Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/62/02. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The draft report began editorial review in March 2016 and was accepted for publication in January 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Ulph et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Newborn (neonatal) bloodspot screening (NBS) is seen as one of the most significant public health achievements in the developed world. 1 In England, NBS began in 1969 with screening for phenylketonuria (PKU)2 and over the following 40 years four additional disorders were added: congenital hypothyroidism (CHT), cystic fibrosis (CF), sickle cell disorders (SCDs) and medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD). Three of these disorders were added since 2007, in keeping with NBS worldwide, where panel expansion has been most noticeable in the last decade. 3 Most recently, in January 2015, four further conditions were added: maple syrup urine disease (MSUD), homocystinuria (HCU) (pyridoxine unresponsive), glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1) and isovaleric acidaemia (IVA).

In England, NBS involves collecting a blood sample between 5 and 8 days after birth. The premise behind screening is that there is a clinical benefit to affected infants of being identified and treated in the neonatal phase. 4 In 2014–15, > 666,000 babies were screened in the UK, of whom 590 had a positive screening result, leading to an urgent referral for diagnostic tests and treatment when necessary. 5 The annual report for the UK National Blood Screening Programme (NBSP) stated that the cost of screening for that year was £1,911,677. 5 Existing economic evaluations of NBS (e.g. Bunnik et al. 6), as well as studies such as retrospective cohort studies,7 have concluded that NBS is a cost-effective use of resources. However, the costs of the associated communication are not currently known.

The prescreening newborn bloodspot screening communication model in England

Newborn bloodspot screening is introduced to parents as a recommended routine screen with the proviso that screening occurs only after parents have given informed consent. 8 The latest version of the Health Professional Handbook9 states that:

When obtaining consent for newborn blood spot screening, you must ensure that parents understand they are consenting to the following:

The sample being taken

The sample being booked in and analysed in the NBS laboratory and used for quality assurance

The laboratory sending the results to the child health records department

The results being stored on the child health information system

The potential identification of their baby as a ‘carrier’ of SCD or CF

A referral to specialist services if a result is positive

The blood spot card being stored for a minimum period by the laboratory, as detailed in the Code of Practice for the Retention and Storage of Residual Spots (see 4.3; please note that this document is currently under review)

Their baby’s anonymised data being used for research studies that help to improve the health of babies and their families in the UK, for example population studies (see 4.3)

In rare circumstances, receipt of invitations from researchers who would like to use their baby’s blood spot card for research (this is optional – see 4.3)

The use of identifiable data on babies, or children under age 5, with SCD or thalassaemia by the NHS Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Screening Programme (see 4.4)

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence 3.09

The handbook guides health professionals to discuss and provide an information booklet, Screening Tests For You and Your Baby,10 at booking (the first appointment) and again after birth. It is recognised in the handbook that not all parents receive the booklet at booking and so health professionals are advised to provide the Screening Tests for Your Baby booklet later in pregnancy. (We refer to these texts as booklets as they are over 30 pages long; however, later in the report the interviewees may refer to them as leaflets.)

The booklets supporting communication changed during the project. As described, at the start of the project there were two booklets: Screening Tests For You and Your Baby was 72 pages long and was given early in pregnancy; Screening Tests For Your Baby was a shorter booklet designed to be given to parents in the last trimester or after birth. In October 2014 Screening Tests For You and Your Baby was revised10 and midwives were told to remove old copies from circulation. Although the Health Professional Handbook refers to both booklets, the provision of Screening Tests For Your Baby was also stopped in October 2014. Screening Tests For You and Your Baby is now 49 pages long, with NBS being covered on pages 44–9. If parents require further information they are signposted back to the booklet, which is available in 12 languages. 11 Thus, the dominant communication model is of midwives communicating with parents using generic screening booklets for support.

Acceptability, parental understanding and the broader impact of current consent and communication models

Provision of information is seen as central to ensuring that the potential harms of NBS (distress following an unexpected diagnosis, concerns about carrier status) are minimised12,13 and the benefits (ensuring quick follow-up of children with abnormal results) are maximised. 12,14–26 Clear screening information and effective communication between health professionals and parents is also seen as a way of balancing the conflicting needs of a public health screening programme with respect for parents’ autonomy. 14 Despite NBS being in place for almost 50 years in some countries, there is still a need to establish an evidenced-based and effective communication model. Although globally both the number and the type of conditions included in the panel vary considerably, as does opinion regarding the appropriate level of consent, there is universal concern regarding the efficacy of communication. 15,16

Consent models for NBS vary along a continuum, from the decision being made by the state (mandatory screening) through to ‘opt-out models’, in which the state advises screening but with parents able to object, and models in which parents are the decision-makers (informed consent). Consent for NBS involves a number of special considerations. First, parents are asked to make screening decisions on behalf of their newborn child – proxy consent. Second, the information provided is complex; screening covers a range of rare diseases that many people will not have heard of previously;17 the blood sample will be used for diagnostic testing, but also potentially anonymised research; across the different conditions there is a range of outcomes from diagnosis to inconclusive diagnosis, carrier, suspected carrier, false positive and normal; and the results of screening can have important implications for people other than the newborn child. Third, consent is often taken just a few days after birth when parents are tired and are being provided with large amounts of information regarding looking after a newborn. Thus, consent in this context is potentially quite different from consent in a range of other settings.

Concerns have been raised about the efficacy of informed consent as there is almost universal uptake of screening across countries. 4,6,15,18–20 Rather than this being because of positive regard, the concern is that parents are not truly making an informed decision because of limitations in the communication or consent process. 21 It has been argued that by making screening a routine part of postnatal care, and aiming for high uptake, NBS is incompatible with the concept of informed consent usually required for testing for serious diseases and disorders. 22

Additional concerns surround repeat findings that parents whose children have been screened have limited knowledge about screening. 19,23–30 Indeed, some parents were unaware that their child had been screened. 25,28,31–33 Within the UK a health technology assessment (HTA) study reported concerns over whether or not parents were adequately informed prior to screening,34 linking this to subsequent distress and resource use when adapting to carrier results. That such anxiety has been linked to impaired relationships with the baby35–37 and stress-related problems enduring into childhood38 demonstrates that lessons from PKU screening, which has triggered the vulnerable child syndrome for some parents,39,40 have not been learned. Unfortunately, such distress commonly has an impact on the wider family. 34 In these scenarios multiple and/or specialist health professional consultations are often needed to allay such anxiety. 34,41 However, the resources related to this further service need are not included in NBS cost estimates. 42 Thus, providing parents with NBS information appears to be complex, with no evidence-based, effective and standardised model in existence, and, critically, the provision of NBS information can have an impact on families and resource use.

Crucially, research suggests that such distress may be avoidable as not only can parents understand NBS information and assimilate the results into their lives with minimal distress but they also positively value the results. 34 The key difference between parents who reported distress and those who received carrier results with minimal service need is that parents who adapted well had a prior awareness of the disease and could understand the relevance of the NBS information provided antenatally. 34 Thus, there are calls for antenatal communication to be optimised to minimise the distress from false-positive37 or carrier13 results. Parents who reported distress did not feel prepared for screening, felt overloaded by information provided antenatally26,34 and felt that the NBS information provided did not meet their needs or was not relevant. 27,34 This fits with an argument made by Climb (an organisation that provides information on metabolic diseases for parents, children and health professionals) that the NBS booklets require users to have pre-existing knowledge to appreciate their relevance. 16

Expanded newborn bloodspot screening

The advent of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) provided the means to screen for numerous disorders with few extra costs. 43 As NBS panels include increasingly rare diseases with less clear treatment benefits, communication will become ever-more critical and yet challenging. 16 Specifically, there is a recognised need to inform parents prior to screening,34,43,44 preferably antenatally,34,45 and that current models may not be meeting parents, needs for clear and timely information. 34 A potential expansion to the NBS panel in England (which was enacted in January 2015) necessitated revisiting the efficacy of providing relevant information antenatally and how to prepare parents for the possibility that their child may have a positive result. 16

The introduction of the expanded NBS panel, within England specifically, needed also to be viewed in the context of providing a national health service from a finite budget, with a requirement to consider the opportunity cost. The additional cost of expanding the NBS panel, potentially requiring extra input from midwives and removing them from other duties, needed to be worth the potential benefits for parents and babies. These may come in the form of both health and non-health benefits, such as the value of the additional information per se that comes from a NBS result and the minimising of distress if parents are adequately prepared. 34

Summary

There is a need to review communication and consent models currently used in NBS in England because of concerns about the efficacy of the current models, which have been further exaggerated by the expansion of the panel. Although there is a paucity of guidelines for developing communication and consent models for NBS, it has been suggested that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) report on guideline development8 can be used as a model. 46 This study used the definition in Stewart et al. 46 of evidence-based medicine as the template for the methods:

the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. It requires a bottom-up approach that integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patient-choice.

Thus, published research on the efficacy, impact and parent understanding of NBS communication and consent was evaluated. Parents and both front-line and clinical specialists were then engaged in qualitative research to develop alternative communication models for use with expanded NBS. These models were then evaluated using quantitative and qualitative methods in the remainder of the study.

