Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/01/34. The contractual start date was in September 2008. The draft report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Samer Nashef received personal expenses from AtriCure, Inc. (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) for contributing to educational courses for surgeons interested in learning the maze procedure, independently of this study. AtriCure, Inc. is one of several manufacturers of atrial fibrillation ablation devices, the technology of which was used in atrial fibrillation surgery in this study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Sharples et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

The health problem

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common disturbance of heart rhythm. It is characterised by an irregular heartbeat caused by low-amplitude, supraventricular oscillations. 1

The normal rhythm of the heart is sinus rhythm (SR). The stimulus to beat is triggered by the sinoatrial node. This results in atrial contraction while the stimulus is conducted to the atrioventricular node, which relays it to the ventricles, initiating ventricular contraction. AF is a condition whereby the atria beat unevenly because of abnormal electrical signals. As a result, there is no SR, the ventricles respond to the disordered atrial electrical activity in a haphazard fashion, the pulse becomes irregular and the entire heartbeat is abnormal.

Atrial fibrillation has a prevalence of 1–2% of the population in high-income countries. 2,3 In the UK, the prevalence of AF is 7.2% in patients aged ≥ 65 years and 10.3% in patients aged ≥ 75 years. 4 Prevalence is associated with age and comorbidities, such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension. With the advancing age of the population and the increasing prevalence of obesity, this proportion is likely to increase. 5

Consequences of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation can cause palpitations, chest pain, dizziness and breathlessness, and imposes a heavy burden on both patients and clinicians, as it has a considerable impact on quality of life (QoL) and NHS resources. 6

When the atria fibrillate, they lose their pumping action, and this has two very important sequelae.

There is blood stagnation in the atria, which can lead to clot formation. Blood clots can then exit the heart (thromboembolism), leading to stroke and other complications. There is an associated four- to fivefold increased risk of thromboembolic stroke in AF, and if AF is left untreated, around 1 in 25 patients will have a stroke. 7 The NHS devotes 5% of its budget to preventing and treating strokes, and 15% of strokes can be attributed to AF. 4 Drugs and other treatments can control AF, but not without complications. Routine anticoagulant drug treatment reduces the risk of stroke in AF patients by two-thirds, but this incurs an increased risk of bleeding and needs careful monitoring. The substantial burden of monitoring anticoagulant therapy usually falls on general practice, anticoagulant clinics and haematology laboratories.

When the atria do not pump, the heart is less efficient. The presence of AF exacerbates heart failure that arises from other heart conditions, and can itself cause heart failure, especially if the fibrillating atria dilate and this results in leakage of the mitral and tricuspid valves.

Treatment of AF and its consequences (antiarrhythmic and anticoagulant drugs, hospital monitoring and stroke treatment) is expensive for the NHS. Implementation of the 2006 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,6 on management of AF, was estimated to cost £21.86M per year. 3

Types of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is classified into three distinct subgroups. In the Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation,8 paroxysmal AF is defined as recurrent AF (more than two episodes) that terminates spontaneously within 4 days, persistent AF is defined as AF that continues beyond 4 days and chronic or longstanding AF is persistent AF beyond 1 year. 8 These patterns of AF have slightly different electrophysiological mechanisms.

Diagnosis of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is confirmed by electrocardiography (ECG) when the patient presents with symptoms of palpitations, as is the case with paroxysmal AF; however, both paroxysmal and more longstanding AF can be asymptomatic and, when that is the case, can be missed on the electrocardiogram, unless the AF coincides with the time at which ECG is carried out. This is especially important in assessing treatments aimed at correcting AF, as many historical series reported only the recurrence of symptomatic AF and have used only intermittent ECG for follow-up. 9 In the majority of published studies, success in the ‘resumption of SR’ was based on a single ECG recording at 12 months, which is not necessarily representative. More recently, there has been recognition of the importance of more robust AF documentation and Holter monitoring records have been reported in some AF trials. 10–12 Better evaluation of any residual AF after treatment, by continuous ECG monitoring over several days, documents the percentage of time for which a patient is in AF, and this is called the ‘AF burden’.

A number of studies (cited in Calkins et al. 8) suggest not only that AF increases the risk of a poor outcome from prospective cardiac surgery, but is also that AF an independent risk factor for early and late morbidity and mortality. This leads to the (unproven) hypothesis that efforts to eliminate pre-existing AF during cardiac surgery may improve survival and reduce adverse cardiac events after surgery.

Current treatment

Until the 1980s, AF was treated using antiarrhythmic drugs and direct current cardioversion. When that failed, AF was managed with rate control medication and anticoagulant drugs to reduce the risk of stroke. There has been a substantial development in our understanding of the pathophysiology of AF, and two very important findings have been the roles of the pulmonary veins and macro-re-entry circuits.

We now know that the majority of electrical trigger points that initiate AF lie within the pulmonary veins and not in the atria themselves. 13 Moreover, the maintenance of AF depends on the presence of macro-re-entry circuits, in which delayed conduction of the electrical signal means that the signal arrives at the originating point when that point is no longer refractory. These circuits are quite large (several centimetres). As a result of this knowledge, the maze procedure was developed in the 1980s by Cox and Boineau. 14 The procedure prescribed a number of surgical cuts aimed at achieving two objectives: electrical isolation of the pulmonary veins from the atria, thus dealing with the site of most AF trigger points, and further cuts in the atria to disrupt macro-re-entry circuits, thereby preventing the maintenance of the AF rhythm. The maze procedure therefore involves multiple cutting and sewing of the atria and pulmonary veins. Several studies have reported freedom from AF ranging from 75% to 90% after the Cox maze procedure (see Huffman et al. ’s9 systematic review and associated references), and one reported a 15-year success rate in restoring SR as high as 94%. 15 This traditional cut-and-sew technique, despite being available since 1987, has failed to achieve widespread use, as it is technically demanding and adds substantially to the operative burden of a heart operation. It is currently in very limited use by a few surgeons in a few centres and tends to be reserved for otherwise fit patients with severely symptomatic AF, who are prepared to take the risk of such a major intervention to relieve their symptoms.

Alternatives to the cut-and-sew maze procedure have been produced. A number of devices have been developed to achieve the electrical block needed, using energy sources to ablate atrial tissue. These have made a technically difficult and time-consuming operation easier, quicker and safer for cardiac surgeons to perform. Ablation devices use an energy source (heat, cold, radiofrequency or microwave) to replicate the lesion set produced by the cut-and-sew maze procedure. 16 As a rule, the procedure is safe and well tolerated and adds little to the length and burden of the operation, but these devices are a new and costly technology, which is currently being heavily marketed to treat AF. 17

There has been no direct comparison between the traditional Cox maze procedure and the ablation maze procedure,9 presumably because of the problems of incorporating such technically demanding surgery into an adequately powered randomised controlled design. However, a propensity analysis that matched patients who underwent the ablation maze procedure with those undergoing the Cox maze procedure showed no differences in freedom from AF at 3, 6 and 12 months afterwards. 18

Patients who have AF before surgery are generally older and have an increased procedural risk and other comorbidities, so that treating AF at the time of cardiac surgery may be advantageous to the patient. When the Amaze trial was planned, the only evidence supporting this came from five small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the ablation maze procedure as an adjunct to surgery. 11,19–22 These trials found that SR was restored in 44–94% of treated patients compared with 5–33% of control patients. The trials were small and follow-up was short. Success was mostly defined on the basis of single ECG recordings. No trial looked at patient-centred outcomes or cost-effectiveness. Despite this lack of robust evidence, the number of patients with AF undergoing open heart surgery and being offered concomitant ablation maze procedures, or ‘adjunct maze procedures’, was increasing. Although there were instances of its use as a standalone procedure, the widest use of the ablation maze procedure in the NHS was in patients already having cardiac surgery for other problems. 23 This trial was designed in response to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme call to evaluate ablation devices that were being rapidly assimilated into NHS practice without formal assessment.

Patient benefit

It is essential to recognise that the primary justification of the ablation procedure is to treat symptomatic AF. 24 When the Amaze trial was in the planning stage, no effectiveness studies had investigated the QoL benefit and cost-effectiveness of maze procedures. Since the original grant application, four small randomised trials have reported on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after the maze procedure. 12,25–27 No difference was reported in the overall QoL scores. However, patients in the studies by Gillinov et al. 12 and Van Breugel et al. 27 were not blinded to the treatment they received, which could have influenced the reporting of QoL outcomes. Cherniavsky et al. 25 reported improvement in the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) score; however, the trial overall reported that the adjunct maze procedure arm did no better than coronary artery bypass graft operation (CABG) alone.

Recent evidence

A Cochrane collaboration review9 assessed the effects of adjunct AF surgery. 9 Using a comprehensive systematic review methodology, the authors identified 22 published trials (1899 participants) comparing cardiac surgery with and without adjunct AF surgery, with five additional ongoing studies and three studies not classified at the time of reporting. 10–12,19,20,22,25–40 All included studies were rated as being at a high risk of bias in at least one domain assessed. The Cochrane review9 found that AF surgery, regardless of technique, doubles the rate of freedom from AF, atrial flutter and atrial tachycardia [51.0% vs. 24.1%; relative risk (RR) 2.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.63 to 2.55], with more patients not taking antiarrhythmic medication 3 months after cardiac surgery. There was little evidence of a difference between patients with AF who were treated and those who were not treated in either 30-day mortality (2.3% vs. 3.1%; RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.71 to 2.20) or all-cause mortality (7.0% vs. 6.6%; RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.59). However, patients who were treated for AF were more likely to be fitted with a permanent pacemaker (6.0% vs. 4.1%; RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.54). The review authors concluded that there remained uncertainty about the effects on cardiovascular mortality, adverse events (AEs), HRQoL and long-term outcomes. 9

In summary, there is little rigorous evidence that attempting to restore SR by treating AF with an ablation device during cardiac surgery is of benefit to the patient. Nevertheless, these devices are being incorporated into routine practice nationally and internationally. The Amaze trial provided a timely evaluation of this technology with the objective of assessing the clinical and HRQoL benefits for patients, as well as cost-effectiveness for the NHS.

Chapter 2 Amaze trial methods

Objectives

Primary objectives

The primary objectives were to compare patients undergoing the maze procedure as an adjunct to routine cardiac surgery with patients undergoing routine cardiac surgery alone, in terms of:

-

return to stable SR at 12 months

-

quality-adjusted survival over 24 months after randomisation.

Secondary objectives

The main secondary objective was to assess the cost-effectiveness of the adjunct maze procedure, relative to cardiac surgery alone, from a NHS perspective.

Other secondary objectives were to compare the following outcomes between the two arms:

-

return to stable SR at 24 months after surgery

-

overall survival

-

thromboembolic neurological complications (e.g. stroke)

-

stroke-free survival

-

anticoagulant and antiarrhythmic drug use up to 24 months post randomisation

-

HRQoL up to 24 months post randomisation, as measured by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), the SF-36 and the New York Heart Association (NYHA)

-

resource use and costs.

Exploratory analyses

Prespecified subgroup analysis was planned to explore differences in treatment effects between:

-

patients with paroxysmal AF and non-paroxysmal AF (i.e. persistent, chronic or longstanding AF)

-

individual centres (as a random effect)

-

cardiac surgical procedures

-

surgeons.

Within the maze treatment arm, analysis was planned to explore differences between:

-

different ablation devices

-

different lesion sets treated.

Design

Overview

The Amaze trial was a Phase III, pragmatic, multicentre, double-blind, parallel-arm RCT to compare clinical, patient-based and cost outcomes for patients with pre-existing AF who undergo routine cardiac surgery either with or without an adjunct device-based ablation procedure.

Eligible patients were randomised (in a 1 : 1 ratio) to receive either:

-

planned routine cardiac surgery with no additional procedure

-

planned routine cardiac surgery with an additional device-based AF ablation procedure.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Essex 1 Research Ethics Committee (reference number 08/H0301/98) and was registered as International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number 82731440 (ISRCTN82731440). The trial protocol can be accessed at www.papworthhospital.nhs.uk/research/data/uploads/ptuc/protocol-v4-may-20151.pdf (accessed 2 March 2018)41 and the HESTER (Has Electrical Sinus Translated into Effective Remodelling?) substudy protocol can be accessed at www.papworthhospital.nhs.uk/research/data/uploads/ptuc/hester-study-protocol-3.pdf (accessed 2 March 2018). 42

As much as possible, the design and reporting of this trial adhered to the guidelines of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement43 and incorporated recommendations of the Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. 24

Patient and public involvement

Mr Brian Elliott was an independent member and lay representative on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), providing input on all aspects of the trial design, conduct and recruitment strategies. Professor Paul Kinnersley has a background in primary care and public health and provided further independent advice on the conduct and progress of the trial through membership of the TSC.

Setting and investigators

Eleven acute NHS specialist cardiac surgical centres (Papworth Hospital, Cambridgeshire; Royal Brompton Hospital, London; Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals, Brighton; University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, Coventry; Glenfield Hospital, Leicester; Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester; Northern General Hospital, Sheffield; Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London; Derriford Hospital, Plymouth; Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne; and Blackpool Victoria Hospital, Blackpool) participated in the study, which was co-ordinated by the Papworth Trials Unit Collaboration. For surgeons to participate, they were required to be experienced in the use of ablation devices for at least 2 years. During the trial design period, participating surgeons met to agree the permissible procedures, ablation methods and lesion sets to be treated.

Participants

Consecutive cardiac surgical patients undergoing major cardiac surgery (e.g. coronary, valve or combined operations), with a history of paroxysmal, persistent or chronic AF beginning > 3 months before the date of the operation, were screened for eligibility.

-

Paroxysmal AF was defined as recurrent AF (two or more episodes) that terminated spontaneously within 4 days. 24

-

Non-paroxysmal but persistent AF was defined as AF that continued for > 4 days.

-

Chronic or longstanding AF was defined as AF that was persistent for > 1 year.

The Amaze trial inclusion criteria included patients who:

-

were aged > 18 years

-

were scheduled to undergo elective or in-house urgent cardiac surgery (coronary surgery, valve surgery, combined coronary and valve surgery or any other cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass)

-

had a history of documented AF (chronic, persistent or paroxysmal) beginning > 3 months before entry into the study

-

were willing to provide written informed consent to participate.

Exclusion criteria included patients who:

-

had had previous cardiac operations

-

had had emergency or salvage cardiac operations

-

had had surgery without cardiopulmonary bypass

-

were unlikely to be available for follow-up over a 2-year period

-

were unable to provide consent.

Recruitment

The procedure for informing and obtaining consent from patients was devised to accommodate local variations in the patient pathway, but was otherwise identical for all centres. At most centres, potential participants were initially given a simple summary of the study by the local investigator at the initial surgical clinic when treatment options were discussed. Before the next attendance, the trial co-ordinator or a research nurse contacted the patients by telephone to assess interest in the trial, and posted the full patient information sheet to the homes of those who expressed an interest. Written consent was taken at the pre-admission clinic, at approximately 2 weeks prior to surgery, by the trial co-ordinator or research nurse. HRQoL questionnaires were administered by the research nurse, after consent, at this pre-admission clinic. Thereafter, patients were registered for the trial and provided with a 4-day ECG recording device and instructions on its use, to take home to monitor their heart rate for 4 days. On admission for surgery, the patient returned the 4-day ECG recorder.

Randomisation

Eligible patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria and provided written consent were randomised (in a 1 : 1 ratio) to receive either their planned cardiac surgery with no additional procedure or their routine cardiac surgery with an adjunct maze procedure.

The allocation sequence was generated by permuted block randomisation (using block sizes of 6 and 8), and randomisation was stratified by surgeon and planned cardiac procedure (CABG, aortic valve, mitral valve or combined procedure). On the day of surgery, when the patient was in the anaesthetic room, the local centre contacted the Papworth Trials Unit Collaboration by telephone. Patient details, surgeon and planned cardiac procedure were registered with the Papworth Trials Unit Collaboration, whose staff were not otherwise involved with the trial. Once registration was complete, the allocation was released to the surgical team, which was also responsible for completing the surgical clinical report form (CRF). The treatment allocation was not made available to any other staff who were directly or indirectly involved in the trial.

Blinding

Although theatre staff could not be blinded to the treatment allocation, the trial was double-blind to the extent that neither the patients themselves, nor any researchers collecting HRQoL outcomes nor the cardiologists assessing the 4-day ECG results were aware of the trial arm to which the patient had been allocated.

Patients’ medical notes were labelled to indicate that they were Amaze trial participants. Routine reports provided details of their elective surgery and the fact that they were randomised within the Amaze trial. The surgical CRF describing the research intervention (maze procedure or no maze procedure) was placed in a sealed envelope labelled ‘The Amaze Trial’ and kept in the patient’s notes. Clinicians were able to access this information in the event of a serious adverse event (SAE) considered to be related to surgery. At discharge, the data management staff retrieved the sealed envelope and uploaded the procedure details onto a secure database, before resealing the envelope and returning it to the notes. Cardiologists who analysed electrocardiograms for the primary outcome and researchers recording HRQoL outcomes did not have notes, including the procedural information, available at the time of outcome assessment.

Interventions

Control arm

The Amaze trial was planned as a pragmatic trial, following standard treatment and care as closely as possible in order to assess outcomes in a real-world context. Patients randomised to the control arm received preoperative management, elective or in-house urgent cardiac surgery and postoperative management in accordance with standardised hospital protocols.

Experimental arm

Patients randomised to the experimental arm received preoperative management and elective or in-house urgent cardiac surgery, as described in standardised hospital protocols. During the operation, the conduct of the adjunct maze procedure and the choice of lesion set was at the surgeon’s discretion. At the time of trial design, there was no evidence for the superiority of one ablation device or one energy source over another. Therefore, any AF ablation device that was routinely used within the NHS by the investigators was permitted. This allowed surgeons to use the devices with which they were most familiar and comfortable, and which were in routine use at their institution. These included bipolar and unipolar radiofrequency, ‘cut-and-sew’, cautery, cryotherapy, ultrasound, laser and microwave energy. Postoperative management, subsequent follow-up and data collection were identical to the control arm.

