Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/141/03. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The draft report began editorial review in June 2016 and was accepted for publication in January 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Amanda J Farrin is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board and the HTA Commissioning Strategy Group. Allan O House is a member of the HTA Efficient Study Designs Board. Sarah Fortune worked as a Consultant Clinical Psychologist in the NHS prior to this project. Sandy Tubeuf is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Programme Grants for Applied Research Committee.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Cottrell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

What is self-harm?

In this study, in accordance with the commissioning brief and in line with current UK clinical practice, self-harm is defined as any form of non-fatal self-poisoning or self-injury (such as cutting, taking an overdose, hanging, self-strangulation, jumping from a height and running into traffic), regardless of the motivation or the degree of intention to die. This definition includes what in the USA would be described as non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidal behaviour. 1

How common is self-harm?

Self-harm in adolescents is a major public health issue and, globally, suicide is the most common cause of death in the 10–24 years age group after road traffic accidents. 2 A relatively recent systematic review reported that 9.7% of adolescents had self-harmed in the previous year in the community,3 and a recent pan-European study reported a lifetime prevalence of 27.6% for NSSI,4 with rates of self-harm higher among females than males, although in later adolescence there is nearly parity between male and female hospital attendances. 2

At the community level, the most common methods of self-harm in young people are cutting and overdose. 5 Only one in eight episodes of self-harm leads to a hospital presentation,5 but, even so, it is likely that > 30,000 adolescents present to hospital in England each year having harmed themselves. 6 In studies based on presentations to general hospitals in the UK, most adolescents have harmed themselves by taking an overdose, with self-poisoning with analgesics being particularly common. 7

Self-harm is associated with an elevated risk of overall mortality2,8–11 and suicide. In one follow-up study of 15- to 24-year-olds who had presented to hospital following an episode of self-harm between 2000 and 2005, the overall number of deaths from all causes was 3% of the cohort at follow-up in 2007, four times higher than expected. This was mainly because of an excess of suicides (2% of the cohort), which were 10 times more frequent than expected. The main risk factors for suicide were male gender, previous multiple episodes of self-harm, prior psychiatric history and high suicide intent. 12,13 Because of the young ages at which these deaths occur, the number of life-years lost to the community as a result of suicide and the impact on family members is significant.

The estimates of the risk of 1-year repetition of self-harm vary between 5% and 25% per year:14,15 18% in a recent UK multicentre monitoring study of > 5000 adolescents16 and as high as 27% over an average of 5 years’ follow-up of around 4000 adolescents. 13 In addition, actual rates may be much higher when repetition that does not come to clinical or medical attention is considered. 17 The risk of repetition persists for many years after an episode9,18 and is associated with self-cutting (rather than overdose), depression, reports of childhood sexual abuse and exposure to models of self-harm. 2

What is the aetiology?

Self-harm behaviour results from the convergence of a range of biopsychosocial risk factors across a number of domains, including genetic, biological, social, environmental and demographic factors, personality and cognitive styles and psychiatric morbidity. 19 Several reviews synthesise the full range of risk factors in adolescents. 2,14,20,21

Family factors are also important. 11,22–24 Difficulties in parent–child relationships, including those related to early attachment problems, and perceived low levels of parental caring and communication are related to increased risk of suicide and self-harm among children and adolescents. 25 Exposure to sexual and physical abuse is an important risk factor. 25 Families are not always aware of, or do not have the capacity to respond to, the suicidal behaviour of their offspring,26,27 particularly families in which there are low levels of social support. Parent reactions to self-harm include a range of strong and often negative emotions. 28

Depression is the most common psychiatric diagnosis associated with suicide in adolescents29–31 and with non-fatal self-harm,20 and hopelessness is an important mediating variable between depression and self-harm. 32 Depression is also a key factor associated with repetition of self-harm in adolescents33 and may also moderate responsiveness to treatment. 34

Parental mental illness and substance abuse are significant risk factors,14 and a family history of self-harm is associated with increased risk of suicide deaths30,35–37 and non-fatal self-harm by adolescents. 5,30 However, although suicidal behaviour runs in families, this risk is over and above the heritability of mental illness between generations. 38–40

Young people who self-harm experience higher rates of exposure to recent stressful life events such as rejection, conflict or loss following the break-up of a relationship, conflicts and disciplinary or legal crises,5 and a strong association exists between adolescent self-harm and both childhood sexual abuse and physical abuse. 41

What might we do to prevent self-harm?

An overall model of suicide behaviour provides a framework to support research studies in addition to formulations and treatment planning by clinicians. There is a long history of psychological and psychosocial models of suicidal behaviour such as Durkheim, Shneidman and, more recently, Beck, although these focus mainly on adults. Two relevant exceptions are Beautrais19 and Bridge et al. ,14 who take a more developmental approach and are pertinent to the Self-Harm Intervention: Family Therapy (SHIFT) trial. Beautrais19 posits that suicidal behaviours are the end point of adverse life events in which multiple risk factors combine to encourage their development. This approach represents a stress–diathesis model (for a review, see van Heeringen42), which suggests that temperamental and genetic factors and early experiences may make some young people particularly vulnerable to subsequent internal or external stressors. Bridge et al. 14 also proposed a developmental transactional model of behaviour, which recognises that most factors associated with suicidal behaviour among children and adolescents are familial. Levers for prevention include positive parent–child connections, active parental supervision and high behavioural expectations.

Building on this and the evidence described above, we suggest that the focus of family-orientated treatment with young people who have self-harmed should be on maximising cohesion, attachment, adaptability, family support and parental warmth, while reducing maltreatment and scapegoating and moderating parental control. 28

However, there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of any clinical interventions for young people who engage in self-harm, with a failure to demonstrate any effect on reducing repetition of self-harm among adolescents receiving a range of treatment approaches, including therapeutic assessments and compliance enhancement in hospitals, involvement of youth-nominated support teams, tokens for hospital admission and home- and family-focused interventions. 21,43–45 Two recent studies have suggested that dialectical behaviour therapy46 and mentalisation-based treatment47 may be effective in reducing self-harm. Both had small numbers of participants, shorter follow-up periods than this study and relied on self-report as the primary outcome measure.

Brent et al. 48 concluded that interventions that activated family support or addressed motivations for change were quickly mobilised (to reflect the elevated risk of repetition immediately post episode) and promoted positive affect are the most likely to be able to demonstrate effectiveness. The reviewers also commented that the heterogeneity of treatment as usual (TAU) and the lack of its characterisation, in addition to the many underpowered studies, have held back advances in this field. 48

Ougrin et al. 49 reviewed 19 studies describing interventions to reduce self-harm in adolescents. They calculated pooled risk differences using the outcome of the proportion of young people who self-harmed at least once in the follow-up period of each study versus those who did not self-harm at all. Overall, the proportion of participants who self-harmed was slightly (but statistically significantly) lower in those allocated to treatment interventions. However, the authors acknowledge that the quality of studies examined was poor and that ‘more research and replication of the positive findings by independent groups are urgently required’.

The limited evidence that we have suggests that properly powered studies involving the family in treatment, and focusing treatment on both child and parent skills, characterises successful treatment approaches in this area. 50,51

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial design

The trial was a pragmatic, Phase III, multicentre, individually randomised controlled trial of family therapy (FT) compared with TAU in 832 adolescents aged 11–17 years who had engaged in previous episodes of self-harm on at least two occasions and where a recent self-harm episode was a key characteristic of the reason for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) contact.

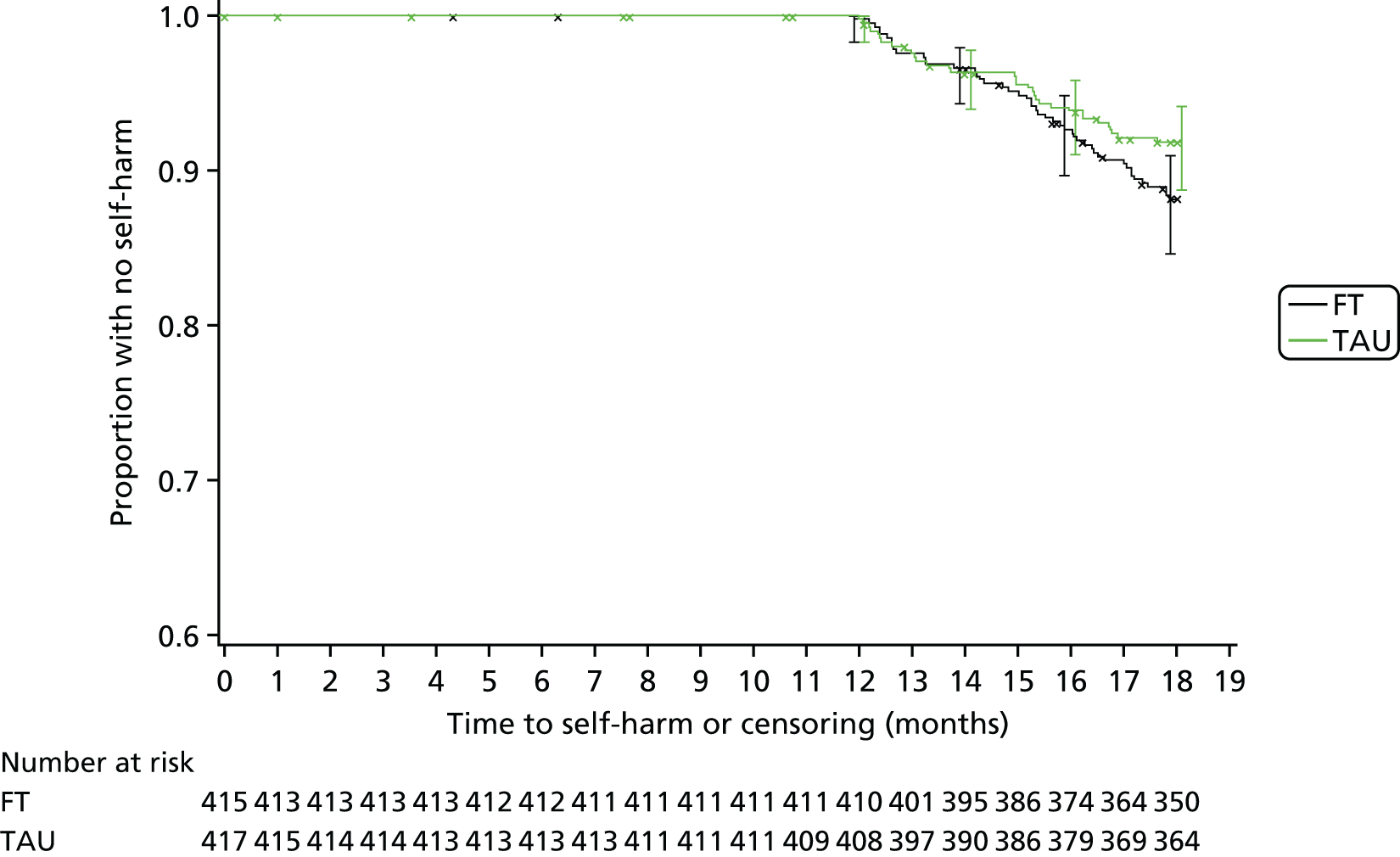

The primary outcome was attendance at hospital following self-harm at 18 months post randomisation.

The design and outcomes were influenced by the fact that this project was funded following a commissioned call for research (see Appendix 1).

Objectives and outcome measures

The primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of FT compared with TAU as measured by young people’s rates of repetition of self-harm leading to hospital attendance 18 months after randomisation.

This outcome was selected following discussion with clinical colleagues and our review of the literature. The following issues were considered:

-

high loss to follow-up in other self-harm intervention studies

-

clinical reports that young people were not always regular attenders following self-harm

-

wide fluctuations in rates of self-harm, with some young people engaging in self-harm many times per day, complicating outcome measurement in other studies

-

high rates of self-harm in young people who do not present to hospital but who are difficult to identify and follow up.

We prioritised an outcome that could be operationally defined and measured even if participants were difficult to follow up. This gave us the potential to assist in answering the clinical question ‘what is the most effective course of action when a young person presents to CAMHS following self-harm’. The implications of this decision are discussed further in the results (see Chapters 3 and 4) and discussion (see Chapter 5).

Secondary objectives were to assess:

-

the effectiveness of FT compared with TAU as measured by repetition rates of self-harm leading to hospital attendance at 12 months after randomisation

-

the characteristics of all further episodes of self-harm leading to hospital attendance

-

the cost per self-harm event avoided as a result of FT, measured using a structured, trial-specific health economics questionnaire

-

the characteristics of all further episodes of self-harm (not just those resulting in hospital attendance). This included the number of subsequent self-harm events, time to next event, severity of event (fatal, near fatal or not) and dangerousness of method used, as measured by the Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII)52

-

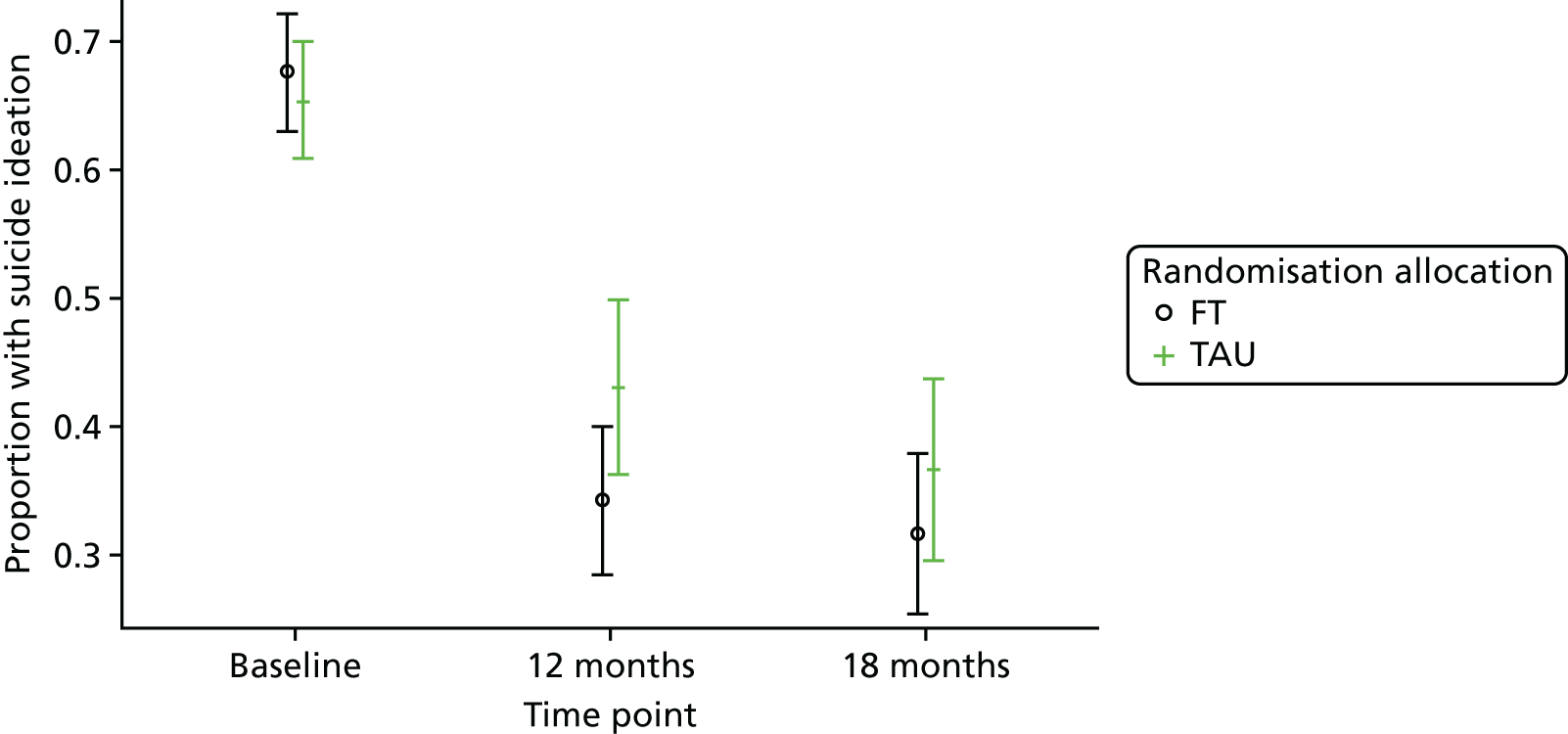

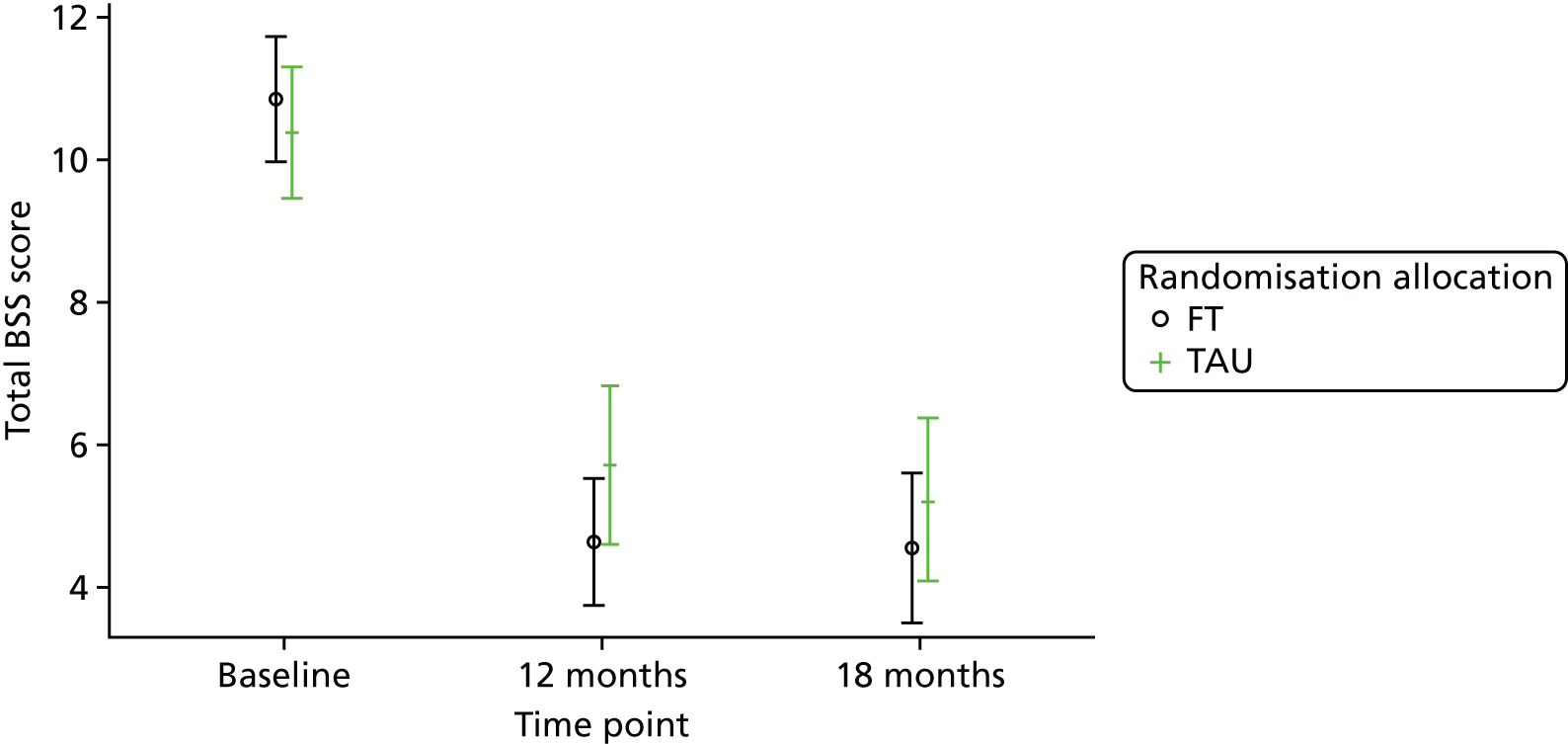

suicidal ideation, measured by the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS)53

-

quality of life, measured by the Paediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q)54 and parental completion of the General Health Questionnaire, 12 questions (GHQ-12)55

-

depression, measured by the Children’s Depression Rating Scale – Revised (CDRS-R)56