Aim

The overall study aimed to determine service providers’ and users’ views about the feasibility, cost, efficiency, impact on understanding and consent process of current practice and preferences for alternative methods of conveying NBS information antenatally. There were nine objectives, which were addressed in two phases:

Phase 1: generation of alternative models, establishing costs and implications of current best practice for parent understanding:

-

collate the characteristics of alternative communication and consent models for NBSPs through a realist review of current NBSP communication models within the UK and countries operating extended NBSPs

-

explore how providers and users envisage that information given antenatally can best meet the challenge of effectively and efficiently providing parents with sufficient understanding of an extended NBSP, including their reflections on the alternatives identified through the review

-

examine parents’ understanding and experiences of NBSP communication to draw inferences regarding best practice within an extended NBSP

-

establish the resource use and costs associated with the current practice(s) of providing NBSP information antenatally.

Phase 2: acceptability, preferences, cost and broader impact of alternative models:

-

examine the preferences of midwives, parents and prospective parents for different models of conveying NBSP information antenatally

-

establish the key parameters affecting the cost-effectiveness of new modes of information provision compared with the current practice(s) of providing NBSP information antenatally

-

outline the key uncertainties in the current evidence base and the value of future research to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of providing NBSP information antenatally

-

explore providers’ and users’ views on the study suggestions, focusing on acceptability, broader impact, effectiveness, efficiency and parent understanding

-

establish how generalisable the study findings are across conditions screened for in the UK NBSP.

