Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/301/233. The contractual start date was in April 2007. The draft report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Bulbulia et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Rationale and study design

The second Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST-2) is a pragmatic international multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) that directly compares carotid surgery with carotid artery stenting (CAS). It includes patients thought to definitely need an intervention for asymptomatic carotid stenosis, but in whom there is substantial uncertainty as to whether or not to opt for carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or CAS. The ACST-2 seeks to randomise such individuals to either CEA or CAS to compare both the immediate hazards of the two procedures when carried out by experienced doctors with an approved track record and the long-term durability of protection against stroke conferred by both procedures. The trial will also collect the stroke rates in the patients over 5–10 years of follow-up, with follow-ups planned until 2025. The trial seeks to recruit any patient with a carotid lesion that has not recently (i.e. within 6 months) caused any symptoms (i.e. an asymptomatic lesion), who would be expected to benefit from a carotid procedure to reduce the risk of future stroke, and in whom there is clinical uncertainty as to which is the preferred treatment.

Potentially eligible trial participants should already be on suitable drug therapy for stroke prevention and be likely to live for at least 5 years, giving them long enough to benefit from a stroke prevention procedure (CEA or CAS). Prior to trial entry, non-invasive arch angiography [computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] is also undertaken to ensure suitability for both procedures. These tests are routinely carried out before CAS and commonly, but not invariably, prior to CEA.

Randomisation of patients is by 1 : 1 allocation to CEA or CAS using a minimisation algorithm to ensure that both groups are well matched for key baseline prognostic factors that may determine early and long-term stroke risk. After intervention, patients are neurologically reassessed, including duplex scanning, and their drug treatment is adjusted if necessary before discharge. Early patient experience with both treatments is similar apart from the discomfort and wound care that is associated with open surgery, and the use of general versus local anaesthetic, which is determined by the centre’s standard of care (see Appendix 1).

Inclusion criteria

Patients being considered for ACST-2 should have:

-

carotid artery stenosis detectable by duplex ultrasonography, with no ipsilateral carotid territory symptoms and no previous procedures carried out on it

-

already started any appropriate medical treatment (e.g. statin, antithrombotic and antihypertensive therapy) and already recovered from any necessary coronary procedures [e.g. coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)]

-

been assessed to be fit and willing for follow-up in person at 1 month post intervention and subsequently by annual letter

-

investigations that show that both procedures (CEA and CAS) appear to be practical and appropriate

-

no definite preference or clinical indication about whether to treat the carotid narrowing with CEA or CAS and their doctor should see no clear indication/contraindication for either procedure.

Exclusion criteria

Patients would be excluded from ACST-2 if they had:

-

a small likelihood of worthwhile benefit (e.g. very low risk of stroke because stenosis is very minor) or major comorbidity or life-threatening disease, such as advanced cancer

-

an assessment showing that they were unsuitable for one of the procedures

-

been found to be unfit for major surgery.

Chapter 2 Recruitment

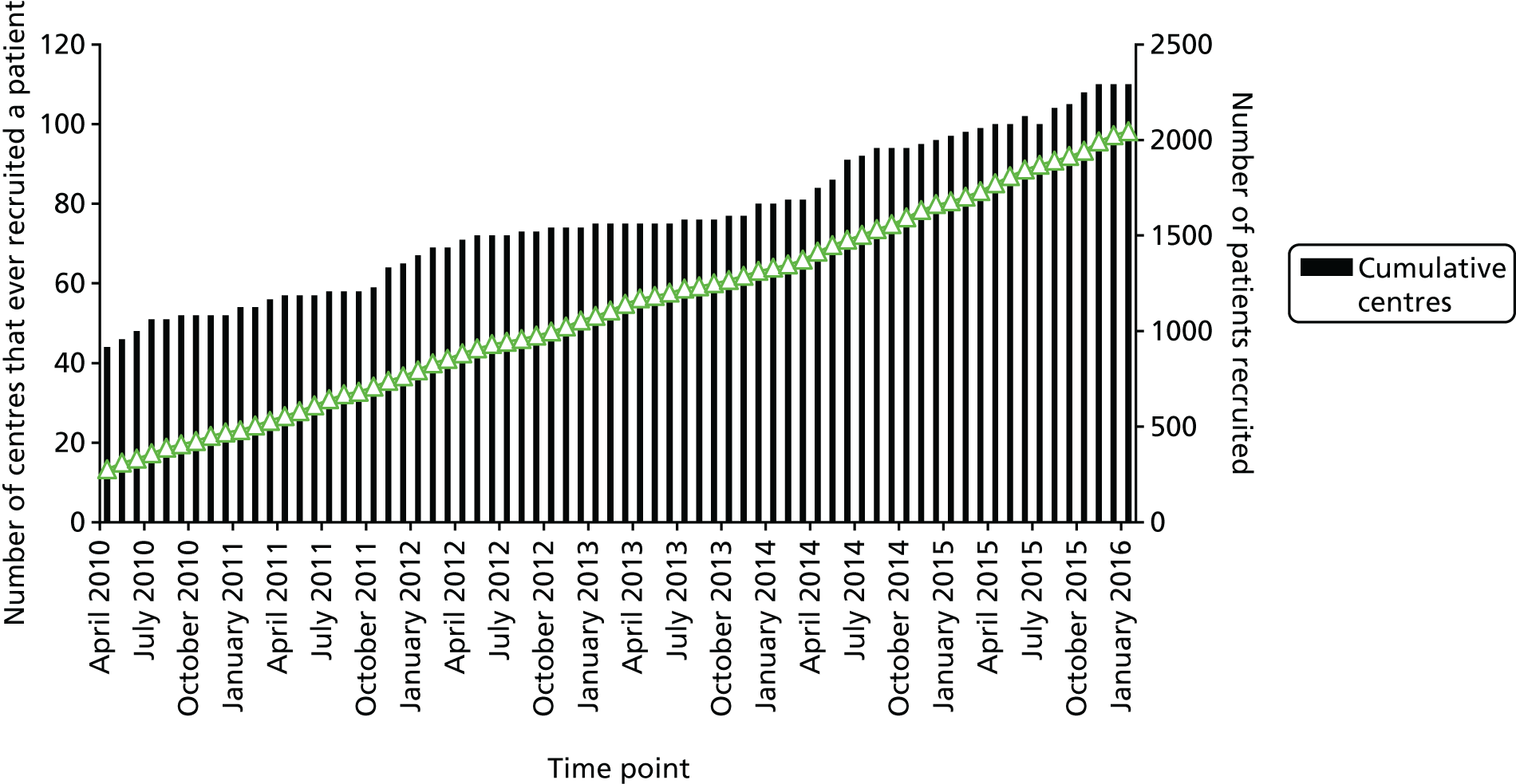

An international collaborative network has been established and comprises doctors across 27 countries. The network has been investigated and approved by our Technical Management Committee and by their local ethics and research committees. By March 2016, 2125 patients had been recruited from 110 centres worldwide. Recruitment pathways in the trial are similar to those used in routine clinical practice.

