Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/104/21. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The draft report began editorial review in October 2015 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Christine Roffe reports personal fees from Air Liquide outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Roffe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Stroke is the third most common cause of death worldwide. 1 With approximately 110,000 strokes per annum in England, it accounts for 11% of deaths. 2 Stroke mortality is cited as 20–30% within 1 month in the 2007 National Stroke Audit report. 2 More recent data suggest lower rates: between 14% and 17% for the UK3 and 14.5% in the USA. 4 Improvements in processes of care have significantly contributed to this reduction. 4 However, half of all stroke survivors are left dependent on others for everyday activities,2 making stroke the largest cause of complex disability. 5 Care on specialist stroke units has been shown to reduce death and disability significantly. 6 It does, however, remain unclear which aspects of stroke care are crucial for improving outcome. Prevention and treatment of hypoxia could potentially be one of the reasons for better outcome with specialist stroke care.

Scientific background

Prevalence of hypoxia and effects on outcome

Mild hypoxia is common in stroke patients and may have significant adverse effects on the ischaemic brain. 7 Hypoxia with oxygen saturations falling below 92% has been observed in 24% of continuously monitored stroke patients within the first 24 hours of symptom onset. 8 While healthy adults with normal cerebral circulation can compensate for mild hypoxia by an increase in cerebral blood flow,9 this is not possible in the already ischaemic brain after stroke. 10–13 Hypoxaemia with oxygen saturations falling below 90% in the first few hours after hospital admission is associated with a doubling of mortality14 and a trebling of the rate of institutionalisation. 15 Patients on a stroke unit are more likely to receive oxygen than patients on a non-specialised general ward16 and less likely to be hypoxic. 17 An observational study of processes of care has shown that hypoxia increases the risk of an adverse outcome fivefold if only some of the hypoxic episodes are treated with oxygen, but has no adverse effect on outcome if all episodes of hypoxia are treated with oxygen. 15 Prophylactic oxygen treatment could prevent hypoxia and secondary neurological deterioration.

Potential adverse effects of oxygen treatment

However, oxygen treatment is not without side effects. 18 It impedes early mobilisation and could pose an infection risk. There is evidence from animal models and in vitro studies that oxygen encourages the formation of toxic free radicals, leading to further damage to the ischaemic brain,19–22 especially during reperfusion. Marked changes in adenosine triphosphate and related energy metabolites develop quickly in response to acute ischaemia and tissue hypoxia. These alterations are only partially reversed on reperfusion despite improved oxygen delivery. Ischaemia-induced decreases in the mitochondrial capacity for respiration result in reduced oxygen consumption and further increase free radical generation during reperfusion. 23 Oxidative stress has also been implicated in the activation of cell signalling pathways, which leads to apoptosis and neuronal cell death. 24,25 While much research points towards adverse effects of hyperoxia in the ischaemic brain, there is also evidence to support the notion that therapy-induced eubaric hyperoxia may be neuroprotective. 19,20,26,27 Routine oxygen supplementation (ROS) for acute myocardial infarction has been abandoned after a clinical trial showed no benefit and potential harm. 28

Randomised controlled trials of oxygen treatment after acute stroke

Evidence from randomised controlled trials of oxygen supplementation after acute stroke is conflicting and insufficient to guide clinical practice. A quasi-randomised study of oxygen supplementation for acute stroke by Rønning and Guldvog29 has shown that routine oxygen treatment in unselected stroke patients does not reduce morbidity and mortality. Subgroup analyses suggested that patients with severe strokes were more likely to benefit than those with mild strokes, but the study size was too small to define patients who are likely to derive benefit with certainty. 29 A very small (n = 16) study of high-flow oxygen treatment after acute stroke showed that cerebral blood volume and blood flow within ischaemic regions improved with hyperoxia. By 24 hours, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed reperfusion in 50% of hyperoxia-treated patients compared with 17% of control patients (p = 0.06) but no long-term clinical benefit at 3 months. 30 In the Stroke Oxygen Pilot Study (ISRCTN 12362720), the flow rate of oxygen was lower (2 or 3 l/minute dependent on baseline oxygen saturation) and treatment was continued for longer (72 hours). Neurological recovery at 1 week was better in the oxygen group than in the control group. 31 While there was no difference in the mRS at 6 months, there was a trend for better outcome with oxygen after adjustment for differences in baseline stroke severity and prognostic factors. 32 In contrast to the earlier study by Rønning and Guldvog,29 oxygen was as effective in mild as in severe strokes. These results are promising, but need to be confirmed in a larger study.

Recommendations for oxygen treatment in national and international clinical guidelines

Clinical guidelines for oxygen supplementation after stroke are not based on evidence from randomised clinical trials, and have changed over time without obvious reason. The European Stroke Organization (2008)33 stated that ROS to all stroke patients had not been shown to be effective, but that adequate oxygenation was important, and that oxygenation can be improved by giving oxygen at a rate of > 2 l/minute (no target saturation or supporting evidence given). In 2003, the American Stroke Association Guideline34 recommended keeping the oxygen saturation at or above 95%. The 2005 update25 of the guideline made no change to the recommendations. In 2007, the advice was revised to say that oxygen saturation should be maintained at or above 92%,35 but in 2013 the Association reverted to recommending maintenance of an oxygen saturation at or above 95%. 36 In the UK, the National Clinical Guideline for the management of people with stroke recommended keeping oxygen saturation within normal limits in 2005 and in 200837,38 and in 201239 it specified that this means maintaining an oxygen saturation ≥ 95%. None of the recommendations is based on evidence from controlled clinical trials. A survey of British stroke physicians showed that there is uncertainty among physicians treating patients with stroke about which treatment approach to take, and when to give oxygen. 40

Rationale for the Stroke Oxygen Study

Hypoxia is common after acute stroke and is associated with worse outcomes. Prevention of hypoxia could avert secondary brain damage and improve recovery. Evidence from randomised controlled trials is conflicting, and insufficient to guide clinical practice. This is reflected in clinical uncertainty and conflicting guidelines based on the same evidence. An adequately powered study of ROS is needed to provide reliable information on which recommendations can be based.

Aims

The aim of the Stroke Oxygen Study (SO2S) is, first, to establish whether or not ROS will improve outcome after stroke and, second, to determine whether or not oxygen given at night only is more effective than oxygen given continuously.

Rationale for the fixed dose oxygen regimen used in the Stroke Oxygen Study

A fixed dosage scheme was chosen to keep the design of the study as simple as possible, so that any recommendations resulting from the study outcome can be carried out in day-to-day clinical practice.

Rønning and Guldvog29 have shown that giving oxygen at a rate of 3 l/minute to all stroke patients during the first 24 hours after hospital admission does not improve overall outcome. They did not report baseline oxygen saturation, or changes in saturation on treatment. It is therefore possible that some patients were undertreated, and that others achieved too high oxygen levels, leading to an increase in free radical generation in the ischaemic penumbra. There were no other data from clinical studies to inform recommendations for the dose of oxygen to give for routine supplementation at the time the study was designed. The European Stroke Organization suggested a dose of 2–4 l/minute and the American Stroke Association Guideline recommended keeping the oxygen saturation at or above 95%,34,41,42 but these recommendations were not based on evidence from controlled clinical trials. In the absence of data to the contrary, it was reasonable to assume that treatment should restore oxygen saturation to the normal range.

Normal oxygen saturation in adults is 95–98.5%,43 in healthy older individuals it is reported to be lower, at 95% [standard deviation (SD) 2.5%]. 44 Oxygen saturation in stroke patients who are normoxic at recruitment is about 1% lower than that of age-matched community control patients. 45 We have conducted a dose titration study for oxygen after acute stroke and found that 2 l/minute oxygen by nasal cannula increases oxygen saturation by 2% and 3 l/minute by 3%. 46 We also found that oxygen masks were less likely to be tolerated than nasal cannulae, leading to poorer treatment compliance with the former. For this study, we therefore decided to give oxygen by nasal cannula. A dosage regimen of 3 l/minute in individuals with a baseline oxygen saturation of ≤ 93% and 2 l/minute in individuals with a baseline saturation > 93% was therefore considered likely to prevent hypoxia without increasing oxygen saturation beyond the upper limit of the normal range.

Rationale for giving routine oxygen supplementation at night only

Patients are more likely to be hypoxic at night

The mean nocturnal oxygen saturation is about 1% lower than awake oxygen saturation in both stroke patients and control patients. 45 This study has also shown that a quarter of patients who are normoxic in the day have significant hypoxia during the night. About 60–70% of stroke patients suffer from sleep apnoea early after stroke. 47–49

The development of hypoxia is more likely to be missed at night

It is more difficult to observe patients in the darkened room, and, unless there are reasons to suspect the patient is unwell, nurses do not usually wake the patient for routine observations. The development of hypoxia is therefore more likely to be missed at night.

Nocturnal hypoxaemia is more likely to lead to brain tissue hypoxia at night

A study in healthy volunteers has shown that hypoxaemia leads to a compensatory increase in cerebral blood flow during wakefulness, but not during sleep, and is therefore more likely to result in brain tissue hypoxia at night. 50

Nocturnal oxygen supplementation does not interfere with the patient’s daytime mobility

Early mobilisation is an important aspect determining good outcome. 16 Patients who are attached to monitoring equipment, or to oxygen supplementation, are less likely to be mobilised than patients not attached to such equipment.

Giving routine oxygen at night only may prevent a significant number of otherwise undetected episodes of hypoxia without interfering with the patient’s daytime rehabilitation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The Stroke Oxygen Study is a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open, blinded-end point (PROBE) trial. For this controlled, single-blind, parallel group trial patients were randomised in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio to one of three study arms:

-

continuous oxygen supplementation

-

nocturnal oxygen supplementation only

-

no ROS, unless required for clinical reasons other than stroke.

Both the Stroke Oxygen Study protocol and the statistical analysis plan have been published in an open-access journal. 51,52

Hypothesis

The main hypothesis was that fixed low-dose oxygen treatment during the first 3 days after an acute stroke improves outcome compared with no oxygen.

The secondary hypothesis was that restricting oxygen supplementation to night-time only is more effective than continuous supplementation.

Participants

Recruitment

Patients were recruited by research nurses and clinicians from 136 hospitals (secondary care) across England, Northern Ireland and Wales (see Appendix 1 for a list of recruiting centres). All recruiting hospitals had acute stroke units, were able to carry out the required observations four times a day and had a stroke-trained principal investigator. Screening, baseline, randomisation and 1-week follow-up data were collected and entered online into the trial database by the research staff based in the local hospital.

Inclusion criteria

-

Adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) with clinical diagnosis of acute stroke.

-

Within 24 hours of hospital admission.

-

Within 48 hours of stroke onset.

Exclusion criteria

-

Definite indication or contraindication to oxygen treatment at a rate of 2–3 l/minute.

-

Stroke not the main clinical problem or patient has another serious life-threatening illness likely to lead to death within the next 12 months.

Consent

Fully informed consent was sought from all research participants. Research nurses or clinicians explained the study to potential participants, who were also given a patient information sheet explaining the trial. Owing to the acute nature of stroke and the intervention being tested, there was not a 24-hour consideration period between receiving the information and taking informed consent. In patients who were unable to give fully informed consent, assent was sought from either the patient’s next of kin or from an independent physician. Fully informed consent was obtained in patients who regained capacity during the first week following randomisation.

Interventions

Patients were randomised to one of the following three groups:

-

Continuous oxygen: oxygen via nasal cannula continuously (day and night) for 72 hours after randomisation. The flow rate was set at 3 l/minute if baseline oxygen saturation was ≤ 93% or 2 l/minute if baseline saturation > 93%.

-

Nocturnal oxygen: oxygen via nasal cannula overnight (21:00–07:00) for three consecutive nights. The flow rate was set at 3 l/minute if baseline oxygen saturation was ≤ 93% or 2 l/minute if baseline saturation > 93%.

-

Control group: no ROS during the first 72 hours after randomisation unless required for other clinical reasons.

The oxygen used for the trial was supplied by the hospital through either wall-mounted sockets or portable or stationary oxygen bottles, depending on local practice.

