Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/104/19. The contractual start date was in November 2011. The draft report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mike Thomas is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Primary Care, Community and Preventive Interventions (PCCPI) Panel. In the last 3 years he has received speaker’s honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings or satellite symposia at conferences from the following companies, marketing respiratory and allergy products: Aerocrine, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Novartis International AG. He has received honoraria for attending advisory panels with Aerocrine, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK and Novartis. He has received sponsorship to attend international scientific meetings from GSK and AstraZeneca and has received funding for research projects from GSK. He is a member of the British Thoracic Society (BTS)/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Asthma Guideline Group and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Asthma Guideline Group. Paul Little is Editor-in-Chief of the Programme Grants for Applied Research journal and is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library Board. Lucy Yardley Is a member of the Public Health Research journal Research Funding Board and a member of the HTA Efficient Study Designs Board and reports grants from the NIHR during the conduct of the study. James Raftery is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group and the HTA and EME Editorial Board and was previously Director of the Wessex Institute and head of the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC). He is also a former member of the NIHR HSDR Research Led Board. Ian Pavord has received speaker’s honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings in the last 5 years from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Aerocrine, Almirall Ltd, Novartis and GSK. He has received honoraria for attending advisory panels with Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, MSD, Schering-Plough, Novartis, Dey Pharma, Napp Pharmaceuticals and RespiVert Ltd. He has received sponsorship to attend international scientific meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, AstraZeneca and Napp. He is Chief Medical Advisor to Asthma UK, a member of the UK Department of Health Asthma Strategy Group, a member of the BTS/SIGN Asthma Guideline Group and joint Editor-in-Chief of Thorax. Neither Ian Pavord nor any member of his family has any shares in pharmaceutical companies. David Price reports other Board Membership (fees paid to Research in Real Life Ltd) from Aerocrine, Almirall, Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi Ltd, Meda, Mundipharma, Napp, Novartis and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd; consultancy (fees paid to Research in Real Life Ltd) from Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Meda, Mundipharma, Napp, Novartis, Pfizer Inc. and Teva; grants from the UK NHS, British Lung Foundation, Aerocrine, AKL Ltd, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Eli Lilly and Co., GSK, Meda, Merck & Co., Inc., Mundipharma, Napp, Novartis, Orion, Pfizer, Respiratory Effectiveness Group, Takeda, Teva and Zentiva; lectures/speaking engagement fees (paid to Research in Real Life Ltd) from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla Ltd, GSK, Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Inc., Meda, Merck, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Skyepharma, Takeda and Teva; manuscript preparation fees (paid to Research in Real Life Ltd) from Mundipharma and Teva; payment for travel/accommodation/meeting expenses (paid to Research in Real Life Ltd) from Aerocrine, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mundipharma, Napp, Novartis and Teva; funding for patient enrolment or completion of research (paid to Research in Real Life Ltd) from Almirall, Chiesi, Teva and Zentiva; and payment for the development of educational materials (paid to Research in Real Life Ltd) from GSK and Novartis, outside the submitted work. In addition, David Price has an AKL Ltd patent pending and owns shares in AKL Ltd, which produces phytopharmaceuticals. He owns 80% of Research in Real Life Ltd (which is subcontracted by Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd), 75% of the social enterprise Optimum Patient Care Ltd and 75% of the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd. Ratko Djukanovic has received fees for lectures at symposia organised by Novartis and Teva and for consultation for these two companies as a member of advisory boards. He is a co-founder and current consultant, and has shares in, Synairgen, a University of Southampton spin-out company.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Thomas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Asthma affects > 5 million people in the UK and costs the NHS in excess of £1B. Although pharmacotherapy is effective and can provide full control for some patients,1 surveys repeatedly show that outcomes remain suboptimal. A recent European survey showed that fewer than half of adults with asthma achieved good symptom control2 and that quality of life (QoL) is affected for most, with consequent costs to the community both directly from health service use and indirectly from lost productivity. Many patients have concerns about taking regular medication, particularly inhaled corticosteroids. Surveys of complementary and alternative medicines in asthma show high levels of use, with up to 79% of adults and 78% of children reporting trying different treatments, include breathing modification. 3 Breathing techniques are among the most commonly used complementary techniques, with up to 30% reporting having used them to control their symptoms. 4 The James Lind Alliance and the patient organisation Asthma UK have both identified breathing exercises for asthma as a priority area for research. 5 Asthma encompasses a variety of phenotypes and different therapeutic approaches may be effective in different patients. 6 Symptoms attributed to dysfunctional breathing have been reported to be more frequent in people with asthma than in the general population. 7,8 A number of controlled studies have investigated breathing modification techniques and have reported beneficial outcomes. Breathing control techniques investigated have included the Butekyo breathing method9–13 and yogic breathing. 14–16 Recent studies have shown clinically important effectiveness of physiotherapist-administered breathing exercises for people with asthma in the UK. 17–19 The evidence base for the effectiveness of breathing therapies for treating asthma has been assessed in several reviews. A recent systematic review of the effectiveness of physiotherapist-taught breathing retraining was carried out as part of a review of physiotherapy interventions in the treatment of respiratory diseases in adults. 20 This was a collaborative multidisciplinary review undertaken by the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Respiratory Care (ACPRC), the respiratory clinical interest group of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP). Its purpose was to critically appraise the evidence for respiratory physiotherapy techniques in respiratory diseases and it used an explicit evidence-based methodology. This consisted of an initial literature search, conducted by the Centre for Research and Dissemination (CRD), York, UK. Papers and abstracts identified were appraised and graded by two trained assessors using Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) methodology, with recourse to a third assessor in the event of disagreements. The review found that ‘Breathing exercises, incorporating reducing respiratory rate and/or tidal volume and relaxation training, should be offered to patients to help control the symptoms of asthma and improve QoL (Grade A)’. In the latest iterations of both the BTS/SIGN UK national asthma guideline21 and the World Health Organization (WHO)-endorsed Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guideline,22 breathing exercises are endorsed as adjuvant treatment for people with inadequately controlled asthma despite standard pharmacological treatment. Previous research from members of this study group has provided evidence supporting this recommendation. A prior Cochrane review of breathing exercises for asthma was performed in 2004,23 before several large studies informing the BTS review had reported. This review stated that, because of the diversity of breathing exercises and outcomes used, it was impossible at that time to draw conclusions from the available evidence. The review stated that trends for improvements were noted in a number of outcomes and that large-scale studies were warranted to clarify the effectiveness of breathing exercises in the management of asthma. Subsequently, Slader et al. 3 reported a double-blind randomised controlled trial (RCT) of breathing techniques in asthma and concluded that breathing techniques may be useful in patients with mild asthma who use a reliever inhaler frequently. This Australian study investigated the effects of two different breathing retraining programmes taught by physiotherapists and delivered as videotaped instruction programmes that the participants completed at home, without face-to-face supervision. Both programmes were associated with improved health status and major reductions in bronchodilator use compared with baseline values.

These instructional interventions have subsequently been made available as internet downloads and have been used in Australia to improve asthma control in routine clinical practice. This study provided provisional evidence that breathing retraining programmes delivered in a self-guided audio-visual format are feasible and may potentially produce beneficial outcomes in asthma. A 2007 UK primary care-based RCT18 demonstrated that breathing retraining taught by a physiotherapist in face-to-face sessions significantly reduced respiratory symptoms and improved health-related QoL compared with usual care. The population studied consisted of community-treated asthmatics with mild and moderate disease. The contents of the breathing retraining programme in this study were very similar to those in our study, but only face-to-face instruction was investigated and no economic analysis was carried out. A Canadian RCT published in 200813 added further support for breathing retraining in asthma, also finding significant reductions in asthma symptoms. In this study, a breathing retraining intervention delivered by physiotherapists in a face-to-face setting was compared with the Butekyo breathing method (also taught in face-to-face sessions by a therapist). Large magnitude but similar improvements in health status and symptoms from baseline levels were seen in both treatment arms.

A further RCT published in 2009 investigated the effects of a physiotherapist-delivered breathing retraining intervention, with similar content to that included in the face-to-face arm of our trial. 17 This study controlled for the non-specific ‘placebo-like’ effect of professional contact and sympathetic attention by giving the control group the same amount of professional contact time (with an experienced respiratory nurse providing asthma education). Significant improvements from baseline were seen in patient-reported asthma outcomes for both treatment arms after 1 month, with trends favouring the breathing retraining group; at 6 months a large and significant difference between treatment arms was found in favour of breathing retraining. Significant improvements were seen between treatment arms in asthma-related QoL, anxiety and depression and Nijmegen questionnaire scores (measuring hyperventilation-related symptoms) and a trend was seen for an improvement in symptomatic asthma control. No effect on airway inflammation or physiology was found. No economic evaluation was carried out.

