Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/201/02. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The draft report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Nefyn H Williams declares membership of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Primary Care, Community and Preventative Interventions Panel. Dyfrig A Hughes reports other grants from National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study and membership of the HTA Clinical Trials Board from 2010 to 2016, the HTA Funding Teleconference from 2015 to 2016 and the Pharmaceuticals Panel from 2008 to 2012. Eifiona Wood reports other grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Nadine E Foster declares membership of the HTA Primary Care, Community and Preventative Interventions Panel. David A Walsh reports grants from Pfizer Ltd and personal fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd outside the submitted work. Kika Konstantinou reports other grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Jaro Karppinen reports personal fees from lectures (Pfizer Ltd, Merck & Co., Inc. and ORION Pharma GmbH), personal fees from a scientific advisory board (Axsome Therapeutics Inc.) and personal fees from stocks (ORION Pharma GmbH) outside the submitted work. Stephane Genevay reports grants from AbbVie Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Pfizer Ltd, University Hospitals of Geneva, the Rheumasearch Foundation, Fondation de bienfaisance Eugenio Litta and Centre de Recherches outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Williams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Sciatica is a symptom defined as unilateral, well-localised leg pain, with a sharp, shooting or burning quality, which approximates to the dermatomal distribution of the sciatic nerve down the posterior lateral aspect of the leg, and normally radiates to the foot or ankle. It is often associated with numbness or paraesthesia in the same distribution. 1 Sciatica is an important clinical problem for the NHS. Although prevalence rates vary widely between studies, in a trial that used a clinical assessment to establish the presence of sciatica, the point prevalence in the general population aged 30–64 years was 4.8%. 2 Some cohort studies have found that most cases resolve spontaneously, with 30% of patients having persistent troublesome symptoms at 1 year, with 20% of the total out of work. 3,4 However, another cohort found that 55% still had symptoms of sciatica 2 years later, and 53% after 4 years (which included 25% who had recovered after 2 years but had relapsed again by 4 years). 5 Current care pathways in the NHS typically involve the prescribing of analgesia by the patient’s general practitioner (GP) and, if troublesome symptoms persist, referral for physiotherapy either in community-based physiotherapy services, musculoskeletal interface services or secondary care spinal clinics. If pain persists, patients are referred for more invasive treatment, such as epidural corticosteroid injection and eventually disc surgery. 6 However, the evidence for most of these non-surgical treatments is poor;7 new treatment strategies are needed. At present between 5% and 15% of patients with sciatica undergo disc surgery. 3,4 In the NHS in England in 2013/14, 8330 lumbar discectomies were performed. 8 Based on a Dutch trial that indicated that the cost of sciatica to society represents 13% of all back pain-related costs, the annual impact on the UK economy is £268M in direct medical costs and £1.9B in indirect costs (inflated from 1998 figures). 9

Sciatica caused by lumbar nerve root pain usually arises from a prolapsed intervertebral disc,3 not only from compression of the nerve root,10 but also the release of proinflammatory factors from the damaged disc. 11,12 Internal disc rupture that does not result in prolapse can also induce disabling radicular pain,13 and the degree of disc displacement, nerve root enhancement and neural compression on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not correlate with sciatic symptoms. 14 Corticosteroids have been used in an attempt to reduce the inflammation of the affected nerve root. Intramuscular corticosteroid injections have been tried, but two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing them with placebo have found no evidence of efficacy. 15 Injection of corticosteroid into the epidural space should increase the amount of steroid reaching the affected nerve root, and it is a commonly used intervention in the NHS. However, systematic reviews of epidural steroid injections have reached conflicting views with regard to their efficacy compared with placebo, and their effectiveness compared with other treatments. 7,15–17 They also require to be administered by a specialist, usually as a hospital day case procedure, which increases their cost of administration. Other, less invasive, treatments to reduce inflammation in the affected nerve root are needed. The most important proinflammatory factor released from the prolapsed intervertebral disc is tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). 11,12 The monoclonal antibodies infliximab and adalimumab (Humira®; AbbVie Ltd, Maidenhead, UK) target TNF-α and are increasingly used to control inflammatory disease such as psoriasis, Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. These so-called ‘biological agents’ bind specifically to TNF-α receptors on the cell surface and modulate biological responses that are induced or regulated by TNF-α, including the inflammatory process. 18 They may also have beneficial effects on the inflamed nerve root in sciatica,19 and have the additional advantage of being administered by intravenous (infliximab) or subcutaneous (adalimumab) injection in a hospital outpatient clinic, rather than by epidural injection as a hospital day case.

This research followed the recommendations of a Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-funded systematic review of management strategies for sciatica. 20 In this review the clinical effectiveness of different treatment strategies for sciatica were compared simultaneously using network meta-analysis. Network meta-analysis allows treatment strategies to be ranked in terms of clinical effectiveness with an estimate of the probability that each strategy is best, and provides estimates for all possible pairwise comparisons, based on both direct and indirect evidence. In terms of overall recovery or global effect, biological agents had the highest probability (0.5) of being best, with an odds ratio (OR) compared with inactive control of 16, but with very wide 95% credible intervals (CrIs) of 0.6 to 1002, reflecting the small number of included studies and lack of data that were available to inform these effect estimates. A CrI is a Bayesian confidence interval (CI). There were large but non-statistically significant effect estimates in favour of biological agents compared with the other treatment strategies, including traction (OR 13, 95% CrI 0.4 to 943), exercise therapy (OR 15, 95% CrI 0.4 to 1085) and passive physical therapies (OR 14, 95% CrI 0.5 to 975). In terms of pain intensity, biological agents had the second highest probability of being best (0.2), and were found to be statistically significantly better than the inactive control, but with wide CrIs, with a weighted mean difference (WMD) of –22 (95% CrI –36 to –8) compared with an opioid WMD of –31 (95% CrI –53 to –9) and a non-opioid analgesia WMD of –18 (95% CrI –33 to –2).

Following this HTA review we updated the literature search of biological agents for sciatica (from inception to February 2012). 21 We identified seven RCTs, one non-RCT and one historical cohort trial. We combined the results of six RCTs22–27 and one non-RCT28 comparing biological agents with placebo in meta-analyses. We found that biological agents resulted in better global effects in the short term (around 6 weeks’ follow-up) (OR 2.0, 95% CI 0.7 to 6.0), medium term (around 6 months’ follow-up) (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.0 to 7.1) and long term (≥ 12 months’ follow-up) (OR 2.3, 95% CI 0.5 to 9.7); improved leg pain intensity in the short term (WMD –13.6, 95% CI –26.8 to –0.4) and medium term (WMD –7.0, 95% CI –15.4 to 1.5), but not the long term (WMD 0.2, 95% CI –20.3 to 20.8); and improved Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) score in the short term (WMD –5.2, 95% CI –14.1 to 3.7), medium term (WMD –8.2, 95% CI –14.4 to –2.0) and long term (WMD –5.0, 95% CI –11.8 to 1.8). It should be noted that there was heterogeneity in the leg pain intensity and ODI results, and improvements were no longer statistically significant when studies were restricted to RCTs. There was a reduction in the need for disc surgery, which was not statistically significant, limited evidence for improved employment outcomes and no difference in the number of adverse effects. There was limited evidence that a biological agent was superior to intravenous corticosteroids (one historical cohort trial),29 but not compared with epidural corticosteroid (two RCTs). 27,30 We concluded that there was some evidence of efficacy, but a paucity of evidence for clinical effectiveness for biological agents. Although there was insufficient evidence to change practice, there was sufficient evidence to suggest that a definitive RCT was warranted.

As part of the HTA review of management strategies for sciatica,20 a decision-analytic model was developed to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of these different strategies. Three different treatment pathways were compared. The first pathway was primary care treatments alone (including the categories usual care, activity restriction, advice, non-opioid and opioid analgesia). The second pathway was stepped care starting with primary care treatments and, for those who did not improve, intermediate care treatment (exercise therapy, passive physical therapy, traction, manipulation, acupuncture and biological agents), epidural steroid injections then finally disc surgery. The third pathway was immediate referral to disc surgery following failed primary care management. The stepped care pathway was the most effective, with the most successful treatment strategy being non-opioid analgesia in primary care, followed by biological agents in intermediate care, followed by epidural corticosteroid injection and disc surgery. The place for biological agents in the therapeutic pathway is as a therapeutic option to be used by intermediate care services in patients for whom primary care treatment has failed, with the potential to reduce the need for more invasive treatments.

