Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/05/11. The contractual start date was in May 2015. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Beresford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Context

In a recent James Lind Alliance (JLA) Childhood Disability Research Priority Setting Partnership for children with neurodisability,1 ‘therapy interventions’ featured strongly in its top 10 priority areas, or research questions (Box 1). Indeed, as we have highlighted in bold, this topic constituted 4 of those 10 areas.

-

Does the timing and intensity of therapies (e.g. physical, occupational and speech and language therapy, ‘early intervention’, providing information) alter the effectiveness of therapies for infants and young children with neurodisability, including those without specific diagnosis? What is the appropriate age of onset/strategies/dosage/direction of therapy interventions?

-

To improve communication for children and young people with neurodisability, (a) what is the best way to select the most appropriate communication strategies? And (b) how to encourage staff/carers to use these strategies to enable communication?

-

Are child-centred strategies to improve children’s (i.e. peers’) attitudes towards disability (e.g. buddy or circle of friends) effective in improving inclusion and participation within educational, social and community settings?

-

Does the appropriate provision of wheelchairs to enable independent mobility for very young children improve their self-efficacy?

-

Are counselling/psychological strategies (e.g. talking therapies) effective in promoting the mental health of children and young people with neurodisability?

-

What is the (long-term) comparative safety and effectiveness of medical and surgical spasticity management techniques (botulinum neurotoxin A, selective dorsal rhizotomy, intrathecal baclofen, orally administered medicines) in children and young people with neurodisability?

-

Does a structured training programme, medicines and/or surgery speed up the achievement of continence (either/or faecal or urinary) for children and young people with neurodisability?

-

What strategies are effective to improve engagement in physical activity (to improve fitness, reduce obesity, etc.) for children and young people with neurodisability?

-

Which school characteristics (e.g. policies, attitudes of staff) are most effective to promote inclusion of children and young people with neurodisability in education and after-school clubs?

-

What is the long-term safety, effectiveness and sustainability of behavioural strategies and/or drugs (e.g. melatonin) to manage sleep disturbance in children and young people with neurodisability (outcomes include time to onset, duration, and reducing the impact on the family)?

From Morris et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

The following overarching research question was generated from this process: what therapy interventions are, could and should be offered to children with neurodisability to help improve participation outcomes?

This question captures the complexity of this topic including issues such as the different ‘schools’, or approaches, to therapy; ‘dosage’ or intensity; the timing and duration of a therapeutic intervention; and the skills and qualifications of staff delivering the therapy. Over and above this is the challenge of identifying and measuring the ‘active ingredients’ of therapeutic interventions.

The existing evidence on this topic is very limited. For example, recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance2 on the management of spasticity in children was not able to provide guidance on the timing or intensity of any of the interventions it included. The Guidance Development Group also noted that interventions are themselves poorly defined. 2 Evidence reviews in this area note the lack of rigorous research and the very limited nature of the current evidence base. 2–8 There are, however, indications of a growing interest, and investment, in research in this area. Studies to date have engaged in exploring the impact of therapy interventions on motor/physical functioning9–11 and participation12–14 using a range of study designs. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) itself has funded research in this area. 3,15

To inform future commissioning of research on this topic, the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme’s Maternal Neonatal and Child Health Panel commissioned a qualitative scoping study into current practice and perceived research needs through one of NIHR’s Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme’s Evidence Synthesis Centres.

Study objectives

The objectives of this scoping study were to:

-

identify and describe the current techniques, practices and approaches to delivering therapy interventions for children with non-progressive neurodisability that seek to improve participation as defined by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2002 International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework16

-

describe therapeutic approaches that are identified by professionals as promising or innovative but are not currently (routinely) delivered by the NHS

-

identify how and why these interventions may vary according to the nature and severity of the impairment

-

describe the factors that influence decision-making regarding the ‘therapeutic prescription’, including the nature and severity of the impairment

-

understand the dimensions that constitute a therapeutic intervention from the perspectives of NHS health professionals, children and parents (e.g. the physical environment, location, use of/access to equipment, staff skills/qualification, parent involvement/delivery and self-management)

-

seek the views of NHS health professionals, parents and children regarding the ‘active ingredients’ of therapy, and how to capture or measure these

-

understand, and compare, the ways in which professionals and families currently conceive therapy outcomes, the meaningfulness of ‘participation’ as a therapy outcome and how these may vary according to the nature and severity of the impairment

-

map NHS health professionals’, parents’ and children’s views of the evidence gaps related to therapy interventions for children with non-progressive neurodisability, and identify views on the issues that need to be accounted for in the design of any future evaluations.

Defining the scope

The scope of the study was set according to the following criteria.

-

Intervention: therapy interventions that meet the ‘patient group’ and ‘setting’ criteria below and target outcomes within the participation component of the ICF framework. 16 The domains captured by this concept include participation in learning and applying knowledge; general tasks and demands; communication; mobility; self-care; domestic life; interpersonal interactions and relationships; major life areas; and community, social and civic life. This criterion includes interventions delivered directly by therapy staff, or by school staff, parents and/or children, in the home or in a school setting, under instruction from therapy staff.

-

Patient group: children and young people up to school-leaving age with non-progressive neurodisability predominated by physical/motor impairment, including those without a specific diagnosis. This includes children with: cerebral palsy (defined as physical, medical and developmental difficulties caused by injury to the immature brain), brain injury, some metabolic and neurogenetic disorders and developmental co-ordination disorder, as well as those without a specific diagnosis. Within and across these patient groups, the extent to which physical/motor abilities are affected varies considerably. For many of these children and young people, the presence of neurodisability results in a number of physical/motor and cognitive impairments.

-

Setting: outpatient, community, school and/or home.

An overview of the therapies under investigation

At the outset, it is useful to offer a brief overview of the therapies included in this scoping study. Thus, this opening section offers a brief definition of each therapy and the ways in which it works in order to achieve its objectives. We also provide a brief history of each discipline within the UK context, noting here that its development and emergence in other countries may not be similar. Finally, in understanding what these three therapies do, it is important at this stage to point out that therapists’ work may involve direct work with a child and/or training and supporting others (e.g. parents, school staff and therapy assistants) to implement and use techniques, procedures and/or equipment.

Occupational therapy

The objective of occupational therapy with children with neurodisability is to provide practical support to enable them to overcome any barriers that prevent them from doing the activities (occupations) that matter to them. ‘Occupation’ refers to practical and purposeful activities that allow people to live independently and have a sense of identity. This could be essential day-to-day tasks, such as self-care, learning or leisure. Occupational therapists use the following techniques:

-

advising on alternative techniques to achieve a desired occupation

-

making changes to the child’s home or school environment

-

providing equipment.

The early history of occupational therapy is located in a response to the need to rehabilitate people recovering from tuberculosis who had been subject to extended periods of bed rest. The idea of graded engagement in activities emerged with the view to support and enable patients to return to employment once they were fully recovered. In responding to the need to rehabilitate soldiers returning from the first world war, the discipline took further significant steps forward, with national training courses and professional colleges established in the 1930s across the UK. These colleges merged in the 1970s, forming the Royal College of Occupational Therapists (RCOT).

Physiotherapy

For children with neurodisability, the objective of physiotherapy is to promote, develop or restore physical movement and strength and the ability of the child to perform functional activities in their daily lives. A further objective is to reduce pain. Physiotherapists treat or manage movement and body structure/function impairments or disorders through:

-

tailored exercises/physical activity

-

manual therapy

-

education and advice.

Physiotherapy’s origins can be traced back to Sweden and the sport of gymnastics. The Royal Central Institute of Gymnastics was established in Stockholm in 1813. [The Swedish word for physiotherapist (physical therapist) is ‘sjukgymnast’ = ‘sick-gymnast’.] In 1887, physiotherapists were officially recognised and other countries soon followed suit. In 1894, four nurses in Great Britain formed the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP), and this remains the profession’s national body. The need to rehabilitate individuals with polio and soldiers returning from the first world war served to promote and develop the profession during the first half of the 20th century.

Speech and language therapy

For children with neurodisability, speech and language therapy addresses difficulties with communication or with eating, drinking and swallowing. To address these difficulties, speech and language therapists can work in a number of ways:

-

providing education and advice

-

developing and supporting the implementation of programmes to help to develop communication and/or the management of eating and drinking problems

-

providing feeding/drinking equipment

-

providing communication aids and devices.