Standardisation between centres

In order to minimise potential confounding by other components of a patient’s care, the following aspects of the trial were standardised across participating hospitals.

Management of patients before, during and after surgery

Management was undertaken in accordance with the local site’s normal practice, irrespective of randomisation. The only exceptions were processes required to maintain the blinding of the patient, cardiologist and QoL interviewer (see Blinding).

Conducting and reporting on the adjunct maze procedure and defining the prescribed lesion set

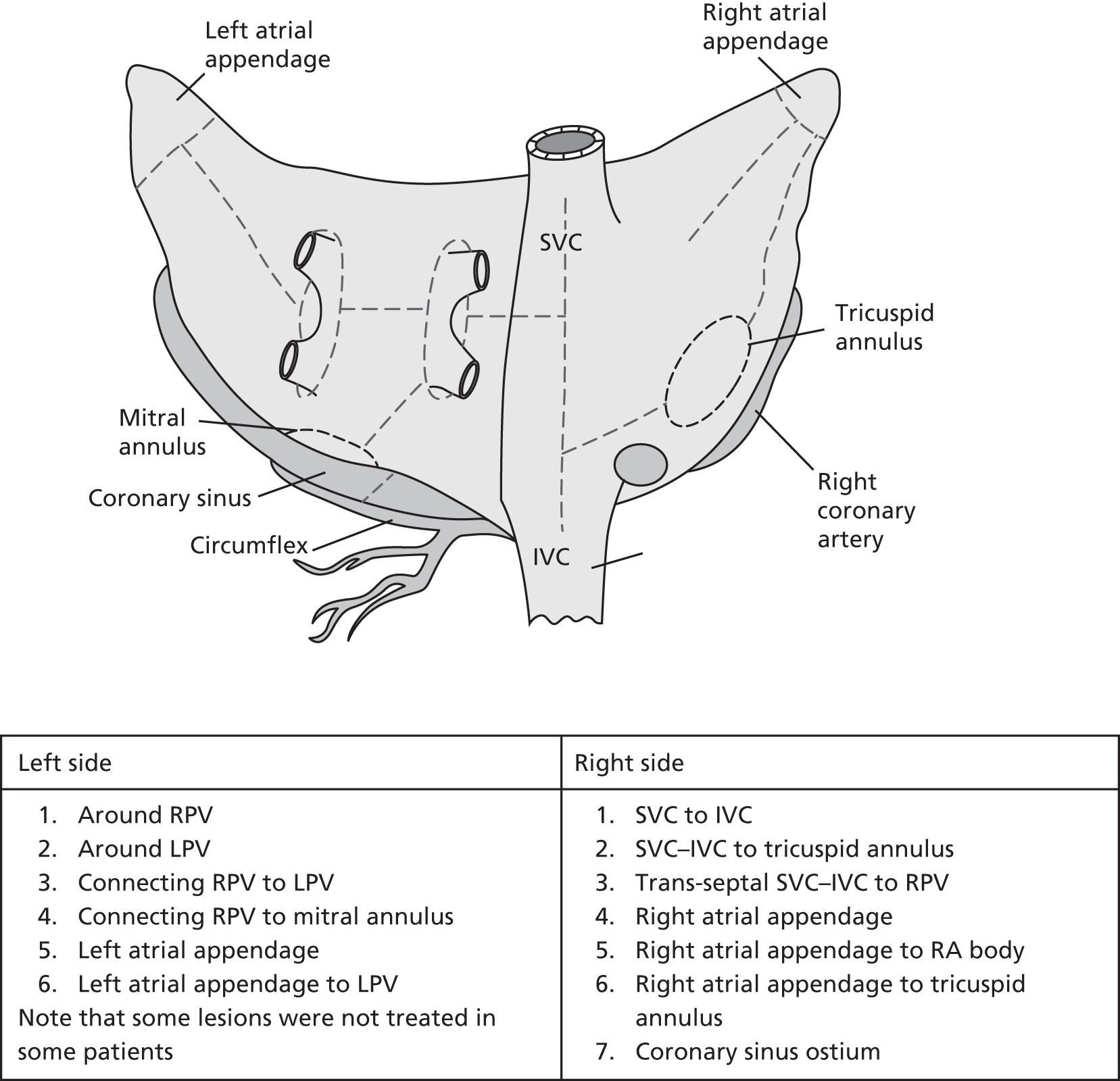

The full lesion set considered is illustrated in Figure 1, although the specific lesion set treated was left to the participating surgeon’s discretion. Details of the ablation procedure and all lesions treated were documented. Published guidelines for reporting data and outcomes for surgical treatment of AF were followed. 8,15

FIGURE 1.

Complete modified Cox maze procedure III lesion set. IVC, inferior vena cava; LPV, left pulmonary vein; RA, right atrium; RPV, right pulmonary vein; SVC, superior vena cava.

Postoperative drug use

-

Amiodarone: unless contraindicated, 200 mg three times per day was prescribed, reducing over a period of 3 weeks to 200 mg per day for 6 weeks. The drug was stopped if stable SR was established at 6 weeks. Further prescription after this period was based on individual clinical judgement.

-

Warfarin: prescribed until the patient was in stable SR. Thereafter, centres adopted normal practice.

-

Beta-blockers: prescribed at the individual clinician’s discretion.

-

Other drugs: prescribed at the individual clinician’s discretion; cardiac drugs with antiarrhythmic, antihypertensive and anticoagulant actions, including aspirin and warfarin, were documented.

Indications for cardioversion, timing and number of attempts

The protocol did not require cardioversion to be carried out at discharge, but if it was performed for clinical reasons, the details were recorded. For patients in AF at the first follow-up appointment, cardioversion was attempted within 3 months of surgery. If cardioversion was unsuccessful, then it was attempted again at 6 months after surgery.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Return to sinus rhythm at 12 months

Sinus rhythm at 12 months after surgery was determined by the absence of any AF on outputs from continuous monitoring by 4-day ECG recorders. All 4-day continuous ECG recordings were analysed centrally at Papworth Hospital. Participating hospitals forwarded the anonymised secure digital cards from the ECG recorders to Papworth Hospital. Analyses using the proprietary automated software package, together with manual checking of the recording in its entirety, were completed by cardiologists who were not aware of the patient’s identity or allocated treatment arm. Total time spent in SR and in AF (AF burden) during the 4-day recording was calculated. Episodes of atrial flutter were noted and included in the AF burden.

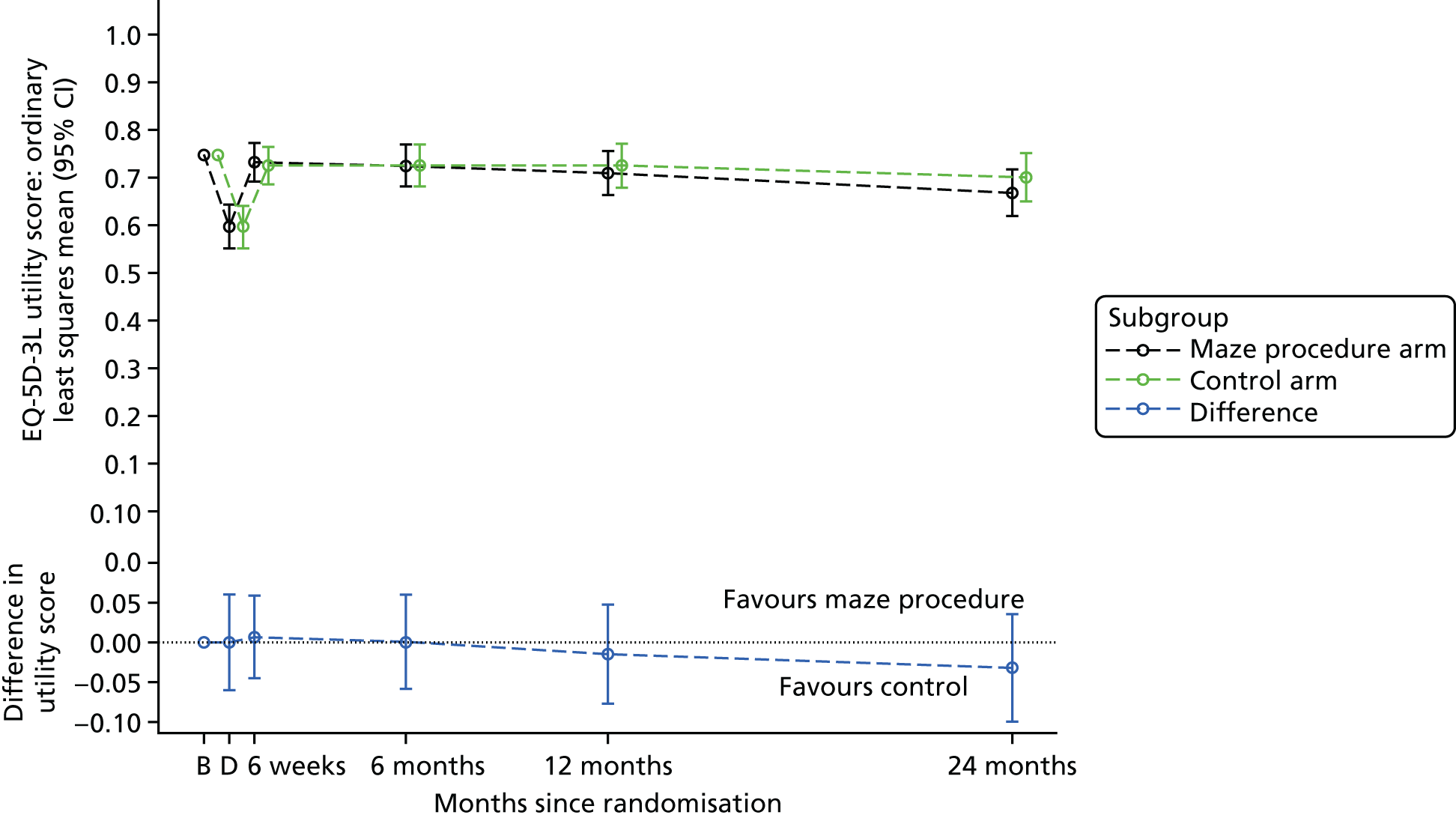

Quality-adjusted survival over 2 years

The EQ-5D-3L was administered at randomisation, on discharge and at 6 weeks and 6, 12 and 24 months after the procedure (Table 1). 44 Although the current version of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions has five levels for each item, when the Amaze trial was designed, the three-level version was recommended for the cost-effectiveness analysis. 45 EQ-5D-3L responses were converted into utility scores reflecting values from a representative sample of the UK population. 46 Clinical effectiveness was measured by quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) over 2 years using the area under the curve method (see Statistical analyses). 47

| Type | Questionnaire | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Generic | EQ-5D-3L |

|

| Generic | SF-36 |

|

| Specific | NYHA | Breathlessness was classified on a four-point scale:

|

Secondary outcomes

Sinus rhythm was determined by the absence of any AF on 4-day ECG recorders at 24 months after surgery. Other secondary outcomes were overall survival from the date of randomisation to date of death (all patients were registered with the Office for National Statistics’ tracking system to allow long-term follow-up of survival); stroke-free survival, defined as the time between randomisation and the date of stroke or death (whichever occurred first); incidence of hospital admission for (anticoagulant-related) haemorrhage, anticoagulant and antiarrhythmic drug usage up to 24 months after randomisation; HRQoL measured by the EQ-5D-3L, the SF-36 and the NYHA for breathlessness (completed at baseline, on discharge and at 6 weeks and 6, 12 and 24 months post surgery after randomisation); and resource use and trial-based cost-effectiveness of the adjunct maze procedure up to 24 months after randomisation.

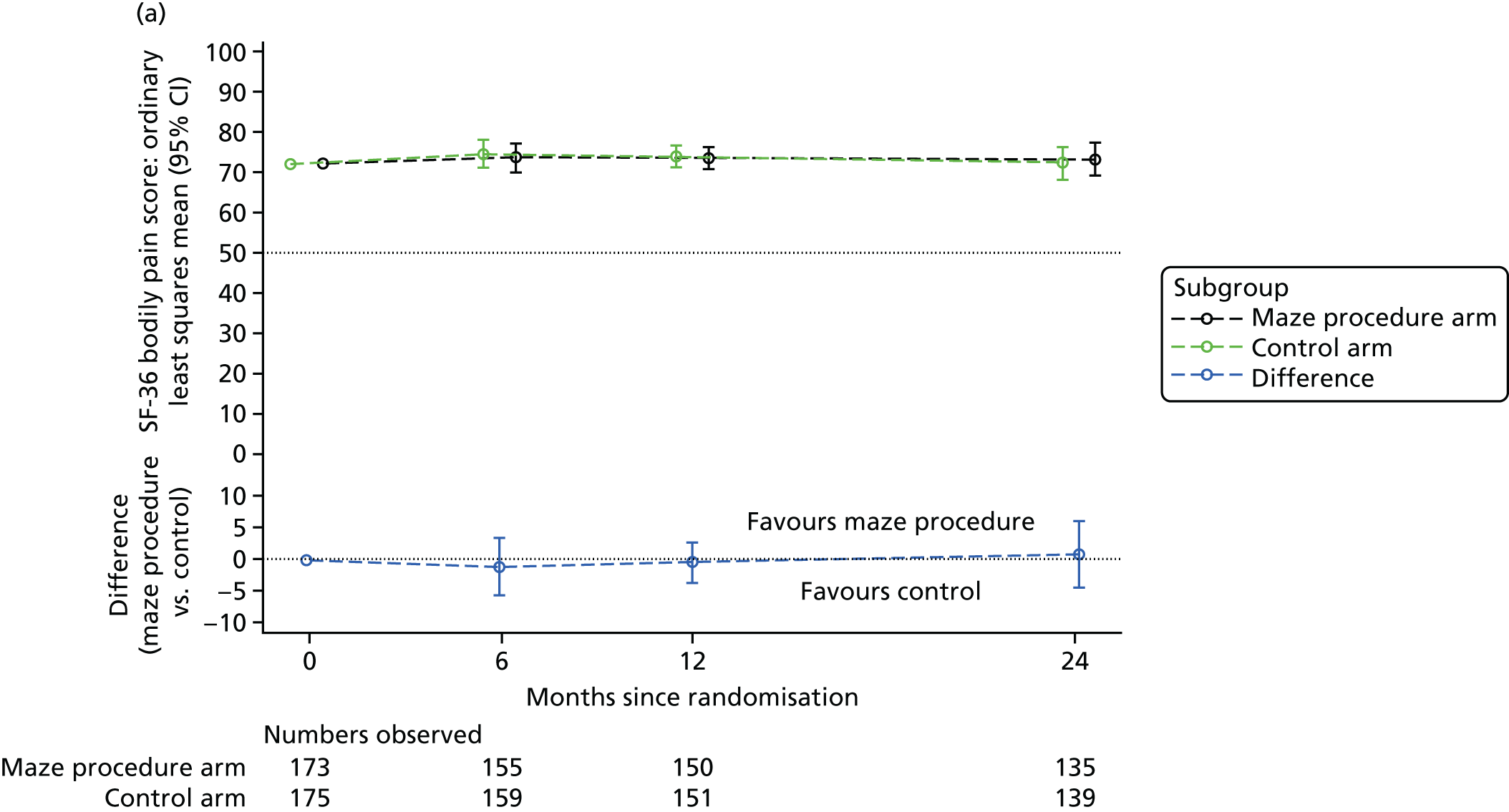

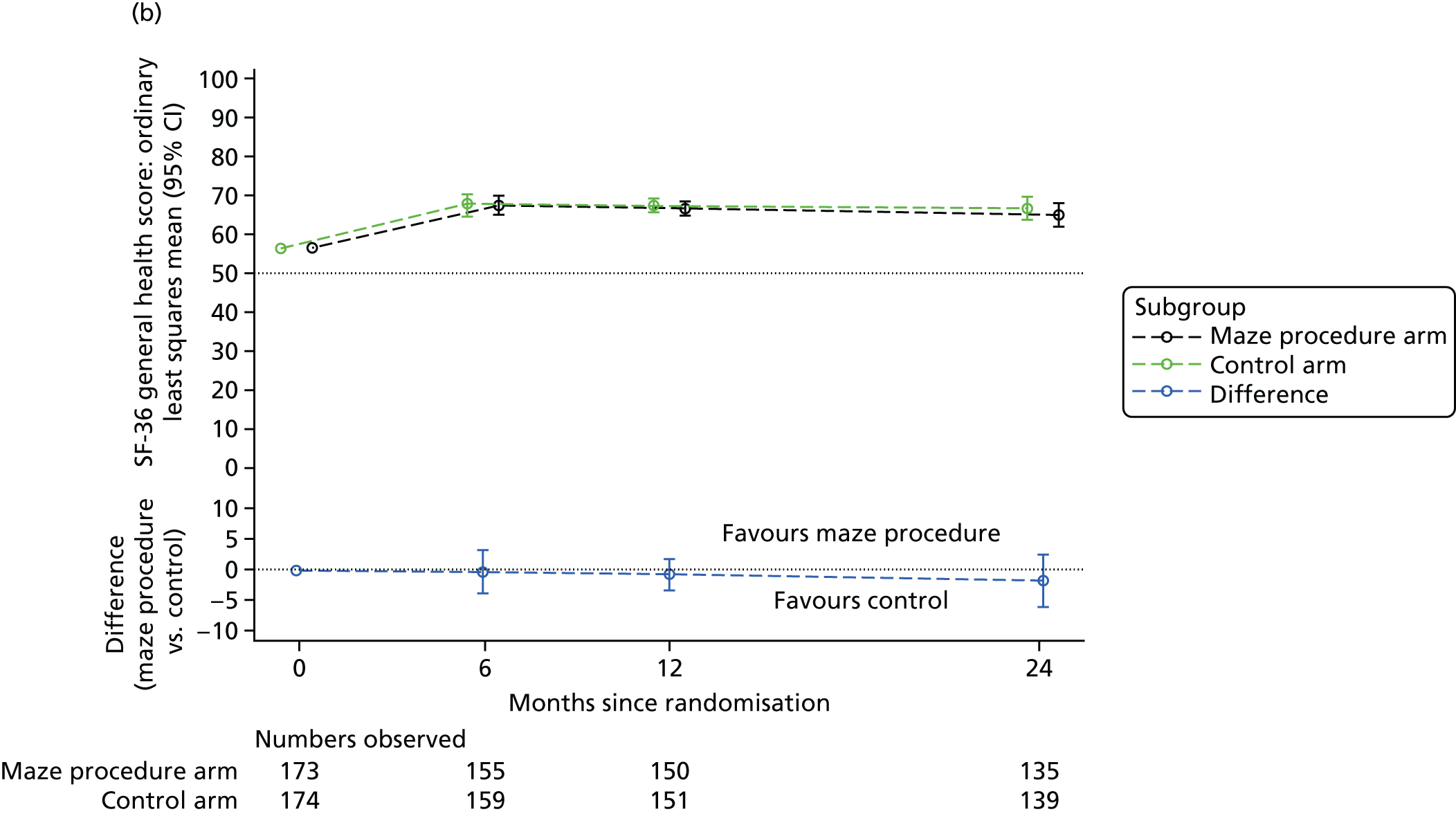

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality-of-life interviews were conducted by clinical research co-ordinators/research nurses in face-to-face interviews at hospital research clinics. Six-month questionnaires were administered by telephone, as patients did not have clinical appointments. The questionnaires administered are summarised in Table 1. The SF-36 consists of eight dimensions, which are the weighted sums of the questionnaire item responses. Each dimension ranges from 0 to 100, with a higher score representing better health or fewer limitations for that domain. Standardised physical and mental health scores were calculated, which, for a general UK population, are expected to be approximately normally distributed with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10. 48 For missing items, we used the methods recommended in the manual. 49 Briefly, if at least half the items were available for any scale, the mean of the recorded items was imputed for the missing items. If more than half the items for a scale were missing, then the scale was recorded as missing.

