Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/01/16. The contractual start date was in August 2013. The draft report began editorial review in August 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Peter Langhorne received funding from the National Institute for Health Research; National Health Medical Research Council Australia; Chest, Heart and Stroke Scotland; the Stroke Association, UK; and Chest Heart and Stroke Association of Northern Ireland to complete this trial. Peter Langhorne is a member of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials Board. Olivia Wu is a member of HTA Evidence Synthesis Board and Systematic Review Programme Advisory Group. Helen Rodgers reports grants from Newcastle University during the tenure of this grant. Julie Bernhardt reports grants from National Health and Medical Research Council Australia; NIHR; Singapore Health, Singapore; Chest, Heart and Stroke Scotland, UK; Chest Heart and Stroke Association of Northern Ireland; Stroke Association, UK, during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Langhorne et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Modern stroke unit care

The management of stroke patients has progressed greatly in the last two decades1,2 and several interventions have provided good evidence of benefit for acute stroke patients. 1–8 These include:

-

stroke unit care3 (a complex package of specialist multidisciplinary stroke care involving nurses, therapists and doctors)

-

aspirin for ischaemic stroke4

-

intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) for ischaemic stroke5

-

mechanical thrombectomy for major ischaemic stroke6

-

emergency decompressive surgery for malignant middle cerebral artery syndrome. 7

Among these interventions, the stroke unit effect has potentially the greatest population impact as it combines both moderate effectiveness and broad applicability. 1,2 However, as it is a complex intervention it is difficult to be certain about the key components of stroke unit care. 8 Descriptive studies have reported that early mobilisation (EM) (starting out of bed, sitting, standing and walking early after stroke) is widely thought to be an important contributor to the stroke unit effect. 8–10 The other potentially important components include (1) co-ordinated multidisciplinary care, (2) skilled and specialised staff, (3) training and education of staff and (4) protocols of care covering common problems. 8,9 This trial focuses on the mobilisation component of the stroke unit rehabilitation intervention.

Rehabilitation

The term rehabilitation covers a broad philosophy and range of interventions aiming to help an individual recovering from disabling illness to minimise the impact of that illness on their level of dependence on external support. 11 The modern classification of diseases in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework considers rehabilitation to comprise an interaction between the impact of the disease, the characteristics of the individual and the nature of their environment. 11 Rehabilitation professionals aim to act on different levels of the illness to minimise the impact on the individual. 11

In the context of acute stroke, early rehabilitation usually covers the key impairments experienced by patients in the acute stage of the illness. 11 These include swallowing impairment, language and speech impairment, motor impairment, reduced mobility, reduced balance and reduced ability to carry out self-care activities. An early focus on mobilisation is one that is likely to be relevant to a substantial majority of acute stroke patients.

Early mobilisation

Early mobilisation comprises the commencement of sitting, standing and walking training out of bed early after stroke. Early descriptions of stroke units frequently refer to EM and it is thought to make an important contribution to the effectiveness of stroke unit care. 9,10 However, there are disagreements about the role of EM. 10

Arguments around mobilisation

The biological rationale for EM is based on three principal lines of argument: (1) there is good evidence that bed rest has a harmful impact on cardiovascular, respiratory, muscular, skeletal and immune systems across many conditions11,12 and is likely to slow recovery; (2) some of the most common and serious complications after stroke are those related to immobility13–16 (we know that the routine day of most acute stroke patients is largely inactive;17,18 therefore, introducing frequent training out of bed may reduce the risk of complications of immobility); and (3) current concepts of biological recovery after brain injury suggest a narrow window of opportunity for brain plasticity and repair. 19 If the brain indeed remodels itself based on experience20 then early task-specific training may well have an important contribution to improving recovery. 21,22

However, we must acknowledge that there are also concerns about potential harm of EM,10,23 particularly in the first 24 hours after stroke onset. These concerns include haemodynamic considerations, such as fears that raising the patient’s head early after stroke will impair cerebral blood flow and cerebral perfusion23 or, in the case of intracerebral haemorrhage, increase the risk of inducing further bleeding. 24 As a result of these theoretical concerns, some clinicians have advocated initial bed rest for stroke patients. 23

Given these uncertainties about the practice of EM in acute stroke patients we sought to carry out A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial (AVERT) in acute stroke patients that focused on very early (commencing within 24 hours of stroke onset), frequent out-of-bed mobilisations in the first 14 days.

AVERT programme

The AVERT programme of work that was run by Professor Julie Bernhardt of the University of Melbourne and began with Phase I observational studies. These studies demonstrated that most acute stroke patients were inactive for most of the time17,18 but that this pattern of inactivity varied between hospitals. 17 She also demonstrated that there was considerable variation of opinion and clinical uncertainty among health-care professionals about the value of very early mobilisation (VEM). 23 These studies led to the AVERT Phase II safety and feasibility randomised controlled trial (RCT)25,26 and the closely related Very Early Rehabilitation or Intensive Telemetry After Stroke (VERITAS) trial27 carried out in Glasgow by Professor Peter Langhorne. These trials indicated that VEM was feasible and in the case of AVERT Phase II could be carried out within 24 hours of stroke onset. This approach was observed to be safe,25–27 showed signals for improvements in recovery25–28 as well as indicating that EM was probably cost-effective. 29

Justification for the current study

The preparatory work carried out in AVERT Phases I and II led to the planning and conduct of the definitive AVERT Phase III trial. 30 This was planned as a pragmatic, international, multicentre Phase III RCT with the power to evaluate the efficacy and safety of VEM after stroke. This report outlines the AVERT Phase III international trial with some specific emphasis on the UK contribution. Much of this work has already been published by the AVERT group. 30–36 We will also refer to two related studies that were nested within the AVERT programme. These studies contribute to the understanding of AVERT, but were not specifically included in the original Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme trial application. These comprise (1) a qualitative process evaluation37 and (2) a study of the generalisability of the AVERT results. 38

Chapter 2 Methods

Aims and objectives

The primary aim of this trial was to investigate the effectiveness of a protocol to implement VEM after stroke; an earlier start with frequent out-of-bed activity compared with usual care (UC), which is traditionally started later (> 24 hours).

The objectives of AVERT were designed addressed four main questions:

-

Does VEM reduce death and disability at 3 months post stroke?

-

Does VEM reduce the number and severity of complications at 3 months post stroke?

-

Does VEM improve quality of life (QoL) at 12 months post stroke?

-

Is VEM cost-effective? [Note: this aspect of the trial programme was not funded by the current National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme grant.]

Our clinical hypotheses were as follows:

-

VEM would improve functional outcome at 3 months.

-

VEM would reduce immobility related complications.

-

VEM would accelerate walking recovery with no increase in neurological complications.

-

VEM would result in improved QoL at 12 months.

-

VEM would be cost-effective.

We aimed to carry out a large multicentre pragmatic trial recruiting a broad range of acute stroke patients including those aged > 80 years, those with intracerebral haemorrhage, those who had received rtPA and those admitted to stroke units in a range of different hospital types (small and large, urban and regional).

Trial design

We carried out a pragmatic, prospective, parallel-group, multicentre, international Phase III RCT with blinded assessment of outcomes and an intention-to-treat analysis. Full details of the trial rationale and statistical analysis plan30 were published in advance.

Study settings

The trial was carried out in the acute stroke unit of 56 hospitals in five countries: UK (England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales), Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Malaysia. Stroke units were housed in a range of hospital settings including local and regional hospitals (see list in Appendix 2).

Participants

We aimed to include all eligible patients aged ≥ 18 years with a confirmed first or recurrent stroke (infarct or intracerebral haemorrhage) who were admitted to a stroke unit within 24 hours of onset. Exclusion criteria are listed below and included significant premorbid disability, acute deterioration, admission to the intensive care unit, competing care needs or physiological instability. Recruitment and informed consent could take place in the emergency room or in the acute stroke unit.

Eligibility

All patients (aged ≥ 18 years) admitted with stroke diagnosis (first or recurrent stroke, infarct or haemorrhage) were screened for suitability for inclusion into the trial. If a patient was found to be ineligible for inclusion into the trial, the reason was recorded on the stroke patient-screening log. A diagnosis of transient ischaemic attack (TIA) would not have been considered eligible and the patient would not have been recruited into the trial. However, if a patient was recruited into AVERT who, clinically, appeared to have stroke symptoms and was considered eligible but later assessment confirmed a TIA or other diagnosis, the patient remained in the trial and continued to be followed up until completion.

Inclusion criteria

-

Informed consent obtained from the patient or a responsible third party.

-

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with a clinical diagnosis of first or recurrent stroke, infarct or haemorrhage.

-

Patients admitted to hospital within 24 hours of the onset of stroke.

-

Patient for admission to the acute stroke unit.

-

Patients who receive thrombolysis could be recruited if the attending physician permits and if mobilisation within 24 hours of stroke was permitted.

-

Consciousness: at a minimum, the patient must at least be able to react to verbal commands.

-

Patients could participate in AVERT if they were already recruited to non-intervention trials (e.g. imaging) if dual recruitment was permitted by the ethics committee.

Exclusion criteria

-

Too disabled before stroke [prestroke modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of 3, 4 or 5].

-

Patient diagnosed with TIA.

-

Deterioration in patient’s condition in the first hour of admission resulting in direct admission to intensive care unit, a documented clinical decision for palliative treatment (e.g. those with devastating stroke) or immediate surgery.

-

Concurrent diagnosis of rapidly deteriorating disease (e.g. terminal cancer).

-

A suspected or confirmed lower limb fracture at the time of stroke preventing the implementation of the mobilisation protocol.

-

Patients could not be concurrently recruited to drug or other intervention trials.

-

Unstable coronary or other medical condition that were judged by the investigator to impose a hazard to the patient by involvement in the trial.

-

Unstable physiological variables:

-

systolic blood pressure of < 110 mmHg or > 220 mmHg

-

oxygen saturation of < 92% with supplementation

-

resting heart rate of < 40 or > 110 beats per minute (b.p.m.)

-

temperature of > 38.5°C.

-

Randomisation and masking

Ethics review boards approved the study at all sites. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their nominated representative. Eligible participants were invited to participate in a trial that was testing ‘different types of rehabilitation’ but were not given specific information about the two approaches. 30

After informed consent was obtained, a medical history and physical examination was performed. The following stroke assessments were carried out:

-

premorbid mRS39

-

baseline mRS39

-

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score40

-

Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project41 classification. A paper case report form (CRF) was completed by the AVERT team member (see Appendix 3).