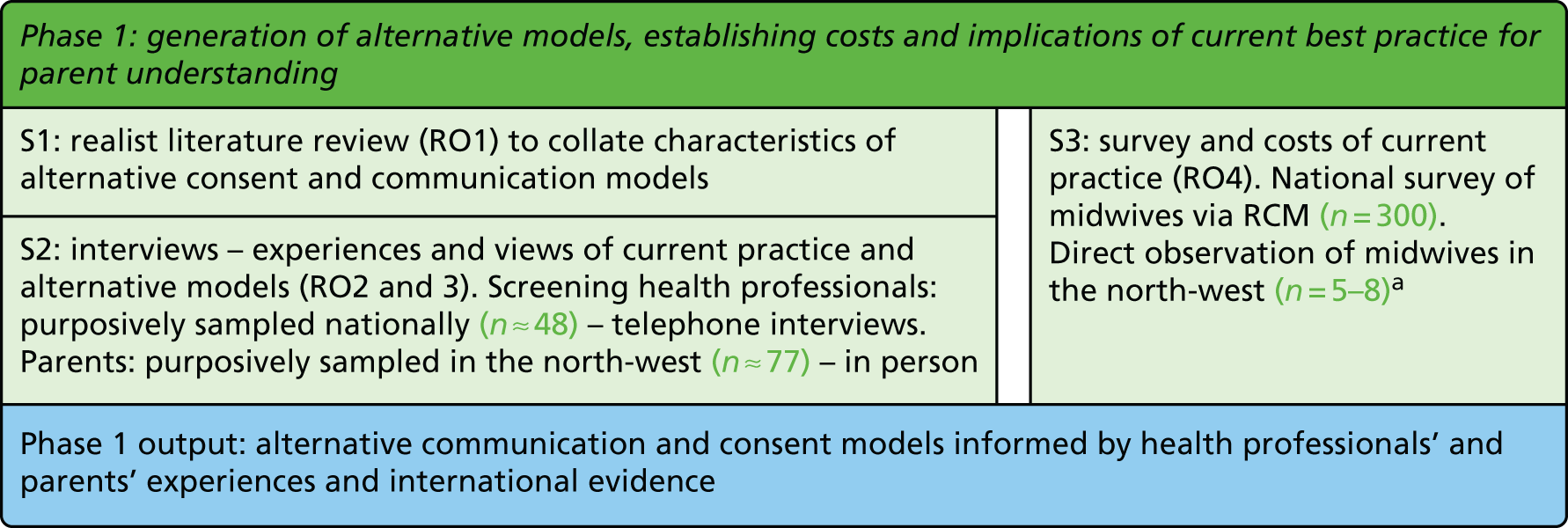

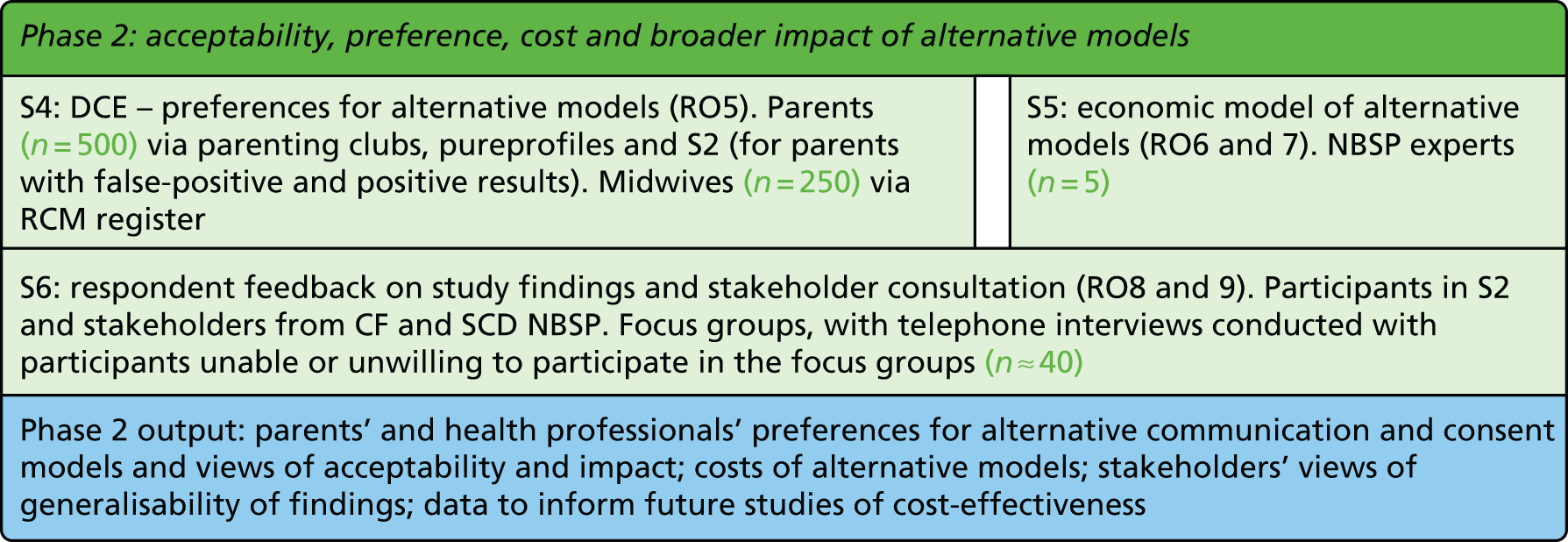

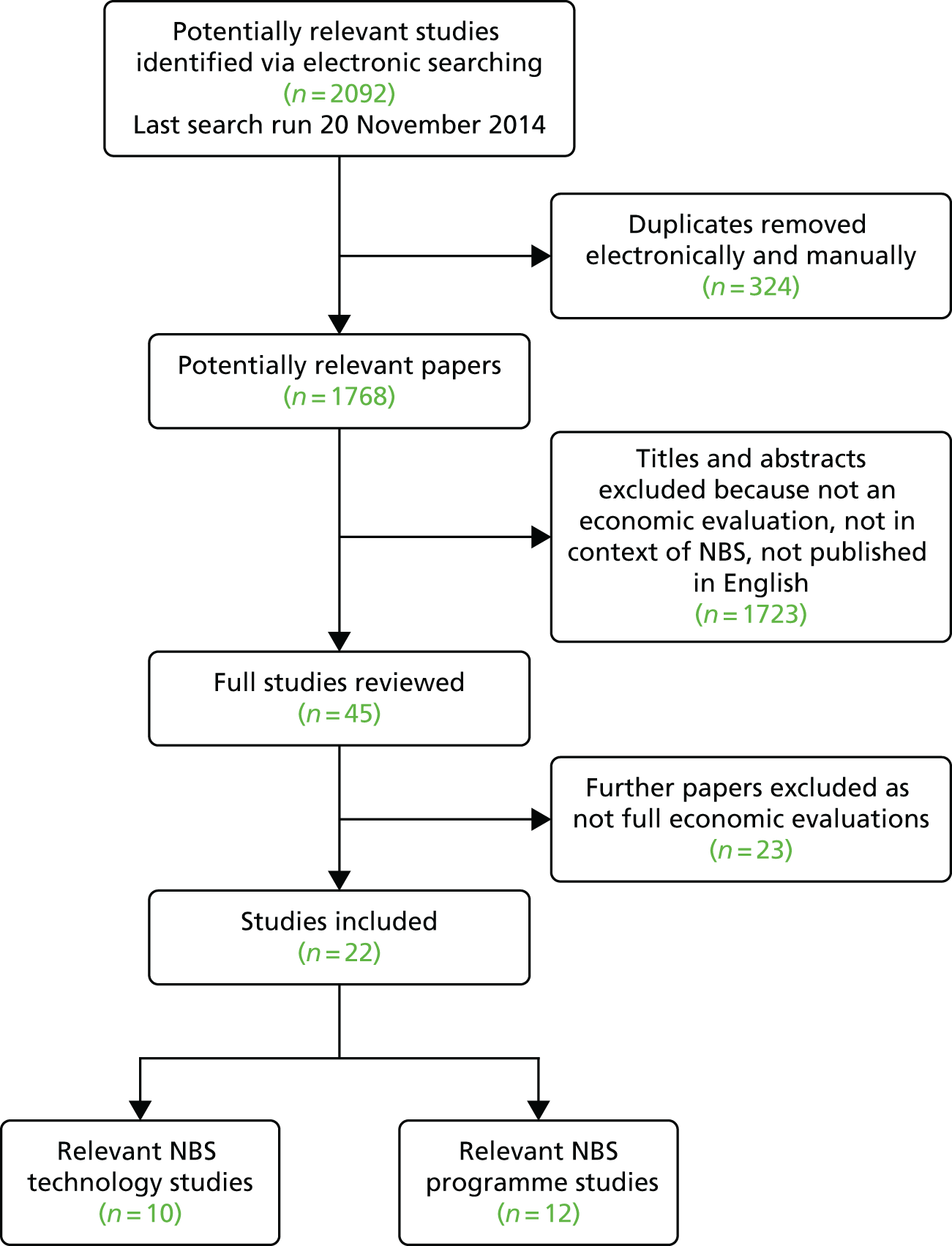

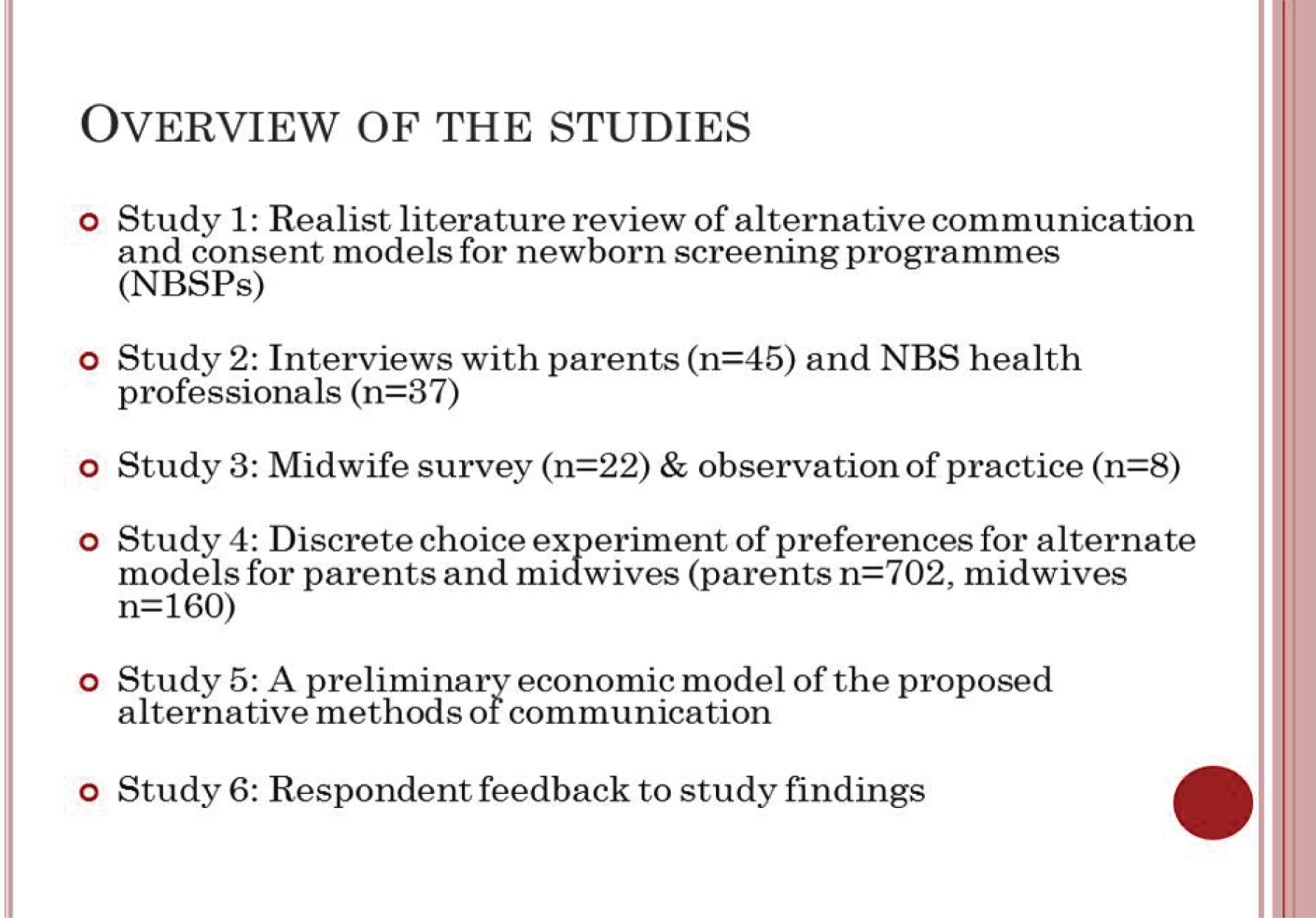

These objectives were met though six studies (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Phases of the study. DCE, discrete choice experiment; RCM, Royal College of Midwives; RO, research objective; S, study. a, Number is planned sample size a priori.

Structure of this report

The next six chapters report each of the studies outlined in Figure 1. The findings of these studies are discussed in Chapter 8. The input of patient and public involvement (PPI) is discussed within each study chapter and is summarised in the following section.

Patient and public involvement

Given that the central aim of this project focused on a communication event between midwives and parents, with the desire to create alternative models that were acceptable to both groups, the involvement of parents and midwives in the research process was crucial. Three groups of advisors worked with the project team.

Parent reference group

Parents were invited to become members of the parent reference group. Four parents joined with differing experiences of NBS results and numbers of children, and differences in how recent their NBS experience was. They advised the team on the interview schedule and study materials for the study reported in Chapter 3. Their opinions were sought about how to introduce the observation study to parents (see Chapter 4). They also advised on the design of the discrete choice experiment (DCE) survey for parents, which led to a complete reformatting of the layout of the information and how questions were phrased (further explanation of the DCE is provided in Chapter 5). They were given the first overview of the project findings and helped design the summaries for parents and advised on the timing of focus groups and strategies to facilitate engagement in the groups. They were invited to the stakeholder consultation. Their involvement was encouraged through a range of face-to-face meetings, e-mail correspondence and telephone calls. Parents had the option to attend meetings on their own, with childcare provided, or with their children. Travel expenses were also provided.

The duration of meetings was kept to a minimum given the competing roles that the parents had. The principal investigator met with group members and asked if they wanted a reminder of the study aims before an overview was provided on the findings to date. The relevant researcher for the task then introduced the problem that the team was considering before handing over to the parent reference group to hear the views of its members. Study materials or measure ‘mock-ups’ were given to the parent reference group to handle and interact with, with notes taken regarding their advice. In subsequent meetings the team reported back to the parent reference group about how their advice had altered the study design. Study updates were sent to parent reference group members when appropriate between meetings, with an open invitation to contact the team should they have any views that they wished to share. When parents were unable to attend, telephone conversations were held to maintain two-way communication between parents and the team. At the final meeting members were asked whether or not they wanted to receive any outputs from the study.

Newborn screening advisory group

The newborn screening advisory group consisted of a NBS laboratory director, a senior quality advisory manager and a research midwife. Meetings with these advisors were held to discuss the project aims and they were invited to participate in the stakeholder consultation at the end of the project. Although advice was sought from group members in terms of measures, for example the interview schedule for the health professional interviews and the DCE for midwives (available on request), the majority of their advice surrounded recruitment issues. This was central to the project’s success. Group members provided guidance on structures within NBS and from that developed the idea of snowball sampling in study 2 (see Chapter 3). They also provided guidance on the observation study practicalities and advised on which trusts to approach (see Chapter 5). They were central to the recruitment of parents in study 2, in which the team approached laboratory directors and midwives to ask them to recruit for the study.

Given that it was less important to seek consensus in the advice arising from this group, the challenges of ensuring that three health professionals were available to meet and the focus of some questions on certain professional groups, engagement more commonly occurred in a way that was directed by the availability of the members. Thus, engagement ranged from semi-formal office-based meetings to informal coffee shop brainstorming sessions, e-mails and telephone calls.

Scientific advisory board

The scientific advisory board included a laboratory scientist, representatives from Genetic Alliance and Climb, and a senior midwife. Formal meetings were held at which overviews of study progress were reported. The board advised on future fieldwork and current policy and practice issues that might impact on the studies. Board members were provided with summaries of the project findings and were invited to comment. They advised on interview schedules for parents and recruitment strategies, specifically for parents whose children had been diagnosed through NBS or who had received a false-positive result.

Key outputs arising from patient and public involvement

Key outputs from PPI were:

-

the interview schedules for study 2 (see Chapter 3)

-

the DCE (see Chapter 5)

-

the stakeholder consultation summary (see Chapter 7)

-

methods for recruiting parents to the interview study, focusing on fathers and specific subgroups of parents

-

methods for recruiting health professionals for interviews and the DCE

-

the observation study protocol.

This project benefited enormously from the combined expertise of the parent reference group, the NBS advisors, the scientific advisory board and the research team. Without this collaborative way of working key questions would have been missed, measures would have been less valid or would have been less likely to engage people in completing them, responses could have been misinterpreted and the quality of the research would have suffered as a result. Each group had a unique insight that, when combined, ensured the quality of the research.

One of the markers of quality engagement is low levels of withdrawal. Despite each parent juggling competing priorities and a young family, and health professionals often doing the same, all members engaged throughout the course of the research, for which we are extremely grateful.

