Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/18/05. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Billie Hunter’s professorship is partly funded by the Royal College of Midwives.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Paranjothy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Breastfeeding rates in the UK

The benefits of breastfeeding for the short- and longer-term health and well-being of babies and mothers in low- and high-income countries are well established. 1 If 45% of women in the UK exclusively breastfed for 4 months, it is estimated that at least £17M could be saved in treatment costs annually for acute illness in infants, in addition to incremental benefits over the lifetime of each annual cohort of first-time mothers. 2

The UK has exceptionally low breastfeeding rates. 1 The 2010 Infant Feeding Survey3 indicated that the majority of mothers in the UK (81%) initiate breastfeeding but that around two-thirds of these women stop breastfeeding before 6 weeks. For most women this is earlier than planned. 1 Only 1% of mothers in the UK currently exclusively breastfeed for 6 months,3 which is the World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended duration. 4 In 2010, eight in 10 mothers who stopped breastfeeding in the first 6 weeks did so before they had planned to, whereas, over the first 9 months, around three-quarters of mothers who stopped had intended to continue for longer. 3 Women’s experience of breastfeeding is not always straightforward, with around one-third reporting problems. In the first weeks, the most commonly given reasons for stopping breastfeeding are a perception of ‘insufficient milk’, a perception that the baby is rejecting the breast, ‘painful breasts/nipples’ and finding that breastfeeding takes too long or is tiring. 1

There are marked inequalities in breastfeeding rates. Geographically, low breastfeeding rates correlate with higher indices of social deprivation. 5 Younger mothers (aged < 20 years) of white British ethnicity and of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to start or continue breastfeeding beyond 6 weeks. 1 Midwives and health visitors provide professional support for breastfeeding and the majority of maternity units and health-visiting services are now working towards the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF)’s UK Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI) standards for support with infant feeding. 6 Nonetheless, mothers who give birth in the UK frequently feel underprepared for breastfeeding and many mothers who might benefit from breastfeeding support do not access professional help. 7

Medical conditions that prevent women from breastfeeding are rare;8 infant feeding decisions involve a complex interplay of psychological, social and cultural factors. 9 At the level of the individual mother, motivation to breastfeed and breastfeeding self-efficacy are associated with continuation of breastfeeding. 10–13 However, a broader set of social and societal drivers are at play, many of which can interact with individual mothers’ confidence, self-efficacy and determination to breastfeed. Extensive marketing of formula milk can denormalise breastfeeding;14 social attitudes and norms, including attitudes and norms of experiencing breastfeeding vicariously, can affect mothers’ confidence; and women’s work and employment conditions can make decisions to continue breastfeeding more difficult. 9,15

Women who are supported and encouraged to breastfeed by key members of their social network are more likely to start and continue breastfeeding for longer. 16 A review of the literature on differences between mothers who continue to breastfeed until 6 months and those who stop indicated that feeding intention and self-efficacy are inter-related with factors relating to social support. 17 Several UK studies have confirmed that attitudes, perceptions and experiences of immediate family members and friends have a strong influence on breastfeeding. 18–22 Mothers benefit from being part of a supportive community of other mothers who breastfeed,23 and women who have friends who have breastfed are more likely to breastfeed their own baby. 1 On the other hand, negative or mixed messages from partners, family, friends and health-care professionals can be confusing and can undermine decisions to breastfeed. 14,22,24 New approaches to support women who are at the highest risk of not continuing breastfeeding are urgently needed. There is a need for interventions that make appropriate use of theory and take into account the circumstances of women who are least likely to continue breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding peer-support interventions

In her concept analysis of ‘peer-support’ interventions, as applied to a wide range of health topics, Dennis25 notes that peer-support interventions seek to extend ‘natural embedded social networks and complement professional health services’. Dennis25 defines peer support as ‘the provision of emotional, appraisal and motivational assistance by a created social network member who possesses experiential knowledge of a specific behaviour or stressor, and has similar characteristics to the target population’. The importance of ‘similar characteristics’ relates to the principle of homophily,26 a key underpinning idea for peer-support interventions. This is the principle that (health education) messages will be more credible and support offered more acceptable because the peer delivering the message and offering the support is perceived by the recipient as being in some way similar to him- or herself – someone who is experiencing or who has experienced the problem being addressed and who shares the same frame of reference in terms of wider social and cultural norms and values.

Breastfeeding peer-support (BFPS) interventions that have been subject to experimental study have paid varying levels of weight to the principle of homophily. Peer supporters tended to be women who had experience of breastfeeding, in some cases from a similar sociodemographic and cultural background to the women whom they were supporting. This principle is itself linked to social learning theory,26 the idea that individuals compare themselves with others who occupy a social role to which they aspire and posits that people learn from one another through mechanisms of observation, imitation and modelling. Compared with health-care professionals, peer supporters may be more approachable, provide role models that mothers can relate to and have direct experience of the challenges of breastfeeding within a social context where it may not be the norm.

A second key underpinning principle for BFPS is the theory of social support, used to explain the ways in which social networks help individuals to manage stressful events. Four types of social support have been distinguished:27 emotional support, instrumental support, informational support and appraisal support. Informational support involves advice and suggestions that can be used to solve problems. Emotional support comes from sharing life experiences and providing empathy, love and caring built on relationships of trust. Instrumental support consists of providing tangible aid and services. Appraisal support facilitates self-evaluation through constructive feedback, for example through motivational interviewing (MI). 28 Intervention theorists distinguish between perceived support (i.e. the mother knows the help is there if she needs it and that in itself helps her to get through a stressful experience) and received support (direct interaction with the peer). The perception that help will be available when needed may be an attribute of BFPS interventions. 29

Breastfeeding peer-support interventions exhibit considerable design heterogeneity. 30 In some cases, BFPS is integrated within an existing health-care system, with peer supporters working alongside/reporting to health-care professionals. In other cases, the support is developed by a third-sector agency and delivered in community settings. Help is sometimes provided on a one-to-one basis (mother to peer) and is sometimes delivered in group settings. Modes of delivery include face to face, over the telephone, by text and online (e-mail, social media, forums). Some interventions are proactive (the peer contacts the mother directly), whereas others are reactive (the mother asks for help). Proactive interventions vary in intensity (the number of contacts) and in the timing of delivery (antenatal or postnatal; starting within 24 hours of the birth or several days afterwards).

Experimental evidence for the effectiveness of BFPS provides an unclear picture. A Cochrane review of ‘additional support’ from lay and professional supporters found that additional help can have an impact on breastfeeding rates. 31 The reviewers concluded that help is more likely to be effective in areas with high initiation rates, that face-to-face interventions are more likely to succeed and that reactive support is unlikely to be effective. The authors also recommended that support should be delivered in a predictable manner and be tailored to the needs of the population group targeted. A systematic review of 11 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of antenatal BFPS found that targeted antenatal BFPS may lead to increases in breastfeeding initiation rates, whereas universal BFPS interventions tended not to be effective. 32

Another systematic review of RCTs looked at the impact of BFPS interventions on exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding continuation rates. 33 This review found these interventions to be effective in increasing breastfeeding maintenance in low- or middle-income countries, reducing the risk of not exclusively breastfeeding by up to 28%. However, the UK-based RCTs of BFPS interventions included in this review did not find increases in breastfeeding continuation rates,34–37 with no increase in breastfeeding maintenance at 8–10 weeks35,37 and 4 months. 36

Two quasi-experimental UK-based studies of BFPS have been published. The first, a community-based controlled trial of peer support delivered in a low-income area with very low breastfeeding rates (around 10%) resulted in no overall change in continuation rates at 6 weeks. 38 More recently, a time series analysis of a UK-based BFPS intervention delivered to a geographically defined population of adolescents found that, after adjusting for underlying trends, by the end of the study period, an additional 6.6 women in every 100 were initiating breastfeeding. 39

The UK-based interventions that have been studied were delivered as low-intensity interventions34,37,38 and several did not include an intended first contact with the mother in the days after the birth;34–36 in one UK-based study mothers were not contacted until their babies were around 3 months old. 36 In a UK context, this lack of early contact means that the intervention misses an important window, as breastfeeding discontinuation in the UK is highest during the early days and weeks after birth. 1 Four UK-based RCTs reported difficulty in achieving the intended number of contacts. 34,37–39

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a counselling approach that is designed to build a client’s confidence and motivation for change, with a focus on eliciting the client’s reasons for behaviour change. MI is a well-defined approach that could be used within the context of BFPS to help provide a clear model for BFPS provision. Miller and Rollnick28 developed MI to be less confrontational, authoritarian and directing than other counselling styles that were available in the 1980s. MI addresses the therapist’s ‘righting reflex’ wherein therapists have the desire to ‘fix’ what seems to be wrong and tell the client how to change. MI has been called a person-centred collaborative conversation,40 as it is designed to ‘strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion’ (p. 29). 28 It was initially developed to help people with addictions, but has since been used in many areas such as medication adherence, weight loss and dental health care. 41,42

Motivational interviewing has been demonstrated to be effective across many areas of health. There have been at least 12 systematic reviews that have found statistically significant effects of MI in relation to health outcomes41–52 and three RCTs53–55 examining MI and breastfeeding support. A health educator,53 a research nurse54 and a practice nurse55 delivered the MI in the RCTs. Two of these RCTs53,54 found no significant effect of MI. The other RCT55 found statistically significant effects of MI on breastfeeding status at 2 and 4 months but not at 6 months post birth. In all three RCTs, it was difficult to disentangle the effects of MI from the other aspects of the intervention. Two of the interventions were MI-based interventions, in which only elements of MI were delivered. 53,55 None of the RCTs was based in the UK. It is possible that MI has a role in helping women to continue breastfeeding by increasing their intrinsic motivation to breastfeed, but there is limited evidence available on the effectiveness of MI in this context. The feasibility and acceptability of using a MI-based approach within a BFPS intervention has not been investigated.

