Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/192/10. The contractual start date was in March 2016. The draft report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Walters et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Although many older people live well, the accumulation of health conditions over time can lead to increasing frailty for some. Frailty in later life is associated with greater risk of hospitalisation, functional decline, falls, worsening mobility and death1 and, consequently, a substantial increase in health and social care usage. Health-care costs over 3 months have been estimated as rising from €642 per person (£562 at the exchange rate in May 2017) for non-frail older adults to €3659 (£3201) for frail older adults, largely as a result of increases in inpatient care and medications. 2 The impact of frailty is likely to increase in the near future as the number of people aged ≥ 75 years is estimated to almost double by 2039 from 5.2 million to 9.9 million,3 with a well-recognised pressure on health and social care systems as well as family carers. Age UK (London, UK) suggests that UK public spending on social care will need to increase by at least £1.65B by 2020/21 to manage the impact of demographic and cost changes. 4

Although approximately 11% of people aged ≥ 65 years are frail, the proportion who are pre-frail is much higher, ranging from 19% to 53% across populations, with an average of 41%. 5 Pre-frailty (or early or mild frailty) is an intermediate stage at which individuals have some loss of physiological reserves but can recover after a stressor event6 and typically feel ‘slowed up’, with increasing dependency on others for assistance in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), such as cooking, shopping and managing finances. 7 Box 1 outlines the different ways in which mild or pre-frailty is commonly defined and measured. Previous interventions have focused on preventing decline or reducing frailty in the highest-risk populations with moderate–severe frailty, with limited success. 11–13 Although moderate–severe frailty has a higher risk of decline than mild frailty, older people with mild frailty are also more likely to transition back to a robust state or remain stable than those who are more frail. 14 This suggests that health promotion interventions may be more effective when targeted at less frail populations. Indeed, positive outcomes of preventative home visits (multidimensional visits addressing medical, functional, psychosocial and/or environmental problems and resources) by nurses on mortality rates appear to be greater for younger-old rather than older-old populations. 15

Pre-frailty’ defined as one or two characteristics from the following: slow gait speed, weight loss, low physical activity, low energy and weakness. 10

Electronic Frailty Index‘Mild frailty’ defined as a score of > 0.12–0.24 on the electronic Frailty Index, which uses the cumulative deficit model to identify frailty according to a range of 30 deficits: symptoms, signs, diseases, disabilities and abnormal laboratory values. 8

Clinical Frailty Scale‘Mild frailty’ defined as people with more evident slowing who need help or support in higher order IADL (e.g. finances, heavy housework) and who have progressive impairment of outdoor mobility, shopping and housework. 7

Modified physical performance test‘Mild frailty’ defined as a score of 25–31 on the Physical Performance Test, assessing performance of nine functional tasks, including activities such as stair climbing or putting on a coat. 9

However, it is currently unclear which intervention components are most beneficial for older people with frailty. 16,17 Home-based interventions appear to be promising, with evidence suggesting that they can have beneficial effects on mortality, functioning and emergency department admissions, with neutral effects on costs. 16–19 Previous evidence supported interventions based on multidimensional geriatric assessment including follow-up visits. 15 However, this type of intervention, typically with involvement from a multidisciplinary team of health and social care professionals, is expensive and difficult to deliver at scale, particularly if targeted at the larger group of up to 41% of older people with mild or pre-frailty living at home. The most optimal content and delivery of services, in terms of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, targeted at this population are therefore unclear, and previous interventions have lacked rigorous development or stakeholder input. We aimed to develop a home-based health promotion intervention according to the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for intervention development,20 targeted at older people with mild frailty and to assess the feasibility of delivering the intervention and of conducting a full-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT) to test clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Objectives

Our study objectives were to:

-

Systematically review and synthesise existing evidence for home-based health promotion interventions for older people with mild frailty.

-

Explore how policy and practice in the health and social care system address health promotion with older people with mild frailty.

-

Explore key components for a new home-based health promotion intervention for older people with mild frailty using interviews and focus groups with older people and carers, home care workers and community health professionals.

-

Develop a new health promotion intervention for older people with mild frailty drawing on principles of ‘co-design’ in partnership with older people, carers, health/care professionals and other experts.

-

Test acceptability and feasibility for delivery in the NHS including testing recruitment, attrition, feasibility of individual randomisation for a future RCT, feasibility/acceptability of study procedures and suitability of outcome measures.

-

Determine the intervention costs and test the feasibility of collecting health economic data to calculate costs and effects. We will also determine the feasibility of calculating the cost-effectiveness for a full RCT from health and social care and societal perspectives, and of conducting a budget impact analysis, scaling up to Clinical Commissioning Group level, estimating where monetary costs and benefits will fall for the NHS and local authority.

-

Conduct a mixed-methods process evaluation exploring the context, potential mechanisms and pathways to impact of the intervention and identify issues to address in scaling up the intervention for a full RCT and/or implementation.

The latest version of the project protocol (V1.3) is available on the Health Technology Assessment website at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1219210/#/. 21

The original commissioning brief is included in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Ethics and governance

The study was approved by the NHS Camden and King’s Cross Research Ethics Committee on 14 October 2014 (reference number 14/LO/1698). A substantial amendment was submitted and approved 16 September 2015 after initial development work to clarify the intervention content, for review of recruitment materials and to approve protocol changes required (see Chapter 3, Modifications to the trial protocol for details). A second substantial amendment (approved 26 May 2016) was submitted to review the process evaluation data collection materials (e.g. interview topic guides, questionnaires, information leaflets). No further protocol changes were made. All research and development approvals were sought and obtained for each site and amendment.

Public involvement and engagement

There was substantial public involvement across the whole project, from development of the initial protocol through to our dissemination processes. Two public members (JH and RE, see Acknowledgements) in particular advised on plain English summaries, study design (in particular approaches to engage older people to participate), study materials including summary leaflets and interview topic guides throughout. JH participated on the interview panel to appoint project staff and RE was an integral part of the process evaluation team, including analysis of qualitative data. Public members had a key role in the intervention development panels that served to shape the evidence base for the intervention into an acceptable and feasible service for older people with mild frailty. Two out of the three intervention development panels were cohosted with our third-sector partner, Age UK London, which helped involve 34 public members in this process (see Chapter 3, Service development).

Chapter 2 Intervention development: identifying effective content for a new service

In accordance with the MRC framework for intervention development,20 we undertook a series of systematic reviews to identify potentially effective components of a new service for mild frailty. These include two systematic reviews, a state-of-the-art review on six different areas of health promotion and a scoping review of policies targeted towards mild frailty. The systematic reviews are registered in PROSPERO (CRD42014010370) and reported below according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 22

Identifying components of effective interventions: systematic review of interventions targeted at community-dwelling older people with mild or pre-frailty

We reviewed the evidence for home- and community-based health promotion interventions targeted at populations with mild or pre-frailty. Original searches were conducted between December 2014 and February 2015 identifying studies from January 1990 to February 2015, prior to intervention development. Few studies were identified meeting our criteria in the original searches and, as this is a rapidly evolving field, these searches were updated in May 2016, reviewing evidence for the period January 1990 to May 2016. This yielded only a small number of extra studies. The findings of RCTs from the updated systematic review have been published in full elsewhere. 23 We have summarised these below in addition to our findings from observational and qualitative studies.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to identify the evidence base for potential components of a new intervention targeted at older people with mild frailty. Our objectives were to systematically review:

-

RCTs of home- or community-based health promotion interventions aimed specifically at older people with mild frailty

-

qualitative studies with older people with mild or pre-frailty, exploring their experiences and perspectives on potential interventions

-

observational studies of people with mild or pre-frailty that identify modifiable risk factors for adverse outcomes (e.g. transitioning to frailty, worsening functioning) that could be potential new targets for intervention.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

We searched the following bibliographic databases using the terms mild and pre-frailty and their synonyms to identify studies that have targeted this group (specific pre-frailty subject headings are currently unavailable; see Report Supplementary Material 2):

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

-

EMBASE

-

Scopus

-

Social Science Citation Index

-

Science Citation Index Expanded

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, NHS Health Economic Evaluation Database, Cochrane Methodology Register, Cochrane Groups

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

-

PsycINFO

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

-

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Centre Register of Health Promotion and Public Health Research

-

Sociological Abstracts

-

Social Care Online

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts.

We also used the following data sources:

-

trials register searches – Health Technology Assessment database, the UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database and ClinicalTrials.gov.

-

screening reference lists of systematic reviews and included studies.

-

contacting authors of relevant protocols and conference abstracts to obtain study outcome reports where possible.

-

forward citation tracking for included studies.