-

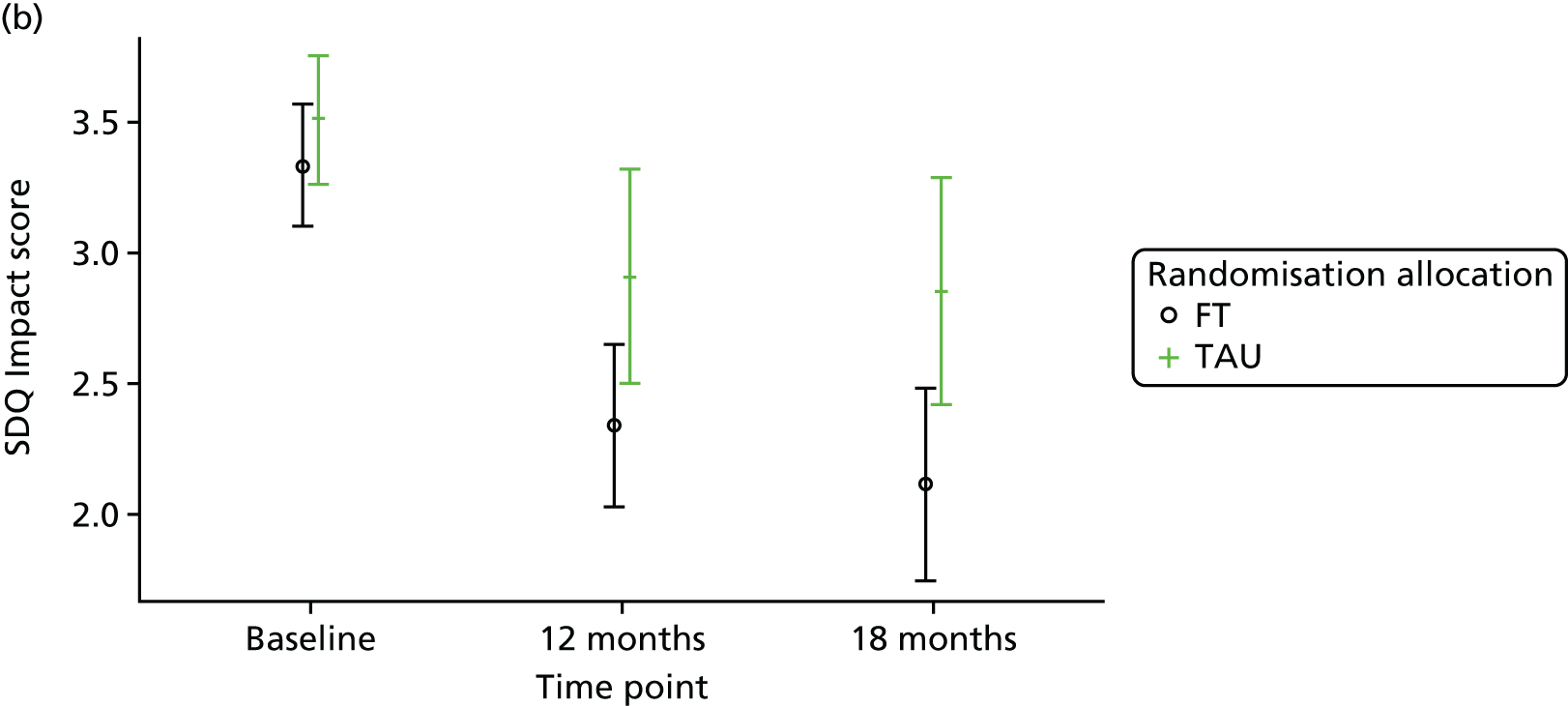

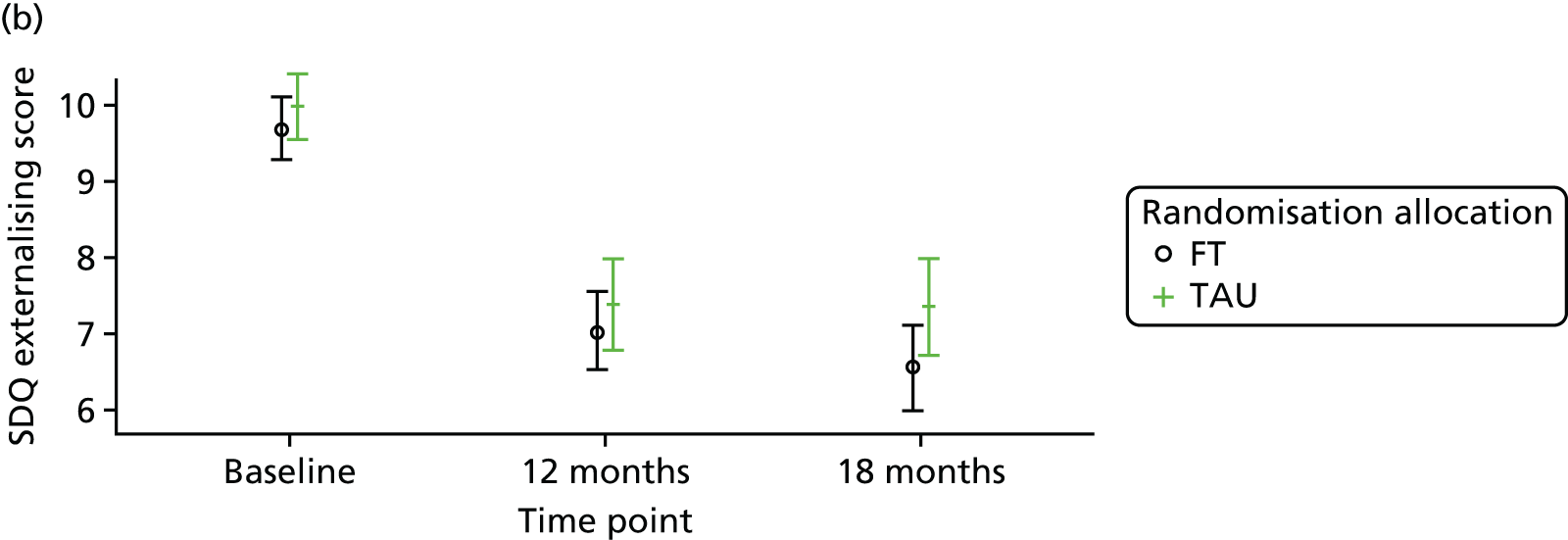

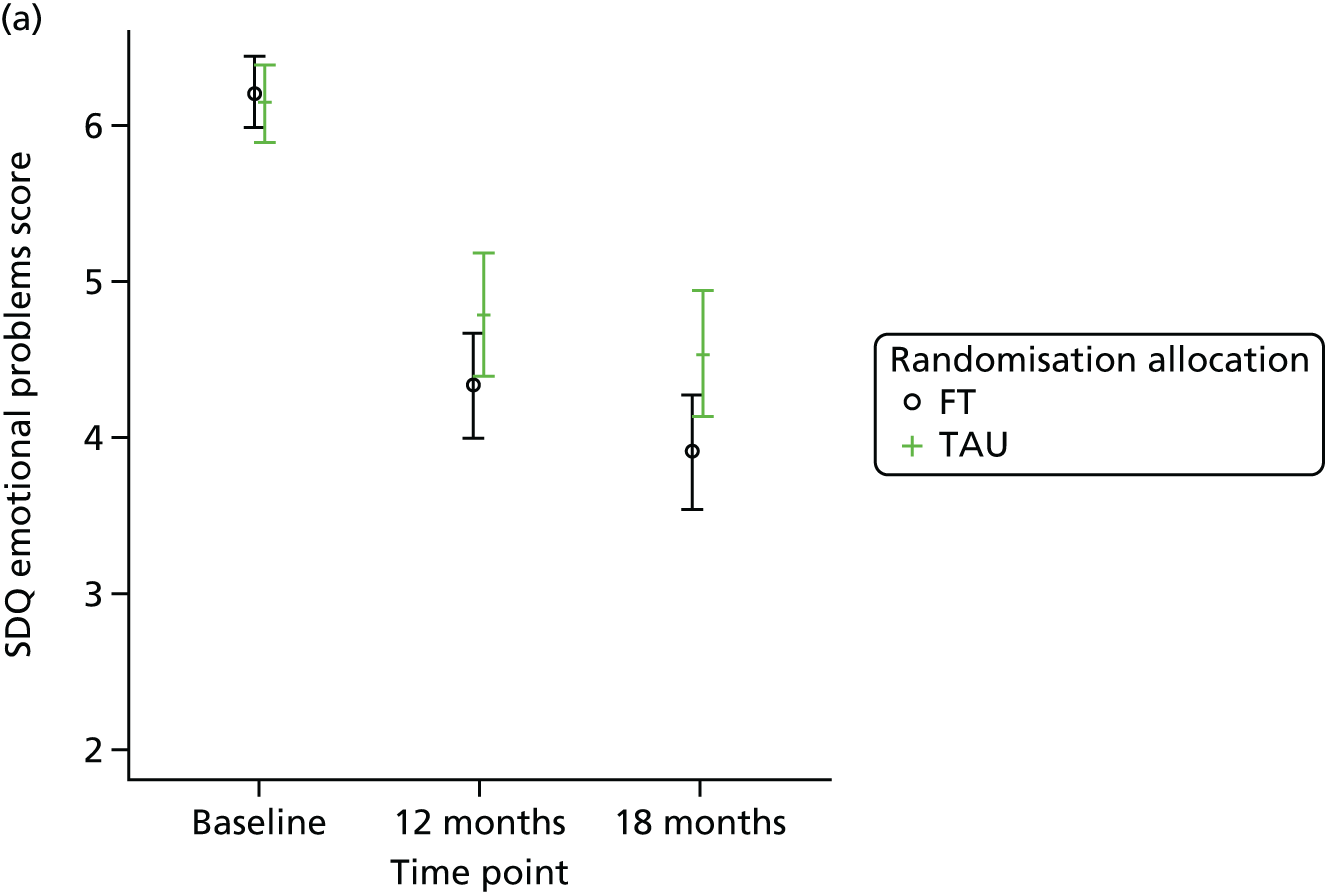

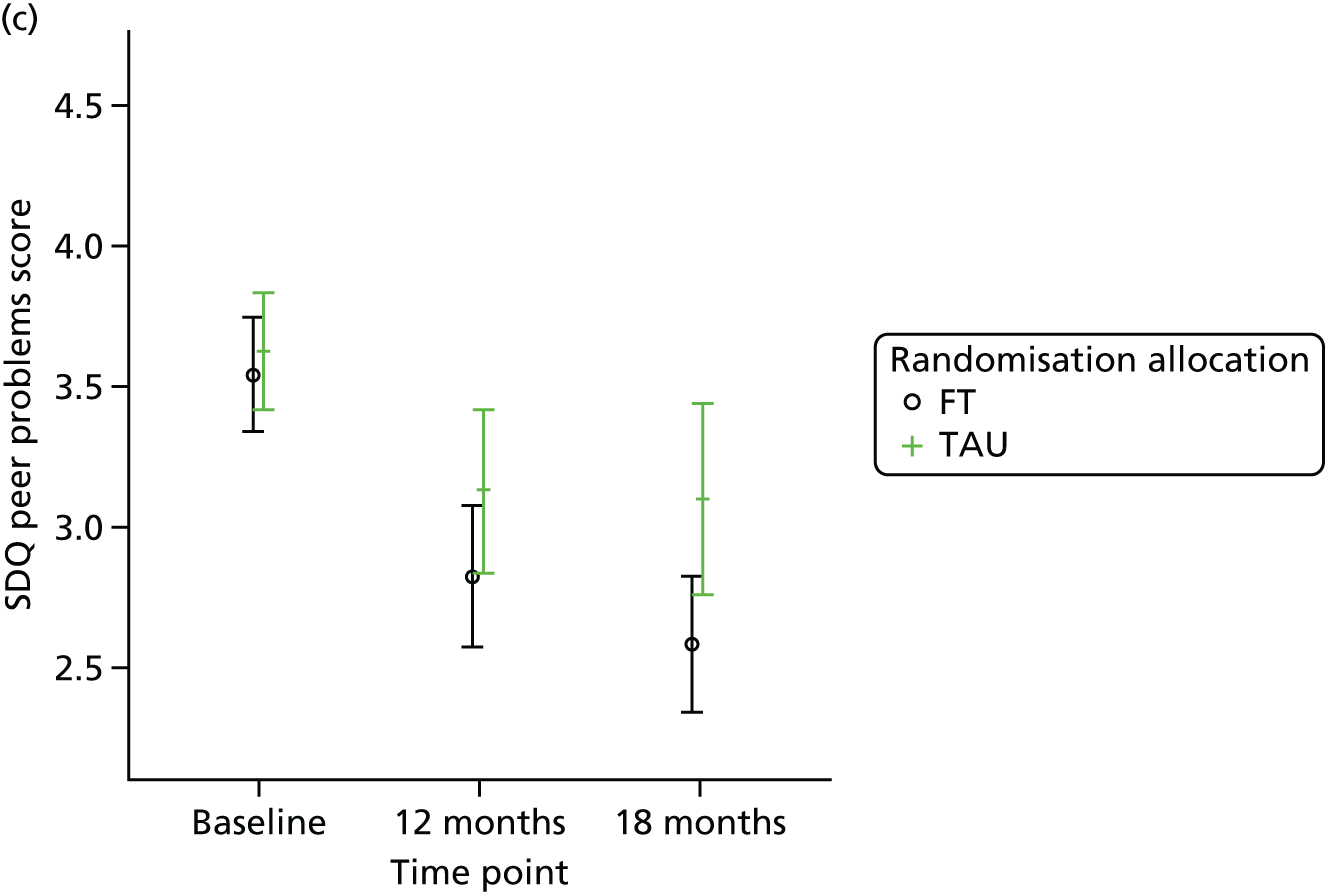

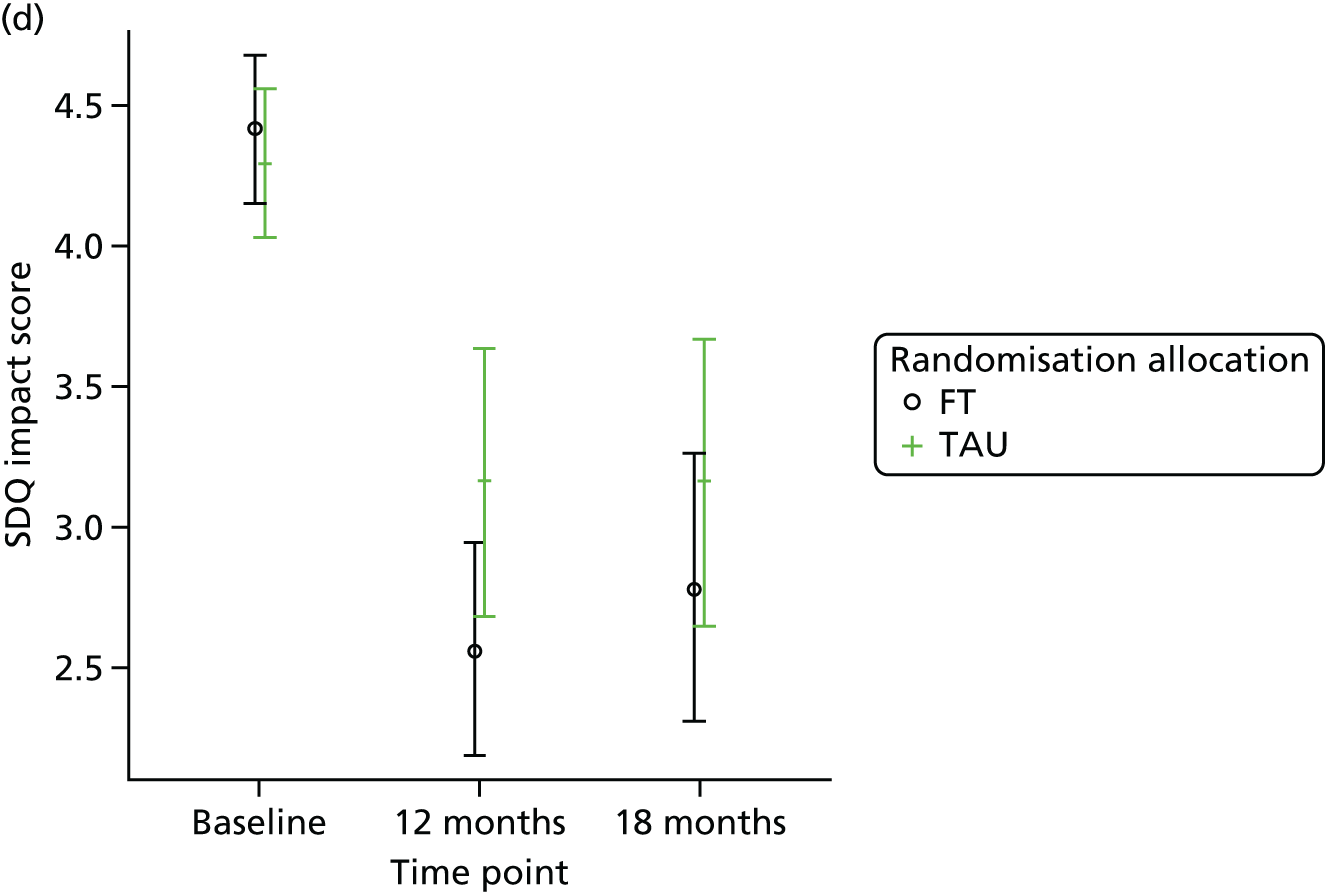

overall mental health and emotional and behavioural difficulties via young person and parental completion of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)57

-

hopelessness, via completion of the Hopelessness Scale for Children58

-

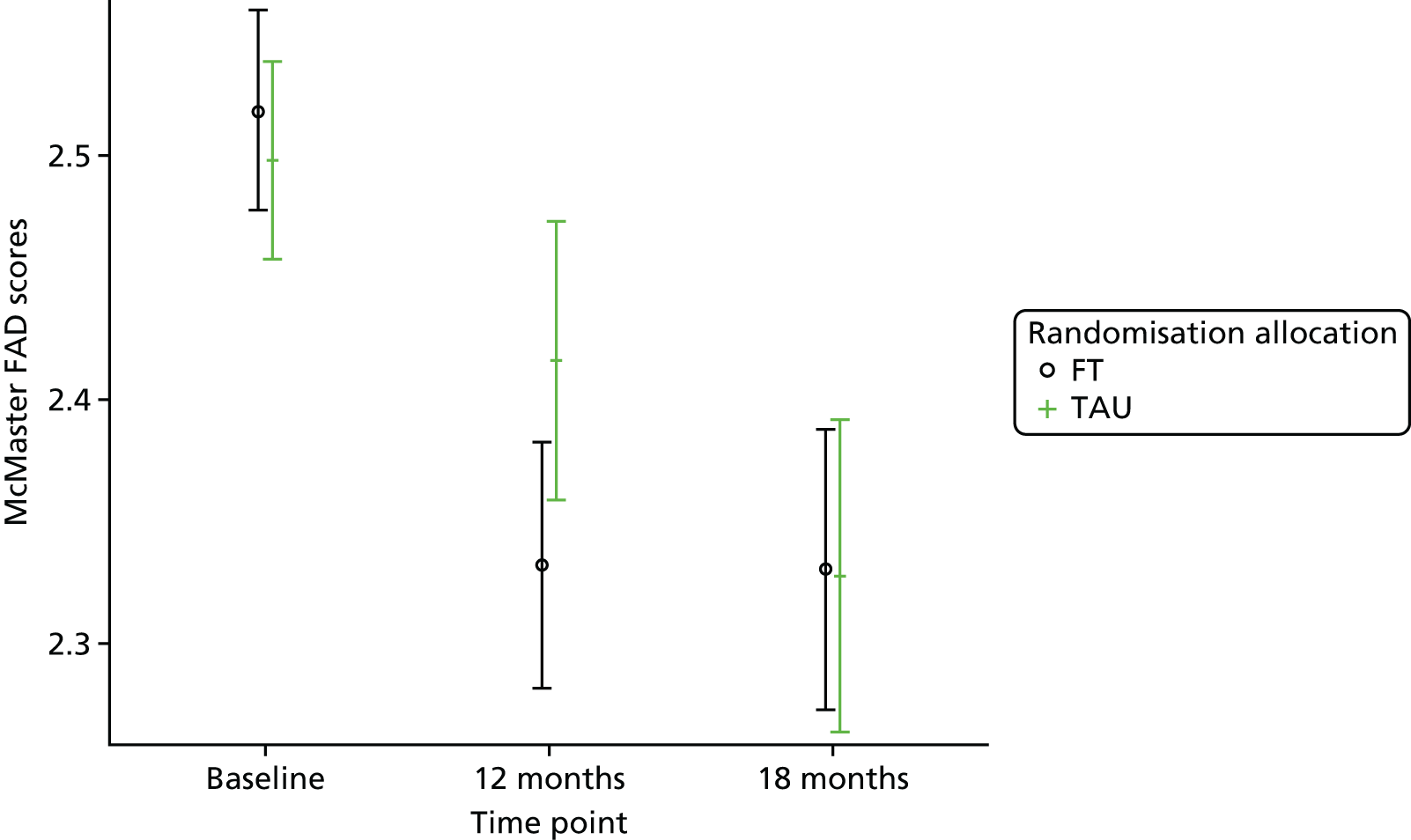

family functioning, measured by the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD)59 and the Family Questionnaire60

-

mediator and moderator variables that influence engagement with and benefit from treatment (e.g. number of sessions, medication use, referrals)

-

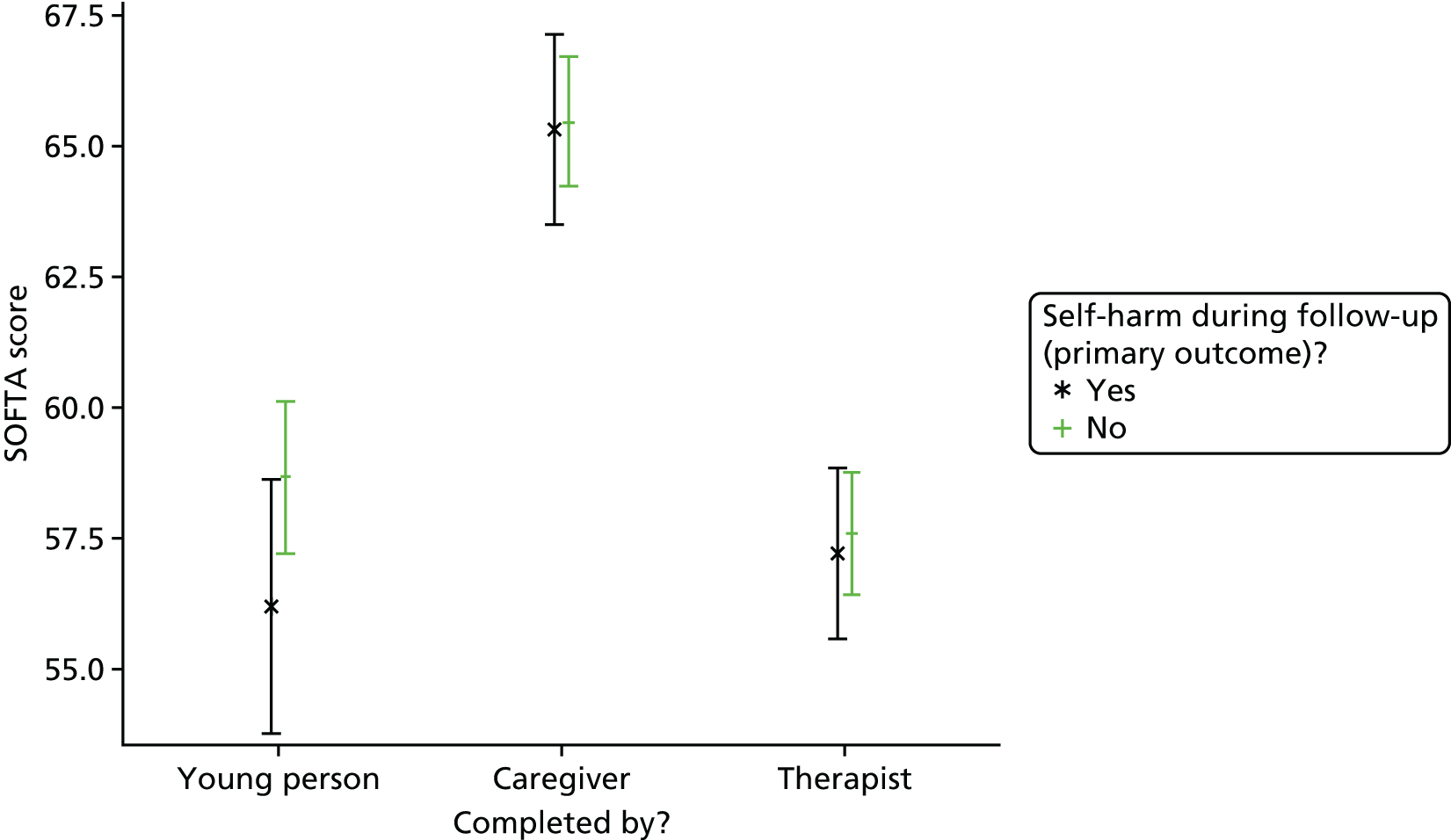

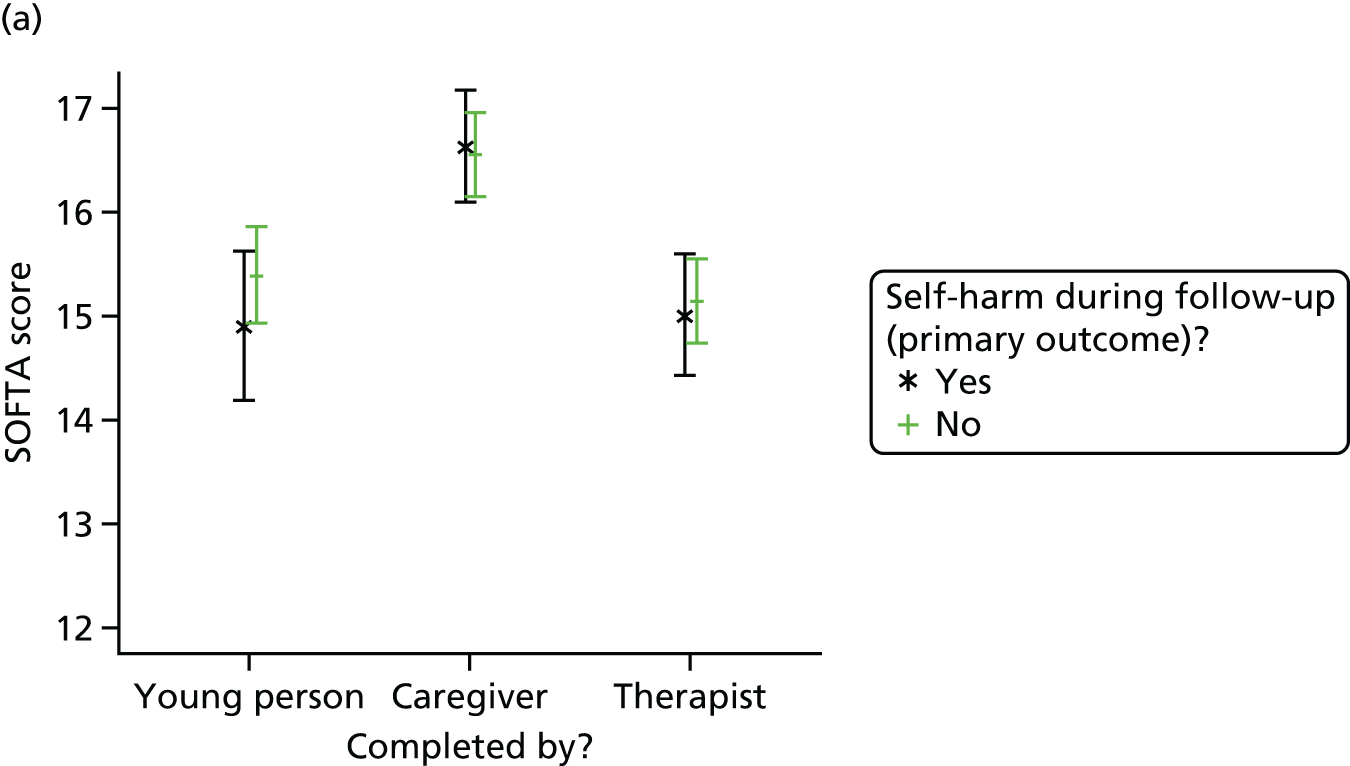

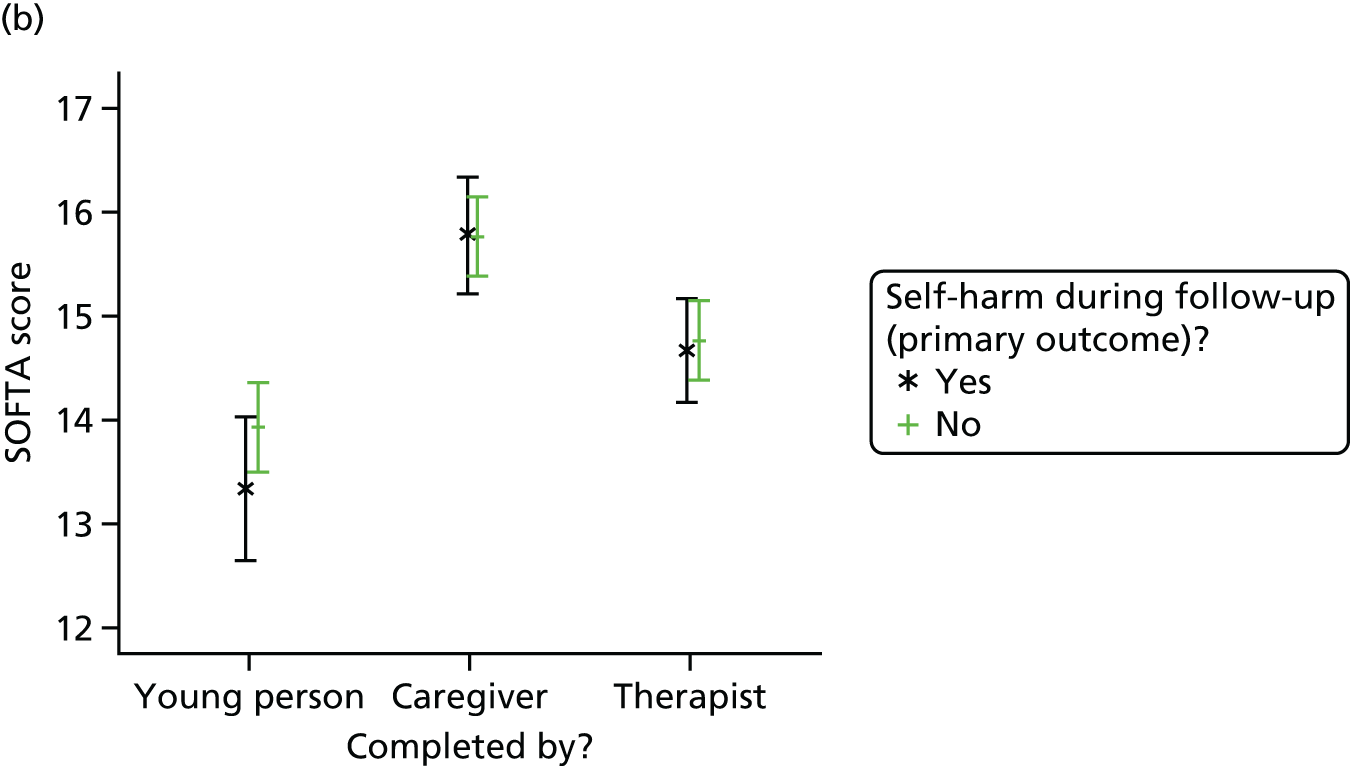

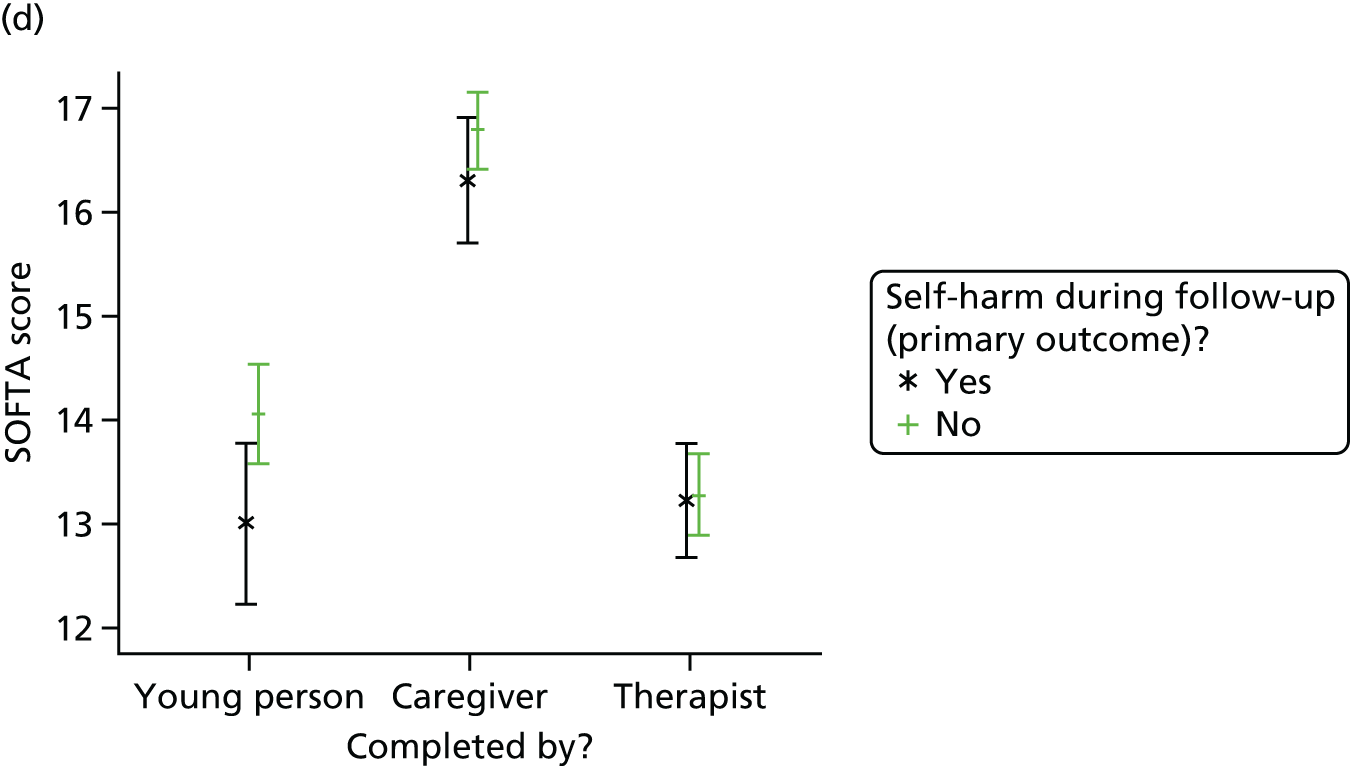

therapeutic alliance to FT, via family therapist, young person and parental completion of the System for Observing Family Therapy Alliances (SOFTA)61

-

therapist adherence to the FT manual.

Participants and setting

Participants were young people who met the eligibility criteria detailed below. In addition, for each young person a primary caregiver was identified who was willing to be involved in the research to provide outcome measures.

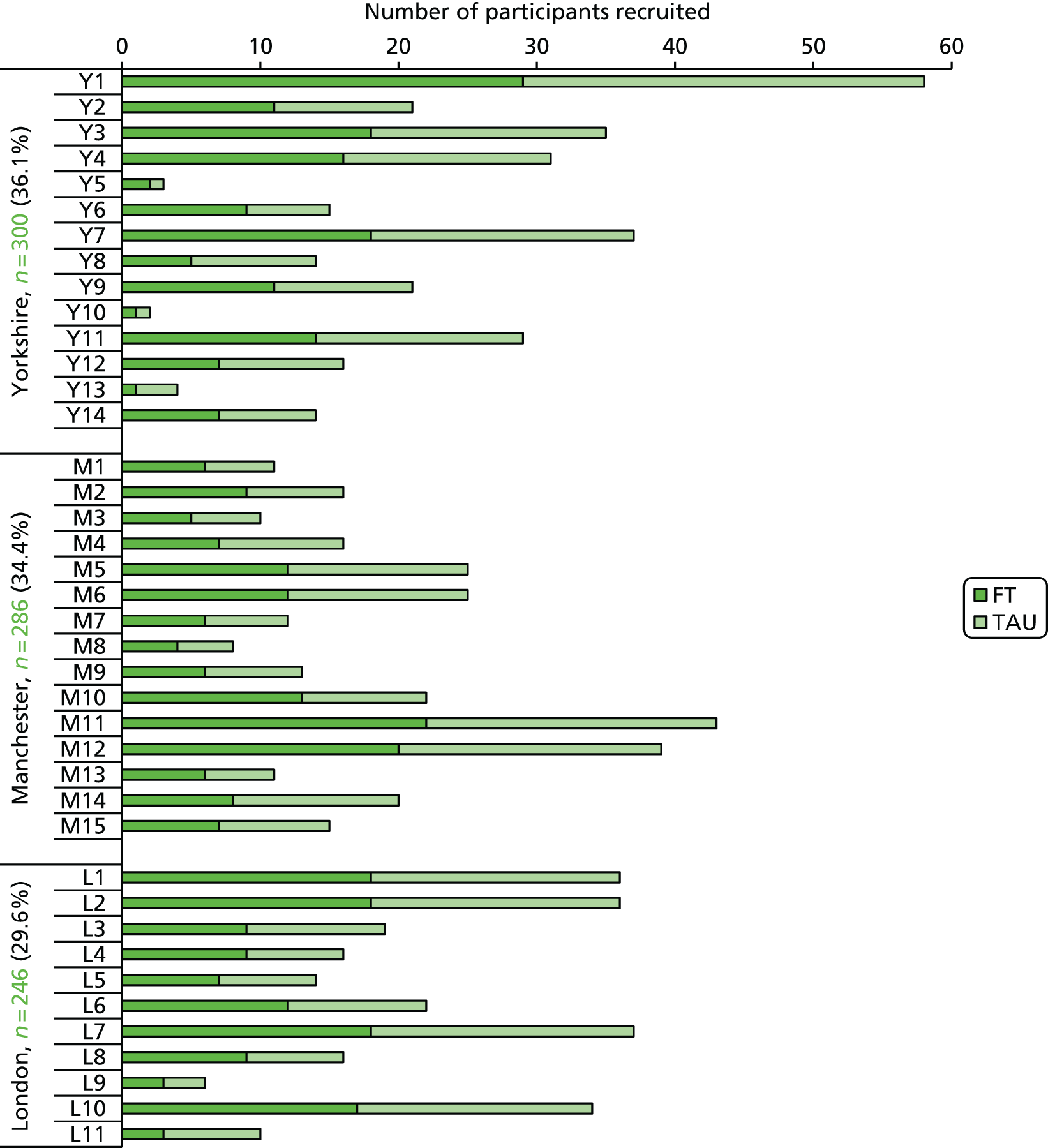

Young people and their caregivers were identified from NHS CAMHS across three ‘hubs’ in England: Greater Manchester, London and Yorkshire. Young people were screened for trial suitability and approached, if eligible, at their first visit to CAMHS following self-harm. To be included in the trial, young people were required to meet the following eligibility criteria and subsequently provide written informed consent, together with their primary caregiver.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged 11–17 years.

-

Self-harmed prior to assessment by the CAMHS team.

-

Engaged in at least one previous episode of self-harm prior to the index presentation.

-

Assessed in hospital following current episode, or referred directly to CAMHS from primary care with recent self-harm as a key feature of presentation.

-

When the presenting episode was because of alcohol or recreational drugs, the young person had explicitly stated that he or she was intending self-harm by use of these substances.

-

The clinical intention was to offer CAMHS follow-up for self-harm.

-

Lived with primary caregiver.

Exclusion criteria

-

At serious risk of suicide (clinical judgement) and so requiring more than TAU.

-

An ongoing child protection investigation within the family, which would have made treatment difficult to deliver.

-

Would ordinarily have been treated not in generic CAMHS but rather by a specific service, and so would not normally have received TAU.

-

Pregnant at time of trial entry and thus likely to have to interrupt treatment in either arm.

-

Actively being treated in CAMHS (as the possibility of randomisation might disrupt ongoing therapy).

-

In a children’s home or short-term foster placement and so no continuity of treatment possible in either arm.

-

Moderate to severe learning disability or lacked capacity to comply with trial requirements.

-

Involved in another research project – at the time of trial entry or within the last 6 months so as not to overburden participants and to avoid possibility of conflicting requirements across two studies.

-

Sibling had been randomised to the SHIFT trial or was receiving FT within CAMHS. As the intervention studied is a family intervention, if a sibling was already in the trial, randomisation would not have been possible.

-

The young person and one main caregiver had insufficient proficiency in English to contribute to the data collection.

