Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/107/01. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The draft report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Soomro et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Cancer of the kidney accounts for 3% of new cancers and 2% of cancer-related deaths, making it the eighth most common cancer in the UK. In the UK, in 2008, 8757 new cases of kidney cancers were diagnosed (approximately two-thirds of these were < 4 cm in size) and 3848 patients died of kidney cancer. 1–4 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data5 show that 65,150 patients were diagnosed with, and 13,680 patients died of, renal cancer in the USA in 2013.

The treatment of small renal masses (SRMs) of < 4 cm in size (80% of these are malignant) is evolving. The standard treatment in the past was radical nephrectomy. It is now accepted that the nephron-sparing techniques have similar oncological outcomes but have an additional benefit of preserving kidney function. 6 Among these techniques, partial nephrectomy has emerged as the preferred treatment of SRMs, as it effectively treats the cancer while broadly preserving the kidney function (dependent on ischaemic time) and has good long-term oncological safety. 7 However, it is associated with postoperative morbidity and long hospital stay and recovery. For these and other reasons, such as lack of surgical skills and patient comorbidities, it remains underutilised. Ablative techniques such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and cryoablation (CRYO) are also being increasingly used in patients with SRMs. These are particularly attractive as the mean age at diagnosis of renal cancer is 64 years and the procedure incurs significantly fewer complications and inpatient bed stay, and is associated with early recovery. 8

However, ablation still represents an invasive procedure with consumables costs, particularly in the case of CRYO. There are also concerns with ablative techniques regarding the possible persistence of microscopic cancer and a slightly higher chance of persistence of tumour, perhaps necessitating secondary treatment. This leads to increased patient anxiety and additional cost for the providers. In view of these factors, and because current evidence is based mainly on single-centre series and a few meta-analyses, there is uncertainty about the best treatment of SRMs. 9–12 Minimally invasive ablation SRMs (of < 4 cm in size) clearly make available a new treatment option, but robust data comparing relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of active surveillance with ablative techniques (RFA/CRYO) are currently not available. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) to answer this question has been identified as a priority by the renal cancer subgroup of the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) and has the support of the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) section of oncology and local National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) clinical research networks. As there remains uncertainty as to the willingness of patients and surgeons to agree to randomisation to this trial and whether or not recruitment and retention would be adequate, a rehearsal pilot addressing the feasibility of a definitive RCT is required.

The natural history of SRMs remains unclear. Almost 66% of newly diagnosed renal cancers are < 4 cm in size. 13 A meta-analysis14 has shown that the majority of small lesions have a slow growth rate (mean rate of 0.28 cm per year) and they rarely metastasise while under active surveillance. Partial nephrectomy became accepted as a standard of care for SRMs when, in a series of 485 patients with renal tumours < 4 cm, followed for over 10 years, cancer-free survival rates at 5 years and 10 years were found to be 96% and 90%, respectively. 15 The local tumour recurrence was 3.5%. Similar results were reported in a meta-analysis16 looking at a series of patients undergoing open partial nephrectomy (OPN) from 1980 to 2000. A study that compared 100 cases of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) with OPN concluded that OPN remains the standard of care for SRM. 17 LPN was associated with longer ischaemic time, major intraoperative complications and increased postoperative urological complications. 17 However, in experienced hands, LPN has a comparable oncological efficacy and complication profile. 18 Despite this clear evidence favouring partial nephrectomy, BAUS cancer registry data19 showed that only 721 partial nephrectomies were performed in England and Wales in 2007/8, whereas approximately two-thirds of patients with renal cancer masses of < 4 cm in size underwent radical nephrectomy. This practice alone is contributing to the net population burden of significantly impaired renal function in a population that may already have other comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

In RFA, radiofrequency probes are applied into the renal tissue percutaneously using ultrasonography (US), computerised tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). There has been some concern that the thermal RFA zone might not be homogeneous and there may be persistence of viable tumour that is not evident on routine radiological surveillance. 20,21 This may be due to the method of tissue heating in RFA, which is considerably reliant on conductive heating. A multi-institutional meta-analysis22 of 1375 renal lesions treated by RFA and CRYO, applied both percutaneously and laparoscopicaly, detailed 600 RFA outcomes at a mean follow-up duration of 15.8 months. Mean patient age was 67 years and mean tumour size was 2.69 cm. This analysis22 yielded a combined subtotal treatment rate and (unexpected) local tumour progression rate of 12.9%, with 8.5% undergoing repeat ablation for treatment completion. It was suggested that true disease persistence might be determined only by delayed post-ablation biopsy. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has accepted the broad efficacy of RFA but centres are still advised to audit results and outcomes carefully. 23

Cryoablation: CRYO can be performed percutaneously under image guidance or laparoscopicaly by direct visualisation. Again, the meta-analysis by Kunkle and Uzzo22 reviewed multi-institutional outcomes from CRYO, with the majority performed in North American practice under laparoscopy. 24,25 A total of 775 renal lesions were treated; mean tumour size was 2.58 mm and mean patient age was 66 years. This yielded a combined subtotal and (unexpected) local tumour recurrence rate of 5.2%, with only 1.3% undergoing repeat ablation, largely because of the difficulties of a repeat LPN procedure. In this meta-analysis,22 the rate of progression to metastatic disease was similar to that of nephron-sparing surgery, CRYO and RFA. However, in these series, ablative techniques were selected in older patients with small tumours, whereas partial nephrectomy was undertaken in younger patients with larger tumours and had longer post-treatment surveillance. NICE26,27 has accepted the broad efficacy of CRYO but centres are still advised to audit results and outcomes carefully.

Active surveillance studies13,14,28–33 have reported on a small series of patients, showing varying growth rates ranging from 0.09 cm per year to 0.86 cm per year, with most concluding that SRMs grow slowly with a low rate of progression. The rate of metastatic disease is low, between 1% and 7%, with varying lengths of follow-up. 14,34,35 In most cases with metastatic disease, the primary tumour had grown to > 4 cm in diameter. 34 It has also been demonstrated that larger renal cell cancers (RCCs) are significantly associated with higher histological grade, advanced stage and distant metastases, with the significant size cut-off point between 3 and 5 cm. 36,37 This has resulted in the current opinion that small RCCs may grow slowly but then become more aggressive at a size threshold of approximately 4 cm.

However, some small RCCs metastasise when they are < 4 cm in size, and this has led some authors35,38 to question the safety of an active surveillance approach. At present, it is not possible to identify these aggressive tumours on standard radiological characteristics alone.

Currently, a strategy of active surveillance, or watchful waiting, is adopted in cases where the perioperative risks are deemed too high, or when an informed choice is made after balancing the potential risks and benefits of surgery.

Many small RCCs have a slow or immeasurable growth rate; as such, these cancers may not lead to symptoms or metastatic disease within the lifetime of the patient.

Although many small RCCs are indolent, there is significant uncertainty as to which small tumours will behave in a benign fashion and which are more likely to progress and metastasise. A reliable means to predict the behaviour of these small RCCs might enable early definitive treatment for those that are likely to progress or metastasise early and avoid unnecessary procedures, along with the associated morbidity and costs, for those patients with slow-growing or non-growing RCCs that are unlikely to progress within the lifetime of the patient.

At present, the main prognostic factor available is tumour size. This is most commonly measured on a CT scan, with follow-up CT performed to identify an increase in tumour size. A systematic schedule of serial CT scans allows growth, and any acceleration in growth, to be identified, which might suggest tumour progression and likely metastasis.

Most of the masses will be discovered incidentally on CT and US scans. Critically, the technique for follow-up must be able to detect significant increases in renal mass size and provide minimal inter-observer and intraobserver variability. US cannot provide reliable measurements sequentially, so either CT or MRI is ideally required.

The literature to date from one randomised controlled study13 and several retrospective studies suggests that active surveillance may be an initial option for the management of SRMs in healthy individuals with careful follow-up. 13,14,28–34 Size progression of the tumour (> 0.5 cm per year or a maximum diameter of > 3.5 cm; approximately 25% of patients) while on active surveillance may identify a more precise cohort who will actually require intervention.

This approach may produce substantial benefits in terms of reduced morbidity, reduced overall mortality and long-term quality of life (QoL) and these may outweigh the small risk of metastatic disease in patients aged ≥ 70 years. However, this is predicated on the relative morbidity of ablation and surgery.

Chapter 2 Pre-feasibility study phase

Objectives

The objectives of the pre-feasibility study were to determine clinician (radiologists and urologists) equipoise around a trial comparing ablation with active surveillance and to assess whether or not they would participate and recruit patients to such a trial. This was because the threshold for advising patients to consider active surveillance was dependent on the size of the tumour weighed against age and comorbidities of the patient. The second objective was to develop patient information for the feasibility study with the input of patients to ensure that it is clear and comprehensive. In addition, we undertook a survey of the potential participating centres and selected 8 out of the 15 centres approached. This was based on their research capabilities, expertise in offering these interventions and previous experience of undertaking clinical trials.

