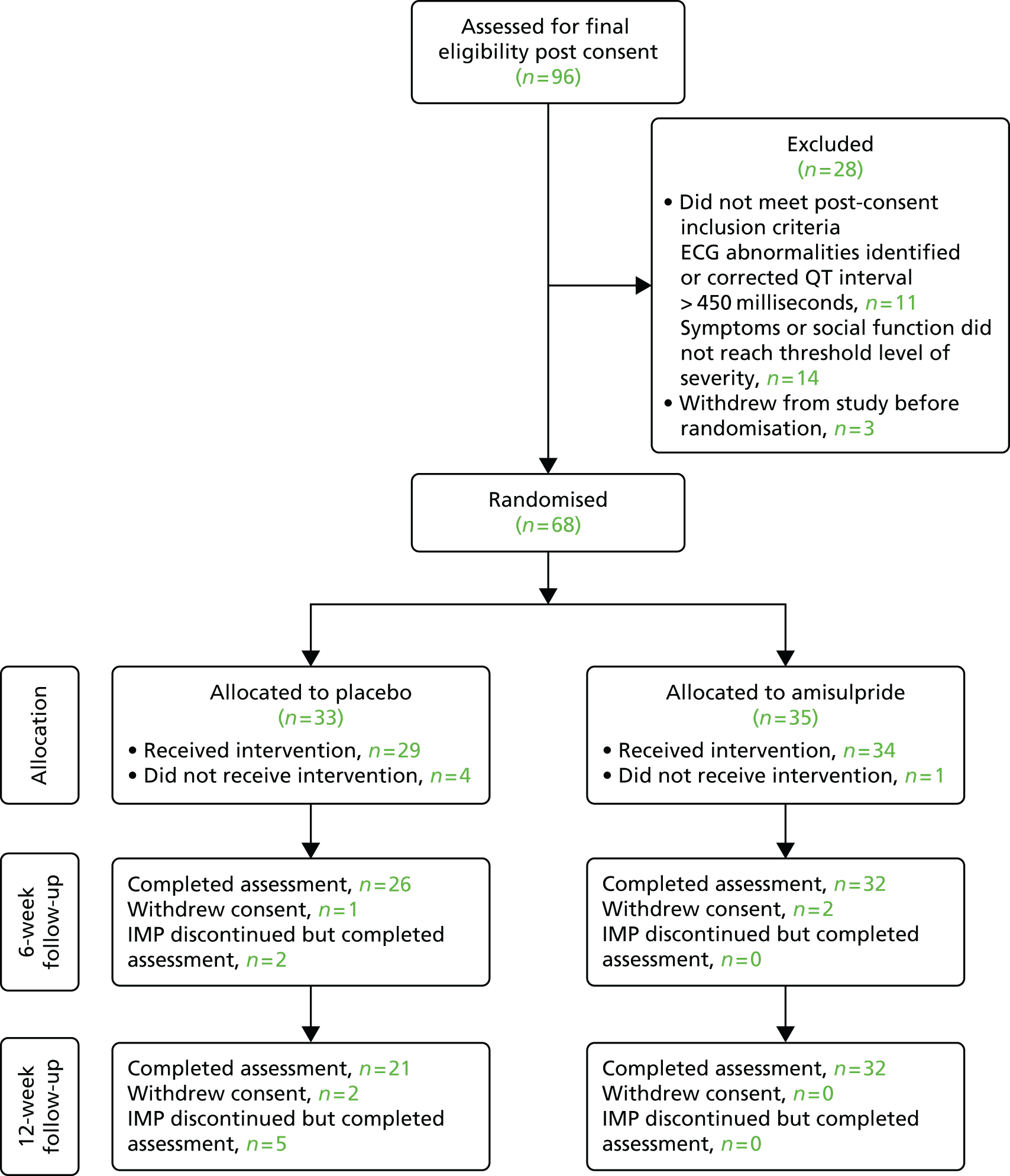

Ninety-six patients were recruited and 68 patients were randomised, with 52 patients completing assigned treatment and assessment at the 12-week follow-up (Figure 2). This number of randomised participants fell well short of the target sample size. Table 1a shows that the participants in both groups were predominantly male and white. The mean age was close to 40 years in both groups. Almost all participants were not in paid work. Most had attended primary care services in the 3 months before baseline. Table 1b shows that, at baseline, the mean PANSS total score was a little higher in the placebo group than in the amisulpride group [98 (SD 24) and 93 (SD 13), respectively], although there were similar proportions with a high PANSS score (stratification variable). Mean PANSS negative symptom subscale scores were similar between the two groups, as were scores on other standardised instruments. Mean body weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were a little higher at baseline assessment in the amisulpride treatment group.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram. IMP, investigational medicinal product.

| Variable | Treatment group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride | Placebo | |||

| n/N or mean | % or (SD) | n/N or mean | % or (SD) | |

| Male | 24/35 | 69 | 23/33 | 70 |

| Age (years) | 39 | (11) | 40 | (10) |

| White | 28/35 | 80 | 24/33 | 73 |

| Living alone | 12/32 | 38 | 11/28 | 39 |

| Living with parents | 5/32 | 16 | 8/28 | 29 |

| Living with others | 15/32 | 47 | 9/28 | 32 |

| Owner occupied flat or house | 0/34 | 0 | 0/29 | 0 |

| Flat or house rented | 19/34 | 56 | 21/29 | 72 |

| Other accommodation | 15/34 | 44 | 8/29 | 28 |

| Not in paid employment because of treatment | 24/25 | 96 | 23/25 | 92 |

| Currently an inpatient | 5/35 | 14 | 4/33 | 12 |

| Psychiatric inpatient in the last 3 months | 1/22 | 5 | 0/20 | 0 |

| Non-psychiatric inpatient in the last 3 months | 0/21 | 0 | 1/19 | 5 |

| Any inpatient in the last 3 months | 5/34 | 15 | 6/30 | 20 |

| Psychiatric outpatient in the last 3 months | 5/22 | 23 | 7/20 | 35 |

