Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/57/43. The contractual start date was in September 2012. The draft report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in February 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Catherine Hewitt is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board. David A Richards reports other National Institute for Health Research grants (NIHR) from the HTA programme (COBRA; CADENCE), a personal award (Senior Investigator) and a Programme Development Grant (ESSENCE) and the European Science Foundation during the conduct of the study. He is also a member of NIHR funding panels, including the Fellowships and Senior Investigator panels. Karen Spilsbury is a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Commissioning Board. Simon Gilbody is a member of the HTA Evidence Synthesis Board and HTA Efficient Study Designs Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Bosanquet et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Depression in older adults

Depression accounts for the greatest burden of disease among all mental health conditions, and is expected to become the second highest among all general health problems by 2020. 1 It is currently estimated that in the UK around 10–20% of people aged ≥ 65 years have depression. 2 Projected demographic changes mean that population strategies to tackle depression will increasingly have to address the specific needs of older adults. 3 Depression often occurs alongside long-term physical health conditions4 and/or cognitive impairment and it is more prevalent among people who live alone in social isolation. All these factors tend to disproportionately affect the older adult population. Among older adults, a clinical diagnosis of a major depressive disorder is the strongest predictor for impaired quality of life. 5 Indeed, beyond personal suffering and family disruption, depression worsens the outcomes of many medical disorders and promotes disability. 6 In 2009, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidelines that acknowledged the coexistence of physical health problems and depression. 7,8 Furthermore, it was recognised that the impairments in quality of life associated with depression are comparable to those of major physical illness. 5

Rationale for the CollAborative care for Screen-Positive EldeRs plus trial

Depression in older people is relatively common. 9 The effects on the individual include poor quality of life, increased morbidity and early mortality,10 and increased health and social care use. 11 Depression is often under-recognised and undertreated in primary care. 12,13 At present, the management of depression tends to be limited to the prescription of antidepressants, with poor adherance an associated problem. 12 In particular, older adults seem to be less likely than working-age adults to be offered psychological treatments. 14,15 So far, the evidence for psychological interventions relates to higher-intensity models of care that cannot feasibly be delivered at scale in primary care. Collaborative care is a framework model for organising and delivering psychosocial interventions at scale. 16 It represents a brief, patient-centred, psychosocial package of care delivered by a case manager who works to a defined protocol and co-ordinates the patient’s medication management with their general practitioner (GP). The case manager is supervised by a specialist who facilitates liaison across the primary care–secondary care interface. 17 In the USA, collaborative care has shown promising trial results among older people;16 however, the transferability of this model of service to the UK NHS cannot be assumed. Consequently, the CollAborative care for Screen-Positive EldeRs with major depression (CASPER) plus trial will substantially enhance the randomised evidence base in the care of older people with depression and inform future service provision.

Collaborative care: an organisational model of providing care

The vast majority of depression in older adults is managed entirely in primary care without recourse to specialist mental health services. 3,18 Although a range of individual treatments have been shown to be effective in the management of clinical depression in older adults, including antidepressants and psychosocial interventions,18 a repeated observation among those with depression has been the failure to integrate these effective elements of care into routine primary care services. 19 In addition, the implementation of any form of care will require a strategy that is low intensity and can be offered within primary care. 20

In recent years, an organisational model of care has been introduced called collaborative care. 21 Collaborative care borrows much from chronic disease management and ensures the delivery of effective forms of treatment (such as pharmacotherapy and/or brief psychological therapy) through augmenting the role of non-medical specialists in primary care. Collaborative care is a model whereby the non-medical specialists, or case managers, form a close collaboration with the person with depression and others involved in their care. The case manager acts as a conduit for the passage of information between all individuals involved and supports the participant to enable effective discussion of important problems. Case managers provide information and help participants to access appropriate services, such as social care and voluntary sector services.

The ubiquity of depression in primary care settings, along with the poor integration and co-ordination of care, has led to the development of, and increased use of, this model of care. In a 2012 Cochrane review22 of 79 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (24,308 participants), clear and robust evidence of the effectiveness of collaborative care was shown. It improved depression outcomes in both the short and medium term. Moreover, there was evidence to suggest that collaborative care can be cost-effective by reducing health-care utilisation and improving overall quality of life. 23,24 However, the greater proportion of studies related to working-age adults. A relative lack of any evidence for older adults was identified, which led to calls for further research on collaborative care among that age group. One important exception was the evidence provided by the US Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) study of the effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults.

The IMPACT study was conducted by Unützer et al. 16 for those aged > 60 years with case-level clinical depression. The main finding was that, at 12 months, depression severity was at least 50% improved from baseline in almost half the participants in the intervention group, but only one in five of those receiving usual care. In 2007, a UK feasibility trial9 of collaborative care in older adults showed some positive results. In recent years, the evidence base has expanded, although not with direct reference to older adults. The CollAborative DEpression Trial (CADET)11 showed that collaborative care was effective at improving depression outcomes in a UK primary care population, and the Collaborative Interventions for Circulation and Depression: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial of collaborative care for depression in people with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease (COINCIDE) trial10 showed a modest effect at reducing depression and improving self-management of chronic disease.

In addition to the provision of collaborative care, the studies also provide information and support to enable participants to undertake brief psychological therapies, in this case behavioural activation. Behavioural activation for the CASPER plus trial was adapted from the behavioural activation intervention delivered in CADET. 11 Manualised psychological interventions, such as behavioural activation, may benefit individuals experiencing depressive symptoms. It focuses on addressing the behavioural deficits common among those with depression by reintroducing positive reinforcement and reducing avoidance. Such interventions aim to manipulate the behavioural consequence of a trigger (environmental or cognitive) rather than directly interpret or restructure cognitions. 25 Behavioural activation is about helping patients to ‘act their way out’ of depression rather than wait until they are ready to ‘think their way out’. Helping people to identify and reintroduce valued activities that they have stopped doing, or to introduce ones they would like to take up, is an important component. The effectiveness of this psychological approach is now well demonstrated. 26,27 Behavioural activation can be readily delivered by a trained case manager either over the telephone or face to face (for those who experience difficulty using or accessing telephone-based therapy). 28

Limitations of previous trials

The major limitation of previous trials was an absence of a definitive UK trial of collaborative care in older adults with depression. The absence of UK trials of collaborative care was highlighted in 2009 guidance for depression issued by NICE, and the need for such trials was highlighted as a research priority. 7 We proposed to measure the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of using collaborative care on older adults with major depression in response to a lack of evidence of its benefit to the older population in UK primary care.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The research objectives of this trial were to:

-

establish the clinical effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention for older people with screen-positive above-threshold (‘major depressive episode’) depression within a definitive RCT

-

examine the cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention for older people with screen-positive above-threshold (‘major depressive episode’) depression across a range of health and social care costs within a definitive RCT.

The definitive RCT was preceded by a developmental phase to produce a manualised collaborative care intervention for older people and an internal pilot trial to optimise recruitment, randomisation and retention, and we report these preparatory objectives within the body of this report.

Chapter 3 Methods

For CASPER plus, those patients identified at the screening phase as having above-threshold, case-level depression will be eligible to enter the CASPER plus substudy.

Trial design

We conducted a pragmatic, multicentred, two-arm, parallel, open RCT. Participants with major depression were individually randomised (1 : 1) to receive either collaborative care in addition to usual GP care, or just usual GP care.

Approvals obtained

This study was approved by NHS Leeds East Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 28 September 2010 (REC reference number 10/H1306/61). Research management and governance approval was obtained for each trial centre thereafter (see Appendix 1). This trial was assigned the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number of ISRCTN45842879.

Trial centres

Four centres in the north of England were selected as trial sites: (1) York centre (the core study centre) covering the city of York, Harrogate, Hull and the surrounding areas; (2) Leeds centre and the surrounding area; (3) Durham centre and the surrounding area; and (4) Newcastle upon Tyne centre, including Northumberland and North Tyneside. Each centre was responsible for co-ordinating the recruitment of participants into the study (trial and epidemiological cohort).

Duration of follow-up

All participants were followed up by questionnaire at 4, 12 and 18 months (see Chapter 4).

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

People for whom both of the following criteria applied:

-

aged ≥ 65 years

-

identified by GP practice as being able to take part in collaborative care.

Exclusion criteria

Potential participants were excluded if identified by primary care clinicians as meeting one of the following criteria:

-

known alcohol dependency (as recorded on GP records)

-

known to be experiencing psychotic symptoms (as recorded on GP records)

-

any known comorbidity that would, in the GP’s opinion, make entry to the trial inadvisable (e.g. recent evidence of suicidal risk or self-harm, significant cognitive impairment)

-

other factors that would make an invitation to participate in the trial inappropriate (e.g. recent bereavement, terminal malignancy).

Sample size

To detect a minimum standard effect size of 0.35 (aligning with the US IMPACT study16 and our previous CASPER trial29,30) with 80% power and a two-sided 5% significance level, 260 patients (130 per arm) would be required. Although this is an individually randomised trial, there may be potential clustering at the level of each collaborative care case manager, and hence the sample size was inflated to account for this. Based upon an estimated intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 and a case load size of 20, the design effect would be 1.38 {1 + [(20 – 1) × 0.02]} and 360 patients (180 in each arm) would be required. Allowing for 20% loss to follow-up, the final sample size needed was 450 patients (225 per arm).

Epidemiological cohort

During the first year of the CASPER plus trial, an epidemiological cohort was assembled. This consisted of people who had consented to participate in the trial but who were not depressed. Through our broad inclusion criteria we successfully recruited a total of 4668 patients aged ≥ 65 years into the CASPER cohort, from who we identified those with major depression who were eligible to participate in the CASPER plus trial. The reasons for this strategy were twofold: first, to recruit an adequate number of potential participants who would subsequently be identified as having depression, as we believed this would not always be recorded on GP records; and, second, to establish an epidemiological cohort of older adults who could be followed up and who would help inform the knowledge base around the health and well-being of older adults. This type of study design is termed a cohort multiple RCT. 31

Recruitment into the trial

Recruitment of all participants into the trial took place through primary care. GP practices agreed to participate after a member of the study team had introduced it to them with written information, followed by a face-to-face visit to explain the study and what participation would involve. Patients were identified by a computer search and then invited to participate in the CASPER study by their general practice, which posted an invitation pack to all eligible patients. The packs comprised an invitation letter (see Appendix 2) signed from the general practice, a consent form (see Appendix 3), a decline form (see Appendix 4), a participant information sheet (see Appendix 5), a background information sheet (see Appendix 6) and a prepaid return envelope addressed to the core study centre. No patient-identifiable data were available to the study teams until patients returned their consent form.

Consenting participants

During the consent stage, potential participants were asked to complete the Whooley questions,32 a two-item depression-screening/case-finding tool. These questions were asked at two different time points – on the background information sheet at invitation and in the baseline questionnaire – both times as self-reports. At the consent stage, participants were informed about the opportunity of participating in other related studies (e.g. qualitative studies) and were asked to indicate if they agreed to be approached in the future by ticking a box on the consent form. All participants who consented to take part in the CASPER study at this stage became part of the CASPER cohort. Participants did not become part of the CASPER plus trial until they had been subsequently assessed for suitability by completing a standardised diagnostic interview and randomisation.

Baseline assessment

On receipt of written consent from participants by the return of their consent form via post, baseline data were collected through a self-report questionnaire. All participants who returned completed consent forms to the core study centre were sent a baseline questionnaire (see Appendix 7). Participants were asked to respond to the Whooley questions32 for a second time and to provide self-report medication data. They were also asked to complete a range of health surveys, which consisted of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9)33 – a measure of depression severity using a nine-item depression scale in reference to how a respondent has been feeling over the past 2 weeks; the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12)34 – a measure of health-related quality of life to obtain health-state utility by estimating the Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D); the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, 3 levels (EQ-5D-3L)35 – a standardised measure of health-state utility, designed primarily for self-completion by respondents; the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 item (GAD-7)36 scale – a severity measure of generalised anxiety used to gauge the past 2 weeks; the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 items (PHQ-15)37 – a measure of somatic complaints using a 15-item scale in reference to the last month; and the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale-2 items (CD-RISC2)38 – used to measure an individual’s resilience and ability to bounce back.

Randomisation

Randomisation was carried out by the York Trials Unit Randomisation Service [www.yorkrand.com (accessed 23 June 2016)], accessed by a trained researcher from the study team. Participants were automatically randomised by a computer on a 1 : 1 basis by simple unstratified randomisation to either the intervention group or control group, following the completion of a diagnostic interview. All diagnostic interviews were conducted over the telephone by a trained researcher from the study team. The major depressive episode module of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was used to ascertain the presence or absence of core depressive symptoms. 39 The MINI shows good agreement with other semistructured diagnostic interviews conducted to internationally recognised standards. 40–42 This allowed potential recruits to be identified as having major depressive disorder (five or more symptoms), subthreshold depression (two to four symptoms) or no depression (one symptom) (Table 1). 39,43,44 All participants diagnosed with major depressive disorder were randomised to either the intervention or the control arm.

| Key symptoms | Other symptoms |

|---|---|

| Depressed mood | Substantial changes in weight/appetite |

| Loss of interest | Change in sleep patterns |

| Change in energy levels | |

| Movement slowing down or speeding up | |

| Feeling guilty or worthless | |

| Unable to make decisions | |

| Thinking of death or suicide |

Once participants had been randomised, they were sent a letter informing them of the outcome of their diagnostic interview. If their MINI outcome was major depression, they were informed of their group allocation, either collaborative care or usual care. The participant’s GP was also sent a letter informing them that the named patient was eligible to take part in the CASPER plus trial owing to the major depression outcome of their diagnostic interview. It also specified which arm of the trial they had been randomised to.

Ineligible participants

All participants whose outcome was not major depression (either non-depressed or subthreshold) were sent a letter informing them that they were ineligible for the CASPER plus trial but that they would remain in the CASPER epidemiological cohort and continue to be followed up via questionnaires. Their GPs were also informed of this. This process of following up non-trial participants was discontinued once the original CASPER trial completed (see Chapter 4).

Trial interventions

Control group

Participants in the control group were allocated to receive usual GP care. They received no care additional to the usual primary care management of major depression offered by their GP in line with NICE depression guidance as implemented by their GP and local service provision. 7,8

Intervention group

Participants in the intervention group were allocated to receive a low-intensity programme of collaborative care using behavioural activation, designed specifically for those aged ≥ 65 years with major depression. Collaborative care was delivered by a case manager [a primary care mental health worker/Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) worker] for an intended 8–10 weeks. This took place alongside participants’ usual GP care. The defining feature of collaborative care is a collaboration of expertise to help support the participant. A case manager works alongside the participant, sharing any relevant information with the GP and a mental health specialist (psychiatrist or psychologist). The case manager is a cohesive link between the participant and other professionals involved in their care. For example, a case manager who deemed a participant’s depressive symptoms to have deteriorated would pass this information on to the participant’s GP, who would optimise the management of the patient’s condition.

Collaborative care in the CASPER plus trial consisted of telephone support, symptom monitoring and active surveillance, facilitated by a computerised Patient Case-Management Information System (PC-MIS) [www.york.ac.uk/healthsciences/pc-mis (accessed 23 June 2016)] and low-intensity psychosocial management (behavioural activation). Participants randomised to the collaborative care intervention group were contacted by a case manager within 1 week of their randomisation to arrange their first collaborative care session. This was carried out face to face, usually at the participant’s home unless an alternative venue was preferred. After this initial meeting, subsequent sessions were carried out on a, more or less, weekly basis by telephone unless the participant had sensory impairments or preferred face-to-face visits. Case managers worked collaboratively with the participants, liaising with GPs and other health professionals involved in their care to discuss issues relating to participants’ mental and physical health, both during routine updates and when any concerns were identified. This included liaising with GPs as necessary to consider reviews of medication, which could relate to depression but also to comorbid physical health problems. It also included discussing with GPs referrals to other services, such as health services (e.g. pain clinics) or engagement with social services. Case managers worked with the participants to identify problems and agree goals for the intervention. They also worked with participants to identify, and subsequently provide, information about other services that may be useful, such as voluntary and statutory sector organisations and services.