Study selection

We stored and deduplicated references in an EndNote [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] database. One reviewer screened titles and abstracts of articles and two reviewers screened full texts according to the following criteria, with disagreements resolved through discussion between reviewers and by consultation with the wider team.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included an English-language cohort, experimental and qualitative studies evaluating single or multiple domain health promotion interventions for community-dwelling older people aged ≥ 65 years with mild or pre-frailty identified using established criteria (including studies reporting separate outcomes for pre-frail subgroups). We excluded non-empirical studies and experimental studies of poor quality (e.g. before-and-after studies). Inpatient interventions and hospital or nursing home populations were excluded. We originally intended to focus on home-based interventions only; however, as a result of the paucity of these studies, we also included community-based interventions. We assessed the following outcomes: frailty or associated variables (e.g. gait speed), physical functioning, quality of life, physical activity and hospital admissions. We excluded studies assessing biological markers of frailty (e.g. inflammatory markers) as outcomes and those with an inadequate reference group (e.g. comparing pre-frail older adults plus a risk factor to non-frail older adults without the same risk factor).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Randomised controlled trials

One reviewer extracted data into a spreadsheet developed for this review on study design, sample size at baseline and follow-up, inclusion/exclusion criteria, frailty definition, intervention, control, outcomes assessed and results. Two independent reviewers assessed risk of bias within RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. 24 Participant blinding was excluded from our overall trial risk-of-bias ratings as a usual-care control is often appropriate in health promotion interventions, although active control treatments (e.g. a flexibility home exercise programme) were considered to be of a low risk of bias. Risk of bias was used descriptively and was not used to weight studies or as an inclusion criterion for meta-analysis.

Observational studies

One reviewer extracted data regarding sample size, independent and dependent variables, covariates controlled for, outcomes and key findings. Only data relating to the mild or pre-frail subgroup and potentially modifiable outcomes were extracted. Quality was assessed by one reviewer using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale,25 which assesses the rigour of participant selection (up to a maximum of four stars), comparability (out of a maximum of two stars) and outcome assessments (out of a maximum of three stars).

Qualitative studies

We intended to extract data on sample characteristics, data collection methods, analysis methods and key findings, as well as evaluate study quality according to Social Care Institute for Excellence guidance. 26

Synthesis of data and data analysis

We inductively developed coding schemes to group types of interventions targeted to pre-frailty (e.g. exercise and nutrition) and summarised the evidence available within each type.

For RCTs, we used meta-analysis to combine the results for similar interventions assessing the same outcome. When studies assessed an outcome using two or more measures, we reviewed the literature and selected the most comprehensive, valid and reliable measure; when studies compared multiple interventions with the same control group, we pooled the mean and standard deviation (SD). 27 For crossover designs, we included first period data only (obtained from the authors). 28 Post-intervention end-point data were used for consistency across trials because intervention and follow-up durations differed. We combined continuous end-point scores using standardised mean difference (SMD) in a random-effects model and quantified heterogeneity using the I2-statistic. For outcome data that could not be synthesised (e.g. change scores rather than end-point scores27), interventions with only a single study and long-term follow-up data we used narrative synthesis. Authors were contacted when possible for further data.

For observational studies, we narratively summarised the data available relating to each modifiable risk factor for frailty progression/adverse outcomes to explore which factors have potential for improving outcomes to include in a new intervention. We intended to synthesise qualitative studies using meta-ethnography,29 but we did not find any qualitative studies meeting our inclusion criteria.