| Non-psychiatric outpatient in the last 3 months | 1/20 | 5 | 0/19 | 0 |

| Any outpatient in the last 3 months | 13/33 | 39 | 9/30 | 30 |

| Psychiatric emergency in the last 3 months | 0/21 | 0 | 0/20 | 0 |

| Attended non-psychiatric A&E department in the last 3 months | 0/21 | 0 | 0/19 | 0 |

| Community-based services used in the last 3 months | 14/33 | 42 | 16/29 | 55 |

| Attended NHS day hospital or day centre in the last 3 months | 0/22 | 0 | 1/20 | 5 |

| Other primary or community care contacts in the last 3 months | 28/33 | 85 | 26/29 | 90 |

| In contact with the criminal justice system in the last 3 months | 0/34 | 0 | 2/29 | 7 |

| Variable | Treatment group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride | Placebo | |||

| n/N or mean | % or (SD) | n/N or mean | % or (SD) | |

| Primary psychiatric diagnosis | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 32/34 | 94 | 29/30 | 97 |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 1/34 | 3 | 0/30 | 0 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 1/34 | 3 | 0/30 | 0 |

| Psychosis NOS | 0/34 | 0 | 1/30 | 3 |

| Medication | ||||

| Any antidepressant | 15/35 | 43 | 13/33 | 39 |

| Any antipsychotic (excluding clozapine and amisulpride) | 3/35 | 9 | 1/33 | 3 |

| Any mood stabiliser | 9/35 | 26 | 4/33 | 12 |

| Cardiac symptoms, checked 7–10 days after starting study medication | ||||

| Irregular heartbeat | 1/31 | 3 | 0/26 | 0 |

| Shortness of breath | 5/32 | 16 | 0/26 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 5/32 | 16 | 1/26 | 4 |

| Fainting | 0/31 | 0 | 0/26 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 0/30 | 0 | 0/26 | 0 |

| Physical health measures | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 96 | (24) | 91 | (19) |

| Height (m) | 1.72 | (0.08) | 1.73 | (0.11) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33 | (8) | 30 | (6) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 112 | (13) | 103 | (13) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126 | (17) | 122 | (11) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 83 | (11) | 82 | (8) |