Baseline NIHSS, OSCP (Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project) classification, premorbid mRS and the date of the stroke were all entered into the AVERT Online electronic data capture system prior to randomisation. AVERT Online randomly allocated the treatment group with the result immediately notified to the investigator. Participants were randomised (in a 1 : 1 ratio) through a secure remote, web-based, computer-generated block randomisation procedure with an average block size of six. Permuted blocks of various lengths were used to ensure allocation concealment.

Randomisation was stratified by:

-

study site

-

stroke severity using the NIHSS score,40 for which mild is a NIHSS score of 1–7, moderate is a NIHSS score of 8–16 and severe is a NIHSS score of > 16. 42

Participants were allocated to receive either usual stroke unit care alone, or usual stroke unit care in addition to the experimental intervention, VEM. VEM patients were provided the first mobilisation as soon as they were recruited and additional mobilisations according to the protocol. The intervention period lasted 14 days or until the patient was discharged from stroke unit care, whichever was sooner.

Patients were not aware of their treatment group and outcome assessors plus the investigators involved in the conduct of the trial and data management were blinded to the group assignment. To try and reduce the risk of contamination of the UC intervention, staff providing the VEM protocol were trained to conceal the mobilisation protocol and group allocation. The patient’s participation would be terminated if consent had been withdrawn or if the patient’s safety had been considered to be at risk.

Procedures

Following randomisation, the trial staff obtained the following patient data within 24 hours:

The AVERT intervention protocol

The intervention protocol was not published or distributed except to trials intervention staff. AVERT staff from within the stroke unit team (i.e. site investigators, physiotherapists, nurses) were trained by clinical trial managers to deliver the AVERT intervention protocol at site initiation and investigator meetings, with refresher and new staff training provided on an ongoing basis. 35 This complex intervention required staff to work together to achieve the VEM and UC mobility targets. Trial staff agreed not to distribute or disseminate the protocol and to keep the protocol in a secure location.

To aid protocol description, the key intervention definitions are summarised in Box 1.

Dose: a session of mobilisation given to AVERT patients.

Very early: the earliest possible time after a consented patient had suffered a stroke to their first mobilisation intervention (≤ 24 hours).

Mobilisation: the patient was assisted and encouraged in functional tasks, including activities such as sitting over the edge of the bed, standing up, sitting out of bed and walking. Upper limb movement would have been integrated into functional activities as appropriate. Mobilisations were performed by the AVERT nurse and/or the AVERT physiotherapist. Support staff such as therapy assistants and students could also be trained to provide mobilisations.

Counting mobilisations: when a patient performed a mobilisation (e.g. walked to the toilet with help or was sat out of bed) and rested for ≥ 5 minutes, then their next mobilising activity (e.g. walking back from the toilet or getting back into bed) would have constituted another mobilisation.

TTFM: this is the time from stroke onset to the time the patient is first mobilised out of bed (assisted or independent). This does not include the initial assessment by the AVERT physiotherapist.

Physiotherapist’s record of mobilisation sessions: the date, time, minutes and content of each session were recorded via AVERT Online. If the online forms were unavailable, paper forms could be used to temporarily collect the information until such time as it could be entered online.

Nurse’s record of mobilisation sessions: the date and time it started and the type of each mobilisation would have been recorded on AVERT Online or, if the website was not available, data were temporarily recorded on the paper nurse recording form until such time as they could be entered online.

Excessive fatigue: if the patient reported a score of > 13 on the Borg Perceived Exertion Scale and/or AVERT staff assess that the patient is excessively fatigued (e.g. the patient’s functional performance worsened significantly during the intervention).

Contamination: when the witnessing of a different intervention makes others change their UC practice consciously or unconsciously.

The intervention protocol was followed for all randomised patients. Information about the group to which the patient had been randomised was known only by the AVERT physiotherapist and nursing staff. The protocol for the interventions was not intended to replace any clinical decision-making of the individual therapists and nurses involved in the treatment delivery. However, the expectation was that they would adhere to the protocol whenever possible.

The protocol for VEM interventions and UC was continued until day 14 of the patient’s stay in the stroke unit or until discharge from the stroke unit (whichever was sooner). If the patient was palliated then VEM was discontinued and follow-up with trial assessments continued until death or 12-month follow-up.

Very early mobilisation interventions

The components of usual stroke unit care, including normal physiotherapy and nursing procedures, were provided at the discretion of the individual sites. In addition to UC, the VEM intervention included four important features.

-

It had to begin within 24 hours of stroke onset.

-

The focus had to be on sitting, standing and walking activities (i.e. out of bed).

-

VEM delivered in at least three out-of-bed sessions per day in addition to UC.

-

Nursing and physiotherapy mobilisations were titrated each day, according to patient’s functional level.

The content of nursing and physiotherapy mobilisations were detailed, task-specific activities targeting the recovery of standing and walking. It was tailored to accommodate four levels of functional ability and was adjusted daily in line with participant recovery. The usual risk assessments and lifting policies were applied to all mobilisations. Even following the protocol, clinician judgement was still required when the patient’s suitability to get out of bed was assessed.

Principles of very early mobilisation

The principles of the VEM intervention were developed in consultation with the early rehabilitation team in the acute stroke unit in Trondheim, Norway,9 and used in AVERT Phase II. 25 Trained physiotherapy and nursing staff helped patients to continue task-specific out-of-bed activity that was focused on recovery of active sitting, standing and walking. The frequency and intensity (amount) was guided by the intervention protocol. This was titrated according to functional activity baseline and monitored daily and adjusted with recovery. For example, low-functioning dependent patients (level 1) had a target of active sitting with assistance with each session lasting between 10 and 30 minutes. Higher-functioning patients (level 4) would have a target of standing and walking with each session lasting 10 minutes and with no restricted maximum. The frequencies of sessions were varied according to the patient’s functional level. Passive sitting was not classified as a mobilisation activity and sitting for > 50 minutes at a time was discouraged. The intervention continued for 14 days or until discharge. Physiotherapists and nurses had separate intervention targets but worked together to deliver the intervention dose. Mobilisation activities were all recorded online.

The key principles were as follows.

-

The target dose (the number of interventions, the type of intervention and the amount of time spent with each VEM patient) was additional to usual stroke unit nursing and therapy and was titrated according to the patient’s level of functional ability.

-

Patients were recruited as soon as possible after stroke onset, until 24 hours (day 0). The first VEM commenced as soon as possible after recruitment and could be provided when the patient arrived on the ward, or earlier if they were in the emergency department. The VEM target TTFM was within 24 hours from stroke. When patients were routinely mobilised within 24 hours at any site, the target VEM time was 5 hours less than UC.

-

Patients should not rest in bed for long periods of the day unless they were medically unstable.

-

If medically stable (not specifically restricted to bed), patients were helped to perform functional (out of bed) activities for the prescribed VEM dose according to the patient’s functional level.

-

Patients who were stable enough to sit out of bed or sit up over the side of the bed with help were assisted to do so for the prescribed VEM dose according to the patient’s functional level. If, on the first 3 days, they required the moderate or maximum assistance of others to move themselves from chair to bed, they could not be left to sit out of bed for longer than 50 minutes each time.

-

When sat out of bed, patients would have been comfortably seated in a supportive chair or wheelchair with the hemiplegic upper limb supported.

-

The VEM safety assessment was strictly adhered to for the first mobilisation out of bed. This involved measurement of vital signs and was critical to the safety of the mobilisation.

-

For patients randomised to the VEM group, the AVERT nurse and physiotherapist worked together to achieve a daily target for the frequency of sessions and minutes of physiotherapy mobilisation.

The target number of sessions and minutes of physiotherapy to be delivered each day was dictated by the level of functional ability at the start of each day

Level of functional ability

The AVERT staff assessed the patient’s functional ability using the MSAS as soon as possible after recruitment and then at the start of each day. The patient was assessed as one of the four functional levels (Table 1). The daily assessment of level and the daily mobilisation targets were communicated to the study team. The level assigned to the patient was not changed throughout the day. If the patient’s level of performance fluctuated, clinicians adjusted VEM interventions according to patient status. Usual risk assessments and lifting policies were applied to all mobilisations.

| Level | Definition | Patient description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equivalent to sitting from supine, MSAS | Low arousal (responded to voice but required physical prompting) |

| Score = 1–4 | Fully dependent. Unable to sit on the edge of the bed without the assistance of 1 or 2 people | |

| 2 | Equivalent to sitting from supine, MSAS | Followed commands (verbal or non-verbal/gestures) |

| Score = 5–6 | Moderate to high dependence. Able to sit on the edge of the bed but would requires assistance and/or supervision. Able to stand with assistance | |

| 3 | Equivalent to gait MSAS | Follows commands |

| Score = 2–4 | Moderate dependence. Able to walk with moderate to maximum assistance | |

| 4 | Equivalent to gait MSAS | Low/no dependence |

| Score = 5–6 | Able to walk with minimal/no assistance |

First very early mobilisation safety assessment

The first VEM mobilisation out of bed was strictly governed by a safety assessment. If the safety assessment failed then the first mobilisation did not commence until the patient achieved the safety criteria.

For the first VEM sit out-of-bed mobilisation post stroke, the following procedure was followed.

Before first mobilisation

Step 1

The following physiological variables were required:

-

systolic blood pressure of 110–220 mmHg

-

oxygen saturation of ≤ 92% supplementation (see note on page 9)

-

resting heart rate of 40–110 b.p.m.

-

temperature of < 38.5 °C.

Note:

-

Oxygen saturation was measured without supplemental oxygen.

-

Oxygen was stopped for 1 minute. If SpO2 was < 92%, oxygen supplementation was resumed and maintained throughout the mobilisation.

-

Blood pressure was measured in the unaffected arm. Oxygen saturation was measured on the affected arm.

-

If blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were within acceptable limits then the patient proceeded to the next step.

Performing the first mobilisation

Step 2

-

The back of the bed was raised to > 70° of hip flexion. The measures of blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were repeated.

-

If blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were within acceptable limits then the patient proceeded to the next step.

-

If blood pressure drop was > 30 mmHg then the patient remained in bed, but was reassessed at a later time.

Step 3

-

The patient was assisted to sit over the edge of the bed (feet on the floor if able). This may have required the assistance of one or two people and the patient may have required the assistance of one person to maintain sitting balance.

-

The measures of blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were repeated.

-

If blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were within acceptable limits then the intervention would have proceeded to the next step.

-

If blood pressure drop was > 30 mmHg then the patient remained in bed and would have been reassessed at a later time.

Step 4

-

Sitting was for 5 minutes and measures of blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were repeated.