Phase 1 Generation of alternative models, establishing costs and implications of current best practice for parent understanding

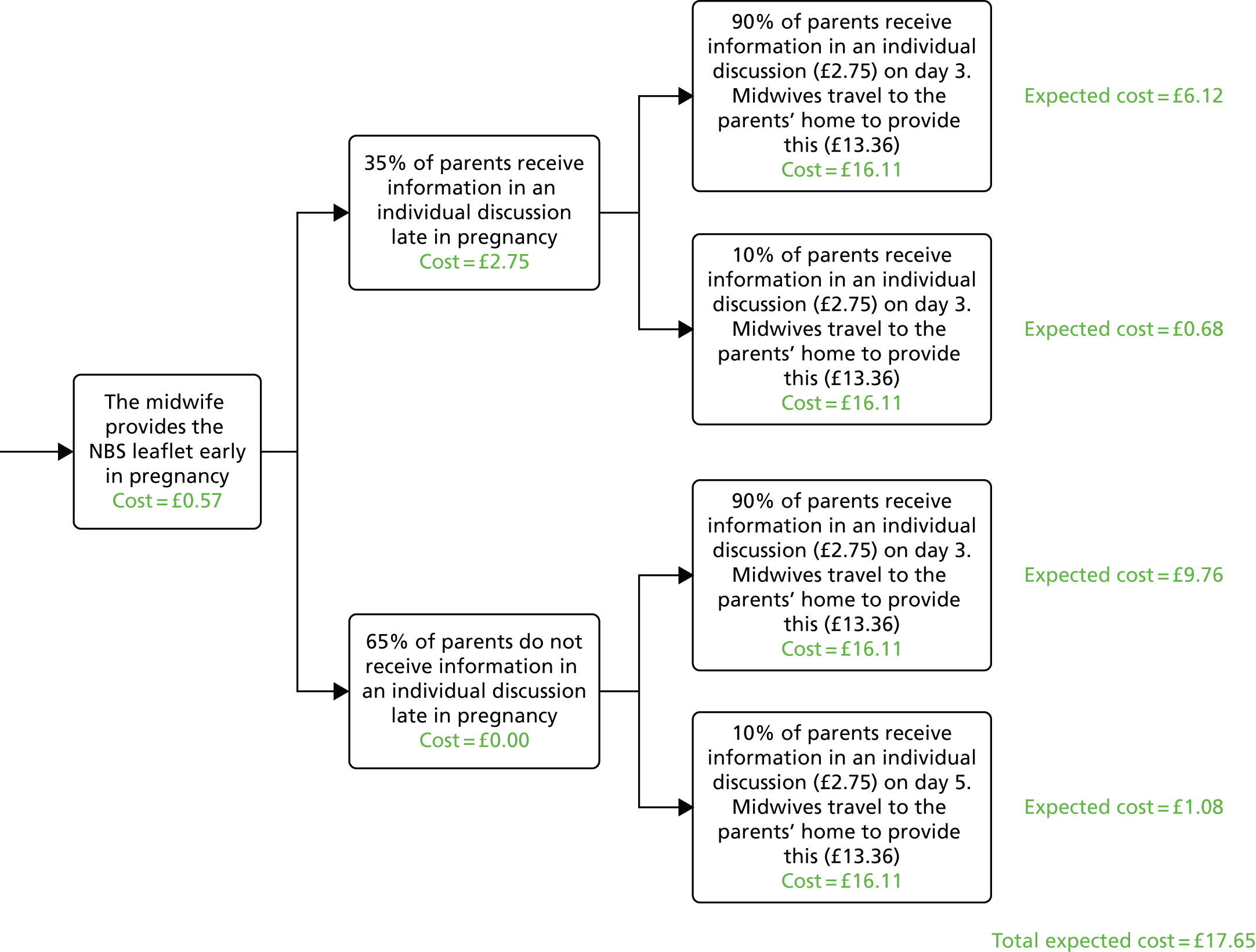

This phase consisted of three studies (Figure 2). A realist review (see Chapter 2) was carried out to collate existing research and practice regarding communication and consent in NBS. From this the range of alternative models in communication and consent practice were mapped out and explored in interviews with health professionals and parents (see Chapter 3). Simultaneously, a costing study was carried out to establish the current cost of the communication and consent model practised in England (see Chapter 4).

FIGURE 2.

Phase 1 of the study. RCM, Royal College of Midwives; RO, research objective; S, study. a, Number is planned sample size a priori.

Chapter 2 Study 1: realist review

Study objectives

-

Collate the characteristics of alternative communication and consent models for NBSPs.

-

Review research examining procedures for consent in NBSPs.

-

Establish what works, for who and under what circumstances to assimilate suggestions for alternatives to the current UK NBSP communication model.

Introduction

As stated in Chapter 1, there is variation across NBSPs in the conditions included, the communication methods and the consent models. Despite universal acknowledgement of the importance of communication, there is not yet an effective, evidence-based approach to providing NBS prescreening information. Thus, a realist review was conducted to examine underlying theories of informed consent, review the empirical literature and populate our theoretical framework. From this we assimilated suggestions for alternative communication and consent models.

Methods

The methodology of realist review focuses first on developing a conceptual or theoretical framework to understand the phenomenon or intervention being studied and then on undertaking a review of the empirical literature to populate that framework. 47 The intention is that the underlying programme theory is used to organise and structure the presentation of the available empirical evidence, while the synthesis of the empirical evidence is used to test out and refine the programme theory. The aim is to bring together our theoretical and empirical understanding.

Publications in English were searched for from the inception of the databases to 2015 using the search terms ‘informed consent’, ‘theor*’, ‘concept*’, ‘defin*’, ‘framework’ and ‘model’. This yielded 214 papers and all titles and abstracts were reviewed for relevance independently by KW and FU. The following papers were excluded: those that were primarily empirical studies of informed consent, with little or no theoretical or conceptual content, those that focused on informed consent primarily in relation to a particular clinical domain and those that were primarily aimed at training or professional development in relation to informed consent. In total, the full texts of 37 papers were retrieved, which were read and summarised to identify key concepts, theories and methodological developments in relation to informed consent.

Theories of informed consent: developing an analytical framework

The dominant theoretical perspective of informed consent was first framed by Faden and Beauchamp48 and is rooted in both legal thinking and ethical theory. It is centred on the concept of autonomous authorisation – the idea that consent requires an act of authorisation undertaken autonomously and that this requires evidence of intentionality, understanding and control.

-

Intentionality means that the person wants or wills what is being consented to and has gone through some cognitive process to reach this position. Of course, capacity to do this may be constrained by the circumstances in which consent is being given or by personal characteristics of the person.

-

Understanding means that the person understands what he or she is consenting to, which involves him or her in both having or receiving relevant information about it and being capable of retaining and grasping that information and using it to reach the decision to consent. Achieving what is sometimes called full and true understanding may be constrained by the complexity of the information and by the personal characteristics of the person.

-

Control means that the person is free of external influences and makes the decision to consent independently. Distinguishing between legitimate advice and forms of persuasion, manipulation and coercion is not straightforward. Control over a decision may be exercised through social norms or expectations and by legal obligations on the person or others.

This approach to defining and operationalising arrangements for informed consent has been widely used in both clinical practice and research and in many areas where consent is often a contested and difficult matter to negotiate, for example neuroscience,49 child psychiatry,50 dementia51 and end-of-life care. 52

It has been observed that the concept of autonomous authorisation leads to ‘theoretical confidence, and practical disquiet’,53 providing a theoretical framework for informed consent that is, in practice, difficult to realise and can be problematic ethically when operationalised. Many authors have argued that it is rare in practice to achieve intentionality, understanding and control,54–56 leaving health-care providers and researchers in a vulnerable position. As a consequence, lower standards of consent are often adopted – ideas such as presumed consent, broad consent and open consent may represent necessary compromises if the ideal of informed consent cannot be realised, but may also dilute and devalue the concept of informed consent. 57

More fundamentally, some have suggested that the theory of autonomous authorisation puts personal sovereignty and autonomy above well-being and can run counter to the established ethical principle of beneficence. 52 In addition, it is noted that wider ideas of the common good, public interest or the collective needs of society are not represented. 58,59 Some have suggested that autonomous authorisation represents a particular set of Western social and cultural values and is not simply transferable to other societies and cultural settings. 60

An alternative and more recent approach to informed consent, termed the ‘fair transaction model’, sets the idea of informed consent in the wider context of consent to other social transactions (e.g. in commerce, employment or personal relationships). 53 It argues that consent is a morally transformative act in that it makes morally permissible something that would otherwise not be morally permissible and asserts that, to be valid, consent must achieve this moral transformation. In this context, it is suggested that we should consider both autonomy and well-being, for the consenter, the health-care provider and in some cases for wider society as well. This means that the balance of risks and benefits in the thing being consented to becomes part of our consideration, as do the effects on those other than the person giving consent.