The addition of these subsequent trials to those in the Cochrane review23 as part of the BTS review20 led the authors to conclude that the evidence supporting breathing retraining for people with asthma was of 1++ strength. However, no recommendation on the most clinically effective or cost-effective way of providing breathing retraining was made. Most of the studies contributing to the evidence base involved face-to-face interventions and it is here that the evidence is strongest. Only two preliminary studies have investigated the use of instructional interventions delivered by videotape or DVD,9,14 with some evidence that this modality may also be effective. To our knowledge, no previous studies have compared a DVD breathing retraining intervention with a face-to-face breathing retraining intervention. In our study we aimed to assess the effectiveness of the intervention not only in comparison with usual care or a placebo but also in comparison with an intervention of known benefit. The logistic and economic implications of making this intervention available to all who could potentially benefit in the UK through a face-to-face physiotherapy programme are considerable. We felt that if comparable effectiveness could be shown for a self-guided breathing retraining programme, this is likely to provide a more efficient, convenient and cost-effective service to patients. The available evidence prior to this study suggested that a programme of breathing retraining consisting of three or more face-to-face sessions delivered by a specialist respiratory physiotherapist was effective in improving patient-reported end points, particularly health status (the outcome measure that most accurately captures patient experiences and QoL impairment) and psychological well-being, for people with asthma, and may be effective in reducing rescue bronchodilator medication usage. There were suggestions that similar beneficial effects may be achieved through the use of self-guided interventions instead of face-to-face instruction. However, the relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different approaches to breathing retraining have not been adequately assessed. If similar benefits could be demonstrated without face-to-face contact with a health-care professional, the health resource implications of providing breathing retraining would be improved and this intervention could realistically be made available to the many people with asthma who could potentially benefit from it. Therefore, we proposed to transfer the key components of the physiotherapist-delivered programme that we (and others) have shown to be effective into a self-guided format (delivered in this study through a DVD, but able to be delivered through internet-based technologies) and to compare the effects of this intervention with those of face-to-face sessions with a physiotherapist and with usual care. Our study included a full health economic evaluation, as previous research has focused on the clinical effectiveness, rather than the cost-effectiveness, of breathing retraining. We also included qualitative research to capture patient perspectives on the interventions and a full process evaluation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The BREATHE (Breathing REtraining for Asthma – Trial of Home Exercises) trial was a pragmatic, observer-blinded, three-arm, parallel-group RCT comparing breathing retraining delivered using a DVD with face-to-face physiotherapy and with usual care (control) for adults with asthma and impaired health status.

Participants

We recruited 655 adult patients with a diagnosis of asthma and impaired asthma-related health status from 34 primary care sites (UK NHS general practices) in the Wessex region. Patients were recruited between November 2012 and January 2015, with follow-up ending in February 2016. Practices were recruited and supported by the UK Clinical Research Network (CRN), who also supported patient recruitment and follow-up.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Full practice registration for 12 months prior to enrolment.

-

Age 16–70 years.

-

Physician-diagnosed asthma in medical records.

-

One or more anti-asthma medication prescriptions in the previous year (determined from physician prescribing records).

-

Impaired asthma-related health status [Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ)24 score of < 5.5].

-

Able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

-

Asthma judged at the baseline assessment to be dangerously unstable and in need of urgent medical review (if these participants were referred back to their usual primary care clinician for review).

-

Patients with an additional documented diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of < 60% predicted.

We aimed to allow broad entry criteria (with the inclusion of smokers and not insisting on physiological demonstration of reversible airflow obstruction) to allow the generalisability of the research findings to mild-to-moderate UK asthma populations treated in primary care NHS practice.

Interventions

Development of the self-guided intervention

The development process for the self-guided intervention is described in detail in Chapter 5.

Briefly, in phase 1 of the study, the development phase, we transferred an existing face-to-face programme of breathing retraining taught by physiotherapists to patients with dysfunctional breathing, and previously shown to be effective for people with poorly controlled asthma, to audio-visual media (trialled in DVD format in this study), and developed printed supportive materials and undertook qualitative piloting of these materials to optimise their acceptability and effectiveness.

Patient educational materials were developed by members of the team including physicians, physiotherapists, health psychologists, communications technology specialists and patient representatives. The DVD and accompanying booklet were created iteratively, with extensive qualitative patient input. The DVD content consisted of:

-

a detailed explanation and illustration of how to carry out the exercises

-

motivational components explaining the rationale for the exercises and addressing common doubts and concerns.

The materials were piloted with a panel of 29 members of the target population, purposively sampled for diversity in terms of age, sex, education and symptom profile. In audio-recorded face-to-face and telephone interviews we used open-ended questions to explore attitudes to the proposed treatment method in the context of health beliefs and then used ‘think-aloud’ methods12 to elicit spontaneous reactions to all of the proposed materials. We modified the scripts based on this feedback. Professional production of the DVD and booklet were undertaken and the materials were reviewed by members of our panel, who provided final feedback in face-to-face and telephone interviews.

Face-to-face physiotherapy

Participants randomised to the face-to-face physiotherapy arm were treated by a single, very experienced respiratory physiotherapist over three sessions, based on the face-to-face breathing retraining interventions studied in previous research and on the standard Papworth breathing retraining programme widely taught by physiotherapists in the UK and globally. 17–19 The content of the programme was very similar to that in the DVD arm of the study. The patient support booklet produced in the development phase to support the DVD-based breathing retraining, as described in the previous section, was also provided to patients in this arm of the study. The details and fidelity assessment of the physiotherapy intervention are described in more detail in Chapter 5.

Control group

Patients randomly assigned to the control arm (usual care) received no additional treatment or care. They underwent the same baseline and 12-month assessments and completed the 3- and 6-month postal questionnaires. Control participants were informed that they would subsequently be offered the DVD intervention if it was shown to be effective in the study, to encourage participation and retention.

Randomised controlled trial processes

We performed a parallel-group, three-arm RCT over a 12-month period to assess the effect of the DVD programme compared with usual care and face-to-face physiotherapist-led training with a similar content on the following parameters: asthma-related health status, parameters of symptomatic and physiological asthma control and asthma-related health resource use. Consenting participants were randomly assigned to (1) receipt of the DVD intervention plus supporting written material, (2) three sessions of face-to-face physiotherapy breathing instruction, consisting of an initial ‘small-group’ (up to five patients) session of approximately 45 minutes and two subsequent individual sessions of up to 45 minutes or (3) usual care, which included recruitment and follow-up assessments but no additional intervention or care.

Identification, recruitment and randomisation of participants

Potentially eligible patients in the participating practices were identified by searches of the practice computerised clinical record and prescribing systems. The searches were facilitated by the CRN, based on the inclusion criteria described earlier. Potentially eligible participants were sent information about the study, an AQLQ questionnaire to complete and return if interested in participating and a stamped return envelope. Contact telephone numbers were provided for patients who wished to discuss the study.

Those returning information and interested in participating in the study and who met the inclusion criteria were seen by one of the study research nurses [from the CRN Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) team] at their own general practice during a prearranged appointment. Patients who met the inclusion criteria at the research nurse review and who still wanted to participate provided written informed consent, had baseline measurements taken and were randomly allocated to one of the three study arms following a telephone call to the randomisation service of the Southampton Clinical Trials Unit (SCTU). Follow-up and intervention arrangements were made according to participant convenience and availability. All participants were informed that they would receive postal questionnaires to complete and return at 3 and 6 months, and would be invited for a further research nurse appointment at 12 months. Usual care for their asthma was otherwise allowed to continue.

DVD arm

Participants allocated to the DVD arm received a copy of the self-guided programme in DVD format and the printed support booklet. To cover the possibility of lack of access to a DVD player we were able to provide an inexpensive DVD player for participant use; however, none of the participants allocated to the DVD arm required this.

Physiotherapy arm

Those allocated to the face-to-face physiotherapy arm consented to be contacted by the physiotherapist delivering the intervention by telephone within the following week to arrange the first session. This took place at their general practice at a mutually convenient time. Subsequent sessions were arranged during the first session.

Usual-care arm

Participants in the control arm received no additional information or care during the study beyond their usual care.

Postal questionnaire

The AQLQ questionnaires were posted to all participants at 3 and 6 months after baseline along with a prepaid return envelope. A single reminder telephone call was made after 4 weeks.

Final visit

All participants were invited to a final study visit with a blinded research nurse (a different research nurse from the research nurse who carried out the baseline assessments) at their usual general practice 12 months after baseline. All baseline physiological and questionnaire measurements were repeated. Process evaluation questionnaires were completed and information on personal costs was collected. Participants who did not attend were sent a reminder and, if they were unwilling or unable to attend for a face-to-face visit but were willing to answer questions over the telephone, the AQLQ was completed to allow maximum collection of the primary efficacy outcome.