| Serum prolactin concentration (ng/ml), median (IQR) | 12 | (5–14) | 12 | (5–18) |

| Plasma glucose concentration (mmol/l), non-fasting sample | 6.8 | (2.7) | 6.2 | (2.9) |

| Total cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 5.1 | (1.3) | 5.4 | (1.2) |

| HDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 1.1 | (0.4) | 1.4 | (1.1) |

| LDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 3.0 | (1.4) | 3.2 | (0.9) |

| Triglyceride concentration (mmol/l), median (IQR) | 2.0 | (1.3–2.5) | 1.7 | (1.0–3.3) |

| Clinical assessment | ||||

| PANSS | 93 | (13) | 98 | (24) |

| PANSS high score (stratification variable) | 16/35 | 46 | 14/33 | 42 |

| PANSS negative symptom subscale score | 25 | (6) | 25 | (7) |

| CDSS, median (IQR) | 5 | (1–10) | 5 | (2–8) |

| SOFAS, median (IQR) | 35 | (32–39) | 35 | (30–40) |

| SES, median (IQR) | 8 | (4–13) | 10 | (4–18) |

| SAI, median (IQR) | 12 | (8–13) | 12 | (9–14) |

| Side effects | ||||

| ANNSERS-E, median (IQR) | 16 | (11–22) | 13 | (10–24) |

| BARS, median (IQR) | 0 | (0–2) | 2 | (0–2) |

| Akathisia present (global clinical assessment score of ≥ 2) | 3/33 | 9 | 4/31 | 13 |

| AIMS positive: tardive dyskinesia | 4/35 | 11 | 4/33 | 12 |

| EPSE, median (IQR) | 0.1 | (0–0.3) | 0.1 | (0–0.3) |

| Parkinsonism present | 10/29 | 34 | 6/24 | 25 |

For each participant, up to three critical, target symptoms and/or behaviours refractory to treatment were identified at baseline by the responsible clinical team. Positive symptoms were most commonly identified: hallucinations were cited for 51% of the participants, delusions for 43% of the participants and suspiciousness/persecutory or paranoid ideas cited for 33% of the participants. Difficulty in abstract thinking or conceptual disorganisation were cited for 8% of the participants. With regard to negative symptoms, 20% of participants were considered to have a lack of drive, motivation, volition and/or spontaneity, whereas general negative symptoms were mentioned for 12% of the participants. Reduced social interaction was identified as a problem for 37% of the participants, and emotional withdrawal for 4% of the participants. Anxiety was relatively common, being identified as a persistent issue for 35% of the participants, whereas depression was a key symptom in only 9% of the participants. Lack of judgement or insight was named as an issue for 8% of the participants and poor attention for 4% of the participants. Poor management of physical health problems or self-care was named for 8% of the participants. One participant had particular difficulty with obsessive behaviour and one with hostility.

Table 2 shows that, at the 6-week study assessment, the mean PANSS score was higher in the placebo group than in the amisulpride group [85 (SD 23) vs. 80 (SD 15)], although the proportion who showed a 20% drop in PANSS score from baseline was the same in both groups (25%). Median SES was lower in the placebo group [7 (IQR 4–14)] than in the amisulpride treatment group [10 (IQR 4–13)]. All other standardised scales show similar scores between treatment groups.

| Variable | Treatment group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride | Placebo | |||

| n/N or mean | % or (SD) | n/N or mean | % or (SD) | |

| Clinical assessment | ||||

| PANSS | 80 | (15) | 85 | (23) |

| 20% reduction in PANSS from baseline | 8/32 | 25 | 7/28 | 25 |

| PANSS negative symptom subscale | 22 | (8) | 23 | (7) |

| CDSS: depression, median (IQR) | 4 | (1–7) | 3 | (1–6) |

| SOFAS, median (IQR) | 38 | (35–40) | 40 | (35–41) |

| SES, median (IQR) | 10 | (4–13) | 7 | (4–14) |

| SAI, median (IQR) | 12 | (8–15) | 12 | (10–13) |

| Side effects | ||||

| ANNSERS-E, median (IQR) | 13 | (9–20) | 15 | (6–22) |

| BARS, median (IQR) | 0 | (0–2) | 1 | (0–2) |

| Akathisia present (global clinical assessment score of ≥ 2) | 3/32 | 9 | 4/28 | 14 |