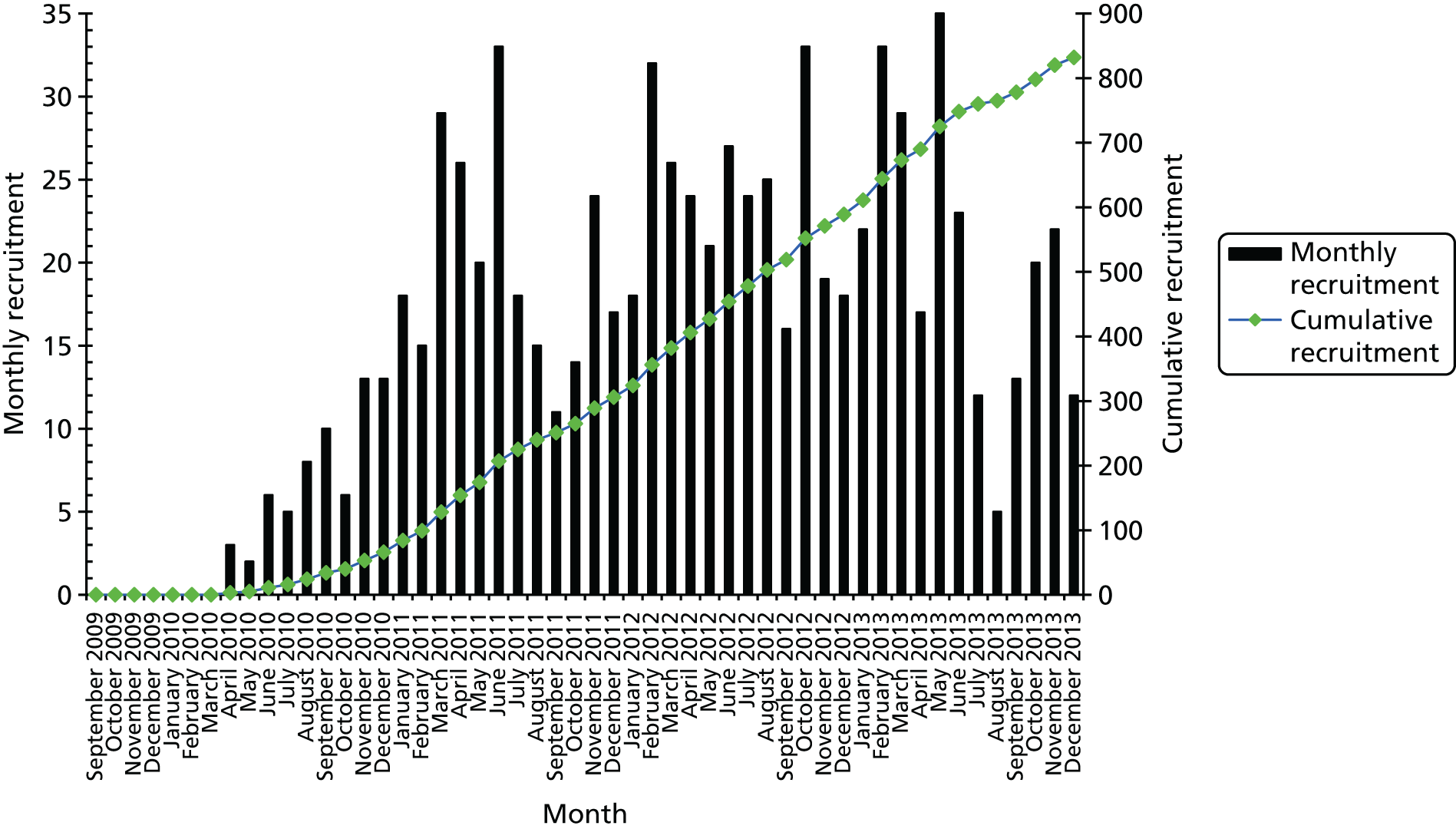

Recruitment

All young people presenting via hospital or from primary care to participating CAMHS following a recent episode of self-harm were screened by CAMHS clinicians. When a young person met the criteria, the assessing CAMHS clinician discussed trial participation at the assessment appointment, passed on the participant information sheets and requested consent (written ideally, but verbal was allowed) for subsequent contact by a researcher. Those providing such consent were contacted by the researcher, who arranged to visit the family at home, discussed the trial in detail, obtained consent for participation and administered the baseline assessment.

Randomisation and blinding

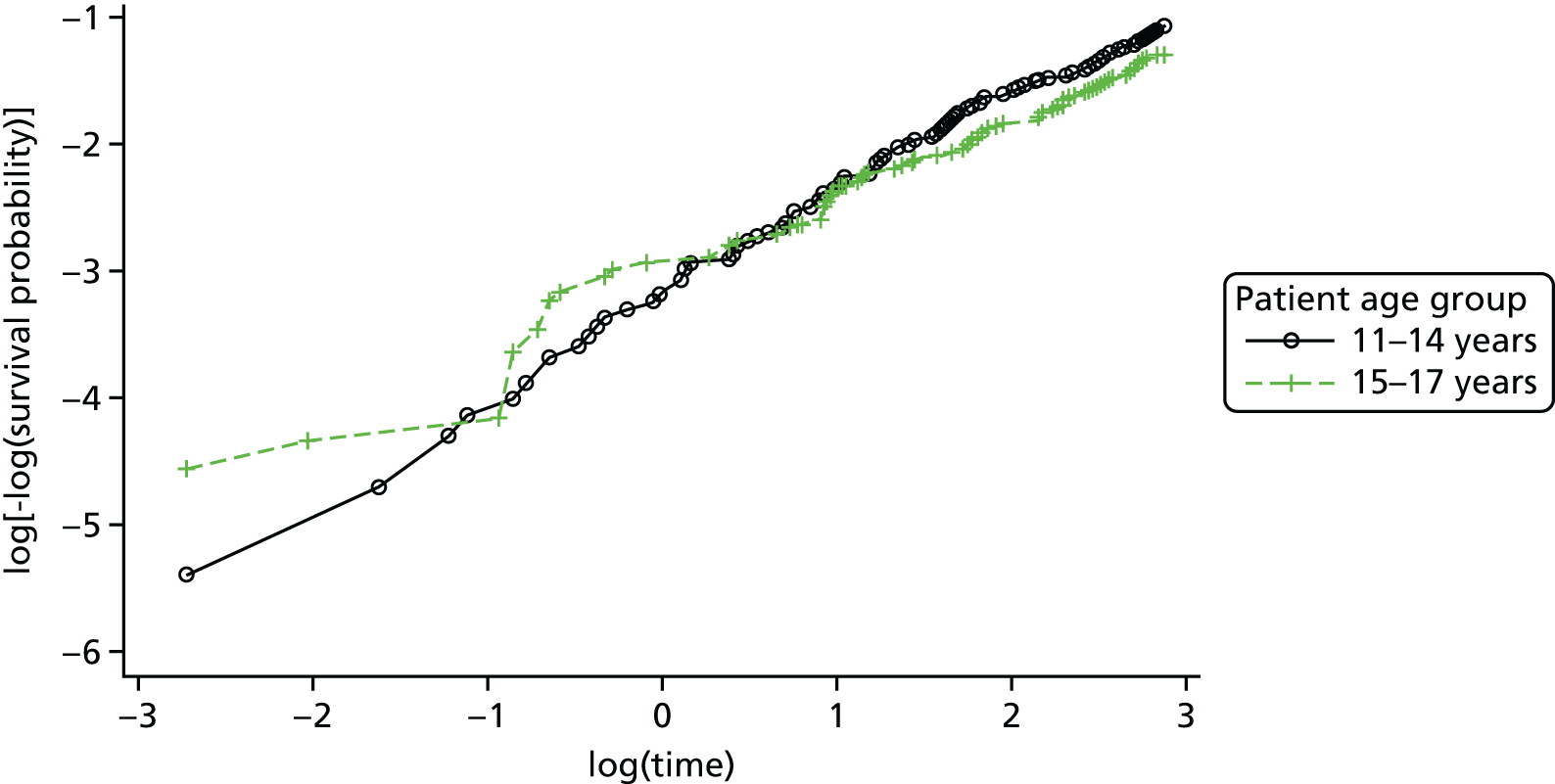

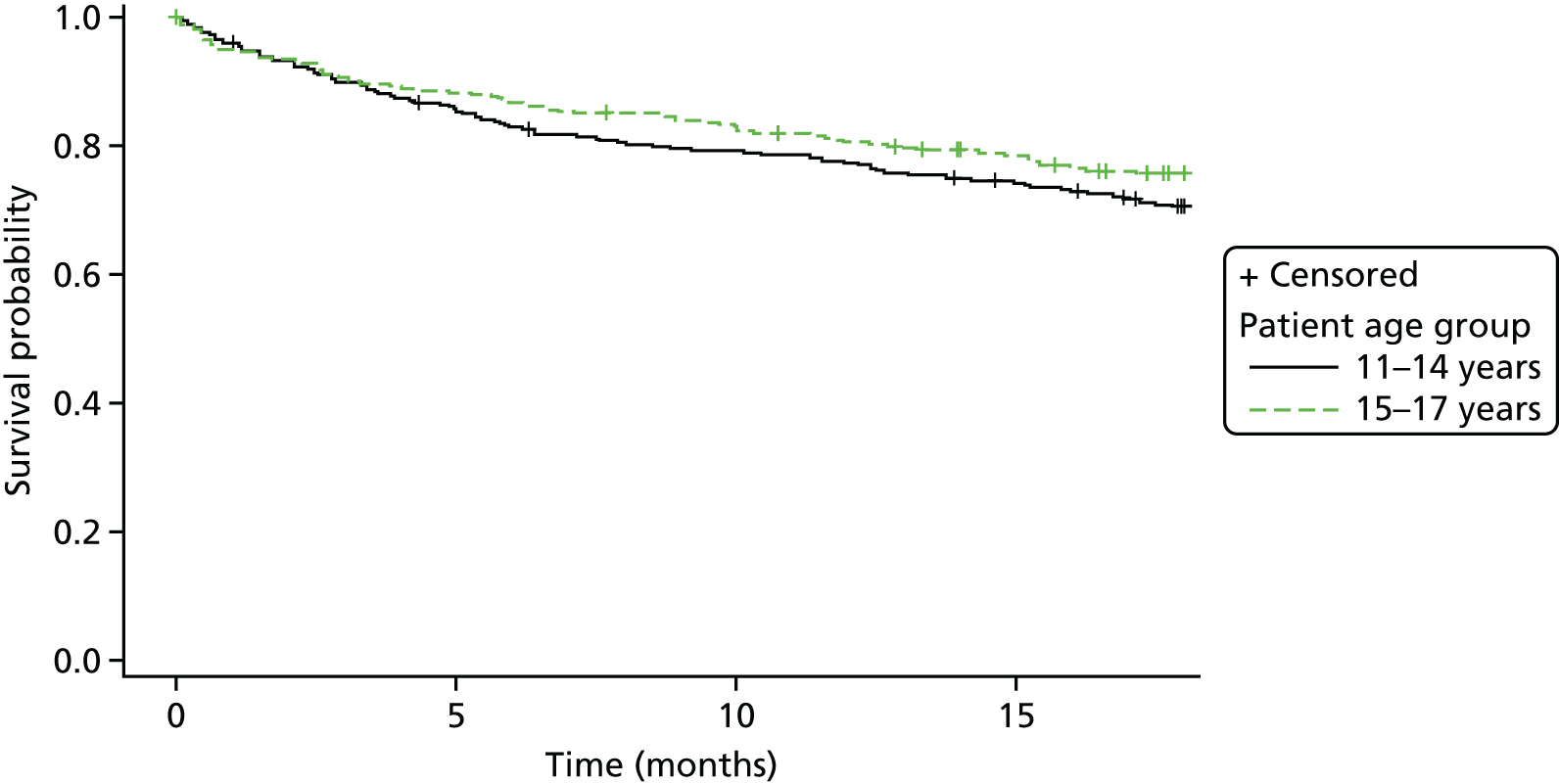

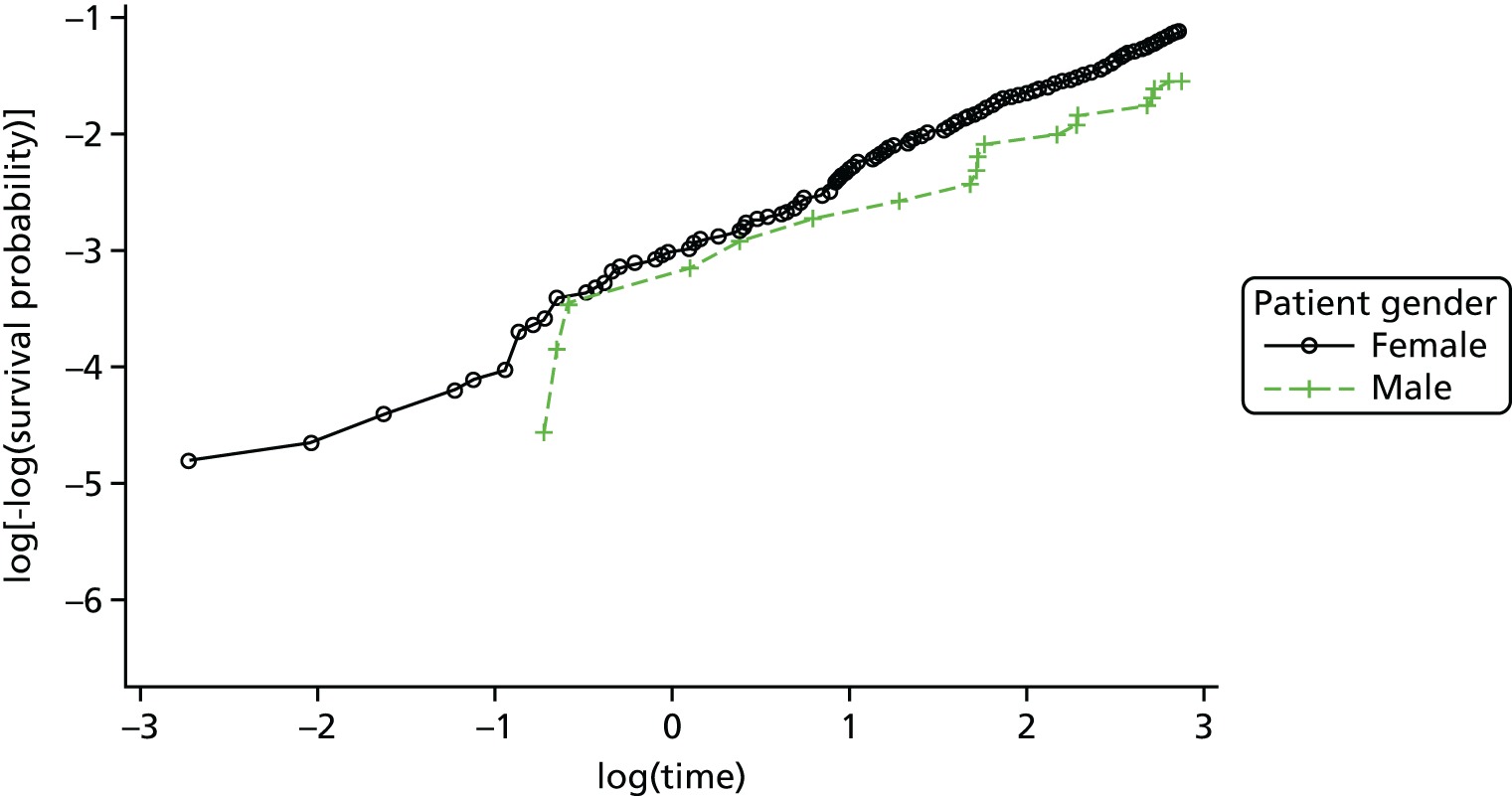

Following consent and baseline assessment, researchers randomised participants sequentially via an automated system at the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) at the University of Leeds. Participants were randomly allocated on a 1 : 1 basis to receive FT or TAU through the use of a computer-generated minimisation program incorporating a random element. The stratification factors were centre (CAMHS team), gender, age (11–14 years/15–17 years), living arrangements (with parents or guardians/foster care), number of previous self-harm episodes including index event (2/≥ 3) and type of index episode (self-poisoning, self-injury, combined). When therapists were not aligned to a specific service but covered a number of services, additional randomisation of the lead therapist took place within the FT team in order to minimise case selection bias. This occurred across the whole Manchester hub, in two sites in Yorkshire and in two sites in London.

The participants and therapists were, of necessity, aware of treatment allocation, but the researchers were blind to allocation to allow the unbiased collection of follow-up data. The CTRU was responsible for informing CAMHS clinicians and family therapists of randomisation outcome in order to maintain researcher blinding. Clinicians and family therapists informed families of their allocation and arranged subsequent appointments for treatment in CAMHS.

Interventions

Both therapeutic interventions were delivered within CAMHS, and all participants were treated within their local service. Family therapists were formally linked with specific CAMHS teams to ensure clear lines of clinical responsibility, and clinicians in both trial arms had access to local child and adolescent psychiatrists if medication or hospitalisation needed to be considered.

Family therapy

The FT intervention was based on a modified version of the Leeds Family Therapy & Research Centre Systemic FT Manual, the development and validation of which was funded by the Medical Research Council to support trials of FT. 62 This manual was updated by the FT expert members from the Trial Management Group (TMG) to ensure that it was appropriate for work with families following self-harm. The SHIFT FT Manual can be requested from the trial team via http://medhealth.leeds.ac.uk/SHIFTManual.

Our systemic orientation to self-harm assumes that there is an interplay between a number of factors that can lead to the development of individual difficulties and problems such as self-harm. However, rather than focus on the causal explanation of individual problems, systemic FT is concerned with the way in which these problems will have become embedded in the matrix of family and wider social relationships, the felt experiences and the meanings and narratives that have become attached to and that shape these difficulties. 63 Looking for a causal account in the individual case is seen as unhelpful, partly because it inevitably oversimplifies the complexity of the individual aetiological pathway and partly because it tends to reinforce disabling, blaming narratives. 64

Self-harm in an individual case will, in part, have been a response and have meaning in relation to particular issues (e.g. problems in emotional regulation, sense of hopelessness, low self-esteem, developmental and life-cycle issues, school and peer issues, attachment difficulties, relationship problems, parental situations or problems in family communication), but it also highlights that, for some reason, alternative, more constructive solutions were unavailable. The self-harming response will have been influenced by and in turn will influence subsequent patterns of interaction and will give new meaning to them. 65 It becomes a means of communicating and constrains alternative responses. By considering these behavioural and linguistic patterns in greater detail, facilitating understanding and noticing and supporting alternatives that encourage more positive narratives to emerge, the therapist can help the client and family create a different response pattern to the issues that showed themselves in self-harm.

Family therapists [those eligible for registration with the UK Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP)] were appointed specifically to work on the trial, following the formal advertisement of a clear job description and subsequent interview. All were qualified systemic family therapists who had trained in the UK to the level of a master’s degree, which included 2 years of supervised practice. The therapists had a primary professional mental health background and qualification (generally social work or nursing), and most of them had experience in CAMHS and post-qualification experience in FT practice.

The therapists joining SHIFT at the outset attended a 2-day group training event prior to the start of the trial and then 1-day training events annually thereafter. The authors of the manual provided the training, which included review and discussion of the manual, reflections on their own experiences with/as young people, their relationship to clinical risk and team building. Additional material on adolescent self-harm was presented by a specialist on the trial. Role play and experiential exercises were included. Each family therapist worked with a pilot case (CAMHS non-trial case) with supervision. After each therapist had completed a number of sessions, they were deemed ready to commence with trial participants. The orientation of replacement family therapists for departing original trial therapists involved one-to-one training with one of the trial’s senior family therapists, a period of observation of the remaining team members’ therapy and a one-to-one session with the supervisor to review the material.

Family therapists worked in teams of three or four and provided trial FT as a team for a cluster of CAMHS. Within each team, each family therapist would be the lead for a subset of participants (the other family therapists in the team would act as observers and make only a small face-to-face contribution for those participants).

Monthly group supervision of 2 hours was provided for each team by senior family therapists (two of whom were authors of the treatment manual). Supervision included discussion of cases, adherence to the manual, broader trial issues and team dynamics. Generally, the focus of the supervision was determined by the family therapists at each meeting.

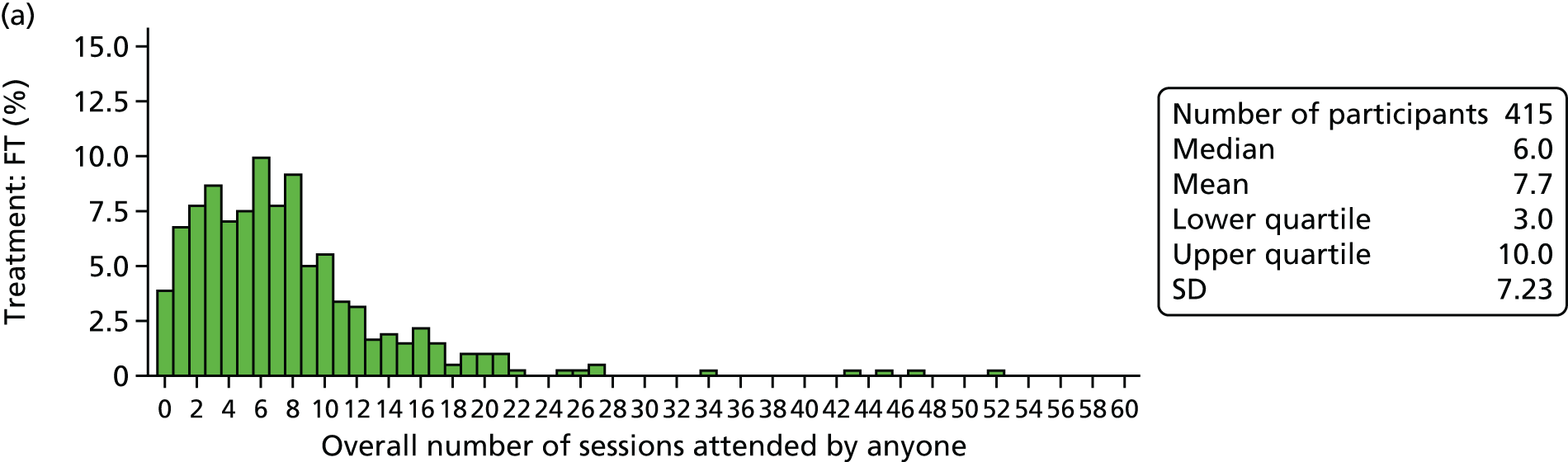

Young people and their families were offered FT sessions of approximately 1.25 hours’ duration each, delivered over 6 months at approximately monthly intervals, but with more frequent initial appointments. This equated to approximately eight sessions, but there was the expectation that some participants would receive fewer sessions because of dropout or mutually agreed termination of treatment. Equally, it was anticipated that some participants might receive more sessions if this was deemed clinically appropriate.

Wherever possible, and when consent was provided, the sessions were video-recorded, as this is part of good FT practice and facilitates supervision.

Originally, it had been intended that supervision would include a review of recordings of current cases. This proved difficult for technical reasons and so most supervision was based on therapist presentation. The adherence measure was developed at a later stage in the trial and applied retrospectively.

A selection of video-recorded sessions was centrally reviewed, whereby the first and a subsequent therapy session were reviewed for each therapist to monitor their adherence to the manual and to allow the reporting of this. Adherence was assessed through use of a tool developed specifically for the trial. 66 In addition, administrative processes that were required in the manual were also monitored, for example number of sessions offered and attended and whether or not formulation letters (summarising the therapist’s understanding of the family situation) were sent to families following attendance at their second therapy session, as expected in the manual.

Treatment as usual

Treatment as usual was the care offered by local CAMHS teams to young people referred following self-harm. It was expected that this treatment would be diverse and involve individual and/or family-orientated work, delivered by a range of practitioners with various theoretical orientations. As SHIFT was a pragmatic trial involving a number of collaborating CAMHS teams, it was not deemed possible or appropriate to specify TAU, although it was expected that CAMHS practitioners would be working in line with best practice as set out in several National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (e.g. guidance on self-harm and depression in childhood). 67,68 Generic TAU was not delivered to the FT group as part of their clinical intervention, unless specific additional assessment or treatment was indicated during or after FT, for example referral for formal mental state assessment or for medication.

Contamination

The possibility of cross-arm contamination was considered during the design stage of the trial, with the following points mandated whenever possible and monitoring processes implemented:

-

Different teams of therapists delivered the two interventions in each CAMHS site and SHIFT family therapists were prohibited from treating participants in the TAU arm for the duration of the trial. There were processes in place to record contamination if this occurred.

-

Owing to the nature of appointment scheduling and the fact that this was family-specific therapy (i.e. not a group intervention), there was little opportunity for participants to meet and discuss treatment, so contamination at the participant level was very unlikely.

-

Any family-orientated clinical interventions in the TAU group were likely to be different from the trial FT intervention, which required adherence to the Leeds Family Therapy & Research Centre manual, fully-trained family therapists eligible for UKCP registration, therapy delivered in a team context and regular supervision. Thus, use of family interventions in the TAU arm was not prohibited, but details of all treatment received by participants in both arms were recorded.

Assessments and data collection

All required data, assessment tools, collection time points and processes are summarised in Table 1.

| Assessment (including who is involved) | Timeline (months post randomisation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 | 6 | 12 | 18 | |

| Eligibility and consent | |||||

| Eligibility (assessed by clinician) | ✗ | ||||

| Consent (young person, P, R) | ✗ | ||||

| Background and demographics (young person, P, R – interview and case notes) | |||||

| Personal details | ✗ | ||||

| Outline ‘index’ event details | ✗ | ||||

| Current comorbid physical/mental health | ✗ | ||||

| Current psychotropic medications | ✗ | ||||

| History of abuse | ✗ | ||||

| Follow-up data (collected from case notes) | |||||

| Therapy details (provided by therapist) | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Therapist supervision details (provided by therapist/supervisor) | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Details of further self-harm episodes since consent (R) | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Psychotropic medication details (R) | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Referrals to other MH services (R) | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Re-referral to CAMHS (R) | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Admissions to hospital relating to mental health (R) | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| All-cause mortality (NHS Digital) | ✗ | ||||

| SAE reporting and hospital attendance (R and NHS Digital) | Ongoing collection | ||||

| Questionnaires (completed at researcher visit unless otherwise stated) | |||||

| Family Questionnaire (P self-report, CTRU postal administration at 3 and 6 months) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| SOFTA (completed by the family therapist and participants at FT session 3) | ✗ | ||||

| SASII (interview with young person) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| BSS (young person self-report) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Hopelessness Scale for Children (young person self-report) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| McMaster FAD (young person and P self-report) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| GHQ-12 (P self-report) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| SDQ (young person and P self-report) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CDRS-R (Interview with young person) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| PQ-LES-Q (young person self-report) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| ICU (young person self-report) | ✗ | ||||

| EQ-5D (young person self-report, postal administration at 6 months) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| HUI-3 (P self-report, postal administration at 6 months) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Health Economics questionnaire (young person and P self-report, postal administration at 3 and 6 months) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Screening

Data were recorded anonymously for young people who did not meet the eligibility criteria, and for those who were eligible but not willing to provide consent, in order to monitor trial uptake and representativeness of the trial population. Screening data for randomised participants were linked to the main trial data, and also provided details of the outline ‘index’ event that had prompted their referral to CAMHS and eligibility for the trial. Screening data, eligibility and consent for researcher contact were assessed and recorded by the screening clinician. During the baseline visit, the researcher confirmed the participant’s eligibility, obtained and recorded consent for trial participation, and obtained further details, including current physical and mental health comorbidities, psychotropic medications and history of abuse.

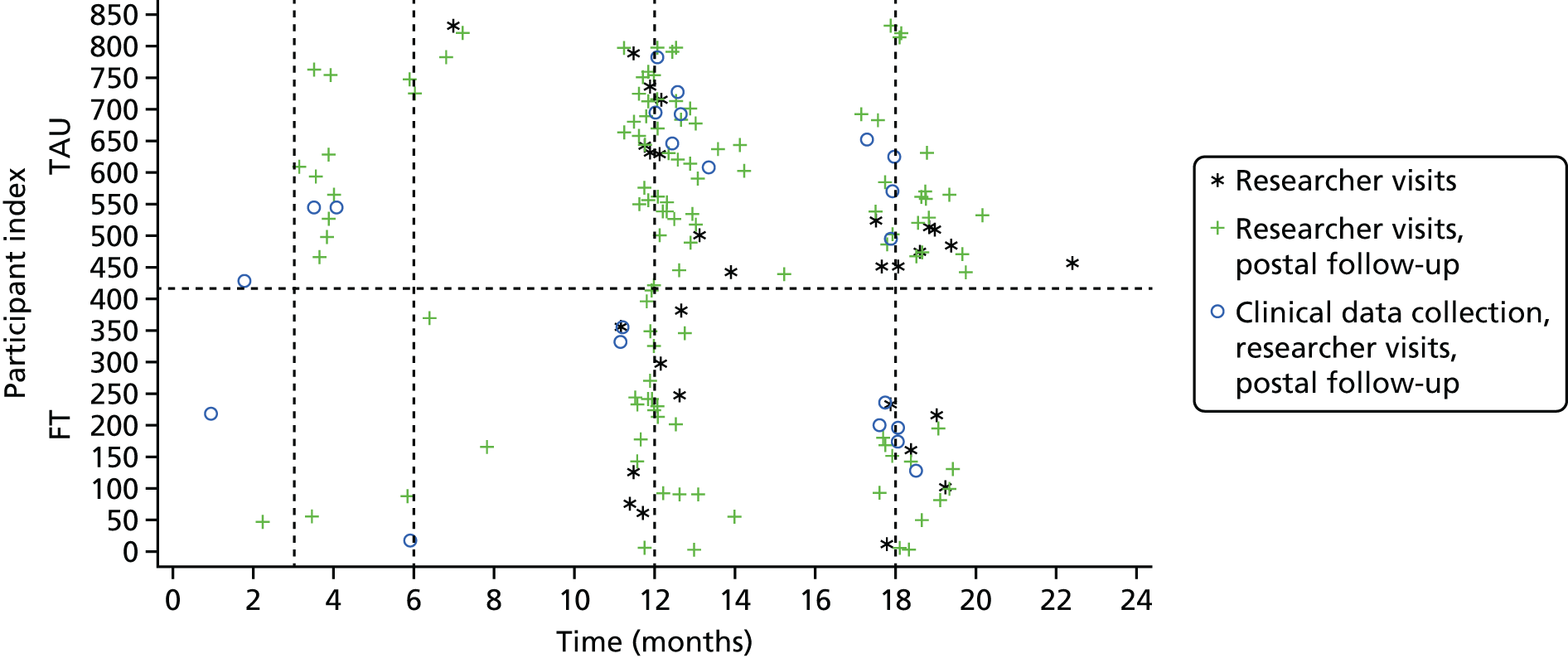

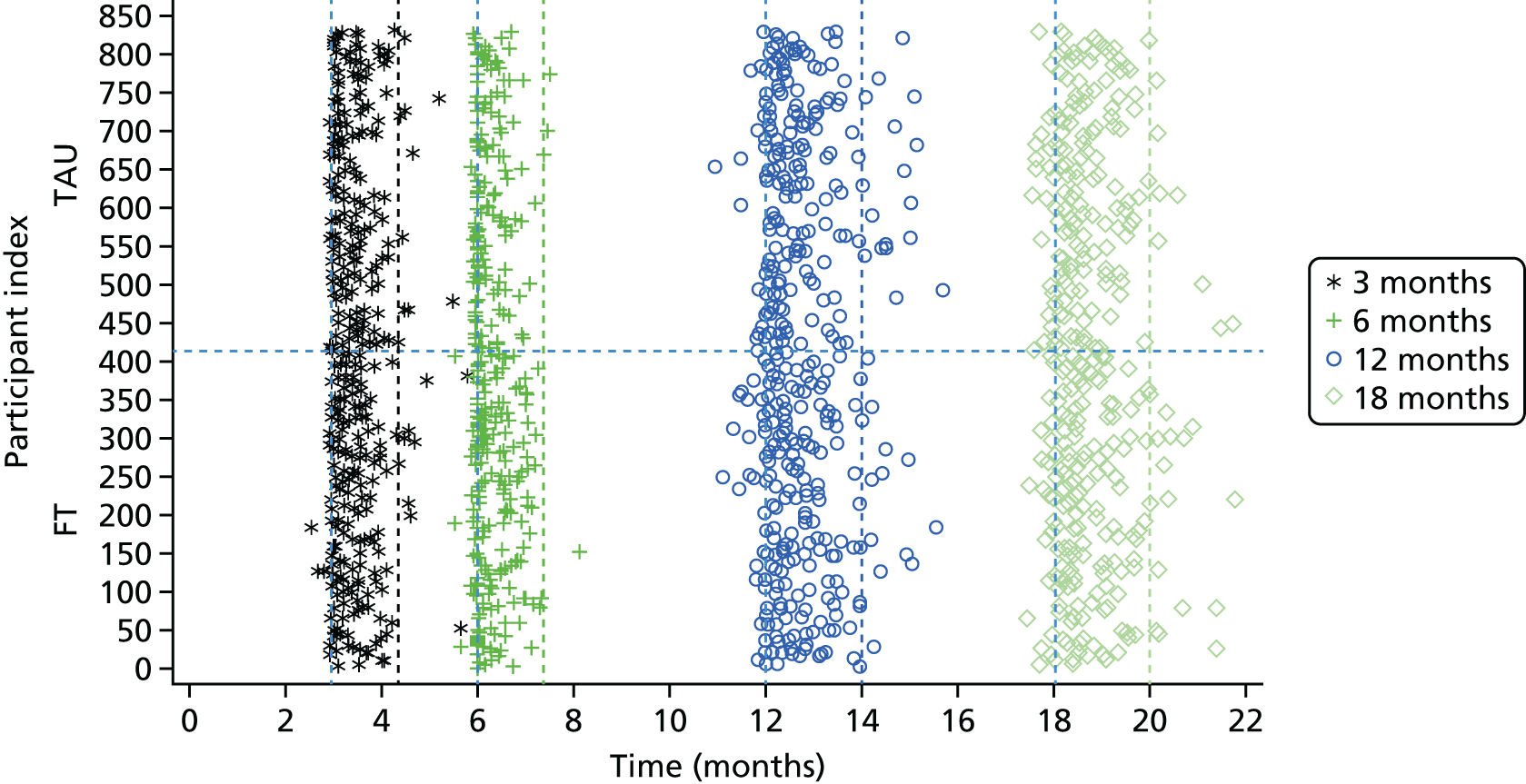

Participant assessments and follow-up

At the baseline assessment the researcher administered questionnaires to the young person, and self-reported questionnaires were also completed by the young person and caregiver.