Refinement of collaborative care/behavioural activation

The delivery of collaborative care and behavioural activation had been established in working-age adults for whom an appropriate training package and manual already existed. 28 However, these had not been tailored for use with older adults diagnosed with major depression. Before the study began, necessary changes were made to both the training package and manual (detailed in this section) to account for differences that may exist in the older adult population.

Training occurred over 2 days and involved a combination of brief lectures and role-play. Topics covered were the collaborative care approach as applied to older adults, medication management in older adults, behaviour theory and behavioural activation as adapted for older adults.

Adaptations to language and content

Adaptations were made to the information gathered at the initial assessment. Older adults are more likely to experience long-term health problems and a reduced level of functioning, with their psychological status often closely linked to their physical functioning. 45 Additional questions regarding health conditions and their impact were added to the standard assessment format. However, case managers were reminded to deliver a person-centred approach and not let preconceptions about the level of functioning of older adults influence their information gathering. Liaison with health professionals who were involved in treating the participant’s long-term health conditions was encouraged to promote a depth of understanding of these issues. Depression in older adults is associated with impaired social support;46 therefore, additional questions regarding social contacts and family were added. The risk assessment (see Appendix 8) was also adapted to enquire about past passive and past active suicide ideation as well as current plans and preparations, as past suicidality is a risk factor for current suicidal behaviour. 47

Information in the manual was tailored to meet the needs of older adults. Age-appropriate examples were used, such as bereavement and loss of role, to facilitate engagement and make it easier to relate to. The psychoeducation material given to participants was also modified to include information about depressive symptoms that occur specifically in older adulthood. As depression is associated with cognitive impairment in older people,48 a larger font and increased space for writing was introduced. In addition, when individuals displayed mild cognitive impairment, simpler language was used and the number of steps in each session, along with the homework, was reduced. Questions were also added to help the case manager assess the participant’s understanding of the treatment principles.

Functional equivalence and keeping well

Case managers were made aware of the importance of helping patients to identify functionally equivalent activities and a section was added to the Keeping Well Plan to prompt participants to identify functionally equivalent activities that may replace enjoyable or rewarding activities they were no longer able to undertake. Further details of the adaptations made can be found in Pasterfield et al. 49

Participant follow-up

All participants in the CASPER plus trial were followed up with questionnaires at 4 months (see Appendix 9), 12 months (see Appendix 10) and 18 months (see Appendix 11). All post-randomisation questionnaires were posted to participants from the York Trials Unit along with a pre-addressed prepaid envelope. Participants could complete the questionnaires manually and return them by post to York Trials Unit or they could complete the questionnaire online; an instruction sheet explaining how to log on to the CASPER study site and complete the process was included with each questionnaire. Reminder letters were sent by post at 2 weeks to any participants who had not returned their questionnaire. Telephone follow-up by one of the study team’s researchers was conducted for any participants who did not return the reminder questionnaire in order to complete the primary outcome measure (PHQ-9) at the very least.

Trial completion and exit

Participants were deemed to have exited the trial when they:

-

withdrew consent (wished to exit the trial with no further contact for follow-up or objective data)

-

had been in the trial for 18 months post randomisation

-

had reached the end of the trial

-

died

-

moved general practice to one not participating in the CASPER study

-

had another reason to exit according to clinical judgement from a health professional.

Withdrawals

Withdrawal could occur at any point during the study at the request of the participant. If a participant indicated that he or she wished to withdraw from the study, a researcher would speak to the participant to clarify to what extent they wished to withdraw: from the intervention, from the follow-up or from all aspects of the study. When withdrawal was only from the intervention, then follow-up data continued to be collected. Data were retained for all participants up to the date of withdrawal, unless they specifically requested for their details to be removed.

Objective data

Once the CASPER plus trial participants of a general practice had completed their follow-up, objective data were collected for each trial participant. Objective data consisted of details on each participant’s prescribed medication and the number of contacts they had with their general practice during their time in the trial. The only exception was for those participants who had withdrawn in full, thereby withdrawing consent to access their medical records. Objective data were collected from general practices via request from the core study centre. A spreadsheet template was e-mailed to the key contact of each general practice that included the identification codes of each trial participant for the practice with prewritten frozen headings: there were no identifiable data. The search dates for each participant were also listed, from the date they were randomised until either the date they completed the study 18 months later or the date that they had died, if that was the case. Data were still collected on participants who had withdrawn from treatment or follow-up, as they had provided us with consent to access their health records for the 18 months that they would have been in the study. The transfer of all objective data via e-mail was approved on the basis that no identifiable data were shared either with the general practice at the request stage or with the core study centre at the stage that objective data were returned.

Suicide protocol

A small but elevated risk of suicide and self-harm was inherent in the study population, all members of which had been identified as having major depression. All participants (both usual care and collaborative care) were subject to usual GP care and GPs were responsible for the day-to-day management of major depression. GPs were accountable for all treatment and management decisions including prescribing of medication, referral and assessment of risk. This arrangement was made clear to all clinicians and general practices that agreed to participate in the study. The pragmatic nature of the CASPER plus trial meant that we did not seek to influence this arrangement. However, we did follow good clinical practice by monitoring for suicide risk during all our encounters with participants. When a patient expressed a risk through thoughts of suicide or self-harm, we followed the study-specific procedure for suicide risk (see Appendix 8).

Patient and public involvement in research

The CASPER plus trial was informed by the involvement of users of mental health services and carers throughout the research period. An advisory group was established in the early stages of study. This consisted of a number of older adults, some of whom had mental health conditions, along with a carer representative. This group provided valuable insights into the relevance and readability of the study documentation. In the future, we plan to engage patient and public involvement in our dissemination strategies to guide on how best to share the findings.

Further studies

Following completion of the CASPER trial, the Self Help At Risk Depression (SHARD) substudy (not described in this report) was introduced to randomise participants identified with subthreshold depression to receive a self-help workbook or usual GP care. Results from the SHARD study will follow.

Clinical effectiveness

Primary outcome

The primary end point for the trial was patient-reported depression severity, as measured by the PHQ-933 at 4 months’ follow-up. Each item is scored from 0 to 3; thus, PHQ-9 scores can range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe depression. Total scores from 0 (non-depressed) to 27 (severely depressed) were calculated based on the nine PHQ-9 items. These data were collected via self-report on the follow-up questionnaires. Any participants who did not return a completed questionnaire were sent a reminder, and those participants who did not respond were telephoned by one of the study team’s researchers to ask them to complete the PHQ-9 over the telephone. Missing items were replaced with the mean of the remaining items if one or two items were missing.

The PHQ-9 data were collected at baseline and randomisation (at the diagnostic interview), as well as at 4, 12 and 18 months’ follow-up. Scores at baseline and randomisation are reported in Chapter 5, Baseline characteristics. When analyses were adjusted for initial PHQ-9 score, the score at randomisation was used. The primary end point for the CASPER plus trial was at 4 months’ follow-up. At that point, treatment differences in the magnitude of a standard effect size of 0.35 were sought, which is of moderate size for psychological interventions and in line with collaborative care effects observed in other studies. Cohen50 classifies a standard effect size of 0.3 as a small to medium effect size, and this is in line with NICE guidelines for depression, which adopts a similar grading of clinical significance. Four months was selected as the primary end point, because it would occur soon after the end of the planned treatment but allow some additional time in the event that it was not possible to see participants on a weekly basis for practical reasons (e.g. holidays).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures used were:

-

depression severity and symptomatology at 12 and 18 months (PHQ-9)

-

binary depression severity at 4, 12 and 18 months (PHQ-9), using scores of ≥ 10 to designate moderate depression caseness

