Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/35/32. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The draft report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Vinidh Paleri is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme Interventional Procedures Panel, and has received travel expenses to disseminate the trial results, as well as expenses from DP Medical Systems (Chessington, UK) and Merck & Co., Inc. (Kenilworth, NJ, USA); the expenses paid by Merck & Co., Inc., include fees to speak at a meeting. Nikki Rousseau and Tim Rapley report grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Paleri et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Each year the NHS in England and Wales treats approximately 9000 new patients with head and neck squamous cell cancers (HNSCCs). Patients with oropharyngeal HNSCC formed the major group of patients who were eligible for this research project. The incidence of oropharyngeal cancer in the UK more than doubled in the 10 years between 1995 and 2006. 1 In Scotland, oropharyngeal cancer is the fastest-rising of all cancers. 2 In the USA, it is estimated that in 2020 oropharyngeal cancer will be more common than cancer of the uterine cervix. 3

Advanced (stages III and IV) HNSCCs are now treated non-surgically by radiation therapy (RT) or chemoradiation therapy (CRT). In CRT, chemotherapy is delivered concurrently with RT, potentiating tumour kill, but also toxicity, and consequently profoundly affecting eating and drinking by causing a range of side effects: loss of taste, dry mouth, pain, loss of appetite and impaired swallow mechanism. Over 90% of patients receiving this treatment option need nutritional support for severe dysphagia and weight loss, both during and after treatment. When necessary, nutritional support can be delivered through a pre-treatment gastrostomy tube or nasogastric tube.

Some clinicians advocate that, to maintain nutritional status, patients whose pre-treatment swallow function and oral intake are adequate should be fitted with a gastrostomy tube pre-treatment and continue with an oral diet during treatment, until they are no longer able to take adequate amounts of oral nutrition. Conversely, others offer patients with adequate pre-treatment swallow function the option of continued oral feeding, until they are unable to take oral nutrition adequate to maintain nutritional status and then proceed with (reactive) passage of a nasogastric tube as and when necessary. 4,5 Generic guidance suggests that gastrostomy tubes should be placed in patients who need enteral tube feeding for > 4 weeks. 6 Each year approximately 2500 gastrostomies are performed in HNSCC patients in the UK. The insertion costs alone are approximately £3M per annum.

Gastrostomy tube placement is an invasive procedure with a small, but defined, risk of acute serious complications;7 25–35% of patients retain the tube for > 1 year after CRT, and 10% retain it for > 2 years. 8 A gastrostomy tube has a major impact on patients’ and carers’ quality of life (QoL),9,10 as it can leak, leading to soiling of clothes and therefore interference with family life, intimate relationships and hobbies. 11 Although nasogastric tube placement is relatively simple, the small diameter of the tube means that it is prone to blockage, and, thus, repeated placement is necessary. If care is not taken to ensure correct placement, nasogastric tube misplacement in the lungs and subsequent feeding can lead to significant morbidity, now categorised as a ‘never event’ by the Department of Health and Social Care. 12 Systematic reviews have failed to demonstrate evidence for functional, nutritional, QoL or health economic benefits of either approach. 13,14 UK practice is correspondingly variable and no robust data are available. 15 Both nasogastric and gastrostomy tube users need community support, with greater needs for nasogastric tube users. The National Patient Safety Agency recommends that a full multidisciplinary-supported risk assessment should be carried out and documented before a patient with a nasogastric tube is discharged from acute care to the community. There is evidence that clinicians in some areas opt for gastrostomy tubes because of barriers to the delivery of nasogastric tube nutritional support in the community. However, a British Society of Gastroenterology survey in 2011 showed that only 64% of gastrostomy tube services offer an aftercare service. 16

Long-term dysphagia is now recognised as the principal functional consequence of CRT for HNSCC, and patients report this as a top concern. 14,17 Dysphagic patients and those dependent on tube feeds (gastrostomy and nasogastric tubes) need significant long-term supportive care, and suffer from an impaired QoL. 9 The effect of an enteral feeding route on the swallowing outcome is not well understood. Gastrostomy placement reduces the need for the patient undergoing chemoradiation to swallow to maintain nutritional status. Thus, it is likely that patients using gastrostomy tubes exhibit a reduction in use of the swallowing musculature. This reduction combined with the mucositis caused by radiation has been hypothesised to increase the risk of fibrosis in the muscles and pharyngo-oesophageal stricture.

The most severe CRT reaction that causes dysphagia is complete closure of the gullet, which is devastating for the individual and has substantial costs for the NHS. The risk of this may be higher with the use of a gastrostomy tube, which bypasses the gullet, unlike a nasogastric tube, which maintains a degree of oesophageal patency. Reconstruction requires complex major reconstructive surgery of the upper aerodigestive tract, with direct care costs of ≈£32,000 per patient18 and significant morbidity for the patients involved, even after intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), a new method of delivering RT that aims to limit morbidity by sparing the dose to some structures such as the salivary glands. There are national guidelines recommending that the proportion of HNSCC patients treated with IMRT should be increased. 19 However, with respect to swallowing outcomes, IMRT has been shown to increase stricture rates by 3.3 times;20 up to 46% of HNSCC patients treated with IMRT may need oesophageal dilatation,21 an intervention that requires inpatient care, is distressing to the patient and is associated with complications. Another intervention to prevent the development of chronic dysphagia is swallowing therapy, prescribed either prophylactically, to maintain function,22 or post treatment, to increase muscle range and flexibility. 23 Research into this field presents numerous challenges, including issues with recruitment, retention and adherence to rehabilitation programmes. 24

A systematic review14 suggested that the feeding route during treatment may have an impact on swallowing performance after CRT. Four retrospective studies,25–28 one prospective study29 and one randomised controlled trial (RCT) with small patient numbers30 identified that swallowing difficulties were more prevalent in patients receiving a prophylactic gastrostomy tube, even in the long term. However, existing research on the association between early gastrostomy tube feeding and long-term swallowing impairment has been inconclusive as a result of low participant numbers, caused by the use of insensitive dysphagia measurements, retrospective observational cohort study design and mixed treatment types with limited long-term follow-up. 31 Only two RCTs have been reported in the literature. 30,32 One recruited from a single Australian centre in an area of low population density. 30 The other recruited two-thirds of eligible patients, but details of gastrostomy tube placement were unclear and the sample included post-surgical patients who received an adjuvant, and, therefore, lower, dose of radiotherapy, with swallowing outcomes limited to a subsection of a QoL questionnaire. 32 A Cochrane review13 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to determine the optimal method of enteral feeding for patients with HNSCC receiving RT or CRT.

The two feeding methods (nasogastric tubes and gastrostomy tubes) have never been properly compared to establish which leads to better swallowing outcomes for patients, despite calls for better information to guide patient and clinician decisions. 13,25,30,31 This RCT was conducted to compare the two feeding methods (pre-treatment gastrostomy tube vs. oral feeding plus as-needed nasogastric tube) in patients with no, or only minimal, swallowing problems. Because a similar trial in Australia30 failed to recruit enough patients, we planned to first carry out a feasibility study to see whether or not a RCT is possible and how it should be conducted. Thus, research in this area may serve to direct resources appropriately, reduce unnecessary interventions and, thus, reduce morbidity and mortality, and improve swallowing outcomes.

Chapter 2 Methods and design

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study was to determine whether or not a definitive RCT in head and neck cancer patients with minimal swallowing problems undergoing CRT, comparing prophylactic gastrostomy tube feeding with oral feeding plus as-needed nasogastric tube feeding, was feasible. The TUBE trial feasibility phase was considered to be a necessary prelude to a full trial of these complex interventions, to assess whether or not an adequate proportion of eligible patients could be recruited into the study, in accordance with both quantitative and qualitative data.

The objectives were to:

-

explore barriers to, and facilitators of, trial implementation, and to use this information to improve recruitment and retention

-

willingness of participants to be randomised, to accept and persist with allocated treatment and to comply with assessments

-

willingness of clinicians [including clinical oncologists, surgeons, nutritionists and speech and language therapists (SALTs)] to recruit patients

-

qualitative assessment of patient and carer perspectives on trial participation, barriers to randomisation among non-participants, acceptability of assessment tools and experience of tube feeding and the conduct of and compliance with the trial protocol, and reasons for, and characteristics of, patients dropping out

-

-

carry out preliminary estimation of key parameters to inform definitive study design and study processes

-

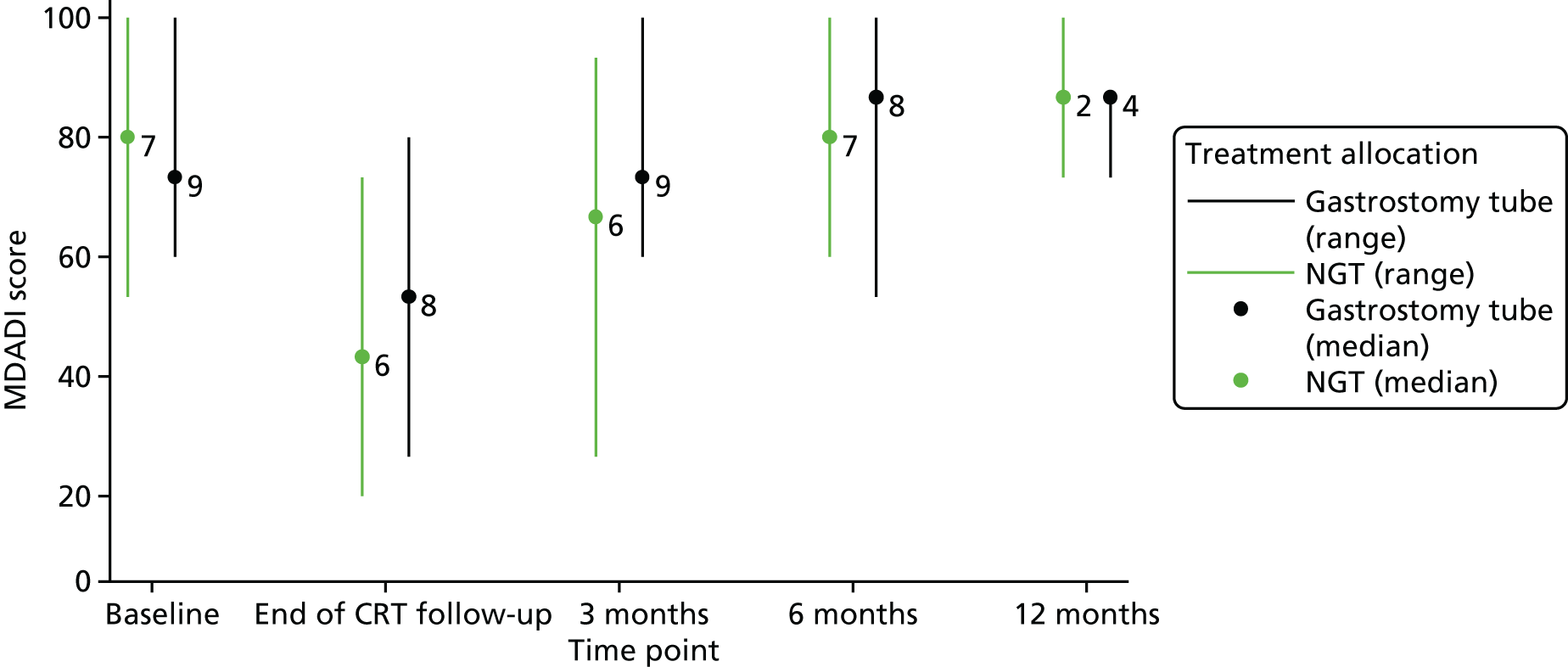

confirm the primary outcome measure and associated power calculations for a definitive trial primary outcome with consideration of possible primary outcomes, including incidence of dysphagia, as measured by the common toxicity criteria, and dysphagia-related QoL, as measured by the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) HNSCC-specific self-report scale (variation and differences in change from baseline over time)