In summary, biological agents have the potential to reduce inflammation and nerve root pain in patients when primary care management has not relieved symptoms, but might they benefit the NHS? Apart from the economic model developed for the HTA review of management strategies for sciatica,31 there have been no economic evaluations of these agents. Although they might be beneficial for patients with sciatica, these agents are expensive costing £352 for 40 mg of adalimumab and £420 for 100 mg of infliximab. 32 Adalimumab is administered by subcutaneous injection, but infliximab confers the additional expense of intravenous injection. We intended to use adalimumab because of its ease of administration and, in order to provide a therapeutic effect lasting 1 month, two subcutaneous injections would be given 2 weeks apart. In order to initiate a rapid response, we used the typical starting dosage when treating psoriasis or Crohn’s disease of 80 mg followed by 40 mg. 18 Despite their cost, they may be cost-effective if shown to be sufficiently clinically effective and/or they reduce the need for more expensive treatments such as disc surgery, the average unit cost of which is between £3676 and £4971. 32 When the patent for adalimumab expires, it may result in the development of cheaper biosimilar drugs that can be used in its place. From searches of databases of current trials (inception to November 2013), we have not identified any large RCTs with a concurrent economic evaluation in a NHS setting.

Trial objectives

-

To evaluate the clinical effectiveness of subcutaneous injections of adalimumab plus physiotherapy compared with a placebo injection of 0.9% sodium chloride plus physiotherapy for patients with sciatica who have failed first-line primary care treatment. Potential participants were planned to be identified during primary care consultation, after referral to musculoskeletal service or following a practice database search.

The primary effectiveness outcome was sciatica-related health status using the ODI. 33 Secondary effectiveness outcomes included pain intensity, location, duration and anticipated trajectory; the risk of poor outcome; psychological measures, including fear-avoidance beliefs, self-efficacy, anxiety and depression; employment status; and adverse effects.

-

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of subcutaneous injections of adalimumab plus physiotherapy compared with a placebo injection of 0.9% sodium chloride plus physiotherapy for patients with sciatica who have failed first-line primary care treatment from a health service and personal social care perspective. The primary economic outcome was the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. QALYs would be estimated by administering the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, 5-level version (EQ-5D-5L)34 at each follow-up visit.

