Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/141/02. The contractual start date was in October 2008. The draft report began editorial review in May 2016 and was accepted for publication in February 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Salkovskis is Editor-in-Chief of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, the official journal of the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, but does not receive any money in connection with this work. Paul Salkovskis and Hilary Warwick developed cognitive–behaviour therapy for health anxiety but have no financial or other interests in its use. Helen Tyrer has written a book (Tyrer H. Tackling Health Anxiety: A CBT Handbook. London: RCPsych Press; 2013), and Peter Tyrer and Helen Tyrer have co-authored online teaching modules on the recognition and treatment of health anxiety for the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Peter Tyrer is Co-Editor of Personality and Mental Health, for which he receives an annual honorarium.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Tyrer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction to health anxiety

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Tyrer et al. 1 This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Health anxiety – and its older synonym, hypochondriasis – is a relatively common problem in both primary and secondary medical care settings. 2–4 It also places a substantial burden on health services,5 as its central feature is sufficient fear of having a serious disease to lead to medical consultation, and, very commonly, this is followed by further investigations. This condition has only recently been recognised, despite its ubiquity and its ability to provoke considerable suffering. Even when the condition is recognised, concerns over litigation in hospital clinics may lead to expensive investigations being carried out unnecessarily. This may provoke further pathology when findings of marginal clinical significance are reported. The extra burden on services is particularly important in secondary medical care. Between 10% and 20% of all attenders at medical clinics have abnormal health anxiety6,7 and patients often rotate between different clinics depending on the focus of their symptoms. The symptoms of abnormal health anxiety show little tendency to spontaneous resolution and persist for months in the absence of treatment. 6

Potential benefits of psychological treatment and previous studies

The failure to detect this serious pathology is perhaps less surprising when there is, or at least has been until very recently, a general belief that there is no adequate treatment. Pharmacological management is generally unsatisfactory, but psychological treatment in the form of cognitive–behaviour therapy (CBT) has been shown to be effective both in primary care8,9 and, more recently, in secondary care. 10 Although these trials suggested efficacy of this intervention, it is less clear if it has a significant impact on costs. Although the total costs were somewhat reduced in those receiving CBT in the only trial in secondary care, these manifested only in the 6 months after treatment had been completed. 10 It is also not known to what extent health anxiety is found in patients with existing medical disease and whether or not this can be successfully treated, as almost all published trials exclude those with definite physical illness.

The precursors to the cognitive–behaviour therapy for health anxiety in medical patients (CHAMP) trial were a series of research studies, mainly carried out at King’s Mill Hospital in north Nottinghamshire. The first of these studies established, in a genitourinary medicine clinic setting, that health anxiety was relatively common, that it persisted in the absence of detection or intervention and that it led to more consultations with doctors. 6 The second suggested that the prevalence of health anxiety was somewhat higher (around 12%) in medical clinics such as cardiology and endocrinology clinics,7 and the third was a randomised controlled trial of a modified form of CBT for health anxiety (CBT-HA) developed earlier by Salkovskis and Warwick11 versus standard care in patients attending a genitourinary medicine clinic. 10 The last of these was the essential precursor to the CHAMP study. Since the trial began in 2008, there have been many more published trials but, as explained in full later in this report, these have all been concerned with somewhat different populations.

Chapter 2 Trial methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Tyrer et al. 1 This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Research objectives

The main objectives of the CHAMP trial were to examine the clinical value, cost and cost-effectiveness of the administration of CBT in health-anxious patients attending five medical clinics in secondary care. Specifically, we hypothesised that (1) between five and 10 sessions of health anxiety-directed CBT using the Salkovskis–Warwick model11,12 are more effective than standard care in reducing health-anxious symptoms measured by the Health Anxiety Inventory (HAI)13 1 year after randomisation to the trial; and (2) the costs of the CBT and the control are equivalent; the end point for this outcome is the cost of health service interventions at 2 years adjusted for baseline values.

The secondary hypotheses were that, compared with the control condition (single interview), CBT-HA would lead to significantly greater improvement in health anxiety at 3, 6, 24 and 60 months measured using the HAI,13 in self-rated generalised anxiety measured using the anxiety section of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),14 in quality of life using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) measure of health-related quality of life15 and in social functioning using the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ),16 all at 6, 12, 24 and 60 months.

In addition, we tested a number of secondary hypotheses. The first of these was that health anxiety-focused CBT (CBT-HA) would be less effective in patients who had additional comorbid pathology in the form of obsessional symptomatology [measured using the Short Obsessive–Compulsive disorder Screener (SOCS)]. 17 We also hypothesised that personality status would have an impact on the effectiveness of treatment, and that those with dependent personalities [measured using the Dependent Personality Questionnaire (DPQ)]18 and other personality disorders19 [measured using the Quick Personality Assessment Schedule (PAS-Q)],20 which were subsequently converted into International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Edition (ICD-11)21 personality disorder categories,22 would have a worse outcome with CBT-HA. We also expected that these comorbid disorders would be associated with increased costs.

The study also allowed prevalence estimates to be made for health anxiety in different age groups and in different medical clinics.

Patient and public involvement

We recognised at the outset of the study that one of the major problems in executing the trial was the relative lack of awareness of health anxiety in medical clinics. These clinics are busy places with clear tasks set for clinicians and, despite regular but fairly vague comments about the importance of mental pathology in patients who are attending, there is no requirement for mental health status to be assessed, with the possible exception of dementia.

With the help of a support group called Confederation of Health Anxiety Sufferers Supporting Increased Services (CHASSIS) we developed a strategy for identifying the patients who might have pathological health anxiety. In a previous study7 we found that many patients with existing, and often successfully treated, medical pathology had a high level of health anxiety, and so excluding such patients was felt to be a mistake.

This led to the two-way strategy of combining feedback from clinics about potentially unsuitable attendees (by consultation with clinical staff) with screening of attenders using the short form of the HAI. As broaching the subject of health anxiety with people who were attending the clinic ostensibly for medical follow-up and consultation only was potentially counterproductive, we asked our CHASSIS group of sufferers with health anxiety to advise on the best way of introducing the subject of health anxiety. We chose ‘worry about your health’ as the core component of this after this consultation.

The CHASSIS group has also been active in disseminating the results of the CHAMP trial, most recently (at the time of writing) by attending a meeting of the All Party Mental Health Group in the House of Commons in December 2014.

Trial summary

The study was a pragmatic randomised controlled trial with two parallel arms and approximately equal randomisation of eligible patients to an active treatment group of 5–10 sessions of CBT or to a control group. During the course of the baseline assessment an explanatory interview was given about the nature of health anxiety; this was the only specific health-anxiety intervention in the control group, but there is some evidence that a simple explanation is of benefit in its own right. 11

Settings

Patients attending cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, neurology and respiratory medicine clinics in five general hospitals (King’s Mill Hospital, north Nottinghamshire; St Mary’s Hospital, London; Charing Cross Hospital, London; Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London; and the Hillingdon Hospital, Middlesex) were considered for the study. A total of 107 consultants agreed to collaborate with the study and to allow their patients to be approached provided that they were not considered inappropriate for the study on account of the severity of their physical pathology.

Form of randomisation

After baseline assessment, randomisation was carried out by a computerised system [Open Clinical Data Management System (openCDMS), Centre for Health Informatics, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK] using block randomisation with no stratification in randomised blocks of four and six. The allocation was carried out by the UK Mental Health Research Network independently of CHAMP personnel.

Target population and procedure

Patients attending clinics of the collaborating consultants, apart from those who were specifically excluded, were approached while waiting for their outpatient appointments and, if they agreed, were given the short form of the HAI,13 a rating scale of 14 questions that takes 5–10 minutes to complete. Those that scored at least 20 points on the scale were offered the opportunity to take part in the trial and given an information sheet about the study. If the patients agreed immediately, they were given an information sheet about the study and baseline assessments were made, provided that they satisfied the inclusion criteria and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnosis of hypochondriasis [derived from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) interview]. 23 Those who were uncertain were approached later.

When each patient had satisfied the criteria for entry to the study, formal consent was obtained and baseline assessments completed. At the baseline assessment all patients received a standard explanation of the nature and significance of health anxiety. After completion of the assessments, the research assistant entered and registered each patient to an online system (openCDMS) and this automatically led to the appropriate randomisation. The study co-ordinator was then informed of the details of the treatment arm allocation. Equal allocation was made to either (1) the active treatment group – between 5 and 10 1-hour sessions of CBT from a psychologist or research nurse at the clinic, backed up by a short take home manual; or (2) the standard care group, which received the normal care in the clinic.

The patients were recruited over a 21-month period beginning in October 2008 and ending in July 2010, and were followed up for 5 years. Because there were so many clinics running simultaneously, we required additional assessment help in recruitment. This was provided by Clinical Studies Officers of the North London and East Midlands hubs of the Mental Health Research Network, and proved to be invaluable.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients suitable for inclusion were those who satisfied the criteria for excessive health anxiety outlined above and who (1) were aged between 16 and 75 years, (2) were permanently resident in the area, (3) had a sufficient understanding of English to read and complete the questionnaires and (4) gave written consent for the interviews and audio-taping of 50% of treatment sessions, and for access to their medical records. The presence of existing medical pathology, provided that it was not new and required further investigation, was not a bar to treatment in the study, and as in preliminary work we had found that many patients with existing pathology have a high level of health anxiety.

Some patients who would otherwise satisfy the inclusion criteria above were excluded if (1) they were felt by their consultants to have a level of continuing major pathology that was too severe for them to take part in the study; (2) they were currently being actively investigated for significant pathology suspected by the clinician and for whom CBT might confuse or cause distress; (3) they had progressive cognitive impairment; or (4) they were currently under psychiatric care.

Assessments

The following assessments were carried out at baseline only:

-

personality assessment using the PAS-Q,20 followed by conversion to the ICD-11 personality levels22 but also including the questions from the hypochondriasis subsection of the full schedule19

-

the SOCS17 (a set of seven questions that identify the likely presence of obsessive–compulsive disorder); and

-

the DPQ,18 an assessment of dependent personality traits (this was included because both dependent personality and obsessional symptoms are associated conditions that may handicap or complicate treatment).

The remaining clinical assessments, in addition to the main health anxiety measure (HAI) were generalised anxiety and depression (measured with the HADS14), as these symptoms are common in patients with hypochondriasis, quality of life (EQ-5D)15 and social functioning (SFQ). 16 These assessments were given at baseline and at 6, 12, 24 and 60 months. To ensure the highest possible follow-up rate, patients were reminded of the next follow-up point at each assessment. The HAI was also given at 3 months by post or telephone with a research assistant.

Service use data for the economic evaluation were collected using the Adult Service Use Schedule (ADSUS).

Methods of overcoming bias

The independent central computerised system involved in randomisation (openCDMS) ensured no bias in allocation of treatments and also full baseline information, as it was only when all necessary data were entered that the patient was randomised. As this was a single-blind study, there was always the danger of disclosure of the form of treatment by the patient, therapist or other investigators in the study. This was minimised by (1) patients being asked by research assessors not to disclose their treatment to the research assessors, (2) the assessors and therapists working in different areas and (3) establishing a system whereby any assessor who was unwittingly informed about the nature of the treatment then ceased to assess that patient, and another research assessor was allotted for continued assessments.

Study interventions

Cognitive–behaviour therapy treatment arm

As the aim was to replicate the conditions of treatment that would be likely to prevail in the future if the trial found benefit from CBT, as much as possible it was aimed to give CBT within or close to the referring clinic, so that it was perceived by patients to be part of the clinic’s function in combining help for mental and physical problems, instead of being a potentially stigmatised external psychiatric service.

At each clinic we therefore trained a psychologist, research nurse or equivalent health professional (G-grade or equivalent) to administer the treatment. Each patient was invited to receive between 5 and 10 sessions of CBT with additional adaptations for health anxiety developed by HT and PS, reinforced by three booklets to be handed to patients at treatment sessions (Box 1). Each therapist attended two workshops at the beginning of the study and received up to 3 months’ training from the senior practitioners in the study, sometimes in vivo with two therapists being present in treatment sessions, before taking on the care of patients alone.

-

Recognition of fear of disease rather than actual disease.

-

Dangers of internet browsing.

-

Avoiding reassurance.

-

Negative consequences of body monitoring and hypervigilance.

-

Recognition that the awful possible explanations of symptoms are rare.

-

Reading of three booklets summarising health anxiety.

Because of the need for training, recruitment was planned to be slower in the first 3 months of the trial than in the later phases of the study. Following the initial period, therapists had fortnightly supervision from senior practitioners until the last patients had been recruited and treated. Therapists were also given a manual of CBT (written by PS and HT) developed for health anxiety. This was prepared in advance of training and used for refreshment during treatment.

Research assistants who had all been trained in the assessment procedures (by SC) carried out both baseline assessments and follow-up. The follow-up at 3 months concerned only the HAI, which was administered by post or telephone. Follow-ups from 6 months onwards were carried out by face-to-face interview with some patients but for those who preferred a telephone assessment this method was used. As the main clinical assessments were all self-ratings, this rarely presented a problem. The ADSUS is administered as a clinical interview, but the answers are all simple factual ones that readily allow the information to be gathered over the telephone.

Training and fidelity of intervention

Four of the applicants (PS, GS, DM and HS) were involved in the training of therapists in two all-day workshops, and also in the assessment of treatment fidelity, and HW, one of the originators of the treatment, also assessed the audio-taped interviews independently.

Approximately half of all treatment sessions were audio-recorded and tapes or discs of these sessions given to patients to help in their progress. Fidelity was tested using a health-anxiety modification of the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale24 (Health Anxiety Version), in which all therapists were assessed before they were regarded as competent. Those who did not reach an accepted grade had further training until they achieved competence. Manuals for the training of therapists and to aid patients in their treatment were also prepared. This issue is important, as better treatment fidelity with CBT has been associated with better treatment effects. 25,26

Standard treatment arm

Patients allocated to the standard treatment arm continued their care in both primary and secondary care settings and were reminded that they would be followed up at regular intervals up to 5 years. No restrictions on treatment were given to this group as the study was a pragmatic trial and the follow-up period was long.

Sample size

We calculated sample sizes for both the primary outcome measure and the first secondary outcome measure, choosing the larger of the two for the study.

Based on the pilot study in a genitourinary medicine clinic,10 we assumed that the true difference in the change of HAI score between CBT and control at 2 years is 5.00 points and that the standard deviation (SD) for the change of HAI score at 2 years is 7.58 points. With these assumptions, the study needed 122 patients to detect the above difference with 95% power at a two-sided 5% significance level. Taking into account 20% dropout by 24 months, the sample size was estimated to be 152 patients. It is also fair to add that when the study was set up there was no knowledge on what was a minimally significant clinical difference in the HAI score, and even now there is little work on this subject, but an improvement of 2 points on the scale appears to be clinically important (see Chapter 5, Meaningful clinical difference in Health Anxiety Inventory scores).

There remains no agreed approach to calculate the sample size required for an economic evaluation, particularly in areas such as health anxiety, in which the willingness to pay for improvements in outcomes is unknown. Based on the pilot study, we considered that the CBT intervention would be cost-effective if it improved HAI score and that it was no more costly than the control treatment. The sample size calculation for the economic evaluation was therefore based on the total costs over 24 months being equivalent.

With a sample size of 186 per group, the study had 80% power to reject the null hypothesis that the costs of the CBT and control are not equivalent (when the difference in mean costs is ≈£150) in favour of the alternative hypothesis that the means of the two groups are equivalent, assuming that the expected difference in means is 0 and the common SD is 580 (from pilot study data).

The sample size was thus powered by the first secondary outcome of the CHAMP study, estimated as 466 patients, assuming a 20% dropout by 24 months, leading to a total of 372 completing treatment and equal randomisation between groups. The sample size calculation uses a one-sided (non-inferiority) test. Thus, with 466 patients, or fewer if the dropout rate was less, the study was adequately powered to both detect the assumed difference in the primary outcome and assess the equivalence in the secondary economic outcome between the CBT group and the control group.

Statistical analysis

All primary statistical analyses used the intention-to-treat principle using the statistical package SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The numbers (with percentages) of losses to follow-up at 12, 24 and 60 months after randomisation will be reported and compared between the treatment arms with absolute risk differences [95% confidence intervals (CIs)]. Deaths were reported separately for each group. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) procedure was used for reporting flow through the trial.