Speech and language therapy began to emerge as a distinct discipline in the late 1800s and early 1900s. A national professional body (the College of Speech and Language Therapy) was formed in 1945; again, the recovery and rehabilitation needs of soldiers returning from a world war drove developments within the profession. The college became the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) in 1995.

The structure of the report

Chapter 2 reports the study design and methods. Chapters 3–10 present study participants’ views of and beliefs about topics and issues relevant to, and contributing to, the study objectives. We start by providing a high-level picture of the way therapy services to children with non-progressive neurodisability are organised and delivered in England (see Chapter 3). Next, in Chapter 4, we move on to a detailed exploration of participants’ accounts of the overall approaches and schools of thought which currently inform physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy. Then, placed under that framework, we offer an overview of how these therapies are being practised. In Chapter 5 we present parents’ accounts of the provision and delivery of therapy. After this, we turn to exploring study participants’ views and beliefs about the active ingredients of therapy interventions: this is reported in Chapter 6. Following this, in Chapter 7, we describe their views about therapy outcomes, including the notion of participation. The next two chapters consider issues relevant to future research. Chapter 8 reports on accounts of the current ‘research environment’ within the therapy professions, and Chapter 9 describes participants’ views on the challenges of evaluative research and reports the methodological research, which participants identified as being necessary to progress research into therapy interventions, including their evaluation. Our final findings chapter (see Chapter 10) reports the priorities for research identified, or nominated, by study participants. The study findings are discussed (see Chapter 11) and reflected on in the remaining chapters of this report (see Chapters 11 and 12).

We would note at the outset that this is a complex topic area and some of the issues investigated were explored from two perspectives (e.g. describing current practice, and the challenges of researching practice). We have strived to avoid unnecessary repetition but it is sometimes required, particularly given that this report may not be read in its entirety.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

A descriptive case study design, taking the delivery and practice of therapy interventions as the case, was adopted. 17 Qualitative research methods (interviews and focus groups) were used and a purposive approach to sampling18 was implemented.

The proposed design was to use group and individual interviews and/or a brief online survey to ascertain the views and experiences of different stakeholder groups, namely:

-

child/disability leads in national professional groups

-

therapy practitioners and assistant practitioners based in community paediatric teams/services, paediatric specialties and tertiary clinics/centres

-

training placement supervisors within therapy services used by therapy training institutions (both undergraduate and master’s qualification routes)

-

clinical academics/researchers currently active in the field

-

community paediatricians and paediatric neurologists

-

parents

-

children and young people.

Deviation from the proposed design

Three changes were implemented during the early stages of fieldwork as it became clear that planned methods of data collection and choice of stakeholder group were not appropriate. The changes implemented were as follows.

-

The method used to consult with community paediatricians and paediatric neurologists was changed from a survey to an interview. Early into fieldwork it became clear that the topics under investigation were complex and nuanced and it was important that representatives of this particular participant group had the opportunity to contribute in the same way as other participant groups. Thus, the decision was made to change the design to individual interview, and to reduce the proposed sample size.

-

Early in the project we discovered that undergraduate qualifications in physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech and language therapy are generic, that is, not specific to particular age groups or conditions. Therefore, we decided that it would not be fruitful to pursue training placement supervisors as a key participant group. We did, however, record participants’ involvement in training and supervision of new trainees, and explored their views on general training curricula when appropriate.

-

Finally, following careful discussion within the team, we added a further ‘miscellaneous’ stakeholder group to the sample. This was in response to emerging findings regarding the importance of the perspectives of managers of children’s community health services, educationalists and private practitioners.

Study participants and rationale for inclusion

A number of different stakeholder groups were identified to take part in the study. Each group was selected on the basis of the unique and valuable perspective that it could bring to the project. Table 1 details each participant group, the data collection method used and the rationale for the group’s inclusion. It should be noted that some study participants were members of more than one stakeholder group (e.g. a research-active therapist). These participants were categorised according to our primary reason for seeking to recruit them to the study. However, we were cognisant of these multiple roles, and the interview topic guides were adjusted according.

| Stakeholder group | Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical academics and researchers (including therapists, other clinicians and academics) | Individual interview | To provide evidence on recent or ongoing research and the issues and challenges associated with evaluating a therapy intervention, and in the case of those in teaching or supervisory roles, the content of training curricula |

| Representatives of national professional groups representing physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech and language therapists | Individual interview | To offer a ‘high-level’ view of different practices and approaches currently being implemented by physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy services |

| Therapy practitioners | Focus groups | To supply a collective detailed picture of the delivery of therapy and decision-making around the therapeutic prescriptions |

| Consultant paediatricians and paediatric neurologists | Individual interview | To allow the scoping study to place and understand therapy interventions within the wider context of the care and management of children with neurodisabilities |

| Parents | Focus groups | To ensure that families’ views and perspectives are represented |

| Children and young people | Focus groups | To ensure that patients’ views and perspectives are represented |

Ethics approval

The study was approved by a subcommittee of the University of York’s Ethics Committee (Department for Social Policy and Social Work) (reference BB06/2016).

Recruitment and consenting

In building the overall sample, within each stakeholder group the research team adopted a purposive sampling approach that aimed to ensure a balance of representatives of physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech and language therapists, as well as representation from different parts of the country. The target sample sizes for each stakeholder group are shown in Table 2.

| Stakeholder group | Sample size, (n) |

|---|---|

| Clinical academics and researchers | ≈10 |

| Representatives of national professional groups | ≈6 |

| Therapy practitioners | 8 × ≈7 group participants (N = ≈55) |

| Consultant paediatricians and paediatric neurologists | ≈6 |

| Parents | 4 × ≈8 group participants (N = ≈32) |

| Children and young people | 4 × ≈6 group participants (N = ≈25) |

Recruitment took place in two overlapping stages: a first stage to recruit individual interview participants, and a second stage to recruit group interview participants. Recruitment materials, including study information sheets and consent forms, can be found in Appendices 1–3.

Stage 1: recruitment

The first stage of recruitment comprised desk-based research to identify individual interview participants. This involved searches of the NIHR funding database and high-impact therapy journals for academic clinicians and researchers currently (or recently) active in the field of therapy interventions. At the same time, the professional bodies for the different therapies were approached, via the leads of their respective paediatric and/or specialist neurodisability divisions, to each nominate representatives who could provide a ‘national’ overview of their profession at a research and a practice level. The research team then used a snowballing method, whereby existing recruits were asked for suggestions of other relevant people to include in the study from among their colleagues and professional networks. This iterative recruitment process continued until, from initial analyses and discussions within the research team, data saturation on key or critical themes had been achieved.

All individual interview participants were sent an e-mail invitation to take part in the study. This e-mail introduced the research, the nature of the interview and the topics for exploration. A study information sheet was attached. If no response was received, a member of the research team followed this up by telephone or a further e-mail. Arrangements were then made with those who responded positively for a suitable date and time to conduct the interview. Finally, a confirmation e-mail was sent, to which was attached an additional information sheet setting out the scope of the interview and giving final details about the interview. For those taking part in a telephone interview, also attached to the confirmation e-mail was a consent form outlining the protocols of the interview so that participants could familiarise themselves with these before giving their recorded verbal consent at the beginning of the interview. The three people who were interviewed in person gave written consent before the interview took place.

Stage 2: recruitment to focus groups

In the second stage of recruitment, we sought groups of frontline practitioners, parents, and children and young people to take part in focus group discussions. Recruitment methods varied according to the group in question.

Practitioner groups were recruited through direct representations to the lead practitioners and heads of therapy services we had recruited to individual interviews, or by securing a workshop slot at forthcoming professional conferences. In the case of the former, a member of the research team liaised with a ‘site co-ordinator’ to make arrangements for the meeting. This included sending the co-ordinator an information sheet with details about the study to forward to all those taking part. This sheet also explained that, at the start of the meeting, participants would be asked to give their written consent to take part in the study. In the case of the latter, when recruitment took place on the day of a conference, participants were given both a study information sheet and a consent form to sign at the beginning of the focus group ‘workshop’. All practitioner focus group participants were also asked to complete a brief pro forma regarding their professional backgrounds. Those attending focus groups were offered a personalised certificate of attendance to include in their career portfolios.

