Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/104/13. The contractual start date was in November 2012. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rumana Omar reports membership of the Health Technology Assessment General Board. Michael King is a member of the PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit, which is funded by the National Institute for Health Research.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Hassiotis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Several passages in this chapter are adapted from Hassiotis et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Intellectual disability (ID) is characterised by significant impairments in cognitive, social and practical skills including activities of daily living and work tasks. 2 Prevalence estimates suggest that as many as 2 in 100 adults have ID worldwide, although prevalence rates may vary according to country, age and socioeconomic status. 3 Individuals with ID have complex and unique care needs, given their pronounced vulnerability to biological, psychological and environmental stressors compared with the general population. 4 A reduced ability to cope with these stressors makes individuals with ID more likely to experience challenging behaviours. 5 Between 10% and 15% of adults with ID present with challenging behaviour, most commonly aggression, which may result in long-term hospitalisation, often in out-of-area facilities, restrictive care practices and neglect as well as an increase in receipt of antipsychotic medication and service use. 6–9 Therefore, effective treatment approaches for challenging behaviour are vital. However, the wide range of factors that could trigger challenging behaviour, as well as the many psychiatric conditions associated with ID, make a clear understanding of challenging behaviour in ID difficult. Although there have been a number of interventional approaches over the years, the literature on pharmacological and psychosocial interventions is limited to observational studies and single-site randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with short follow-up periods, which therefore are subject to significant bias. 10–13 Furthermore, these studies did not include a health economic evaluation, which is important in guiding policy-makers and service commissioners.

Cost of challenging behaviour to society

The presence of challenging behaviour increases the cost of care for people with ID, mostly due to increases in support and long-term inpatient care, often in expensive out-of-area placement;14–17 and also increases family-carer burden. 18 Hunter19 argues that the limited economic data currently available make use of information based on services that are many years old and superseded by advances in community health and social care.

The psychosocial intervention with the greatest evidence base for efficacy is Positive Behaviour Support (PBS). It is described in detail in the following section.

Positive Behaviour Support

Positive Behaviour Support has arisen out of the tenet that challenging behaviour is shaped by personal and psychological experiences and helps the person to exert some control over their environment. It is considered a cornerstone of good-quality care that is also supported by policy objectives to maintain individuals in their local communities and encourage commissioning that rewards skilled care provision. 20,21 The challenging behaviour may be a response to environmental cues or ‘schedule induced’, that is, may be the result of interactions between the individual and the environment. 22 These concepts have influenced the definition of challenging behaviour as ‘behaviour of such intensity, frequency or duration that the physical safety of the person or others is placed in serious jeopardy or behaviour which is likely to seriously limit or deny access to the use of ordinary community facilities’. 23 PBS is ‘the application of the science of applied behaviour analysis (ABA) in the support of people with challenging behaviour’ and is an essentially complex intervention in terms of its components and range of outcomes. 24 PBS is a flexible, multicomponent approach that takes a lifespan perspective and emphasises prevention, and so far is the only treatment with evidence of efficacy. It focuses on reducing challenging behaviour and improving quality of life in individuals with intellectual disabilities25 and other population groups across the lifespan, for example in education or in individuals with brain injury. 26–29 It aims to help professionals and family or paid carers understand the behaviour that an individual displays by focusing on the individual’s interaction with his/her environment and identifying the context in which the behaviour takes place by means of a functional assessment that should lead to personalised, non-restrictive approaches to challenging behaviour designed to foster prosocial actions.

Staff training in Positive Behaviour Support

Positive Behaviour Support can be implemented in a number of ways, including by a single practitioner co-ordinating all elements of the framework and leading each stage of the process,30–32 by professional teams in which different members contribute to different elements of the PBS framework or process,13,33 and systemwide, whereby the PBS framework is implemented at varying levels of intensity via a tiered model of prevention that covers an entire organisation or geographical area. 33–35 Specific staff competencies have an impact on the effectiveness of PBS in improving challenging behaviour. However, as a result of the resources required to deliver PBS, this type of support is not always available. Despite PBS being a well-known intervention framework, only about half of adults with ID and challenging behaviour may receive it. 36 Even in areas with specialist support teams providing applied behaviour analysis or PBS, patients often have to wait several months to receive help. Therefore, training paid carers and professional staff in PBS is thought to increase awareness of good care for this population group and extend the expertise in managing challenging behaviour in the community. McClean et al. 36 and Grey and McClean37 have reported on training 132 paid carers in a non-randomised clinical study (n = 60). The authors found significant reductions in challenging behaviour in groups supported by trained carers compared with controls. However, the instrument used to measure the primary outcome does not have established psychometric properties and the study was uncontrolled and included training paid carers (rather than professionals) who are likely to require a different set of skills and knowledge from the outset. The authors estimated that paid carer training in PBS may lead to savings of €2000 per person treated.

A pilot RCT of PBS incorporating applied behaviour analysis delivered by a specialist behaviour team in one area in England showed significant reductions in irritability, lethargy and hyperactivity. 11 A naturalistic 2-year follow-up of the same cohort showed a continued positive effect of the intervention on reducing challenging behaviour compared with TAU. 13

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK has produced a guideline38 that recommends the implementation of PBS in routine care and highlights the importance of working with the individual and their carers, understanding the function of the behaviour and ensuring that interventions are provided in the least restrictive manner. However, it has been acknowledged that staff in community ID services are not sufficiently skilled to deliver PBS. Training programmes for front-line staff have been developed and delivered nationally, showing an increase in knowledge and perceived confidence in understanding and managing challenging behaviour. 39

In the light of the widespread implementation of PBS, a rigorous evaluation of the clinical effectiveness of staff training in PBS was required. Furthermore, the economic evaluation would test whether or not any reductions in challenging behaviour resulted in reduced service-use costs and improved health-related quality of life. Therefore, we conducted a real-world multicentre evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of staff training in PBS for treating challenging behaviour in adults with ID compared with TAU in ID services in England.

Trial objectives

Primary objective

Examine the clinical effectiveness of staff training in PBS on carer-reported ratings of challenging behaviour over 12 months as measured by the Aberrant Behaviour Checklist – Community total score (ABC-CT)40 in community-dwelling adults with ID.

Secondary objectives

-

Examine the cost-effectiveness of staff training in PBS.

-

Examine the impact of the intervention on the prescription of psychotropic medication, paid-carer and family-carer burden, and service user mental status as well as participation in community-based activities over 12 months when compared with treatment as usual (TAU) alone.

-

Measure the influence on the primary outcome of the level of ID, adaptive behaviour scores, mental health status and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) status.

-

Carry out an exploratory analysis of the impact of the intervention on all measures in a subsample of participants with an ASD over 12 months.

-

Understand factors that promote and hinder the successful training of staff and the delivery of PBS within community ID services.

Rationale for the long-term follow-up

It has been suggested that some treatments may have delayed beneficial or harmful effects, which may not be known until well after the trial has been completed, showing that the true value of a therapy may change in the light of long-term data. 41,42 There is some evidence from cancer research, cardiovascular medicine and mental health research for long-term treatment effects. A recent RCT of prevention of depression in primary care43 showed little difference in the incidence of major depression after 6 months, but a substantial reduction after 18 months. The collection and analysis of longitudinal data can provide further insight into not only clinical, but also economic, outcomes.

The PBS study is the first large-scale RCT of a complex behavioural intervention for adults with ID and challenging behaviour. Conducting an additional final follow-up assessment would provide further information about the clinical and economic long-term outcomes as well as any potential treatment effect of PBS compared with TAU over time, and would therefore contribute to the existing knowledge of evidence-based care for people with ID who have challenging behaviour.

Chapter 2 Methods

Several passages in this chapter are adapted from Hassiotis et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design

This was a multicentre, single-blind, parallel two-arm cluster RCT evaluating clinical outcomes of manual-based face-to-face staff training in PBS for managing challenging behaviour in adults with ID. A cluster randomised designed was deemed appropriate for this type of complex educational intervention in order to avoid transfer of the intervention skills between the two different arms. 44

Sample size

The primary outcome is the ABC-CT measured repeatedly at 6 and 12 months following recruitment. The pilot study11 generated a mean baseline Aberrant Behaviour Checklist – Community (ABC-C) score of 45.4 [standard deviation (SD) 26.4]. A SD reduction of 0.45 on the ABC-C score in the PBS arm compared with the control arm is considered to be clinically important. Using an analysis of covariance approach, based on a correlation of 0.48 between the baseline and post-intervention ABC-C measurements (estimated from the pilot study), 80 participants per arm were required to detect a SD difference of 0.45 with 90% power and 5% significance level. Inflating for clustering within the community ID services, using the formula proposed by Eldridge et al. ,45 which accounts for variable cluster sizes and an intracluster correlation of 0.062 (estimated from the pilot study), an average cluster size of 12 (we expected it to be 13, however, allowing for 10% attrition and rounding it up to the nearest integer we have used a cluster size of 12 in our calculations) and a SD for the cluster size of 3, a total of 276 participants were required. However, this sample size can be reduced as each participant provided two measurements of ABC-C score. Using a correlation of 0.6 between the 6 and 12 months’ post-intervention ABC-C measurements (estimated from the pilot study) and a cluster size of 2, a total of 442 ABC-C measurements; thus, 221 participants, were required. In performing this calculation, we have assumed that there would be no treatment by time period interaction over 12 months, which was supported by the pilot studies. 11,13 To allow for 10% attrition over the 12-month period, a total of 246 participants had to be recruited in to the trial thus requiring 19 clusters. The sample size calculation was based on the program and formulae in Stata® version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Service and participant recruitment

Twenty-three community ID services in England were recruited to the study. All participating services treat adults with ID and challenging behaviour, which tends to be remitting and relapsing so that patients may experience periods of exacerbation of behaviours but also periods of relative stability. The services were recruited through the Clinical Research Networks across several regions in England (London, Leicestershire, Kent, Surrey, Bradford, and Coventry and Warwickshire), which cover urban, semi-rural and rural areas. The number of registered adults with ID ranged from 100 to 1000 and ID services employed a median of 23 full-time equivalent health and/or social care staff (range 4–70). A maximum of 16 participants (range 5–16) with ID were recruited from each cluster.

Two volunteer health staff in each service (henceforth called therapists) from a variety of professions (i.e. psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists and speech and language therapists) received PBS training. We considered it beneficial to have two therapists per team, as this would enable peer support and cover in the event that one of the therapists subsequently became unavailable, thus ensuring continuity of the intervention and implementation. Interested staff required the agreement of their line managers to take part.