Results

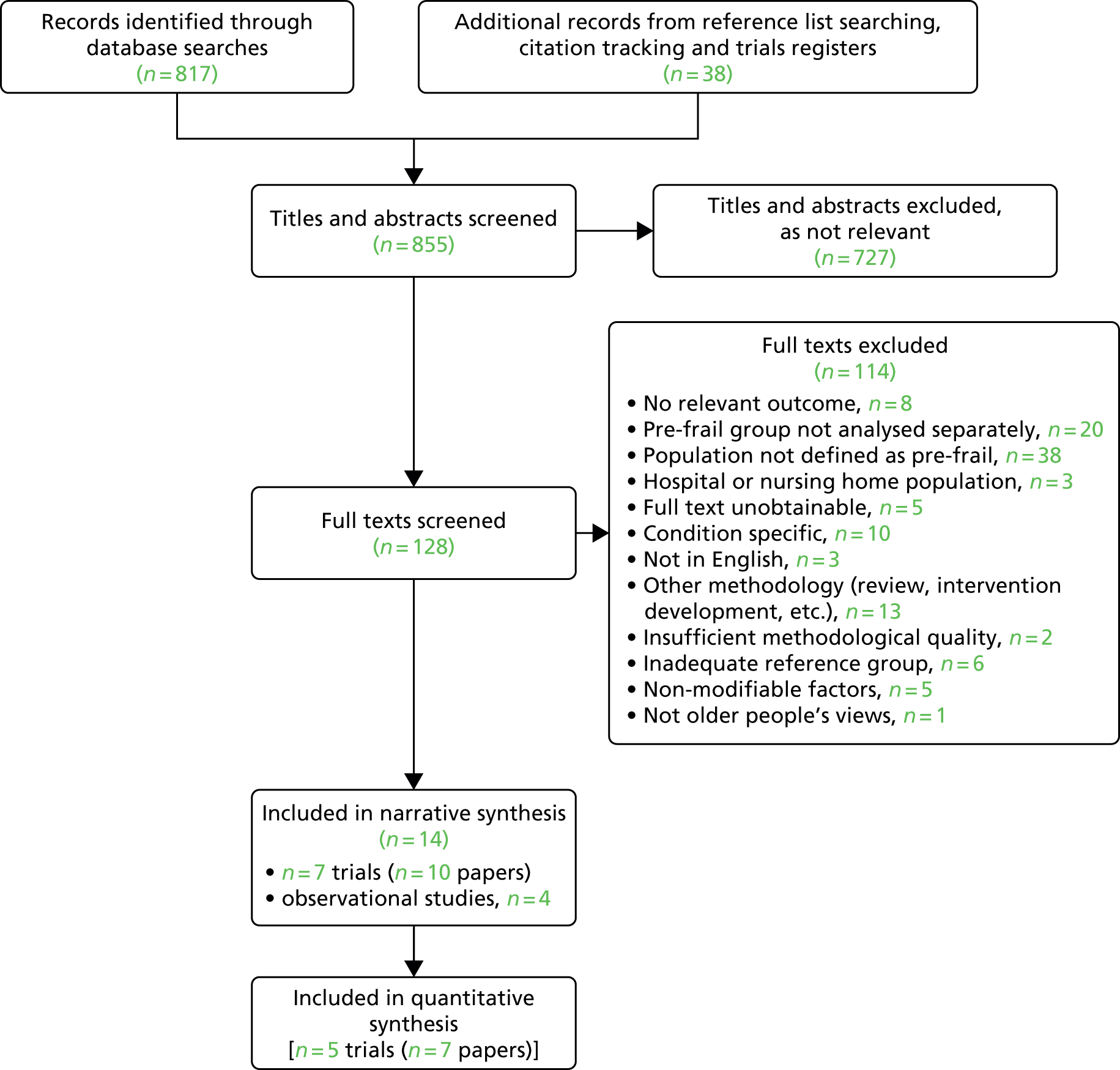

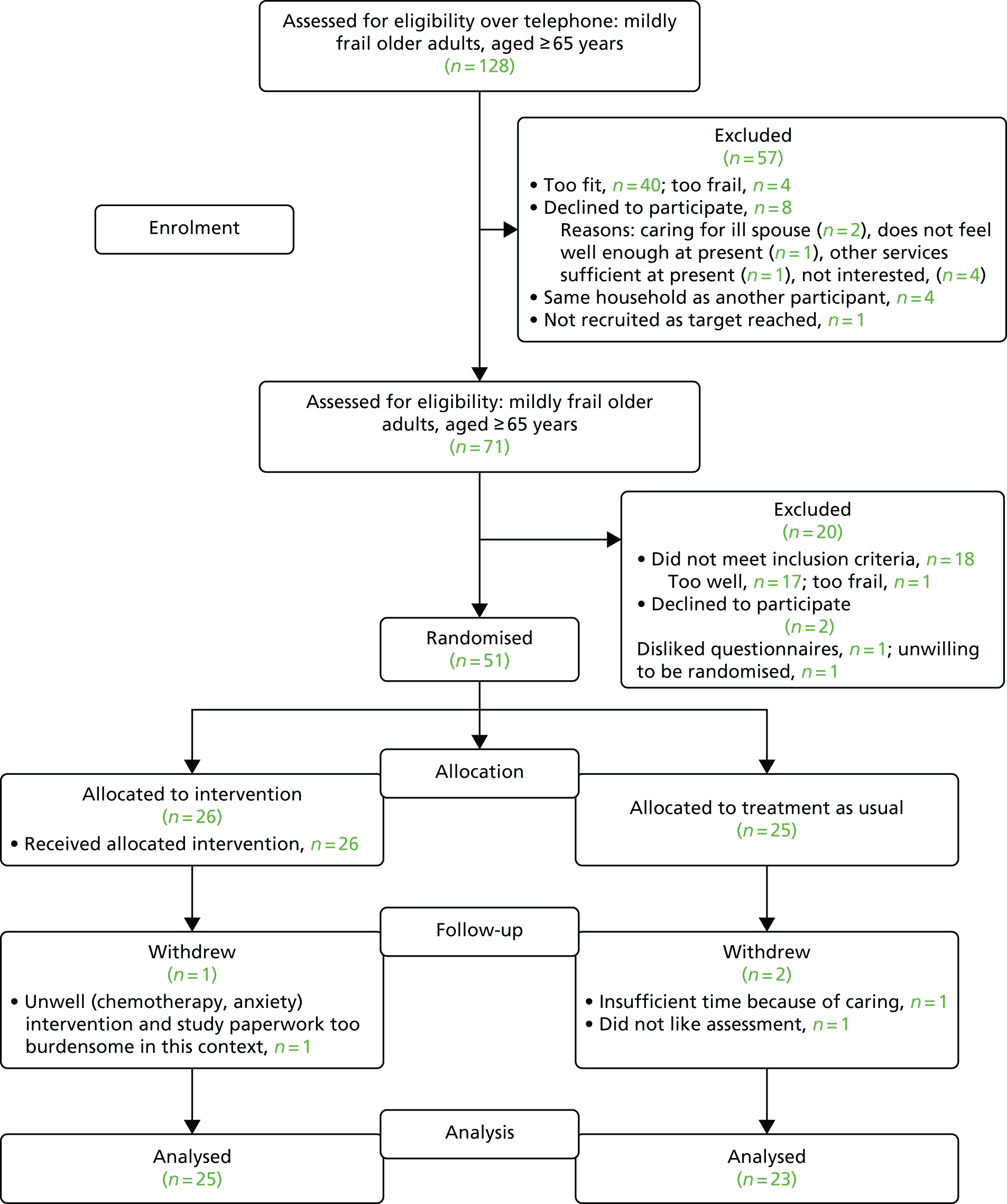

The flow diagram for this review is reported in Figure 1. We identified 855 unique references through database searches and citation tracking of eligible papers. We excluded 727 citations on title and abstract, screened 128 full texts and excluded 114, largely attributable to population (n = 71; e.g. combined outcome data for frailty and pre-frailty, frailty in a specific condition). Three were reported in Japanese and five were unobtainable. Therefore, the review included 10 papers reporting on seven RCTs and four observational studies. Of these, 13 were identified through database searches and one from citation tracking.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of studies included in the review.

Description of included randomised controlled trials

A full description of studies is included elsewhere23 and a brief summary of study details is outlined in Tables 1 and 2.

| Study ID (first author and year of publication) and country | Participants (n, frailty, inclusion/exclusion criteria) | Intervention | Control | Outcomes assessed | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Binder et al. , 200230 USA |

119 adults aged ≥ 78 years with mild–moderate frailty (defined by modified PPT score) | Group balance, flexibility, co-ordination, reaction speed and strength exercises (9 months) | Low-intensity flexibility home programme (9 months) |

Performance-based physical functioning Self-reported functioning Balance Muscle strength Quality of life |

|

|

Brown et al. , 200031 USA |

87 adults aged > 78 years; adults with mild frailty (defined by PPT score) | Group flexibility, balance, body handling skills, speed of reaction, co-ordination and strength exercises (3 months) | Home range of motion exercises (3 months) |

Performance-based physical functioning Muscle strength Balance Gait speed |

|

|

Daniel, 201232 USA |

23 adults aged ≥ 65 years with pre-frailty (Fried criteria)10 |

1. Group Wii Fit™ (Nintendo® Nintendo Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) basic games with weight vest (15 weeks) 2. Group seated upper and lower body strength and flexibility exercise (15 weeks) |

Usual activity (15 weeks) |

Self-reported functioning Physical activity Timed up and go |

|

|

Germany |

69 adults aged 65–94 years with pre-frailty (modified Fried criteria)10 |

1. Power training (upper and lower body), walking and balance exercises in groups (12 weeks) 2. Strength training (upper and lower body), walking and balance exercises in groups (12 weeks) |

Usual activity (12 weeks) |

Performance-based physical functioning Self-reported functioning Muscle strength |

|

|

Kwon et al. , 201535 Japan |

89 women aged ≥ 70 years with pre-frailty (modified Fried criteria)10 |

1. Group strength and balance training and cooking class focusing on protein- and vitamin D-rich foods (12 weeks) 2. Group strength and balance training alone (12 weeks) |

Monthly general health education sessions (12 weeks) |

Gait speed Balance Muscle strength Quality of life |

|

|

Lustosa et al. , 2011;36 and Lustosa et al. , 201337 Brazil |

32 women aged ≥ 65 years with pre-frailty (Fried criteria)10 | Group lower limb resistance exercise (10 weeks) | Usual activity (10 weeks) |

Gait speed Timed up and go Muscle strength |

|

|

Upatising et al. , 201338 USA |

87 adults aged ≥ 60 years with pre-frailty (modified Fried criteria)10 | Telemonitoring with individualised measurement (12 months) | Usual care (12 months) | Frailty state |

|

| Study ID (first author and year of publication) | Population | Independent variables | Dependent variable | Covariates | Follow-up duration (total number out of baseline number) | Findings | Qualitya (selection maximum 4*, comparability maximum 2*, outcome maximum 3*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jamsen et al., 201639 | Community-dwelling men aged ≥ 70 years in Australia (Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project),40 number of pre-frail men not reported |

Total number of medications (regular prescribed medications) Drug Burden Index (pharmacological risk assessment of cumulative exposure to sedative and anticholinergic medications) |

Frailty status (Fried phenotype)10 Death |

Age Baseline dementia or mild cognitive impairment diagnosis Comorbidity Education level Living status |

2 years (1366/1705) 5 years (954/1705) |

Number of medications had no effect on transitions from pre-frailty to other states (HR pre-frail-robust 0.99, pre-frail-frail 1.06, pre-frail-death 1.02) Drug Burden Index had no effect on transitions from pre-frailty to other states (HR pre-frail-robust 0.90, pre-frail-frail 1.03, pre-frail-death 1.18) |

Selection **** Comparability ** Outcome ** |

| Lee et al., 201441 | Community-dwelling men and women aged ≥ 65 years, equally distributed by age bracket and gender, in Hong Kong. A total of 48.7% of men and 52.5% of women pre-frail at baseline |

Smoking BMI MMSE score (Other non-modifiable characteristics also assessed) |

Frailty status (Fried phenotype)10 | Age | 2 years (1519/1745 men, 1499/1682 women) |

Pre-frail men: normal and overweight BMI was protective against worsening frailty compared with underweight [OR normal 0.47 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.99), overweight 0.36 (95% CI 0.16 to 0.81)], but no effect on odds of improving to robust. Obesity and smoking had no effects. Higher MMSE score predicted greater likelihood of improvement from pre-frail to robust [OR 1.10 (1.02–1.18)] Pre-frail women: BMI, smoking and MMSE scores had no effect on frailty transitions In multiple stepwise regression models (male: adjusted for age and stroke, female: adjusted for age, hospital admissions and stroke), higher MMSE score was a protective factor in both genders |

Selection **** Comparability * Outcome *** |

| Mohler et al., 201642 | Older adults aged ≥ 65 years from primary, secondary, and tertiary health-care settings, community providers, assisted living facilities, retirement homes, and ageing service organisations, without gait or mobility disorders in Arizona, USA (Arizona Frailty Cohort Study),43 n = 57 (48%) pre-frail |

Gait parameters (five inertial sensors worn walking 4.57-metre distance) Balance parameters (five sensors worn while standing with eyes open and closed) Physical activity parameters (all measured over 48 hours using triaxial accelerometer) |

Falls (yes/no, weekly log and telephone interview) | History of falls (use of assistive device, fear of falling, percentage body composition of muscle excluded from parsimonious model with sensitivity analysis) | 6 months (119/128) | Predictors of falls in pre-frail older adults (sensitivity analysis of one model only) included centre of mass sway (OR 8.8, p < 0.001), mean walking bout duration (OR 1.1, p = 0.02) and mean standing bout duration (OR 0.95, p = 0.03). Other predictors were not statistically significant and so were not included in the model |

Selection *** Comparability * Outcome ** |

| Shardell et al., 201244 | Random sample of residents aged ≥ 65 years in Italy (Invecchiare in Chianti Study),45 352 out of 1005 pre-frail | Vitamin D (serum 25(OH)D) classed as high or low (< 20 ng/ml) |

Frailty status (Fried phenotype)10 Mortality |

Alcohol consumption Calcium intake MMSE score Depression (CES-D) Comorbidities (congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, hypertension, angina, osteoarthritis, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) Age Education BMI Smoking Gender Blood collection season |

3 years 6 years (733/904) |

Lower serum 25(OH)D concentration significantly increased risk of mortality by 8.9% (95% CI 2.5% to 15.2%) and 5 ng/ml reductions were associated with greater odds of dying than becoming robust. Some non–significant associations with frailty state transitions |

Selection **** Comparability ** Outcome *** |

We included parallel-group RCTs,30,31,33,35 one pilot RCT,32 one randomised crossover trial36 and one secondary analysis of a RCT38 in our review, including 506 randomised participants (sample size range 23–194 participants) from a range of countries (see Table 1). Five trials used pre-frailty, defined through the Fried phenotype10 or modifications of this, to identify eligible older adults or women. 32,34–36,38 Two defined mild–moderate frailty according to the modified physical performance test,31 with two additional fitness and activities of daily living (ADL) criteria in one study. 30 Participants’ mean ages ranged from 72 to 83 years (inclusion criteria ranging from ≥ 60 to ≥ 78 years).