-

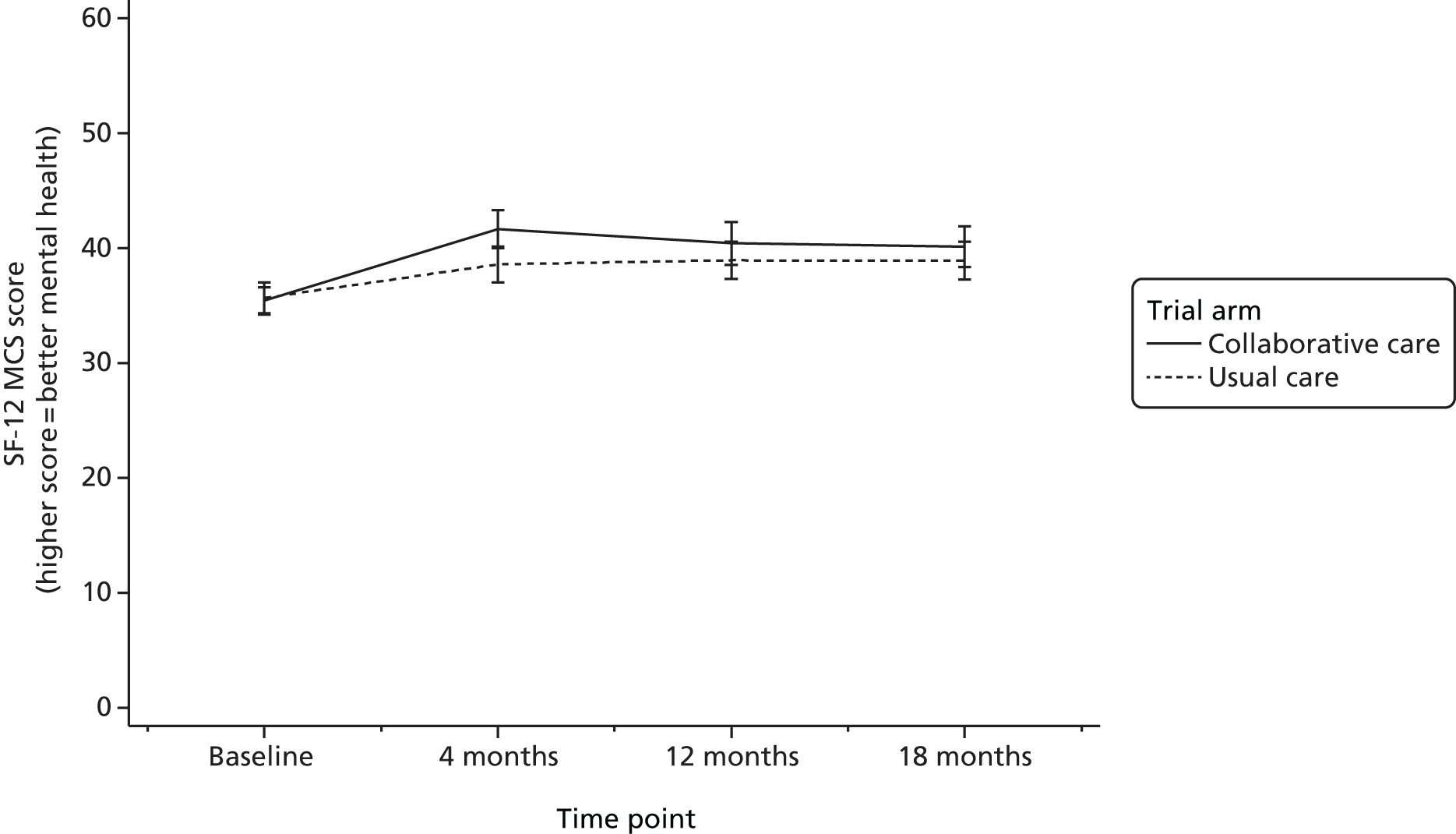

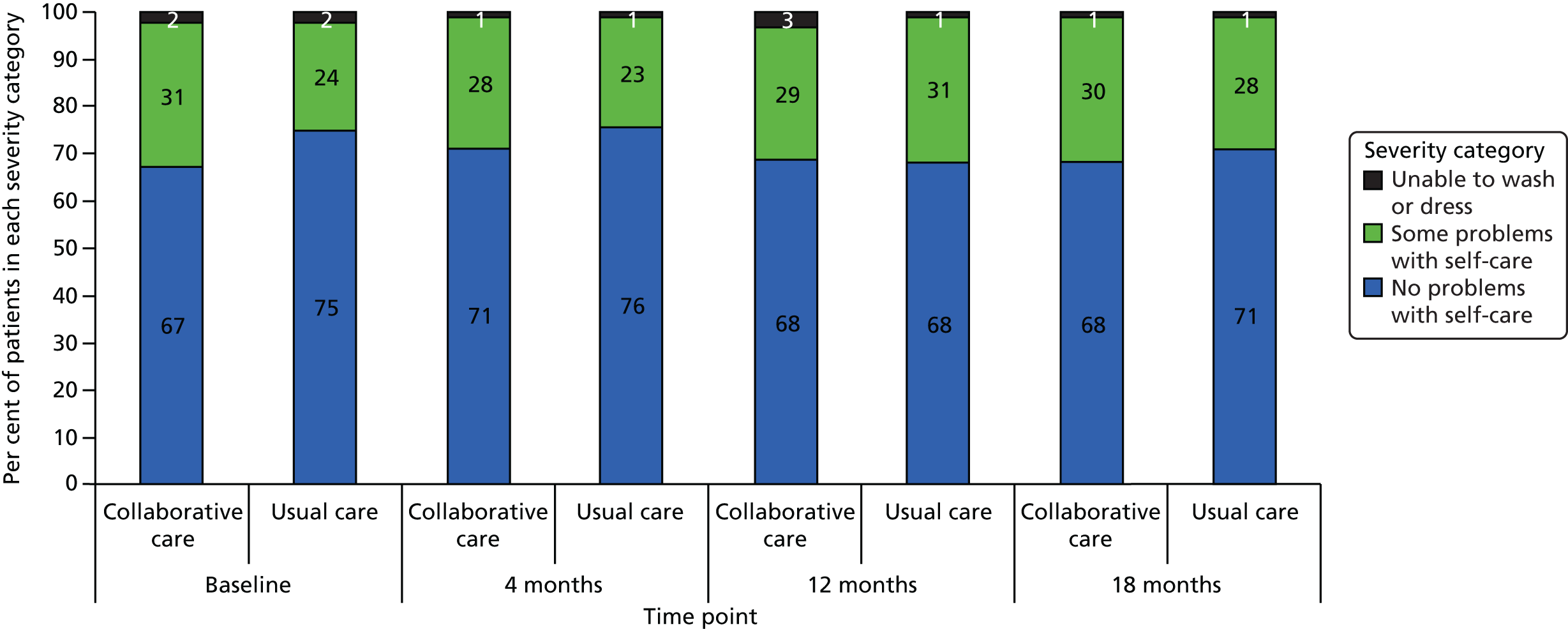

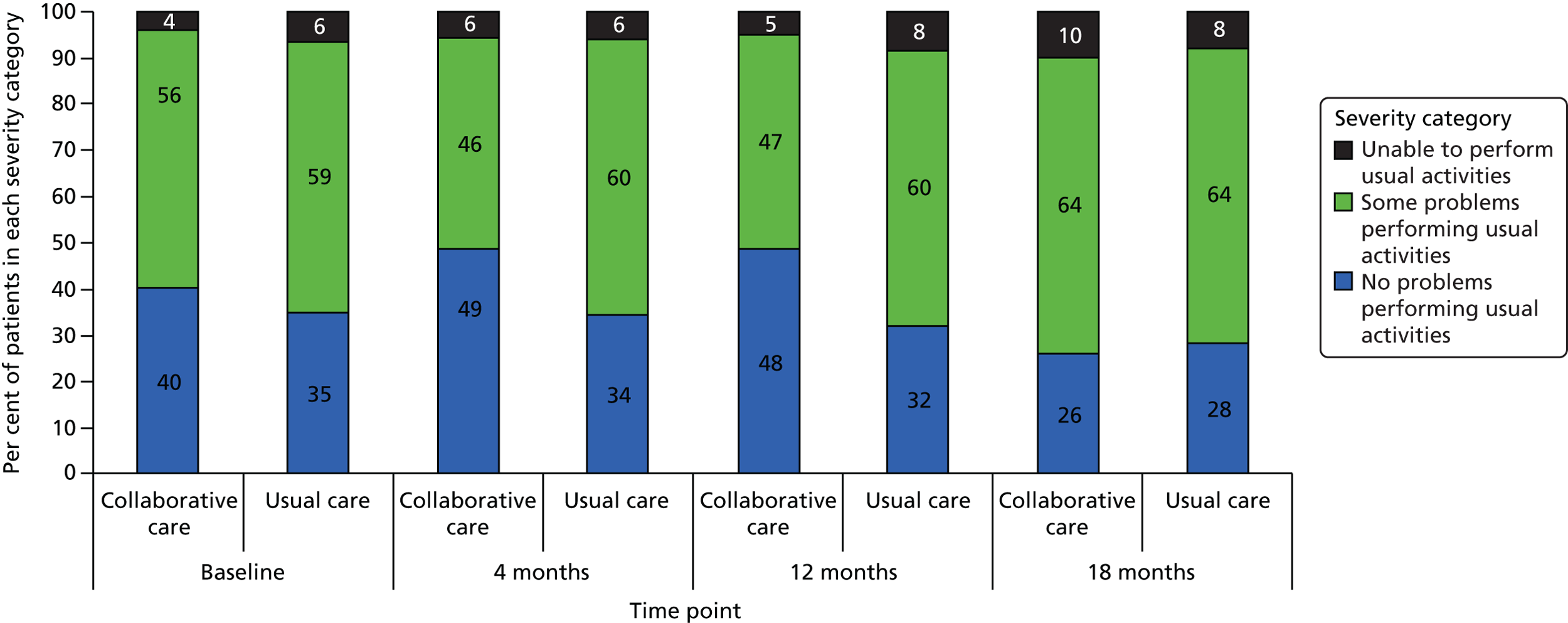

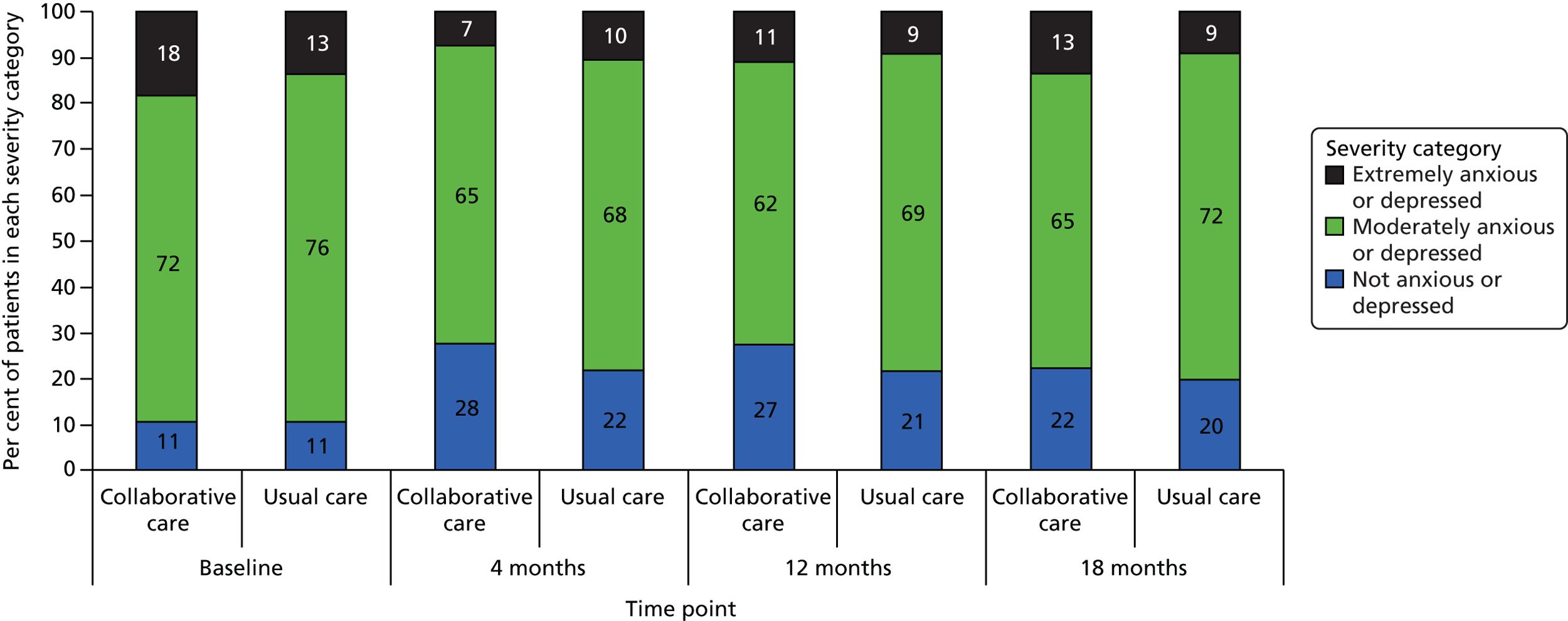

quality of life at 4, 12 and 18 months (SF-12 and EQ-5D-3L)

-

psychological anxiety at 4, 12 and 18 months (GAD-7)

-

mental health medication at 4, 12 and 18 months

-

physical health problems at baseline, 4, 12 and 18 months (PHQ-15)

-

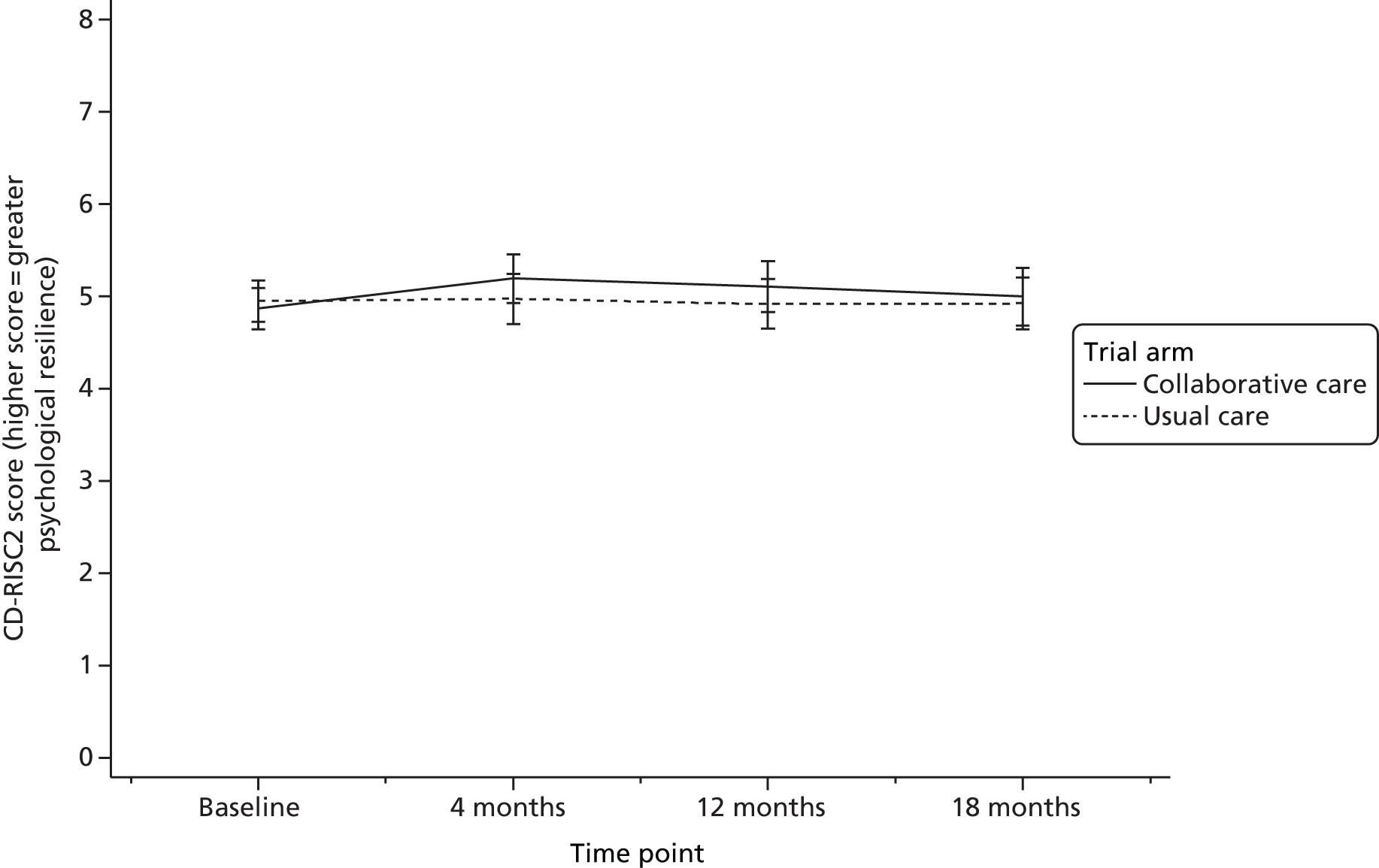

psychological resilience at baseline, 4, 12 and 18 months (CD-RISC2)

-

mortality at 4, 12 and 18 months.

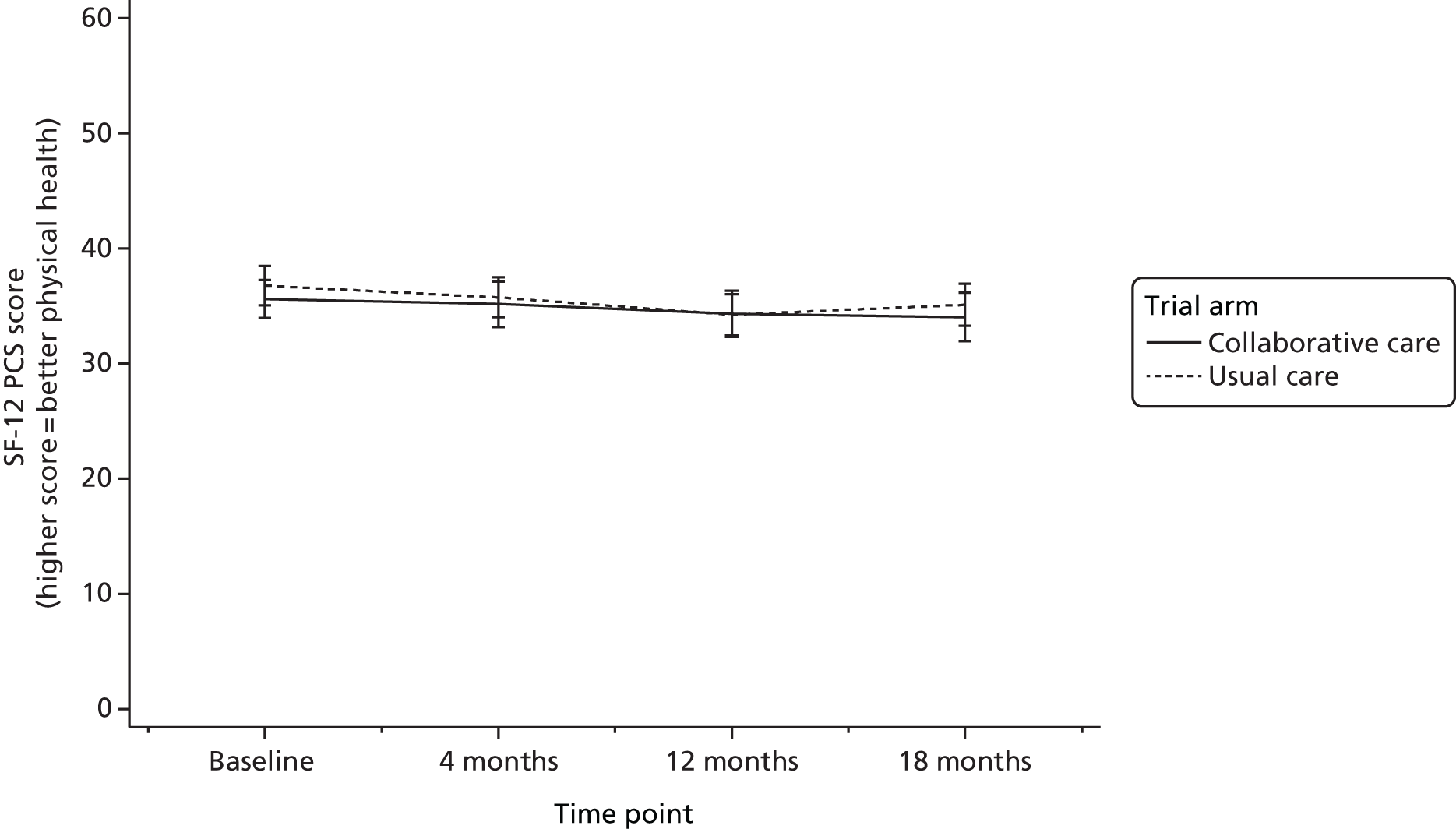

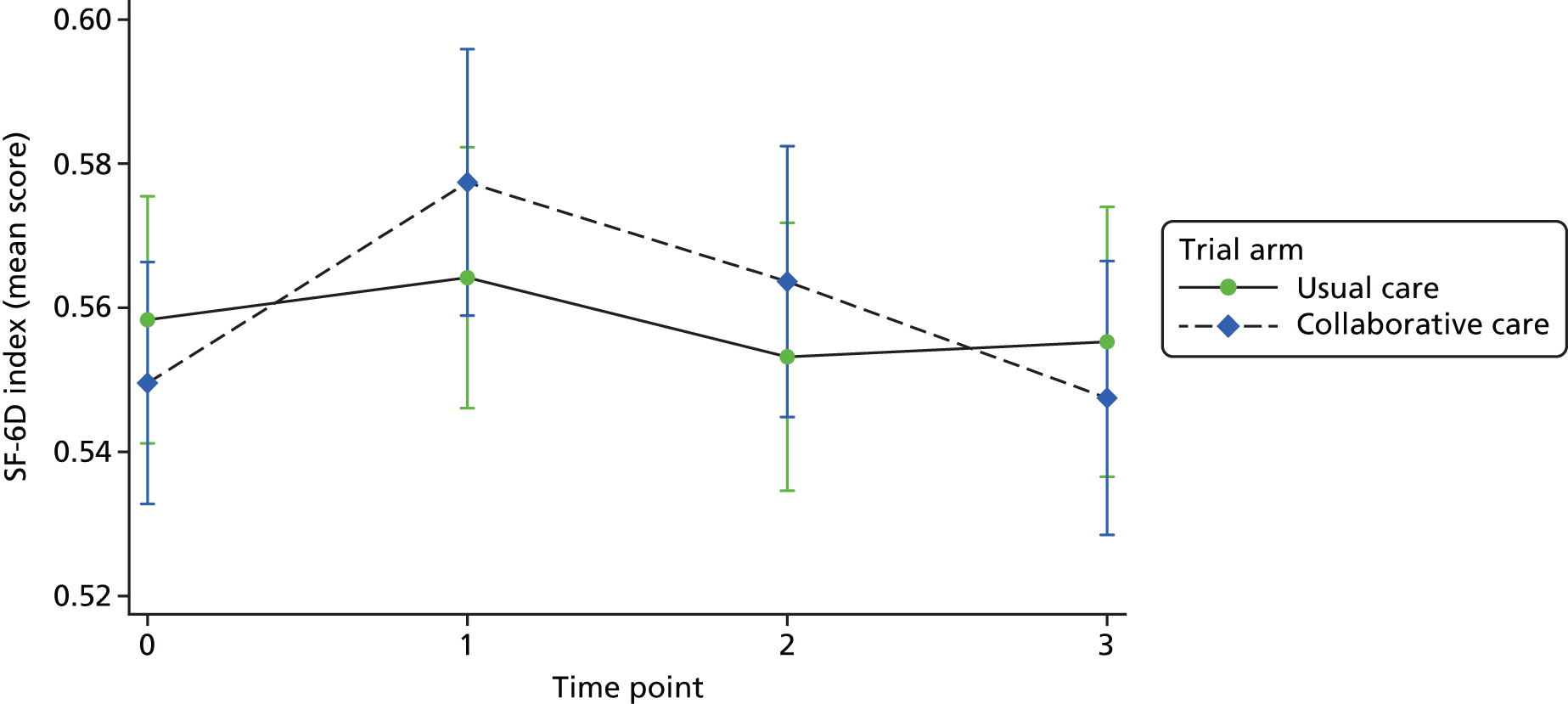

Short Form questionnaire-12 items

The SF-1234 is a generic health status measure and a short form of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items health survey. It consists of 12 questions measuring eight domains (physical, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health) rated over the past month. Questions have three or five response categories, and responses are summarised into a physical component summary (PCS) score and mental component summary (MCS) score. The PCS and MCS scores range from 0 (the lowest level of health) to 100 (the highest level of health) and were designed to have a mean score of 50 in a representative sample of the US population. Therefore, scores > 50 represent above average health status, and vice versa. The SF-6D was estimated from responses to the SF-12 questionnaire and provided health-state utilities to inform cost–utility analysis.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, 3 levels

The EQ-5D-3L35 is a standardised measure of current health status developed by the EuroQol Group for clinical and economic appraisal. The EQ-5D-3L consists of five questions each assessing a different quality-of-life dimension (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each dimension is rated on three levels: no problems (score = 1), some problems (score = 2) and extreme problems (score = 3). A weighted summary index can be derived to give a score between 1 (perfect health) and 0 (death). For the purpose of the clinical effectiveness analysis, only scores of the individual dimensions were utilised. Health-state utilities (along with SF-6D) were estimated to potentially inform the cost–utility analysis; however, the SF-6D was ultimately found to be more sensitive to change in this cohort.