Trial flow

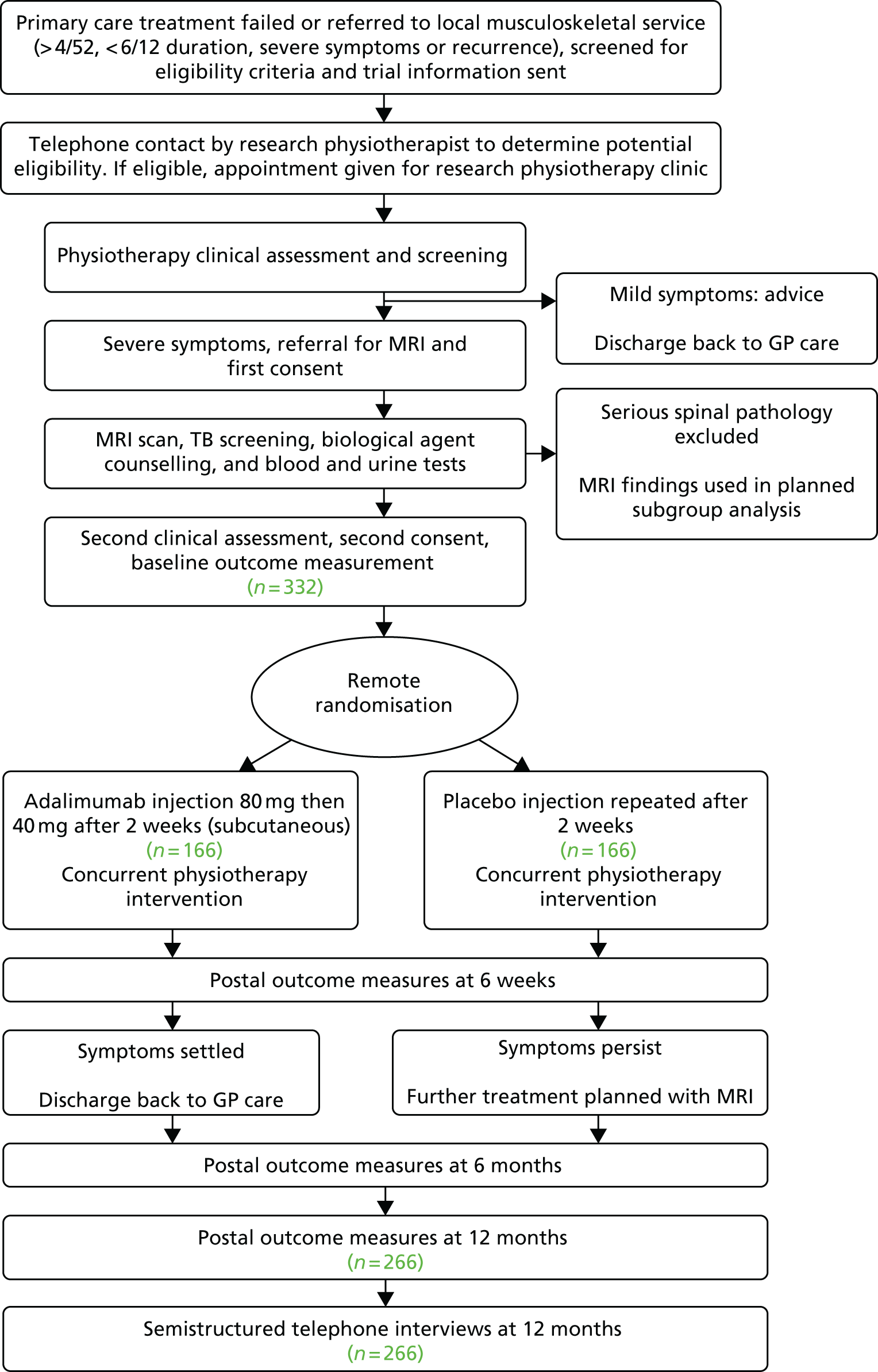

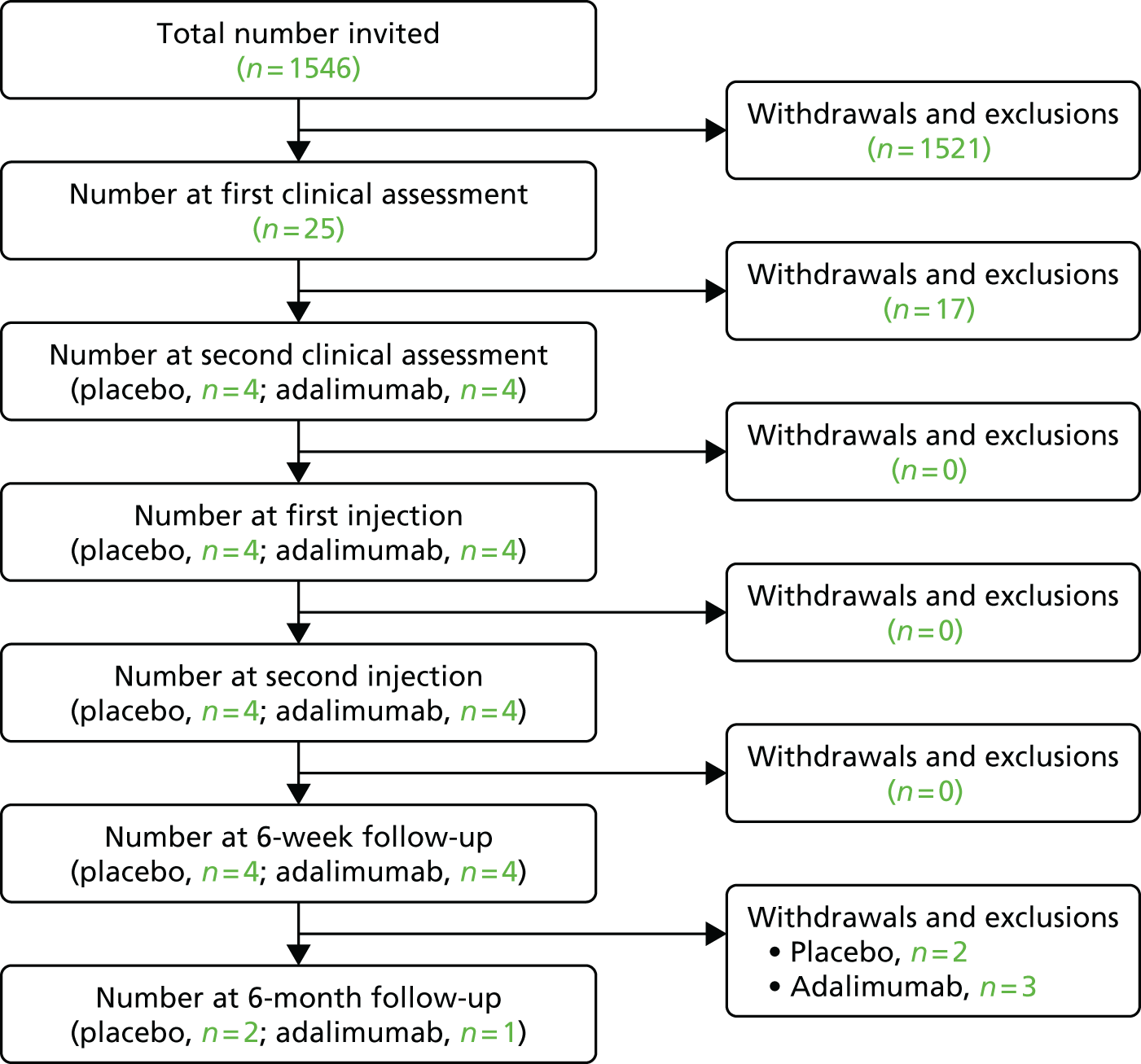

The flow chart to show the different stages of the trial is presented in Figure 1. The flow chart to show the experience of the participant through the trial is in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow chart. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TB, tuberculosis.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow chart. CXR, chest radiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TB, tuberculosis.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

Pragmatic, multicentre RCT with blinded participants, clinicians, outcome assessment and statistical analysis with concurrent economic evaluation and internal pilot.

Main centres

The RCT was planned to recruit from sites overseen by five collaborating centres in North Wales, London, Keele, Nottingham and Cardiff.

Selection and withdrawal of participants

Each collaborating centre oversaw one or more treatment sites that were delegated responsibility for delivering the interventions. Each treatment site had a number of patient identification centres, which consisted of general medical practices and local musculoskeletal services. The target population was adults with suspected sciatica for whom primary care treatment had failed. This was defined as troublesome symptoms (e.g. back and leg pain, pins and needles, numbness in leg, weakness), persisting for > 4 weeks and < 6 months. As the recruitment process took at least 4 weeks before participants were randomised, we did not have a lower time limit for duration of symptoms when identifying the target population and had an upper time limit of 20 weeks. These patients were identified in three ways:

-

by their GP

-

following a search of the general practice patient record database

-

after referral to local musculoskeletal services.

General practitioner referral

Patients identified during the primary care consultation with suspected sciatica were provided with information about the trial and invited, if interested, to return the reply slip to the research team in the pre-paid envelope. In North Wales and Keele, the primary care database displayed ‘pop-up’ screen messages to remind GPs about the study when potential patients were consulted.

Following a search of the general practice patient record database

Potential participants were identified by regular searches of the general practice patient record database by the practice management staff, directed by research officers from either the Health and Care Research Wales workforce or the local Clinical Research Network in England. The database was searched for diagnostic codes for sciatica. Participants were excluded if they had a known serious spinal pathology or a contraindication to adalimumab injection, such as serious infection [e.g. active or latent tuberculosis (TB)], transplanted organ, demyelinating disorders, malignancy, cardiac failure, low white blood cell count or pregnancy. Those identified as potentially eligible were invited to participate by a written invitation from their GP on the practice’s headed notepaper, and hand signed by a GP. Those who were interested returned the reply slip to the research team in the pre-paid envelope.

Local musculoskeletal services

Potential participants with suspected sciatica were also identified from referrals to local musculoskeletal services. Those identified were invited to participate by a written invitation from the local service on headed notepaper. Those who were interested returned the reply slip to the research team in the pre-paid envelope.

The centres in North Wales, Keele and Cardiff planned to identify and recruit participants in three ways: by their GP, following a search of the general practice patient record database or after referral to local musculoskeletal services. Nottingham and London planned to recruit and identify participants who had been referred to their local musculoskeletal services.

Telephone contact by the research physiotherapist

All those who had contacted the research team to state that they were interested in participating were sent a participant information sheet and were contacted by telephone by the research physiotherapist. The telephone call determined if they had unilateral leg pain and, if back pain was present, that leg pain intensity was worse than, or as bad as, the back pain. It also determined whether or not symptoms had persisted for > 20 weeks (to allow participants to be within the 6-month limit at randomisation). Finally, the telephone call allowed them to discuss any questions that they may have had about the study or their symptoms.

Research clinic

Those who satisfied the eligibility criteria were given an appointment slot in a research clinic run by research physiotherapists. At this research clinic all potential participants were assessed by the research physiotherapist for eligibility. Eligible participants who gave initial consent were registered and provided with a unique participant identification number. The following data were recorded on case report forms:

-

demographic details such as age, sex, height and weight

-

clinical findings such as pain location, pain duration, other presenting complaints, straight-leg raise test (left and right), femoral stretch test, muscle power, pinprick and light-touch sensation, quadriceps and Achilles tendon reflexes.

The research physiotherapist arranged for the participant to have the following blood tests taken by the phlebotomist to exclude haematological and biochemical abnormalities: full blood count, urea and electrolytes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, liver function test and glycosylated haemoglobin. The participant received TB screening in accordance with local practice and biological agents counselling. The research physiotherapist then arranged an appointment for MRI to exclude serious spinal pathology. All of these tests were completed within 2–3 weeks of the initial clinic visit and were recorded on the case report forms. The presence or absence of a disc prolapse on MRI was not to be used as an inclusion criterion, because the degree of disc displacement, nerve root enhancement or neural compression found on MRI does not correlate with sciatic symptoms. 14 MRI was reported by the local radiologist using a trial-specific standard operating procedure. The initial report stated whether or not the participant had serious spinal pathology that required a different treatment. A full MRI report was available only after completion of the study. Individual results were made available if a report was needed in an emergency, or if a spinal surgery referral was contemplated.

The research physiotherapist ensured that the participant received all the required tests. If there was any issue that required action, then the participant’s referring GP or musculoskeletal clinician was informed. When MRI had excluded serious spinal pathology, participants were contacted by the research physiotherapists either by telephone or post to attend the research clinic, where they received a second clinical assessment by the research physiotherapist, 2–3 weeks after their initial visit, to assess if they were still eligible. If they were still eligible, further consent was obtained for trial entry and randomisation when they were provided with a unique participant identification number. Table 1 shows the schedule of forms and procedures.

| Time point | Study period | Follow-up period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolment | Randomisation (within 2–3 weeks of registration) | Treatment visit 1 (within 3 days of randomisation) | Treatment visit 2 | 6 weeks | 6 months | 12 months | |

| Eligibility | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Registration to trial | ✗ | ||||||

| FBC | ✗ | ||||||

| Urine pregnancy test | ✗ | ||||||

| U&E | ✗ | ||||||

| TB screening | ✗ | ||||||

| MRI | ✗ | ||||||

| MRI reportinga | ✗a | ✗a | |||||

| Eligibility confirmed | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Randomisation | ✗ | ||||||

| Subcutaneous injection of allocated treatment | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Physiotherapy treatment | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| ODI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| RMDQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| SBI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| STarT Back Screening Tool | ✗ | ||||||

| PSEQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| HADS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| TSK | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| RUQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Pain outcome | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Manikin pain diagram | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Pain duration | ✗ | ||||||

| Pain trajectory | ✗ | ||||||

| Days of work | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Global assessment of change | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Adverse events | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Clinical features of sciatica.