The prevailing model of autonomous authorisation was widely used and cited in the NBS literature and so it was selected to be the theoretical framework for this chapter. For the review of the empirical literature on informed consent and communication in NBS, the three main concepts of autonomous authorisation (intentionality, understanding and control) formed the analytical framework. However, understanding was subdivided into four subcomponents: the provision of relevant information, information retention, understanding that information and the capacity to use that information while consenting. This was done partly because initial scoping suggested that the literature was largely focused on understanding, rather than on intentionality and control, and because some literature reported on research in jurisdictions where mandatory screening is practised and issues of intentionality and control are not addressed, although there is still a belief that understanding is important. Also, subdividing the model more closely aligned it with the applied legal test of informed consent to medical treatment, testing or research, which involves enabling individuals to make as authentic a decision as possible. For this decision to be deemed valid, a number of conditions need to apply. Individuals must have the intellectual capacity to make this decision, they must have relevant information to make this decision, they must be able to understand and retain this information and they must not be coerced in their decision. The resultant framework was as follows:

-

Relevant information. Had papers examined whether or not relevant information was provided? (content). How was information given, for example in person, through leaflets, through media or via the internet? (mode). Did the information provided meet parents’ needs (i.e. what information did parents want)? Was there a difference between parents’ information needs and those inferred by the authors?

-

Understanding. Had papers examined parents’ understanding of the information (through surveys, interviews or direct tests of knowledge)? Is there any evidence that parents’ knowledge/understanding was checked (by a health professional)? Were there any language barriers that prevent understanding? Was information on readability tests of the written information provided or is there any evidence that the necessary understanding to make this decision was lacking?

-

Retention. Had it been assessed whether or not parents retained the information that they were given about NBS? Could parents recall the information at the time of the decision? Were any attempts made to check whether parents retained this information? How long was the gap between the provision of information and the decision being made?

-

Intellectual capacity. Had papers considered the capacity of parents at the time of the screening decision (e.g. in high-stress/emotive circumstances, such as with premature or special care babies)? Had papers examined any key groups who might have compromised capacity (e.g. people with learning difficulties, mental illness or brain injury, or teenagers), and is there any evidence that capacity was lacking or that the issue of capacity was ignored?

-

Control. Had papers examined the level of control/coercion/influence/persuasion that was at play during the decision? Is there any information on the level of choice that parents had over whether or not their baby was screened? How much of the screening decision was part of parents’ free will? Is there any evidence that screening was carried at as routine practice/proceduralised or that the parents’ decision was coerced in any way?

-

Intentionality. Had papers examined whether a cognitive process took place (e.g. weighing up of the risks and benefits of screening) or whether the decision was based on individuals’ pre-existing beliefs/values? Did parents intend to have their baby screened? Is there any evidence on how valued (important to parents) the decision was? Did parents know that their child was being screened?

Regardless of the consent model, it is hoped that prescreening communication provides relevant information that is understood and retained to maximise benefits (follow-on care) and limit harms (such as the psychological impact of a false-positive result). All other concepts become important once the goal of the communication model is to achieve informed consent.

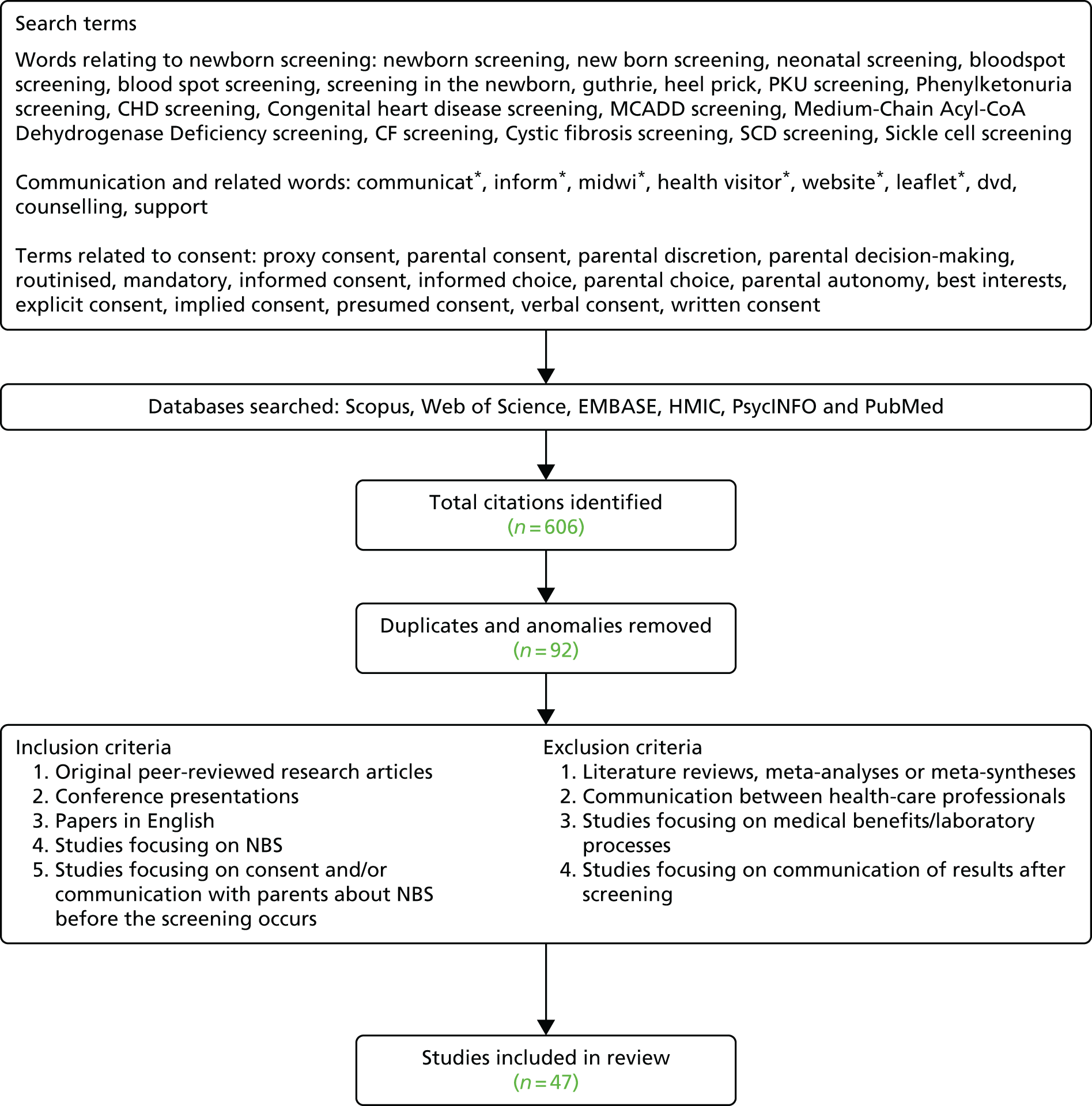

Search strategy for empirical newborn bloodspot screening research

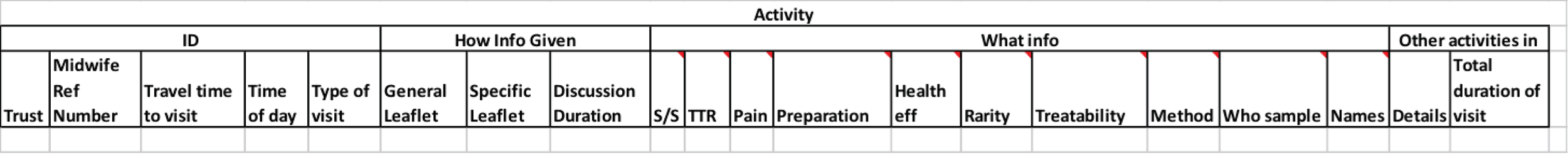

Publications in English were searched for from the inception of the databases to 2015. Search terms, databases and inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Search strategy for empirical literature. CHD, congenital heart disease; HMIC, Health Management Information Consortium.

Searches were iterative and the final searches were completed in August 2015. The consent and communication searches were conducted separately and then combined. The database searches yielded 606 articles. These were entered into EndNote (version 5; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). Next, all titles and abstracts were scanned by ND and FU for relevance according to the following inclusion/exclusion criteria. Papers were included if they reported empirical peer-reviewed research and focused on research on consent and/or communication in NBS, research on the knowledge of consent and/or communication and attitudes towards consent and/or communication of parents who had experienced NBS or the views of health professionals involved in the consent and communication process. Papers were excluded if they were commentaries or review papers, reported screening policy or different screening technologies, described communication between health professionals or focused on post-result communication, the impact of false-positive results or the medical benefits of screening. Papers without abstracts were retained for examination of the full text. When the full text of a paper was not available, authors were contacted for further information on whether or not a manuscript was available. In total, this strategy resulted in 47 papers being included in the review,8,12,14,15,17,19,20,25,26,28–30,33,61–94 covering NBS in a number of different countries: England (n = 118,14,25,62,66,70,72,78–80,83), Wales (n = 285,86), France (n = 189), Germany (n = 115), the Netherlands (n = 129), USA (n = 2017,19,26,30,33,61,63,64,71,74–76,81,82,84,87,88,90,91,93), Canada (n = 412,65,73,77), Australia (n = 320,28,68), New Zealand (n = 269,94), Taiwan (n = 192) and Hong Kong (n = 167). Within this there were variations in the conditions screened for and the consent models used, which are noted in the literature overview table in Appendix 1.

Synthesis

The following information was extracted from papers: country, tests included in screening, consent practice, aim of the study, relevant participant characteristics (e.g. sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, language), study design, sample size, any outcome measures and findings (see Appendix 1). The included papers were then imported into NVivo (version 10; QSR International, Warrington, UK) and coded according the programme theory concepts.