Follow-up

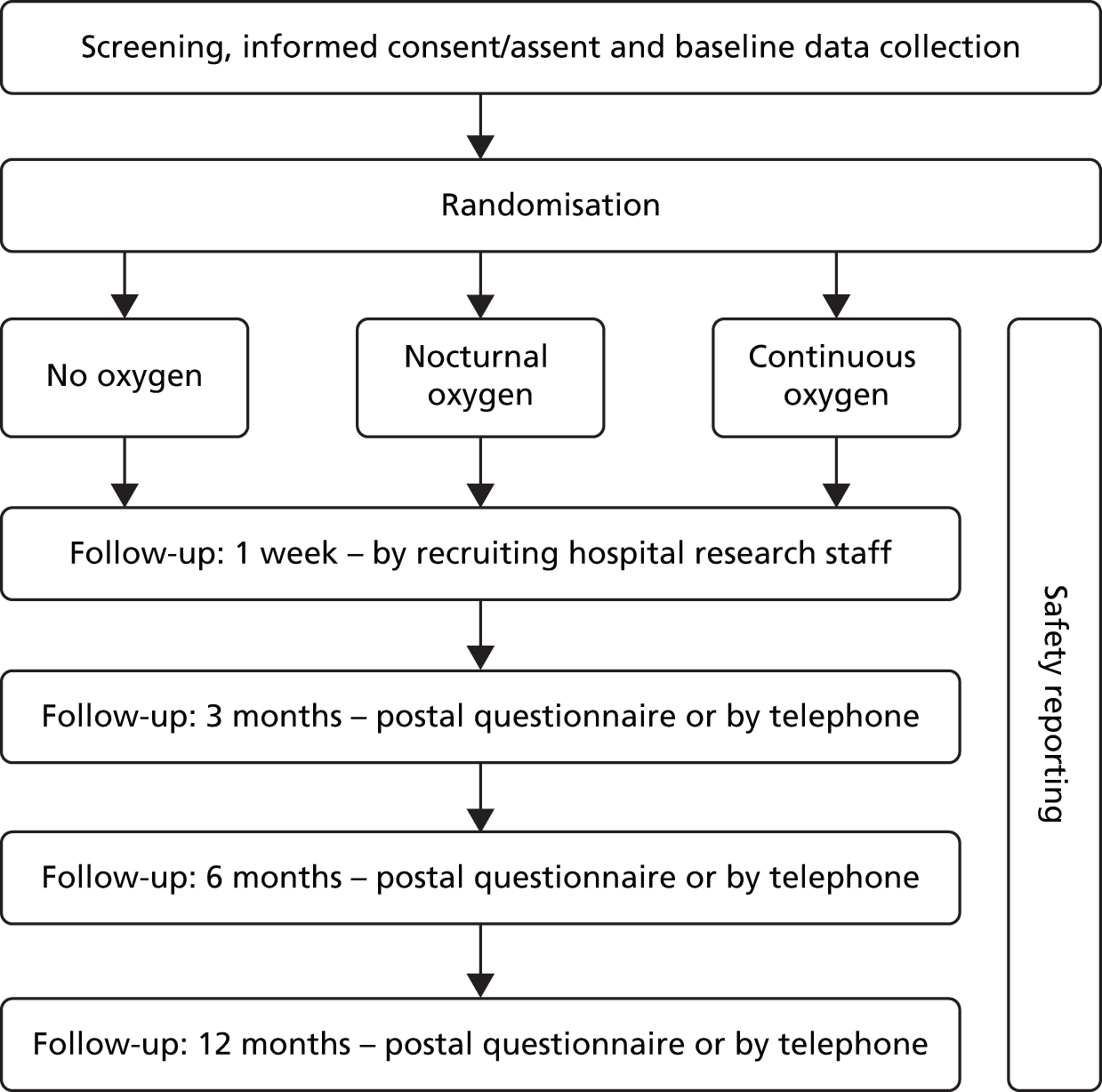

Patients were followed up at 1 week by research staff at the recruiting hospital, and then at 3, 6 and 12 months via a postal questionnaire from the trial co-ordinating centre (Figure 1). The case report form is presented in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 1.

Trial design.

Assessments

See Table 1 for a summary of patient assessments and timings.

| Outcome measure | Screening | Baseline | Week 1 | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | ✓ | |||||

| Demographics | ✓ | |||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | ✓ | |||||

| Medical history | ✓ | |||||

| Oxygen treatment prior to randomisation | ✓ | |||||

| Prognostic factors (SSV) | ✓ | |||||

| NIHSS (neurological function) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Antibiotics, antipsychotics and sedatives during week 1 | ✓ | |||||

| Highest blood pressure and highest heart rate during first 72 hours | ✓ | |||||

| Oxygen saturation during first 72 hours | ✓ | |||||

| Compliance with oxygen/control treatment | ✓ | |||||

| CT/MRI diagnosis | ✓ | |||||

| Final diagnosis | ✓ | |||||

| Date of discharge (when appropriate) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Discharge locationa | ✓ | |||||

| TOAST classification | ✓ | |||||

| Modified Rankin Scale (disability) | ✓b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Adverse events | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Living arrangements | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Hospital readmissions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Barthel Index (activities of daily living) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| EQ-5D-3L (quality of life) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| NEADL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Patient-reported outcome measures (memory, sleep, eyesight and speech) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Participants’ awareness of trial allocation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Who completed the follow-up questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Co-recruitment with other trials | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Baseline assessment

This was done by the research team randomising the patient, and was either entered online for patients randomised via the web or sent to the trial centre by fax for patients randomised via telephone. The initial assessment included baseline demographics, date and time of the event, whether or not the patient had been given oxygen in the ambulance or in the emergency department, and how much, comorbidities [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, other chronic lung problems, heart failure (congestive cardiac failure), ischaemic heart disease, and atrial fibrillation], the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score,53 score on the Six Simple Variables (SSV) outcome predictor tool,54 the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score,55,56 the type of consent (by patient or legal representative) and the date and time of randomisation.

Week 1 assessment

The week 1 assessment was performed by a member of the local research team trained in the assessment tools at 7 days (± 1 day) after enrolment. In patients who were discharged before the end of 1 week, or who could not be followed at 7 days, the assessment was conducted at discharge. Data were entered online or sent to the trial centre via fax. The week 1 assessment included neurological function (NIHSS), vital status, adverse events, whether or not the patient was prescribed oxygen for clinical indications during the first 72 hours, information on compliance with the treatment, details of other treatments (antibiotics during week 1, thrombolysis, sedatives or antipsychotics), physiological variables (highest heart rate, highest systolic and diastolic blood pressure, highest and lowest oxygen saturation during the first 72 hours, and the highest temperature during week 1), the result of the computerised tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging head scan (cerebral infarct/primary intracerebral haemorrhage/subdural haemorrhage/brain tumour/head scan not performed/other), the final diagnosis [ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA)/primary intracerebral haemorrhage/cerebrovascular accident (CVA) without CT confirmation of aetiology/other], and the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification of stroke aetiology. 57 Compliance was assessed by asking whether or not oxygen was prescribed on the drug chart, whether or not it was signed, and whether or not it was stopped before the end of 72 hours. After an amendment of the case report form [version 1, amendment 3 (30 August 2009)], additional details were recorded for the final 4143 patients. These included a more in-depth assessment of compliance with a record of oxygen saturation at 06:00, 12:00 and 00:00, whether or not oxygen treatment was in place at 06:00 and 00:00; whether or not the patient had been enrolled into another study, and which, the pre-stroke modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, three levels (EQ-5D-3L), whether or not this was reported by the patient or a relative, discharge destination (if discharged), and whether or not a new brain haemorrhage was identified on a second CT of the head (if conducted).

Three-, 6- and 12-month assessments

The 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments were performed centrally by the Stroke Oxygen Study team. Following a call to the participant’s general practitioner to confirm that the participant was alive and the contact details were the same as those on the trial database, postal questionnaires were sent to all participants at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. The questionnaires contained the discharge date, the mRS,58 the Barthel Index (BI),59 the EQ-5D-3L and the EQ-VAS,60–62 the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living scale (NEADL),63 questions regarding current abode, whether or not the patient had been readmitted to hospital since the stroke, patient-reported outcome measures (sleep, speech and memory), and a question on whether or not they remembered which treatment they were randomised to. If the questionnaire was not returned within a few weeks, a data assistant at the trial co-ordinating centre telephoned the patient and completed the questionnaire over the telephone with either the patient or a relative/carer. See Table 1 for a summary of all patient assessments and timings.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was disability assessed by the mRS at 90 days post randomisation. 58,64 The mRS is an ordinal scale that ranges from 0 for a patient with no disability to 5 for extreme disability. Death was included in the scale as a score of 6.

Secondary outcome measures at 1 week

The number of patients with neurological improvement (≥ 4-point decrease from baseline in the NIHSS score or a value of 0 at day 7),55,56 NIHSS score, mortality, the lowest and highest oxygen saturation during the 72-hour treatment period and the number of patients whose oxygen saturation fell below 90% were all secondary outcome measures.

Secondary outcome measures at 3, 6 and 12 months

Mortality, the number of patients alive and independent (mRS score of ≤ 2), the number of patients living at home, the BI of activities of daily living, quality of life EQ-5D-3L and European Quality of Life Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) and the NEADL index were all secondary outcome measures for 3-, 6- and 12-month time points.

Sample size

The original sample size calculation of 6000 patients was based on a mean mRS score of 3.51 (SD 2.03). These values came from the first 200 patients in the Stroke Oxygen Pilot Study. 32 A 5% dropout rate was assumed, along with 5% missing outcome data, giving a total of 10% lost to follow-up. The sample size of 6000 patients provided 90% power to detect small (0.2 mRS point) differences between ROS (continuous and nocturnal groups combined) and no oxygen (control group) at a p-value of ≤ 0.01 and 90% power at a p-value of ≤ 0.05 to detect small (0.2 mRS point) differences between continuous and nocturnal oxygen supplementation.

The sample size calculation was revised in October 2012 without any knowledge of interim results. Recalculation was conducted using ordinal methods to match with the Statistical Analysis Plan. The study size was subsequently consequently revised to 8000 patients. Protocol version 2 amendment 4 (18 October 2012) gave greater power to investigate any differential effectiveness of oxygen compared with control within subgroups, in particular those with more severe disease.

Randomisation and allocation

Patients were randomised via a computer-generated web-based randomisation system at the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit. Randomisation was performed using minimisation with the following factors: the SSV prognostic index for independent survival at 6 months (cut-off points ≤ 0.1, > 0.1 to ≤ 0.35, > 0.35 to ≤ 0.70 and > 0.70), oxygen treatment before randomisation (yes, no and unknown), baseline oxygen saturation on air (< 95% and ≥ 95%), and time since stroke onset (≤ 3 hours, > 3 to ≤ 6 hours, > 6 to ≤ 12 hours, > 12 to ≤ 24 hours and > 24 hours). Study centre was not included as a minimisation variable to avoid potentially high rates of allocation prediction and selection bias. Patients were randomised via a web-based randomisation program at the level of the individual on a 1 : 1 : 1 basis to either no oxygen, nocturnal oxygen or continuous oxygen. Enrolment and intervention assignment was performed by the clinical team at the recruiting centre.

Blinding

This study was open, as placebo treatment (room air) would have similar side effects as the active treatment (e.g. infection and immobilisation), but no potential benefit, and could thus bias the data in favour of the treatment group. The main outcomes were ascertained at 3 months by central follow-up, which ensured that the assessor was blind to the intervention. Assessment was by postal questionnaire, or, when participants did not respond to the letters, by telephone interview. It is possible that the patients completing the follow-up questionnaire or responding to the interview questions may have had some recollection of being treated with oxygen or not. Patients were asked to state on the questionnaire if they remembered/could guess which treatment group they were in. This was compared with the actual allocation to quantify potential bias.

Statistical methods

The analysis is by intention to treat. The primary outcome measure is disability (mRS) at 90 days after randomisation. The mRS is an ordinal scale ranging from 0 (no disability) to 5 (extreme disability). Patients who were classified as dead at the 3 months were allocated a mRS score of 6, thus creating a 0 to 6 scale.

The mRS was analysed using an ordinal logistic regression model. Both an unadjusted (primary) and adjusted (secondary) analysis were performed. For each outcome variable, the unadjusted analysis is the primary analysis and the covariate-adjusted analysis is the secondary analysis. Adjusted analyses incorporated the following covariates: age, sex, baseline NIHSS score, baseline oxygen saturation and the SSV prognostic index for 6-month independence. For analysis of mortality data, the prognostic index for 30-day survival was used in place of that for 6-month independence.

Participants who died before the assessment point did not have data for NIHSS, BI, EQ-5D and EQ-VAS, or NEADL. To avoid bias in favour of the treatment arm with higher mortality (should this be the case), death was included in the analysis of the NIHSS, BI, EQ-VAS and the NEADL as the worst outcome on the scale. 65

For continuous outcomes means and SDs or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are reported, as appropriate. Unadjusted analyses used an unrelated t-test, with the mean difference between treatments and corresponding confidence interval (CI) reported. In the event of major deviations from the assumptions of the t-test, an appropriate alternative analysis was used. The adjusted analysis used analysis of covariance methods, with the covariates specified earlier included in the analysis.

For dichotomous outcomes, percentages were compared across the treatment comparisons using a chi-squared test (unadjusted analysis). The adjusted analysis of dichotomous outcomes used binary logistic regression with the covariates listed earlier. Odds ratios (ORs) and CIs are reported. The number needed to be treated was to be calculated, if significant effects were to be seen. 66 As there were no differences, this was not done.

For ordinal secondary outcomes, the analyses described for the mRS were applied.

Data at 6 and 12 months

The longer-term follow-up data at 6 and 12 months were analysed at each time point using the same methods as those listed previously. In addition, analyses were performed across 3-, 6- and 12-month time points using a longitudinal repeated measures analysis, in this case linear mixed models. 67

The treatment effect was initially assumed to be constant over time; further analyses were carried out to investigate the effects of including time and a treatment-by-time interaction in the models.

Mortality was analysed using log-rank methods (unadjusted analysis) with Kaplan–Meier plots. The adjusted analysis used Cox regression methods, including the covariates listed above. In the covariates, the prognostic index for 30-day survival replaced that for independence at 6 months. The proportional hazards assumption associated with the Cox regression was tested via Schoenfeld residuals. Hazard ratios and 95% CIs are reported for both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

Planned subgroup analyses

These were performed in respect of the primary outcome measure only, based on a risk-stratification approach. 68 The subgroups comprise:

-

NIHSS score at baseline as indicator of stroke severity (0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–20 and > 20)

-

baseline % oxygen (O2) saturation (< 94%, 94–94.9%, 95–97% and > 97%)

-

treatment with O2 prior to randomisation (yes/no)

-

time in hours since onset of stroke (< 4 hours, 4 to < 7 hours, 7 to < 13 hours, 13 to < 24 hours and ≥ 24 hours)

-

final diagnosis (haemorrhage, infarct, TIA and other)

-

TOAST classification of infarct aetiology

-

GCS score (motor plus eye score:< 10 and 10)

-

age (< 50 years, 50–80 years and > 80 years)

-

history of chronic obstructive airway disease or asthma (yes/no)

-

history of heart failure (yes/no)

-

thrombolysed (yes/no)

-

baseline SSV risk score for independence at 6 months (≤ 0.1, > 0.1 to 0.35, > 0.35 to 0.7 and > 0.7).