The ACST-2 has been designed to minimise the burden of research on the collaborators. The initial patient assessment determines that they are on suitable drug therapy for stroke prevention and that the patient is likely to live for at least 5 years, giving them long enough to benefit from a stroke prevention procedure (CEA or CAS). Prior to trial entry, non-invasive MRI or CT arch angiography is undertaken to ensure suitability for both procedures; this is usually done before CAS and commonly, but not invariably, done prior to CEA, and hence can be readily integrated into the participant’s care pathway.

The usual CAS procedure involves passing a guide wire from the femoral artery up to the aortic arch to gain access to the carotid artery. In some cases the anatomy of the aortic arch can be sufficiently tortuous to make CAS more difficult or hazardous; pre-randomisation aortic arch imaging with MRI or CT ensures that CAS is likely to be technically feasible. In routine practice, a duplex Doppler scan is often performed 1 month after the procedure to check the artery is open. Therefore, such a scan is used in this trial to check patency of the carotid artery 1 month after intervention, thereby confirming technical success. At least one clinical follow-up in outpatients is routine care for all carotid interventions and this is usually done 1 month after the procedure in this trial.

Within the UK we used a novel hub-and-spoke recruitment model, which allowed centres (i.e. the ‘spoke’) that offered one, but not both, treatments (usually CEA but not CAS) to identify patients who were eligible to enter the trial. The patients were then assessed (including use of MRI or CT) and then, after randomisation and depending on the treatment allocated, treated locally using CEA or sent for CAS to the ‘hub’ hospital (see Appendix 2).

One-third of European carotid procedures are performed in Italy, one-third are performed in Germany and the remaining one-third are performed in other European countries. Although Italy is the top recruiting country in the ACST-2, the UK is the second highest recruiter, accounting for about 20% of randomised patients (Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment per country (to the end of December 2015).

FIGURE 2.

Total recruitment by month (March 2010 to December 2015). Number of centres that ever recruited a patient and cumulative recruitment.

Chapter 3 Data collection

Randomisation is carried out by a telephone randomisation service (24-hour freephone number) or via a password-protected website via the internet. The collaborator is informed of the allocated treatment and the participant is ascribed a unique patient identifier number. The collaborator then either faxes or posts the randomisation form and the signed consent form to the ACST-2 trial office, which is based in the Nuffield Department of Surgical Science, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Procedural and post-procedure data are subsequently collected on a 1-month follow-up form completed by the collaborator and returned to the ACST-2 trial office. Data from these forms are entered on a trial database, which is held on secure servers on behalf of ACST-2 at the Clinical Trials Service Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK [that have worked with us in designing and carrying out much of the work in the first Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST-1) and ACST-2].

Annual follow-up of the patients in the trial is co-ordinated by the central ACST-2 office and annual questionnaires are sent either directly to the patient or to the collaborator, depending on local agreements.

Major events

These are classified as:

-

strokes within the first post-procedural month or during the long-term follow-up

-

peri- or post-procedural myocardial infarction (MI) within the first 30 days

-

death.

Information on these events is collected on the 1-month follow-up form or on the annual follow-up form. Further information, if required, is then requested from the collaborator. Once this information has been received by the ACST-2 office, a summary of the anonymised information is passed for adjudication. The Endpoint Review Committee reviews all such events and classifies the nature and severity of any of the strokes. Information on the types and number of major events is reviewed by the independent Data Monitoring Committee.

Chapter 4 Patient and public involvement

The aims and design of ACST-2 have been discussed with the Oxford Clinical Trial Service Unit (CTSU) patient focus group, which was established in 2012 to allow members of the public who have, or are at risk of, vascular disease to criticise and help evaluate ongoing and planned studies conducted by the CTSU.

Mr David Simpson is the lay member on the ACST-2 Trial Steering Committee. He was closely involved in study design, drafting the trial protocol and original patient information leaflet, and eloquently represents the public interest, both formally at annual Trial Steering Committee meetings and informally throughout the years. His role is ongoing as the trial continues.

The ACST-2 trial was adopted by the Stroke Research Network as soon as funding was confirmed by Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. This helped us with local contacts, meetings, ethics approval applications, recruitment (of the planned 20% of UK patients) and follow-up in the UK. Annual Stroke Network meetings in Newcastle and London were particularly helpful by enabling us to give platform presentations of our work and discuss it with attendees from potential new centres in front of our posters. We also attended, presented and had stands at the Thames Cardiovascular Network Group meetings in 2013 and 2014, the Vascular Society (the UK National Society for Vascular Surgery) and the British Society of Interventional Radiology (for UK interventional radiologists). The annual UK Stroke Forum was also important; attendees came from every stroke care discipline and included stroke sufferers and representatives from patient groups. We have had a stand at most of these meetings since the trial’s inception, winning a prize for our novel UK hub-and-spoke recruitment model at the UK Stroke Forum.

Chapter 5 Economic evaluation and quality of life

The design of ACST-2 includes a health economic component with evaluation of resource use during treatment and follow-up. The use of UK data will be particularly relevant to the NHS because much of the evidence on costs of CEA and, particularly, CAS has been based on evidence from studies outside the UK. The main components for current and future study will be (1) initial procedural costs, (2) short-term retreatment costs (repeat or further procedures within 1 month), (3) costs of any MIs and strokes within the first month and (4) the costs of any strokes after the first month, almost all of which will not be procedural. Duration of hospital stay is also recorded. At annual follow-ups with the patients, we seek information about strokes or carotid procedures beyond the first month and standard costs will be assumed for these procedures. Economic analyses will evaluate stroke-related quality of life at 1 month after the trial procedures as well as short- and longer-term stroke outcomes and costs.