The primary end point was analysed using a mixed model with time, treatment, and time × treatment interaction as fixed effects, baseline measurement as covariate and patient as random effect. The treatment differences at each time point together with the 95% CI were derived from the mixed model. Missing data were treated as missing at random in the mixed-model analysis. To assess the sensitivity of the result to missing values, the last observation carried forward strategy was used to compute the missing HAI score at the follow-up visits. Other assessments were analysed in a similar way. In addition, covariate-adjusted analysis was performed on the primary outcome analysis by mixed model, controlling for three pre-specified potential predictors for the primary end point (clinic type, site and age). In addition, the percentage of patients achieving normal levels of health anxiety (HAI score of ≤ 10 points) was compared using a generalised estimating equation model with visit, treatment, interaction between visits and treatment as fixed effect, baseline measurement of HAI score as covariate and patient as random effect (an exchangeable covariance structure).

Subgroup analyses were also carried out to determine if there was heterogeneity in any of the main groups identified for analysis.

Chapter 3 Results

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Tyrer P, Wang D, Tyrer H, Crawford M, Cooper S. Dimensions of dependence and their influence on the outcome of cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety: randomized controlled trial. Pers Ment Health 2016;10:96–105. 27 Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

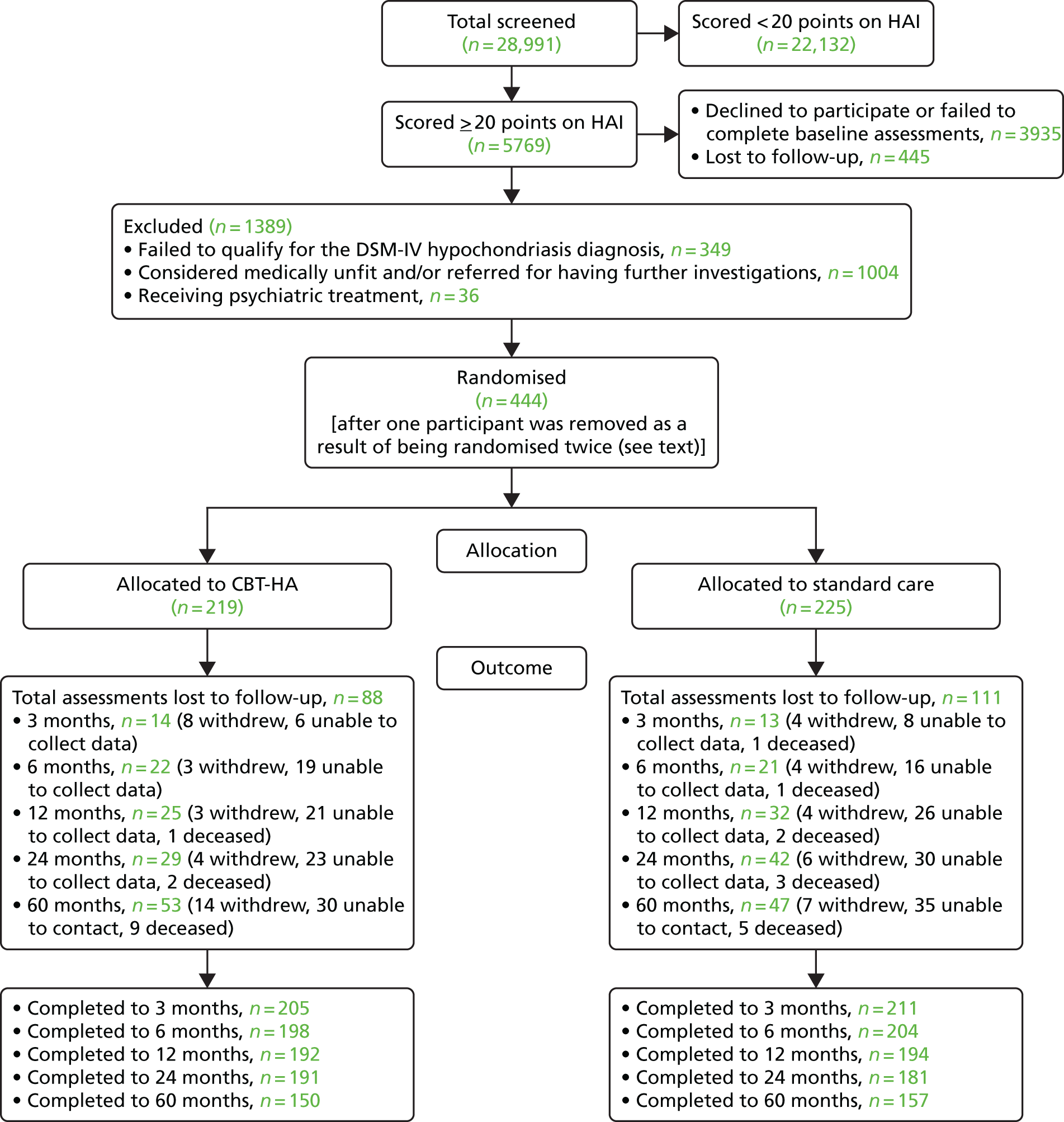

A total of 219 patients were allocated to CBT-HA and 225 to standard care. The CONSORT diagram for all phases in the trial is illustrated in Figure 1. Of the 444 patients (including those who had died), 416 (94%) were followed up at 3 months, 402 (91%) at 6 months, 386 (87%) at 12 months, 372 (84%) at 2 years and 308 (69%) at 5 years. The CONSORT details are notable in several respects. First, nearly 20% (2991) of all 5769 patients who completed the HAI scored ≥ 20 points and were therefore eligible to proceed to the next phase of the trial. After exclusions and refusals, only 444 were randomised. Possible explanations for this are given later in this report and, in particular, we suspect, but cannot confirm, that the sample that entered the trial was roughly a representative one. Second, although there were many reasons why high HAI scorers did not take part, only a minority (n = 349, 6%) were excluded because they did not have a DSM-IV diagnosis of hypochondriasis. The other finding worthy of note is that dropout rates were very similar in both groups, and at 5 years were greater in the CBT-HA group than in the standard care one. This is somewhat unusual in trials of psychological treatments, for which retention is usually greater in the psychological treatment arm.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram (numbers assessed for some variables differ because of missing data). Reprinted from the Lancet, vol. 383, Tyrer P, Cooper S, Salkovskis P, Tyrer H, Crawford M, Byford S, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety in medical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial, pp. 219–25. Copyright (2014),28 with permission from Elsevier.

The main baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups are shown in Table 1; the table shows that the two groups were essentially similar in important respects.

| Variable | Treatment group | All (N = 444) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-HA (N = 219) | Standard care (N = 225) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 50.3 (13.6) | 47.0 (13.4) | 48.6 (13.6) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 113 (51.6) | 123 (54.7) | 236 (53.2) |

| Male | 106 (48.4) | 102 (45.3) | 208 (46.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White British | 145 (67.8) | 151 (68.0) | 296 (67.9) |

| White other | 26 (12.1) | 18 (8.1) | 44 (10.1) |

| Black/black British: African | 6 (2.8) | 9 (4.1) | 15 (3.4) |

| Black/black British: Caribbean | 5 (2.3) | 7 (3.2) | 12 (2.8) |

| Asian/Asian British | 15 (7.0) | 23 (10.4) | 38 (8.7) |

| Asian/Asian British: other | 8 (3.7) | 8 (3.6) | 16 (3.7) |

| Arab/Middle East | 7 (3.3) | 4 (1.8) | 11 (2.5) |

| Chinese/Far East | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 4 (0.9) |

| Hospital, n (%) | |||

| Chelsea and Westminster Hospital | 26 (11.9) | 23 (10.2) | 49 (11.0) |

| Charing Cross Hospital | 31 (14.2) | 26 (11.6) | 57 (12.8) |

| Hillingdon Hospital | 56 (25.6) | 63 (28.0) | 119 (26.8) |

| King’s Mill Hospital | 70 (32.0) | 74 (32.9) | 144 (32.4) |

| St Mary’s Hospital | 36 (16.4) | 39 (17.3) | 75 (16.9) |

| Clinic type, n (%) | |||

| Cardiology | 53 (24.2) | 57 (25.3) | 110 (24.8) |

| Endocrinology | 41 (18.7) | 43 (19.1) | 84 (18.9) |

| Gastroenterology | 77 (35.2) | 72 (32.0) | 149 (33.6) |

| Neurology | 20 (9.1) | 22 (9.8) | 42 (9.5) |

| Respiratory medicine | 28 (12.8) | 31 (13.8) | 59 (13.3) |

| HAI score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.9 (4.2) | 25.1 (4.5) | 25.0 (4.4) |

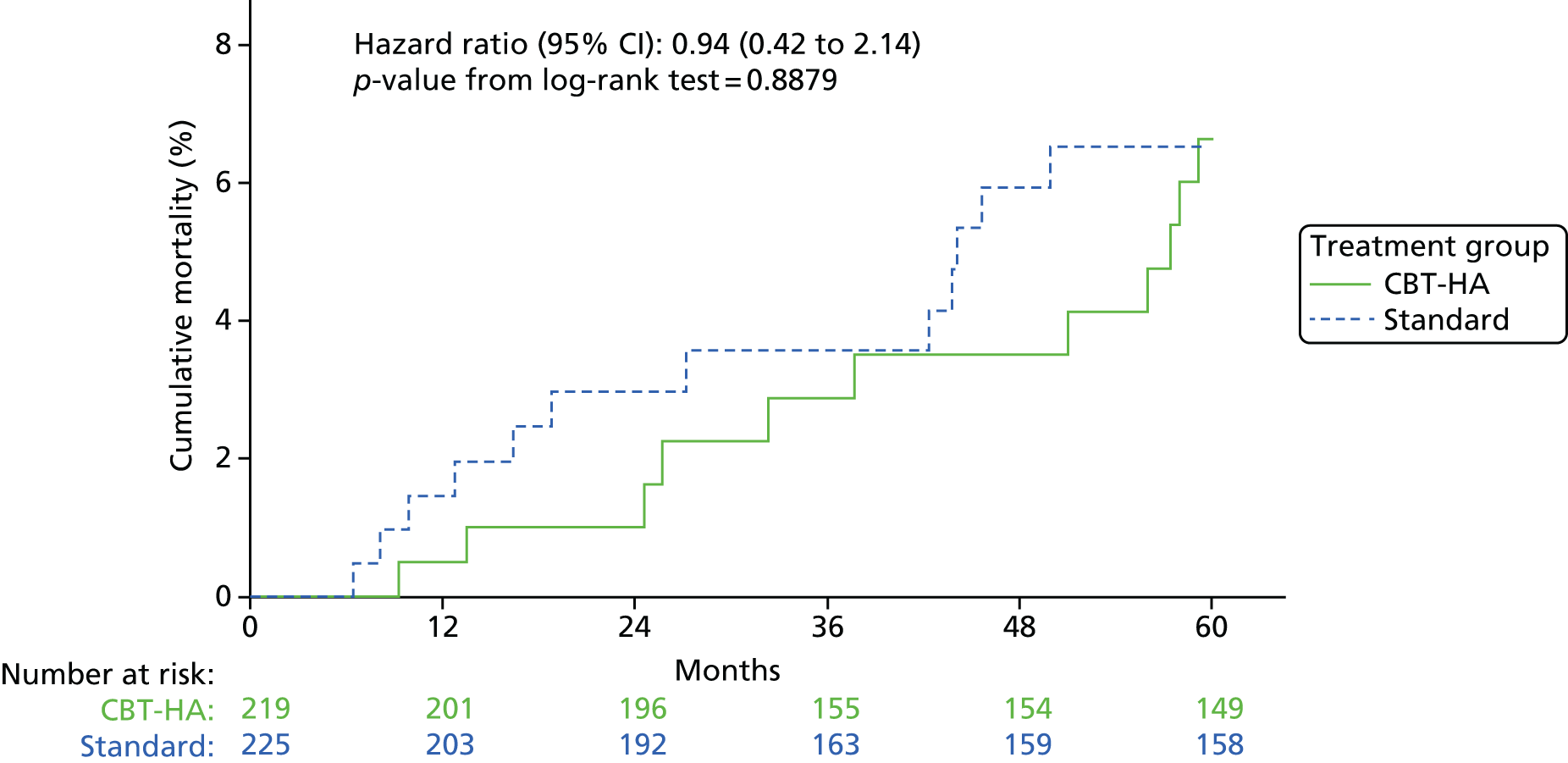

There were 24 deaths during the trial, 12 in each treatment group. All were from natural causes. The Kaplan–Meier plot of deaths showed a non-significant trend for lower mortality in the CBT-HA arm early in the trial (Figure 2). One patient in the standard care group had an episode of deliberate self-harm during follow-up. The 219 patients in the trial allocated to CBT-HA were seen by 11 therapists; assessment of the fidelity of therapists’ treatment showed that all except one scored at an adequate competence level or higher, and this was confirmed by the independent assessor (HW). The therapist who failed to achieve this level saw five patients in the trial.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot of deaths over the 5-year period of the trial.

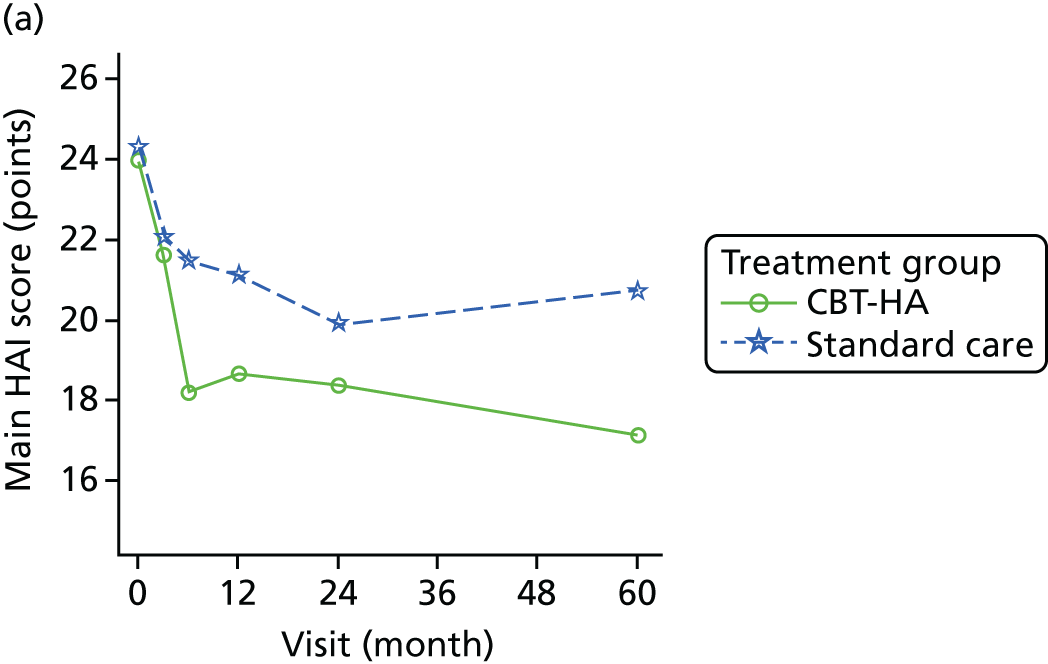

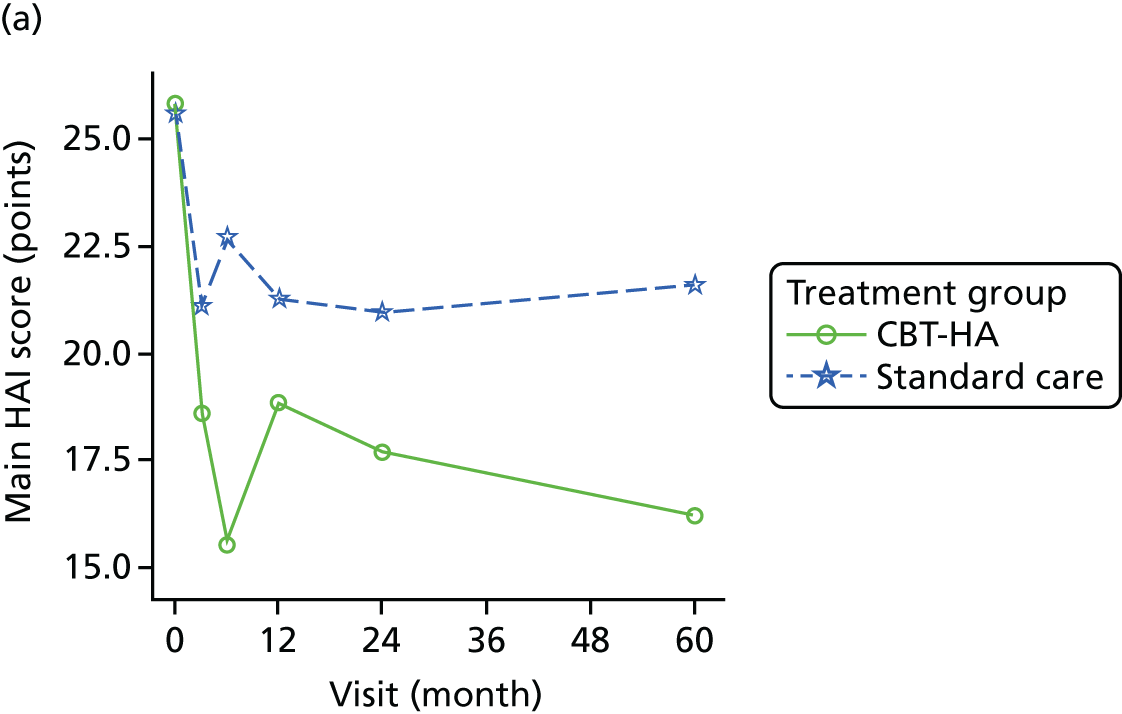

Primary outcome

The scores on the HAI showed greater improvement with CBT-HA than with standard care at all times of testing, with maximal differences at 6 months (Table 2 and Figure 3).