The behaviour change wheel

Developing a complex intervention that utilises both peer support and MI-based techniques to support breastfeeding continuation requires integration of the MI and peer-support approaches, identification of potential mechanisms and consideration of how the intervention could be implemented. The behaviour change wheel (BCW) provides a unified and systematic framework for developing and characterising complex behaviour change interventions. 56 The BCW outlines a process for working out what needs to change (sources of behaviour), how to change it (intervention functions and behaviour change techniques) and how the intervention can be implemented (mode of delivery). 56 Within the BCW framework, the capability opportunity motivation – behaviour (COM-B) model helps to explain how interactions between people’s physical and psychological capability (C), social and physical opportunity (O) and automatic and reflective motivation (M) can influence behaviour (B). 57 The BCW uses the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy v1 (BCTTv1)58 to identify and classify the content of behaviour change interventions. The affordability, practicability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, acceptability, side effects and safety and equity (APEASE) criteria are used within the BCW process as a control point to consider the feasibility of an intervention. 56 The BCW process would therefore provide a unified framework for developing and characterising a MI-based BFPS intervention that could both guide its design and categorise the behaviour change techniques included in the intervention. This would provide a much greater understanding of the potential mechanisms of the intervention, which would facilitate future evaluation, refinement and replication of the intervention.

Mam-Kind: a UK feasibility study

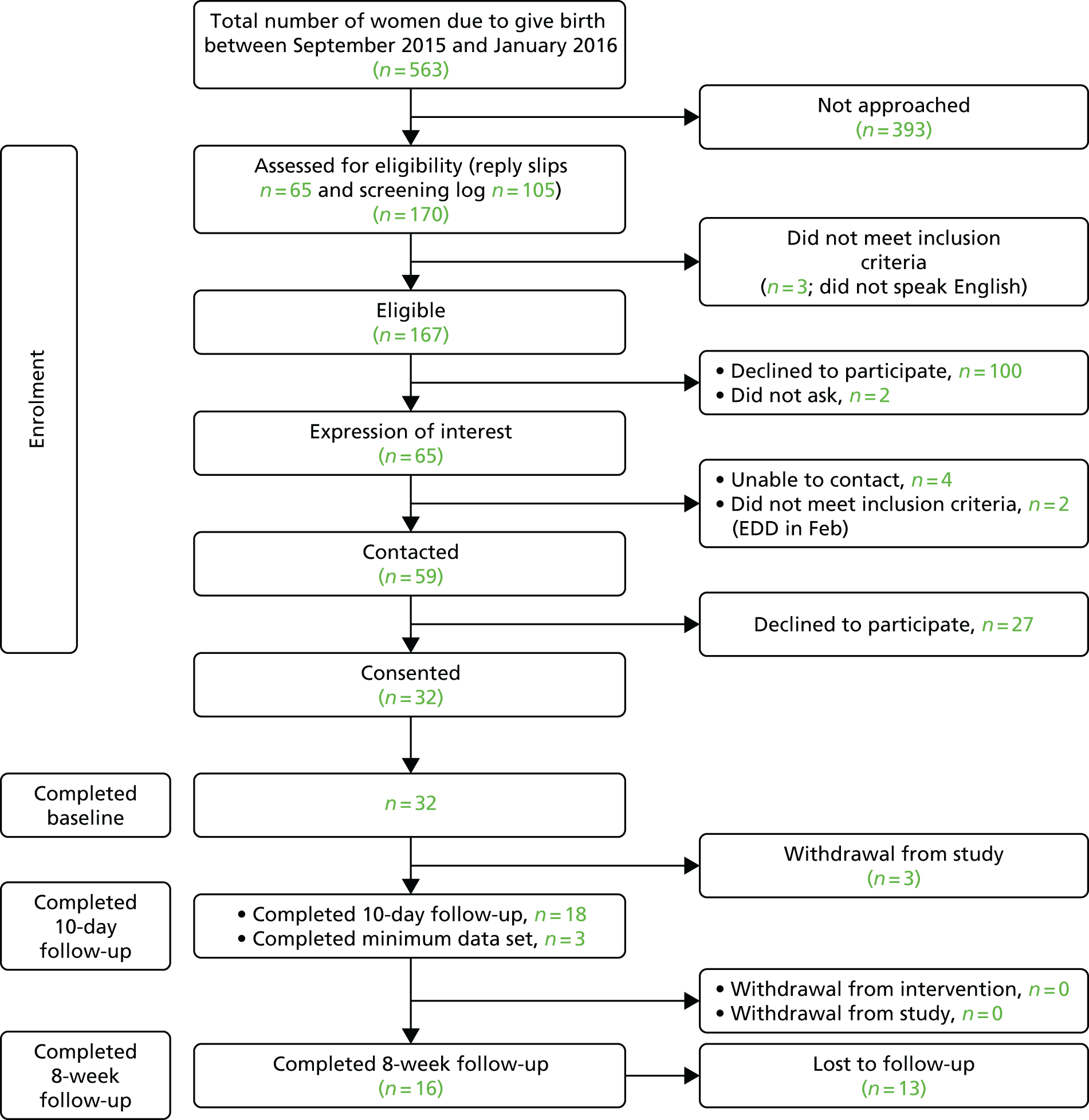

The National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme called for primary research in the form of a feasibility study to answer the following research question: ‘Can peer support for breastfeeding in the UK contribute to the maintenance of breastfeeding, particularly in groups of the population who are less likely to breastfeed?’.

This study aimed to develop and test the feasibility and acceptability of delivering a BFPS programme using a MI approach. The target population was women living in areas with lower than average breastfeeding initiation rates and high levels of social deprivation, who have expressed an interest in breastfeeding. We identified the key feasibility questions to be addressed prior to a full trial (outlined below) and designed our study to address these.

Although BFPS is recommended as part of the strategy for increasing breastfeeding rates in the UK, current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance does not specify how this should be provided, resulting in a variety of models being used across the UK. We therefore planned a rapid evidence review to understand how BFPS is currently provided in the UK and identify any underpinning theoretical models, elements of best practice and facilitators of, and barriers to, implementation of the service within a NHS or community setting. These data would also allow us to contextualise usual care across the UK and inform the care pathway in the control group of a full trial.

We planned to carry out qualitative research in the form of focus groups and interviews with pregnant women, mothers, fathers, peer supporters and health-care professionals to inform the intervention content and design and develop a training module that was specific to the intervention being developed.

Four UK RCTs,34–37 both individual and cluster randomised trials, had already demonstrated that it was feasible and acceptable to randomise pregnant women in the antenatal period to receive either BFPS or usual care. Two RCTs that randomised individuals recruited 70%35 and 82%34 of their intended sample size and cited difficulties in recruitment resulting from resource constraints. We therefore planned to use the qualitative work in the developmental phase of our study to explore the challenges to recruitment, investigate specific barriers to participation and develop strategies for recruitment and consent. Our approach was based on the work by the Bristol Medical Research Council (MRC) ConDuCT (Collaboration and innovation in Difficult and Complex randomised controlled Trials In Invasive procedures) methods hub,59 which demonstrated the utility of qualitative work for developing and testing optimal strategies for recruitment during the feasibility stage of trials to improve recruitment.

The previous UK RCTs of BFPS34–37 also highlighted the uptake of, and adherence to, the intervention as possible reasons for non-effectiveness. We therefore included a process evaluation in the design of this feasibility study, to include an assessment of the extent to which the MI-based BFPS intervention that we developed can be delivered as intended to the target population. We planned to test the feasibility of the MI-based BFPS intervention in three community maternity sites that had high levels of social deprivation [most deprived quintile of the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD)60 and below UK average rate of breastfeeding initiation (< 70%)]. We were specifically interested in establishing the feasibility and acceptability of:

-

recruiting and retaining peer supporters from the community of women to whom MI-based BFPS is to be delivered

-

delivering MI-based BFPS as specified, including an assessment of the extent to which peer supporters utilised MI techniques in their interactions with the mothers they were supporting

-

the recruitment, data collection and follow-up strategies (for clinical outcome measures and resource usage and costs) and study materials.

A summary of the study aims and objectives are provided in Box 1. We intended to use the results from objectives 1–5 to inform the optimal strategy for recruitment, consent timing and approach and data collection in a full trial. Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the different components of this study.

-

Develop a novel BFPS intervention for breastfeeding maintenance based on MI.

-

Test the feasibility of delivering MI-based BFPS to mothers living in areas with high levels of social deprivation.

-

Establish the necessary parameters to inform a possible full trial to test the effectiveness of MI-based BFPS for breastfeeding maintenance.

-

Identify, categorise and describe the range of BFPS interventions in the UK.

-

Develop MI-based BFPS programme content and identify the requirements for implementation using a user-informed approach, guided by the BCW framework.

-

Finalise the specification of MI-based BFPS (using the BCTTv1 to categorise behaviour change techniques) and the corresponding logic model with stakeholders.

-

Assess the feasibility and acceptability of providing MI-based BFPS to women living in areas with high levels of social deprivation.

-

Assess the feasibility of collecting resource usage and costs associated with the implementation of the Mam-Kind intervention.

-

Use the findings from objectives 1–5 to make recommendations about the need for and design of a full RCT to test the effectiveness of MI-based BFPS for breastfeeding maintenance compared with usual care.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the Mam-Kind study.

Chapter 2 Availability and range of breastfeeding peer-support interventions in the UK: a cross-sectional survey of infant feeding co-ordinators

In this chapter we address the first study objective, which was to identify, categorise and describe the range of BFPS interventions used in the UK.

Introduction

Peer support was recommended by NICE61 as part of the strategy to increase breastfeeding in the UK. Current NICE guidance on the commissioning of BFPS in England does not specify the theoretical basis, critical components or optimal delivery mode of BFPS. 62 This has resulted in a wide variety of models being used in current practice. 63,64 We wanted to explore the range of BFPS interventions that were currently available to identify lessons from current practice that could be used to inform intervention development. We carried out a survey of infant feeding co-ordinators (IFCs) in the four UK nations to map the current provision of BFPS and obtain an understanding of what peer-support services consist of and how these are provided. In addition to informing intervention development, these data would provide an understanding of ‘usual care’ to inform the planning of a future effectiveness trial, if warranted.

Method

Survey development and piloting

We adapted a previous survey of IFCs carried out in the seven health boards in Wales. 63 We invited three IFCs who worked outside Wales to pilot the adapted questionnaire and provide feedback to us on the acceptability and clarity of the questions. All three agreed to take part; they were sent the link to the questionnaire and provided verbal feedback to a member of the study team. This pilot work identified the need to update the list of potential employers in England to take account of recent changes affecting service commissioners and providers following public health’s move from the NHS to local government in April 2013. We amended the participant information, first, to highlight the ways in which the data collected would be used and, second, to inform respondents of the need to access reports and statistics relating to their service to fully complete the survey. As all questions remained the same, we included the data obtained in the pilot phase in the main analysis.