Annual follow-up questionnaires sent by the trial office to the patient are used to collect data on whether or not the patient has had a subsequent stroke or further treatment on their carotid arteries. In addition, we have extended collection of the standard EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D®) from the UK alone to five more countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Serbia and Sweden), accounting for 85% of the patients recruited so far. All stroke patients will be and have been asked annually how their stroke still affects them. Their current medication, including names and dosage of all blood pressure, antithrombotic and lipid-lowering drugs prescribed, has been recorded for analysis.

Chapter 6 Interim blinded results

Unblinded results for the trial will be reported after patient recruitment is complete (and, if recruitment continues at the present rate, the target of 3600 participants will be reached by December 2019) and this report is planned for 2021. Long-term follow-up (which is less onerous and usually by direct patient letter with confirmation of any strokes through the participating physician) will continue until December 2025, after which a final publication will report long-term results in late 2026.

Data on the baseline characteristics of participants recruited to date are available (Table 1). Around one-quarter of participants are > 75 years old and around one-third are female. Diabetes mellitus is more common in ACST-2 than in ACST-1 (one-third of ACST-2 participants have diabetes mellitus), and almost half of the participants had prior evidence of stroke (clinically evident stroke or a silent infarction detected on pre-procedural cross-sectional brain imaging), leaving them at higher stroke risk without appropriate carotid intervention. Owing (in part) to the minimisation algorithm used during randomisation, these characteristics are similar in patients randomised to stenting and surgery.

| Characteristic | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| CEA (N = 1061) | CAS (N = 1064) | |

| Characteristic, n (%) | ||

| Female | 316 (30) | 319 (30) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 63 (6) | 64 (6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 319 (30) | 320 (30) |

| Age (years), n (%) | ||

| < 65 | 315 (30) | 315 (30) |

| 65–74 | 476 (45) | 476 (45) |

| ≥ 75 | 271 (26) | 272 (26) |

| Median age (years) | 69 | 69 |

| Echolucent, n (%) | ||

| No | 339 (32) | 339 (32) |

| Yes | 311 (29) | 312 (29) |

| Unknown | 411 (42) | 412 (39) |

| Contralateral stenosis, n (%) | ||

| < 50 | 664 (63) | 665 (63) |

| 50–79 | 278 (26) | 280 (26) |

| 80–99 | 43 (4) | 36 (3) |

| 100 | 76 (7) | 82 (8) |

| Median | 35 | 30 |

| Ipsilateral stenosis, n (%) | ||

| < 50 | 14 (1) | 15 (1) |

| 50–59 | 6 (1) | 8 (1) |

| 60–69 | 29 (3) | 29 (3) |

| 70–79 | 346 (33) | 344 (32) |

| 80–99 | 666 (63) | 667 (63) |

| 100 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Median | 80 | 80 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), n (%) | ||

| ≤ 140 | 653 (62) | 643 (60) |

| 141–160 | 311 (29) | 328 (31) |

| 161–180 | 80 (8) | 72 (7) |

| > 180 | 17 (2) | 20 (2) |

The use of triple medical therapy is excellent at baseline and maintained or improved during long-term follow-up (Tables 2 and 3). Predictably, CAS is associated with a much higher rate of dual antiplatelet therapy at 1 month post procedure than with CEA, but this difference largely disappears with longer-term follow-up. Over 50% of patients are receiving either rosuvastatin or atorvastatin, with one-quarter taking simvastatin.

| Therapy | Allocated to | Total (N = 1871) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAS (N = 932) | CEA (N = 939) | ||

| Antihypertensive, n (%) | 797 (86) | 822 (88) | 1619 (87) |

| Lipid lowering, n (%) | 812 (87) | 835 (90) | 1647 (88) |

| Antiplatelet or anticoagulant, n (%) | 929 (99) | 935 (99) | 1864 (99) |

| On at least one of aspirin or clopidogrel, n (%) | 908 (97) | 894 (95) | 1802 (96) |

| Both aspirin and clopidogrel, n (%) | 616 (66) | 138 (15) | 754 (40) |

| Therapy | Allocated to | Allocated total (N = 1363) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAS (N = 676) | CEA (N = 687) | ||

| Antihypertensive, n (%) | 556 (82) | 575 (84) | 1131 (83) |

| Lipid lowering, n (%) | 562 (83) | 578 (84) | 1140 (84) |

| Antiplatelet or anticoagulant, n (%) | 632 (93) | 634 (93) | 1266 (93) |

| On at least one of aspirin or clopidogrel, n (%) | 583 (86) | 583 (85) | 1166 (86) |

| Both aspirin and clopidogrel, n (%) | 87 (13) | 50 (7) | 137 (10) |

Compliance: because the trial is ongoing, final compliance is not available. As of March 2016, the overall crossover rate was 3.6% and a further 5.3% of patients were still awaiting intervention, but this number will likely reduce with time (Table 4). The mean time from randomisation to treatment was similar for both CEA (23 days) and CAS (26 days).

| Allocated procedure | 1-month follow-up form entered and verified | Procedure not yet done | Crossover from allocation | Procedure as allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS | 960 | 61 | 41 | 858 |

| CEA | 961 | 41 | 29 | 891 |

| Total | 1921 | 102 | 70 | 1749 |

Techniques: similar numbers of CEA were performed under general anaesthesia (56%) and local/regional anaesthesia (44%), but the majority of carotid stents were performed under local anaesthetic (94%). Carotid patching was used in 44% of patients undergoing CEA and 22% of CEA patients were shunted. For CAS, eight types of stent were used (46% tapered) and WALLSTENT™ (Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough, MA, USA) was the most commonly used device. Cerebral protection devices were used for 86% of CAS (Table 5) and eight types of cerebral protection device were employed (79% filters, 10% proximal systems), including flow reversal and flow arrest systems (see Table 5).