| Visit | Observed value | Mixed-model analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-HA | Standard care | Treatment difference (points) (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| n | Mean score (points) (SD) | n | Mean score (points) (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 219 | 24.88 (4.23) | 225 | 25.12 (4.52) | ||

| Improvement from baseline | ||||||

| 3 months | 205 | 4.41 (7.63) | 212 | 2.62 (6.17) | 1.74 (0.38 to 3.11) | 0.0123 |

| 6 months | 197 | 7.11 (7.83) | 204 | 2.33 (5.76) | 4.83 (3.45 to 6.21) | < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 194 | 6.44 (7.47) | 193 | 3.20 (6.54) | 2.97 (1.57 to 4.37) | < 0.0001 |

| 24 months | 190 | 5.90 (7.54) | 183 | 3.66 (6.57) | 2.01 (0.60 to 3.42) | 0.0052 |

| 5 years | 149 | 6.45 (8.57) | 157 | 4.34 (7.75) | 2.20 (0.70 to 3.70) | 0.0040 |

| Overall | 2.75 (1.65 to 3.85) | < 0.0001 | ||||

FIGURE 3.

Change in HAI scores between CBT-HA and standard care (treatment as usual) over the 5-year period. Note: the change in HAI scores between the two treatments at 12 months is the primary outcome. Adapted from the Lancet, vol. 383, Tyrer P, Cooper S, Salkovskis P, Tyrer H, Crawford M, Byford S, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety in medical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial, pp. 219–25. Copyright (2014),28 with permission from Elsevier.

Last observation carried forward analyses

The analysis using the last observation carried forward method for the primary outcome (HAI) showed very similar results. Because similar agreement was found with other outcomes they are not included in the report.

| Comparison | Difference in score (points) (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| CBT-HA vs. standard care at 3 months | –1.72 (–3.03 to –0.41) | 0.0099 |

| CBT-HA vs. standard care at 6 months | –4.52 (–5.82 to –3.21) | < 0.0001 |

| CBT-HA vs. standard care at 12 months | –2.93 (–4.24 to –1.63) | < 0.0001 |

| CBT-HA vs. standard care at 24 months | –2.07 (–3.38 to –0.77) | 0.0019 |

| CBT-HA vs. standard care at 5 years | –2.06 (–3.36 to –0.75) | 0.0021 |

| CBT-HA vs. standard care at all times | –2.66 (–3.72 to –1.60) | < 0.0001 |

Secondary outcomes

Generalised anxiety and depression

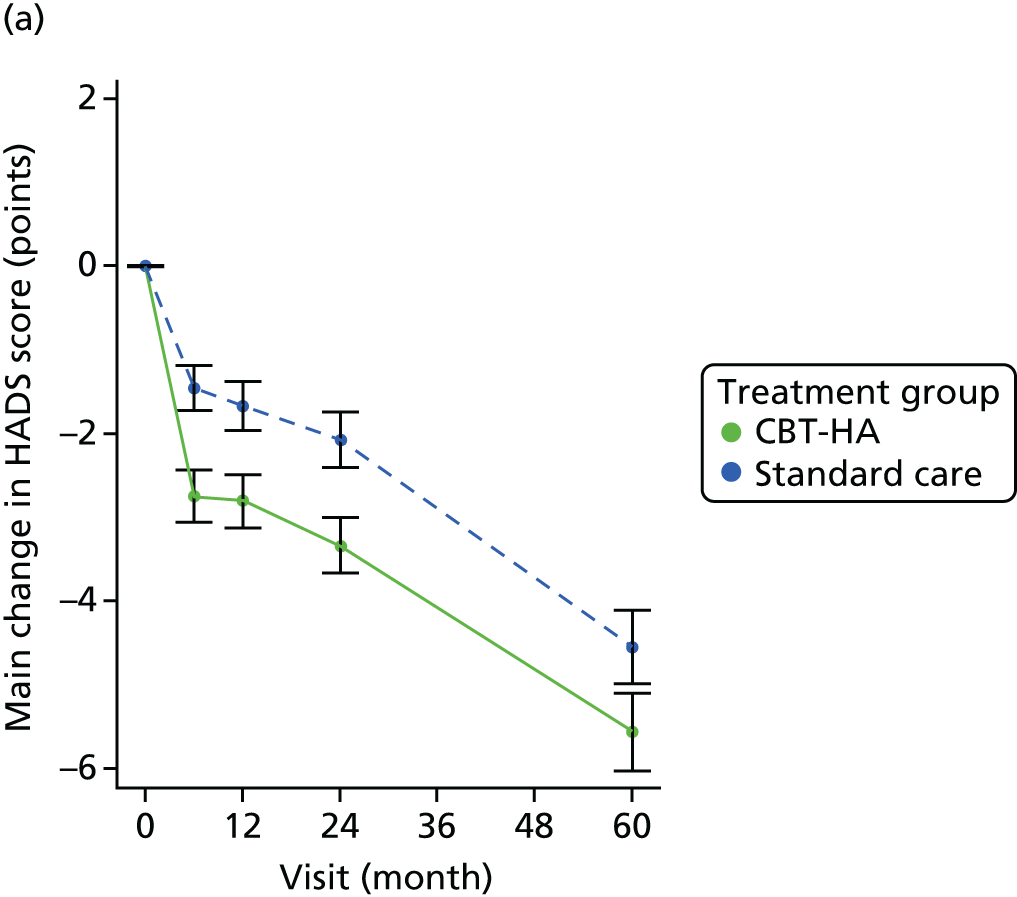

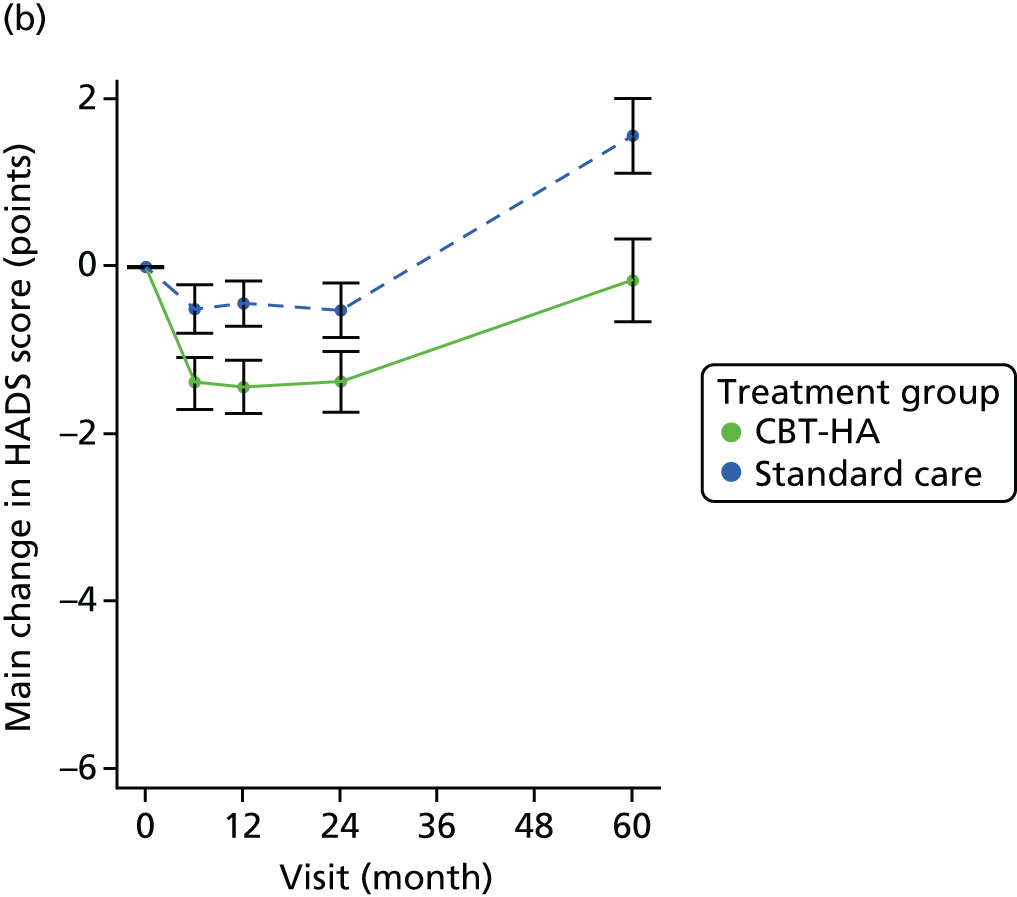

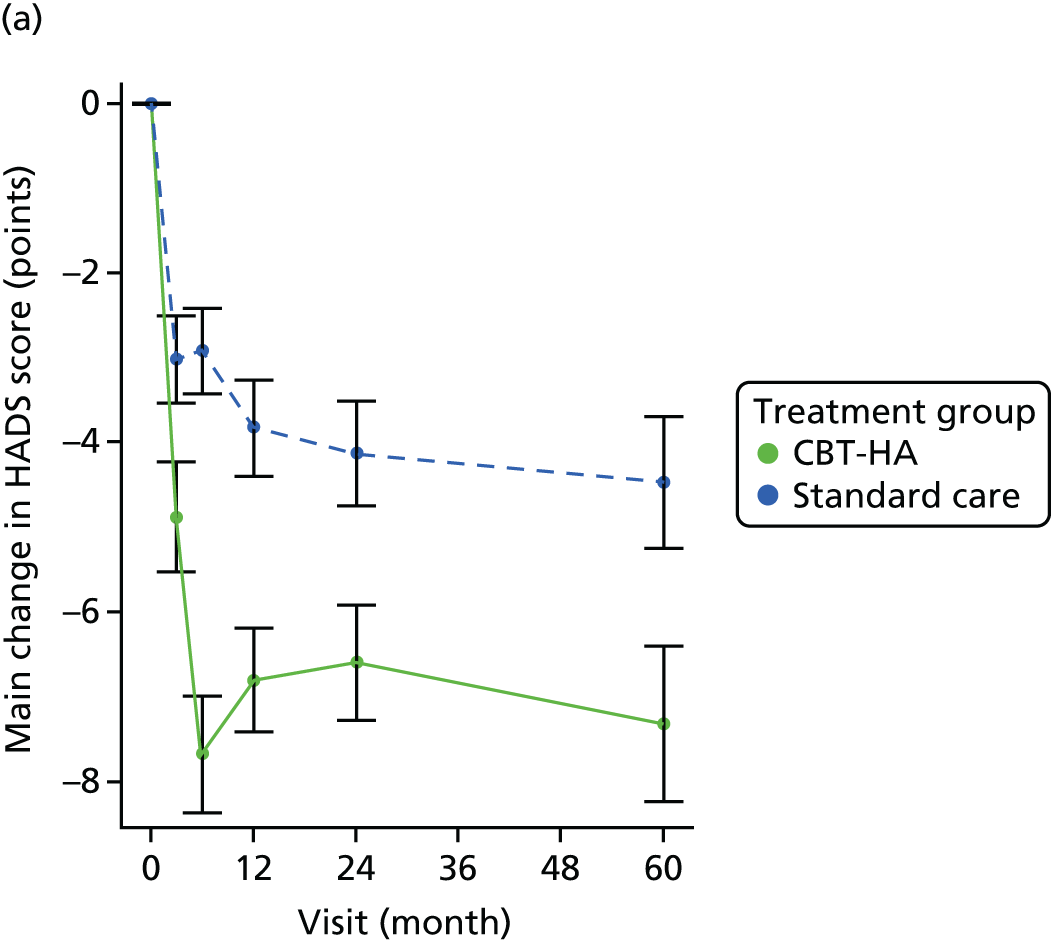

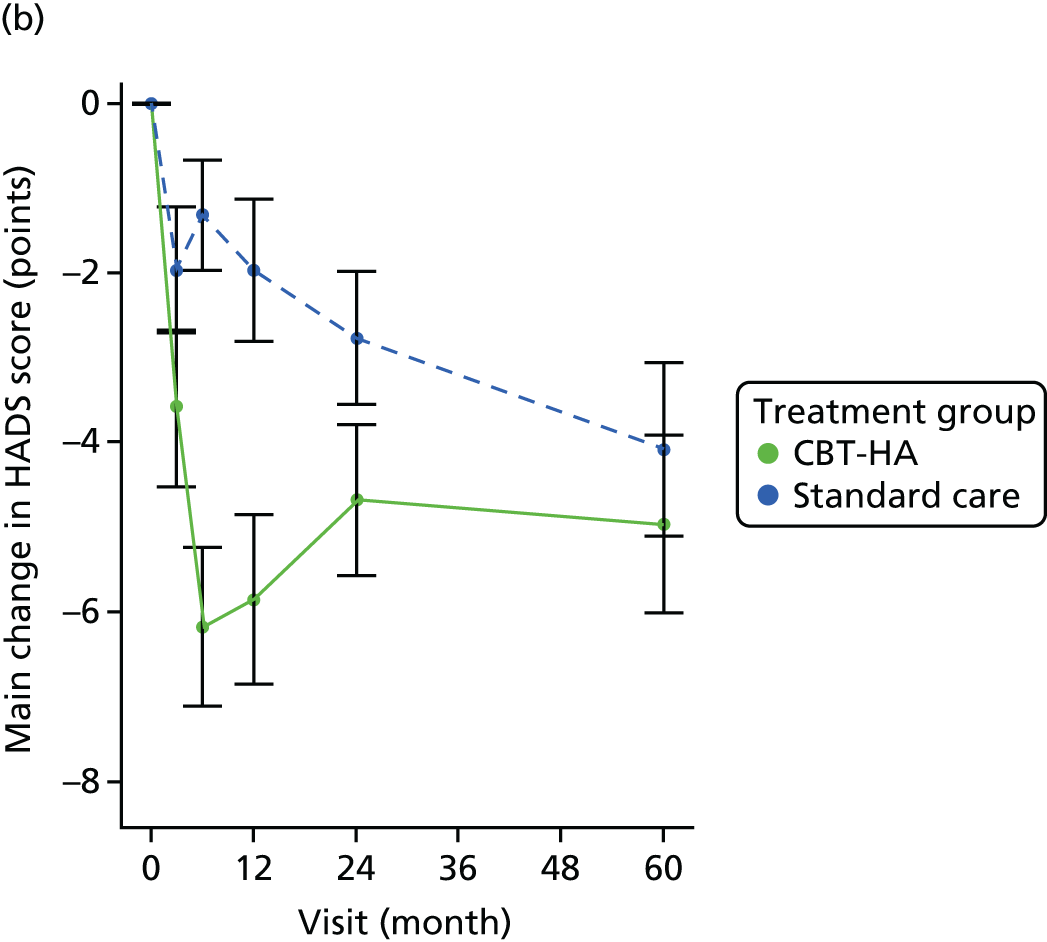

Generalised anxiety and depression as recorded using the HADS anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) sections also showed significant differences between the two treatments over the 5-year period, with those for generalised anxiety (HADS-A) being maximal at 6 months (Table 4 and Figure 4) and those for depression (HADS-D) being maximal at 5 years (Table 5 and Figure 4).

| Visit | Observed value | Mixed-model analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-HA | Standard care | Treatment difference (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| n | Mean score (points) (SD) | n | Mean score (points) (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 219 | 12.56 (3.74) | 225 | 12.25 (3.88) | ||

| Improvement from baseline | ||||||

| 6 months | 197 | 2.74 (4.41) | 204 | 1.46 (3.89) | 1.30 (0.48 to 2.11) | 0.0019 |

| 12 months | 194 | 2.80 (4.40) | 193 | 1.67 (4.04) | 1.02 (0.19 to 1.85) | 0.0165 |

| 24 months | 190 | 3.33 (4.57) | 183 | 2.07 (4.35) | 1.01 (0.17 to 1.86) | 0.0186 |

| 5 years | 150 | 5.56 (5.72) | 158 | 4.54 (5.48) | 0.71 (–0.20 to 1.61) | 0.1245 |

| Overall | 1.01 (0.38 to 1.64) | 0.0018 | ||||

| Visit | Observed value | Mixed-model analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-HA | Standard care | Treatment difference (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| n | Mean score (points) (SD) | n | Mean score (points) (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 219 | 9.12 (4.34) | 225 | 8.83 (4.58) | ||

| Improvement from baseline | ||||||

| 6 months | 197 | 2.74 (4.41) | 204 | 1.46 (3.89) | 0.75 (–0.09 to 1.58) | 0.0797 |

| 12 months | 194 | 2.80 (4.40) | 192 | 1.67 (4.04) | 0.75 (–0.10 to 1.60) | 0.0821 |

| 24 months | 189 | 3.33 (4.57) | 181 | 2.07 (4.35) | 0.63 (–0.23 to 1.49) | 0.1521 |

| 5 years | 150 | 5.56 (5.72) | 157 | 4.54 (5.48) | 1.41 (0.48 to 2.33) | 0.0029 |

| Overall | 0.88 (0.25 to 1.52) | 0.0065 | ||||

FIGURE 4.