Most interventions were community-based group exercise (eight interventions reported in six studies30–32,34–36), with one three-arm study containing an additional exercise and nutrition group. 35 Exercise interventions were supervised by trained instructors, exercise physiologists or physiotherapists and delivered in 45- to 60-minute sessions one to three times per week over 12–36 weeks. Control groups were usual activity,32,34,36 a low intensity flexibility home exercise programme30,31 and monthly general health education sessions. 35 One study contained an 8-week run-in phase of vitamin D supplementation prior to randomisation. 34 Upatising et al. 38 carried out a subgroup analysis of a home individualised telemonitoring intervention compared with usual care.

Risk of bias was variable. One study was rated as having a low risk of bias,34 but three were unclear (two with some low-risk domains)30–32 and three were rated as having a high risk of bias. 35,36,38 The risk-of-bias plot can be found in the paper arising from this review. 23

Two further studies with poor methodological quality were identified in this review but not included. One compared 28 pre-frail elderly women with 28 non-randomly selected healthy controls undertaking a group exercise programme. 46 The other used a non-randomised trial design to assess the effects of a group compared with home control exercise programme on mild–moderately frail older women taking hormone replacement therapy; however, the only relevant outcome (muscle strength) was assessed in the exercise group alone. 47

Observational studies

We identified four observational studies that met our inclusion criteria (including reporting separate findings from a mild or pre-frail population and including potentially modifiable risk factors as the exposure; see Table 2). 39,41,42,44 They assessed the impact of medication burden on frailty status and death,39 the effects of smoking and body mass index (BMI) and Mini Mental State Examination score on frailty status,41 gait parameters on falls in pre-frail older adults,42 and the effects of high or low vitamin D on frailty and mortality. 44 Follow-up ranged from 6 months to 6 years. Total sample sizes ranged from 128 to 3018 at baseline and, within these, pre-frailty prevalence ranged from one-third to half of the sample. Study quality was good across all studies.

Qualitative studies

No qualitative studies of health promotion/behaviour change interventions from the perspectives of older people with mild or pre-frailty were identified.

Synthesis

Randomised controlled trials

Out of the six studies evaluating group exercise interventions, five contained sufficient intervention end-point data for meta-analysis across six outcomes. This is summarised in Table 3 reporting the SMD between exercise intervention and control groups for each trial.

| Outcome, study ID (first author and year of publication) | Outcome measure | SMD (95% CI) | Meta-analysis (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported physical functioning | |||

| Binder et al., 200230 | Physical function subscale of Functional Status Questionnaire | 0.83 (0.44 to 1.21) |

0.19 (–0.57 to 0.95) p = 0.62 I2 = 80% |

| Daniel, 201232 | Late life function and disability index – function total | –0.74 (–1.79 to 0.32) | |

| Drey et al., 201234 | Short Form Late Life Function and Disability Instrument | 0.12 (–0.39 to 0.62) | |

| Performance-based (observed) physical function | |||

| Binder et al., 200230 | Modified physical performance test | 0.58 (0.20 to 0.96) |

0.37 (0.07 to 0.68) p = 0.02 I2 = 31% |

| Brown et al., 200031 | Physical Performance Test | 0.40 (–0.04 to 0.84) | |

| Drey et al., 201234 | SPPB | 0.03 (–0.47 to 0.54) | |

| Gait speed | |||

| Brown et al., 200031 | Preferred gait velocity (pressure-sensitive foot switches, m/min) | 0.27 (–0.16 to 0.69) |

–0.06 (–0.49 to 0.37) p = 0.79 I2 = 50% |

| Drey et al., 201234 | SPPB usual gait speed (3–4 m, points) | –0.10 (–0.61 to 0.40) | |

| Lustosa et al., 201136 | Usual speed (10 m, m/s) | –0.55 (–1.25 to 0.16) | |

| Balance | |||

| Binder et al., 200230 | Berg balance test | 0.40 (0.03 to 0.78) |

0.33 (0.08 to 0.57) p = 0.009 I2 = 0% |

| Brown et al., 200031 | Berg balance test | 0.39 (–0.03 to 0.82) | |

| Drey et al., 201234 | SPPB multicomponent static balance (points) | 0.09 (–0.42 to 0.60) | |

| Mobility | |||

| Daniel, 201232 | Timed up and go (8 feet) | 0.69 (–0.36 to 1.74) |

0.57 (–0.01 to 1.16) p = 0.06 I2 = 0% |

| Lustosa et al., 201136 | Timed up and go (3 m) | 0.52 (–0.19 to 1.22) | |

| Muscle strength | |||

| Binder et al., 200230 | Knee extension (Cybex isokinetic dynamometry) | 0.76 (0.38 to 1.14) |

0.44 (0.11 to 0.77) p = 0.009 I2 = 47% |

| Brown et al., 200031 | Knee extensors (Cybex isokinetic dynamometry) | 0.56 (0.13 to 0.99) | |

| Drey et al., 201234 | Sit-to-stand transfer power | 0.24 (–0.27 to 0.75) | |

| Lustosa et al., 201136 | Knee extensor (isokinetic dynamometer Byodex System) | –0.09 (–0.79 to 0.60) | |

Other outcomes that could not be meta-analysed as a result of insufficient number of studies were:

-

quality of life – no significant differences for exercise30,35 or exercise and nutrition35 interventions

-

physical activity – a WiiFit intervention showed a within-group increase in self-reported physical activity32

-

frailty – slightly fewer people transitioned to non-frail or frail from pre-frail over 6 months after telemonitoring compared with usual care. 38

Observational studies

The key findings from the four observational studies included in this review were as follows.

-

There is evidence that the number of medications and drug burden in pre-frail older adults have no effect on transitions to robustness, frailty or death. 39

-

There is evidence that a normal or overweight BMI in pre-frail men is protective against transitioning to frailty, with no evidence for the effects of smoking or obesity. In pre-frail women, there was no evidence for the effects of BMI, smoking or cognition scores on frailty transitions. When adjusting for key covariates, better cognition was protective in both genders. 41

-

In pre-frail older adults, low vitamin D levels significantly increase the risk of mortality by 8.9%. 44

-

Greater centre of mass sway and longer bouts of walking are associated with an increased falls risk, while longer bouts of standing are associated with reduced falls risk in pre-frail older adults. 42

Key findings

Currently, both observational and experimental research targeted at pre-frail or mildly frail older people is sparse. RCTs are mostly small and/or of poor quality and focused on group exercise to improve mobility and physical functioning, with mixed evidence that group exercise may have some effects on functioning. Observational studies were large, of good quality and suggested that BMI, cognition and vitamin D levels may influence future transitioning to frailty, but that the number and burden of medications is unlikely to have an effect. There were no qualitative studies exploring perspectives on health promotion interventions in populations with mild or pre-frailty.

Implications for intervention development

-

No interventions can currently be recommended for widespread use in pre-frail or mildly frail older people, but exercise may be an effective component for a new intervention. Including a nutritional or cognitive component may have potential in frailty prevention.

-

Broader, multidimensional interventions targeted to mildly frail populations have not previously been assessed.

-

Further qualitative work is needed to help clarify potential components for an intervention tailored for people with mild or pre-frailty. Current interventions for pre-frailty lack developmental input from service users or other stakeholders. Future interventions may benefit from this.

-

From observational studies, nutrition, including ensuring the use of vitamin D supplements (as per standard guidance for older people) and addressing low weight/weight loss, may be an important component of an intervention.