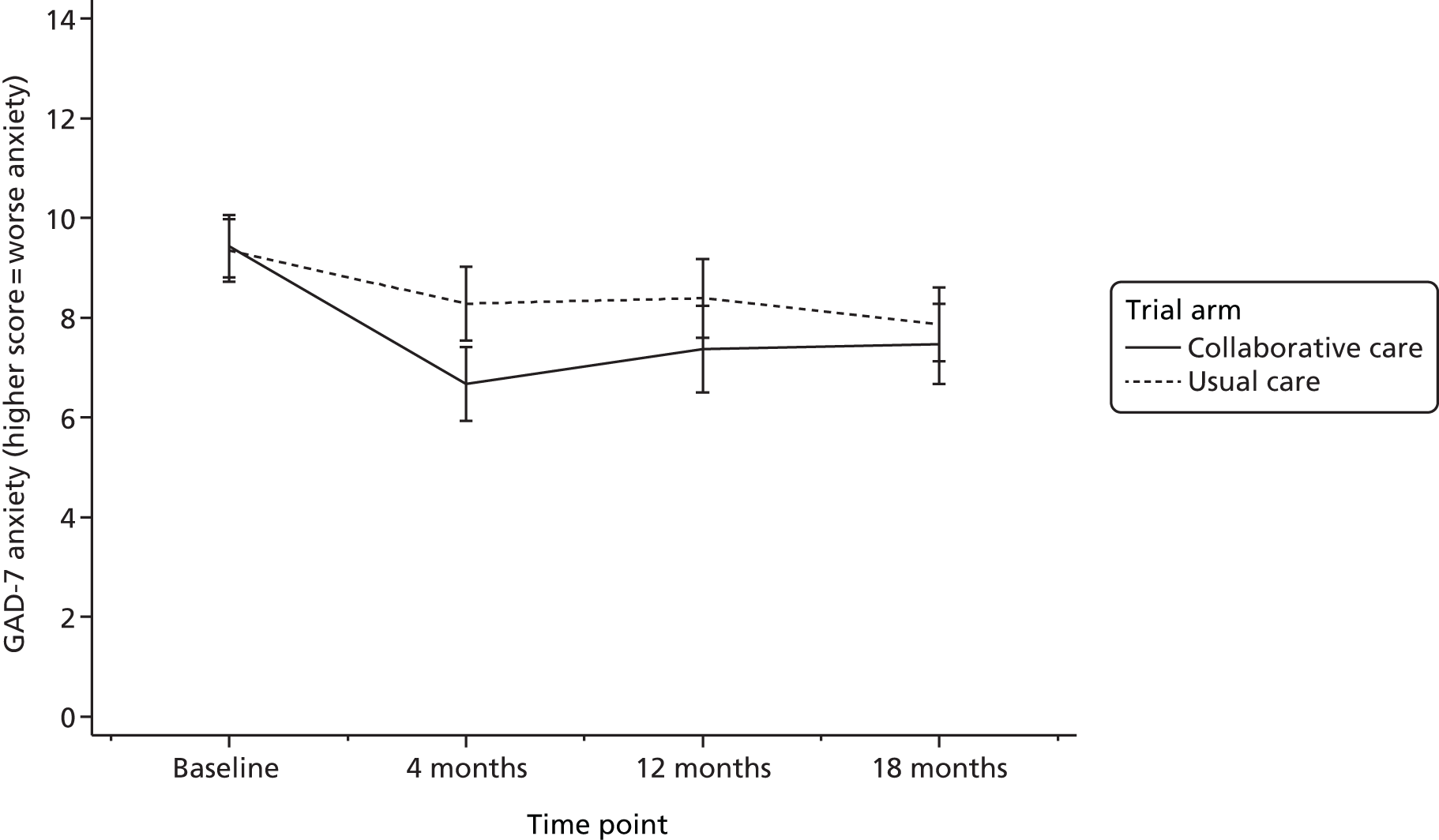

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 items scale

The GAD-736 is a brief measure of symptoms of anxiety based on diagnostic criteria described in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition. 43 It consists of seven questions and is calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2 and 3 to the response categories of ‘not at all’, ‘several days’, ‘more than half the days’ and ‘nearly every day,’ respectively. GAD-7 total score for the seven items ranges from 0 to 21. Scores of 5, 10 and 15 represent cut-off points for mild, moderate and severe anxiety, respectively.

Patient Health Questionnaire-15 items

The PHQ-1537 is a 15-item physical health problems questionnaire. Each health issue is rated as 0 (not bothered), 1 (bothered a little) or 2 (bothered a lot). Items are added to form a scale from 0 to 30, higher scores indicating worse symptom severity. Scores of 5, 10 and 15 have been used as cut-off points for low, medium and high symptom severity. Item 4 of the PHQ-15 (menstrual problems) was deemed not relevant for the older CASPER patient population and omitted from all questionnaires. Therefore, the total possible PHQ-15 score was 28.

Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale two-items

The CD-RISC238 is a two-item short form of the full Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale-25 items. It is a psychological resilience measure with specific items for bounce-back from adversity and adaptability to change. Agreement with the two items is scored from 0 to 4, resulting in a total score of 0 to 8, where a higher score indicates greater resilience.

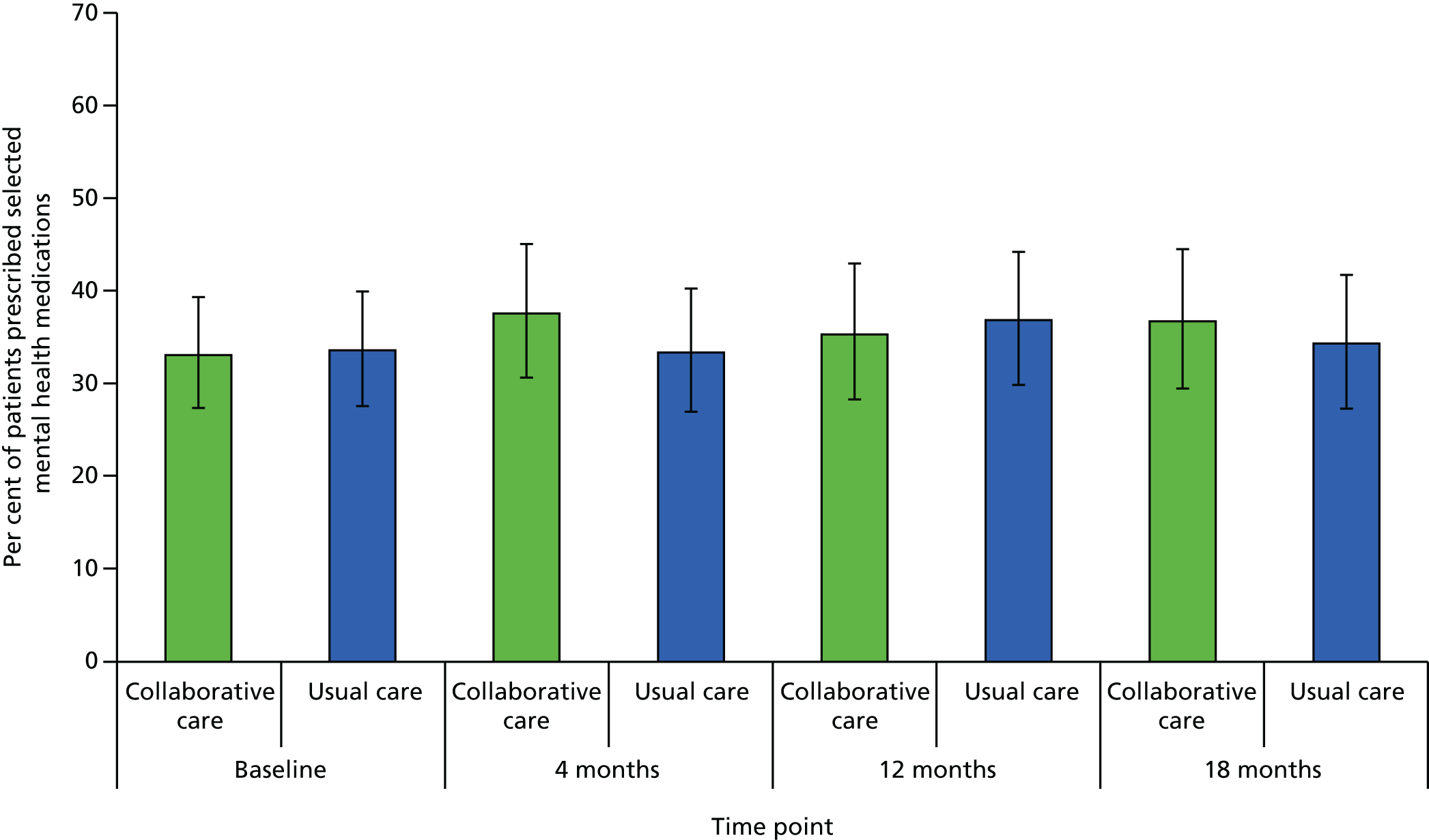

Mental health medication

Medication data were captured by self-report on the follow-up questionnaires. Participants indicated prescribed medication by selecting from a list of 10 antidepressants, as well as listing any other medications they were prescribed.

Mortality data

A data linkage service was established with the NHS Digital to provide regular updates from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality data on any trial participants who had died while in the study. Members of the research team recorded any identified deaths, date and cause of death on the study management database.

Other collected patient questionnaire data

Adverse events

The CASPER plus study was not a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product and was, therefore, not subject to any additional restrictions. Decisions regarding prescription of medications were made by the participant in conjunction with their GP: participation in the study had no bearing on this process. Any participants who asked a member of the CASPER plus study team for an opinion on medication issues were strongly encouraged to seek advice from their GP.

The study recorded details of all serious adverse events (SAEs). Any judged to have been related to the study were required to be reported to the REC under the terms of the standard operating procedures for RECs. 51 In the context of the older adult population of the CASPER plus study, many of the SAEs were expected: unscheduled hospitalisations, life-threatening conditions, incapacitating illnesses and deaths. These were not perceived as unexpected events; therefore, they would be reported as SAEs only if they appeared to be related to an aspect of taking part in the study (e.g. participation in treatment, completion of follow-up questionnaires, participation in qualitative substudies or telephone contact).

When a SAE was identified, the trial manager was informed by e-mail using a participant’s trial identification number, and not by any identifiable data. He or she then informed the chief investigator and two members of the Trial Management Group, who jointly decided if the event should be reported to the REC as a SAE. A SAE form was completed and a copy was filed securely at the core study centre. Any unexpected SAEs that were also judged to have been related should have been reported to the main REC within 15 days of the chief investigator becoming aware of the event. In the CASPER plus study, none of the SAEs were judged to have been related to the trial.

The occurrence of adverse events during the trial was monitored by an independent Data Monitoring Ethics Committee and the Trial Steering Committee. The Data Monitoring Ethics Committee/Trial Steering Committee would have seen immediately all SAEs thought to be treatment related.

Data collection schedule

An overview of the time points at which trial data were collected is presented in Table 2.

| Data collected | Time point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invitation | Baseline | Diagnostic interview/randomisation | 4 months’ follow-up | 12 months’ follow-up | 18 months’ follow-up | |

| Consent/decline | ✓ | |||||

| Demographics | ✓ | |||||

| Whooley questions | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Physical health problems | ✓ | |||||

| MINI major depressive module | ✓ | |||||

| PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| SF-12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| EQ-5D-3L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| GAD-7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| PHQ-15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| CD-RISC2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mental health medication | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mortality | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| SAEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Statistical assumptions

Participants, care deliverers and the study team were not blinded to treatment allocation. However, allocations were concealed (group A and group B) for interim study reports, for example for the purpose of independent data monitoring reporting. The trial statistician who was responsible for the final statistical analysis was kept blind to group allocation until the primary analysis had been completed.

All analyses were conducted on intention-to-treat basis, using a two-sided statistical significance level of 0.05 unless otherwise stated. A full specification of the statistical analyses is documented in the CASPER plus statistical analysis plan (version 1.0). Any additional data assumptions for data, once received from the York Trials Unit data management team and the CASPER plus trial management team, for the purpose of this report, are documented separately.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics

All participant baseline data (demographics from the background information form, outcome data from the baseline questionnaire, PHQ-9 and MINI responses from the diagnostic interview) were summarised descriptively by trial arm for all randomised participants and all participants included in the primary analysis.

The analysis population included all patients in their randomised groups with available outcome data (for the primary analysis: PHQ-9 score at 4, 12 or 18 months’ follow-up) as well as complete baseline covariates specified for the analysis.

Primary analysis

Unadjusted descriptives of depression severity (PHQ-9) at all follow-up time points were presented. A covariance pattern linear mixed-effects model was used to compare collaborative care with usual care on PHQ-9 scores at 4 months. Effects of interest and baseline covariates were specified as fixed effects, and the correlation of observations within patients over time was modelled by a covariance structure to describe the random effects. The mixed model provided increased statistical power by utilising all patients with outcomes for at least one follow-up time point.

The outcome modelled was PHQ-9 at 4, 12 and 18 months. The model included time, trial arm and time-by-treatment interaction as fixed effects, adjusting for PHQ-9 score at randomisation and physical/functional limitations (as measured by the baseline SF-12 PCS score). Different covariance structures for the repeated measurements available in the analysis software were explored, and the most appropriate pattern was used for the final model based on the model Akaike information criterion. The primary end point was the estimate of the effect of the intervention at 4 months, which is presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and associated p-values.

Secondary analyses

The primary analysis model was repeated (1) including case managers as a random effect to account for clustering within case managers, (2) including additional covariates predictive of PHQ-9 scores at 4 months as identified by univariate regressions, (3) including additional covariates predictive of non-response at 4 months as identified by univariate regressions and (4) using multiply imputed data. Results from the secondary analyses were compared with those from the primary analysis in order to ascertain the robustness of any observed treatment differences.

Secondary outcomes

Patient Health Questionnaire 9-items depression severity estimates at 12 and 18 months were extracted from the primary analysis model and presented with 95% CIs and associated p-value. A logistic mixed-effects model was used to compare PHQ-9 depression caseness (scores of ≥ 10), using the same covariates as the primary analysis. Odds ratios and 95% CIs are presented for the effect of the intervention at 4, 12 and 18 months. Analyses of other secondary outcomes were conducted using linear or logistic mixed models, depending on the outcome measure, adjusting for PHQ-9 score at randomisation and baseline SF-12 PCS score as well as the outcome measure at baseline. Treatment effects at each time point were reported. EQ-5D-3L responses were reported descriptively as part of the statistical analysis and analysed fully as part of the economic analysis. Frequencies of adverse events were reported descriptively by treatment arm, including breakdown by type and estimated relatedness to the intervention. The number of deaths occurring in the 18-month trial period was summarised by trial arm and overall. A chi-squared test was used to compare proportions between trial arms if more than five participants died in each arm.

