Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/17/01. The contractual start date was in February 2015. The draft report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in April 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Wailoo et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common chronic inflammatory disease that typically affects the joints of the body that are lined with synovium, such as those in the hands and feet. It is characterised by progressive, irreversible joint damage, impaired joint function and pain and tenderness caused by swelling of the synovial lining of joints (synovitis), and manifests as increasing disability and reduced quality of life. 1 As RA is a systemic disease, it affects much more than the joints. The primary symptoms are pain, morning stiffness, swelling, tenderness, loss of movement, fatigue and redness of the peripheral joints. 2,3 Fever, sweats and weight loss may be experienced. More significant inflammatory manifestations may lead to serious pathology. 4 RA has long been reported as being associated with increased mortality,5,6 particularly as a result of cardiovascular events,7 which may result from reduced mobility and ongoing inflammation. For example, a 50-year-old woman with RA is expected to die 4 years earlier than a 50-year-old woman without RA. 4

The costs of RA are substantial. Treatment costs associated with drug acquisition and hospitalisation are major components of this. Reduced work productivity is also a significant cost burden in this patient group. 3 The total costs of RA in the UK, including indirect costs and work-related disability, have been estimated at between £3.8B and £4.75B per year. 8

Epidemiology

Symmons et al. 9 estimated a prevalence of 0.8% in a study of the population in Norfolk. This leads to an estimated 400,000 people in England and Wales with RA,10 with approximately 10,000 incident cases per year. 11 The disease is about 2–4 times more common in women (1.16%) than in men (0.44%),11 with the majority of cases being diagnosed when patients are aged between 40 and 80 years,12 with peak incidence among those in their seventies. 11 Thus, a large proportion of people affected by RA are of working age.

Significance for the NHS

The treatment of RA is costly to the NHS and the wider economy. Many of the treatment options for patients are based on drug therapy, some of which (particularly biologic therapies) are extremely costly. The cost of treating patients whose disease is not well controlled from an early stage is also driven substantially by the need for joint surgery and hospitalisation.

Treat to target (TTT) has the potential to allow more effective treatment strategies to be given to patients. Given in early disease, this may result in better disease control. Remission has been shown to correlate strongly with long-term structural damage identifiable on radiographs and with patient function. Disease control may also allow the tapering of drug doses over time and avoid the need to progress to costlier biologic therapies.

Current service provision

A series of drug-based treatments have contributed to the rapid improvement in the care of patients with RA over the last 20 years. Traditionally, patients have been treated with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (cDMARDs), which include methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine (SSZ), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), leflunomide (LEF), ciclosporin and gold injections, as well as corticosteroids, analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). More recently, a group of drugs has been developed consisting of monoclonal antibodies and soluble receptors that specifically modify the disease process by blocking key protein messenger molecules (such as cytokines) or cells (such as B lymphocytes). 4 Such drugs have been labelled as biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs).

Given the number of treatments available, there is a vast number of potential treatment strategies for patients in both early and established disease.

Clinical guidelines

For people with newly diagnosed RA, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline number 794 recommends a combination of cDMARDs [including MTX and at least one other disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) plus short-term glucocorticoids (GCs)] as a first-line treatment, ideally beginning within 3 months of the onset of persistent symptoms. Where combination therapies are not appropriate (e.g. where there are comorbidities or pregnancy), DMARD monotherapy is recommended, this was considered a more standard treatment approach prior to the NICE guidelines.

Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Technology Appraisal guidance

The NICE guidance [Technology Appraisal (TA) number 37513] recommends the use of adalimumab (ADA), etanercept (ETN), infliximab (IFX), certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab (TOC) and abatacept, in combination with MTX, in people with RA only if:

-

disease is severe, that is, Disease Activity Score, 28 joints (DAS28) is > 5.1

-

disease has not responded to intensive therapy with a combination cDMARDs

-

the manufacturers provide certolizumab pegol, golimumab, abatacept and TOC as agreed in their patient access schemes.

Adalimumab, ETN, certolizumab pegol or TOC can be used as monotherapy for people who cannot take MTX, because it is contraindicated or because of intolerance, when the above criteria are met.

At least a moderate European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response must be achieved at 6 months for treatment to continue.

The NICE has also issued guidance on the treatment of RA after the failure of a tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) (TA195,14 TA22515 and TA24716).

Description of technology under assessment

Dramatic improvements in the treatment of RA have been seen in the last 20 years (see Smolen et al. 17), particularly through the development of more targeted bDMARDs and non-bDMARDs. A more recent development that has consolidated these improvements is the concept of TTT. Rather than referring to a single, precise technology or treatment strategy, TTT in rheumatology can be better described as a treatment ‘paradigm’17 encompassing a range of broad features. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/EULAR have issued a series of recommendations on TTT based on analysis of a series of trials that test varying treatment strategies. There is therefore no single set of interventions constituting a TTT treatment approach.

Treat to target has a strong history in the treatment of other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Long-term outcome data supporting the TTT approach in these conditions have motivated the drive for successful TTT approaches in RA.

The central component of the TTT concept is the setting of a treatment target. Recommendations typically specify low disease activity (LDA) or remission as appropriate targets. This was the case in EULAR’s 2010 recommendations (see Smolen et al. 18) and EULAR’s 2016 updated recommendations (see Smolen et al. 17), both of which recommended clinical remission as the primary treatment goal. The ACR/EULAR’s 2011 definition of remission was originally designed specifically to be a predictor of good patient outcomes in terms of a later lack of radiography-detected joint damage and good, stable function and quality of life for patients,19 more so than other disease activity states (including LDA). 17 These goals have become realistic targets with the availability of newer drugs.

The ACR/EULAR definition of remission is:

-

Boolean-based definition: at any time point, a patient must satisfy all of the following: a tender joint count (TJC) of ≤ 1, a swollen joint count (SJC) of ≤ 1, a C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration of ≤ 1 mg/dl and a patient global assessment of ≤ 1 (on a scale of 0–10) or

-

index-based definition: at any time point, a patient must have Simple Disease Activity Index (SDAI) of ≤ 3.3.

Low disease activity as an acceptable, alternative therapeutic goal, particularly in long-standing disease, is a recommendation intended to imply that there are situations where remission may not be a feasible outcome.

However, TTT, as a concept, is also often described as comprising more than just a treatment goal. Different commentators refer to different elements of the TTT strategy that aim to take action to reach and maintain the treatment goal. Common to most is the concept of regular treatment adaptation in response to the assessment of a patient in comparison to the target. Sometimes treatment adaptation is described in broad terms;17,18 in other instances reference is made to ‘aggressive treatment’. 20 Terminology also varies, with some referring to ‘tight control’. 21

Solomon et al. 20 also refers to TTT as a ‘proactive’ treatment approach. In many studies of TTT this is evident through more frequent assessment of patients than would normally be the case in standard practice. Assessments are often made as frequently as monthly under TTT principles. The ACR/EULAR’s recommendations state that assessments should be made ‘as frequently as monthly’ and drug therapy should be altered at least every 3 months, until the target is reached. Less frequent (6-monthly) monitoring of patients is required once the target is reached.

Treat to target can therefore be composed of a range of different features that leads to a continuum of ‘weak’ to ‘strong’ TTT principles. We define the entirety of those features as the ‘treatment strategy’. The inclusion of a treatment target is a necessary condition for a strategy to be considered a TTT strategy. Additional components of the strategy include the frequency with which patients are assessed against the target and the provision of a treatment protocol that specifies how treatments are to be changed in response to assessments. Thus, the weakest TTT strategy would be one where a treatment target is specified, but no further instruction is provided on which treatment protocols should be used to reach that goal.

Treat-to-target studies have often focused on the optimal strategy for patients with newly diagnosed RA. This links to the concept of there being a ‘window of opportunity’ that has emerged in the RA literature, which posits that the earlier DMARD therapy is introduced, the greater the impact on long-term health outcomes. 21

Additional costs associated with TTT depend on the nature of the overall treatment strategy. Of course, the setting of a target itself incurs no additional resources, but the increased frequency of visits to a rheumatologist and the potential for a more intense use of drug treatments can make TTT a more resource-intensive option for the initial treatment period.

A simplified schematic of operationalising a TTT strategy has been provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

A simplified conceptual model of TTT.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

We aim to systematically review evidence on the use of TTT strategies for the treatment of RA compared with standard care with non-TTT strategies.

Decision problem

Interventions

The intervention of interest is a TTT approach to care. At a minimum, for a treatment strategy to be considered TTT in this review it must contain the explicit setting of a target, assessment of that target and use of that information by the treating clinician. TTT strategies may also include additional elements; for example, in the frequency of assessment or in providing a treatment protocol that provides instruction to the treating clinician on treatment changes in the light of assessments. Our review will seek to distinguish these different types of TTT.

Population including subgroups

Adult patients aged ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of RA were eligible for the study. We will consider two groups of patients separately: (1) those with early disease (≤ 3 years since diagnosis) and (2) those with established disease (> 3 years since diagnosis). We used definitions of early and established RA as defined in the trials. When no definition was provided, a cut-off point of 3 years was used, which is generally consistent across the literature (e.g. Scott et al. 22), bearing in mind that no fixed consensus exists. Examining definitions and mean disease durations across trials, a 3-year cut-off point seems appropriate.

Relevant comparators

The comparator is treatment of patients without a TTT strategy. This includes sequential non-bDMARD therapy in early disease, clinician preference and any treatment protocol that lacks an explicit treatment target.

Outcomes

A number of outcomes were assessed. Primarily, we examined the proportion of patients achieving target, remission and LDA. We also examined changes in DAS28/ Disease Activity Score, 44 joints (DAS44), SJC, TJC, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), joint erosion and quality of life, as well as EULAR and ACR response.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The aim of this review is to identify and evaluate the evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of TTT strategies compared with routine care for adult patients with RA.

Patient and public involvement

Two members of the public who have RA were asked to peer review the following sections of the report: the abstract; plain English summary; scientific summary; discussion; and conclusions. The full report was provided to supply further information and the patient and public involvement representatives could comment on other sections too. The report was then amended based on the comments received to improve the clarity and readability of the text.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

The search for evidence of clinical effectiveness was undertaken systematically following the general principles recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (URL: www.prisma-statement.org/; accessed 30 October 2017). Search strategies are described in Appendix 1.

Identification of studies

There were two search phases conducted for this review.

Phase I scoping searches were carried out to identify the extent of potentially relevant literature, the range and types of TTT strategies that have been subject to clinical study, the types of clinical study and the relevance of these strategies to UK NHS practice.