Using behavioural science to develop a new complex intervention: an exploratory review of the content of home-based behaviour change for older people with frailty or who are at risk of frailty

The effects of changing health behaviours to prevent frailty are mixed,12,48 which could arise from ineffectiveness in achieving behaviour change or the ineffectiveness of the behaviour change upon the outcome. Health behaviours can be defined as activities that may contribute to disease prevention, disease or disability detection, health promotion or protection from risk of injury. 49 Behaviour change interventions typically contain multiple interrelated components and so active ingredients may vary depending on the intervention target, the number of behaviours targeted and the amount of tailoring required. 50 Using behaviour change theory provides a systematic approach to identify a full range of mechanisms of change and potential causal associations. 50 To our knowledge, no previous review has described the behaviour change strategies used for health promotion in frailty and their impact on behaviour change and clinical outcomes.

Intervention functions

Michie et al. ’s51,52 behaviour change wheel and behaviour change technique (BCT) taxonomy identify and classify the content of interventions aimed at changing behaviour. Their systematic review of behaviour change frameworks identified nine intervention functions (broad, non-exclusive categories of means by which an intervention can change behaviour), namely:

-

education – increasing understanding or knowledge around the behaviour

-

persuasion – inducing positive or negative feelings or action through communication

-

incentivisation – creating the expectation of a reward

-

coercion – creating the expectation of cost or punishment

-

training – teaching skills

-

restriction – reducing the opportunity to engage in a target behaviour or reducing competing behaviours to increase engaging in a target behaviour, using rules

-

environmental restructuring – changing the social or physical context for a behaviour

-

modelling – providing an example for people to imitate or aspire to

-

enablement – reducing barriers, or increasing means, to improve capability or opportunity for a behaviour (beyond education, training or environmental restructuring).

Behaviour change techniques

Intervention functions describe broad mechanisms rather than specific ones. As such, the actual active components of effecting the changes needed are described as BCTs. BCTs are the active components of behaviour change interventions that are observable, replicable and irreducible. 52 Michie et al. ’s53 taxonomy of 93 BCTs was developed through a Delphi study in order to facilitate consistent description and replication of behaviour change interventions, as well as define mechanisms of action to use in intervention development and refinement.

Aims

In order to develop a new intervention from a rigorous theoretical basis, we undertook a systematic review to (1) identify behaviour change components used in home-based health promotion interventions in frail and pre-frail older adults and (2) explore how these components may be associated with intervention effectiveness.

This review is summarised in brief here – see Jovicic et al. 54 for the review protocol and Gardner et al. 55 for a comprehensive report of the findings.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

We searched the following databases from January 1980 to September 2014 (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for search terms), using:

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

-

EMBASE

-

Scopus

-

Science Citation Index Expanded

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, NHS Health Economic Evaluation Database

-

PsycINFO

-

Health Economics Evaluations Database

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

-

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Centre Register of Health Promotion and Public Health Research

-

Bibliomap

-

Health Promis and Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (manual search as automated searches were unavailable).

We also used the following data sources:

-

trials register searches – Health Technology Assessment database, the UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database and ClinicalTrials.gov

-

backwards and forwards citation tracking of included trials and relevant systematic reviews

-

contacting authors for additional material.

Study selection

Two reviewers screened titles, abstracts and full texts, with disagreements resolved through consulting a third reviewer. We included peer-reviewed English-language RCTs of home-based interventions aiming to change health behaviours delivered in person by a health professional, but not requiring specialist expertise. The population was community-dwelling older adults aged ≥ 65 years who were either frail/at risk of frailty (including those defined as at risk of hospitalisation, with functional/mobility difficulties or aged ≥ 75 years with multiple comorbidities). Nursing home residents and hospital inpatients were excluded. We included interventions compared with no treatment or usual care, assessing behavioural, health or well-being outcomes relevant to frailty.

Data extraction and coding

Two reviewers extracted data into a spreadsheet developed for this review on study, sample and intervention characteristics; risk of bias (coded for descriptive purposes only); and behavioural, health or well-being measures at baseline and first follow-up. Using the definitions in Intervention functions and Behaviour change techniques, we coded behaviours targeted (when explicitly reported), intervention function and BCTs used. Practical, emotional and unspecified social supports were each divided into intervention provider support and family, friend or other caregiver (paid) support to give 96 possible BCTs.

Analysis and synthesis

We examined the relationship between intervention effectiveness and behavioural components. We classified outcomes into behavioural (behaviours or necessarily contingent outcome, e.g. medication adherence), health and social care use (e.g. hospital admission), mental health and functioning (e.g. depression), physical functioning (e.g. ADL), social functioning and well-being (e.g. loneliness) and generic (not captured by other clusters, e.g. quality of life). We defined an outcome as showing evidence of potential effectiveness when there was a statistically significant (p < 0.05) between-group change favouring the intervention in at least one outcome in the cluster. Intervention components were deemed to show potential effectiveness where the component was present in more effective than ineffective interventions (i.e. more than half of studies).

Results

Out of 1213 unique references identified from database searches and citation tracking, we screened 267 full texts and included 19 full texts describing 22 interventions (see Gardner et al. 55 for flow diagram). We excluded 248 full texts, largely attributable to an irrelevant population (n = 201).

We included 19 studies of people who were frail or at risk of frailty: 16 RCTs,12,13,56–69 two clusters RCTs48,70 and one pseudocluster RCT71 (see Report Supplementary Material 3 for study characteristics). Most (n = 16) compared one intervention to control, with three three-arm trials. Overall, trials were fairly good quality. All were rated as having a low risk of bias on four out of seven criteria and three were rated as having an overall low risk of bias. Interventions largely took the form of a personalised assessment, focused on care or health needs (n = 15), compared with usual care or no treatment (n = 18) and delivered by nurses (n = 21/22). Some studies included more than one intervention. A small number of studies included other professionals such as physiotherapists or social workers. Physical health and functioning outcomes were most commonly assessed (n = 19), followed by mental health and functioning, health and social service use and generic health and well-being (n = 11). Social functioning and well-being was assessed in seven12,57,64–66,70,71 studies and behavioural outcomes in four. 58,65–67

Behavioural targets

Regarding behaviour, only three reported using behaviour change theories. 48,63,64 Most interventions (n = 11/22) targeted a single behaviour,12,61–64,66–68,70,71 while nine targeted two or three behaviours13,56–59,65,69 and two targeted four or more behaviours. 48,60 The behaviours most commonly targeted were medication adherence or management (n = 16),13,48,56,58–61,63–66,68,69 physical activity (n = 11)12,13,48,56,57,59,60,65,70 and diet (n = 8),13,48,56,57,60,69,71 with one or two studies addressing areas such as alcohol, sleep etc. Targeting a particular behaviour did not appear to be associated with positive results for any outcomes (Table 4).

| Number of trials out of total showing evidence of effectiveness (n/N) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning outcomes | Behavioural outcomes | Health and social care use | Mental health and functioning | Social functioning and well-being | Generic health and well-being outcomes | |

| Behaviours targeted | ||||||

| Dietary consumption | 3/7 | – | 1/4 | – | – | 2/5 |

| Medication adherence or management | 5/13 | – | 2/9 | 2/7 | – | 3/8 |

| Physical activity | 3/11 | – | 1/5 | – | 0/4 | 2/5 |

| Intervention functions | ||||||

| Education | 5/6 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Enablement | 7/13 | – | 2/6 | 2/5 | – | 3/9 |

| Environmental restructuring | 2/5 | – | – | 1/4 | – | – |

| (None identified) | 1/5 | – | – | 1/6 | 0/3 | – |

| BCTs | ||||||

| Adding objects to the environment | 3/5 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Goal-setting (outcome) | 4/9 | – | – | 3/6 | 1/5 | 1/4 |

| Instruction on how to perform the behaviour | 3/4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Monitoring of the behaviour by others without feedback | 2/4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Monitoring of the outcomes of behaviour by others without feedback | 3/12 | 2/4 | 1/10 | 2/9 | 1/7 | 0/6 |

| Restructuring the physical environment | 3/5 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Social support from intervention provider (practical) | 5/10 | – | 2/5 | 2/4 | - | 3/6 |

| Social support from intervention provider (unspecified) | 4/11 | – | 2/9 | 2/7 | 1/6 | 0/7 |

Intervention functions

Intervention functions included:

-

enablement (n = 16/22) – increasing older adults’ means or reducing barriers to increase their capability (above and beyond education or training) or opportunity (above and beyond environmental restructuring) to undertake a behaviour

-

education (n = 7/22) – increasing knowledge or understanding

-

environmental restructuring (n = 4/22) – changing the context for a behaviour (including physical and social)

-

training (n = 2/22) – imparting skills

-

persuasion (n = 2/22) – inducing or stimulating positive or negative feelings or actions through communication.

No intervention used any other function. Functions could not be identified in five interventions. 12,66,68,69,71 More studies including education and enablement had positive results for physical functioning outcomes than those that did not including education and enablement (see Table 4); however, in other studies, all functions had less than half of the studies showing positive effects.