Each therapist had a maximum caseload of eight individuals at any time during the trial, which meant a maximum of 16 service users having treatment per team. Therapists may have continued to provide generic input for other service users, such as taking part in dysphagia assessments, assessment of capacity or day activities/home environment if practicable. However, as therapists who received PBS training were delivering an intensive intervention (suggested time of 12.5 hours per participant excluding travel and writing up), we asked their clinical managers to reduce their routine caseloads to allow them sufficient time to deliver the intervention. We anticipated that, once the training was completed, 12–14 service users per month would be taken on for treatment across the intervention sites.

Randomisation and masking

Once the clusters were recruited and potential participants had been screened for eligibility by their participating ID services and had provided verbal consent to be approached about the study, they were randomised using an independent web-based randomisation system (Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK) and random permuted blocks on a 1 : 1 basis. The following data were taken into account in our randomisation planning: team size (number of full-time equivalent staff), clusters located in or out of London and number of service users registered per team (cluster). We calculated the ratio of staff to service users in in-London and out-of-London teams and no difference was found. We stratified the randomisation by calculating the staff-to-patient ratio for each cluster, thus creating a binary factor that indicated whether a cluster was below or above the median ratio. A second wave of randomisation was prepared because of delays in the recruitment of some of the participating teams. The sites were informed of their treatment allocation by the trial manager.

Although clusters, participants and carers were aware of arm allocation, the research assistants (RAs) and clinical studies officers (CSOs) from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network conducting the study assessments were blind to treatment arm allocation. They were asked to guess treatment allocation for each participant at each follow-up assessment and to report any incident of unblinding. In the analysis, we compared treatment allocation guesses to identify potential bias attributable to unblinding.

Possible sources of bias

One possible source of bias we took into account was the transfer of PBS-trained therapists between the intervention and control teams during the trial. We examined the health staff turnover rates in a number of services that had expressed interest in participating and this was well below 13%, which is considered very low based on agreed service performance data such as balanced scorecards. Therefore, the chance of such leaks of the intervention were considered to be very small. Any therapist changes were recorded throughout the study duration and none found a new post within teams in the control arm. We judged that contamination between study arms was unlikely given the more intensive nature of the intervention. However, PBS principles are being taught widely and, therefore, some knowledge of PBS in teams in the control arm was unavoidable. Selection bias resulting from recruiting participants after cluster allocation is revealed was avoided by completing recruitment and screening assessment prior to randomisation. A degree of variation in participant characteristics between the study arms can be accounted for by the cluster RCT design. 46

Inclusion criteria

Participants

The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows:

-

eligible to receive care from ID services

-

age ≥ 18 years

-

mild to severe ID

-

an ABC-CT of ≥ 15 at initial screening (indicating a degree of challenging behaviour taking place at least weekly, including verbal or physical aggression, hyperactivity, refusal to attend activities and non-responsiveness that requires professional input).

Community intellectual disability services

The inclusion criteria for community ID services were as follows:

-

willingness to participate in the study

-

availability of at least two staff members willing to train

-

written agreement by the service manager to participate.

Exclusion criteria

Participants

Participants could not be included in the study if:

-

they had a primary clinical diagnosis of personality disorder or substance misuse, as PBS is not considered first-line treatment for those disorders

-

there was a relapse in pre-existing mental disorder

-

there was a decision by the clinical team that a referral to the study would be inappropriate.

Community intellectual disability services

Community ID services could not be included in the study if:

-

there were not two team members who were willing to train

-

the service has already received PBS training and was implementing PBS for their service users.

Interventions

Positive Behaviour Support-based staff training (in addition to treatment as usual)

The therapists from clusters randomised to the intervention arm received face-to-face PBS training supported by a training manual,47 which consisted of the following topics:

-

functional behavioural assessment and formulation skills using the Brief Behavioural Assessment Tool (BBAT) for brief functional analyses

-

primary prevention

-

secondary prevention and reactive strategies

-

periodic service review and problem solving –

-

developing individualised periodic service reviews

-

troubleshooting.

-

The training was delivered by expert trainers who deliver training in PBS in a variety of health and social care settings, run accreditation and academic courses in PBS and also carry out research on this topic. It was conducted over a total of 6 days and delivered in three 2-day workshops that were 6–8 weeks apart, over a course of 15 weeks. Between the first and second workshop, the therapists were expected to begin undertaking work with participants who had completed a baseline assessment. The final 2-day workshop focused on effective implementation of behavioural plans and providing problem-solving strategies. The training outline is shown in Appendix 1.

The therapists were offered post-training mentoring for the time they were treating participants and they were responsible for utilising this facility. The mentoring was intended to maintain motivation and enhance practice skills. The mentoring arrangements were as follows:

-

Months 1–6 post training – therapists were offered up to 2 hours of support per month (1 hour for the mentor to read the submitted materials and 1 hour for feedback). Therapists were asked to submit the following material for two further cases: BBAT/summary statement, intervention plan table, PBS plan, training plan and fidelity checklist. Subsequently, they received feedback on all submitted material from their designated mentor (mentoring responsibility was shared equally among the four tutors).

-

Months 7–12 post training – therapists were offered up to 1 hour of support per month, during which they could raise specific technical or theoretical issues about their remaining sample cases.

-

In all, therapists were offered detailed mentoring on three cases (one during training and two post training).

-

This model reflected a tapering mentoring model that fits ‘real-world’ conditions.

-

Although mentors took all practical steps to ensure that appropriate contacts were put in place, responsibility for making the best use of supervision rested with the therapists.

In addition, the trial manager, the chief investigator and trainers held monthly teleconferences with therapists in order to discuss issues in relation to the treatment delivery, aiming to maintain and enhance practice skills and motivation.

Clinical responsibility of the cases remained with the local clinical teams, which also managed any emergencies as they arose.

Treatment as usual

Staff in the clusters that were randomised to TAU continued with their existing treatment approaches and were able to use any resource they had available to them. Most community ID services in England employ a variety of health and social care professionals, and patients have access to standard behavioural, psychosocial and pharmacological interventions, for example strategies to improve communication, physical health checks, simple behavioural modification and prescribing and monitoring of psychotropic medication. In some cases, the participants lived in accommodation where paid carers were PBS aware, that is, the accommodation provider had offered PBS-awareness seminars or employed an external consultant to advise care staff on PBS. We did not influence the approaches that those teams used. All clinical and social care aspects of TAU were also available to the participants in the intervention arm.

Initially, we had committed to offer a 1-day seminar in PBS for the services in the control arm. However, because of the long-term follow-up, this has not been carried out, in order to minimise systematic bias. Policy changes post 2014 meant that teams in the control arm were subsequently able to access such training through an NHS England initiative. 48

Frequency and duration of follow-up

All participants received a baseline assessment and were followed up at 6 and 12 months after baseline. We allowed for a window of ± 4 weeks around the due date for each follow-up assessment with every individual participant.

Ethics issues, research governance and consent

The study received ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – Harrow (reference 12/LO/1378). Research and development approvals were obtained from all NHS trusts involved in the study. Details can be found in Appendix 2. The study was sponsored by University College London (UCL). It was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice,49 the Research Governance Framework50 and according to the standard operating procedures of the PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit at UCL. All data were stored securely and anonymised in accordance with the Data Protection Act. 51

The study’s Trial Steering Committee (TSC) consisted of two independent and two non-independent members and met twice per year. The study’s Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) consisted of three independent members and convened twice a year.

Easy-to-read information sheets and consent forms for the study were prepared with the assistance of the study service users reference group Camden SURGE (Speaking Up Rights Group Experts), The Advocacy Project. RAs and CSOs were trained in obtaining informed consent (including assessing capacity to consent), good clinical practice and data collection. Initially, they contacted those who had given verbal consent to be approached about the study by telephone to discuss the study. Subsequently, they sent written information about the study procedures to family or paid carers and participants with ID, and followed this up with a telephone call ≥ 7 days later to discuss whether or not they were interested in taking part in the study. The RAs or CSOs then visited the participants and carers in their home (or place of work for paid carers) and obtained their written informed consent to take part in the study. If the participants with ID lacked capacity as per the Mental Capacity Act 2005,52 a person was identified or nominated to act as consultee on their behalf.

We notified the participant’s general practitioner (GP) of his/her participation in the trial. All of the research team members followed the required risk assessment procedures including the guidelines for risk management and safeguarding processes.

Serious adverse events

Reports of serious adverse events (SAEs) were collected for the duration of the trial. They were defined as events that:

-

resulted in death

-

were life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolonged existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

were otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Any events that were related to the trial (i.e. resulted from the administration of any of the research procedures) and were unexpected (i.e. the type of event was not listed in the protocol as an expected occurrence) were reported to the Research Ethics Committee in line with their reporting timelines. The SAE form is shown in Appendix 3.

In addition, we collected information on the following events for participants for the duration of the study: medications taken including psychotropic medication, out-of-area placements and police contacts.

Outcome measures and instruments

Quantitative assessments

The Case Report File collected participant demographic information (sex, age and ethnicity), level of ID as measured by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI)53 and carer-reported adaptive behaviour as measured by the Adaptive Behaviour Scale (ABS)54 at baseline (Tables 1 and 2). Information on the cause of ID was recorded if known. The postcode of the participant’s residence was recorded for linkage with the Index of Multiple Deprivation,55 obtained via the UK Data Service website. 56

| Measures | Assessment time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (T1) | 6 months (T2) | 12 months (T3) | |

| WASI | ✓ | ||

| Short-form ABS | ✓ | ||

| ABC-C | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mini PAS-ADD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ASD scale | ✓ | ||

| EQ-5D-Y | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| GCPLA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Uplift/Burden Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CDS-ID | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| GHQ-12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CSRI-LD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Medication use including psychotropic medication | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Measures | Respondent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Service user | Paid carer or family carer/keyworker | Family carer | |

| WASI | ✓ | ||

| Short-form ABS | Either family or paid carer | ||

| ABC-C | Either family or paid carer | ||

| Mini PAS-ADD (including ASD scale) | ✓ (if able) | Either family or paid carer | |

| GCPLA | Either family or paid carer | ||

| Uplift/Burden Scale | ✓ | ||

| CDS-ID | Paid carer only | ||

| CSRI-LD | ✓ | ✓ | |

| GHQ-12 | ✓ | ||

| EQ-5D-Y | ✓ (if able) | Either family or paid carer | |

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was challenging behaviour as measured by the ABC-CT at 6 and 12 months. 40 The ABC-C has been widely used for monitoring changes in behaviour in people with ID following treatment and has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity. The ABC-C scores can be separated into five different domains: (1) irritability, agitation and crying (15 items), (2) lethargy and social withdrawal (16 items), (3) stereotypic behaviour (seven items), (4) hyperactivity and non-compliance (16 items) and (5) inappropriate speech (four items). Each domain is rated on a 4-point scale (0–3). A total score can be obtained by adding up all domain scores. A higher score indicates more severe challenging behaviour. The ABC-CT was administered by a paid carer or family carer at all three assessment time points.