Four databases and one clinical trials registry were searched (Table 1). Terms for RA (see Appendix 2, statements 1 and 2) were combined with TTT terms (see Appendix 2, statements 4–18). Terms for TTT were obtained and adapted from the review by Schoels et al. 23

| Source, date searched from | Phase (date of search) | |

|---|---|---|

| I (May 2015) | II (January 2016 and August 2016) | |

| MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and MEDLINE(R) (via Ovid), from 1948 | ✓ | ✓ |

| EMBASE (via Ovid), from 1980 | ✓ | ✓ |

| CDSR (via Wiley Online Library), from 1996 | ✓ | ✗ |

| CENTRAL (via Wiley Online Library), from 1898 | ✓ | ✓ |

| NHS EED (via Wiley Online Library), from 1995 to 2015 | ✓ | ✓ |

| HTA database (via Wiley Online Library), from 1995 | ✓ | ✗ |

| DARE (via Wiley Online Library), from 1995 | ✓ | ✗ |

| WoS Citation Index Expanded (Thomson Reuters), from 1900 | ✓ | ✓ |

| WoS Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Index (Thomson Reuters), from 1990 | ✓ | ✓ |

| BIOSIS Previews (Thomson Reuters), from 1969 | ✗ | ✓ |

| CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), from 1982 | ✗ | ✓ |

| EconLit (via Ovid), from 1886 | ✗ | ✓ |

| EULAR (via Web of Science, Thomson Reuters) | ✓ | ✗ |

| ACR (via Web of Science, Thomson Reuters)) | ✓ | ✗ |

| ClinicalTrials.gov (US National Institutes of Health) (www.clinicaltrials.gov) | ✓ | ✓ |

| ICTRP (www.who.int/ictrp/en/) | ✗ | ✓ |

| NICE Evidence (www.nice.org.uk/) | ✗ | ✓ |

The search was combined with specific search filters for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (see Appendix 2, statements 21 and 22), systematic reviews (see Appendix 2, statements 26–28) and economic evaluations (see Appendix 2, statements 32–34). The RCT and systematic reviews search was limited by date from 2008 until May 2015, whereas for recent cost-effectiveness studies, the last 2 years were searched (2013–15).

The Phase II search was informed by the literature identified from the Phase I searches to refine and carry out a full systematic search of the evidence.

Additional free-text terms for TTT were added to the Phase I search strategies to increase the sensitivity of the search (see Appendix 2). Only RCT and economic evaluations were searched by combining the strategies with sensitive search filters. Three further databases, one trials registry and a search engine were searched (see Table 1). No date or language limits were applied in the search. Records retrieved from the search were combined and duplicate titles were removed from the Phase I search.

The number of records retrieved from the various sources in Phase I and II searches can be found in Table 2.

| Source | Phase | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | |||||

| RCTs (specific and 2008–) | SRs (specific and 2008–) | Cost-effectiveness (2013–) | RCTs | RCT update (August 2016) | Cost-effectiveness | |

| MEDLINE | 475 | 168 | 73 | 3778 | 294 | 417 |

| EMBASE | 1315 | 302 | 290 | 7633 | 423 | 923 |

| CDSR | – | 81 | – | – | – | – |

| DARE | – | 79 | – | – | – | – |

| CENTRAL | 1588 | – | – | 2243 | 45 | 0 |

| HTA database | – | 7 | – | – | – | – |

| NHS EED | – | – | 9 | 0 | 0 | 45 |

| WoS Citation Index Expanded and WoS Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Index | 2179 | 641 | 199 | 5435 | 245 | 444 |

| BIOSIS | – | – | – | 1753 | 32 | 0 |

| CINAHL | – | – | – | 789 | 66 | 642 |

| EconLit | – | – | – | 0 | – | 6 |

| EULAR | 650 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ACR | 792 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | 122 | – | – | 26 | 6 | 0 |

| ICTRP | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NICE Evidence | – | – | – | 0 | – | 2 |

| Total retrieved | 7121 | 1278 | 571 | 21,657 | 1115 | 2479 |

| Unique | 4937 | 946 | 436 | 10,093a | 635b | 913a |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

The population was adults with clinically diagnosed RA, with or without prior cDMARDs or bDMARDs, commencing or currently undergoing treatment anywhere on the RA treatment pathway.

Intervention

The intervention is the use of TTT strategies to guide treatment decisions for individual patients, as defined in Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness. Sufficient description of the intervention needed to be reported for a study to be included in the review.

Comparators

The following comparators were permitted: (1) usual care, in which TTT strategies were not used, (2) a different TTT strategy, in which an alternative target was used and (3) a different TTT strategy, in which an alternative treatment protocol was used.

Outcomes

A number of outcomes were assessed. Primarily, we examined the proportion of patients achieving target, remission and LDA. We also examined score changes in the DAS28/DAS44, SJC, TJC and HAQ, joint erosion and quality of life, as well as EULAR and ACR response. According to the TTT ACR/EULAR international task force, TTT strategies should use composite measures that include joint counts to assess disease activity as related to the target. 17

Study design

Randomised controlled trials were included. The reference lists of any systematic reviews identified through the searches were checked for potentially relevant trials.

Exclusion criteria

-

Animal models.

-

Pre-clinical and biological studies.

-

Narrative reviews, editorials, opinions.

-

Non-English-language papers.

-

Reports published as meeting abstracts only, where insufficient methodological details are reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality.

-

Trials of personalised medicine.

-

Non-randomised clinical trials and other study types, such as cohort studies.

-

Trials designed to test an active drug versus placebo (PBO) where both arms pursue the same target and treatment strategy.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were examined by one reviewer and 5% were checked by another reviewer. Study selection based on full texts was decided by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved by discussion.

Data extraction strategy

Data relevant to the decision problem were extracted from all studies by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form. Data on the study characteristics (population, type of comparison, study type, method of RA diagnosis, sample size, treatment arms relevant to the review, duration of RCT phase, duration of follow-up, primary outcome, geographical location and funding source); population characteristics (mean age, number and percentage female, number and percentage rheumatoid factor positive, mean disease duration, mean baseline DAS28, mean baseline SJC, mean baseline TJC, mean baseline pain score, mean baseline HAQ score); TTT characteristics (target, treatment protocol, frequency of assessment); and key outcomes (number and percentage completing randomised phase, reasons for withdrawal, number and percentage meeting study target, number and percentage attaining LDA, number and percentage attaining remission, treatment adaptations, total dose of each drug given over the trial period, mean DAS28, mean DAS44, mean SJC, mean TJC, EULAR response, ACR 20/50/70 response, mean HAQ, joint erosion, quality of life), including adverse events (AEs) [proportion of patients experiencing any AE, any serious adverse event (SAE), death, withdrawal as a result of an AE, musculoskeletal AEs, endocrine and metabolic AEs, cardiovascular AEs, dermatological AEs, ophthalmological AEs, gastrointestinal AEs, infectious AEs, psychological AEs and other AEs] were extracted.

All data extracted were checked thoroughly by a second reviewer, who checked the first reviewer’s extraction against the article(s). Data were extracted without blinding to authors or journal. Discrepancies were discussed and an agreement was reached. We planned that a third reviewer would be consulted when no consensus could be reached; however, this was not necessary in any instance.

Quality assessment strategy

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed by one reviewer, and checked by a second reviewer, who checked the first reviewer’s quality assessment against the article(s). Discrepancies were discussed and an agreement was reached. We planned that a third reviewer would be consulted when no consensus could be reached; however, this was not necessary in any instance.

The methodological quality of RCTs, identified from the literature search for inclusion, was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias assessment criteria. This tool addresses specific domains, namely sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data; and selective outcome reporting. 24 Judgements for domains are made as low, high, or unclear risk of bias. For cluster RCTs we also included three additional domains for recruitment bias (were participants recruited prior to clusters being randomised), risk of baseline differences between clusters and attrition of clusters. We classified RCTs as being at overall ‘low risk’ of bias if they were rated as ‘low’ for each of three key domains – allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment and completeness of outcome data (> 10% attrition25). RCTs judged as being at ‘high risk’ of bias for any of these domains were judged as overall ‘high risk’. RCTs not judged as being at ‘high risk’ for any of these domains, or ‘low risk’ for all of these domains, were judged as overall ‘unclear risk’.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

Evidence examining the clinical effectiveness of TTT was reported according to the TTT comparison, namely (1) TTT compared with usual care, (2) a comparison of different targets against each other and (3) a comparison of different treatment protocols against each other. Two trials did not fit into this framework and so were examined separately, under ‘other comparisons’. Within these comparisons, trials were further grouped according to whether they used early RA populations or established RA populations, as patients with early and established RA may respond to treatment differently. 17,18,22 We used definitions of early and established RA as defined in the trials, and, when no definition was provided, a cut-off point of 3 years was used, which is generally consistent across the literature (e.g. Scott et al. 22), bearing in mind that no fixed consensus exists. Examining definitions and mean disease durations across trials, a 3-year cut-off point seems appropriate. Two trials used populations with both early and established RA patients, so these trials were reported separately from those with early RA and those with established RA populations. Statistical meta-analysis was planned where the evidence allowed. Because of the heterogeneity in treatment protocols, the data from trials in comparison 3 were not narratively combined and examined by outcome, as with the previous two comparisons, and results were reported separately by trial.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