In the case of parents and children and young people, we aimed to recruit pre-existing groups in the belief both that this would be more time efficient and that pre-existing groups can move more quickly onto the particular task or discussion and, within the context of a single data collection event, are therefore more likely to yield high-quality data. For parents, we were able to use an established parent group co-ordinated by our own research unit. The study topic was introduced as an agenda item and discussed accordingly at a regular meeting. We then approached several condition-specific voluntary organisations for potential parent groups as well as local groups of the National Network of Parent Carer Forums (www.nnpcf.org.uk). For children and young people, we took a similar route and made representations to sports teams, youth and social clubs and school/university groups, a national voluntary umbrella organisation that represents disabled children and their families, and, via colleagues, existing young people’s research advisory groups. A flier was designed and distributed for this purpose. A ‘thank-you’ shopping voucher (worth £20 for parents and £10–15 for children and young people) was used.

When groups agreed to participate, a member of the research team liaised with the group co-ordinator to arrange a venue, date and time for the meeting and to request that they distribute study information sheets on behalf of the research team. Participants were asked to sign a consent form at the start of the meeting.

Sample

In all, 109 people took part in the study. Thirty-eight individual interviews (including one joint interview) and 10 focus groups were carried out.

Individual interviews: sample

Ninety-three per cent of those invited to participate in an interview accepted the invitation. Of those who did not, one was unable to take part because they were abroad when fieldwork was taking place; one (who had recently changed jobs) failed to respond to our invitation; and one declined to take part as they felt that others would be more suitable. Table 3 displays the role, or post, of the professionals who took part in individual interviews.

| Role | Number of individual interview participants |

|---|---|

| Academic researcher based at university | 9 |

| Cliniciana based in the NHS | 17 |

| Cliniciana based in a specialist centreb | 5 |

| Private practitioner operating nationally | 3 |

| Professional body employee operating nationally | 5 |

| Total | 39 |

Some of those recruited were at the forefront of research on childhood neurodisability. Areas of research interest were diverse, encompassing a range of specific interventions and approaches within physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy, participation outcomes and tools of outcome measurement. Similarly, clinical expertise covered a range of health conditions associated with childhood neurodisability and significant motor impairment, but primarily neuromuscular and skeletal movement disorders and oromotor and communication disorders.

Academic researchers and clinical academics were based in universities and specialist research institutes, in NHS hospital and community trusts and in specialist treatment and rehabilitation centres serving the NHS. As well as leading their own research and managing under- and postgraduate teaching programmes or large clinical caseloads, many had additional roles and responsibilities. Within their own organisations these included managing research strategy, building research capacity and capability, providing clinical and student supervision, and positions as heads of service and professional leads. Externally they included providing strategic leadership via active membership of networks such as the British Academy of Childhood Disability; the European Academy of Childhood Disability; NHS clinical governance networks and independent clinical advisory bodies; and organisations such as Disability Matters. A few had been members of guidance development groups for NICE.

Individual interview participants were drawn from across the disciplines of physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy, and from paediatric medicine (Table 4). Of those recruited who had a therapy background, all were members of their national professional body. Within these organisations, some were members of specialist sections providing professional direction and guidance to their members, such as the Specialist Section Children, Young People and Families of the RCOT and the Association of Paediatric Chartered Physiotherapists within the CSP. Of those who were members of the RCSLT, some were voluntary specialist advisors in their field of expertise and/or members of local Clinical Excellence Networks that meet regularly to share and develop common interests and expertise. In the same way, some of the paediatricians recruited held voluntary roles within the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, such as on the Specialist Advisory Committee for Neurodisability.

| Type of training | Number of individual interview participants |

|---|---|

| Occupational therapist | 12 |

| Physiotherapist | 7 |

| Speech and language therapista | 10 |

| Paediatrician/paediatric neurologist | 9 |

| Otherb | 1 |

| Total | 39 |

As was our aim, there was also representation in the interview sample from across the country as defined by the four broad areas of NHS England’s regional teams (Table 5). The largest group, from the North of England, was made up of nine people from the north-east and three from the north-west. Representatives from RCOT, CSP and RCSLT worked countrywide, as did two of the private practitioners.

| Region (based on NHS regional teams) | Number of individual interview participants |

|---|---|

| North of England | 12 |

| Midlands and East of England | 3 |

| London | 7 |

| South of England | 7 |

| Countrywide | 8 |

| Othera | 2 |

| Total | 39 |

Practitioner focus groups: sample

Forty-four therapists took part in one of six focus groups. Over half of these were physiotherapists, the smallest therapy profession represented among those interviewed individually. Most worked for the NHS in the community, predominantly in the north of England. Overall, the therapies they represented, and the organisation, type of setting and locations in which they were based, are reported in Table 6.

| Participant characteristics | Practitioner group (n) | Total (N) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (N = 4) | B (N = 7) | C (N = 15) | D (N = 9) | E (N = 3) | F (N = 6) | ||

| Therapy | |||||||

| OT | 4 | 5 | 9 | ||||

| PT | 2 | 14 | 9 | 25 | |||

| SLT | 3 | 6 | 9 | ||||

| Other | 1a | 1 | |||||

| Organisation base | |||||||

| NHS | 7 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 32 | ||

| Charitable | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 | |||

| Private | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Other | 1a | 1 | |||||

| Practice base | |||||||

| Hospital | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Community | 5 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 29 | ||

| Mix | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Other | 4b | 1a | 3b | 9 | |||

| Missing | 1 | ||||||

| Regional base (based on NHS regional teams) | |||||||

| North | 7 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 26 | ||

| Midlands and East | 3 | 3 | |||||

| London | 2 | 2 | |||||

| South | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | |||

| Other | 2c | 2 | |||||

| Missing data | 3 | 3 | |||||

The practitioners had wide-ranging experience within physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy. The mean number of years that practitioners had been qualified was 14.2 years (median 11 years). Most were employed in band 6 or 7 posts. Over 60% reported some previous experience of research, although this varied: investigator, involvement in delivering a programme under evaluation, research within undergraduate/postgraduate studies, service audit and/or membership of research discussion forums. These characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 7.

| Practitioner group | Number of years qualified | Grade of post | Previous research experience | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 3 | 3–10 | 11–20 | > 20 | Other | Band 5 | Band 6 | Band 7 | Band 8 | Other | Yes | No | |

| A (n = 4) | – | 2 | 2 | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | – | – | 4 | – |

| B (n = 7) | 1 | 3 | 3 | – | – | 1 | 3 | 3 | – | – | 3 | 4 |

| C (n = 15) | 1 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 1a | 1 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2a,b | 12 | 3 |

| D (n = 9) | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | - | 2 | 3 | 4 | – | – | 1 | 8 |

| E (n = 3) | – | 2 | 1 | – | – | – | – | 3 | – | – | 3 | – |

| F (n = 6) | – | 1 | 2 | 3 | – | – | 2 | 3 | 1 | – | 4 | 2 |

| Total | 4 | 15 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 15 | 20 | 3 | 2 | 27 | 17 |

The participants’ caseloads were also diverse in the type of neurological conditions covered, but often their patients had multiple impairments. Box 2 lists the main neurodisabilities represented in the sample’s caseloads.

-

Acquired brain injury.

-

Cerebral palsy.

-

Complex motor disorders.

-

Congenital and rare syndromes.

-

Developmental co-ordination disorder.

-

Dysphagia.

-

Genetic disorders/chromosomal abnormalities.

-

(Global) developmental delay.

-

Head injuries.

-

Learning disabilities.

-

Metabolic disorders.

-

Neuromuscular conditions.

-

Spina bifida.

-

Spinal injuries.