Sample

Infant feeding co-ordinators from the UK were invited to take part in the online survey or to pass the details on how to access the survey to a colleague if they did not feel that they had the appropriate knowledge to complete the survey themselves. We raised awareness of the survey at the annual UNICEF BFI conference (Newcastle upon Tyne, 27 November 2014), which is the annual professional meeting for UK IFCs. An e-mail invitation to complete the survey was circulated to those listed on four national e-mail distribution lists in December 2014: (1) the National Infant Feeding Network (serving England), (2) the Scottish Infant Feeding Advisors Network, (3) the All Wales IFC Forum and (4) the Northern Ireland Breastfeeding Coordinators Forum (total n = 696 individuals within 177 NHS trusts). We believe that these distribution lists included all individuals who undertook an IFC role in the UK, and also included some other health-care professionals and academics with an interest in infant feeding. Follow-up e-mails were sent to members of all four networks 1 week later, and a final reminder was circulated 12 days after the initial invitation.

Questionnaire and data collection

Participants completed a questionnaire consisting of a combination of closed- and open-text questions. The questions examined the way in which BFPS was organised in the geographical area for which participants had responsibility, with a focus on breastfeeding groups and other activities that breastfeeding peer supporters were engaged in (Table 1). For the majority of questions, participants were asked to describe their service using closed responses or to rate how well they perceived their service to be doing on a six-point Likert scale. Participants were then asked to provide more detail regarding why they answered in that way using open-text boxes. All data collection took place using a purpose-built web-based survey hosted on a secure server at the Centre for Trials Research, Cardiff University.

| Theme | Subquestion topics |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Nation; NHS trust; annual number of births in area; staff roles in relation to breastfeeding; IFC role descriptiona |

| Breastfeeding support groups | Number of groups; who organises groups; presence of records on attendance, support provided, problems with feeding, referrals, other records;a other thoughts on support groups;a funding for non-NHS breastfeeding groupsa |

| Training peer supporters | Number of trained peer supporters; what training is provided; who delivers training;a additional training for peer supportersa |

| Peer support | Recruitment of new peer supporters; supervision; activities that peer supporters are engaged in; integration of peer support with NHS services;a accessibility of peer support for mothers from poorer backgrounds;a other thoughts on peer supporta |

| Other non-NHS support for breastfeeding | Details of support available; provider of support; third-sector activities; presence of active breastfeeding counsellors |

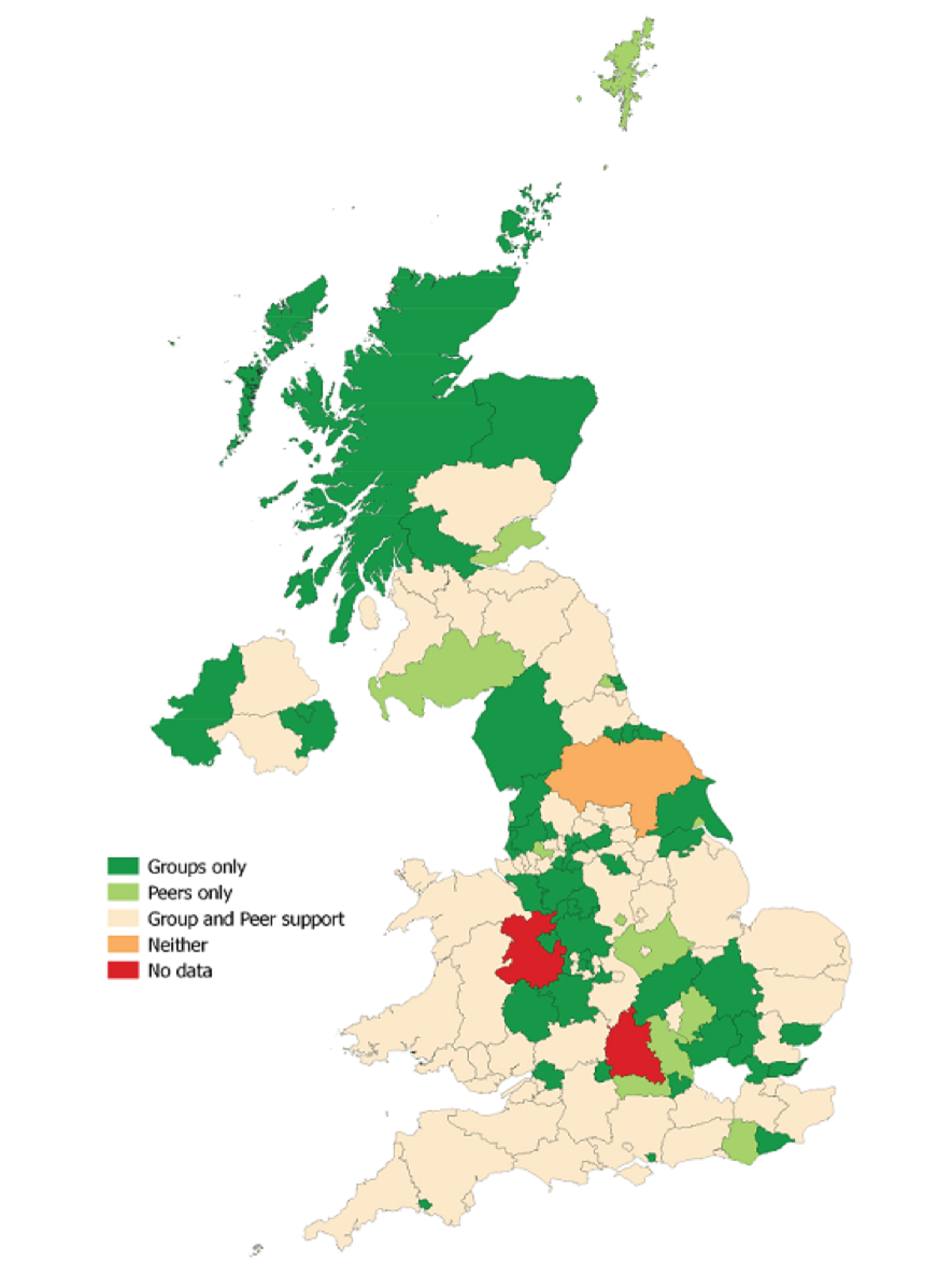

We searched the internet for breastfeeding services in all NHS trusts and health boards (n = 177) to obtain data for the 75 sites for which we did not receive a survey response. We validated the information from sites that responded to the survey and found that the two sources of information were consistent, making it feasible to combine these data. In this report, we present a map of the provision of BFPS and breastfeeding support groups in the UK using data from both of these sources (see Figure 2). There were no material differences in the maps produced using the two sources of data.

Data analysis

We adopted a mixed-methods analysis strategy. Descriptive statistics summarising responses were generated from closed questions using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Open-text responses were thematically coded by one researcher facilitated by NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Individual case studies that illustrated barriers to, and facilitators of, successful delivery were extracted and discussed, but these are not reported here, to maintain anonymity. Themes were developed from responses within each question domain (such as barriers to, and facilitators of, training peer supporters) and across domains throughout the data set (e.g. financial issues, staffing levels). We used inductive thematic analysis to understand responses. 65 Open-text responses were interpreted alongside Likert scale scores when appropriate.

Ethics issues

We received confirmation from the chair of the NHS Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) 3 that this survey constituted an audit of current service provision of BFPS and did not require ethics approval. Participants were provided with an information sheet and consented to take part in the survey via the web-based platform prior to completing the survey. All responses were anonymised.

Results

The following sections provide an overview of respondents’ characteristics, followed by the survey results in relation to six key themes: (1) recruitment, training and support for breastfeeding peer supporters, (2) peer-supporter roles, (3) descriptions of the management and implementation of breastfeeding groups, (4) the interaction between BFPS and health-care professionals, (5) the accessibility of BFPS and (6) resource and financial considerations.

Respondents

A total of 136 individual responses with usable data were received (response rate 19.5%), representing 58% of NHS trust/health board areas (Table 2). Within the 136 responses, there were multiple responses (total n = 34) from 21 NHS trust/health board areas. Seven of these were instances in which provision in England was split between the NHS trust and another provider, such as the local authority. We retained all individual responses in the analysis because the multiple responses from NHS trust/health board areas provided different information in response to open-text questions.

| Response | Location, n (%) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | Scotland | Wales | Northern Ireland | ||

| Individual responses | |||||

| Individual invitations | 617 | 40 | 19 | 20 | 696 |

| Individual responses | 113 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 136 |

| NHS trust/health board coverage | |||||

| NHS trusts/health boards | 151 | 14 | 7 | 5 | 177 |

| Total response within NHS trust/health board areas | 84 (56)a | 9 (64) | 7 (100) | 2 (40) | 102 (58) |

Breastfeeding peer support was available in 80 (78%) NHS trust/health board areas and breastfeeding support groups were available in 92 (90%) NHS trust/health board areas of the UK for which we had survey data. These data should be interpreted with caution, as we attributed individual responses to NHS trusts and, for larger trusts, these responses may not be representative of the whole catchment area. Neither BFPS nor breastfeeding support groups were available in 10% (n = 10) of the areas for which we had survey data. About half of the survey respondents reported that there were breastfeeding groups in their NHS/health board area that were funded by local authority or non-NHS organisations (n = 62, 54%) and that there were breastfeeding counsellors working in the area who regularly received referrals from health-care professionals (n = 31, 46%).

In total, 62% of the survey respondents (n = 66) reported that there had been a review, evaluation or report of the breastfeeding support service in their NHS trust/health board area. We requested copies of evaluations and received six reports from two respondents and written descriptions of evaluations from two further respondents. These reports were aimed at evaluating service development, such as breast pump loans and attempting to standardise delivery of breastfeeding support within an area, as opposed to evaluating the effectiveness of BFPS.

We searched the internet for information on the availability of BFPS services in the 81 (46%) NHS trusts that did not provide data on breastfeeding support (either because there was no response to the survey or no data were provided in response to the question). In total, 58% (n = 47) of these non-responder trusts provided breastfeeding support groups, 15% (n = 12) provided a one-to-one peer-supporter service, 24% (n = 20) provided both groups and a one-to-one peer-supporter service and 3% (n = 2) provided neither.