-

If blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were within acceptable limits, the intervention proceeded to the next step.

-

If blood pressure drop was > 30 mmHg then the patient remained in bed, and reassessed at a later time.

Step 5

-

An appropriate level of assistance was used (hoist or manual assistance dependent on routine assessment findings) and the patient was transferred to a comfortable chair with adjustable back to allow an angle of 90°–100° hip flexion.

-

Measures of blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation were repeated.

-

If measures were within acceptable limits then the patient maintained sitting and was monitored for comfort.

The first out-of-bed mobilisation was interrupted and the patient returned to bed if:

-

in the clinician’s judgement, the patient was not tolerating the mobilisation (i.e. became less responsive, developed a headache, became nauseated or vomited or became pale or clammy)

-

systolic blood pressure was < 100 mmHg or > 230 mmHg

-

systolic blood pressure decrease was > 30 mmHg

-

heart rate was > 120 b.p.m.

-

oxygen saturation was < 90%.

Maximum sitting time for sitting out of bed was 50 minutes each time, for the first 3 days.

What if a very early mobilisation patient could not have achieved the first mobilisation?

Factors that would have affected a patient’s ability to mobilise may have included (but were not limited to) (1) vital signs not within the normal listed limits, (2) an adverse event (AE) that would have led to a mobilisation restriction for a period of time (e.g. acute myocardial infarction, lower limb fracture, pneumonia, carotid endarterectomy) or (3) a deterioration which led to palliation.

In the case of a temporary interruption to mobilisation due to an event similar to those listed above, mobilisation was recommenced as soon as possible. The patient’s physiological variables were reviewed every few hours (step 1). Clinical judgement was used and the first mobilisation was attempted when the patient physiological variables were within limits. When a mobilisation was planned, but not able to be performed, staff submitted a therapist or nurse recording form with the time and reason not mobilised. Whenever possible, VEM resumed at the earliest opportunity.

Usual care group

Participants who were randomised to receive UC received the usual post-stroke unit care. Prior to trial commencement, baseline UC was reported by trial staff at each site. Typical UC is described in Table 2. Mobilisation activity was not prescribed but all mobilisations were recorded. UC patient mobilisations at each site were monitored for change during the trial.

| Level | Patient description | Nursing activities | Physiotherapy activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low arousal | Approximately one mobilisation every 1 or 2 days | Approximately one treatment every 1 or 2 days |

| Fully dependent | |||

| 2 or 3 | Moderate – high dependence | Approximately two mobilisations per day | Approximately one treatment per day, including a mobilisation |

| 4 | Low dependence | Approximately four mobilisations per day | Approximately may/may not have received treatment, would have been encouraged to have mobilised independently |

| Note: this aspect varied greatly | Note: this aspect varied greatly |

Recording of mobilisation sessions

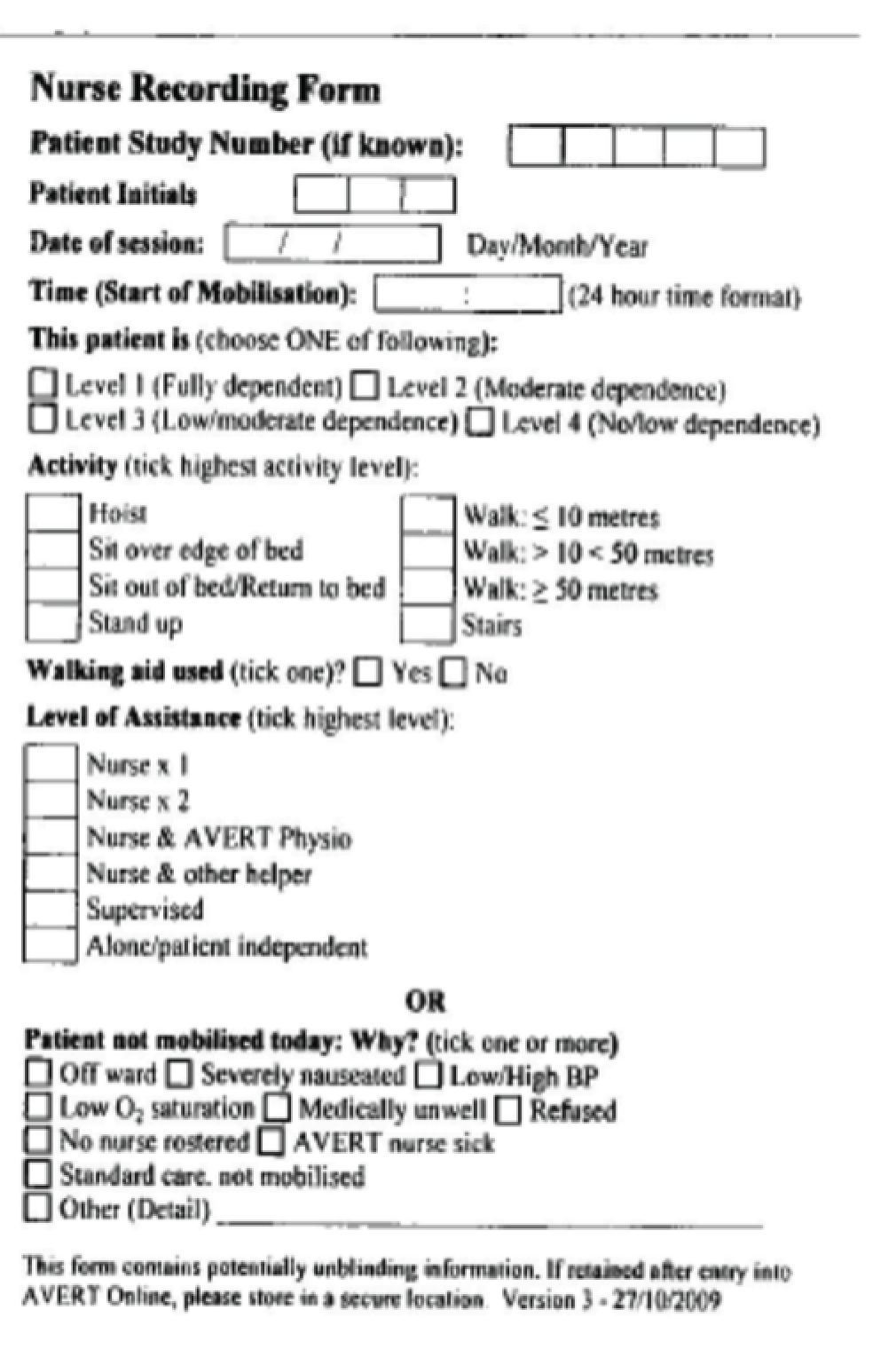

Mobilisation data for both UC and VEM patients were recorded by the AVERT physiotherapist, ward physiotherapist and occupational therapist and/or the AVERT nurse(s) using therapist and nurse recording forms, respectively, on AVERT Online. For convenience, paper therapist and nurse recording forms (Figures 1 and 2) were sometimes used to initially record mobilisations and then the data were transferred to AVERT Online. VEM interventions were not recorded in routine medical records.

FIGURE 1.

Example of the paper therapist recording form.

FIGURE 2.

Example of the paper nurse recording form.

The AVERT nurse(s) recorded all mobilisations that they were responsible for initiating that were conducted alone or with an AVERT physiotherapist, ward physiotherapist, occupational therapist or other assistant. Mobilisations in which the AVERT nurse helped either the AVERT physiotherapist or ward physiotherapist/occupational therapist for study patients (either group) were recorded by the therapist that initiated the mobilisation. The nurse involvement was acknowledged in the recording of the mobilisation. This prevented double reporting of a same mobilisation.

Equipment

Existing equipment (e.g. beds, standing hoists, standing frames, tilt tables, chairs, lap trays, gait aids, arm supports, safety belts, etc.) from each hospital were utilised as per usual ward policy and availability. Ward lifting policies were applied to all mobilisations for AVERT patients. The vulnerable hemiplegic shoulder was cared for with the use of lap trays when the patient was seated and the provision of slings used for transfer and walking activities.

Adherence to protocols

The online recording system allowed the intervention staff to document all mobilisations, including attempted mobilisations and reasons for when the patient was not mobilised according to protocol. Intervention staff received feedback from an external monitor about their compliance with the trial protocol. These were provided in quarterly compliance summaries and were reviewed regularly by the Data Safety and Monitoring Committee.

Contamination was a potential problem for this trial. This was because all patients in this study were situated on a single ward. This made it difficult to keep other staff on the ward from seeing the intervention staff work with patients who had been randomised to VEM. If contamination had occurred, the results of the trial would have been diluted because intervention and UC would have become more alike.

Contamination was considered to have occurred if VEM was provided to UC patients or became UC for a large number of patients. Measures to reduce the potential of the intervention practices to be adopted by staff other than the AVERT staff included security of the intervention protocol and procedures to stop ward staff observing VEM sessions. The Data Safety and Monitoring Committee monitored contamination throughout the trial.

Data collection

Source data relating to each patient were maintained in the patient’s medical record.

Source data relating to the intervention therapy given to the patient were not recorded in the patient’s medical record. The therapy information was recorded in the web-based therapy/nurse forms (see Figures 1 and 2) on AVERT Online; data were also recorded in the individual patient’s paper CRF, which would have been supported by information documented in the patient’s medical record or clinical notes.

Blinding

We recognise that blinding is vital for the integrity of any RCT. As the AVERT physiotherapists and nurses were delivering the interventions, they were not blinded to the interventions but protocols were in place to conceal allocation group to all other ward staff.

The following measures were followed to maintain blinding for the AVERT study:

-

A patient or their family were never told of the group to which they had been randomly allocated, even if they asked.

-

The AVERT physiotherapists never wrote VEM interventions in the medical record and AVERT nurses recorded only standard information and did not refer to frequency of intervention provided.

-

Anyone who did not need to know the patients group were never told, even if they asked.

-

The AVERT staff ensured that other staff and AVERT patients did not become aware of the details of the VEM. VEM activities were conducted behind curtains with patients screened from other ward staff, and mobilisations performed off the ward were provided whenever this was possible.

-

The blinded assessors assigned to the trial site were not on the ward when the trial took place and did not witness treatments that patients had received.

-

The blinded assessor, who conducted assessments, was never told the group to which patients were allocated. The assessor had been trained in what they could and could not ask participants, therapists, nurses and other staff whom they encountered.

-

The blinded assessor informed AVERT ward staff if it was necessary to visit the ward for any reason, which minimised the risk of an intervention session being witnessed. Every effort was made by AVERT staff to ensure that a session was not witnessed by the blinded assessor.