Results

The results are split into two sections: concepts that are central to all communication models irrespective of consent model and concepts that become important once parents are asked to make a decision.

Universal goals of all communication models

This section discusses the literature related to relevant information, understanding and retention. In doing so it looks at what is considered to be relevant information in NBS and how this might be provided. It also examines when information should be provided so that it can be retained for use by parents. In the setting where decisions are not necessary parents would need to recall the information to prepare for, and adapt to, NBS results.

Relevant information

Providing relevant information was valued across consent models. 12,19,61 Indeed, one paper suggested that information was valued more than choice. 45 Although effective information provision was seen as central to choice12 and the quality of the choices made,62 it was also valued for minimising distress if further testing was required or a diagnosis given. 63 In countries that rely on parents actively seeking further care this was improved if parents were given relevant information. 64 Others argued that information enabled parents to feel respected65 or that parents had a need to know what was happening to their child. 19 Of concern, then, is the finding that numerous papers reported that parents believed that they had never received any information. 29,66,67 For example, parents in the Netherlands reported that they had received no or little official NBS information, including about what the screening programme was for. 29 Parents cited their information sources as being the television and pregnancy books. More recently, 19.8% of parents in England reported that they had received no information on NBS66 and 83% of 177 parents in Hong Kong were not aware of NBS (although their child would have recently had it), with 99.4% of the sample wanting more information. 67 This was a repeated claim in the papers. 29,33,63,66–68

There may be numerous reasons for this pattern. First, it could be that the information really is not given for some reason. Interestingly, even health professionals have reported that parents do not receive any information. 69 Although their study took place in a research setting, Hargreaves et al. 70 showed that midwives would sometimes select not to give women leaflets if they felt that they would not be able to understand them or appeared uninterested. Also, if parents were having their second or subsequent child, either party may have assumed that they already had knowledge and so NBS information was not given. 18 Indeed, parents reported that they probably say that they have enough information without actually having a full awareness of the current screening information. 18 Another factor could be the lack of a clear protocol stating which health professional is responsible for providing information. This has been shown to result in health professionals assuming that it is someone else’s responsibility. 69,71 These issues appear to feed into another narrative in the data about who is responsible for ensuring that parents have the relevant information. Hayeems et al. 61 found that health professionals recognised their responsibility to provide parents with information by signposting, but felt that it was the responsibility of parents to educate themselves. In a public engagement exercise by the same team, participants thought that parents were able to, and would, take such a responsibility. 12

Second, it could be that information is given but parents cannot assimilate it for some reason. Indeed, it has been argued that it is difficult to establish if information is not given or if it is given but not recognised/read by parents. 66 For example, it is a repeat finding that parents do not read leaflets,12,29,66,68,72 sometimes because of time constraints. It is questionable whether or not ensuring that parents read leaflets would solve this issue as a paper that examined information resource use found that very few parents used leaflets to make their NBS decision. 72

One of the dominant narratives about relevant information surrounded the level of detail needed. However, although a common finding was that parents want more information,29,63,67,68 it was rarely stated what this would look like. Focusing specifically on expanded screening, two characteristics appeared to trigger parents to want more information: the inclusion of diseases for which treatment benefits were less clear and asking parents to be more involved in the decision. 29 However, the issue of providing more NBS information to parents is complicated by the repeat finding that parents feel overwhelmed by information in pregnancy (e.g. Tluczek et al. 63). Indeed, papers talked about the need for brief information29,66 or needing not to overload parents. 61 In one study, participants in a focus group evaluating the current screening booklet for use in England talked about the balance needing to be in favour of not enough information rather than too much. 66 One suggestion was to convey a sense of what is being screened for (i.e. metabolic conditions) without naming all of the conditions. 73 However, work with the public has stated that ‘parents need to be informed about every single part of the screening’ (citizen focus group)12 or that parents could make a decision only if ‘all the implications were clear’. 29 One possible solution to this is that health-care professionals should ask parents how much they want to know. 73 This may address the issue of parents varying in the amount of information sought, implied by differences not only between papers but also within them. For example, in one study, 45% of parents reported that they wanted more information whereas 51% reported that they wanted the same amount of information. 66 Some parents felt that they had the right level of information, others wanted more and some suggested that they had already received too much and that it had triggered anxiety. Thus, taking a population-wide approach to balance overwhelming parents and creating anxiety with underpreparing parents and triggering profound distress may not be effective. One suggestion is that people receive ‘basic’ facts but can access more detailed information on an individually driven level. However, what the basic level of information would be is rarely specified.

Content of relevant information

Establishing what information is deemed relevant is the first step in establishing whether the standard of providing relevant information has been met. Some guidance comes from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Newborn Screening Task Force95 and some have used this as a yardstick to see whether or not materials are suitable. 74 It suggests that the following should be included: the purpose of NBS, benefits of NBS, how testing is carried out, how results will be received, the need for repeat testing/follow-up, the purpose of the repeat testing/follow-up, the importance of responding quickly to results, how to make contact with the NBS programme, the risk of a false-positive result, the risk of pain/infection, a list of the conditions screened and information regarding storage and the use of bloodspot samples. Additional information found in documents included whether or not consent was needed and whether or not parents had the option to refuse. 75

Another way to address this issue is to examine what information parents want. Nicholls and Southern72 highlighted that, if the information provided does not match what parents think is important, it is likely to be dismissed. Although numerous papers focused on parents’ information needs, these were sometimes inferred from guidelines or from health professionals’ views rather than by asking parents directly. Studies using parent samples found that the following topics were valued:

-

the need for further samples/how to respond if in the USA26,78

-

where to get further information70

-

reassurance70

-

results – range and meaning77

-

what happens if a test is positive70

-

test accuracy70

-

information about the fact that screening uses deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)70

-

heritability76

-

screening alternatives (e.g. testing later in life)76

Although placed in order of frequency, little can be inferred from this as often papers would use the generic term ‘more information’ and cite examples of information that were particularly salient or currently missing from the information that parents received. A clear message from the literature was the value of tailored information, with parents choosing the level of information received. This was either explicitly found or implied by findings that parents reported wanting very different levels of information. 12,66

How can relevant information be provided?

Parents most frequently received verbal information from health professionals,68,69 leaflets66,69 or leaflets plus verbal information from health professionals. 66,69 Some concerns in an evolving screening programme were reports that the second most likely information source was a previous pregnancy. 68

The use of leaflets seems ubiquitous in NBS. However, concerns have been raised about inherent barriers as a result of literacy levels or cultural competency74 (this will be addressed further in Understanding). In addition, information coverage in leaflets has been reported as being incomplete or presenting a biased picture. 14 As stated previously, it was repeatedly found that parents do not read leaflets12,29,66,68,72 and their efficacy in providing useful information has been argued to be limited in this setting. 30 These issues may explain the finding that only half of the parents sampled in one study had read the leaflets. 72 A related finding is that, in research carried out to evaluate leaflets, they were not given to women who appeared uninterested or for whom English was not their first language. 70 Thus, in this study leaflet design was informed by interested women who may not have had access issues. A further issue is that when leaflets are provided alongside non-health service materials they are not seen as being important. 72 As the authors of this study argue, one of the key issues with the effectiveness of written information is its visibility.

Parents indicated that leaflets should not be relied on and that health professionals should discuss NBS with them directly. 63 However, health professionals appeared to value leaflets, with 80% of them finding leaflets extremely or very useful. 69 Even when leaflets were used, parents wanted information confirmed by verbal communication with a health professional,70 known as a ‘layered approach’. 65 Parents who had questions after reading a brief leaflet wanted to be able to have a discussion with a health professional and written information to back this up. 66

The accessibility of information in leaflets may have contributed to the repeat finding that parents in England wished to receive information from a health professional. 66,72,79 Asian participants or participants for whom English was not their first language were especially likely to prefer information provision by a health professional. 66 This option has some merit as it has been found to be the most effective way to convey complex information96 and parents had a higher recall after verbal conversations45 with midwives. 72 In addition, in a study that reported some of the highest levels of awareness across the literature, the majority of mothers in the sample (34%) had received their information from midwives. 68 Likewise, post-partum nurses were the most frequent informers in a study in Texas. 30 Importantly, although this study uncovered important omissions in the mothers’ knowledge, those who had been informed by a health professional were significantly more likely to know about key issues. Of interest, a range of health professionals were included in this study.

Another way that health professionals were viewed was as ‘gatekeepers’ to information for parents. 72 It has been argued that they can be central in ensuring that parents are sufficiently informed about NBS. 66 Another benefit is the universal acceptance of health professional communication; passive information processers gained information only from midwives, whereas active information processors valued communication with a midwife even though they sought information from other sources. 72 Some reasons offered for this were that parents had already allocated time for this communication (i.e. they did not need to find time to seek information) and that it was easy. 72 Health professionals were valued also in terms of being able to clarify existing understanding, provide sufficient information or signpost to further information.