Postal questionnaires were administered by CTRU at 3 and 6 months post randomisation. These were preceded by a telephone call from researchers, when it was possible to make contact. If questionnaires were not returned, postal reminders were sent 2 weeks after the initial mailing and then again a further 2 weeks later.

Further follow-up to administer questionnaires took place at 12 and 18 months following randomisation via face-to-face researcher interviews. When it was not possible to arrange face-to-face interviews and when participants agreed, self-reported questionnaires were posted to participants for completion. The offer of incentives to young people for participating in the 12- and 18-month follow-up interviews was introduced in August 2013 (see amendments in Appendix 2) in an effort to improve compliance.

Clinical follow-up

The primary outcome measure was obtained from accident and emergency (A&E) and inpatient Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data downloads from NHS Digital. This method of primary outcome data collection was augmented by directed hospital record searches, which were undertaken by researchers at frequent intervals throughout the trial. Researchers searched acute trust records for further details of all attendances that were unclear from the central HES data (i.e. where self-harm relatedness or method of self-harm could not be determined from HES data alone) and for any hospital attendances for those participants who had not consented to data sharing with NHS Digital or could not be linked to HES. Given that HES data sets are England-wide, this maximised the collection of hospital attendance data, allowing for participants moving out of the catchment area (within England). The collection of these routine data also minimised bias by eliminating the possibility of preferential researcher data collection at certain acute trusts. Further details of the comparison of HES records and researcher-collected hospital records and the success of using HES data for the trial will be published separately.

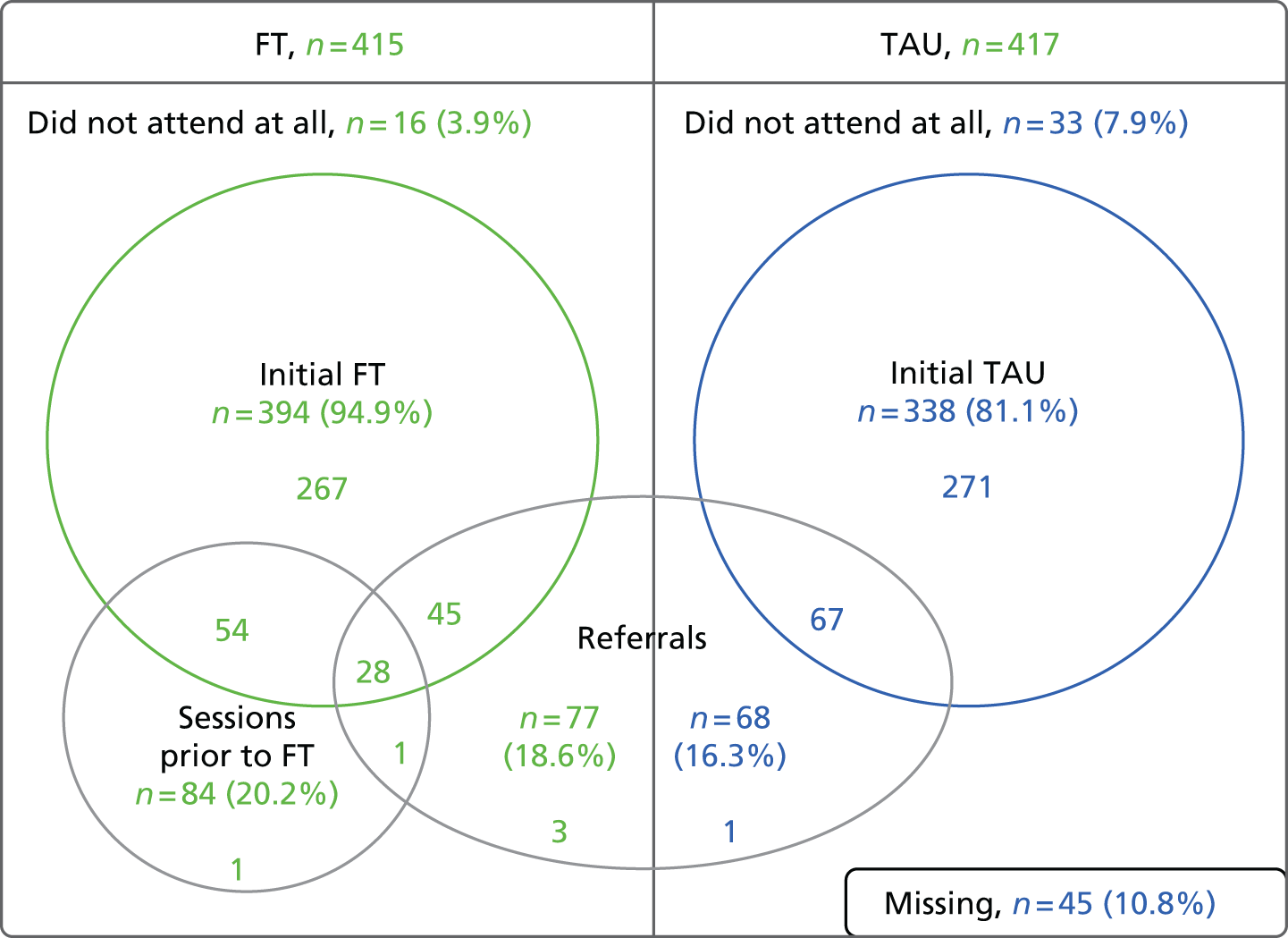

Data relating to treatment received in CAMHS following trial entry were provided by the treating CAMHS clinicians or family therapists, by clinical studies officers (CSOs) employed by the Research Networks in each locality and by the researchers when blinding was no longer required (i.e. after participant-reported follow-up data had been collected). Data included initial session attendance (FT and TAU), therapeutic approach (for TAU), referrals within CAMHS for additional or alternative sessions, requirements for psychotropic medications, liaison and referrals to other agencies outside CAMHS and re-referral to CAMHS following discharge. In addition, treating clinicians and participants completed the SOFTA44 at the end of the third treatment session. Supervision sessions for family therapists and routinely provided clinical supervision for CAMHS clinicians were also recorded. Details of the scoring of questionnaires are in Appendix 3. These appendices provide further detail concerning the collection of clinical follow-up data.

Safety

Non-serious adverse events (AEs) were operationally defined in SHIFT as treatment on an emergency outpatient basis and re-referral to CAMHS, as these events were expected to occur within the adolescent study population. Deaths and hospital admissions were defined as serious adverse events (SAEs).

Adverse event data were obtained through researcher collection of data from CAMHS and acute trusts and via data transfer from NHS Digital.

Assessment instruments

Assessment instruments were incorporated into participant assessment packs for both the young person and their caregiver. The standardised questionnaires used were selected following our literature review because they related to factors thought to be important secondary outcomes in their own right or possible mediators or moderators of treatment effects. In selecting individual measures, we also tried to use those measures that would enable comparisons with other studies in the field. In one case [the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits (ICU)] we were influenced by our knowledge of a large randomised controlled trial about to commence at the same time as SHIFT with a similar age group that we wanted to be able to compare with our sample. All measures were appropriate to the age range of young people and have been widely used in a range of ethnic communities. Appendix 3 contains details of scoring.

Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview

The researcher completed the SASII52 during the interview with the young person. The SASII is designed to assess the factors involved in non-fatal suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. It contains six screening items, nine open-ended questions to provide information for interviewer coding, and 22 items and associated subitems measuring timing and frequency of self-injurious acts, methods used and lethality of the method, suicidal as well as non-suicidal intent associated with the episode, communication of suicide intent before the episode, impulsivity and rescue likelihood, physical condition and level of medical treatment. The SASII also collects a timeline of all self-reported self-harm with details of the timing, methods and treatment received. At baseline the SASII focused on the index episode of self-harm and provided a timeline over the preceding 12 months; at 12-month completion the focus was on the first post-randomisation episode and the timeline since baseline; and, at 18 months, the focus was on the first episode following the 12-month researcher visit and a timeline since the 12-month researcher visit.

Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits

The ICU71 was completed by the young person and by the caregiver in reference to the young person. It is a 24-item questionnaire in which participants are asked to indicate how well each statement describes them on a 4-point scale and is designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of callous and unemotional traits, with three subscales: callousness, uncaring and unemotional. Higher scores represent higher callous and unemotional traits. ICU measures are helpful in predicting different outcomes and developmental pathways in children with conduct disorder.

Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation

The BSS53 was completed by the young person and is used to examine suicidal intent. The first 19 of 21 items measure the severity of actual suicidal wishes and plans, each on a 3-point scale, with a higher score indicating a higher level of suicide ideation. The first five items also serve as a screen for suicide ideation.

Paediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

The PQ-LES-Q54 was completed by the young person and is used to examine quality of life. It consists of 15 items, each on a 5-point scale, providing a single overall score with higher total scores indicative of greater enjoyment and satisfaction.

Children’s Depression Rating Scale – Revised

The CDRS-R56 was completed by the researcher during the young person interview and is used to assess the severity of depressive syndrome. It is a brief rating scale based on a semistructured interview rating 17 symptom areas on a 5- to 7-point scale, including impaired schoolwork, difficulty having fun, appetite disturbance, excessive fatigue and low self-esteem. Higher scores are indicative of greater depression and are categorised to indicate mild, moderate, severe and very severe depression.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The SDQ57 was completed by the young person and the caregiver, giving their views of the young person’s behaviours, and is a brief behavioural screening questionnaire assessing levels of emotional and behavioural problems. Both young person and caregiver versions ask about 25 attributes, each with three responses, across five scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems and prosocial behaviour. A ‘Total difficulties’ score combines all scales except the prosocial scale. ‘Externalising’ and ‘Internalising’ scores are also generated and an impact supplement is included in the caregiver version, in which the respondent is asked whether or not they think the young person has a problem, enquiring further about chronicity, distress, social impairment and burden to others. Higher scores in all but the prosocial score represent greater issues in that category. For the prosocial score, lower scores represent greater issues. Responses are also categorised according to a four-band categorisation.

Hopelessness scale

The Hopelessness Scale58 was completed by the young person and is used to measure the degree to which young people have negative expectancies about themselves and the future. It consists of 17 items with true or false responses, providing a single overall score with higher scores reflecting greater hopelessness or negative expectations towards the future.

McMaster Family Assessment Device

The McMaster FAD59 was completed by the young person and caregiver. It measures family functioning across 60 items, each on a 4-point scale measuring agreement, based on the McMaster Model on six different dimensions: problem-solving (ability to resolve problems), communication (exchange of clear and direct verbal information), roles (division of responsibility for completing family tasks), affective responsiveness (ability to respond with appropriate emotion), affective involvement (degree to which family members are involved and interested in one another) and behaviour control (manner used to express and maintain standards of behaviour); it also includes an independent dimension of general functioning (overall functioning of family). Higher scores are indicative of poorer family functioning. Miller et al. 72 documented clinical cut-off scores differentiating ‘healthy’ versus ‘unhealthy’ family functioning for each dimension (see Appendix 3).

Family Questionnaire

The Family Questionnaire60 was completed by the consenting caregiver in reference to the young person and is a brief 20-item self-report questionnaire relating to the different ways in which families try to cope with everyday problems. It assesses expressed emotion directed at the young person by family members with responses on a 4-point scale. In addition to the total score, it has two subscales: critical comments (unfavourable statements about the personality or behaviour of the young person) and emotional overinvolvement (overintrusiveness, protectiveness and identification). Higher scores indicate greater levels of expressed emotion.

Parent General Health Questionnaire, 12 questions

The GHQ-1273 was completed by the caregiver and is a measure of current mental health focusing on two major areas: the inability to carry out normal functions and the appearance of new and distressing experiences. It includes 12 items, each on a 4-point scale to indicate whether or not symptoms of mental ill health are present, with high total scores indicative of greater psychological distress.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions

The EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)74 was completed by the young person. The respondents are asked to describe their levels of health problems using a descriptive system comprising five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), each with three levels: no problems, some problems, extreme problems. The combination of answers leads to a health profile of five digits (243 unique health profiles) that can then be converted into a utility that represents the overall quality of life of the young person. The EQ-5D utility score varies from 0 to 1, with 0.0 meaning death and 1.0 complete health. While the original protocol suggested the use of the Health Utilities Index 3 (HUI-3) to measure the young person’s quality of life, we undertook a pilot study in a school setting and decided that the EQ-5D was easier for young people to complete. 75

Health Economics Questionnaire

The Health Economics Questionnaire was completed by the young person and the caregiver. The caregiver reported health care use for the young person as well as for their own care. The questionnaire was designed for use in the SHIFT trial to collect information on A&E attendances, inpatient/outpatient attendances, primary/community care provided by the NHS/social services and medications. Data on personal costs were also collected, such as out-of-pocket expenses and productivity costs to both young persons and caregivers and any use of education and justice services. A reduced self-reported questionnaire was used within the trial from the autumn of 2011; it excluded questions on A&E attendances, inpatient attendances as this was obtained via data downloads from NHS Digital records and questions on private expenses and time off work. The recall period was the past 3 months at every data collection point.

Health Utilities Index 3

The HUI-376 was completed by the caregiver and is widely used in population health surveys, clinical studies and cost–utility analyses. The HUI3 is a health status classification system including eight attributes (vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition and pain), each with five or six levels of ability/disability. Answers are then scored using a multiattribute scoring function derived from community preference measures for health states. The scoring systems provide a utility score on a generic scale where dead = 0.00 and perfect health = 1.00.

System for Observing Family Therapy Alliances

The SOFTA61 was completed in clinic by the lead family therapist, young person and caregiver after the third therapy session and is a self-reported questionnaire used to evaluate the strength of the therapeutic alliance in FT. If the consenting primary caregiver was not present, it could be completed by another member of the family, or during another therapy session. It includes 16 items, each on a 5-point scale, measuring agreement for behaviours in four dimensions: engagement in the therapeutic process, emotional connection with the therapist, safety within the therapeutic system and shared sense of purpose within the family. Higher scores represent greater alliance.

Scoring and missing item data

When a questionnaire was received but questionnaire item data were missing (item non-response), documented instructions for dealing with missing data were followed when these were available (EQ-5D, SDQ, McMaster FAD77). Otherwise, in the absence of documented instructions, the half rule78 was used (CDRS-R, BSS, PQ-LES-Q, Hopelessness Scale, Family Questionnaire, GHQ-12, ICU, SOFTA), allowing for substitution of the mean of answered questions of specific subscales/totals provided that at least half the questions on a given scale were answered. Further details of scoring and categorisation can be found in Appendix 3.

Data quality and monitoring

Data were monitored for quality and completeness by the CTRU using established verification, validation and checking processes. Missing data, except individual data items collected via the postal questionnaires, were chased for until they were received or confirmed as not available or until the trial was at analysis.

Protocol adherence, trial uptake, loss to follow-up, withdrawal, participant safety, data quality and data/questionnaire return rates were monitored, as appropriate to each group, at each TMG, Trial Steering Committee (TSC) [which included a patient and public involvement (PPI) member] and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) meeting.

The DMEC reviewed, on an annual basis and by trial arm, the number and frequency of hospitalisations and deaths as a consequence of self-harm. Processes were in place to escalate any concerns raised by the DMEC or to escalate concerns identified by the trial team to the DMEC in the interim periods between meetings. The DMEC reviewed interim primary outcome data after half the events had occurred.

Quality assurance

The trial was conducted in accordance with current Medical Research Council good clinical practice guidelines, the NHS Research Governance Framework and through adherence to CTRU standard operating procedures.

The trial was reviewed and approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee (NRES) Yorkshire and the Humber – Leeds West [Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference 09/H1307/20]. SHIFT also received research and development approval from all participating CAMHS’ host organisations. For the purposes of collecting routine data from acute trusts to inform the primary outcome, the REC agreed that the study was exempt from site-specific assessment, but researchers required letters of access from each trust to access records.

Protocol amendments

There were 11 substantial amendments to the protocol (see Appendix 2 for full details) throughout the lifetime of the SHIFT trial. The methods detailed here cover all protocol amendments.

Three substantial amendments were made prior to the start of recruitment. These included clarification of the eligibility criteria and of the secondary outcome measures to be used.

After recruitment commenced, eight further substantial amendments were made, some of which covered more than one issue.

In brief, these included an amended process for obtaining consent for FT sessions to be video-recorded (and confirmation of data transfer processes), clarification of eligibility criteria, randomisation of family therapists (prior to the relevant teams commencing recruitment), augmenting follow-up processes (additional researcher contact prior to postal follow-up, thank-you letters at 12 or 18 months where questionnaires were returned by post), inclusion of verbal consent to researcher contact where written consent was not possible, clarification of who is appropriate to take on the consenting caregiver role, production of a FT leaflet for those allocated FT, sending Christmas cards to participants, collection of multiple contacts at baseline to aid follow-up, introduction of participant incentives and participant information amendments to confirm duration of follow-up.

Patient and public involvement contribution

A local young persons’ group in Leeds was consulted regarding the content of the participant information sheets.

A PPI expert was a member of the TSC from the first meeting in 2010 to October 2012.

Unsuccessful attempts were made to invite a young person and her primary caregiver to join the TSC.

Over the course of the trial there was further consultation with young people who work with the charity Young Minds and with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Young People’s Mental Health Advisory Group.

Statistical methods

Sample size

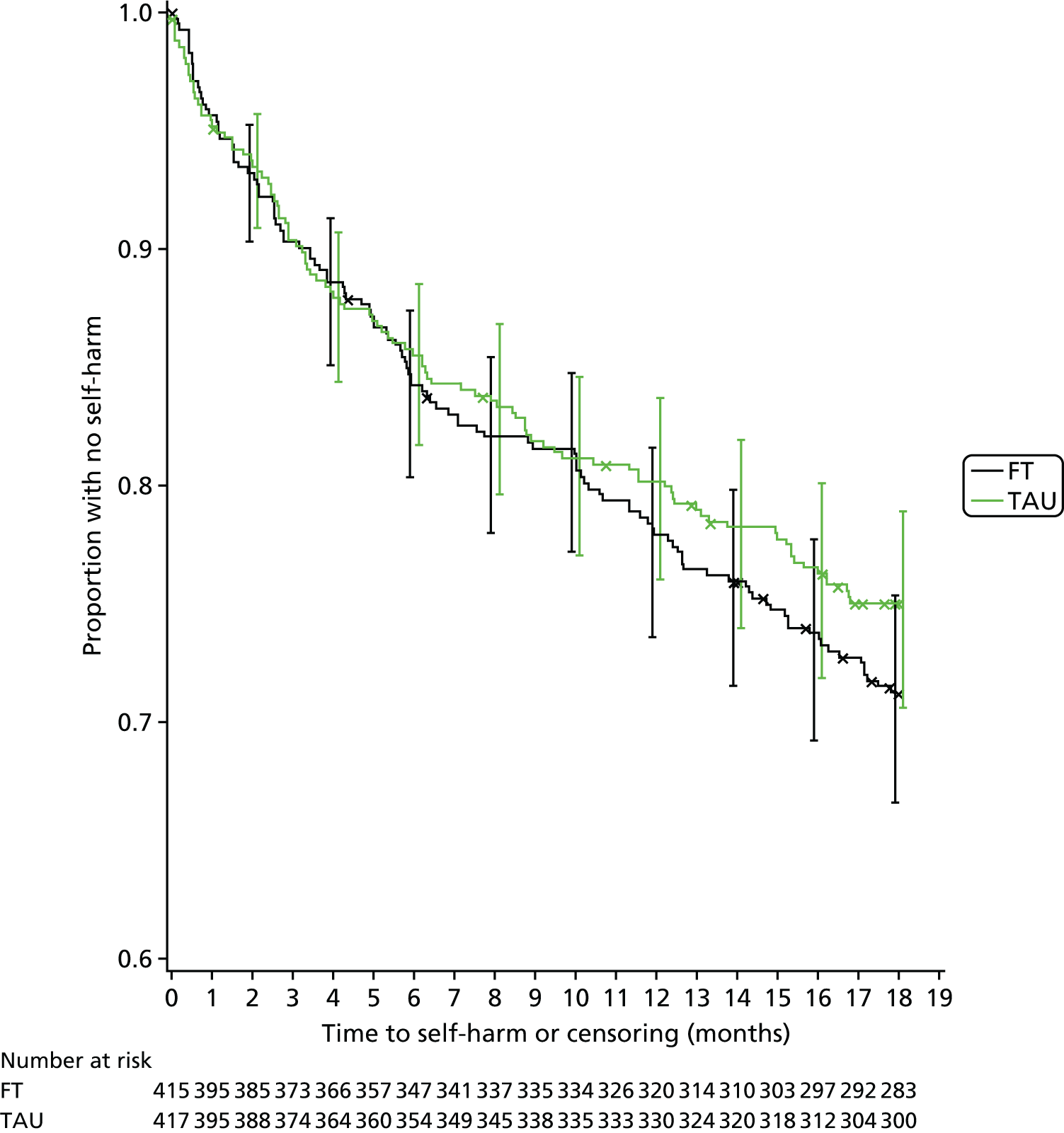

The power calculation was based on a minimally important reduction in 18-month repetition rates of self-harm (leading to hospital attendance) from 29% in participants receiving TAU6 to 18.8% in participants receiving FT, that is, a reduction of 35%, providing a constant hazard ratio (HR) of 1.64. Using a 5% significance level log-rank test for equality of survival curves, 374 participants per arm were required, with 172 total events, to give 90%. Assuming, at most, 10% loss to follow-up by 18 months, the total sample size required was 416 per arm, 832 in total.

Although SHIFT was individually randomised, the inherent clustering of participants nested within therapists is known to have an impact on power and is related to the level of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) and the cluster size. It was expected that the level of clustering would be low, possibly around 0.01 but no higher than 0.05 (owing to the use of therapy manuals, therapist selection, training, supervision and monitoring). It was also expected that the number of participants per therapist would be small. It was estimated that between 8 and 15 therapists would be available in the TAU team at any one centre, so across the anticipated 15 participating trusts there would be 120–225 therapists available to treat 416 participants; thus, each therapist would treat between two and four participants (maximum cluster size of four). In FT, we estimated that there would be approximately 35 therapists available across all sites to treat 416 participants; thus, each lead therapist would have direct contact with approximately 12 participants (maximum cluster size).

The design effect, describing the extent to which the sample size must be increased to obtain the same power as an individually randomised study without clustering, was therefore assumed likely to be no greater than 1.55 (ICC of 0.05), effectively reducing the sample size from 416 per group to 270 per group and the power from 90% to around 75%. If the ICC were as low as 0.01, then the design effect would be 1.11, reducing the sample size to 374 per group and the power to around 85%. We anticipated that the ICC would be towards the lower end of the possible range and therefore the trial would still be adequately powered with the sample size planned.

Participant populations

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population consisted of all randomised young people who had consented, regardless of non-compliance with the intervention, whether they were found to be ineligible post randomisation and/or remained in the trial and were analysed according to the treatment they were randomised to receive.

The per-protocol population consisted of all randomised, consented young people, excluding those who were found not to satisfy the eligibility criteria.

Statistical analysis

A single formal interim analysis was planned for the primary end point, repetition of self-harm leading to hospital attendance within 18 months of randomisation, when at least half the required number of events were reached (86 events). It was planned that the DMEC, in light of interim data, would if necessary report to the TSC with a recommendation of trial adaptation or early closure if, compared with TAU, the effect of FT was significantly inferior (p < 0.005). Final analyses were planned after all participants had reached the end of the 18-month follow-up period, when it was expected that at least 172 events would have occurred.

Analysis methods

All data analyses and summaries were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA), and, unless otherwise specified, were conducted on the ITT population. An overall two-sided 5% significance level was used for all end-point comparisons; however, for the primary end point, the O’Brien and Fleming79 alpha spending function was used to account for the interim analysis, allowing an alpha level of 0.047 for the final analysis and 0.005 for the interim analysis.

General calculations

Time from randomisation was calculated in days with estimates presented in months, where 1 month was defined as time in days/30.44, and 18 months calculated as 528 days.

All clinical data included data up to 18 months post randomisation. Attendances and other clinical data, that is, referrals, occurring post 18 months were excluded from the analysis as these data were not collected reliably for all participants.

Covariates

All multivariable analyses were adjusted by the randomisation stratification factors age, gender, number of previous self-harm episodes, type of self-harm (if there were errors during randomisation the true value was used) and by participants’ recruiting trust and source of referral (through hospital or not). The stratification factor ‘living arrangements’ was not included as a covariate as all but two young people were living with parents/guardians. Adjustment was made for centre grouped at the trust level as, with 40 centres recruiting to SHIFT and between two and 58 participants recruited from each centre, an adjusted analysis by centre could prove problematic because of instability and lack of convergence (i.e. there could be some small centres where no events were observed).

Study summary, baseline characteristics, treatment and safety

Summaries of screening, accrual, protocol violators, withdrawals, participants’ follow-up rates and unblinding were produced and an overall CONSORT diagram presented. All baseline characteristics of participants, treatment received and safety data were summarised by treatment group and described descriptively without statistical comparison.

Primary end-point analysis

Derivation

The timing of repeat self-harm was calculated from the date of randomisation to the date of hospital attendance corresponding to the first instance of repeat self-harm within 18 months of randomisation. Young people without any reported instances of repeat self-harm leading to hospital attendance were censored at their final date of hospital follow-up or 18 months post randomisation, whichever was earlier. Young people without follow-up (i.e. withdrawn prior to a hospital follow-up search) were censored at baseline.

Timing of young people’s final hospital follow-up was based on the most recent data cut-off point for HES data collected via NHS Digital and researchers’ Acute Trust searches. Follow-up dates based on researchers’ Acute Trust searches were calculated for each young person based on the hospital(s) most frequented for participants recruited from the same CAMHS service. For the majority of young people, full 18-month follow-up was achieved via successful linkage to HES, with HES data covering participants’ full follow-up period; or, where HES linkage was not possible, via full researcher follow-up at the Acute Trusts to which participants would most likely present. However, full 18-month hospital follow-up was not achieved for participants for whom the final HES data download did not cover their full follow-up period (owing to HES data being provided 3 months in arrears); HES linkage was not possible and researcher follow-up did not cover participants’ full follow-up period; or where consent was withdrawn for further clinical data collection and hospital follow-up was based on the HES data cut-off or researcher follow-up preceding the withdrawal.

Attendances at minor injury units (MIUs) and walk-in centres (WIC) identified via HES, without subsequent A&E or inpatient attendance, did not fit the definition of the primary outcome and were excluded.

Attendances reported via both HES and the researcher were combined, in order to avoid double counting. Where there was conflicting information, the more serious case was used, that is, admissions to hospital were deemed more serious than attendance at A&E only, self-harm more serious than non-self-harm and, if uncertain, HES data were used to ensure consistency.

Full details of data cleaning, derivation and use of HES data to identify attendances resulting from self-harm will be published separately.

Missing data

Missing presenting (resulting from self-harm or not) details for hospital attendances reported in HES were queried by trial researchers at relevant acute trusts. At the time of analysis, attendances with missing details were reviewed by the chief investigator (blind to treatment allocation). Information was provided on the length of hospital stay, diagnoses where available and treatment received and as a result it was possible to further categorise 73 of all 915 hospital attendances (8%; A&E, MIU or WIC) as not being self-harm related. Remaining unclassified attendances were assumed not to be related to self-harm in the primary analysis.