| AIMS positive: tardive dyskinesia | 1/32 | 3 | 1/28 | 4 |

| EPSE, median (IQR) | 0.2 | (0.1–0.4) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.3) |

| Parkinsonism present | 11/29 | 38 | 6/23 | 26 |

| Medication | ||||

| Any antidepressant | 11/32 | 34 | 13/28 | 46 |

| Any antipsychotic (excluding clozapine and amisulpride) | 4/32 | 13 | 1/28 | 4 |

| Any mood stabiliser | 7/32 | 22 | 5/28 | 18 |

Table 3a provides a comparison of the clinical characteristics and status of the amisulpride and placebo treatment groups at 12 weeks. Table 3b allows for comparison of primary and secondary outcomes at 12 weeks between the two treatment arms. The data show that the percentage of participants who showed a 20% reduction in PANSS score between baseline and 12 weeks was similar in both groups (44% of amisulpride participants and 40% of placebo participants). Mean weight, BMI, waist circumference and blood pressure were greater in the amisulpride group than in the placebo group. Median plasma prolactin concentration was higher in the amisulpride group than in the placebo group [43 ng/ml (IQR 9–87 ng/ml) vs. 11 ng/ml (IQR 7–12 ng/ml), respectively], as was mean plasma glucose concentration [6.9 mmol/l (SD 2.8 mmol/l) vs. 5.4 mmol/l (SD 0.7 mmol/l), respectively].

| Variable | Treatment group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride | Placebo | |||

| n/N or mean | % or (SD) | n/N or mean | % or (SD) | |

| Living alone | 12/31 | 39 | 11/25 | 44 |

| Living with parents | 5/31 | 16 | 5/25 | 20 |

| Living with others | 14/31 | 45 | 9/25 | 36 |

| Owner occupied flat or house | 0/32 | 0 | 0/25 | 0 |

| Flat or house rented | 18/32 | 56 | 17/25 | 68 |

| Other accommodation | 14/32 | 44 | 8/25 | 32 |

| Not in paid employment because of treatment | 22/25 | 88 | 19/20 | 95 |

| Psychiatric inpatient in the last 3 months | 3/22 | 14 | 0/14 | 0 |

| Non-psychiatric inpatient in the last 3 months | 1/22 | 5 | 0/15 | 0 |

| Any inpatient in the last 3 months | 5/32 | 16 | 3/25 | 12 |

| Psychiatric outpatient in the last 3 months | 5/19 | 26 | 3/14 | 21 |

| Non-psychiatric outpatient in the last 3 months | 2/19 | 11 | 1/14 | 7 |

| Any outpatient in the last 3 months | 12/32 | 38 | 6/32 | 24 |

| Psychiatric emergency in the last 3 months | 0/22 | 0 | 0/14 | 0 |

| Attended A&E department in the last 3 months | 0/22 | 0 | 0/15 | 0 |

| Community-based services used in the last 3 months | 10/30 | 33 | 14/25 | 56 |

| Attended NHS day hospital or day centre in the last 3 months | 0/21 | 0 | 0/14 | 0 |

| Other primary or community care contacts in the last 3 months | 23/32 | 72 | 19/25 | 76 |

| In contact with the criminal justice system in the last 3 months | 0/32 | 0 | 1/25 | 4 |

| Medication | ||||

| Any antidepressant | 11/32 | 34 | 12/25 | 48 |

| Any antipsychotic (excluding clozapine and amisulpride) | 2/32 | 6 | 2/25 | 8 |

| Any mood stabiliser | 6/32 | 19 | 5/25 | 20 |

| Incomplete participation in the study | 5/34 | 15 | 6/30 | 20 |

| Variable | Treatment group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride | Placebo | |||