These subgroup effects were analysed by means of an interaction term;69 however, pairwise hypothesis tests between the levels of the subgroup factor were not performed owing to the likely low level of statistical power. Subgroup-specific estimates are reported descriptively with 99% CIs and displayed graphically on a forest plot.

Health economics methods

Overview

A within-trial economic evaluation was conducted alongside the clinical trial in order to estimate the cost-effectiveness and cost–utility of ROS compared with no oxygen supplementation (no ROS) after stroke, over 12 months’ follow-up. Further analysis compared all three trial arms: (1) no ROS, (2) nocturnal oxygen for three nights, and (3) 72 hours’ continuous oxygen. The base-case economic evaluation adopted an NHS/Personal Social Services perspective. The cost-effectiveness analysis calculated the cost per additional day of home time gained, using information on length of stay in hospital and discharge destination. The cost–utility analysis (CUA) used quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) as the benefit measure, in which QALYs take into account the survival and quality of life of an individual. The reporting of this analysis follows the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS). 70

Health outcomes

Information on length of stay in hospital due to stroke, discharge destination and any readmissions to hospital were used to calculate the number of home time days per patient over a 12-month period. Home time has been previously used as an outcome measure in other stroke trials. 71,72 When data on actual discharge location were not available, the response to a question regarding place of residence at 3 months was used as a proxy for the discharge location. Discharge to institutional care (nursing home or residential care) was not counted as home time. The actual length of stay for readmissions was not available for all patients in the trial; therefore, a sample of 100 readmissions was analysed to determine the mean length of stay for a readmission. This value was attached to all patients who had a readmission, and used in the calculation of home time gained. Although the intention was to calculate home time gained in the first 90 days, as there were poor data on the date of readmission, home time gained was calculated over the full 12 months.

The EQ-5D-3L questionnaire73 was completed at 3, 6 and 12 months, and when a patient had died during the 12 months, the date of death was noted and a value of zero (equivalent to dead) was assumed from the date of death. EQ-5D-3L data were not collected at baseline, as it was not possible for a patient admitted for a stroke to fill in a health-related quality of life questionnaire. Therefore, we used a previously published method74 and assumed that the EQ-5D-3L score for all patients at baseline was zero, and the change in quality of life between baseline and 3 months was linear. An alternative method for baseline EQ-5D-3L score was used in a sensitivity analysis by assuming that the baseline quality of life was equal to the EQ-5D-3L value at 3 months. Quality of life estimates were derived from EQ-5D-3L responses provided by patients at each time point by applying the standard UK tariff values. 75 These estimates were then used to calculate total QALYs over 12 months for every individual in the study, using the area under the curve approach.

Resource use and costs

The costs included in the analysis related to oxygen administration as prescribed by the trial, additional oxygen required for other clinical reasons, length of stay in hospital, readmission to hospital and long-term care on discharge from hospital. All costs in the analysis were in UK pounds (£), based on a price year of 2013–14. Unit costs were obtained from published standard sources of costs for NHS procedures,76 staff costs77 and previously published research (Table 2). Health and Community Health Services pay and price indices were used to inflate costs, when appropriate. 77 Unit costs are listed in Table 2.

| Health-care resource | Unit cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen supplementation | ||

| Staff costs (per hour) | ||

| Sister/charge nurse | 51 | Curtis, 201477 |

| Registered nurse | 34 | |

| Student/research nurse | 21 | |

| Registrar | 40 | |

| Consultant | 101 | |

| Physiotherapist | 33 | |

| Allied professional | 23 | |

| Housekeeping | 26 | |

| Equipment cost (per item) | ||

| Oxygen tubing | 6.35 | University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust supplies document, 201578 |

| Portable oxygen cylinder | 20.52 | |

| Nasal tubes | 4.85 | |

| Oxygen mask | 4.79 | |

| Stroke inpatient stay | ||

| Non-elective stay (10 days) | 4171 | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 76 |

| Excess bed-day | 275 | |

| TIA/mimic inpatient stay | ||

| Non-elective stay (4 days) | 1775 | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 76 |

| Excess bed-day | 235 | |

| Readmission | 2837 | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 76 |

| Long-term carea | ||

| Stroke care after discharge for an independent patient (annual cost) | 1412 | Sandercock et al., 200279 |

| Stroke care after discharge for a dependent patient | 18,578 | |

For the purposes of estimating the cost of oxygen administration as prescribed in the trial, it was assumed that, once a patient was allocated to a treatment arm, costs of treatment were incurred. The cost of oxygen administration was adjusted for those patients for whom continuous oxygen was prescribed for clinical reasons outside the trial treatment, as described in Table 3. Information on resources required for oxygen administration, including any additional staff time and equipment required for each treatment group, was collected prospectively during the trial using a short questionnaire filled in by a representative in 24 participating hospitals (see Appendix 3). The cost of each resource type was calculated in order to determine the cost of oxygen supplementation per trial arm (Table 4). All institutions included in the trial were assumed to have the same expertise and to have followed similar protocols in the management of patients.

| No oxygen | Nocturnal oxygen | Continuous oxygen |

|---|---|---|

| Add 3 days of continuous oxygen | Add 1.5 days of continuous oxygen | Double the cost for the amount of oxygen given |

| Resource use and cost per patient (UK £, 2013/14) | Value (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Nocturnal ROS | ||

| Nursea | 23.6 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Allied professionalsb | 23.0 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Doctorc | 1.9 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Physiotherapist | 1.5 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Housekeeping | 0.1 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Oxygen tubing | 4.4 | SO2S trial data |

| Portable oxygen cylinder | 2.7 | SO2S trial data |

| Nasal tubes | 6.5 | SO2S trial data |

| Oxygen mask | 0.6 | SO2S trial data |

| Total cost per patient | 64.0 | |

| Continuous ROS | ||

| Nursea | 32.1 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Allied professionalsb | 29.0 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Doctorc | 1.8 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Physiotherapist | 2.2 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Housekeeping | 0.1 | SO2S trial data (Curtis, 201477) |

| Oxygen tubing | 4.4 | SO2S trial data |

| Portable oxygen cylinder | 5.6 | SO2S trial data |

| Nasal tubes | 6.7 | SO2S trial data |

| Oxygen mask | 0.6 | SO2S trial data |

| Total cost per patient | 83.0 | |

Patients in the trial had a stroke, TIA or a stroke mimic. For a stroke, a NHS reference cost for a CVA was assumed, as the majority of strokes were ischaemic. As there were five different categories for CVA, taking into account the number of complications and comorbidities, the median was calculated for the cost of a non-elective long stay, cost of an excess bed-day and average length of stay. These values were then adjusted for the length of stay in hospital for each patient, either adding or subtracting a bed-day cost for length of stay under or over the median length of stay. For patients who had a TIA or stroke mimic, the NHS reference cost for a TIA was assumed, using the same methodology as for CVA to adjust for length of stay. As full data on the details and length of stay of any non-elective readmissions during the 12 months were not available, the overall average cost of a non-elective admission (for all categories) was used.

Patient-level resource use on long-term care beyond the initial hospital admission was unavailable; however, the responses to the mRS provided information on the level of dependence. Patients were categorised as independent (mRS score of 0–2) or dependent (mRS score of 3–5) using data from the 3-month questionnaire. The annual cost of independent and dependent stroke after discharge from hospital was obtained from Sandercock et al. 79 and updated to 2013/14 costs. This annual cost was then adjusted to take into account the time not in hospital over the 12-month period.

For the purpose of the analysis, the costs of acute stay in hospital and long-term care were not included in the cost-effectiveness analysis to avoid double counting, as the measure of outcome was home time gained.

Analysis

The EQ-5D-3L and mRS data were not available for all randomised patients, and therefore, multiple imputation (MI) was used. MI is a statistical technique that retains overall population variability and the relationship between observations, and is considered useful when > 10% of data are missing. As > 10% of the data were missing within the trial, these were treated as missing at random and estimated using the Markov chain Monte Carlo MI method. Imputation of missing EQ-5D-3L scores used methods proposed by Simons et al. ,80 in which the whole index score was imputed. The percentage of missing EQ-5D-3L data at 12 months was 18%; therefore, 25 simulated, complete versions of the data set were produced using Stata 12.1 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The results of each of the simulated data sets were combined to produce estimates and CIs to incorporate missing data uncertainty. MI was carried out at all time points. Appendix 4 contains further detail on the imputation methods.

As the majority of cost and outcome data are usually skewed, normal parametric methods are not appropriate for calculation of the differences in means. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric approach that can be used to compare arithmetic means without making any assumptions regarding the sampling distribution. In this analysis, 3000 bootstrapping replications were undertaken in order to calculate the 95% CIs around the differences in mean costs and outcomes.

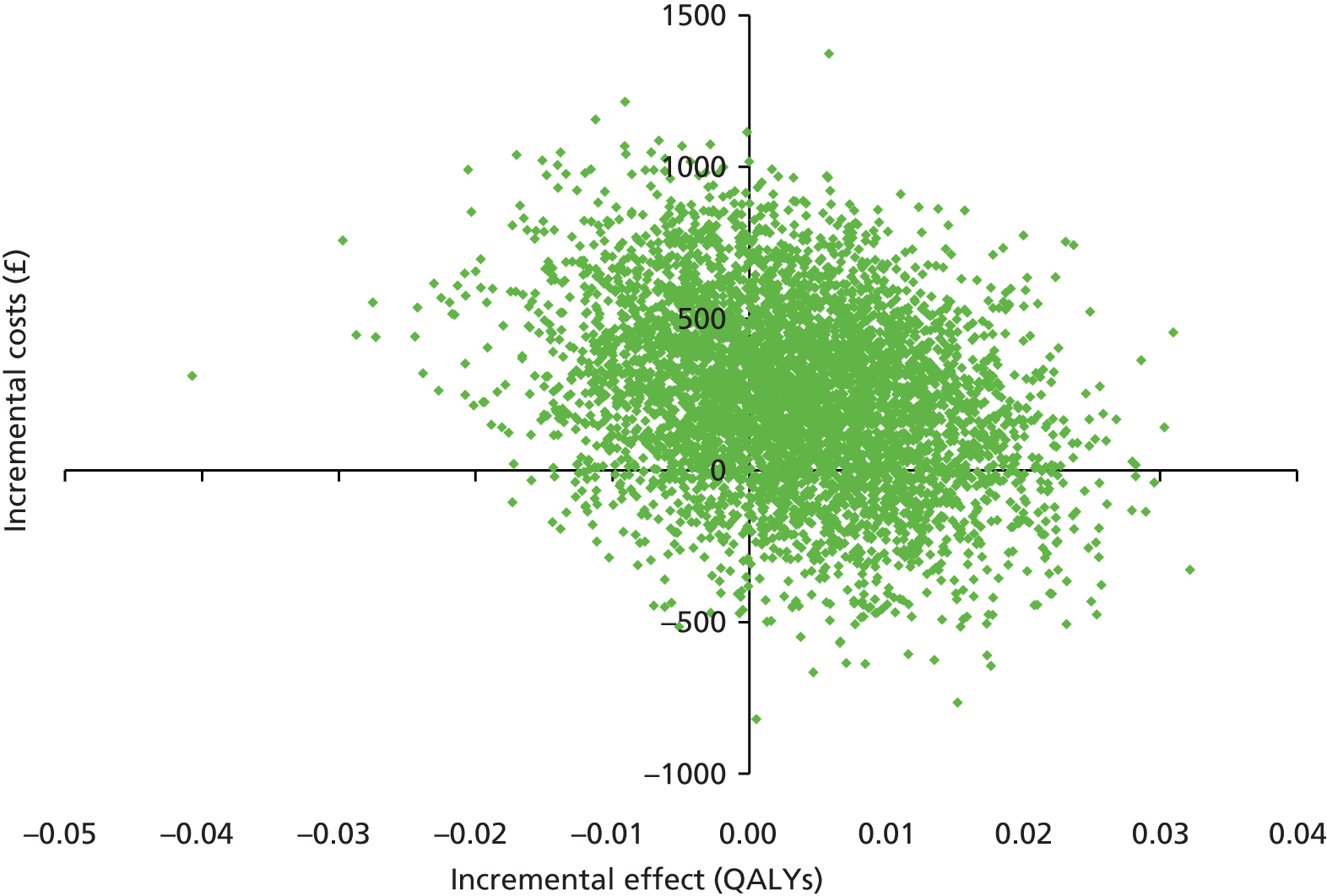

The incremental cost-effectiveness analysis was carried out at 12 months, based on the outcome of home time gained, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was expressed in terms of the cost per 1 additional day of home time gained at 12 months. A CUA was also carried out at 12 months and the ICERs were expressed as cost per additional QALY gained. The presentation of results in QALYs allows comparison of the results with other available published studies. The analysis was conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle, in line with the main trial analysis, and discounting was not applied as the duration of follow-up was only 1 year. First, an analysis of ROS compared with no ROS was conducted by including all patients in the nocturnal and continuous ROS arms in the overall ROS comparator. A subsequent analysis considered all three trial arms, using the principle of dominance: that is, if one of the trial arms was shown to be both more costly and less effective than at least one of the alternative interventions, then that option would be seen as dominated and excluded from remainder of the analysis.