Survey: clinician equipoise in relation to a trial of ablation or active surveillance in patients with small cell renal tumour

Introduction

Clinician equipoise is assumed to have a negative impact on recruitment to clinical trials. 39 Others40 have demonstrated that equipoise and opinions on a particular trial or design can be explored using a questionnaire survey. A survey of the relevant clinical community was included in the initial funding application, to be conducted in the stage 1 pre-feasibility phase, to determine equipoise and views on a trial comparing ablation with active surveillance in the management of patients with small cell kidney cancer. Ethics approval was sought from the Newcastle University Faculty of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (00774/2014). This section reports the response to the survey and the survey findings.

Objectives

To determine the point of equipoise for clinicians (in the use of ablation or active surveillance in the management of small cell kidney tumours) to inform the pilot feasibility study, we conducted a survey of radiologists and urologists across the UK. Willingness to recruit patients to a trial comparing these two management options was also explored.

Study subjects

The target sample of clinicians for the survey was interventional radiologists and urologists based in the UK. The British Society of Interventional Radiology (BSIR) kindly circulated a covering e-mail and a link to the questionnaire on our behalf. The BAUS supplied the SURAB (a two-stage randomised feasibility study of SURveillance versus ABlation in the management of incidentally diagnosed SRMs) team with a list of urologists.

Methods

This was a questionnaire survey. The questionnaire was developed within the team, pilot tested with a small number of interventional radiologists and urologists and amended accordingly. The questionnaire included a mix of open and closed questions, multiple-choice questions and vignettes. The content of the questionnaire covered available options for the management of small cell kidney tumours and questions exploring the willingness to randomise to a trial of ablation versus active surveillance in this patient group. A series of vignettes were used to explore which patient clinicians would be happy to recruit to a trial (Table 1). The questionnaire was available online, with the option of a paper version if requested. Completion of the questionnaire was anonymous.

| Would you approach to participate in a trial of active surveillance versus ablation? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aged 50 years | Tumour size (cm) | Charlson score of comorbidity | |

| Patient A | 2.0 | 0 |

Charlson score (points) 0 = no comorbidity |

| Patient B | 2.5 | 0 | |

| Patient C | 3.0 | 0 | |

| Patient D | 3.5 | 0 | |

| Patient E | 2.0 | 2 |

Charlson score (points) 2 = two comorbid conditions (e.g. myocardial infarction and dementia) or a single, more severe condition (e.g. hemiplegia, moderate/severe renal disease) |

| Patient F | 2.5 | 2 | |

| Patient G | 3.0 | 2 | |

| Patient H | 3.5 | 2 | |

A covering e-mail explained the purpose of the survey and a link to the survey was circulated by the BSIR on 4 August 2014. The study team circulated the e-mail and a link to a list of members eligible for the survey provided by the BAUS on 21/22 August 2014, with a second request (owing to a low initial response) 2 weeks later. Members of the study team also circulated both the e-mail and link to their network of clinical colleagues.

Results

A total of 29 out of 666 radiologists and 22 out of 50 urologists responded to the survey. The number of interventional radiologists for whom this survey was relevant is small and the view within the study team was that 29 respondents was an excellent response. In the following sections, we will report the responses to the survey but, because of the small sample size, statistical analysis is not valid and the results are presented descriptively.

To provide a picture of the management options for small cell kidney tumour, respondents were asked about what was available for this patient group in their centre from a choice of active surveillance, RFA and CRYO. Active surveillance was offered by the majority (95%) of centres, with 58% offering RFA and 51% offering CRYO to patients with small cell kidney tumour. Eight respondents skipped this question, but it is not clear whether or not this is because they did not offer any of the options listed.

Attitudes to a trial of active surveillance versus ablation

A total of 79% of the respondents said they would take part in a trial of ablation versus active surveillance in this patient group. Some of those who would not, or were unsure, gave their reasons in the open questions (Box 1).

I’m not sure if it’s reasonable to randomise ‘fit’ patients unless there’s an age cut-off.

I would be unsure due to the ethics of randomising a group we have been treating for many years, admittedly without any level of evidence.

I think there would be problems getting patients to agree to participate. There may be a reluctance to have no treatment. The trial may involve more frequent imaging and that could be an inconvenience.

Almost half (47.5%) of respondents anticipated problems in patients agreeing to a trial comparing ablation with active surveillance, 27.5% did not anticipate problems and 25% were unsure. The reasons given by those who believed it would be problematic to recruit were centred around patient preference for one particular option and patients not being at ease with active surveillance: ‘Some patients are uncomfortable with knowing they have a “tumour” and not having it “dealt with” ’. More than half (55%) of respondents did not envisage any other problems with a trial of this kind. Of the remaining 45%, the other problems given were related to the patients’ perspective, covered in the previous question, but the next most commonly mentioned problem was the lack of a surgical arm and what this would mean for patients who were eligible for surgery or ablation. There were comments that this is a much needed trial but consideration should be given to the potential problems within the clinical community.

Factors that influence which patients are approached

Age was explored as a factor that may have an impact on which patients are approached for the trial. Respondents were asked what age of patients they would feel comfortable recruiting to such a trial from an age range of 45 years to ≥ 80 years. The majority (80%) would be happy to recruit patients aged 75 years, but this dropped to 65% for patients aged 70–89 years and to 25% for patients aged ≥ 80 years; 47% would recruit patients aged 65 years and 15% would recruit patients aged 45–55 years.

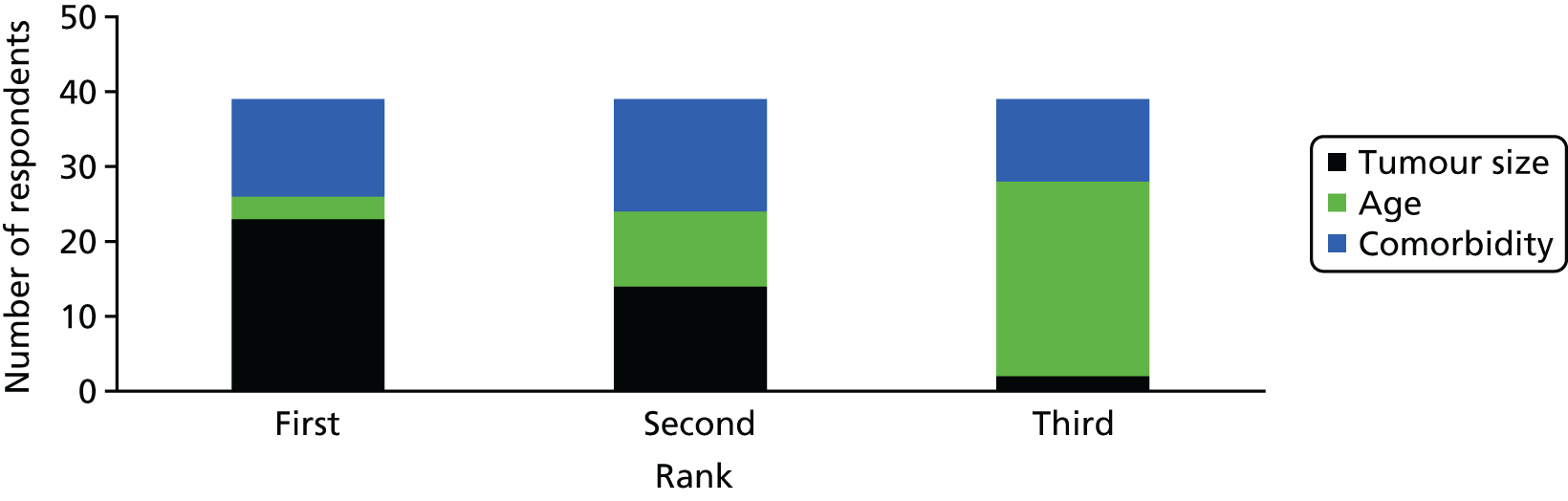

When asked to rank the potential influential factors in the identification of patients for the trial of tumour size, age and presence of comorbidities, tumour size was ranked as the most important for 59% of respondents (Figure 1). The ranking of comorbidity was interesting, with a similar number of respondents ranking it first (n = 13), second (n = 15) or third (n = 12), indicating, perhaps, that opinions on the importance of comorbidities were divided.

FIGURE 1.

Factors ranked as most influential in identifying patients for the trial.

Vignettes

Respondents were asked to consider a series of vignettes (see Table 1, for example) with a range of ages (50–80 years), tumour sizes (2–3.5 cm) and level of comorbidity (Charlson score of 0 or 2 points) in relation to willingness to recruit to the trial.