| n/N or mean | % or (SD) | n/N or mean | % or (SD) | |

| PANSS | 76 | (16) | 80 | (24) |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| 20% reduction in total PANSS score from baseline | 14/32 | 44 | 10/25 | 40 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| PANSS negative symptoms | 21 | (7) | 21 | (8) |

| SES, median (IQR) | 8 | (3–13) | 7 | (3–13) |

| CDSS, median (IQR) | 5 | (2–8) | 3 | (1–7) |

| SAI, median (IQR) | 12 | (10–13) | 14 | (9–15) |

| Physical health measures | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 100 | (25) | 93 | (22) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34 | (9) | 31 | (7) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 112 | (15) | 103 | (14) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 124 | (14) | 119 | (11) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 82 | (10) | 79 | (6) |

| Serum prolactin concentration (ng/ml), median (IQR) | 43 | (9–87) | 11 | (7–12) |

| Plasma glucose concentration (mmol/l), non-fasting sample | 6.9 | (2.8) | 5.4 | (0.7) |

| Total cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 5.1 | (1.4) | 4.7 | (1.3) |

| HDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 1.3 | (0.6) | 1.3 | (0.5) |

| LDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 2.8 | (1.6) | 2.9 | (1.1) |

| Triglyceride concentration (mmol/l), median (IQR) | 2.0 | (1.3–3.8) | 2.1 | (1.2–2.9) |

| Side effects | ||||

| ANNSERS-E, median (IQR) | 12 | (7–22) | 12 | (9–15) |

| BARS, median (IQR) | 1 | (0–2) | 1 | (0–2) |

| Akathisia present (global clinical assessment score of ≥ 2) | 2/32 | 6 | 4/25 | 16 |

| AIMS positive: tardive dyskinesia | 1/32 | 3 | 2/25 | 8 |

| EPSE, median (IQR) | 0.1 | (0.0–0.4) | 0.2 | (0.0–0.5) |

| Parkinsonism present | 8/28 | 29 | 7/18 | 39 |

Table 4 shows descriptive statistics about possible predictors of whether or not the primary outcome (20% reduction in PANSS score between baseline and 12-week follow-up) was missing (‘missingness’). These may be of limited use because of the small numbers in the missing primary outcome group, some numbers being very small (with a maximum of 11).

| Variable | Missingness of primary outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Not present | |||

| n/N or median | % or (IQR) | n/N or median | % or (IQR) | |

| Male | 40/57 | 70 | 6/10 | 60 |

| Age (years) | 38 | (31–46) | 37 | (31–42) |

| White | 44/57 | 77 | 7/10 | 70 |

| Living alone | 21/54 | 39 | 2/6 | 33 |

| Living with parents | 12/54 | 22 | 1/6 | 17 |

| Living with others | 21/54 | 39 | 3/6 | 50 |

| Flat or house rented | 35/57 | 61 | 5/6 | 83 |

| Other accommodation | 22/57 | 39 | 1/6 | 17 |

| Not in paid employment because of treatment | 44/46 | 96 | 3/4 | 75 |

| Currently an inpatient | 9/57 | 16 | 0/10 | 0 |

| Psychiatric inpatient in the last 3 months | 1/38 | 3 | 0/4 | 0 |

| Non-psychiatric inpatient in the last 3 months | 0/36 | 0 | 1/4 | 25 |

| Any inpatient in the last 3 months | 10/57 | 18 | 1/7 | 14 |

| Psychiatric outpatient in the last 3 months | 11/38 | 29 | 1/4 | 25 |

| Non-psychiatric outpatient in the last 3 months | 1/35 | 3 | 0/4 | 0 |

| Any outpatient in the last 3 months | 19/56 | 34 | 3/7 | 43 |

| Psychiatric emergency in the last 3 months | 0/37 | 0 | 0/4 | 0 |

| Attended A&E in the last 3 months | 0/36 | 0 | 0/4 | 0 |

| Community-based services used in the last 3 months | 25/56 | 45 | 5/6 | 83 |

| Attended NHS day hospital or day centre in the last 3 months | 1/38 | 3 | 0/4 | 0 |

| Other primary or community care contacts in the last 3 months | 48/56 | 86 | 6/6 | 100 |