Changes in the anxiety and depression sections of the HADS over 5 years. (a) HADS anxiety total score; and (b) HADS depression total score.

Social functioning

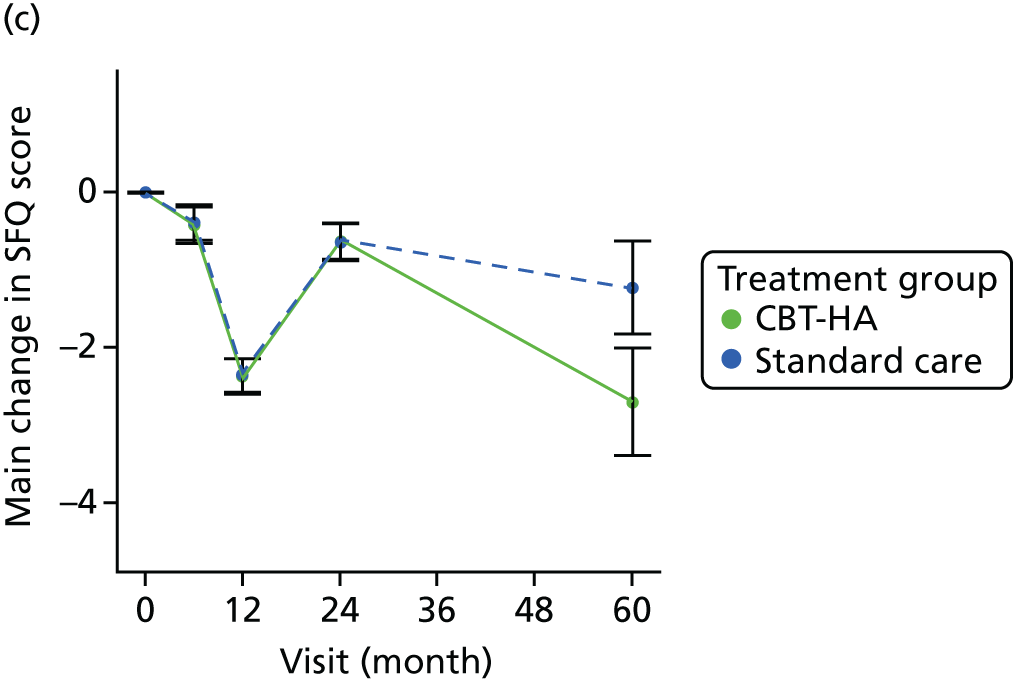

There was very little difference between the scores on the SFQ between the two groups over the 5-year period. The scores at baseline indicated a moderate degree of social dysfunction (the normal population average is 4.6 points and a mean score of 7.7 points is found with patients attending general practice with common mental disorders. 13 The higher than expected SFQ scores were partly explained by comorbid medical pathology but also by personality status (see Table 9). Over the course of the study there was a modest improvement in social functioning in both groups (Table 6).

| Visit | Observed value | Mixed-model analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-HA | Standard care | Treatment difference (points) (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| n | Mean score (points) (SD) | n | Mean score (points) (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 219 | 8.52 (2.07) | 225 | 8.59 (2.00) | ||

| Improvement from baseline | ||||||

| 6 months | 197 | 0.32 (1.71) | 204 | 0.33 (1.77) | 0.02 (–0.47 to 0.50) | 0.9508 |

| 12 months | 194 | 2.21 (1.75) | 192 | 2.30 (1.69) | –0.09 (–0.58 to 0.41) | 0.7335 |

| 24 months | 190 | 0.70 (1.93) | 182 | 0.58 (1.85) | 0.12 (–0.38 to 0.63) | 0.6355 |

| 5 years | 150 | 1.20 (4.88) | 157 | 1.27 (4.56) | –0.06 (–0.62 to 0.50) | 0.8367 |

| Overall | –0.00 (–0.32 to 0.32) | 0.9908 | ||||

Influence of obsessional symptoms on outcome

Scores on the SOCS scale were dichotomised at the level of 6 points, as recommended by the original and subsequent authors. 17,29 The results showed that patients with higher SOCS scores had somewhat lesser improvement in HAI scores with CBT-HA over the 5-year period (Figure 5) and that at 5 years the difference between CBT-HA and standard care was not significant (see Table 13).

FIGURE 5.

Mean change in HAI score by initial scores on the SOCS, with scores dichotomised at the recommended score of 6. (a) SOCS score of ≤ 6 points; and (b) SOCS score of ≥ 6 points.

Influence of personality status on outcome

Personality assessment was carried out using the PAS-Q,20 derived from its parent instrument,30 which records both the severity and the type of personality disorder with an algorithm to identify the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)31 personality disorders, including dependent personality disorder. SC trained all raters in advance on a standard course. During the progress of the study the Working Group for the Reclassification of Personality Disorder in ICD-11 completed its initial work on a classification based on severity criteria (April 2010). 22 The PAS-Q data were subsequently reclassified to the ICD-11 severity equivalents. Good reliability between assessors in this exercise was achieved. 32

Using the ICD-11 classification, only 63 (14.2%) had no personality dysfunction but 197 (44.3%) had personality difficulty (a subthreshold condition not qualifying for disorder). Only three people assessed had severe personality disorder and so they were included with the moderate group. No differences in patient characteristics at baseline were identified and there was an even spread of male/female and a similar age profile between the ICD-11 personality groups (Table 7). However, there were significant differences in symptoms of health anxiety and generalised anxiety, depression and social functioning at baseline; participants with moderate to severe personality disorder had significantly higher scores than those with no personality disturbance (see Table 7). There were no differences in total cost at baseline apart from somewhat greater costs for each increment of personality severity.

| Variable | Personality status | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (N = 63) | 1 (N = 197) | 2 (N = 142) | 3–4 (N = 42) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Female | 29 (46.0) | 109 (55.3) | 76 (53.5) | 22 (52.4) | 0.642 |

| Male | 34 (54.0) | 88 (44.7) | 66 (46.5) | 20 (47.6) | – |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.6 (14.8) | 49.5 (13.6) | 47.5 (13.6) | 47.9 (11.3) | 0.592 |

| Minimum to maximum (range) | 18.3 to 73.9 | 17.3 to 74.3 | 17.0 to 75.5 | 21.7 to 72.4 | – |

| HAI score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.0 (3.2) | 24.8 (4.5) | 25.2 (4.3) | 26.9 (4.9) | 0.006 |

| HADS-A score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.1 (3.6) | 12.1 (3.7) | 13.4 (3.6) | 14.0 (3.6) | < 0.001 |

| HADS-D score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (3.7) | 8.2 (4.1) | 10.0 (4.4) | 12.4 (4.7) | < 0.001 |

| SFQ score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.9 (3.4) | 8.6 (4.0) | 11.3 (4.4) | 12.7 (3.8) | < 0.001 |

| Total cost (preceding 6 months) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 2405.2 (2526.3) | 2601.8 (2837.2) | 2668.1 (2887.1) | 2692.5 (2708.3) | 0.954 |