-

Leg pain worse or as bad as back pain, elicited by asking the participant.

-

Unilateral leg pain approximating a dermatomal distribution (contralateral buttock pain permitted if it did not succeed the inferior gluteal margin), obtained by asking the participant.

-

One of the following:

-

positive neural tension test, such as straight-leg raise test restricted to < 50° by leg pain; positive femoral stretch test; muscle weakness or loss of tendon reflex affecting one myotome

-

loss of sensation in a dermatomal distribution.

-

-

Persistent symptoms for at least 4 weeks and < 6 months despite first-line treatment in primary care, obtained by asking the participant.

-

Moderate to high severity (score of ≥ 30 points on the ODI). 33

Female partners of sexually active male participants had to use adequate contraception for at least 5 months after the last injection. Female participants were required to have had a negative urine pregnancy test within 2 weeks prior to randomisation, unless they were post menopause or had been sterilised. Sexually active male partners of female participants were also required to use adequate contraceptive methods. The researcher ensured that the risks, and consequences, of not using adequate contraception were fully understood by the participants and provided information and pathways as deemed necessary.

Exclusion criteria

-

Symptoms persisting for > 6 months (elicited by asking the participant).

-

A previous episode of sciatica in the last 6 months.

-

Unable to undergo MRI (e.g. magnetic metal implants, potential metallic intraocular foreign bodies, claustrophobia, extreme obesity), obtained from the medical records and by asking the participant.

-

Serious spinal pathology (including cauda equina syndrome, malignancy, recent fracture, infection or very large disc prolapse), which might require an urgent spinal surgery opinion, identified from participants’ previous medical history in their medical records or from MRI.

-

Incidental serious pathology identified by MRI (e.g. adrenal tumour).

-

Neurological deficit involving muscle weakness requiring an urgent spinal surgery assessment (e.g. foot drop).

-

Widespread pain throughout the body including the upper limb. 35 Pain was considered widespread when all of the following were present: pain in the left side of the body, pain in the right side of the body, pain above the waist and pain below the waist. Axial skeletal pain (cervical spine or anterior chest or thoracic spine or low back) had also to be present.

-

Prior use of biological agents targeting TNF-α within the previous 6 months obtained from the medical records and by asking the participant.

-

Previous lumbar spinal surgery, elicited from the medical records and by asking the participant.

-

Contraindications to adalimumab injection including serious infection such as active or latent TB, transplanted organ, demyelinating disorders, malignancy, cardiac failure, low white blood cell count, pregnancy (determined from the medical records, the results of investigations and by asking the participant).

-

Pregnant or breastfeeding (women must not breastfeed for at least 5 months after the last adalimumab injection).

-

Unable to communicate in English or Welsh.

-

Unable or unwilling to give informed consent.

Informed consent

At the initial physiotherapy clinic, the research physiotherapist determined preliminary eligibility, explained the nature of the trial and gave a repeat participant information sheet. The participant information sheet had been approved by the ethics committee and set out all of the key information, including the practicalities of the trial, the possible benefits and risks, and trial assessments. Participants were registered onto the trial and details were recorded on a database and a screening log at each of the trial treatment sites, and were assigned a unique participant identification number. Anonymised details labelled with the unique participant identification number were transferred to a separate database in the trials unit, which was used for recording all of the trial data. This ensured that the outcome measurement and statistical analysis would be performed blind to treatment allocation. All databases were password protected. The participant consent forms were stored in a locked filing cabinet in each treatment site. Clinical findings were recorded on case report forms.

Eligible participants who gave initial consent had blood tests to exclude haematological and biochemical abnormalities (full blood count, urea and electrolytes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, liver function test, glycated haemoglobin levels). They received TB screening, including plain chest radiography, biological agents counselling and MRI to exclude serious spinal pathology within 2–3 weeks of their initial visit. When MRI had excluded serious spinal pathology, and TB screening, a pregnancy test (in the case of eligible women) and biological agent counselling had been completed, participants attended a further appointment with the research physiotherapist. A second clinical assessment was performed and those who were still eligible were asked to complete a second informed consent form, approved by the ethics committee. In order to enter the RCT, the participant was randomised by the research physiotherapist using a remote web-based system. The treatment site sent a letter to each participant’s GP, informing them of their patient’s participation in the trial and requesting that the GP make a note of this in the patient’s record. In addition, GPs were asked to inform the trial team if they became aware that the participant had experienced an adverse event during the trial.

Three copies of the consent form were signed by the participant. The original was kept by the research team, one copy was kept by the participant and the third was filed in the participant’s hospital medical records. All participant information sheets, letters of invitation and consent forms were provided in Welsh and English in the two Welsh centres.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Participants who had given initial informed consent underwent MRI to exclude serious spinal pathology, but the presence or absence of a disc prolapse was not used as an inclusion criterion. The MRI scans were read and reported by a local radiologist, using a trial-specific standard operating procedure at each treatment site, who was independent of the trial team. Only results that showed serious pathology or suspected serious pathology were revealed to the research team, referring GP and the musculoskeletal clinician, who would then exclude the participant and refer for urgent assessment. Otherwise, the research team were informed that no serious spinal pathology was identified. The findings of MRI would be made available to the participant’s treating clinician only after completion of the study. Individual results were made available if a report was needed in an emergency, or if a spinal surgery or epidural injection referral was being contemplated, and were distributed to the clinical team, referring GP and the musculoskeletal clinician. The MRI findings were to be used in a planned a priori subgroup analysis. For clinical purposes, radiologists from each site provided a clinical report of the MRI. For the purpose of reporting standardised findings for research, two independent radiologists reported the MRI findings for all trial participants. The radiologists interpreted the report according to the MRI findings only.

Tuberculosis screening and biological agent counselling

The screening and counselling protocols used routinely by the rheumatology departments in each of the treatment sites were used and administered by an experienced rheumatology specialist nurse. All of the participating centres had access to either a specialist TB clinic or an infectious disease service, where any identified cases were referred and managed.

Second physiotherapy assessment

Participants attended a second appointment with the research physiotherapist 2–3 weeks after the initial appointment, after the MRI results had been reported and following TB screening and biological agent counselling. A second clinical assessment was performed and all the results of the tests performed were checked. If the participant remained eligible, a second consent form was completed. Participants completed a baseline questionnaire and were randomised using a remote web-based system. If they no longer fulfilled the criteria for trial entry, because their symptoms had improved at or below the 30-point threshold on the ODI, they were given advice about managing their remaining symptoms and discharged back to the care of their GP. Clinical findings were recorded on case report forms.

Registration

Once the first consent had been obtained, participants’ details were recorded on a database in the trial centre and each participant was assigned a unique participant identification number. Anonymised details labelled with the unique participant identification number were transferred to a separate database in the trials unit, which was used for recording all of the trial data. All databases were password protected. The participant consent forms were stored in a locked filing cabinet in each treatment site. Participants’ GPs were informed in writing about their participation in the trial.

Randomisation

After completion of the second consent form and once baseline outcome measures had been collected, participants were individually randomised. Randomisation to the Subcutaneous Injection of Adalimumab Trial compared with Control (SCIATiC) was achieved by secure web access to the remote randomisation system at the trials unit. This system was maintained and monitored independently of the trial statistician and any trial staff who needed to remain blind to the treatment allocation. In order to protect against subversion, while ensuring that the trial maintained good balance to the allocation ratio of 1 : 1 both within each stratification variable and across the trial, the randomisation was performed using a dynamic adaptive randomisation algorithm. 36 Participants were stratified by (1) treatment centre and (2) presence of neurological signs (motor weakness or sensory loss). The research physiotherapist who obtained informed consent requested the randomisation code from the web-based randomisation system, the result of which was e-mailed to the pharmacy and the rheumatology nurse, but not the research physiotherapist. The dispensing pharmacist logged and dispensed the appropriate injection in line with Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guidelines. The injection was given on the day of randomisation; if this was not possible, a further appointment was arranged by the research physiotherapist so that the treatment could be given within 3 days from randomisation.