| Device type | Device name | Number used |

|---|---|---|

| Filter | Emboshield (Abbott Vascular, CA, USA) | 204 |

| Filter | FilterWire (Boston Scientific Corp., MA, USA) | 171 |

| Filter | Spider (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) | 116 |

| Filter | Accunet (Abbott Vascular, CA, USA) | 60 |

| Filter | AngioGaurd (Cordis, Baar, Switzerland) | 44 |

| Filter | FiberNet (Lumen Biomedical Inc., MN, USA) | 1 |

| Filter | Wirion System (Gardia Medical, Caesarea, Israel) | 1 |

| Proximal occlusion | Mo.Ma (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) | 131 |

| Proximal occlusion | Gore Flow Reversal (Gore & Associates, Putzbrunn, Germany) | 28 |

| Distal balloon | Twin One (Minvasys, Paris, France) | 3 |

| Distal balloon | Viatrac (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) | 1 |

| None | 127 (14%)a | |

| Total | 887 |

The ACST-2 provides yearly reports to the independent Data Monitoring Committee of confirmed strokes, MI and deaths within 1 month of treatment and of long-term stroke rates. With their consent, in our first 1000 patients we have reported an overall (i.e. blinded) 30-day rate of disabling stroke or death of around 1%, which compares favourably with that seen for CEA alone in ACST-1 (1.7%), confirming that ACST-2 collaborators are performing trial procedures to a high standard.

Chapter 7 Statistical analysis

No material difference in fatal or disabling procedural events is expected (≈1% in each group), so power calculations for this outcome are not given. The primary outcome of particular interest is the stroke risk in the period > 30 days post procedure, but the rates > 5 years post procedure will provide an important subgroup analysis. Accordingly, person-years accrued are more relevant than numbers of patients randomised. For the main outcome of the annual stroke rate after day 30 (i.e. after the end of the perioperative period), ACST-2 will have 18,000 person-years in its first report (2021) and 36,000 by December 2025.

If mature results from ACST-2 show little difference in long-term stroke rates, this key result will be established reliably in the first report and even more reliably by the time of the final report (2026). However, there could be important absolute differences in long-term stroke rates. Suppose, for example, that the stroke rate per decade is 6% after CEA and 9% after CAS, a clinically meaningful difference (with stroke rate ratio = 0.67, easily compatible with the results from the previous trials). Then, with 18,000 person-years by mid-2020, the stroke rate would have about a 70% chance of getting a p-value < 0.05 and a 50% chance of getting a p-value < 0.01. However, with 36,000 person-years (as of December 2025), it would have a 93% chance of getting a p-value < 0.05 and an 82% chance of getting a p-value < 0.01. Moreover, its expected result of 120 versus 180 strokes would ensure high significance (p = 0.002) in a meta-analysis combining it with the apparently null final results from the previous (small) trials.

Chapter 8 Discussion

Almost 200,000 carotid procedures (surgery or stenting) are performed annually, commonly on asymptomatic patients with carotid stenosis, although numbers in the UK are presently lower than in some other European countries. Regardless of how many should be performed here or elsewhere, as long as such procedures continue to be performed widely, large-scale randomised evidence directly comparing surgery with stenting is needed.

Among 1990s-era asymptomatic patients who were on triple-drug therapy (blood pressure-lowering, lipid-lowering and antithrombotic treatment) in the ACST-1 trial of carotid surgery compared with those who were not, there was net benefit from surgery despite the protective effects of the triple therapy. 1 Two new trials, ECST-2 (European Carotid Surgery Trial) and CREST-2 (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial) (surgery vs. no surgery in Europe, surgery vs. no surgery in the USA, stenting vs. no stenting in Europe and stenting vs. no stenting in the USA) are currently recruiting to determine whether or not, for the 2010s era triple therapy asymptomatic patients, carotid procedures are still of net benefit. 2,3 If these trials confirm by the early 2020s that such procedures are of net benefit, then this will greatly increase use in the UK as well as elsewhere (especially as carotid screening is increasing), strengthening the need, both in the UK and elsewhere, for directly randomised evidence to be available from ACST-2 during the 2020s as to which procedure is better.

The procedural hazards are substantially lower for asymptomatic (1.0% disabling stroke or death in the first 1000 patients in ACST-2) than for symptomatic patients. Even 1.0% is a serious risk, but so too is the risk (over the next 5 or more years) of entirely trusting drug therapy and not doing any protective procedure when severe carotid disease is found in a currently asymptomatic patient. Moreover, recent claims that asymptomatic patients with serious carotid disease are at negligibly low risk on triple-drug therapy are methodologically unsound.

The ACST-2 is already the world’s largest trial of CEA versus CAS in asymptomatic patients. It currently randomises 350–400 patients per year, which is the highest recruitment rate of any large trial of carotid interventions.

Many (43%) of the > 2000 patients recruited to date have had previous ipsilateral stroke symptoms or symptoms in another cerebral territory, or have evidence of brain infarction at the time that they enter ACST-2. A recent analysis of our previous ACST-1 trial data has shown that these patients have a 50% higher risk of future stroke than those who have never had neurological symptoms. 4

The medical treatments that ACST-2 trial patients take will be analysed in much greater detail than in any previous trial of carotid intervention. The findings from ACST-1, SPARCL (Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels)5 and individual patient data meta-analyses from the Cholesterol Treatment Triallists’ Collaborative Group6 suggest that addition of statins to antiplatelet and antihypertensive medications will lower overall stroke risk by about one-third (in ACST-1 from about 20% to about 14% over 10 years), but that the addition of CEA will reduce stroke risk still further (halving it in the first 5 years and reducing risk from 15% to 8–9% by 10 years). 1

If CAS, a newer and less invasive treatment, offers stroke protection which is as good as, or better than, CEA, then it is likely to replace invasive surgery for suitable patients in the future. This would lead to a significant change in practice in the UK as, in marked contrast to practice seen in continental Europe and the USA, very few routine CAS procedures are performed in ‘normal risk for surgery’ patients outside trials. With increasing use, costs of stents, filters and wires for CAS are decreasing and, in some higher-volume centres, costs of CEA and CAS are broadly similar. The shorter hospital stay associated with CAS would also be an advantage, saving hospital in-patient costs. In addition, most CAS is carried out under local anaesthetic, in contrast to CEA for which general anaesthesia is currently used for 50% of patients.