Sample size

The dual primary outcomes were a clinical end point (return to SR at 12 months) and an outcome of importance to patients and service providers (quality-adjusted survival over 2 years). The maze procedure was considered effective if there was a significant effect for return to SR or if the mean difference in QALYs between the groups did not include zero. No adjustments were made to the sample size to accommodate the multiple testing of these two outcomes, which is inherent in this approach, as the focus for the QALY end point was on estimation of the treatment effect, rather than hypothesis testing. However, to guard against overinterpretation of hypothesis tests, we recommend that p-values between 0.025 and 0.05 are considered to have borderline significance.

Return to sinus rhythm at 12 months

Prior to the trial, published RCTs of ablation as an addition to cardiac surgery reported rates of return to SR at 12 months ranging from 44% to 87% in the maze procedure arms, and from 5% to 33% in the control arms. 19,22 We took a conservative estimate of the difference between the arms (45% vs. 30%) as the target effect. In order that a realistic recruitment target was achieved, 80% power was used in the calculation. Combining this with a two-sided significance of 5%, an estimated sample size of 176 in each arm (total of 352) would be sufficient to detect this effect. With planned recruitment of 400 patients, this allowed for approximately 15% death/loss to follow-up at 12 months.

Quality-adjusted survival over 2 years

The emphasis in cost-effectiveness studies is on estimation, rather than hypothesis testing, so that formal sample size calculations were considered less important. However, we provided a power calculation based on the effectiveness measure ‘QALYs at 2 years post randomisation’. We could find no studies reporting comparative QALYs in similar patients undergoing ablation and cardiac surgery. From previous studies of patients undergoing angiography for suspected ischaemic heart disease and patients with refractory angina, the SD of QALYs over 12 and 18 months was at most 0.3. 50,51 Over 2 years, the minimum clinically important improvement was considered to be 1 extra month of quality-adjusted life or 0.083 QALYs. With a sample of 200 patients per arm (total of 400), we would have exactly 79% power to detect a difference of 0.083 QALYs (at a two-sided significance of 5%).

If the accepted threshold for cost-effectiveness was in the range £20,000–30,000 per QALY and we could demonstrate a significant increase in QALYs of 0.083, then the procedure would be cost-effective for an incremental cost of, at most, £2500.

Failure to reach target recruitment

Based on audit data, our target recruitment of 400 patients was expected to be achieved in 18 months at six centres. Owing to the slower than expected accrual, recruitment terminated in September 2014, when 352 patients had been randomised, with approximately 70% power to identify the target treatment effects.

Analysis populations

Intention-to-treat population

The primary analysis used the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, defined as all randomised patients, regardless of eligibility, withdrawal, compliance with the protocol, loss to follow-up or actual treatment received. No patients withdrew consent for their data to be used, despite withdrawing from trial follow-up. Multiple imputation was used for missing primary outcomes.

Quality-of-life population

For each instrument (the SF-36 and the EQ-5D-3L), all patients who returned a completed baseline questionnaire, regardless of subsequent questionnaire return, were included in the analysis. In addition, imputation (based on planned procedure and centre) of missing baseline EQ-5D-3L scores was completed for two patients.

Safety population

All patients were included in the safety population if they underwent a surgical procedure. Patients were included in the arm corresponding to the intervention received (maze procedure completed vs. no maze procedure).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses and reporting complied with CONSORT guidelines where possible. 52

Formal analyses were conducted using a two-sided 5% level of significance, with no adjustment for multiple testing. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The statistical analysis plan is provided in Appendix 1.

In descriptive summaries, the number of non-missing items and the mean (SD) or median (upper and lower quartiles) were summarised for continuous variables, and the number and proportion by treatment arm were summarised for each level of categorical variables.

Return to sinus rhythm

The odds of being in SR for maze procedure patients was compared with the odds for control patients, and estimated using a binary logistic regression model, including surgeon (normal random effects on the logistic scale), baseline heart rhythm and planned surgical procedure (fixed effects). The odds ratio (OR) for return to SR was reported with the 95% CI and p-value from this model. Validity of logistic regression models was assessed by examining the following statistics and graphical summaries:

-

Pearson residuals/deviance (half-normal plots)

-

leverage values

-

Cook’s distance

-

cross-validation probabilities (the probability of a particular observation, conditional on the remaining observations)

-

L-statistics (the influence of an observation on the difference in deviance as a result of fitting the treatment effect).

The percentage of time in AF across the 4 days of monitoring at baseline and at 12 months was summarised by treatment arm.

Quality-adjusted survival

For the primary outcome, QALYs over 2 years were estimated from serial measurements of the EQ-5D-3L for each patient. The UK social tariff for the EQ-5D-3L, completed at baseline and on discharge, and at 6 weeks and 6, 12 and 24 months post surgery, as estimated by Dolan et al. ,46 was applied to calculate utility values. Using actual rather than nominal times of assessment, and assuming a linear change in values between time points, patient-specific utility curves up to 24 months post randomisation were calculated. A value of zero was assigned at the date of death for patients who died. QALYs were calculated as the area under the utility curve to 24 months or date of death, whichever occurred first. In order to adjust for differences in baseline utilities, a linear regression was fitted to the utilities post treatment, with baseline utility and treatment arm as explanatory variables. For patients who did not complete all EQ-5D-3L questionnaires or those who were censored, multiple imputation was used to estimate mean QALYs (see Missing data). Model fit was assessed by examining standardised residuals and association with the predicted values, as well as identifying influential observations by referring to leverage statistics. A CI for the true difference in QALYs was estimated using a non-parametric bootstrap resampling approach. 53

Note that, for the primary outcome analysis, no discounting of the QALYs estimates was applied. However, when costs and benefits were estimated for the health economics analysis, both were discounted at 3.5% for the second year.

Missing data

Proportions of, and reasons for, missing data were investigated.

For the clinical primary end point (return to SR at 12 months), if a patient withdrew consent or was lost to follow-up within 12 months, the missing outcome (AF or SR at 12 months) was multiply imputed as a function of the baseline heart rhythm, surgeon, surgical procedure and treatment arm. 54 Rubin’s rules were used to combine imputed data sets. 55

For the patient-based primary end point (QALYs), whereby a patient died before the end of follow-up, the utility value of 0 was imputed for all subsequent assessments. If the response was missing, and the patient was alive, the missing value was imputed using the method of multiple imputation. 54 A number of sensitivity analyses related to missing data were completed; further details are provided in Appendix 1. In response to a reviewer’s request, we also provided a supportive analysis using complete cases, but with predictors of missingness included in the model.

Subgroup analysis

Prespecified subgroups are listed above (see Exploratory analysis).

For the SR end point, a logistic regression model was fitted to heart rhythm at 12 months, including baseline heart rhythm, surgeon, surgical procedure, treatment arm and subgroup variable of interest and its interaction term with the treatment arm. Within-subgroup treatment effects and the interaction effect between subgroup and treatment arm were estimated with 95% CIs and p-values.

For the QALYs end point, a linear regression model was fitted to the area under the utility curve, with baseline EQ-5D-3L score, surgeon, surgical procedure, treatment arm, subgroup variable and the subgroup-by-treatment interaction variable.

Because analysis revealed an increasing OR for the maze procedure arm relative to the control arm as the trial progressed, we explored changes in baseline characteristics, surgery and cointerventions throughout the trial in an attempt to explain this finding.

Secondary end point analysis

Return to stable SR at 24 months was analysed in a similar way to return to SR at 12 months, using a binary logistic regression model, including baseline heart rhythm, surgeon, surgical procedure and treatment arm.

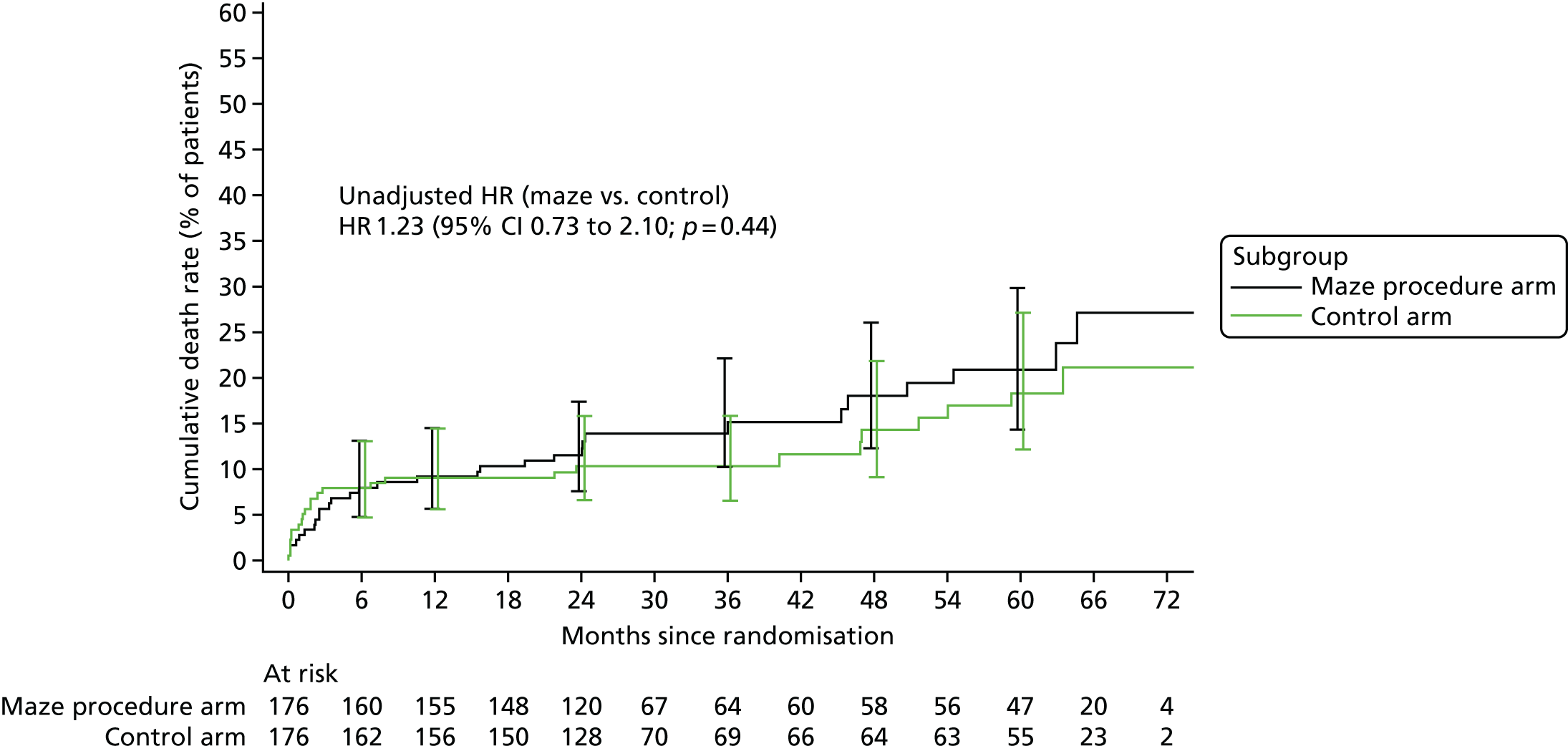

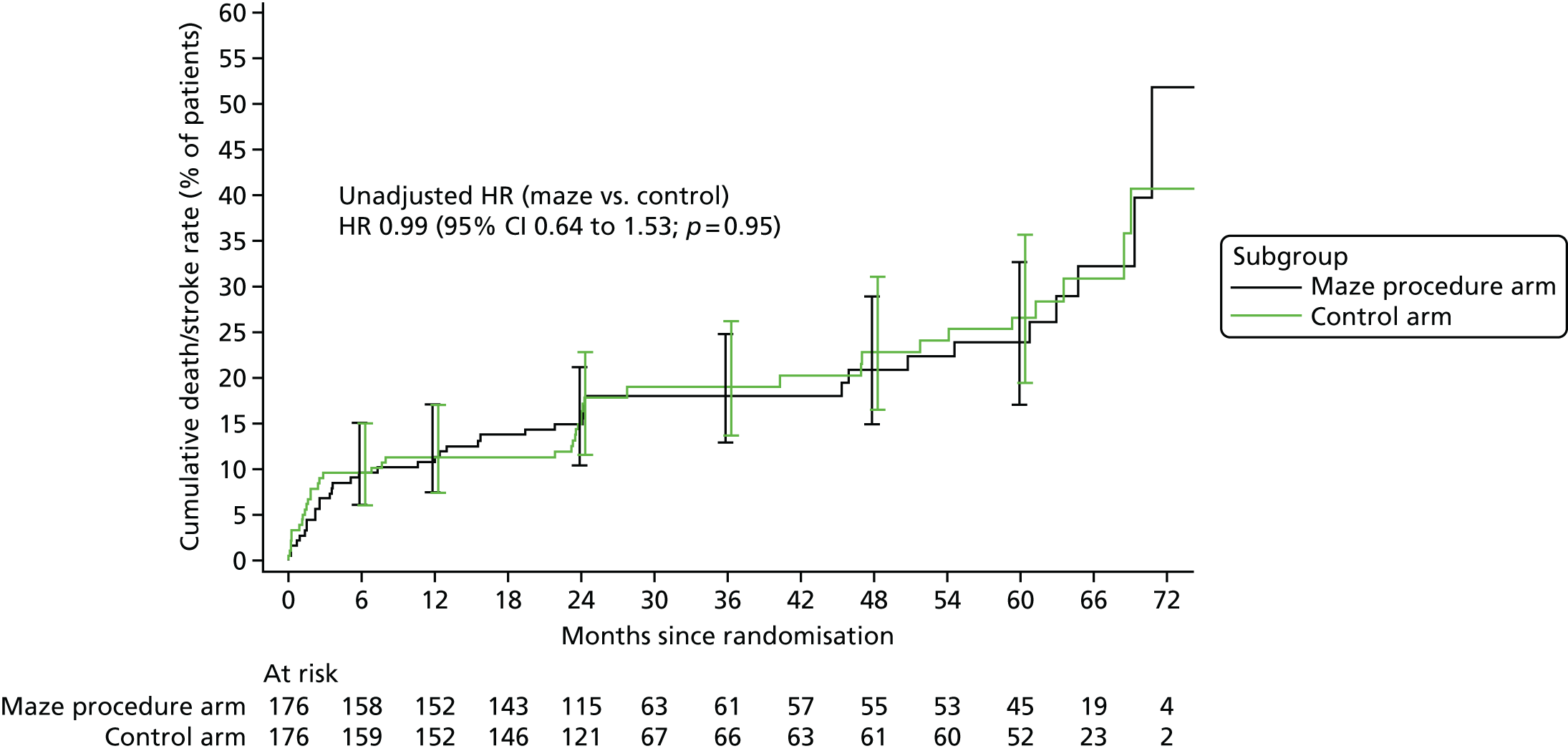

Overall survival was summarised using Kaplan–Meier methods for the time between randomisation and death. Patients who were alive at the end of the study, or who withdrew before the end of follow-up, were censored at the date they were last seen. Similarly, stroke-free survival, defined as the time between randomisation and the date of stroke or death, whichever occurred first, was summarised using Kaplan–Meier methods. Patients who were alive and stroke free at the end of the study, or who withdrew without having suffered a stroke before the end of follow-up, were censored at the date they were last seen. Cox regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for maze procedure patients relative to control patients.

Patients who had a stroke within 12 months of surgery, and the overall proportion of stroke events, were calculated by treatment arm, using the total number of patients participating in the trial as the denominator. The relationship between stroke and treatment arm was tested by Fisher’s exact test, and the difference in stroke rates was reported along with 95% CIs for differences in proportions.