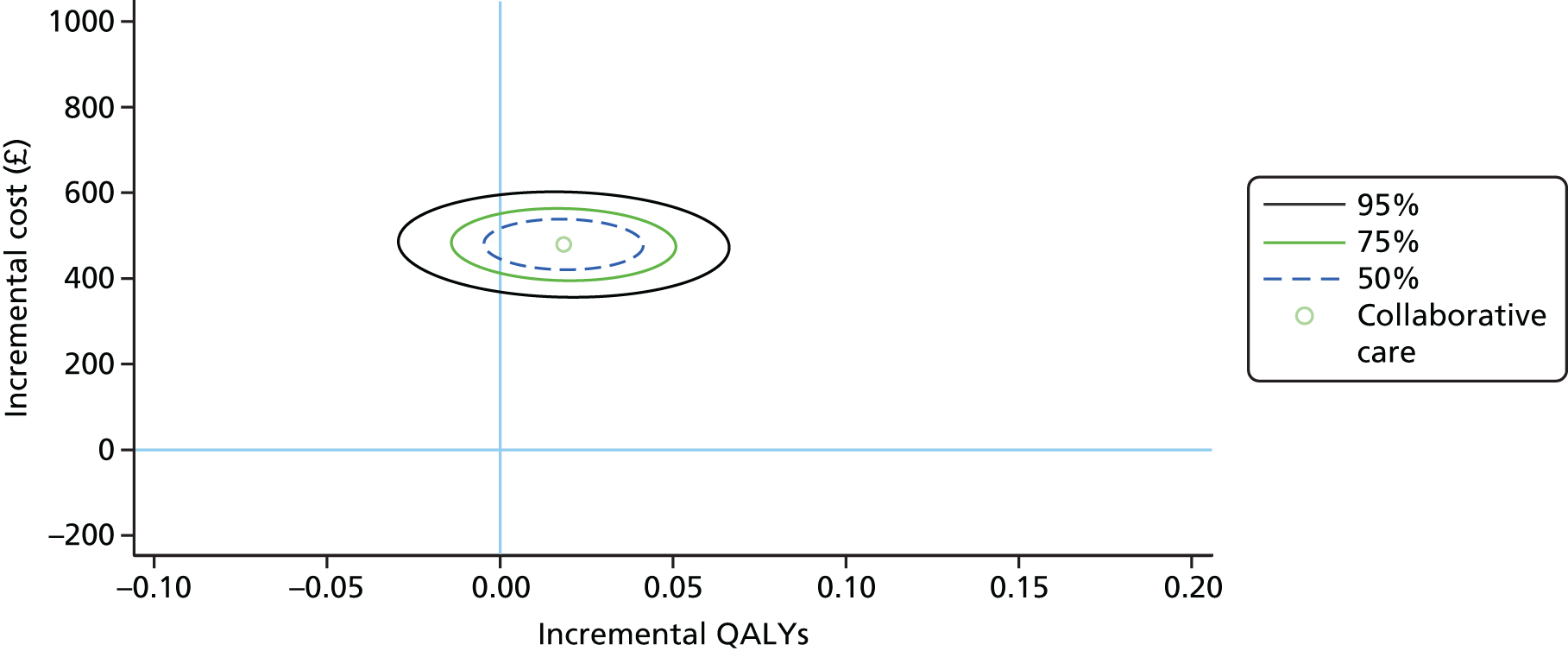

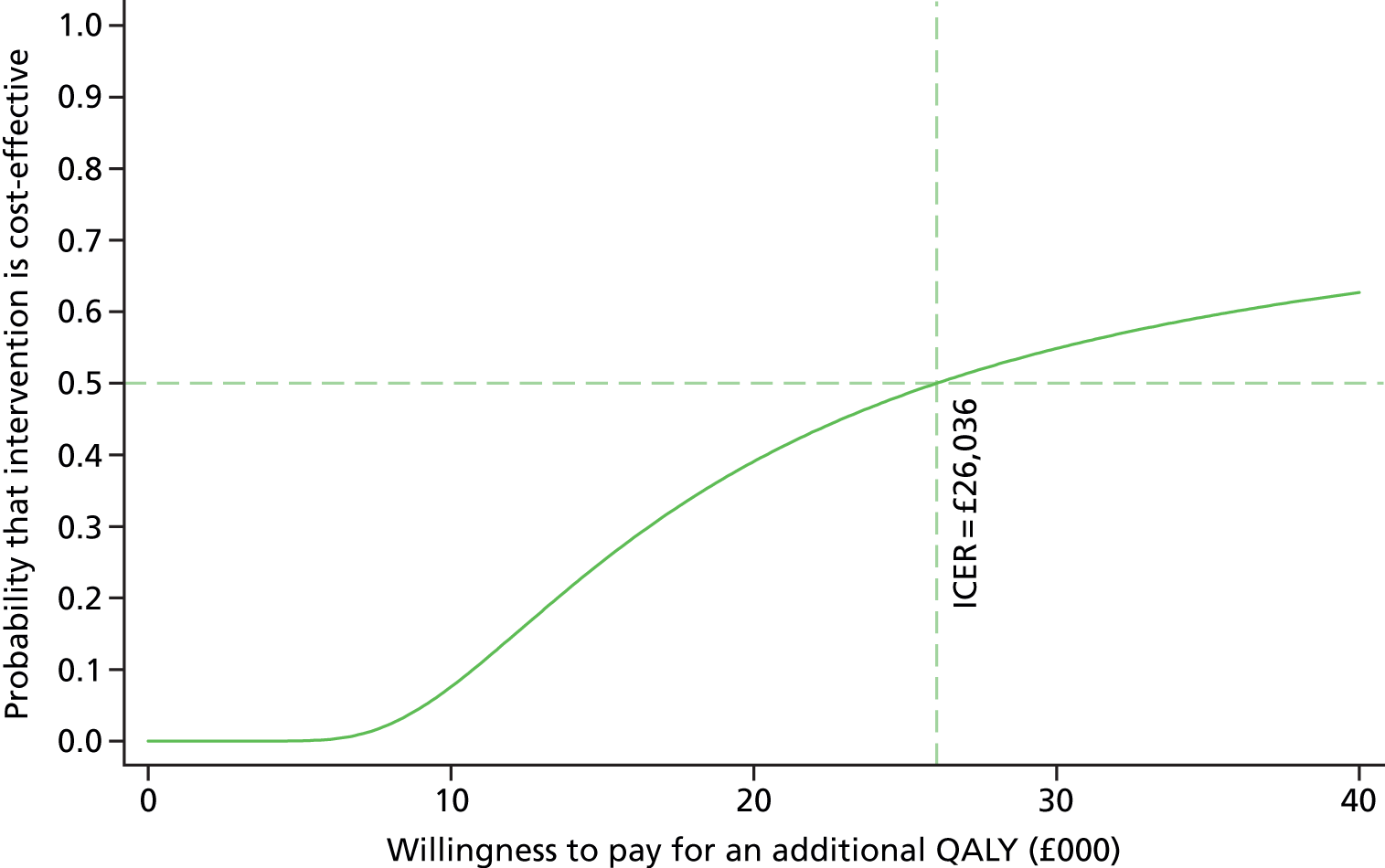

Economic analysis

Economic analysis took the form of a cost-effectiveness analysis and, in line with NICE guidance,52,53 adopted the perspective of the health and personal social services. The aim of the analysis was to estimate the value for money of providing collaborative care as compared with usual care. The time horizon for the analysis was 18 months from the date of randomisation; therefore, costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were discounted at 3% for observations beyond 12 months. The analysis was conducted in Stata® version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Quality-adjusted life-years were estimated from responses to the SF-12 questionnaire to estimate SF-6D health state utilities. 54 This enables comparisons to be made across different health interventions and provides extra information for decision-makers. QALYs were estimated by measuring the area under the curve55 that joins the baseline and follow-up SF-6D utility scores, which was derived from population-based values.

A base-case cost of collaborative care was estimated, based on the case manager training manual, which describes the treatment protocol (the manual is available from the authors on request). Over the full intended duration of the study (i.e. 18 months), participants’ health-care resource use was collected to estimate total cost of health care during treatment and the follow-up period. Various methods of collecting resource use data were initially considered (e.g. self-report questionnaires and medical record checks). Objective data were obtained from general practices giving information on participants’ (1) contacts with GPs (appointments, home visits or telephone consultations), (2) contacts with practice nurses (appointments or telephone consultations) and (3) prescriptions (although we were unable to analyse these data owing to methodological challenges). Given the sample age (≥ 65 years), additional ‘self-report questions’ were not added in order to limit overall questionnaire burden. National unit costs applied to the quantities of resources utilised. 56

For decision analysis, costs of the intervention, health-care use and changes in QALYs in the RCT will be combined to calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) using the following formula:

where C is the costs and E is the effects (as QALYs) in the intervention (I) or control (C) arm.