Participant assessments

Outcome assessments were done in person or by telephone by a trained assessor who was not working in the study stroke unit and was blinded to treatment allocation.

Three-month assessment

At 3 months post stroke, the assessor located the patient and conducted the assessment, which included the following. 30

-

mRS:39 a commonly used scale for measuring the degree of disability or dependence in the daily activities of people who have suffered a stroke or other causes of neurological disability.

-

Irritability, anxiety and depression assessment (IDA):44,45 following stroke.

-

Barthel Index:46 an ordinal scale used to measure performance in activities of daily living.

-

assessment of quality of life (AQoL). 47

-

Rivermead Motor Assessment Scale48 (RMAS): assesses the motor performance of patients with stroke and was developed for both clinical and research use.

-

50-metre walk:30 assessed if the patient had not achieved walking during the 14-day intervention period.

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA):49 a cognitive screening test designed to assist health professionals in detecting mild cognitive impairment.

-

Cost of care: the cost CRF collects resource use on acute hospital length of stay, discharge location, ambulance services, rehabilitation, stroke-related rehospitalisations, change of accommodation, aids, home modifications, community services, return to work, informal care hours and country-specific services (e.g. UK outpatient therapy; Asian maid services in the home).

-

AEs, important medical events (IMEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) (see below).

Adverse events

An AE is defined as any untoward medical occurrence in any participant involved in the study and that does not have a causal relationship to the study intervention. This included any worsening of a pre-existing event. AEs were recorded in the patient’s medical record and reporting commenced from the time of informed consent. Events were recorded in the patient’s CRF and included the date of onset, description, severity and duration and whether or not it was thought to be related to the study intervention.

All AEs were collected from the time of the patient’s consent until the end of the intervention period and were followed until the event was resolved or had been stabilised.

Important medical events

The IMEs were prespecified events that are important outcomes measures for this study. These events included:30

-

falls (with no soft tissue injury, with soft tissue injury, with bone fracture)

-

stroke progression (defined as a worsening stroke, in the clinician’s view, in the same vascular territory as the initial event occurring during the first 14 days)

-

recurrent stroke (defined as a new stroke event beyond 14 days (in the clinician’s view)

-

pulmonary embolism

-

deep-vein thrombosis

-

myocardial infarction

-

angina

-

urinary tract infection

-

pressure sores

-

pneumonia

-

depression (clinically diagnosed).

Serious adverse events

A SAE was an AE or IME that met any one of the following criteria:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required inpatient hospitalisation

-

prolonged hospitalisation (if an event occurs while the patient is in hospital, which in itself prolongs the patient stay)

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability.

Up to 3-month follow-up all IMEs, serious or not serious, were reported. After 14 days, we recorded new AEs that were classified as serious but were not IMEs. From 3–12 months, SAEs were collected.

Twelve-month assessment

At 12 months, the final assessment was conducted by the blinded assessor. The assessor made contact with the patient/relative/carer and organised the meeting.

At this visit, all 3-month assessments were repeated, except for the MoCA.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was survival without major disability (mRS score of 0–2) at 3 months after stroke. A favourable outcome was defined as mRS score of 0 (no symptoms), 1 (impairment but no disability) or 2 (independent but with minor disability). A poor outcome was defined as mRS score of 3 (disability but able to walk), mRS score of 4 (disabled and unable to walk), mRS score of 5 (bed-bound and in need of full nursing care) or mRS score of 6 (death).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included an assumption-free ordinal shift39,40 of the mRS across the full range of the scale. This measures a change in the mRS across the whole range of the scale rather than just across one threshold. We also obtained time taken to achieve unassisted walking for 50 m and the proportion of patients achieving walking by 3 months. Death and the number of non-fatal SAEs were recorded up to 3 months.

Serious adverse events were recorded according to standard definitions and included IMEs relevant to acute stroke patient recovery (see above). Serious adverse events and deaths were independently adjudicated by an outcome committee who were blinded to treatment allocation. This included a review of the source data if necessary. The classification of complications of interest were neurological (stroke progression and recurrent stroke) and complications of immobility (deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, urinary tract infection and pressure sores). At 12 months, we recorded health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and items of patient costs.

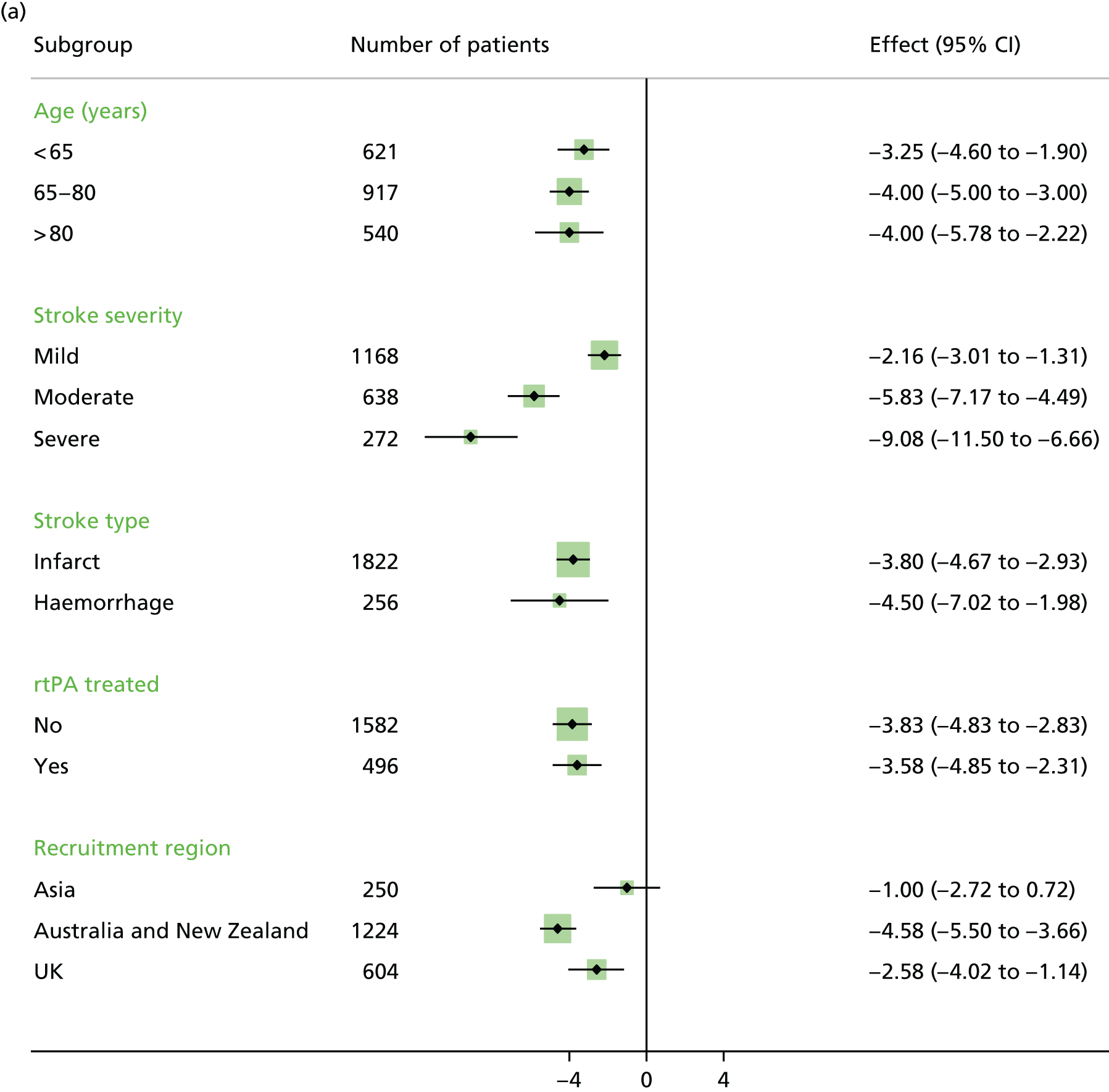

Subgroup analyses

In view of the complex nature of the VEM intervention a number of exploratory analyses were prespecified. 30 In particular, subgroup analysis by age, stroke severity, stroke subtype (infarct or haemorrhage), treatment with thrombolysis (rtPA) and TTFM. We also prespecified an exploration of the dose of the intervention in terms of (1) TTFM, (2) frequency of mobilisation and (3) total amount of time undergoing the intervention.

Withdrawal from treatment and data collection

We anticipated that some participants would wish to withdraw from treatment. In that circumstance, the reason and date of withdrawal were documented and they were invited to allow further collection of follow-up data. Clearly, if the participant refused further follow-up then all treatment and data collection ceased at that point. We considered analyses based on last result carried forward in the event of significant loss of information.

Data retention

All study documents were confidential. Each site was issued with an investigator site file in which to store study documents. All of the study-related documents were stored in a locked area and accessible only to study staff.

At the completion of the study, all site study data and materials have been archived, at site, and have been stored in a secure area for a period of ≥ 7 years if required by hospital procedures.

Power calculation and sample size

The trial was powered to detect an absolute risk reduction of a poor outcome (mRS score of 3–6) of at least 7.1%. This threshold was based on (1) a consensus among clinicians and researchers that an absolute risk reduction of this size would be clinically meaningful and (2) observational data indicating that a hospital routinely practising EM compared with a similar Australian data set had a 9.1% better outcome on the similar variable of death or institutional care (31.8% vs. 40.9%). If EM accounted for 78% of this benefit9 then the absolute difference would be 7.1%.