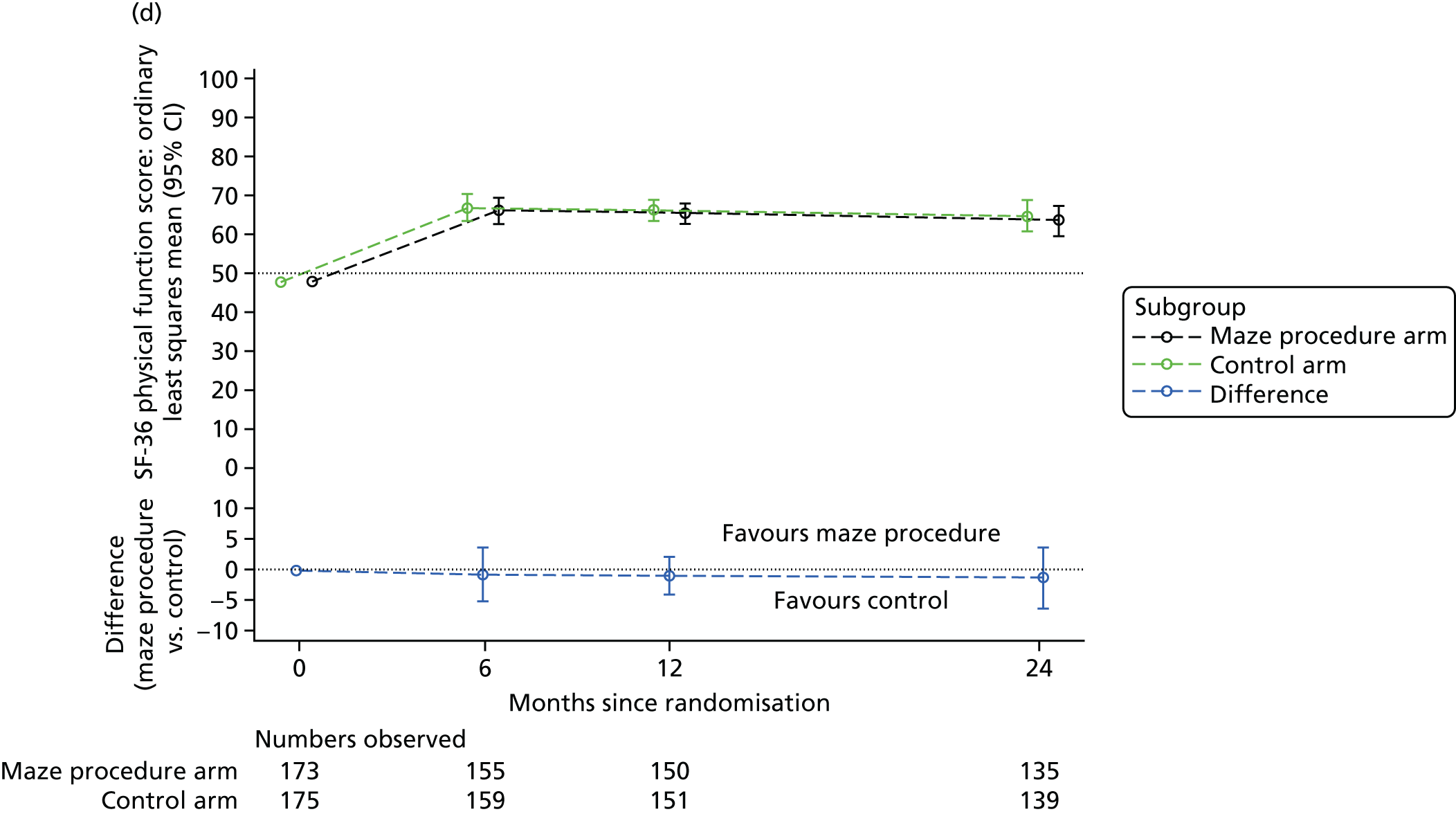

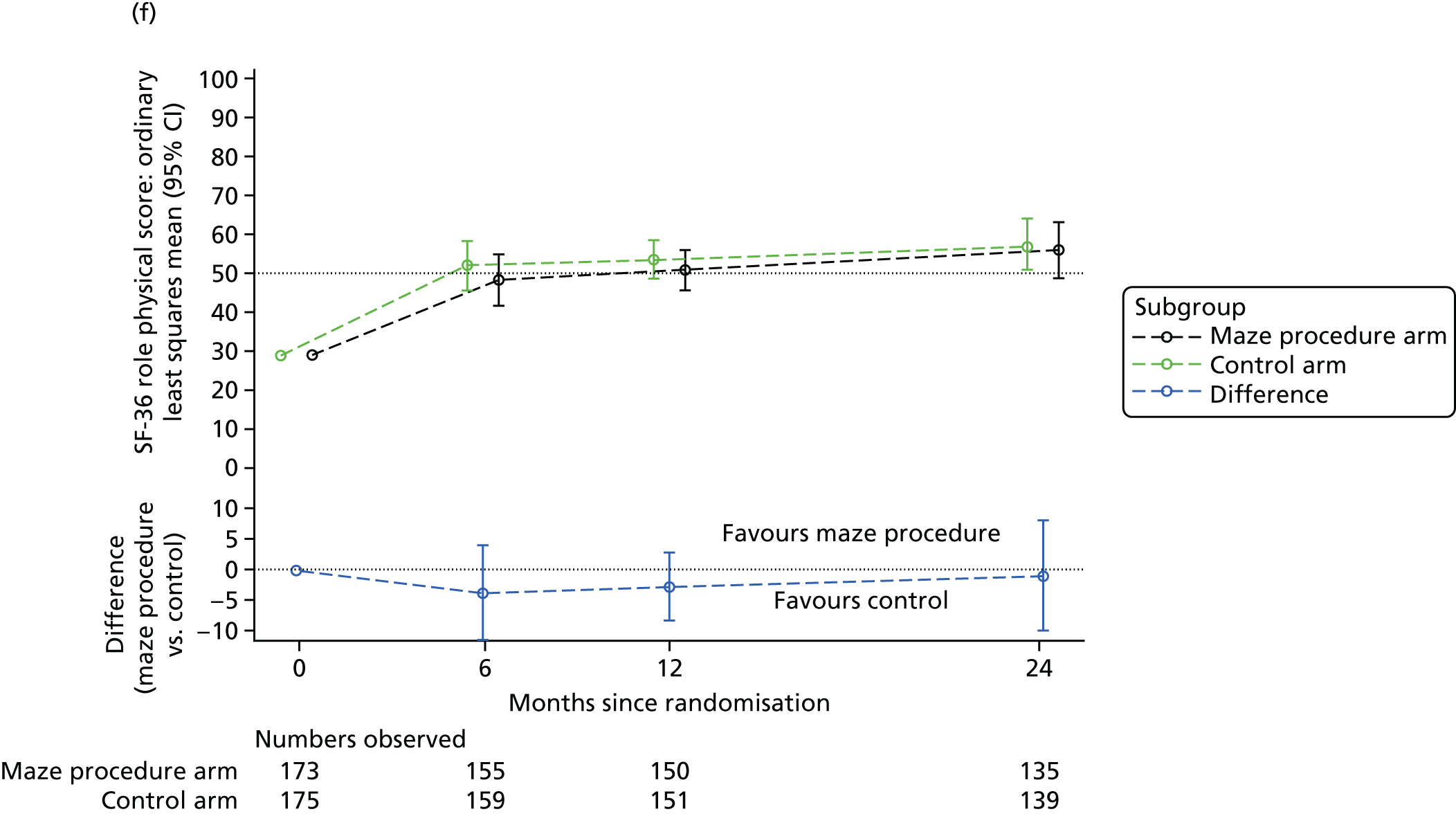

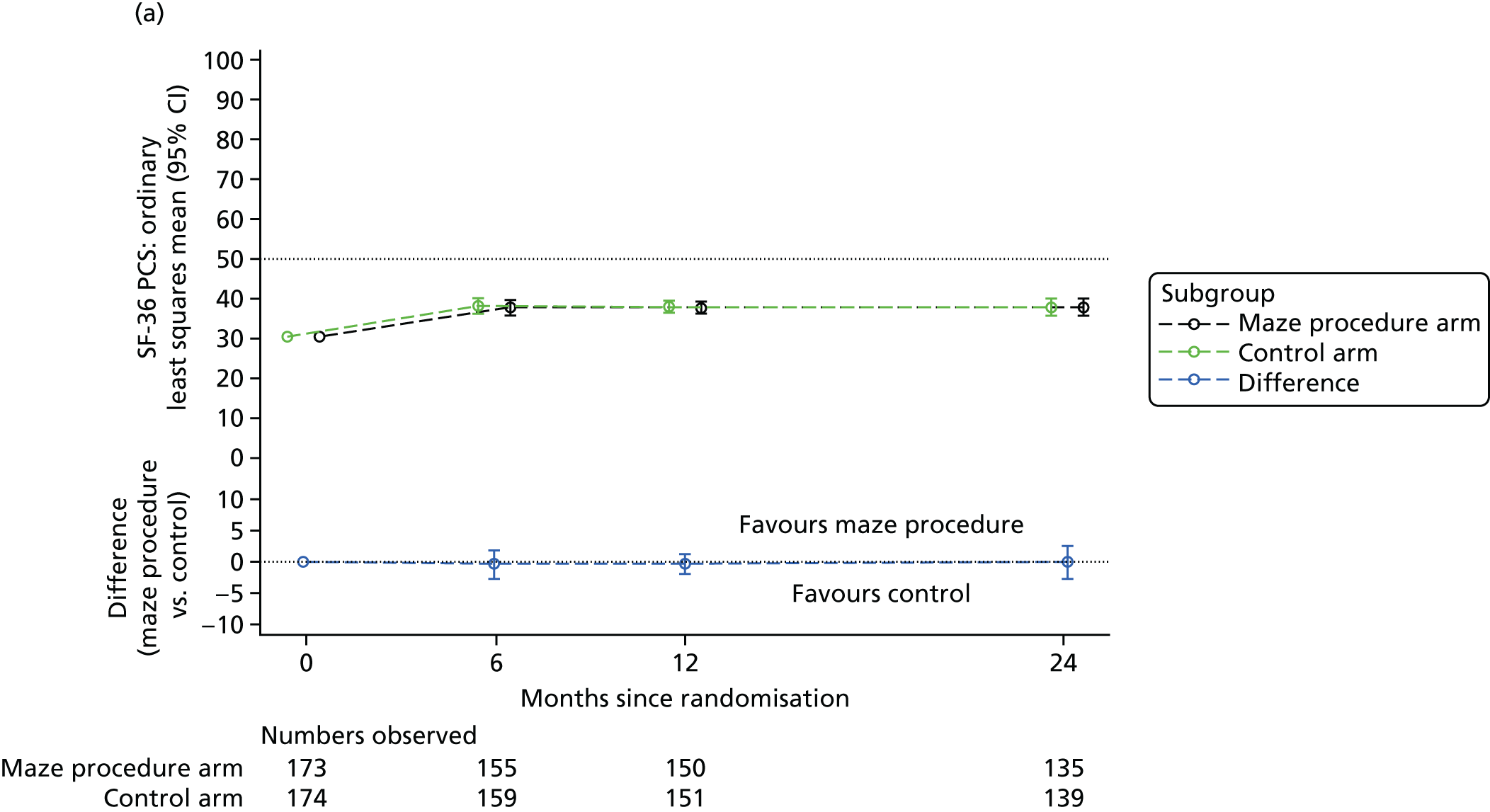

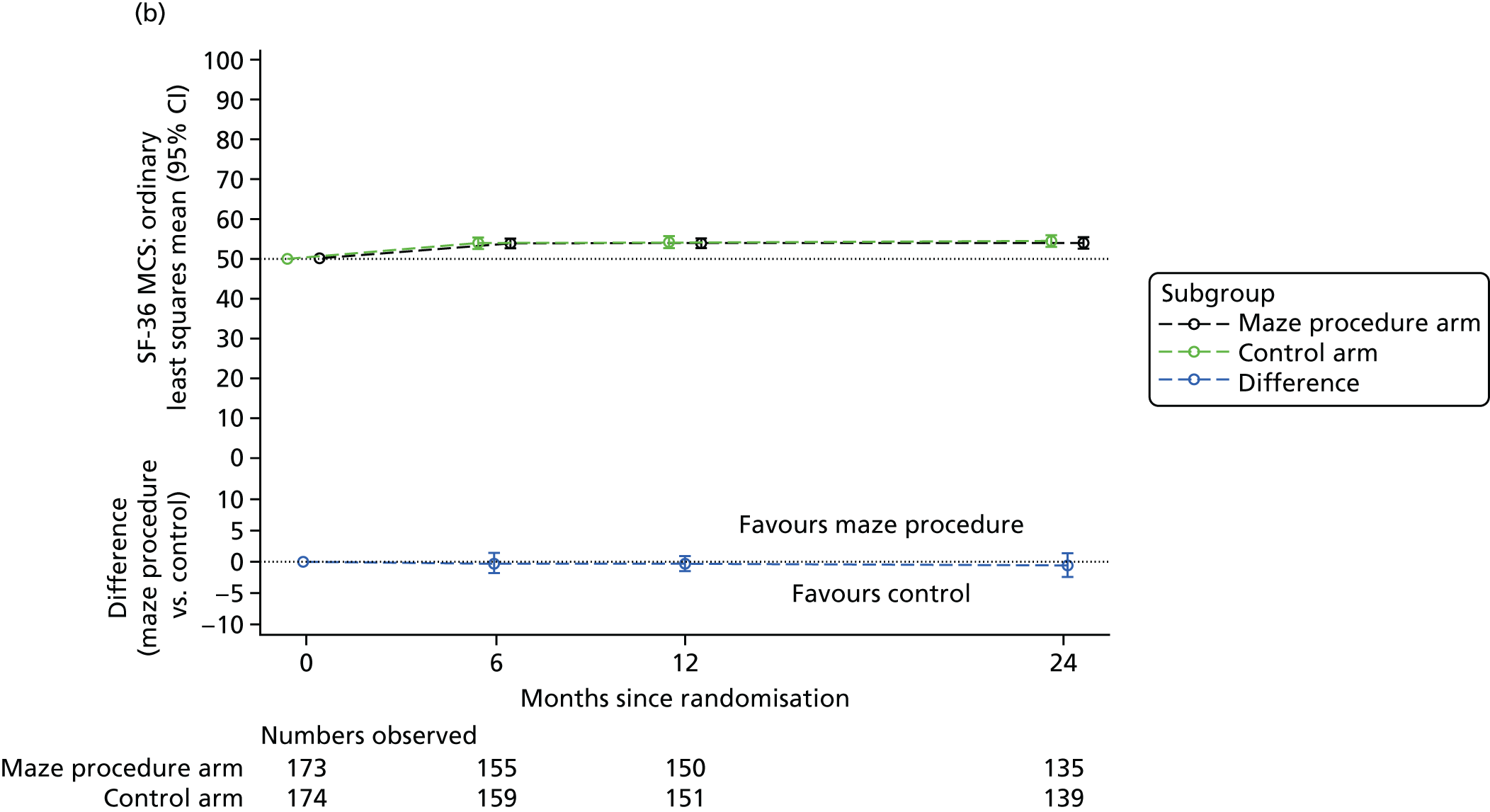

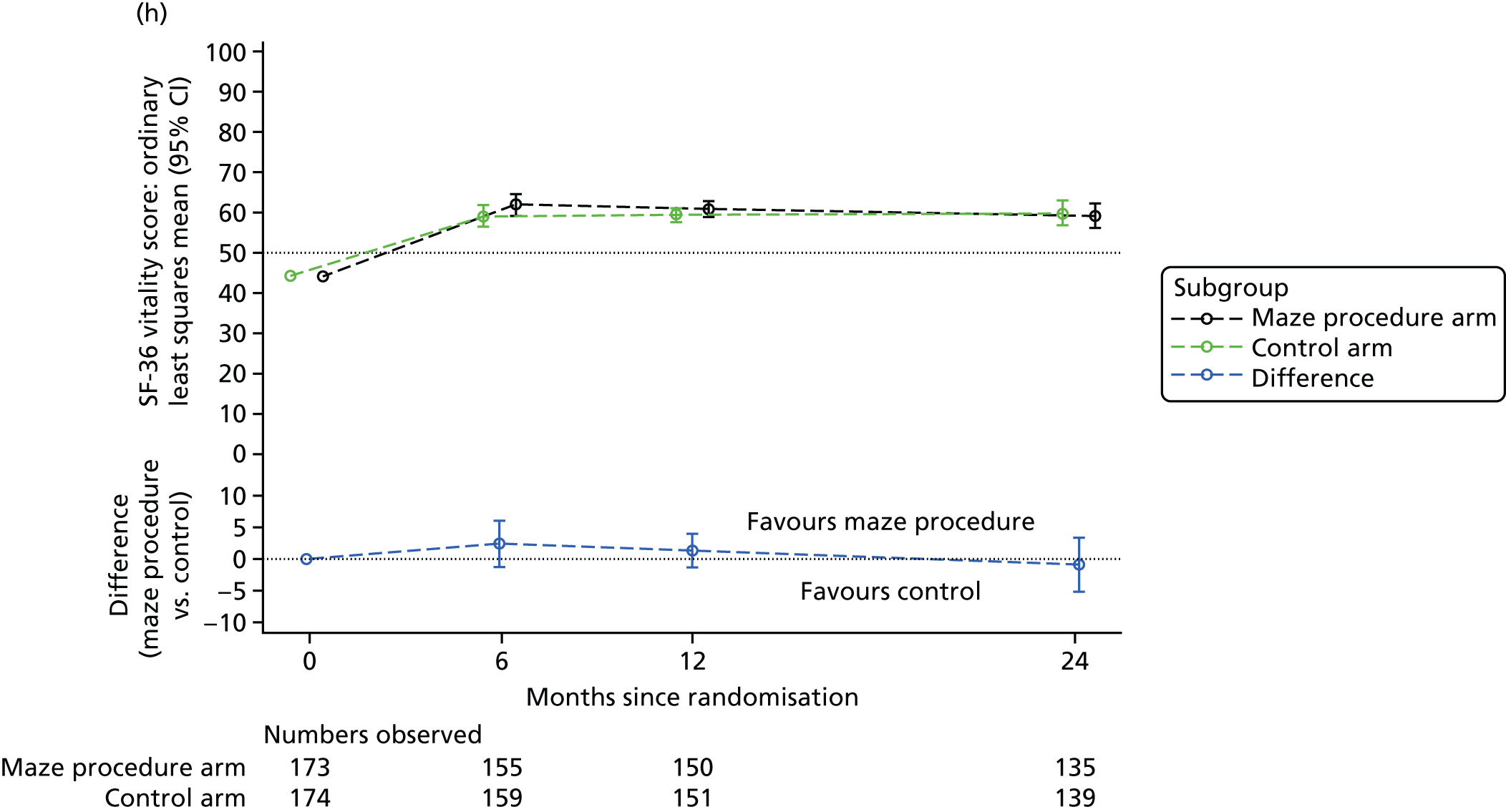

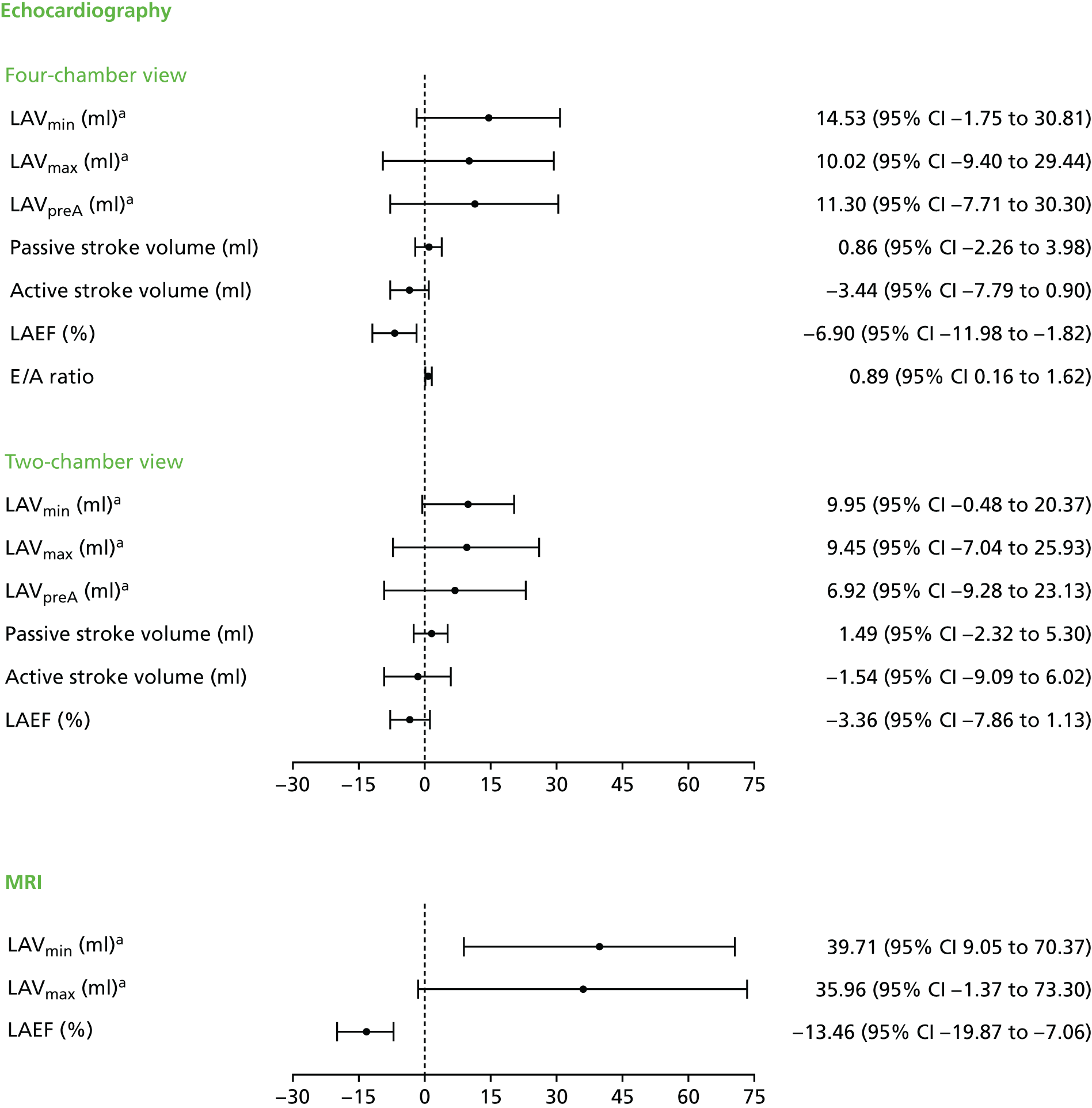

Short Form questionnaire-36 items dimension scores and summarised mental component score (MCS) and physical component score (PCS) were analysed using a linear regression model, including time point, treatment arm, time-by-treatment-arm interaction and baseline SF-36 scores (all modelled as fixed effects), and allowing random intercepts for patients.

Drug use for each arm was tabulated by time point (at baseline, discharge, 6 weeks and 6, 12 and 24 months) and drug category. Logistic regression for the outcome of each patient (1 = have one or more drugs during time period t, 0 = have no drugs during time period t) was fitted, including drug category, time period of drug usage, baseline drug usage and treatment arm as independent variables. ORs were estimated with 95% CIs and p-values.

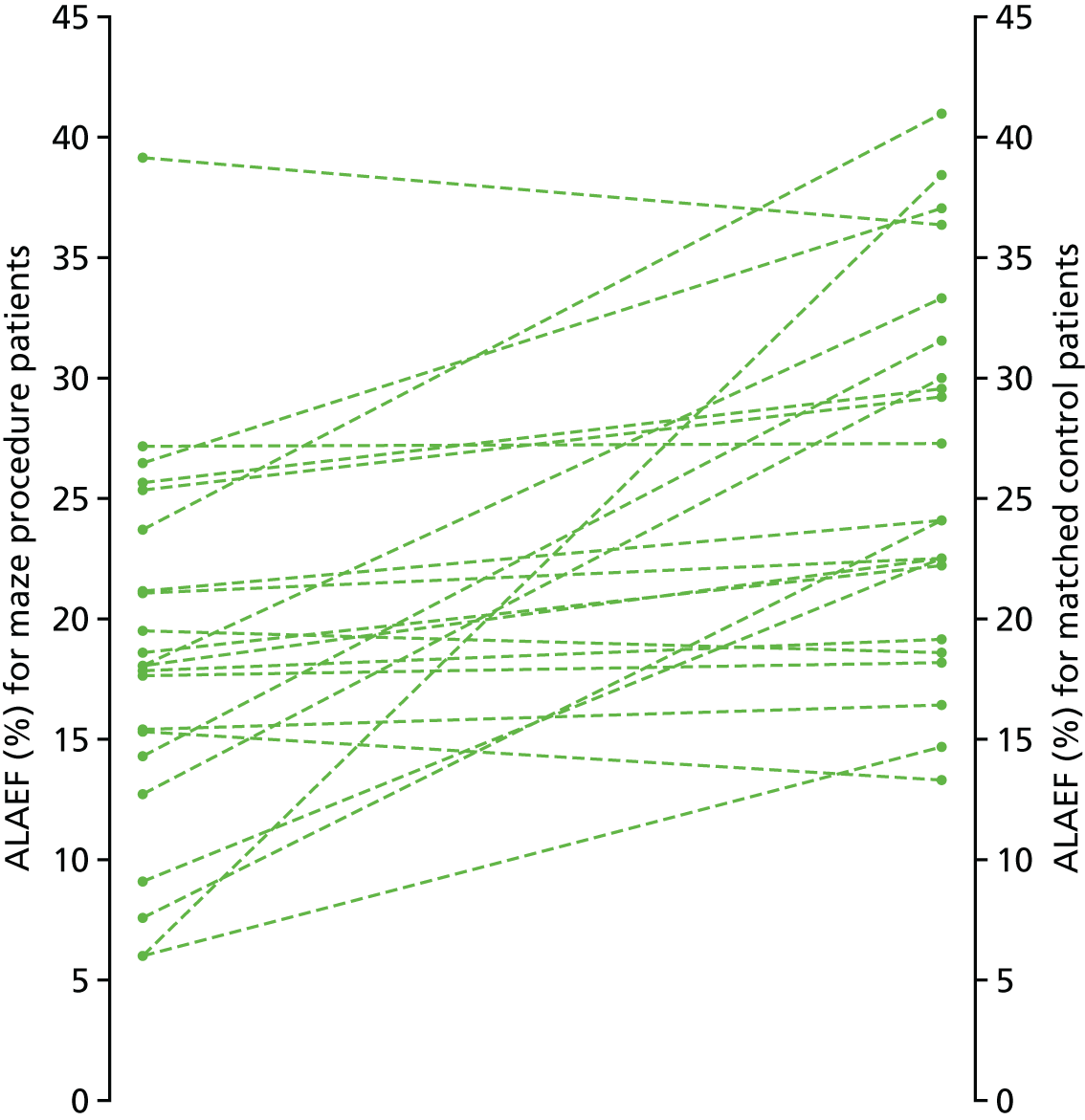

The occurrence of atrial flutter and atrial tachycardia (organised atrial arrhythmia) and junctional rhythm were summarised by arm. The relationship between the completeness of the lesion set and the occurrences of organised atrial arrhythmia and junctional rhythm was tabulated.

Safety analysis

The number of AEs in each category and deaths from any cause were summarised by treatment arm, corresponding to the treatment received. Events were summarised according to whether or not they met the criteria of SAEs, severity and relationship to the procedure.

Economic analysis

Data collection and sources

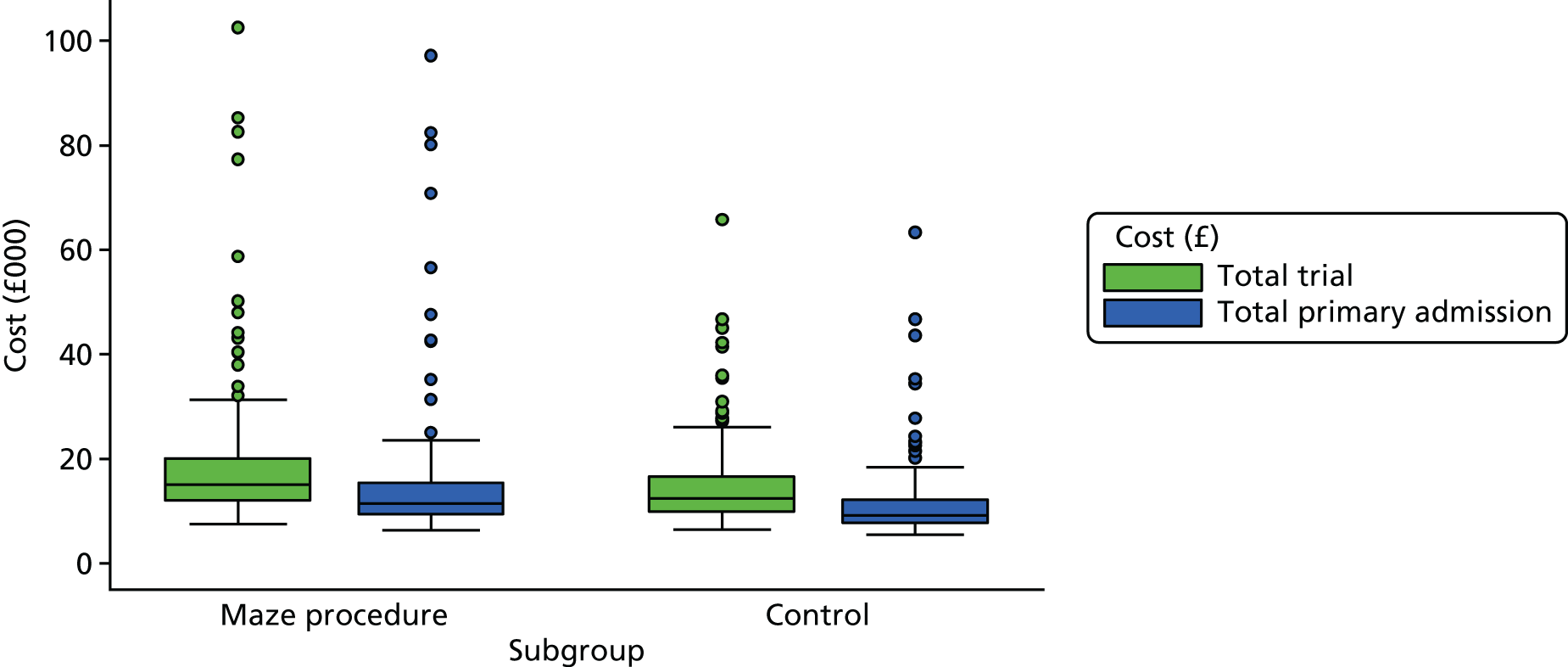

NHS resource use was collected during primary admission and at the 6-week and 6-, 12- and 24-month follow-ups. Research nurses/clinical trial co-ordinators extracted data about inpatient stay from individual patient records and administered bespoke questionnaires about follow-up health service use either face to face or by telephone/post (for those who missed an appointment). Hospital records were checked to validate patient-reported hospital readmission.

Resources related to the primary admission (from randomisation to discharge) included theatre use (initial operation and returns to theatre), intensive care (days) and cardiac and acute care wards (days). The total length of stay was compared with the sum of recorded days in an intensive care unit (ICU) and ward, and any double-counting that was identified was subtracted. For patients who were not discharged home, subsequent admissions to rehabilitation centres or acute hospitals were added. Surgery-specific resource use, including equipment and energy sources for the maze procedure, were retrieved from patient notes.

The resource use recorded during follow-up was divided into three categories: hospital readmissions (length of stay in hospitals or rehabilitation centres), 16 types of test [e.g. cardiac related, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and radiographic] and 12 types of health-care visit [e.g. accident and emergency (A&E), outpatient, primary and community health services]. In all resource-use calculations, a value of zero was assigned to any unused resource item, including all resource items after death.

Medication use was limited to antiarrhythmic, anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs and seven classes of cardiac drugs (beta-blockers, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and statins). The daily dose of each drug type was based on patient record review for inpatient stay and patient reports after discharge. As specific drug names were not recorded for cardiac drugs, the chief investigator (SN) identified the most likely drugs to be prescribed, and the daily dose was taken to be the most common reported daily dose in the CRFs for that category of drugs. For example, bisoprolol and atenolol were the assumed drugs when beta-blocker was indicated, with the dose equalling that reported by 90% of respondents.