Health resource use

Health resource use information was extracted from medical records for all participants following the 12-month assessment. This included all respiratory-related medical encounters (primary and secondary care), investigations relating to asthma and respiratory-related prescribing.

Outcomes

Prespecified outcome measures were between-group and within-group changes from baseline to the end of the study (12 months). The statistical analysis plan (SAP) is provided below (see Statistical analysis plan).

The primary outcome was the between-group [intention-to-treat (ITT) population] change in asthma-specific health status [AQLQ (short version)] score, adjusted for potential confounders.

Secondary outcome measures were between-group (ITT population) change in Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)25 score, lung function [FEV1, forced volume vital capacity (FVC), FEV1-to-FVC ratio, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR)], fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), health status [EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)26], anxiety and depression [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)27], hyperventilation (Nijmegen) questionnaire28 score, oral corticosteroid courses for asthma exacerbations and bronchodilator use.

Sensitivity analyses included analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes in both the ITT and per-protocol (PP) populations. We also performed a prespecified sensitivity analysis including participants with missing baseline or outcome data for the primary efficacy parameter, the AQLQ, as described below and in the SAP. In addition, health economic and process evaluation analyses were carried out and are presented in Chapters 4 and 6 respectively.

Sample size

For equivalence of the DVD-delivered and face-to-face programmes

In a previous Health Technology Assessment (HTA) study,29 treatments were deemed to be equivalent if the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the mean difference in AQLQ score between treatment arms was wholly included between –0.3 and +0.3. The BREATHE sample size calculation for equivalence used the same equivalence boundary (i.e. between –0.3 and +0.3). However, we assumed that the standard deviation (SD) of the between-group difference in AQLQ score would be a conservative 25% smaller (i.e. SD 0.77) than that reported in a previous study (SD 1.03). 18 The justification for this was that the proposed equivalence analysis compared two breathing retraining interventions as opposed to a breathing intervention compared with usual care, as in the GLAD study. As this was an equivalence study, as opposed to a non-inferiority study, a two-tailed 5% significance level was used in the calculations.

Sample sizes of 210 in the DVD breathing retraining group and 105 in the face-to-face physiotherapy group were required to assess treatment equivalence with 90% power using an equivalence boundary for AQLQ score of 0.3. This assumed that the expected between-group difference in mean AQLQ score was zero; a two-tailed 5% significance level; a common SD for the AQLQ score of 0.77; and a lower/upper limit of –0.3/+0.3 for the 95% CI of the between-group difference in AQLQ score.

In the unlikely event that the between-group AQLQ score SD was higher than our estimated 0.77, assuming that all other parameters stayed the same, we would still have 80% power to declare equivalence between the DVD breathing retraining group and the face-to-face physiotherapy group as long as the between-group SD was no higher than 0.89.

For superiority of both the DVD-delivered and the face-to-face programme over usual care

For the superiority sample size calculations, there was no widely acceptable minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for between-group change in AQLQ score, although the MCID for within-person change in AQLQ score was reported to be 0.5 (SD 0.41). 24 Therefore, two approaches were used for the superiority sample size calculation: (1) using the published within-person MCID of 0.5 and (2) using the estimate from the previous study18 – a between-group mean (SD) difference in AQLQ score at 6 months of 0.38 (1.03). Although the original sample size calculations for the superiority study were carried out using a one-sided 5% significance level, subsequent open discussions between the trial team and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and the Trial Management Group (TMG) resulted in a protocol change and the decision to use a two-sided 5% significance level. The following superiority study sample size calculations have been updated to reflect this change:

-

Using a MID of 0.5. A two-group t-test with a two-sided 5% significance level will have 90% power to detect a difference in mean AQLQ score of ≥ 0.5, assuming that the common SD is 0.41, when the sample sizes are 12 in the face-to-face breathing retraining group and 24 in the usual-care group. Similarly, a two-group t-test with a two-sided 5% significance level will have 90% power to detect a difference in mean AQLQ score of ≥ 0.5, assuming that the common SD is 0.41, when the sample size is 16 in both the DVD-delivered breathing retraining group and the usual-care group.

-

Using a MID of 0.38. A two-group t-test with a two-sided 5% significance level will have 90% power to detect a difference in mean AQLQ score of ≥ 0.38, assuming that the common SD is 1.03, when the sample sizes are 117 in the face-to-face breathing retraining group and 234 in the usual-care group. Similarly, a two group t-test with a two-sided 5% significance level will have 90% power to detect a difference in mean AQLQ score of ≥ 0.38, assuming that the common SD is 1.03, when the sample size is 156 in both the DVD-delivered breathing retraining group and the usual-care group.

Final sample size

Assuming a 10% dropout rate and a two-sided 5% significance level for each of the equivalence and superiority studies, we therefore aimed to recruit a total sample size of 650 patients (260 each in the DVD and usual-care arms and 130 in the face-to-face physiotherapy arm).

Changes to the original protocol

There were two significant amendments to the original protocol developed in 2012. There was concern from the DMEC that the attrition rate may be higher than the 10% initially anticipated. The protocol was subsequently amended to allow recruitment to be extended to ensure that the original target of 525 complete data sets was reached.

The second noteworthy amendment was to the hypothesis tests of the statistical analysis. The decision was made to change the trial’s superiority sample size calculations from a one-sided 5% analysis to a two-sided 5% analysis. The trial was adequately powered for either option but, after extensive discussions with the funder, sponsor, Trial Steering Committee (TSC), TMG and DMEC, it was agreed that the use of a two-sided sample size calculation would be optimum.

Statistical analysis plan

Statistical analysis plan objective

The objective of this SAP is to describe the quantitative statistical analyses to be carried out for the equivalence and superiority studies within BREATHE. This SAP is based on protocol version 7 (25 November 2015).

General principles

Categorical variables will be described with number and percentage in each category. Continuous variables will be described with mean and SD or median and interquartile range (IQR) depending on their distribution. The number of missing data will be provided for each variable.

Software

All analyses will be carried out using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) or SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Data will be stored on a secure drive, with limited access to those who need it.

Study populations

All primary efficacy analyses are carried out on the ITT population. Safety analyses are carried out on the safety population.

Intention-to-treat population

All participants who were randomised and for whom at least one follow-up observation of the primary outcome (AQLQ score) is available. Participants will be analysed in the treatment arm to which they were randomised.

Per-protocol population

All participants of the ITT population excluding participants who were not compliant with their randomised study arm. Non-compliance is defined as those not having any primary outcome data and/or those not attending at least two physiotherapy appointments in the physiotherapy arm.

Effectiveness outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure will be the 12-month post-intervention AQLQ score.

Secondary outcomes

Clinical

-

ACQ score.

-

Lung function (FEV1, FEV1-to-FVC ratio, PEFR).

-

FeNO.

-

Health status (EQ-5D).

-

Anxiety and depression scores (HADS questionnaire).

-

Hyperventilation (Nijmegen) questionnaire.

-

Oral corticosteroid courses.

-

Bronchodilator use.

-

Smoking status.

-

Process evaluations.

-

Patient-reported process evaluations (qualitative).

Engagement

-

Estimates of engagement with use of physiotherapy exercises in the physiotherapy arm.

-

Estimates of engagement with the breathing retraining.

Economic

-

Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

-

Asthma-related health resource use.

-

Cost-effectiveness/utility.

Safety outcomes

-

Serious adverse events.

-

Non-serious adverse events.

-

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions.

Analysis

General principles

For the equivalence study, the adjusted repeated-measures mixed-model ITT analysis will be deemed the primary analysis with an adjusted repeated-measures mixed-model per-protocol analysis as a sensitivity analysis. For the superiority study, in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines, all comparative analysis will be conducted on an ITT repeated-measures mixed-model basis with a per-protocol repeated-measures mixed-model analysis performed as a sensitivity analysis. All analyses will be governed by this comprehensive SAP which will be agreed by the TSC and approved by the independent DMEC prior to any analyses being undertaken. There will be no formal interim analyses undertaken. Unless prespecified, a 5% two-sided significance level will be used to denote statistical significance throughout. As we specify a clear sequence of tests with a priori effect sizes to inform treatment selection, no adjustments will be made for multiple testing.

Data description

All variables will be described for each treatment group separately and for all participants together. This will be the number and percentage within each category for binary and categorical variables. Continuous variables will be described using the mean and SD (if normally distributed) or median (IQR) if skewed.

Missing data

A CONSORT flow diagram will provide the detail of the flow of trial participants, withdrawals and post-randomisation exclusions.

Missing baseline data

As this is collected at clinic by the research nurse it is anticipated that missing baseline data will be minimal (< 10%). Missing baseline data will be reported in the form of the number and percentage [n (%)] by variable and by randomised group. If a baseline variable has more than 10% missing data, we will use the missing indicator method recommended by White and Thompson. 30 This method is deemed a good approach irrespective of whether any missing baseline data does or does not predict the outcome. For missing baseline AQLQ scores, the method specified in Juniper et al. 24 was adopted. Values for each domain were calculated provided at least two-thirds of the items were scored; otherwise the domain value was set to missing. If any domain score was missing the overall AQLQ score was set to missing.