Withdrawal of participants

Withdrawal from the trial did not affect participants’ medical care, something that was emphasised in the participant information sheet. Failure to complete any one follow-up assessment did not constitute formal withdrawal from the trial, and, unless participants requested complete withdrawal of their data, data were used to impute values for the analysis. The imputation of missing values ensured that the data set was utilised to its full power. The full imputation details were prespecified as part of the statistical analysis plan.

Expected duration of trial

We planned to recruit participants over a 20-month period and to follow them up for 12 months.

Subcutaneous injections

All participants were randomised to receive two doses of subcutaneous injection, 2 weeks apart, into the posterior thigh. The intervention group received 80 mg of adalimumab followed by 40 mg,18 in order to achieve a therapeutic dose of adalimumab for a period of 4 weeks. The control group received an equivalent volume of 0.9% sodium chloride.

Injection process

The injections were prescribed by a consultant rheumatologist and administered by a rheumatology nurse experienced in the administration of these injections. The first injection was given on the same day as randomisation; if this was not possible, a further appointment was arranged by the research physiotherapist so that the treatment could be given within 3 days of randomisation. It was not possible to make the adalimumab and placebo syringes indistinguishable in appearance, nor was it possible to blind the pharmacy or the rheumatology nurse who administered the injections. Blinding of participants and the other clinicians was maintained using the following strategies. The rheumatologist wrote a prescription for ‘SCIATiC trial injection’ and was kept blind to treatment allocation. The research physiotherapist who obtained informed consent requested the randomisation code from a web-based randomisation system. The randomisation code was not sent to this physiotherapist, but was e-mailed to the pharmacy and the rheumatology nurse. The rheumatology nurse collected the injection from the pharmacy, which was transported in an undistinguishable box containing the adalimumab inside its original packaging or the 0.9% sodium chloride-containing ampoules. Communication between the participant and rheumatology nurse concerning the injection was kept to a minimum, and the rheumatology nurse administered the injections into the participant’s posterior thigh. The research physiotherapist was not present and did not communicate with the rheumatology nurse about the injection. In addition, in order to provide reassurance that other clinicians were not present, a log was kept of all people present in the room when each injection was administered. All research staff received full training on the blinding procedures. In order to assess whether or not blinding had been maintained, the participants were asked to complete a five-point Likert scale that asked if the participant considered the treatment to be:

-

definitely in the 0.9% sodium chloride injection group

-

more likely to be in the 0.9% sodium chloride injection group

-

equally likely to be in the 0.9% sodium chloride injection group or the adalimumab injection group

-

more likely to be in the adalimumab injection group

-

definitely in the adalimumab injection group.

Concurrent physiotherapy

Physiotherapy is usually considered normal practice for those participants who fail to improve with GP care alone. In this trial we aimed to investigate the clinical effectiveness of adalimumab in addition to physiotherapy. Current evidence on physiotherapy interventions for participants with sciatica indicates that specific exercise approaches (directional preference-based exercises or ‘McKenzie’ exercises based on certain spinal movements with or without manual therapy techniques) seem to relieve pain. 37 There was also evidence that exercise-based physiotherapy treatment added to GP care was beneficial. 38 Regimes including strengthening exercises of the lumbar and pelvic muscles also show some promise in terms of improvements in this group of participants. In this trial, both groups received a concurrent course of physiotherapy intervention that could be described as ‘best conservative care’. It was delivered in local physiotherapy departments by ‘treating’ physiotherapists and not by the ‘research’ physiotherapists who were carrying out the assessments of eligibility and randomisation. The physiotherapy intervention consisted of a package of directional preference (McKenzie), strengthening exercises or other exercises,37,38 and manipulative techniques that had been determined by consensus using a panel of extended scope physiotherapists. Treatments were intended to take into account and address participants’ individual needs, including clinical monitoring; appropriate advice and reassurance; assessment of psychosocial obstacles to recovery, such as excessive worrying or unhelpful beliefs about physical activity; and encouragement of appropriate, gradual return to full function, including work when applicable. The first session was expected to last approximately 45 minutes, with subsequent sessions lasting 30 minutes each. The therapy sessions were to be provided over a period of 12 weeks. The number of sessions provided would be determined by participant and therapist preference, and also response to treatment. We captured and described these aspects of physiotherapy treatment as part of the trial. The physiotherapy treatment started at the same time as the injection intervention in both arms of the trial. Participants were discouraged from receiving any other NHS-based co-intervention until this physiotherapy treatment had finished.

Clinical management of persistent symptoms

The protocol was designed such that, once the participants had completed their course of physiotherapy, and symptoms had settled or were improving, then no further intervention would be organised. They were to be discharged to the care of their GP and followed up by the research team. If troublesome symptoms persisted, then further treatment could be planned, as appropriate, by referral to musculoskeletal interface clinics or secondary care specialists according to local arrangement in each of the centres. The plans for further treatment were at the discretion of the treating clinicians and could include epidural corticosteroid injections or referral for disc surgery. The full result of MRI was to be made available if a spinal surgery referral was contemplated. All additional treatments were recorded in detail in a case report form.

Internal pilot trial

The pilot built on previous research in this participant group undertaken by team members,20,21,30,39 which had already provided information on trial administration, the characteristics of sciatica participants and the effects of biological treatments from previous studies. The internal pilot was designed to rehearse the procedures and logistics to be undertaken in the main trial. It was designed to assess the feasibility of the arrangements for delivering the interventions, recruitment rate and initial retention rate. The internal pilot would be based on the first 50 participants recruited into the trial. We planned to start recruitment in two centres (North Wales and London) and then to roll out recruitment in the other three centres over the following 3 months. We expected the recruitment rate to build up over the first 3 months to the target rate of four participants per collaborating centre per month. We anticipated that this would take 7 months. The indicative stopping criteria at the end of this internal pilot were recruitment, which failed to reach 80% of the planned recruitment rate target, dropouts up until the 6-week postal questionnaire assessment exceeding 20% or more than one centre failing to commence recruiting. Any procedural changes identified in the pilot would be implemented across all trial sites subject to ethics approval of the appropriate major amendment. Data from participants in the internal pilot would be automatically rolled into the main trial data unless the Trial Management Group (TMG) believed that data were incompatible with the remaining data. No interim analysis at the primary end point (1 year) was proposed and, therefore, this internal pilot would not affect the overall power of the trial. Wittes and Brittain’s40 method would be used for sample size recalculation if required.

Primary outcome

The primary clinical outcome was back pain-specific disability measured using the ODI33 at 12 months. The primary economic outcome was the incremental cost per QALY gained, estimated by administering the EQ-5D-5L34 at each follow-up visit.

Outcome measures

Condition-specific outcomes

-

Back pain-specific disability using the ODI. 33

The ODI is an outcome assessment tool that is used to measure a participant’s impairment and quality of life (i.e. how badly the pain has affected their life). The participant questionnaire contains items concerning intensity of pain, lifting, ability to care for oneself, ability to walk, ability to sit, sexual function, ability to stand, social life, sleep quality and ability to travel. Each topic category is followed by six statements describing different potential scenarios in the participant’s life relating to the topic. The participant then checks the statement that most closely resembles their situation. Each question is scored on a scale of 0–5, with the first statement being zero and indicating the least amount of disability and the last statement scoring 5 and indicating the most severe disability. The index is converted to a percentage score from 0 to 100. Zero is equated with no disability and 100 with maximum disability. It was used at the first clinical assessment to assess eligibility and also at the second clinical assessment to confirm eligibility. If recruited onto the trial, this score was used as the baseline measurement. It would also be measured at follow-up after 6 weeks, and at 6 and 12 months.