The total amount of each drug used per patient was estimated by taking a mid-value of daily dose at consecutive follow-up time points, multiplied by duration between follow-up time points, and costed using the NHS Prescription Services Electronic Drug Tariff56 and the British National Formulary (2016). 57 Missing drug use at each time point was replaced, depending on the nature of missingness, as follows: patients who died were assigned zero medication use from date of death; if a patient indicated use of a drug at only one follow-up, the duration was taken to be the mid-point between this and the next follow-up (except for drugs recorded only at baseline, which were excluded, as the trial focused on drugs post randomisation). For patients who either had completely missing drug data at a follow-up time point or were lost to follow-up, costs were multiply imputed using chained equations with predictive mean matching, stratified by treatment arm (see Missing data).

Unit costs were multiplied by the frequency of resource use to provide total resource cost for each item. National estimates of unit prices were sourced58,59 to increase generalisability. For resources for which national prices were not available, estimates were sourced either from the literature (e.g. 24-hour blood pressure monitoring and chest radiography) or from Papworth Hospital (e.g. theatre cost and cost of device). The hospital and community health services pay and price index58 was applied to adjust for inflation when necessary (see Appendix 2, Table 23). The ablation device was costed at £3000 per patient for high-intensity focused ultrasound, and £1250 per patient for all other methods. All resource costs, from the date of operation (randomisation) up to 2 years post randomisation, were summed, with year 2 costs discounted at 3.5%. 45

Health-related quality of life, assessed using the EQ-5D-3L and SF-36 questionnaires, was an important outcome, and is described in Secondary end point analysis. SF-36 health state responses were converted to the Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) utility scale using values from the UK population. 47 QALYs, as described in Statistical analyses on page 12, were discounted at 3.5% in year 2 for the cost-effectiveness analysis. 45

Missing data

Missing baseline variables that were required for the imputation model, for example missing baseline EQ-5D-3L assessments, were replaced by the mean value for each trial arm. 60 Logistic regression identified variables that were related to missingness.

Missing resource use and utility data were imputed jointly using chained equations with predictive mean matching. The imputation models included age, sex, paroxysmal AF and baseline EQ-5D-3L score, and were stratified by trial arm. A total of 60 imputed data sets were created to attain a stable imputation. The distribution of imputed values was checked for comparability with observed data [e.g. counts of general practitioner (GP) visits, matched observations].

For 28 resource-use variables (tests and health-care visits), multiple imputation at each data collection point was not possible, as a result of the small numbers of events, and, therefore, the annual average for each resource-use variable was imputed for each arm. To assess the sensitivity of results to this assumption, an alternative imputation model was fitted, in which each test and health-care visit was multiplied by the corresponding unit cost. All tests and (separately) all health-care visits were grouped for each trial data collection point using total cost, and multiple imputation was applied to these categories of resource-use cost.