Secondary outcome measures

Participants were screened for mental health and ASDs using the Mini Psychiatric Assessment Schedules for Adults with Developmental Disabilities (Mini PAS-ADD). 57 The instrument comprises 86 psychiatric symptoms with threshold scores for the following psychiatric disorders: depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, hypomania/mania or expansive mood, obsessive–compulsive disorder, psychosis, dementia or an unspecified disorder, and a screen for pervasive developmental disorder.

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions Youth (EQ-5D-Y) was used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in line with accepted guidance. 58 The EQ-5D-Y is a five-domain (usual activity, self-care, mobility, pain and anxiety/depression), three-level (no problems, some problems and extreme problems) questionnaire. It was administered at all time points. The youth version was used in our study, as it was assumed that individuals with ID would find this version easier to complete.

Community participation was measured by the Guernsey Community Participation and Leisure Activities Scale (GCPLA). 59 It was developed to monitor the impact of interventions on the service user’s daily living. It contains six categories of activity that refer to 49 operationally defined contacts. The frequency of participation in any of the activities over the course of the previous 6-month period is rated on a five-point scale.

Family-carer burden was assessed by the Uplift/Burden Scale,60 which is a 23-item scale that has six uplift and 17 burden items. The scale has been used previously with individuals with ID. 61

Family carer psychiatric morbidity was assessed using the General Health Questionnaire – 12 items (GHQ-12). 62

Paid-carer burden was measured by the Caregiving Difficulty Scale – Intellectual Disability (CDS-ID). 63 It is adapted from an existing scale and measures subjective burden.

Costs of care were collected using a modified version of Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI) for people with ID. 64 It was administered at all time points, asking about health care, social care, housing, carer input and criminal justice contacts for the preceding 6 months.

All secondary outcome measures were administered by a family carer or paid carer at all three assessment time points.

The instruments were piloted prior to commencing assessments in order to establish any problems in their administration and completion. A RA guidance document was developed and all RAs and CSOs had an induction and monthly supervision.

Data entry

Data were entered into a study-specific web-based database developed by Sealed Envelope Ltd. Data entry was undertaken by the study researchers. As agreed with the trial statisticians, the trial manager conducted source data verification (SDV) checks on 100% of the primary outcome measure (ABC-C) at all three assessment time points; for secondary outcome measures, 100% SDV checks were conducted for 20% of all study participants at all three assessment time points. The trial manager prepared a SDV check report that was discussed with the trial statisticians. No further SDV checks were required.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the PBS and control arms have been summarised using means, SDs and proportions as appropriate. These summaries are based on observed ratings only.

Primary outcome

A three-level regression model, adjusting for baseline ABC-C measurements, time period and effects of clustering by services, and accounting for repeated measures within subjects, was used for the primary analysis. We adjusted for the staff-to-service user ratio (low/high) stratification variable. In a supportive analysis we adjusted for the participant characteristics that are not balanced across arms and are potentially related to the primary outcome (ethnicity and the accommodation that the service user lived in). For the primary analysis, we used an all-available-case analysis. As we have two follow-up time points for the ABC-CT, the missing post-randomisation data should be dealt within our model.

The primary analysis was performed by two statisticians (VV and RO) separately to ensure its accuracy.

Bias attributable to missing data was initially investigated by comparing the characteristics of the trial participants with complete follow-up measurements and the characteristics of those with incomplete follow-up or no outcome data, descriptively. No predictors were found that were associated with both the missing data and the outcomes.

Subgroup analyses

In order to explore the heterogeneity (or otherwise) of the intervention effect, we examined the treatment effect across the following characteristics: sex, age, ethnicity, ASD and mental disorder (if the participant is positive on Mini PAS-ADD). The estimates of intervention effect in each subgroup is shown in a forest plot. The results from these analyses should be treated as exploratory.

Sensitivity analyses

The following sensitivity analyses were carried out: (1) adjusting for area deprivation as measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation;55 (2) the primary outcome score can be completed either by a family carer or by a paid carer – we fitted the primary analysis model adjusting for this variable; (3) exploring a model that includes two random effects at the service level, one for each of the intervention and control arms;65 (4) adjusting for the percentage of participants per cluster who had a completed PBS plan; and (5) a ‘Baseline Observation Carried Forward’ approach was also used to include participants with missing values for the ABC-CT.

Exploratory multivariate analysis

An exploratory analysis was carried out to examine the effect of the staff training in PBS on the different domains of the ABC-CT using a three-level multivariate outcome linear regression model with outcomes nested within time periods, which are nested within patients. 66 This model allows an estimation of the intervention effects for multiple outcomes (all five subscales of the ABC-C) simultaneously. We adjusted for each baseline subscale score and time period.

Secondary outcomes

Similar analyses were conducted for the secondary outcomes using appropriate regression models depending on the type of outcome. The results from all secondary analyses have been presented as estimates with confidence intervals (CIs) and should be treated as exploratory.

Blinding and unmasking

The researchers’ treatment arm allocation guesses were evaluated using a chi-squared test.

All statistical tests and CIs are two-sided. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). We conducted all analyses by treatment allocation. A detailed statistical analysis plan was developed and discussed with the Trial Management Group and further agreed with the DMEC and the TSC prior to the analysis of unblinded data.

Health economic evaluation

The primary aim of the economic evaluation was to calculate the mean incremental cost per QALY gained by the intervention arm compared with the control arm from a health and social care perspective. Utility scores calculated from proxy responses to the EQ-5D-Y were used to calculate QALYs over 12 months.

A secondary aim of the economic evaluation was to calculate the mean incremental cost per QALY gained of staff training in PBS compared with TAU from a societal cost perspective. In addition to health and social care costs, the societal perspective includes the cost of housing, criminal justice costs and out-of-pocket costs for health and social care.

The mean incremental cost per change in ABC-C from a health and social care cost perspective and societal cost perspective will also be reported in Chapter 3.

Quality-adjusted life-years

Utility scores were calculated from proxy responses to the EQ-5D-Y at baseline, 6 and 12 months and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) tariff formula. 67 The EQ-5D-Y was used instead of the EQ-5D-3L as patients with ID find it easier to complete than the EQ-5D-3L and so the same version was completed by proxies and participants to allow for comparability. QALYs were calculated from the baseline, 6-month and 12-month utility scores as the area under the curve adjusting for the baseline responses.

Mean utility scores at baseline, 6 months and 12 months, and for the intervention arm and the control arm, were calculated using bootstrapped 95% CIs based on 5000 draws. Baseline-adjusted total QALYs for the treatment and control arms, including clustering by site, were calculated along with 95% CIs. 68 For the primary economic analysis, the complete case for QALYs is reported assuming that data are missing at random and that there is a low level of missing data (< 15%).

Cost of training in Positive Behaviour Support

To calculate the cost of the intervention, data were collected on the resources associated with training the therapists. This included the cost of staff time to attend the training sessions, the cost of specialist and academic staff time to run the training sessions, training materials and travel costs. The total cost of training per patient is calculated as the total cost of training divided by the number of participants in the intervention arm as a conservative estimate. This is because a clinical staff member’s caseload (and hence the number of participants that PBS training for a staff member may have an impact on) will be greater than the number of patients who consent to be involved in the trial.

Information was also collected on the amount of time that community team staff spent on delivering the intervention. This included the time spent on conducting assessments, direct contact time with patients delivering PBS and time spent assessing and working with other staff, patients and carers, and having an impact on the wider environment. Trial-related activities were not included in the calculation of the resources required to deliver PBS. The mean total hours spent per participant was calculated and multiplied by the cost per hour of a band 6 community-health professional to deliver the intervention. 69

Health-care, social care, criminal justice and out-of-pocket costs

We calculated the percentage of participants that used the service and the mean number of contacts greater than zero for each resource category at each assessment point; the 95% CIs are based on bootstrapping with 5000 draws.

Resource use was multiplied by the unit costs reported in Appendix 4, Table 21, to calculate the mean total cost per participant of each resource use type at baseline, 6 months and 12 months. The total cost of each contact has been calculated as the hourly cost of face-to-face contact [based on Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) costs] multiplied by the average duration of an appointment for that service. Medication has been costed using the British National Formulary 2016 costs. 70 All costs are in 2014/15 Great British pounds (GBP).

The mean incremental total cost of the intervention compared with control and 95% CIs were calculated using regression analysis adjusting for baseline, and includes clustering by site and bootstrapping with 5000 draws. The unit costs are shown in Appendix 4.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

The mean costs and QALYs calculated above were used to calculate the mean incremental cost per QALY gained with PBS compared with TAU.

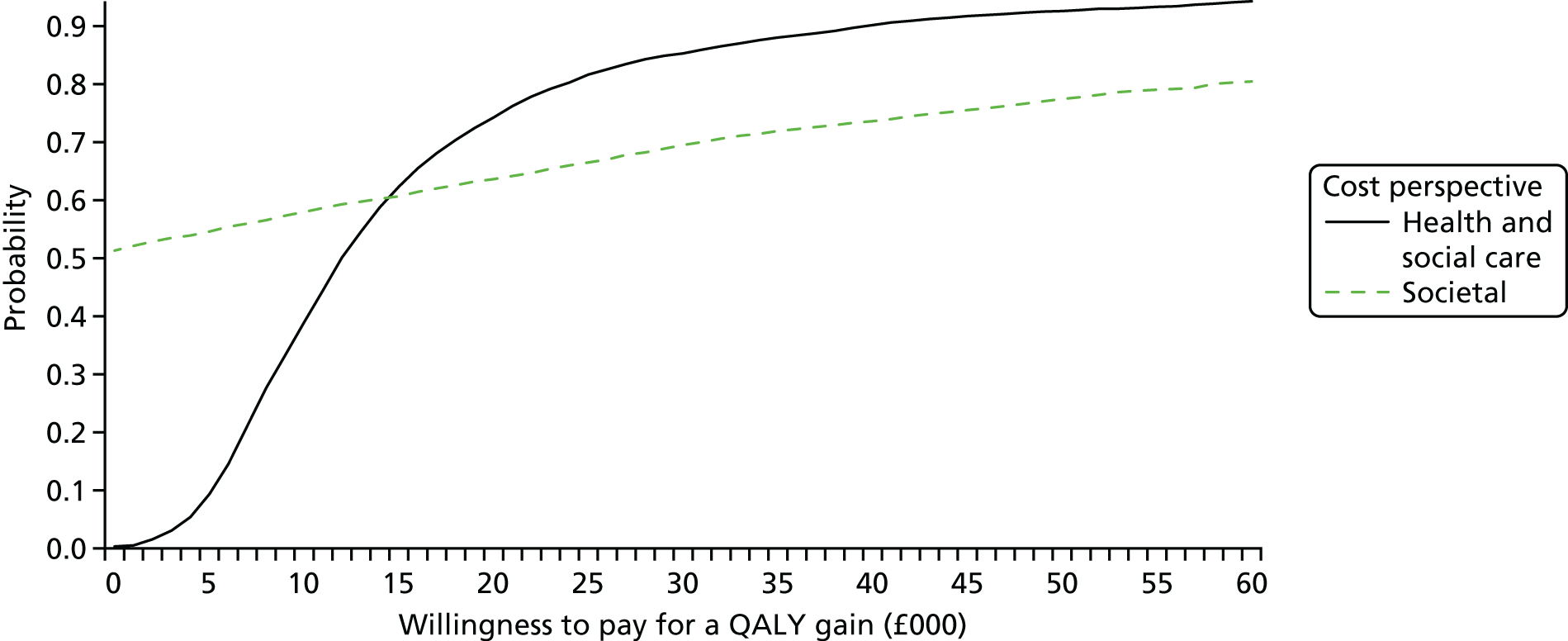

Cost-effectiveness plane and cost-effectiveness acceptability curve

The results of the bootstrap are presented on a cost-effectiveness plane (CEP). A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) is also reported using the bootstrap data for a range of values of willingness to pay per QALY gained. 68 The probability that the intervention is cost-effective compared with TAU at a threshold for willingness to pay per QALY gained of £20,000 is reported.