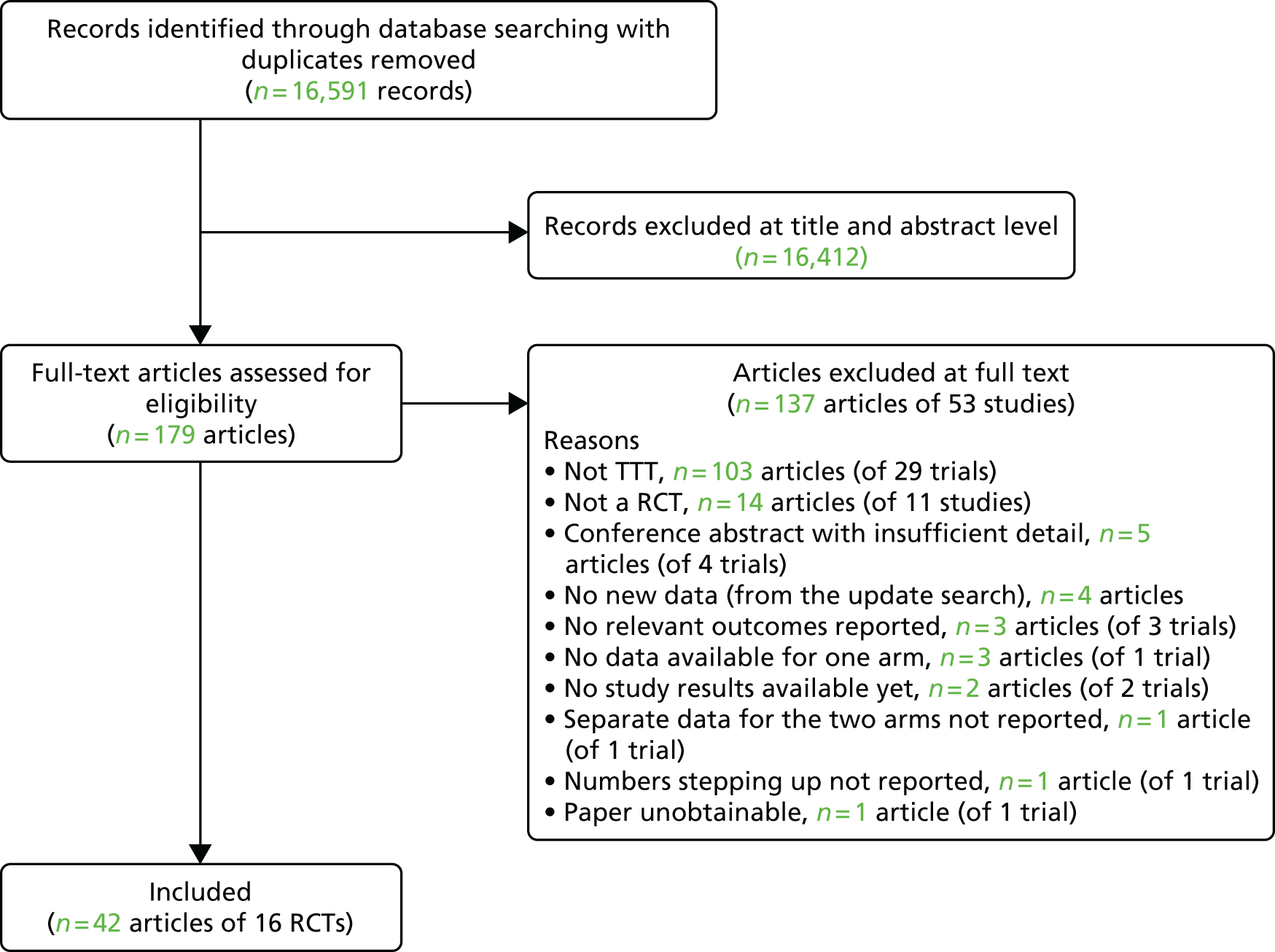

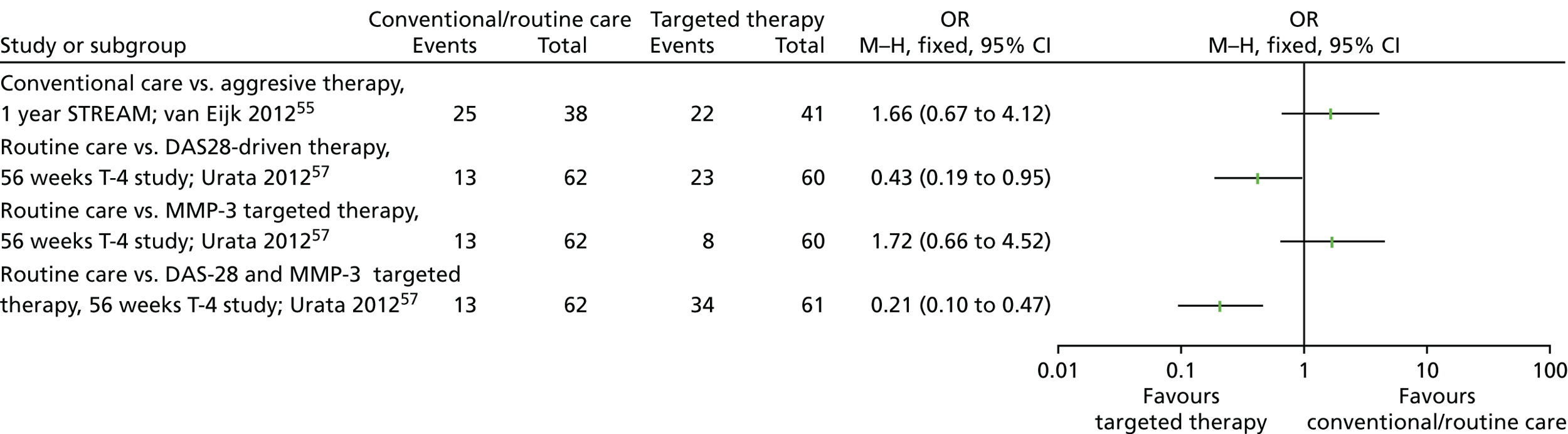

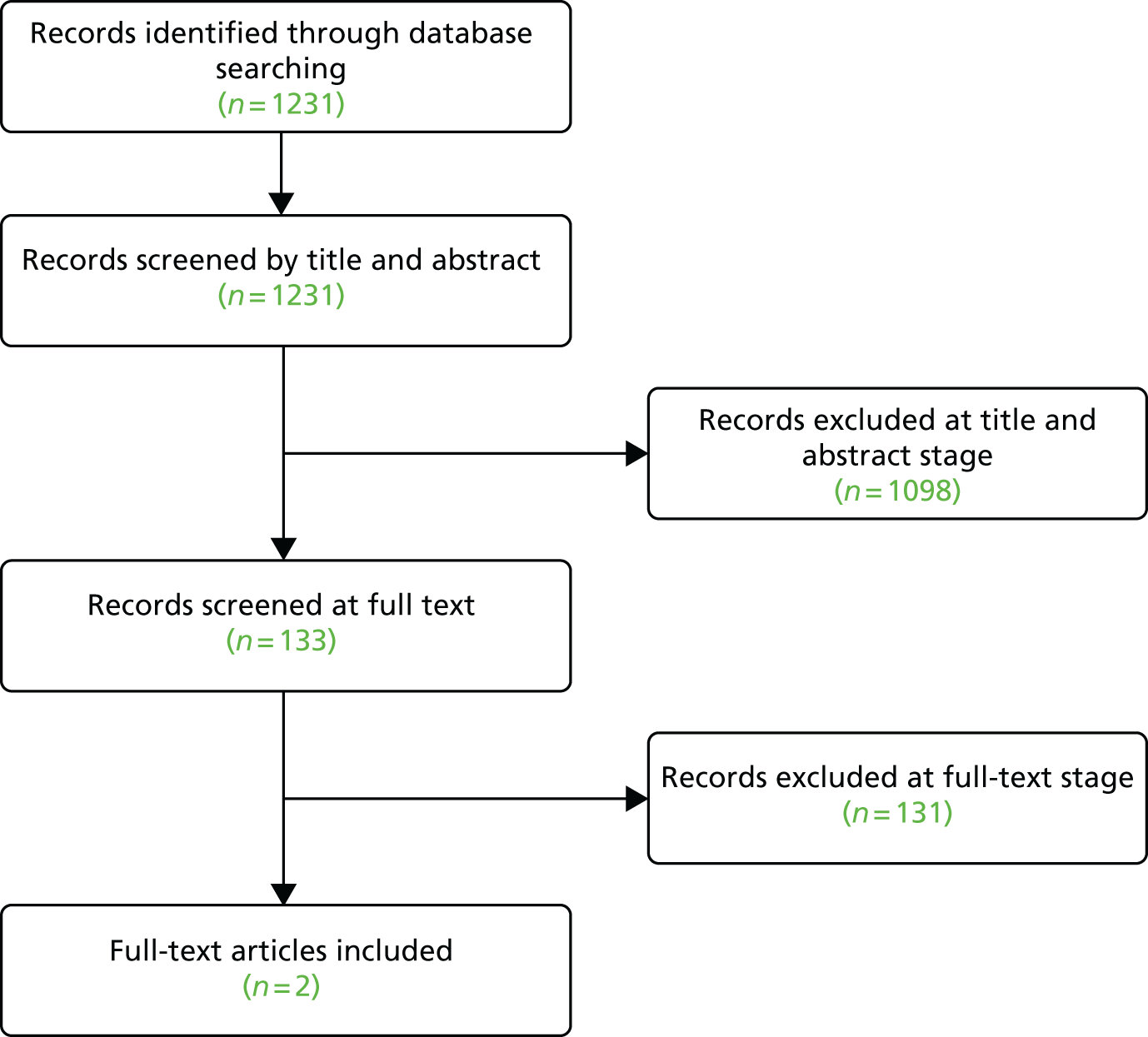

A total of 16,591 records were identified from electronic databases for the clinical effectiveness systematic review, following deletion of duplicates. The study selection process is represented as a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2). A total of 16,412 records were excluded at title and abstract level and 137 articles (reporting 53 separate studies) were excluded in the full-paper sift (see Appendix 3 for a comprehensive list with rationale for exclusion). A total of 42 articles describing 16 trials were included in the review (Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of study inclusion.

| Trial acronym or first author and year of publication | RA population | Type of comparison | Study type | Trial start date | RA diagnosis | Sample size (randomised) | Treatment arms for which data extraction performed | Duration of RCT phase | Duration of follow-up | Primary outcome | Geographical location | Funding source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BeSt26–34 | Early RA | Comparison of different treatment protocols | RCT | April 2000 | ACR 1987 | 508 |

|

12 months | 10 years | Functional ability (D-HAQ), and radiographic joint damage (modified SHS) | The Netherlands | Dutch College of Health Insurances, Schering-Plough B.V. (Houten, the Netherlands) and Centocor Inc. (Horsham, PA, USA) |

| BROSG trial9 | Established RA | Other comparisons | RCT | 1997 | ACR 1987 | 466 |

|

3 years | 3 years | HAQ score | UK | HTA |

| CAMERA35–37 | Early RA | Other comparisons | RCT | 1999 | ACR 1987 | 299 |

|

2 years | 2 years | Sustained remission (no swollen joints and any two of number of painful joints ≤ 3, ESR of ≤ 20 mm/hour, VAS general well-being ≤ 20 mm for ≥ 3 months) | The Netherlands | NR |

| CareRA trial38–43 | Early RA | Comparison of different treatment protocols | RCT | January 2009 | ACR 1987 | 289 high-risk patients; 90 low-risk patients | High-risk patients:

|

16 weeks | 16 week | Proportion of patients in remission (DAS28-CRP of < 2.6) at week 16 | Flemish countries | Flemish governmental grant |