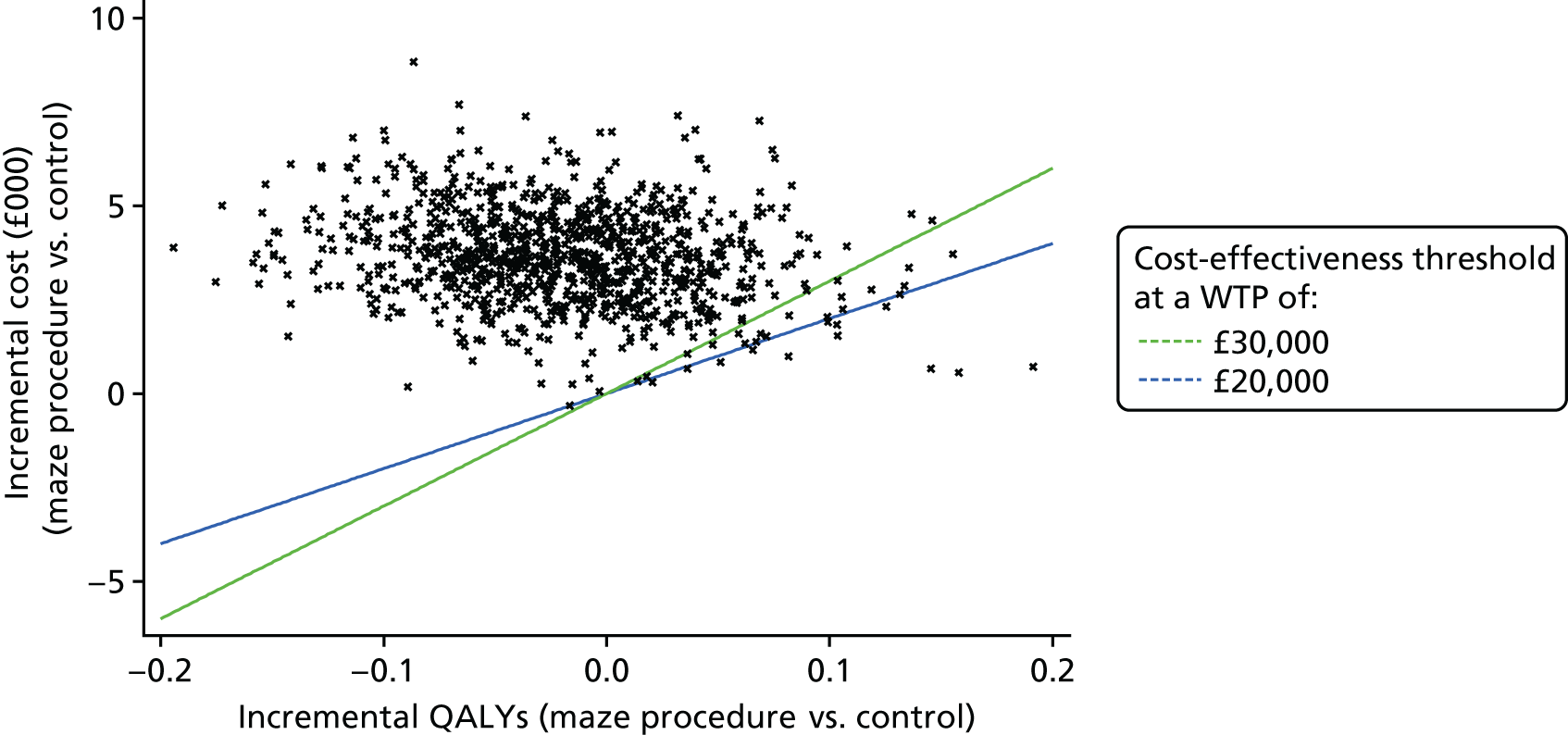

Incremental cost-effectiveness analysis and sensitivity analyses

Differences in estimated costs and QALYs between trial arms were explored using two-sample t-tests with equal variances. Linear regression analysis was used to adjust for differences in age, sex, baseline EQ-5D-3L score, AF at baseline and, for QALYs only, the primary surgery [isolated mitral valve replacement or repair (MVR), isolated CABG, isolated aortic valve replacement or repair (AVR), CABG and MVR, CABG and AVR and all others]. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated using adjusted mean estimates of costs and QALYs from ‘seemingly unrelated regression’, to allow for correlation between costs and effects at the patient level, and for skewness of data.

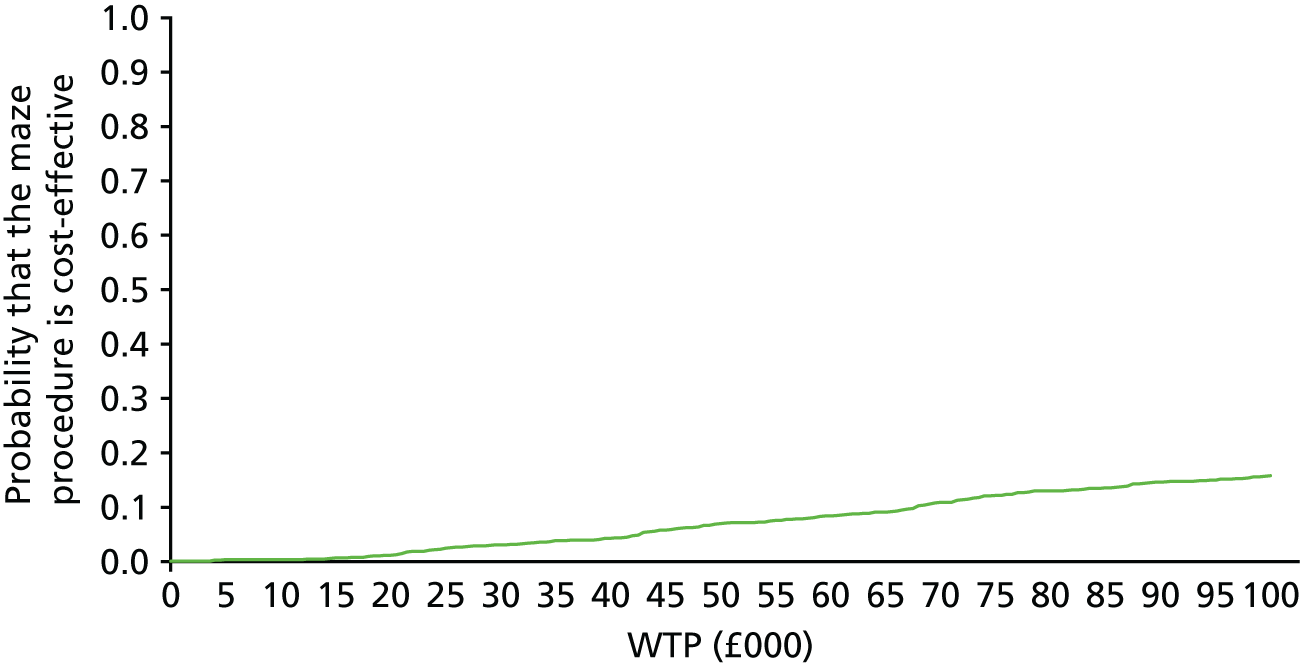

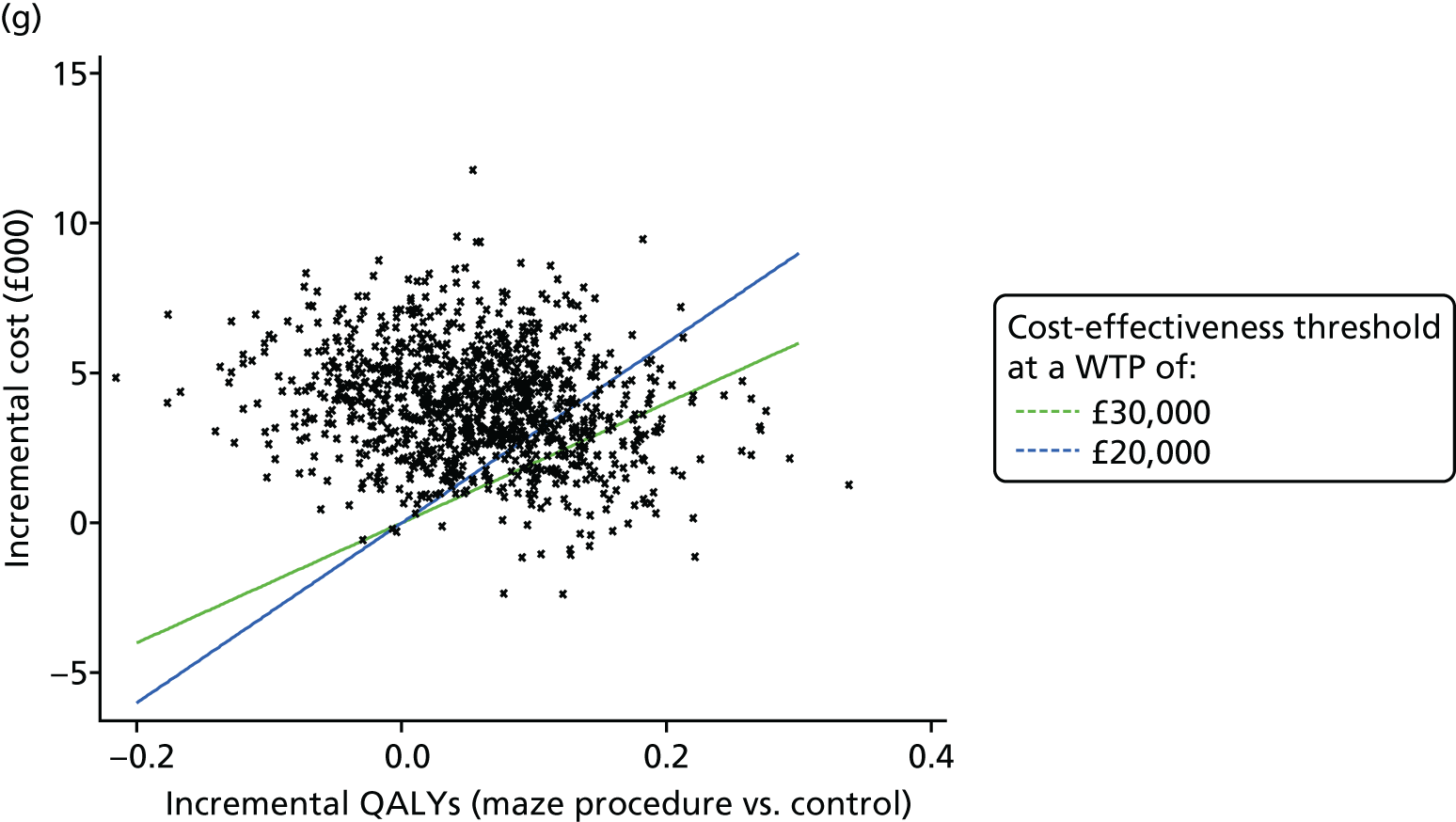

One thousand bootstraps were generated for each sample for the probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Costs for the resource-use components were sampled from gamma distributions and applied to the bootstrapped samples, and the total costs and QALYs for each sample were estimated using seemingly unrelated regression. The probability that the maze procedure was cost-effective was considered at varying willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold values, using cost-effectiveness planes, the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve and incremental net monetary benefit (INMB).

Deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were used to explore the robustness of cost-effectiveness results that adopted different methodological approaches or assumptions. These analyses included the use of SF-6D QALYs, clinical effectiveness as measured by conversion of AF to SR, complete case analysis, examining costs and QALYs only up to discharge, examining the impact of outliers, excluding maze device cost, limiting the patient group to those randomised from April 2001 (to match the time-based post hoc statistical analysis) and an alternative imputation technique. The probability distribution of unit costs could not be resampled when the alternative imputation technique was used, as the imputation was for cost at each follow-up point, rather than resource use.

Chapter 3 Trial results: clinical effectiveness and health-related quality of life

Recruitment and compliance

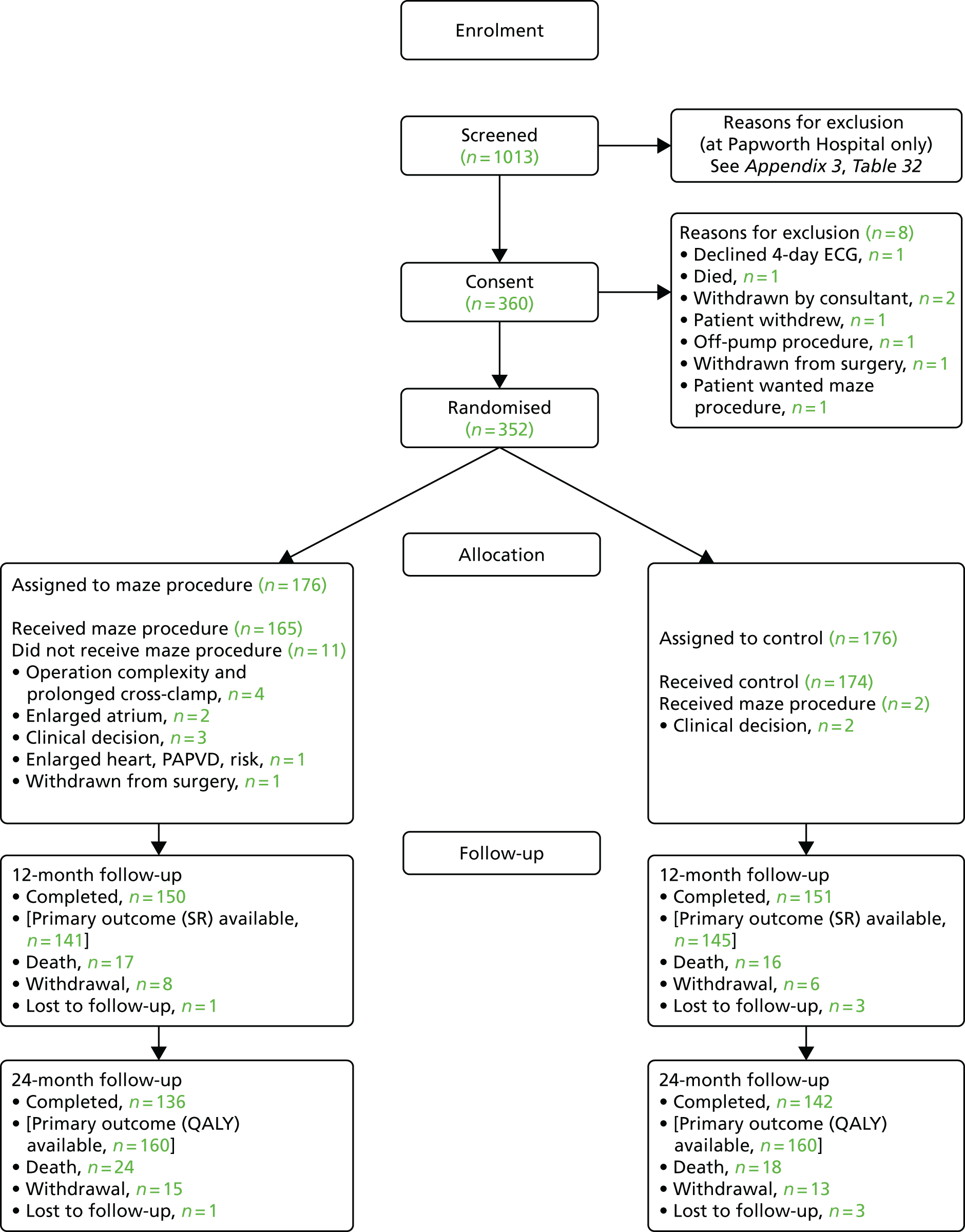

Between 25 February 2009 and 6 March 2014, 1013 patients were screened for the Amaze trial in 11 UK specialist cardiac surgery centres: (1) Papworth Hospital, Cambridgeshire (n = 546); (2) Glenfield Hospital, Leicester (n = 186); (3) Derriford Hospital, Plymouth (n = 95); (4) Freeman Hospital, Newcastle (n = 72); (5) Northern General Hospital, Sheffield (n = 49); (6) Blackpool Victoria Hospital, Blackpool (n = 27); (7) Royal Brompton Hospital, London (n = 16); (8) Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London (n = 13); (9) Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester (n = 10); (10) University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, Coventry (n = 4); and (11) Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals, Brighton (n = 3). The flow of Amaze trial patients from the initial screening to final follow-up is illustrated in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Patient flow through the Amaze trial. PAPVD, partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage.

A total of 661 patients were excluded at screening, but screening logs were only completed for all patients in the co-ordinating centre (Papworth Hospital). At Papworth Hospital, 366 out of 546 patients (67%) were excluded between registration and randomisation (see Appendix 3, Table 32); 107 of these patients declined to participate, mostly because of concerns about either the trial requirements or the planned surgery they were about to undergo. Only one patient cited concerns about not knowing the treatment arm until 2 years after the procedure (as a result of patient blinding), although 38 patients declined without giving a reason. A further 115 patients were excluded by the consultant surgeon, with 49 (43%) of these patients undergoing the maze procedure outside the trial (as a result of severe or symptomatic AF or patient preference) and 11 patients opting for minimally invasive access or another procedure. The reason for exclusion by the surgeon was not recorded for 23 cases. Other reasons were related to trial exclusion criteria, such as patient participation in other clinical trials (n = 19), lack of time to recruit some in-house urgent cases (n = 6), not having a well-documented history of AF (n = 5) and having previous cardiac surgery (n = 3). Between screening and randomisation, eight patients died, and for a further four, their conditions deteriorated to such an extent that trial participation was not considered appropriate. A further 42 patients were excluded for various administrative reasons (see Appendix 3, Table 32).

After exclusions, 352 patients were randomised to either the planned cardiac procedure alone (n = 176) or maze procedure in addition to the planned procedure (n = 176). Thirteen patients (3.7%) did not receive their allocated treatment: 11 (6.3%) maze and two (1.1%) control patients. The maze procedure was not completed for a number of patients, as a result of (1) operation complexity and concern about prolonged cross-clamp time (n = 4); (2) an enlarged atrium or other technical difficulty (n = 3); (3) patient withdrawal from surgery after randomisation was revealed (n = 1); and (4) unrecorded surgeon decision (n = 3). Two control patients had the maze procedure as a result of perceived patient benefit by the consultant post randomisation.