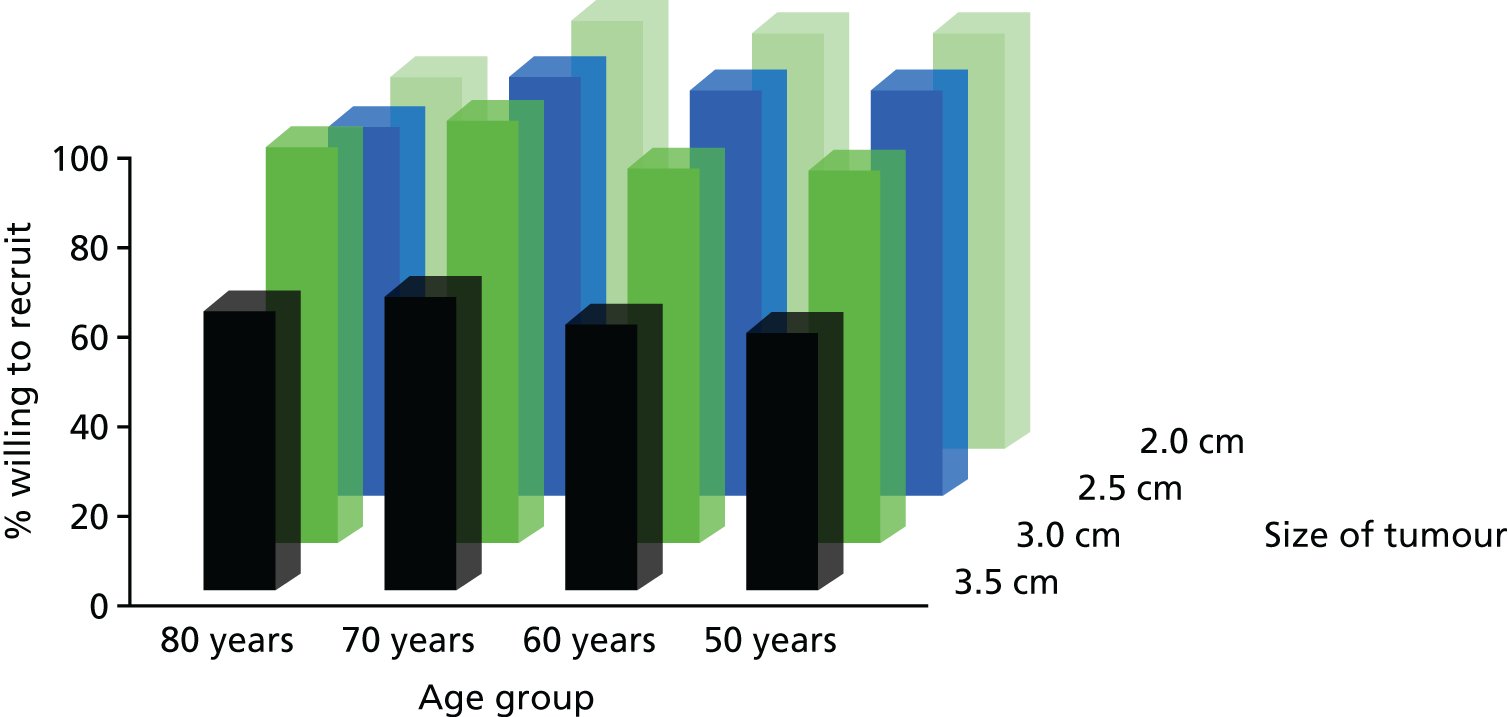

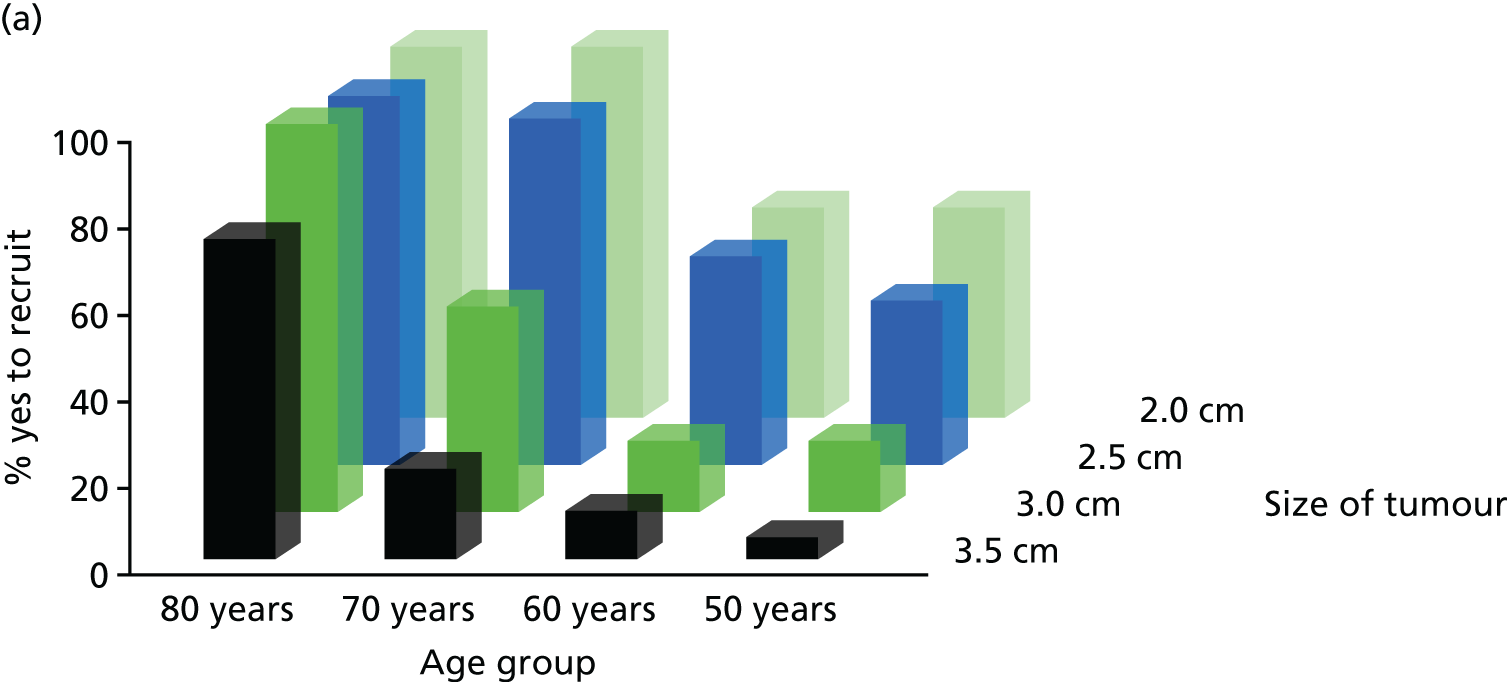

Less than half (45%) of respondents would be willing to recruit patients in the 50–59 years and 60–69 years age groups with tumour size of 2–2.5 cm and no comorbidity (Figure 2). As tumour size increased in this age group, willingness decreased to 23% for tumour size of 3 cm and to 15% for tumour size of 3.5 cm. There was a marked difference in the views of urologists: 47% agreed to approach when tumour size was 2 cm, but figure this dropped to 8% for a tumour size of 3.5 cm (Figure 3). For radiologists this figure was 44% and 22%, respectively (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 2.

Willingness to recruit by age and tumour size and no comorbidity.

FIGURE 3.

Willingness to recruit by age and tumour size with comorbidity.

For patients aged 70–80 years, the majority (86%) of respondents would recruit if tumour size was of 2 cm and there was no comorbidity. This dropped substantially in the 70–79 years age group with increased tumour size: 48% at 3 cm and 30% at 3.5 cm. Similarly, for the 80–89 years age group, fewer (64%) would recruit if the tumour size was of 3.5 cm than of 3 cm (89%).

The presence of comorbidity (Charlson score of 2 points) had an influence. The majority (86%) of respondents would recruit patients aged 50–69 years with a tumour size of 2–2.5 cm or 3 cm (81%), but this figure dropped to 58% for tumour size of 3.5 cm (Figure 3). There was little or no difference in urologists’ willingness to recruit patients aged 50–79 years with tumours from 2 cm to 3 cm (89–100%) and comorbidity, but this proportion fell to 74% (aged 50–59 years) and 79% (aged 60–69 years) for tumours of 3.5 cm (Figure 4). For radiologists, this dropped from 83% for tumours of size 2–2.5 cm to 72% and 39%, respectively, for tumours of 3 cm and 3.5 cm in size (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Willingness to recruit by clinician type, age, tumour size and comorbidity. (a) Urologists’ willingness to recruit – no comorbidity; (b) urologists’ willingness to recruit – comorbidity (Charlson score of 2 points); (c) radiologists’ willingness to recruit – no comorbidity; and (d) radiologists’ willingness to recruit – comorbidity (Charlson score of 2 points).

There was an increase in the proportion of respondents who would recruit patients with comorbidity in the 70–79 years age group, to 91% for a tumour size of 3 cm, but this dropped to 64% for a tumour size of 3.5 cm (see Figure 3). For the 80–89 years age group with comorbidity, the percentages dip for a tumour size of 2–2.5 cm (77%), increase for a tumour size of 3 cm (86%) and drop for a tumour size of 3.5 cm (62%). The main difference between radiologists and urologists was in the percentage who would recruit patients aged 80–89 years with comorbidity and a tumour size of 2–2.5 cm (89% of radiologists, compared with 66% of urologists; see Figure 4).

Discussion

The results of this survey demonstrate that clinicians are more likely to recruit to a trial of ablation versus active surveillance patients who have some level of comorbidity and a tumour size of no greater than 3 cm. Willingness to recruit is lower for patients, in all age groups, with larger tumours,. In the case of patients without comorbidity, the majority of clinicians were willing to recruit patients in the 70–79 years age group with tumours of up to 2.5 cm and patients in the 80–89 years age group with tumours of up to 3.5 cm.