Combining the results from the survey and online search, 40% (n = 71) of NHS trusts provided breastfeeding support groups, 7% (n = 13) provided a peer-supporter service, 49% (n = 86) provided both groups and a peer-supporter service and 3% (n = 5) provided neither. Data were unobtainable for two NHS trusts (1%).

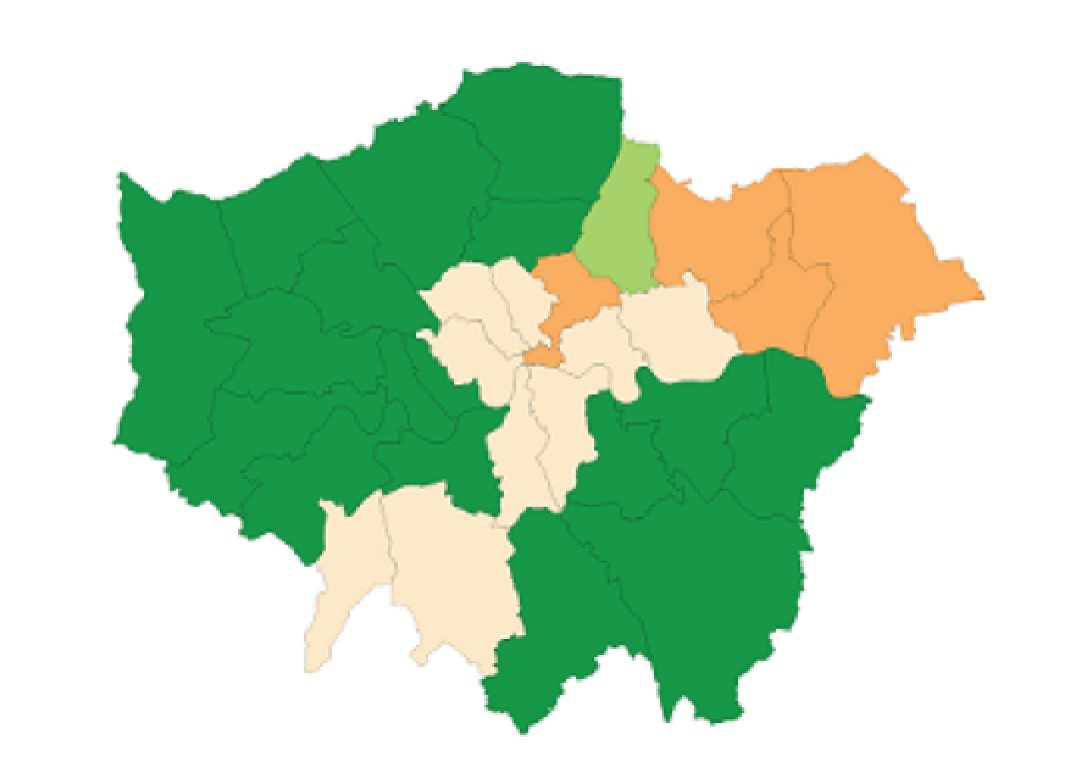

Figure 2 illustrates the areas in which breastfeeding support (groups, peer support, both groups and peer support or neither groups nor peer support) was provided throughout the UK, with Figure 3 providing a detailed map of London. It should be noted that these data indicate which services were available in any given region, but do not provide information on service coverage within the region, accessibility or uptake.

FIGURE 2.

The provision of BFPS and breastfeeding support groups in the UK.

FIGURE 3.

The provision of BFPS and breastfeeding support groups in the London region.

The visual representation uses current health board boundaries in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. We were unable to produce a map for England using current health board boundaries and, therefore, we used primary care trust boundaries as a proxy, as these were most closely matched. However, some NHS trusts in England covered multiple geographical areas and, in these cases, all areas of the map have been coloured. Service coverage may vary within these boundaries, as some participants reported variation within the areas they managed in open-text responses and it was not possible to tease out the exact coverage from the available data.

Recruitment, training and support for breastfeeding peer supporters

The survey responses indicated that IFCs, who were employed by the NHS, were most often involved in managing peer supporters, although, in some cases, this was reported to be a shared responsibility between staff from the NHS, local authority staff and third-sector staff.

There was a multipronged approach to the recruitment of peer supporters (using multiple sources such as breastfeeding groups, midwives, health visitors, children’s centre staff and peer supporters), with 26 out of 103 (25%) respondents selecting all five responses available and only 11 out of 103 (11%) respondents selecting a single recruitment approach. Other methods used to recruit participants included external advertisements, which were disseminated via social media, traditional media and volunteering forums.

The median number of peer supporters who had been provided with initial training over the previous 12-month period in each area was 15 (range of 0–64). Participants were asked to describe in an open-text box who provided the training. The third sector was the most common provider for the initial training of peer supporters [including the Breastfeeding Network (BfN) and the National Childbirth Trust (NCT)], with IFCs and NHS and community centre staff also playing a key role. Initial training varied in duration and some included the potential for participants to gain qualifications. Some respondents (n = 45) provided further details about the initial training that was provided to peer supporters. This included examples of highly structured and comprehensive training in some areas, to less structured examples or no training provided in other areas. Based on the information in the survey responses, we developed a framework to illustrate the range of training approaches that were in use (Table 3).

| Framework | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| Highly structured and comprehensive | Less structured or comprehensive | |

| Availability | Available to all peer supporters | Available to selected peer supporters (e.g. regular group attendees) |

| Integration with health-care professionals | Joint training with health-care professionals | Available only to peer supporters |

| Content | Infant feeding plus additional professional training (e.g. confidentiality, child protection, setting boundaries, public health) | Infant feeding only |

| Formal qualifications from peer-support training | Available | Not available |

| Duration | Training plus ongoing support | Training with no ongoing support |

Training and/or ongoing support in addition to the initial training was provided in 70 of the 107 (65%) areas for which we had data and, in two-thirds of these areas (63%, n = 44), more than one type of support was provided. This was commonly in the form of regular local training (n = 69, 64%). In 13 of the areas, peer supporters were able to access BFI training. Other types of training included safeguarding (n = 15), joint training with NHS staff (n = 13), mandatory NHS staff training and local service updates. The extent to which training was mandated or optional varied between areas.

Peer supporters’ roles

Attending breastfeeding groups was the main activity that peer supporters were involved in, followed by working on the postnatal ward (Figure 4). In general, delivery seemed to be more focused on group support, with one-to-one forms of delivery being less common. Most peer supporters saw mothers in both the antenatal and postnatal periods (50% of survey responses, n = 68), but some saw mothers only in the postnatal period (29%, n = 39). The comprehensiveness of services was described through open-text responses, with some areas viewed as having a complete model of service delivery:

The Peer-support Service is a 7 days service 356 days of the year. Team of 10 members, total 7.5 whole time equivalent from 9–5 man a 24 telephone support line. The Service is integrated into [child health care], works alongside Health Visitors, School Nurses, and support staff. The service delivers Health Promotion sessions within Primary schools, they provide bedside support within the three feeder hospitals, provide support groups with Children’s Centre Groups. It is an excellent service provided by a dedicated team.

FIGURE 4.

What activities are peer supporters in your area engaged in?

In contrast, other areas indicated that they were not currently resourced to provide a comprehensive service:

I have one breastfeeding support worker who is employed by [the NHS], this isn’t enough for a birth rate of 2500. We are currently writing a business case for 10 × paid peer-support workers.

Breastfeeding support groups

It was most commonly reported that > 10 groups were running within individual areas (Figure 5). Respondents stated that NHS staff, children’s centre staff and trained peer supporters most commonly organised breastfeeding support groups. Alongside this, it was noted in open-text responses that coverage of breastfeeding support groups was not uniform throughout NHS trust areas and that this was not necessarily related to the numbers of births. Respondents also noted within the open-text boxes that group sessions took place in a broad range of settings, including community venues (café, garden centre café) and children’s centres, and alongside health visitor (weighing) clinics. Some groups ran as ‘baby cafes’, ‘first friends’ or generic ‘parenting support groups’ with a focus on breastfeeding, rather than explicitly as breastfeeding support groups. In response to questions about record-keeping in the groups, less than one-third of survey respondents reported that notes were kept on individual mothers who received support (n = 31, 26%), mothers who have problems (n = 34, 29%) and referrals for additional support (n = 32, 27%).

FIGURE 5.

If you have peer-support groups, how many groups are currently running?