Complete blinding was maintained for 339 (96%) patients. Treatment allocation was revealed in the notes of 13 patients (nine at Papworth Hospital, three at Derriford Hospital and one at Wythenshawe Hospital); of these, 10 underwent the maze procedure and three were control patients. The unblinding was attributable to initial protocol misunderstanding; after re-education of trial personnel, complete blinding was achieved for subsequent patients. The cardiologist reviewing the ECG recording did not have access to the patient’s medical notes. All patients and HRQoL assessors remained unaware of treatment allocation.

At 12 months, 150 maze procedure patients and 151 control patients (85% and 86%, respectively) remained in the trial. The reasons recorded for loss to follow-up at 12 months were death in 33 cases, patient withdrawal in 14 cases and loss to follow-up in four cases. Note that one maze procedure patient (out of 33) died just after 12 months, but the patient was too sick to complete follow-up. The clinical primary end point (SR at 12 months post randomisation) was completed for 141 (80%) maze procedure patients and 145 (82%) control patients, as 11 patients declined the 4-day ECG (eight maze procedure patients and three control patients) and, for four patients, the recordings were not usable (one maze procedure patient and three control patients). The frequency of missing outcomes and associated reasons was similar for the two trial arms.

The patient-based primary end point (QALYs up to 24 months post randomisation) was completed for 160 patients in each arm (91%). We note that patients who died during follow-up were included in the calculation of QALYs, contributing zero to the estimate from the date of death. Thirty-two patients were excluded from this analysis, as a result of either patient withdrawal from the study (n = 28) or loss to follow-up (n = 4).

Baseline characteristics

Patient characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 2. Almost 50% of cases were recruited in the co-ordinating centre (Pathworth Hospital) by 13 surgeons, and over one-quarter were recruited in the second highest recruiting centre (Glenfield Hospital) by four surgeons. The Amaze trial population had a mean age of 71.9 years (SD 7.67 years), almost two-thirds (65.9%) were men and the mean risk of in-hospital death as a result of the procedure [the 2003 logistic European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE)61] was 6.79% (SD 5.18%). The characteristics of Amaze patients were broadly similar to those of UK NHS cardiac surgery patients, but Amaze patients were slightly older and more likely to be female, and had a slightly lower average EuroSCORE. 62 On average, the two treatment arms had similar characteristics.

| Characteristic | Treatment arm | Total (n = 352) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | ||

| Number of patients at each randomising centre, n (%) | |||

| Papworth Hospital | 89 (50.6) | 85 (48.3) | 174 (49.4) |

| Glenfield Hospital | 49 (27.8) | 44 (25.0) | 93 (26.4) |

| Derriford Hospital | 16 (9.1) | 16 (9.1) | 32 (9.1) |

| Northern General Hospital, Sheffield | 12 (6.8) | 14 (8.0) | 26 (7.4) |

| Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne | 3 (1.7) | 5 (2.8) | 8 (2.3) |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London | 1 (0.6) | 5 (2.8) | 6 (1.7) |

| Wythenshawe Hospital | 4 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (1.4) |

| Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| Royal Brompton Hospital | – | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| Blackpool Victoria Hospital | – | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| Patient age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 72.3 (7.53) | 71.4 (7.81) | 71.9 (7.67) |

| Range | 50.0–86.0 | 48.0–89.0 | 48.0–89.0 |

| Patient sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 112 (63.6) | 120 (68.2) | 232 (65.9) |

| Female | 64 (36.4) | 56 (31.8) | 120 (34.1) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.1 (5.27) | 27.6 (4.62) | 27.9 (4.96) |

| Range | 17.4–46.0 | 17.9–42.8 | 17.4–46.0 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE61 (%)a | |||

| Mean score (SD) | 6.94 (5.489) | 6.64 (4.869) | 6.79 (5.184) |

| Range | 0.88–30.41 | 1.40–23.85 | 0.88–30.41 |

Table 3 summarises symptoms at baseline. Heart failure symptoms, defined by the NYHA classification, were common, with 40.3% of patients reporting mild symptoms or slight limitations during ordinary activity, and 41.4% of patients reporting either marked or severe limitations, even during mild activity or at rest. Symptoms of angina, as defined by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society’s grading scale for angina pectoris, were less common, with 73.3% of patients being angina free at baseline and only a small proportion (5.7%) reporting moderate or severe limitations as a result of angina.

| Classification | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total number of patients (n = 352), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | ||

| CCS classification | |||

| Class 0 | 125 (71.0) | 133 (75.6) | 258 (73.3) |

| Class 1 | 13 (7.4) | 17 (9.7) | 30 (8.5) |

| Class 2 | 21 (11.9) | 16 (9.1) | 37 (10.5) |

| Class 3 | 10 (5.7) | 8 (4.5) | 18 (5.1) |

| Class 4 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| Missing/not known | 6 (3.4) | 1 (0.6) | 7 (2.0) |

| NYHA classification at baseline | |||

| I | 31 (17.6) | 30 (17.0) | 61 (17.3) |

| II | 74 (42.0) | 68 (38.6) | 142 (40.3) |

| III | 59 (33.5) | 71 (40.3) | 130 (36.9) |

| IV | 10 (5.7) | 6 (3.4) | 16 (4.5) |

| Missing/not known | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) |

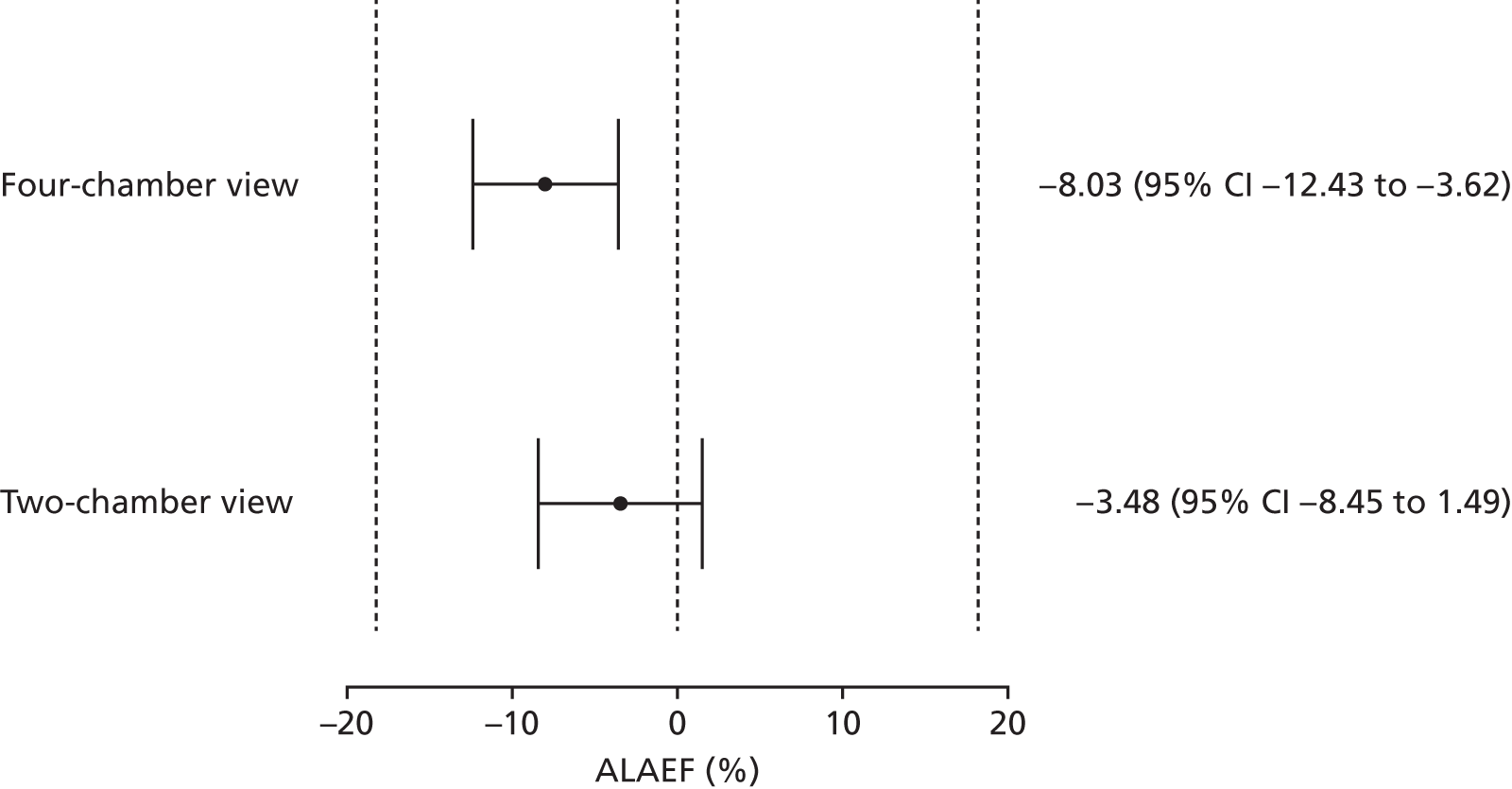

Other markers of cardiac function were also similar between the two arms (Table 4). For example, approximately two-thirds of patients (66.5%) had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of > 50% at baseline, and 2.6% of patients had suffered a recent myocardial infarction (MI). The frequency of other risk factors for heart disease was similar between the two arms: 3.4% of patients were insulin-dependent diabetics, 12.5% were non-insulin-dependent diabetics, 37.8% were treated for high cholesterol and 57.4% had hypertension. The frequency of comorbidities was similar in both treatment arms, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) present in 9.7% of patients and pulmonary hypertension present in 15.1% of patients. In both treatment arms, 6.3% of patients had a history of cerebrovascular accidents and 8.8% had previous transient ischaemic attacks, with 2.8% of these patients having neurological dysfunction at baseline (see Appendix 3, Table 33).

| Marker | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total number of patients (n = 352), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | ||

| Left ventricular function | |||

| Poor (LVEF of < 30%) | 4 (2.3) | 8 (4.5) | 12 (3.4) |

| Moderate (LVEF of 30–50%) | 50 (28.4) | 56 (31.8) | 106 (30.1) |

| Good (LVEF of > 50%) | 122 (69.3) | 112 (63.6) | 234 (66.5) |

| Recent MI | 4 (2.3) | 5 (2.8) | 9 (2.6) |

| Previous PCI | 16 (9.1) | 14 (8.0) | 30 (8.5) |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 5 (2.8) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (1.7) |

| Diabetes | |||

| Insulin dependent | 5 (2.8) | 7 (4.0) | 12 (3.4) |

| Non-insulin dependent | 27 (15.3) | 17 (9.7) | 44 (12.5) |

| Hyperlipidaemia/hypercholesterolaemia | 70 (39.8) | 63 (35.8) | 133 (37.8) |

| Systemic hypertension | 103 (58.5) | 99 (56.3) | 202 (57.4) |

Table 5 documents patients’ medical history associated with AF. For 26.1% of patients, AF was paroxysmal; the 73.9% of patients who had non-paroxysmal AF included almost 60% of patients classed as having chronic/longstanding AF and 13.9% classed as having persistent intermittent symptoms. Over two-thirds (68.5%) of patients had AF for > 12 months. Only 4.3% of patients had been fitted with a permanent pacemaker and 13.4% had previously undergone cardioversions; previous ablation had been attempted in slightly more maze procedure patients (1.7%) than control patients (0.6%). Anticoagulant and antiarrhythmic drugs were prescribed for 77.6% and 83.2% of patients, respectively.

| Marker of AF | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (n = 352), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | ||

| AF classification | |||

| Paroxysmal (intermittent) | 44 (25.0) | 48 (27.3) | 92 (26.1) |

| Persistent (intermittent) | 30 (17.0) | 19 (10.8) | 49 (13.9) |

| Chronic/longstanding (continuous) | 102 (58.0) | 109 (61.9) | 211 (59.9) |

| AF-related medical history | |||

| 0–3 months ago | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) |

| 3–6 months ago | 25 (14.2) | 25 (14.2) | 50 (14.2) |

| 6–12 months ago | 31 (17.6) | 23 (13.1) | 54 (15.3) |

| > 12 months ago | 115 (65.3) | 126 (71.6) | 241 (68.5) |

| Not known | 1 (0.6) | – | 1 (0.3) |

| Permanent pacemaker | 7 (4.0) | 8 (4.5) | 15 (4.3) |

| Time of pacemaker implant | |||

| 0–3 months ago | – | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| 3–6 months ago | 2 (1.1) | – | 2 (0.6) |

| 6–12 months ago | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| > 12 months ago | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.3) | 7 (2.0) |

| Previous cardioversions | |||

| 0–3 months ago | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| 3–6 months ago | 1 (0.6) | – | 1 (0.3) |

| 6–12 months ago | 5 (2.8) | 3 (1.7) | 8 (2.3) |

| > 12 months ago | 17 (9.7) | 19 (10.8) | 36 (10.2) |

| Previous ablation | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.1) |

| Arrhythmias other than AF/flutter | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Any anticoagulant use at baseline | 137 (77.8) | 137 (77.3) | 274 (77.6) |

| Any antiarrhythmic use at baseline | 145 (82.4) | 148 (84.1) | 293 (83.2) |

Table 6 summarises the HRQoL for the EQ-5D-3L utility score and the SF-36 dimensions at baseline. The mean EQ-5D-3L utility score was 0.75 (SD 0.22) at baseline, which compares well with the UK norms of 0.78 (SD 0.26) for people aged 65–74 years and 0.73 (SD 0.27) for people aged ≥ 75 years. 63 Thus, patients selected for cardiac surgery, who entered the Amaze trial, have comparable limitations to the general population of the same age, as measured by this generic HRQoL scale. In contrast, the mean scores for the SF-36 dimensions were very much lower than the published norms at baseline, particularly for the physical dimensions (see Table 6). 64 The mean standardised MCS at baseline was 50.19 (SD 10.32) for this population, almost exactly the same as the mean score for the UK population, whereas the mean for the standardised PCS was 30.59 (SD 13.36), which is significantly lower than the mean (SD) score for the UK population.

| HRQoL measurement | Treatment arm, mean score (SD) | Total, mean score (SD) (n = 352) | UK norm, mean score (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | |||

| EQ-5D-3L utility score | 0.74 (0.22) | 0.75 (0.21) | 0.75 (0.22) | – |

| SF-36 dimensions | ||||

| Bodily pain | 72.00 (28.47) | 72.26 (26.18) | 72.13 (27.30) | 81.49 (21.69) |

| General health | 57.22 (19.11) | 55.61 (20.76) | 56.41 (19.94) | 73.52 (19.90) |

| Physical function | 47.18 (26.16) | 48.40 (27.33) | 47.79 (26.72) | 88.40 (17.98) |

| Role emotional | 71.10 (41.76) | 65.90 (45.61) | 68.49 (43.75) | 82.93 (31.76) |

| Role physical | 27.75 (37.20) | 30.57 (40.84) | 29.17 (39.04) | 85.82 (29.93) |

| Social functioning | 64.73 (29.19) | 64.44 (31.81) | 64.58 (30.49) | 88.01 (19.58) |

| Vitality | 43.67 (21.73) | 44.71 (23.76) | 44.19 (22.74) | 61.13 (19.67) |

| Mental health | 75.24 (15.44) | 73.51 (18.21) | 74.37 (16.88) | 73.77 (17.24) |

| PCS | 30.18 (13.17) | 31.00 (13.56) | 30.59 (13.36) | 50 (10) |

| MCS | 50.81 (9.92) | 49.58 (10.69) | 50.19 (10.32) | 50 (10) |

Surgical results

Table 7 summarises the surgical procedures completed; the most common were isolated MVR (24.7%), CABG (19.6%) and AVR (15.6%), followed by combined CABG with either AVR (10.5%) or MVR (7.7%). All other procedures were combinations of CABG and/or multiple valve procedures, with the exception of two patients for whom no procedure could be completed.

| Procedure | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (n = 352), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | ||

| Actual procedure category | |||

| MVR | 39 (22.2) | 48 (27.3) | 87 (24.7) |

| CABG | 35 (19.9) | 34 (19.3) | 69 (19.6) |

| AVR | 32 (18.2) | 23 (13.1) | 55 (15.6) |

| CABG and AVR | 16 (9.1) | 21 (11.9) | 37 (10.5) |

| CABG and MVR | 14 (8.0) | 13 (7.4) | 27 (7.7) |

| All other procedures, including none | 40 (22.7) | 37 (21.0) | 77 (21.9) |

Descriptions of surgical indices are given in Table 8. As expected, the time spent in theatre was longer for the maze procedure arm; the difference (maze procedure vs. control) in the mean length of time spent in theatre was 13.8 minutes (95% CI –4.4 to 32.0 minutes; p = 0.1375). Similarly, there was a mean difference in the time taken for cross-clamp of 5.1 minutes (95% CI –4.0 to 14.2 minutes; p = 0.2725) and in the time taken for cardiopulmonary bypass of 18.9 minutes (95% CI 9.9 to 27.8 minutes; p < 0.0001). Note that three patients’ surgical procedures were completed with a beating heart (with one patient randomised to the maze procedure arm and two patients randomised to the control arm), so that the time taken for both cross-clamp and cardiopulmonary bypass was zero minutes; on these occasions, the maze procedure was not performed. One more maze procedure patient had zero minutes recorded for cross-clamp, but 205 minutes recorded for the time taken for cardiopulmonary bypass.

| Procedure characteristic | Treatment arm | Total (n = 352) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | ||

| Total length of time (minutes) taken for cross-clamp | |||

| Mean (SD) | 82.2 (37.25) | 77.2 (48.60) | 79.7 (43.31) |

| Median (quartiles) | 74.0 (57.5–102.0) | 67.5 (51.0–92.0) | 72.0 (53.0–99.0) |

| Range | 0.0–245.0 | 0.0–530.0 | 0.0–530.0 |

| Total length of time (minutes) taken for cardiopulmonary bypass | |||

| Mean (SD) | 118.1 (43.39) | 99.3 (41.81) | 108.7 (43.59) |

| Median (quartiles) | 110.5 (84.0–145.0) | 93.0 (72.5–120.0) | 100.5 (80.0–132.0) |

| Range | 0.0–342.0 | 0.0–300.0 | 0.0–342.0 |

| Total length of time (minutes) spent in theatre | |||

| Mean (SD) | 261.2 (79.68) | 247.5 (93.27) | 254.4 (86.89) |

| Median (quartiles) | 260.0 (210.0–300.0) | 218.0 (195.0–277.5) | 240.0 (198.0–291.5) |

| Range | 75.0–582.0 | 100.0–775.0 | 75.0–775.0 |

| Excised left atrial appendage, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 97 (55.1) | 53 (30.1) | 150 (42.6) |

| No | 79 (44.9) | 123 (69.9) | 202 (57.4) |

The left atrial appendage was also significantly more likely to be excised in the maze procedure arm (55.1%) than in the control arm (30.1%).