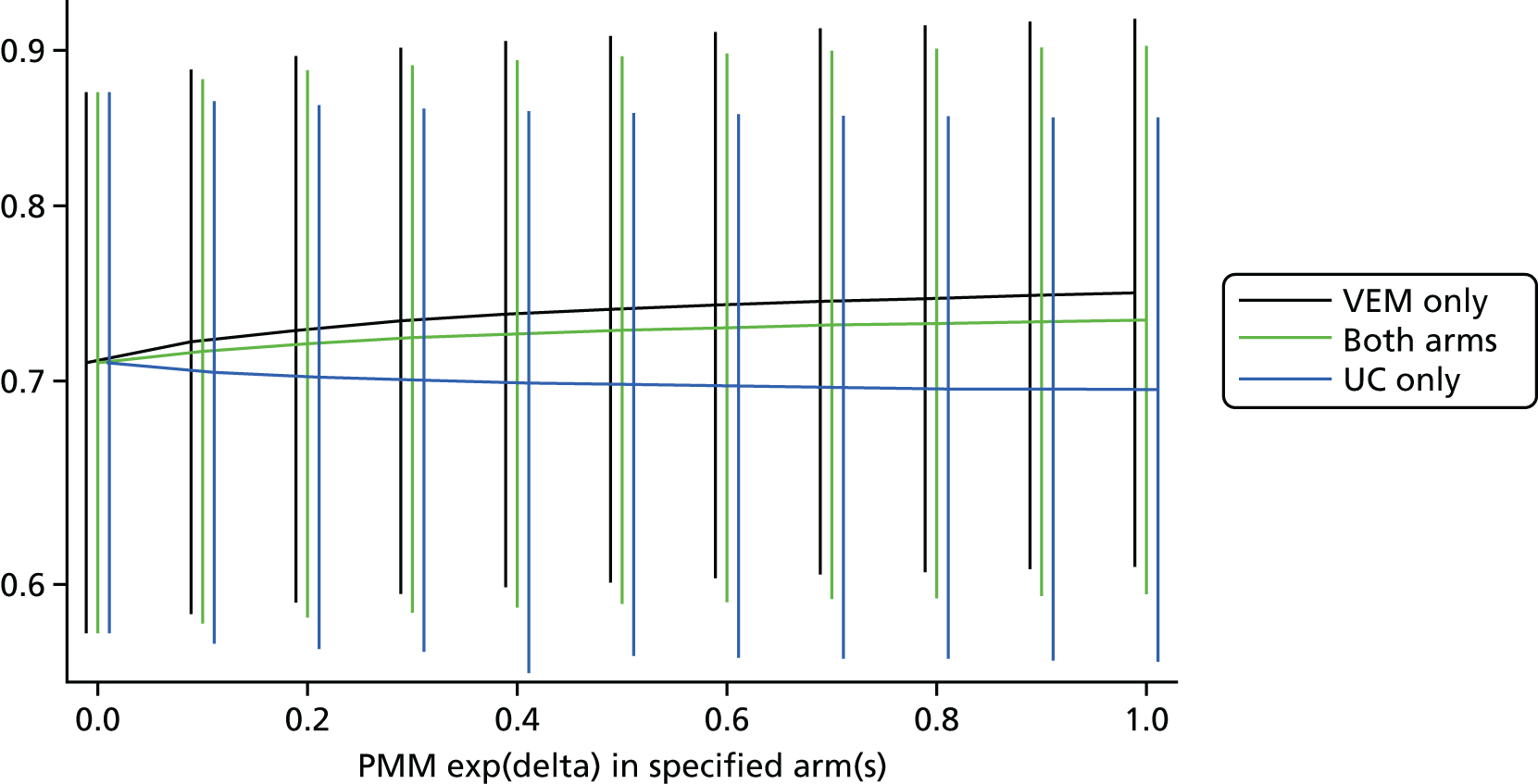

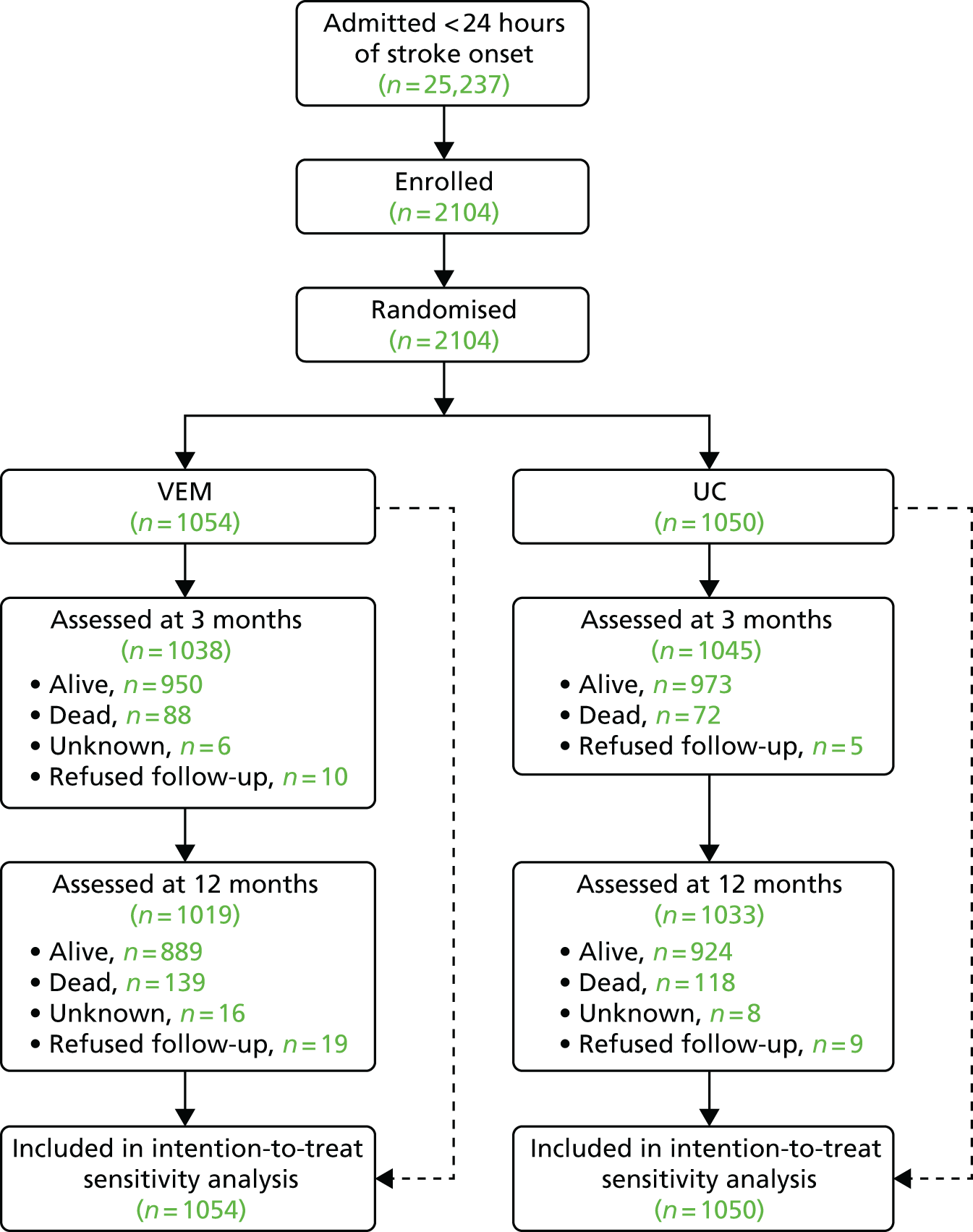

We estimated that a sample of 2104 patients would be required to provide 80% power to detect a significant intervention effect (two-sided p = 0.05) with adjustments for 5% drop-in and 10% drop-out. Statistical analysis was prespecified and published in advance. 30 Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA)/IC (version 13) was used for all analysis. For the primary analysis we used an intention-to-treat approach with the assumption that data were missing at random. We also explored the sensitivity of our results to plausible departures from this assumption. This used both a selection model (to model the mechanism of missing data) and a pattern mixture model (modelling the differences between observed and missing data).

Statistical methods

We used standard methods for handling of missing data. 30,50 The primary efficacy analysis was carried out on an intention to treat basis with an assumption that data were missing at random. 30 We explored the sensitivity of our conclusions to plausible departures from this assumption and used both a selection model and pattern mixture model of the differences between observed and missing data. The results were plotted out over a range of assumptions.

We did the primary efficacy analysis used the binary logistic regression model, with treatment group as an independent variable and mRS outcome at 3 months as the dependent variable. This was dichotomised into scores of 0–2 as favourable outcome and scores of 3–6 as poor outcome. Baseline stroke severity (NIHSS) and age were included as treatment covariates for adjustment purposes.

The primary outcome analysis included subgroup analysis based on age (< 65 years, 65–80 years and > 80 years), stroke severity (mild NIHSS 1–7, moderate 8–16 and severe > 16), stroke type (ischaemic vs. haemorrhagic), treatment with tissue plasminogen activator, TTFM (< 12 hours, 12–24 hours and > 24 hours) and geographical region (Australia/New Zealand vs. UK, Australia/New Zealand vs. Asia), with adjustment for stroke severity and age.

We also estimated the treatment effect on the mRS using an ordinal analysis at 3 months with the assumption-free Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney U-test generalised odds ratio (OR) approach. 51,52 This provided a measure of effect size with confidence interval (CIs), which was stratified by age and stroke severity. Time (days) taken to achieve unassisted walking of 50 m was analysed using the Cox regression model with treatment group as the independent variable, the time to unassisted walking (censored at 3 months) as the dependent variable, and age and baseline NIHSS as covariates. The estimated effect size is presented as a hazard ratio (HR) with corresponding 95% CI. The analysis of walking status (yes or no) was analysed with a binary logistic model using treatment group as the independent variable and walking status as the dependent variable.

We used a binary logistic regression model to analyse mortality outcomes. Treatment group was the independent variable and death at 3 months was the dependent variable. Age and stroke severity were treatment covariates. We used negative binomial regression to compare the expected counts of serious complications between groups at 3 months. We report the estimated effect sizes and corresponding 95% CI as incidence rate ratios (IRRs) adjusted for age and stroke severity.

We wished to determine whether or not practice had shifted during the course of this trial. We did this by testing the association between treatment effect and trial duration by including an appropriate interaction term into the logistic regression model used in the primary analysis. We also did an exploratory analysis in which we examined the effect of time since the start of the trial on differences in dose characteristics between the two groups. We used regression models with an interaction term for treatment by time since the start of the trial; a median regression model was used for TTFM and median session frequency and a binomial regression model was used for median daily minutes per session and total treatment time over the intervention period (total minutes).

End-point analyses

Primary end point: the primary outcome was planned as a ‘between-group’ comparison of mRS at 3 months, analysed across the whole distribution of scores subject to the validity of shift analysis model assumptions. If the assumptions for shift analysis were not met, 3-month mRS was to be dichotomised into good outcome (mRS score of 0–2) and poor outcome (mRS score of 3–6), and the groups were compared using a binary logistic model. Although the trial was under way, new ordinal approaches to analysis were developed, tested and gained acceptance in acute stroke trial (see the statistical analysis plan). The management committee determined that an assumption-free ordinal approach to analysis should be included as a secondary outcome (statistical analysis plan). Therefore, the analysis plan was changed such that the 3-month mRS results were dichotomised into good outcome (mRS score of 0–2) and poor outcome (mRS score of 3–6), and the groups compared using a binary logistic model. 30 The primary analysis was adjusted with baseline NIHSS and premorbid mRS as covariates. Unadjusted results were also to be shown. The intervention effect was represented in terms of ORs. Other potential prognostic variables such as age, stroke type and side of stroke were included in subgroup efficacy analyses.