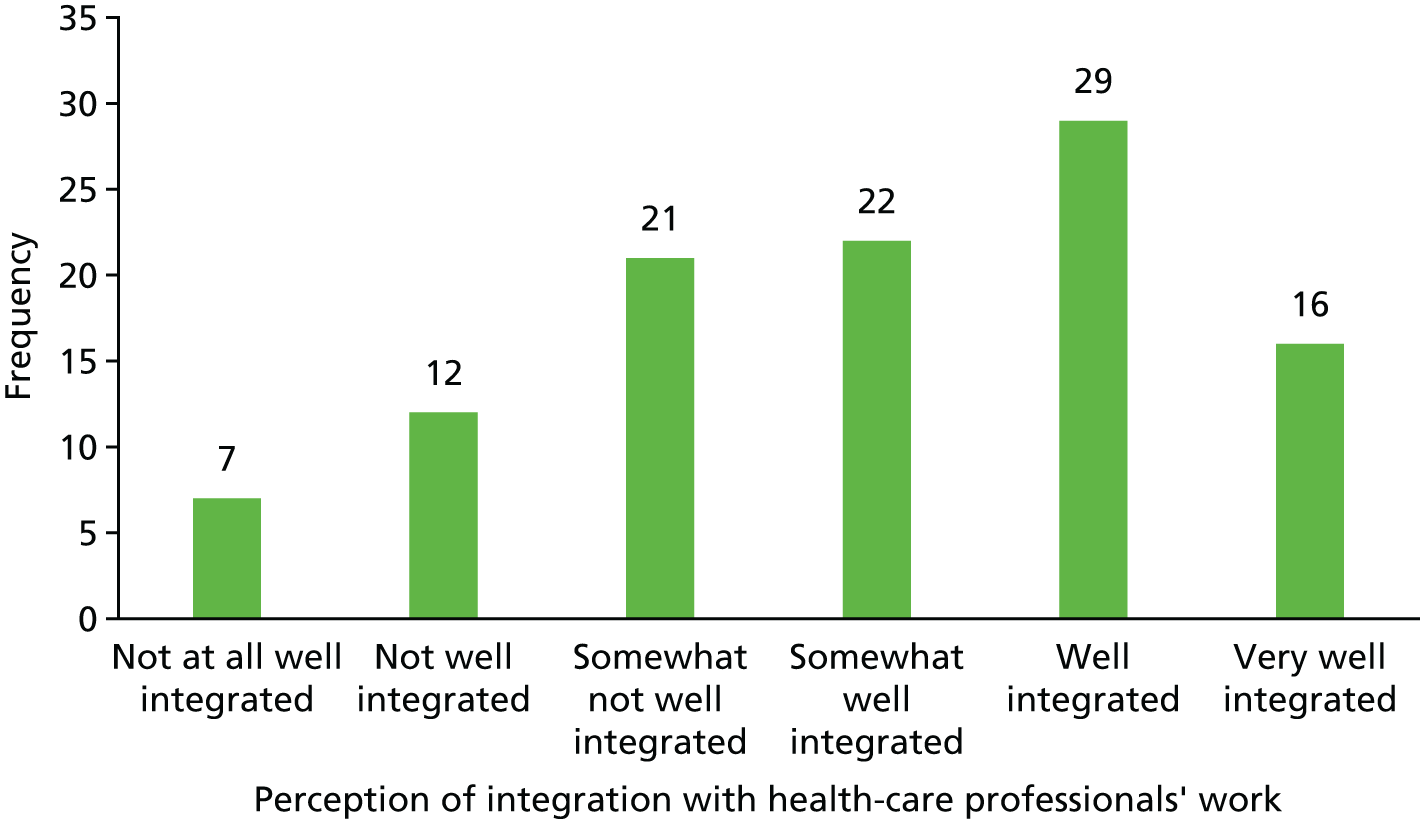

Interaction between breastfeeding peer support and health-care professionals

The majority of participants (63%, n = 67) felt that peer support was well integrated with other NHS services (Figure 6). Alongside the closed question, which asked participants to describe how well they thought peer support was integrated with other health services, respondents were asked to explain their answer. The majority of open-text comments were consistent with respondents’ answers on the six-point Likert scale. Participants described a range of factors that were responsible for integration, including:

-

guidance on peer-supporters’ roles, with clear responsibilities (n = 15)

-

visibility to health-care professionals, such as working on postnatal wards or other shared working practices (n = 14)

-

peer support being trusted and valued by local health-care professionals (n = 9), including as a result of an evaluation or feedback from parents (n = 3)

-

a health-care professional acting as a ‘champion’ and communicating the value of peer supporters to other health-care professionals (n = 5).

FIGURE 6.

Do you think that BFPS provided in your area is well integrated with the breastfeeding support work that health-care professionals do?

In areas with less integration, the converse occurred: staff did not understand the peer-supporter role and did not feel that peer supporters were suitably qualified and, as such, there was a lack of trust, resulting in a lack of referrals from health-care professionals to peer supporters.

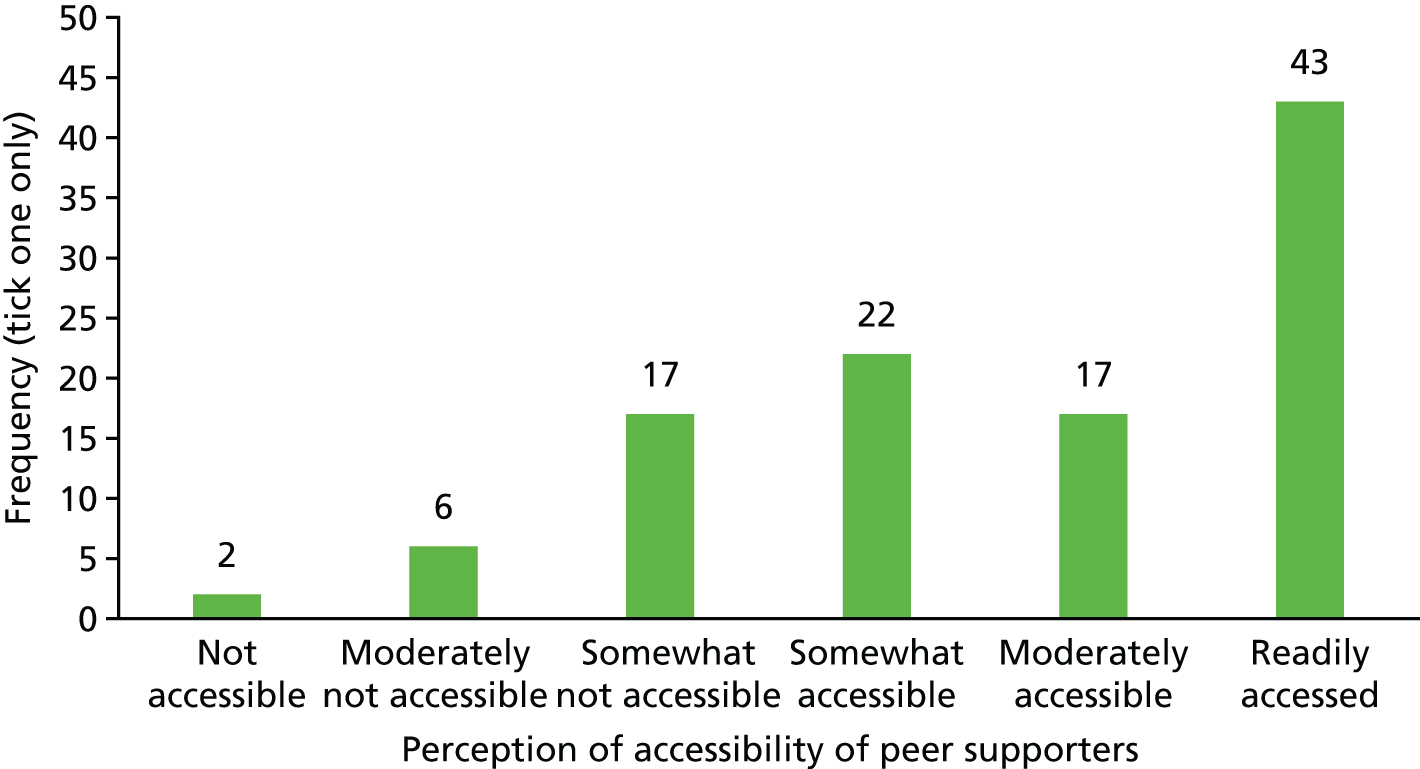

Accessibility of breastfeeding peer support

In response to the question about how accessible peer support was to mothers from poorer social backgrounds, 24% (n = 25) of respondents used the three negative options (not/moderately, not/somewhat, not accessible) (Figure 7). However, some responses did not corroborate with the additional open text provided, suggesting that some respondents may have unintentionally ticked the wrong box. An example of this was a response that indicated an accessible service on the Likert scale, but conversely stated that ‘the most vulnerable and poorer mothers may be “put off” from attending groups as the groups are seen to have women in a slightly higher social class than themselves’.

FIGURE 7.

Is the BFPS provided in your area accessible to breastfeeding mothers from poorer social backgrounds?

However, this could also mean that, although access is good overall, there are certain aspects of the service that could be improved. When asked to explain the rationale for their responses to the above question, participants suggested that services were working well when they:

-

were held in areas of high deprivation, and worked with providers who aimed to support women in areas of high deprivation and used informal conversations in areas with low levels of breastfeeding (school gates, social media)

-

were well accessed by mothers living in deprived areas (some responders had data to show this and, when there were no data, this was supported by the breastfeeding co-ordinators’ impressions)

-

recruited peers from areas of deprivation and provided proactive contact.

Barriers to accessibility included:

-

attracting women from deprived areas to breastfeeding support groups

-

inadequate numbers of peer supporters

-

being reactive as opposed to proactive

-

not being able to provide home visits.

Resource and financial issues

One of the main themes interwoven throughout the open-text responses was financial support for community breastfeeding services. This was often referred to as a problematic issue throughout the data, with some services continuing to face a reduction in available funding. Some respondents from England noted that their services had previously been funded through NHS community budgets and that NHS hospital budgets were not continuing to fund peer-support services following the move of public health from the NHS to local government in England. The reported shortfall affected finances to train peer supporters and pay travel expenses and health-care professional time for the supervision of peer supporters. In a small number of cases it was reported that BFPS services had been decommissioned. In a minority of areas, respondents reported that peer supporters were paid for their time, but, in most services, funds were not available for this. Several respondents noted that they were attempting to secure funding from charitable trusts or their own employers by writing business cases, and this was often to provide a basic service (supervisor time, travel expenses for peer supporters) rather than to pay for peer-supporters’ time. In contrast, in some areas, investment was being made in peer-supporter co-ordinator roles.

Discussion

Peer support for breastfeeding is recommended as part of a strategy to address low breastfeeding rates in the UK. 62 Within this context, our UK-wide survey of 136 UK-based IFCs found wide variation in service provision. As in previous studies,63,66,67 we found that there was wide availability of peer supporters across the country, both within and between NHS trust/health board areas. A key finding from our survey was that there was no standardised provision of BFPS in the UK. Services were regularly adapted in response to unstable financial circumstances, with services being reduced or increased in line with the funding available. None of the models that were implemented at the time of this survey had been robustly evaluated for effectiveness.

This survey has provided information about how peer support for breastfeeding is provided in the UK and identified some of the facilitators of, and barriers to, the delivery of peer-support services, which were further explored in our qualitative research and through discussions with the Stakeholder Advisory Group (see Chapter 3). A clear tension was reported in some areas between BFPS and health-care professionals, and this may be related to a lack of clear guidance regarding roles and responsibilities and a lack of visibility of BFPS to health-care professionals. We explored this further in our discussions with the Stakeholder Advisory Group and in qualitative work with health-care providers to ensure that the local health service context was considered in planning for intervention delivery in the feasibility sites (see Chapter 3). Accessibility to parents from poorer backgrounds was noted as a challenge. Services that considered themselves to be accessible to poorer mothers noted elements of good practice, including being held in areas of deprivation, working in partnership with organisations who support women from deprived areas and the use of informal conversations with peers.