Analysis

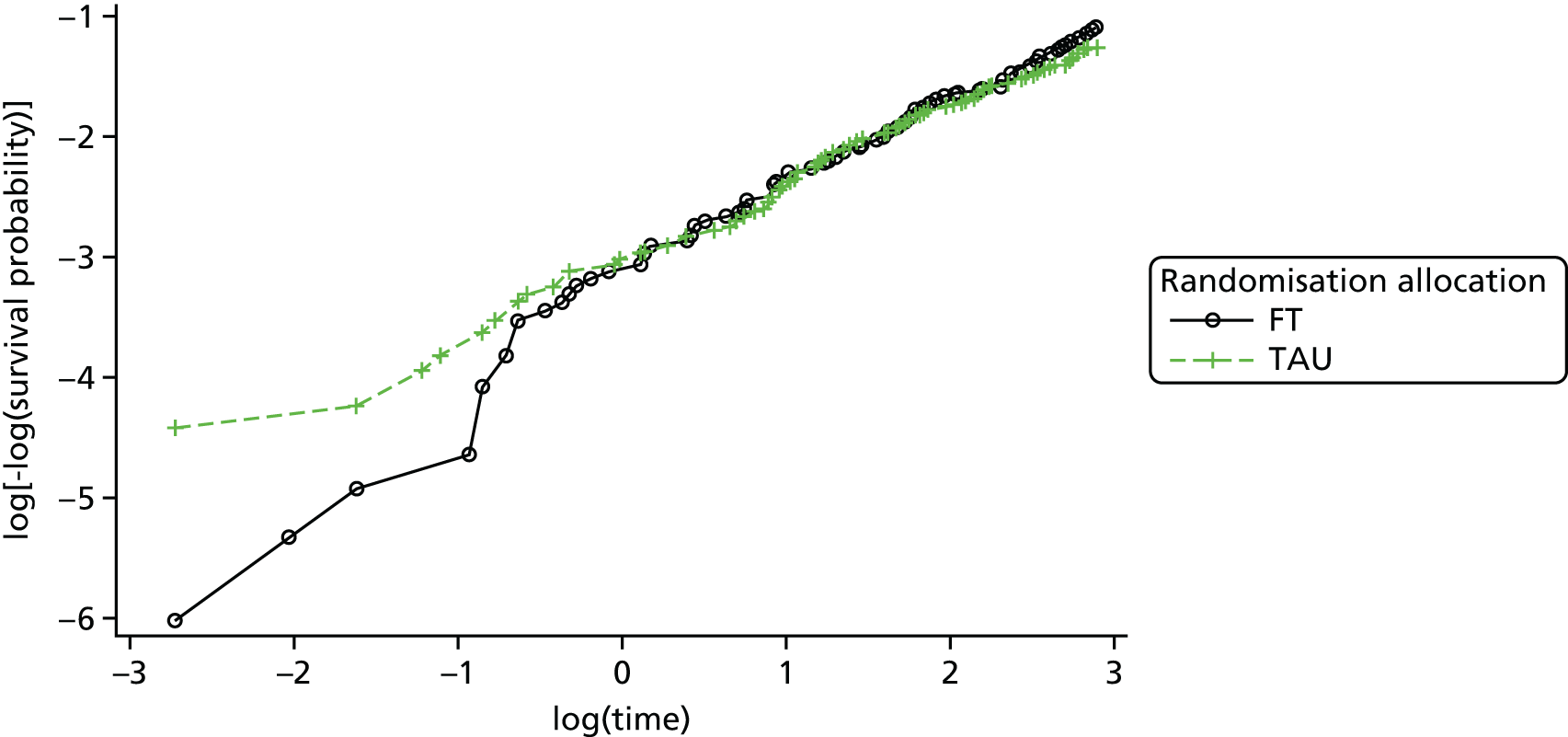

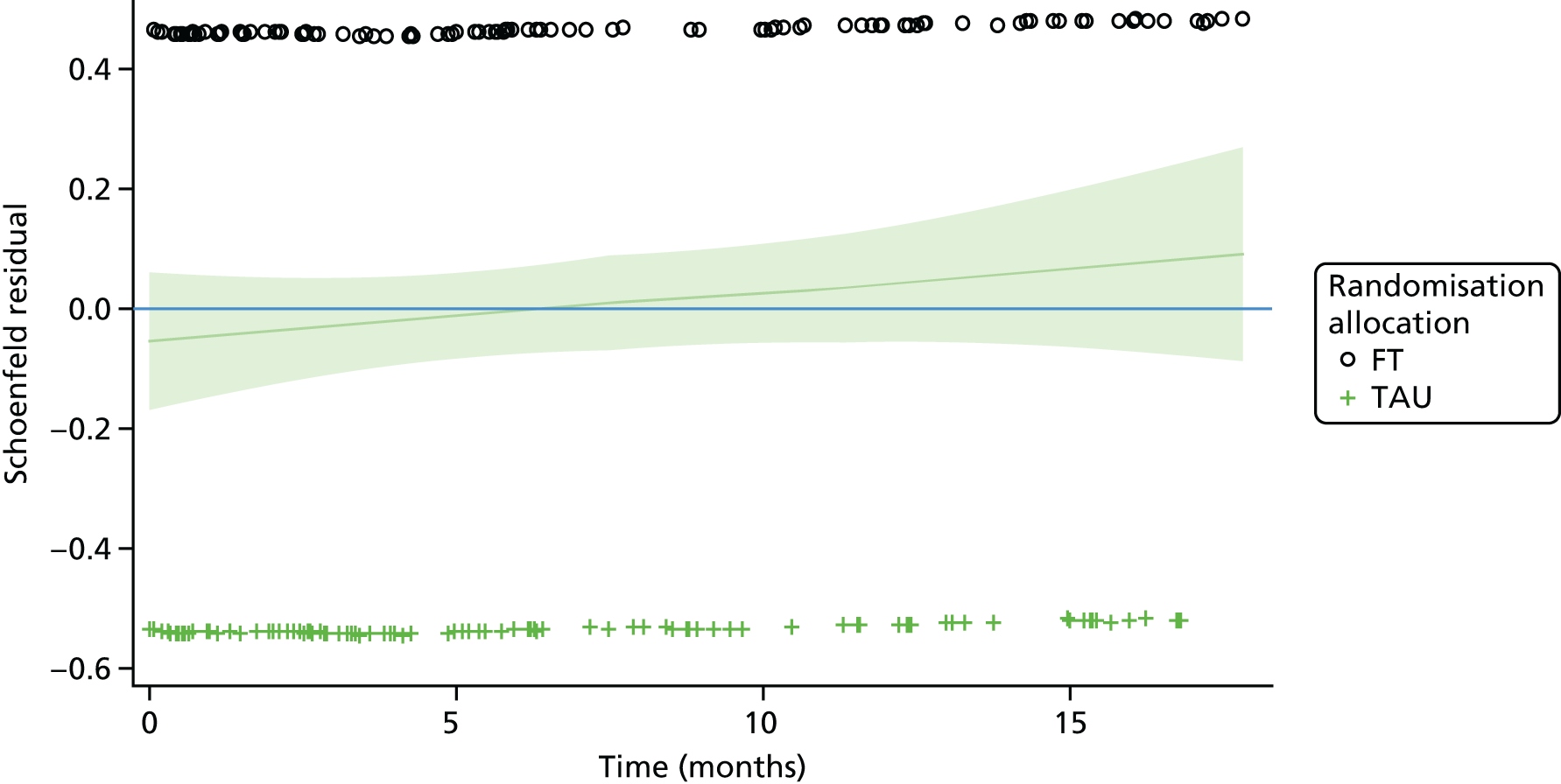

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, accounting for covariates, was used to test for differences in 18-month repetition rates between treatment arms. The assumption of proportional hazards was assessed by plotting the hazards over time (i.e. the log-cumulative hazard plot) and the methods of Lin et al. 80 were further used to check the adequacy of the model.

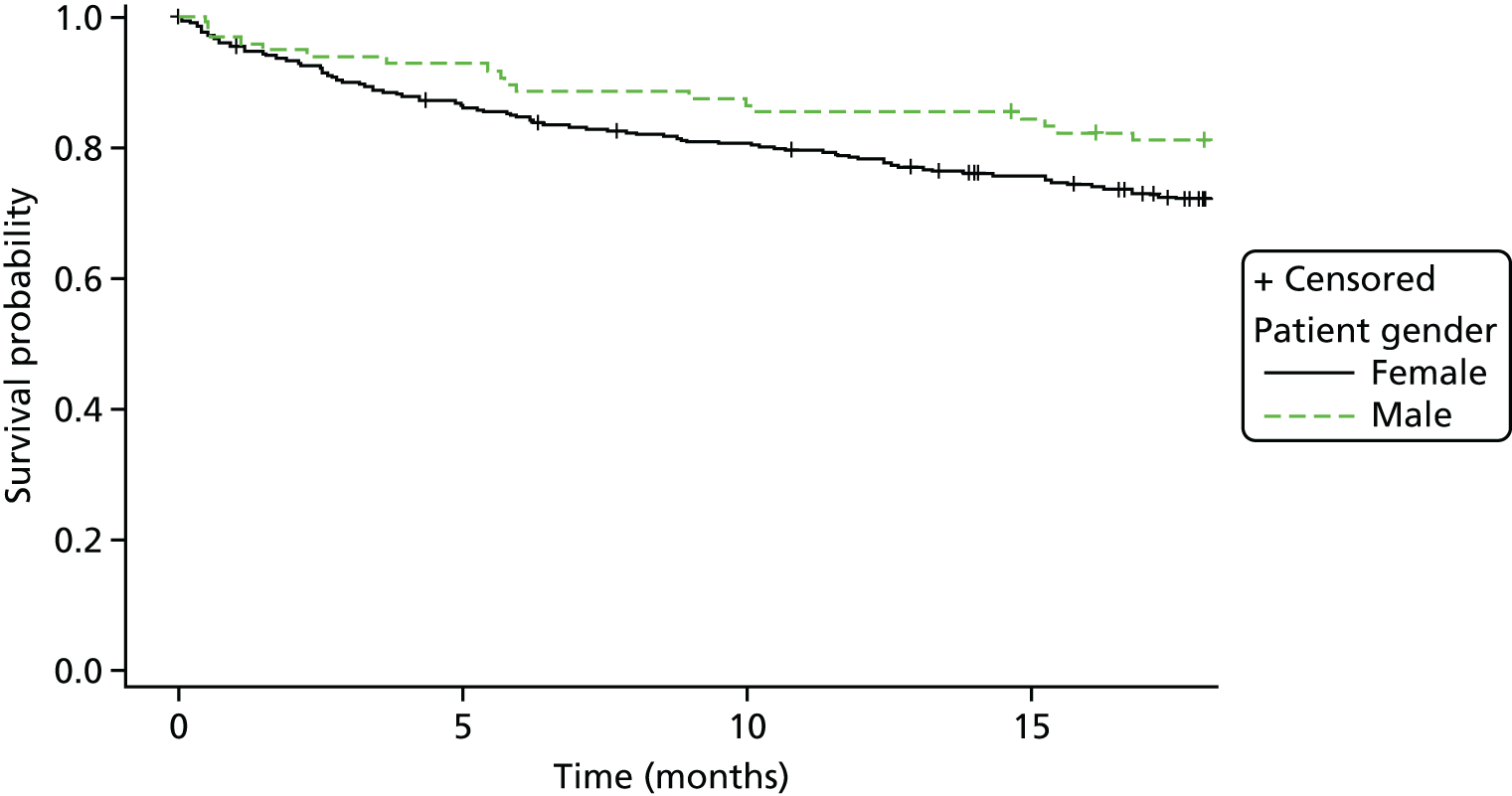

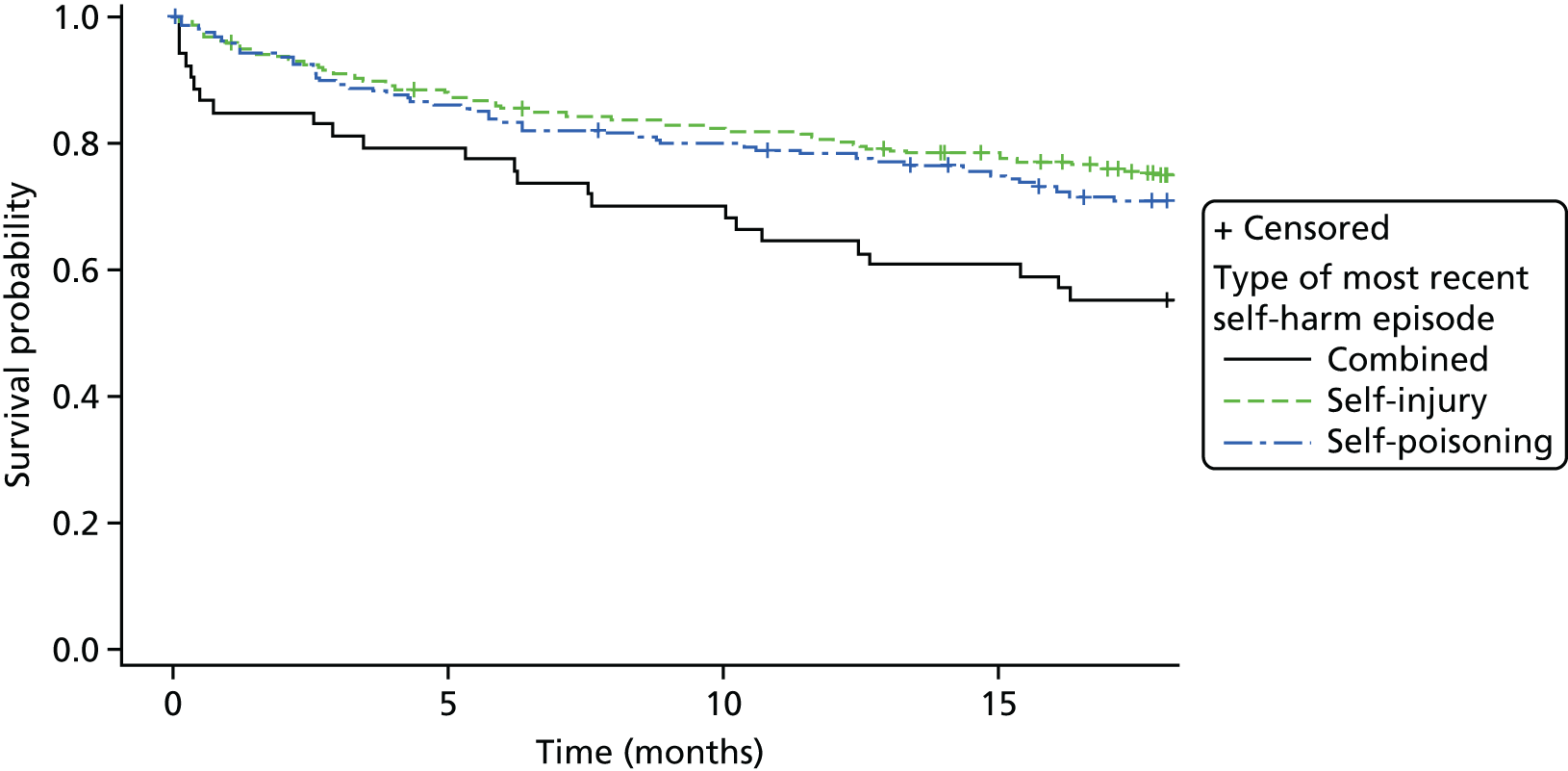

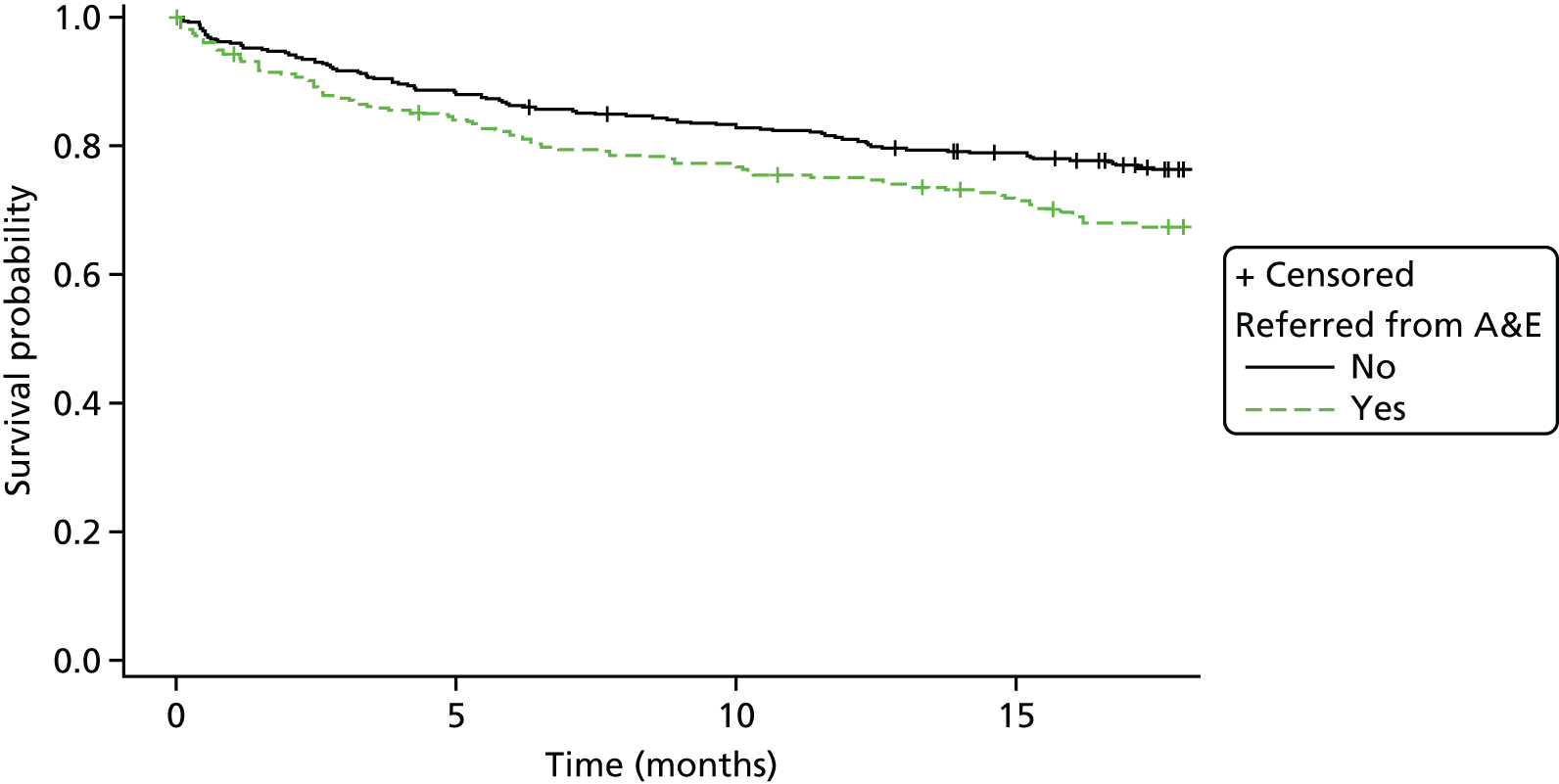

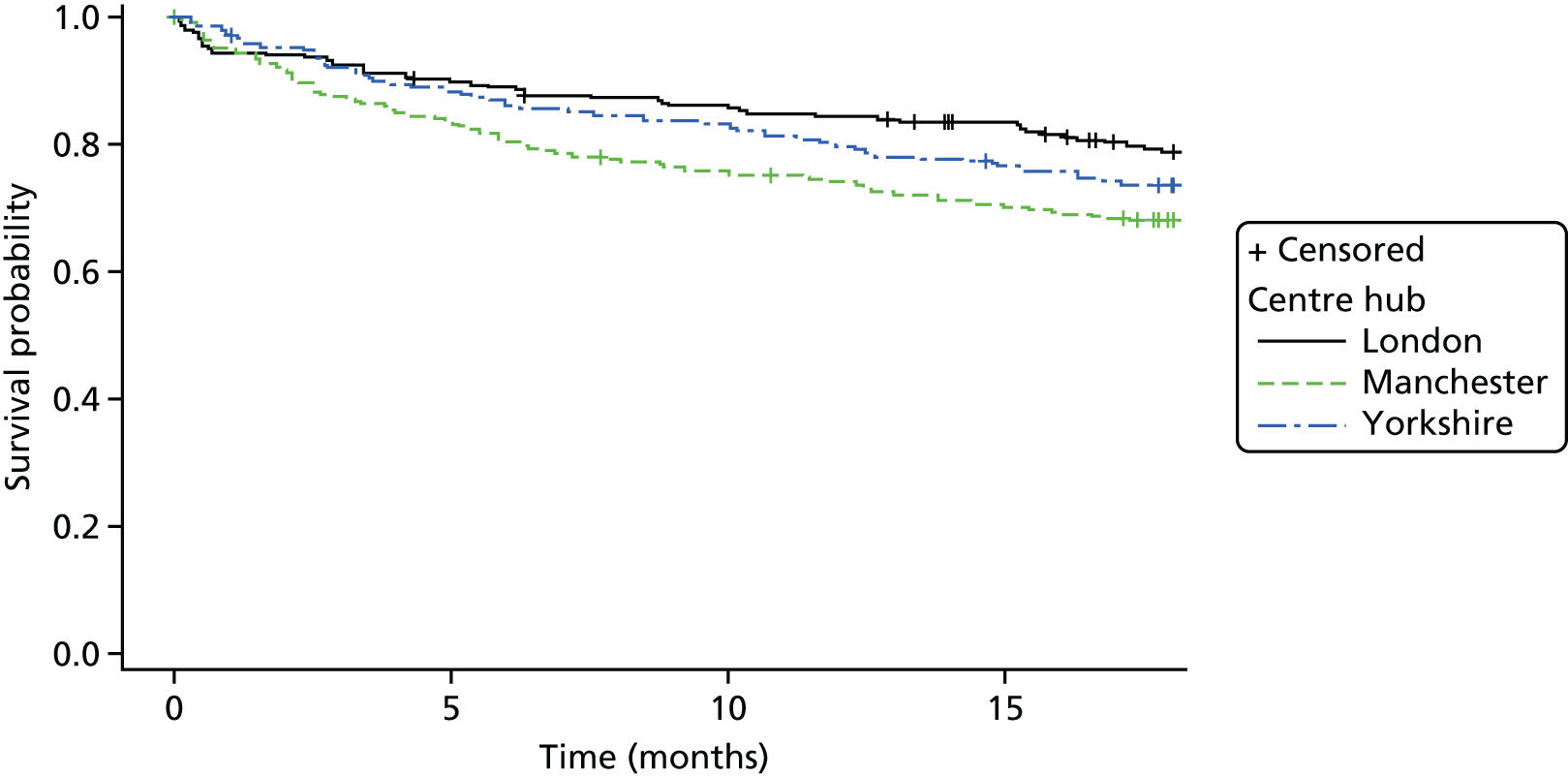

Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed for each group. Repetition estimates at each month post randomisation with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are also presented for each treatment arm and for the difference between arms.

Although the significance level was reduced to account for an interim analysis, CIs are still presented at the 95% level.

Sensitivity analysis

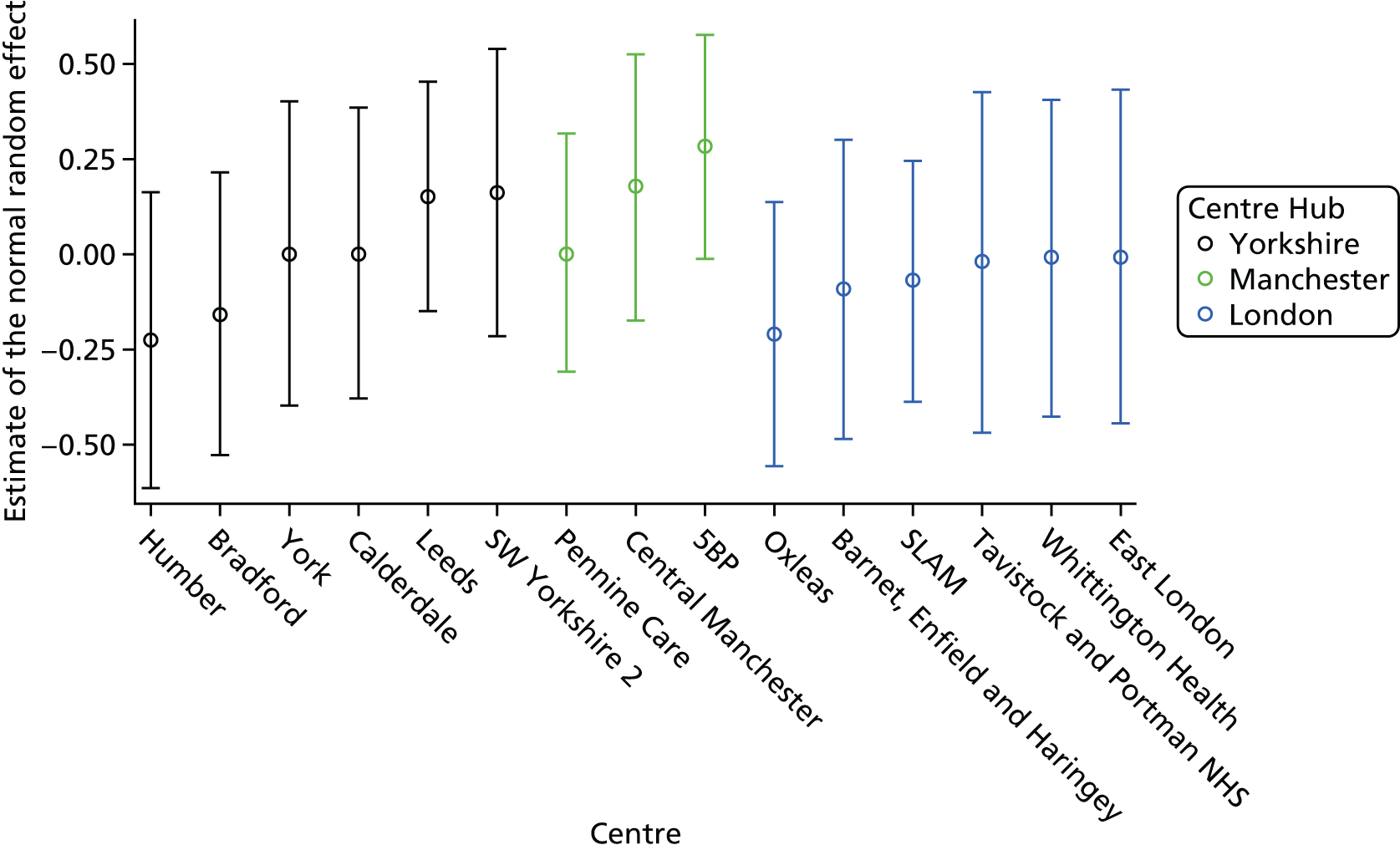

The extent of clustering caused by therapists and the impact on the precision of the treatment effect estimate was investigated using a multivariable multilevel survival frailty model,81,82 in which a common frailty for individuals treated by the same therapist allows for heterogeneity between groups of participants treated by different therapists and accounts for within-group correlations (using the RANDOM statement in PROC PHREG).

Clustering by therapist was derived according to the ‘main’ therapist delivering the greatest number of sessions for FT or TAU. Where an equal number of sessions were delivered by different therapists, the main therapist was defined as the earliest of the therapists involved. Participants who received no treatment, were missing treatment data or missing the name of their main therapist were classed as belonging to their own individual cluster of size 1.

A sensitivity analysis was also conducted to assess the impact of missing details of hospital attendance (i.e. where it is unclear whether or not an attendance had resulted from self-harm), in which unclassified attendances were classed as self-harm related, thus contributing to the primary outcome.

Given that the proportional hazard assumption was questionable for a number of trusts, further multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were fitted to investigate the effect on the treatment estimate without trust in the model and with hub, and associations between trust and other covariates were explored. The primary analysis model was also fitted accounting for the shared frailty by trust, therefore treating trust as a random effect rather than a fixed effect.

Secondary end-point analysis

Repetition rates of self-harm leading to hospital attendance 12 months after randomisation

The analysis of 12-month repetition rates followed that of the 18-month data detailed in the primary end-point analysis, with events and follow-up curtailed at 12 months rather than 18 months.

Characteristics of further episodes of self-harm leading to hospital attendance

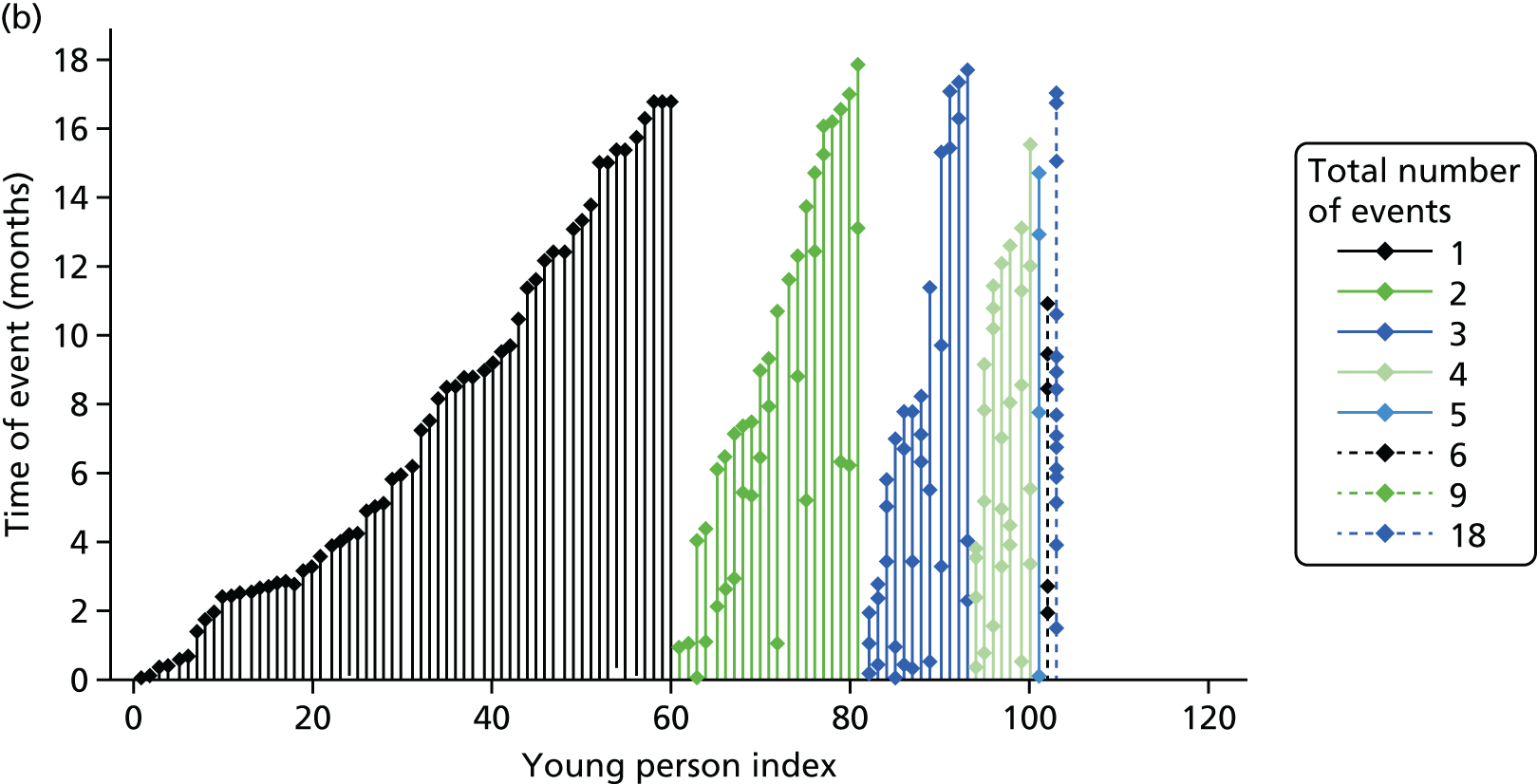

Further episodes of self-harm were analysed using a multivariable recurrent event analysis, incorporating the timing and cumulative number of self-harm events. We used a counting process model83 with robust sandwich variance estimator for standard errors (SEs) of coefficients84 to take account of the within-subject correlation (also known as the proportional means model or the independent increment model). The counting process model is an extension of the Cox regression model and, when unrestricted (as per the Andersen and Gill83 model), regards all subjects to be at risk of an event regardless of the number of events experienced thus far. Sensitivity analysis further analysed recurrent events using the conditional, restricted gap time model of Prentice et al. ,85 which assumes that the occurrence of the first event increases the likelihood of further recurrence and participants are considered to be at risk of an event only if the previous event occurred.

Characteristics of all self-harm events (SASII)

No formal statistical analysis was undertaken; characteristics are summarised descriptively only.