Discounting

As costs and QALYs are for 12 months only, no discounting was included.

Missing data

For the primary analysis, participants lost to follow-up were not included in the calculation of resource use and costs for the CSRI. Participants who reported that they used a resource but did not report the number of times they used the resource were not included in the calculation of means and SDs, but were included in the proportion of those who used a service. For their total health and social care and societal cost, that service is missing from their total cost and hence is effectively included as zero.

Reported total costs and QALYs used in calculating the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), CEP and CEAC were based on complete case analysis given that no baseline predictors of missing outcomes were identified and missingness occurred at a low level (< 15%).

Societal costs

Unpaid carers (family and close others) often provide essential support and care to patients with ID. Their contribution to care needs to be recognised and valued. If it is not, this can represent an undervaluing of the total cost of care if an unpaid carer provides a significant amount of care for a patient. As a result, an analysis will include health and social care costs in addition to the cost of care if the unpaid carer was paid at the same rate as a paid carer. This has been costed based on the cost of an hour of face-to-face time with a home care worker at £24 per hour. 69 We asked about the typical number of hours spent per week providing informal care over the past 6 months and what categories these included.

Societal costs also include private service use or out-of-pocket costs. These were costed at the same level as health-care costs.

Housing costing methodology

Data on participant employment and benefits, carer employment and benefits, and criminal justice contacts were also collected. Descriptive statistics, costs per unit change and mean total participant costs for the intervention and control arms are reported with 95% CIs.

Accommodation was divided into residential, supported living and independent living with floating support. Costs for residential accommodation were based on the number of bedrooms in the property. 70,71 The cost of supported living was divided into (1) with 24-hour care and (2) without 24-hour care.

Cost-per-point change on the Aberrant Behaviour Checklist – Community

As there were concerns about the performance of the EQ-5D-Y in this trial, a secondary analysis was conducted in which the cost-per-point change in ABC-C was calculated for health and social care costs as well as societal costs.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, CEACs and CEPs are reported for the secondary analyses.

Sensitivity analyses

Participant-completed responses to the EQ-5D-Y are available for those who had the capacity to complete the questionnaire. The mean incremental cost per QALY gained for the intervention compared with TAU for these participants only is reported in Health economic evaluation.

We have reported the total cost of training in PBS for staff on different pay bands, assuming a range of caseloads, to estimate the cost per participant of training. If a staff member has a higher caseload, the cost of training will be lower because the total cost of training is divided by a larger number of potential participants.

Participants with autism

All participants were screened for the presence of an ASD using the autism subscale of the Mini PAS-ADD. However, as this is unreliable in ascertaining all those who are likely to have an ASD, we examined the clinical record documented by the researchers in the Case Report File. These records stated if participants had a diagnosis or suspected diagnosis of ‘autism spectrum disorder’, ‘ASD’ or ‘Asperger syndrome’ and the clinical records had a higher yield of cases than screening alone (37 vs. 113). We therefore concluded that an autism spectrum group should be defined using clinical data, and used a two-stage process to validate our assumptions: first, two raters (AH and AS) independently grouped the clinical diagnoses and relevant terms into those that could help to define an autism and non-autism group, reaching consensus by discussing any cases that were unclear (see Appendix 5); second, we tested the Mini PAS-ADD ASD scores between the two categories. The autism group had higher overall scores than the non-autism group (mean of 8.14 vs. 5.76; Figure 1). A total of 113 participants were thus identified as having broadly defined autism (46%).

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of Mini PAS-ADD scores between participants with and without autism. Kernel density plot of Mini PAS-ADD score. N, threshold of 4; P, threshold of 1; R, threshold of 3.

Changes to study protocol

The following changes were made to the original study protocol:

-

Five community ID teams dropped out prior to randomisation.

-

In the Trial Management Group meeting on 10 May 2013, it was agreed that the screening assessment would be completed before randomisation and this was subsequently amended in the study protocol.

-

In addition to interviewing staff, service managers and carers, we also intended to interview service users with severe ID as part of the process evaluation. This has been amended in the protocol.

-

A protocol addendum describes the rationale and procedure for using video recordings for qualitative interviews with service users with severe ID in order to capture visual responses by service users during the interview.

-

A no-cost long-term follow-up of the participants was conducted at a mean of 36 months post randomisation. The rationale for this is described in Chapter 1. The procedures of the long-term follow-up are further described in the following section.

Long-term follow-up

Once the National Research Ethics Service and Health Research Authority approval had been obtained for the long-term follow-up, we contacted all available participants and carers who had taken part in the PBS study to discuss the additional final follow-up assessment with them. We obtained either verbal or written consent for the long-term follow-up assessment prior to conducting it. Verbal consent was obtained from carers and consultees of participants lacking capacity. We obtained written consent from participants who had capacity to consent. For written consent, we followed the same consent procedures as per the original protocol. Prior to obtaining verbal consent, we sent the relevant information sheet in advance and subsequently contacted the person by telephone in order to gain their consent to participate. The verbal consent process was audio-recorded and the recordings were securely stored.

Follow-up assessments were conducted either face to face or over the telephone. The follow-up data are limited to the primary outcome (ABC-C40) as well as service use (CSRI64), health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-Y58) and medication use including psychotropic medication (Table 3).

| Measures | 19–44 months (T4) |

|---|---|

| ABC-C | ✓ |

| EQ-5D-Y | ✓ |

| CSRI-LD | ✓ |

| Medication use including psychotropic medication | ✓ |

Furthermore, we collected information on SAEs including hospital admissions. A total of 184 participants (75%) were seen at a mean of 36 months after entry to the study (range 19–44 months). Fifty-nine participants dropped out (reasons include refused consent, died, were uncontactable and did not returned consent forms). The PRIMENT Clinical Trials Unit continued to provide statistical and health economical support for the analyses. The DMEC and TSC agreed to, and remained involved in, the study overview during the long-term follow-up.

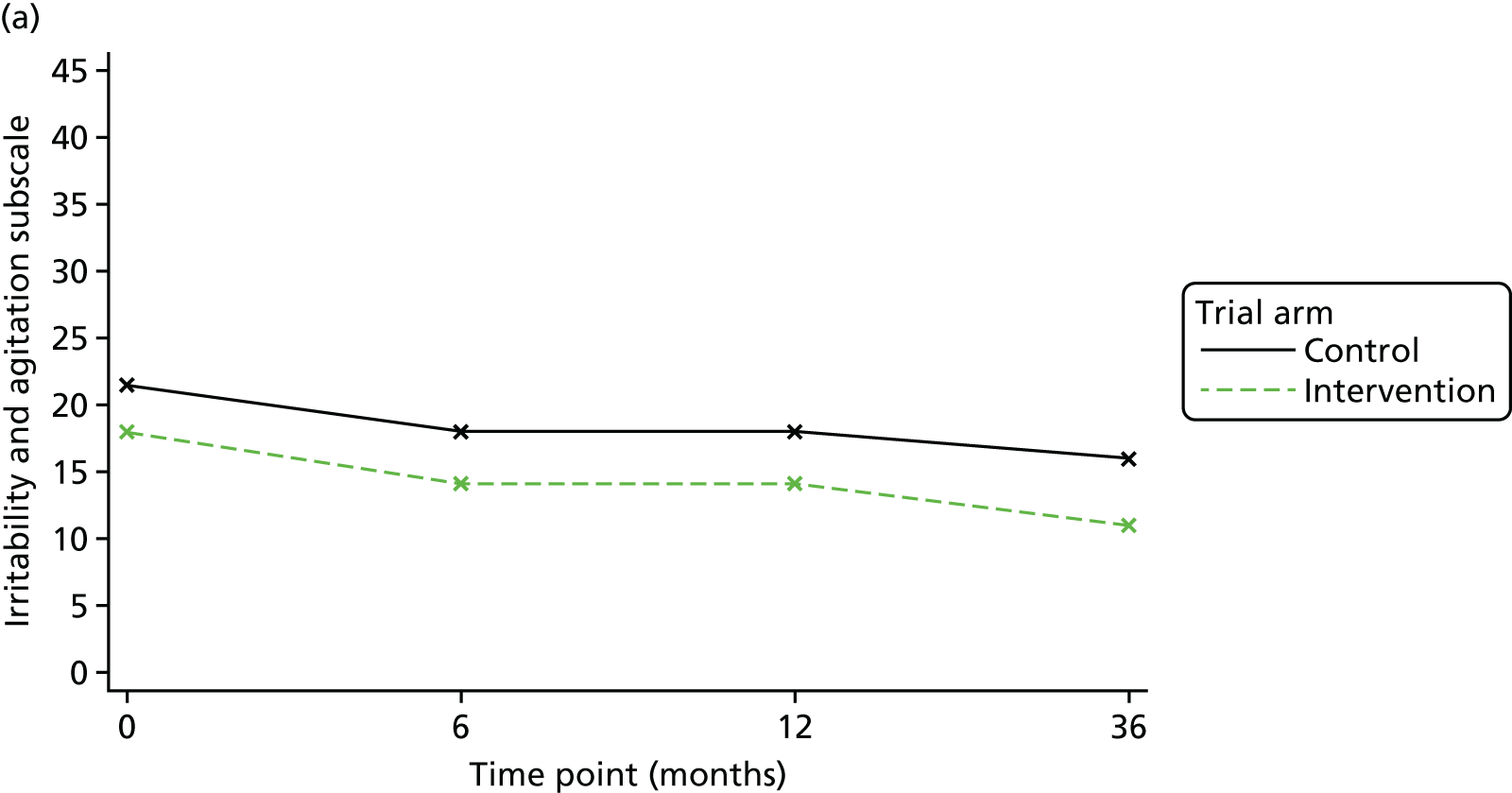

Sample size estimates and analysis plan

The outcome of interest was the ABC-CT measurements using the total score at three time points (6 months, 12 months and a mean final follow-up time point of 36 months).