There was a similar pattern among radiologists and urologists in willingness to recruit patients without comorbidity. A clear cluster of patients that respondents would recruit were those in the 70–79 years and 80–89 years age groups with a tumour of size 2–2.5 cm and patients in 80–89 years age group only with a tumour size of 3 cm. Considering the upper end of the tumour size, a slightly higher proportion of radiologists than urologists were willing to recruit patients with a tumour size of 3–3.5 cm in the 50–70 years age group.

The presence of comorbidity led to a marked increase in the proportion of both radiologists and urologists who would recruit patients in the 50–59 years age group with a tumour size of 2–3 cm. For some reason, urologists were slightly less willing to recruit patients in the 80–89 years age group with a tumour size of 2–2.5 cm. Radiologists remained cautious about recruiting patients with a tumour size of 3.5 cm, but the proportion willing to recruit such patients was higher than the proportion willing to recruit patients with tumours of the same size but without comorbidity.

Although clinicians who responded to this survey ranked tumour size as the most important factor in recruitment to a trial of ablation versus active surveillance, they considered tumour size less important in the case of patients with comorbidity. Uologists considered ablation or active surveillance to be viable treatment/management options for all age groups and with tumours of all sizes (suggested in the survey) when comorbidity is present. The same can be said for radiologists with the exception of patients with tumours of a size of 3.5 cm.

Limitations

The response rate from urologists was disappointing and was a limitation of this survey as we were able to canvass the views of only half of this group of clinicians. The BAUS, unlike the BSIR, did not circulate the request on our behalf, which might have raised the profile of the survey and resulted in a better response rate. However, the number of interventional radiologists in the UK who conduct ablation is small, and we believe that we were able to capture the views of the majority of this group.

Participatory design study: development and testing of the SURAB trial patient information

Introduction

Recruiting to time and target in clinical trials is a longstanding problem. 41 The reasons for this may be multifactorial, but research conducted to explore patient factors in cancer trials have identified issues such as a dislike of randomisation and the inclusion of a placebo or a no-treatment arm. 42 As the SURAB feasibility study included both randomisation and a no-treatment arm, it was imperative that the rationale for, and importance of, both was fully addressed in the patient information. To do so, it was clear that patient involvement in producing user-friendly and comprehensive information for the SURAB feasibility study was needed. Consumer involvement has also been shown to improve the readability and relevance of patient information. 43 A plan was included in the initial funding application to develop patient information materials, in the stage 1, pre-feasibility, phase, for the patients approached to take the part in the subsequent pilot feasibility study. This stage of the research had ethics approval from the Newcastle University Faculty of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (00774/2014). The process of recruiting patients for (and conducting) the patient and public involvement (PPI) activity is described in this section.

Objectives

The aim was to produce patient trial recruitment materials that were clear and comprehensive and included all of the information required for the recipients of the trial information. The plan was to develop and test information with patients who have been newly diagnosed with a SRM and those who have recently received treatment (including those under active surveillance). At the same time, their views on the proposed trial and trial processes were also explored.

Methods

As we were working on patient information developed for another trial and the need for the information to meet regulatory requirements, we opted for a participatory design. This means that all stakeholders (in this instance, patients, clinicians and the clinical trial unit team) are actively involved in the process and the end result is information that meets the needs of the patients that the SURAB trial is targeting. We also hoped that the information sheet would facilitate the recruitment process and be something that research nurses in particular could work with when discussing the trial with potential recruits.

It was envisaged that around eight patients would be involved in the design of the information, in either group or one-to-one sessions (whichever was preferable to those involved) with the trial team researcher (JL). We considered that spouses could be included as decisions around research participation are often made in consultation with the patient’s partner. In the group or one-to-one sessions, the pilot feasibility trial was explained (the two interventions being compared, the risks and benefits, what is required of participants in the trial, etc.). We then worked through the information and explored the appropriate content and amount of trial information, and how best to convey the information, including conveying risks and benefits. In addition, patients’ views were sought on the acceptability of approaching participants after they have declined to participate or dropped out of the trial (for the parallel qualitative study) and how best to phrase this in the trial patient information. It was also explained that the patient information had to comply with NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) guidelines and there were certain elements that had to be included.

The next stage was to test the revised version of the trial information with a new group of patients using cognitive interviews and refine the information accordingly. The two main methods of cognitive interviewing used were (1) thinking aloud and (2) probing. Based on our personal experience with this more tightly focused work, a saturation point is normally reached after 8–10 interviews, when no new comments or issues are raised. We believed that up to eight cognitive interviews would be sufficient. The development work and cognitive interviews were recorded digitally and notes and observations made throughout with the permission of those involved.

Initially, it was hoped that the materials would be developed with patients from scratch. However, it was agreed that this would be a much lengthier process and would require greater buy-in and time from the patients involved. The Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU), overseeing the conduct of the trial, had already submitted patient information materials to the NHS REC with a caveat that a revised version would be submitted at a later date after PPI. The information materials the NCTU submitted were based on those used previously in a similar trial and amended accordingly. It was decided that these materials would be the starting point for the participatory design process and the basis of the information for the SURAB trial.

Contact information for activity: getting it right

Designing the information sheet about involvement in the development of the trial information was not straightforward. In order to explain the purpose of, and rationale for, this activity, it was necessary to mention the trial, and there was a concern that patients may think that they were being approached to be trial participants. We needed patient involvement in the design of our information sheet, particularly to ensure it was clear that those approached were not being asked to take part in a trial. However, after contacting two sources (PPI leads from local and national NIHR Clinical Research Networks and a local cancer patient group), support was not forthcoming. To avoid running into difficulties with the timetable for this activity, we had to accept that the best we could do was to rely on our SURAB lay coapplicant and a clinical colleague from a local trust, who commented on the content of the information sheet and suggested some changes.

Identification and contact of patients for the activity

It was considered important to involve patients who had been diagnosed with small cell renal cancer and successfully treated within the last 12 months. They would remember when they received their cancer diagnosis and understand how it would feel being approached to take part in a trial, particularly one that has a no-treatment arm. One hospital site had agreed to send out a letter from the clinician who had cared for the patient, with an information sheet to explain why they were being contacted, a reply sheet they could complete and return (to the researcher) if they were happy to be contacted and a pre-paid envelope. These patients were then contacted by the qualitative researcher who answered any questions they had and determined if they were willing to help. As this was PPI, consent was not required.

Results

Response rate

In the first tranche, 20 letters were sent to patients in one hospital site. Unfortunately, none of those who returned the slip wished to be contacted. We then had to contact another hospital site to request help. One of the research nurses and the database manager from that site helped to identify eligible patients. A second tranche of 20 letters was sent, and 13 patients (nine men and four women) responded to say they were willing to be contacted. Telephone contact was made to answer any questions about the activity and to ascertain whether they had a preference for a group or one-to-one session. Only one person had misunderstood and thought they were being asked to take part in a trial. After learning more about what was required, one person declined any further involvement. Of the remaining 12, three expressed a preference for working in a group session and seven for a one-to-one session; two expressed no preference.

Stage 1: group session

Over several telephone calls with the five people willing to attend a group session, a convenient date and time were arranged. We asked if they would be able to attend for 3 hours. As we had no information other than their name and telephone number from the form they returned, we requested their home address (so we could send out an invitation letter and details of venue) and asked how they would travel to the venue (to organise parking spaces and permits), whether or not they wished to bring a partner and if they had any health or mobility problems we should be aware of. We also sent a copy of the information materials we would be working with should they have the time to look through them before the group met.

Three women and two men attended the group session. No one brought a partner. Ages ranged from 54 years to 77 years. Based on postcode and past or present occupation, four of the five group members’ socioeconomic status was categorised as A/B, which is described as professional and qualified to a high level.

The task began with the researcher (JL) briefly explaining the trial and the purpose of the activity. The participants gave some background on their experience of kidney cancer and what treatment they had received. The patient information materials were handed out and we began to go through each section of the patient information sheet (PIS) in detail.

Several general points were made: the sheer length was off-putting; it was repetitive; it had inconsistencies; and a higher than average level of literacy would be required to fully understand it. The key condition was described in different ways throughout the PIS as ‘renal tumour’, ‘kidney tumour’, ‘kidney cancer’ and ‘mass’. Similarly, the no-treatment arm was described as ‘active surveillance’ or ‘careful observation’. Some parts were considered superfluous or repetitive and some caused alarm. In response to the sentence ‘The tumour normally grows very slowly and can often be safely observed for a period of time’, the group wanted to know ‘how often?’ and ‘for what period of time?’. They thought that the positive aspects about being involved in the trial should be brought to the fore. It was suggested that bullet points of key information be given on the first page, then patients could make a decision if they want to read on. Alternatively, they thought that a short information sheet could be provided, with a longer, more detailed sheet given to patients who wish to know more and who agree to participate. A smaller booklet format was discussed, and it was thought that this might be less daunting. The bullet points should emphasise that patients would not have been approached if they were at risk, and the slow growth rate of this tumour, and should describe what action would be taken if patients in the active surveillance group patients experience any change in their condition. It was felt to be unnecessary to have the information sheet divided into parts 1 and 2. The group did not believe that there was a need to explain why patients are randomised. It was felt that there was too much detail about assessments and it was suggested that a flow chart be included. It was also suggested that information about the qualitative interviews could be reduced and simplified, and the need to call them ‘qualitative’ was queried.