-

Leg pain-related functional disability using the leg pain version of the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ). 41,42

The RMDQ is a measure of disability in which greater levels of disability are reflected by higher numbers on a 24-point scale. The RMDQ is a self-administered outcome measure. Participants are asked to read the list of 24 sentences and place a tick against appropriate questions based on how they feel each sentence describes them on that day. If the sentence does not describe their symptoms that day, participants are asked to leave the space next to the sentence blank. The RMDQ is scored by adding up the number of items checked by the participant. The score can therefore vary from 0 to 24 points. If a participant indicates in any way that an item is not applicable to them, the item is scored ‘no’ (i.e. the denominator remains 24). It was measured at baseline and at 6 weeks’ and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

-

Leg pain interference using the Sciatica Bothersomeness Index. 43

This is an index based on participants reporting symptoms that reflected the trouble the participant is going through with his/her sciatica symptoms. The index included self-reported ratings of symptom intensity of leg pain; numbness or tingling in the leg, foot or groin; weakness in the leg/foot; or back or leg pain while sitting. Each symptom item is rated on a scale from 0 to 6, with 0 being not bothersome, 3 somewhat bothersome and 6 extremely bothersome. It was measured at baseline and at 6 weeks’ and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

-

Pain location using a pain manikin. 44

This is a picture of a human figure (manikin) on which pain is indicated by the participant and can be used to measure musculoskeletal pain. It was used at baseline, 6 weeks’, and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

Generic outcomes

-

Health utility using the EQ-5D-5L. 34

This is a participant-completed index of health-related quality of life, which gives a weight to different health states. It consists of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each has five levels of severity (no problems/some/moderate problems/extreme problems and unable to). It was used at baseline and at 6 weeks’ and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up. It allowed the calculation of QALYs, using the area under the curve method, which would be used as part of the economic analysis.

-

Global assessment of change since baseline.

The global assessment of change is a measure of changes in levels of pain over a set time period. It was measured at 6 weeks’ and at 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

Psychological outcomes

-

Anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. 45

This is a participant-completed outcome measure of anxiety and depression. It is designed to measure anxiety and depression in participants with physical health problems. It has seven items related to common symptoms of anxiety and seven items for depression. Participants are asked whether they experience the symptom definitely, sometimes, not much or not at all. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale was designed for use in the hospital setting but has been used successfully with the general population. It was used at baseline and at 6 weeks’ and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

Use of health-care and social-care services

Employment

-

Questions on employment status, work absence, sick certification and self-certification.

These were used at baseline and at 6 weeks’ and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

Process measures (potential predictors and mediators of outcome)

Risk of persistent disabling pain was assessed using the following tools:

-

STarT Back Screening Tool. 48

This screening tool assesses patients’ risk of persistent disabling pain. Patients’ risk subgroup (low, medium or high risk) has been shown by team members to be predictive of outcomes, including patients with back pain and with suspected sciatica. This was measured at baseline only.

-

Pain trajectory based on a single question. 49

This question is used to classify low back pain duration and asks ‘How long is it since you had a whole month without any back pain?’. There are seven discrete response categories: < 3 months, 3–6 months, 7–12 months, 1–2 years, 3–5 years, 6–10 years and > 10 years. This shows that recalled duration of pain is a predictor of outcome in patients with low back pain, independent of baseline severity and psychological status.

-

Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ). 50

The PSEQ is a 10-item questionnaire, developed to assess the confidence people with ongoing pain have in performing activities while in pain. The PSEQ is applicable to all persisting pain presentation. It covers a range of functions, including household chores, socialising and work, as well as coping with pain without medication. It was used at baseline and at 6 weeks’ and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

-

Fear of movement using the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia. 51

The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia is a 17-item checklist that is used to measure the fear of movement (re)injury related to chronic back pain. The scale is based on the model of fear avoidance, fear of work-related activities and fear of movement/reinjury. It was used at baseline and at 6 weeks’ and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

Follow-up

The questionnaires followed best practice in their design, to maximise response rate. The baseline questionnaire was administered by the research physiotherapists and completed by the participant. We planned to send follow-up postal questionnaires at 6 weeks, and at 6 and 12 months. Non-responders were to be sent an additional copy of the questionnaire. Persistent non-responders were to be contacted by telephone in order to collect a minimum data set. We planned to contact all participants by telephone 2 weeks after the 12-month questionnaire was sent. This would allow us to collect a minimum data set from non-responders, and to conduct a a brief semistructured interview with all participants asking about their overall experience of the trial and subsequent follow-up treatment. Blinding to treatment allocation would be maintained during these telephone interviews. Once again, in order to assess if blinding had been maintained, participants would be asked to complete a five-point Likert scale about which treatment group they believed that they were in.

Assessment of safety

As part of site initiation, training included an overview of possible side effects/potential adverse reactions associated with adalimumab.

Recording adverse events and adverse reactions

All trial staff and clinicians in contact with trial participants were responsible for noting adverse events reported by participants and making them known to appropriate medical staff. Trial participants were encouraged from the outset to contact the research team at the time that an event occurred. Participants were given a leaflet or card containing a contact address and telephone number. All adverse events, including non-serious adverse events, were recorded in the participant’s medical records and on their case report form. All adverse events were reported up to 1 month after the conclusion of the physiotherapy intervention. Adverse events included:

-

an exacerbation of a pre-existing illness

-

an increase in frequency or intensity of a pre-existing episodic condition

-

a condition (even though it may have been present prior to the start of the trial) detected after trial drug administration

-

continuous persistent disease or symptoms present at baseline that worsened following administration of the trial treatment.

The following were not included as adverse events:

-

medical or surgical procedures in which the condition that led to the procedure was the adverse event

-

pre-existing disease or conditions present before treatment that did not worsen

-

overdose of medication without signs or symptoms.

Recording serious adverse events and serious adverse reactions

The definition of a serious adverse event was any medical event that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening (refers to an event during which the participant was at risk of death at the time of the event; it does not refer to an event that might have caused death had it been more severe in nature)

-

required hospitalisation, or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent/significant disability or incapacity

-

was a congenital abnormality or birth defect.

Serious adverse events also included were other important medical events that, based on appropriate medical judgement, may have jeopardised the participant and may have required medical or surgical intervention.

Any serious adverse events and serious adverse reactions were recorded in the ‘Investigator Site File’ and the ‘Trial Master File’.

Statistics

Sample size

From the WMD in our previous meta-analysis,21 we found a relative improvement of 8 points in the ODI at 6 months’ follow-up in the group receiving biological agents compared with placebo, with a standard deviation of 16 points, giving an effect size of 0.5. In order to detect a more conservative effect size of 0.4 with 90% power, with a significance level of 5% for a two-tailed t-test, a sample size of 133 in each treatment group was needed. We aimed for a 90% return rate of the final questionnaires but, for a more conservative retention rate of 80%, 332 participants needed to be recruited. If, as is likely, there was any correlation between the baseline and outcome measure, the size of effect detectable would be smaller (or the power to detect a 0.4 effect enhanced).

Recruitment rate

Calculations of recruitment rates for SCIATiC were based on data available from an observational study, led by co-applicants at Keele, which recruited adult patients seeking treatment in primary care for low back-related leg pain including sciatica [Assessment and Treatment of Leg pain Associated with the Spine (ATLAS) trial cohort]. 39 The ATLAS study recruited 609 patients from 17 general medical practices (approximate total adult population of 90,200) over 24 months. Analysis of the recruitment data shows that 219 (36%) participants in this cohort had sciatica with pain in one leg only (with > 80% diagnostic confidence,) with a RMDQ score of > 7 points (equivalent to an ODI score of ≥ 30 points). On average, per month, 86 potential participants were identified by GPs and referred to the ATLAS study, 54 attended the physiotherapy-led research clinic and 25 gave consent and were eligible for the study, nine of whom had a clinical diagnosis of sciatica (spinal nerve root pain) satisfying the conditions described in Inclusion criteria and Exclusion criteria in terms of disability score and diagnostic confidence. Based on these figures and taking into account that in the ATLAS study cohort approximately nine participants per month were recruited, and making the assumption that half this number would consent to be randomised in a RCT, our target rate of recruitment was four participants per collaborating centre per month, with centres covering similar sized populations. For SCIATiC, North Wales, Keele and Cardiff aimed to recruit from GP practices with a combined registered population of at least 100,000 per centre.

Data analysis

All data were anonymised and coded so that data collection and statistical analysis were performed blind to treatment allocation. The code would be broken only after the primary analysis had been completed. The analysis would be performed on a ‘treatment as allocated’ principle to ensure protection against unintended bias. The data would be fully imputed using a multiple imputation by chain equations approach52 in line with a predefined statistical analysis plan to minimise data loss as a result of missing values or time points. Participants who needed to be referred for disc surgery would be labelled as ‘treatment failures’ and their last test results prior to surgery would be carried forward in the analysis. Sensitivity analyses (best case/worst case) would be performed to assess the influence of different imputation assumptions. All trial reporting was Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials53 compliant.