-

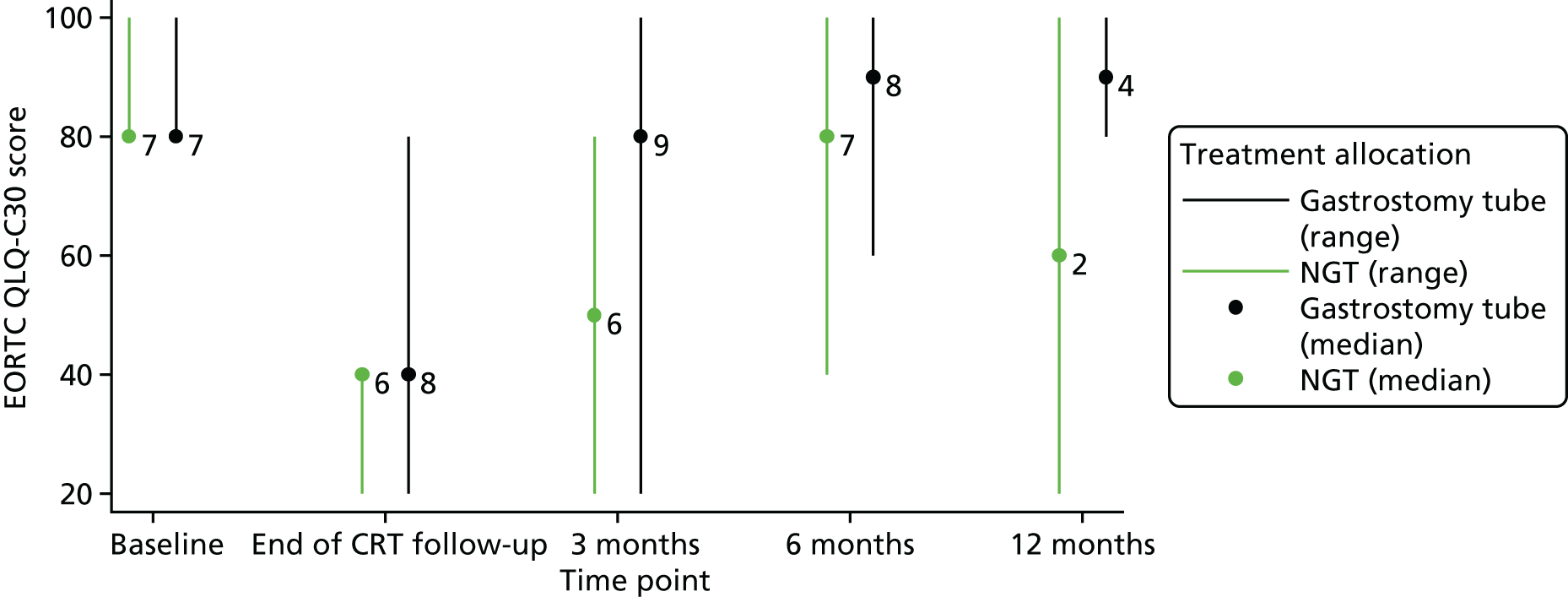

trial subsidiary QoL outcomes, measured using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaires, the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire – C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) and the EORTC QLQ – Module for Head and Neck Cancer (EORTC QLQ-H&N35), and the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36), a multipurpose, short-form health survey and data collection tool for use of health and Personal Social Services (PSS) and patient costs

-

monitor nutritional parameters – body mass index, weekly weight changes (during treatment) and quantity of enteral nutrition consumed

-

derivation of an algorithm for when the nasogastric tube should be placed in the oral intake arm that is acceptable to patients and nutritionists

-

-

explore the cost-effectiveness of the two tube-feeding options and provide health economics metrics

-

assess the economic value of information based on a modelling exercise informed by the feasibility study and the existing systematic reviews

-

provide a preliminary estimate of the costs, effects and relative cost-effectiveness of the alternative methods of nutritional support based on the modelling exercise.

-

Design

A mixed-methods multicentre study to establish the feasibility of a RCT of feeding methods in patients with stage III or IV head and neck cancer receiving CRT with curative intent. The work was conducted over 24 months.

The components were a:

-

multicentre randomised controlled pilot trial comparing oral feeding plus pre-treatment gastrostomy tube with oral feeding plus as-required nasogastric tube feeding in patients with HNSCC. Patients were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis and stratified by IMRT and by the treating centre

-

qualitative process evaluation to inform the trial design by investigating patient, carer and staff experiences of trial participation

-

modelling exercise to synthesise available evidence and provide preliminary estimates of cost-effectiveness and value of information to inform future research.

Setting

The trial recruited from five tertiary NHS centres for HNSCC, two in the north and one in the south of England, and two in Wales, identified from respondents to our national survey. 15

Ethics considerations

Ethics approval was sought and granted by the Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 Committee, NHS Health Research Authority, reference number 14/NE/0045.

Target population

The target population was patients with stage III or IV HNSCC who received primary CRT with curative intent.

The inclusion criteria were:

-

grade 1 pre-treatment dysphagia, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0 (defined as asymptomatic/symptomatic/able to eat a regular diet)

-

consent to be randomised.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

declined to participate

-

unable to give informed consent

-

could not receive a gastrostomy for medical reasons

-

did not receive treatment with curative intent

-

malnourished and requiring immediate initiation of enteral feeding.

Primary outcomes for pilot trial

The primary outcome is feasibility, defined as the willingness of:

-

patients to be randomised, assessed by a review of patient screening logs and defined as –

-

the number of patients consenting to be randomised as a proportion of all patients approached about the trial, with reasons for non-consent

-

a qualitative assessment of the barriers to, and facilitators of, recruitment

-

-

clinicians to randomise patients, assessed by qualitative interviews

-

an assessment of retention and drop-out rates, defined as –

-

the number of patients who start randomised treatment as a proportion of the number randomised, with reasons for early drop-outs

-

the number of patients who complete randomised treatment as a proportion of the number randomised, with reasons for early drop-outs (including death)

-

a qualitative assessment of the barriers to, and facilitators of, data collection and participant retention.

-

-

Interventions

Pre-chemoradiation therapy gastrostomy arm

The endoscopic or radiologic gastrostomy tube was placed before the commencement of CRT. Given the pragmatic nature of this study, and the equivalent success rates of either technique, the choice of insertion method was left to the treating centre’s local protocols. Patients continued with oral feeding and commenced using liquid nutrition through the gastrostomy tube when they were unable to maintain an adequate oral intake to meet their nutritional requirements (< 75% of requirements based on a dietetic assessment of 24-hour recall by patients).

No pre-chemoradiation therapy gastrostomy arm

This group continued with oral feeding or had a nasogastric tube, if required, during treatment. The decision to place a nasogastric tube was based on clinical assessment, patient request and published guidelines. 6

Secondary outcome measures

Compliance with interventions and trial processes was defined as the number of patients who completed patient-reported outcomes at each time point, including baseline, with reasons given for non-compliance. Outcome measures for a definitive trial were to be rehearsed in the pilot trial, and applied before treatment and at 3 and 6 months after treatment (5 and 8 months from randomisation). The following measures were used:

-

The MDADI is a self-administered questionnaire designed specifically for evaluating the impact of dysphagia on the QoL of patients with head and neck cancer. 33 This is the proposed primary outcome measure in a definitive trial.

-

Performance Status Scale Normalcy of Diet scale, a clinician-rated scale of diet textures.

-

Two questionnaires were used to assess QoL outcomes. The EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) is a cancer-specific instrument, has a multidimensional structure, is appropriate for self-administration and is applicable across a range of cultural settings. 34 The EORTC QLQ-H&N35 is the head and neck module for EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and is intended for use in conjunction with the QLQ-C30 in patients with head and neck cancer. 35

-

The SF-36 is a multipurpose, short-form health survey with 36 questions. It yields an eight-scale profile of functional health and well-being scores, as well as psychometrically based physical and mental health summary measures and a preference-based health–utility index that will be used to derive quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for a cost–utility analysis conducted as part of a subsequent full trial.

-

The use of health and PSS and costs to patients and their families/carers: as it will be necessary to elicit the costs to patients, their families/carers, and the NHS and PSS for the definitive economic evaluation, the tools required to elicit these costs were identified. These included case report forms and questionnaires to capture use of services and patient/family/carer costs. The content of these forms was developed in consultation with the study team, our existing item bank of questions, web-based resources, such as www.dirum.org, and experience of other RCTs of nutritional interventions, such as the recent SIGNET (Scottish Intensive care Glutamine or selenium Evaluative Trial). 36 The tool developed was administered at 3 and 6 months after treatment.

-

Monitoring nutritional parameters – body mass index before treatment and at 3 and 6 months following treatment, weekly weight changes during treatment and the quantity of enteral nutrition consumed.

-

Monitoring oral health – oral health assessment before commencing treatment and the end of 6 months for all dentate patients, including a full dental chart with panoramic radiographs before treatment and at 6 months, periodontal and oral hygiene assessment and plaque scores.

-

Other clinical outcomes to be recorded –

-

the number of pharyngeal/oesophageal dilatations per patient

-

tumour status at follow-up (decisions made as per local practice); clinically disease free, alive with disease, died of disease or died of other causes

-

tube dislodgements

-

migration from nasogastric group to gastrostomy tube group.