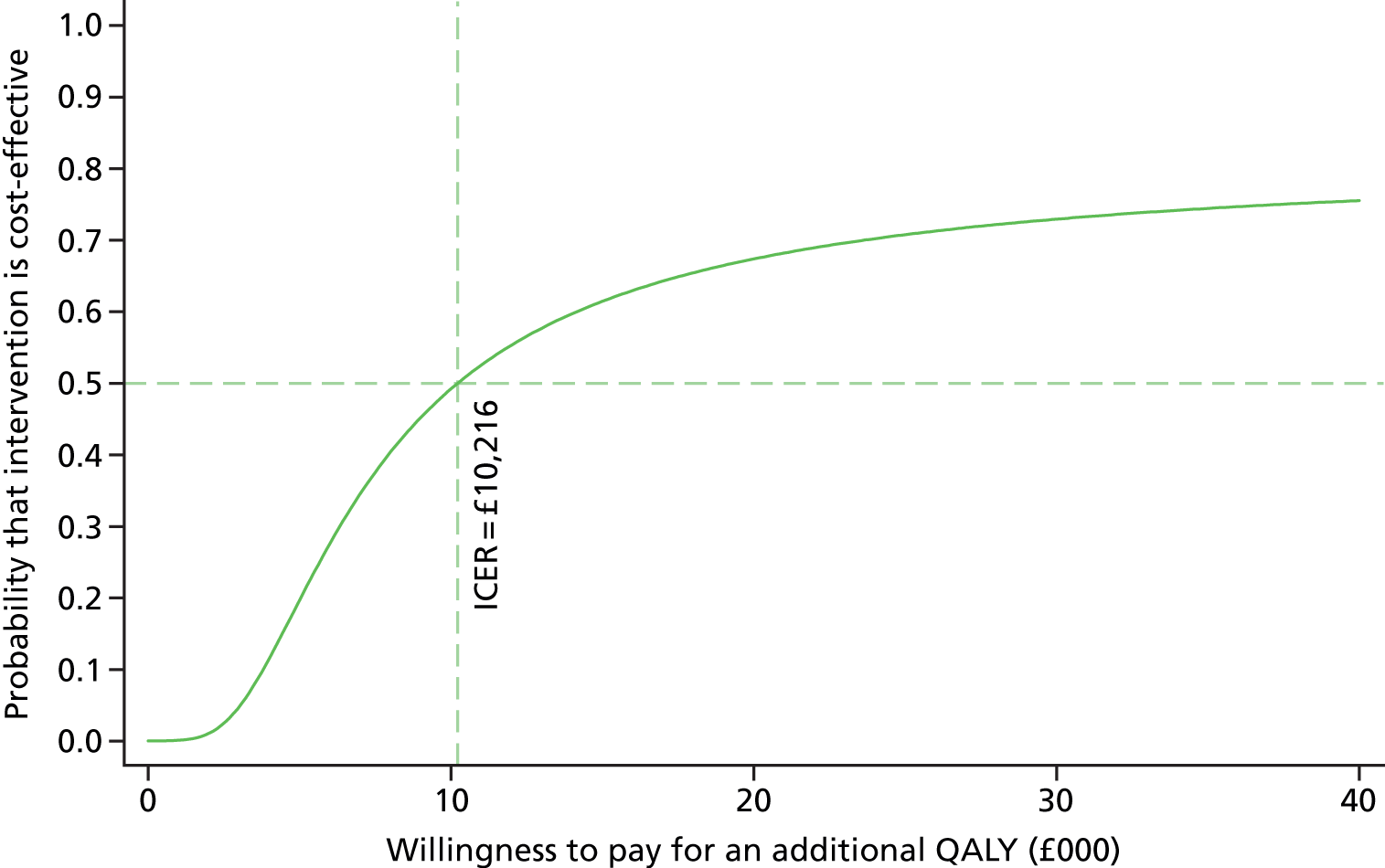

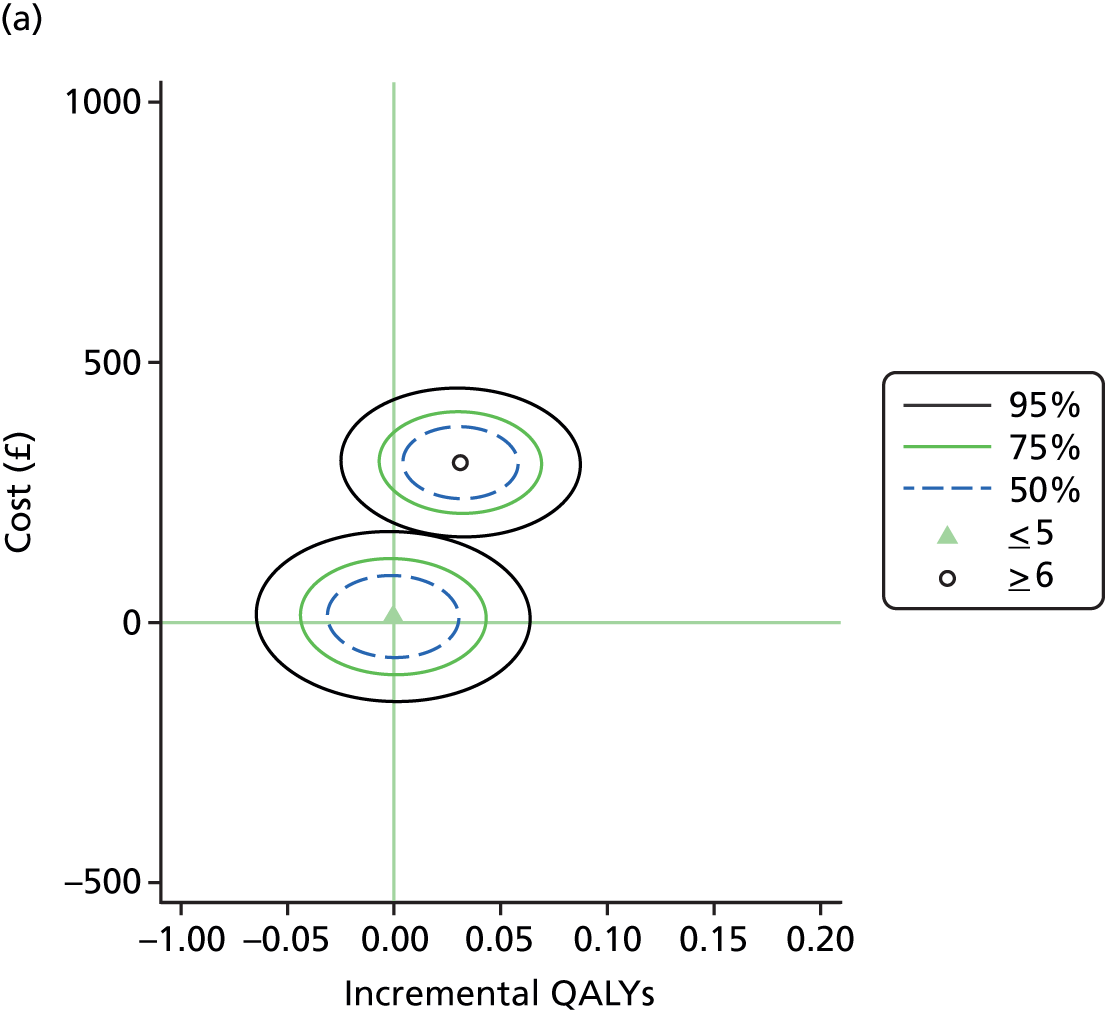

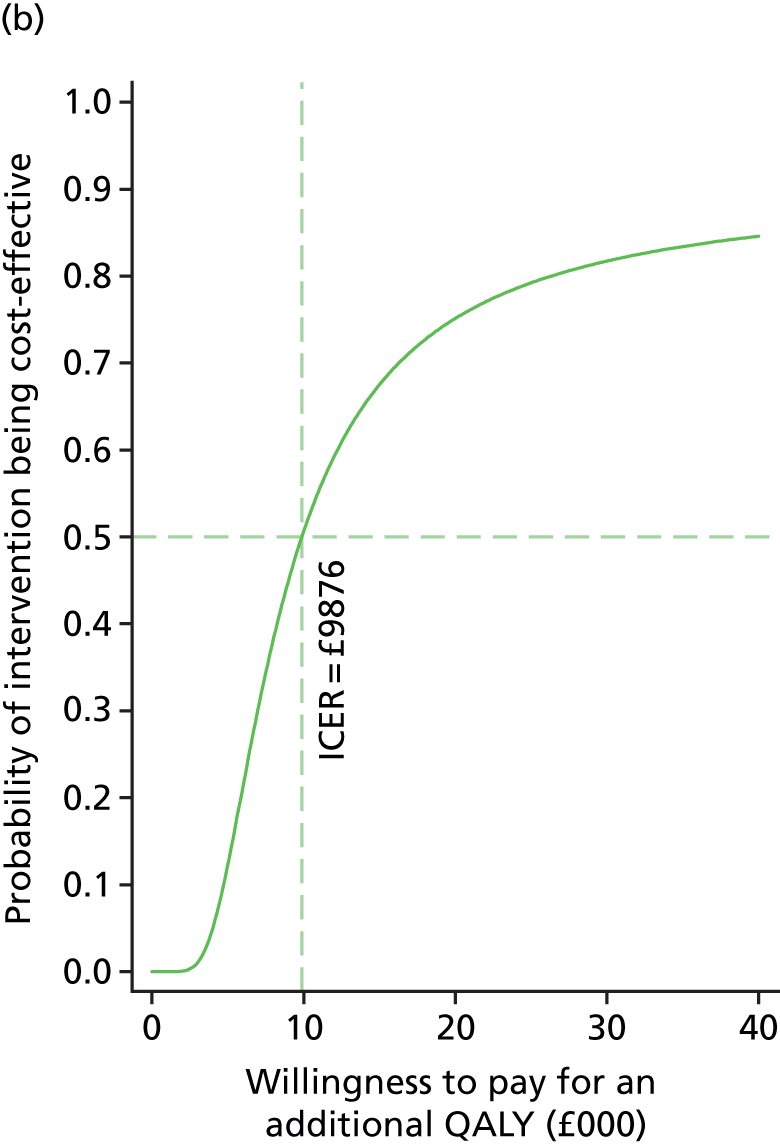

To estimate the joint distributions of cost and QALYs, non-parametric bootstrapping was conducted on the observed data. 57 This non-parametric bootstrap resampling technique allows us to assess uncertainty in the ICER. 58 First, results of the bootstrapped cost and QALYs are presented on the cost-effectiveness plane. The confidence ellipse indicates the incremental costs and QALYs on the 50%, 75% and 95% CIs, indicating the probability space in the cost-effectiveness plane within which we are confident that the true ICER is found.

To further evaluate the joint distributions of costs and benefits, a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) is generated. 59 The CEAC summarises information on uncertainty in cost-effectiveness estimate and illustrates how the probability that collaborative care will be cost-effective as the willingness-to-pay of decision-makers increases. According to NICE, the willingness-to-pay threshold for an additional QALY ranges between £20,000 and £30,000; the CEAC indicates the probability that collaborative care is within this range.

Participants’ take-up of collaborative care was recorded during sessions by case managers. This allowed deterministic sensitivity analysis of the potential variation in direct costs of intervention. Over the course of treatment, the case managers recorded information on the duration of the contact and how this took place for each contact with the participants. This information was used to adjust the expected cost of collaborative care when the patient, the case manager and supervisors agreed to deviation from the manualised intervention. The results were expressed on a CEAC and adjusted probabilities of falling within the NICE range of willingness to pay are presented.

Sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the implication to fidelity to intervention sessions and an ex post adjustment of the expected direct cost of collaborative care. The prescription of a programme of collaborative care is based on an assumption that all participants received the full course of treatment (i.e. 8–10 sessions) and this is an ex ante assumption underlying our base-case cost-effectiveness analysis.

Given that a service provider has intention to treat, the resources required to supply all of the intended sessions for collaborative care must be allocated and, therefore, the budget must include the total expected cost. However, after the allocation of a treatment package, individuals will have varying levels of fidelity to the programme and the expected direct cost of collaborative care may be adjusted when non-attendance of sessions is clearly documented.

All case managers were asked to log their activities with patients on PC-MIS (Patient Case Management Information System; www.york.ac.uk/healthsciences/pc-mis/; accessed 29 May 2016), which has been designed for IAPT. As collaborative care involves both assessment and treatment, demand may vary in relation to the specific levels of need of individuals. The number and duration of a participant’s contact with the case manager was contemporaneously logged on PC-MIS. It was noted whether or not these occurred face to face or by telephone.

Chapter 4 Protocol changes

The following changes were made to the original protocol, after it was initially approved by the REC on 28 September 2010 and the substantial amendment (number 6 of the CASPER trial) to run CASPER plus was approved on 20 April 2012 (see www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25409776; accessed 7 June 2016).

CollAborative care for Screen-Positive EldeRs plus trial

In the original CASPER protocol, the objective was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention for older adults with subthreshold depression. In order to broaden the reach of CASPER, the CASPER plus trial and qualitative substudy were introduced to run concurrently, using the same recruitment procedure, interventions and measures to evaluate an adapted intervention for case-level depression. A separate CASPER plus protocol and amended study documents were developed and approved on 20 April 2012.

Recruitment methods

Direct referral

In order to maximise recruitment in an often difficult to reach group, an additional method of recruitment was introduced. In addition to the original strategy of sending an invitation pack by post to all patients (aged ≥ 65 years) who were identified by computer search as eligible for invitation by the general practice, this was supplemented with direct GP referral at patient consultation. GPs from participating practices were given a number of patient invitation packs (identical to those currently sent by post) that could be handed to patients aged ≥ 65 years who may be consulting about depression and who did not meet the exclusion criteria.

Targeted search

In order to optimise the search strategy, there was a move from an all-inclusive approach to a more targeted approach. The targeted search strategy was developed to include only patients who had a diagnosis of depression or those who were prescribed depression medication and had other conditions associated with an increased risk of depression (e.g. depression, low mood, antidepressant medication, ischaemic heart disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis or being a carer). This was done using the aforementioned Read codes (a coded thesaurus of clinical terms that have been used in the NHS since 1985), the choice of which was left to the discretion of the participating general practice.

Follow-up

Eighteen-month follow-up questionnaire

An 18-month follow-up questionnaire was introduced to obtain longer-term outcomes.

Cohort

In the original protocol, it was stated that all participants who returned screening questionnaires would be followed up at 4 and 12 months via post or online. This included participants both in the RCT and those in the epidemiological cohort. On completion of the CASPER trial of subthreshold depression, this policy was discontinued in order to maximise recruitment and retention to the CASPER plus trial. For the remainder of the trial, only CASPER plus trial participants were followed up. All potential cohort participants who had consented but did not meet the criteria for major depression at diagnostic interview were not followed up.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

In the original protocol participants were excluded owing to alcohol dependency, any known comorbidity that would, in the GP’s opinion, make entry to the trial inadvisable (e.g. recent evidence of self-harm, known current thoughts of self-harm, significant cognitive impairment) and other factors that would make an invitation to participate in the trial inappropriate (e.g. recent bereavement, terminal malignancy) and/or because they were currently experiencing psychotic symptoms. During the trial there were several withdrawals from CASPER plus collaborative care condition as participants were already undergoing therapies and wished to continue with those therapies. Therefore, a screening question was added at the end of the diagnostic interview. This was not done at the invitation stage, to allow for people who had been referred to psychological services but had either not engaged with the service or who were still on a waiting list to participate in the study. People who answered ‘yes’ to this question did not proceed with the diagnostic interview and were excluded from the trial.

Recording of sessions

In the original protocol, there was no quality assurance procedure in place. In order to monitor and improve the quality of the collaborative care intervention delivered during the trial, a purposive sample of sessions was to be recorded. The sample was selected to reflect a range of backgrounds and experience of case managers. The allocation letter received by participants following randomisation was adapted from one that simply informed the participant that a case manager would be in touch shortly to a new letter that informed participants that we may wish to record some of their sessions with their case manager as a quality evaluation, stressing that the decision to agree to this was the participant’s alone and would not affect the treatment that he or she would receive. They also received an additional participant information sheet and consent form regarding the audio-recording.

Telephone delivery

In the original protocol all collaborative care participants were seen for their first session face to face. In the final stages of recruitment it was necessary to enable initial contacts to also be delivered by telephone to ensure that all participants could begin their collaborative care programme without delay. Some IAPT services deal exclusively with their patients via the telephone and so this mix of contacts reflects current practice in IAPT.

Chapter 5 Clinical results

Recruitment and flow of participants through the trial

Recruitment and follow-up

Participants were randomised into the CASPER plus trial between September 2012 and August 2014 from four UK sites and their surrounding areas in the north of England: York, Leeds, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne. A total of 74 general practices screened their practice lists and identified patients who met the initial inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria consisted of any known alcohol dependency and/or psychotic symptoms as recorded on GP records, any known adverse comorbidities or any other factors that GPs deemed made it inadvisable to invite patients, such as recent bereavement.

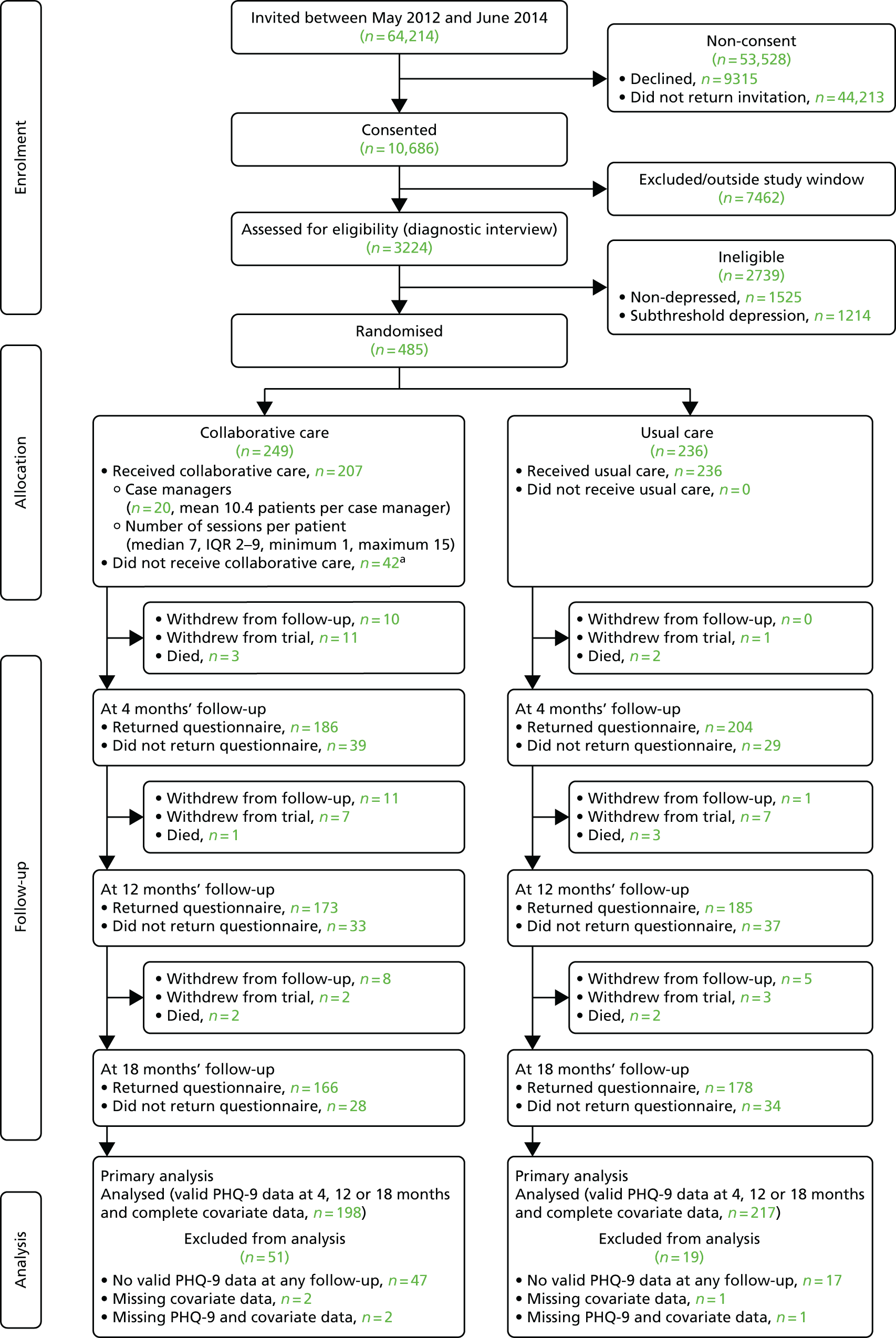

A total of 64,214 patients were identified by GP practices between 5 May 2012 and 10 June 2014 and invited by letter to take part in the CASPER study. Of 10,686 patients who consented, 3224 patients were assessed for eligibility by diagnostic interview. Based on the diagnostic interview, 485 (15%) patients were identified to have a major depressive episode and were randomised into the CASPER plus trial. Of the 485 participants randomised, 249 were allocated to collaborative care and 236 to usual care. The remaining patients were classified as having either below threshold depression (n = 1525) or subthreshold depression (n = 1214). They became part of the epidemiological cohort or were entered into the CASPER or CASPER SHARD trials if within the recruitment window for these trials. The randomised number of 485 participants exceeded that of the planned sample size of 450. The flow of participants is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. a, Reasons for not receiving collaborative care: Carer – no time (n=1), causing marital unrest (n = 2), cognitive impairment (n = 1), did not wish to engage (n = 10), died (n = 2), invasive (n = 6), lost interest (n = 3), not low in mood (n = 1), physical disability (poor hearing) (n = 1), physical ill health (n = 8), receiving other counselling (n = 1), too busy (n = 2), too severely depressed (n = 1) and unable to contact (n = 3). IQR, interquartile range.