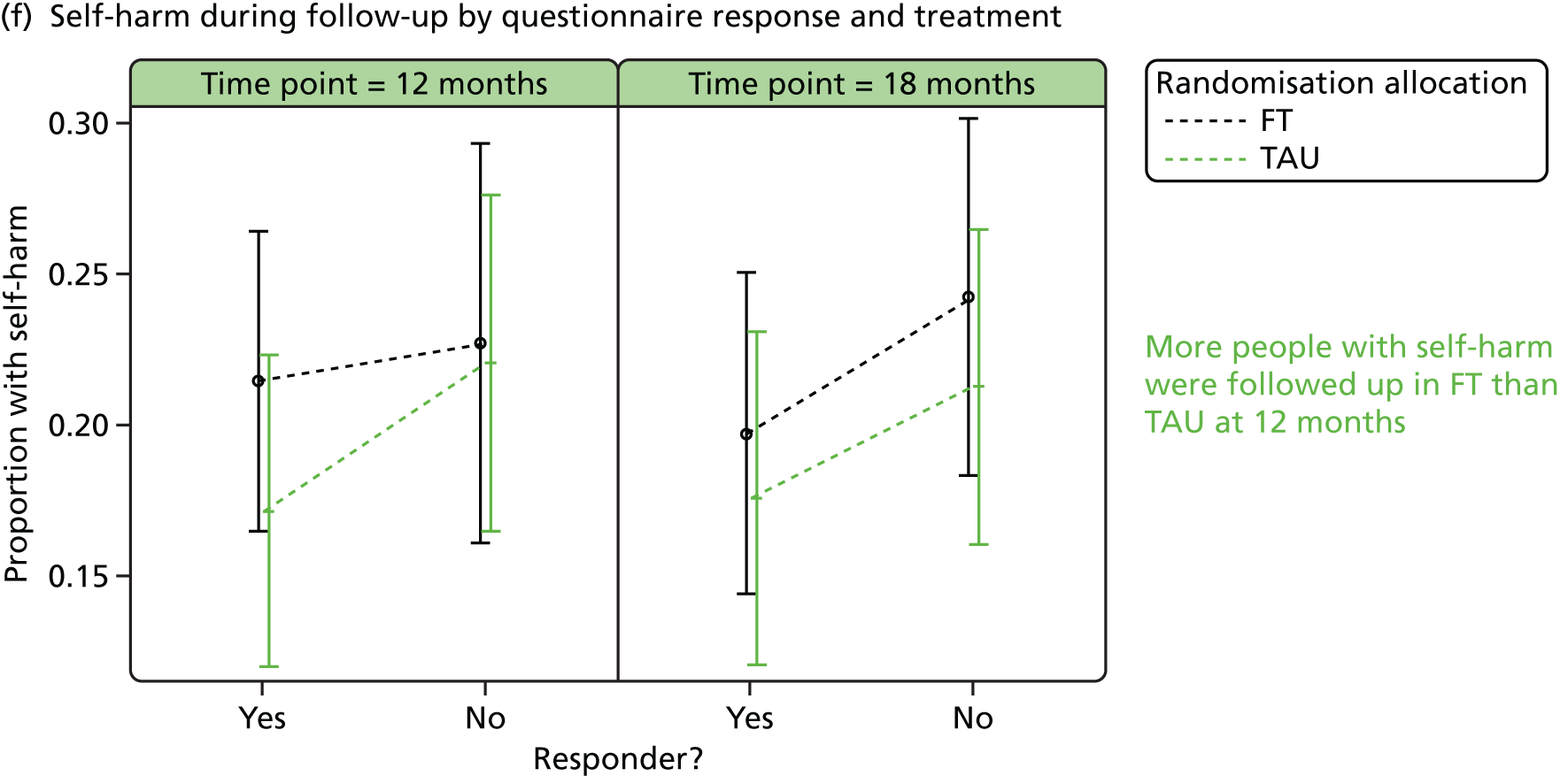

Characteristics of the first self-reported self-harm episode (regardless of hospital attendance) were summarised for participants with sufficient SASII completion from baseline to 12 or 18 months, that is, completion at the 12-month researcher visit at least or at both the 12- and 18-month visits. Furthermore, participants with an 18-month researcher visit only (not a 12-month visit) with self-harm reported between 12 and 18 months post randomisation were included in the overall number of participants with self-harm reported, as these instances of self-harm during follow-up were known.

The timing of first self-reported self-harm post baseline was calculated from the date of randomisation to the first reported date of self-harm within 18 months of randomisation. Participants without any self-reported self-harm and with sufficient SASII completion were censored at their date of follow-up, that is, the date of either the 12-month researcher visit or the 18-month visit if both 12- and 18-month visits were conducted. Participants missing the 12-month SASII were censored at baseline, including those where self-harm was known to have occurred between 12 and 18 months as the timing of the first self-harm post randomisation could not be determined.

Owing to the large variability in the level of self-reported self-harm over the SASII timeline, responses were summarised according to the occurrence and frequency of self-harm for each 3-month period post randomisation (0–3 months, 3–6 months, etc.) with frequency categorised as none (0 episodes), less than once per month (fewer than three episodes), less than once per fortnight (3–6 episodes), less than once per week (7–12 episodes), once or more per week (13–25 episodes), twice or more per week (26–45 episodes), most days (46–91 episodes).

Patient-reported outcomes

For the secondary end points (Beck Scale, CDRS-R, PQ-LES-Q, SDQ, GHQ-12, Hopelessness Scale, McMaster FAD and Family Questionnaire) repeated-measures models were used to estimate differences between the treatment groups over time. Linear repeated-measures models for continuous scores were used for all end points with the exception of the Beck Scale, for which the proportion of participants identified as having suicide ideation was modelled using a logistic repeated-measures model owing to a zero-inflated total score. A covariance pattern model was used, which accounts for repeated measures on the same participant, which may be correlated, with a first-order heterogeneous autoregressive covariance matrix and allowing for randomised treatment, time effects, baseline score, covariates and treatment–time interactions as fixed effects. This model was chosen over a random-effects model, as there were just two follow-up time points at 12 and 18 months (3 and 6 months for the Family Questionnaire), with only a small proportion (< 3%) of questionnaires completed outside the 2-month acceptable time window. Model assumptions were checked using Pearson and Studentised residuals.

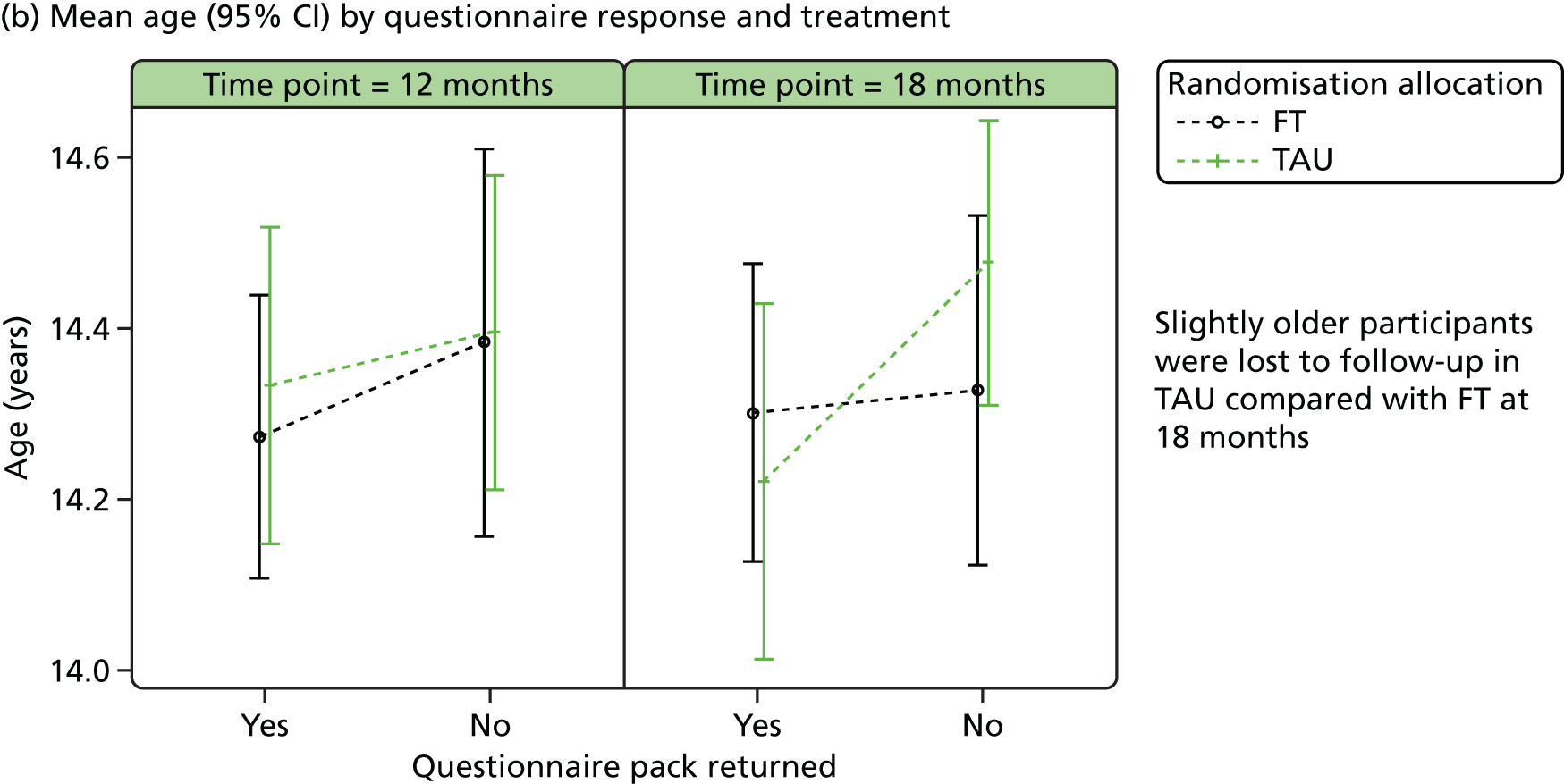

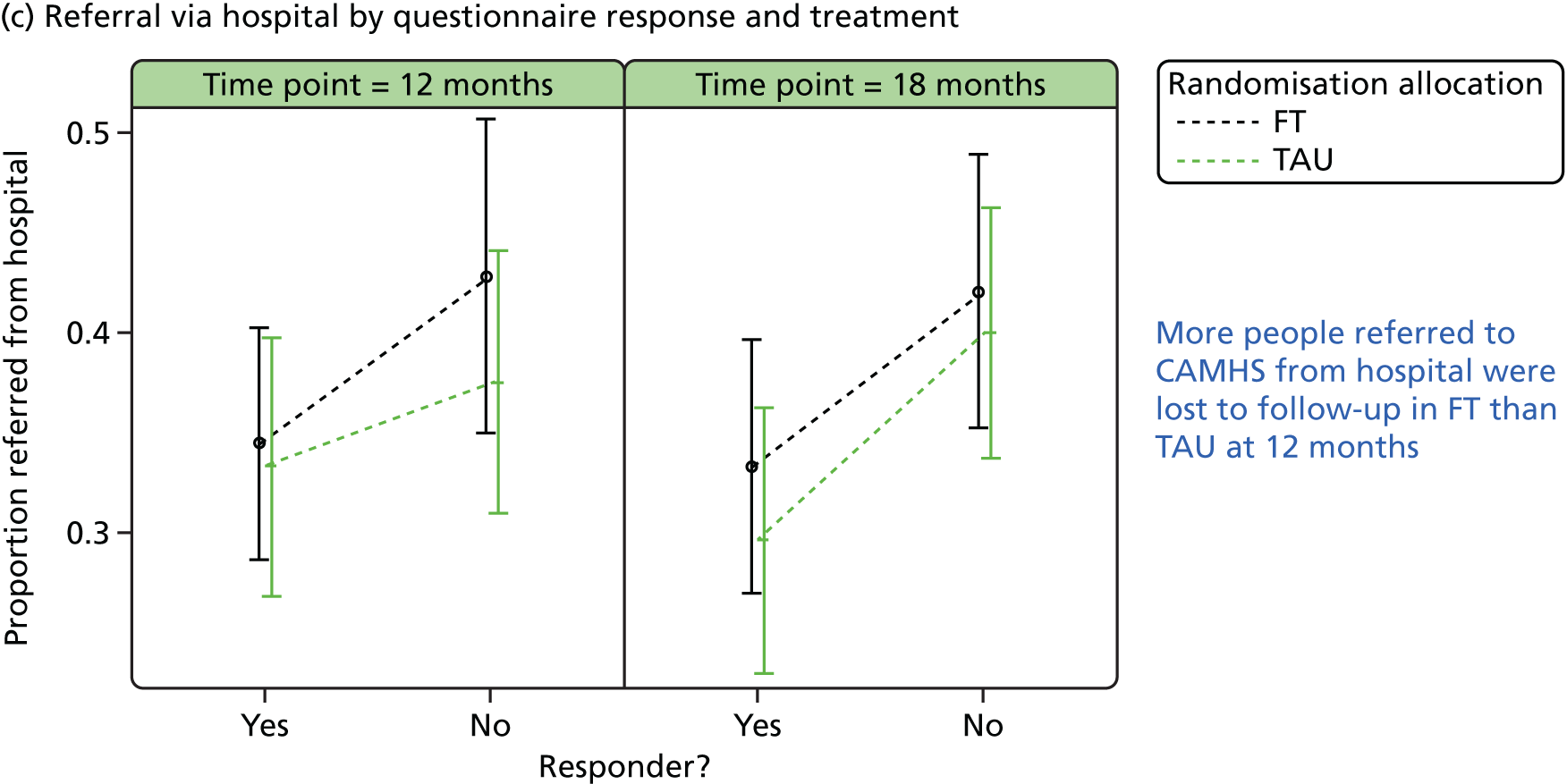

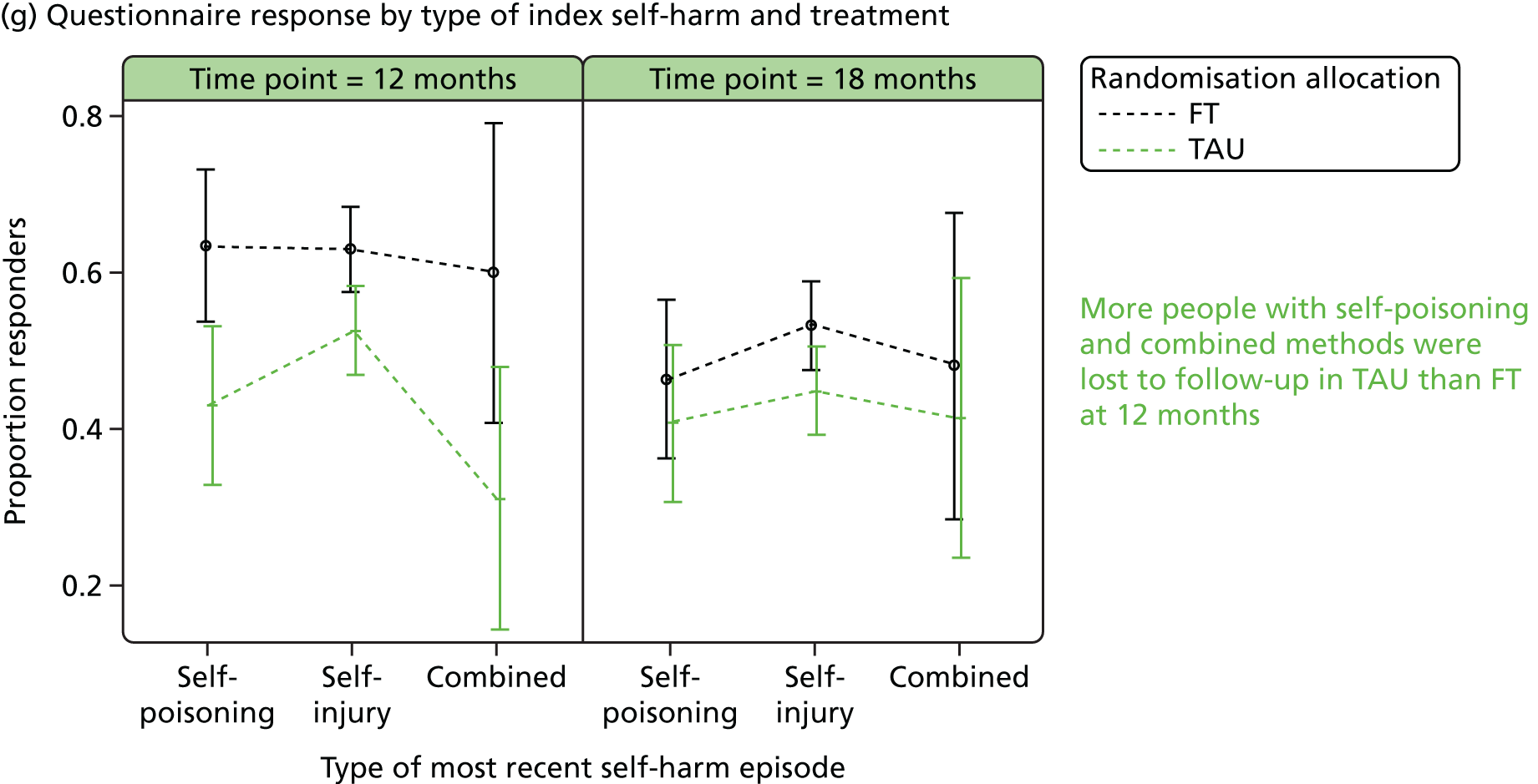

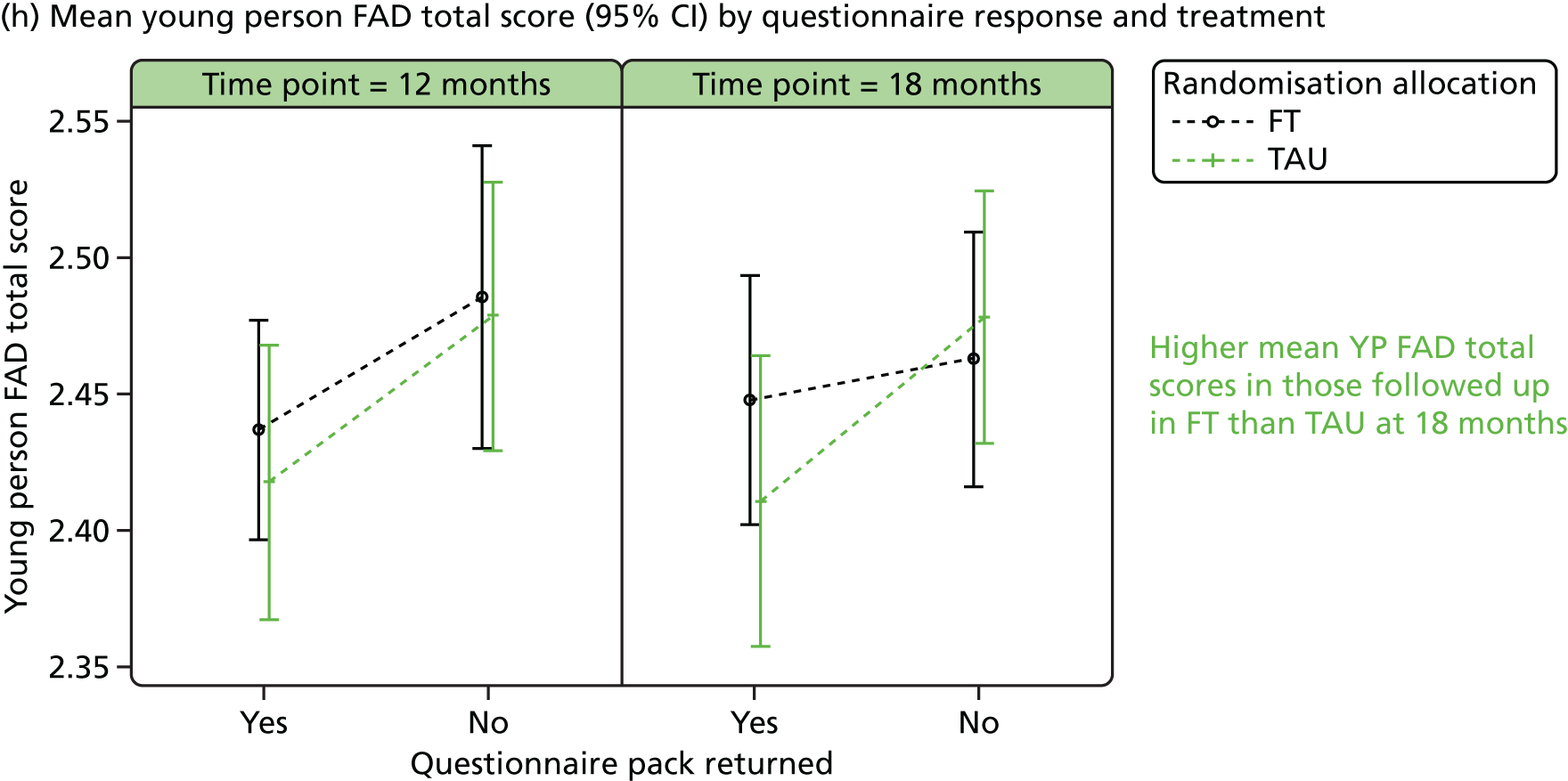

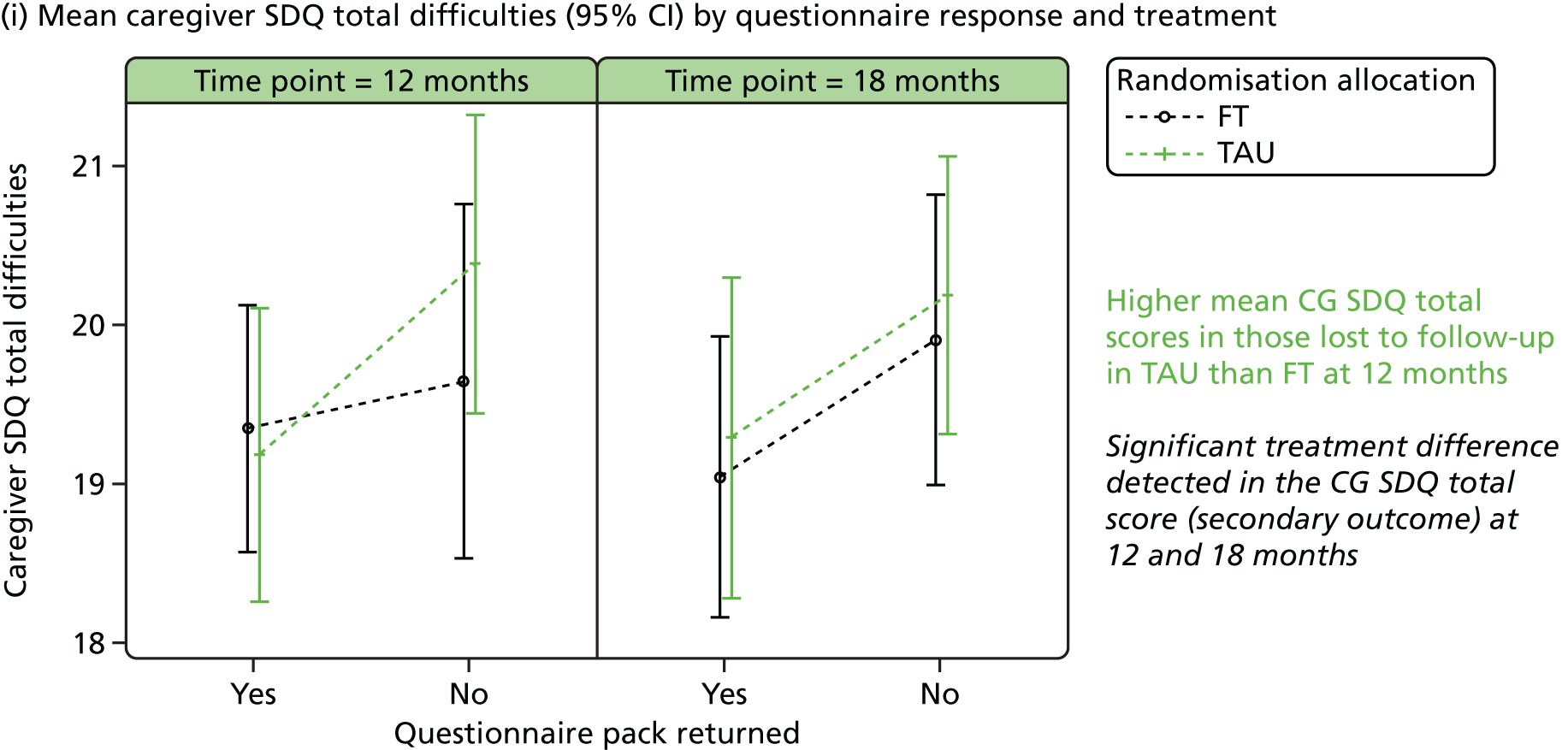

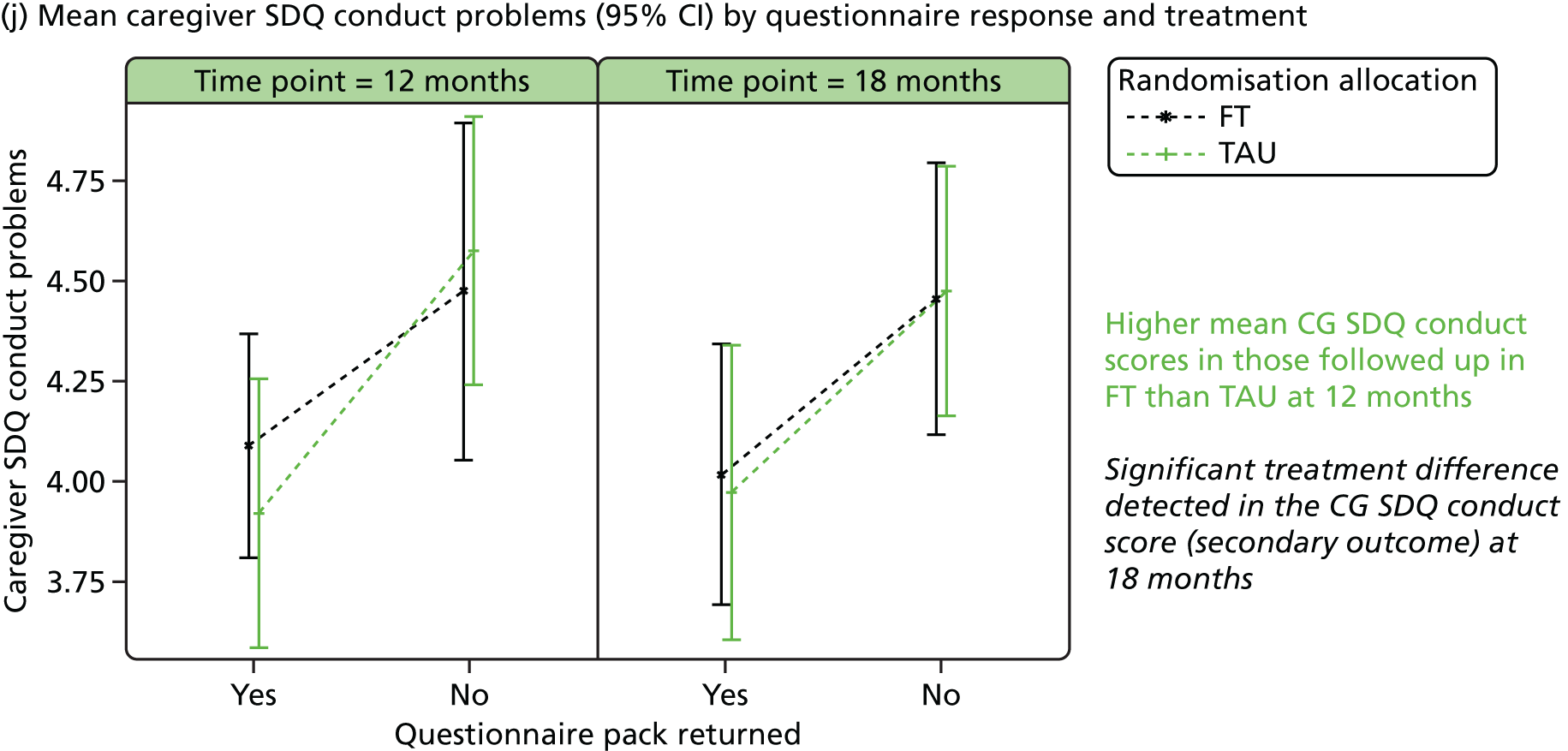

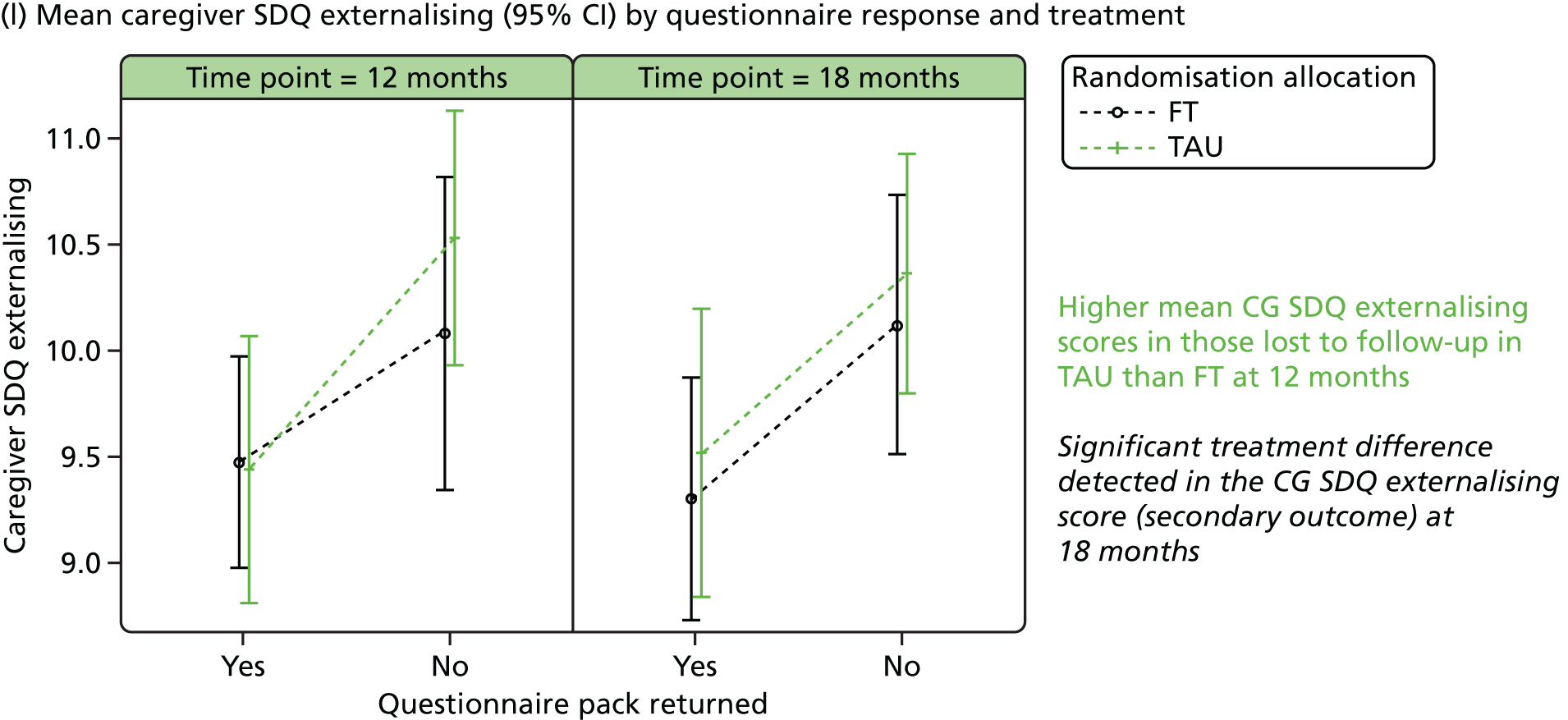

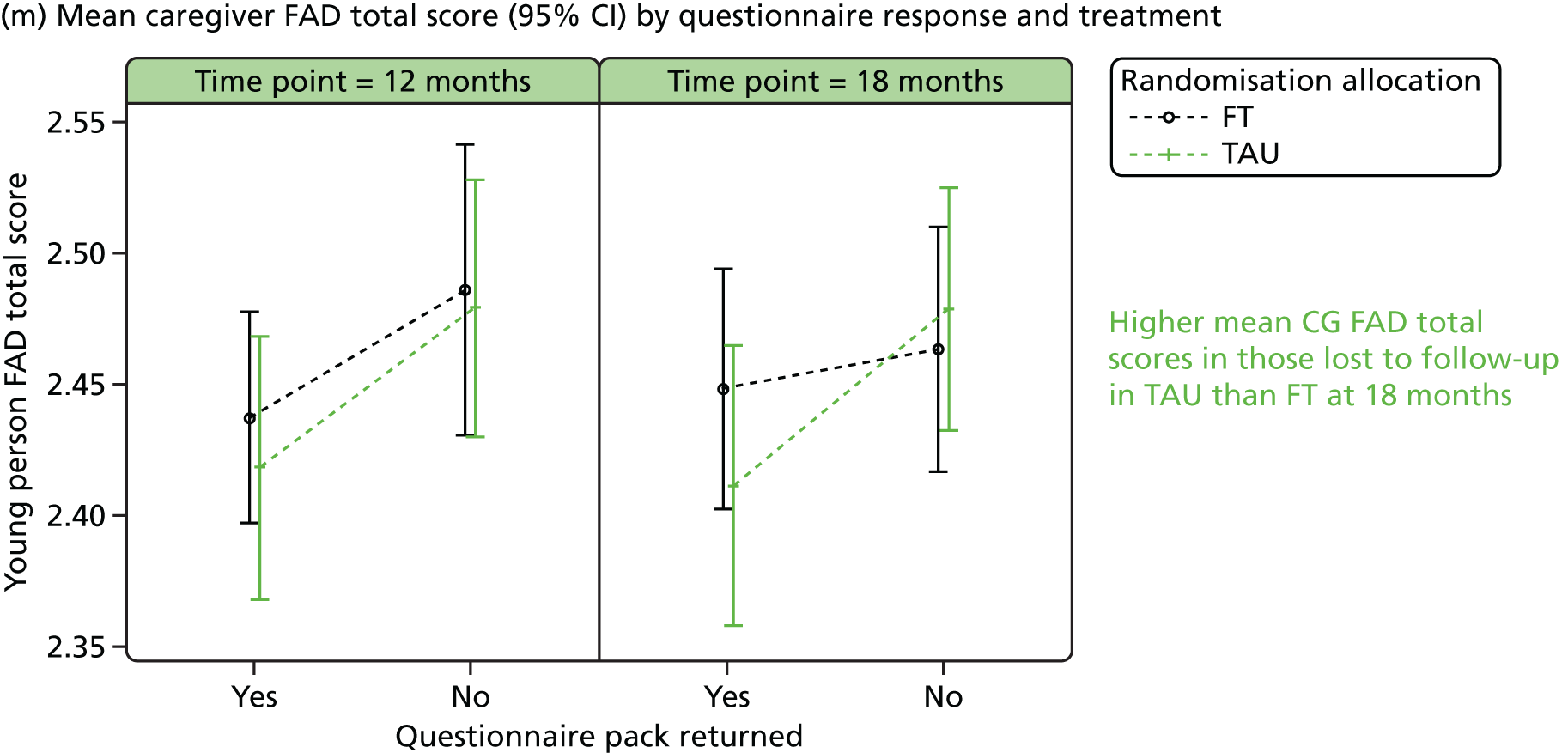

Responder characteristics were summarised by trial arm to explore whether or not differential patterns existed that could impact on the conclusions for the secondary outcomes; characteristics explored included self-harm during follow-up, covariates, age, questionnaire total scores and questionnaire subscales, for subscales for which significant (p < 0.05) treatment effects were detected at 12 or 18 months. Logistic regression modelling was used to assess participants’ response status against participant characteristics and treatment.