Parent focus groups: sample

In total, four focus groups were conducted with 26 parents. Of these parents, 20 were mothers, five were fathers and one was a grandfather (Table 8).

| Parent group | Mothers (n) | Fathers (n) | Grandfathers (n) | Total in group (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| B | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| C | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| D | 6 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| Total | 20 | 6 | 1 | 26 |

Parents were recruited locally from parent-carer forums and our unit’s parent consultation group, and at a weekend-long event held by a condition-specific children’s charity and attended by parents of preschool-aged children from across the country (Table 9).

| Parent group | Type of organisation (n) | Regional base of parents (based on NHS regional teams) (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local parent-carer forum | Condition-specific charity | In-house parent consultation group | North of England | Midlands and East of England | South of England | Missing data | |

| A (N = 4) | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | ||

| B (N = 7) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| C (N = 6) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | ||

| D (N = 9) | – | 1 | – | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

Within these four parent focus groups, 28 children and young people (15 boys, 13 girls) were represented. There was some variation in age (Table 10).

| Parent group | Gender of children represented (n) | Total number represented (n) | Age of children (years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Mean | Median | ||

| A (N = 4) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 14.5 | 16 |

| B (N = 7) | 7 | 3 | 10 | 13 | 14.5 |

| C (N = 6) | 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 8 |

| D (N = 9) | 3 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 3 |

| Total | 15 | 13 | 28 | 9 | 7 |

The health conditions represented by these groups were various and, again, included children with multiple complex needs. The conditions reported by parents are listed in Box 3. It should be noted that, as would be expected for this population, many children had more than one diagnosis, including some degree of learning disability and/or autism and/or sensory impairment.

-

Asperger’s, autism and ADHD.

-

Ataxia and dystrophy.

-

Cerebral palsy (mild to severe).

-

Communication and sensory processing needs.

-

Complex epilepsy.

-

Down syndrome.

-

Dyspraxia.

-

Fine motor impairments.

-

Genetic syndromes.

-

Hemiplegia.

-

Hydrocephalus.

-

Learning disabilities (mild to severe).

-

Non-verbal AAC users.

-

Scoliosis.

-

Spina bifida.

AAC, alternative communication; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Children typically had more than one diagnosis.

Challenges of recruitment

Whereas recruitment of the individual interview participants was straightforward, recruitment of the focus group participants proved more difficult. These challenges of recruitment are reported separately for the focus groups with practitioners, parents, and children and young people.

Practitioner groups

We aimed to recruit practitioner groups through therapy service departments. The practitioner contacts made through the individual interviews proved invaluable as a ‘way in’ to these departments. Although services were always supportive of the research, resource issues meant that our approaches were not always successful because of limited staff capacity.

Parent groups

With parents, the difficulty was finding pre-existing groups of parents with children who met the study inclusion criteria. There are many more parent-led/voluntary organisations for other neurodisabilties (e.g. autism or progressive conditions) or that focus particularly on learning difficulties. We approached several condition-specific voluntary organisations with this in mind, but we were unable to find existing groups of parents we could access. In the end, a compromise was reached, whereby we accessed groups of parents through voluntary organisations that were brought together specifically for the purpose of the study.

Children and young people groups

Various avenues were pursued to recruit pre-existing groups of children and young people with neurodisability. Given the abstract nature of the subject matter to be discussed, we were wary of the difficulties of capturing thoughts on this, in a meaningful way and in the time scale available, from young people who had moderate or severe learning disabilities. We therefore sought pre-existing groups of children and young people who did not have significant cognitive impairment.

Approaches were made to special schools, disability/special needs sports teams, youth and social clubs, and school/university groups, through a national umbrella organisation for disabled children’s charities, and through professional research networks with established young people’s research advisory groups. When relevant, we also sought suggestions from some of the practitioner and parent focus groups for appropriate children’s and young people’s groups to contact. In the event, none of these avenues was fruitful. We would note that this was not entirely unexpected. Securing meaningful engagement of children and young people in studies such as this – which are constrained by time and resources – is often very challenging. 1 We would recommend that a specific piece of work exploring children’s and young people’s views be carried out, informed by the findings from this scoping study. It is useful to note here that Morris et al. 1 made a similar recommendation in response to their experiences of conducting the JLA research priority setting exercise for children with neurodisability.

Data collection

Individual and group interviews were used to ascertain the views and experiences of different stakeholder groups. Individual interviews aimed to collect in-depth data on the participant’s particular area of expertise, whether that was within or across different therapy services. Group interviews allowed a collective exploration of the topics presented for discussion.

The interview topic guides

The content and focus of the interviews and focus groups differed across the stakeholder groups in accordance with the rationale for recruiting them to the study.

Semistructured topic guides of key themes and subthemes to cover were developed for the individual and group interviews. Table 11 reports on the broad themes covered in the different stakeholder topic guides. (See Appendix 4 for exemplar topic guides.)

| Stakeholder group topic guide | Themes covered | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current state of research evidence | Participation outcomes and outcome measurement | Active ingredients of therapy interventions | Challenges to evaluating interventions | Research priorities | Overview/experiences of current therapy practice | Role in building and promoting evidence-based practice | Role of practice therapies | Parental involvement in delivering therapies | |

| Clinical academics/researchers (n = 13) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Professional bodies (n = 7) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Other practitioners (n = 12) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Paediatricians (n = 7) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Practitioner groups (n = 6) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Parent groups (n = 4) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

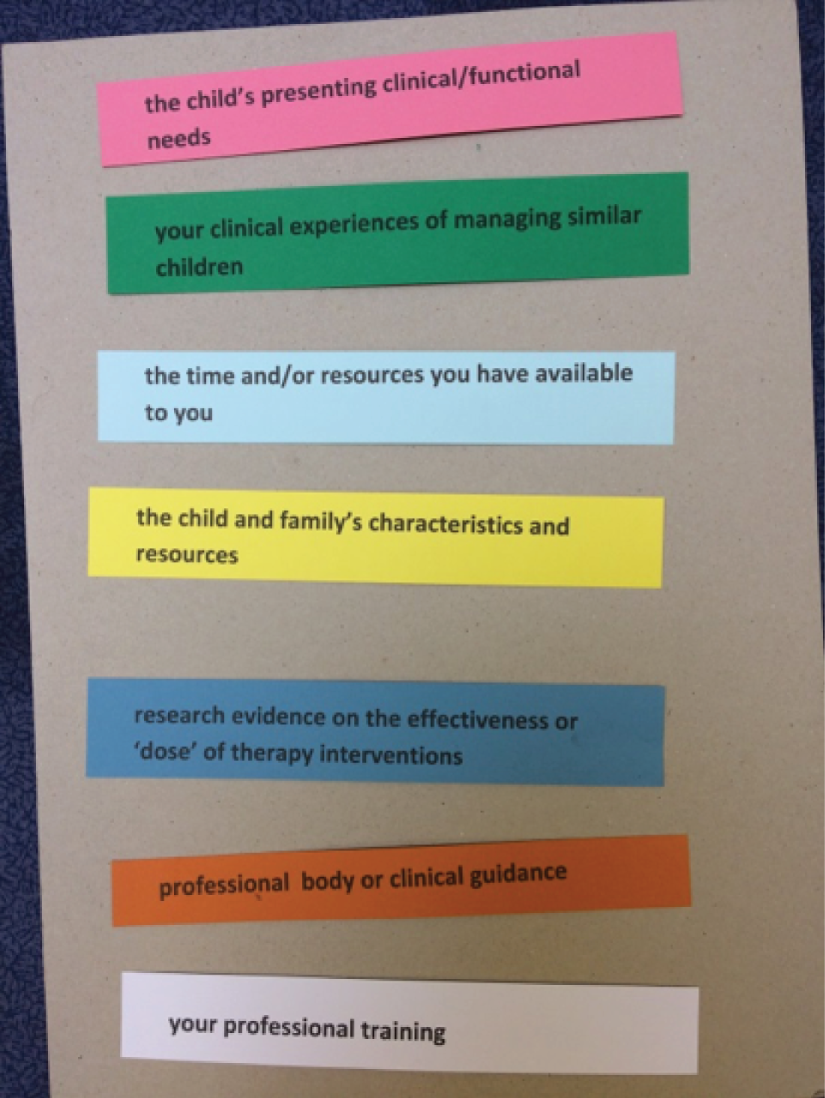

Two group exercises were used during the focus groups to facilitate discussion. In larger groups, subgroups were created to work on these tasks. The first was to rank, in order of priority, factors that influenced or informed decision-making about the management of a case. Participants were given a set of cards, each describing one factor. Once they had discussed and agreed a ranking order, they were asked to affix the cards to a mounting board in order of most to least important (Figure 1). The boards were then displayed and discussed among the whole group.