A further issue was that, in many sites, the current level of support provided was not regularly documented or evaluated. Two-thirds of participants reported that registers of attendees were kept in their area, but details of any support provided or signposting to additional services were rarely kept. Documentation and record-keeping are important to enable evaluation in the context of a research study. This highlights the importance of engaging with peer supporters during the development phase of the study to explore the options for data collection to capture reliable information.

The most common theme found in the open-text responses was the challenge of running services with limited financial support, although this was not experienced equally by all services, with a minority of services reporting recent investment. Linked to this financial shortfall, some services reported the challenges of recruiting, training and providing ongoing supervision for peer supporters, with one-third of participants reporting no ongoing training and support in their area. Understanding this variation will enable the selection of sites in which a future RCT could be undertaken and may influence the extent to which sites are able to fully roll out an intervention.

The majority of survey respondents indicated that there had been a review or evaluation of BFPS in their NHS trust/health board area over the last 5 years; however, to our knowledge, these were service evaluations to inform service provision rather than formal assessments of efficacy or effectiveness.

This study is the first attempt to map and describe the provision of peer support for breastfeeding throughout all four nations of the UK. We received responses from around the UK and achieved a response rate that covered 58% of NHS trusts/health board areas. We searched the internet to obtain information about the availability of BFPS in the NHS trust/health board areas for which there were no survey data available to describe the current provision. We checked the consistency of the data provided in survey responses and those obtained from the internet and were satisfied that these two sources of information were compatible. The survey was open for a period of 3 weeks in December 2014, and it may be that we would have received further responses if the survey had been kept open for a longer period. We were also made aware that two participants were unable to access our online survey from their NHS computers. Although we provided support that enabled those participants to take part, it may be that other potential participants did not contact us and were thus unable to access the survey. The response rate to the survey was low. We did not receive a response from 42% of the NHS trust/health board areas, and, although we were able to obtain internet information on the types of BFPS available, we were unable to understand how these services were run and any potential facilitators or barriers in these areas. We mapped the data on BFPS availability to NHS trust and health board areas and, in doing so, we have had to assume that the responses for each health-care area were applicable across the board. This may not be the case for larger NHS trusts, in which the availability of services may vary greatly; however, our survey was not sensitive enough to capture availability at smaller geographical levels. Further information on the availability and accessibility of BFPS could potentially have been obtained through direct contact with NHS trust/local authorities and third-sector organisations, but we did not have the resources to do this within the scope of this study.

Chapter 3 Development of a novel motivational interviewing-based breastfeeding peer-support intervention to support breastfeeding maintenance

This chapter addresses study objective 2, to develop MI-based BFPS programme content and identify the requirements for implementation, and study objective 3, to finalise the specification of MI-based BFPS and the corresponding logic model with stakeholders.

Introduction

The theoretical basis of BFPS and its active behaviour change components have not been well described or characterised, so there is currently limited understanding of what components are required for an effective BFPS intervention. Motivation, self-efficacy, affective attitudes, social norms and strong beliefs that breastfeeding is the normal and healthiest way to feed an infant are associated with continuation of breastfeeding. 10,11,18,68 Applying the theory of constraints thinking to breastfeeding problems, Trickey and Newburn7 found that support should be proactive and mother centred, consistent with the data from our survey of IFCs. It is therefore important to address the ‘why’ (motivation) and ‘how’ (confidence, skills, resources) of breastfeeding maintenance in this context.

Framework for intervention development

The BCW57 provided a framework for identifying the behaviours to be addressed, the required functions of the MI-based BFPS intervention and the relevant service requirements. 56 We utilised the COM-B theoretical model, which hypothesises that interactions between people’s physical and psychological capability (C), social and physical opportunity (O) and automatic and reflective motivation (M) can be used to understand what needs to change to achieve the desired behaviour change (B). 57

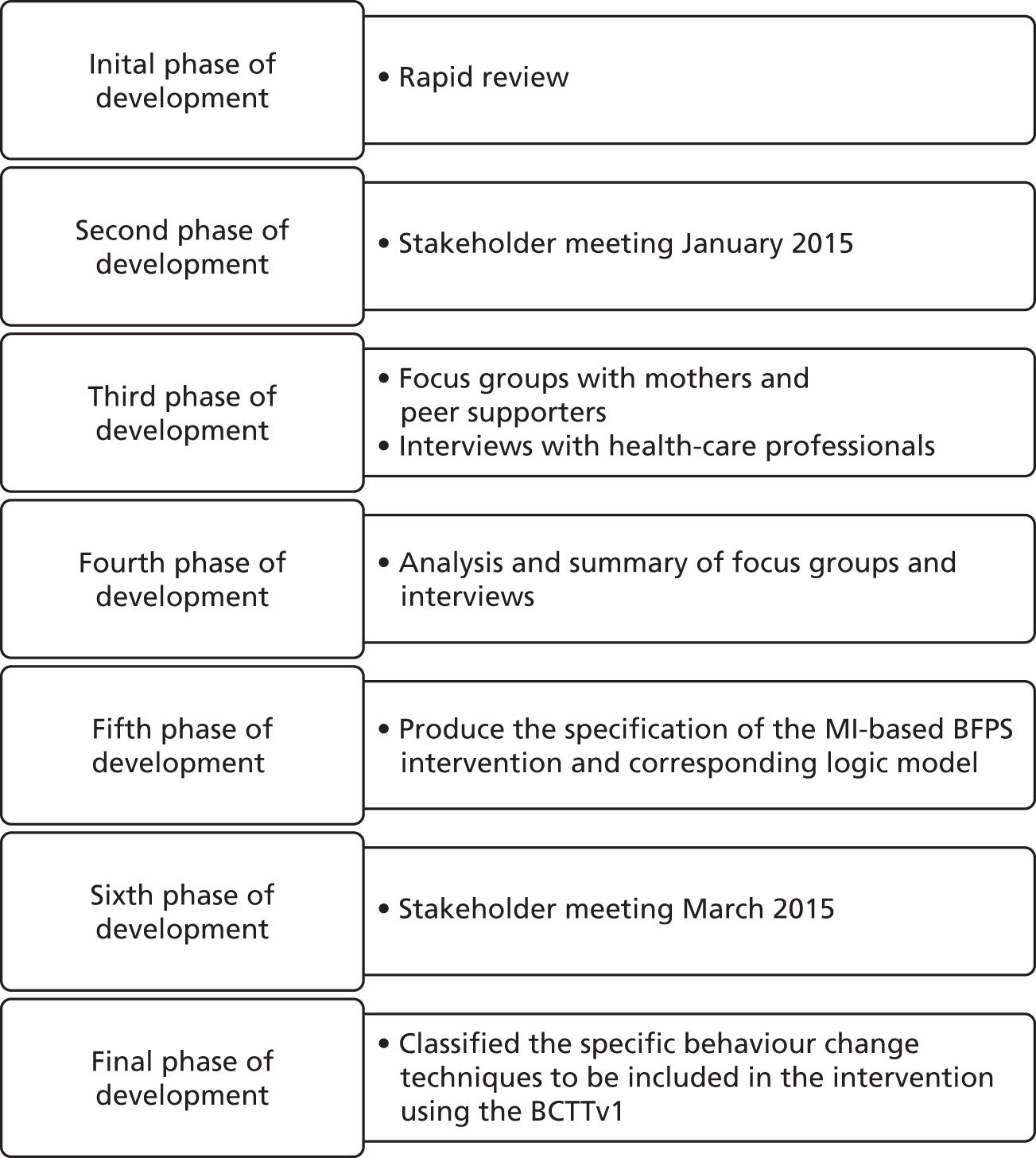

We used a flexible iterative process to develop this intervention, which is summarised in Figure 8. We used the survey findings reported in Chapter 2, a rapid literature review and qualitative research to identify the behaviours associated with breastfeeding to be addressed by the intervention and the underpinning theoretical models and design factors that influenced the delivery of the BFPS intervention. We aimed to explore parental, health-care professionals’ and peer-supporters’ views of what the features of a feasible, acceptable and effective BFPS intervention would be. We examined their perceived barriers to, and facilitators of, breastfeeding that a BFPS intervention would be able to address, what current peer support is like and what it should be like. We clarified the sources of behaviour to be addressed by the intervention through discussion with the Stakeholder Advisory Group, informed by the findings from the rapid evidence review and qualitative research, and categorised these according to the COM-B model. This enabled us to follow up on issues identified in the survey and literature review in more depth and explore issues directly relevant to the design of a MI-based BFPS intervention and define its function, content and mode of delivery.

FIGURE 8.

Development process.

Integrating the motivational interviewing approach with breastfeeding peer support

We proposed to develop a BFPS intervention that uses a MI approach. Self-determination theory (SDT) has been proposed as an explanatory theory for MI. 69,70 SDT is a theory about a person’s self-motivation to change behaviour. It shares a common principle with MI that ‘people have an innate organisational tendency toward growth, integration of the self and the resolution of psychological inconsistency’. 69 SDT seeks to explain what drives human behaviour and places motivation on a continuum of autonomy ranging from external regulation (no autonomy) to intrinsic regulation (full autonomy). By examining people’s different motivations for achieving goals, for example pleasure compared with obligation,71 SDT identifies three elements that are critical to support the process of changing motivation from external to intrinsic: competence support, autonomy support and relatedness. MI provides support for each of the psychological needs that are identified by SDT. 72

Motivational interviewing involves four key processes: engaging [establishing a ‘mutually trusting and respectful helping relationship to collaborate toward agreed-upon goals’ (p. 3)73], evoking (eliciting the client’s own motivation for a particular change), focusing (clarifying a particular goal or direction for change)73 and planning (developing a specific change plan that the client is willing to implement). 28 These processes are sequential and recursive and are used throughout the MI session. 28 A MI practitioner aims to clarify and resolve a client’s ambivalence about choosing a particular behaviour and does so in conversation with the client in a spirit of acceptance and collaboration. The process aims to help make complex behaviour changes feel clear and more achievable by allowing the client to decide on the changes in their life that they feel that they can make. Skilful MI practitioners use a range of skills and techniques to guide clients through this process. Central to these is a technical skill of attending differentially to client language that is indicative of change (change talk), while consciously not reinforcing client sustain talk, which is language in favour of the status quo. As MI is a conversation style, these techniques are not specific to a type of behaviour change; rather, they are used in response to where the client is in the MI process. In the case of breastfeeding, these techniques can be used to support initiation and continuation (Box 2).