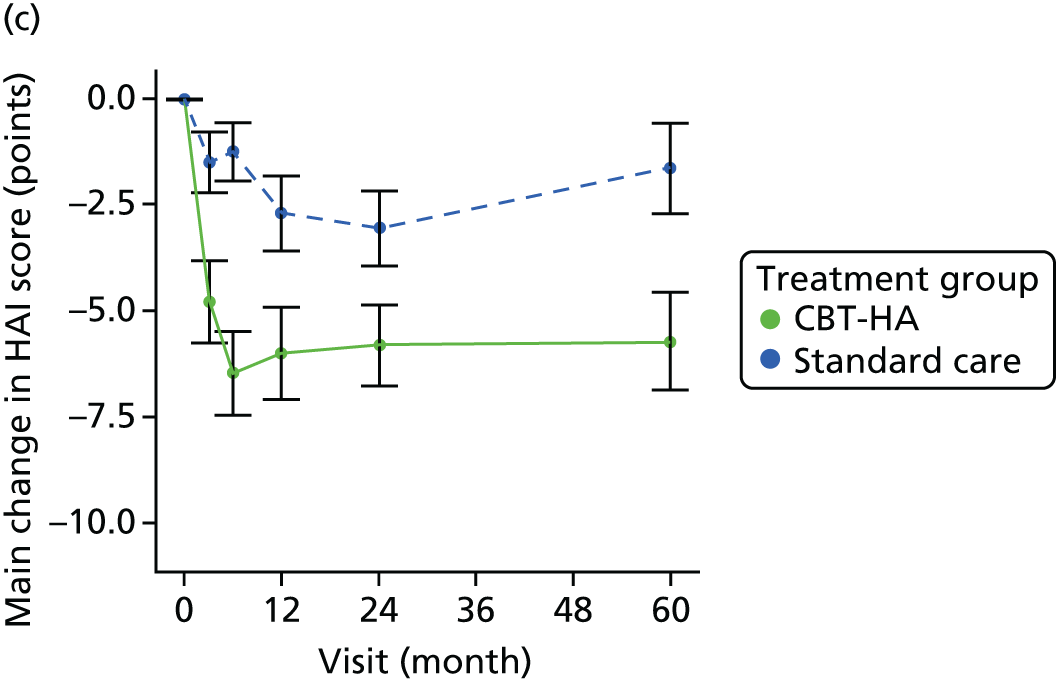

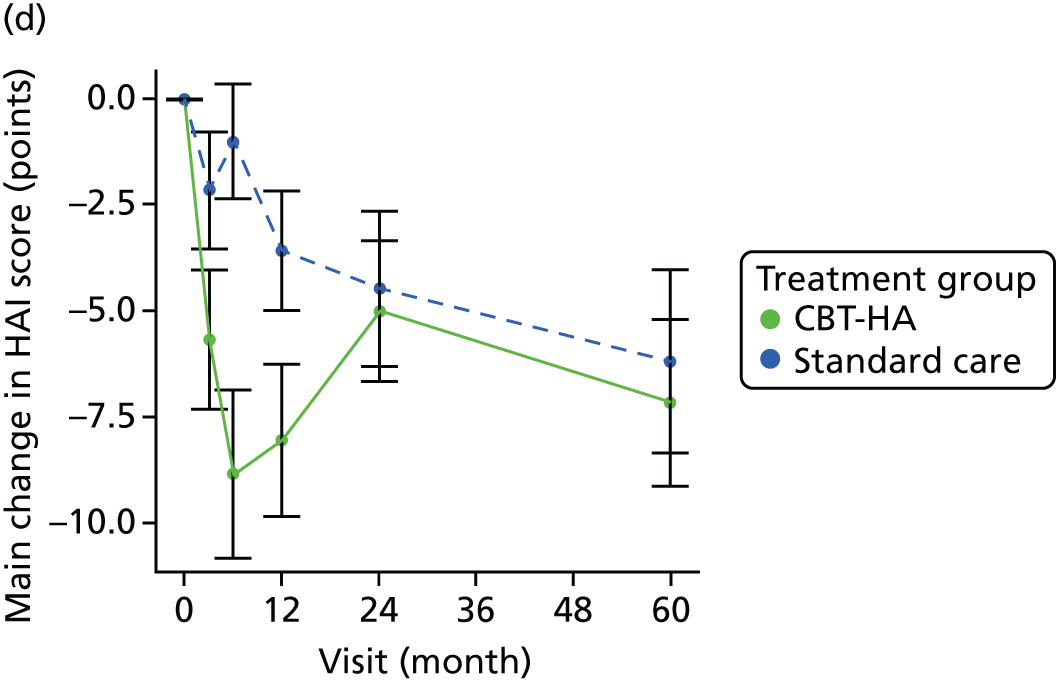

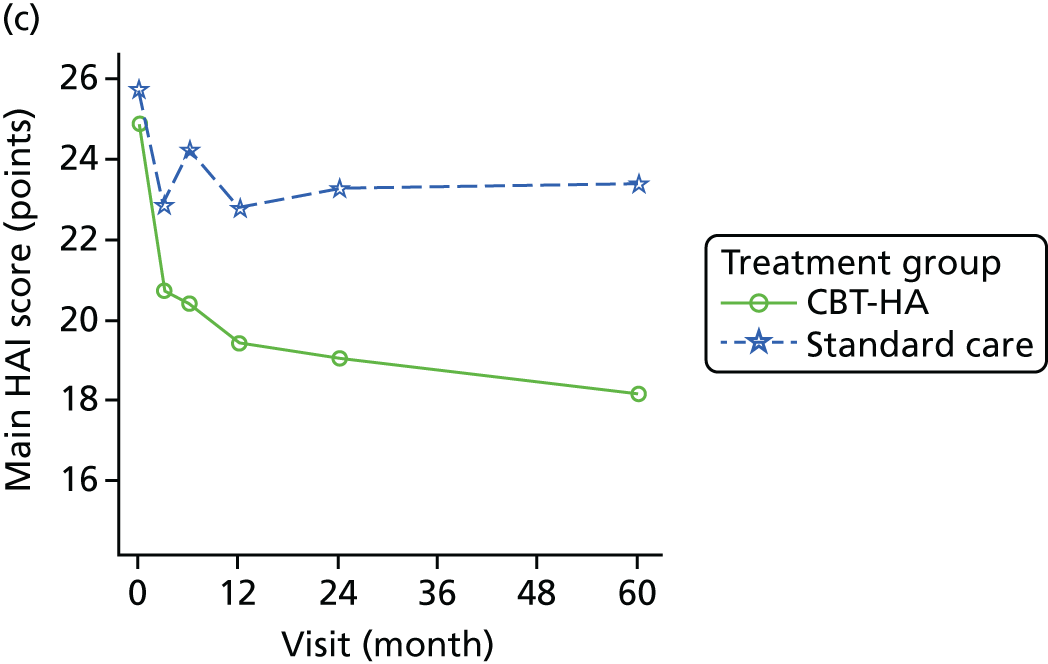

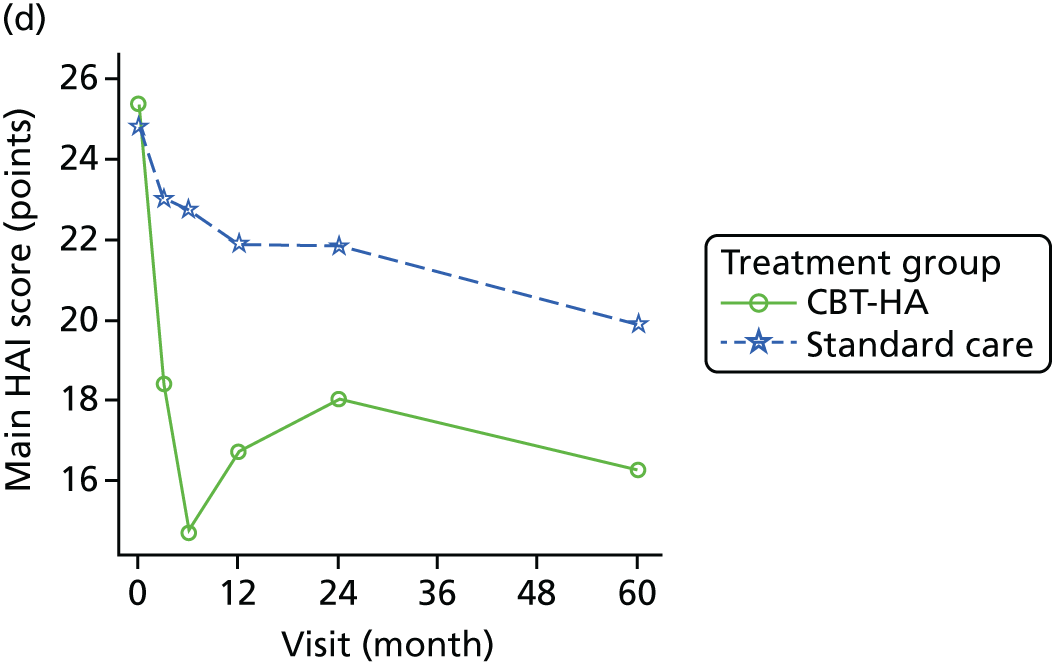

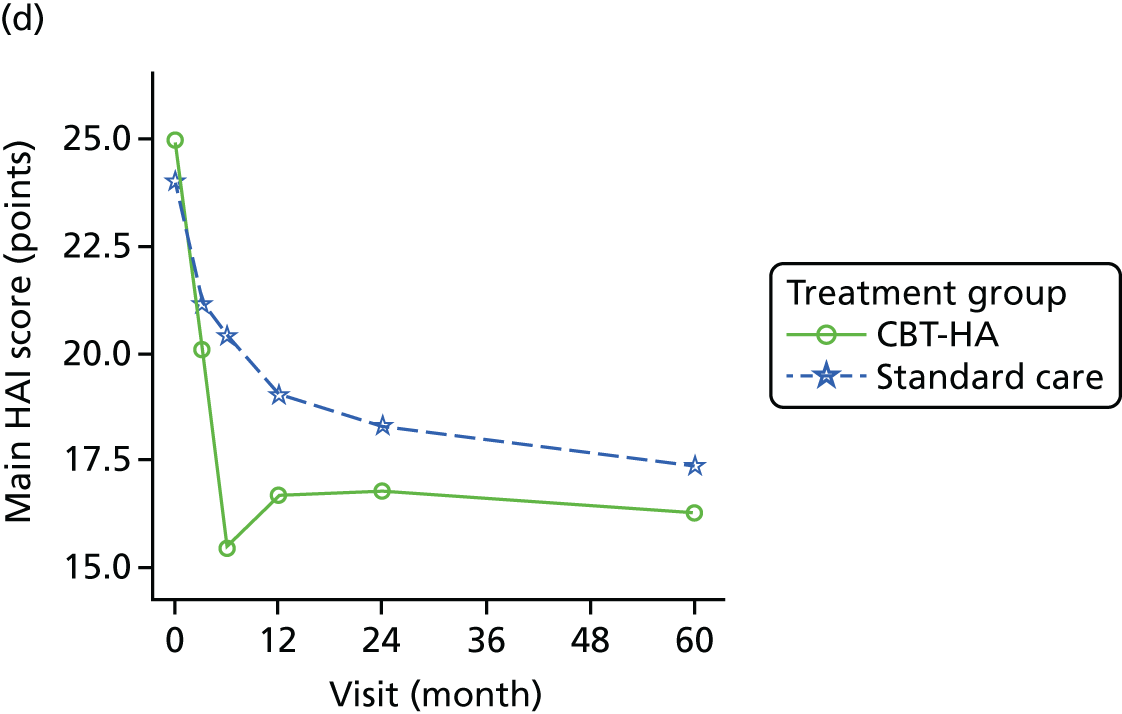

The outcome data over follow-up by ICD-11 classification are detailed in Table 8 and Figure 6. Contrary to our hypotheses, the results show that those with no personality dysfunction showed no benefit from CBT-HA at any time point in the study; overall standard care was superior (p < 0.05). For all other groups the picture was different. For participants with personality difficulty and mild personality disorder, there was evidence of strong gains from CBT-HA at all time points compared with standard care (p < 0.001), and these were maintained at 5 years, especially in those with mild personality disorder. For participants with moderate and severe personality disorder, the initial benefit was not retained at 2 years, resulting in a weaker relationship over follow-up (p < 0.05), and by 5 years benefit was lost. Improvement in social function was similar in all groups except in those with no personality dysfunction (p < 0.02 in favour of standard care) and in those of mild personality disorder at 5 years, whose SFQ scores were significantly lower in the CBT-HA group (Figure 7). Clinical symptomatology increased and social dysfunction was greater with each increment of personality pathology, and although the results were most marked in those with health anxiety they were also found with generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms (see Table 7).

| Variable | Difference between CBT-HA and standard care (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-11 personality level 0 (N = 63) | ICD-11 personality level 1 (N = 197) | ICD-11 personality level 2 (N = 142) | ICD-11 personality level 3–4 (N = 42) | |

| HAI score | ||||

| 3 months | 2.12 (–1.41 to 5.64) | –1.62 (–3.56 to 0.31) | –3.24** (–5.57 to –0.92) | –3.76 (–8.24 to 0.71) |

| 6 months | –1.29 (–4.9 to 2.31) | –4.80*** (–6.77 to –2.84) | –5.51*** (–7.85 to –3.16) | –8.13** (–12.59 to –3.66) |

| 12 months | 0.47 (–3.11 to 4.05) | –3.55** (–5.54 to –1.57) | –3.32** (–5.69 to –0.96) | –4.42 (–8.99 to 0.14) |

| 24 months | 1.45 (–2.12 to 5.03) | –2.98** (–4.98 to –0.97) | –2.96* (–5.35 to –0.56) | –0.31 (–4.93 to 4.31) |

| At all time points | 0.69 (–2.23 to 3.6) | –3.24*** (–4.84 to –1.64) | –3.76*** (–5.78 to –1.74) | –4.16* (–7.99 to –0.33) |

| HADS-A score | ||||

| 6 months | 1.45 (–0.5 to 3.39) | –1.47* (–2.64 to –0.29) | –1.71* (–3.05 to –0.36) | –2.03 (–4.7 to 0.65) |

| 12 months | 2.68 (0.75 to 4.62) | –1.70** (–2.89 to –0.51) | –1.42* (–2.78 to –0.06) | –1.32 (–4.05 to 1.41) |

| 24 months | 2.21* (0.25 to 4.16) | –1.81** (–3.01 to –0.60) | –1.00 (–2.38 to 0.38) | –1.00 (–3.77 to 1.77) |

| At all time points | 2.11** (0.51 to 3.71) | –1.66*** (–2.62 to –0.70) | –1.38* (–2.56 to –0.20) | –1.45 (–3.79 to 0.89) |

| HADS-D score | ||||

| 6 months | 2.17* (0.11 to 4.24) | –1.33* (–2.49 to –0.17) | –1.1 (–2.49 to 0.28) | –1.42 (–4.32 to 1.48) |

| 12 months | 1.79 (–0.27 to 3.85) | –1.27* (–2.45 to –0.09) | –0.69 (–2.10 to 0.71) | –2.64 (–5.62 to 0.33) |

| 24 months | 3.29** (1.22 to 5.36) | –0.69 (–1.88 to 0.49) | –1.84* (–3.27 to –0.41) | –2.06 (–5.08 to 0.96) |

| At all time points | 2.42** (0.62 to 4.21) | –1.10* (–2.06 to –0.13) | –1.21* (–2.41 to –0.02) | –2.04 (–4.55 to 0.47) |

| SFQ score | ||||

| 6 months | 2.32* (0.19 to 4.45) | –0.42 (–1.57 to 0.73) | –0.31 (–1.68 to 1.06) | –1.89 (–4.54 to 0.77) |

| 12 months | 1.52 (–0.61 to 3.64) | –0.08 (–1.25 to 1.09) | –0.66 (–2.05 to 0.73) | –1.91 (–4.64 to 0.82) |

| 24 months | 2.88** (0.75 to 5.01) | –0.19 (–1.37 to 0.98) | –1.49* (–2.9 to –0.08) | –0.88 (–3.65 to 1.89) |

| At all time points | 2.24* (0.41 to 4.07) | –0.23 (–1.19 to 0.73) | –0.82 (–1.97 to 0.33) | –1.56 (–3.83 to 0.71) |

FIGURE 6.

Differential outcome of patients over 5 years treated by CBT-HA and standard care groups separated by ICD-11 personality status at baseline (see Table 8 for significance of differences). (a) No personality dysfunction; (b) personality difficulty; (c) mild personality disorder; and (d) moderate/severe disorder.

FIGURE 7.

Change in social functioning separated by ICD-11 personality status in CBT-HA and standard care groups over a 5-year period. (a) No personality dysfunction; (b) personality difficulty; (c) mild personality disorder; and (d) moderate/severe disorder.

Costs were lower in patients treated with CBT-HA for all levels of personality disturbance apart from moderate and severe personality disorder, when costs were greater (Table 9).

| ICD-11 personality status | Treatment group | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard care | CBT-HA | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| No personality disorder, 0 (n = 49) | 7565.45 | 9840.9 | 6204.83 | 5731.1 | 6926.79 | 8121.8 |

| Personality difficulty, 1 (n = 153) | 8436.81 | 8835.34 | 8166.55 | 9302.32 | 8297.26 | 9050.66 |

| Mild personality disorder, 2 (n = 106) | 7754.32 | 10021.78 | 6819.05 | 5558 | 7277.86 | 8037.21 |

| Moderate and severe personality disorder, 3 (n = 31) | 5363.28 | 3266.24 | 6529.42 | 3876.78 | 5927.54 | 3563.55 |

Effect of personality: dependent personality traits

Dependent personality status was also assessed dimensionally in the same way as the ICD-11 severity levels (range 0–24) using the DPQ. 18 A previous epidemiological study in general practice33 had identified the range of scores associated with disability with 0–6 (no personality dysfunction), 7–11 (personality difficulty), 12–16 (mild personality disorder) and ≥ 17 (moderate personality disorder) linking to ICD-11 severities. The DPQ does not allow severe dependent personality disorder to be identified because none of its questions address self-harm or aggression, even though these may sometimes be present in association with dependent personality. 34

As with the main study using ICD-11 diagnostic criteria for all personality disorders, most patients in the study had some degree of dependent personality disturbance at baseline, with women having more dependent traits than men (Table 10). The generalised anxiety and depression scores were higher in those who were more dependent, although this was not the case for the HAI scores, and there was significantly greater social dysfunction in higher scorers (see Table 10). The mean number of treatment sessions was higher in those with more dependent personality dysfunction (p < 0.005) (Table 11).

| Variable | Dependent personality dysfunction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (N = 76) | 1 (N = 186) | 2 (N = 141) | 3 (N = 41) | p-value | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.64 (13.03) | 49.88 (13.61) | 46.48 (12.89) | 46.56 (15.62) | 0.0507 |

| Female, n (%) | 29 (38.2) | 100 (53.8) | 85 (60.3) | 22 (53.7) | 0.0206 |

| HAI score, mean (SD) | 24.31 (4.18) | 24.85 (4.38) | 25.29 (4.50) | 25.95 (4.14) | 0.1957 |

| HADS-A score, mean (SD) | 10.46 (3.53) | 11.97 (3.81) | 13.45 (3.62) | 14.41 (2.86) | < 0.0001 |

| HADS-D score, mean (SD) | 7.70 (4.55) | 8.46 (4.44) | 9.42 (3.71) | 12.12 (5.22) | < 0.0001 |

| SFQ score, mean (SD) | 8.28 (4.41) | 8.70 (4.35) | 9.65 (4.09) | 12.88 (4.91) | < 0.0001 |

| Statistics | Dependent personality dysfunction group | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| n | 47 | 86 | 65 | 21 | 0.0046 |

| Mean | 5.40 | 5.28 | 6.49 | 8.62 | |

| SD | 4.174 | 3.794 | 3.857 | 5.390 | |

| Minimum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Median | 5.00 | 5.00 | 8.00 | 7.00 | |

| Maximum | 21.00 | 15.00 | 14.00 | 22.00 | |

Of the 444 patients, 47 had an ICD-10 diagnosis of dependent personality disorder, seven with dependent disorder alone and 18 in conjunction with other personality disorders. Agreement between the DPQ and the PAS-Q groups was significant but relatively low (weighted kappa 0.16; p < 0.01).

Contrary to the initial hypotheses, patients treated with CBT-HA who had greater levels of dependence showed superior improvement in health-anxiety scores to those receiving standard care at all times of testing, and this was equally strong after 5 years (Table 12). The score differences were of greater magnitude in those with moderate dependent personality disorder, among whom, at 5 years, the mean score of 13.9 was fairly close to the normal level in the population (around 11)18 (see Table 12). Generalised anxiety and depression scores (HADS) were also significantly more improved in those who received CBT-HA than in those who received standard care. Social function showed no significant differences between the allocated treatments separated by dependence groups (see Table 12).

| Outcome (CBT-HA group vs. standard care group) | Dependent personality dysfunction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n = 76) | 1 (n = 186) | 2 (n = 141) | 3 (n = 41) | |

| HAI score | ||||

| 3 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.81 (–4.92 to 3.31) | –1.03 (–3.05 to 0.99) | –3.23 (–5.62 to –0.84) | –1.37 (–5.60 to 2.87) |

| p-value | 0.6998 | 0.3168 | 0.0082 | 0.5244 |

| 6 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –3.82 (–7.93 to 0.29) | –4.33 (–6.40 to –2.26) | –5.20 (–7.62 to –2.78) | –6.52 (–10.7 to –2.30) |

| p-value | 0.0683 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0027 |

| 12 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –2.80 (–7.03 to 1.43) | –2.30 (–4.37 to –0.24) | –3.32 (–5.76 to –0.89) | –4.91 (–9.33 to –0.49) |

| p-value | 0.1938 | 0.0291 | 0.0076 | 0.0296 |

| 24 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.47 (–3.83 to 4.78) | –2.02 (–4.13 to 0.09) | –3.26 (–5.70 to –0.82) | –1.90 (–6.35 to 2.55) |

| p-value | 0.8292 | 0.0601 | 0.0090 | 0.3996 |

| 5 years | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –4.60 (–9.13 to –0.08) | –1.26 (–3.46 to 0.94) | –1.65 (–4.32 to 1.03) | –4.08 (–8.71 to 0.55) |

| p-value | 0.0463 | 0.2608 | 0.2273 | 0.0837 |

| Overall | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –2.31 (–5.66 to 1.03) | –2.19 (–3.80 to –0.58) | –3.33 (–5.28 to –1.38) | –3.76 (–7.29 to –0.23) |

| p-value | 0.1748 | 0.0078 | 0.0008 | 0.0372 |

| HADS-A score | ||||

| 6 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –1.75 (–3.83 to 0.34) | –1.22 (–2.53 to 0.08) | –1.08 (–2.49 to 0.33) | –2.41 (–5.00 to 0.18) |

| p-value | 0.0997 | 0.0658 | 0.1330 | 0.0676 |

| 12 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.80 (–3.00 to 1.40) | –0.57 (–1.87 to 0.73) | –1.21 (–2.63 to 0.21) | –2.87 (–5.65 to –0.09) |

| p-value | 0.4745 | 0.3907 | 0.0957 | 0.0433 |

| 24 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.79 (–3.02 to 1.43) | –0.90 (–2.25 to 0.44) | –1.09 (–2.51 to 0.34) | –1.89 (–4.69 to 0.92) |

| p-value | 0.4828 | 0.1884 | 0.1345 | 0.1843 |

| 5 years | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.80 (–3.18 to 1.58) | –0.72 (–2.12 to 0.69) | –0.98 (–2.57 to 0.60) | –1.53 (–4.49 to 1.43) |

| p-value | 0.5095 | 0.3147 | 0.2230 | 0.3064 |

| Overall | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –1.03 (–2.63 to 0.56) | –0.85 (–1.83 to 0.12) | –1.09 (–2.21 to 0.03) | –2.17 (–4.20 to –0.15) |