Low-risk patients:

|

||||||||||||

| COBRA-light44,45 | Early RA | Comparison of different treatment protocols | RCT | March 2008 | ACR 1987 | 164 |

|

12 months | 24 months | Change in DAS44 after 26 weeks of treatment compared with baseline (ΔDAS44) | The Netherlands | The Dutch Top Institute Pharma (TIPharma, Leiden, the Netherlands) and Pfizer (New York City, NY, USA) |

| FIN-RACo46–49 | Early RA | Comparison of different treatment protocols | RCT | April 1993 | ACR 1987 | 199 |

|

2 years | 11 years | Remission – modified version of ACR 1981 definition (no swollen or tender joints) | Finland | Finnish Society for Rheumatology, Rheumatism Research Foundation in Finland, Medical Research Foundation of Turku University Central Hospital and the Finnish Office for Health Care Technology Assessment, Finland |

| Fransen et al., 200550 | Established RA | TTT vs. usual care | Cluster RCT | March 2000 | ACR (date NR) | 384 (142 in subsample reporting DAS) (24 clusters) |

|

24 weeks | 24 weeks | Proportion reaching LDA (DAS28 of ≤ 3.2) at week 24 in a subgroup of patients; DMARD treatment changes during 24 weeks, in all patients | The Netherlands | Pfizer |

| Hodkinson et al., 201551 | Early RA | Comparison of different targets | RCT | April 2011 | ACR 2010 | 102 |

|

12 months | 12 months | Proportion of patients achieving at least LDA by DAS28 at 12 months | South Africa | Carnegie Corporation (New York, NY, USA) and the Connective Tissue Fund of the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Optimisation of Adalimumab study52,53 | Established RA | TTT vs. usual care; comparison of different targets | Cluster RCT | August 2006 | NR | 308 (31 clusters) |

|

18 months | 18 months | Change in DAS28 between baseline and 12 months of treatment | Canada | Abbott Canada (Abbott Laboratories, Québec, QC, Canada) |

| Saunders et al., 200854 | Early RA | Comparison of different treatment protocols | RCT | February 2003 | NR | 96 |

|

12 months | 12 months | Mean decrease in the DAS28 at 12 months | UK | Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive (Edinburgh, UK) |

| STREAM55 | Early RA | TTT vs. usual care | RCT | July 2004 | 2–5 swollen joints and SHS of < 5 | 82 |

|

2 years | 2 years | Progression of radiographic joint damage at 2 years | The Netherlands | Abbott (Hoofddorp, the Netherlands) |

| T-4 study56,57 | Early RA | TTT vs. usual care; comparison of different targets | RCT | August 2008 | ACR 1987 | 243 |

|

56 weeks | 56 weeks | Proportion of patients in clinical remission (DAS28 of < 2.6) | Japan | NR |

| TEAR58–60 | Early RA | Comparison of different targets; comparison of different treatment protocols | RCT | May 2004 | ACR 1987 | 755 |

|

102 weeks | 102 weeks | Change in DAS28-ESR between week 48 and week 102 | USA | Amgen, NIH [study drugs provided by Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), Barr Pharmaceuticals (Montvale, NJ, USA) and Pharmacia (Kalamazoo, MIUSA)] |

| TICORA61 | Both | TTT vs. usual care | RCT | August 1999 | Criteria NR (all patients had a DAS44 of > 2.4) | 111 |

|

18 months | 18 months | Mean fall in DAS, and the proportion of patients with a EULAR good response | UK | Chief Scientist’s Office, Scottish Executive (Edinburgh, UK) |

| U-Act-Early62 | Early RA | Comparison of different treatment protocols | RCT | January 2010 | ACR 1987/2010 or EULAR | 317 |

|

2 years | 2 years | Number of patients achieving sustained remission | The Netherlands | Hoffmann-La Roche/Roche Nederland BV |

| van Hulst et al., 201063 | Both | TTT vs. usual care | Cluster RCT | June 2001 | NR | 248 (7 clusters) |

|

18 months | 18 months | Change in DAS28 and the number of medication changes over 18 months | The Netherlands | CVZ/VAZ doelmatigheidsprojecten ‘Doelmatigheid Academische Ziekenhuizen’ (efficiency projects in academic hospitals) |

Table 3 displays the characteristics of the studies included in this review. Eleven trials26–36,38–49,51,54–60,62,64–67 examined an early RA population (defined as disease duration of < 3 years; see Chapter 4, Inclusion and exclusion criteria) [i.e. BehandelStrategieën in Reumatoïde Artritis (BeSt),26–34,64–66 the Computer-Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA) studies,35,36,67 Care in early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CareRA) trial,38–43 the COmBination theRApy with rheumatoid arthritis (COBRA)-light trial,44,45 FINnish Rheumatoid Arthritis Combination therapy (FIN-RACo) trial,46–49 Hodkinson et al. ,51 Saunders et al. ,54 the STRategies in Early Arthritis Management (STREAM) trial,55 the TreaTing to Twin Targets (T-4) study,56,57 the Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid arthritis (TEAR) trial58–60 and the early rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab, methotrexate or their combination (U-Act-Early) trial62], three trials9,50,52,53 examined an established RA population [i.e. British Rheumatoid Outcome Study Group (BROSG) trial,9 Fransen et al. 50 and the Optimisation of Adalimumab study52,53] and two trials61,63 examined populations that include both patients with early RA and those with established RA [i.e. the TIght COntrol for RA (TICORA) trial61 examined patients with a disease duration of < 5 years and van Hulst et al. 63 reported including both newly diagnosed patients and those with established disease (and did not report on the findings for these patients separately at all)]. Six studies50,52,53,55–57,61,63 compared one or more TTT approaches with usual care (i.e. Fransen et al. ,50 the Optimisation of Adalimumab study,52,53 the STREAM trial,55 the T-4 study,56,57 the TICORA trial61 and van Hulst et al. 63), four studies51–53,56–60 compared different targets against each other (Hodkinson et al. ,51 the Optimisation of Adalimumab study,52,53 the T-4 study56,57 and the TEAR trial58–60) and six studies26–34,38–42,44–49,54,58–60 compared different treatment protocols against each other (BeSt,26–34 the CareRA trial,38–42 the COBRA-light trial,44,45 the FIN-RACo trial,46–49 Saunders et al. 54 and the TEAR trial58–60). Two studies9,35,36,67 made other comparisons which did not seem to fit with any of the above comparisons (i.e. the BROSG trial9 and the CAMERA trial35,36,67). The BROSG trial9 had two arms: intensive management, which used a DAS44 of ≤ 2.4 target and employed a seven-step treatment protocol based on the target, where patients were seen in a hospital setting; and a routine management arm, which had no target and patients were seen in the community as well as in the clinic, with treatment escalation based on clinical opinion. The CAMERA35,36,67 trials employed a conventional strategy group and an intensive strategy group, which used (different) compound improvement-based targets, different frequencies of assessment and the same treatment protocol.

Most studies specified a RA diagnosis based on ACR 1987 or 2010 criteria; however, the STREAM trial55 required patients to have 2–5 swollen joints (and did not require an ACR diagnosis), the TICORA trial61 required a DAS44 of > 2.4 and RA diagnosis was not reported in the Optimisation of Adalimumab study,52,53 Saunders et al. 54 or van Hulst et al. 63 Sample sizes ranged from 82 to 755 participants and study durations (randomised phase) ranged from 24 weeks to 3 years. Six trials took place in the Netherlands,26–37,44,45,50,55,62,63 three in the UK,9,54,61 one in Flemish countries (actual countries were not stated),38–43 one in Finland,46–49 one in South Africa,51 one in Canada,52,53 one in Japan56,57 and one in the USA. 58–60

Risk-of-bias assessment

Risk-of-bias judgements for included non-cluster randomised controlled trials

A summary of the risk-of-bias judgements for the included non-cluster RCTs is presented in Figure 3, with details presented in Table 4.

FIGURE 3.

Risk-of-bias judgements for included non-cluster RCTs. +, low risk of bias; –, high risk of bias; ?, unclear risk of bias.

| Trial acronym; first author and year of publication | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Overall rating and reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BeSt; Goekoop-Ruiterman et al., 200530 | Unclear: method of random sequence generation not reported | Unclear risk: closed envelopes used but not reported if opaque and sequentially numbered | Unclear risk: blinding of participants and personnel not reported | Low risk: assessors were blinded | Low risk: < 10% withdrew from each group | Low risk: all outcomes in online protocol (reported in van der Kooij 200968) reported | Unclear: allocation method not reported |

| BROSG trial; Symmons et al., 20059 | Low risk: using a minimisation computer program | Unclear: concealment of allocation not reported | High risk: not blinded | Low risk: reported as observer blinded | High risk: > 10% withdrew from both arms | Unclear risk: protocol details ‘Not provided at time of registration’ from the ISRCTN | Unclear: allocation method not reported |

| CAMERA; Verstappen et al., 200736 | Unclear: method of random sequence allocation not reported | Unclear: reports allocation performed by an independent person, but method not reported | High: patients and clinicians not blinded (not possible, two different monitoring/treatment strategies) | Unclear: radiographs scored independently by blinded assessors, unclear on other outcomes | High: 31% withdrew | Unclear: no protocol available | High risk: attrition bias |

| CareRA; Verschueren et al., 201542 | Unclear: method of random sequence generation not reported | Unclear: concealment of allocation not reported | High risk: reports that no blinding was implemented | High risk: reports that no blinding was implemented | Low risk: < 10% withdrew from each group | Low risk: all outcomes in online protocol reported | High risk: outcome assessment not blinded |

| COBRA-light; den Uyl et al., 201444 | Low risk: online randomisation software was used | Unclear risk: sequentially numbered envelopes were used, but not reported if sealed and opaque | High risk: reported as open label | Low risk: reports that to minimise influence performed by trained research nurses uninvolved in the routine care | Low risk: < 10% withdrew from each group | High risk: radiological progression reported as an outcome in the protocol, but not reported in publication. Publication states that this outcome will only be reported at 12 months | Unclear: allocation method not reported |

| Fin-RACo; Mottonen et al., 199946 | Unclear: method of sequence generation not reported | Unclear risk: centrally organised, numbered envelopes, but not reported if sequentially numbered and opaque | High risk: open label | High risk: clinical measures not blinded | Low risk: < 10% lost from each group | Unclear: no protocol available | High risk: outcome assessment not blinded |

| Hodkinson et al., 201551 | Low: computer-generated sequence | Unclear: concealment of allocation not reported | Unclear: blinding of patients and personnel not reported | High: outcome assessment not blinded | Low risk: < 10% lost from each group | Unclear: no protocol available | High risk: outcome assessment not blinded |

| Saunders et al., 200854 | Low risk: randomisation software used | Unclear: concealment of allocation not reported | High risk: single-blind study (only outcome assessment blind) | Low risk: metrologist was blinded to treatment allocation; also radiologists assessing Sharp score were blinded | Low risk: < 10% attrition both groups | Low risk: outcomes in online protocol reported | Unclear: allocation method not reported |

| STREAM; van Eijk et al., 201255 | Unclear: method of random sequence allocation not reported | Unclear: concealment of allocation not reported | High risk: described as single blind | Low: DAS and radiographs assessed by blinded assessors | Low risk: < 10% lost from each group | High risk: QoL in protocol but not in paper; everything else as per protocol | Unclear: allocation method not reported |

| T-4 study; Urata et al., 201257 | Unclear risk: sequence generation not reported | Unclear: concealment of allocation not reported | High risk: reported limitation that study was ‘open’ | High risk: primary outcome DAS assessed by physicians not radiologists | High risk: > 10% withdrew from groups 2 and 4; reasons not stated | Unclear risk: trial registration not reported, unable to locate protocol | High risk: attrition bias |

| TEAR; Moreland et al., 201258 | Low risk: treatment was allocated via a computerised data entry system | Low risk: treatment was allocated via a computerised data entry system | Low risk: all subjects and site personnel (including the treating rheumatologists) were blinded (for the duration of the trial) to treatment assignment and change to active medication at the step-up period | Low risk: all subjects and site personnel (including the treating rheumatologists) were blinded (for the duration of the trial) to treatment assignment and change to active medication at the step-up period | High risk: > 10% withdrew from all groups | High risk: methods state SF-12 used to assess HRQoL, but no results presented | High risk: attrition bias |

| TICORA; Grigor et al., 200461 | Low risk: randomisation software used | Unclear risk: treating doctor telephoned an administrative co-ordinator, but not reported if the allocation was concealed | High risk: only the assessors were blind ‘single blind’ | Low risk: a metrologist assessed patients from both groups, unaware of participants’ assigned treatment groups | Low risk: < 10% lost from each group | Unclear: no protocol available | Low risk: allocation, assessor blinding and attrition all low risk |