If CAS is as effective as CEA, practice could also change for high stroke risk patients prior to coronary bypass grafting. In the past, prophylactic CEA to reduce stroke risk from bypass has been hazardous, particularly when patients have had recent stroke symptoms, or have ongoing coronary symptoms; with CAS, future hazards might be significantly less.

Large-scale randomised evidence comparing the long-term durability of carotid surgery with carotid stenting is needed to avoid moderate biases and random errors

Some treatments are so clearly beneficial [e.g. antibiotics for severe sepsis or protease inhibitors for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection] that RCTs are not required to prove their efficacy. However, most currently unevaluated treatments are likely to have, at best, only moderate treatment effects. But such effects may be worthwhile if the condition being treated is both common and also a significant cause of premature death and major morbidity (e.g. heart attacks and strokes). 7

In Europe, > 1 million carotid procedures will be performed on asymptomatic patients during the next decade, thereby preventing around 60,000 strokes. Both carotid surgery and carotid stenting are now established procedures that can be performed with low rates of immediate complications in carefully selected patients treated by experienced clinicians. 8 However, it is not clear which procedure provides the most durable long-term protection against stroke. Although RCTs can provide some information about the short-term periprocedural hazards following CEA and carotid artery stenting, such events (i.e. strokes, heart attacks and deaths within 30 days of the procedure) will occur so infrequently that even quite a large trial (e.g. 3000–4000 participants) will lack statistical power to detect a plausible difference in treatment arms. Furthermore, trials always recruit patients from the past, but provide information for patients of the future. Hence, it is possible that the interventions performed during the trial will not accurately reflect contemporary clinical practice. This is particularly relevant in trials of carotid artery stenting, which has a significant learning curve9 and is also undergoing major technological innovation (e.g. new stent designs, cerebral protection devices and direct cervical access) all of which aim to reduce periprocedural stroke risk. Accordingly, estimates of contemporary risks associated with CAS and CEA are best assessed in large registries (and ideally those with mandated patient entry and validated outcomes such as the German mandatory national quality assurance registry published by the Federal Agency for Quality Assurance and the Institute for Applied Quality Improvement and Research in Health Care). 10 Such registry data may have sufficient demographic or clinical information to identify particular patient populations in whom carotid surgery or stenting is particularly hazardous.

In contrast, RCTs are necessary to compare the long-term durability of carotid surgery with carotid stenting following a successful procedure. Such a comparison cannot be done reliably in a large cohort study because the choice of intervention is likely to have been strongly influenced by specific patient characteristics, which could determine long-term survival and stroke risk (e.g. more frail patients preferentially being offered a minimally invasive stent procedure, while fitter patients are treated surgically). Data from smaller RCTs of largely symptomatic patients suggest that both carotid surgery and stenting offer good long-term protection against stroke11 and almost all patients receive good triple medical therapy following intervention. Consequently, the rate of stroke in these patients is low (around 5–10% per decade). Therefore, to detect a moderate but clinically worthwhile difference in stroke rates between stenting and surgery, large numbers of patients need to be recruited and, importantly, followed up for at least 5 (but preferably 10) years.

At the outset, sample size calculations suggested a trial of around 5000 participants would allow detection of a 60% decrease in the rate of periprocedural MI with stenting versus surgery (e.g. 2% CEA vs. 0.8% CAS) and an increase of around 60% in the 5-year stroke rate (e.g. 3% CEA vs. 5% CAS) at a p-value of 0.001 with 80% statistical power or at 2P of < 0.05 with 95% power. These possible event rates are based on data from other similar trials and are plausible, clinically meaningful and worthwhile. The ACST-1 had recruited > 3000 patients in 10 years and clearly demonstrated benefits of carotid surgery in asymptomatic patients < 75 years. Following the presentation of these results to the ACST collaborative group, it was agreed that a trial directly comparing carotid surgery with stenting in asymptomatic patients was the next important step in carotid research. The collaborative group’s previous experience in recruiting substantial numbers of patients to ACST-1 (and mindful of the fact that a ‘non-intervention’ arm in this trial was thought to have made recruitment harder) led to the belief that a target of 5000 for a trial comparing two different interventions for asymptomatic carotid disease was achievable. However, recruitment proved challenging, initially due to unanticipated regulatory hurdles and subsequently due to a change in clinical practice in certain countries and a shift in the balance of ‘uncertainty’ in favour of carotid surgery over stenting.

Regulatory challenges in conducting an international trial

The improvements in clinical trial regulation and oversight that have occurred quite recently in the UK (e.g. multicentre ethics committee reviews and research portfolio status allowing rapid local research and development approvals) have made the conduct of trials in the UK a little easier, but these have not been replicated across continental Europe. Furthermore, rigid interpretation of good clinical practice coupled with strict adherence to the European Clinical Trials Directive has become commonplace. Although both framework documents have some merit, they have made research (and particularly resource-limited academic studies) much more difficult to conduct. In contrast to the UK, where there is now a single interpretation of legal, ethical and regulatory requirements which was applied across all study sites, in continental Europe each study site had an Institutional Review Board, or equivalent, who reviewed the trial protocol, consent, patient information leaflet and indemnity arrangements to satisfy compliance with their interpretation of the prevailing regulatory framework (which differed substantially across institutions). Requests were made frequently for protocol amendments, site-specific consent forms and dedicated indemnification arrangements. Although these were always rebutted, this introduced substantial delays in trial set-up at each site and, hence, recruitment was slow to start.