The analysis estimated the difference in the ABC-CT between participants randomised to intervention or TAU on an intention-to-treat basis over time. A three-level regression model (adjusting for baseline ABC-CT measurements and time period, and accounting for clustering within services and the repeated measures of the ABC-CT at 6 months, 12 months and the final follow-up time point) was used to examine the intervention effect over time. This model also investigated whether or not the intervention effect varied over time by including an intervention by time period interaction term in the model. We carried out an all-available-case analysis but were aware of the fact that some data would be missing and the proportion was likely to increase sequentially at each follow-up point. We dealt with this by adopting the assumption that the missing data were missing at random. We also investigated whether there were any outliers or observations with high leverage. We had already recruited 246 participants, and this number was required in the original study to detect a difference of 0.45 SD with 90% power at a 5% significance level, accounting for the repeated measures at 6 months and 12 months, the effect of clustering and 10% attrition over the 12-month period. The design of the extended follow-up remained the same. Attrition was 4% at 12 months, but we predicted that this figure was likely to be larger for the additional final follow-up, leading to a smaller sample size, and our analysis could therefore be underpowered. As a result, we regarded the results from the extended follow-up analysis as exploratory.

The study statisticians were unblinded following the original study and, therefore, were not blinded for the analyses of the long-term follow-up data. However, we did not unblind the RAs who carried out the long-term follow-up assessments.

Health economic evaluation

The primary cost-effectiveness analysis for the long-term follow-up remained the same and was conducted from a health and social care perspective as well as a societal cost perspective. The cost-effectiveness measure was the incremental cost per QALY gained from the intervention compared with TAU. This was calculated as the mean cost difference between the intervention and TAU divided by the mean QALY difference to derive at the ICER. QALYs were calculated using the EQ-5D-Y, as recommended by NICE. 72 Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations given the high percentage of missing data at 36 months. Current living situation, accommodation and level of disability were found to be predictors of missing EQ-5D-Y and CSRI at 36 months.

Process evaluation

The aim of process evaluations was to facilitate the understanding of complex observed phenomena needed to guide policy-makers in allocating resources and contributing to improvements in delivery and implementation of evidence-based clinical practice. 73

Interventions usually aim to alter the regular functioning of a system with unpredictable consequences and non-linear outcomes. 74 The Medical Research Council framework73 established a series of dimensions to assess the complexity of the intervention:

-

the number of skills required to deliver the intervention

-

the number of groups affected by the intervention

-

the variability and number of outcomes (i.e. unattended outcomes)

-

how flexible the intervention is to be adapted to different circumstances.

Process evaluations can further facilitate the understanding of how the intervention may be implemented elsewhere75 by examining the context, implementation and mechanisms of impact. The process evaluation covered the domains of (1) context, (2) implementation and (3) mechanisms of impact.

Context

Context responds to the questions ‘what is facilitating the delivery?’ and ‘what is challenging the delivery?’.

The context represents anything external to the intervention that may act either as a barrier to or as a facilitator of its delivery. 76 Many pre-existing factors (i.e. factors intrinsic to the population receiving the intervention) also play a role in determining the effect of the intervention and this explains the high variability of an intervention when implemented in different contexts. 77

Implementation

Implementation responds to the questions ‘how is delivery carried out?’ and ‘what is delivered?’.

The implementation further describes the process of delivery of the intervention through the assessment of key dimensions:

-

implementation process: comprising the resources and mechanisms essential for the intervention to be delivered

-

fidelity: representing the consistency of what is delivered

-

adaptations: representing the changes made to the intervention to reach a better fit with the context

-

dose: describing how much of the intervention has been implemented

-

reach: reporting how many participants received the intervention.

Mechanisms of impact

Mechanisms of impact responds to the question ‘how is change attained through intervention?’.

The understanding of the participants’ experience of the intervention can be achieved through the employment of qualitative interviews.

Logic model

Although all interventions assume that change is gained on delivery, the theory behind the functioning of interventions is far more complex and it requires a logic model, that is, a description of the mechanisms of the intervention to allow the consideration of all of the interplaying factors and expected outcomes. 73

The logic model is based on Kirkpatrick’s Four-Level Training Evaluation Model. 78 This logic model is further used as a reference framework against which we compare the views of our participants to assess the effectiveness of the training in PBS (Figure 2), comprising the following.

-

Level 1: inputs. This level measures what has been put in place to enable the carrying out of the training and intervention. This includes the quality and number of professionals acting as therapists, the trainers employed and the type of training delivered, the quality and quantity of support provided by the PBS research team (teleconference meetings, telephone calls and site visit), the quality and type of support provided for clinical supervision for therapists training in PBS, the quality and type of mentoring scheme offered by the trainers throughout the engagement of therapists with participants for the duration of the trial.

-

Level 2: processes. This level measures how the training was delivered and what has been delivered.

-

Level 3: actions. This level measures what elements of the interventions have been implemented by therapists and the quality of the plans implemented.

-

Level 4: results. This level measures what outcomes have been achieved as a consequence of the delivery of PBS. This last level of investigation takes into account the qualitative interviews of stakeholders in the intervention arm.

FIGURE 2.

Logic model for PBS-based staff training intervention.

Each level measures key dimensions of delivery of the intervention: the initial inputs provided in order for the intervention to be delivered, the training received by therapists, the intervention including the specific components implemented and the resulting outcomes.

Objectives

The process evaluation aimed to identify the different mechanisms of the staff training in PBS, to explore the factors that had an impact on the outcome of the intervention and to present stakeholders’ (participants with ID, paid and family carers, therapists, managers and trainers) experiences of taking part in the trial.

Participants

For the process evaluation, we interviewed the following stakeholder groups:

-

participants with ID in the intervention arm

-

family and paid carers for their views and experience of the intervention

-

service managers to explore their viewpoint regarding the impact of the training on the service

-

therapists who received PBS training, to explore their views on the training and challenges that they experienced because of participation in the study

-

the PBS trainers who delivered the training and provided mentoring to therapists during and after the training.

Procedure

Interview guides were developed by a group of co-applicants with extensive experience in qualitative research (further described in Qualitative data analysis) and were based on research literature. Further advice on the wording of interview questions for service users was provided by the study service users reference group Camden SURGE, The Advocacy Project. Individual semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with all participants. Interview questions varied according to the group of participants and questions were revised iteratively to further explore any issues that arose from the interviews. The interviews were conducted by the qualitative research assistant and audio-recorded. In accord with existing literature on good practice in qualitative interviewing,79 general questions about participants’ experience of PBS were discussed in the first part of the interview and more specific questions about the study were asked further on.

Qualitative data analysis

The audio-recordings of the interview sessions were transcribed verbatim and data were extracted by means of NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). For the analysis of the transcripts, we used the inductive approach of thematic analysis by Braun and Clark,80 according to whom themes and subthemes emerge from the text and are not predefined by the researcher. Topics were given the status of ‘theme’ when they emerged more than twice from the transcript. However, when a topic did not appear at least twice in the text, but was still deemed relevant to the present work, the researcher would consider whether or not to include it in the analysis. Subthemes were further developed for each of the themes.

Once themes and subthemes had been generated, the RA created a codebook to be utilised by co-raters to test inter-rater reliability by independently rating the interviews. Co-raters were co-applicants: one lead clinical psychologist, three consultant ID psychiatrists and one representing the family carers’ group for people with ID. Inter-rater reliability was measured using the Kappa coefficient (Cohen’s Kappa). 81 The parameters were based on the ranges proposed by Landis and Koch,82 as follows:

-

< 0.00 = poor

-

0.00–0.20 = slight

-

0.21–0.40 = fair

-

0.41–0.60 = moderate

-

0.61–0.80 = substantial

-

0.81–1.00 = almost perfect.

Co-raters met frequently during the qualitative analysis to discuss the accuracy and quality of the codebook. A total of three rounds of codebook revisions were necessary to define themes and subthemes.

The frequency of themes was further calculated through an aggregate mean, weighted according to the number of stakeholders interviewed in the study. This strategy helped to factor the number of participants for each stakeholder group into the calculation.

Fidelity assessment

The quality assessment of behavioural plans was conducted by an independent reviewer (a consultant clinical psychologist with extensive PBS experience) by means of the Behaviour Intervention Plan Quality Evaluation Scoring Guide II (BIP-QE II). 83

The BIP-QE II is designed to measure the extent to which key domains of a behaviour plan are present in the plan assessed. This scale comprises 12 domains for behavioural plan evaluation: problem behaviour, predictors of behaviour, analysis of what is supporting the problem behaviour, environmental changes, predictors related to function, function related to replacement behaviours, teaching strategies, reinforcement, reactive strategies, goals and objectives, team co-ordination and communication.

Good reliability and validity were found to be associated with the BIP-QE II. Scores from the scale are interpreted according to the following ranges: a score of ≤ 12 points indicates a weak plan, a score of 13–16 points indicates an underdeveloped plan, a score of 17–21 points indicates a good plan and a score of 22–24 indicates a superior plan (Box 1). A higher score on the scale indicates an increased likelihood that a behaviour intervention plan will be implemented with fidelity.

-

Problem behaviour.

-

Predictors of behaviour.

-

Analysing what is supporting problem behaviour.

-

Environmental changes.

-

Predictors related to function.

-

Function related to replacement behaviours.

-

Teaching strategies.

-

Reinforcement.

-

Reactive strategies.

-

Goals and objectives.

-

Team co-ordination.

-

Communication.

-

≤ 12 points (weak plan): this plan may affect some change in behaviour but the written plan is weak.

-

13–16 points (underdeveloped plan): this plan may affect some change in problem behaviour but would require a number of alterations.

-

17–21 points (good plan): this plan is likely to affect a change in behaviour.

-

22–24 points (superior plan): this plan is likely to affect a change in problem behaviour and embodies best practice.

Patient and public involvement

A local group of service users with ID from the Camden SURGE, The Advocacy Project, provided advice for the entire duration of the trial. One of the study’s RAs and the chief investigator met with the group on a regular basis. The group provided support for the development of accessible information materials for the study instruments, participant information sheets and consent forms, the study website, topic guides for qualitative interviews, recruitment and the dissemination of findings. Reports from the meetings between the RA and the group were provided to the TSC.