To allow the ITT population to be used, missing questionnaire data were assumed to be missing at random and missing scores were estimated using multiple imputations for all participants. Multiple imputation uses the distribution of the observed data to estimate a set of plausible values for the missing data. The multivariate normal model via the MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) method was used to impute missing values for each of the questionnaire scores, allowing for the imputation of normally distributed data with a non-monotone missing pattern. 86 Missing values for each score were imputed separately and the following predictor variables were incorporated in the model: covariates, randomised treatment and participants’ scores at all available assessments (i.e. baseline, 6 and 12 months). The imputation process was repeated according to the percentage of missing data. If 20% were missing, then 20 imputations were made, with a minimum of 10 imputations. Results reported were calculated using Rubin’s rules87 for combining the results of identical analyses performed on each of the imputed data sets.

A sensitivity analysis based on an alternative modelling strategy, also assuming that data are missing at random, using data observed for at least one follow-up time point, was also conducted. In this case, as baseline score was a covariate in the model, participants’ missing baseline scores were imputed by the mean across observed baseline values. 88

Predictive and process measures

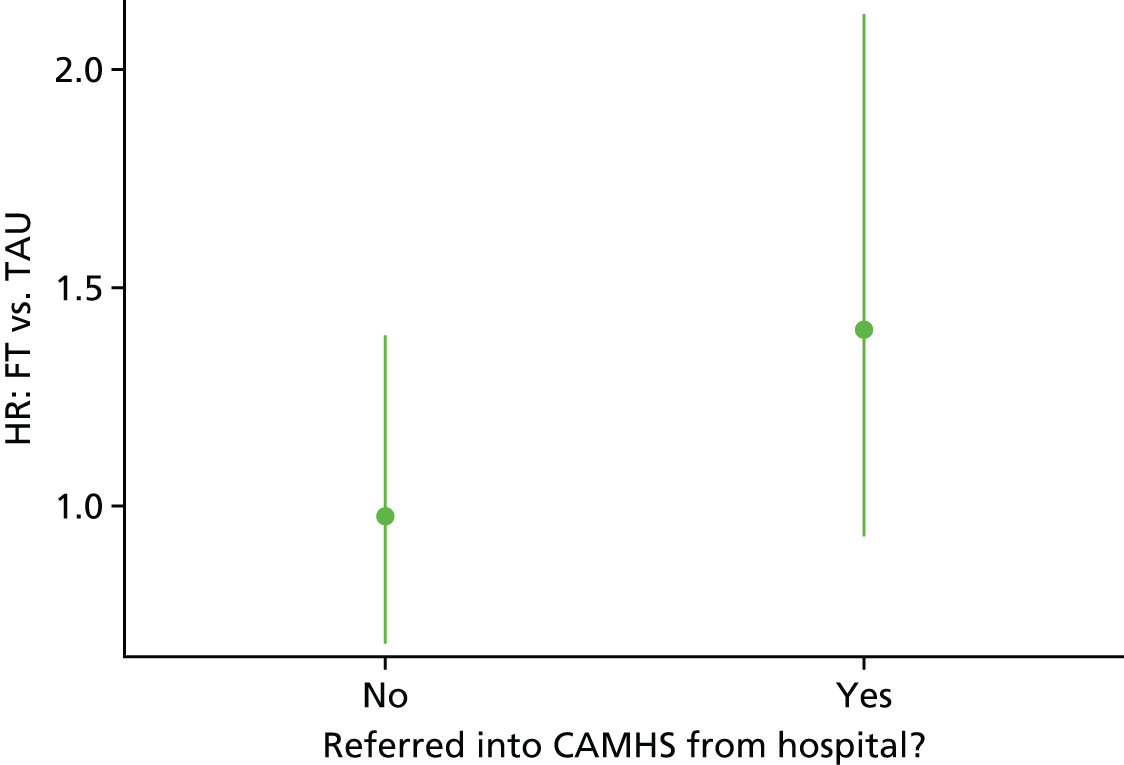

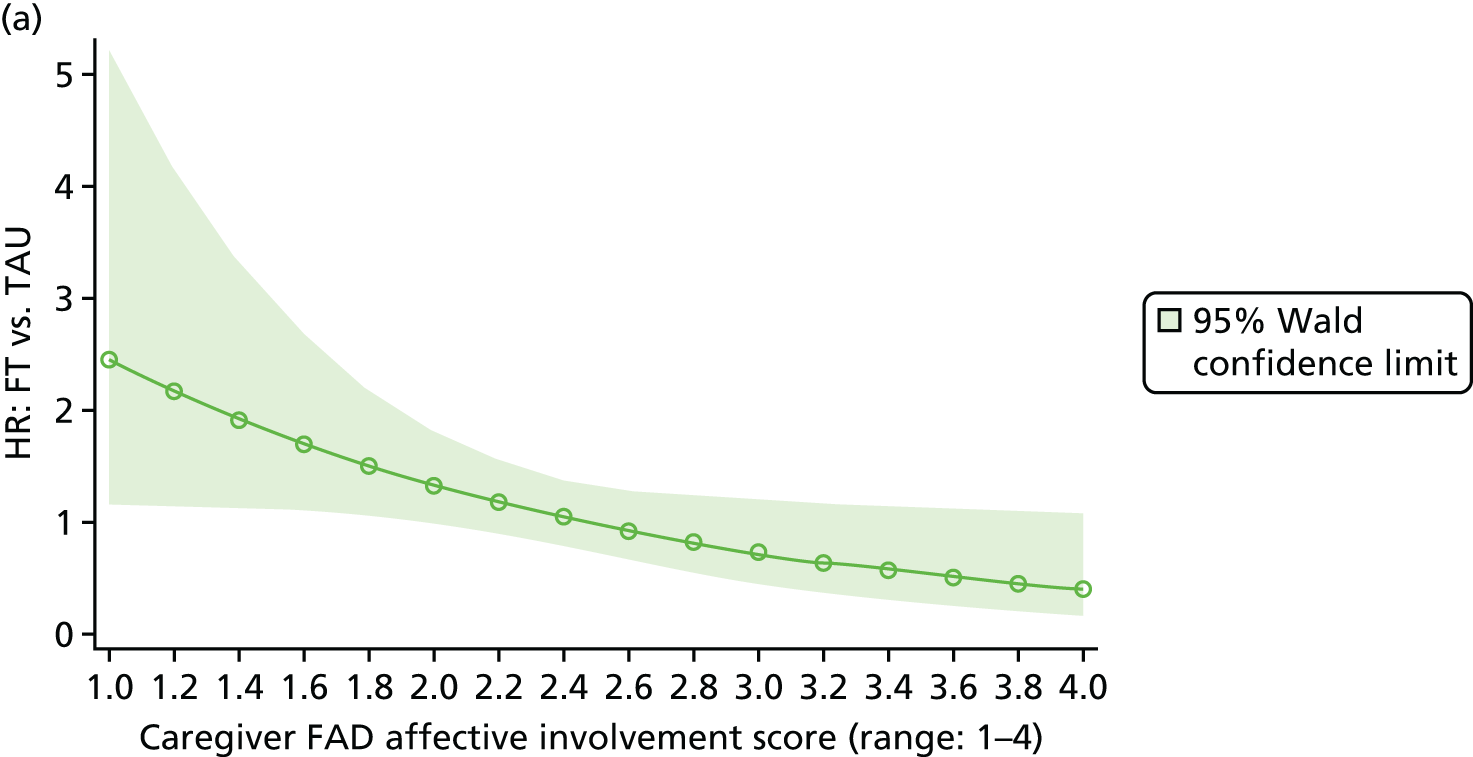

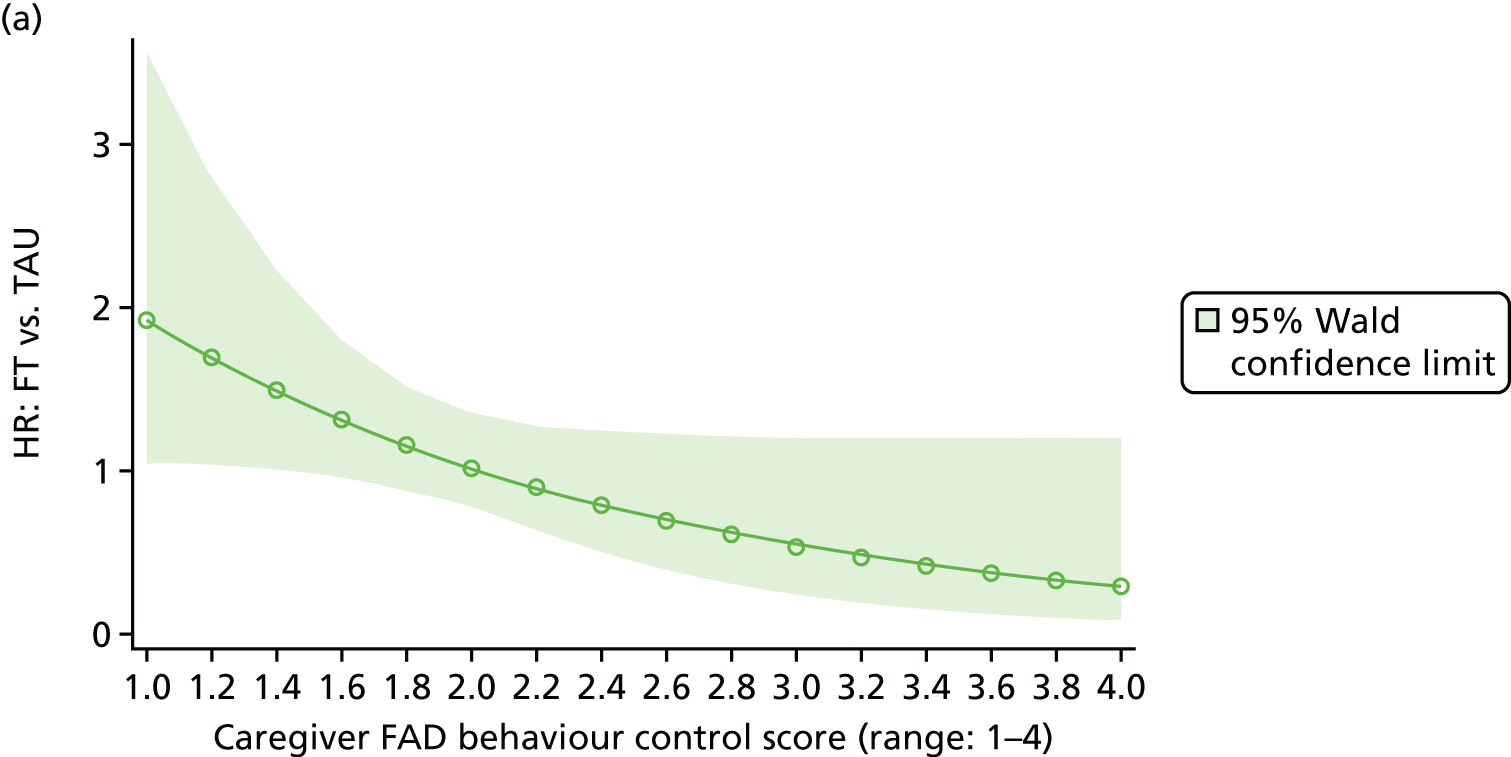

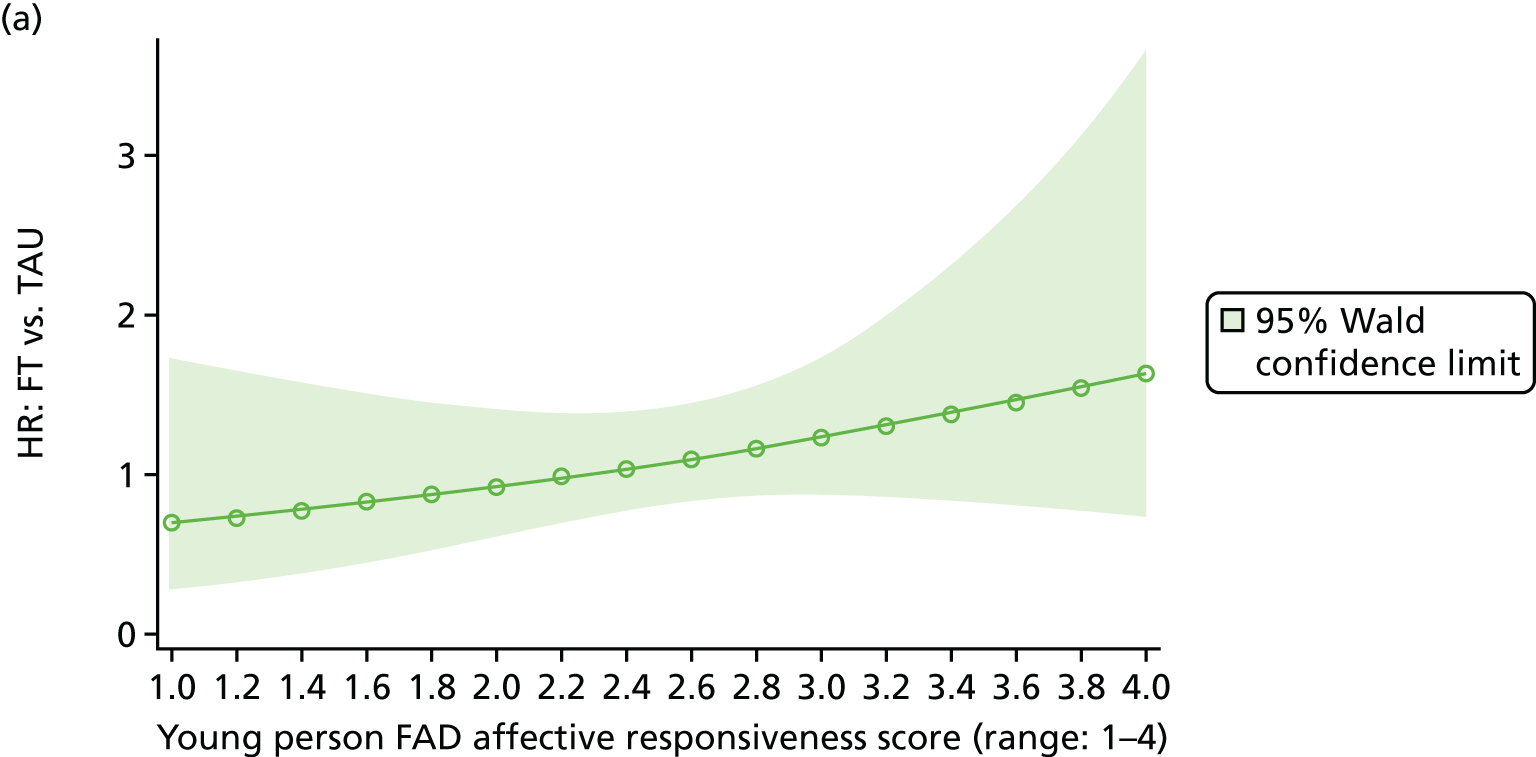

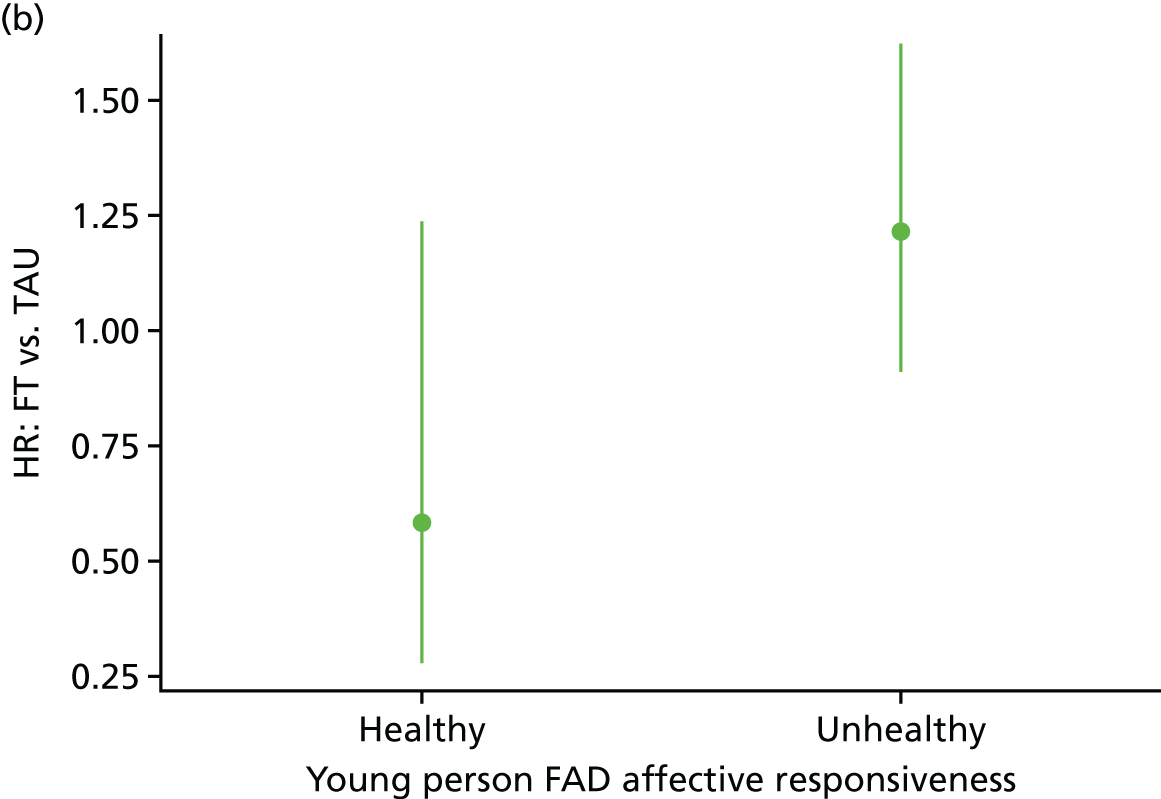

Moderator analysis

Moderator analysis explored whether or not the treatment effect in the primary analysis Cox proportional hazards model depended upon participants’ baseline characteristics via inclusion of the proposed moderator alongside the interaction effect of treatment × moderator in the primary analysis model (including covariates). Covariates and responses to all baseline questionnaires were explored for moderation. Questionnaire responses were also categorised for the young person Beck Scale to indicate whether or not suicidal ideation was present; the young person CDRS-R for whether or not depression was present; and the young person and caregiver McMaster FAD subscales to indicate whether family functioning was healthy or unhealthy. A 5% significance level was used to identify moderation through the interaction of the potential moderator with treatment, irrespective of the main effect of the potential moderator, although it is acknowledged that interaction testing is not a powerful test for moderation. Analysis was of the ITT population to availability of data (complete case) for each proposed moderator.

Mediator analysis

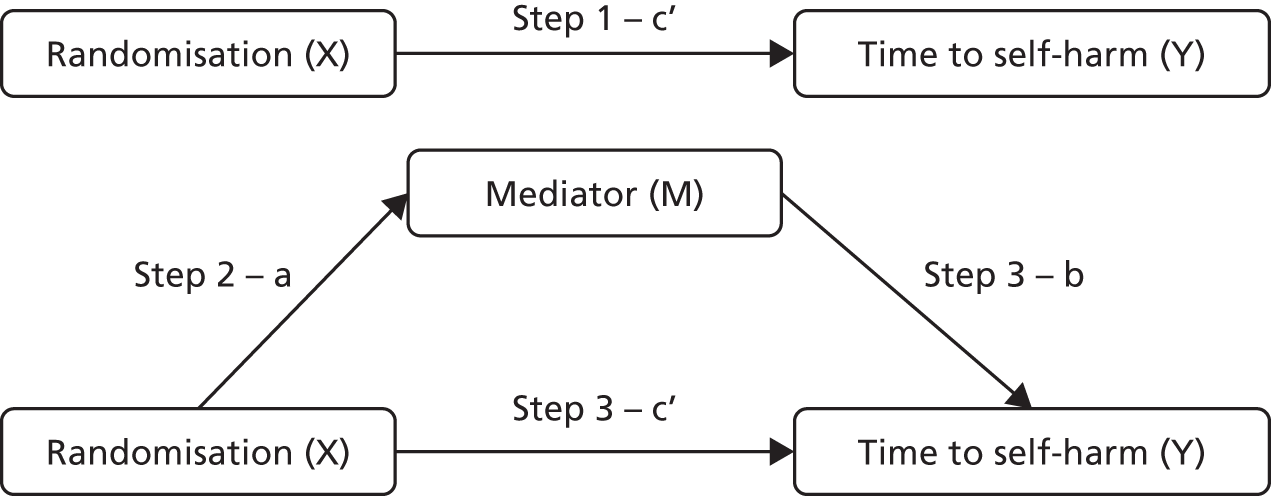

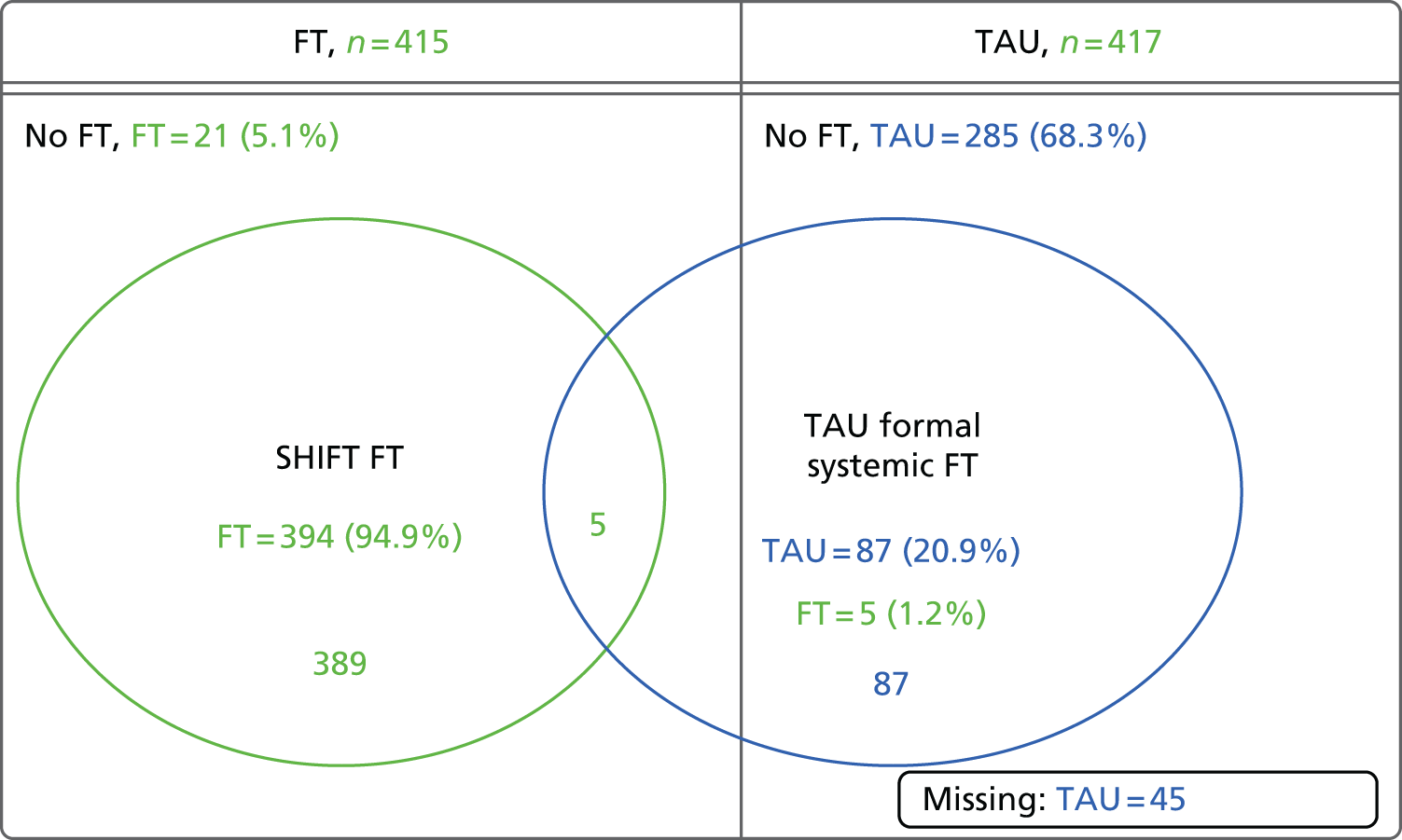

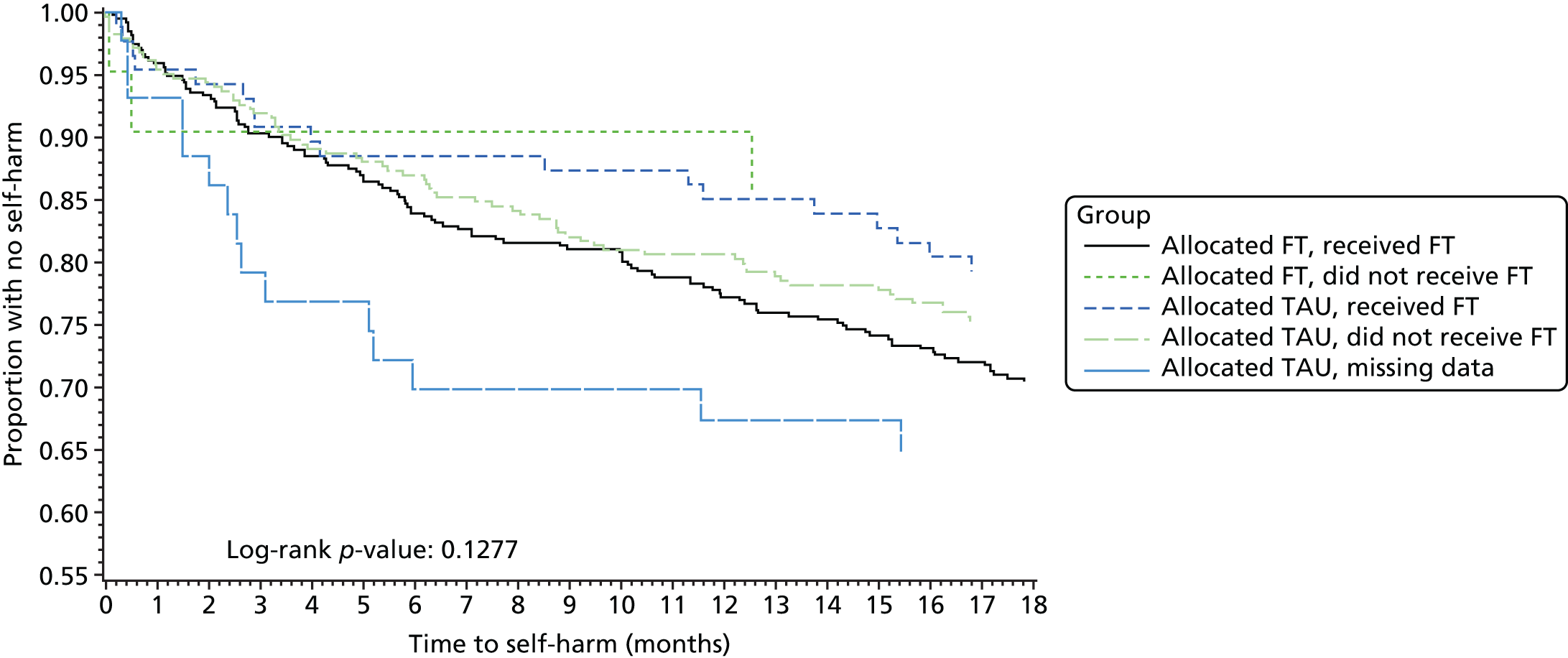

A complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis was conducted to model the causal effect of FT receipt (as opposed to randomisation) on the primary outcome (Figure 1). An instrumental variable model was used to adjust for potential selection bias occurring because of participants who did not receive their allocated treatment, while addressing potential confounds. Randomisation allocation was used as the instrumental variable, creating additional variance unaccounted for by FT receipt alone to obtain an unbiased estimate of the effect of FT receipt, in a two-stage instrumental variable analysis using the qualitative and limited dependent model (QLIM) procedure in SAS,89 to simultaneously estimate the first equation of treatment selection (stage 1) and the second equation of the unbiased effect of treatment on outcome (stage 2). Covariates were included in each stage of the model. The primary outcome was considered as a binary variable and a probit transformation was used. The primary ITT analysis was repeated on this transformed scale for comparison with the CACE estimates, alongside a further ‘as treated’ analysis (using the QLIM procedure). TAU participants with missing treatment data were assumed to have not received FT in the analysis. Kaplan–Meier curves were also constructed for each group by receipt of FT and receipt of FT overall.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of CACE analysis.