| In contact with the criminal justice system in the last 3 months | 2/57 | 4 | 0/6 | 0 |

| Primary psychiatric diagnosis | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 53/56 | 95 | 8/8 | 100 |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 1/56 | 2 | 0/8 | 0 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 1/56 | 2 | 0/8 | 0 |

| Psychosis NOS | 1/56 | 2 | 0/8 | 0 |

| Clinical assessment | ||||

| PANSS high score (stratification variable) | 89 | (84–98) | 98 | (86–111) |

| PANSS negative symptoms | 25 | (21–29) | 28 | (24–30) |

| CDSS depression | 5 | (1–10) | 7 | (4–14) |

| SOFAS | 35 | (31–40) | 35 | (30–39) |

| SES | 9 | (4–15) | 9 | (4–19) |

| SAI | 12 | (9–14) | 13 | (9–14) |

| Side effects | ||||

| ANNSERS-E | 15 | (10–24) | 20 | (14–57) |

| BARS | 0 | (0–2) | 3 | (1–4) |

| Akathisia present (global clinical assessment score of ≥ 2) | 4/56 | 7 | 3/8 | 38 |

| AIMS positive: tardive dyskinesia | 5/57 | 9 | 3/11 | 27 |

| EPSE | 0.1 | (0.0–0.3) | 0.0 | (0.0–0.1) |

| Parkinsonism present | 16/48 | 33 | 0/5 | 0 |

| Other psychotropic medication | ||||

| Any antidepressant | 25/57 | 43 | 3/11 | 27 |

| Any antipsychotic (excluding clozapine and amisulpride) | 4/57 | 7 | 0/11 | 0 |

| Any mood stabiliser | 11/57 | 19 | 2/11 | 18 |

| Physical health measures | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 89 | (79–103) | 84 | (80–91) |

| Height (m) | 1.72 | (1.68–1.78) | 1.70 | (1.69–1.72) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30 | (27–34) | 29 | (25–29) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 105 | (100–115) | 106 | (96–106) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 121 | (115–133) | 121 | (112–129) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80 | (77–87) | 83 | (76–93) |

| Serum prolactin concentration (ng/ml) | 12 | (5–15) | 11 | (5–14) |

| Plasma glucose concentration (mmol/l), non-fasting sample | 5.4 | (5.0–6.6) | 5.9 | (4.0–8.3) |

| Total cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 5.3 | (4.5–6.1) | 4.8 | (4.0–5.5) |

| HDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.7 | (1.1–1.9) |

| LDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 3.2 | (2.5–3.7) | 2.4 | (2.1–3.1) |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 2.0 | (1.4–3.2) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.5) |

The data in Table 5 show that the patients in the amisulpride group had higher odds than those assigned to placebo of achieving the primary outcome response criterion of a 20% reduction in PANSS total score at 12 weeks [OR 1.17 (95% CI 0.40 to 3.42)]. Table 6 presents the unadjusted, per-protocol analysis in terms of the amisulpride intervention. This analysis excluded those participants who were prescribed an additional antipsychotic medication, a mood stabiliser or antidepressant at either 6 or 12 weeks, which was a substantial proportion. The findings are, therefore, hard to interpret: the estimates are close to zero and the 95% CIs are wide.

| Variable | OR or coefficient | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||

| 20% reduction in PANSS from baseline | 1.17a | 0.40 to 3.42 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| PANSS negative symptoms | –0.71 | –3.22 to 1.81 |

| SES | 1.17 | –1.63 to 3.97 |

| CDSS | 0.23 | –1.54 to 2.00 |

| SAI | 0.02 | –1.33 to 1.37 |

| Side effects | ||

| Non-neurological | ||

| ANNSERS-E | 1.58 | –3.60 to 6.76 |

| Metabolic side effects | ||

| Weight (kg) | 0.79 | –1.40 to 2.99 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | –0.02 | –1.05 to 1.01 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 1.05 | –2.33 to 4.42 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 3.49 | –3.66 to 10.63 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 3.33 | –1.65 to 8.31 |