A change in clinical practice favouring treatment of asymptomatic carotid patients with medical therapy alone

The ACST-1 showed clearly that, even among patients taking triple-drug therapy (i.e. statins, antithrombotic and antihypertensive medications), immediate carotid surgery halved the long-term risk of stroke1 (see Scientific summary, Figure a). Despite this finding, many commentators argued strongly that, because of improvements in medical therapy and a resulting reduction in the risk of carotid-related stroke, the risks of intervention were no longer justified. Although the use of antithrombotic and antihypertensive therapies was high in ACST-1, statin use was uncommon at the start of the trial but increased to around 80% by the end of follow-up. Statin therapy has been proven to reduce ischaemic strokes and may be particularly effective against carotid-related events (e.g. the risk of CEA was halved by allocation to 40 mg of simvastatin in the Heart Protection Study). 12 Accordingly, it is possible that better statin therapy (higher doses and longer duration) may have reduced the prevalence of ischaemic stroke observed in ACST-1. However, counterbalancing this, periprocedural risks seen in ACST-1 are higher than currently seen in large registries, and intention-to-treat analyses of ACST-1 also substantially underestimate the actual benefit of immediate carotid surgery in long-term stroke prevention (as many patients in the no-surgery arm went on to have surgery without having symptoms). Nevertheless, rates of carotid intervention for asymptomatic disease have fallen in several northern European countries, that contributed strongly to ACST-1 (e.g. Norway, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands, UK), and this has undoubtedly impaired recruitment to ACST-2.

Concerns about the short-term safety of carotid stenting

In 2010, a study comparing carotid stenting with surgery in symptomatic patients [International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS)] reported interim results, which showed a significantly higher stroke risk associated with stenting. 13 Asymptomatic patients are different from symptomatic patients in whom atheromatous carotid stenosis has recently caused a stroke and, hence, are likely to be unstable and at a high risk of distal embolisation during stenting. Furthermore, some stenters in the ICSS were very inexperienced and there is a clear relationship between individual and centre CAS volume and clinical outcomes. But, despite the fact that the ICSS did not provide a fair comparison of stenting versus surgery and recruited a different patient population to ACST-2, many commentators and clinicians mistakenly applied the results of the ICSS to asymptomatic carotid patients and preferred CEA to stenting for those patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis in whom intervention was considered necessary.

Meta-analysis plans

Over 5000 patients randomised to carotid endarterectomy versus carotid artery stenting can detect plausible differences in outcomes between carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stenting, and ACST-2 will provide most of these patients

Individual surgical trials are frequently too small to answer important questions reliably, particularly when considering clinically relevant subgroups (e.g. women and the elderly), who are commonly under-represented in RCTs. In 2014, it became apparent that a target of 5000 ACST-2 participants was no longer realistic. But current and projected recruitment rates suggest that a total of 3600 patients by the end of 2019 is achievable.

The Carotid Stenosis Triallists’ Collaboration (CSTC) was formed to pool the results of individual carotid studies to allow individual patient data meta-analyses and hence provide uniquely reliable evidence to answer key questions facing clinicians who manage patients with carotid artery stenosis. Through the CSTC, ACST-2 investigators have secured agreement to pool individual patient data from ACST-2 and three other trials that directly compared CEA with CAS in asymptomatic patients – CREST-1 (1182 patients), SPACE-2 (Stent Protected Angioplasty in asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis versus endarterectomy) (320 patients randomised to CAS vs. CEA before three-way trial abandoned) and ACT-1 (NCT00106938: 1450 patients randomised 3 : 1 CAS vs. CEA, equivalent to two-thirds as many randomised 1 : 1) – thereby yielding the equivalent of about 2400 additional patients. 14–16 If ACST-2 recruits 3600 patients and pools these data with the CREST-1, SPACE-2 and ACT-1 cohorts, the resulting total of 6000 should more than suffice to identify types of patient in whom one procedure is clearly better than the other, and to assess reliably any effects on disabling and fatal stroke.

Recruitment strategy developed to reach target of 3600 by end 2019

One-third of all carotid procedures performed in Europe are carried out in Italy, a further one-third are carried out in Germany and the remainder are carried out in the rest of Europe. Accordingly, a recruitment strategy was developed focusing on Italy, which was already the top recruiting country in ACST-2, and Germany, where participation in ACST-2 had been hampered by SPACE-2 (another carotid trial being run in Germany, Austria and Switzerland and which was perceived as competing with ACST-2).

To maximise recruitment in Italy, we sought to encourage established sites to recruit more patients and to set up new high-volume sites. An ACST-2 recruitment co-ordinator was appointed who was fluent in Italian and English, had prior experience of working in carotid research and had access to a wide network of vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists across Italy. Working closely with the other ACST-2 office staff and the principal investigators, several new Italian sites were established and recruitment activity in existing Italian sites was maintained or enhanced. Trial profile-raising activities occurred at key Italian vascular meetings and communication between collaborators and trial staff was improved by a dedicated Italian collaborators’ newsletter (see Appendix 3).

In Germany, the closure of SPACE-2 facilitated ACST-2 expansion. SPACE-2 was originally designed as a three-way trial (CAS vs. CEA vs. medical therapy) but it failed to recruit. It was subsequently redesigned as two ‘two-arm trials’, directly comparing either CAS with medical therapy or CEA with medical therapy (a design subsequently employed by CREST-2). Unfortunately recruitment to this new design also failed, largely because participating hospitals received no payment for managing carotid patients medically, but substantial income for treating them with either surgery or stenting. Consequently, in 2015 the German funding agency withdrew support but has prudently provided funds to allow continued follow-up of all 513 randomised participants in both trial designs. 15

For some time ACST-2 had been in dialogue with several SPACE-2 investigators, who had sought to encourage SPACE-2 centres in Germany to consider randomising patients to ACST-2 when not suitable for the redesigned SPACE-2 (i.e. when intervention was considered necessary and hence enrolment in a trial with a medical therapy alone-arm inappropriate). However, it had proved difficult to successfully run both trials side by side. Hence, the closure of SPACE-2 enabled several high-volume German (and Austrian) sites to join ACST-2. Some of these sites, which have a strong track record of participating in randomised carotid trials, are now recruiting well and German recruitment rates are expected to rise over the next few years. These recruitment rates could conceivably approach those seen in Italy. We have German representation on our Trial Steering Committee and ACST-2 principal investigators attend German vascular surgical and interventional radiology meetings regularly, thereby raising the profile of ACST-2 in Germany, identifying new collaborators and encouraging recruitment nationally.