The exercise took around 2 hours and attendees preferred to take refreshments (water, tea, coffee and biscuits) while they worked. Reimbursement was offered for travel and a gift voucher was given to each attendee as a gesture of thanks for their time.

Stage 2: one-to-one session

Amendments were made to the PIS in the light of the comments and suggestions of the group. The major changes were that bullet points were added to the front of the PIS and some of the information around the process for patient participants was replaced with a flow chart. As a result, the number of pages was reduced from 11 to nine.

The seven people who expressed a preference for one-to-one sessions were contacted again and a time was arranged to speak to them face to face. In six cases, the session took place in the participant’s home, and one session, at the request of the individual, was held at the university where the study team was based. The dates and times were confirmed in a letter, which was accompanied by the second version of the PIS so that participants could look through it beforehand.

Six of the sessions went ahead; one patient cancelled due to illness. Five participants were male and one female. This group spanned a broader range of socioeconomic status, categorised as C1/2 to D/E, which ranges from lower qualified professionals (e.g. nurses) to unskilled and casual workers.

As with the group exercise, the background to the study and the purpose of the visit was explained. Two people were slightly perplexed and bemused by the idea of PPI in research and some of the allotted time was taken to explain this in greater depth. The PIS was introduced and, as before, we went through it in detail, exploring each section using cognitive interviewing techniques. Most preferred the researcher to read each sentence and then explore the understanding and identify anything that was not clear.

Individuals tended to remark on similar points in the PIS. The main comments about the bullet points were to tighten up and simplify the text and give further reassurance about the active surveillance arm (that these tumours are slow growing). Comments on the ‘What is the purpose of the study?’ question can be summarised as ‘cut to the chase’ and include only the key points. This section was also perceived to indicate a great deal of uncertainty. Potential trial participants were mainly concerned about the risk of the cancer spreading if untreated and wanted to know how slowly the tumour normally grows, how long it can be observed for, how often these tumours can be observed and what the criteria for observation are. They also thought that the two interventions should be explained. There was a dislike of the term ‘randomisation’ and a preference for ‘random allocation’ or ‘allocated at random’. Some individuals did not understand the rationale for randomisation and thought this should be included. Patients liked the flow chart, and the only comment was about the term ‘randomisation’.

It was considered insensitive to mention in the risk information the minor risk of cancer associated with CT scans when the target population has just been diagnosed with cancer. It was also thought tha, in the same section, the text ‘some people may feel anxious about not receiving treatment and the possible risk of their cancer growing’ may cause concern in patients who had not considered this. One individual was participating in a cohort study and the study information was in a small (A5 size) booklet format that he found easy to read.

Stage 3: Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit and clinical team

The NCTU team reviewed the amended PIS following the group and one-to-one sessions to ensure that the PIS met the regulatory standards. The team members, in general, were very happy with the revised version but, as there is a requirement to inform potential trial participants of alternative treatments, requested that the section ‘What are the alternative treatments?’ be reinstated. The group had found this confusing (as two of the alternative treatments were part of the trial) and thought that this was already covered in the section on the purpose of the study. A compromise was to ensure that details of all potential treatment and management options were listed in the purpose of the study section at the front of the PIS. The clinical team was satisfied that the information around the condition and treatments and the rationale for the SURAB trial were fully explained. The amended PIS was submitted to the NHS REC, which accepted the changes without question.

Discussion

A number of issues were raised and lessons learned from conducting this work to develop patient-relevant materials for a clinical trial. First, securing help to ensure that written communication materials clearly conveyed the message that patients were being approached in a PPI capacity, and were not being asked to participate in a clinical trial, turned out to be rather perplexing. The response for help with this was disappointing but, ultimately, we appear to have managed, apart from in one case, to convey our meaning satisfactorily. Second, we underestimated the amount of time required to liaise with the hospital site that agreed to identify patients and contact them about the study. Furthermore, we had not envisaged the need for a contingency plan, a second hospital site, in the event that none of the patients contacted agreed to help. Fortunately, in the second hospital site, the staff pulled out the stops to identify patients and send our information to them. Third, and by chance, we managed to include patients from a range of socioeconomic groups in our activity, possibly by offering two forms of engagement, namely the group and the one-to-one work. Finally, the patients involved completely transformed the PIS, and the suggestion of a flow chart to replace the rather lengthy and difficult-to-follow patient route through the trial was inspired. The other stakeholders, such as the NCTU team and the trial team, were happy with the majority of changes and were willing to work to come to a resolution that respected the views of the patients involved in developing the materials and also adhered to regulatory and governance requirements.

Chapter 3 Feasibility study

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of this study was to determine whether or not a RCT comparing ablation with active surveillance in the management of SRMs is feasible in terms of recruitment and retention before embarking on a definitive trial. This was a multicentre study with two arms to evaluate the relative clinical effectiveness of ablation and active surveillance in patients with SRMs (< 4 cm). As this was a feasibility study, it was not expected to produce definitive results but would provide a basis for planning a larger definitive, fully powered trial.

The objectives were to:

-

test patient information to gauge comprehensibility and ensure that information perceived to be important for study participants is included

-

quantify the number of eligible patients

-

test patient identification systems and randomisation

-

test appropriateness and feasibility of outcome measures and time scales for collection

-

assess factors that promote or inhibit recruitment and retention in the trial

-

assess potential bias in recruitment and retention, systematic differences between those eligible to be randomised and those eligible but unwilling either by the clinician or the patient

-

examine the mechanism of data collection and assess the completion rates of data collection instruments to inform the full trial.

Trial interventions

In this study, patients who consented to participate were randomised to either ablation or active surveillance. All patients undergo routine biopsy of the renal tumour to confirm that it is a cancerous growth. At centres for which this biopsy is not routine, the participant must consent to the biopsy and the study prior to the biopsy being performed.

Patients randomised to the ablation arm undergo a second compulsory biopsy 6 months after treatment, conducted under US or CT guidance using local analgesia.

The ablation methods used depended on what expertise was available at the study sites. Sites offered only one form of ablation. The permitted ablation methods included RFA, CRYO and microwave ablation (MWA). The paragraphs below provide more detail about the ablative procedures and active surveillance.

Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency probes are carefully positioned into the renal mass lesion percutaneously by image guidance (usually using CT) and laparoscopicaly by direct vision. Radiofrequency probes deliver localised monopolar currents at ‘radiofrequency’ (400–500 kHz) to generate frictional heating in the adjacent tissue. Through direct and conductive heating, this achieves temperatures of up to 105 °C. Tissue destruction occurs by protein denaturation, cell destruction and coagulative necrosis in a sometimes ill-defined sphere around the probe tip. This ablation zone can be compromised by tissue perfusion-mediated cooling and larger adjacent flowing vessels but can usually achieve ablation zones of up to 4–5 cm in diameter. Sometimes probes may be repositioned to achieve the required ablation volume. The procedure is well tolerated but now more usually performed under general anaesthesia to achieve optimal probe positioning and outcomes. When necessary, adjacent bowel or other structures are displaced by contrast-tinted 5% dextrose for retroperitoneal hydrodissection; however, carbon dioxide can also be used. Therapeutic outcomes are confirmed by contrast-enhanced CT or MRI within 3 months post ablation. 44

Cryoablation

Cryoprobes are applied laparoscopicaly or percutaneously by image guidance. Localised tip temperatures of –150 °C and lower can be achieved by utilising the phase change of compressed argon gas delivered through multiple closed-needle applicators, arranged in a pattern to create a confluent ‘therapeutic’ ice ball. Within the induced ice ball, a range of tissue-lethal temperatures are achieved. At the –30 °C isotherm, a double freeze–thaw cycle is believed to yield uniform cell death. Tissue destruction is achieved through disruptive cell necrosis and microvascular injury.

Microwave ablation

Microwave ablation is very similar to RFA. A similar-sized needle/probe is inserted into the lesion under imaging guidance exactly as for RFA. The microwave probe causes heating of the tissue by heating the water molecules within it achieving similar temperatures to RFA, causing cell destruction and coagulative necrosis.

Active surveillance

Patients randomised to active surveillance were asked to adhere to the following schedule – urea and electrolytes including estimated glomerular filtration rate, modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) equation if performed clinically (there is no need to report this to the study team) and 6-month CT of the abdomen. Participants will undergo aCT of the abdomen (phasing and sequencing details were determined by site as per their local practice).

In case of progression of the growth rate or the size of the tumour in patients on the active surveillance arm, ablation or partial nephrectomy was offered depending on the facilities available in the participating centre.

Progression was considered to have occurred if:

-

growth rate exceeded 2.5 mm per 6 months or

-

tumour volume doubled within 6 months.

Ablation treatment

Our expectation was that ablative treatment would ideally be provided within 1 month of randomisation (SD 14 days) or as per standard national NHS protocols.

The following data were copied into the study electronic case report forms (eCRFs) from NHS medical records in relation to the provision of ablative treatment:

-

type of ablative treatment provided and date/time

-

whether or not the treatment was provided as per the randomisation allocation

-

any reason(s) for not providing treatment as per the randomisation allocation

-

any alternative treatments provided (e.g. surgical excision as an alternative)

-

complications of treatment and adverse events (AEs).