| Serum prolactin concentration (ng/ml) | 50.47 | –8.86 to 109.80 |

| Lnb serum prolactin concentration (ng/ml) | 1.43 | 0.71 to 2.14 |

| Plasma glucose concentration, non-fasting sample (mmol/l) | 0.66 | –0.22 to 1.54 |

| Total cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 0.48 | –0.11 to 1.07 |

| HDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 0.09 | –0.23 to 0.41 |

| LDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 0.11 | –0.62 to 0.85 |

| Triglycerides concentration (mmol/l) | 0.78 | –0.10 to 1.65 |

| Motor side effects | ||

| BARS | –0.23 | –0.73 to 0.27 |

| Akathisia present (global clinical assessment score of ≥ 2)c | 0.35a | 0.06 to 2.09 |

| AIMS positivec | 0.37a | 0.03 to 4.34 |

| EPSE | –0.04 | –0.22 to 0.14 |

| Extrapyramidal side effects presentc | 0.63a | 0.18 to 2.20 |

| Variable | OR or coefficient | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||

| 20% reduction in PANSS from baseline | 3.00a | 0.57 to 15.77 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| PANSS negative symptom subscale | –2.70 | –9.53 to 4.13 |

| SES: service engagement | –0.73 | –6.44 to 4.97 |

| CDSS: depression | 0.06 | –3.41 to 3.53 |

| SAI: insight | 1.07 | –2.63 to 4.77 |

| Physical health measures | ||

| Weight (kg) | –1.86 | –23.03 to 19.32 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.72 | –5.79 to 7.23 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 11.27 | –3.60 to 26.14 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.81 | –11.72 to 13.34 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 2.23 | –6.19 to 10.65 |

| Serum prolactin concentration (ng/ml) | 41.66 | –57.26 to 140.59 |

| Lnc serum prolactin concentration (ng/ml) | 1.54 | –0.13 to 3.20 |

| Plasma glucose concentration: non-fasting sample (mmol/l) | 0.72 | –1.13 to 2.57 |

| Total cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 0.06 | –1.42 to 1.53 |

| HDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 0.19 | –0.19 to 0.57 |

| LDL cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 0.40 | –1.35 to 2.16 |

| Triglyceride concentration (mmol/l) | –0.56 | –2.22 to 1.09 |

| Side effects | ||

| ANNSERS-Eb | –1.25 | –17.57 to 15.07 |

| BARS | –0.27 | –1.42 to 0.88 |

| Akathisia present (global clinical assessment score of ≥ 2)d | – | – |

| AIMS positive: tardive dyskinesiad | – | – |

| EPSE | 0.05 | –0.21 to 0.32 |

| Parkinsonism present | 1.56a | 0.21 to 11.37 |

Table 7 presents the results of mixed-effects modelling to take time into account in terms of the amisulpride intervention. These reveal a time effect associated with a 20% reduction on the PANSS; the odds of 20% reduction on the PANSS at 12 weeks is 4.19 times that of a 20% reduction of 6 weeks (95% CI 1.20 to 14.56), controlling for baseline PANSS score and including the randomised condition (OR 1.43, 95% CI 0.24 to 8.44). Likewise, the PANSS negative subscale score shows that there is a slight decrease in score at 12 weeks compared with 6 weeks (coefficient –1.32, 95% CI –2.20 to –0.44), controlling for baseline negative PANSS score and including the randomised condition (coefficient –0.60, 95% CI –2.58 to 1.39).

| Variable | OR or coefficient | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||

| 20% reduction in PANSS from baseline | 1.43a | 0.24 to 8.44 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| PANSS negative symptom subscale | –0.60 | –2.58 to 1.39 |

| SES | 1.75 | –0.54 to 4.04 |

| CDSS: depression | 0.19 | –1.10 to 1.49 |

| SAI | –0.52 | –2.32 to 1.28 |

| Side effects | ||

| ANNSERS-E | 3.11 | –0.91 to 7.13 |

| BARS | –0.11 | –0.57 to 0.35 |

| Akathisia present (global clinical assessment score of ≥ 2) | 0.29a | 0.01 to 7.82 |