In some samples parents of affected children suggested that website addresses should be provided to signpost to support groups. 78 This sample also endorsed the internet as a way of providing NBS information antenatally. However, the internet appeared to be used by some parents to gain supplemental information, rather than being a central information source. 72 Such usage may be appropriate currently as mothers who received information via the internet were less likely to have key information, such as how to seek further testing. 30 This was a crucial omission in a sample from the USA, where parents need to actively seek further testing from their provider. However, screening programme websites were used as a key way to engage the public in 13 states in the USA. 17 One benefit is that it may engage parents with low levels of trust in their health-care professionals, as those who reported gaining information primarily from the internet had the lowest levels of trust in midwives. 18 In a study in England, parents indicated that they were less inclined to use the internet because they could not judge whether or not the information was trustworthy and there was a lack of guidance to navigate them to appropriate sites. 62

The use of videos antenatally has generated mixed findings. Yang et al. 64 reported that a brief 10-minute video resulted in parents being more likely to retain information postnatally and engage in appropriate post-result behaviours. However, others have reported that mothers did not find videos to be an effective communication model30 or that few parents value videos and posters beyond their use during antenatal classes. 78 Indeed, in one study a majority of health professionals (70%) believed that parents received information about NBS through antenatal classes. 69 It should be noted, however, that one of these samples78 was supportive of providing audio information and it could be that the use of the term ‘video’ has changed. Once it was a static format but now it is commonly embedded in websites. Indeed, the comments from the participants in this study suggest that this is the case. Therefore, views of video usage may change.

Understanding

Parents who felt that they understood NBS information were more likely to say that they believed that they had made an informed choice. 80 Likewise, although the data are very sparse, they do suggest that the main reason that parents refuse screening is a lack of understanding. 19 Thus, understanding is central to parents’ views on their choice, but also the choices that they make. A recent report on the expansion of NBS in England argued that midwifery support is needed to ensure that parents’ understanding is checked. 73 However, few studies reported whether or not health professionals checked parents’ understanding. 18

One study suggested that health professionals believe that parents can understand NBS information – it is ‘not rocket science’. 73 However, a common finding in the literature was that parents have knowledge gaps that raise concerns about their preparedness to make an informed decision. 26,28–30,33,68,93 Some parents were aware of this and admitted that they had made a decision about NBS without knowing information about symptoms, treatment, severity and hereditability. 76 Other studies, however, suggested that parents were not aware of their limited knowledge. For example, in one of the studies reporting the highest levels of awareness of the purpose of NBS (82%; n = 712), only one-third of parents knew that it was possible to receive a false-positive result,77 an important part of preparing parents for the outcomes of NBS. A further survey of 154 parents from one laboratory in England found that parents had a greater understanding of the process of and rationale for screening than of condition-related information. 80 In addition, although parents in the Netherlands recognised the term ‘heel prick’ and knew that it had been performed, this had usually been without their knowledge of what the screening was for. 29 This pattern has subsequently been reported in a sample of English parents. 66 Interestingly, within this study, parents were asked directly whether or not they understood the NBS information, with 62% indicating that they did. However, within this sample there was poor knowledge and understanding of the conditions screened for or the implications of screening. Furthermore, in a sample of 750 mothers in Ontario, the variation in understanding across topics was as follows: purpose of NBS, 88% understood; how screening is conducted, 85%; the importance of screening, 72%; and how the results would be stored or what happens to the sample after testing, < 15%. 77 This pattern was repeated in a study of 548 post-partum mothers in Texas: 59.1% of women did not know what newborn bloodspots were30 and 68.2% and 71.4%, respectively, did not realise that a positive result indicated that there could be alterations in either their own or the father’s DNA. Knowledge about where they would go to get a second sample or how they would receive the results of screening was also very low, which is of importance in the USA as there is a reliance on parents to proactively seek further testing. The authors of this study highlighted that this raises questions about whether or not parents were aware of the retention of bloodspots. Concerns about the level of understanding that parents have about the retention of bloodspots were also raised by Tarini et al. ,81 who suggested that parents might not understand the utility of the stored bloodspots as those who refused storage were more likely to have lower education levels or children with good health, potentially suggesting a conflation with umbilical storage.

Some of the studies that assessed the readability of NBS materials repeatedly found that materials were written at too high a level. 74,82 One study that examined parent educational materials82 found that the mean Flesch Reading Ease score of the materials was at 10th grade level (the recommendation is grade 6 or below), with one-quarter of leaflets written at college level. Grade 10 was also used for consent forms in a different study. 19 Indeed, only 8% of the materials about NBS designed for parents were written at an accessible level. There were also issues with the images used, which were felt to be misleading, such as ones depicting a toddler, which may lead parents to infer that this is information needed at a later stage. A survey of 106 materials from the USA, the UK and Australia found that 36 used unexplained technical terms and 14 would need expert levels of knowledge to understand. 14 These results are similar to those of an earlier study that reported that 60% of materials provided by USA NBS programmes were at grade 10–11 level. 74 However, importantly, this study found that materials that covered more of the recommended messages did not necessarily have a higher reading age. Thus, there is nothing inherent in the information that causes materials to be complex. Indeed, although a pilot study of earlier versions of the UK NBS materials found few issues, a repeat criticism was that they were too technical and that parents did not need a ‘biology lesson’. 70,78 This was also raised in the piloting of the expanded NBS materials. 66 Collectively, then, there are repeat recommendations that information should be provided in as simple a form as possible,66,78 with a specific finding that the current information booklet in England may benefit from further simplification. 66

There were some more basic, yet hugely important, barriers identified, for example information and consent forms not being provided in the appropriate language,70 despite this repeatedly being highlighted as important17,69,70,78,83 and being policy in many countries. Reasons for this may be gleaned from the study by Stewart et al. ,78 in which health professionals queried who was going to fund these alternative versions. Not having the leaflet available in the language needed was a rationale given by health professionals in New Zealand for not using leaflets at all. 69

Thus, there are issues over information being provided in such a way that it creates barriers to understanding, in terms of level, language or timing. It has recently been highlighted that there is still insufficient evidence regarding the optimal communication model for NBS to achieve understanding. 77 One interesting finding that may suggest a solution to this is that women’s understanding of, and ability to recall information about, NBS increased remarkably if they were asked to sign a consent form. It appears that this process triggered parents to attend to and assimilate information. 19,84 Indeed, this appeared to account for more of the variance in knowledge scores than demographic variables. 84

Some of the issues with research in this area include the difference between understanding per se and knowledge. For example, although 62.2% parents reported that they understood the information that they were given, they also thought that they had low levels of knowledge about the conditions screened for. 66 The link between understanding and choice should also be carefully handled as parents have reported being happy with the decision that they have made, despite illustrating low levels of knowledge of screening, the conditions screened for and the impact of screening. 66

Retention

Although few papers addressed this concept directly, some of the findings discussed in Relevant information are relevant here. One of the standard ways to measure retention is to ask whether or not parents can recall receiving information about NBS or what information they can recall about NBS (it is accepted that the two are not entirely synonymous). For example, the finding that parents reported that they received no information may be linked to retention, as in many studies there was a significant time lag between NBS and parents’ participation in the research. Thus, it is hard to establish whether or not it was the study design or the communication model that was causing the recall problems. In studies in which there was a delay in measuring retention, retention levels varied from 69% of parents recalling having received NBS information77 to the majority of parents of healthy and affected children not being able to recall being given any explicit information about NBS. 29 This lower level of awareness was repeated across several studies,19,33,66,67 with parents also reporting being unaware of what conditions their children had been screened for. 14,28,33 There were also issues over study design in terms of how retention should be measured. For example, although parents might have NBS knowledge that they could recall, this might have been derived from other sources such as the television;29 thus, measuring knowledge is not a direct measure of the success of a NBS communication model as that material may not have been retained.

Although it is arguably very important that parents can recall information if one wants to moderate the levels of anxiety that parents feel when receiving further testing, from the perspective of consent a potentially more important question was whether or not parents could recall the information at the point of making the decision. Newcomb et al. 30 surveyed mothers within 24–72 hours of their child being screened and found incomplete knowledge about NBS and bloodspot storage. Important gaps in their knowledge were that just under half did not know whether or not further tests would be performed, the majority did not know when they would receive the test results or what the implications of positive results were for family members and 63% did not realise that their child’s blood would be stored. Whether or not this is truly an issue of retention and subsequent recall, however, is a moot point as there were significant differences between the mothers based on how they had received their information. Furthermore, Nicholls and Southern62 put forward a very valid argument that measuring recall alone is insufficient as it does not indicate that those recalled facts actually contributed to decision-making. However, the above indicates that, if parents wanted to incorporate information provided by their health service, there is a barrier to them doing so and that parents appear to have low levels of knowledge to draw from.

When should information be given so that it can be retained at the time of decision-making?