| p-value | 0.2031 | 0.0871 | 0.0572 | 0.0352 |

| HADS-D score | ||||

| 6 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.45 (–2.74 to 1.83) | –0.41 (–1.74 to 0.91) | –1.36 (–2.78 to 0.07) | –1.47 (–4.00 to 1.07) |

| p-value | 0.6950 | 0.5409 | 0.0626 | 0.2543 |

| 12 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.05 (–2.46 to 2.35) | –0.41 (–1.73 to 0.91) | –1.23 (–2.67 to 0.21) | –2.26 (–5.01 to 0.49) |

| p-value | 0.9644 | 0.5429 | 0.0929 | 0.1062 |

| 24 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | 2.16 (–0.27 to 4.59) | –0.65 (–2.02 to 0.71) | –1.87 (–3.32 to –0.43) | –1.56 (–4.34 to 1.22) |

| p-value | 0.0808 | 0.3482 | 0.0111 | 0.2686 |

| 5 years | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –4.09 (–6.68 to –1.51) | –0.87 (–2.30 to 0.56) | –0.83 (–2.44 to 0.77) | –1.52 (–4.49 to 1.45) |

| p-value | 0.0021 | 0.2317 | 0.3083 | 0.3120 |

| Overall | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.61 (–2.42 to 1.20) | –0.59 (–1.57 to 0.40) | –1.32 (–2.46 to –0.18) | –1.70 (–3.42 to 0.01) |

| p-value | 0.5069 | 0.2414 | 0.0229 | 0.0519 |

| SFQ score | ||||

| 6 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.17 (–1.46 to 1.12) | 0.26 (–0.53 to 1.06) | –0.10 (–0.91 to 0.71) | –0.85 (–2.38 to 0.67) |

| p-value | 0.7946 | 0.5138 | 0.8094 | 0.2683 |

| 12 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.26 (–1.63 to 1.11) | 0.30 (–0.49 to 1.10) | 0.15 (–0.67 to 0.97) | –1.01 (–2.66 to 0.64) |

| p-value | 0.7090 | 0.4546 | 0.7231 | 0.2263 |

| 24 months | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.47 (–1.86 to 0.92) | –0.04 (–0.86 to 0.78) | 0.02 (–0.80 to 0.85) | –0.79 (–2.46 to 0.88) |

| p-value | 0.5067 | 0.9323 | 0.9556 | 0.3480 |

| 5 years | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.40 (–1.12 to 1.92) | –0.00 (–0.89 to 0.89) | –0.14 (–1.11 to 0.83) | –0.56 (–2.39 to 1.27) |

| p-value | 0.6041 | 0.9998 | 0.7772 | 0.5431 |

| Overall | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | –0.12 (–1.05 to 0.80) | 0.13 (–0.37 to 0.64) | –0.02 (–0.56 to 0.53) | –0.81 (–1.87 to 0.26) |

| p-value | 0.7906 | 0.6052 | 0.9507 | 0.1357 |

Differences in outcome by site, clinic and age

These outcomes were considered relevant in the covariate-adjusted analyses and are summarised here, but it is important to emphasise that there were no particular hypotheses linked to these outcomes and randomisation did not take account of these. The five sites covered a mix of urban, suburban and rural areas, including two main teaching hospitals (St Mary’s Hospital and Charing Cross Hospital), two hospitals linked to teaching hospitals (Hillingdon and Chelsea and Westminster) and one district general hospital (King’s Mill Hospital). Four of the clinics concerned (cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology and respiratory medicine) had been identified previously as having at least 12% of attenders with a high level of health anxiety,7,35 and during the course of the study another clinic type, neurology, was added.

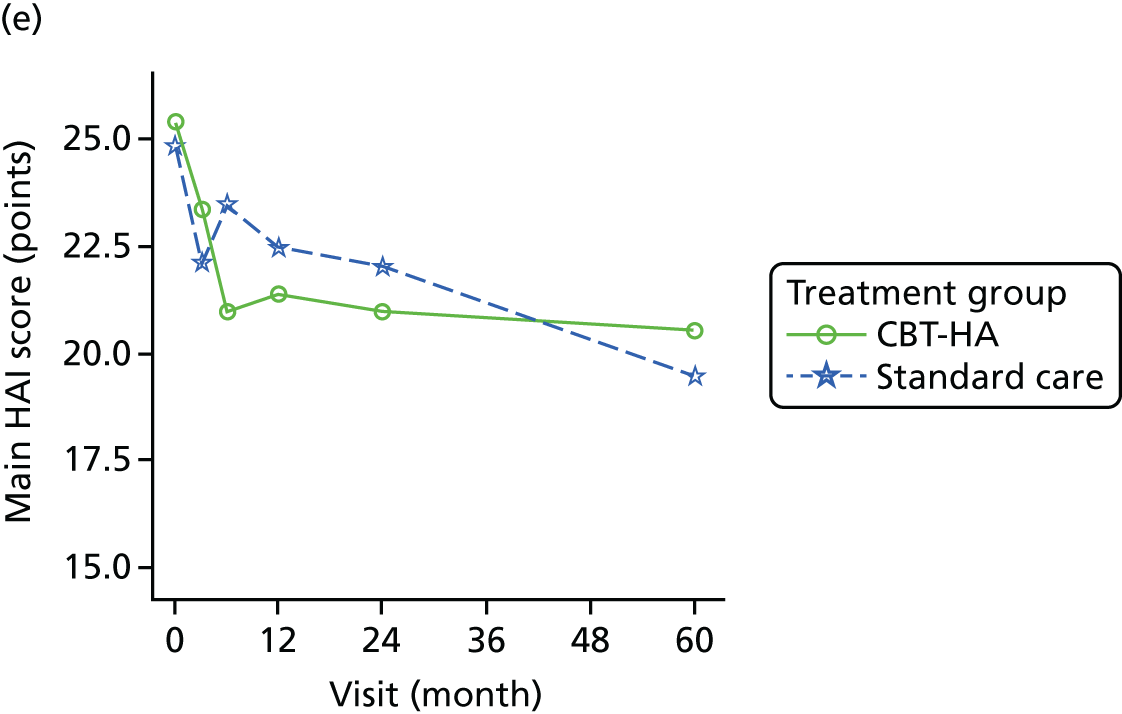

The differences between sites are shown in Figure 8. In general, the non-teaching hospitals showed the largest differences between the patients receiving CBT-HA and those receiving standard care. There is no obvious explanation for this difference except in terms of therapist type (see Subgroup analyses). There were also differences in HAI outcome by clinic. Patients seen in cardiology clinics showed the largest differences between those who received CBT-HA and those receiving standard care, maximal at 5 years (Figure 9), and respiratory medicine patients showed the least differences between groups (with no benefit after the first 6 months of treatment).

FIGURE 8.

Differences in outcome by HAI scores separated by site. (a) Chelsea and Westminster; (b) Charing Cross Hospital; (c) Hillingdon Hospital; (d) King’s Mill Hospital; and (e) St Mary’s Hospital.

FIGURE 9.

Differences in outcome by HAI scores separated by clinic type. (a) Cardiology; (b) endocrinology; (c) gastroenterology; (d) neurology; and (e) respiratory medicine.

Older patients derived greater benefit from CBT-HA compared with standard care than younger patients. This was not an expected finding and possible reasons for it are discussed later in this report.

Subgroup analyses

There were several subgroup analyses that showed generally similar findings. The subgroup analysis to examine the heterogeneity of the variables of interest is shown for the primary outcome, the HAI, in Table 13. There were no significant interactions, suggesting that the data were consistent and robust. The only variable approaching heterogeneity was the study site. King’s Mill Hospital had a better outcome than the other sites over the period of the study; this was also the site where the nurses were the main therapists.

| Variable | Mixed-model result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-HA | Standard care | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | p-value from interaction test | |

| n, mean (SD) | n, mean (SD) | ||||

| Age group (years) | |||||

| ≤ 49 | 63, 6.68 (8.36) | 79, 5.69 (7.06) | 1.78 (–0.46 to 4.01) | 0.1197 | 0.2051 |

| > 49 | 86, 6.28 (8.76) | 79, 2.98 (8.21) | 2.78 (0.77 to 4.79) | 0.0067 | – |

| Hospital | |||||

| Charing Cross Hospital | 20, 5.10 (9.81) | 19, 6.58 (8.64) | –3.32 (–7.50 to 0.86) | 0.1186 | – |

| Chelsea and Westminster Hospital | 14, 6.93 (6.47) | 15, 3.12 (6.39) | 3.60 (–1.10 to 8.30) | 0.1321 | 0.0669 |

| Hillingdon Hospital | 43, 6.33 (8.47) | 46, 2.37 (7.09) | 3.56 (0.83 to 6.29) | 0.0107 | – |

| King’s Mill Hospital | 45, 8.89 (7.62) | 53, 4.85 (7.49) | 4.78 (2.15 to 7.42) | 0.0004 | – |

| St Mary’s Hospital | 27, 3.35 (9.50) | 25, 5.88 (9.06) | –1.66 (–5.32 to 2.00) | 0.3718 | – |

| Clinic | |||||

| Cardiology | 33, 8.73 (7.93) | 38, 3.56 (8.62) | 5.21 (2.08 to 8.34) | 0.0012 | 0.4715 |

| Endocrinology | 28, 4.89 (6.82) | 30, 3.70 (6.30) | 1.39 (–2.06 to 4.83) | 0.4286 | – |

| Gastroenterology | 57, 5.77 (9.02) | 55, 4.78 (7.73) | 1.45 (–1.07 to 3.98) | 0.2591 | – |

| Neurology | 13, 9.08 (9.05) | 17, 5.53 (8.19) | 1.15 (–3.52 to 5.82) | 0.6274 | – |

| Respiratory medicine | 18, 4.97 (9.87) | 18, 4.53 (8.27) | –0.13 (–4.39 to 4.12) | 0.9507 | – |

| SOCS score | |||||

| ≤ 6 points | 94, 7.32 (8.93) | 103, 4.47 (7.87) | 2.73 (0.87 to 4.58) | 0.0040 | 0.4376 |

| > 6 points | 55, 4.97 (7.76) | 55, 4.09 (7.59) | 1.31 (–1.23 to 3.84) | 0.3112 | – |

| DPQ score | |||||

| ≤ 15 points | 127, 6.51 (8.86) | 140, 4.57 (7.78) | 2.02 (0.41 to 3.64) | 0.0140 | 0.5229 |

| > 15 points | 22, 6.09 (6.75) | 18, 2.50 (7.52) | 3.30 (–0.62 to 7.22) | 0.0983 | – |

| PAS-Q | |||||

| 0 | 20, 5.02 (9.46) | 17, 4.59 (7.61) | 0.25 (–4.24 to 4.74) | 0.9118 | 0.2902 |

| 1 | 79, 6.27 (8.84) | 97, 4.05 (7.81) | 2.30 (0.35 to 4.25) | 0.0207 | – |

| 2 | 39, 8.10 (7.77) | 33, 4.03 (8.26) | 3.83 (0.62 to 7.03) | 0.0194 | – |

| 3 | 11, 4.55 (7.66) | 11, 7.36 (5.95) | –0.93 (–6.81 to 4.94) | 0.7537 | – |

Outcome by therapist type

When the CHAMP trial started it was hoped that sufficient excess treatment costs might be available to fund dedicated therapists at all sites in the study; this was not possible, but at one site (King’s Mill Hospital) a subvention grant allowed two general nurses (SM and YL-S) to be employed for approximately 80% of their time in giving CBT-HA. In other centres somewhat less funding was obtained for other therapists, mainly trainee psychologists, but also other health professionals, including a dietitian, to be employed on a mainly part-time basis.

Apart from the nurses and the dietitian, the other therapists had at least some knowledge of the principles of CBT before the trial began and some had practised, but none had been trained in, CBT-HA. All therapists were involved in the initial 2-day workshop and, once trained at this standard level, received supervision from established trainers at each site.

The results, also reported elsewhere,36 showed that although the patients treated by all three therapist groups (nurses, assistant psychologists and graduate workers) showed superior HAI outcomes after 6 months, the nurses group showed the largest benefit across the initial 2-year period (Figure 10 and Table 14). After 2 years, 23.5% of patients in standard care had improved to a score of 15 on the HAI (mild but not pathological health anxiety), whereas the proportions in the three therapist CBT-HA groups were 28.9% (assistant psychologists), 34% (graduate workers) and 44.3% (nurses) (Table 15).

FIGURE 10.

Mean differences in HAI scores between the outcomes of 219 patients with health anxiety treated by nurses (n = 66), graduate workers (n = 66) and assistant psychologists (n = 87) over 2 years. Reprinted from the International Journal of Nursing Studies, vol. 52, Tyrer H, Tyrer P, Lisseman-Stones Y, McAllister S, Cooper S, Salkovskis P, et al. Therapist differences in a randomised trial of the outcome of cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety in medical patients, pp. 686–94. Copyright (2015),36 with permission from Elsevier.

| Visit | HAI score (points), n of patients, mean score (SD) | Difference between nurses and other groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard care | CBT by assistant psychologists | CBT by graduates | CBT by nurses | All | Mean (95% CI); p-value | |

| Baseline | 225, 25.12 (4.52) | 87, 24.76 (3.91) | 66, 24.38 (4.15) | 66, 25.53 (4.67) | 225, 25.12 (4.52) | – |

| 3 months | 212, 22.37 (6.71) | 82, 21.65 (6.62) | 59, 21.33 (6.97) | 64, 18.15 (9.07) | 212, 22.37 (6.71) | 4.10 (6.1 to 3.1); p < 0.0001 |

| 6 months | 204, 22.62 (6.81) | 78, 20.13 (7.26) | 56, 17.77 (8.42) | 63, 14.67 (7.53) | 204, 22.62 (6.81) | 4.93 (7.0 to 2.9); p < 0.0001 |

| 12 months | 193, 21.54 (7.45) | 75, 19.80 (6.96) | 57, 18.53 (8.31) | 62, 16.81 (8.31) | 193, 21.54 (7.45) | 3.24 (5.3 to 1.2); p < 0.002 |

| 24 months | 183, 21.35 (7.67) | 76, 19.51 (7.22) | 53, 18.98 (8.14) | 61, 17.95 (8.63) | 183, 21.35 (7.67) | 2.49 (4.5 to 0.5); p < 0.02 |

| All periods | 3.7 (5.4 to 2.0); p < 0.0001 | |||||

| Therapist group | Number of patients (%) with HAI scores of ≤ 15 points | Odds ratio of improvement (CBT-HA vs. standard care): all times (significance) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard care | |||

| 3 months | 31 (14.6) | – | – |

| 6 months | 30 (14.7) | ||

| 12 months | 42 (21.8) | ||

| 24 months | 43 (23.5) | ||

| CBT-HA: assistant psychologists | |||

| 3 months | 16 (19.5) | 1.58 (p = 0.05) | 0.99 to 2.51 |

| 6 months | 24 (30.8) | ||

| 12 months | 19 (25.3) | ||

| 24 months | 22 (28.9) | ||

| CBT-HA: graduates | |||

| 3 months | 10 (16.9) | 2.05 (p = 0.005) | 1.25 to 3.36 |

| 6 months | 24 (42.9) | ||

| 12 months | 24 (42.1) | ||

| 24 months | 18 (34.0) | ||

| CBT-HA: nurses | |||

| 3 months | 28 (43.8) | 3.16 (p < 0.0001) | 1.97 to 5.06 |

| 6 months | 40 (63.5) | ||

| 12 months | 33 (53.2) | ||

| 24 months | 27 (44.3) | ||

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

Perspective

The economic evaluation took a health and social care perspective, which included the costs of the CBT intervention, other health-care costs and other community health and social services. In addition, we completed the sensitivity analysis from a societal perspective, to include all resources in the health and social care perspective plus productivity losses.

Identification of resources

The calculation of costs was separated into three stages: identification, measurement and valuation of resources.

We identified relevant resources based on the results of our pilot study10 and in discussion with study clinicians and patient representatives. Resource use was collected in the following domains:

-

delivery of CBT-HA

-

use of NHS secondary care services

-

inpatient stays

-

day-case procedures

-

outpatient appointments

-

accident and emergency attendances

-

use of NHS primary care services

-

General practitioner [(GP) in practice, at home or by telephone]

-

community nurse (practice nurse, district nurse, health visitor, midwife)

-

community mental health services

-

community medical services (walk-in clinic)

-

community medical professional (physiotherapist, chiropodist)

-

use of all medication

-

use of social care and voluntary sector services

-

social worker

-

voluntary sector advice worker

-

housing services

-

service-provided accommodation

-

productivity losses measured as absenteeism.