Primary analysis

The main outcome variable was the ODI measured at 12 months. A linear mixed-model approach for repeated measures would be used to assess the effects of time and group, while time × group effects would further describe and explain the overall finding (the interaction term would assess whether or not the effect of the intervention was the same at each time point). The use of a linear mixed model for analysis should take care of missing data; however, if imputation was required, then the multiple imputation by chain equations approach described would have been used. This model would be fully defined in the statistical analysis plan prior to all analyses. This statistical analysis plan would be approved by all lead investigators and site principal investigators (PIs), and available for comment by the independent committees prior to sign-off.

Secondary analysis

Secondary continuous outcome variables would be assessed in a similar way to the primary outcome variable, with the exception of time to referral for surgery, which would be measured from trial entry (this is the date of second consent) and analysed using Kaplan–Meier survival analyses and the log-rank test. Dichotomous variables would be explored using logistic regression. These analyses would be repeated using prespecified participant subgroups (including the presence of neurological deficit on entry to the trial and MRI findings). Subgroups would be defined within the statistical analysis plan prior to the analyses beginning.

Economic analysis

The health economic analysis would adopt the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services, with the inclusion of indirect costs (e.g. time off work) as a secondary analysis. Costs included those of treatment, tests, procedures and investigations, contact with primary and secondary care services and personal social services. Resource use would be obtained from participants’ self-reporting of resource use, captured by questionnaire administration. 46,47 Unit cost data would be obtained from standard sources54 and other resources such as the British National Formulary. 32 The primary economic outcomes would be the incremental cost per QALY gained, estimated by administering the EQ-5D-5L at each follow-up point. The number of QALYs gained by each participant would be calculated as the area under the curve, using the trapezoidal rule, applying the UK tariffs and corrected for baseline utility score. When appropriate, missing resource use or health outcome data would be imputed. 55 Non-parametric bootstrapped 95% CIs would be estimated (10,000 replicates). Stratified cost-effectiveness analyses would be conducted on important, prespecified participant subgroups. Total costs would be combined with QALYs to calculate the incremental cost–utility ratio of the package of adalimumab plus physiotherapy compared with a 0.9% sodium chloride injection plus physiotherapy. Estimates of incremental cost–utility ratios would be compared with the £20,000–30,000 per QALY threshold of cost-effectiveness, and a range of one-way sensitivity analyses would be conducted to assess the robustness of the analysis. Multivariate sensitivity analyses would be applied when interaction effects were suspected. The joint uncertainty in costs and benefits would be considered through the application of bootstrapping and the estimation of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. 56

Trial management

Trial Management Group

Individuals responsible for the day-to-day running of the trial were included in a TMG, which included the chief investigator, lead investigators, PIs, trial manager, statistician, health economist, site co-ordinators, research staff, data manager and collaborating clinicians, as necessary. The TMG’s role was to monitor all aspects of the trial’s set-up, conduct and progress. The group ensured that the protocol was adhered to, and would take appropriate action to safeguard participants and ensure the overall quality of the trial. The TMG reported to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC), and met every 1–2 months.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was set up to oversee the running of the trial on behalf of the sponsor and funder, and had the overall responsibility for the continuation or termination of the trial. The TSC had an independent chairperson and a majority of independent members and included a patient representative. The role of the TSC was to ensure that the trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of ‘good clinical practice’ and the relevant regulations, and it provided advice on all aspects of the trial. The trial protocol and any subsequent amendments were agreed by the TSC. The TSC reported to the TMG, the sponsor and the funder and it met every 6 months.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

A DMEC monitored the progress of the trial and reviewed all adverse events. The DMEC would have reviewed results from the internal pilot trial and advised the TSC as needed. It met every 6 months.

Reporting

The TMG reported to the DMEC and TSC. The DMEC reported to the TSC and the TSC reported to the TMG, the sponsor and the funder. Safety reports were submitted every 6 months to the Research Ethics Committee (REC), the sponsor and the funder. Development update safety reports were submitted to the MHRA.

Direct access to source data and documents

Source data were the hospital-written and NHS electronic medical records. Access to these data was through the participant’s clinicians, physiotherapist and research nurse. Trial-related monitoring, audits, REC reviews and regulatory compliance inspections were permitted, allowing access to data and documents when required.

Quality assurance

This trial was conducted in line with the trial protocol and followed the principles of good clinical practice outlined by the International Committee of Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice E6 (R1) Current Step 4 Version57 and complied with the European Union directive 2001/20/EC. 58

A monitoring plan was developed based on a trial risk assessment, which provided details of day-to-day quality control, audits, etc., and was delegated to members of the trial team to ensure that collected data adhered to the requirements of the protocol; only authorised persons completed case report forms; the potential for missing data was minimised; data were valid through validation checks (e.g. range and consistency checks); and recruitment rates, withdrawals and losses to follow-up were reviewed overall and by hospital site.

Data handling

The sources of data for the trial were as follows: recruitment details; baseline outcome measures captured electronically onto password-protected and encrypted computers by the research physiotherapists or research nurses; postal questionnaires at 6 weeks’ and at 6 and 12 months’ follow-up entered into the MACRO system (version 4; InferMed, London, UK); and telephone minimum data collection from non-responders captured on computers by researchers. Additional health service use data obtained from primary and secondary care records, with participants’ consent, would be recorded electronically on the computers. Each centre would input data into the MACRO data management program, which is a web-based system allowing controlled access to data by all centres and allows a full audit trail.

Trial sponsor

Bangor University (reference number 12/201/02; contact Dr Huw Roberts).

Ethics approval

Wales REC-3 granted approval on 27 May 2015 (15/WA/105). Clinical trial authorisation was approved from the MHRA on 15 April 2015 (21996/0002/001-0001).

Chapter 3 Results

Trial progress

Funding for the trial was approved by the HTA programme on 11 August 2014; the intention at that time was for the trial to open in January 2015 and close in June 2018. It had been planned that all the trial documentation for the regulatory approval for the trial would be completed between July 2014 and December 2014 so that regulatory approval could be obtained by January 2015.

Five collaborating sites planned to participate in the trial – North Wales, Cardiff, London, Keele and Nottingham – with training at the five sites taking place between February 2015 and April 2015. The initial plan was that the trial would be set up and recruiting participants at North Wales and London by April 2015, with the other sites opening to recruitment in June to October 2015. The trial documentation for the regulatory approval was not in place until December 2014. Regulatory approval was obtained from the MHRA on 15 April 2015 and from the REC on 27 May 2015. During this time the three English sites submitted requests for excess treatment costs (ETCs) to the NHS England for Clinical Commissioning Groups, ETCs for the two Welsh sites were agreed, and contracts were sent to both lead and collaborating sites from the sponsor, Bangor University. There were delays and unforeseen complexities in obtaining the ETCs for the English sites. Contracts also proved an issue and caused major delays because of difficulties with the delegation of the roles and responsibilities and what was required within the different contracts between university and university, and university and NHS sites. One of the sites withdrew from the trial in February 2016 because of concerns about the dosage of the biologic used and its patient population, which was higher than the standard dose used for patients with rheumatoid arthritis but similar to dosage in other conditions. This withdrawal led to a risk review for the other sites, which felt that, as no new data were available, the risk of infection for participants was acceptable, and they all agreed to continue participating in the trial.

The trial opened to recruitment on 8 December 2015 at North Wales and Nottingham, with Keele opening to recruitment on 11 August 2016. At the time of trial closure, contractual discussions were still ongoing between Bangor University, Cardiff University and Cardiff and Vale University Health Board.

During this time all sites dealt with a number of challenges. In North Wales, a research physiotherapist was seconded to the trial in September 2015 but, because of a shortage of physiotherapists in the department, was required by the health board to return to their previous employment and then left the post in February 2016 for personal reasons. As a result of physiotherapy staffing shortages within Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board (BCUHB), the site was unable to employ a replacement research physiotherapist for the required research physiotherapist time. Participants were identified and recruited via the musculoskeletal clinic and physiotherapy clinics. The PI at the site contacted fellow consultants throughout the health board to ensure that all potential participants were identified. Only three participants were recruited at this site between March and July 2016.