The ACST-2 has also sought to broaden its recruitment base by expanding into Brazil and China. Our experience in Brazil is limited to São Paolo (a large conurbation with a population of > 40 million and a recognised destination for complex health care in South America). The identification of potential centres in Brazil is co-ordinated by an academic vascular surgeon in a local university hospital. He has already recruited substantial numbers of patients to ACST-2 since joining in 2015 and several other high-volume sites are in the late stages of set-up. In contrast, our experience in China has been less positive despite long-standing collaborative links with several large academic hospitals throughout China, facilitated by the Fuwai–Oxford Research Collaboration, which has led to the inclusion of > 70,000 patients in CTSU trials. Four ACST-2 sites were established in Beijing and Shanghai with enthusiastic local collaborators but they failed to recruit significant numbers of patients. The barriers to recruitment in China were twofold: first, patients commonly had a strong preconception as to their preferred treatment, with most preferring carotid stenting and; second, carotid stents were much more expensive than surgery. Consequently, those who could afford to pay for a carotid stent were unwilling to be randomised to either surgery or stenting, with a 50% chance of being allocated to a procedure they perceived to be inferior. Moreover, those unable to afford the extra costs of a carotid stent could not be randomised in ACST-2, lest they be allocated to carotid stenting.

Cost analysis

Streamlined trial design necessary to provide reliable evidence at reasonable cost

High-quality RCTs are needed to guide clinical practice and there have been many examples of clinicians being misled by non-randomised studies or small RCTs, resulting in either under- or overtreatment and consequent patient harm. With good background therapies and declining event rates, modern trials need to be large scale and this fact, coupled with an increasing regulatory burden, may make appropriately sized studies unaffordable. However, if sufficient attention is paid at the outset to ensure a streamlined trial design, such studies can be delivered at a reasonable cost. Examples of streamlining in ACST studies include a brief trial protocol, broad inclusion criteria based entirely on the ‘uncertainty principle’, simplified clinical record forms at randomisation and follow-up (i.e. limited to a single side of A4, unless a periprocedural stroke or death has occurred, in which case a further single-sided form is required). As a consequence, ACST studies are relatively inexpensive, costing one-tenth of the equivalent era US trials and with 50% more patients (Table 6).

| ACAS – US$24M (1700 patients) | ACST-1 – £1.2M (3100 patients) |

| CREST-1 – US$80M (2500 patients, half asymptomatic) | ACST-2 – £1.8M spent; estimated ≈£4M by 2019 (3600 patients) |

Large trials commonly need to recruit internationally, particularly when rates of intervention using procedures under investigation in the UK are low. Some may argue that if a procedure is not commonly performed in the UK then it should not be the subject of a UK-funded trial. However, the UK is recognised as being a slow adopter of innovation in health care, partly owing to constrained health-care resources and also to the centralised control on NHS budgets. Such innate conservatism may have some advantages but it is both unreasonable and possibly harmful to delay the rigorous evaluation of new technologies until they become widely used in the UK.

Around 80% of ACST-2 participants are from countries outside the UK and, hence, some overseas expenditure is inevitable. In ACST-2, this spending is limited to a modest £100 per-patient payment to local collaborators on receipt of the 1-month post-procedure follow-up and, more recently, a contribution to the salary of a part-time recruitment co-ordinator for Italy. However, the overwhelming majority of funding is spent in the UK on staff costs and overheads to support the ACST-2 office.

Trials such as ACST-1 and ACST-2 not only need to be large but also need to last long enough to determine the long-term durability of the procedures being assessed to prevent stroke. ACST-1 reported results at 5 and 10 years and is currently acquiring data to assess the lifetime effects of carotid surgery in asymptomatic patients. The ACST-2 will report 4-year follow-up results in 2020, but much more informative results may only emerge in 2025, when 10-year follow-up data are available, which will provide uniquely reliable evidence about the long-term durability of carotid surgery versus CAS for the prevention of stroke. No responsible funding agency can commit large sums of money for ≥ 10 years at the outset of a study. However, particularly in trials of preventative surgery for which the early years of follow-up are inevitably dominated by periprocedural hazards, prolonged follow-up must be an absolute requirement. When the trial has been carefully and correctly carried out, funding after the trial interventions should follow. Recruitment without retention and follow-up is a pointless and disincentivising exercise, a waste of research resources and arguably unethical.

Using a careful trial design, long-term follow-up of trial participants after intervention can be achieved at a low cost. In ACST-1 and ACST-2, clinicians report 1-month outcomes (periprocedural stroke, MI and death), thereafter, annual follow-up (for stroke and death) is achieved by means of an annual questionnaire (usually mailed directly to the participant). For ACST-2, this has proven to be a robust and acceptable method of follow-up, with a 95% response rate for the most recent questionnaire (in 2015). In ACST-1, data on incident stroke and cause-specific mortality are currently being sought from routine health records held by the Health and Social Care Information Centre (now known as NHS Digital) thereby enabling effectively life-long follow-up at minimal expense.

Chapter 9 Conclusion

Carotid artery stenosis causes around 20,000 strokes in the UK each year. Many patients have no prior symptoms or have failed to recognise warning signs, and about half die or are severely disabled by their first stroke. Our ACST-1 trial showed that, even on good triple therapy (including statins), stroke risk for the next 10 years could be halved by preventative surgery (CEA). Two recent carotid trials are now including asymptomatic patients (ECST-2, current recruitment 180/2000 planned, and CREST-2, current recruitment 300/2840 planned) comparing a stenting or surgery procedure with no procedure. 2,3 Should these confirm the ACST-1 finding of additional benefit from a procedure in certain patients then, throughout the 2020s and beyond, the key question will be which procedure to recommend. With new technology and increasing experience, CAS can now rival or prove superior to CEA. The ACST-2 is the only trial now recruiting that directly compares CEA with stenting and will provide uniquely reliable evidence about the short-term safety and, perhaps more importantly, the long-term durability of surgery compared with stenting in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis. There will be an initial report in 2020, describing 4-year follow-up for 3600 patients randomised to CEA versus CAS, and a subsequent report in 2025 with around 10-year follow-up. Until then, how to intervene on asymptomatic patients with a carotid stenosis will be based on patient and professional preferences alone.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, the principal acknowledgement is to the patients taking part in the trial, now and in the future. Second, to the funders to date (HTA programme and BUPA Foundation), to the UK Stroke Association, to all the UK and international collaborators, our office staff, the Steering and Data Monitoring Committees as well as to the trial Endpoint Review and Technical Management Committees. We also acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Programme. Finally, to the CTSU and Epidemiological Studies Unit, the Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, and the Nuffield Department of Surgery, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, for their invaluable support.