Secondary patient end points: regression models for count data were used to compare SAEs between groups at 3 months. Risk ratios, adjusted as per primary analysis, including age and NIHSS as covariates, were reported.

The odds of achieving unassisted walking at 3 months was analysed using binary logistic regression analyses [adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% CIs]. Cox regression analysis was used to analyse the time (days) to achieve unassisted walking. This was presented as adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) with 95% CIs and was censored at 3 months.

Mortality outcomes at 3 months were analysed using binary logistic regression with death as the dependent variable (aOR with 95% CI). The dose effect on counts of SAE was analysed using binomial regression (adjusted incident rate ratio with 95% CI). Different subtypes of SAE (immobility related, neurological) were analysed separately.

Health-related QoL analysis was planned as a multivariable median regression model with a treatment group as independent variable and the AQoL score as the dependent variable. To estimate the effect of intervention group on AQoL scores at 12 months, treatment covariates for adjustment purposes would include baseline NIHSS, age and sex.

Data sharing and archiving

All deidentified trial data have been archived in secure facilities for a minimum period of 7 years. The options of data sharing arrangements were not available at the trial commencement and were not included in participant consent processes.

Economic evaluation at 12 months

The economic evaluation was not included in the NIHR HTA programme funding. However, the wider AVERT programme did include a health economic analysis;34 therefore, we summarised the resource use data collected for an economic evaluation. We prospectively collected resource use data within the trial using standard data collection tools. The primary economic evaluation planned is a cost-effectiveness analysis comparing resource use during the 12 months of follow-up. The health outcomes of the VEM intervention were measured against a UC comparator. It was also intended to have included a cost–utility analysis.

For the cost-effectiveness analysis, the primary outcome is a mRS score of 0–2 at 12 months. It was intended that the cost–utility analysis used HRQoL expressed as quality-adjusted life-years gained over a 12-month period. This was measured using the mRS and the assessment of QoL.

Data collection tools to capture resource use were piloted in the AVERT pilot study29 and then further adapted to accommodate local service provision in different countries. An exploratory analysis of the resource use data was planned to consider the relationship between patterns of service use in health outcomes within the trial. These health outcomes included QoL. A further objective explored economic impacts of stroke on patients, families, the broader community and the health sector.

The methods for assessing safety, effectiveness and QoL have already been published in the statistical analysis plan. 30 The economic analysis plan complements the statistical analysis plan and was finalised prior to the 12-month data collection period being completed. 34

The economic analysis plan describes key study variables for the economic evaluation, outlines the primary cost-effectiveness analysis and describes proposed exploratory analysis. The development of the economic analysis plan was guided using recommended standards. 53 The economic analyses are under way; however, a UK-specific economic evaluation will not be undertaken as not supported with NIHR HTA programme funding.

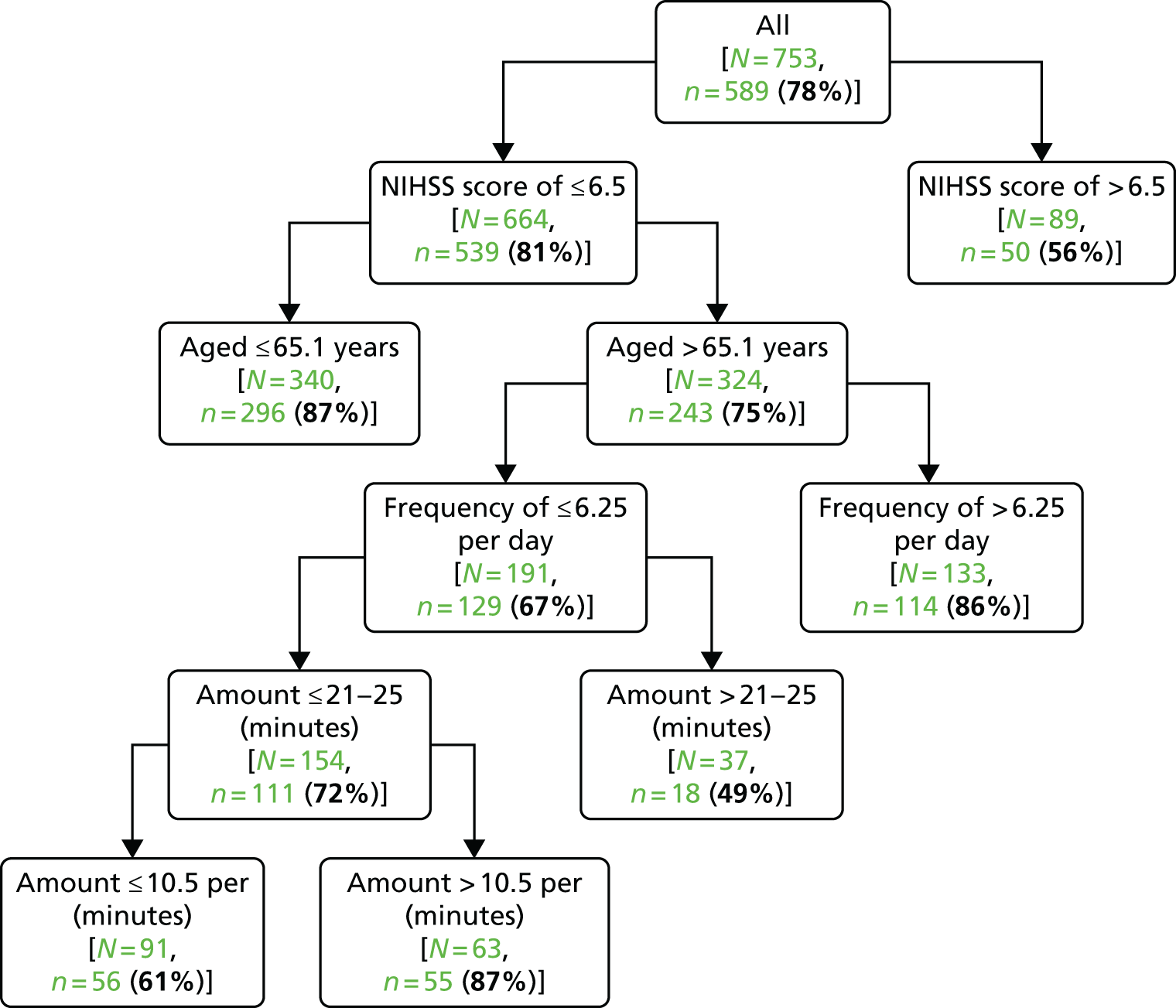

Exploratory analyses

To further investigate the interaction between dose characteristics and patients and a favourable outcome we used (1) binary regression analysis and (2) a classification and regression tree (CART) analysis (Salford predictive modeller software suite version 7, Salford Systems, San Diego, CA, USA).

The CART is a binary partitioning statistical method that starts with the total sample. It then uses a stepwise approach to split the sample in to subsamples that are homogeneous in a defined outcome. 54 The input variable that achieves the most effective split is dichotomised by automated analysis at an optimal threshold, maximising the homogeneity within, and separation between, resulting subgroups. A 10-fold internal cross-validation is used to maximise model performance that is assessed as the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The internal cross-validation divides the data randomly into 10 groups with nine used to build the model (training data set) and one used to validate the model (testing data set). CART also numerically ranks each input to build the tree by relative importance. In our analysis, we included all prespecified subgroup variables (patient age, NIHSS, stroke type, treatment with rtPA), group allocation and the three dose characteristics (TTFM, frequency and daily amount). This analysis explored the relative importance of each variable in association with achieving a favourable outcome (mRS score of 0–2). A further analysis (CART II) investigated multidimensional relationships between dose characteristics alone and favourable outcome. 55

Both approaches to exploratory analysis examined the three main characteristics of treatment dose:

-

TTFM out of bed (hours)

-

frequency – median number of out-of-bed sessions per patient per day

-

daily amount – median minutes of out-of-bed activity per patient per day.

We also recorded total amount (total minutes of out-of-bed activity over the whole intervention period) to account for varying lengths of stay in hospital.

Nurses recorded the type of activity and the time of the day each activity began. This did not include total time in minutes as this was not routine practice. Physiotherapists recorded the type of activity, the time that the activity began and the total out-of-bed activity (minutes), as this was incorporated in normal practice. Therefore, physiotherapy data alone contributed to the variables of daily amount (minutes) and total amount (minutes) of out-of-bed activity. Both nursing and physiotherapy data contributed to TTFM and frequency of mobilisations. For the definition of frequency of mobilisation, episodes of sitting, standing or walking activity had to be separated from another episode of activity by more than 5 minutes of rest (e.g. in a chair).

In an attempt to avoid excessive collinearity between daily amount and total amount we tested two different models that were adjusted for age and baseline stroke severity for all the analysis:

-

Model 1 – TTFM, frequency (median daily number of out-of-bed sessions) and amount (median daily out-of-bed session time in 5-minute increments),

-

Model 2 – TTFM, frequency (median daily number of out-of-bed sessions) and amount (total minutes out-of-bed activity over the whole intervention period in 5-minute increments).

The primary exploratory analysis was carried out using binary logistic regression models with favourable outcome (mRS score of 0–2) at 3 months as the dependent variable.

Meta-analysis of comparable trials

We wished to set the AVERT results in the context of other similar RCTs. We updated the searches of the existing systematic review,56 searching MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Cochrane Stroke Group trials register, several international ongoing trials registers, reference lists of articles and also performed citation searching up to 2015. Foreign language translations were sought. Two review authors assessed trial eligibility, quality and performed data extraction. We included any trial that compared EM after stroke (within 48 hours) with a more delayed mobilisation. The primary outcome was death or poor outcome (dependency or institutionalisation) at follow-up with the use of a mRS score of 3–5 as the preferred definition of poor outcome. We used a fixed-effects model to estimate ORs and 95% CIs, with the use of a random-effects model in the event of substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%).

Patient and public involvement

Stroke survivors in Australia contributed to the original trial development. In particular, Ms Brooke Parsons (a stroke survivor) was involved in the development of the proposal and the monitoring and progress of the trial through her role on the Trial Steering Committee. Each individual study site had varying degrees of patient and public involvement.

Role of the funding source

The various funders of the AVERT international trial had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation or in the writing of the report. The author team had full access to all data in the study.