Measurement of resources

The identified resources were measured using the following methods.

The CBT-HA therapists recorded information on attendance and non-attendance at treatment sessions together with the duration of each session. These data were extracted for analysis from trial records.

The computerised records of the host hospital trusts (Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and The Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) were examined and accident and emergency attendances, inpatient stays, day-patient procedures and outpatient appointments were extracted for analysis by hospital trust-based information specialists co-ordinated by AP.

Other service use data for the economic evaluation were collected using the ADSUS, based on previous economic evaluations in adult mental health populations37 and on the data collected in the pilot study. 10 The ADSUS was completed at baseline, at 6, 12 and 24 months and at the 5-year follow-up. At baseline, the ADSUS covered the previous 6 months and at each of the follow-up interviews, service use since the previous interview was recorded so that the entire period from baseline to final follow-up was covered. The ADSUS records the number and duration of contacts with a range of health and social service professionals and medications taken.

The number of days taken off work because of ill health was collected with the relevant questions from the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire. 38

Valuation of resources

The cost of the CBT-HA intervention was estimated using the bottom-up approach set out by the Personal Social Services Research Unit at the University of Kent. 39 The salary cost for the therapist was based on that of an experienced nurse or therapist (Agenda for Change Band 6),40 onto which employer costs (National Insurance and pension contribution) were added. Overhead costs were then added to include building costs, administrative and managerial costs and capital costs. An hourly cost was calculated on the working time assumptions set out in the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care,41 and then weighted to account for the therapist spending time on non-patient-facing activities. In addition, the final cost per hour included an allowance for the cost of time spent by the therapist in supervision and the cost of supervisor time.

For each type of other service use, an appropriate unit cost was identified. All unit costs were for the financial year 2009–10 and costs with their sources are listed in full in Table 16. When necessary, unit costs were inflated to 2009–10 costs using the Hospital and Community Health Services inflation index or the Retail Price Index as appropriate. 41 Costs in the second, third, fourth and fifth years were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 44

| Service | Unit | Cost (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Medication42 | Per daily dose | Various |

| Inpatient43 | Per night | 382–726 |

| Outpatient43 | Per appointment | 39–989 |

| Diagnostic procedure43 | Per procedure | 1–553 |

| Accident and emergency43 | Per attendance | 103 |

| Ambulance43 | Per trip | 222 |

| GP surgery41 | Per minute of patient contact | 2.40 |

| GP home41 | Per home visit minute | 4.00 |

| GP telephone41 | Per minute of patient contact | 2.40 |

| Community medical professionals41 | Per minute of contact | 0.37–1.13 |

| Community social care professionals41 | Per minute of contact | 0.42–2.63 |

The cost of productivity losses was calculated using the human capital approach, when each day off work is valued at the daily salary for that individual. 45

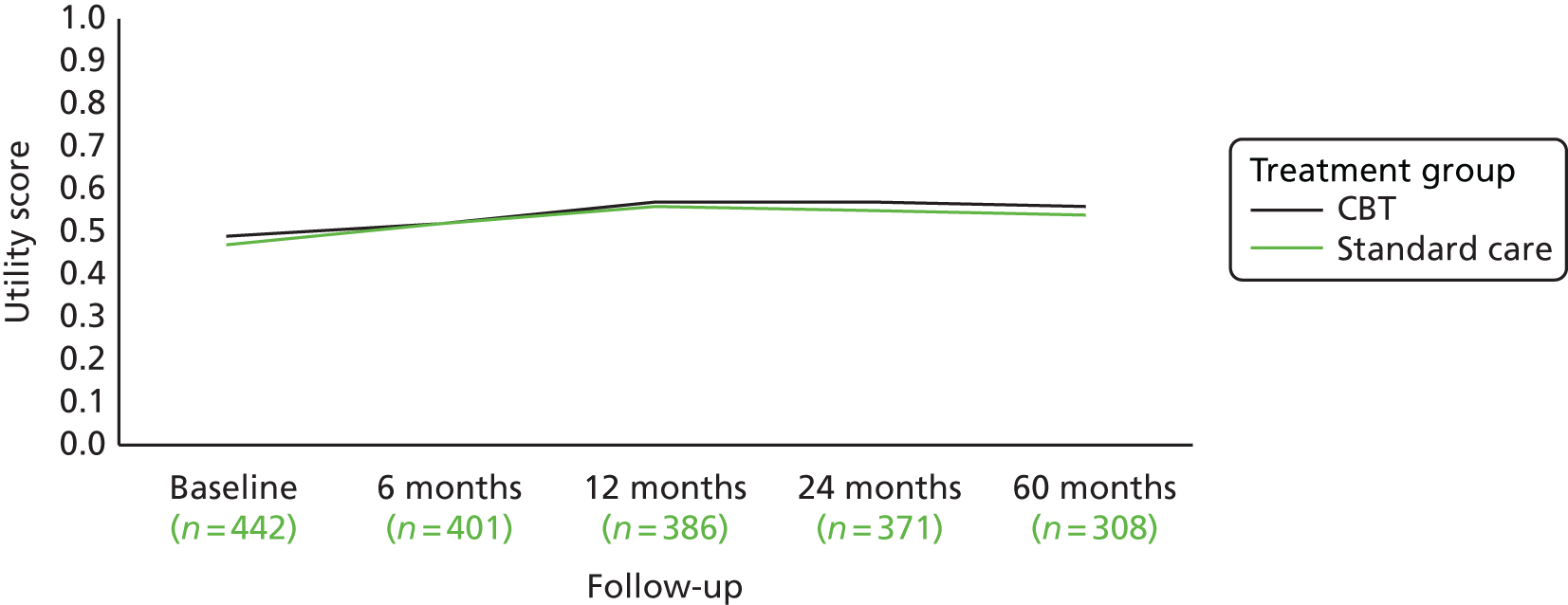

Calculation of quality-adjusted life-years

Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were calculated on the basis of the EQ-5D health state classification instrument46 and the health states were assigned a utility score using responses from a representative sample of adults in the UK. 47 QALYs were then calculated as the area under the curve defined by the utility values at baseline and at the 6-, 12-, 24- and 60-month follow-ups. We assumed that changes in utility score over time followed a linear path. 48 QALYs in the second to fifth years were discounted at a rate of 3.5% as recommended by NICE44 and all analyses were adjusted for baseline utility scores to take into consideration the impact of baseline differences on the area under the curve. 49

Data analysis

For the economic evaluation the base case was a complete-case analysis.

We report the mean average resource use by randomised groups at 24 months’ and 5 years’ follow-up, as well as the percentage of people in each randomised group who have had at least one contact with each service. No between-group statistical comparisons are made in order to avoid the problems of multiple comparisons and because the focus of the economic evaluation is on cost and cost-effectiveness.

Our hypothesis was that the cost of the CBT intervention would be recouped through a reduction in the use of health and social care services. We tested this through a non-inferiority (equivalence) test, with a pre-specified equivalence test of £150. The equivalence was declared between active and control groups if the 95% CI fell between –£150 and £150. These analyses were adjusted for baseline differences in cost.

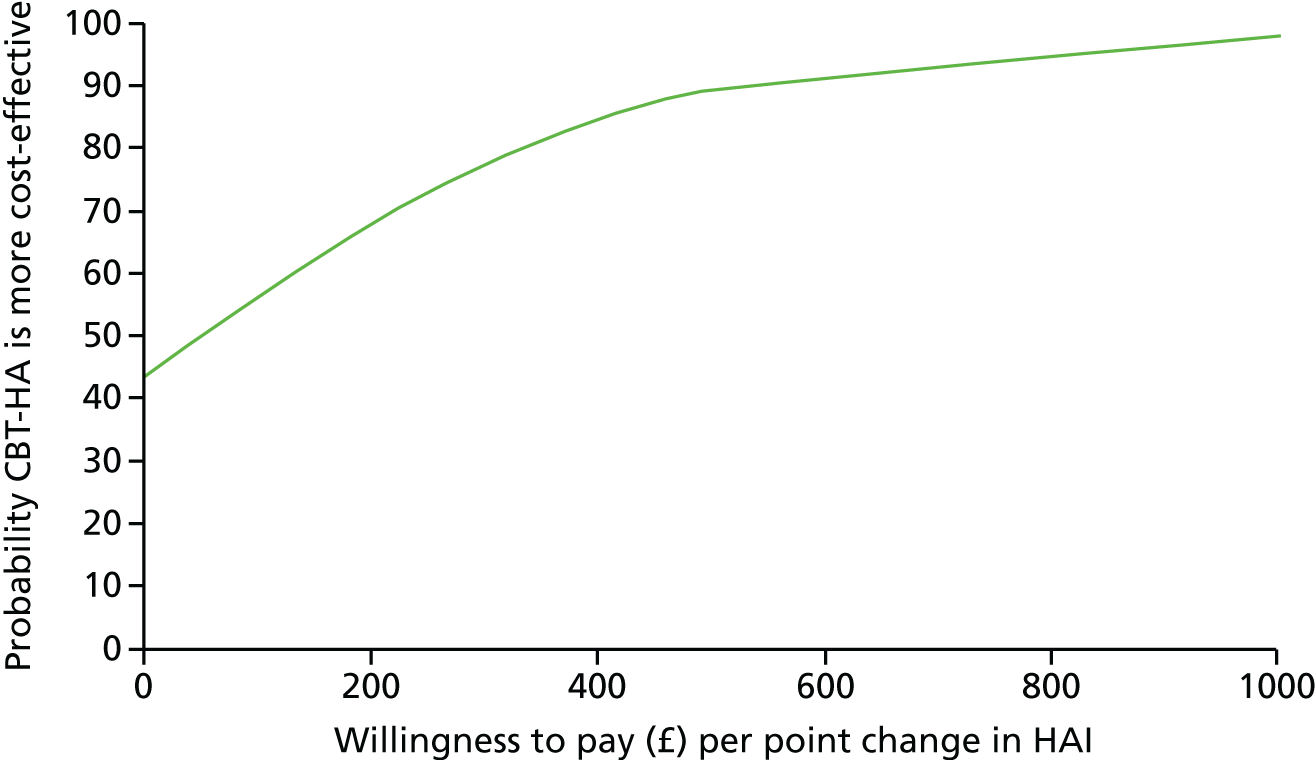

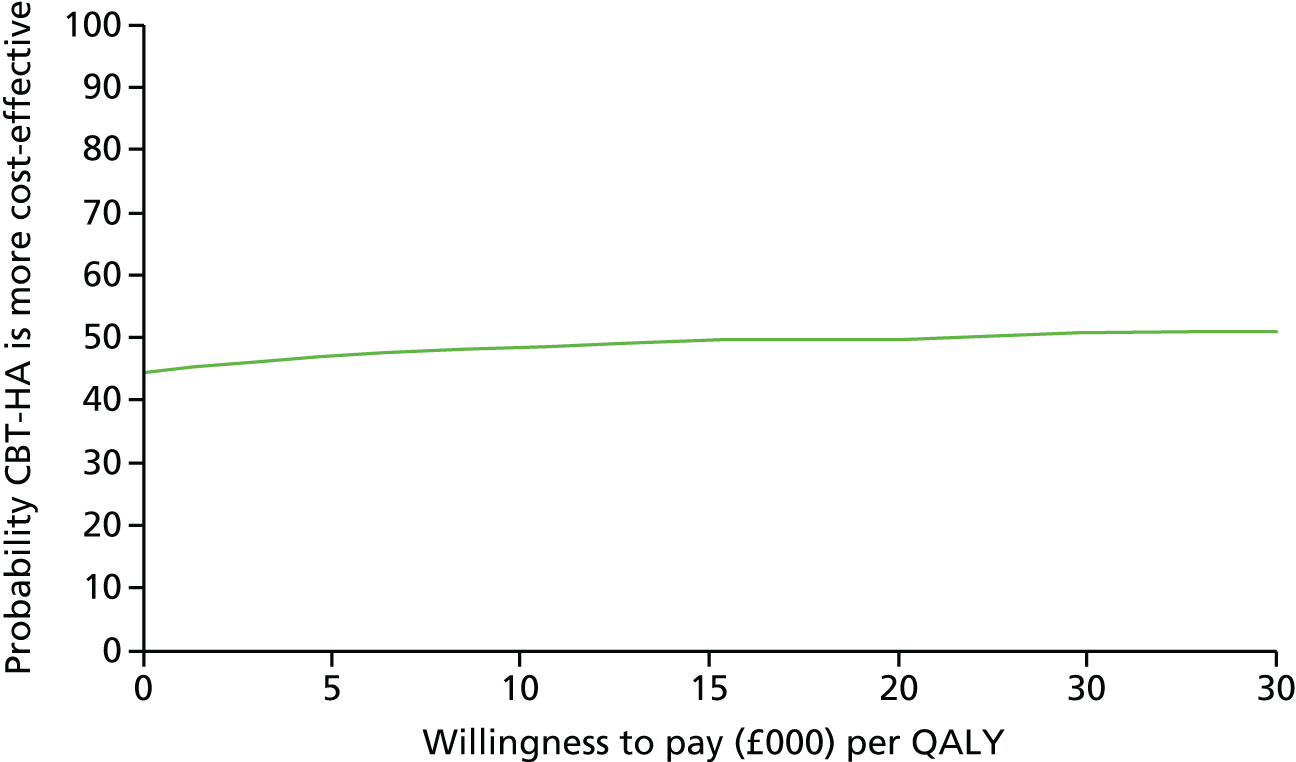

Cost-effectiveness was considered for two outcomes: QALYs and the HAI score. Cost-effectiveness was initially explored through the calculation of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), a ratio of differences in cost by differences in outcomes between the CBT-HA and standard care groups. ICERs are a useful decision-making tool when there is no uncertainty around the costs and outcomes used in the ratio. Here, the ICERs are based on four sample means; therefore, the uncertainty around the ICER was explored.