FIGURE 1.

Example of output from focus group ranking exercise.

The second exercise involved participants completing a worksheet about their priorities for research. The worksheet was divided into three sections for this purpose: research about specific interventions, research about particular groups of children (e.g. diagnosis, need, age) and research about the way therapy is organised and delivered. Participants were advised that they did not have to complete all of the sections. Again, the responses were shared and discussed among the group.

Fieldwork

Fieldwork took place between August and December 2016 and was shared by the three members of the research team. Most of the individual interviews were conducted over the telephone, but three were carried out face to face. Except for two instances when focus groups were convened via a national meeting with participants attending from across the country (one practitioner group and one parent group), the group interviews took place in the localities of the participants. The groups were facilitated by one or two researchers. Interviews lasted approximately 1 hour and, with permission, were digitally recorded.

Data analysis

Audio-recordings of the interviews and focus groups were used to create detailed summaries, using a template derived from the headings and subheadings of the relevant topic guide. These summaries included verbatim quotations. The position of verbatim quotations on the audio-recording (in terms of minutes and seconds) was noted.

The research team met regularly throughout the data collection period to reflect on a priori and emerging topics and issues. Once all interview/focus group summaries were complete, the team met again on three separate occasions to discuss and develop, through consensus, ‘mind maps’ of the themes and subthemes covered in the data relevant to the research questions.

These maps were then modified to create a structure into which analytical writings, summarising findings on each theme, could be organised. These formed the basis of the project report. Drafts of the findings sections of the project report were shared and reviewed by all members of the research team, and final versions were agreed.

Verbatim quotations are used extensively throughout the report to illustrate points made in the text and to ensure that the voices of study participants are directly presented. For professional study participants, each individual participant or focus group is identified by a unique code (A1–X2; C1–H1 focus group participant). The use of this coding system allows the reader to evaluate the use of quotations from across the breadth of the sample. To ensure anonymity, we do not provide details of the characteristics of individuals quoted. When appropriate, in the preceding text, we do specify individuals’ profession or other relevant information.

Chapter 3 An overview of the organisation and delivery of therapies

Introduction

This chapter reports the evidence gathered from professionals regarding the way in which therapy services for children with non-progressive neurodisability are currently organised and delivered, and non-statutory sources of physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy. It is important to note that this study did not systematically map service organisation and delivery issues. However, study participants included those with a ‘national-level’ view and those who had worked in a number of service settings and geographical locations, or reported themselves to be at the forefront of service development and service organisation. This chapter describes a variable and changing landscape, with those changes being driven by a number of different factors. Parents’ views and experiences of therapy provision are reported in Chapter 5.

The organisational settings of therapy services

Therapy services for children with non-progressive neurodisability are located in tertiary, secondary and community health-care settings. Tertiary provision includes single-centre and ‘hub-and-spoke’ models. Tertiary (and some secondary-level) services take the form of ‘standalone’ therapy-specific teams (e.g. complex communication needs, neurorehabilitation, respiratory physiotherapy) and therapists within specialist (sometimes residential) provision for particular populations (e.g. acquired brain injury, profound physical impairment, dysphagia) working within either multidisciplinary or single-therapy teams. Such services may also support the work of non-specialist children’s therapy teams.

Children with neurodisability may use one or more of these different levels of provision at some stage during their lives. For example, a child with acquired brain injury may be initially cared for in a specialist centre before being transferred to the care of the local community-based team. Therapists in secondary care settings tend to have a more time-limited involvement – addressing transitory, acute needs (e.g. respiratory interventions; rehabilitation following hip surgery) – or being the first point in a therapy intervention pathway before discharge to community teams (for example, early rehabilitation following a stroke). In terms of community-based therapy services, where therapy services sit, and how they are organised, is largely determined by the wider structure of community paediatric services in that locality. Within this provision, therapy teams or services may be organised in terms of population groups and/or the type of functional impairment. The usual care pathway appears to be referrals being made to therapy teams via a consultant paediatrician-led service. However, as described below, alternative models were reported.

Finally, in addition to occupational therapy services within the NHS, occupational therapists work in local authority housing and social care departments. Here they are involved in assessments and delivery related to the adaptation of children’s homes and the provision of associated equipment (e.g. hoists, bathing aids or toileting aids). They may also be directly employed by schools.

The locations in which therapists work

Therapists work in a number of settings: the hospital ward, outpatient clinic, nurseries, schools, homes and the community settings or services a child uses. However, this was reported to vary between therapies, the therapist’s remit and local practices or commissioning arrangements. Occupational therapists were most likely to report seeing children in their home or other community settings. Physiotherapists based in community health teams reported working out of clinics and through home visits, although the extent to which the latter was implemented appeared to be highly variable. A preference for this way of working appears to be connected to adopting participation-focused approaches and incorporating therapy exercises or procedures into everyday activities. However, local commissioning arrangements and a service lead’s opinion appeared to influence the extent to which this was routine practice. For children with long-term therapy needs, the move into school, particularly if to special school, typically meant that sessions or appointments with physiotherapists and speech and language therapists took place at school.

The organisation of therapy provision

The traditional model

Across all of these settings, the traditional model is that physiotherapy, speech and language therapy and occupational therapy services work as ‘unitherapy’ teams, with assessment and intervention delivery occurring separately, or in isolation, from other types of therapy interventions a child may be receiving. Physical barriers were reported as acting to prevent even informal modes of integrated working:

We are often still based in separate buildings by profession, or separate offices. Right down to what desk you sit at. A huge amount of clinician time and effort goes into trying to mitigate the negative impact of that.

L1

Although not necessarily regarded as a problematic model for children with a short-term need for a specific therapy, difficulties with this model with respect to children with complex long-term needs were identified across all study participant groups. It had the potential to lead to different or conflicting priorities in terms of the purpose or focus of therapy interventions and the perceived objectives.

Alternative models

In addition to the traditional model of service organisation and provision described above, study participants reported other models. These were typically presented as ‘atypical’ or ‘ground-breaking’ and were observed across all levels of care: tertiary, secondary and community services. They included the following.

Multitherapy teams

Perhaps the most frequently reported alternative to ‘unitherapy’ teams, multitherapy teams comprised two or all three therapies. When described, ‘joint/bitherapy’ teams were always a collaboration of physiotherapy and occupational therapy. This was explained by the two therapies being more likely to be interdependent in terms of achieving the desired outcomes for the child.

Integrated, multiprofessional approaches

This model comprises an integrated approach to the assessment and care of children with neurodisability involving therapists, relevant paediatric specialisms and, potentially, other professionals working together. This approach includes integrated working arrangements across teams as well as multiprofessional teams. There is also variability in the extent of integrated working. For example, the assessment and care planning process may be integrated but actual intervention delivery may still be located across ‘unitherapy’ rather than ‘multitherapy’ teams.

Transdisciplinary or ‘primary provider’ models

A couple of interviewees described a ‘transdisciplinary model of working’. For example, a joint physiotherapy and occupational therapy team had implemented a ‘generic therapist’ role. Here, a single therapist – physiotherapist or occupational therapist – works with the child, but draws on both occupational therapy and physiotherapy intervention approaches. A similar model was described within the context of a multitherapy occupational therapy/physiotherapy/speech and language therapy service, whereby each profession is recognised as having a ‘unique contribution’ but a single therapist acts as the main conduit by which all the therapies are delivered. These interviewees believed that families preferred this model, as it offered a co-ordinated approach.

Therapist-led services

Therapist-led services were also described. Regarded as innovative and recently implemented, this model appeared to be used to manage impairments of function that required brief, time-limited intervention, and when a diagnosis from a paediatrician, or another relevant specialist, was not required to proceed with therapy.

Factors driving changes in service organisation

Three main factors emerged from interviewees’ accounts as appearing to drive these changes.

-

A policy driver: the Children and Families Act (2014)19 – which demands joint working across health, education and social care, a single, overall assessment of need, and co-ordination and integration of services – was identified as prompting reviews of the way therapy services are organised.