None of the included non-cluster RCTs was rated as being at high risk of bias for random sequence generation. Only one RCT was rated as being at low risk of bias for allocation concealment. 58 The remaining RCTs were rated as having an unclear risk for this domain. 9,30,36,41,44,46,51,54,55,57,61 Nine RCTs were rated as having a high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel,9,36,41,44,46,54,55,57,61 and one RCT was rated as having an unclear risk for this domain. 30 Only one RCT was rated as having a low risk for this domain. 58 It should, however, be borne in mind that in most cases it would be difficult for patients to be blinded, given the differences in treatment approach between trial arms in most trials. Seven RCTs were rated as having a low risk of bias for blinded outcome assessment,9,30,44,54,55,58,61 four RCTs were rated as having a high risk of bias41,46,51,57 and one RCT36 was rated as having an unclear risk for this domain. Four RCTs reported withdrawals of > 10% and were rated as having a high risk of attrition bias. 9,36,57,58 The remaining RCTs were rated as having a low risk of bias for this domain. 9,36,57,58 Trial protocols were unavailable for six RCTs that were rated as having an unclear risk of selective reporting. 9,36,46,51,57,61 Three RCTs were rated as having a low risk of bias for this domain30,41,54 and three were rated as having a high risk of bias, as some outcomes were not reported in either the protocol44,55 or the methods section of the trial report58. Based on the judgements for allocation concealment, blinded outcome assessment and attrition domains (see Quality assessment strategy), six RCTs were rated as having an overall high risk of bias36,41,46,51,57,58 and five RCTs were rated as having an overall unclear risk of bias. 9,30,44,54,55 Only one RCT was rated as having an overall low risk of bias. 61

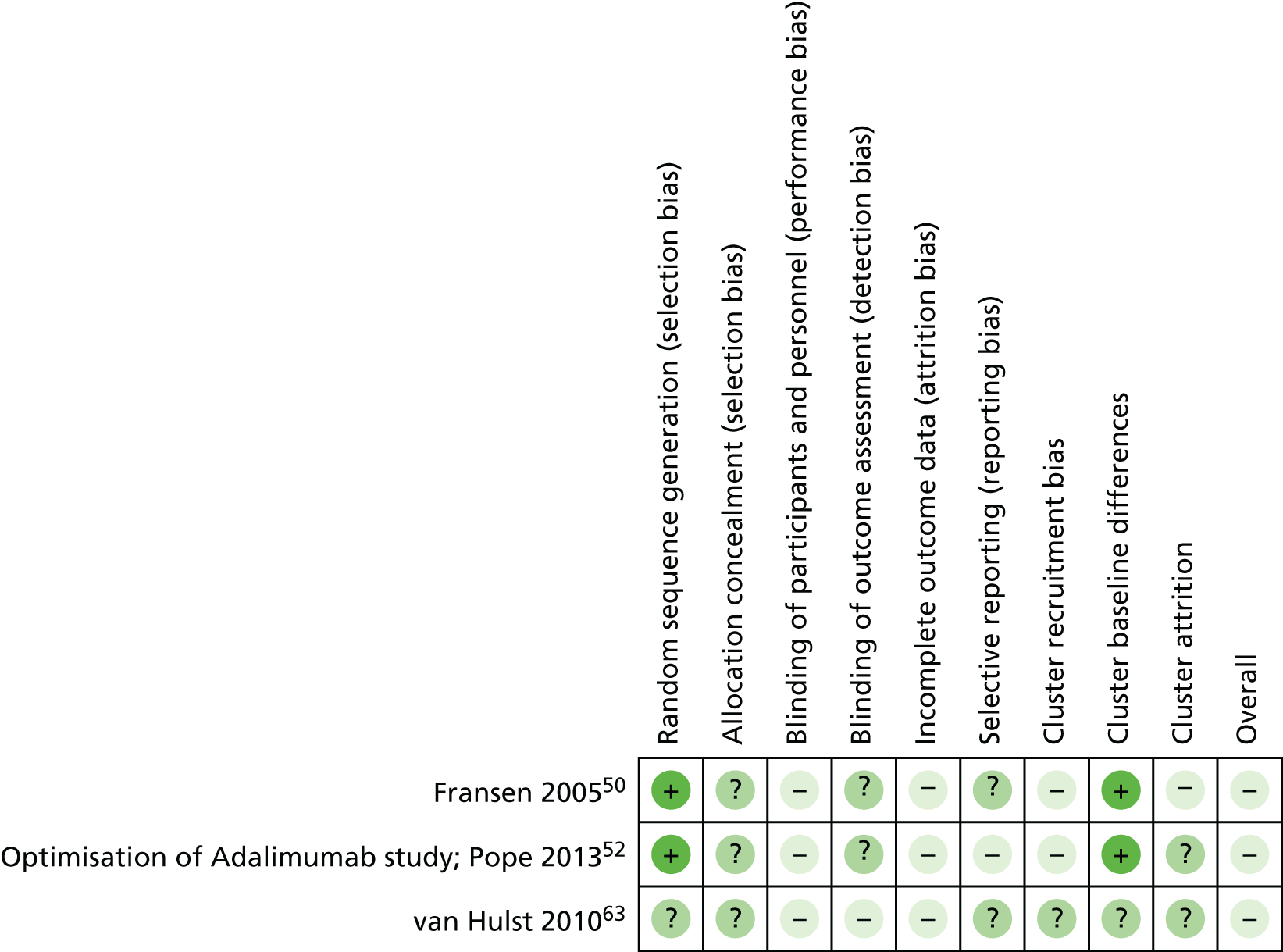

Risk-of-bias judgements for included cluster randomised controlled trials

A summary of the risk-of-bias judgements for the included cluster RCTs is presented in Figure 4, with the details presented in Table 5.

FIGURE 4.

Risk-of-bias judgements for included cluster RCTs. +, low risk of bias; –, high risk of bias; ?, unclear risk of bias.

| Trial acronym; first author and year of publication | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Cluster recruitment bias | Cluster risk of baseline differences | Cluster attrition | Overall rating and reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fransen et al., 200550 | Low risk: random number generator used to allocate the centres randomly to DAS (12 centres) or UC (12 centres) | Unclear risk: not reported if clusters were randomised at the same time | High risk: single blind | Unclear risk: reports as the participating physicians could not be blinded, it was necessary to measure the DAS28 independently. However, unclear if the independent assessors were blind to treatment allocation | High risk: > 10% withdrew from both groups | Unclear risk: study protocol not available (Dr Jaap Fransen, Radboud University Medical Center, 2016, personal communication) | High risk: centre allocation remained concealed until the start of patient recruitment | Low risk: randomisation took place in two strata: one stratum comprised the participating centres in the predetermined region; the other of all other participating centres. The data were analysed using linear regression with random coefficients (mixed models), correcting for clustering of the data in centres | High risk: only three DAS and four UC centres provided DAS assessments | High risk of recruitment bias, performance bias and participant attrition bias |

| Optimisation of Adalimumab study; Pope et al., 201352 | Low risk: using a computer-generated, site-stratified blocked schedule that assigned physicians from the same geographic region to one of the three groups | Unclear risk: not reported if clusters were randomised at the same time | High risk: only patients blinded | Unclear: not reported | High risk: > 10% withdrew from all groups | High risk: AEs classified according to MedDRA as in the NCT protocol not reported | High risk: physician randomisation took place prior to initiation of enrolment | Low risk: reports clusters were randomised using a site-stratified blocked schedule and models were used with shared frailty to account for the clustered design considering baseline covariates | Unclear risk: loss of clusters not reported | High risk of recruitment bias, performance bias, participant attrition bias and selective reporting |

| van Hulst et al., 201063 | Unclear: method of random sequence allocation not reported | Unclear risk: not reported if clusters were randomised at the same time | High risk: clinicians not blinded | High risk: DAS28 assessment not blinded, HAQ blinding unclear, medication changes blinded | High: attrition was 4% in intervention group, but 12% in usual-care group | Unclear: no protocol available | Unclear risk: not reported if rheumatologists recruited patients before or after randomisation | Unclear: baseline comparability of clusters not reported | Unclear risk: loss of clusters not reported | High as a result of selection bias, differential attrition, unclear blinding and unclear randomisation |

Two of the included cluster RCTs were rated as being at low risk of bias for random sequence generation50,52 and one63 was rated as being at unclear risk for this domain. All three cluster RCTs were rated as being at unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. 50,52,63 All three cluster RCTs were rated as being at high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel. 50,52,63 One cluster RCT was rated as being at high risk of bias for blinded outcome assessment,63 whereas the other two cluster RCTs were rated as being at unclear risk for this domain. 50,52 All three cluster RCTs were rated as being at high risk of attrition bias (> 10% participants withdrawing). 50,52,63 A trial protocol was not available for two cluster RCTs that were rated as being at unclear risk of bias for selective reporting. 50,63 One cluster RCT was rated as being at high risk of bias for this domain, as AEs that were reported as an outcome in the trial protocol were not included in the trial report. 52 Two RCTs reported that participant recruitment occurred after clusters were randomised to treatment allocation, thus these trials were rated as being at high risk of bias for cluster recruitment bias. 50,52 The remaining cluster RCT was rated as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain. 63 Two cluster RCTs reported statistical methods to accommodate for baseline differences across clusters and rated as being at low risk of bias for cluster baseline differences. 50,52 The remaining cluster RCT was rated as being at unclear risk for this domain. 63 One cluster RCT reported that DAS28 outcomes were available for only a subset of the original clusters that were randomised. This RCT was rated as being at high risk of bias for cluster attrition. 50 The other two cluster RCTs were rated as being at unclear risk for this domain. 52,63 All three included cluster RCTs rated as being at an overall high risk of bias. 50,52,63

Assessment of characteristics of individual study arms

We considered the features of each arm of the included studies, with a view to drawing out common features across them. If strategies in different study arms are considered sufficiently similar, that would allow a grouping of TTT ‘types’ and subsequent analysis at this group level, drawing on evidence from more than one study.