Alison Halliday and Richard Bulbulia, together with Richard Peto, Hongchao Pan (Statistical Co-principal Investigators) and Leo Bonati (Neurological Co-principal Investigator) are responsible for the design, conduct and analysis of ACST-2.

Contributions of authors

Richard Bulbulia (Co-principal Investigator and Consultant Vascular Surgeon) and Alison Halliday (Chief Investigator and Professor of Vascular Surgery) coauthored this report.

Publications

Rudarakanchana N, Dialynas M, Halliday A. Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2): rationale for a randomised clinical trial comparing carotid endarterectomy with carotid artery stenting in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Eur J Vas Endovasc Surg 2009;38:239–42.

Halliday A, Harrison M, Hayter E, Kong X, Mansfield A, Marro J, et al. 10-year stroke prevention after successful carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic stenosis (ACST-1): a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:1074–84.

Rudarakanchana N, Halliday A, Kamugasha D, Grant R, Waton S, Horrocks M, et al. Current practice of carotid endarterectomy in the UK. Br J Surg 2012;99:209–16.

Bulbulia R, Halliday A. ACST-2 – A large, simple randomised trial to compare carotid endarterectomy versus carotid artery stenting to prevent stroke in asymptomatic patients. An update. Gefässchirurgie 2013;18:626–32.

den Hartog AG, Halliday A, Hayter E, Pan H, Kong X, Moll FL, de Borst GJ. Risk of stroke from new carotid artery occlusion in the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-1. Stroke 2013;44:1652–9.

Halliday A, Bulbulia R, Gray W, Naughten A, den Hartog A, et al. and the ACST-2 Collaborative Group. Status update and interim results from the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2013;46:510–18.

Data sharing statement

The ACST-2 data will be held in accordance with the Nuffield Department of Population Health Data Access and Sharing Policy. 17 We have agreed to pool ACST-2 data with other similar trials under the auspices of the CSTC.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health.

References

- Halliday A, Harrison M, Hayter E, Kong X, Mansfield A, Marro J, et al. 10-year stroke prevention after successful carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic stenosis (ACST-1): a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:1074-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61197-X.

- UCL Institute of Neurology . ECST-2 Protocol Summary: Version 3.10 n.d. http://s489637516.websitehome.co.uk/ECST2/protocolsummary.htm (accessed 3 April 2017).

- CREST-2 Trial Website . The Carotid Revascularisation and Medical Management for Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis Study n.d. www.crest2trial.org/ (accessed 1 August 2016).

- Streifler JY, den Hartog AG, Pan S, Pan H, Bulbulia R, Thomas DJ, et al. Ten-year risk of stroke in patients with previous cerebral infarction and the impact of carotid surgery in the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial. Int J Stroke 2016;11:1020-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493016660319.

- Sillesen H, Amarenco P, Hennerici MG, Callahan A, Goldstein LB, Zivin J. Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels Investigators . Atorvastatin reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with carotid atherosclerosis: a secondary analysis of the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial. Stroke 2008;39:3297-302. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.516450.

- Cholesterol Treatment Triallists’ (CTT) Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376:1670-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5.

- Baigent C, Peto R, Gray R, Parish S, Collins R, Warrell DA, et al. Oxford Textbook of Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Gray WA, Chaturvedi S, Verta P. Investigators and the Executive Committees . Thirty-day outcomes for carotid artery stenting in 6320 patients from 2 prospective, multicenter, high-surgical-risk registries. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2009;2:159-66. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.823013.

- Smout J, Macdonald S, Weir G, Stansby G. Carotid artery stenting: relationship between experience and complication rate. Int J Stroke 2010;5:477-82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00486.x.

- Kallmayer MA, Tsantilas P, Knappich C, Haller B, Storck M, Stadlbauer T. Patient characteristics and outcomes of carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stenting: analysis of the German mandatory national quality assurance registry – 2003 to 2014. J Cardiovasc Surg 2015;56:827-36.

- Bonati LH, Dobson J, Featherstone RL, Ederle J, van der Worp HB, de Borst GJ, et al. Long-term outcomes after stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of symptomatic carotid stenosis: the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS) randomised trial. Lancet 2015;385:529-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61184-3.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group . MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20 536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3.

- International Carotid Stenting Study Investigators . Carotid artery stenting compared with endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis (International Carotid Stenting Study): an interim analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:985-97.

- Brott TG, Howard G, Roubin GS, Meschia JF, Mackey A, Brooks W, et al. Long-term results of stenting versus endarterectomy for carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1021-31. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1505215.

- Eckstein HH, Reiff T, Ringleb P, Jansen O, Mansmann U, Hacke W, et al. SPACE-2: A missed opportunity to compare carotid endarterectomy, carotid stenting, and best medical treatment in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenoses. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2016;51:761-5.

- Rosenfield K, Matsumura JS, Chaturvedi S, Riles T, Ansel GM, Metzger DC, et al. Randomized trial of stent versus surgery for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1011-20. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1515706.

- Nuffield Department of Population Health . Data Access and Sharing Policy for the Nuffield Department of Population Health 2016. www.ndph.ox.ac.uk/about/rdca_dataaccessandsharingpolicy_2016-08-26.pdf (accessed 10 April 2017).

Appendix 1 Trial flow diagram

Appendix 2 Hub-and-spoke model for ACST-2 in North East England

Appendix 3 Italian collaborators’ newsletter

Appendix 4 Randomisation

Appendix 5 One-month form

Appendix 6 One-year form

List of abbreviations

- ACST-1

- The first Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial

- ACST-2

- The second Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial

- CABG

- coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAS

- carotid artery stenting

- CEA

- carotid endarterectomy

- CSTC

- Carotid Stenosis Triallists’ Collaboration

- CT

- computed tomography

- CTSU

- Clinical Trial Service Unit

- EQ-5D

- EuroQol-5 Dimensions

- HTA

- Health Technology Assessment

- ICSS

- International Carotid Stenting Study

- MI

- myocardial infarction

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- NIHR

- National Institute for Health Research

- RCT

- randomised controlled trial