Trial withdrawals

Participants were able to withdraw from the study at any point. They were offered the options of withdrawing from the intervention only, from questionnaire follow-up (allowing continued collection of objective data) or from all aspects of the study. Data up to the date of withdrawal were retained for all participants, unless they specifically requested for their details to be removed. This happened on one occasion. The total number of trial withdrawals by trial arm is given in Table 3. Participants could withdraw from only collaborative care treatment but remain in the trial for follow-up purposes. A total of 83 participants (33%) in the collaborative care arm withdrew from treatment at some point, and the numbers of full or partial withdrawals were greater in this arm (n = 55) than in the usual-care group (n = 24).

| Type of withdrawal | Trial arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (N = 55 withdrawn) | Usual care (N = 24 withdrawn) | |||

| n | % of 249 | n | % of 236 | |

| By 4 months’ follow-up | ||||

| Withdrawal from follow-up | 10 | 4.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Full withdrawal | 11 | 4.4 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Died | 3 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.1 |

| By 12 months’ follow-up | ||||

| Withdrawal from follow-up | 21 | 8.4 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Full withdrawal | 18 | 7.2 | 8 | 3.4 |

| Died | 4 | 1.6 | 5 | 2.1 |

| By 18 months’ follow-up | ||||

| Withdrawal from follow-up | 29 | 11.7 | 6 | 2.5 |

| Full withdrawal | 20 | 8.0 | 11 | 4.7 |

| Died | 6 | 2.4 | 7 | 3.0 |

When reasons for withdrawal were provided by the participant, these were documented in the study management database. Following completion of the trial, reasons were grouped into common categories, and these are listed in Tables 4–6 for the different types of follow-up.

| Reason for withdrawal | Trial arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (N = 83 withdrawn) | Usual care (N = 0 withdrawn) | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Carer – no time | 4 | 4.8 | – | – |

| Causing marital unrest | 3 | 3.6 | – | – |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 | 1.2 | – | – |

| Did not wish to engage | 23 | 27.7 | – | – |

| Died | 2 | 2.4 | – | – |

| Does not need further support | 2 | 2.4 | – | – |

| Intervention not useful | 1 | 1.2 | – | – |

| Invasive | 7 | 8.4 | – | – |

| Lost interest | 3 | 3.6 | – | – |

| Not low in mood | 5 | 6.0 | – | – |

| Physical disability (poor hearing) | 1 | 1.2 | – | – |

| Physical ill health | 13 | 15.7 | – | – |

| Receiving other counselling | 3 | 3.6 | – | – |

| Too busy | 5 | 6.0 | – | – |

| Too severely depressed | 1 | 1.2 | – | – |

| Unable to contact | 7 | 8.4 | – | – |

| Unknown | 2 | 2.4 | – | – |

| Total | 83 | 100.0 | – | – |

| Reason for withdrawal | Trial arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (N = 29 withdrawn) | Usual care (N = 6 withdrawn) | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Carer – no time | 1 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Did not wish to engage | 1 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Invasive | 3 | 10.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Lost interest | 14 | 48.3 | 1 | 16.7 |

| Moved out of area | 1 | 3.5 | 2 | 33.3 |

| Physical disability (poor sight) | 1 | 3.5 | 1 | 16.7 |

| Physical ill health | 4 | 13.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Suffered recent bereavement | 1 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Too busy | 2 | 6.9 | 1 | 16.7 |

| Too much effort | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 16.7 |

| Too severely depressed | 1 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 29 | 100.0 | 6 | 100.0 |

| Reason for withdrawal | Trial arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (N = 20 withdrawn) | Usual care (N = 11 withdrawn) | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Carer – no time | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 9.1 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 9.1 |

| Did not wish to engage | 5 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Does not need further support | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Invasive | 2 | 10.0 | 3 | 27.3 |

| Lost interest | 2 | 10.0 | 2 | 18.2 |

| Moved out of area | 2 | 10.0 | 2 | 18.2 |

| Physical ill health | 4 | 20.0 | 1 | 9.1 |

| Too much effort | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unable to contact | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 9.1 |

| Unknown | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 20 | 100.0 | 11 | 100.0 |

The trial sample size calculation allowed for losses to follow-up of 20% at the primary end point at 4 months. The primary outcome (PHQ-9 depression severity) was available for 390 patients at that point, equating to an actual loss to follow-up of 19.6% (25.3% in the collaborative care arm and 13.6% in the usual-care arm).

The intervention: collaborative care

Collaborative care was offered to all patients in the intervention arm. A total of 21 case managers were trained to deliver the intervention, although only 12 delivered it in practice (a case load of 11.9 randomised patients per case manager). In practice, the intervention was delivered by 20 case managers (a case load of 10.4 patients who completed at least one session). Further details on the case load of each individual case manager are given as part of the practitioner analysis (see Chapter 3, Secondary analyses).

An overview of received treatments is provided in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram in Figure 1 and further details are presented in Tables 7 and 8. Of 249 randomised patients, 83% had at least one collaborative care session. Participants received on average six sessions over 8–9 weeks, of which, on average, one was delivered face to face and five were delivered over the telephone. The average session duration was 37 minutes. The most frequent reasons for not wanting to receive any collaborative care were not wishing to engage, physical ill health and invasiveness (Table 9).

| Collaborative care status | Patients randomised to collaborative care (N = 249) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Did not start treatment | 42 | 16.9 |

| Started treatment | 207 | 83.1 |

| Collaborative care details | Patients who received some collaborative care (N = 207) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Days from referral to first session | 207 | 34.4 | 25.5 | 27 | 7 | 220 |

| Number of sessions received | 207 | 6.0 | 3.48 | 7 | 1 | 15 |

| Face to face | 207 | 1.3 | 1.44 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| Telephone | 207 | 4.8 | 3.37 | 5 | 0 | 11 |

| Average length of session (minutes) | 207 | 36.7 | 8.24 | 37 | 0 | 62 |

| Days from first to last session | 207 | 62.0 | 50.38 | 58 | 0 | 333 |

| Reason | Patients who received no collaborative care (N = 42) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Carer – no time | 1 | 2.4 |

| Causing marital unrest | 2 | 4.8 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 | 2.4 |

| Did not wish to engage | 10 | 23.8 |

| Invasive | 6 | 14.3 |

| Lost interest | 3 | 7.1 |

| Not low in mood | 1 | 2.4 |

| Physical disability (poor hearing) | 1 | 2.4 |

| Physical ill health | 8 | 19.1 |

| Receiving other counselling | 1 | 2.4 |

| Too busy | 2 | 4.8 |

| Too severely depressed | 1 | 2.4 |

| Unable to contact | 3 | 7.1 |

| Died | 2 | 4.8 |

Baseline characteristics

Characteristics at consent, baseline and diagnostic interview (point of randomisation) for randomised participants and participants included in the primary analysis (‘as analysed’ population: patients with a valid PHQ-9 score at 4, 12 or 18 months’ follow-up) and valid covariate data (PHQ-9 score at randomisation and baseline SF-12 PCS score) are presented in Tables 10–12.

| Characteristic | As randomised | As analyseda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (N = 249) | Usual care (N = 236) | Collaborative care (N = 198) | Usual care (N = 217) | |

| Age at consent (years) | ||||

| n | 248 | 236 | 198 | 217 |

| Mean (SD) | 72.5 (6.57) | 71.8 (6.07) | 71.9 (6.03) | 71.6 (5.96) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 71 (64, 98) | 70 (65, 92) | 70 (64, 88) | 70 (65, 92) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 98 (39.4) | 85 (36.0) | 81 (40.9) | 80 (36.9) |

| Female | 150 (60.2) | 151 (64.0) | 117 (59.1) | 137 (63.1) |

| Educated past 16 years of age, n (%) | 108 (43.4) | 101 (42.8) | 88 (44.4) | 95 (43.8) |

| Degree or equivalent professional qualification | 57 (22.9) | 68 (28.8) | 44 (22.2) | 62 (28.6) |

| Smoking (yes), n (%) | 30 (12.0) | 28 (11.9) | 25 (12.6) | 27 (12.4) |

| Three or more alcohol units/day, n (%) | 31 (12.4) | 26 (11.0) | 23 (11.6) | 23 (10.6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 241 (96.8) | 233 (98.7) | 193 (97.5) | 215 (99.1) |

| Asian or Asian British | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Black or black British | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 3 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (0.9) |

| Health problems, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 59 (23.7) | 47 (19.9) | 49 (24.7) | 42 (19.4) |

| Osteoporosis | 36 (14.5) | 25 (10.6) | 28 (14.1) | 22 (10.1) |

| High blood pressure | 120 (48.2) | 111 (47.0) | 96 (48.5) | 103 (47.5) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 50 (20.1) | 36 (15.3) | 38 (19.2) | 31 (14.3) |

| Osteoarthritis | 81 (32.5) | 75 (31.8) | 60 (30.3) | 71 (32.7) |

| Stroke | 21 (8.4) | 22 (9.3) | 18 (9.1) | 18 (8.3) |

| Cancer | 31 (12.4) | 21 (8.9) | 23 (11.3) | 20 (9.2) |

| Respiratory conditions | 71 (28.5) | 68 (28.8) | 52 (26.3) | 64 (29.5) |

| Eye condition | 84 (33.7) | 67 (28.4) | 64 (32.3) | 62 (28.6) |

| Heart disease | 55 (22.1) | 71 (30.1) | 42 (21.2) | 64 (29.5) |

| Other | 63 (25.3) | 50 (21.2) | 54 (27.3) | 47 (21.7) |

| Whooley: Over the past month have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 227 (91.2) | 202 (85.6) | 178 (89.9) | 186 (85.7) |

| No | 21 (8.4) | 34 (14.4) | 20 (10.1) | 31 (14.3) |

| Whooley: Over the past month have you been bothered by having little or no interest or pleasure in doing things?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 210 (84.3) | 186 (78.8) | 164 (82.8) | 171 (78.8) |

| No | 38 (15.3) | 50 (21.2) | 34 (17.2) | 46 (21.2) |

| Characteristic | As randomised | As analyseda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (N = 249) | Usual care (N = 236) | Collaborative care (N = 198) | Usual care (N = 217) | |

| PHQ-9 | ||||

| n | 248 | 236 | 198 | 217 |

| Mean score (SD) | 12.4 (5.43) | 12.1 (5.31) | 12.3 (5.43) | 12.0 (5.32) |

| Median score (minimum, maximum) | 12 (0, 27) | 12 (1, 27) | 12 (0, 27) | 12 (1, 27) |

| PHQ-9 grouping, n (%) | ||||

| No depression | 19 (7.6) | 15 (6.4) | 16 (8.1) | 15 (6.9) |

| Mild depression | 64 (25.7) | 64 (27.1) | 52 (26.3) | 59 (27.2) |

| Moderate depression | 79 (31.7) | 85 (36.0) | 61 (30.8) | 77 (35.5) |

| Moderately severe depression | 67 (26.9) | 51 (21.6) | 53 (26.8) | 47 (21.7) |

| Severe depression | 19 (7.6) | 21 (8.9) | 16 (8.1) | 19 (8.8) |

| PHQ-15 | ||||

| n | 246 | 234 | 196 | 215 |

| Mean score (SD) | 12.3 (4.51) | 11.9 (4.33) | 12.0 (4.46) | 11.9 (4.36) |

| Median score (minimum, maximum) | 12 (2, 26) | 11 (2, 24) | 12 (2, 24) | 11 (2, 24) |

| SF-12 (PCS) | ||||

| n | 245 | 234 | 198 | 217 |

| Mean score (SD) | 35.6 (13.08) | 36.8 (13.32) | 36.1 (13.16) | 36.6 (13.39) |

| Median score (minimum, maximum) | 34.5 (7.1, 66.3) | 35.8 (5.9, 69.6) | 34.9 (7.1, 66.3) | 38.8 (5.9, 69.6) |

| SF-12 (MCS) | ||||

| n | 245 | 234 | 198 | 217 |

| Mean score (SD) | 35.4 (9.51) | 35.7 (10.53) | 35.5 (9.66) | 36.0 (10.52) |

| Median score (minimum, maximum) | 35.8 (10.3, 60.2) | 36.2 (2.2, 62.9) | 35.9 (10.3, 60.2) | 36.4 (2.2, 62.9) |

| GAD-7 | ||||

| n | 247 | 234 | 197 | 215 |

| Mean score (SD) | 9.4 (5.03) | 9.3 (4.92) | 9.4 (5.12) | 9.2 (4.95) |

| Median score (minimum, maximum) | 9 (0, 21) | 9 (0, 21) | 9 (0, 21) | 9 (0, 21) |

| EQ-5D-3L, n (%) | ||||

| Mobility | ||||

| No problems | 71 (28.5) | 76 (32.2) | 61 (30.8) | 70 (32.3) |

| Some problems | 176 (70.7) | 157 (66.5) | 136 (68.7) | 144 (66.4) |

| Confined to bed | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) |

| Self-care | ||||

| No problems | 163 (65.5) | 175 (74.2) | 134 (67.7) | 160 (73.7) |

| Some problems | 75 (30.1) | 55 (23.3) | 58 (29.3) | 52 (24.0) |

| Unable to wash/dress | 5 (2.0) | 4 (1.7) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.4) |

| Usual activities | ||||

| No problems | 64 (25.7) | 66 (28.0) | 52 (26.3) | 62 (28.6) |

| Some problems | 159 (63.9) | 151 (64.0) | 131 (66.2) | 138 (63.6) |

| Unable to perform | 24 (9.6) | 18 (7.6) | 14 (7.1) | 16 (7.4) |

| Pain/discomfort | ||||

| No pain | 34 (13.7) | 27 (11.4) | 30 (15.2) | 24 (11.1) |

| Moderate pain | 156 (62.7) | 152 (64.4) | 129 (65.2) | 140 (64.5) |

| Extreme pain | 57 (22.9) | 54 (22.9) | 38 (19.2) | 50 (23.0) |

| Anxiety/depression | ||||

| Not anxious/depressed | 26 (10.4) | 25 (10.6) | 21 (10.6) | 25 (11.5) |

| Moderately anxiety/depression | 176 (70.7) | 178 (75.4) | 141 (71.2) | 161 (74.2) |

| Extremely anxiety/depression | 44 (17.7) | 31 (13.1) | 34 (17.2) | 29 (13.4) |

| Prescribed antidepressants | 82 (32.9) | 79 (33.5) | 67 (33.8) | 77 (35.5) |

| Whooley: Over the past month have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 238 (95.6) | 219 (92.8) | 190 (96.0) | 201 (92.6) |

| No | 10 (4.0) | 17 (7.2) | 8 (4.0) | 16 (7.4) |

| Whooley: Over the past month have you been bothered by having little or no interest or pleasure in doing things?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 220 (88.4) | 210 (89.0) | 177 (89.4) | 195 (89.9) |

| No | 28 (11.2) | 26 (11.0) | 21 (10.6) | 22 (10.1) |

| Characteristic | As randomised | As analyseda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (N = 249) | Usual care (N = 236) | Collaborative care (N = 198) | Usual care (N = 217) | |

| PHQ-9 | ||||

| N | 248 | 236 | 198 | 217 |

| Mean score (SD) | 14.0 (5.37) | 14.0 (4.93) | 13.9 (5.42) | 13.9 (4.80) |

| Median score (minimum, maximum) | 14 (3, 27) | 14 (4, 27) | 14 (3, 26) | 14 (4, 27) |

| PHQ-9 grouping, n (%) | ||||

| No depression | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.8) |

| Mild depression | 60 (24.1) | 46 (19.5) | 51 (25.8) | 41 (18.9) |

| Moderate depression | 77 (30.9) | 77 (32.6) | 57 (28.8) | 73 (33.6) |

| Moderately severe depression | 69 (27.7) | 76 (32.2) | 57 (28.8) | 73 (33.6) |

| Severe depression | 40 (16.1) | 33 (14.0) | 32 (16.2) | 26 (12.0) |

| From MINI: Were you ever depressed or down, most of the day, nearly every day for 2 weeks?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 213 (85.5) | 207 (87.7) | 170 (85.9) | 191 (88.0) |

| No | 35 (14.1) | 29 (12.3) | 28 (14.1) | 26 (12.0) |

| From MINI: For the past 2 weeks, were you depressed or down, most of the day, nearly every day?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 182 (73.1) | 172 (72.9) | 141 (71.2) | 157 (72.4) |

| No | 31 (12.4) | 35 (14.8) | 29 (14.6) | 34 (15.7) |

| From MINI: Were you ever much less interested in most things or much less able to enjoy things you used to enjoy most of the time for 2 weeks?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 234 (94.0) | 218 (92.4) | 190 (96.0) | 202 (93.1) |

| No | 14 (5.6) | 18 (7.6) | 8 (4.0) | 15 (16.9) |

| From MINI: In the past 2 weeks, were you much less interested in most things or much less able to enjoy the things you used to enjoy, most of the time?, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 214 (85.9) | 205 (86.9) | 178 (89.9) | 190 (87.6) |

| No | 20 (8.0) | 13 (5.5) | 12 (6.1) | 12 (5.5) |

Primary outcome

Near-complete PHQ-9 responses were available for participants at diagnostic interview (one participant asked for all data to be destroyed at the point of withdrawal). At follow-up, 300 patients (62%) had valid PHQ-9 scores at all three follow-up times, 118 patients (24%) had a valid PHQ-9 score at 4 months or 12 months only, and for 67 patients (14%) no PHQ-9 scores were available at 18 months’ follow-up.