Chapter 3 Qualitative process evaluation

Introduction

As stated in the introduction, we also refer to two related studies that were not specifically included in the original HTA programme trial application but were nested within the AVERT programme and contribute to its understanding. These are a qualitative process evaluation,37 which is summarised here, and a study of the generalisability of AVERT,38 which appears in the results (see Chapter 4).

It is particularly challenging to implement multidisciplinary stroke rehabilitation interventions when the intervention is both complex and multifaceted. This part of the trial programme aimed to better understand how the implementation of the VEM intervention was experienced by the staff involved. It has been reported that efforts to implement evidence-based recommendations in acute stroke units have had mixed success. In particular, changing clinician behaviour is particularly challenging when incorporated within pragmatic trials. 57 The qualitative process evaluation summarised here aimed to help us better understand the implementation of the VEM intervention protocol from the perspective of the health-care professionals who were responsible for its delivery. We believed that understanding the knowledge and perspectives of these staff would be important to both develop effective guidance in the future and implement the VEM intervention if it was found to be effective.

The main component of this chapter was published in Luker et al. 37 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text in this chapter includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Methods

We used the standard qualitative methodological methodologies58,59 involving AVERT trial collaborators in Scotland, Australia and New Zealand. Ethics approvals were obtained for all three countries. The Scottish component of recruitment was carried out as part of a Stroke Association-funded Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) by Ms Louise Craig, who was also our first AVERT manager in the UK. The raw Scottish data relevant to the main AVERT trial were reanalysed by colleagues in Australia using the same approach for all included study sites.

Study sample

We used purposive sampling at participating AVERT sites. This was overseen by the trial manager in Australia and New Zealand and by Louise Craig in Scotland. Of the 72 staff who expressed interest, six did not eventually consent to take part and one moved abroad. We obtained informed consent from 33 physiotherapists, 18 nurses, one physiotherapy assistant and one speech pathologist. These staff members are based in four stroke units in Scotland, 14 in Australia and one in New Zealand.

The qualitative data were collected and analysed before the primary outcome of the trial was available. We conducted semistructured interviews facilitated by interview guides that permitted additional questions or probes if interesting information arose. 37 The main focus of the interview was on the implementation of the VEM protocol. The Scottish interviews were conducted between 2010 and 2011 and the Australian and New Zealand interviews took place in 2014. They could be by telephone or face to face. Telephone interviews commonly ran for 30 minutes, while face-to-face interviews averaged 59 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, cross-checked with participants and deidentified prior to analysis.

Analysis

We used a thematic analysis to explore the experience and perspectives of staff involved in the trial. This approach is said to be especially relevant to multimethods health research58,59 and uses low-inference interpretation. We inductively coded the data and set about identifying themes. Each stage incorporated independent consideration by two or more researchers with subsequent discussion and consensus forming. We coded the transcripts to small sections of meaning and then through an iterative process we grouped the codes into logical and meaningful clusters in a hierarchical tree structure. This resulted in categories, descriptive themes and subthemes (Table 3). Emergent themes, each with subthemes, were grouped into three categories: staff experience of implementing the trial intervention, barriers to implementation of the trial intervention and strategies to overcome barriers to intervention (see Table 3). Stroke unit staff described the challenges of taking part in the trial and how their unit set about implementing the VEM protocol. The recent publication37 describes the findings in detail but for the purposes of this report we have summarised the main themes as follows.

-

Staff experience of implementing the trial intervention.

-

Extra work but rewarding: the extra work was felt to be justified by the hope that the trial might benefit stroke patient outcomes.

-

Team practice changes: several staff reported a positive impact on teamwork at their site. In particular, closer working of nurses and physiotherapists and some changes in their professional roles.

-

– Changes to usual practice: over the duration of the trial some staff perceived a change in UC. This was not a universal perception but was noted by a substantial minority.

-

-

-

Barriers to intervention implementation.

The main reported barriers related to the general implementation of a trial and also those specific to the VEM intervention, in particular, the frequency of the intervention.

-

Team challenges: implementation difficulties were notable at sites that appeared to lack established interdisciplinary team working practices.

-

Staffing challenges: a common theme was that inadequate staffing levels made it difficult to consistently implement the VEM protocol particularly in the face of competing demands. It was recognised that experienced and trained staff were essential for successful implementation of the protocol.

-

Organisational or workplace barriers.

-

– The acute model and culture: there was a common view that the rapid pace and focus on early discharge of acute hospitals rendered rehabilitation a low priority.

-

– Barriers to acute stroke unit access: a particular problem was that significant delays were experienced while patients waited for a bed in the acute stroke unit.

-

– Competing priorities: competing organisational priorities such as discharge pressure, accreditation work and transfer policies were commonly reported as being a challenge.

-

-

Physical environmental barriers: environmental barriers such as lack of equipment and chairs were reported to be barriers.

-

Staff attitudes and beliefs.

-

– Resistance to change of practice: resistance to changing practice was identified at some sites particularly among staff who were not experienced in clinical trials.

-

– Beliefs about roles and capabilities: mobilisation delays at some sites were due to nurses awaiting physiotherapists to begin mobilisation.

-

– Beliefs about consequences: many staff assumed a positive treatment effect from VEM, which appeared to influence their perceptions of the treatment and anecdotal outcomes.

-

-

Patient barriers.

-

– Acuity, instability and complexity: acute health problems including unstable medical conditions and complex problems were viewed as a common barrier.

-

– Severity of stroke: early delivery of the VEM protocol was viewed as challenging in patients with drowsiness or reduced cognition. They would require more staff to assist mobilisation. The challenges with milder strokes were mainly due to the high frequency mandated by the VEM protocol.

-

– Fatigue: staff reported that fatigue was a common problem reported by patients sometimes preventing mobilisation.

-

– Family anxiety: on some occasions families raised concerns that the VEM intervention was preventing necessary rest.

-

-

-

Overcoming implementation barriers.

Many interviewees described strategies for implementing the VEM intervention in the face of the observed barriers. These are summarised below.

-

Teamwork is central to success: units that felt they had been successful in providing the VEM protocol frequently reported shared interdisciplinary roles with nurses, physiotherapists and others working closely together through flexible work practices and mutual trust.

-

– Communication and co-ordination: a component of good interdisciplinary working was effective communication and co-ordination between different members of staff.

-

-

Getting staff on board: an almost universal theme was the importance of spending time and effort to get staff engaged with the new VEM practice.

-

– Staff education and training: this was felt to be a cornerstone of getting staff involved.

-

– Leadership for change: implementing the VEM protocol was seen as a whole team responsibility but required leadership.

-

-

Working differently: a positive attitude to implementing the VEM protocol was seen in sites determined to work around organisational barriers and foster a culture appropriate to the trial. This included a willingness to relinquish some control of traditional roles and practices.

-

– Staffing model changes: some units reported using different staffing models involving nursing or allied health assistants.

-

– Managing patient fatigue: some units reported innovative approaches to timetabling therapy to accommodate patient fatigue.

-

-

| Themes | Interviewsa | Subthemes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1: Staff experience of implementing the trial intervention | |||

| 1 | Extra work but rewarding | 27 | |

| 2 | Team practice changes | 24 | |

| Changes to UC | |||

| Category 2: Barriers to intervention implementation | |||

| 3 | Team challenges | 19 | |

| 4 | Staffing challenges | 37 | |

| 5 | Organisational or workplace barriers | 28 | |

| The acute model and culture | |||

| Barriers to Acute Stroke Unit access | |||

| Competing priorities | |||

| Physical environment barriers | |||

| 6 | Staff attitudes and beliefs | 32 | |

| Not ‘on board’ | |||

| Beliefs about roles and capabilities | |||

| Beliefs about consequences | |||

| 7 | Patients’ barriers | 35 | |

| Acuity, instability and complexity | |||

| Severity of stroke | |||

| Fatigue | |||

| Family anxiety | |||

| Category 3: Overcoming implementation barriers | |||

| 8 | Teamwork central to success | 43 | |

| Communication and coordination | |||

| 9 | Getting staff ‘on board’ | 35 | |

| Staff education and training | |||

| Leadership for change | |||

| 10 | Working differently | 29 | |

| ‘This is what we do here’ | |||

| Shifting control | |||

| Staffing model changes | |||

| Dealing with fatigue | |||

Discussion

The interview with staff identified some common themes. 37 First, implementing the VEM protocol within AVERT was acknowledged as being a challenging task. However, despite the challenges encountered there was substantial enthusiasm about participation in the trial. This enthusiasm was largely driven by an interest in the research question and the potential benefit to future stroke patients. A strong feature of these interviews was the importance of highly effective interdisciplinary teamwork. This was widely acknowledged as being an important factor in implementation of the VEM protocol. A second key feature was the importance of effective leadership to champion and encourage the trial within their units.

A strength of the qualitative study was that information was collected and analysed prior to the main AVERT trial results becoming available. Participants were generally optimistic that the trial would be positive and this seemed to be a factor in sustaining interest over a number of years. Another study strength was that experiences were collected across three countries, and, although there were some minor intercountry differences,37 the similarities were more striking than the differences.