-

-

The assessment and reporting of incidence of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs).

Sample size

The feasibility trial sample size and target recruitment is a total of 60 patients (30 per randomised intervention). 37 As a feasibility study, the trial will provide an assessment of recruitment and compliance rates to inform future definitive trial design. Statistical analyses will be conducted in accordance with a confidence interval (CI) approach rather than a hypothesis-testing approach. Analyses will be descriptive, reporting rates as proportions with CIs and graphical analyses of longitudinal data. Recruitment is dependent on the number of patients approached, but should be no lower than 50%. The upper limit of the 95% CI for the proportion of patients recruited should exceed 50%. If 120 patients were approached and 50% were recruited (60 patients randomised), the 95% CI for the recruitment rate would have a width of ± 9%. This would provide a good level of accuracy to assess the acceptability of the recruitment rate.

Screening, recruitment and consent

Identification and screening of participants

All potentially eligible patients were identified from the head and neck cancer multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings, subject to satisfying the trial inclusion and exclusion criteria. This information was captured on site screening records and later transferred into an electronic screening form on the trial electronic data capture system. Whether or not a patient is eligible to participate in a trial can often be ascertained by referring to their records; in this trial, when further information was necessary, the principal investigator (PI) gathered it by taking a careful history from the participant. An eligibility screening form was completed by the investigator to document participants’ fulfilment of the entry criteria for all patients who were considered for the study and who were subsequently included or excluded.

Following recruitment discussions and randomisation, the screening records were updated to document the recruitment outcome details of everyone invited to participate in the study. The log-recorded information related to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and whether patients wanted to be part of the randomised feasibility trial and/or the qualitative interviews. The regular review and completion of the screening logs by sites ensured that potential participants were approached only once.

The screening assessments (as per routine clinical practice) usually occurred 1–2 weeks before the collection of baseline data and randomisation.

Recruitment procedures

All recruitment sites were full research sites. Eligible patients were seen at routine appointments for CRT planning. The PI or a delegated member of the clinical team (often a research nurse) invited patients to participate in the trial; they explained the trial to the patient, gave them the patient information sheet (PIS) and answered any questions.

There were two versions of the PIS to account for whether patients allocated to the pre-CRT gastrostomy arm were to have the gastrostomy tube inserted under X-ray guidance or endoscopically. Sites determined which version was appropriate for their patients depending on the sites chosen method of insertion.

Because the subject population was small, the information sheets and consent forms were available only in English. Interpreters were to be provided, if necessary, for patients who had difficulty understanding English.

Patients were encouraged to take the information leaflet home and discuss it with their family and friends. After receiving the study information, they were given a reasonable length of time (a minimum of 24 hours) to decide whether or not they wanted to participate. A research nurse followed up all invited patients with a telephone call and arranged to discuss the study further and/or take consent at the patient’s next hospital appointment (e.g. this could be a mould-making appointment, kidney function test appointment or magnetic resonance imaging-planning appointment).

If a patient refused to join the trial, their reason for refusal was sought. If the patient initially joined and subsequently withdrew, the reason for withdrawal was also sought. The rights of patients to refuse to participate or to withdraw without giving a reason were respected.

Consent procedures for the randomised trial

Informed consent discussions for the randomised feasibility trial were undertaken by appropriate site staff involved in the study (as per the delegation log), including medical staff and research nurses, and patients were given the opportunity to ask any further questions.

The delegated site staff taking consent ensured that patients had understood the information and that they would be asked to sign and date the consent form. The consent form was witnessed and dated by a member of the research team who had documented and delegated responsibility to do so.

The original signed consent form was retained in the investigator site file; a copy was placed in the clinical notes and another copy was given to the participant. Copies of consent forms were faxed to Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit to centralise the monitoring of the consent process. Patients provided specific consent for their general practitioner (GP) to be informed of their participation in the study. At the time of giving consent, participants were asked to fill in the baseline study questionnaires, which were sent to or kept in the site trial office.

Patients’ rights to refuse to participate without giving reasons were respected.

At this stage, patients were asked to indicate whether or not they were happy for the qualitative researcher to approach them later for an interview. Both those who did and those who did not consent to participate in the randomised trial were invited to take part in the qualitative interviews. The outcomes of the consent process were updated on the screening logs.

Study intervention details

Study participants were randomised to one of two treatment arms: the pre-CRT gastrostomy arm or the no pre-CRT gastrostomy arm.

Patients in both arms were given information about the treatment and the intervention involved. This was delivered by the PI at the centre and reinforced by the research nurse. Other health-care professionals (HCPs), such as dietitians, gastrostomy nurses, clinical nurse specialists and SALTs, also participated in the information-giving process.

Pre-chemoradiation therapy gastrostomy arm

The insertion of the gastrostomy tube took place before CRT commenced, approximately 2 or 3 weeks after most patients were randomised. When patients were receiving induction chemotherapy, gastrostomy tube insertion took place in either the week before cycle 2 of induction or during the week before CRT.

Gastrostomy tubes were inserted into the stomach, through an abdominal incision, by either endoscopic or radiological guidance, both being functionally equivalent. Given the pragmatic nature of this study, and the equivalent success rates of the techniques, the choice of insertion method was left to the treating clinician/centre. Patients were encouraged to continue with oral feeding throughout CRT, unless, or until, they were unable to maintain an adequate oral intake to meet their nutritional requirements (see guidance below) or were unable to swallow. At this stage, the use of liquid nutrition through the gastrostomy tube was commenced.

No pre-chemoradiation therapy gastrostomy arm

This group of patients continued oral feeding throughout CRT, unless, or until, they were unable to maintain an adequate oral intake (see guidance below) or were unable to swallow when a nasogastric tube was inserted under local anaesthesia and liquid nutrition via a nasogastric tube commenced. Confirmation of correct placement was made based on National Patient Safety Agency and local guidelines. The decision to place a nasogastric tube was based on clinical assessment, patient request and published guidelines.

Guidance on when to initiate enteral feeding in both treatment arms

National guidelines state that tube feeding should commence when a patient is at risk of malnutrition and has an inadequate oral intake. In practice, this is quite difficult to determine without collecting detailed food or oral supplements intake data to determine when oral intake is inadequate. Such an exercise was beyond the scope of this study.

As a guideline for this protocol, we set a figure of < 75% of requirements as a measure of inadequacy, and this would equate to about 1–2 lb (0.5 kg) of weight loss per week. This guideline applied to both treatment groups. The < 75% threshold was not ascertained by exact measurement, but based on a dietetic assessment of 24-hour recall by patients.

This < 75% guideline is more conservative and would lead to less weight loss in this patient population than the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines, which stipulate a threshold of 60% and predict continued poor oral intake for > 10 days.

Tube removal in both treatment arms

Tube removal was determined by dietetic assessment. Once a patient was able to take > 75% of estimated nutritional requirements by mouth, and their weight was stable, the gastrostomy tube or nasogastric tube was removed.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation

Randomisation was administered centrally by the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit internet-accessed secure web-based system with accessibility 24 hours per day, with inbuilt validation/plausibility checks at time of data entry.

A block-stratified block method (based on permuted random blocks of variable length) was used to allocate participants to the two groups in a 1 : 1 ratio. Randomisation was stratified by centre to allow for any differences in care or case mix that could alter outcomes. The use of induction chemotherapy was not a stratification factor in this feasibility trial, but it was recorded at the time of randomisation to inform possible stratification factors in a definitive trial. An individual not otherwise involved with the study produced the final randomisation schedule for use by this system.

The PI at the site, or an individual with delegated authority, was able to access the web-based randomisation system. Patient screening identification, their initials and the details of stratifying variables, was entered into the web-based system, which returned a unique patient trial number and the randomised treatment allocation. Participants were informed of their treatment group at the point of randomisation.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the tube-feeding interventions, it was not practicable to blind the research nurses to the treatment allocated to patients for the follow-up assessments. The baseline data assessments were completed by research nurses before randomisation to reduce the chance of bias.

Trial data

Patient assessments and data collection

Research nurses in each unit co-ordinated the assessments and data collection, once written consent had been taken. Whenever possible, the first research visits were co-ordinated with patients’ pre-treatment planning appointments, and took place in the treating hospital. Some of the assessments were collected as part of routine clinical information (i.e. height/weight, oral health assessment) and permission was sought as part of the consent process to access this clinical information in order to avoid duplication. Whenever possible, patients were encouraged to complete the questionnaires at the research visit while the research nurse was available to give assistance as appropriate and to increase the rate of returns. The research nurse identified the time point for the follow-up research visits. These visits were combined with follow-up cancer surveillance appointments at the head and neck cancer unit, whenever possible.

The patient visits for the feasibility RCT and associated data were collected as follows.

Initial screening visit

At this appointment patients were provided with information about the trial and an eligibility screening form was completed.

Consent and baseline visit(s), and randomisation

The consent and baseline visit took place at least 24 hours after the patient had been provided with the trial information. The patient’s eligibility was reconfirmed and their informed consent was taken, after which the baseline assessments and baseline questionnaires were completed.

The baseline data included site of disease, patient demographic information, tumour, node and metastasis classification, a record of whether or not induction chemotherapy was planned, a record of whether or not IMRT was planned, and whether or not the patient had been given any pre-treatment swallowing exercises and, if so, if the patient had complied with these (recorded as yes or no). Questionnaires included the MDADI, EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0), EORTC QLQ-H&N35 and the SF-36.

Clinical assessments included body mass index and usual weight, measurement on the Performance Status Scale, normalcy of diet and data from oral health assessment performed as standard NHS care (includes information from a panoramic radiograph, a dental chart, periodontal and oral hygiene assessment plaque scores, oral opening measurement and oral dryness).

After the baseline data and consent visit took place, randomisation was performed. Patients were informed of their randomisation allocation and given the opportunity to ask further questions.

Intervention visit

Interventions were performed as follows (timing was dependent on the treatment arm):

-

pre-CRT gastrostomy arm – gastrostomy tubes were inserted after the consent and baseline visit, and randomisation, but before any treatment (CRT/IMRT) took place

-

no pre-CRT gastrostomy arm – nasogastric tube was inserted after the consent and baseline visit, and randomisation, at a point when the patient and/or clinician assessed that this was most appropriate.