A range of one-way deterministic sensitivity analyses were carried out to explore the robustness of the base-case cost–utility results for ROS compared with no ROS, and to assess the uncertainty associated with input parameters. The following sensitivity analyses were undertaken:

-

changing the costs of oxygen treatment (increasing/reducing the costs by 20%)

-

changing the acute inpatient costs of stroke (reducing/increasing the costs by 20%)

-

changing the costs of stroke care after discharge (reducing/increasing the costs by 20%)

-

assuming that quality of life changes between base-case and 3 months took place immediately, therefore allocating the 3 month EQ-5D-3L value to baseline.

In addition, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis of the base-case analysis (cost-effectiveness analysis and CUA) was carried out to enable the simultaneous exploration of uncertainty in the cost and outcome data, using 5000 simulations. The results of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis are presented using cost-effectiveness planes and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs). The CEAC graphically represents the probability that an intervention is cost-effective at different ICER thresholds.

All analyses were carried out using Stata version 12.1 and Microsoft Excel® 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Patient and public involvement

We conducted focus group meetings with stroke survivors when preparing the protocol for SO2S (see Ali et al. 46 for detail). Stroke survivors and their carers considered the study important. They considered the outcomes relevant, but suggested others that were not adequately covered by the formal assessment tools. These included memory, speech problems and sleep. We designed questions to specifically address these points and included them in the assessments at 3, 6 and 12 months. We also discussed consent issues, as many stroke patients are unable to give fully informed consent soon after the stroke, because of the nature of their brain injury. Some of the stroke patients were concerned that asking relatives to provide consent on behalf of the patients would put them under too much stress at a time when they were anxious and worried. We explained that there was an option of allowing an independent physician to consent on behalf of the patient. We included patient and carer representatives as collaborators and as members of the trial management group. Over the time of the study the initial collaborators (Linda and Peter Handy) became unable to contribute further for health reasons. Towards the end of the study Norman Phillips and Brin Helliwell provided advice to the trial management group and input into the report.

Ethical approval

The protocol was approved by the North Staffordshire Ethics Committee (06/2604/109) on 24 January 2007. The protocol can be accessed at http://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1745-6215-15-99 (accessed 1 June 2016).

Clinical trials registration

European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) number 2006-003479-11 and Current Controlled Trials International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) 52416964.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

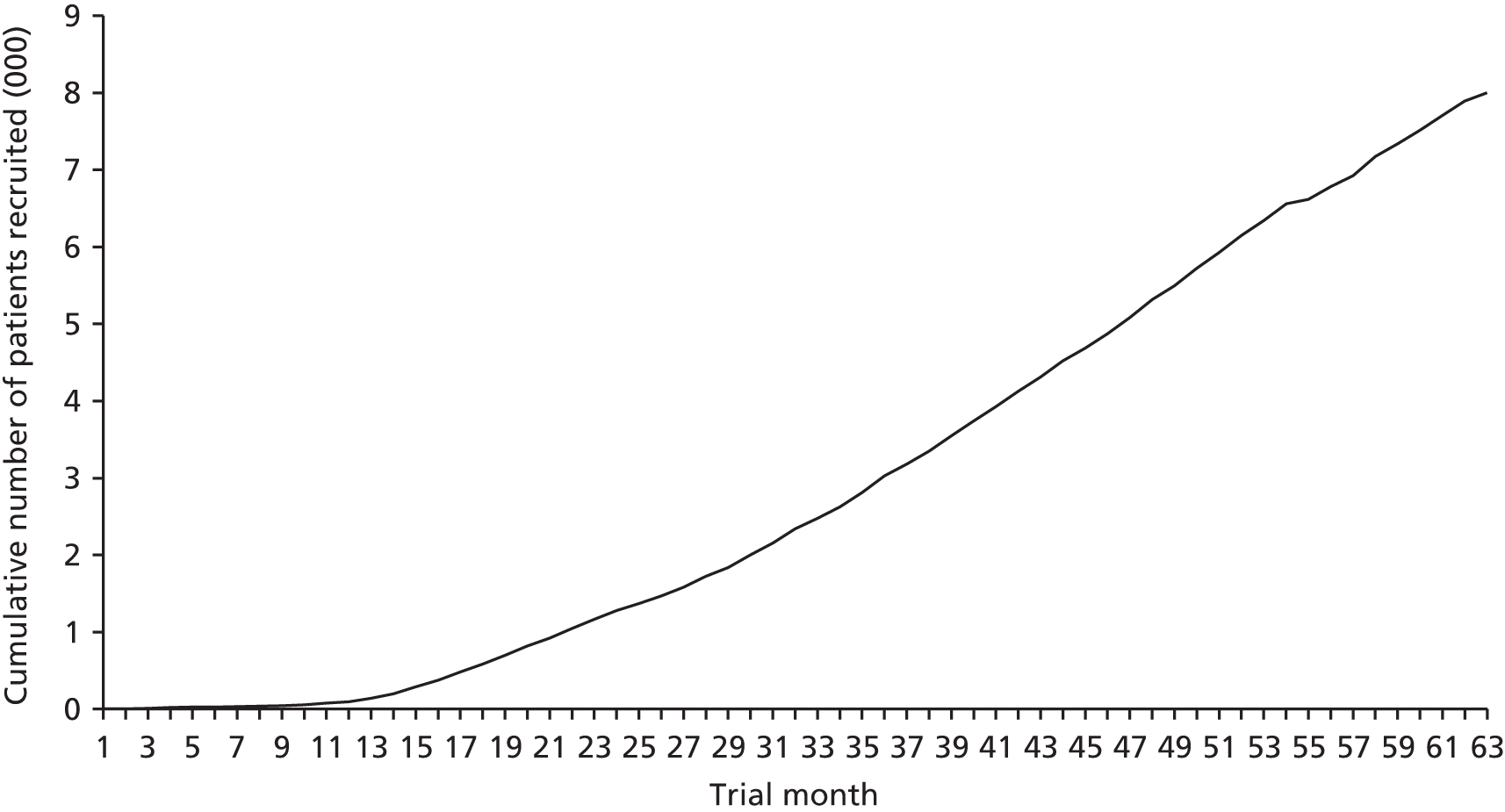

In total 8003 patients were recruited between 24 April 2008 and 17 June 2013 (Figure 2). Participants were randomised to the three groups: 2668 to the control group, 2668 to the continuous oxygen group and 2667 to the nocturnal oxygen group. All follow-up assessments were completed by December 2014.

FIGURE 2.

Timeline of patients recruited to SO2S over a 5-year period.

Consent and patient flow through the study

Fully informed consent was given by 6991 (87%) of patients and assent was given by a relative, carer or independent legal representative for 1012 (13%) patients (Table 5). At the 7-day review, six (0.7%) assented patients refused consent and were withdrawn from the study. A further 22 assented patients were withdrawn between days 7 and 90, six between days 90 and 180, and two between day 180 and the end of the study. Of those patients who gave informed consent, 40 were withdrawn by day 7, 114 were withdrawn from the study between day 7 and day 90 post randomisation, 37 were withdrawn between day 90 and 180, and 30 withdrew between days 180 and 365 (Figure 3).

| Variable | Trial arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous oxygen (N = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (N = 2667) | Control (N = 2668) | |

| Consent given by the patient, n (%) | 2329 (87) | 2340 (88) | 2322 (87) |

| Consent given by a relative, carer or independent legal representative, n (%) | 339 (13) | 327 (12) | 346 (13) |

| Withdrawal from trial by 7 days, n (%) | |||

| Total | 16 (0.6) | 20 (0.7) | 4 (0.15) |

| Patients who gave initial consent themselves | 14 (0.5) | 17 (0.6) | 3 (0.11) |

| Patients included by a legal representative | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.04) |

| Withdrawal from trial by 90 days, n (%) | |||

| Total | 56 (2.1) | 63 (2.4) | 57 (2.1) |

| Patients who gave initial consent themselves | 48 (1.8) | 56 (2.1) | 44 (1.6) |

| Patients included by a legal representative | 8 (0.3) | 7 (0.3) | 13 (0.5) |

| Withdrawal from trial by 180 days, n (%) | |||

| Total | 77 (2.9) | 72 (2.7) | 70 (2.6) |

| Patients who gave initial consent themselves | 67 (2.5) | 63 (2.4) | 55 (2.1) |

| Patients included by a legal representative | 10 (0.4) | 9 (0.3) | 15 (0.6) |

| Withdrawal from trial by 365 days, n (%) | |||

| Total | 89 (3.3) | 81 (3.0) | 81 (3.0) |

| Patients who gave initial consent themselves | 78 (2.9) | 71 (2.7) | 66 (2.5) |

| Patients included by a legal representative | 11 (0.4) | 10 (0.4) | 15 (0.6) |

FIGURE 3.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart for SO2S.

Baseline data

Patient age and sex distribution were similar in all three groups. Overall mean age was 72 years (SD 13 years) and in total 4398 (55%) patients were male. Prognostic factors, including independence in activities of daily living before the stroke (n = 7332, 92%), were also well matched across the trial arms. There was little to no difference in the participants’ medical history, with ischaemic heart disease (n = 1602, 20%), heart failure (n = 657, 8%), atrial fibrillation (n = 1995, 25%) and chronic lung conditions (n = 812, 10%) recorded in each group. Patients were enrolled relatively late at a median 20:43 (IQR 11:59–25:32) hours:minutes after symptom onset. The majority of patients had a final diagnosis of ischaemic stroke (n = 6555, 82%) recorded at the 7-day review. Primary intracerebral haemorrhage was diagnosed in 588 (7%) patients, TIA in 168 (2%) and non-stroke conditions in 292 (4%); this information was missing for 106 patients (1%). The median GCS score was 15 (IQR 15–15) and mean and median NIHSS scores were 7 and 5, respectively (range 0–34); again these were well balanced across the trial arms. Twenty per cent of patients received oxygen prior to randomisation and the mean oxygen saturation was 96.6% in the continuous (SD 1.7) and nocturnal oxygen (SD 1.6) treatment groups, and 96.7% (SD 1.7) in the control group (Table 6).

| Variable | Trial arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous oxygen (N = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (N = 2667) | Control (N = 2668) | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD)a | 72 (13) | 72 (13) | 72 (13) |

| Median (IQR) | 74 (64–82) | 75 (65–82) | 74 (64–82) |

| Male sex; n (%)a | 1466 (55) | 1466 (55) | 1466 (55) |

| Prognostic factors | |||

| Living alone, n (%)a | 861 (32) | 857 (32) | 907 (34) |

| Independent in basic activities of daily living, n (%)a | 2451 (92) | 2431 (91) | 2450 (92) |

| Normal verbal response, n (%)a | 2190 (82) | 2207 (83) | 2196 (82) |

| Able to lift affected arm, n (%)a | 1998 (75) | 2022 (76) | 1996 (75) |

| Able to walk, n (%)a | 660 (25) | 704 (26) | 677 (25) |

| Probability of 30-day survival, median (IQR) | 0.92 (0.86–0.95) | 0.92 (0.86–0.95) | 0.92 (0.86–0.95) |

| Probability of being alive and independent at 6 months, median (IQR)a | 0.44 (0.12–0.71) | 0.42 (0.12–0.71) | 0.42 (0.12–0.71) |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 7.1 (2.5) | 7.0 (2.4) | 7.1 (2.5) |

| Concomitant medical problems | |||

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 573 (21) | 515 (19) | 514 (19) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 224 (8) | 217 (8) | 216 (8) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 638 (24) | 673 (25) | 684 (26) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma, n (%) | 253 (9) | 242 (9) | 245 (9) |

| Other chronic lung problem, n (%) | 29 (1) | 24 (1) | 19 (1) |

| Details of the qualifying event | |||

| Time since symptom onset (hh:mm), mean (IQR)b | 20:44 (11:53–25:33) | 20:32 (12:05–25:31) | 20:45 (11:57–25:31) |

| Ischaemic stroke, n (%)b | 2187 (82.0) | 2165 (81.1) | 2203 (82.6) |

| Intracranial haemorrhage, n (%)b | 185 (6.9) | 207 (7.8) | 196 (7.3) |

| TIA, n (%)b | 52 (1.9) | 50 (1.9) | 66 (2.5) |

| Stroke without imaging diagnosis, n (%)b | 104 (3.9) | 106 (4.0) | 84 (3.1) |

| Not a stroke, n (%)b | 101 (3.8) | 98 (3.7) | 93 (3.5) |

| Missing, n (%)b | 39 (1.5) | 41 (1.5) | 26 (1.0) |

| GCS score (3–15), median (IQR) | 15 (15–15) | 15 (15–15) | 15 (15–15) |

| Thrombolysed, n (%)b | 447 (17) | 410 (15) | 447 (17) |

| NIHSS score (0–42), median (IQR) | 5 (3–9) | 5 (3–9) | 5 (3–9) |

| Oxygenation | |||

| Oxygen given prior to randomisation (yes), n (%)a | 531 (20) | 531 (20) | 539 (20) |

| Oxygen saturation on room air (%), mean (SD)a | 96.6 (1.7) | 96.6 (1.6) | 96.7 (1.7) |