One school of thought is that the most likely factor affecting retention is the delay in the time between receiving information and utilising it in a decision. However, it is also possible in this setting that, if information is provided at a time when it can not be assimilated, this would also lower retention levels. Indeed, a main conclusion from a survey of 600 mothers post birth is that information needs to be provided at a time that enables assimilation. 68 This study found that, although 51% of mothers were satisfied with the information that they had been given, they felt that the time at which it was provided determined whether or not they could use it. Another study reported that parents felt that they had received information at the wrong time. 29 Although this is not necessarily easily solved, as parents have different views on when information should be provided, there appears to be a clear message that information should not be provided post birth. 63 Some argue that providing information after birth does not give parents sufficient time to absorb the information. 96 Thus, there appears to be no doubt that there may be barriers to interacting with information,18,66 with communication policies seeming to recognise this. For example, the AAP Newborn Screening Task Force suggests that information on NBS be provided in the third trimester. 74 However, providing information just before the test or at the time of the test (i.e. after birth) is a common finding. 30,33,69,77

There is strong support for information provision in pregnancy. 17,29,33,66,78 An interesting study that explored the impact of providing information about SCD prenatally found that parents were more likely to retain the information given postnatally if they had also received some information prenatally,64 suggesting that priming parents, or providing information repeatedly, may aid retention. Some reported that information should be provided in early pregnancy,29,78 with it being refreshed after birth. 66 However, Moody and Choudhry66 suggested that information is often forgotten if given in early pregnancy. Indeed, this is cited as a reason why some health professionals do not give information in early pregnancy70 and across the literature there seem to be relatively low levels of people giving information at that time. 69

Another common message was that parents wanted information to be given at 36 weeks or during the last trimester. 66,70 They believed that this would provide them with the time to assimilate the information70 and was a time when thoughts of the child were more central. 29 Health professionals also reported that this is the most common time at which they provide information. 69 However, interestingly, midwives have also been reported as stating that parents would not appreciate the provision of NBS information at 28 weeks,78 believing that it is best to give NBS information early in pregnancy and in a written format only. Furthermore, another study based on an English sample reported that some midwives thought that it was not feasible to provide information leaflets at 28 weeks. 70 This partly seemed to be because of workload, but was also driven by a belief among health professionals that providing information postnatally is preferable to prevent it being lost or forgotten. 70 Although this belief was held by a minority of participants, and in this study there was also a discourse about information not being given ‘too late’,70 it does show that there can be resistance to providing information antenatally and that there are differing views between and within parent and health professional samples. What this highlights is that people may want information at different times. 29 For example, it has been reported that first-time mothers especially wanted time to read and digest the information. 66 This was also echoed in data from a CF nurse in the study by Hargreaves et al. 70 To fit this need a flexible approach could be taken, with information provided any time after the anomaly scan. 78

Concepts that are important when parents are decision-makers

The following concepts became more important to factor into communication models when the aim was to enable informed consent. In this section the literature related to intellectual capacity, control and intentionality is reviewed. Suggestions for alternative models of consent based on the literature are also outlined.

Intellectual capacity

There is a reported belief among parents that teenage parents may struggle with NBS information,33 yet there were no data in the papers examining this. There were also no data that examined directly whether or not certain groups of parents would lack intellectual capacity to understand NBS information.

Another consideration is whether or not NBS occurs at a time when parents may temporarily lack capacity. Currently in England, although policy states that parents should be informed about NBS before birth, they are asked to consent to NBS after birth. Parent data suggest that this is a time when there are competing demands on parents’ attention. 66,69,70,78 Mothers are recovering from the birth69 and will be tired78 and some parents admitted that this meant that they probably did not pay attention to what was being said to them. 14 A lot of information is provided at this time70 and new parents are having to make many decisions. 69 However, direct data examining parents’ intellectual capacity at this time seem sparse. 73 Hargreaves et al. 70 appear to suggest that parents’ ability to assimilate information may be hampered and Nichols79 reports data from mothers suggesting that this is the case. It should be noted that not all data fitted with this pattern, as Nicholls and Southern62 found that only 10.6% of 154 parents felt that they were too tired and 9.7% felt that they were too emotional to make a decision.

Control

The requirement to gain informed consent from individuals before they undergo medical treatment or procedures is founded on the idea that individuals should have control over what happens to them in a health-care setting. Thus, even if individuals make what others see as an unwise decision, as long as we feel that those making the decision are sufficiently informed, have the mental capacity to make this decision and are not coerced, we feel that this decision should be accepted. To do otherwise would be to move backwards to the days of medical paternalism. Thus, one of the main foundations of valid consent is that people have control and are not coerced into giving consent against their wishes. Therefore, for consent to be judged as valid, parents must be clearly aware that there is a choice to be made, that is, it must be made clear to parents that they can decline NBS screening. Indeed, if parents recalled that screening was presented as optional, this was a significant predictor of whether or not they felt that they had made an informed choice. 80 The literature discussed previously suggests that there are many cases in which is it not clear that the ability to refuse was made clear to parents and thus whether or not the voluntariness of the consent given could be said to be confidently met.

Another related question is whether or not parents feel that they really do have a choice to decline, even when the option of declining testing is made clear. One study suggested that only 7% of health professionals would accept a parent’s choice to refuse NBS without taking further steps. 69 Although most commonly this would be providing more information (64%), it could also include actively persuading (13%). 69 Liebl et al. 15 report that if screening has not been performed parents are contacted and counselled on the importance of NBS. Thus, although declining screening may well be theoretically possible, the reality is often that parents are not aware of this option or a great deal of pressure is put on parents to agree.

Nicholls and Southern62 argue that there is a need to look at context to understand parents’ decision-making. What follows is an overview of a range of contextual factors that may contribute to parents’ feeling of choice. Kemper et al. 17 report that 15 out of 51 states in the USA have no requirement to inform parents that they have a right to refuse the screening. In an evaluation of 106 leaflets from the UK, the US and Australia, only 38 mentioned whether or not screening was mandatory. 14 Of the 25 leaflets that discussed choice, 10 presented this along with a recommendation for screening and four highlighted the negative consequences of declining screening. Furthermore, there was an overwhelming bias towards presenting the benefits of NBS compared with the limitations. Nicholls18 used this to argue that subtle pressures operate in NBS rather than overt coercion. This was also echoed by Newson,83 who stated that, although legal intervention is unjustified in PKU screening refusal, the state still has an influence (not overt coercion) through health professionals. It is important to note, however, that some parents do welcome direction. 79 Some studies examined whether or not parents felt that they had a choice and found that parents were not aware that they could opt out of or decline screening,19,20,29,66,77 as it was not presented as optional14,18,66,80 or midwives just assumed that screening would take place. 14,66,70 Some parents also feel that choosing screening is expected of them. 80 In a recent study in England, 41% of parents felt that they could not decline NBS and believed it to be compulsory. 66 Nicholls18 argues that the lack of perceived choice or the perception that NBS is mandatory may suppress parents’ information seeking or knowledge, possibly as parents perceive little need for it. However, parents who perceive greater choice have higher perceived knowledge of NBS and hold more positive attitudes towards screening. 18

Another form of coercion is to allow insufficient time for parents to make their decision, resulting in them being more likely to follow the guidance of the person offering the intervention. Indeed, Nicholls and Southern80 found that, if parents felt that they had had sufficient time to make a decision, it significantly predicted a feeling that they had made an informed choice. When asked how long they needed to make a decision regarding expanded NBS, 58% of parents reported that they wanted between 1 day and 1 week to decide. 66 However, parents also reported not being given any time to decide; they were just told that screening would be carried out or were given information just before the bloodspot was taken. 18

The timing of information provision can also be detrimental to informed decision-making, for example being asked to make an informed decision postnatally,18 which some may argue is a form of coercion. Indeed, Moody and Choudhry66 argue that parental control is lacking in NBS for a number of reasons, including because of anxiety, dependence on and trust in health-care professionals, the challenge of new parenthood and the ability to read and retain information in the postnatal period. 66 In one of the largest interview studies of parents’ experiences of being informed about NBS, the issue of the timing of information provision was more prominent than how parents were informed or who informed them. 63 However, in one study most parents (68%) felt that they had had enough time to make some form of a decision and > 70% felt that they had made an informed choice. 80 The problem with this may be that people do not know what they do not know, as highlighted earlier.

In the study by Nicholls,18 participants stated that they believed that raised hormone levels had altered their ability to make decisions. This led some participants to talk about how, even if they would have questioned the screening information antenatally, they would fail to do so postnatally. This is a vitally important insight that illustrates how, although parents may not lack the intellectual capacity to make a decision per se, actively engaged people can become passive if information is provided postnatally. Nicholls18 concluded that this highlights that the postnatal period is not the right time for information to be provided. Arguably, this could be extended to include that the decision should not be made at this time either if the goal is to ensure that parents make an autonomous decision.

Another practice that is recognised as being detrimental to a person’s ability to make a choice is to make a process routine. It can be argued that making the screening process routine sends a message to parents that screening is important and recommended, which may make it increasingly difficult for them to voice alternative views. This was indicated across multiple studies, with parents reporting routinisation of NBS and that they had not explicitly consented but health-care professionals had assumed consent. 14,18,29,65,79,85,86 Even when explicit consent was sought, parents were encouraged to comply with a highly routinised procedure. 73 Nicholls79 argues that the inclusion of NBS with the other postnatal checks that are readily accepted makes NBS more automatic.

Intentionality

Although a minimal number of data related to the concept of intentionality directly, tangential evidence raises concerns whether or not a cognitive process took place whereby parents made a choice. Stewart et al. 78 outlined that an informed decision is one where all the available information about the health alternatives is weighed up and used to inform the final decision: the resulting choice should be consistent with the individual’s values.

However, Nicholls18 raised the concern that the view that parents consider the information provided by the health professional and then make a decision based on this is not only simplistic, but also wrong in some cases. In addition, as discussed earlier, many parents were unaware that screening had taken place,28,97 indicating that no cognitive appraisal of beliefs and choice could have been made. This raises the question of how to change the current process to ensure that a cognitive appraisal is made and that parents feel that they have a choice. One suggestion from parents was that asking them to sign a form would make intentions clearer. 14 This process was seen as being even more important if the bloodspot sample was going to be stored. 70 There was also a belief that this would trigger cognitive appraisal, but it was also noted that for parents to engage with the screening properly they must be provided with all of the necessary information. There was recognition, however, that parents may need different information depending on their values to support them in their decision-making. 65