-

Missing primary outcome data. The repeated-measures mixed-model approach will account for missing data as long as at least one assessment of outcome is available. Compared to analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), a mixed-model approach is thought to give a more precise estimate of treatment effect at the final time point. Participants who do not provide any primary outcome follow-up data will therefore be excluded from the analysis. However, a prespecified sensitivity analysis will be carried out to include all randomised participants using the strategy reported by White et al. 31 This involves substituting the missing baseline AQLQ score by the specific trial arm mean and for missing 12-month AQLQ scores the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) will be applied. If 12-month value is missing, the 6-month AQLQ score will be used to replace. If both 12-month and 6 month are missing, the 3-month AQLQ score will be used to replace the 12-month score. If all 3-month, 6-month and 12-month are missing, i.e. no follow-up information is available, then it will be assumed that the patient returned to their baseline AQLQ value.

-

Missing secondary outcome data. The number of baseline missing data per secondary outcome will be reported per randomised group and overall. Secondary outcomes analysed by repeated-measures mixed-effects models will assume missing at random. If this assumption is thought to be violated, we will consider alternative modelling strategies such as pattern mixture models.

Analysis of the primary outcome

Equivalence study

A 95% CI will be constructed for the mean difference in 12-month total AQLQ score between the DVD arm and the ‘face-to-face’ breathing retraining arm. Since the equivalence boundary is set at 0.3, equivalence will be declared if the 95% Cl is wholly included between –0.3 and +0.3. If equality is not evident, then a repeated-measures mixed-model will be used to examine whether the ‘face-to-face’ breathing retraining arm is superior to the DVD arm via examination of the difference (and 95% CI) of 12-month total AQLQ score (and each of the four domain scores) before and after adjustment for baseline AQLQ score and a set of prespecified variables. The prespecified variables are AQLQ score at baseline and the fixed effects of treatment arm, time, arm by time interaction plus the random effects of general practice and the patient-level covariates of age, sex, smoking status, BTS treatment step, baseline HADS score and baseline Nijmegen score. Correlations between baseline variables will be explored for the overall population on unblinded data and, if collinearity is evident, the most appropriate variables will be included in the final model. Models with different covariance assumptions were compared by using the Akaike information criterion (AIC); changes at 12 months between physiotherapy vs. usual care; DVD vs. usual care; DVD vs. physiotherapy were estimated from these models. Results from the adjusted ITT repeated-measures mixed model are deemed the primary analyses.

For participants that are lost to follow-up at some time during the 12-month follow-up their information will be included in the statistical analysis up to the point that they are lost to follow-up. The mixed-effects model assumes that data are missing at random and allows for unbalance or missing observations within subject.

Superiority study

Baseline comparability between the three arms of the trial will be evaluated by examination of summary statistics (the mean and SD or median and IQR for continuous variables, dependent on their distribution, and the number and percentage for categorical variables). In accordance with CONSORT guidelines, all comparative analysis will be conducted on an ITT basis with a per-protocol analysis performed as a sensitivity analysis.

For the primary outcome, a repeated-measures mixed model will be used to examine the 12-month total AQLQ score (and each of the four domain scores) across the three arms with adjustment for baseline AQLQ score and a set of prespecified variables. The same model procedure used in the equivalence study will be adapted here. Pairwise comparisons of AQLQ differences will be examined between the ‘usual-care’ arm and each of the DVD and ‘face-to-face’ breathing retraining arms via calculation of two sided 95% CIs. If the CI includes +0.3 then superiority of either the DVD or ‘face-to-face’ breathing retraining arms over usual care will be rejected.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Equivalence study

A repeated-measures mixed model will be used to analyse the difference (and 95% CI) for the secondary outcome measures (ACQ, EQ-5D, HADS score) at 12 months before and after adjustment for baseline values and a set of prespecified variables. The list of prespecified variables is general practice (as a random effect), age, sex, smoking status, BTS treatment step, baseline HADS score and baseline Nijmegen score. For those secondary outcomes collected only at baseline and 12 months’ follow-up such as lung function, FeNO, Nijmegen score, ANCOVA will be used to analyse 12-month group differences before and after adjustment for baseline values and a set of aforementioned prespecified variables.

For those secondary outcomes that involve count data (i.e. oral corticosteroid courses, bronchodilator use, asthma-related health-care resource use), Poisson regression analysis (or negative binomial regression on failure of the assumptions of Poisson regression) with a log link function will be performed to give rate ratios (and their 95% CIs) in the DVD and ‘face-to-face’ breathing retraining arm both before and after adjustment for prespecified variables of general practice, age, sex, smoking status, BTS treatment step, baseline HADS score and baseline Nijmegen score. The exact number of covariates that will be included in the adjusted model will be dependent on the distribution of the secondary outcome and avoidance of loss of power.

Superiority study

A repeated-measures mixed model will be used to analyse the continuous secondary outcome measures [ACQ, EQ-5D and HADS score (both anxiety and depression scores)]. The ‘usual-care’ arm will be compared with each of the DVD and ‘face-to-face’ breathing retraining arms in turn.

For those secondary outcomes collected only at baseline and 12 months’ follow-up, such as lung function, FeNO and Nijmegen score, ANCOVA will be used to analyse 12-month group differences before and after adjustment for baseline values and a set of aforementioned prespecified variables.

For those secondary outcomes that involve count data (i.e. oral corticosteroid courses, bronchodilator use, asthma-related health-care resource use), Poisson regression (or negative binomial regression on failure of the assumption of Poisson regression) with a log link function will be performed to give rate ratios (and their 95% CIs) in the DVD and ‘face-to-face’ breathing retraining arm compared with ‘usual care’ both before and after adjustment for list of prespecified variables such as general practice, age, sex, smoking status, BTS treatment step, baseline HADS score and baseline Nijmegen score. The exact number of covariates that will be included in the adjusted model will be dependent on the distribution of the secondary outcome and avoidance of loss of power.

Engagement

The proportion (n) of participants who attended none, one, two and all three physiotherapy sessions in the physiotherapy arm will be tabulated.

Primary and secondary efficacy (equivalence study) analyses relating to the AQLQ (and each of the four domain scores) at 3 and 12 months will be repeated as a sensitivity analyses in two ways:

-

Engagement. Participants who did not engage with the breathing retraining at 3 months will be excluded. Engagement will be included as a binary variable defined by any response above ‘never started’ to any of the first three questions (number of weeks, days per week and times per day) in the ‘carrying out the breathing retraining’ block of treatment engagement questions at 3 months.

-

Amount of practice. Participants who did not engage with the breathing retraining at 3 months will be excluded and a new covariate – the amount of practice undertaken – will be added to the models. Amount of practice is a continuous variable which will be calculated by multiplying weights from each of the three questions shown in Table 1.

| Question | Response | Score | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. For how many weeks did you carry out the breathing retraining? | Never started | 0 | If a participant carried out breathing retraining for 3–5 weeks, for 3–4 days at least twice a day, this would be a score of 32 (4 × 4 × 2) for the number of practice sessions completed |

| 1 week | 1 | ||

| 1–2 weeks | 2 | ||

| 3–5 weeks | 4 | ||

| 6–8 weeks | 7 | ||

| ≥ 9 weeks | 10 | ||

| Q2. How many times a week, on average, did you carry out the breathing retraining? | Never started | 0 | |

| 1–2 days | 2 | ||

| 3–4 days | 4 | ||

| 5–6 days | 6 | ||

| Most days | 7 | ||

| Q3. How many times a day, on average, did you carry out the breathing retraining? | Never started | 0 | |

| Once a day | 1 | ||

| At least twice a day | 2 |

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

We recruited patients from 34 primary care sites in Wessex through the PCRN (subsumed during the study into the CRN). We identified potential recruits to the study by searching general practice electronic medical records for patients with a coded diagnosis for asthma, undergoing current treatment and meeting inclusion criteria. Potential recruits were sent information about the study, the AQLQ (as impaired disease-specific health status was an inclusion criteria to enable an improvement to be demonstrated) and a prepaid return envelope.