Weekly data collection

Information recorded included:

-

dates of induction chemotherapy plus number of cycles received

-

regime of concomitant chemotherapy and number of cycles received

-

details of RT technique, dose and field size, including mean dose to the pharyngeal constrictors

-

weekly weight

-

Performance Status Scale measurement, normalcy of diet

-

gastrostomy tube site infections

-

radiographs associated with tube placements

-

pH problems requiring nasogastric tube placement

-

tube changes (e.g. nasogastric tube to nasojejunal tube or nasogastric tube to another nasogastric tube)

-

degree of reliance on feeding tube use (nasogastric tube, nasojejunal tube or gastrostomy tube)

-

feed-related hospital admissions

-

number of dietetic consultations

-

quantity of enteral feed prescribed and quantity consumed

-

district nurse visits and dates

-

tumour status – clinically disease free, alive with disease or died of disease or other causes

-

AEs.

Follow-up visit at chemoradiation therapy completion

All outcome measures were recorded at the end of treatment in addition to the migration of patients from nasogastric tube to gastrostomy tube, replacement episodes and removal of nasogastric tube/gastrostomy tube, if applicable.

Follow-up visit at 3 months post chemoradiation therapy completion

All outcome measures were collected as per the end of treatment. In addition to the use of health and PSS and costs to patients and their families/friends (excluding the use of weekly/biweekly services in a cancer clinic), data on the number of pharyngeal/oesophageal dilatations were collected per patient. Information on access to rehabilitation services was recorded, including frequency of dietetic and speech and language therapy follow-up.

Follow-up visit at 6 months post chemoradiation therapy completion

The same measures as per 3 months post CRT were recorded. Oral health assessment data were included.

Criteria for progression to a Phase III trial

The decision to move to a Phase III trial is based on:

-

adequate timely recruitment with a 50% recruitment rate

-

completeness of outcome measurement (MDADI at 6 months) – excluding those individuals who died during the study period, these outcome data should be successfully collected in at least 80% of participants, as this is the proposed primary outcome of a definitive Phase III trial

-

economic criteria of the economic value-of-information analysis to suggest that further research is likely to be worthwhile.

Qualitative process evaluation (objective 1)

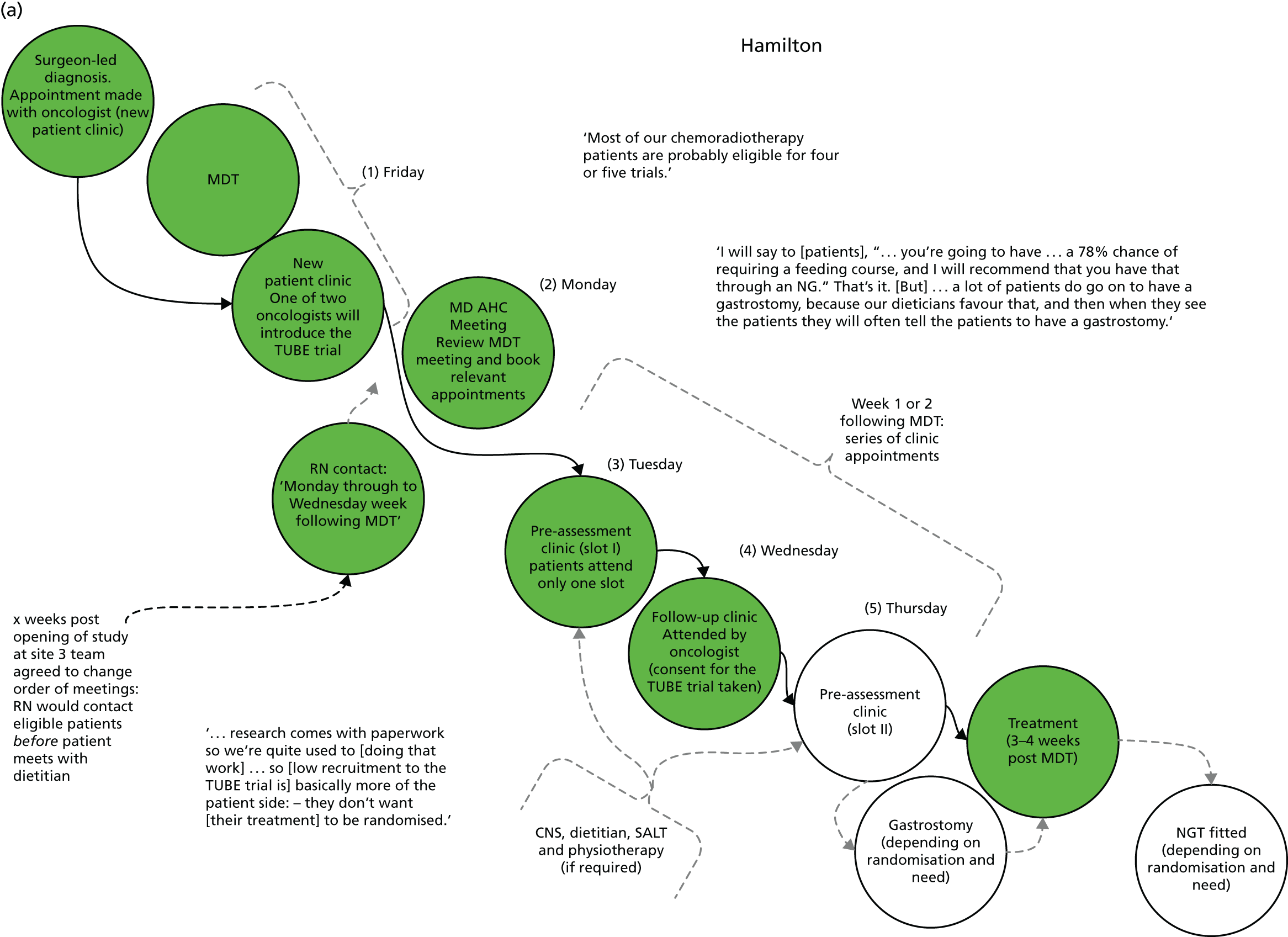

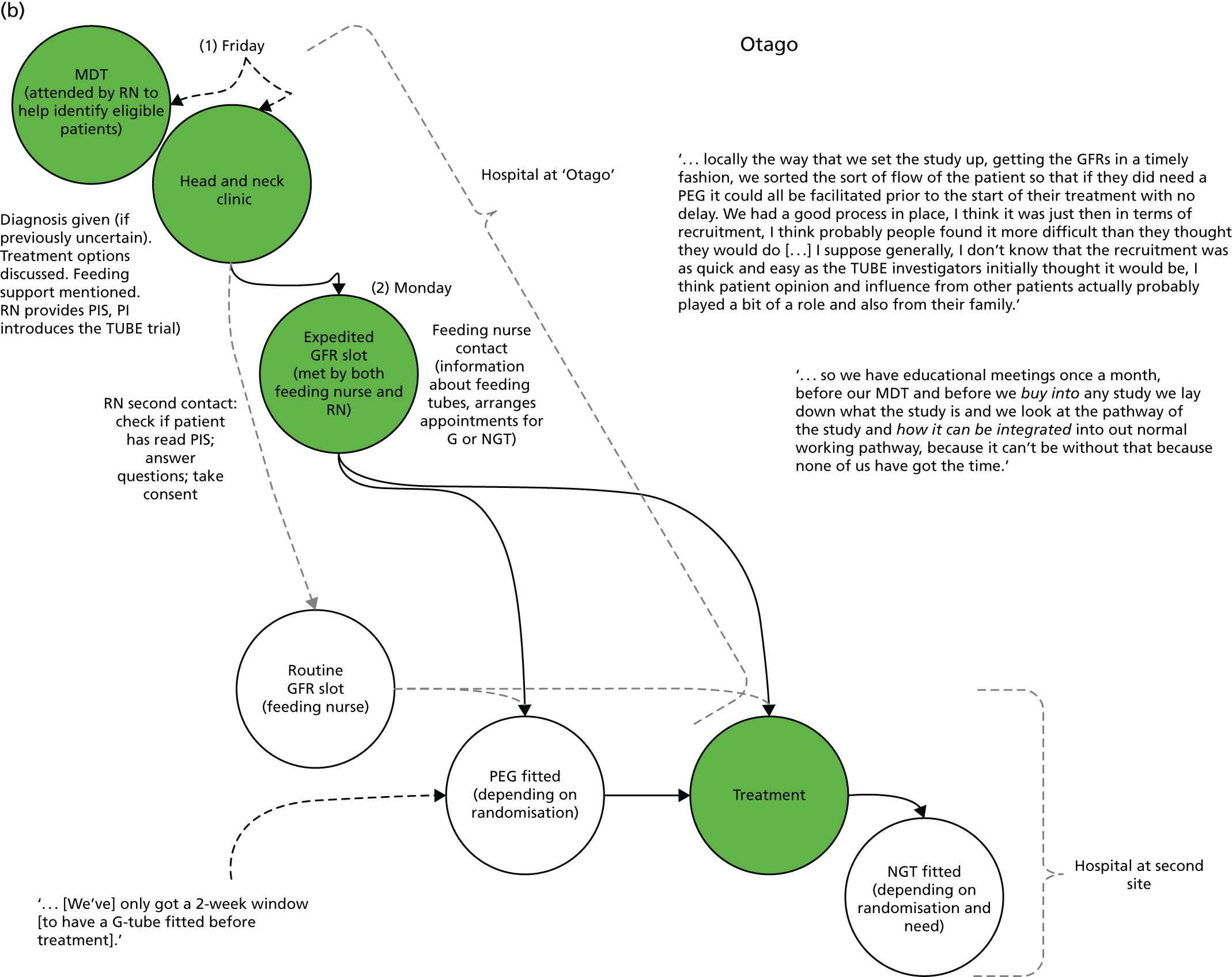

The integrated qualitative process evaluation explored the barriers to, and facilitators of, trial implementation. Through regular feedback of emerging findings to the trial team, this process informed the day-to-day running of the feasibility trial and optimised recruitment and retention. It also aimed to identify aspects of trial processes that could be improved for the definitive trial.

Normalisation process theory

Analyses of barriers to, and facilitators of, trial participation were informed by normalisation process theory (NPT). 38 NPT considers factors that affect implementation in relation to four key areas: (1) how people make sense of a new practice, in this case the trial (coherence); (2) the willingness of people to sign up and commit to the new practice (cognitive participation); (3) people’s ability to take on the work required of the practice (collective action); and (4) activity undertaken to monitor and review the practice (reflexive monitoring). This theory is increasingly being used in studies of the implementation of interventions in health care (www.normalizationprocess.org). In the TUBE trial, an assessment was made of how well trial processes were introduced and incorporated at each site for both patient and professional groups.

Methods and sampling

In keeping with the principles of rigorous qualitative research, the actual sample size was informed by the point of data saturation. In response to the study context, in some cases fewer interviews or observations were conducted and in others additional data were collected in the light of emerging analysis or study events. A balance was achieved between spread of data (to avoid missing key events or issues) and depth of data (a manageable data set that allowed for in-depth analysis).