Behaviour change techniques

A minority, 21 out of 96 possible BCTs, were identified in at least one intervention (median 4.5, range 1–9). Social support (practical and unspecified) and monitoring outcomes of behaviour without feedback were used most commonly; however, only adding objects to the environment and instruction on how to perform the behaviour had a majority of studies with positive findings (see Table 4).

Key findings

-

Studies rarely assessed behavioural outcomes, used explicit theoretical approaches or reported intervention components clearly.

-

No single BCT or intervention function showed potential for outcomes other than physical functioning. Studies rarely measured specific behavioural outcomes.

-

Targeting a particular behaviour did not appear to lead to improvements in physical functioning.

-

No intervention functions or BCTs appear to be uniformly effective, but education and enablement and adding objects to the environment and instruction on how to perform the behaviour were more promising.

Implications for intervention development

In the light of the findings from this review, a new intervention for early frailty should be explicit about its theoretical basis, with clear development and definition of intervention components. Within a trial, behavioural outcomes (e.g. physical activity) should be assessed in addition to clinical outcomes in order to explore whether or not behaviour change led to better outcomes. The most promising components were the intervention functions education and enablement, which showed the most promise for improving physical functioning (a key frailty indicator), and the BCTs ‘adding objects to the environment’ and ‘instruction on how to perform the behaviour’. We found insufficient evidence to support the omission of other intervention functions or BCTs at this point.

What can we learn from effective single-domain health promotion interventions with frailer older populations? ‘State-of-the-art’ scoping review of systematic reviews

Our systematic reviews as outlined above located only limited evidence as to what components should be included in a multidomain health promotion service tailored specifically to those with mild or pre-frailty. In order to maximise the potential for intervention effectiveness, we scoped the evidence on single-domain home-based health promotion approaches that might work with older frailer populations more generally (e.g. those at risk of hospital admission), including six key domains: (1) exercises/physical activity, (2) falls prevention, (3) nutrition and diet, (4) social engagement and addressing loneliness, (5) mental health (depression and anxiety) and (6) memory (cognitive stimulation/memory adaption strategies in those with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment). The purpose of this review was to identify evidence on which domains have the best evidence for inclusion in a new multidomain intervention.

This was not part of our original protocol and given time constraints it was not possible to conduct full systematic reviews in each of these areas. State-of-the-art reviews rapidly summarise the quantity and main characteristics of the evidence in a topic area, include comprehensive searches to identify the most relevant current evidence, followed by narrative synthesis without formal quality assessment. 72 Therefore, we conducted a state-of-the-art review using systematic search methods to identify key systematic reviews within each of the domains or topic areas listed above, to inform the development of the intervention. To rapidly appraise the evidence in each key area, we included only the strongest forms of evidence: systematic reviews of RCTs or, when the field was extensive, overviews of systematic reviews.

Objectives

To identify key systematic reviews of home- or community-based health promotion strategies, delivered by non-specialists, in the following domains and to extract key messages to inform components to include in a new health promotion service for mild frailty:

-

exercise/mobility/physical activity

-

falls prevention

-

nutrition and diet

-

social engagement

-

mental health

-

memory.

Methods

In the light of the paucity of studies focused on older adults with mild frailty, we took a broader approach to including reviews that could provide relevant evidence on which to base intervention components. Our inclusion criteria were:

-

Community-dwelling older adults who could be defined as ‘at risk’ or frailer than a general population (e.g. non-healthy, at risk of falls or hospitalisation, with frailty).

-

Interventions that could be delivered by non-specialists with or without minimal training, in the light of emerging findings from our qualitative work suggesting that a non-specialist support worker would be the most suitable professional (see Chapter 3, Person to deliver the service).

-

Any control treatment.

-

Outcomes relevant to each area of intervention (e.g. depression, social isolation, strength, frailty).

-

Systematic reviews of RCTs or overviews of systematic reviews. As we aimed to synthesise the most up-to-date evidence, we excluded earlier reviews that had been updated and superseded.

We searched three key databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and Scopus) from inception to April 2015 (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for search terms) and one reviewer screened titles, abstracts and full texts and extracted key data from reviews meeting our eligibility criteria in each domain. Two reviewers then identified the main findings of relevance to the development of our new service from each review, with reference to the original articles. As this was a state-of-the-art review, quality assessment and formal synthesis were not carried out. 72 We summarise the key findings from the included reviews that informed intervention development below.

Key findings of relevance to design of our new intervention

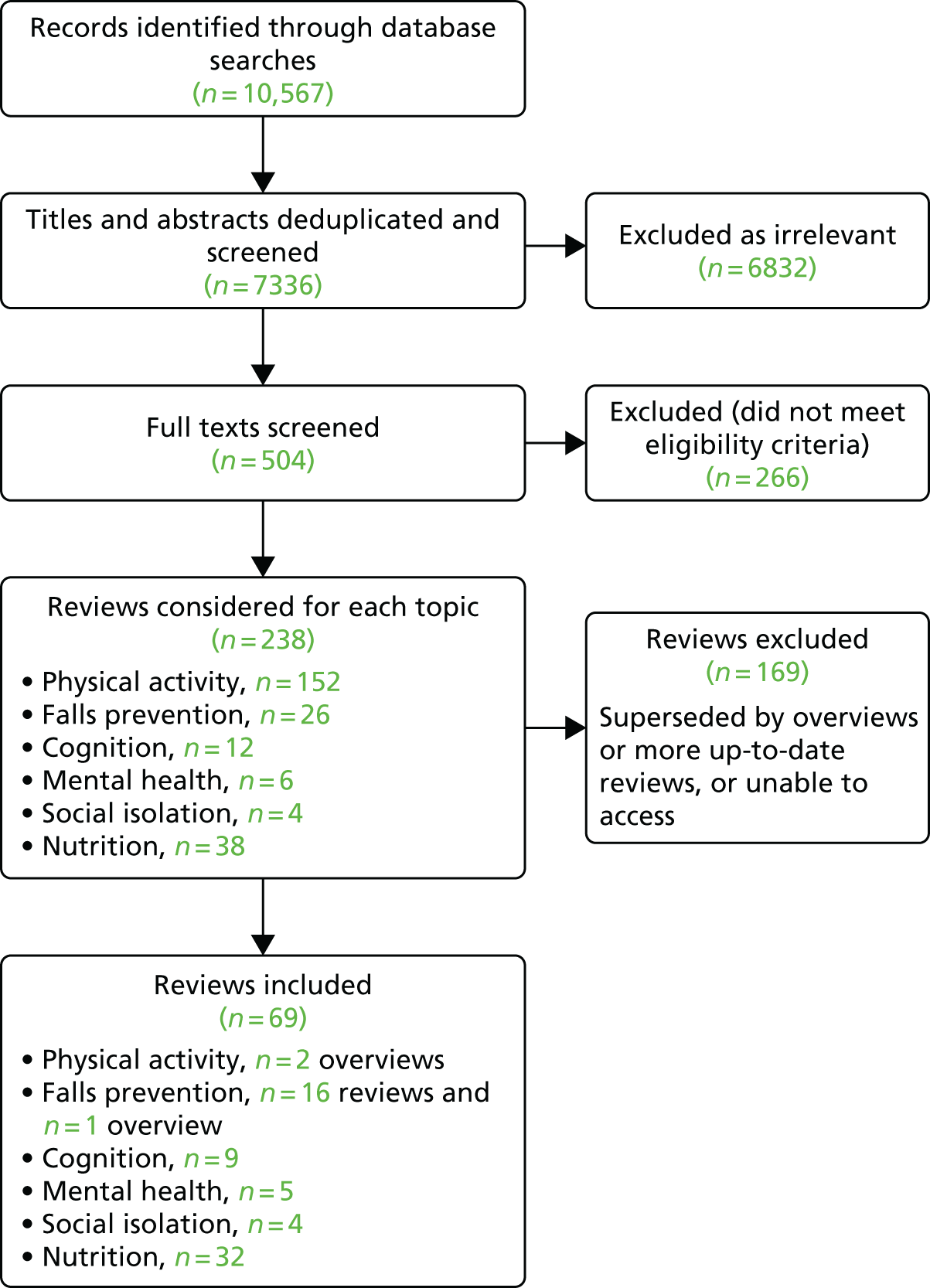

We extracted evidence from 66 reviews and three overviews of systematic reviews (Figure 2). We found the largest evidence base for physical activity and falls prevention (178 systematic reviews identified, including three overviews of reviews used for evidence extraction) and nutrition interventions (38 reviews), with limited evidence for social and mental health interventions and very limited evidence for cognitive interventions. Some reviews contained a mixture of systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram of studies included in the state-of-the-art review.