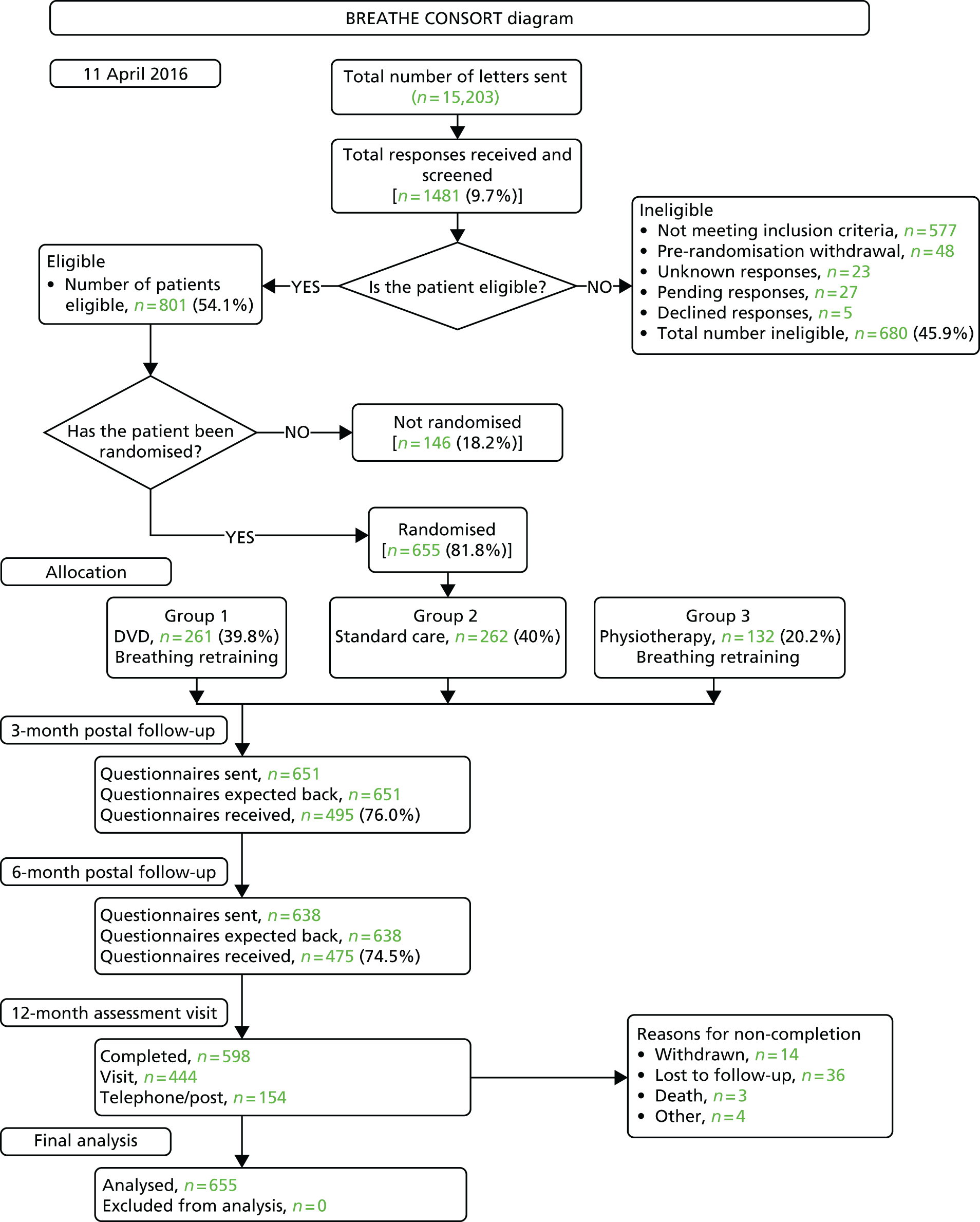

A total of 15,203 invitation letters were mailed to potential participants and 1481 responses were received (a response rate of 9.7%). In total, 680 (45.9%) respondents were deemed ineligible, with lack of impairment according to AQLQ score being the most common reason for ineligibility; 655 participants (81.8% of the eligible respondents) were randomised, 261 (39.8% of randomised participants) to the DVD-delivered breathing retraining group, 262 (40.0%) to the usual-care group and 132 (20.2%) to the physiotherapist breathing retraining group (Table 2). The numbers of patients randomised from the different practices are shown in Appendix 1. The CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants through the trial is provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

| Population | Treatment arm, n | Overall, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVD | Physiotherapy | Usual care | ||

| ITT | 261 | 132 | 262 | 655 |

| PP | 215 | 110 | 231 | 556 |

Because of errors in completion of the primary outcome (AQLQ) at baseline for 45 out of 655 participants (7%), it was not possible to assign an AQLQ score to these patients. However, one or more AQLQ returns was achieved for all randomised participants.

Baseline characteristics and demographics

Baseline demographic and clinical features of the participants in the study are shown in Table 3. The demographic and clinical profiles of the recruited population were typical of adult patients with mild-to-moderate asthma in the community and were similar between treatment arms. More women than men consented to participate in the trial and the median age of participants was 57 years, with approximately one-third of participants aged < 50 years. The median (IQR) age at diagnosis of asthma was 29 (11–45) years. In total, 8% of participants were current smokers and 33% were ex-smokers. Approximately one-third of participants had a family history of asthma. The most common self-reported asthma triggers were dust (77%), pollen (64%), smoke (64%), exercise (63%), stress (46%), cats (41%), dogs (24%) and food (19%).

| Characteristic | Treatment arm | Overall (N = 655) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVD (N = 261) | Physiotherapy (N = 132) | Usual care (N = 262) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 97 (37.2) | 41 (31.1) | 98 (37.4) | 236 (36.0) |

| Female | 164 (62.8) | 91 (68.9) | 164 (62.6) | 419 (63.9) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 56 (45–65) | 55 (47–63) | 57 (47–65) | 57 (46–64) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | ||||

| ≤ 40 | 47 (18.0) | 21 (15.9) | 43 (16.4) | 111 (16.9) |

| 41–50 | 54 (20.7) | 28 (21.2) | 45 (17.2) | 127 (19.4) |

| 51–60 | 59 (22.6) | 35 (26.5) | 73 (27.9) | 167 (25.5) |

| > 60 | 101 (38.7) | 48 (36.4) | 101 (38.5) | 250 (38.2) |

| Weight (kg) | ||||

| Number included | 258 | 132 | 261 | 651 |

| Mean (SD) | 79.9 (17.6) | 80.6 (20.2) | 83.1 (18.1) | 81.3 (18.4) |

| Height (cm) | ||||

| Number included | 258 | 132 | 261 | 651 |

| Mean (SD) | 167.1 (9.0) | 165.7 (8.8) | 166.1 (9.1) | 166.4 (9.0) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Current smoker | 16 (6.1) | 13 (9.8) | 21 (8.0) | 50 (7.6) |

| Ex-smoker | 74 (28.4) | 43 (32.6) | 102 (38.9) | 219 (33.4) |

| Never | 169 (64.8) | 76 (57.6) | 139 (53.1) | 384 (58.6) |

| What they currently smoke, n (%) | ||||

| Cigarettes | 10 (3.8) | 8 (6.1) | 15 (5.7) | 33 (5.0) |

| Tobacco | 6 (2.3) | 5 (3.8) | 7 (2.7) | 18 (2.7) |

| Cigars | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Cigarettes/tobacco | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Tobacco/cigars | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| What they used to smoke, n (%) | ||||

| Cigarettes | 69 (26.4) | 40 (30.3) | 96 (36.6) | 205 (31.3) |

| Tobacco | 6 (2.3) | 4 (3.0) | 8 (3.1) | 18 (2.7) |

| Cigars | 3 (1.1) | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.4) | 7 (1.1) |

| Cigarettes/tobacco | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (0.8) |

| Tobacco/cigars | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Cigarettes/cigars | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (0.8) |

| Cigarettes/tobacco/cigars | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Average number of cigarettes per day for ever smokers | ||||

| Number included | 78 | 47 | 111 | 236 |

| Median (IQR) | 20 (10–21) | 15 (10–20) | 15 (6–20) | 15 (8–20) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1, 80 | 3, 60 | 1, 100 | 1, 100 |

| Pack-years of smoking among ever smokers | ||||

| Number included | 82 | 49 | 113 | 244 |

| Median (IQR) | 15 (5–30) | 13 (3–27) | 10 (3–23) | 12 (3–25) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.05, 112.5 | 0.25, 159 | 0.05, 300 | 0.05, 300 |

| Age diagnosed with asthma (years) | ||||

| Number included | 259 | 132 | 259 | 650 |

| Median (IQR) | 27 (12–45) | 32 (14–45) | 28 (8–46) | 29 (11–45) |

| Family history of asthma, n (%) | ||||

| Mother | ||||

| Yes | 35 (13.4) | 28 (21.2) | 43 (16.4) | 106 (16.2) |

| No | 220 (84.3) | 99 (75.0) | 212 (80.9) | 531 (81.1) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.8) | 4 (3.0) | 7 (2.7) | 13 (2.0) |