The ablation methods used depended on what expertise was available at study sites. Sites offered only one form of ablation. The permitted ablation methods included RFA, CRYO and MWA. More details about the ablative procedures and active surveillance are given below:

-

Patients recruited to the feasibility study who agreed to be randomised to either ablation or active surveillance underwent routine biopsy of the renal tumour to confirm that it was a cancerous growth. At centres where this biopsy is not routine, the participant must consent to the biopsy and to the study before the biopsy can be performed.

-

Patients randomised to the ablation arm undergo a second compulsory biopsy 6 months after treatment. This was conducted under US or CT guidance using local analgesia.

Methods

This was a multicentre RCT to establish the feasibility of ablation compared with active surveillance in patients with SRMs (< 4 cm). The study was conducted over 30 months.

The components were:

-

a feasibility multicentre RCT comparing ablation with active surveillance in patients with SRMs (< 4 cm) randomising on a 1 : 1 basis

-

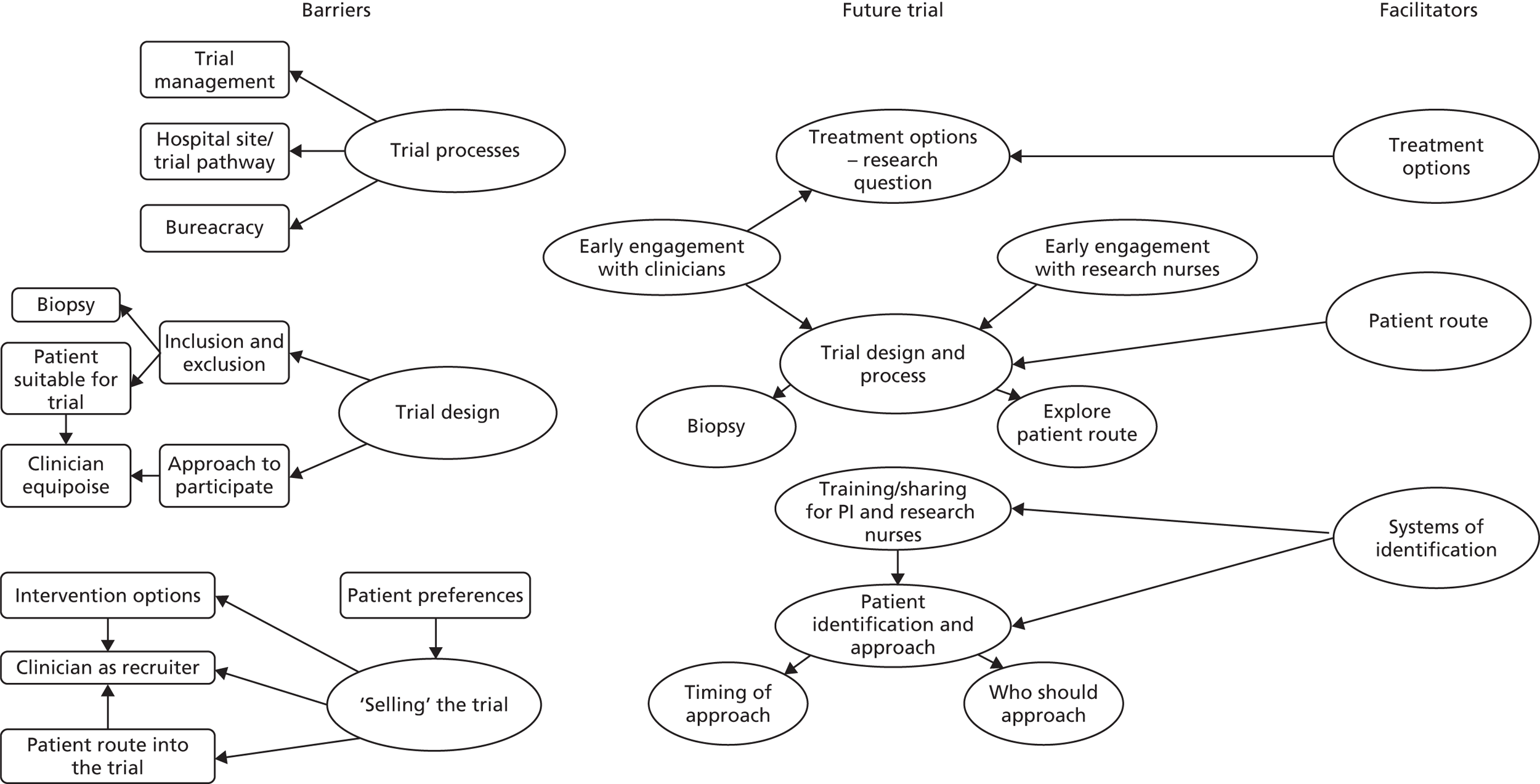

a qualitative process evaluation to inform future trial design by exploring patient, clinician and delivery staff experiences of the trial and barriers to participation and recruitment (see Parallel qualitative study)

-

a rehearsal of health economic data collection (see Economic analysis).

Target population

Participants were patients with renal cancer masses < 4 cm.

Inclusion criteria

-

Adults with a renal tumour < 4 cm (confirmation by radiology or by biopsy) in size.

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification system grades 1 or 2.

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

A CT/MRI scan of abdomen/chest with no evidence of metastases.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patient’s clinician does not feel they would be suitable for the trial (e.g. because of concomitant disease).

-

Multiple SRMs in one kidney.

-

Coagulopathy that cannot be corrected.

-

Previous participation in this study.

-

Inability to give informed consent (carer/proxy consent will not be allowed in this study).

Setting

The trial recruited from eight tertiary NHS centres offering kidney cancer treatment: one centre was in Scotland, two in the north of England and five in the south and south-west of England. These centres were identified from respondents to a national survey implemented by the NCTU.

Outcome measures

Primary

The primary outcome of the trial is feasibility defined as:

-

willingness of patients to be randomised, assessed by reviews of patient screening logs and defined as:

-

number of patients consenting to be randomised as a proportion of all eligible patients approached about the trial, with reasons for non-consent

-

qualitative assessment of barriers to, and facilitators of, recruitment

-

-

willingness of clinicians to randomise patients, assessed via qualitative interviews

-

assessment of retention and dropout rates, defined as:

-

number of patients who started randomised treatment as a proportion of the number randomised, with reasons for early dropout

-

number of patients who completed randomised treatment as a proportion of the number randomised, with reasons for early dropout (including death)

-

qualitative assessment of barriers to, and facilitators of, data collection and participant retention.

-

Secondary

Compliance with interventions and trial processes, defined as the number of patients who completed patient-reported outcomes at each time point as a proportion of the number randomised, including baseline, with reasons for non-compliance. Outcome measures for a definitive trial will be tested in the feasibility study and applied before treatment, at baseline and 3 months and 6 months after treatment.

The following measures were collected:

-

The Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) score. The SF-36 is a 36-item questionnaire that measures QoL across eight domains, which are both physically and emotionally based. A single item is also included that identifies perceived change in health, making the SF-36 a useful indicator for change in QoL over time and treatment. A summary of physical QoL [physical component summary (PCS)] and emotional QoL [mental component summary (MCS)] is produced. The percentage scores range from 0% (lowest or worst possible level of functioning) to 100% (highest or best possible level of functioning).

-

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G) score. The FACT-G is a 27-item compilation of general questions divided into four primary QoL domains: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being and functional well-being. It is considered appropriate for use with patients with any form of cancer.

-

The State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) score. The STAI is a measure of the severity of current symptoms of anxiety. There are two subscales: (1) state evaluates the current state of anxiety and subjective feelings of apprehension, tension, nervousness and worry; and (2) trait evaluates relatively stable aspects of ‘anxiety proneness,’ including general states of calmness, confidence and security. The range of scores for each subtest is 20–80 points, with a higher score indicating greater anxiety.

We also developed and tested health economic data collection tools in the form of a participant costs questionnaire (PCQ). The PCQ has two parts: (1) part A, to be administered at 3- and 6-month follow-ups, and (2) part B, to be administered at 6 months only.

The end of study was the last participant’s final study contact at their 6-month post-treatment follow-up.

Clinical trial screening, recruitment and consent

Identification and screening of patients for the feasibility study and parallel qualitative component

The trial flow chart (Figure 5) illustrates this process as well as data collection time points.

FIGURE 5.

Trial flow chart.

Potential participants were identified in the renal cancer clinics at participating sites. Site principal investigators (PIs) and/or clinical colleagues with documented delegated responsibilities for patient identification and screening performed this task.

An eligibility screening log was completed by the investigator to document participants’ fulfilment of the entry criteria for all patients considered for the study and parallel qualitative component and, subsequently, included or excluded. This information was anonymised and transcribed into screening logs on an ongoing basis via a secure online database.

Patients who agreed or declined to take part in the feasibility study were given an information sheet about the qualitative study and their permission to pass on their contact details to the qualitative researcher was requested. These patients were then contacted by the qualitative researcher, who answered any questions they had and, if they were happy to participate, arranged a convenient time to conduct an interview.

Clinical trial consent

Eligible patients were contacted by the centre PI/nurse lead/nurse specialist to invite them to participate in the trial and parallel qualitative component.