Mrs Vivien Cooper, OBE, the founder and Chief Executive of the Challenging Behaviour Foundation, is one of the study’s co-applicants. Mrs Cooper was involved in the development of the study, advised on recruitment, reviewed study-related documentation such as information sheets, consent forms and qualitative interview topic guides and was involved in the dissemination of the findings.

The study team produced a newsletter twice a year that was disseminated to the participants, their family or paid carers and the local investigators.

Chapter 3 Results

Participants

A total of 23 clusters took part in the study, of which 11 were allocated to the intervention plus TAU arm and the remaining 12 to TAU-only arm. In the 11 intervention clusters, one therapist provided training in four clusters, two therapists provided training in another four clusters and three therapists provided training in the remaining three clusters. A total of 382 potential participants were screened, of whom 246 (64%) consented to take part in the trial. One participant was erroneously consented as they did not meet the inclusion threshold on the ABC-CT and, therefore, was excluded from the analysis.

The median number of participants who were recruited per cluster was 13 [interquartile range (IQR) 6–14]. The details are shown in the trial Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 3). Recruitment took place from 2 June 2013 to 24 November 2014. The 6-month follow-up assessments were conducted between 10 December 2013 and 21 May 2015, and 12-month follow-up assessments were conducted between 3 June 2014 and 30 November 2015.

FIGURE 3.

Trial flow chart. nfc, number of family carers; npc, number of paid carers; nsu, number of service users; nt, number of teams. From Hassiotis A, Poppe M, Strydom A, Vickerstaff V, Hall IS, Crabtree J, et al. Clinical outcomes of staff training in positive behaviour support to reduce challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry, vol. 212, iss. 3, pp. 161–8, 2018,84 reproduced with permission.

A total of 215 participants (87%) completed the 6-month follow-up and 225 (92%) completed the 12-month follow-up assessments. There was no difference in attrition between the arms (7% in the intervention arm and 9% in the control arm). Table 4 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 245) | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAU (N = 137) | PBS (N = 108) | ||

| Demographic | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 37 (25–51) | 33 (24–51) | 42 (27–50) |

| Sex: male, n (%) | 157 (64) | 90 (66) | 67 (62) |

| Ethnic origin: white, n (%) | 176 (72) | 95 (69) | 81 (75) |

| Service-reported level of ID, n (%) | |||

| Mild | 41 (17) | 17 (12) | 24 (22) |

| Moderate | 77 (31) | 46 (34) | 30 (28) |

| Severe | 127 (52) | 73 (53) | 54 (50) |

| Short-form ABS score, median (IQR) | 48 (29–68) | 42 (25–64) | 55 (35–73) |

| WASI score (full scale IQ 4) (N = 95) | 44 (40–52) | 43 (40–50) | 46 (41–53) |

| Current accommodation, n (%) | |||

| Residential | 105 (43) | 52 (38) | 53 (49) |

| Supported living | 69 (28) | 36 (27) | 33 (30) |

| Family home | 64 (26) | 47 (34) | 17 (16) |

| Own flat/house | 7 (2) | 2 (1) | 5 (5) |

| Clinical | |||

| ABC-C score, median (IQR) | |||

| Total score | 64 (44–86) | 68.5 (47–87.5) | 60 (43–80) |

| Irritability | 20 (13–29) | 21.5 (15–29) | 18 (11–26) |

| Lethargy | 12 (7–21) | 13 (6.5–21) | 12 (7–21) |

| Stereotypy | 5 (2–10) | 5.5 (2–10) | 4 (2–9) |

| Hyperactivity | 20 (12–26) | 21 (13–28) | 18 (11–24) |

| Inappropriate speech | 4 (1–8) | 4 (1–8) | 5 (1–8) |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Any | 217 (89) | 122 (89) | 95 (88) |

| Antipsychotic | 162 (66) | 89 (65) | 73 (68) |

| Other psychotropic | 177 (72) | 100 (73) | 77 (71) |

| Mini PAS-ADD, n (%) | |||

| Common mental disorder | 117 (49) | 61 (46) | 56 (52) |

| Severe mental illness | 47 (20) | 27 (20) | 20 (19) |

| ASD | 50 (21) | 31 (23) | 19 (18) |

| ASD broad definition | 113 (46) | 66 (58.4) | 47 (41.6) |

| Physical health problems, n (%) | 180 (74) | 107 (80) | 73 (68) |

| Mobilitya (N = 180) | 64 (36) | 38 (36) | 26 (36) |

| Sensory | 43 (24) | 29 (27) | 14 (19) |

| Epilepsy | 67 (37) | 42 (39) | 25 (34) |

| Incontinence | 78 (43) | 46 (43) | 32 (44) |

| Other | 103 (57) | 63 (59) | 40 (55) |

Primary outcome

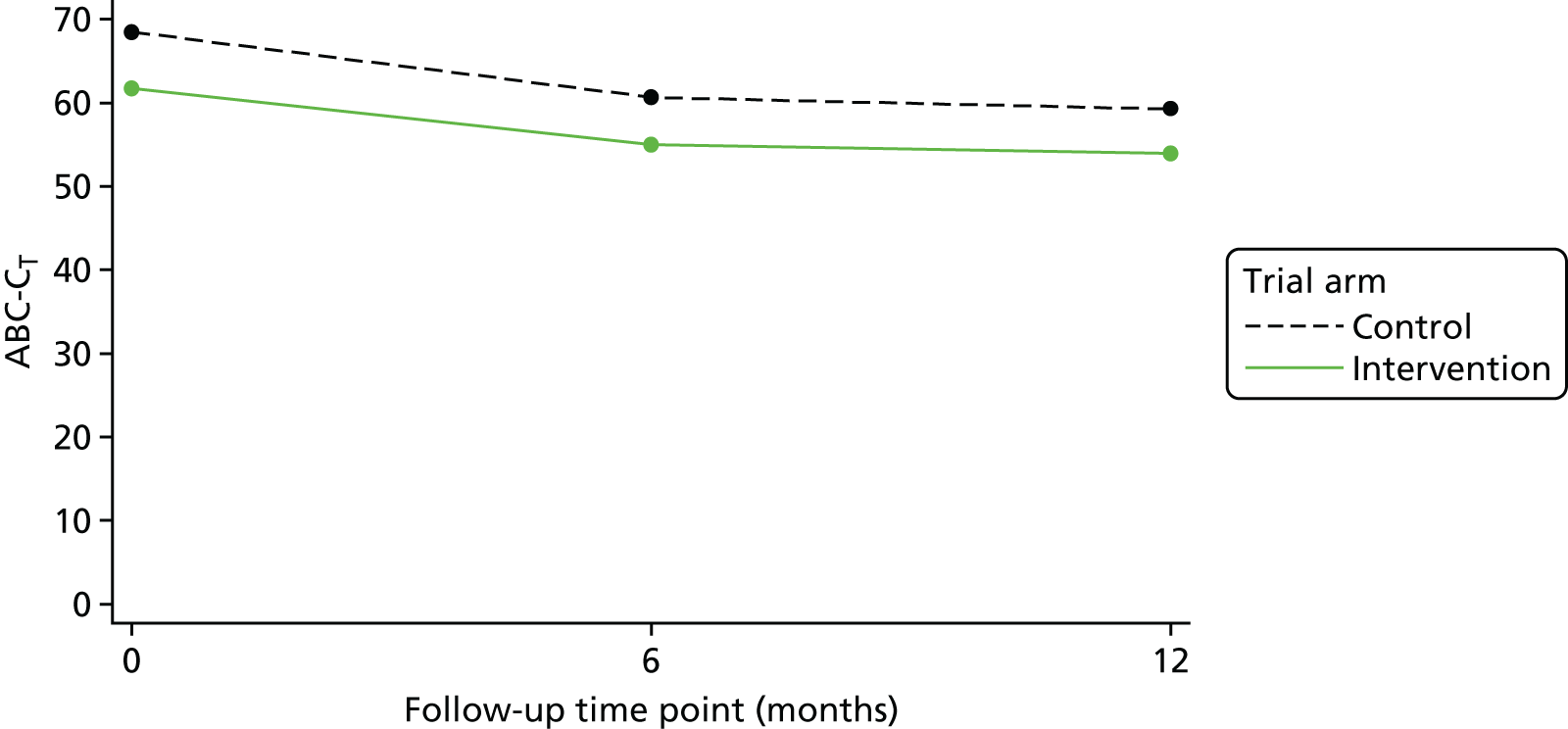

At baseline, the median ABC-CT was 60 (IQR 43–80) in the intervention arm, compared with 68.5 (IQR 47–87.5) in the control arm. In the intervention arm, the median ABC-CT reduced to 50.5 (IQR 30–75) at 6 months and to 49.0 (IQR 32–73) at 12 months. In the control arm, the median ABC-CT was 54 (IQR 37–81) at 6 months and 55 (IQR 42–75) at 12 months. The primary model used 439 ABC-CT measurements from 233 participants over the two follow-up time points. There was no statistically significant difference between arms in ABC-CT over 12 months (mean ABC-CT difference –2.41, 95% CI –8.79 to 4.51; p = 0.528) (Table 5 and Figure 4).

| Time point | Trial arm | n | Mean | SD | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | TAU | 136 | 68.5 | 29.0 | 68.5 | 47–87.5 |

| PBS | 107 | 61.8 | 27.7 | 60 | 43–80 | |

| 6 months | TAU | 116 | 60.6 | 32.6 | 54 | 37–81 |

| PBS | 98 | 55.0 | 32.5 | 50.5 | 30–75 | |

| 12 months | TAU | 125 | 59.2 | 28.8 | 55 | 42–75 |

| PBS | 100 | 54.0 | 32.1 | 49 | 32–73 |

FIGURE 4.

Aberrant Behaviour Checklist – Community total score over 12 months. From Hassiotis A, Poppe M, Strydom A, Vickerstaff V, Hall IS, Crabtree J, et al. Clinical outcomes of staff training in positive behaviour support to reduce challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry, vol. 212, iss. 3, pp. 161–8, 2018,84 reproduced with permission.

The intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for the ABC-CT at the service level was 0.021 (95% CI 0.001 to 0.286). The ICC for the repeated measures within participants was 0.625 (95% CI 0.542 to 0.702).