An example of an interaction in which the client is expressing change talk:

I think I want to give breastfeeding a try. I know it is really good for my baby’s health.

Your baby is so important to you and you want to provide him with a healthy start.

An example of an interaction in which the client is expressing sustain talk:

I’m not sure breastfeeding is right for me as I really want my partner to be involved in feeding baby as well.

Whether you choose to breastfeed is your choice. Are there any ways you can think of in which your partner could be involved in feeding if you decide to breastfeed?

Self-determination theory is one of the theories that was considered during the development of the BCW framework56,74 and, therefore, it is likely that the BCW framework will be applicable in the context of MI-based BFPS. However, it has been suggested that the BCW may not capture some of the therapist skills that form a key element of the MI approach. 75 Therefore, in addition to using the BCW as a guide in developing and characterising the MI-based BFPS intervention, we assessed its applicability in the context of a MI-based approach and investigated whether or not there were any important potential mechanisms for change included in the intervention that were not incorporated in the current BCW framework and BCTTv1 taxonomy.

Methods

Rapid literature review

We searched 14 electronic databases on Ovid for BFPS studies to identify the features of one-to-one peer support that contributed to the successful delivery (or otherwise) of the interventions. The search was carried out in December 2014, with an update search carried out in March 2016. We used both keywords and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, as detailed in the search strategy in Appendix 1. The literature review was designed to examine how BFPS interventions were provided: who provided peer support, where, when and how. The search was limited to English-language-only publications between the years 2000 and 2014, and was restricted to studies undertaken in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. We included RCTs and controlled studies that evaluated BFPS interventions that included one-to-one support. We extracted data from these studies to describe the study population, intervention (including any cited or explicitly described underpinning theories), delivery context and usual care, characteristics of peer supporters, factors associated with the uptake of the intervention, outcomes and lessons for study design and intervention delivery. We used this information to develop a narrative summary of the key features of BFPS interventions and the facilitators of, and barriers to, delivery of the interventions. These findings were presented at the first Stakeholder Advisory Group meeting in January 2015. Prior to writing this report, we updated the search to include publications up to 2016 and contacted study authors to obtain supplementary information, for example the results of process evaluations, when there was insufficient information in the primary publication of a study.

Qualitative interviews and focus groups

We conducted focus groups with mothers, fathers and peer supporters to understand their expectations and the required functions of MI-based BFPS, explore factors relevant to the delivery of the intervention and identify different experiences and perspectives within and across the groups. 76,77 Focus groups were chosen to facilitate reflections on the social realities of infant feeding. Participants all had experience of either being a new mother/father or being a peer supporter. By discussing this in a group, it is likely that new insights were extracted beyond those that we would have uncovered if we had discussed these issues with each participant alone during an interview. 78 One-to-one in-depth telephone interviews were conducted with health-care professionals to enable them to discuss their views on, and experiences of, BFPS within their local service and perceived facilitators of, and barriers to, implementation. We interviewed health-care professionals separately for two reasons. First, we may reasonably expect that, when investigating a relatively homogeneous group of health-care professionals, their experiences may vary. This may be problematic when health-care professionals do not know each other well, are at different levels of the professional hierarchy (e.g. some band 3 unqualified maternity care assistants and some band 7 infant feeding leads) and may be aware of practices that are not officially sanctioned. Accordingly, we believed that it was ethically appropriate to undertake individual interviews. 79 In addition, from a practical perspective, using individual interviews rather than focus groups allowed us to complete the data collection more easily, without having to co-ordinate the busy diaries of health-care professionals.

Setting

The qualitative work to inform intervention development was conducted in the three sites that would later be used to test the feasibility of the intervention. The study sites, two in South Wales and one in England, were selected because they included communities with high levels of socioeconomic deprivation and low breastfeeding rates. In two study sites, the existing peer-support services were voluntary and group based, whereas, in the other site, there was a one-to-one BFPS service that employed peer supporters. Prestudy discussions in the third site indicated that the model of peer support provided was proactive and peer-supporter led in the early postnatal period, and it was felt that it would be possible to adapt this and test the feasibility of delivering the new MI-based BFPS intervention that was being developed. Interviews with health-care professionals and focus groups with peer supporters were conducted in all study sites; focus groups with pregnant women, mothers and fathers were held in two of the three study sites for logistical reasons.

Participants and sampling

We conducted one focus group with fathers (n = 3), three focus groups with mothers and pregnant women (n = 14) and three focus groups with peer supporters (n = 15). Mothers and fathers were recruited through existing community-based antenatal and parenting groups, who invited parents to participate in a local focus group. They were the intended target population for the intervention and therefore did not necessarily have experience of peer support or breastfeeding. Peer supporters working in the study areas were identified through local service managers/IFCs or through databases of qualified peer supporters and were invited by e-mail, telephone and social media to participate in focus groups held in their local community. No incentives were offered for participation.

We conducted 14 telephone interviews with health-care professionals whose role included breastfeeding support: health visitors (n = 2), service managers (n = 2), community midwives (n = 4), postnatal/hospital-based midwives (n = 3), an early years practitioner (n = 1) and midwifery support workers (n = 2). We worked with the service managers in these areas to develop a sampling frame of health-care professionals who had managerial and/or service delivery roles to support breastfeeding. The service managers sent out invitations to those in the selected health-care professional roles. Fifteen of the 18 invited health-care professionals responded and consented to take part.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval for the qualitative work that informed the intervention development was granted by the NHS Health Research Authority, Wales REC 3 Panel, in November 2014 (reference 14/WA/1123). All focus group participants provided written informed consent. Health-care professionals provided audio-recorded verbal consent for their interviews following a standardised script.

Procedure

Flexible topic guides were developed for each participant group (see Appendices 2–5). These were based on emergent themes from the rapid evidence review that required further development or clarification and the proposed research design (e.g. challenges for recruitment, retention and data collection, and study materials, such as information leaflets and consent forms). Intervention topics included past experience of breastfeeding support, BFPS, the appropriate timing and method of contact between mothers and peer supporters, training and support needs of peer supporters, partners’ involvement in peer support, factors that would encourage/discourage engagement with the intervention and intervention integration with local services. The MI concept was briefly described and participants were asked for their views on using this approach when providing breastfeeding support. All participants were given a study information sheet and completed a consent form or gave verbal consent. All interviews and focus groups were digitally audio-recorded.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data were fully transcribed, anonymised and analysed thematically using an approach that was both deductive and inductive. 65 An initial coding framework was developed using the BCW as a guide. This enabled us to map themes identified in the data against the different levels of the BCW (i.e. sources of behaviour, intervention functions, service/policy categories and mode of delivery). Analysis was facilitated by the use of NVivo 10 qualitative software. The qualitative researchers (LC and HT) met regularly during the analysis process to discuss coding and the interpretation of the findings. A sample of transcripts (one focus group and three interviews) was independently dual coded by a third researcher (HS) to assess the validity of the coding framework and showed a high level of agreement between coders. When NVivo identified discrepancies of > 10% during dual coding, this was the result of differences in how coded sections were highlighted or a lack of description within the coding framework. These discrepancies were discussed and resolved, leading to some themes in the initial coding framework being more explicitly defined, collapsed and relabelled, to simplify the coding structure and ensure that it fitted with the BCW definitions. Pseudonyms were allocated to participants to protect anonymity in reporting findings.

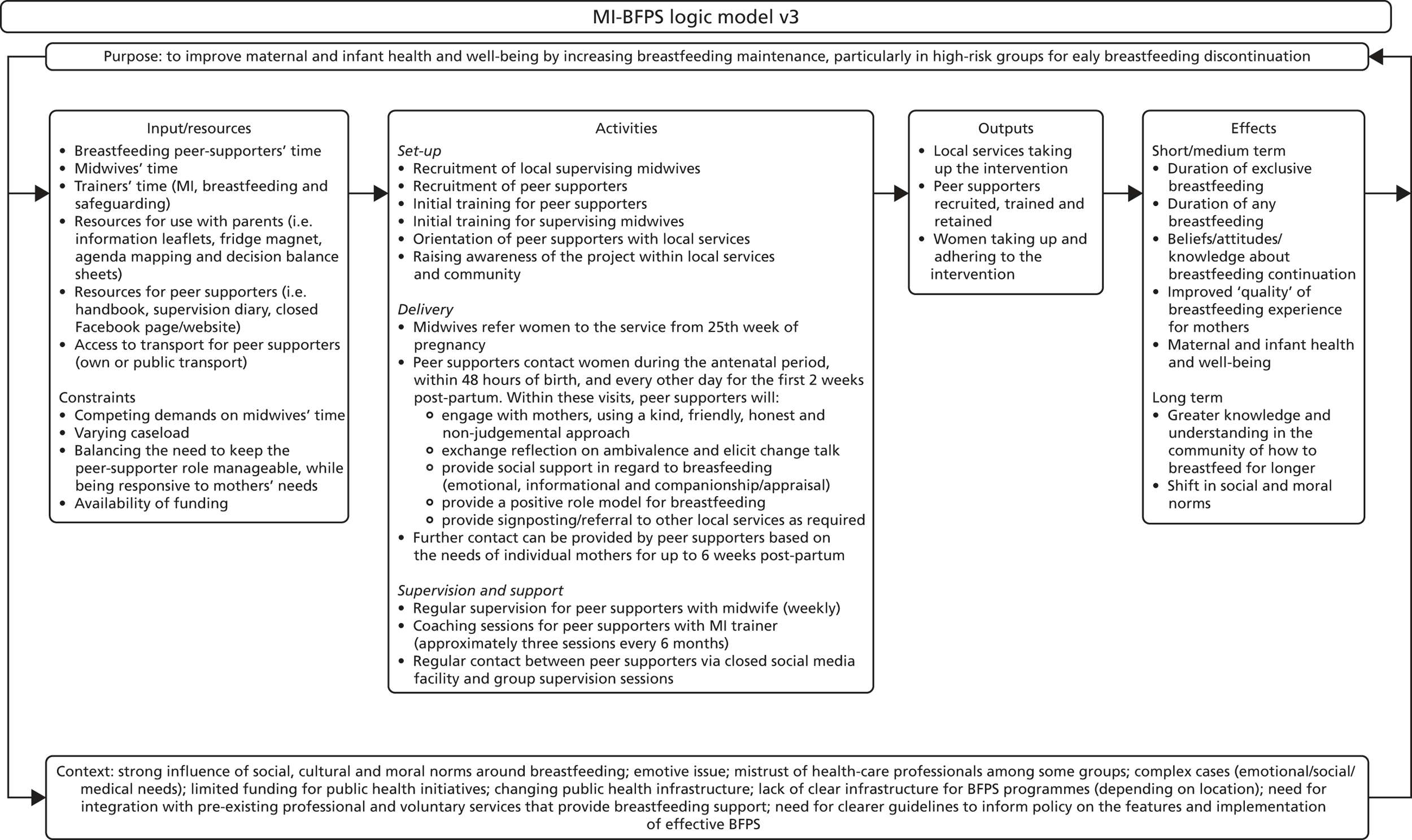

Production of the intervention specification

The results of the rapid review and qualitative work were mapped onto the COM-B model and the BCW to identify the relevant sources of behaviour to be addressed and the relevant behaviour change techniques and implementation requirements using the BCTTv1. 58 We then produced the specification of the MI-based BFPS intervention and corresponding logic model for discussion and endorsement by the Stakeholder Advisory Group.