Data collection focused on three inter-related phases during the trial. After appropriate consent was obtained, interviews were undertaken with health professionals and patients, and recruitment discussions were observed.

Pre-implementation of the TUBE pilot trial

To understand the context of the trial, professionals’ views and expectations and patient pathway mapping, formal interviews were conducted with key individuals involved in treatment planning for HNSCC (e.g. nurses, speech therapists and ear, nose and throat surgeons).

Patient recruitment phase

Patients’ and professionals’ experiences of recruitment were the focus of this phase. Patients were recruited from multidisciplinary clinics, with research nurses providing trial information. Qualitative interviews were conducted with patients who consented to take part in the trial. The focus of these interviews was the patients’ experiences and understandings of trial processes (e.g. the information they were given, the recruitment encounter, their ideas and/or concerns about randomisation and consent) and the intervention (their willingness to undergo either feeding option; their ideas and/or concerns about the impact on health and acceptability).

Patients were interviewed within 2 weeks of the recruitment discussions and offered a choice of location and method of interview (telephone or face to face). As people often discuss clinical decisions with others,39 those patients who wanted to involve a family member in their interview were able to do so. Further interviews were conducted with professionals involved in some aspect of patient recruitment. Research nurses were given a digital voice recorder and asked to record their recruitment discussions with patients (with the appropriate permission).

Patient follow-up phase

Patients took part in qualitative interviews approximately 8 months after recruitment to explore the acceptability of the assessment tools and investigate their experiences of the intervention.

Qualitative study consent details: interviews

During the recruitment discussion, as part of which written consent was taken for participation in the TUBE trial, patients, and any friends or family present, were asked if they were willing to be contacted about an interview for the qualitative substudy. If so, their written consent was taken and their contact details were made available to the qualitative researcher, who accessed the data on the study database. In addition, patients were given a separate information sheet. Written consent was obtained before the start of the face-to-face interviews; the qualitative researcher kept a record of verbal consent for those interviews conducted over the telephone.

Patient and family/friend interviews

The qualitative researcher telephoned patients who expressed interest in the qualitative interview element of the study (including those who consented to and those who declined randomisation) to further discuss their participation. Patients and family/friends from sites in the North of England were offered a choice of location and method of interview (telephone or face to face). Patients and family/friends elsewhere were offered telephone interviews only. Patients who wanted to involve a family member in their interview were able to do so.

Interviews with patients took place at two time points: 1 or 2 weeks after the initial recruitment discussions (to understand the barriers to, and facilitators of, recruitment) and during patient follow-up (to understand patients’ experiences of trial participation).

Summary of interview data collection

-

Took place 1–2 weeks after the recruitment discussion.

-

Trial participants’ experiences of recruitment, views on supplementary feeding, reasons for participation and feelings about randomised allocation.

-

Family and friends’ (of participants) experiences of recruitment, views on supplementary feeding, reasons for participation and feelings about randomised allocation.

-

Trial decliners’ experiences of recruitment, views on supplementary feeding and reasons for declining.

-

Family and friends’ (of decliners) experiences of recruitment and views on supplementary feeding.

-

Eight months’ follow-up.

-

Trial participants’ experiences and views of the TUBE trial (outcome measurement, etc.) and experiences of supplementary feeding.

Patient consent for observation/audio-recording of recruitment discussions

The observation and audio-recording of recruitment discussions have been key to improving recruitment processes in other randomised trials. We designed a three-stage consent process for this part of the study, balancing the need for informed consent with the need to not disrupt the process of consent for the TUBE trial. The main study information sheet, given to patients before the recruitment discussion, included a brief outline of the purpose and design of the observation or audio-recording of recruitment discussions.

-

At the start of the recruitment discussion, verbal consent to record the conversation was obtained. It was explained that more information about this would be given during the discussion and that there would be an opportunity to rescind consent at the end. Everyone present had to give verbal consent; if anyone declined, then the audio-recording did not take place.

-

Written consent for audio-recording was taken as part of the consent process for the TUBE trial. There were separate consent forms for those declining participation in the TUBE trial and for family/friends present. Everyone present had to give written consent for audio-recording; if anyone declined, then the recording had to be deleted immediately (while the person declining was present).

-

Those patients and family/friends who gave written consent for the audio-recording to be kept were given a follow-up information sheet. Prominently on the front page of this information sheet was the information that patients and family/friends had a further opportunity to change their minds about audio-recording by getting in touch with either the recruitment nurse or the qualitative study team.

Clinician interviews and observations

A qualitative researcher conducted the interviews with clinicians. Written informed consent was obtained to audio-record the face-to-face interviews and recruitment discussions. When telephone interviews were conducted, verbal consent was obtained at the start.

The aim of these interviews was to:

-

understand and map processes of care in relation to supplementary tube feeding in patients undergoing CRT for head and neck cancer

-

understand perspectives on supplementary feeding in patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer

-

understand experiences of the TUBE trial, including those of patient recruitment.

The selection of clinicians for interview was purposive and informed by factors such as emerging variation in recruitment rates between sites and changes in key personnel.

Qualitative data management and analysis

The interviews and recruitment discussions were audio-recorded with participants’ consent, transcribed verbatim and edited to ensure anonymity of the respondent. Data were managed using NVivo version 10 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The analysis was theoretically informed by the NPT and conducted in accordance with the standard procedures of rigorous qualitative analysis,39 including open and focused coding, constant comparison, memoing,40 deviant case analysis41 and mapping. 42 We undertook independent coding and cross-checking and a proportion of data were analysed collectively in ‘data clinics’, where the research team shared and exchanged interpretations of key issues emerging from the data.

Relationship between process evaluation and pilot trial

The findings were regularly fed back to the study team and appropriate changes were made to processes during the lifetime of the study. These included a ‘feed-forward’ to sites aiming to address health professionals’ concerns about patient overload, and content in the TUBE newsletters.

Economic analysis (objective 3)

The aims of the economic analysis were to (1) perform a within-trial economic evaluation for this feasibility study; (2) carry out a preliminary estimate of the relative cost-effectiveness of the alternative methods of nutritional support assessed through a modelling exercise from a NHS and PSS perspective; and (3) use the decision-analytic model to estimate the value of future research using variants of a value-of-information analysis.

Within-trial economic evaluation

Should a definitive economic evaluation be conducted in the future, costs to patients and their families/carers, the NHS and PSS would need to be elicited. In a trial-based economic evaluation, the resources used by each patient, such as hospital admissions, consultations and medication use, are normally recorded during the trial. 43 As part of this feasibility study, we planned to develop the tools necessary to elicit these costs, that is, data collection forms and questionnaires to capture the use of hospital and primary care services and patient/family/carer costs, and to summarise the data collected using these tools to inform a future trial. We also intended to use the data to inform the model-based economic evaluation and the adjustments to the data collection tools that would be required for a full economic evaluation. These data collection tools were tailored to reflect the needs of the study participants and to ensure that there was no double-counting of the use of services.

All patients randomised to one of the two trial arms – pre-treatment gastrostomy tube feeding or nasogastric tube feeding – were followed during the trial, and, when available, information was recorded about their health service utilisation related to tube feeding. The data collected were not statistically analysed but, rather, summarised descriptively for completeness.

Economic modelling

A bespoke decision-analytic economic model was developed to estimate the costs, effects and relative cost-effectiveness of the two methods of nutritional support. The clinical pathways of patients in the feasibility study were used to help inform the model structure. For the purposes of clarity, and for improved flow, the methodology for the economic model is discussed in Chapter 3.

Value-of-information analysis

The economic model was able to provide only a preliminary indication of the relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the different methods of nutritional support. An additional purpose was to help inform decisions about the direction of future research. This was explored through variants of a value-of-information analysis: an expected value of perfect information (EVPI) analysis and an expected value of partial perfect information (EVPPI) analysis.

A value-of-information analysis can quantify the expected gain in net benefit from obtaining further information to inform a decision. A decision based on existing information will be uncertain, so it may turn out to be incorrect if more information becomes available in the future. If the decision turns out to be incorrect, then there will be a cost in terms of lost health benefit and wasted resources. Quantifying the value of an incorrect decision, alongside the probability of making an incorrect decision, allows us to estimate the EVPI. The EVPI for a decision problem must exceed the cost of future research to make additional investigation worthwhile.

As well as determining the EVPI around the decision as a whole, value-of-information approaches can be used for particular elements of the decision with the purpose of focusing research in areas in which the elimination of uncertainty might have the most value. An EVPPI analysis can be used to estimate the expected value of removing uncertainty surrounding specific parameters or groups of parameters to identify areas in which future research should focus on identifying more precise and reliable estimates of specific pieces of information, such as relative effectiveness, costs or utilities. EVPI places an upper value on conducting further research overall, while EVPPI places an upper value on conducting further research on a specific area of information. Therefore, if the EVPI or EVPPI exceeds the expected costs of that additional research, then it is potentially cost-effective to acquire more information by undertaking this research.

Expected value of perfect information and EVPPI at an individual level were estimated non-parametrically from the model. However, to inform decisions, population EVPI estimates were also assessed based on the number of individuals who would be affected by the additional information over the anticipated lifetime of the technology. Given the fact that additional research in the present will produce net monetary benefits in the future, a discount rate was applied. Formally, a population EVPI estimate can be expressed as:

where I is the incidence in the period, t is the period, T is the total number of periods for which information from research would be useful and r is the discount rate. 44

To estimate population EVPI, we estimated that there are > 9000 patients diagnosed with HNSCC per year in the UK, based on epidemiological data. However, only half of these patients require nutritional support post CRT. Consequently, an approximate estimation of the number of patients who are going to benefit from further research is 4500 per year. It was assumed that this incidence was constant over time. Because of the uncertainty in the length of time over which the information from further research would be useful, a number of time horizons were included in the analysis (10 years, 20 years, 64 years45 and an unbounded time horizon). 46 A discount rate of 3.5%, the current UK recommendation, was applied.

The EVPI and EVPPI were assessed for both the base-case cost-effectiveness analysis and the worst-case scenario for the nasogastric tube-feeding cost-effectiveness analysis, which were explored in the alternative probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement has played a key role in the design of this study. Jeremy Franks, our ‘expert patient’ and co-author, has been a member of our research team from the outset, regularly attending Trial Management Group (TMG) meetings to ensure that a patient perspective was consistently presented during decision-making throughout the study, and also attending Trial Steering Committee meetings.