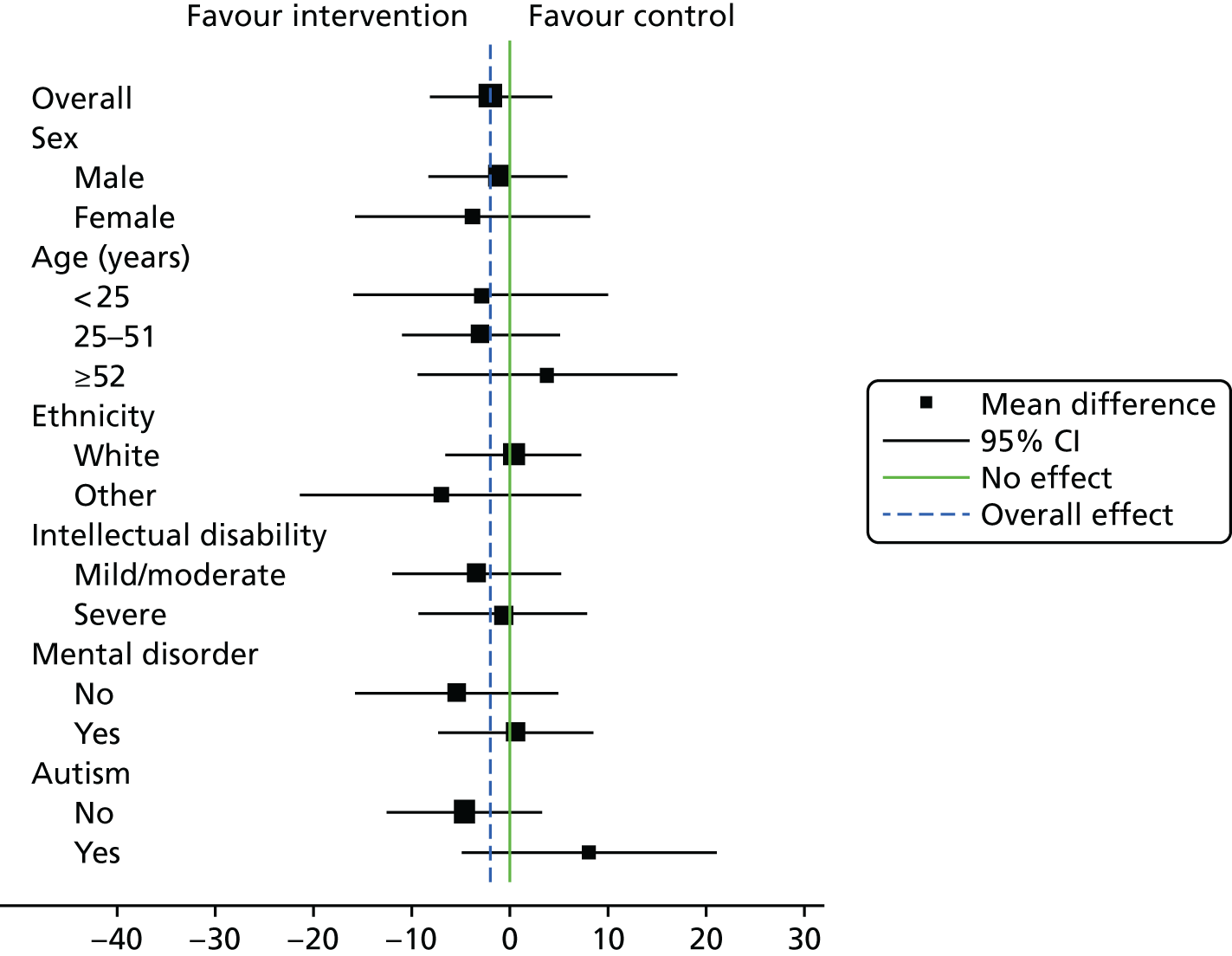

Subgroup analysis

The estimates of the intervention effect on participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in a forest plot (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Subgroup analysis. From Hassiotis A, Poppe M, Strydom A, Vickerstaff V, Hall IS, Crabtree J, et al. Clinical outcomes of staff training in positive behaviour support to reduce challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry, vol. 212, iss. 3, pp. 161–8, 2018,84 reproduced with permission.

Sensitivity analysis

A series of analyses were conducted as follows: (1) adjusting for area deprivation, (2) adjusting for the nature of the respondent (participant or carer), (3) adjusting for the unbalanced baseline characteristics (ethnicity and participant’s cohabitant), (4) adjusting for the percentage of PBS plans written, (5) a model including two random effects and (6) imputing missing values with ‘Baseline Observation Carried Forward’. All of these analyses gave similar results, with differences in ABC-CT between the arms ranging from –3.45 to –0.81. None of the service user baseline demographics nor the presence of a mental disorder predicted missing data and, therefore, no further analyses were conducted.