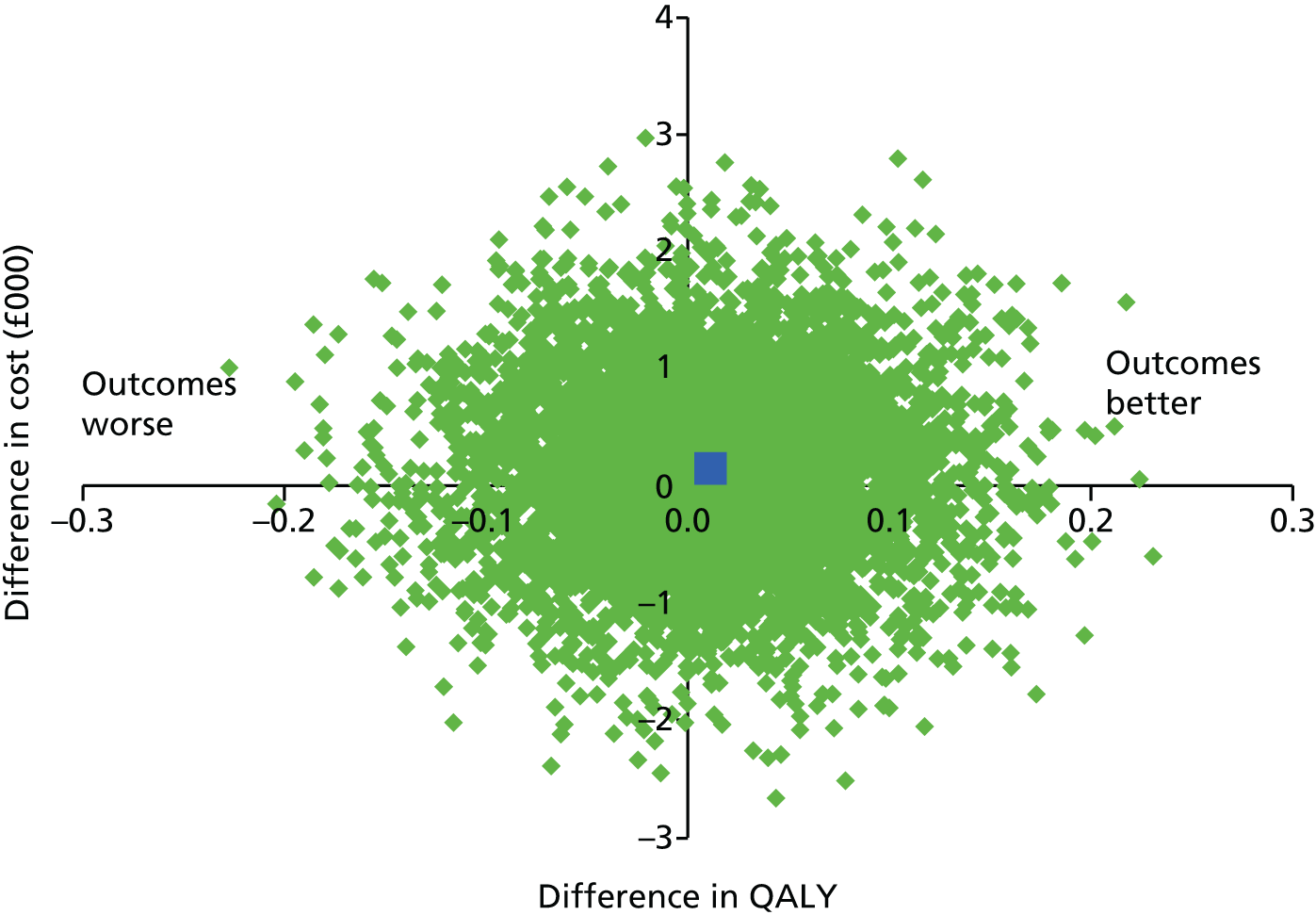

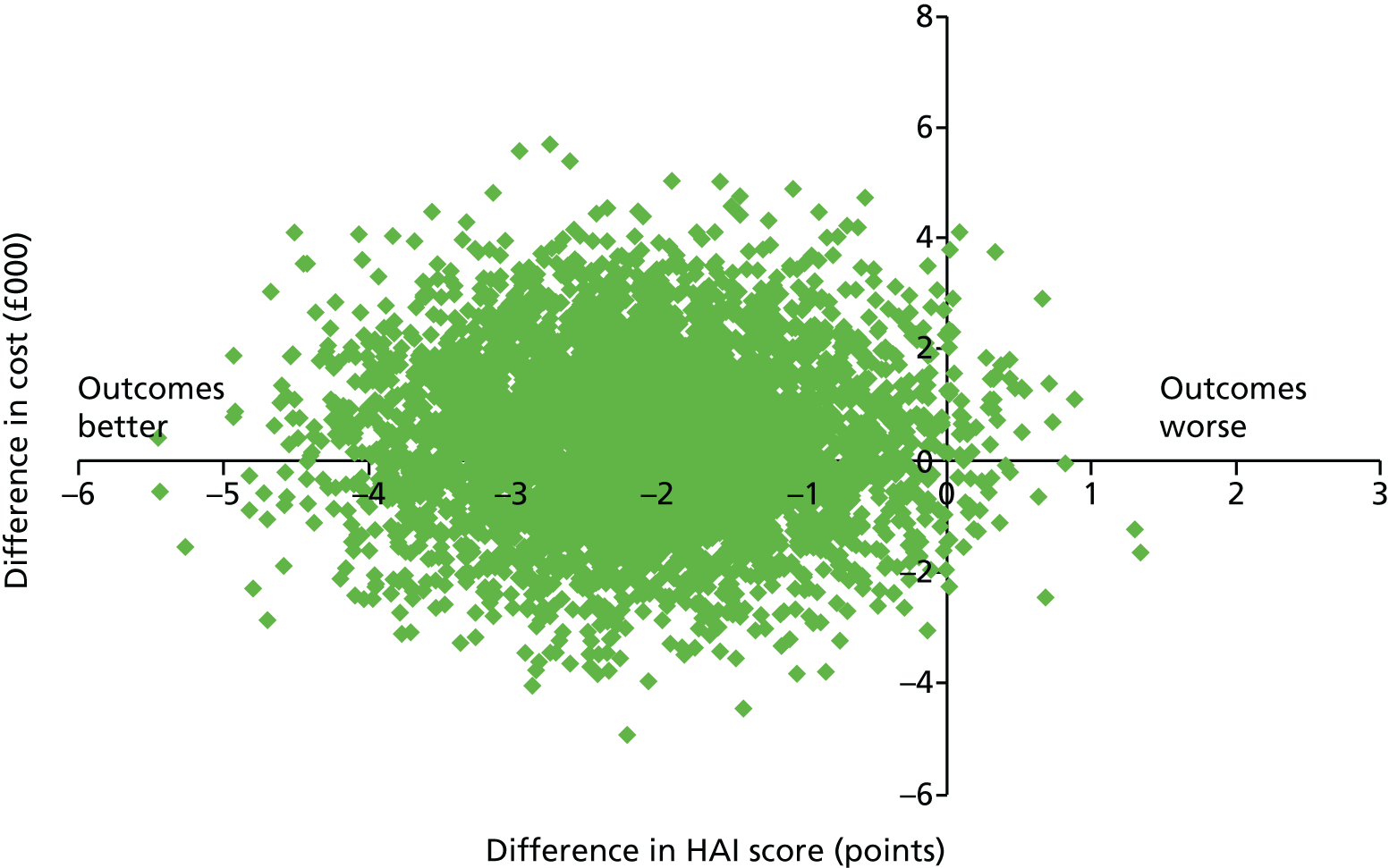

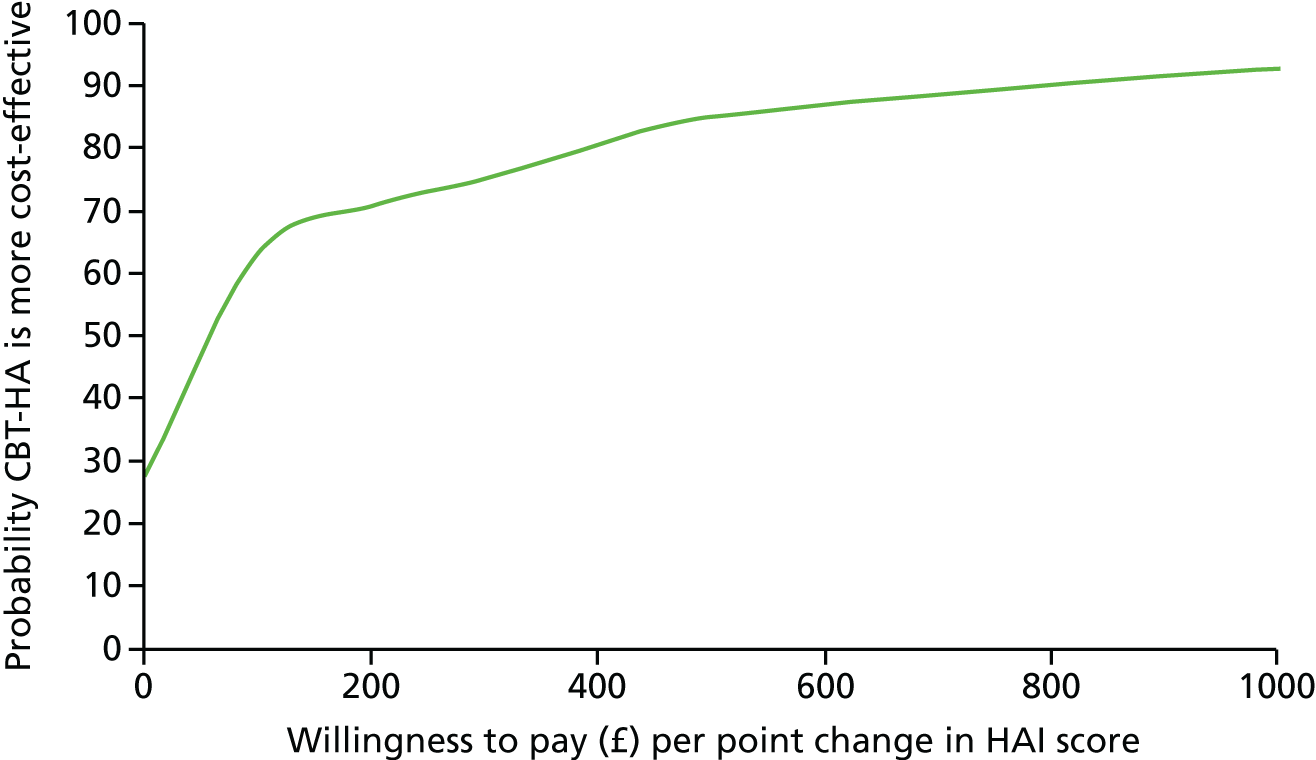

Cost-effectiveness planes were produced by the production of bootstrapped regressions (5000 replications) of study group on total costs and HAI score or QALYs, with covariates for baseline costs or outcomes as appropriate. The coefficients of group differences were then plotted on to a graph.

Replications in the north-east quadrant suggest that CBT-HA is more effective and more costly than standard care, replications in the south-east quadrant suggest that CBT-HA is more effective and less costly than standard care, replications in the south-west quadrant suggest that CBT-HA is less effective and less costly than standard care and replications in the north-west quadrant suggest that CBT-HA is more costly and less effective than standard care.

Knowledge of uncertainty around incremental cost-effectiveness is not sufficient for decision-making, which will depend on the how much society is willing to pay for improvements in outcomes. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were therefore constructed, and these show the likelihood that CBT is cost-effective for different values a decision-maker is willing to pay for improvements in outcome. 50 All analyses were adjusted for baseline costs and for baseline HAI and EQ-5D scores as appropriate.

We completed a number of sensitivity analyses. First, we used the Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) impute command (a regression-based single imputation) to impute missing costs at 24 months and 5 years. Second, we undertook an analysis of differences in costs, including the estimates of the cost of productivity losses.

Results

At 24 months, full ADSUS and hospital records data were available for 172 participants in the CBT-HA group and 170 in the standard care group (77% of those randomised). At 5 years, full ADSUS and hospital records data were available for 149 participants in the CBT-HA group and 157 in the standard care group (69% of those randomised). For total costs over 5 years we needed data from the 24-month and 5-year interviews and there were 141 participants in the CBT-HA group and 133 in the standard care group who met this criterion (62%). We were able to collect hospital service use for 442 randomised participants (99%).

We examined the cost data in order to examine the impact of highly influential observations, which, as defined by Weichle et al. ,51 were those that were above the 99th centile and when removed would have resulted in major changes to the results. Following this, two observations were identified and were removed from the main analysis as recommended.

Resource use

Service use over 24 months’ follow-up is detailed in Table 17. There were no between-group differences in service use and no evidence that CBT-HA reduced service use over this period, as the use of some hospital and community services remained high.

| Service | Treatment group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT (n = 172) | Standard care (n = 170) | |||||

| Mean | SD | % | Mean | SD | % | |

| Service-provided accommodation | 0.13 | 0.87 | 2.33 | 0.27 | 1.49 | 3.53 |

| Inpatient number of nightsa,b | 2.57 | 7.09 | 32 | 2.18 | 8.07 | 29 |

| Outpatient number of appointmentsa,b | 13.08 | 13.64 | 99 | 12.88 | 16.84 | 99 |

| Accident and emergency number of attendancesa,b | 1.22 | 4.14 | 37 | 0.87 | 1.37 | 41 |

| GPa | 13.33 | 11.12 | 97.67 | 14.61 | 16.26 | 97.65 |

| Community medical professionalsa | 10.15 | 13.54 | 93.02 | 9.76 | 13.84 | 84.71 |

| Community social service professionalsa | 5.01 | 27.08 | 21.51 | 6.09 | 30.85 | 22.94 |

| Community mental health servicesa | 0.05 | 0.32 | 2.33 | 0.29 | 1.78 | 5.29 |

| Community other professionalsa | 0.43 | 1.52 | 11.05 | 1.39 | 6.65 | 11.76 |

Use of service-provided accommodation such as hotels, refuges and emergency accommodation (e.g. bed and breakfast) was low, being accessed by 2–4% of the sample over the 24 months.

Hospital outpatient appointments were attended by 99% of the study participants and the average number of appointments was 13. Around one-third of the study participants were admitted as inpatients and the average length of stay among the whole sample was between two and three nights. Attendance at accident and emergency departments was low.

The use of GPs and community medical services such as community nursing, physiotherapy, pharmacy and walk-in centres was common. Almost all participants (up to 98%) had at least one contact with a GP and the average number of appointments was between 13 and 16. Interestingly, the use of community mental health services was low; only 2–5% of participants had any contact with a community mental health professional.

In some areas, the use of services between 2 and 5 years continued the pattern set at 24 months, as detailed in Table 18. For example, around one-third of the sample in both groups had an inpatient stay. However, there was a 20% drop in the percentage of participants having at least one outpatient appointment and, as a yearly average, the number of appointments was lower. Similarly, over the 2–5-year period there were, on average, only five GP appointments, compared with 14 over the first 24 months.

| Resource use | Treatment group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-HA (n = 149) | Standard care (n = 157) | |||||

| Mean | SD | % | Mean | SD | % | |

| Inpatient number of nightsa | 3.05 | 9.52 | 29 | 3.85 | 17 | 30 |

| Outpatient number of appointmentsa | 11.5 | 14.97 | 78 | 12.01 | 15.27 | 78 |

| Accident and emergency number of attendancesa | 1.81 | 3.22 | 53 | 1.43 | 2.64 | 48 |

| GPb | 5.15 | 6.61 | 88 | 5.72 | 6.83 | 91 |

| Community medical professionalsb | 13.99 | 33.41 | 72 | 13.74 | 34.14 | 71 |

| Community social service professionalsb | 2.27 | 16.5 | 9 | 2.39 | 16.47 | 8 |

| Community mental health servicesb | 0.53 | 3.08 | 6 | 1.24 | 4.37 | 14 |

| Community other professionalsb | 0.43 | 2.65 | 7 | 0.39 | 2.63 | 4 |

Over the 5-year follow-up period, almost all inpatient stays were medical admissions and there were no admissions to mental health units. Similarly, almost all non-trial outpatient appointments were to medical specialties rather than to a mental health professional. In common with the numbers at 24 months, the use of community mental health services was very low.

Total cost

The mean cost of the CBT-HA intervention in the intervention group was £421.51 per patient (range 0–2383) for an average of six sessions.

Table 19 shows total costs per patient over 24 months’ follow-up. For all cost categories, total costs were lower for the CBT-HA group than for the control group. Overall, total health and social care costs, including the cost of the intervention, were lower in the CBT-HA group (mean £7314) than in the control group (mean £7727). In analyses adjusted for baseline cost, however, the adjusted mean difference between the two groups was £156 (95% CI –£1446 to £1758; p = 0.848). Although equivalence was not achieved, there was no evidence of a significant difference in cost between the CBT-HA and standard care groups.

| Individual cost item | Treatment group | Adjusted coefficient | 95% CI (adjusted, bootstrapped) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT (n = 172) | Standard care (n = 170) | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| CBT-HA | 421.51 | 308.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – | – | – |

| Service-provided accommodation | 134.52 | 1025.45 | 235.83 | 1640.25 | – | – | – |

| Hospital services | 3946.81 | 5583.89 | 4223.31 | 6353.28 | – | – | – |

| Community services | 774.02 | 1153.36 | 891.53 | 1639.54 | – | – | – |

| Medication | 2037.33 | 2760.75 | 2376.74 | 4487.03 | – | – | – |

| Total | 7314.20 | 7429.58 | 7727.40 | 8970.80 | 155.86 | –1446.20 to 1757.93 | 0.848 |

The total cost for the 5-year follow-up is detailed in Table 20. The second row of the table reports costs in years 3, 4 and 5 as £5055 in the CBT-HA group and £4835 in the standard care group. The adjusted mean difference in cost is –£557, thus rejecting the null hypothesis that costs are equivalent at follow-up. Taking the costs between randomisation and 24 months and 2 and 5 years together gives the total costs over 5 years’ follow-up. These are also listed in Table 19. In total, costs were £12,591 in the CBT-HA group and £13,335 in the standard care group. The regression adjusted for baseline costs also showed that these costs were not equivalent [coefficient = 545, 95% CI (–2375 to 3466); p = 0.713]. The direction of the difference in costs changes when the adjustment is made for baseline costs.

| Cost | Treatment group | Adjusted mean difference | 95% CI | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | Standard care | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Years 1 and 2 (n = 342) | 7314.20 | 7429.58 | 7727.40 | 8970.80 | 155.86 | –1446.20 to 1757.93 | 0.848 |

| Years 3, 4 and 5 (n = 303) | 5054.56 | 6581.72 | 4834.74 | 6908.10 | 557 | –919.82 to 2034.65 | 0.458 |