Informed consent was undertaken by appropriate site staff, as per the site delegation log. The delegated staff member (usually the centre PI/nurse lead/nurse specialist) explained the trial and parallel qualitative component to the patient, gave them the information leaflet and answered any questions they had.

Patients were encouraged to take the information leaflet home to discuss it with family and friends and asked to arrange a suitable time for a second meeting (allowing at least 24 hours for this). However, if participants had travelled a long distance to the hospital and would not be returning until an intervention visit, and if returning to hospital for the consent process would be a burden, consent was taken on the same day as information provision. In this case, a member of the local study team phoned the participant 48 hours later to confirm that they still wished to take part. This conversation was documented in the patient’s medical notes.

If a patient declined to participate in the trial and/or qualitative component, the study team (with permission from the patient) documented any reasons available for non-participation in the eligibility screening form and transferred this to the anonymised site screening log. The screening forms and logs ensured that potential participants were approached only once.

After ensuring that the patient had understood the information provided, the research team member delegated to take consent asked the patient to sign and date the consent form agreeing to participate in the feasibility study and/or the parallel qualitative component. Consent by the patient was witnessed and dated by the delegated research team member taking consent.

Written informed consent was always performed before randomisation or any other study-specific procedures/investigations.

The original signed consent form was retained in the investigator site file, with a copy in the clinical notes, a copy faxed to the NCTU (for centralised monitoring) and a copy provided to the participant.

For patients who agreed to take part in the qualitative study, a different consent form was completed at the time of the interview. Owing to the small subject population, the information sheet and consent forms were available only in English.

Clinical trial randomisation and blinding

Randomisation

When all eligibility checks had been made and written informed consent had been obtained, participants in the feasibility study were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio (stratified by centre) to either active surveillance or ablative treatment (RFA, CRYO or MWA as per centre practice). Randomisation was undertaken using the central web-based randomisation service provided by the NCTU.

The PI at the site or the individual with delegated authority accessed the web-based randomisation system. Patient screening ID, initials and centre (the stratifying variable) were entered into the web-based system, which then returned the allocation status (successful randomisation was followed up by an automated confirmatory e-mail to the site and relevant staff).

Participants were then informed of their allocated treatment group by the site PI or delegated individual following randomisation.

Following allocation, the site organised:

-

the procedure date for those allocated for ablative treatment

-

the active surveillance protocol for those allocated to the active surveillance arm.

Blinding

This was a feasibility study with the primary outcome defined as recruitment and retention rates and qualitative exploration of the patients’ experiences and understanding of the randomisation process and treatment options. Randomised treatments could not be blinded owing to the type of interventions being researched. For this reason, staff were not blinded for the follow-up assessments.

The baseline data capture assessments were to be completed before randomisation in order to reduce any bias in terms of patient attitude to allocated treatment affecting baseline data.

Data collection time points

Baseline

Following written informed consent, a routine, standard care biopsy was performed post consent as part of standard care prior to randomisation in study participants who had not already received this clinically. In sites that did not perform this procedure as standard care, the participant consented to the procedure and the study prior to the biopsy. A compulsory renal biopsy at the core of the ablated lesion was to be performed on all patients who had received ablative treatment. There were three possible biopsy outcomes based on the histology and immunohistochemistry interpretation:

-

failed biopsy

-

no tissue or non-renal tissue

-

normal renal tissue

-

-

fibrosis

-

suggestive of ablation site (inflammation, haemorrhage or haemosiderin)

-

not suggestive of ablation site (old fibrosis, no evidence of recent inflammation or haemorrhage).

-

inconclusive

-

-

renal tumour (classification and grade)

-

tumour cells with Ki67 reactivity

-

tumour cells without Ki67 reactivity

-

The baseline (pre-randomisation) visit involved collection and retrospective collation of the following data:

-

Demographics (e.g. age, sex).

-

Medical history.

-

Blood tests and urinalysis (taken as per local policy, with no requirement to report these to the study team or record them on the study eCRF).

-

SF-36.

-

STAI.

-

FACT-G.

-

Biopsy results were recorded in the baseline eCRF to document relevant details and presence of cancerous growth. If a routine diagnostic biopsy was not standard care at site, consent for the biopsy and the study was given prior to the biopsy procedure.

-

Tumour size and volume were recorded from routine CT/MRI scans already obtained during diagnosis of the tumour. Size was recorded in three planes of measurement (volume = 0.5326 × diameter 1 × diameter 2 × diameter 3). The volume calculation was not to be completed by site.

-

Confirmation was recorded in the eCRF that study inclusion criteria was fulfilled and no exclusion criteria applied.

Patients were randomised only after the baseline visit, review of biopsy results and checking of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Patients were not randomised if the biopsy showed a non-cancerous result.

Three-month follow-up (for all participants)

It was planned that the 3-month follow-up of patients in the ablation arm would take place 3 months (SD 14 days) after the treatment date. In the case of patients in the active surveillance arm, it was planned that this should take place 3 months post randomisation (SD 14 days).

At the 3-month follow-up, the following information was requested for all patients:

-

results of blood tests and urinalysis (taken as per local policy, with no requirement to report these to the study team or record them on the study eCRF)

-

SF-36 score

-

STAI score

-

FACT-G score.

Imaging results were obtained in order to document any changes in tumour progression as follows:

-

For patients receiving ablation (using any of the methods), data were to be captured from a routine CT/MRI of the abdomen performed within 3 months of the ablative procedure.

-

For patients receiving active surveillance, a 3-month post-randomisation scan of the abdomen was optional depending on routine practice at site.

The imaging should allow capture of the following data on the eCRF:

-

Tumour size and volume. Size was recorded in three planes of measurement (volume = 0.5326 × diameter 1 × diameter 2 × diameter 3). The volume calculation was not to be completed by site.

-

Confirmation of any progression of the tumour.

The following additional data were requested for all patients:

-

any changes in treatment plan (e.g. switching from active surveillance to ablation or surgical excision) with dates, times and types of procedures recorded and reasons for a switch in treatment (i.e. reason for crossover)

-

complications of treatment and AEs

-

results of the administration of the health economics questionnaire: PCQ (part A).

Six-month follow-up (for all participants)

It was planned that the 6-month follow-up of patients in the ablation arm would take place 6 months (SD 14 days) after the treatment date. In the case of patients in the active surveillance arm, it was planned that this should take place 6 months post randomisation (SD 14 days).

At the 6-month follow-up the following was requested for all patients:

-

results of blood tests and urinalysis (taken as per local policy, with no requirement to report these to the study team or record them on the study eCRF)

-

SF-36 score

-

STAI score

-

FACT-G score.

For patients who received an ablative procedure, data were captured from a routine follow-up CT/MRI scan of the abdomen performed at 6 months after the procedure in order to document any changes in tumour progression.

For patients receiving active surveillance, data were captured from a routine follow-up CT/MRI scan of the abdomen performed at 6 months after randomisation in order to document any changes in tumour progression.

The imaging allowed capture of the following data on the eCRF:

-

Tumour size and volume. Size was recorded in three planes of measurement (volume = 0.5326 × diameter 1 × diameter 2 × diameter 3). The volume calculation was not to be completed by site.

-

Confirmation of any progression of the tumour.

Tumour volume was calculated from the three-dimensional diameters using the formula to calculate an ellipsoid volume:

If there was progression of the growth rate or the size of the tumour in patients on the active surveillance arm, ablation or partial nephrectomy would be offered depending on the facilities available in the participating centre.

Progression was to be considered to have occurred if growth rate exceeded 2.5 mm per 6 months or tumour volume had doubled by 6 months.

The following additional data were captured for all patients:

-

any changes in treatment plan (e.g. switching from active surveillance to ablation or surgical excision) with dates, times and types of procedures recorded and reasons for a switch in treatment (i.e. reason for crossover)

-

complications of treatment and AEs

-

results of the administration of the health economics questionnaire: PCQ (parts A and B).

Sample size

The target recruitment was a total of 60 patients (30 randomised to the active surveillance arm and 30 to the ablation arm). This figure was based on a recommendation by Lancaster et al. 45 with respect to the number of patients required to yield meaningful estimates of parameters of interest in feasibility studies. With eight participating centres, it was estimated up to 120 patients could be approached; assuming a successful recruitment rate of no less than 50%, this would provide the 60 patients required.

Progression criteria to main trial

Recommendation to move to a definitive, fully powered, multicentre trial is based on the following calculations:

-

The upper 90% confidence interval for the proportion of patients recruited should exceed 50%. The trial should recruit at least 49 patients from 120 approached. This was based on a requirement that the underlying recruitment rate should be at least 50%. The exact 90% confidence interval corresponding to 49 successes from 120 Bernoulli trials is from 32.0% to 50.2% (with 48 successes from 120 trials, the upper interval drops to below 50%). Should recruitment be < 49 patients, this would provide evidence that the recruitment rate is too low and the feasibility of a RCT would be questionable. The upper 90% confidence interval for the retention rate (the proportion of patients recruited who have been followed up) should be ≥ 80%.

-

Economic assessment should suggest that further research likely to be worthwhile.

Adverse events and serious adverse events

The procedure for recording and handling of AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) was set out in the study protocol.