-

Participation outcomes and goals-focused approaches: the shift to regarding participation as a key outcome for therapy interventions, and the accompanying move to goals-focused approaches to assessment and intervention, emerged as a key driver to changing the way therapy services were organised and delivered. (We report this in more detail in Chapter 4.) Interviewees described how the achievement of a goal will require the inputs and interventions from all, or two, of the therapies as well as from other professionals.

-

The need/desire for greater efficiency: reduced resources, coupled with high demand, were reported to have led to alternative approaches being sought. Reconfigurations of service models in order to reduce wait times, prevent duplication both within assessment processes and in the delivery of interventions, and make best use of therapists’ skills and expertise were all cited as reasons for seeking to change models of service organisation and delivery.

Interviewees who had been involved in restructuring or reorganising therapy provision typically described this as a difficult process. Creating multitherapy teams that were truly integrated was challenging and, often, ‘work in progress’.

Approaches to provision

Interviewees described two broad approaches to therapy provision, particularly within physiotherapy and speech and language therapy. First, and the more traditional approach, is open-ended involvement with a case until ‘recovery’ or broad therapy objectives have been achieved. For some children, this may mean a relatively short period of contact with a therapist. For others, with significant and enduring physical and motor impairment, their involvement with therapists is long term – often up to the point of transfer to adult services. Second, and presented as a relatively recent innovation, is an ‘episodes of care’ model, with re-referral into the service for further input.

The driver behind this shift in approach was primarily attributed to limited resources and managing demand. Managers and senior staff interviewed reported significant and sustained cuts in funding:

In the past children will have come on to our caseload and stayed on it. Now we discharge children after a block of intervention and then the child has to be re-referred after 12 weeks to get further support. A lot of services operate an episode of care model. It seems to be a capacity-based decision rather than a clinical need-based one.

V2

Within occupational therapy, given the focus of this particular therapy, it appears that involvement may have always been more episodic, although it is not clear from our data if the duration of those episodes is changing over time.

Across all approaches to provision, parents and school staff are often those delivering the actual intervention to the child. To some extent this model of delivery has been in place for a while, but interviewees’ accounts suggest that this is being further embedded in the way services are organised and therapy interventions are delivered. We return to this issue in Chapter 4.

Private providers

Among some groups of children with neurodisability, private providers are not an uncommon source of therapy provision. A number of factors seem to be at play here. Interviewees noted that a dominant belief among parents is that the amount and intensity of direct work on a child – delivered by a therapist (or themselves, under instruction from a therapist) – was the predominant reason for purchasing additional therapy:

Often parents come along with the idea that more therapy is always better . . .

W1

. . . [it] ends up with a battling mentality in which parents feel that NHS professionals aren’t doing their best for them. And that’s very, very counterproductive.

V1

This belief, coupled with concerns about the level, or amount, of therapy being received from statutory health care, led to parents seeking alternatives. It was frequently observed that private providers tended to use more traditional, high-dose/high-intensity intervention approaches. This aligned with parents’ desires to be ‘doing all they can’ for their child. For some parents, the appeal of private providers can be that it removes demands on them, as parents, to deliver therapy to their child. A further reason identified by study participants as to why parents seek private provision is that parents can learn (via word of mouth, or through internet searches) about an intervention, or intervention approach, that they believe would benefit their child but that is not available through the NHS, owing to a perceived evidence gap, resource constraints and/or commissioning decisions.

Professionals reported that the use of private providers could introduce another aspect of their management of a case. Sometimes this related to co-ordinating the two sources of therapy or managing conflicting advice. They were aware that parents did not always reveal the non-NHS interventions they were purchasing or using, which could, in itself, lead to difficulties.

Parent-identified and -delivered ‘therapies’

In addition, our work with parents revealed that some had sought out, and were using, additional therapy interventions without any therapy professional input or oversight. Again, seeking these alternative sources of therapy was driven by a perceived inadequacy of statutory provision. Some professionals expressed concerns that the roll-out of personal health budgets may mean increasing numbers of parents purchasing ‘unproven’ interventions:

I worry about the vested interests of companies trying to make money out of parents and their personal budgets. I would love a decent evidence base with which to advise families.

V1

There are companies selling things, yet what they do isn’t based on published evidence nor does it do what they claim. Yet parents will come to us and say ‘Why aren’t you doing this?’.

H1

As a parent, your natural instinct is to do anything you can for your child. But you are rubbing up against salesmen of equipment manufacturers, many of whom are very moral and decent people. [But] my fear is that sales sometimes drive the agenda.

O2

Chapter 4 Therapy interventions: approaches and techniques

Introduction

An objective of this study was to describe current approaches and practices in the delivery of therapy interventions to children with non-progressive neurodisabilities. In this chapter, we present findings regarding this that have emerged from our interviews with professionals. We offer a broad view of the current situation placing this, when necessary, in the historical context of the development of physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech and language therapy. Parents’ reports of their experiences of therapy – for example the approaches and specific techniques – are presented in Chapter 5.

Understanding therapy interventions

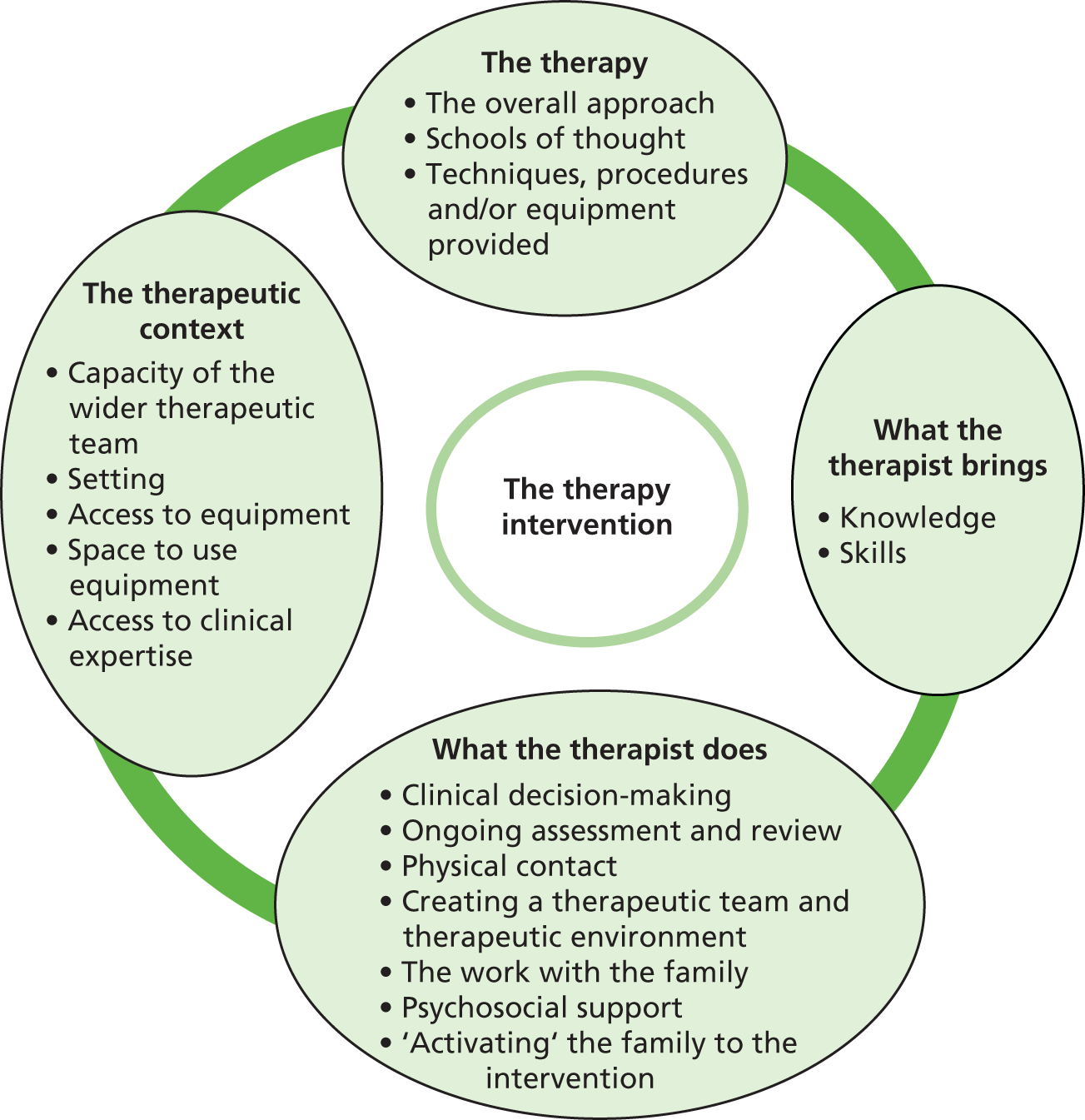

Physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech and language therapy can be described and understood at three levels:

-

the overall approach a therapist brings to the assessment and management of a case

-

the schools of thought that inform views regarding the appropriate way to manage a case

-

the specific techniques, procedures, activities and equipment used.