Tables 6–13 display information about each of the study types. We report information on (1) the treatment target, (2) the treatment protocol and (3) the frequency of clinician contacts with the patient. For point 3, the focus is on the frequency of visits during the period while the patient has not achieved the target, as less frequent assessment is often required once target is achieved. These are considered to be the key distinguishing features of ‘TTT’ strategies as a whole.

In addition, study arms were grouped together using a broad categorisation of the treatment protocol. This approach was taken by the NICE clinical guideline for RA,4 where the focus was purely on treatment protocols using conventional DMARDs in early disease. We used the following eight classification categories.

Sequential monotherapy without a treatment target

Study arms in this classification would typically be control arms in studies compared with other TTT strategies. The arms identified within this classification category are included in Table 6.

| Trial acronym or first author and year of publication | Description of target | Protocol | Frequency of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

| BeSt26–34 | Treatment adjustments were made every 3 months in an effort to obtain a DAS44 of ≤ 2.4. Remission was defined as a DAS44 of < 1.6 |

|

3 months |

| Optimisation of Adalimumab study52,53 | A DAS28 of < 2.6 in the DAS-targeted arm and a SJC of 0 in the SJC-targeted arm |

|

0, 6, 12 and 18 months. Assessments at 2, 4 and 9 months were also recommended |

| Symmons et al., 20059 | To control joint pain, stiffness and related symptoms | NSAIDs, intra-articular steroid injections (up to a maximum of one per month), DMARDs (antimalarials, SSZ, intramuscular gold, penicillamine, azathioprine, MTX, LEF) and low-dose steroids (≤ 7.5 mg daily). Non-drug modalities, such as physiotherapy referral, were also used as the GP felt appropriate. DMARD therapy was monitored using the standard guidelines in current use in the five centres | Every 4 months |

| Fransen et al., 200550 | A DAS28 of ≤ 3.2 | Systematic monitoring of disease activity by assessment of the DAS28 by the treating rheumatologist. According to the study guidelines the aim was to reach a DAS28 of ≤ 3.2 (LDA) by changing DMARD treatment if the score was > 3.2 | Systematic monitoring of disease activity was carried out at weeks 0, 4, 12 and 24 |

| van Hulst et al., 201063 | A DAS28 of ≤ 3.2 | None | 3 months |

Sequential disease-modifying antirheumatic drug monotherapy, or no treatment protocol, with a treatment target

This refers to study arms that could be seen as comprising only a limited component of ‘TTT’, the weakest form of TTT strategy feasible under our definition of TTT. The arms identified within this classification category are included in Table 7.

| Trial acronym or first author and year of publication | Target | Protocol | Frequency of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

| TICORA61 | A DAS44 of ≤ 2.4 | DMARD monotherapy was given in patients with active synovitis. Failure of treatment (because of toxic effects or lack of effect) resulted in a change to alternative monotherapy, or addition of a second or third drug at the discretion of the attending rheumatologist. Intra-articular injections of corticosteroid were given to patients assigned routine care with the same restrictions as those in the intensive group | 3 months |

| T-4 study56,57 | A DAS28 of < 2.6 (DAS-targeted arm);a MMP-3 concentration of < 121 ng/ml (men)/< 59.7 ng/ml (women) (MMP-3-targeted arm); and a DAS28 of < 2.6 and a MMP-3 concentration of < 121 ng/ml (men)/ < 59.7 ng/ml (women) (combined DAS- and MMP-3-targeted arm) |

|

20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 40, 44, 48, 52 and 56 weeks |

| CAMERA35,36,67 |

|

3 months | |

| STREAM55 | The following order of drugs was suggested to the treating rheumatologist: HCQ, SSZ, MTX and LEF | 3 months | |

| Fransen et al., 200550 | No guideline to adapt treatment strategy was supplied | ||

| van Hulst et al., 201063 | 3 months | ||

| FIN-RACo46–49 |

|

Baseline and at months 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 |

Steroid step-down, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug step-up combination

Study arms classified in this group involved initial combination therapy with steroids and non-bDMARDs (either alone or in combination), with the option of increasing the dose or adding in DMARDs. The steroid dose is tapered downwards over time. The arms identified within this classification category are included in Table 8.

| Trial acronym or first author and year of publication | Description of target | Protocol | Frequency of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

| den Uyl et al., 201369 | A DAS44 of < 1.6 | 60 mg/day prednisolone (tapered to 7.5 mg/day in 6 weeks), 7.5 mg/week of MTX and 1 g/day of SSZ (increased to 2 g/day after 1 week). MTX increased to 25 mg/week after 13 weeks of treatment if the DAS44 was ≥ 1.6 | 3 months |

| A DAS44 of < 1.6 |

|

3 months | |

| CareRA42 | A DAS28-CRP of < 3.2 | 15 mg of MTX weekly, 2 g of SSZ daily and a weekly step-down scheme of oral GCs (60 mg to 40 mg to 25 mg to 20 mg to 15 mg to 10 mg to 7.5 mg PDN) | Baseline, 4, 8 and 16 weeks. If a treatment adjustment was required at week 8, an optional visit was held at week 12 |

| A DAS28-CRP of < 3.2 | 15 mg of MTX weekly with a weekly step-down scheme of oral GCs (30 mg to 20 mg to 12.5 mg to 10 mg to 7.5 mg to 5 mg PDN) | ||

| A DAS28-CRP of < 3.2 | 15 mg of MTX weekly, 10 mg of LEF daily and a weekly step-down scheme of oral GCs (30 mg to 20 mg to 12.5 mg to 10 mg to 7.5 mg to 5 mg PDN) |

Step-up disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to biologics

In this classification the treatment protocols start patients on non-bDMARDs and outline increases in dose and/or combinations with other DMARDs, with the option of switching to bDMARDs as part of the sequence. The arms identified within this classification category are included in Table 9.

| Trial acronym | Description of target | Protocol | Frequency of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-4 study57,57 | A DAS28 of < 2.6 |

1. 1 g/day of SSZ plus oral 4 mg/week of MTX – the dosage of was not changed if the patient had responded compared with the previous visit otherwise |

Variable, but approximately monthly |

| A MMP-3 concentration of < 121 ng/ml for men and < 59.7 ng/ml for women |

2. The dosage of oral MTX was increased in a stepwise manner to a maximum of 8 mg/week if patient had not responded. Change of therapy based on improvement in the number of tender joints (0–28), swollen joints (0–26) and concentration of CRP from pre-assessment values, without access to current DAS28 and MMP-3 values |

||

| A DAS28 of < 2.6 and a MMP-3 concentration of < 121 ng/ml for men and < 59.7 ng/ml for women |

3. If the maximum tolerable dose of MTX that introduced a dose-dependent side effect was reached and the patient still did not fulfil a sustained response, TNF blockers were allowed. If patients on the administration of TNF blockers did not show improvement compared with the previous measurement, TNF blockers were changed to another biological agent, or the TNF blocker dose increased, or the interval for TNF administration was shortened. Maximum dosages were 1 g/day of SSZ, 20 mg/day of LEF, 300 mg/day of bucillamine,a 25 mg/week of gold sodium thiomalate, 3 mg/day of tacrolimus hydrate, 10 mg/kg bimonthly or 6 mg/kg monthly of IFX, 50 mg/week of ETN, 40 mg of ADA fortnightly and 8 mg/kg of TOC monthly. DMARDs including bucillamine,a gold sodium thiomalate, tacrolimus and LEF were given, as allowed by the rheumatologist at all times. Combination therapy with DMARDs other than MTX was allowed for two kinds of agents. Intra-articular GC (to a maximum of 10 mg of triamcinolone acetonide on a single visit) was permitted for persistently swollen and tender joints |

||

| STREAM55 | Remission (a DAS44 of < 1.6) | Treatment was started with 15 mg/week of oral MTX. If the DAS was ≥ 1.6 at a given time point:

|

|

| TEAR58–60 | A DAS28-ESR of ≥ 3.2 | Oral MTX, escalated to a dosage of 20 mg/week or to a lower dosage if treatment resulted in no active tender/painful or swollen joints by week 12. Corticosteroid use at entry tapered. If the DAS28-ESR was ≥ 3.2 at week 14, patients were stepped up to MTX plus SSZ at a dosage of 500 mg twice daily, escalated (if tolerated) to 1000 mg twice daily at 6 weeks, plus HCQ at a dosage of 200 mg twice daily |

Step-up combinations not including to biologics

Similar to the previous set of treatment protocols, study arms in this category start patients on a non-bDMARD and subsequently allow increases in dose and/or combinations with other non-bDMARDs and steroids. The arms identified within this classification category are included in Table 10.

| Trial acronym or first author and year of publication | Description of target | Protocol | Frequency of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

| BeSt26–34 | Treatment adjustments were made every 3 months in an effort to obtain a DAS44 of ≤ 2.4. Remission was defined as a DAS44 of < 1.6 |

|

3 months |

| TICORA61 | A DAS44 of ≤ 2.4 | Escalation of DMARDs in patients with persisting disease activity:

|

Monthly |

| FIN-RACo46–49 | ACR remission | Combination therapy started with:

|

Baseline and at months 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 |

| Saunders et al., 200854 | A DAS28 of < 3.2 |

|

Monthly |

| CAMERA35,36,67 | 20%, 50% responses based on ESR, SJC, TJC and VAS of overall well-being |

|

|

| Symmons et al., 20059 | The goal was to control joint pain, stiffness and related symptoms and to suppress clinical and laboratory evidence of inflammation. CRP concentrations below twice the upper limit of normal | NSAIDs, intra-articular steroid injections (up to a maximum of one per month), DMARDs (antimalarials, SSZ, intramuscular gold, penicillamine, azathioprine, MTX, LEF) and low-dose steroids (≤ 7.5 mg daily) plus, if necessary, ciclosporin, parenteral steroids, medium-dose oral steroids (up to 10 mg daily) and cyclophosphamide | Every 4 months |

| TEAR58–60 | A DAS28-ESR of ≥ 3.2 | Oral MTX, escalated to a dosage of 20 mg/week or to a lower dosage if treatment resulted in no active tender/painful or swollen joints by week 12. Corticosteroid use at entry tapered. If the DAS28-ESR was ≥ 3.2, patients were stepped up to triple therapy (MTX + SSZ + HCQ) | Every 6 weeks for 48 weeks, then every 12 weeks |

| Hodkinson et al., 201551 | A SDAI of ≤ 11 (LDA) | 15 mg/week of MTX, increased to 20 mg and then 25 mg | Monthly (3 months) then every 3 months |

| A CDAI of ≤ 10 (LDA) | If this failed, triple therapy of 1000 mg/day of SSZ and 200 mg/day of chloroquine in combination with 25 mg/week of MTX was introduced |