Chapter 4 Statistical trial results

The main component of this chapter was published by the AVERT Trial Collaboration Group,31 (an Open Access article) distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text in this chapter includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Screening and exploring threats to generalisability in the AVERT

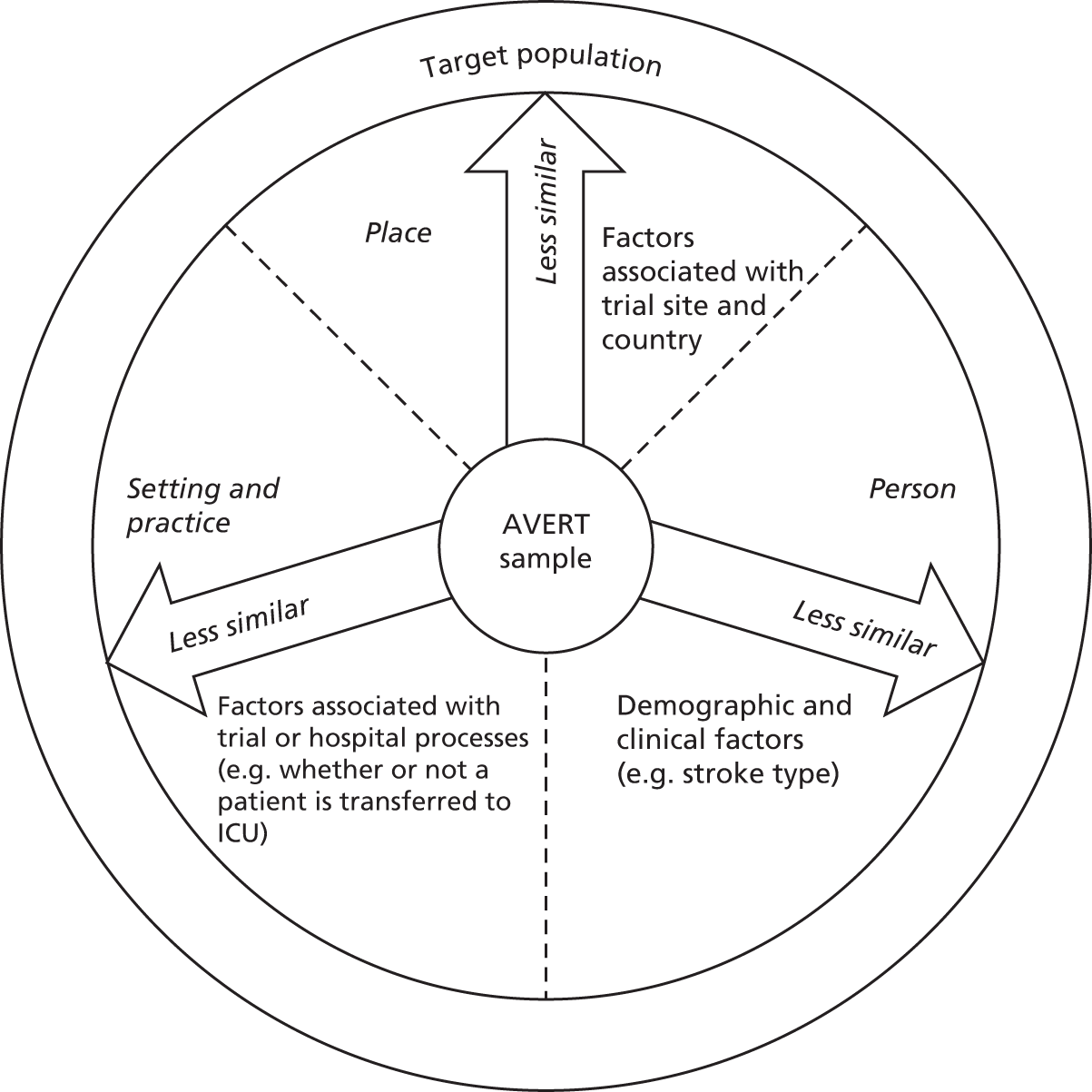

In parallel with the main trial of AVERT, we also carried out a study to explore potential threats to generalisability of the main results of AVERT. 38 We wished to consider the impact of person, place, setting and practice as a framework for considering generalisability. Therefore, we used a proximal similarity model (Figure 3) to carry out this analysis of the first 20,000 patients screened for inclusion in AVERT, which involved 44 hospitals in five countries. Of the first 20,000 patients screened for inclusion, 1158 were recruited and randomised in AVERT.

FIGURE 3.

Proximal similarity framework applied to the AVERT trial: a model for conceptualising the dimensions along which the sample of patients may be similar to the target population. Each dimension (person, place, setting and practice) is affected by specific factors that may threaten external validity. ICU, intensive care unit. Reproduced with permission from Bernhardt et al. 38 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

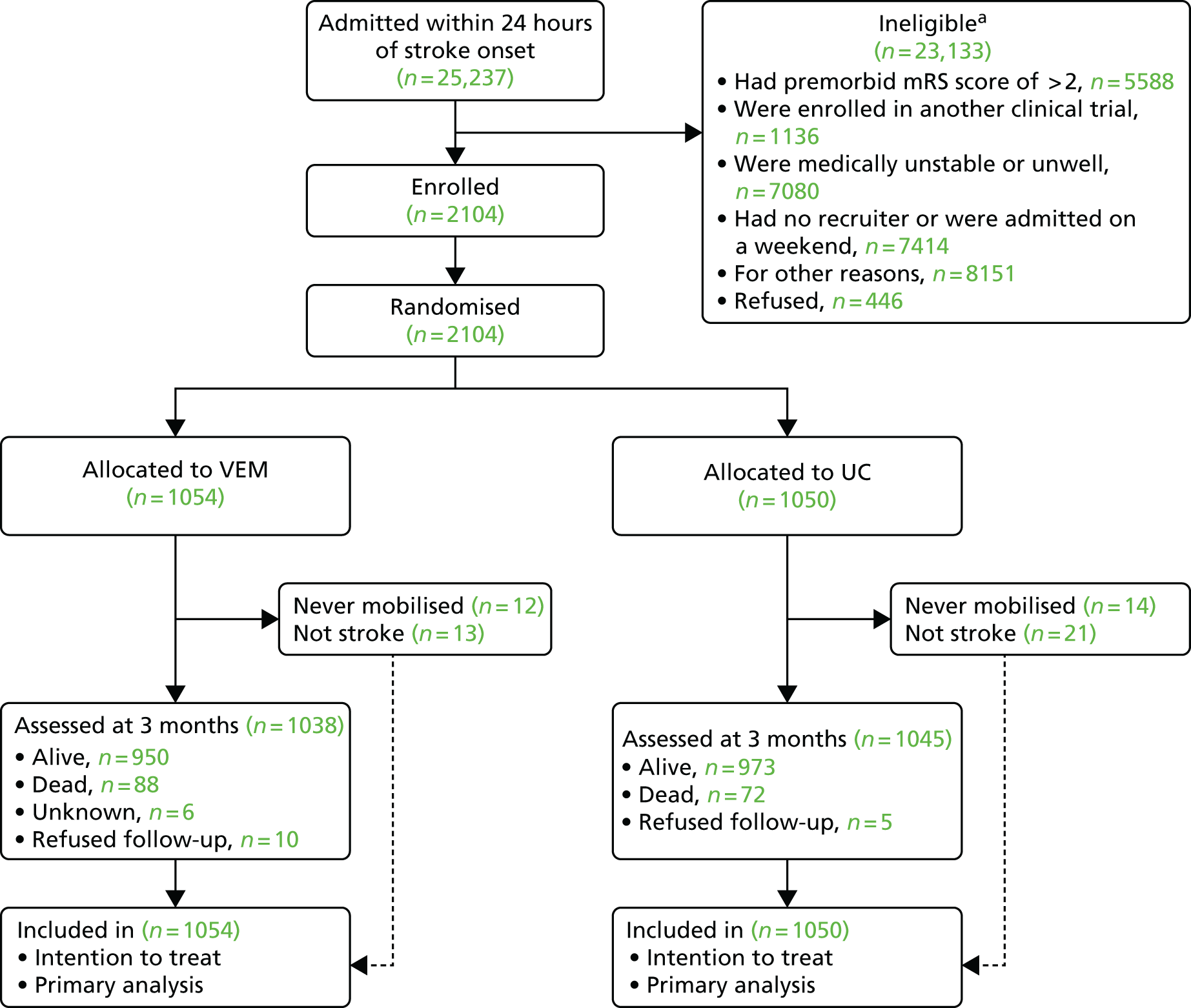

We compared recruited patients with the target population and also explored the factors (demographic, clinical process and site factors) that were associated with participant recruitment using a proximal similarity model (see Figure 3) that incorporated inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Relationship between trial inclusion/exclusion criteria and screening log categories in AVERT. a, other reasons included (but are not limited to) patients not admitted to a stroke unit, lower limb fractures and no treating therapist available. ICU, intensive care unit. Reproduced with permission from Bernhardt et al. 38 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

The characteristics of participants included in the trial were broadly similar in terms of demographic and stroke characteristics with the exception that recruited participants had a greater proportion of men (Table 4). Late arrival to hospital (after 24 hours) was the most commonly reported reason for non-recruitment. Overall, older and female participants were less likely to be recruited to the trial. The reasons for exclusion of women rather than men applied to a range of reasons including refusal. Among severe stroke patients, the odds of exclusion because of early deterioration was particularly common (OR 10.4, 95% CI 9.3 to 11.7, p < 0.001).

| Features | AVERT, non-recruited | AVERT, recruited | Difference (p-value) – recruited : non-recruited |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 18,842 (94) | 1158 (6) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 75 (64–82) | 73 (63–80) | < 0.001 |

| Range | 15–102 | 18–100 | |

| Female age (years), median (IQR) | 78 (61–80) | 76 (66–82) | |

| Male age (years), median (IQR) | 71 (68–85) | 71 (61–79) | |

| Female, % (95% CI) | 47 (47 to 48) | 37 (34 to 40) | < 0.001 |

| NIHSS, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Mild (1–7) | 10,012 (53) | 619 (53) | |

| Moderate (8–16) | 4934 (26) | 358 (31) | |

| Severe (> 16) | 3896 (21) | 181 (16) | |

| Stroke type, n (%) | 0.504 | ||

| Ischaemic | 16,328 (87) | 1012 (87) | |

| ICH | 2514 (13) | 146 (13) |

We found that using a screening log that captured a broad range of reasons for non-recruitment added to the collection of demographic data. 38 Similarly, the use of a model to explicitly explore generalisability was informative. However, a large screening log can only collect a limited amount of demographic and clinical information and it is quite possible that other factors may have influenced our recruitment. The proximal similarity model which explores person, place, practice and setting did provide some important information about the generalisability of this trial. Overall, the external validity appeared reasonably good.

Screening and recruitment

A summary of trial recruitment in the UK and other recruiting regions, during the period of the NIHR HTA programme grant (2012–16), is shown in Table 5. Recruitment from UK sites stood at 319 participants at the start of 2013 (average UK recruitment rate of seven participants per month). This compared with 19 participants per month in all other sites in Australia, New Zealand and Asia. The expansion that was possible through the NIHR HTA programme grant allowed us to recruit 291 UK participants in 2013–14 (average recruitment per month of 14 participants compared with 16 participants per month in all other sites).

| Country/centre | January to December 2011 | January to December 2012 | January to December 2013 | January to October 2014 | Final total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Ireland total | 20 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 59 |

| Antrim | 8 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 18 |

| Belfast City | 5 | – | – | – | 15 |

| Craigavon | 0 | – | – | – | 0 |

| Daisy Hill | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| Ulster | 6 | 5 | 1 | – | 25 |

| Wales total | 5 | 1 | 5 | 12 | |

| Neville Hall | 5 | 1 | 5 | 12 | |

| Scotland total | 13 | 26 | 25 | 30 | 171 |

| Aberdeen | 5 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 33 |

| Crosshouse | – | – | – | – | 3 |