There is some interaction, or interdependency, between these levels (Figure 2). Certainly, the two higher levels influence what a therapist actually ‘does’ with a child. Equally, the overall approach will determine, at least to some extent, what are regarded as legitimate or acceptable schools of thought.

FIGURE 2.

Therapy intervention constructs and their interconnections.

In this chapter, we report what our interviews with professionals reveal about these different ways of conceptualising or understanding therapy interventions. We also report how thinking on these matters is shifting and changing. We do not claim that this is the only way to understand and conceptualise therapy interventions, but is the clearest solution we found to presenting interviewees’ accounts.

The overall approach

Four different, but interconnecting, facets appear to contribute to this concept of the ‘overall approach’:

-

the objective of the intervention

-

the role of the therapist

-

the role of the child and family

-

the place of the therapy in the life of the child.

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

Before moving on to describe each aspect of ‘overall therapy approach’ in turn, it is useful to offer a brief overview of the WHO’s ICF, published in 2002. This conceptual model was widely referred to in our interviews. It was clear that it not only offers a language and framework by which therapy interventions can be understood, but has also been a catalyst for change in the overall approach of therapies. It is a conceptual model that has been endorsed by all three profession,20–22 with guidance issued to support its implementation (e.g. College of Occupational Therapists, 2004; Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, 2005) as well as being integrated into the training of new therapists. 23

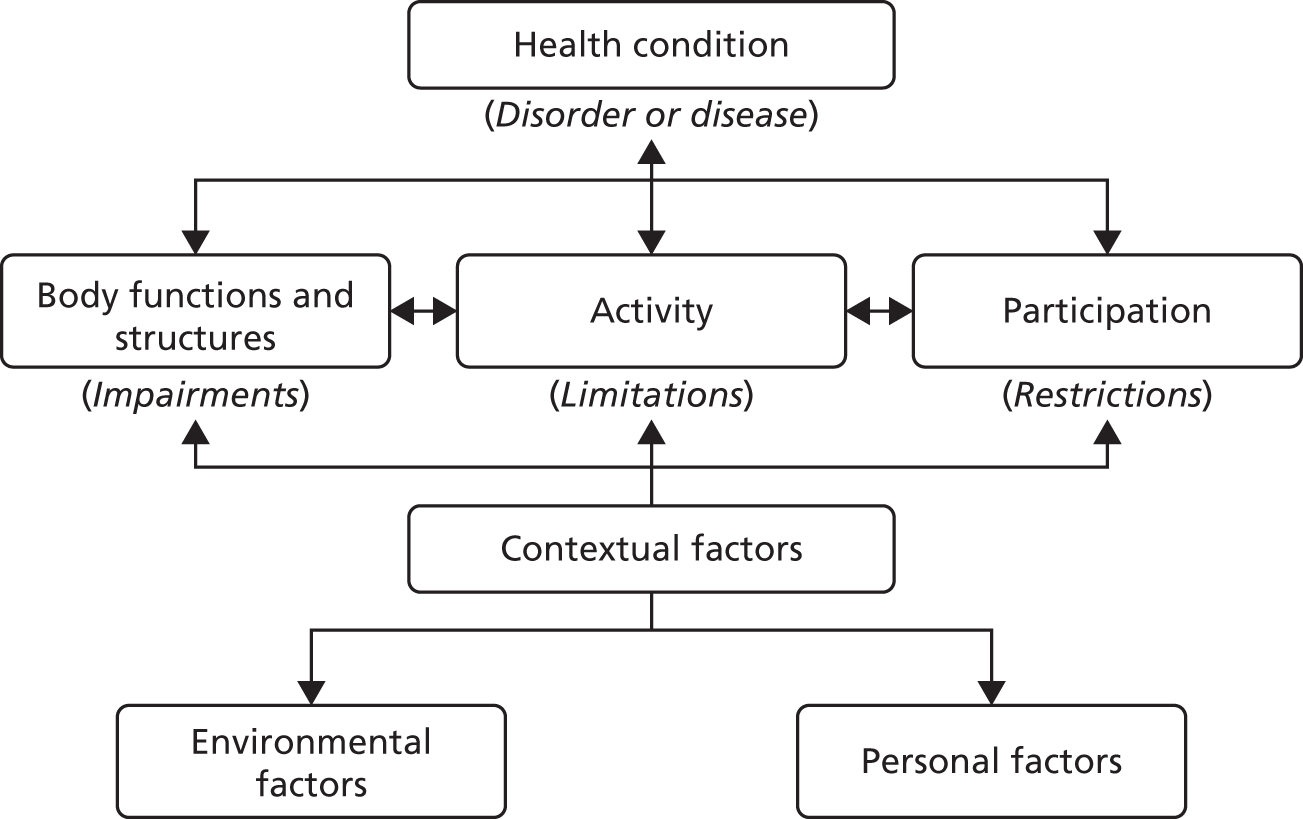

In 2002, WHO proposed a conceptual model of disability that sought to bring together elements of the pre-existing medical and social models of disability, and incorporate them into a biopsychosocial model of disability. 16 Figure 3 offers a representation of this model.

FIGURE 3.

The ICF model of disability and health.

The meanings of the terms used in this model are as follows.

p. 10. 16 Reprinted from Towards a Common Languages for Functioning, Disability and Health: International Classification Framework. World Health Organization, © 2002. URL: www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf (last accessed 21 December 2017)

Overall approach: the objective of the intervention

In describing the overall objectives of a therapy intervention, interviewees framed this in terms of the ICF model. Three possibilities were described.

-

First, the ‘deficit model’: here remedying physical/body dysfunction and distortion is seen as the end point, or objective, of therapy interventions or, as one interviewee described it, ‘fixing the child’ (OT-PB-01). This model can be regarded as the original starting point of all three professions.

-

The second approach focuses on the achievement of specific activities, or occupations, that the child’s physical impairments have limited or rendered difficult, for example walking or articulating verbal speech. When interviewees offered a chronology of the emergence of these different models, this approach was described as emerging in the 1990s.

-

The third approach is child/family focused, goals focused, in which the objectives of therapy are driven and guided by the child’s/family’s goals and desires. These goals should be expressed in terms of the child’s participation in everyday life, or life situations, that is relevant and meaningful for a child of that age (e.g. learning, self-care, communicating, moving about, friendships and being part of a family), rather than outcomes related to body structure/function or achievement of specific skills or activities. Within this approach, addressing dysfunction or impairment is no longer the key focus. This opens up alternative ways of intervening which may be as, or more, successful. One example is achieving independent mobility through the use of a wheelchair rather than through a lengthy and intensive physiotherapy programme. Another example is teaching a child to use augmentative and alternative communication systems and devices to communicate, or supplement verbal communication, rather than simply seeking to achieve verbal communication through speech and language therapy input:

The really complex ones, you can do as much therapy as you like, and it probably won’t make much difference – so let’s focus on the environment and the equipment and stuff . . .

A1

A slightly different, or concurrent, conceptualisation emerged from interviews with occupational therapists. It had a more dichotomous stance: a ‘deficit-focused’ model versus a focus on achieving occupation, or participation, through modifications to the environment and/or providing equipment to facilitate the child’s engagement or participation.

The operationalisation of these approaches

A number of issues emerged during our discussions with interviewees regarding these three possible approaches to understanding the objectives of a therapy intervention.