Score distribution

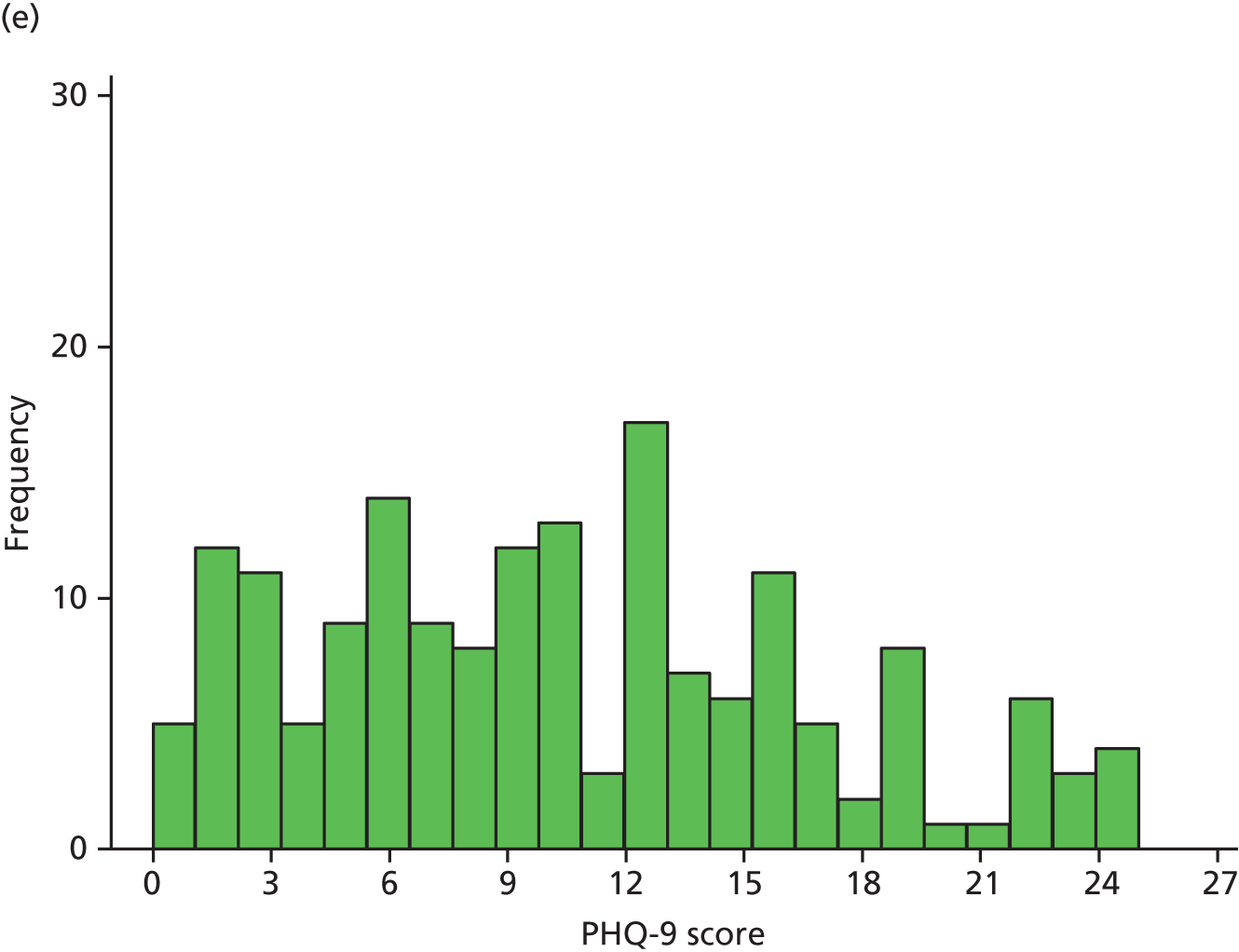

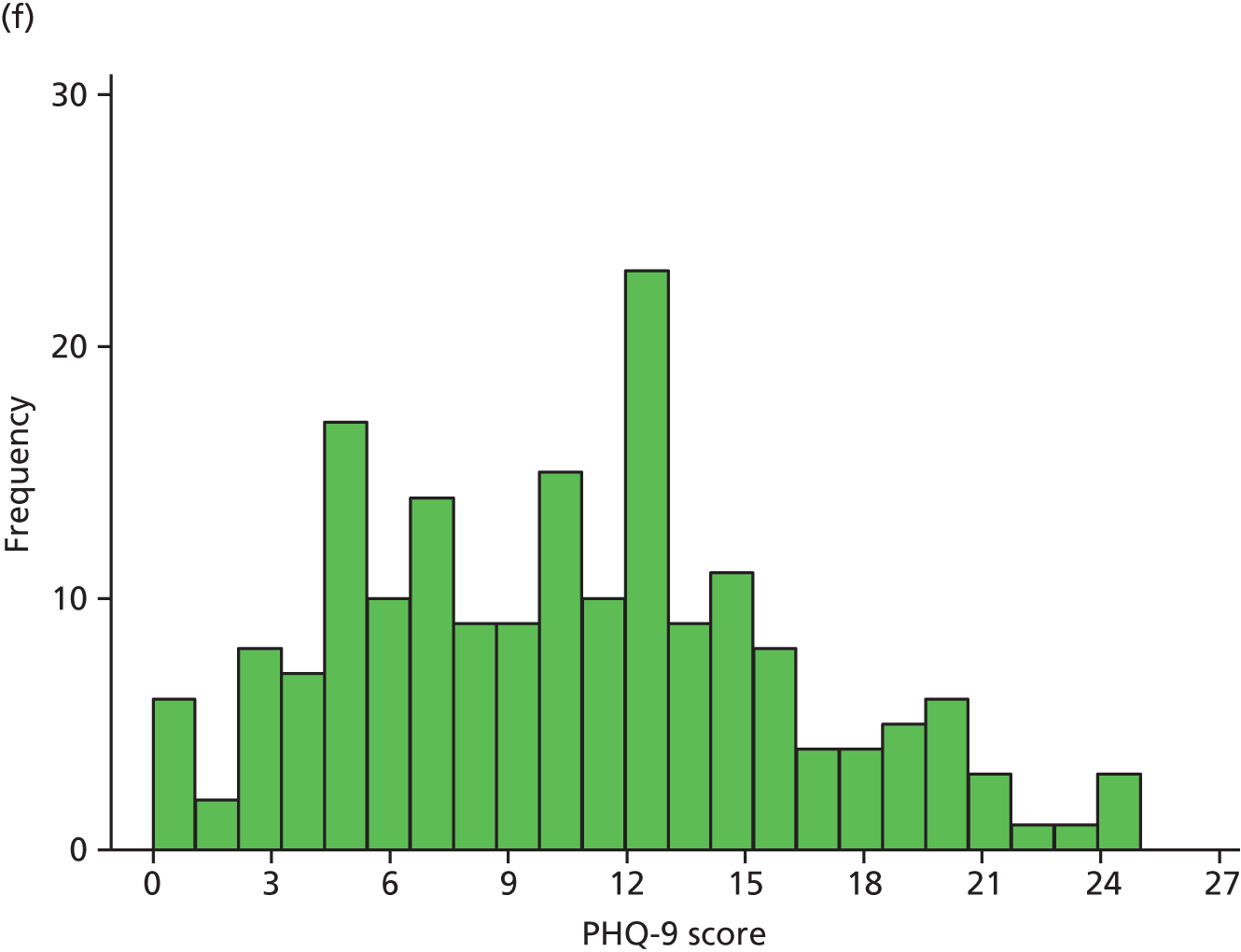

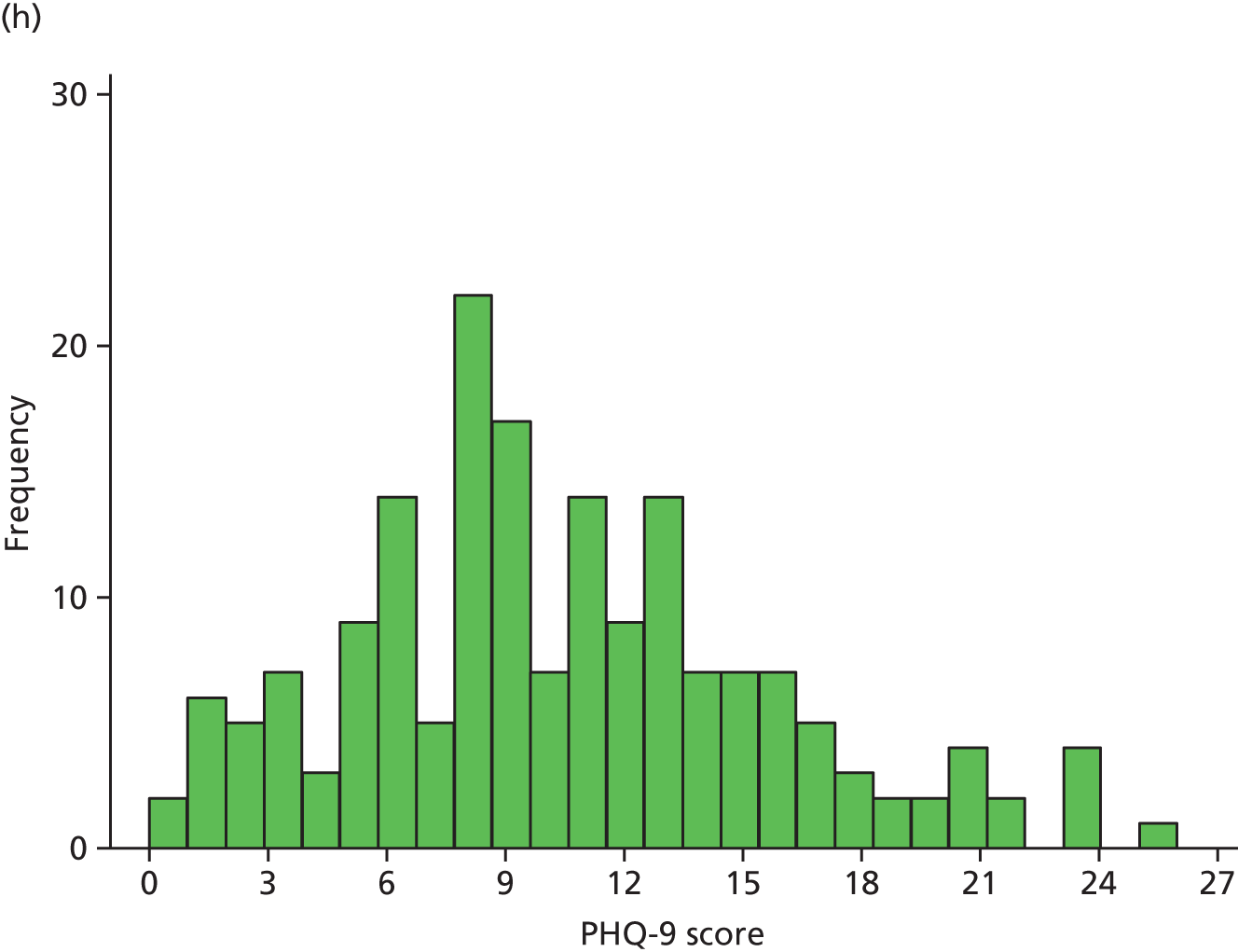

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of PHQ-9 scores for each trial arm over time. At randomisation, scores were distributed approximately normal with a slight right skew, which became more pronounced over the follow-up period, as patients in both arms improved.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of PHQ-9 scores by trial arm. (a) Randomisation, collaborative care; (b) randomisation, usual care; (c) 4 months’ follow-up, collaborative care; (d) 4 months’ follow-up, usual care; (e) 12 months’ follow-up, collaborative care; (f) 12 months’ follow-up, usual care; (g) 18 months’ follow-up, collaborative care; and (h) 18 months’ follow-up, usual care.

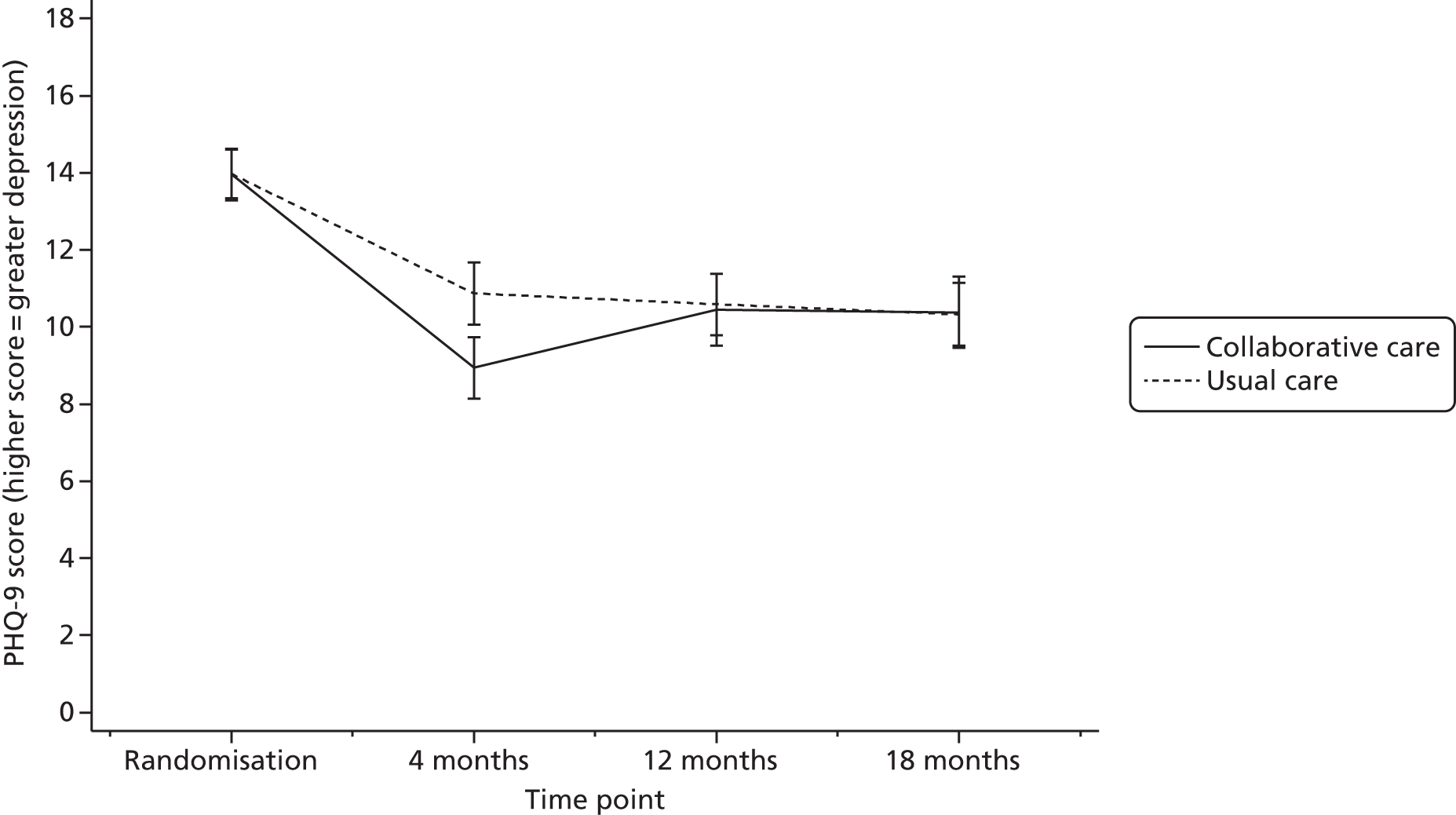

Unadjusted summary statistics

Summary statistics of the raw PHQ-9 scores are given in Table 13 and are illustrated in Figure 3. Average depression severity, as measured by the PHQ-9, was around 14 score points at randomisation. Scores in both treatment arms improved between randomisation and 4 months’ follow-up, but to a greater extent in the collaborative care group (to a score of around 9) than in the usual-care group (to a score of around 11). By 12 and 18 months’ follow-up, average depression scores continued to improve slightly in the usual-care group, whereas scores in the collaborative care group increased again to similar levels.

| Time | Trial arm | Total (N = 485) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care (N = 249) | Usual care (N = 236) | ||

| Randomisation, n (%) | 248 (99.6) | 236 (100) | 484 (99.8) |

| Mean (SD) | 14.0 (5.37) | 14.0 (4.93) | 14.0 (5.15) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 14 (3, 27) | 14 (4, 27) | 14 (3, 27) |

| 4 months, n (%) | 186 (75) | 204 (86) | 390 (80) |

| Mean (SD) | 8.9 (5.53) | 10.9 (5.89) | 9.9 (5.79) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 8 (0, 24) | 11 (0, 26) | 9 (0, 26) |

| 12 months, n (%) | 172 (69) | 185 (78) | 357 (74) |

| Mean (SD) | 10.4 (6.25) | 10.6 (5.52) | 10.5 (5.87) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 10 (0, 25) | 10 (0, 25) | 10 (0, 25) |