Adverse events

All non-serious AEs during study participation were to be reported on the study eCRF and sent to the trial manager within 1 month of the form being due. Severity of AEs was graded on a three-point scale (mild, moderate or severe). Relation (causality) and seriousness of the AE to the treatment was to be assessed by the investigator at site in the first instance. The individual investigator at each site was responsible for managing all AEs according to local protocols.

Serious adverse events

All SAEs during study participation were to be reported to the chief investigator (CI) within 24 hours of the site learning of their occurrence. The initial report could be made by telephone or fax. In the case of incomplete information at the time of initial reporting, all appropriate information was to be provided at follow-up as soon as it became available. The relationship of the SAE to study procedures was to be assessed by the investigator at site, as was the expected or unexpected nature of the AE.

Statistical considerations

As a feasibility study, the aim was to provide the foundations for future research in this area and to ensure that a larger-scale research project was feasible and acceptable. We therefore decided to estimate (1) subject availability; (2) the willingness of clinicians to randomise subjects to the trial, and of subjects to be randomised; (3) the proportion of randomised subjects who would complete the trial treatments and data collection; and (4) variability in the data necessary to inform sample size calculations for a future definitive Phase III trial. Our primary focus was, therefore, on descriptive statistics rather than hypothesis testing.

Statistical analyses

The primary purpose of this feasibility study was to assess recruitment and retention. This feasibility study was not designed to make an assessment of treatment efficacy and sample sizes will be too small to make an interim assessment of efficacy. We anticipate that, even if the initial rates are disappointing, the qualitative research might suggest improvements that could be made to recruitment procedures; hence, we have not defined a stopping rule for futility. This trial does not involve the use of drugs and hence issues of toxicity are not expected to be a concern. Complications and AEs are recorded as is usual.

Interval estimates (using 95% confidence intervals) of key parameters of interest will be determined including:

-

the number of patients who agree to be randomised as a proportion of eligible patients identified

-

the number of patients receiving ablation who experience perioperative complications, as a proportion of those randomised to ablation

-

the number of patients for whom we can collect outcomes at 3 and 6 months post treatment, as a proportion of those randomised

-

an estimate of variability (standard deviation) of the QoL measures that will be used in the Phase III trial.

Summary of changes to the project protocol

Changes to the protocol that were made and submitted to the REC are as follows.

Substantial amendment 1: 13 November 2014 (protocol version 2.0)

Changes were made to allow more flexibility for CT/MRI scanning at sites. Post-ablation CT/MRI would be undertaken at 3 and 6 months after treatment (ablation) and at only 6 months in the active surveillance arm. However, the participating centres could carry out additional scanning as per clinical policy of the centre. The scans at 3 and 6 months should be abdominal (we had originally stated chest and abdominal) but the scan phase used should be determined by standard practice at site. Sites can perform other scans as they deem clinically necessary. This change was based on feedback from participating sites. It was also decided that urine and blood values were not required for a feasibility study and there was no requirement for sites to report these results to the study team.

Substantial amendment 2: 16 December 2014 (protocol version 3.0)

Information on how to report SAEs was added.

Updates were also made regarding the baseline biopsy for participants, which resulted in changes to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Substantial amendment 3: 26 February 2015 (protocol version 4.0)

The requirement for patients to have a physical status classified as ASA grade 1 or 2 was removed. This was because many patients who would be suitable for randomisation would be elderly and may have other comorbidities that may place them in ASA 2/3 grade. Although patients being considered for surgery should be classified as ASA grade 1/2, it may not be necessary for patients who are being randomised to either active surveillance or ablation to meet this criterion and imposing this restriction might have adversely affected recruitment into the trial.

Following the first independent Data Monitoring Committee meeting, the protocol was altered with regard to statistical analysis. Sites were also allowed to tell participants who were unable to complete the follow-up questionnaires at the clinic appointment that these could be returned by post.

Substantial amendment 4: 12 February 2016 (protocol version 5.0)

Following the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme’s request to close the study early to recruitment in November 2015, a close-down plan was prepared and agreed by the HTA, which involved removing the collection of the 6-month follow-up data.

The following protocol changes were made:

-

Obtain verbal consent for the qualitative interviews that are carried out over the telephone.

-

Interview patients who agree to take part in the main study at two time points.

-

Reflect that all study data will be kept for 5 years, as per the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Archiving Clinical Research Documents standard operating procedure. 46

-

Inform patients about their contribution to the study at the end of the trial in a newsletter, which will include a lay summary of results.

-

Interview all health professionals that are involved in the recruitment process as well as clinicians.

Results

Trial approval and procedures

Ethics consideration

Ethics approval was sought and granted by the Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 Committee, NHS Health Research Authority (reference 14/NE/0155).

Clinical trial assessments/data collection

Pre-screening and screening

-

PIS provided.

-

Eligibility criteria checked.

Recruitment and randomisation

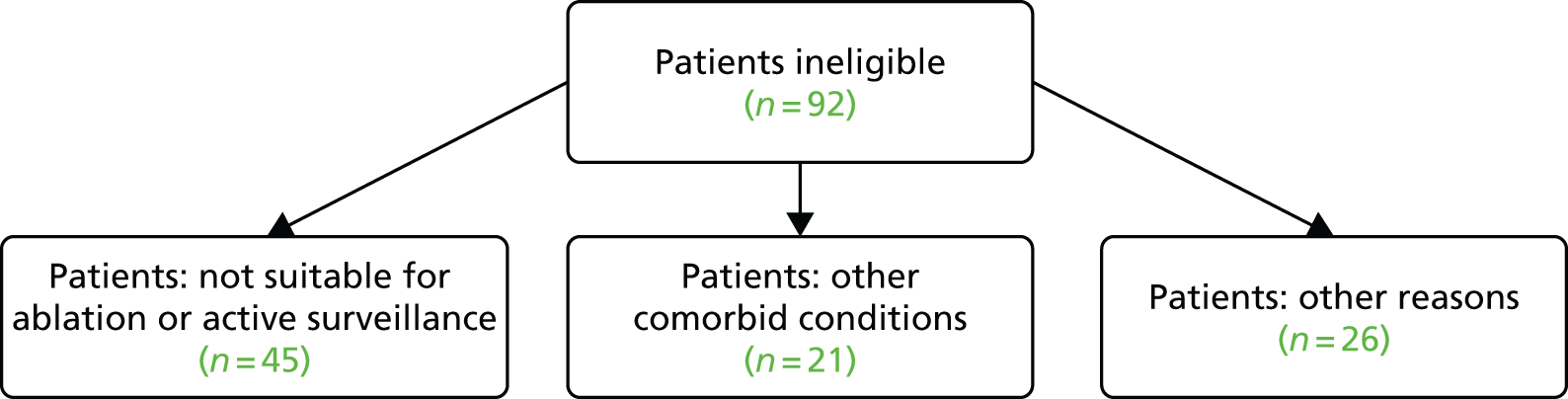

Eight sites screened a total of 154 patients as part of the trial recruitment, of whom 119 (77%) were deemed not eligible, including one patient found to be ineligible post consent (Table 2 and Figure 6).

| Site | Total number of patients screened | Total number of patients randomised |

|---|---|---|

| Newcastle | 69 | 1a |

| Southampton | 33 | 0 |

| St George’s | 23 | 3 |

| Glasgow | 10 | 2 |

| Bristol | 8 | 0 |

| UCLH/Royal Free | 6 | 0 |

| Stevenage | 5 | 0 |

| Leeds | 0 | 0 |

| Oxford | Never opened as a site | Never opened as a site |

FIGURE 6.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. a, A list of reasons for patients not being approached and other comorbidities can be found in Table 4, and reasons for declining in Table 5. b, Some sites did not have biopsy as part of standard care and therefore the patients needed to consent to the trial to confirm if their biopsy was cancerous.

The trial recruited the first patient on 11 June 2015 and its last patient on 12 November 2015. Three sites recruited six patients in total before the trial was closed to recruitment. Patients were followed up for a minimum of 6 months and the database was frozen on 23 May 2016.

A total of 81 (68%) of 119 patients were not approached about the trial, the reasons for which are tabulated in Table 3. The majority of patients were not approached because they were deemed to be suitable for surgery (40%) or because of early termination of the trial (33%) and 14% were not approached owing to suitability for active surveillance.

| Reason | Total number of patients |

|---|---|

| Clinician feels patient is more suitable for surgery | 32 |

| Trial closed early to recruitment prior to site approaching the patient | 27 |

| Clinician feels patient is more suitable for active surveillance | 11 |

| Size of the tumour | 3 |

| Clinician feels there is too much to consider in relation to clinical diagnosis | 2 |

| Patient not suitable for surgery | 2 |

| Renal biopsy prior to management plan | 1 |

| Clinical decision to ablate | 1 |

| Referral to local hospital for treatment | 1 |

| Location of tumour | 1 |

| Total | 81 |

A total of 21 (18%) of 119 ineligible patients had other comorbidities as listed in Table 4.

| Number | Information provided by site regarding other comorbidities |

|---|---|

| 1 | Previous lung cancer, cardiac complications, respiratory problems – COPD |

| 2 | Previous colon cancer and radical surgery (April 2015), lung and liver lesions, only for surveillance |