Physical activity and falls

From two overviews of reviews encompassing evidence from numerous (n = 152) previous systematic reviews on exercise/physical activity interventions and other falls prevention reviews (containing 11–159 trials), we found moderate evidence that exercise, physical activity and falls prevention interventions can have positive effects on balance and physical functioning, but not in those with cognitive impairment. 73–76 We also found evidence that targeted supervised home strength and balance exercise programmes plus walking practice, delivered by a trained health professional, can prevent falls. 77 Untargeted group exercise (particularly balance) may also prevent falls. Combined group and individual approaches are most effective. 78 Individual prescriptions may be more important in frailer older adults. 77

Exercise may improve mental well-being, but the research quality was limited. Older adults should be encouraged to exercise at low-to-moderate intensity and walk for leisure. 79 Exercise does not appear to have an effect on depressive symptoms. 80

From 16 reviews including 11–159 trials and one overview regarding falls prevention,73–76,78,80–90 we found that exercise programmes assessing risk for falls and managing this, anti-slip devices in shoes, home safety assessment and modification and training in walking aid use, may help prevent falls. The strongest evidence related to exercise, which reduces the risk and rate of falls in community-dwelling older adults,73,75,78,81–85 though some authors advocate caution with using exercise interventions in frailer older adults. 81 Home assessment and modifications appear to be effective,84,86,87 especially in frailer older adults or previous fallers. 78,81

Falls risk assessment and management appears to be effective. 81,83 Falls prevention programmes may reduce falls risk by up to 10% and may also reduce the fear of falling and falls-related injuries;75,76,80,85,88–90 however, results are inconclusive in cognitively impaired older adults. 74 Walking aids should be correctly sized and adapted, recommended by a health professional and only used when necessary with training. 78 Fall-related injuries may be reduced by strength and balance training, vitamin D and calcium and hip protectors. 87

There was insufficient evidence to support the use of education alone or cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), and mixed evidence regarding vitamin D and calcium supplementation for falls prevention. 81,84,86,87

Social isolation and loneliness

We found limited evidence (four reviews, including 11–32 studies, both RCTs and quasi-experimental designs) summarising interventions for social isolation and loneliness. The most effective interventions were those that included a group component, particularly in which the older person was an active participant91–94 and those with a theoretical basis. 92 There was mixed evidence for home visits and befriending services93 and little evidence to support the use of telephone or internet support interventions. 93,94

Mental health

Five reviews including 5–69 studies assessed mental health interventions. 95–99 All reviewed interventions for preventing major depression in older adults with subthreshold depression symptoms (sometimes also including general older adult populations). There was evidence to support the use of psychotherapy interventions for preventing depression. 95 The effect of psychosocial interventions appeared to be weaker but still significant for depression and positive mental health;96,97 however, when evaluating intervention subgroups, only social activities had significant effects on depression,96,97 a component also highlighted as increasing the effectiveness for older people in another review. 98 Interventions using behavioural methods only98 or lasting < 3 months97 may be less effective in older adults.

Memory

Ten reviews including 7–35 studies assessed memory training strategies,100–109 but two of these were updated in a later review. The research was largely laboratory based and contained mixed evidence of varying quality. Reviews suggested that for healthy persons and persons with mild cognitive impairment, memory training can improve the type of memory being trained but that this may not transfer to other types of memory, everyday activities or functioning. 100–107 Strategies to compensate for mild memory loss and targeting learning-specific information were therefore recommended.

Nutrition

Evidence for nutritional advice and education interventions was mixed: positive effects were found in a review of 23 trials on diet, physical functioning and depression, but not anxiety, quality of life or service use. 110 However, within a nutritional counselling review of 15 trials, interventions containing active participation and collaboration with older adults showed greater promise for improving dietary behaviour changes. 111 Certain BCTs, including ‘barrier identification/problem-solving’, ‘plan social support/social change’, ‘goal-setting (outcome)’, ‘use of follow-up prompts’ and ‘provide feedback on performance’ were associated with greater intervention effects across 22 trials of increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. 112 There was evidence in a review of 22 studies that good adherence to a Mediterranean diet may reduce the risk of depression or cognitive impairment. 113 A further review of nine studies of carer interventions for malnutrition suggests these may also be effective. 114

Regarding individual supplements, vitamin D (with or without calcium) was the supplement most frequently evaluated. Twelve reviews including 8–42 trials indicated that vitamin D may reduce falls risk, increase muscle strength and improve function, though evidence was mixed. 115–126 Some individual reviews suggested that vitamin D may be more effective when calcium is added118,124 or in deficient populations,120 while evidence was mixed regarding the effects of dose. 121,122 Long-term supplementation may be required for effects on mortality. 115

Low-fat dairy products may benefit neurocognitive health,127 while protein and energy supplementation in malnourished people recovering from illness appears to reduce complications and hospital readmissions and increase grip strength. 128 Supplements not supported by the literature included multivitamins,129,130 B vitamins,131–133 omega-3 fatty acids134–137 or supplementing older people without malnutrition with amino acids or protein. 138 High doses of betacarotene, vitamin E and vitamin A are likely to be harmful and should be avoided in older adults. 139 The effects of carbohydrates on cognition or daily functioning are currently unclear. 140

Implications from the ‘state-of-the-art’ review

-

Physical activity is a beneficial intervention to improve functioning and reduce falls and should form part of a tailored intervention, with a focus on individualising activity to frailty status and signposting to group classes when appropriate.

-

Although promoting social activities has limited evidence, older people may benefit most from being signposted to local groups with a shared interest they can participate in, depending on their preferences.

-

The most beneficial ways to prevent depression in later life may be signposting to psychological services or encouraging socialising.

-

As there was very little evidence for effective methods to improve memory, this should not currently be included as part of an evidence-based intervention. Strategies to compensate for mild memory loss could be considered.

-

Owing to the supporting evidence for some nutritional interventions, it may be beneficial to include these within a new service.

Policy context: how does a new health promotion service for people with mild frailty fit with current policy and practice?

We completed a narrative health and social care policy analysis141 that investigated the extent to which health and social care policy in England addressed health promotion with older people with mild or pre-frailty, or frailty prevention. The purpose was to understand the policy context in which the intervention we developed could be implemented.

Background

Policy review and analysis helps explain past successes and failures, identify gaps and plan for future reforms. 142 In conducting this policy review we were informed by the work of Walt et al. 142 Our review was framed by theories of public policy as processes including problem analysis, formulation and implementation in which different interests, institutions and ideas interact. 143 These theories include recognition of the exercise of power by different interest groups, including the influence of ageism. 144

Public policy-makers internationally need to address increasing demand for health care and old-age support in the context of a declining labour force. 144 The Political Declaration and Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing,145 agreed by the United Nations in 2002, addressed three priority areas: older persons and development, advancing health and well-being into old age, and ensuring enabling and supportive environments. Regional implementation strategies have been agreed at ministerial level, to work towards maintaining quality of life and promoting independence, health and well-being throughout the life course, underpinned by policies supporting health promotion and disease prevention. 146

In England, evidence of changing demography and potential impact on public spending costs has been known to governments for some decades and was recently requantified. 3 A ministerial commitment has translated into a range of policies that specify the promotion of well-being for older people as a strategic objective including those for longer working lives,147 for housing,148 and for transport. 149 We now summarise our analysis specifically of health and social care policies for frailty prevention.

Method

The design drew on the interpretative tradition in undertaking a narrative review using a method of documentary analysis. 141 It encompassed policy as created at three levels in the state:143

-

state laws

-

strategies and plans of government-mandated national bodies for the delivery of health and social care

-

government-mandated bodies at local administrative levels for health and social care.

The public policies for inclusion in our review had to be published and/or current to the period of the study (2014–17) and address one of the following:

-

a population of older people (without an age-specific definition)

-

public health and well-being for whole populations including older people

-

publicly funded health and social care services for whole populations, including older people.

Internet searches of government and a representative sample of local government and NHS commissioning websites were conducted in 2015 and updated in 2017. A snowball technique was used to follow linked policies. A total of 79 national level and 78 local level documents were included. Each document was scrutinised for key words of interest, such as ‘older people’, ‘elderly’, ‘frail’, ‘frailty’, ‘health promotion’ and ‘ageing well’. Relevant surrounding text on the problem analysis, the formulation of actions and stated intent as well as absence of attention to the question of interest, was noted. Iterative analysis was discussed within the research team meetings and a final narrative analysis written.

Findings

The findings are reported within the following themes: problem analysis, formulation, solutions and delivery mechanisms.

The policy problem analysis of the ageing population with a changing epidemiological profile and the consequences for society (national and local) was restated at the beginning of every policy document.