| Father | ||||

| Yes | 31 (11.9) | 17 (12.9) | 26 (9.9) | 74 (11.3) |

| No | 218 (83.5) | 108 (81.8) | 219 (83.6) | 545 (83.2) |

| Unknown | 8 (3.1) | 6 (4.6) | 17 (6.5) | 31 (4.7) |

| Siblings | ||||

| Yes | 67 (25.7) | 35 (26.5) | 61 (23.3) | 163 (24.9) |

| No | 180 (69.0) | 84 (63.6) | 176 (67.2) | 440 (67.2) |

| n/a | 7 (2.7) | 13 (9.9) | 23 (8.8) | 43 (6.6) |

| Children | ||||

| Yes | 85 (32.6) | 38 (28.8) | 83 (31.7) | 206 (31.5) |

| No | 125 (47.9) | 66 (50.0) | 129 (49.2) | 320 (48.9) |

| n/a | 48 (18.4) | 27 (20.5) | 50 (19.1) | 125 (19.1) |

| Other family members | ||||

| Yes | 87 (33.3) | 50 (37.9) | 94 (35.9) | 231 (35.2) |

| No | 159 (60.9) | 76 (57.6) | 159 (60.7) | 394 (60.2) |

| Unknown | 5 (1.9) | 3 (2.3) | 4 (1.5) | 12 (1.8) |

| Asthma triggers, n (%) | ||||

| Cats | 119 (45.6) | 60 (45.5) | 109 (41.6) | 288 (43.9) |

| Dogs | 68 (26.1) | 37 (28.0) | 73 (27.9) | 178 (27.2) |

| Dust | 214 (81.9) | 108 (81.8) | 215 (82.1) | 537 (81.9) |

| Exercise | 185 (70.9) | 100 (75.8) | 191 (72.9) | 476 (72.7) |

| Pollen | 164 (62.8) | 89 (67.4) | 177 (67.6) | 430 (65.7) |

| Smoke | 186 (71.3) | 97 (73.5) | 174 (66.4) | 457 (69.8) |

| Stress | 133 (50.9) | 67 (50.8) | 133 (50.8) | 333 (50.8) |

| Food | 42 (16.1) | 33 (25.0) | 58 (22.1) | 133 (20.3) |

| Other | 211 (80.8) | 92 (69.7) | 198 (75.6) | 501 (76.5) |

| FeNO (p.p.b.) | ||||

| Number included | 238 | 126 | 242 | 606 |

| Median (IQR) | 21 (14–35) | 23 (15–23) | 23 (14–34) | 22 (14–34) |

| FEV1 (l) | ||||

| Number included | 246 | 130 | 253 | 629 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.8) |

| FVC (l) | ||||

| Number included | 246 | 130 | 253 | 629 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) |

| FEV1-to-FVC ratio | ||||

| Number included | 246 | 130 | 253 | 629 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) |

| FEV1% predicted | ||||

| Number included | 246 | 130 | 253 | 629 |

| Mean (SD) | 90.5 (18.8) | 88.8 (18.1) | 91.9 (21.6) | 90.7 (19.8) |

| PEFR (l/second) | ||||

| Number included | 244 | 129 | 249 | 622 |

| Mean (SD) | 425.5 (115.8) | 414.9 (110.0) | 423.4 (120.7) | 422.5 (116.5) |

| BTS treatment step,a n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 19 (7.3) | 8 (6.1) | 20 (7.6) | 47 (7.2) |

| 2 | 65 (24.9) | 41 (31.1) | 69 (26.3) | 175 (26.7) |

| 3 | 107 (41.0) | 52 (39.4) | 117 (44.7) | 276 (42.1) |

| 4 | 26 (10.0) | 16 (12.1) | 33 (12.6) | 75 (11.5) |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Unknown/unspecified | 44 (16.9) | 15 (11.4) | 22 (8.4) | 81 (12.4) |

Participants had mildly impaired lung function, with a mean FEV1% predicted of 91% and a mean FEV1-to-FVC ratio of 0.8. The median (IQR) FeNO, a measure of eosinophilic airway inflammation, was 22 (14–34) parts per billion, which is at the top end of the normal range; over one-quarter of participants had a raised reading, indicative of persisting active inflammation despite inhaled steroid treatment. In terms of the BTS treatment step, our patient sample was typical of adult asthma patients treated in the community, with 7% at step 1 (needing short-acting beta-agonists only), 27% at step 2, 42% at step 3 and 12% at step 4 or 5. Self-reported atopic comorbidity was common (Table 4), with approximately two-thirds of participants reporting allergic problems including allergic rhinitis (69%) and eczema (31%), with most requiring pharmacological treatment. Over one-third of participants reported psychological problems (anxiety and depression), again with most requiring medication. Diagnosed COPD was present in only 2% of participants and had to be mild to meet entry criteria.

| Comorbidity | Treatment arm | Overall (N = 655) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVD (N = 261) | Physiotherapy (N = 132) | Usual care (N = 262) | ||

| Allergies | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 179 (68.6) | 81 (61.4) | 177 (67.6) | 437 (66.7) |

| If yes, on current medication, n | 179 | 81 | 175 | 435 |

| Unknown, n | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Hay fever/rhinitis | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 183 (70.1) | 94 (71.2) | 174 (66.4) | 451 (68.9) |

| If yes, on current medication, n | 183 | 94 | 173 | 450 |

| Unknown, n | 3 | 0 | 8 | 12 |

| Eczema | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 75 (28.7) | 46 (34.8) | 80 (30.5) | 201 (30.7) |

| If yes, on current medication, n | 75 | 46 | 78 | 199 |

| Unknown, n | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| Heart disease | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 19 (7.3) | 13 (9.8) | 22 (8.4) | 54 (8.2) |

| If yes, on current medication, n | 19 | 13 | 22 | 54 |

| Unknown, n | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| Depression/anxiety | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 92 (35.2) | 50 (37.9) | 91 (34.7) | 233 (35.6) |

| If yes, on current medication, n | 92 | 50 | 90 | 232 |

| Unknown, n | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Documented diagnosis of COPD | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | 11 (4.2) | 15 (2.3) |

| No, n (%) | 259 (99.2) | 130 (98.5) | 251 (95.8) | 640 (97.7) |

Baseline questionnaire data (Table 5) showed moderate impairment in asthma-specific QoL, with a mean (SD) AQLQ score of 4.3 (0.9), and also impaired symptomatic asthma control, with a mean (SD) ACQ score of 1.5 (0.9). The baseline psychological assessment with the HADS questionnaire showed a median (IQR) anxiety score of 6 (4–9) and depression score of 3 (1–5). A score of ≤ 7 on this tool is considered ‘normal’ and so > 255 patients had scores suggestive of significant anxiety, in keeping with population-based survey data. Across the five domains of the EQ-5D generic QoL questionnaire, 42% of participants reported problems with pain or discomfort, 31% with activities, 27% with anxiety or depression, 23% with mobility and 5% with self-care.

| Questionnaire | Treatment arm | Overall (N = 655) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVD (N = 261) | Physiotherapy (N = 132) | Usual care (N = 262) | ||

| Mini AQLQ | ||||

| n | 244 | 120 | 246 | 610 |

| Mean (SD) score | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) |

| Nijmegen questionnaire | ||||

| n | 259 | 132 | 262 | 653 |

| Mean (SD) score | 19.0 (8.8) | 19.0 (10.5) | 19.4 (9.4) | 19.2 (9.4) |

| HADS | ||||

| n | 257 | 131 | 261 | 649 |

| Anxiety, median (IQR) score | 7.0 (4–8) | 6.0 (4–9) | 6.0 (4–9) | 6.0 (4–9) |

| Depression, median (IQR) score | 3.0 (1–5) | 2.0 (1–5) | 3.0 (1–5) | 3.0 (1–5) |

| EQ-5D | ||||

| Mobility | ||||

| n | 259 | 132 | 262 | 653 |

| No problems, n (%) | 202 (78.0) | 97 (73.5) | 203 (77.5) | 502 (76.9) |

| Some problems, n (%) | 57 (22.0) | 35 (26.5) | 59 (22.5) | 151 (23.1) |

| Self-care | ||||

| n | 258 | 131 | 262 | 651 |

| No problems, n (%) | 251 (96.3) | 120 (91.6) | 246 (93.9) | 617 (94.8) |

| Some problems, n (%) | 7 (2.7) | 11 (8.4) | 16 (6.1) | 34 (5.2) |

| Usual activities | ||||

| n | 259 | 132 | 262 | 653 |

| No problems, n (%) | 186 (71.8) | 82 (62.1) | 183 (69.8) | 451 (69.1) |

| Some problems, n (%) | 73 (28.2) | 50 (37.9) | 79 (30.2) | 202 (30.9) |

| Pain/discomfort | ||||

| n | 259 | 131 | 261 | 651 |

| No problems, n (%) | 161 (62.2) | 79 (60.3) | 137 (52.5) | 377 (57.9) |

| Some problems, n (%) | 98 (37.8) | 52 (39.7) | 124 (47.5) | 274 (42.1) |

| Anxiety/depression | ||||

| n | 259 | 132 | 262 | 653 |

| No problems, n (%) | 187 (72.2) | 99 (75.0) | 192 (73.3) | 478 (73.0) |

| Some problems, n (%) | 72 (27.8) | 33 (25.0) | 70 (26.7) | 175 (27.0) |

| EQ-5D VAS | ||||

| n | 256 | 131 | 258 | 645 |

| Median (IQR) | 80 (69.3–88.8) | 75 (60–85) | 80 (68–89) | 80 (67.5–88) |

| Mean (SD) | 74.9 (16.8) | 71.7 (19.5) | 74.4 (16.9) | 74.1 (17.4) |

| ACQ | ||||

| n | 258 | 132 | 262 | 652 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.9) |

In summary, we successfully recruited a population of primary care asthma patients with mild-to-moderate asthma and with evidence of incomplete asthma control and QoL impairment, our target group. Their demographic profile was similar between randomisation arms and appears to be typical of the demographic and disease control profile of UK primary care adult asthma populations reported in recent surveys of asthma control.