Treatment adherence

Treatment adherence in the two intervention arms was similar, with 2158 (81%) patients completing the 72 hours of continuous oxygen therapy and 2225 (83%) patients receiving the nocturnal oxygen. In the continuous group, 433 (16%) patients did not receive the full 72 hours of oxygen therapy, and in the nocturnal group 361 (14%) did not. Discharge from hospital was the main reason for stopping before the 72 hours had passed (Table 7). In the control group trial oxygen was not prescribed for 2229 (84%) participants, but was prescribed for 23 (1%) participants; this information was not available for 406 (15%) control participants.

| Variable | Trial arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous oxygen (N = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (N = 2667) | Control (N = 2668) | |

| Trial oxygen prescribed in the drug chart and signed, n (%) | 1369 (51.3) | 1426 (53.5) | 21 (0.8) |

| Trial oxygen prescribed in the drug chart but not signed, n (%) | 789 (29.6) | 799 (30) | 2 (0.1) |

| Trial oxygen stopped before 72 hours, n (%) | 433 (16.2) | 361 (13.5) | 10 (0.4) |

| No oxygen prescribed for the trial as per randomisation, n (%) | 4 (0.2) | 10 (0.4) | 2229 (83.5) |

| No data, n (%) | 73 (2.7) | 71 (2.6) | 406 (15.2) |

In a subgroup of 4144 patients spot checks of adherence to oxygen treatment were made at 00:00 and 06:00 on nights 1, 2, and 3 of the intervention (Table 8). On the first night, adherence to oxygen treatment was reasonable, with oxygen in place for 82% and 78% for the continuous and nocturnal oxygen groups, respectively, at midnight and in 82% and 72%, respectively, at 06:00. During nights 2 and 3, considerably fewer spot checks were recorded as positive, with the lowest being 56% and 51% for the continuous and nocturnal oxygen groups at 06:00 of night 3. In the control group, oxygen was recorded as being in place at 00:00 in 2%, 3%, and 3% at 00:00 on nights 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and in 3% at 06:00 for each of the 3 days. The percentages are for a total of all patients randomised after the protocol change and included patients who were no longer in hospital.

| Variable | Trial arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous oxygen (N = 1381) | Nocturnal oxygen (N = 1381) | Control (N = 1382) | |