State policy solutions included directions for ‘preventative actions’ as one theme for all adults for local authorities,150 the NHS151 and for social care provision. 152 It is worth noting that the term health promotion, which featured in the English National Service Framework for Older People, published in 2001 and re-endorsed by the government in 2014,153 was not evident in relation to this age group. In recent years prevention of ill health has become a priority strategy for the health and social care system in addressing the changing population, as evidenced by policy commitments and subsequent legislation for the public health function within government, local authorities,150 the NHS153 and the care system. 152 For the first time in England, social care policy mandated the promotion of well-being and prevention or delaying the development of needs for care:152 domains previously associated with the responsibilities of the ‘health’ system. The associated guidance provides definitions of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. 154 This policy shift reflected the wider policy aspiration of integration between the health and social care systems. 155

A shift in the target populations for prevention had also occurred. In 2001, three groups were identified within the older population: the well and healthy, the frail, and then a transition group (i.e. the pre-frail or mildly frail). 153 However, policies reviewed here give little explicit consideration of those with pre-frailty.

Policy solutions and delivery mechanisms

Within current public health policy, the aim for older people is to support prevention, promote active ageing and tackle inequalities while targeting depression, chronic loneliness, winter excess deaths of frail older people, vascular components of dementia and falls. 153 The government-mandated outcomes for the public health, NHS and adult social care in relation to an older adult age group are summarised in Box 2.

Improved older people’s perception of community safety.

Prevention of social isolation.

Prevention and improvement of excess weight in adults.

Improvement of the proportion of physically active and decrease in inactive adults.

Prevention and improvement in smoking prevalence – adults (> 18 years).

Prevention through uptake of national screening programmes (breast cancer screening for women aged 50–70 years, bowel cancer screening for men and women aged 60–74 years, and abdominal aortic aneurysm screening for all men aged ≥ 65 years).

Prevention through population vaccination coverage – flu (aged ≥ 65 years), shingles (70 years).

Prevention in premature mortality in those aged < 75 years from all cardiovascular diseases (including heart disease and stroke), cancer, liver disease, and respiratory diseases.

Prevention and reduction of excess mortality in adults aged < 75 years with serious mental illness.

Prevention of sight loss caused by age-related macular degeneration.

Prevention of injuries because of falls in people aged ≥ 65 years.

Prevention of hip fractures in people aged ≥ 65 years.

Prevention of excess winter deaths, with particular attention to those people aged > 85 years.

Improvement in the proportion of older people (≥ 65 years) who were still at home 91 days after discharge from hospital into reablement/rehabilitation services.

Improving health-related quality of life for people with multiple long-term conditions, and their carers.

In government health service policy, the term frail older people was only used in relation to improved integration of services for those most vulnerable, particularly for those with long-term conditions. 157

The mechanisms for policy delivery for prevention for older people are described in state and national agency policies as described in Box 3.

-

Preventative actions for older people included in all local authority areas of responsibilities (e.g. safe neighbourhoods, leisure and housing). 152

-

Voluntary sector creation of community agent roles and community groups to prevent social exclusion in those aged > 60 years. 151

-

Local authority duties to provide or arrange for resources to prevent, delay or reduce individual’s needs for care. 154

-

The NHS Health Check programme funded by the public health function of local authorities aimed to prevent heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus and kidney disease, and raise awareness of dementia for those aged 40–74 years. 158

-

The provision of primary prevention (e.g. recording smoking status in public health element of the Quality and Outcome Framework of general practice contracts). 159

-

The provision of a named and accountable GP for all those patients aged > 75 years,160 with an accompanying responsibility to provide a health check.

-

The proactive care programme as an enhanced service element of general practice contracts161 aimed at preventing hospital admissions in the frailest older patients.

GP, general practitioner.

The extent to which the preventative actions address those with mild or pre-frailty is debatable. The NHS Health Check is primarily a public health programme to reduce long-term condition risk, such as cardiovascular disease, in a younger population. 162 The provision of a health check for those aged > 75 years did not specify the activities or suggest that it presented the opportunity for prevention in those with mild frailty. The proactive care programme161 was targeted at the frailest with no consideration of those with mild or pre-frailty.

The extent to which the other mechanisms listed in Box 3 were visible in local strategies in 2015 varied. Most were described in more overarching language. A third of the nine local areas’ Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies that we examined contained no specific priorities for older people. This was replicated in 2017 when we reviewed the corresponding areas’ Sustainability and Transformation Plans. All had priorities for preventative activities, only four specifically mentioned these with the older population. Four others discussed objectives in relation to frail older people but in relation to the medically unwell.

Policy iterations and outcomes

Quantifying the implementation and impact of preventative measures is challenging. 163 There has been no specific published evaluation of impact for this group. Explanations for this could be the inherent localism in implementation or a pervasive ageism resulting in lack of due attention. 164

In those delivery mechanisms without specified public funding, such as community agents, it is hard to judge the extent of implementation and outcomes. Those with public funding have some published evaluations. The NHS Health Check has had greater take-up by those aged 60–74 years than those < 60 years,165 but it is not aimed at preventing frailty or likely to include large numbers with mild frailty. The Proactive Care Programme focused on the frailest and by 2015 only 410 general practices of the 7841 in England were not providing this service. 166 Some local Clinical Commissioning Groups also promoted preventative activities with those with mild frailty. 167 The general practice contract for 2017–18 has changed. 168 The Proactive Care Programme has been replaced with a requirement for all general practices to identify and focus clinical attention on those with severe frailty. There are no explicit specific health promotion or prevention components to this contractual requirement.

Discussion and conclusion

This review has analysed contemporary health and social care policy for health promotion for older people with mild or pre-frailty in England. The review is time limited, our searches may not have been complete and the volume of material identified at the local level, and subject to amendments by changing governments, may have been incomplete. We have tried to mitigate this through our iterative processes.

We found that the older adult population was not always identified separately as a policy priority: the extent to which this represented a positive lack of age discrimination or a lack of attention to specific problems of some older people cannot be judged from the documentary evidence alone. Over time, the discourse changed to be more specific regarding prevention of ill health rather than promotion of health and was targeted either at the most frail and at risk of adverse outcomes or to those in mid-life (i.e. an ‘upstream’ public health solution169 and earlier in the life course). We found an absence of policy consideration for preventative actions for those on a pathway to frailty – a population that is predicted to grow in all countries. Publicly funded or supported services seeking to develop health promotion for older people with mild frailty may find it difficult to provide a policy ‘rationale’ amid other priorities. Addressing the individual and societal consequences of adverse experiences of those with the greatest frailty may require that some attention is paid further ‘upstream’ in the life course.

Evidence reviews: discussion

Although previous evidence suggests that interventions aimed at lower-risk populations may be more effective,15 our reviews found only limited evidence regarding interventions targeted at people with mild frailty and no qualitative work specific to this population. The evidence base largely consisted of exercise-based interventions, even when widening the remit to include a broader range of at-risk populations in our state-of-the-art review. Though there was some evidence for the effects of exercise on physical performance and falls prevention, evidence in other areas (e.g. socialising, mental health) was sparse. A focus on physical functioning alone has been criticised by stakeholders, some of whom have advocated addressing cognitive, social and psychological dimensions of frailty. 170

Our behaviour change review suggested that some BCTs and intervention functions as potentially effective components of a new service. There was a notable absence of local and national preventative policies targeted to older people on a pathway to frailty, despite wider European policies aimed at frailty prevention and improvement. 170

The findings from our reviews of the evidence are consistent with other frailty prevention literature. A scoping review of studies aimed at preventing or delaying frailty across robust, pre-frail and frail populations found mixed evidence of clinical effectiveness with a focus on physical activity, sometimes in comparison with a nutrition or cognition intervention. 170 There was some evidence that inclusion of physical activity can lead to reductions in frailty, but mixed effects for geriatric assessment and no effects of home modifications. Exercise may also have positive effects in frailer populations, but the most effective components of this are unclear. 171 Two further RCTs that have been published since our systematic review searches, of l-carnitnine supplementation172 and an exercise and nutrition intervention,173 found similarly mixed effects on frailty symptoms and physical functioning.

In spite of the lack of literature in some areas, we were able to scope and incorporate a large evidence base and identify potentially effective components to include in a new intervention, based on comprehensive database searches. Our behaviour change review included a novel methodology and enabled us to consider how interventions may be effective, as well as whether or not they were effective. The policy review appraised a range of current national and local policies, and included an iterative approach to maximise the documentation available. In combination with the mild frailty systematic review, these highlighted the lack of attention to and evidence for preventative interventions in people with mild frailty.

There were some limitations to the reviews. The first review found very little evidence and, for the evidence we retrieved, there were mixed results across outcomes (see Chapter 2, Results and Synthesis). 23 To our knowledge, this is the first review to focus solely on mild and pre-frail populations, rather than grouping them with frail or robust older adults. However, pre-frailty and mild frailty were defined inconsistently across studies and some possessed stringent exclusion criteria (e.g. history of orthopaedic fracture, mild cognitive impairment) that limited the generalisability of the results to the broader pre-frail population, in which multiple physical and cognitive comorbidities are fairly common.