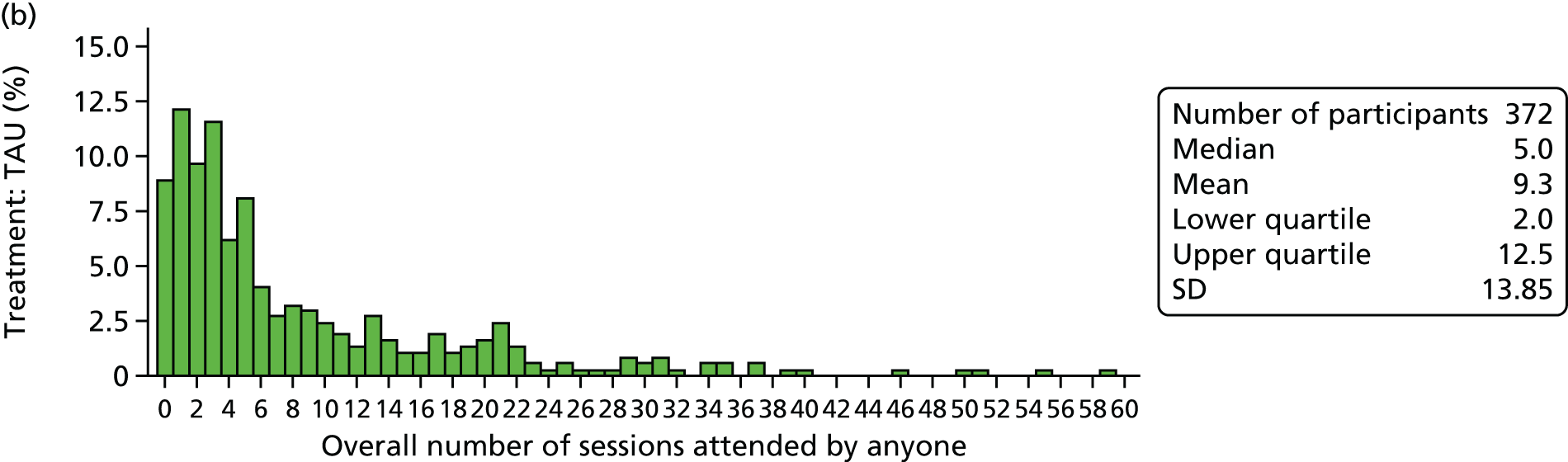

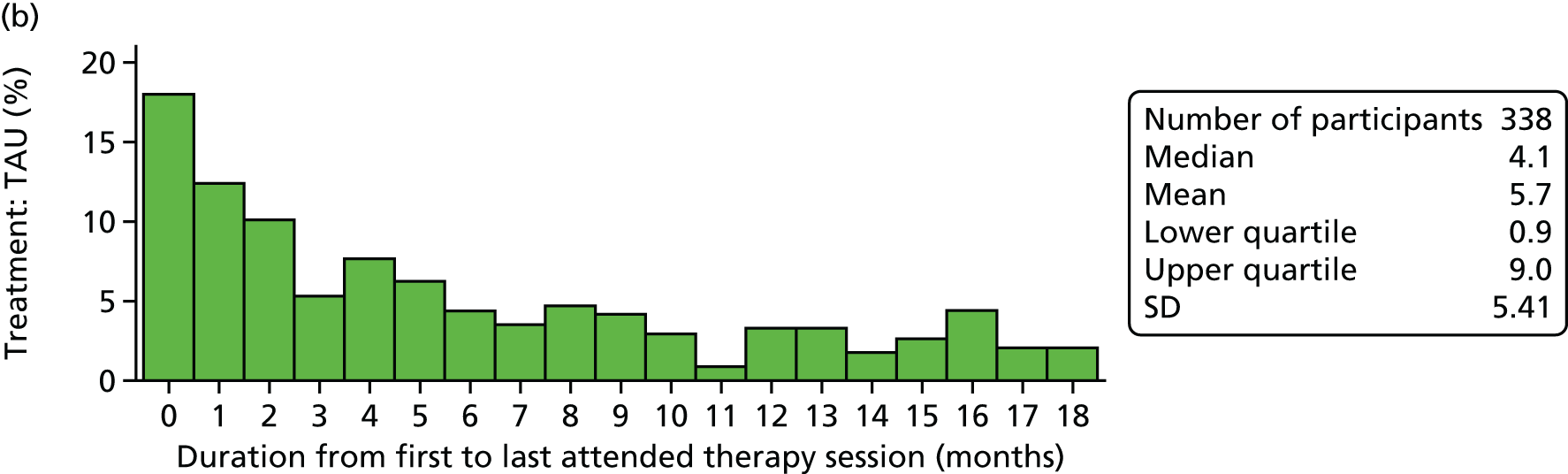

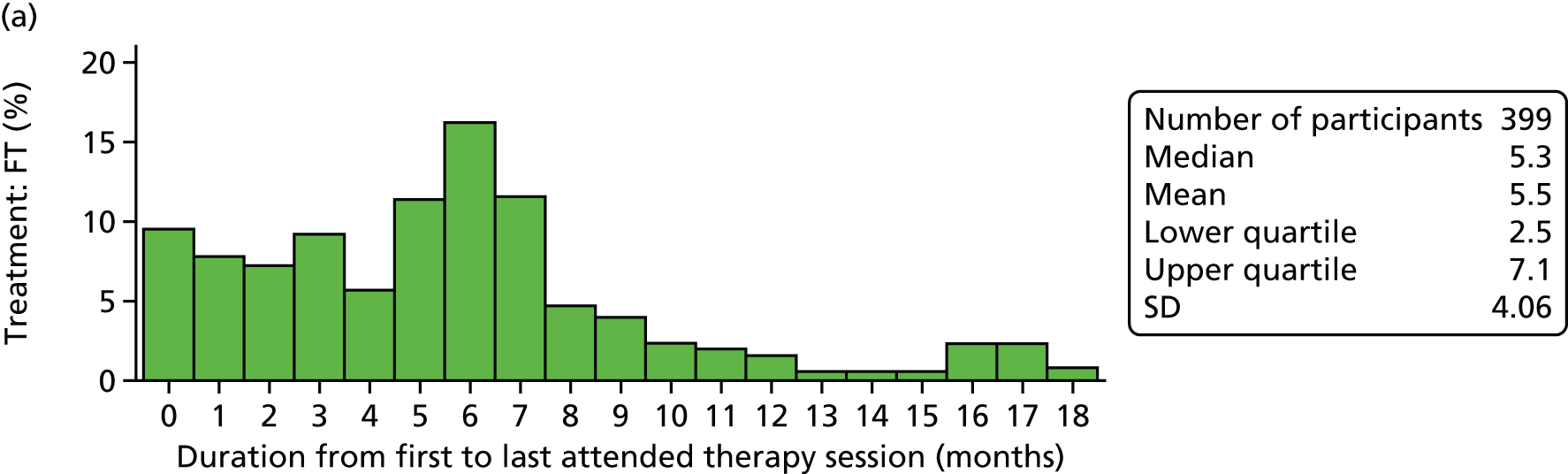

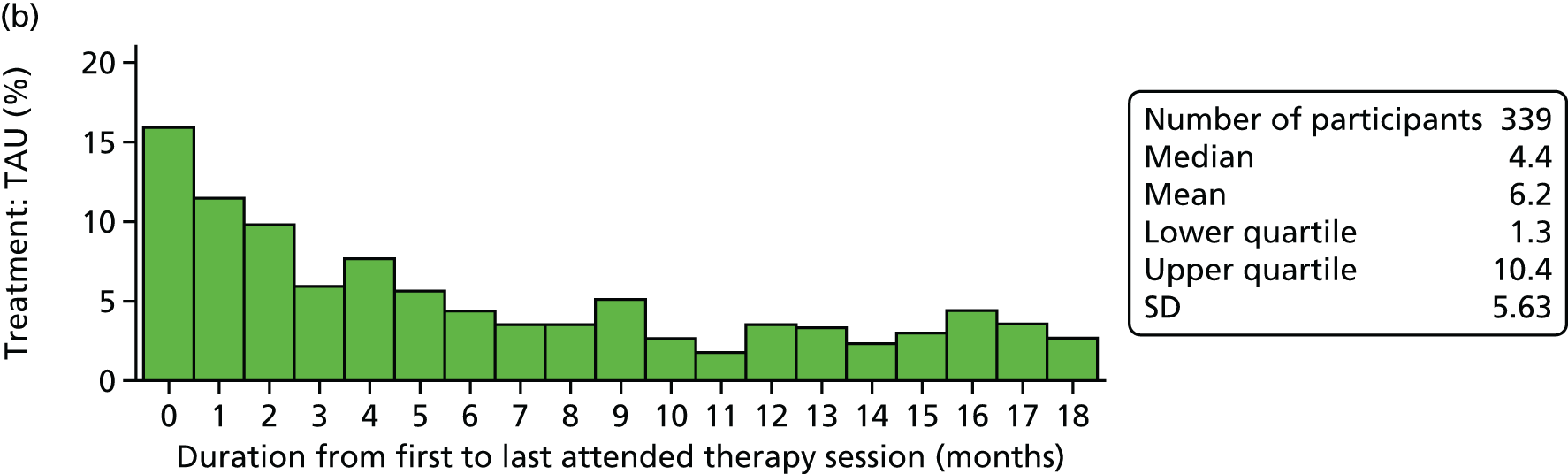

Process variables identified as potential mediators included the overall number of sessions attended, the use of psychotropic medications and therapist characteristics.

Responses to the 3- and 6-month Family Questionnaire (subscores) and 12-month questionnaires (total scores and subscales found to have a significant treatment effect at 12 months in the secondary end-point analysis or moderator analysis) were also explored for mediation. For questionnaire responses, mediation was explored in relation to the time to event, self-harm resulting in hospital attendance, after measurement of the potential mediator. Therefore, events after 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation were included for 3-, 6- and 12-month questionnaires, respectively. Responses at 18 months were not considered in the analysis, as outcomes were collected up to 18 months only and responses could not mediate an outcome observed before this date.

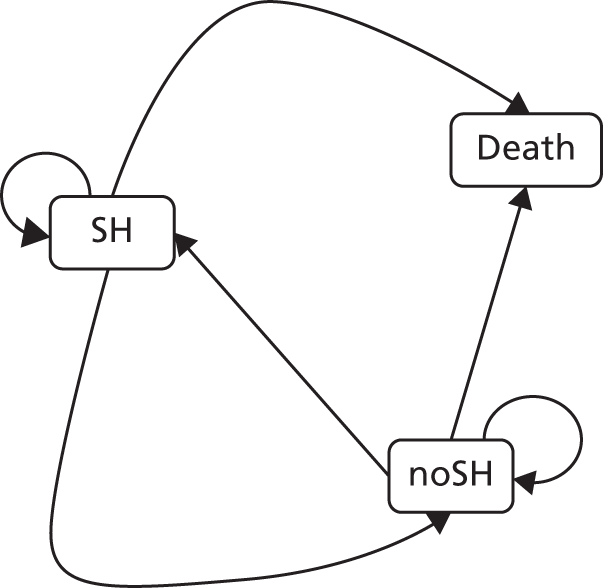

The Baron and Kenny90 steps were employed to explore mediation (Figure 2):

-

Step 1 – establish an effect of randomisation on outcome that may be mediated, that is, Cox regression with Y as the dependent variable and X as predictor, estimate and test path c the total effect:(1)Y=h0(t)exp(β10X).

-

Step 2 – establish that there is an effect of randomisation on the mediator, that is, linear or logistic regression with M as the dependent variable and X as predictor, estimate and test path a:(2)Me=β20+β21X.

-

Step 3 – establish that there is an effect of mediator on outcome while controlling for randomisation, that is, Cox regression with Y as the dependent variable and X and M as predictors, estimate and test paths b and c’:(3)Y=h0(t)exp(β31X+β32Me).

FIGURE 2.

Baron and Kenny mediation model.

Following these steps, complete mediation is the case in which variable X (randomisation) no longer affects Y (time to self-harm) after M (mediator) has been controlled and so path c’ is zero. Partial mediation is the case in which the path from X (randomisation) to Y (time to self-harm) is reduced in absolute size but is still different from zero when the mediator is introduced.

Steps 1 and 3 were fitted using a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for all covariates. For continuous mediators, Step 2 was fitted using a linear regression model containing randomised treatment and all covariates; and for binary outcomes (Beck suicide ideation, psychotropic medications, therapist characteristics) logistic regression was used containing randomised treatment and all covariates apart from NHS trust (owing to lack of convergence). For mediators based on questionnaire responses, the baseline score was also included as a covariate in each step.

Adherence and alliance to family therapy

Summaries of therapist baseline characteristics, training, therapy session recordings, initial and specialist adherence review, formulation letters to families and therapist supervision were produced. In addition, mean scores and 95% CIs are presented for the total score and for each subscale of the SOFTA.

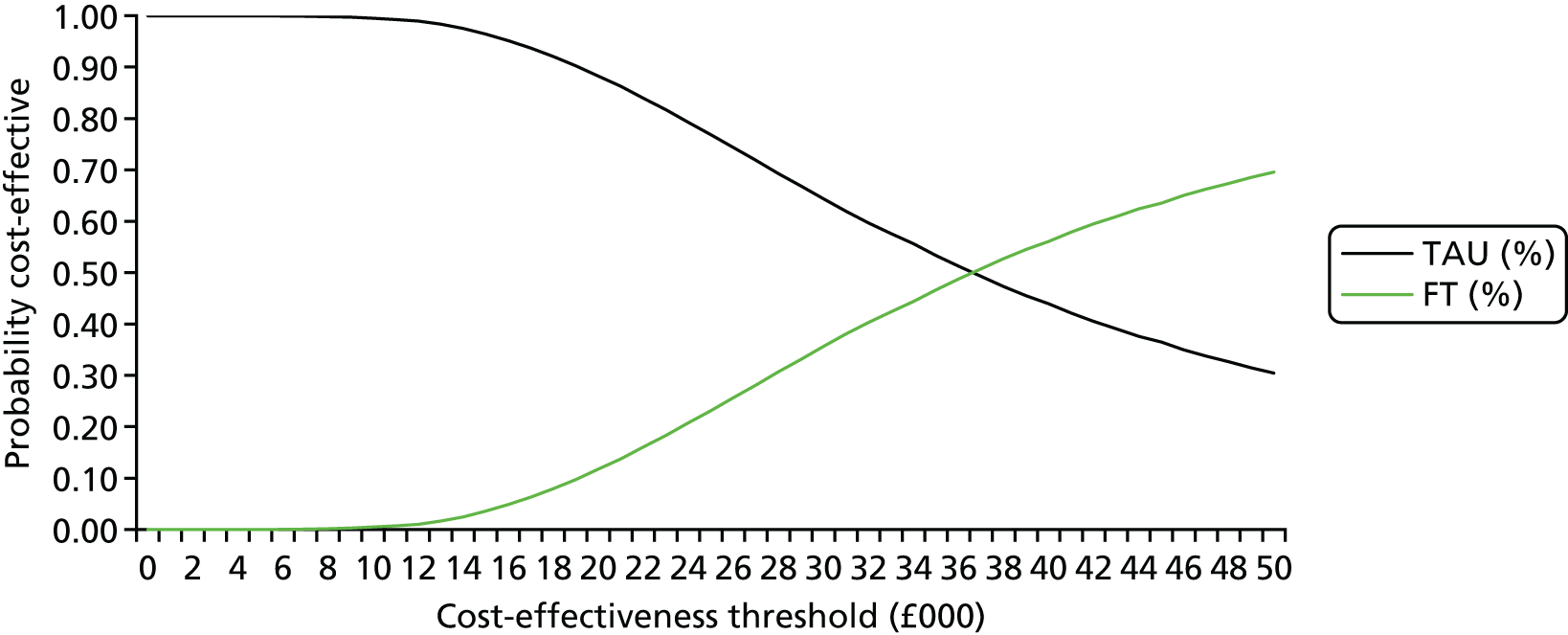

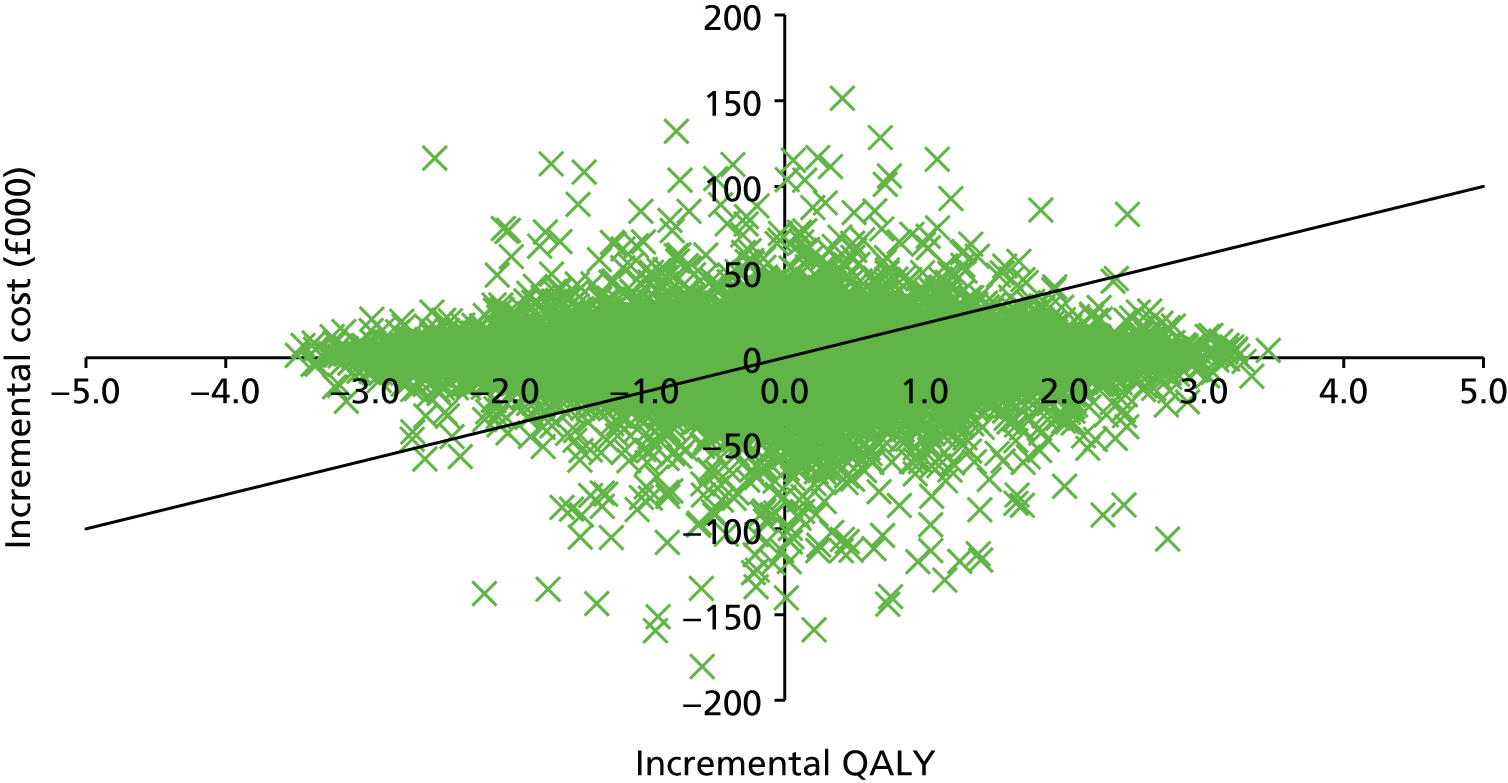

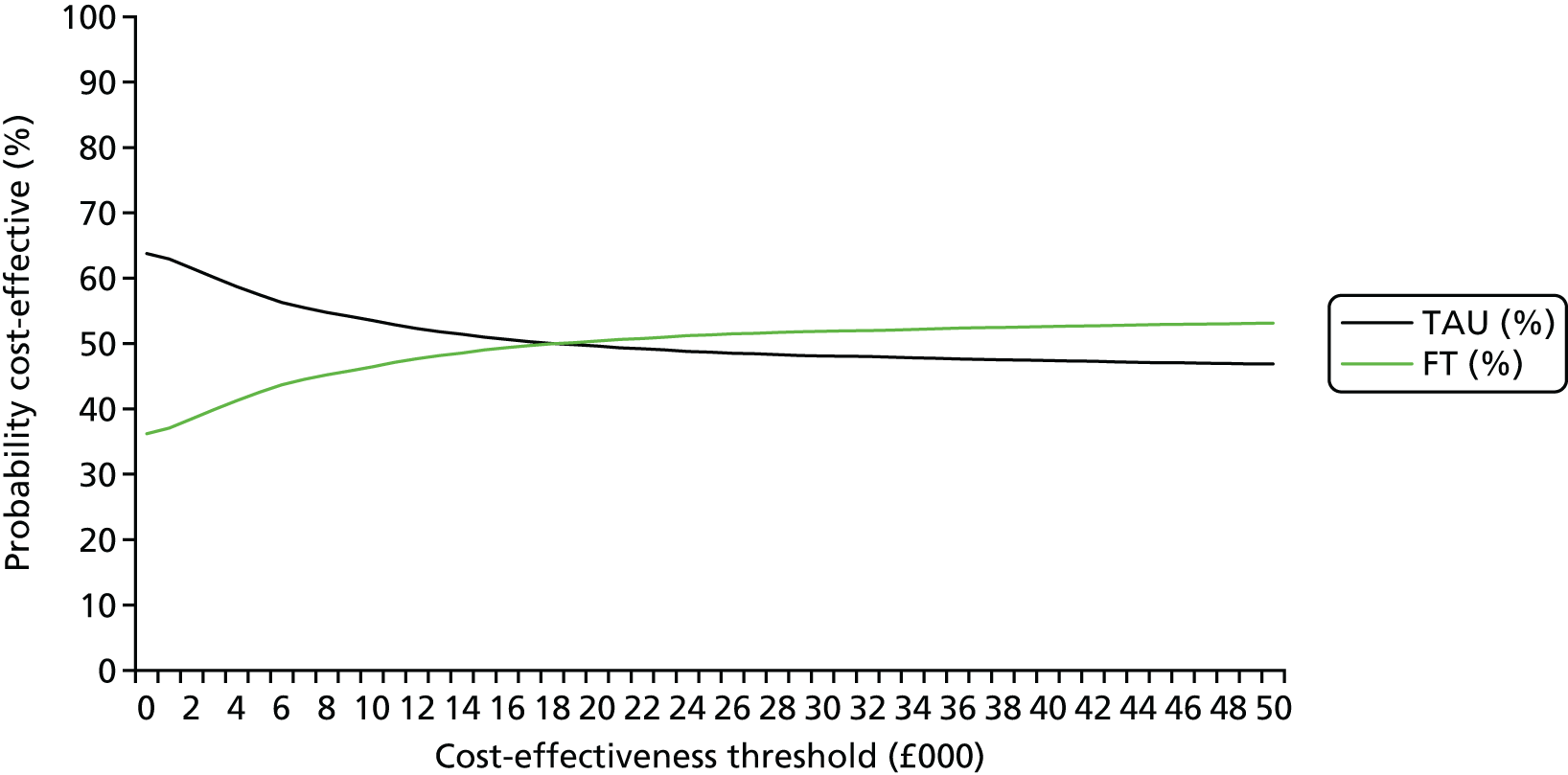

Economic methods

The economic evaluation aimed to assess the cost-effectiveness of FT compared with TAU in the management of self-harm in adolescents from a health and social care costs perspective. It consisted of a within-trial analysis, in which cost-effectiveness was assessed within the 18-month trial period and a decision-analytic model in which cost-effectiveness was assessed by extrapolating the trial results to a longer time horizon.

Outcomes

Young people’s health-related quality of life was assessed using the EQ-5D,91,92 which was included at baseline and along with the young person’s resource use questionnaire at 6, 12 and 18 months. Changes in EQ-5D scores across time points were evaluated using two-sample t-tests to explore any important differences in these end points within the time frame of the trial. These tests are useful in understanding the impact of the length to follow-up on the health outcome measures, as insufficiently long follow-up periods may introduce biases in the subsequent cost-effectiveness analysis. In line with the NICE reference case93 the primary outcome for the economic evaluation was quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Young people’s responses to the EQ-5D were converted into health state utility values and multiplied by the proportion of 1 year the time period represented (baseline to 6 months = 0.5; 6 to 12 months = 0.5; 12 to 18 months = 0.5) to calculate QALYs. 94 Average QALYs between adjacent time points were calculated to generate smoothed estimates between time points. Therefore, QALYs were calculated using the area under the curve approach as shown below:

Quality-adjusted life-years represent a quality-of-life-weighted survival value in which 1 QALY is equivalent to 1 year of full health.

The number of self-harm events avoided at 18 months was considered as a secondary outcome. Additionally, the sensitivity analysis used the aggregated QALY gain for both the young person and his/her main carer as the health outcome. The caregiver’s health-related quality of life was assessed using the HUI,95,96 which was included along with the carer resource use questionnaire. The carer’s responses to the HUI were converted into health state utility values76 and the carer’s QALYs were calculated in a similar way to the young person’s QALYs.

Resource use

Resource use data were collected at baseline and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months from the young person and from his/her main carer. Resource usage was converted into costs using unit cost figures from the British National Formulary (BNF), Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) and the Department of Health’s National Schedule of Reference Costs. 97–99 The base-case economic evaluation focused on health and social care costs. The currency used was the pound sterling (£) and 2014 was used as the reference financial year.

Costs and benefits were discounted at 3.5% per annum.

Missing data

Missing data were imputed using multiple imputations via chained equations86,100,101 as recommended for economic analyses alongside clinical trials. 102 For consistency with the statistical analysis and to ensure best fit, imputations were based on predictor variables including treatment allocation, gender, age, centre, total number of self-harm episodes, type of index episode, source of referral from hospital and derived scores for a number of assessment instruments (BSS, CDRS-R, Hopelessness Scale for Children and PQ-LES-Q).

Within-trial cost-effectiveness

The within-trial analysis aimed to determine the intervention that maximised health outcomes at 18 months. It used an ITT perspective.

Base-case analysis 1 was a cost–utility analysis over 18 months examining the cost per QALY gained for all participants. Descriptive statistics of costs and EQ-5D scores and parametric tests to evaluate any important differences between the two trial arms at each time point in the trial were produced. Thereafter, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated by dividing the average difference in costs between the two arms by the average difference in QALYs between the two trial arms:

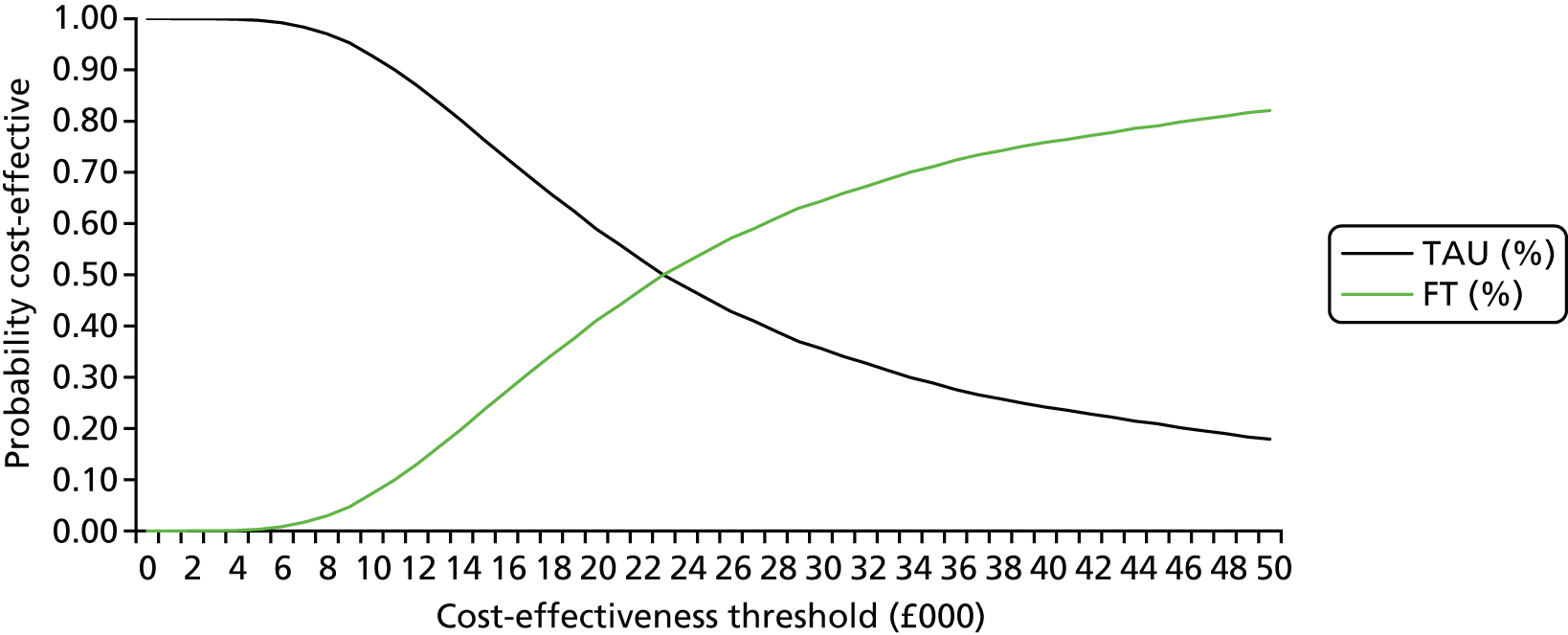

The ICER represents the additional cost per unit of outcome gained. This indicates the trade-off between total cost and effectiveness when choosing between FT and TAU. When compared against the cost-effectiveness threshold, this gives an indication of whether or not spending additional money on FT appears efficient. As a rule, the NICE implicit cost per QALY threshold of £20,000–30,000 per QALY was used. An intervention is cost-effective so long as its ICER is within or below the £20,000–30,000 per QALY range.