| Staff checked and signed that oxygen is in place at midnight | |||

| Night 1, n (%) | 1134 (82) | 1074 (78) | 31 (2) |

| Night 2, n (%) | 970 (70) | 931 (67) | 38 (3) |

| Night 3, n (%) | 803 (58) | 772 (56) | 37 (3) |

| Staff checked and signed that oxygen is in place at 6 am | |||

| Night 1, n (%) | 1132 (82) | 994 (72) | 37 (3) |

| Night 2, n (%) | 954 (69) | 863 (62) | 45 (3) |

| Night 3, n (%) | 774 (56) | 703 (51) | 39 (3) |

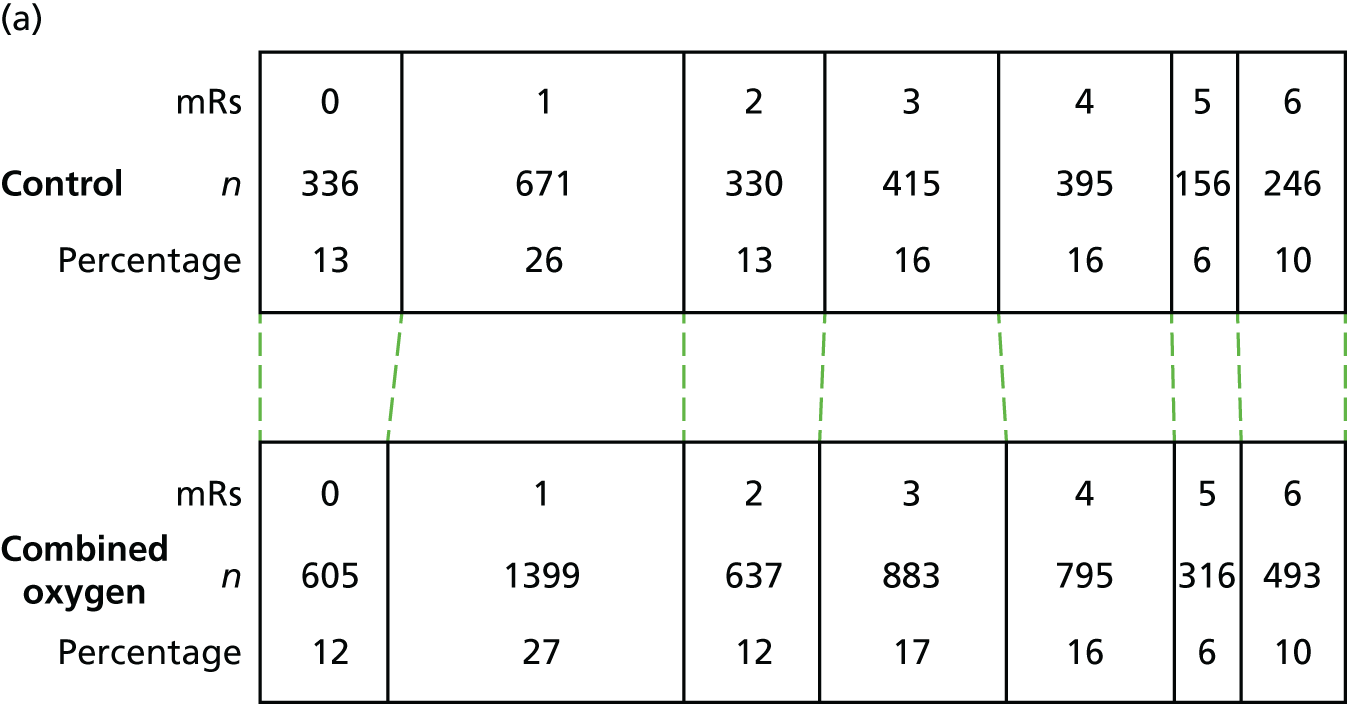

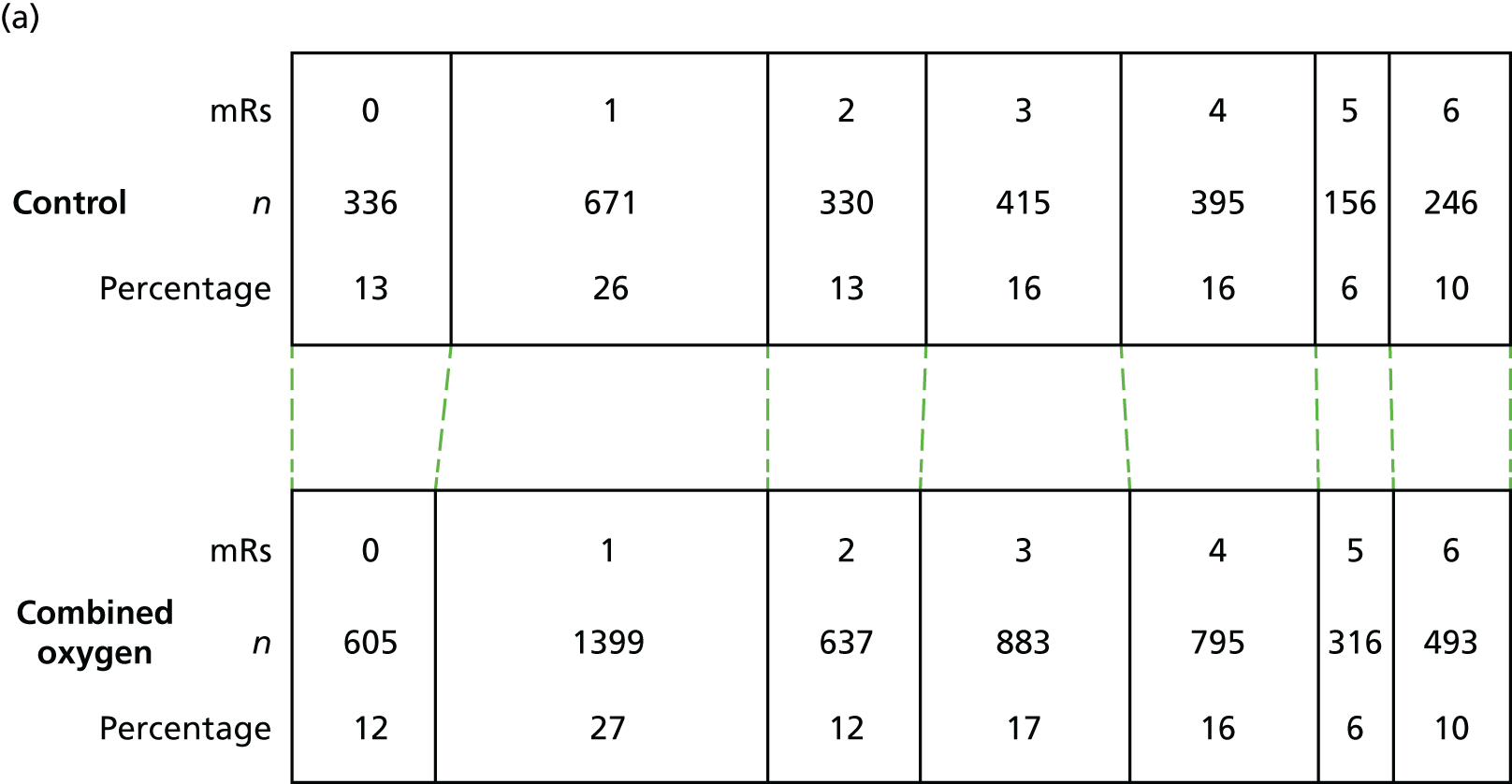

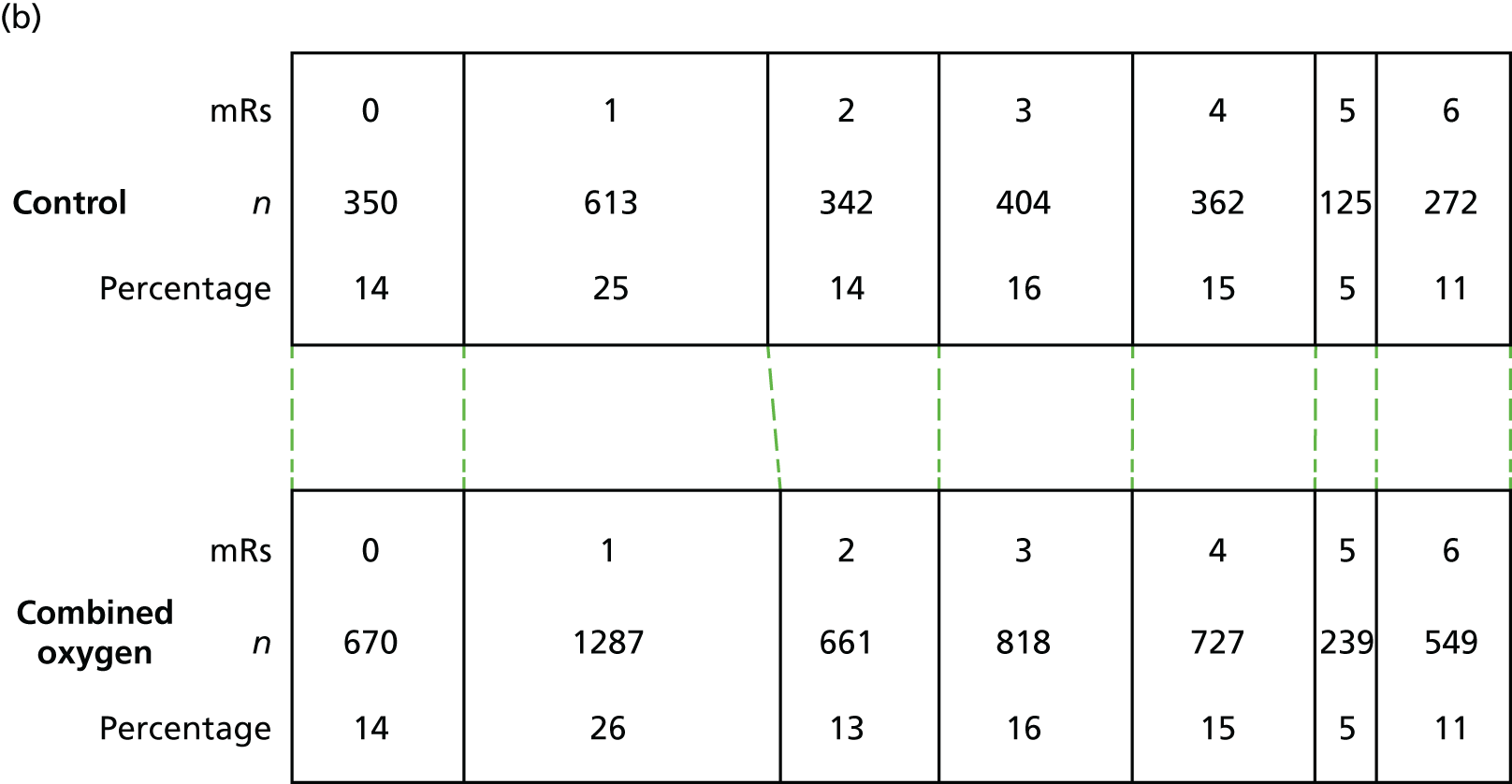

Primary outcome

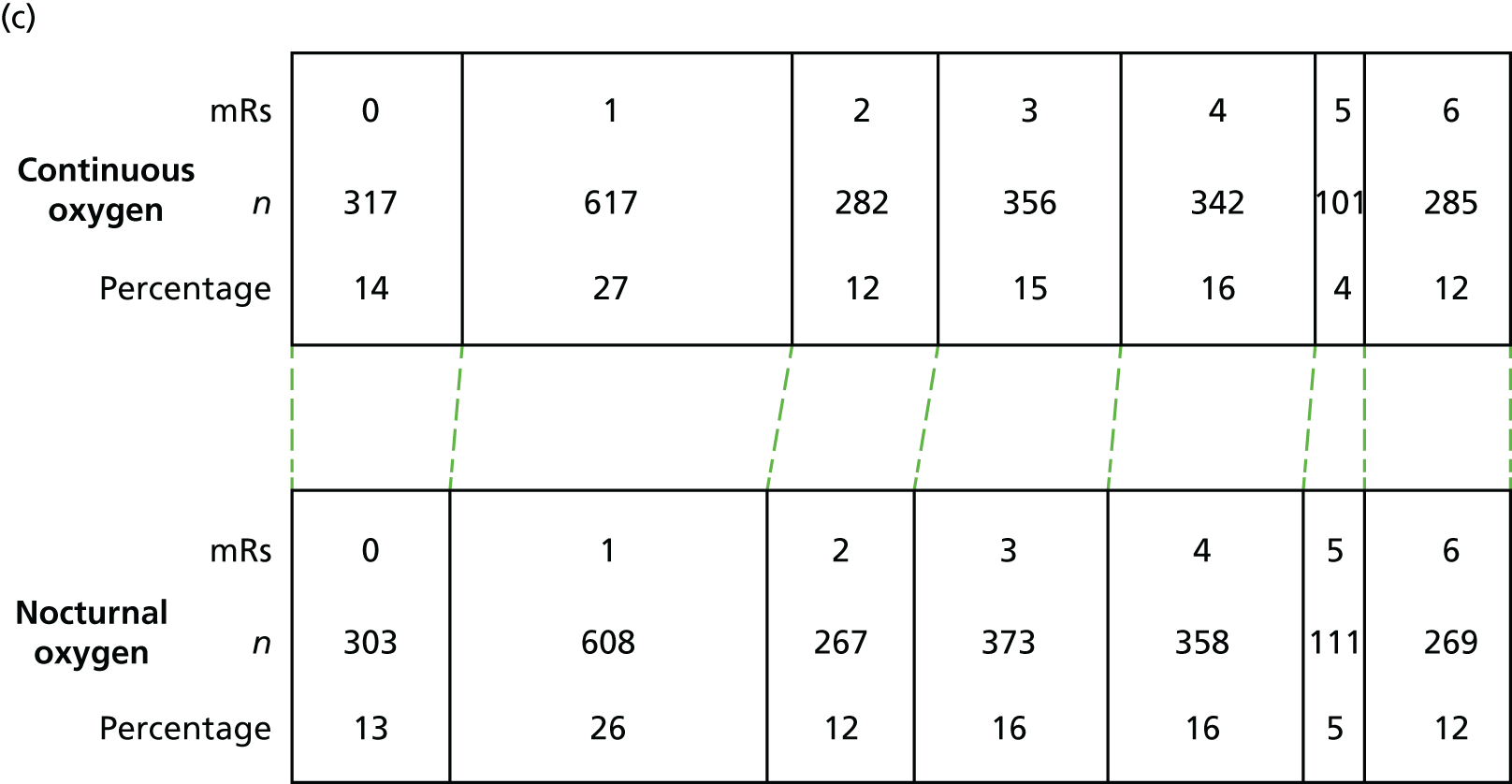

The distribution of scores for mRS at 90 days is shown in Figure 4. Oxygen supplementation did not improve the level of disability either in the comparison of the combined oxygen group against control or in the comparison of continuous versus nocturnal oxygen, both in the primary unadjusted analysis and in the covariate-adjusted analysis. The unadjusted OR for a better outcome (lower mRS) was 0.97 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.05; p = 0.5) for combined oxygen versus control (see Figure 4a), and 1.03 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.13; p = 0.6) for continuous oxygen versus nocturnal oxygen (see Figure 4b). Analyses adjusted for the covariates age, sex, baseline NIHSS score, baseline oxygen saturation and the SSV prognostic index yielded very similar results [an OR of 0.97 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.06; p = 0.5) for the combined oxygen group vs. control and an OR of 1.01 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.12; p = 0.8) for continuous oxygen vs. oxygen at night only].

FIGURE 4.

The primary outcome: mRS at 3 months. (a) Comparison 1 (combined oxygen vs. control); and (b) comparison 2 (continuous oxygen vs. nocturnal oxygen). Adapted with permission from Roffe et al. 81

The primary outcome of the SO2S was the mRS score at 90 days post stroke as a measure of disability and dependence: (1) comparing the control group (no oxygen supplementation) with both the continuous (72 hours, day and night) and nocturnal (for three nights only) groups combined; and (2) comparing continuous oxygen with nocturnal oxygen.

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome

Sensitivity analyses (Table 9) show very similar results for the complete case analysis and the analysis using MI for missing values, both confirming that oxygen treatment does not improve the primary outcome. The best- and worst-case imputations indicate the plausible maximum bounds of any potential bias from missing data (under a missing not at random assumption), showing improvement in outcome for oxygen for the best-case analysis and worse outcomes with oxygen for the worst-case analysis, with similar effect sizes in both directions. The adherers-only analyses showed a minor difference between the combined oxygen groups and control, with slightly lower odds for a good outcome with oxygen for the comparison of the combined oxygen groups with control, which was not statistically significant.

| Variable | OR (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen vs. no oxygena | Continuous vs. nocturnalb | |

| Complete case analysis | 0.970 (0.892 to 1.054); 0.471 | 1.025 (0.931 to 1.129); 0.611 |

| MI analysisc | 0.974 (0.895 to 1.061); 0.549 | 1.031 (0.933 to 1.135); 0.530 |

| Best-case imputationd | 1.178 (1.085 to 1.279); < 0.001 | 1.221 (1.111 to 1.342); < 0.001 |

| Worst-case imputatione | 0.803 (0.740 to 0.872); < 0.001 | 0.862 (0.784 to 0.947); 0.002 |

| Adherers onlyf | 0.925 (0.833 to 1.028); 0.148 | 0.981(0.853 to 1.127); 0.782 |

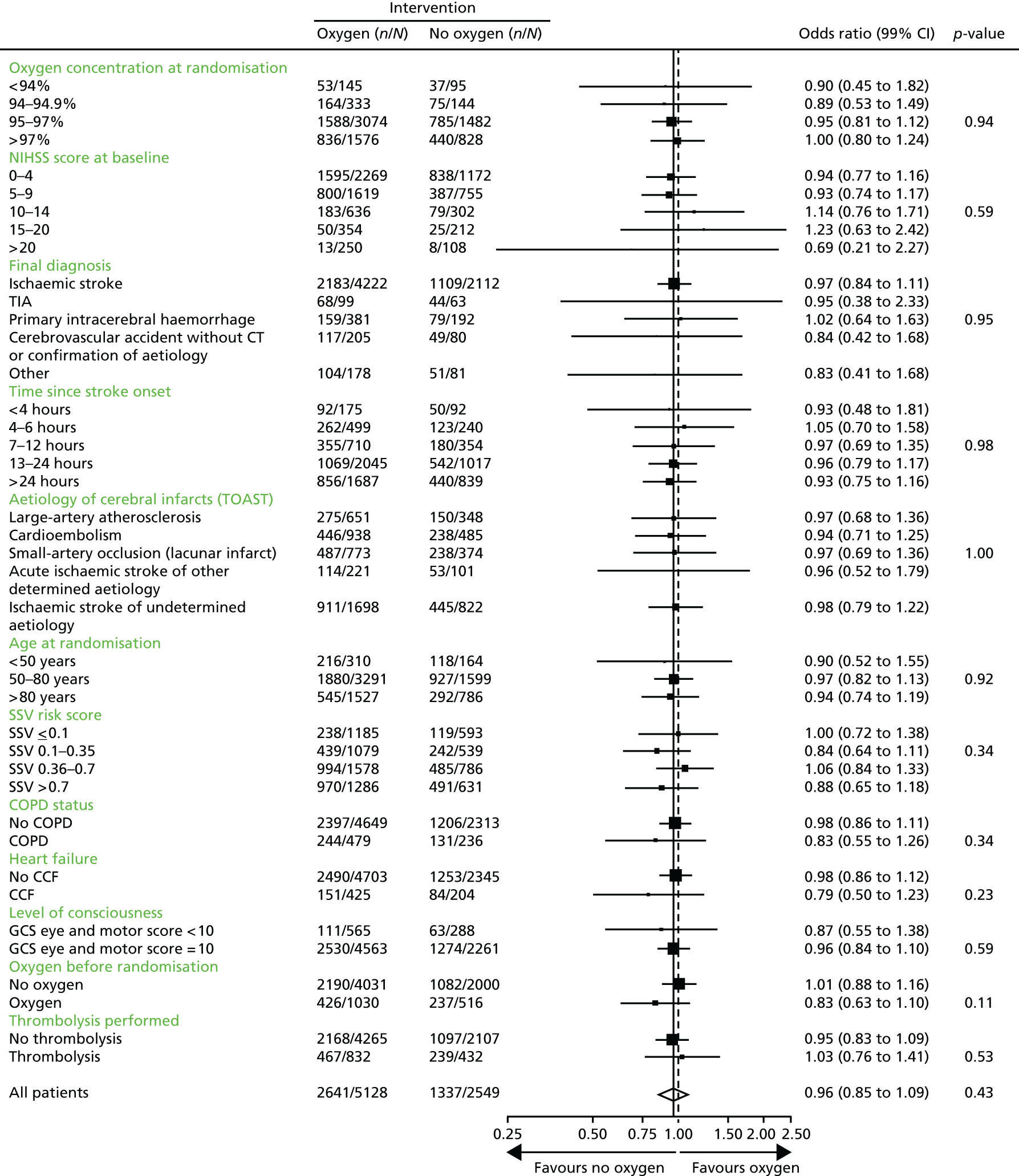

Subgroup analyses

The predefined subgroup analyses are shown in Figure 5. There was no indication that treatment effectiveness differed for any of the predefined subgroups (oxygen treatment before enrolment, oxygen saturation on air at randomisation, NIHSS score, final diagnosis, time since stroke onset, aetiology, age, SSV prognostic index, level of consciousness, and history of heart failure or of chronic obstructive airways disease).

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of subgroup analyses: alive and independent (mRS score of ≤ 2) at 3 months of oxygen (continuous and nocturnal combined) compared with control. n is the total number of events and N is the total number of events plus non-events for that group. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CCF, congestive cardiac failure.

Secondary and explanatory outcomes at 1 week

Oxygenation

Results for the highest oxygen saturation, the lowest oxygen saturation, the number of patients who had desaturations below 90% and the number of patients who needed additional oxygen over and above the trial prescription during the first 72 hours are shown in Table 10. The highest and lowest oxygen saturations recorded during the treatment period increased significantly (p < 0.001), by 0.8% and 0.9% respectively, in the continuous oxygen group when compared with the control group. This was also seen in the nocturnal oxygen group with highest and lowest oxygen saturations increased by 0.5% and 0.4%, respectively (p < 0.001). Severe hypoxia was recorded in a small number of patients (143, 2%), but was significantly less common in the combined oxygen group than in the control group. Significantly more patients in the combined oxygen group than in the control group required oxygen in addition to the trial intervention (OR 1.36, 99% CI 1.07 to 1.73; p = 0.0008). This was also not statistically different when comparing continuous with nocturnal oxygen (OR 1.23, 99% CI 0.96 to 1.59; p = 0.03), as significance was defined as < 0.01 for secondary outcomes.

| Variable | n (N = 8003) | Trial arm | Oxygen vs. control, OR or MD (99% CI) | Oxygen vs. control, p-value | Continuous vs. nocturnal, OR or MD (99% CI) | Continuous vs. nocturnal, p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous oxygen (n = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (n = 2667) | Control (n = 2668) | ||||||

| Highest oxygen saturation (%)a | 7860 | 99.1 (99.1 to 99.2), n = 2620 | 98.8 (98.7 to 98.9), n = 2609 | 98. 3 (98.2 to 98.3), n = 2631 | 0.69 (0.61 to 0.77) | < 0.0001c | 0.32 (0.22 to 0.41) | < 0.0001c |

| Lowest oxygen saturation (%)a | 7860 | 95.0 (94.9 to 95.1), n = 2619 | 94.5 (94.4 to 94.6), n = 2610 | 94.1 (94.0 to 94.2), n = 2631 | 0.62 (0.48 to 0.76) | < 0.0001c | 0.48 (0.32 to 0.63) | < 0.0001c |

| Oxygen saturation < 90%b | 7860 | 39 (1.5%), n = 2619 | 30 (1.1%), n = 2610 | 74 (2.8%), n = 2631 | 0.46 (0.30 to 0.71) | < 0.0001d | 1.30 (0.69 to 2.44) | 0.27d |

| Need for additional oxygenb | 7809 | 254 (9.8%), n = 2599 | 209 (8.1%), n = 2589 | 176 (6.7%), n = 2621 | 1.36 (1.07 to 1.73) | 0.0008d | 1.23 (0.96 to 1.59) | 0.03d |