Nottingham had intended to recruit its participants for the trial from the Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Back Pain Unit diagnostics clinics only, based on pre-study clinic data. During the first 3 months after the start of recruitment at that site, no eligible participants were identified. The site PI extended screening to include orthopaedic clinics in addition to back pain unit clinics, but without any significant increase in recruitment. The PI at this site investigated whether or not there had been a change in referral pathways for people with sciatica in the region that might have affected referrals into these clinics. The PI confirmed, in February 2016, that this had been the case. GPs had been given direct access to MRI scans for sciatica, and were requesting and reviewing the results of MRI before requesting opinion or treatment from the back pain service. As well as introducing delay to referrals, the local GPs were tending to refer those with sciatica and a congruent disc prolapse on MRI to an alternative spinal surgical unit (e.g. Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust). A potential participant referred to the PI had already received MRI, which made them ineligible. Trial progress was an agenda item at the TMG. Owing to changes in pathways at Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Back Pain Unit, it was agreed by the TMG that the protocol should be amended to include participants who had already undergone MRI. This was approved by the REC on 15 April 2016 and by the MHRA on 27 May 2016. During this time, Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust had also been in discussions with local primary care colleagues to arrange identification of potentially eligible participants from local GP practices through database searches or opportunistic referral. This was agreed and implemented in June 2016. Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust recruited five participants to the trial between February and September 2016.

During this period, Keele had obtained agreements for its ETCs and contract negotiations were finalised between Bangor University and Keele University, and between Bangor University, Keele University and Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, and also between Bangor University, Keele University and Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Partnership Trust. The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust was opened to recruitment on 11 August 2016; one potential participant was identified prior to the trial closure on 20 September 2016. Randomisation of this participant was not permitted as a result of trial closure on 26 September 2016.

The TSC met on 11 January 2016. The problems with recruitment were discussed at the meeting, and the members were very sympathetic to the trial team’s frustration of the poor recruitment to the study. The TSC recommended the following steps if the funders allowed the trial to continue:

-

optimise recruitment for the two sites that were open

-

work harder to reduce bottlenecks (e.g. more MRI slots in North Wales)

-

increase the number of general practices searching for potential participants

-

approach the musculoskeletal triage clinics to join the study as sites

-

inform Keele and Cardiff at the next management group meeting that if they were not about to start recruiting then they would no longer be part of the trial

-

contact other possible sites that would be able to recruit to the study within the next 6 months.

The chief investigator contacted four sites one each in north, south and mid-Wales, and also the Royal Free Hospital in London.

Although the additional North Wales site was eager to participate and there was sufficient staff, there was a lack of clinical space to accommodate the trial within the rheumatology department. The rheumatology consultant submitted a case to the hospital managers with plans to increase the space available to carry out clinical trials. Unfortunately, this request was turned down because of competing demands on clinical space in the hospital, so it was not possible for the rheumatology department to be involved with SCIATiC and other clinical trials.

The hospital site in south Wales had expressed interest in participating in the trial in April 2016, and the site was arranging to accommodate the trial when we had to notify them that the trial was terminating early.

The hospital site in mid-Wales had also expressed interest in participating and had notified us on 17 August 2016 that its physiotherapy team had agreed to accommodate the trial. Unfortunately, we informed the site on 18 August 2016 about the discussions that we had with the funders and the expected termination of the trial.

The Royal Free Hospital had been discussing increasing their portfolio of clinical trials within the physiotherapy department and in April 2016 had expressed interest in participating. Unfortunately, it later informed us that it was doubtful if it would receive funding for the intervention arm of the trial. The hospital also felt that it would have difficulty recruiting participants with a symptom duration of < 6 months. In addition, its rheumatology department did not have spare capacity as it was already busy with existing research activities.

Owing to concerns with the slow recruitment, the chief investigator and Bangor trial team met with the funders on 28 January 2016, who informed the trial team that they should:

-

finalise existing contracts immediately

-

open sites that had not yet opened within the month

-

start recruiting from all sites

-

complete recruitment to the internal pilot of 50 participants by June 2016.

Another meeting with the funders was held on 16 August 2016. At the meeting the funders requested that the project team should submit closedown proposals as soon as possible and, ideally, by no later than 31 August 2016. Two different scenarios were proposed:

-

an immediate closedown of recruitment with submission of the project report by the end of December 2016

-

closure of recruitment in 6 months, until which time the study team should seek to establish the most effective recruitment routes for any future study, with submission of the project report by the end of June 2017.

From 16 August to 26 September 2016 only one participant was randomised to the trial by the Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust site. This information was relayed back to the funder, and on 26 September 2016 the chief investigator confirmed that the funders had asked for the trial to be closed immediately and the project report to be completed by the end of December 2016.

Trial timetable

The trial timetable is outline in Table 2.

| Event | Date of completion | |

|---|---|---|

| Expected | Actual | |

| Finalised protocol and trial documentation | July–December 2014 | January 2015 |

| Ethics and NHS R&D permission/MHRA approvals | September 2014–February 2015 | MHRA – April 2015 |

| REC – May 2015 | ||

| BCUHB R&D approval – July 2015 | ||

| SFHT R&D approval – November 2015 | ||

| RWT R&D approval – August 2016 | ||

| Contracts signed and completed | January–March 2015 | BCUHB – April 2015 |

| SFHT – October 2015 | ||

| Bart’s Health NHS Trust – September 2015 | ||

| RWT – July 2016 | ||

| Staff training and site initiation | March–May 2015 and November–December 2015 | June 2015, July 2015, September 2015 and November 2015 |

| Set up of centres to recruitment | February–March 2015 | BCUHB – December 2015 |

| SFHT – December 2015 | ||

| RWT – August 2016 | ||

| Identification of potential participants | February 2015–August 2016 | December 2015 |

| Telephone screening | March 2015–September 2016 | December 2015 |

| Physiotherapy clinical assessment | April 2015–October 2016 | December 2015 |

Trial recruitment

Recruitment data for the trial are presented in Figure 3 and reasons for withdrawal or exclusion in Table 3. Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and BCUHB recruited from December 2015 to September 2016. The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust recruited from August 2016 to September 2016. During this time, eight participants were randomised. No adverse events or adverse reactions were recorded for any of the participants.

FIGURE 3.

Participant flow diagram for Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, BCUHB and the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust.

| Reason for withdrawal and exclusion | n |

|---|---|

| From invitation to first clinical assessment | 1520 |

| Did not confirm interest | 963 |

| Symptoms persisting for > 6 months | 173 |

| Previous episode of sciatica in the last 6 months | 2 |

| Contraindications to MRI | 6 |

| Serious spinal pathology | 4 |

| Incidental serious pathology identified by MRI | 1 |

| Widespread pain throughout body | 25 |

| Previous use of biological agents targeting TNF-α | 1 |

| Previous lumbar spinal surgery | 16 |

| Contraindications to adalimumab | 1 |

| Pregnant or breastfeeding | 1 |

| Unable to communicate in English or Welsh | 3 |

| Mental health problems | 3 |

| No sciatica | 210 |

| Previous surgery | 11 |

| No leg pain | 20 |

| Complicated symptoms | 18 |

| Pain in both legs | 7 |

| Expressed interest but delay in telephone screening attributable to site staffing issues means no longer meet criteria for inclusion (e.g. no longer in pain or have recently breached the > 22-week exclusion window since replying) | 6 |

| No response or no longer interested | 23 |

| Symptoms resolved/improved | 10 |

| Current leg pain worse than or as bad as back pain | 3 |

| Trial closed early to recruitment | 14 |

| From first to second clinical assessment | 17 |

| Over time limit for second clinical assessment | 1 |

| Study closure | 5 |

| Mild symptoms – discharged to GP care | 7 |

| TB screening failed | 1 |

| Participant revealed long-term history of widespread pain at screening – particularly in shoulders | 1 |

| No positive neurological test | 1 |

| Patient did not attend appointment and could not be contacted | 1 |

| From 6-week to 6-month follow-up | 4 |

| Study closure | 4 |

Contracting delays