First, there was clear evidence that all the approaches are being used by therapists. Furthermore, not all interviewees believed that the different approaches were incompatible. Thus, some viewed them as being necessarily connected, with achievements of particular skills or reducing pain, for example enabling higher-level outcomes (expressed in the goals identified by children or parents) to be achieved, even if not explicitly identified at the outset of the intervention:

[Let me give you this example] . . . A 7-year-old boy, with quite a severe impairment, was delighted that his newly acquired ‘pick-up and release skills’ meant he could now take a tissue out of a box and wipe his nose himself. He is now independently participating in his own personal care, and this gave him better self-esteem in the classroom.

K1

Start with the child or impairment, working on the body structure and functions as a means to an end to achieving the desired occupation. Start with the occupation, looking both at the child and the environment to see what can be done to achieve the occupation. Both approaches are still occupational therapy. Yet the same situation can be looked at in different ways, involving different interventions, and with different people. That can be confusing and challenging . . . and it’s a sensitive topic within the profession. Some favour one, some the other, and others use a bit of both.

N1

Second, a goals-focused approach was widely endorsed and, reportedly, operationalised. However, the implementation of participation-oriented, goals-focused approaches within the therapies was viewed by some as ‘under development’ as opposed to already achieved:

. . . in my service you can see a three-generation approach. The first generation used to do ‘body function/structure stuff’ working on things like fine motor skills, co-ordination, range of movement and postural stability. Then, about 12 years ago, with the second generation, it became much more about targeting an activity and participation. However, in reality it was more about targeting activity and the child’s skills than true participation. Now a third-generation model is needed, where [we] really target participation. [So my question is] . . . ‘What’s our third-generation approach going to be so that it actually targets participation head-on through the right hypothesis-change mechanism?’.

L1

There’s been a bit of a shift in terms of whether body structure and function is meaningful in its own right, or whether it’s an intervention which enables children to participate in something. We’ve started on that shift, but we aren’t all the way.

F1

This was also evidenced in some of our interviews when interviewees described goals that ranged across all of the ICF concepts. Thus, a goals-focused approach was being operationalised, but not necessarily within a framework of participation.

Third, it was not clear whether the shift to goals-focused approaches was simply a matter of the influence of new ‘ways of thinking’ informed by both ICF and family-centred practice,24 or whether stringent cuts in funding had forced therapists and services into a position where intense work on body structure and function was no longer possible.

Fourth, there appeared to be a degree of confusion about the differences between the ICF concepts of ‘activities’ and ‘participation’, and the definitions offered for both varied considerably. Participation, as set out in the WHO report, was viewed by some as challenging in terms of its definition and measurement, in terms of both appropriate time points and the indicators of participation used. This is something we discuss in detail in Chapter 7.

Finally, new ways of working, intervention programmes and practices have emerged or been developed in response to this shift in approach from deficit to activities or goals-focused approaches. Examples of these referred to by study participants included, for physiotherapy, the MOVE programme (www.move-international.org/) and for occupational therapy, goals-directed training. 25

Overall approach: the role of therapist

There was a consistent view that, over recent years, the role of therapists in the delivery of interventions to children with neurodisability has shifted. A number of interviewees – and across all therapies – referred to a ‘consultative model’ whereby the therapist assesses the child, develops an intervention programme and then trains, or ‘upskills’, others (assistant practitioners, parents, child, classroom assistant and/or teacher) to deliver it, with supervision and ongoing monitoring. This approach was regarded as more prevalent within community, rather than secondary care or acute, settings.

Two drivers for this change were presented by interviewees. First, many interviewees noted the reduction in funding for therapies for children with neurodisability, which had forced changes in the way therapists worked. The way NHS trusts have chosen to address resource constraints has, however, differed. In some trusts, specialty posts have been maintained – albeit operating in a consultative role – whereas in others, posts have been lost and/or downgraded. A second driver – attributed to the number of ‘influential leaders’ in the field – was the acknowledgement that, to be effective, therapy interventions cannot be restricted to what are relatively occasional sessions with a qualified therapist in a clinic setting:

. . . it’s an intelligent way of capacity building. Also, in schools it’s the staff who know the children better than the therapist does. The therapist will come in one or two times a term so it would be ludicrous to expect a change with that amount of contact.

R2

There was a diversity of opinion as to whether or not this change is for the better. The dominant concern was that non-therapists may not be sufficiently skilled or competent to respond to changes in functioning or to evaluate the impact of the interventions and adjust the intervention accordingly:

There is something about the skill of the therapist in working with any one child with particularly complex needs, to be able to tune in to how the child is responding to what you are doing with them. . . . To make the kind of adjustment that you need to do to make the therapy work there and then, and to know whether you can push onto something more complex . . .

O2

. . . I think intervention effectiveness is actually being diluted . . . by having less skilled staff. I can understand why they are doing it, but I think it’s short-sighted.

Z1

A second concern was adherence to intervention programmes. This was typically spoken about in terms of the multiple demands on people’s time and/or a lack of understanding of the intervention programme and its objectives. Finally, this represented a very significant change in the day-to-day work of therapists that may be difficult to accept and assimilate:

Within practice there is a reluctance to change that [move to less hands-on and more activity-based therapy], particularly among those who have been trained in manual handling of patients and how to support and help them move.

F2

Furthermore, it was noted that parents may struggle to accept the consultative approach. Many interviewees believed that seeking the input of private practitioners was often due to a desire for more intense input from a qualified therapist.

Overall approach: the role of the child and family

The goals-focused approach described earlier was often spoken about alongside descriptions of a change in the way children, and their families, are regarded within the context of a therapy intervention. The shift in thinking described was from regarding the child/family as passive recipients to viewing them as active participants in the therapy intervention. Some interviewees referred to this is a move from the ‘expert practitioner’ model to the ‘expert parent’ model:

We are looking for children and families to be active in the rehabilitation process. So, instead of a child coming into hospital and having all this therapy done to them, they are a real active participant in what they are doing and they’re actively involved in their rehabilitation process.

L2

Occasionally, this shift was located, or attributed, within a wider change in the NHS to a focus on self-management. This was perceived to be driven by both an outcomes-focused approach and constrained resources.

Again, there was a sense that this study was being conducted at a time when thinking within each of the professions on such matters was in a state of change. Thus, we had interviewees who firmly advocated opposing approaches. Equally, there were interviewees who described the approach they were working towards, but had not yet attained:

I want us to get to the situation where we are working with families, giving them the right information – and doing that well and early enough – so that they can be empowered to . . . make decisions.

A1

Therapists have always worked very closely with parents, and older children too, in terms of goal-setting and goal preferences. The idea of offering people informed choice is not there . . . at the moment.

P2

With respect to the move to place children and families more centrally in decision-making and ‘condition management’ processes, a number of interviewees referred to ‘health-coaching’ models or programmes which were informing or influencing changes in their ways of working.

Overall approach: integrating therapy into everyday life

The final interconnecting strand within the concept of ‘therapy approaches’ is integrating therapy interventions into everyday life. Again, interviewees spoke of a shift in thinking: taking therapy out of clinic settings, and delivering in the settings and environments where the child spends his or her time. Linked to this were notions of integrating the therapy procedures into everyday activities and aiming to design the intervention to maximise engagement and motivation:

I say to families that it’s no good just doing things for a short time, so it’s better to incorporate activities into everyday life, or position their child so they can do something else as well. That way activities get embedded and done more often, and so more likely to make a difference.

F1

Once more, the extent to which this approach was dominant in an individual therapist’s practice was dependent on the extent to which their practice reflective goals-focused, participative approaches.

A number of constraints to adopting such an approach – particularly around the settings in which therapists practised – was noted, particularly when, in the past, therapy was delivered in outpatient clinic settings. Here, commissioners could be reluctant to resource therapists working in the child’s everyday settings.

Schools of thought

One of the topic areas NIHR wanted this study to investigate and report on was current ‘schools of thought’ within physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech and language therapy. This has proved difficult to elucidate.

However, it is possible to present three sets of ‘schools of thought’ revealed in our interviews with study participants:

-

‘traditional’ schools of thought

-

emerging schools of thought

-