Neurological recovery at 1 week

Data for neurological recovery and mortality at 1 week are shown in Table 11. The median (IQR) NIHSS score at week 1 was 2 (1–6) in all three treatment groups. There was no difference in the number of patients who improved by 4 or more NIHSS points between baseline and week 1. Mortality by day 7 was very low in all three treatment groups with 50 (1.9%), 35 (1.3%) and 45 (1.7%) deaths in the continuous oxygen, nocturnal oxygen and control groups, respectively.

| Variable | n (N = 8003) | Trial arm | Oxygen vs. control, OR or MD (99% CI) | Oxygen vs. control, p-value | Continuous vs. nocturnal, OR or MD (99% CI) | Continuous vs. nocturnal, p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous oxygen (n = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (n = 2667) | Control (n = 2668) | ||||||

| Neurological improvement, n (%) | 7778 | 1016 (39.2%), n = 2591 | 1029 (39.7%), n = 2591 | 1037 (39.9%), n = 2596 | 0.98 (0.86 to 1.11) | 0.68a | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | 0.71a |

| NIHSS, median (IQR) | 7778 | 2 (1–6), n = 2591 | 2 (1–6), n = 2591 | 2 (1–6), n = 2596 | –0.04 (–0.43 to 0.34) | 0.78b | 0.12 (–0.32 to 0.57) | 0.47b |

| Death by 7 days, n (%) | 7959 | 50 (1.9%), n = 2651 | 35 (1.3%), n = 2645 | 45 (1.7%), n = 2663 | 0.95 (0.59 to 1.53) | 0.78a | 1.43 (0.81 to 2.54) | 0.11a |

| Highest heart rate (b.p.m.), mean (SD) | 7859 | 87.2 (16.6), n = 2618 | 88.0 (16.5), n = 2609 | 87.7 (15.7), n = 2632 | –0.07 (–1.06 to 0.92) | n/a | –0.83 (–2.01 to 0.35) | n/a |

| Highest systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 7864 | 162.4 (24.6), n = 2621 | 162.8 (24.8), n = 2610 | 164.6 (24.7), n = 2633 | –1.96 (–3.48 to 0.44) | n/a | –0.35 (–2.11 to 1.41) | n/a |

| Highest diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 7861 | 89.5 (15.3), n = 2621 | 90.2 (15.5), n = 2609 | 90.9 (15.7), n = 2631 | –1.10 (–2.06 to 0.15) | n/a | –0.72 (–1.82 to 0.37) | n/a |

| Highest systolic blood pressure > 200 mmHg (n) | 7864 | 180, n = 2621 | 186, n = 2610 | 205, n = 2633 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Highest diastolic blood pressure > 100 mmHg (n) | 7861 | 531, n = 2621 | 552, n = 2609 | 606, n = 2631 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Sedative use, n (%) | 7916 | 140 (5.3%), n = 2634 | 161 (6.1%), n = 2631 | 154 (5.8%), n = 2651 | 0.98 (0.76 to 1.28) | n/a | 0.86 (0.63 to 1.17) | n/a |

| Antibiotic treatment, n (%) | 7916 | 400 (15.2%), n = 2634 | 393 (14.9%), n = 2631 | 403 (15.2%), n = 2651 | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.17) | n/a | 1.02 (0.84 to 1.24) | n/a |

| Highest temperature (°C) up to 7 days, mean (SD) | 7877 | 37.1 (0.6), n = 2623 | 37.2 (0.6), n = 2617 | 37.1 (0.6), n = 2637 | 0.01 (–0.03 to 0.04) | n/a | –0.01 (–0.05 to 0.03) | n/a |

Explanatory analysis at 1 week

Exploratory analyses (see Table 11) did not show evidence of increased stress levels (higher heart rates, higher blood pressure, or need for sedation) in oxygen-treated patients compared with control patients. There was also no evidence that oxygen treatment was associated with more infections, with no differences in the highest temperature or the need for antibiotics.

Secondary and exploratory outcomes at 3 months

There was no difference in mortality, the number of patients alive and independent at 3 months, the number of participants who lived at home, the BI, the NEADL, EQ-5D-3L, EQ-VAS, sleep, speech or memory between the oxygen-treated and control groups or between the groups receiving continuous and nocturnal oxygen treatment (Table 12).

| Variable | n (N = 8003) | Trial arm | Oxygen vs. control, OR or MD (99% CI) | Oxygen vs. control, p-value | Continuous vs. nocturnal, OR or MD (99% CI) | Continuous vs. nocturnal, p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous oxygen (n = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (n = 2667) | Control (n = 2668) | ||||||

| Death by 3 months | 7677 | 257 (10.0%), n = 2567 | 236 (9.2%), n = 2561 | 246 (9.7%), n = 2549 | 1.00 (0.81 to 1.23) | 0.96b | 1.10 (0.86 to 1.40) | 0.33b |

| Death by 90 daysa (date) | 8003 | 222 (8.3%), n = 2668 | 194 (7.3%), n = 2667 | 214 (8.0%), n = 2668 | 0.97 (0.77 to 1.22) | 0.73b | 1.16 (0.89 to 1.51) | 0.15b |

| Alive and independenta | 7677 | 1325 (51.6%), n = 2567 | 1316 (51.4%), n = 2561 | 1337 (52.5%), n = 2549 | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.09) | 0.43b | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17) | 0.87b |

| Living at homea | 6859 | 1961 (85.8%), n = 2285 | 1947 (84.8%), n = 2295 | 1947 (85.4%), n = 2279 | 0.99 (0.82 to 1.20) | 0.91b | 1.08 (0.87 to 1.34) | 0.35b |

| Barthel ADL index [0 (worst) to 100 (best)]c | 6549 | 70.2 (68.7 to 71.8), n = 2169 | 71.1 (69.6 to 72.6), n = 2194 | 70.9 (69.3 to 72.4), n = 2186 | –0.18 (–2.60 to 2.24) | 0.85d | –0.86 (–3.65 to 1.93) | 0.43d |

| Nottingham Extended ADL [0 (worst) to 21 (best)]c | 7528 | 9.66 (9.38 to 9.93), n = 2520 | 9.54 (9.26 to 9.81), n = 2501 | 9.77 (9.49 to 10.05), n = 2507 | –0.17 (–0.62 to 0.28) | 0.32d | 0.12 (–0.40 to 0.64) | 0.55d |

| Quality of life (EQ-5D-3L) [–0.59 (worst) to 1 (best)]c | 7248 | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.51), n = 2413 | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.51), n = 2428 | 0.49 (0.48 to 0.51), n = 2407 | 0.004 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.71d | –0.003 (–0.03 to 0.03) | 0.78d |

| Quality of life (EQ-VAS) [0 (worst) to 100 (best)]c | 6675 | 55.4 (54.2 to 56.7), n = 2251 | 55.7 (54.4 to 56.9), n = 2216 | 55.5 (54.2 to 56.7), n = 2208 | 0.10 (–1.93 to 2.12) | 0.90d | –0.24 (–2.57 to 2.09) | 0.79d |

| Sleep as good as before the strokea | 6584 | 1407 (64%), n = 2194 | 1436 (65%), n = 2208 | 1419 (65%), n = 2182 | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | – | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.13) | – |

| No significant speech problemsa | 6716 | 1957 (88%), n = 2229 | 1957 (87%), n = 2246 | 1939 (87%), n = 2241 | 1.09 (0.89 to 1.32) | – | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.34) | – |

| Memory as good as before the strokea | 6646 | 981 (44%), n = 2222 | 1000 (45%), n = 2224 | 971 (44%), n = 2200 | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.16) | – | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.13) | – |

Long-term outcomes (3, 6 and 12 months)

Survival

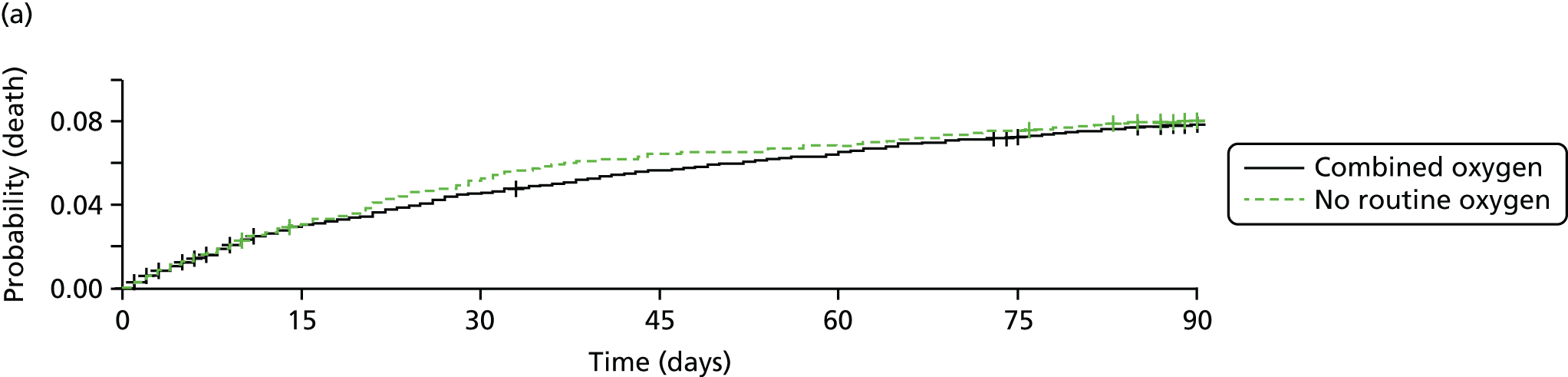

Mortality at 90 days (Figure 6) was similar in the oxygen (both groups combined) and control groups (hazard ratio 0.97, 99% CI 0.78 to 1.21; p = 0.8) and in the groups recieving continuous oxygen or oxygen at night only (hazard ratio 1.15, 99% CI 0.90–1.48; p = 0.1).

FIGURE 6.

Kaplan–Meier survival graph comparing (a) oxygen (combined) with control (no ROS) at 90 days; and (b) continuous vs. nocturnal oxygen. Oxygen compared with no oxygen: unadjusted hazard ratio for a worse outcome – 0.97 (99% CI 0.78 to 1.21; p = 0.8). Continuous compared with nocturnal oxygen: unadjusted hazard ratio for a worse outcome –1.15 (99% CI 0.90 to 1.48; p = 0.1).

Survival was the same throughout the 365 days of follow-up for patients treated with continuous oxygen and with nocturnal oxygen, and those in the control group (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Kaplan–Meier survival graph comparing (a) oxygen (combined) with control (no ROS) at 365 days; and (b) continuous compared with nocturnal oxygen.

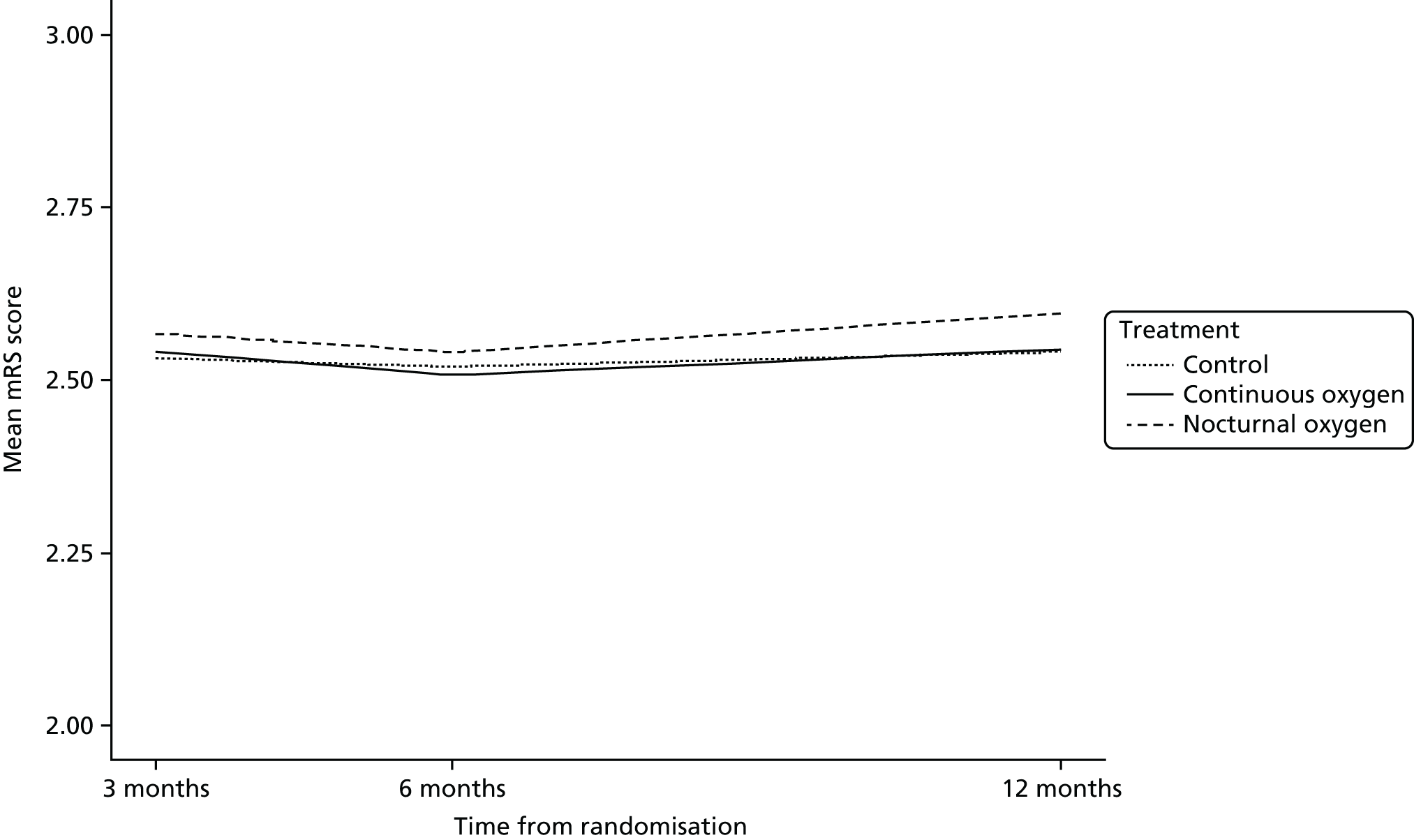

Functional outcomes

Figure 8 shows the mean mRS score at 3, 6 and 12 months. There was no change in the level of disability over the 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up assessment points in any of the three groups. The proportion of patients in each mRS score category is shown in Figure 9 for the combined oxygen group compared with the control group and in Figure 10 for the continuous oxygen group compared with the nocturnal oxygen group. Oxygen has no effect on the level of disability at any time point, whether given continuously or at night only.