Consultation with the Stakeholder Advisory Group

A Stakeholder Advisory Group (n = 23) was convened to advise on all aspects of study design, including intervention development. This group consisted of service users (n = 2), peer supporters (n = 1), peer-support co-ordinators (n = 3), IFCs (n = 1), service managers (n = 4), midwives (n = 1), health visitors (n = 2), MI trainers (n = 2) and voluntary sector representatives (n = 7). Two half-day creative workshops were held. In January 2015, the stakeholder group met to discuss the preliminary findings from the rapid evidence review and qualitative research and the initial generation of the intervention plan by the research team. Between January and March 2015 the analysis of the qualitative work was completed and used to inform the development of a more detailed specification of the intervention; this was presented to the stakeholder meeting in March 2015. The multidisciplinary research team led the sessions and moderated group work. Group discussions were audio-recorded and key points extracted. Drafts of the intervention description and logic model were circulated to this group for comment between meetings.

We consulted with mothers who were waiting to be trained by the NHS as peer supporters and those going through the training using a closed Facebook group (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). This group was also consulted on the name of the intervention and the participant materials.

Results

Rapid evidence review

The rapid literature review aimed to (1) describe heterogeneity in intervention theory and design among one-to-one BFPS interventions delivered in developed country settings that have been subject to experimental study and (2) identify opportunities and modifiable weak points associated with the design of BFPS interventions delivered across different contexts that could be addressed in the design and implementation of the MI-based BFPS intervention that we were developing.

The rapid review identified 15 BFPS interventions that were subject to experimental study, which were reported in 16 papers published between the start of January 2000 and the end of January 2016. 29,34,35,37–39,80–89 Nine interventions were delivered in the USA, all associated with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). 80–87,89 Five papers related to UK-based interventions34,35,37–39,88 and one intervention was delivered in Canada. 29

Studies were included if they pertained to a model of BFPS that included planned one-to-one contact between a mother and a peer supporter, reported breastfeeding rates (initiation, continuation or exclusivity) as an outcome measure and if they had been delivered in a developed country setting. Studies were excluded if the support was primarily intended to be group based. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram90 describing the different stages of study identification is presented in Figure 9.

FIGURE 9.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram. BF, breastfeeding. Adapted from Moher et al. 90 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Study quality

Eleven studies were RCTs,29,34,35,37,80,81,84,86–89 three were area-based controlled studies38,82,83 and two were natural experiments. 39,85 Applying Cochrane risk of bias criteria,91 we found that only three studies had a low risk of bias. 34,81,86 Six of the evaluations were at a risk of selection bias,29,38,39,82,83,85 attrition may have affected six evaluations35,37,80,83,87,88 and one evaluation89 was at a risk of detection bias. Implementation issues affected 11 of the 15 evaluations. 34,35,37–39,80,84,86–89 Among the five UK studies, there were difficulties in achieving the intended number of contacts34,38,39,88 and in ensuring intervention fidelity. 35,37,88. Of the nine studies of US-based cases, four reported significant implementation problems. 80,86,87,89

Heterogeneity between studies

Within the relatively narrow inclusion criteria, the rapid review found considerable heterogeneity in the type and scale of the breastfeeding rate ‘problems’ that were addressed, the background social norms and the wider health-care delivery context, as well as the underpinning intervention theory and specific intervention components.

With regard to the breastfeeding rate problem being addressed in the studies, nine interventions aimed to increase initiation rates33,35,38,39,80,83,85,87,88 and 12 sought to improve continuation rates,29,34,35,37–39,80,81,84,85,87,89 measured at varying time points. Two interventions were intended to improve the rates of exclusive breastfeeding. 86,89 The scale of the problem of low rates of breastfeeding varied. One intervention was implemented against a backdrop of a breastfeeding continuation rate of around 10% at 6 weeks,38 whereas two interventions were delivered in the context of background initiation rates of 90% in a low-income population of Latina – predominantly Puerto Rican – women. 86,87 The majority of included studies focused on populations that were socially deprived. 38,39,80–87,89 Many interventions were interlinked with a wider agenda to reduce health inequalities. Only three studies were not specifically located/targeted to address the needs of mothers experiencing social disadvantage. 29,34,35

Overwhelmingly, study papers did not include a description of the theoretical models underpinning the interventions that they described. The theory of social support27 seemed to be implied across many studies; however, different configurations of intervention components suggested differences of emphasis on informational, emotional, instrumental or appraisal support among the included interventions. Two studies explicitly referred to social influence or role modelling as a concept underpinning intervention design. 29,89

The emphasis on a similarity between the mother and the peer (adherence to the principle of homophily) varied. Most used peers selected on a locality basis, suggesting an intention to recruit from a similar social background. Six interventions attempted to individually match mothers to peers by ethnicity or language. 80,82,84,86,87,89 Two interventions targeted to adolescents used adolescent peers. 39,84 One intervention, targeted to recent Spanish-speaking immigrants, did match peers by first language. 87

Interventions differed considerably in accordance with indicators of peer professionalisation,25 and were not equally well embedded in existing health services. At one extreme, peers were trained to university diploma level34 whereas, at the other, peers received only 2 hours of orientation. 29 In some cases, peers were employed or were managed by health-care professionals. 37,39,80,83,85–88 Several settings had previous experience of BFPS. 81,85–87 In most settings, the intervention was funded for the lifetime of the evaluation only.

Comparison across interventions indicated considerable heterogeneity in the timing, frequency and intensity of contacts and the setting for contacts. Two interventions did not include an antenatal contact29,84 whereas one was entirely reactive in the postnatal period. 34 Six interventions intended more than five contacts with each mother. 35,80,81,84–86 Three interventions involved contact in hospital prior to discharge. 80,81,86

Design opportunities and modifiable weak points

Within these included studies, peer supporters were described as role models, affirming and normalising experiences and empowering mothers to identify solutions that work for them. The BFPS interventions across these studies aimed to address issues related to the mothers’ own capacity and resources (lack of knowledge, unhelpful beliefs, attitudes, low breastfeeding self-efficacy) and issues related to health-care professional support or capacity. All studies applied the principle of homophily (the tendency for people to identify with others who are similar to themselves)92 such that peer supporters were mothers who had breastfed, but there was variation between studies in the extent to which peers had similar social or cultural backgrounds to the mothers who they supported. The content of the interventions included in these studies is summarised in Appendix 6 (see Table 22).

Thematic cross-case analysis of extracted data resulted in the identification of five areas for consideration in intervention development. These were:

-

achieving cultural acceptance

-

successfully integrating with existing health-care services

-

ensuring that peer qualities enhance uptake and acceptance

-

ensuring that the peer is practically and emotionally accessible to the mother

-

ensuring that the peer–mother relationship promotes change in line with intervention goals.

We summarised the facilitators of, and barriers to, the delivery of BFPS within the context of each theme and identified delivery implications for the MI-based BFPS intervention. These lessons for design were endorsed by the Stakeholder Advisory Group in January 2015 (Table 4).

| Characteristic of BFPS | Facilitators | Barriers | Implications for the Mam-Kind BFPS intervention design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociocultural norms |

|

|

|

| Qualities of the peer |

|

|

|

| Accessibility of the peer |

|

|

|

| Peer–mother relationship |

|

|

|

| Successfully integrating with existing health-care services |

|

|

|

Intervention functions

We mapped the sources of behaviour identified in the literature review and our findings from the qualitative work to the COM-B model and the corresponding intervention functions (Table 5). The relevance and acceptability of these intervention functions were explored in the qualitative interviews and focus groups. These results are presented in the following sections.

| Sources of behaviour: barriers (–) and facilitators (+) to breastfeeding continuation | COM-B domain | Potential BCW intervention functions |

|---|---|---|

| Social norms: formula feeding (–) or breastfeeding (+) – includes wider cultural/social norms and beliefs and attitudes of significant others (e.g. partner, mother, sister) that formula feeding (–) or breastfeeding (+) is easier/convenient/healthier/more natural |

|

|

| Feel comfortable (+) or uncomfortable (–) about breastfeeding in front of others |

|

|

| Social support: social isolation (–) or feeling emotionally supported (+) |

|

|

| Beliefs that formula feeding (–) or breastfeeding (+) is easier/convenient/healthier/more natural; beliefs/expectations about what is ‘normal’ breastfeeding (e.g. frequency of feeding or how milk let-down feels) |

|

|

| Planning for formula feeding (–) or breastfeeding (+), e.g. buying equipment, formula, clothing |

|

|

| Intention to breastfeed: determination to overcome challenges encountered (+) vs. intention to formula feed if there are difficulties (–) |

|

|

| Confidence (+) and autonomy (+), for example feeling able to try out and find their own techniques for feeding rather than having to stick to ‘textbook’ methods |

|

|

| Positive (+) or negative (–) prior experience of breastfeeding and/or breastfeeding support |

|

|