Missing data, withdrawals and study retention

Missing baseline data (see Appendix 2)

Because of errors in completion of the primary outcome questionnaire (AQLQ) at baseline for 45 out of 655 participants (7%), it was not possible to assign an AQLQ score to these patients. There was a very low level of missing baseline data for the other questionnaires (< 2%).

Spirometry values (FEV1, FVC and FEV1-to-FVC ratio) were missing for 4% of participants, PEFR values for 5% and FeNO values for 7.5%, with similar proportions of missing data between randomisation arms.

Withdrawals

Only 21 of the 655 randomised patients withdrew from the study (3.2%), with similar withdrawal rates between the DVD (5.4%), physiotherapy (2.3%) and control (2.3%) arms. The reasons for withdrawals are provided in Appendix 3. The baseline characteristics of those who withdrew were similar to the baseline characteristics of the randomised population (see Appendix 4).

Primary outcome measure: disease-specific health status measured using the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

The primary efficacy analysis was a comparison of between-group changes in AQLQ scores in the ITT population, with adjustments for prespecified covariates. Secondary analyses included an unadjusted comparison of between-group changes in AQLQ scores in the ITT population, adjusted and unadjusted comparisons of between-group changes in AQLQ scores in the PP population and analyses of the subdomains measured by the AQLQ instrument. Prespecified sensitivity analyses are also reported. We also assessed the time course of changes in AQLQ score from 3-month and 6-month AQLQ postal questionnaire data.

Table 6 presents the baseline and 12-month mean (SD) AQLQ scores and the unadjusted mean changes in AQLQ scores (with 95% CIs) in the DVD, physiotherapy and usual-care arms in the ITT and PP populations. Table 7 presents the primary efficacy analysis, the adjusted mean difference in 12-month AQLQ scores in the DVD, physiotherapy and usual-care treatment arms in the ITT and PP populations, with comparisons between the DVD arm and the control arm and between the physiotherapy arm and the control arm (superiority analysis) and between the DVD arm and the physiotherapy arm (equivalence analysis). The total AQLQ score (the primary efficacy measure) and the scores on the four subdomains of the AQLQ (which may be analysed and compared individually, measuring symptoms, activity, emotions and environment) are presented. The time course of AQLQ score changes in the ITT and PP populations is shown in Table 8.

| AQLQ domain | Time point, mean (SD) score | Unadjusted mean difference (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 months | ||||||||

| DVD | Physiotherapy | Usual care | DVD | Physiotherapy | Usual care | Physiotherapy vs. usual care | DVD vs. usual care | DVD vs. physiotherapy | |

| ITT population | |||||||||

| n | 244 | 120 | 246 | 231 | 121 | 246 | |||

| Total | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) | 5.4 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.1) | 5.1 (1.2) | 0.32 (0.08 to 0.56)** | 0.27 (0.08 to 0.47)** | –0.04 (–0.28 to 0.20) |

| Symptoms | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.1) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.2) | 0.41 (0.13 to 0.70)** | 0.24 (0.01 to 0.47)* | –0.17 (–0.45 to 0.11) |

| Activities | 5.0 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.5) | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.9 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.3) | 0.23 (–0.04 to 0.51) | 0.23 (0.002 to 0.44)* | –0.01 (–0.29 to 0.28) |

| Emotion | 4.0 (1.3) | 4.0 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.4) | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.0 (1.6) | 0.42 (0.08 to 0.75)* | 0.36 (0.08 to 0.63)** | –0.06 (–0.39 to 0.28) |

| Environment | 4.0 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.0 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.5) | 0.28 (–0.02 to 0.57) | 0.31 (0.05 to 0.56)* | 0.03 (–0.27 to 0.33) |

| PP population | |||||||||

| n | 215 | 110 | 231 | 215 | 110 | 231 | |||

| Total | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.3 (1.1) | 5.1 (1.2) | 0.32 (0.08 to 0.55)** | 0.28 (0.08 to 0.47)* | –0.04 (–0.28 to 0.20) |

| Symptoms | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.0) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.2) | 0.39 (0.10 to 0.68)** | 0.24 (0.01 to 0.47)* | –0.16 (–0.44 to 0.13) |

| Activities | 5.0 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.4) | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.9 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.3) | 0.22 (–0.06 to 0.50) | 0.22 (0.01 to 0.44) | 0.01 (–0.28 to 0.28) |

| Emotion | 4.0 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.4) | 4.0 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.0 (1.5) | 0.43 (0.09 to 0.77)* | 0.37 (0.09 to 0.65)** | –0.06 (–0.40 to 0.28) |

| Environment | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.5) | 0.26 (–0.04 to 0.56) | 0.31 (0.06 to 0.57)* | 0.05 (–0.24 to 0.35) |

| AQLQ domain | ITT population | PP population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted mean differencea (95% CI) | Adjusted mean differencea (95% CI) | |||||

| Physiotherapy vs. usual care | DVD vs. usual care | DVD vs. physiotherapy | Physiotherapy vs. usual care | DVD vs. usual care | DVD vs. physiotherapy | |

| Total | 0.24 (0.04 to 0.44)* | 0.28 (0.11 to 0.44)** | 0.04 (–0.16 to 0.24) | 0.22 (0.02 to 0.43)* | 0.26 (0.10 to 0.43)** | 0.04 (–0.17 to 0.25) |

| Symptoms | 0.27 (0.04 to 0.49)* | 0.24 (0.05 to 0.42)* | –0.03 (–0.26 to 0.20) | 0.25 (0.02 to 0.49)* | 0.21 (0.02 to 0.40)* | –0.04 (–0.27 to 0.19) |

| Activities | 0.08 (–0.14 to 0.31) | 0.21 (0.04 to 0.41)* | 0.13 (–0.10 to 0.36) | 0.08 (–0.15 to 0.30) | 0.21 (0.02 to 0.39)* | 0.13 (–0.10 to 0.36) |

| Emotion | 0.43 (0.16 to 0.71)** | 0.38 (0.16 to 0.60)** | –0.06 (–0.33 to 0.22) | 0.41 (0.14 to 0.68)** | 0.35 (0.13 to 0.58)** | –0.05 (–0.33 to 0.22) |

| Environment | 0.19 (–0.06 to 0.44) | 0.32 (0.11 to 0.53)** | 0.13 (–0.12 to 0.39) | 0.18 (–0.07 to 0.44) | 0.32 (0.11 to 0.54)** | 0.14 (–0.12 to 0.40) |

| AQLQ domain | Time point, mean (SD) score | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||||

| DVD | Physiotherapy | Usual care | DVD | Physiotherapy | Usual care | DVD | Physiotherapy | Usual care | DVD | Physiotherapy | Usual care | |

| ITT population | ||||||||||||

| n | 244 | 120 | 246 | 171 | 105 | 226 | 163 | 101 | 217 | 231 | 121 | 241 |

| Total | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) | 5.1 (1.2) | 5.2 (1.0) | 4.9 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.3) | 5.3 (1.0) | 4.9 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.1) | 5.1 (1.2) |

| Symptoms | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.1) | 5.1 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.2) | 5.2 (1.2) | 5.3 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.2) |

| Activities | 5.0 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.5) | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.4) | 5.6 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.4) | 5.9 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.3) |

| Emotion | 4.0 (1.3) | 4.0 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.4) | 5.0 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.6) | 5.2 (1.4) | 5.3 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.0 (1.6) |

| Environment | 4.0 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.4) | 4.5 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.4) | 5.0 (1.2) | 4.5 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.0 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.5) |

| PP population | ||||||||||||

| n | 215 | 110 | 231 | 154 | 94 | 204 | 148 | 92 | 197 | 215 | 110 | 231 |

| Total | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.2 (1.0) | 4.9 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.2) | 5.3 (1.0) | 4.9 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.3 (1.0) | 5.1 (1.2) |

| Symptoms | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.0) | 5.1 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.2) | 5.3 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.3) | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.2) |

| Activities | 5.0 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.4) | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.4) | 5.9 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.3) |

| Emotion | 4.0 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.3) | 5.0 (1.4) | 5.2 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.5) | 5.2 (1.4) | 5.4 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.3) | 5.0 (1.5) |

| Environment | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.1) | 4.8 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.4) | 4.5 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.4) | 5.0 (1.2) | 4.5 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.5) |

Within-group Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score changes

There was a large within-group change in mean AQLQ score of 1.1 from baseline to the 12-month assessment in both breathing retraining arms. There was also a smaller improvement of 0.8 in the control arm. The MCID in AQLQ score for an individual patient is 0.5 and a change of 1.0 equates to a large difference.