Table 9 provides details of the lesion sets completed. Eleven patients in the maze procedure arm did not have the adjunct procedure at all. The most common ablation procedure was applied to the left and right atria and the mitral annulus (43.8%), with 22.2% applied to the left atrium and mitral annulus and 18.2% applied to the left atrium only. The mean number of lesions was 6.5 (SD 3.55) in the maze procedure arm, with 47.7% of patients having 5–9 lesions and 23.3% of patients having ≥ 10 lesions. The most common mode of delivery was bipolar radiofrequency ablation (81.8%), with unipolar radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy and ultrasound applied to smaller numbers of maze procedures; no procedures applied laser or microwave energy.

| Lesion sets | Treatment arm | Total (n = 352) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | ||

| Number of lesions treated | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.5 (3.55) | 0.1 (0.91) | 3.3 (4.11) |

| Median (quartiles) | 7.0 (4.0–9.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–7.0) |

| Range | 0.0–14.0 | 0.0–11.0 | 0.0–14.0 |

| Lesion number category, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 11 (6.3) | 174 (98.9) | 225 (63.9) |

| 1–4 | 40 (22.7) | – | 40 (22.7) |

| 5–9 | 84 (47.7) | 1 (0.6) | 85 (24.1) |

| ≥ 10 | 41 (23.3) | 1 (0.6) | 42 (11.9) |

| Lesion set treated, n (%) | |||

| I: minimal left atrial lesion set: pulmonary vein isolation either with or without left atrial appendage line | 32 (18.2) | – | 32 (9.1) |

| II: more extensive left atrial lesion set, excluding mitral annulus | 4 (2.3) | – | 4 (1.1) |

| III: more extensive left atrial only lesion set, including mitral annulus | 39 (22.2) | 1 (0.6) | 40 (11.4) |

| IV: minimal left atrial lesion set and right atrial lesion set | 2 (1.1) | – | 2 (0.6) |

| V: more extensive left atrial lesion set excluding mitral annulus and right atrial lesion set | 11 (6.3) | – | 11 (3.1) |

| VI: more extensive left atrial lesion set including mitral annulus and right atrial lesion set | 77 (43.8) | 1 (0.6) | 78 (22.2) |

| No lesions | 11 (6.3) | 174 (98.9) | 185 (52.6) |

At least one perioperative complication was recorded for 34 (19.3%) maze procedure patients and 38 (21.6%) control patients (see Appendix 3, Table 34). As expected, the most common complication was bleeding (for 10.8% of maze procedure patients and 9.7% of control patients) and pleural effusion (for 8% of maze procedure patients and 13.6% of control patients). There were no important differences in the number of patients requiring transfusion of red blood cells, platelets, fresh-frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate or human albumin (see Appendix 3, Table 35).

Intensive care unit and hospital stay did not vary by treatment arm. The median (quartiles) duration of stay in an ICU was 1.1 days (0.9–2.9 days) in the maze procedure arm and 1.0 days (0.9–2.0 days) in the control arm, whereas the median (quartiles) total length of hospital stay was 9 days (7–13 days) and 8 days (6–12 days) for the maze procedure and control arms, respectively. Eleven maze procedure patients and 12 control patients returned to an ICU on one or more occasions, with those returning having a median (quartiles) total length of stay of 4.6 days (1.3–6.5 days) and 2.5 days (1.5–10.4 days) in the maze procedure and control arms, respectively.

Primary outcome results

Sinus rhythm at 12 months

Despite a history of AF, 30 patients (17.0%) in the maze arm and 32 patients (18.2%) in the control arm did not have any arrhythmias recorded by the 4-day ECG at baseline. At 12 months, 286 (81.3%) patients completed the 4-day ECG recording; of these patients, 266 (93.0%) were either in SR 100% of the time or in AF 100% of the time. Patients were classified as being in AF if any AF was observed during the 4-day ECG recording; this was decided before linking trial outcomes to either treatment arm. Among complete cases in the maze procedure arm, 87 out of 141 patients (61.7%) were in SR compared with 68 out of 145 (46.9%) control patients. In the ITT analysis, using multiple imputation of missing data, the OR for return to SR was 2.06 (95% CI 1.20 to 3.54; p = 0.0091); see Appendix 3, Table 36 for the full results. Overall, results varied substantially by surgeon, with an associated intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.089, suggesting that 8.9% of the total variation in return to SR rates over both treatment arms resulted from surgeon effects. However, there were no differences in the treatment effect (maze procedure vs. control) among surgeons (the ICC on the treatment coefficient was zero). Table 10 shows that the difference between the treatment arms arises almost solely from an additional 19 patients in the maze procedure arm changing from having AF to SR (61 vs. 42) and 21 fewer patients remaining in AF at 12 months (50 vs. 71).

| Rhythm changes | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (n = 352), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maze procedure (n = 176) | Control (n = 176) | ||

| Change from baseline to 12 months in AF/SR | |||

| Either baseline or follow-up missing | 39 (22.2) | 33 (18.8) | 72 (20.5) |

| SR at baseline, SR at 12 months | 23 (13.1) | 25 (14.2) | 48 (13.6) |

| SR at baseline, AF at 12 months | 3 (1.7) | 5 (2.8) | 8 (2.3) |

| AF at baseline, SR at 12 months | 61 (34.7) | 42 (23.9) | 103 (29.3) |

| AF at baseline, AF at 12 months | 50 (28.4) | 71 (40.3) | 121 (34.4) |

| Change from baseline to 24 months in AF/SR | |||

| Either baseline or follow-up missing | 62 (35.2) | 50 (28.4) | 112 (31.8) |

| SR at baseline, SR at 24 months | 18 (10.2) | 23 (13.1) | 41 (11.6) |

| SR at baseline, AF at 24 months | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.3) | 7 (2.0) |

| AF at baseline, SR at 24 months | 47 (26.7) | 23 (13.1) | 70 (19.9) |

| AF at baseline, AF at 24 months | 46 (26.1) | 76 (43.2) | 122 (34.7) |

Sensitivity analysis

An exploratory analysis of the ITT population highlighted four outlying patients in accordance with cross-validation probabilities of having undue influence; a secondary analysis excluding these patients was conducted, with little change in the results (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.27 to 3.82). In the sensitivity analyses, the OR changed to 2.00 (95% CI 1.21 to 3.32) if only complete cases were included, 1.70 (95% CI 1.07 to 2.69) if patients who died or withdrew were assumed to have been in AF, 1.92 (95% CI 1.17 to 3.15) if patients who died were assumed to have been in AF and 1.75 (95% CI 1.10 to 2.79) using the last observation carried forward; all remained statistically significant. An additional analysis, including the variables that were most associated with a missing status for 12-month SR (baseline SR, sex, diabetes, left ventricular function, history of rheumatic fever, non-AF/atrial flutter arrhythmias and COPD), resulted in a treatment effect estimate of 2.13 (95% CI 1.27 to 3.59). As the treatment effect was significant in all sensitivity analyses, we were confident that it was robust. Finally, in order to assess the treatment effect in patients for whom the surgery was completed as planned, the complier average causal effect for the difference in 12-month SR rates between the groups (maze procedure vs. control) was calculated; this was 15.8% (95% CI 3.9% to 27.6%) compared with 14.8% (95% CI 3.2% to 26.3%) for completers.

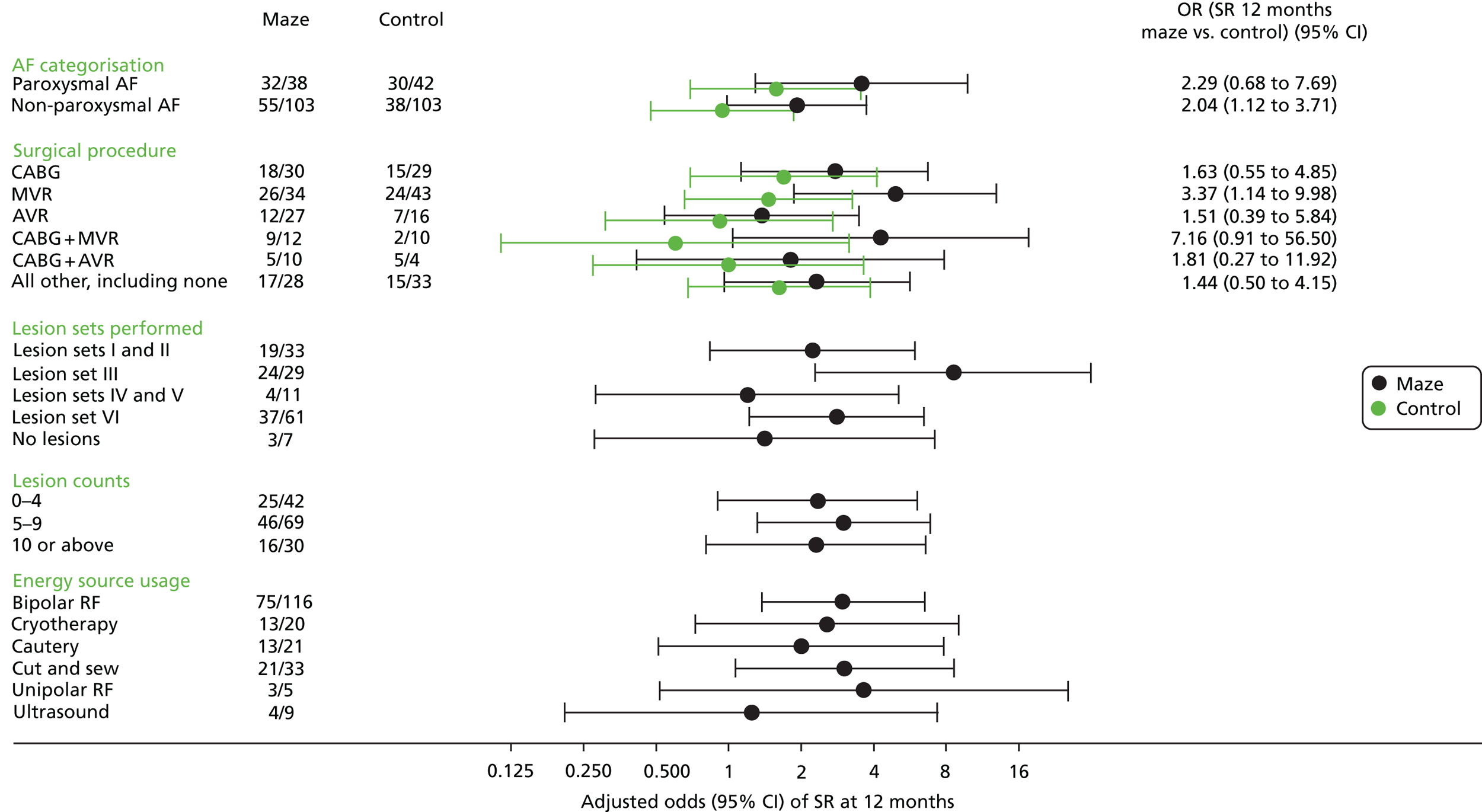

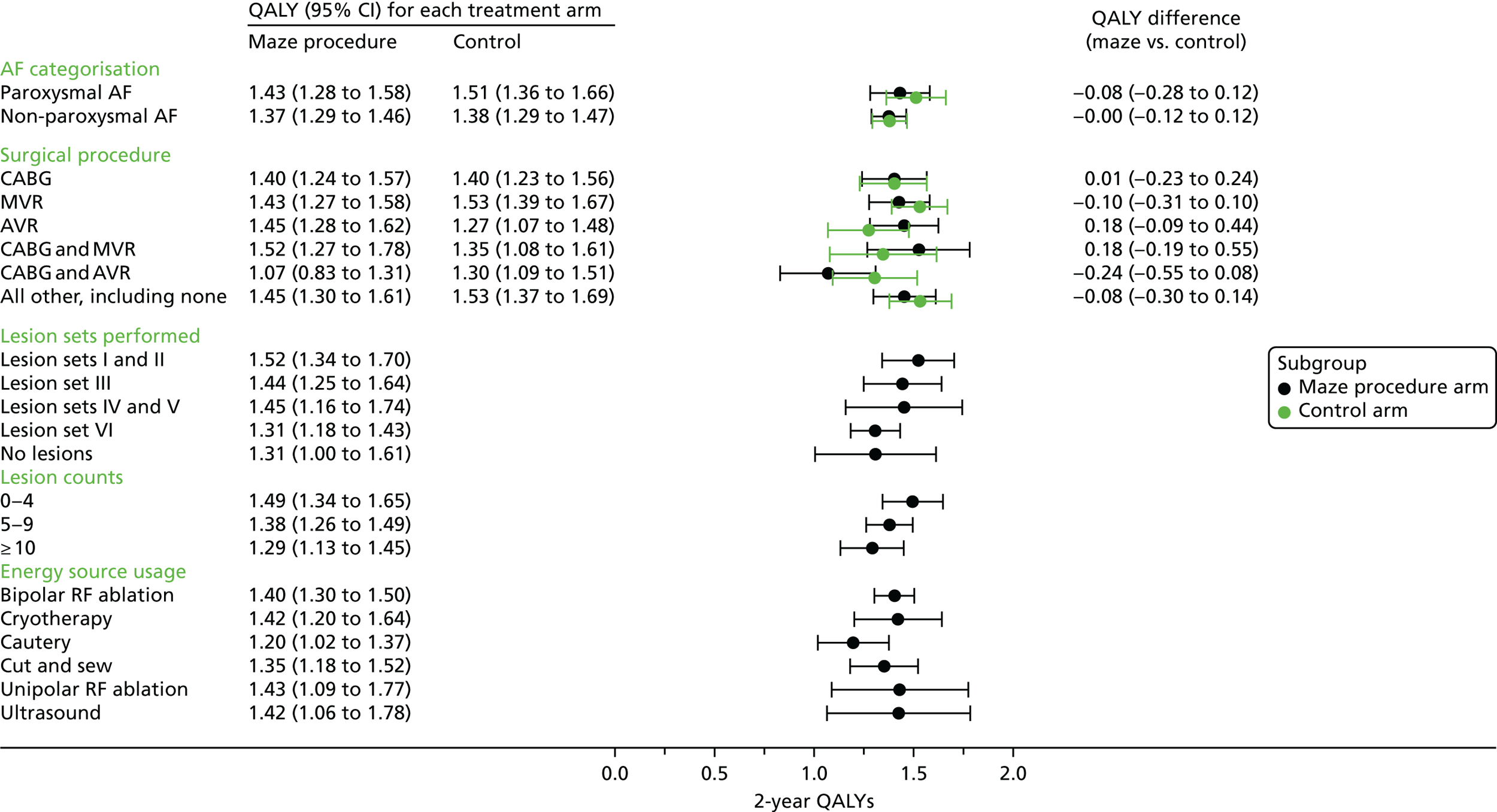

Subgroup analysis

Figure 3 shows the results of the subgroup analysis (see also Appendix 3, Table 37); no interactions were statistically significant. The odds on returning to SR were increased by the adjunct maze procedure for both paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal AF groups. The maze patients had increased ORs on return to SR irrespective of the planned procedure, although the small numbers of patients in each subgroup meant that the ORs varied widely and were not significant in most cases.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot showing (adjusted) odds on return to SR at 12 months after randomisation (details of lesion sets are given in Table 9). RF, radiofrequency.

Within the maze procedure arm, there was little evidence that return to SR was associated with the number of lesions treated, although this may simply reflect the skill of the surgeon in identifying the areas to be treated (Table 11). Moreover, there was no evidence of variation in return to SR between different ablation techniques, although bipolar ablation was clearly the preferred technique for many surgeons.

| Subgroup | Number in SR/number in subgroup | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion sets performed | |||

| Lesion sets I and II | 19/33 | 2.236 | 0.838 to 5.962 |

| Lesion set III | 24/29 | 8.585 | 2.295 to 32.109 |

| Lesion sets IV and V | 4/11 | 1.198 | 0.282 to 5.095 |

| Lesion set VI | 37/61 | 2.803 | 1.214 to 6.472 |

| Lesion counts | |||

| No lesions | 3/7 | 1.412 | 0.279 to 7.142 |

| 0–4 lesions | 25/42 | 2.337 | 0.903 to 6.050 |

| 5–9 lesions | 46/69 | 3.009 | 1.320 to 6.861 |

| ≥ 10 lesions | 16/30 | 2.312 | 0.813 to 6.577 |

| Energy source usage | |||

| Bipolar RF ablation | 75/116 | 2.991 | 1.372 to 6.521 |

| Cryotherapy | 13/20 | 2.561 | 0.731 to 8.971 |