FIGURE 8.

Modified Rankin Scale score at 3, 6 and 12 months.

FIGURE 9.

Functional outcome of the combined (continuous and nocturnal) oxygen group compared with the control group at (a) 3; (b) 6; and (c) 12 months post randomisation.

FIGURE 10.

Functional outcome of the continuous oxygen group compared with the nocturnal only oxygen group at (a) 3; (b) 6; and (c) 12 months post randomisation.

The number of patients who are alive and independent was similar in all three treatment groups and did not change with time (52%, 53% and 53%, respectively, at each of the three time points). Performance of activities of daily living (BI), ability to conduct extended activities of daily living (NEADL), and quality of life (EQ-5D-3L) were no different between the combined oxygen groups or between continuous and nocturnal oxygen at 90, 180 and at 365 days and were similar at each of the three time points (Table 13).

| Variable | Time point | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||

| Continuous oxygen (n = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (n = 2667) | Control (n = 2668) | Continuous oxygen (n = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (n = 2667) | Control (n = 2668) | Continuous oxygen (n = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (n = 2667) | Control (n = 2668) | |

| Death by follow-up time pointa | 257 (10.0%), n = 2567 | 236 (9.2%), n = 2561 | 246 (9.7%), n = 2549 | 280 (11.3%), n = 2475 | 269 (10.9%), n = 2476 | 272 (11.0%), n = 2468 | 285 (12.4%), n = 2300 | 269 (11.8%), n = 2289 | 279 (12.3%), n = 2268 |

| Death by 90 daysa (date) | 222 (8.7%), n = 2566 | 194 (7.6%), n = 2565 | 214 (8.4%), n = 2550 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alive and independenta | 1325 (51.6%), n = 2567 | 1316 (51.4%), n = 2561 | 1337 (52.5%), n = 2549 | 1313 (53.1%), n = 2475 | 1305 (52.7%), n = 2476 | 1305 (52.9%), n = 2468 | 1216 (52.9%), n = 2300 | 1178 (51.5%), n = 2289 | 1215 (53.6%), n = 2268 |

| Living at homea | 1961 (85.8%), n = 2285 | 1947 (84.8%), n = 2295 | 1947 (85.4%), n = 2279 | 1910 (87.6%), n = 2181 | 1932 (88.0%), n = 2196 | 1888 (86.4%), n = 2184 | 1774 (88.4%), n = 2006 | 1766 (88.0%), n = 2007 | 1728 (87.1%), n = 1983 |

| Barthel ADL index [0 (worst) to 100 (best)]b | 70.2 (68.7 to 71.8), n = 2169 | 71.1 (69.6 to 72.6), n = 2194 | 70.9 (69.3 to 72.4), n = 2186 | 71.4 (69.9 to 72.9), n = 2175 | 70.9 (69.4 to 72.5), n = 2158 | 71.1 (69.6 to 72.7), n = 2158 | 70.3 (68.6 to 72.0), n = 1945 | 70.1 (68.5 to 71.7), n = 1963 | 70.7 (69.0 to 72.3), n = 1954 |

| Nottingham Extended ADL [0 (worst) to 21(best)]b | 9.66 (9.38 to 9.93), n = 2520 | 9.54 (9.26 to 9.81), n = 2501 | 9.77 (9.49 to 10.05), n = 2507 | 9.85 (9.57 to 10.14), n = 2442 | 9.74 (9.45 to 10.02), n = 2442 | 10.01 (9.72 to 10.30), n = 2426 | 10.09 (9.79 to 10.39), n = 2254 | 9.80 (9.50 to 10.10), n = 2239 | 10.15 (9.84 to 10.45), n = 2218 |

| Quality of Life (EQ-5D-3L) [–0.59 (worst) to 1 (best)]b | 0.44 (0.42 to 0.46), n = 2413 | 0.44 (0.42 to 0.46), n = 2428 | 0.43 (0.41 to 0.45), n = 2407 | 0.42 (0.40 to 0.44), n = 2338 | 0.43 (0.41 to 0.45), n = 2353 | 0.43 (0.40 to 0.45), n = 2328 | 0.41 (0.39 to 0.43), n = 2103 | 0.42 (0.40 to 0.45), n = 2110 | 0.41 (0.39 to 0.44), n = 2081 |

| Quality of life (EQ-VAS) [0 (worst) to 100 (best)]b | 55.4 (54.2 to 56.7), n = 2251 | 55.7 (54.4 to 56.9), n = 2216 | 55.5 (54.2 to 56.7), n = 2208 | 56.9 (55.6 to 58.2), n = 2164 | 57.1 (55.8 to 58.4), n = 2148 | 56.9 (55.6 to 58.2), n = 2133 | 56.1 (54.7 to 57.6), n = 1900 | 57.0 (55.6 to 58.4), n = 1903 | 56.7 (55.3 to 58.1), n = 1872 |

| Sleep as good as before the strokea | 1407 (64%), n = 2194 | 1436 (65%), n = 2208 | 1419 (65%), n = 2182 | 1339 (64%), n = 2103 | 1368 (65%), n = 2114 | 1363 (65%), n = 2100 | 1249 (66%), n = 1888 | 1243 (64%), n = 1930 | 1196 (63%), n = 1889 |

| No significant speech problemsa | 1957 (88%), n = 2229 | 1957 (87%), n = 2246 | 1939 (87%), n = 2241 | 1923 (89%), n = 2152 | 1921 (89%), n = 2163 | 1900 (89%), n = 2140 | 1739 (90%), n = 1940 | 1749 (90%), n = 1954 | 1750 (91%), n = 1925 |

| Memory as good as before the strokea | 981 (44%), n = 2222 | 1000 (45%), n = 2224 | 971 (44%), n = 2220 | 888 (42%), n = 2127 | 914 (43%), n = 2132 | 888 (42%), n = 2110 | 800 (42%), n = 1920 | 782 (41%), n = 1930 | 762 (40%), n = 1893 |

Outcomes considered important by stroke survivors

Outcomes considered important by stroke survivors during the pre-study focus group meetings (sleep, speech and memory) are shown in Table 13. There was also no difference in these outcomes between the continuous oxygen, nocturnal oxygen and control groups. At 90 days, 87% had no significant speech problems and 65% considered their sleep as good as before the stroke, but only 44% reported their memory as being as good as before the stroke. The data were similar at 180 and 365 days.

Length of hospital stay and readmissions

Data on length of stay were available for 2435 (91%), 2401 (90%) and 2446 (92%) of participants in the continuous oxygen, nocturnal oxygen and control groups. The mean (SD) length of stay in hospital was 18.6 days (50.9 days), 18.6 days (52.0 days) and 18.0 days (56.4 days), respectively (Table 14). The rate of readmissions (Table 15) increased with time, but was similar for all three treatment groups (14%, 17% and 20% at 3, 6 and 12 months, respectively).

| Length of stay in hospital | Trial arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous oxygen (N = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (N = 2667) | Control (N = 2668) | |

| Randomisation to final discharge, mean (SD) | 18.6 days (50.9 days) | 18.6 days (52.0 days) | 18.0 days (56.4 days) |

| No data, n (%) | 233 (9%) | 266 (10%) | 222 (8%) |

Place of abode

Details of place of abode throughout the follow-up period are shown in Table 15. The proportion of patients living in their own homes, with relatives, in residential nursing, or continuing care homes was similar in all three groups. The proportion of participants living in their own homes or with family members was 76%, 74% and 68% at 3, 6 and 12 months. Only a few patients were residing in institutions (care home, nursing home or continuing NHS care) at each of the three time points (7%, 7% and 6%, respectively).

Blinding

Details of who completed the follow-up questionnaires, and whether or not the person completing the questionnaire remembers the treatment the participant was allocated to, are presented in Table 16. The proportion of participants who completed the follow-up questionnaires personally and unaided by another person was 33%, 29% and 28% at 3, 6 and 12 months. The proportions were similar for all three groups. As participants were not blinded to the intervention, we included a question at follow-up to assess whether or not they remembered which treatment group they were in. At 3 months, 49%, 35% and 45% in the continuous oxygen group, the nocturnal oxygen group and the control group, respectively, remembered their allocation correctly. At 6 months, 46%, 32% and 41%, respectively, remembered allocation correctly, and at 12 months correct memory of allocation was still recorded in 41%, 28% and 35% of participants.

| Variable | Time point | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||

| Continuous oxygen (N = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (N = 2667) | Control (N = 2668) | Continuous oxygen (N = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (N = 2667) | Control (N = 2668) | Continuous oxygen (N = 2668) | Nocturnal oxygen (N = 2667) | Control (N = 2668) | |

| Where do you live now? | |||||||||

| In own home, n (%) | 1961 (73.5%) | 1948 (73.0%) | 1947 (73.0%) | 1911 (71.7%) | 1932 (72.4%) | 1888 (70.8%) | 1774 (66.5%) | 1766 (66.2%) | 1728 (64.8%) |

| In the home of a relative, n (%) | 86 (3.2%) | 79 (3.0%) | 62 (2.3%) | 78 (2.9%) | 69 (2.6%) | 61 (2.3%) | 67 (2.5%) | 54 (2.0%) | 56 (2.1%) |

| In a residential home, n (%) | 62 (2.3%) | 63 (2.4%) | 73 (2.7%) | 57 (2.1%) | 57 (2.1%) | 75 (2.8%) | 54 (2.0%) | 53 (2.0%) | 72 (2.7%) |

| In a nursing home, n (%) | 70 (2.6%) | 114 (4.0%) | 111 (4.2%) | 97 (3.6%) | 114 (4.3%) | 120 (4.5%) | 92 (3.45%) | 118 (4.4%) | 109 (4.09%) |

| In a continuing care home, n (%) | 37 (1.4%) | 34 (1.3%) | 25 (0.9%) | 15 (0.6%) | 8 (0.3%) | 9 (0.3%) | 6 (0.2%) | 1 (0.04%) | 5 (0.19%) |

| Not left hospital yet since stroke, n (%) | 60 (2.3%) | 50 (2.0%) | 43 (1.6%) | 7 (0.3%) | 4 (0.1%) | 12 (0.5%) | 1 (0.04%) | 2 (0.07%) | 1 (0.04%) |

| Other, n (%) | 9 (0.3%) | 9 (0.3%) | 18 (0.7%) | 17 (0.6%) | 12 (0.5%) | 19 (0.7%) | 12 (0.5%) | 13 (0.49%) | 12 (0.4%) |

| Withdrawn or no data, n (%) | 383 (14.4%) | 370 (14.0%) | 389 (14.6%) | 486 (18.2%) | 471 (17.7%) | 484 (18.1%) | 662 (24.81%) | 660 (24.8%) | 685 (25.68%) |

| Have you been admitted to hospital again for any reason after you were discharged? | |||||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 379 (14%) | 356 (13%) | 380 (14%) | 456 (17%) | 457 (17%) | 434 (16%) | 540 (20%) | 550 (21%) | 546 (21%) |

| No, n (%) | 1831 (69%) | 1883 (71%) | 1850 (69%) | 1717 (64%) | 1732 (65%) | 1743 (65%) | 1456 (55%) | 1449 (54%) | 1423 (53%) |

| No data, n (%) | 458 (17%) | 428 (16%) | 438 (17%) | 495 (19%) | 478 (18%) | 491 (19%) | 672 (25%) | 668 (25%) | 699 (26%) |

| If yes, how many times? | |||||||||

| Once, n (%) | 285 (11%) | 272 (10%) | 296 (11%) | 305 (11%) | 322 (12%) | 295 (11%) | 341 (13%) | 358 (13%) | 363 (14%) |

| More than once, n (%) | 91 (3%) | 80 (3%) | 83 (3%) | 145 (5%) | 131 (5%) | 134 (5%) | 195 (7%) | 186 (7%) | 181 (7%) |

| No data, n (%) | 3 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) | 1 (< 0.1%) | 6 (0.2%) | 4 (0.1%) | 5 (0.2%) | 4 (0.1%) | 6 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) |

Co-enrolment in other research studies