Exploratory multivariate analyses

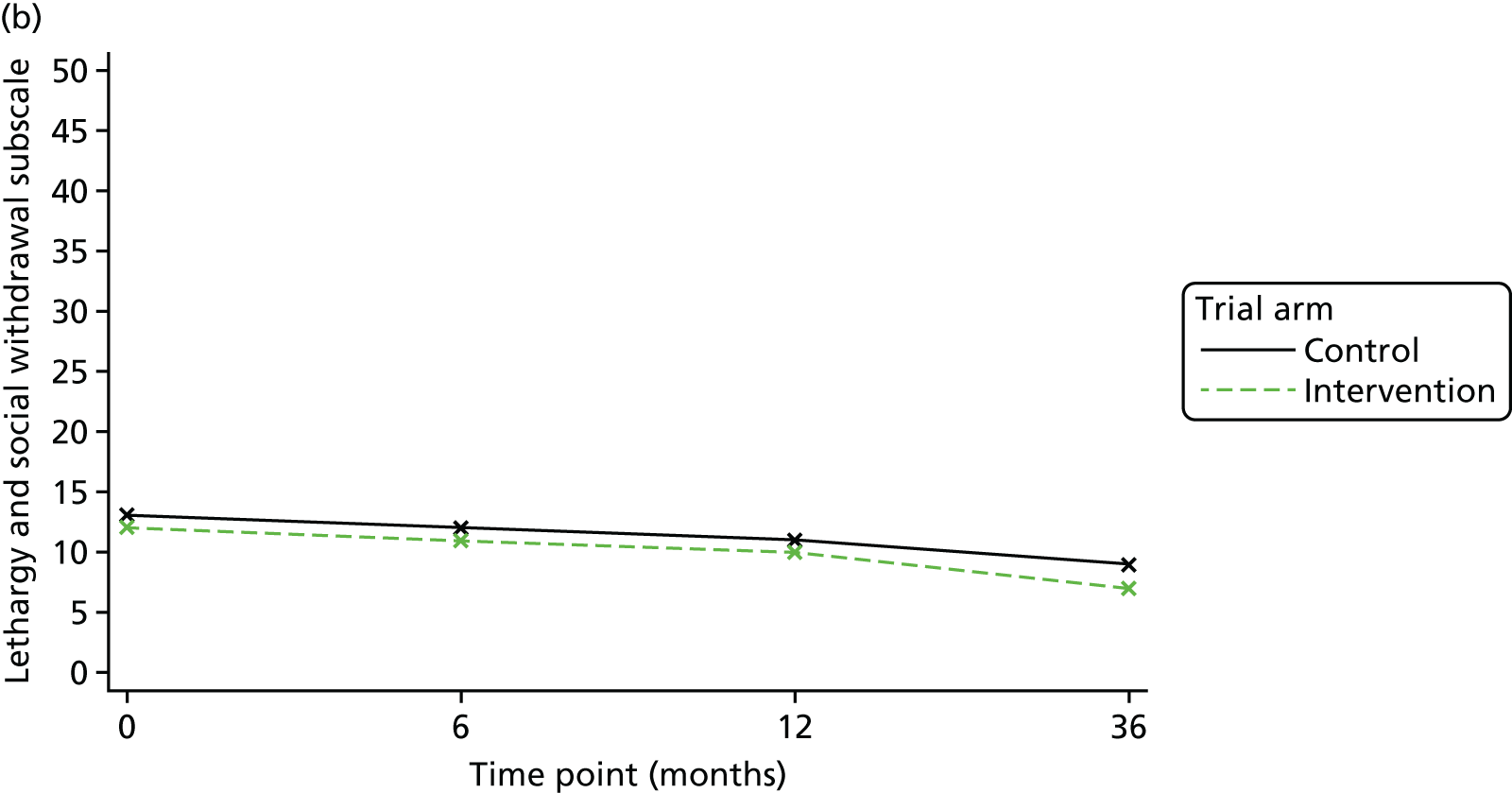

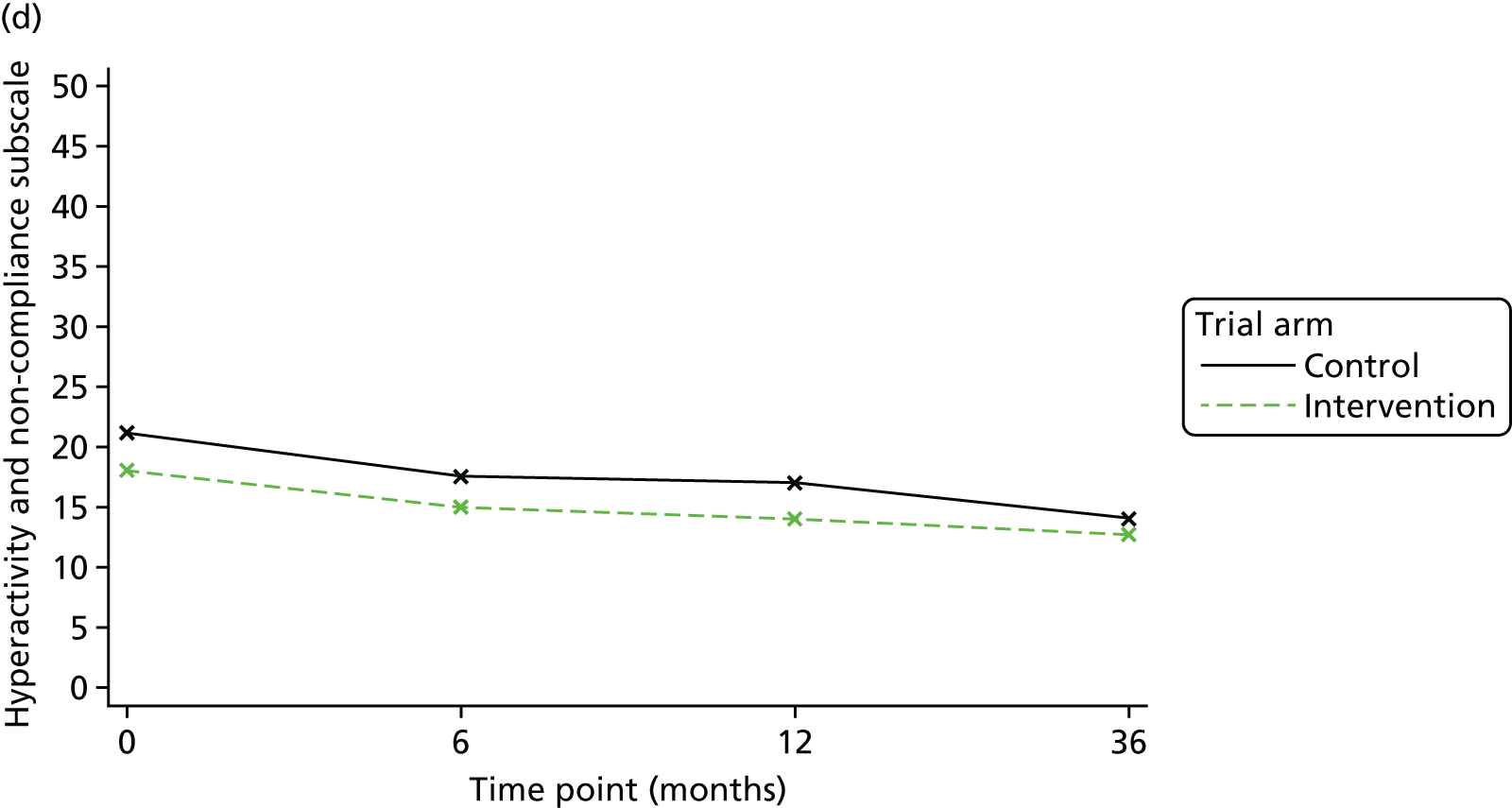

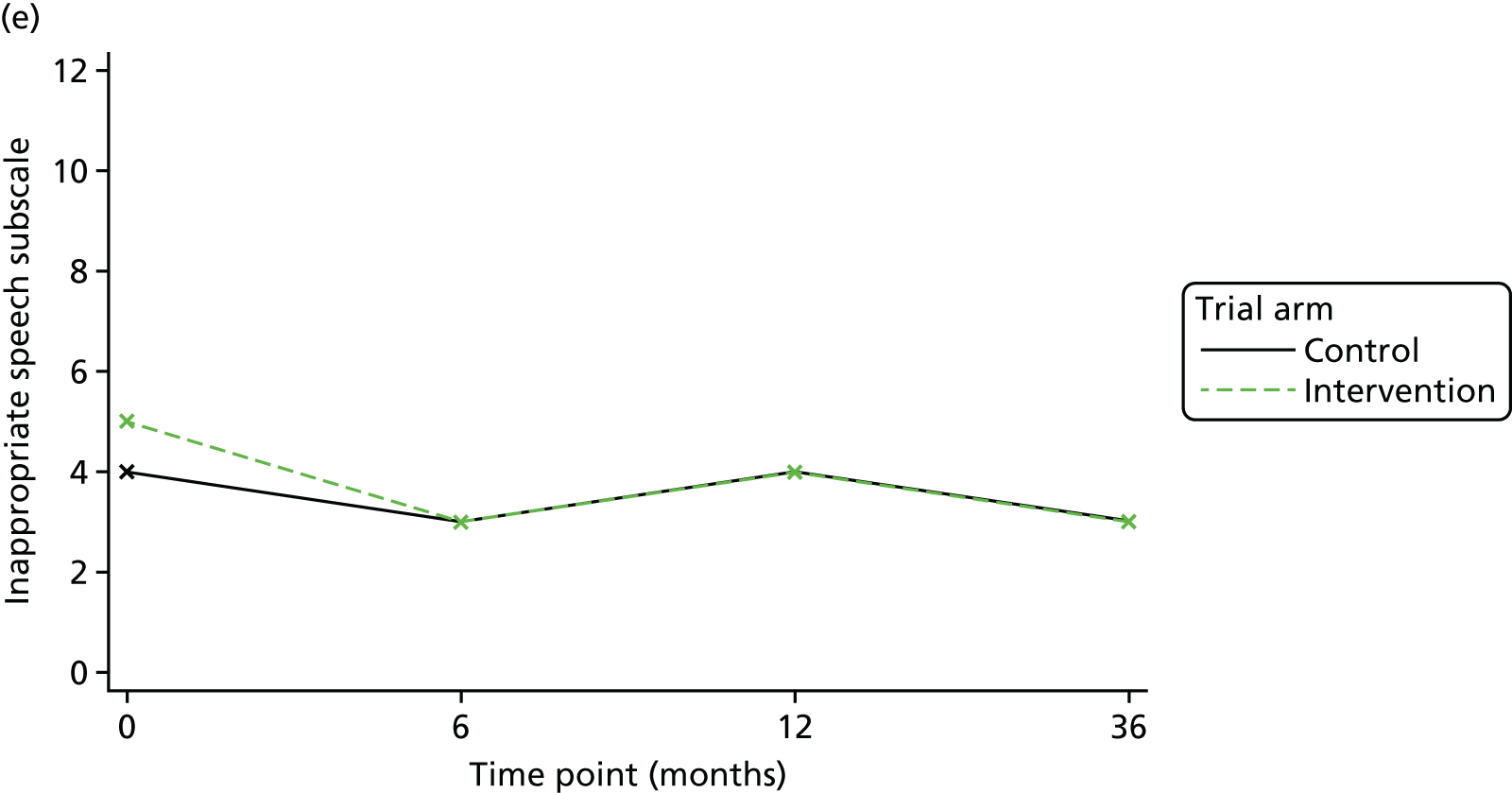

Multivariate analysis examined the effect of training staff in PBS on the individual domains of the ABC-C. The inappropriate speech domain was not included in the multivariate model as it had low correlations (0.300, 0.094, 0.175 and 0.360) with the (1) irritability, agitation and crying, (2) lethargy and social withdrawal, (3) stereotypic behaviour and (4) hyperactivity and non-compliance domains, respectively. The intervention had a similar effect on all four domains; it varied from a standardised difference of –0.016 (95% CI –0.22 to 0.19) for the lethargy and social withdrawal domain to –0.050 (95% CI –0.25 to 0.14) for the stereotypic behaviour domain between the two arms. These analyses are shown in Table 6.

| Model | Difference | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity analyses | |||

| Primary model | –2.14 | –8.79 to 4.51 | 0.528 |

| Area deprivation | –2.39 | –9.19 to 4.41 | 0.491 |

| Completed by family/paid carer | –1.21 | –8.20 to 5.79 | 0.735 |

| Missing data (BOCF) | –1.83 | –8.42 to 4.76 | 0.586 |

| Heteroscedastic model | –2.35 | –9.24 to 4.55 | 0.505 |

| Imbalance in baseline characteristics | –0.81 | –7.95 to 6.32 | 0.824 |

| % of participants who had at least one intervention component (e.g. plan, observations, goodness to fit) | 1.41 | –15.5 to 18.3 | 0.870 |

| Multivariate analysis (ABC-C subdomains) | |||

| Irritability, agitation and crying | –0.041 | –0.22 to 0.14 | |

| Lethargy and social withdrawal | –0.016 | –0.22 to 0.19 | |

| Stereotypic behaviour | –0.050 | –0.25 to 0.14 | |

| Hyperactivity and non-compliance | –0.049 | –0.23 to 0.13 | |

Secondary outcomes

There was no difference in the prevalence of mental disorders (measured using the Mini PAS-ADD) or frequency of activities (measured using the GCPLA) over 12 months. In total, 69 family carers were included in the study, 19 in the intervention arm and 50 were in the control arm. The majority (n = 59, 86%) were female with a median age of 54 years (IQR 48–59 years). As a result of the small numbers in the intervention arm, only descriptive analyses of these secondary outcomes were performed. There was no difference in the Uplift/Burden Scale and GHQ-12 scores over the 12 months. A total of 175 paid carers took part in the study, 89 in the intervention arm and 86 in the control arm. Two-thirds of the paid carer participants (n = 108, 67%) were female and the median age was 41 years (IQR 32–53 years). Over the 12 months, 86 paid carers (49%) left their posts (control arm, n = 49; intervention arm, n = 37) and, therefore, no further analyses were carried out. Details of the treatment effect on the secondary outcomes are given in Table 7.

| Outcomes | Descriptive | Analysis over 12 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | Number of service users | Odds ratio/difference | 95% CI | |

| Service users | ||||||

| Mini PAS-ADD, n (%) | ||||||

| Common mental disorder | ||||||

| Control | 61 (46) | 43 (37) | 54 (44) | 230 | 1.07 | 0.61 to 1.87 |

| Intervention | 56 (52) | 45 (46) | 42 (42) | |||

| Severe mental illness | ||||||

| Control | 27 (20) | 13 (11) | 21 (17) | 229 | 1.24 | 0.32 to 4.81 |

| Intervention | 20 (19) | 17 (18) | 15 (15) | |||

| Autistic spectrum | ||||||

| Control | 31 (23) | 31 (27) | 40 (33) | 230 | 0.70 | 0.26 to 1.88 |

| Intervention | 19 (18) | 24 (24) | 22 (22) | |||

| GCPLA, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Range | ||||||

| Control | 17 (12–22) | 16.5 (13–21) | 17 (13–21) | 232 | 0.587 | –0.57 to 1.74 |

| Intervention | 19 (13–23.5) | 19 (14–23) | 17 (13.5–22) | |||

| Busy | ||||||

| Control | 10 (7–13) | 11 (7–13) | 11 (8–13) | 232 | 0.377 | –0.59 to 1.34 |

| Intervention | 11 (8–15) | 11 (8–14) | 12 (8–14) | |||

| Family carers, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Uplift | ||||||

| Control | 15 (13–17) | 15 (12–17) | 15 (13–17) | |||

| Intervention | 14 (13–16) | 15 (14–17) | 15 (13–16) | |||

| Burden | ||||||

| Control | 33 (28–39) | 31 (25–36) | 30 (25–39) | |||

| Intervention | 28 (26–31) | 29 (25.5–32.5) | 30 (28–32.5) | |||

| GHQ-12 score | ||||||

| Control | 4 (1–8) | 4 (2–7) | 3 (1–6) | |||

| Intervention | 3 (0–4) | 2.5 (1–6.5) | 2 (0–3) | |||

| Paid carers, median (IQR) | ||||||

| CDS-IDa | ||||||

| Control | 24 (15–37) | |||||

| Intervention | 21 (13–31) | |||||

Subsample with autism spectrum disorders

A total of 113 participants (46.1%) constituted the ASD+ group (control arm, n = 66; intervention arm, n = 47) and 132 participants constituted the ASD– group (control arm, n = 71; intervention arm, n = 61). The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of a subgroup of participants with broadly defined ASD compared with those without can be found in Table 8.