In planning the research, we consulted two HNSCC support groups, one in Newcastle upon Tyne and one in Sunderland. Attendees included patients and carers following surgery or chemoradiotherapy treatment. All had experience of either a gastrostomy tube or a reactive nasogastric tube. They strongly agreed that research into swallowing outcomes was warranted. Members were presented with five potential research topics, and rated this study as a high priority. A further group of nine patient volunteers also reviewed this study and made suggestions, such as the time point and approach for patient interviews, which were incorporated into the study design.

An additional patient and carer group, attended by 12 patients and family members, was convened after funding was achieved during the development of the patient recruitment process and materials. The meeting was chaired by Jeremy Franks, with support from other team members. Attendees were provided with draft copies of the patient recruitment materials in advance of the meeting, and these were discussed in detail during the meeting. A particular focus of the discussion was the timing of patient contact: patients highlighted the risk of overload at the point of treatment planning, but agreed that some information about the trial did need to be provided at this stage. It was agreed that brief initial information would be provided at treatment planning, but the detailed information and discussion about the trial would be organised for a subsequent occasion. Discussion also focused on the need for verbal consent to audio-record recruitment consultations. Patient feedback – that this was very acceptable, that it was routine in many other situations (e.g. telephone calls to call centres) and that, if anything, it would give greater confidence in the quality of the information being provided – was also helpful when seeking research ethics approvals.

Jeremy Franks’ involvement in the study has been facilitated by his employment at Newcastle University, albeit in a different faculty (the Department of Agricultural Sciences). This has enabled him to attend project meetings regularly, which would have been very difficult for someone in employment in another organisation. Jeremy Franks’ employment at Newcastle University did not impede his ability to present a patient perspective; he had no prior familiarity with health research, commenting, for example, on his observation of the demanding organisation and approvals needed to conduct health research. Our study, therefore, benefited from the combination of an expert patient providing management input throughout, plus ‘responsive’ as-needed input from a broader patient panel.

Chapter 3 Results

Preliminary estimation of key parameters for definitive study

Recruitment and randomisation

Recruitment

The trial is closed to recruitment. The first patient was randomised on 10 July 2014 and the trial closed to recruitment with a total of 17 patients randomised. The last patient was randomised on 30 June 2015. The database was frozen on 5 May 2016.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to either the pre-CRT gastrostomy arm or the no pre-CRT gastrostomy arm using a block-stratified block method (based on permuted random blocks of variable length), implemented using the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit internet-accessed secure web-based system. Randomisation was stratified by site (Table 1).

| Site | Eligible (N = 84) | Approached (N = 75) | Declined (N = 58) | Consented (N = 17) | Treatment allocation, n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrostomy (N = 9) | Nasogastric (N = 8) | |||||

| 1 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 28 | 19 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 37 | 37 | 27 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Ineligible patients

Ineligible patients were those randomised who were later found not to adhere to the trial eligibility criteria. No ineligible patients or protocol violators were recorded in this trial.

Trial population

Baseline patient characteristics

Demographic, clinical and surgical baseline characteristics and trial stratification factors at randomisation were compared across treatment groups descriptively. Descriptive statistics were tabulated by treatment group and overall. No significance testing was carried out owing to the randomised nature of the study.

Demographic characteristics included age, sex, weight and height. Clinical characteristics included the tumour, node and metastasis classification, dental characteristics and Performance Status Scale score (eating in public, understandability of speech, normalcy of diet). Trial factors included stratification factors (site), whether or not induction chemotherapy was planned and whether or not IMRT was planned (Tables 2 and 3).

Limited data are available on the characteristics of all eligible patients, including those not approached and/or recruited (n = 84). Age at screening was available for 83 out of 84 patients; the median age of these 83 individuals was 62 years [interquartile range (IQR) 58–67 years; range 38–85 years].

Table 2 shows that the majority of patients were recruited from site 3 (59%) and were male (94%), with a median age of 64 years (range 49–76 years) and a median weight of 84.8 kg (range 54.6–113 kg), balanced between the randomised groups. No patients had restrictions with eating in public and all had full normalcy of diet.

| Patient characteristic | Treatment allocation | Total (N = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrostomy (N = 9) | Nasogastric (N = 8) | ||

| Site, n | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Sex, n | |||

| Male | 9 | 7 | 16 |

| Female | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR, range) | 65 (64–67, 59–68) | 60 (58–72, 49–76) | 64 (60–68, 49–76) |

| Height (cm) | |||

| Median (IQR, range) | 171 (161–183, 152–185) | 173.5 (170–177.5, 162–185) | 172 (170–180, 152–185) |

| Usual weight (kg) | |||

| Median (IQR, range) | 81.1 (74.8–85, 54.6–104) | 89.4 (82.8–96.2, 77.3–113) | 84.8 (77.5–91.2, 54.6–113) |

| Given pre-treatment swallowing, n | |||

| No | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Yes | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Not known | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Performance Status Scale, n | |||

| Eating in public | |||

| No restriction of place, food or companion | 9 | 8 | 17 |

| Understandability of speech | |||

| Always understandable | 9 | 7 | 16 |

| Understandable most of the time | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Normalcy of diet | |||

| Full diet with no restrictions | 9 | 8 | 17 |

Table 3 shows that 65% of patients had human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive oropharyngeal tumours, and three patients in the nasogastric arm had nasopharynx tumours. Two out of nine patients (22%) randomised to the gastrostomy group and six out of eight patients (75%) randomised to the nasogastric group had a T3/T4 tumour stage. One out of nine patients randomised to the gastrostomy group and three out of eight patients randomised to the nasogastric group were node negative. All nine patients randomised to the gastrostomy group and six out of eight patients randomised to the nasogastric group were free of distant metastases.

| Tumour characteristics | Treatment allocation, n | Total (N = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrostomy (N = 9) | Nasogastric (N = 8) | ||

| Site of disease, n | |||

| Nasopharynx | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Oropharynx (HPV-positive) | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Oropharynx (HPV-negative) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Larynx | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hypopharynx | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Primary tumour, n | |||

| T1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| T2 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| T3 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| T4 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Regional lymph nodes, n | |||

| N0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| N1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| N2 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| N3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Distant metastasis, n | |||

| MX | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| MO | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| M1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Table 4 shows that dental information was not complete for all patients at baseline; the highest number of patients providing information for any particular component was 13 (76%). Initial decay, missing and filled teeth scores appeared balanced between the randomised groups, as did oral opening and oral dryness. Ten patients (59%) had oral hygiene aggregate scores recorded. Higher scores were reported in the gastrostomy arm, with a non-overlapping range of scores.

| Dental characteristics | Treatment allocation | Total (N = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrostomy (N = 9) | Nasogastric (N = 8) | ||

| Initial presentation | |||

| Decayed (score 0–32) | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 2.5 (0–5, 0–9), 6 | 1 (1–1, 0–1), 5 | 1 (0–4, 0–9), 11 |

| Missing (score 0–32) | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 10.5 (8–14, 5–22), 6 | 12 (5–13, 4–18), 5 | 12 (5–14, 4–22), 11 |

| Filled (score 0–32) | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 7 (2–10, 1–14), 6 | 8 (8–8, 3–9), 5 | 8 (3–9, 1–14), 11 |

| Baseline | |||

| Decayed (score 0–32) | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 0 (0–0, 0–4), 6 | 0 (0–1, 0–1), 7 | 0 (0–0, 0–4), 13 |

| Missing (score 0–32) | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 19 (14–32, 6–32), 6 | 12 (5–14, 5–18), 7 | 14 (12–18, 5–32), 13 |

| Filled (score 0–32) | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 1 (0–7, 0–10), 6 | 7 (3–8, 2–9), 7 | 5 (1–7, 0–10), 13 |

| BPI | |||

| BPI_Upper L Posterior, n | |||

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| BPI_Upper Anterior, n | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| BPI_Upper R Posterior, n | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| BPI_Lower L Posterior, n | |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| BPI_Lower Arch, n | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| BPI_Lower R Posterior, n | |||

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| OHSa | |||

| OHS_Upper Plaque, n | |||

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| OHS_Upper Calculus, n | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| OHS_Upper Debris, n | |||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| OHS_Lower Plaque, n | |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| OHS_Lower Calculus, n | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| OHS_Lower Debris, n | |||

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Oral opening | |||

| Upper to lower R incisors | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 45 (43–52, 43–53), 5 | 45 (39–48, 35–50), 5 | 45 (43–50, 35–53), 10 |

| Nearest adjacent pair | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | No observations | ||

| Oral dryness (1–10) | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 0 (0–0, 0–0), 5 | 0 (0–0, 0–0), 6 | 0 (0–0, 0–0), 11 |

| Dental OHS aggregate | |||

| Median (IQR, range), n | 2.17 (2.00–2.25, 1.50–3.00), 5 | 0.83 (0.50–1.00, 0.33–1.33), 5 | 1.42 (0.83–2.17, 0.33–3.00), 10 |

Defining populations for analysis

All patients who were approached about the trial are referred to as the screening set. All patients randomised to treatment are included, retaining patients in their randomised treatment groups and including protocol violators and ineligible patients. This group of patients is referred to as the intention-to-treat (ITT) set. All patients who started treatment are referred to as the treatment set.

Treatment received

The analysis set was the ITT set. Treatment was defined as CRT plus randomised intervention. CRT treatment was delivered as per usual centre practice and was usually completed within 2 months.

Pre-chemoradiation therapy gastrostomy arm

Gastrostomy tubes were inserted after the consent and baseline visit and after randomisation, but before any treatment (CRT/IMRT) took place. Gastrostomy tubes were inserted during induction chemotherapy if necessary.

No pre-chemoradiation therapy gastrostomy arm

Nasogastric tubes were inserted after the consent and baseline visit and after randomisation, at a point when patient and/or clinician felt that this was most appropriate. Nasogastric tube placement was flexible, that is, it was carried out during or after CRT treatment, as required.

Owing to the nature of the tube-feeding interventions, it was not practicable to blind research nurses to the treatment allocated to patients for the follow-up assessments. The baseline data capture assessments were completed by research nurses before randomisation to reduce the chance of bias (see Tables 5–8).