Combination disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs plus steroids

Patients are treated from the outset with two non-bDMARDs and steroids. Adjustments to treatments do not allow bDMARDs. The arms identified within this classification category are included in Table 11.

| Trial acronym | Protocol | Frequency of assessments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BeSt26–34 | Treatment adjustments were made every 3 months in an effort to obtain a DAS44 of ≤ 2.4. Remission was defined as a DAS44 of < 1.6 |

|

3 months |

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug and biologic combinations

Treatments for patients from the beginning of the protocol include both bDMARDs and non-bDMARDs in combination. The arms identified within this classification category are included in Table 12.

| Trial acronym | Description of target | Protocol | Frequency of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

| BeSt26–34 | Treatment adjustments were made every 3 months in an effort to obtain a DAS44 of ≤ 2.4. Remission was defined as a DAS44 of < 1.6 |

|

3 months |

| Optimisation of Adalimumab study52,53 | A DAS28 of < 2.6 in the DAS-targeted arm and a SJC of 0 in the SJC-targeted arm |

|

0, 6, 12 and 18 months. Assessments at 2, 4 and 9 months were also recommended |

| A SJC of 0 |

|

Triple disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy

Three non-bDMARDs are used in combination from the outset. The arms identified within this classification category are included in Table 13.

| First author and year of publication | Description of target | Protocol | Frequency of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saunders et al., 200854 | A DAS28 of < 3.2 (to correspond with a EULAR good response) |

|

Monthly |

Even with this relatively large number of TTT treatment strategy classifications (which are designed to differ in terms of the treatment protocol, except for the control arms of studies), there is substantial variation. Tables 6–13 show that, within each classification group, study arms exhibit significant differences. These can be seen within each grouping in terms of the treatment target and the frequency of assessment. For example, within the group of study arms classified as ‘step-up non-biologic combination therapy’, the frequency of assessments was monthly in some studies (e.g. the TICORA trial,61,63 Saunders et al. 54) and every 3 months in others (e.g. BeSt26–34). Within the same classification group, treatment targets varied enormously. A DAS44 of ≤ 2.4 was used in two studies (BeSt26–34,65,68 and TICORA61,63). A range of different measurement scales [ACR, SDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), DAS28 and other multifaceted measures] and cut-off points (remission, other measures of response) were used in the other study arms.

Differences are also apparent in the details of the treatment protocols within each broad grouping. Study arm treatment protocols exhibit substantial variation in the study drugs used, the combinations in which they may be used, the doses used (both initially and when changing dose in response to assessment of treatment response), and the ordering of study drugs in the sequence of the protocol.

This variation would be present even if an alternative classification approach were to be adopted. For these reasons, it is not considered desirable to conduct analyses that synthesise results quantitatively across different sets of studies. The extent of variation between study arms would make interpretation of results difficult and potentially result in misleading conclusions.

Assessment of effectiveness

Population characteristics and treat-to-target characteristics

Trials examining early rheumatoid arthritis populations

Eleven trials reported on early RA populations (BeSt,26–34,64–66 CAMERA,35,36,67 CareRA,38–43 COBRA-light,44,45 FIN-RACo,47–49,70 Hodkinson et al. ,51 Saunders et al. ,54 STREAM,55 T-4 study,56,57 TEAR58–60 and U-Act-Early62). Population characteristics are presented in Table 14. The mean age of trial participants ranged from 46 to 62 years and trial arm samples ranged from 58% to 84% female and from 23.4% to 91.7% rheumatoid factor positive. Mean disease duration at baseline ranged from just < 2 weeks to just > 1 year. The mean DAS28 at baseline ranged from 4.4 to 6.9, indicating moderate to severe RA at baseline among the early RA population. The mean SJC (on 66 joints) ranged from 10.0 to 14.0 and the mean TJC (0–68 joints) ranged from 12.3 to 20.0, across all trial arms. The mean HAQ score at baseline ranged from 0.92 to 2.0.

| Trial acronym or first author and year of publication | Treatment arm | Number of participants | Characteristic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | Female, n/N (%) | Rheumatoid factor positive, n/N (%) | Mean disease duration (months) (SD) | Mean DAS28 at baseline (SD) (ESR or CRP where stated) | Mean SJC (0–66) (SD) | Mean TJC (0–68) (SD) | Mean pain score (100-mm VAS) (SD) | Mean HAQ score (SD) | |||

| BeSt26–34,64–66 | Sequential monotherapy | 126 | 54 (13) | 86/126 (68) | 84/126 (67) | 2 (1–5) weeksa,b | DAS44, 4.5 (0.9) | NR | NR | NR | D-HAQ, 1.4 (0.7) |

| Symptom duration 23 (14–54) weeksa | |||||||||||

| Step-up combination therapy | 121 | 54 (13) | 86/121 (71) | 77/121 (64) | 2 (1–4) weeksa,b | DAS44, 4.5 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR | D-HAQ, 1.4 (0.6) | |

| Symptom duration 26 (14–56) weeksa | |||||||||||

| Initial combination therapy with PDN | 133 | 55 (14) | 86/133 (65) | 86/133 (65) | 2 (1–4) weeksa,b | DAS44, 4.4 (0.9) | NR | NR | NR | D-HAQ, 1.4 (0.7) | |

| Symptom duration 23 (15–53) weeksa | |||||||||||

| Initial combination therapy with IFX | 128 | 54 (14) | 85/128 (66) | 82/128 (64) | 3 (1–5) weeksa,b | DAS44, 4.3 (0.9) | NR | NR | NR | D-HAQ, 1.4 (0.7) | |

| Symptom duration 23 (13–46) weeksa | |||||||||||

| CAMERA35,36,67 | Intensive strategy group | 151 | 54 (14) | 104/151 (69) | 89/151 (66) | NR | 5.6 (1.2), n = 102 | 14 (6) | 15 (7) | 51 (26) | 1.2 (0.7) |

| Conventional strategy group | 148 | 53 (15) | 97/148 (66) | 77/148 (62) | NR | 5.6 (1.0), n = 103 | 14 (6) | 14 (7) | 47 (25) | 1.2 (0.7) | |

| CareRA: high-risk patients40,42,43 | COBRA Classic | 98 | 53.2 (11.9) | 64/98 (65) | 78/98 (80) | 1.8 (3.1) weeks | DAS28 (ESR), 5.4 (1.3); DAS28 (CRP), 5.0 (1.2) | 11.9 (8.9); DAS28 joints 7.9 (6.0) | 14.7 (9.5); DAS28 joints 9.5 (6.0) | 59.5 (23.6) | 1.2 (0.7) |

| Symptom duration 33.8 (35.5) weeks | |||||||||||

| COBRA Slim | 98 | 51.8 (131) | 63/98 (64) | 82/98 (84) | 2.6 (3.3) weeks | DAS28 (ESR), 5.2 (1.2); DAS28 (CRP), 4.9 (1.1) | 10.8 (6.5); DAS28 joints 7.1 (4.6) | 13.7 (8.2); DAS28 joints 8.5 (5.5) | 56.5 (21.9) | 0.98 (0.69) | |

| Symptom duration 33.2 (38.2) weeks | |||||||||||

| COBRA Avant-Garde | 93c | 51.2 (12.8) | 64/93 (69) | 70/93 (75) | 3.1 (6.4) weeks | DAS28 (ESR), 5.0 (1.3); DAS28 (CRP), 4.7 (1.2) | 10.6 (6.7); DAS28 jointsc,e 7.0 (5.1) | 14.1 (9.0); DAS28 jointsc,e 8.2 (5.5) | 57.5 (23.8) | 1.0 (0.6) | |

| Symptom durationd 44.3 (65.9) weeks | |||||||||||

| CareRA: low-risk patients40,43 | MTX-TSU | 47 | 51.0 (14.0) | 38/47 (81) | 11/47 (23) | 3.17 (6.62) weeks | DAS28 (ESR), 4.83 (1.68); DAS28 (CRP), 4.55 (1.63) | 10.00 (6.98); SJC28g 6.89 (6.11) | 14.06 (8.61); TJC28g 9.49 (7.46) | Pain (range 0–100) 52.09 (23.23); Nocturnal pain (yes)g 34/47 (72.3%) | 0.99 (0.67) |

| Symptom durationf 33.11 (62.21) weeks | |||||||||||

| COBRA Slim | 43 | 51.4 (14.4) | 33/43 (77) | 11/43 (26) | 1.86 (2.70) weeks; | DAS28 (ESR), 4.88 (1.64); DAS28 (CRP), 4.50 (1.63) | 10.93 (7.55); SJC28g 7.79 (6.0) | 13.14 (10.70); TJC28g 8.51 (7.80) | Pain (range: 0 to 100) 48.23 (31.19) nocturnal pain (yes)g 21/43 (48.8%) | 0.92 (0.85) | |

| Symptom durationg 34.42 (68.16) weeks | |||||||||||

| COBRA-light44,45 | COBRA | 81 | 53 (13) | 54/81 (67) | 47/81 (58) | 16 (9–28) weeksa | 5.67 (1.13) | 13 (10–17)a | 17 (12–24)a | NR | 1.36 (0.66) |

| COBRA-light | 83 | 51 (13) | 58/81 (70) | 48/83 (58) | Median 17 (8–33) weeksa | 5.45 (1.29) | 11 (9–14)a | 16 (10–23)a | NR | 1.37 (0.71) | |

| FIN-RACo47–49,70 | Combination treatment | 99 (97 in ITT) | 47 (23–65)h | 56 (58) | 68 (70) | 7.3 (2–22)d | NR | 13 (6) | 18 (8) | NR | NR |

| Single-drug treatment | 100 (98 in ITT) | 48 (20–65)h | 65 (66) | 65 (66) | 8.6 (2–23)d | NR | 14 (7) | 20 (10) | NR | NR | |

| Hodkinson et al., 201551 | SDAI arm | 42 | 50.1 (13.4)c | 34/42 (81) | 36/42 (86) | Symptom duration 2.6 (3.1) years | 6.1 (1.2) | 11 (5.7) | 12.5 (8.5) | 66.7 (22.6) | HAQ-DI, 1.7 (0.8) |