| AIMS positive: tardive dyskinesia | 0.18a | 0.00 to 32.67 |

| EPSE | 0.05 | –0.09 to 0.19 |

| Parkinsonism presentb | – | – |

Side effects

The data in Table 7 regarding side effect assessment using the ANNSERS-E show that, over the course of the study, the mean ANNSERS-E total score was 3 points higher in those participants assigned to amisulpride than in those in the placebo group. The information in Table 1b shows a greater frequency of cardiac symptoms in the amisulpride group, when checked 7–10 days after starting study medication. The data in Table 5 on plasma prolactin concentration (including following logarithmic transformation, i.e. ln prolactin) reveal that those participants in the amisulpride group had, on average, a much higher level during the study. Plasma prolactin concentration is 24% lower (95% CI 12% to 49%) in the placebo group than in the amisulpride group.

Table 8 shows the data relating to the nature and frequency of adverse events reported during the trial. There were 65 adverse events in 31 participants; more of these events were in the amisulpride intervention group than in the placebo group (47 events vs. 18 events, respectively). Almost half of adverse events in the amisulpride group were in the cardiac, general or endocrine systems. With regard to the nature of the cardiac adverse events in the amisulpride-treated group, dizziness and breathlessness were the most common symptoms, each reported by six participants, with postural dizziness, irregular heartbeat and tachycardia each reported by two participants.

| Treatment group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride | Placebo | |||

| n / N | % | n / N | % | |

| Adverse events as the denominator | ||||

| Body system classification | ||||

| Blood/bone marrow | 1/47 | 2 | 1/18 | 6 |

| Cardiac: general | 12/47 | 26 | 1/18 | 6 |

| Dermatological | 1/47 | 2 | 3/18 | 17 |

| Endocrine | 10/47 | 21 | 0/18 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 5/47 | 11 | 4/18 | 22 |

| Infection | 3/47 | 6 | 0/18 | 0 |

| Metabolic/laboratory | 2/47 | 4 | 0/18 | 0 |

| Neurology | 1/47 | 2 | 1/18 | 6 |

| Pain | 1/47 | 2 | 0/18 | 0 |

| Pulmonary/upper respiratory | 4/47 | 9 | 0/18 | 0 |

| Renal/genitourinary | 0/47 | 0 | 1/18 | 6 |

| Vascular | 3/47 | 6 | 0/18 | 0 |

| Other | 4/47 | 9 | 7/18 | 39 |

| Serious adverse event | 1/45 | 2 | 2/18 | 11 |

| Adverse event severity | ||||

| Mild | 24/42 | 57 | 13/17 | 76 |

| Moderate | 15/42 | 36 | 2/17 | 12 |

| Severe | 3/42 | 7 | 2/17 | 12 |

| Adverse event resulted in unblinding | 1/44 | 2 | 2/18 | 11 |

| Trial drug related | ||||

| Unrelated | 17/47 | 36 | 1/18 | 6 |

| Unlikely to be related | 7/47 | 15 | 5/18 | 28 |

| Possibly | 7/47 | 15 | 10/18 | 56 |

| Probably | 13/47 | 28 | 2/18 | 11 |

| Definitely | 3/47 | 6 | 0/18 | 0 |

| Adverse event unexpected | 18/45 | 40 | 7/17 | 41 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Resolved | 24/44 | 55 | 12/14 | 86 |

| Persisting | 17/44 | 39 | 2/14 | 14 |

| Not assessable | 3/44 | 7 | 0/14 | 0 |

| Participants as the denominator | ||||

| Any adverse event | 21/35 | 60 | 10/33 | 30 |

| Serious adverse event | 1/35 | 3 | 2/33 | 6 |

| Most severe adverse event | ||||

| None | 14/35 | 40 | 23/32 | 72 |

| Mild | 9/35 | 26 | 5/32 | 16 |

| Moderate | 10/35 | 29 | 2/32 | 6 |

| Severe | 2/35 | 6 | 2/32 | 6 |

| No adverse event | 14/35 | 40 | 23/33 | 70 |

| Adverse event not resulting in unblinding | 20/35 | 57 | 8/33 | 24 |

| Adverse event resulted in unblinding | 1/35 | 3 | 2/33 | 6 |