Table 5 reports on 16 out of 17 patients receiving a randomised intervention. One patient was given the opposite intervention, as clinical staff were unable to insert a gastrostomy tube when they attempted to do so.

| Did the patient receive the intervention? | Treatment allocation, n | Total (N = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrostomy (N = 9) | Nasogastric (N = 8) | ||

| Yes | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| No | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 9 | 8 | 17 |

Table 6 reports how pre-CRT gastrostomy tubes were inserted, a median of 14 days after randomisation (75% were inserted within 18 days; all were inserted within 28 days). Nasogastric tubes were inserted a median of 40 days after randomisation (75% were inserted within 53 days; all were inserted within 72 days).

| Treatment allocation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrostomy (n = 9a) | Nasogastric (n = 8) | |||||

| Median | IQR | Range | Median | IQR | Range | |

| Number of days | 14 | 11–18 | 8–28 | 40.5 | 32–53.5 | 26–72 |

Table 7 shows that two out of nine patients randomised to receive gastrostomy tubes and and two out of eight randomised to nasogastric tubes intended to have induction chemotherapy. All patients planned to have IMRT.

| Intention at randomisation | Treatment allocation, n | Total (N = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrostomy (N = 9) | Nasogastric (N = 8) | ||

| Induction chemotherapy? | |||

| Yes | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| No | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| Is the patient to have IMRT? | |||

| Yes | 9 | 8 | 17 |

Table 8 shows that two patients in each randomised arm were to receive a median of two cycles of induction chemotherapy. Eight patients in each randomised arm received a median of 65 Gy of CRT in 30 fractions. Induction chemotherapy and radiotherapy appeared to be balanced between the randomised groups.

| Received | Treatment allocation, n | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrostomy (N = 9) | Nasogastric (N = 8) | |||||||

| n | Median | IQR | Range | n | Median | IQR | Range | |

| Number of cycles of induction chemotherapy | 2 | 2 | 2–2 | 2–2 | 2 | 2 | 2–3 | 2–3 |

| Total number of fractions of radiotherapy | 8a | 30 | 30–30 | 30–30 | 8 | 30 | 30–30 | 30–65 |

| Total radiotherapy dose received (Gy) | 8a | 65 | 65–65.5 | 65–66 | 8 | 65 | 65–65 | 54–66 |

Safety analysis

Adverse events

The analysis set is the treatment set. AEs were graded on a three-point scale of intensity (mild, moderate and severe):

-

mild – discomfort is noticed, but there is no disruption of normal daily activities

-

moderate – discomfort is sufficient to reduce or affect normal daily activities

-

severe – discomfort is incapacitating, leading to an inability to work or perform normal daily activities.

A total of 230 AEs were reported in a total of 15 patients (Table 9).

| AE severity | Relatedness, n (%) | Total, N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrelated | Possibly | Probably | Definitely | Missing | ||

| Mild | 126 (54.78) | 2 (0.87) | 2 (0.87) | 3 (1.30) | 0 (0.00) | 133 (57.83) |

| Moderate | 74 (32.17) | 1 (0.43) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.43) | 0 (0.00) | 76 (33.04) |

| Severe | 20 (8.70) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 20 (8.70) |

| Missing | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.43) | 1 (0.43) |

| Total | 220 (95.65) | 3 (1.30) | 2 (0.87) | 4 (1.74) | 1 (0.43) | 230 (100.00) |

Nine (3.9%) AEs reported were possibly, probably or definitely related to the randomised intervention. These were reported in six patients. Table 10 provides a line listing of all reported AEs; shading is used in the table to show those nine events that were possibly, probably or definitely related to the randomised intervention.

| PID_ae | Rand_No | AESTDAT | AETERM | AECausality | AESER | AESeverity | RndArm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01S006 | 101 | 26 August 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 26 August 2014 | Constipation | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 2 September 2014 | Vomit | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 9 September 2014 | Tinnitus | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 9 September 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 9 September 2014 | Low haemoglobin | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 16 September 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 16 September 2014 | Nausea | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 22 September 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Severe | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 22 September 2014 | Vomit | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 23 September 2014 | Oral thrush | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 23 September 2014 | Nausea | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 23 September 2014 | Throat pain | Unrelated | N | Severe | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 1 October 2014 | Throat pain | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 15 October 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S006 | 101 | 20 November 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 22 August 2014 | Pain at gastrostomy site | Probable | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 10 September 2014 | Constipation | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 10 September 2014 | Constipated | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 10 September 2014 | Xerostomia | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 10 September 2014 | Loss of taste | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 17 September 2014 | Thick saliva | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 17 September 2014 | Xerostomia | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 17 September 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 17 September 2014 | Loss of taste | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 17 September 2014 | Mucositis | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 17 September 2014 | Dysphagia | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 8 October 2014 | Thick saliva | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 5 December 2014 | Mucositis | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 15 December 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S009 | 102 | 5 January 2015 | Thick saliva | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 24 November 2014 | Constipation | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 24 November 2014 | Sore mouth | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 26 November 2014 | Trismus | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 26 November 2014 | Altered taste | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 26 November 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 26 November 2014 | Altered voice | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 26 November 2014 | Salivary change | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 26 November 2014 | Dysphagia | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 1 December 2014 | Sore mouth | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 10 December 2014 | Dysphagia | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 10 December 2014 | Salivary change | Unrelated | N | Severe | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 15 December 2014 | Alopecia | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 17 December 2014 | Skin reaction | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 17 December 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Severe | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 17 December 2014 | Dysphagia | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 30 December 2014 | Thick saliva | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 18 June 2015 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S014 | 106 | 18 June 2015 | Altered taste | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 November 2014 | Low mood | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 26 November 2014 | Taste changes | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 26 November 2014 | Thick saliva | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 26 November 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 26 November 2014 | Xerostomia | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 3 December 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 3 December 2014 | Taste changes | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 5 December 2014 | Tinnitus | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Mucositis | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Infection at RIG site | Definitely | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Dysphagia | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Trismus | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Altered voice | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Constipation | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Fatigue | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Skin reaction | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 10 December 2014 | Trismus | Unrelated | N | Mild | Gastrostomy |

| 01S016 | 107 | 17 December 2014 | Mucositis | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |

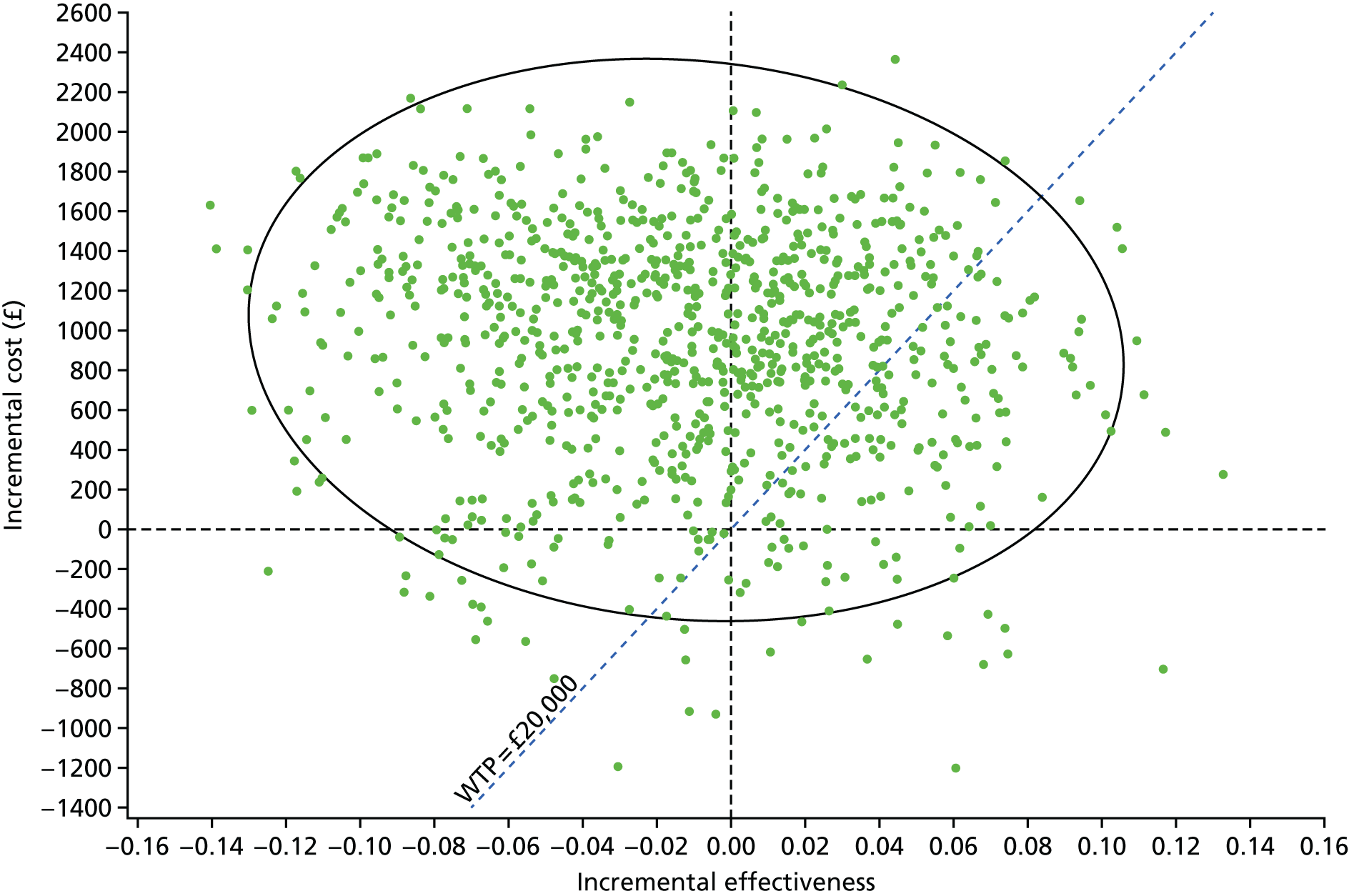

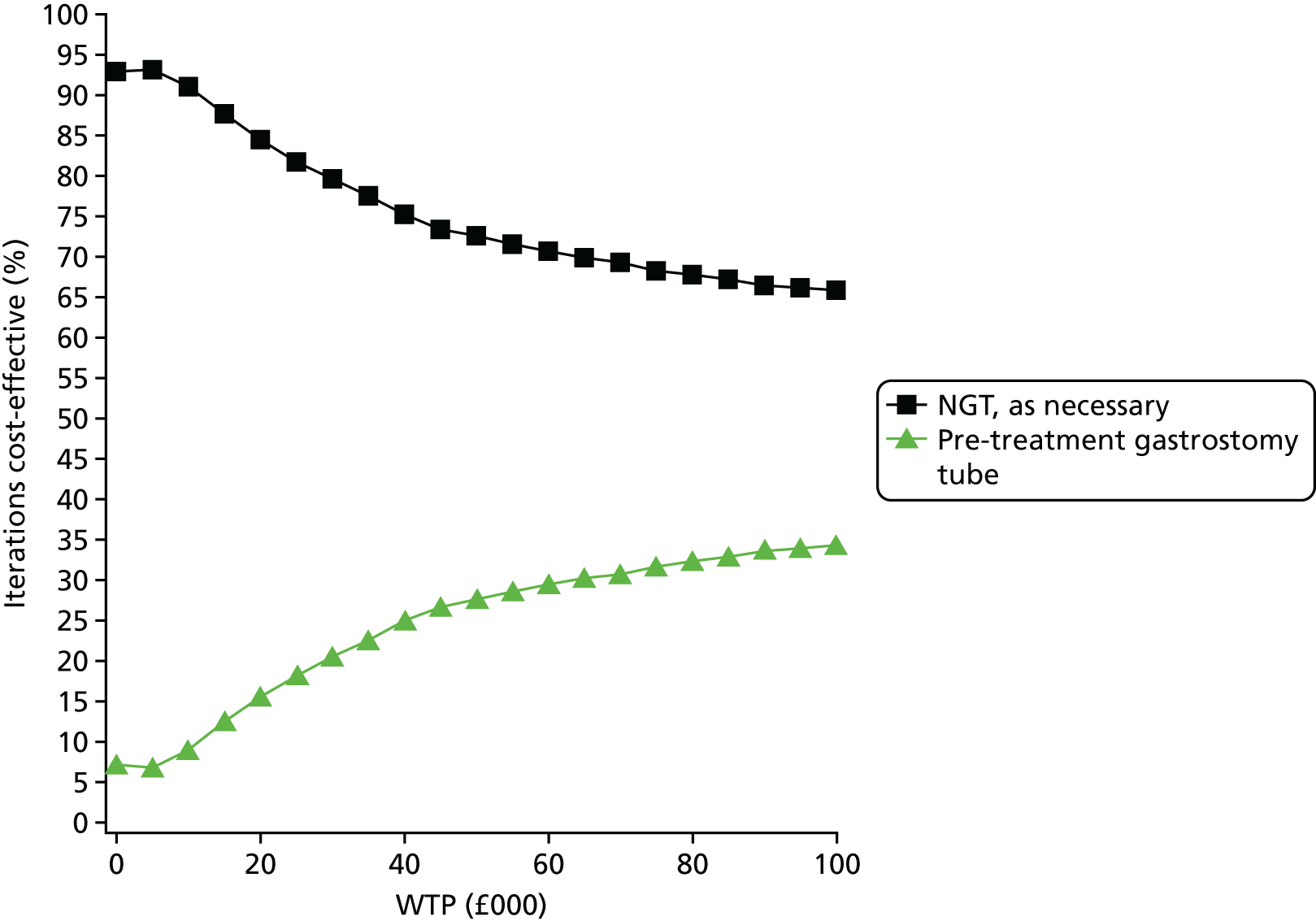

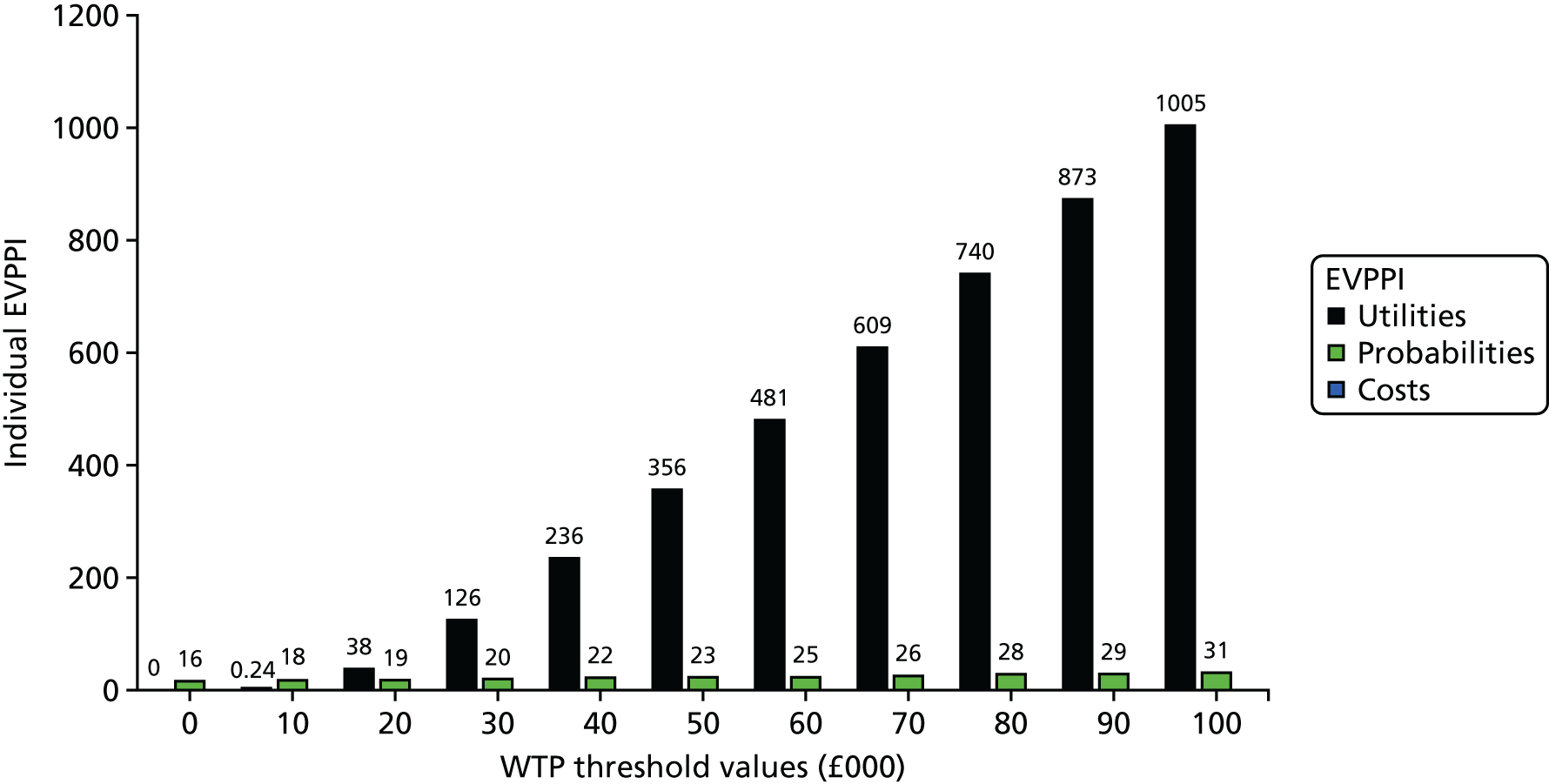

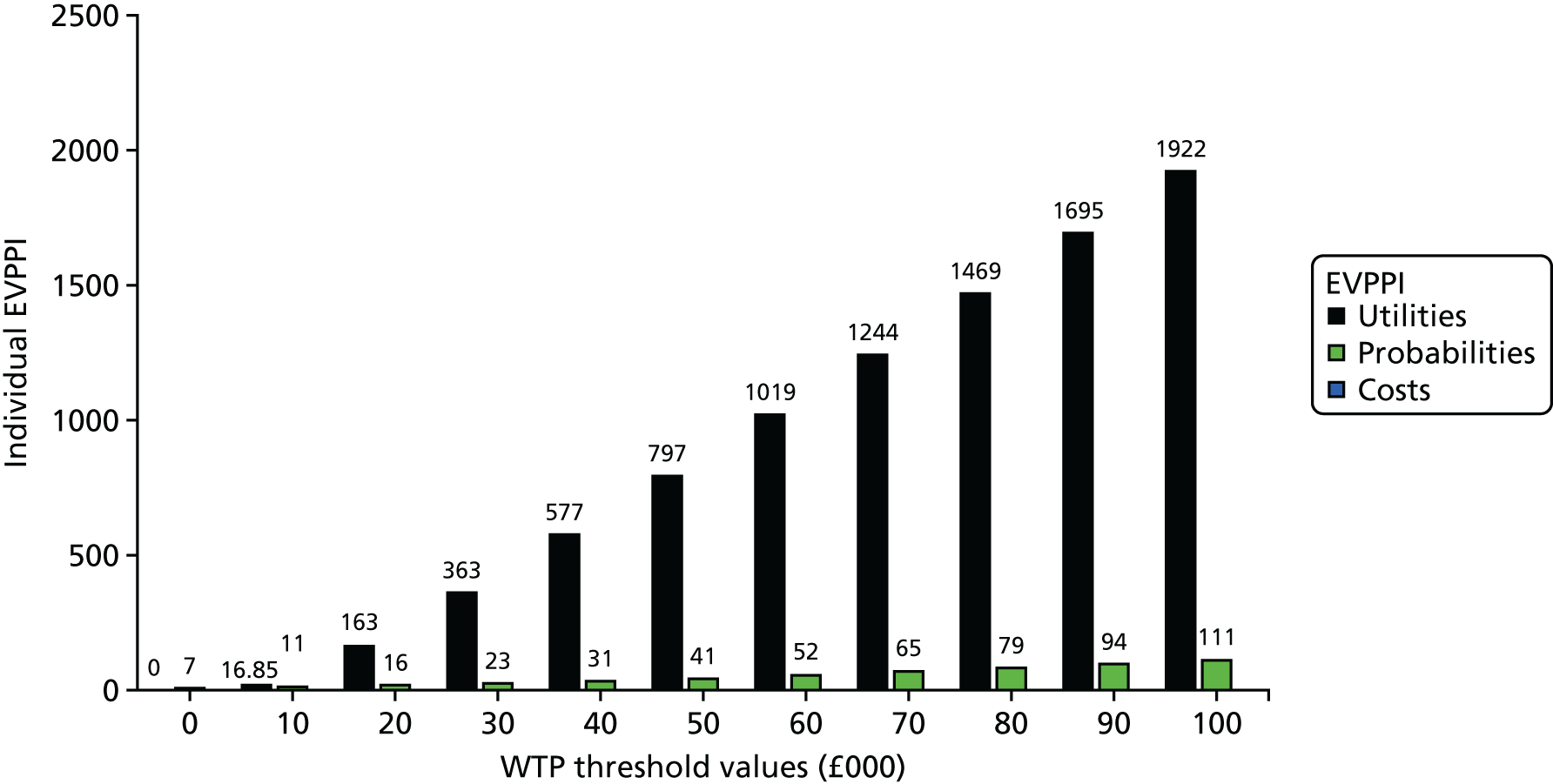

| 01S016 | 107 | 17 December 2014 | Xerostomia | Unrelated | N | Moderate | Gastrostomy |