Between-group Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score changes

In the primary efficacy analysis, the between-group comparison of AQLQ scores in the ITT population adjusted for the prespecified covariates, we observed a statistically significant improvement in mean AQLQ score of 0.28 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.44; p < 0.001) in the DVD arm compared with the control arm and of 0.24 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.44; p < 0.05) in the physiotherapy arm compared with the control arm, confirming the superiority of the two active interventions over usual care. The adjusted mean difference between the DVD arm and the physiotherapy arm was 0.04 (95% CI –0.16 to 0.24), which was not significantly different; the 95% CI was within the prespecified equivalence margin, confirming the equivalence of the two active interventions. Across the AQLQ subdomains, the largest improvements in AQLQ scores for the active treatments compared with usual care were in the emotions subdomain (DVD vs. control: adjusted mean difference 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.60; p < 0.001; physiotherapy vs. control: adjusted mean difference 0.43, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.71; p < 0.001); significant improvements were also seen in the symptoms, activities and environment domains in the DVD arm compared with the usual-care arm and in the symptoms domain in the physiotherapy arm compared with the usual-care arm (with non-significant numerical improvements in the physiotherapy arm compared with the usual-care arm for activities and environment). There were no significant differences in subdomain scores between the DVD arm and the physiotherapy arm.

The overall messages were unchanged in the PP population analyses, with superiority of both active treatment arms over usual care and equivalence between the active arms, with the magnitude of the improvements very similar to the magnitude of the improvements in the ITT population. Similarly, in the unadjusted analyses in both the ITT and the PP populations, the overall messages were identical, with superiority of both interventions over usual care and equivalence of the active interventions and only minor differences in the magnitude of the differences between treatment arms.

Time course of Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score improvements

The improvements in AQLQ scores in both active arms compared with the control arm were observed at the first post-intervention assessment at 3 months and were maintained or increased over the 12-month study period. In the DVD arm, the improvement in mean total AQLQ score compared with baseline in the ITT population was 0.9 at 3 months, 1.0 at 6 months and 1.1 at 12 months; the equivalent values in the physiotherapy arm were 1.0, 1.1 and 1.1, respectively, and in the control arm were 0.6, 0.6 and 0.8 respectively. Similar patterns of change were seen in the PP population and for the subdomain scores in both the ITT and the PP populations.

Number needed to treat to achieve a clinically important improvement in the primary outcome measure, Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire score

The number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated using the formula recommended by Guyatt et al. 32 (Juniper and Guyatt produced the AQLQ24 and ACQ25 tools). This analysis is based on an individual patient assessment of the proportions in each treatment arm showing a clinically significant improvement (≥ 0.5), the proportions showing unchanged scores (–0.49 to 0.49) and the proportions with a clinically significant deterioration (≤ –0.5) (see Appendix 5).

We found that, in the ITT population, 62% of participants in the DVD group reported a clinically significant improvement compared with 64% in the physiotherapy group and 56% in the control group (Table 9). The corresponding figures for deterioration were 5% in the DVD group, 4% in the physiotherapy group and 9% in the control group. The proportions in the PP population were slightly higher (see Table 9), with 74% of the DVD group, 76% of the physiotherapy group and 62% of the control group showing an improvement in QoL and 6% of the DVD group, 5% of the physiotherapy group and 10% of the control group showing a deterioration in QoL.

| Change in AQLQ score | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVD | Physiotherapy | Usual care | ||

| ITT population | ||||

| n | 261 | 132 | 262 | 655 |

| Improved | 161 (61.7) | 85 (64.4) | 146 (55.7) | 392 (59.8) |

| Stayed the same | 47 (18.0) | 24 (18.2) | 71 (27.1) | 142 (21.7) |

| Deteriorated | 14 (5.4) | 5 (3.8) | 24 (9.2) | 43 (6.6) |

| Could not be calculated | 39 (14.9) | 18 (13.6) | 21 (8.0) | 78 (11.9) |

| Total | 261 (100.0) | 132 (100.0) | 262 (100.0) | 655 (100.0) |

| PP population | ||||

| n | 215 | 110 | 231 | 556 |

| Improved | 159 (74.0) | 83 (75.5) | 142 (61.5) | 384 (69.1) |

| Stayed the same | 43 (20.0) | 22 (20.0) | 67 (29.0) | 132 (23.7) |

| Deteriorated | 13 (6.0) | 5 (4.5) | 22 (9.5) | 40 (7.2) |

| Total | 215 (100.0) | 110 (100.0) | 231 (100.0) | 556 (100.0) |

In between-group comparisons, these figures equated to a NNT for one patient to have a clinically relevant improvement in QoL in the ITT population of eight for the DVD arm compared with the usual-care arm (Table 10), seven for the physiotherapy arm compared with the usual-care arm (Table 11) and 41 for the physiotherapy arm compared with the DVD arm (Table 12). In the PP population the corresponding NNTs were eight, seven and 56 (Tables 13–15).

| Usual care | DVD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved (0.725) | Stayed the same (0.212) | Deteriorated (0.063) | |

| Improved (0.606) | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| Stayed the same (0.295) | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Deteriorated (0.010) | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| NNT for DVD vs. usual carea | 8.2 | ||

| Usual care | Physiotherapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved (0.746) | Stayed the same (0.211) | Deteriorated (0.044) | |

| Improved (0.606) | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| Stayed the same (0.295) | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Deteriorated (0.010) | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| NNT for physiotherapy vs. usual carea | 6.8 | ||

| Physiotherapy | DVD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved (0.725) | Stayed the same (0.212) | Deteriorated (0.063) | |

| Improved (0.746) | 0.54 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Stayed the same (0.211) | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Deteriorated (0.044) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| NNT for physiotherapy vs. DVDa | 41.0 | ||

| Usual care | DVD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved (0.725) | Stayed the same (0.212) | Deteriorated (0.063) | |

| Improved (0.614) | 0.45 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| Stayed the same (0.290) | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Deteriorated (0.010) | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| NNT for DVD vs. usual carea | 7.92 | ||

| Usual care | Physiotherapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved (0.755) | Stayed the same (0.2) | Deteriorated (0.045) | |

| Improved (0.614) | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| Stayed the same (0.290) | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Deteriorated (0.010) | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| NNT for physiotherapy vs. usual carea | 6.86 | ||

| Physiotherapy | DVD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved (0.725) | Stayed the same (0.212) | Deteriorated (0.063) | |

| Improved (0.755) | 0.56 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| Stayed the same (0.2) | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Deteriorated (0.045) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| NNT for physiotherapy vs. DVDa | 55.52 | ||

Prespecified sensitivity analysis on the primary outcome

As per the prespecified SAP, we carried out a sensitivity analysis on the primary outcome data, the change in AQLQ scores between baseline and 12 months adjusted for the prespecified covariates. In this analysis we included all randomised patients regardless of whether baseline or follow-up AQLQ data were present and we used the following rules (based on recommendations from Juniper) to assign values to missing data:

-

For missing baseline AQLQ scores, the following rules were adopted. Values for each AQLQ subdomain (symptoms, emotions, activities, environment) were calculated provided at least two-thirds of the items were scored, otherwise the domain value was set to missing. If any domain score was missing, the overall AQLQ score was set to missing and step 2 was followed.

-

Following step 1, any remaining missing baseline AQLQ scores were replaced by their cohort mean (as specified in the SAP).

-

For missing 12-month AQLQ scores, the method of LOCF was applied. If the 12-month score was missing, the 6-month score was used. If both the 12-month and 6-month scores were missing, the 3-month score was used to replace the 12-month score. If the 3-month, 6-month and 12-month scores were missing, that is, no follow-up information was available, then it was assumed that the patient returned to his or her baseline AQLQ score. Hence, the baseline and 12-month scores were the same.