| CDAI arm | 60 | 46.7 (13.0)c | 50/60 (83) | 54/60 (90) | Symptom duration 3.3 (4.2) years | 6.3 (1.2) | 10.0 (5.7) | 12.3 (7.3) | 59.2 (26.0) | HAQ-DI, 1.7 (0.7) | |

| Saunders et al., 200854 | Parallel triple therapy | 49 | 55 (15) | 37/49 (76) | 34/49 (69) | 10 (9) | 6.8 (0.9) | 12 (4) | 18 (6) | 71 (26) | 1.9 (0.7) |

| Step-up therapy | 47 | 55 (11) | 37/47 (79) | 34/47 (72) | 13 (12) | 6.9 (0.9) | 13 (5) | 18 (6) | 65 (22) | 2.0 (0.7) | |

| STREAM55 | Aggressive group | 42 | 48 (13) | 24/42 (58) | 20/42 (48) | 6 (3–10)a | DAS44, 2.2 (0.5) | NR | NR | NR | 0.50 (0.25–0.88)a |

| Conventional care | 40 | 46 (12) | 32/40 (79) | 13/40 (33) | 6 (4–9)a | DAS44, 2.4 (0.7) | NR | NR | NR | 0.69 (0.32–1.06)a | |

| T-4 study56,57 | Routine care | 62 | 62 (12); n = 55 | 42/55 (76) | NR | 1.5 (1.1) years; n = 55 | 4.4 (1.1); n = 55 | NR | NR | NR | mHAQ score, 0.3 (0.4); n = 55 |

| DAS28-driven therapy | 60 | 60 (11); n = 56 | 42/56 (77) | NR | 1.3 (1.1) years; n = 56 | 4.6 (1.3); n = 56 | NR | NR | NR | mHAQ score, 0.4 (0.6); n = 56 | |

| MMP-3-driven therapy | 60 | 62 (13); n = 53 | 44/53 (83) | NR | 1.3 (1.2) years; n = 53 | 4.8 (1.3); n = 53 | NR | NR | NR | mHAQ score, 0.4 (0.8); n = 53 | |

| DAS28 and MMP-3-driven therapy | 61 | 56 (13); n = 58 | 49/58 (84) | NR | 1.3 (1.2) years; n = 58 | 4.6 (1.3); n = 58 | NR | NR | NR | mHAQ score, 0.3 (0.4); n = 58 | |

| TEAR58–60 | Immediate ETN | 244 | 50.7 (13.4) | 181/244 (74) | 216/244 (89) | 3.5 (6.4) | DAS28-(ESR), 5.8 (1.1) | 12.7 (5.8) | 14.3 (6.6) | mHAQ pain score 5.3 (2.6); n = 243 | mHAQ score, 1.1 (0.4); n = 227 |

| Immediate triple therapy | 132 | 48.8 (12.7) | 101/132 (77) | 121/132 (92) | 4.1 (7.2) | DAS28-(ESR), 5.8 (1.1) | 12.1 (5.8) | 14.1 (6.8) | mHAQ pain score 5.3 (2.5); n = 131 | mHAQ score, 1.0 (0.4); n = 125 | |

| Step-up ETN | 255 | 48.6 (13.0) | 176/255 (69) | 232/255 (91) | 2.9 (5.6) | DAS28-(ESR), 5.8 (1.1) | 13.1 (6.2) | 14.2 (6.9) | mHAQ pain score 5.2 (2.4) | mHAQ score, 1.0 (0.4); n = 237 | |

| Step-up triple therapy | 124 | 49.3 (12.0) | 87/124 (70) | 108/124 (87) | 4.5 (7.6) | DAS28-(ESR), 5.9 (1.1) | 13.1 (6.1) | 14.6 (7.0) | mHAQ pain score 5.1 (2.5) | mHAQ score, 1.0 (0.4); n = 117 | |

| U-Act-Early62 | TOC + MTX | 106 | 53.0 (46.0–60.0)a | 65/106 (61) | RF, 75 (71); CCP, 72 (68); both, 79 (75) | Symptom duration: 24.5 (16.0–41.5)a days | 5.2 (1.1) | 9 (6–15)a (44 joints) | 10 (7–17)a (44 joints) | NR | 1.1 (0.67) |

| TOC + PBO–MTX | 103 | 55.0 (47.0–63.0)a | 78/103 (76) | RF, 68 (66); CCP, 67 (65); both, 77 (75) | Symptom duration: 25.5 (18.0–45.0)a days | 5.3 (1.1) | 11 (7–16)a (44 joints) | 11 (7–18)a (44 joints) | NR | 1.3 (0.66) | |

| MTX + PBO–TOC | 108 | 53.5 (44.5–62.0)a | 69/108 (64) | RF, 86 (80); CCP, 84 (78); both, 93 (86) | Symptom duration: 27.0 (15.0–46.0)a days | 5.1 (1.2) | 9 (5–15)a (44 joints) | 10 (5.5–17)a (44 joints) | NR | 1.1 (0.59) | |

Characteristics of the TTT features of the early RA trials are presented in Table 15. Targets included LDA [a DAS44 of ≤ 2.4 (BeSt26–34,64–66); a Disease Activity Score, 28 joints with C-reactive protein concentration (DAS28-CRP) of ≤ 3.2 (CareRA38–43); a SDAI of ≤ 11 (Hodkinson et al. 51); a CDAI of ≤ 10 (Hodkinson et al. 51); a DAS28 of < 3.2 (Saunders et al. 54); a Disease Activity Score, 28 joints with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) of < 3.2 (TEAR58–60)], remission [a DAS44 of < 1.6 (COBRA-light44,45 and STREAM55); modified ACR 1981 definition (FIN-RACo46–49); a DAS28 of < 2.6 (T-4 study56,57 and Optimisation of Adalimumab study52,53); a DAS28 of < 2.6 and a SJC (28 joints) of ≤ 4 (U-Act-Early62)] response [defined by thresholds of SJC, TJC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and general well-being visual analogue scale (VAS) (CAMERA35,36,67)]: and matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP-3) concentration (< 121 ng/ml for men or < 59.7 ng/ml for women; T-4 study56,57). Treatment protocols for attaining the target varied considerably across studies in terms of the number of steps in the treatment protocol and the treatments used at each step, the only similar ones being in the COBRA Classic arms of the CareRA40,42,43 and COBRA-light44,45 trials (which were similar, but not exactly alike). Assessments were made every 3 months or less in all trials with an early RA population.

| Trial acronym or first author and year of publication | Type of comparison | Treatment arm | Number of participants | Target | Treatment protocol | Frequency of assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BeSt26–34,64–66 | Comparison of different treatment protocols | Sequential monotherapy | 126 | A DAS44 of ≤ 2.4 |

|

Every 3 months |

| Step-up combination therapy | 121 |

|

||||

| Initial combination therapy with PDN | 133 |

|

||||

| Initial combination therapy with IFX | 128 |

|

||||

| CAMERA35,36,67 | Other comparisons | Conventional strategy group | 151 | Response (> 20% improvement in SJC, > 20% improvement in any two of ESR, TJC and VAS general well-being), avoiding inadequate response (≤ 50% improvement from baseline for SJC and ≤ 50% improvement from baseline for two of ESR, TJC and VAS general well-being) |

|

Every 3 months |

| Intensive strategy group | 148 | Response (decrease in SJC, if SJC unchanged, assessors’ judgement looking at TJC, ESR and VAS general well-being), avoiding inadequate response (SJC ≥ 6, number of painful joints ≥ 3, ESR ≥ 28 mm/hour and a morning stiffness of ≥ 45 minutes) | Every 4 weeks | |||

| CareRA: high-risk patients40,42,43 | Comparison of different treatment protocols | COBRA Classic | 98 | DAS28-CRP ≤ 3.2 | 15 mg of MTX weekly, 2 g of SSZ daily and a weekly step-down scheme of oral GCs (60 mg to 40 mg to 25 mg to 20 mg to 15 mg to 10 mg to 7.5 mg of PDN), then:

|

Screening: baseline, weeks 4, 8 and 16. If a treatment adjustment was required at week 8, an optional visit was held at week 12 |

| COBRA Slim | 98 | 15 mg of MTX weekly with a weekly step-down scheme of oral GCs (30 mg to 20 mg to 12.5 mg to 10 mg to 7.5 mg to 5 mg of PDN), then:

|

||||

| COBRA Avant-Garde | 93a | 15 mg of MTX weekly, 10 mg of LEF daily and a weekly step-down scheme of oral GCs (30 mg to 20 mg to 12.5 mg to 10 mg to 7.5 mg to 5 mg of PDN), then:

|

||||

| CareRA: low-risk patients40,43 | Comparison of different treatment protocols | MTX-TSU | 47 | A DAS28-CRP of ≤ 3.2 | 15 mg of MTX weekly, no oral steroids allowed, then:

|

Screening: baseline, weeks 4, 8 and 16. If a treatment adjustment was required at week 8, an optional visit was held at week 12 |

| COBRA Slim | 43 | 15 mg of MTX weekly with a step-down scheme of daily oral GCs (30-20-12.5-10-7.5-5 mg of PDN). From week 28, GCs were tapered on a weekly basis by leaving out one daily dose each week over a period of 6 weeks until complete discontinuation, then:

|

||||

| COBRA-light44,45 | Comparison of different treatment protocols | COBRA | 81 | A DAS44 of < 1.6 |

|

Every 3 months |

| COBRA-light | 83 |

|

||||

| FIN-RACo47–49,70 | Comparison of different treatment protocols | Combination treatment | 99 (97 in ITT) | Remission – a modified version of ACR 1981 defined remission (Pinals et al.71) – on any drug treatment, no swollen or tender joints (modified by excluding fatigue and duration definition) |

|

Baseline and at months 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 |

| Single-drug treatment | 100 (98 in ITT) |

|

||||

| Hodkinson et al., 201551 | Comparison of different targets | SDAI arm | 42 | A SDAI of ≤ 11 (LDA) | 15 mg/week of MTX, then if not achieving a SDAI of ≤ 11:

|

Monthly for the first 3 months then every 3 months until the end of 12 months |

| CDAI arm | 60 | A CDAI of ≤ 10 (LDA) | 15 mg/week of MTX, then if not achieving a CDAI of ≤ 10:

|

|||

| Saunders et al., 200854 | Comparison of different treatment protocols | Parallel triple therapy | 47 | A DAS28 of < 3.2 |

|

Every 3 months by an independent, blinded assessor |

| Step-up therapy | 49 |

|

||||

| STREAM55 | TTT vs. usual care | Aggressive group | 42 | Remission (a DAS44 of < 1.6) | Treatment was started with 15 mg/week of oral MTX. If the DAS was ≥ 1.6 at a given time point:

|

Every 3 months |